Diesel Traction on the East African Railways and Harbours Lines (1948 – 1977)

As the 20th Century progressed, railway networks and locomotive manufacturers began to turn away from steam and to look at a variety of alternative drive mechanisms and loco types. In East Africa the focus turned from steam to diesel.

Perhaps one of the most telling images that I have found while reading around the story of the East African Railways is the graph below. Sadly, the quality is not great but it makes a very important point. [7]

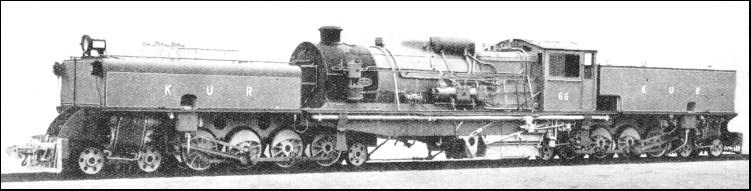

It is impossible to exaggerate the tractive effort required from the motive power on the line through Kenya and Uganda. In the UK we make a great deal of fuss over the strain placed on standard-gauge locomotives on the West Coast Mainline. Shap, Beattock and Drumuachdar are significant climbs which taxed the most powerful of locomotives. The gradients and the heights which the East African lines surmounted dwarf that UK mainline. These feats of endurance and the relative power of the locomotives required to achieve them on narrow-gauge lines is astounding. The diesels which would eventually replace the Garratts, which for many years dominated services on East African lines, would need to efficiently supply significant power with great adhesion if they vwere ever to makeva success of a role on these metals.

Class 90 (later Class 87) English Electric Diesels

Decisions were taken in the 1950s which led to the ordering of a series of different classes of diesel locomotives. The first diesel-electrics to be designed for the mainline, the Class 90 diesel-electrics first ran on the network in 1960. These locomotives ran for a time with Class 90 numbers before being re-numbered as Class 87. Class 90 1-Co-Co-1 diesels introduced in 1960, seen here at Nairobi Shed. The first diesels to operate on the main line they were originally rostered to run between Nairobi and Nakuru, © Kevin Patience. [1]

Class 90 1-Co-Co-1 diesels introduced in 1960, seen here at Nairobi Shed. The first diesels to operate on the main line they were originally rostered to run between Nairobi and Nakuru, © Kevin Patience. [1]

john Ashworth quotes Steve Palmano’s comments that “the EAR&H 90 class was the second English Electric (EE) 12CSVT-engined model to be delivered, but the first to be ordered. The initial order, for 8 units was announced in October 1958, and an increase to 10 units was announced in March 1959. This was EAR&H’s first order for line-service diesel locomotives. A 13.5 ton maximum axle loading was imposed, to enable the locomotives to work northwest of Nairobi to Nakuru and Kampala, as well as between Mombasa and Nairobi, which section alone would have allowed a higher axle loading. This axle loading constraint required a multi-axle design, as it is unlikely that EE could have built a compliant 12-cylinder Co-Co model. Unsurprisingly, EE used a 1-Co-Co-1 wheel arrangement. The resulting locomotive was largely a new design, although it included features drawn from the QR 1250 class (body style and general layout) and the Rhodesian Railways (RR) 16-cylinder DE2 class (running gear and in-frame fuel tank). What it was not, though, was simply a 1-Co-Co-1 variant of the QR 1250 with 12CSVT in place of 12SVT engine.” [2]

“Notwithstanding the 13.5 tons axle loading specification, the first series were built to a slightly lower 12.8 tons number, giving an adhesive weight of 76.8 tons. The total weight was 97.5 tons. The continuous tractive effort is consistently quoted as 44 500 lbf, although there is some variety in the corresponding minimum continuous speed, which is variously reported as 11.5, 11.7 and 12¼ mile/hr. The top speed is usually reported as 45 mile/hr, but this would have been a track limited speed, as the expected 72:15 gearing would have allowed 60 mile/hr, and there is no reason why the running gear would not have accommodated this on suitable track.” [2]

Class 90 English Electric diesel 9007 accompanies a 13 Class 4-8-4T built by North British, © Malcolm McCrow. [1]

Class 90 English Electric diesel 9007 accompanies a 13 Class 4-8-4T built by North British, © Malcolm McCrow. [1]

90 Class 9003 at Nairobi Steam Shed (c) Kevin Patience. [1] 9003 with a 59 Class on the left and a 29 Class on the right. Later in life the 90 Class was to become EAR&H’s 87 Class (c) Kevin Patience. [1]

