I received a few welcome gifts for Christmas 2025. This article is the second in a short series:

- Colin Judge; The Locomotives, Railway and History 1916-1919 of the National Filling Factory No. 14, Hereford; Industrial Railway Society, Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, 2025. [1] This review and notes can be found here. [18]

- Anthony Burton; The Locomotive Pioneers: Early Steam Locomotive Development – 1801-1851; Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2017. [2]

- Christian Wolmar; The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground was Built and How it Changed the City Forever (2nd extended Edition); Atlantic Books, 2020. This edition includes a chapter on Crossrail. [3] The review and notes can be found here. [19]

- Neil Parkhouse; British Railway History in Colour Volume 6: Cheltenham and thme Cotswold Lines; Lightmoor Press, Lydney, Gloucestershire, 2025. [4]

2. The Locomotive Pioneers

Anthony Burton’s book published by Pen & Sword is a little older, dating from 2017.

His book comes out of a series of different initiatives that he was involved in as a television journalist and author, such as:

- The Past at Work – a series about the remains left from the Industrial Revolution up to 1825 which included two railways (the Middleton Railway and the Stockton & Darlington Railway);

- The Rainhill Story – which followed the construction of the replicas of the three engines which took place in the original trials.

- A biography of Richard Trevithick – which included seeing more replicas coming to life. He particularly notes a time when he “was invited onto the footplate of the replica of the 1803 engine at the Ironbridge Gorge Open Air Museum and was invited to drive, though, … [he] did nothing more than open and close the regulator but that made it none the less thrilling.” [2: Preface]

He says that these experiences “gave [him] a new appreciation of just how in entice the early engineers were, who has to devise these engines for themselves with no precedents to work on.” [2: Preface]

In his second chapter, Burton navigates us through the complex competitive relationship between Boulton & Watt and Trevithick which seems to have been driven by some very strong egos! He notes the way in which that dispute both strengthened and hampered the development of mobile steam engines on road and rail.

I particularly enjoyed a specific step in the history of steam on the move which Burton says is only sketchily documented – interesting to me as it relates to Coalbrookdale.

“In 1802, Trevithick went up to the famous Darby ironworks at Coalbrookdale to install one of his puffer engines. [5] The letter he wrote from there is remarkable in showing how far he had pushed high-pressure steam in a short time. One has to remember that Watt considered a pressure of 10psi to be more than adequate, but here he was describing an engine working up to 145psi. In a long letter describing the working of this engine he added this intriguing postscript: ‘The Dale Co. have begun a carriage at their own cost for the real-roads (sic) and is forcing it with all expedition.’ The railroad referred to would probably have been one of the tramways linking the works to a wharf on the Severn, along which goods would have been hauled down railed tracks by horses. Some commentators have suggested that the experimental railway locomotive was never built, but there is some evidence that it was completed. The man in charge at Coalbrookdale at that time was William Reynolds and his nephew, W.A. Reynolds, described being given ‘a beautifully executed wooden model of this locomotive’ when he was a boy. He broke it up to make a model of his own, ‘an act which I now repent of as if it had been a sin’. He also recalls the boiler being used as a water tank and seeing other parts of the engine in the yard at a nearby ironworks. A visitor to Coalbrookdale in 1884 also recorded being shown a cylinder, preserved as a relic of the locomotive. None of these relics have survived, but a drawing does exist, dated 1803, simply labelled as the ‘tram engine’, which shows a locomotive fitted with a 4.75-inch diameter cylinder with a 3-foot stroke. For a long time, this was thought to be a drawing for the 1804 engine …, but it now seems more likely to have been for the Coalbrookdale locomotive. So it seems more than probable that an engine was indeed built at Coalbrookdale and if so it can claim to be the world’s very first railway locomotive. The drawing was used as the basis for the replica that now runs at the Blists Hill Museum site.” [2: p14-15]

Burton goes on to follow Trevithick further endeavours, particularly the Penydarren locomotive (although the drawing he provided is unlikely to be a good representation of that locomotive given the height of the bore on a tunnel on the tramway which probably would not have accommodated either the flywheel or the chimney of the locomotive).

Ultimately Trevithick’s locomotive was not used for any significant length of time because it was too heavy for the cast iron L-playe rails use on the tramway in the Taff valley.

Burton notes that ” Trevithick’s importance in the development of the steam locomotive was played down after his death, largely because of the growing reputation of George Stephenson.” [2: p21-22]

Burton’s third chapter focussed on developments resulting from wars with France which significantly increased the price of fodder and resulted in much fewer horses available to operate coal tramways in Leeds and the Northeast of England. Burton takes his readers through the development of the use of Steam on the Middleton Railway and then the work of William Hedley and George Stephenson on industrial railways.

Chapter 4 focusses on the Stockton& Darlington Railway which Burton describes as “in effect, a colliery line that suffered from its predecessors only in the scale of its operations.” [2: p43]

Burton also describes how a breakdown in relationships with William Losh, with whom Stephenson shared a patent for a particular form of cast iron rail, resulting from Stephenson’s recommendation of the use of wrought iron to the Stockton and Darlington Railway board, meant that Stephenson could no longer rely on Losh to build locomotives for him. This, according to Burton, was a significant reason why George Stephenson, Edward Pease and Michael Longbridge decided to set up their own locomotive works. Supported by Pease and Longbridge, George Stephenson and his son Robert Stephenson set up their new works in Newcastle, the first in the world to focus primarily on the building of steam locomotives.

Burton concludes the fourth chapter with these words: “If the Stockton & Darlington was, [as] it is often said to be, a model for later developments, then it was certainly not one without many problems. It remained a hybrid with all the attendant difficulties. Having two companies running the passenger service was not a recipe for smooth working. The locomotives, restricted to moving heavy goods, were built more with the idea of hauling the heaviest loads than with any idea of speeding on their way, but at least the inclines, once initial difficulties had been sorted out, worked well. One other railway was approved in the same year as the Stockton & Darlington opened, the Canterbury & Whitstable, described in [its ] Act as ‘Railway or Tramroad’ … had a number of steep sections, worked by stationary engines, and only used locomotives on short sections. Overseas there were railways being constructed in both Austria, opened 1827, and France, 1828, but both still relied on horses to do the work. The case for the steam railway had not yet been conclusively argued.” [2: p54]

Chapter 5 covers the Rainhill Trials. The early pages of the chapter cover the difficulties that the Liverpool & Manchester Railway had in coming to an agreement over the king of propulsion to be used – stationary engines or travelling engines. Ultimately, the Company decided to undertake a locomotive trial at Rainhill.

