‘Modern Tramway’ in January 1964 carried an article by J.H. Price about the process involved in getting Snaefell rolling-stock to Derby Castle for maintenance. [1] The featured image for this article shows Snaefell Car No. 4 on the Mountain Railway in May 2005, © John Wornham and included here under a Creative Commons Licence, (CC BY-SA 2.0). [3]

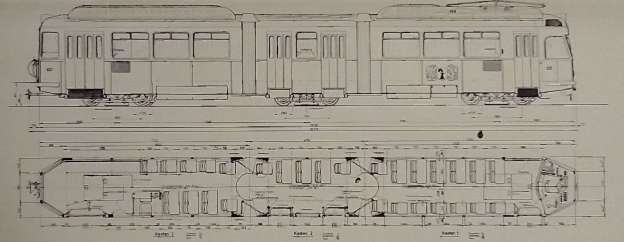

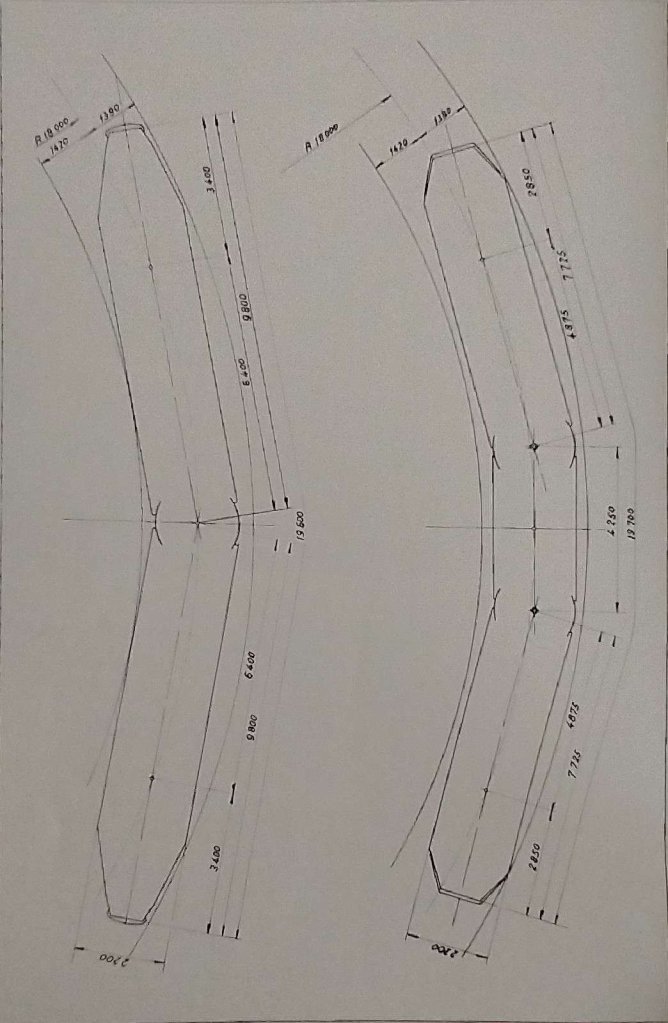

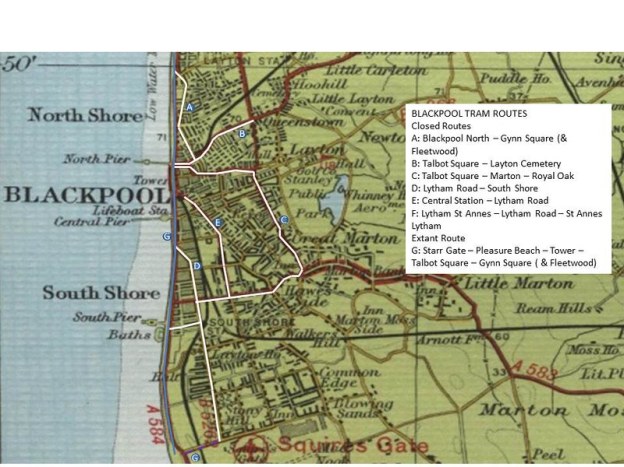

In the early 1950s, Price tells us, “A considerable stir was caused in railway circles by the news that the Russian and Czech railways had introduced a service of through sleeping-cars between Prague and Moscow, overcoming the break of gauge at the Russian frontier. It appeared that the cars could be lifted on jacks, complete with their passengers, while the standard-gauge bogies were run out and replaced by others of the wider Russian gauge. This method was later extended to other routes, and the accompanying photograph, taken in 1957, shows the cars of the Moscow-Berlin Express raised up on electric jacks in the gauge-conversion yard at Brest-Litovsk, on the frontier of Russia and Poland. … Unknown to the Ministry of Communications of the U.S.S.R., something very similar has been going on quite unobtrusively here in these islands, not just in the last decade, but ever since 1933. The place is Laxey, Isle of Man, and the cause is the six-inch difference in gauge between the Manx Electric Railway’s Douglas-Ramsey line and the Snaefell Mountain Railway. The