9003 with a 59 Class on the left and a 29 Class on the right. Later in life the 90 Class was to become EAR&H’s 87 Class (c) Kevin Patience. [1] An EAR&H Class 90 diesel locomotive accompanied by other diesels and a Class 31 (c) Anthony Potterton. [1]

An EAR&H Class 90 diesel locomotive accompanied by other diesels and a Class 31 (c) Anthony Potterton. [1] English Electric Class 90 No. 9008 at Nakuru at the head of No 2 Down (Kampala to Nairobi and Mombasa), © James Lang Brown.[4]

English Electric Class 90 No. 9008 at Nakuru at the head of No 2 Down (Kampala to Nairobi and Mombasa), © James Lang Brown.[4] Class 90 No. 9010 waits to take over from the Class 58 which has brought the train from Kampala, © Malcolm McCrow. [4]

Class 90 No. 9010 waits to take over from the Class 58 which has brought the train from Kampala, © Malcolm McCrow. [4] Class 90 No. 9010 awaits the right away for Nairobi, © Malcolm McCrow. [4]

Class 90 No. 9010 awaits the right away for Nairobi, © Malcolm McCrow. [4] English Electric 90 Class diesel in the cutting by Speke and Lugard Houses of Duke of York School © Paul Tanner Tremaine. [5]

English Electric 90 Class diesel in the cutting by Speke and Lugard Houses of Duke of York School © Paul Tanner Tremaine. [5]

Mail Kisumu – Nairobi, diesel class 87 (originally Class 90), approaching Nairobi 1976. [3]

Mail Kisumu – Nairobi, diesel class 87 (originally Class 90), approaching Nairobi 1976. [3] Class 87, No. 8729 at Tororo in 1971. [6]

Class 87, No. 8729 at Tororo in 1971. [6]

Other Diesels

By 1975, the roster of diesels on the East African Railway had increased to include shunters and mainline locomotives for goods and passengers. Initially most of these diesels were sourced from the UK. [8] The range included:

A. 4 classes of smaller shunting locomotives which were 200hp diesel mechanical locos:

- Class 32 (originally Class 80)

- Class 33 (originally Class 81)

- Class 34 (originally Class 82)

- Class 35

Details are tabulated below …

B. Some larger goods/shunting locomotive classes:

- Class 43 (originally Class 83)

- Class 44 (originally Class 84)

- Class 45 (originally Class 85)

- Class 46 (originally Class 86)

Details are tabulated below …

C. Mainline classes:

- Class 61

- Class 71 (originally Class 91)

- Class 72

- Class 79

- Class 87 (originally Class 90)

- Class 88

- Class 92

As tabulated below (all these tables are taken from files supplied by by Rob Dickinson. [8]):

Class 32 (originally Class 80)

The Class 32(80) 0-6-0 locos were built for the EAR&H by John Fowler & Co Engineers of Leathley Road, Hunslet, Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK. The company produced traction engines and ploughing implements and equipment, as well as railway equipment. [10] The image immediately below is taken from a series of photographs placed on-line by Rob Dickinson. [8]

Class 32 at Nairobi Railway Museum. [9]

Class 32 at Nairobi Railway Museum. [9] 3206 Fowler 0-6-0 diesel shunter at the Railway Technical Institute, Nairobi. Probably one of the oldest surviving diesel locomotives in East Africa. [11]

3206 Fowler 0-6-0 diesel shunter at the Railway Technical Institute, Nairobi. Probably one of the oldest surviving diesel locomotives in East Africa. [11] The loco diagram above is from a series of pictures taken by Rob Dickinson at the Nairobi Shed. [12]

The loco diagram above is from a series of pictures taken by Rob Dickinson at the Nairobi Shed. [12] 111447: No. 3204 at Nairobi Kenya Railway Workshops, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

111447: No. 3204 at Nairobi Kenya Railway Workshops, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

Class 33 (originally Class 81)

Locomotives of this class were supplied by the Drewry Car Co.

