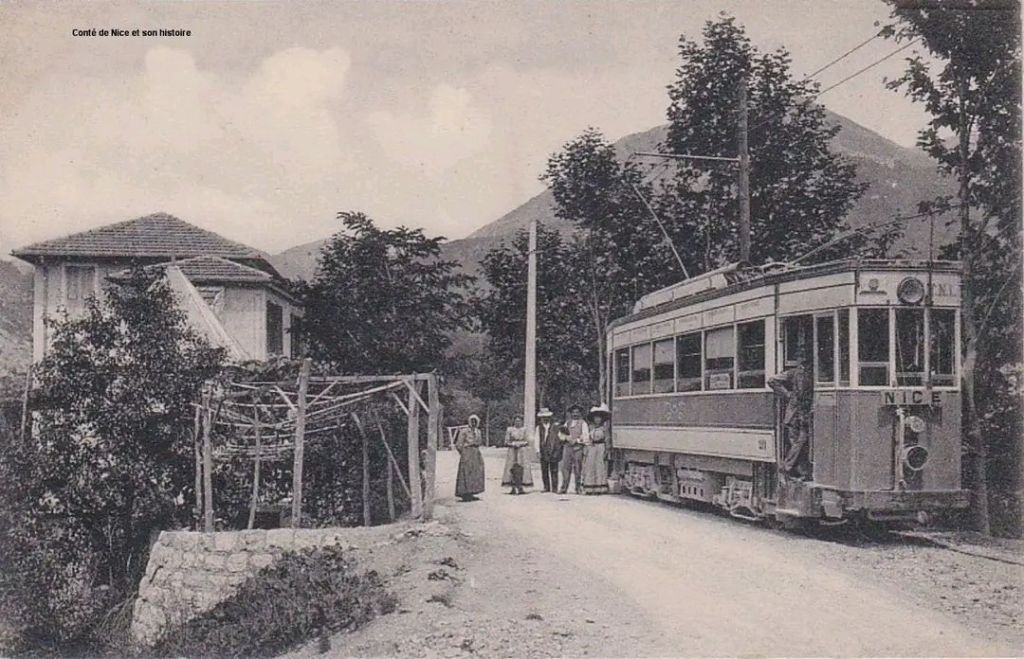

This article looks at two tramway routes which were built. The first ran from Nice to Bendejun via Pont de Peille and Contes. The second branched of the first at Pont de Peille and ran to along the valley of the Paillon de Peille to La Grave de Peille. It also covers a proposed tramway to l’Escarene which was not constructed.

Nice to Contes and Bendejun

This line was approximately 18.6 km long. The first part of the route (from Nice Place Garibaldi as far as La Trinite Victor) ran along the same rails as the urban service – a length of around 6.5km.Just over 9 km of line (which was deemed to be part of the coastal (littoral) network) brought trams to Contes. The final length of the line was regarded as part of the TNLs ‘departemental’ network and took trams to the terminus at Bendejun.

Only approximately 0.5 km of the line and (as far as Contes) was on the level. The remainder of the line was set at varying gradients with the steepest being 55mm/m. The line rose from 12 metres above sea-level at Place Garibaldi to 189 metres above sea-level at Contes, and 260 metres above sea-level at Bendejun.

The following notes on the significant dates associated with the line are gleaned from Jose Banaudo’s book. [1: p70] …

The line from Garibaldi to Abbatoirs opened to the public on 21st February 1900. On 2nd June of the same year, the line opened from Abbatoirs to Contes. Goods were carried on this section of the line from 1st October 1900.

It was not until 1st February 1909 that passengers could travel between Contes and Bendejun and no goods were carried along that length of the line until 1st January 1911.

After just over a year, in February 1912, subsidence closed the length of the line between Contes and Bendejun. The line opened again in March. During the winter of 1916-1917, the line was closed by snow and landslides.

On 1st January 1923 tram services were given new numbers: Nice to La Trinite or Drap became No. 26; Nice to Contes or Bendejun, No. 27.

Sadly, after further problems with landslides, the line between Contes and Bendejun was permanently closed from 18th November 1926.

On 8th October 1934 renumbering led to the line to La Trinite being numbered 36 and the Nice to Contes service, 37.

A landslide affected the line between the cement works and Contes. It was closed from November 1934 to March 1935.

Late in 1935, the Nice terminus of these services was moved from Place Garibaldi to Rue Geoffredo.

After damage to the electricity substation adjacent to Pont-de-Peille on 12th February 1938, the passenger service from Drap to Contes was curtailed and the No. 37 service was replaced by buses.

