This article follows on from three other articles which covered the Wellington to Severn Junction Railway and which reached as far along the line as Buildwas. Those articles can be found on these links:

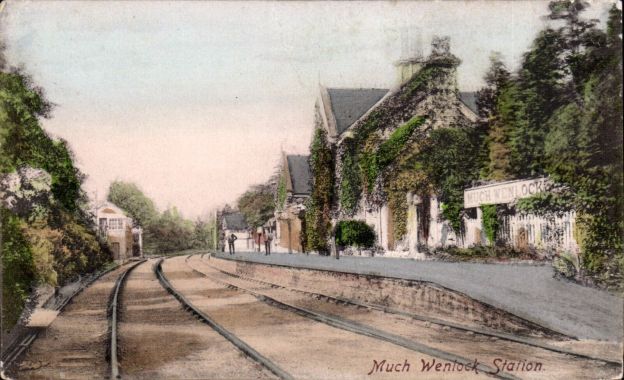

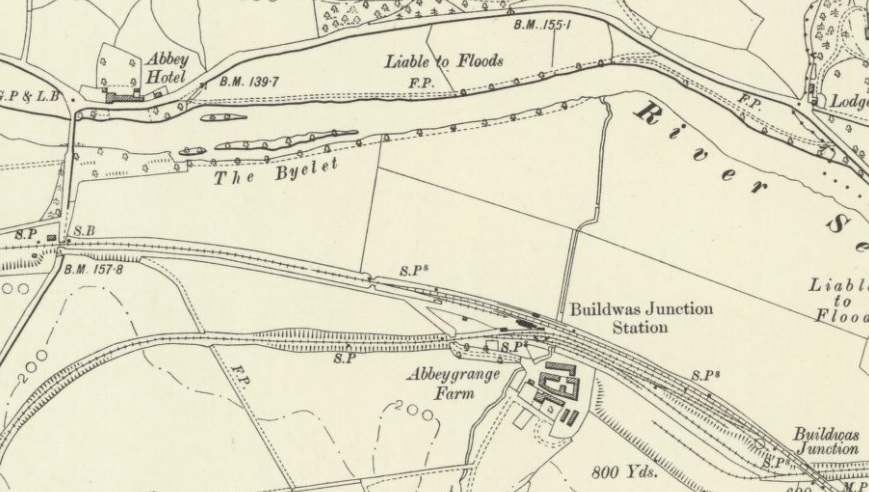

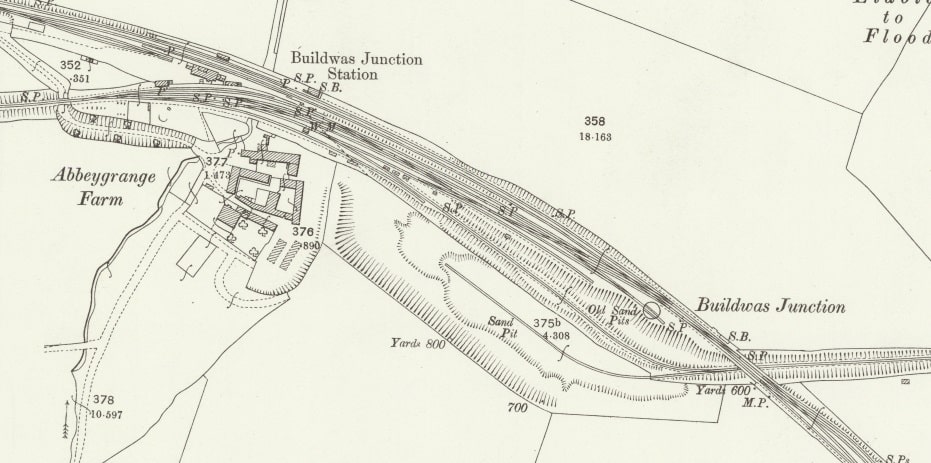

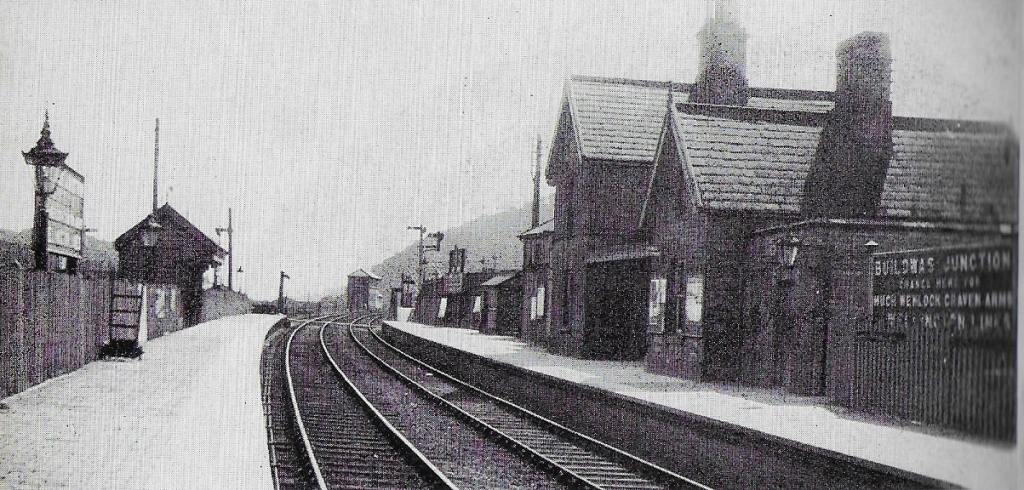

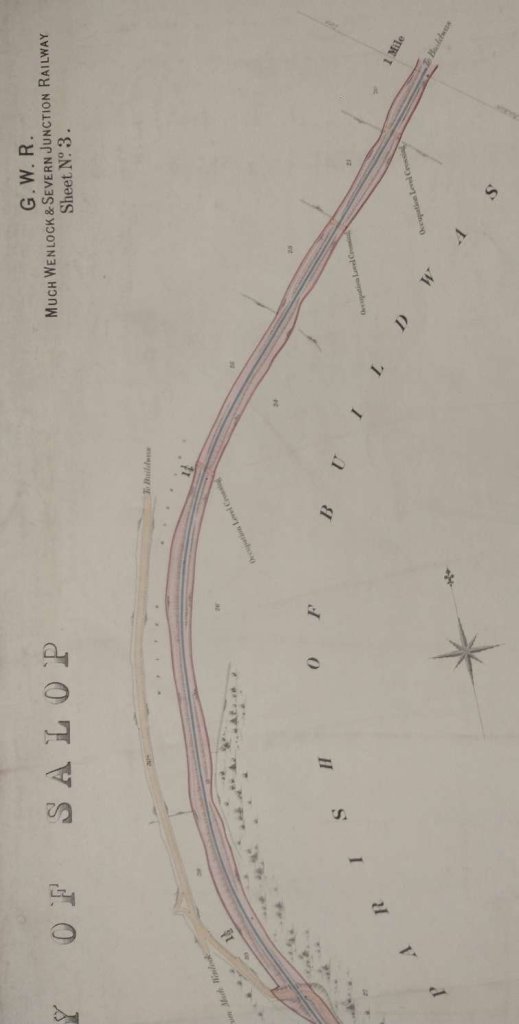

In this article we follow the line from Buildwas to Much Wenlock which was initially the Much Wenlock and Severn Junction Railway, “established by the Much Wenlock and Severn Railway Company. The company itself was formed on 21 July 1859. The railway was later constructed between 1860 and 1862 forming part of the Wellington to Craven Arms Railway.” [1]

The Wellington to Craven Arms Railway was formed by a group of railway companies that eventually joined the Great Western Railway family, and connected Wellington and Shifnal with Coalbrookdale, Buildwas, Much Wenlock and a junction near Craven Arms on the route between Shrewsbury and Hereford. It’s purpose was particularly focussed on the iron, colliery and limestone industries around Coalbrookdale.

The line was built over a number of years by what started out as a number of different independent ventures:

- the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway Coalbrookdale branch from Madeley Junction (near Shifnal) to Lightmoor;

- the Wellington and Severn Junction Railway from Ketley Junction (near Wellington) to Lightmoor;

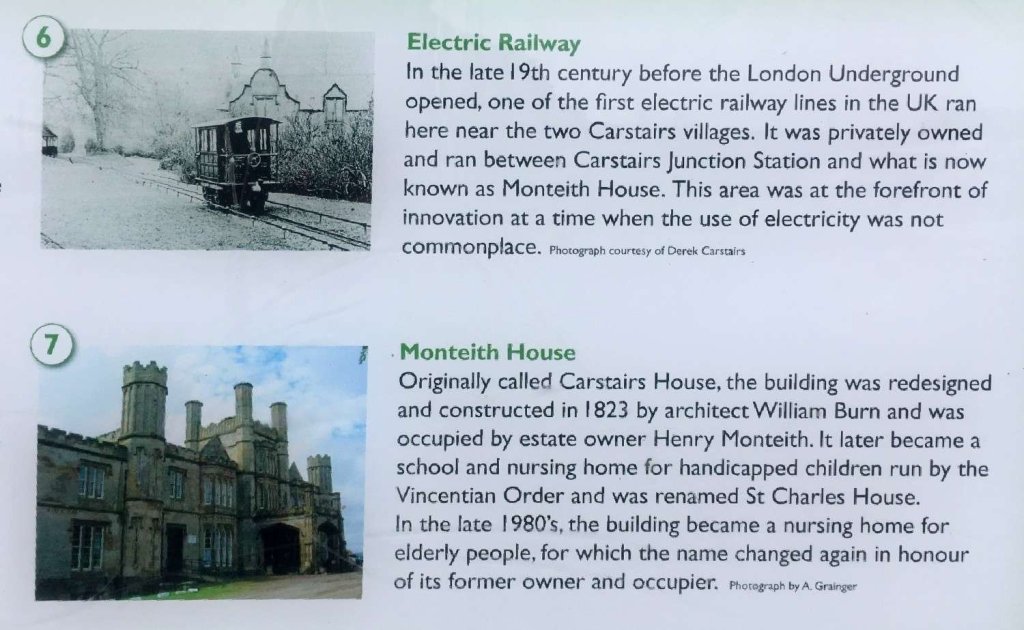

- the Great Western Railway Coalbrookdale extension from Lightmoor to Coalbrookdale;

- the Wenlock Railway from Coalbrookdale to Buildwas;

- the Much Wenlock and Severn Junction Railway from Buildwas to Much Wenlock;

- the Wenlock Railway from Much Wenlock to Marsh Farm Junction, north of Craven Arms. [2]

“The Wenlock branch, with its four original constituent companies passed through areas as complex and diverse as its original organisation: from the slag tips and pennystone pit mounds of the East Shropshire coalfield to the wooded crest of Wenlock Edge and Ape Dale. The one central strand however on which the companies focused their attention was the ironworks nestling in the tree-lined Coalbrookdale valley, the success of their venture depending solely on the support which they would receive from the Coalbrookdale Company.” [61: p5]

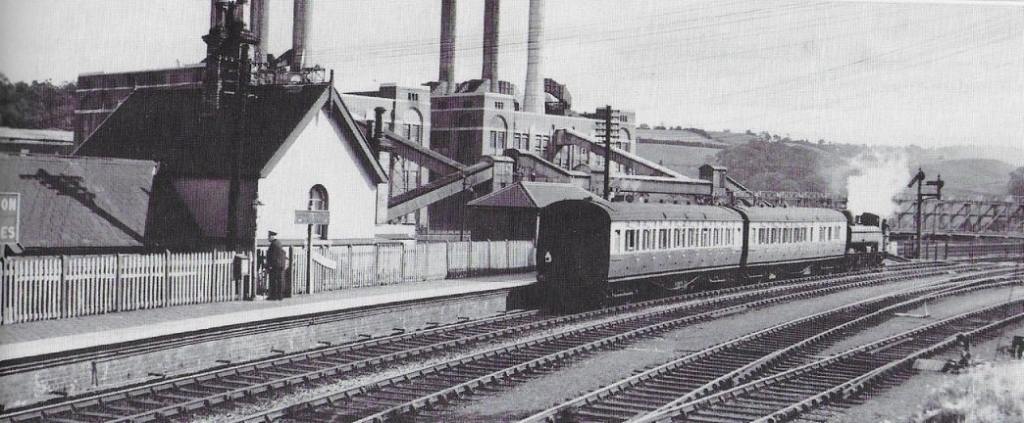

The railways were opened to traffic between 1854 and 1867. The railways local to Coalbrookdale were heavily used by mineral traffic; the hoped-for trunk hauls to and from South Wales via Craven Arms were not realised. Passenger traffic was never heavy, and was sparse between Much Wenlock and Craven Arms. Passenger traffic closures took place from 1951 and ordinary goods traffic closed down in the 1960s. Ironbridge B Power Station generated significant volumes of merry-go-round coal traffic between 1967 and 2015. The line is now entirely closed to ordinary traffic, but the heritage Telford Steam Railway operates on a section between Lawley and Doseley. [2]

The immediate location of the railway station at Buildwas disappeared under the redevelopment of the power station.

