Henry Robinson Palmer (1793-1844) was a British engineer who designed the first monorail system and also invented corrugated iron!

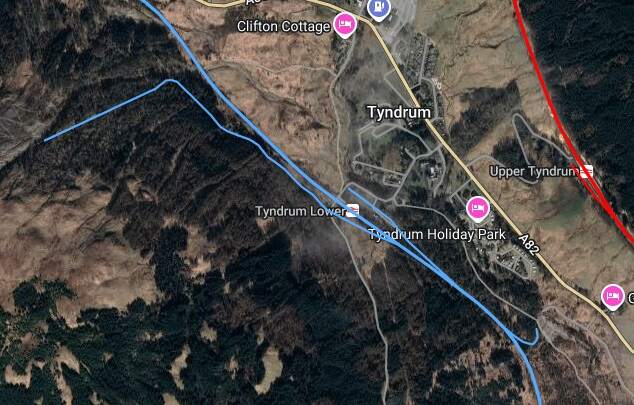

Born in 1793 in Hackney, he was the son of the Revd Samuel Palmer, a nonconformist minister, and his wife, Elizabeth, née Walker. [1] He was baptised in Tooting [2] and was educated at the academy run by his father and between 1811 and 1816 was an apprentice at 1811-16 Apprenticed to Bryan Donkin and Co.

When he finished his apprenticeship, Palmer was taken on by Thomas Telford, working for him for 10 years and involved with a variety of road/canal surveys and associated designs. In 1818, Palmer was one of three young engineers key to the founding of the Institution of Civil Engineers and on 23rd May 1820, he formally became a member of the Institution. [3]

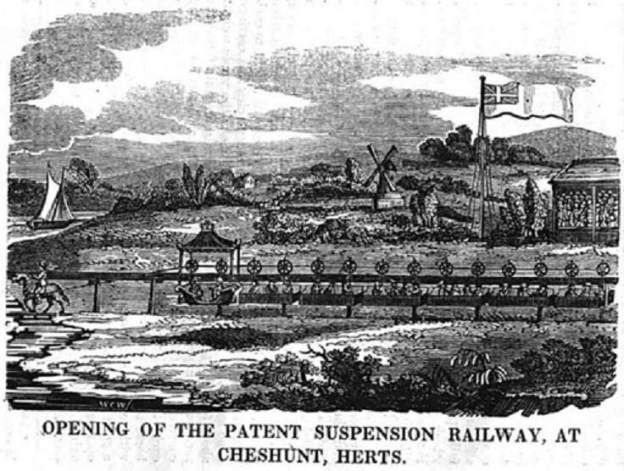

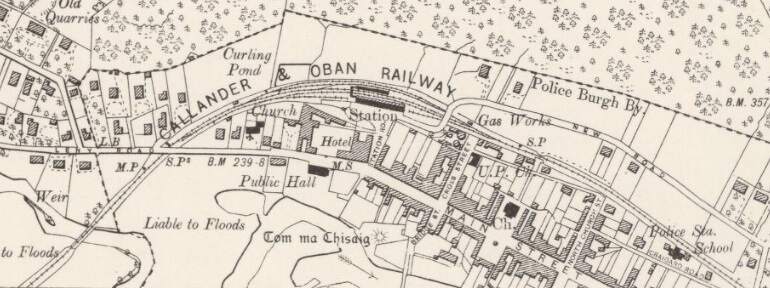

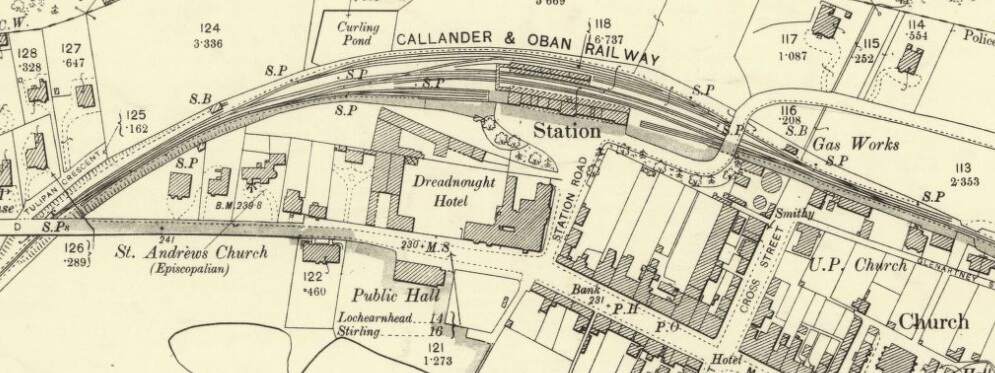

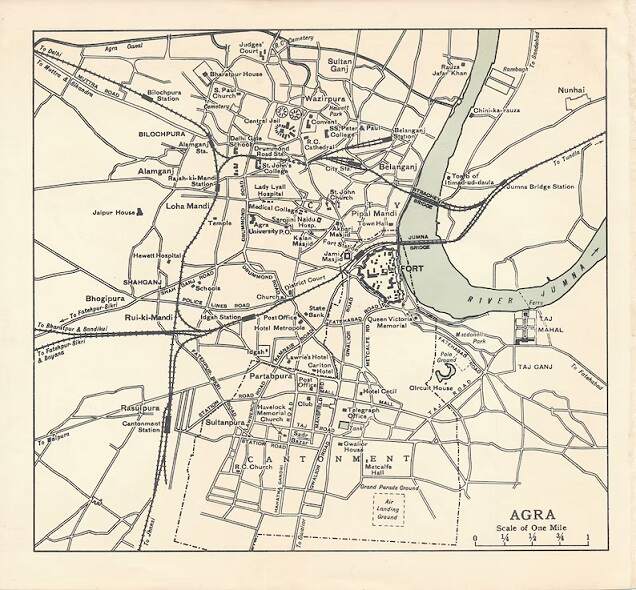

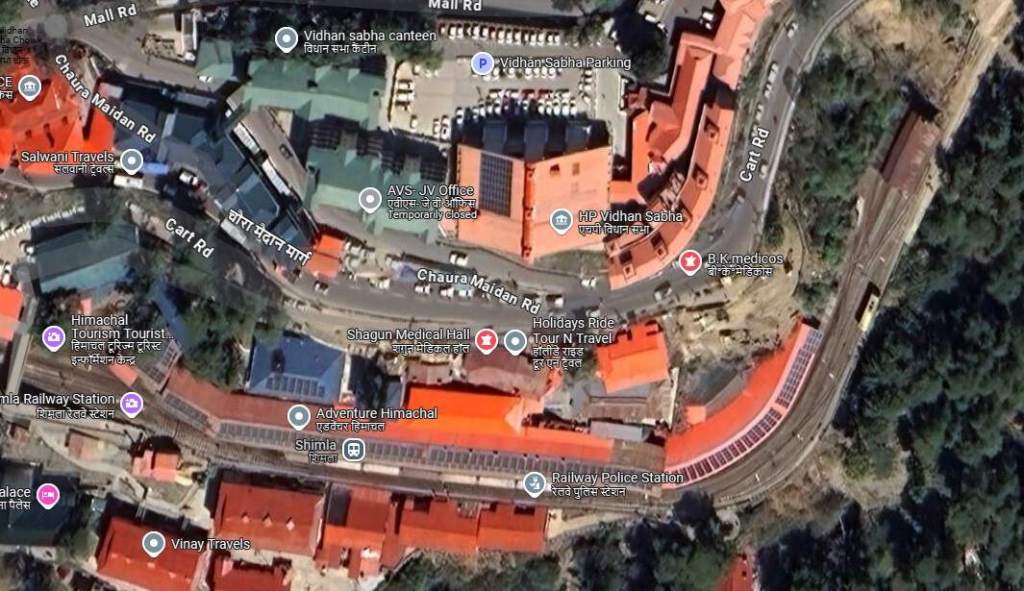

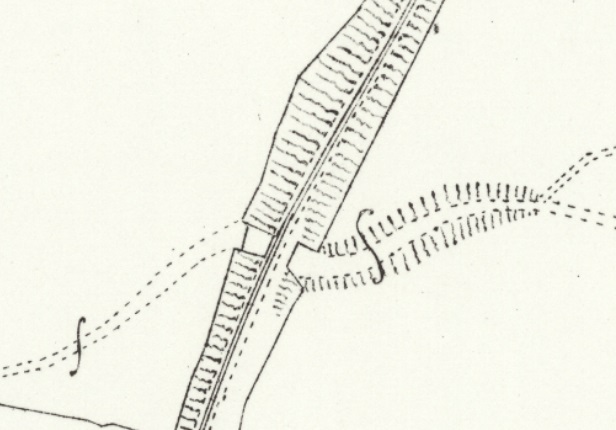

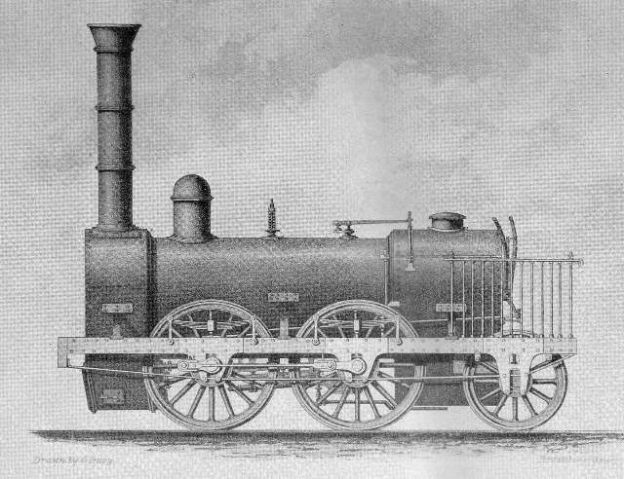

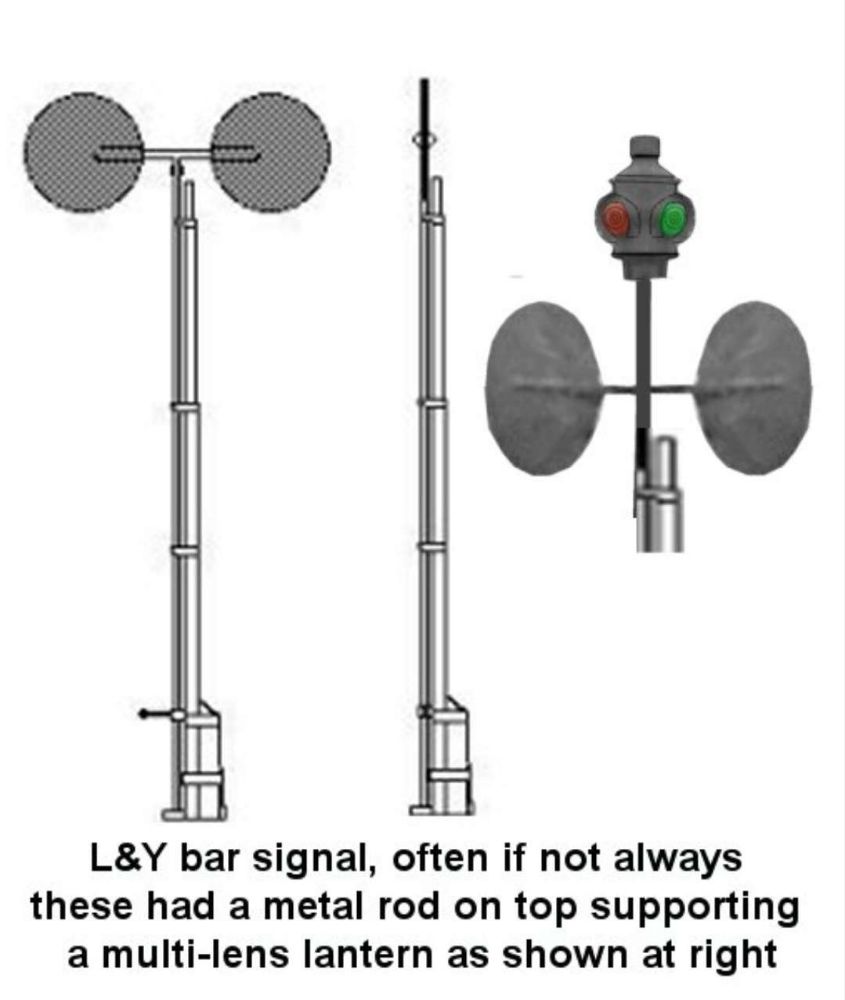

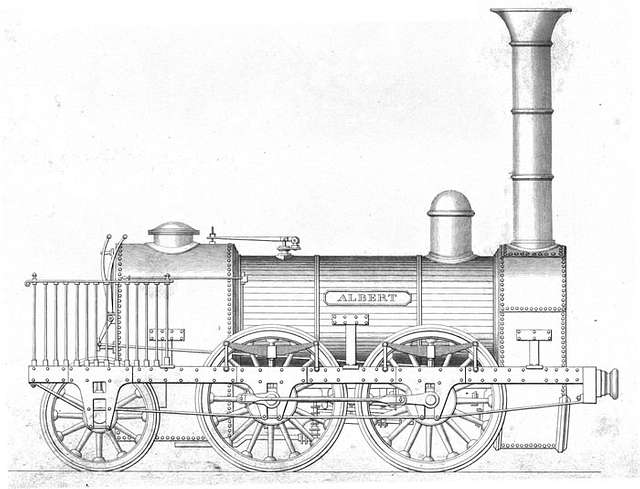

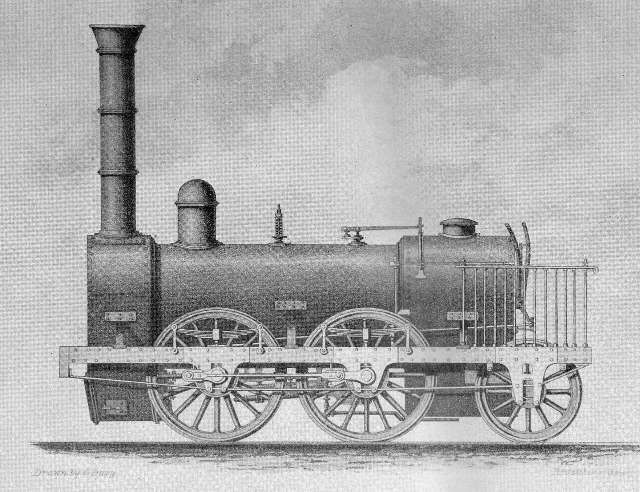

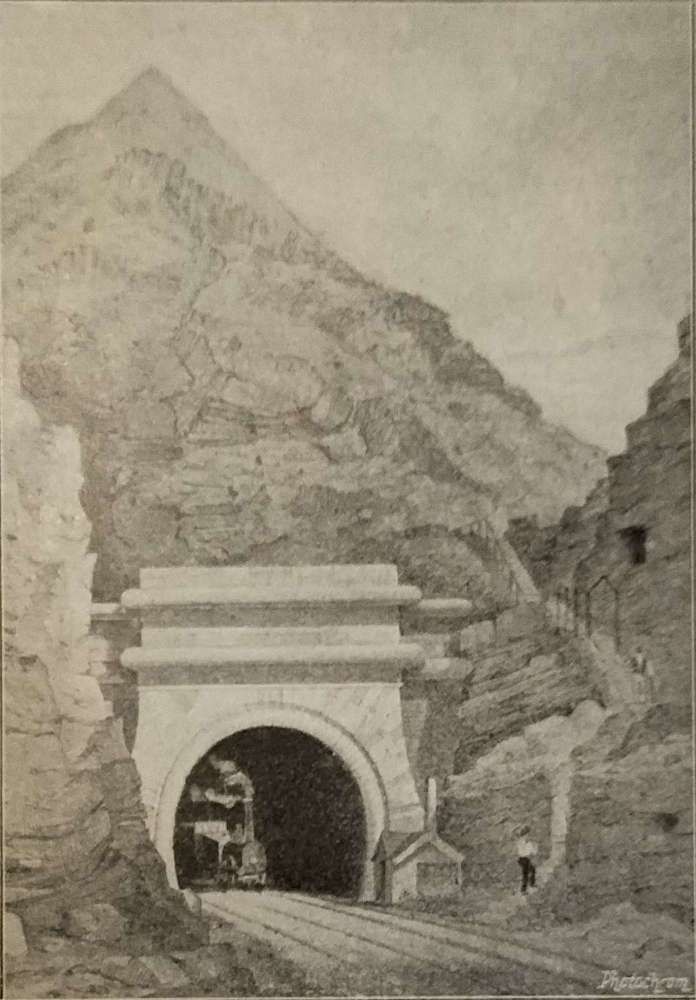

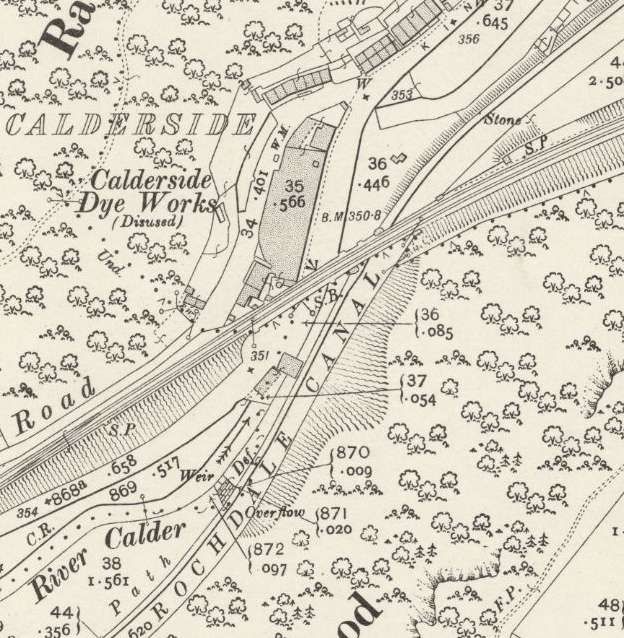

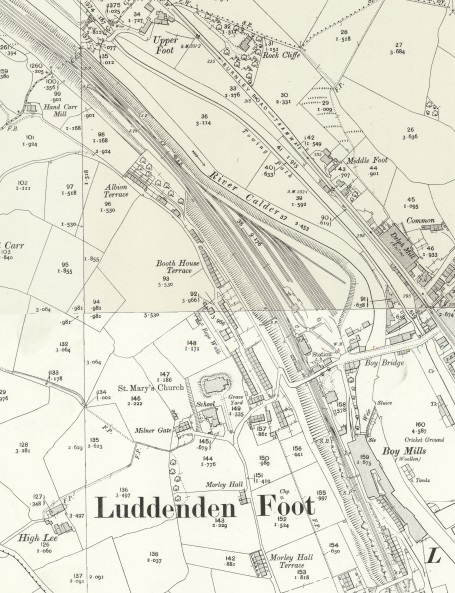

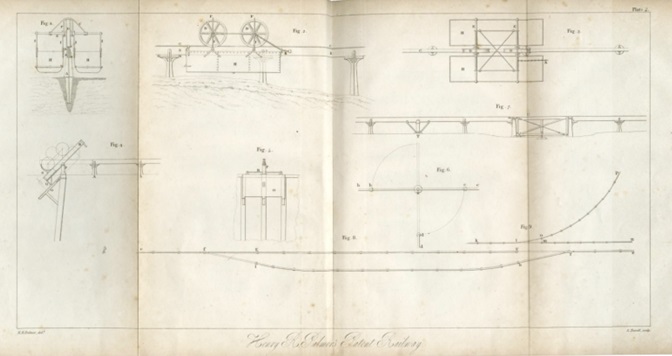

Elijah Golloway recorded Palmer’s ideas for a Suspension Railway in the image above which is dated 1822. It seems as though Galloway’s book, History of the Steam Engine, From Its First Invention to the Present Time: Illustrated by Numerous Engravings From Original Drawings, Made Expressly for This Work, was not published until 1828 by B. Steill. [4][5]

