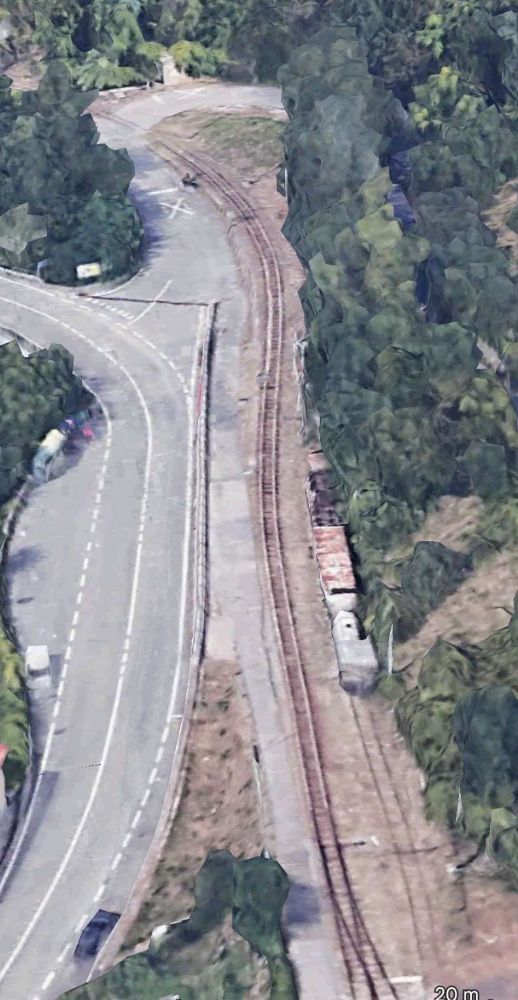

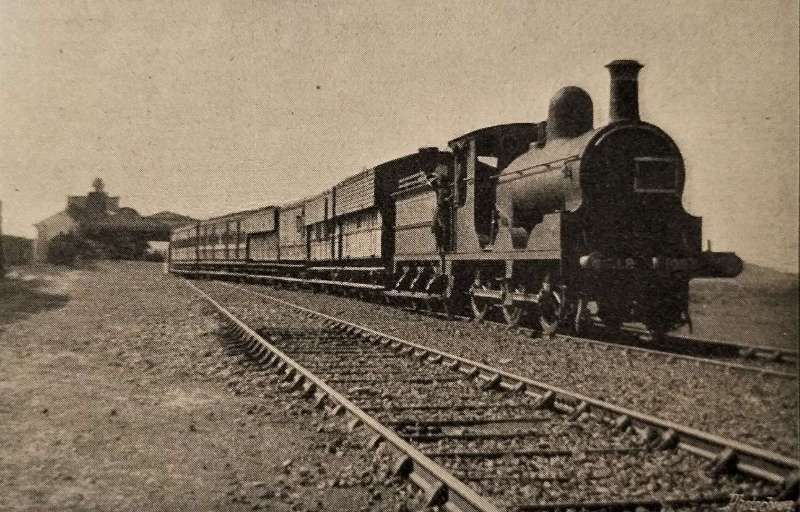

The featured image captures the Metropolitan Railway locomotive No. 23 during the London Underground centenary celebrations in 1963. The locomotive is an ‘A’ Class 4-4-0T condensing steam engine, built by Beyer Peacock in Manchester in 1866. It was designed specifically for use on the Metropolitan Railway’s Inner Circle line, where it was intended to limit smoke emissions in the tunnels. It was withdrawn from underground use in 1905 after the lines were electrified. Its appearance in 1963 at Neasden was a special event, marking 100 years of the London Underground. [93]

I received a few very welcome gifts for Christmas 2025. This article is the third in a short series:

- Colin Judge; The Locomotives, Railway and History 1916-1919 of the National Filling Factory No. 14, Hereford; Industrial Railway Society, Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, 2025. [1]

- Anthony Burton; The Locomotive Pioneers: Early Steam Locomotive Development – 1801-1851; Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2017. [2]

- Christian Wolmar; The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground was Built and How it Changed the City Forever (2nd extended Edition); Atlantic Books, 2020. This edition includes a chapter on Crossrail.

- Neil Parkhouse; British Railway History in Colour Volume 6: Cheltenham and the Cotswold Lines; Lightmoor Press, Lydney, Gloucestershire, 2025.

3. The Subterranean Railway

Christian Wolmar’s book published by Atlantic is a 2nd extended edition of a book published in 2004, dating from 2020. The chapter about Crossrail is the last chapter of the book on pages p323-342. This article provides a potted history of the London Underground and a quick look at other similar systems around the world, which comes out of reading Wolmar’s excellent book.

“Since the Victorian era, London’s Underground has played a vital role in the daily life of generations of Londoners. ‘The Subterranean Railway’ celebrates the vision and determination of the 19th-century pioneers who made the world’s first, and still the largest, underground passenger railway: one of the most impressive engineering achievements in history. … From the early days of steam, via the Underground’s contribution to 20th-century industrial design and its role during two world wars, to the sleek and futuristic Crossrail line, Christian Wolmar reveals London’s hidden wonder and shows how the railway beneath the streets helped create the city we know today.” [3: back cover]

Simon Jenkins: “A total delight… Brings a much-neglected period of the city’s history splendidly to life.”

Tom Fort, Sunday Telegraph: “I can think of few better ways to while away those elastic periods awaiting the arrival of the next east-bound Circle Line train than by reading [this book].”

Christian Wolmar wrote his preface to the 2nd edition at a time when the London Underground was carrying fewer passengers than at any time since the Second World War. As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic the whole of Transport for London was a on life support. He was concerned enough about the state of the Underground to suggest that the future of the system was in doubt. Writing this article in 2025, his concerns seem to be a little dramatic. It is already quite difficult to remember just how disturbing life in the pandemic really was.

Wolmar comments: “While the crisis caused by the pandemic will eventually be overcome, the situation it will leave behind is mixed. On the positive side, there is much to cheer. Compared with when the first edition of this book was published more than a decade and a half ago, there have been substantial improvements, with new trains, refurbished stations and easier ticketing systems. Crossrail, now to be called the Elizabeth Line, provides the most significant improvement to London’s railway network in a generation, if not since 1906-7 when three Tube lines were opened within a year. The Elizabeth Line is rather misnamed since it is not like the existing Tube services, but rather it is a full-sized railway running under the centre of the capital, built to modern standards of safety and space. Air-conditioned, with platform doors and serving nine large below-the-surface stations in central and southeast London, it will relieve overcrowding on several Underground lines and will give many people far quicker access to the centre of the city than was hitherto possible, as it will obviate the need for many to access the Underground via a mainline station. Although Crossrail’s opening, now expected, though not confirmed, to be in 2021, has been delayed by three years and costs have gone up by at least £3bn to £18bn, Londoners will be amazed when the services start running. It is a genuine twenty-first century railway, quite unlike the dingy Tube lines, and will offer a standard of comfort that is far above that on any other local rail services in the capital.” [3: pxiii]

“Yet, hanging over the future of the London Underground is the concern about whether the peak numbers attained in the late 2010s will ever be reached again. There is no doubt that many people will have discovered the possibility of working at home, at least for part of the week, and therefore passenger numbers are bound to be depleted for some time to come. It goes further than that. The very nature of the central London economy is dependent on the hustle-bustle created by its cafés, restaurants, sandwich bars, cinemas and theatres. If a significant number stop going to work, offices will become empty, and the kind of inner-city decline seen the world over in the post-war car-oriented period will return. We have got so used to complaining about overcrowded trains and buses that we have forgotten that without these vast numbers using public transport, it no longer becomes viable. Therefore, if many of these passengers fail to return to use the system, not only will it reduce the likelihood of further investment and perhaps a return to the dog days of the post-war period described in this book, but also it may result in a much wider loss: the vibrancy and buzz of one of the world’s most successful cities. The London Underground is the beating heart of the capital and when it is ailing, so is London.” [3: pxiv]

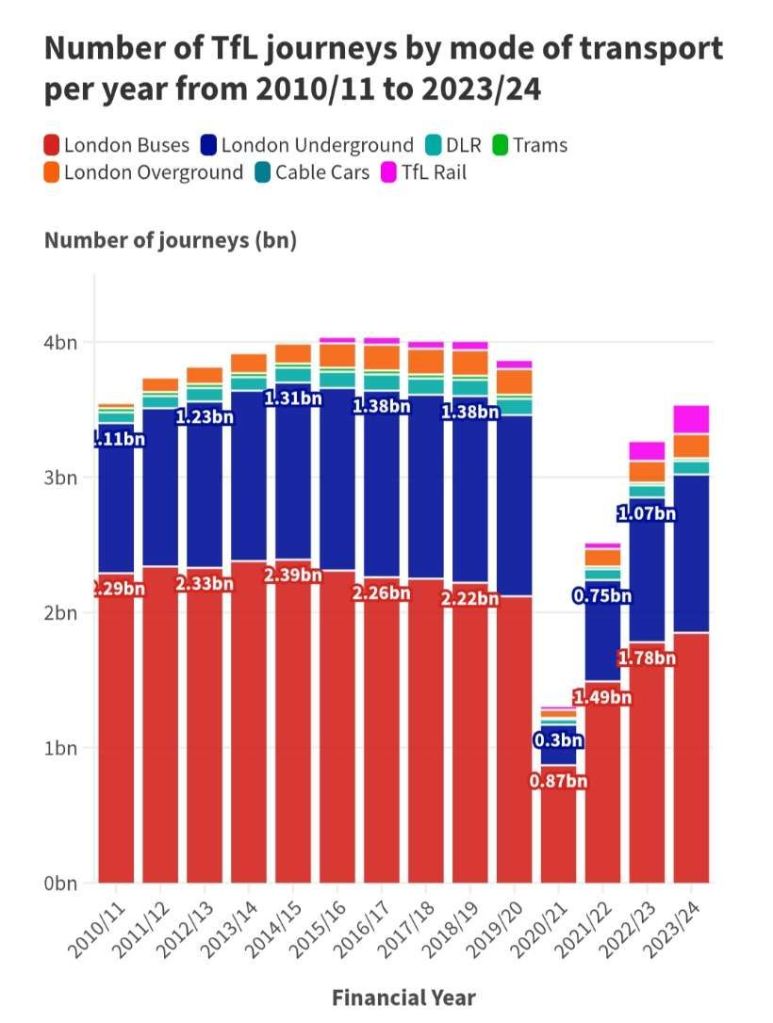

On 24th November 2023, passenger numbers exceeded 4 million/day for the first time since the pandemic. [5] This was up 7.6 per cent on the equivalent day in 2022 (24th November 2022), when ridership was about 3.76m.

In 2023/24 daily rider numbers averaged around 3.23 million.

Before the pandemic (around 2019), the London Underground saw much higher usage, with daily ridership often hitting 5 million journeys.

The graph above shows that passenger numbers have been gradually recovering from a very low ebb. The picture is considerably better than Wolmar feared.

Wolmar, in his introduction to the 2nd edition says: “Oddly, even many biographies of London pay little attention to the system hidden anything from thirty to 250 feet beneath its surface. Of course there are many books which concentrate on the engineering achievements of the railway and its haphazard construction. The spectacular feat of building a railway underneath a built-up area, a concept so brave and revolutionary that it took nearly forty years for any other country to imitate it, should not be underestimated. The people who devised and developed the concept were visionaries, ready to risk ridicule and bankruptcy to push forward their ideas. This book explains how they did it, but the achievements of the Underground go way beyond its mere construction. Its role in the development of London and its institutions is probably greater than that of any other invention apart, possibly, from the telephone. Without the Underground London would just not be, well, London. Oddly, that is recognized more often abroad where the famous roundel, the ‘logo’ of the system created long before that word was ever in common parlance, is the emblematic image of the English capital.” [3: p5]

Wolmar says that his book is an attempt “to do justice to the achievement of the Underground pioneers not only for having produced a transport system which, for a time, was unparalleled anywhere in the world, but also for having helped create and transform the city. It tells both their story and that of the system they made, and shows that their achievements go far beyond the realm of transport.” [3: p8]

Chapter 1 – Midwife to the Underground

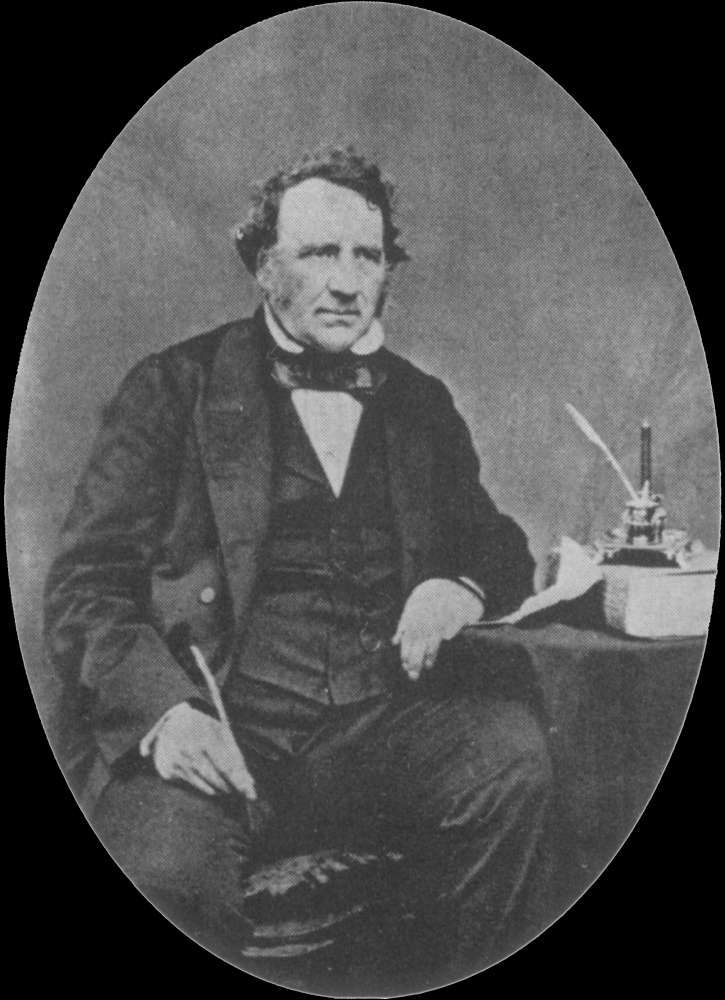

As Wolmar tells the story, the Underground was a concept invented by Charles Pearson who was born in the late 18th century – October 1793, more than two decades before Napoleon met his Waterloo.

Pearson was the City of London solicitor who set out an idea in a pamphlet in 1845 – “a railway running down the Fleet valley to Farringdon that would be protected by a glass envelope. … The trains were to be drawn by atmospheric power so that smoke from steam engines would not cloud the glass. This, of course, was not the scheme that was eventually built, but Pearson’s concept was certainly the kernel of the idea that was to become the Metropolitan Railway two decades later along broadly the same route.” [3: p9]

It was Pearson who masterminded the financing of the Metropolitan which saved the scheme at the eleventh hour. It could also be argued that had he failed in his mission, the underground may never have been built as other transport solutions became available in following decades. However, Paris Metro (1900) and the New York underground (1904) learnt much from London’s experience.

