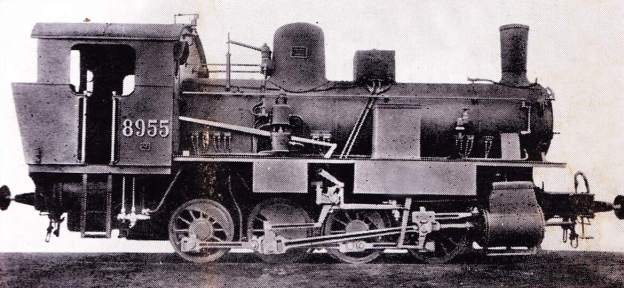

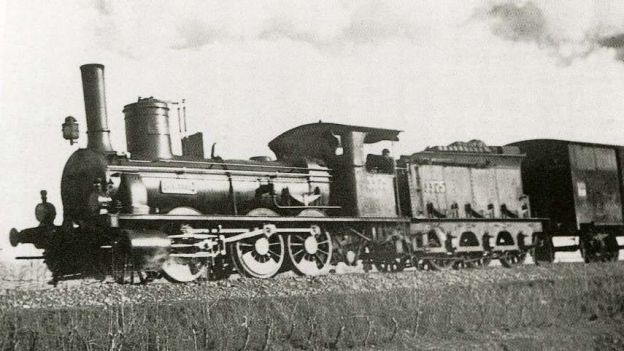

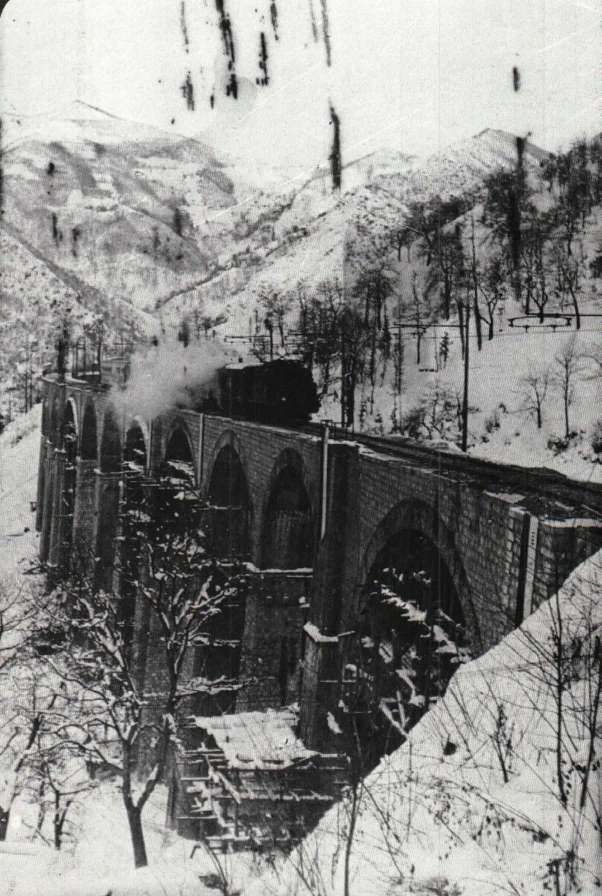

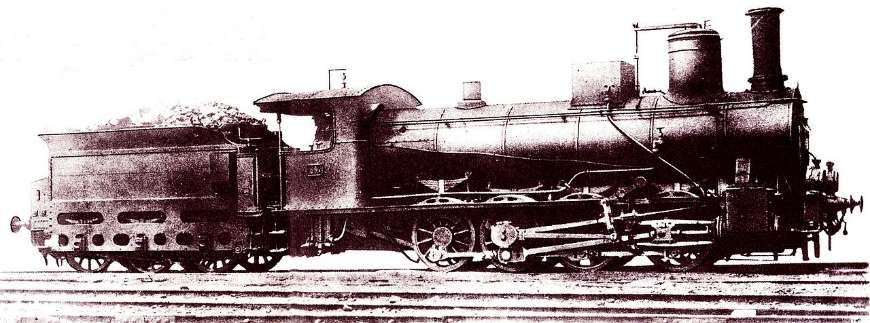

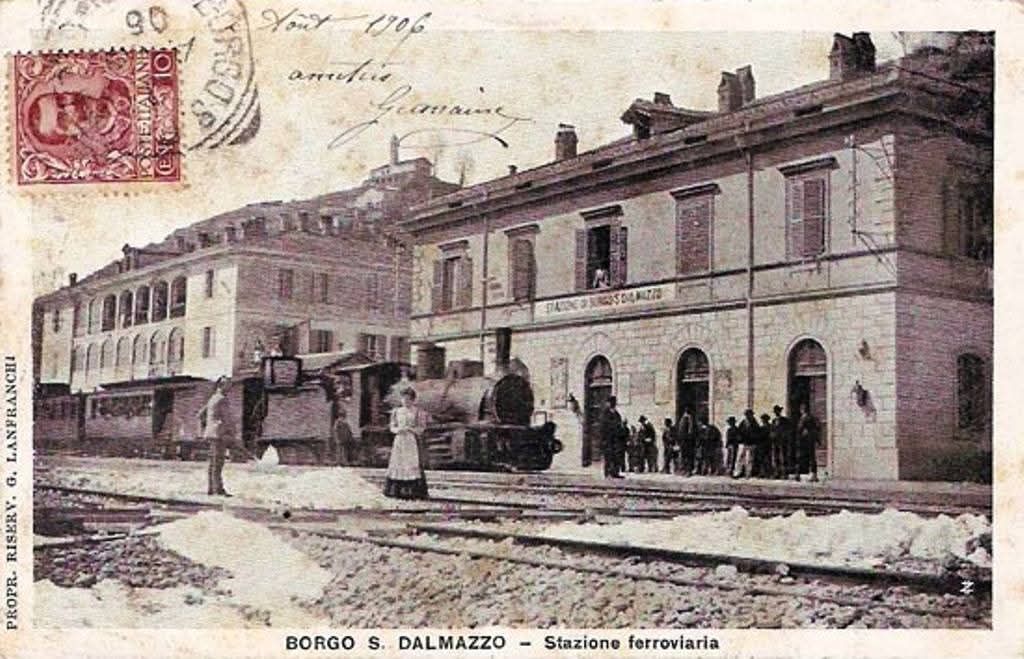

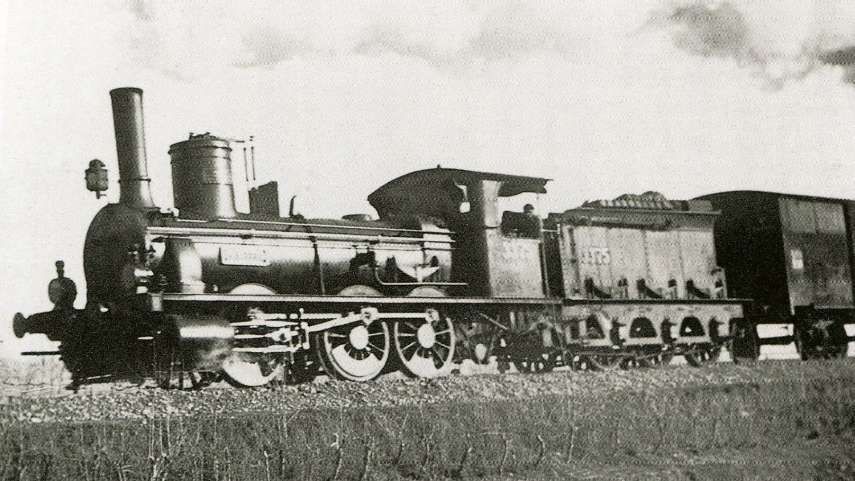

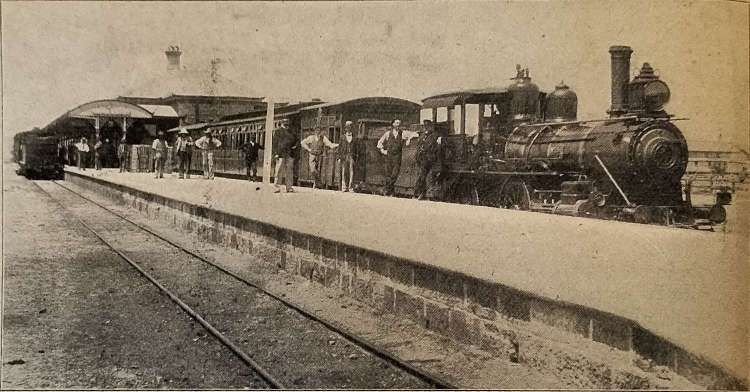

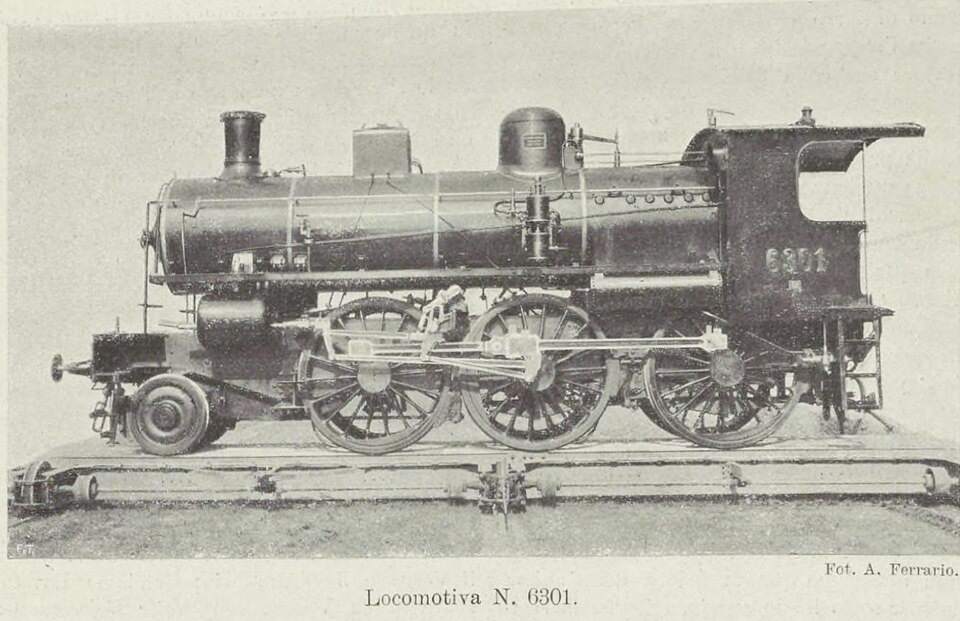

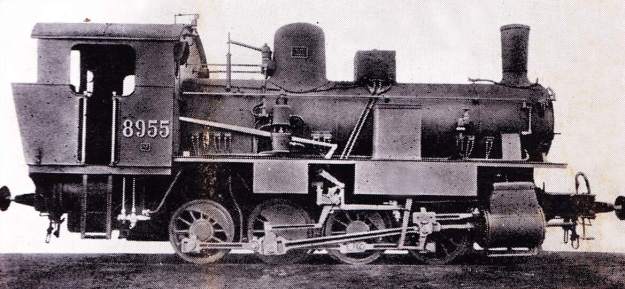

The first decade of the 20th century saw the existing roster of locomotives on the line South of Cuneo supplemented by two additional series : 130s (UK, 2-6-0) tender locos of the FS 630 series; and 040T (UK, 0-8-0T) tank locos of the FS 895 series. The featured image for this article is one of the tank locomotives of the FS 895 series. [65]

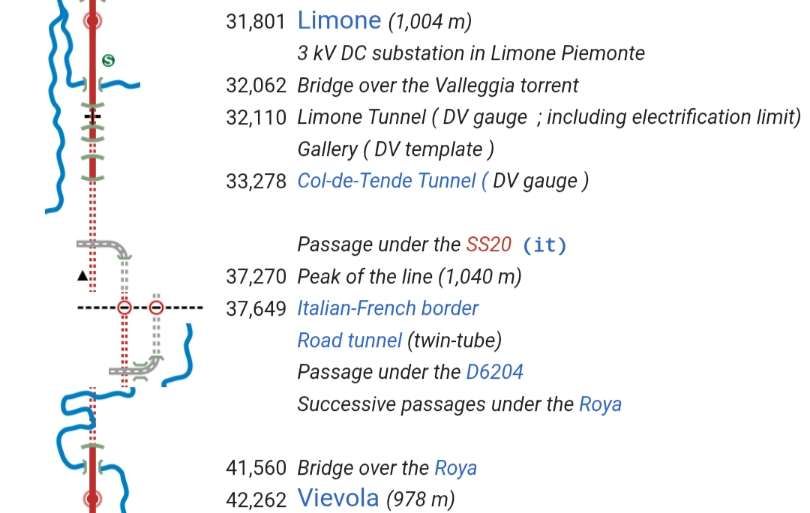

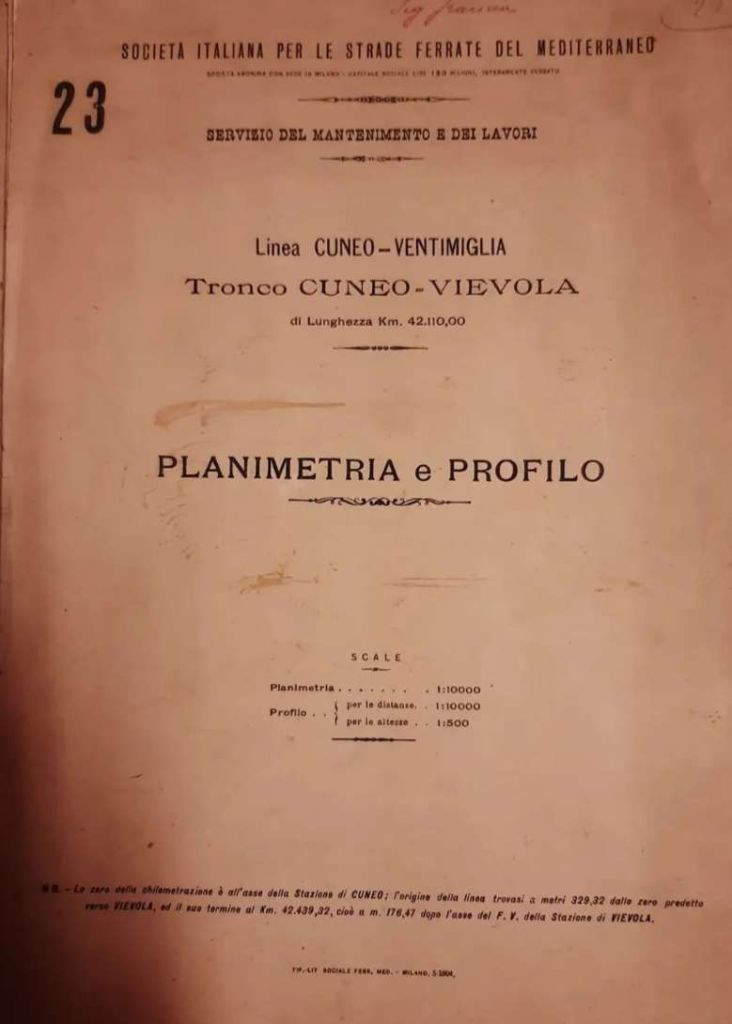

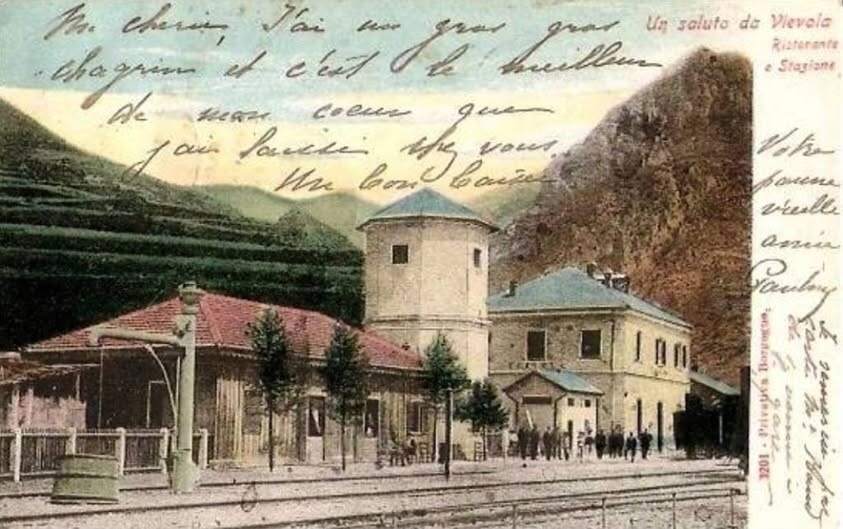

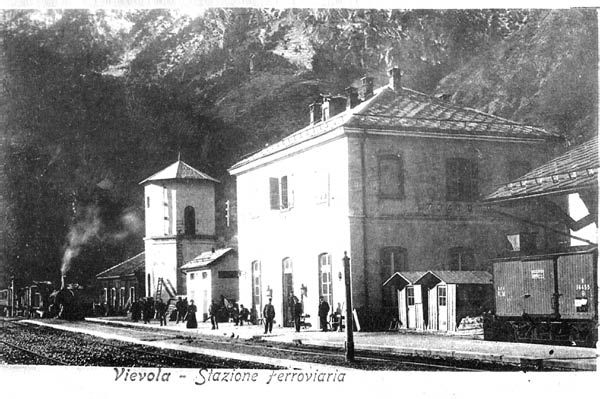

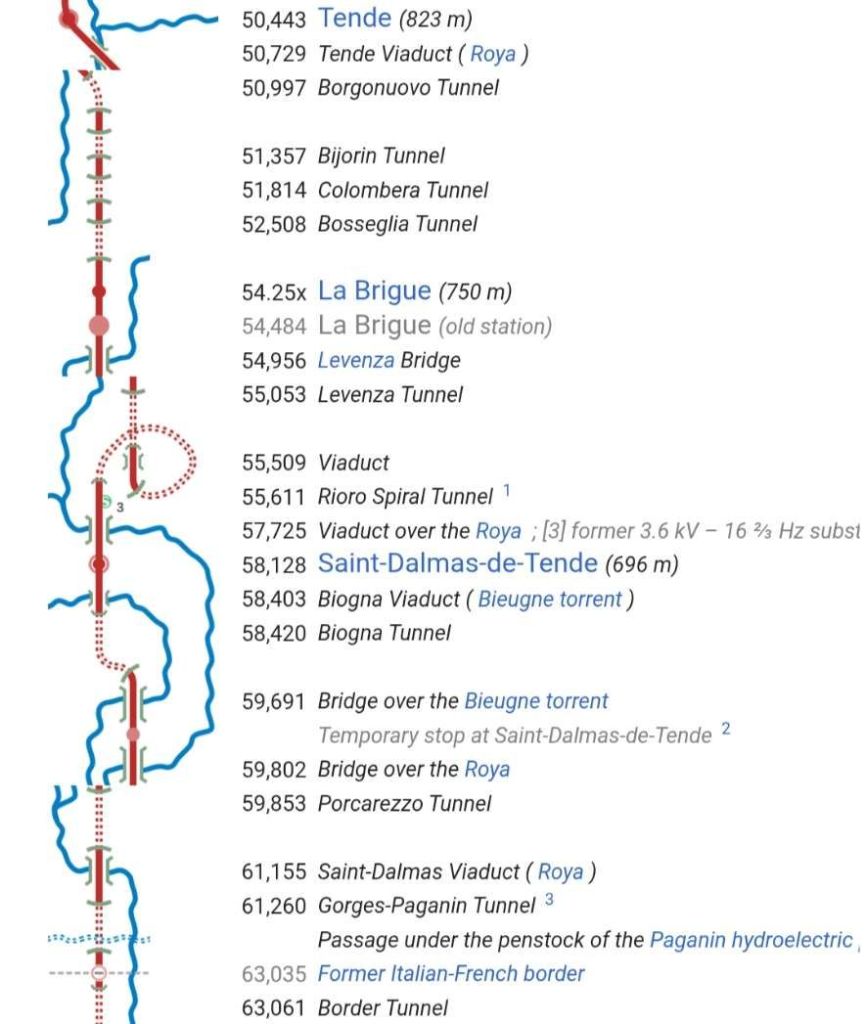

In the first two articles about the line from Cuneo to the sea we covered the length of the line from Cuneo to Vievola. These articles can be found here [9] and here. [10]

I also want to acknowledge the assistance given to me by David Sousa of the Rail Relaxation YouTube Channel https://www.youtube.com/@RailRelaxation/featured and https://www.railrelaxation.com and particularly his kind permission given to use still images from rail journeys that he has filmed on the Cuneo Ventimiglia railway line. [35][55]

The Line South from Vievola

Our journey South down the line continues from Vievola. …

Vievola Railway Station, seen from a north-bound train in the 21st century. [35]

Vievola Railway Station, seen from slightly further South from the cab of a train heading North through the station back in the 1990s. [8]

Before we can head South from Vievola on the railway, it needs to have been built! This, it turns out, was dependent on international agreements and their ratification by national parliaments. This process was fraught with difficulty! It would take until 21st March 1906 for agreements to be ratified!