Drewry & Sons ran a motor and cycle repair business in Herne Hill, London, and started building BSA engined inspection railcars. A ready market was found in South America, Africa, and India. Drewry Car Co Ltd was registered on 27 November 1906. In 1908 BSA (of motor-cycle fame) took over building the railcars at Small Heath, Birmingham. In 1911 building was taken over by Baguley Cars Ltd, Burton-on-Trent. From 1930 a lot of Drewry locomotives were built by English Electric companies. In 1962 Drewry acquired a controlling interest in what had become E E Baguley Ltd, and formed Baguley-Drewry Ltd in 1967, thus once again building its own locomotives, in Burton-on-Trent. The company closed in 1984. [10]

Locomotive diagram for Class 33. [12]

Locomotive diagram for Class 33. [12]

Class 34 (originally Class 82)

The Class 34 locos were Hunslet 0-6-0 designs. The Hunslet Engine Company was founded in 1864 in Hunslet, Leeds, England. The company manufactured steam-powered shunting locomotives for over 100 years, and currently manufactures diesel-engined shunting locomotives. [13]

Locomotive diagram for Class 34. [12]

Locomotive diagram for Class 34. [12]

Class 35

The Class 35 locos were Andrew Barclay 0-6-0 diesel shunters. Andrew Barclay Sons & Co. are a builder of steam and later fireless and diesel locomotives. The company’s history dates to foundation of an engineering workshop in 1840 in Kilmarnock, Scotland. After a long period of operation the company was acquired by the Hunslet group in 1972 and renamed Hunslet-Barclay; in 2007 the company changed hands after bankruptcy becoming Brush-Barclay as part of the FKI Group. In 2011 Brush Traction and Brush-Barclay were acquired from FKI by Wabtec – as of 2012 the company still operates in Kilmarnock providing rail engineering services as Wabtec Rail Scotland. [14]

3505 Barclay 0-6-0 diesel-hydraulic shunter by the workshop at Nairobi. [11]

3505 Barclay 0-6-0 diesel-hydraulic shunter by the workshop at Nairobi. [11] Locomotive diagram for Class 35. [12]

Locomotive diagram for Class 35. [12]

Class 43 (originally Class 83)

These locos were built by the North British Locomotive Company. The North British Locomotive Company (NBL, NB Loco or North British) was created in 1903 through the merger of three Glasgow locomotive manufacturing companies; Sharp, Stewart and Company (Atlas Works), Neilson, Reid and Company (Hyde Park Works) and Dübs and Company(Queens Park Works), creating the largest locomotive manufacturing company in Europe and the British Empire. [15]

Its main factories were located at the neighbouring Atlas and Hyde Park Works in central Springburn, as well as the Queens Park Works in Polmadie. A new central Administration and Drawing Office for the combined company was completed across the road from the Hyde Park Works on Flemington Street by James Miller in 1909, later sold to Glasgow Corporation in 1961 to become the main campus of North Glasgow College (now Glasgow Kelvin College).

The two other Railway works in Springburn were St. Rollox railway works, owned by the Caledonian Railway and Cowlairs railway works, owned by the North British Railway. Latterly both works were operated by British Rail Engineering Limited after rail nationalisation in 1948. [15]

Class 43, No. 4306 0-8-0 in its later guise as No. 8306. [8]

Class 43, No. 4306 0-8-0 in its later guise as No. 8306. [8] 111567: No. 43110 at Mombasa, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

111567: No. 43110 at Mombasa, (c) Weston Langford. [22] Class 43 Locomotive Diagram. [12]

Class 43 Locomotive Diagram. [12]

Class 44 (originally Class 84)

This 0-8-0 class was also built by the North British Locomotive Company.

111593: No. 4402 alongside No. 87 42 at Kilindini Locomotive Depot, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

111593: No. 4402 alongside No. 87 42 at Kilindini Locomotive Depot, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

Class 45 (originally Class 85)

Still another North British 0-8-0 class of loco.

111573: Shunter No. 4503 at Mombasa, (c) Weston Langford [22]

111573: Shunter No. 4503 at Mombasa, (c) Weston Langford [22] 111615: Shunter No. 4504 moving No. 2410 at Voi, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

111615: Shunter No. 4504 moving No. 2410 at Voi, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

Class 85, No. 8503 (later Class 45, No. 4503) working dead Class 90 (later Class 87) diesel electric to Makadara MPD, (c) Iain Mulligan [1]

Class 85, No. 8503 (later Class 45, No. 4503) working dead Class 90 (later Class 87) diesel electric to Makadara MPD, (c) Iain Mulligan [1]

Class 46 (originally Class 86)

The Class 46 (86) 0-8-0 central cab locos were built for the EAR&H by Andrew Barclay Sons & Co.

