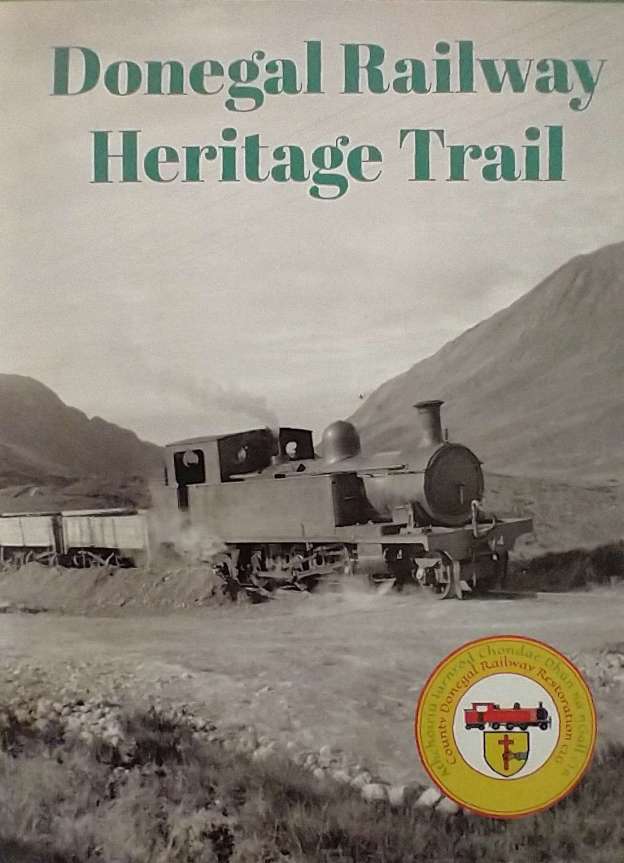

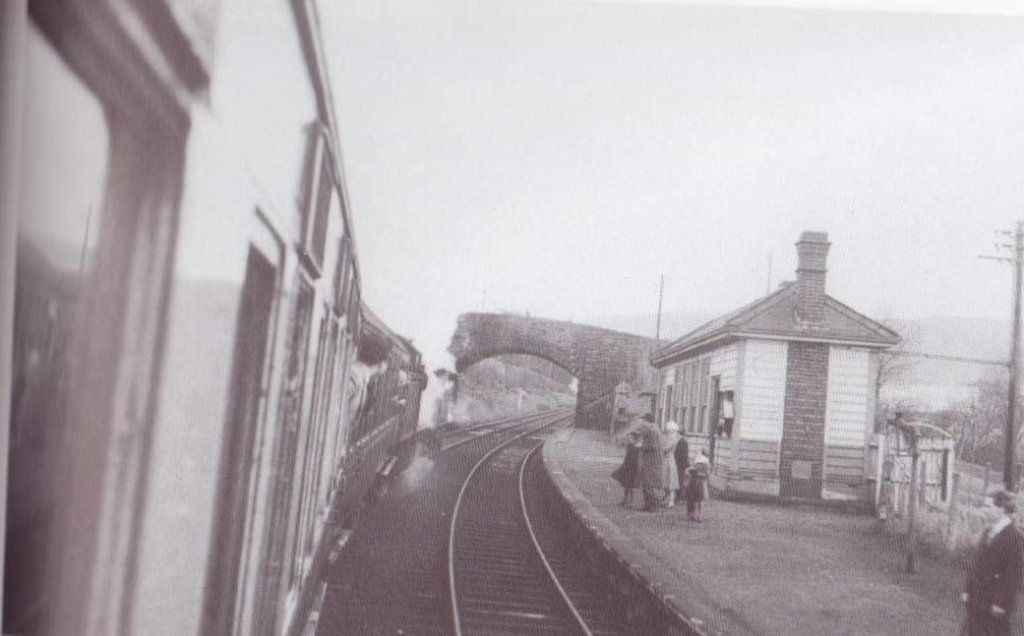

The featured image shows Govilon Railway Station looking East with a train approaching from Abergavenny, © R.W.A. Jones . [20]

About 9 months after my first article about Govilon, Richard Purkiss contacted me to offer a wander around the area immediately to the West of my last walk.

That first article can be found here. [1]

