In addition to the references referred to in the text below, a significant study of the GWR Railmotors can be found in John Lewis’s book, “GWR Railmotors.” [13]

After borrowing a LSWR railmotor/railcar in the early years of the 20th century and running trials between Stroud, Chalford and Stonehouse on the ‘Golden Valley Line’, the GWR embraced this new technology. In fact, out of a total of 197 purpose-built steam railmotors/railcars built in the period from 1902 to 1911 across the UK, the GWR had 99 and was by far the largest user. [1: p9] These 99 units “represented the only truly serious attempt by a major British company to persevere with this particular solution to the fundamental operating problem.” [1: p13]

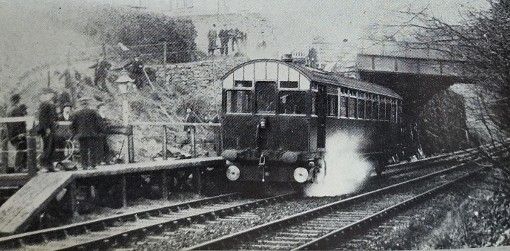

Talking of the Stroud Valley line M.G.D. Farr had a very short illustrated article about the GWR railmotors/auto-trains on that line carried by the Ian Allan journal, ‘Railway World‘ in January 1965. It followed the closure of the railcar/Railmotor/auto-train service in the valley on 31st October 1964. [14: p30]

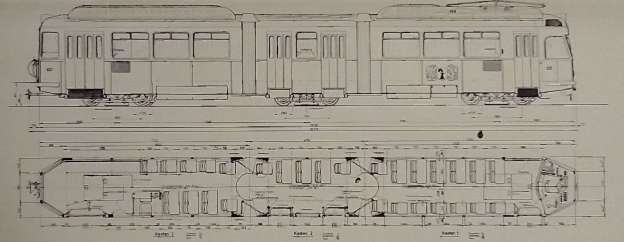

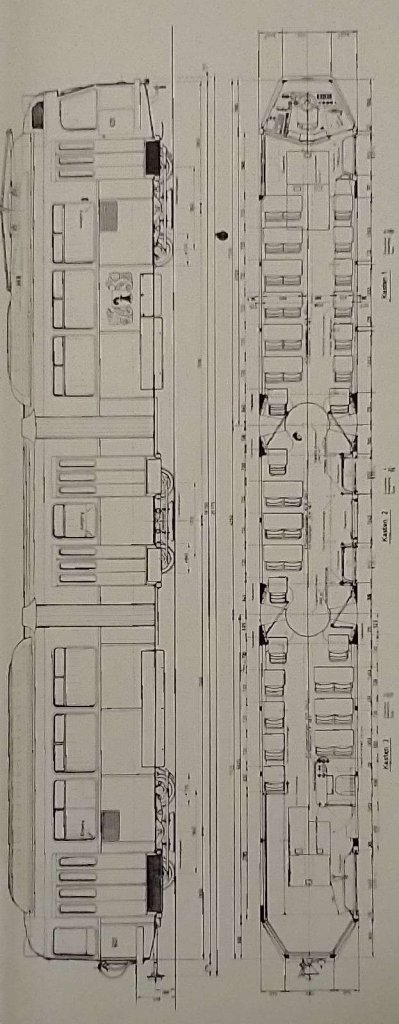

The GWR separated its Railmotors into 2 different types: ‘Suburban’ and ‘Branch line’. The principal difference being the provision of a luggage compartment on those designed for branch line use which was not provided in those intended for suburban use. The first 16 units built did not have luggage space and were designated ‘suburban’. [6]

