I spent 3 weeks in Uganda in February 2026. This short article picks up on local news reports about developments relating to railways in East Africa early in 2026. …. This article follows on from one published early in December 2025 which can be found here. [3]

The featured image above shows one of the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) locomotives and its passenger train on the existing network in Kenya. [13]

Uganda

EOI – Uganda – Consultancy Services for the Development/Preparation of the Railway Transport Master Plan – EAC – Railway Rehabilitation Support Project

On 16th February 2026, the African Development Bank Group reported [1] that, the Government of Uganda had received financing from the African Development Fund (ADF) towards the cost of the EAC-Railway Rehabilitation Support Project (Refurbishment of Kampala-Malaba MGR), and intends to apply part of the agreed amount for this Grant to payments under the contract for Consultancy Services for the Development/Preparation of the Railway Transport Master Plan for the Uganda Railwaiys Corporation.

The overall objective of the assignment is for the Consultant to formulate a comprehensive railway transport master plan for the railway subsector in Uganda, including an international/multimodal transport strategy for Uganda 2026-2040.

Government Pushes to Secure 13 trillion UgX loan for Eastern SGR Line

NilePost reported on 19th February 2026 [2] that Uganda is fast-tracking final financing for the Malaba–Kampala Standard Gauge Railway, with talks underway with the Islamic Development Bank to unlock 13 trillion UgX. The project promises faster, cheaper cargo transport and stronger regional trade links!

High-level discussions with the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) are seen as a critical step toward ‘financial closure’, which would trigger full-scale construction of the 273-kilometre Eastern Route.

The Minister of State for Works and Transport, Musa Ecweru, hosted an IsDB Appraisal Mission led by Dr. Issahaq Umar Iddrisu, Regional Hub Manager.

Discussions focused on integrating the SGR into a broader 3.9 trillion UgX ($800 million) Country Engagement Framework being finalised by IsDB with Uganda for 2025–2027.

‘This railway is transformative for Uganda and the wider region… time is of the essence; we should close financing early and proceed without delay’, Ecweru told the delegation.

The SGR is a strategic effort to replace Uganda’s century-old Metre Gauge Railway (MGR). Between 2015 and 2023, Uganda partnered with China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC), but Chinese lenders withdrew due to concerns over connectivity with Kenya’s SGR.

In October 2024, Uganda signed an Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) contract with Turkish firm Yapı Merkezi, drawing on the company’s experience with Tanzania’s SGR.

Subsequently, Uganda sought diversified financing from European export credit agencies and Islamic finance institutions, including IsDB, to fill the multibillion-euro funding gap.

The railway is designed for electric traction, supporting speeds of up to 120 km/h for passengers and 100 km/h for freight. It will carry up to 25 million tonnes of cargo annually, with 40% of the contract value reserved for Ugandan firms.

Currently, transporting a 40-foot container from Mombasa to Kampala costs about 14.6 million UgX ($3,500) by road. Once operational, the SGR is expected to reduce this to 6.3 million UgX ($1,500) while cutting transit times from several days to under 24 hours. Each train will be able to carry 216 containers—the equivalent of 200 trucks—significantly lowering road maintenance costs and carbon emissions.

Over 60 percent of the railway’s right-of-way has been acquired, with nearly 150 kilometres of land secured across Tororo, Butaleja, Namutumba, Luuka, Iganga, Mayuge, Jinja, and Buikwe districts.

Current efforts focus on the densely populated corridors of Mukono, Wakiso, and Kampala. The government has already invested more than 328 billion UgX in compensation and early works to mitigate risks associated with the project for international lenders.

The Malaba–Kampala line is a cornerstone of the Northern Corridor Integration Projects, linking Uganda to Kenya’s SGR and connecting the Great Lakes region—including Rwanda, South Sudan, and the DRC—to the Indian Ocean.

Bilateral talks with Kenya aim to ensure interoperability between Uganda’s European-standard line and Kenya’s Chinese-built tracks, supporting seamless “port-to-door” rail service. Although a change of traction will be required between diesel and electric systems at the international border