Before the underground, London was growing too fast and its burgeoning traffic was throttling the life out of the economy. Various schemes sought to address the problem: horse drawn omnibuses; horse drawn trams. Both resulted in an even faster growth in the population. London was “a vortex, sucking in an ever greater proportion of the nation’s population. It was the most exciting city in the world and everyone wanted or needed to live there.” [3: p13] A failure of imagination by railway companies left the immediate areas outside the compact city limits with very few stations. No one appreciated the lucrative market that would develop if it was resourced effectively. The railways as a result had a much lesser effect on London than they did in the regions. [7]

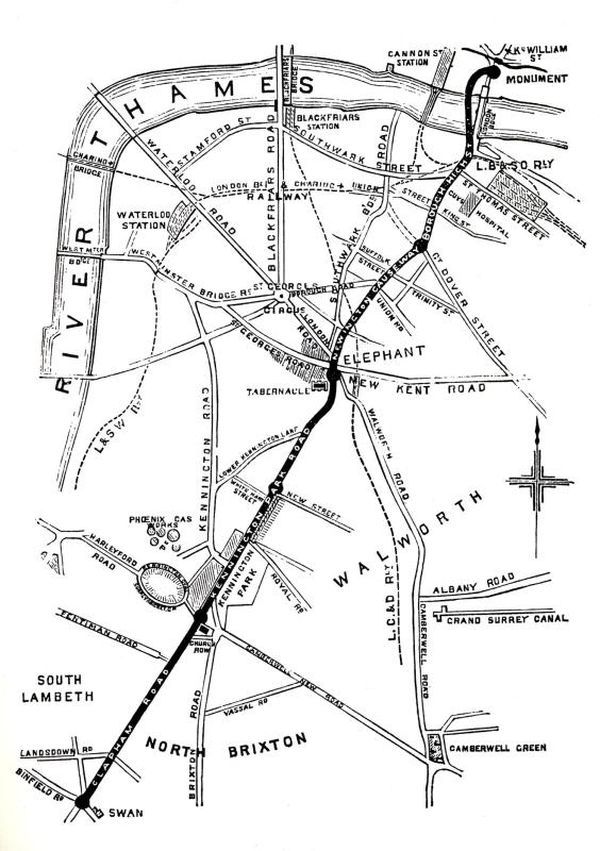

Land values South of the Thames were lower than on the North side of the river and overground services developed alongside urban expansion to the South of the river in a way that just was not possible North of the river. The first of those lines, the London & Greenwich was built on 878 arches and its promoters sought to serve the local population rather than long distant destinations. “The line was soon carrying 1,500 people per day … on trains that ran every quarter of an hour throughout the day. … By the mid-1840s, … 5,500 people were being carried daily. … It was not until the invention at the end of the nineteenth century of tube railways,which ran deep into the London clay,that the underground system was to reach across the Thames.” [3: p15-16]

The popularity of the London & Greenwich Railway showed that railways could successfully be used for short journeys. Pearson’s vision transcended modes of transport, he sought to create affordable housing outside the city linked by affordable transport which would allow even lowly paid workers access to good housing and onto the city for work. Pearson was a campaigning social reformer but faced opposition in most areas where he sought to bring reform. It seems as though “his tenacity, perhaps prompted by these setbacks, brought the scheme for an underground railway to fruition.” [3: p19]

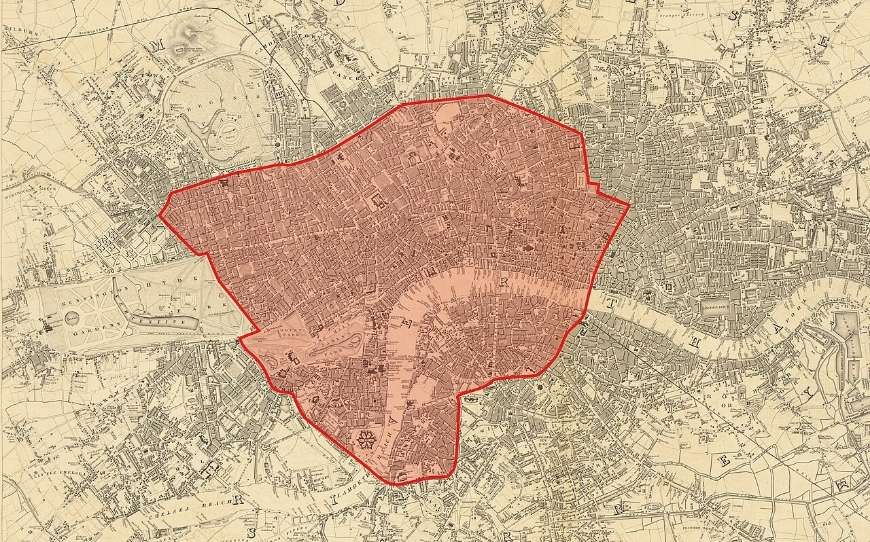

The Royal Commission on Metropolitan Railway Termini of 1846 ruled against the vast majority of proposals seeking to access the core of the City of London. Seventeen of the nineteen proposals were rejected, and only conditional assent to two schemes which were extensions South of the Thames. This commission’s decisions effectively created the need for the underground.

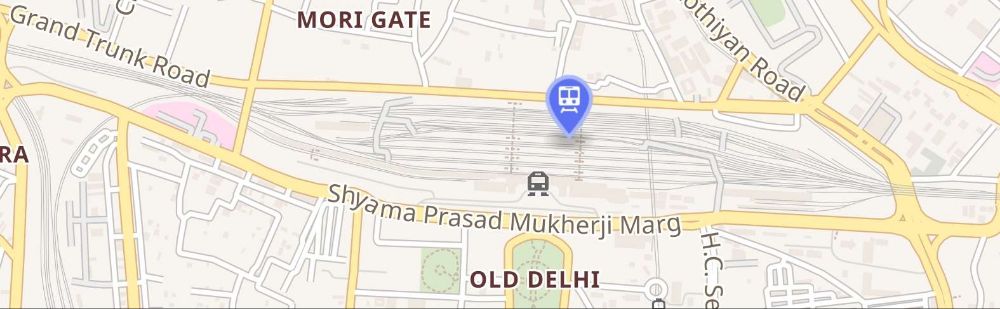

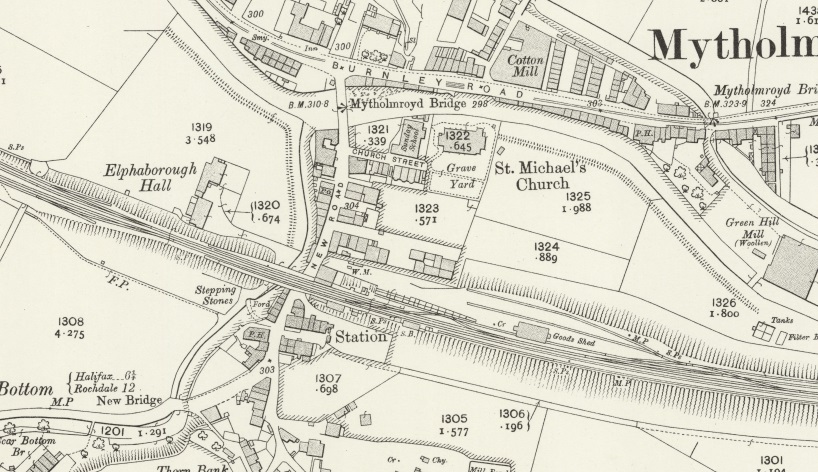

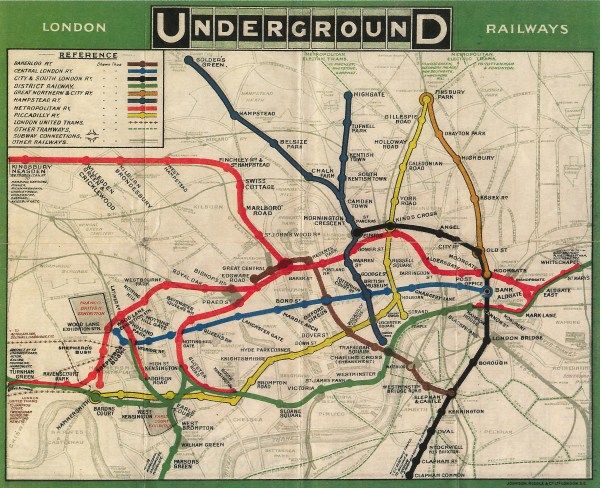

Map: J Henshall (engraver and printer). Outline: David Cane based on description contained Royal Commission’s report. This image is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 4.0). [27]

The next inquiry took place in 1854-1855. It again rejected the majority of railway schemes but recommended an ‘orbital’ railway connecting the various Termini, the Post Office and the docks, and foreshadowed the Metropolitan Railway.

Pearson’s plan for an underground railway required “bloody-minded persistence … to persuade investors to stump up the money, even though the scheme had been endorsed … by Parliament.” [3: p26]

Chapter 2 – The Underground Arrives

Wolmar takes some time to outline the nefarious practices of the Metropolitan Railway driving their line down the Fleet valley. The Company was not alone in these practices. Wealthy landowners fought either to keep the railway off their land or to maximise the compensation paid. Most people, particularly slum-dwellers, were unable to fight powerful companies. Railways probably picked the alignment of their lines so as to avoid those most able to fight them. They were required to report the numbers of those displaced. The official figure for those displaced on the length from Paddington to Farringdon Street was 307. A contemporary source (Wolmar cites George Godwin) [8] claimed that the actual numbers for the length from King’s Cross to Farringdon Street were 1000 houses demolished with approximately 12,000 people displaced.

However, by 1857, the Metropolitan Railway was struggling to draw together enough finance for the scheme and were closed to winding up the business. Instead, in 1858, they decided to spend £1000 in a final attempt to attract investors. Pearson (not a director of the Company) came to the rescue, persuading the City of London Corporation to invest in the project. It was the congestion on the streets that ultimately convinced the Corporation that the project was necessary. Construction began in 1860 [3: p33]

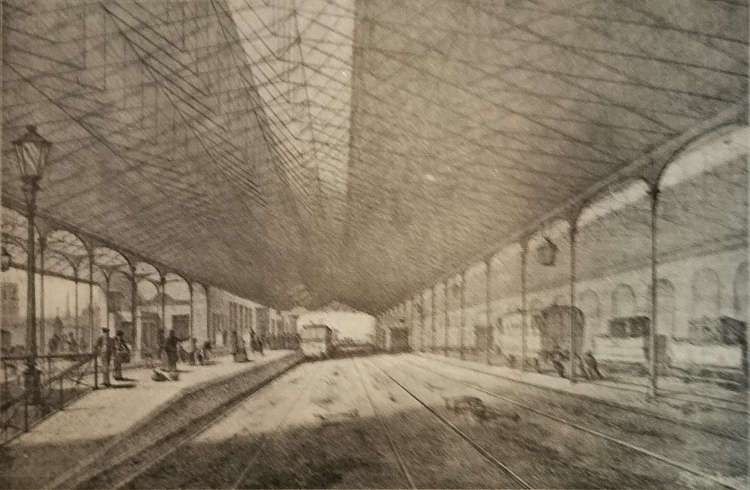

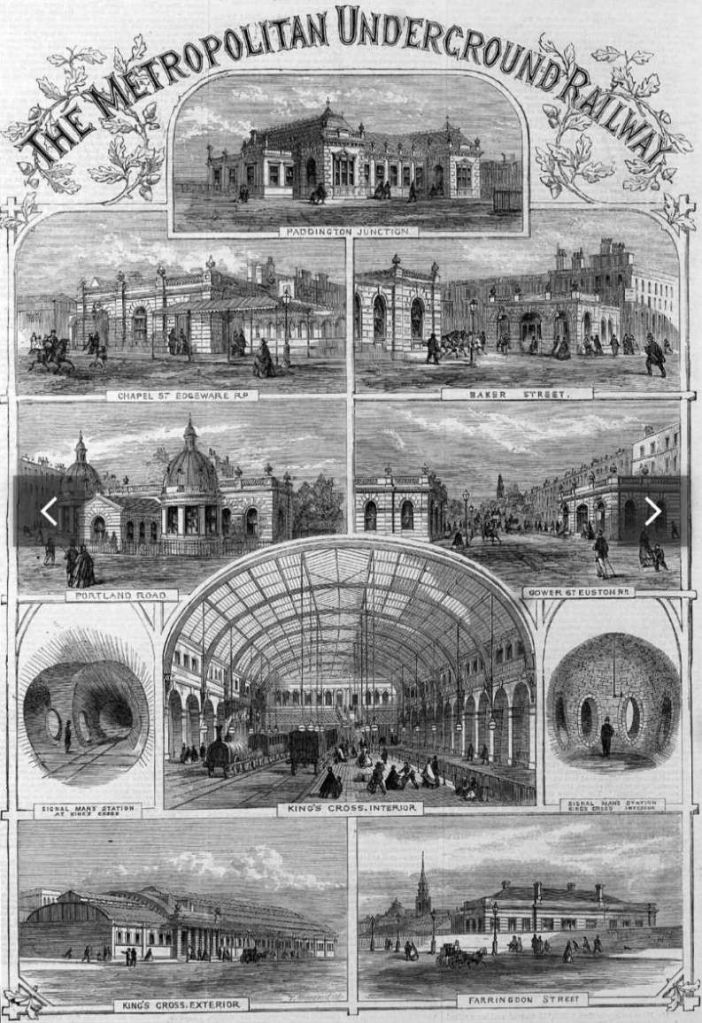

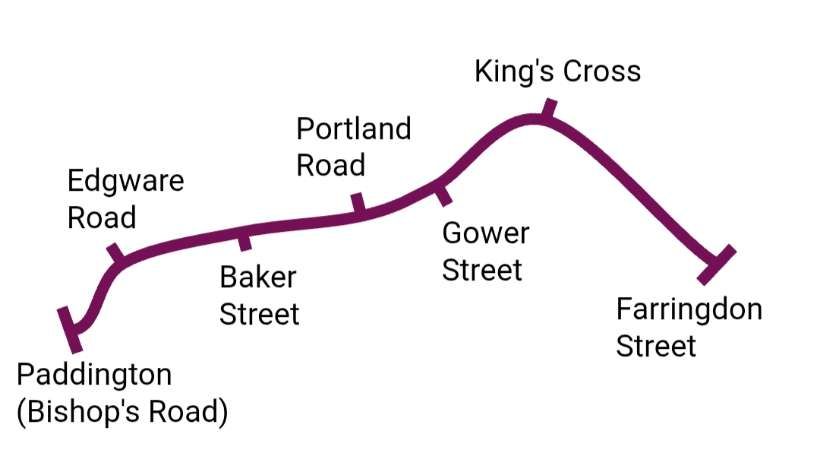

Despite some significant obstacles to be overcome the line opened officially on 9th January 1863. The first length of the Metropolitan Railway, the world’s first underground railway, was 3¾ miles (6 km) long, running between Paddington (Bishop’s Road) and Farringdon Street.