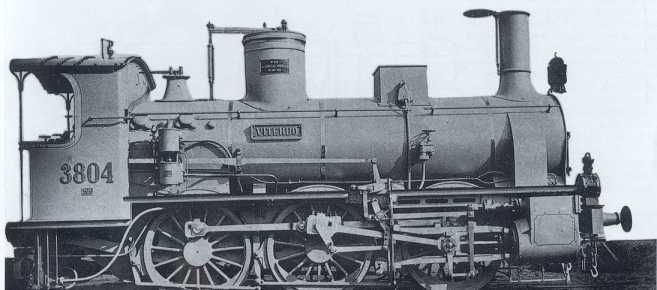

Banaudo et al tell us that over the final decades of the 19th century, the various interests on the French side of the border sought to persuade the French government that the line from Nice to Cuneo was an important investment which should be made. As a result, the French government “invited the PLM company to undertake a route study from Nice to Sospel in circular dated 30th September 1890, renewed on 28th January 1892, given the lack of response from the railway administration. On 12th May, a prefectural decree authorized the company’s engineers to enter properties to conduct the first surveys.” [1: p57]

Banaudo et al continue: “To meet the requirements of the Ministry of War, the route had to include Lucéram. This resulted in a 15 km extension of the direct route between Nice and Sospel. In 1895, the General Staff showed an initial sign of goodwill by agreeing to the study being extended beyond Sospel towards Italy, subject to certain conditions. On 19th April 1898, Gustave Noblemaire (1832-1924), director of the PLM company, submitted a preliminary proposal for a line from Nice to the border via the Paillon de Contes valley, the Nice pass, L’Escarène, the Braus pass, Sospel, Mount Grazian, Breil and the Roya valley. The Lucéram service was included as a branch line from L’Escarène, other solutions were not technically feasible.” [1: p57-59]

The military response arrived on 27th September 1899, when the principle of the branch line was accepted. It was a few months, 10th January 1900, before the military confirmed their requirements, specifically: “commissioning of the Lucéram branch line at the same time as the L’Escarène – Sospel section; construction of the extension beyond Sospel after reinforcing the installations at Fort du Barbonnet and orientation of the tunnel under Mont Grazian so that it could be held under fire from the fort in the event of war; development of mine devices and defensive casemates at the heads of the main tunnels between L’Escarène and the border; and authorization for Italy to begin laying the track from San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda to Fontan only after the completion of the Nice-Fontan section by France.” [1: p59]

Cross-border discussions took place between the French departmental Bridges and Roads Department and “its counterpart in the civil engineering department of the province of Cuneo to determine the main technical characteristics of the railway line built by the RM between Cuneo and Vievola, in order to adopt equivalent standards for the French section in terms of grades, curves, and gauge.” [1: p59]

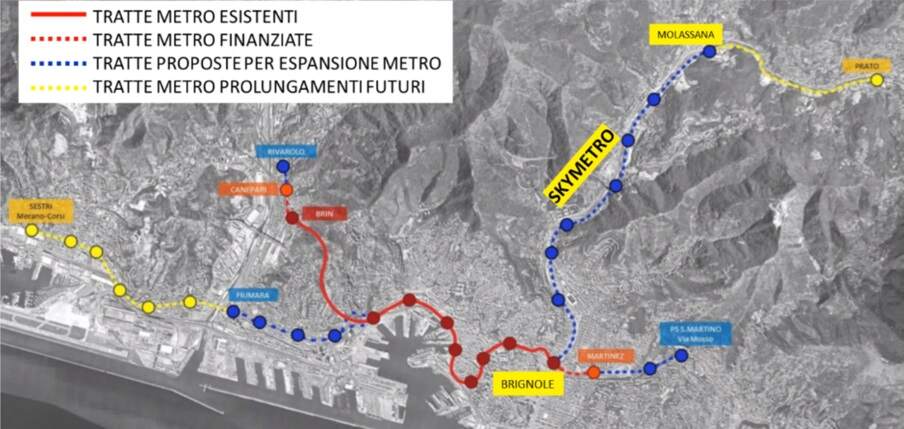

Banaudo et al continue: “At the dawn of the 20th century, while the choice of a route from Nice to the Italian border at San-Dalmazzo via the Paillon, Bévéra, and Roya rivers was no longer in doubt in France, the same was not true in Italy. Indeed, although this solution was preferred by Piedmontese business circles, it was opposed by multiple pressure groups weary of twenty years of French policy of opposition and uncertainty. For many localities on the Riviera or in the Ligurian hinterland, as well as for a persistently Francophobic segment of the general staff, the construction of a line entirely within Italian territory appeared to be the best way to avoid diplomatic and strategic complications.” [1: p59]

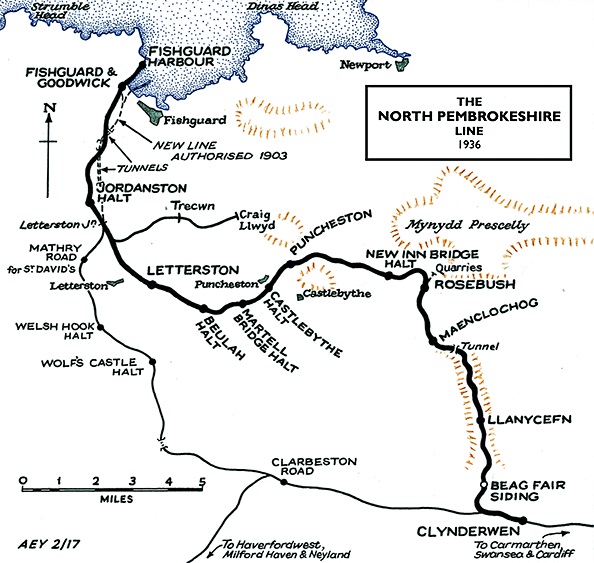

In Italy, Piedmont and Liguria had differing views about the appropriate railway routes. Piedmont secured a promise, in the Italian parliament, to extend the railway to Tende and a decision to connect it to the coast soon. In Liguria, the desire was to secure a connection to Ventimiglia via either the Roya Valley or the Nervia Valley. Serious consideration was given to a tramway in the Roya Valley, the central section of which would run through French territory but this was rejected by the French military. [14]

A number of alternative schemes were put forward by Italian interests and by the city of Marseille. The city of Turin appointed a commission to look at all the options and after its report “concluded that it preferred the most direct route via the Col de Tende and the Roya, towards Ventimiglia and Nice. Similarly, the French Chamber of Commerce in Milan supported this choice in March 1900, also proposing the construction of a new 47 km line between Mondovi and Santo Stefano Belbo, designed by the engineer Ferdinando Rossi to shorten the journey between Cuneo, Alessandria and Milan.” [1: p60-61]

In 1901, French and Italian diplomats and then the Turin authorities agreed the main principles for an international agreement. On 24th January 1902 the PLM was granted the concession for the railway from Nice to the Italian border via Sospel, Breil-sur-Roya, and Fontan, as well as the beginning of the line from Breil-sur-Roya to Ventimiglia. This was ratified by law on 18th July 1902.

After this a further military inspection led to the strategic Lucéram branch being temporarily left aside with the possibility of a replacement by an electric tramway from Pont-de-Peille to L’Escarène, to be operated by the Compagnie des Tramways de Nice et du Littoral (TNL).

Banaudo et al continue: “On Monday 6th June 1904, delegations from both countries met in Rome to sign the bipartite convention regulating the terms and conditions of operation of the future line and its implementation into international service. … In its broad outline, the agreement provided for the completion of the works within eight years (i.e. by 1912) and the possibility for the Italian railway administration to have its Ventimiglia-Cuneo trains transit French territory, with reciprocal authorization for the French operator to run its own vehicles in Italy on direct Nice-Cuneo trains and to establish a local service between Breil, Fontan and San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda. … Initially, passenger services on the line would be provided by three direct daily connections Nice-Cuneo and Ventimiglia-Cuneo, and vice versa, offering carriages of all three classes.”

Banaudo et el describe the main points of the convention in respect of the transport of people and goods, particularly for transit between the two borders. “Police and customs controls would be simplified as much as possible for nationals of both countries. Nevertheless travelling between two Italian stations via the international section would require a passenger to have a valid passport. Italian postal vehicles would be permitted to travel duty-free on this section, as would goods and baggage in transit, provided they were placed in sealed vehicles and, for livestock, had undergone a prior health inspection at an Italian station. A special clause authorized the passage of Italian military transports of men, equipment, and animals through French territory, while conversely, the French army would be permitted to transit its consignments from Nice to Breil via Ventimiglia. Article 20 of the convention regulated a legal situation that was probably unique in Europe, that of the Mont Grazian tunnel, whose straight route would pass over a distance of 2,305 metres in Italian subsoil, although its two portals would be in France: ‘It is understood that for the part of the Mont Grazian tunnel located under Italian territory, the Italian government delegates to the French government its rights of control over the railway and its police and judicial rights’. This unusual situation resulted from a modification of the route decided at the request of the General Council of the Alpes-Maritimes. … This more direct route passing under Italian soil was finally preferred to the entirely French route under the Brouis pass, which would have been longer and would have moved the Breil station further from the village.” [1: p62-63]

In Italy, the ratification of the agreements made at the convention took three weeks – it was all done by 28th June 1904. In France thins would be quite different. “On 27th March 1905, as the convention was about to be submitted to a parliamentary vote, the Ministry of War decided to abandon the branch line to Lucéram, which was too costly and difficult to implement. Instead, the nearest stations, L’Escarène and Sospel, would need to be equipped with facilities for the rapid disembarkation of troops and equipment. At L’Escarène in particular, the station would need to be able to accommodate ten twenty-car trains per day and would have to include a military platform opening onto a large open area, an engine shed, and several water columns/supplies. In addition, the road from L’Escarène to Lucéram would need to be improved to facilitate access to the defensive sector of L’Authion.” [1: p63]

Banaudo et al comment: “The French Chamber of Deputies finally ratified the agreement on 3rd July 1905, more than a year after its Italian counterpart, but the Senate would continue to procrastinate until 8th March 1906. The senators demanded financial participation from the Alpes-Maritimes department in the land acquisition costs, and the French Consul in Italy, Henri Bryois, made numerous appearances in Paris to convince them. The day after the Senate’s vote, on 9th March 9, a parade, speeches, and demonstrations of sympathy for France enlivened the streets of Cuneo. … On 20th March, a final law officially ratified the agreement. … The municipality of Nice organized a grand celebration to celebrate the culmination of fifty years of effort. On 21st March 1906, Prime Minister Giolitti and Ambassador Barrère exchanged the documents ratified by the parliaments of both countries. Work could finally begin!” [1: p63]

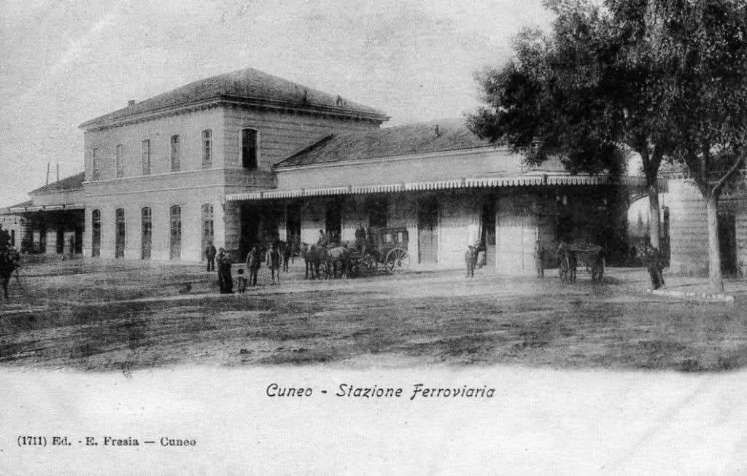

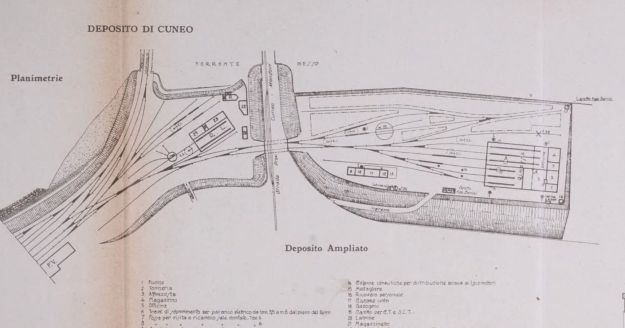

In Italy, the ratification of the international convention led to the money for the completion of the works being set aside (24 million lire for the length South from Vievola to the then border, and 16 million lire for the length North from Ventimiglia to the southern border). In addition, the decision was taken to build the new station in Cuneo to accommodate the increased traffic that would arise from the new line.

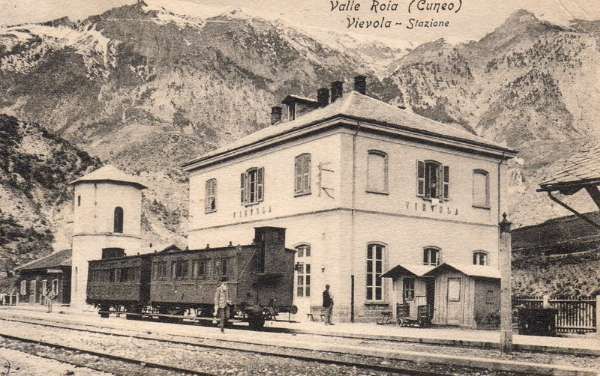

A year later, on 1st July 1905, the Italian state brought all nationally significant rail routes/networks under the direct authority of the Ministry of Public Works (the Ferrovie dello Stato (FS)). This had only a limited impact on the Cuneo-Vievola line. “The 3200, 3800, and 4200 series locomotives of the Rete Mediterranea now formed series 215, 310, and 420 of the [FS}. … At that time, the Torino depot had a complement of 128 locomotives, including 20 from the 215 series and 18 from the 310 series deployed in the line, to which were added ten locos from the 320 series. These were also 030s [in UK annotation, 0-6-0s] with three-axle tenders, initially ordered by the RM as series 3601 to 3700 and gradually delivered by five manufacturers between 1904 and 1908.” [1: p64]

The first decade of the 20th century saw the existing roster of locomotives supplemented by two other series:

- 130s (UK, 2-6-0) tender locos of the FS 630 series; and

- 040T (UK, 0-8-0T) tank locos of the FS 895 series.

In 1906, a subsidised bus service was introduced to complement and replace the various horse-drawn and motor services already in existence on the roads between Vievola, Ventimiglia and Nice. [1: p64][c.f. 14] The connection to Nice was later (in 1912) taken over by the Truchi company of Nice. [1: p64]

