The new companies which came into existence with the grouping in 1923 addressed once again the best way to serve lightly populated rural communities. The options available to them centred on various forms of light railcars. Two forms of propulsion were available, the internal combustion engine and the steam engine. Electricity, in many cases required too large an investment for the likely traffic on the intermediate routes in rural areas.

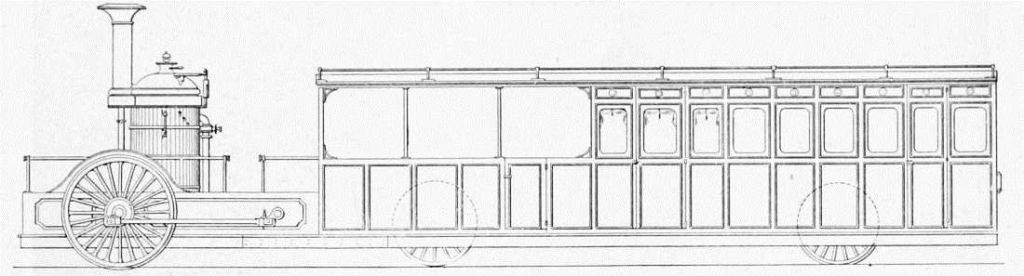

Given, the lack of success of the steam railmotor experiment in the first two decades of the 20th century, it must have seemed unlikely that steam railcars/railmotors woul prove to be a success in the inter-war years. But the LNER’s persistence and the arrival of a new articulated “form of steam railcar developed by the Sentinel Waggon Works Ltd. in association Cammell Laird & Co. Ltd. [brought about] a renewed assessment of the role of the railcar.” [1: p46]

Jenkinson and Lane say that rather than simply using railcars to replace existing services, the aim became one of enhancement of services. A greater frequency of service would reduce the need for unsuitable powered units to pull trailers. Higher speeds would shorten journey times.

But, to do this “in the steam context … meant using a vehicle which, owing to its lightness and simplicity, needed a smaller and less complicated power unit than was offered by the conventional locomotive style of construction. … A tricky balancing act … because railway vehicles need to be much stronger than the road equivalent, … but the Sentinel-Cammell steam railcars were a very fine attempt.” [1: p46]