Apart from various difficulties during construction, Wolmar tells that “the most intractable problem … was for the Underground’s engineers to devise a way of operating trains that did not choke their passengers. As one account puts it, ‘Pearson’s main problem was finding an engine suitable for use underground. The users’ problem was managing to breathe’. [9: p132] In fact it was more Fowler’s problem than Pearson’s and, canny engineer though he was, not all his ideas were sensible. He had originally envisaged that trains should be blown through an airtight container using giant compressors at each terminal but … the problem with such ‘atmospheric railways’ was the difficulty of keeping a tight seal.” [3: p39]

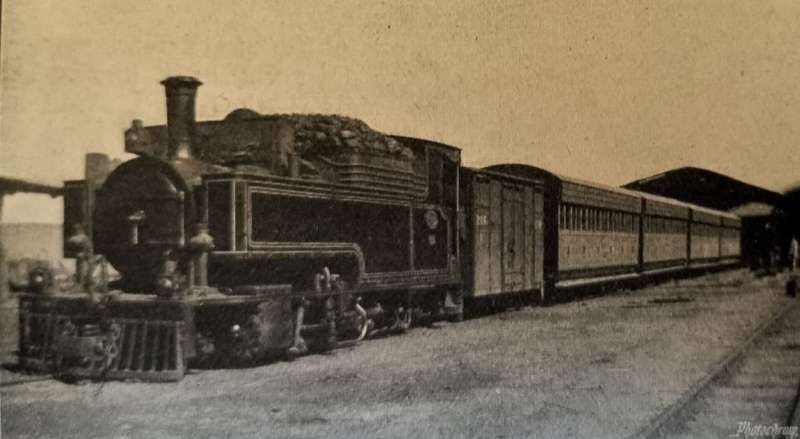

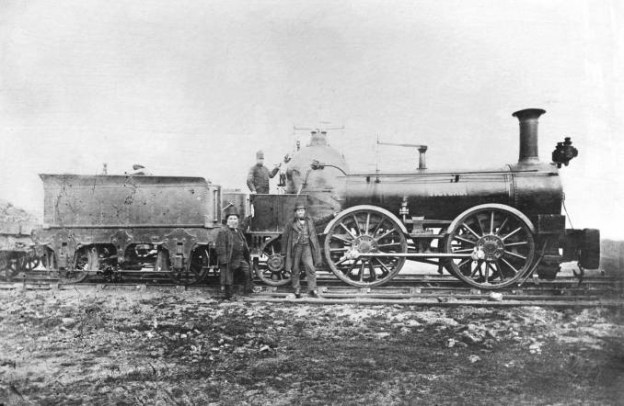

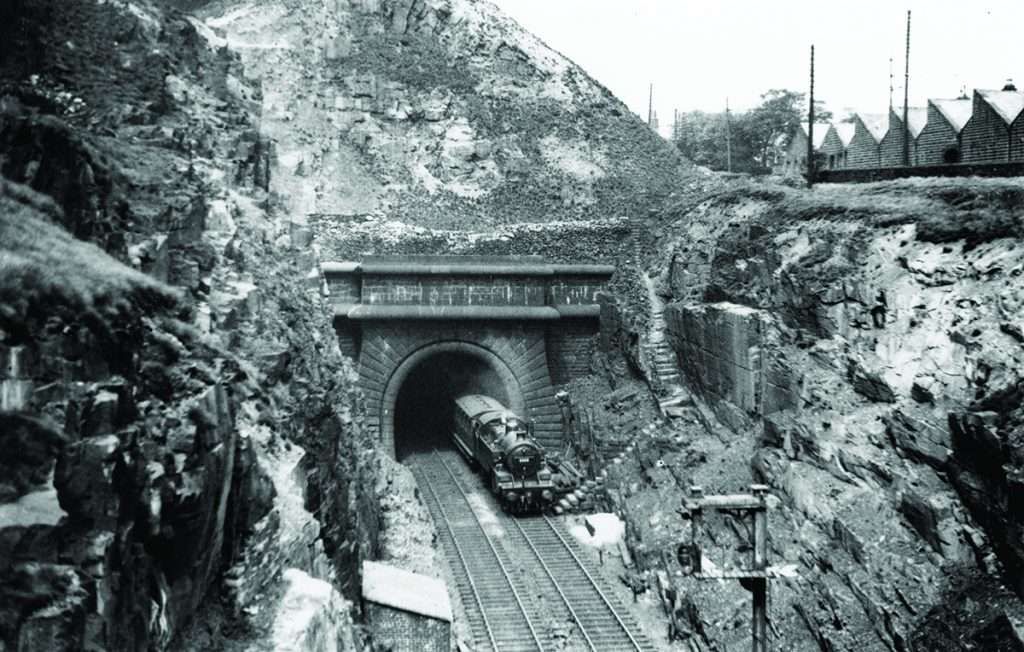

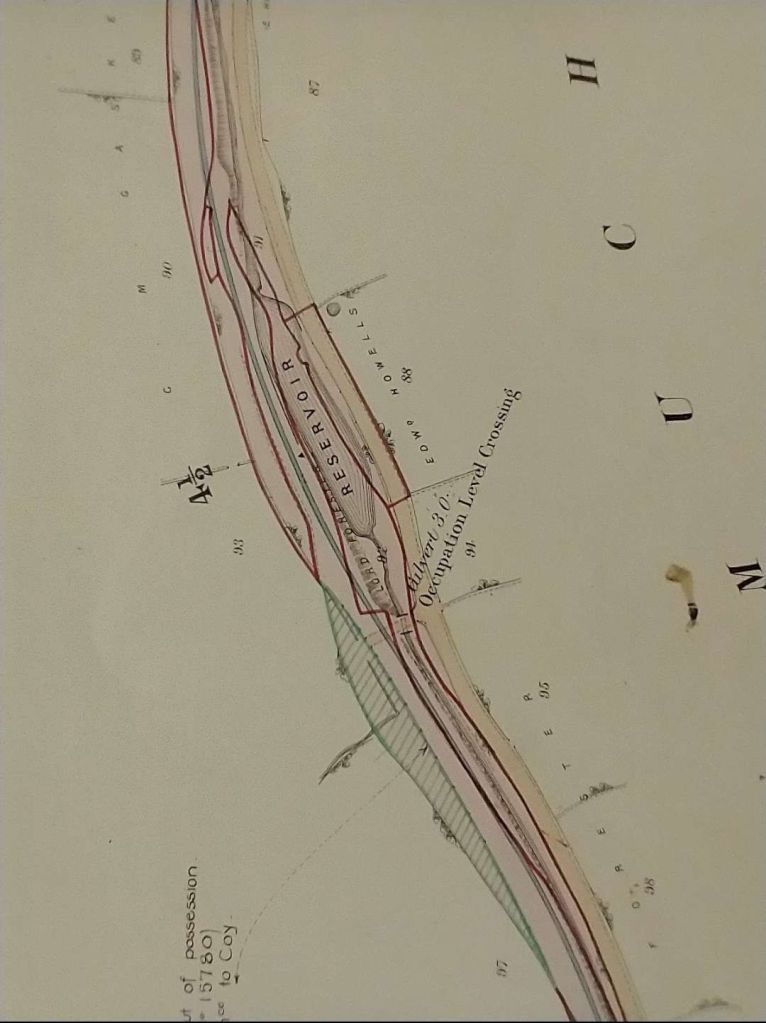

Smoke pollution and steam emissions were a very significant problem. A hybrid system was designed by Robert Stephenson “at Fowler’s behest – known as Fowler’s Ghost – which used bricks as heat storage when in tunnels and operated normally outside, proved to be too unreliable, and was rejected after trials.” [3: p40] Daniel Gooch was then asked to design an engine that would divert steam into a cold water condensing tank. This engine used coke rather than coal to minimise smoke emissions. Coke was, however, proven to be more toxic than coal and the Metropolitan later reverted to coal. [3: p40]

Pearson died in September 1862, still refusing to accept any reward for his work beyond his salary from the Corporation! His widow, however, was granted an annuity of £250/year despite Pearson not being a Company employee.

Chapter 3 – London Goes Underground

Wolmar tells us that the Metropolitan Railway was very popular. On the first day of timetabled services, 10th January 1863, 30,000 people travelled on the line! The takings that day amounted to £850.

Problems with smoke and steam persisted and complaints increased. The Company installed ventilation shafts between King’s Cross and Edgware Road in the early 1870s. Wolmar comments that these acted like “boreholes whose sudden emission of smoke and steam frequently startled passing horses.” [3: p47] Whatever was tried to alleviate the problem, it remained an issue until electric trains replaced steam in the first decade of the 20th century.

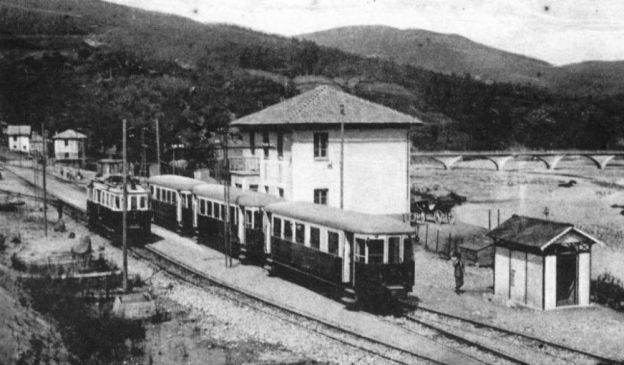

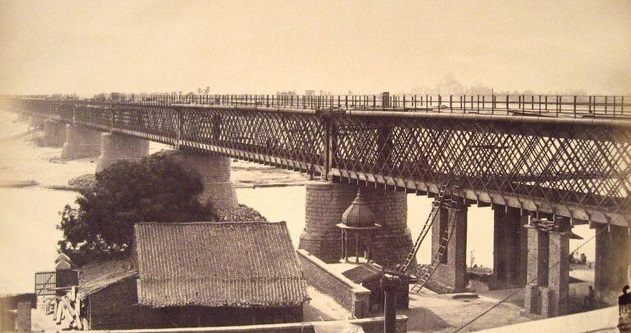

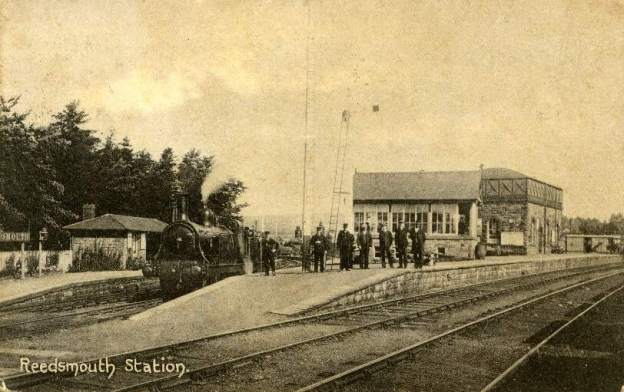

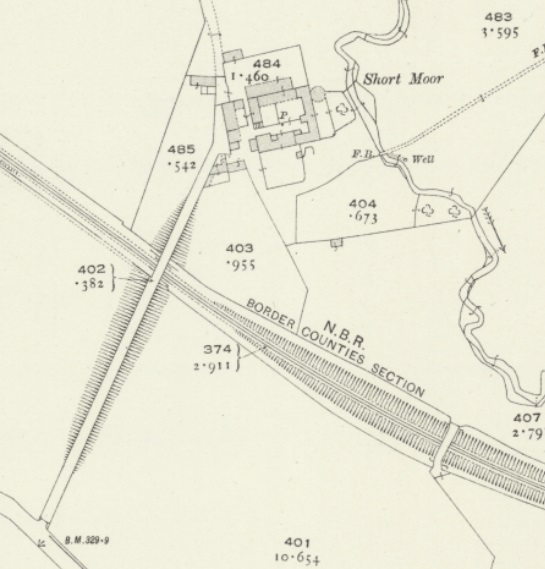

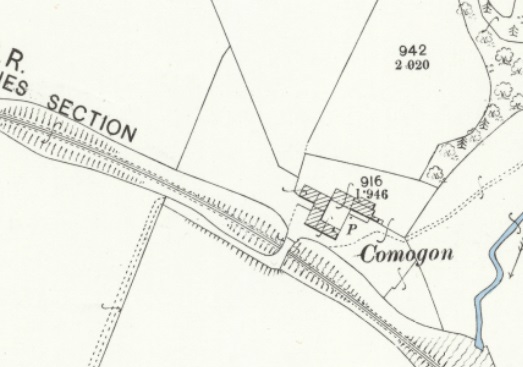

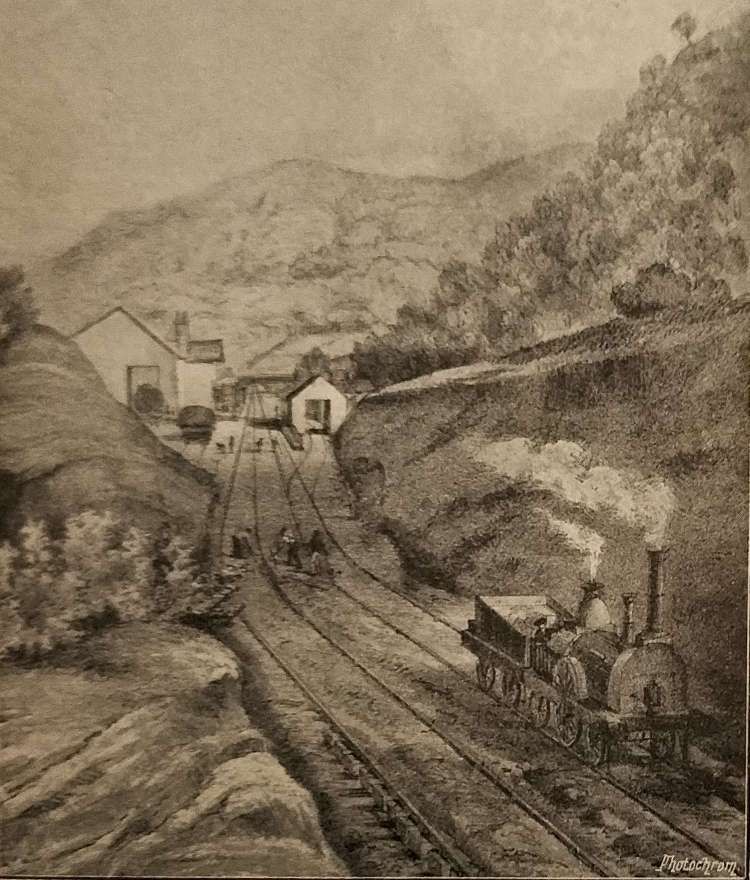

Rather than continuing to employ standard steam locomotives, the Company “ordered eighteen tank locomotives from … Beyer, Peacock. … The key feature was the condensing equipment which prevented most of the steam from escaping in the tunnels although partly this depended on the diligence of the driver who needed to refill the water as often as possible in order to keep it cool. … They were beautiful little engines, painted green and distinguished particularly by their enormous external cylinders. The design proved so successful that eventually 120 were built, providing the basis of traction on the Metropolitan and all the other early ‘cut and cover’ Underground lines until the advent of electrification.” [3: p48]

Instead of steam exhausting up the chimney, it was redirected along pipes back into side tanks where it condensed, for re-use. Although not massively successful, it was an active attempt to address tunnel conditions. [13]