coastal tramway was constructed to the usual Manx gauge of 3 ft. 0 in., but on the Snaefell line this would not have left sufficient room for the centre rail and the gripper wheels and brake-gear, with the result that the mountain line uses a gauge of 3 ft. 6 in. instead.” [1: p19]

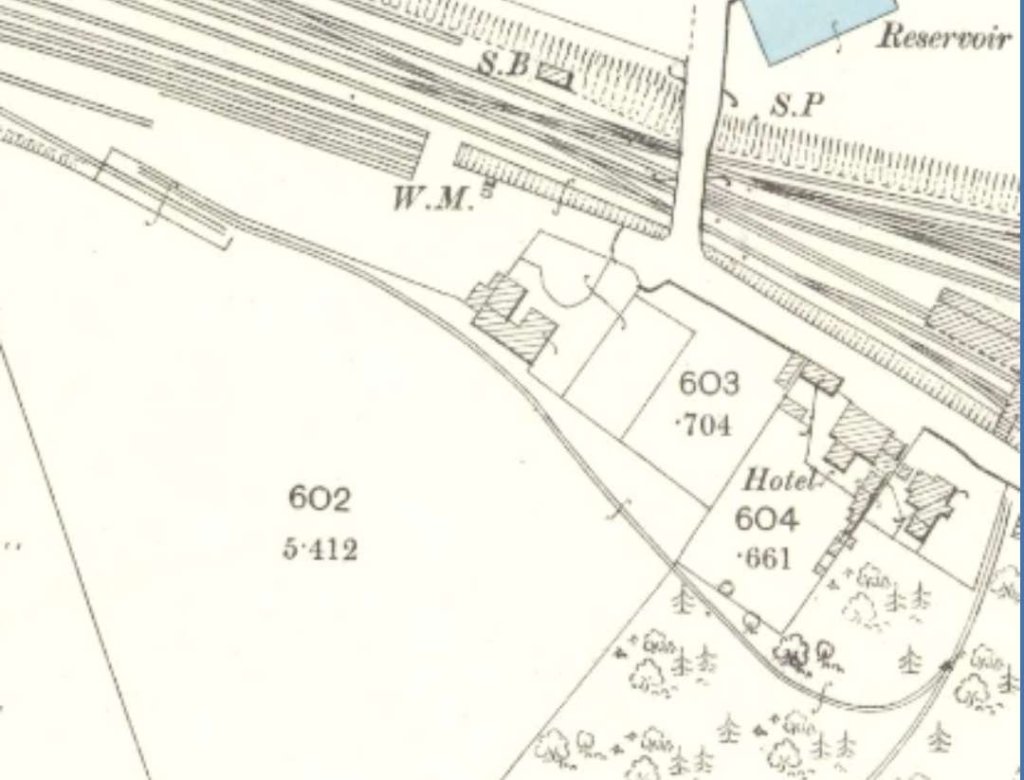

Both the MER and the Snaefell lines “have always been under a common management, and in past years, repainting of Snaefell cars was carried out at the mountain line’s car shed by staff who travelled up each day from Derby Castle. Since Snaefell car shed at Laxey is narrow and rather dark, the work was mostly done out of doors, the car being run in and out of the shed each time it rained. After the 1933 fire at the other Laxey car shed had created a float of spare plate-frame bogies, the management decided to use a pair of these to bring Snaefell cars due for overhaul down to the principal Manx Electric workshops at Derby Castle, Douglas. Controller overhauls and motor repairs were already carried out at Douglas, and since 1933 work at Laxey has therefore been confined to routine maintenance, running repairs and truck overhauls.” [1: p19]

The result of this decision was that every now and again (once or twice a year) a Snaefell car had to be lifted off its 3 ft. 6 in. gauge trucks and mounted on 3 ft. gauge bogies to be towed down to Douglas, returning by the same means when its overhaul was completed. This operation was rarely seen by visitors to the Isle of Man as it took place out-of-season.