The LNER Sentinel Steam Railcars

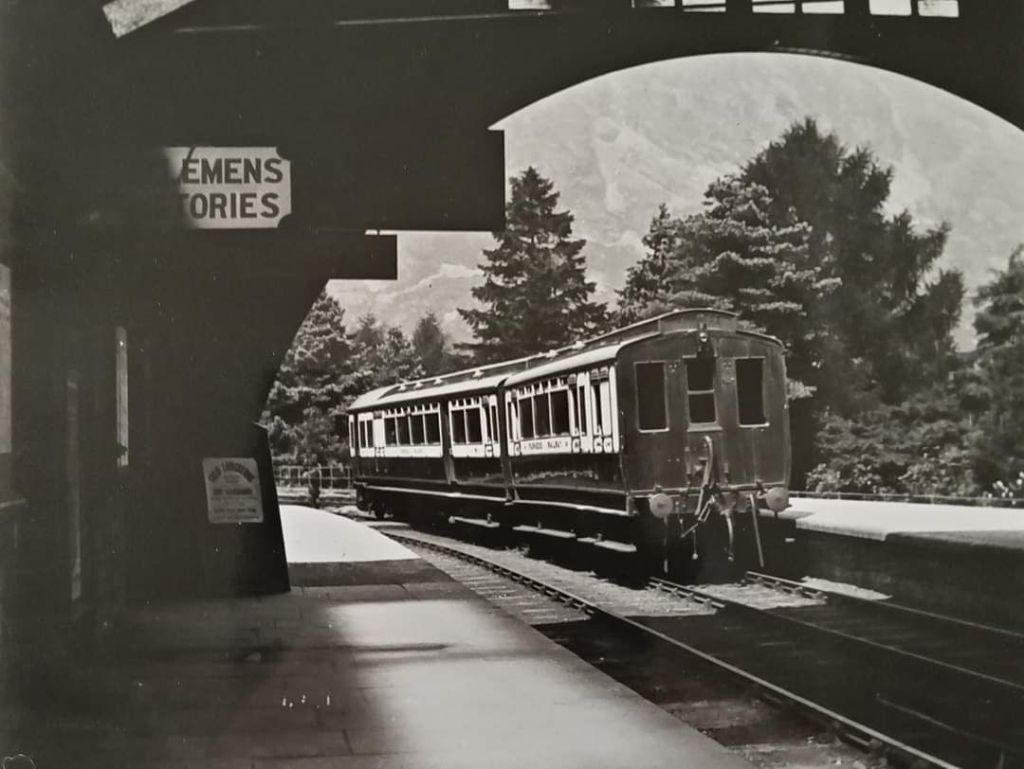

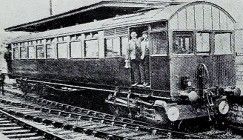

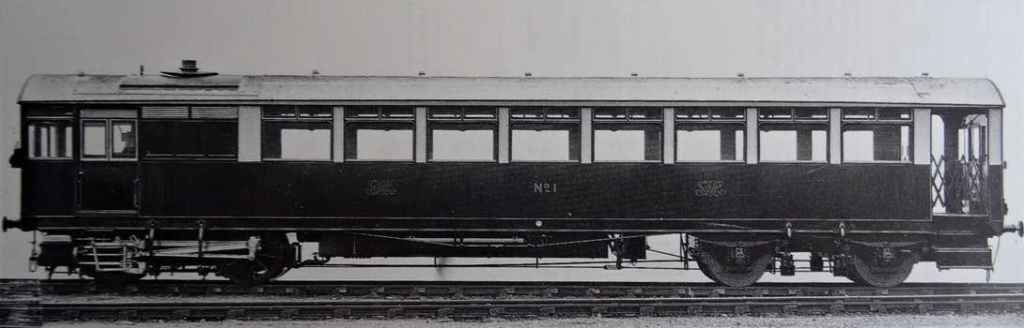

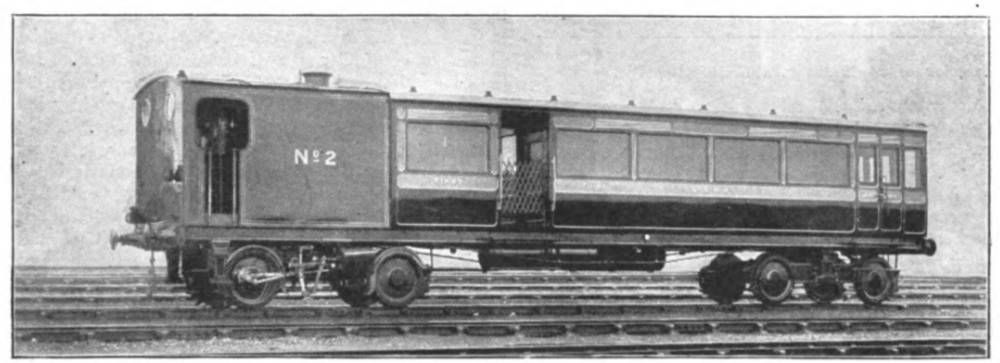

The “Sentinel Waggon Works of Shrewsbury built their first steam railcar in 1923 for the narrow gauge Jersey Railways & Tramways Ltd. This used coachwork constructed by Cammell Laird & Co. of Nottingham, and was reportedly successful.” [2] This partnership with Cammell Laird continued when Cammell Laird became a part of Metropolitan-Cammell Carriage, Wagon & Finance Co. Ltd (‘Metro-Cammell’) in February 1929.

