A first article about the Cornwall Minerals Railway can be found here:

https://rogerfarnworth.com/2020/05/17/the-cornwall-minerals-railway-part-1. [32]

In this second article we look at Par and its harbour, include some information about Treffry’s Tramway which transported goods to and from the Port and take note of St. Blazey Loco Shed. …

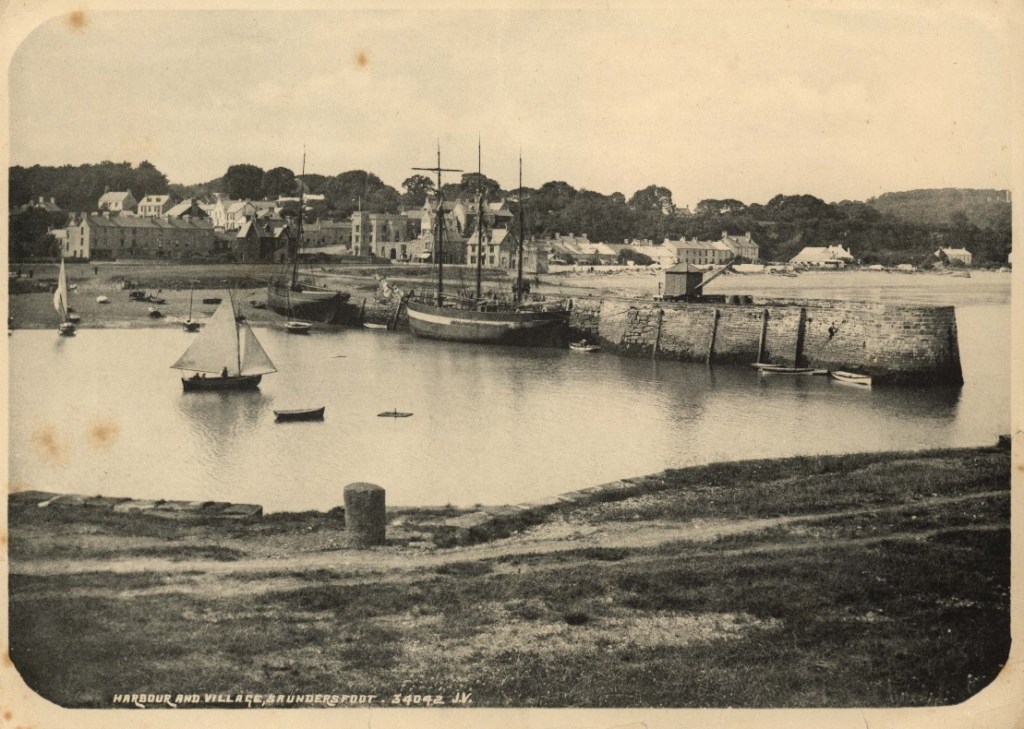

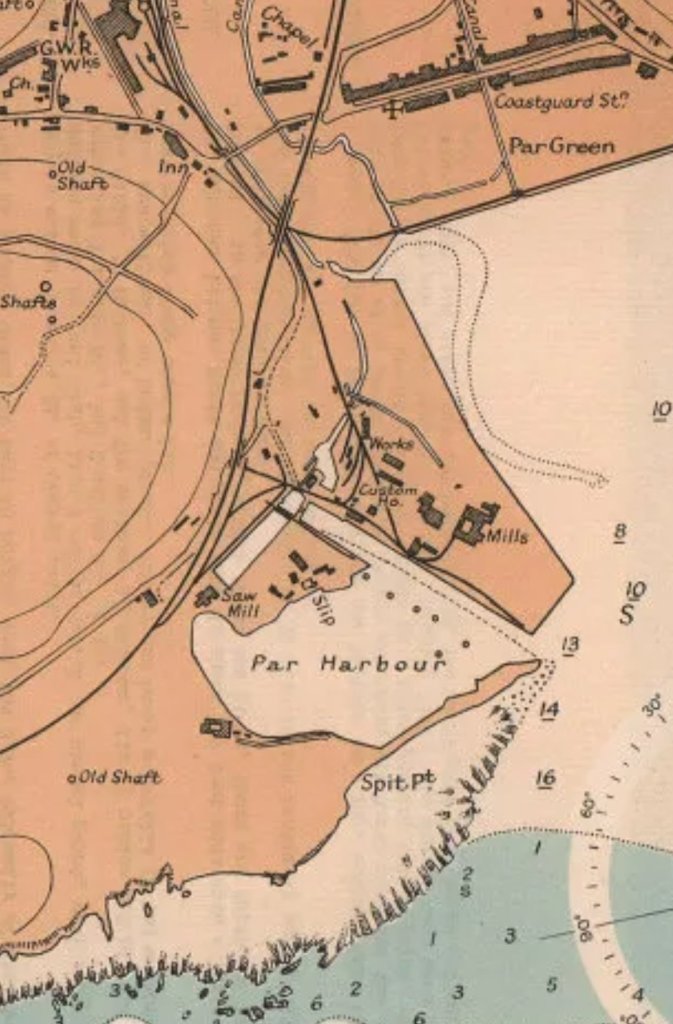

“Par Harbour was built in 1829 by a local entrepreneur Joseph Thomas Treffry who was known as the “King of Mid Cornwall”. [1: p13]

“The first ships used the port at Par in 1833 and it was finished in 1840. The breakwater enclosed 36 acres (15 hectares) of harbour and was capable of taking up to about 50 vessels of 200 tons each. The port is tidal so the vessels would sit on the bottom at low tide. Cornish granite was exported from Par in the early days for such famous landmarks as Waterloo Bridge in London, Chatham Docks, Gibraltar Docks & Glasgow Docks.” [33] As the china clay industry grew during the 19th century this became the main export through the port.

