The June 1922 issue of The Railway Magazine celebrated its Silver Jubilee with a number of articles making comparisons between the railway scene in 1897 and that of 1922 or thereabouts.

In celebrating its Silver Jubilee, The Railway Magazine was also offering, in its June 1922 edition, its 300th number.

Reading through the various celebratory articles, a common theme encountered was statistical comparisons between 1897 and 1922.

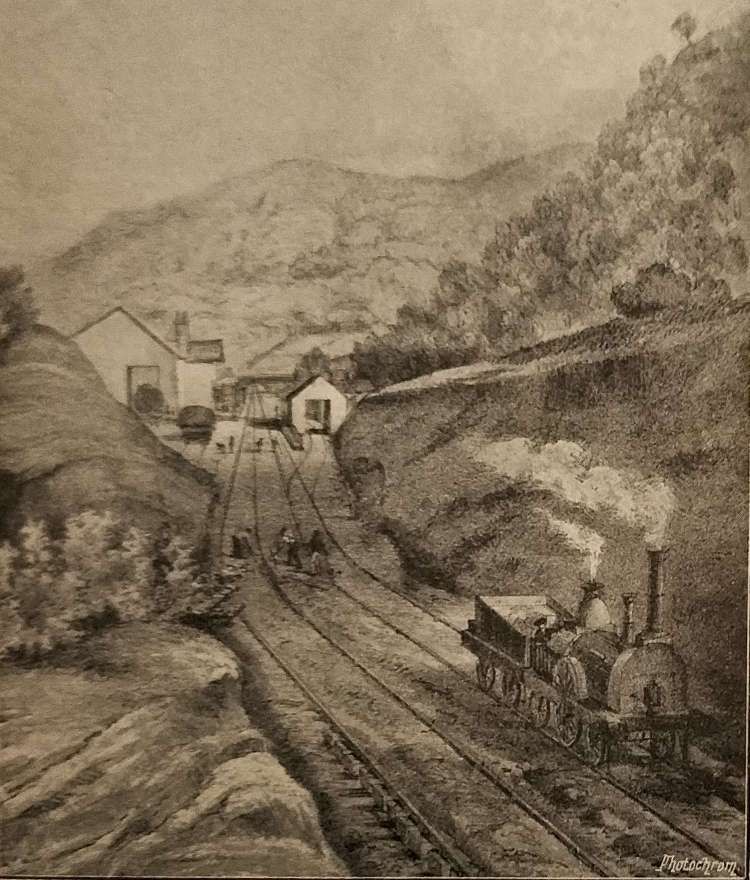

This started in the first few words of J.F. Gairns article, Twenty-five Years of Railway Progress and Development: [1]

“Railway mileage in 1897 was officially given as 21,433 miles for the British Isles, of which 11,732 miles were double track or more. In the course of the past 25 years the total length of railway (officially stated as 23,734 miles according to the latest returns available) has increased by 2,300 miles, and double track or more is provided on no less than 13,429 miles. Detailed figures as to the mileage laid with more than two lines in 1897 cannot be given; but there are now about 2,000 miles with from three to 12 or more lines abreast. Therefore, while the total route mileage increase is not so great indeed, it could not be, seeing that all the trunk lines and main routes except the Great Central London extension were completed long before 1897, and additions are therefore short or of medium length – there has been a very large proportionate increase in multiple track mileage. As the extent to which multiple track is provided is an important indication of traffic increase, this aspect calls for due emphasis. … The total paid-up capital of British railways, including in each case nominal additions, has increased from £1,242,241,166 to £1,327,486,097, that is, by some £85,000,000, apart from the cost of new works, etc., paid for out of revenue.” [1: p377]

Gairns went on to highlight newly constructed railways during the period which included:

- The London Extension of what became the Great Central Railway in 1899;

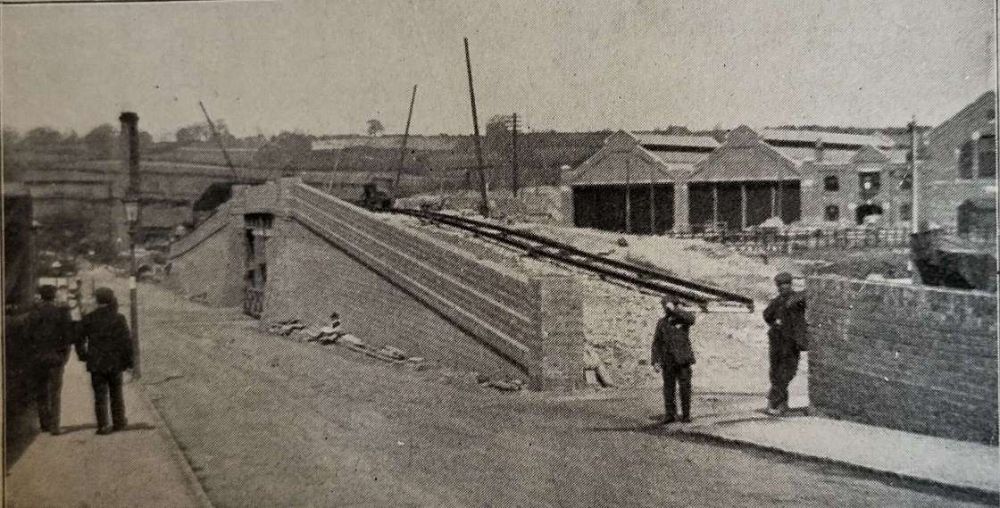

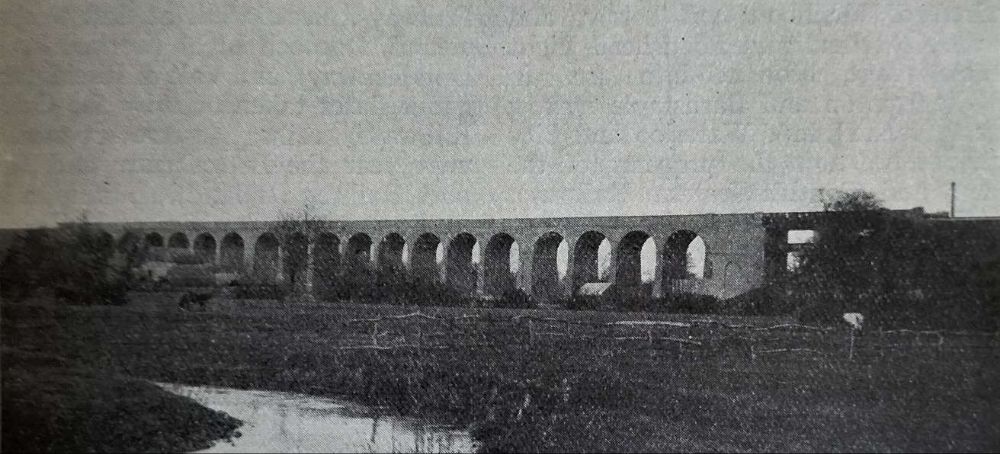

- The Cardiff Railway at the turn of the 29th century, which “involved a number of heavy engineering works. … Nine skew bridges, five crossing the Merthyr river, three across the Glamorganshire Canal, and one across the River Taff. Near Nantgawr the River Taff [was] diverted. The various cuttings and embankments [were] mostly of an extensive character. Ten retaining walls, 12 under bridges, 10 over bridges, a short tunnel and a viaduct contributed to the difficult nature of the work.” [2]

- The Port Talbot Railway and Docks Company, which “opened its main line in 1897 and reached a connection with the Great Western Railway Garw Valley line the following year. A branch line to collieries near Tonmawr also opened in 1898. The lines were extremely steeply graded and operation was difficult and expensive, but the company was successful.” [3]

- The London Underground, which had its origins in “the Metropolitan Railway, opening on 10th January 1863 as the world’s first underground passenger railway. … The first line to operate underground electric traction trains, the City & South London Railway… opened in 1890, … The Waterloo and City Railway opened in 1898, … followed by the Central London Railway in 1900. … The Great Northern and City Railway, which opened in 1904, was built to take main line trains from Finsbury Park to a Moorgate terminus.” [4] Incidentally, by the 21st century, “the system’s 272 stations collectively accommodate up to 5 million passenger journeys a day. In 2023/24 it was used for 1.181 billion passenger journeys.” [4]

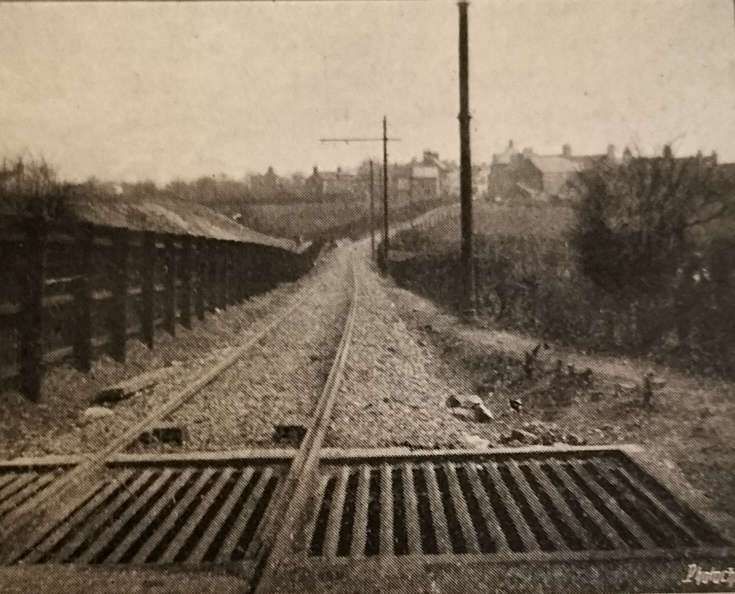

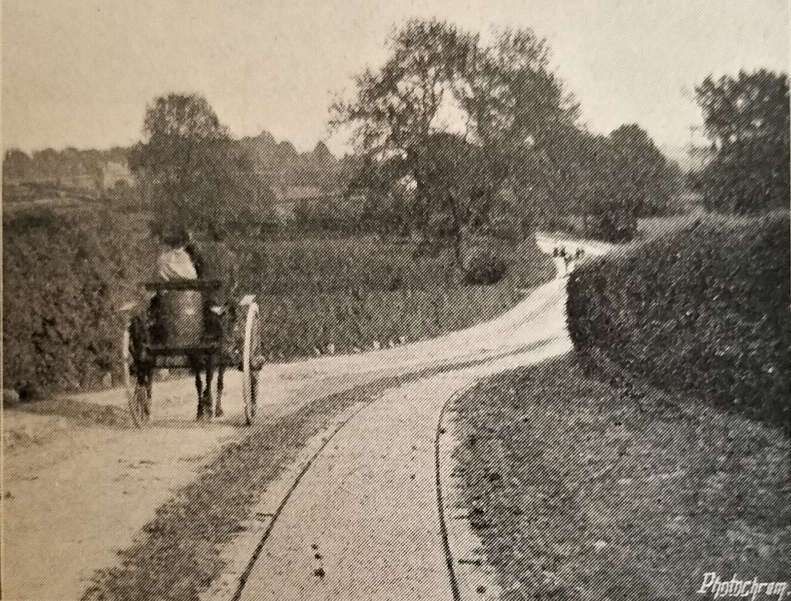

- Many Light Railways “by which various agricultural and hitherto remote districts have been given valuable transport facilities.” [1: p377]

Gairns goes on to list significant lines by year of construction:

“In 1897, the Glasgow District Subway (cable traction, the first sections of the Cardiff and Port Talbot Railways, and the Hundred of Manhood and Selsey, and Weston, Cleveland and Portishead Light Railways were brought into use.

In 1898, the Lynton and Barnstaple narrow gauge (1 ft. 11 in.), Waterloo and City (electric tube, now the property of the London and South Western Railway), and North Sunderland light railways, were added.

In 1899, … the completion and opening of the Great Central extension to London, the greatest achievement of the kind in Great Britain in modern times.

In 1900, the Rother Valley Light Railway was opened from Robertsbridge to Tenterden, and the Sheffield District Railway (worked by the Great Central Railway) and the Central London electric railway (Bank to Shepherd’s Bush) were inaugurated. …

In 1901 the Bideford, Westward Ho! and Appledore (closed during the war and not yet reopened), Sheppey Light (worked by South Eastern and Chatham Railway), and Basingstoke and Alton (a “light” line worked by the London and South Western Railway, closed during the war and not yet reopened), were completed.

In 1902, the Crowhurst and Bexhill (worked by the South Eastern and Chatham Railway), Whitechapel and Bow (joint London, Tilbury and Southend – now Midland – and Metropolitan District Railways, electric but at first worked by steam), Dornoch Light (worked by Highland Railway), and Vale of Rheidol narrow gauge (later taken over by the Cambrian Railways) railways were opened.[In 1903], the Letterkenny and Burtonport Railway (Ireland), 49 miles in length 3 ft. gauge; [the] Llanfair and Welshpool, Light (worked by Cambrian Railways), Lanarkshire and Ayrshire extension (worked by Caledonian Railway), Meon Valley and Axminster and Lyme Regis (worked by London and South Western Railway), Axholme Joint (North Eastern and Lancashire and Yorkshire – now London and North Western Railways), and Wick and Lybster Light (worked by Highland Railway) railways were opened.” [1: p377-378]

A number of the lines listed by Gairns are covered in articles on this blog. Gairns continues:

In 1904, the Tanat Valley Light Railway (worked by the Cambrian Railways), Great Northern and City Electric (now Metropolitan Railway), Leek and Manifold narrow gauge (worked by North Staffordshire Railway but having its own rolling-stock), Kelvedon, Tiptree and Tollesbury Light (worked by Great Eastern Railway), Mid-Suffolk Light and Burtonport Extension Railways were opened.

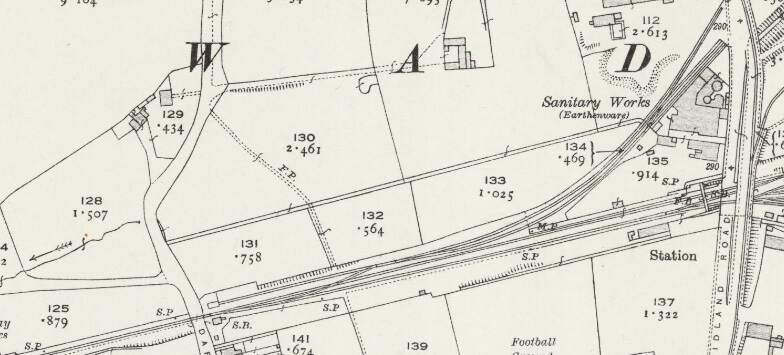

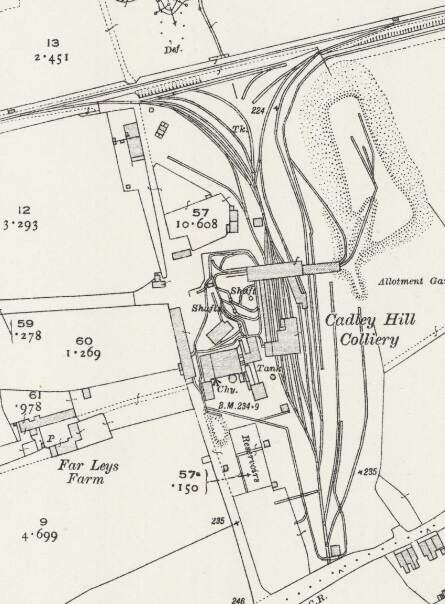

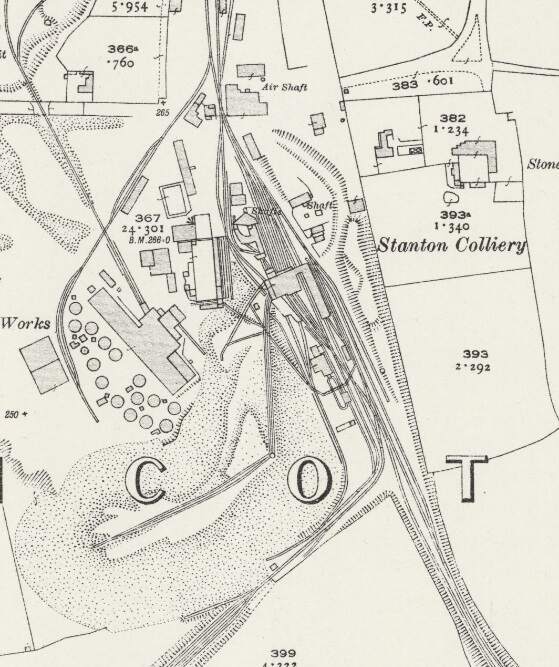

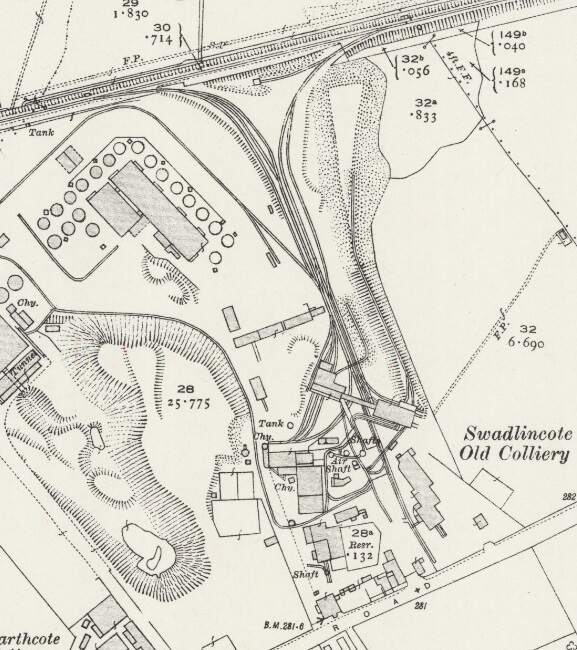

1905 saw the Cairn Valley Light (worked by Glasgow and South Western Railway), and Dearne Valley (worked by Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway, now London and North Western Railway) railways opened.