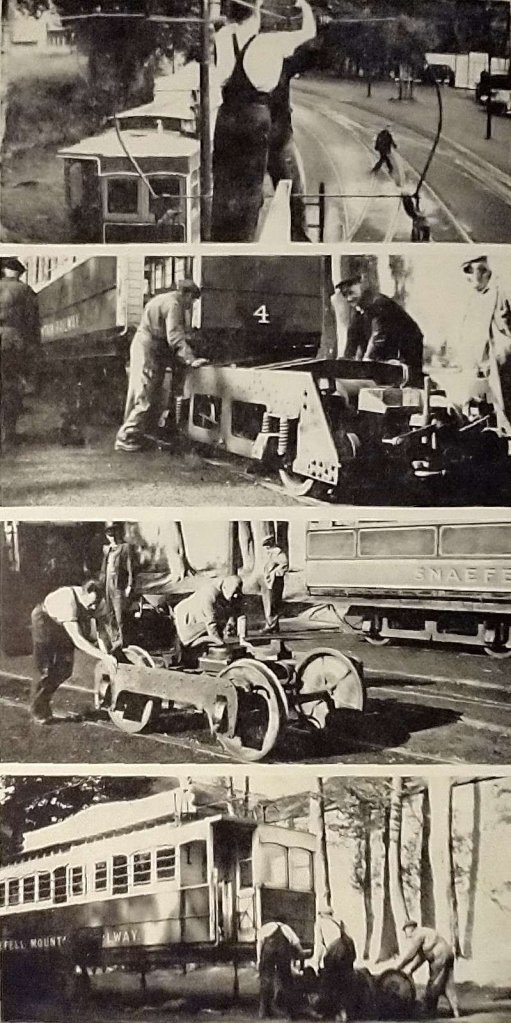

“The Snaefell 1963 operating season ended on Friday 13th September, and the moving operation started soon after eight o’clock next morning, when Snaefell car No. 4 was brought down from the car shed and run on to the dual-gauge siding. With it came a set of traversing-jacks, various tools, and the necessary wooden packing, kept in the Snaefell car-shed for this twice-yearly operation and any other less foreseeable. eventualities. Four … men then set to work … following a sequence which, like many other Manx Electric operations, is handed down from one generation to the next without ever having found its way into print.” [1: p22]

J.H. Price continues:

“First, the brake-gear and bogie-chains are disconnected, and the bow-collectors roped to the trolley-wire so that the pins can safely be removed, after which the collectors are untied again and lowered to the ground. Once this is done, no part of the car’s circuit can become ‘live’, and next the motor and field connections are broken at their terminals in the junction-boxes, which are housed under the seats and above the motor positions. The body is now merely resting on its two bogies, with no connection between them.

