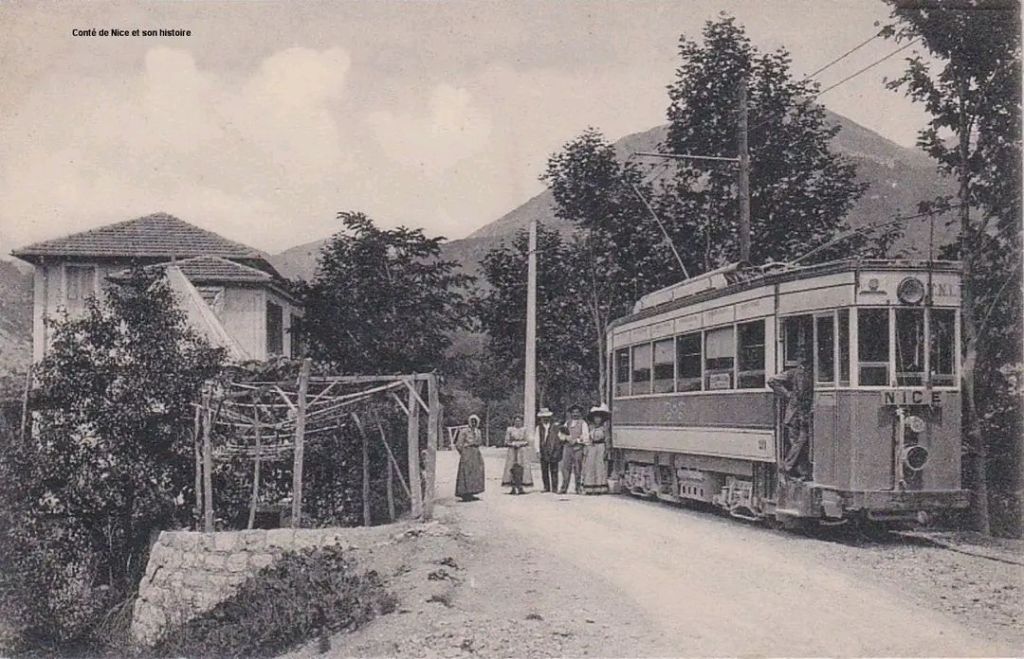

The featured image above shows the inaugural train arriving at Breil-sur-Roya in March 1928, © Public Domain, shared by Jean-Paul Bascoul in the Comte de Nice et son Histoire Facebook Group on 25th January 2017. [15]

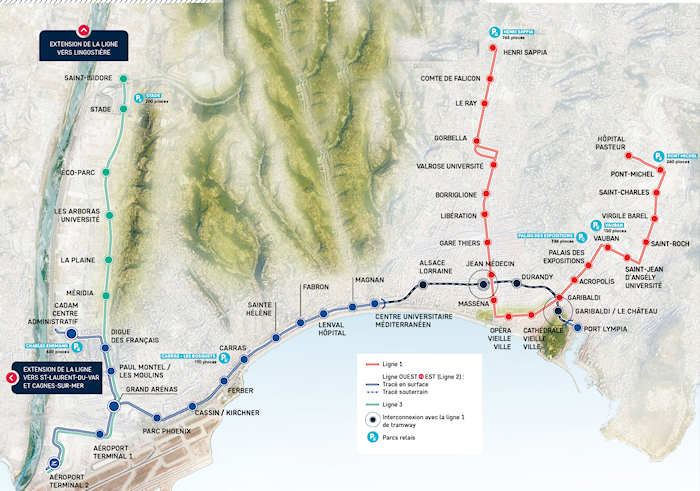

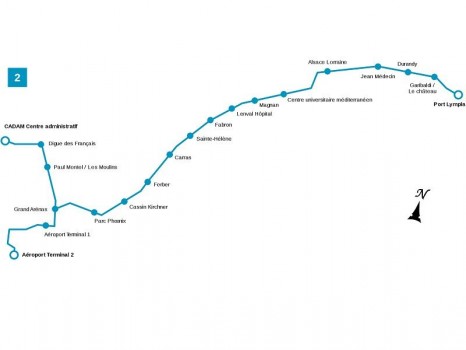

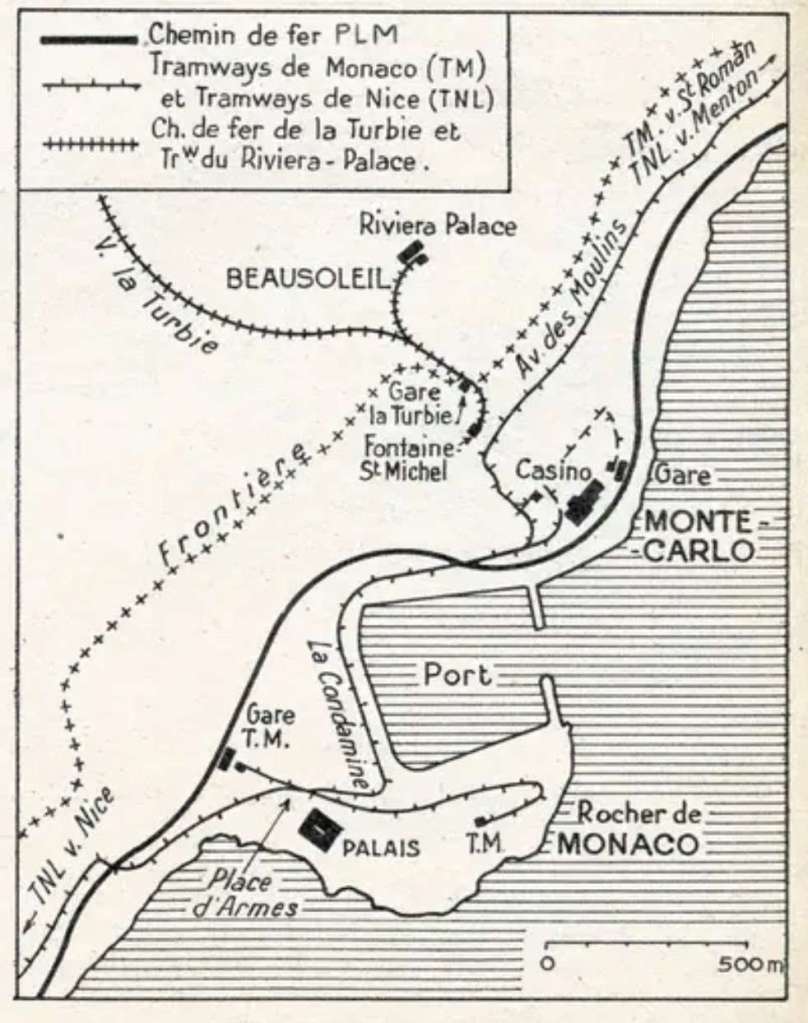

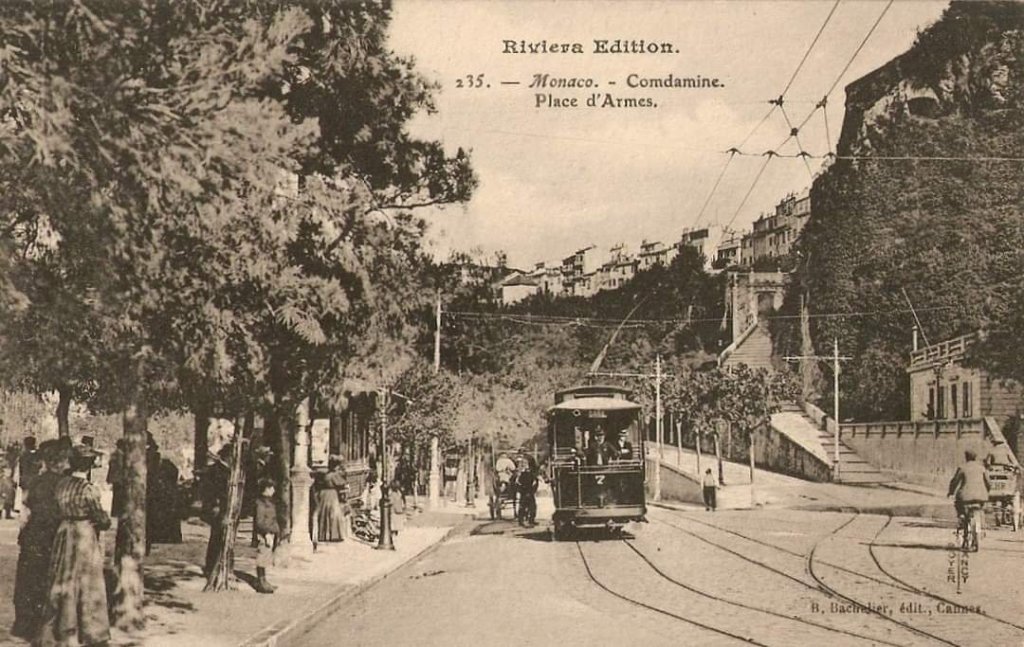

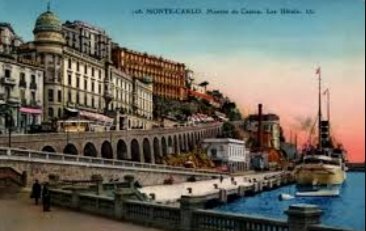

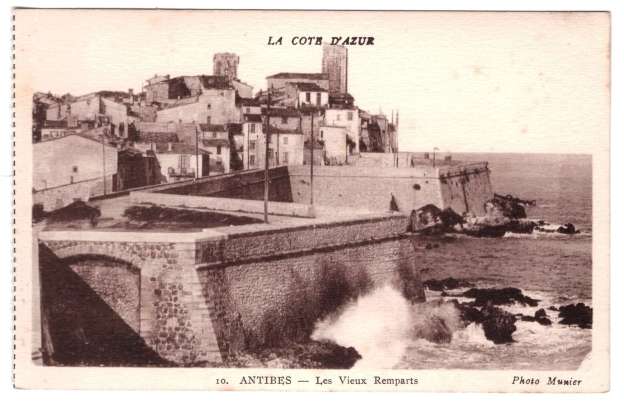

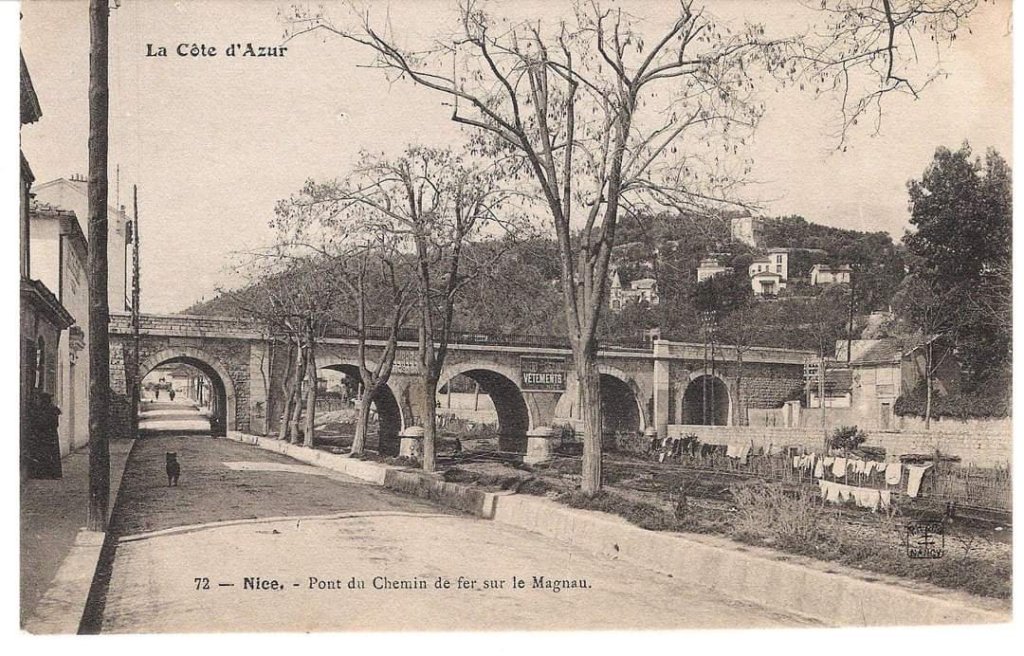

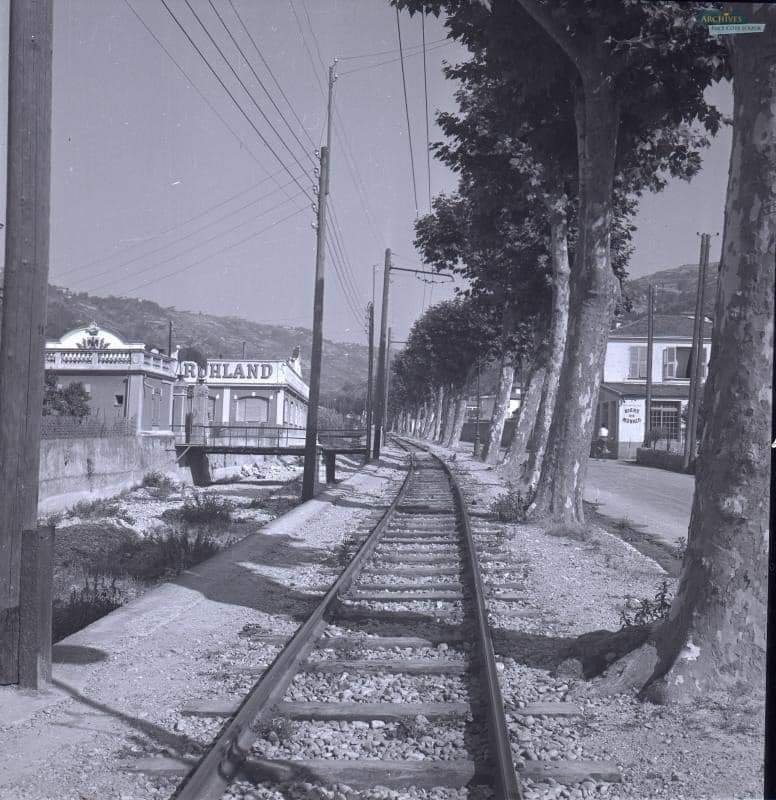

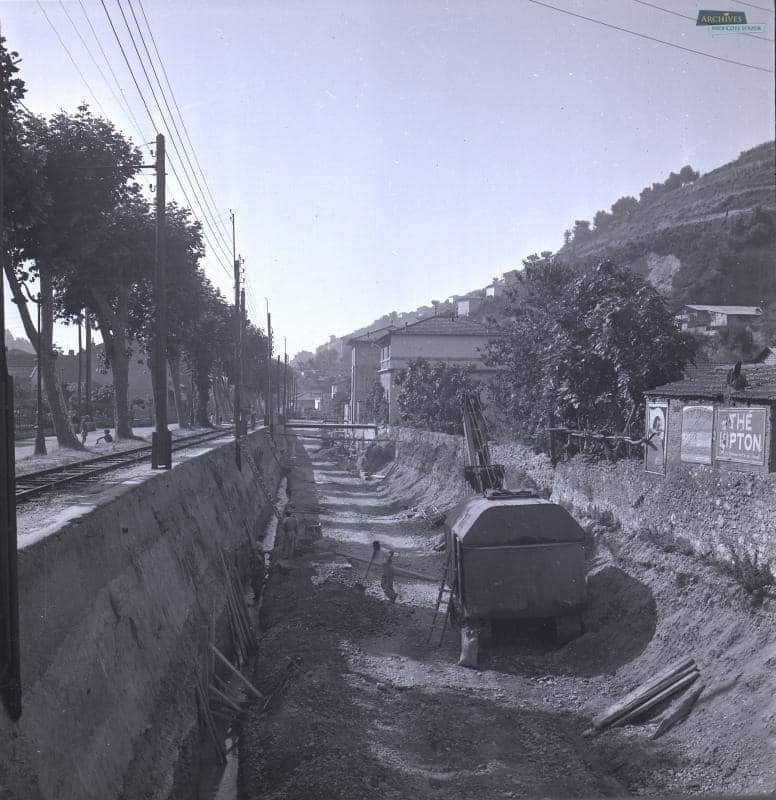

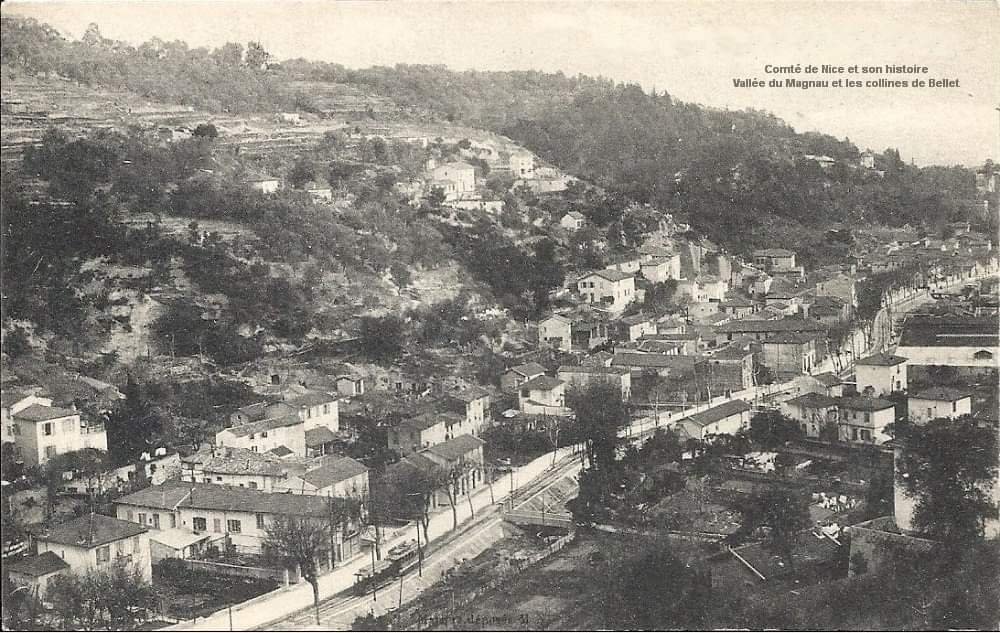

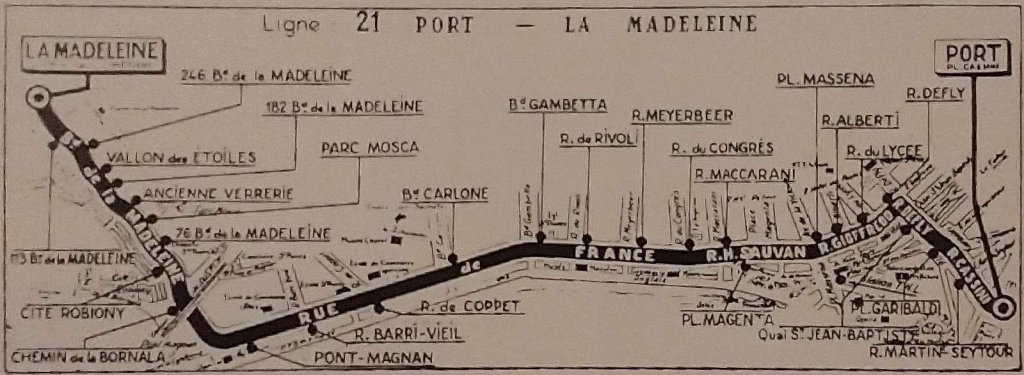

The railway from Nice PLM Station to Tende was completed in 1928. It was long in the gestation and in construction. The story stretches back more than a century and a half. ‘Le Chemin de fer du Col de Tende’ is historically a significant local and international line. Its inverted Y-shaped layout and its crossing of international borders means that it is known by a number of different names:

- in Nice it is known as the Nice – Coni Line;

- generally in Italy it is officially Ferrovia Cuneo Ventimiglia

- in the Piedmont city of Cuneo’s economic/political circles, sitting at the top of the inverted ‘Y’, it is often referred to as the Cuneo – Nizza line in recognition of good relations with the community of Nice.

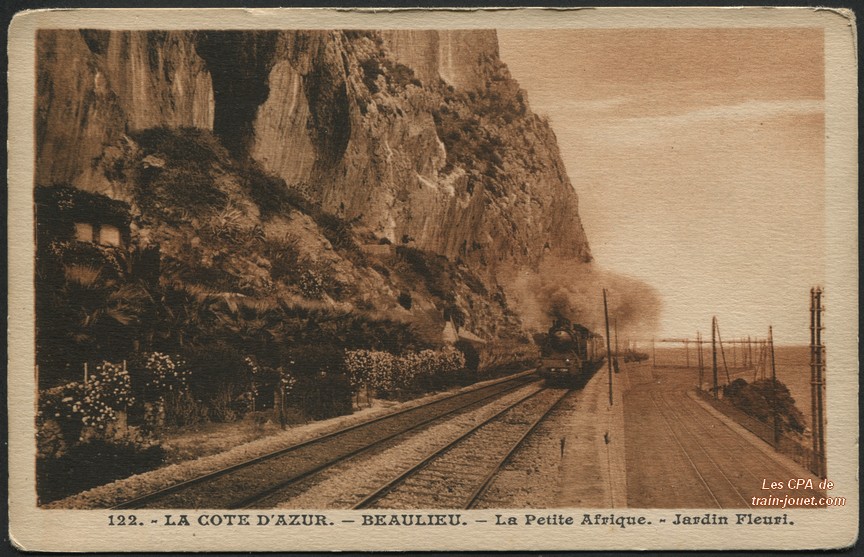

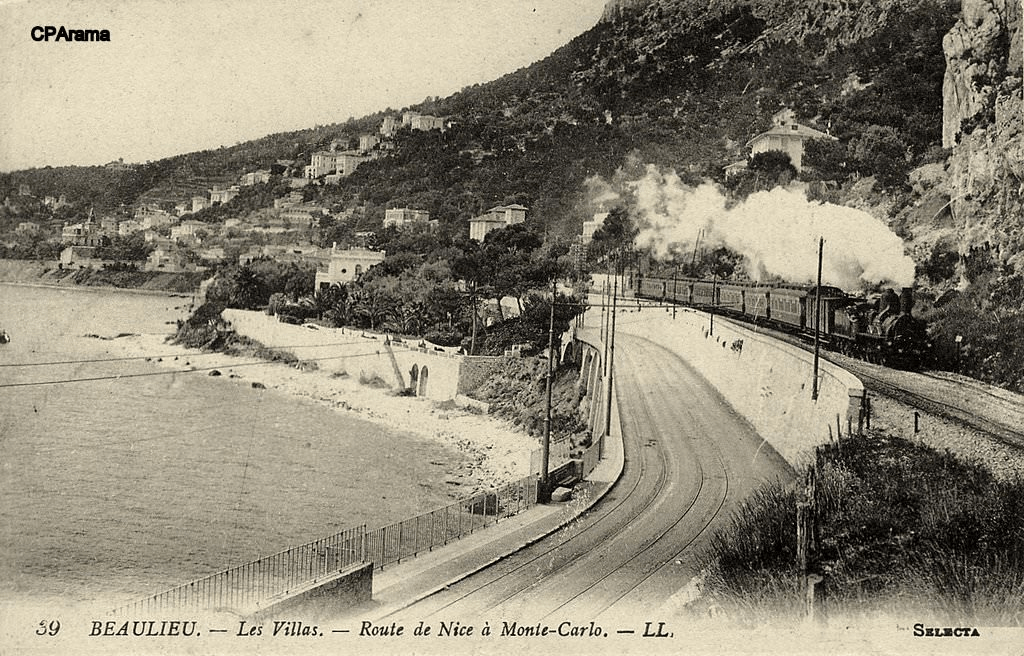

Its story is a saga of significant technical achievement: gaining 1000 metres in height ; having a dozen tunnels longer than 1 kilometre (including those of the Col de Tende (8098 m), the Col de Braus (5939 m) and the Mont Grazian tunnel (3882 m), which are among the longest structures on the French and Italian networks); having four complete helical loops, several S-shaped loops and a multitude of bridges and viaducts (some of which, such as those of Scarassouï or Bévéra, are architecturally significant railway structures. Of a total route of 143.5 km, 6.5 km are on bridges or viaducts and over 60 km are in tunnels. This means that close to 42% of the journey along the line(s) is on or within structures.

The line warrants a comprehensive detailed treatment and Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos have provided just such a work. The 3 volumes of their work cover three distinct periods in the life of the line:

- Volume 1: 1858 until the completion of construction in 1928; [1]

- Volume 2: 1929 through to 1974 [2]

- Volume 3: 1975 to 1986. [3]

The line’s construction spanned over 40 years and as a result a variety of different structural techniques were used. The first length built in Italy in the 19th century has some substantial stone and brick structures. Later work on the length from Nice to Fontane which was built between the two world wars employs much lighter design techniques. Then even later, after sections of the line were destroyed in the second world war, prestressed concrete construction techniques were used in the rebuilding of the line. [1]

The history of the area through which the line has been built has been tumultuous. This meant that the process of developing the line was tortuous. It took more than 75 years for the line(s) to be completed and then after a few short years of operation, the lines usage was disturbed by the machinations of dictatorships and then the second world war literally destroyed the region. Post war recovery was slow but nowhere more so than the length of the line between Ventimiglia and Breil-sur-Roya which was not fully reopened until 35 years after the end of the second world war. [1]

The reopening of the line after the second world war was vital for the economic development of Piedmont, the Riviera dei Fiori, and the Côte d’Azur – between which there was no efficient road connection and where the difficult terrain favored rail access. [1]

The immediate area offered tremendous tourism potential, both the train itself and the region it served. Ski resorts became accessible, particularly Limone, excursion trains came from all over Europe. But, after just a few decades of development the approach of the 21st century saw increased bureaucracy, financial disputes between the increasing number of partners, contradictory regulations and increased journey times. The result was that the line’s value and existence was called into question and that too sparked further conflict. “Paradoxically, European unification, which should have fully promoted this symbolic communication route, marginalized it!” [1: p5]

In 2014, my wife and I stayed in the village of Saorge in the valley of La Roya for the first time. We had travelled by train from Nice to Tende in an earlier year. In 2014, we had a hire car and on one occasion we followed the old road to the Col de Tende. In subsequent years it was not possible to drive up the old road as works on the much more modern tunnel seemed to have blocked access to the old road. On a more recent visit, we stayed in Saorge a year after serious flooding had destroyed much infrastructure in the valley. Travel towards the Col de Tende from Tende was not possible.

Early attempts to create a route from Cuneo to Tende

In 2014, we drove up a road which was constructed by le duc Charles-Emmanuel 1er de Savoie (Duke Charles Emmanuel 1st of Savoy). It seems that he constructed a road over the pass between 1592 and 1616. Of this road, Banaudo et al say that, “the northern road [up to the pass] has about twenty hairpin bends, while access from the south requires an extraordinary … sixty hairpin bends.” [1: p9]

Our hire car was a very small vehicle, but nonetheless needed some careful manoeuvring at each hairpin bend. Once at the top, we were able to walk quite a distance between the different forts that stood on the ridge.

Banuado et al, tell us that since that route was constructed, a series of attempts were made to tunnel from lower points on the pass. Attempts from the North were made: in 1612 (achieved just 75m of tunnel before being halted); in 1781 which was abandoned 3 years later (164m of tunnel was achieved). [1]

In 1784, a carriage managed to traverse the pass for the first time.