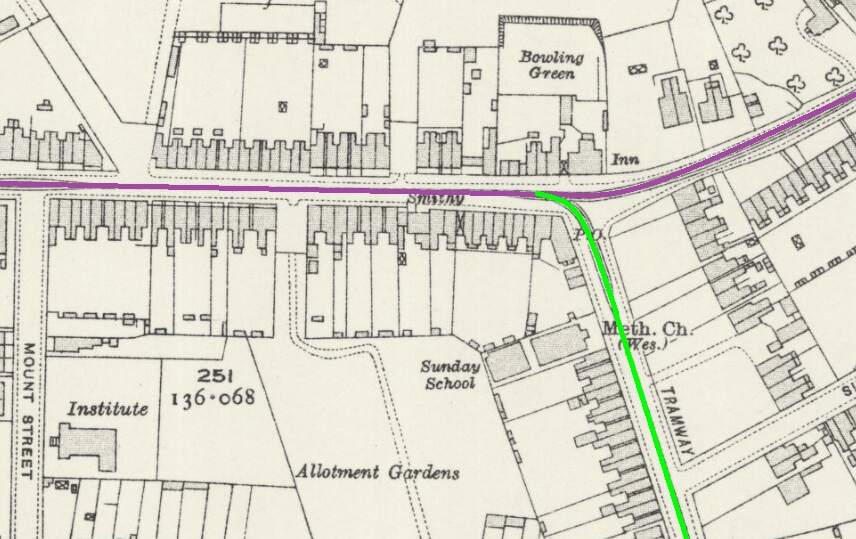

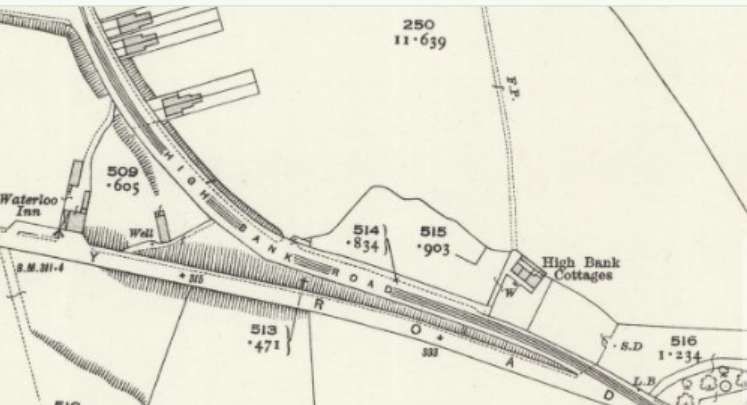

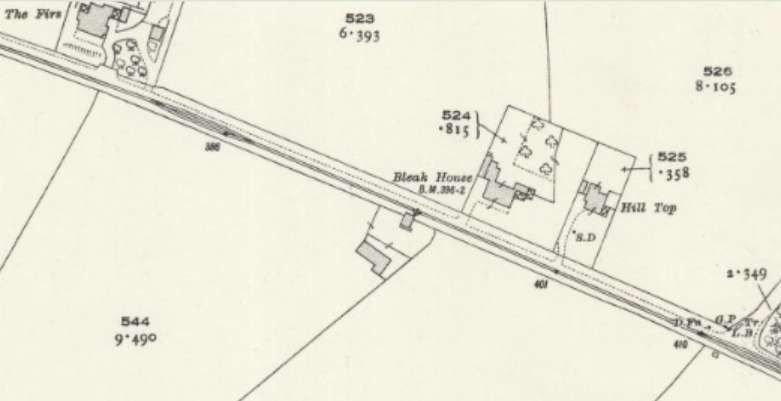

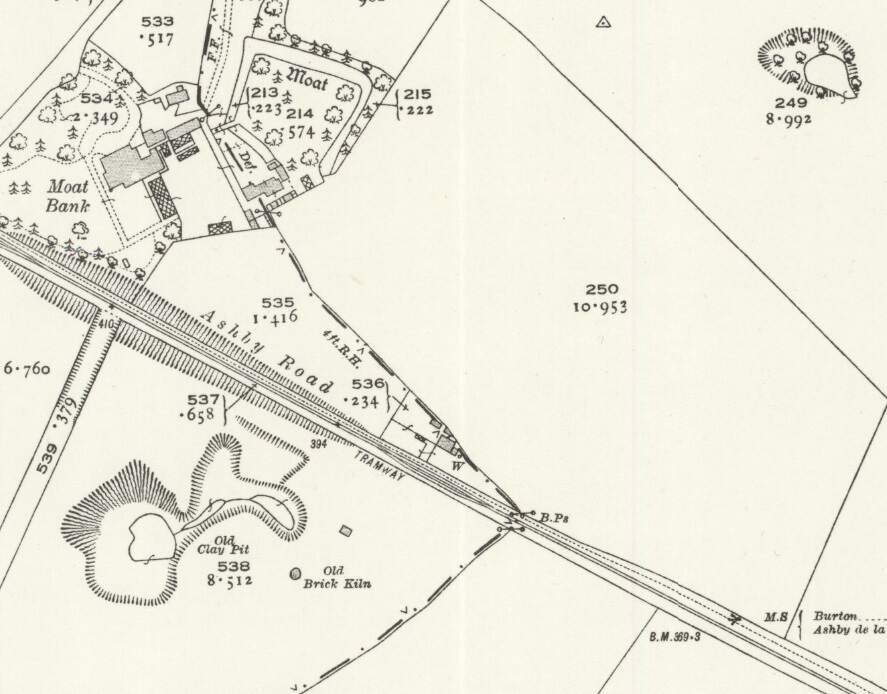

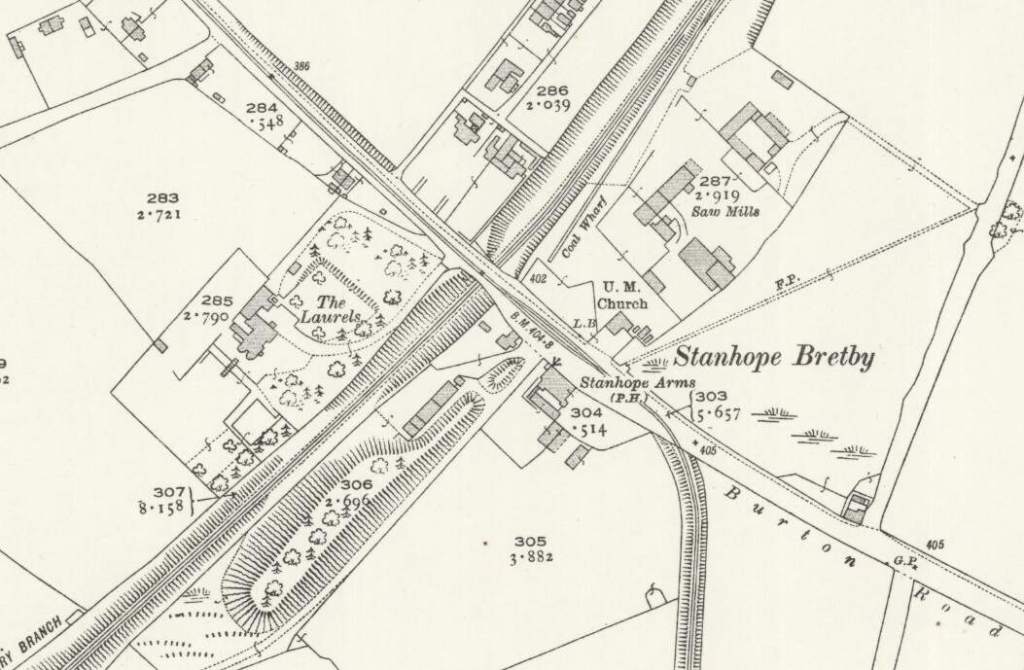

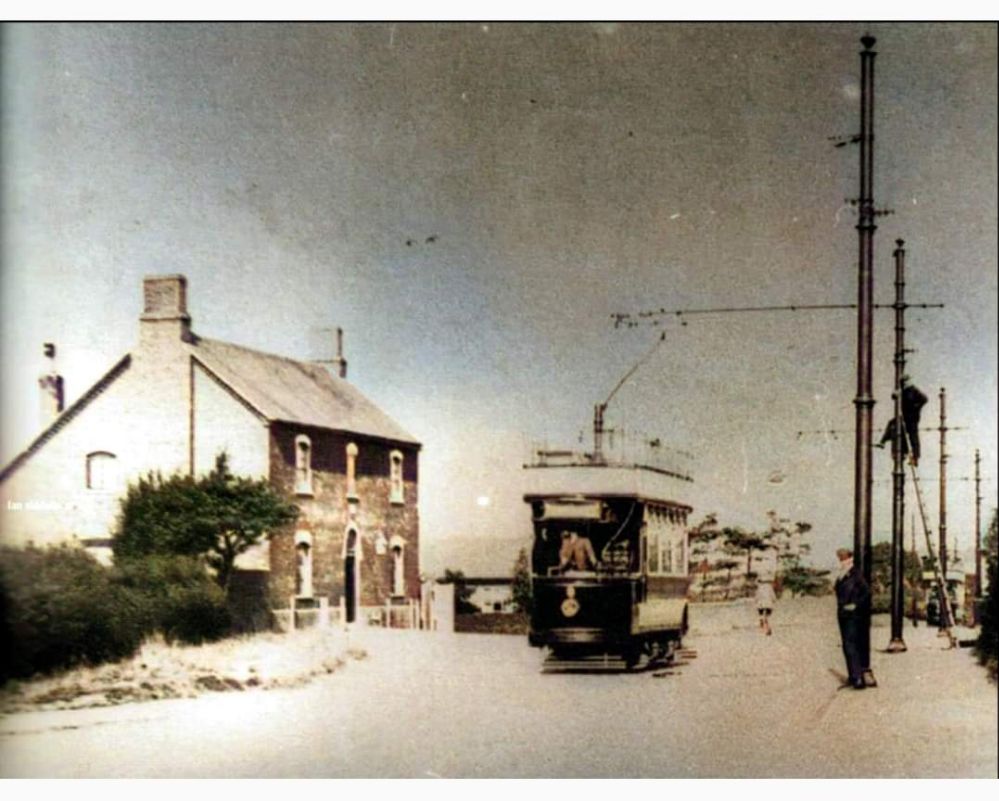

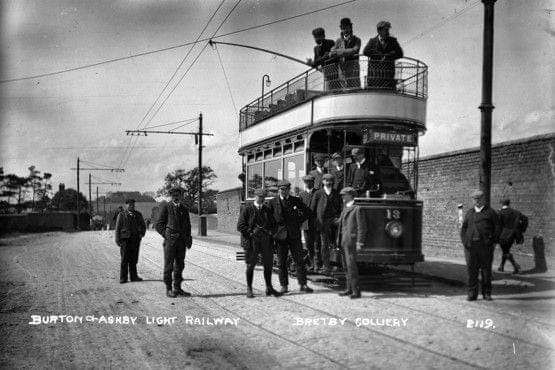

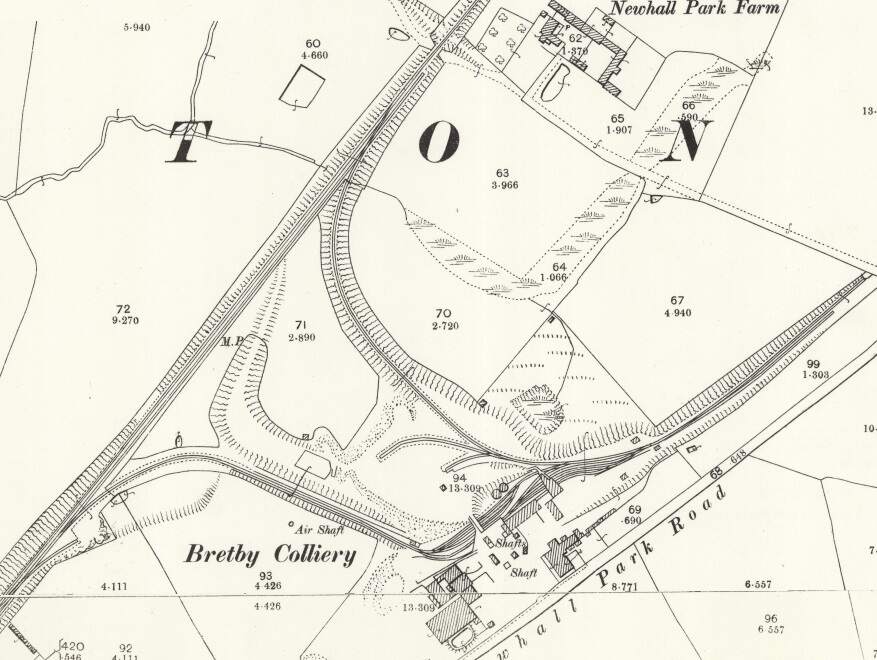

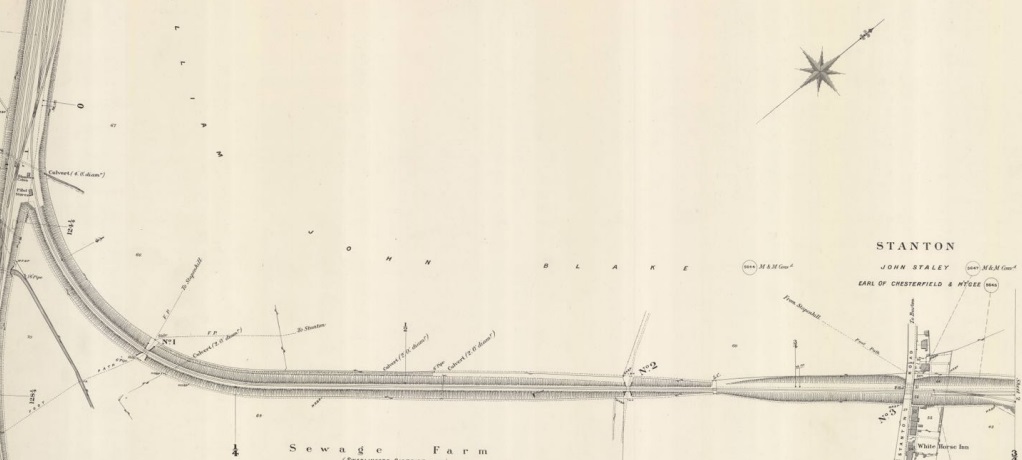

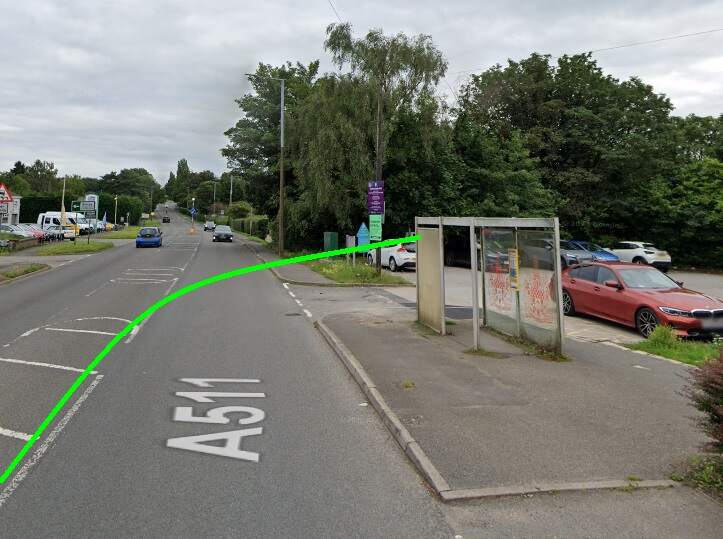

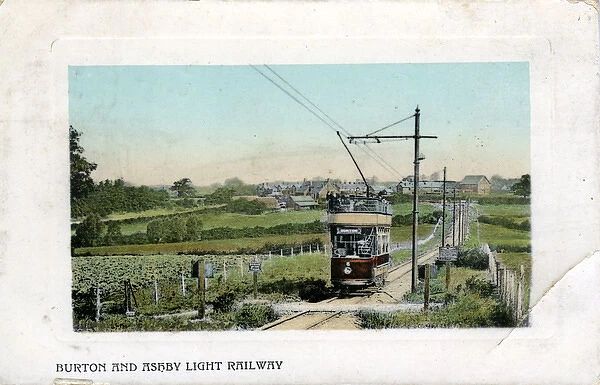

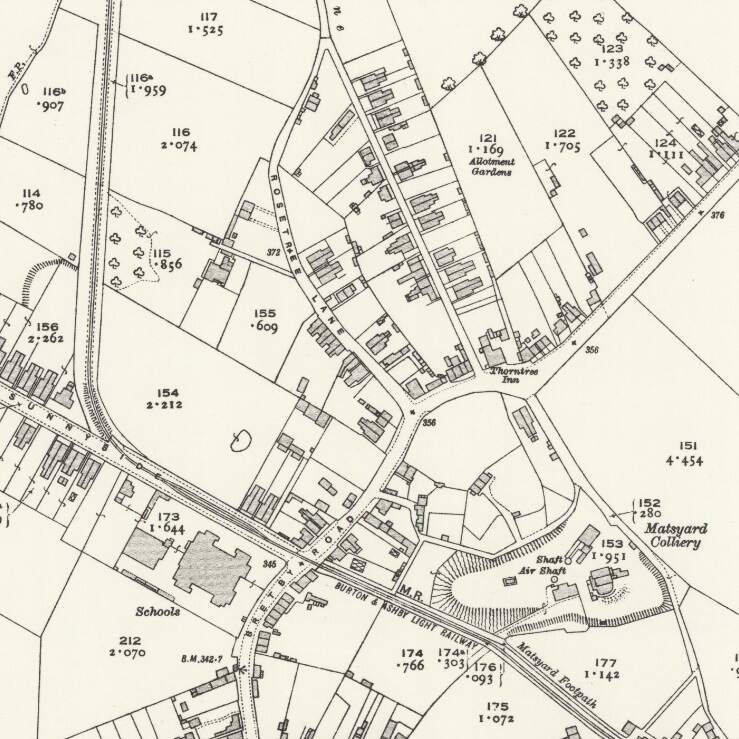

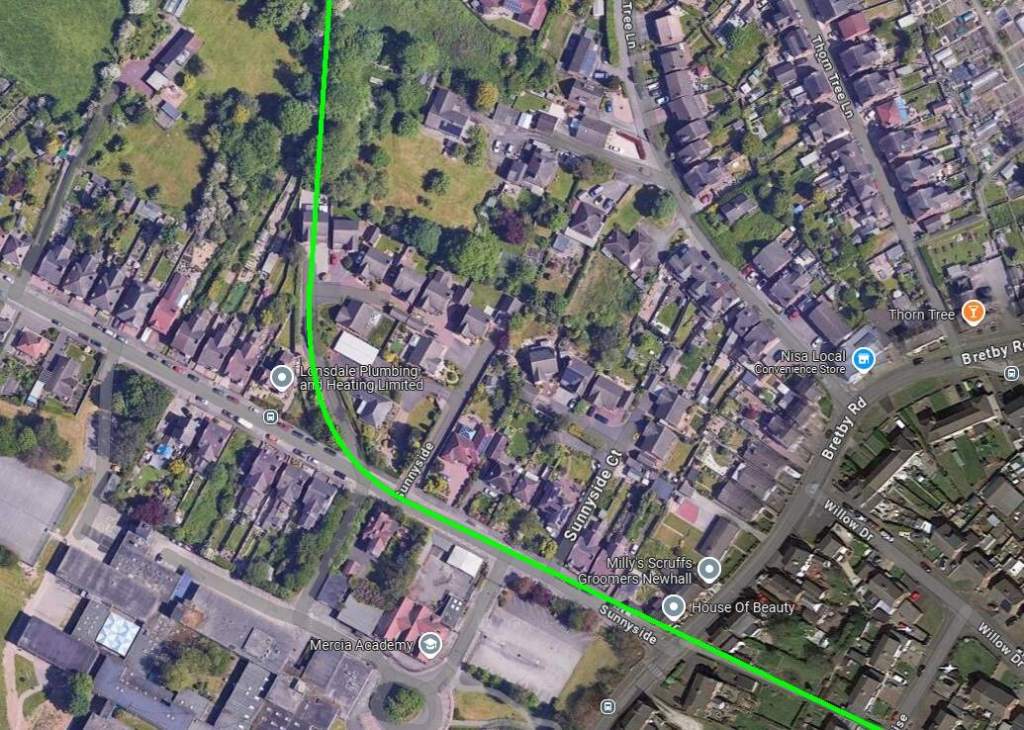

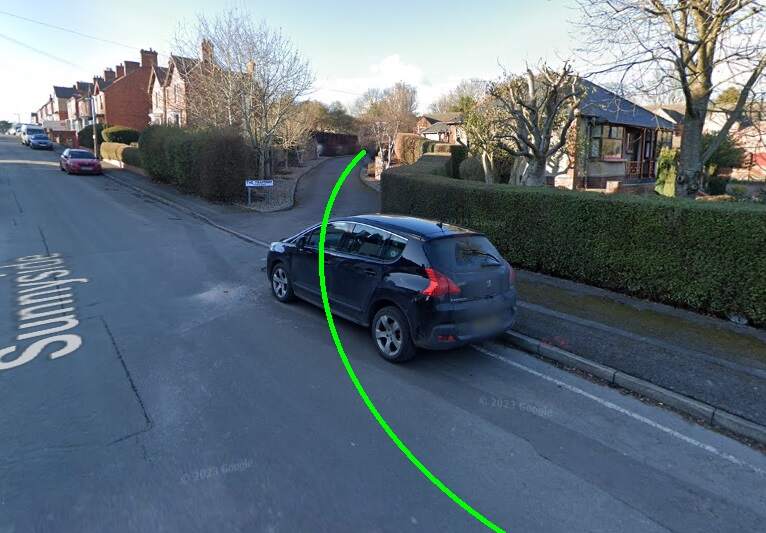

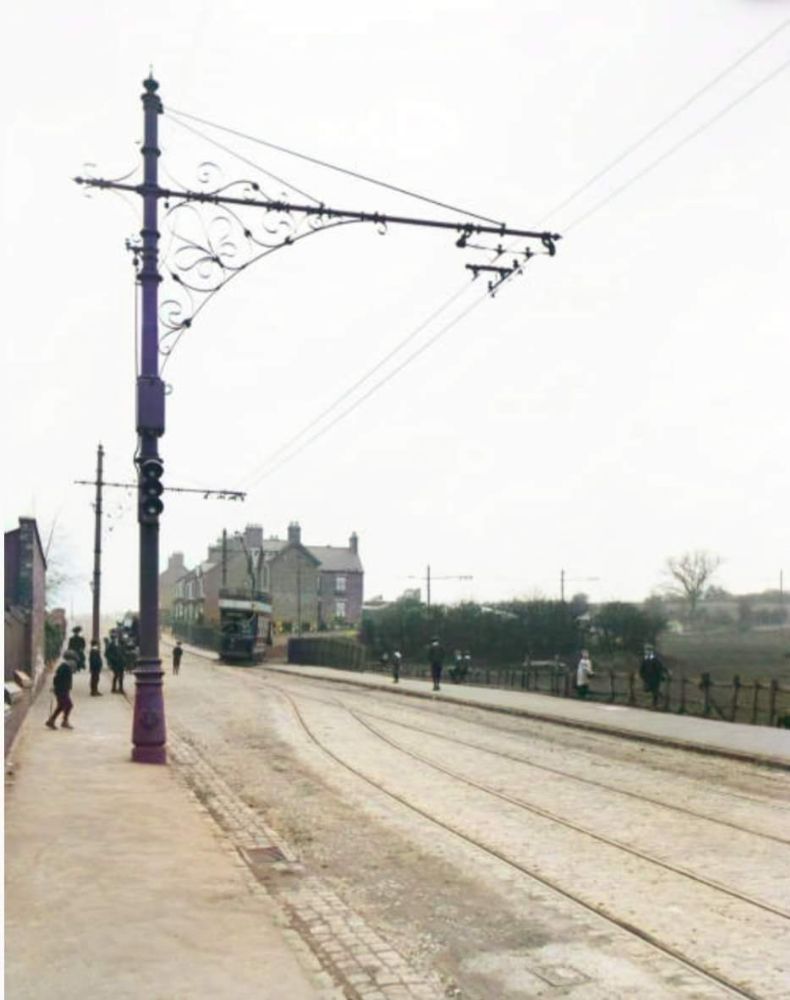

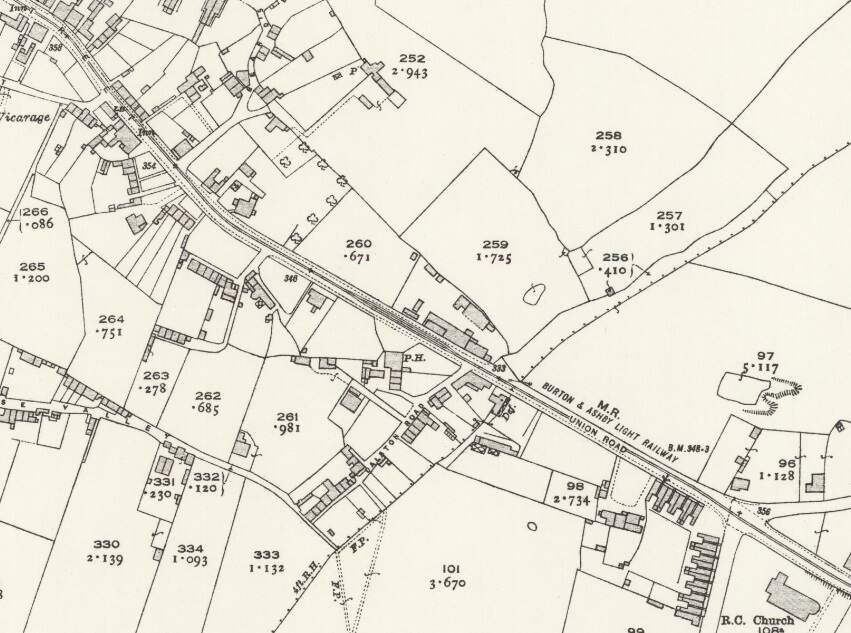

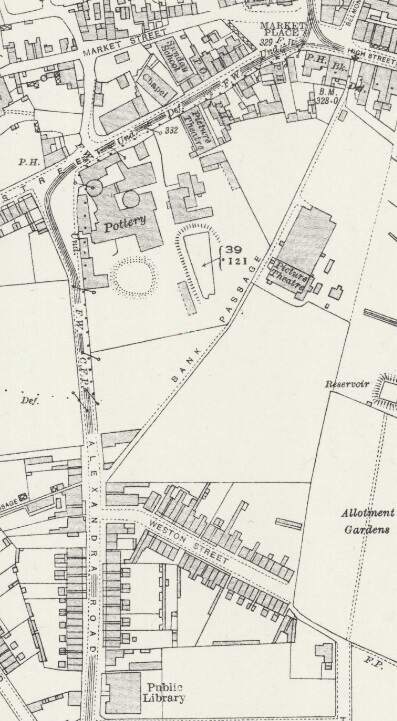

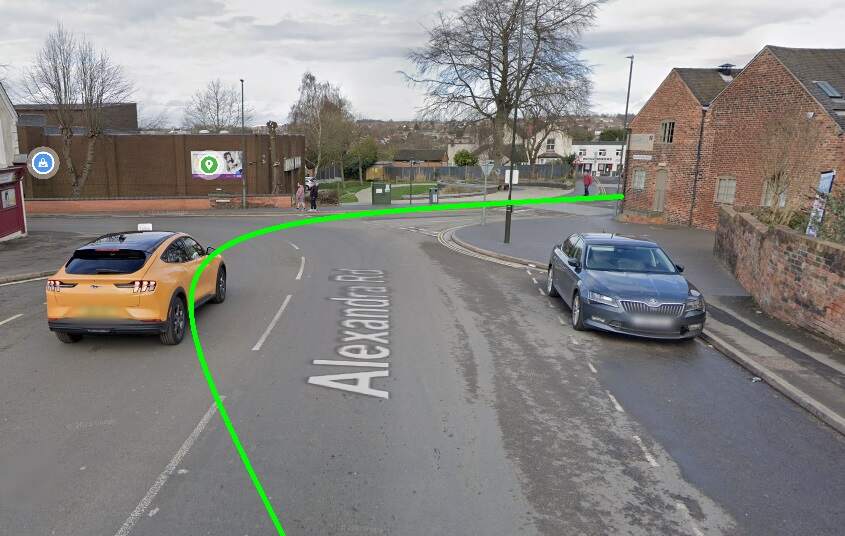

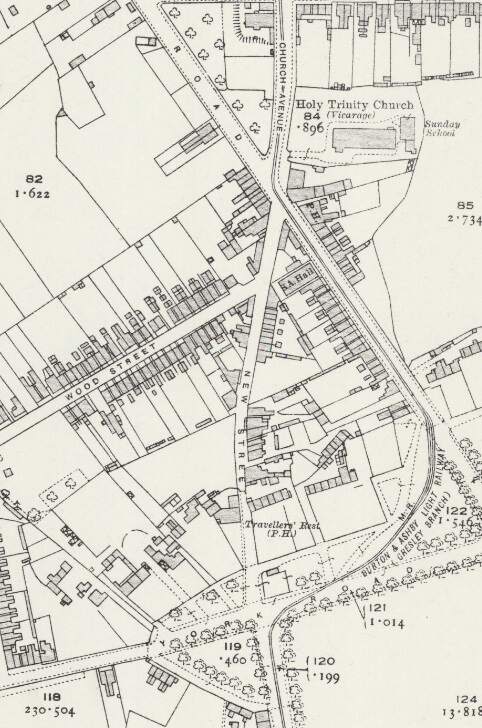