A completion was determined to be the best way to proceed and advertisements were placed in the leading northern newspapers. Burton tells us that the conditions entrants had to meet, were exact. “The engine had to ‘effectively consume its own smoke’, which in practice meant that it would have to burn coke not coal. The engine could weigh up to six tons if carried on six wheels and up to four and a half tons on four wheels. The six-ton engine ‘must be capable of drawing after it, day by day, on a well-constructed Railway, on a level plane, a Train of Carriages of the gross weight of Twenty Tons, including the Tender and Water Tank, at the rate of Ten Miles per Hour, with a pressure of steam in the boiler not exceeding Fifty Pounds on the square inch’. The weight to be hauled was to be reduced proportionately with the weight of the locomotive. Other conditions included springing to support the boiler and two safety valves, one of which had to be out of the driver’s reach; the latter clause was a precaution against tampering and boiler explosions.” [2: p63]

Burton then talks his readers through the design and construction of what was to become known as ‘Rocket’. [2: p63-66]

On the first day of the trials Rocket and Sans Pareil made runs at the modest speed of 12 mph while pulling loads. Rocket, running light’ also made a demonstration run at between 15 and 25 mph. It was Novelty that “stole the show, dashing along at great speed and at one point reaching just over 30 mph.” [2: p69]

However, on the second day only one of the locomotive motives was able to complete the required ten double runs up and down the track – Rocket. Burton concludes: “It was as well that the Stephenson engine won as it was the one that contained all the elements that were to be crucial for later development: the multi-tube boiler and separate firebox, exhaust steam blast; and cylinders lowered from their former vertical position. Had Sans Pareil succeeded it could well have been selected if only because it was based on well-established practices and could have been thought more reliable than the rivals. But it was built by an engineer looking back over previous successes, not forward to new developments. Novelty would never have had the power for working a busy line. It was Rocket that proved that a railway really could be worked more efficiently by steam locomotives than by any other means then available. It was the future.” [2: p72]

Chapter 6 is entitled ‘Coming of Age’. Burton highlights two different reactions to the speed of the locomotives. One a nervous and terrified response, the other a sense of exhilaration. The directors of the line couldn’t but be nervous about how the line would be received. The locomotives to be used represented the pinnacle of engineering achievement. The line itself was still a mix of old and new. “Unlike the Stockton & Darlington, which had used a mixture of cast iron and wrought iron rails, Stephenson had this time settled for wrought iron fish bellied rails throughout, but mostly they were still mounted on stone blocks, even though there was no longer any intention to use horses for any part of the traffic. However on some sections, especially over Chat Moss, he had set his rails on transverse wooden sleepers. It was soon discovered that with the heavier, faster traffic of the new line, stone blocks were easily shifted out of place, while the wooden sleepers remained firm. Within seven years of the opening, the stone blocks had all been replaced by the new wooden sleepers that would become the norm for railway construction for many years to come. The changes to the track were important. With an improved permanent way, engineers could feel confident in building bigger, more powerful locomotives. The Liverpool & Manchester would show whether there was a real demand for this kind of transport.” [2: p76]

“It was soon evident that there was a real hunger for rail travel. Up until then, railways had been all about freight, with passenger transport as an afterthought. Now it was becoming obvious that the two types of rail transport were achieving something like parity, and engineers would have to plan accordingly.” [2: p78]

Robert Stephenson was already designing a new series of locomotives named after the first in the class, Planet. Burton goes on to describe the design principles for this new class which was a significant advance over the technology employed on Rocket. He also devotes a few pages to the working replica of Planet which was first steamed in 1992.

Other designers are also covered: Timothy Hackworth, Edward Bury, Foster & Rastrick, and Todd, Kitson & Laird.

Chapter 7 looks across the Atlantic and describes very early developments in the United States. [2: p86-97]

Chapter 8 looks first across the Channel, [2: p p98-105]first at the horse-powered line, the Saint-Etienne a Lyon Railway. Its chief engineer was Marc Seguin, who began experimenting with steam-power after his visit to the Stockton & Darlington Railway. He ordered two locomotives from the Stephenson works in Newcastle, one for testing, and one to work immediately on the line. It seems that Seguin was the first to use a multi-tubular boiler and that Robert Stephenson was the first to combine it with an efficient firebox. Burton tells us that after Seguin, french locomotive development was becalmed for a time.

Burton goes on to write about developments in Russia in which the Hackworth family were to play a part. In the 1830s railways spread to other countries in Europe: Belgium and Germany in 1835; Austria, 1838, the Netherlands and Italy, 1839.

Burton covers developments in Ireland in the same chapter. It entered the railway age with “three lines and three gauges. This meant that two of the three could not order ‘off the peg’ locomotives. … It also meant chaos once a joined-up system was developed. Eventually, a gauge commission was to agree on 5ft 3in as the Irish standard.” [2: p105]

Chapter 9 considers the UK broad gauge and is quite frank about the contradictions that were a part of the personality of the mercurial Isambard Kingdom Brunel. He particularly notes the way in which Brunel could be so exacting in his design of the permanent way yet so contrary in the way he specified locomotives to run on the broad gauge. His appointment of Daniel Gooch as Locomotive Superintendent at the age of 20 (just one week short of his 21st birthday) was an enlightened decision. Gooch was not frightened to challenge Brunel and was the saving of his Great Western Railway. Gooch went on to “design locomotives that would help secure the reputation of the Great Western and the reinterpretation of the initial GWR as God’s Wonderful Railway.” [2: p111-112]

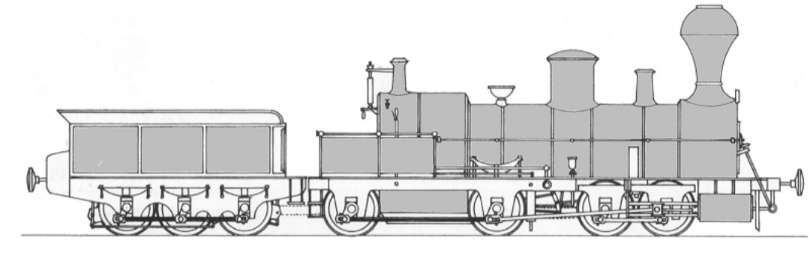

Gooch brought a locomotive from Robert Stephenson’s works originally built for an overseas client at 5ft 6in-gauge Patentee Class locomotive. It was re-gauged to suit Brunel’s broad gauge and became the first successful locomotive on the broad gauge. It was named North Star. Its success encouraged Gooch to “develop the design into a Star class of locomotives. The first of the class, the 2-2-2 Fire Fly went into service in 1840. … On initial trials [it] was recorded as travelling at 58mph while pulling three vehicles. Over the years sixty-two locomotives of this class were built, doing sterling work and the last was retired as late as 1879.” [2: p112-113]

Burton tells us though that the class was not without its problems. But that was not uncommon. “By 1840, there were some thirty works turning out locomotives and few arrived in a condition that allowed them to go straight into service without tinkering or more major adjustments, and servicing and repairs left much to be desired.” [2: p113]

Apparently, Gooch was to go on to develop a larger experimental locomotive, Great Western, with larger, 8ft diameter drive wheels which heralded a new class of which Iron Duke was the first. The class has much larger fireboxes and did not have the large dome of the Firefly class.

Burton tells us that as the GWR expanded westward past Exeter its route took it along the Devon coast through Dawlish, Teignmouth, Newton Abbot and across the edge of Dartmoor. That later length of line required three sections with heavy gradients. Dainton Bank was the most demanding with the steepest length at 1 in 38. There was well-proven technology to address this particular circumstance – cable-haulage by a stationary steam engine. Brunel chose a different option which had mixed success, in 1835 (a failure) and 1840 (a success).