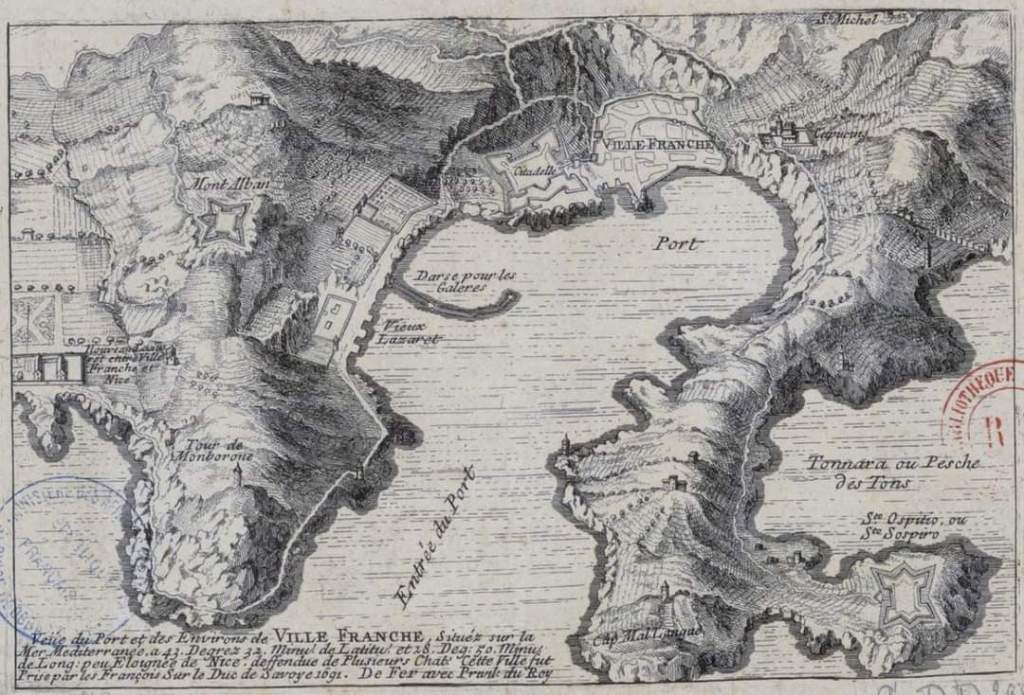

Banaudo et al. Tell us that “the public works engineer Deglioli submitted an initial report on 3rd June 1852, supported by the diplomat Francesco Sauli (1807-1893), on the extension of the Marseille-Var railway, then planned in France, to Nice, Ventimiglia, the Roya Valley, and Piedmont, namely Cuneo or Mondovì.” [1: p11]

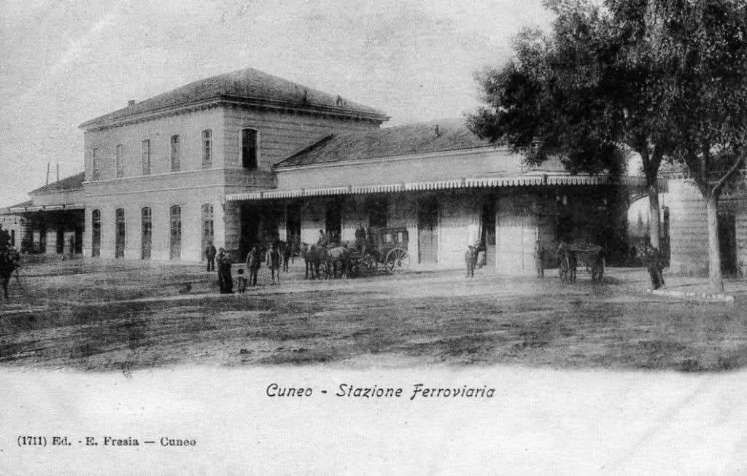

In 1854, the first train of the Società della Ferrovia Torino Cuneo arrived in Cuneo from Turin (via Trofarello, Savigliano, and Fossano). The first terminus was built in the Cuneo suburb of “Madonna-dell’Olmo, on the left bank of the Stura below the city. Ten months later, the time required for the completion of the viaduct over the Stura, Cavour and the Minister of Public Works, Pietro Paleocapa (1788-1869), presided over the inauguration of the new Cuneo platform/station on 5th August 1855, established in a temporary location at Basse-di-San-Sebastiano. The permanent station would not be built until 1870 on the plateau preceding the confluence of the Stura and Gesso rivers.” [1: p11]