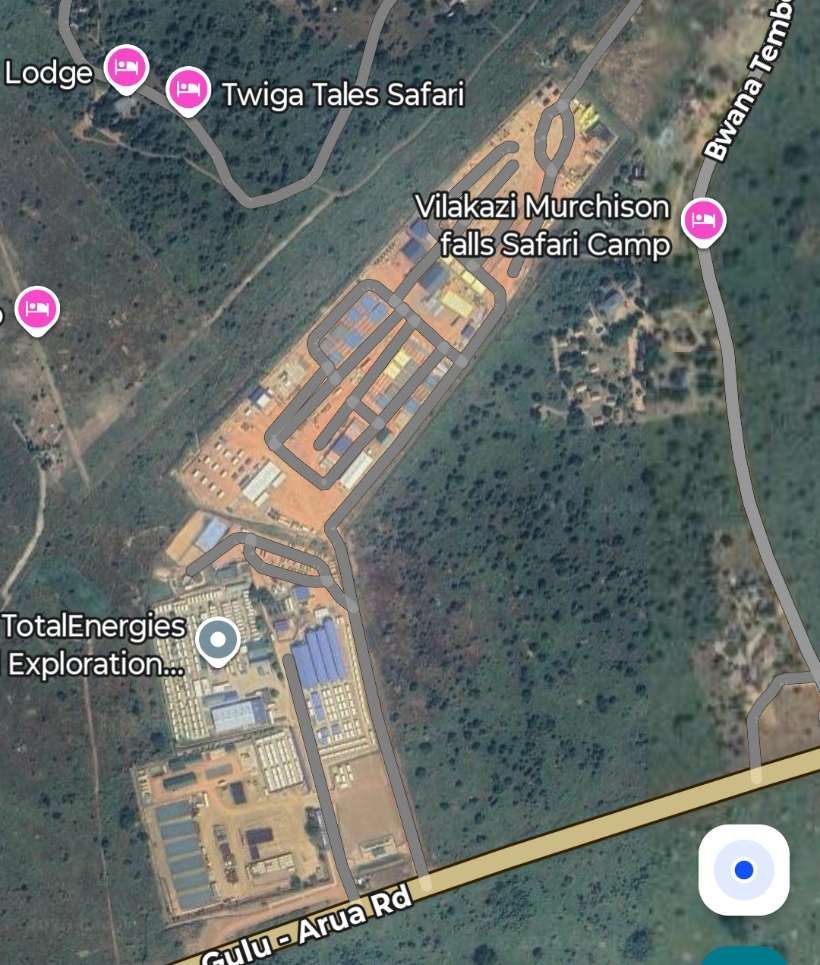

Under a ‘Limited Notice to Proceed’, Yapı Merkezi is already setting up sleeper factories and construction camps along the route, preparing for full-scale construction once financing is finalised.

On 20th February 2026, NTV Uganda reported that the Islamic Development Bank had agreed to inject 410 million euros into the Standard Gauge Railway project for the line from Malaba at the Uganda–Kenya border to Kampala. According to the Ministry of Works and Transport, the funding will cover 272 kilometres of the main Standard Gauge Railway corridor, as well as an additional 232 kilometres of lines linking key industrial hubs across the country. [10]

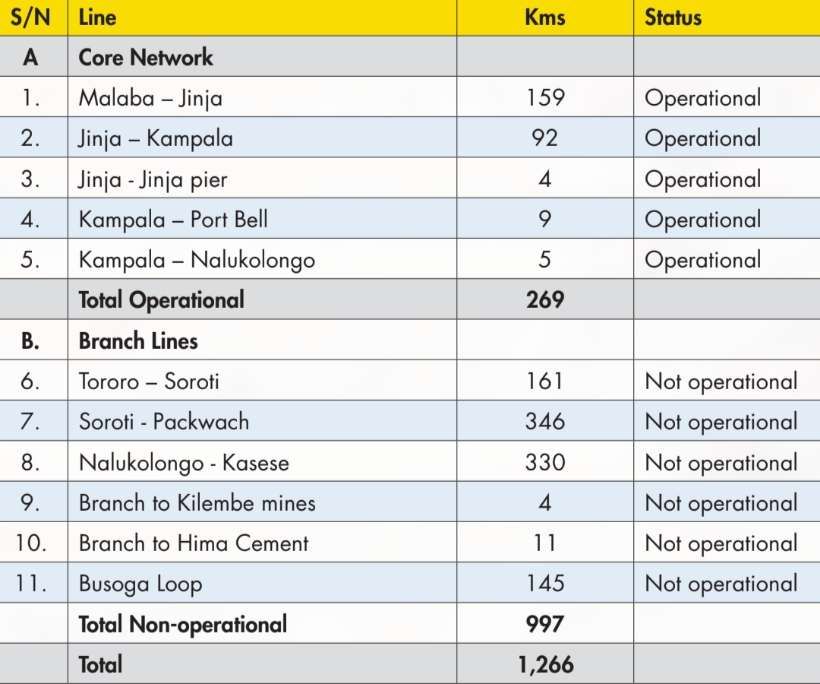

Uganda Railways Corporation Strategic Plan 2025/26 to 2029/30

Uganda Railways produced their strategic plan for the period to 2029/30 in September 2025. [4]

The Strategic Plan says: “Even with the ongoing efforts to rehabilitate the MGR, much of the railway network remains un-operational, with the few operational sections in poor condition characterised by low handling capacity, limited speeds amid occasional temporary speed restrictions, and low reliability and safety. This has resulted in an over-reliance on road transport in transporting cargo even when rail would be most suited. The impact is the increased costs of transportation that

continues to impact productivity, competitiveness and economic growth of Uganda.” [4]

An example of the current condition of the rail infrastructure is the state (in February 2026) of the line close to Pakwach in the North of Uganda.