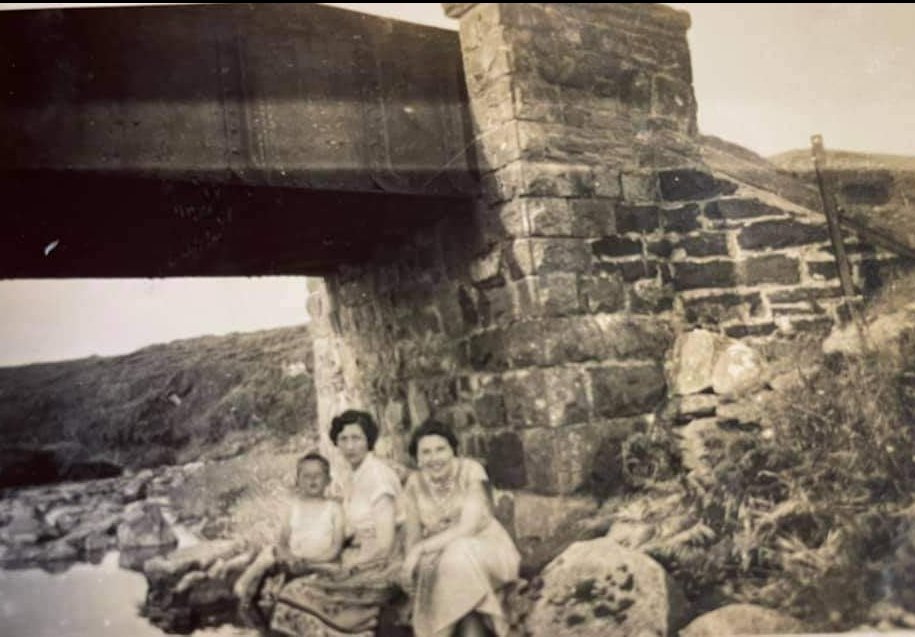

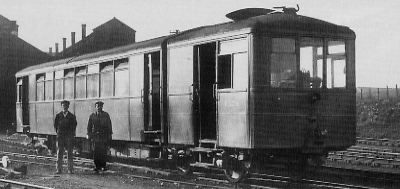

The first narrow-gauge railcar on Jersey plied its trade on the line between St. Hellier and St. Aubin. [4][2] The remains of a later steam railcar is shown below, It was supplied to Jersey as a standard-gauge railcar.

Essery and Warburton note 3 such vehicles being employed on the narrow-gauge. [12: p7] These vehicles were probably re-gauged to standard-gauge when the narrow-gauge line closed. They also note a later purchase of 2 standard-gauge units. Although they give a date of 1924 for the later units [12: p7] which, given that this unit appears not to be articulated, is quite early. Is this, perhaps, actually one of the later rigid-bodied units? If so it would perhaps have been supplied to Jersey between 1927 and 1932.

This image was shared on the Narrow Gauge Enthusiasts Facebook Group on 20th December 2018 by John Carter, permission to include this image here is awaited. [3]

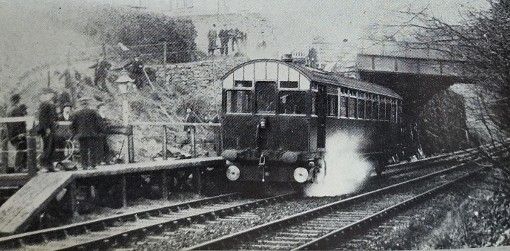

Sentinel exhibited a railcar at the British Empire Exhibition in 1924, which was noticed by Gresley. “The LNER was in need of vehicles that were cheaper than steam trains but with better carrying capacity than that of the petrol rail bus and autocar on trial in the North East (NE) Area. Hence Chief General Manager Wedgwood informed the Joint Traffic and Locomotive Committees on 31st July 1924 that a railcar would be loaned from Sentinel for a fortnight. If successful, this would be followed by the purchase of two railcars. The trial took place from 17th to 31st August 1924 in the NE Area.” [2]

The successful trial resulted in the purchase of eighty Sentinel steam railcars from 1925 to 1932.[2] (Essery & Warburton suggest that the very early Sentinel railcars were rigid-bodied units with later versions being articulated vehicles. [12: p4] This does not seem to have been the case. Early Sentinels were, in fact, articulated. There was a period when Sentinel railcars were rigid-bodied, Jenkinson and Lane talk of rigid-bodied Sentinel railcars being delivered in the years from 1927 up to 1932, [1: p54] which may have been a response to competition from Clayton. Clayton’s steam Railcars are covered below.)

