I was asked to give a talk in 2020 to a clergy discussion group on the subject ‘Clergy and Trains’. This group had decided to have its annual outing on The East Lancs Railway and I was to be the after dinner ‘entertainment’! It did not work out, for obvious reasons in 2020, as the Covid-19 pandemic altered everyone’s plans!

However, as a result of the request, I began to study what was available online and in the press on this subject and the place it takes in the wide range of interests available to the clergy. … Whether my research counts as original research, I very much doubt. However, you might find what follows of interest!

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that the clergy love trains.” So started an article by Ed Beavan in the Church Times on 15th June 2011, entitled ‘All Steamed Up About Trains’. [1] On the centenary of the birth of the Revd W. V. Awdry, creator of Thomas the Tank Engine, Ed Beavan asked, in his article in the Church Times, why so many clergy are railway buffs.

The statement, ‘so many clergy are railway buffs’, seems to me to be the kind of statement which becomes more and more true as time goes by. Once we begin to believe that it is true, we then begin to validate our own understanding and our own take on reality.

I know of no independently accredited study of clergy interests which proves that there is a greater preponderance of railway interest among the clergy when compared with other professions. Although there will probably be someone out there to correct me. Nor, I think is there a similar study which compares the range of different interests held by the clergy and determines the most prevalent.

Model railways (and even railways themselves) are a relative latecomer in the various fields open to clergy to pursue. There are a number of good examples of clergy in previous generations who had interests beyond their own parish, church or flock.

Clergy with interests in Science

In Palaeontology, most early fossil workers were gentleman scientists and members of the clergy, who self‐funded their studies in this new and exciting field. [2]

Wikipedia lists Catholic Clergy who have made significant contributions to Science, [3] and there are many from other denominations too. Examples from across the spectrum of Clergy allegiance to denominations, include:

Roger Bacon – a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empiricism. [7]

Nicolaus Copernicus – a Renaissance-era mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic clergyman who formulated a model of the universe that placed the Sun rather than Earth at its centre. [4]

Gregor Mendel – a scientist, Augustinian friar and abbot of St. Thomas’ Abbey in Brno, Margraviate of Moravia. He gained posthumous recognition as the founder of the modern science of genetics. [5]

Georges Lemaître – a Belgian Catholic priest, mathematician, astronomer, and professor of physics at the Catholic University of Louvain. He was the first to identify that the recession of nearby galaxies can be explained by a theory of an expanding universe. [6]

John Michell – an English natural philosopher and clergyman provided pioneering insights iin astronomy, geology, optics, and gravitation. He was the first person known to: propose the existence of black holes; suggest that earthquakes traveled in (seismic) waves; explain how to manufacture an artificial magnet; and, recognise that double stars were a product of mutual gravitation …. [9]

The extensive Wikipedia list is merely a snapshot of a longer list which extends down to the present day. There have been many people who have combined their scientific eminence with a role as a member of the clergy. A prime example is Revd. John Polkinghorne, [10] Other in the contemporary age include Revd. Arthur Peacocke, the first director of the Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion and the first director of the Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion. [16] Others include: Canon Eric Jenkins, [17]; Revd. John Chalmers, moderator of the Church of Scotland and who has been involved with Church of Scotland projects such as Society Religion and Technology, [18] and Grasping the Nettle. [19]

There is also today, a society for priest-scientists. The Society of Ordained Scientists is a society within the Anglican Communion. The organisation was founded at the University of Oxford by Arthur Peacocke following the establishment of several other similar societies in the 1970s, in order to advance the field of religion and science. [11][15]

Other interests are also shared by clergy and the religious.

One particularly engaging study of clergy interests and proclivities was produced recently by Revd Fergus Butler-Gallie, “A Field Guide to the English Clergy: A Compendium of Diverse Eccentrics, Pirates, Prelates and Adventurers; All Anglican, Some Even Practising.” [12]

Waterstones comment: “Judge not, lest ye be judged. This timeless wisdom has guided the Anglican Church for hundreds of years, fostering a certain tolerance of eccentricity among its members. Good thing, too!” [13] Given my interests in blogging, railways and model railways, I have no alternative but to echo the sentiment. … “Yes, it is a good thing too!”