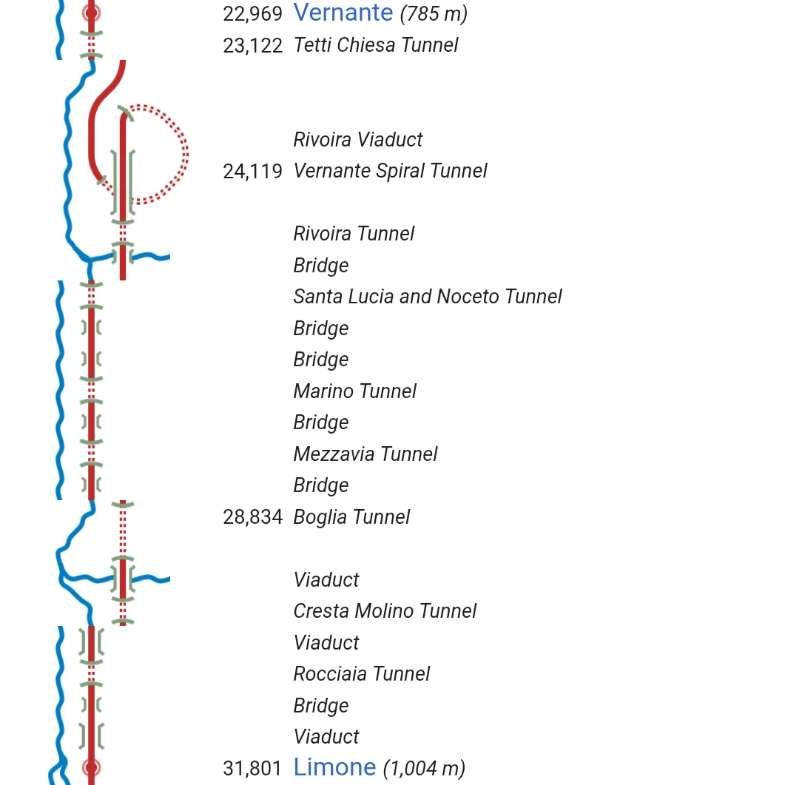

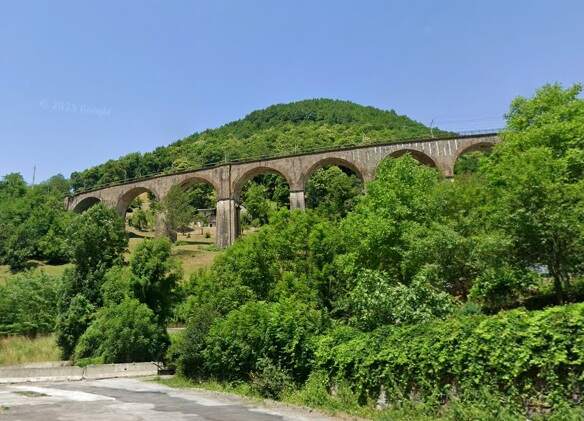

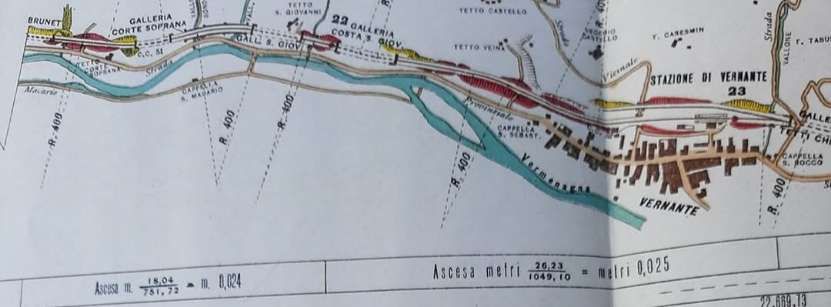

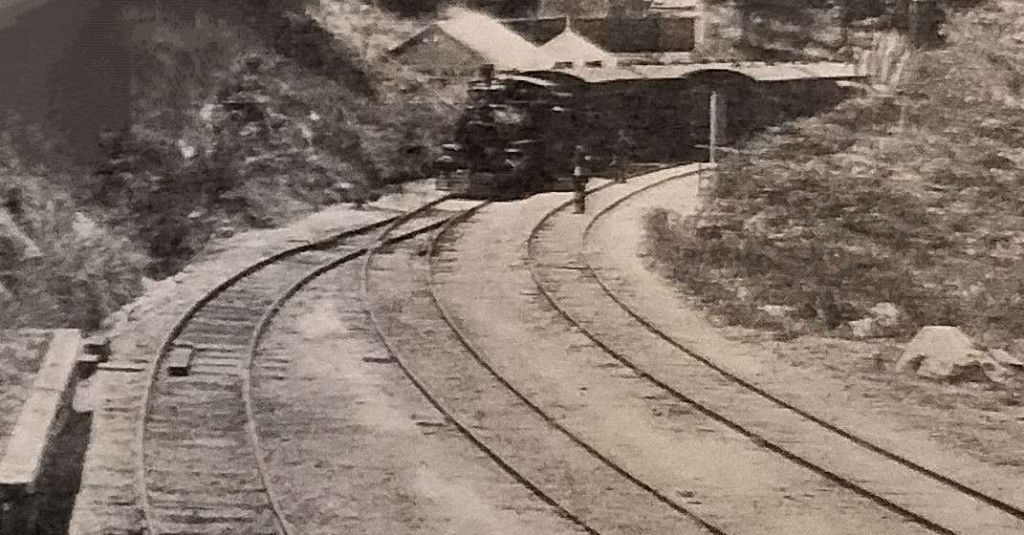

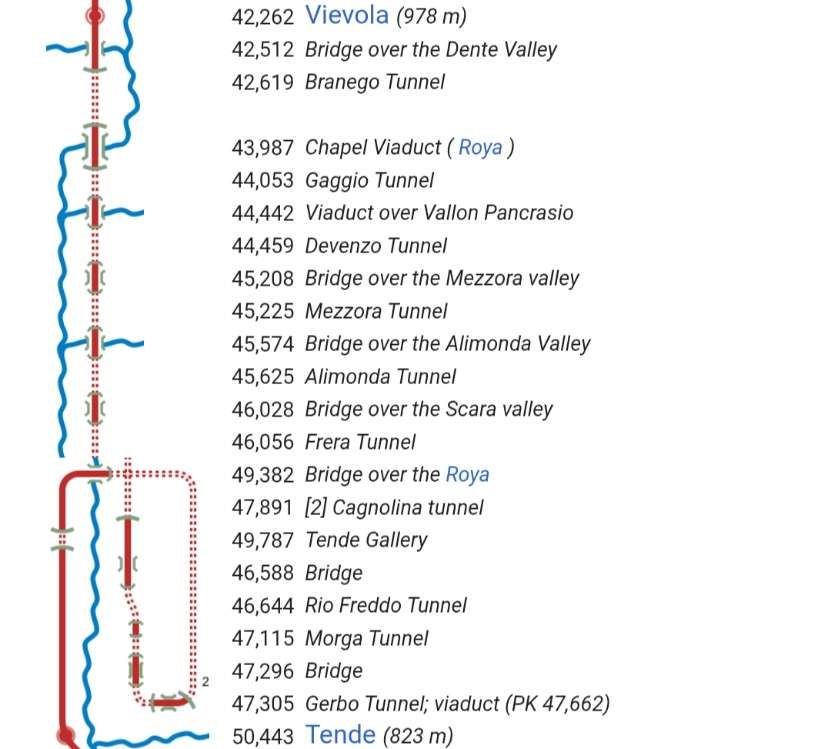

Vievola to Tende

Banaudo et al, again: “In August 1907, the first of eleven work packages between Vievola and the [then] border were awarded: package 1 from Vievola to the Gaggeoetlen tunnel, and package 4 of the Cagnolina tunnel to Tenda. In June 1911, it was the turn of package 2, between the Gaggeo and Alimonda tunnels, and the following month, package 3 from Alimonda to Cagnolina. These contracts were signed with the Tuscan companies Sard and Faccanoni and the Ghirardi company, originally from the region of Lake Maggiore. Over 8.2 kilometres, the line crosses Triassic and Permian terrain cut by Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Carboniferous veins. There are ten tunnels covering a distance of 5.90 kilometres, or 72% of the route, as well as seven bridges and viaducts totaling seventeen masonry arches. The section has no level crossings, but seven “caselli” (houses) were built to house the road workers and their families. Some are isolated in the mountains, sometimes between two tunnels, and accessible only by railway.” [1: p64-67]

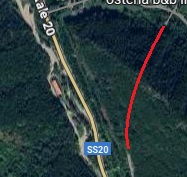

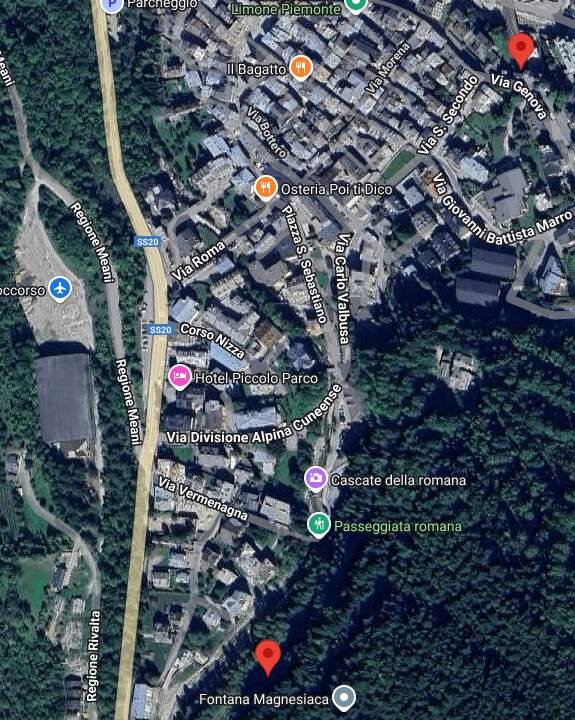

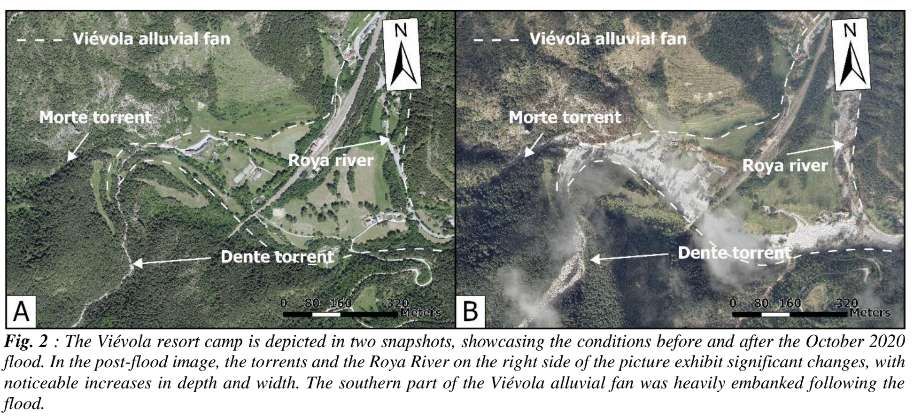

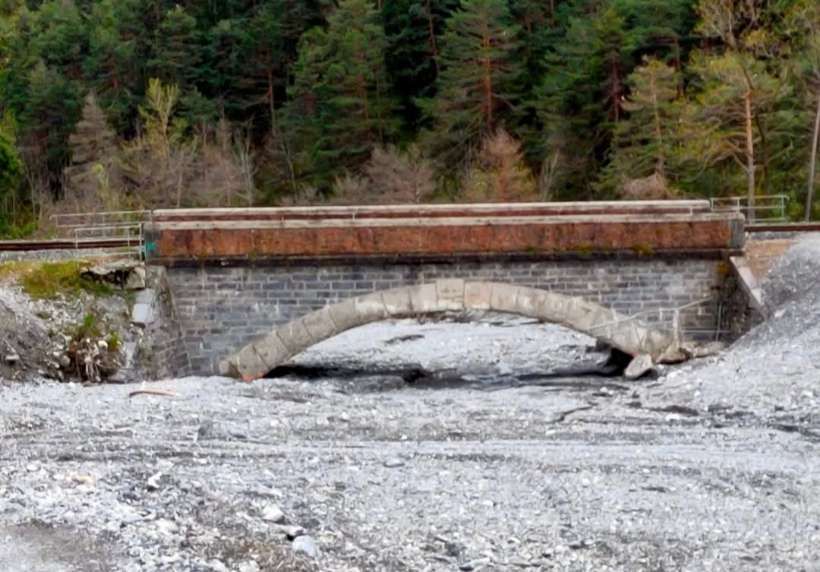

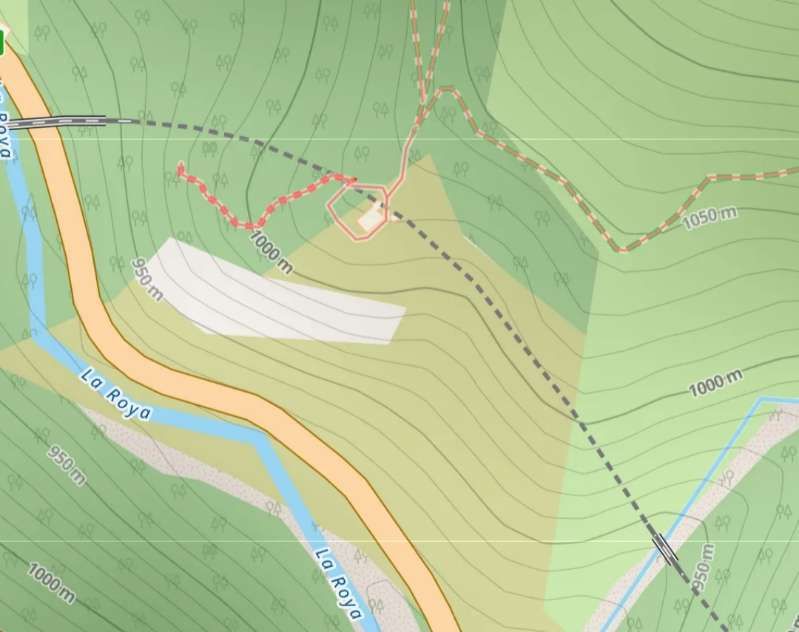

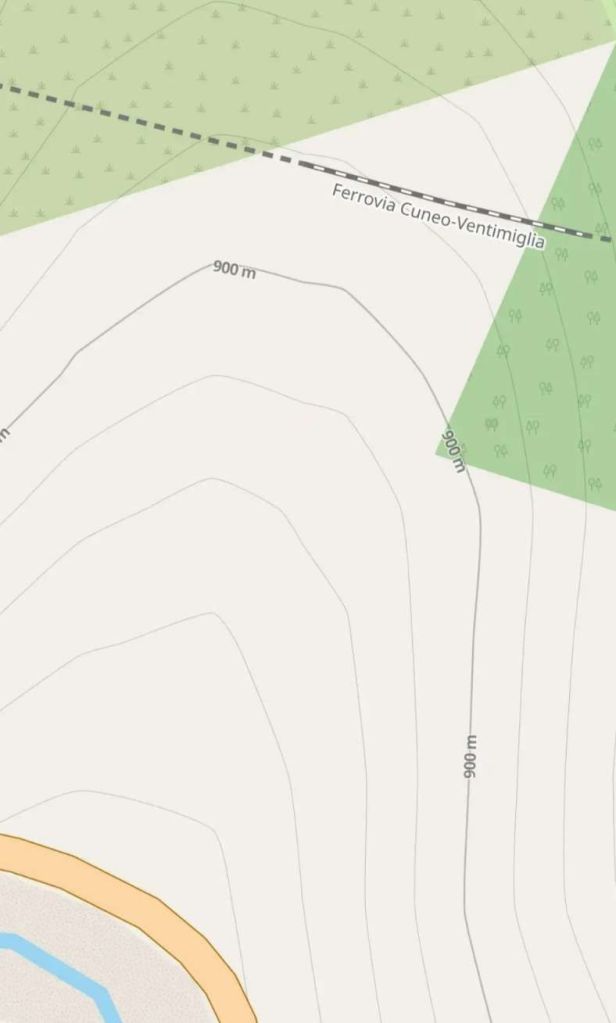

From Vievola, the line begins its journey down the valley of La Roya by crossing a single-arch bridge over the Dente valley which suffered some disruption resulting from Storm Alex in October 2020.

A short distance South of the bridge over the river, looking North towards Vievola from the cab of a north-bound train. [35]

Taken from a point a little further to the South, this photograph shows the parapets of a bridge over a small stream to the South of the Dente river. This image is also taken from the cab of a north-bound train in the 2020s. [35]

After crossing the 12 metre span bridge the line enters the 1273 metre long Branego horseshoe tunnel.

This photograph looks North from the mouth of the Branego Tunnel towards Vievola Railway Station. It is taken from the cab of the same North-bound train. [35]

The tunnel opens onto the right bank of La Roya about 25 metres above the river. The Vievola Viaduct spanned the river on five 15 metre masonry arches. Banaudo et al tell us that, “this structure would later be called the ‘Chapel viaduct’ due to its proximity to the Sanctuary of the Visitation or Madonna of Vievola.” [1: p67]

The East Portal of Branego Tunnel taken from the cab of a train approaching Vievola Railway Station from the South. [35]

The Vievola (Chapel) Viaduct seen from the cab of a train approaching it from Tende. [35]

I believe that the viaduct was fatally damaged by the German forces retreating at the end of WW2. It has been rebuilt in concrete as a 5-span concrete viaduct.

Now on the left bank of La Roya, the line passes through a series of tunnels with very brief open lengths spanning narrow valleys or slight depressions. The first tunnel on the Left bank is shown below. …

The Southeast Portal of Gaggio Tunnel seen from the cab of a Northbound train at the mouth of Devenzo Tunnel. The parapets of the 12-metre span arched bridge over the San Pancrazio valley can be seen between the two tunnels. [35]

The tunnel portals are generally made of local stone as are the arched bridges. The next tunnel is the Devenzo tunnel, shown below. …

This photograph is another still from a video taken from the cab of a train travelling North from Tende. It shows the short length of open line mentioned above. The parapets are those of the viaduct of two 6 metre arches. [35]

The Southeast portal of the Mezzora Tunnel can be seen in this image taken from the tunnel mouth of the Alimonda Tunnel. It is possible to see along the full length of this tunnel to the short opening mentioned above. In the course of travelling this short length of open line the railway crosses the Alimonda Valley. [35]

The next tunnel, the Alimonda Tunnel begins immediately the Alimonda valley has been crossed. The tunnel is 380 m long.

The short length of track and bridge in the Scara Valley between the Alimonda Tunnel and the Frera Tunnel, seen from the cab of a service which has just left the Frera Tunnel heading for Vievola and on to Cuneo. [35]