On 22nd November 1821, Palmer patented his proposed monorail system. [6][19: p57]

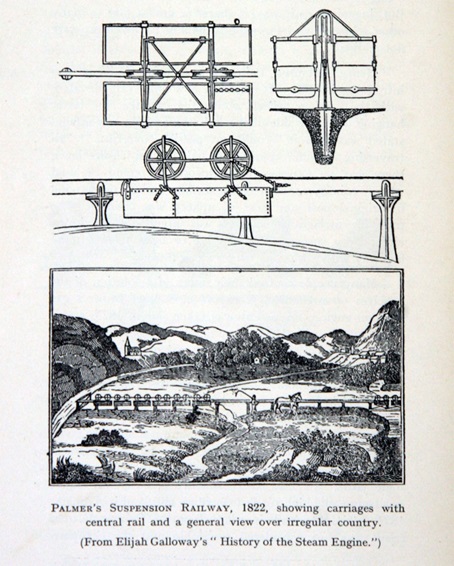

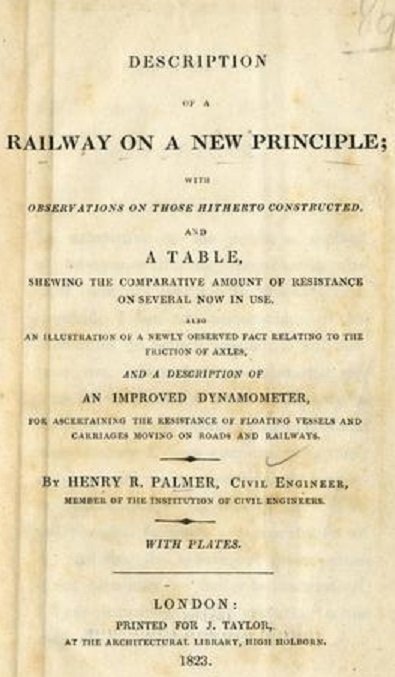

In 1823, Palmer wrote his short book, Description of a Railway on a new Principle, (J. Taylor, 1823) about his monorail ideas. [7]

The illustrations immediately below come from a copy of that book which is held by the Science Museum. [7]

Palmer was unaware of the experimental work being undertaken in Russia at around the same time. The work of Ivan Kirillovich Elmanov is covered here. [26]

and are released by the Science Museum under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) [7]