There was opposition to the bus service being provided by a single company. This saw a reopening of the tram service on Ligne 37 on 15th March 1938. There followed a period between 3rd August 1938 and December 1944 when tramway services were interrupted relatively frequently for a variety of reasons which included damage during WW2.

On 23rd December 1944 the tram service resumed from Nice to Pont-de-Peille with a bus service covering the remainder of the route to the North.

On 17th January 1945, goods transport between Contes and Nice resumed and, on 20th January 1945, passenger trams returned to Contes.

In the winter of 1948-1949 bad weather saw the interruption of services North of La Pointe de Contes.

January 1950 saw the closure of the line to passenger services with buses used to replace that service on a permanent basis. In May 1950, the goods service was also closed permanently.

The line to Bendejun followed the left bank of the River Paillon between the centre of Nice and its terminus in Bendejun. Its terminus in Nice was at the Northwest corner of Place Garibaldi, where a wooden kiosk served as its station building. It used the same tracks as the urban services through Abattoirs to La Trinité-Victor.

For a short distance trams ran on the verge of Route Nationale No. 204. Stops at Roma and Random (which had a passing loop) were followed by the stop in the village of Drap which was adjacent to the bridge to Cantaron.

It appears that as late as 1955, the tram track was visible in the road surface in the centre of Drap. The two parallel images from the IGN website show it present on Avenue de General de Gaulle when the map on the left was surveyed in 1955.

Leaving the centre of Drap, trams then passed under the PLM line between Nice and Cuneo for the third time at Pont des Vernes which also spanned the River Paillon. Trams ran between the river and the road.

The confluence of two arms of the River Paillon lay shortly beyond the railway bridge (Paillon de Contes and Paillon de L’Escarène). The Paillon de L’Escarène flowed in from the Southeast from the heights of Peillon, L’Escarène and Lucéram. It was spanned by a five-arched viaduct, some 140 metres in length which carried both the Route Nationale and the tramway. The construction of the bridge was started in the last years of the 18th century. While the bridge may well have been completed within a few years, the construction of the road of which it was a part, between Turin and Nice, was interrupted by conflict and was not completed until 1838. [1: p67]

Trams faced gradients on either side of the central arch of the bridge – 41mm/m and 34mm/m. Very soon after crossing the bridge in a northbound direction, trams encountered the stop at Pont-de-Peille, “where an electrical substation was located and from which the La-Grave-de-Peille line branched off to the east.” [1: p67]

Beyond the hamlet of La Pointe-de-Contes, the line crossed the Ruisseau de la Garde (a tributary to Le Paillon de Contes) on a single-span bridge.

Banaudo says that the road junction adjacent to the bridge was the point at which the L’Escarene tram line would have branched off the line to Contes. Work on that line wasn’t completed. [1: p67]

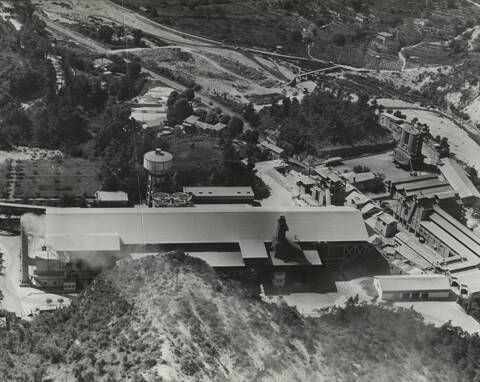

From this bridge, the line to Contes and Bendejun followed RN15 (now D15) North past the Lafarge lime and cement factory. “This, which was the main reason for the line’s existence, was served by two branches allowing the reception of fuel and the shipment of its products to Nice and its port.” [1: p67]

About a kilometre further North, the Contes station was located in the La Grave district adjacent to the footbridge leading to Châteauneuf.

At Contes, the tramway had a small building and a siding by the river beneath the perched village.

From there, the line continued up the left bank of the Paillon. Banaudo tells us that there was only one further passing-loop which was in the district of Roccaya, near the Rémaurian footbridge. “The Bendéjun terminus was in the Moulins district, in a steep site where the road crosses the Paillon and definitively leaves the bottom of the valley to rise in bends towards this village and that of Coaraze.” [1: p67]

We have already noted that the tramway service North of Pont-de-Peille was frequently interrupted by landslides, subsidence and weather events. Banaudo also writes of significant problems with the trailers used for goods services which were often in poor condition or overloaded and as a result caused damage to the relatively light-weight rails of the tramway. [1: p71]

Pont de Peille to La Grave de Peille

Two branch-lines from the tramway to Contes were planned, the first was a line to La Grave de Peille. When built it had a total length of just short of 6.6 km. Its maximum gradient was 39 mm/m and only 360m of the route was on the level. The line ran from 112 m above sea-level to 195 m above sea-level at La Grave de Peille.

