Hyères-Ville to Bormes

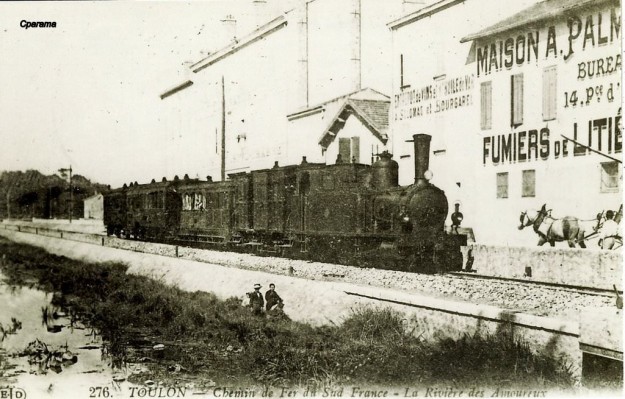

Details of the Chemin de Fer du Sud de la France from Toulon to Saint-Raphael are culled from a number of sources. Three significant ones are: Roland Le Corff [1], Marc Andre Dubout [2] and Jean-Pierre Moreau [3]. Others will be referred to as we follow the route of the line.

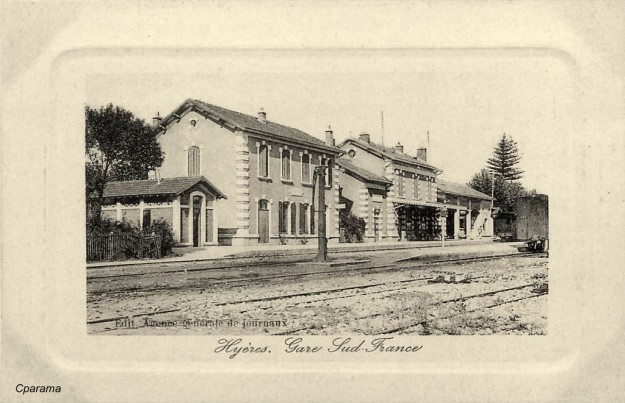

We start this section of our journey at Hyères and head eastward along the Chemin de Fer du Sud towards St. Raphael. But first a bit about the station at Hyères.