Pakwach is on the West bank of the Albert (White) Nile. At its immediate location, a loop in the river means that it flows almost West to East with Pakwach on its North side. At Pakwach, there is a significant bridge over the Albert Nile. The two pictures below show the bridge and can be found on Google Maps (February 2026).

1 hour agoSomali Regional State Distributes 110 Motorcycles to 64 Districts2 hours agoSomalia’s Electoral Body to Resume Voter Card Distribution, 400,000 IDs Uncollected

The Pakwach Bridge, built in 1965 and commissioned in 1969, is a crucial, aging structure crossing the Albert Nile to connect Uganda’s West Nile region, South Sudan, and Congo. Currently experiencing structural cracks and flooding issues, it is being redesigned by China Communications Construction Company to support modern, heavy, multi-modal transport. The replacement structure will be designed to accommodate both road and rail (metre-gauge and standard-gauge), pedestrian walkways and will also be able to accommodate the largest shipping that might use the Albert Nile. The project aims to facilitate the revival of the Pakwach Riverport (which became ineffective due to the poor headroom of the current bridge), and support regional trade. The bridge condition is very poor and at risk of collapse. Temporary measures are currently being considered to sustain vehicular and pedestrian traffic in the period before the new bridge is designed, built and opened. [6][7]

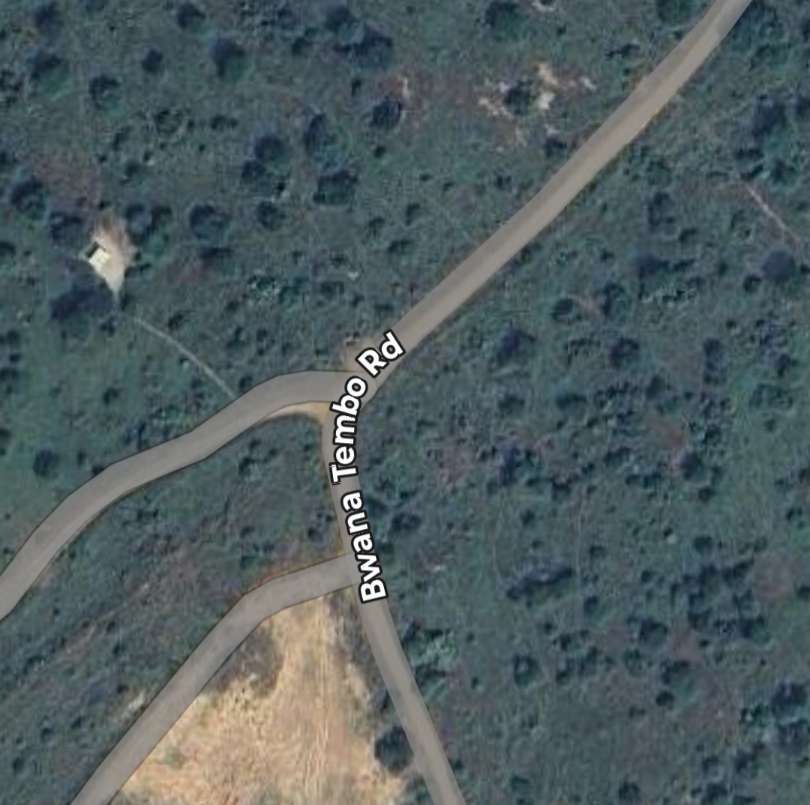

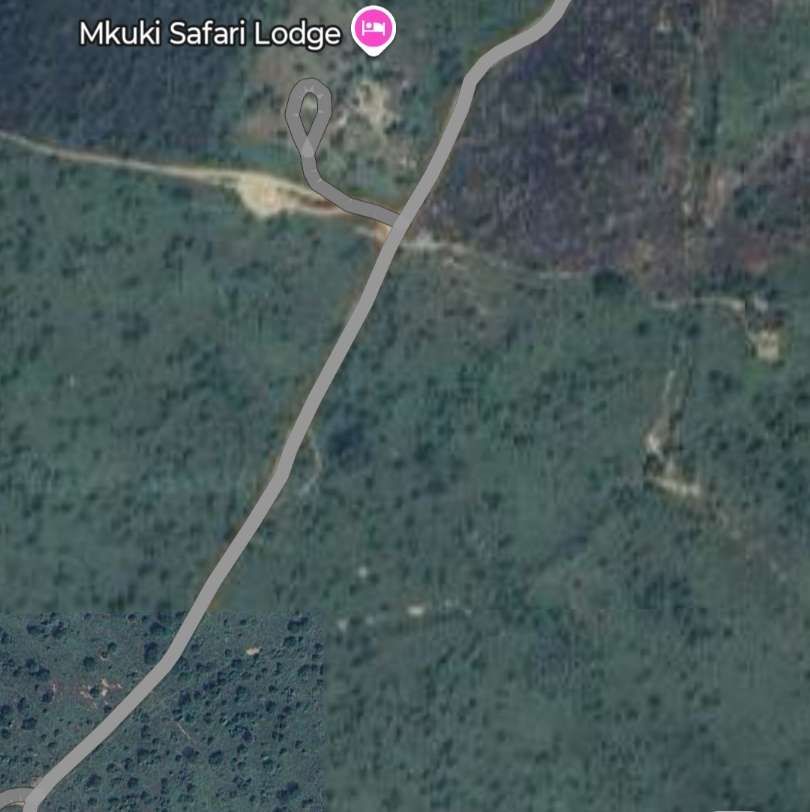