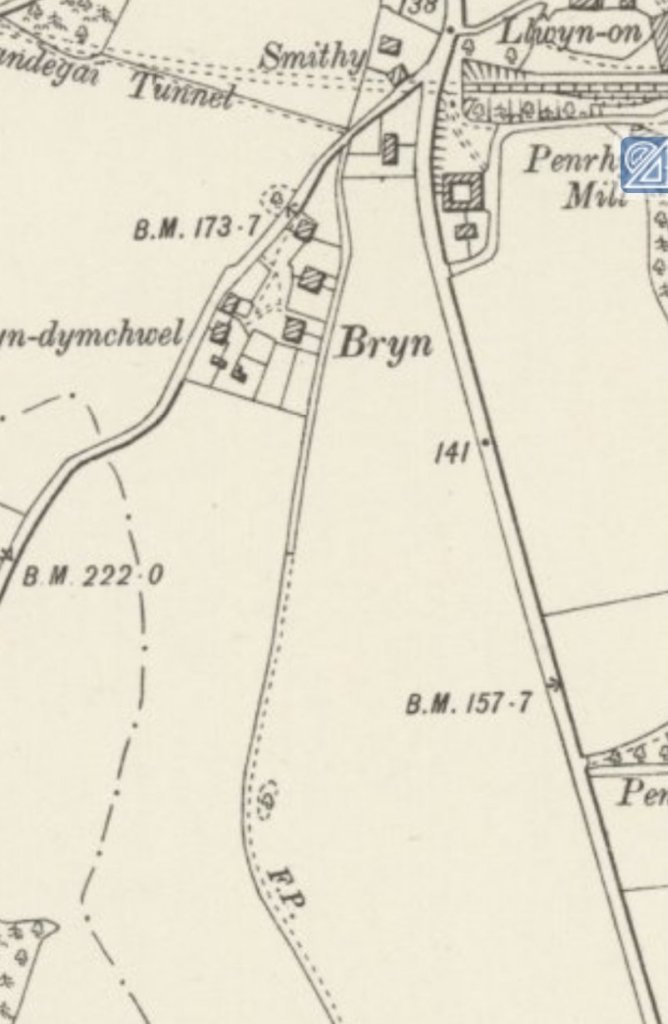

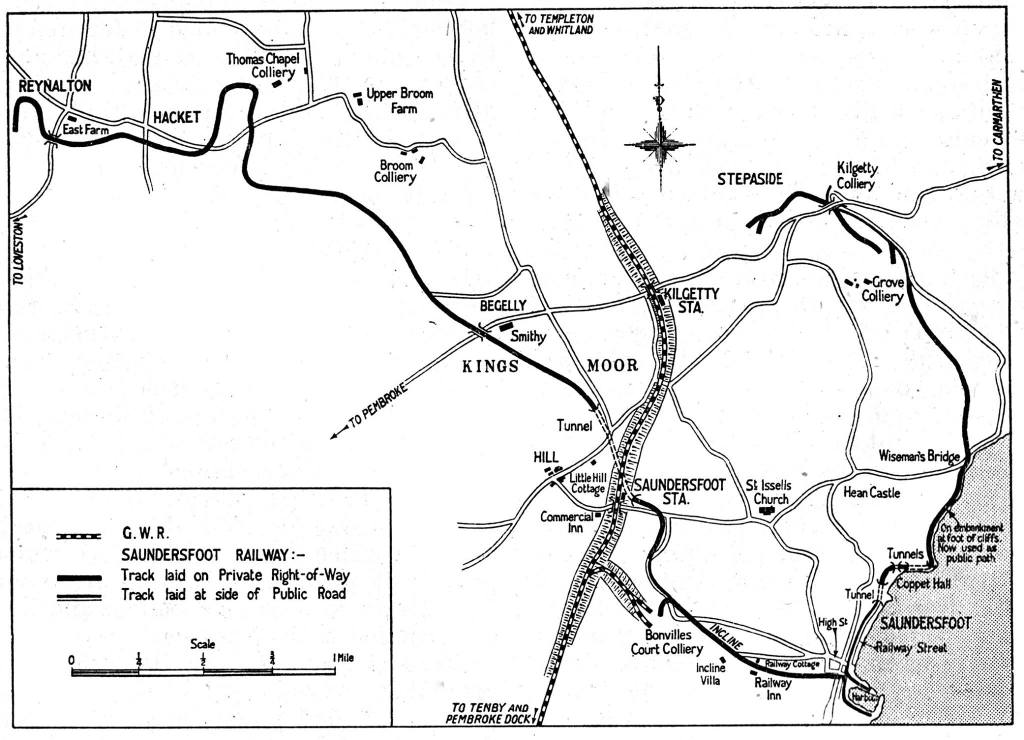

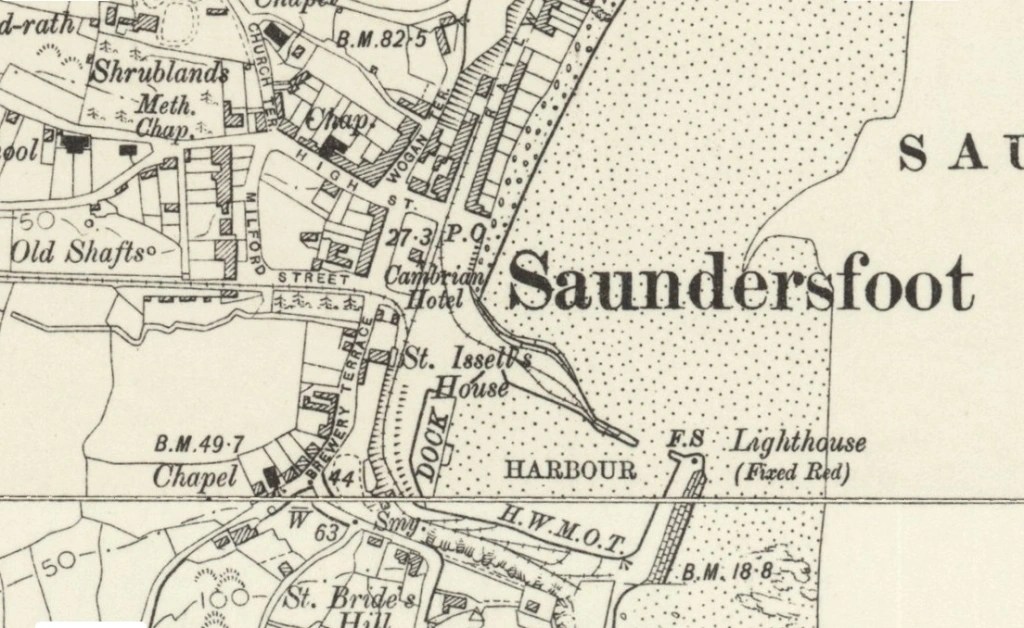

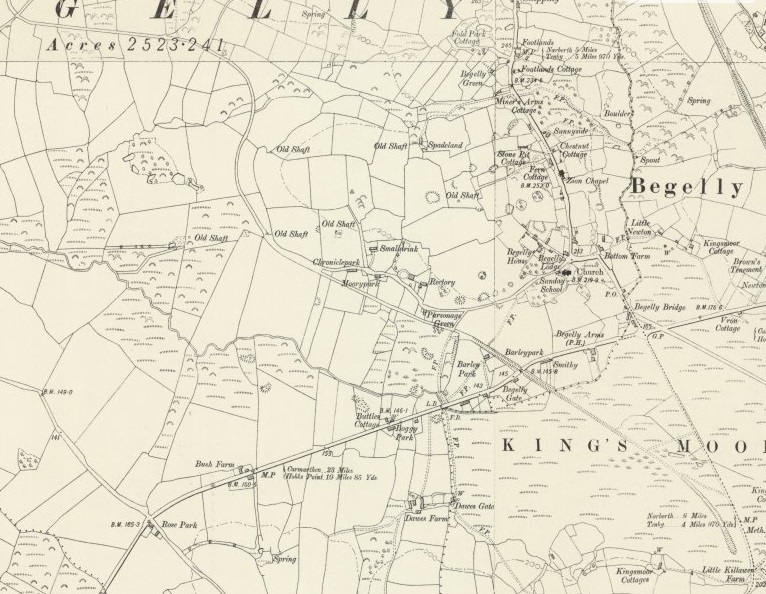

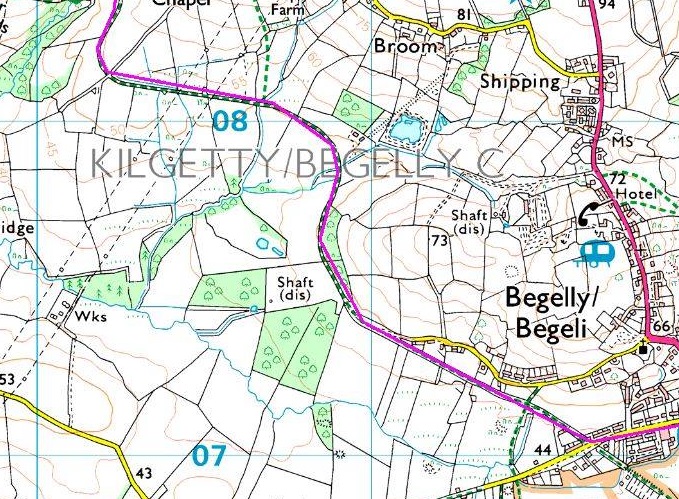

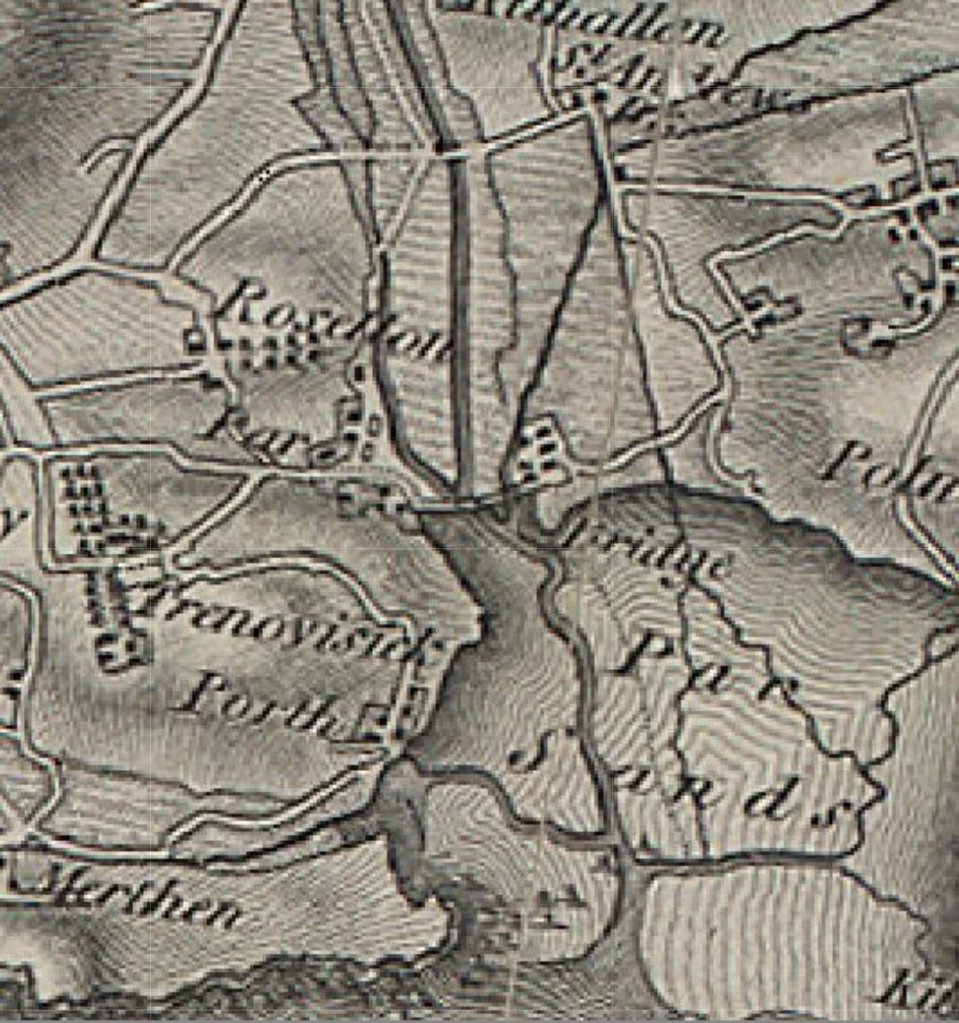

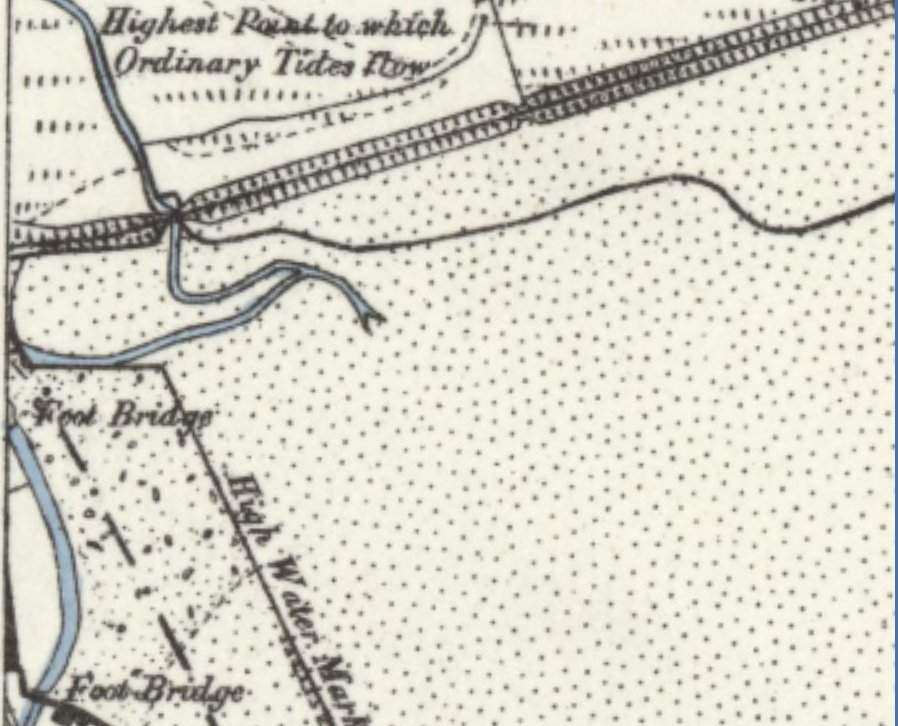

The first map below comes from the Ordnance Survey 1st series of the very early 19th century.

Coal needed to be imported from Wales to power Treffry’s mines, and copper, lead, and granite needed to be exported all over the country. Treffry, as a leading industrialist of the time, “had an urgent need for a harbour to serve his mines and quarries and the narrow streets of Fowey hampered the process when cargos could only be transported from the mines by mules and wagons. After he had completed his safe haven, up to fifty small sailing vessels of the time could be accommodated in the harbour, while larger ships lay at anchor in St Austell bay where their cargoes were loaded from barges. Other industries and businesses developed inside the port area such as ship repair, rope works, sail making, timber and coal merchants and brickworks.” [1: p13]

Hugh Howes notes that the new harbour “was a vital outlet for minerals particularly the expanding china clay industry and a rival to Fowey, Pentwan and Charlestown. [Teffry’s] Fowey Consols Mine was reaching its peak production in the late 1830s at 15,000 tons. The output at Par Consols Mine peaked a little later at nearly 8,500 tons. They were producing profitable amounts of copper at that time. … He had brought industrial success firstly with the copper mines in Tywardreath and St. Blazey, then with the granite workings at Luxulyan, and finally with china clay extraction to serve the fast developing ceramics industry in the Potteries.” [27: p48-49]