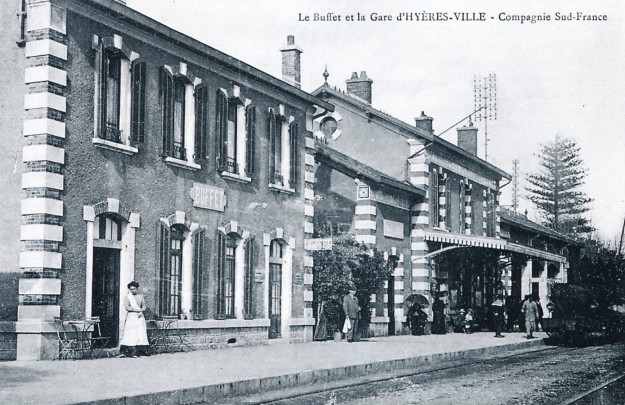

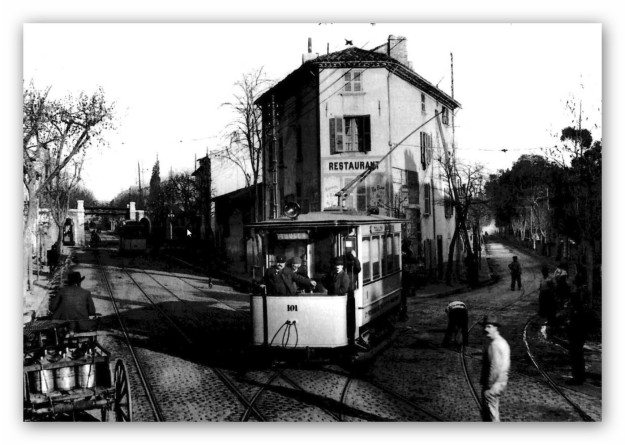

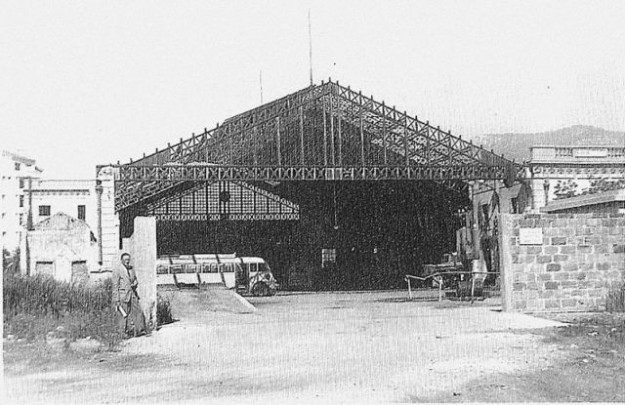

Situated approximately 22.5 kilometeres from Toulon Station, the Station closest to Hyères, Hyères-Ville was opened in 1890, it had the status ‘1st Class’ which put it on a par with the Gare du Sud in Toulon. It had three passenger platforms and 4 goods tracks. In 1907 the engine shed at Hyères-Echange was abandoned and a new facility, suitable for two engines was constructed at Hyères-Ville. Later in 1908 a restaurant/buffet building was constructed at the station.

The aerial view above shows the conditions extant at the station in the middle of the 20th Century, the land immediately around the station to its West and South is undeveloped. The town of Hyères is on its north side. In the 21st Century there is a very different story to tell. The station site has been swallowed up by the town of Hyères. The next image is taken from Jean-Pierre Moreau’s web pages and shows the old station plan superimposed on a modern satellite image from Google earth.

The station is long-gone and the area has been completely re-developed. The final plan-view is of the site taken from Google Earth.

The station was demolished in 1967 and has been replaced by tax collection offices, the municipal library and the town’s museum.

With nothing remaining of the station we are reliant on old pictures to help us appreciate the site better. Both of the pictures below show the station after the construction of the station buffet building. The designation of the first refers to avenues of palms which bordered roads in the town and which give it the name Hyères-les-Palmiers.

With nothing remaining of the station we are reliant on old pictures to help us appreciate the site better. Both of the pictures below show the station after the construction of the station buffet building. The designation of the first refers to avenues of palms which bordered roads in the town and which give it the name Hyères-les-Palmiers.

The Station Buffet Bar on Platform 1 (Jean-Pierre VIGUIER Collection)

A number of these images come from the webpages maintained by Jean-Pierre Moreau. All of these pictures show the buffet-bar building and so date from after the first year of operation of the line. The image at the top of these pages can be dated to the first year of operation as there is no buffet-bar building at the side of the platform. The image immediately above is taken in the 1930s, a mixed train from St.Raphaël to Toulon station is standing at platform 3. An open car “jardinière” is located behind the 230T SACM # 61 locomotive. (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – Pierre VIROT collection).

A number of these images come from the webpages maintained by Jean-Pierre Moreau. All of these pictures show the buffet-bar building and so date from after the first year of operation of the line. The image at the top of these pages can be dated to the first year of operation as there is no buffet-bar building at the side of the platform. The image immediately above is taken in the 1930s, a mixed train from St.Raphaël to Toulon station is standing at platform 3. An open car “jardinière” is located behind the 230T SACM # 61 locomotive. (Photo Marcel CAUVIN – Pierre VIROT collection).

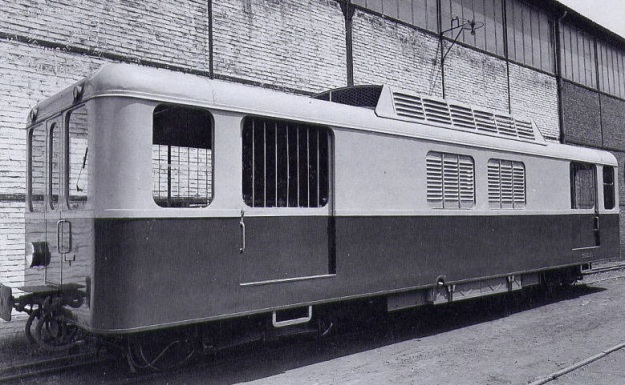

The image below was taken in 1937 at Hyeres. It is a two-axle 2nd Class A-2013 Decauville (José BANAUDO Collection).