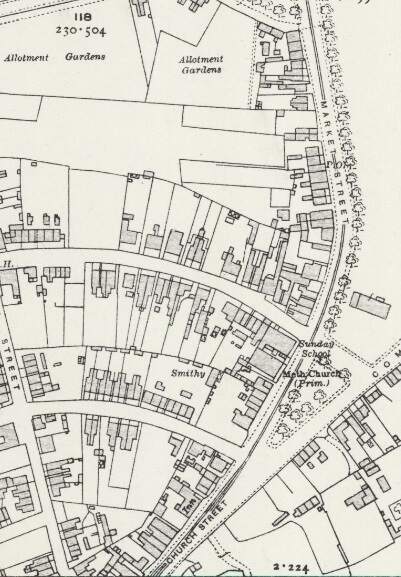

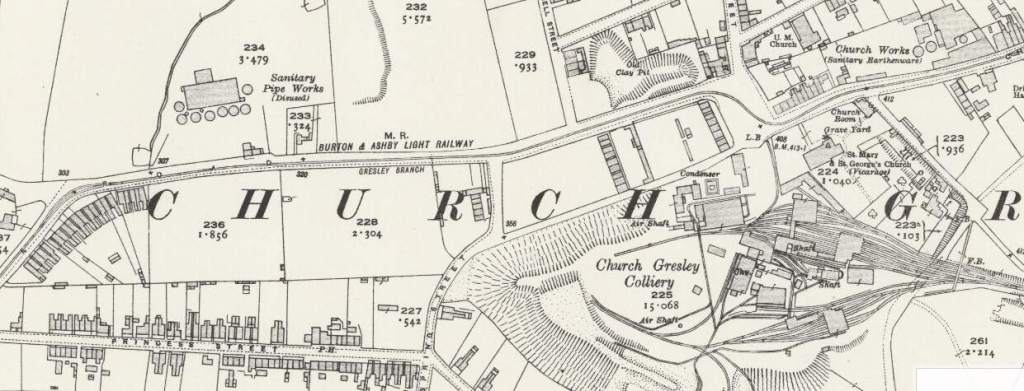

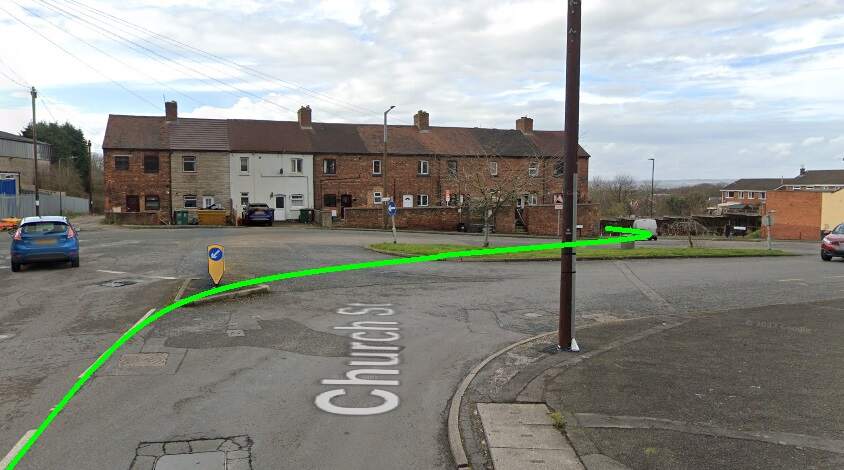

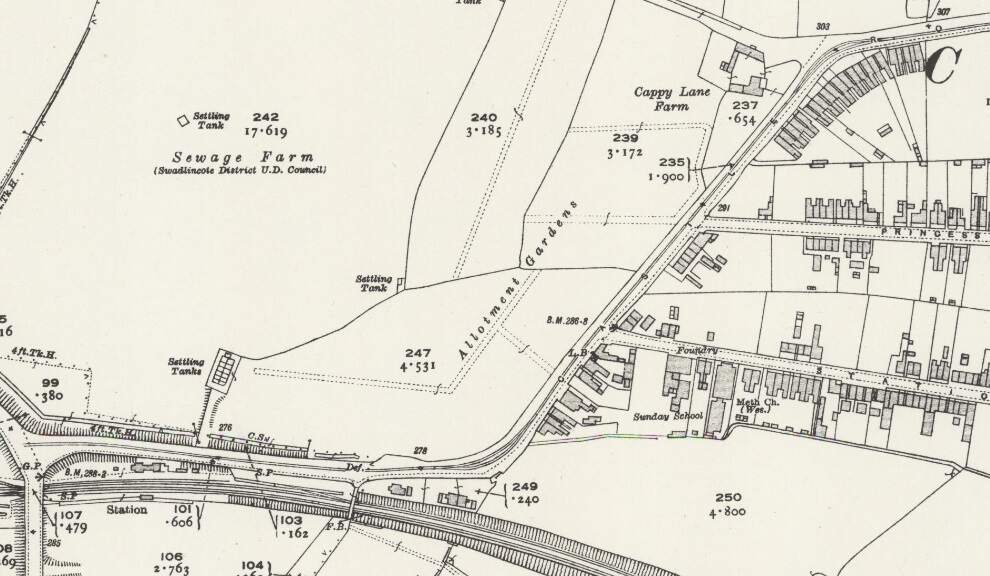

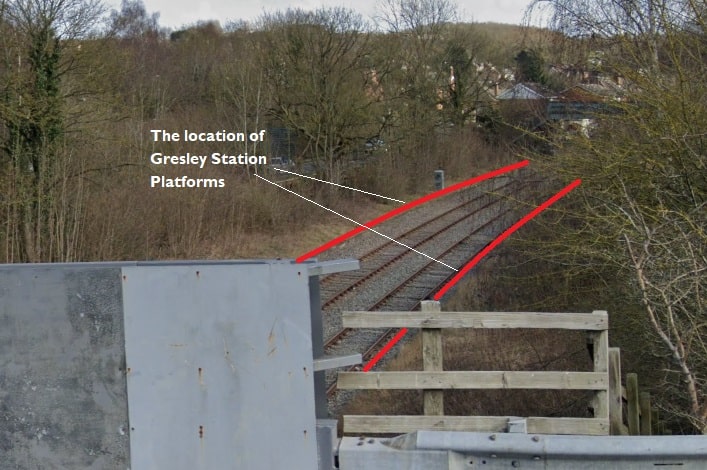

1906 includes quite a lengthy list: part of the Baker Street and Waterloo electric (now London Electric), Bankfoot Light (worked by Caledonian Railway), Amesbury and Bulford Light (worked by London and South Western Railway), Burton and Ashby Light (Midland Railway, worked by electric tramcars), Corringham Light, North Lindsey Light (worked by Great Central Railway), Campbeltown and Machrihanish (1 ft. 11 in. gauge), and Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton (now London Electric) railways.

In 1907, the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway(now London Electric) was added.