In addition to the LNER’s own railcars, the Cheshire Lines railcars (4 No.) were maintained by the LNER and the Axholme Joint Railway (AJR) railcar No. 44 was transferred to the LNER when the AJR ceased serving passengers in 1933.

The first two Sentinel railcars purchased by the LNER were set to work in “East Anglia to operate between Norwich and Lowestoft and from King’s Lynn to Hunstanton.” [1: p46]

The East Anglian pair of railmotors “were considered to be lightweight. Later LNER Sentinel railcars were more substantial and included drawgear and buffers. Both railcars were withdrawn from traffic in November 1929 and sent to Metro-Cammell to be rebuilt into heavier railcars.” [2]

Sentinel offered two options. “One scheme was to rebuild the cars so that they resembled the later cars as closely as possible. The LNER chose to rebuild railcar No. 12E to this scheme, and was described as Diagram 153. The second scheme was to rebuild the railcars to the minimum necessary to meet the requirements. No. 13E was rebuilt to this scheme, and was described by Diagram 152.” [2]

Initially No. 13E was rebuilt without conventional drawgear and buffers. This was corrected within a few months of re-entering LNER service in 1930. [1: 46-47][2].

“No. 13E was renumbered as No. 43307 in April 1932 and withdrawn in January 1940 with a mileage of 269,345 miles.” [2]

No. 12E was subject to an almost complete rebuild. It returned to the LNER by Metro-Cammell on 29th May 1930 and started trials at Colwick. After repainting at Doncaster in late June, it entered traffic on 26th September 1930. The body was raised by just over 10 inches and a third step was added below the doors. Drawgear and buffers were fitted before it re-entered service on the LNER network. [2]

“No. 12E was renumbered as No. 43306 in November 1931, and was withdrawn in April 1940 with a mileage of 232,462 miles.” [2]

The RCTS tells us that, “The majority of the Sentinel railcars were named after former horse-drawn mail and stage coaches. The exceptions were the two original cars, Nos. 12E and 13E, No.51915 taken over from the Axholme Joint Railway and Nos. 600-3 on the Cheshire Lines which were all nameless. In addition the two 1927 cars, Nos. 21 and 22, ran without names for a while, before becoming Valliant (sic) and Brilliant respectively. The named cars had a descriptive notice inside detailing what was known about the running of the mail coach from which the car took its name and offering a reward for additional information.” [5: p13]

The story of the various Sentinel Railcars is covered in some detail in the LNER online Encyclopedia here. [2] If greater detail is required, then the RCTS’s Locomotives of the LNER Part 10B considers the Sentinel Railcars in greater depth. This can be found here. [5]

Sentinel produced their steam railcars for the LNER in a series of relatively small batches. Each batch varied in detailed design.

Rigid-bodied railcars were supplied by Sentinel in the period from 1927. The last rigid-bodied units being delivered in 1932. [1: p54,56] The first was an experimental unit which was in use on LNER lines in 1927 but not purchased until June 1928. [1: p58] A further 49 rigid-bodied Sentinels were ordered in 1928, 12 in 1929, 2 in 1930 [1: p56] and 3 further in 1932 [1: p54]

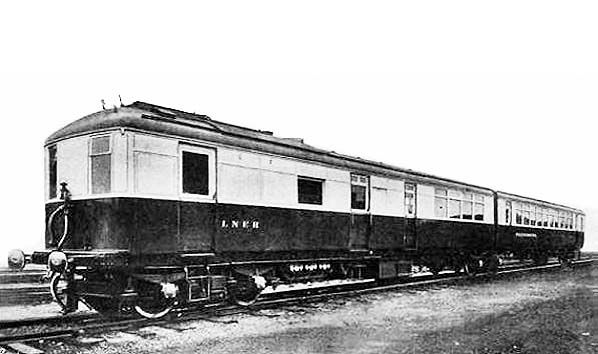

Jenkinson and Lane tell us that a solitary twin unit, LNER Sentinel No. 2291 ‘Phenomena‘, was developed in 1930. The rear bogie on the powered unit was shared with the trailer. They explain that the articulation between the coaches “allowed the individual unit lengths to be reduced compared with a single unit car. A more than doubled carrying capacity was achieved with only a 25% increase in tare weight.” [1: p64]