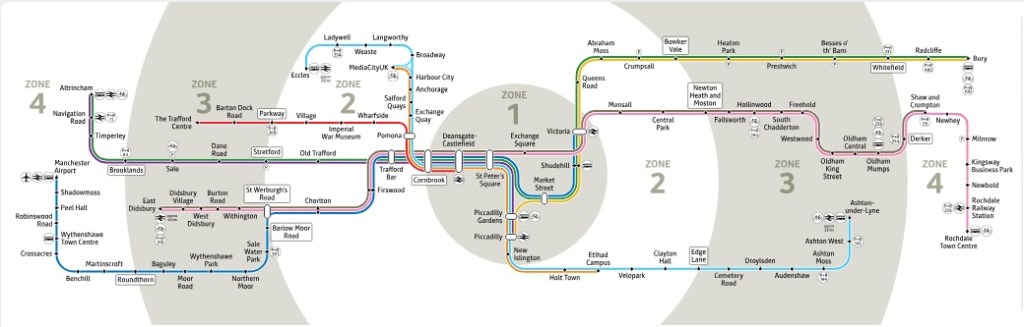

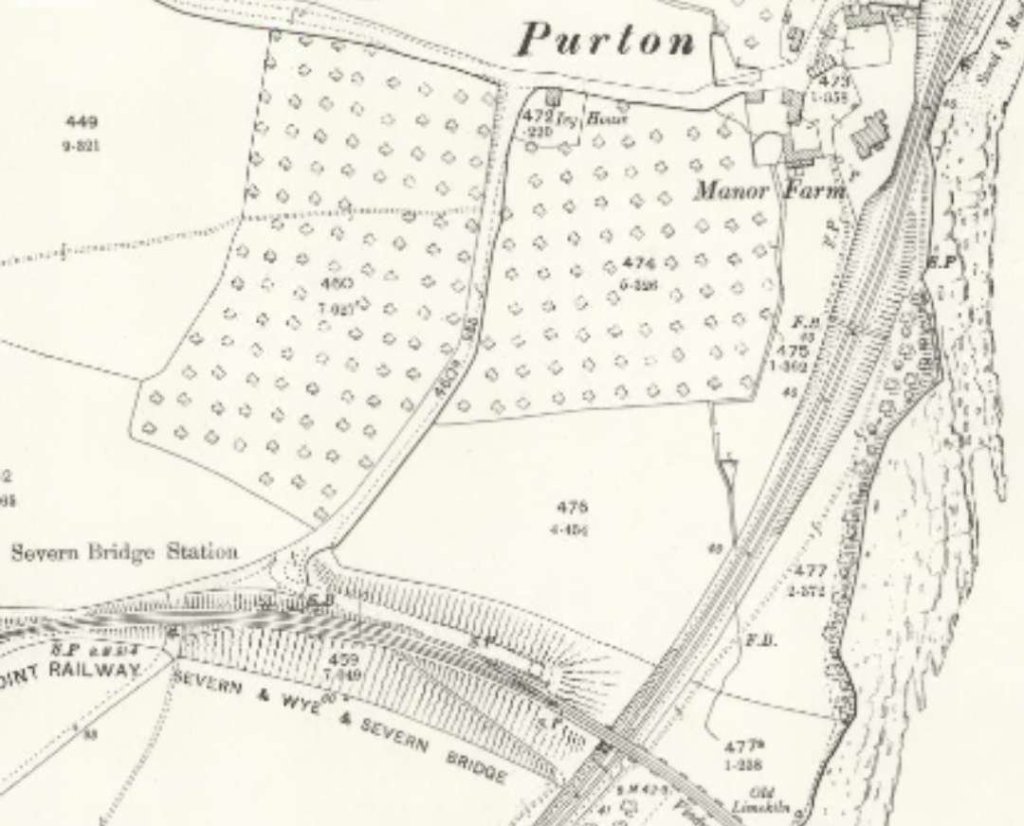

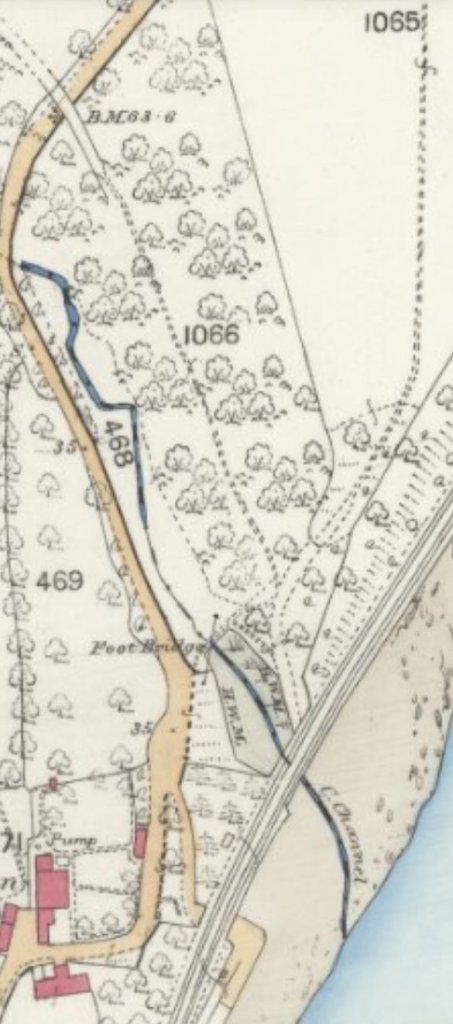

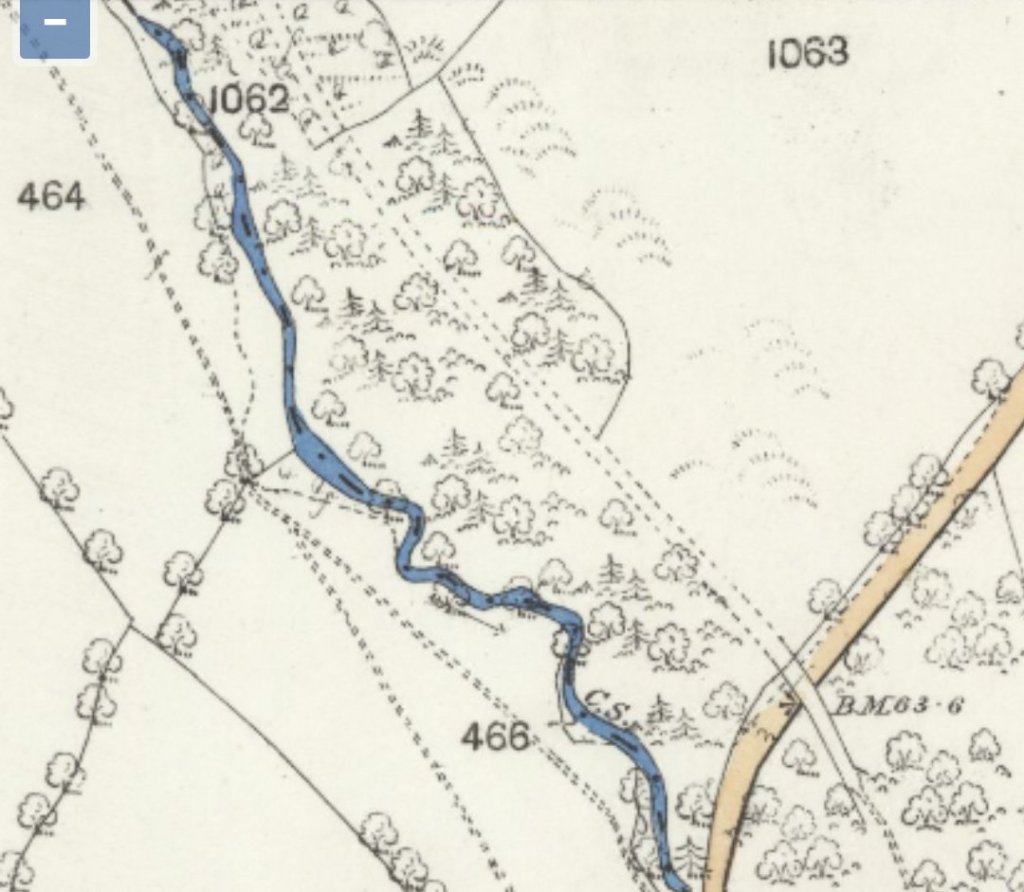

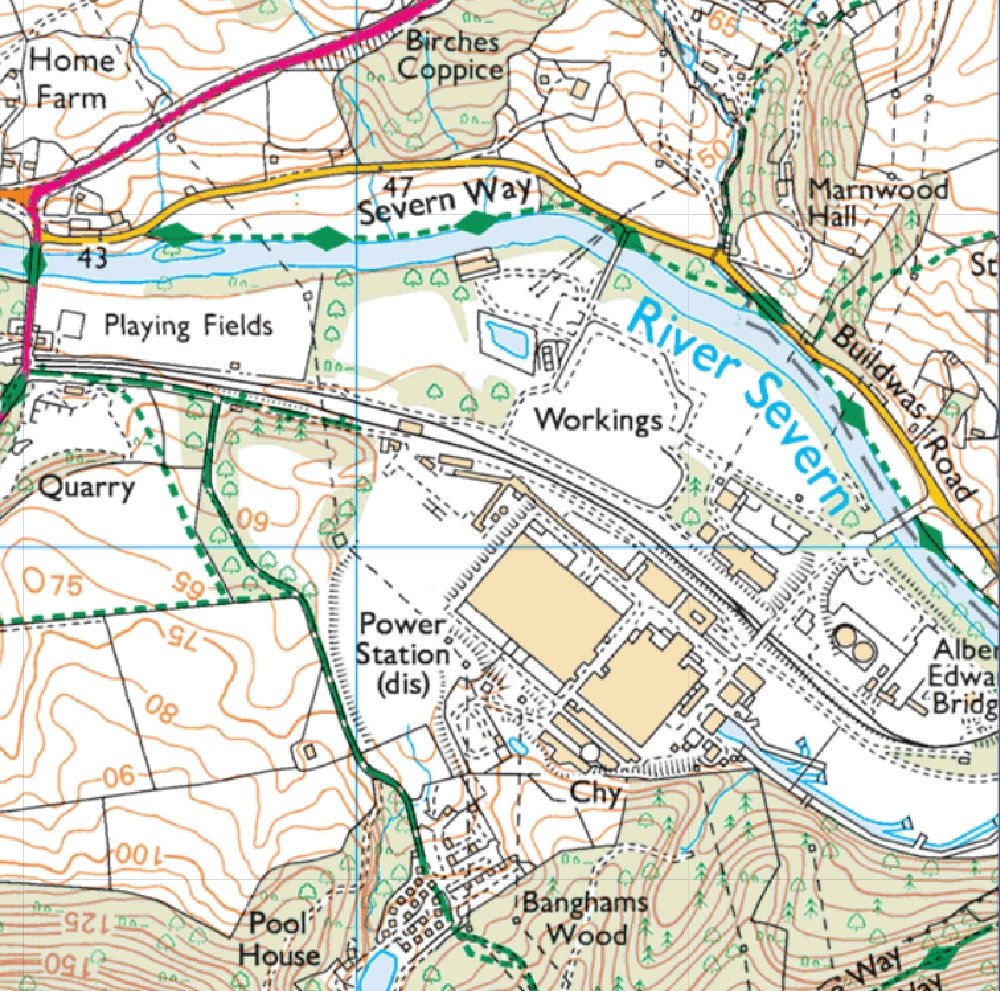

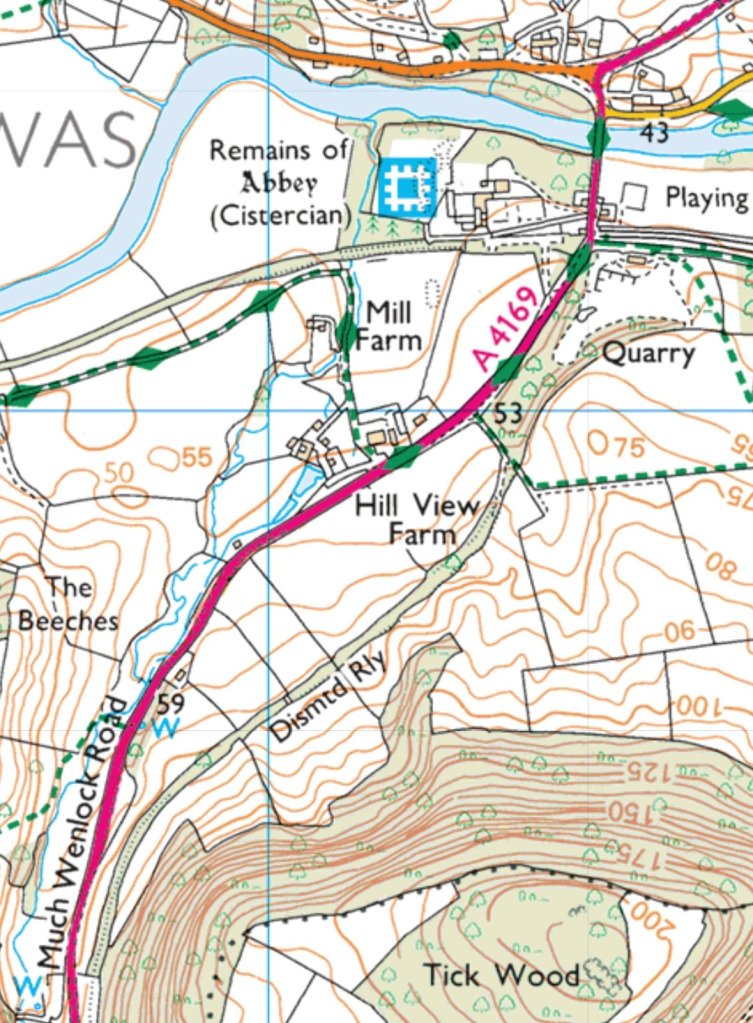

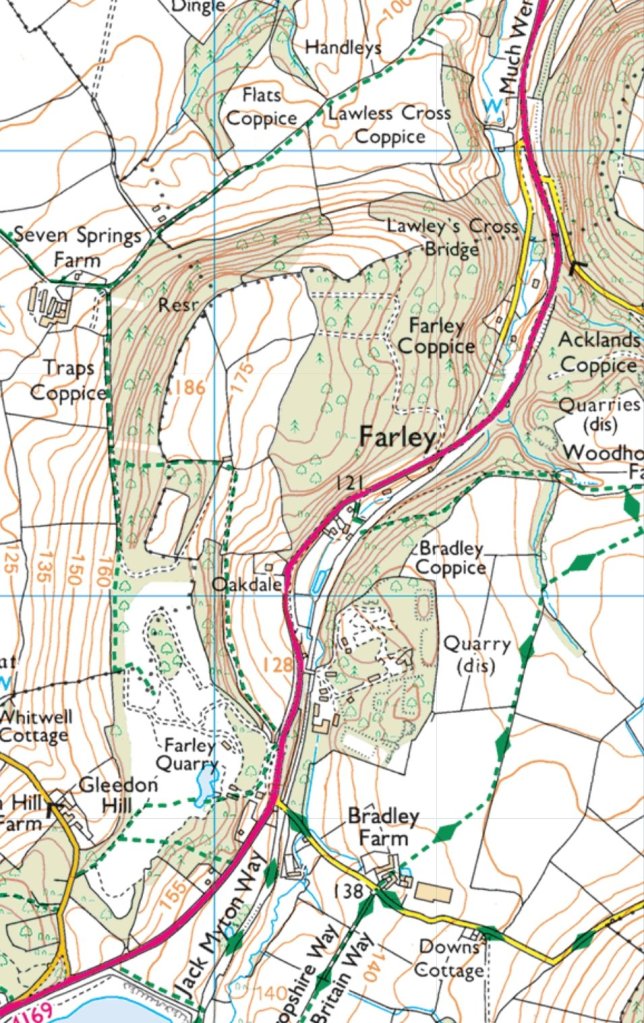

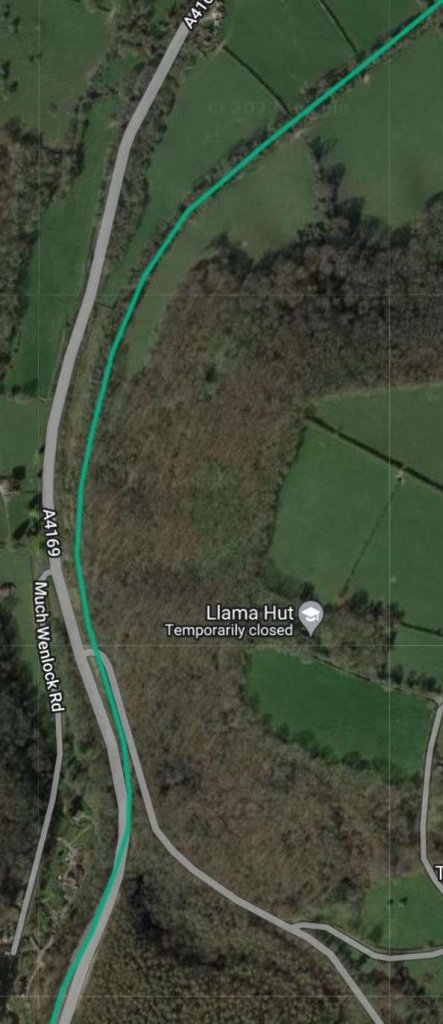

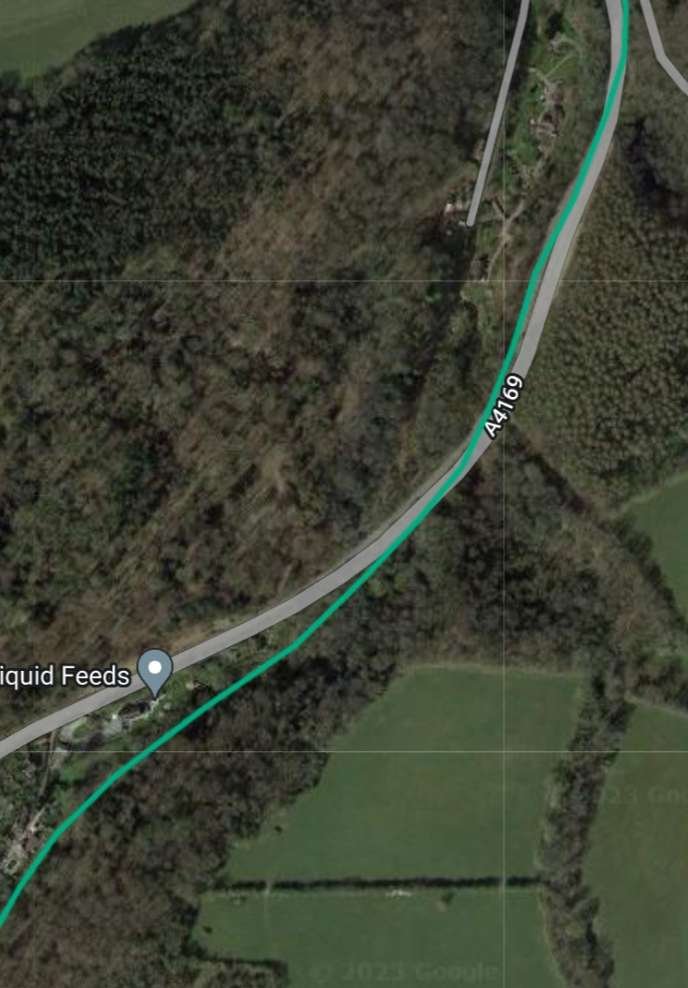

These first few maps are taken from StreetMap.co.uk [17] and show the route of the railway South from Buildwas through Much Wenlock as it appears on 21st century Ordnance Survey mapping. …..

Buildwas to Much Wenlock – The Route

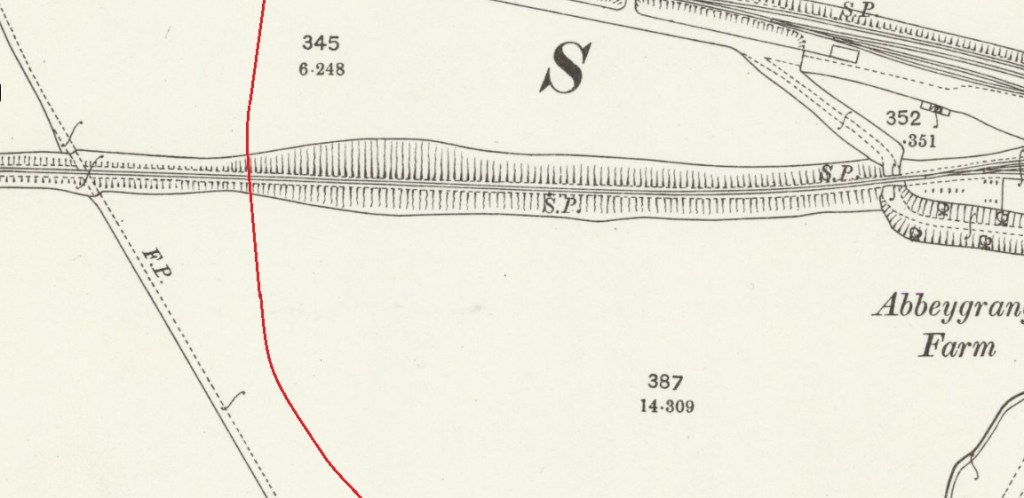

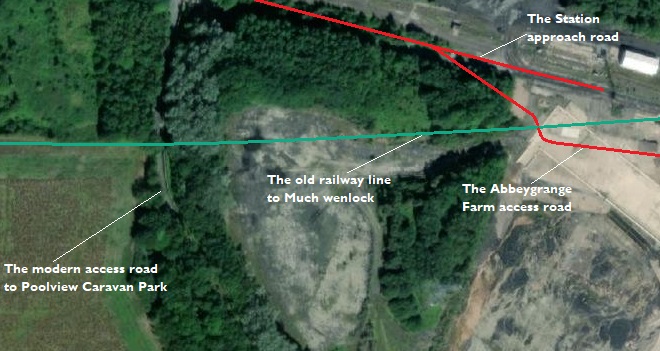

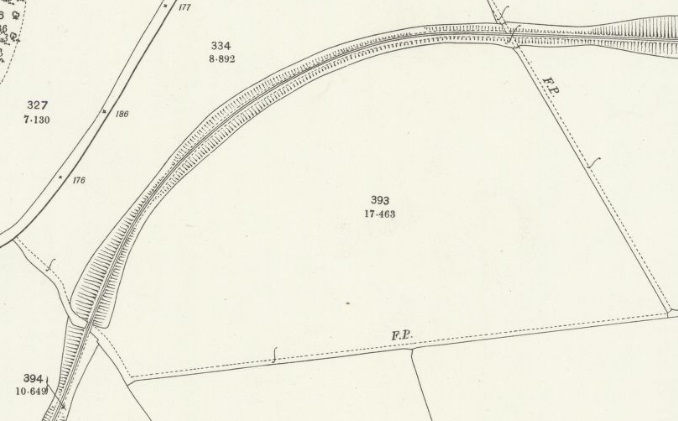

The footpath shown on the map extract above was accessible from the old station access road as far as the field boundary on the North side of railway land but not beyond that point. A public footpath runs East-West across the field shown to the West of the access road and to the South side of the old railway. In 2023, the field was in use to grow potatoes. Walking West along that path brings one to the first remaining significant structure on the line to Much Wenlock. The map extract below shows the line curving round to the South before crossing a farm access road.

A steep track alongside the underpass leads South-southwest alongside the old railway route to allow field access and it is possible, at the top of that access road, to step onto the old railway formation and follow it for a short distance to the Southwest through increasingly dense vegetation. Walking Northeast along the formation over the accommodation bridge was not feasible because vegetation obstructed the route over the bridge.

As the picture above shows, the trackbed from a point just to the West of the accommodation bridge is inaccessible. The next location where access is possible is at the next minor road on the East side of the A4169.

After clearing the bridge the old line was on embankment for a short distance with the minor road rising to the same height and continuing then on an upward grade. The next two pictures show the old railway formation at the point where the minor road and the old railway formation were at a similar height.