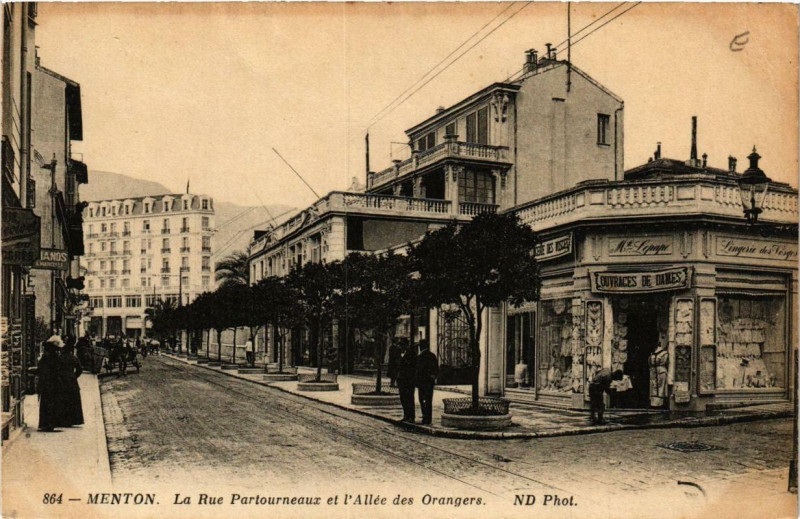

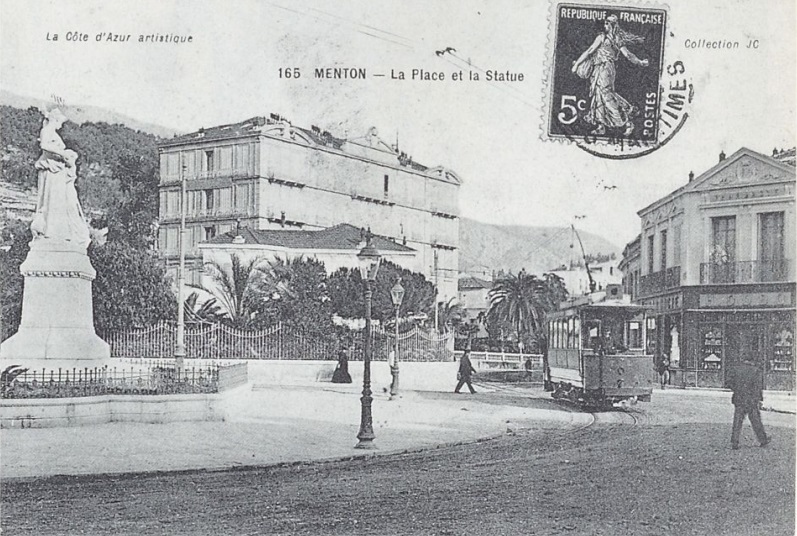

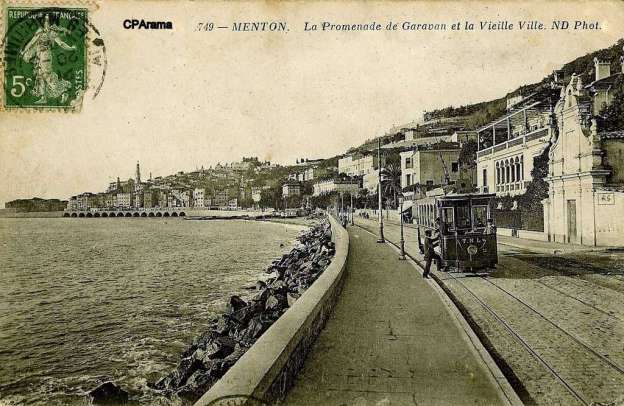

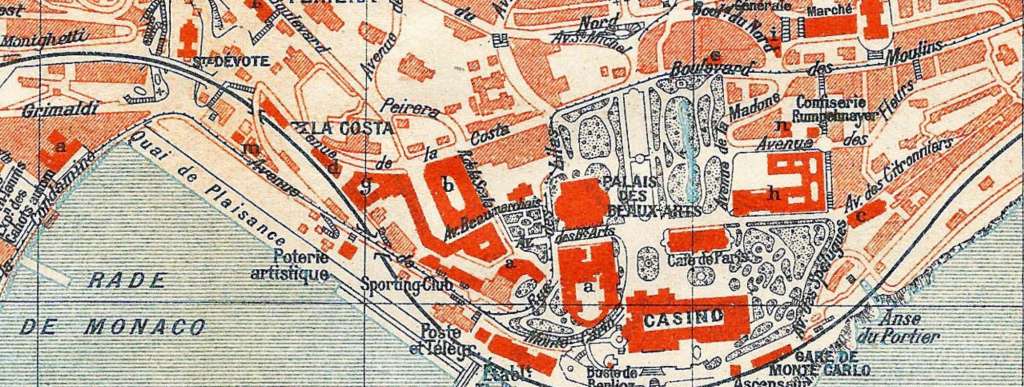

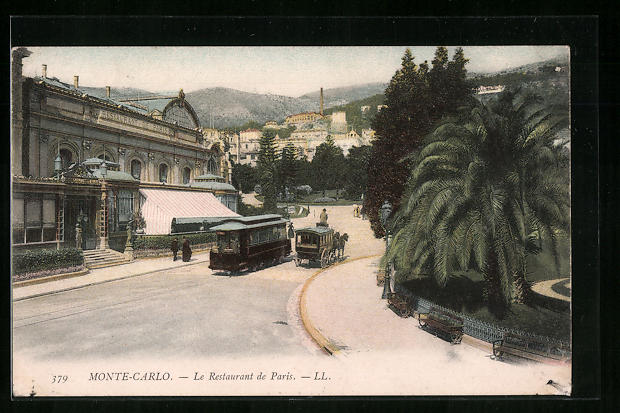

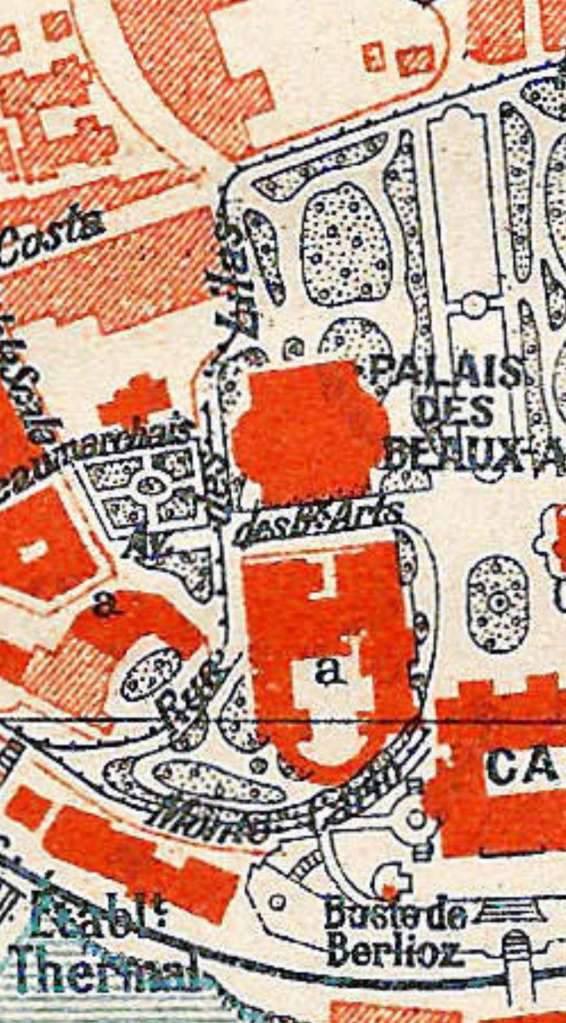

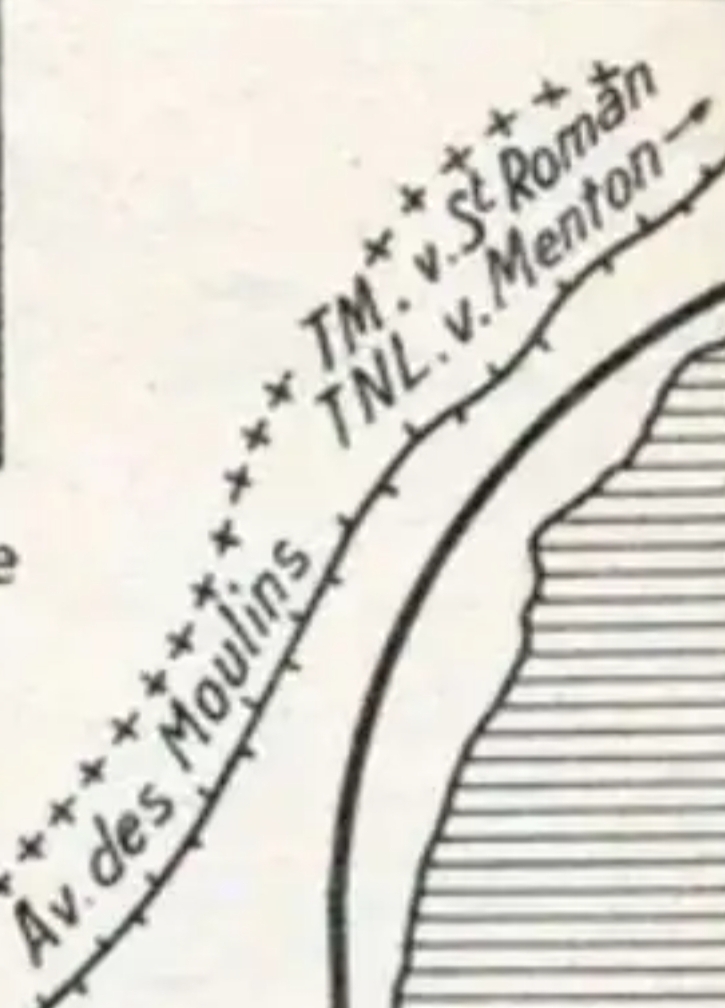

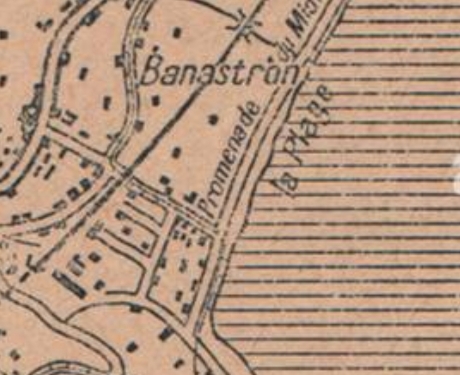

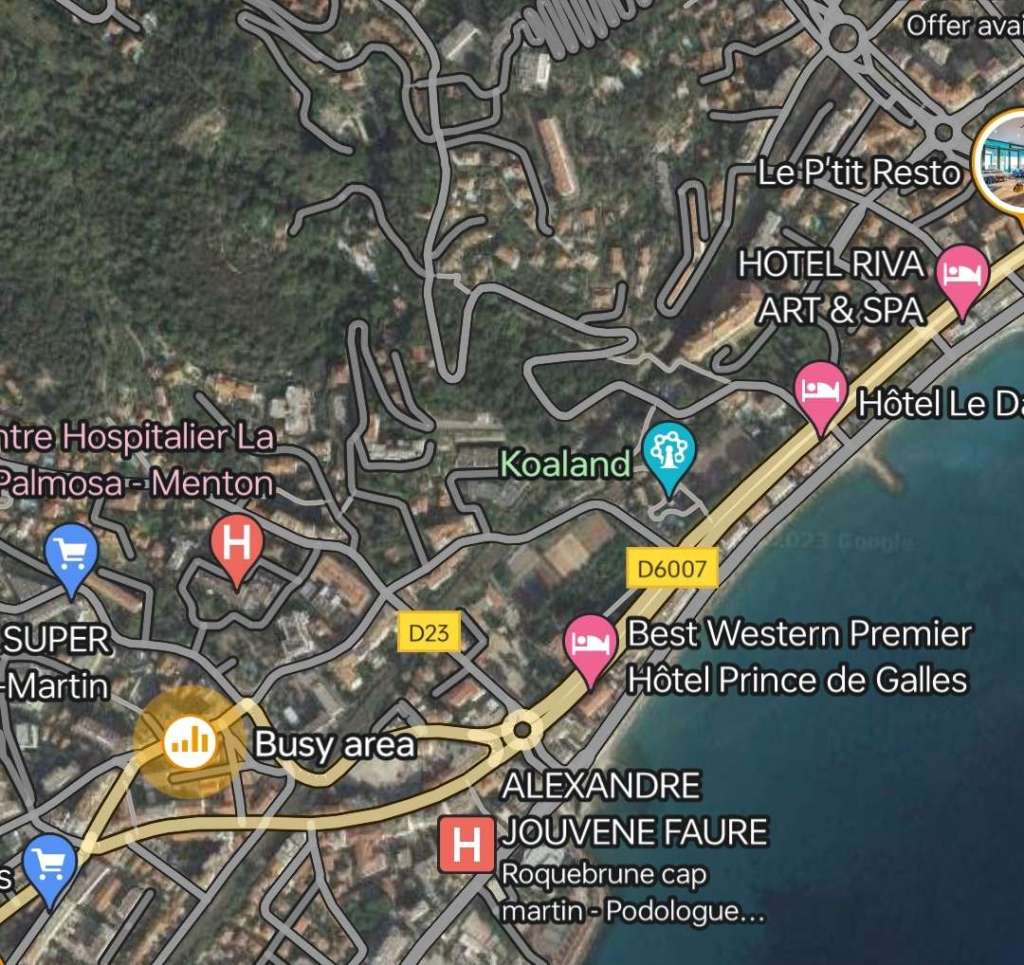

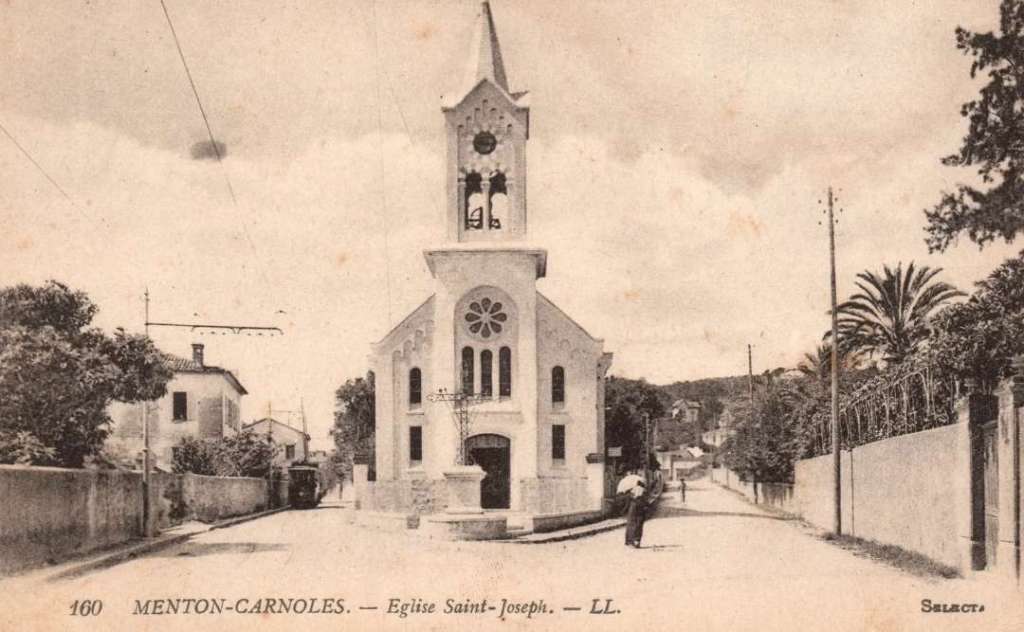

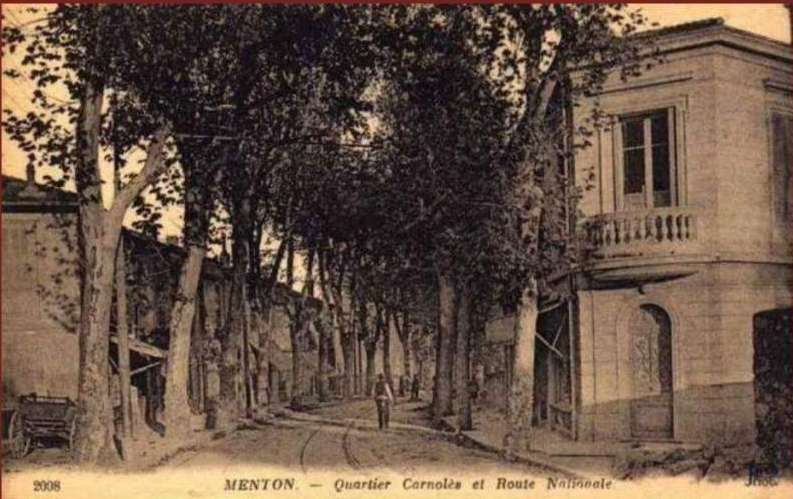

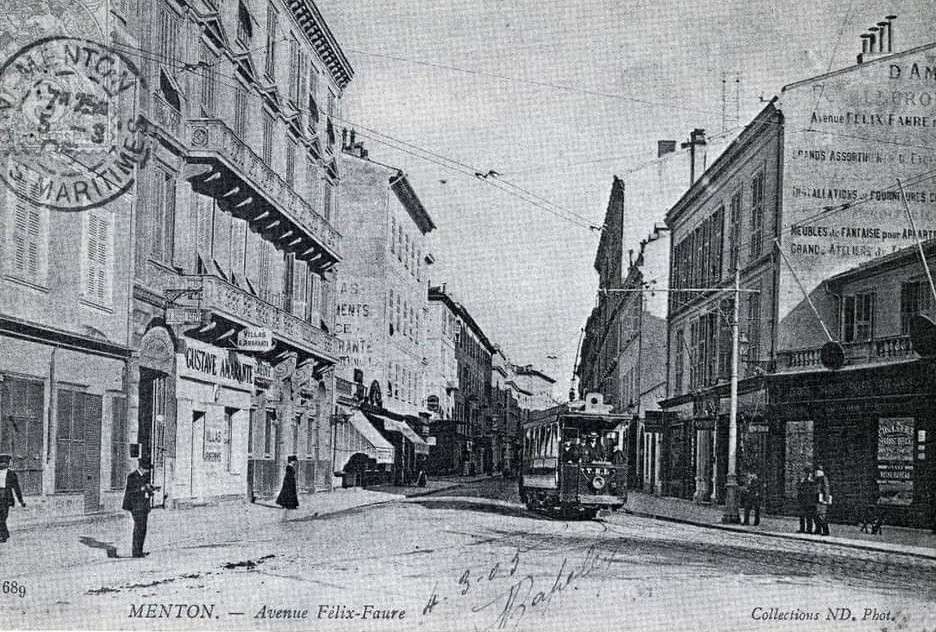

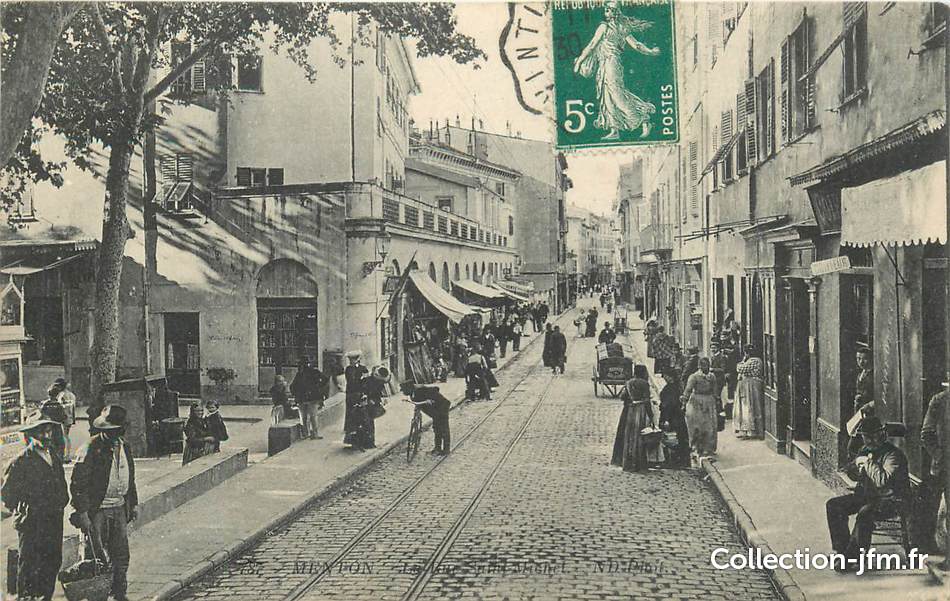

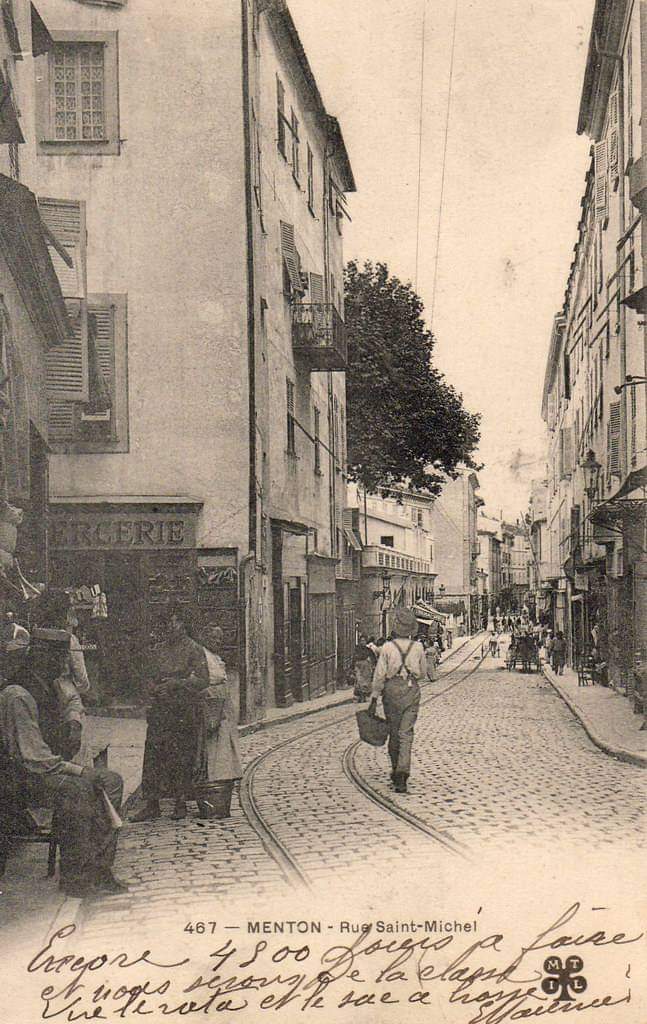

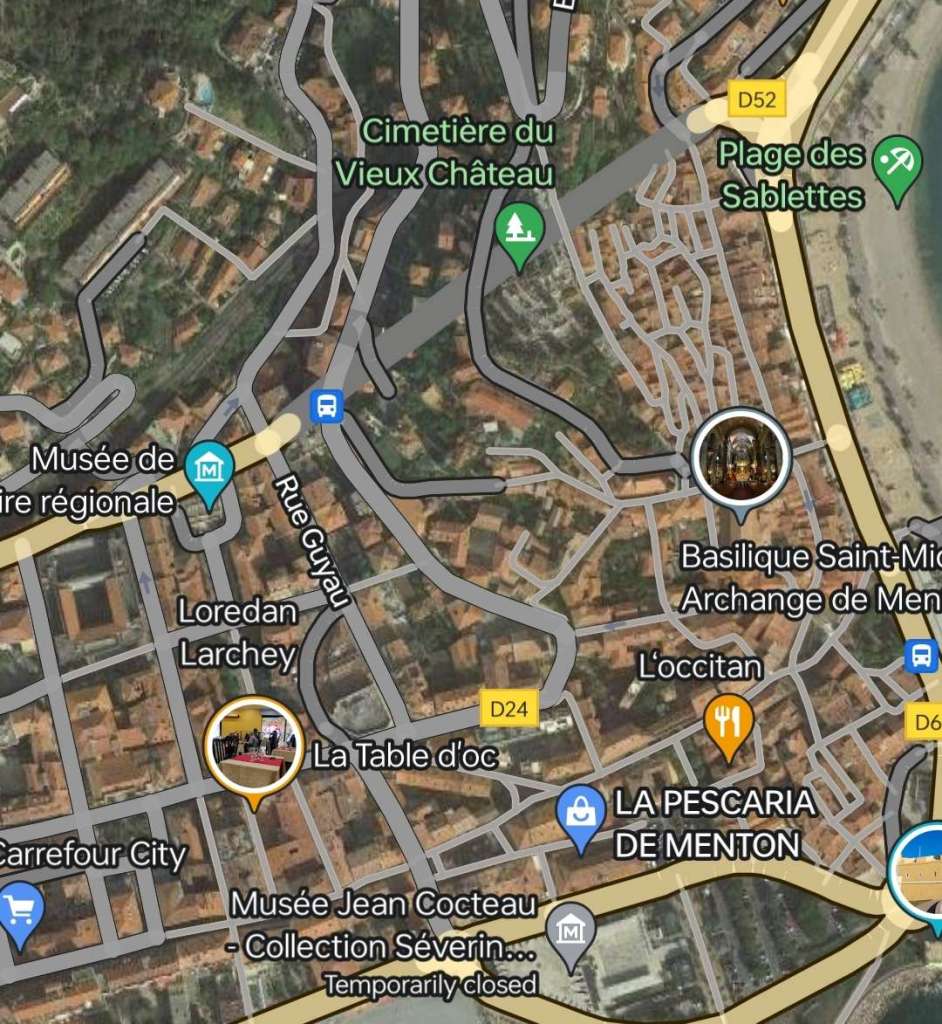

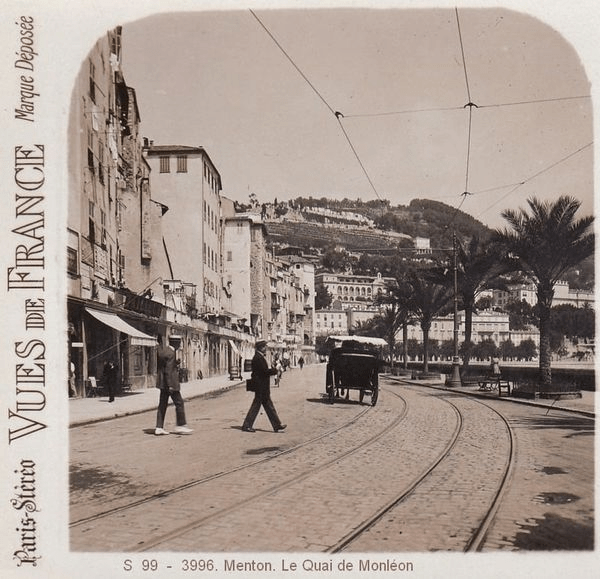

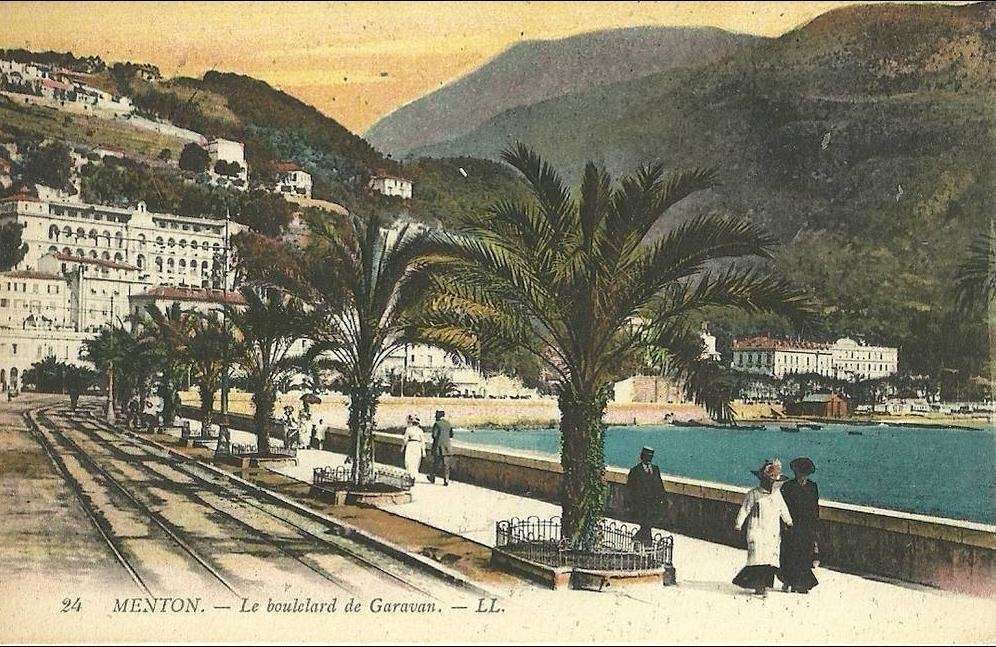

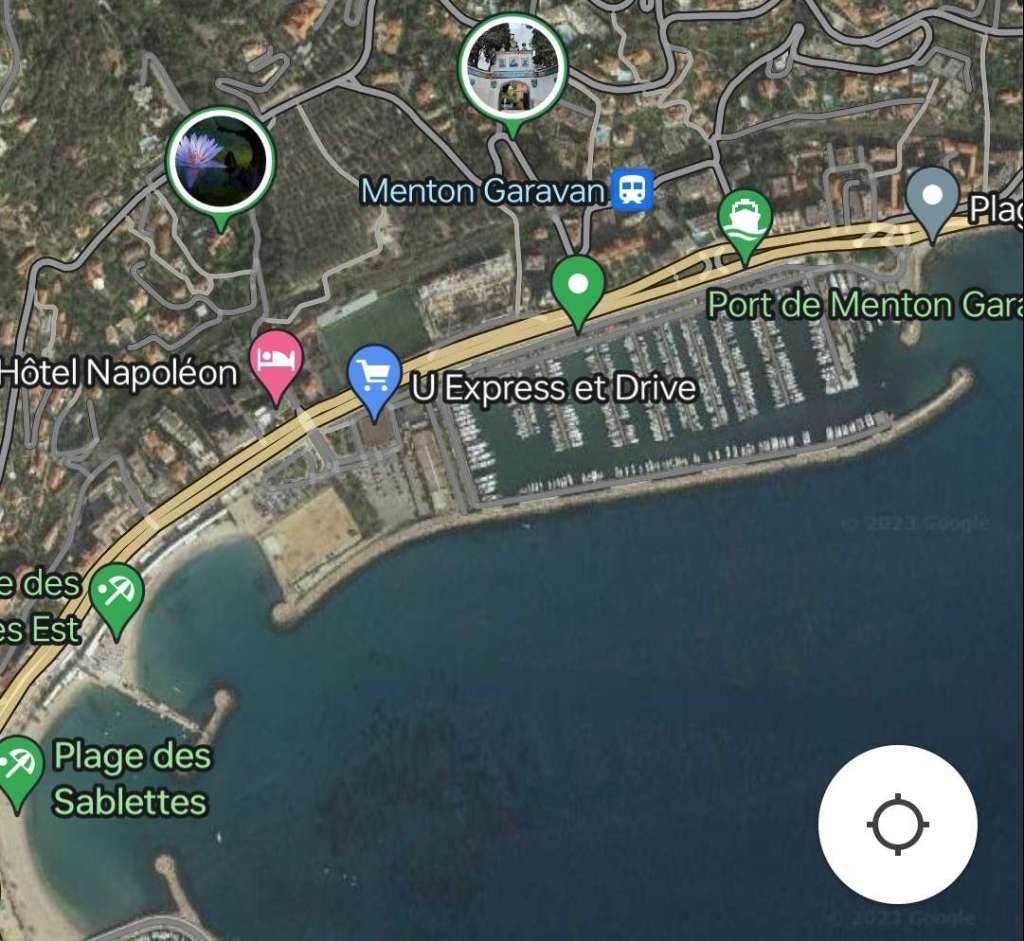

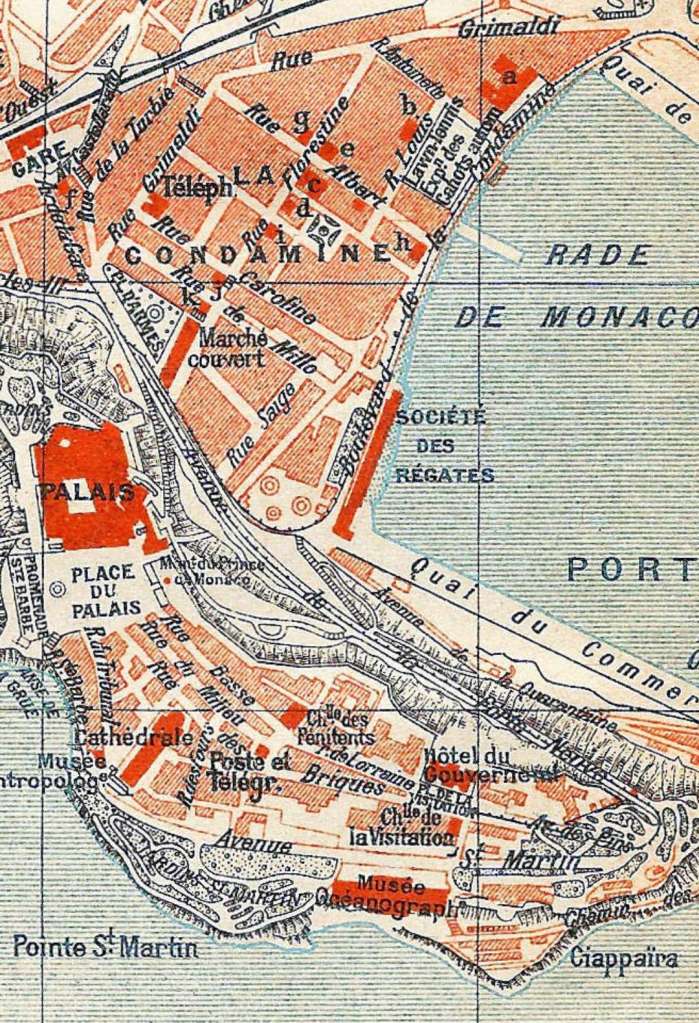

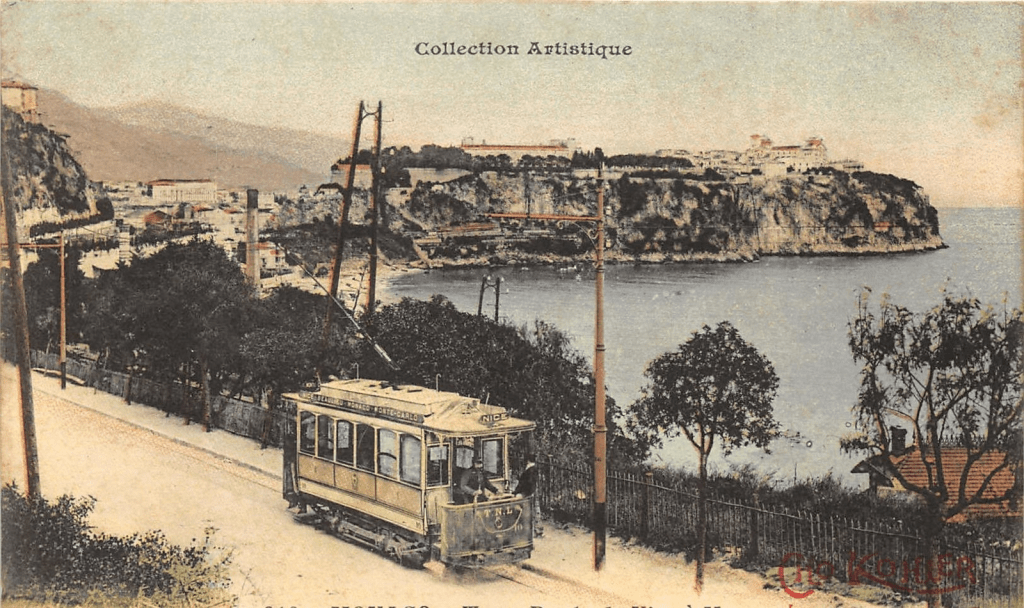

In 1856, “Victor Emmanuel II, King of Sardinia, Cyprus and Jerusalem, Duke of Savoy and Aosta, Prince of Piedmont, Count of Nice and Tende, visited [Nice and] personally promised [a] railway to the people of Nice and distributed a lithograph depicting him, ostentatiously bearing a map bearing the dedication ‘Ferrovia da Cuneo a Nizza. Ai Fedeli Nizzardi’. … The Minister of Public Works commissioned a Roman military engineer, Filippo Cerrotti (1819-1892), to conduct a more in-depth study. On 29th May 1856, Cerrotti submitted a preliminary design for a standard-gauge line from Cuneo, ascending the Gesso and Vermegnana valleys, crossing the Col de Tende through a 6.5 km tunnel accessible by inclined planes powered by hydraulic funiculars, to emerge in the Roya River, which it followed to Airole. From there, two tunnels successively would take it through the Bévéra Valley and then into the Latte Valley, through which it reached the coast, which it then followed to Menton, Monaco, and Nice.” [1: p11]

The Nicois authorities accepted the proposed scheme in September 1856, their counterparts in Cuneo quickly endorsed the plans in principle but asked that an alternative route via the Col des Fenestres and the Vésubie, be explored and that a modification to the initial proposal should be explored, specifically a locomotive-powered line without the use of inclined planes. The municipality of Nice then commissioned another survey of alternative routes by Louis Petit-Nispel, but proposals were rejected by the Ministry of Public Works on 4th March 1858. [1: p11, p14]

Nothing happened, so the Nice authorities sent a petition to the Sardinian parliament (16th July 1858) but the request got lost in the midst of political machinations which surrounded the cession of Savoy and the County of Nice to France which was eventually confirmed on 22nd April 1860.

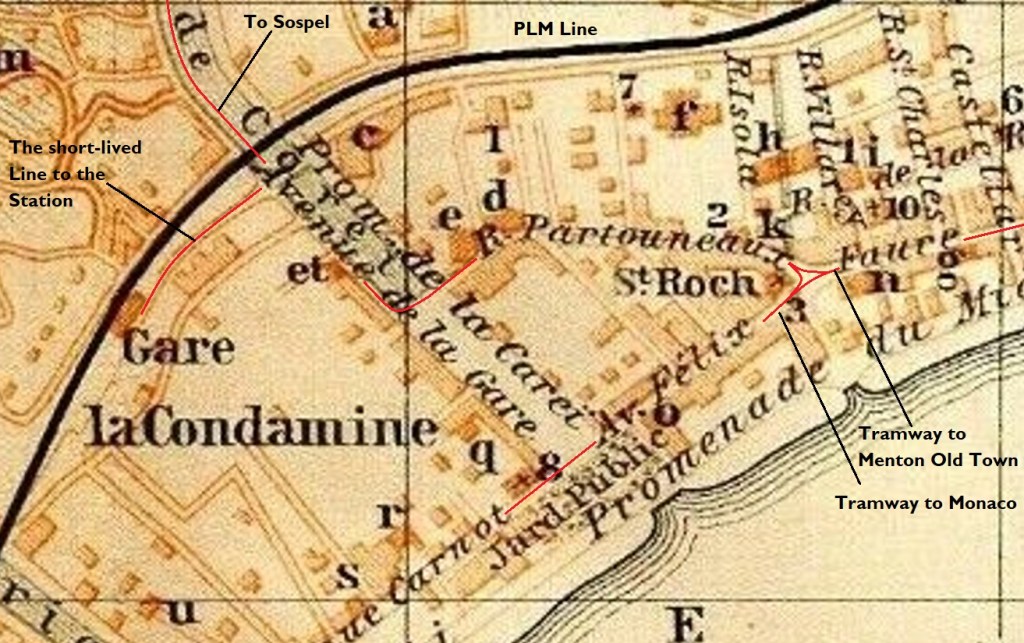

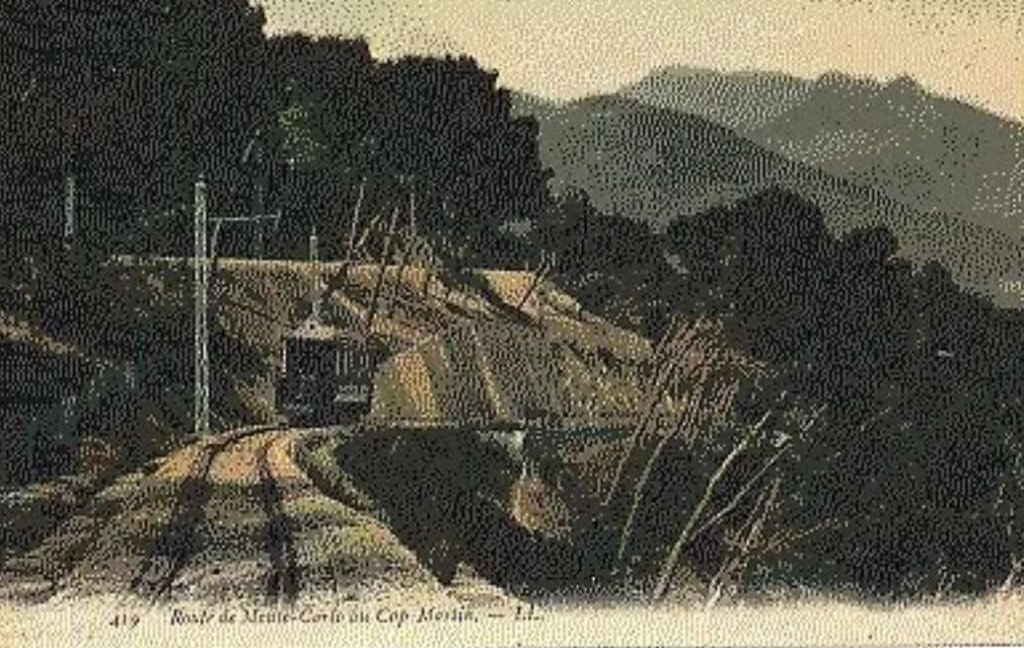

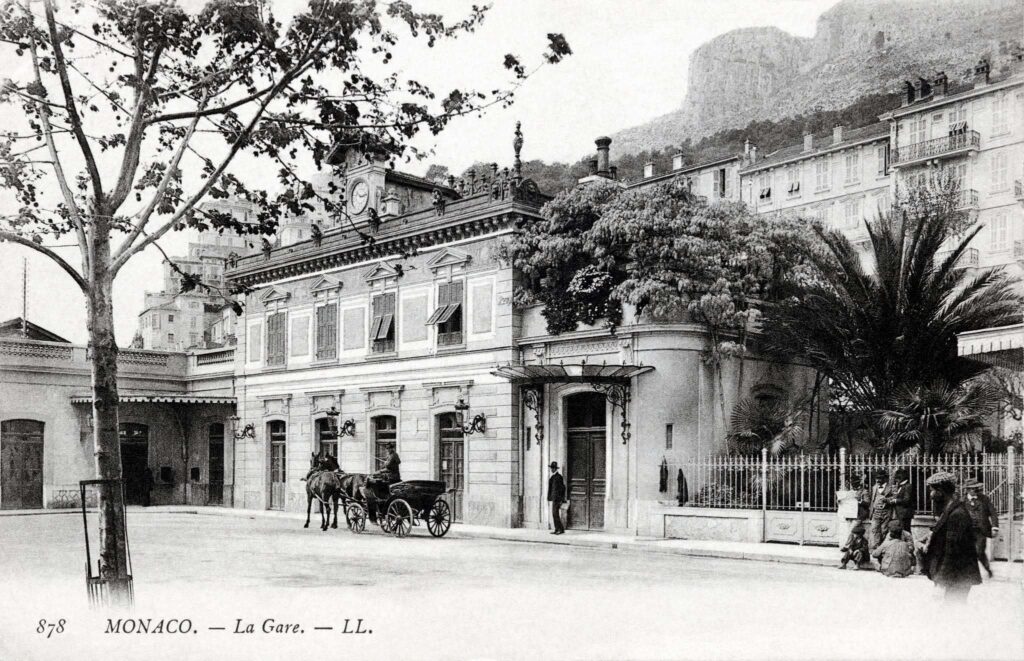

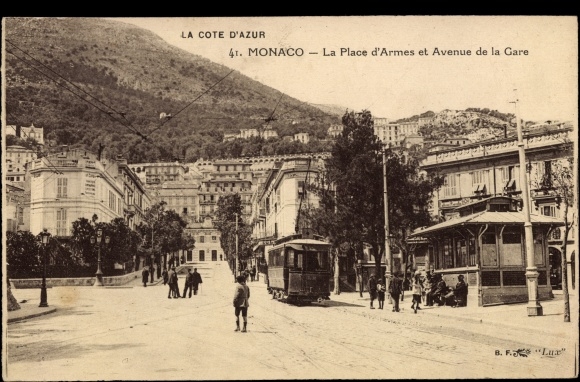

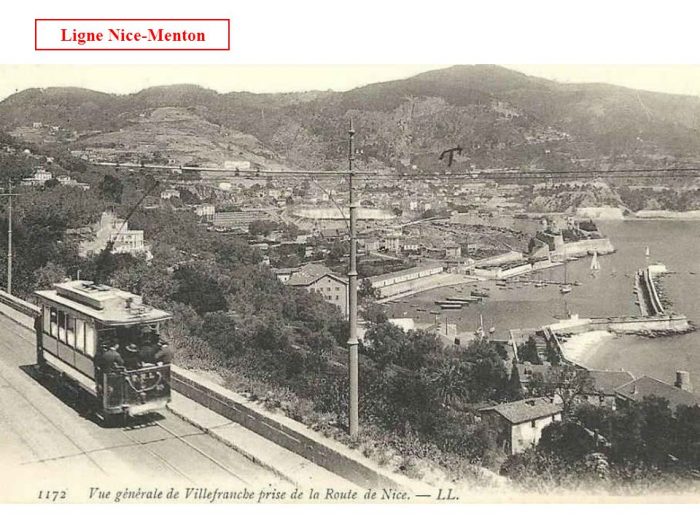

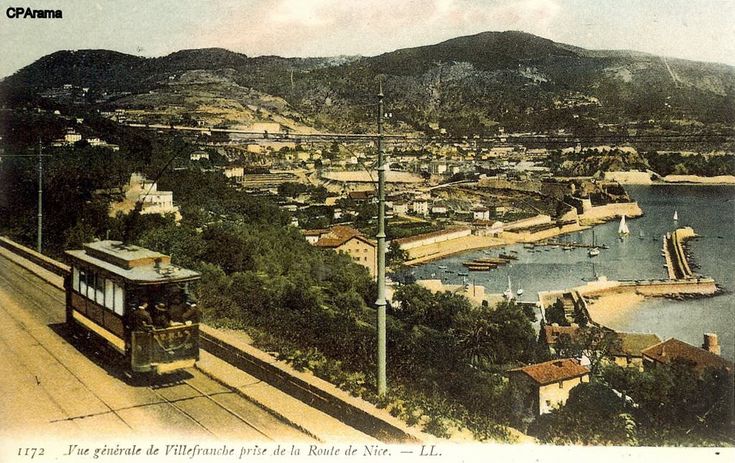

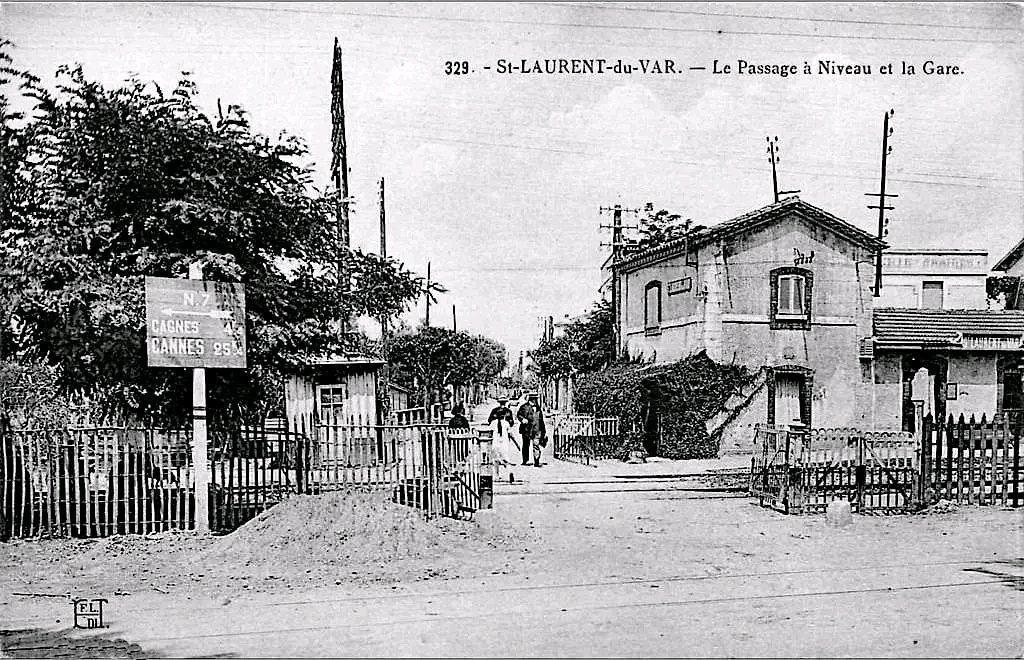

“During his first visit to the new border department in September 1860, the French Emperor promised the people of Nice a rapid connection to Marseille and the rest of the country via the Paris-Lyon-Mediterranean Railway Company (PLM) line, whose construction was then well advanced beyond Toulon.” [1: p14]

Nice got its connection to Marseille by 18th October 1864, but hopes for a Nice to Cuneo link were overshadowed by the desire to have a direct link between Marseille and Turin via Sisteron, Gap, Briançon, the Col de l’Echelle, and Bardonecchia – a plan was eventually shelved (even though it was favoured by the French government and the PLM company) as a result of the deal-making associated with the Saint-Gothard line.

In the mid-1860s the Piedmontese railway network became part of the Società per le Ferrovie dell’Alta Italia (SFAI). Its focus became developing internal infrastructure in Italy, with the exception of a very large project … a 13.7 km (8.5 mile) long tunnel, carrying the Turin-Modane railway line under Mont Cenis, linking Bardonecchia in Italy to Modane in France under the Fréjus. [1: p17][8]

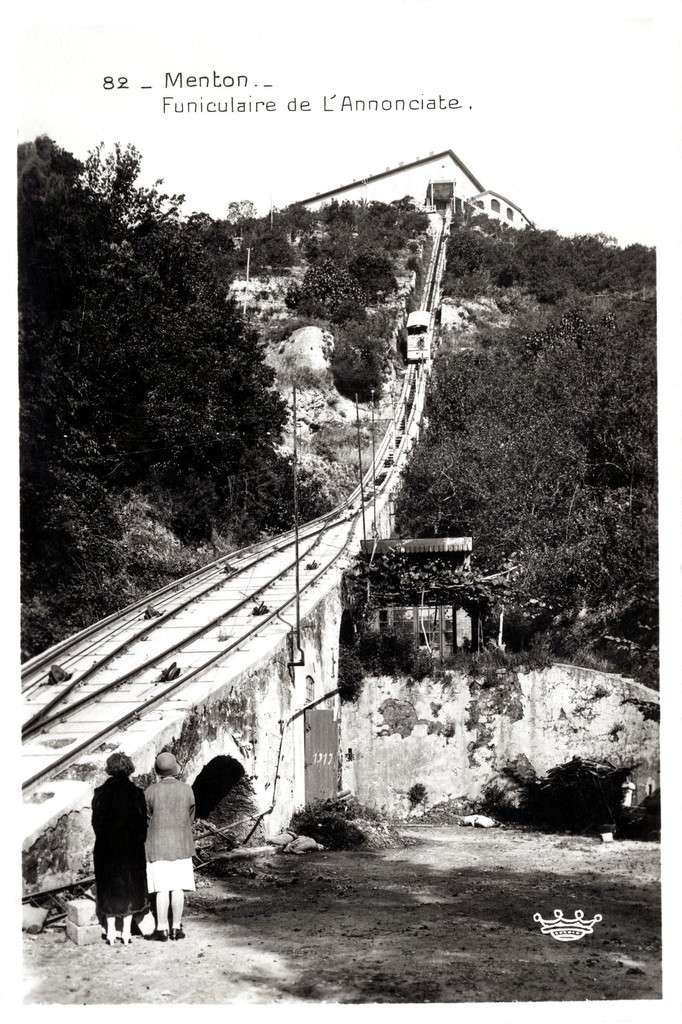

Despite this, economic and political groups in Cuneo remained committed to having a rail link and in 1868 proposed a joint commission of French and Italian engineers. The following year, “the provincial authorities granted a loan of 500,000 lire to the Lombard engineer Tommaso Agudio (1827-1893), who sought to develop the possibilities offered by funicular traction. He, in collaboration with the engineer Arnaud, recommended the construction of a narrow-gauge railway alongside the SS 20 national road, along its entire route from Cuneo to Ventimiglia. This hypothesis suggested curves with a radius of less than 50 m and gradients of 45 mm/m. The Tende Pass was to be crossed by the planned road tunnel, with two access ramps sloping at 87.5 mm/m, on which traction would be provided by a hydraulically counterweighted cable.” [1: p17]

His project was approved by the Italian parliament in 1862 but no progress was made on the French side of the border. The project failed and Tommaso Agudio moved on to other things, “experimenting with his cable traction system in 1874 in Lanslebourg, then by applying it in 1884 to the railway linking the Turin suburb of Sassi to the famous Basilica of Superga.” [1: p17]

With little progress being made on a rail link, road links became paramount, a commission chaired by the civil engineering inspector Sebastiano Grandis (1817-1892) renewed interest in 1870 in a road tunnel under the Col de Tende which Grandis imagined would obviate the need for a railway.

