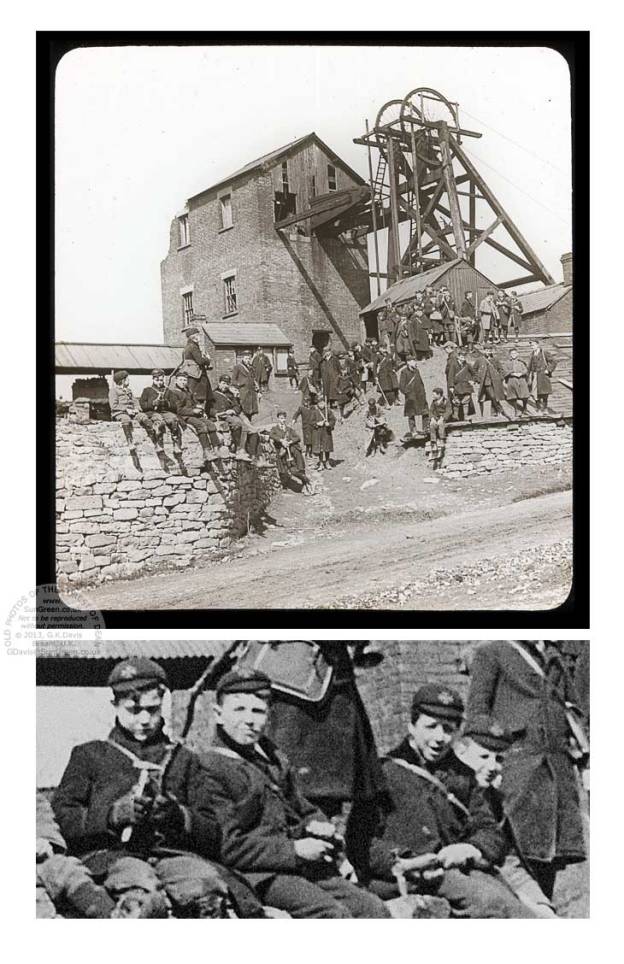

OS Grid Reference: SO625144 – The featured image above is taken from the Way-Mark site covering the Forest of Dean . [3]

The History of the Colliery and its Tramway and Railway Connections

The Trafalgar gale was leased to Corneleus Brain in 1842, but work does not to seem to have commenced until 1860. After 1867, coal from the adjacent Rose-in-hand gale was also worked. [1]

Since at least 1847 Corneleus and Francis Brain had been lessees of the Rose-in-Hand gale and in 1867 they obtained permission from the Crown to effectively amalgamate the two games into one for the purpose of working the coal which would have been raised via the shafts at Trafalgar. No record a shaft for the Rose-in-Hand exists. Coal, prior to 1867, was brought to the surface via the Royal Forester gale which ultimately became part of Speech House Hill Colliery. [2]

It seems as though the Brains also acquired the Strip-and-at-it Colliery which lay close to Trafalgar across a small ridge. Strip-and-at-it had already been worked for some time ,The probably since 1832. The gale was surrendered to the Crown in 1864 and was then acquired by the Brains. [2]

There were two shafts at Trafalgar, which were worked by the same winding engine. They extended through the Upper Coal Measures (Supra-Pennant Group) down to the Churchway High Delf Seam at a depth of 586 ft. The two shafts were less than 40 yards apart. Coal was lifted up one shaft and empties were taken down the other shaft. [1][2]

The Lightmoor Press website comments as follows :

“One shaft was the downcast, where fresh air went down into the workings, and the other had a kind of bonnet fitted over the tacklers which covered the top of the land pit so that very little air was lost. The main upcast shaft was called Puzzle, as the pit had been driven up-hill to the surface.

The cage was guided down the shaft by wooden guides running inside metal shoes on the side of the cage. Wooden guides were used on both pits. Ten men and boys could ride in each cage.