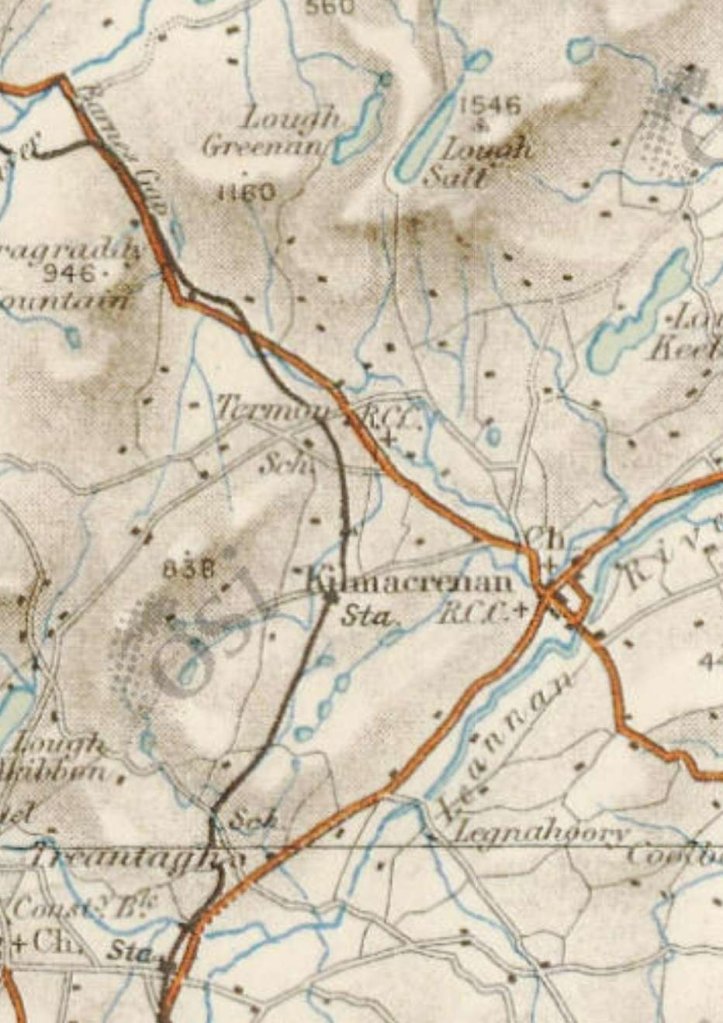

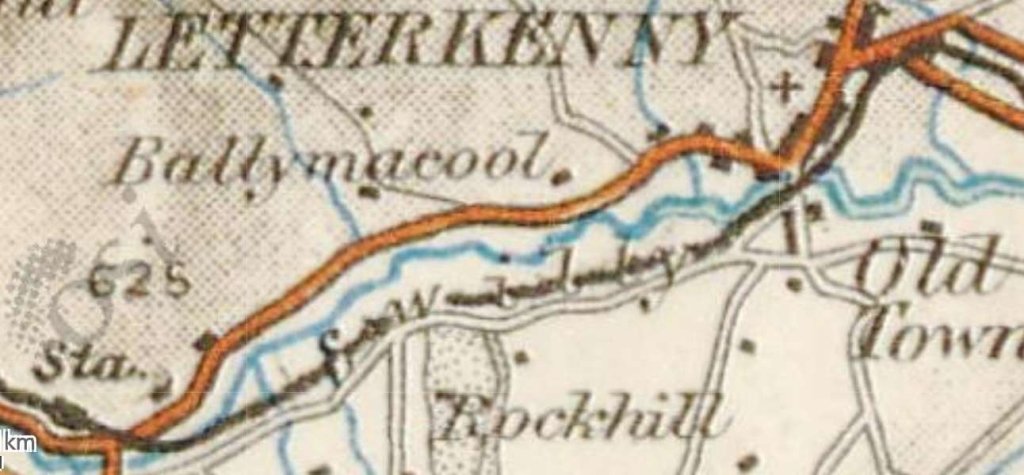

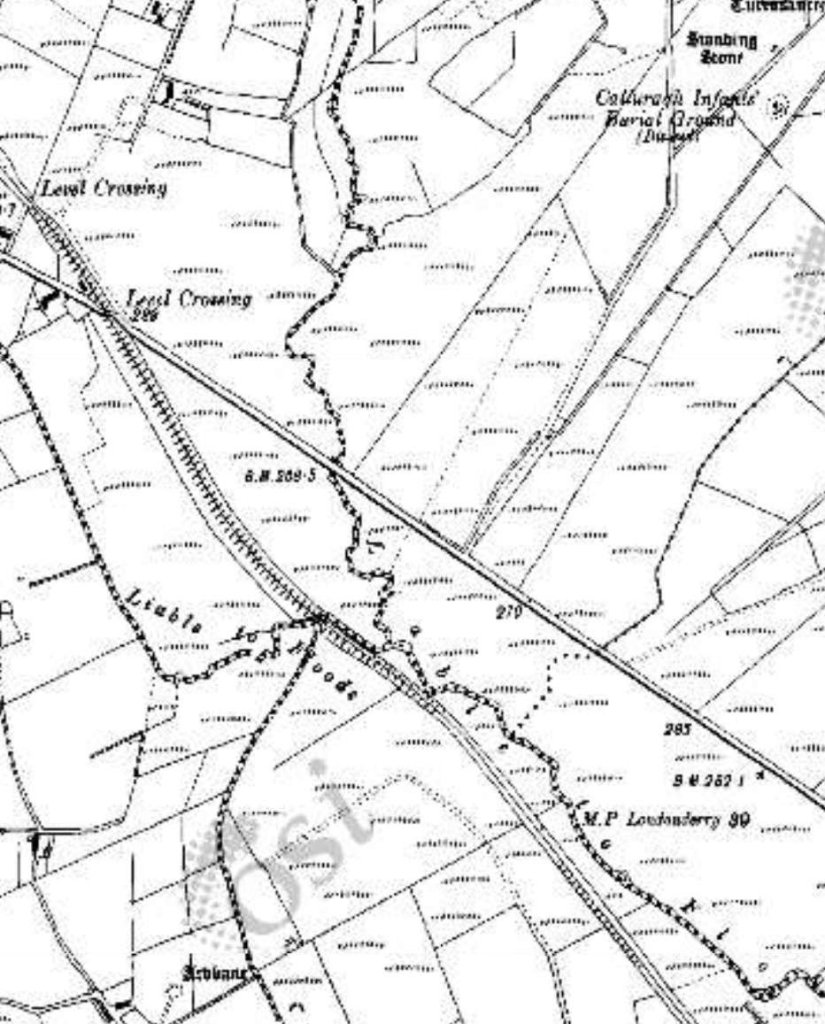

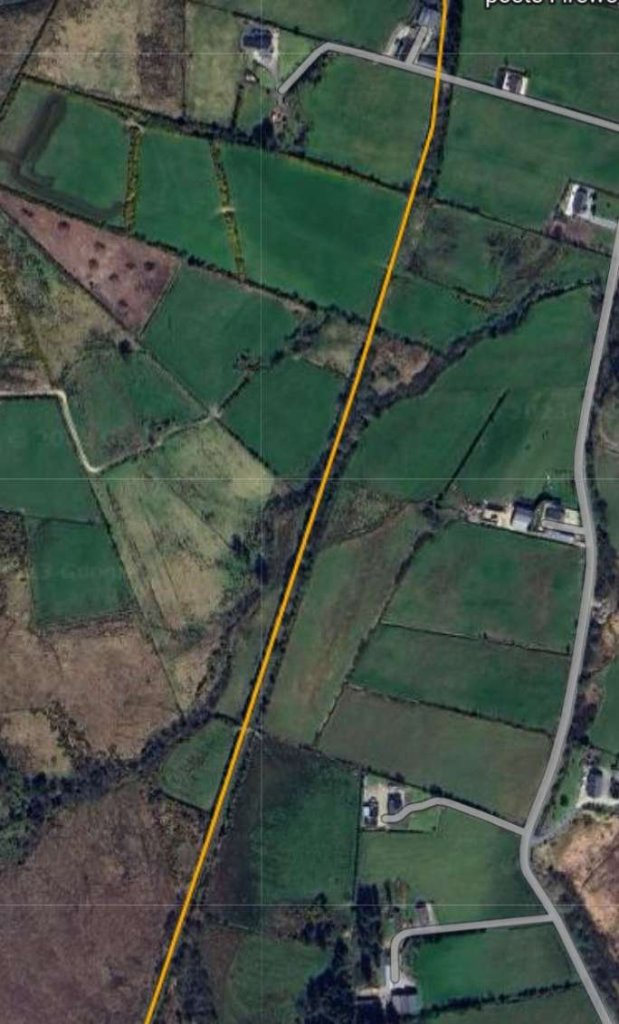

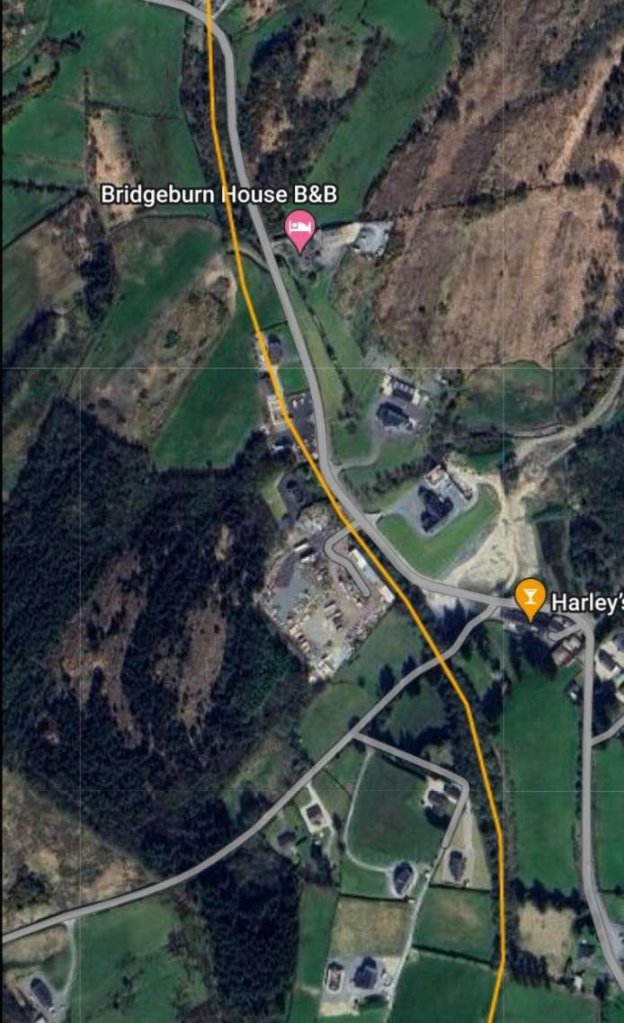

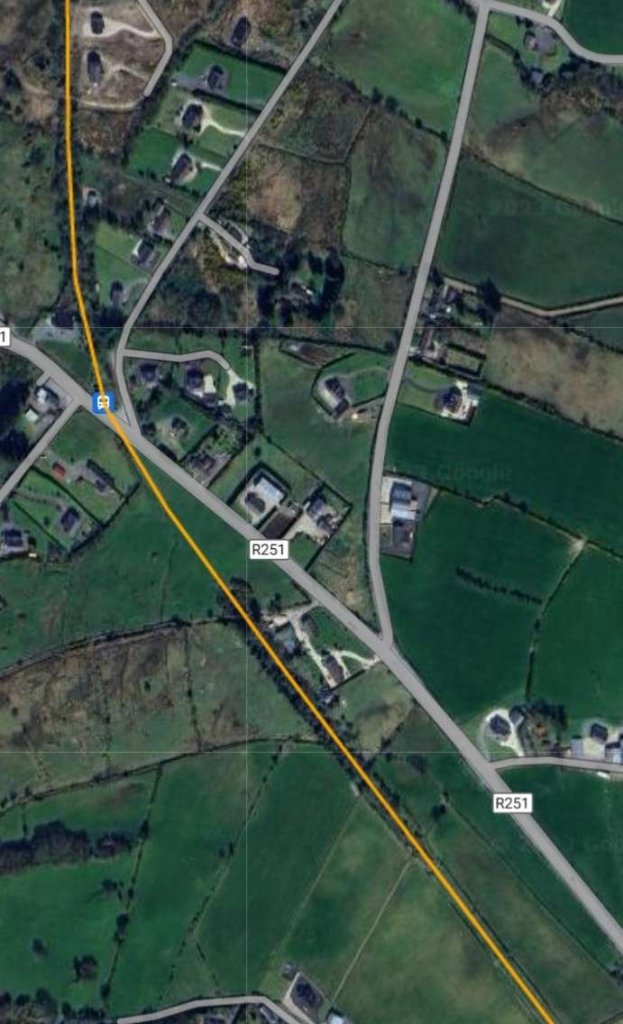

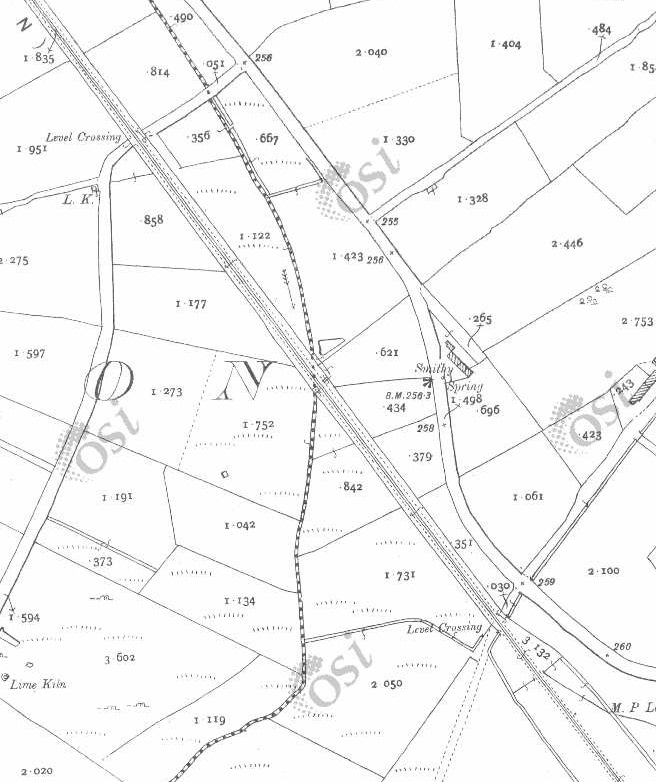

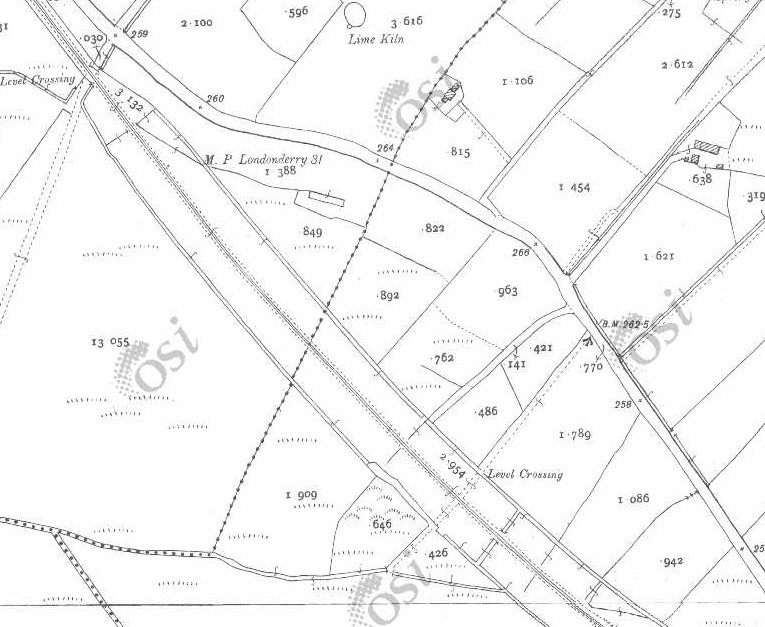

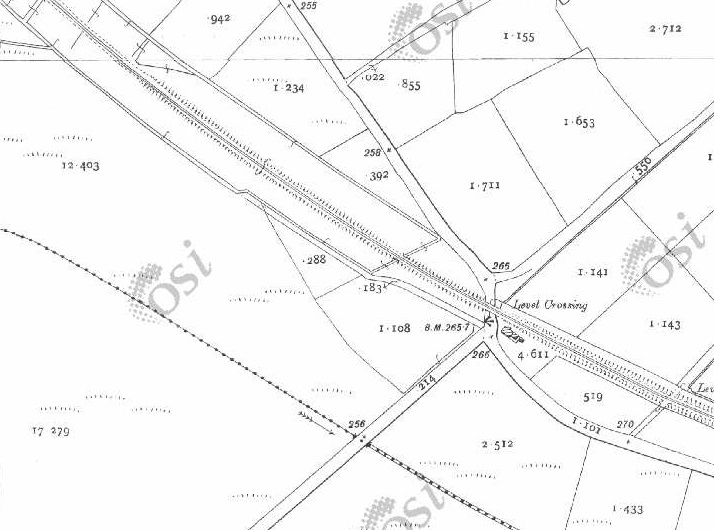

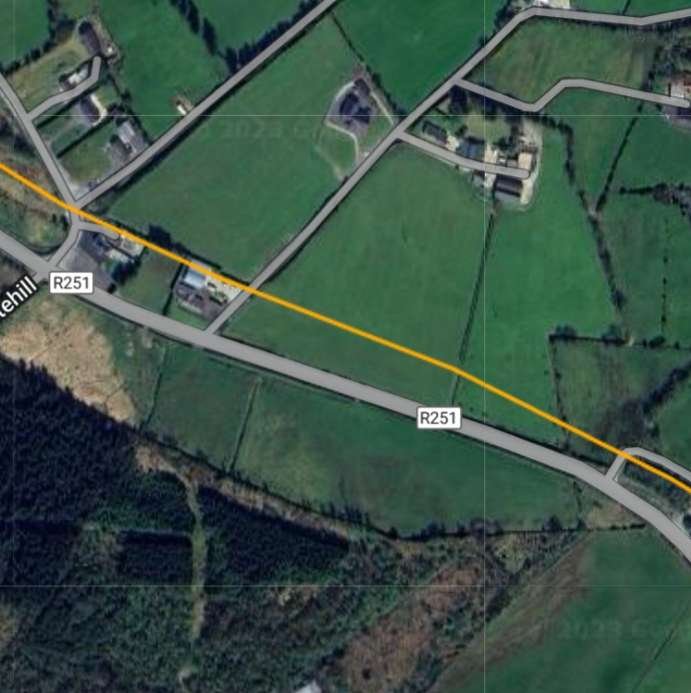

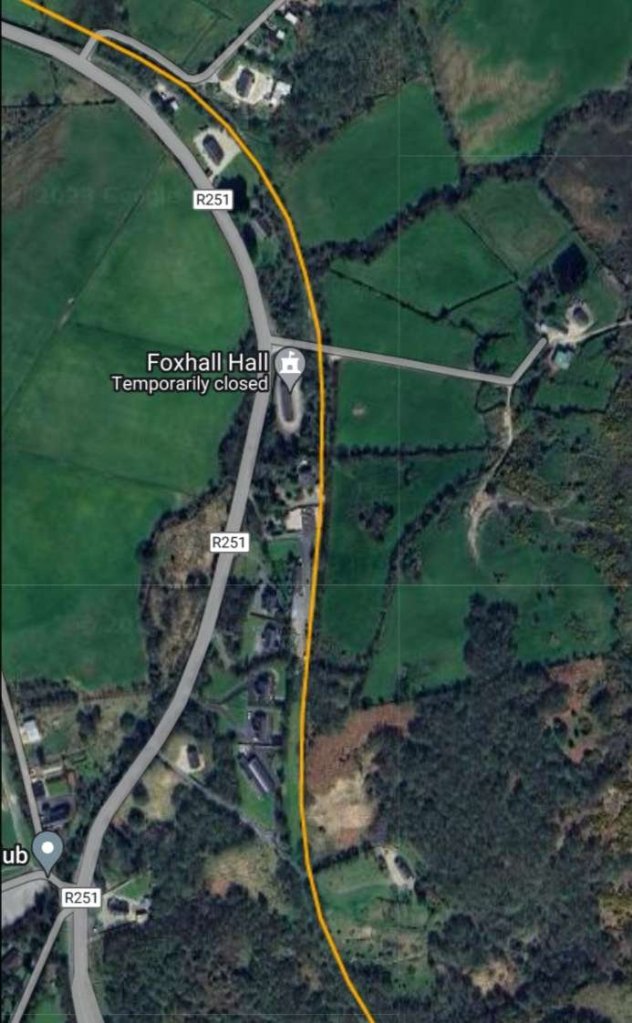

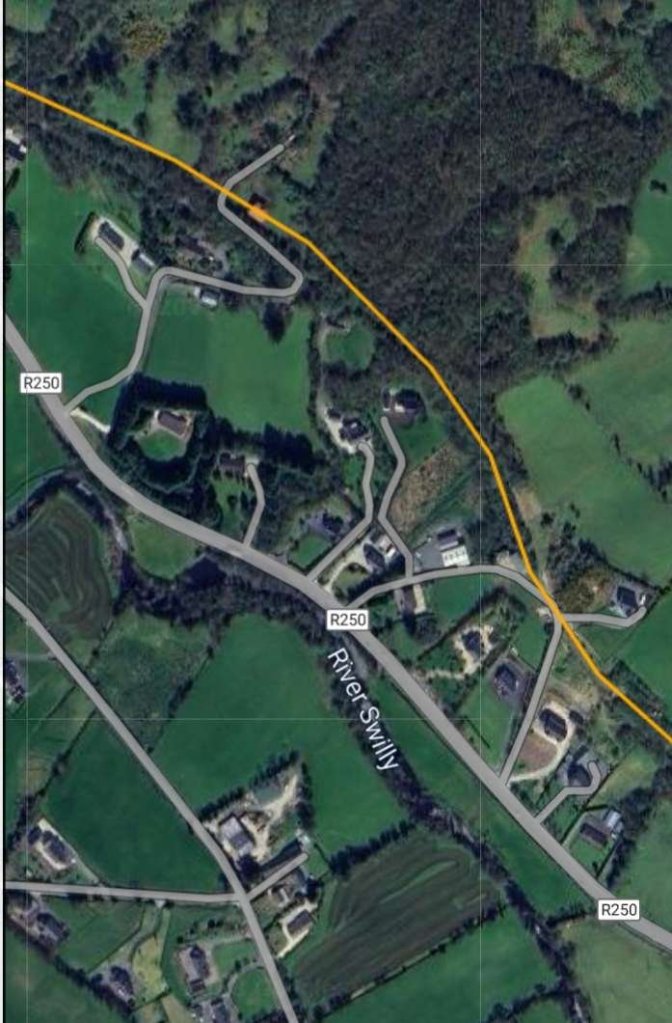

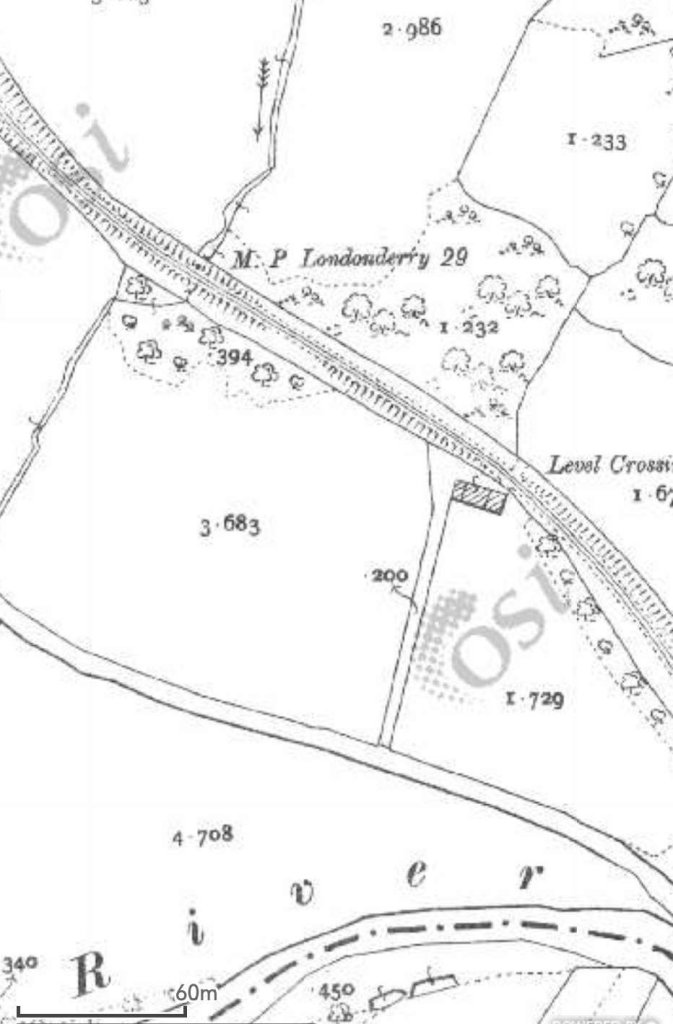

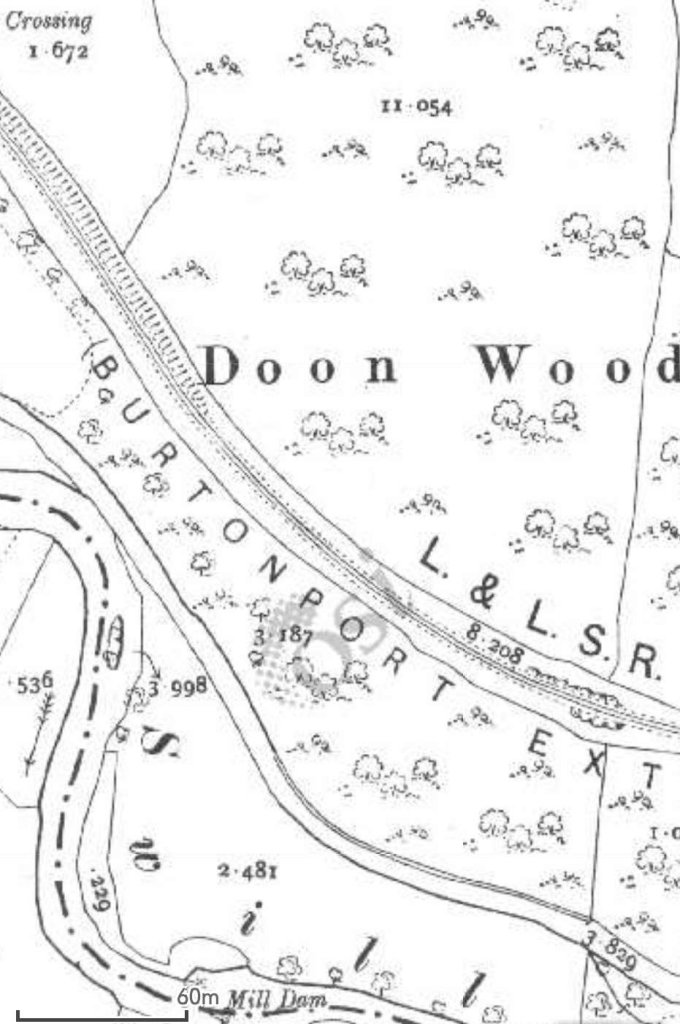

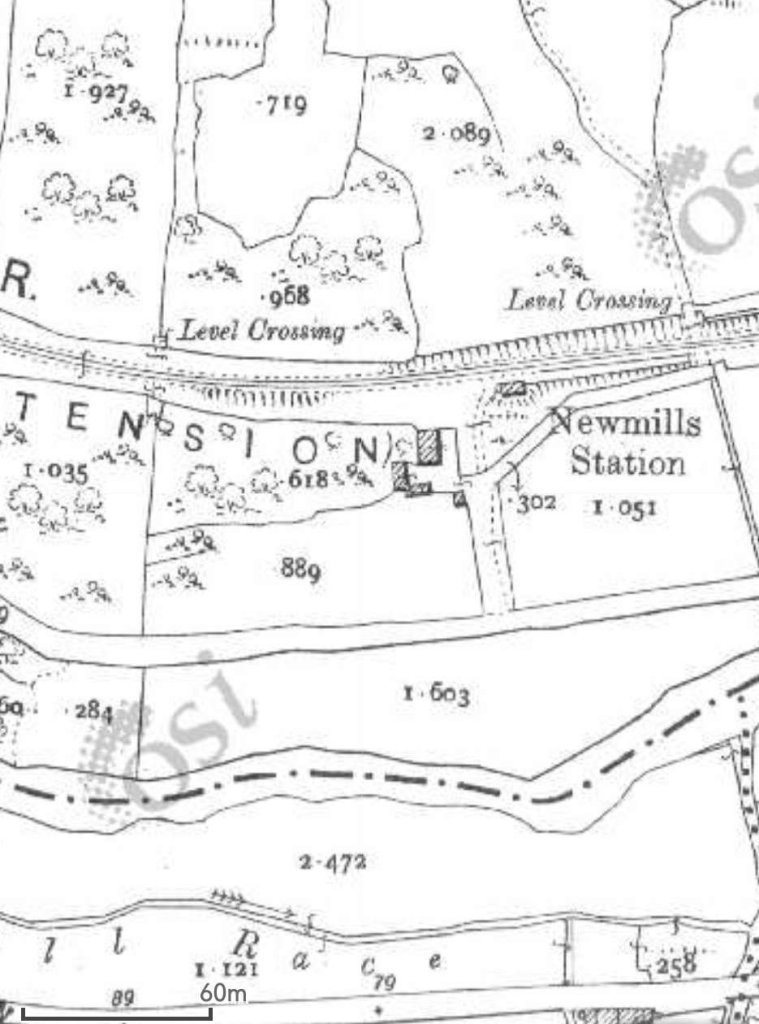

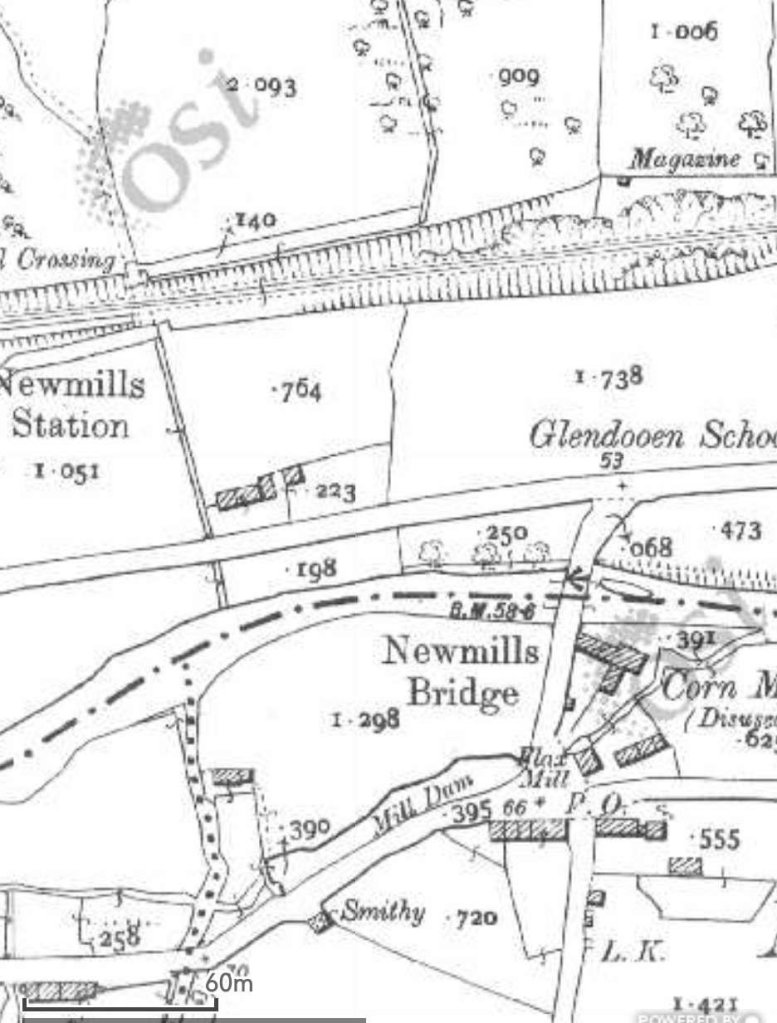

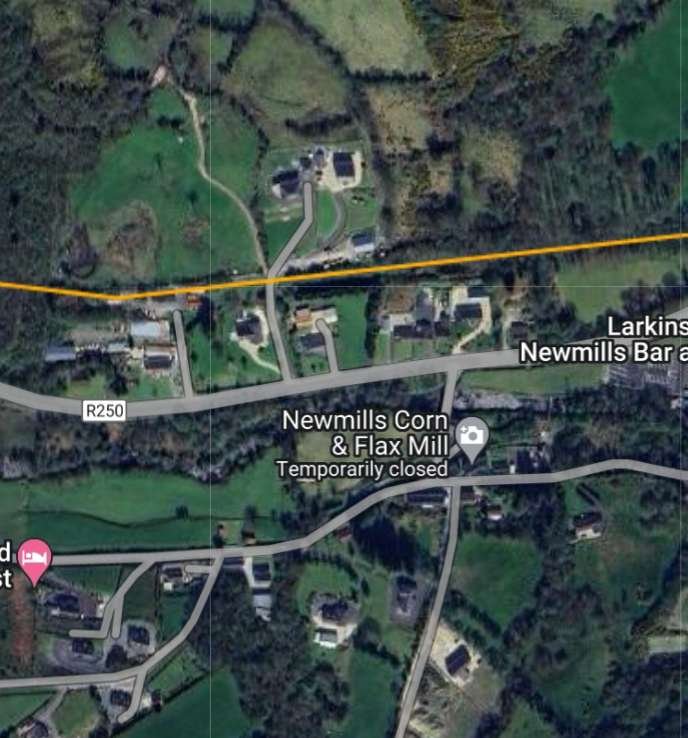

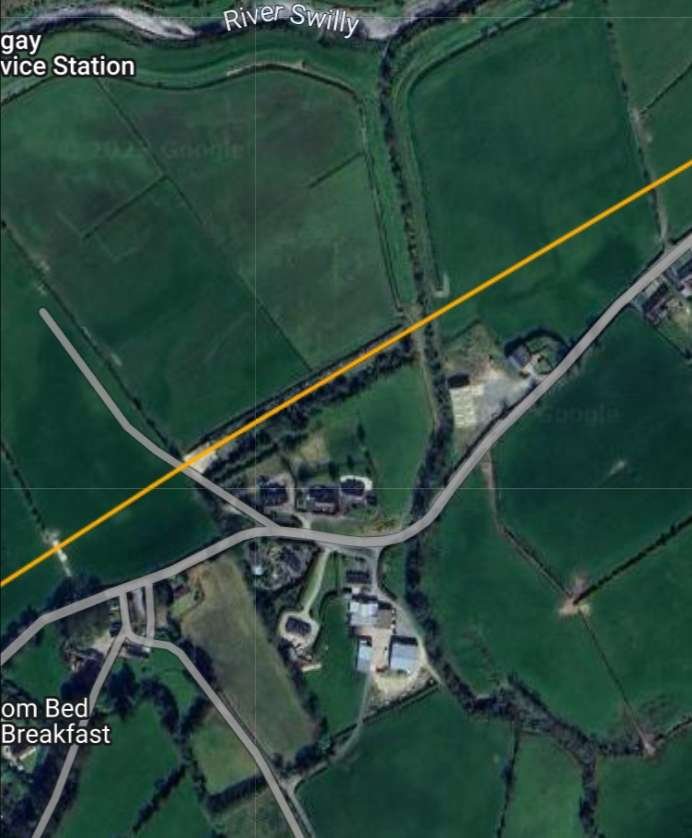

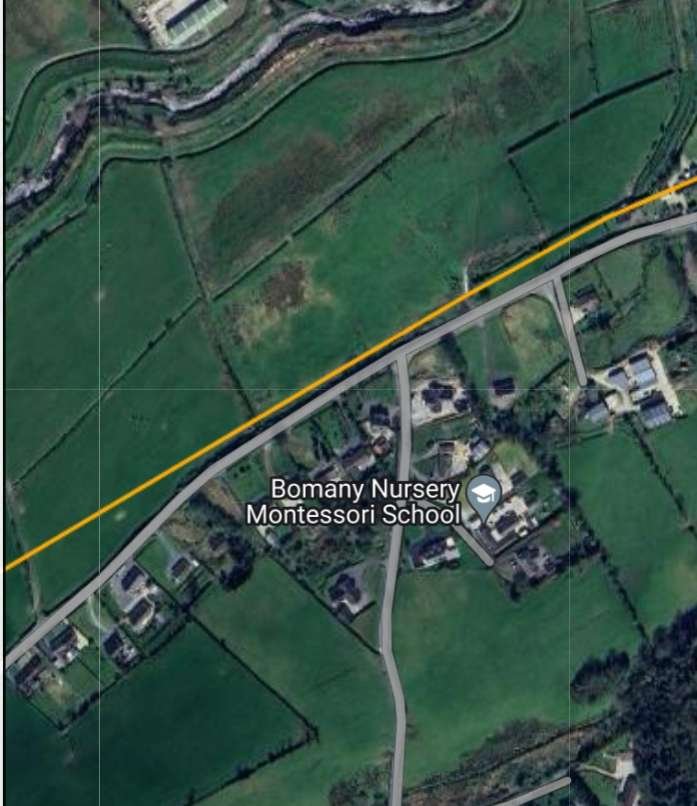

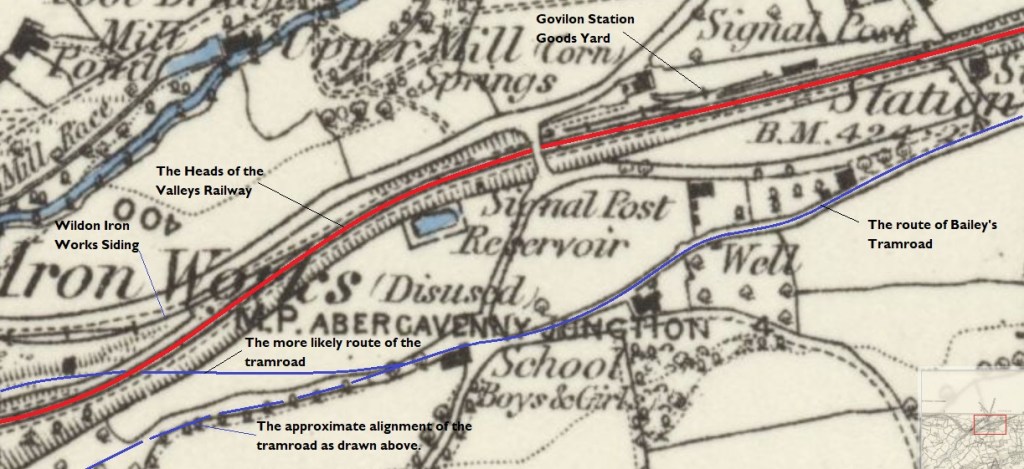

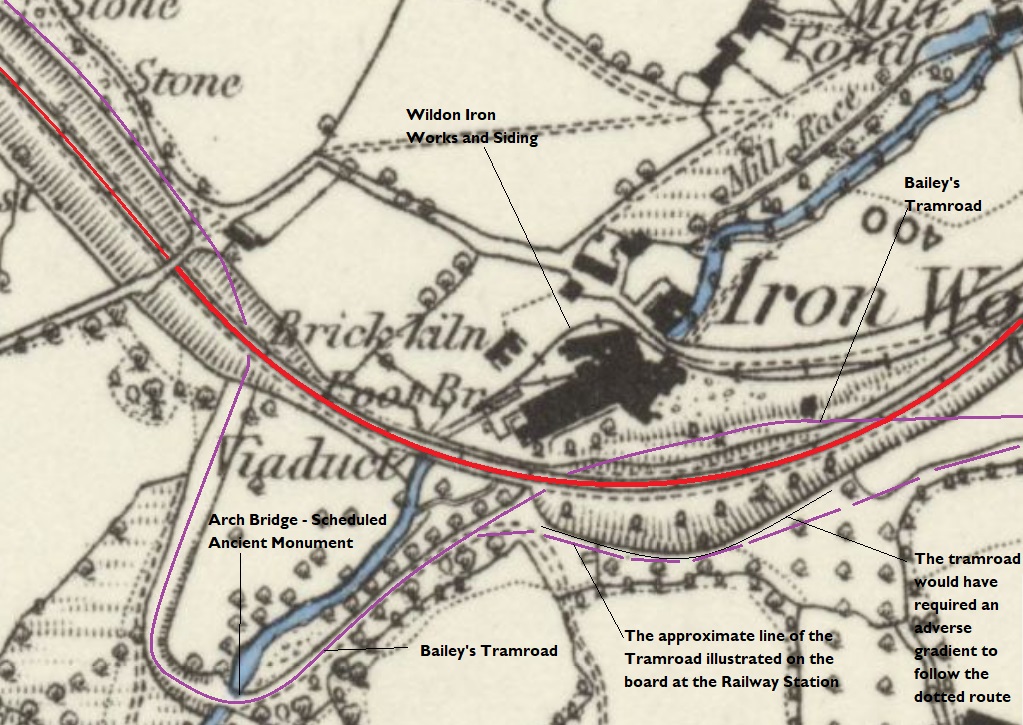

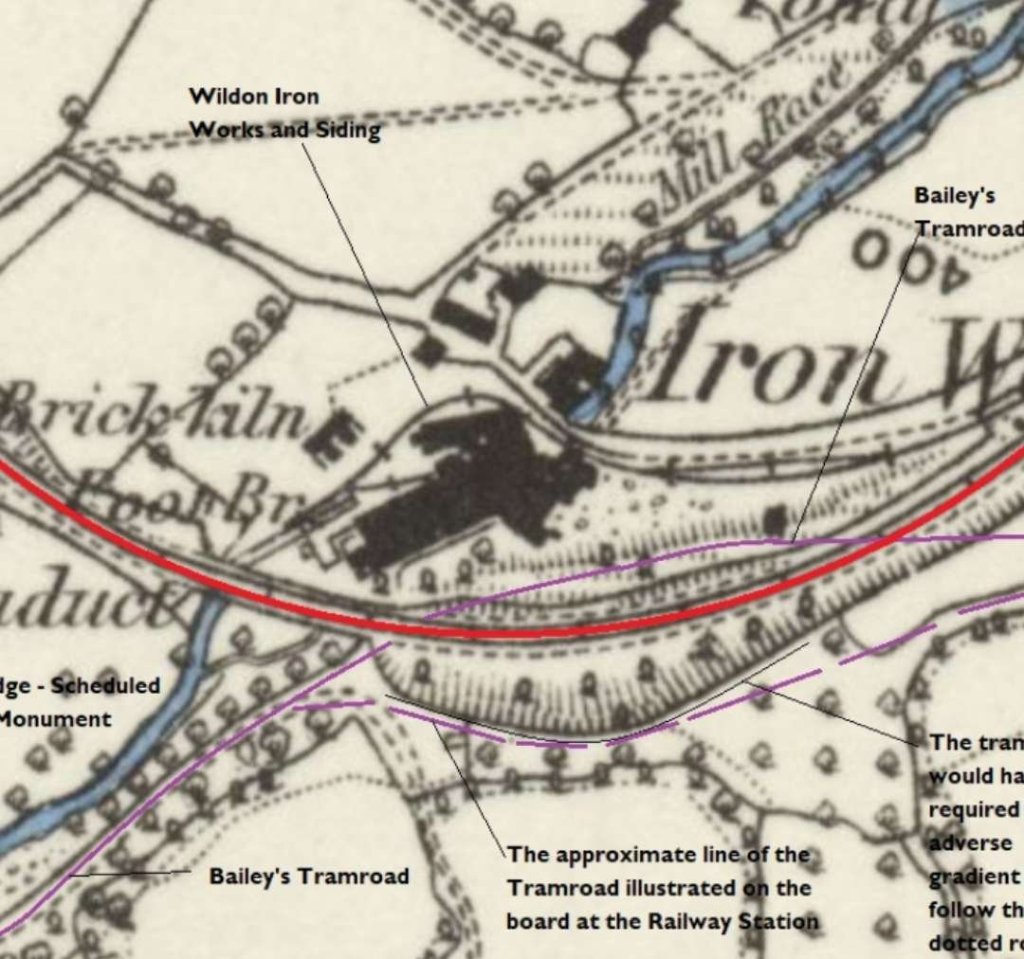

In this second article we explore the route of Bailey’s Tramroad and the adjacent Railway as they are shown on the left side of the sketch map above.

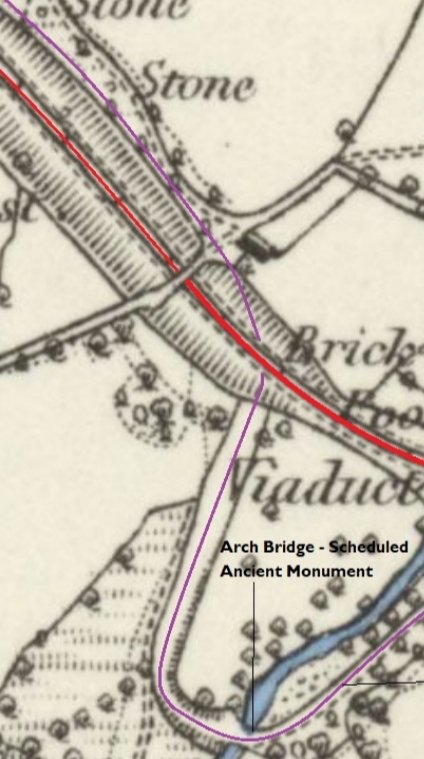

The dotted line representing Bailey’s Tramroad on the plans above should be taken as a schematic representation rather than an accurate alignment. It is clear, when walking the route, that the section of the Tramroad close to Forge Car Park actually passed under the location of the viaduct and was for a very short distance on the North side of the later standard gauge line. I will try to show this in the images below which were taken on site.

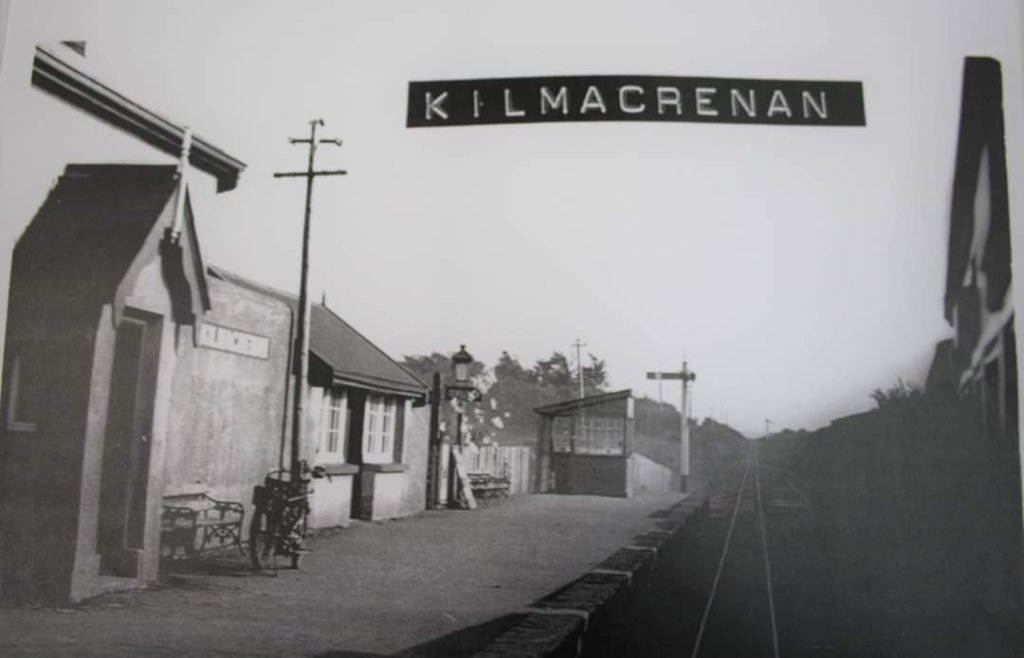

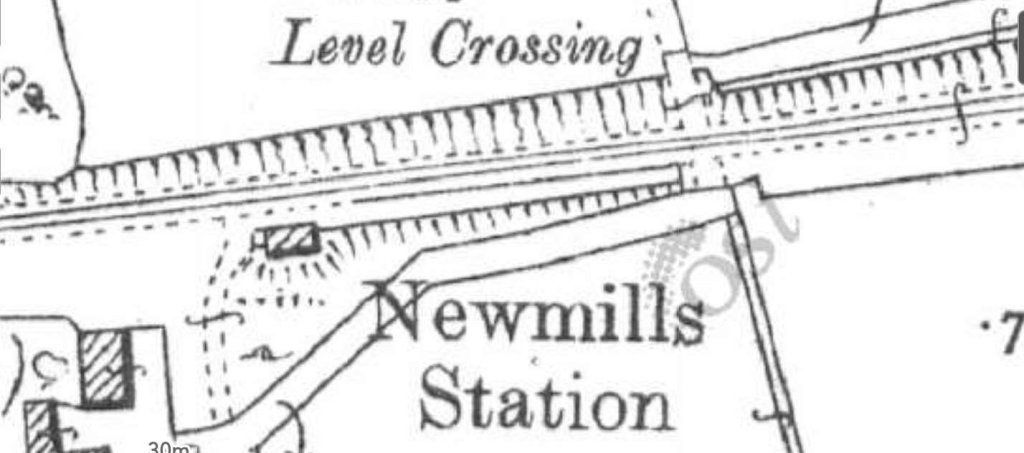

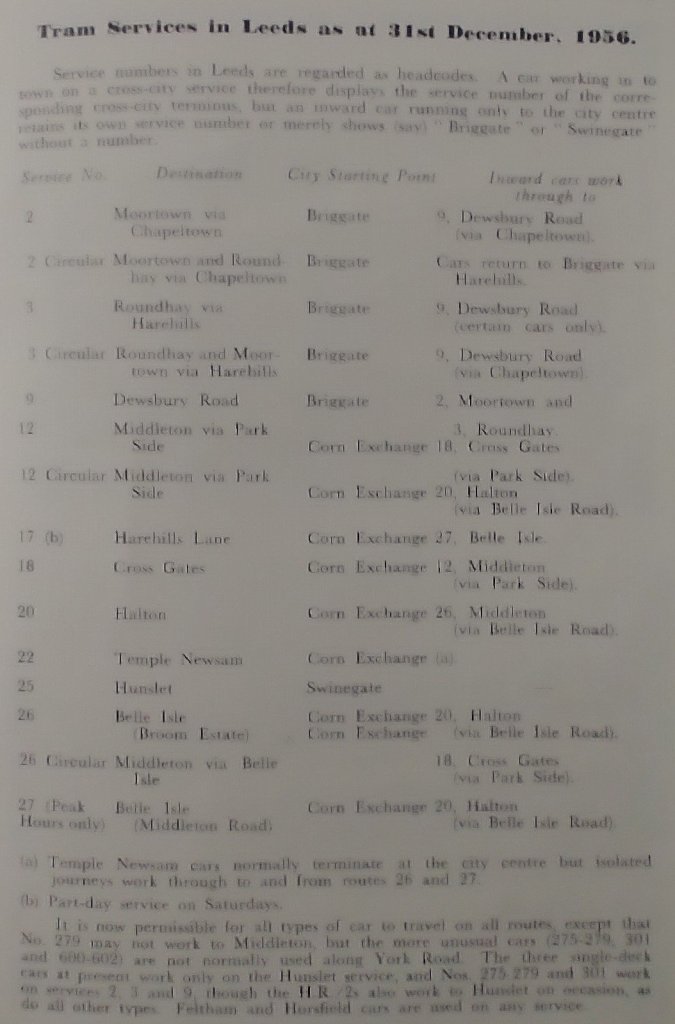

We start this article back at Govilon Railway Station and looking West along the old standard gauge railway line. ….