In 1908, the Bere Alston and Callington section of the Plymouth, Devonport and South Western Junction Railway, worked with its own rolling-stock, was opened.In 1909, the Strabane and Letterkenny (3 ft. gauge) Railway in Ireland. Also the Cleobury Mortimer and Ditton Priors Light, Newburgh and North Fife (worked by North British Railway), and part of the Castleblaney, Keady and Armagh Railway (worked by Great Northern Railway, Ireland) in Ireland.

In 1910, the South Yorkshire Joint Committee’s Railway (Great Northern, Great Central, North Eastern, Lancashire and Yorkshire – now London and North Western – and Midland Railways) was opened.

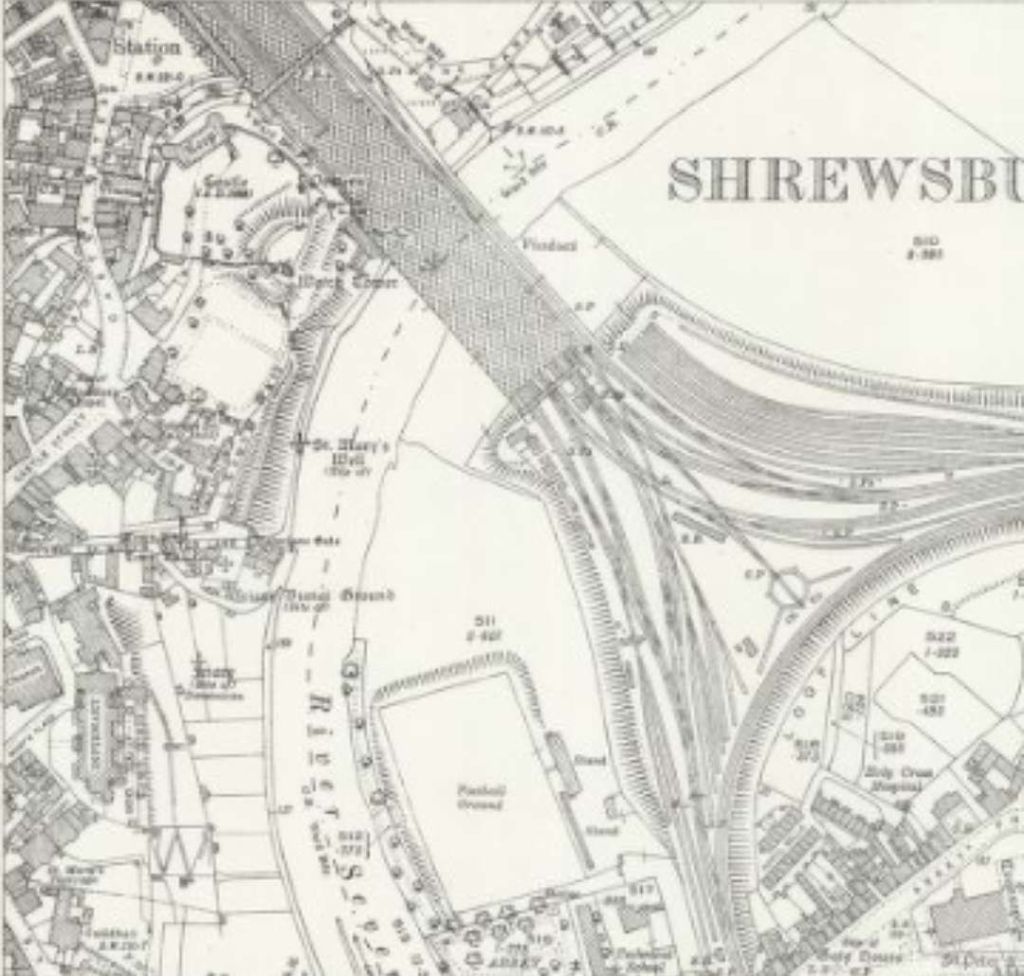

1911 saw passenger traffic inaugurated on the Cardiff Railway, and the Shropshire and Montgomeryshire Light, East Kent, and Mawddwy (worked by Cambrian Railways) lines opened.

In 1912 the Cork City Railway was opened, the Dearne Valley line brought into use for passenger traffic, and a section of the Derwent Valley Light Railway opened.

In 1913 the Elsenham and Thaxted Light Railway (worked by Great Eastern Railway) was opened, and a part of the Mansfield Railway (worked by Great Central Railway) brought into use for mineral traffic.

Then came the war years, which effectively put a stop to much in the way of new railway construction, and the only items which need be mentioned here are: a part of the old Ravenglass and Eskdale, reopened in 1915 as the Eskdale Railway (15 in. gauge), and the Mansfield Railway, brought into use for passenger traffic (1917). The Ealing and Shepherd’s Bush Electric Railway, worked by the Central London Railway, was opened in 1920.

A lengthy list, but including a number of lines which now count for a great deal, particularly in regard to the London electric tube railways, … It must be remembered, too, that except where worked by another company and as noted, most of these lines possess their own locomotives and rolling-stock.” [1: p378-379]

Despite the extent of these new lines, Gairns comments that it is “the extensions of previously existing railways which have had the greatest influence.” [1: p379] It is worth seeing his list in full. It includes:

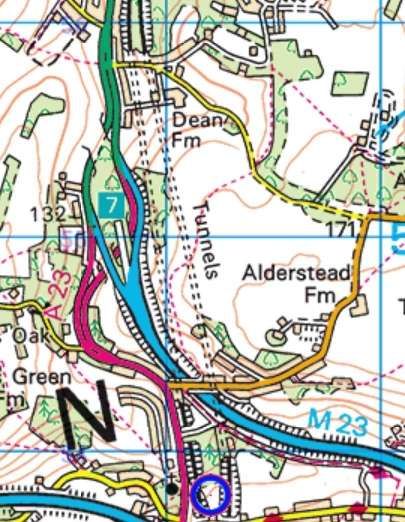

“In 1897, the Highland Railway extended its Skye line from Stromeferry to Kyle of Lochalsh, and in 1898 the North British Railway completed the East Fife Central lines. 1899 was the historic year for the Great Central Railway, in that its London extension was opened, giving the company a main trunk route and altering many of the traffic arrangements previously in force with other lines. Indeed, the creation of this ‘new competitor’ for London, Leicester, Nottingham, Sheffield, Manchester and, later, Bradford traffic, materially changed the general railway situation in many respects. In the same year, the Highland Railway direct line, from Aviemore to Inverness was opened, this also having a considerable influence upon Highland traffic. In 1900 the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway completed the new ‘Quarry’ lines, giving an independent route from Coulsdon to Earlswood.

In 1901, the Great Western Railway opened the Stert and Westbury line, one of the first stages involved in the policy of providing new and shorter routes, which has so essentially changed the whole character of Great Western Railway train services and traffic operation. In that year, also, the West Highland Railway (now North British Railway) was extended to Mallaig, adding one of the most scenically attractive and constructionally notable lines in the British Isles. The Bickley-Orpington connecting lines of the South Eastern and Chatham Railway, brought into service in 1902, enabled trains of either section to use any of the London termini, and this has essentially changed the main features of many of the train services of the Managing Committee.

In 1903, the Great Western Railway opened the new Badminton lines for Bristol and South Wales traffic, a second stage in the metamorphosis of this system. In 1906 the Fishguard-Rosslare route was completed for Anglo-Irish traffic, while the opening of the Great Central and Great Western joint line via High Wycombe materially altered London traffic for both companies in many respects. The same year saw the completion of connecting links whereby from that time the chief route for London-West of England traffic by the Great Western Railway has been via Westbury instead of via Bristol.