Burton describes the 1840 experiment which was associated with the Birmingham, Bristol & Thames Junction Railway and based on an idea developed by Clegg and improved by Jacob and Joseph Samuda. Over a length of one and a quarter miles, a considerable load was moved using air pressure generated by a stationary steam engine. [2: p114]

Brunel was enthusiastic about the use of this technology (George Stephenson much less so). The technology was first applied on a branch of the Dublin & Kingstown Railway in Ireland, between Kingstown and Dalkley. The system was quite successful. The stationary steam engines created a vacuum behind a piston in a large pipe between the rails. The vacuum sucked the train forward. The system offered potential advantages like speed and efficiency and served for a decade before being replaced. [2: p114-115]

The system was also used in France, on 1.5km length of the Paris to St. Germain Railway which was on a gradient of 1 in 28. The system was technically successful, but the development of more powerful steam locomotives led to its abandonment from 3rd July 1860, when a steam locomotive ran throughout from Paris to Saint Germain. [7]

The London & Croydon Railway also employed the system. It was used on a third track beside the main line. It operated from January 1846 but was abandoned in May 1847.

The use of the system on the branch line in Ireland was enough to persuade Brunel to undertake a much more significant ‘trial’ on his line between Exeter and Newton Abbot. The line between Exeter and Teignmouth was operated as an Atmospheric Railway from September 1847 and to Newton Abbot from 2nd March 1848. Its operation presented problems from the start, with underpowered stationary engines, costly maintenance of leaky leather seals (damaged by tallow-seeking rats and weather), leading to its abandonment in September 1848. [2: p115-117]

Burton comments: “Brunel has been feted as Britain’s greatest engineer, but if he were to be judged purely on his contribution to railway technology it would be difficult to uphold the verdict. His genius can certainly be seen in the civil engineering, culminating in his bridge over the Tamar that brought rails from the rest of Britain to Cornwall. … However logical his decision to build to a broad gauge might have been, it ignored the needs of a national system that was already well under way. … Brunel’s instructions for constructing locomotives for the start of the Great Western were perverse and the atmospheric railway was a costly failure. Looked at solely as a locomotive pioneer, he eouldt be no more than a footnote in most reference books. He was, however, to move on to new worlds, when he famously declared that he saw no reason why the Great Western should stop at Bristol – why not go on to New York? His steamships represented a quite extraordinary achievement and opened up the world to steam navigation. In this he proved himself to be a true genius and worthy of his place in the engineering pantheon.” [2: p117]

Chapter 10 – Valve Gear: A short chapter covers developments in valve gear over the period examined by the book. The simple arrangement of a four-way cock letting steam in or out of the piston was displaced by a number of different inventions. Burton notes:

- James Forrester’s 1834 introduction of a new type of valve gear, using two eccentrics on the driving axle, one for forward movement and the other for reverse. [2: p118 & p120]

- John Gray’s patented ‘horse leg’ gear of 1838 which was generally ignored by his contemporaries.

- William Williams and William Howe appear to have developed a ‘slotted link’ which permitted “the change from forward to reverse to be made smoothly as a continuous operation.” [2: p120] Edward Cook sent Robert Stephenson a model of the new arrangements in August 1942. Their adapted linkage became known as ‘Stephenson Valve Gear’. It was quickly patented by Robert Stephenson. [2: p121]

- Daniel Gooch was the first to adapt the Stephenson valve gear for his own locomotives. In the Stephenson valve gear ,(see the image above), “the valve spindle is fixed, and the reversing rod moves the expansion link and the forward and backward eccentric rods. In the Gooch system, the arrangement was effectively reversed; the expansion link was attached to a fixed bearing and this time the reversing rod moved the valve rod. It found very little, if any, use other than on the broad gauge lines.

- Alexander Allan was the engineer in charge of the Grand Junction Railway’s locomotive works. He devised his own variation on the Stephenson Valve Gear in which the reversing lever moved the eccentric rods, the link and the valve rod.

- In Belgium, the first railway opened in 1835 between Brussels and Mechelen. Egide Walschaerts was 15 years old at the time. By the time that he had completed his studies at the University of Liege, the Belgian State Railways had opened workshops at Mechelen. He took a job there and quickly rose to the position of works superintendent. He developed valve gear that worked by a different pattern to the Stephenson valve gear. Walschaert valve gear has “just a single eccentric attached to the eccentric rod, which in turn [is] attached to the expansion link that allows for both reversing and varying the cut-off point. A second system, based on a radius rod attached to both the piston cross-head and the valve spindle, ensures that the lead on the valve remains constant in both directions, regardless of the cut-off point.” [2: p122-123] The Walschaert valve gear was used extensively throughout Europe but not in Britain until the late 19th century.

- Richard Roberts had a knack for working with machinery and worked at a number of locations picking up knowledge before ending up, in 1814, working with Henry Maudsley (an eminent machine manufacturer). By 1817, Roberts had set up in business for himself in Manchester. Burton tells us that he was soon producing significant machinery: an early planer; a new type of lathe; gear-cutting and slotting machines; and the first successful gas meter. By 1825, he made a self-acting spinning mule which remained in use in the British textile industry until the second half of the twentieth century. In 1828, Roberts “went into partnership with iron merchant Thomas Sharp to form Sharp, Roberts & Co. to manufacture locomotives at their new Atlas Works in Manchester.” [2: p124] … Roberts interest in the company faded, although a brilliant Mechanical Engineer, he was a terrible businessman that ended his days in poverty. Burton tells us about Roberts because it was men like him that made it possible for the celebrity engineers to realise their designs, using templates and gauges to standardise production. “Without men like him, the necessary accuracy of construction for complex valve gears could never have been realised. It is difficult for us to understand just how badly equipped in terms of machine tools even the best workshops were at the start of the railway age.” [2: p124]

Burton entitles his eleventh chapter New Directions. In that chapter, he highlights:

- Developments in railways in North America.

- The replacement of stone blocks in Britain with wooden sleepers with metal chairs which maintained the gauge of the track.

- A similar arrangement in North America but without the metal chairs which allowed tracks to be laid very quickly with tighter bends, but resulted in a much poorer ride than in Britain.