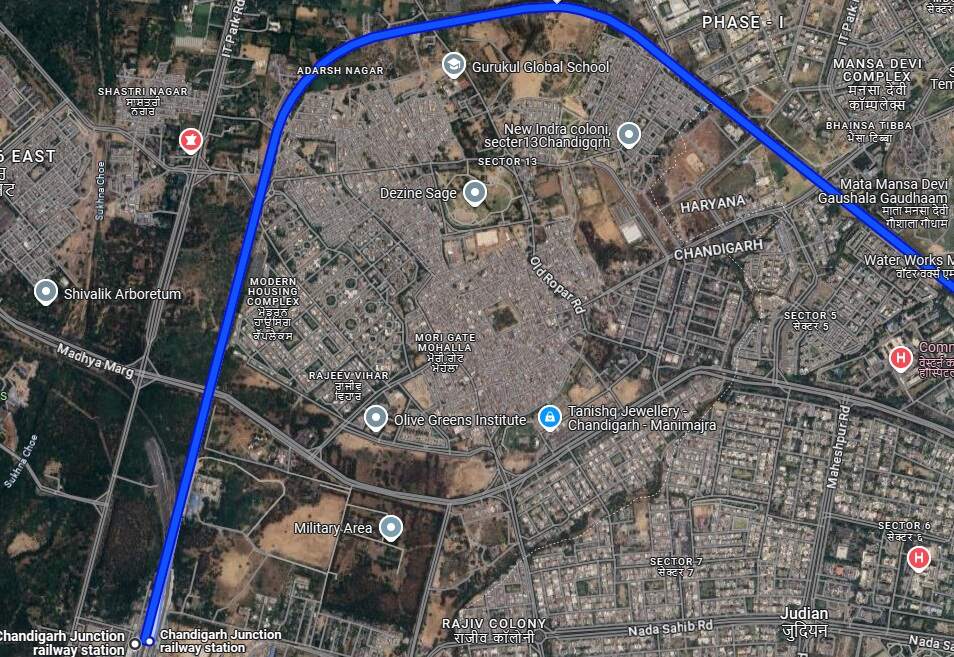

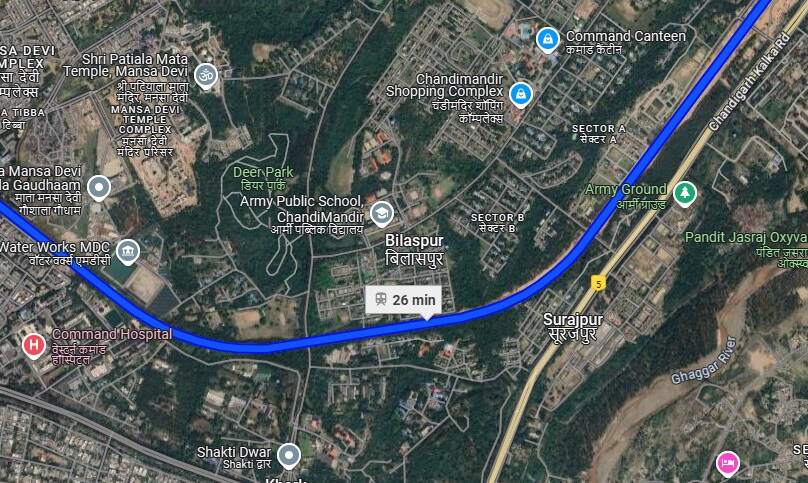

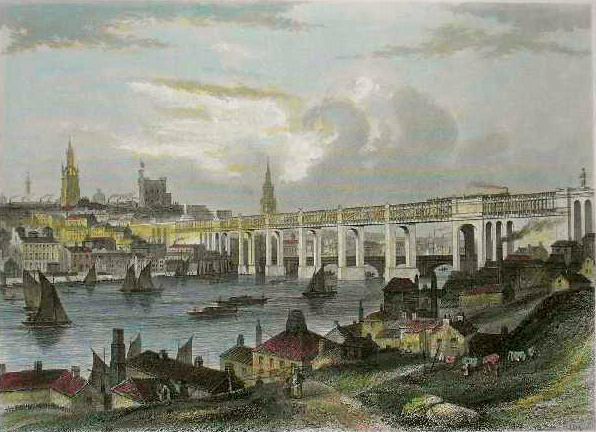

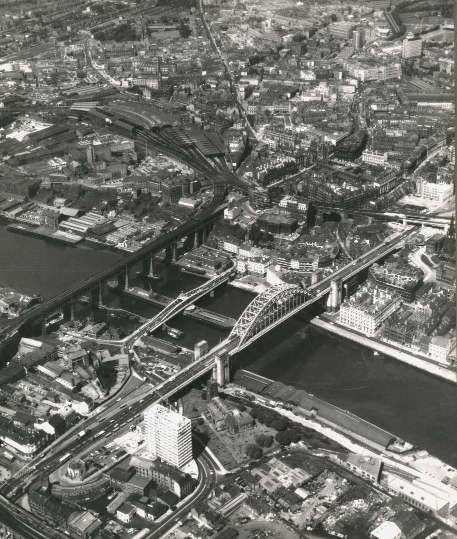

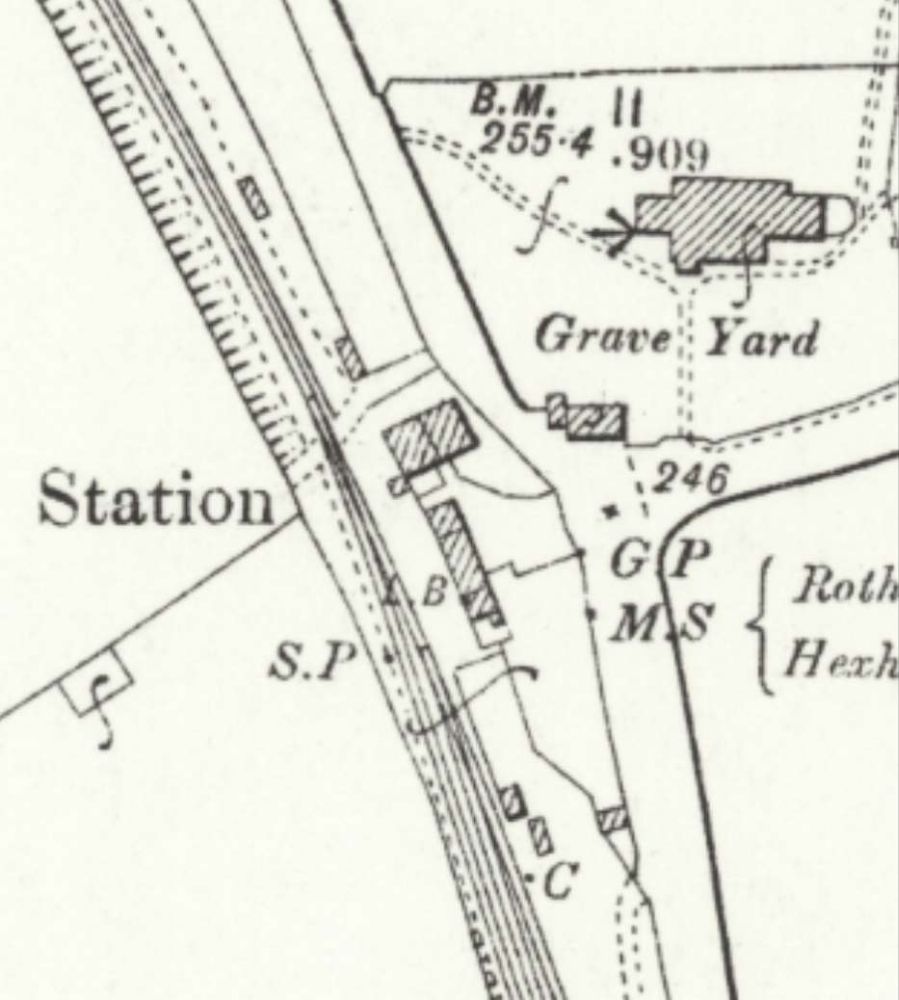

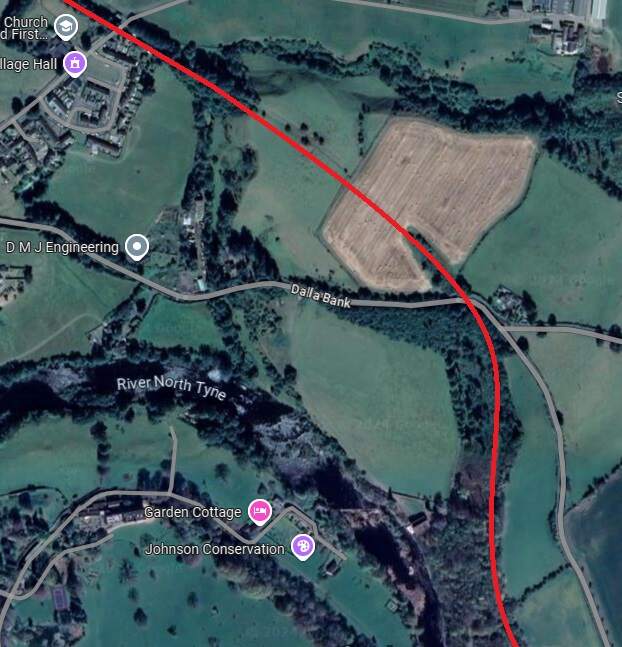

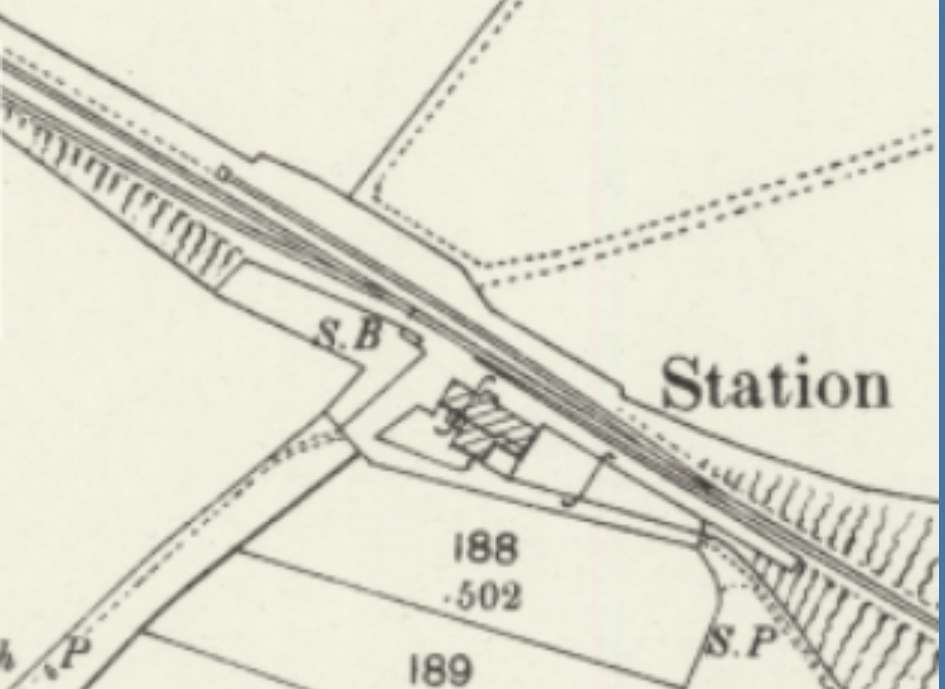

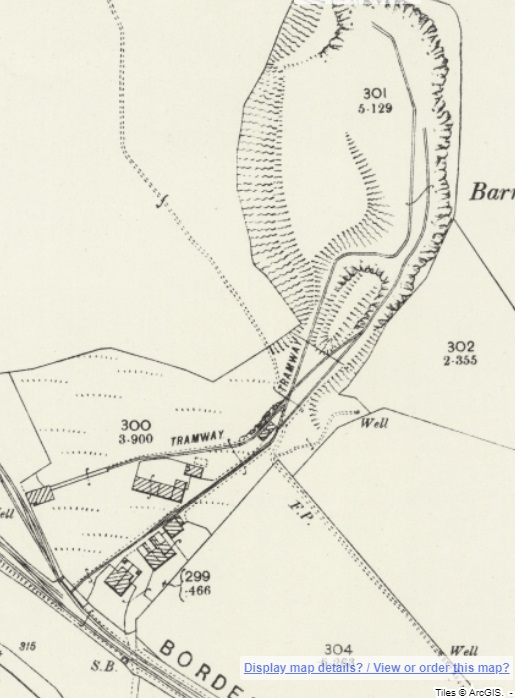

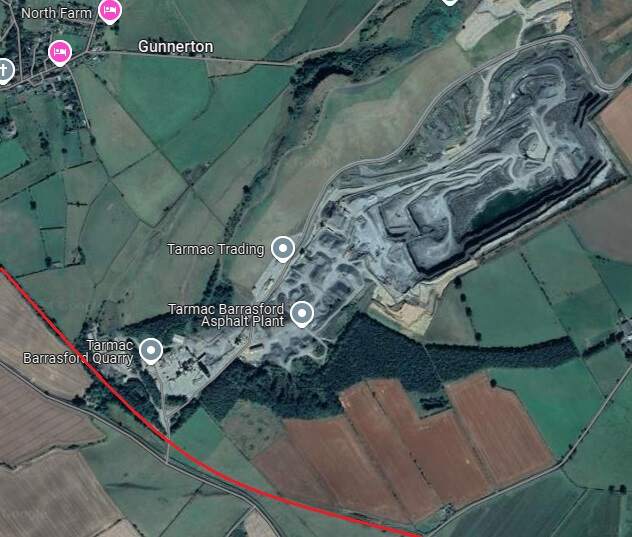

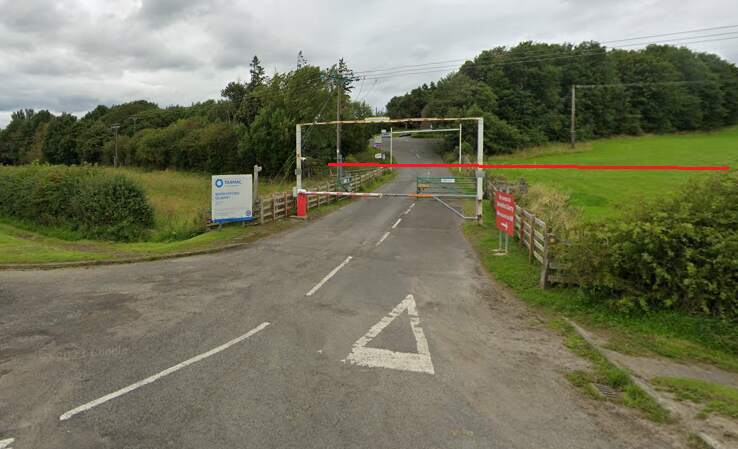

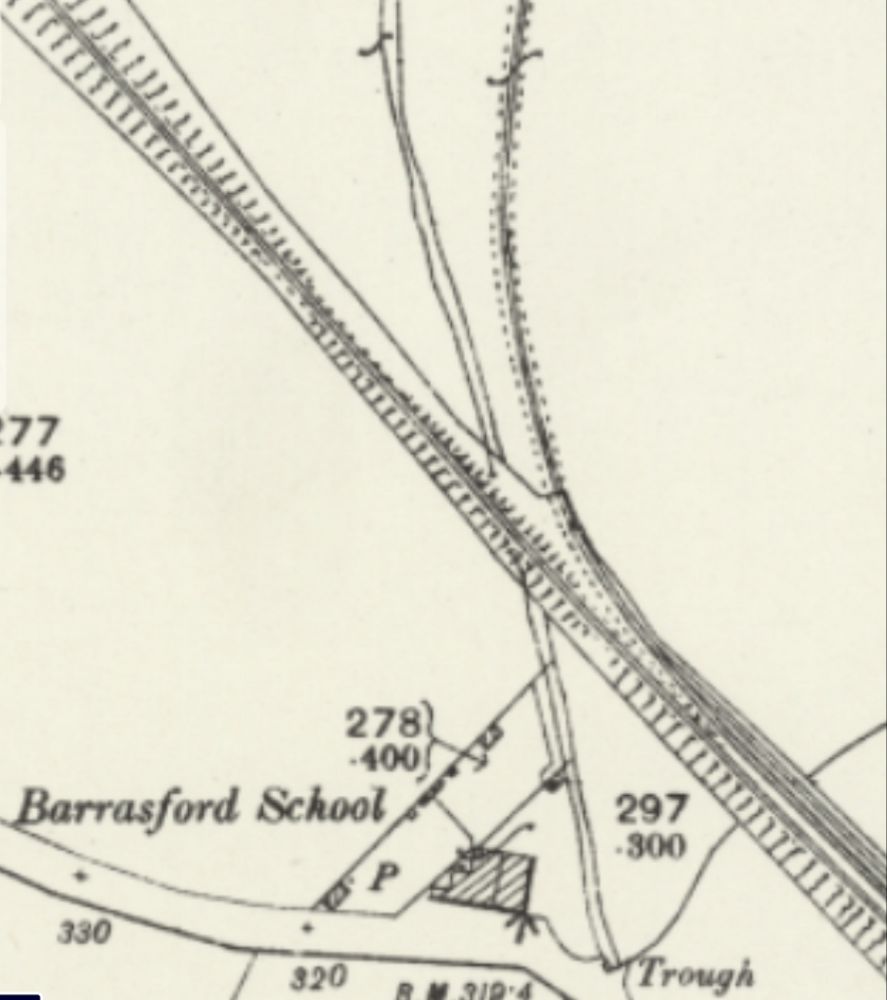

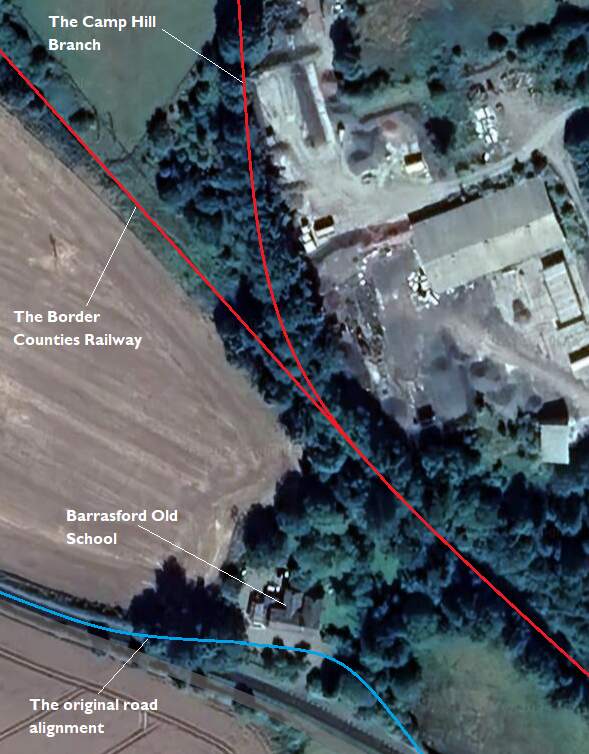

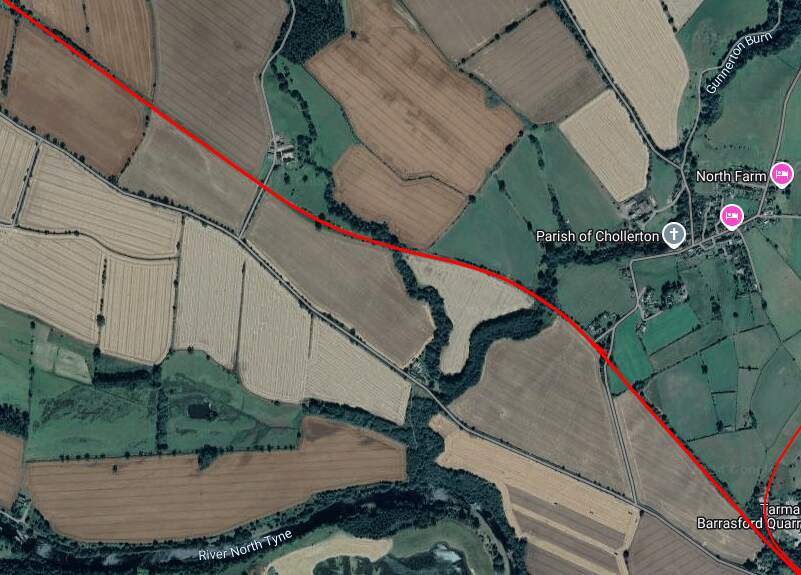

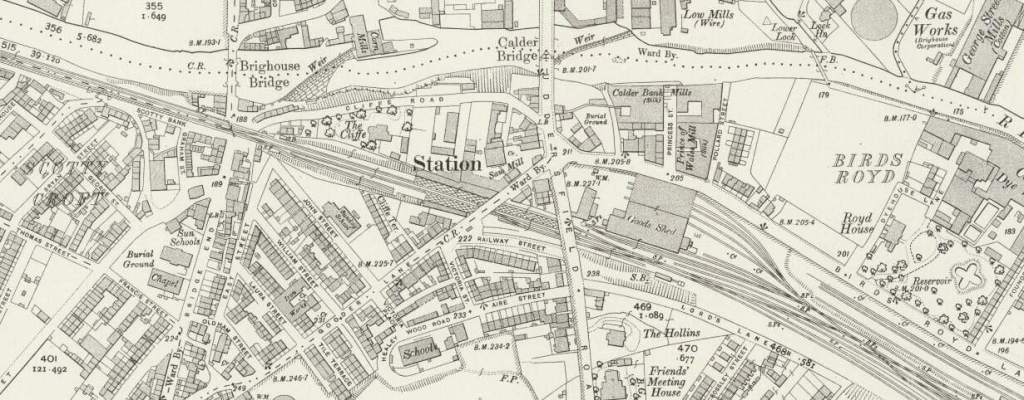

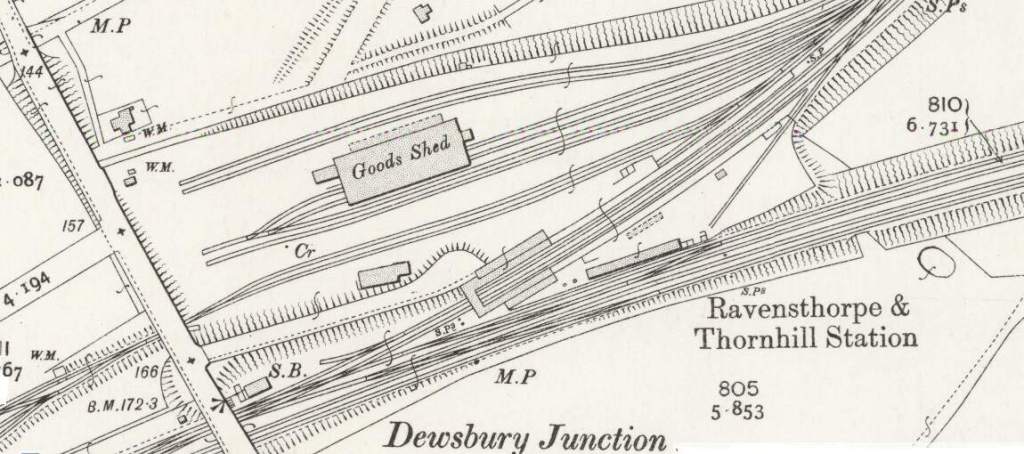

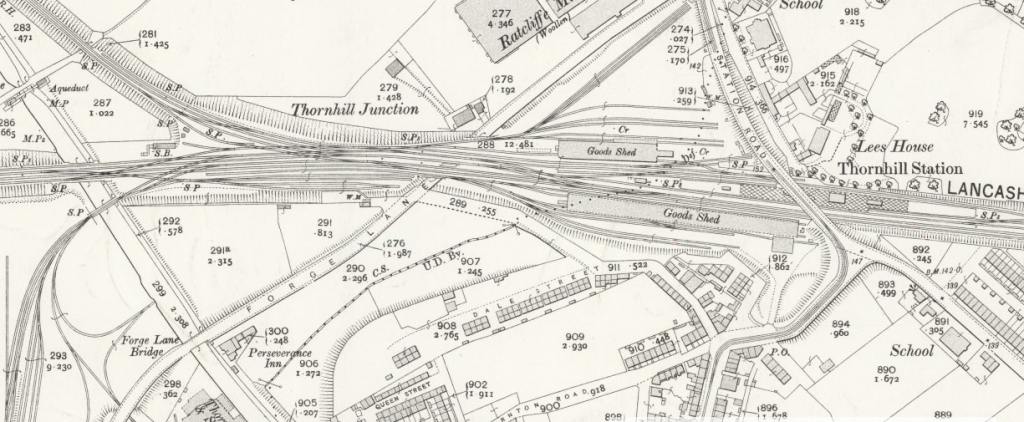

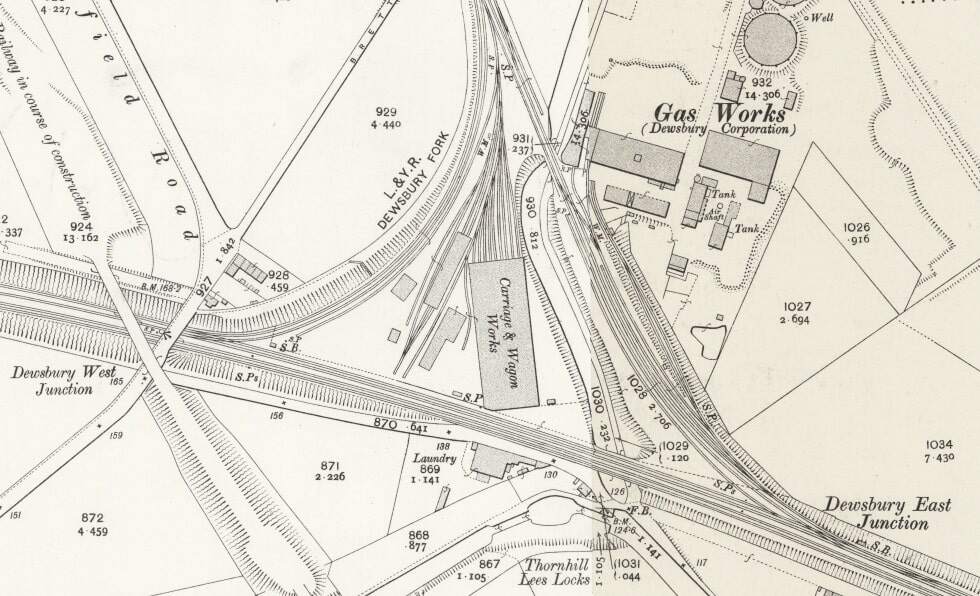

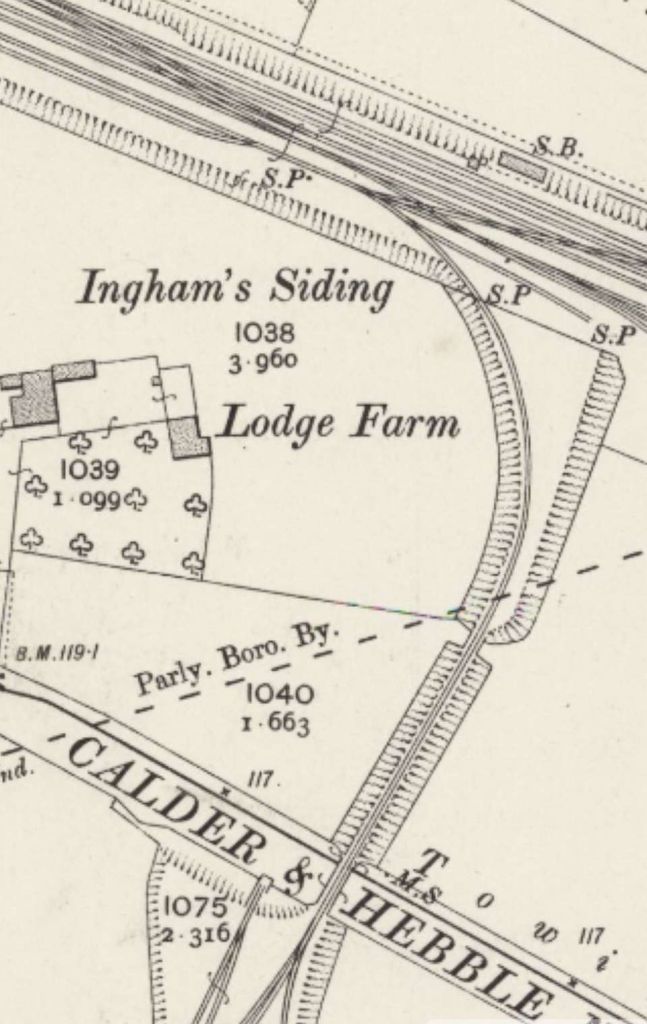

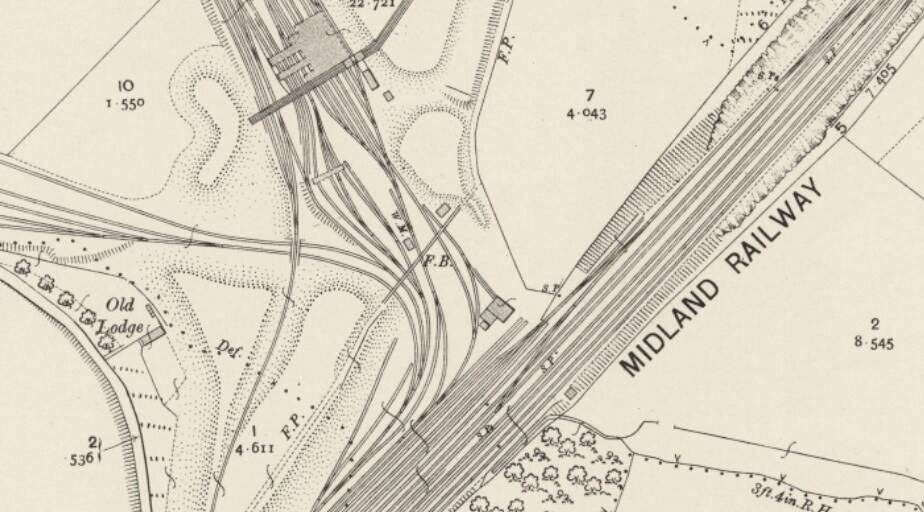

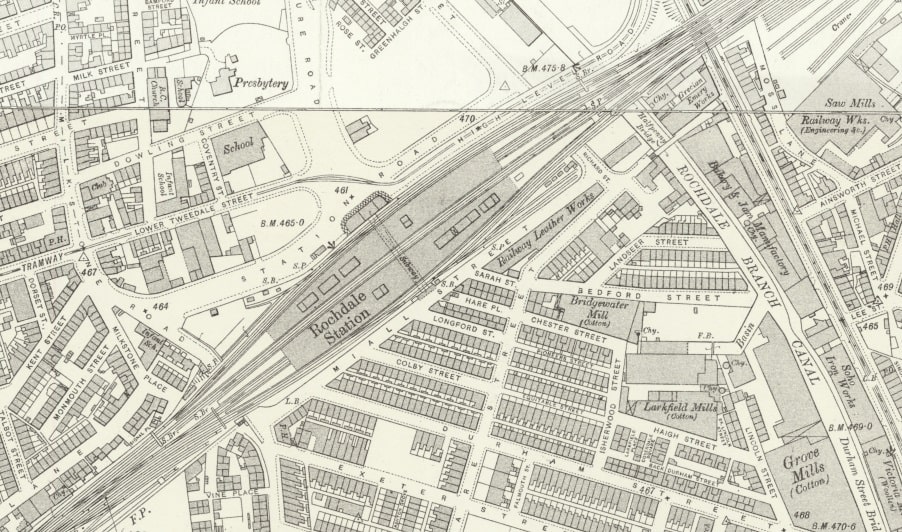

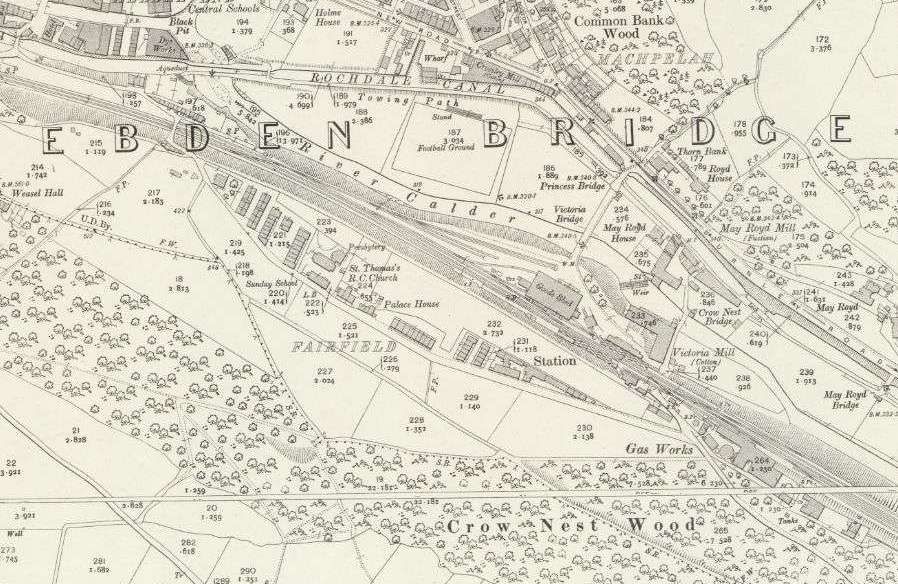

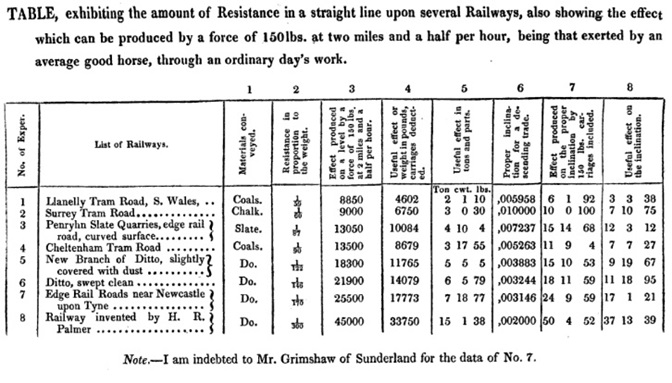

In his book, Palmer refers to examples of railways already constructed. It is clear that he is talking of railways which operate on more traditional principles. He tabulates those to which he is referring in a table which is reproduced below: the Llanelly Tramroad; the Surrey Tramroad; the Penrhyn Slate Quarries, edge rail road; the Cheltenham Tram Road; a branch of the Cheltenham Tram Road; Edge Rail Roads near Newcastle-upon-Tyne. These he compares with his own proposed railway which was built in Deptford Dockyard in London in 1824. [6]