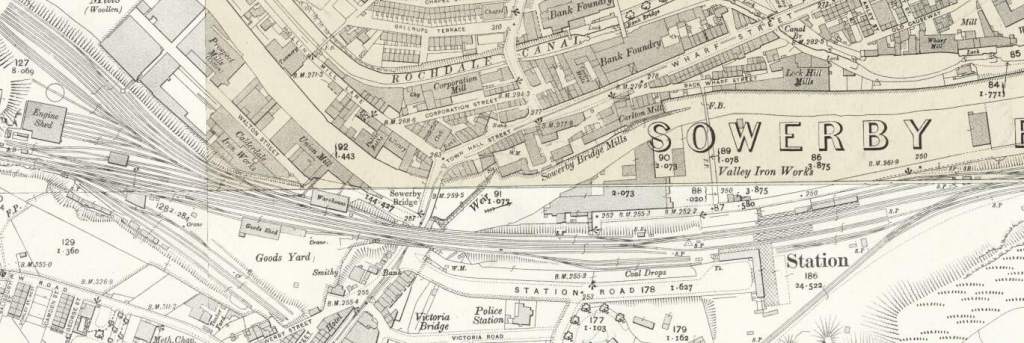

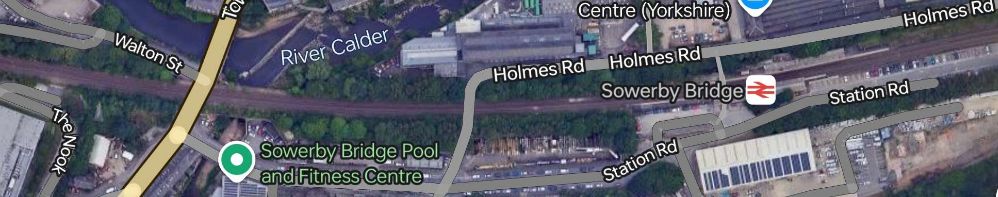

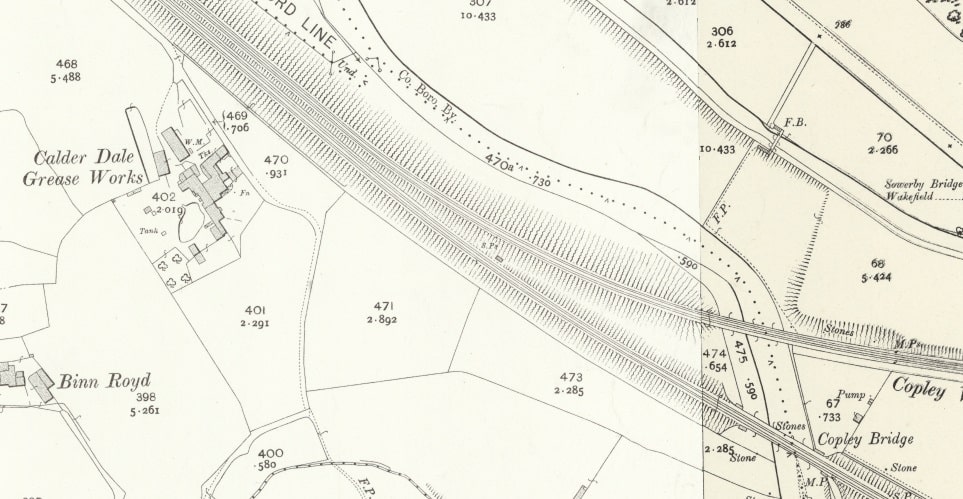

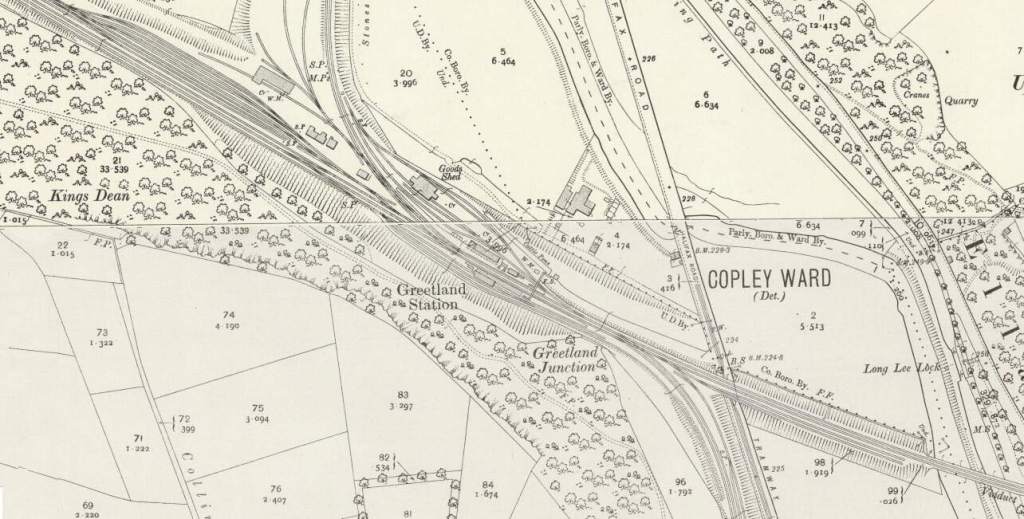

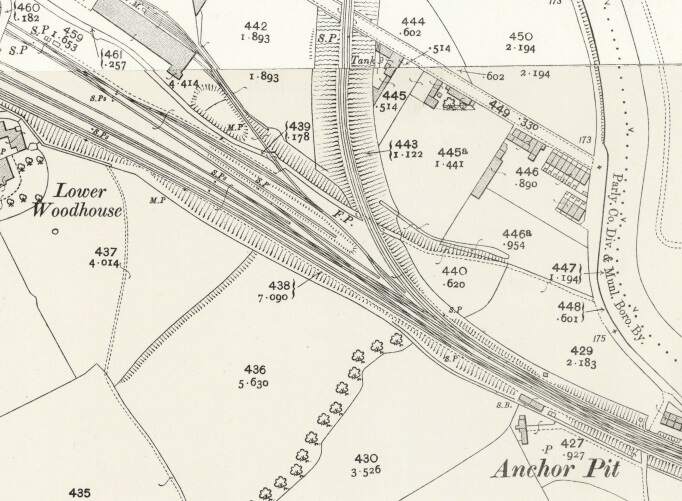

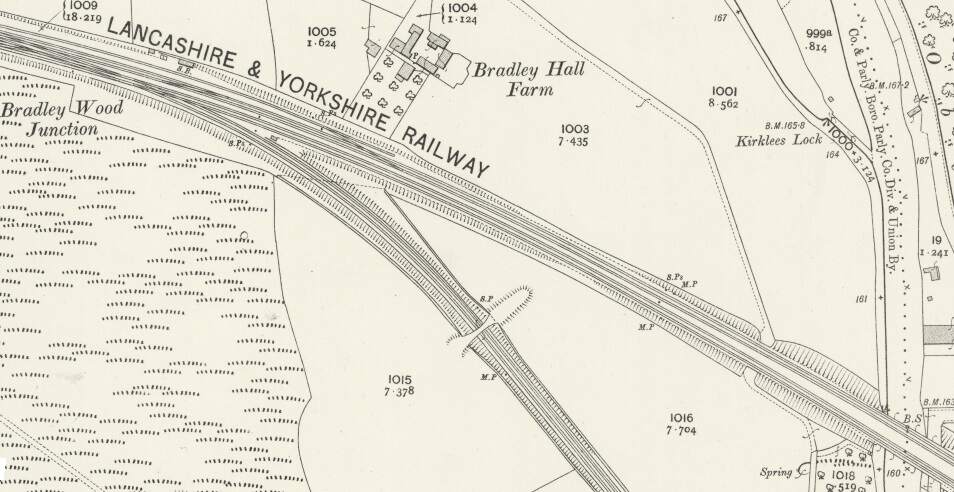

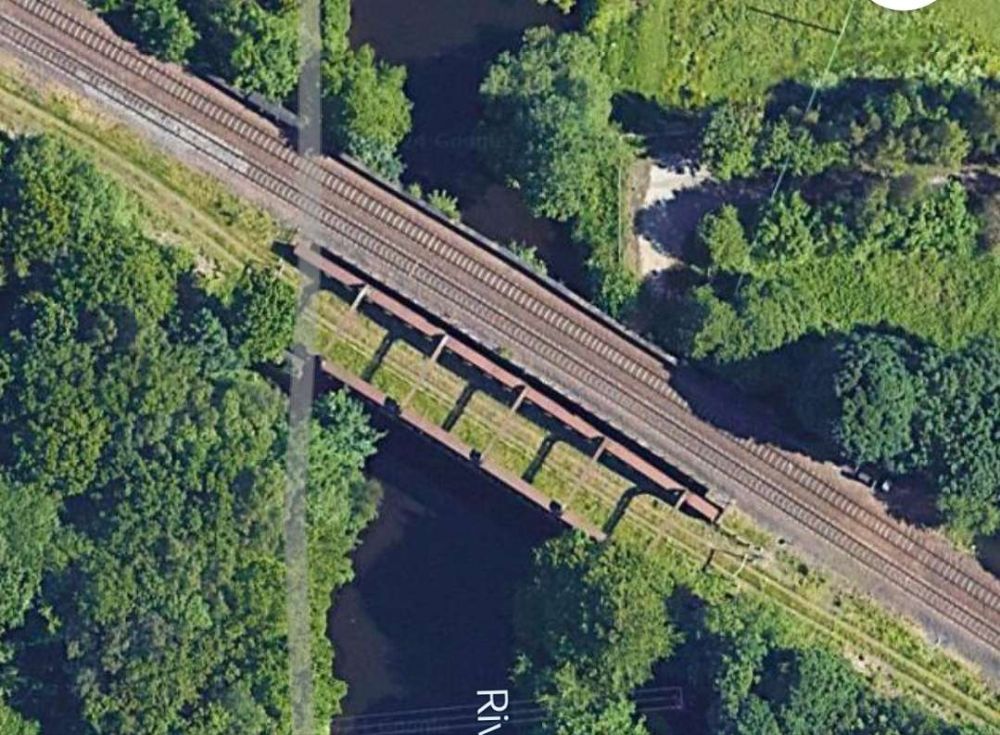

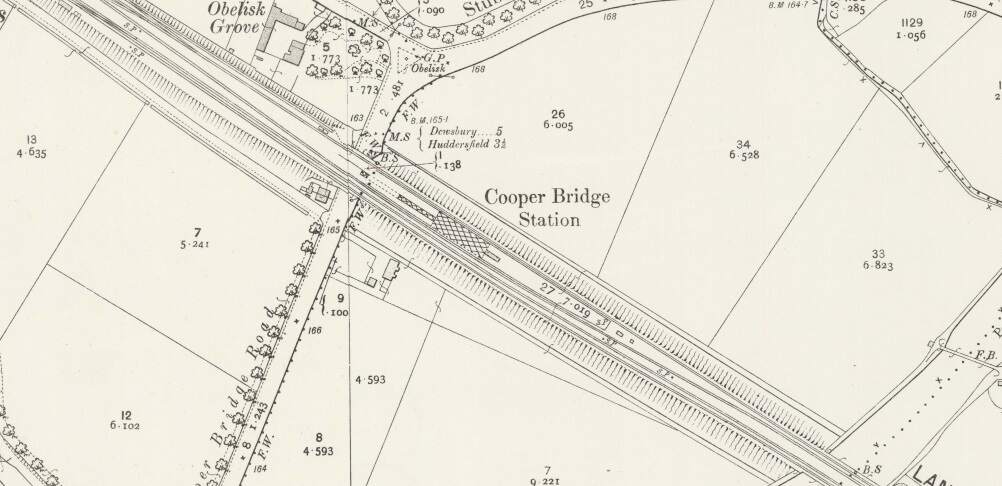

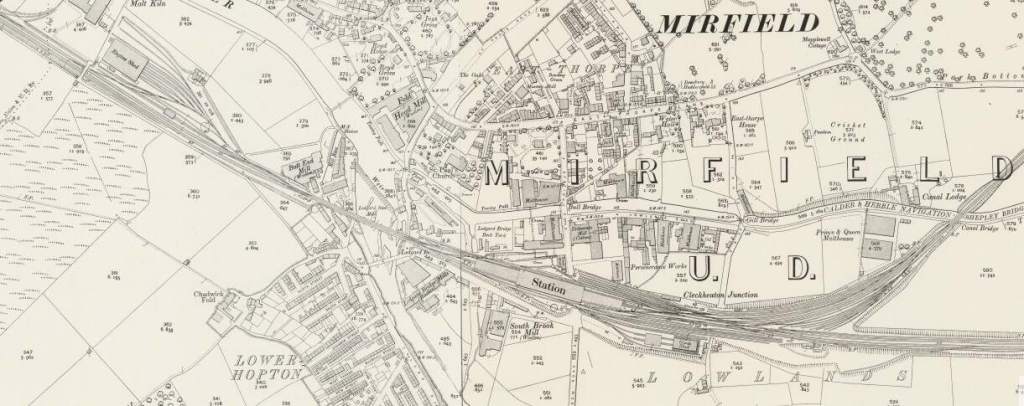

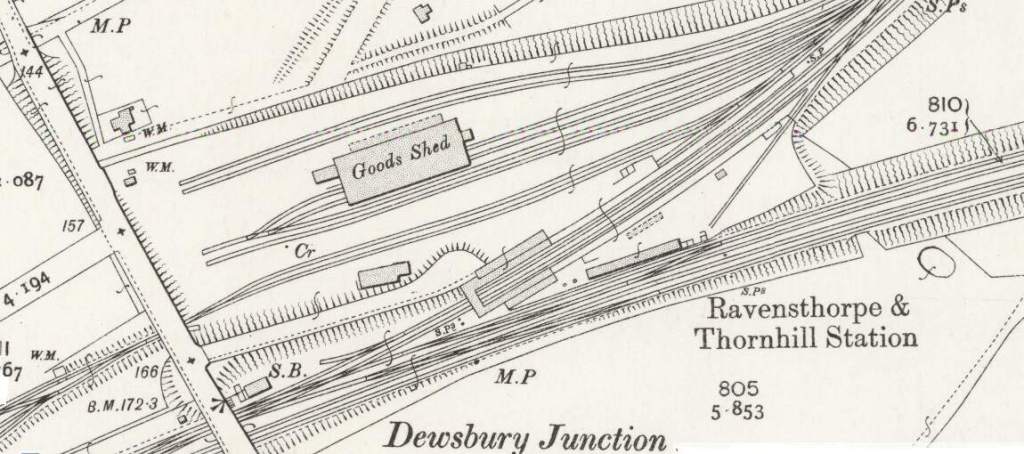

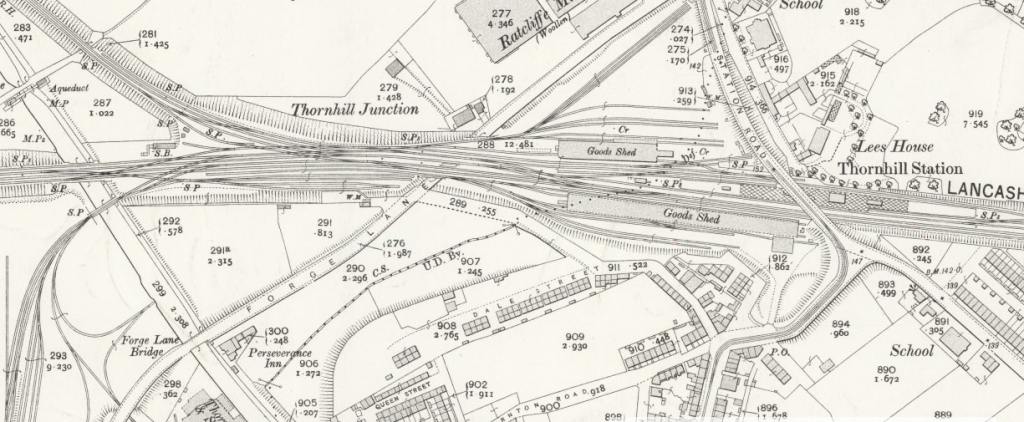

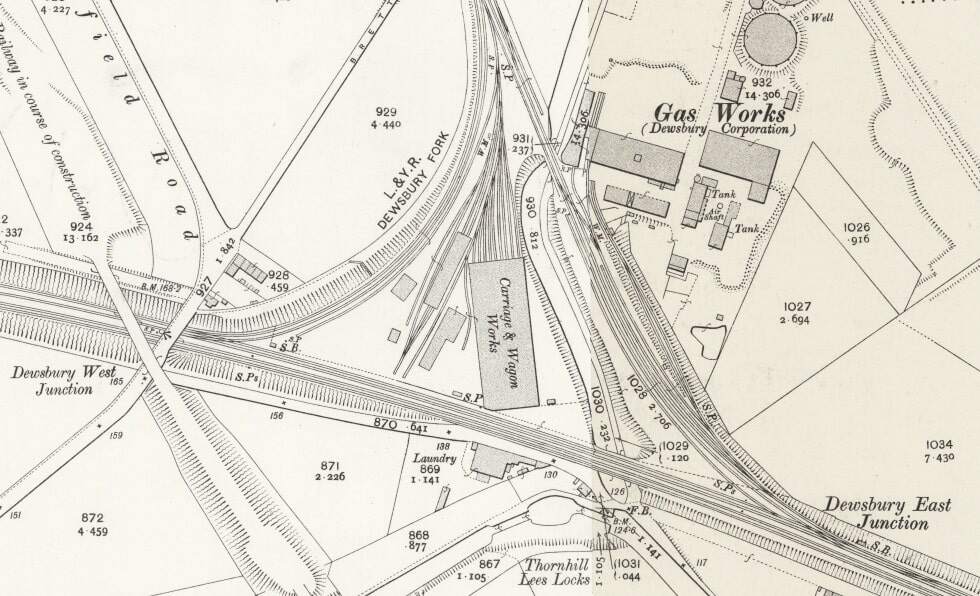

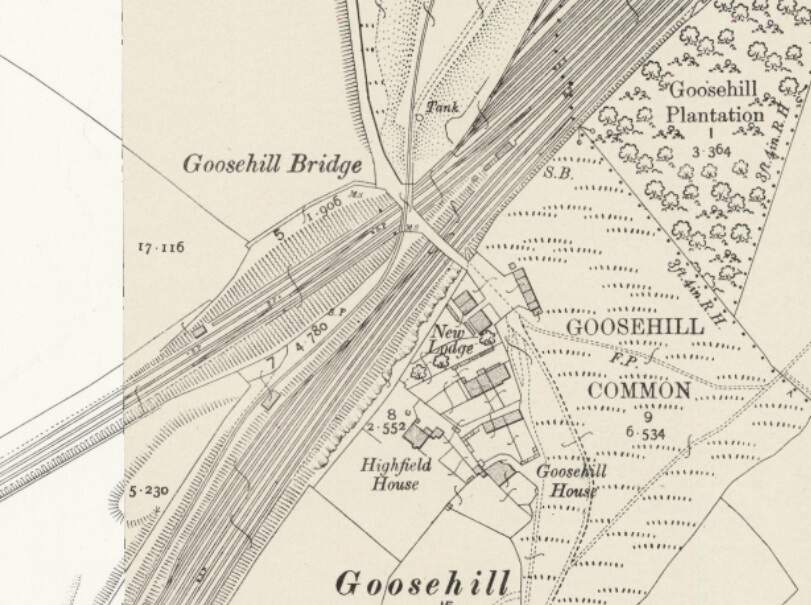

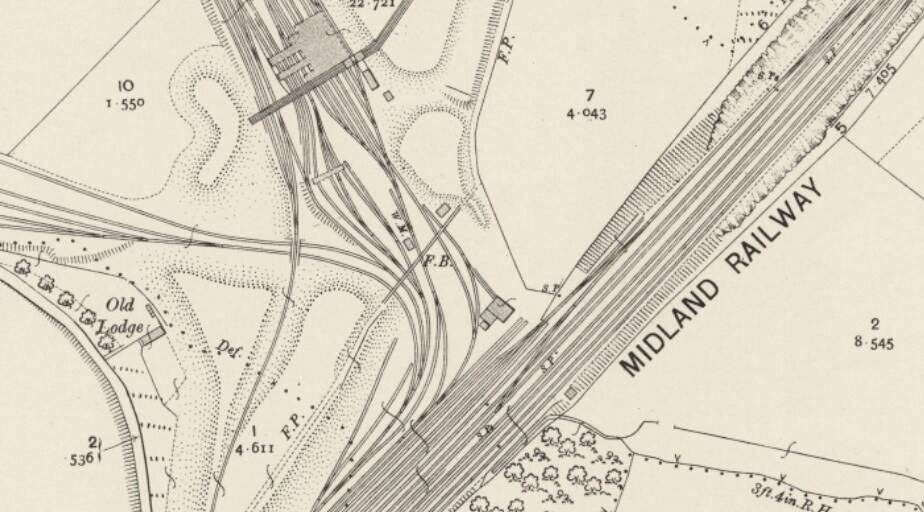

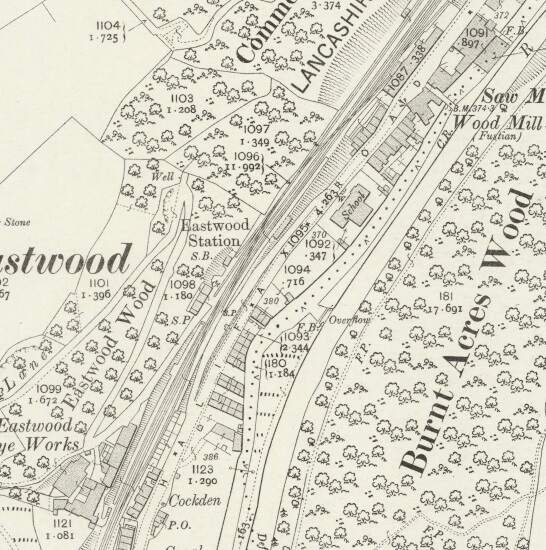

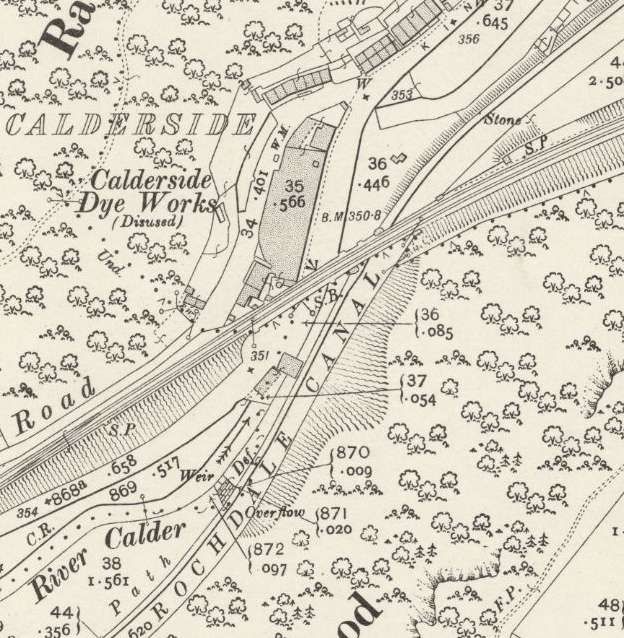

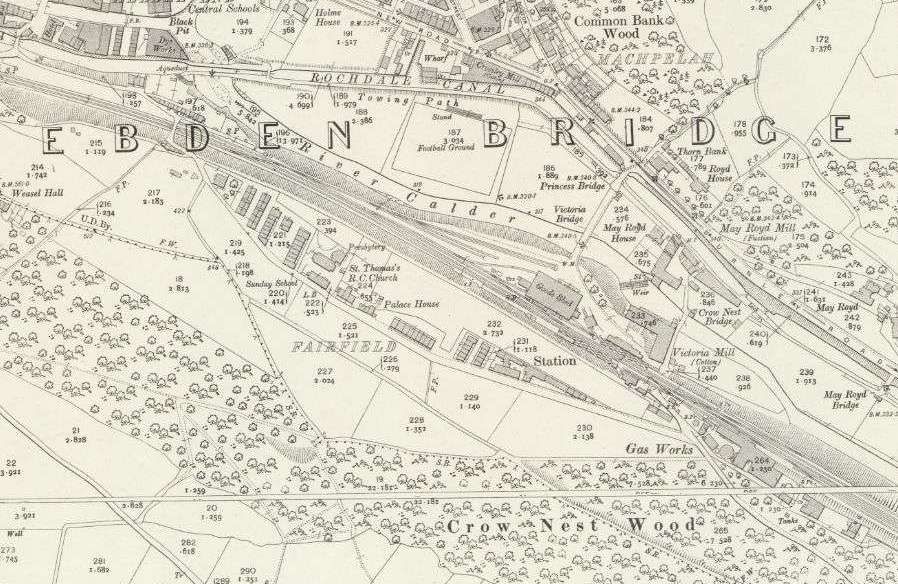

The year 1908 provided still another Great Western innovation, the completion of the Birmingham and West of England route via Stratford-on-Avon and Cheltenham.In 1909 the London and North Western Railway opened the Wilmslow-Levenshulme line, providing an express route for London-Manchester traffic avoiding Stockport. In that year also the Thornhill connection between the Midland and the then Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway introduced new through facilities.

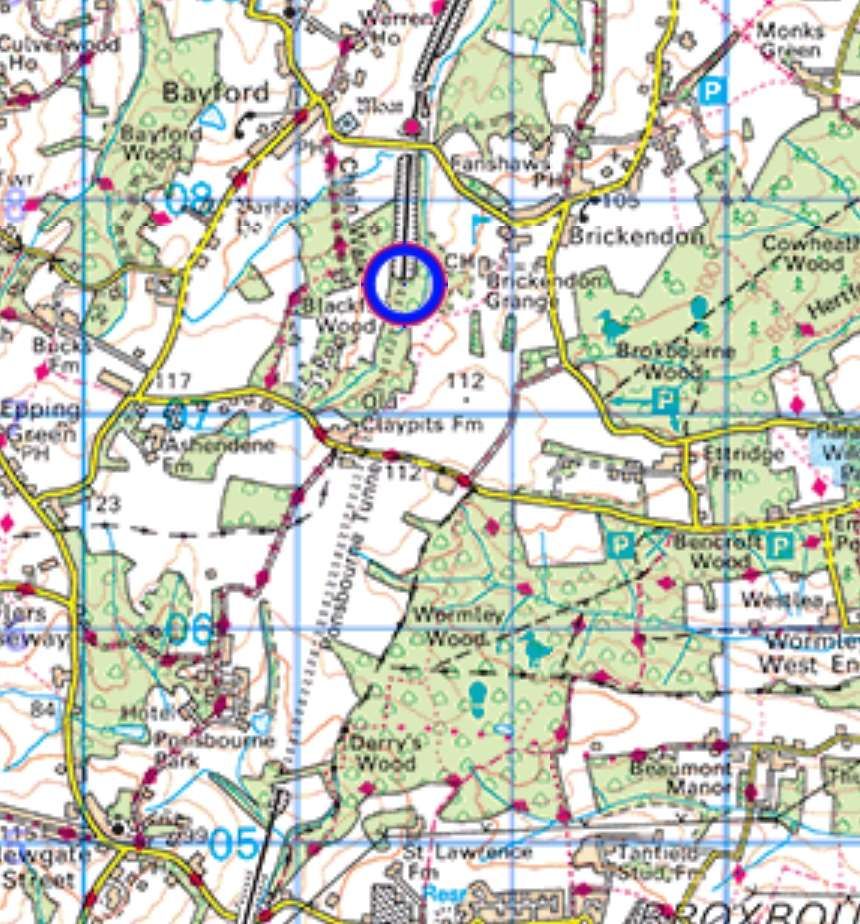

In 1910 the opening of the Enfield-Cuffley line of the Great Northern Railway provided the first link in a new route for main line traffic to and from London, though this is even yet only partially available, and opened up a new suburban area for development. The same year saw the advent of the Ashenden-Aynho line, by which the Great Western Railway obtained the shortest route from London to Birmingham, with consequent essential changes in the north train services, and the inauguration of the famous two-hour expresses by that route and also by the London and North Western Railway.