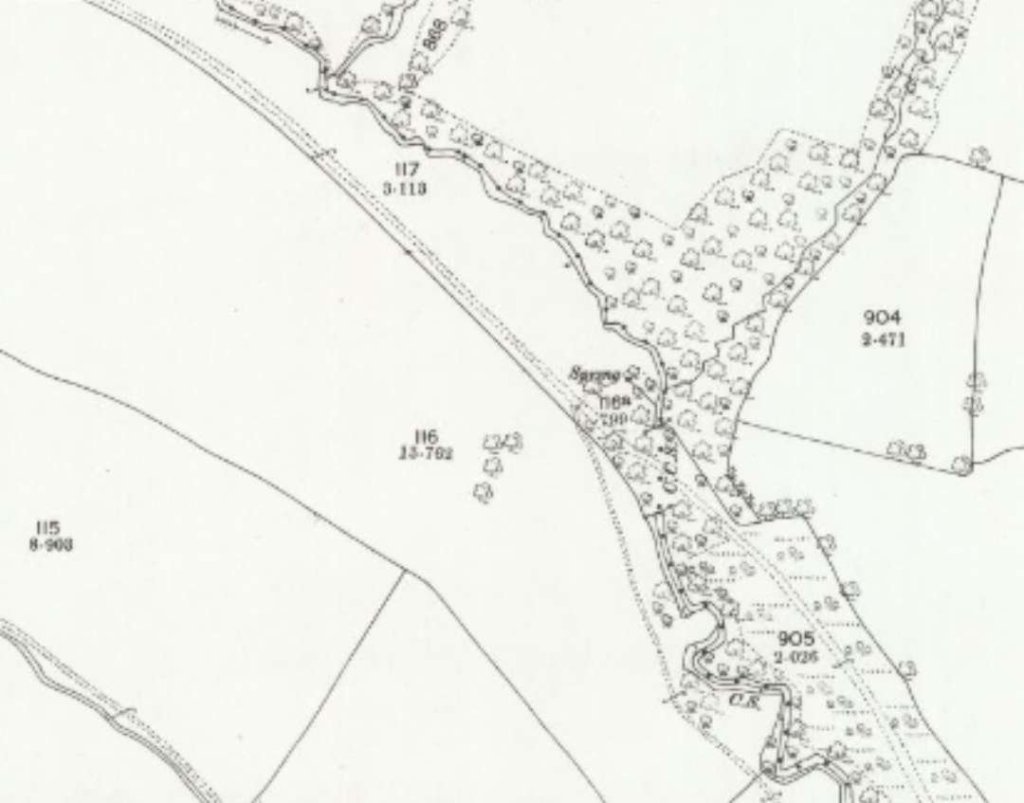

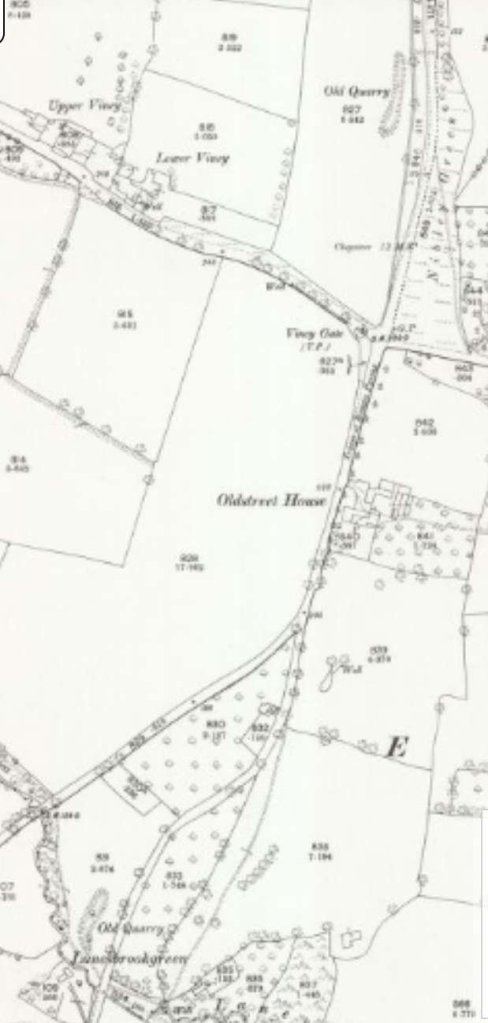

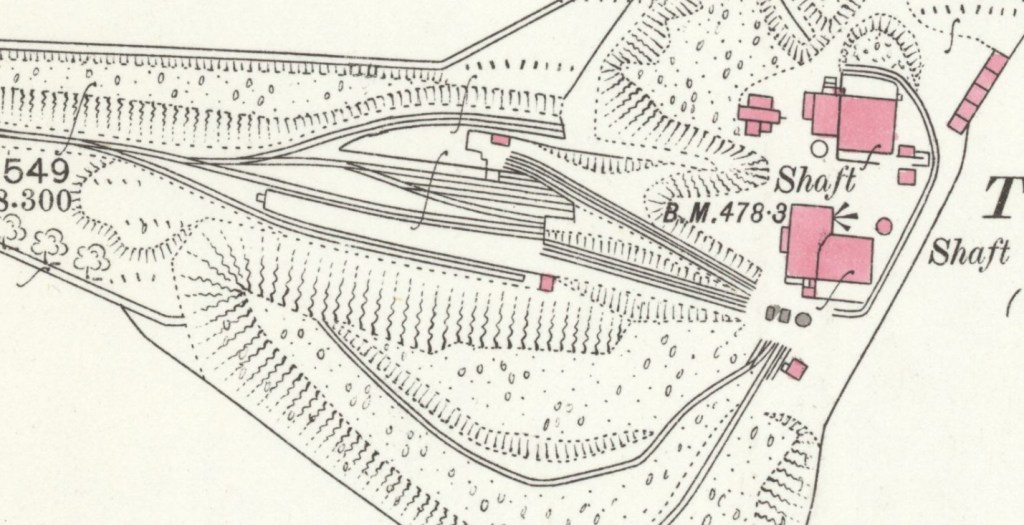

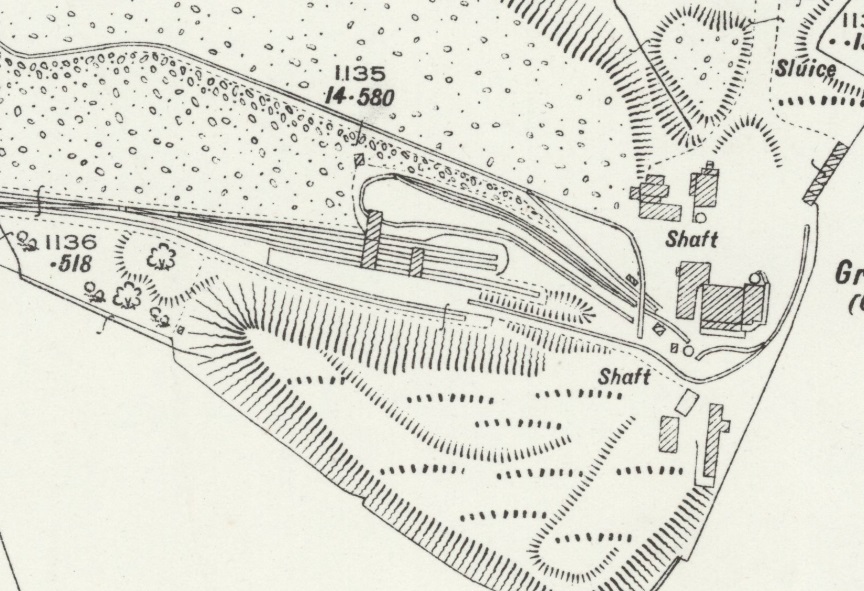

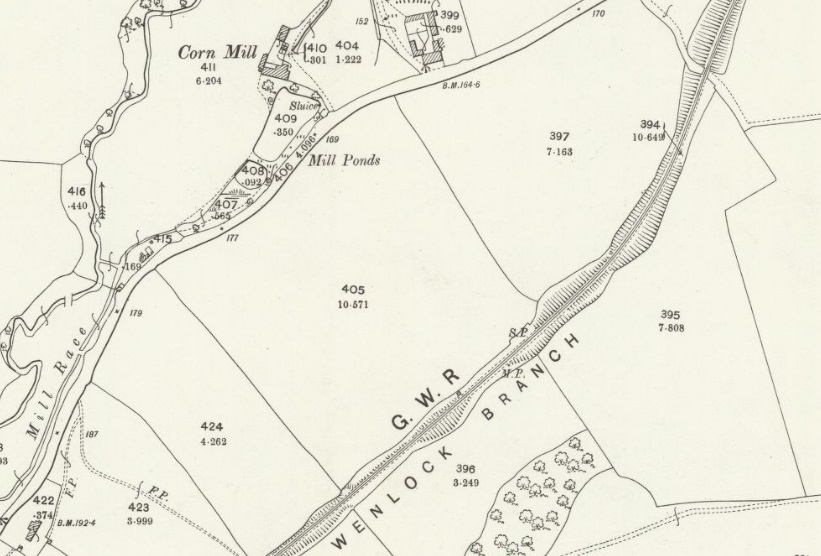

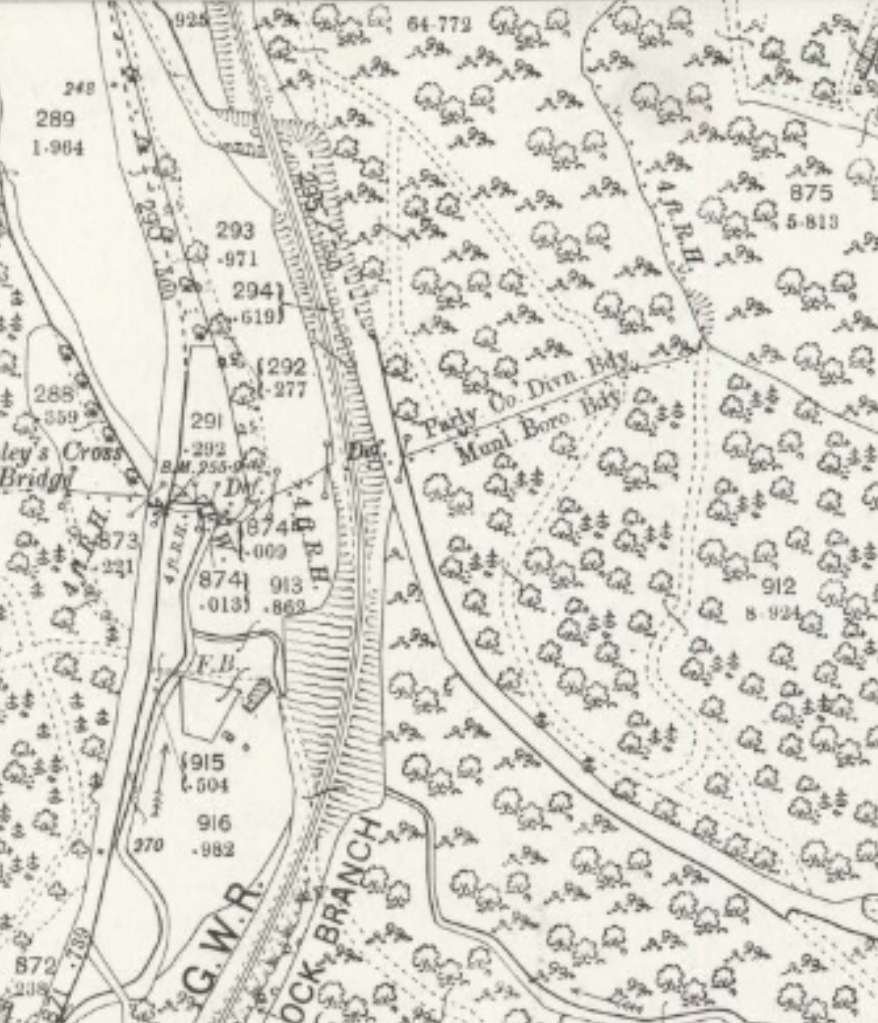

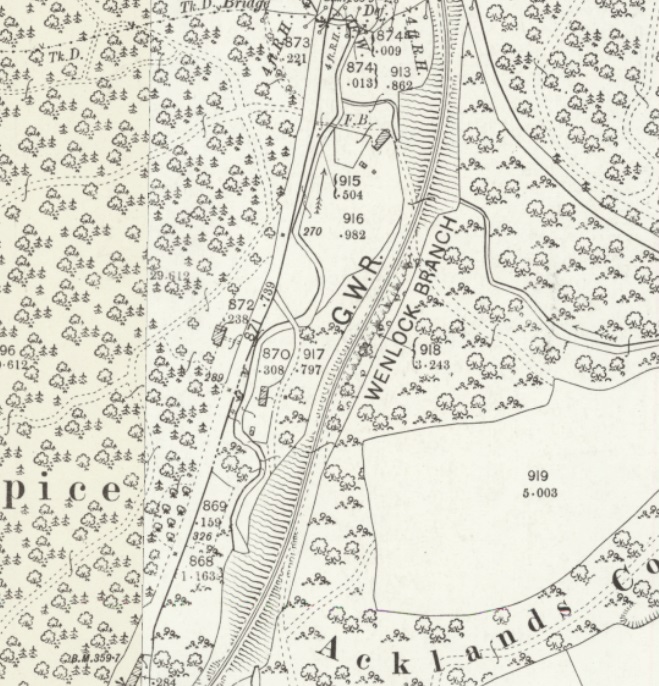

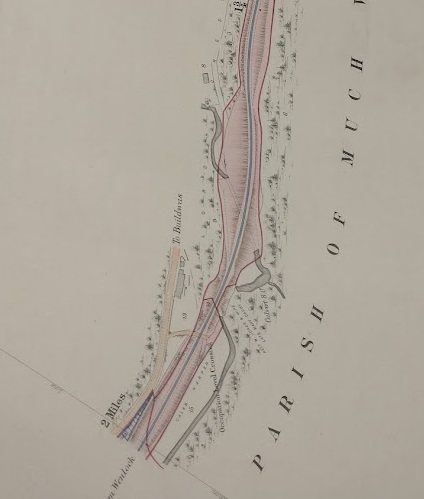

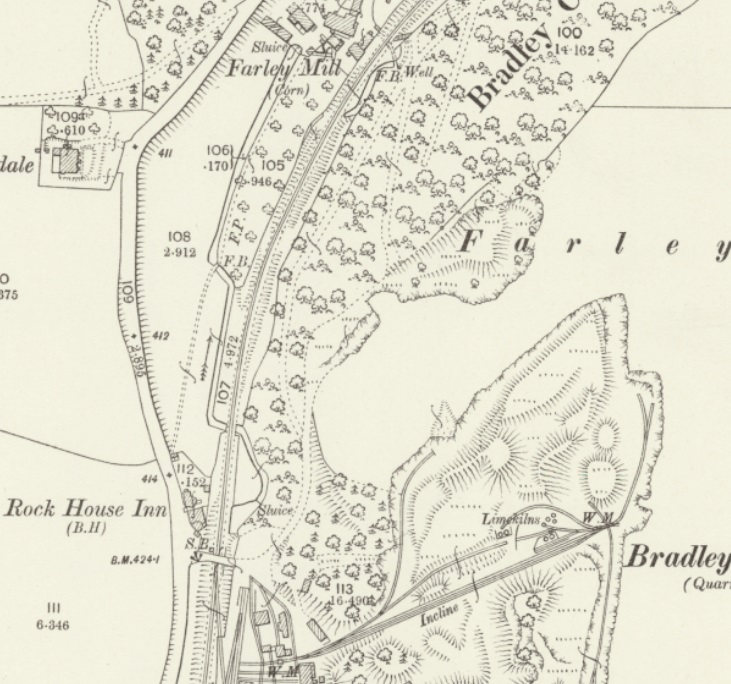

The next two extracts from the 1901/1902 OS mapping take us as far as Farley Halt.

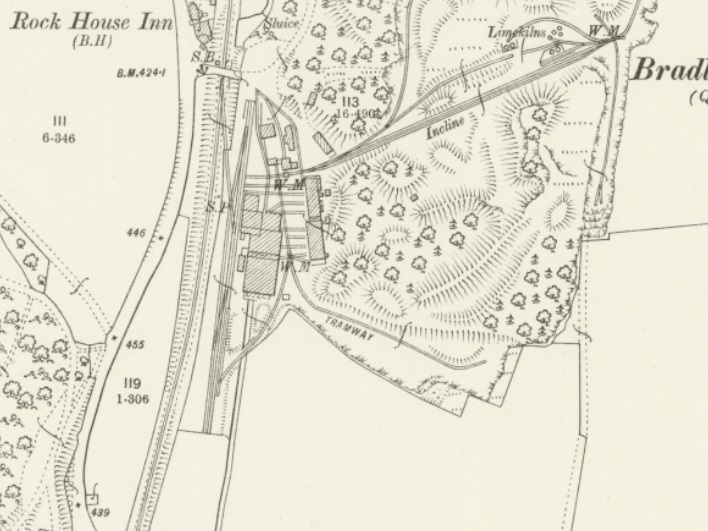

Farley Halt was opened in 1934 and closed in 1962. It had a short timber edged platform with a wooden shelter on the west side of the line behind the former Rock House Inn. The halt could be accessed by steps down from a road over bridge to the south. On the other side of the overbridge was an access siding to Bradley Rock Quarry. The halt has been demolished, but its nameboard can be found displayed 400 metres to the north of the site on a stone barn adjacent to the A4169 Much Wenlock Road. [28]