In early February 2026, as part of a visit to the Murchison Falls National Park we travelled alongside remnants of the old railway to the East of Pakwach on the East bank of the Albert Nile.

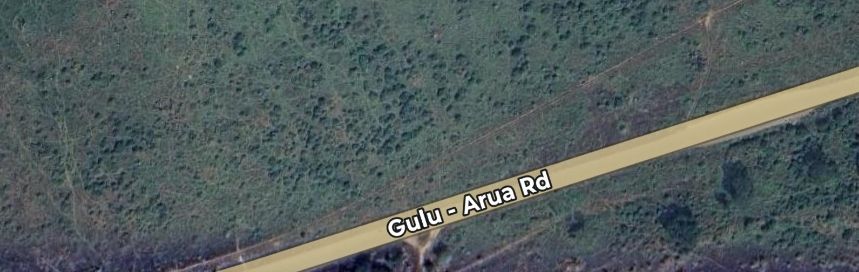

The railway heading for Gulu runs alongside the Gulu/Arua Road on the East bank of the Albert Nile. The pictures immediately below show remnants of the line which once sat on a low embankment between the road and the river. ….

Hopefully, these few photographs, together with the images from Google Maps have given some impression of the condition of the metre-gauge line close to Pakwach in the 21st century.

Everything that I have seen of the metre-gauge (with the exception of the line between Torroro and Kampala) is reflected in these most recent pictures.

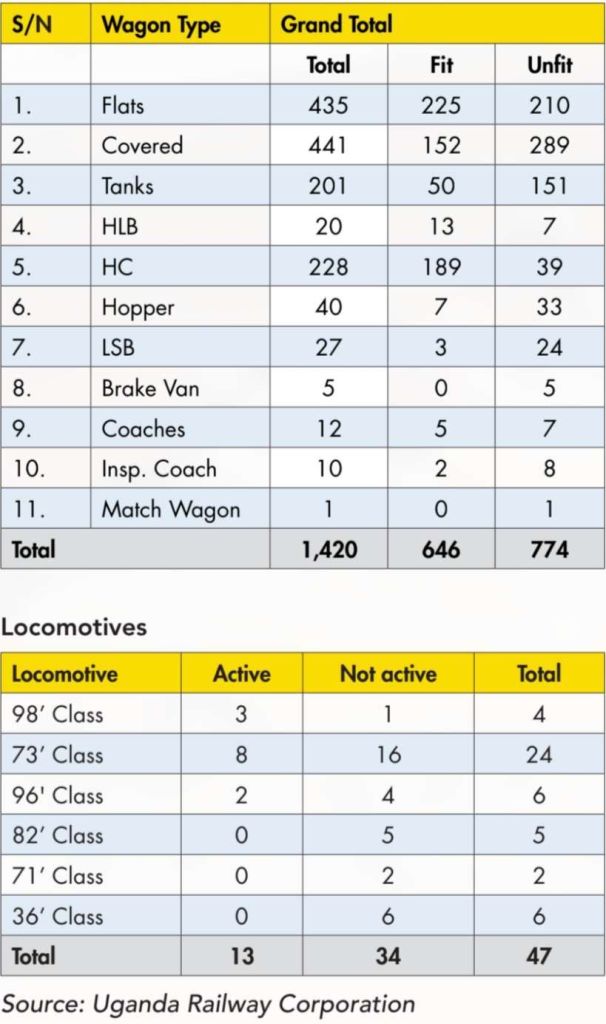

The Strategic Plan itemises the rolling stock that it owns – a total of 1,420 wagons of different types including flatbeds, tanks, covered wagons among others, and spread across the entire network (including Kenya and Tanzania). However, it says, the URC still faces

a big challenge of availability of rolling stock throughout the year with wagon and locomotives availability standing at 40% (505 fit wagons) and 46.5% respectively in the 2023/24 year. “Of the fit wagons, only 35% were flat beds yet they have a higher demand. Table 2 below shows the state of the Corporation’s wagons, plant & machinery as

at the end of December 2024.” [4: p12]

in terms of operating stock. Therefore, there is a need to improve rolling stock availability through timely maintenance as well and improvement of facilities at the different maintenance

workshops. [4: p12]