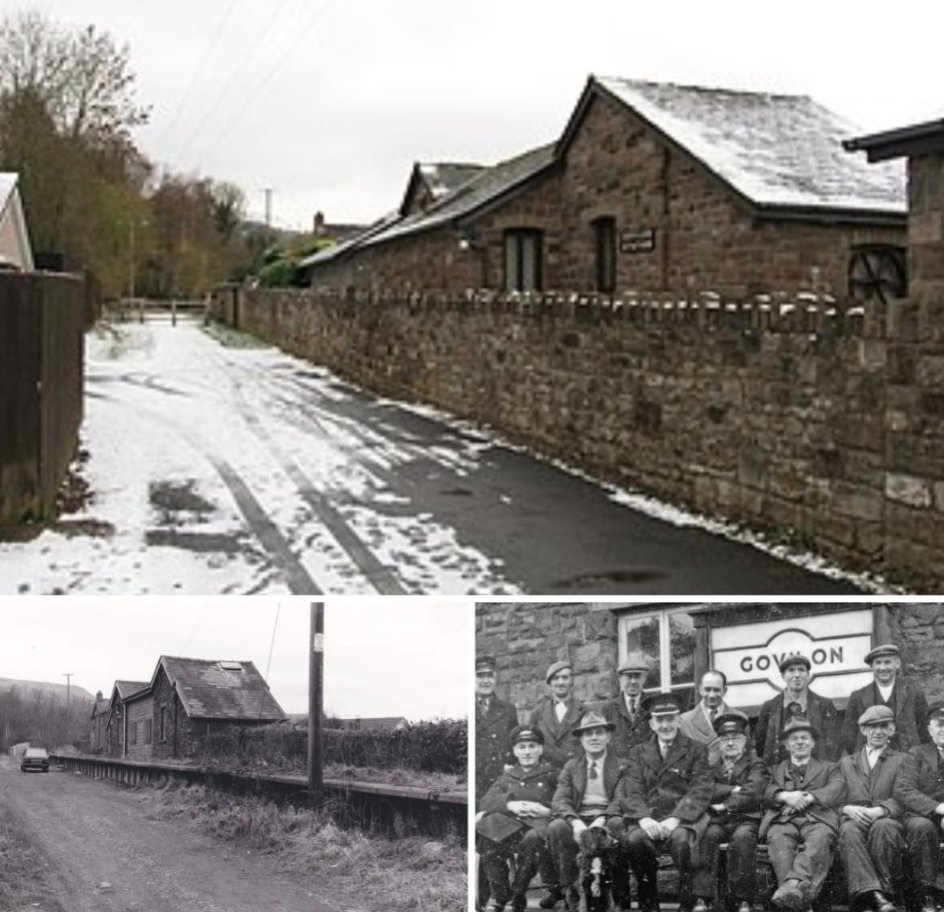

Govilon Railway Station

Govilon Railway Station opened on 1 October 1862, [7: p191][8: p107] a couple of days after the ceremonial opening of the first section of the railway. It was the first station beyond Abergavenny Brecon Road. [9] The 1st October was also the first day of the LNWR’s lease of the line. [10: p112] There is a possibility that Govilon was the first station opened on the line because of its proximity to Llanfoist House, the residence of Crawshay Bailey who by this time was a director of the MTAR. [11: p20]

Wikipedia notes that “Decline in local industry and the costs of working the line between Abergavenny and Merthyr led to the cessation of passenger services on 4th January 1958. [13: p139][14: p68] The last public service over the line was a Stephenson Locomotive Society railtour on 5th January 1958 hauled by LNWR 0-8-0 No. 49121 and LNWR Coal Tank No. 58926. [13: p139][15: fig. 65] Official closure came on 6 January.” [12][7: p184][16: p55][8: p107][17: p191]

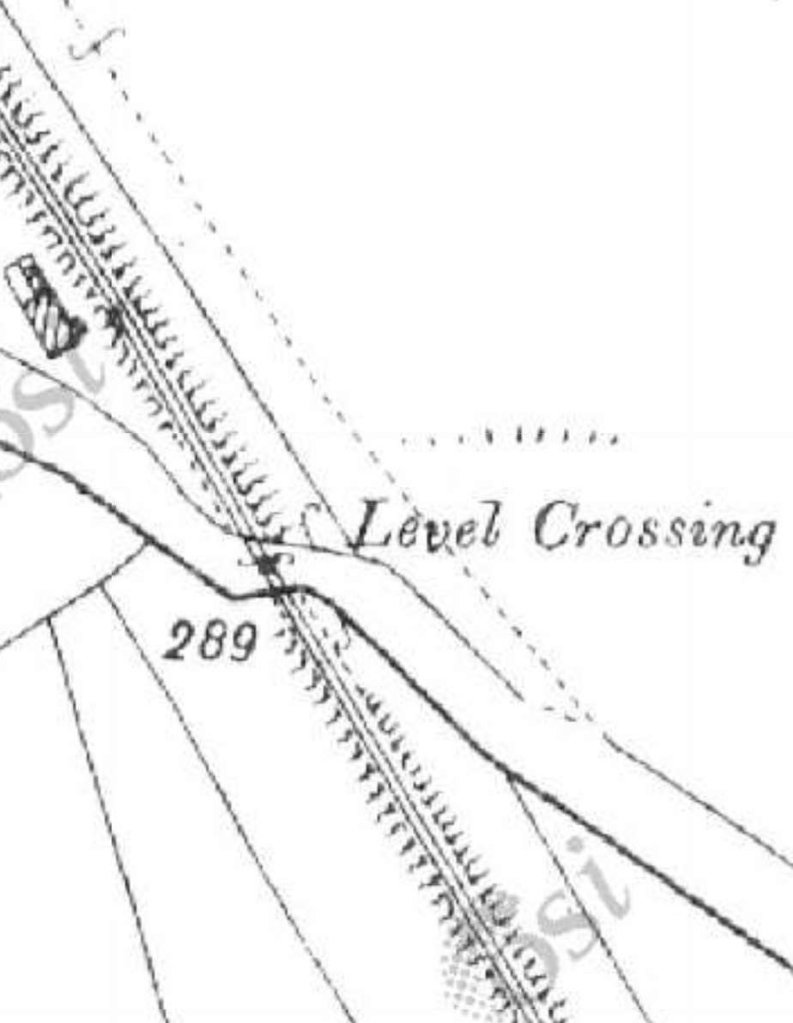

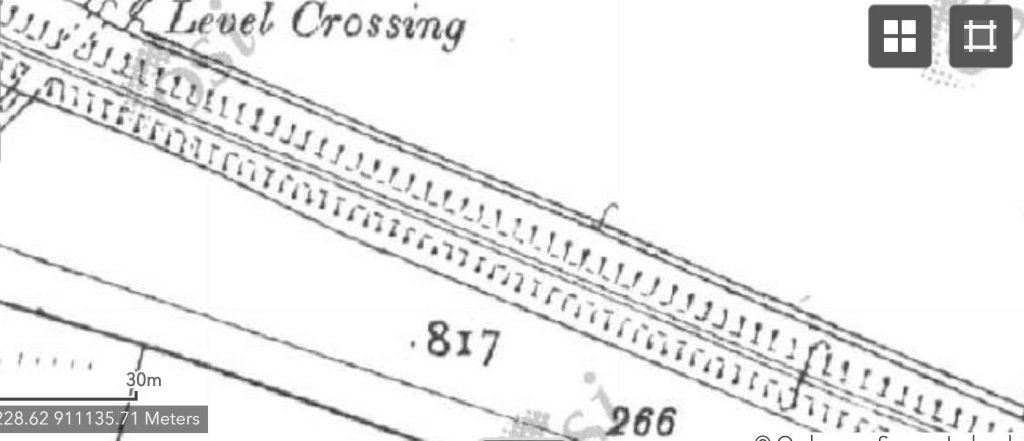

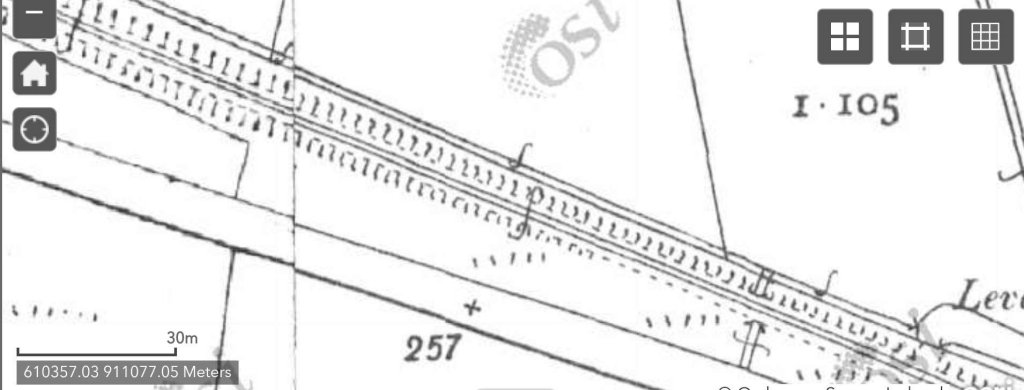

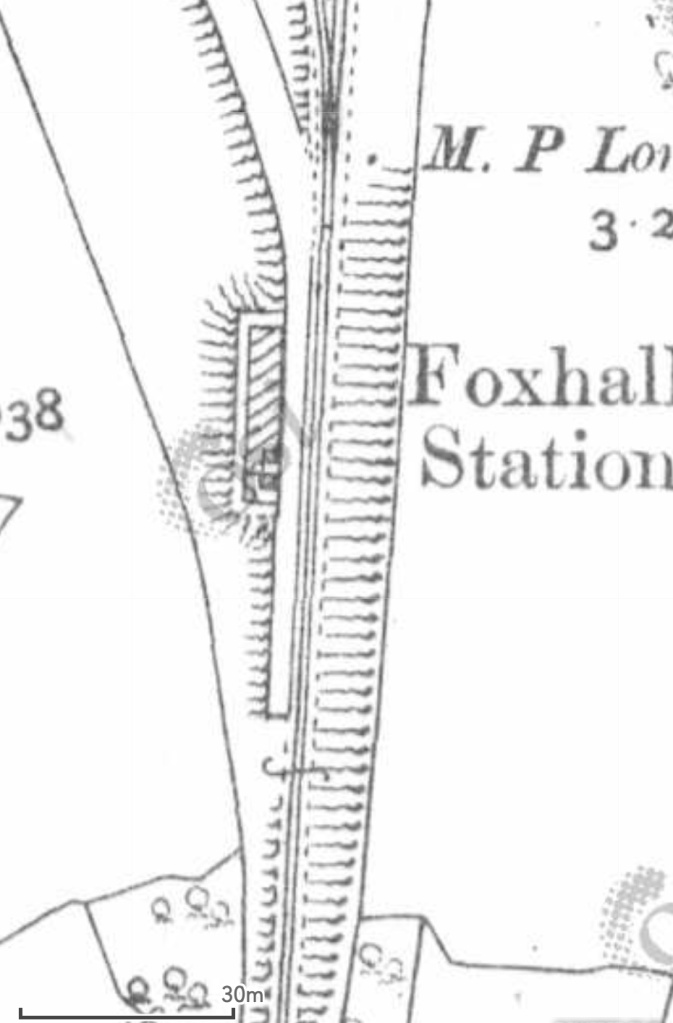

Govilon Railway Station was “situated on a steep 9-mile (14 km) climb from Abergavenny at gradients as severe as 1 in 34. [14: p68][17: p164] A gradient post showing 1 in 80 /1 in 34 was installed on one of the station platforms.” [12][13: p116]