- Locomotive design in North America needing to accommodate poorer track construction and as a result developed locomotives with a greater separation between a front bogie and the drive wheels. The first American standard engines were 4-2-0 locomotives, then 4-4-0 locomotives, and by 1847, the first 4-6-0 engine was in service

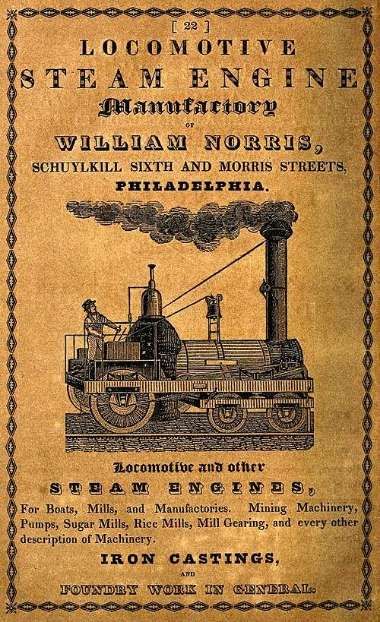

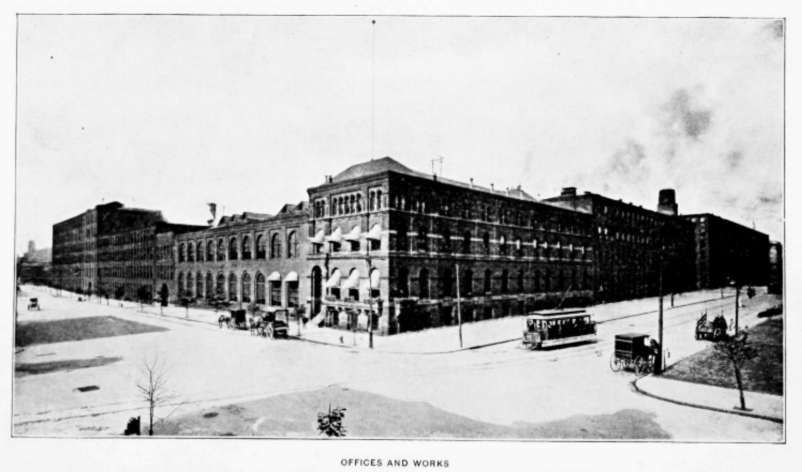

- The first need in Britain for locomotives from North America. Norris Locomotive Works was at the forefront of locomotive development in North America. Norris locomotives were successful on very steep inclines in North America. The Birmingham & Gloucester Railway which had the 2.5 mile long Lickey Incline with a gradient of 1 in 37, “ordered fourteen engines from Norris, specifically to cope with [that] section of line. They served well as banking engines, joining their more conventional running mates to overcome the obstacle.” [2: p130]

A Norris advert featuring one of their 4-2-0 locomotives. [8] Construction advanced rapidly. In just eleven years, four-wheeled 6.5 ton locos had given way to ten-wheeled locomotives weighing 22 tons. [2: p130] Norris was, by the start of the 1850s, “employing about a thousand men and the works was said to be capable of turning out 159 locomotives a year.” [2: p132]

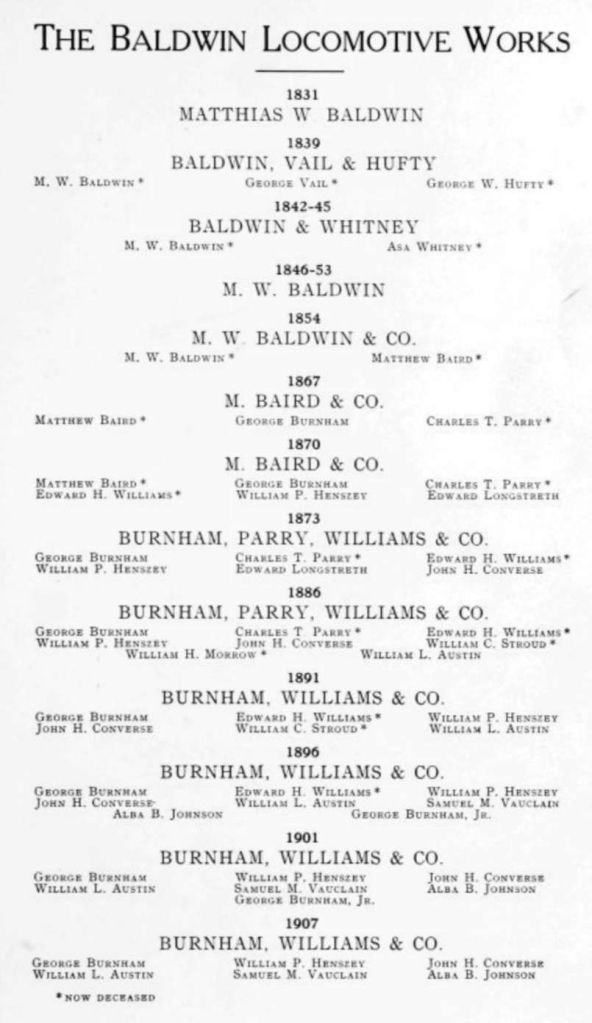

- the way in which Baldwin became the best known of the American manufacturers. Matthias Baldwin started small with a single novelty engine running round a circular track giving rides to passengers. Then he built a locomotive for the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad Co. which was based on the Planet class locomotive supplied by Robert Stephenson & Co. to the Camden & Amboy Railroad. Baldwin inspected the delivered loco, ‘John Bull’ while it was still in pieces. He built a replica but without the leading pony truck. [2: p132]

- Baldwin’s move into bigger workshops and that by the end of the next he had built 128 locos. He offered a limited range of three different locomotives, all based on the same design. He worked on standardisation of parts for his locos. He thought that there would be no need for more powerful locomotives than he was producing, but by the 1840s he had to design more powerful locomotives. [2: p134]

- Kestler’s rise to prominence in Germany and his willingness to copy Norris’ designs but with alterations based on British practice. All the manufacturers faced the need to produce more powerful locomotives. [2: p135]

Burton’s twelfth chapter focusses on ‘Speed and Power‘. [2: p136-155] He follows developments in the 1840s in Britain. Timetables needed to be published to allow people to plan journeys and James Bradshaw’s Railway Guides came into being (in 1839). Demand for rail transport was increasing at an incredible rate. Requirements for passenger and goods locomotives diverged with dedicated classes of locomotives being developed. Speed was important for passenger services, power to haul the largest load possible was important for goods services.

This twelfth chapter is wide-ranging, showing the relatively slow rate of development in Britain compared to the United States of America noting the problems in Britain caused by the two main line track gauges. Burton looks at developments in braking which culminated with the air brakes, especially the Westinghouse brakes, in the 1860s. He considers developments in continental Europe pointing particularly to the need of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to link its capital (Vienna) with its main seaport on the Adriatic coast (Trieste). The government decided that it needed “a rail link between the two, but the line would have to cross the Alps via the Semmering Pass at an altitude of 936 metres. Trains were not required to go quite that high, as a tunnel was created below the summit at an altitude of 878 metres. Even so, the track had to twist and turn and the route out of Vienna had a 29 km section with a gradient that constantly hovered around the 1:40 mark. There was considerable doubt whether any locomotive could manage such a climb, certainly none in existence at that time could have done so. There was talk of relying on fixed engines and cable haulage. A writer to a technical publication pointed out that this was exactly the scenario that had been played out at Rainhill, cable haulage versus locomotive. That had been settled by a trial, so why not have a Semmering Trial?” [2: p151]