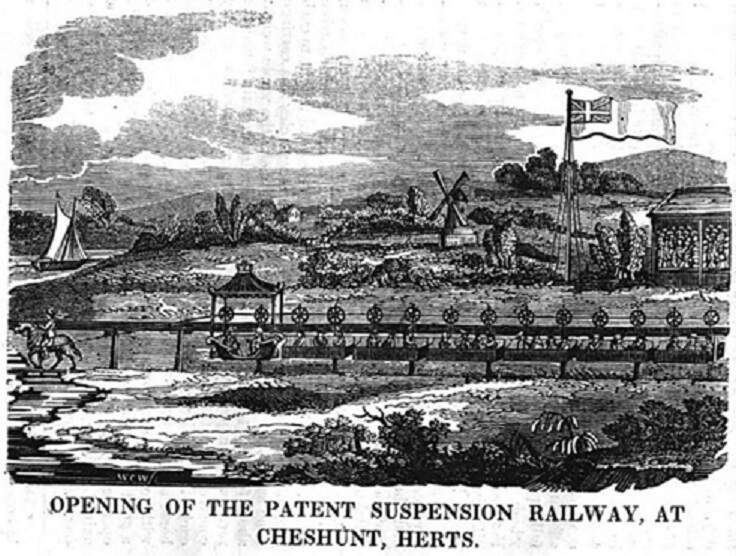

History only seems to record two of Palmer’s monorails in the UK. The first was constructed at Deptford as we have already noted. The second was built at Cheshunt and opened about 3 months prior to the Stockton & Darlington Railway (in June 1825) and was described, that month, in The Times newspaper. [9] Although his ideas were attempted in at least one other place. The railway built in what is now Hungary in 1827 (15th August). It was a fleeting experiment about which more details can be found here. [10]

Palmer is recorded as having given evidence, in 1825, in favour of navigation interest and against the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. [4] He was appointed resident engineer to the London Docks in 1826, where, for 9 years, he designed and executed the Eastern Dock, with the associated warehousing, entrance locks, bridges, and other works. While undertaking this role, in 1828, he inventedthe “Corrugation and Galvanisation” of sheet iron. [11]

Regarding Palmer’s invention of corrugated iron, Dr. Pedro Guedes wrote that “Palmer exploited the unique properties of metal, creating a lightweight, rigid cladding material, capable of spanning considerable distances without any other supports, helping to make lightweight iron buildings and roofs possible. Palmer’s invention completely broke with precedent and tapped into another level of thinking. The sinusoidal corrugations that Palmer imagined as the means to impart strength to his sheets of wrought iron have continued virtually unchanged for close on two centuries.” [11]

In 1831, he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society, publishing two papers on the movement of shingle in Philosophical Transactions, 1831 and 1834. In 1833, he took out patents for improvements in the construction of arches and roofs. [12] In 1835, he moved to Westminster and worked as a consulting engineer and was involved in numerous surveys for projected railways, and the design and construction of several docks and harbours, including those at Port Talbot, Ipswich, Penzance, and Neath. He carried out the original surveys for the South Eastern Railway, assisted by P. W. Barlow, and would have executed the scheme but ill health intervened. His original surveys for a Kentish railway dated from the time he was associated with Telford.

He died on 12th September 1844. [13]

C. von Oeynhaussen & H. von Dechen inspected both of Palmer’s monorails during their visit to the UK in 1826 and 1827 and comment on both. First they describe the principles involved: “To facilitate laying out a railway with reduced friction, and to make it independent of the small unevennesses of the ground, Mr Palmer has proposed and built a kind of railway which consists of a single bar, and the wagons have only one wheel on each axle. The track is erected on posts or columns at a suitable height above the ground, and the load hangs so far below the wheels that the wagon frame cannot overturn. [16] This railway has the disadvantage that its construction is not solid, or it becomes very expensive; that it can compensate only for very small unevenness of the ground; that the motive power can operate only with an inclined pull; and that special precautions must be taken for unloading and loading the wagons. Therefore, the scheme has not come into general use. Excepting the two now to be mentioned, no railways of this kind appear to have been built in England.” [14: p75-76]

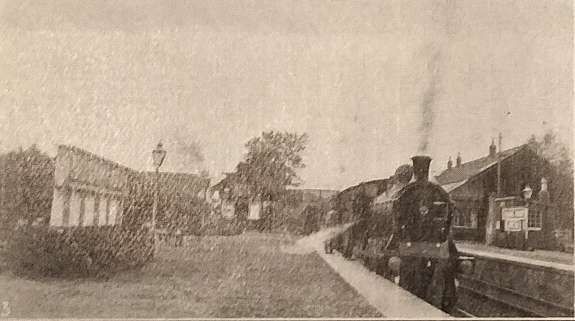

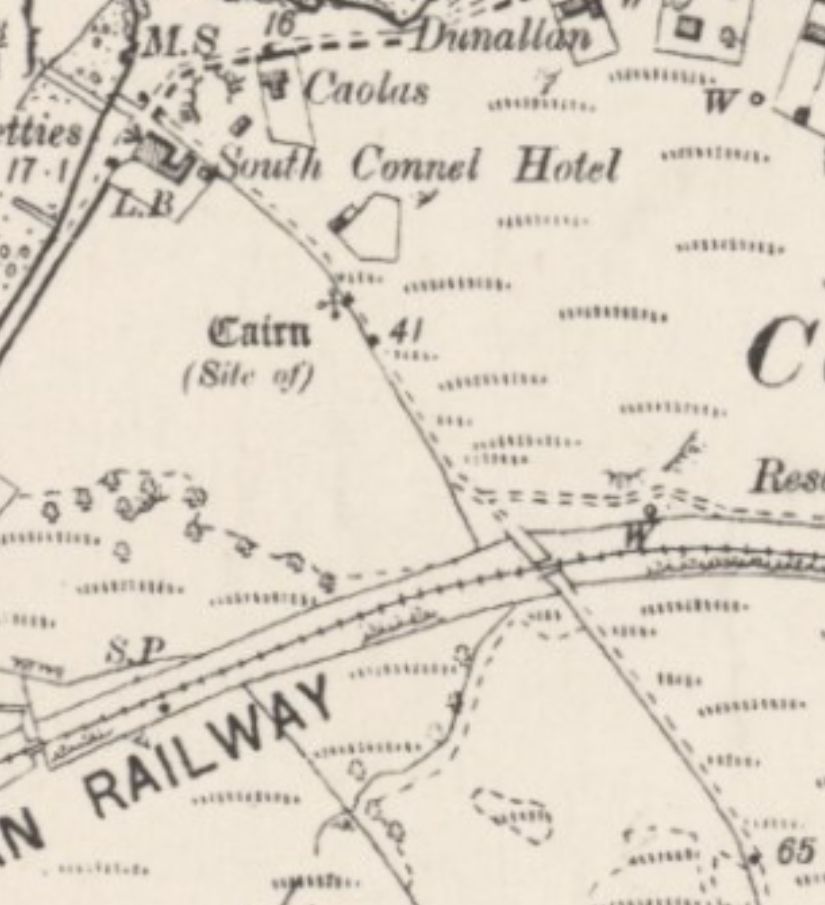

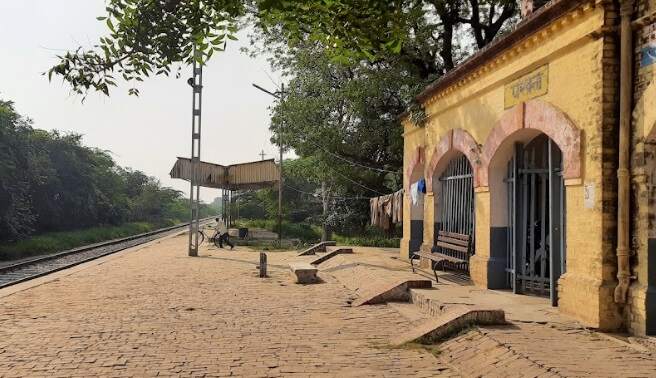

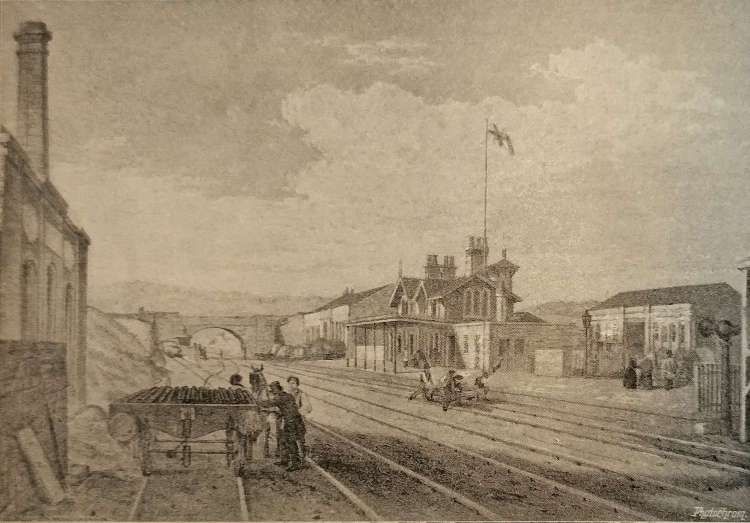

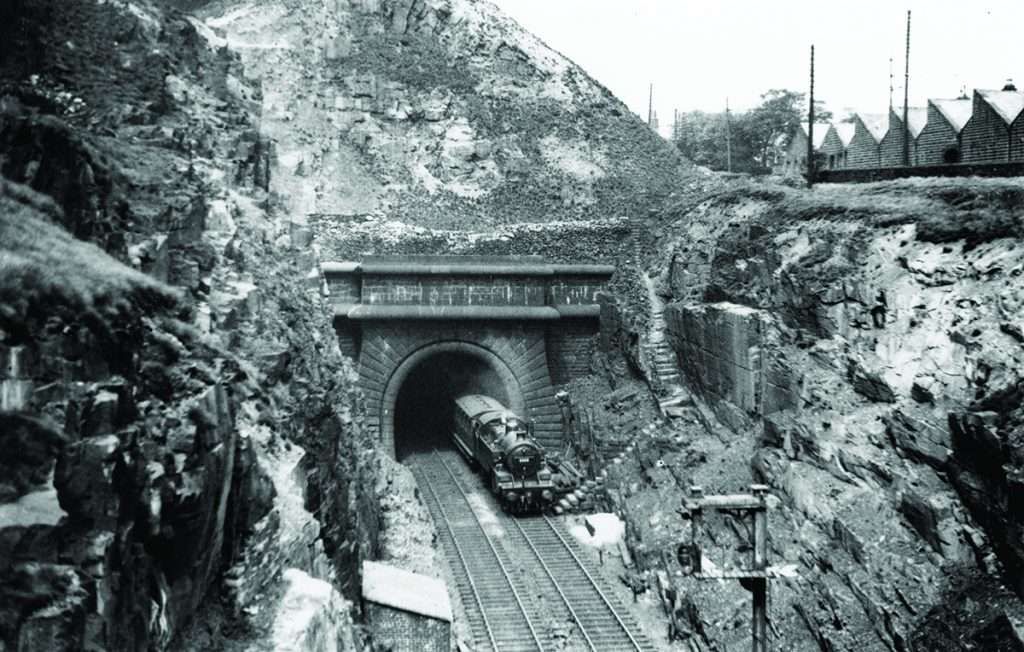

Palmer’s Deptford Railway

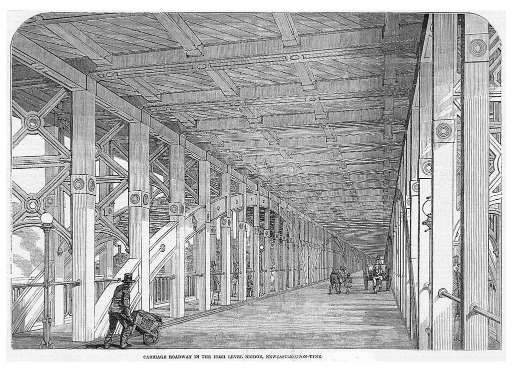

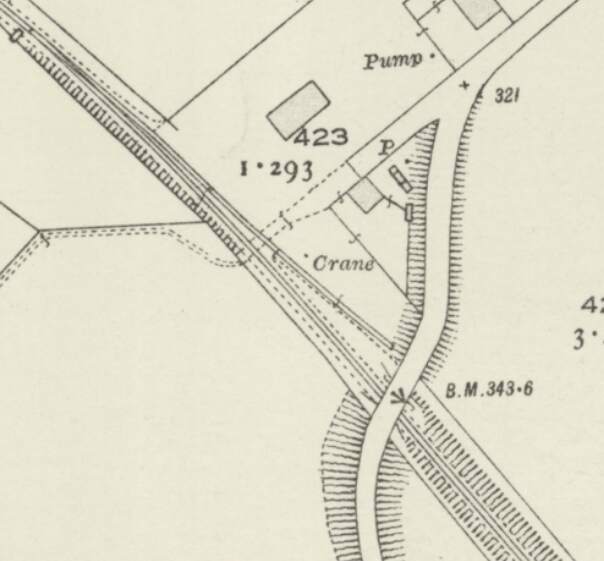

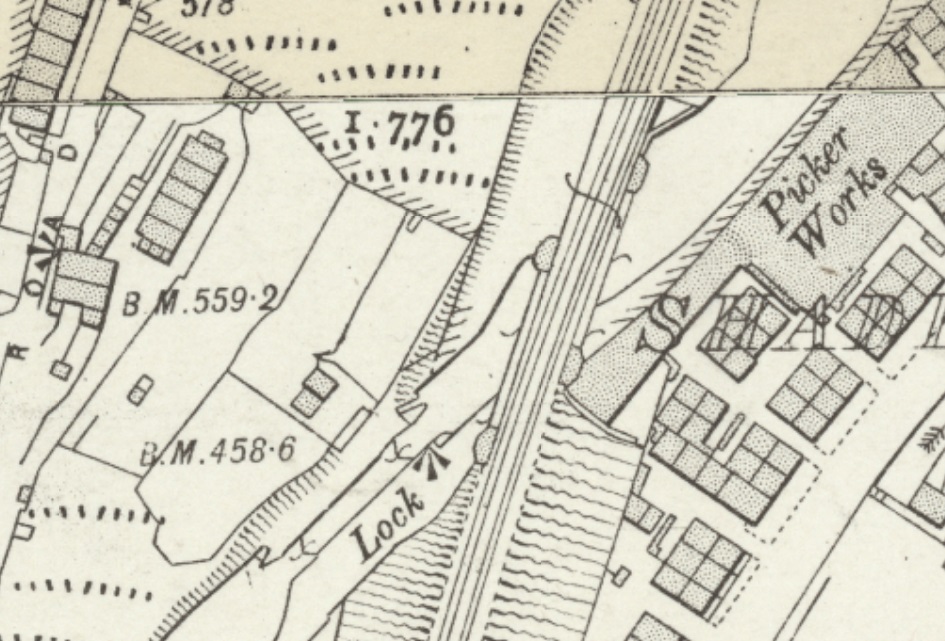

C. von Oeynhaussen & H. von Dechen describe this railway: “This railway leads from the Thames across the yard of the Victualling Office up to the warehouse, and serves to transport provisions out of the warehouse to the ships, or the reverse. The railway consists of cast-iron columns which project from 3 to 5 ft out of the ground; these are provided with fork-shaped seats at the top and are spaced 10 ft apart. Planks 9 in. high and 3 in. thick rest in the forks on double wooden wedges, so that they can be set at the correct level very easily. On the upper edge of these planks, wrought-iron bars are spiked, which are 3½ in. wide, somewhat convex, and in. thick in the middle. The ends of these bars are not square, but cut in a broken line, and rest, not directly on the plank, but on a small iron plate let into the wood.” [14: p76]