In 1912 the latter railway brought into operation part of the Watford lines, paving the way for material changes in traffic methods, and in due course for through working of London Electric trains between the Elephant and Castle and Watford, and for electric traffic to and from Broad Street and very shortly from Euston also. In 1913 part of the Swansea district lines were brought into use by the Great Western Railway, and in 1915 the North British Railway opened the new Lothian lines. [1: p379-380]

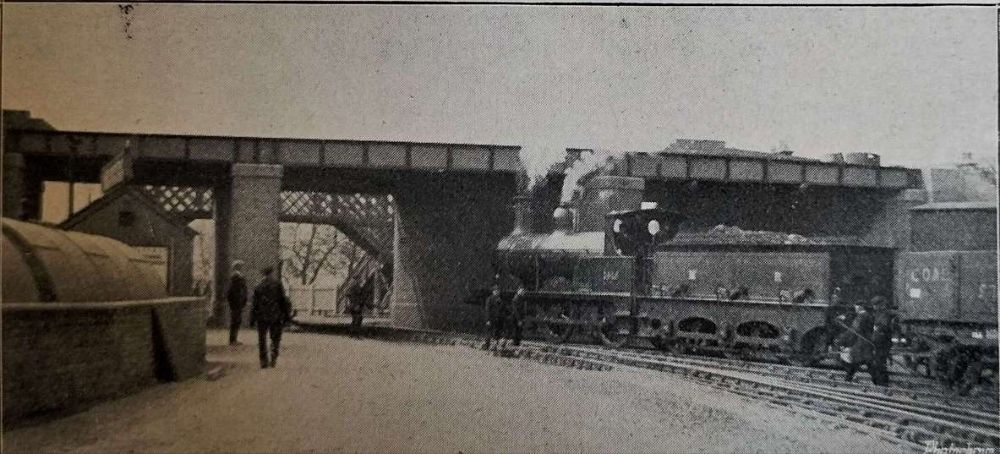

Many of the changes over the 25 years were far-reaching in character others were of great local significance, such as station reconstructions, widenings, tunnels, dock/port improvements and new bridges.

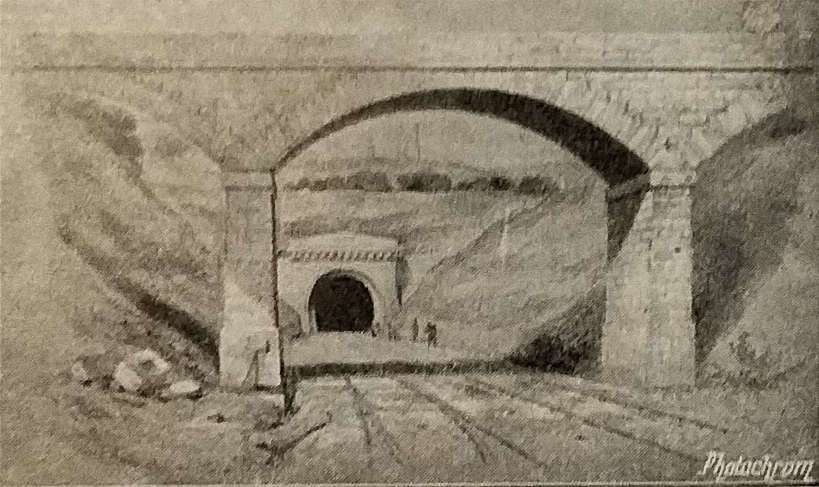

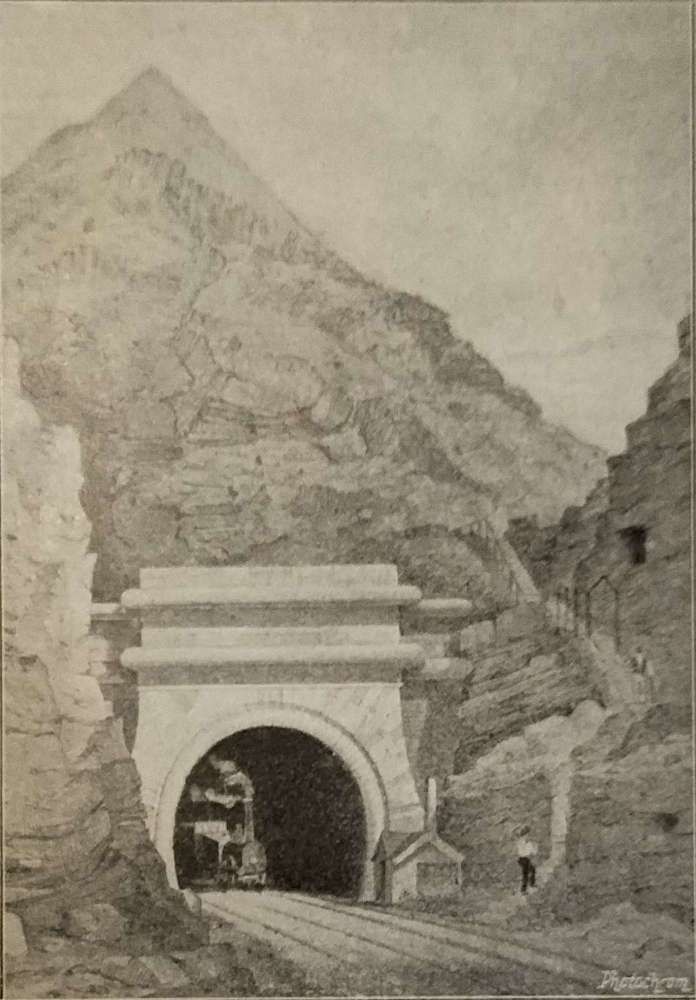

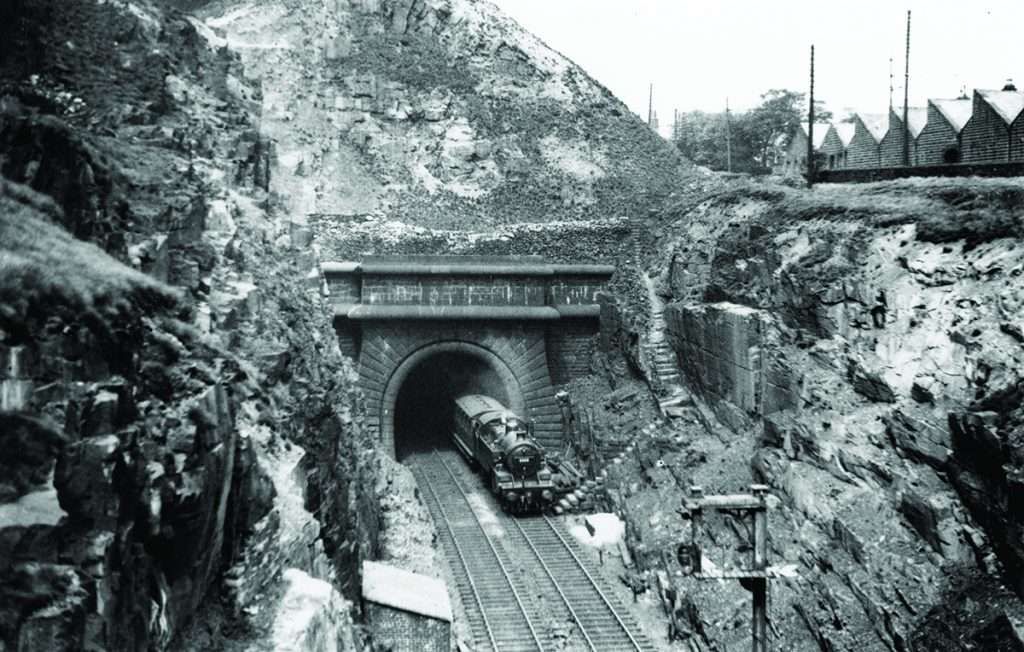

New long tunnels included: Sodbury Tunnel on the GWR Badminton line; Ponsbourne Tunnel on the GNR Enfield-Stevenage line; Merstham (Quarry) Tunnel on the LB&SCR ‘Quarry’ line.

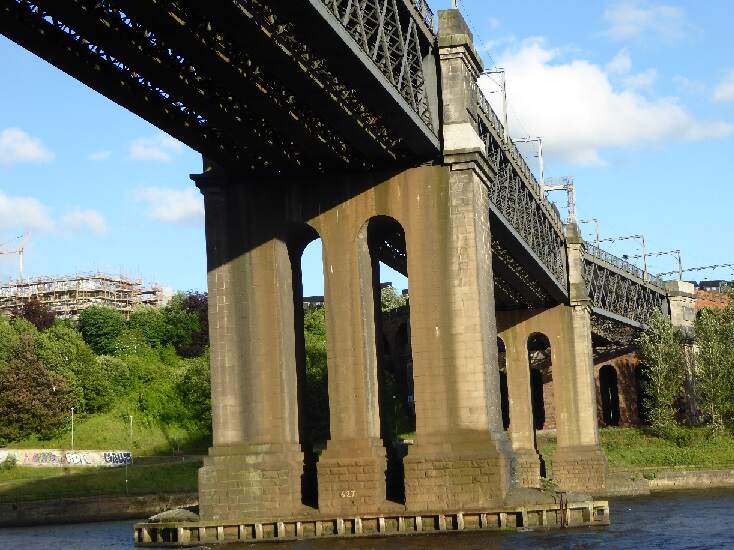

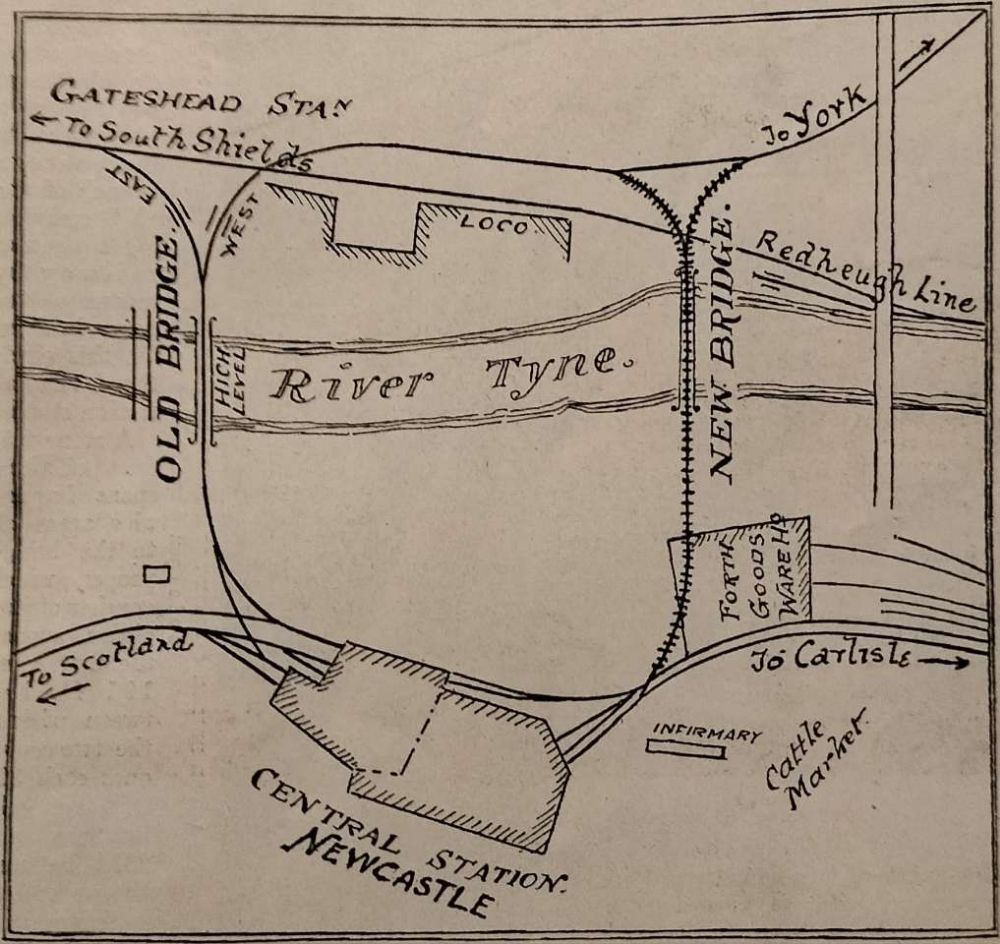

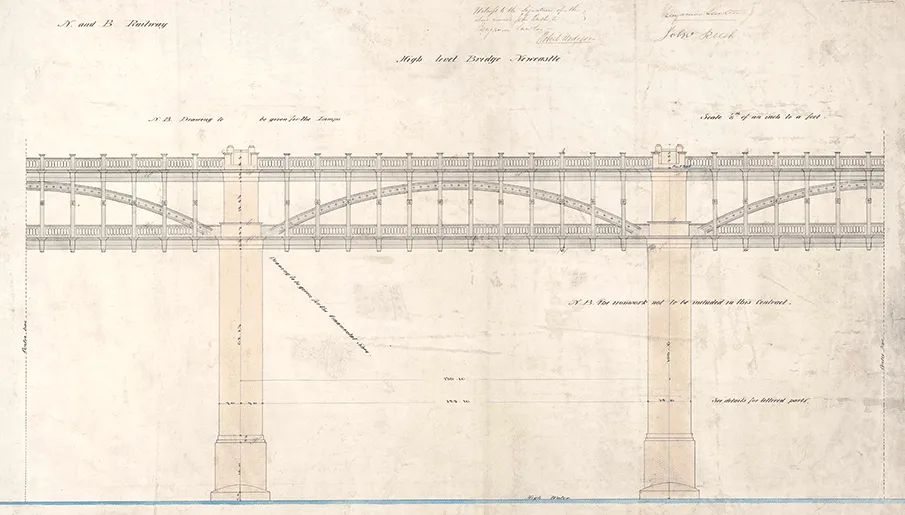

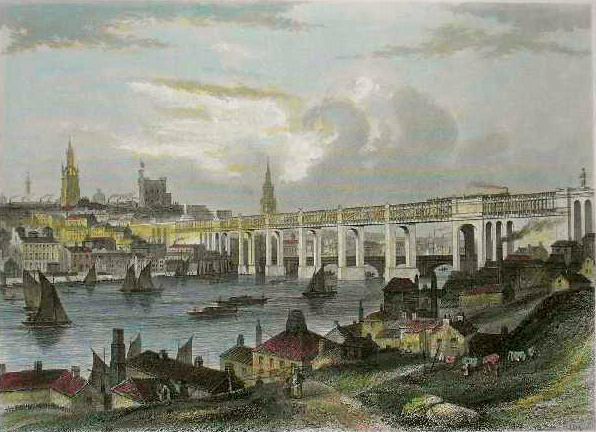

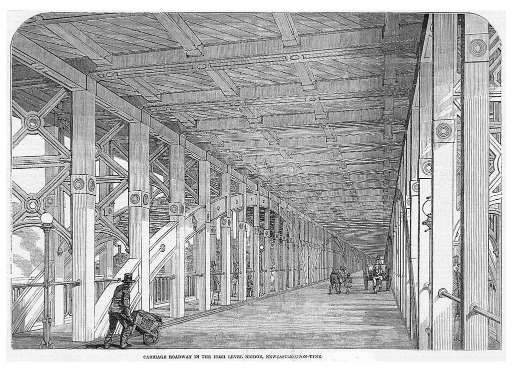

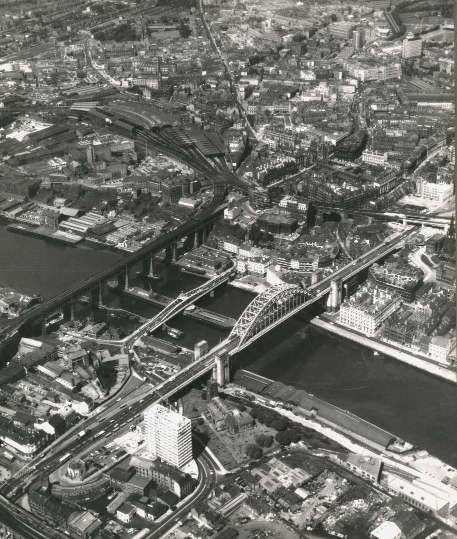

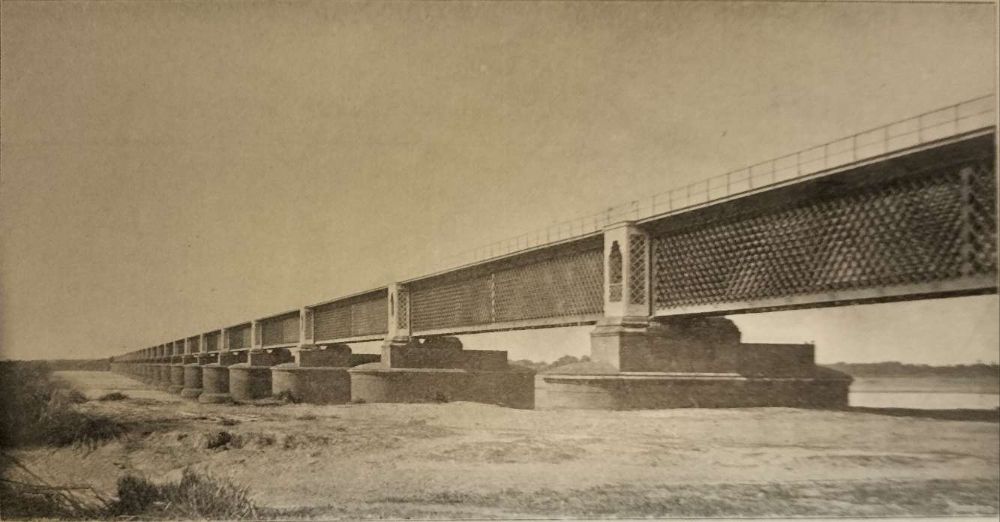

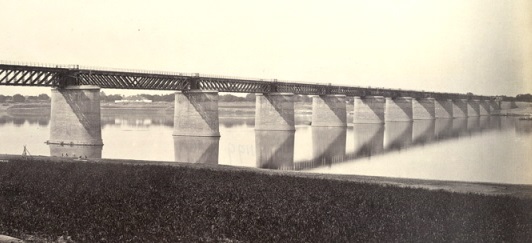

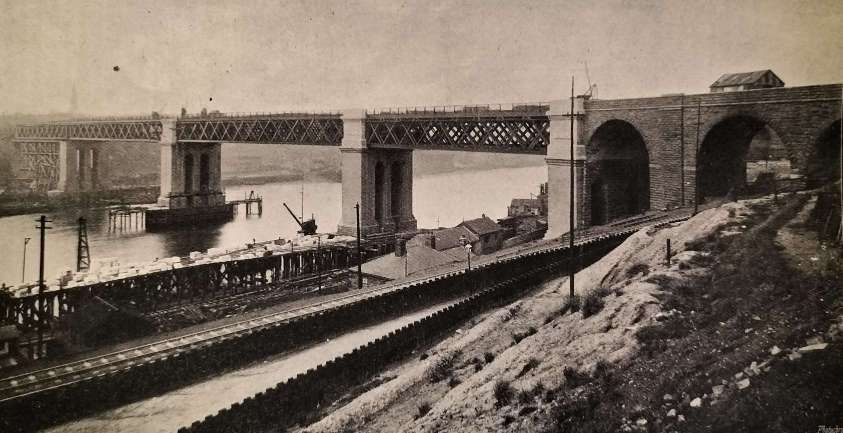

Notable bridges included: the King Edward VII Bridge in Newcastle and the Queen Alexandra Bridge in Sunderland.