As the number of Railcars on the LNER network increased the company felt that it would be prudent to undertake a review of the performance of all its railcars in use on its network. This review covered the year ending 30th September 1934. The best Sentinel steam railcars out-performed others on the network (particularly those of Armstrong-Whitworth). The fleet of “Sentinel railcars recorded over 2.25 million miles in the year, with railcar mileages often exceeding 30,000 miles.” [2].

“With the exception of No. 220 ‘Waterwitch’ which was wrecked in 1929, all of the Sentinel steam railcars were withdrawn between 1939 and 1948.” [2]

The LNER Armstrong-Whitworth Diesel-Electric Railcars

As a quick aside, the Armstrong Whitworth Railcars were direct competitors for the Sentinel Steam Railcars. They were early diesel-electric cars, diesel-powered precursors of what, from different manufacturers, became the dominant form of power source for railcars as the steam railmotors were retired; although what became the dominant form of diesel railcar was to use direct drive rather than traction motors. [1: p71] What became the GWR railcars were privately developed by Hardy Motors Ltd., AEC Ltd., and Park Royal Coachworks Ltd. [1: p72-73] The story of the GWR diesel railcars is not the focus of this article, but the Armstrong Whitworth Diesel-Electric railcars were direct competitors for the Sentinel railcars and, as such, worth noting here.

In September 1919, Armstrong Whitworth became a Sulzer diesel engine licensee. During 1929 the board of Armstrong Whitworth approved the decision to enter the field of diesel rail traction and obtained a license from Sulzer Brothers for the use of their engines in these rail vehicles.

In 1931, Armstrong Whitworth began construction of “three heavy diesel electric railcars [for the LNER] which operated under the names of ‘Tyneside Venturer’, ‘Lady Hamilton’ & ‘Northumbrian’. They were powered by an Armstrong-Sulzer six cylinder 250hp four stroke diesel engine coupled to GEC electrical equipment. The vehicles were 60 feet long with a cab at each end and a compartment for the engine. They weighed 42tons 10cwt, could carry sixty passengers and luggage at 65mph. The bodywork was provided by Craven Railway Carriage & Wagon Co of Sheffield. The body was of sheet steel panels riveted together. Operating costs were expected to be half those of a steam service of similar capacity.” [8]

As well as running singly the railcars could haul a trailer coach.

“A fourth Armstrong-Whitworth diesel-electric vehicle entered service with the LNER in 1933. This was the un-named No. 294 lightweight railbus. Completed in May 1933, it performed six months of trials before entering regular services in the Newcastle area in September 1933. It was not taken into official LNER stock until August 1934, and is believed to have only been kept as a standby for one of the larger railcars.” [9][cf: 1: p70]

All of the Armstrong Whitworth railcars gave their best performances during the initial trials. “During regular operation, the Armstrong Whitworth diesel-electric railcars suffered from gradually declining performance. This was probably partly due to relatively poor maintenance on what was still a steam railway.” [9]

Ultimately, these units retired relatively early in April, May and December 1939. [9]