“The line is nearly horizontal, and has a fall of only about 20 minutes of angle to the river. … The wagons which run on this line have three wheels of 18 in. diameter, one behind the other; they have two flanges and the groove is shaped to fit the rail. These wheels are fixed to a wrought-iron frame which consists of three stirrups going over the wheels with connecting pieces below. The stirrups reach 2 or 3 ft below the railway, and are provided on both sides with an inclined platform, on which are placed the casks to be conveyed. For loading the wagons, there are two sloping frames at the same height as the wagon platforms, and between which the wagon has just room to pass. A wagon is loaded with 10 casks which weigh about 4½ cwt each, therefore totalling 45 cwt. The wagon can be taken at 5 cwt, so that the whole weight comes to 50 cwt, which can be moved up the line easily by four men.” [14: p76]

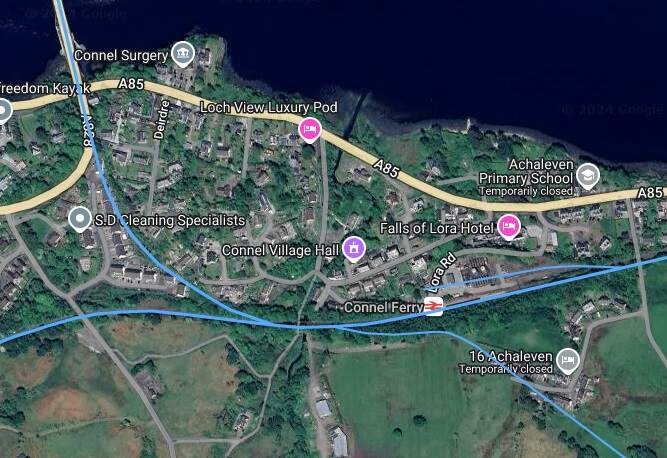

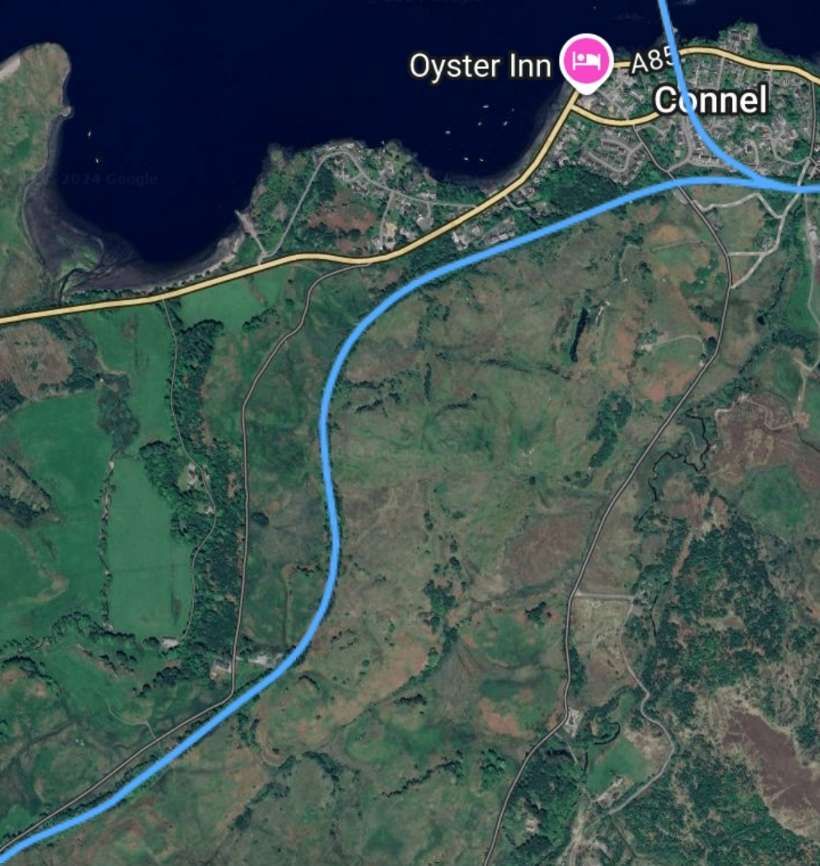

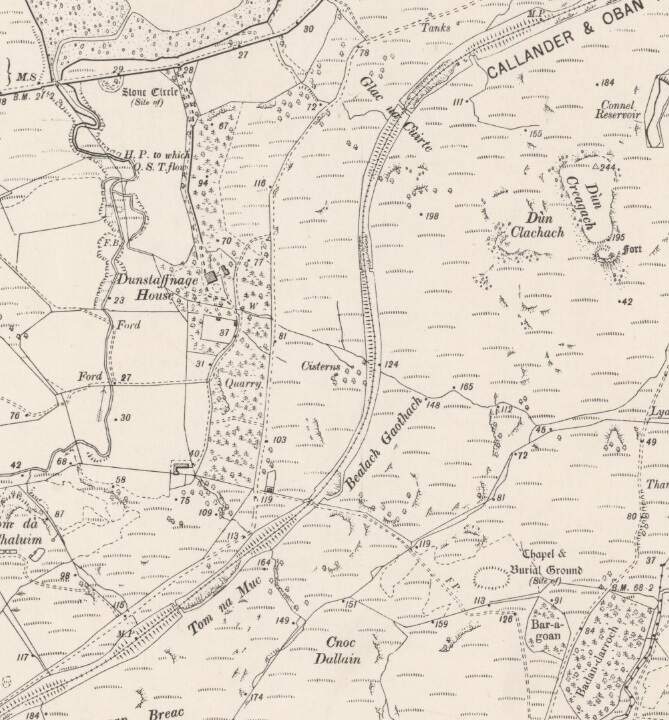

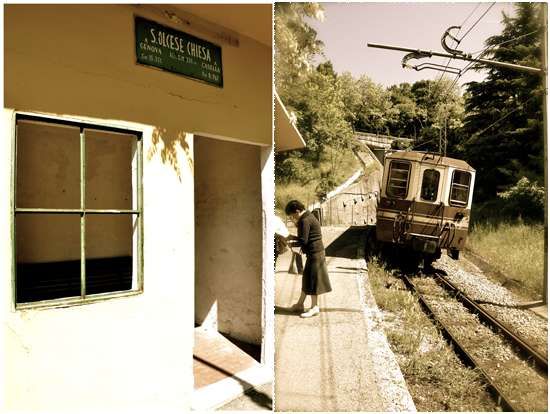

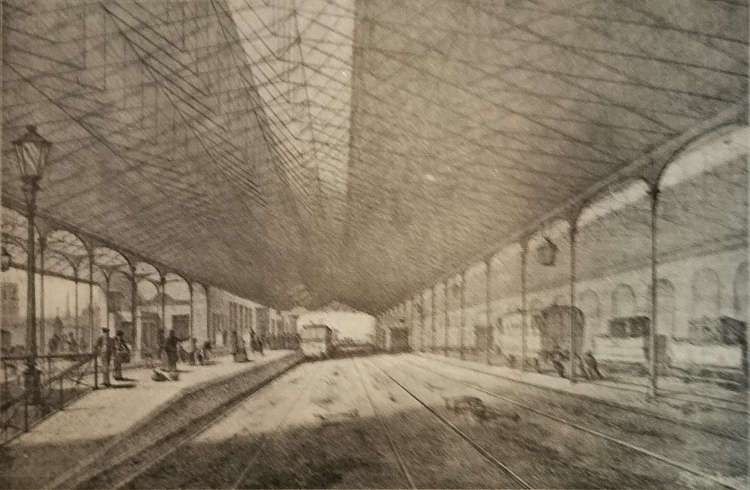

The Cheshunt Railway – The first passenger carrying monorail

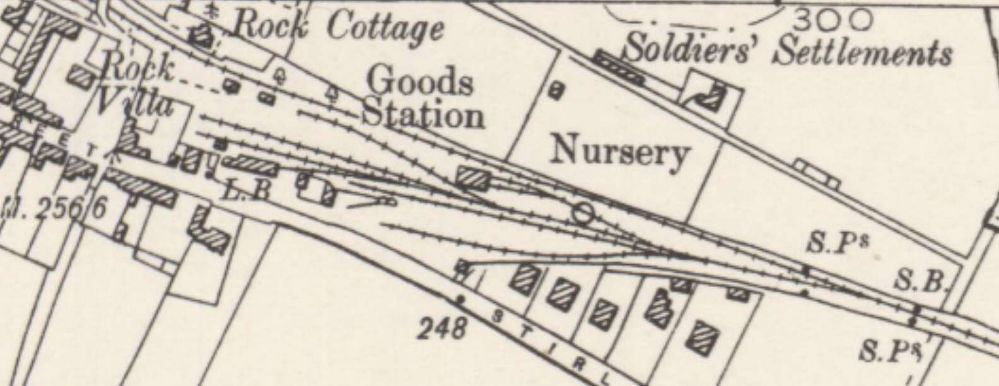

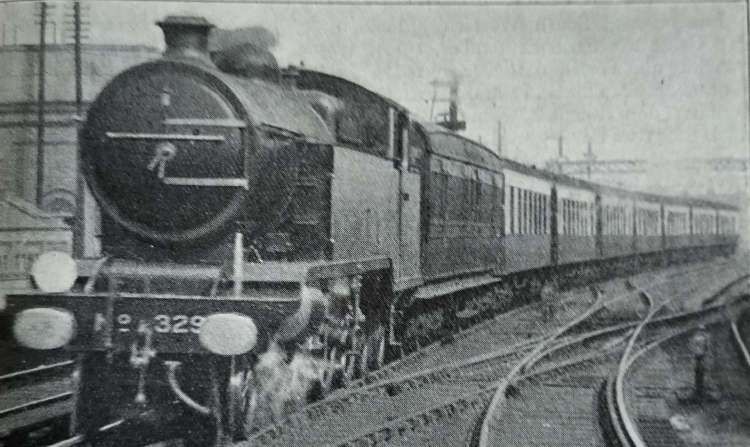

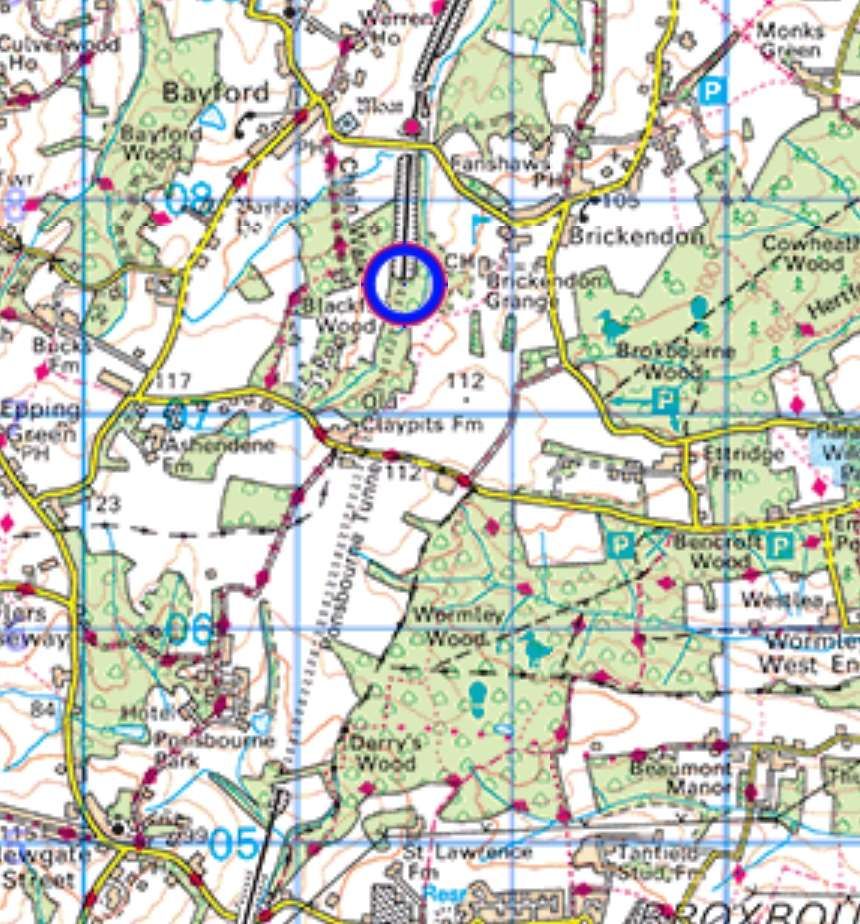

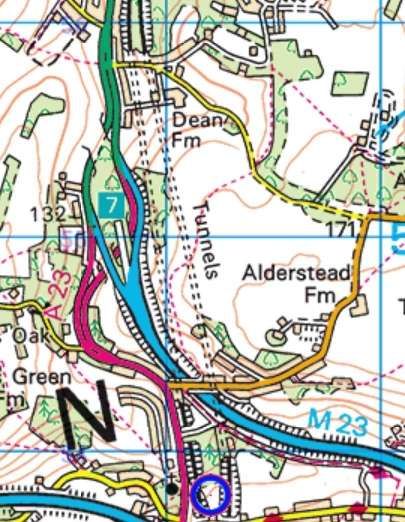

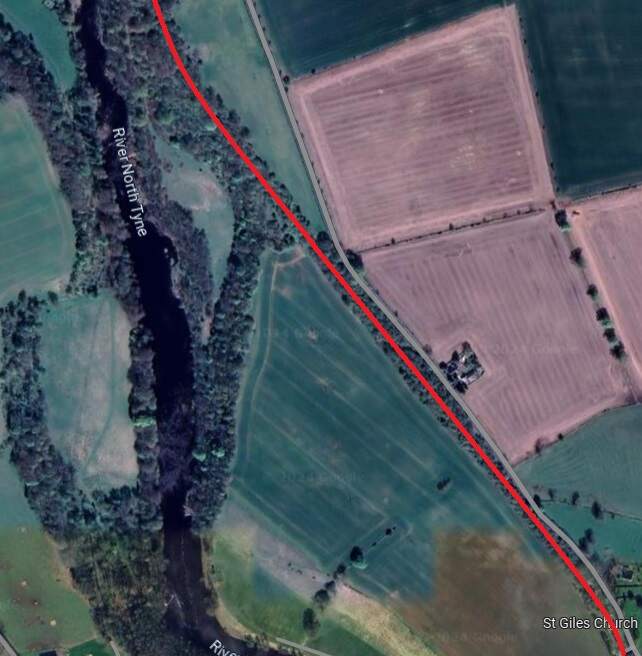

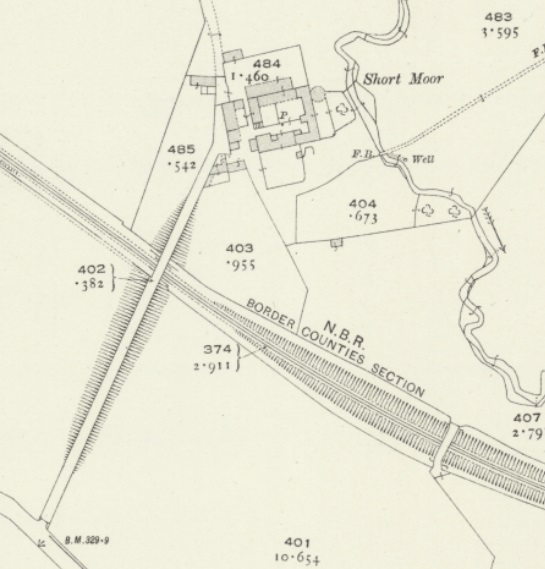

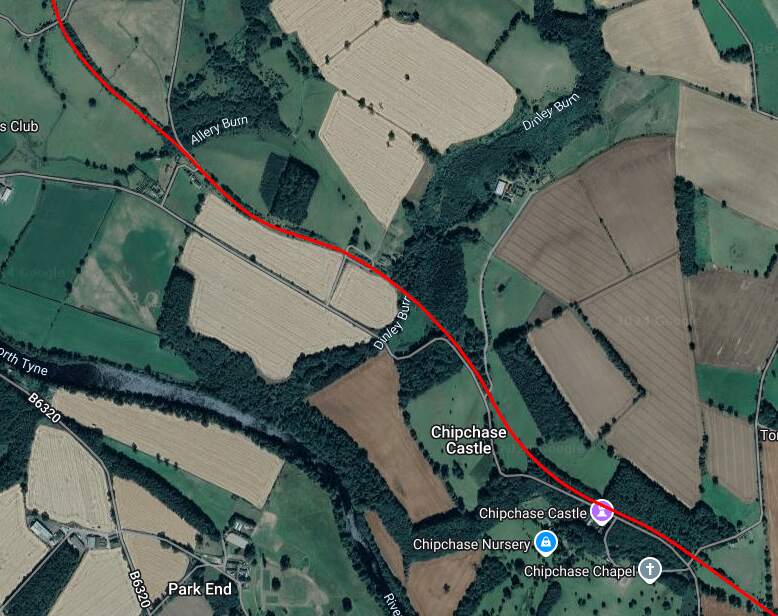

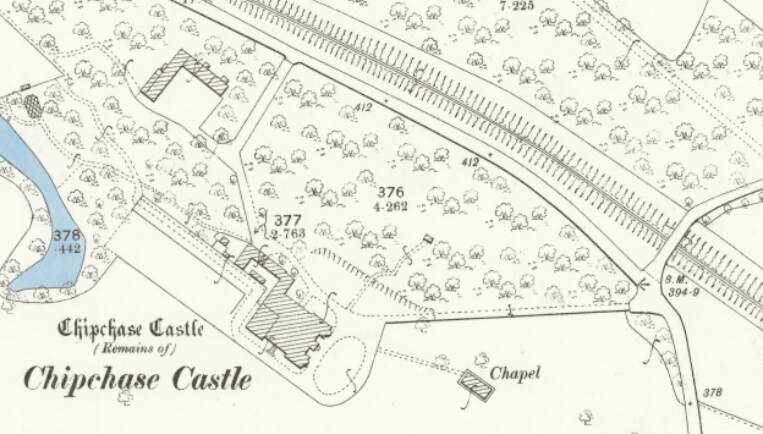

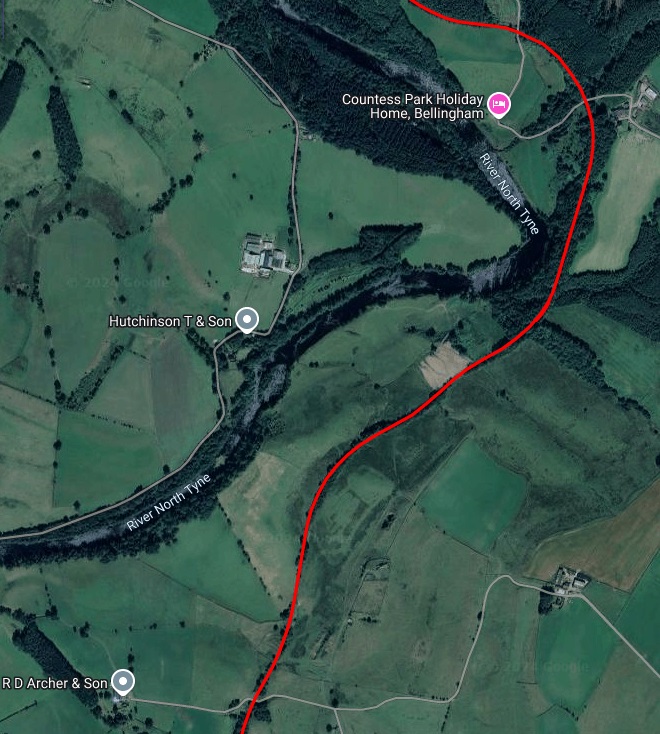

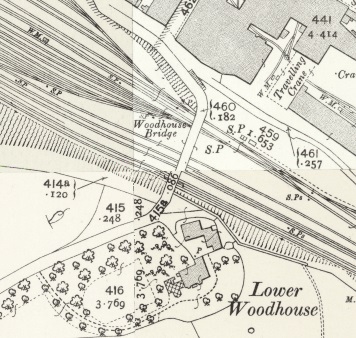

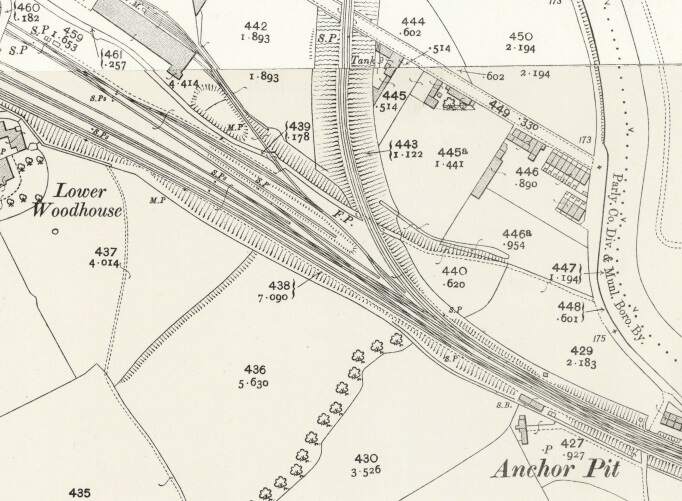

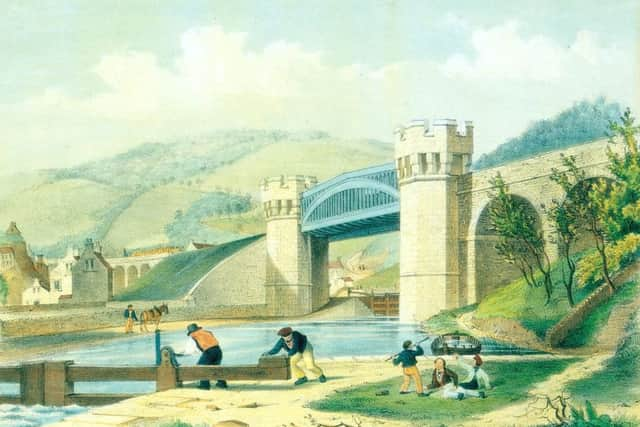

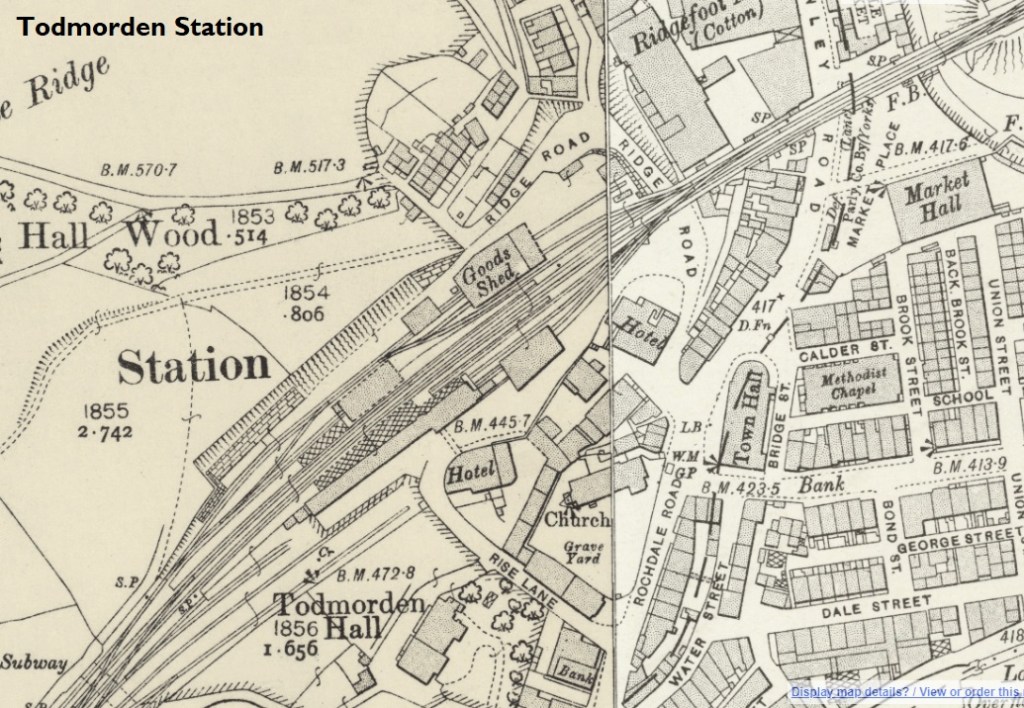

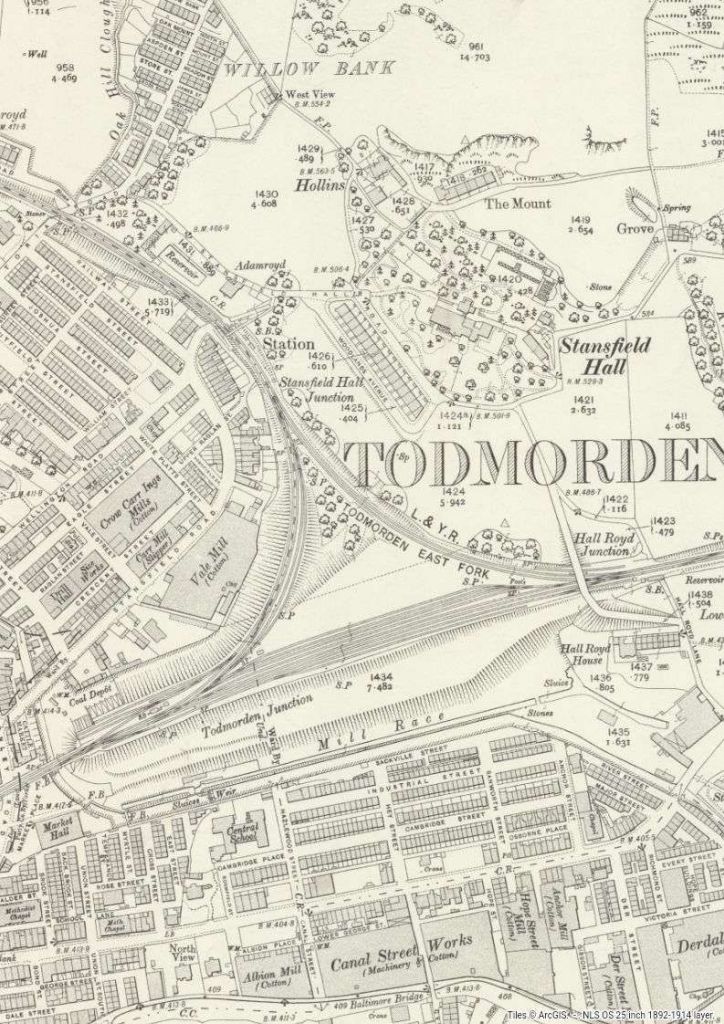

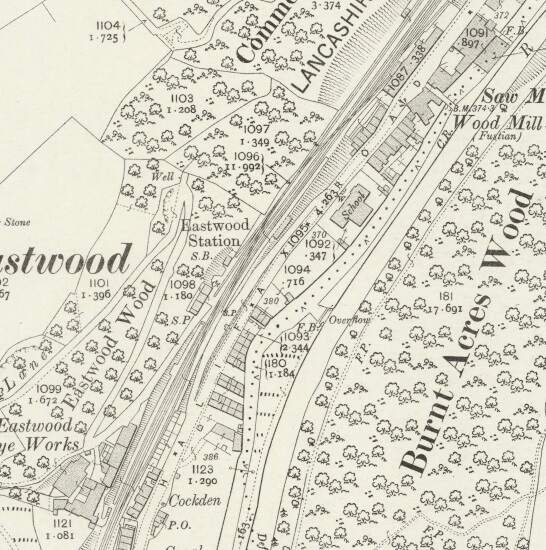

Cheshunt had a railway three months before the Stockton and Darlington line was opened. It was a horse-drawn monorail, built by Henry Robinson Palmer, who had previously built one in Deptford Dockyard, the first in the UK. The Cheshunt Railway, his second venture, was opened on 26th June 1825, running from Mr Gibbs’ Brick Pit (to the west of Gews Corner), to a wharf on the River Lea, not far from the site of the current Cheshunt Station. Its original purpose was to haul bricks, but it was also utilised for carrying passengers. For such a short distance, it must have been principally a novelty; regardless of this, it was the first passenger monorail in the world. [15]

The design was an overhead track from which carriages were suspended, drawn by a single horse. The line crossed the main road by a section hinged like a gate, enabling it to be moved off the road. No sign of the monorail has survived, but its legacy gives Cheshunt a vital, if little-known, position in the history of railways. [15]

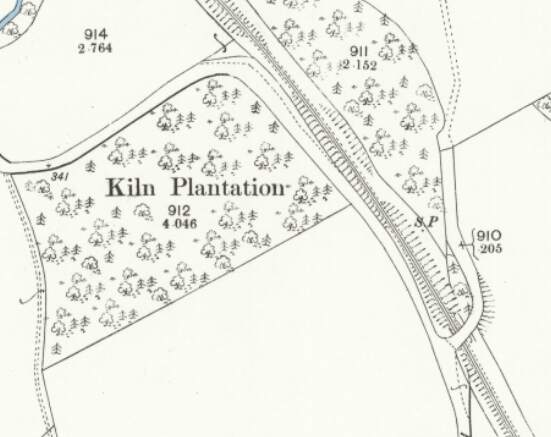

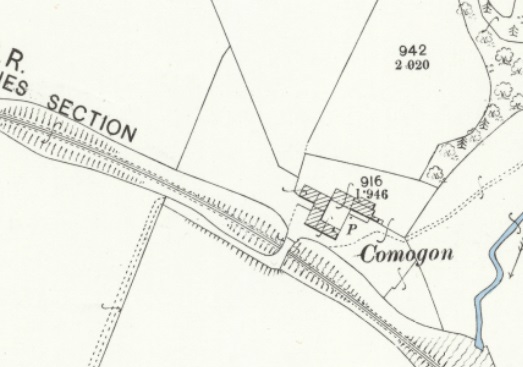

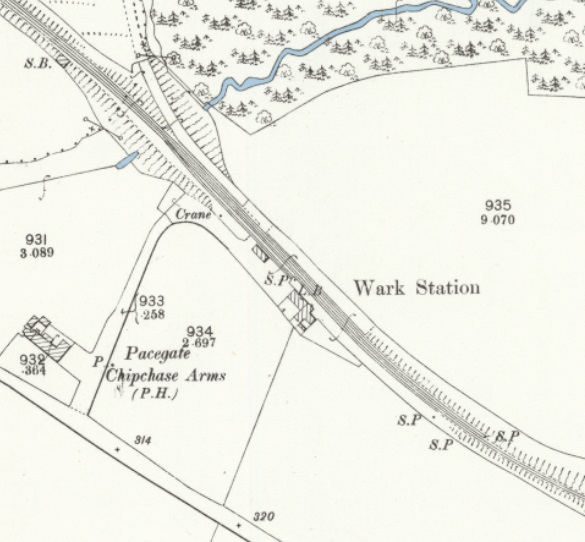

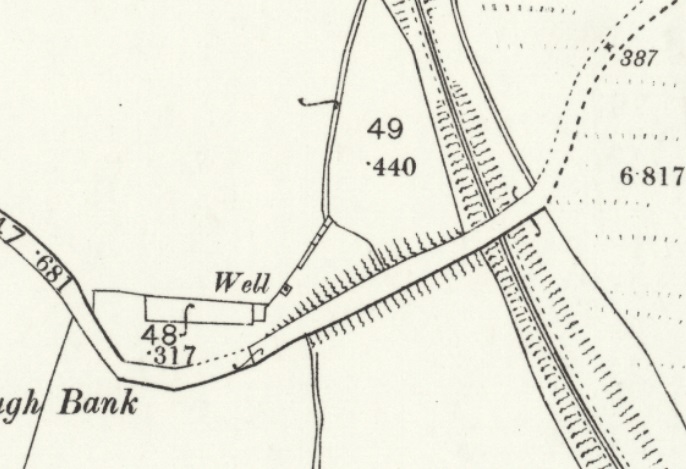