Butler-Gallie regales us with “eye-popping tales of lunacy, debauchery and depravity … he has done a splendid job presenting a smorgasbord of most peculiar parsons.” [14]

Among many other things, he tells us of a variety of different eccentrics who somehow found themselves within the ranks of the clergy. Examples include Revd Robert Hawker, Vicar of Morwenstow who was the first to institute a church Harvest Festival, but who at one time also used to dress as a mermaid. There was also an erstwhile Rector of Carrington whose fear of photography meant that he led services from behind a screen and who during a very long ministry built the largest folly ever constructed within these shores. Butler-Gallie goes on the describe a pantheon of eccentrics, nutty professors, bon viveurs, prodigal sons and rogues, all of whom appear to have somehow ended up either with their own parish or in the position of senior clergy. [12]

My current curate, while definitely not being an eccentric, has been an avid player of computer games, he plays regularly in a variety of different local bands, and he has taken up roller-blading. One Franciscan friar, Brother Gabriel, spends his spare time at a Bloomington, Indiana, Skate Park several times a week after participating in evening Mass and prayers. [8]

This article is, in no way, a formal survey of clergy interests, and all these examples are, of course, very obviously anecdotal.

So, are there any grounds for believing that an interest in railways is more typical of the clergy than these other things?

I suspect not.

Nevertheless, there do seem to be a good number of clergy who are interested in both full-scale and model railways.

Clergy with an interest in Railways.

Font to Footplate – Teddy Boston’s autobiography completed while he was in hospital just before he died at the age of 61. [48]

Butler-Gallie directs our attention to one

Revd. Teddy Boston. [12: p19-22] who was for 26 years Rector of Cadeby and Vicar of Sutton Cheney, in Leicestershire, (1960 – 1986). He built a light railway in the grounds of the Rectory at Cadeby. It was U-shaped, with a total length of 110 yards. He opened the line to passengers in 1963 [20] and named the line, “Cadeby Light Railway.”

Wikipedia tells us that Boston, “was a close friend of the Rev. W. V. Awdry OBE, creator of Thomas the Tank Engine, a kindred spirit with whom he shared many railway holidays. In Small Railway Engines (1967), Awdry relies on a trip the two made together to the Ravenglass and Eskdale Railway, and they appear in the book as ‘the Fat Clergyman’ (Boston) and ‘the Thin Clergyman’ (Awdry). [21]

The Rev Wilbert Awdry “controlling” Thomas on the Ffarquhar Branch in Railway Modeller, December 1959. [21]

Wilbert Awdry is perhaps the best know clergy railway fanatic across the world. The ‘Thomas’ franchise is still very popular on the 2020s and Covid-permitting brings in significant revenue for Heritage Railway organisations each year. Awdry himself wrote 26 books in “the Railway Series”. His son Christopher went on to publish a further 16 books between 1983 and 2011. The series has also spawned a number of related books and a significant number of TV/Video/DVD programmes in English. [22] and in many other languages. [23]

Another star in this firmament was Revd. Peter Denny who for many years was a regular feature in the Model Railway Press. [24] He was known alongside others for being at the forefront of the development of the hobby after the Second World War. He was known for modelling which exceeded the expectation of the times for realism. He innovated in the management of his model railway and the timetabling of train movements. His layout Buckingham went through a number of incarnations as it developed in size. There are a variety of books written about his modelling achievements [25] and he is still feted online as well. [26] His layout is described by Tony Wright as, “one of the most important layouts in the hobby’s history since WW2.” [27]

Rt. Revd Eric Treacy MBE was an English railway photographer and Anglican bishop. He was Suffragan Bishop of Pontefract and then Bishop of Wakefield (1968-1976). his passion outside of office was railway photography. The Treacy Collection of 12,000 photographs forms part of the National Railway Museum’s archive of over 1.4 million images. His published works were almost entirely railway photograph albums. [28]