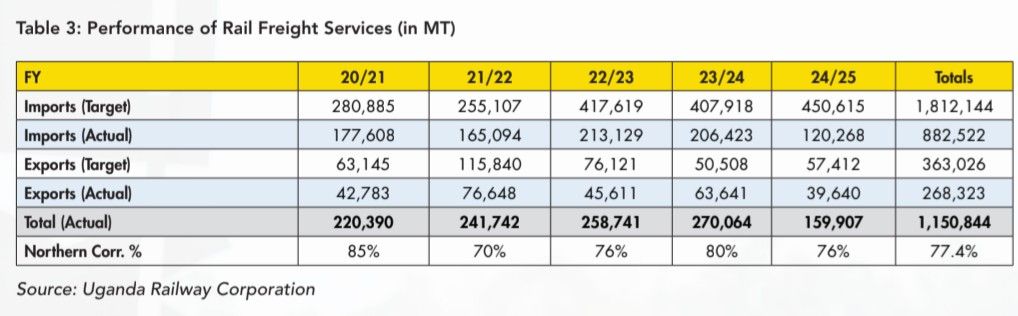

The reality is that URC has missed its freight targets by a significant margin over recent years as Table 3 shows.

Table 3 shows that during the period July 2020 – December 2024, the URC network carried a total of 1,150,844 MT against a target of 2,175,170 MT, that is 53%. Of this, 77% were imports while 23% were exports.

Passenger Services

Passenger services were reintroduced under a pilot project in December 2015 as a response

to the increasing traffic congestion in Kampala City due to absence of organized public transport. Currently, the passenger train plies four trips daily between Kampala and Namanve. There was a hiatus of around 12 months in the provision of this service while the metre-gauge line between Kampala and Mukono was refurbished, with services restarting in May 2024. “The 30-minute journey has various halts in Nakawa, at Spedag, Kireka, and Namboole, finally terminating at Namanve with an average ridership of 4000 commuters per day.” [4: p15]

Logistics, Warehousing & Terminals

The URC operates three fully licensed, one-stop centres for warehousing, customs clearance, and UNBS checks: Mukono Inland Container Depot, PortBell and Jinja Piers (with the capacity to handle consolidation and

deconsolidation of cargo). Warehousing includes Gulu Logistics Hub, Mukono ICD,

Kampala Good shed, Mbale Good Shed, and Tororo Good Shed. [4: p16]

Challenges

The URC honestly reports a number of challenges which must be addressed in coming years [4: p34-36]

- An outdated and inadequate policy, legal and regulatory framework, especially with standards in railway and inland water transport. Particularly, harmonisation of railway policies across the East African region.

- Dilapidation of railway transport infrastructure and other assets. The larger portion of the existing MGR network remains in a poor state due to ageing of equipment, dilapidation of the network and out of date technology. In addition, the URC’s regional assets including upcountry stations, staff quarters,

offices are in a poor state, poorly managed and left to the oversight of unknown occupants. - An increasing potential demand for passenger services in the Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area. The need for additional passenger stock in good serviceable condition. The need for new feasible passenger routes.

- Limited integration with other modes of transport (road, water, air). The need for railway stations to become intermodal hubs is expressed in the strategic plan, but this would require new or replacement stations to be built and there to be a much more structured approach to other transport (boda-boda, matatu and long-distance buses) and a significant improvement in the rail network.

- Very limited funding being made available for the URC Strategic Plan priorities. The previous plan set funding targets but only 9% of planned expenditure actually occurred! A serous increase in stakeholder funding is a paramount need for the URC’s future.

- The human resource capacity is limited – at the end of March 2025 the URC had only been able to fill about 56% of its agreed staff structure.

- Weak data management and reporting frameworks. A lack of a robust monitoring and evaluation system. It is, however, difficult to perceive what could usefully be measured that would produce a meaningful positive impact.

- Massive encroachment onto URC land and vandalism of railway materials and property. In some regions of the country, encroachers have secured illegal land titles to URC land and illegal developments have taken place. The URC needs to complete a full survey of its property and must implement a land management strategy.

- Public attitude to the railway is poor, many are unaware of its value, advertising of plans and services is poor, and big battles remain to be fought with those who have encroached on its assets

The situation is dire, the future of the metre-gauge seems to be uncertain and bleak!

The strategic plan sets, what must seem to all involved to be, and unobtainable goal: “A developed, adequate, safe, reliable and efficient multi–modal transport system in Uganda.” [4: p38] The fact that the overall goal is unrealistic means it is difficult to give a great deal of credence to any of the intentions which develop from it.