Adrian Knowles

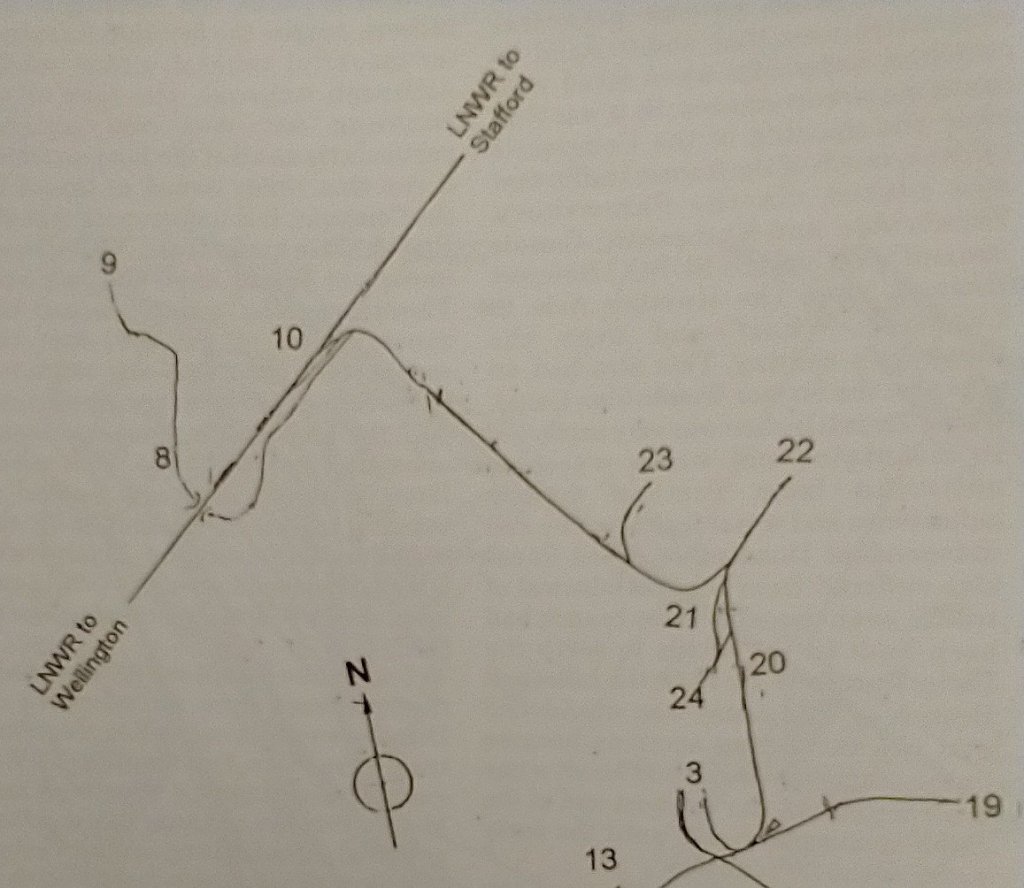

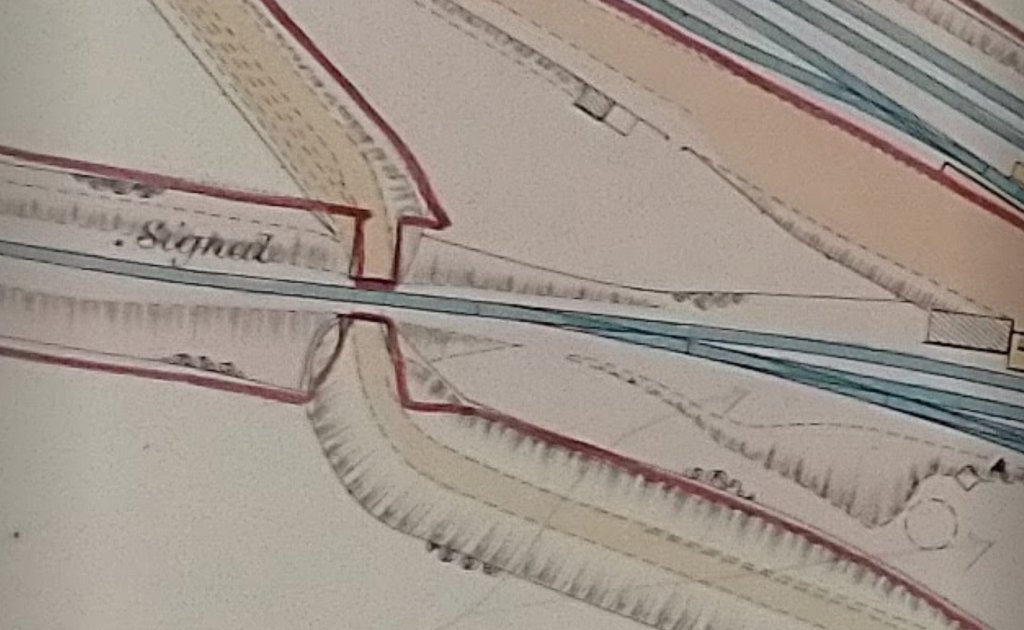

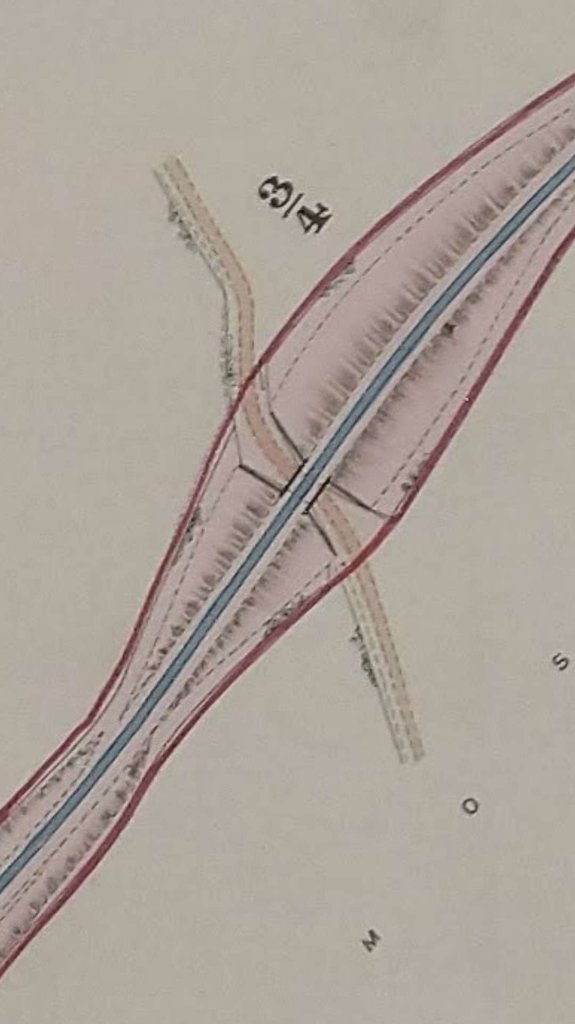

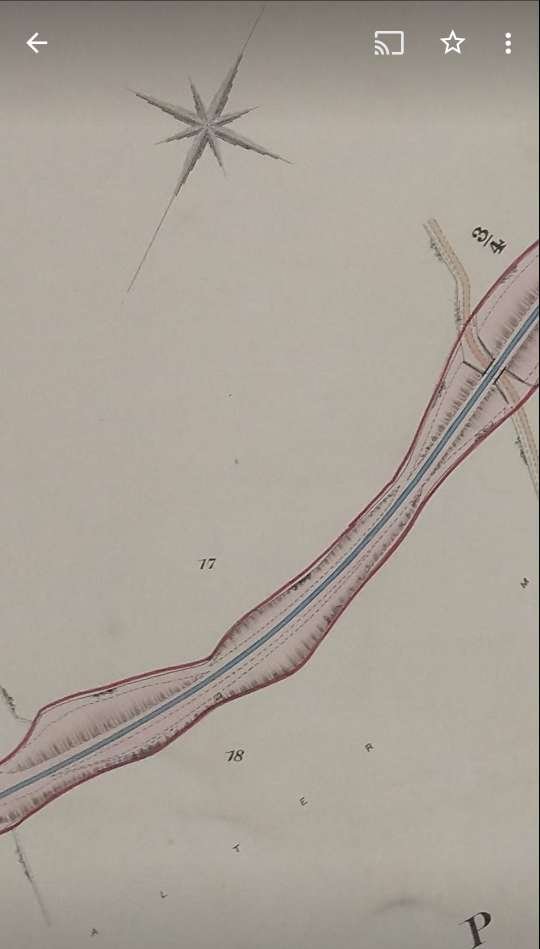

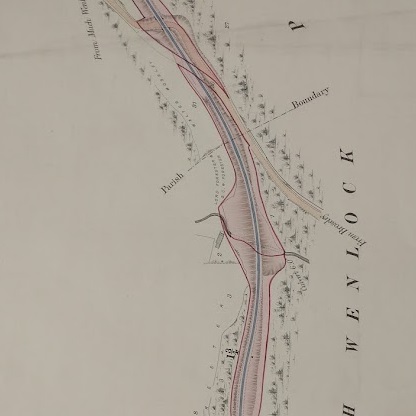

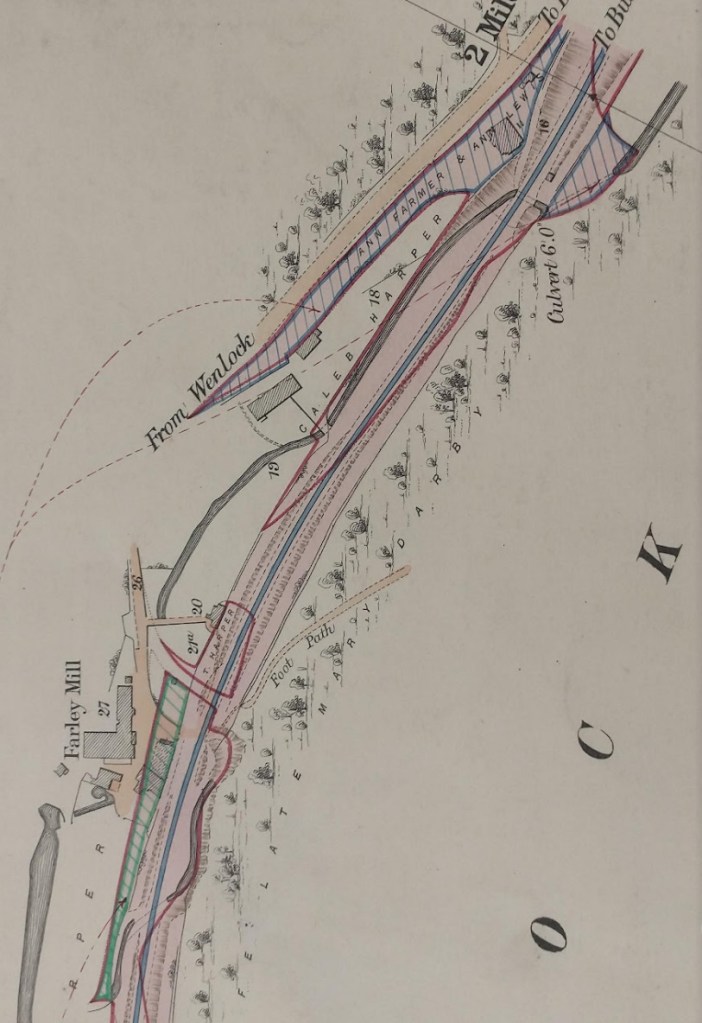

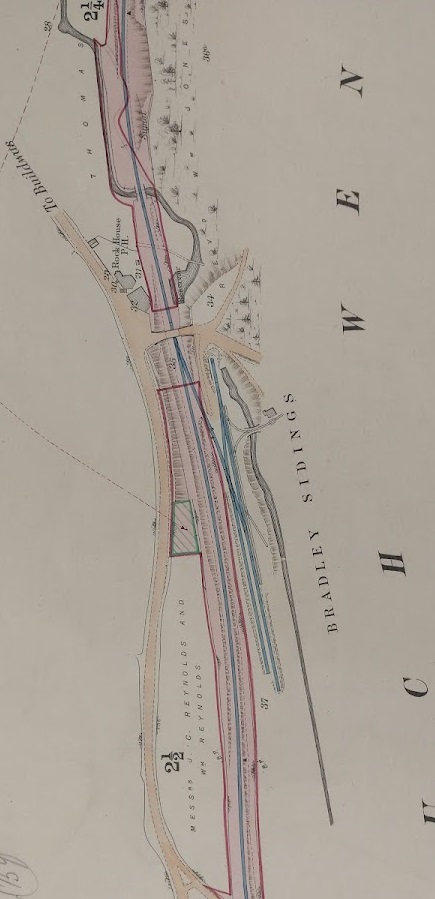

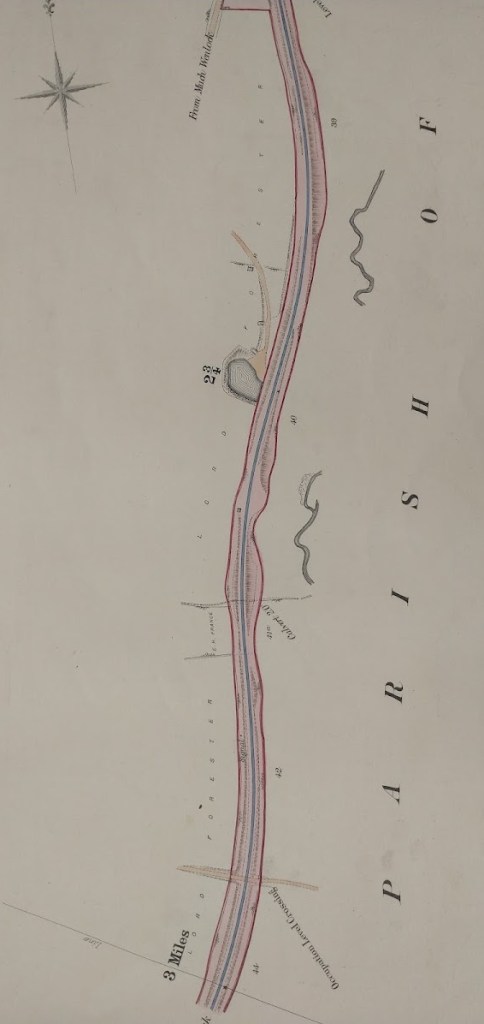

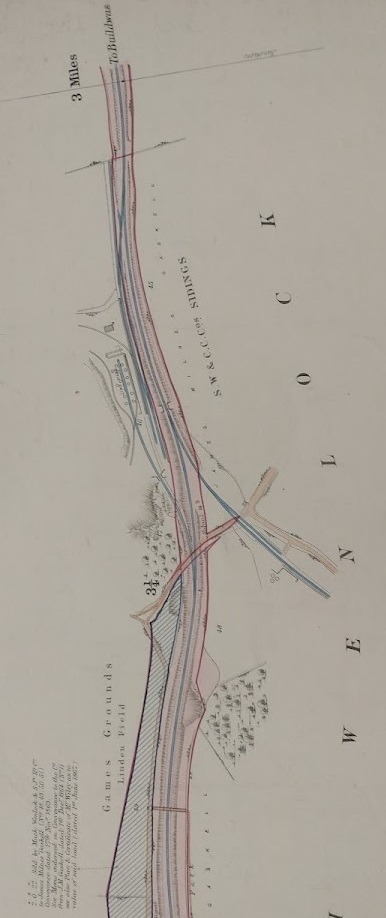

On the South side of the accommodation bridge were Bradley Rock Sidings. They can be seen clearly on the precontract plan below.

Bradley Rock Quarry appears to have been a relatively significant operation at the turn of 20th century. The Quarry is also known as Farley Quarry and it is under this name that more details can be found online. Much Wenlock is situated in the area of a Limestone outcrop. Kent Geologists Group comment on the Quarry: “The strata exposed in Farley Quarry consist mainly of Wenlock Reef Facies interbedded with nodular and tabular limestones of Silurian age and display clearly the particular feature known as “ball stones”. In the deeper parts of the quarry the strata gradually pass downwards into the Farley member. … The Wenlock Series was subdivided by Bassett et al (1974) into bio-zones based on graptolite fauna and the Farley Member is placed at the top of the Coalbrookdale Formation. Within the Coalbrookdale formation, the uppermost mudstones of the underlying Apedale strata grade upwards over some ten metres into an alternating sequence of grey, shaley mudstones and thin, nodular, buff to blue-grey limestones – the Farley Member.” [31]

The two images above were taken in Farley Quarry/Bradley Rock Quarry and illustrate the kind of rock encountered, © Richard Law and licensed for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-SA 2.0). [32][33]