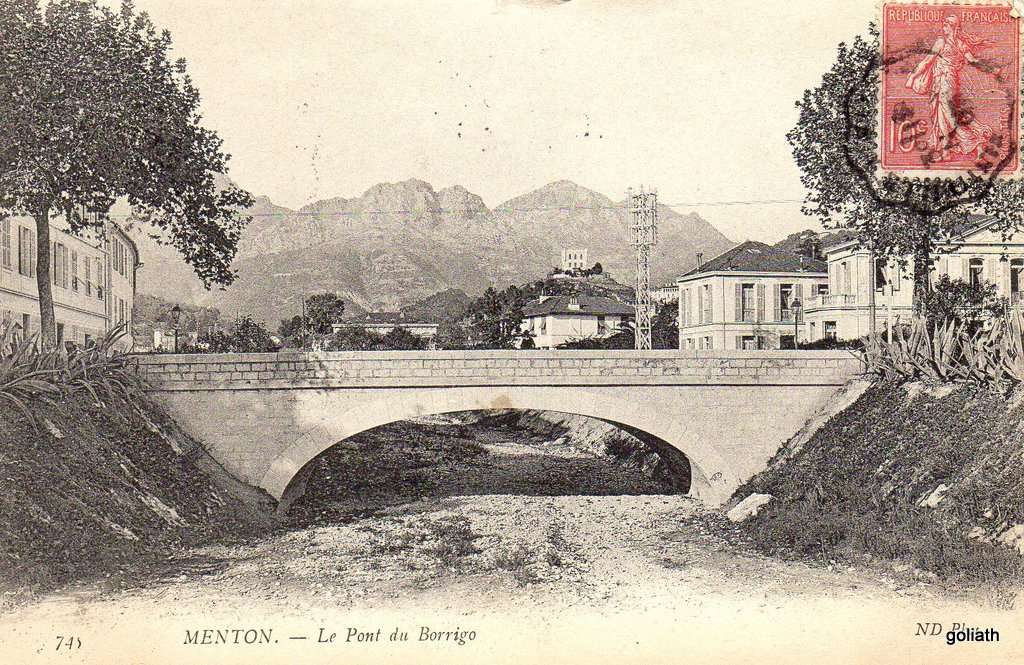

“Following the fall of the Empire, France and Italy were finally connected by rail, first through the Fréjus Tunnel, opened between Modane and Bardonecchia on 17th September 1871, and then through the Menton and Ventimiglia on the coast on 23rd February 1872. At the same time, traffic between Piedmont and the former County of Nice was growing at an encouraging pace: the Fontan customs post recorded an annual transit of 22,000 tons of goods and 76,447 head of cattle. Under these rather favorable conditions, Nice’s business community sought to revive discussions with a view to attracting to their port a share of the benefits of the upcoming opening of the Saint-Gothard line, whose traffic, they feared, would exclusively benefit Genoa via the Via Giovi, or Marseille in the event of the construction of the Col de l’Echelle route. In April 1871, a group of industrialists and politicians from the region, including the mayor of Nice, Auguste Raynaud (1829-1896) and his counterpart from Toulon, Vincent Allègre (1835-1899), founded a Syndicate for the Nice Cuneo Line with the support of the Alpes-Maritimes Chamber of Commerce. On 7th November, the municipal council sent a personal letter to Adolphe Thiers, the new President of the French Republic, to express the desire of the people of Nice to see this project, which had been on hold for some twenty years, realized. On 29th November, the syndicate appointed a study commission headed by engineer Joseph Durandy (1834-1912), … to establish contacts with interested Italian parties and determine the advantages and disadvantages of each proposed route.” [1: p19]

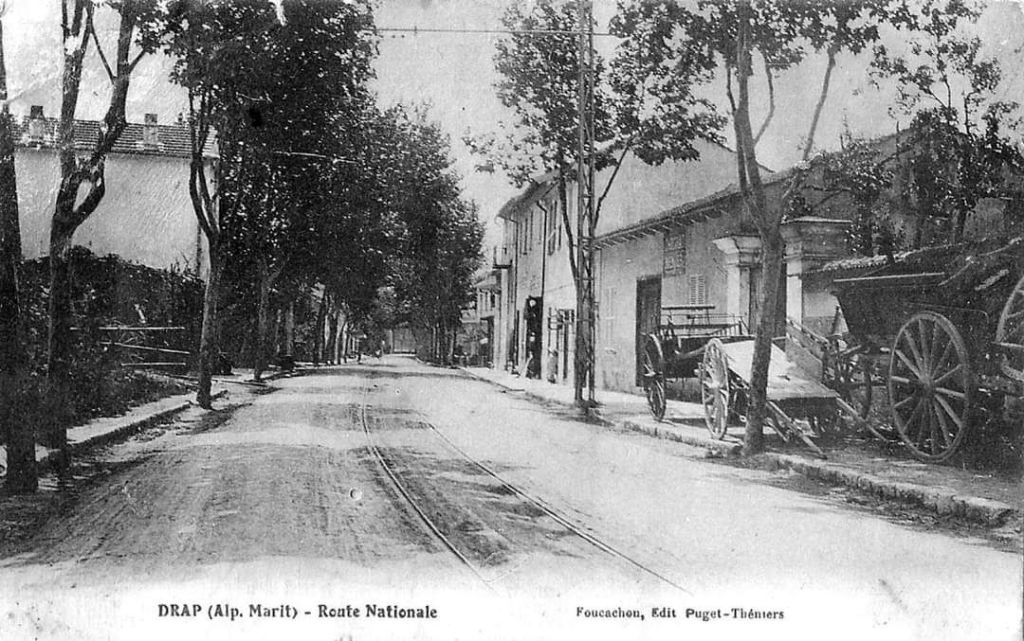

“In March 1872, the engineer Henry Lefèvre (1825-1877), a public works contractor and member of parliament for the Alpes-Maritimes, published an ambitious programme comprising two railway lines, Nice – Digne and Nice – Cuneo. They would run as a common trunk up the Var valley to the confluence of the Vésubie; from there, the branch towards Piedmont would follow this river to its source, crossing the Pagari pass under a 7000 m tunnel drilled at an altitude of 1300 m, to then reach Cuneo via the Gesso valley. The gradients would not exceed 35 mm/m, which would however require several reversals from Venanson, as well as the use of articulated Fairlie locomotives.” [1: p19][9]

Lefèvre’s project was based on poor maps and went through areas with a high risk of avalanches and heavy snowfall. Durandy suggested that a longer tunnel (almost 15km long) could be employed, Delestrac suggested following the undulations/contours on the left bank of the Vésubie as much as possible to reduce the number of engineering structures and limit the gradients to 25 mm/m.” [1: p19] Both these suggestions significantly increased the costs of Lefèvre’s 120 km project.

Other projects were proposed:

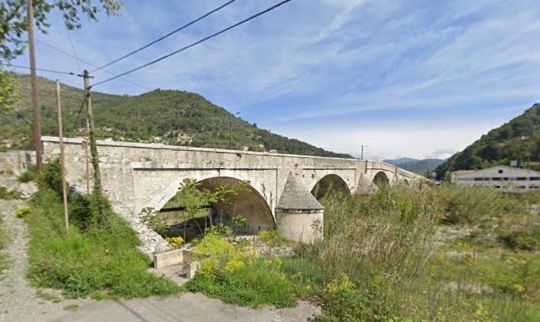

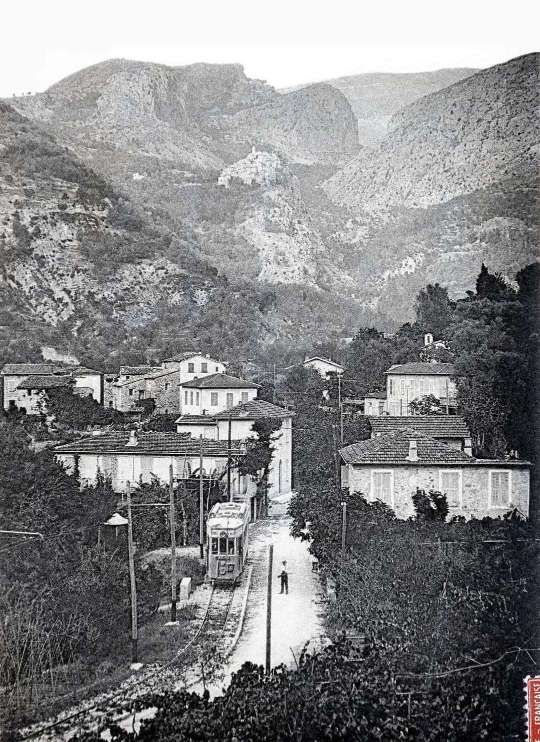

- In 1872, Séraphin Piccon proposed a “103 km long narrow-gauge route, crossing the Col de Tende through a 5100 m tunnel at a height of 1150 m. Descending the valley of la Roya to Piena, reaching the Bévéra basin and Sospel through a 1300 m tunnel under the Col de Vèscavo, then heading up the Merlanson valley to pass under Mont Méras through a new tunnel leading to Peille, and thence to Nice through down the valley of the Paillon. Access to the Col de Tende would be via two inclined planes with inclinations of 40 to 85 mm/m totaling a length of 6100 m, while a 60 mm/m gradient over 4700 m would allow the line to gain altitude north of Peille.” [10] On these steep gradients, traction would be assisted by a rack or an auxiliary central rail (the Fell System). [11][1: p20]

- Also in 1872, Baron A. Cachiardy de Montfleury of Breil submitted a renewed proposal to the Conseil General, based on the Narrow-Gauge route between Cuneo and Ventimiglia funicular sections developed by engineers Agudio and Arnaud. [12][1: p20]

- Then in April 1873, Baron Marius de Vautheleret. presented a proposal for a narrow-gauge Cuneo-Ventimiglia line using the planned Col de Tende road tunnel, passing through Briga, then through a 13,000 m tunnel under the Marta peak and then along the Nervia valley to its mouth near Ventimiglia. This route aimed to simplify administrative procedures by bypassing French territory, even if it meant creating a costly underground tunnel to connect the Roya to the Nervia river valleys. Gradients would not exceed 35 mm/m except for 22 km on either side of the Col de Tende, where gradients of 38 to 40 mm/m would require the adoption of a rack or hydraulic funicular. [13][14][1: p20]

These last two projects were discarded, partly because they were narrow gauge and required steep gradients, neither of which would suit the anticipated important international traffic and partly because they only linked two Italian cities while passing through French territory and not serving Nice. Both the protagonists continued to push their case until the end of the 19th century.

The first project proposal by Piccon was also deemed incompatible with heavy traffic flows but in its favour was the intent to link the railway to Nice. The “Durandy Commission preferred this option, subject to significant technical adjustments, such as adopting the standard gauge and replacing the inclined planes with longer base tunnels. On this route, the syndicate hoped for annual freight traffic of 90,000 tons despite a higher cost per kilometre than the routes via the Tinée or the Careï, as well as a revival of passenger traffic.” [1: p20]

The PLM had little enthusiasm for the proposed line as their experience of lines in the Alps encountered technical difficulties and had profitability problems