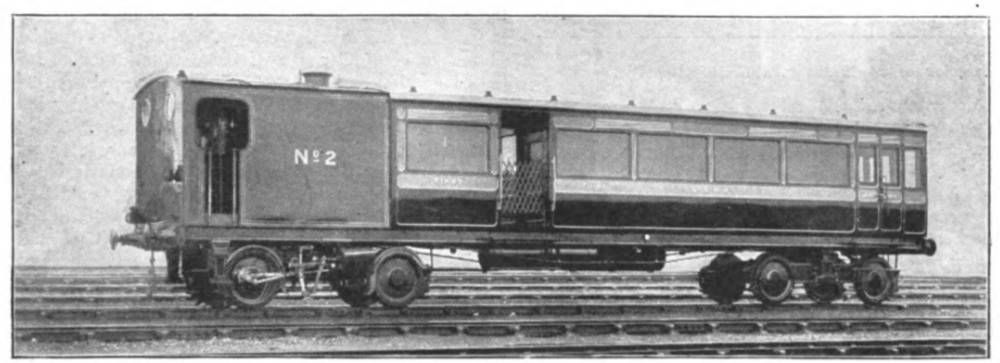

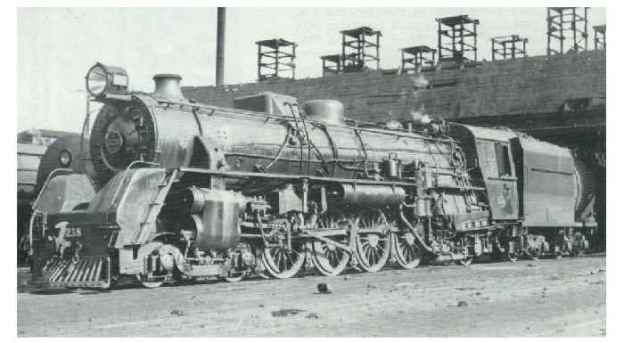

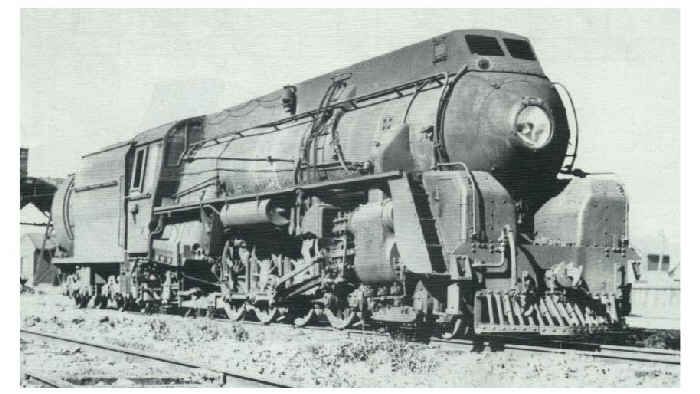

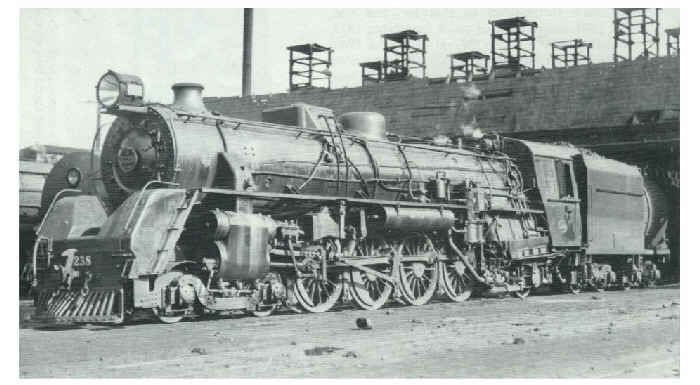

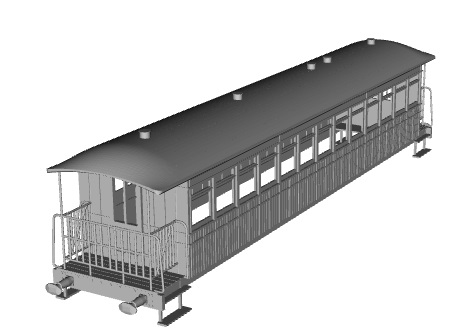

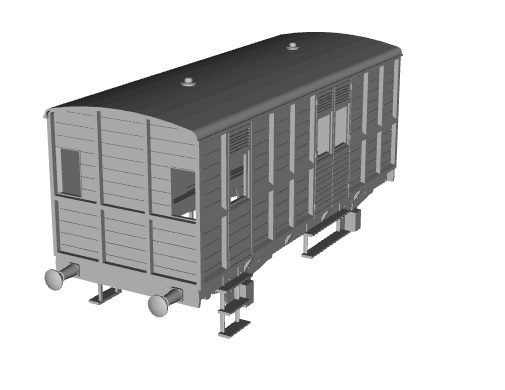

The majority of the GWR Railmotors were rigid framed with no articulation. Just two exceptions were articulated (No. 15 and No. 16). The remaining examples fell into two different variants. The first had an austere slab-sided appearance with matchboard side panels below the waist. They were flat-ended, as can be seen below. “Two ‘prototypes’ were built in 1903, followed by the main batch in 1904 (Nos. 3-14, 17-28).” [1: p13]

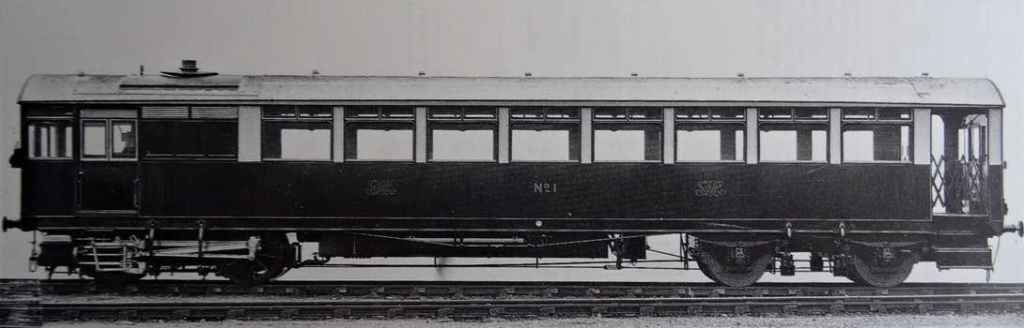

Later GWR Railmotors (Nos. 29-99) were built between 1905 and 1908, were bow-ended and were of a much more attractive design. They had higher waist-lines than contemporary locomotive-hauled coaching stock on the GWR and retained those lines when ultimately converted to auto-trailers. [1: p13]

GWR Railcar No. 93 has been reproduced in model form by Kernow Model Railway Centre. Details can be found here. [12]

The GWR Railmotors were generally successful in developing patronage on the lines where they were used. Often generating sufficient traffic to warrant the provision of a passenger trailer car.

The first trailer built had the same flat-ended design as the early GWR Railmotors. The remaining trailers were built to the bow-ended format.

Gibbs tells us that “Such was the demand for trailers that in 1906 existing selected coaching stock was introduced to the conversion programme. Conversion was applied to six 1890s clerestory and two four-wheelers dating back to the 1870s, the 1870s-1900s supplying some of the first conversions, with demand increasing and later periods supplying more examples for conversion, each with varying seating patterns and internal format. Thus the two four-wheel, 28.5ft-long 1870 versions were running with the new 70ft latest additions to the fleet.” [9]

The design of the GWR Railmotors had not anticipated their success. While being adequately powered as single cars they were generally, particularly which had anything but shallow gradients, “incapable of pulling an extra trailer to carry the new customers which their success had generated.” [1: p13]

Inevitably, when passenger loads increased, alternatives to the Steam Railmotors had to be found. “The emerging ‘auto train’ was showing its usefulness and adaptability. Thus we find that, from 1915, the steam railmotors themselves were on the downward path to becoming trailers, and a serious conversion programme was initiated. These were dealt with year by year in varying sized batches, not strictly in order of age, but the match-boarded designs preceded those of wood-panel format, and it will be noted that conversions were not applied to all railmotors and nor were such activities an annual event.” [9]