A more effective goal which did not aim at an unobtainable outcome might produce definite steps forward for the existing rail transport network.

Major societal change would be needed to create any form of intermodal transport system. Road transport is in the hands of a myriad of private business concerns all with their own interests and this appears to be very unlikely to change, especially not within the 5 year time frame of the plan.

Perhaps a more focussed and implementable plan is needed. Perhaps limited to improvements in the maintenance of the rail network itself. Perhaps focussing on passenger capacity on the one route currently available with a demonstrable improvement in commuting time on both road and rail as a result of an improved rail service. Perhaps setting realistic goals for the recovery of illegally occupied land over lengths of the metre-gauge line with a significant possibility of being brought back into effective use.

Recent and Upcoming Railway Tenders

UgandaTenders.com lists tendering opportunities for Railway activity in Uganda. These included:

- Supply & Commissioning of Ten (10) New Diesel Electric Locomotives and Training of Maintenance & Operation Personnel – the East Africa Community Railway Rehabilitation Support Project (19th December 2025);

- Rehabilitation of Malaba-jinja and Port Bell-kampala-kyengera Railway Line Sections Including Support Infrastructure (19th January 2026);

- Drainage Improvement works on Kampala – Mukono Railway Line Section (5th March 2026);

- Permanent way (Railway line works)(12th March 2026);

- Consultancy Services to Develop the National Railway Transport Policy in Uganda – EAC-Railway Rehabilitation Support Project (12th March 2026); and

- Consultancy Services for the Development/Preparation of the Railway Transport Master Plan – EAC-Railway Rehabilitation Support Project (12th March 2026).

Kenya

Kenya Railways Blog

In January 2026, the Kenya Railways Blog carried two articles:

A. Statement on Upcoming Railway Developments under the Nairobi Commuter Rail Service to Support AFCON 2027

Following a successful bid to co-host the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) in 2027 alongside Uganda and Tanzania, the Government of Kenya is making preparations to host a successful tournament.

In Kenya, the games will be hosted at Nyayo National Stadium, Talanta Sports City Stadium and Moi International Sports Centre, Kasarani. Nyayo National Stadium is designated as a training centre during the tournament because of its central position.

One of the key initiatives being undertaken includes provision of an effective transport solution that will ensure easy access to and from the venues of the soccer event.

With this in mind, the Government intends to construct a railway station adjacent to Nyayo National Stadium and a railway spur line from the Nairobi Central station through Nyayo National Stadium area, Kibera to Talanta Sports City Stadium Stadium.

Kenya Railways is in the process of evicting any illegal occupiers of its land as it prepares for the construction of the line. All illegal structures and property found on the land within the corridor will be removed without further notice, at the cost of the individual or concern that built a structure or placed property on the land.

B. Successful Testride Signals Readiness of Uplands–Longonot–Kijabe MGR corridor

On 23rd January 2026 it reported that on 19th January 2026 that a successful test ride on the Uplands–Longonot–Kijabe Metre Gauge Railway (MGR) line had taken place, signalling renewed readiness to restore services along the critical corridor.

The exercise confirmed the safety, integrity and operational soundness of the restored infrastructure after months of intensive rehabilitation necessitated by severe washaways caused by unprecedented rains in 2024. Works carried out included embankment stabilisation, bridge strengthening, drainage reconstruction and track realignment to improve the corridor’s resilience to extreme weather conditions.

The Uplands–Longonot–Kijabe MGR line forms a key link within the MGR network, supporting passenger movement from Nairobi to Kisumu and freight movement from the Port of Mombasa to Kenya’s hinterland and regional markets across East and Central Africa. Its restoration reinforces Kenya Railways broader strategy of maintaining an integrated, resilient, and efficient rail system.

As the Corporation prepares for the progressive resumption of services along the corridor, the test ride marks not only a technical achievement, but a renewed commitment to reliability, safety and national development.

Kenya Railways Begins Preparations for Naivasha-Kisumu-Malaba SGR Phases 2b and 2c

In an article dated 20th February 2026, Capital FM (Nairobi) reported that Kenya Railways has commenced preparations for the construction of the Naivasha-Kisumu-Malaba Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) Phases 2B and 2C.

The railway operator, in partnership with the National Land Commission (NLC), has deployed survey teams to the proposed Kisumu Terminus site, marking the boundaries for Phase 2B.

In a statement, Kenya Railways said the exercise involves identifying project boundaries, confirming affected land parcels, and measuring land sizes to facilitate the gazettement process.

The survey teams are using Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) technology, a modern satellite-based system, to ensure precise and reliable measurements.