The concession for the operation of the line to La Grave de Peille was given to the TNL in June 1904. The line opened to passengers and freight on 12th June 1911. The route was numbered 28 on 1st January 1923 and saw construction traffic for the Nice-Cuneo Railway between 1923 and 1928. The cement works at La Grave was established in 1924.

At the end of 1926 the service was interrupted by a landslide. Work was undertaken between 1926 and 1927 to improve the electrical supply and September 1928 saw the official inauguration of the freight service associated with the cement works.

The Bridges and Roads Authority undertook paving work along the line in the winter of 1928-29. In August 1929, a landslide disrupted the service once again and a deviation was put in place.

On 8th October 1934, the line was renumbered, Ligne 38. The service was interrupted, once again, in November 1934. This time it was by a landslide at Châteauvieux.

The terminus in Nice was moved, along with that of the line to Contes and Bendejun, from Place Garibaldi to Rue Geoffredo in November 1935 and another landslide interrupted the service at Ste. Thecla between December 1935 and December 1936.

This tale of woe continued throughout the next decade with closures due to landslides, floods, the failure of bridges, or deterioration of trackwork. Banaudo provides a full list of these events. [1: p75]Such an unreliable service maintained at significant cost was of little use to users (passengers and goods). Closure became inevitable and it occurred on 1st April 1947.

The route started immediately to the North of the Pont de Peille stop on the line to Contes. Banaudo describes this connection as “une aiguille en rebroussement” (literally, ‘a turning needle’). [1: p72] In context, this appears to be a point which allowed access to the branch-line from the North. Trams from Nice would stop at Pont de Peille and then execute a reversal just to the North of the stop to gain access to the branch. This presumably involved a powered car running round its trailer at the tram stop and then reversing towards Contes. Banaudo provides one photograph of the manoeuvre taking place. [1: p72]

Such an unreliable service maintained at significant cost was of little use to users (passengers and goods). Closure became inevitable and it occurred on 1st April 1947.

The route between Pont de Peille and La Grave de Peille started immediately to the North of the Pont de Peille stop on the line to Contes. Banaudo describes this connection as “une aiguille en rebroussement” (literally, ‘a turning needle’). [1: p72] In context, this appears to be a point which allowed access to the branch-line from the North. Trams from Nice would stop at Pont de Peille and then execute a reversal just to the North of the stop to gain access to the branch. This presumably involved a powered car running round its trailer at the tram stop and then reversing towards Contes. Banaudo provides one photograph of the manoeuvre taking place. [1: p72]

The branch-line followed the valley of the River Paillon de L’Escarène valley, a route also used by the PLM Nice-Cuneo line. Banaudo tells us that “the tram first took the right bank, sometimes on the shoulder and sometimes on the roadway of Route Nationale No. 21 (now departemental road No. 21). It passed through the hamlet of Borghéas, then entered the Châteauvieux gorge where a three-arch bridge brought the road and the track over to the left bank. After passing the pumping station of a spring which supplied part of the city of Nice with drinking water, trams reached the hamlet of Ste. Thecla.” [1: p72]

The next stop was in the valley closer to Peillon and set among the mills. This stop provided a passing loop, the only one on the line. Banaudo continues: “On the right, the picturesque village of Peillon stands at 376 m at the top of a rocky spur in a site worthy of a postcard. Immediately afterwards, the valley narrows once again and forms the narrow Bausset gorge where the tramway line was established over 567 m on its own site overlooking the road, finding it again to cross the Paillon on a single-arch bridge.” [1: p72]

These comments from Banaudo suggest that the line was on the East side of the road, perhaps indicated by the single black line on the 1955 map extract above which crosses the side road to Peillon only a few meters to the East of the main road. It seems that North of this point the tramway was very close to the road but held above it by a retaining wall. Road and tramway came together again at the next bridge over the Paillon de l’Escarene. That bridge is marked on both of the map extracts (1955 and 2023) above. The bridge used by the old road and tramway is marked in grey on the modern map.

Beyond this point, with the tramway and the D21 now on the West bank of the river, the valley opens out and the route of the old tramway passes through Novaines before reaching the location of its terminus at La Grave-de-Peille.