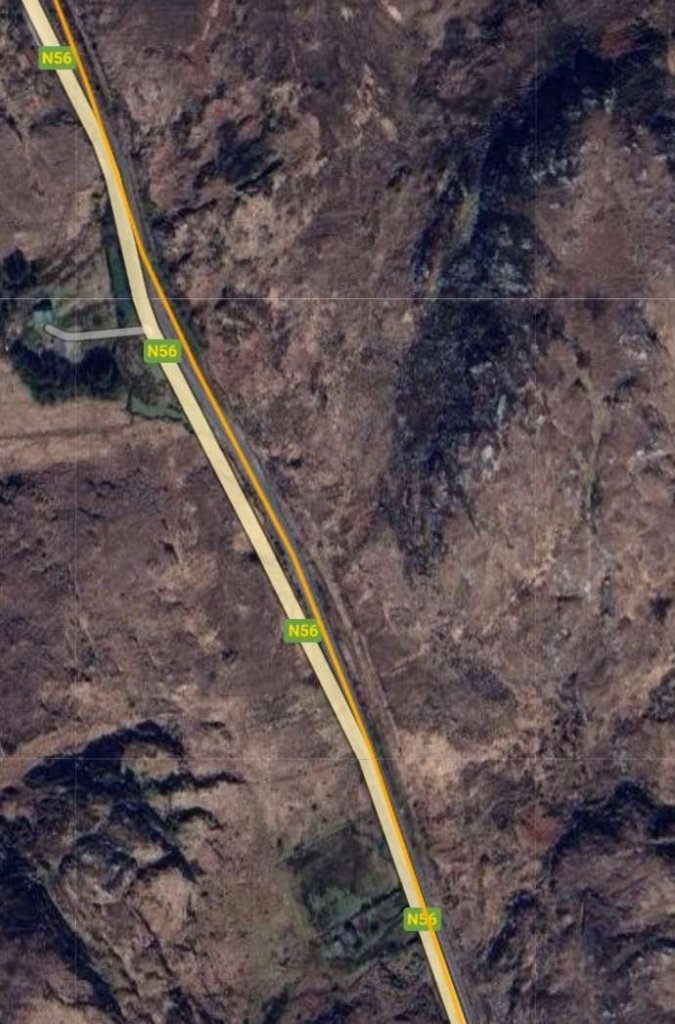

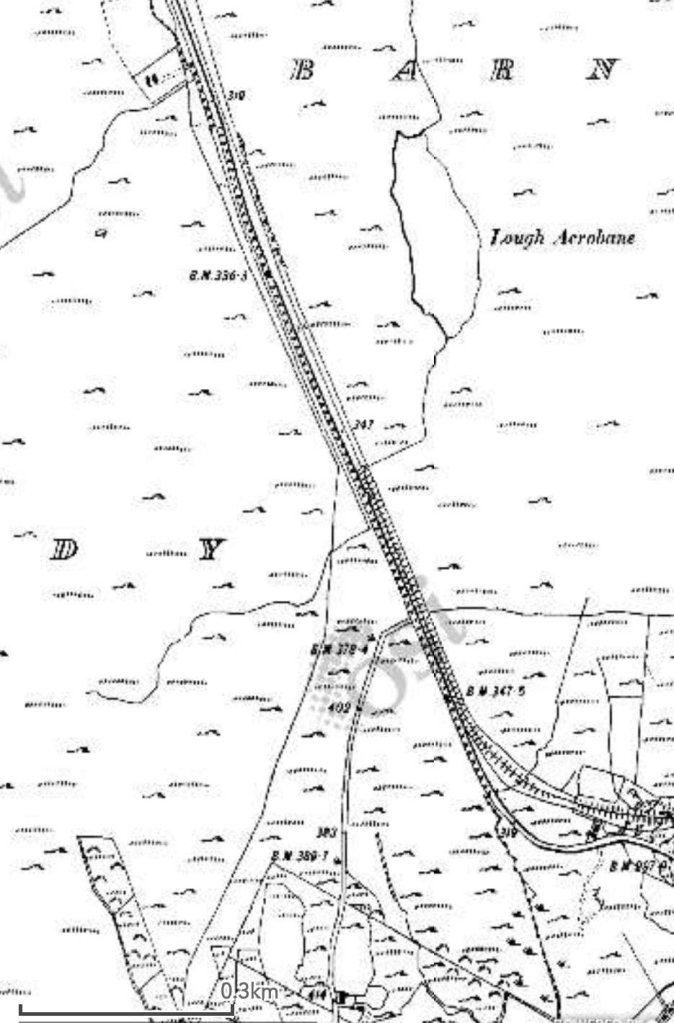

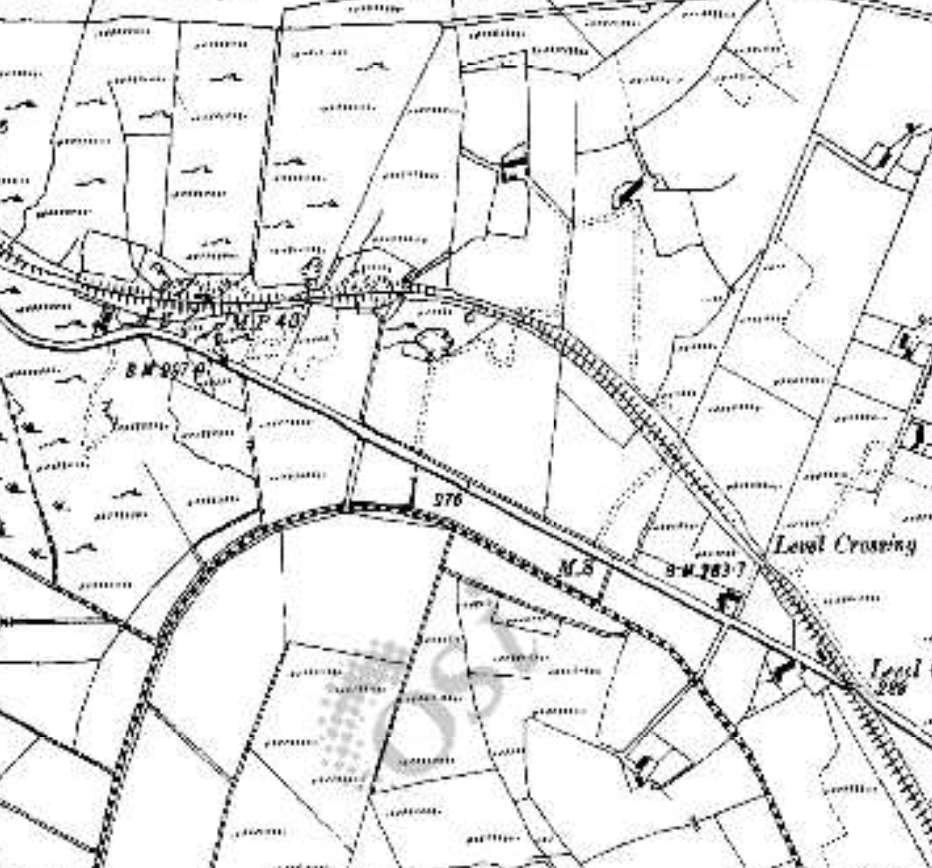

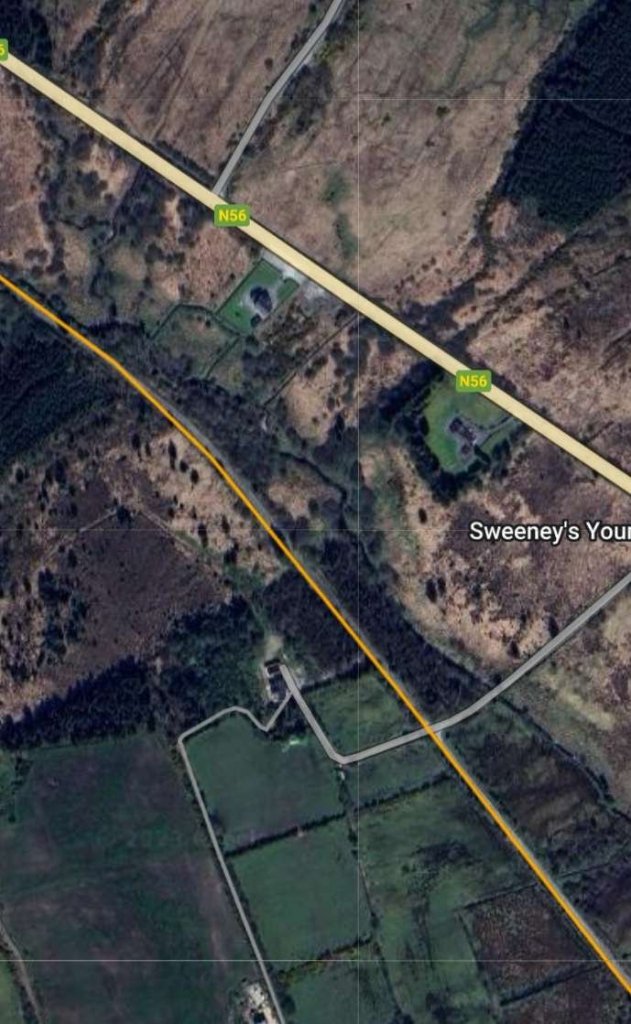

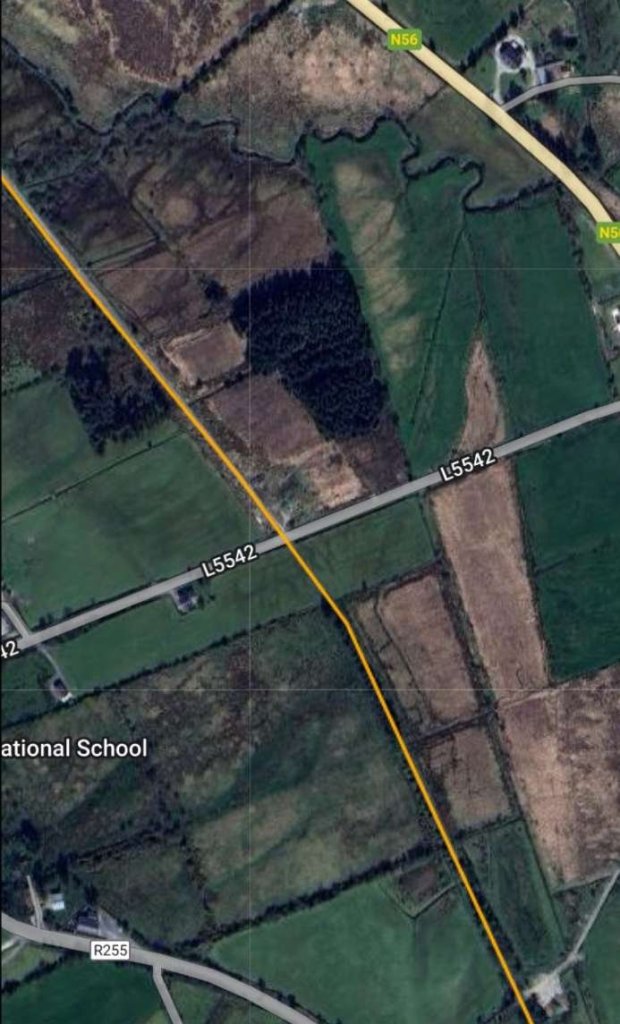

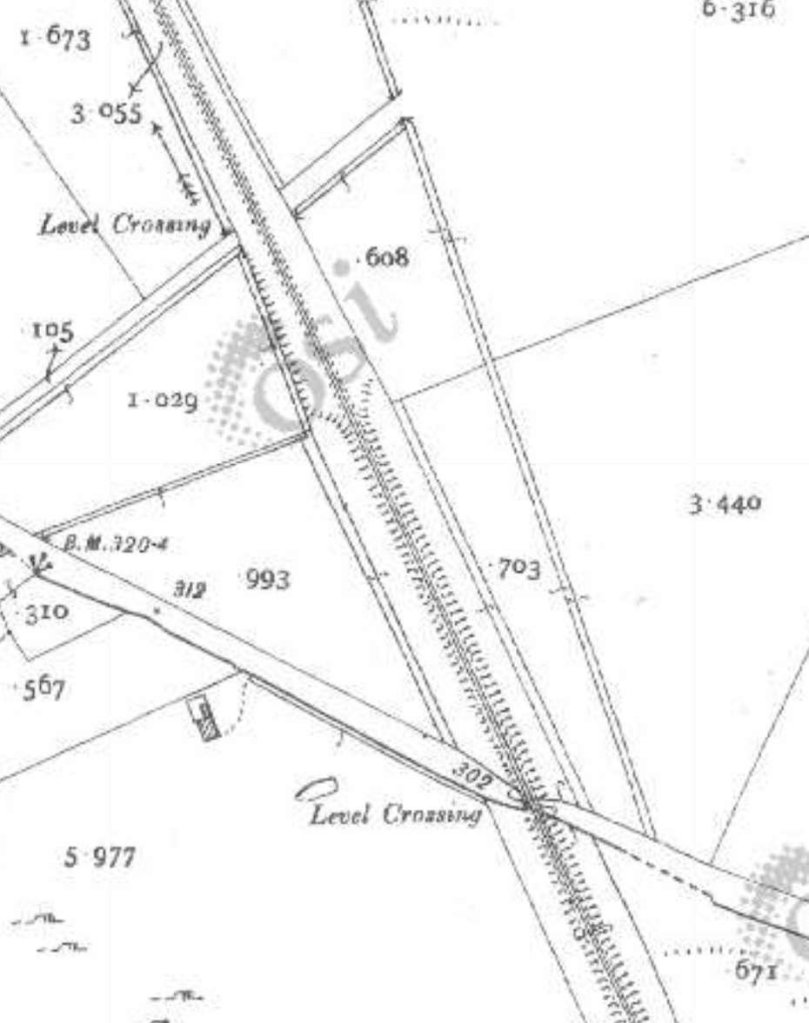

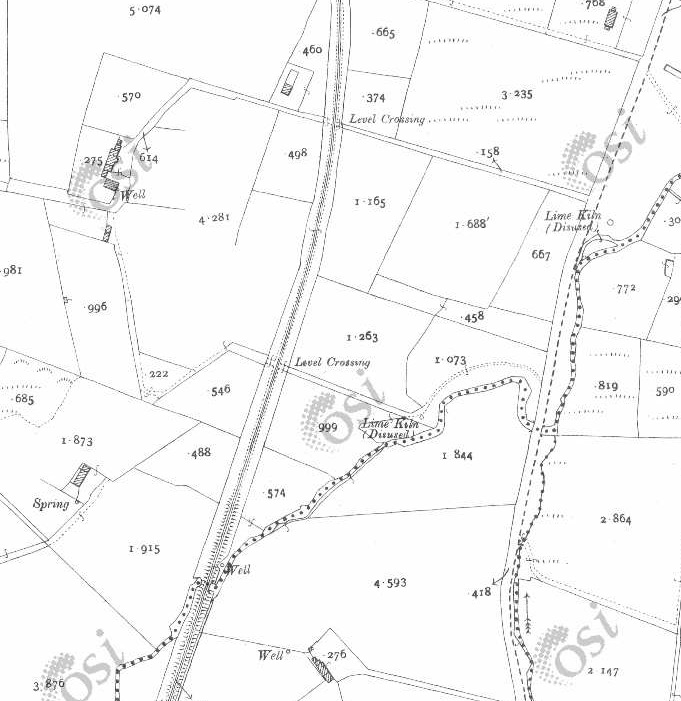

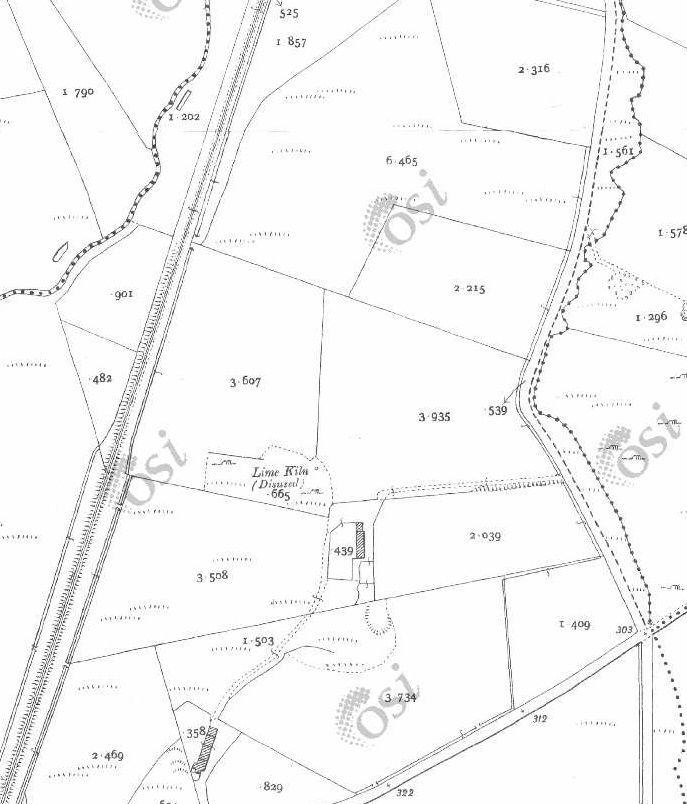

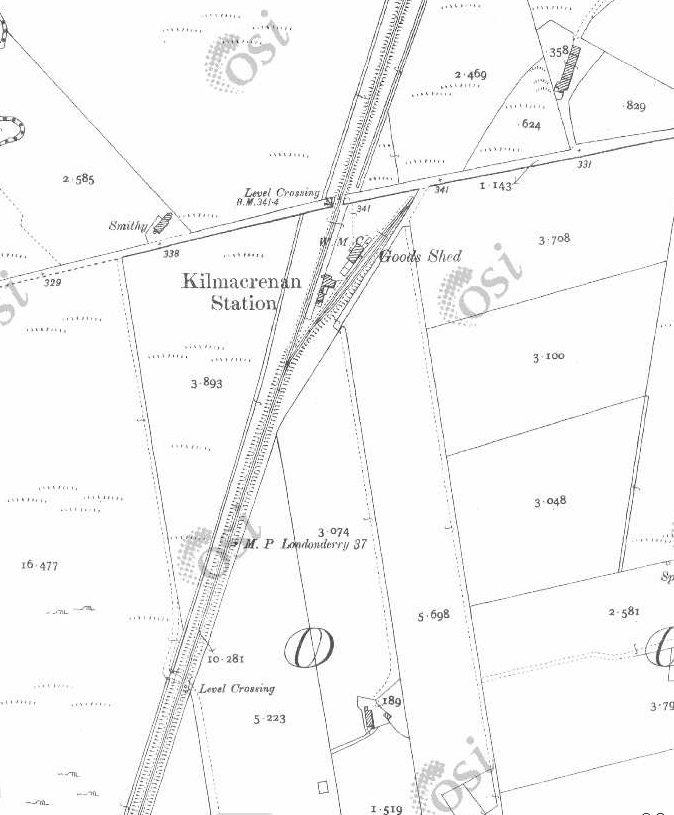

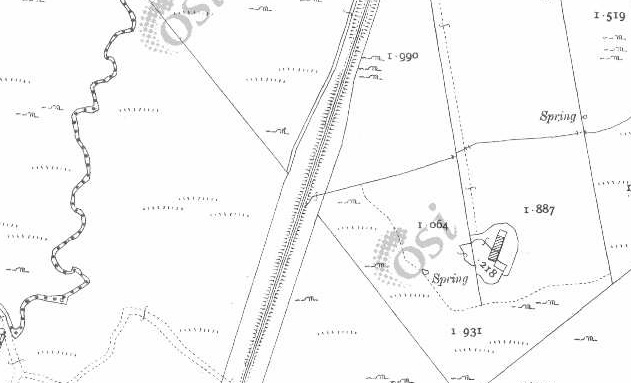

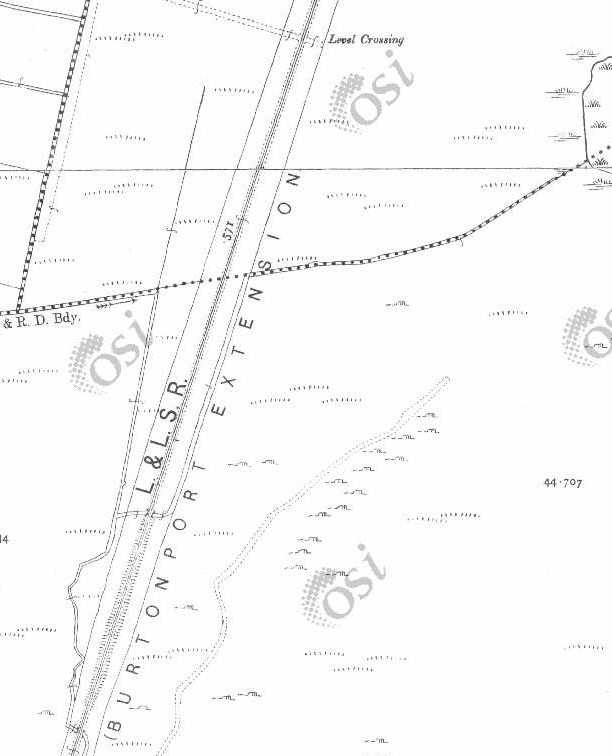

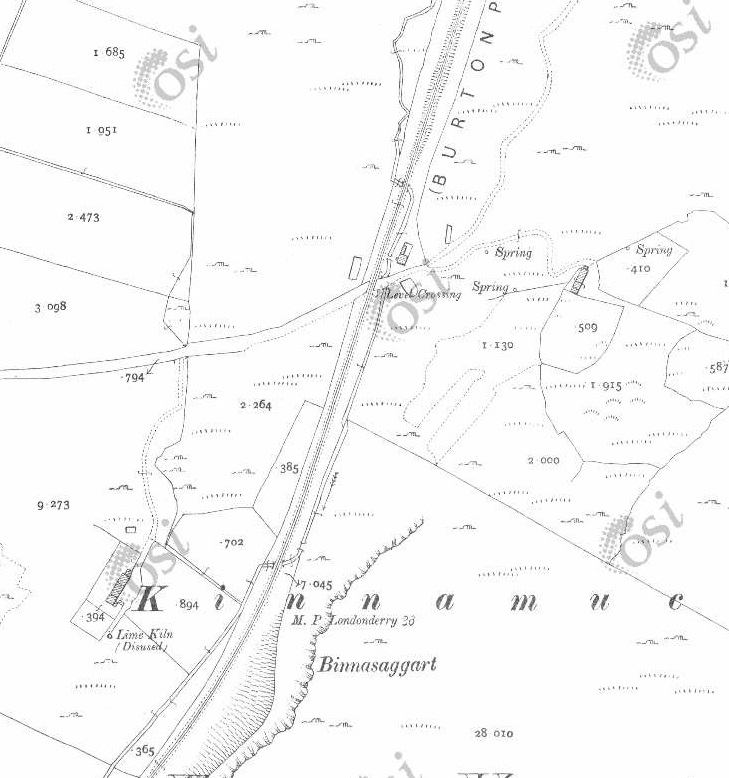

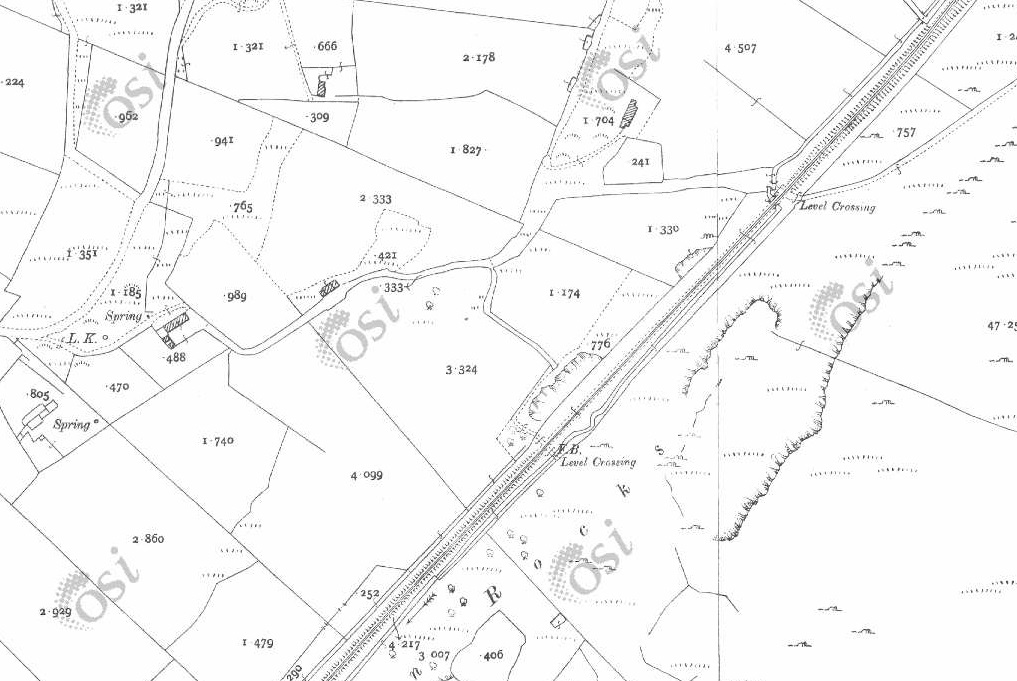

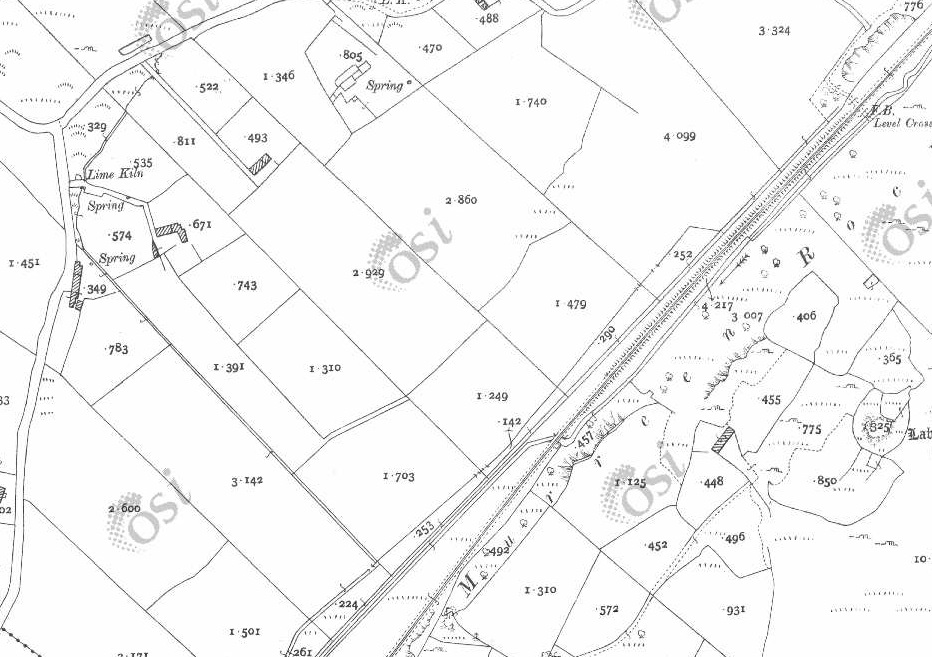

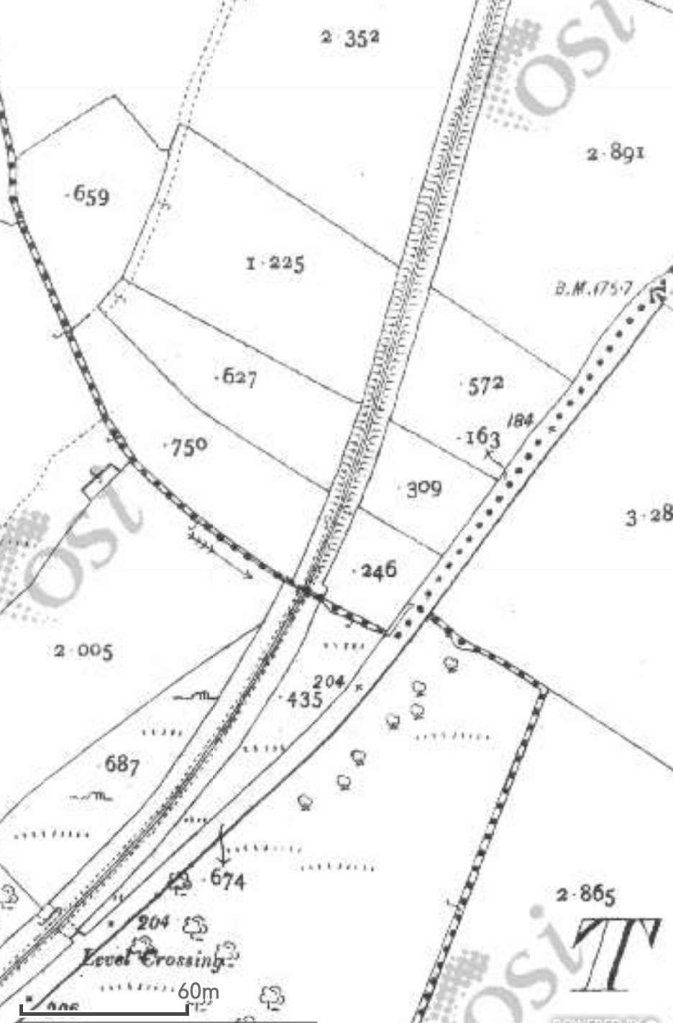

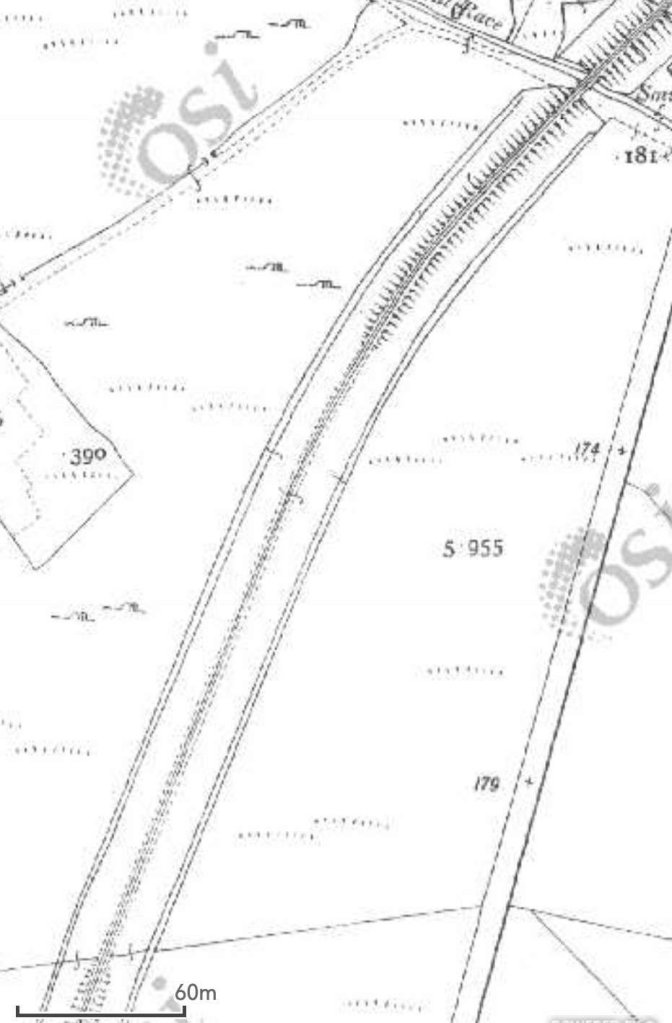

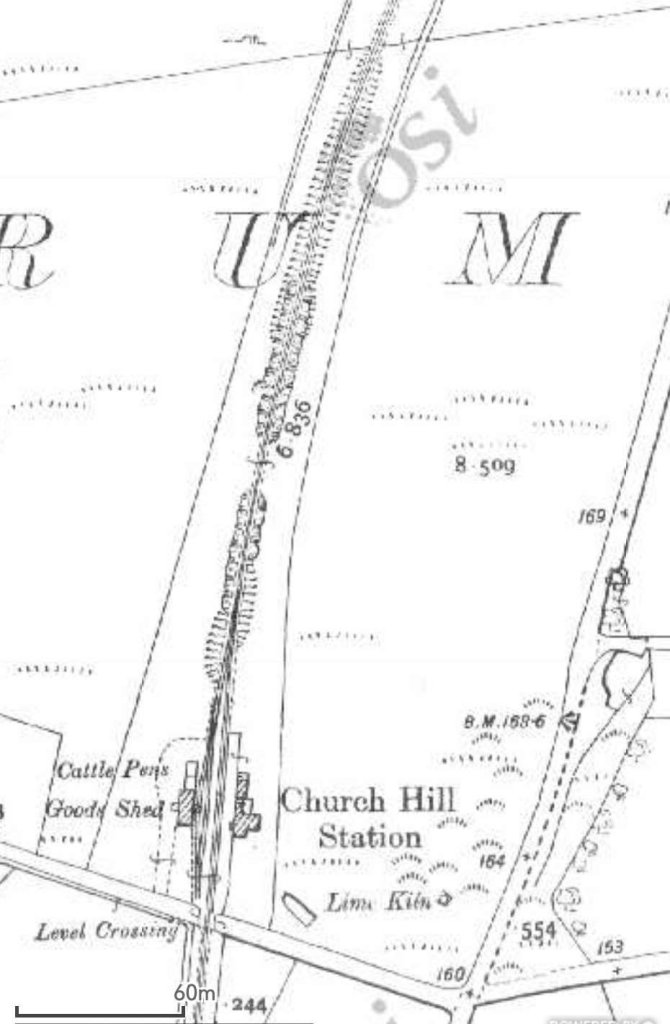

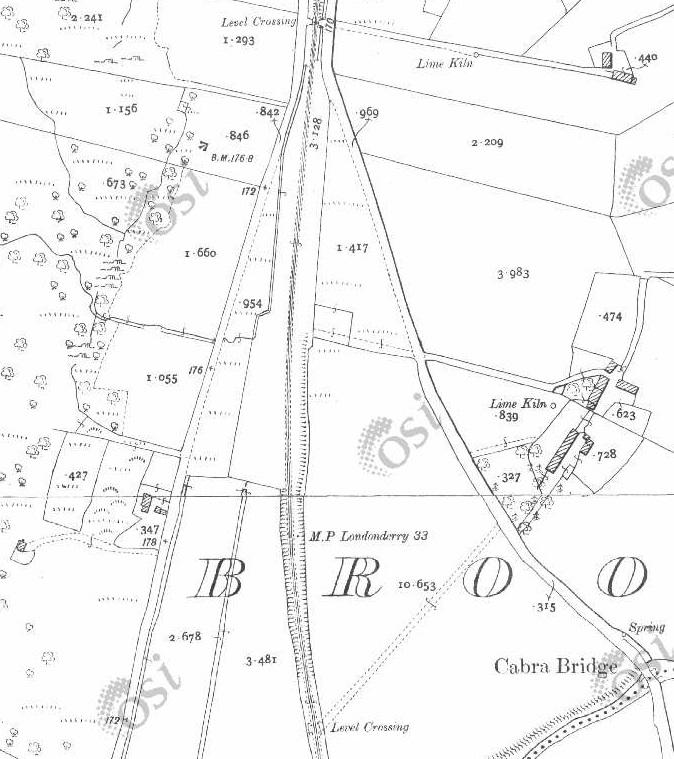

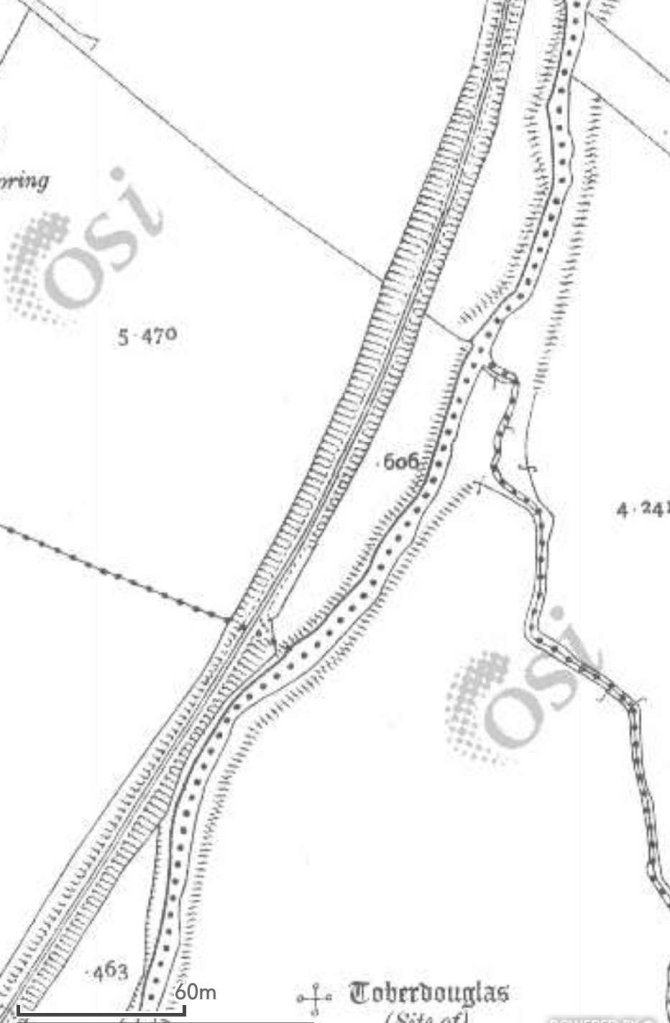

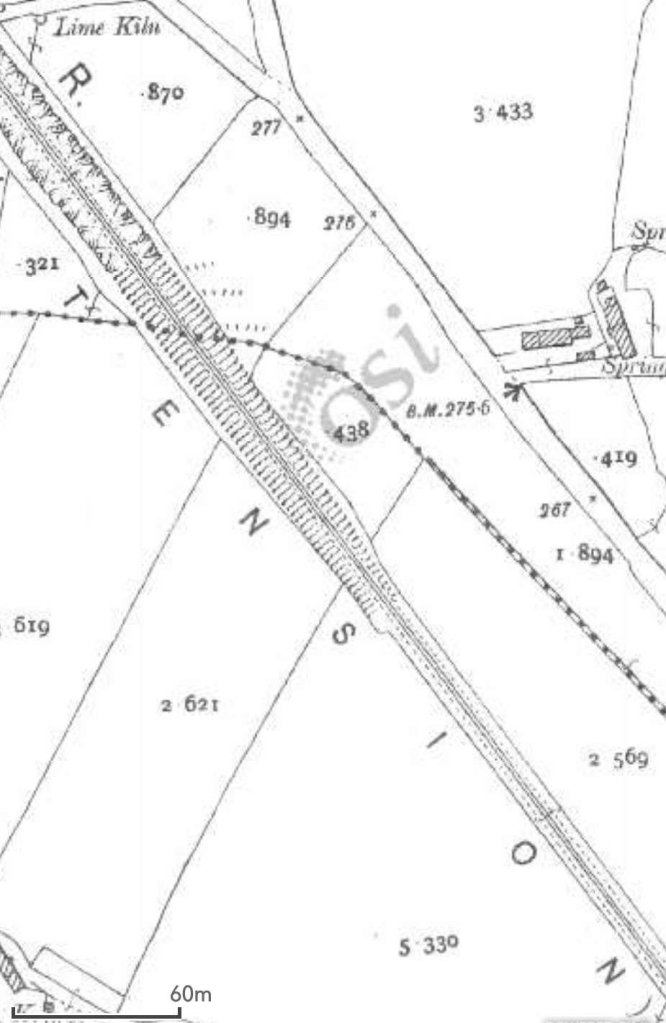

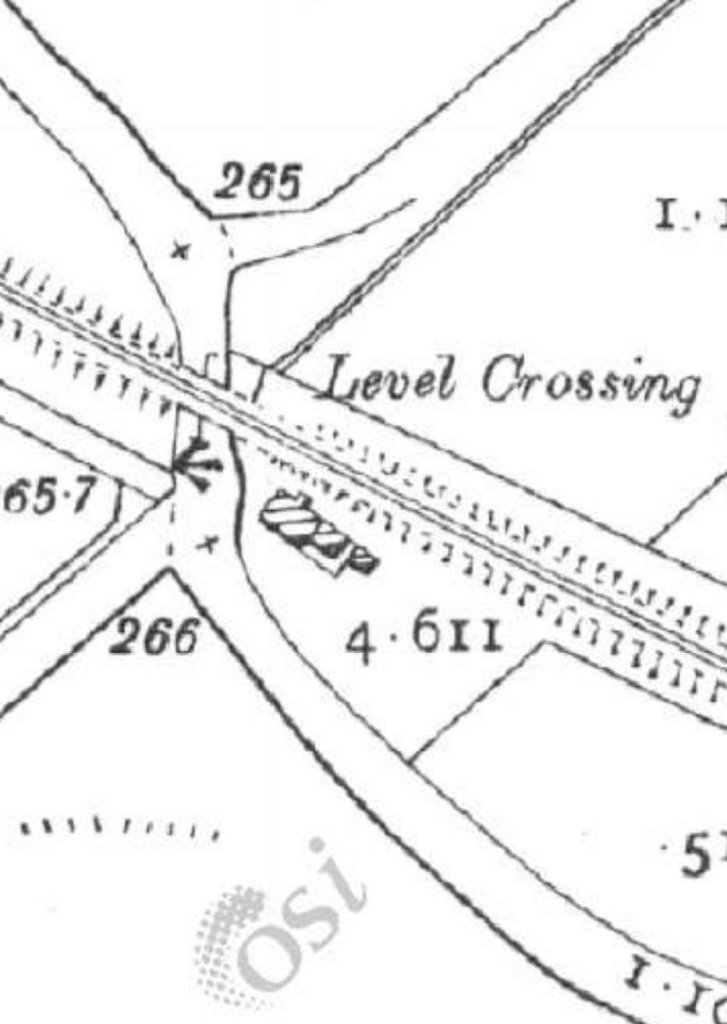

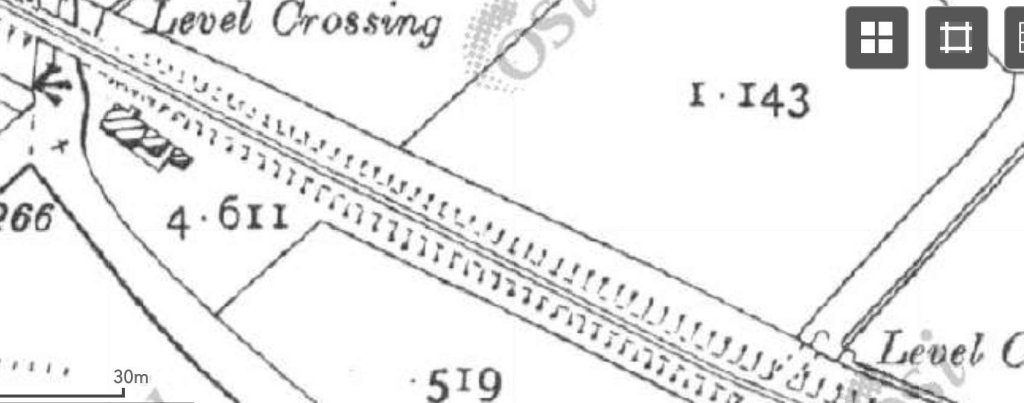

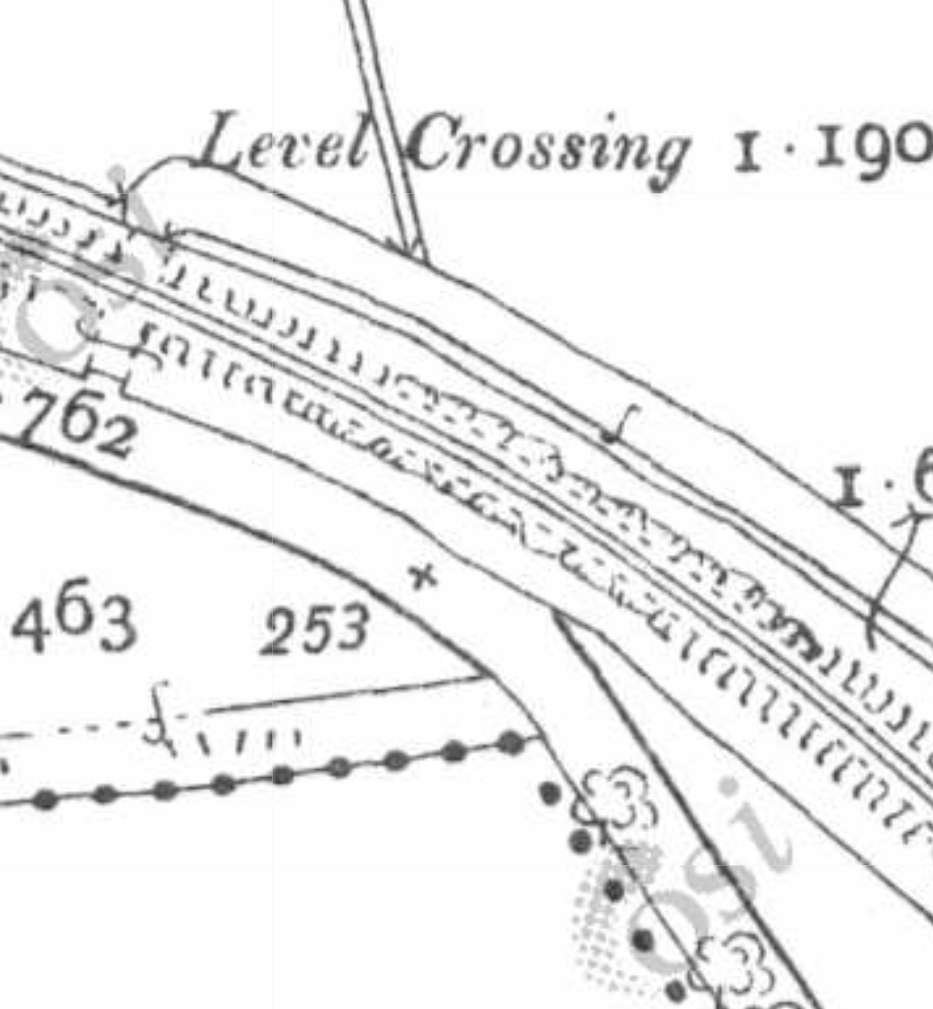

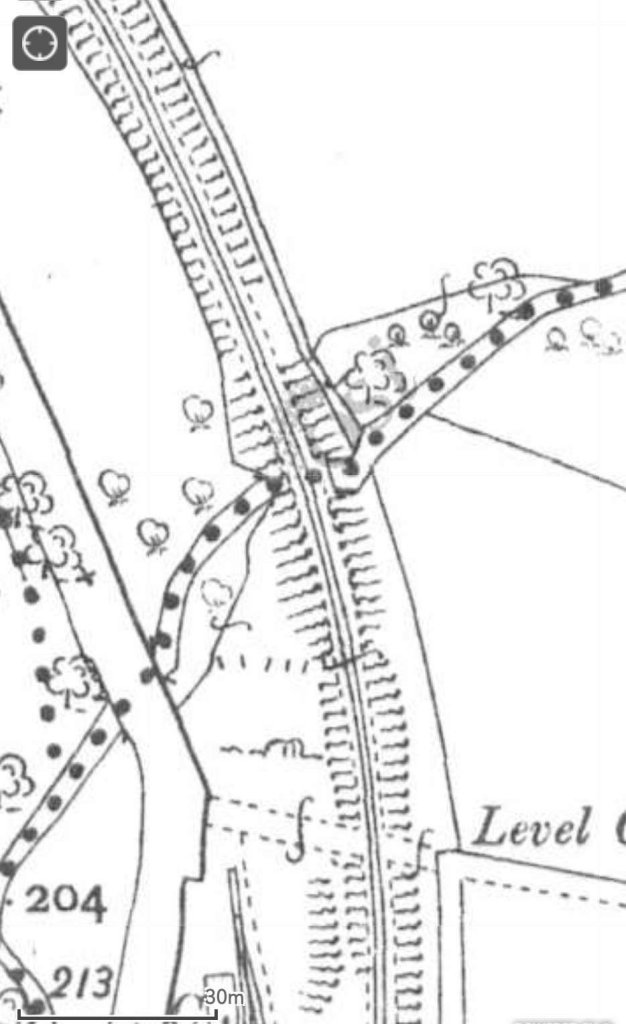

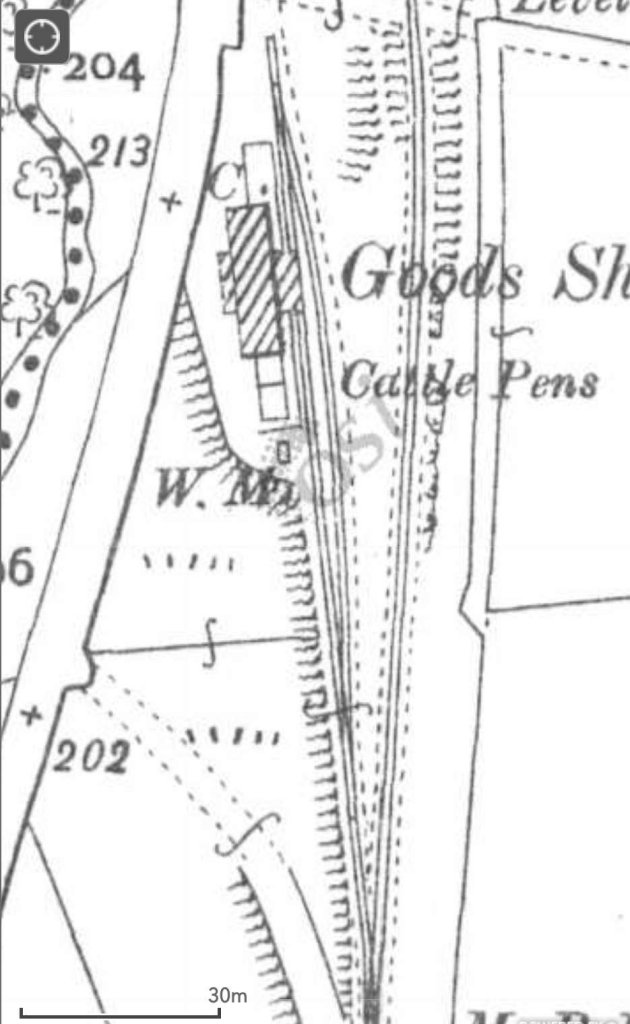

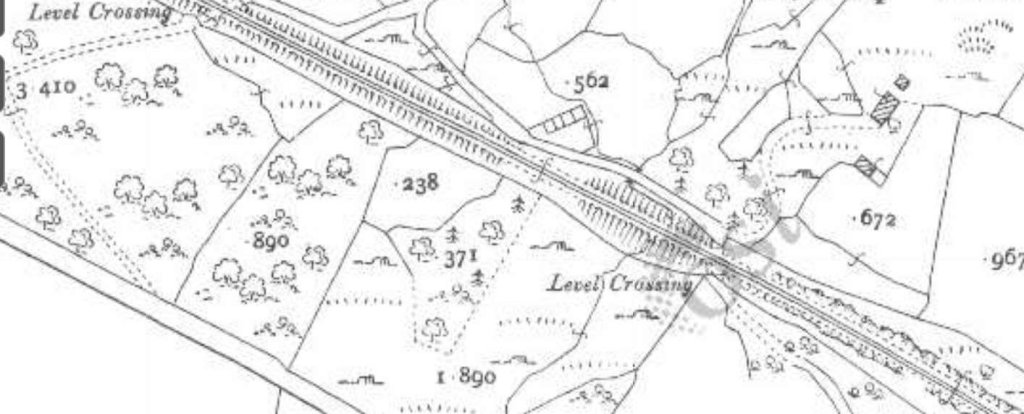

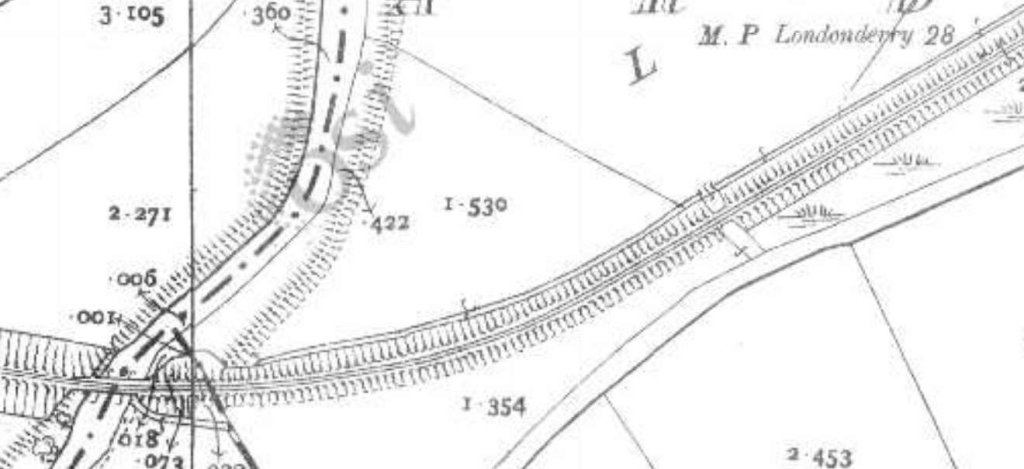