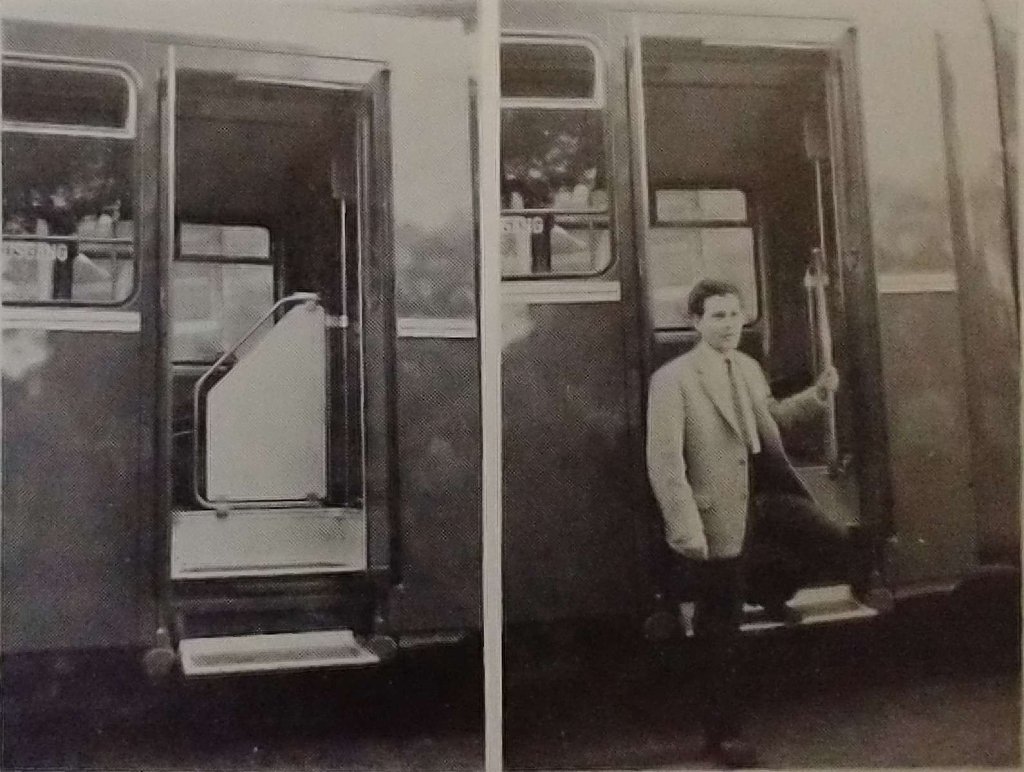

Generally, the powered-bogie end of each unit was converted to a luggage compartment while the drivers position at the other end of the unit was retained “with controls for regulator and brakes connected through to the tank locomotive, suitably modified.” [9]