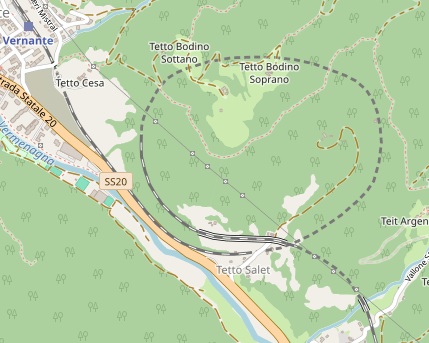

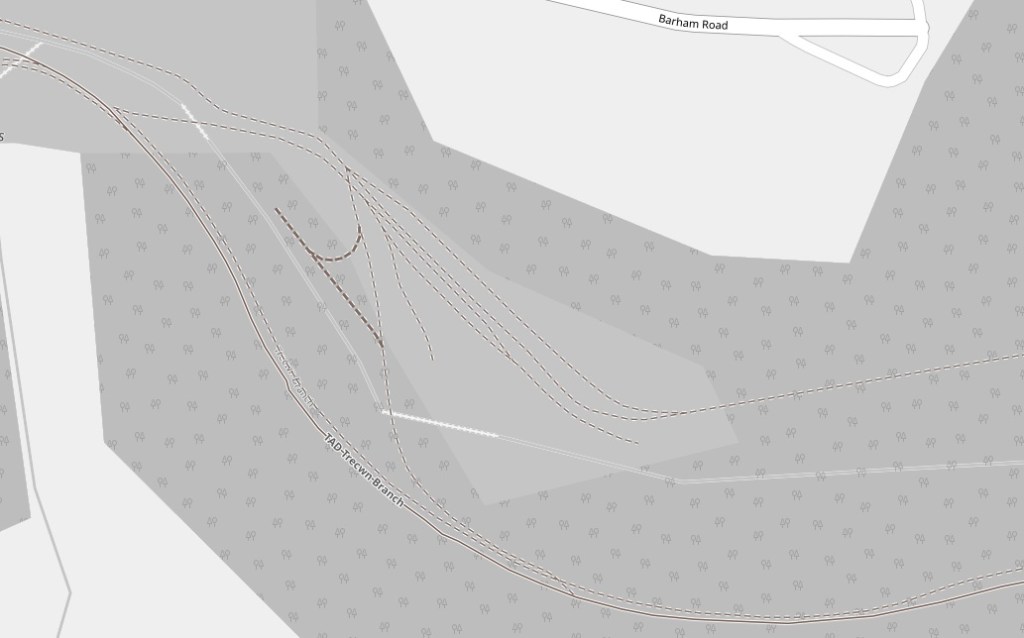

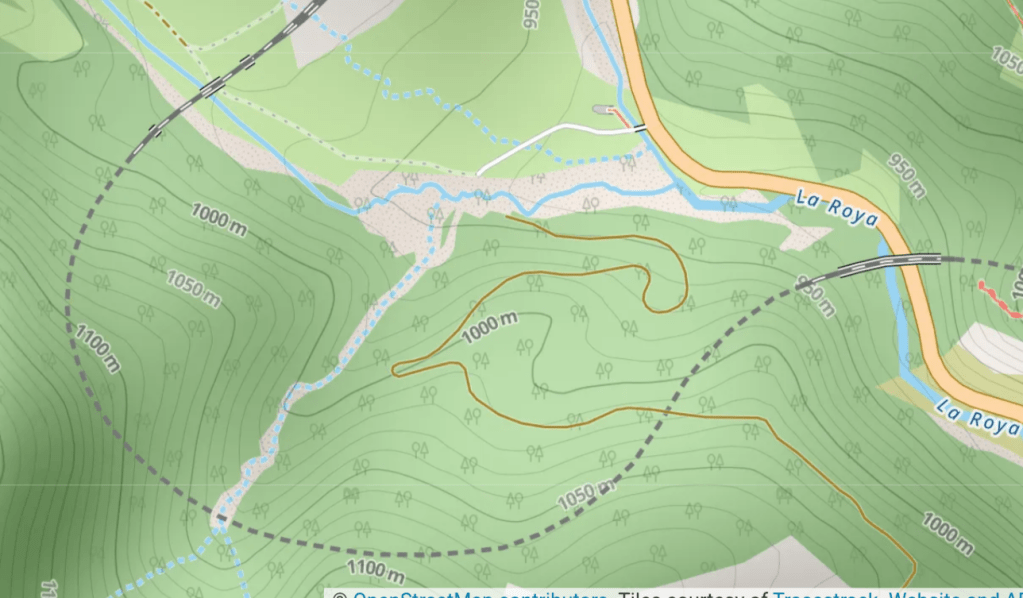

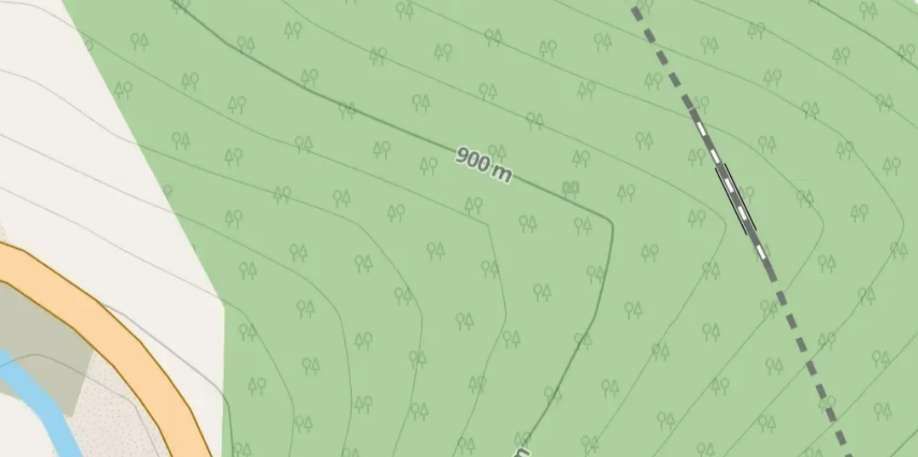

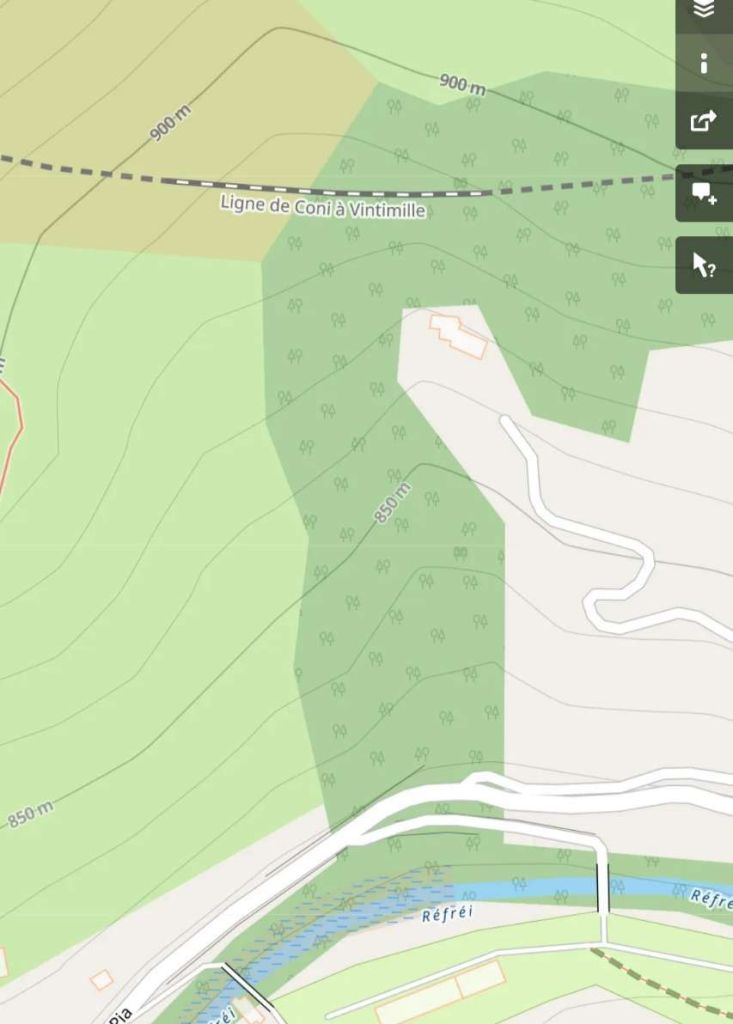

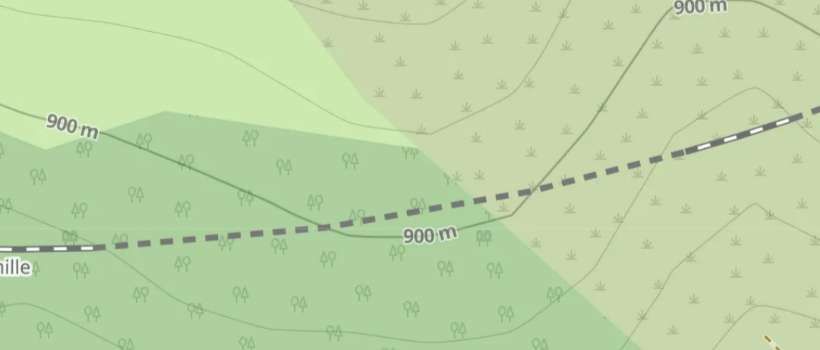

Before entering the Frera Tunnel, it is worth pulling back a little to see the route of the line ahead. This is the first ‘spiral’ on the line down towards Ventimiglia and Nice. A large section of the spiral is within one tunnel but the engineers made use of the Valley of the Refrei to avoid having to put the entire spiral in tunnel. [36]

The short length of track and the bridge between the Frera and the Rio Freddo tunnels. [35]

The short length of line between the Rio Freddo and the Morga Tunnels, seen from the cab of a train just leaving Morga Tunnel. The Rio Freddo tunnel mouth is ahead. Between the two tunnel mouths is the Morga Bridge (two 8-metre arches). [35]

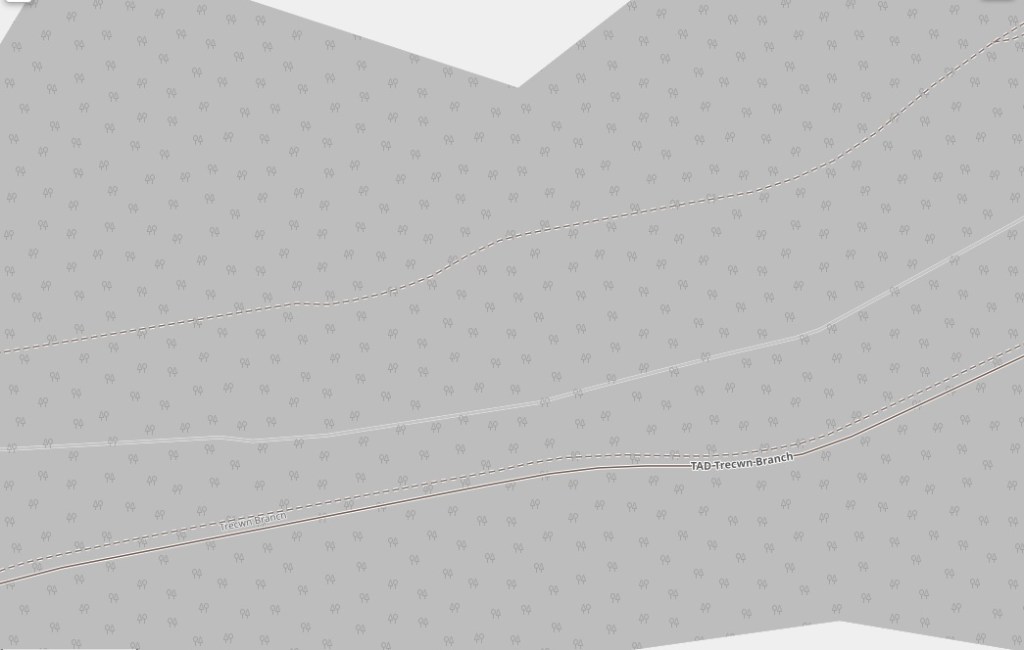

Banaudo et al tell us that “from the exit of the Rio-Freddo tunnel [on the North flank of the Refrei valley], the village of Tenda (Tende) appears below and the railway describes a helical loop which ends at [the lower end of] the Cagnolina tunnel. … This loop loses about sixty metres of altitude in less than 3 km of travel.” [1: p70]

The short open length of track between Morga and Gerbo tunnels, seen from the cab of a Cuneo-bound service and framed by the Southwest mouth of Gerbo Tunnel. [35]

The Northeast Portal of Gerbo Tunnel seen from the cab of a Cuneo-bound train in the 2020s. [35]

A short distance further along the line, the Bazara Viaduct (of five 8 m arches) is seen here, with the Gerbo Tunnel beyond – these are seen from the cab of a Cuneo-bound service in the 21st century. [35]

Here the Cuneo-bound train is just leaving the South Portal of Cagnolina Tunnel (at the right of the above map extract) and crossing a small bridge close to the tunnel mouth. [35]

The lower (West) portal of the Cagnolina Tunnel and the bridge over La Roya. Taken from the cab of a train heading North from Tende. The bridge over La Roya has a 12 metre span. [35]

A significant retaining wall to the West of the line, above which runs the E74/D6204. [35]

A short tunnel (Tende Galleria) part way along the length that the E74/D6402 run parallel and in close proximity to each other. The view looks North-northwest along the line. [35]

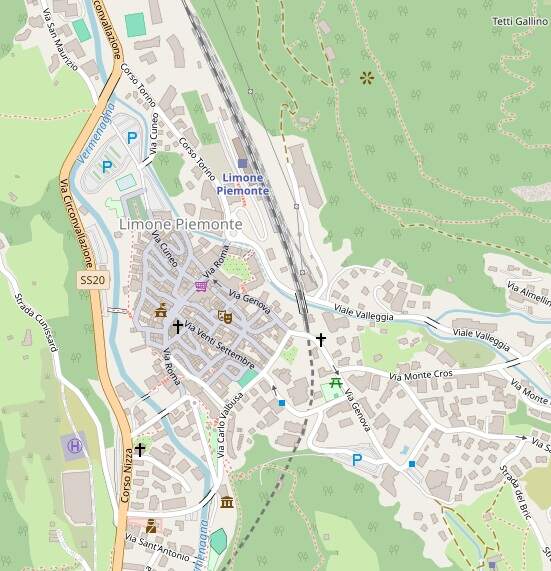

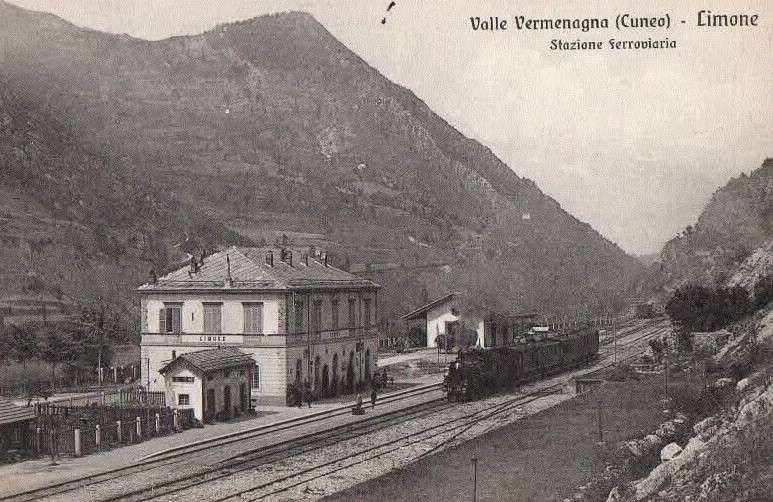

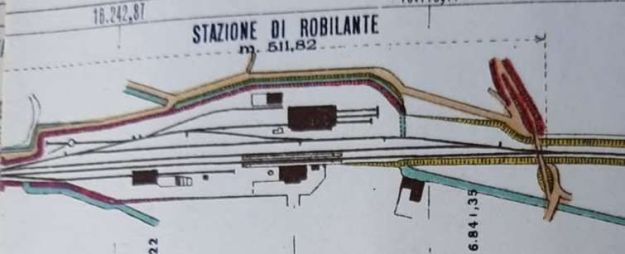

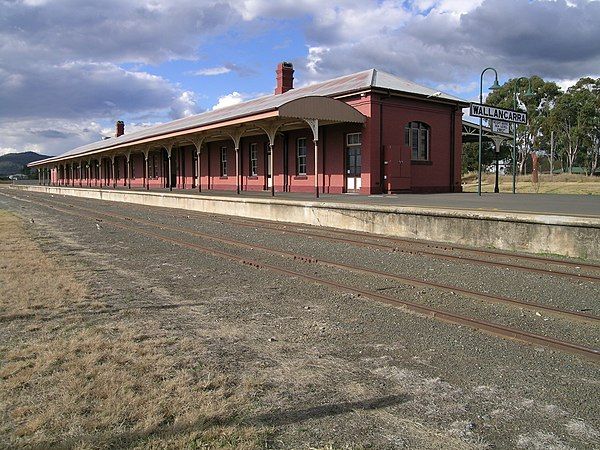

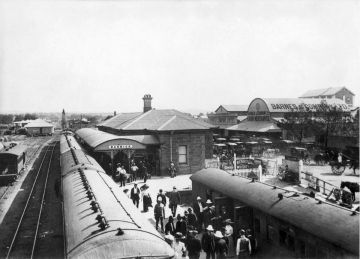

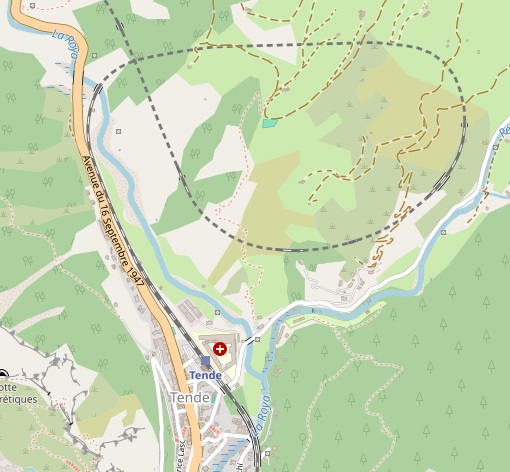

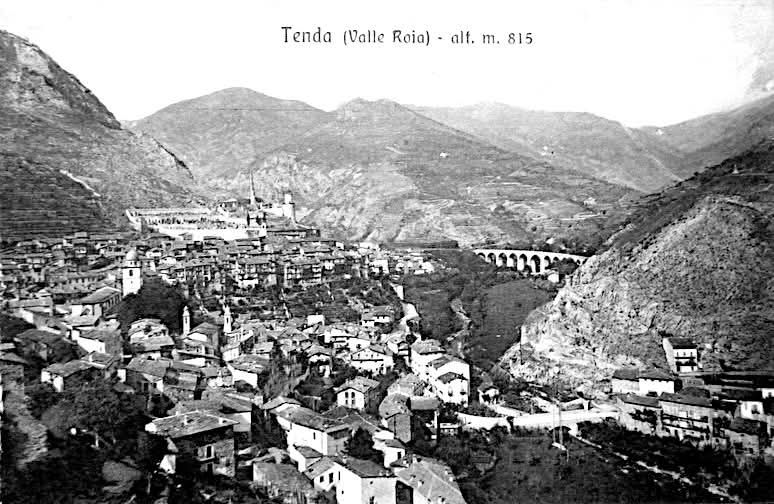

The Tende Railway Station today has a passenger building and two platform faces. In the past, it had three platform faces and a goods shed of classic Italian design, “the station had a number of goods tracks, two reinforced concrete water tanks supplying two hydraulic cranes, as well as an 8.50 metre turntable which was probably transferred from Vievola when the line was extended.” [1: p70]

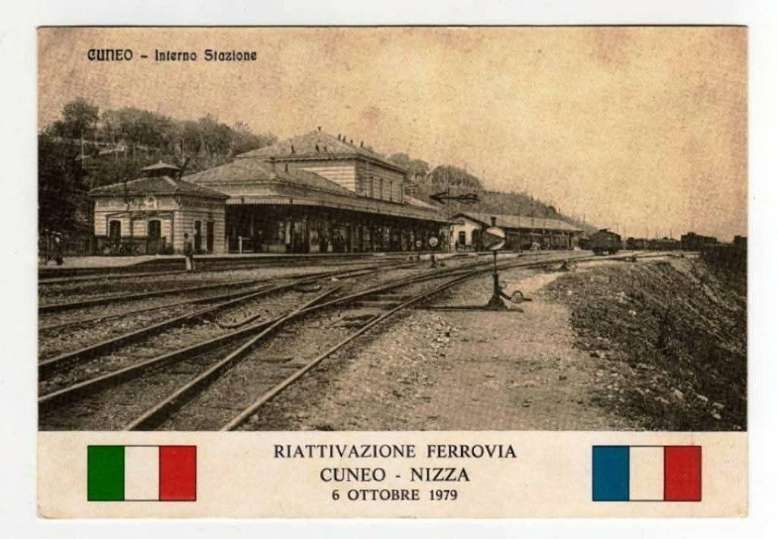

Wikipedia tells us that Tende Railway Station “opened on 7th September 1913. [40: p146] … Tende remained the temporary terminus for almost two years, until the opening of the Tende – Briga Marittima – San Dalmazzo di Tende section, which took place on 1st June 1915.” [39][40: p149]

The station and yard were electrified along with the line in 1931. [40: p171-172]

Tende “became isolated from the railway network after the destruction of bridges and tunnels by the retreating Germans between 15th and 26th April 1945.” [39][41: p15] .