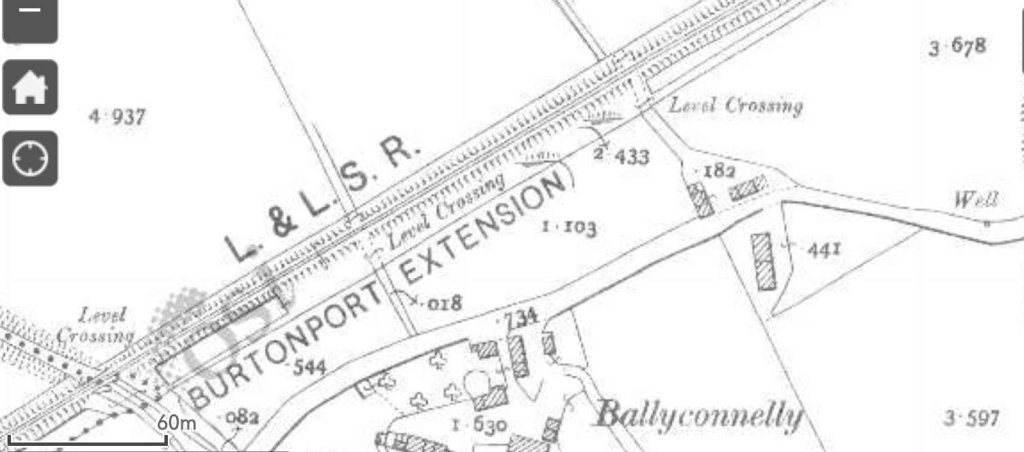

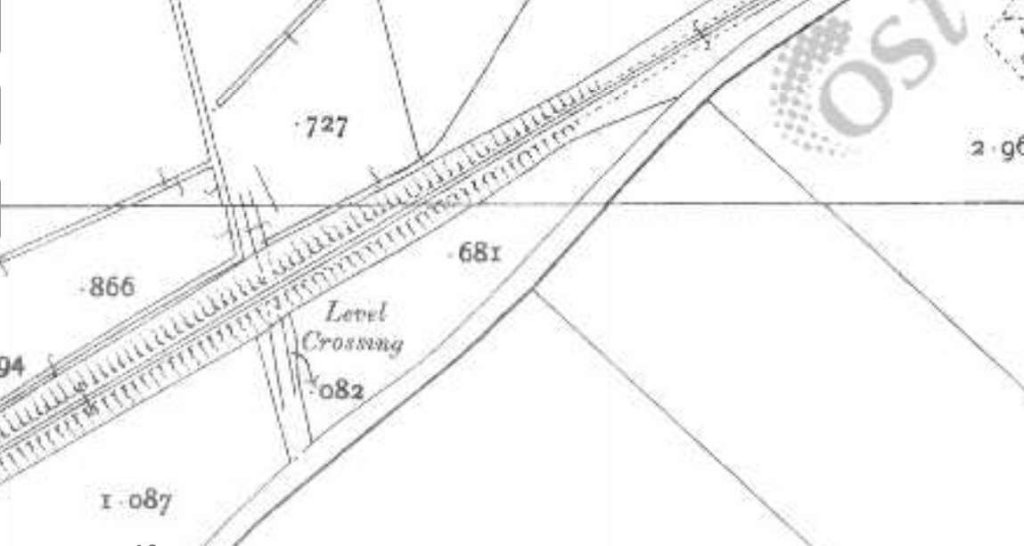

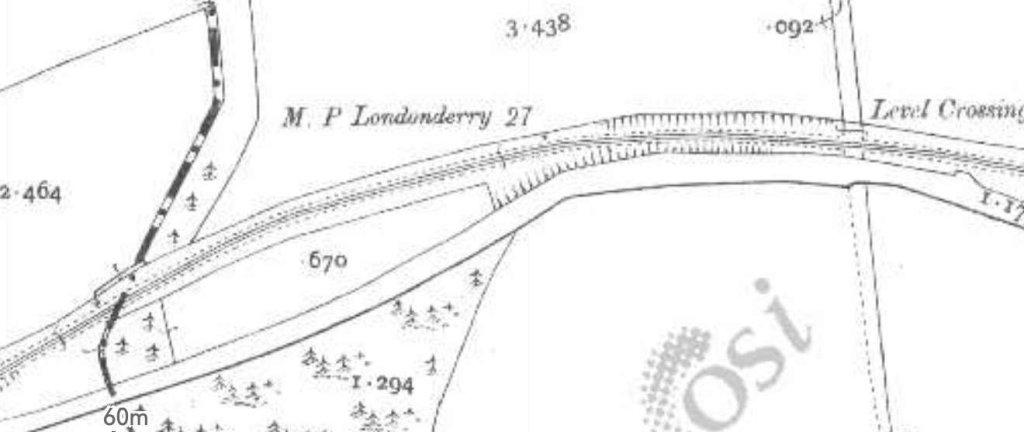

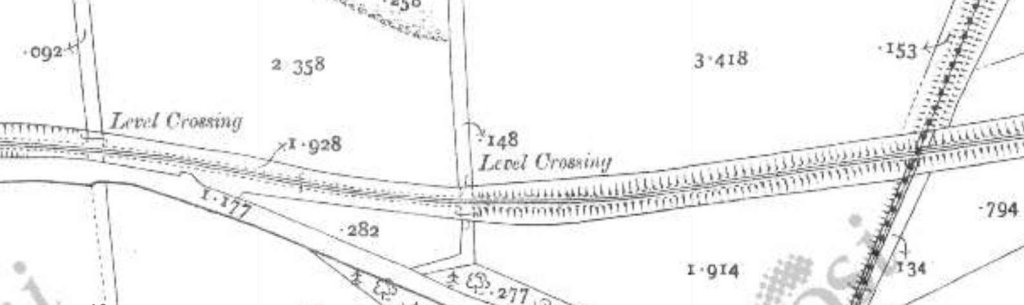

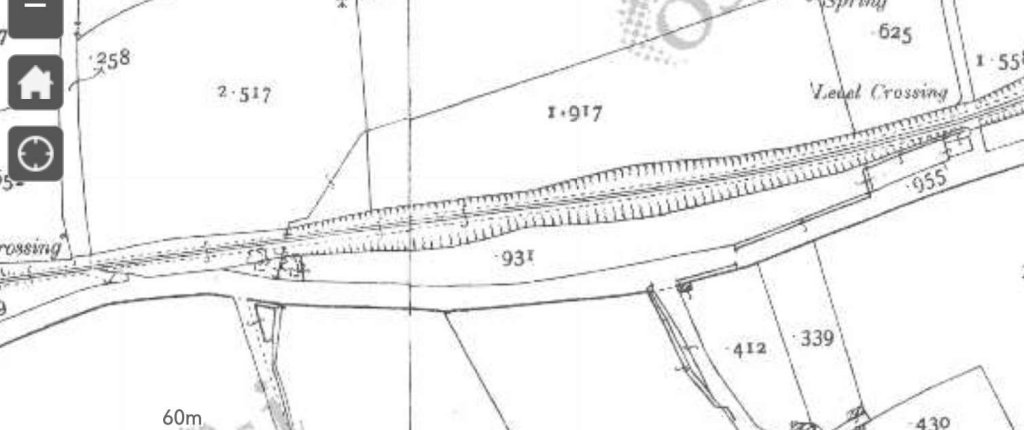

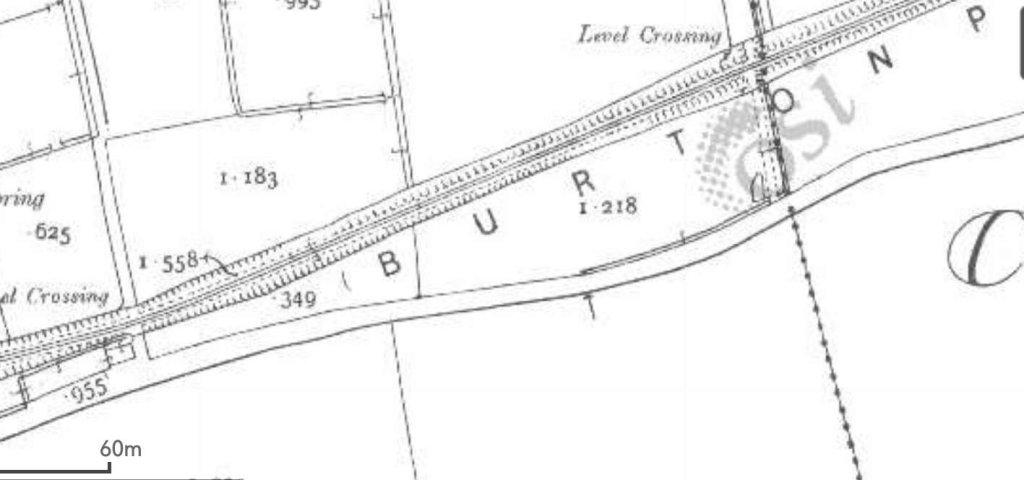

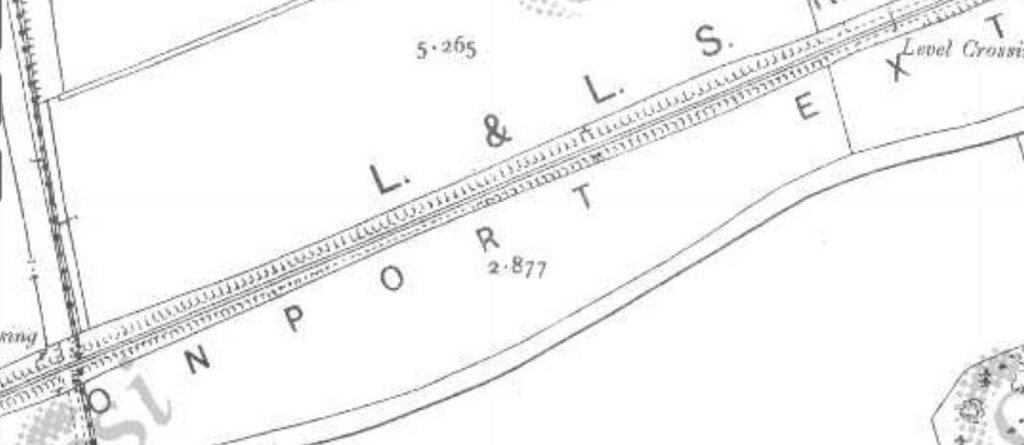

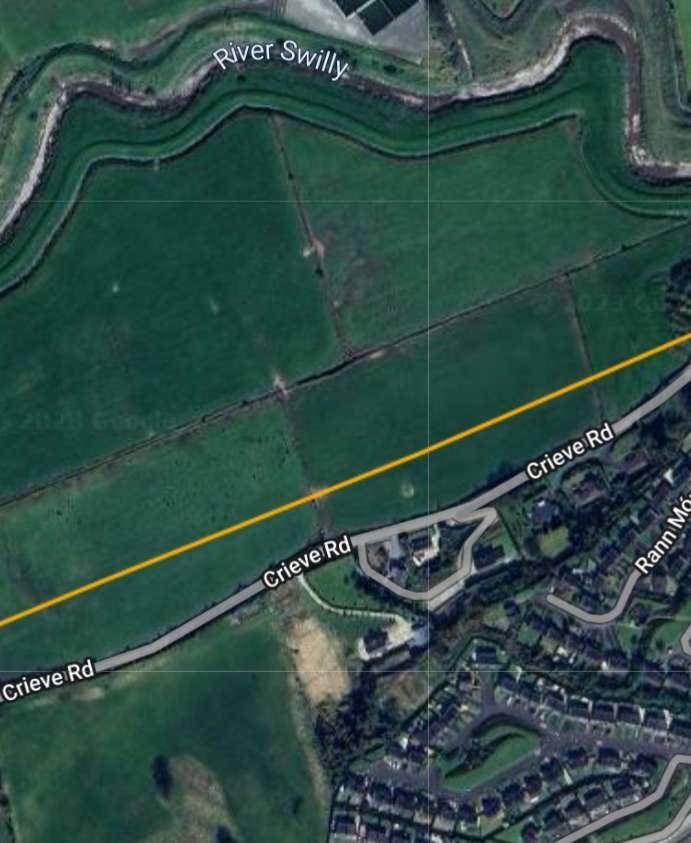

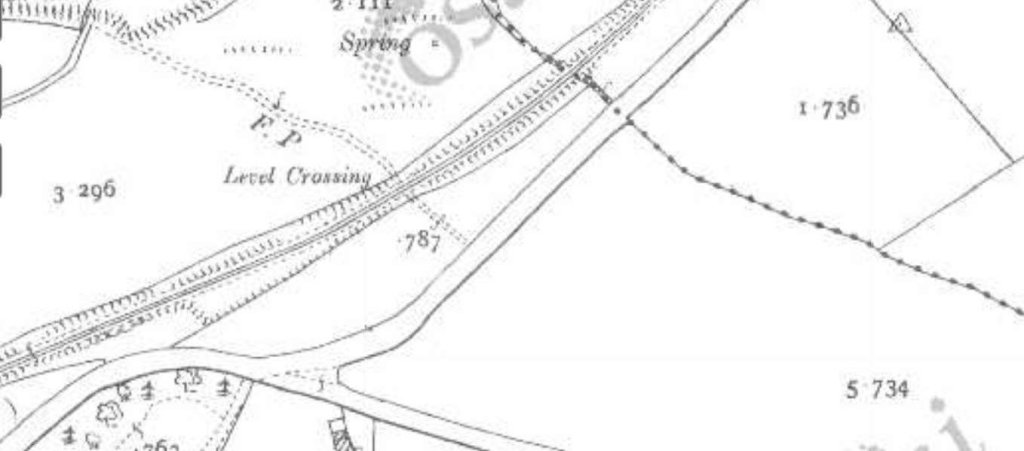

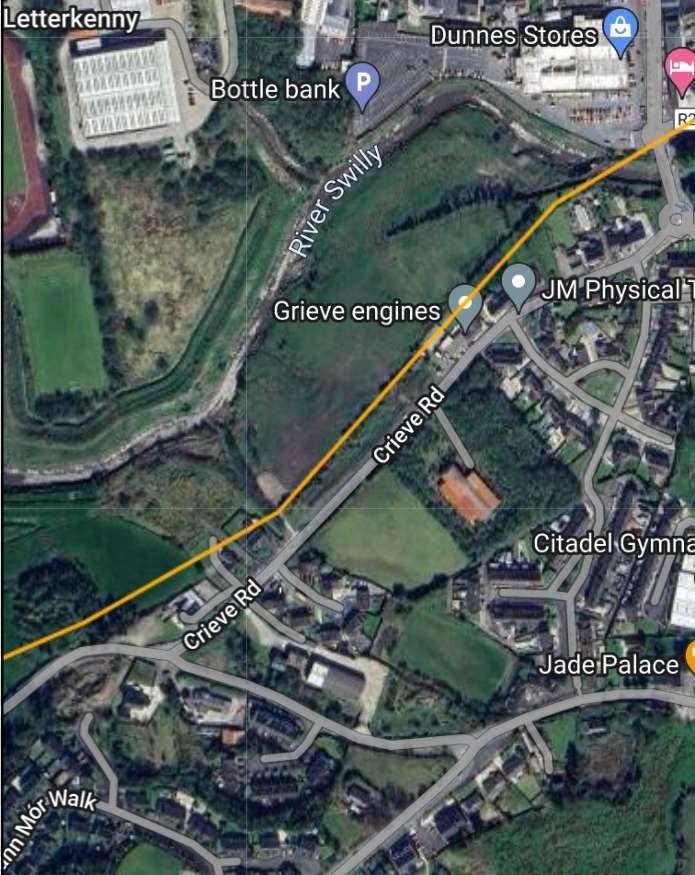

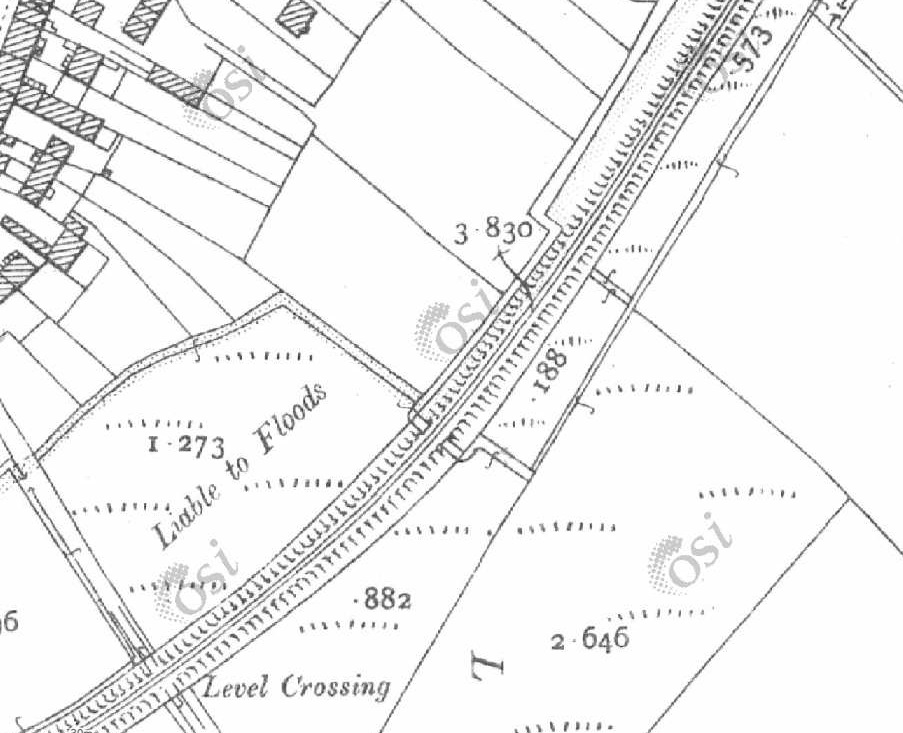

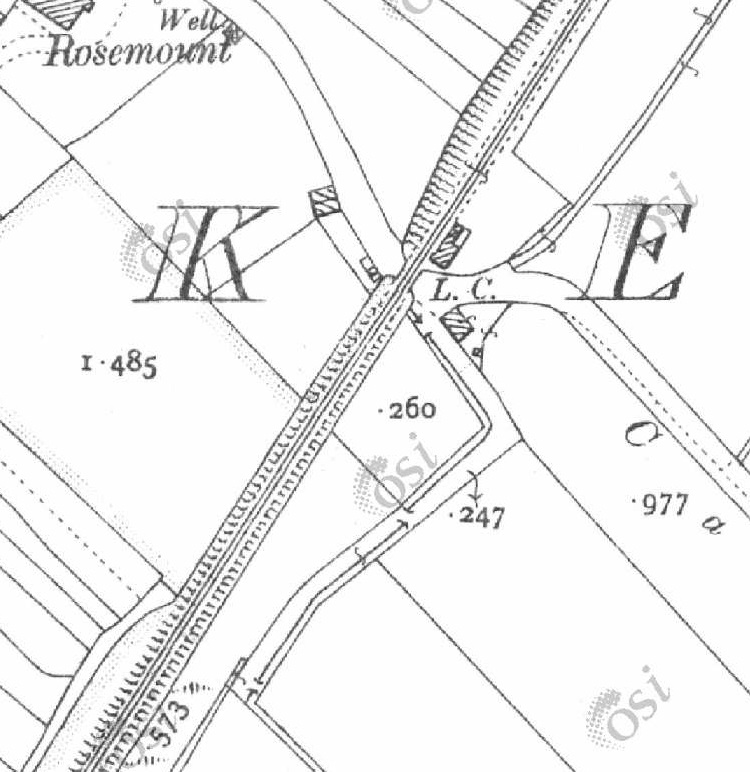

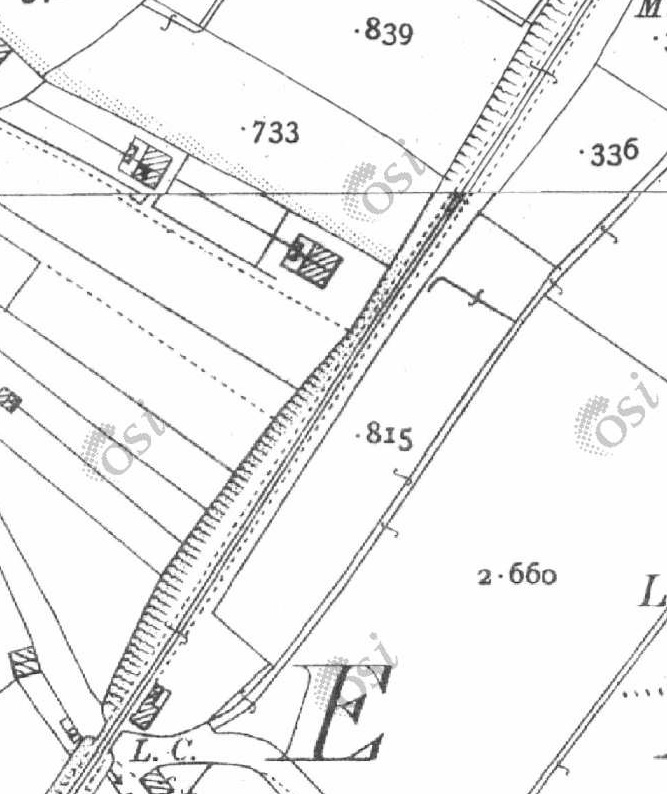

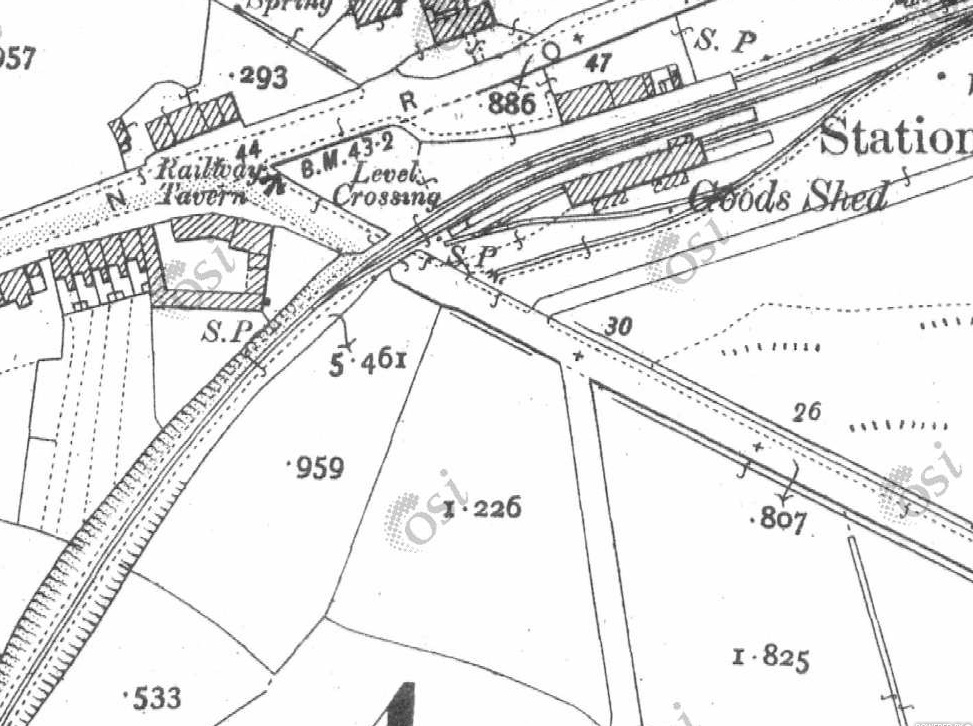

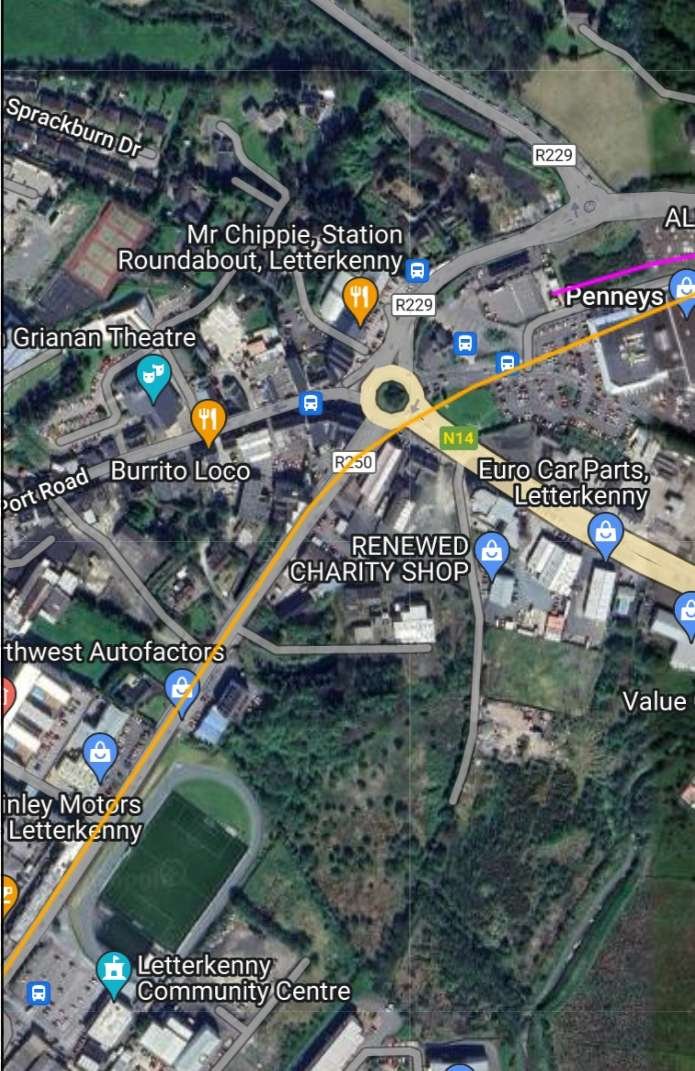

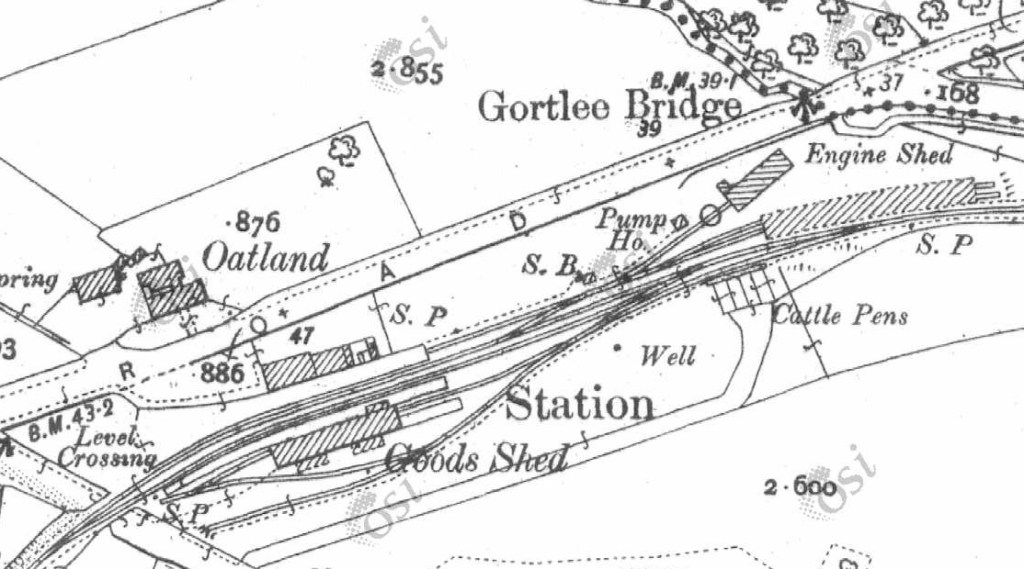

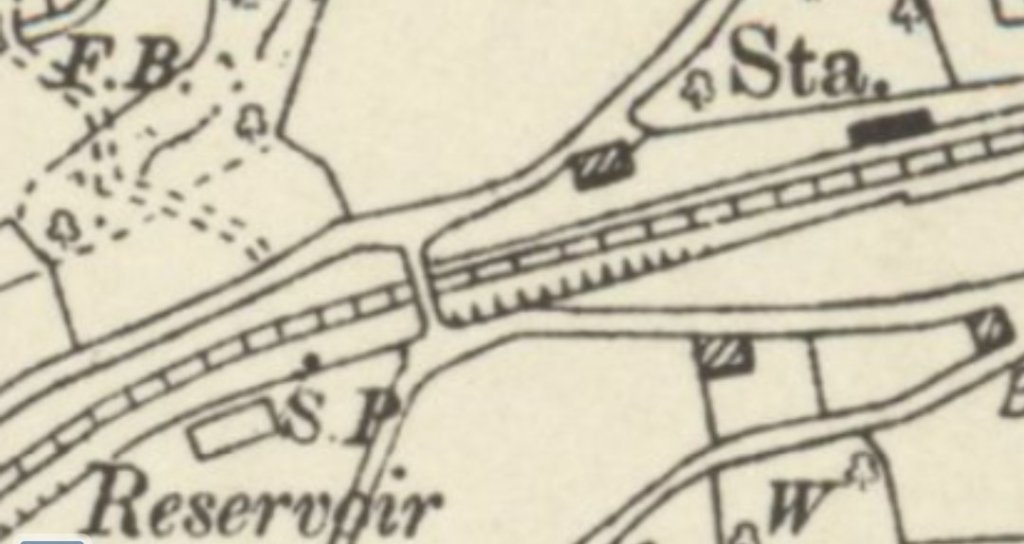

The plan below shows this length of the Merthyr, Tredegar & Abergavenny Railway leaving the Govilon Station (on the right of the extract), and passing under the road bridge before curving towards the Southwest and then back towards the West. On the North side of the double-track mainline are the sidings at Govilon Railway Station and then further West at the left edge of the extract, the sidings used by Wildon Iron Works.