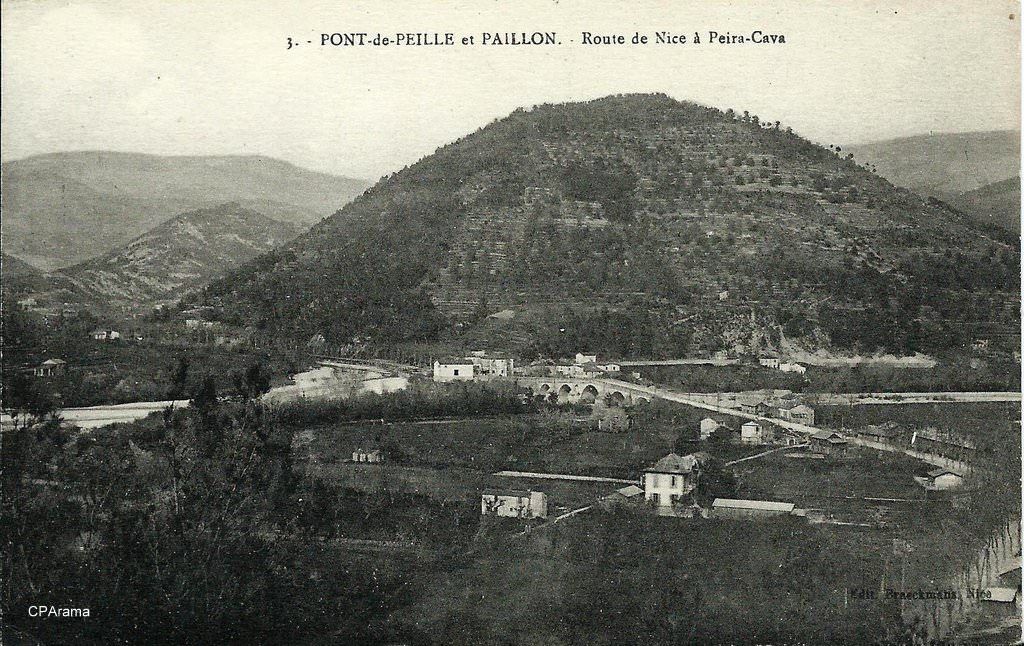

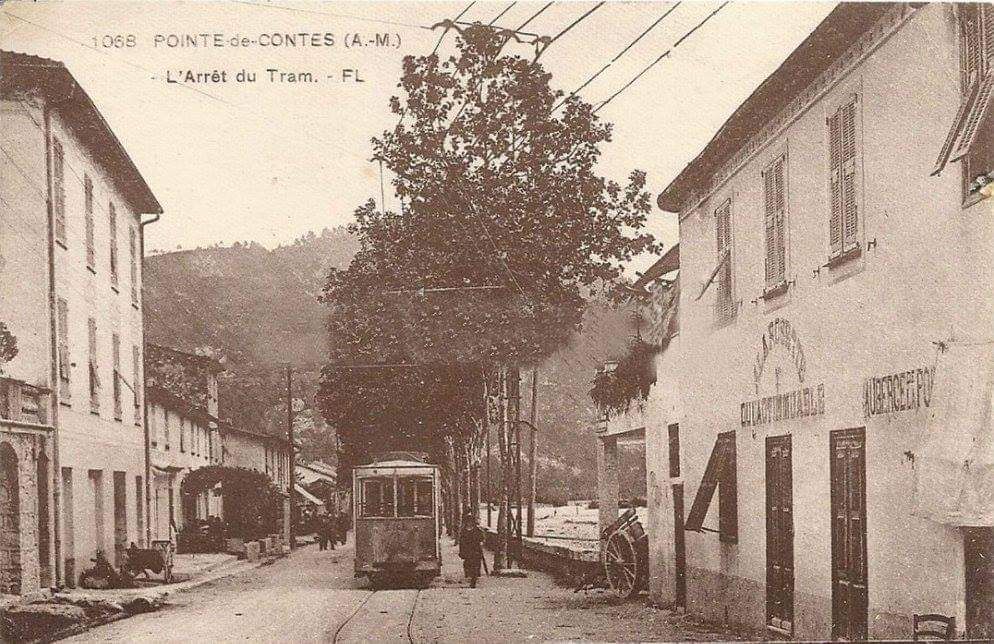

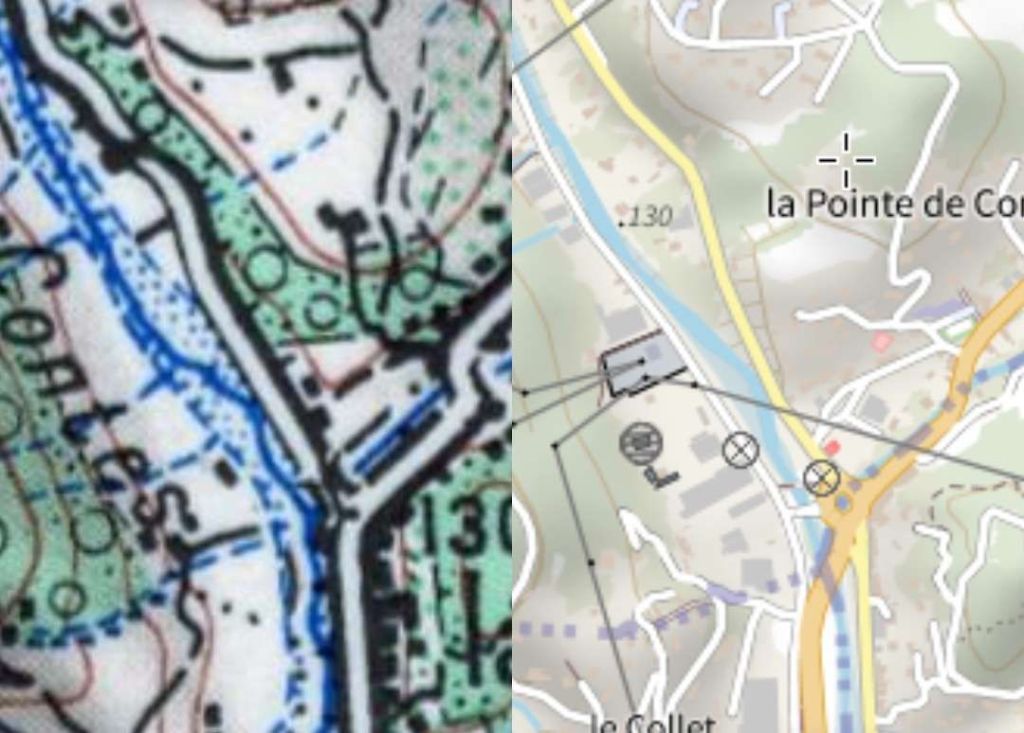

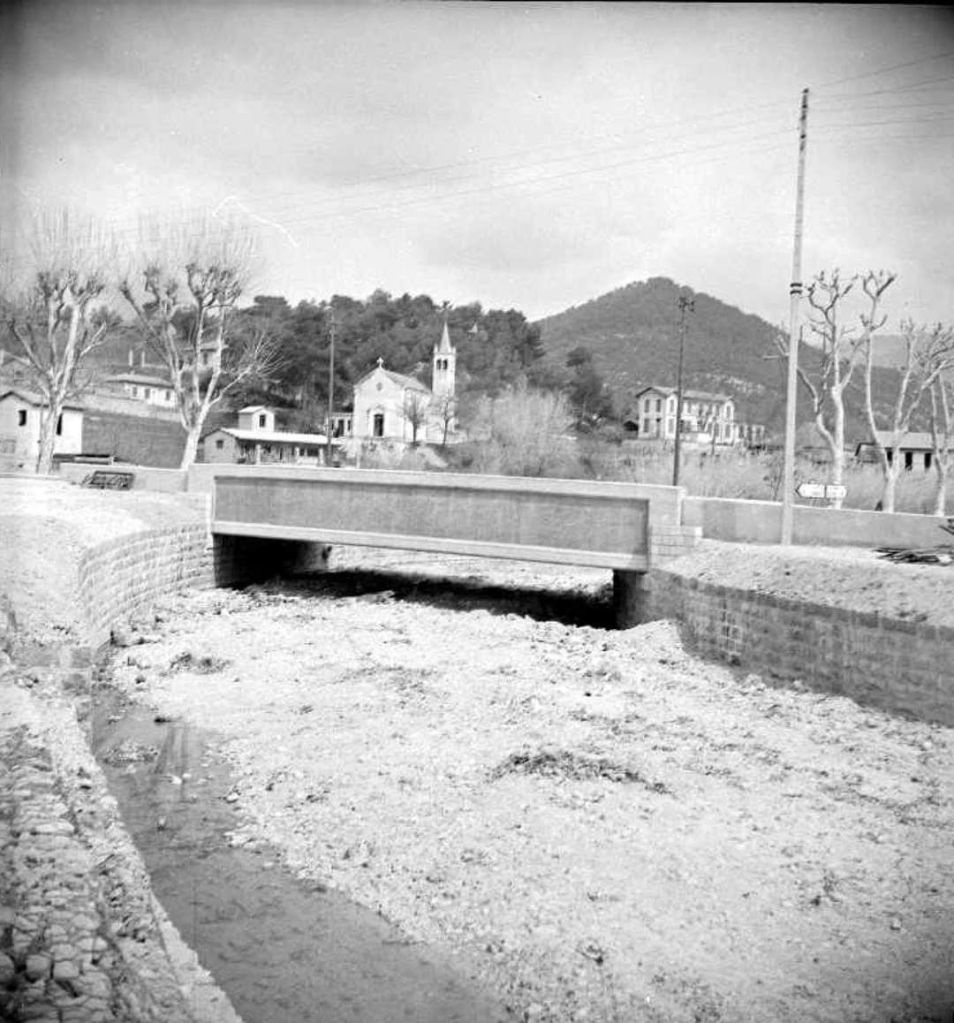

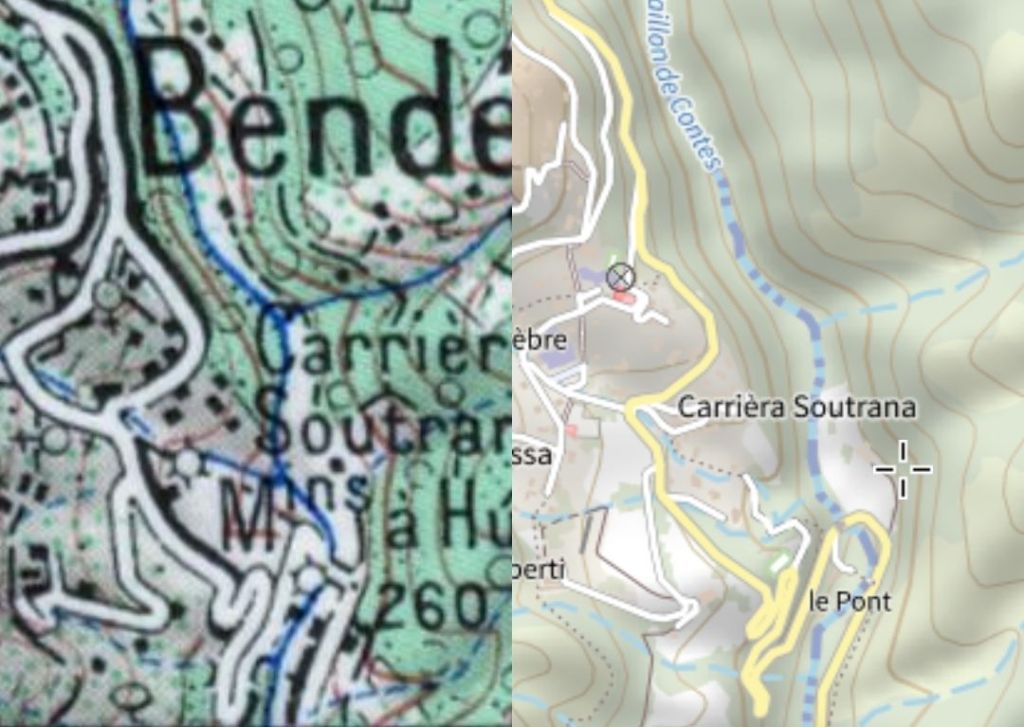

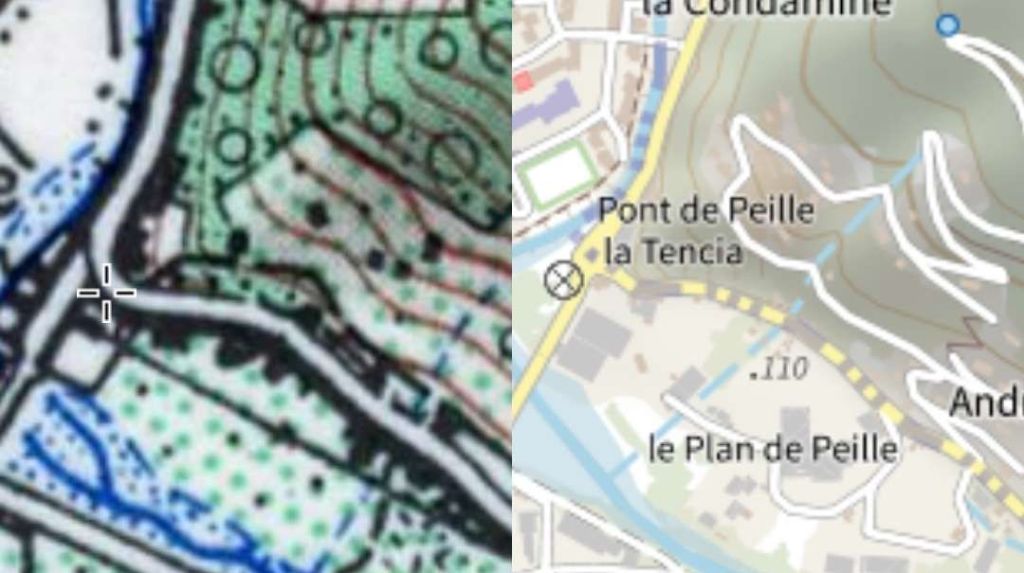

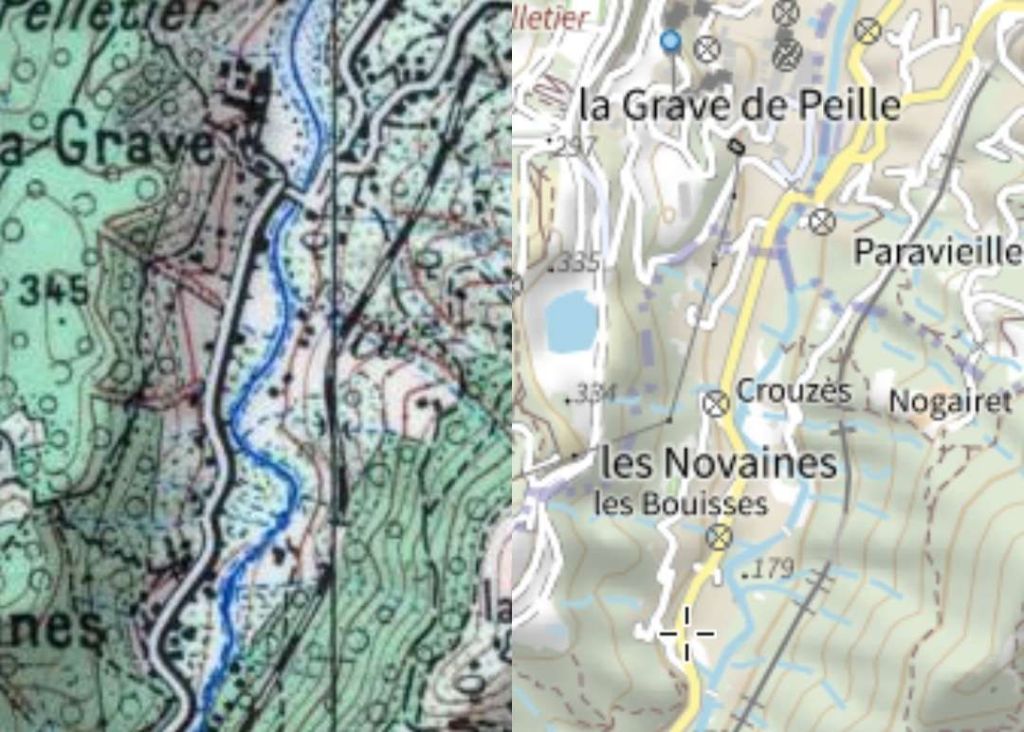

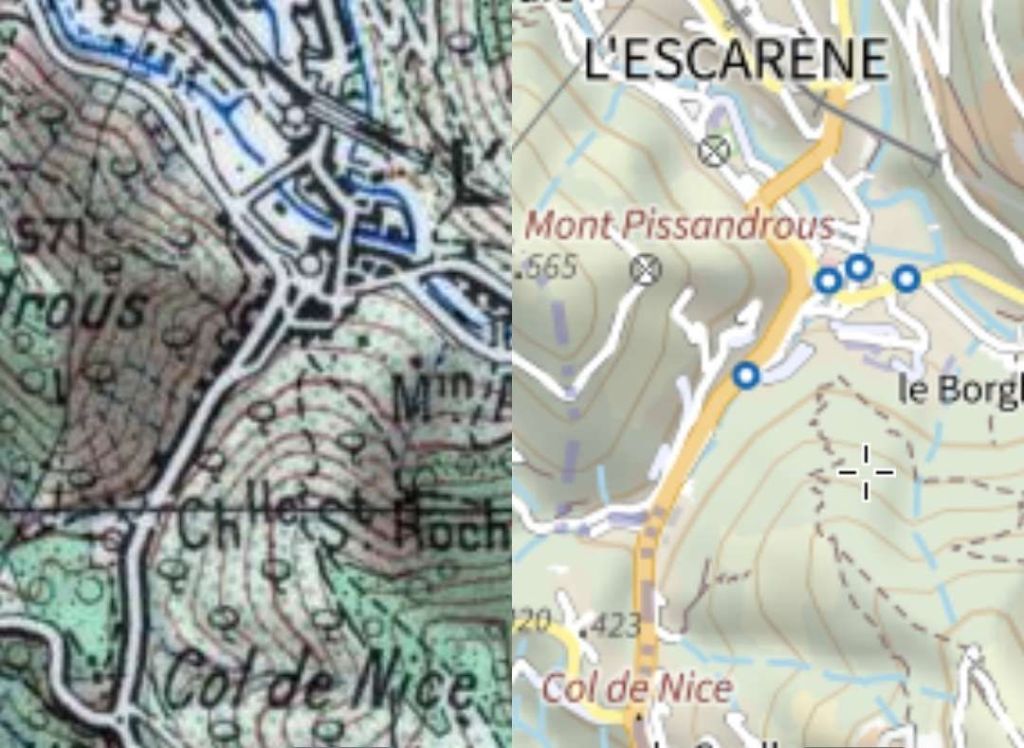

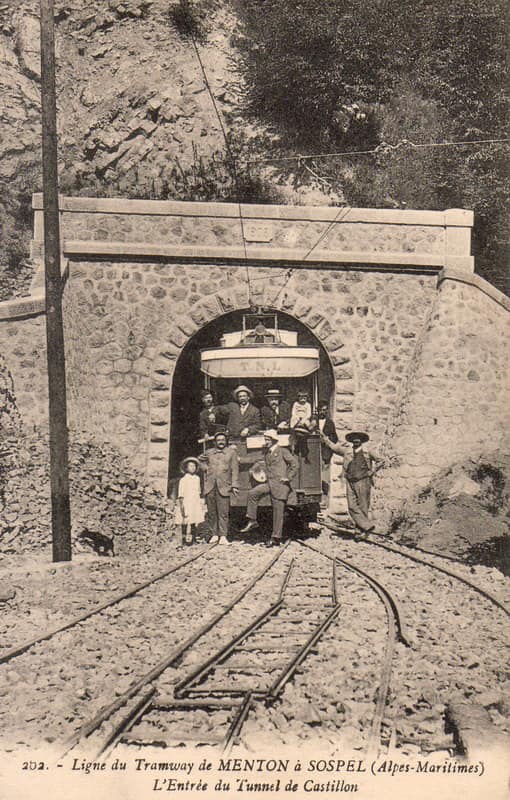

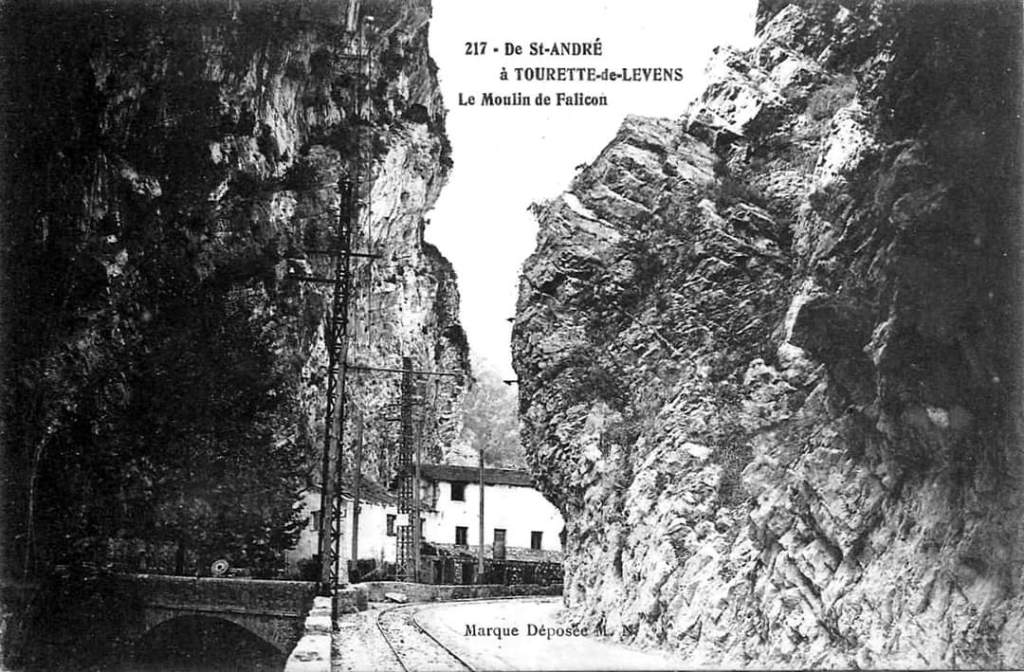

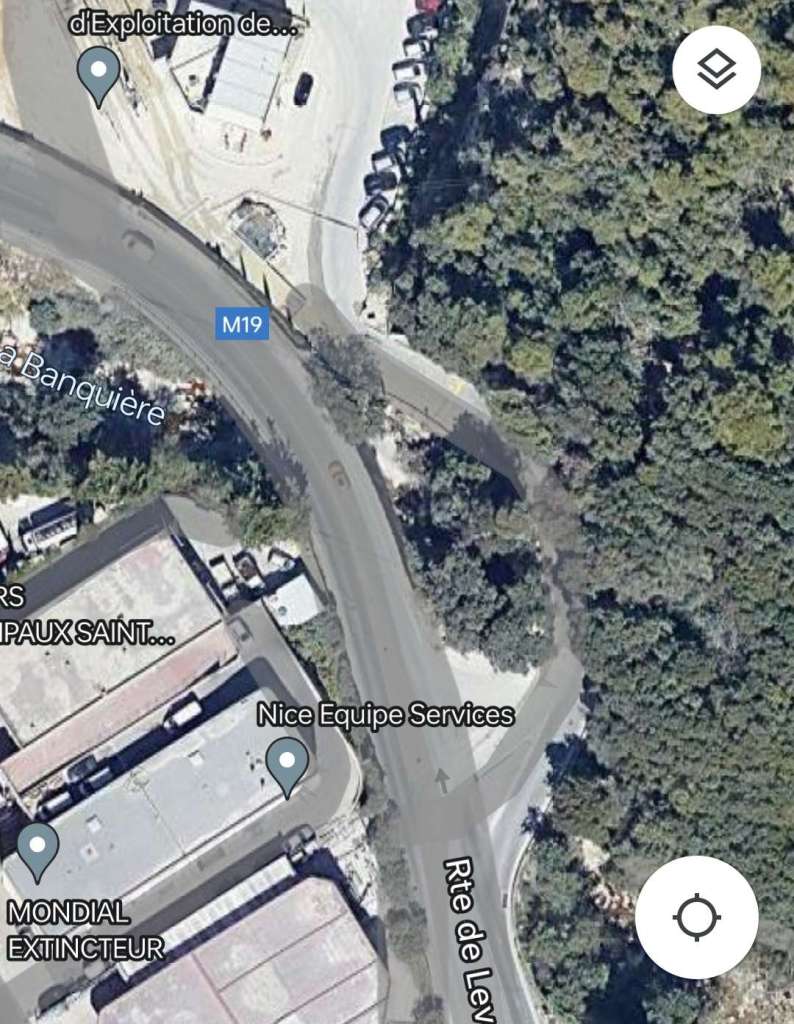

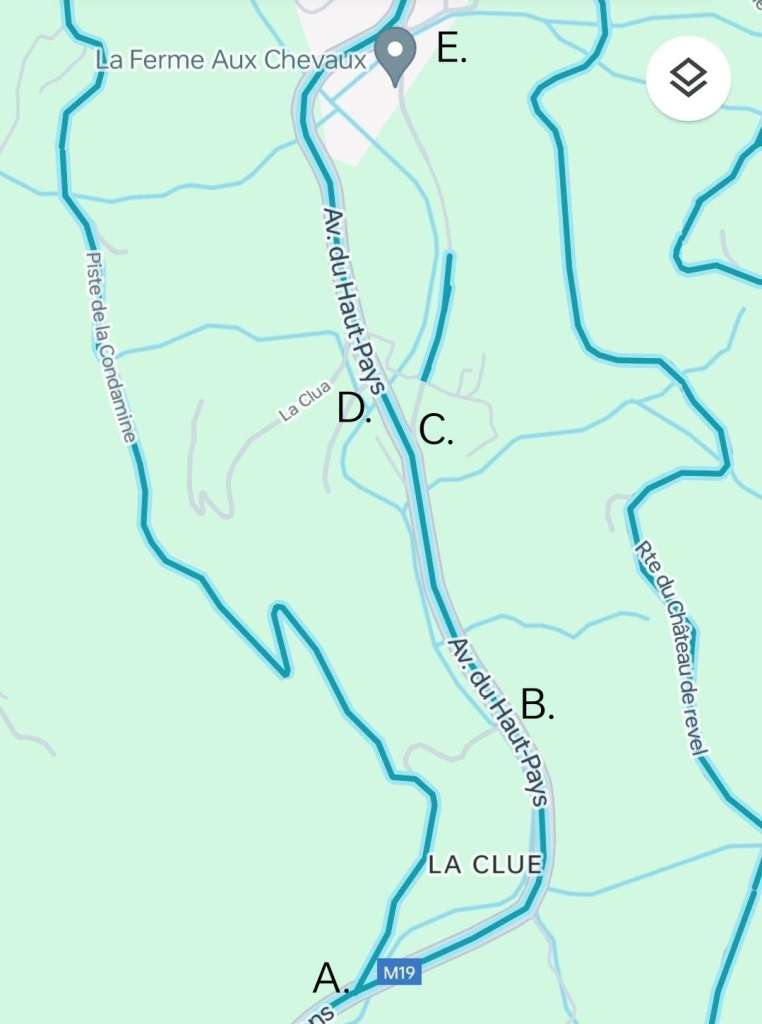

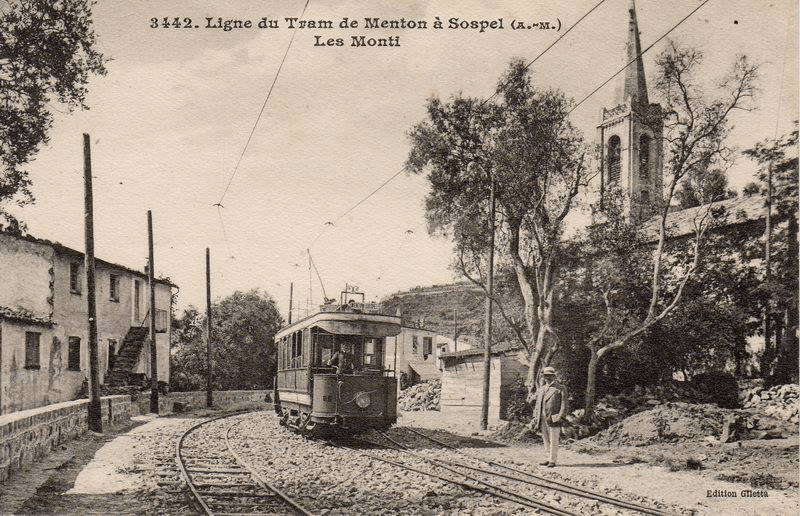

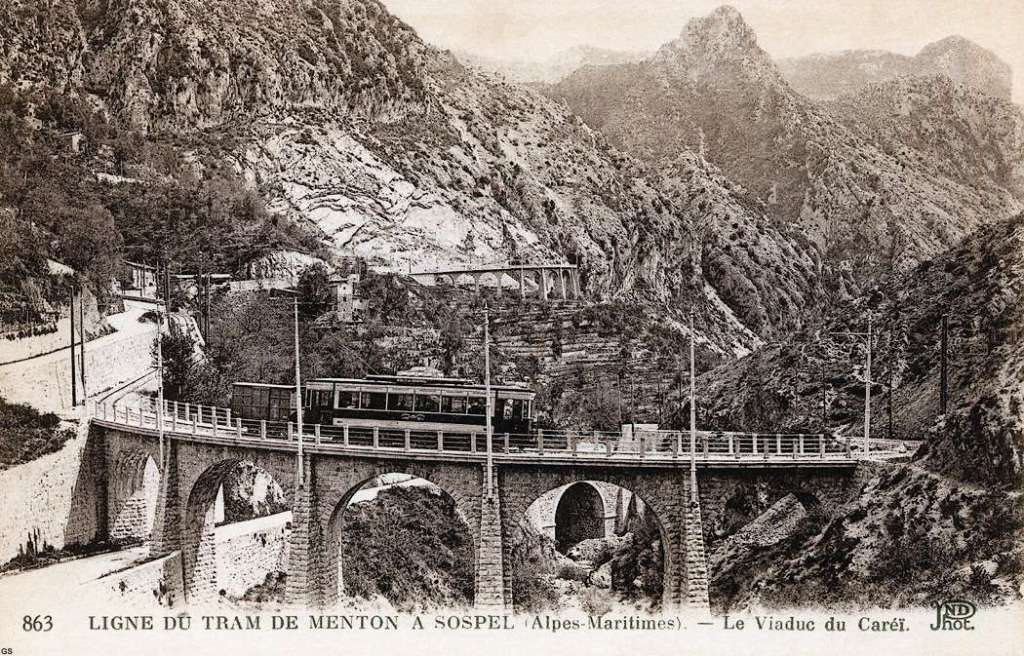

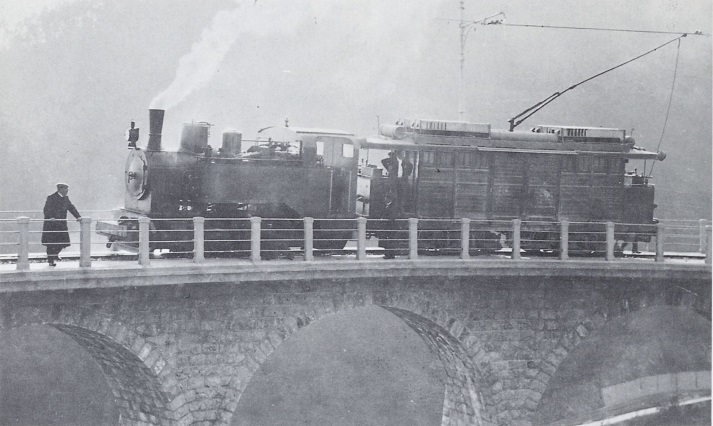

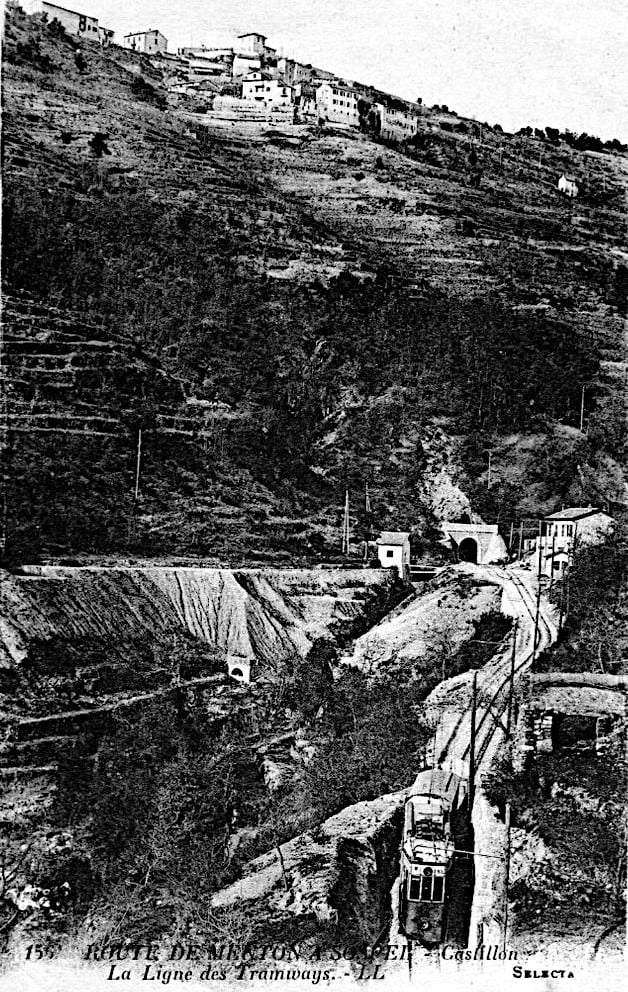

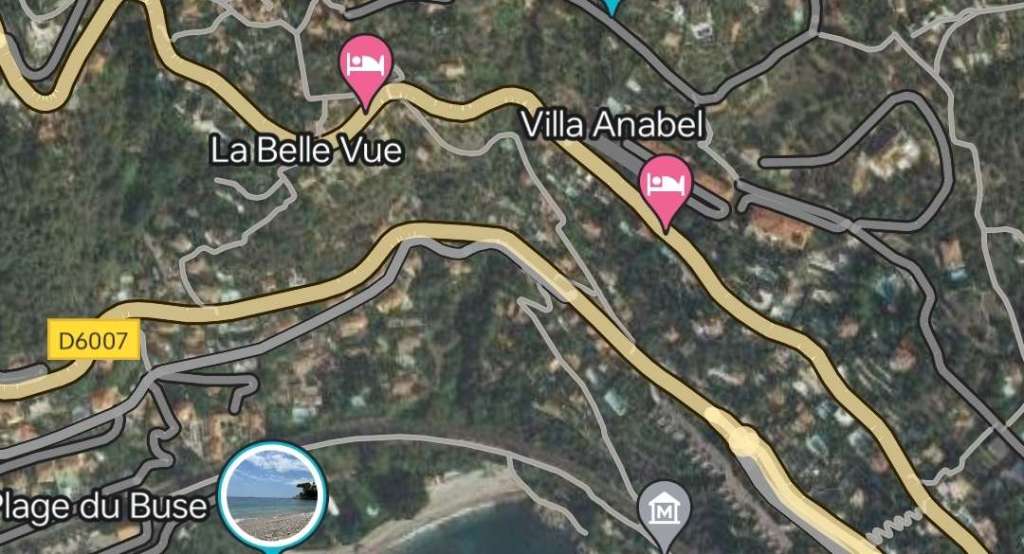

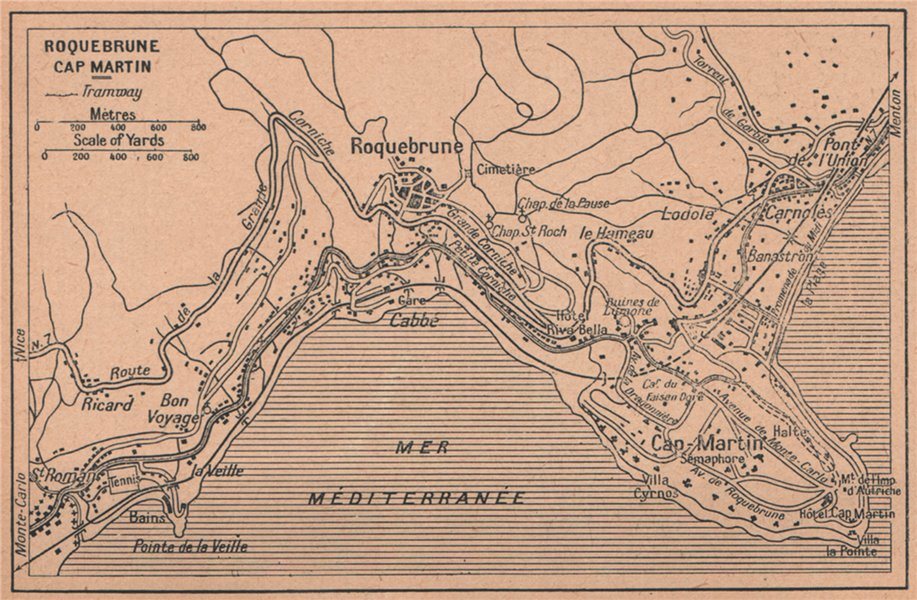

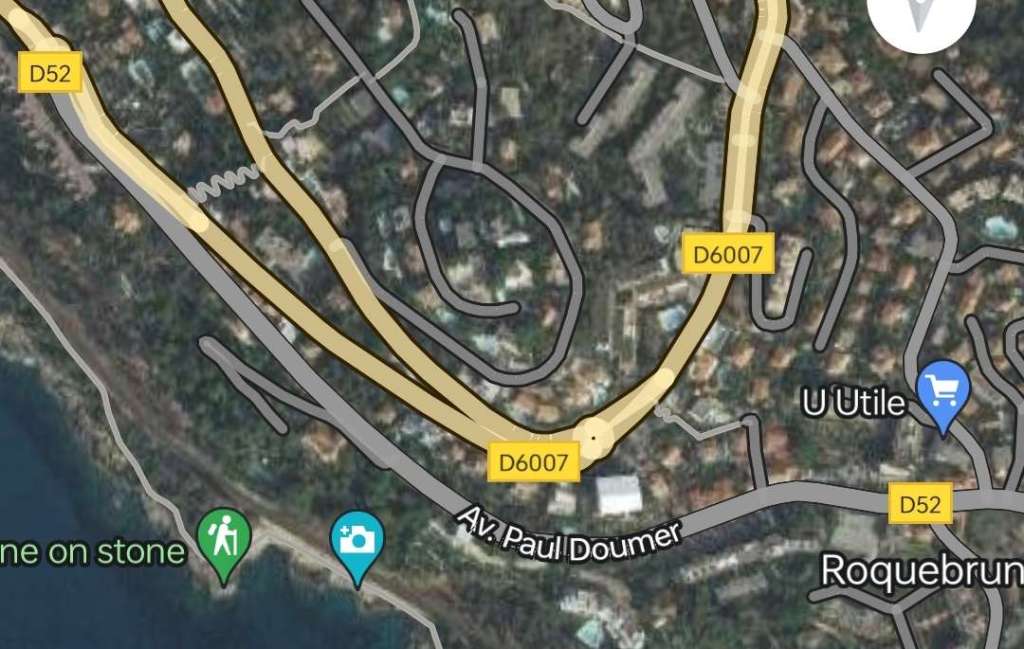

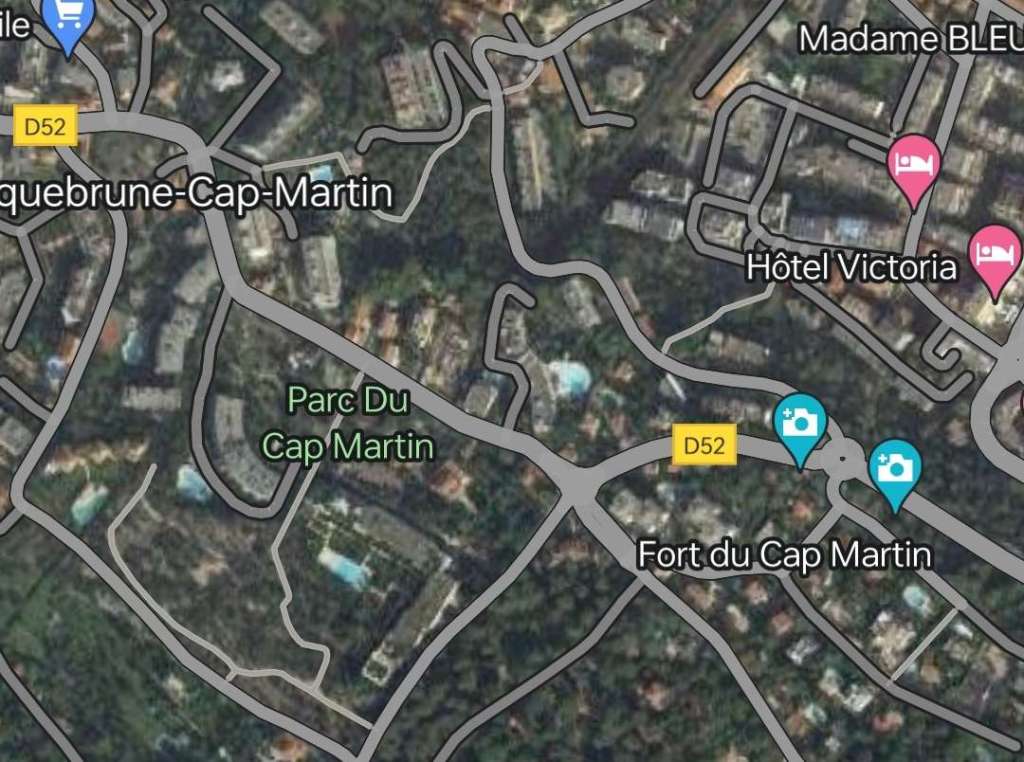

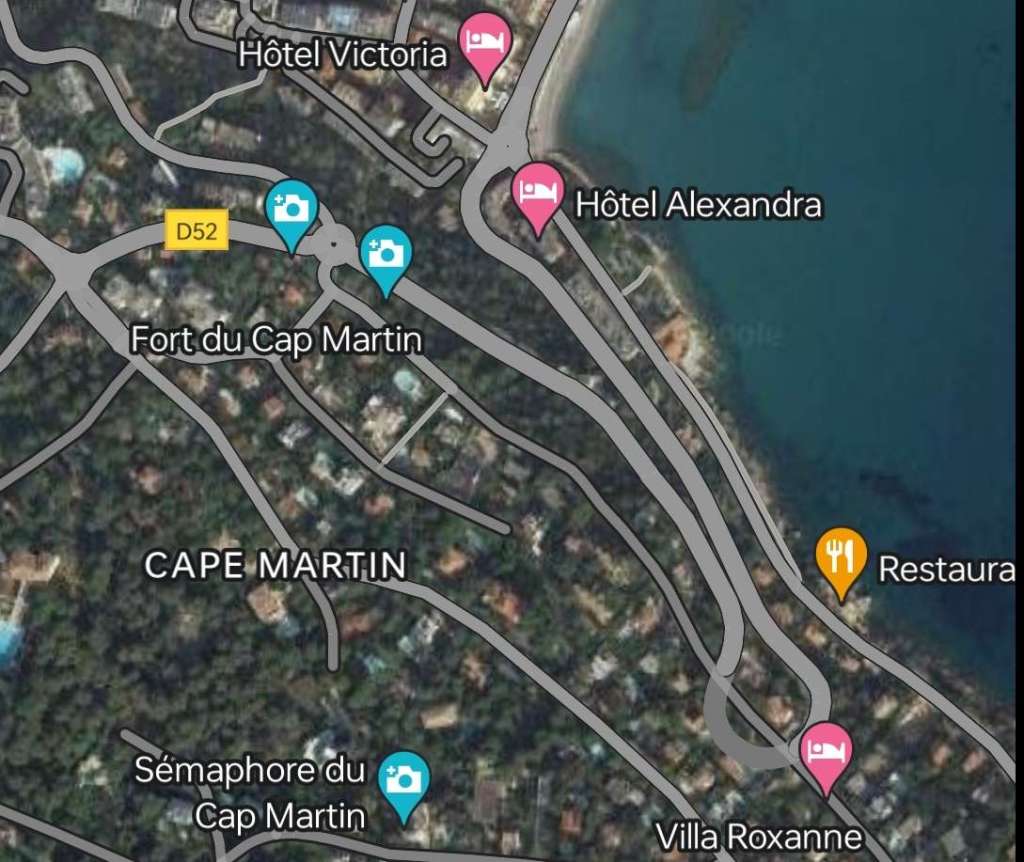

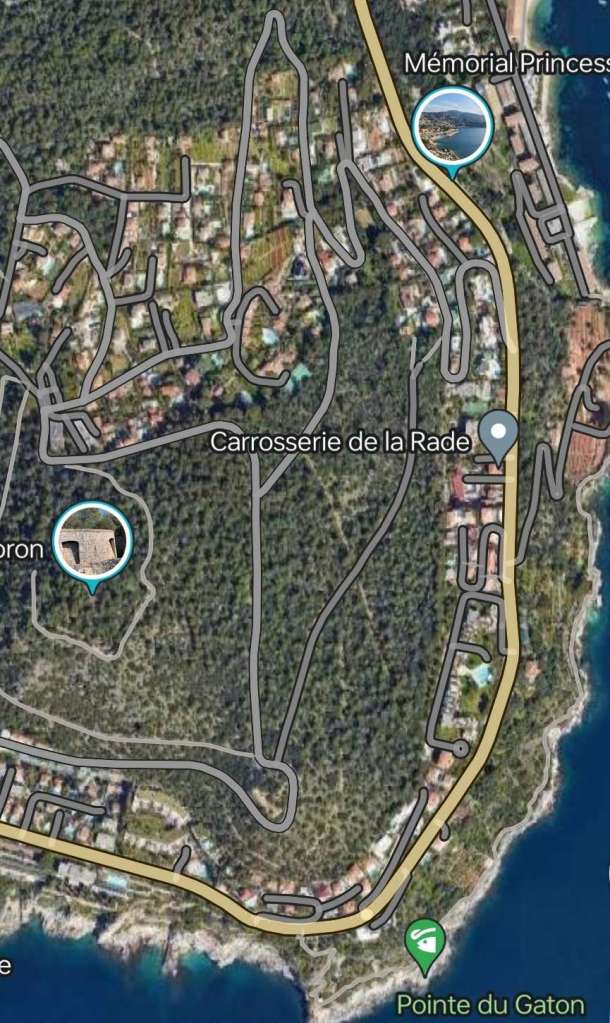

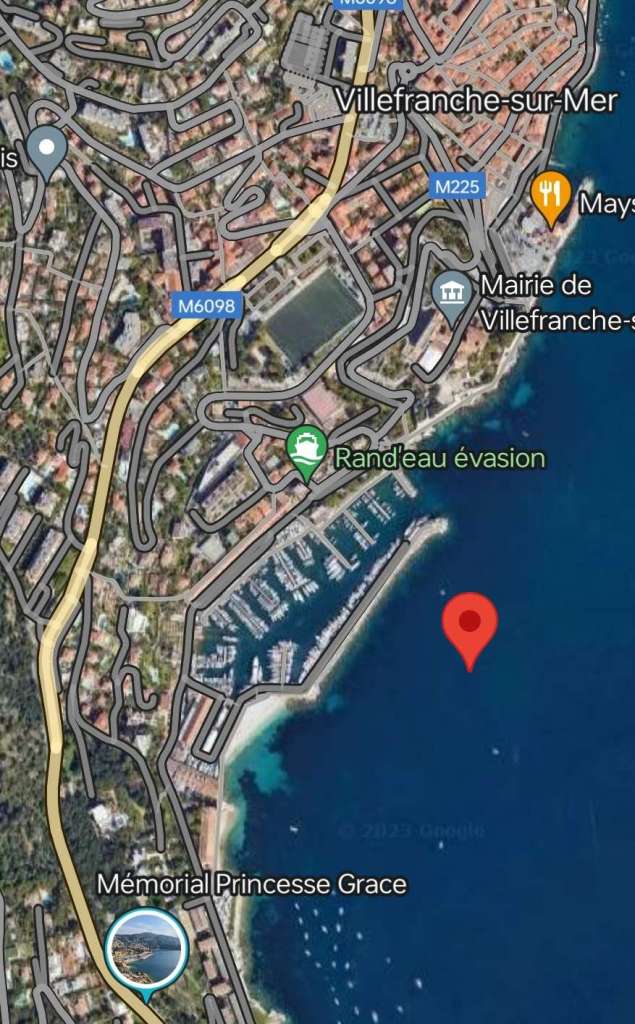

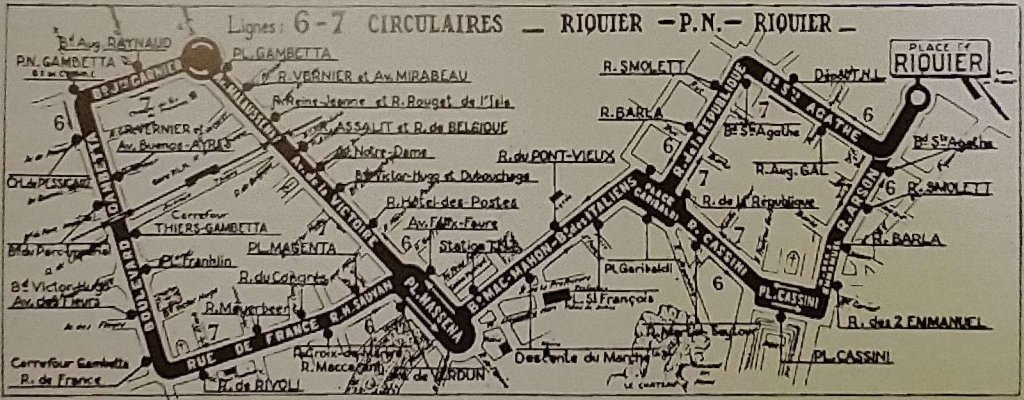

In 1878, the Minister of Public Works, Charles de Freycinet (1828-1923), asked regional authorities to consider possible lines to become part of a network of secondary lines across the country. The Prefect of the Alpes-Maritimes submitted the line ‘from Nice to the Italian border’, running from Nice to Turin via the Paillon Valley, the Col de Nice, L’Escarène, the Col de Braus, Sospel, the Col de Brouis, Breil, the Roya Valley, and the Col de Tende. This route was registered No. 142 in the network in the law of 17th July 1879, where it appeared alongside the Nice – Digne via Saint-André and Nice – Draguignan via Grasse lines. [1: p21]

While the Cuneo-Nice line was a low priority for the national government in Italy, but Piedmont and Liguria did not give up, encouraged by the interest on the French side of the border. A number of different schemes were considered (from Baron de Vautheleret, Giacomo Pisani and Domenico Santelli).

Renewed interest at a national level led, in April 1876, the ‘conseil superieur des Travaux Publics’ approved the principle of a Cuneo – Ventimiglia railway, following the Roya along its entire course, including crossing French territory. The estimated cost for the 86 km on Italian soil was 38 million lire.

Two years later, while France was preparing its “Freycinet plan”, Italy had its ‘loi Baccarini’ (law 5002) which was passed in parliament on 25th July 1879 and included for a secondary line ‘from Cuneo to the sea’, “leaving all options open South of the Col de Tende so as not to prematurely offend any interests.” [1: p23]

By the end of July 1879, the process seemed well underway but no one allowed for the political machinations that would follow.

“The first disappointments emerged in France in 1880 during the budget debates, where the President of the Chamber of Deputies, Léon Gambetta (1838-1882), postponed the vote on construction funding. On 22nd July, the General Council of Bridges and Roads rejected an initial project, which included 30 mm/m gradients and 300 m radius curves, as too costly. In November 1881, the Ministry of War was even more categorical, formally opposing the extension of the railway beyond Sospel, and demanding that it serve the village of Lucéram from L’Escarène, the supply base for the defensive sector of L’Authion, Turini and Peïra-Cava. In this case, the line would have to adopt even more severe characteristics: 40 mm/m gradients, 150 m radius curves, switchbacks to cross the Col de Nice and helical loops to reach Lucéram…” [1: p24]

“In 1882, an important step towards opening up the Haute Roya region was taken with the commissioning of the Col de Tende road tunnel. … This structure, remarkable for its time, was designed for the movement of carts, horses, pedestrians and. cannons, because the defense of the Tenda and Briga area was a major concern for the Italian general staff! The journey now avoided the countless hairpin bends of the pass and the risk of snowstorms and avalanches.” [1: p24]

But while economic and emotional ties remained strong between Cuneo and Nice, they were weakening between Rome and Paris due to political, commercial, and colonial rivalries that would poison relations … for about fifteen years. The attitude of the city of Marseille was also difficult. The business community in Marseille was hostile to a new rail link between Nice and Italy. Fearing the expansion of the port of Nice at their expense. They lobbied against any possible expansion of the port of Nice, even to the extent of thwarting standard-gauge lines from Nice to Digne and Draguignan, ensuring that the lines were built to metre-gauge (with less transport capacity and obligatory double-handling of loads). [1: p24]