A report in the Gloucester Journal in February 1867 tells how in working the ‘large vein of coal’ at the colliery the declavity was so great that the ordinary method of hauling to the bottom of the shaft, presumably horse or man power, was impracticable. Corneleus’ son, William Blanch Brain, the colliery engineer therefore erected a small winding engine on the surface close to the pit’s mouth in order to draw the loaded carts from the coal face to the bottom of the shaft. The carts were connected to a long chain which ran to the far extremities of the workings. Initially the great drawback was the delay in communication between the coal face and the pit bank when hauling was required. So W. B. Brain, who was also an electrician, procured a pair of electric bells and placed one in the winding engine house and the other at the top of the ‘dipple’ or haulage road. Several tappers were then placed along the road allowing the men in any part of the works to signal for the starting or stopping of the haulage engine. The bell at the top of the dipple kept the men at pit bottom informed as to what was happening. The success of the system was such that communication between pit bottom and the main winding engineman was also electrified. At pit bottom, a pair of tappers, one white and one red, were provided and on touching the white one a bell in the engine room sounded and the words ‘go on’ appeared on the dial plate attached. On touching the red the word ‘stop’ was shown.

Electrical communication was also used on the surface, enabling W. B. Brain in his office to be kept in touch with the happenings at the pit. Another snippet mentioned in the article was that a patent pump was in use at the colliery which instead of throwing successive stream of water threw a continuous one.” [2]

It is of interest that in the 1880s, when the Forest of Dean was a highly industrialised area, people were chosing to take a holiday in the forest and choosing too to visit working pits. John Bellows wrote a guide book in 1880 entitled, ‘A Week’s Holiday in the Forest of Dean’. It contains a commentary about the Trafalgar Colliery. The Lightmoor Press website quotes from it:

The Trafalgar colliery was unique in Dean in being lit by gas, and electric pumps were installed underground in 1882, the first recorded use of electric power in a mine. [1] Gas was forced down the shaft by means of a one horse horizontal engine erected in the gas house at the pit bank. The gas house appears as a building shown on the 1898 Severn & Wye plans containing a circular structure. [2][8] It appears on the 5th map extract below.“Before going down (underground) we may as well look at the large sandstone quarry on the premises where stones are cut for supporting the galleries below. Let us pass through the tramway tunnel, 150 yards long, cut through the ridge of the hilltop, to a shaft on the other side. This narrow ridge is the outcrop of the measures, and in the tunnel we can examine, rock, clod and duns, and a little thin coal with rock again below it. Having seen this we turn back again, enter the cage, and, closing our eyes to avoid the giddiness, are lowered 600 feet so smoothly, that we are hardly conscious of motion. At the bottom we go into the underground office, and are supplied with a little brass lamp, and a bunch of cotton waste to wipe our hands upon, and then attended by ‘the bailey’ enter one of the main roadways. … Where necessary, the underground workings are lighted with gas, and one of the partners, Mr. William Brain, is now preparing to adopt the electric light (which is already in use on the surface at night) and also to utilise electricity as a motive power at many of the underground inclines, or dipples, in the colliery, where steam is not available; and thus save many horses. There are more than forty horses living in this pit. They never return to daylight until worn out or disabled. Some of them have been down here a dozen years, and are in excellent health.

Fire damp is wholly unknown in the Forest of Dean, and miners work with naked lights. Choke damp breaks in rarely, and seldom gives any trouble. The pit is remarkably free from water, and being furnished with every known appliance, and most admirably kept, is probably one of the best in the Forest, or out of it. Eleven hundred men and boys are employed here: 600 underground getting coal, and 500 as labourers &c., above ground, and in subsidiary occupations. Good colliers earn, at present, 3s 8d per day; masons 3s 4d; and labourers, 2s 4d. One can hardly imagine anything more severe in the way of labour than that of a miner lying on his side in a four foot passage, cutting away with his pick the hard rock encasing the seam. … The output from Trafalgar, at the moment we are writing, which is a dull season is seven hundred tons of coal per day.” [2][4]

Francis William Thomas (Frank) Brain had been associated with the use of electric floodlights on the Severn Bridge in 1879 where they had been used to enable construction work to continue at night to make the best use of the tides. After use on the bridge, the apparatus, consisting of a couple of powerful lamps supplied by a Gramme machine, was re-erected at Trafalgar on the surface to light the colliery yard. The Lightmoor website continues:

“Electricity was also used at Trafalgar when the first underground pumping plant was installed in December 1882. The installation at Trafalgar was the first recorded use of electric power in mines. The equipment consisted of a Gramme machine on the surface driven by a steam engine and a Siemens dynamo used as a 1.5 horse power motor belted to a pump underground. The Gramme machine still exists today, preserved in the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff. It attained such success that three additional plants were erected in May 1887 and these did the larger part of the pumping. The last installation consisted of a double-throw nine inch plunger, by ten inch stoke, situated 2,200 yards from the generator and 1,650 yards from the bottom of the shaft. The pipe main was seven inches in diameter and at its maximum speed of twenty-five strokes a minute the pump lifted 120 gallons to a height of 300 feet. The current was conveyed to the motor by an 13/16 copper wire carried on earthenware cups. The E.M.F. was 320 volts and the current required was 43 amperes. The installation cost of the engine and the electrical plant was £644, whilst the weekly cost for maintenance, including 15% for depreciation and interest on capital was £7 17s. or .002d. per horse power per hour. The efficiency attained throughout was only 35% but the engine which was an old one lost 6.49 horse power, or 22% alone. If this was removed from the equation then the efficiency was 45%.” [2]

In the mid-1880s, the Trafalgar Colliery got into some financial difficulty. This was resolved in a way that kept the creditors at bay and left the Brain family in overall control. To do this a new company was formed – the Trafalgar Colliery Co. Ltd. This new company saw the amalgamation of the interests of the Brain family at Trafalgar and the Wye Colliery Co. who leased Speculation Colliery. Both mines came under the control of this new company. [2]

A narrow-gauge tramway (Brain’s Tramway) was built soon after the opening of the colliery to connect to the Great Western Railway’s Forest of Dean Branch at Bilson [1] The single line of 2ft 7.5in gauge utilised edge rails laid on wooden sleepers and ran east from the colliery, turning south-east at Laymoor, and terminated 1.5 miles away at interchange sidings at Bilson. It would appear that the authorisation for its construction was a Crown licence for ‘a road or tramway 15 feet broad’ dated May 1862. The date the line was opened for traffic is unknown as, although the first of three locomotives used on the tramway was built in 1869, it is possible that it may have been horse worked before this date. [2] Brain’s Tramway will, I hope, be the subject of a future post in this series.  6″ OS Map from 1901 showing both Mr Brain’s Tramway and the standard-gauge sidings of the Colliery and their connection to the Severn & Wye Railway close to Drybrook Road Station. [8]

6″ OS Map from 1901 showing both Mr Brain’s Tramway and the standard-gauge sidings of the Colliery and their connection to the Severn & Wye Railway close to Drybrook Road Station. [8] The extent of Mr Brain’s Tramway when first built to the Bilson Exchange Sidings. The point of conflict with the Severn and Wye near Laymoor (as mentioned below) can easily be picked out on the map extract. [8]

The extent of Mr Brain’s Tramway when first built to the Bilson Exchange Sidings. The point of conflict with the Severn and Wye near Laymoor (as mentioned below) can easily be picked out on the map extract. [8]

Two pictures above taken along the line of Brain’s tramway – August 2017. [14]

Two pictures above taken along the line of Brain’s tramway – August 2017. [14]

Tramway locomotives hauled trains of 20-25 trams of coal on each trip along Brain’s Tramway to Bilson, until 1872 when the Severn & Wye built their branch to Bilson. This crossed the tramway on the level near Laymoor and resulted in the need for the two companies to negotiate an acceptable coexistence. This became more urgent once the Servern and Wye extended beyond Drybrook Road an when, in 1878, passenger trains began running over the crossing.

Although a connection had been made to the Severn and Wye Railway in 1872 [1] at a point between Serridge Junction and Drybrook Road station, a large element of Trafalgar’s output still travelled along the tramway to Bilson. [2]

In 1872, agreement had been reached between the Severn and Wye and Trafalgar Colliery for sidings to be put in to serve the colliery screens. Soon after the Mineral Loop of the Severn and Wye was completed, a loop off the main line was installed and sidings were laid. However, the Severn and Wye was dismayed to note that Trafalgar was still making heavy use of the tramway.

The Lightmoor Press website comments that:

An approach was made to the colliery company to provide arrangements for loading hand picked nut coal on the Severn & Wye sidings as well as on the Great Western at Bilson. This was rejected at first but by January 1887, after further negotiations, Trafalgar approved a proposal whereby the Severn & Wye altered the sidings and shed whilst the colliery company altered the screens, thus resolving this ‘vexed question’.