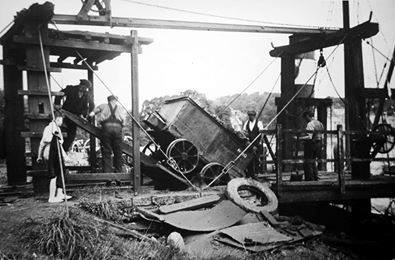

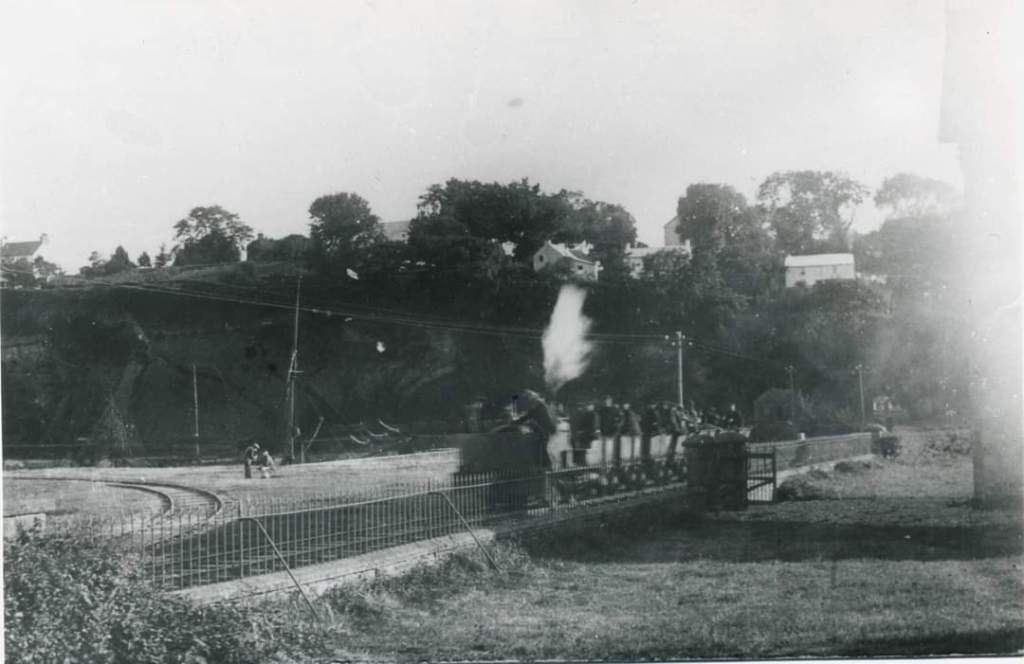

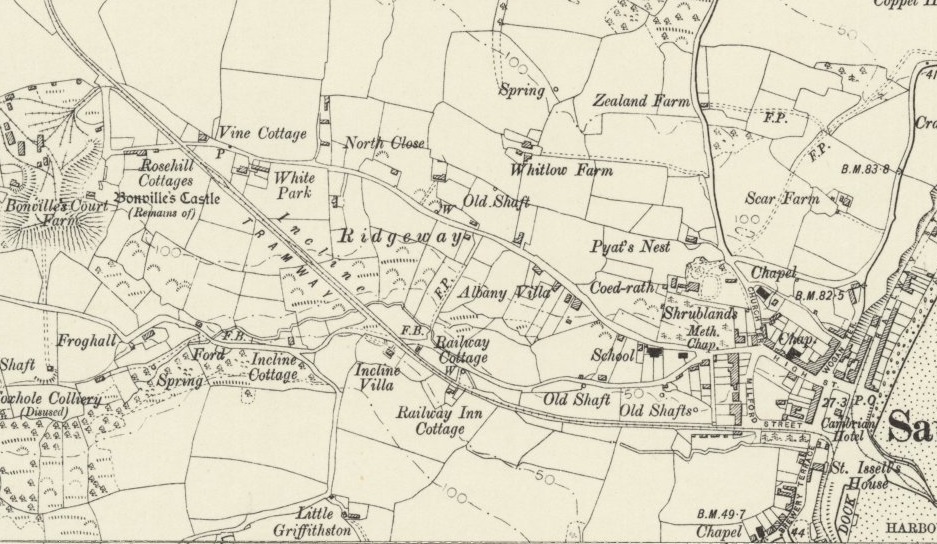

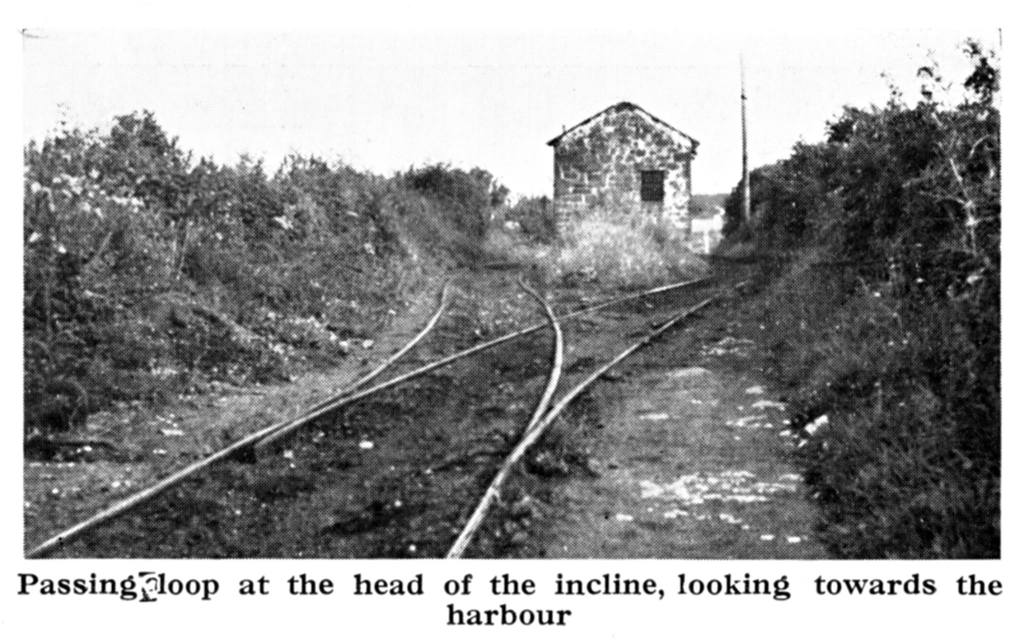

The Par Canal was built by Treffry to transport his minerals from Pontsmill to Par Harbour and was operational from 1833 [8][33], 1842 [1: p21] or 1844 [10], depending on which source you rely on. A number of tramway inclines were associated with it. One from Fowey Consols Mine to a location to the South of Pontsmill was in use by 1835. A second, was built a little to the South of the first, both seem to have served Fowey Consols Mine. A third tramway inclined plane was built between Par Consols Mine and Par Harbour. That inclined plane was working by 1841. [8] The Canal was closed in 1873. [10]

The Treffry Tramway was built in stages. The first length headed North from Pontsmill to Colcerrow Quarry and included an incline to lift the line out of Pontsmill. This line was extended to Molinnis near Bugle. To get there a large viaduct was needed, to cross the valley of the River Par (the Luxulyan Valley). The Teffry Viaduct, was 648 feet in length with ten arches, and was 98 feet high. It was the first large granite viaduct in Cornwall. This section of Treffry’s tramway opened in early 1844. [8]

Construction of the Tramway continued from it’s planned Northern terminus at Newquay. There were delays as a result of Treffry’s death in 1850 but his work was eventually continued by his cousin who had the Hedra Incline operational by 1857 at the latest, possibly as much as five years earlier. [7]

The Fowey Consols Mine was geologically exhausted by 1865. It closed, as did the connecting tramway inclines. Copper extraction in the area was in steep decline, tin ore extraction proved commercially unsuccessful, but granite quarrying “enjoyed an upsurge, and new quarries opened on a small scale at Rock Mill Quarry and Orchard Quarry, above Pontsmill on the south-west side of the river. In 1870 a branch of the tramway was extended from near Pontsmill to serve the two quarries. The line was on the north-east side of the river, and it had two branches for the quarries; each of them crossed the river, and the Orchard Quarry line had an incline to reach the site. The tramway on the incline may have been narrow gauge and was probably gravity operated.” [7][12][14]

Joseph Treffry’s decision in 1844 to use horse-power meant that by the 1870s his tramways were becoming inefficient. Modernisation was essential but the Teffry Estate’s finances precluded that work being undertaken solely by the estate. [7]

In 1872 William Richardson Roebuck leased the tramways. He formed a limited company, the Cornwall Minerals Railway Limited and obtained “parliamentary authority on 21st July 1873 to acquire the lines, form a new railway to connect them, and to make an extension to Fowey, and to improve the original tramway sections so as to make them suitable for operation by steam locomotive.” [7][11][6][15]

“The Cornwall Minerals Railway (CMR) took over Treffry’s lines and improved them. They quickly built the link between Hendra and Molinnis, and their new line to Fowey, and Treffry’s vision of a through line from Newquay to Fowey was realised when on 1 June 1874 the CMR opened the line throughout.” [7] The line required a “new route up the Luxulyan Valley so as to avoid the rope-worked Carmears Incline.” [7]

“The new line in the Luxulyan Valley by-passed the Treffry Viaduct, but Colcerrow Quarry continued to be rail served. Traffic from the quarry reversed at the junction with the old main line at the Par end of the viaduct, and then crossed it, joining the new line at Luxulyan. This operation was horse worked, and the track was still the original Treffry stone-block type in 1933.” [7][17] By 1959 the Colcerrow route at Luxulyan had been shortened to a stub siding. [7][16: p21]

Passenger operation commenced in 1876. The GWR leased the lines from the CMR in 1877, and purchased them in 1896. “The East Wheal Rose branch remained a mineral section until the Great Western Railway (GWR) … built its line from Newquay to Perranporth and Chacewater, partly taking over the line of route.” [7]

The Treffry Tramways and the Par Canal warrant separate articles in this series which will be written in due course. …..