Wolmar comments that despite all the problems, “Londoners seemed to have been prepared to venture down to use the line. Indeed, the bad publicity before the opening may even have contributed towards the Metropolitan’s success by lowering expectations so that travellers were then surprised to find it was not quite as bad as they had been led to expect. By the standards of Victorian railway building the Metropolitan was highly successful, even in financial terms. In the first full year of operation, 11.8 million people used the line, more than four times the population of the capital – a daily average, including Sundays, of 32,300, which was a remarkable achievement given the limited route it served. … The peak day in the first year for the Metropolitan was Saturday, 7th March, when Princess Alexandra of Denmark arrived in London for her marriage to the Prince of Wales: 60,000 people, double the usual number, travelled on the line.” [3: p50]

In May 1864 the Metropolitan Railway’s gross receipts were £720/mile/week. The comparative figure for the London, Chatham & Dover, which was the next best performing line, was £80. Profits in the first year were £102,000 and a dividend of 6.25% was paid to shareholders. In its first 44 years the Metropolitan Railway “did not experience a single railway accident resulting in the death of a passenger, which is extraordinary given the intensity of service, the use of steam engines and high passenger numbers. Indeed, according to the definitive history of London’s transport, ‘during the whole period of steam operation, there was no fatal accident to any passenger in these cuttings and tunnels’ [15: p118] caused by a train collision or derailment. The first serious accident on the underground system involved a head-on collision near Earls Court in August 1885 between a District train and a Great Western service, which killed the two crew of the Great Western train.” [3: p54]

The Metropolitan was not just a local passenger line. The GWR ran through passenger trains via Paddington and the Great Northern via King’s Cross to and from Farringdon Street Station. The Metropolitan Railway was also used for freight. In fact, “freight was carried until well after World War Two.” [3: p62]

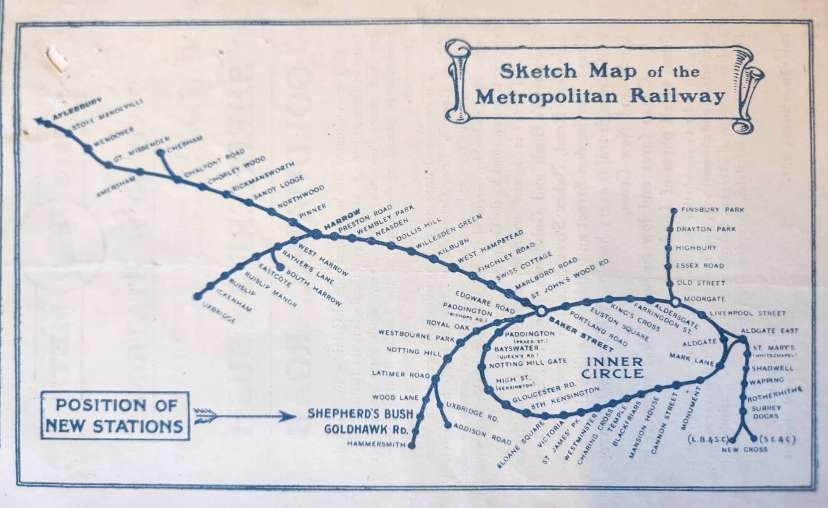

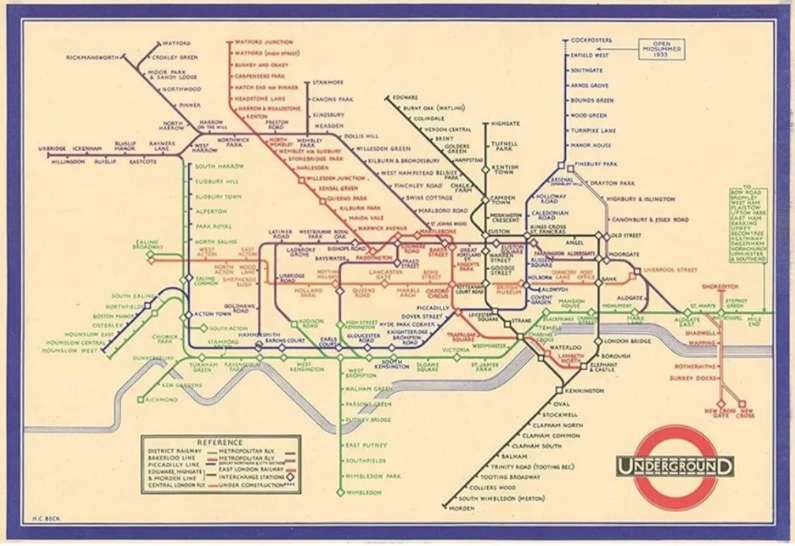

Wolmar goes on to identify the development of the underground network:

The Metropolitan Railway’s own expansion plans took time to realise (a quarter of a century), but various connections and lines were added to allow the major railway companies in the capital to make use of the line. The short line became even more profitable!

Its success resulted in what Wolmar says were 259 different projects for creating 300 miles of railway. Wolmar says that “if all the lines had been built, four new bridges would have been needed across the Thames and only a quarter of the existing city would have been left standing.” [3: p62]

It seems that the City could not contemplate a free-for-all. It set new parameters for railway schemes in the capital and referred around 20 schemes to a joint committee of both Houses of Parliament. That committee rejected all but four of the lines affecting the Metropolitan. Three were for sections of what would become the inner Circle and one which would allow the company to expand out from Baker Street to the Northwest. [3: p63]

The Metropolitan expanded first by widening (adding tracks) to accommodate heavy traffic loads which were added to by the completion of St. Pancras and its connection to the Metropolitan. It then extended into the City via Aldergate Street to Moorgate (1865). The London, Chatham & Dover Railway crossed the Thames in 1864 and joined the Metropolitan at an extended Farringdon Street Station in 1866. [3: p64]

By 1871 when a connection was made between Snow Hill Junction and Smithfield, there were half a dozen main line railways connected to the Metropolitan Railway and it provided the only North-South cross-London rail route.

While passenger services began to decline in the early years of the 20th century with the advent of more direct bus services, goods trains remained heavy users of the line. “The vital link through the Snow Hill Tunnel fell into disuse in the 1960s but was reopened in 1988 … and is used by heavily loaded Thameslink trains.” [3: p66]

The Metropolitan’s first extension left Baker Street and ran as far as Swiss Cottage in April 1868. This insignificant line became “the start of a major extension of the Metropolitan that would stimulate growth of a whole quadrant of London.” [3: p67]

The Metropolitan began to spread its tentacles, but first London was to get its Circle line. “The line would be controlled by two rival companies, led by railway pioneers who hated each other: James Starts Forbes and Edward Watkins.” [3: p70]

Chapter 4 – The Line to Nowhere

Wolmar says that before completion of the Circle line, the Metropolitan was little more than a tunnel under London. “The Circle changed that. London would, thereafter, have a genuine underground railway with many journeys both starting and ending beneath the streets.” [3: p71]

In 1863, a House of Lords Committee determined “that a connection between the main line termini would best be achieved by extending the Metropolitan eastwards from Moorgate and westwards from Paddington, eventually meeting the Thames.” [3: p72]

A second committee, a joint committee of the Lords and Commons, examined proposals submitted by Sir John Fowler and a series of other schemes and decided in favour of Fowler’s proposals. Three bills were quickly drawn up and we’re on the statute books in July.

Work between Paddington and South Kensington began immediately and by 1868 the line to South Kensington was open. The planned connection to the District line was under construction from Kensington to Westminster. It took 3 years to build and because of the constraints placed on it cost £3 million.

Construction of the Underground was used as a catalyst for reshaping large swathes of London. Reading Wolmar’s description of these changes suggests that it was an excellent excuse for the redevelopment of different areas. [3: p73-85]

Work on the Embankment started in 1869 which was meant to include a stretch of the District line. The District line wanted time to recover from the excessive costs associated with construction between Kensington and Westminster. The Metropolitan Board of Works pressed for the railway to continue construction. It took until 1870 for the District to obtain powers to raise the necessary £1.5 million. But by May 1870, the line was open through to Blackfriars. [3: p75]

Wolmar says that, six weeks after the extension to Blackfriars, the Embankment was opened but “the East and West Ends were very different worlds and it would be another fifteen years before the underground linked them as well.” [3: p76]

Once the line reached Mansion House (July 1871, [16]), services on the District Line ran all the way round to the Metropolitan’s new terminus at Moorgate. Both companies had over-extended themselves. The obvious way forward was for the two companies to merge. However, each company had appointed an individual to lead them out of financial difficulty. The two individuals concerned, J.S. Forbes and E. Watkins, had a shared history that meant cooperation would be extremely unlikely! [3: p76]

Wolmar comments: “Forbes and Watkin were very different characters who had headed rival railways. James Staats Forbes had worked for Brunel on the construction of the Great Western and had gone on to save the London, Chatham & Dover Railway – which had been on a path of almost suicidal expansion and cut-throat competition with the South Eastern – from bankruptcy. He started there as general manager in 1862, taking the railway out of receivership and then going on to stay nearly four decades, the last twenty-five years as chairman and described as a past master in the art of bunkum’, [17] and was, on the surface, an easygoing and cultured character who built up an extensive art collection with the money he made from the railways. He also had a steely backbone that was to help fuel the thirty-year feud with Watkin, who had an even more aggressive and domineering personality. The District’s directors were so desperate to obtain Forbes’s services that they reduced their own allowance by £1,250 in order to pay him a salary of £2,500 without imposing a further financial burden on the shareholders. Forbes became the managing director of the District in 1870 and chairman when he ousted the Earl of Devon a couple of years later. ” [3: p76-77]

Wolmar describes Forbes as a company doctor resolving a legacy of unrealistic expansion. He describes Watkins as a great visionary, ever espousing grand plans. He had access to family wealth and associates who could help promote his railway ambitions. He was a campaigner, seeking the provision of public parks, and pushing for workers to have Saturday afternoons off. He was an MP for a while. Wolmar tells us that, “At one time or another during his long career he was a director of most of the major main line railway companies in England, and he was involved in many railway projects abroad, notably in Greece, and in Canada where his efforts to save the Grand Trunk Railway ensured that the country eventually obtained a transcontinental line.” [3: p77]

Wolmar cites a few sources that described Watkins and which build up a picture of someone who, “was a difficult man to work with. Although he was, at times, extremely affable, he was ruthless and enjoyed nothing more than a good fight, including public disputes with the directors of companies he chaired. His belligerence resulted in a battle with Forbes that lasted for over three decades, but fortunately for Londoners, most of the conflict between the pair was fought out in the Kent countryside. Even today, the pattern of the railway network and the existence of two stations in many modest-sized towns such as Maidstone, Sevenoaks and Margate, serving different London termini, is a reflection of the long battle between the two railways when they were led, respectively, by Forbes and Watkin. Watkin was secretive and abrasive in negotiations, while Forbes, possibly disingenuously, presented himself as more amenable. Forbes refused to bow to pressure from his rival and set out to expand to survive. The ruinous competition, which was to the detriment of both passengers and shareholders of the two railways, only ended when Waking retired in 1894; within five years the two companies had effectively merged.” [3: p78]

Although not as wasteful as in the Kent countryside, Forbes and Watkin’s animosity cost their respective companies dear. The Metropolitan’s expansion eastward came to a halt after connecting with Liverpool Street Railway Station, Bishopsgate and Aldgate in 1876. Cut and cover construction was just too expensive to contemplate further expansion.

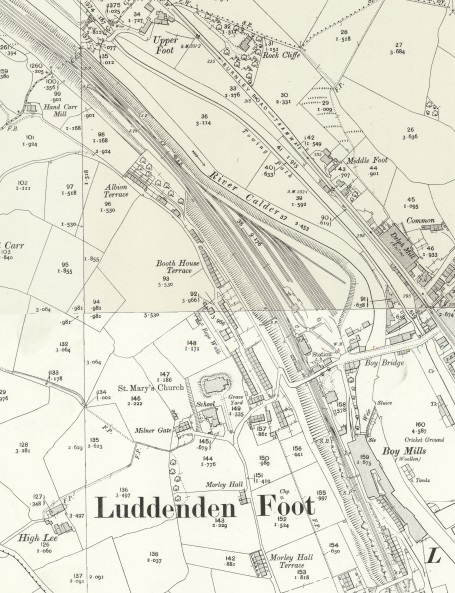

James Forbes expanded south-westward, connecting the towns of Ealing, Richmond and Wimbledon to Westminster by 1879. As much of the land was not heavily developed, it was significantly cheaper to build above ground out west than to go underground in central London. The expansion was popular, and facilitated London’s growth to encompass many once separate towns and villages. [17]

Meanwhile, Edward Watkin was creating new branches of his railway, going west and north. His intention was to link his underground section in London to the other railways he owned in the North of England. It was a project which ran out of funds, and ground to a halt 50 miles outside of the capital. [18]

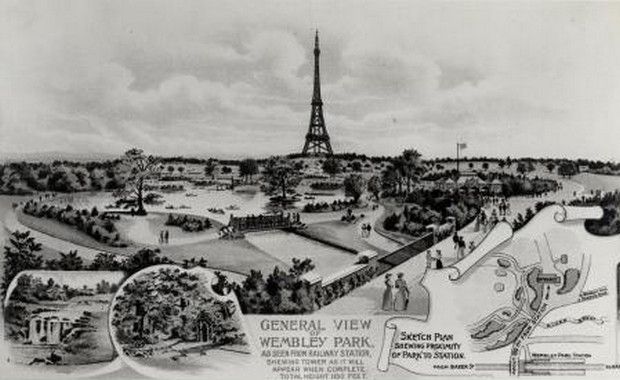

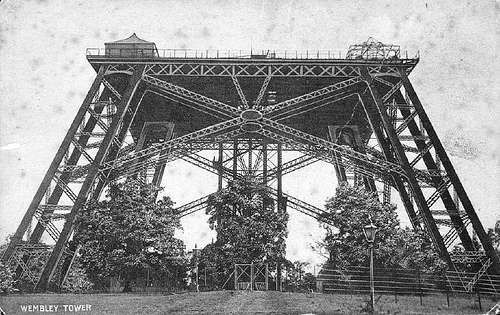

Watkin’s plan included creating tourist attractions along his line to increase passenger numbers. He decided to build his own version of the Eiffel Tower, on a hill overlooking the capital, in Wembley, © Public Domain. [18]

He intended his scheme to be considerably more grand than Eiffel’s scheme in Paris. He planned an hotel, a theatre and restaurants. Eiffel was asked to design the landmark, but declined.

Watkins still went ahead with construction in 1891. This project also ran out of money and his ‘tower’ became known as “Watkin’s Folly” and “The London Stump.” It survived until 1907 when it was demolished, © Public Domain. [19]

But we have digressed from the time line of the creation of the Underground and slipped away from Wolmar’s story. …

Wolmar tells us that, “The need for the completion of the Circle was apparent from the high usage of the sections that were already built. By 1875, the Metropolitan was carrying 48 million passengers per year, and the District, though continuing to struggle, managed to carry around half that number, still a substantial achievement. Three quarters of these passengers used third class, suggesting they were manual workers and low-paid clerks attracted by the low fares, but interestingly, as it expanded, the Underground managed to attract a substantial body of first-class passengers.” [3: p82]

Interestingly, “rather than the Underground eating into the traffic of its main rival, the horse drawn omnibus, usage of both … increased after the creation of the Metropolitan. The number of omnibus users rose from 40 million in the year of the Metropolitan’s opening to nearly 50 million in 1875.” [3: p83]

There was an early recognition in some locations in London of the need for an integrated transport system. “In some cases, the Underground companies had to subsidize … feeder services in order to boost passenger numbers on their trains. When the District first opened, there was no public transport between Regent Street and Church Lane (now High Street) Kensington, or anything along Park Lane or Palace Road. … In this affluent area of Central and West London people could afford their own carriages. … The District had to guarantee the revenue for the first omnibuses between Victoria and Paddington along Park Lane. Similarly, the Metropolitan paid for services from Piccadilly along Regent Street to what is now Great Portland Street station.” [3: p83]

‘Fun London Tours‘ comment: “with Watkin and Forbes going every which way but round, by the 1880s the government was getting frustrated with the lack of a Circle Line, so a third, separate company was formed to fill in the gaps between the Metropolitan and District Railways. Watkin wasn’t happy with this at all, bought it out and decided to finish the job himself.” [20] This somewhat over simplifies what actually happened..