Class 86, No. 8607. [24]

Class 86, No. 8607. [24] 111396: No. 4622 alongside No. 8714 at Nairobi, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

111396: No. 4622 alongside No. 8714 at Nairobi, (c) Weston Langford. [22] 111576: No. 4615 alongside Westbound Goods pulled by No. 3110 Bakiga. The picture is taken from Nairobi East Box (c) Weston Langford. [22]

111576: No. 4615 alongside Westbound Goods pulled by No. 3110 Bakiga. The picture is taken from Nairobi East Box (c) Weston Langford. [22]

Class 46 shunter re-positioning cabooses at Nairobi Station. [16]

Class 46 shunter re-positioning cabooses at Nairobi Station. [16]

Class 61

These locos were supplied by Henschel & Son (German: Henschel und Sohn), a German company, located in Kassel, best known during the 20th century as a maker of transportation equipment, including locomotives, trucks, buses and trolleybuses, and armoured fighting vehicles and weapons.

These locos were supplied by Henschel & Son (German: Henschel und Sohn), a German company, located in Kassel, best known during the 20th century as a maker of transportation equipment, including locomotives, trucks, buses and trolleybuses, and armoured fighting vehicles and weapons.

Georg Christian Carl Henschel founded the factory in 1810 at Kassel. His son Carl Anton Henschel founded another factory in 1837. In 1848, the company began manufacturing locomotives. The factory became the largest locomotive manufacturer in Germany by the 20th century. [17]

Diesel-hydraulic locomotive No. 6107 working an up-country freight in 1975. Ten of these Henschel built Class 61 locomotives entered service in 1972 and in 1975/6 were generally in use on branch-lines. [18]

Diesel-hydraulic locomotive No. 6107 working an up-country freight in 1975. Ten of these Henschel built Class 61 locomotives entered service in 1972 and in 1975/6 were generally in use on branch-lines. [18]

Class 71 (originally Class 91)

This Class was supplied by English Electric.

Class 72

This Class was also supplied by English Electric.

Class 79

There was just one locomotive in this class. No. 7901 was supplied as an experimental type by AEI Lister-Blackmore. Looking at the export market in the late 1950s British Tomson-Houston (BTH), with Clayton and Lister-Blackstone commissioned the Explorer CM-gauge prototype, which was ready in 1959. This featured a Lister-Blackstone engine, BTH electrical equipment and mechanical parts by established partner Clayton. Possibly Lister-Blackstone saw this as a pathway into the mainline locomotive market, as the cost was shared between itself and BTH. [19]

At 1100 hp (gross), with Co-Co running gear and weighing 72 long tons, the Explorer may be compared with standard shunters from the major worldwide builders. Previous engine partner Paxman offered high-speed engines which were in a lower power range than needed for the Explorer. The Alco DL531 was slightly lighter (in CM-gauge form) and marginally less powerful, at 975 hp (gross). The GE U9C was somewhat heavier and had a nominal power of 990 hp (gross), but this was a high-altitude, high-ambient temperature rating, and the UIC number was 1060 hp. The Alco & GE utilised 6-cylinder in-line engines, whereas the Lister-Blackstone featured the relatively complex 12-cylinder double-bank form, albeit still medium-speed. This complexity allied to its weight put it at an immediate major disadvantage. There were no production orders from this prototype. [23]

In 1959 EMD did not yet have a six-motor model in this power class. English Electric no doubt could have offered a Co-Co version of its existing eight-cylinder Latin American model with either the 8SRKT or 8SVT engine, by 1959 delivering 1100 hp. And more power would have been available from the 8CSRKT or 8CSVT engine with but minor weight penalty. Within two years Alco offered the DL535, delivering 1350 hp (gross), still with six cylinders, and weighing around 72 long tons in CM-gauge form. [19]

In 1959 EMD did not yet have a six-motor model in this power class. English Electric no doubt could have offered a Co-Co version of its existing eight-cylinder Latin American model with either the 8SRKT or 8SVT engine, by 1959 delivering 1100 hp. And more power would have been available from the 8CSRKT or 8CSVT engine with but minor weight penalty. Within two years Alco offered the DL535, delivering 1350 hp (gross), still with six cylinders, and weighing around 72 long tons in CM-gauge form. [19]

The Explorer was built by the Clayton Company of Hatton, Derbyshire, order number 3548 of January 1959, it was powered by a Lister Blackstone ERS.12T 12 cylinder twin-bank engine powering BTH electrics. Cylinders were 8.75 x 11.5 inches, maximum crankshaft speed was 800rpm, output speed through the phasing gears was 1,320rpm providing 1,100hp. Either crankshaft could be uncoupled in an emergency.