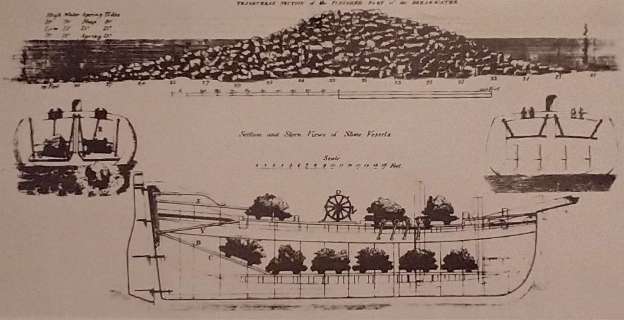

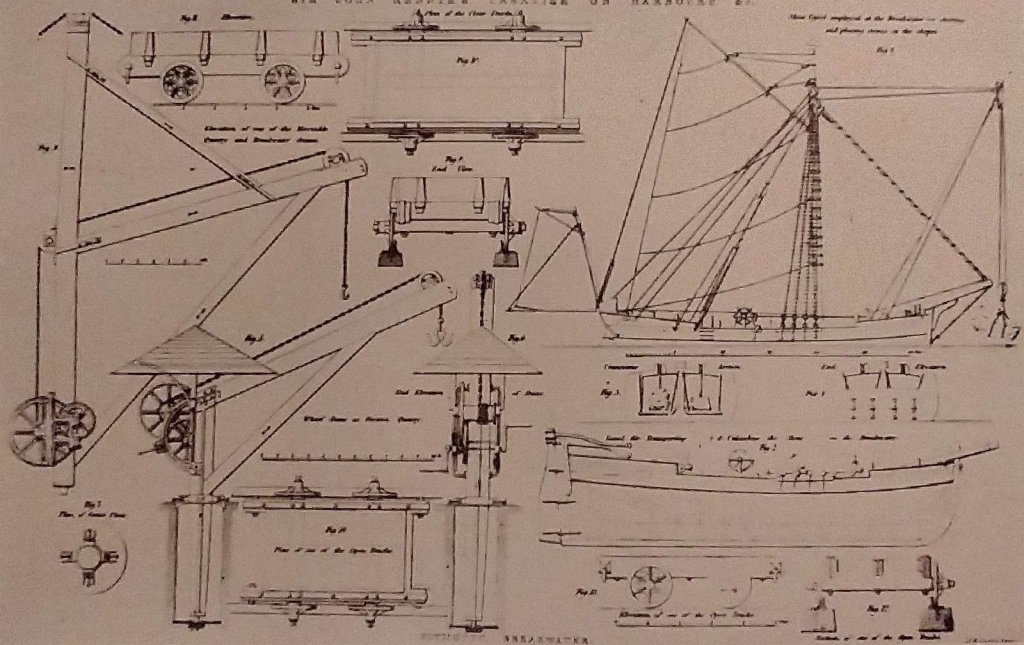

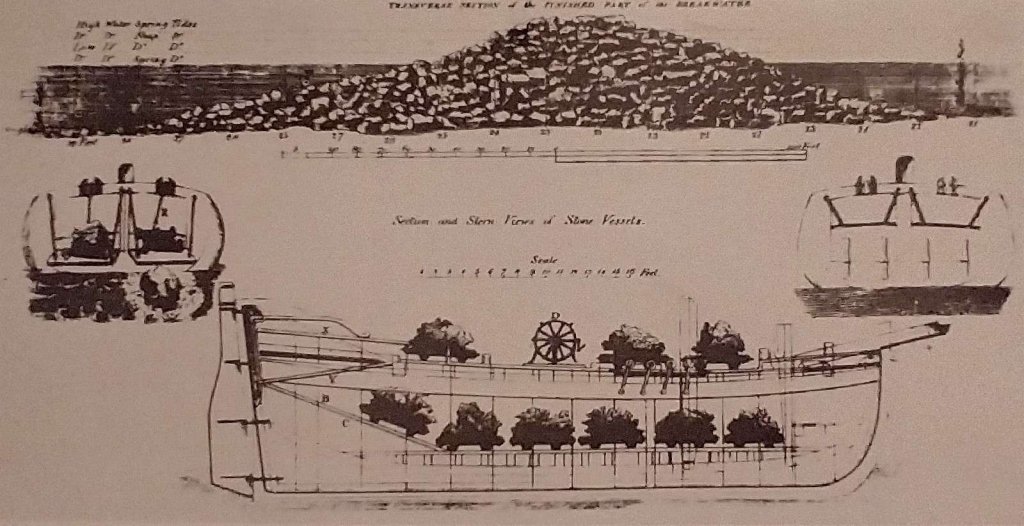

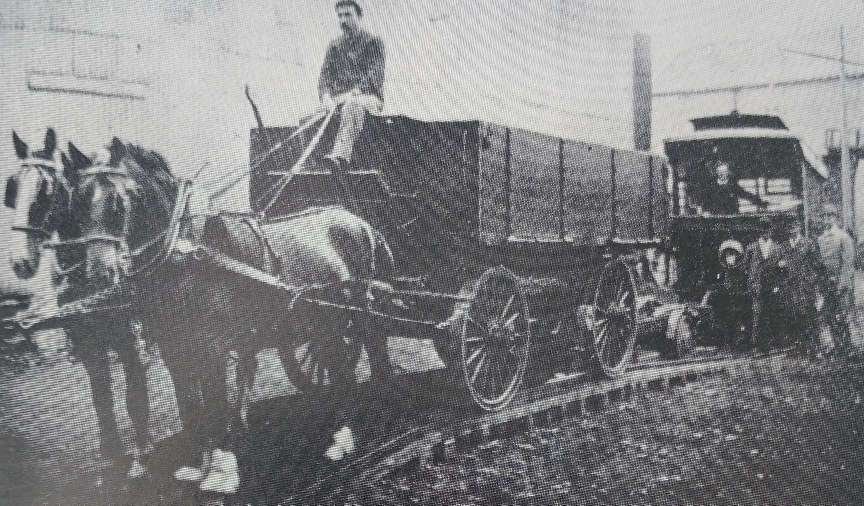

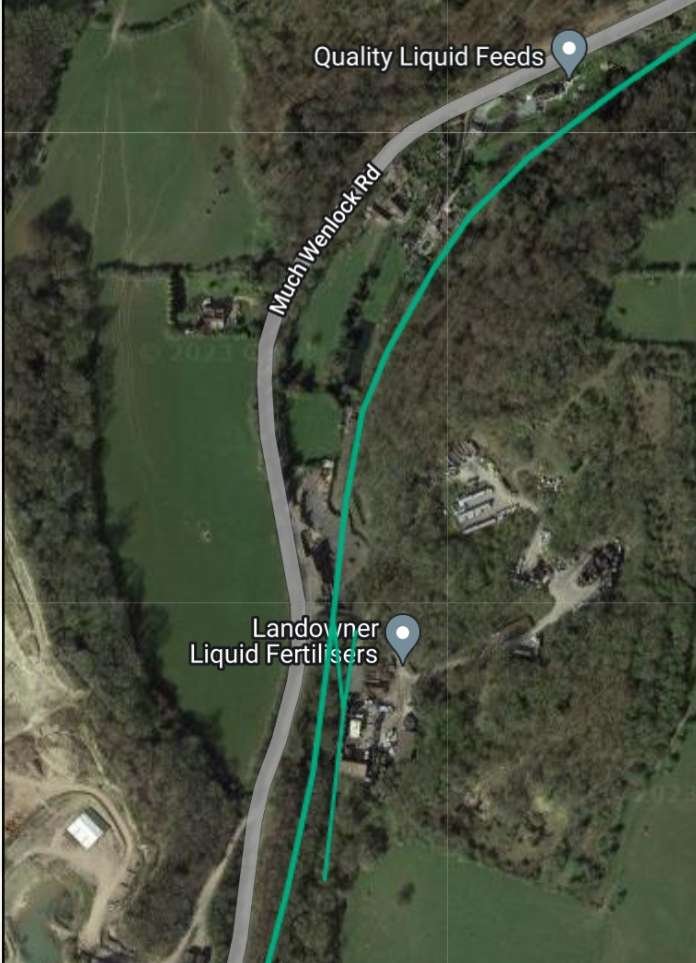

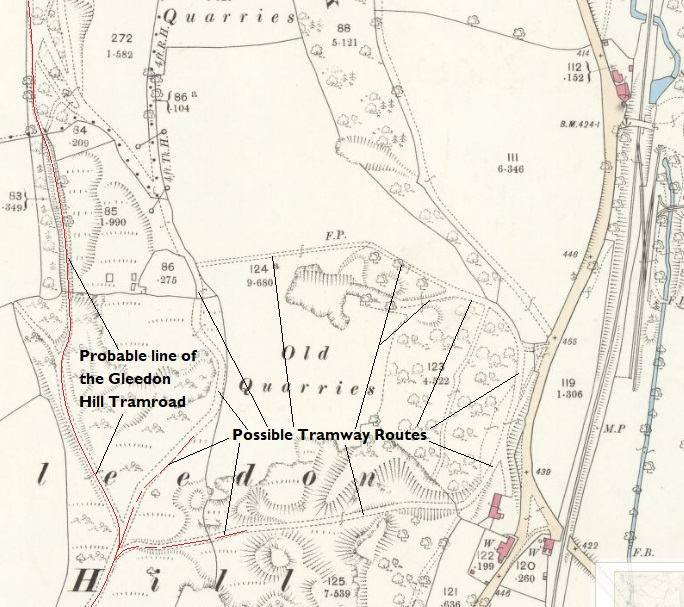

It is worth pausing our journey along the Much Wenlock & Severn Junction Railway to wonder what might have been the way in which stone and lime from Bradley Rock Quarry was exported to the probable primary users along the River Severn and to its immediate North. There appears to be no evidence of a tramway along the line of the Much Wenlock & Severn Junction Railway. This suggests that transport from the quarry followed one of two possible routes. The first option was to use the old road from Much Wenlock to Buildwas, and that would have been the original route used. An alternative option was to gain access in some way to the Gleedon Hill Tramroad. John Wooldridge tells us about the tramways/tramroads which served this area. [34]

“In the early 18th century Abraham Darby brought Wenlock stone for iron smelting in Coalbrookdale. As the local iron industry expanded, quarries between Much Wenlock and the River Severn were acquired by ironmasters operating in the southern part of the East Shropshire coalfield. The Wenlock-Buildwas road (now A4169) led to a wharf on the River Severn downstream (East) of Buildwas bridge from where stone was carried downriver to the ironworks. In 1780 William Ferriday of Lightmoor leased stone quarries near Gleedon hill and the Coalbrookdale Company leased quarries nearby. In 1800 William Reynolds leased quarries at Tickwood and Wyke. In the early 19th century the Madeley Wood Company succeeded to the Wenlock quarries of Richard and William Reynolds (probably the quarries at Tickwood and Wyke) and also to the Coalbrookdale Company quarries (probably near Gleedon Hill). The late 19th-century decline of Shropshire’s iron industry curtailed demand for Wenlock stone and Gleedon Hill quarries closed between 1882 and 1901.

The first stone carrying railway may have been built some time after 1800 – the date when William Reynolds took a lease on quarries at Tickwood and Wyke – to transport stone north eastwards, probably to a Severnside wharf on the Buildwas-Benthall boundary (perhaps the area now occupied by Buildwas power station). This railway had gone by 1833 and I have found no other reference to it, nor indeed any trace of it on the ground. Between 1824 and 1833 the Madeley Wood Company built a railway north from Gleedon Hill to a Severnside wharf [a short distance] upstream (west) of Buildwas bridge. In 1862, mainly to improve the transport of limestone to the Severn, and of coal from there to the kilns at Much Wenlock, a steam railway was opened from Buildwas to Much Wenlock [35].” [34]

The railway built by the Madeley Wood Company between 1824 and 1833 was probably the route which was known as the Gleedon Hill Tramroad. This did not follow the valley in the way that the later railway did but ran South from wharves on the River Severn to the West of Buildwas. Bertram Baxter noted that this was about 1.75 miles in length. [34]