After a major, 11-year, £600,000 overhaul by volunteers on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway, which was completed in 2010, you would have found 70 clergy in the carriages behind the newly named locomotive, ‘Eric Treacy’ on it inaugural run. The then Bishop of Wakefield, the Rt. Revd. Stephen Platten, held a re-dedication service for the train at Pickering Station on 27th August 2010. He was joined by Rt. Revd. Dr David Hope, former Archbishop of York, and Stephen Sorby, of the National Railway Chaplaincy. [32]

Revd Richard Patten, in the late 1960s, bought his own full-size steam locomotive, 73050, and so began the restoration of the Nene Valley Railway near Peterborough. [35]

An interest in railways is something that a number of clergy own up to when talking about themselves. For example:

The Revd. Timothy L’Estrange, MA, DipMin, FRSA, Vicar of North Acton and Surrogate: Spent his spare time as a first aider with the St John Ambulance Brigade, and pursuing a life-long interest in railways, especially the narrow gauge. His parish Reader also expresses an interest in dabbling ‘in the ancient art of railway modelling’. [33]

The Restless Rector, who is not keen to divulge his identity, wrote in his blog of his love of trains. In 2009, he said: “My own theory is that railways are all about order and communication. For some clergy the stress of parish life, and the number of awkward people that one sometimes has to deal with, can be forgotten about in the ordered environment of a model railway. Here you are in complete control, with no-one to answer back or contradict. Yes, trains sometimes get derailed, but no-one gets hurt. Some model railway enthusiasts run their trains to a strict timetable – another layer of order and control. But running a railway can be a very social activity. In real life trains are passed from the control of one signalbox to another with great care. Nowadays this is all computerised, but it used to be by a series of bell codes and telephones.” [34]

He goes on to ask: “Is there anything theological or biblical in all of this? I’m not sure, but maybe building and running a model railway reflects something of the creativeness of God, and his fatherly care.” [34] … In addition, he suggests that because railways are about communication – travel to a destination, the news and the post – then interest in railways may be found more often in the evangelical wing of the church where, “a high priority is put on taking the good news to new places.” [34]

His final comment is perhaps quite Anglican. Talking of his interest in railways, he says: “it’s just something I’ve grown up with and embraced for myself – rather like my faith I suppose.” [34]

In my own experience, interest in railways is relatively evenly spread between clergy colleagues and a particular churchpersonship does not seem to increase the likelihood of that interest. The ecumenical nature of railway interests is illustrated by two clerics invovled with the Railway Preservation Society of Ireland. …

Fr. Eddie Creamer (RPSI). [39]

Revd. Canon John McKegney (RPSI) [39]

a part-time prison chaplain, aged 77, talked in 2017, when he had already been a member of the RPSI for nearly 40 years, of his fascination with trains from his childhood. He goes on to explain that, “

When [he] was working in the Philippines [he] joined the RPSI just to get their magazine sent to [him], but when [he] returned to Ireland [he] came to Whitehead to take a few photographs of the trains. I asked if they needed anyone to help them and they haven’t let me go. And now I’m here once a week. I find it very relaxing.” [39]

In 2017, the Chair of the RPSI was Revd. Canon John McKegney, a retired Church of Ireland rector. In 2017, he had been involved with the RPSI for over half-a-century. [39]

Railways and Religion

The interaction between the church and the railways goes right back to the very early days of what was then a new mode of transport. Revd. Michael Ainsworth points out that “the coming of the railways in the 19th century excited deep passions among churchmen, as many novels of the time illustrate. … For some the speed, the smoke, the ‘blot on the landscape’, were unnatural and diabolical – particularly when Sunday trains broke the sabbath commandment. The vast church of St Bartholomew, Brighton was built on a commanding site, and allegedly on the dimensions of Noah’s Ark, as a witness to those travelling down for ‘dirty weekends’.” [29]

He goes on to say: “Clergy joined with landowners in resisting encroachment. (They had limited success – note, for example, how the line curves round Sacred Trinity Church in Salford.) … But others hailed railways as a godsend and a sign of divinely-blessed progress (despite blighting the urban landscape). … By the latter part of the century, they had certainly revolutionised episcopal ministry. The late 19th-century renewal of enthusiasm for confirmation would not have been possible without the railways. For example, of James Fraser, Bishop of Manchester 1870-85, it was written he spent the week travelling through his diocese, so that there were few days in which he was not somewhere on the railways.” [29]

So, why are a number of clergy interested in railways?