“It remained under the jurisdiction of the Italian State Railways (FS) until 15th September 1947 and was passed into the hands of the Société Nationale des Chemins de fer Français (SNCF) the following day, when the upper Roja valley was separated from the province of Cuneo and became French territory by virtue of the peace treaty with France.” [39]

“After thirty-four years of inactivity, it was reopened on 6th October 1979 , the day of the inauguration of the rebuilt Cuneo-Ventimiglia line.” [39][40: p243]

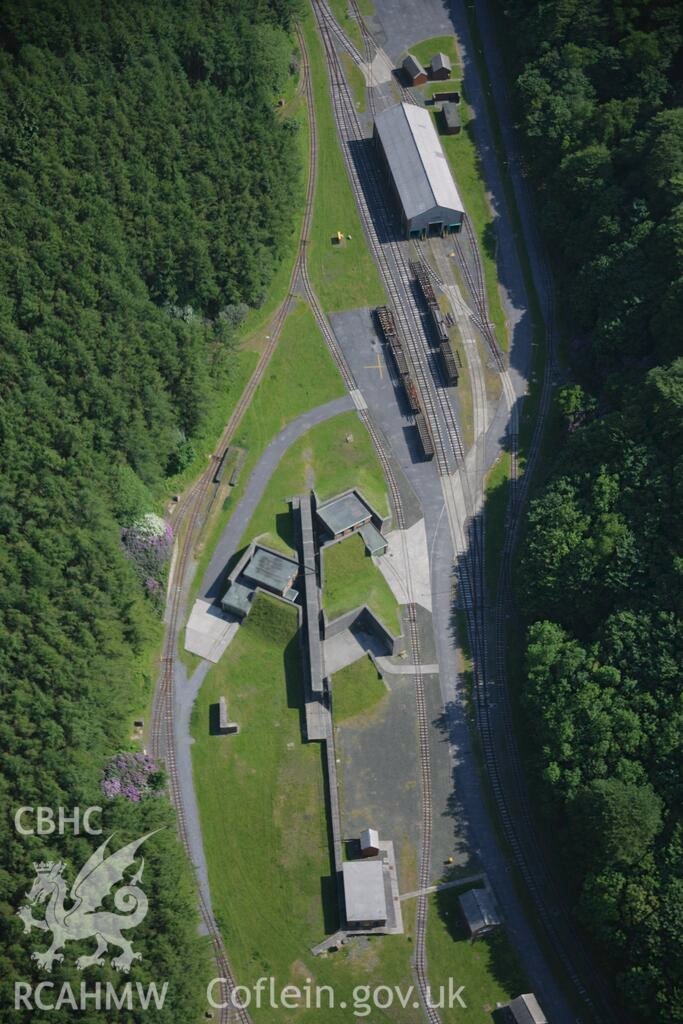

The station yard was originally of a significant size. [42: p81] For the reopening of the Limone-Ventimiglia line to traffic … it was initially planned that the Tende station would be transformed into a stop equipped with only a single track, but it was subsequently decided to build a loop [43: p34] with a useful length of 560 metres and a single track serving the loading platform and the goods warehouse. [43: p29]

A French and an Italian train pass at Tende in 2022. The train on the right is, I believe, an ALe501 trainset commissioned by Trenitalia in the early 2000s and produced by Alstom Ferroviaria, (c) Tomas Votava. [Google Maps, August 2025]

TER No. 76671 on the Train des Merveilles service from Nice stands at Tende Station, (c) Kenta Yumoto. [Google Maps, August 2025]

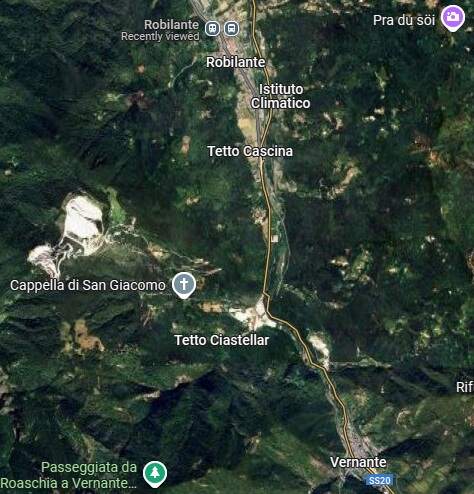

We have travelled as far as Tende Railway Station and noted that the line reached the village in 1913 and remained the terminus of the line from Cuneo until 2015. While the line as far as Tende was still under construction, Banaudo et al tells us that there were continued contacts “between the Italian and French authorities to resolve the remaining issues concerning the connection between the two networks in the Roya Valley. On 3rd January 1910, the Ministers of Public Works of both countries … met to discuss the problems of Franco-Italian communications. On 15th May 1910, the Cuneo Chamber of Commerce approached the government to request the acceleration of work between Vievola and Tenda. … During the same period, … efforts were being made to produce [hydroelectric power]. … The first plants were installed in Airole and Bevera in 1906, and later in San-Dalmazzo between 1909 and 1914.” [1: p70-74]

“The Roya hydroelectric power plants were intended to supply the Vallauria Mining Company and its ore processing facilities, public lighting, industries and the tramways of the Ligurian Riviera as far as Savona and Genoa.” [1: p74]

In France, two small power plants were built at the beginning of the century at Pont d’Ambo, downstream from Fontan, and in Breil. Between 1912 and 1914, a larger power plant was built opposite the village of Fontan.

Banaudo et al tell us that “In both France and Italy, the simultaneous construction of the railway and power plants turned the Roya Valley into a huge construction site for a dozen years. The companies had to house, feed, and entertain several hundred workers, most of them from other regions of Italy.” [1: p74]

After the opening of Tende Railway Station in September 1913, “the FS improved the service which had remained unchanged for a quarter of a century. Four Cuneo – Tenda return trips would now run every day, including a mixed goods-passenger one. From July to September, a fifth return trip was added. The 50 km journey took an average of 1 hour 50 minutes.” [1: p75]

Meanwhile, the project to divert the railway line and build a new station on the Altipiano in Cuneo which we noted in the first of these articles, [9] was being developed. Work began in September 1913 [1: p80] but it was to be 7th November 1937 before the new station opened! [44]

“While the line was creeping southwards from Cuneo to Tenda, work had begun in Ventimiglia on the northbound line up the Roya Valley. However, by the outbreak of World War I it had only covered 20 kilometres to Airole. Meanwhile, and again interrupted by the war, another line was being built northeast from Nice to join the Cuneo-Ventimiglia line at Breil sur Roya.” [39] Progress on these two lines is covered in other posts in this series of articles. [45][46][47][48]

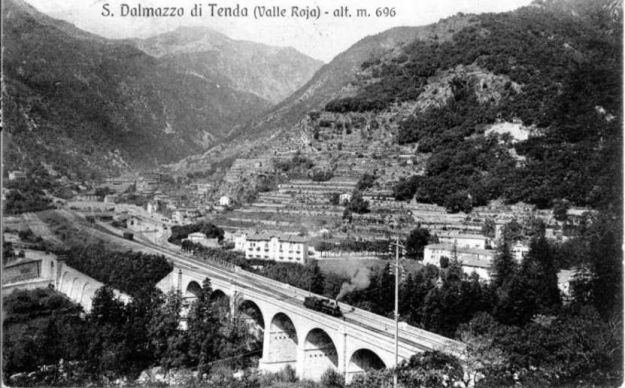

From Tende to St. Dalmas de Tende (San Dalmazzo di Tenda)

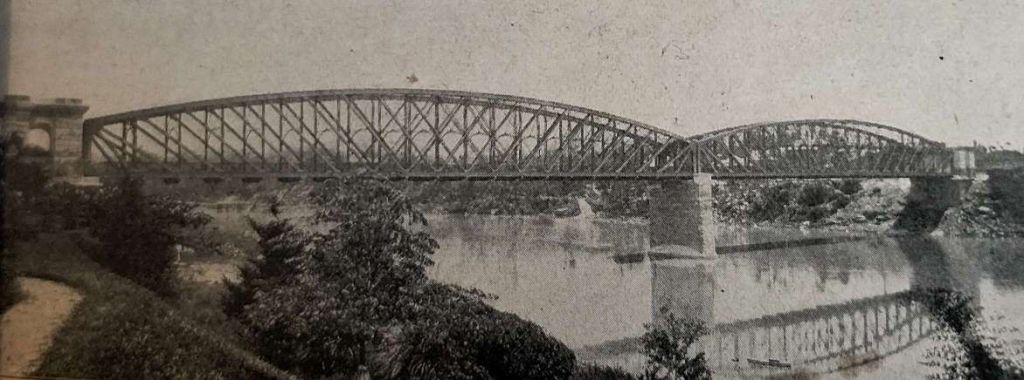

“In the first half of 1912, calls for tenders were issued for six lots of the section between Tenda, Briga, San-Dalmazzo, and the northern border of the Paganin Valley, followed in April 1913 by the award of the seventh and final lot. Here again, the tunnels, fifteen in number, account for more than two-thirds of the route, or 8,576 metres out of 12,335 metres. There are also seven bridges and viaducts, comprising a total of thirty-five masonry arches, about ten short-span structures, and there were ten roadside houses.” [1: p127]

Tende Railway Station seen from the cab of a South-bound service. [55]

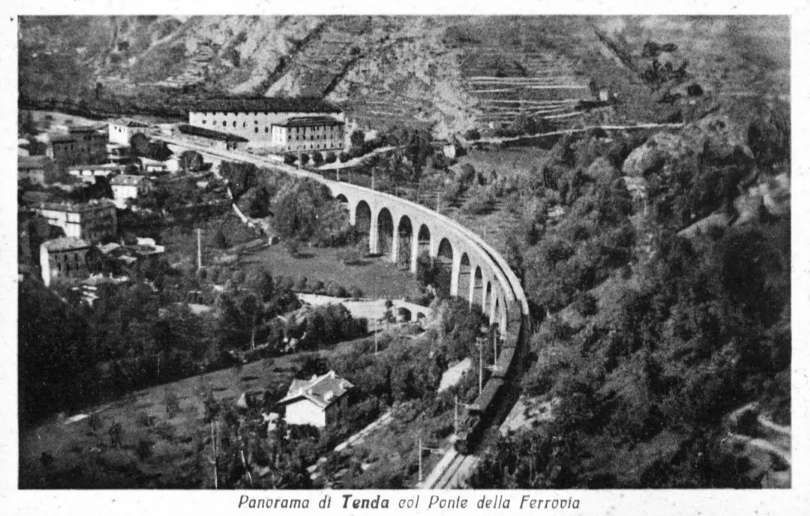

Leaving Tende Railway Station, the line soon passes onto the curved viaduct spanning the Roya River opposite the village. The viaduct has one 20-metre arch and eleven 15-metre arches.

A South-bound service crosses Tende Viaduct. This is the view from the cab. [55]

We were in Tende in November 2023 so saw something of the major work being undertaken after Storm Alex hit the area in October 2020 and took these photographs of the viaduct

Once across the viaduct, trains heading South ran on through three tunnels on the left bank of La Roya on a falling grade of 25mm/m. These were:

Borgonuovo Tunnel (200 metres long) …

The approach to Borgonuovo Tunnel, seen from the cab of a South-bound train. [55]

Looking North from the mouth of Borgonuovo Tunnel, from the cab of a North-bound train. [35]

The view South from the mouth of Borgonuevo Tunnel., [55]

The southern portal of Borgonuovo Tunnel, seen from the cab of an approaching train. [35]

The view from above the South portal of Borgonuovo Tunnel, (c) Tito Casquinha, June 2019. [Google Maps, August 2025]

Bijorin Tunnel (248 metres long) …

The North portal of the Bijorin Tunnel. [55]

The view from the northern portal of Bijorin Tunnel. [35]

The view South from the mouth of Bijorin Tunnel. Colombera tunnel is just visible ahead. [55]

The South portal of Bijorin Tunnel is ahead in this still from a video taken from the cab of a North-bound train. This image also shows avalanche warning wires above the line. [35]

Colombera Tunnel (212 metres long) …

The North portal of Colombera Tunnel. [55]

The view North towards Bijorin Tunnel from the mouth of Colombera Tunnel. [35]

An over exposed view South from the South Portal of Colombera Tunnel. [55]

The South Portal of Colombera Tunnel seen from the cab of a Northbound train. [35]

A short distance further South the railway bridges a minor road. These are the bridge parapets seen from the cab of a South-bound train. The minor road is just visible to the left of the image. [55]

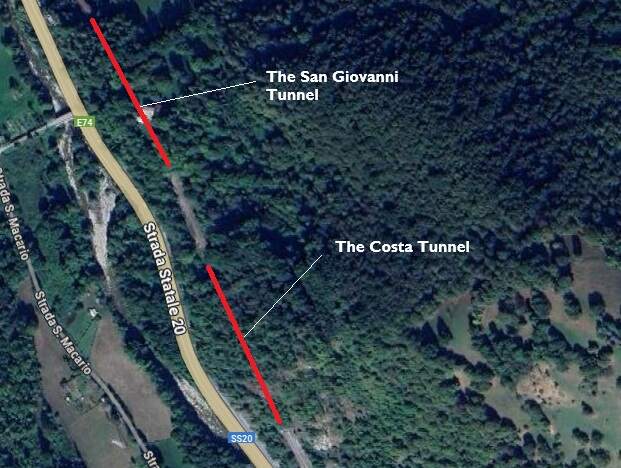

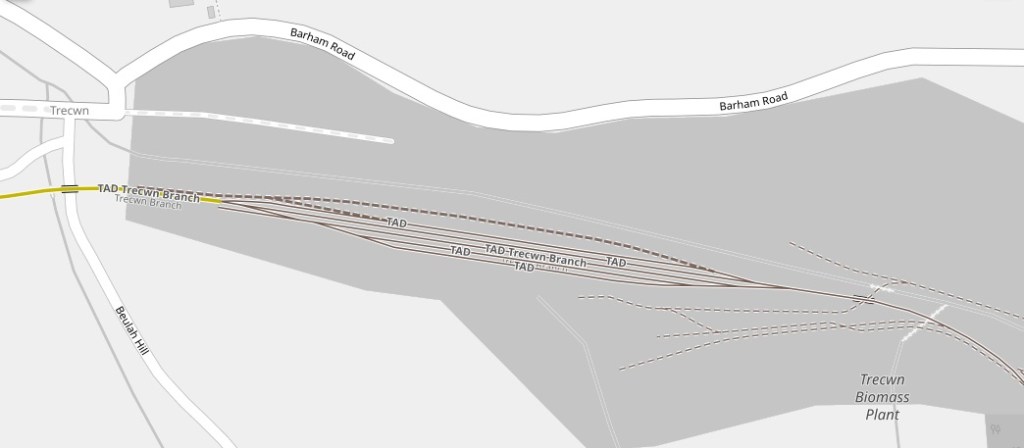

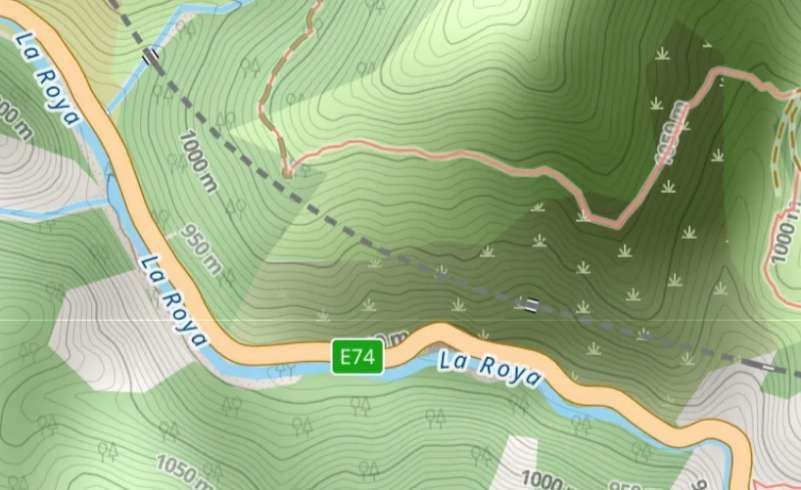

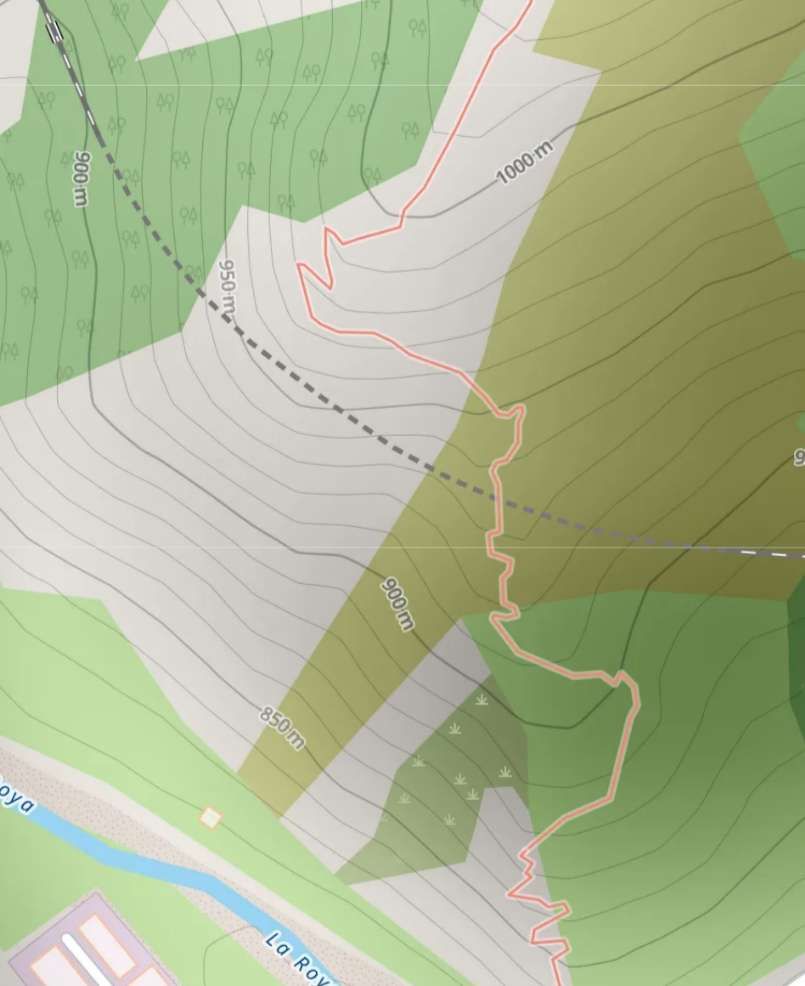

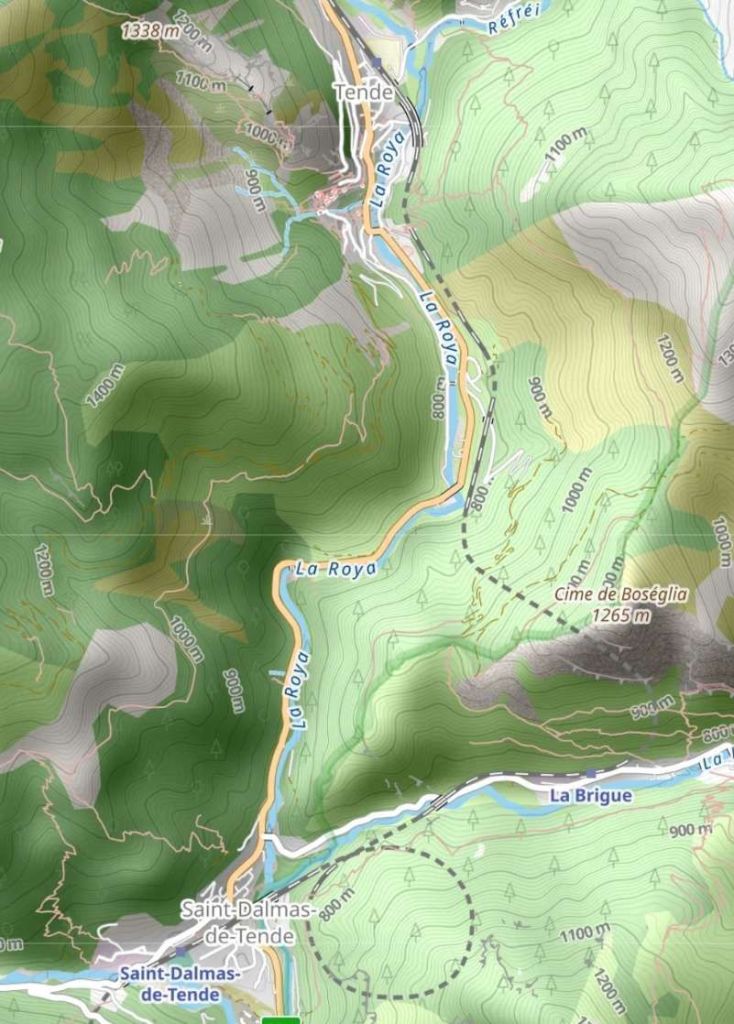

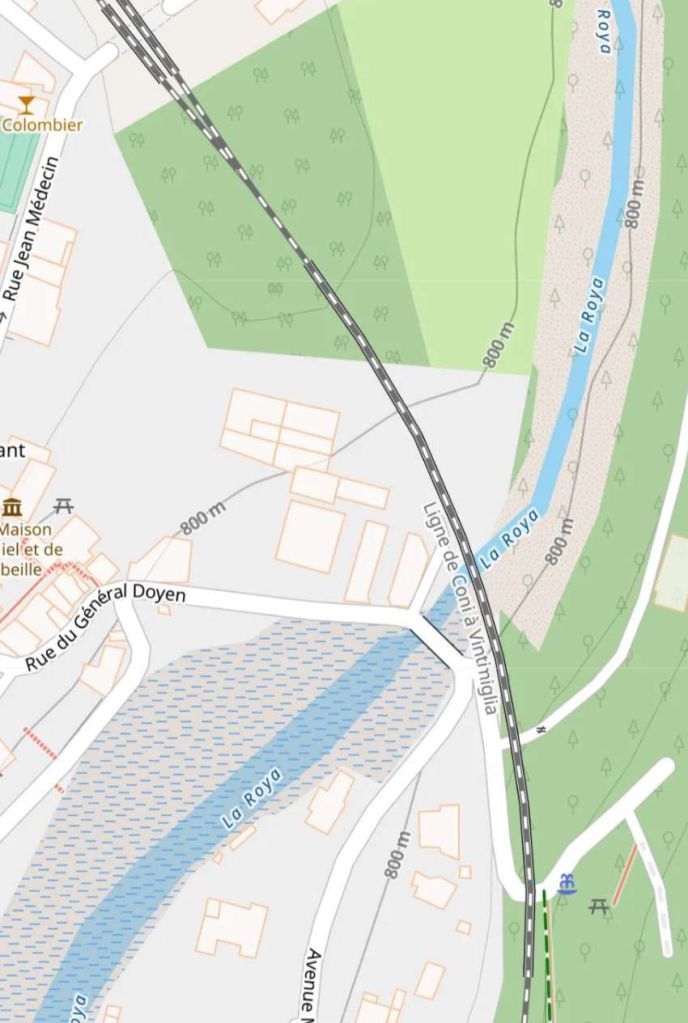

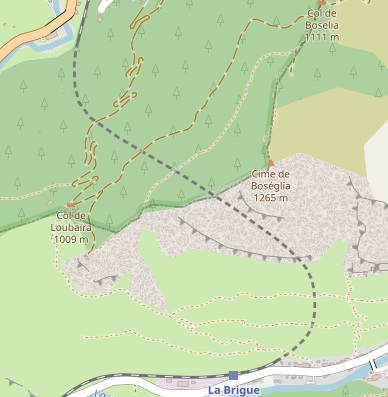

The next tunnel is Bosseglia Tunnel. The railway and the main road separate as the line heads into the tunnel which is S-shaped and 1585 metres in length. The southern portal of the tunnel opens out into the Levenza valley, a short distance to the East of La Brigue Railway Station. Banaudo et all refer to the station as Briga-Marittima station, which appears to be the name of the station in Italian. [1: p127]