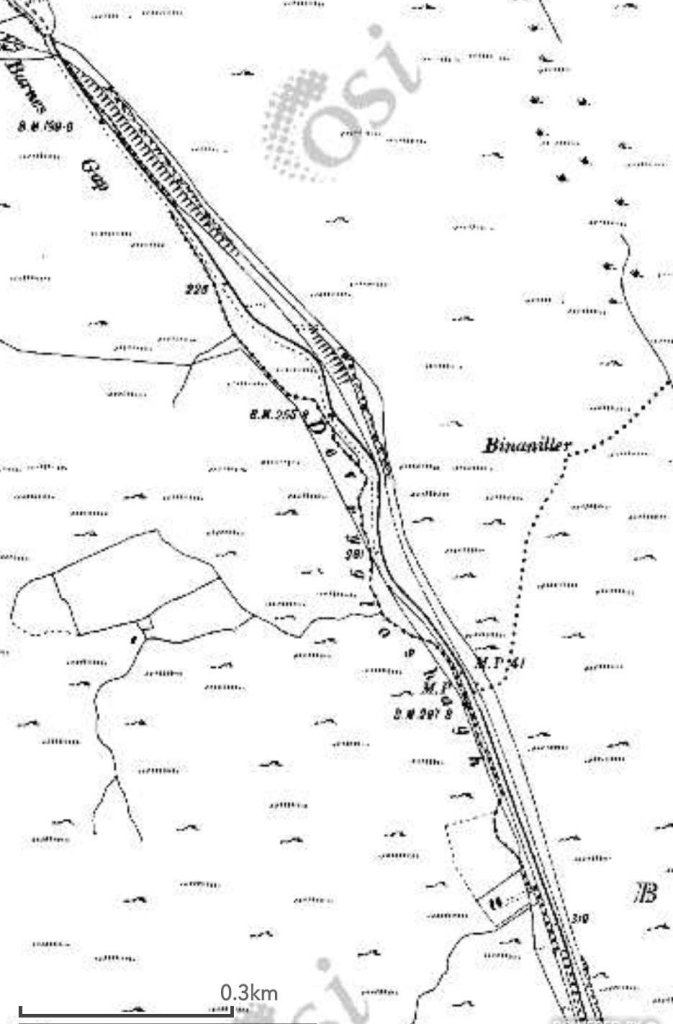

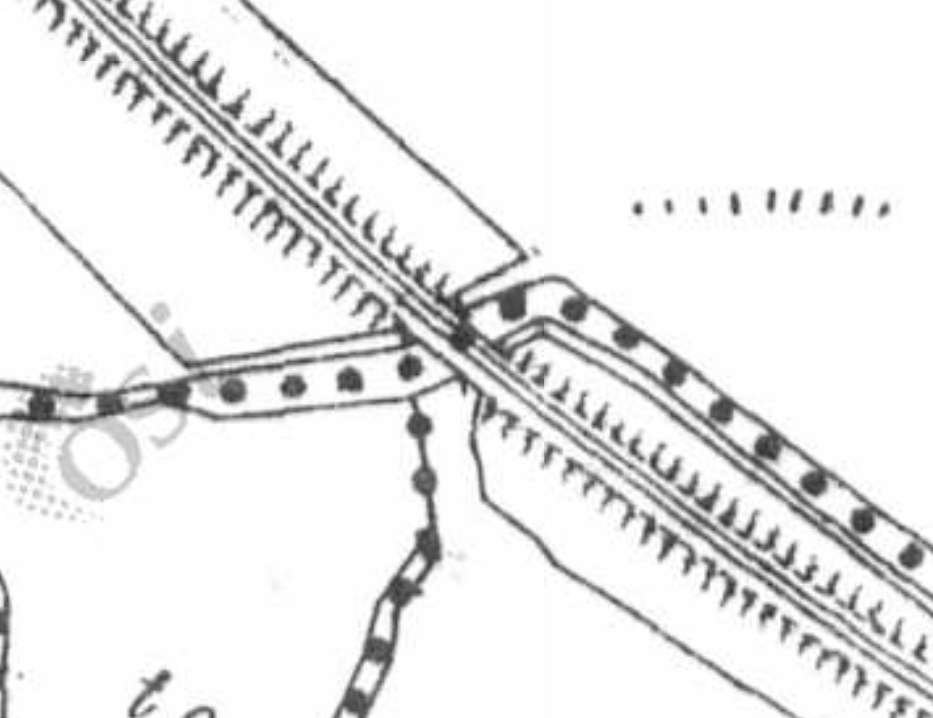

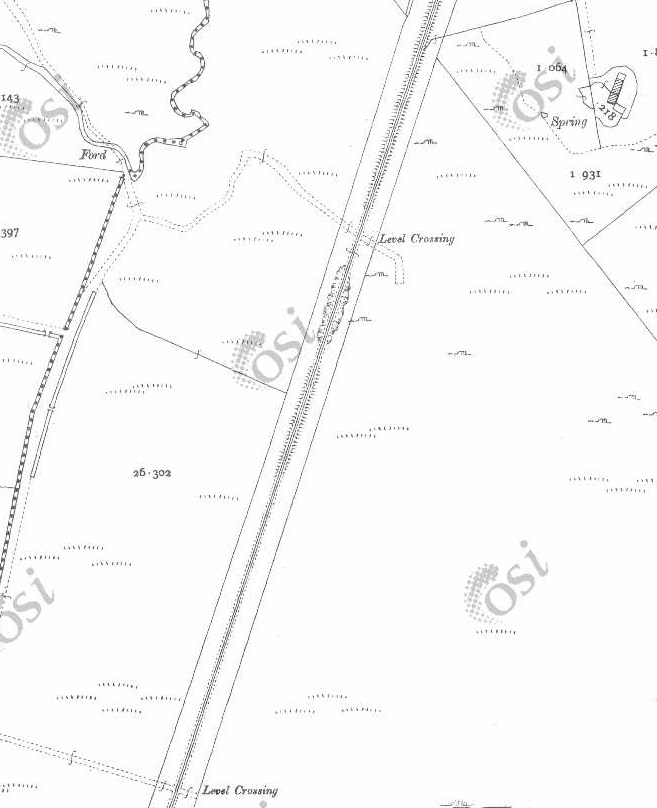

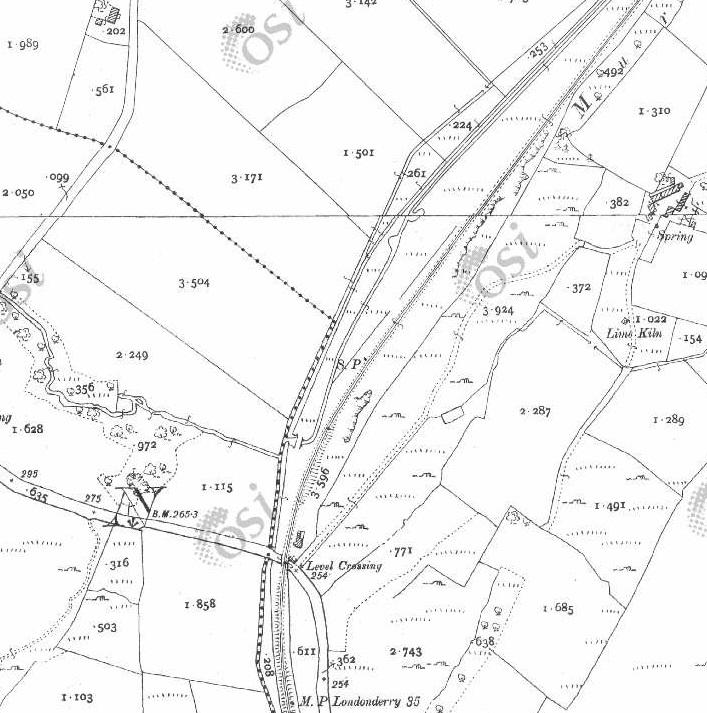

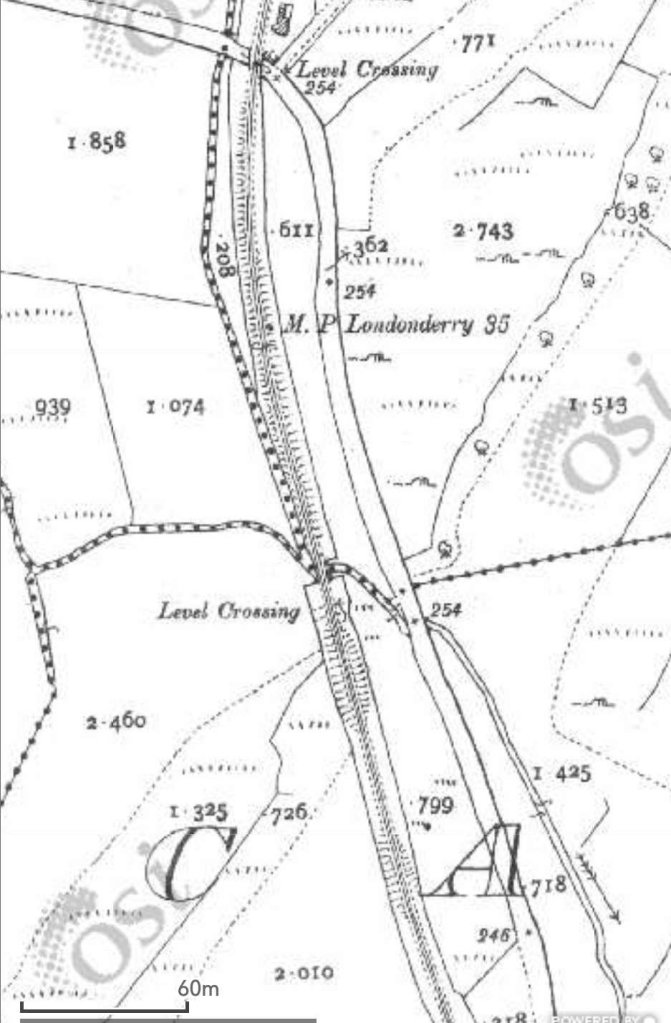

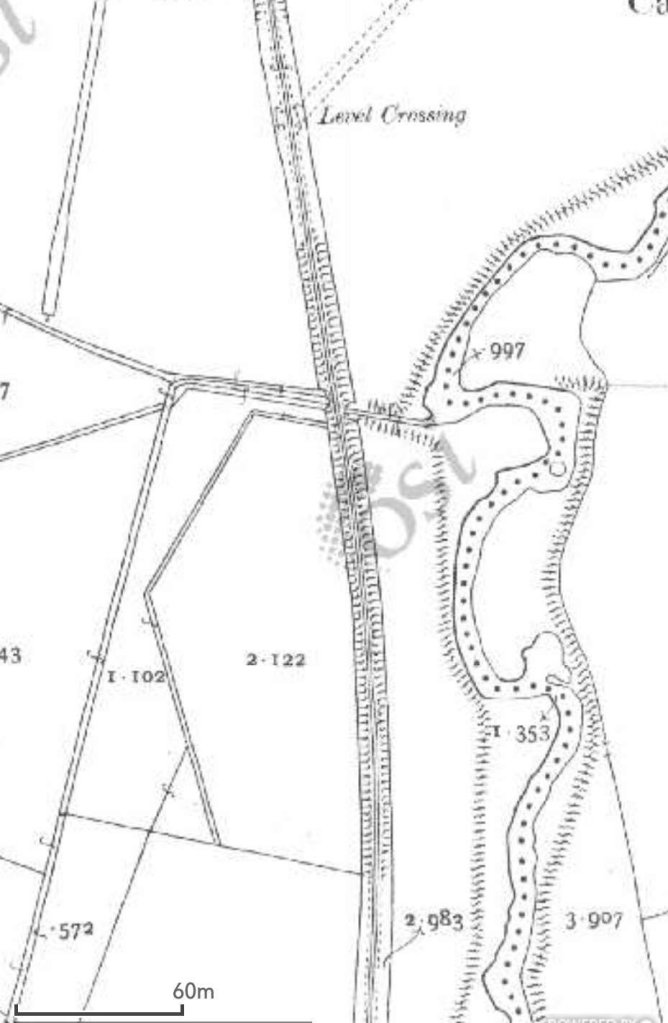

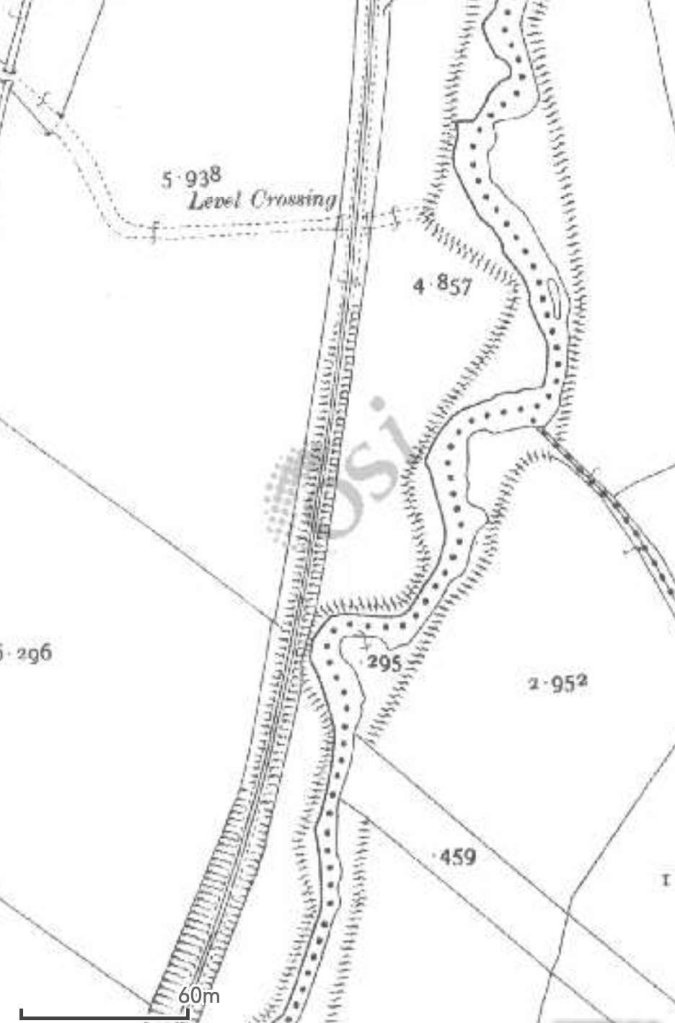

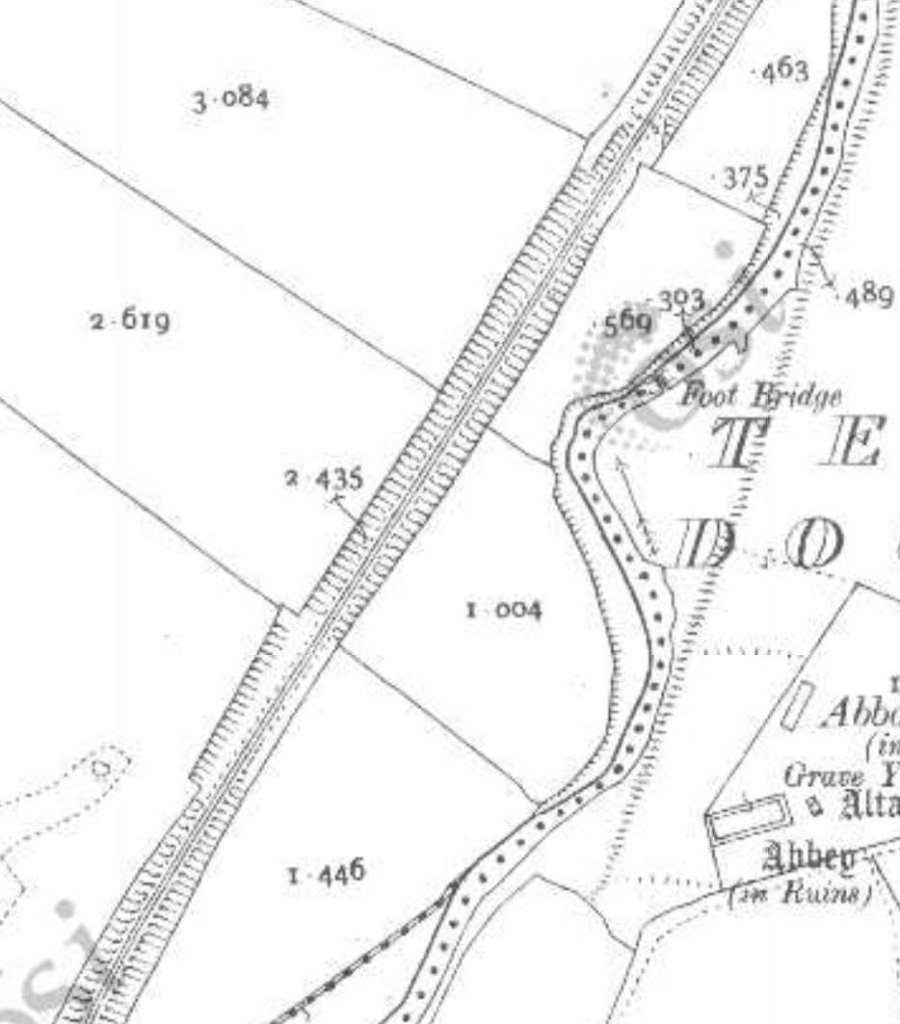

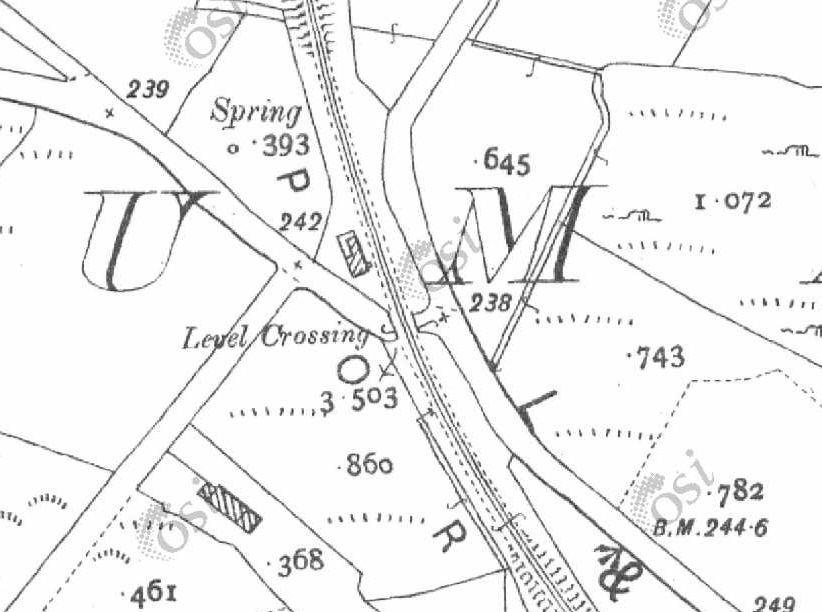

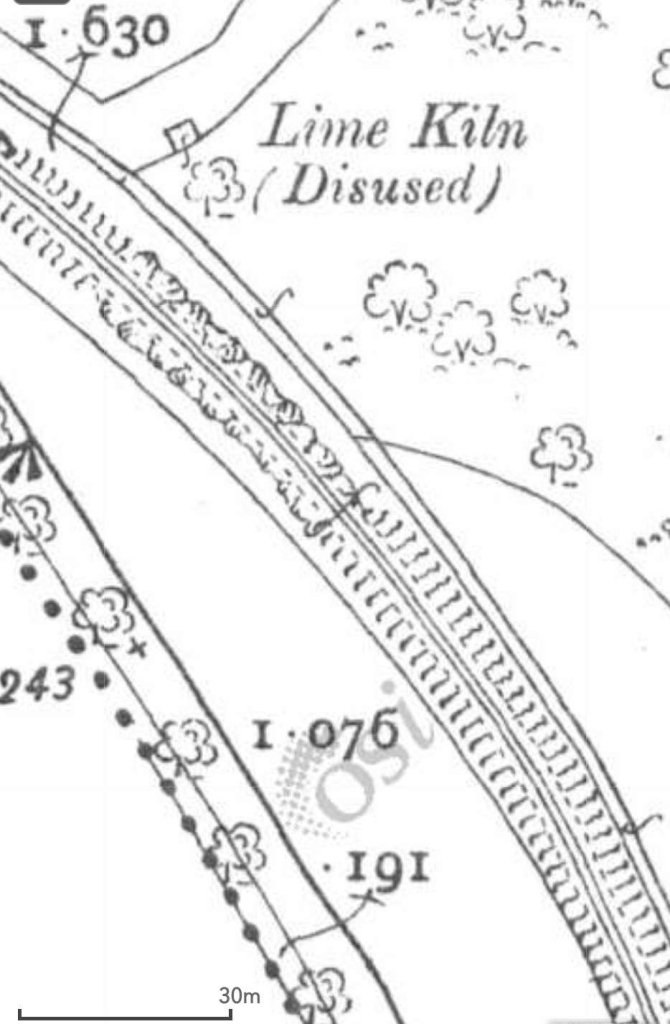

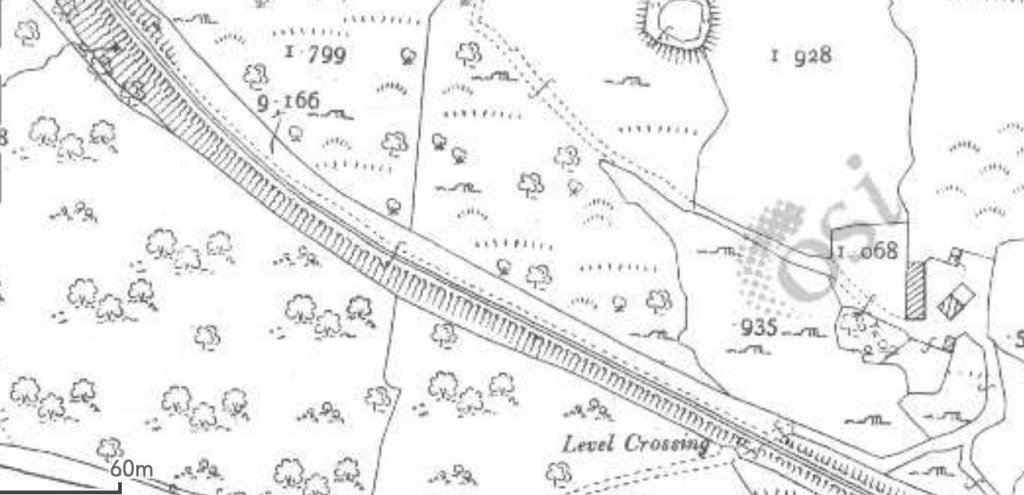

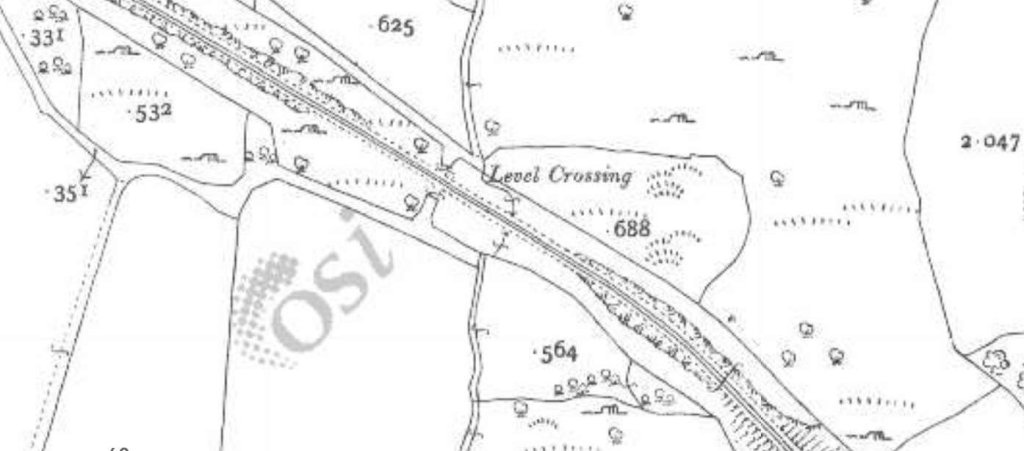

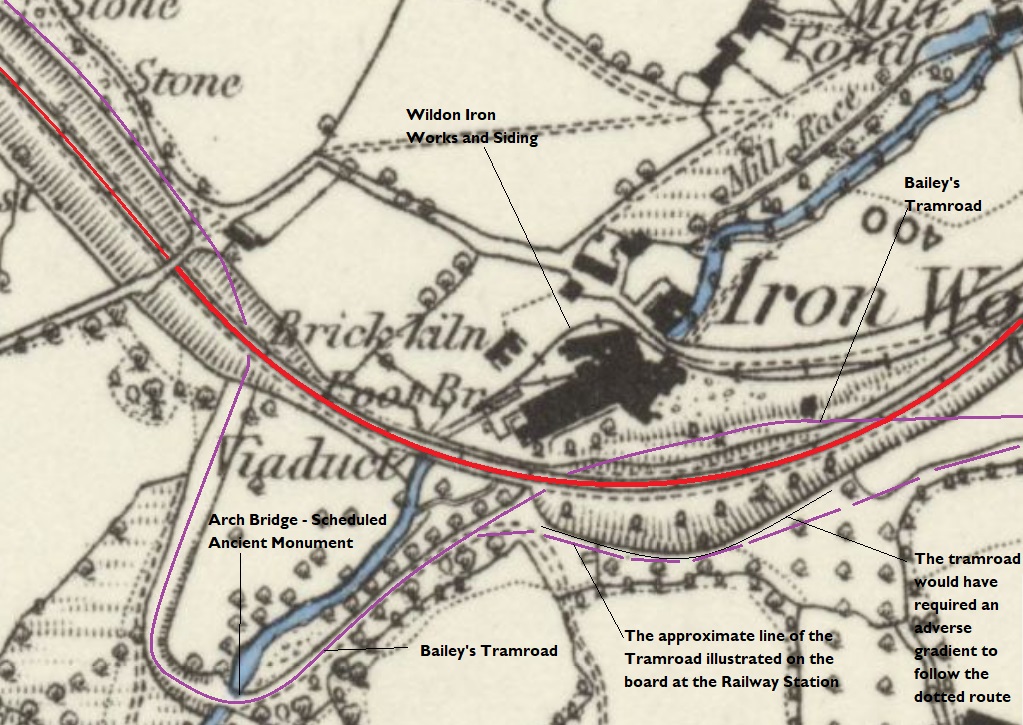

The map extract above shows Bailey’s Tramroad deviating away to the South from the line of the more modern standard-gauge railway and following the contours of the valley as it sought a suitable crossing point over the stream which sustained a suitable gradient on the Tramroad. The more modern standard-gauge line crossed the stream valley on a stone viaduct.

The standard-gauge line’s viaduct was flanked by two significant local structures, one of which remains in place, the other of which has been substantially removed.

The Tramroad Bridge is a scheduled ancient monument. It has had some work done to secure it’s future, but is again in need of remedial work if it is not soon to collapse into the stream it crosses. We will see pictures of this bridge later in this article.