Revd. Michael Ainsworth again: “It has often been said that the reason why some clergy – probably male rather than female – and others, including church musicians, are keen on railways is because they are reassuringly ‘closed systems’, and Awdry’s setting of his railways on the Isle of Sodor confirms this. Lines and boundaries are set, detailed timetables can be pored over, structures are clear: a joy for those who run model railways in their attics for their own pleasure, or larger versions in their gardens to raise funds. … This joy is less pronounced now that the real railways have been franchised and fragmented. Responsibility for trains, track, signalling, stations and all else is dispersed among many bodies – providing more benefit to lawyers than to passengers …‘customers’.” [29]

Revd. Michael Ainsworth again: “It has often been said that the reason why some clergy – probably male rather than female – and others, including church musicians, are keen on railways is because they are reassuringly ‘closed systems’, and Awdry’s setting of his railways on the Isle of Sodor confirms this. Lines and boundaries are set, detailed timetables can be pored over, structures are clear: a joy for those who run model railways in their attics for their own pleasure, or larger versions in their gardens to raise funds. … This joy is less pronounced now that the real railways have been franchised and fragmented. Responsibility for trains, track, signalling, stations and all else is dispersed among many bodies – providing more benefit to lawyers than to passengers …‘customers’.” [29]

The Rt Revd Michael Bourke comments about 19th Century Clergy in the Church Times Letters page in July 2011, that, “Many feared the pace of change, and some religious conservatives denounced the new world, including trains, as the work of the devil. In that context, clerical railway fever (across churchmanship divides) signified an affirmation of modernity. Both railwaymen and churchmen (mostly men in both cases) were re-engineering the nation with their networks of new lines and junctions, new parishes, church schools, and forms of spirituality.” [30]

He goes on to say: “For broad churchmen, the railways spelled enlightened progress; for Evangelicals, the new emphasis on punctuality embodied the Protestant work ethic; and for Catholics, the shared wisdom and co-operation of engineers, locomotive crews, and signalmen represented the mystery of a dedicated priesthood. No wonder the great stations were compared with cathedrals! … Clergy’s instinctive sympathy with this world led to support for the people who ran it, in what amounted to early forms of industrial mission.” [30]

He continues, in his letter, to draw parallels with “a similar clerical enthusiasm for the brave new world of computers.” [30]

It seems that, in the early days of the railways, at least, a clergyperson’s attitude to the newfangled railways said something significant, and provided one uniting factor in the midst of clerical division. However, this is not enough to justify a modern clergy interest in the railways.

Rev Clifford Owen was longing eagerly for his retirement at the age of 70. He was delighted to be surprised by his retirement gift from his last parish in Brugge and Oostende in Belgium: a 5 year membership of the Nene Valley Railway. He describes his joy at the gift and goes on to describe some of the pleasures of being involved with the life of that heritage line near Peterborough and particularly the connection he discovered with his grandfather through undertaking a job that his grandfather would have undertaken 70 years previously. [31]

Revd Preb Mike Kneen.