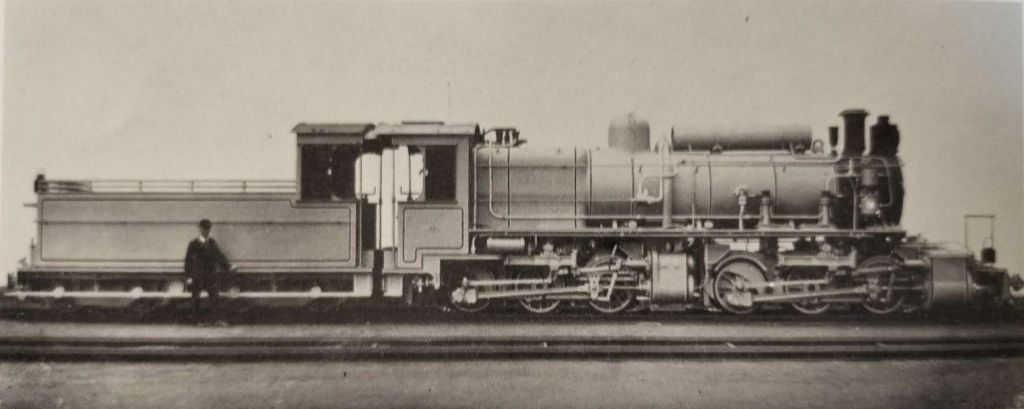

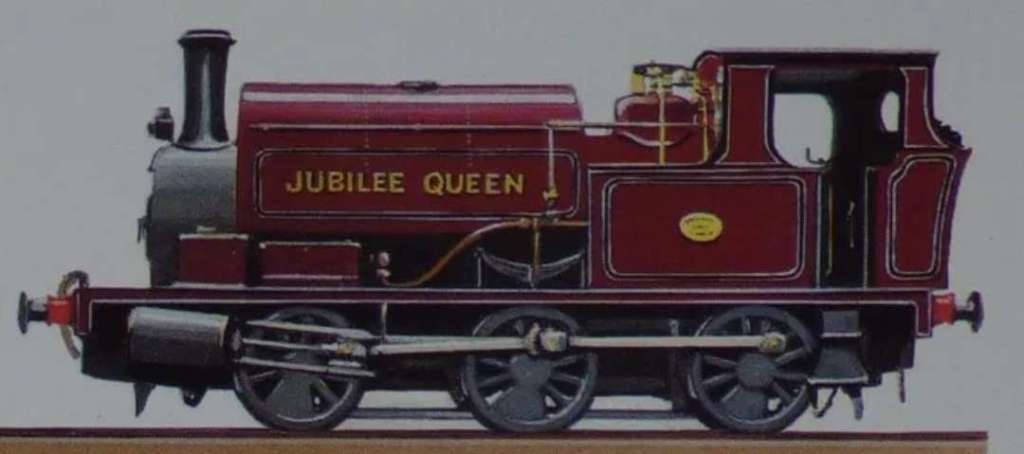

GWR Articulated Steam Railmotors

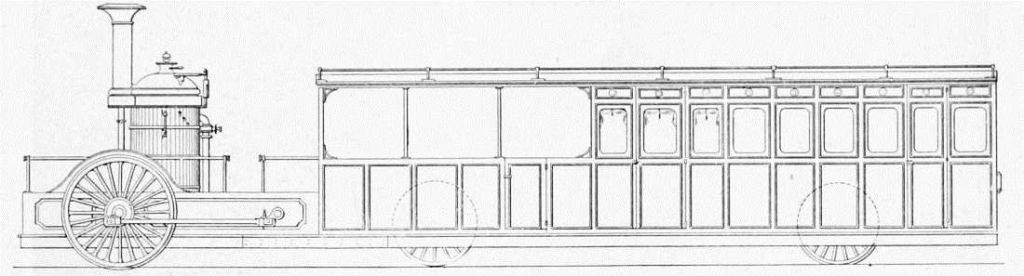

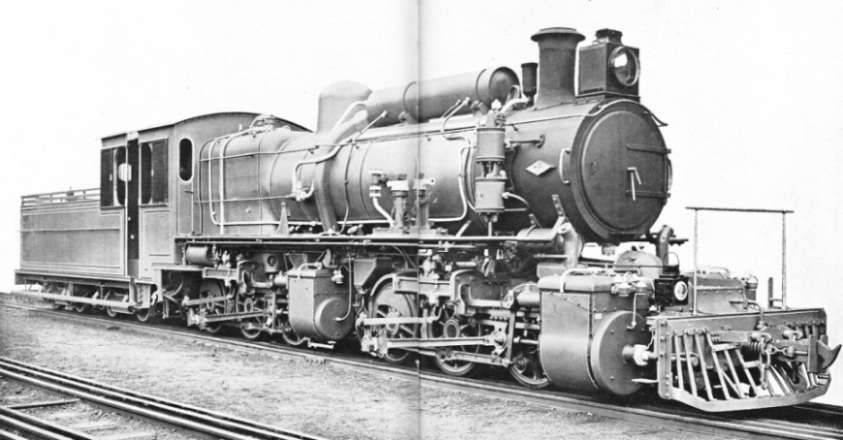

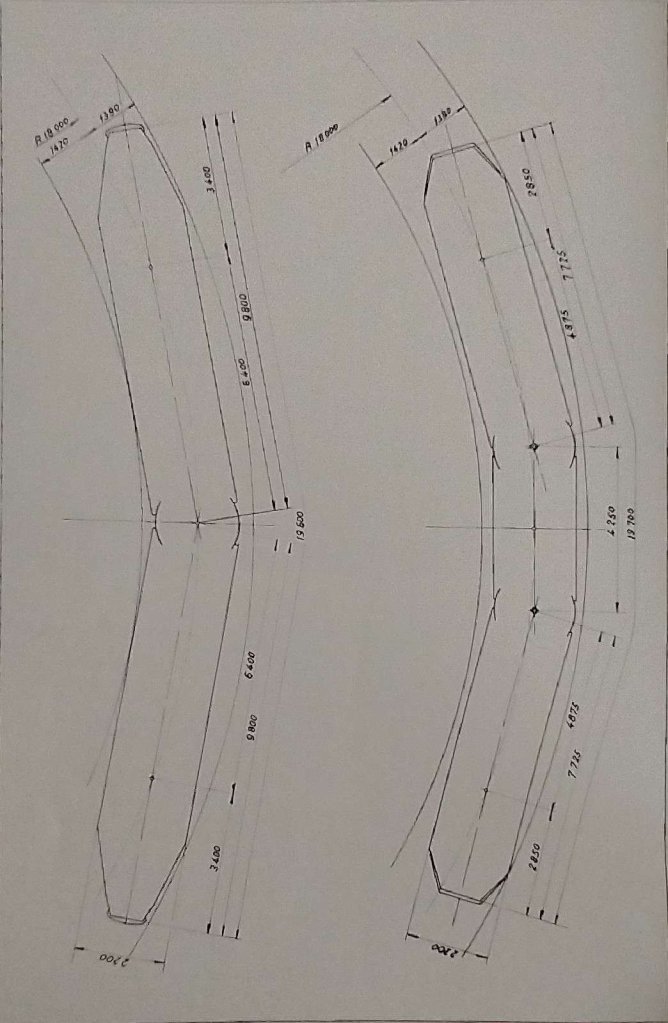

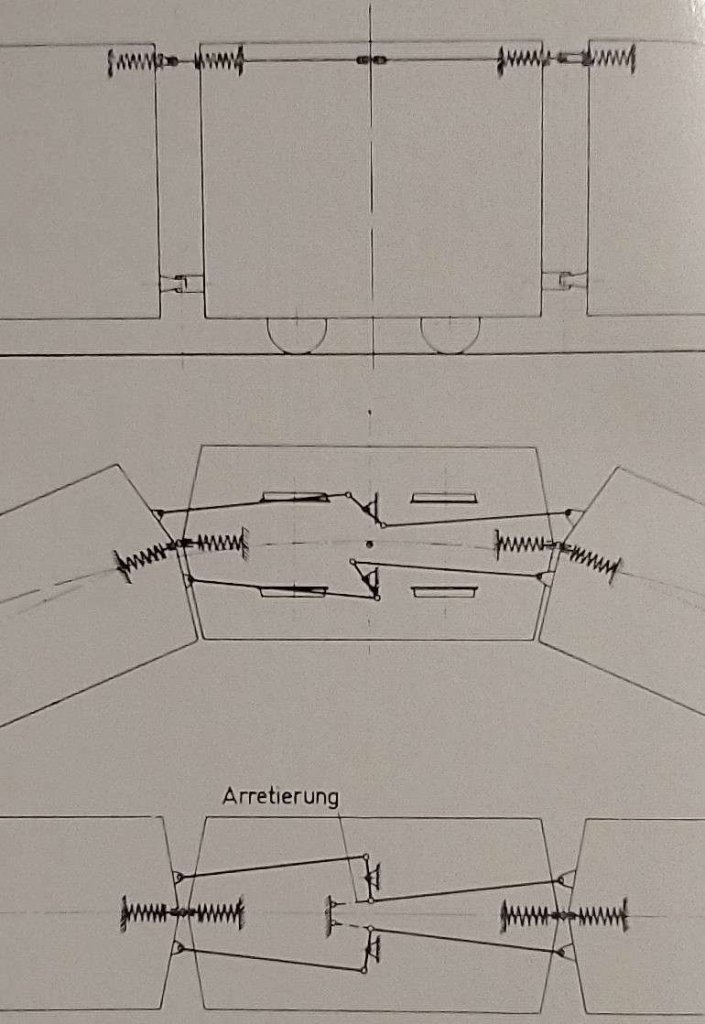

As we have already noted, the vast majority of GWR Steam Railmotors were rigid-bodied. Just two (GWR Nos 15 and 16) were articulated.

Articulated units had the advantage of being relatively easily separated for maintenance purposes and allowed for the possibility of providing more powerful locomotive sections. Throughout the UK, where articulated Railmotors were provided the locomotive section looked more like a small standard locomotive.

Often, additional power units were purchased to allow the immediate replacement of a unit in need of maintenance. An example of this practice was the deployment of articulated railmotors on the Taff Vale Railway. The Taff Vale railmotors were built between 1903 and 1905 “in the form of one prototype and three main batches. There were 18 engine units and 16 carriage portions, thus permitting stand-by power units to be available. … The pioneer power unit came from the company’s own workshops (the last ‘locomotive’ to be built by the TVR in its shops at West Yard, Cardiff), followed by six each from Avonside and Kerr-Stuart and a final five from Manning Wardle.” [1: p21]