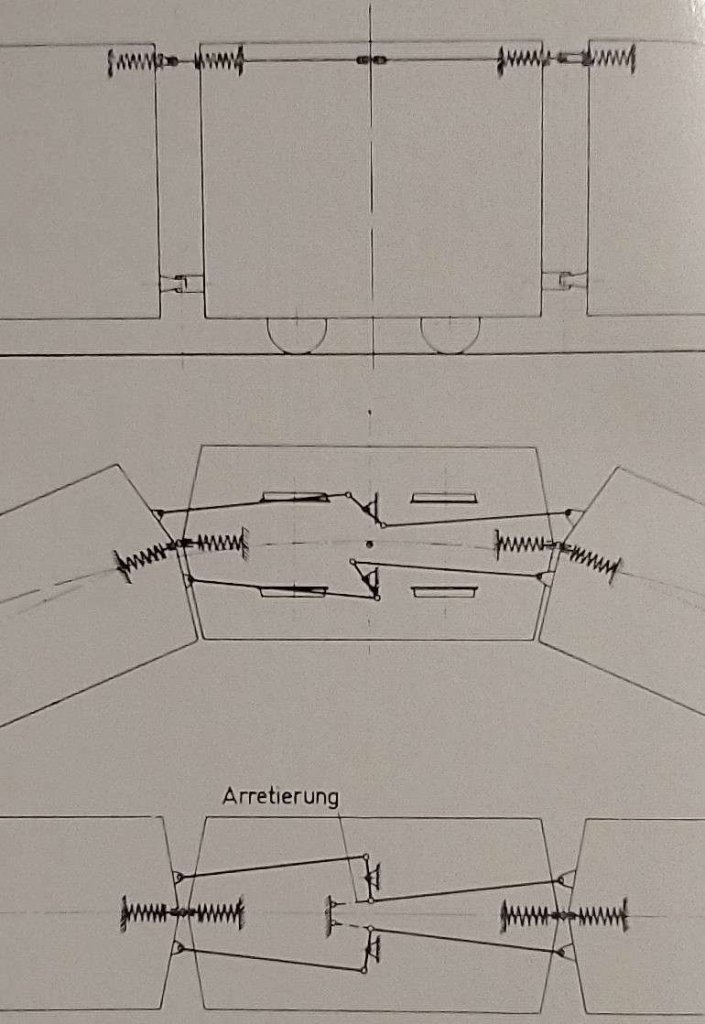

The next stage is to lift the car and exchange the 3 ft. 6 in. gauge bogies for others of 3 ft. 0 in. gauge. In the case of the Russian sleeping-cars mentioned earlier, the two gauges are concentric and the car. bodies need only a straight lift and lowering, but Laxey siding has three rails (not four), and the car body therefore has to be traversed laterally by three inches from the centre-line of the 3 ft. 6 in. gauge to the centre-line of the 3 ft. 0 in. To do this, the staff use a pair of special traversing-jacks with a screw-thread in the base that enables the load to be moved sideways; similar jacks are used by the Royal Engineers to re-rail locomotives, and were also used by them to place Newcastle tram No. 102 on rails at Beaulieu in March, 1959.

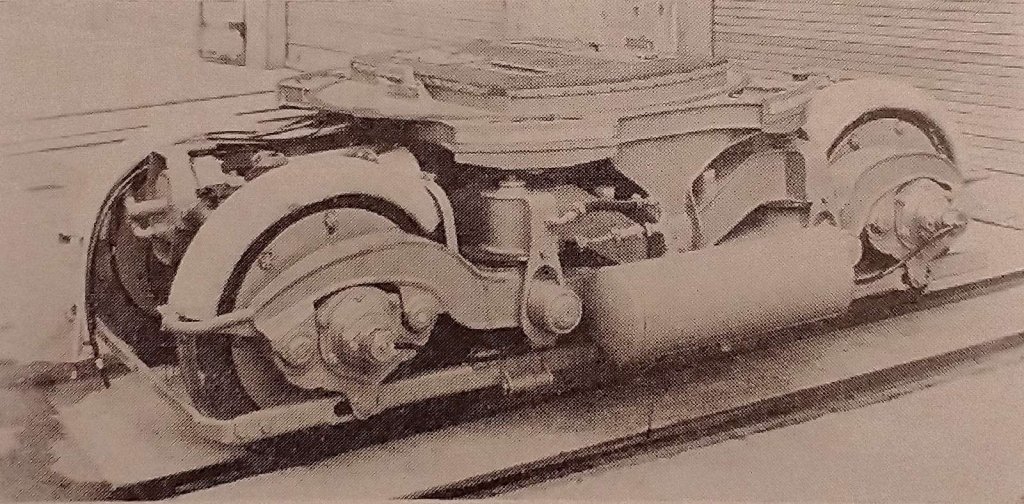

Considerations of safety make it preferable to keep one end of the car resting on a chocked bogie, so the Manx Electric use only one pair of jacks, tackling first one end of the car and then the other. First the Snaefell end of the car is lifted, and the 3 ft. 6 in. gauge bogie is pushed out; in this case, it was then towed up to the car shed by Snaefell car No. 1. Meanwhile, two men fetch a 3 ft-gauge plate-frame trailer bogie from Laxey Car Shed and push it by hand along the northbound running line to Laxey station, where it is shunted on to the three-rail siding and run in under the Snae- fell car. The body is then lowered to the horizontal, traversed to suit the centre of the 3 ft. gauge bogie, and landed on the bogie baseplate. A king-pin is then inserted, the loose retaining-chains are secured, and the jacks taken out and re- erected at the other end of the car.