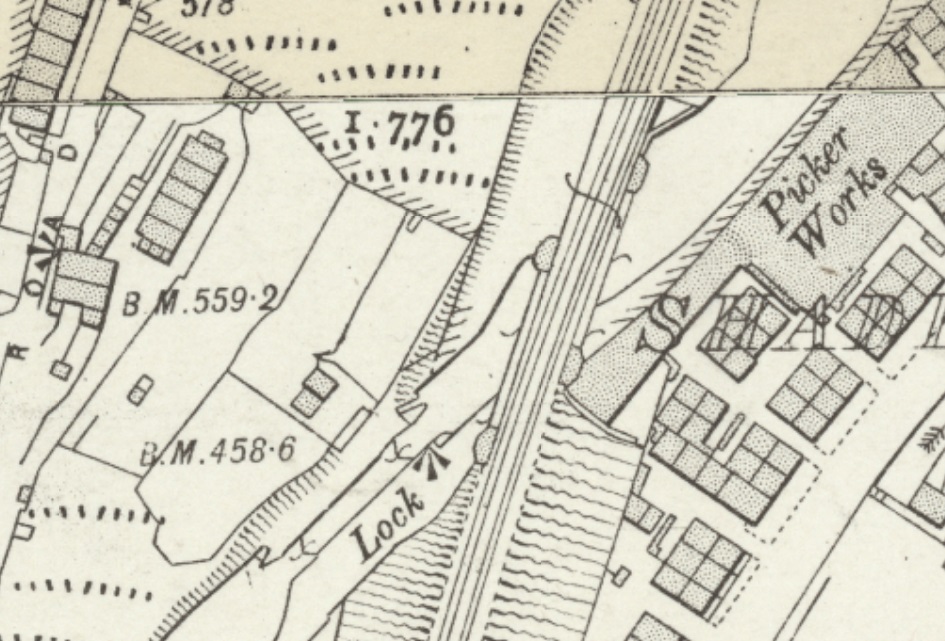

Wolmar talks of the two companies ailing, and of others trying to fill the gap. A group of city financiers formed the Metropolitan Inner Circle Completion Company (MICCC) in June 1873. They planned to build the link between Mansion House and Bow and to link with three other railways’ metals (the North London, the Great Eastern and the East London [21][23][25]). “This scheme … obtained Parliamentary powers in 1874 [which] prompted a couple of years of wheeling and dealing, with Watkins, as ever, behaving badly.” [3: p84]

When the MICCC failed to raise enough capital, only one solution was left. Forbes and Watkin would have to work together!

Wolmar tells the story: “A contractor, Charles Lucas, compersuaded the two enemies, Forbes and Watkin, to meet and agree a short-term peace agreement in order at last to complete the Circle. They managed to persuade the Commissioners of Sewers to raise their offer to £250,000 and the [Metropolitan Board of Works] to £500,000. Even then, it took an outsider to knock the heads of the two companies together. With several other schemes being put forward by promoters, there was an inquiry chaired by Sir John Hawkshaw who, arbitrating, recommended that the joint scheme by the two existing railways should be selected, presumably on the basis that the involvement of a third party would have led to chaos.” [3: p85]

The first train to travel in a loop around London was at the opening of the final link on 17th September 1884. Public services started on 6th October 1884. It appears to have been chaos! … “In addition to the 140 trains scheduled on the inner Circle in each direction, a further 684 were timetabled to use part of the line, entering at Cromwell Road from the west, Praed Street (near Paddington) from the north-west and Whitechapel from the east. That meant a total of 964, around a hundred more than the line could cope with. The financial arrangements between the Metropolitan and the District were at the root of this attempt to run too many trains as the District essentially paid a fixed fee irrespective of the number of trains it operated.” [3: p87][28]

Wolmar extensively describes the turmoil which occurred on pages 87 to 90 of his book. In addition, financial problems, mostly due to the high capital costs of construction but exacerbated by the route being designed (effectively) by parliamentary commission.bWhen the first short section of the Metropolitan Railway opened there were 9.5 million journeys each year, receipts of £101,000 and a healthy divided for shareholders. “In the first year of operation of the Circle there were 114.5 million passengers. However, that was still not enough to pay adequate dividends given the expenditure on the Circle’s construction and the cost of operating the line.” [3: p90]

Wolmar highlights factors which affected the comparative viability of the underground service and particularly the District line: [3: p90-92]

- Cheaper omnibus fares meant that those horse-drawn services were still attractive to the paying customers. Operators could keep prices lower because: turnpike tolls and mileage duties had been scrapped; business rates for the omnibus companies were subsidized; road conditions were much improved along routes followed by the underground as surfaces were renewed as part of the construction of the underground; the railways had to pay a passenger tax for all fares above a penny a mile; new highways had been introduced as part of a city-wide project to create wider and better streets which unblocked congestion; horse-trams were excluded from central London giving free-reign to the omnibuses on the streets. the price of maize for horse-feed dropped considerably in the 1880s.

- Completion of the Circle did little to improve the situation for the District (many prospective passengers from South of the Thames could choose their London terminus to avoid having to change onto the Underground)

- The geography of the line was not helpful to the District (at the East the progress of trains was held up by watering at Aldgate and congestion ahead on the line, it was often quicker to walk into the City and particularly to the Bank of England which was some distance from any available underground station).

In effect, while the northern section could be profitable, the Southern section may well never be. Ultimately though, Wolmar states, “Underground entrepreneurs … were building a fantastic resource for Londoners whose value could never be adequately reflected through the fare box which was their only source of income.” [3: p93]

Chapter 5 – Spreading Out

In this chapter, Wolmar highlights Sir Edward Watkin’s grandiose vision for the Metropolitan. We have already seen his plans for the Wembley area. He also imagined a line to Worcester and to the Northwest. He dreamt of a line running from the Northwest, through London to the Kent coast and on through a tunnel under the Channel to meet up with one of his French investments which would carry passengers all the way to Paris. He also imagined an extensive suburban network to the Northwest of the City of London. This vision would become known by an unofficial name – Metroland.

Watkin’s original powerbase was the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR). [3: p96] He was never one to sell himself short. He was an ambitious visionary, and presided over large-scale railway engineering projects to fulfil his business aspirations, eventually rising to become chairman of nine different British railway companies. [30]

His vision for the Northwest suburbs of London was allied to his desire to see his MS&LR connected to the capital. Although other projects did not come to fruition, both Metroland and the MS&LR’s London Extension (opened in 1899 and which became the Great Central Railway) certainly did. [30]

In addition to his railway interests, Watkins was three times an MP before becoming a Baronet. From April to August 1857 he was an MP for Great Yarmouth. He was an MP for Stockport from 1864 to 1868, and for Hythe from 1874 to 1895. He was Baronet of Rose Hill from 1880 until his death in 1901. [30]

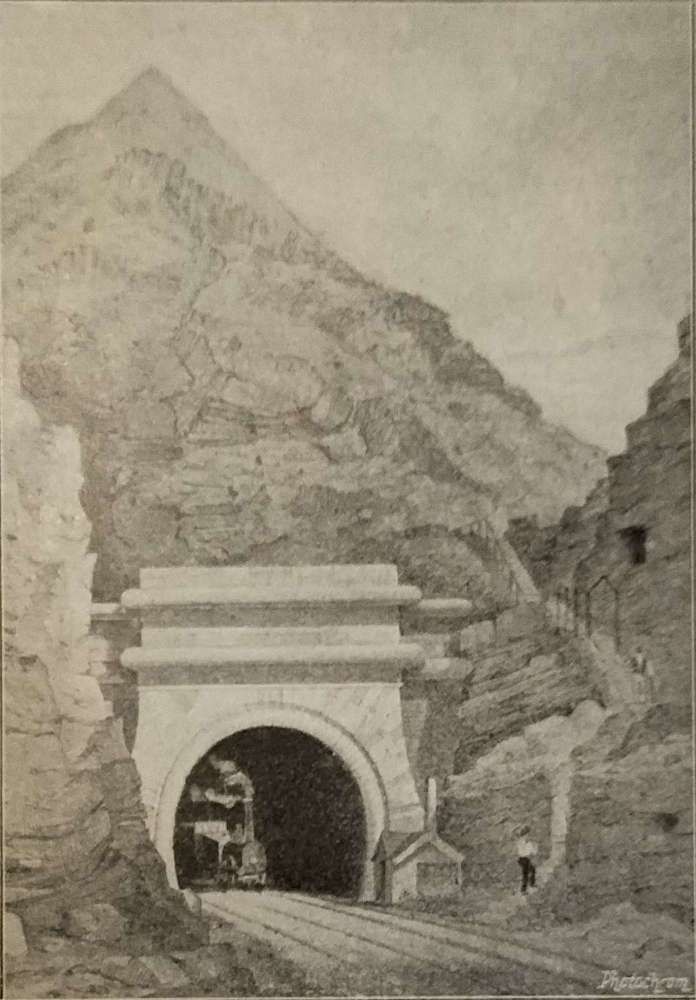

Watkins had cultivated relationships in Parliament and across the establishment which meant that his schemes were given credence and considered seriously. Ultimately, however, despite some geological promise and early digging success, [31] Watkin’s Channel tunnel scheme failed because:

- military concerns about it being used by invading forces outweighed perceived benefits; [32]

- Watkin’s scheme and other similar proposals could not garner sufficient political support in Parliament; [33] and,

- insufficient financial support could be envisaged. [35]

I suspect that until electrical technology had developed significantly beyond what was available in the 1880s, a suitable form of propulsion would not have materialised. Problems experienced with steam and smoke on the Underground and no effective method of dealing with those problems having been found, would have meant that Watkin’s scheme would have foundered technically.

This short digression to focus on Watkin’s ultimately unsuccessful Channel tunnel scheme, supported by a series of notes below, shows something of Watkin’s capacity to move from ideas towards practical implementation of large projects through the political process. The suburban area to the Northwest of the City of London and the London extension of the MS&LR benefitted from those skills! [37]

Returning to Wolmar’s book about the Underground and its expansion. … He says that, at least in Watkin’s thinking, his goal of creating what would become the Great Central Railway might more readily be achieved politically by the Metropolitan Railway breaking out of London than for the MS&LR to break in. [3: p96][38: p22]

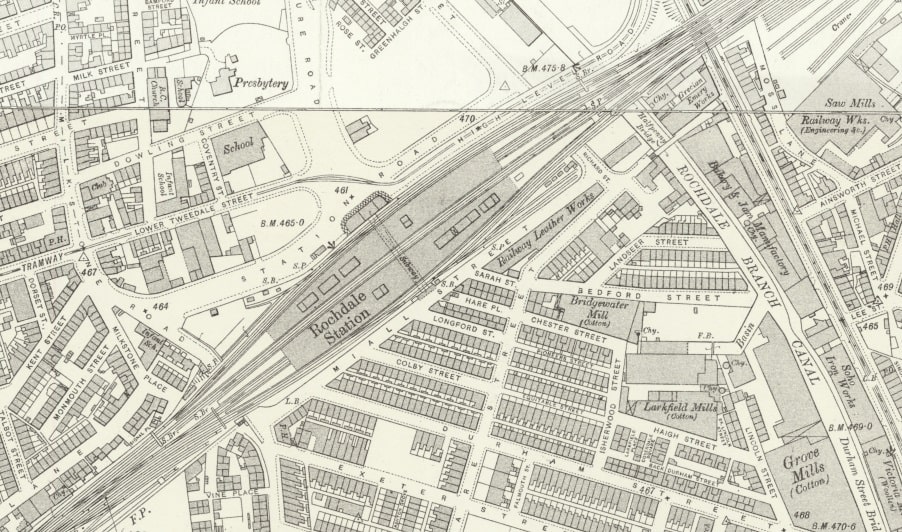

Watkin first focussed on developing the potential of the short stubby single track line from Baker Street to Swiss cottage. “Once out of the immediate vicinity of central London, the railway was built on the surface, which … was much cheaper. Powers were … obtained for the tunnel to be continued from Swiss Cottage to Finchley Road and then for the railway to run in the open air through to West Hampstead, Kilburn and Willesden Green, which was reached in 1879.” [3: p97]

Harrow was reached in 1880. Within five years the Harrow line reached Pinner. Rickmansworth and Chesham were added by the end of the 1880s.

Aylesbury Railway Station was rebuilt by the Metropolitan by 1892 and the Metropolitan then extended 50 miles from central London. The MS&LR was to connect to the Metropolitan at Aylesbury but Watkins quickly realised that Baker Street would be an inadequate terminus. He pushed for a new terminus at Marylebone, leaving Baker Street to serve suburban services, either stopping there or running onto the Underground.

When Watkins died in 1901, he had not seen the astonishing future of his line and the creation of ‘Metroland’.

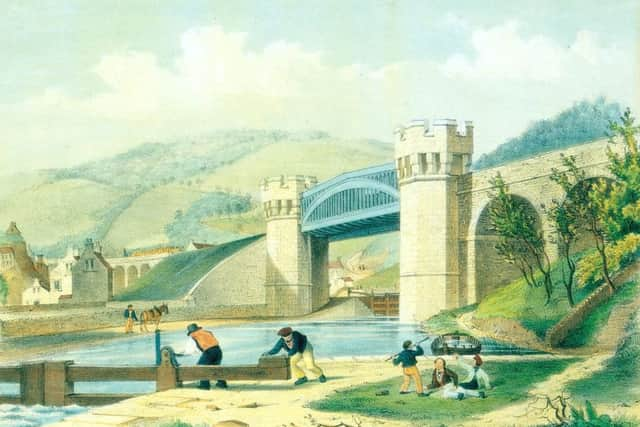

Wolmar also covers the history of the East London line which was built to make use of the tunnel built by Marc and Isambard Brunel. This line was something of an anomaly on the London underground map until refurbishment and reopening as part of the London Overground.

We have spent quite a bit of time focussing on Watkins and his schemes (of which the East London became one) Wolmar now turns to look at Forbes’ plans. He “had ambitions for the District to make … incursions into East London, but [would have] to wait until 1902, just two years before his death, when the long-mooted Whitechapel and Bow section finally opened.” [3: p103] It extended to Upminster and opened up areas of what was the Essex countryside.

It was a different story to the West of the City, although with none of the aspirations of the Metropolitan to become a main line. The District spread westwards. Wolmar says that Forbes “looked to Hammersmith, Kew and Richmond as potentially lucrative markets.” [3: p105] Hammersmith was reached in 1874 (10 years after the Metropolitan). It became the area to the West of London best served by the Underground. Three years later, the District reached Richmond (partly using London & South Western Railway metals).