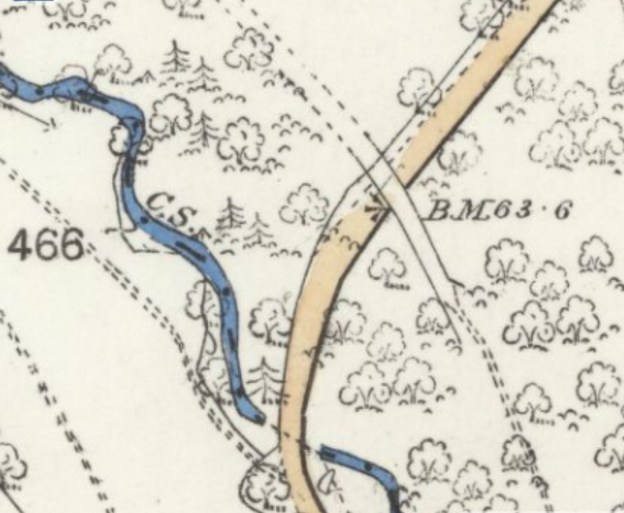

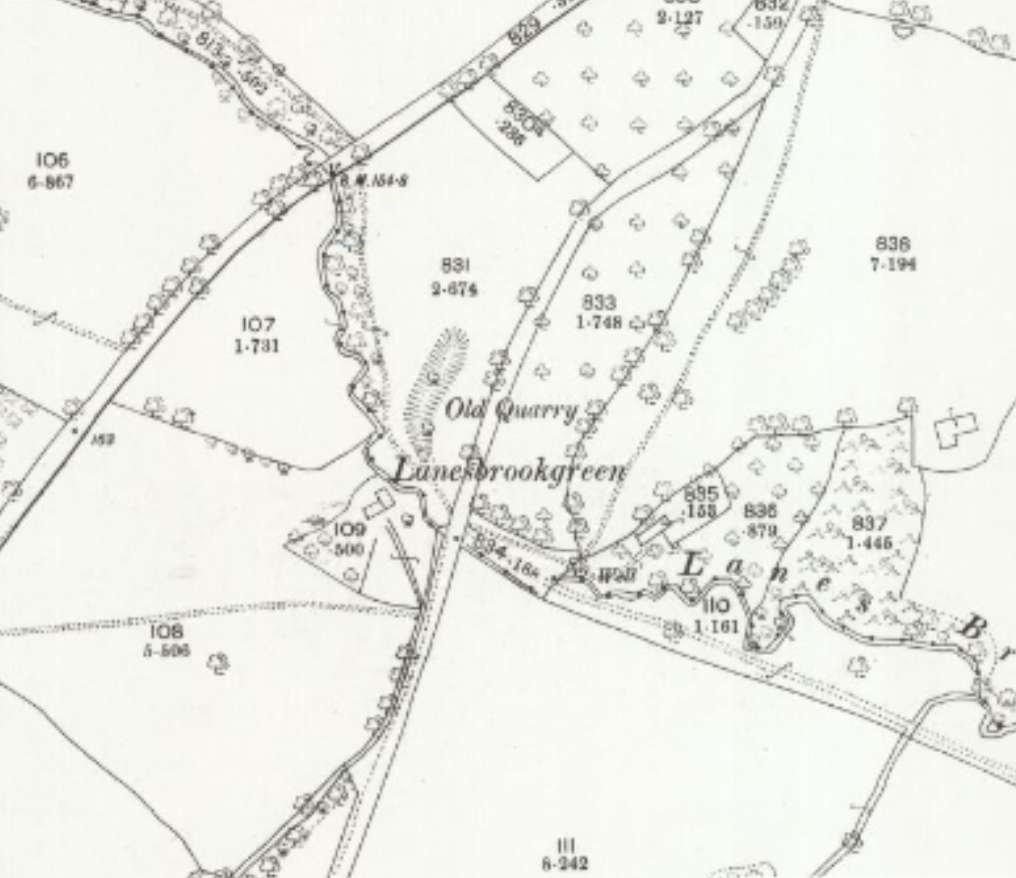

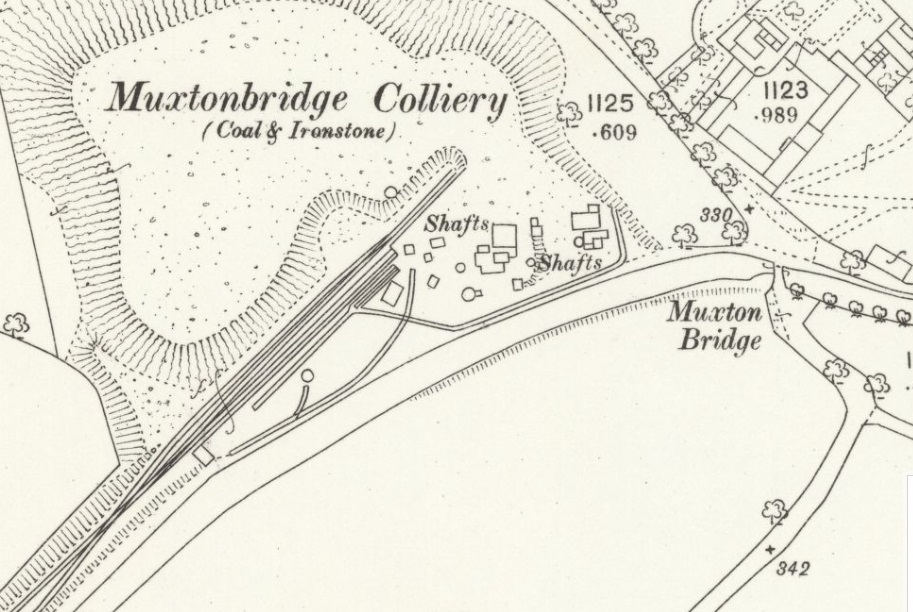

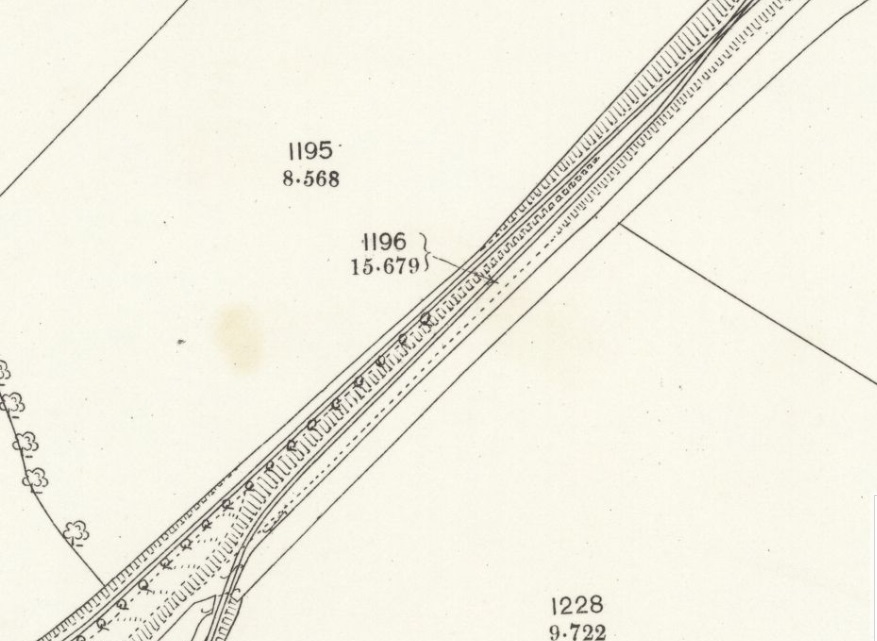

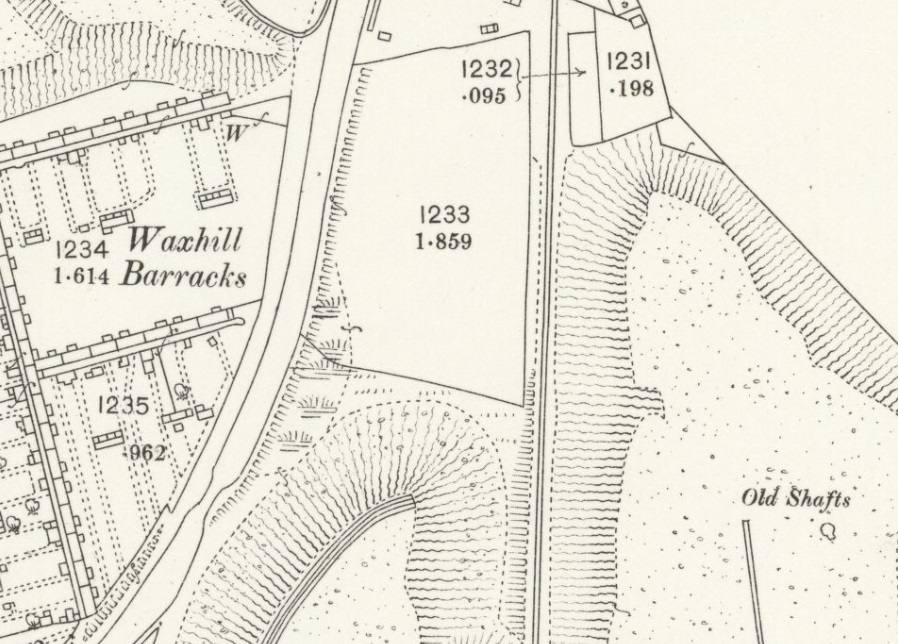

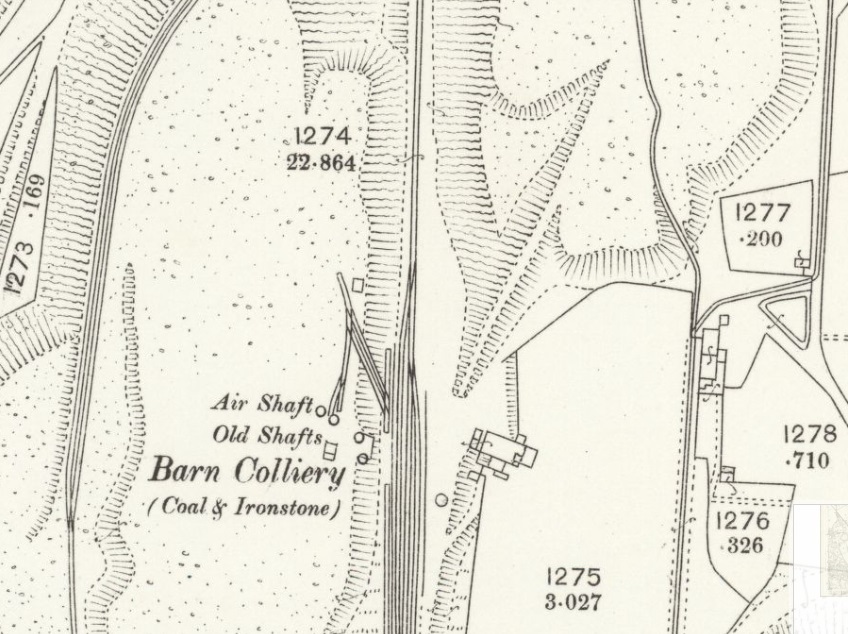

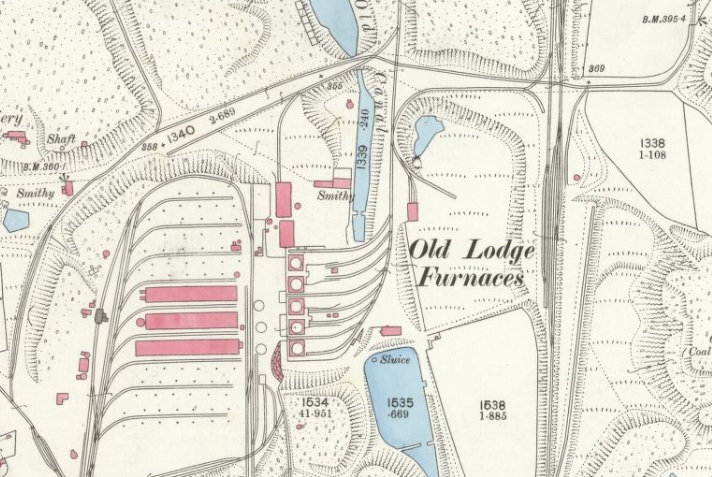

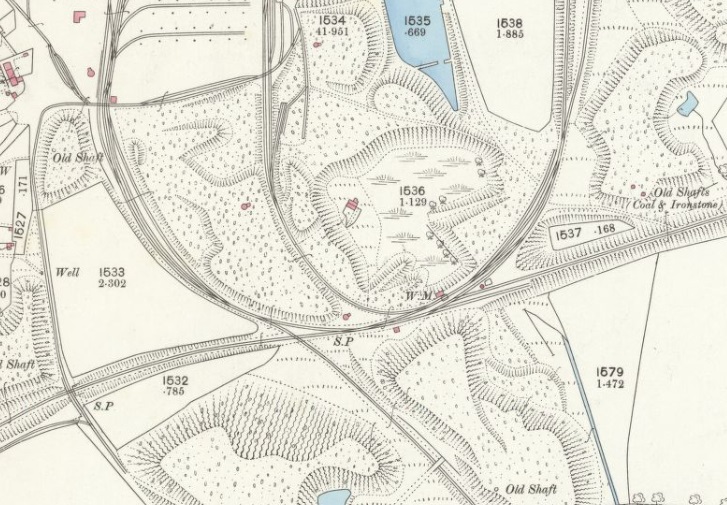

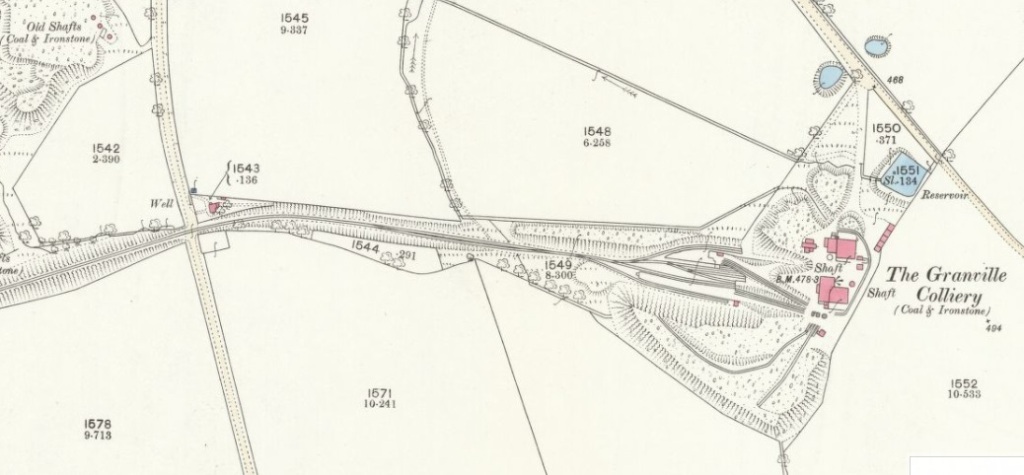

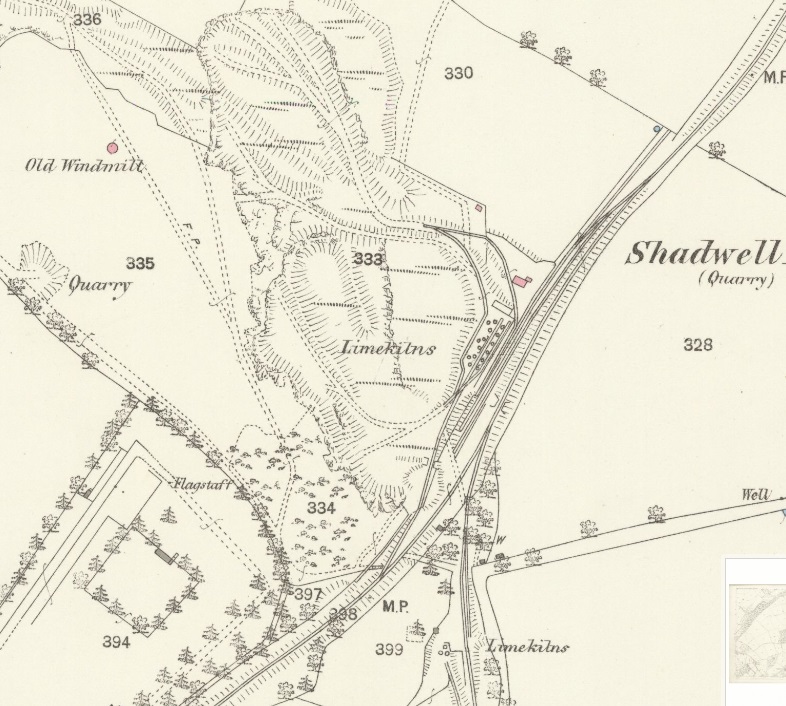

The route of the tramway can be followed on the 25″ Ordnance Survey of 1881/1882. Doing so, is beyond the scope of this article but one extract from the 1881/1882 Ordnance Survey will illustrate its relative proximity to the Bradley Rock Quarry.

Adrian Knowles, in his excellent book about the line, “The Wellington, Much Wenlock and Craven Arms Railway, that quarrying ceased at the Bradley Rock Quarry in 1927, “and this ended a quaint tradition. Each morning, just before 10.00am, the quarry timekeeper had stood at the connection to Bradley Sidings from where the crossing keeper’s cottage at Farley could just be seen down the line. The crossing keeper would stand at the door with his arm raised and at the instant he dropped his arm the quarry man would know that the Greenwich time signal had been relayed by telephone. Thus, for many years, railway time was quarry time.” [40: p105]

Apparently, “The redundant quarry buildings were later purchased by the Midland Counties Dairy for conversion to a creamery, mainly engaged in cheese production, which opened in April 1934 under the name ‘Dingle Dairy’. Bradley Sidings were left intact but were seldom used as the Midland Counties Dairy operated its own lorries to collect milk from surrounding farms and despatch the finished cheeses. Even the small tramway, which ran into the old quarry from Bradley Sidings, was left in place but was not used.” [40: p105]

The dairy was active until the mid-to late 1930s, but after its closure the newly formed Railway Executive Committee brought about an agreement for the Sidings to be taken over by the Air Ministry “which cleared most of the old buildings in 1938 and installed 16 large underground oil storage tanks. The original quarry tramway, which had been left in place while the dairy had occupied the site, was removed at this time, but the standard gauge siding and connection to the branch were retained. The establishment of the Air Ministry fuel depot was to have dramatic and exciting implications for the Much Wenlock branch and a hint of what was to come was given when strengthening work was undertaken on an occupation bridge near Farley.” [40: p115-116]

When, on 1st September 1939, the Railway Executive Committee took control of the railways, weight restriction on the Much Wenlock line were substantially lifted. “All ‘red’ engines (except ’47xx 2-8-0s and the ’60xx King’ Class) were now permitted to run from Madeley Junction and Ketley Junction to Builders and as far South as Much Wenlock, subject to a 20mph overall maximum speed limit.” [40: p116]

Local airfields were supplied by the oil stored at Bradley and regularly ’63xx’ Moguls and ’28xx’ heavy freight 2-8-0s were seen on the branch. There may even have been the occasional ‘USA’ 2-8-0 as well.

Since completing this article, I have been contacted by Eddie Challoner. His grandfather had time as the crossing-keeper at this location in the mid-1950s. This article brought back a series of memories for him and he very kindly provided two photographs from that time ….

The next few images were taken along the length of the line to the South of the cottage which is now a public footpath and part of the Jack Mytton Way.

The line runs South passed a lagoon to its right which was not present when the line was built.

Shadwell Rock Quarry was located at the South side of the modern lagoon. It grew significantly in size during the 20th century and its workings have now formed the lagoon which remains into the 21st century.