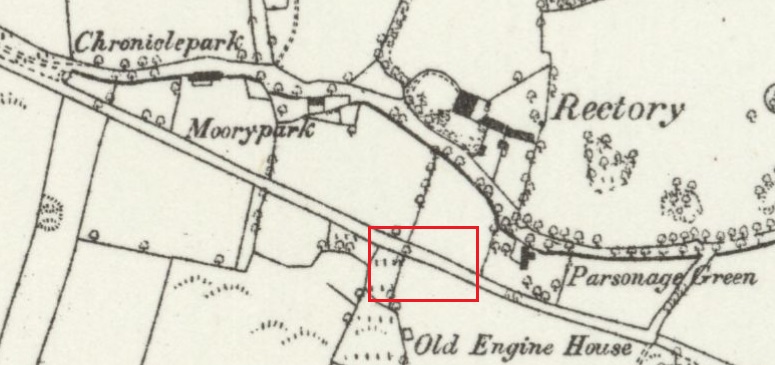

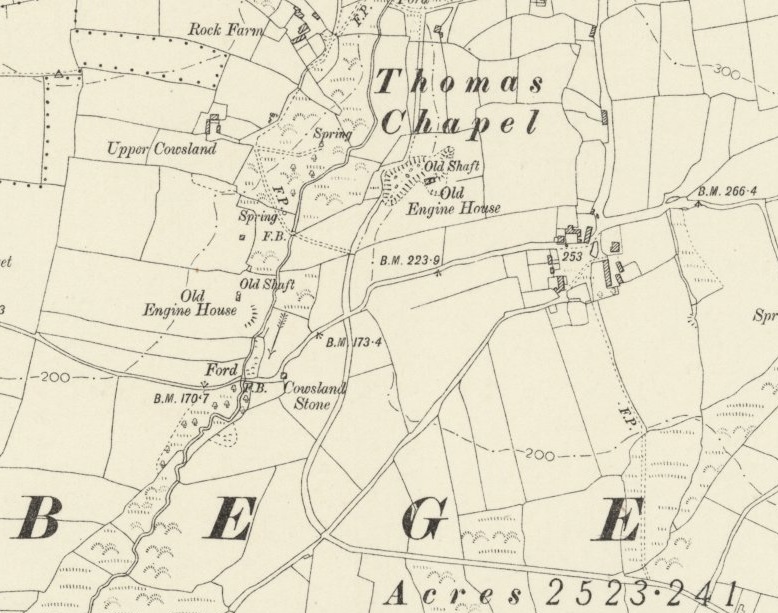

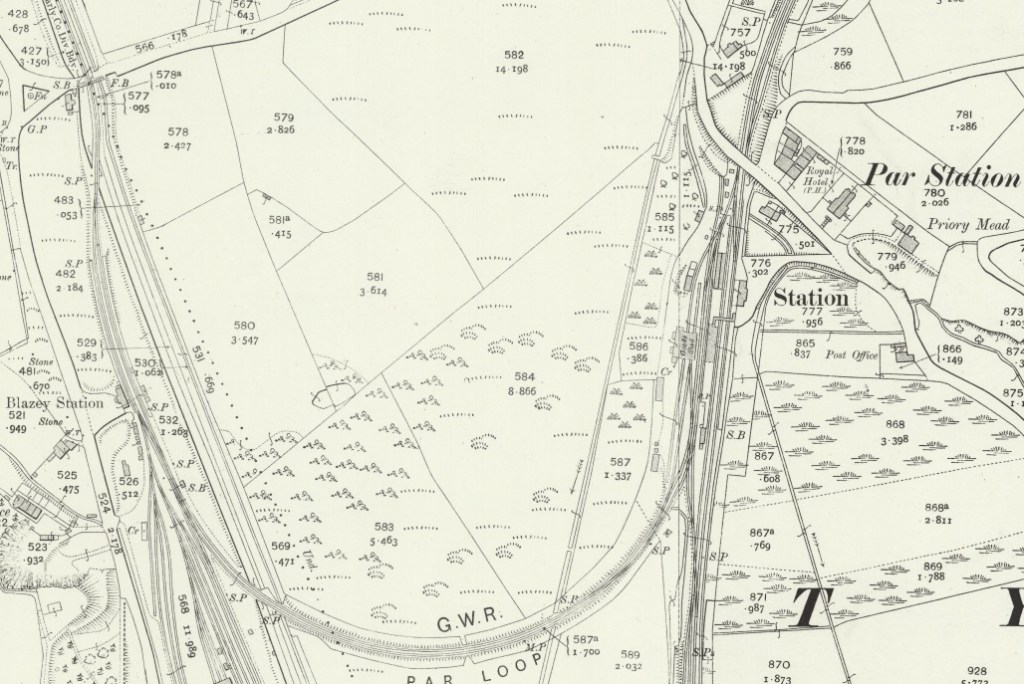

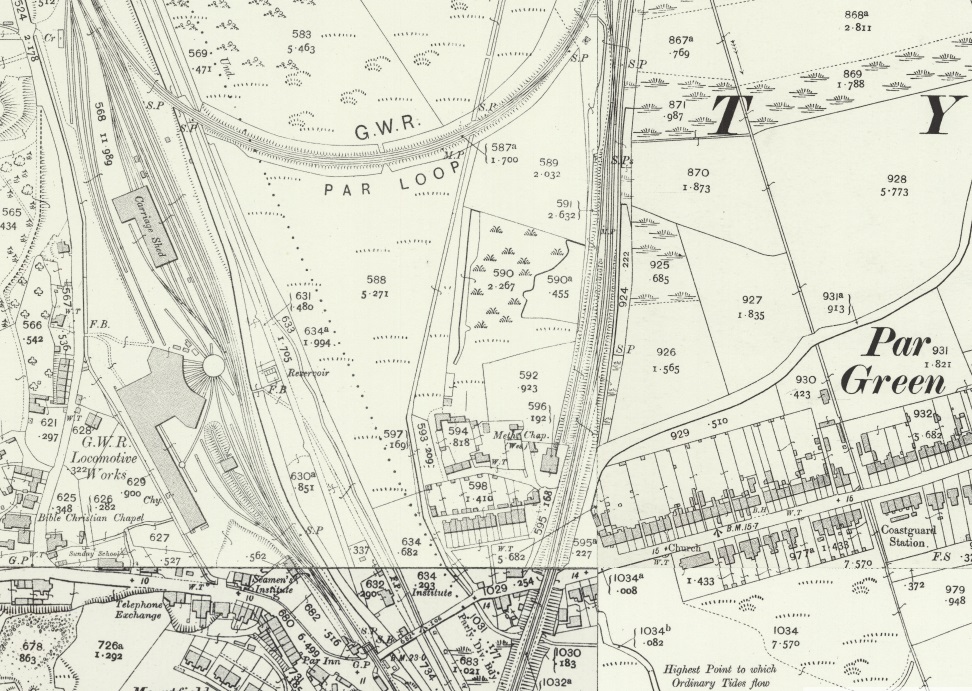

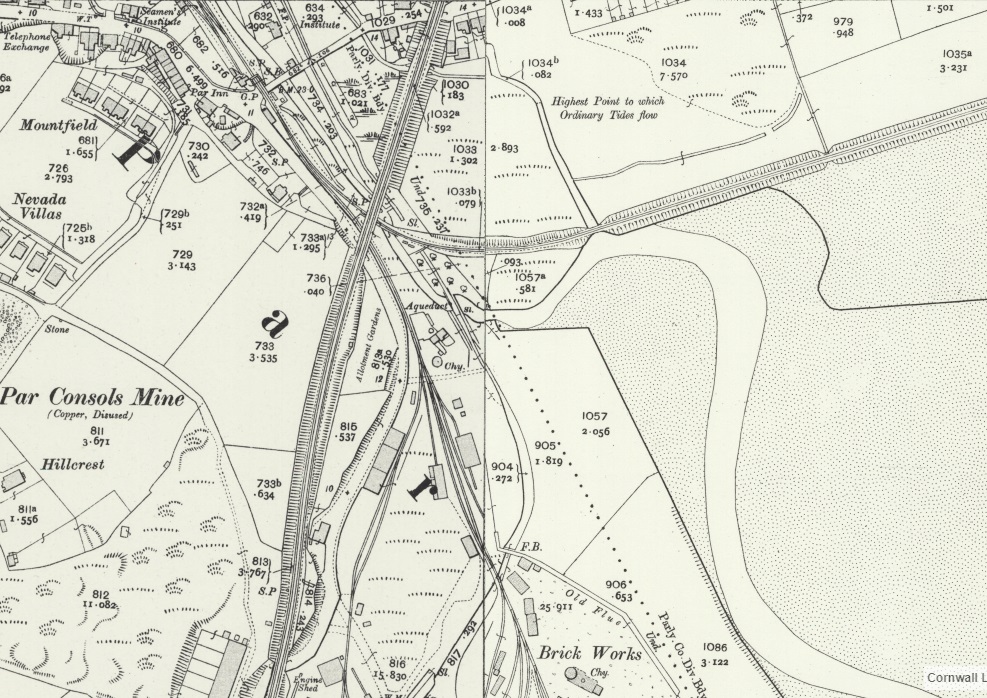

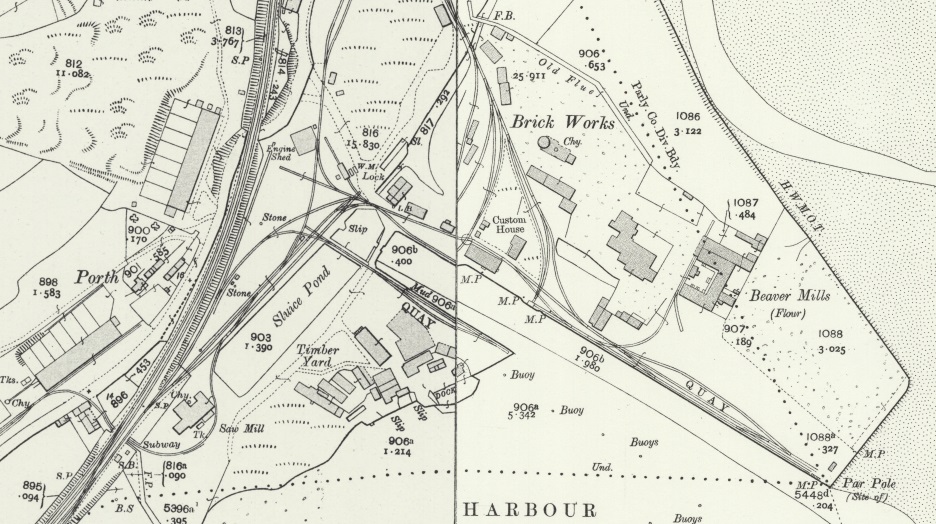

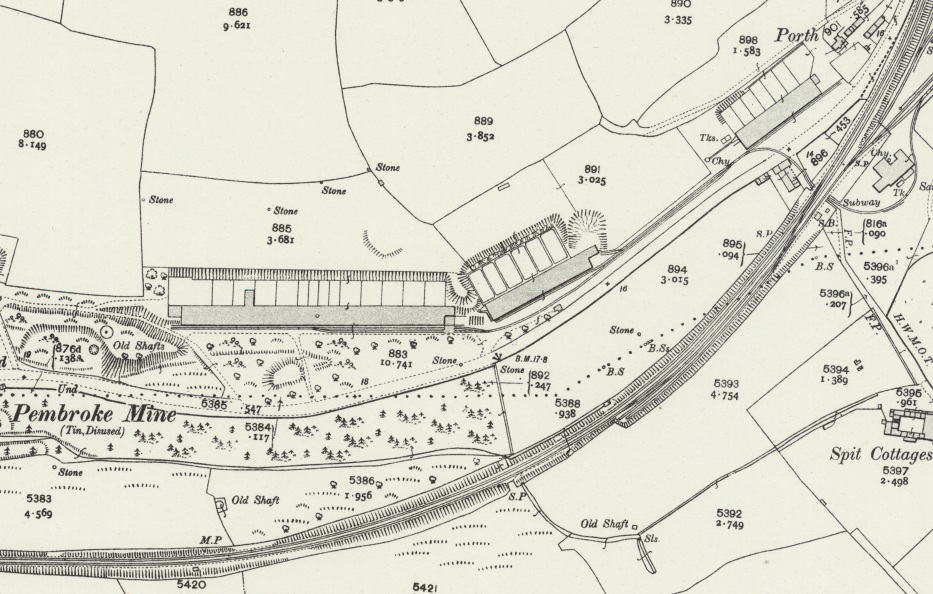

These next set of extracts from the Ordnance Survey belong together but cross the boundary between two OS Map sheets and come from the 1881 survey which was published in 1888. Treffry’s harbour is shown, as is the canal he built. The rail track shown running alongside the canal follows the route of the Treffry Tramway.

As well as the Treffry Tramway and the, already closed, Par Canal, there is a railway shown running roughly North to South on the first two map extracts. This was the Cornwall Railway, the railway company which built the majestic Royal Albert Bridge over the River Tamar. Because of the difficult terrain it traversed, it had a large number of viaducts, built as timber trestles because of the shortage of money. It was a 7 ft 1⁄4 in (2,140 mm) broad gauge railway from Plymouth in Devon to Falmouth in Cornwall, built in the second half of the nineteenth century. It was constantly beset with shortage of capital for the construction, and was eventually forced to sell its line to the Great Western Railway (GWR) in 1889, a little after the date of the 1881 Survey. [9]

Stephen Austin, in a May 2003 article in Steam Days, describes the workshops and depot this:

“At Par, the Cornwall Minerals Railway set up a new headquarters and engineering depot on a piece of flat ground between the river and the original valley side where once ships moored in front of the Sloop Inn.

It was fortunate that the Cornwall Railway line, at the south end of this site, was elevated on a viaduct, for its five arches now spanned the canal, the Cornwall Mineral Railways main line to Fowey, a branch into Par Harbour, the river, and a public road. At the north end the new line swung across the river on a sharp reverse curve to join the 1855 causeway. On this length from Par Bridge to Middleway Bridge the original railway between the river and canal was abandoned, and is today a public footpath where some of the sleeper blocks may still be seen.