Finally, in December 1889, an agreement was entered into between the Severn & Wye and the Trafalgar Colliery Company who, it was said, ‘are desirous of obtaining railway communication to Bilson Junction in lieu of their existing trolley road.’

It was agreed that on or before 31 March 1890 the colliery company would construct new sidings and the railway company would lay in a new junction at Drybrook Road. Although the new junction was a quarter of a mile closer to Drybrook Road than the old sidings, the mileage charge was to remain the same. The accommodation, on approximately the same level as Drybrook Road station, was to be constructed so that traffic to and from the Great Western would be placed on a different siding to that which was to pass over the Severn & Wye system. For taking traffic to Bilson Junction for transfer to the Great Western the colliery was to be charged 7d per loaded wagon, although empties were to pass free. The transfer traffic also had to be conveyed ‘at reasonable times and in fair quantities so as to fit in with the ordinary workings of the Railway Company trains’.The new sidings were brought into use on 1st October 1890.” [2]

This agreement resulted in the abandonment of the length of the tramway from Laymoor to Bilson Junction. Two of the colliery’s narrow gauge locomotives were put up for sale, neither sold. [2]

The colliery appears to have owned three locomotives: ‘Trafalgar’ and ‘The Brothers’ were 0-4-2 side-tank locos. The third locomotive was ‘Free Miner’, an 0-4-0 side-tank. Trafalgar continued in use until 1906, working on the northern extension of the tramway, built in 1869, to the Golden Valley Iron Mine at Drybrook. [2]

Trafalgar was one of the larger pits, employing 800 men and boys in 1870, and producing 88,794 tons of coal in 1880 and about 500 tons/day in 1906. [1]

However, by 1913 difficulties were being encountered with water. The managements of both Foxes Bridge and Lightmoor Collieries were worried about the threatened abandonment of Trafalgar. They feared that if pumping ceased, their own collieries might be under threat from the build-up of water within Trafalgar’s workings. The colliery was offered for sale to Crawshay’s, the owners of Lightmoor and with an interest in Foxes Bridge, but at a figure they would not entertain at that time. [2]

At the beginning of 1919 the main dip roadway at Trafalgar was suddenly, and unexpectedly, flooded. A report in the Gloucester Journal on 25 January stated that as a result of the flooding 450 men were temporarily unemployed. Apparently the electric pump, which had drained the deep workings for over 30 years, failed. [1][2]

The flooding once again led to worries by the Foxes Bridge and Lightmoor managements about the dangers to their concerns. Trafalgar was now offered for sale at £16,000. The Foxes Bridge and Lightmoor managements were prepared to offer £10,000 and, in an attempt to meet the difference, the Crown agreed to provide £4,000 should the sale go through. It was estimated at this time that there was still 2.5 million tons of coal to be worked in the pit and its associated gales which would give the Crown an annual return from tonnage rates of £1,000 for 20 years, certainly paying back the £4,000. Trafalgar was sold in November 1919. It continued to be worked until 1925, producing around 4,500 tons of coal each year. After closure, it may have been that pumping continued for a while but was interrupted by the coal strike in 1926, one report stating that upon the conclusion of the strike the workings were found to be flooded. The effects of the colliery were sold off by auctions between 1925 and 1927. [1][2][3]

Various Locations around the site of the Colliery

- Trafalgar Arch – between Serridge Junction and Drybrook Road, the Severn and Wye Railway ran very close to the large spoil heap of Trafalgar Colliery. The line was protected by a stone retaining wall braced at one point by a brick-lined stone arch. This was built by the S&WR at a cost of about £200 in 1878 or thereabouts, after lengthy negotiations with the colliery company, who wanted to tip spoil on the other side of the line. It is uncertain whether or not the bridge was used for this purpose and tipping appears to have continued on the original site. In 1887 the retaining wall was damaged by a major slip. It was replaced by a stronger one in 1904, but this soon collapsed, and was eventually rebuilt. The bridge was renovated when the old railway track-bed became a cycleway. The arch was restored to as-new condition before October 2001. [9] It is highlighted on the 25″ OS Map extract below. [8]

We walked to the colliery location in September 2019 and took the picture of the arch below.

We walked to the colliery location in September 2019 and took the picture of the arch below.