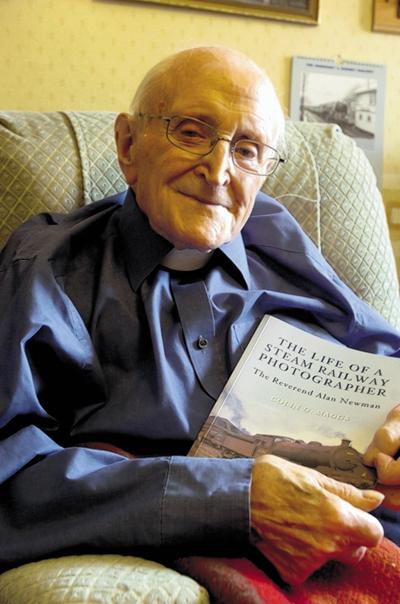

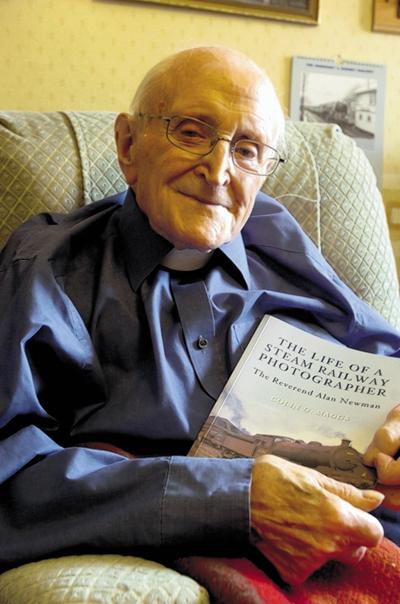

Revd. Alan Newman. [41]

Revd. Preb. Mike Kneen who retired as Rector of Leominster in September 2020 has had a lifelong interest in steam locomotives. His farewell statement on the Leominster Priory Website says nothing of this interest but it is accompanied by a picture of him as an Engine Driver on the Severn Valley Railway – a pastime which he enjoyed throughout his ministry.

The former vicar of Christchurch, Bradford on Avon, Revd. Alan Newman was another significant railway photographer who became part of the photographic triumvirate of himself, Ivo Peters and Norman Lockett, and he was friendly with two other notable railway clerics that we have already encountered above: the Rev. W Awdry and the Rev Teddy Boston. His story is told by Colin Maggs in a book published by Amberley Press. [40]

Newman was born and brought up in Bath near to the Great Western Railway, which sparked a lifelong interest in steam trains in particular. He took extensive trips throughout the country, hoping to see a train of every class in Britain, recording his finds as detailed notes supported by photographs. [41]

David Self in the Church Times in January 2008 asked the same question as this article: ‘What draws clerics to railways?’ [35] It is worth quoting parts of that piece here.

Self says: “In the 1950s, most enthusiasts were merely trainspotters. Folklore suggests that a few clerics could always then be found on the ends of platforms at Crewe, York, and (for some mysterious reason) Worcester Shrub Hill.” [35]

He continues: “There was nothing comic in the ’50s about being interested in trains. Boys wanted to become engine-drivers. In the 1952 Ealing comedy The Titfield Thunderbolt, it was perfectly natural that the leading light in the village’s attempts to preserve its branch line should be the parson, the Revd Samuel Weech. Over the next ten years, however, the railway enthusiast became a figure of fun: a gormless, spotty loner, obsessed by numbers and timetables, and always clutching Biro and notebook.” [35]

In research reported in ‘Trends in Cognitive Sciences’ in June 2002, [42] there was an attempt to define trainspotters as people with a form of Asperger syndrome, as they had a strong desire to order the world. In 2001, the National Autistic Society conducted research among children with autism to explore their frequent attraction to Thomas the Tank Engine. “Among the survey’s findings was the way that many children with autism regard Thomas much as others cherish a comfort blanket. They seem to appreciate the clear plot lines of the stories, the predictability of the characterisation, and the fact that, if something goes wrong, it will be put right by the conclusion. They also seem[ed] fascinated by the engines’ faces.” [35]

David Self says that, “this is not to draw cheap parallels or to make bad jokes about clerics and those with autism or Asperger syndrome. Even so, it is possible to see both ecclesiastical and psychological reasons why watching trains should appeal especially to those in ministry.” [35]

“To the cognoscenti … railways are predictable. For every delay, there is a cause. It is a world of facts and realities, a world where (with luck) it is possible to see all — even if it is only every locomotive of a given type. It is the perfect antidote to the often more nebulous realm of theology.” [35]

“Similarly, for the clerical railway modeller, the layout in the loft presents an opportunity to create a parallel world, where everything runs to order, and at times and in ways you dictate — unlike normal parish life.” [35]

It was David Self’s article that pointed me to an American website (www.steamingpriest.com) that revels something of the breadth of interest among Roman Catholic priests, Protestant ministers, and Rabbis in ‘playing trains’. [36] On that website, as well as seeing something of the scope of his hobby, we are introduced by Fr. Fanelli to his interest in live steam modelling. His interest in railway modelling developed throughout his ministry from first, N scale, through to large scale, live steam models. [37]