These two images show the same Brissonneau & Lotz railcar in Hyères-Ville around 1938 (Edmond DUCLOS & GECP collections).

These following two images of workers on the line were taken in 1943 (during WW2) in Hyères. They show the same class of engine, a locomotive 141 Corpet-Louvet type. The engine in the first photo is named “Dakar.” Three engine drivers from Toulon pose in berets, and a station agent and train agent pose in caps in the first picture (GECP collection). Moreau says that the second locomotive is No. 21 (Marcel CAUVIN & LUGAN – GECP collection).

The final image at Hyères is taken in August 1947. In summer, railcars were coupled, making it possible for each movement to have a capacity of 216 seats (the seating capacity of 120 per unit was often exceeded through overcrowding). This train is travelling from Toulon to St. Raphael (Collection José BANAUDO).

The final image at Hyères is taken in August 1947. In summer, railcars were coupled, making it possible for each movement to have a capacity of 216 seats (the seating capacity of 120 per unit was often exceeded through overcrowding). This train is travelling from Toulon to St. Raphael (Collection José BANAUDO).

Having spent some time at Hyères, we leave travelling Eastward, the track formation follows what id now Rue de Soleil Levant on a sweeping curve down to what is now the D98. This road is now a dual carriageway with the East-bound (south-side) carriageway over the formation of the railway line.

There was a Halt at Riondet (Riondet-Golf) and then the line bridged the River Gapeau on a bridge designed by Gustav Eiffel.