The locomotive weighed 72tons and rode on metre gauge Co-Co bogies of rubber cone pivot Alsthom style. Alsthom (originally ALS-Thom(son)) had a similar relationship with GE as did BTH, and it appeared that design ideas also travelled ‘horizontally’ between GE ‘associates’. This aspect of the Explorer design was carried over to the later AEI Zambesi type.

It was leased to the East African Railways who later bought it outright. In the late 1960s EAR reclassification it was assigned Class 79. It was allotted to the Kenya Railways in 1977, though by October of that year it was recorded as ‘stabled for scrap’ on the roster. [19] As of 2005, the ‘Explorer’ locomotive still exists, very much intact and still bearing its number and nameplates. It is earmarked for the Nairobi Railway Museum when funds become available. [19][20]

As of 2005, the ‘Explorer’ locomotive still exists, very much intact and still bearing its number and nameplates. It is earmarked for the Nairobi Railway Museum when funds become available. [19][20] Class 79, No. 7901 Explorer AEI Lister-Blackmore Co-Co at the Railway Technical Institute, Nairobi, still displaying the faded remnants of the EAR&H maroon livery and cast letters. Now confirmed as destined for the museum. [11]

Class 79, No. 7901 Explorer AEI Lister-Blackmore Co-Co at the Railway Technical Institute, Nairobi, still displaying the faded remnants of the EAR&H maroon livery and cast letters. Now confirmed as destined for the museum. [11]

Unique pioneer diesel Class 79, No. 7901 ‘Explorer’ at Nairobi (c) Iain Mulligan. [1]

Unique pioneer diesel Class 79, No. 7901 ‘Explorer’ at Nairobi (c) Iain Mulligan. [1]

No. 7901 ‘Explorer’ at the purpose built diesel depot at Makadara on 31 July 1962 (c) Iain Mulligan. [1]

No. 7901 ‘Explorer’ at the purpose built diesel depot at Makadara on 31 July 1962 (c) Iain Mulligan. [1] Green and yellow liveried Class 79 ‘Explorer’ at Nairobi Shed, alongside a Class 13, No. 1308, a Class 59 can just be seen in the shed (c) Anthony Potterton. [1]

Green and yellow liveried Class 79 ‘Explorer’ at Nairobi Shed, alongside a Class 13, No. 1308, a Class 59 can just be seen in the shed (c) Anthony Potterton. [1]

Class 87 (originally Class 90) Pictures and details of this 1-Co-Co-1 Class of Diesel-Electric are shown above.

Pictures and details of this 1-Co-Co-1 Class of Diesel-Electric are shown above. Class 87, No 8701 English Electric 1Co-Co1 delivered in 1960. Lead locomotive of a class of 44 of which 11 are still in working order. They are normally confined to the Nakuru-Kisumu section of the main line. 8701 is seen abandoned at Nakuru, still painted in the later EAR&H green and yellow livery. [11]

Class 87, No 8701 English Electric 1Co-Co1 delivered in 1960. Lead locomotive of a class of 44 of which 11 are still in working order. They are normally confined to the Nakuru-Kisumu section of the main line. 8701 is seen abandoned at Nakuru, still painted in the later EAR&H green and yellow livery. [11]

A double-header goods train close to Nairobi. Class 87s in green and yellow livery (c) Kevin Patience. [18]

A double-header goods train close to Nairobi. Class 87s in green and yellow livery (c) Kevin Patience. [18] 111393 No. 8714 at Nairobi, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

111393 No. 8714 at Nairobi, (c) Weston Langford. [22] 111395: No 8714 at Nairobi Kenya, on the 1030am Kampala Mail, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

111395: No 8714 at Nairobi Kenya, on the 1030am Kampala Mail, (c) Weston Langford. [22] 111396: No. 8714 at Nairobi alongside shunter No. 4622, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

111396: No. 8714 at Nairobi alongside shunter No. 4622, (c) Weston Langford. [22]

Class 88

The Class 88 locomotives were lighter cousins of the Class 92 locos below. In all, 20 units were delivered to the EAR&H. [18] They were built by the Montreal Locomotive Works (MLW), a Canadian railway locomotive manufacturer which existed under several names from 1883 to 1985, producing both steam and diesel locomotives. For a number of years it was a subsidiary of the American Locomotive Company. MLW’s headquarters and manufacturing facilities were located in Montreal, Quebec. [21]