David Self reminds us that the former Chancellor Dennis Healey once stressed the importance of a politician’s hinterland — an interest in areas other than politics. Winston Churchhill had his painting, Ted Heath had his sailing and music, and John Major his cricket, and Gordon Brown, an interest in soccer. Lord Healey enjoyed photography and literature. Self says that, “Such interests are not just a means of escape or relaxation, important as these may be. They are evidence of a rounded personality.” [35]

That idea of a ‘hinterland’ to describe interests outside of ‘work’ is useful when thinking of clergy interests. David Self suggests that a ‘hinterland’ of interests outside of the theological and ecclesiastical is essential for clergy, “not just for their own sanity, but to help them relate more easily to the world outside the Church. It can also contribute to developing an inner calm. For some, their hinterland will be their family. For others, it will be cricket — a world where, for a few hours, you are isolated on the pitch and unable to be got at. Many have found a similar escape at the end of a station platform.” [35]

There is more to an interest in railways than trainspotting but I think that Self’s conclusion to his article is apposite to all interest in railways: “Why mock such happiness? Trainspotting must be one of the most harmless and inexpensive hobbies. It can be pursued alone or with friends, and is surprisingly democratic. Your profession (or lack of one) is irrelevant: it is the trains that matter.” [35]

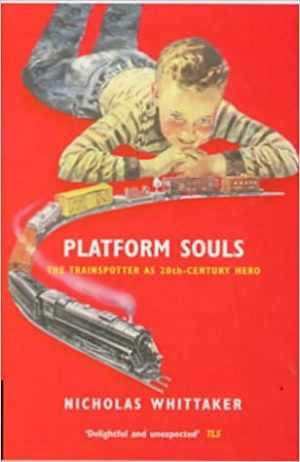

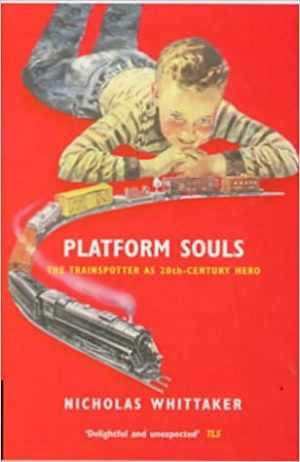

Although Nicholas Whittaker‘s book, “Platform Souls” is purportedly about trainspotting, it acknowledges a wider interest in the realm of railways and, unsurprisingly, within its pages we also encounter the clergy.

Although Nicholas Whittaker‘s book, “Platform Souls” is purportedly about trainspotting, it acknowledges a wider interest in the realm of railways and, unsurprisingly, within its pages we also encounter the clergy.

He describes an open day at a railway depot. “Hauling myself up into the cab of E3003 . . . I bump into my first clergyman. He is semi-disguised in trainers and jeans, but his tweedy jacket and dog collar are a dead giveaway. Perched in the driver’s seat, he . . . whistles high-speed fantasies through his teeth.” [38: p221-222]

Whittaker manages to capture some of the factors that seem inexorably to draw some individuals to the railway. “Trainspotting: here was a real boy’s hobby with its own gaberdine camaraderie. It was dirty and mechanical, proudly masculine and solid, yet at the same time … romantic and educational.” [38: p19]

He talks of a time when as a young boy he first managed to slip unnoticed through a small door in the side of one of Burton-on-Trent MPD’s two roundhouses: “In that moment, you slipped from a fresh-smalling open-air into a strange sepulchral atmosphere, silent but for the his of escaping steam. This was the first time I’d been so close to a railway engine and, without a station platform to bring me level, I stood feeling small and awed by the scale of it.” [38: p23]

One ‘interesting’ footnote is the range of society stars that could be seen while standing at the end of a station platform but of even greater significance to a young Nicholas Whittaker, was the possibility that you might encounter one of the dignitaries of the railway interest establishment such as Cecil J. Allen or C. Hamilton-Ellis. In the light of the purpose of this article, it is worth recording that Whittaker goes on to say: “The one we all wanted to meet was… Eric Treacy, Bishop of Wakefield. We knew that, for some reason, railways attracted the clergy, but a bishop was something special!” [38: p43]

My own interest in railways and railway modelling stems, I believe, from a childhood fascination with trains and from a pre-ordination career in civil engineering. My interest in railways is pretty eclectic, but I accept that for many people it will be perceived as a niche interest.