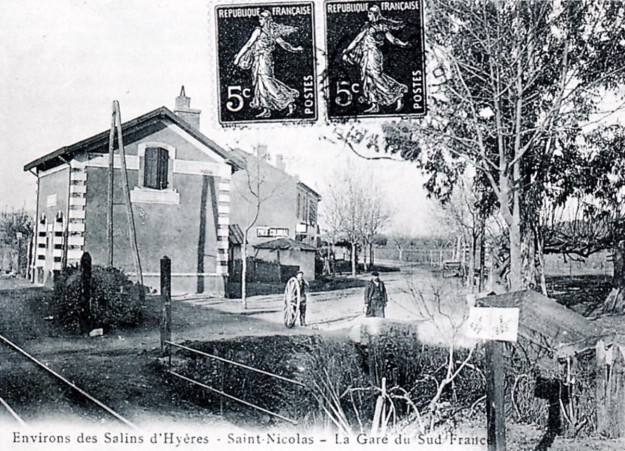

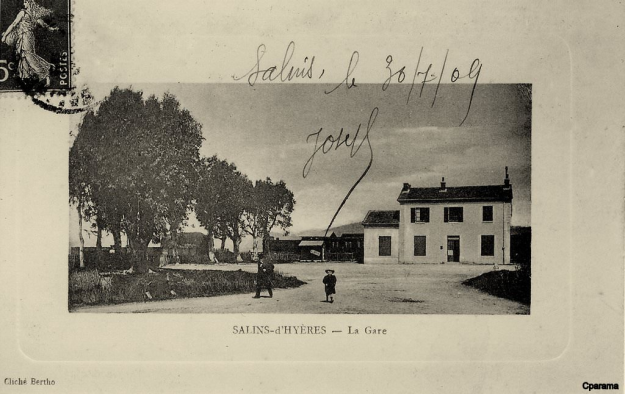

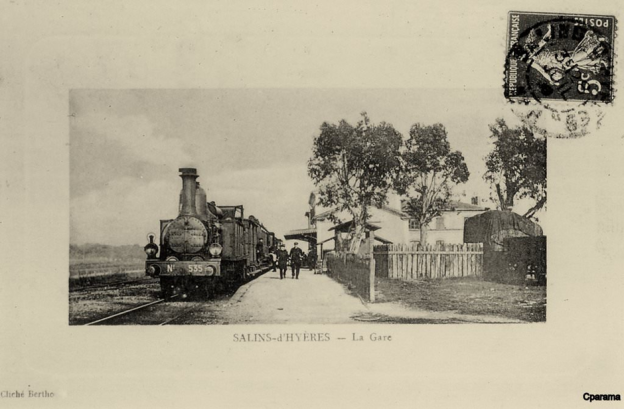

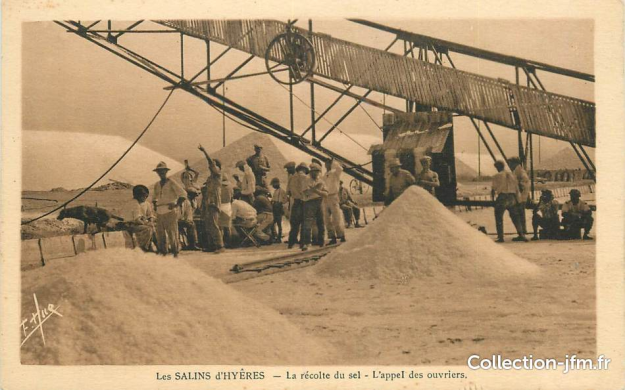

After having crossed the River Gapeau the line by-passed Les Salins d’Hyères to the south. There was a small halt at St.Nicolas-Mauvanne at the level-crossing on the road leading to Vieux Salins. In the picture below a 121T SACM 51-56 locomotive enters the halt from the St. Raphael direction (Collections Jean-Paul PIGNEDE & Jean-Pierre VIGUIE).

The building is still intact. The line is now running on the north side of the D98, the building is visible from the road but over a concrete wall. The first image is from Google Streetview and is taken from the D98. Moreau provides photographs of the rail-side of the building which were taken in 2014 from the other side of the wall. And finally at this location, a view of the building from the D559A which runs parallel to the D98 to the North. The building is marked on the photograph.

From the halt at halt at St.Nicolas-Mauvanne the railway formation remains under the D98 dual carriageway. Then as the D98 begins to drift northwards, the line of the railway follows the D559A into La Londe. On the way into La Londe the railway formation follows the verge on the D559A (Avenue Albert Roux) and crosses the River Pansard. The bridge trusses remain. The monotone picture below was taken by Robert ROSTAGN in 1996 the second image comes from Google Streetview. The old bridge now carries the cycleway.

This smaller image shows the bridge in plan alongside the highway.

This smaller image shows the bridge in plan alongside the highway.

After a re-alignment northwards, the railway line crossed Avenue de l’Eglise (probably Place André Allègre, today). The crossing point is visible below.

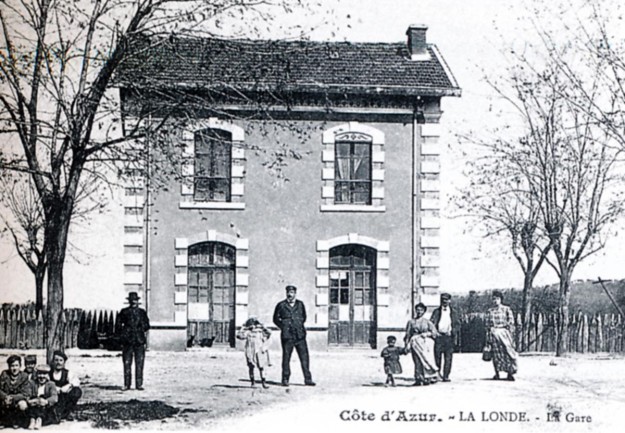

The railway line then approached the station at La Londe, still following the line of what is now the D559A. The station at La Londe was rated ‘3rd Class’ but during the war had quite high traffic volumes because of the nearby torpedo factory. The first three pictures below show trains arriving from Saint-Raphael. The fourth shows a train heading towards Saint-Raphael.