The railway depot, finished by the end of 1873, had two main buildings. One was a wagon repair shed and the other contained a Signal & Telegraph repair shop, smithy, boiler room, water tank, a two-storey office suite, machine shop, and locomotive repair shop. Adjoining the latter was a locomotive running shed constructed in what was then a frequently-used layout – a segment of a circle-covering tracks which radiated from a turntable in the centre of the circle. This shed, which became known locally as ‘the roundhouse’, contained nine tracks, each with its own gable-ended roof, of which the middle three extended through the back wall into the repair shop.

The buildings at the depot were handsome, elegantly-proportioned brick structures. The whole workshop group cost £16,000 and was a huge development for the time and place of its construction, exceeding the Cornwall Railway Works at nearby Lostwithiel. … The reason for the nine roads in the running shed was that it was to accommodate the whole of the company’s locomotive fleet. They ordered eighteen 0-6-0Ts from Sharp Stewart & Company of Manchester. The design was attributed to Francis Trevithick, formerly of the L&NWR and a descendant of the great Richard Trevithick, and was conventional except that the cab had no back. The intention was to run the locomotives in pairs, coupled back to back, with one crew. This was because Robert Fairlie had recently created a sensation with his double-ended locomotive mounted on two power bogies, able to do the work of two smaller engines without the expense of two engine crews; the Cornwall Mineral Railways’ idea was to obtain this last benefit without having to pay royalties to Robert Fairlie.