Now comes the turn of the Laxey end (the two ends of the mountain cars are referred to as Laxey end and Snaefell end, not as No. 1 and No. 2, or uphill and down). The car body is raised again on the jacks, and the other Snaefell bogie pushed to the end of the siding. A second plate-frame trailer bogie is then brought up to a nearby position on the northbound Douglas-Ramsey road, derailed with pinch-bars, and manhandled across the tarmac on to the three-rail siding. Once re-railed, the bogie is then run in under the car end, which is lowered, traversed and secured in the same way as before. The Snaefell car is now ready for its trip to Douglas, and as soon as it has been towed away, another Snaefell car collects the remaining 3 ft. 6 in. gauge bogie and takes it up to the Snaefell car-shed, together with the ladder, tools, packing and jacks. [1: p22]

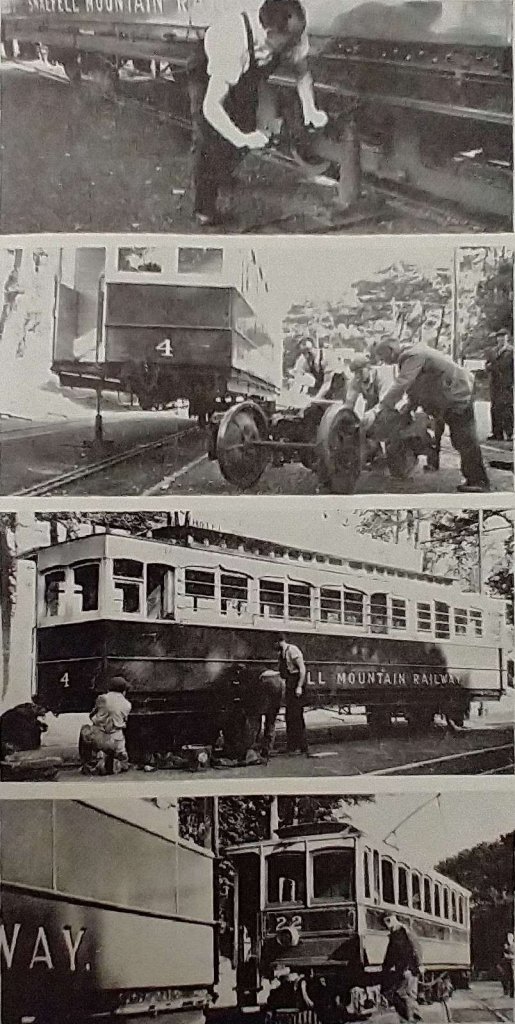

At the suggestion of ‘Modern Tramway’ a member of staff of the MER agreed to make a photographic record of the whole process. The images were then reproduced in ‘Modern Tramway’. The sequence of images appears below, starting with the Snaefell car No.4 being run into the three-rail siding.