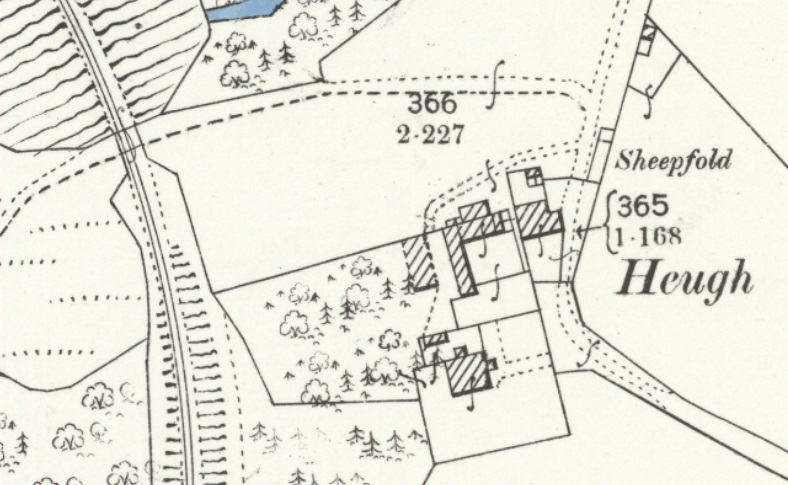

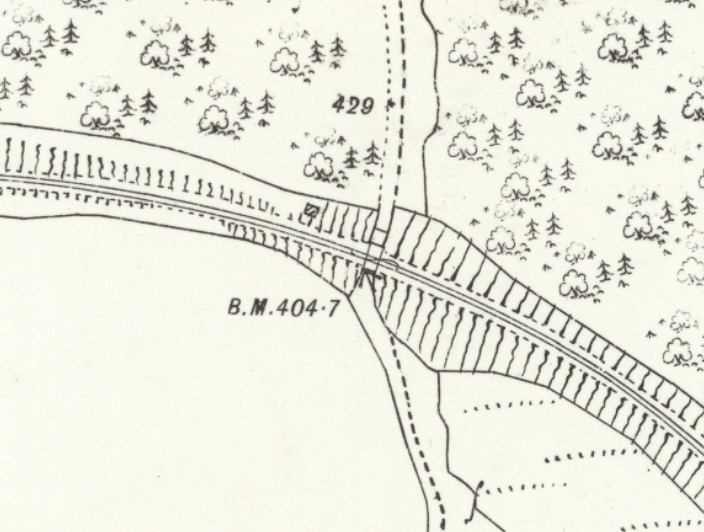

C. von Oeynhaussen & H. von Dechen describe the railway: “From the lime and brick kilns at Cheshunt, in Hertfordshire, about 20 miles north of London, which lie on a main road, a Palmer railway leads to the Lee Canal in the flat and level Lee valley. The railway has a fall of 5 to 10 minutes of angle towards the canal; it is mile Engl. (580 fathoms Pruss.) long and serves to transport lime and bricks. The line rests on wooden posts which project on average 34 ft out of the ground; towards the limekiln, however, the bottom of the line is in a cutting in the ground, so that the posts stand in a kind of dry trench, the base of which is 9 ft wide. The wooden posts stand 10 ft apart, are 4 in. thick, and 7 in. wide; the top is fork-shaped 3 in. wide and cut 16 in. deep. In the bottom of this fork lies a block 12 to 15 in. long, in different heights, which is supported by a pair of inserted angle-pieces 14 in. high and 2 in. thick. Two wedges 2 ft long rest on this block with their inclined faces lying against one another, so that a horizontal support is always afforded to the plank which lies thereon. The planks are 101 in. high and 3 in. thick; they are 30 ft long and always meet in the middle of a post. Iron bolts with screws go through the post to hold together its fork-shaped end. There are oblong holes in the planks through which these bolts pass, so that the underlying wedges can be adjusted when necessary. On top of the planks a wrought-iron convex rail is laid, 4 in. wide, 1 in. thick at the edges, and in. thick in the middle. [14: p76]

C. von Oeynhaussen & H. von Dechen continue: “The rails are 20 ft long with their ends cut obliquely, and they are fixed by no more than two or three spikes of in. diameter with their heads countersunk in the rails. The rails have some spare holes which are used when one or other of the spikes breaks. Some posts are made of three parts fixed together. The pieces are 6 in. wide; the middle piece is 3 in. thick, the side pieces are 21 in. thick, and they are bound together by three screw-bolts; the wedges lie upon screwed-in blocks which are 1 ft long at the top. Although these planks are very thick, they have become bent at some places because of the great distance between the posts and are propped up by pillars set under them subsequently.” [14: p77]

“There is a siding on the railway in the vicinity of the canal. Here the line is made double for a length of about 30 ft, and between the double piece and the single track there is a strong door 10 ft wide which is hinged to the single rail and may be fastened to either of the two tracks. The railway lies on the upper edge of the door. Directly over the hinge is a small turning piece of rail by which the severe angle which the door makes with the main railway is reduced. This railway passes over an ordinary road by a similar door.” [14: p77]