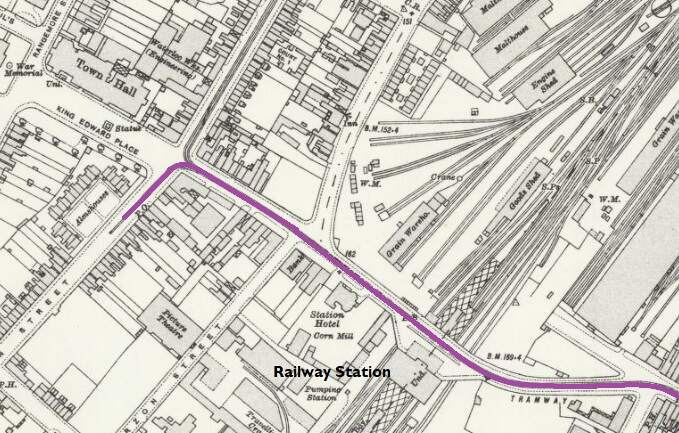

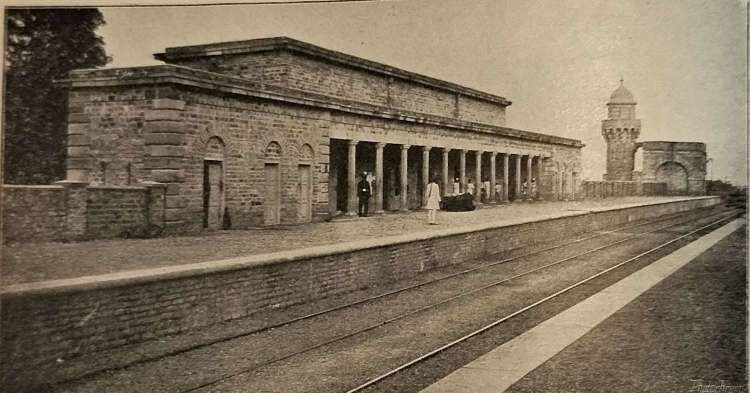

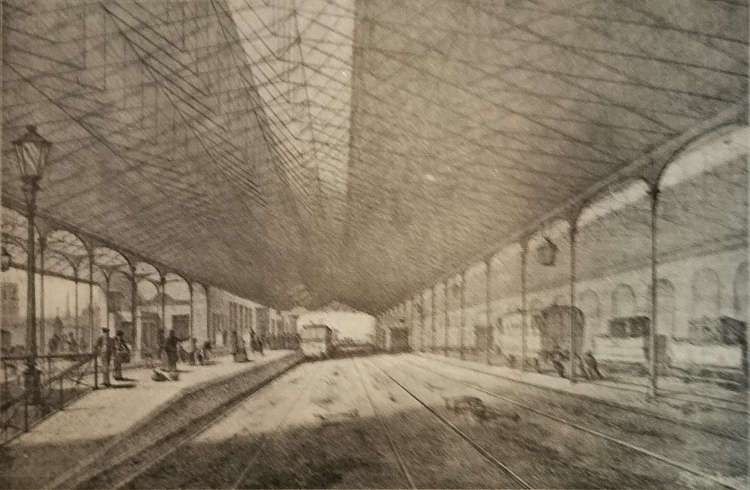

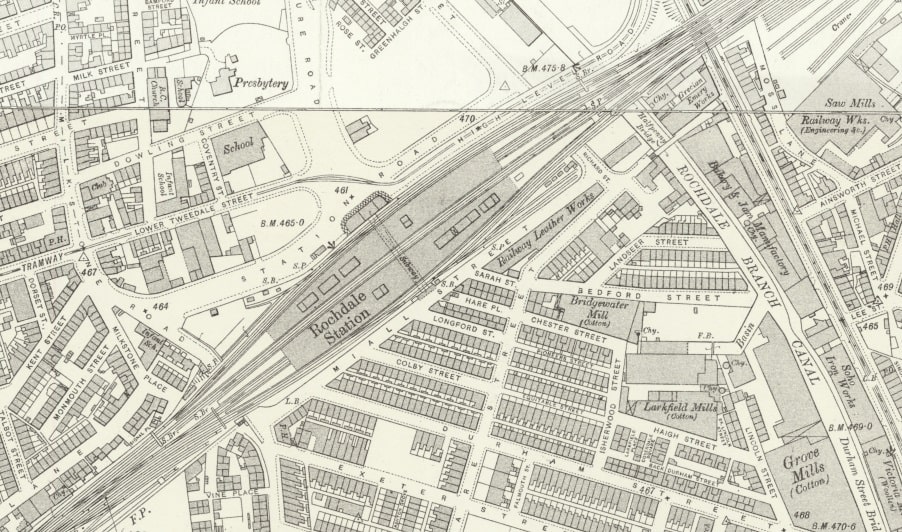

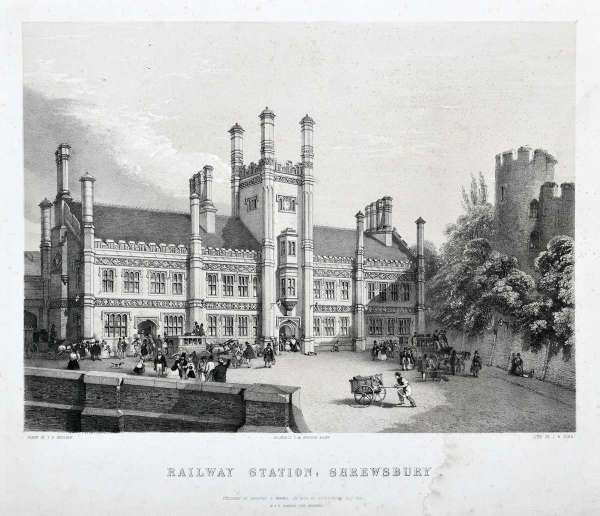

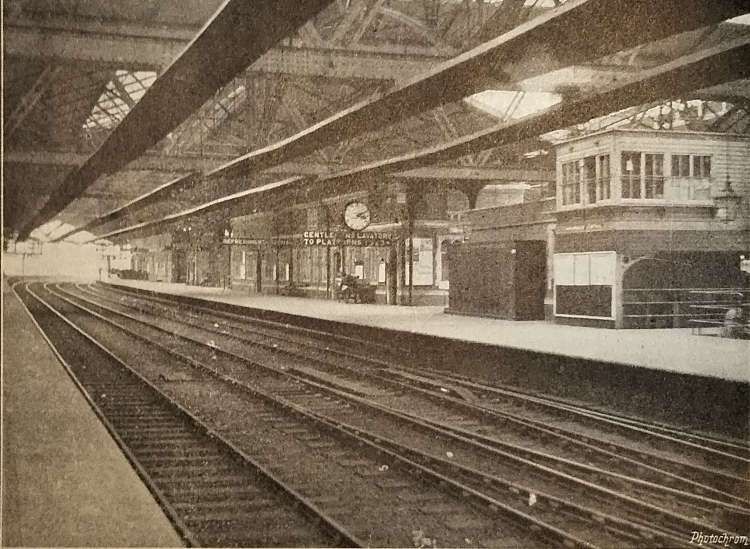

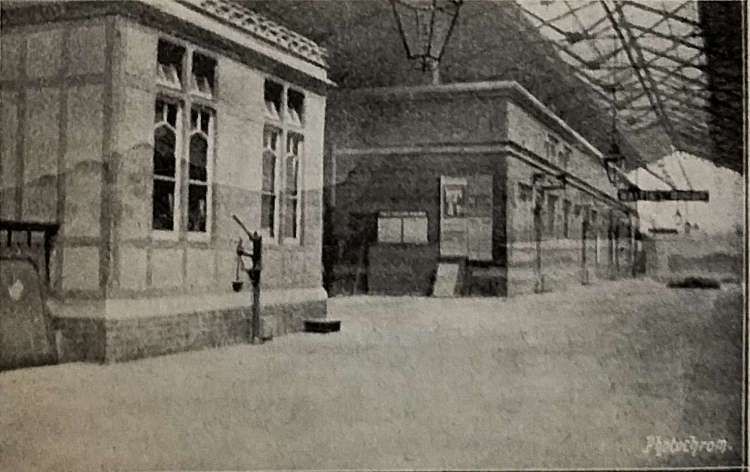

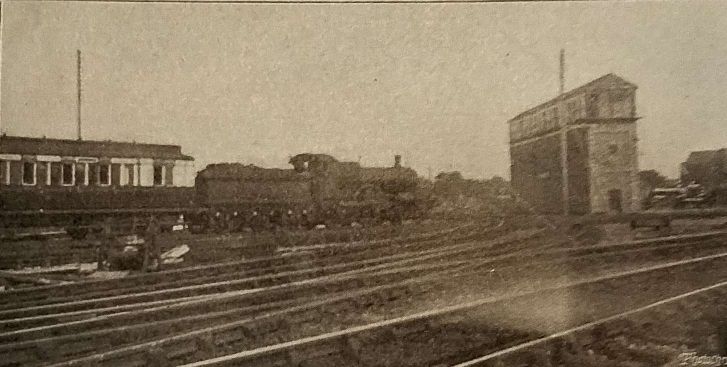

Reconstructed/new/enlarged stations included: Victoria (LB&SCR); Glasgow Central (CR); Manchester Victoria (L&YR); Waterloo (L&SWR); Birmingham Snow Hill (GWR); Euston (LNWR); Crewe (LNWR) and Paddington (GWR)

Among a whole range of Capital Works undertaken by the GWR, was the new MPD at Old Oak Common. The LNWR’s new carriage lines outside Euston and the Chalk Farm improvements were significant, as were their system of avoiding lines around Crewe.

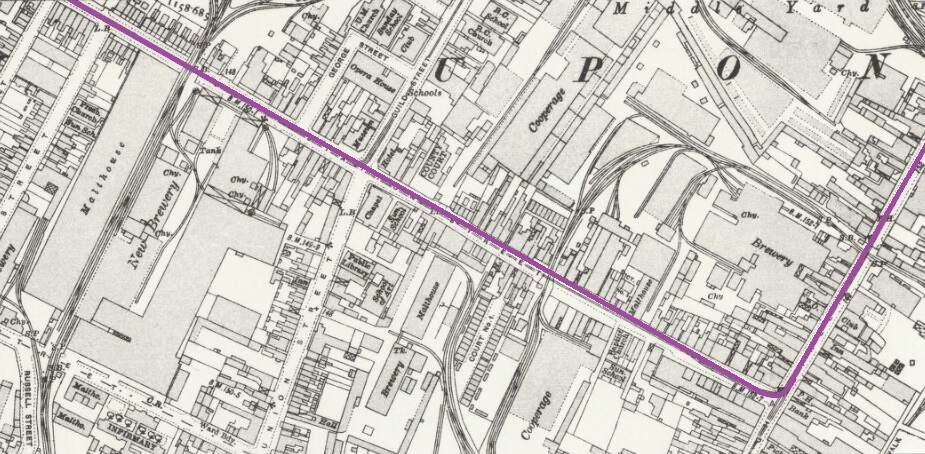

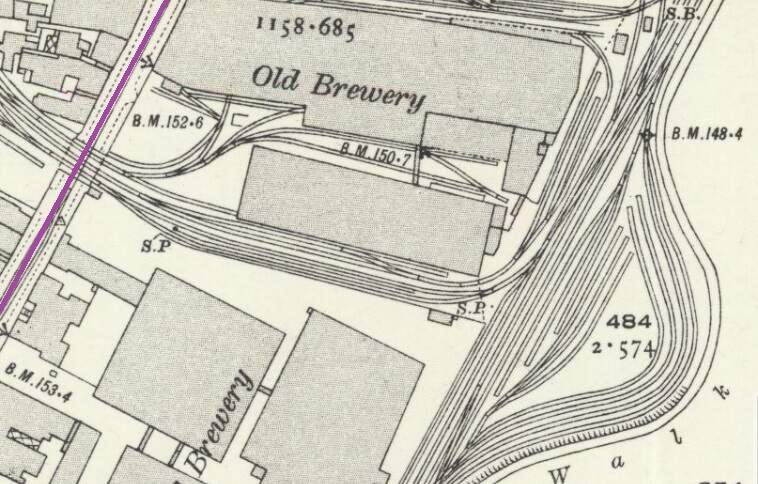

The MR takeover of the LT&SR in 1912 and their works between Campbell Road Junction and Barking are noteworthy. The L&SWR undertook major electrification of suburban lines, built a new concentration yard at Feltham, and made extensions and improvements at Southampton.

The LB&SCR’s widenings/reconstructions of stations on the ‘Quarry’ lines, which enabled through trains to run independently of the SE&CR line through Redhill were of importance. As we’re the SE&CR’s works associated with the improvements at Victoria, the new lines around London Bridge, the new Dover Marine Station and changes throughout their system.

The GCR London Extension is equalled in importance by the High Wycombe joint line and the GCR’s construction and opening of Immingham Dock in 1912. Gairns also points out that the NER and the H&BR works associated with the King George Dock in Hull should not be forgotten.

Also of significance were some railway amalgamations and some other events of historic interest between 1897 and 1922. Gairns included:

- In 1897, the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railways name changed to ‘Great Central Railway’.

- In 1899, the South Eastern and Chatham Joint Committee was set up.

- In 1900, the Great Southern & Western Railway took over the Waterford & Central Ireland Railway and absorbed the Waterford, Limerick & Western Railway in 1901.

- In 1903, the Midland Railway took over the Belfast & Northern Counties Railway.

- In 1905, the Hull, Barnsley & West Riding Junction Railway & Dock Company became the Hull & Barnsley Railway; the Great Central Railway headquarters were moved from Manchester to London.

- In 1906 the Harrow-Verney Junction section of the Metropolitan Railway was made joint with the Great Central Railway.

- In 1907, the Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway was amalgamated with the Great Central Railway; the Dublin, Wicklow & Wexford Railway became the Dublin & South Eastern Railway; and the greater part of the Donegal Railway was taken over jointly by the Great Northern of Ireland and Midland (Northern Counties section) under the County Donegal Railways Joint Committee.

- In 1912, the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway was taken over by the Midland Railway.

- In 1913, the Great Northern & City Railway was absorbed by the Metropolitan Railway.

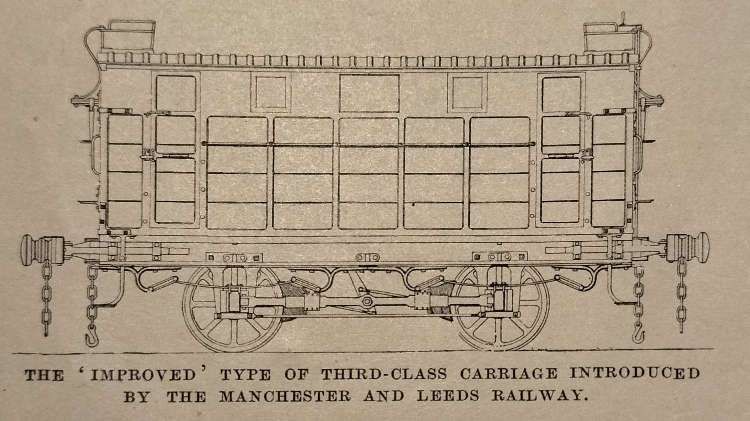

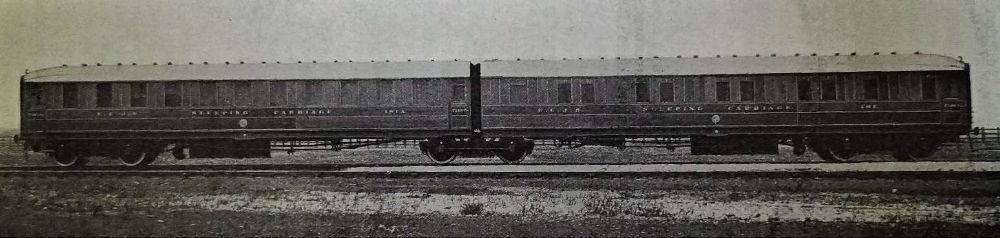

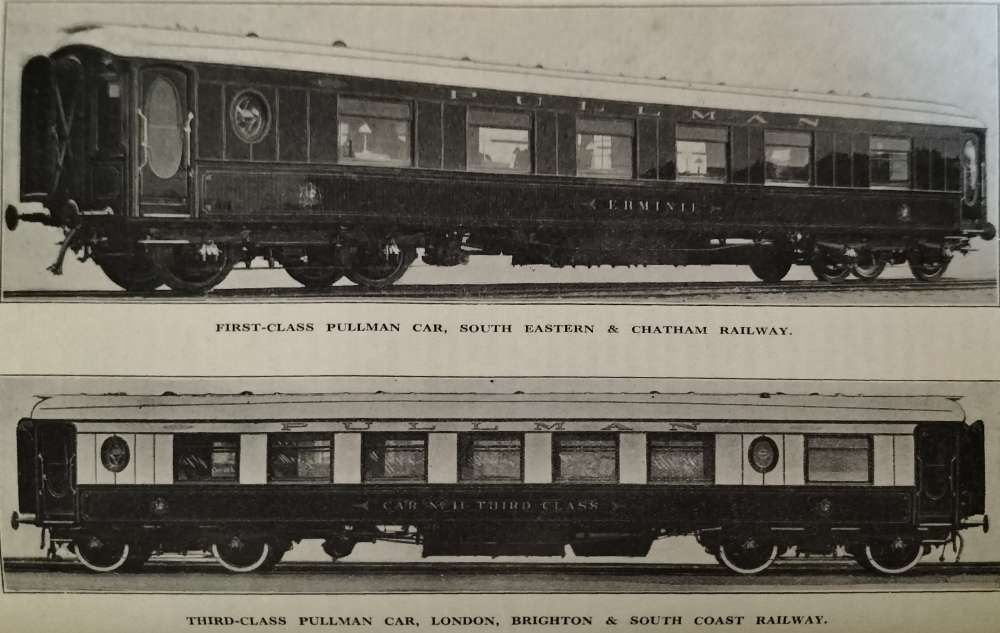

Gairns also noted “the now almost universal provision of restaurant cars and corridor carriages of bogie type, Pullman cars upon many lines, and through carriages providing a wide variety of through facilities, culminating in the introduction last year of direct communication without change of vehicle between Penzance, Plymouth and Aberdeen, Southampton and Edinburgh, etc.” [1: p382]