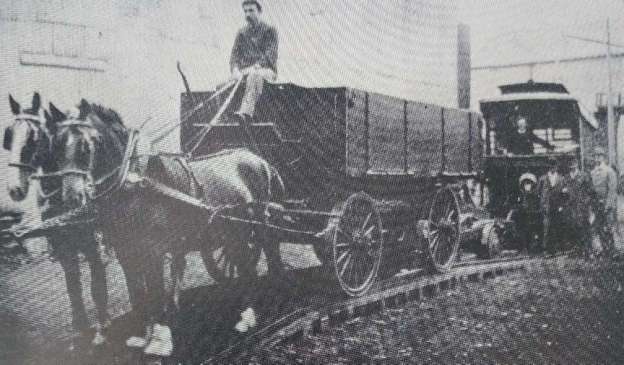

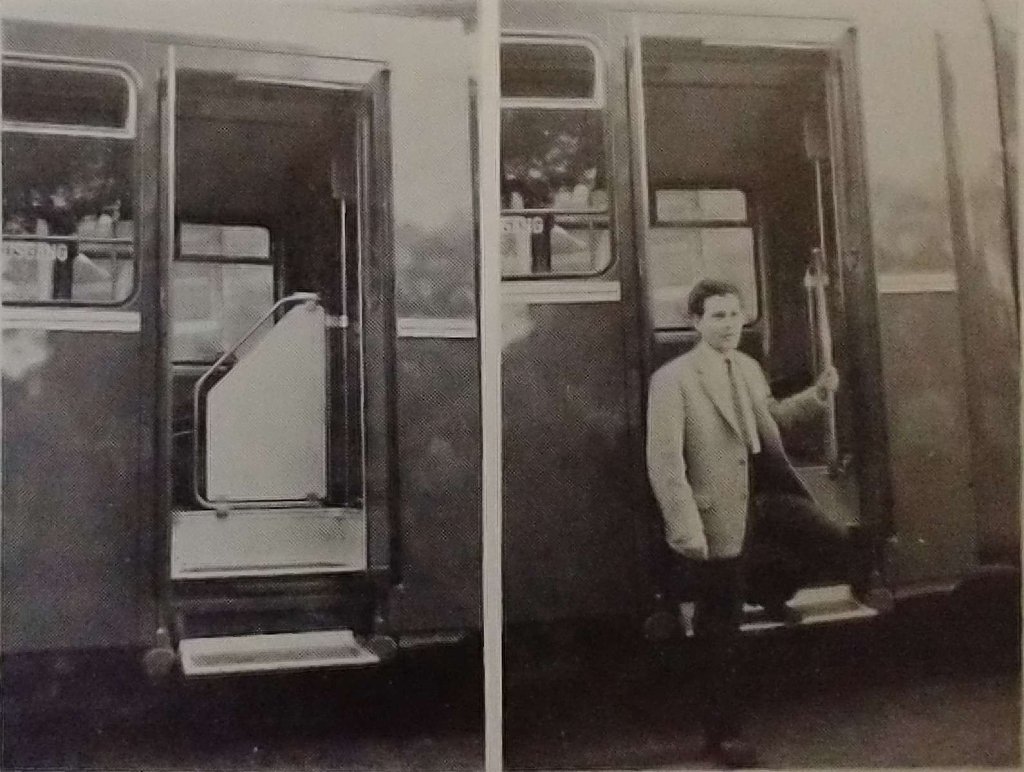

Photograph 1: Snaefell No. 4 “is run on to the three-rail siding at Laxey Station; linesmen tie each bow collector to the trolley wire to take the strain off the mountings, then remove the pins from the spring bases, untie the bow and lower it to the ground.” [1: p20]

Photograph 2: “The car body is disconnected from the trucks (electrically and mechanically) and raised on jacks, and the first 3 ft. 6 in. gauge motor bogie pushed out and towed by another car to the Snaefell depot.” [1: p20]