The District reached Ealing in 1879. A connection with the GWR, meant that trains could provide a service from Mansion House to Windsor, although the service was not well-patronised.

Local interests promoted a new company – the Hounslow & Metropolitan high linked Hounslow to the District’s Ealing Branch. It was completed in 1886 and was worked by the District.I

In the South, the line to West Brompton was extended towards the Thames and Putney Bridge and opened in March 1880, just in time for the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race.

After a campaign by local interests the planned line across Wimbledon Common to Wimbledon was diverted to avoid the Common. Wolmar states: “Apart from an extension to South Harrow and then Uxbridge (the latter actually eventually passed to the Metropolitan), and a loop to South Acton, all completed in the first decade of the new century, this was the end of the District’s expansion westwards.” [3: p108]

Chapter 6 – The Sewer Rats

Arguably, the District did more than the Metropolitan to stimulate suburban development because of the relative density of its lines. The District’s tracks were incredibly busy. By 1880, trains were serving Fulham, Richmond and Ealing. By 1904, the District was carrying 51 million passengers per year and, on average, running nearly twenty trains per hour between South Kensington and Mansion House, with more during the peak. [3: p109]

Wolmar says: “The vexed issues of ventilation had never gone away and remained a source of controversy until the electrification of the lines in 1905.” [3: p110] He allocated a number of pages to a description by the journalist Fred Jane of travel on the Underground in the days of steam. [3: p110-114] Another quoted is R.D.Blumenthal. [3: p114]

“The District … sponsored many bus services, run by contractors, to feed into its system and it made sure that it laid on extra services for special events. … Exhibitions were a major source of traffic and many were held at the then open grounds between the Albert Hall and South Kensington.” [3: p115] Until December 1908, when tolls were abolished, the District controlled access via a pedestrian subway under Exhibition Road from South Kensington station. “The opening of the passage in May 1885 coincided with the start of an Inventions Exhibition and thereafter the District, rather meanly, only allowed it to be used on special occasions. … Many of the … exhibitions … in the 1880s attracted huge crowds, including fisheries (attended by 2.75 million people), health, and ‘colonial & Indian’ (the biggest, which brought in 5.5 million). … After 1886, when the site was developed for what is now Imperial College, the exhibitions moved to Earls Court.” [3: p115]

Passenger traffic on the Underground was enhanced by a booming entertainment industry – theatres and music halls. While Wolmar notes the importance of leisure travellers to the financial health of underground companies, he emphasises the fact that in the case of the underground it was the presence of the railways that brought about demand and significant long-term growth. [3: p117]

Once the main line companies recognised the fact that suburbs were developing around stations on the Underground and the suburban network. “Whole swathes of the Greater London area were filled in as railways focussed on local traffic. In particular, the railways made travel to the outer suburbs such as Croydon, Bromley, Harrow, Wanstead and Walthamstow possible, as no other form of transport could have brought so many people into the capital fast enough.This was mostly a middle class phenomenon. The working classes could not afford the cost of commuting added to the rents which, in most of the areas reached by the railways, were still relatively high.” [3: p119]

The Underground in particular played, “a vital role in stimulating this growth not just because of the suburban incursions made by the District and Metropolitan but also because it took people right into the heart of the City and the West End, whereas rail passengers were left on the fringes. Without the Underground to connect the various termini, the extensive development in the second half of the nineteenth century could never have taken place so quickly. London grew from a population of 2.8 million in 1861 to over 7 million fifty years later. That outward push was further accelerated by the development of a new office economy, centred around the West End which had a burgeoning number of offices and was also establishing itself as London’s premier retail centre. Employment in the City was also expanding, with many former residences being turned into offices, and resulting in more commuting.” [3: p120]

Wolmar comments: “Despite the Underground’s success in attracting custom, until electrification, travelling on it remained an experience which ranged from broadly acceptable to downright awful, depending on the passengers’ stoicism. There was growing pressure from the passengers for better conditions. … While there had been some improvements, such as heaters on trains and station indicators on platforms, during the last few years of the nineteenth century there was a growing clamour for a major improvement of the system. There were suggestions of doubling the District line on its busy section between Earls Court and Mansion House, possibly through a deep tube railway, but this expensive project was never really feasible. Instead, electrification was seen as the only way of making the required modernization.” [3: p123]

In spite of the clamour, and the fact that the first tube railways, the City & South London Railway (which opened in 1890), was electrically powered, [39] the Metropolitan and District railways were slow to embrace the new technology. It was not until 1905, that steam was finally replaced.

Wolmar notes that, “The construction of the second deep tube railway, the Central, which ran parallel to the two main east-west sections of the Circle, together with increased competition from horse buses and the rising price of the high-quality coal which the Underground companies were forced to use in order to limit pollution in the tunnels, meant that by the turn of the century electrification could be put off no longer. The more affluent Metropolitan braved the issue first, installing two conductor rails as test track on a long siding in Wembley Park in 1897. More substantially, in 1898, the District and the Metropolitan made an agreement to conduct an experiment by electrifying the short section of track between High Street Kensington and Earls Court with power being supplied from a third rail. The line was opened to the public in May 1900, offering the chance to ride in the large and very heavy purpose-built six-car electric trains for a shilling. That was not a great bargain since for the past decade Londoners had been able to ride on the City & South London for a mere twopence and the following month the Central opened with the same fares.” [41][3: p124]

The Metropolitan favoured overhead lines, surprisingly Forbes also favour overhead lines, but little did that matter. He was ousted from the board of the District by Charles Yerkes, an American businessman with experience of the use of third rail in the USA. He forced through a third rail policy at the District, and immediately clashed with the Metropolitan. It took the Board of Trade to step in and arbitrate. The judge working for the Board of Trade found in favour of the District’s third rail. [3: p125] The decision was based on the proven technology in use on the City & South London.

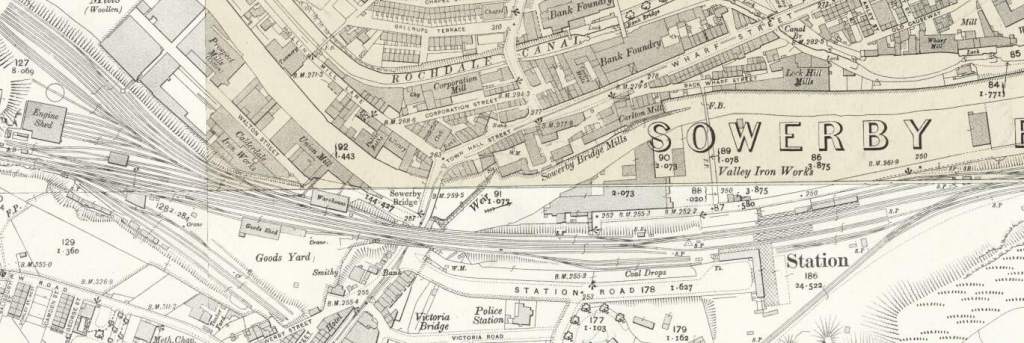

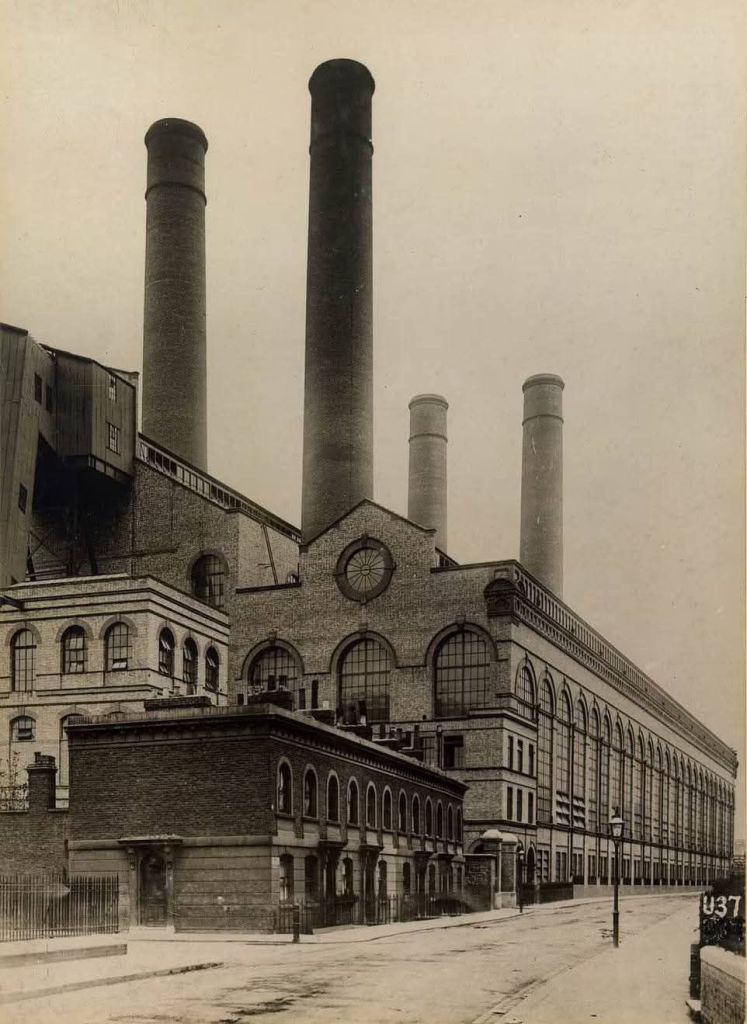

The idea of cooperation remained an anathema! It would not be countenanced by the Metropolitan and the District. “The District built an enormous power station at Lots Road on the Fulham and Chelsea border, a site chosen for ease of access for the barges bringing coal along the Thames. … The Metropolitan obtained most of its electricity from a plant at Neasden in Northwest London, where the coal could be delivered easily by rail.” 3: p129]

For 44 years steam operated in cramped tunnels without major mishap! Across the world, the early years of the 20th century saw a number of underground networks constructed – all bar two were operated by electricity. Glasgow: opened in 1896, used stationary steam engines hauling a cable to pull trains; [43] and Liverpool: the trains if the Mersey Railway were steam-hauled from 1886 until electrification in 1903. [44]

By 2nd September 1907 all steam passenger services had been replaced by electric-powered service. All that remained powered by steam were some maintenance trains and overnight freight services which continued until the 1960s. [3: p128]

Wolmar goes on to describe underground systems in:

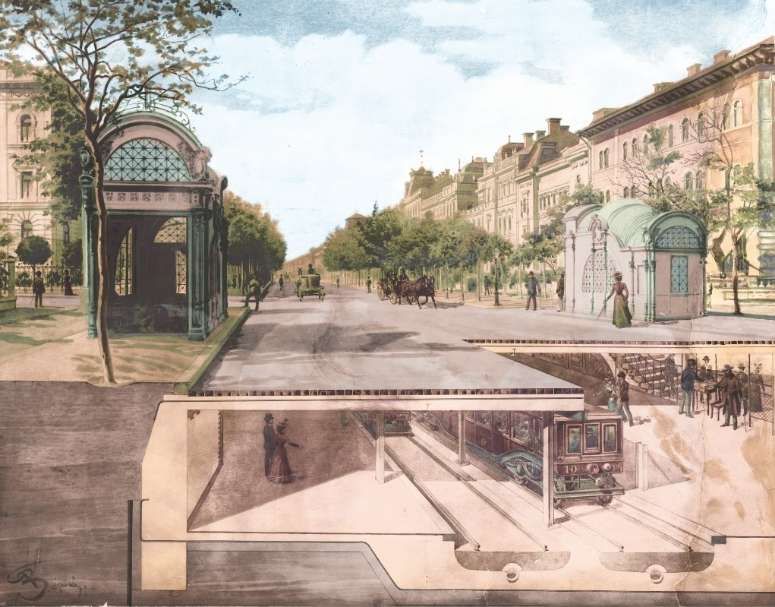

- Budapest: the first line (now known as M1) was built to serve a major exhibition in the main city park in 1896. [3: p129] In fact, this was the first of a number of lines in Budapest. Between 1970 and 1990 the metro was extended with metro line M2 and M3. Metro line M4 was completed in 2014. Since 2014 the length of the entire metro system is 39.4 kilometers and it has 52 stations. … Among the railway’s innovative elements were bidirectional tram cars; electric lighting in the subway stations and tram cars; and an overhead wire structure instead of a third-rail system for power. [45]

- Vienna: the idea of an underground railway was mooted as early as 1843 but it was the late 1890s when the Stadtbahn opened. “While there were some tunnel sections on the three lines, most of this steam-operated railway was at street level or above.” [3: p130] … The system was opened in stages between 11th May 1898 and 6th August 1901. [47] Sadly, the Stadtbahn proved to be inadequate, less effective than the city’s tramway network. A series of different schemes were considered over the years. [48] An extended article about the Vienna network can be found here. [49]

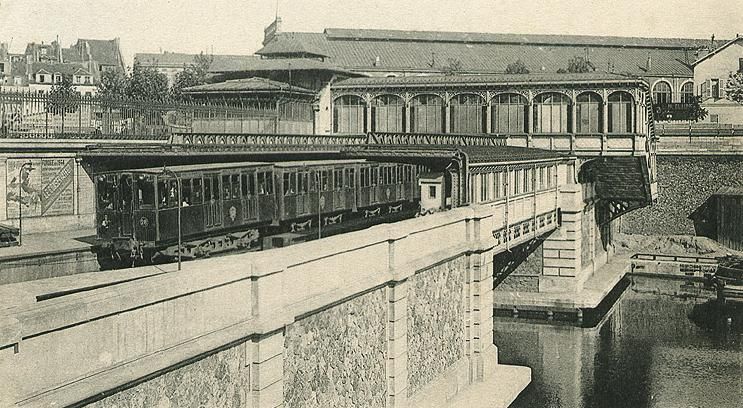

- Paris: Wolmar tells us that, “the system which opened in 1900 was electrically powered.” [3: p130] The Paris Metro’s history began with construction in 1898 for the 1900 World Exposition, opening Line 1 on 19th July 1900, to serve the games and boost city mobility, utilizing innovative underground engineering for a largely subterranean system with electric trains, becoming an instant success and rapidly expanding into one of the world’s most extensive urban rail networks by the 1930s. A history of the Paris Metro can be found here. [50]

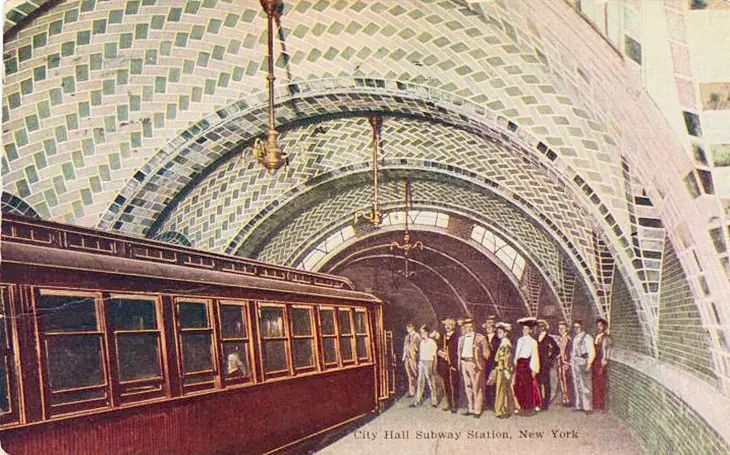

- New York: Wolmar says that the new subway in New York was electrically-powered. “Elevated railways built above roads had proliferated from 1872, being preferred to underground railways on the grounds of cheapness and because of the lack of historic buildings whose aspect would be ruined by unsightly railways. … New Yorkers finally tired of the noisy, steam-hauled trains passing their second-floor windows at all times of the day, and work on a subway system, using electric trains to replace some of them, started in 1901.” [3: p130] “The first underground line of the subway opened on 27th October 1904, almost 36 years after the opening of the first elevated line in New York City. … The 9.1-mile (14.6 km) subway line, then called the “Manhattan Main Line”, ran from City Hall station northward under Lafayette Street (then named Elm Street) and Park Avenue (then named Fourth Avenue) before turning westward at 42nd Street. It then curved northward again at Times Square, continuing under Broadway before terminating at 145th Street station in Harlem.” [52] A detailed history of the New York Subway can be found here. [52]

Wolmar then discusses the results of electrification of the London Underground, which were not as significant as the companies hoped. Nonetheless, “by the early years of the 20th century, London had an extensive, mostly electrified overground network linking in with the Underground. … But the real task was to improve services in central London, given its rapidly growing employment, and this could only be done through … new tunnelling techniques.” [3: p131-132]

Chapter 7 – Deep Under London

Marc and Isambard Brunel developed a shield to build the first tunnel under the Thames. Later, Peter Barlow improved the technique utilising cast-iron circular segments bolted together to form the tunnel as the shield moved forward. [3: p134] It was 20 years after Barlow’s scheme that the first tube tunnel was completed using technology enhanced by a former pupil of Barlow, James Greathead. He perfected a system which allowed concrete to be cast behind the advancing shield preventing collapse.