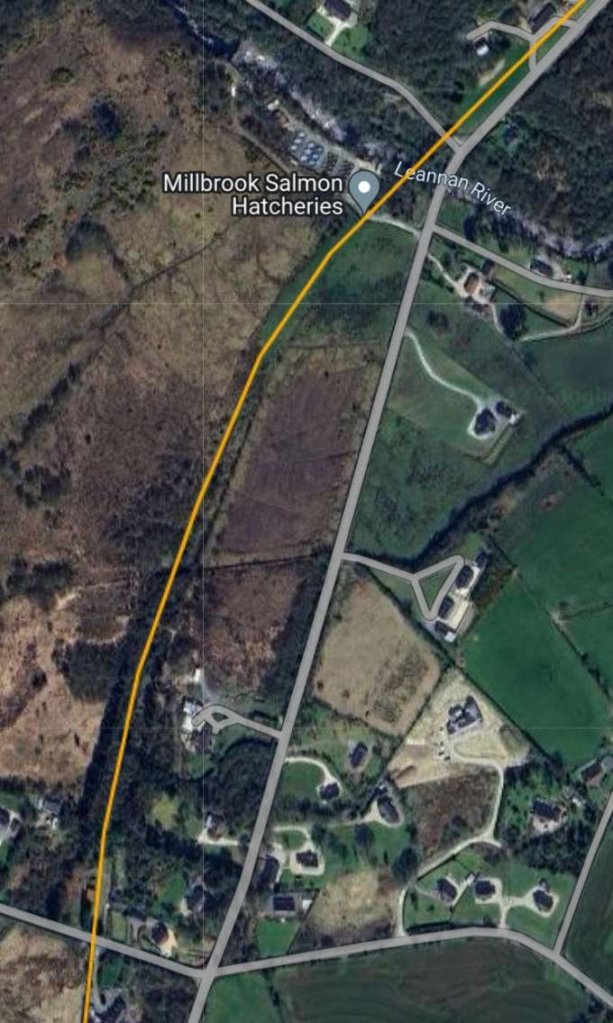

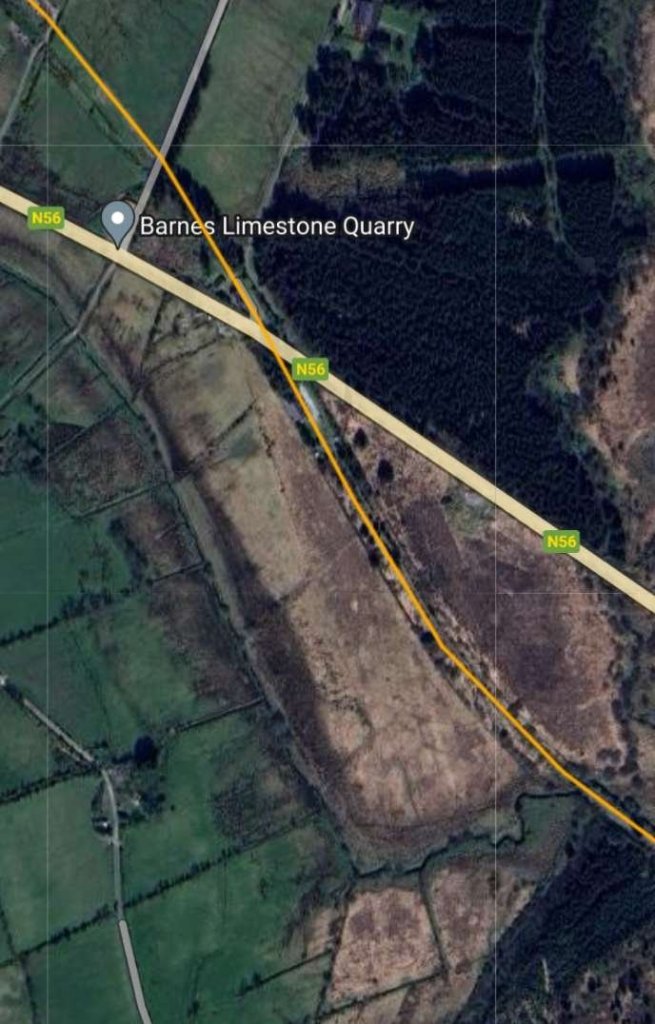

Wildon Iron Works closed in the 1870’s. The remains can be viewed from the railway viaduct or, with permission, by walking over privately owned land.

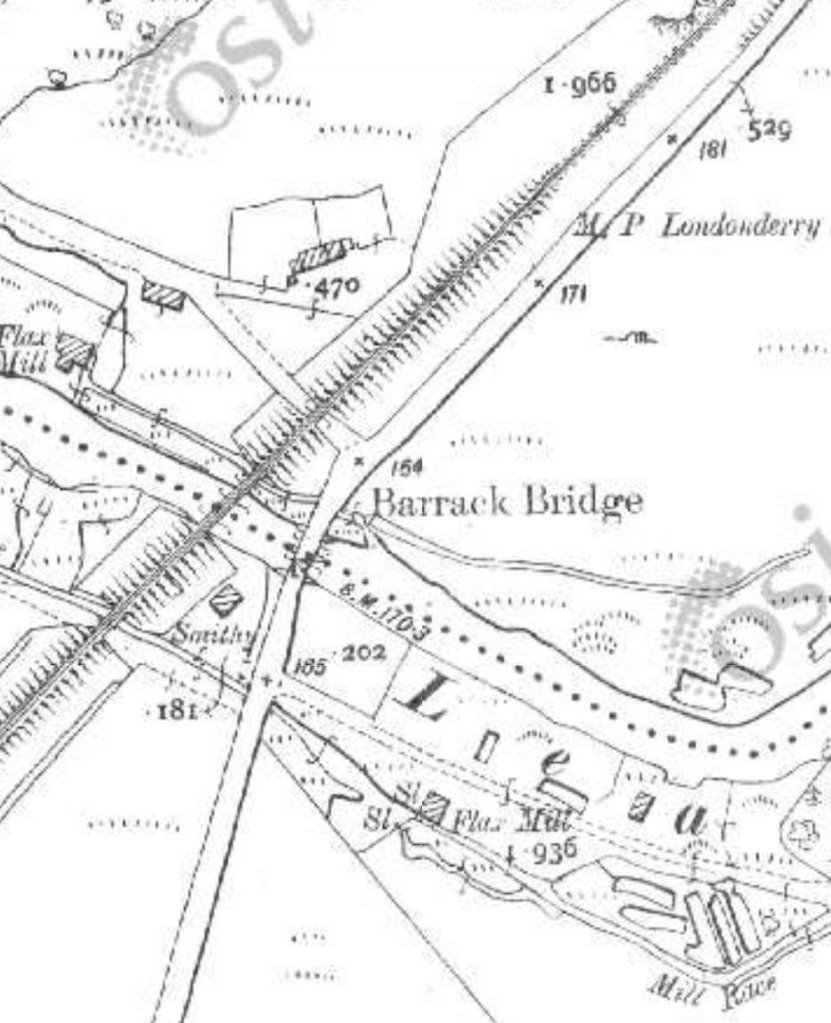

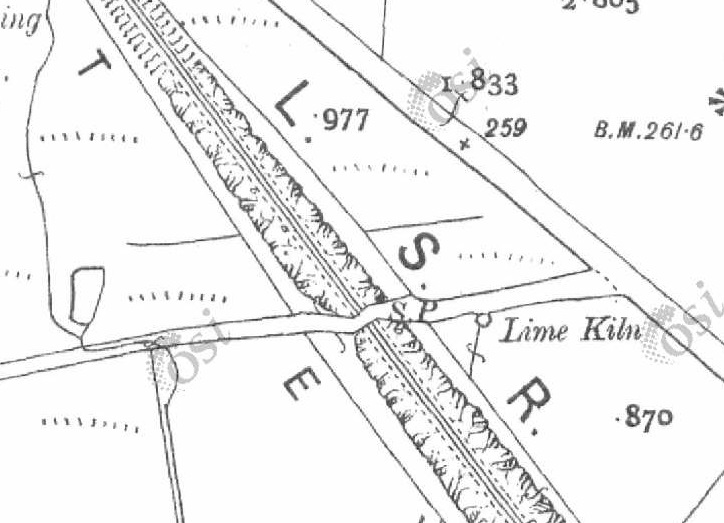

“The origins of the works are not documented but pre-date a 1790 entry in Bradney’s History of Monmouthshire. An 1846 map shows a number of workshops and outbuildings. Later this was expanded into a single complex. The site had a small furnace from which wire rod and nails were made from bar iron. It had its own water wheel fed from a large rectangular reservoir, and the site also housed a lime kiln. It expanded in the latter half of the nineteenth century, resulting in the stream being culverted and the addition of a number of buildings including a brick kiln. At this time it was known as Wilden Wireworks and therefore, may have been related to the wireworks of the same name in the Stour Valley, Worcestershire.” [26]

“Over the road to the North of the works were 4 small cottages in front of a managers house (whose deeds date from 1675 when the owners were the Prosser family). A cottage and the managers house still remain today. Near the cottages was the works weighing machine, stables and a blacksmiths shop – now 2 private houses. An incline ran down the valley, passing Upper Mill and stopping at the canal ”dry dock”. A branch of Bailey’s tramroad was run into the works, and later this was replaced by a railway siding running from the location of the current Forge car park.” [26]

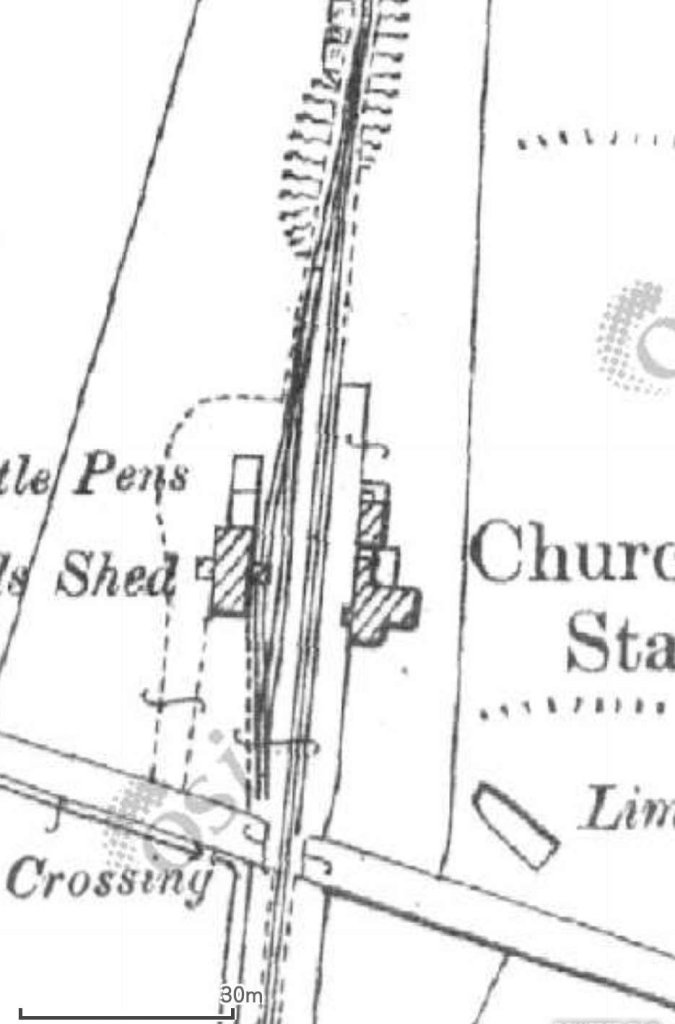

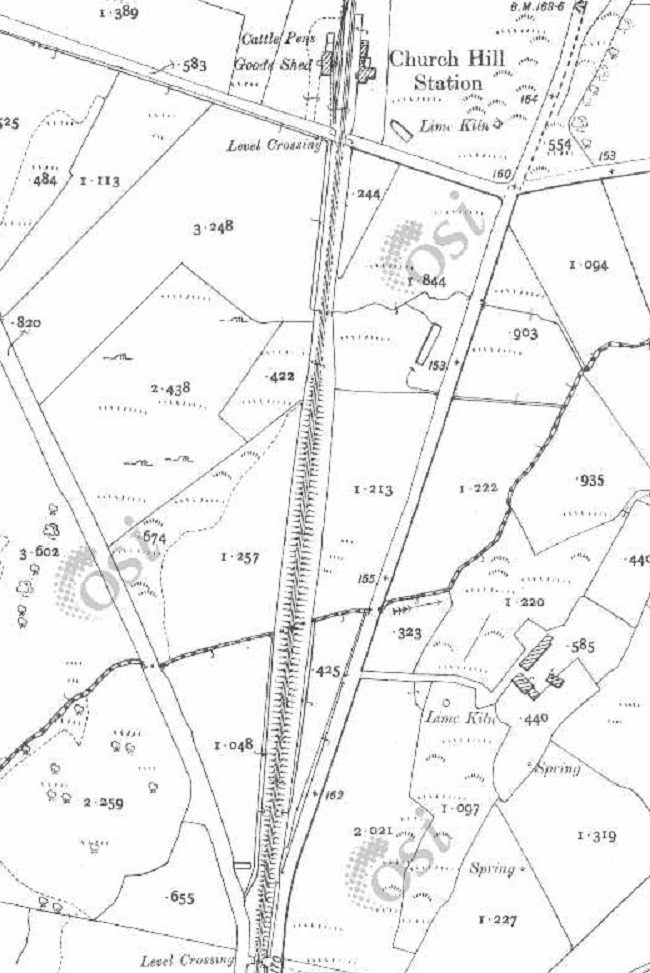

The 1879-1881 Ordnance Survey map some distance above is repeated immediately above. It shows the railway siding running into Wildon Iron Works. The track layout immediately adjacent to the buildings suggests that it predated the railway. The curve at the Northwest corner of the buildings it probably too tight a radius for locomotive movements. Shunting on the private siding may well have been undertaken by horses.