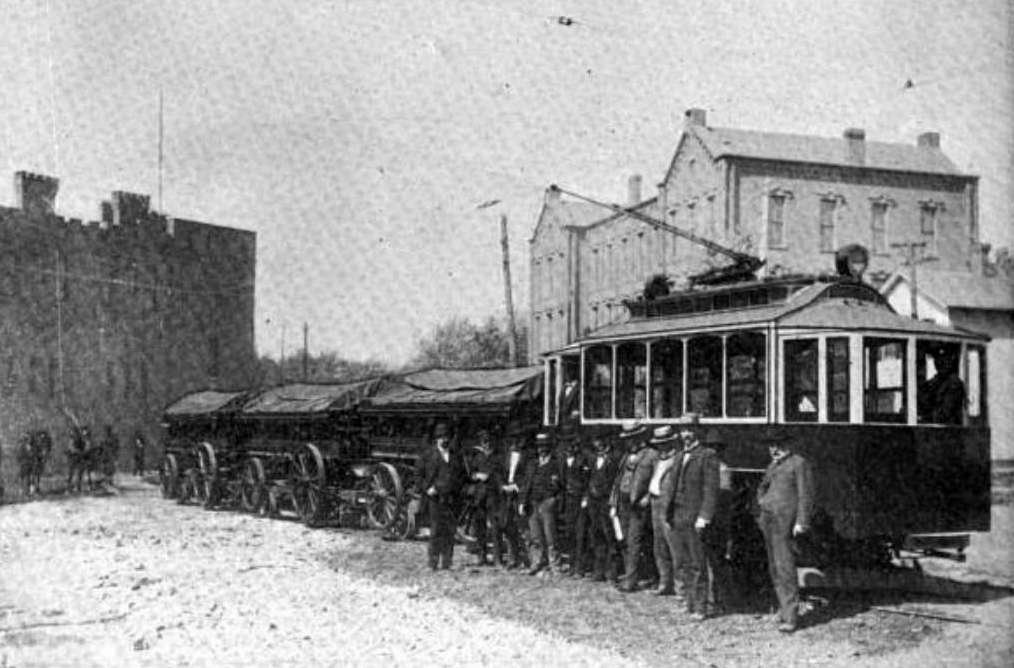

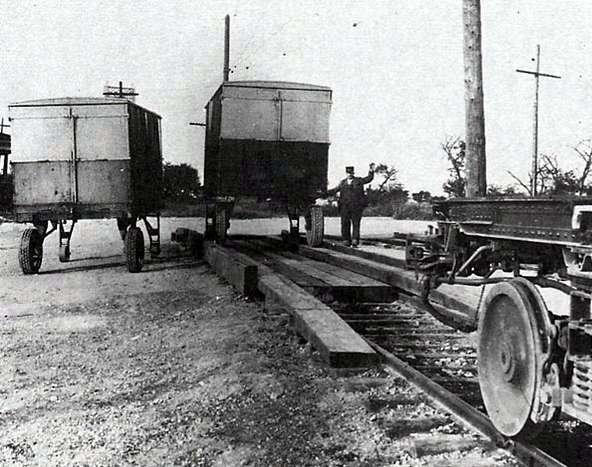

Photograph 3: “A 3 ft. gauge plateframe trailer bogie is brought up by hand from Laxey Car Shed, ready to be placed beneath the mountain end of No. 4.” [1: p20]

Photograph 4: “The trailer bogie is run in under the car, and the body lowered and traversed sideways on to the bogie centre-plate, then secured by a king-pin and side chains.” [1: p20]

Photograph 5: The traversing jacks are re-erected at the other end of the car, the body lifted off the second motor bogie which is then pushed on to the end of the three-rail siding.

Photograph 6: A second plate-frame trailer bogie brought up on to the running line, derailed with crow-bars, and pushed across the tarmac to the three-rail siding.

Photograph 7: The bogie is run in under the Laxey end of No. 4, and the body lowered, tra- versed and secured. The conversion from 3 ft. 6 in. gauge to 3 ft. gauge is now complete.

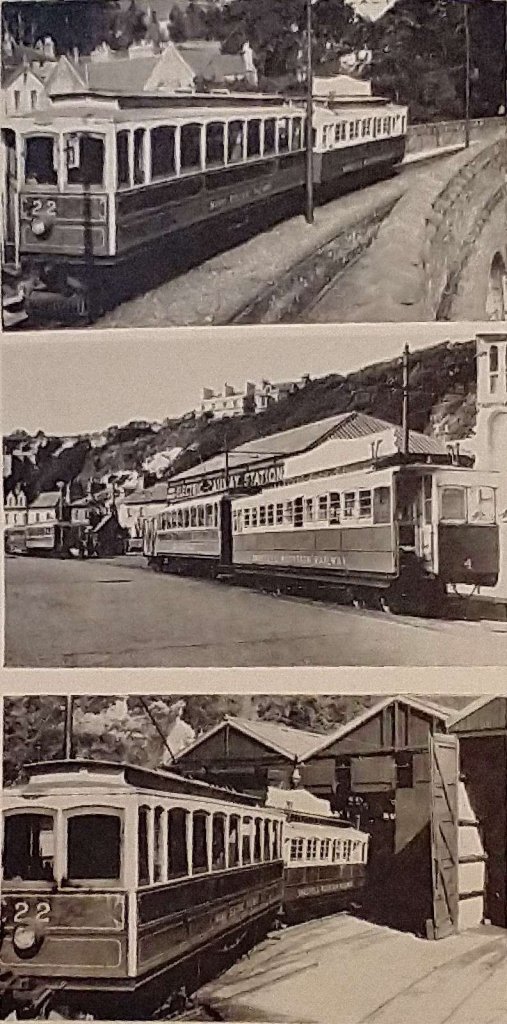

Photograph 8: MER. saloon No. 22 enters the transfer siding by the rarely-used 3 ft. gauge crossover and is coupled by bar and chain to Snaefell No.4, ready for the trip to Douglas.

With this work taking place on a Friday, Snaefell car No. 4 was taken to Laxey car shed and then moved on Monday 16th September to Douglas.