If you were to read my blog you would find that I have a particular interest in Secondary French railways and tramways, many of which fell into disuse soon after the Second World War but whose routes can still be followed through the French countryside by car and bicycle. Jo and I have done just that in a variety of contexts in Southern France on regular Autumn visits. [45][46]

You will find that I have developed a childhood interest in the 3ft Gauge railways of Ireland into a series of narratives following the routes of those old lines which disappeared in the early second-half of the 20th Century. [44]

You will see that one seminal moment for me was travelling on the ‘Lunatic Express’ in East Africa, and you can, if you wish, follow a full journey along the line from Mombasa to Kampala and beyond. [43]

You will, I hope, be delighted to follow the story of the building of an N-Gauge model railway in the vicarage loft. [47] At times these interests have been all-consuming, they certainly have allowed me to escape from times when ministry has been particularly stressful.

A few pictures of my own layout in the vicarage loft bring the main narrative of this article to a close. The layout focuses on the railways in and around the city of Hereford. Sadly, the ‘day job’ has meant little progress on the layout in the past few years. as retirement beckons there will be a significant effort involved in deconstructing what has been built … Building the Baseboards!

Building the Baseboards! Laying the track!

Laying the track! Hand-made, card Coaling Stage – Hereford MPD

Hand-made, card Coaling Stage – Hereford MPD Hereford, Barrscourt Station Footbridge under construction.

Hereford, Barrscourt Station Footbridge under construction. Hereford, Barrscourt Railway Station in its location on the layout.

Hereford, Barrscourt Railway Station in its location on the layout. The station approach, showing the footbridge in position.

The station approach, showing the footbridge in position. One of Hereford Station’s two signal boxes also of a card construction. Beyond are the two large goods sheds which framed the station approach from the North – these are also of card constriction.

One of Hereford Station’s two signal boxes also of a card construction. Beyond are the two large goods sheds which framed the station approach from the North – these are also of card constriction. The view from the station yard across the allotments to Aylestone Hill.

The view from the station yard across the allotments to Aylestone Hill. The view across the station yard to Aylestone Hill and bridge.

The view across the station yard to Aylestone Hill and bridge. Aylestone Hill Signal Box and carriage sidings.

Aylestone Hill Signal Box and carriage sidings.

Conclusion

It seems that whether a cleric’s interest in railways comes from a past outside the church, or is borne in the midst of theological formation, it has some significant things going for it. In particular, like many other interests, it forms an alternative world to the world of work.

I’m not sure that, ultimately, any further justification is required.

References

- Ed Bevan; All Steamed Up About Trains; Church Times, 15th June 2011; https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2011/17-june/features/all-steamed-up-about-trains, accessed on 9th February 2020.

- Russell J. Garwood, Imran A. Rahman, Mark D. Sutton; From Clergy to Computers; Geology Today, Volume 26, Issue 3, 2010; p96-100; https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2451.2010.00753.x, accessed on 5th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Catholic_clergy_scientists, accessed on 5th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicolaus_Copernicus, accessed on 5th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel, accessed on 5th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_Lemaître, accessed on 5th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Bacon, accessed on 5th November 2020.

- https://www.osvnews.com/2019/04/07/what-clergy-and-religious-do-in-their-spare-time, accessed on 5th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Michell, accessed on 5th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Polkinghorne, accessed on 5th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Society_of_Ordained_Scientists, accessed on 6th November 2020.

- Revd Fergus Butler-Gallie; A Field Guide to the English Clergy: A Compendium of Diverse Eccentrics, Pirates, Prelates and Adventurers; All Anglican, Some Even Practising; Oneworld Publications, London, 2018.

- https://www.waterstones.com/book/a-field-guide-to-the-english-clergy/the-revd-fergus-butler-gallie/9781786074416, accessed on 6th November 2020.

- Sebastian Shakespeare; The Daily Mail, 2018.