The preparatory work marks a key milestone in the expansion of Kenya’s SGR network, which aims to enhance regional connectivity and boost trade along the Nairobi-Kisumu-Malaba corridor. [11]

View of Chinese-built Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) in Kenya

In a short publicity article dated 21st February 2026, the Chinese newsagency Xinhua uses pictures to describe travel on the SGR in Kenya on 17th February 2026. It can be found here … [13]

“Stretching 472 km from the port city of Mombasa to the capital Nairobi in Kenya, the Chinese-built Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) was launched on 31st May 2017. It is the first new railway built in Kenya since independence and a flagship project of China-Kenya cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative.” [13]

Recent and Upcoming Railway Tenders

A snapshot of current and planned tenders for railway work.

- Consultancy Services For Design Review And Construction Supervision For The Proposed Construction Of Nairobi Railway City Central Station, Public Realm And Other Associated Infrastructure Works (15th January 2026);

- Consultancy Services For Design Review And Construction Supervision For The Proposed Standard Gauge Railway From Naivasha \U2013 Kisumu (Phase 2B) (15th January 2026);

- Proposed Construction Of Limuru Railway

Station And Associated Facilities (23rd January 2026); and - Supply And Delivery Of Rail Fittings And Fasteners For Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) (20th February 2026).

Kenya 2026 Budget Policy Prioritises Rail And Logistics Modernisation

Phillippa Dean of Railways Africa reports [15]that:

Kenya’s 2026 Budget Policy Statement sets out a programme of infrastructure and policy interventions aimed at accelerating economic transformation, lowering the cost of doing business and improving the movement of people and goods. Transport and logistics feature prominently, with rail identified as a key enabler of national competitiveness and regional connectivity.

The Government confirms that it has completed construction of the Miritini MGR Station at the Mombasa Terminus, including a new metre gauge railway link and a railway bridge across the Makupa Causeway. The works are intended to provide seamless first- and last-mile connectivity for Standard Gauge Railway passengers.

As part of efforts to strengthen the transport policy framework, the Government has developed the National E-Mobility Policy to guide the transition to clean and sustainable transport technologies, the National Road Safety Action Plan 2024 to 2025, and the National Logistics and Freight Strategy for horticulture exports.

A comprehensive ten-year infrastructure programme is planned to address existing gaps. This includes dualling 2,500 kilometres of priority highways, surfacing an additional 28,000 kilometres of roads and expanding strategic transport corridors through Public Private Partnerships. Rail development forms part of this wider transport and logistics modernisation agenda.

The extension of the Standard Gauge Railway from Naivasha to Kisumu and onward to Malaba has begun, marking a step towards enhanced regional connectivity. The statement also identifies modernisation of the railway system as a priority within the broader transport and logistics investment framework.

Performance data included in the statement show that the services sector recorded growth of 4.8 percent in the first quarter, 5.5 percent in the second quarter and 5.4 percent in the third quarter of 2025. Within this, the transportation and storage sub-sector expanded by 3.7 percent, 5.4 percent and 5.2 percent respectively, across the same quarters. Growth in the sub-sector was supported by increased activity in road, water and air transport, as well as railway operations.

Transport and logistics investments also extend to the modernisation of Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, the building of a new international airport, development at the Ports of Mombasa and Lamu and reforms aimed at restoring the operational and financial stability of Kenya Airways. Additional priorities include completing port berths, establishing logistics hubs and enhancing maritime safety through programmes such as Vijana Baharia.

The statement highlights the scale of public sector exposure within the rail sector. The cumulative on-lent loan portfolio stands at KSh 1,051.1 billion, of which Kenya Railways Corporation accounts for KSh 547.4 billion, representing 52 percent of the total. This concentration reflects a significant exposure within a single entity.

Overall, the Budget Policy Statement frames the modernisation and expansion of transport and logistics infrastructure, including rail, as essential to connecting markets, reducing the cost of doing business and reinforcing Kenya’s position as an aviation and commercial hub for East and Central Africa. [15]

Freight Trains Poised for Return as Kenya Railways Clears Key Rift Valley Corridor

An article carried by Dawan Africa on 19th January 2026 reported that: [16]

After months of silence on the tracks, freight trains are edging closer to a comeback along the vital Uplands–Kijabe–Longonot railway corridor, offering fresh hope to traders and businesses that rely on rail transport across the region.

Kenya Railways Corporation has confirmed that rehabilitation works on the route, which was severely damaged by heavy rains in April 2024, have been fully completed. The disruption forced a suspension of freight services, cutting off a key link in the transport chain between the coast, western Kenya and neighbouring countries.

In a statement issued on Monday, the corporation said the line has undergone successful test runs, clearing it for safe operations.

Engineers are now finalising slope protection works, a precautionary measure aimed at reinforcing the corridor and preventing future damage, especially during periods of heavy rainfall.

“Rehabilitation works on the Uplands–Kijabe–Longonot railway corridor are now 100% complete, with successful test rides conducted to confirm the safety and operational readiness of the line,” Kenya Railways said. “The only remaining activity is slope protection works, which are being finalised to enhance long-term stability and safety.”