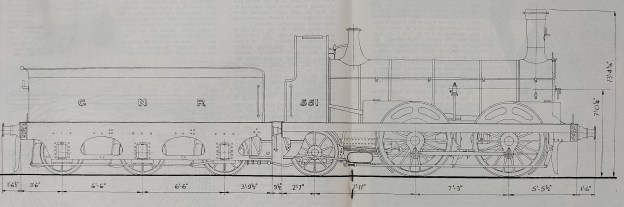

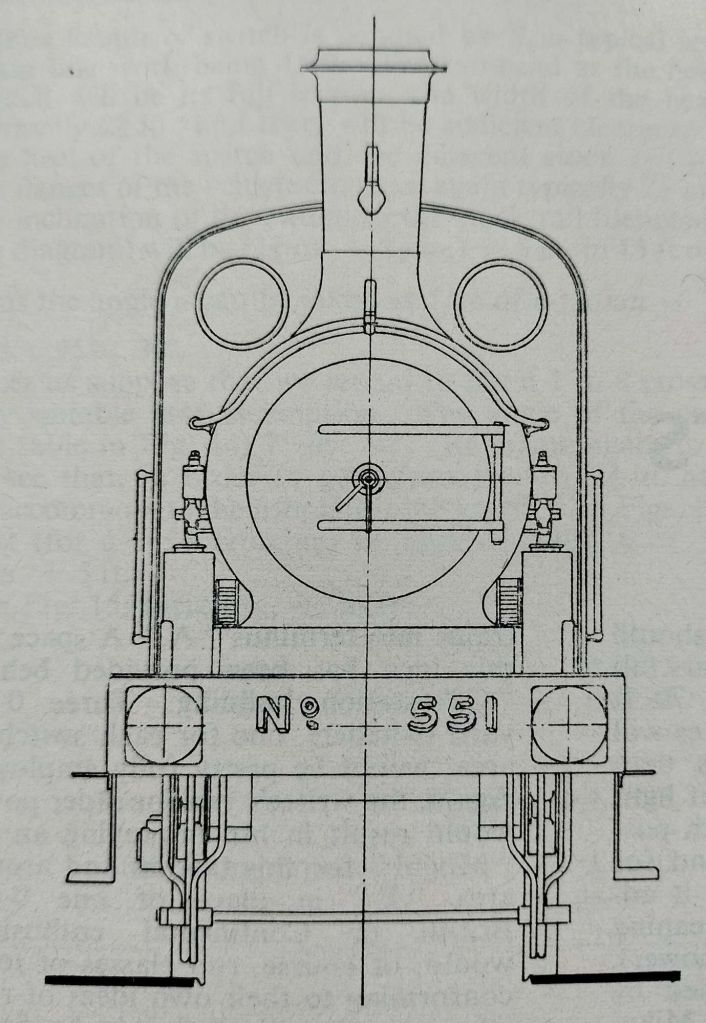

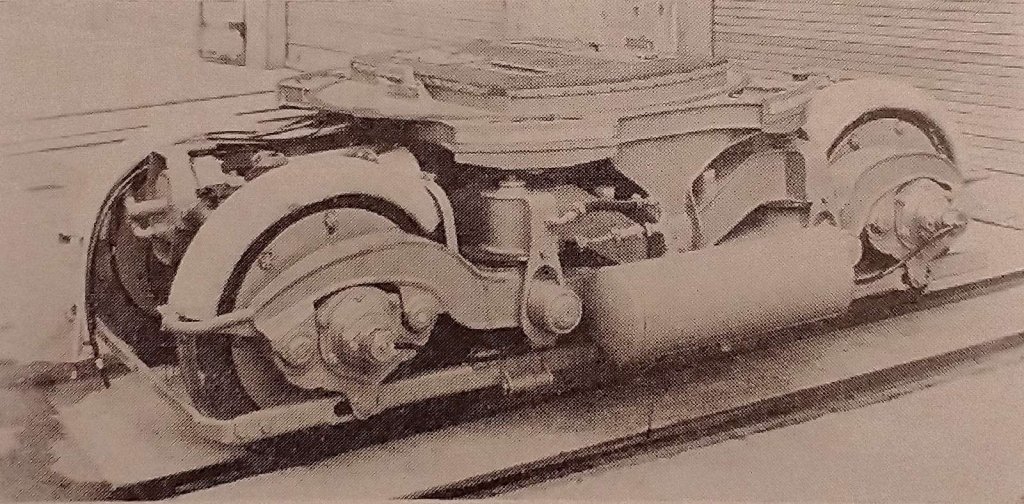

GWR Steam Railmotors No. 15 and 16 were ordered from Kerr Stuart. They were built in 1905 to Kerr Stuart’s design. Bristol Wagon and Carriage Company were subcontractors, providing the bodywork for each unit. [1: p32] There being only two units, exchangeable power sections was not an option fiscally.

In 1920 No. 15 was sold by the GWR to J.F. Wake and sold on, in 1921, to the Nidd Valley Light Railway (NVLR). [1: p32]

References

- David Jenkinson & Barry C. Lane; British Railcars: 1900-1950; Pendragon Partnership and Atlantic Transport Publishers, Penryn, Cornwall, 1996.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_steam_railcars, accessed on 14th June 2024.

- R.M. Tufnell; The British Railcar: AEC to HST; David and Charles, 1984.

- R.W. Rush; British Steam Railcars; Oakwood Press, 1970.

- https://victorianweb.org/victorian/technology/railways/locomotives/27.html, accessed on 16th June 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/GWR_steam_rail_motors, accessed on 17th June 2024.

- https://didcotrailwaycentre.org.uk/zrailmotor93/history/pictures/sub_gubbins.html, accessed on 17th June 2024.

- https://www.nrmfriends.org.uk/post/motoring-in-1903, accessed on 17th June 2024.

- Ken Gibbs; The Steam Railmotors of the Great Western Railway; The History Press, Cheltenham, 2015.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GWR_Steam_Railmotor_No_93_At_the_Didcot_Railway_Centre,_cropped.jpg, accessed on 17th June 2024.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/29903115@N06/51337152220, accessed on 17th June 2024.

- https://www.kernowmodelrailcentre.com/pg/144/KMRC-Locomotive—GWR-Steam-Railmotor, accessed on 23rd June 2024.

- John Lewis; Great Western Steam Rail Motors and their services; Wild Swan Publications, Bath, 2004.

- M. G. D. Farr; Stroud Valley Railcars; in Railway World, January 1965, Ian Allan Publishing.