La Londe-les-Maures is at the edge of the Maures Mountains and faces out onto the lles d’Or (Golden Islands). Côtes de Provence Wine, flowers (roses, tulips etc.) and herbs, olive groves and cork oaks all add to the appeal of the town. The beaches stretch from the old salt marshes (a nudist beach) to Estagnol (near Fort Bregangon), Miramar, Argentière and on to Pellegrin. All of this makes this small town a prime holiday destination! However, our real interest is the railway and its history and hopefully these pictures aid in gaining a good idea of the station as it was.

La Londe began to develop as a municipality in 1875 when Victor Roux discovered rich mineral deposits. Lead and zince were responsible for turning nan essentially rural laocation dependent on farming and forestry into and industrial area. Mining strated on an industrial scale in 1885 and created numerous jobs.

From 1890 onwards, other veins of minerals were identified across almost two-thirds of the Commune and in parts of Bormes and Collobrières. These mines were so prosperous that they necessitated the construction of a railway in 1899 for the transport of workers and the transport of the ore to the factory where its treatment was done, and its shipment by sea.

Lead ore initially had to be taken away from the area for processing. A foundry was developed to treat the lead locally. It was completed in 1897.

The prosperity of the mine contributed directly to the development of the village (construction of houses, a church, creation of schools, a post office and telegraph office, a gendarmerie, etc …) and the creation of the municipality. Gradually gaining autonomy, La Londe asked for independence from Hyères and was made a commune on 11th January 1901.

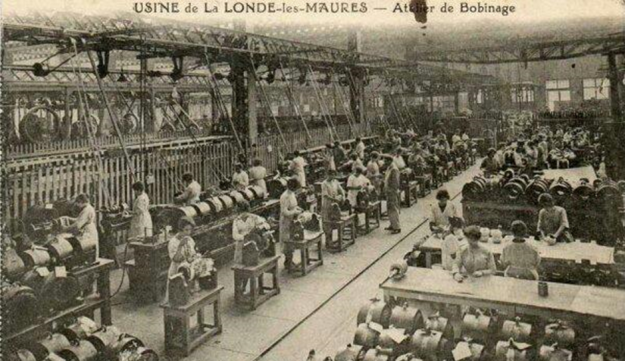

The town then took the official name of “Londe Les Maures”. Sadly, as the town grew, the prosperity of the mines decreased. All activity at the mines ceased in 1929. Taking advantage of the available workforce from the declining mine, the Schneider group was formed in Bormettes in 1907, and in 1912 built an armament factory, a subsidiary of the Creusot factories in Burgundy .

This company contributed to the development of the town by building accommodation for its wrokers close to the plant. In 1920, a railway line was created to transport workers, tools and goods to the town. The “Promenade des Annamites”, named in memory of Indochinese soldiers mobilized in France during the First World War and living near this path, follows part of the route today.

In the 1940s, the Navy made use of some buildings and land in Les Bormettes’ It owned, among other things, Château Vernet and the Astrolabe building which had been appropriated by the occupying German troops. After liberation a maritime training centre was developed. In 1972, following a regrouping of Marine schools in St Mandrier, the site became the property of the Ministry of PTT and France Telecom.

Since the 1950s, the town has gradually reinvented itself as a seaside resort with a hinterland of 22 estates and wine chateaux, many greenhouses and the largest olive grove in the Var.

It is the local branch-lines that most interest me. The first was developed around the turn of the 20th Century to serve mining operations and the second served the armaments factory later in the 20th Century.

The armaments factory was on the sea-shore at point ‘A’ on the satellite image provided by Moreau. The route of the later branch-line is marked in yellow and left the main line just to the East of La Londe Station, shown in the top left of the satellite image below.

After the main satellite image below, there is a close up of the station and junction positions. The main-line left the station along the line of what is now called the Impasse du Ruisseau to the South side of the D559A It continued 50 metres or so to the South of the road until close to the River Maravenne. At this point the D559A heads North-east., The railway turned Eastward and crossed the river on a concrete arch bridge.