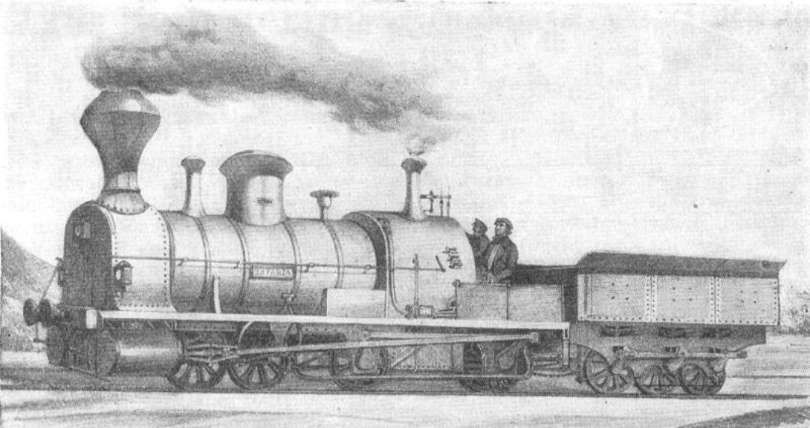

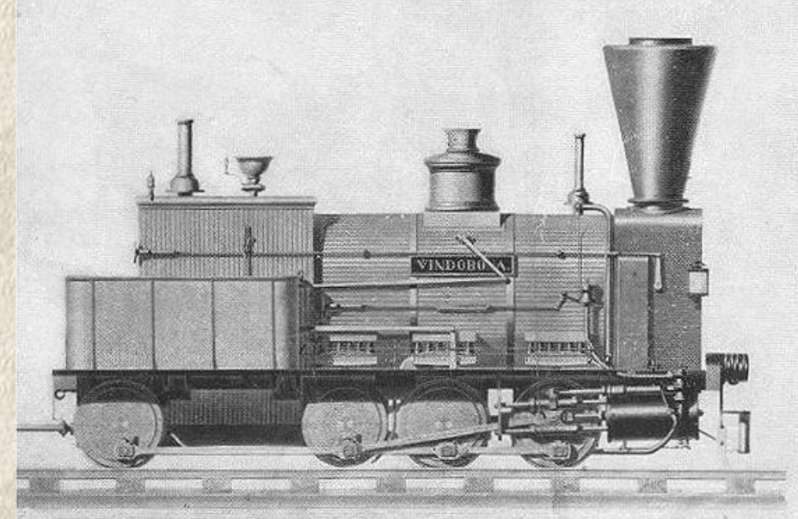

Four locomotives were sent to ‘compete’ at the Trial. Burton tells us that these were, Bavaria, Seraing, Neudstadt and Vindobona.

At the trial, “a successful locomotive had to ascend the pass with its train at a speed of 11.5kph and limitations were set that engines should not exceed 14 ton axle load though a very generous boiler pressure for the time was permitted at 120psi. No British companies offered up candidates, but four locomotives by four different European manufacturers were entered.” [2: p151] Burton tells us that these were, Bavaria, Seraing, Neudstadt and Vindobona.

Bavaria: “There were inevitable British connections. The winning entry [Bavaria] came from the company established in 1836 by Joseph Anton Maffei in Munich a company that was to survive in various forms and was still to be at the forefront of locomotive development in the twentieth century. It was designed with the help of the English engineer Joseph Hall. It was unlike anything seen on rails before. There were four axles under the locomotive, the front two mounted on a bogie. All were connected via a mixture of conventional rods and chains. There were a further three axles under the tender, also connected to the drive axles, spreading the tractive effort over engine and tender. The wheels were small, just 3ft 6in diameter and the locomotive managed to haul its 132 ton train up the slope at a very creditable 18 kph, well in excess of the competition target. The three other locomotives also managed to pass the test, but Bavaria was considered the most reliable. This turned out not to be … true in practice, as there were problems with the chain drive almost from the start and it was taken out of service.” [2: p151]

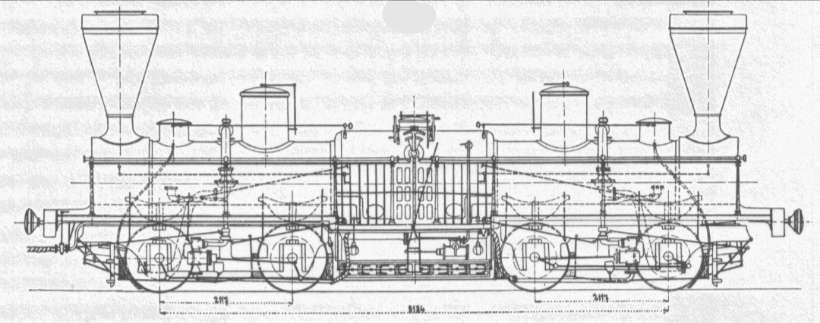

Seraing: “Perhaps the most interesting of the other locomotives came from the John Cockerill Company, which, was by far the most important manufacturing concern in Belgium … by 1840 … it had been taken over by the state, while still retaining the Cockerill name. It was from this factory that the locomotive Seraing was sent to Semmering.” [2: p151]

“Seraing was an articulated locomotive, with a central firebox, and a boiler at each side. The appearance was of two locomotives that had backed into each other and become irretrievably stuck together. A set of four wheels set on a bogie beneath each of the boilers made it possible for this locomotive to have a large boiler capacity, a long overall wheelbase of 27ft, but still be capable of coping with the tight curves of the Semmering. The description of this engine probably sounds familiar; it could, of course, equally well describe the Double Fairlies built for the Ffestiniog Railway. In fact they appear to have been remarkably similar in many respects.” [2: p151-152]

“The Seraing only came third in the competition, but having met the conditions, was bought by the state for 9,000 ducats. The problems that led to its withdrawal were shortage of steam (despite having two boilers) and leakage from the flexible steam pipes.” [9]

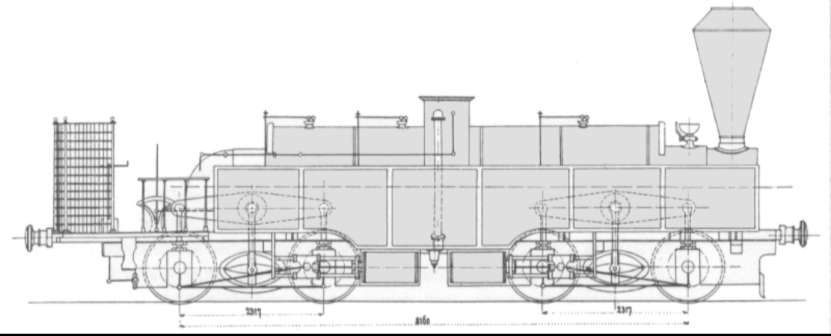

Neudstadt: “was built by the Wiener Neudstadt locomotive factory, south of Vienna, the largest locomotive and engineering works in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It too had two 4-wheel bogies, but a single boiler.” [2: p152]

“The Wiener-Neustadt had two four-wheel bogies, driven by outside cylinders. Power transmission between the axles was by conventional coupling rods. Each bogie was sprung with one set of springs attached to a large beam that equalised the load between the axles; it looks like rather heavy and clumsy way of doing it, but all the weight of it was available for adhesion. Two steam pipes ran down to a set of four telescoping pipes with stuffing-boxes that led steam to the four cylinders. The exhaust steam was routed, via more telescopic piping, to a central pipe that ran forward to the blastpipe in the smokebox. Boiler pressure was 111 psi. Water was carried in side-tanks. … The front bogie had a central pivot, and the rear bogie moved in a radial manner that is not at present clear. According to Wiener the great defect of the locomotive was that the bogies could not move transversely with the respect to the main frame of the locomotive. Presumably this gave trouble with derailments and damaged track.” [9]