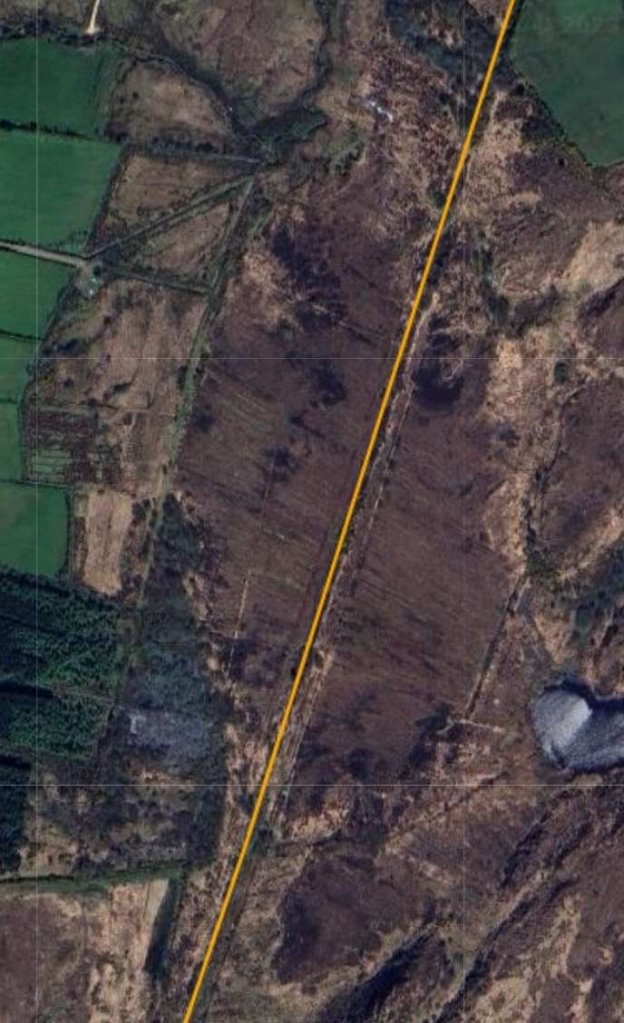

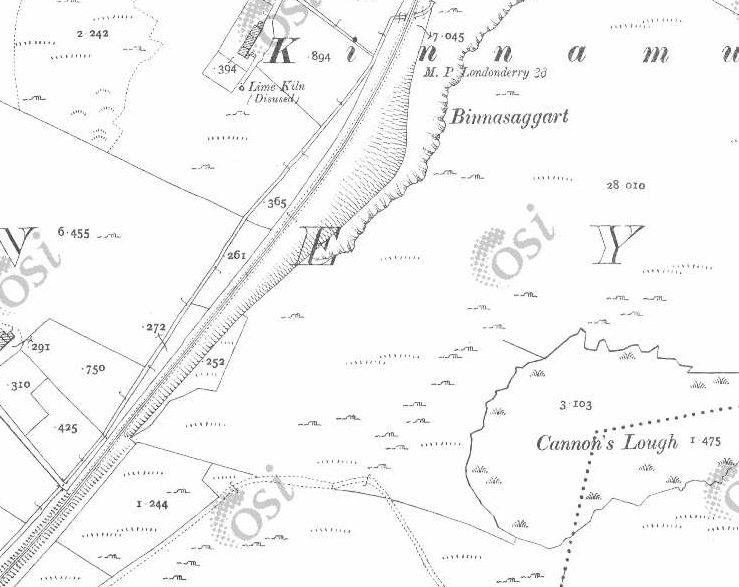

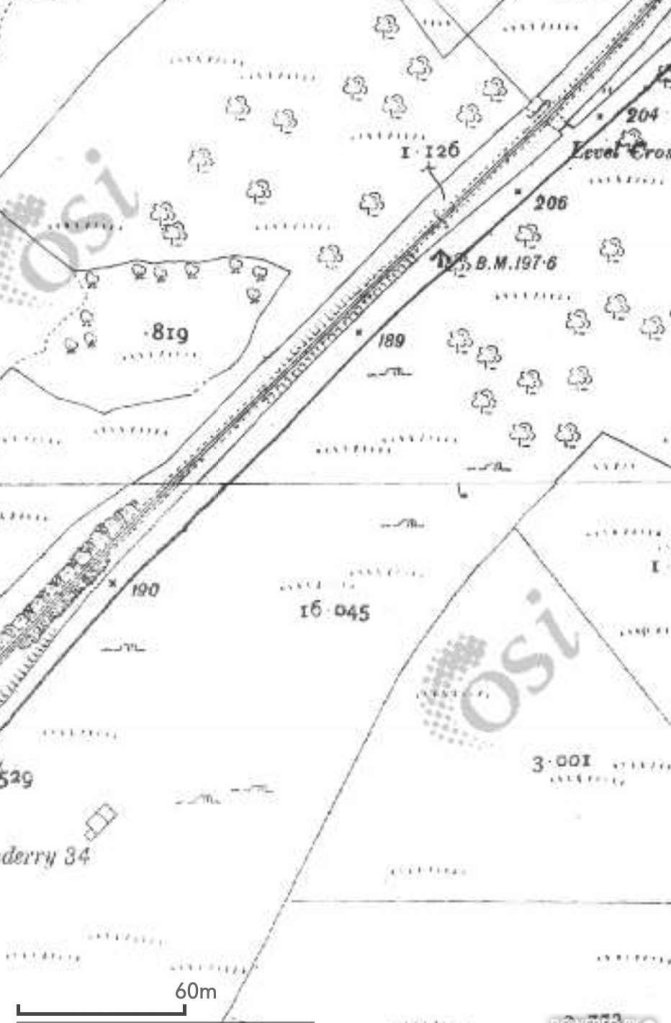

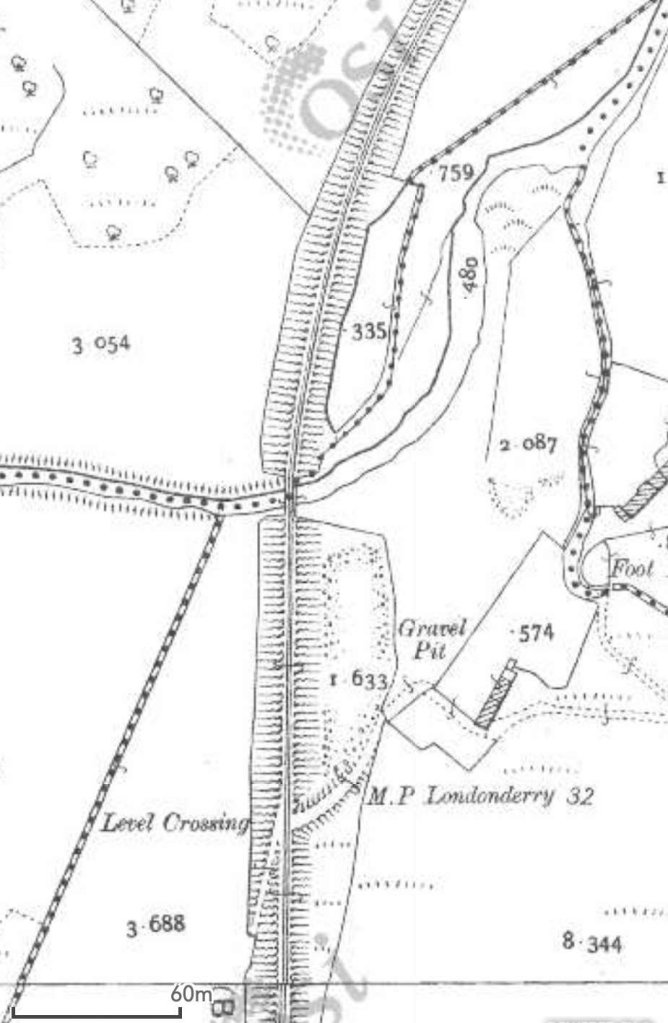

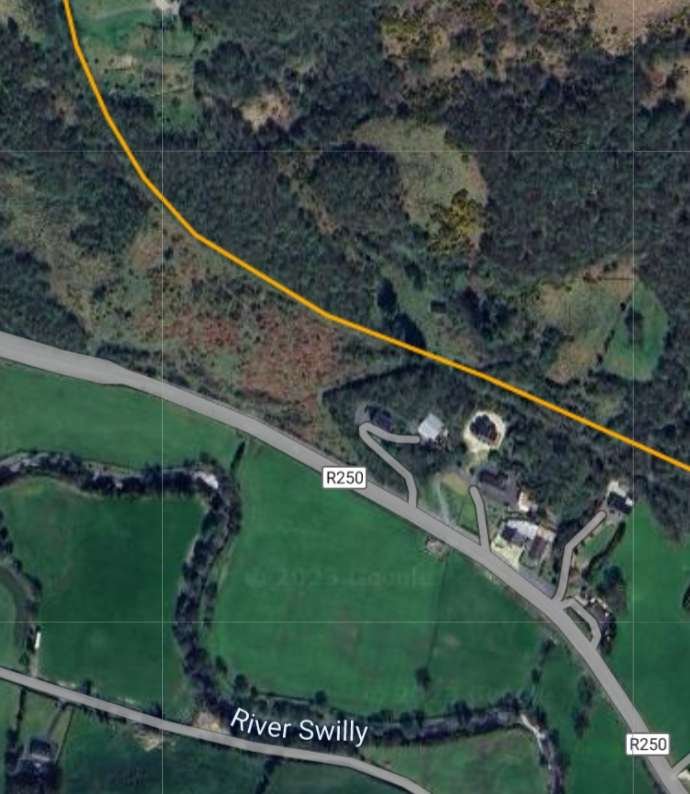

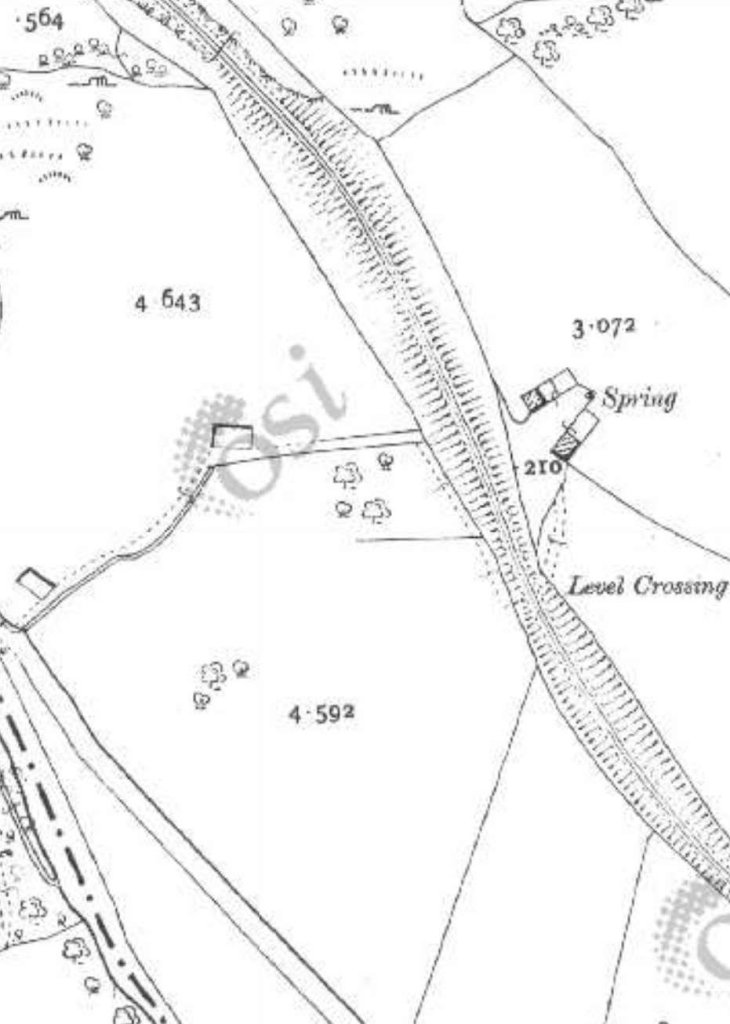

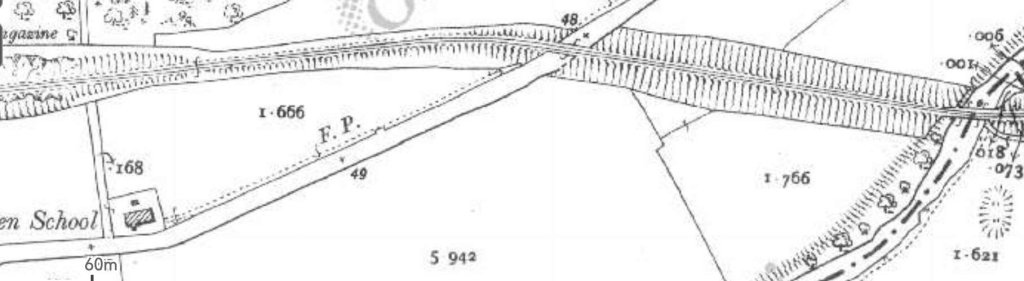

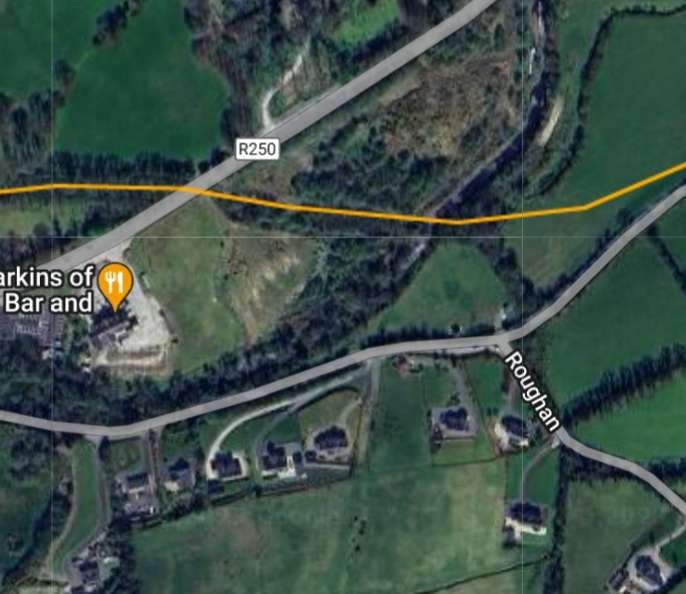

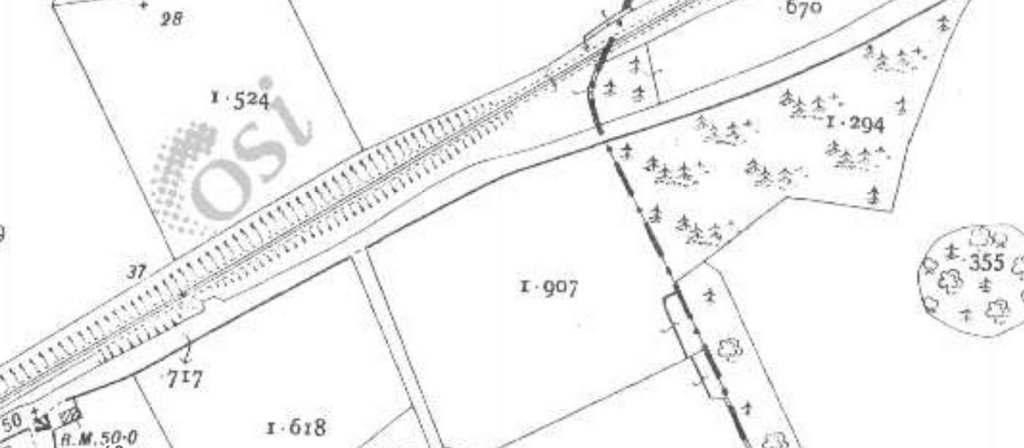

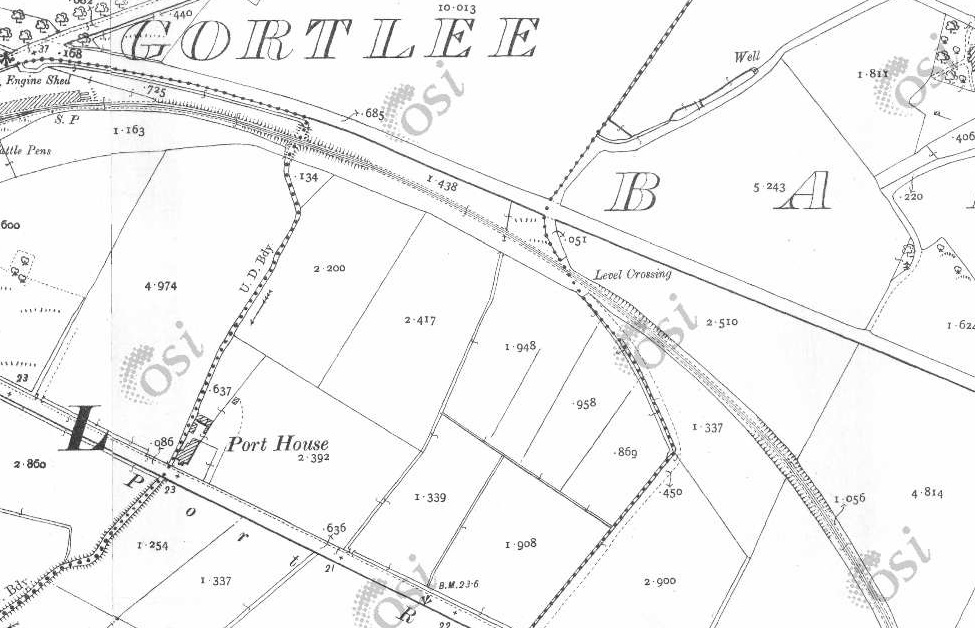

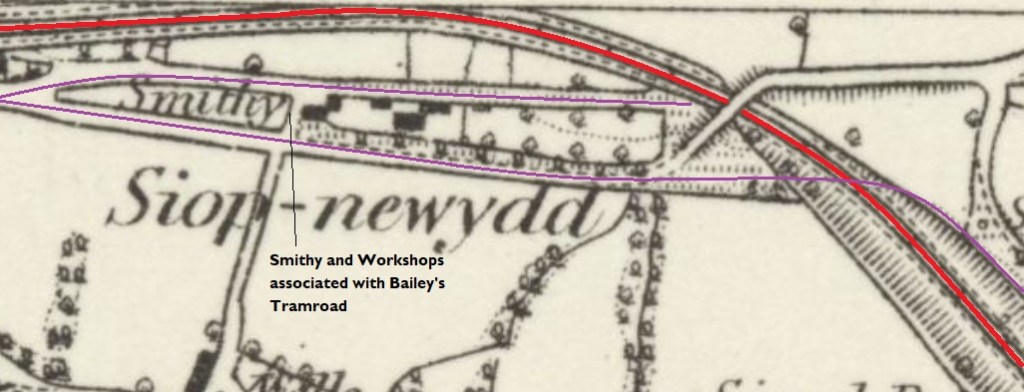

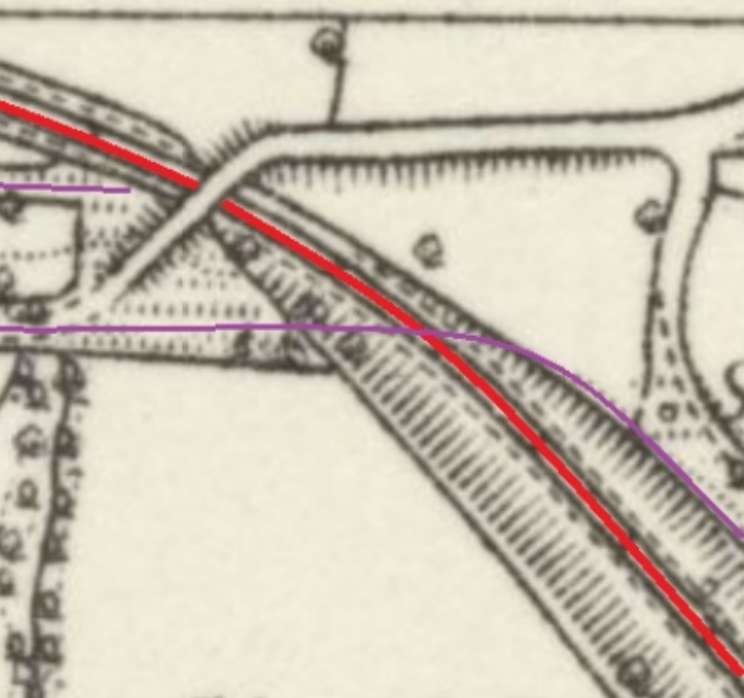

To the West of the standard-gauge railway’s Viaduct, the line of the Tramroad, shown on the map extract above, now considerably higher than the later railway, followed a line on the North side of the railway cutting before switching back to the South side of the railway as shown on the next map extract below.

[24]

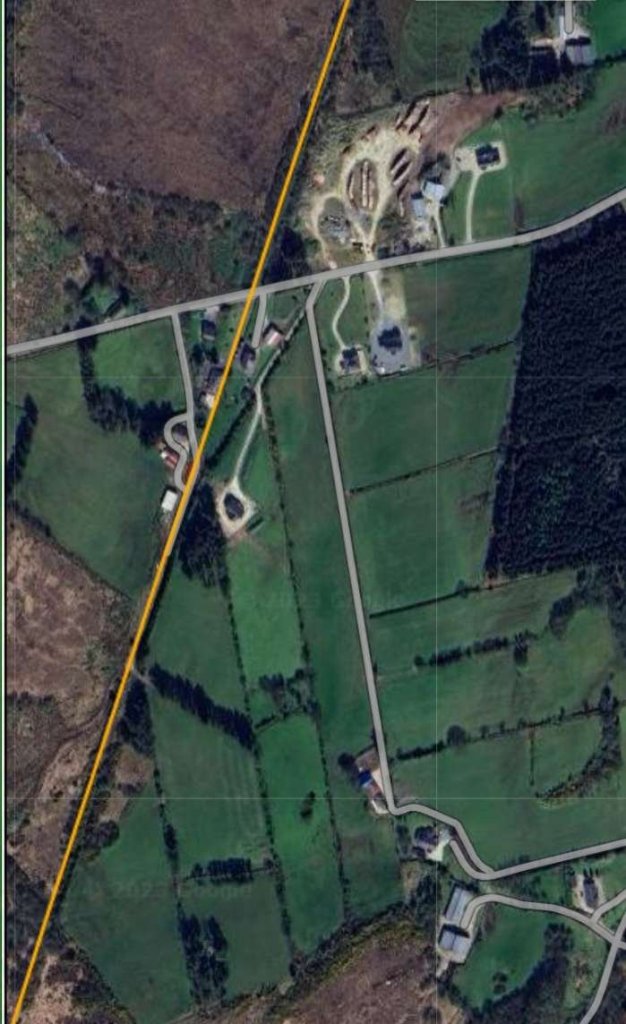

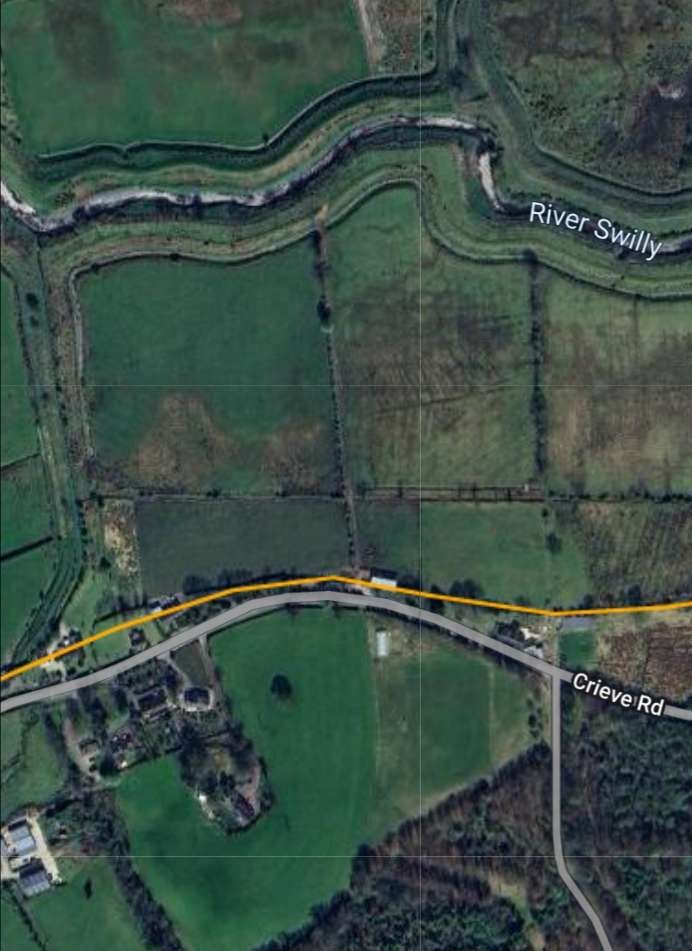

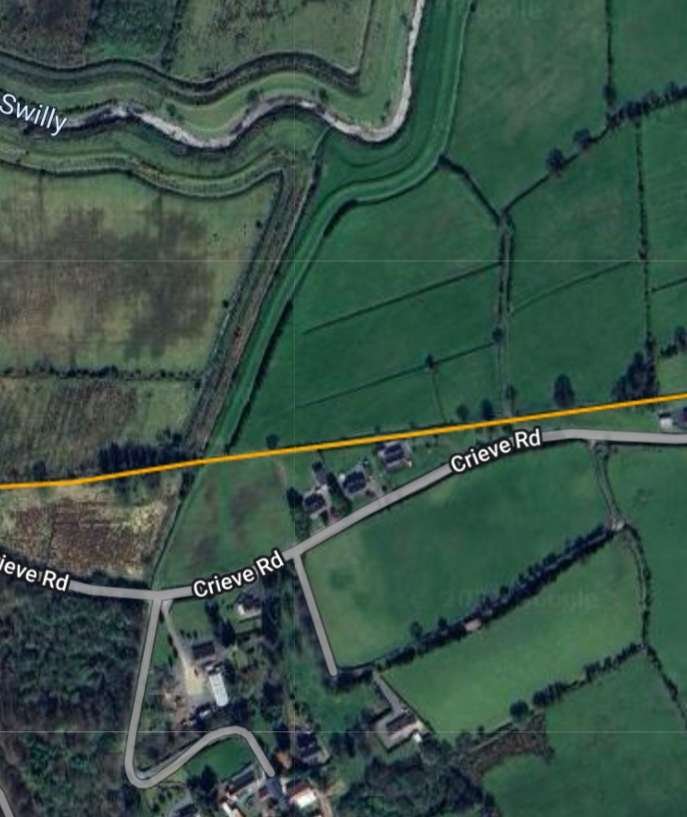

At its peak, up to 14 blacksmiths were employed at Siop-newydd for repairs and maintenance. This included shoeing horses used to pull the trams. The tramway sidings are clearly recognisable in the field between the lane and the railway track. [28]

The next few photographs focus on this area. …

Ancient Monuments UK, is an online database of historic monuments that are listed as being of particular archeological importance. It lists this Tramroad bridge on Bailey’s Tramroad as being scheduled on 3rd January 1980 by Cadw (Source ID: 302, Legacy ID: MM204).

The website records the structure as being to carry Bailey’s Tramroad as it “crossed the steep valley of Cwm Llanwenarth by a loop following the contour of the valley. … The tramroad bridge is a simple single arched structure of excellent quality ashlar masonry. The springings of the arch are set back from the jambs leaving a step, a feature not uncommon on early 19th century industrial structures. … The monument is of national importance for its potential to enhance our knowledge of medieval or post-medieval construction techniques and transportation systems. It retains significant archaeological potential, with a strong probability of the presence of associated archaeological features and deposits. The structure itself may be expected to contain archaeological information concerning chronology and building techniques.” [27]

To the East of the old bridge, the Tramroad turned North following the contours of the valley.

We have covered much of what is possible relating to railways just to the West of Govilon, with one exception. There is a reference on the Govilon History website to “An incline ran down the valley, passing Upper Mill and stopping at the canal ”dry dock”.” [26] The route of that incline may well be the straight track shown to the North if the stream and Mill Race on the map extract below.

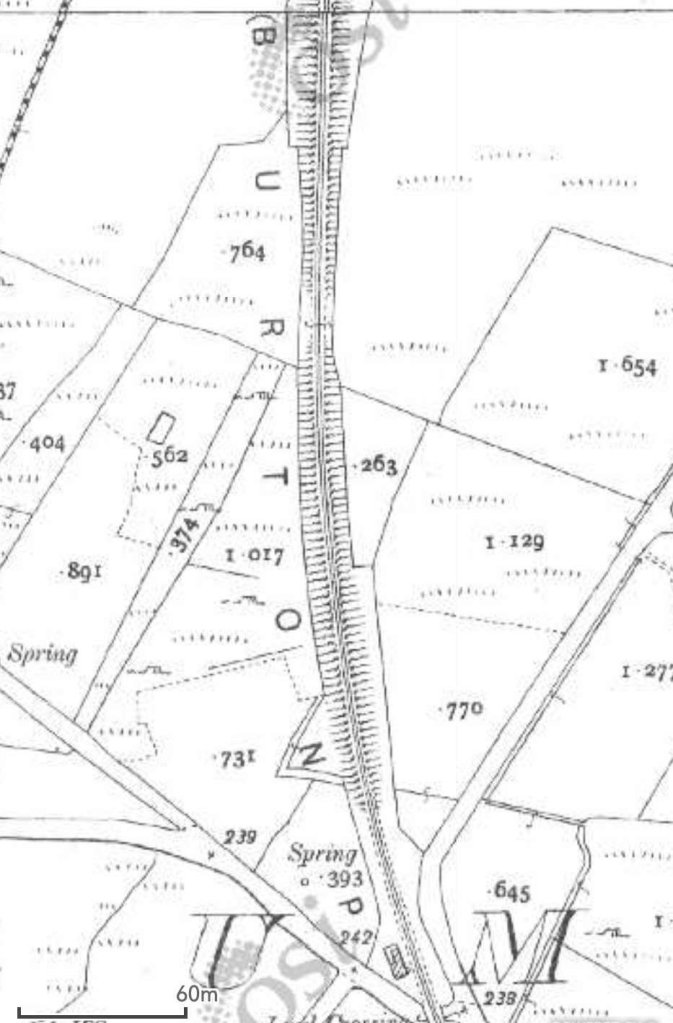

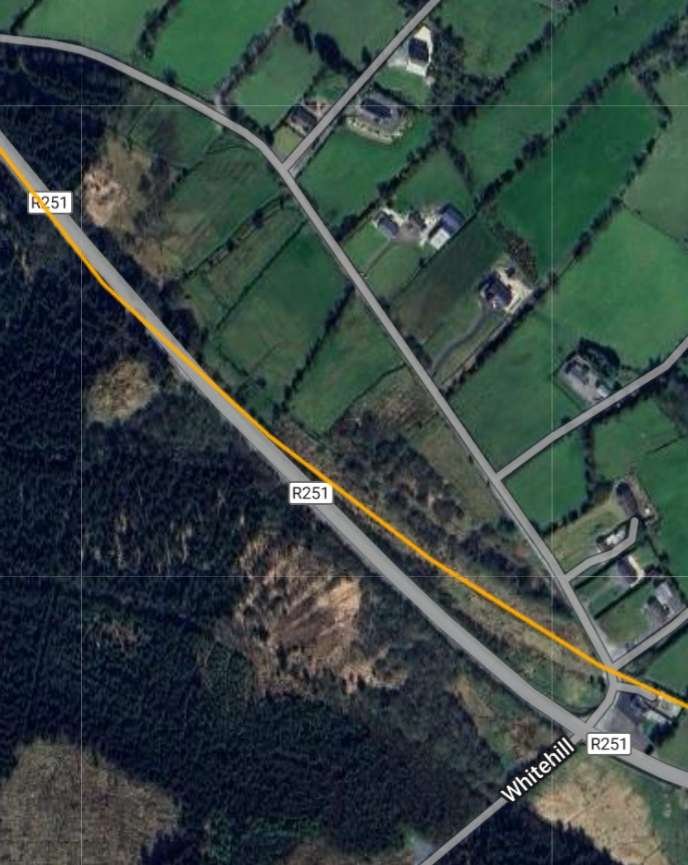

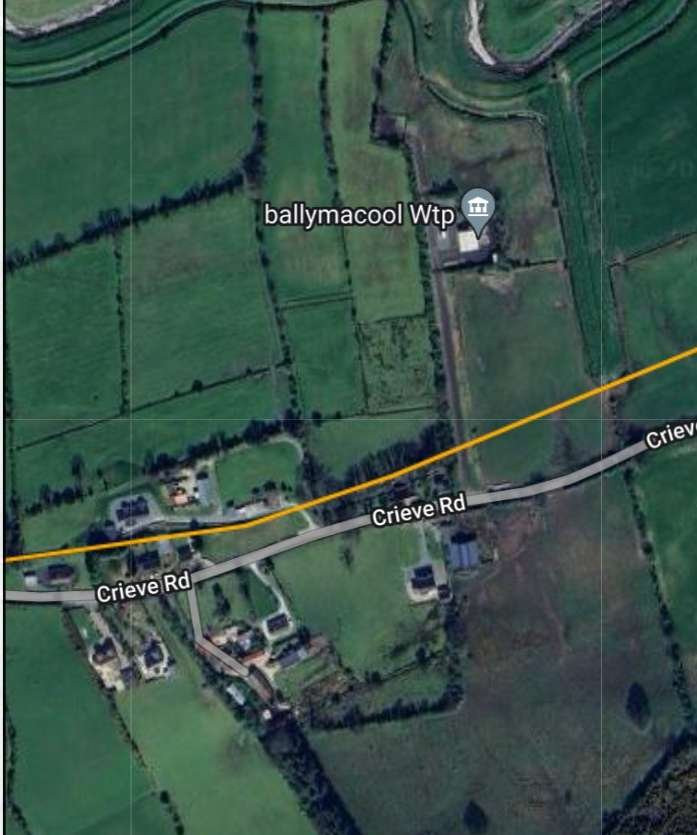

Bailey’s Tramroad and the Merthyr, Tredegar and Abergavenny Railway West of Siop-newydd

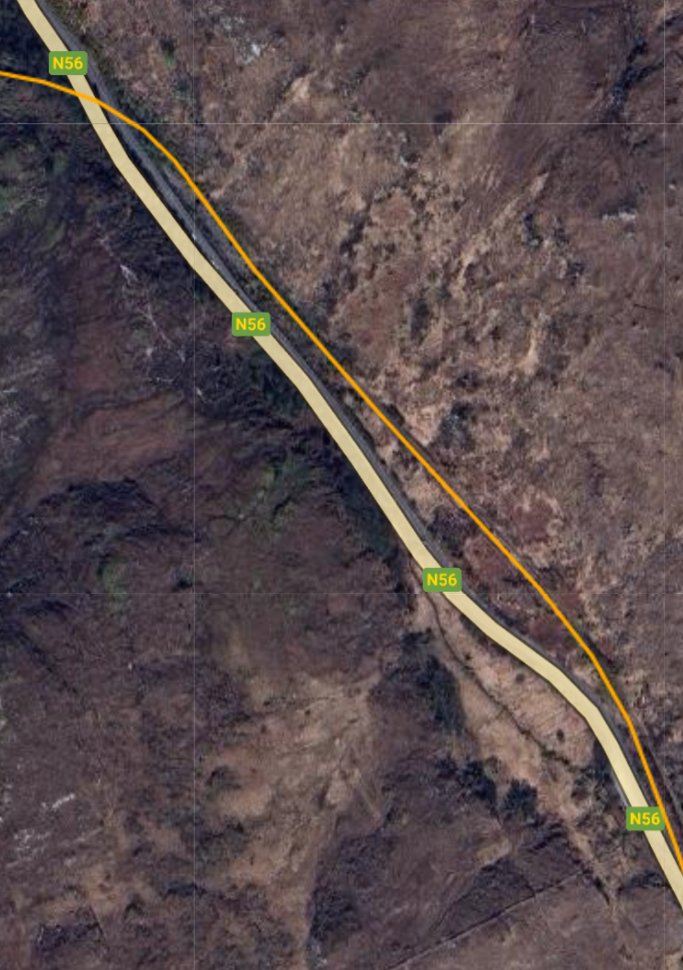

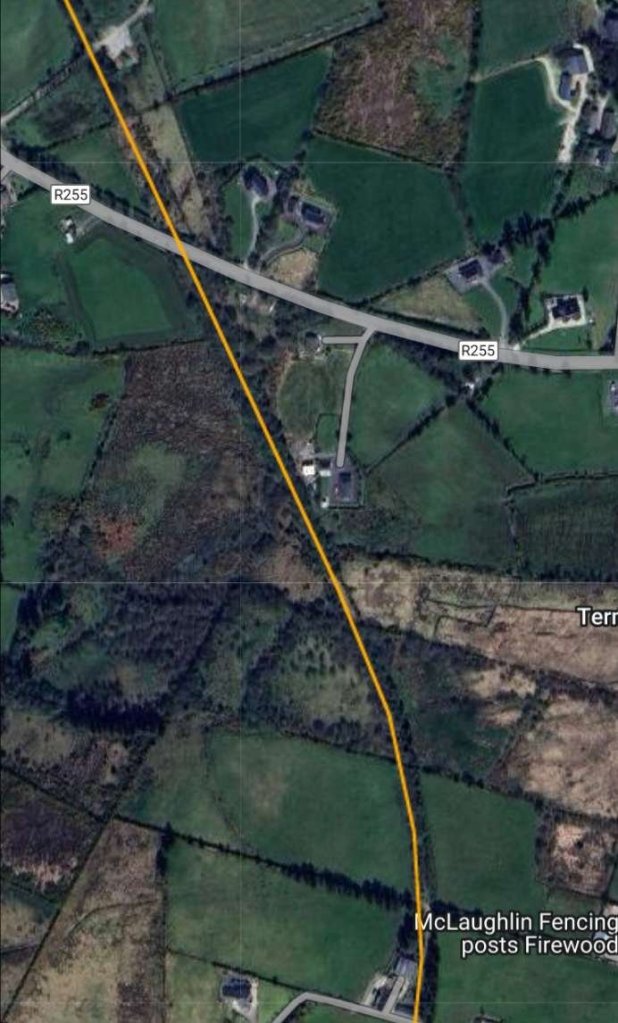

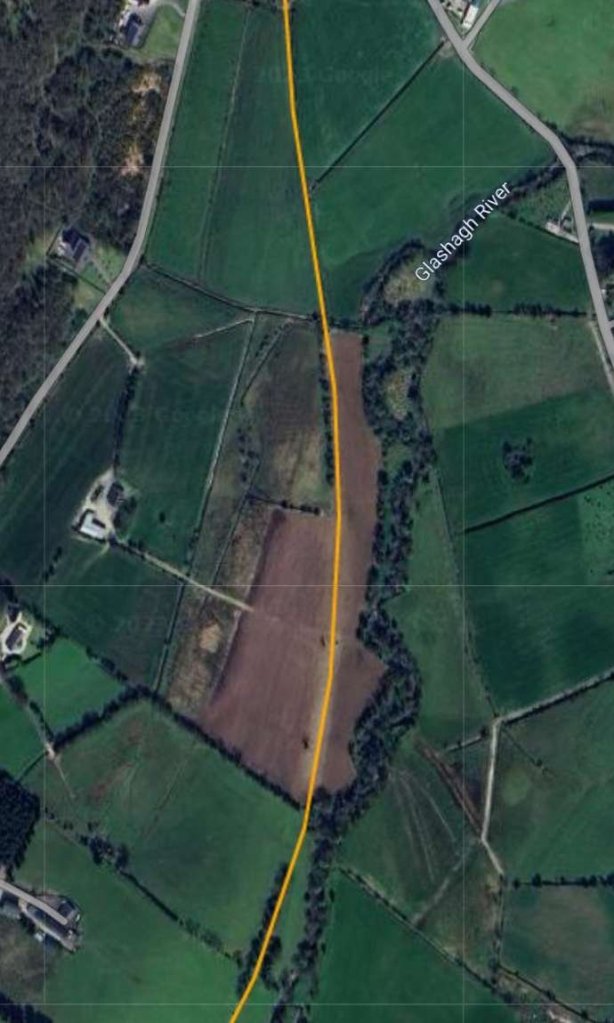

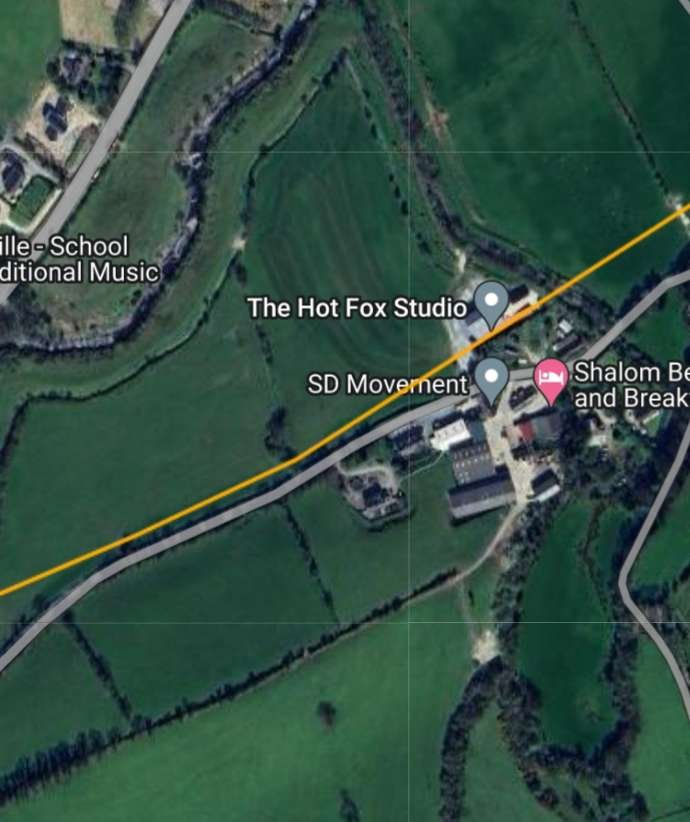

The footpath/cycleway continues to follow the Merthyr, Tredegar and Abergavenny Railway route to the West of Siop-newydd with Bailey’s Tramroad running parallel to it to the South. The route of railway and Tramroad to the West will be the subject of future articles in this short series, as a taster, here is one photo taken further to the West.

Further ahead of this location, the line curves round once again to the West and passes through Gilwern Station some distance ahead.

References

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2022/04/27/baileys-tramroad-part-1-the-monmouthshire-and-brecon-canal-and-an-introduction-to-the-heads-of-the-valley-line-or-more-succinctly-a-short-walk-at-govilon.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/gandg1236mths/permalink/440164962745034, accessed on 19th April 2013.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Govilon_railway_station, accessed on 26th April 2022

- This picture was a result of a Google search on 26th April 2022 (https://www.google.com/search?q=govilon+railway+station&client=ms-android-motorola-rev2&prmd=minv&sxsrf=APq-WBu4LJDnd981z48Kikjqyx97uz0X_A:1651026323274&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwinzY2smLP3AhXMT8AKHalNCcIQ_AUoAnoECAIQAg&biw=412&bih=726&dpr=2.63#imgrc=acn9kC5OQt_5yM) it does not however feature on the Facebook page of The Railway Shop, Blaenavon, to which the photograph is linked.

- John Bartlett’s father, Cyril, was Station Master in the period before the closure of Govilon Railway Station. This picture was shared by John Bartlett on the Facebook group ‘Govilon and Gilwern Past’, accessed on 26th April 2022.

- http://www.coflein.gov.uk/en/site/403520/images/DI2005_0544.jpg, accessed on 26th April 2022

- Michael Quick; Railway passenger stations in Great Britain: a chronology (4th ed.); Railway & Canal Historical Society, Oxford, 2009.

- R.V.J. Butt; The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.); Patrick Stephens Ltd., Sparkford, 1995.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abergavenny_Brecon_Road_railway_station, accessed on 26th April 2022.

- M.C. Reed; The London & North Western Railway; Atlantic Transport, Penryn, 1996.

- http://www.industrialgwent.co.uk/e22-govilon/index.htm, accessed on 25th April 2022.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Govilon_railway_station, accessed on 26th April 2022.

- W.W. Tasker; The Merthyr, Tredegar & Abergavenny Railway and branches; Oxford Publishing Co., Poole, 1986.

- Mike Hall; Lost Railways of South Wales; Countryside Books, Newbury, 2009.

- David Edge; Abergavenny to Merthyr including the Ebbw Vale Branch; Country Railway Routes; Middleton Press., Midhurst, 2002.

- C.R. Clinker; Clinker’s Register of Closed Passenger Stations and Goods Depots in England, Scotland and Wales 1830–1980 (2nd ed.); Avon-Anglia Publications & Services, Bristol, 1988.

- James Page; Rails in the Valleys. London: Guild Publishing, London, 1989.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/505407821802279/permalink/524472699895791, accessed on 19th April 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/505407821802279/permalink/516785993997795, accessed on 19th April 2023.

- I have lost the full details of the source of this image. If you know anymore about this photograph, please let me know. If you hold copyright for this image please also make contact. As far as I know it is out of copyright but I may be wrong. It can be taken down if necessary.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2177380, accessed on 19th April 2023.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2177362, accessed on 19th April 2023.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2177370, accessed on 19th April 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/101605952, accessed on 19th April 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.2&lat=51.81665&lon=-3.06869&layers=6&b=1, accessed on 14th July 2023.

- https://history.govilon.com/trails/places-of-interest/ironworks, accessed on 14th July 2023.

- https://ancientmonuments.uk/131818-tramroad-bridge-baileys-tramroad-govilon-llanfoist-fawr, accessed on 14th July 2023.

- https://history.govilon.com/trails/forge-and-railway/tour, accessed on 15th July 2023.