While no specific date has been given for the resumption of freight services, the corporation said preparations are already underway. Once operational, the corridor is expected to play a critical role in easing the movement of goods from the Port of Mombasa to Nyanza and Western Kenya, while also strengthening regional trade links with Uganda, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan.

The announcement signals renewed momentum in Kenya Railways’ broader recovery efforts following weather-related disruptions. It also comes just weeks after the corporation reinstated the Kisumu Safari Train, which had been grounded for nearly a year.

That service was revived in December to meet increased festive season travel demand to the lakeside city, offering passengers a safer and more affordable alternative during one of the busiest periods of the year. Kenya Railways said the move helped ease pressure caused by last-minute bookings and limited transport options.

With freight trains now set to follow suit, the reopening of the Kijabe corridor is expected to reduce pressure on roads, cut transport costs and restore confidence in rail as a dependable backbone for trade and travel across the region. [16]

A Formal Start to Construction of the SGR Extension

Baringo News reports that on 19th March 2026, President William Ruto is scheduled to launch the extension of the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) from Suswa to Western Kenya, culminating at the Kenya–Uganda border. [17]

References

- https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/eoi-uganda-consultancy-services-development/preparation-railway-transport-master-plan-eac-railway-rehabilitation-support-project, accessed on 19th February 2026.

- Muhamadi Matovu; Government Pushes to Secure 13 trillion UgX loan for Eastern SGR Line; Nile Post, 19th February 2026; via https://nilepost.co.ug/news/321483/government-pushes-to-secure-shs13tn-for-eastern-sgr-line, accessed on 19th February 2026.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/12/08/east-africa-railway-news-november-december-2025

- https://urc.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/UGANDA-RAILWAYS-CORPORATION-STRATEGIC-PLAN-2025-2030.pdf, accessed on 19th February 2026.

- https://www.google.com/search?q=pakwach+railway+bridge&oq=pakwach+railway+bridge&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIHCAEQIRigATIHCAIQIRigATIHCAMQIRigATIHCAQQIRigATIHCAUQIRifBTIHCAYQIRifBTIHCAcQIRifBTIHCAgQIRifBTIHCAkQIRifBTIHCAoQIRifBTIHCAsQIRifBTIHCAwQIRifBTIHCA0QIRifBTIHCA4QIRifBdIBCDgyNzNqMGo0qAIOsAIB8QUKhe7sSbfrtg&client=ms-android-motorola-rvo3&sourceid=chrome-mobile&ie=UTF-8#ebo=0, accessed on 20th February 2026.

- https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&source=web&rct=j&url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v%3Dx7OnY4J7P-A%26t%3D1&ved=2ahUKEwj5v9jBsueSAxX_AfsDHe6CDOEQ1fkOegQIBhAC&opi=89978449&cd&psig=AOvVaw2NRWNatNO6rcpgYu80wHyD&ust=1771653710053000, accessed on 20th February 2026.

- https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&source=web&rct=j&url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v%3DGaSzMHwCeJE&ved=2ahUKEwj5v9jBsueSAxX_AfsDHe6CDOEQ1fkOegQIBhAH&opi=89978449&cd&psig=AOvVaw2NRWNatNO6rcpgYu80wHyD&ust=1771653710053000, accessed on 20th February 2026.

- https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&source=web&rct=j&url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v%3DvE6zWiVqrAU%26t%3D176&ved=2ahUKEwj5v9jBsueSAxX_AfsDHe6CDOEQ1fkOegQIBhAM&opi=89978449&cd&psig=AOvVaw2NRWNatNO6rcpgYu80wHyD&ust=1771653710053000, accessed on 20th February 2026.

- https://www.ugandatenders.com/products-services/railway-tenders, accessed on 21st February 2026.

- https://ntv.co.ug/business/islamic-development-bank-injects-e410-million-into-standard-gauge-railway-project, accessed on 21st February 2026.

- https://allafrica.com/stories/202602200111.html, accessed on 21st February 2026.

- https://www.capitalfm.co.ke/news/2026/02/kenya-railways-begins-preparations-for-naivasha-kisumu-malaba-sgr-phases-2b-and-2c, accessed on 21st February 2026.

- https://english.news.cn/africa/20260221/bc972d7830534c8d8f7007b18e2a39b5/c.html, accessed on 21st February 2026.

- https://www.tendersontime.com/kenya-tenders/railway-tenders, accessed on 21st February 2026.

- https://www.railwaysafrica.com/news/kenya-2026-budget-policy-prioritises-rail-and-logistics-modernisation, accessed 21st February 2026.

- https://www.dawan.africa/news/freight-trains-poised-for-return-as-kenya-railways-clears-key-rift-valley-corridor, accessed on 21st February 2026.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1CWEsPiTbk, accessed on 21st February 2026.