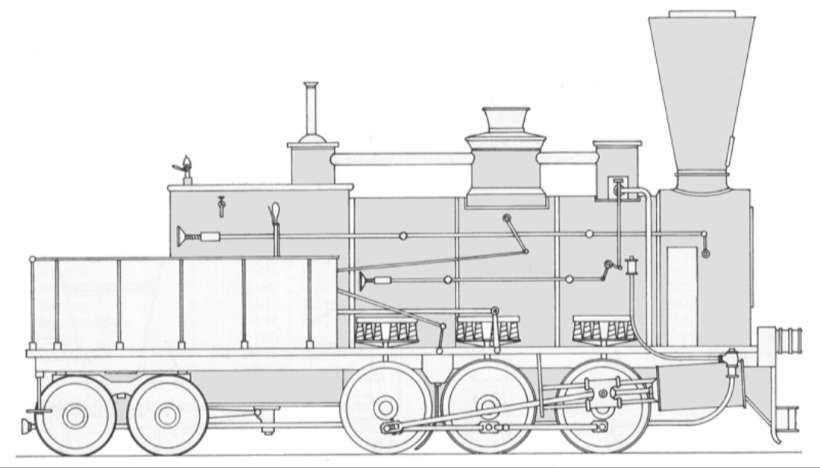

Vindobona: “The fourth contender was designed by a Scotsman, John Haswell. Born in Glasgow, he received his early experience at the Fairfield shipyard on the Clyde, before leaving for Austria to help set up the repair works for the Wien-Raaber Railway. He became superintendent of the works, which soon began constructing locomotives and rolling stock as well as repairing them. Their locomotive Vindobona was a rather strange form of 0-8-0, with three axles conventionally placed under the boiler and the other connected by a long connecting rod, under the tender.” [2: p152]

Burton’s twelfth chapter also highlights developments in American design aimed at increasing power in locomotives which were able to accommodate the smaller radius curves on the American network. Baldwin patented a design in 1842 for an unusual type of locomotive. It had “outside cylinders, set at an angle, with long connecting rods to the drive wheels at the rear. These drive wheels were then connected to the other wheels on a form of truck. These were held in a separate frame, and arrangements were made so that the two pairs of wheels could move independently of each other when going round bends. The coupling rods had ball and socket joints to allow for the necessary flexibility.” [2: p153-154]

Baldwin’s patent application (Patent No.2,759) was filed with an accompanying model. The patent was issued on 25th August 1842. It specifically covered a design for a flexible beam truck for the driving wheels of a locomotive. “The goal of the design was to increase the proportion of the engine’s total weight resting on driven wheels thus improving traction and thereby the ability of the engine to pull heavier loads. While then existing locomotives had multiple driven axles, their designs made them unsuitable for use on the tight curves that were common on American railroads at the time. Baldwin’s design allowed for multiple driving wheel axles to be coupled together in a manner that would allow each axle to move independently so as to conform to both to sharp curves and to vertical irregularities in the tracks.” [12][13]

“The new engine was tried out on the Central Railway of Georgia, where it was recorded that the 12-ton engine drew nineteen trucks, loaded with 750 bales of cotton, each weighing 450lb up a gradient of 36ft to the mile with ease. Railroad managers were soon writing in praise of the new design and orders began to flow: twelve engines in 1843; 22 in 1844; and twenty-seven in 1845.” [2: p154]

Baldwin continued to innovate: trying iron tubes instead of copper in boilers. He incorporated developments made by others into his locomotives (e.g. when French & Baird designed a far more efficient stack (chimney) in 1842 (Burton suggests it was 1845), Baldwin adopted it immediately for all of his locomotives). [13]

Later, Baird was to become the sole proprietor of the Baldwin Locomotive Works (in 1866/7). [14]

Burton tells us that Baldwin focussed first on construction of freight locomotives and maximising pulling power. In 1848, he was challenged to make an express locomotive capable of travelling at over 60 mph. He built the Governor Paine in 1849. It was a very different form of 8-wheel engine with a pair of 6 ft 6 in. driving wheels set behind the firebox and a smaller pair of wheels in front of it. The carrying axles at the front of the locomotive were on a conventional bogie.

At the end of his twelfth chapter, Burton comments: “As the 1840s came to an end, the variety of locomotives on lines all over the railway world was remarkable. The number of builders also increased; some small and specialised, others, especially those run by the bigger companies, were developing into massive industrial units employing hundreds and even thousands of workers.” [2: p155]

Chapter 13 – The Works: Burton notes that prior to the opening of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) there had been no need for special repair shops as mines already had their own maintenance facilities for their steam piping and winding engines. The S&DR set up its works at Shildon and in doing so set a pattern that was followed by other companies. The Shildon works, “such as they were, consisted of one, narrow building, divided between a joiner’s shop and a blacksmith’s shop with two hearths. There was also an engine shed, which remained roofless for years, which could hold two locomotives. Gradually, more cottages were built and the workforce grew from twenty to fifty men. Machine tools were almost non-existent, consisting of little more than hand operated lathes, and screw jacks for lifting parts for erection. According to an old workman, interviewed in 1872 for the Northern Echo, the place was so cold in winter that tallow from the candles froze as it dripped. The nature of the work ensured that if there was no heating, they were kept warm by their exertions. Wheels were always a problem, frequently cracking, and having to be laboriously hammered on and off the axles. For many years it remained no more than a repair shop, but Hackworth established his own Soho Works for building locomotives close by in 1833. Because of his official duties, he passed over the control to his brother, Thomas, and a local iron founder, Nicholas Downing. By 1840, Hackworth had resigned from the Stockton & Darlington and concentrated solely on Soho. It is interesting to see just how much had changed in a short time.” [2: p156]

By the time Hackworth died in 1850, the Soho works “had developed into a major complex. The main range of buildings consisted of a foundry, with three cupola furnaces, a machine shop and a blacksmith’s shop. There were separate buildings for stores and for the pattern makers and joiners workshops. Unlike the Cockerill works in France, the Soho foundry was not based on a blast furnace fed with iron ore, but on furnaces that were used to melt either pig iron or scrap iron. The wheel lathe was capable of turning wheels up to 10ft in diameter and a boring machine for cylinders up to 8ft diameter. The blacksmiths’ shop had twenty-two hearths, with a fan blast to raise the temperature, and a separate furnace for wheel tyres. The works required skilled craftsmen of all kinds, from machinists to pattern makers.” [2: p156]

Burton goes on to highlight the vital skills of carpenters who had to make wooden patterns for items to be cast – a highly skilled activity which had to be completed to very tight tolerances. Foundry skills and carpentry skills are only examples of a panoply of trades which had to be brought together to achieve the manufacture and maintenance of railway locomotives.