Locally, in Nice, some pushed for the line to be metre-gauge, thinking that might iron out the technical difficulties and strategic objections. [1: p24] Faced by the administrative impasse which stalled the project in France , the French Ministry of Public Works decided to close its Nice design office on 1st September 1887. Italy, however, worked unilaterally with the intention of opening up the Haute Roya without prejudging the continuation of the route towards France. [1: p24]

From 1882 until 1900 it was the Italians that took the initiative. A delegation from Cuneo secured 29.5 million lire from the Italian Minister of Public Works. The first length of the scheme received local approval on 25th March 1882. Work on site started in April 1882 on the length of the line from Cuneo to Vernante.

The first length of the line – Cuneo to Vernante

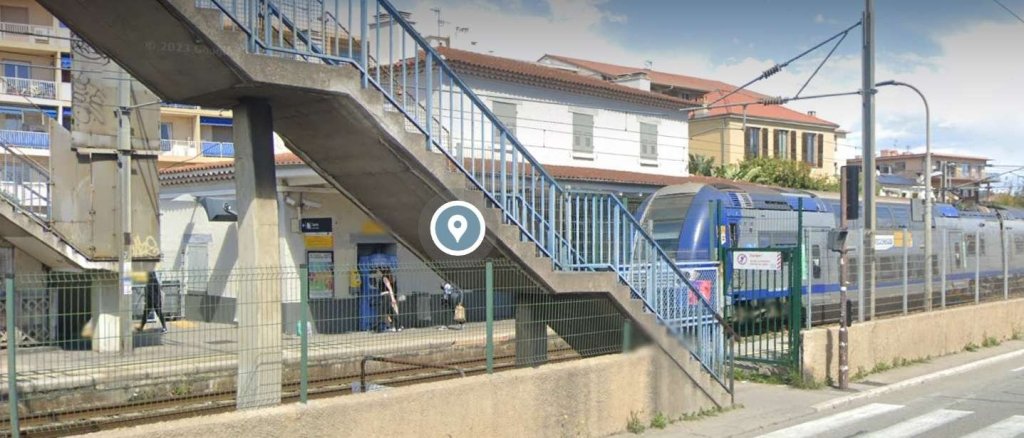

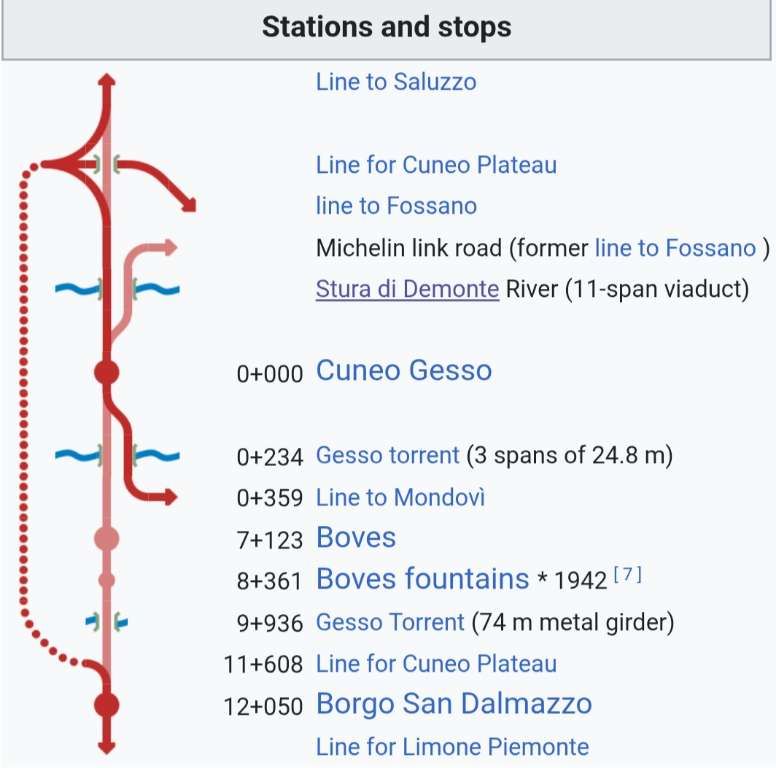

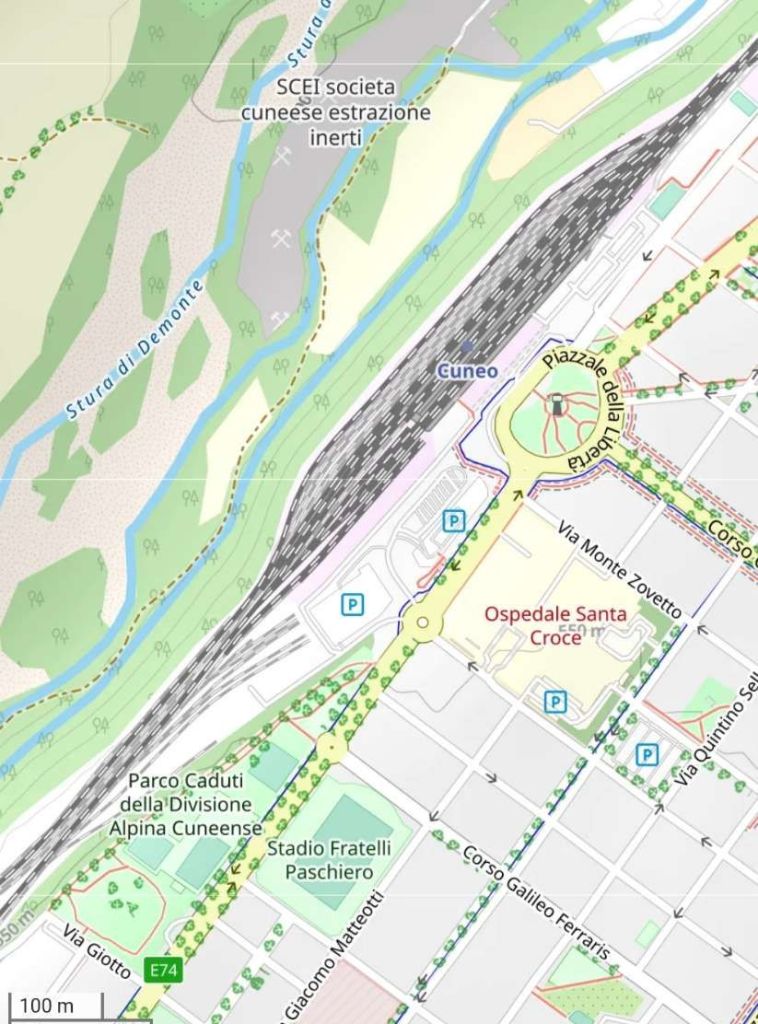

The present railway station in Cuneo dates from the late 1930s the older station is known as Cuneo Gesso Statzione. At the time of the building of the Line from Cuneo towards Nice and Ventimiglia, Cuneo’s railway station sat alongside the Gesso River across the town from the present station.

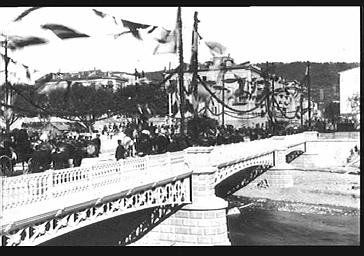

The railway initially arrived from Turin, via Fossano. It came as far as Madonna dell’Olmo opposite Cuneo across the Sturia River on 16th October 1854 where a small building was built to serve as a temporary station. On 5th August 1855 the inaugural train from Cuneo left for Turin. In the same year the municipality built a bridge over the Sturia (at its own expense). After the construction of the bridge over the Stura, a second temporary station was built on an embankment in the San Sebastiano plain (where Giuseppe Garibaldi had arrived to visit his “Alpine Hunters” in 1856). Only in 1870 was a significant edifice completed which became Cuneo’s railway station. It was alongside the Gesso River and it was again built entirely at the town’s expense. [19]

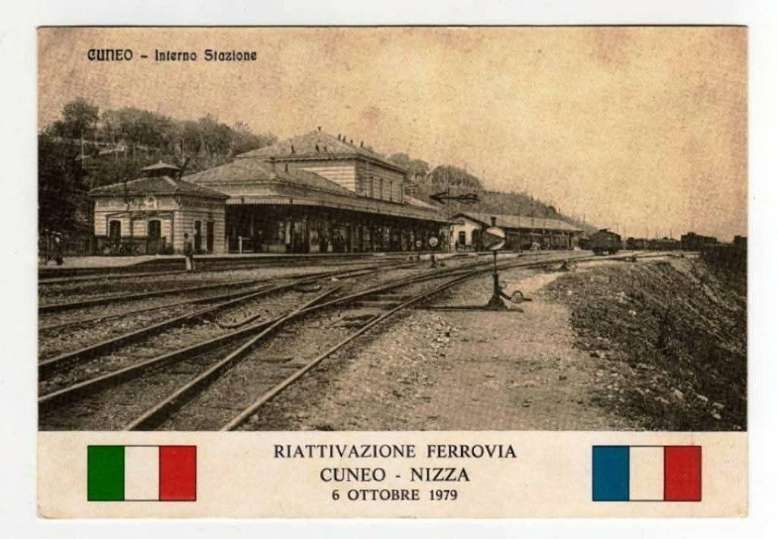

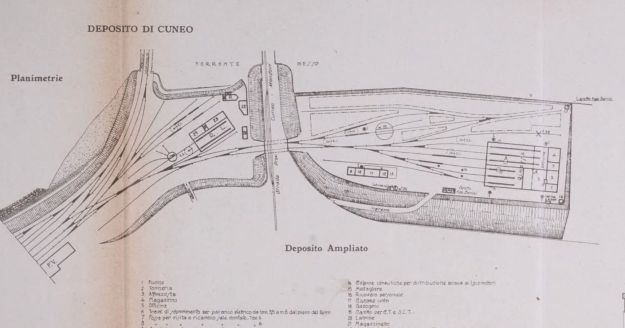

The complete opening of the Cuneo-Ventimiglia line, which took place on 30th October 1928, caused significant logistical problems for both travellers and rolling stock at Cuneo station. The old depot, dating back to 1864, soon became insufficient to house the locomotives of the new line, [23: p41] a hastily built locomotive depot was provided (because of delays creating the new line and new railway station, and in the construction of the large mixed-use viaduct over the Stura di Demonte. [24][25]

The new depot was placed beyond the embankment of the road to Mondovì. A double track arched bridge took the tracks under the road. [26][27] On 7th November 1937[24] the new Cuneo Altipiano station was opened, located to the west of the city centre and connected to the new locomotive depot built on the right side of the Stura River. [24][25]

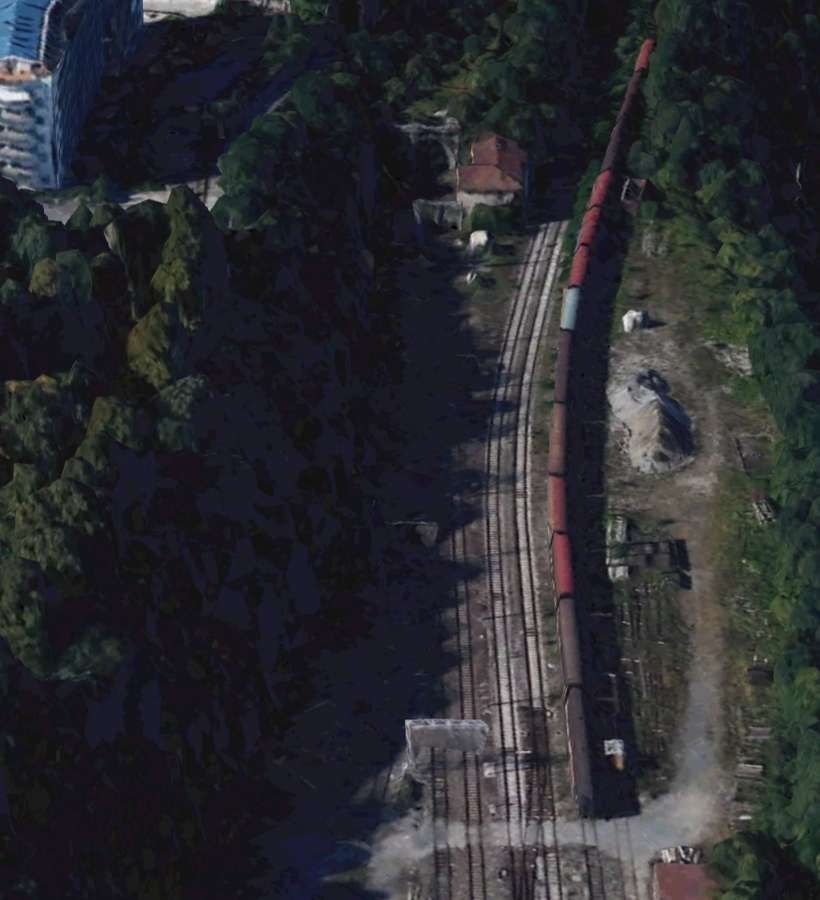

Cuneo Gesso quickly lost importance, remaining active only as a stopping point for the lines to Mondovì and Boves , the latter closed to traffic in 1960. [23: p55-57][25]

Near the station was the terminus of the Cuneo-Dronero, [28] Cuneo-Saluzzo [29] and Cuneo-Boves [30] tramways, active for different years between 1879 and 1948 [25][31: p120]. The Cuneo Boves line opened in 1903 and closed in 1935.

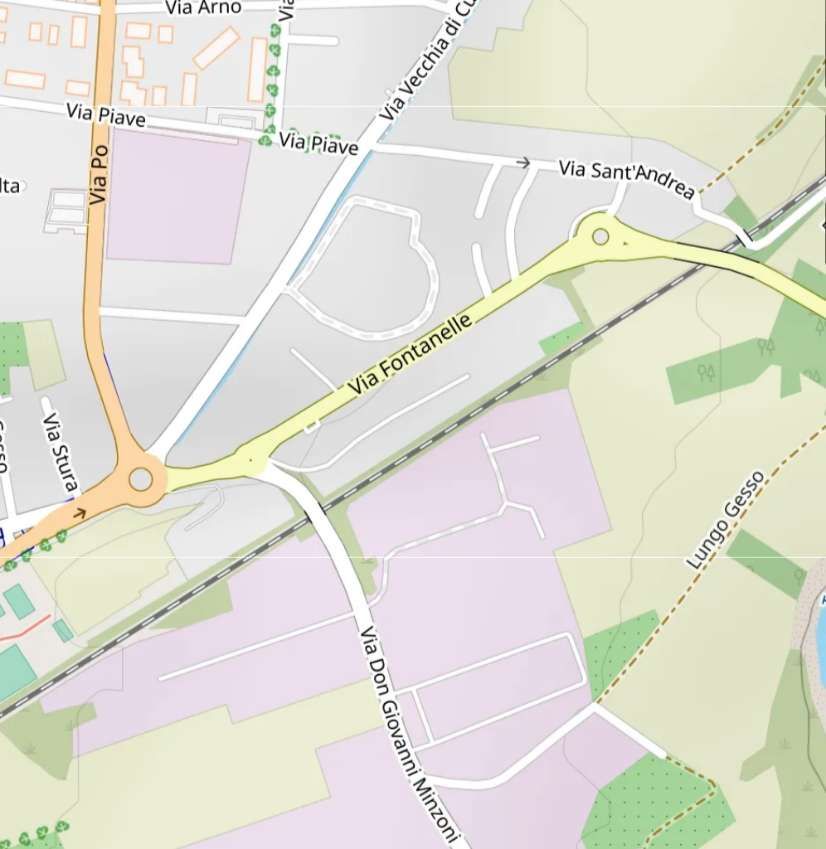

Construction of the new line started in 1882, it left the station to the South curving sharply to the left to cross the Gesso River on a 3-arch brick viaduct (each span was 24.8 metres) shared with the line from Cuneo to Mondovi which was under construction at the same time. [1: p25]

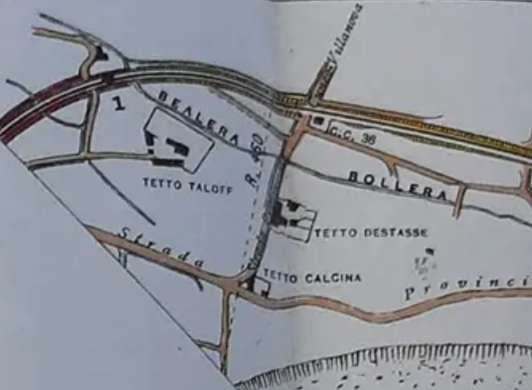

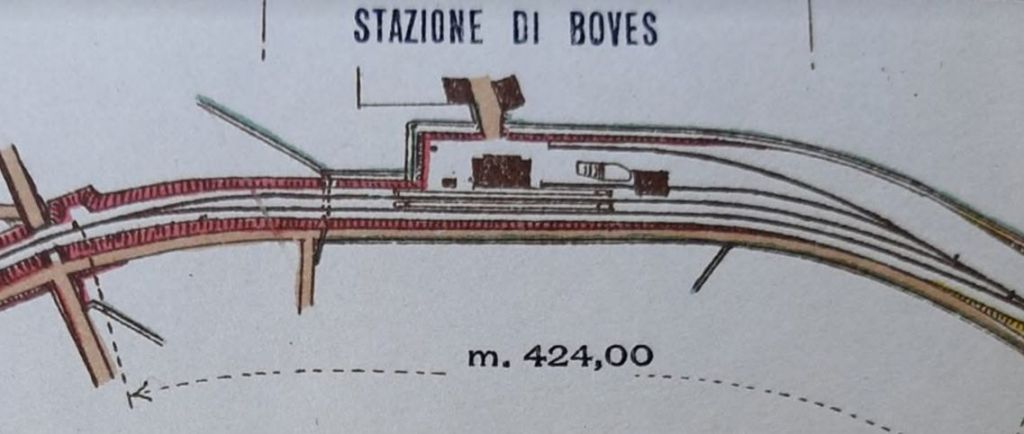

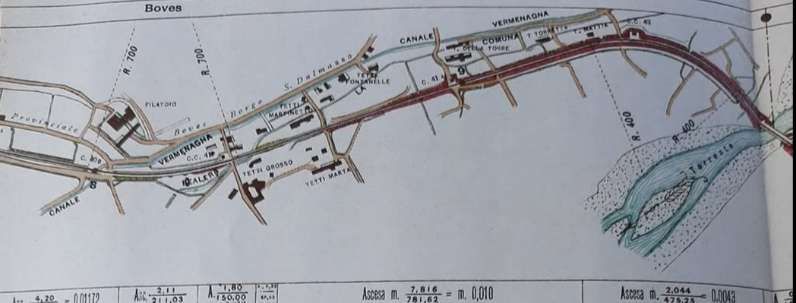

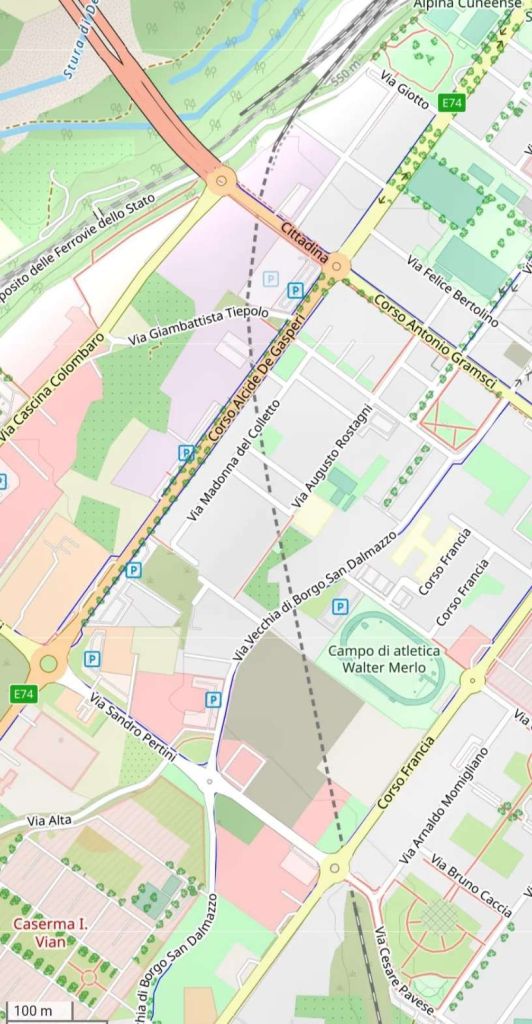

The line to Mondovi remains today, but no passenger trains use the line any longer. The line we are following from Cuneo to Vernante, left the line to Mondovi heading Southwest and passing through the villages of Boves and Fontanelle-di-Boves. Provision for freight and passengers was made at Boves, just for passengers at Fontanelle-di-Boves.