After the main satellite image below, there is a close up of the station and junction positions. The main-line left the station along the line of what is now called the Impasse du Ruisseau to the South side of the D559A It continued 50 metres or so to the South of the road until close to the River Maravenne. At this point the D559A heads North-east., The railway turned Eastward and crossed the river on a concrete arch bridge.

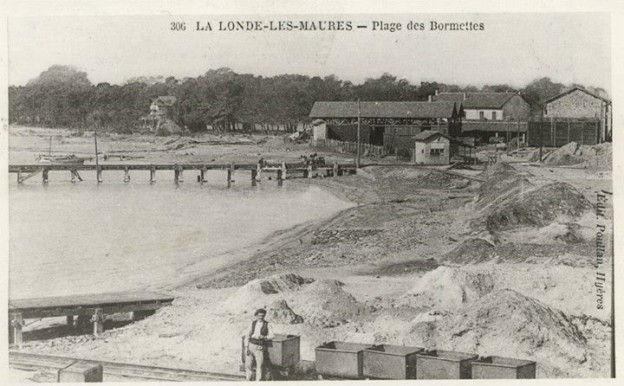

Dubout says that the image here is of the branch-line to the munitions factory. The works at the coast can be seen on the following images. There are pictures of the mines and of the factory as well as the loading jetty for shipments by sea.

Dubout says that the image here is of the branch-line to the munitions factory. The works at the coast can be seen on the following images. There are pictures of the mines and of the factory as well as the loading jetty for shipments by sea.

A number of copyright images have been reproduced here from a variety of sources. This image is a case in point. It appears on a search of images relating to La Londe and clearly bears the copyright stamp across the image. Copyright of other images is very difficult to establish as the images are of a significant age. This image is of the jetty on the older branch.

These next few images relate to the munitions and torpedo factory on the seashore and to parts of the line which preceded Schneider’s railway and served the mines which closed in 1929.

Moreau provides images of trains on the branch-line to the factory.

The first is a view of locomotive 0-6-0T No. 79 “Luronne” at the head of the workers’ train from the Schneider torpedo factory in La Londe, circa 1921 (Edmond DUCLOS Collection). The next image is also of the workers’ train at the entrance of the Schneider torpedo factory in La Londe. The locomotive could be the 0-6-0T Krauss No. 78 “La Madeleine” (Gilbert MARI Collection).

The branch shown on Moreau’s plan is the later branch-line built to serve the munitions and torpedo factory. More details of this line and the preceding mineral line are provided in a separate post in this series.

The branch shown on Moreau’s plan is the later branch-line built to serve the munitions and torpedo factory. More details of this line and the preceding mineral line are provided in a separate post in this series.

Back to the mainline …. After leaving La Londe the Chemin de Fer du Sud travelled Eastwards on the line of what is now the D559A crossing the River Maravenne and running along what is now the Route de Caroubier before rejoining the D98. Initially, the track formation is hidden by the D98 road construction, but later the formation can be seen on the South side of the road.

Back to the mainline …. After leaving La Londe the Chemin de Fer du Sud travelled Eastwards on the line of what is now the D559A crossing the River Maravenne and running along what is now the Route de Caroubier before rejoining the D98. Initially, the track formation is hidden by the D98 road construction, but later the formation can be seen on the South side of the road.

The line disappears once again under the D98 and then bears off to the left before swinging back across the line of the road. A short distance later a crossing keepers cottage (or maybe a halt) is visible at the point where the line drifts away from the modern D98. Its position relative to the road suggests that the line was at a lower level and on the South side of the modern road. From this point on the D98 and the old railway diverge and the railway heads into the forest.

The line disappears once again under the D98 and then bears off to the left before swinging back across the line of the road. A short distance later a crossing keepers cottage (or maybe a halt) is visible at the point where the line drifts away from the modern D98. Its position relative to the road suggests that the line was at a lower level and on the South side of the modern road. From this point on the D98 and the old railway diverge and the railway heads into the forest.