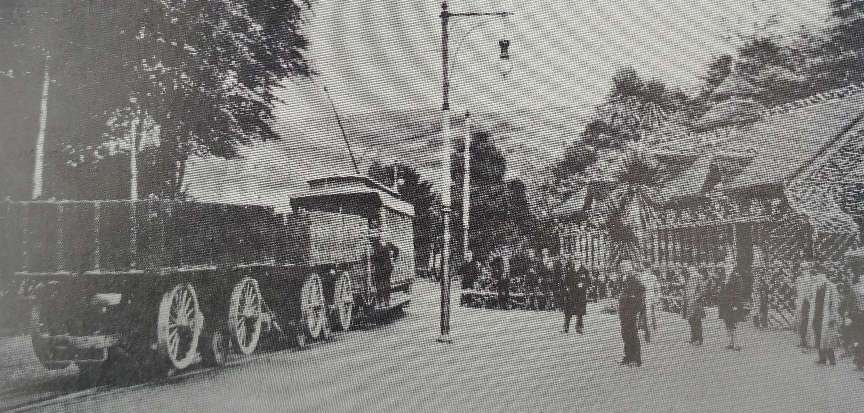

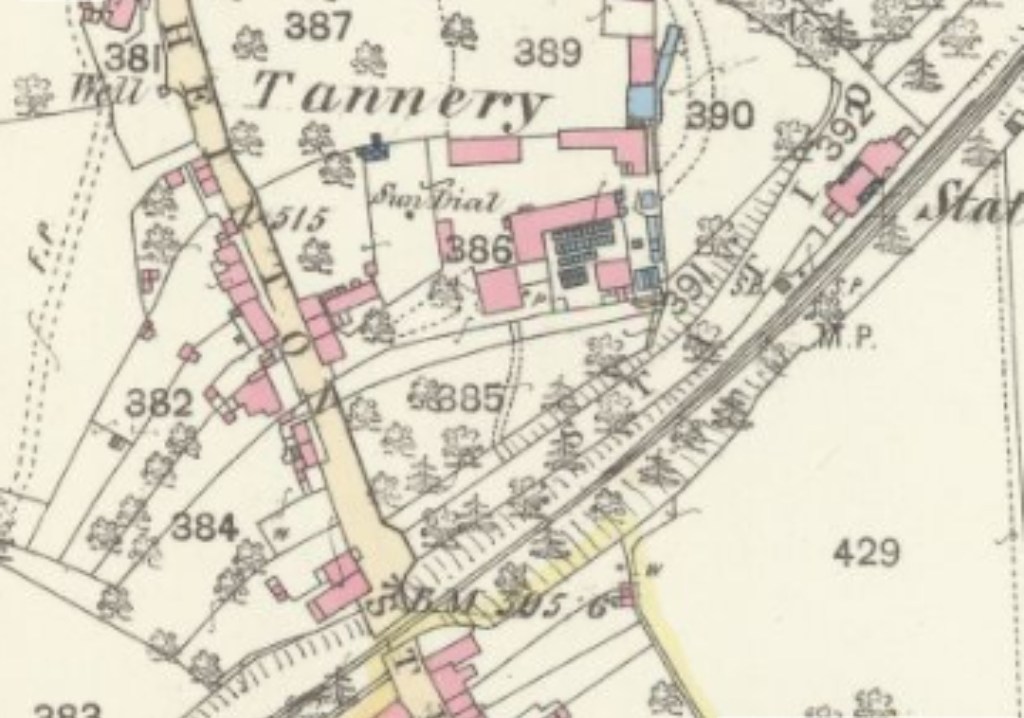

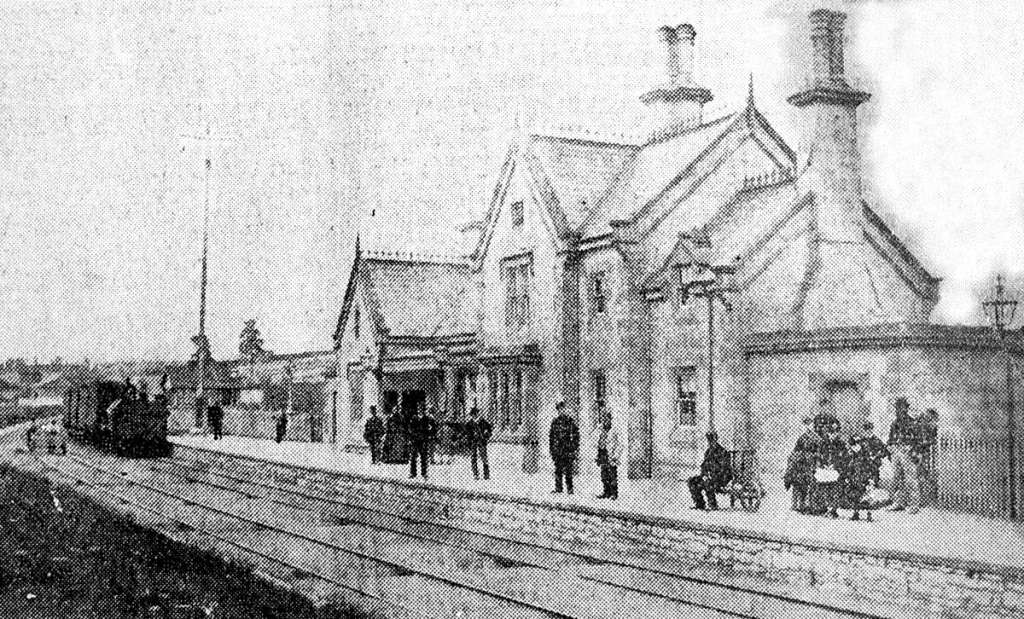

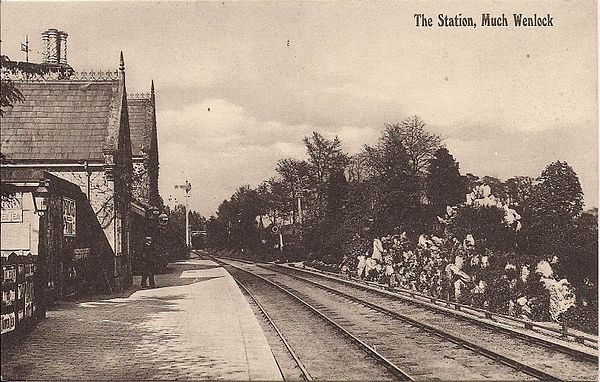

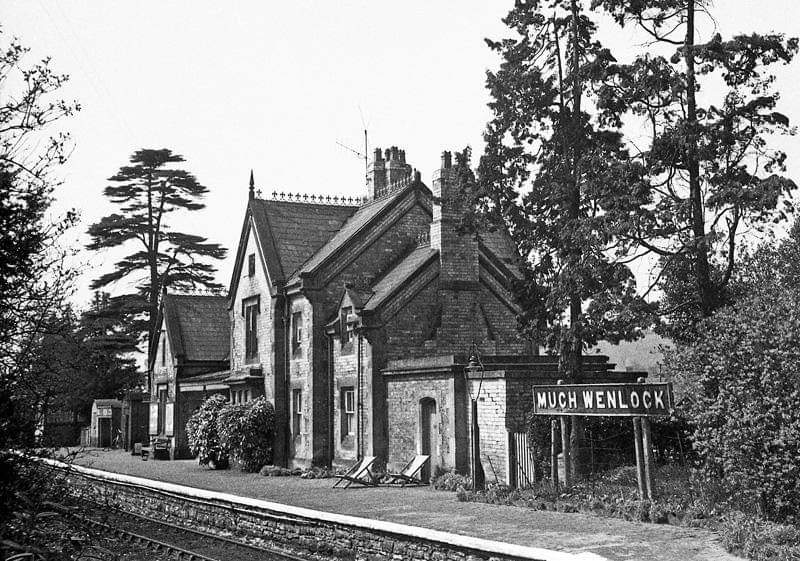

The various maps above and below show ‘Games Grounds’ or ‘Recreation Ground’. This were called Linden Field. This was the site of the very earliest revival of the World Olympic Movement. the field was immediately to the North of Much Wenlock Railway Station. The first Olympic games were held in 1850 on this field and continue to be held in the 21st century. The 130th games were held in July 2016.

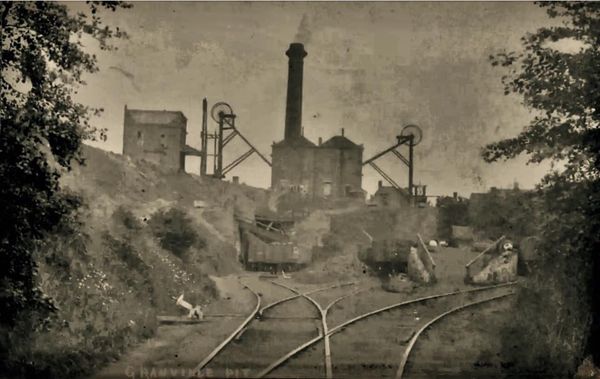

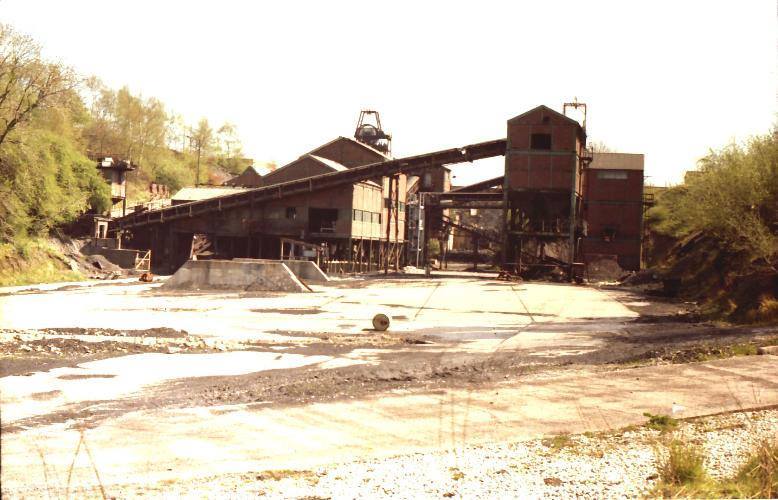

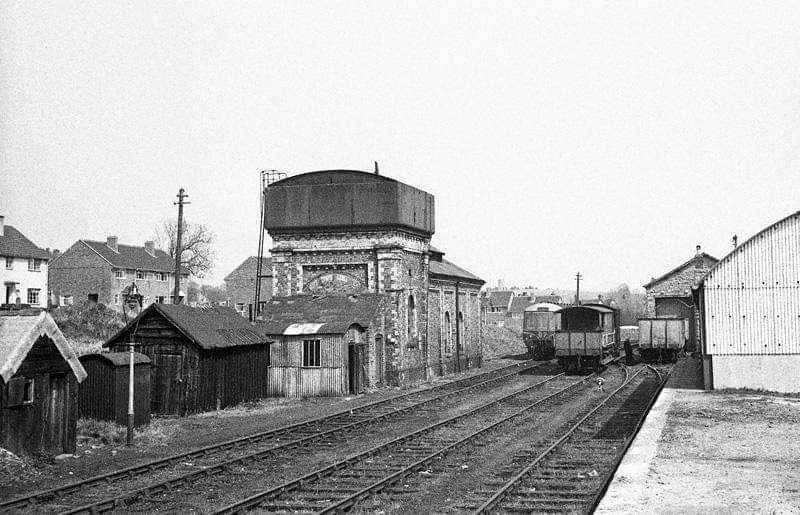

Travelling Southwest from the passenger station, trains crossed Sheinton Street at high level and the either entered the goods yard or continued on towards Craven Arms rising up above the town and along the flanks of Wenlock Edge.

The station goods yard and engine shed were immediately to the Southwest of the railway bridge. We finish this part of our journey along the Wellington to Craven Arms railway in the goods yard at Much Wenlock.

References

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Much_Wenlock_and_Severn_Junction_Railway, accessed on 2nd March 2023.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wellington_to_Craven_Arms_Railway, accessed on 2nd March 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/101594479, accessed on 4th March 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/121150853, accessed on 18th July 2022.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17&lat=52.63304&lon=-2.51557&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 18th July 2022.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1844651349192200&set=gm.1655719937779336, accessed on 18th JUly 2022.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=409683050025369&set=gm.4793839370634028, accessed on 18th July 2022.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=255663442093998&set=gm.3788208897863752, accessed on 18th July 2022.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=10205802893027076&set=gm.2905708482780469, accessed on 18th July 2022.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=251261995867476&set=gm.3765229570161685, accessed on 18th July 2022.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=251261115867564&set=gm.3765224093495566, accessed on 18th July 2022.

- http://www.nrm.org.uk/ourcollection/photo?group=Sellick%20collection&objid=1997-7219_RJS_SV_46, sourced from https://www.svrwiki.com/File:Buildwas-SVR-Wenlock-1961-06-09.jpg, accessed on 4th March 2023.

- http://www.nrm.org.uk/ourcollection/photo?group=Sellick%20collection&objid=1997-7219_RJS_SV_43, sourced from https://www.svrwiki.com/File:Buildwas-4-trains-1961-06-09.jpg, accessed on 4th March 2023.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EPW034013, accessed on 18th July 2022.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/EAW012667, accessed on 4th March 2023.

- https://www.railmaponline.com/UKIEMap.php, accessed on 23rd May 2023.

- https://www.streetmap.co.uk, accessed on 25th May 2023.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-shropshire-34876922, accessed on 25th May 2023.

- https://www.investinshropshire.co.uk/locations/former-ironbridge-power-station, accessed on 25th May 2023.

- https://www.shropshirestar.com/news/local-hubs/telford/ironbridge/2020/11/04/hi-tech-railcars-idea-for-new-ironbridge-park-and-ride-service, accessed on 25th May 2023.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EAW012578, accessed on 26th May 2023.

- These photographs were taken by myself and show extracts from the construction plans held in the Shropshire Archive. There is a standard charge of £10 per visit for taking photographs of their records.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=52.63386&lon=-2.52054&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 26th May 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=52.63327&lon=-2.52504&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 26th May 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/352799184389/permalink/10158618389784390, accessed on 8th April 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.3&lat=52.61992&lon=-2.53764&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.3&lat=52.61696&lon=-2.53998&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Farley_Halt_railway_station, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.3&lat=52.61423&lon=-2.54290&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.3&lat=52.61163&lon=-2.54320&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://www.kgg.org.uk/farleyh.html, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1841547, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1841545, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- http://www.telford.org.uk/tramways/gleedon_hill.html, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- A History of the County of Shropshire, Volume 10: Munslow Hundred (part), The Liberty and Borough of Wenlock, 1998, p339-477: http://www.british-history.ac.uk., accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/121151300, accessed on 14th August 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=52.60946&lon=-2.54796&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 15th August 2023.

- https:/https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3042155/maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=52.60637&lon=-2.54931&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 15th August 2023.

- https://www.shropshirestar.com/news/nostalgia/shrewsbury-nostalgia/2021/07/16/memories-of-a-1960s-train-journey-never-to-be-repeated, accessed on 15th August 2023.

- Adrian Knowles; The Wellington, Much Wenlock and Craven Arms Railway; Lightmoor Press, Lydney, Gloucestershire, 2022.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3042155, accessed on 17th August 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/121151333, accessed on 30th August 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=52.60319&lon=-2.55248&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 30th August 2023.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/services-skills/education/educational-images/shadwell-quarry-near-much-wenlock-4267, accessed on 30th August 2023.

- https://www.muchwenlock-tc.gov.uk/property-and-assets/the-gaskell-recreation-ground, accessed on 30th August 2023.

- https://wp.me/p2zM3f-67v, accessed on 13th October 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/121151333, accessed on 13th October 2023.

- https://scontent.fbhx4-1.fna.fbcdn.net/v/t1.6435-9/171398056_5264731283601330_7585531238603702981_n.jpg?_nc_cat=104&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=bd3046&_nc_ohc=tjiydGZcDfcAX-DYKVT&_nc_ht=scontent.fbhx4-1.fna&oh=00_AfBZDkK_GfCn6WMHmKJ0ASZWiMiwyiHjEE0dM8Vxgk47nA&oe=65511915, accessed on 13th October 2023.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=871714362892537&set=pcb.1583276891885898, accessed on 13th October 2023.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Much_Wenlock_railway_station.jpg, accessed on 14th October 2023.

- https://www.shropshirestar.com/news/features/2019/12/02/final-days-of-wenlock-station, accessed on 14th October 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/1470137459866509/permalink/3753567794856786, accessed on 15th October 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/1470137459866509/permalink/1482470245299897, accessed on 15th October 2023.

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/1532191000361509/permalink/2075425426038061/?app=fbl, accessed on 16th October 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/1532191000361509/permalink/2670607383186526, accessed on 17th October 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/1532191000361509/permalink/2624088597838405, accessed on 17th October 2023.

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/1532191000361509/permalink/3363056680608256, accessed on 17th October 2023.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4879308, accessed on 19th October 2023.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4354465, accessed on 19th October 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=19.0&lat=52.59812&lon=-2.55899&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 19th October 2023.

- Ken Jones; The Wenlock Branch; The Oakwood Press, Usk, Monmouthshire; 1998.