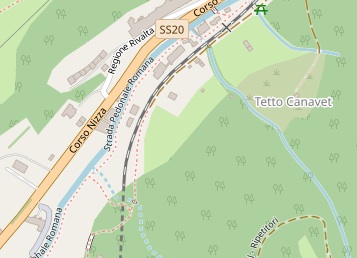

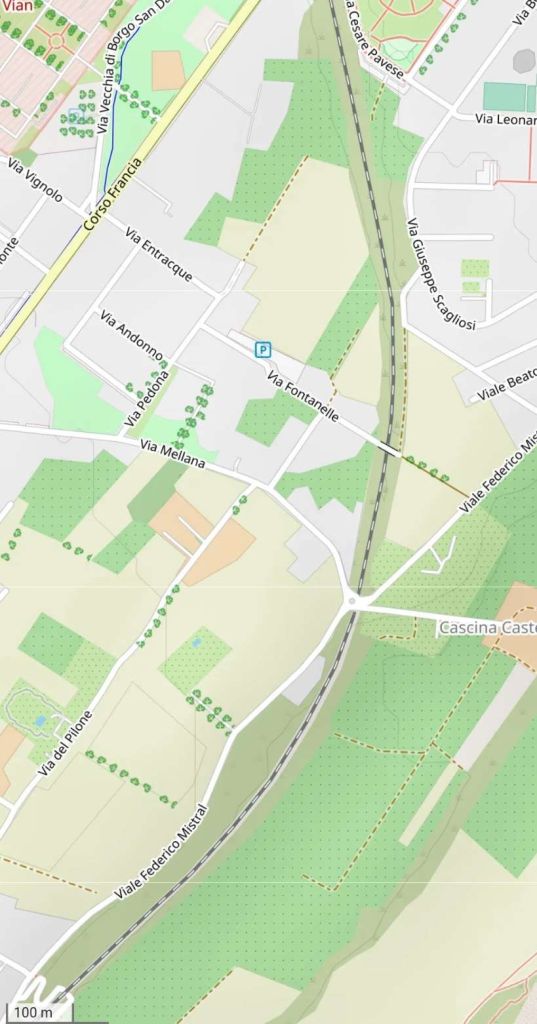

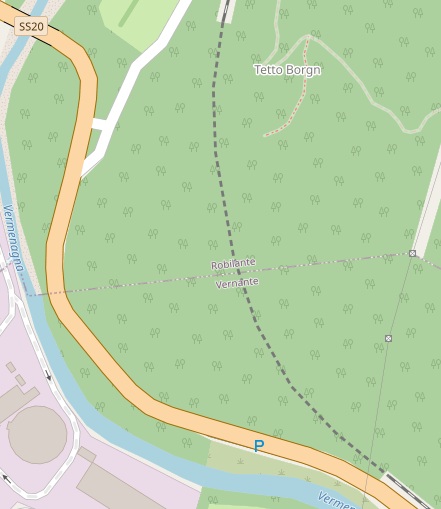

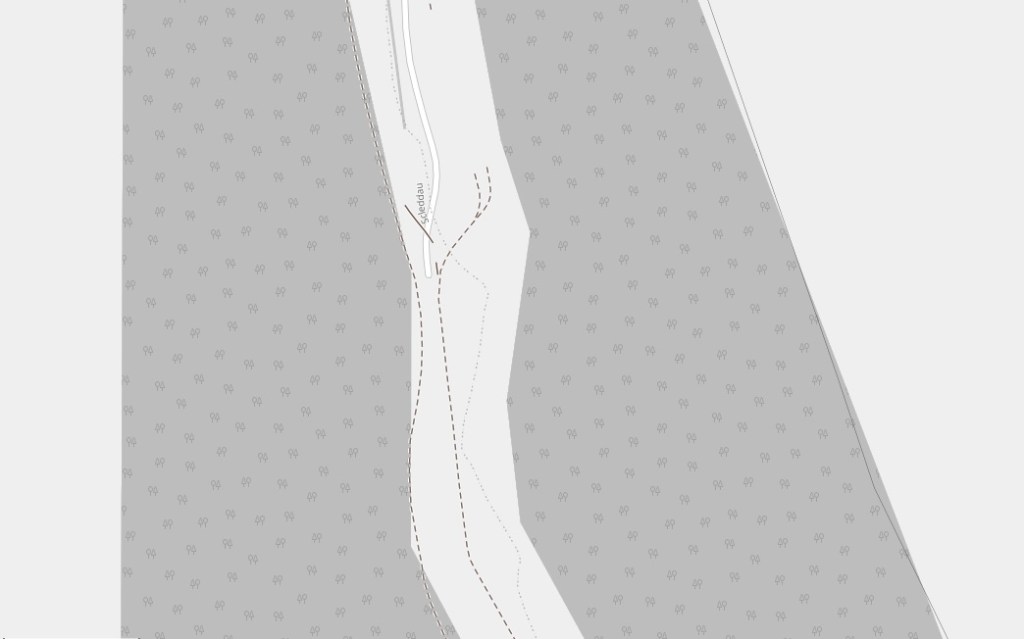

The Bosselgia Tunnel (which is over 1.5 km long) and the railway station at La Brigue as they appear on OpenStreetMap. [56]

Looking South, this is the northern portal of the Bosseglia Tunnel. [55]

Looking North from the mouth of Bosseglia Tunnel. [35]

Looking West from the southern portal of Bosseglia Tunnel towards La Brigue Railway Station. [55]

Turning through 180 degrees, this is the southern portal of the Bosseglia Tunnel seen from a North-bound train. [35]

La Brigue Railway Station once comprised a passenger building, two platform faces (a third would be built during electrification), three freight tracks with a good shed and a raised platform. The modern station is situated to the East of the old station. [1: p127]

Looking West along La Brigue Railway Station platform, © Remontees, and licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-SA 4.0). [57]

A similar view with an ALn501+502 train set in the station, © Georgio Stagni, June 2014 and authorised for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-SA 3.0). [57]

Looking East along the station platform, © JpChevreau and licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-SA 4.0). [57]

Looking West from the modern La Brigue Station through the site of the original station. [55]

Further through the site of the old railway station and continuing to face West down the Levenza valley. The old goods shed is on the left. [55]

The original station building at La Brigue, seen from the cab of a train heading for Ventimiglia. [55]

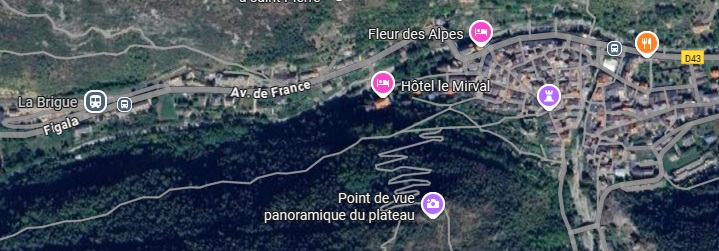

The bridge over the D43 and the River Levenza. [59]

The bridge over the D43 and the River Levenza. [55]

The bridge which carries the railway over the D43 and the River Levenza, seen from the East. [Google Streetview, August 2016]

The view back across the bridge over the River Levenza towards La Brigue Railway Station. The D43 can just be made out to the right of the bridge. [35]

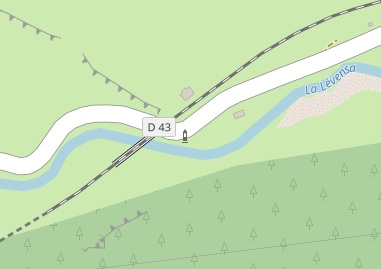

Leaving La Brigue Railway Station the line resumes following a falling grade of 25 mm/m. This continues through the Levenza viaduct, which, as we have seen consists of three 8-metre arches abutting a single span road bridge. Beyond this is the Levenza tunnel (418 m long). …

The Northeastern portal of the Levenza tunnel. [55]

The view back along the line from the Northeast portal of the Levenza tunnel. [35]

This overexposed view looks Southwest from the Southwest tunnel mouth of the Levenza tunnel. [55]

The Southwest portal of the Levenza tunnel seen from the cab of a North-bound service. [35]

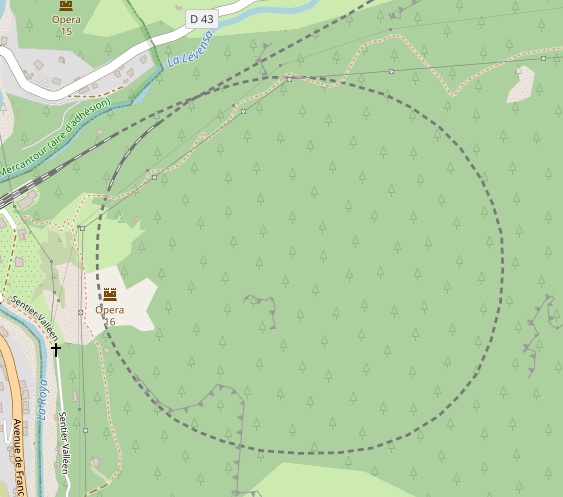

Beyond the Levenza Tunnels is and an unnamed viaduct of three 8-metre arches) and the line then enters the Rioro Spiral Tunnel.

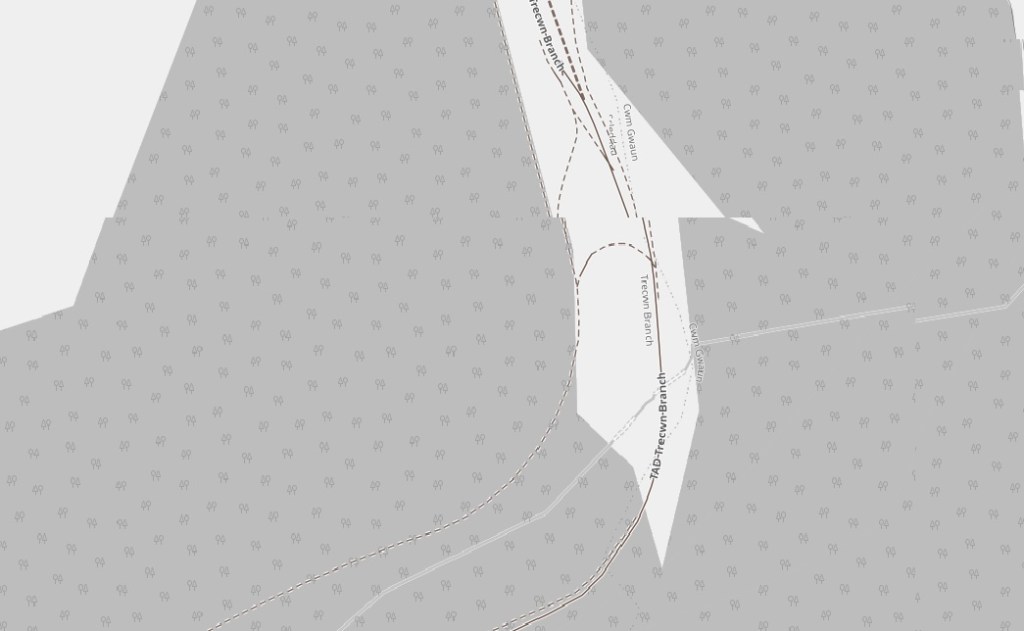

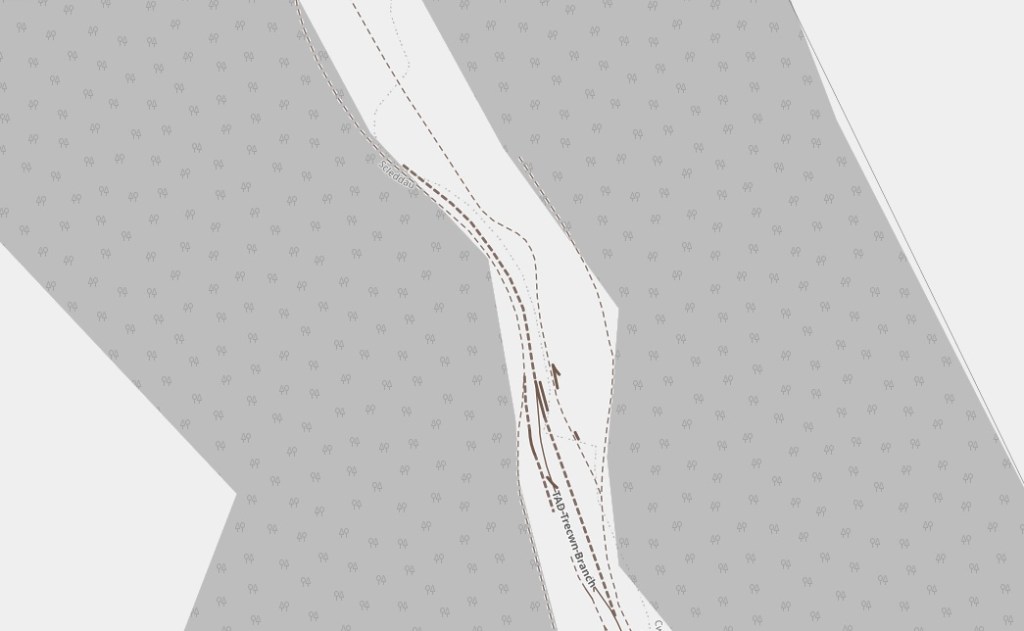

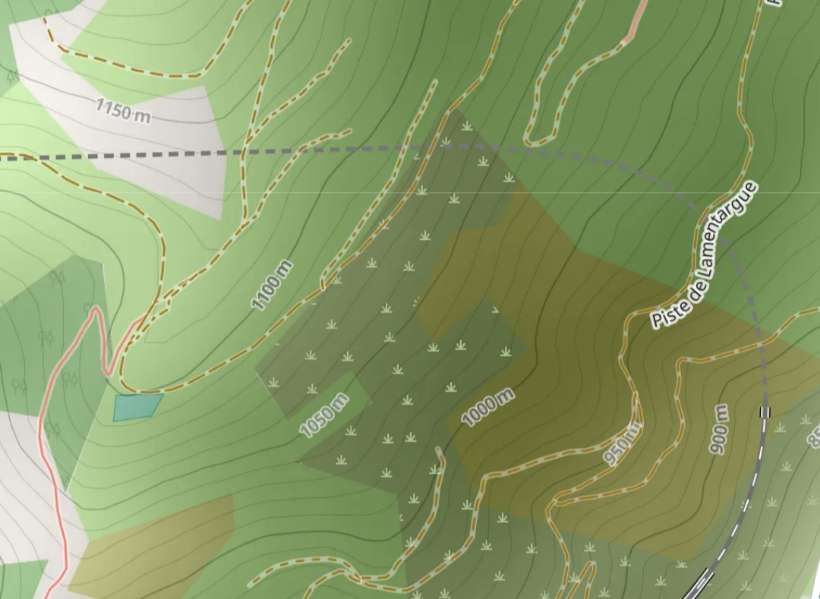

The Rioro Tunnel forms a loop which describes a circle of 300-metre radius and accommodates a 30-metre drop.