In the period from 1897 to 1922, there had been essential changes to traffic characteristics:

- “notably in the abolition of second-class accommodation by all but a very few lines in England and Scotland, though it is still retained generally in Ireland and to some extent in Wales.” [1: p382]

- “the generous treatment of the half-day, day and period and long-distance excursionist, who in later years has been given facilities almost equal, in regard to speed and comfort of accommodation, to those associated with ordinary traffic.” [1: p383]

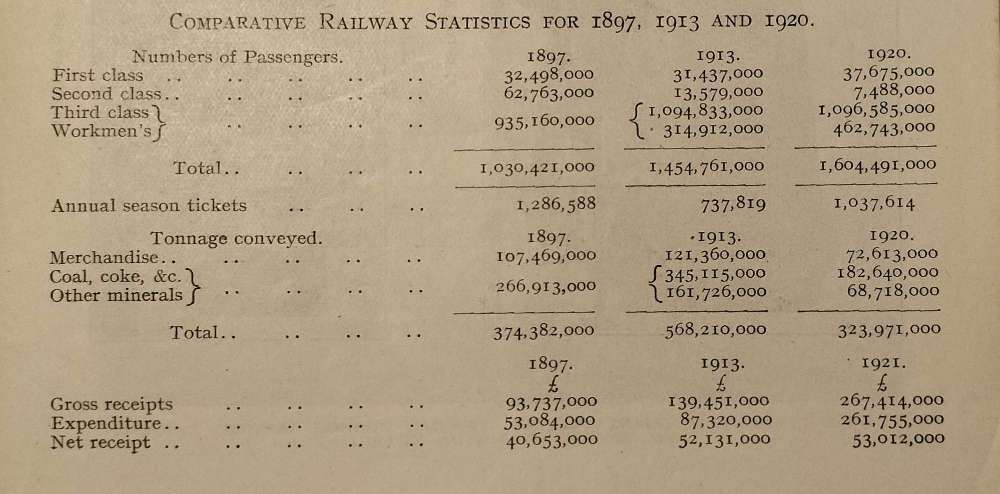

Gairns also provides, in tabular form, comparative statistics which illustrate some remarkable changes over the period from 1827 to 1922. His table compares data from 1897, 1913 and 1920.

In commenting on the figures which appear in the table above, Gairns draws attention to: the decline in numbers of second class passengers, the dramatic fall and then rise in the number of annual season tickets; the rise and then fall in tonnages of freight carried by the railways; and the significant increase in turnover without a matching increase in net receipts.

In respect of season tickets, Gairns notes that “whereas in 1897 and 1913 each railway having a share in a fare included the passenger in its returns, in 1920 he was only recorded once. … [and] that in later years the mileage covered by season tickets [had] considerably increased.” [1: p383]

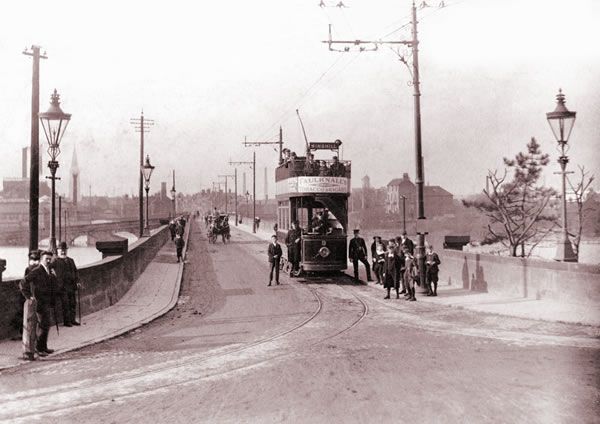

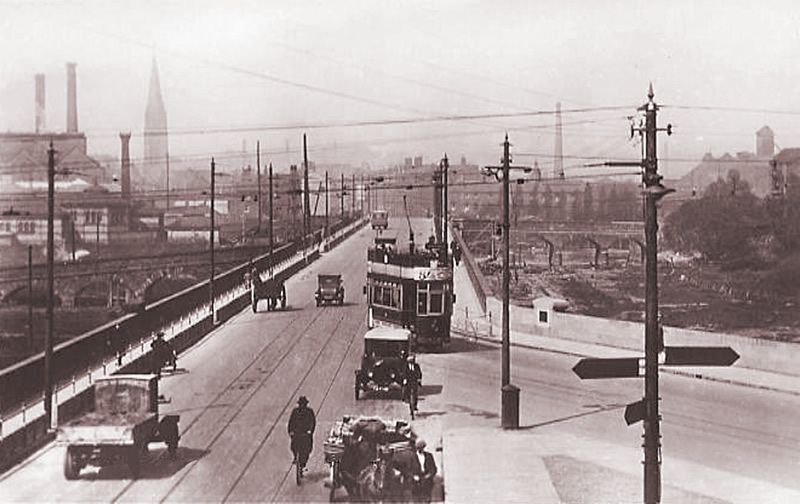

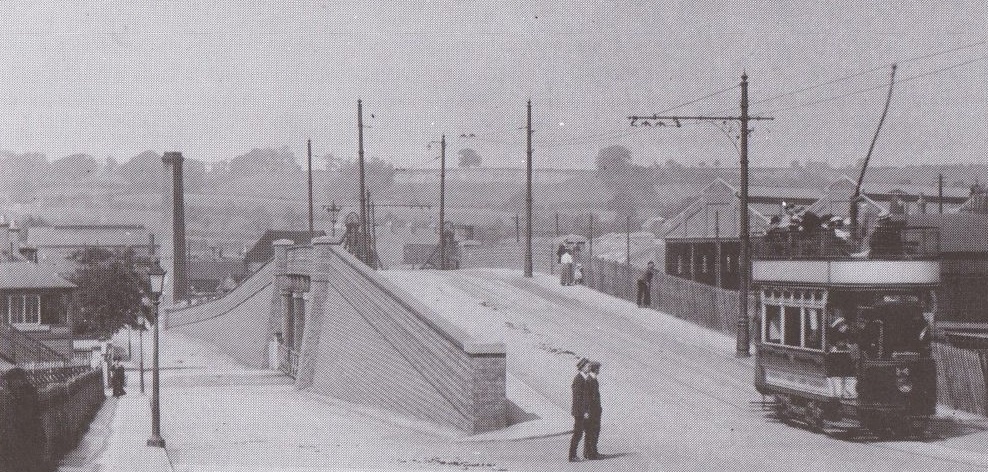

He also comments on the way that in the years prior to the War, local tramways took significant suburban traffic from the railways, whereas, after the War, that traffic seemed to return to the railways.

Gairns also asks his readers to note the limited statistical changes to goods traffic over the period and to appreciate that in the 1920 figures freight movements were only records once rather than predicted to each individual railway company.

In respect of gross receipts and expenditure, he asks his readers to remember that in 1920 the Government control of railways under guarantee conditions was still in place and to accept that, “the altered money values, and largely increased expenditure (and therefore gross receipts) figures vitiate correct comparison, so that the 1897 and 1913 figures are of chief interest as showing the development of railway business.” [1: p383]

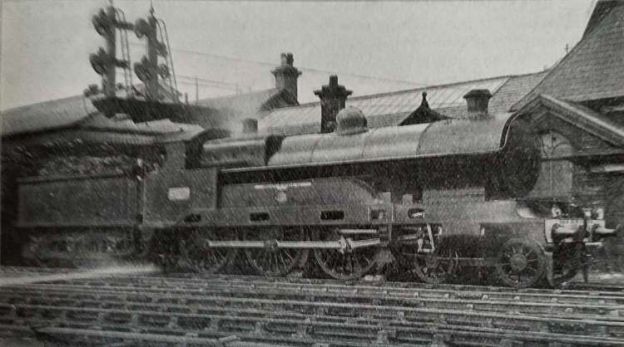

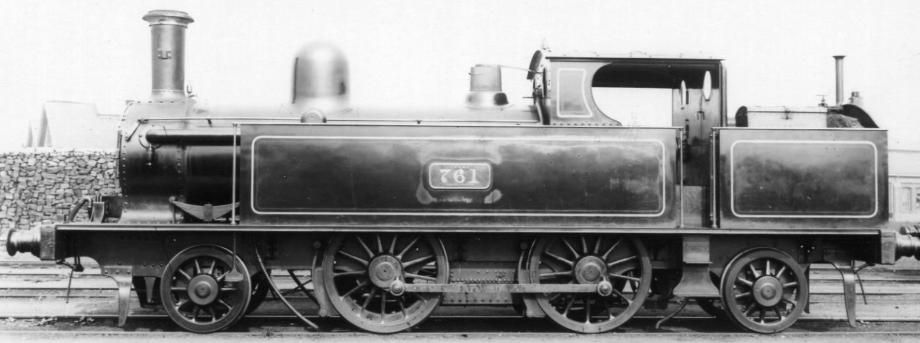

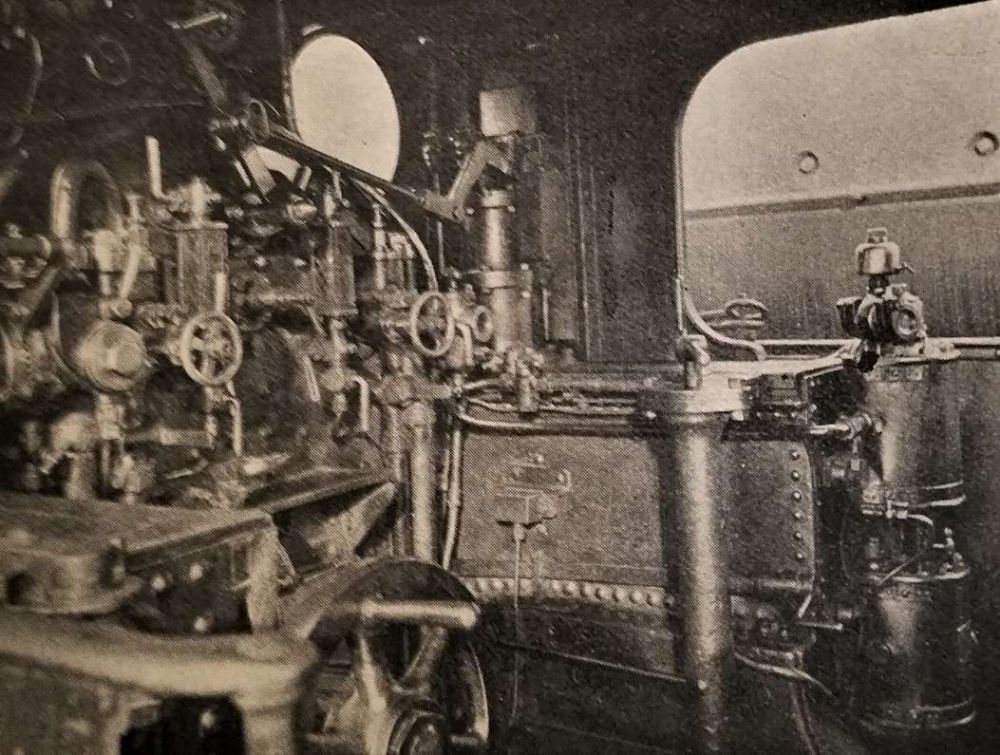

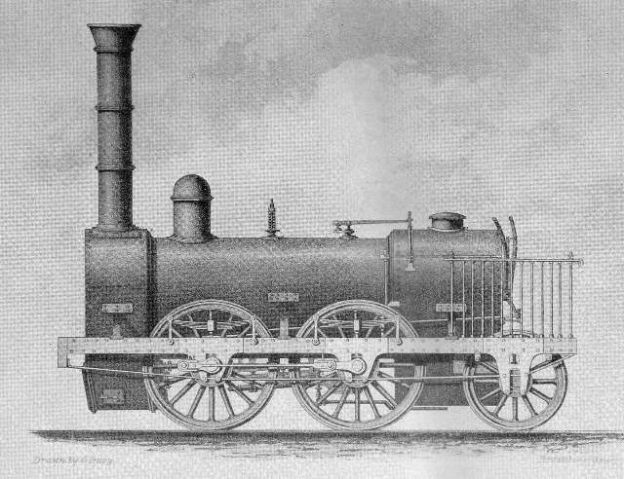

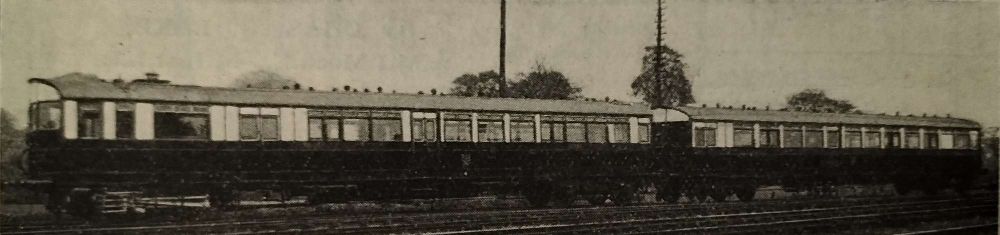

Gairns goes on to show rolling-stock totals for 1897 and 1920. …

Steam Loco numbers increased from 19,462 to 25,075; Electric Loco numbers rose from 17 to 84; Railmotor cars rose from 0 to 134; Coaching vehicles (non-electric) increased from 62,411 to 72,698; Coaching vehicles (electric, motor and trailer) rose from 107 to 3,096; Goods and mineral vehicles rose from 632,330 to 762,271.

“In 1897 the 17 electric locomotives were all on the City and South London Railway, and 44 of the electric motor cars on the Liverpool Overhead, and two on the Bessbrook and Newry line, with the 54 trailer cars on the City and South London, and seven on the Liverpool Overhead.” [1: p383-385]

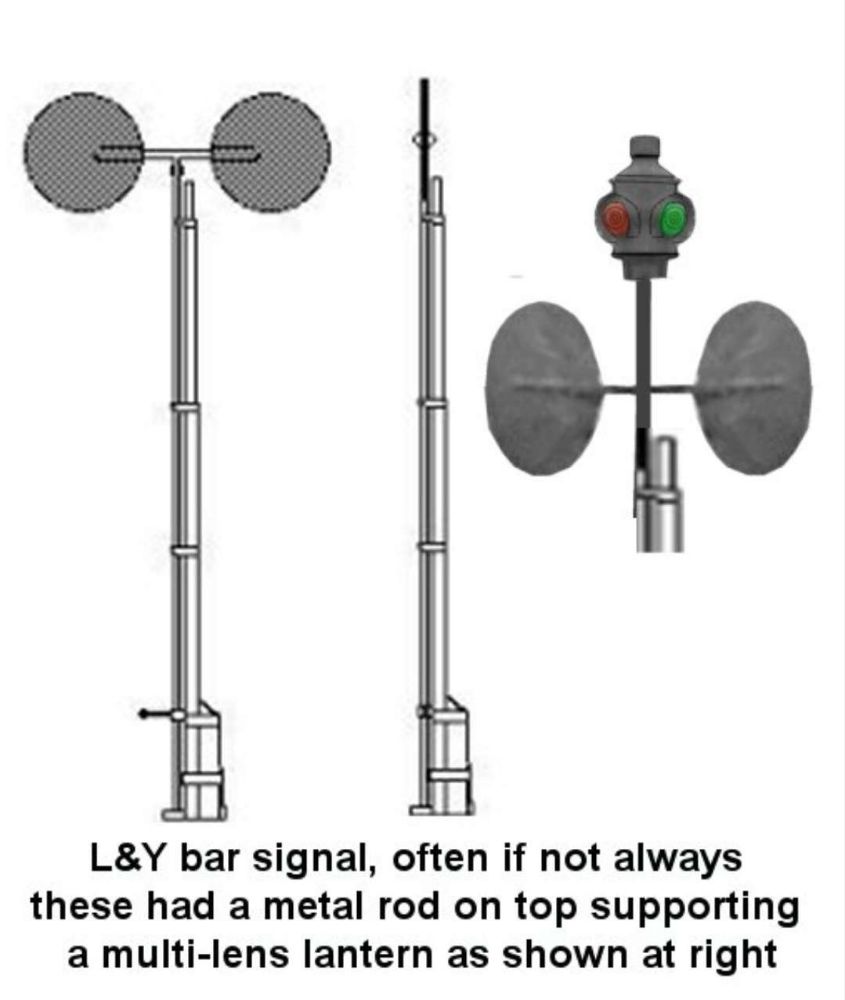

Gairns notes as well that by 1922 there was a “widespread use of power for railway signalling with its special applications for automatic, semi-automatic and isolated signals.” [1: p385]G

Gairns completes his article with an optimistic look forward to the new railway era and the amalgamations that would take place as a result of the Railways Act, 1921. Changes that would come into effect in 1923.

References

- G.F. Gairns; Twenty-five Years of Railway Progress and Development; in The Railway Magazine, London, June 1922, p377-385.

- The Cardiff Railway in The Railway Magazine, London, April 1911.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_Talbot_Railway_and_Docks_Company, accessed on 26th October 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chipping_Sodbury_Tunnel, accessed on 28th October 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/782781, accessed on 28th October 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/804338, accessed on 28th October 2024.

- https://www.streetmap.co.uk/map/idld?x=378500&y=182500&z=120&sv=378500,182500&st=4&mapp=map[FS]idld&searchp=ids&dn=607&ax=373500&ay=183500&lm=0, accessed on 28th October 2024.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/10/26/the-new-high-level-bridge-at-newcastle-on-tyne-the-railway-magazine-july-1906.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/EAW003166, accessed on 28th October 2024.

- https://www.railwayarchive.org.uk/getobject?rnum=L2431, accessed on 29th October 2024.