The prospect of a driver having to leap from one footplate to another whenever a control needed adjusting is an alarming one, but in practice it was seldom, if ever, put to the test. Far from needing two locomotives to a train, one was ample, and half of the new fleet of locomotives was never used at all. The staple traffic on which the hopes of the firm were raised iron-ore from the Perran Iron Lode never appeared. All that was offered was stone, and the then-modest output of china-clay, and within a year it was clear that the railway was a financial failure.” [31: p279-280]

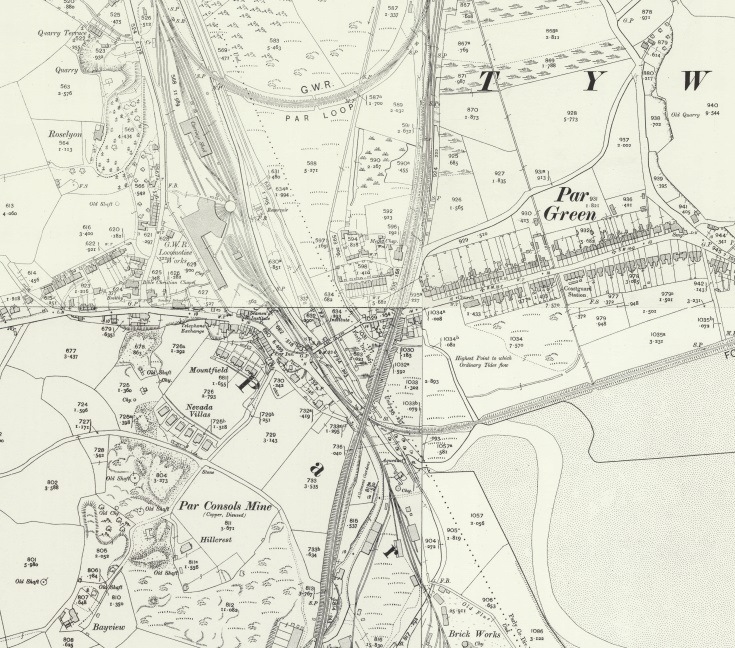

The next images show the area as recorded for the 25″ Ordnance Survey in 1905/1906 and published in 1907.

The next few images show a number of the areas in greater detail. All these extracts come from the 25″ OS mapping published in 1907.

Par Docks saw significant developments in the late 1940s. The image below is an aerial image of Par taken in 1950 for English China Clay.

Railway Bylines has at least two articles about Par Harbour. The first, a 10 page article about the history of the Harbour, appeared in Railway Bylines Volume 2 No. 5 of August/September 1997. The second, an article entitled ‘Cornish Cream’ with text and photography by Tom Heavyside, was included in Railway Bylines Volume 9 No. 12 of November 2004. [28] It focussed on the diminutive locomotives which served the port’s railways. … Alfred and Judy were still at Par in 1977 when Tom Heavyside visited. Judy was no longer in working order. Alfred was ‘in steam’ on Wednesday 15th June. Alfred was stood-down in August 1977 with its duties being undertaken by a tractor with the occasional use of a BR ’08’ shunter from St. Blazey depot as and when required. Both Alfred and Judy were subsequently removed from the site and saved for posterity.

Tom Heavyside comments: “Fortunately, Alfred and Judy we both saved for posterity. Initially, Alfred went to the Cornish Steam Locomotive Society depot at Bugle and Judy to the Wheal Martyn China Clay Museum near St.Austell. However, in 1987 Alfred moved to the Bodmin & Wenford Railway and in the autumn of 2002 Judy also moved to the Bodmin & Wenford. Fittingly, Alfred became something of a celebrity, not only at Bodmin but elsewhere; I well remember e it making a guest appearance at the Exeter Rail Fair in April/May 1994 when it mingled with a number of much larger steam locomotives including a couple of Bulleid Pacifics and a GWR King.” [28: p590]

Wikipedia tells us that: “Alfred and Judy are two 0-4-0 saddle tank steam locomotives. They were built by W. G. Bagnall for use at Par Docks in Cornwall, United Kingdom. The unusually low design was required to cope with extremely tight curves and a very low bridge under the Cornish Main Line. The locomotives are both preserved in operational condition on the nearby Bodmin and Wenford Railway and inspired the Reverend Wilbert Awdry to include them in The Railway Series of children’s books as Bill and Ben.” [29]

The bridge under the Cornish Mainline served the china clay works. It had a maximum headroom of 8ft. Operating curves in the Port were as tight as 70ft radius. The locomotives used in the Port needed to meet these stringent restrictions. A series of different locomotives were used over the years. One of those locomotives was ‘Toby’, a low-profile Sentinel, which served the Port throughout much of the first half of the 20th century. By September 1937, demands on the older locomotives were such that a new locomotive was required to work alongside Toby.

W. G. Bagnall & Co. built a suitable locomotive which was delivered to Par in 1937. That locomotive was to be given the name ‘Judy’ in 1955. The locomotive was delivered at a cost of £1200 carrying the works number 2572. “By 1952, ‘Toby’ required replacement and an upturn in traffic meant an order was placed for another locomotive. In 1954, Alfred was delivered (named after the manager of the harbour Alfred Truscott). Whilst nominally the same, Alfred had some differences to Judy with different bunker style, tank and handrail alterations (such as a tank filler that opened in the opposite direction) and a different purchase price – this time £7500.” [30]

The Imerys Blueprint for Cornwall, published in 2003, provided information about the history of china clay production in Cornwall. It included information about the amount of china clay that was shipped out of Par Docks between 1858 and 2002:

1858 – 15,154 tons of china clay

1885 – 86,325 tons of china clay

1987 – 700,000 tons of china clay

2002 – 313,425 tons of china clay, 134,810 tons of aggregates.

Incidentally, the blueprint also noted: the sale of the harbour by the Teffry Estates to English China Clay (ECC) in 1964; the construction of dryers at the site in the 1950s and 1960s; and the closure of the port in 2007.

After closure the port was used as a Milling Centre and a Grade Dryer with all bins clay shipment being handled by Fowey Docks.

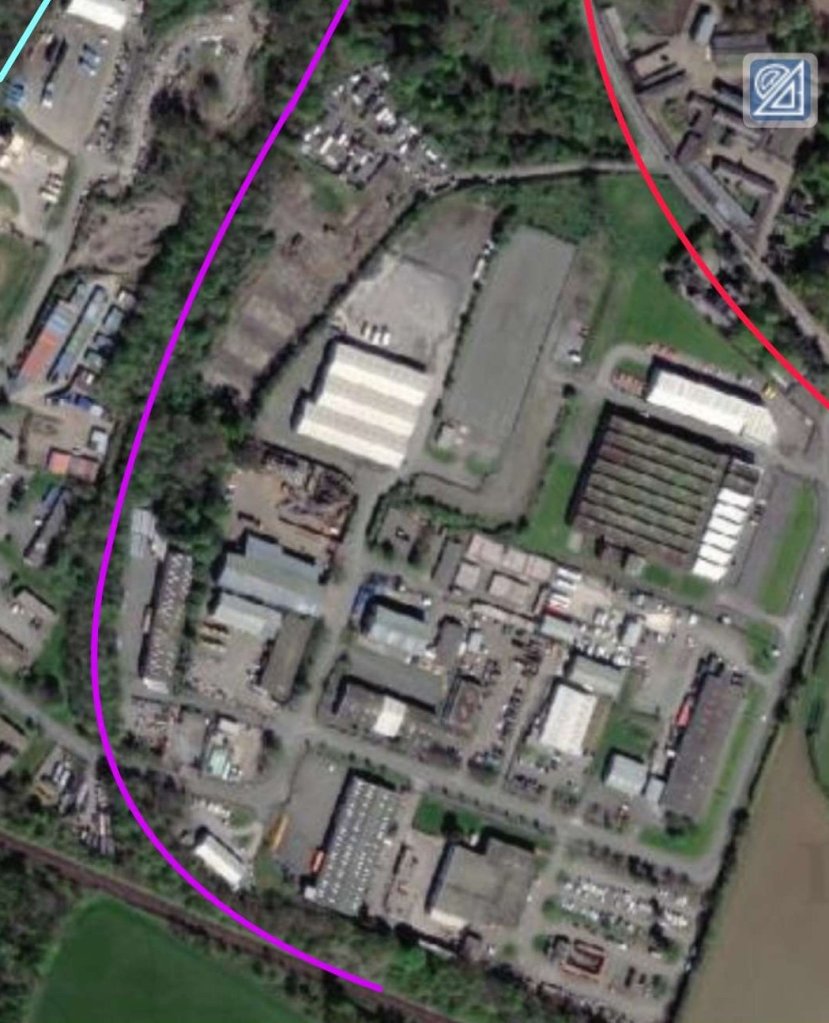

Stephen Austin notes the use of the locomotive shed over the years from the 1980s to the new millennium as follows:

“St Blazey depot, much diminished as it was, was still very much alive. It maintained a dedicated fleet of china-clay wagons introduced in 1954, and from 1970 a fixed cover for these wagons was designed and fitted in the Wagon Works, producing the distinctive ‘Clay Hood’. The staff was proud of their self-sufficiency, and when the Clay Hoods were replaced by the Type CDA hopper wagons in 1987 the fitters, on their own initiative, rebuilt the example which now stands as gate-guardian at the Wagon Works. Other freight business disappeared, and the Newquay line was reduced to a long siding on which a railcar shuttled desultorily, but following the break-up of British Rail in 1993 there was renewed optimism.