Under much of London is a thick layer of clay with an overburden of gravel. The clay is relatively easy to cut through. The tube tunnels were bored between 45 ft. and 105 ft. below ground but to avoid any potential conflicts with basements or old foundations the tunnels followed, as much as possible the route of highways. Wolmar says that this was shortsighted as it meant harsh gradients and sharp curves which, although no problem for the shield during construction, were to prove operationally difficult.

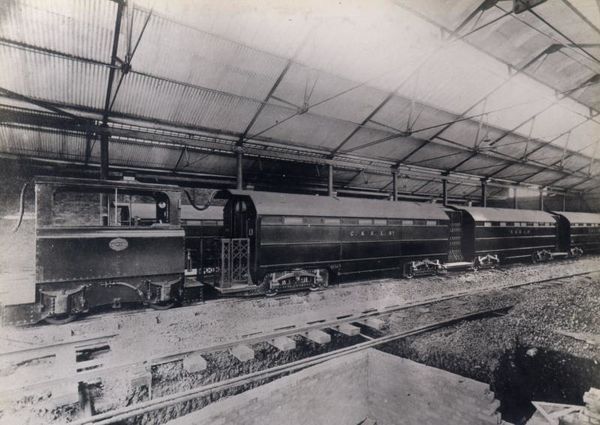

The City & South London Railway (C&SLR), the first constructed in this way, opened in November 1890. Its most significant problems were that the electricity supply was inadequate for the demand and the locomotives underpowered.

When opened the line had six stations and ran for 3.2 miles (5.1 km) in a pair of tunnels between the City of London and Stockwell, passing under the River Thames. The diameter of the tunnels restricted the size of the trains, and the small carriages with their high-backed seating were nicknamed padded cells. The railway was extended several times north and south, eventually serving 22 stations over a distance of 13.5 miles (21.7 km) from Camden Town in north London to Morden in south London. [56]

The next line after the City & South London to obtain approval was the Central London line in 1891 and that was quickly followed by a series of applications. “No fewer than six tube railways bills were put to Parliament in 1892 and … a joint select committee was appointed to set out some principles for this type of development. … It agreed that tube railways could use the subsoil under public property without having to pay compensation, which made future developments economically feasible.” [3: p144]

Wolmar notes that, “several schemes which were to form the basis of London’s tube network were given the go-ahead following the committee’s deliberations but all struggled to find money, notably the lines that were to become the Bakerloo and the Northern line’s Charing Cross branch. As Hugh Douglas put it, ‘Acts, acts, acts. They were everywhere in the nineties but where was the cash to implement them?… Commercial enterprises offered far greater returns to investors than railways’.” [58: p 139]

Wolmar describes a complex, convoluted process that promoters of underground schemes had to negotiate, often against a backdrop of a Parliament that was predisposed to side with objectors and doubters. There was also a perception that a left leaning London City Council might at any time in the future municipalize the underground network. It was a decade after the C&SLR was opened that the Central was finally opened. [3: p144-145]

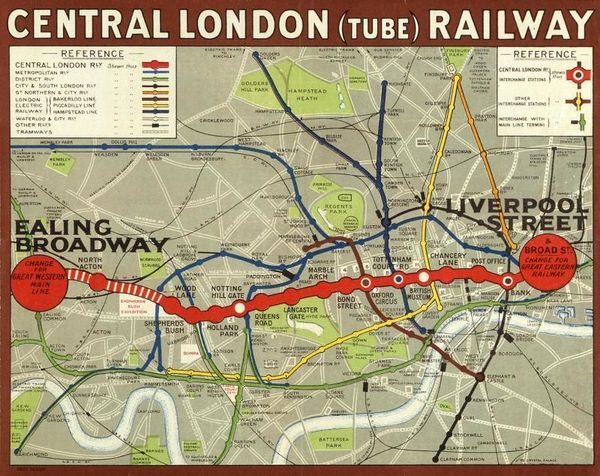

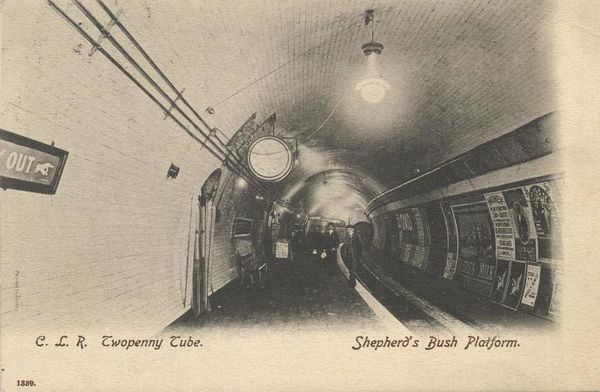

The Central Underground Railway (CLR) in London refers to the Central Line, London’s longest and busiest Tube line, known as the “Twopenny Tube” at its 1900 opening due to its flat two-pence fare, connecting Epping in the east to Ealing Broadway and West Ruislip in the west via central London. It was London’s first Tube to serve the city center and featured early innovations like electric lighting and large ventilation fans. “The CLR opened on 30th July 1900 as a cross-London route from Shepherd’s Bush to Bank. It was extremely well used from the outset, partly because of the flat fare of two old pence (2d), which inspired the name the ‘Twopenny Tube’. The fact that it appealed to shoppers as well as commuters was also crucial. In 1908, the line was extended West to Wood Lane to serve the White City exhibition site, and four years later was extended eastwards from Bank to Liverpool Street. In 1920, the line was further extended West to Ealing Broadway.” [59]

However, the first line to receive Parliamentary consent following the partial success of the C&SLR “was to become London’s only underground line that could accommodate full-size main line trains. Such large tunnels had been ruled out on cost grounds but the Great Northern & City from Moorgate to Finsbury Park was conceived as a bypass to King’s Cross for the Great Northern’s suburban trains. … The line was authorised … in 1892.” [3: p146] It took more than a decade to come to fruition, during which time the Great Northern first lost interest in the project and then became quite hostile to it. Ultimately, it was never used for its intended purpose.

Wolmar cites this as another example of the way in which competition failed to produce a worthwhile outcome. He compares London to Paris, “where the first Metro lines were being built as a network of six lines conceived by the local municipal council.” [3: p146] Lack of strategic planning resulted in this line not being extended beyond Moorgate and it became little more than an historical footnote!

Wolmar complains that the private system of commissioning of these underground lines made any strategic plan impossible and prevented any effective linking of the suburban networks North and South of London. [3: p147]

Another scheme which achieved Parliamentary approval was the Waterloo and City (W&CR). It was designed to take LSWR passengers on from Waterloo Station into the City.

Wolmar comments that, “The most innovatory aspect of the Waterloo & City was that the trains were operated by powered motor coaches at each end, a system that was common in the USA, rather than a separate locomotive. There were four, later five, cars, including the two powered coaches which, apart from the section occupied by the motors, could be used by passengers. This was the first use of such electric multiple units in the UK and it meant that the trains were much lighter, and consequently cheaper to operate. Painted in a chocolate and salmon livery, they looked elegant and were so robust that they lasted forty years. Another innovation was sliding doors which gave access to platforms between the coaches that were protected by folding iron gates.” [3: p149]

The W&CR fulfilled a significant need and was well patronised.

These smaller schemes were not the most significant developments resulting from the Parliamentary committee’s work. These were embryonic forms of the Bakerloo line and the Northern (Charing Cross branch) line. But these were slow to come to fruition. The Central, on the other hand made much more rapid progress. Its funding stream was secure and Wolmar explains some of the intricacy integral to it. One significant innovation was to build stations at “the top of slight inclines which meant that trains automatically were slowed down by the gradient as they approached the station and sent faster on their way on departure.” [3: p151]

After it’s opening in 1900, “people flocked to the [Central] line. Within weeks, 100,000 were travelling on the railway daily. On the day of the triumphal return from the Boer War of the City Imperial Volunteers, who made a state entry into the capital, a staggering 229,000 travelled on the Central. During the early 1900s, the annual total was around 45 million annually, nearly 125,000 daily.” [3: p157] In the 21st century, the Central Line is the second busiest tube line after the Northern with 600,000 users daily on weekdays!

It seems that there were a number of reasons for this success. “First, the line was on a transport artery and took a lot of existing business off both buses and the underground lines. … As its directors had feared when they objected to the building of the Central, the Metropolitan, still steam-hauled, lost out heavily to the new line with its modern electric trains. Secondly, the Central had been built to a high standard. Even the Board of Trade inspector reckoned the stations and passageways were ‘commodious’. Access to the trains was by lift and the bigger stations had three or four – there were forty-eight in the whole system. Thirdly, the line benefited from the growing economy which boosted not only employment but travel to the growing number of shops in Oxford Street; when, in 1908, Harry Gordon Selfridge was building his eponymous store, he wanted Bond Street station to be renamed Selfridges and tried to connect it with a passage under Oxford Street, but in the end was unsuccessful in both enterprises. And finally, the supportive press coverage provided free advertising for the line.” [3: p157-158]

Wolmar notes that, “blessed with such good patronage, the Central, uniquely of the majority underground lines, paid good dividends right from the start. There were such large numbers travelling on the line that the operating expenses only represented just over half the revenue. … The company managed to pay a healthy 4% divided in each of its first 5 years and 3% until its merger into the Underground Group shortly before … the First World War.” [3: p159]

At first, the line used locomotives but it was quickly discovered that their size and weight caused significant vibrations at the surface. Management addressed this in very short shrift and ordered replacement motor coaches which were operational by 8th June 1904.E

The early success of the line led to plans for extensions and also spawned plans from competitors. Another Parliamentary joint committee was set up to evaluate the different proposals.

Chapter 8 – The Dodgy American

We have already encountered Charles Tyson Yerkes. More than anyone else, he was responsible for creating the greatest possible integration across the London Underground network. An American businessman, Yerkes left the USA under something of a cloud. Wolmar gives an account of his life before London and then the convoluted story of his acquisition of the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (eventually to become the Charing Cross branch of the Northern Line) and the way in which that purchase led to him being helped to acquire a majority share in the District line in June 1901. He soon also took on two projects which would become the Bakerloo and the Piccadilly lines. The three projects (Charing Cross, Bakerloo and Piccadilly) opened between March 1906 and June 1907. Wolmar tells us that it would be another 61 years before another deep tube line, the Victoria, was dug under central London. [3: p164-170]

Wolmar notes that “between 1903 and 1907, if one includes the Great Northern & City and the Angel to Euston extension of the City & South London, a staggering twenty-six and a half miles of tube railways were built under London. The construction of each of these railways is a complex and intertwined story of Parliamentary bills, heroic efforts to raise capital, opaque financial deals and amazing feats of engineering and construction, most of which passed off with remarkably few mishaps.” [3: p170]

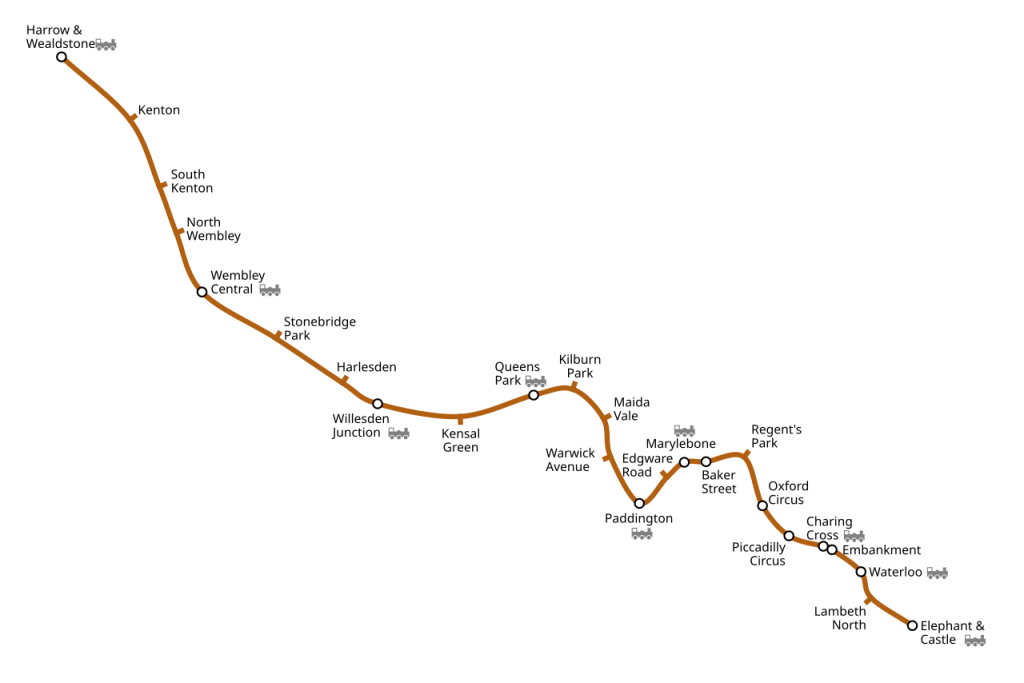

Wolmar goes on to describe the development of the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway (which became known as the Bakerloo line – which was partly developed by another American, Whittaker Wright before his company fell into bankruptcy. Yerkes bought the partially completed line and merged it with his other interests “to create the Underground Electric Railways Company of London Limited (UERL), which was to run much of London’s transport network until the creation of London Transport in 1933. The UERL gained control of the other two big tube projects: the Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway, the central section of the future Piccadilly Line; and the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway; … as well as the District Line. That left only the Central, the City & South London and the Metropolitan outside UERL control and before the start of the First World War the first two of these would be incorporated into the empire created by Yerkes.” [3: p173]

Yerkes then set about raising finance and was surprisingly successful. It was during a period when large amounts of American capital were moving into Britain. Without US investors, the tube network would never have been built. Investors in Boston and New York bought nigh on 60% of the shares, with the British taking a third and the rest being bought by Dutch investors. [3: p175]

Even so, Yerkes had to resort to an Edwardian version of junk bonds which were sold on the basis that their value was bound to increase. His scheme brought in the remainder of what was required. He raised £18 million to invest in the Underground. (Investors were to live to regret their decisions!)