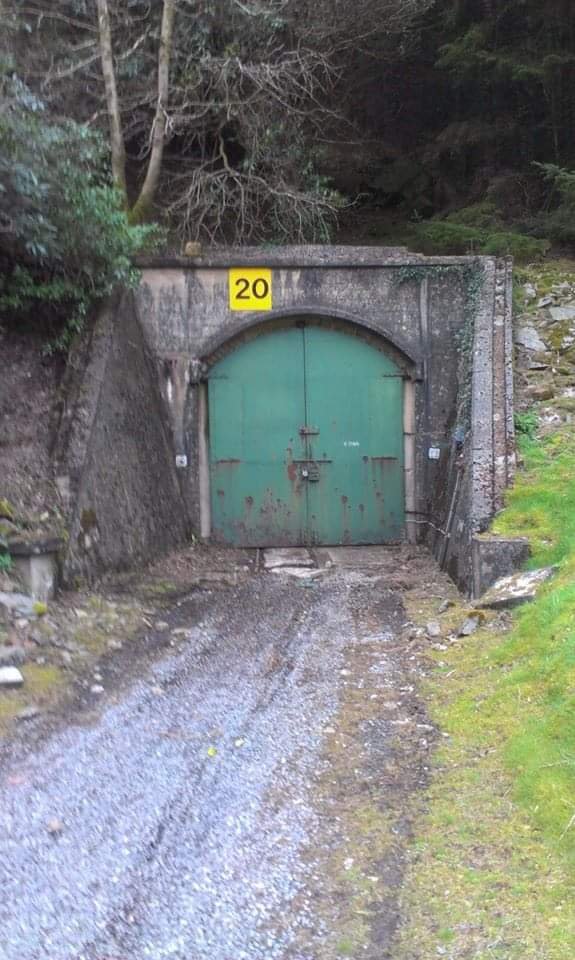

Banaudo et al tell us that the tunnel “is officially divided into two sections: Rioro I (282 m) and Rioro II (1527 m), connected by an artificial tunnel with a lateral opening closed by a gate. At this opening, a ‘casello’ (a ‘hut’) was built into the mountainside to house a road worker and his family.” [1: p127]

Looking Northeast from the mouth of the Rioro spiral tunnel. [35]

The Northeastern portal of the Rioro sprial tunnel. [55]

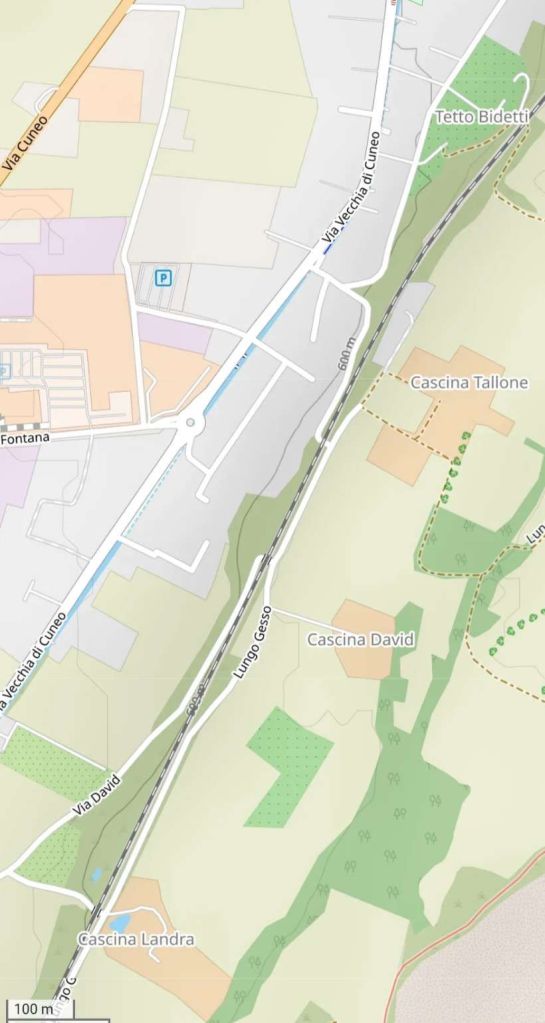

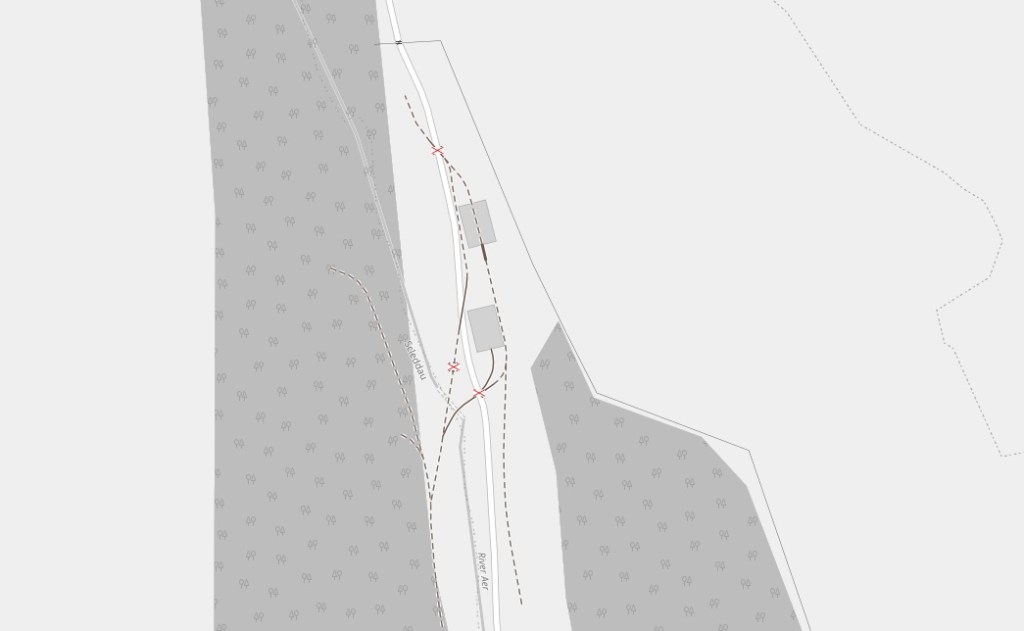

The Rioro Spiral Tunnel between La Brigue and St. Dalmas de Tende is 1828 metres in length. [60]

Trains are within the tunnel for some minutes as they cover nearly two kilometres of turning track within the tunnel. This view comes from the cab of a South-bound train. [55]

Facing Southwest along the line at the mouth of the Rioro Spiral Tunnel. The picture is overexposed as the camera is reacting to daylight after running through the tunnel. [55]

The Southwest Portal of the Rioro Spiral Tunnel, seen from the cab of a North-bound train. [35]

The Rioro Spiral Tunnel opens onto the left bank of the Levenza River, just before its confluence with the Roya River.

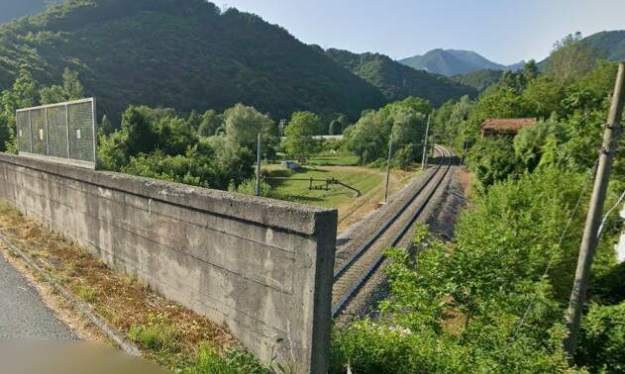

To the Southwest of the tunnel, the line is carried alongside the River Levenza on a retaining wall. The parapet of this wall, protected by railings, can be seen on the right of this image. [55]

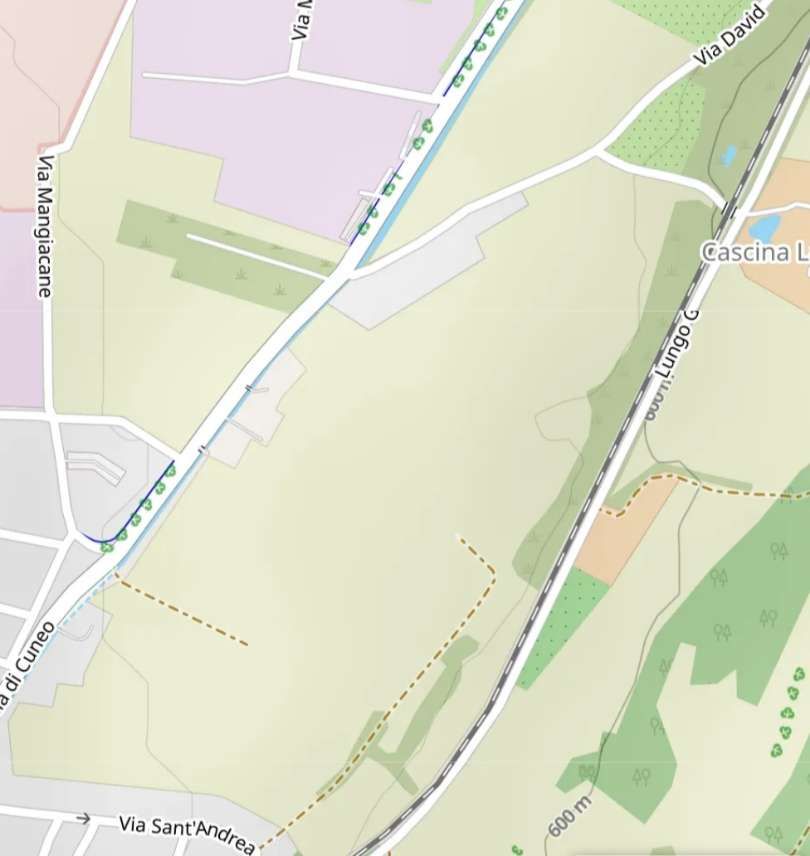

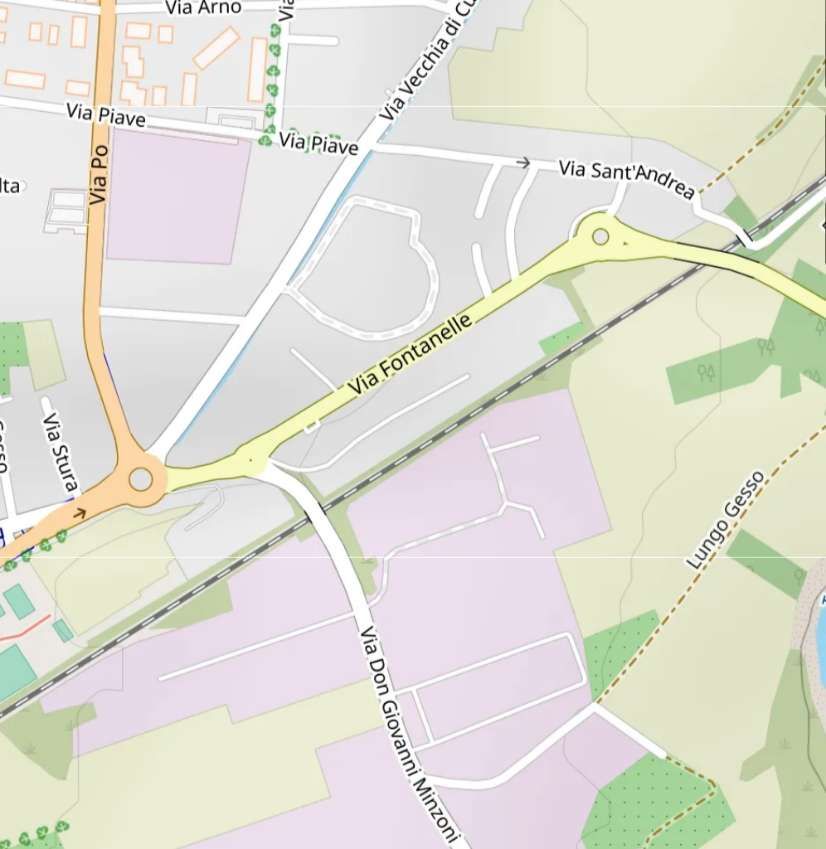

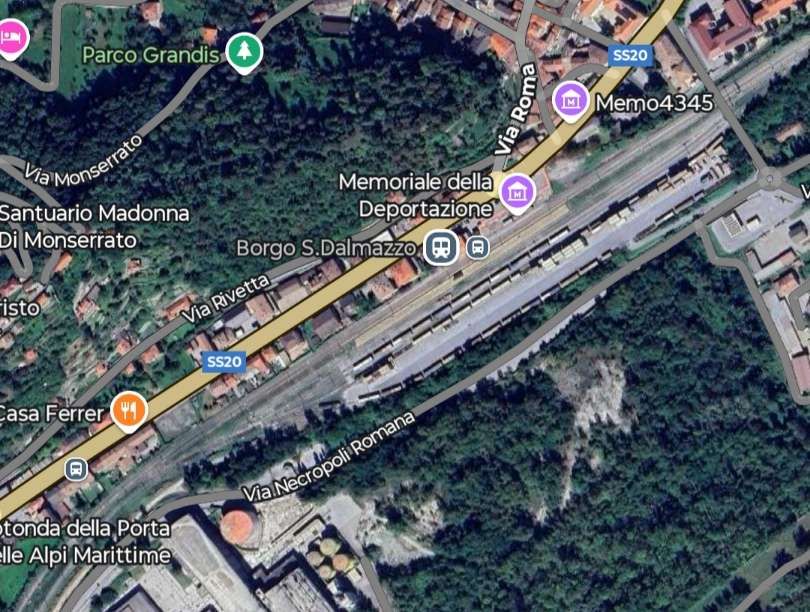

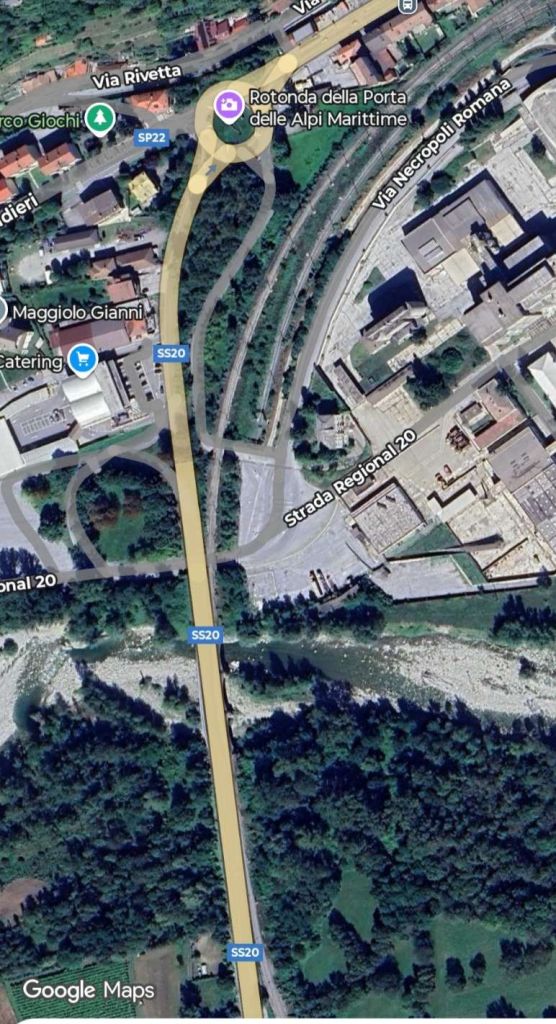

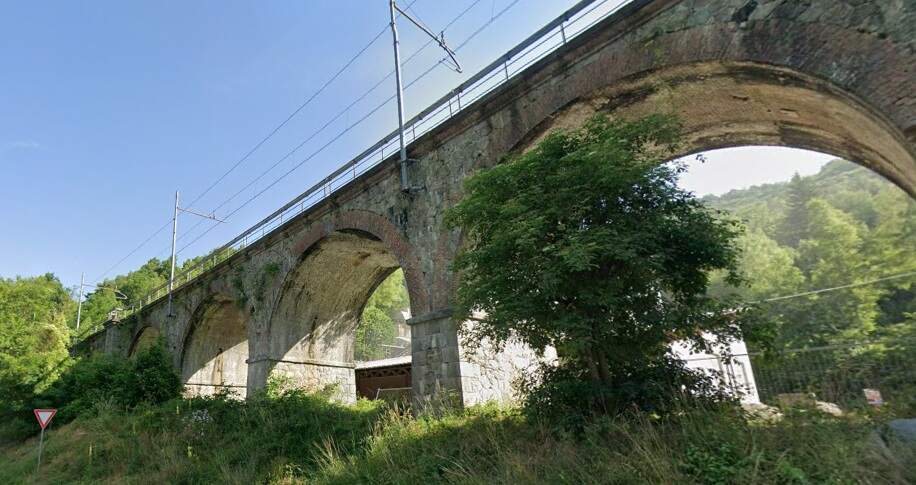

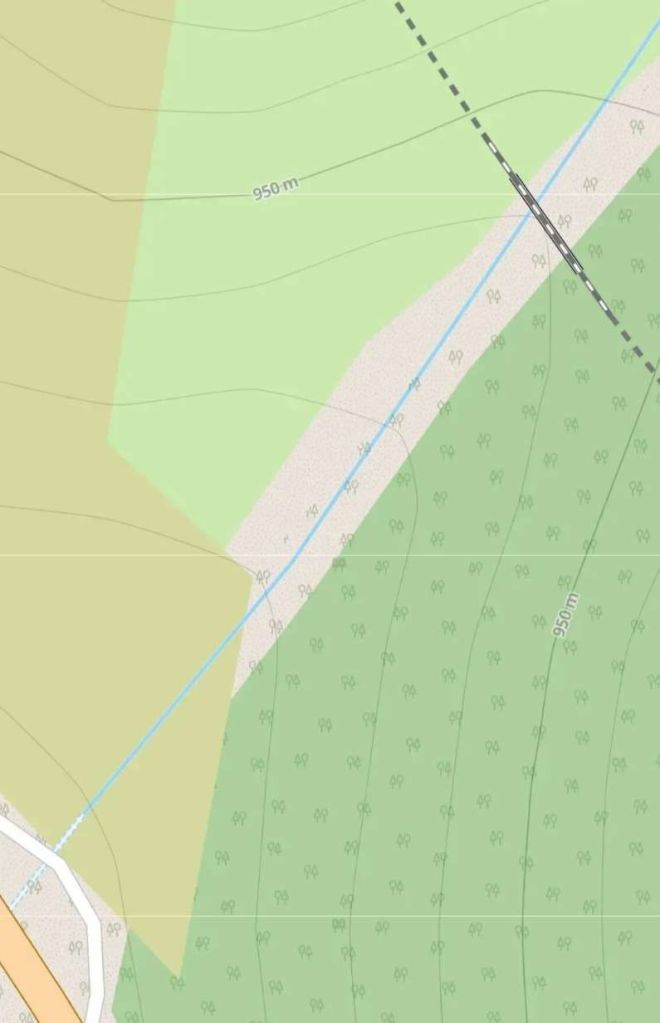

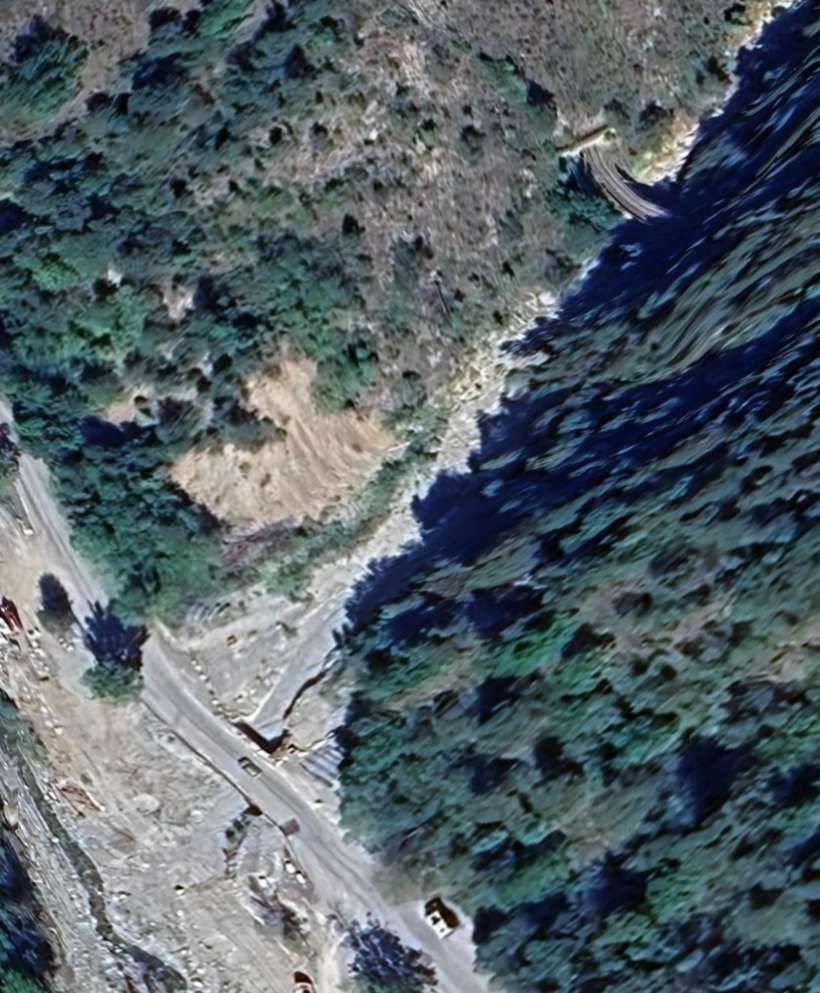

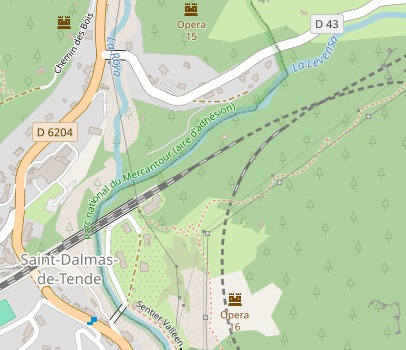

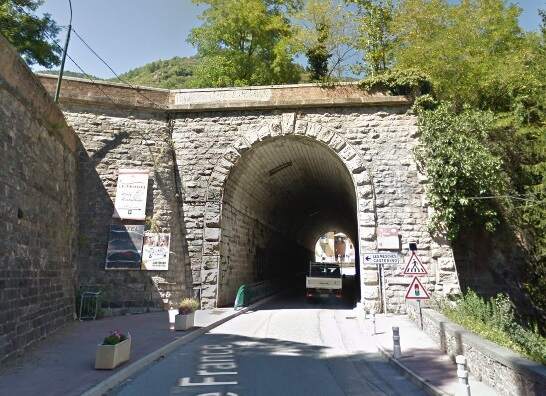

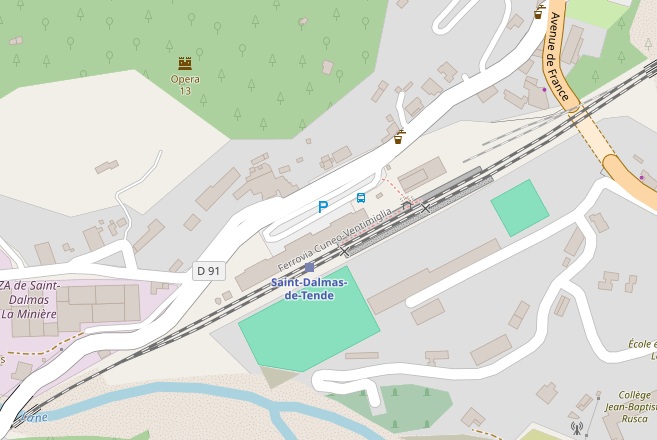

The River Roya is crossed by the San-Dalmazzo I viaduct. Banaudo et al tell us that “the seven 15-metre masonry arches of this structure were widened to carry three tracks to accommodate the approach to the station, built on a vast embankment. An underpass beneath it provides a route for the [E74/D6204].” [1: p127]