The terminus of the route was sited at the meeting point of the boundaries of three communes, Peillon, Peille and Blausasc, adjacent to a cement works which was operating from the mid-1920s and had its own branch-line from the tramway. The cement works became particularly significant in the life of the branch-line once the PLM opened its line between Nice and Cuneo in the late-1920s. Passengers deserted the trams as a much quicker journey to and from Nice was offered by the PLM from its two stations, Peillon-Ste. Thecle and Peille.

Banaudo highlights a particular problem with the line to La Grave de Peille. [1: p74] The tramway was built with minimal investment – just enough to reach its terminus. Rails were the lightest possible; the TNL used existing bridges not designed for the loads imposed by trams and trailers; road carriageway widths were decreased to provide space for the trams, (ather than setting the rails in the roads).

Local protests began as early as 1908, but issues becameore acute after the Great War because of the increased traffic on both the road and the tramway resulting from the construction of the Nice-Cuneo railway and the opening of the cement plant at La Grave. “Neither the road nor the railway were able to withstand this additional load. On 21st November 1928, the municipal council of Peillon reported that the Bausset bridge was in a lamentable state and, for lack of urgent measures, serious misfortunes occurred during the winter of 1928-29. Despite the protests of the TNL company which rightly feared for the sustainability of its rails, the Bridges and Roads Authority covered the rails with macadam to widen the roadway accessible to cars. What was predictable happened: insufficiently drained under this coating and tired by high tonnages, the rails were too weak and the already tired sleepers soon began to disintegrate.” [1: p74]

In 1937 proper maintenance was undertaken between Borghéas and Châteauvieux, “but the alarming state of the track, the insufficient electricity supply and the shortage of wagons led the TNL to provide its passenger service by bus” [1: p74] The cement factory also began to use road vehicles.

WW2 resulted in traffic (both goods and passengers) returning to the rails in the summer of 1940, but by the beginning of 1941 the track had deteriorated to such an extent that all tramway traffic had to be suspended.

Sufficient maintenance was undertaken to allow goods services to resume within a few weeks but the condition of the bridge at Bausset meant that the line North of the bridge could not be used by trams. Lime and cement, “went down by truck to the Peillon stop (Les Moulins), where it was transhipped on a train of two wagons limited to 6 km/h to Pont-de-Peille… The end-to-end service resumed on 7th July 1941, but it was again interrupted in September 1943 by the destruction of the Pont de Peille then at the end of August 1944 by that of the Pont de Bausset bridge.” [1: p74]

A temporary structure of steel beams and a wooden deck was quickly provided but “the track formed such tight curves on either side of the structure that derailments were not rare.” [1: p74]

Early 1945 saw the reintroduction of passenger and freight services but the following winter saw heavy flooding which destabilised the temporary bridge at Bausset and the line was again closed, this time for two and a half months. Ultimately the increasingly erratic service on the line resulted in its final closure in the spring of 1947.

La Pointe de Contes to l’Escarene

Sadly, this line was never used in earnest. Much was done to create the line but circumstances combined to mean the work done did not come to fruition. Initially, l’Escarene was chosen as the final destination for the tramway from Pont de Peille via La Grave de Peille in 1904. The concession for the line between La Grave and L’Escarene was awarded on 26th June 1904, but it was rescinded early in 1906.

Banaudo tells us that, “after several decades of procrastination, the construction of a Nice-Cuneo railway line had been approved by an international convention, granted to the PLM and made public. As the route of this line was established by the Paillon de L’Escarène valley which the tramway should have taken.” [1: p76]

The result of that decision was the truncation of the route from Pont de Peille to La Grave de Peille and L’Escarène at La Grave.

Banaudo goes on to explain that “the idea of connecting L’Escarène to the tram network was not abandoned, especially since some were still considering extending a line as far as Luceram and even Peirs Cava, at an altitude of 1400 m.” [1: p76]

In 1910 the Bridges and Roads Authority commenced discussions with the TNL. The steep Gradients likely to be required saw the TNL propose an option of a rack system.

It was not until 1913 that the route from La Pointe de Contes was confirmed. Work began in January 1914. The Great War saw work come to a standstill.

It was 1919, before rearranged contracts saw work recommence on the line. Ok about was in short supply and priority was given to the construction of the PLM line between Nice and Cuneo. In the end, the Departement suspended work on the line in 1926 because costs of materials had risen dramatically.

In 1928, Banaudo tells us, “at the request of the municipality of Blausan, the general council took the decision to develop the length of the tramway formation which was remote from the existing road, from Fuont-de-Jarrier to the Col de Nice which became the departmental road 321.” [1: p76] The planned tramway to L’Escarène was finally abandoned/decommissioned on 29th June 1933.