It is possible, however, that Yerkes had even more devious plans relating to property. It seems that his underground schemes may well have been a device with which to enhance land values. He seems to have invested in land on and around the proposed routes of underground lines. Wolmar mentions the Finchley Road & Folders Green Syndicate as the most likely vehicle through which Yerkes purchased land. [3: p176][15: Volume 2, p82-84]

Once Yerkes had his investment funds he was quick to proceed with work on the Baker Street & Waterloo line. Apart from being required to rebuild his Oxford Circus station, work proceeded without major incident. The first section of the line (Kennington Road (later Labeth North) to Baker Street).was opened in March 1906. The scheme included a “host of innovations – all of US origin – which helped improve both performance and safety:

- automatic signalling using track circuits to indicate when a train was in a particular section of the line, a system that became universal throughout busy sections of Britain’s railways;

- a train stop system, a mechanical device which stopped trains automatically if they went through a signal at red;

- people management systems which could be reversed at different times of the day, aiding flow to and from lifts and platforms.

- Electric multiple units were used from the start of operations

Wolmar notes that the London Evening News called the line ‘Baker-loo’ in an early article and by July 1906 ‘Bakerloo’ was adopted officially by the railway – something that The Railway Magazine deplored. [3: p178]

While 37,000 travelled on the line on its opening day, generally patronage was well below what had been anticipated. Even so, it was “soon extended further south to Elephant & Castle. By June 1907 it had reached Edgware Road to the north and had 11 stations. … The next extensions were not built until 1913, when the line opened to Paddington. Other stations followed despite the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. New tunnels enabled a connection to Willesden in 1915 and over the London & North Western Railway’s lines as far as Watford Junction two years later.” [60]

The next of Yerkes’ lines to open was the Great Northern Piccadilly & Brampton Railway. Work was done to pull a series of smaller proposed schemes into one larger scheme. Yerkes got construction work started some 5 years after approval by Parliament. But only once a major obstacle in the form of J.P. Morgan was dealt with. Wolmar tells the story of how Yerkes outsmarted Morgan, eventually causing Morgan to withdraw from his involvement with the London Underground. [3: p182-185]

Effectively with the field to himself, Yerkes got on with developing the Underground, “melding various sections of the Great Northern and Brompton schemes into what became the Piccadilly.” [3: p185]

Once on site, the work proceeded without major mishap. The line was effectively complete by the autumn of 1906. It was opened on 15th December 1906. Innovations on the Piccadilly included:

- the first functioning railway escalator in London which was opened on 4th October 1911 at Earls Court, between the Piccadilly and District line platforms.

- the practice of skipping less-used stations in order to reduce running times. This was a short-lived practice used for stations placed very close to each other.

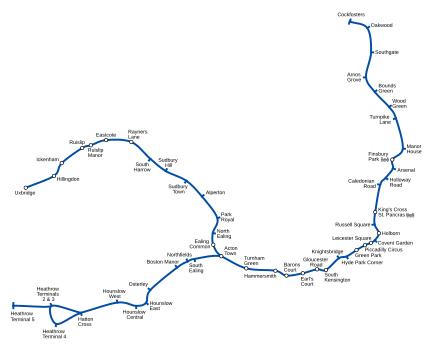

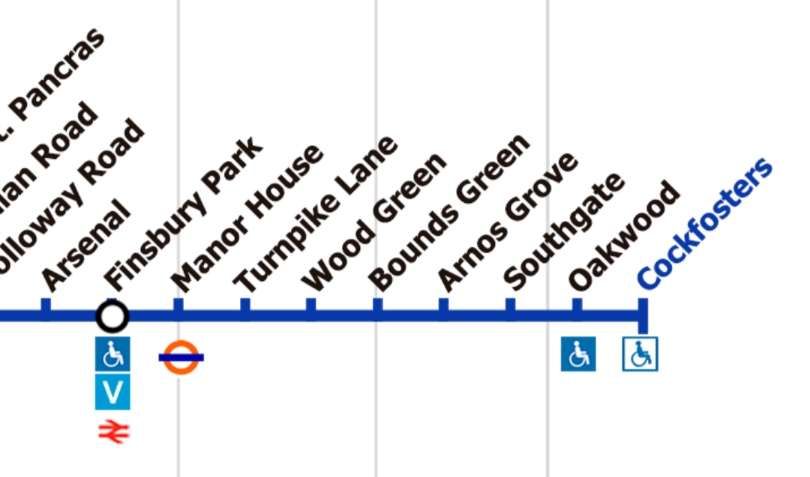

The modern Piccadilly line is a 45.96 mile (73.97 km) long north–west line, with two western branches splitting at Acton Town, serving 53 stations. At the northern end, Cockfosters is a four-platform three-track terminus, and the line runs at surface level to just south of Oakwood. Southgate station is in a tunnel, with tunnel portals to the north and south. Due to the difference in terrain, a viaduct carries the tracks through Arnos Park to Arnos Grove. The line then descends into twin tube tunnels, passing through Wood Green, Finsbury Park and central London. The central area contains stations close to tourist attractions, such as the London Transport Museum, Harrods, Buckingham Palace and Piccadilly Circus. The 9.51 miles (15.3 km) tunnel ends east of Barons Court, where the line continues west, parallel to the District line, to Acton Town. A flying junction, in use since 10th February 1910, separates trains going to the Heathrow branch from the Uxbridge branch. [62]

The Heathrow branch remains at surface level until the eastern approach to Hounslow West station, where it enters a cut-and-cover tunnel. West of Hatton Cross, the line enters tube tunnels to Heathrow Airport and branches to the Terminal 4 loop or to a terminus at Terminal 5. On the Uxbridge branch, the line shares tracks with the District line between Acton Town and south of North Ealing. Traversing terrain with cuttings and embankments, it continues to Uxbridge, sharing tracks with the Metropolitan line between Rayners Lane and Uxbridge.bThe distance between Cockfosters and Uxbridge is 31.6 miles (50.9 km). [62]

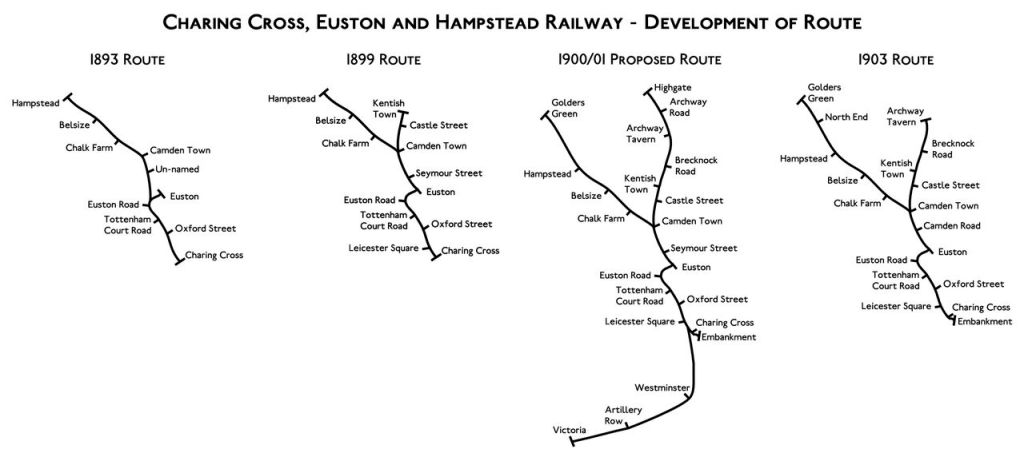

The third line, the scheme which was Yerkes’ first investment in London, took time to come to fruition. The Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead line saw a contractor appointed in 1897 but no work had been undertaken before Yerkes took an interest in the line. Wolmar says that, the company was bought by Yerkes in October 1900 for £100,000. A variety of different plans were considered for the line before a final version of the route was determined. Yerkes decided to seek Parliamentary approval for an extension to Golders Green. Gaining local support took some time and tunneling work only began in September 1903. It was completed by December 1905.

Most things went well during construction, a few things are worth noting:

- “There were very few problems with tunnelling, except at Euston where watery sand proved an obstacle.” [3: p189]

- At the original Charing Cross terminus, lack of coordination between railway companies caused unnecessary difficulty “because the South Eastern Railway, rather than seeing the arrival of the Tube as a great boon, was more concerned with ensuring that there would be no interference to the cab traffic at the front of Charing Cross.” [3: p189] Apartment, this was resolved when the arched roof of Charing Cross Station collapsed on 5th December 1905. A 3 month closure of the station permitted the tube contractors to dig out the forecourt and erect a steel girder structure over the site of the underground station before replacing the station forecourt.

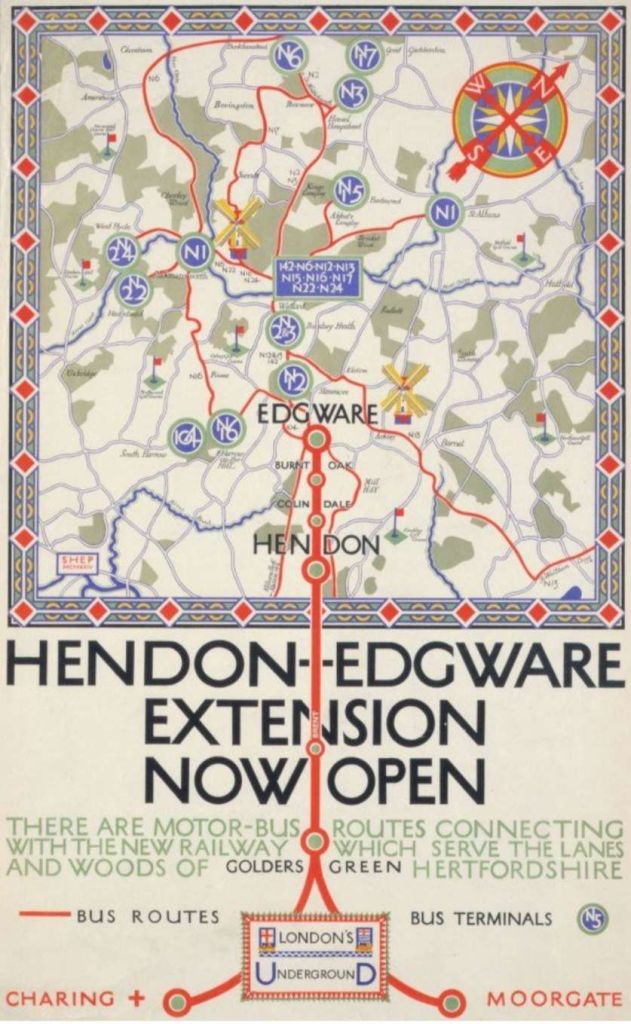

A final alteration to the route of the line was authorised by Parliament. It “allowed for a split into two branches at Camden Town, with the eastern section, originally planned to go only as far as Kentish Town, stretching as far as Archway. On the western side, permission had been obtained to continue another four miles to Hendon and Edgware, but that extension was not built until the 1920s; a plan to reach Watford never materialized. The Hampstead tube would remain as a separate railway to the City & South London until after the Great War and the name ‘Northern line’, by which both routes are now known, was not used until 1937.” [3: p189]

The line was opened on Saturday 22nd June 1907. 127,000 people took advantage of free travel on the line on that day!

Wolmar notes how the sighting of the terminus of the line at Golders Green was an example of the way in which the building of the tube encouraged the expansion of London. [3: p190-191]

Wolmar explains that the timing of the construction of the tube lines was fortuitous as anything beyond a ten year delay and the growing competition for the motor bus would have discussed investors. Yerkes was an absolutely crucial player in the game. Poor to his involvement, all planned schemes had gained Parliamentary approval, but had stalled through the vagaries of the planning system and by financial difficulties. [3: p195]

Wolmar comments that, “The depth of Yerkes’s achievement is made greater, too, by the fact that he built the central parts of the system, which were the most expensive and technically difficult, rather than bringing in a semi-suburban railway to meet the Circle line at the edge of the capital in the hope of raising revenue to continue work. Moreover, Yerkes bravely raised all the funds in one huge deal. What he told the investors to persuade them to stump up the money is unclear, but the poor souls did not make any money.” [3: p196]

Yerkes died on 29th December 1905 at the age of 68. He did not see the fruits of his efforts. His debts ate up most of his intended bequests. His great legacy, the UERL survived with Yerkes’ banker at the helm.

Wolmar tells us that “When the UERL took over two more tube lines just before the Great War, the City & South London section of what became the Northern, and the Central, it would become known as the Combine, controlling all major underground lines apart from the Metropolitan. Thanks to Yerkes, London had its tube system. Melding it into a coherent network was the task of his successors” [3: p196]

Chapter 9 – Beginning to Make Sense

The laissez-faire approach of the establishment to the Underground, with no central government control or direct planning involvement meant that the Underground was effectively “a random collection of uncoordinated lines.” [3: p197] This had to change and “the next two decades of Underground history were more about consolidation and creating a coherent administrative structure following the exciting Edwardian period of development.” [3: p197]

Wolmar notes that, after WW1, there were significant extensions into the London suburbs and the establishment of the London Passenger Transport Board was a triumph. This period did not need pioneers as such but still needed two significant players who would bring about change:

Albert Stanley (later Lord Ashfield), who joined the UERL as general manager in 1907, eventually became chairman of London Transport. Albert Stanley was born Albert Henry Knattriess was born near Derby in 1874. His family emigrated to the United States when he was a child and changed their surname to “Stanley.” © Public Domain. [68]

Educated in America, Stanley was determined to become an engineer. It was arranged for him to start working with the Detroit Citizens’ Street Railway Company (a horse tram operator) when he was fourteen years old. His abilities and ambition helped him progress rapidly and he was made general superintendent by the time he was 28 years of age. Albert Stanley joined the Street Railway Department of the Public Service Corporation of New Jersey as Assistant General Manager in 1903. By 1907, he had been appointed General Manager and had built a reputation as one of the leading managers of urban transit in the U.S. He was appointed General Manager of UERL in 1907 and Managing Director in 1910. [68]

Frank Pick was born on 23rd November 1878 in Lincolnshire, into a devout Quaker family. From 1897, he worked for a York solicitor. He joined the UERL at a junior managerial level in 1906 and eventually became the chief executive of London Transport.

Pick was Stanley’s deputy, working with him to create an integrated transport system, © Public Domain. [68]

In 1902, Pick earned an honours degree in Law from the University of London. However, that same year he decided on a dramatic career change by joining the Traffic Statistics Office of the North Eastern Railway Company (NERC) under general manager Sir George Gibb. In 1907, Pick was put in charge of publicity. He effectively created this job for himself since, at that time, separate publicity and design departments did not exist. It was in this role that his talents became evident. He changed the look of the new underground system. Pick eliminated the clutter from stations where, until then, commercial advertising could be displayed anywhere. He designated far larger areas for essential Underground signage, including route maps and station names. It was Pick who developed the Roundel.