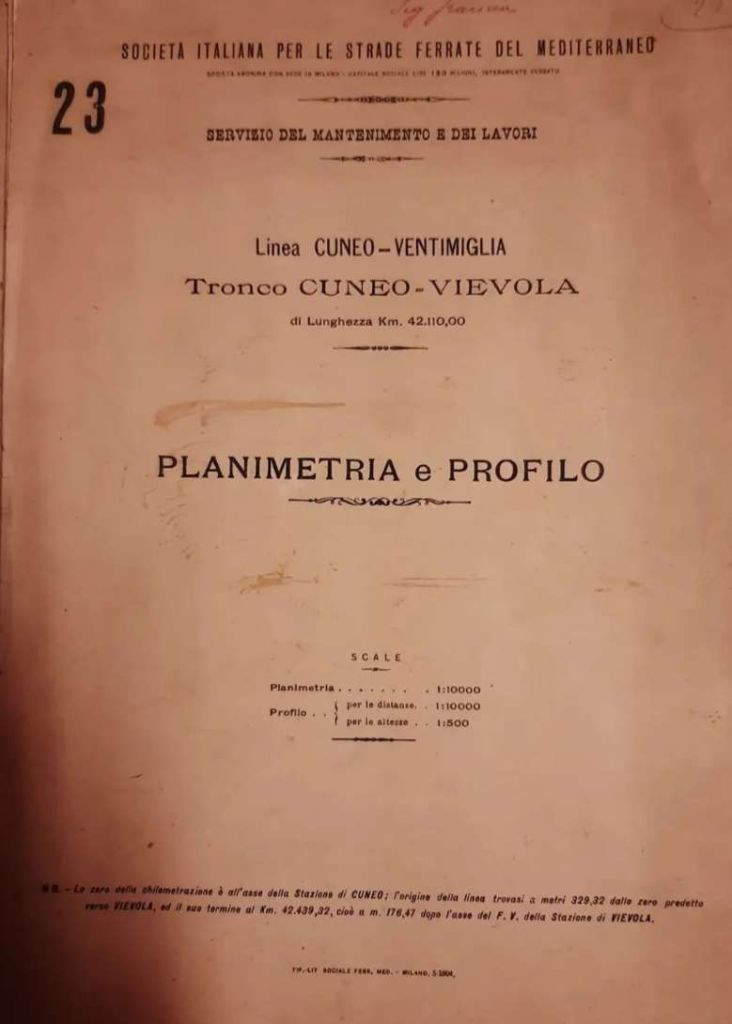

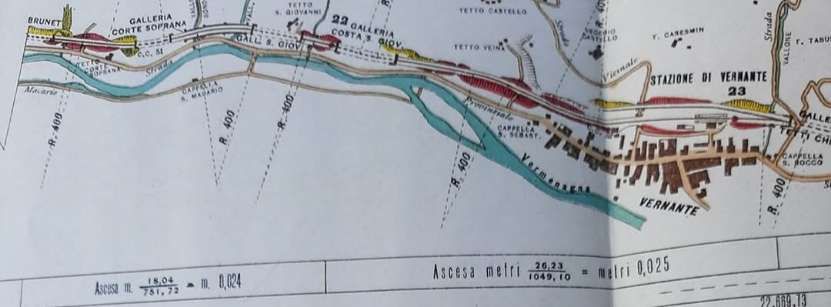

Preparing for this article, I found a document from 1904 which included the plans and profiles of the line on the Ferrovia Internazionale Cuneo-Ventimiglia-Nizza Facebook Group. It was shared as a series of photographs by Davide Franchini on 2nd March 2022.

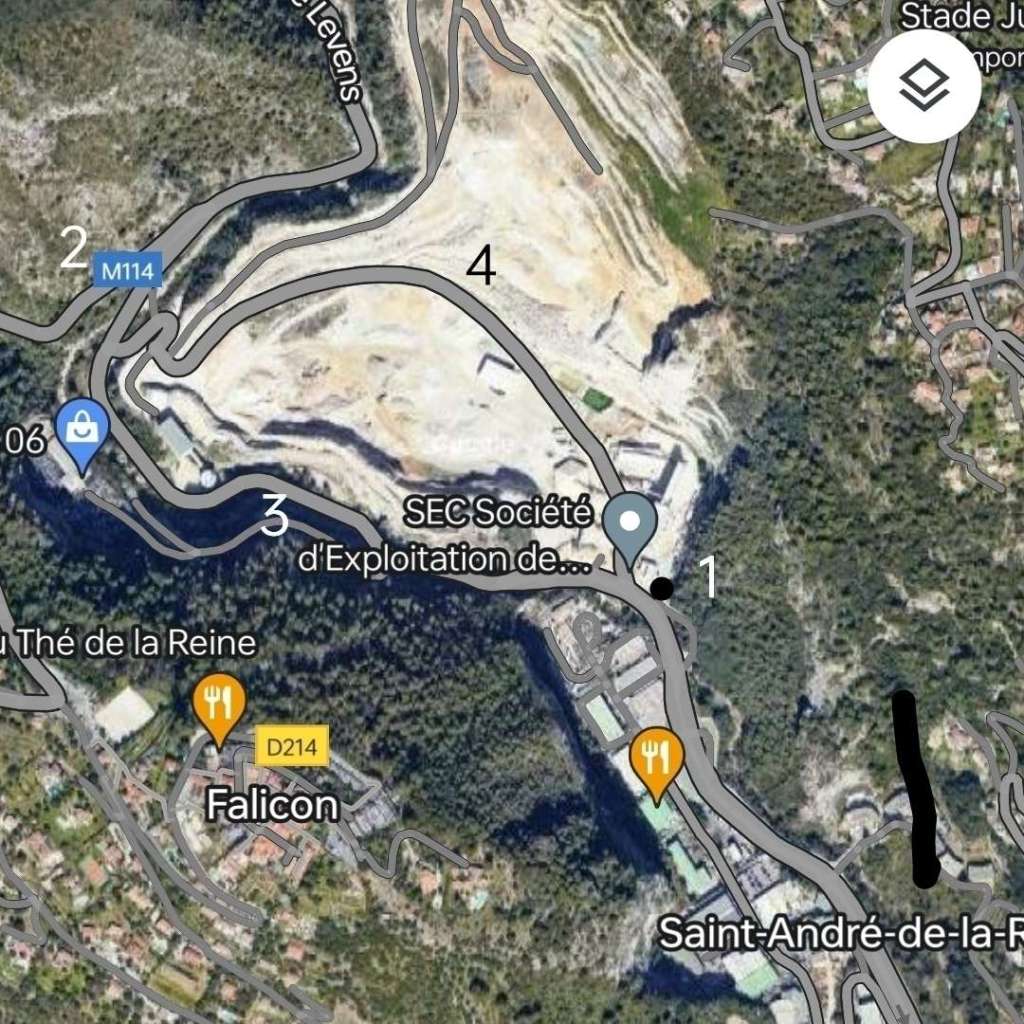

As far as I can tell, the line to Boves has been built over. It seems to have followed the route of Via del Borgo Gesso South from the river bridge, then Via Bisalta, then Highway SP21 to Boves where the line curved back towards the River Gesso. Boves station was on a relatively sharp curve in the line. [33]

Boves station had a passing loop and two sidings. The passenger building, converted into residential housing several years ago, was adjacent to a goods warehouse, now used as a provincial warehouse. [35]

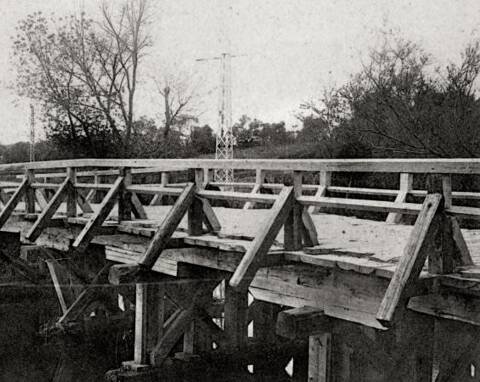

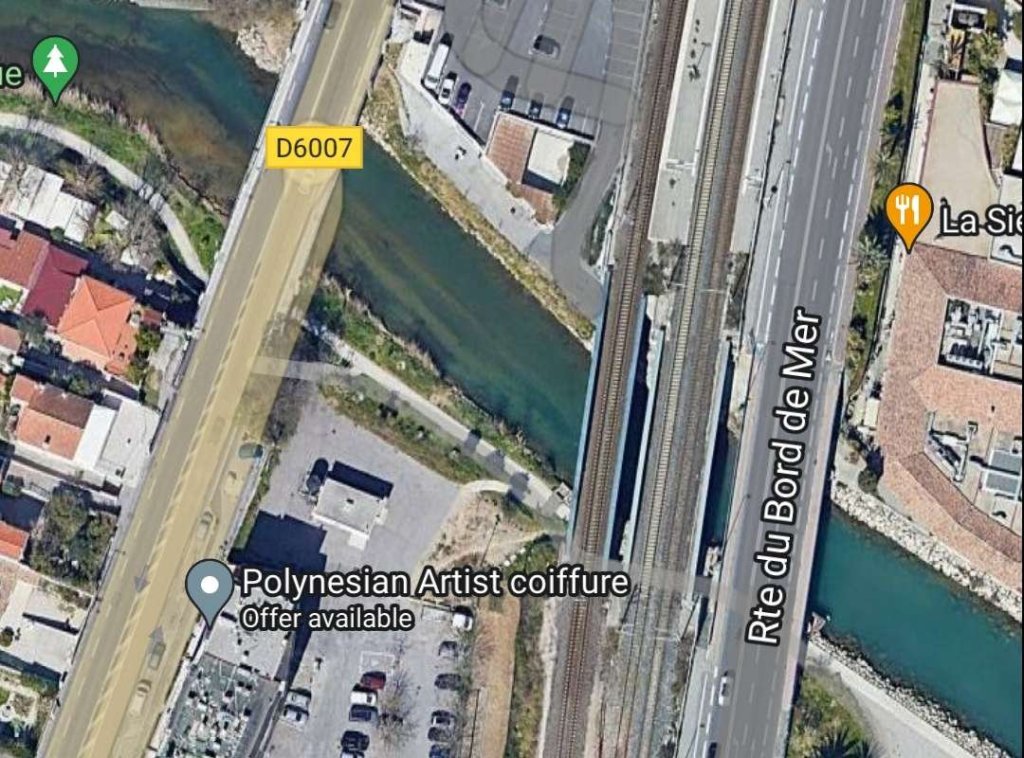

The hamlet of Fontanelle di Boves was just a short distance beyond Boves Railway Station. It had its own passenger station which opened in 1942 after the line from here back to Cuneo was replaced by a new line on the other side of the River Gesso which ran into the new station at Cuneo. Just a short distance further down the line was the viaduct which took the line back over the River Gesso. Originally, this was a masonry structure of three 24.8 metre arched spans. [1: p25] The viaduct was overwhelmed and destroyed by a flood of the Gesso on the afternoon of 2nd October 1898. It was then replaced with the current 74 m metal truss girder bridge. [34]

The bridge is known as Ponte di Sant’Andrea, a second truss was positioned alongside the railway bridge and together the two bridges now carry the SP21.

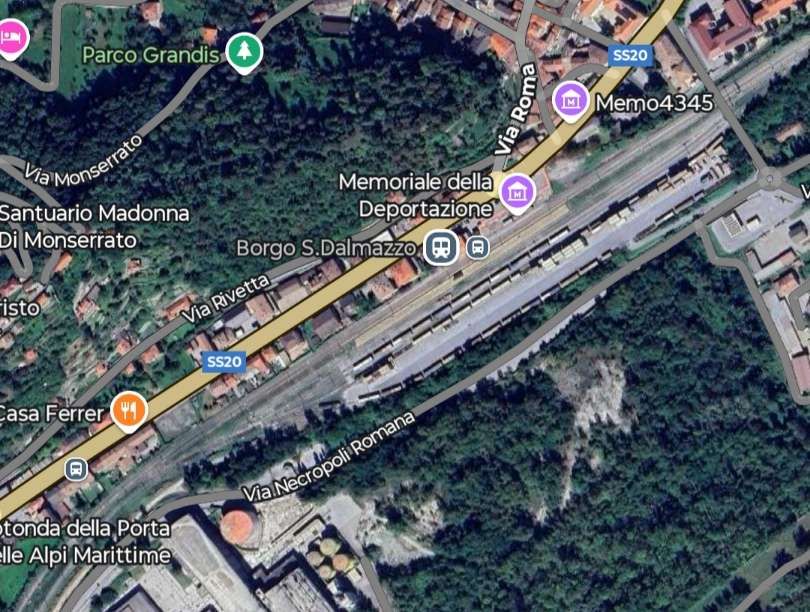

After crossing the River Gesso and at about 12 km from Cuneo the line arrived at Borgo-San-Dalmazzo.

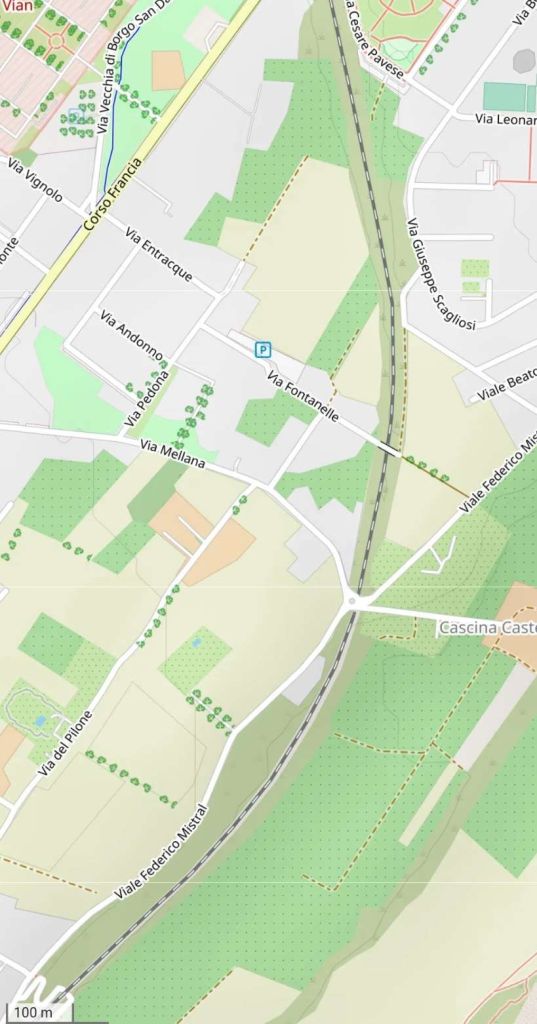

Returning to the 1937-built Cuneo Railway Station, the line from that station leaves Cuneo in a South-southwest direction. It is easiest to see the route of the line on a sequence of extracts from global mapping provided by OpenStreetMap. …

A twilight view of Cuneo railway station taken from the cab of a multiple unit entering the station from the Southwest. [45]

A rain-spattered cab view from the South, taken in the late evening, of the Southern portal of the tunnel which sits to the South of Cuneo Railway Station. [45]

Looking North in the evening light under a footbridge close to Via Giuseppe Scagliosi through the cab widow of a multiple unit on the line. [45]

A three arch bridge carries Via Fontanelle over the railway, seen again in the evening light from the South through the rail-spattered cab widow of a multiple unit. [45]

A short tunnel carries the roundabout at the meeting of Via Mellana and Viale Federico Mistral over the railway, seen again from the South through the rail-spattered cab widow of a multiple unit. [45]

Vegetation around the roundabout means that it it not possible to see into the cutting from the road.

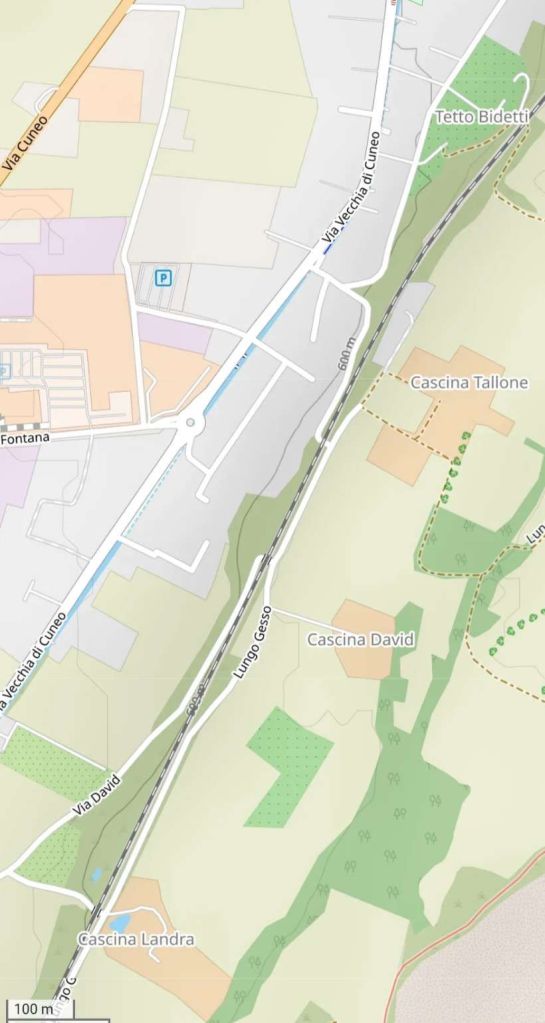

A brick-ringed arch bridge carries the railway over a side road off Viale Federico Mistral. This view is from the Southeast. The structure is at the top-right of the map extract immediately above. [Google Streetview, June 2025]

A very similar arch bridge carries the railway over a further side road off Viale Federico Mistral. The bridge is located in the bottom-left quadrant of the map extract above. [Google Streetview, June 2025]

Silhouetted in the evening light, this bridge crosses the line carrying a footpath over the railway. The image, again comes from the cab of a multiple unit heading for Cuneo. [45]

Close to Cascina Tallone, the line crosses Lungo Gesso by means of another brick ringed arch. This view looks under the railway from the Southeast. [Google Streetview, May 2022]

Near Cascina David another brick-arched bridge pierces the railway embankment where Via David passes beneath the railway. Again this view is from the Southeast on Via Sant’Andre. [Google Streetview, May 2022]

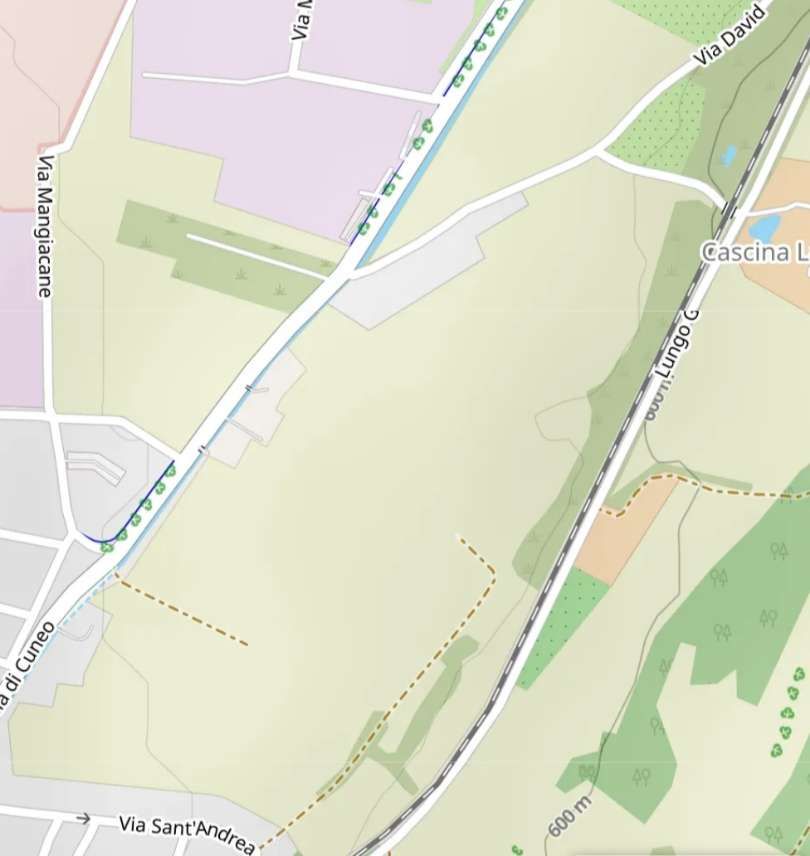

Near Cascina Landra another brick-arched bridge pierces the railway embankment. Again this view is from the Southeast on Via Sant’Andre. Thestructure appeasr bottom-left on the map extract above and top-right on the extract below. [Google Streetview, May 2022]

Via Sant’Andrea passes over the line. This view looks Northeast towards Cuneo. [Google Streetview, May 2022]

Also taken from the bridge carrying Via Sant’Andrea over the railway, this view looks across the road SP21 towards Borgo San-Dalmazzo. [Goog;e Streetview, May 2022]

The view Southwest from the bridge carrying the SP21 over the railway. The route of the older line is marked by the field boundary visible to the left of the line. [Google Streetview, June 2025]

The older line curved round to the Southwest and followed a straight course towards Borgo-San-Dalmazzo Railway Station. The newer line has taken its place on the approach to the Station from the Northeast.