“The wagons on this railway have only two cast-iron wheels, 26 in. diameter, with two flanges; they are 51 in. wide including the flanges, which are in. thick and project 11 in. They have six spokes and a nave 6 in. long and 2 in. wide. The wheel turns with a hollow cast-iron axle 2 in. thick and 12 in. long, which lies in round brass bushes at both ends; these have an inside diameter of 11 in., an outside diameter of 2 in., and are 3 in. long inside. They are fitted to seats on the wrought-iron stirrups which form the main frame of the wagon. Through the hollow cast-iron axle and the brass bushes is a wrought-iron axial bar 26 in. long, and 1 in. thick, the ends of which are fastened to the stirrup. This makes a firmer connection with the wagon frame. The two wheel centres are 46 in. apart. The platforms on which the wagon bodies are placed are 40 in. below the axle centres and are 17 in. apart. There is one wagon body on each side of the wagon, and each holds 20 cu. ft. One such body is laden with 20 cwt of lime or bricks, and therefore a wagon takes 40 cwt. One horse draws two such wagons or 80 cwt, exclusive of the bodies and the wagon.” [14: p77]

“On a disused standing wagon, there is a special arrangement for reducing the friction of the wheels on the axles, which is neither properly devised according to theory nor well carried out practically. The brass bushes wherein the cast-iron axle turns have a circular-segment-shaped slot, in. wide, cut in the upper part, and in this notch rests a 4 in. high iron friction wheel, on which the whole load of the wagon bears, while the brass bush is not entirely held fast in the wagon frame.” [14: p77]

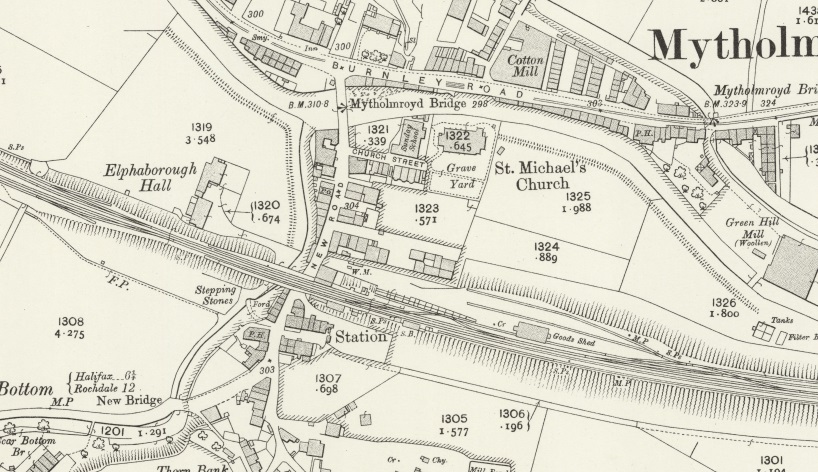

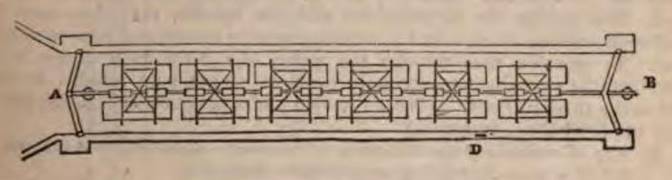

The Cheshunt Railway is also featured in the Register of Arts and Sciences No. 47, 2nd July, 1825, [17] where the illustration below appears, along with a detailed description of the opening of the railway.

The article is reproduced in full below at Appendix A.

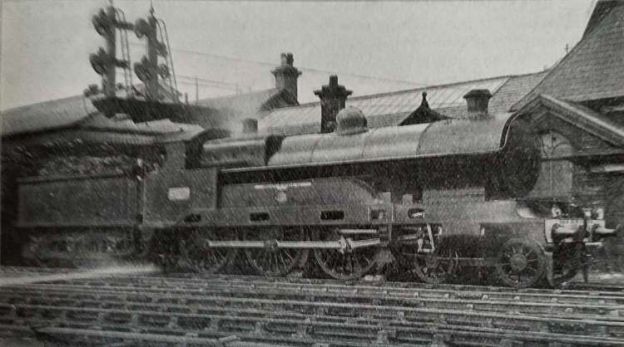

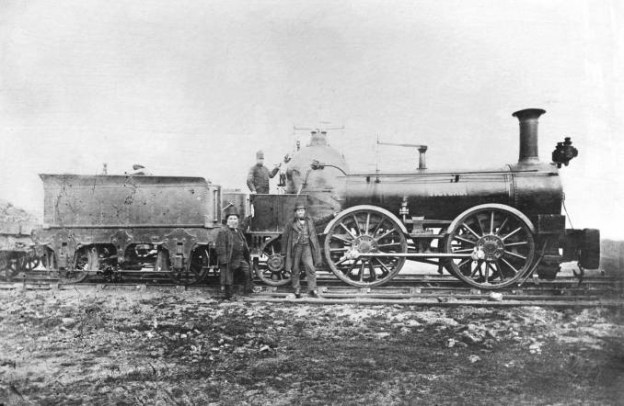

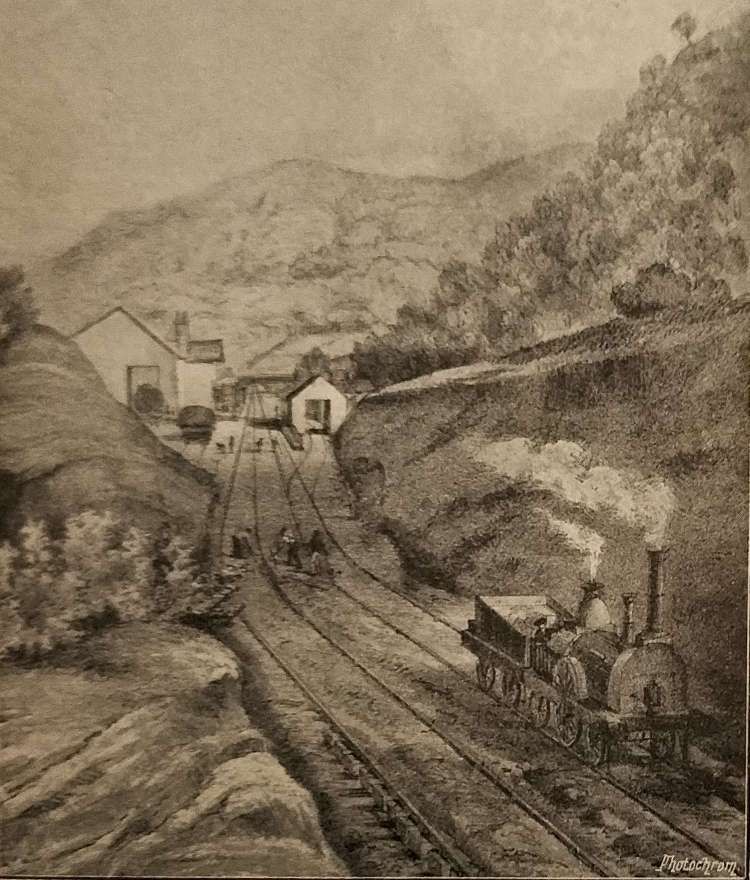

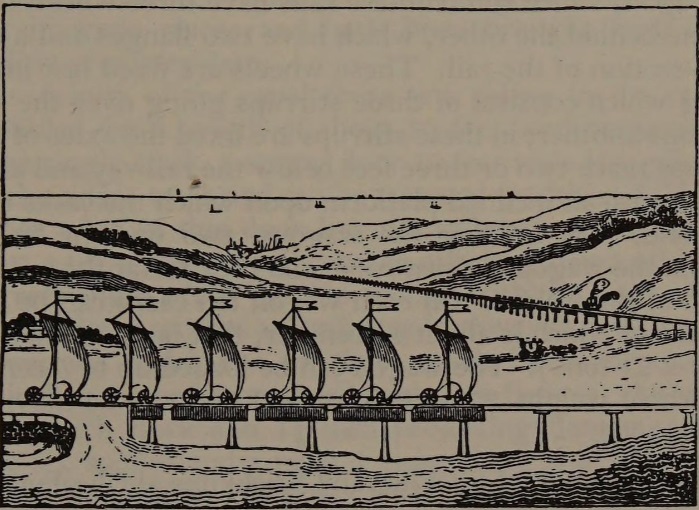

C.F. Dendy Marshall also refers to Palmer (and his monorails) in his history of railways to 1830. He notes that “Palmer was prominent in connexion with the London and Brighton schemes, and was [a] principal founder of the Institution of Civil Engineers. He wrote a paper in the Journal of the Franklin Institute in 1828, advocating the use of sails on railways. An illustration is given [below] of his railway with that method of propulsion, from Hebert’s Practical Treatise on Rail Roads (1837). [19] Two short lines were made on Palmer’s principle, on which horses were used: one at the Victualling Yard, Deptford; and one from some lime-kilns and tile-works near Cheshunt to the Lea Canal. The best account of these lines is given by von Oeynhausen and von Dechen, in ‘Ueber Schienen Wage in England, 1826-27.” [18: p171]

Marshall was writing in 1935, over 30 years before the Newcomen translation of von Oeynhausen and von Dechen’s German text was published, so he took the trouble to provide his own translation of their words in full. [18: p171-173] He also points his readers to an article in the Mechanics Magazine of 6th August 1825 which concluded: “One carriage, which has been constructed for the purpose of trying the application of the plan to the conveyance of passengers, differs from the others. Its boxes partake partly of the shape of a gig, and partly that of a balloon-car; in each are two cushioned seats vis-à-vis, with a little dickey behind, the whole carriage being covered with an awning.” [18: p173-174]

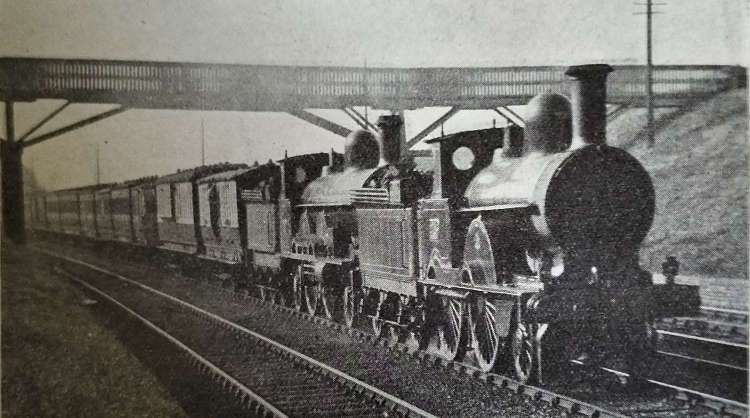

Hebert discusses Palmer’s ideas in his book, Practical Treatise on Rail Roads (1837): “Mr. Palmer’s railway consists of only one, which is elevated upon pillars, and carried in a straight line across the country, however undulating and rugged, over hills, valleys, brooks, and rivers, the pillars being longer or shorter, to suit the height of the rail above the surface of the ground, so as to preserve the line of the rail always straight, whether the plane be horizontal or inclined. The waggons, or receptacles for the goods, travel in pairs, one of a pair being suspended on one side of the rail, and the other on the opposite side, like panniers from the back of a horse. By this arrangement only two wheels are employed, instead of eight, to convey a pair of waggons; these two wheels are placed one before the other on the rail, and the axle-trees upon which they revolve are made of sufficient length and strength to form extended arms of support, to which are suspended the waggons.” [19:p57]

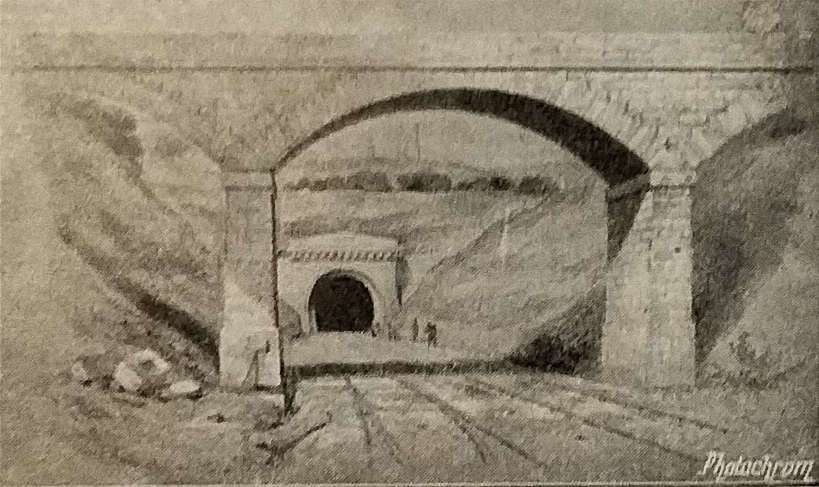

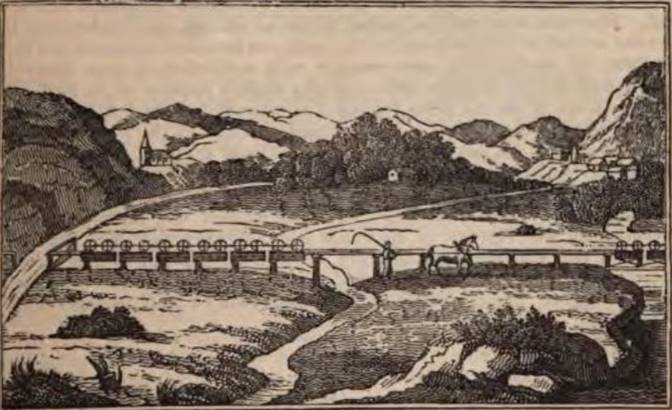

Hebert provides an illustration of the line in use. And the principles by which various obstacles were overcome. In the image below, “on the left is seen a jointed rail, or gate, that crosses the road over which the carriages have just passed, and the gate swung back, to leave the road open; the horse and man having just forded, the train of carriages is proceeding in its course, and following another train, part of which is seen on the right, crossing a rail bridge, simply constructed for that purpose.” [19:p59]

“Provision is made for trains of carriages that are proceeding in opposite directions, by means of ‘sidings’ or passing places. With respect to loading, if both receptacles be not loaded at the same time, that which is loaded first must be supported until the second is full. Where there is a permanent loading place, the carriage is brought over a step or block; but when it is loaded promiscuously, it is provided with a support connected to it, which is turned up when not in use. From the small height of the carriage, the loading of those articles usually done by hand becomes less laborious. The unloading may be done in various ways, according to the substance to be discharged, the receptacles being made to open either at the bottom, the ends, or the sides. In some cases, it may be desirable to suspend them by their ends, when, turning on their own centres, they are easily discharged sideways.” [19:p59]

“Among the advantages contemplated by the patentee of this railway, may be mentioned that of enabling the engineer, in most cases, to construct a railway on that plane which is most effectual, and where the shape of the country would occasion too great an expenditure on former plans – that of being maintained a perfectly straight line, and in the facility with which it may always be adjusted; in being unencumbered with extraneous substances lying upon it; in receiving no interruption from snow, as the little that may lodge on the rail is cleared off by merely fixing a brush before the first carriage in the train; in the facility with which the loads may be transferred from the railway on to the carriages, by merely unhooking the receptacles, without displacing the goods, or from other carriages to the railway, by the reverse operation; in the preservation of the articles conveyed from being fractured, owing to the more uniform gliding motion of the carriages; in occupying less land than any other railway; in requiring no levelling or road-making; in adapting itself to all situations, as it may be constructed on the side of any public road, on the waste and irregular margins, on the beach or shingles of the sea-shore, indeed, where no other road can be made; in the original cost being much less, and the impediments and great expense occasioned by repairs in the ordinary mode, being by this method almost avoided.” [19: p59-60]

Hebert goes on to talk of the line built in Cheshunt in 1825. In that case, “The posts which support the rails are about ten feet apart, and vary in their height from two to five feet, according to the undulations of the surface, and so as to preserve a continuous horizontal line to the rail. The posts were made of sound pieces of old oak, ship timber, and in a, the slot or cleft at the upper ends of the posts, are fixed deal planks twelve inches by three, set in edgeways, and covering with a thin bar of iron, about four inches wide, flat on its under side, and very slightly rounded on its upper side; the true plane of the rail being regulated or preserved by the action of counter-wedges between the bottom of the mortices, and that of the planks. By this rail, on the level, one horse seemed to be capable of drawing at the usual pace about fourteen tons, including the carriages.” [19: p60]

Hebert quotes Tredgold, who commented: “We expect that this single railroad will be found far superior to any other for the conveyance of the mails and those light carriages of which speed is the principal object; because we are satisfied that a road for such carriages must be raised so as to be free from interruptions and crossings of an ordinary railway.” [19: p60][20]