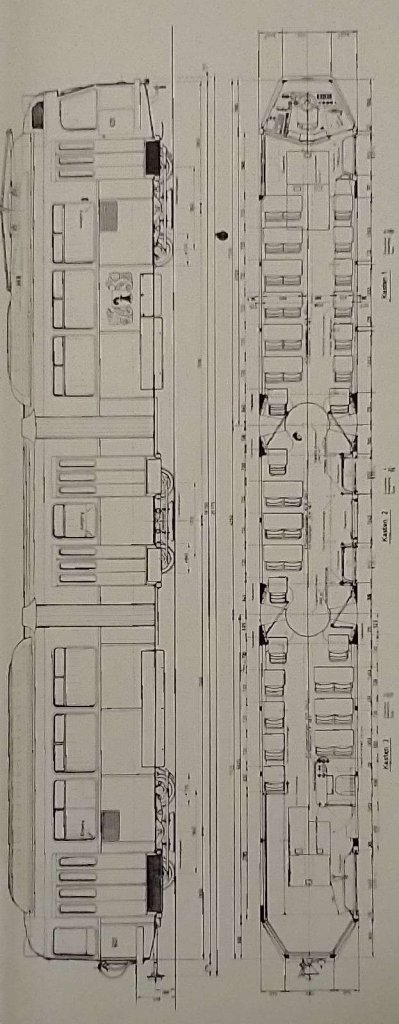

Snaefell Car No. 4 was built in 1895 as the fourth of a batch of 6 cars and arrived at Laxey in the spring of 1895. MER’s website tells us that, “Power for the Car was by Bow Collectors with Mather and Platt electrical equipment, trucks and controllers, and Braking using the Fell Rail system. As new, the cars were delivered without glazed windows and clerestories. Both were fitted in Spring 1896 (following complaints of wind, as the original canvas roller blinds did not offer much protection).” [2]

“Car No.4 was one of two Snaefell Cars (Car No.2 the other) to carry the Nationalised Green livery, applied from 1958. No.4 became the last car/trailer in the MER/SMR fleets to carry the scheme, it being moved to Derby Castle Car Sheds for repaint and overhaul during September 1963.” [2]

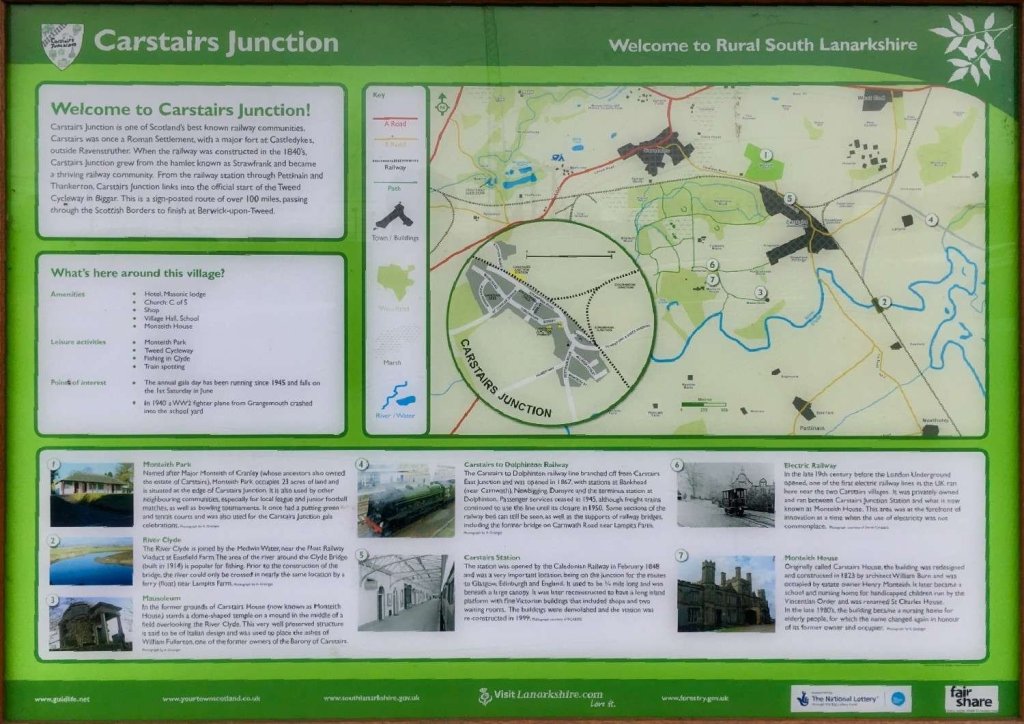

Car No. 4’s last trip on the MER for overhaul was during Winter 1993, moving back by Spring 1995. After this all maintenance on Car No. 4 was undertaken at Laxey. Laxey was significantly remodelled in 2014. The dual-gauge siding is no longer used and in the remodelling a token 3-raol length was included for effect.

References

- J.H. Price; The Secret of Laxey Siding; in the Modern Tramway and Light Railway Review, Volume 27, No. 313; Light Railway Transport League and Ian Allan, Hampton Court Surrey, January 1964, p19-23.

- https://manxelectricrailway.co.uk/snaefell/stocklist/motors/snaefell-no-4, accessed on 30th August 2023.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/31454, a ceased on 30th August 2023.