- The Disused Tunnel – the tunnel between Trafalgar and Strip-and-at-it Collieries was cut through a small ridge between the two collieries. It had a very narrow bore as is evident in the adjacent pictures. The north portal, in the first of the photographs, is very difficult to access. The south portal was in the wall of an old quarry facing the site of the Trafalgar Pit.

- The Colliery Screens – there are remains of retaining walls from the screens which can still be seen on site, a picture appears below.

- The tip – the Colliery spoil heap still exists on the north side of the cycleway which follows the Severn and Wye Railway formation. “The earthwork remains of the Trafalgar Colliery spoil heap are visible as an earthwork on aerial photographs. This massive spoil heap was situated to the south west of the colliery buildings and is centred on SO 6223 1424. It measures 485 metres in length and up to 120 metres in width. North east of the spoil heap at SO 6241 1445 is a quarry where stone was extracted for colliery buildings and shaft linings.” [13] It was later used as the route of the tramway through the tunnel to Strip-and-at-it Mine. The spoil heap material is derived from the Supra-Pennant Coal Measures.

- The Shafts – the two shafts are marked in the early 21st Century by two large standing stones, as shown in the adjacent image.

- Trafalgar House – the home of Sir Francis Brain is still in use as a private dwelling. Two modern pictures are shown below. These are followed by a small extract from the 25″ OS Map [8] and a picture of the house and tramway which is in an article by Ian Pope in Archive Journal No. 84. [16]

- https://www.forestofdeanhistory.org.uk/resources/sites-in-the-forest/trafalgar-colliery, accessed on 30th August 2019.

- http://lightmoor.co.uk/forestcoal/CoalTrafalgar.html, accessed on 30th August 2019.

- http://way-mark.co.uk/foresthaven/historic/trafalgr.htm, accessed on 30th August 2019.

- John Bellows; A Week’s Holiday in the Forest of Dean; 1880, replica edition Holborn House, 2013.

- Cyril Hart; The Industrial History of Dean; David & Charles, Newton Abbott, 1971.

- https://rogerfarnworth.wordpress.com/2017/09/28/the-branch-tramways-and-sidings-of-the-severn-and-wye-tramroad, collated in February 2018. This link gives some background information on all of the branch tramways of the Severn and Wye. I hope to be able to provide some more specific detail on a number of these tramways in the future.

- Gloucestershire County Council Historic Record Archive which holds a great deal of source information. Monument No. 5701; https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=4329&resourceID=108, accessed on 20th September 2019. … The Severn and Wye Co built a branch from Mirystock to Churchway, where a junction was made with the Bullo Pill tramroad in 1812 (This became the GWR Forest of Dean Branch). A short loop line at Mirystock was constructed in 1847 to give better access to the Churchway branch from the south, a second spur to the Churchway branch was constructed in 1865. … The Churchway Tramway closed in 1877 and was lifted almost immediately. I hope that this tramway will be the subject of a future post. The 25″ OS Maps of the time, very fortunately, were drawn over a significant time frame. This means that one part of the Mirystock Mine appears on the maps (below) but not the southern half which was the part which obliterated the junction of the Churchway Tramway with the Severn and Wye Main line. Four extracts from those maps appear below. The first three show the length of the Churchway tramway, the fourth shows the junction with the Severn & Wye Tramroad in slightly greater detail. These are sourced from reference 8 below.

- https://maps.nls.uk/os/25inch-england-and-wales, accessed on 20th September 2019.

- https://www.forestofdeanhistory.org.uk/resources/sites-in-the-forest/trafalgar-arch, accessed on 22nd September 2019.

- http://way-mark.co.uk/foresthaven/historic/hstcin0e.htm, accessed on 22nd September 2019.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/8812089@N06/15926122657, accesed on 22nd September 2019. … Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

- https://aboutangiekay.blogspot.com/2019/04/strip-and-at-it-and-other-reprehensible.html?m=1, accessed on 22nd September 2019.

- https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=8597&resourceID=108, accessed on 24th September 2019.

- http://www.industrialgwent.co.uk/wuk12c-fodne/index.htm, accessed on 24th September 2019.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4957275, accessed on 24th September 2019.

- Ian Pope; Mr Brain’s Tramway; in Archive No. 84, Black Dwarf, Lightmoor Press, Lydney, 2014; p3-31.