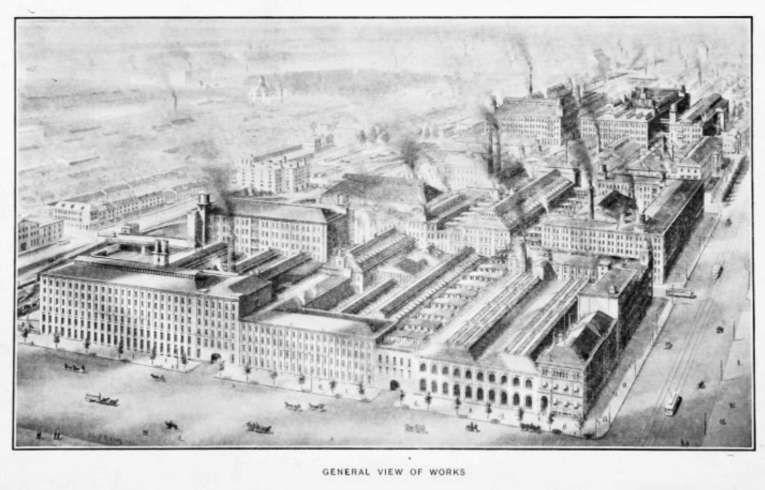

For much larger concerns than the S&DR, works inevitably had to be of truly significant size. The choice of the site for these large works was critical, Gooch prevailed on Brunel to support the proposed Swindon Work. He had to weigh up convenience across the GWR as a whole and selected a location that was not central to the GWR at the time but was situated at the point where a change of locomotive would be required as the profile of the line changed sufficiently to warrant a different class of engine. Gooch’s letter to Brunel is detailed enough to extend to approximately a full page in Burton’s thirteenth chapter. [2: p157-158]

Once a site for a works was chosen there was an inevitable need to provide housing for skilled workers. The S&DR saw the need for some construction work at Shildon and also at their new port, Port Darlington on the Tees which formed the kernel of the urban area that would become Middlesbrough. The GWR created a railway village, New Swindon. Its design needed to be good enough to attract skilled workers and their families. The design of this new community was given to Matthew Rugby Wyatt, the architect of Paddington Station. As the works grew, so did the railway village. By the end of the 1840s it accommodated some two thousand workers and their families. The village grew to include a school, a Mechanics Institute, bath houses and a health scheme. Gas and water were supplied, a brickworks was established, a library and a church were built.

The Swindon works of the GWR began building locomotives in 1846 and it became the centre for all locomotive construction for the broad gauge. By 1847, the wagon department had to be moved to allow expansion of the loco works which in 1847 were completing one new locomotive every Monday morning! Much of the work had to be done by hand. Wrought iron sheets were limited in size. Large objects could only be built by riveting several plates together. Rivets required one man to “push a rivet though the aligned holes and hold the head in place with a heavy hammer. The man on the opposite side would then hammer his end, so that it spread out against the plate, holding the two pieces firmly together. Apart from being hard work, which required speed and precision, it was also incredibly noisy; deafness was a common complaint among boilermakers in later life. The boiler would be made up in short sections that were then butt-ended and joined together.” [2: p163]

“One of the problems in manufacture was wheel construction. … Before 1850, wheel hubs were almost entirely forged by hand. There were various types of spoke, round or square cross section and various methods of attaching them between the hub and the rim. The earliest reference to a lathe specifically designed for turning locomotive wheels appeared in an advert for Nasmyth, Gaskell & Co. in 1839, capable of turning wheels up to 7ft in diameter. Joseph Beattie of the London & South-Western Railway patented a lathe in 1841 that was capable of turning two wheels simultaneously.” [2: p163]

Burton continues to discuss the forging of crank axles for inside cylinder engines. He highlights a major step forward in the manufacture of both railway locomotives and paddle steamers when Jane’s Nasmyth designed a Steam-powered vertical drop hammer.

He goes on to reflect that the work of constructing a locomotive was not organised around a series of standard parts made in a quality controlled way. There was no smooth production line. Rather, disparate groups of workers were “responsible for their particular part of the whole, perhaps consisting of s master craftsman and an apprentice, with one or more labourers.Unifirmity was made more difficult by the absence of standards. ” [2: p164-165]

For example, “centre-to-centre distances for connecting rods were not marked on Crewe drawings until 1859. When a rod was fabricated, it had to be sent to the smithy to be adjusted to fit the actual distance between wheel centres.” [2: p165]

Standardisation was slow to arrive in Britain, perhaps partly because each railway company had its own works. In North America things were different. Railway companies were much more reluctant to set up their own works. They preferred to rely on private manufacturers such as Baldwin and Norris. As early as 1839, Baldwin was stressing the value of standardisation, although it was to be 1860 before standard gauges were introduced.

Burton’s fourteenth chapter focusses on the Great Exhibition of 1851 which had as one of its themes the way in which railways would transform life on every continent of the world. Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace was built to hide the exhibition. The building itself reflected the exhibition’s theme of technological innovation. There were some 200 numbered items in the exhibition catalogue which were devoted to railways.

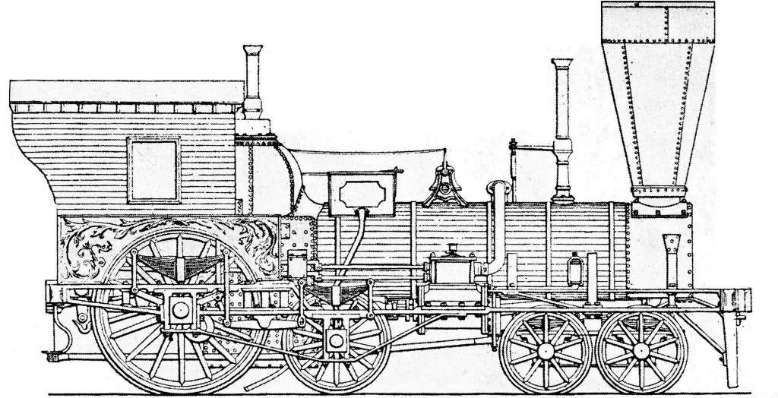

At the time of the Great Exhibition, engineers appear to have agreed that the future for speed on the railways was to be found in locomotives with one driving axles with large wheels. The British scene, however, remained marked by a diversity of manufacturers and products. In America things were different. There was remarkable agreement on what best suited their railroads. The American Standard 4-4-0 locomotive was introduced in the 1830s.