Had it been built, the total length of the tramway would have been just under 7.6 km with a maximum gradient of 55mm/m. It would have risen from a height of 131m above sea-level at La Pointe de Contes to around 410 m above sea-level at the Col de Nice.

The route was to have been served entirely by a single-track tramway leaving the line to Contes at La Pointe de Contes.

Initially, it would have followed the Route Nationale No. 204 (now the D2204) up the valley of the Ruisseau de la Garde.

At the hamlet of La Fuont-de-Jarrier, the tramway left the road and the valley to embark on a dedicated length of almost 4 km. Banaudo tells us that the route ran through “a landscape of arid hills where only pines managed to grow on ridges of gray marl. The only locality encountered was the village of Blausasc, below which a stopping point was to be established. The line continued northwards, passing through a small tunnel at a place called La Blancarde, to join the road approaching the Col de Nice.” [1: p76]

This next sequence of photographs show the road (CD321) running from the bottom of the twin extracts above towards the tunnel which can just about be picked out on the modern map extract above.

This next sequence of three photographs show the CD321 in the vicinity of the tunnel built for the planned tramway.

North of the tramway tunnel, the last kilometre or so of the CD321 and hence the last length of the independent tramway formation required the construction of a series of retaining walls. These next few photographs illustrate the size of the task undertaken by the contractors in the early 20th century. The four photos follow the Route de Blausasc North towards its junction with the Route de la Col de Nice.

A few hundred metres before its junction with the D2204, the CD321 runs parallel to it with the two roads gradually reaching the same height above sea level.

Banaudo talks of the tramway running in a cutting below and to the right of the road and then reaching L’Escarène at the end of a steep descent. [1: p76]

In the first instance, the tramway would have been within the width of the modern highway, but as shown below it did run below and to the right of the road on its way down into L’Escarène.

I have not been able to establish the location in L’Escarène planned for the terminus of the tramway.

This article completes a series of articles about the early 20th century metre-gauge tramways and railways of Nice and its hinterland. Perhaps the next series of articles centred on Nice will look at the standard-gauge line between Nice and Cuneo? ……

References

- Jose Banaudo; Nice au fil du Tram: Volume 2: Les Hommes et Les Techniques; Les Editions du Cabri, 2005.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3819952794917228, accessed on 14th December 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/2035313676714491, accessed on 15th December 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3394462134132965, accessed on 15th December 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3026585994253916, accessed on 15th December 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3777927129119795, accessed on 15th December 2023.

- https://www.cparama.com/forum/pont-de-peille-t16850.html, accessed on 15th December 2023.

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/2308750299370826, accessed on 15th December 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/1875504749362052, accessed on 15th December 2023.

- https://www.nicematin.com/vie-locale/lafarge-cest-notre-stade-du-ray-la-colere-des-habitants-de-contes-apres-lannonce-de-fermeture-de-lusine-640714, accessed on 16th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.319900&y=43.756498&z=16&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 16th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.320322&y=43.760848&z=16&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 16th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.330307&y=43.766719&z=16&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 16th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.337594&y=43.781496&z=16&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 16th December 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3012578788987970, accessed on 16th December 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3563932950519215, accessed on 16th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.314738&y=43.809287&z=16&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 17th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.297577&y=43.835103&z=15&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 17th December 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/3690729567839552, accessed on 17th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.333183&y=43.768166&z=16&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=ORTHOIMAGERY.ORTHOPHOTOS&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 19th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.351098&y=43.766957&z=16&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 19th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.363747&y=43.771203&z=14&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 21st December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.372927&y=43.771664&z=15&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 21st December 2023.

- https://www.thatonepointofview.com/peillon-france, accessed on 21st December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.374619&y=43.788157&z=14&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 21st December 2023.

- https://www.cparama.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=11&t=14570, accessed on 22nd December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.338814&y=43.782147&z=16&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 26th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.343790&y=43.787018&z=15&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 26th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.354474&y=43.794817&z=15&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 27th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.359935&y=43.800718&z=15&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 27th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.360607&y=43.809370&z=15&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap,vaccessed on 28th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.357550&y=43.814629&z=15&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 29th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.353730&y=43.821348&z=15&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 29th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.355818&y=43.816082&z=16&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 29th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.352163&y=43.826648&z=14&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 29th December 2023.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.353504&y=43.833178&z=14&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.PLANIGNV2&mode=doubleMap, 29th December 2023.