A side-road off the D98 passes this side of the crossing keepers cottage in the last of this sequence of photos. The railway line passed just the other side of the building and is the route of a cycle track (Chemin des Renoncules) which runs south of the road swinging away to the South before bridging a small river on Viaduc du Bataillier which was a series of three masonry arches, the side spans being approximately 5 metres and the central span about 10 metres. The viaduct still exists carrying the cycle track. Replacement parapets have been provided in a form more suited to the cycleway.

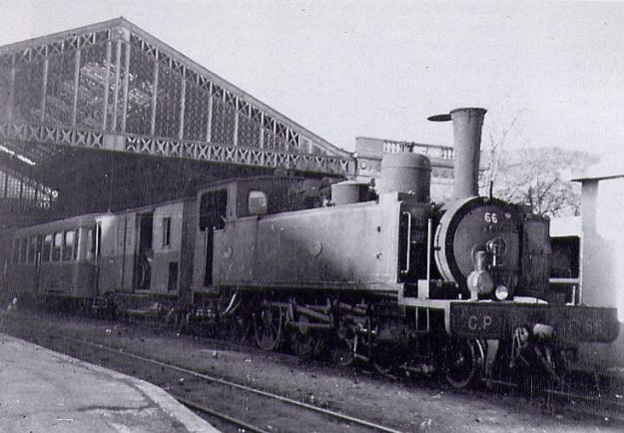

Immediately after crossing the river there was a small halt called ‘Les Bataillier’ of which nothing remains except steps leading up from the D559. The line then crossed the road at high level. There are photos of this bridge following those of the viaduct. The train seen on the overbridge in 1947 is a 4-6-0T Pinguely series 63 to 66. (Photo Jean-P SCHOEN – LAEDERICH collection)

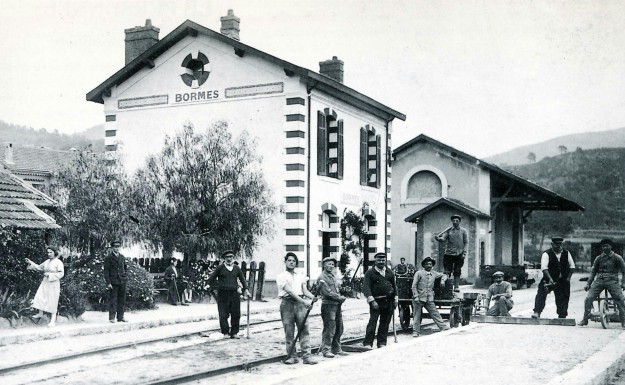

After crossing the viaduct, trains continued along the line toward Bormes.

References

[1] Roland Le Corff; http://www.mes-annees-50.fr/Le_Macaron.htm, accessed 13th December 2017.

[2] Marc Andre Dubout; http://marc-andre-dubout.org/cf/baguenaude/toulon-st-raphael/toulon-st-raphael1.htm, accessed 14th December 2017.

[3] Jean-Pierre Moreau; http://moreau.fr.free.fr/mescartes/ToulonGareSudFrance.html, accessed 24th December 2017.

[4] José Banaudo; Histoire des Chemins de Fer de Provence – 2: Le Train du Littoral (A History of the Railways of Provence Volume 2: The Costal Railway); Les Éditions du Cabri, 1999.

[5] Roger Farnworth; Ligne du Littoral (Toulon to St. Raphael) – Part 5 – Toulon to Hyeres (Chemin de Fer de Provence 40); https://rogerfarnworth.wordpress.com/2017/12/26/ligne-du-littoral-toulon-to-st-raphael-part-5-toulon-to-hyeres-chemin-de-fer-de-provence-39.

[6] Roger Farnworth; Ligne du Littoral (Toulon to St. Raphael) – Part 7 – La Londe & Les Bormettes (Chemin de Fer de Provence 42); https://rogerfarnworth.wordpress.com/2017/12/29/ligne-du-littoral-toulon-to-st-raphael-part-7-la-londe-les-bormettes-chemin-de-fer-de-provence-42.