The depot was taken over by a company named English, Welsh & Scottish Railway Company … and St Blazey was that company’s only depot in Cornwall. It stabled and serviced the TPO coaches of the mail services which were tripped empty from and to Plymouth and Penzance every day, and wagons carrying cement to Blue Circle at Moorswater and products from Fitzgerald Lighting Ltd at Bodmin were staged through the yard. In 1995 some of the locomotives allocated in Cornwall were given names of local association. Among them was No. 37674 St Blaise Church 1445-1995, named after the nearby parish church and unveiled in the yard. In 1998 St Blazey began operating the new locomotives imported by EWSR (Class 66) on the china-clay trains.

On 11th August 1999, in its 125th anniversary year, St Blazey hosted perhaps the biggest assembly of preserved coaches ever gathered on the national network, and excursions brought people down to view the total eclipse of the sun. On 26th February 2000 diesel locomotive No 67008 arrived to begin the depot’s association with the Class 67 diesel then the fastest true self-contained locomotives running anywhere in the world, and worthy successors to those little Sharp Stewart tank engines. …… The new millennium brought more uncertainty to St Blazey’s future. The last train conveying Fitzgerald Lighting’s wagons, the last consignment of any West Country manufacturer’s goods to be sent out by railway, left the yard on 25th July 2001. The remaining customers, the cement, china-clay, and the mails, made it clear that if the railway did not satisfy them on price and speed they would take to the roads. The only hope [lay] in the fact that … after 128 years of service, St Blazey is still very much a going concern.

Notwithstanding the unique nature of St Blazey Works, it received no attention at all from the enthusiasts in the fields of railways, architecture, or history, nor from the ‘official’ bodies paid to safeguard these things. The roundhouse building was divided up and rented by local traders, and the yard was a dump for rubbish and wrecked cars. However, even the tracks into the building remained intact, and apart from the demolition of the coaling stage nothing else was done until the summer of 2001 when the ownership changed hands, and plans were announced for new building on the site. Thus the original character of the Works, and the practicality of returning it to railway use, will finally be extinguished.” [31: p284, 286]

The news in 2024/2025 is that the anticipated removal of the St. Blazey roundhouse did not occur. St. Blazey Engine Shed has recently been restored as the base for MPower Kernow CIC (MPower), a new Cornish social enterprise company. [34]

In April 2023, World of Railways reported that “the ongoing restoration of the turntable and the creation of a servicing facility for steam locomotives is expected to provide many and varied training opportunities for a broad cross section of the community and MPower is already working with local education and training organisations to provide hands-on experience in a range of skills, from woodwork to plumbing, electrics, construction and engineering.” [34]

Future articles?

It is, finally, worth noting that the Cornwall Minerals Railway had a total of 46 miles of track with “a main line from Fowey to Newquay … and branches from Bugle to Carbis, St Dennis Junction to Melangoose Mill and Newquay to East Wheal Rose. These connected clay works, quarries, mines and harbours (Newquay, Par and Fowey) in the area with the headquarters and works being sited at St Blazey (part of which is still in use).” [1: p21]

“Other clay lines were built in later years, Bugle to Carbean Siding in 1893 and Trenance Junction (just West of St Austell on the main line), to Bojes Sidings in 1520 Two narrow gauge lines were also in use at various times. The Gothers Tramway of … from Pochin’s siding near St Dennis Junction to a clay works a Gothers opened in 1884 and closed in 1931.” [1: p22]

These lines will hopefully be covered in future articles.

References

- Pit to Port; The Cornish Steam Locomotive Preservation Society, 2009.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/101438942, accessed on 20th January 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/101438954, accessed on 20th January 2023.

- Admiralty Chart Misc. 645, corrected 15th April 1943; https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/274499586563?mkcid=16&mkevt=1&mkrid=711-127632-2357-0&ssspo=F5J0o5CiRha&sssrc=2349624&ssuid=afQhrar7TGK&var=&widget_ver=artemis&media=COPY; accessed on 20th January 2023.

- http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/maps/series, accessed on 20th January 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=pfbid0Py845Q675ooziPmV7A5PJqJVKMkFTs9xPnmrFARWQPpX7arVtvHGEMqosiKtEtXWl&id=171605006288707, accessed on 20th January 2023.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lux_valley_1835.gif#mw-jump-to-license, accessed on 20th January 2023.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treffry_Tramways, accessed on 20th January 2023.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornwall_Railway, accessed on 21st January 2023.

- https://www.cornwall-calling.co.uk/mines/tramways/par-canal.htm, accessed on 21st January 2023.

- John Vaughan; The Newquay Branch and its Branches; Haynes/Oxford Publishing Company, Sparkford, 1991.

- Martin Bodman; Inclined Planes in the South West; Twelveheads Press, Chacewater, 2012.

- E T MacDermot; History of the Great Western Railway, Vol II; the Great Western Railway, London, 1931.

- Cornwall Archaeological Unit; The Luxulyan Valley Project: an Archaeological and Historical Survey; Cornwall County Council, Truro, 1988.

- E F Carter; An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles; Cassell, London, 1959.

- Maurice Dart; Images of Cornish Railways; Halsgrove House, Wellington, Somerset, 2007.

- D S Barrie and “Precursor”; Railway Relics in West Cornwall; Railway Magazine, December 1933.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Blazey_engine_shed, accessed on 21st January 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=50.35131&lon=-4.70645&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 1st March 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=50.34419&lon=-4.70495&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 1st March 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=50.34387&lon=-4.71396&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 1st March 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=50.34528&lon=-4.70401&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 1st March 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=50.34883&lon=-4.70290&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 1st March 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=50.35257&lon=-4.70492&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 1st March.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=50.35595&lon=-4.70647&layers=168&b=1, accessed on 1st March 2023.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Par_Docks#/media/File:Par_Docks_ECC_Aerial_Photograph.jpg, accessed on 1st March 2023.

- Hugh Howes; The Struggle for the Cornwall Railway – Fated Decisions; Twelveheads Press, Truro, 2012.

- Tom Heavyside; Cornish Cream; in Railway Bylines Volume 9 No. 12, November 2004, p586-590.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bagnall_0-4-0ST_%22Alfred%22_and_%22Judy%22, accessed on 8th March 2024.

- https://rapidotrains.co.uk/port-of-par-bagnall-tanks, accessed on 8th March 2024.

- Stephen Austin; St. Blazey: At the Heart of West Country History; in Steam Days, May 2003, p278-286.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/202y0/05/17/the-cornwall-minerals-railway-part-1.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Par_Docks, accessed on 24th January 2025.

- https://www.world-of-railways.co.uk/news/st-blazeys-restored-turntable-set-for-scotsman-visit, accessed on 24th January 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/15WHnYinBM, accessed on 24th January 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/104676, accessed on 24th January 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3824704, accessed on 24th January 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/14r1jXREEN, accessed on 25th January 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/18VjPfoZGu, accessed on 25th January 2025.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/EPW033131, accessed on 25th January 2025.