In 1975, the emerging Quebec based Bombardier purchased a 59% stake in MLW from Studebaker-Worthington. Under Bombardier, the MLW organization continued locomotive design into the early 1980s, and also benefited from its geographic location. During the 1970s, Bombardier began to enter the railway passenger coach/locomotive business with domestic orders for commuter and subway systems. Based on a prototype trainset constructed in the mid-1970s, in 1980 MLW began production of a fleet of high-speed diesel-powered passenger locomotives for the LRC (Light, Rapid, Comfortable) passenger trains being built for the newly created federal Crown corporation Via Rail. Similar equipment was also used briefly by Amtrak.The last of the locomotives were retired from service in 2001. [21]

Class 92

This Class was also supplied by the Montreal Locomotive Works. There were 15 locomotives, they were diesel-electrics and were delivered in 1971 for main line service. [18]

Class 92, No. 9211 heads a Uganda bound freight train. [18]

Class 92, No. 9211 heads a Uganda bound freight train. [18] No. 9212 undergoes maintenance at Nairobi workshops. [18]

No. 9212 undergoes maintenance at Nairobi workshops. [18]

References

- http://www.mccrow.org.uk/EastAfrica/EastAfricanRailways/NairobiMPD.htm, accessed on 1st June 2018.

- http://www.friendsoftherail.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=10472, 2nd & 8th January 2018, accessed on 26th June 2018.

- http://trains-worldexpresses.com/700/704.htm, accessed on 26th June 2018.

- http://www.mccrow.org.uk/eastafrica/eastafricanrailways/KampalaNairobi.htm, accessed on 24th May 2018.

- http://www.mccrow.org.uk/eastafrica/duke%20of%20york%20school/PTannerTremaine.htm, accessed on 27th June 2018.

- https://thetransportlibrary.co.uk/index.php?route=product/product&product_id=30014, accessed on 27th June 2018.

- A. E. Durrant; Garratt Locomotives of the World (rev. and enl. ed.). Newton Abbot, Devon, UK, 1981.

- http://www.internationalsteam.co.uk/eastafrica/diesel.htm, accessed on 28th June 2018.

- https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/544302304935454660, accessed on 28th June 2018.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drewry_Car_Co., accessed on 28th June 2018.

- http://www.greywall.demon.co.uk/rail/Kenya/diesels.html, accessed on 28th June 2018.

- https://www.dropbox.com/sh/lzmuuq1odbv6r48/AABZLSCp51DXZr6R4zdnF4TSa?dl=0, accessed on 28th June 2018.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hunslet_Engine_Company, accessed on 28th June 2018.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Barclay_Sons_%26_Co., accessed on 28th June 2018.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_British_Locomotive_Company, accessed on 29th June 2018.

- http://www.mccrow.org.uk/EastAfrica/EastAfricanRailways/NairobiMombasa.htm, accessed on 29th June 2018.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henschel_%26_Son accessed on 29th June 2018.

- Kevin Patience; Steam in East Africa; Heinemann Educational Books, Nairobi, 1976.

- https://www.derbysulzers.com/AEI.html, accessed on 29th June 2018.

- http://www.trevorheath.com/livesteaming/Kenyadiesels.htm, accessed on 29th June 2018.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montreal_Locomotive_Works, accessed on 29th June 2018.

- https://www.westonlangford.com, accessed on 30th June 2018.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/124446949@N06/39846520124/in/photostream, accessed on 30th June 2018.

- https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/313352086548265694, accessed on 3rd July 2018.

- https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/313352086548265707, accessed on 3rd July 2018.

An Incline was built to move construction materials to the valley floor, two sections of the incline were set at 45 degrees, special cars had to be constructed to carry equipment and in particular locomotives. The incline opened in May 1900 and remained in use until November 1901. Use of the incline advanced the rail-head westward by 170 miles while the line down the escarpment was being built. The pictures immediately adjacent, above and below show the top of the escarpment and two images of a locomotive being lowered to the valley floor. [2]

An Incline was built to move construction materials to the valley floor, two sections of the incline were set at 45 degrees, special cars had to be constructed to carry equipment and in particular locomotives. The incline opened in May 1900 and remained in use until November 1901. Use of the incline advanced the rail-head westward by 170 miles while the line down the escarpment was being built. The pictures immediately adjacent, above and below show the top of the escarpment and two images of a locomotive being lowered to the valley floor. [2]

Above, Kasese Humanist School taken across the tracks at Kasese MPD

Above, Kasese Humanist School taken across the tracks at Kasese MPD