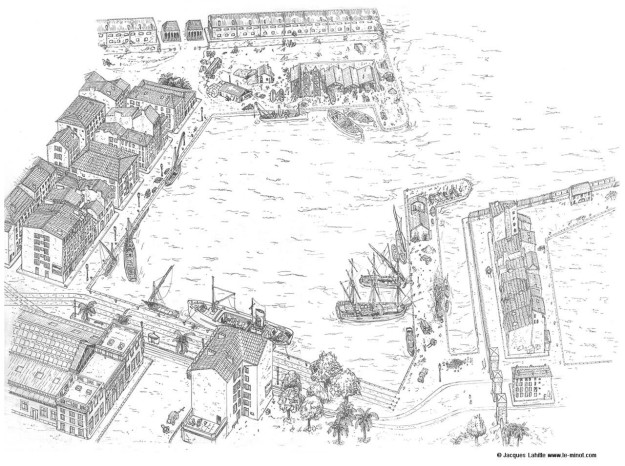

8.7 kilometres from The Gare du Sud in Toulon we arrive at La Pradet Station. It was a more significant stop on the line with passenger facilities, a goods shed, two goods sidings, a passing loop serving two platforms, a 50 cubic-metre water tower and three hydraulic cranes. The Station building still exists, converted into housing it sits close to a cultural centre – “Espace des Arts”, effectively enveloped by it! Little else of the site remains. The first image was taken in 2004 by Jacques Lahitte. The second modern image was taken from Google Streetview in 2017.

8.7 kilometres from The Gare du Sud in Toulon we arrive at La Pradet Station. It was a more significant stop on the line with passenger facilities, a goods shed, two goods sidings, a passing loop serving two platforms, a 50 cubic-metre water tower and three hydraulic cranes. The Station building still exists, converted into housing it sits close to a cultural centre – “Espace des Arts”, effectively enveloped by it! Little else of the site remains. The first image was taken in 2004 by Jacques Lahitte. The second modern image was taken from Google Streetview in 2017.

In the image above, Les Salins d’Hyères is in the top right and Hyères Station can be seen in the top left. The tight radius as the line approaches the coast is clearly visible centre-bottom of the image below the airport.

In the image above, Les Salins d’Hyères is in the top right and Hyères Station can be seen in the top left. The tight radius as the line approaches the coast is clearly visible centre-bottom of the image below the airport.

These two pictures show the station after closure and the cycle track which replaced the railway alongside the coast road. The following picture shows a hotel and the airport. The line of the railway is still visible alongside the coast road.

These two pictures show the station after closure and the cycle track which replaced the railway alongside the coast road. The following picture shows a hotel and the airport. The line of the railway is still visible alongside the coast road.

The station after closure

The station after closure

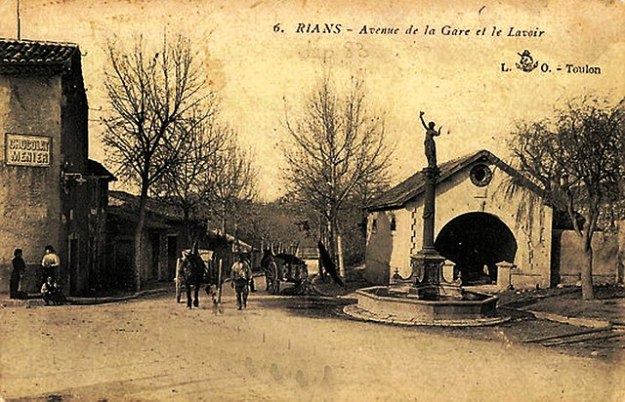

Rians is a commune in the Var department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region in south-eastern France. It is a provençal village in the Upper Var located north east of the Montagne Sainte-Victoire. It is on a narrow farming plain between the hills north-east of Sainte-Victoire and south of the Durance/Verdon hills.

Rians is a commune in the Var department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region in south-eastern France. It is a provençal village in the Upper Var located north east of the Montagne Sainte-Victoire. It is on a narrow farming plain between the hills north-east of Sainte-Victoire and south of the Durance/Verdon hills.