- https://ordsci.org, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- https://ordsci.org/history, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2007/9-february/news/uk/canon-eric-neil-jenkins, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- https://www.churchofscotland.org.uk/speak-out/science-and-technology, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- https://www.churchofscotland.org.uk/news-and-events/news/2016/moderator-why-i-support-grasping-the-nettle, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_Boston, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- http://www.pegnsean.net/~railwayseries/awdryobit.htm, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_books_in_The_Railway_Series#Thomas_the_Tank_Engine, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- https://ttte.fandom.com/wiki/Other_Languages, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- For example: Peter Denny; The Railway Modeller Magazine July and August 1958.

- For example: Peter Denny; Peter Denny’s Buckingham Branch Lines: 1945-1967 Pt. 1; Peter Denny’s Buckingham Branch Lines: 1967-1993 Pt. 2; Wild Swan, Oxfordshire; 1993, 1994

- For example: https://highlandmiscellany.com/tag/peter-denny, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- Tony Wright – https://www.world-of-railways.co.uk/model-railways/famous-model-train-layouts-and-their-creators–part-1, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Treacy, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- Revd. Michael Ainsworth; Thoughts on railways, clergy, religion and the law; in Law & Religion UK, 17 April 2015; https://lawandreligionuk.com/2016/04/18/thoughts-on-railways-clergy-religion-and-the-law, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- Rt. Revd. Michael Bourke; https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2011/8-july/comment/letters-to-the-editor/clergy-who-fall-in-love-with-railways-article-was-on-the-right-track, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- Rev Clifford Owen; Retired Clergy Don’t Run Out Of Steam; Diocese of Europe; https://europe.anglican.org/main/latest-news/post/994-retired-clergy-donat-run-out-of-steam, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- Clergy carrying train tribute to former railway fan vicar; The Northern Echo, 2010; https://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/news/local/northyorkshire/8358957.clergy-carrying-train-tribute-former-railway-fan-vicar, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- https://sites.google.com/site/stgabrielacton/our-priests, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- http://coulsdonrectory.blogspot.com/2009/06/clergy-and-trains.html, accessed on 7th November 2020.

- David Self; What draws clerics to railways?; Church Times , 30th January 2008; https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2008/1-february/comment/what-draws-clerics-to-railways, accessed on 8th November 2020.

- https://www.steamingpriest.com, accessed on 8th November 2020.

- https://www.steamingpriest.com/about/fathers-rr-story, accessed on 8th November 2020.

- Nicholas Whittaker; Platform Souls; Orion, London, 1995 (Revised Edition, 2015).

- https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/life/features/love-of-railways-sent-clerics-off-on-a-totally-new-track-36257796.html, accessed on 8th November 2020.

- https://www.amberley-books.com/discover-books/transport-industry/railways/the-life-of-a-steam-railway-photographer.html, accessed on 8th November 2020.

- https://www.wiltshiretimes.co.uk/news/5072513.with-god-and-gwr, accessed on 8th November 2020.

- Simon Baron-Cohen; The extreme male brain theory of autism; in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Volume 6, Issue 6, 1st June 2002, p248-254.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/category/railways-blog/uganda-and-kenya-railways.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/category/railways-blog/ireland.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/category/railways-blog/railways-and-tramways-around-nice.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/category/railways-blog/railways-and-tramways-of-south-western-france.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/category/railways-blog/model-railway.

- Revd. E. R. Boston & P.D. Nicholson; Font to Footplate; Line One Publications, 1986.

My brothers-in-law travelled there at the end of 1989 and picked up a souvenir piece of the wall. Pieces of the Berlin wall are still on sale today.

My brothers-in-law travelled there at the end of 1989 and picked up a souvenir piece of the wall. Pieces of the Berlin wall are still on sale today.

![Ships unloading at the Abadan waterfront in 1942. The rail lines and some wagons are in evidence. [30]](https://rogerfarnworth.files.wordpress.com/2020/11/544d896ed9c6b6a35c82d4b191f17d5e-e1606245014691.jpg?w=625&h=698)

Building the Baseboards!

Building the Baseboards! Laying the track!

Laying the track!