The LNER Clayton Steam Railcars and Trailers

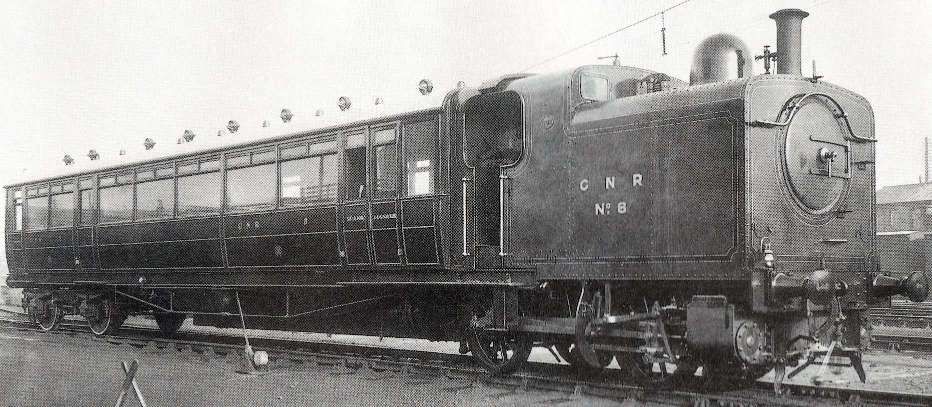

The LNER on-line Encyclopedia comments that, “Clayton Wagons Ltd of Lincoln started to build steam railcars in 1927. The LNER purchased a total of eleven between 1927 and 1928.” [10]

Jenkinson and Lane note an earlier date for Clayton Wagons Ltd’s entry into the market. They say that the Clayton cars originated in 1925, originally for use in New Zealand.

These cars were handicapped by the financial instability of Clayton Wagons Ltd. [10][1: p50] The LNER at times had to manufacture parts which were not available from suppliers. The first was withdrawn in July 1932. “With increasing maintenance problems, and a shortage of less strenuous short mileage work, the remainder were withdrawn between April 1936 and February 1937. Due to their short lives and persistent problems, none of the Clayton railcars clocked up significant mileages.” [10] Final mileages ranged from 72,774 to 174,691.

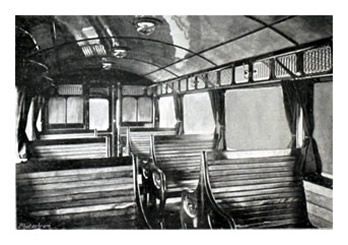

Trailer cars were supplied to the LNER by Clayton Wagons Ltd. The trailers were 4-wheeled with very basic accommodation. Their 4-wheel chassis may well have affected their riding quality. [1: p65] They were “classed as ‘Trailer Brake Thirds’, eight only were built and never seem to have very popular. Pictures of them in use are somewhat rare and little is on record of their working life; they were all withdrawn between March 1948 and March 1949.” [1: p55]

Three photographs can be found in Jenkinson and Jane’s book, one external and two internal views. [1:p 65]

The LMS Steam Railcars

In parallel with the LNER, the LMS had its own programme trials of Sentinel railcars. Jenkinson & Lane tell us that trials were carried out in 1925, “with a hired prototype on the Ripley Branch and a fleet of thirteen cars (the prototype plus a production batch of twelve) was put in service during 1926-7, a year or so ahead of the main LNER order. The LMS cars were all of lightweight low-slung design with less of the working parts exposed below the frames and no conventional drawgear. They were unnamed and finished in standard crimson-lake livery.” [1: p49]

In many respects these railcars were very similar to the two early lightweight LNER vehicles. Differences were minor: “the LMS cars had only 44 seats and a slightly over 21T tare weight whereas the LNER lightweights were quoted with 52 seats at 17T tare. … The later … LNER … cars were almost 26T except for the 1927 pair (just over 23T).” [1: p49]

Essery and Warburton say that, “The thirteen LMS Sentinel/Cammell vehicles were authorized by LMS Traffic Minute 1040 dated 28th July 1926 at a cost of £3800 each and were allotted Diagram D1779 and ordered as Lot 312. The numbers first allocated are not known except one that was number 2232 with the 1932/3 renumbering scheme allocating numbers 29900-12 with all receiving the LMS standard coach livery in the first instance. … These early models suffered from poor riding qualities and so in 1928 a gear driven 100 hp vehicle was designed. The boiler was on the mainframe and the vertical two cylinder engine was mounted over the rear axle of the power bogie with the axle driven through gearing. The LNER purchased the only one built (named ‘Integrity’) that suffered from severe vibration.” [12: p4]