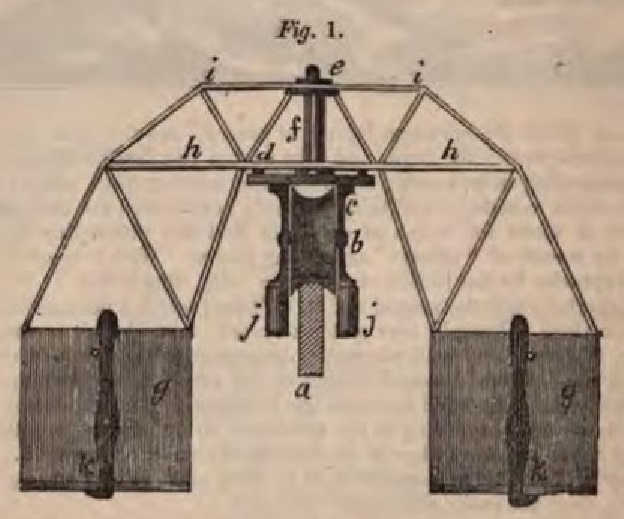

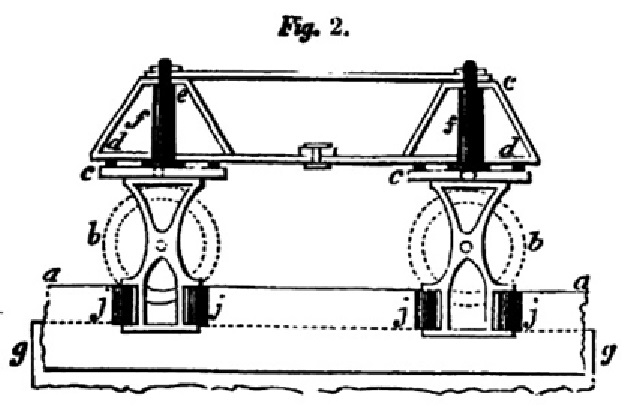

Hebert notes a particular problem with Palmer’s design: “It has generally been considered a defect in Mr Palmer’s arrangement, that in order to make turns in the road, it is necessary that a portion of the rail should be made to turn with the carriages upon it. This defect, Mr. T. Chapman, of Royal Row, Lambeth, proposed to remedy, by so constructing the carriage, as to enable it to turn itself upon a fixed suspension rail, whether curved or straight, or from one angle to another. Fig. 1 … exhibits an end view of the carriage, and Fig. 2 a side view of the same, partly in section. … aa is the rail, bb two wheels on the rail; these carry the turning plates cc, each having four friction-rollers: ee, upper plates; ff, the vertical axis of the wheel-frames or turn-plates cc; they pass through the plates d and e, from which the boxes gg are suspended, by the lateral arms hh and ii. Now as the wheels and frames b c can turn freely on their axis ff, they each require four guiding rollers jjjj to keep them in a right line with the rail, and to cause them to turn as the rail turns. These carriages should not be further asunder than is absolutely necessary for the required curve of the rail. The bottom of the carriage has a joint at one third of its length, and is held up at this by the hooks kk; by removing these, the contents may be let out: the fixed portion of the bottom is made sloping, so that it may be readily emptied.” [19: p60-61]

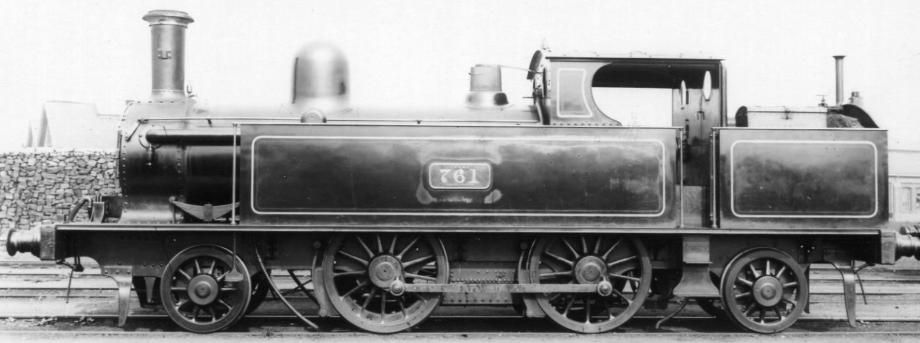

Hebert now turns to consideration of the force of the wind: “About thirteen years ago it occurred to [him], that the force of the wind might be beneficially employed as an auxiliary power for propulsion on railways; and considering that the suspension principle, which had just then been promulgated by Mr. Palmer, was better adapted to that object than any other, he wrote a short paper on the subject, which was inserted in the eighth number of the Register of Arts, for January, 1824, under the signature of “L. H.” The plan also embraced a proposition for enabling boats from the sea, a river, or canal, to pass out of the water, at once upon the rail, and thereon be propelled precisely in the same manner as the receptacles provided by the inventor are, and from which they scarcely need to differ in shape. Both of these propositions have been treated with abundance of ridicule, by persons who were either incapable or indisposed to reason. But one of them having, according to the newspapers, been recently carried into actual practice at Sunderland, and under less favourable circumstances, (i.e. on the common ground rail) the writer need not dilate upon its feasibility. And as respects the other propositions, he will only observe, that believing it to contain the germ of something that may hereafter prove of public benefit, he hesitates not to place it before the judgment of the reader. The following are extracts from the paper alluded to. ‘The inhabitants of small islands, and of the sea-coast gene-rally, subsist chiefly upon fish; and as they are remarkable for robust constitutions, it follows that their food must be strengthening and wholesome. I propose, therefore, a railway, on Palmer’s principle, from London to the nearest seaport town or fishing-place, that shall give to the inhabitants of this city the advantages of a plentiful supply of the cheap and wholesome food enjoyed by those in maritime situations. In the drawing which accompanies this [see the sail propulsion drawing above], the scene sketched is entirely imaginary, and intended, first to represent a railway leading to a sea-port, with the carriages being propelled, according to the modes projected by Mr. Palmer; the first train of carriages being drawn along the rail by a locomotive steam-engine, the second, more in the perspective, is supposed to be drawn by a horse. Brighton is perhaps the most eligible situation for such an undertaking. By a railroad from that place, the London market might be supplied with a prodigious quantity of fish within three or four hours after their being taken from the sea, at the mart trifling expense of carriage; and if the wind were to be employed as an auxiliary propelling force, which I propose, the rapidity with which the fish might generally be brought lo our markets would give us all the advantage of a sea-port town in the purchase of it If the Hollanders have found it practicable (as is well known) to sail over land in four-wheeled carriages, how much more practicable and advantageous would it be to bring into use the admirable facilities furnished by Mr. Palmer in his new suspension railway, in which the resistance to the motion of the carriages is reduced to one-twentieth part; or in other words, wherein the facilities are twenty times greater. As objections will of course he raised, on the score of the variableness of the wind, I must repeat, that I only propose it. as an auxiliary power. It would rarely happen that the wind would not he favourable in going or returning; and it is well known that S.W. winds prevail more than any other in our quarter, which would be favourable for the principal traffic; that is to London. In the absence of a steam-engine, a horse should always be in attendance; so that when employed in drawing a train of carriages, if a favourable breeze should spring up, the sails might be spread, and the horse be-put into one of the receptacles, where, over his bag of corn, he might regale and invigorate himself for fresh exertions, should the wind fall off.” [19; p61-62]

Hebert goes on, even more fancifully in my view, to explain how Palmer’s design can be adapted to one of Hebert’s own ideas of overcoming the need for transshipment between canals and railways, and perhaps to overcome the need for locks altogether as lengths of canal could be linked by Palmer’s monorail, provided the canal vessels were designed to suit. So, Hebert says: “The railway I propose Is to be constructed as usual, elevated upon pillars, and not to terminate on arrival at the look gates B, but to pass over it, and terminate at the other end, just within the second gates A, and be supported upon pillars from the floor of the lock, the same as on dry ground. In [drawing](which is a plan) the double train of vessels are supposed to have all entered the lock, half on one side of the rail, and half on the other, and they are hooked on to the axle-trees of the wheels which are already upon the rail for that purpose. The gates next to the river or canal are then closed, and all being fast, the water is let out of the lock by a sluice at D. till it falls below the bottom of the outer gates; at which time the vessels are all suspended on their axles in the air. The gates being next opened, and the wind fair, they sail across the valley or are propelled by other means provided by the patentee.” [19: p62-63]

Further Immediate Developments

As early as 1826, the German railway pioneer Friedrich Harkort had a demonstration line of Palmer’s system built at his steel factory in Elberfeld (today part of Wuppertal), but objections prevented the construction of a public railway. [22]

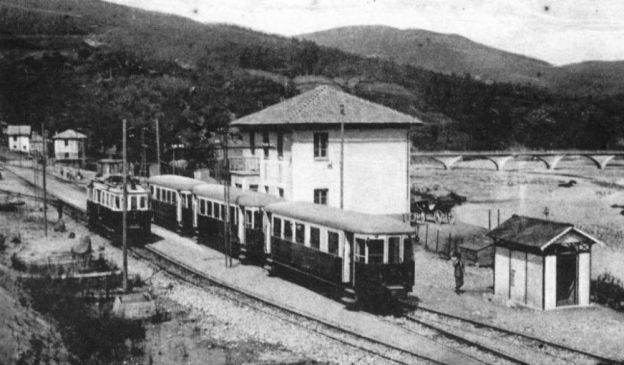

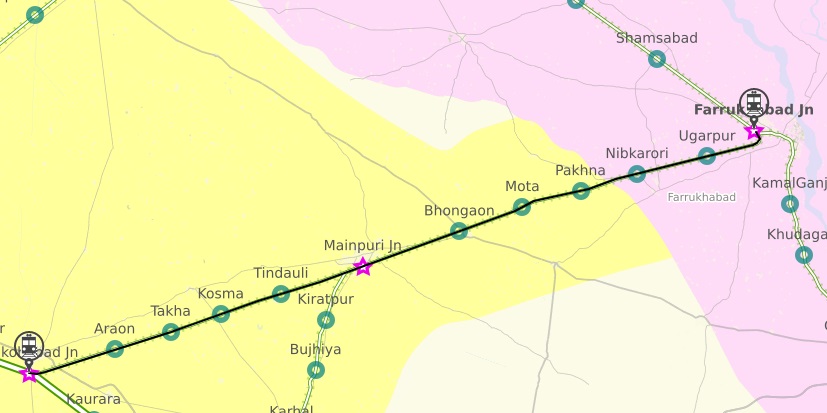

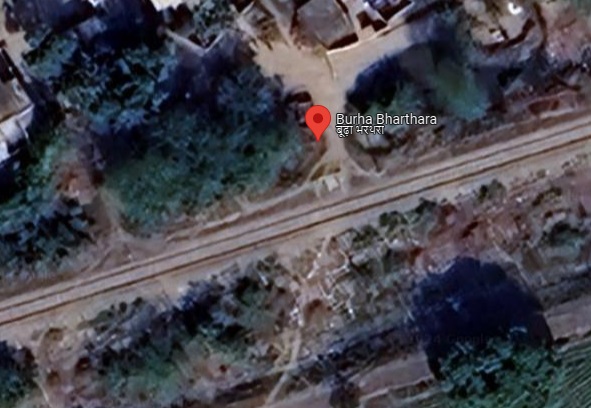

Soon after, the first Hungarian railway line was completed on 15th August 1827, and led from Pest to Kőbánya. It was a monorail built on the principles outlined by Palmer. [23][24]

That Hungarian scheme is described here. [25]

References

- Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Records.

- Parish records.

- https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/1820_Institution_of_Civil_Engineers:_New_Members, accessed on 18th February 2025.

- https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Henry_Robinson_Palmer, accessed on 18th February 2025.

- https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/History_of_the_Steam_Engine_from_Its_Ear.html?id=5yOk_AeOFTMC&redir_esc=y, accessed on 18th February 2025.

- https://www.urban-transport-magazine.com/en/monorails-on-the-rise, accessed on 18th February 2025.

- https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co474278/description-of-a-railway-on-a-new-principle, accessed on 18th February 2025.

- H.R. Palmer; Description of a Railway on a New Principle: With Observations on Those Hitherto Constructed and a Table Shewing the Comparative Amount of Resistance on Several Now in Use; J. Taylor, London, 1823. [NB: a second edition was published by J. Taylor in 1824]

- The Times; Monday 27th June 1825.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/02/07/a-first-short-lived-horse-powered-railway-in-hungary.

- https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/data/UQ_225741/n01_Thesis_text_Guedes.pdf?Expires=1739979301&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJKNBJ4MJBJNC6NLQ&Signature=Mta6J-AfDmIox2Cyn9W0thOJLfTU~R9QiqLT8VT89xVPRJgExbS1S4QfcUKrb6UlMbRmQMlQia08caTuBVwGTTKWPfuHEw6uOtvyS4iXAAasj4oOU-UnDKHCJaFRy7vXuI~GVvFmYSTbsUlZYjZTJ0aNnXX9GMN91PPH54y3dqOwpOEQwMxrYNiqlUvLIzSs40wveXwq3Hwlr~Cc7JSz1dvO6B8Xp~H4JM2PCvroy8IvgFCZqxjuwHnYEUXj7fY-INLhfV-Jqf6jTiGa48vSr-VHKQPy9xaupA0dsyXbFU711pyxy76s0kSvdXD9gW8oFX19LtveL9ohve2r3YAJSQ__, accessed on 18th February 2025.

- The Leicester Chronicle, or Commercial and Agricultural Advertiser; Saturday, 15th February 1834.

- The Ipswich Journal, Saturday, 14th September 1844.

- C. von Oeynhaussen & H. von Dechen; Railways in England 1826 and 1827; translated by E.A. Forward and edited by C. E. Lee & K. R. Gilbert; Heffer &b Sons Ltd, Cambridge, for the Newcomen Society, 1971.

- Nicholas Blatchley; Cheshunt Railway, 1825; via https://www.hertsmemories.org.uk/content/herts-history/topics/transport/railways/cheshunt_railway_1825, accessed on 18th February 2025.

- This refers to a device patented by Henry Robinson Palmer (1795-1844) on 22nd November 1821 (Patent No. 4618). The line in the Royal Victualling Yard, Deptford, appears to have been brought into use in the latter part of 1824. The Cheshunt line was opened with considerable ceremony on 25th June 1825.

- Register of Arts and Sciences No. 47, 2nd July 1825; via https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Register_of_the_arts_and_sciences._Volume_2,_1825._(IA_s1id13655130).pdf, accessed on 18th February 2025.

- C.F. Dendy Marshall; A History of British Railways Down to the Year 1830; Oxford, 1938.

- Luke Hebert; Practical Treatise on Rail Roads and Locomotive Engines; Thomas Kelly, London, 1837.

- Thomas Tredgold; A Practical Treatise on Rail-roads and Carriages; J. Taylor, London, 1825.

- The Railway Magazine; H. R. Palmer, A Forgotten Railway Pioneer; Volume 99 March 1953, p658ff.

- https://www.urban-transport-magazine.com/en/monorails-on-the-rise, accessed on 19th February 2025.

- https://pestbuda.hu/en/cikk/20220812_the_first_hungarian_railway_was_built_195_years_ago_the_special_structure_delivered_construction_materials_from_kobanya, accessed on 6th February 2025.

- https://pestbuda.hu/en/cikk/20230322_the_downfall_of_the_first_hungarian_railway, accessed on 6th February 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/02/07/a-first-short-lived-horse-powered-railway-in-hungary.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/02/19/early-monorail-proposals-in-russia.

Appendix A – The Opening of the Patent Suspension Railway at Cheshunt, Herts

The Register of Arts and Sciences No. 47, 2nd July, 1825

We had the gratification on Saturday last of witnessing a practical demonstration of the advantages of Mr. Palmer’s new Suspension Railway, the nature and construction of which having been fully described in the 7th and 8th numbers of this Work, to those articles we refer our readers, as connected with our present account.

A line of railway on these beautiful principles having been erected at Cheshunt, in Hertfordshire, by Mr. Gibbs of that place, the same was opened for public inspection on the above-mentioned day, when a numerous and highly-respectable company of persons attended by invitation to witness the operation of the carriages, and partake of a rural entertainment provided for the occasion. The weather proved fine during the forenoon, but the rain which after-wards occasionally descended in showers, would have been felt very inconveniently by the numerous fair visitors, had they not been provided with large booths, in which were erected ranges of elevated seats, commanding a view of the entire piece of rail-road, besides affording a fine prospect of the surrounding country, which is beautifully picturesque. Near to these was stationed a band of music, which played a variety of national airs; and the flags of England, France, America, and other nations, waving their colours in different parts of the beautiful meadows, gave a delightful effect to the scene, independently of the highly interesting business of the day.

The chief object of the proprietor of this undertaking is the conveyance of bricks across the Marsh to the River Lea for shipment, and the carriages have consequently receptacles adapted to that peculiar purpose. But on the present occasion each receptacle was fitted up with temporary seats, for the conveyance of the persons in the manner represented in the engraving; each receptacle being likewise loaded with a quantity of bricks as ballast, which were stowed away under the seats, making, perhaps, a total weight to each receptacle of one ton; and there being two receptacles to a carriage (one suspended on each side of the rail) will make the whole weight about fourteen tons. The first carriage shewn in the train * had the receptacles expressly made for passengers, and were elegantly constructed in the barouche style, the passengers sitting opposite to each other. The whole of this immense train was drawn by a single horse by means of a towing rope attached to the first carriage, and with so little exertion apparently, that it was evident the strength of a good average horse would be sufficient to draw double the weight operated upon. The rail was proved to be upon a level plane by the animal drawing the load with equal facility, in either direction. The posts which support the rail are about ten feet apart, and vary in their height from two to five feet according to the undulations of the ground, so as to preserve the horizontal line of the rail. Under the rail, and between a cleft of each of the posts are placed reverse wedges, which admits of a facile and almost instantaneous adjustment of the plane, in the nicest manner. [a] The posts are made of that almost ever-lasting stuff, sound old ship timber, and securely fixed in the ground in a peculiar manner; the rail is constructed with 3-inch planks, 12 inches wide, which are placed edgeways between the clefts of the pillars. The upper surface of the rail is covered with a bar of iron four inches wide and about a quarter of an inch thick, and a little con-vexed on the upper side, to suit the occasionally inclined position of the wheels, and to prevent (as we suppose) a too extended contact of their surfaces.

Our object in giving another sketch of this truly excellent invention has been, chiefly to shew its admirable application for the conveyance of persons as well as goods. The vehicles glide so smoothly over the surface of the country, as to be compared only to the floating of boats in the stream of a river; and it is evident that no mode of travelling can possibly be less free from danger.

The simplicity and effectiveness of this new railway was the subject of general admiration; among the spectators we noticed several engineers of eminence, who, very honourably to themselves, awarded their meed of praise, so justly due to the inventor, for the erection of (unquestionably) the best rail-way hitherto constructed. [b] The uses and advantages are indeed so obvious to every observer, that it is impossible not to believe that it will become of general adoption in all situations suited to a work of the kind.

Notes

- This simple method of adjustment is one of very considerable importance in every point of view. In the common railroads, when the surface has become irregular by the sinking of particular parts, the rails must be taken up of necessity, and a complete re-bedding of their foundations made, which is of course attended with considerable expense and inconvenience. By Mr. Palmer’s plan a tap or two with a hammer sets the whole straight.

- Even Mr. Vallance, who may be regarded as unfriendly to railways generally, very candidly says in his pamphlet on the subject, “By the effects produced on different railroads, it is proved, that a power which will raise one pound perpendicularly, will move above 100 lbs. horizontally at the same rate; and on a railway of Mr. H. R. Palmer’s invention, it may at any time be seen, that the same power will produce the same effect on above 300 lbs!”