“The 4-4-0 was built continuously through to the end of the 19th century. It handled both freight and passenger assignments, and its use among railroads was nearly universal – so much so that it acquired the name ‘American Standard’, or simply ‘American’. In 1884, 60 percent of all new U.S. steam locomotives were 4-4-0s. … As train lengths and speed increased, the 4-4-0 also grew, with the addition of bigger cylinders, a larger boiler, and a bigger firebox. The 4-4-0 was a well-balanced design with natural proportions. (In other words, the size of the boiler, grate area, firebox, and cylinders were closely matched to its service requirements.) In short, it was hard to build a bad one.” [17]

Classic Trains magazine tells us that it was the widespread application of air brakes in the 1880s that heralded the end of the 4-4-0. “Air brakes made it possible to run longer and heavier trains, and that in turn created a demand for bigger locomotives. Freights that once could have been handled by 4-4-0s soon needed 2-6-0s and 2-8-0s. Passenger trains were put in the charge of 4-6-0s and 4-4-2s. … Once heavier power appeared, major railroads consigned the 4-4-0 to light passenger jobs, often on branch lines, although some short lines continued to use it in freight service. … After 1900 few new 4-4-0s were built, with the very last going to the Chicago & Illinois Midland in 1928. Along with two other Americans received the prior year, the engine was used on a couple of local passenger runs. … By this time, over 25,000 Americans had been built. The 4-4-0 lasted into the diesel era and some examples ran into the late 1950s. Many still exist today in museums and on tourist railroads.” [17]

By 1850, much of what constituted the basic elements of Steam-powered traction was in place. Burton tells us that “there were still innovations to come that would lead to a steady development in all aspects of locomotive power and performance. One of the most important changes in Britain in the 1850s was the change from coke to coal as the main fuel at considerable savings in cost, though it required changes in firebox design. The range of locomotives was increased by the use of steam injectors topping up the boiler while the engine was on the move. These and other changes were improvements rather than revolutionary changes. Perhaps the biggest change of all was not in the railway world itself but in metallurgy, in the manufacture of steel. It would make a great impact on railways as a whole.” [2: p178]

As the decades unfurled, steam-power developed to its zenith in the early 20th century. However, by the 1950s the use of steam-power was in terminal decline across the world. In particular locations it would remain a viable option into the 21st century. Not only was it challenged by factors beyond the rail network: the coming of the mass-produced private car and bus and freight transport by road; but electric power and diesel power would inexorably replace steam on the railways themselves.

Burton concludes his book, which I found to be an enjoyable read: “If one looks back over history it is possible to realise just what an achievement it was to develop the steam locomotive. In the first century since Newcomen’s engine first nodded its ponderous head over a mine shaft, the engine had developed from an atmospheric engine to a true steam engine, but it was still a monstrously large beam engine, rooted to the spot. To turn such an engine into a machine that could thunder across railed tracks at high speed was one of the greatest achievements of the nineteenth century. The pioneers who achieved this feat had no patterns to work from, no precedents to follow and very little in the way of theoretical background to draw on. Yet in just fifty years they transformed the locomotive from an unwieldy contraption, rumbling along at little more than walking speed, to an efficient engine that is easily recognised as having the essentials that would enable it to develop and thrive for another hundred years. It ranks as one of the great achievements not just of their own age but in the whole history of mankind.” [2: p181-182]

Burton’s book concludes with a short Glossary, a Select Bibliography and an Index. [2: p183-192]

References

- Colin Judge; The Locomotives, Railway and History 1916-1919 of the National Filling Factory No. 14, Hereford; Industrial Railway Society, Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, 2025.

- Anthony Burton; The Locomotive Pioneers: Early Steam Locomotive Development – 1801-1851; Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2017.

- Christian Wolmar; The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground was Built and How it Changed the City Forever (2nd extended Edition); Atlantic Books, 2020. This edition includes a chapter on Crossrail.

- Neil Parkhouse; British Railway History in Colour Volume 6: Cheltenham and the Cotswold Lines; Lightmoor Press, Lydney, Gloucestershire, 2025.

- Puffers: “By the beginning of the nineteenth century Trevithick had already successfully developed his high-pressure steam engine for work in the local mines as a whim engine, hauling men and material up and down the shaft. They became known as ‘puffers’ because of the way the exhaust steam puffed noisily out at each stroke. In a trial against a traditional Boulton & Watt engine to measure their relative efficiency, the Trevithick engine came out the clear winner, which did nothing to improve relations between the two camps. Now Trevithick began working on a puffer that would not merely turn a wheel above a shaft, but would move itself too. His first question was one that we would not even consider today, could a vehicle be moved simply by turning the wheels round, relying on the effect of friction between the wheels and the ground? He settled that matter with a simple experiment by taking an ordinary cart, and, instead of pulling it, simply turned the wheels by hand; it moved. He was now ready to build a prototype. The engine was assembled from a variety of sources; the boiler and cylinder were cast at the works of the Cornish engine manufacturer, Harvey’s of Hayle, an obvious choice as Trevithick had married Henry Harvey’s sister, Jane. The ironwork was prepared by the Camborne blacksmith Jonathan Tyack. Some of the more intricate work was entrusted to Trevithick’s cousin and friend Andrew Vivian, who had his own workshop and lathe.” [2: p9]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GWR_Firefly_Class#/media/File%3AFire_Fly_2_(5646634337).jpg, accessed on 28th December 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atmospheric_railway, accessed on 28th December 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norris_Locomotive_Works, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- http://www.douglas-self.com/MUSEUM/LOCOLOCO/semmering/semmering.htm, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semmering_railway, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Du_Bousquet_locomotive, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- https://www.si.edu/object/baldwins-patent-model-flexible-beam-locomotive-ca-1842%3Anmah_843732, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- “The ‘flexible beam’ referred to heavy iron beams that were connected to each side of the engine’s frame with a vertical, spherical pin so that they could pivot horizontally and vertically in relation to the frame. The beams on each side of the frame moved independently of each other. At each end of the beams were journal boxes for the axles, and these boxes were constructed to an earlier Baldwin patent with cylindrical pedestals that allowed them to rotate vertically inside the beam. The result was that when rounding a curve one driving axle could move laterally in one direction while the other axle could move independently in the other direction thus adapting the wheels to the curve while at the same time keeping the axles parallel to each other. The coupling rods were made with ball-and-socket joints to allow them to adapt to the varying geometry due to lateral axle motion. While this geometry would also result in the coupling rod lengths varying as the axles moved laterally, in actual use the variation was very small – on the order of 1/32 of an inch – and was allowed for via a designed-in slackness in the bearings. The patent was applied by Baldwin to a large number of engines manufactured up until 1859 when the design was superseded by heavier and more advanced engines. … The patent model [was] constructed of wood and metal and … mounted on rails attached to a wooden base. A brass plate attached to the boiler [was] inscribed with ‘M.W. Baldwin Philadelphia’. The boiler [was] painted wood as [were] the cylinders and coupling rods. The engine frame [was] steel, and the wheel rims … made of brass. The key element of the patent, the flexible beams [were] present on the front two axles. The beams and leaf springs [were] made of wood. The vertical pins appear to [have been] made of steel. While the axle journal boxes [were] shown it appears the details of the cylindrical pedestals and other moving parts [were] not modelled.” [12]

- https://www.mainlinemedianews.com/2010/07/06/ml-history-the-luck-and-hard-work-of-our-foreign-born-successes, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- http://users.fini.net/~bersano/english-anglais/LocomotivesAndDetailParts.pdf, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1CNNsgPe8m, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- https://www.trains.com/ctr/railroads/locomotives/steam-locomotive-profile-4-4-0-american, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/12/26/christmas-2025-book-reviews-no-1-colin-judge.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2026/01/20/christmas-2025-book-reviews-and-notes-no-3-christian-wolmar-the-subterranean-railway

Pingback: Christmas 2025 Book Reviews and Notes No. 1 – Colin Judge … | Roger Farnworth