Essery and Warburton also provide more detail about the Axholme Joint Railway (AJR) Sentinel railcar. The line was jointly owned by the LMS and LNER “with the motive power supplied initially by the LYR and then the LMS after the grouping. The LMS supplied one of the thirteen steam railcars purchased in 1926/7 to the AJR. In February 1930 a larger car was ordered from Sentinels numbered 44 in the LMS carriage list and carried a green/cream livery carrying the name “Axholme Joint Railway” on each side. On 15th July 1933 the passenger service ceased. The car having done 53,786 miles was then purchased by the LNER and numbered 51915.” [12: p4] It seems as though the AJR railcar was rigid-bodied. [1: p62] Which suggests that the full series of LMS railcars were rigid-bodied. The illustration of the AJR railcar provided by Jenkinson and Lane shows it with drawgear and buffers which must have been added after it’s transfer from the LMS.

The Southern Railway (SR) Steam Railcar

The last steam railcar to be devised for use in the UK was an unusual unit supplied by Sentinel to run on the Southern Railway’s steeply graded branch line from Hove to Devil’s Dyke. Its design was signed off by Richard Maunsell at much the same time as the SR was introducing its new electric services to Brighton in 1933. [1: p67]

The unit was a lightweight Sentinel-Cammell railcar. It was numbered No 6 and had wooden wheel centres to reduce noise but this created problems with track circuit operation on the main line and necessitated the provision of lorry-type brake drums. [13][14][15]

Jenkinson and Lane do not have much that is positive to say about this railcar. They talk of, “the strange ‘torpedo’ shape of the solitary Southern Railway Sentinel … that … was designed for one man operation: the Devil’s Dyke branch was very short and the nature of the machinery was such as to make it possible to stoke up for a complete trip at the start of each journey.” [1: p66]

“Instead of using one of the well-proved LNER type cars (or even the lighter weight LMS alternatives), the whole operation was made the excuse for creating a new sort of one-man operated bus unit … [with] a fashionably streamlined ‘Zeppelin’ type body which seemed to be perched on top [of the chassis] as an afterthought.” [1: p67]

References

- David Jenkinson & Barry C. Lane; British Railcars: 1900-1950; Pendragon Partnership and Atlantic Transport Publishers, Penryn, Cornwall, 1996.

- https://www.lner.info/locos/Railcar/sentinel.php, accessed on 20th June 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/djAxz1U23mUmaXFb, accessed on 20th June 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sentinel_Waggon_Works, accessed on 20th June 2024.

- Locomotives of the LNER Part 10B: Railcars and Electric Stock; RCTS, 1990; via https://archive.rcts.org.uk/pdf-viewer.php?pdf=Part-10B-Sentinel-Cammell, accessed on 21st June 2024.

- https://archive.rcts.org.uk/pdf-viewer.php?pdf=Part-10B-Armstrong-Whitworth-D-E-Railcars, accessed on 21st June 2024.

- https://archive.rcts.org.uk/pdf-viewer.php?pdf=Part-10B-Clayton, accessed on 21st June 2024.

- https://www.derbysulzers.com/aw.html, accessed on 21st June 2024.

- https://www.lner.info/locos/IC/aw_railcar.php, accessed on 21st June 2024.

- https://www.lner.info/locos/Railcar/clayton.php, accessed on 21st June 2024.

- https://www.pressreader.com/uk/model-rail-uk/20160505/282961039318286, accessed on 21st June 2024.

- R.J. Essery & L.G. Warburton; LMS Steam Driven Railcars; LMS Society Monologue No. 14, via https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:EU:1bd3492c-9d09-4294-889b-7a2406986bca, accessed on 22nd June 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brighton_and_Dyke_Railway, accessed on 22nd June 2024.

- Frank S. White; The Devil’s Dyke Railway; in The Railway Magazine, March 1939, p193-4.

- Vic Mitchell and Keith Smith; South Coast Railways: Brighton to Worthing; Middleton Press, Midhurst, 1983, caption to image 42.

- https://www.geocaching.com/geocache/GC4F7QY, accessed on 22nd June 2024.

- This illustration appeared in ‘The Engineer’ of 28th November 1930. It was included in the third page about Cambridge in the era of the Big Four on the Disused Stations website: http://www.disused-stations.org.uk/c/cambridge/index6.shtml, accessed on 25th June 2024.