The line is retained above the Levenza River and then crosses La Roya on a viaduct of seven 15-metre masonry arches. A short tunnel under the wide embankment to the Southwest of the river allows the D6204 to pass under the railway. [61]

The bridge over La Roya on the approach to St. Dalmas de Tende. [55]

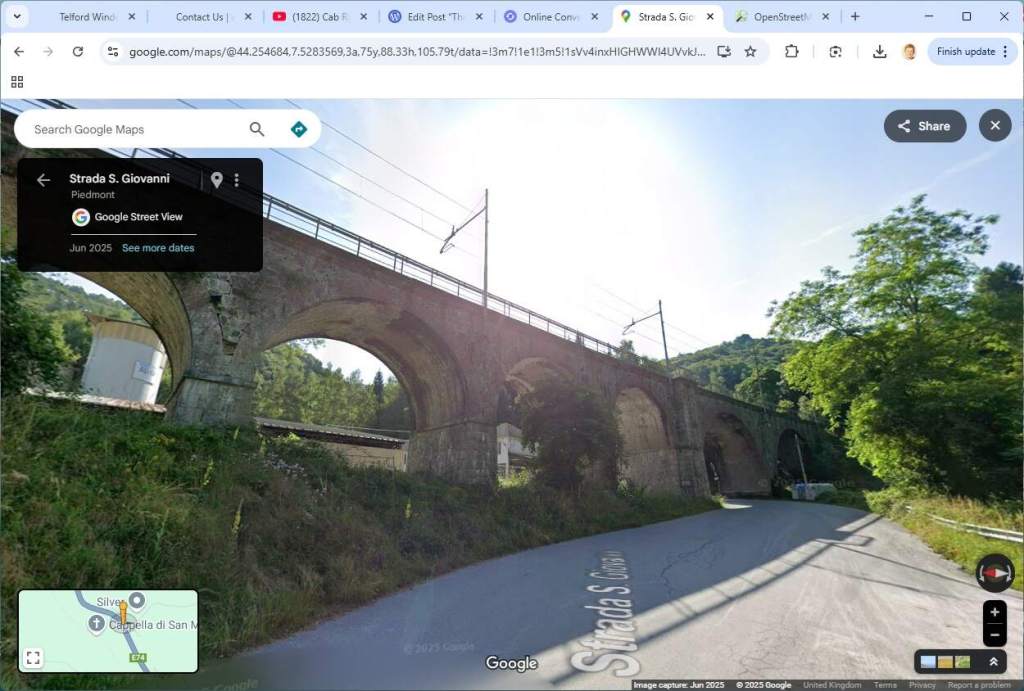

The bridge over the Avenue de France (the D6204/E74) seen from the North. The road is in tunnel as a large area was dedicated to the station complex at St. Dalmas de Tende as it was originally a border station in Italy. [Google Streetview, August 2016]

The same bridge/tunnel seen from the South on the Avenue de France. [Google Streetview, August 2016]

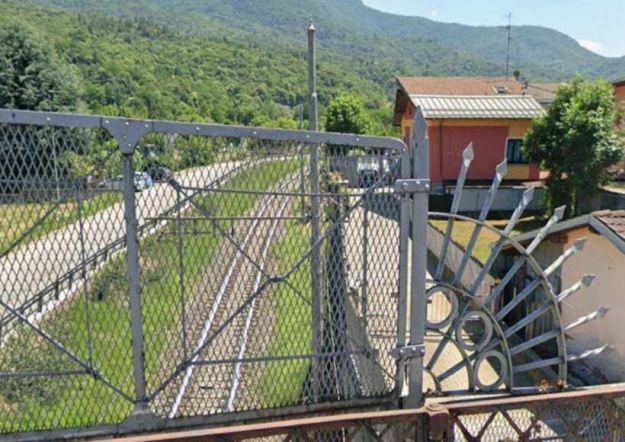

A long double-track section of the line runs through the station at St. Dalmas de Tende. A small yard remains on the North side of the line entered vis the point seen in this image. [55]

The final approach to St. Dalmas Railway Station from the Northeast. [55]

St. Dalmas de Tende Railway Station seen, looking Southwest, from the cab of a South-bound train. [55]

St. Dalmas de Tende Railway Station seen, looking Northeast, from the cab of a North-bound service. [35]

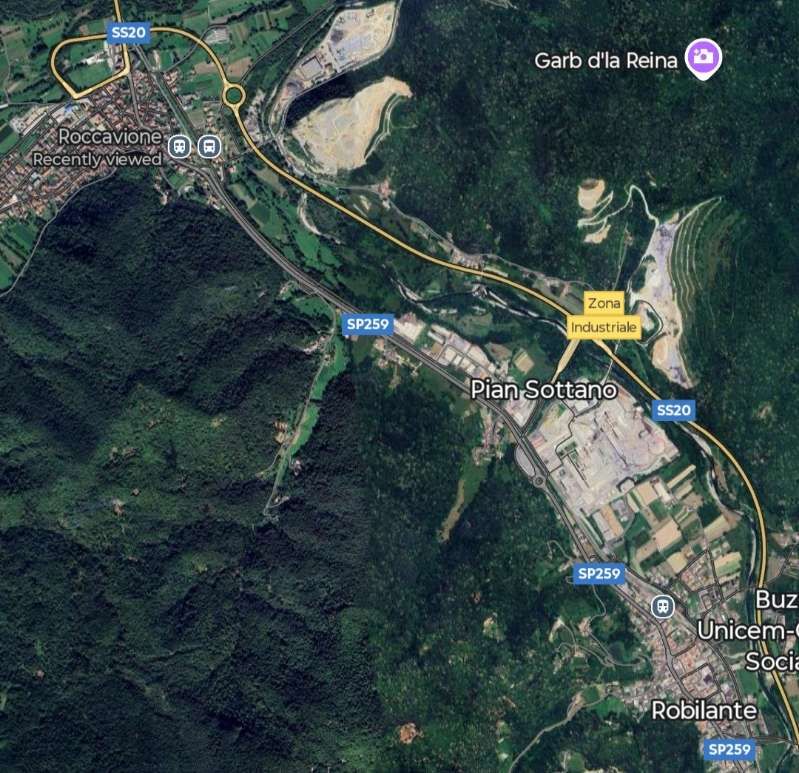

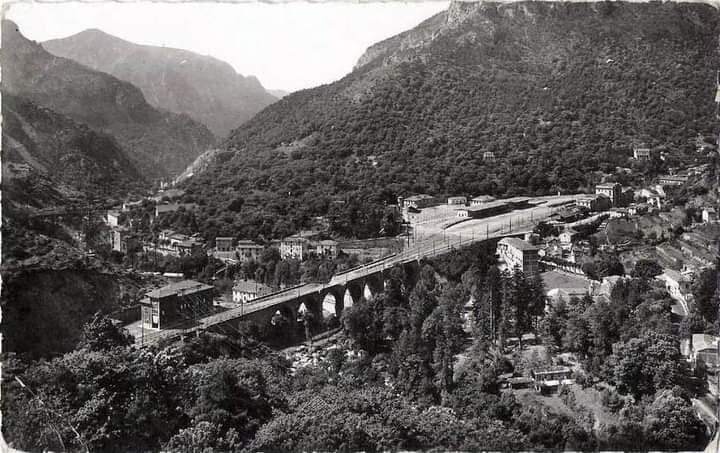

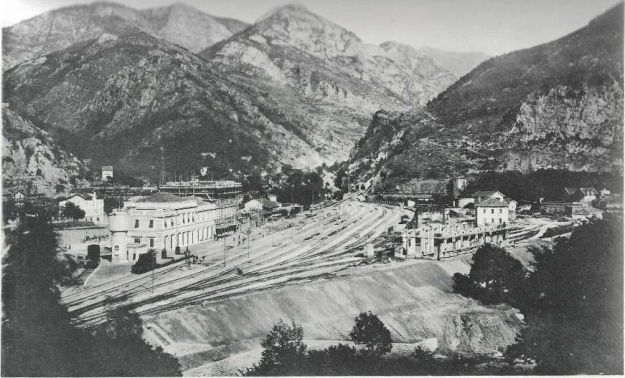

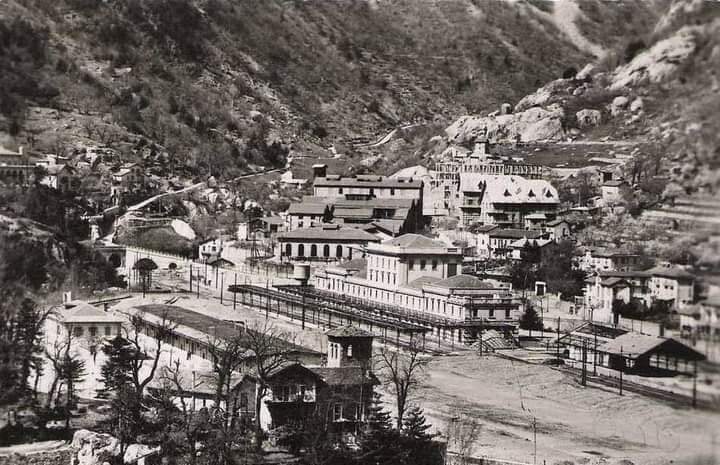

St. Dalmas de Tende (San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda in Italian) was “the last station on Italian territory, before the northern border. This is where the French Forces would install a large-scale border station that will handle customs clearance operations in addition to the French facilities at Breil. In the first phase, a temporary passenger building and a small freight shed were built on the vast embankment created from the spoil from the tunnels upstream of the confluence of the Roya and Biogna rivers. The original layout includes four through tracks, one of which is at the platform, five sidings, three storage tracks, a temporary engine shed, a 9.50 m turntable, and a hydraulic power supply for the locomotives.” [1: p127]

It is here, at St. Dalmas de Tende, that we finish this third part of our journey from Cuneo to the coast.

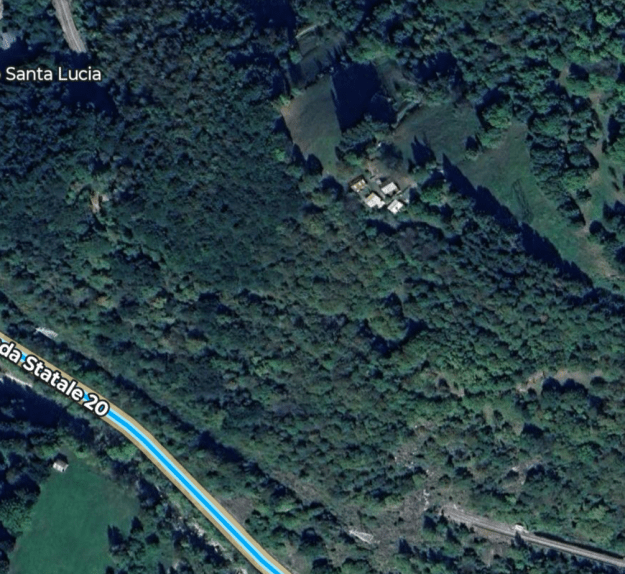

Located at the confluence of the Roya River with the side valleys of the Levenza and Biogna, San-Dalmazzo-di-Tende “was built around a former Augustinian convent that became offices of the Vallauria mining company and then a spa. Since the border was established in 1860 a few kilometers downstream in the Paganin Gorges, first a few dozen, then hundreds of workers, employees, and civil servants gradually settled in San-Dalmazzo with their families. Jobs were plentiful, with the development of mining in the neighboring Val d’Inferno, the creation of a sawmill, the construction of dams and hydroelectric power plants, the emergence of tourism, and the permanent presence of a large number of police, customs, and tax guards. This influx … was reinforced during the railway works, which attracted many workers: earthmovers, masons, stonemasons, miners, carpenters, etc. These newcomers, who mostly came from other regions, sometimes far away, slowly integrated into the local population.” [1: p130]

The line to San-Dalmazzo-di-Tende was opened on 1st June 1915. The three of the four daily services were connected to the Southern arm of the line which by this time had reached Airole, by a coach shuttle. [1: p131]

A temporary station was provided as a terminus of the line from Cuneo. It was sited to the Northeast of the present large station building which was not built until 1928.

The next length of the line can be found here. [67]

References

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 1: 1858-1928; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 2: 1929-1974; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 3: 1975-1986; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/19U2VzU6gT, accessed on 8th August 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/FerroviaCuneoVentimiglia/permalink/5329737250380256/?rdid=6Xne0EJn2Z4xCUiE&share_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fshare%2Fp%2F1C8mWmX57o%2F#, accessed on 8th August 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/FerroviaCuneoVentimiglia/permalink/1747294131957937/?rdid=QhA9x5D943zrICPG&share_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fshare%2Fp%2F1E6w5RsWSL%2F#, accessed on 8th August 2025.

- TBA

- https://youtu.be/2Xq7_b4MfmU?si=1sOymKkFjSpxMkcR, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/07/22/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-1.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/07/26/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-2.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vievola_staz_ferr_ALn_663.jpg, accessed on 26th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1430625447210493&set=gm.755686417785385, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stazione_Vievola_1910.jpg, accessed on 27th July 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/07/27/a-tramway-in-the-valley-of-the-river-roya-early-20th-century

- http://www.lmm.jussieu.fr/~lagree/TEXTES/PDF/RK_Landslides_Vie%CC%81vola_Revised.pdf, accessed on 29th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/16iQbYtjAB, accessed on 29th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1YwoXQBLiR, accessed on 29th July 2025.

- https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sch%C3%A9ma_de_la_ligne_de_Coni_%C3%A0_Vintimille, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.10895/7.56098&layers=P, accessed on 29th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.108596/7.571928&layers=P, accessed on 30th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=19/44.106950/7.573406&layers=P, accessed on 30th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=15/44.10372/7.58022&layers=P, accessed on 30th July 2025.

- https://youtu.be/cHWVUYznw6g?si=lGZhcr09_Lx2RIpd, accessed on 30th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=19/44.102247/7.586114&layers=P, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.101422/7.588175&layers=P, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.100292/7.590059&layers=P, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.098049/7.591515&layers=P, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.094337/7.595475&layers=P, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=18/44.092624/7.597449&layers=P, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=18/44.093422/7.599427&layers=P, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=18/44.093468/7.600340&layers=P, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.095803/7.602404&layers=P, a cessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.09671/7.60013&layers=P, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.09483/7.59382&layers=P, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_qX8v5gceVU, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=15/44.09608/7.59520, accessed on 2nd August 2025.

- https://youtu.be/K6aAQ_zTWds, accessed on 2nd August 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gr_gare_de_tende_en_2004.jpg, accessed on 2nd August 2025

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stazione_di_Tenda, accessed on 2nd August 2025

- Franco Collidà, Max Gallo & Aldo A. Mola; CUNEO-NIZZA History of a Railway; Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo, Cuneo (CN), July 1982.

- Franco Collidà; 1845-1979: the Cuneo-Nice line year by year; in Rassegna – Quarterly magazine of the Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo; No. 7, September 1979, pp. 12-18.

- Stefano Garzaro & Nico Molino; THE TENDA RAILWAY From Cuneo to Nice, the last great Alpine crossing; Editrice di Storia dei Trasporti, Colleferro (RM), EST, July 1982.

- SNCF Region de Marseille; Line: Coni – Breil sur Roya – Vintimille. Reconstruction et équipement de la section de ligne située en territoire Français; Imprimerie St-Victor, Marseille (F), 1980.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuneo_railway_station, accessed on 3rd August 2025.

- T.B.A.

- T.B.A.

- T.B.A.

- T.B.A.

- https://ventimigliaaltawords.com/2013/10/14/all-steamed-up-about-the-ventimiglia-cuneo-rail-link, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- https://trainconsultant.com/2020/10/09/nice-coni-incroyable-derniere-nee-des-grandes-lignes-internationales, accessed on 17th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=14/44.07112/7.59577&layers=P, accessed on 3rd August 2025.

- https://ebay.us/m/aao3zt, accessed on 3rd August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=18/44.087616/7.595785&layers=P, accessed on 3rd August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.08095/7.59714&layers=P, accessed on 3rd August 2025.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hbzk68KoRj8&t=4533s, accessed on 4th August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=15/44.06722/7.59971, accessed on 4th August 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Gare_de_La_Brigue, accessed on 4th August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=18/44.062224/7.604105, accessed on 4th August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.061282/7.597185, accessed on 4th August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.05701/7.59374, accessed on 5th August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.05690/7.58934, accessed on 5th August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.055854/7.584440, accessed on 5th August 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/194416750579024/search/?q=st.%20dalmas%20de%20tende, accessed on 5th August 2025.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Locomotiva_N._6301.jpg, accessed on 6th August 2025

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FS_895.jpg, accessed on 6th August 2025.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stazione_Vievola_1910.jpg, accessed on 6th August 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/08/16/the-railway-between-nice-tende-and-cuneo-part-4-st-dalmas-de-tende-to-breil-sur-roya/

- This image appeared on an Italian Facebook Group but I did not record which one and cannot now find the image or the group, accessed on 1st October 2025.