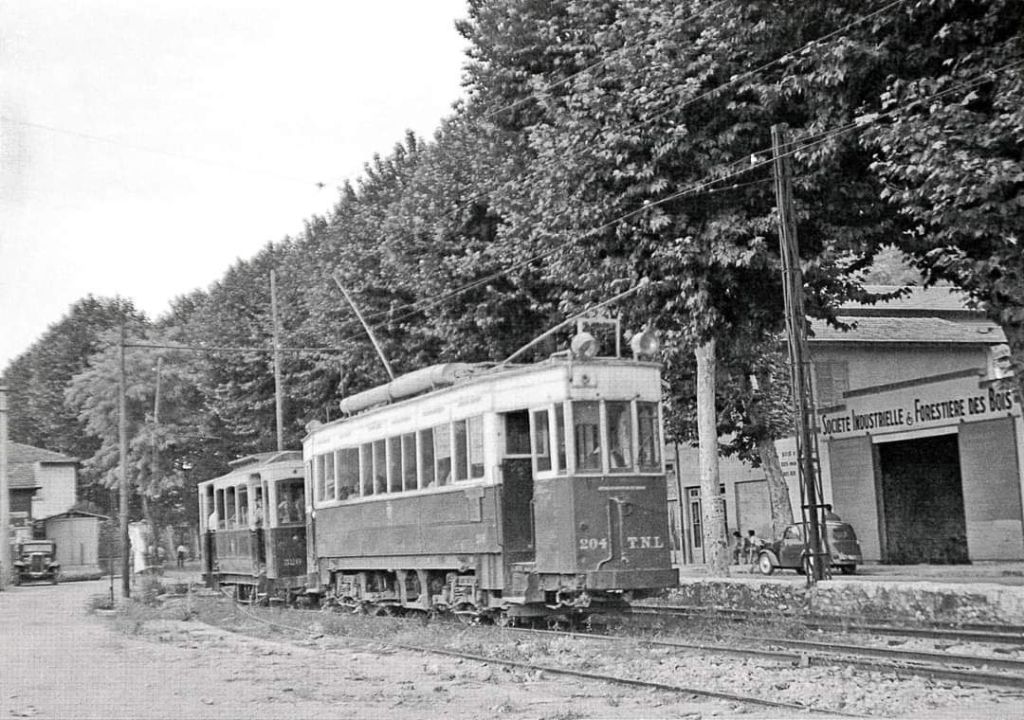

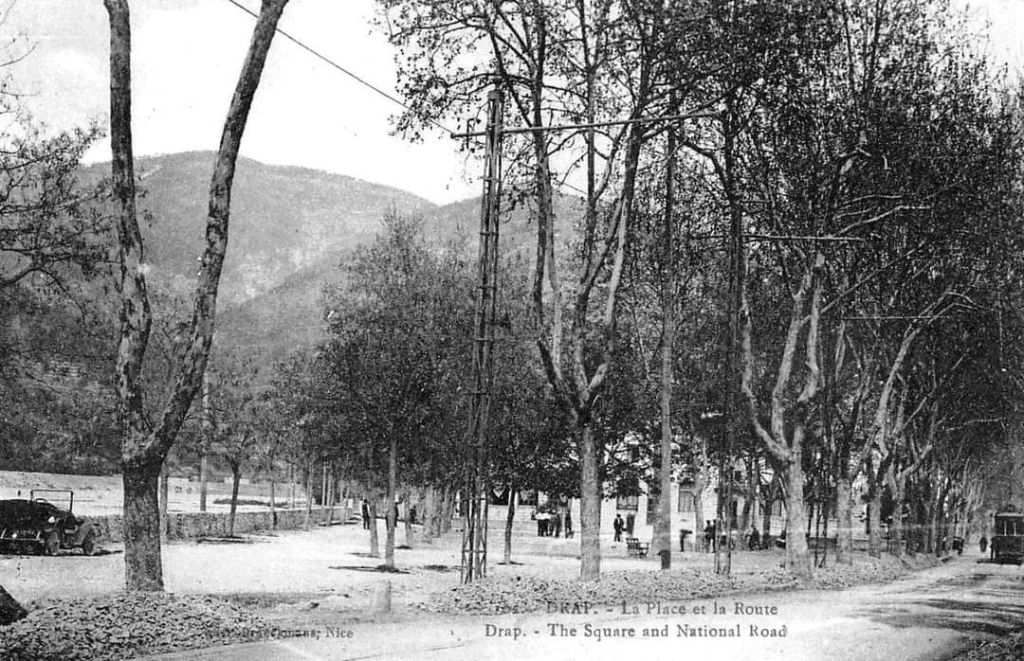

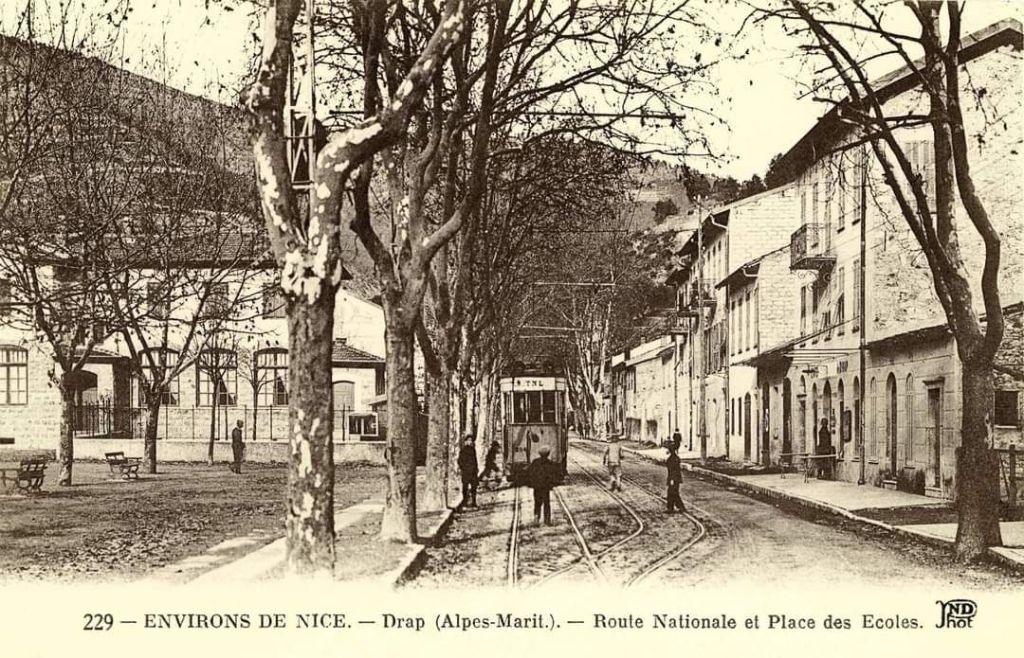

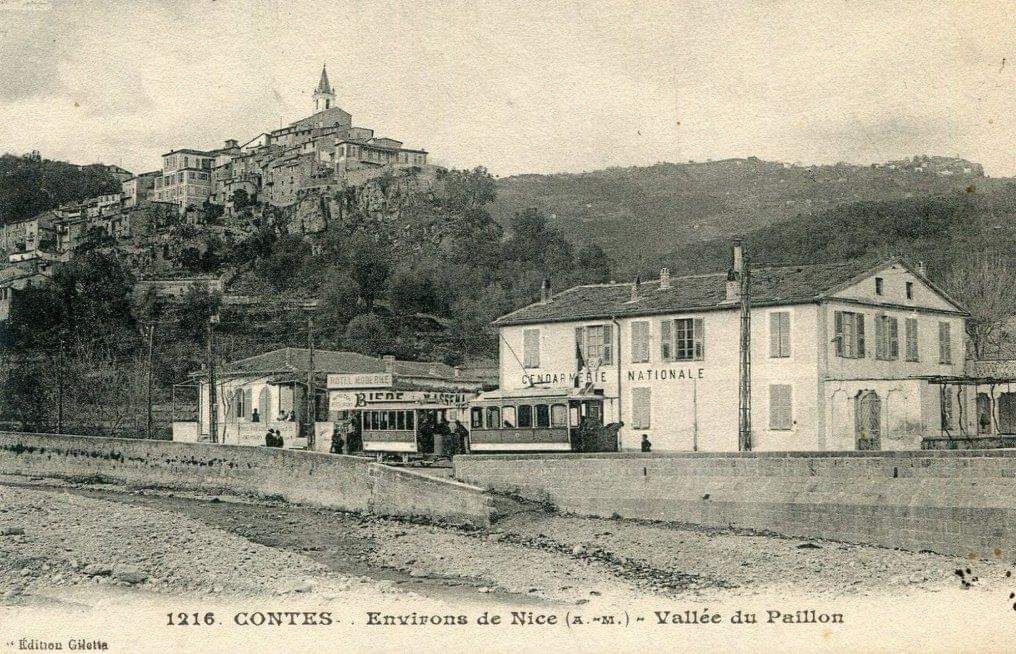

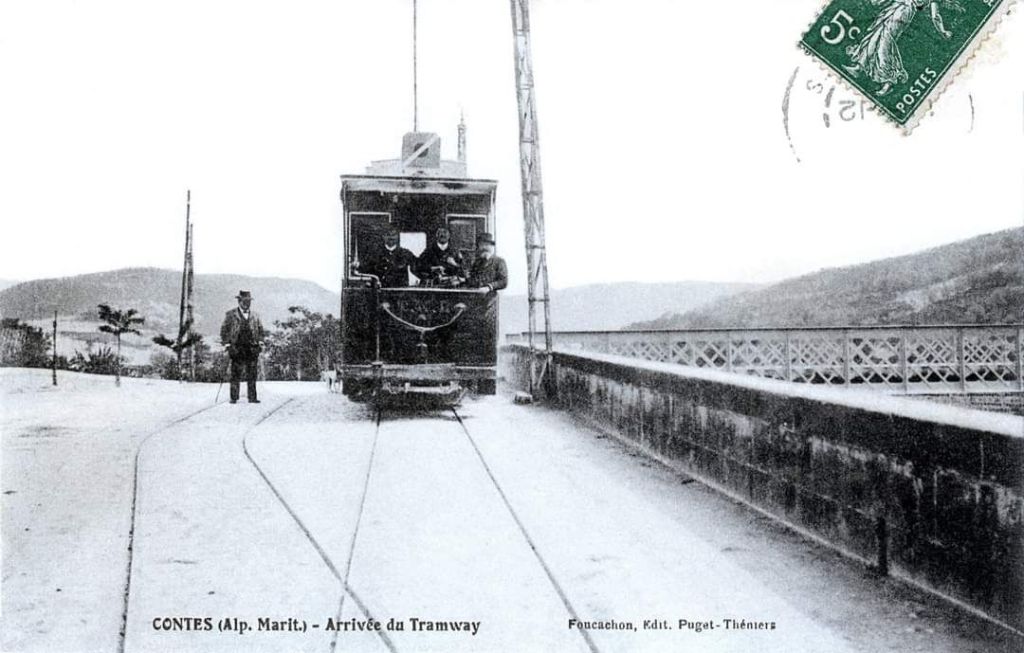

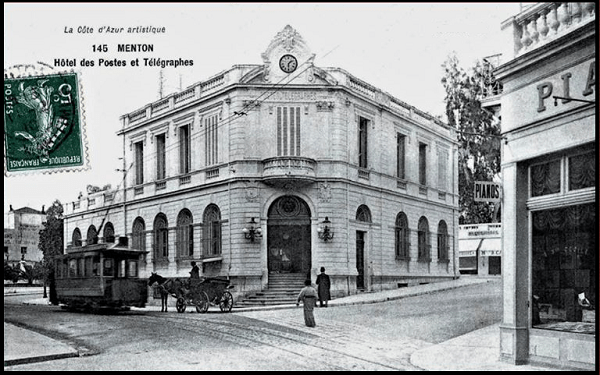

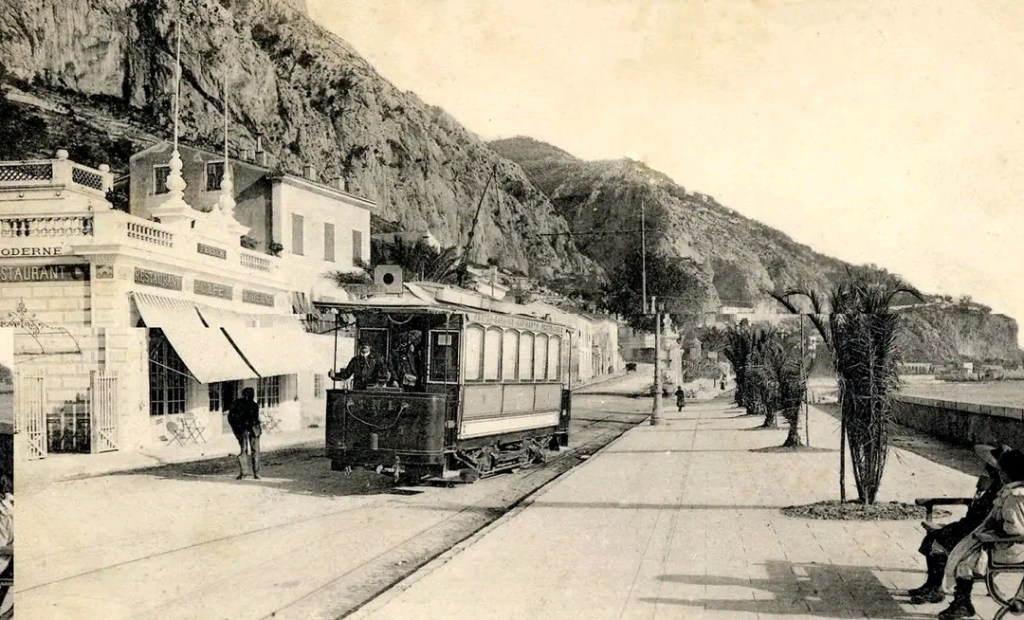

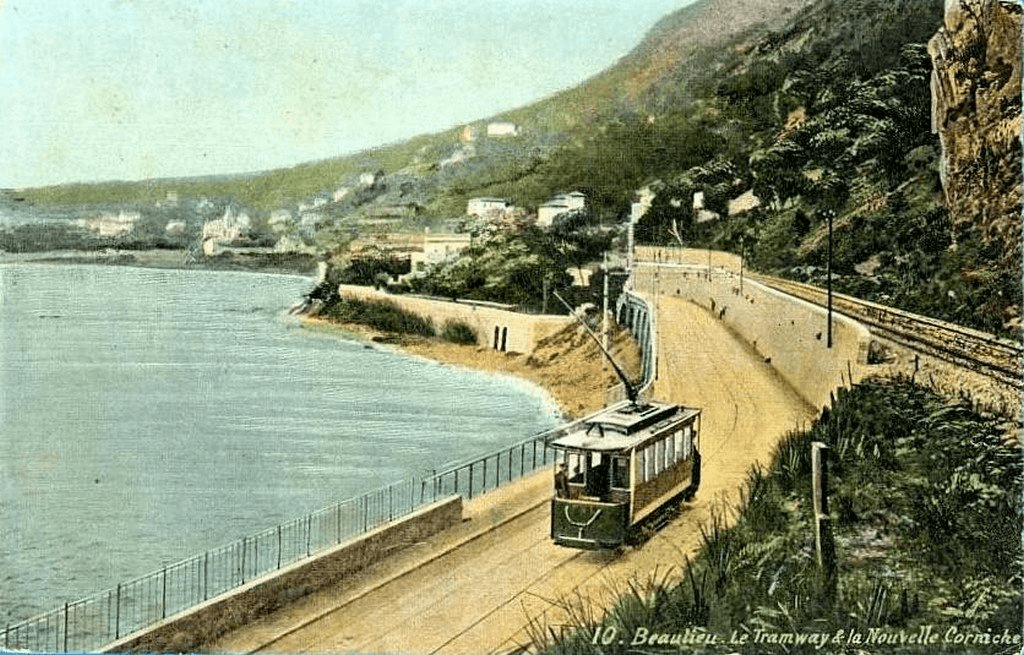

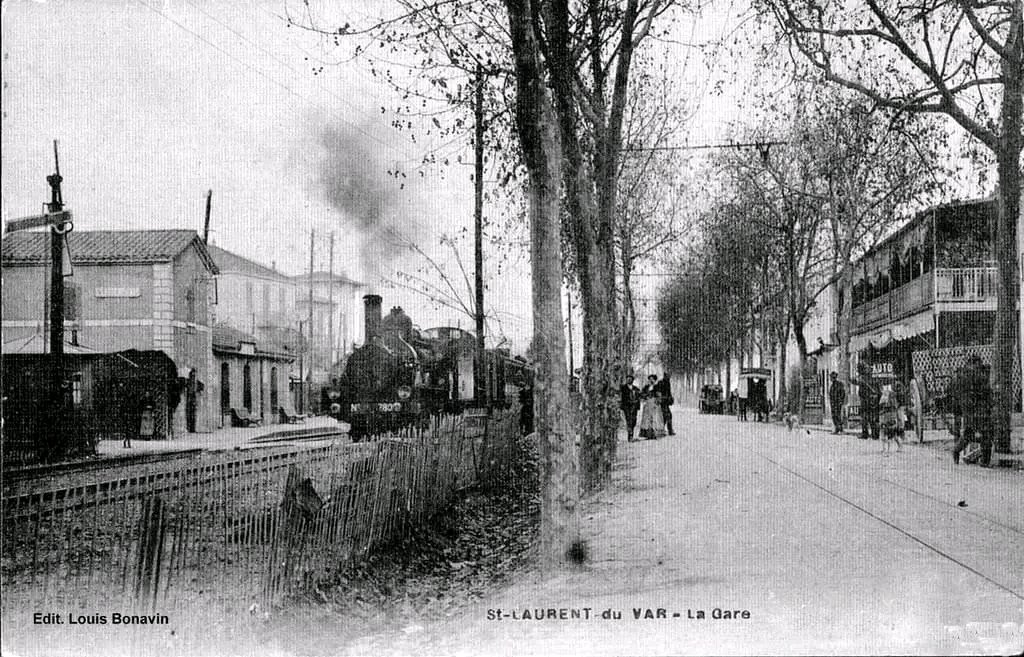

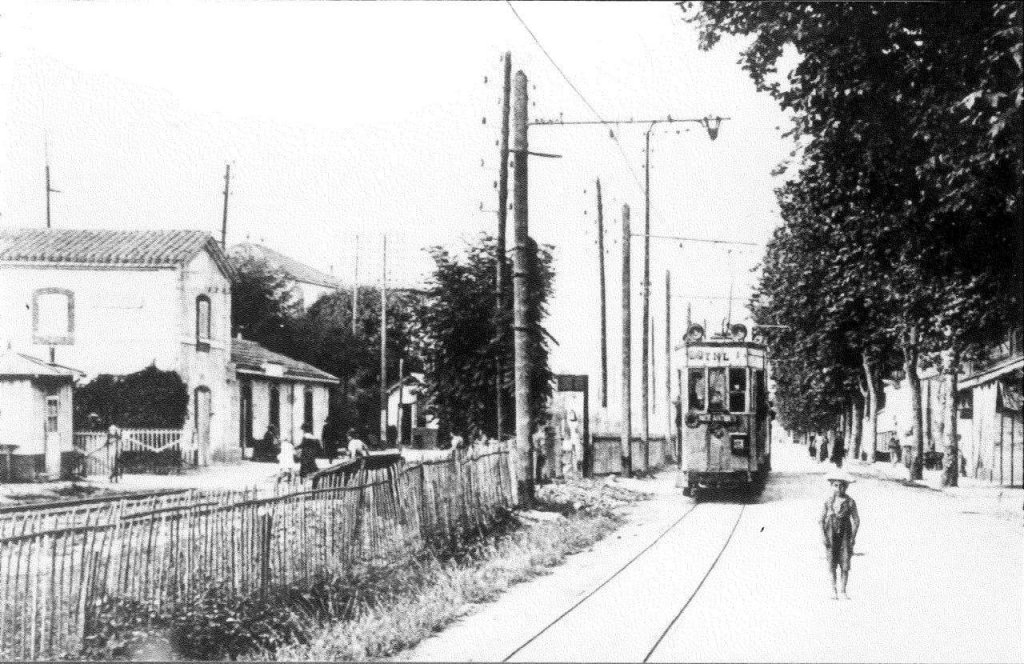

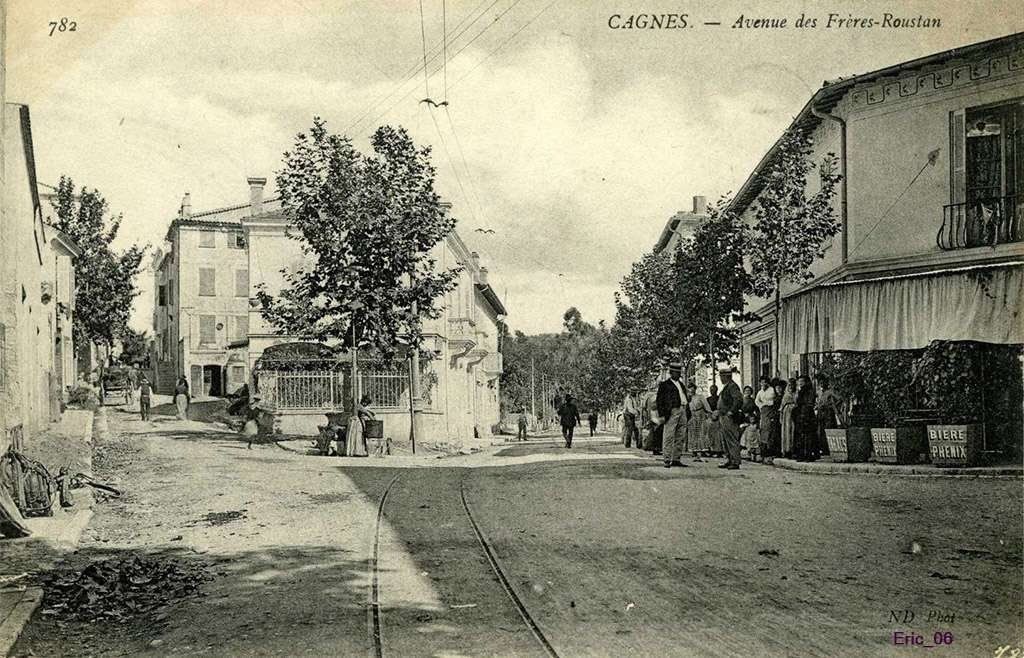

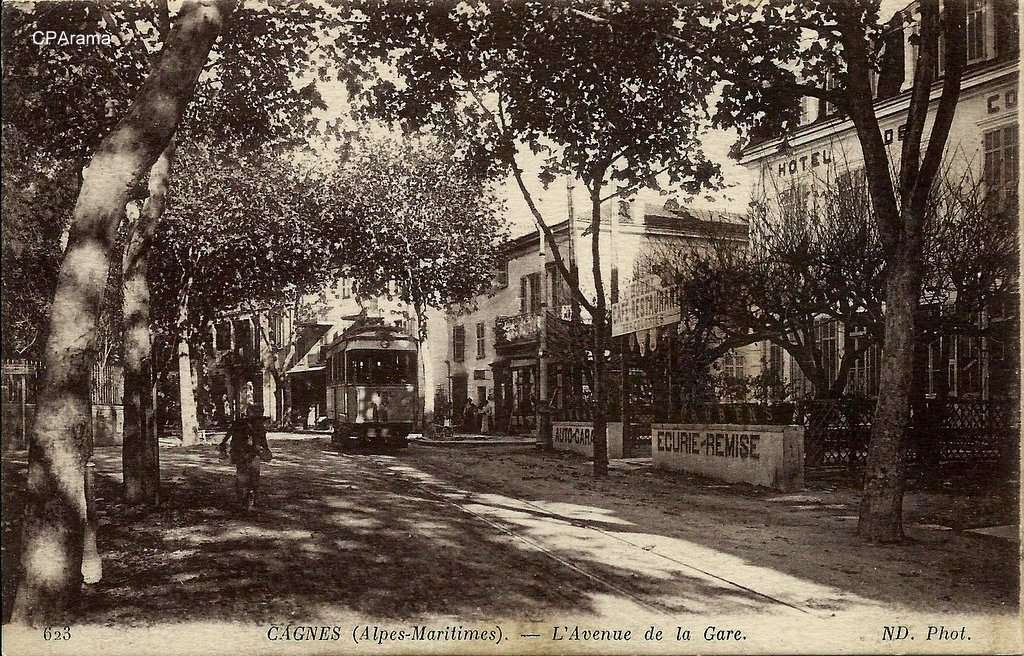

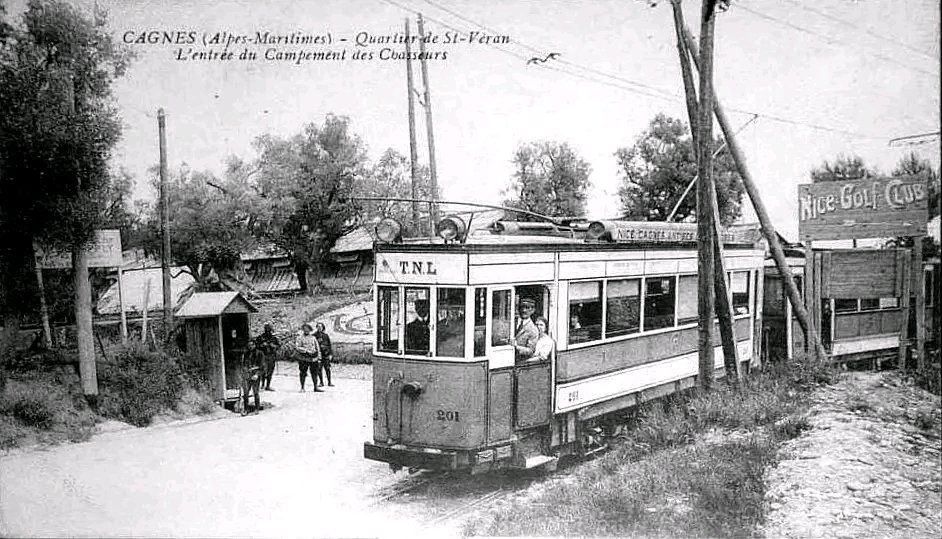

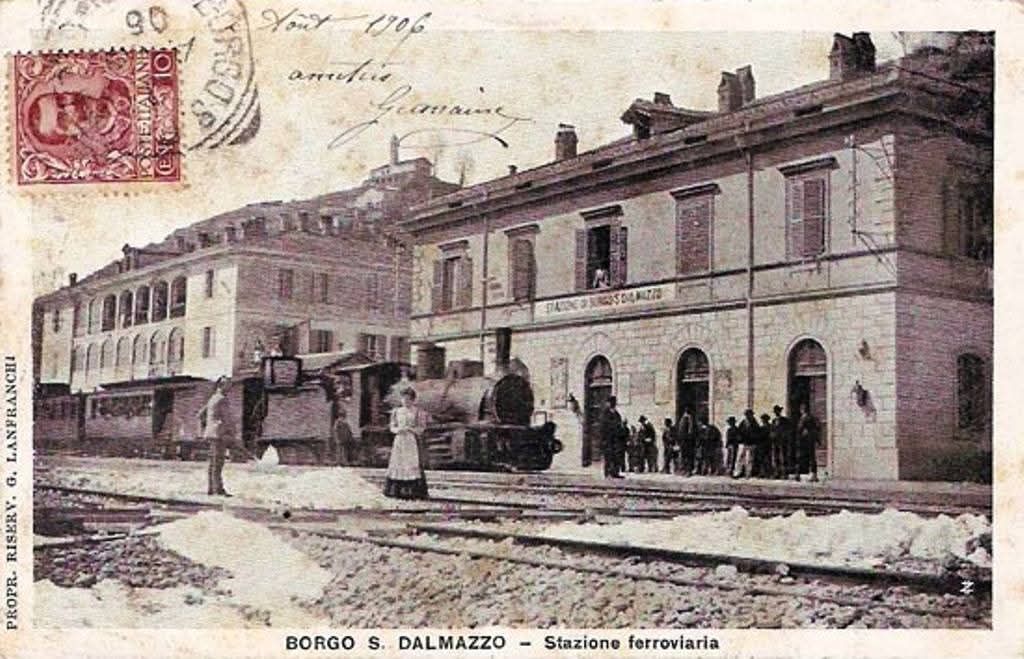

San-Dalmazzo is a very old trading town located at the crossroads of three valleys: the Stura, the Gesso and the Vermenagna. The station had three platforms, a goods yard, a 5.50 m turntable and a large overflow yard that could be used for the embarkation and disembarkation of military units deployed in the area. “When the railway arrived in Borgo-San-Dalmazzo, this small town had already had a rail service for several years. In fact, private entrepreneurs Ercole Belloli and Carlo Chiapello opened a 1.445 m gauge horse-drawn tramway between Cuneo and Borgo in 1877, passing through the San-Rocco-Castagnaretta district on the left bank of the Gesso. Horse-drawn traction was replaced by steam locomotives on this modest 8-km line in 1878.” [1: p27][48]

The Cuneo-Borgo San-Dalmazzo-Demonte tramway linked the cities of Cuneo, Borgo San Dalmazzo and Demonte from 1877 to 1948. In the late 1870s, following the success of similar initiatives in the Turin area, the construction of tramways was pursued in the province of Cuneo. [48] As we have already noted, this was just one of a number of such tramways in the area.

The Cuneo Borgo-San-Dalmazzo tramway was extended in 1914 to Demonte (26.4 km) and converted on this occasion to a 1.10 m gauge to facilitate the exchange of goods with the Compagnia Generale dei Tramways Piemontesi (CGTP) which operated the Cuneo Boves line (8.3 km) from 1903. The Boves steam tramway disappeared in 1935 and that of Borgo and Demonte in 1948. [1: p28] The story of these tramways seems worth investigating, but their histories are a matter for a different article!

The station had an ignominious place in history. During the Second World War two convoys of Jewish deportees departed from the Borgo San Dalmazzo railway station bound for Auschwitz , coming from the adjacent Borgo San Dalmazzo concentration camp. The first convoy, on 21st November 1943, completed its journey via Nizza Drancy with 329 people on board. Only 19 survived. The second convoy, on 15th February 1944, with 29 people on board, headed instead for the Fossoli transit camp where it was combined with transport no. 8 bound for Germany. Only 2 survived. [49][50]

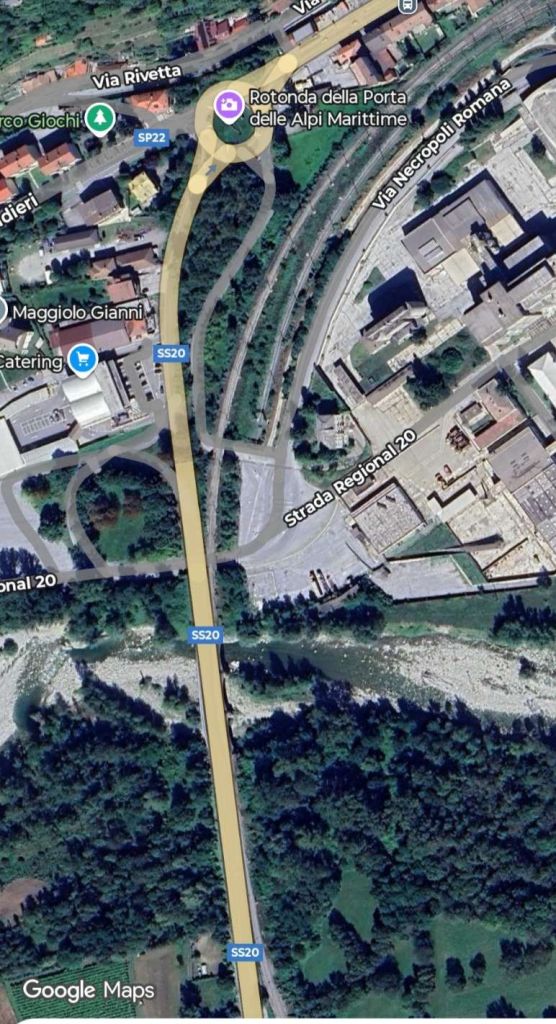

Burgo San-Dalmazzo to Robilante: The second construction contract covered the length from Borgo San-Dalmazzo to Robilante. Work began in late 1883. From Burgo San-Dalmazzo the line leaves the plain and begins its ascent up the Vermenagna Valley, heading towards the Tende Pass. The route, was designed to accommodate heavy traffic, so the line does “not include any curves with a radius less than 300 m, with two exceptions: one at the southern end of Cuneo station and one at the exit from Borgo station, where the route curves sharply to the left in a 257-meter curve to reach the left bank of the Gesso River. There, a 21 m three-arched masonry viaduct, shared by the railway and the SS20 road, crosses this Alpine torrent for the third and final time.” [1: p27]

As the railway curves round towards the river its embankments are pierced twice to allow local roads to pass beneath the line.

The southern approach to Borgo San-Dalmazzo Railway Station, seen from the cab of a multiple unit. The line to the right of the image is a siding which terminates close to the River Gesso. [45]

A view from the South showing the road on the left. This is a view from the cab of the multiple unit again. [45]

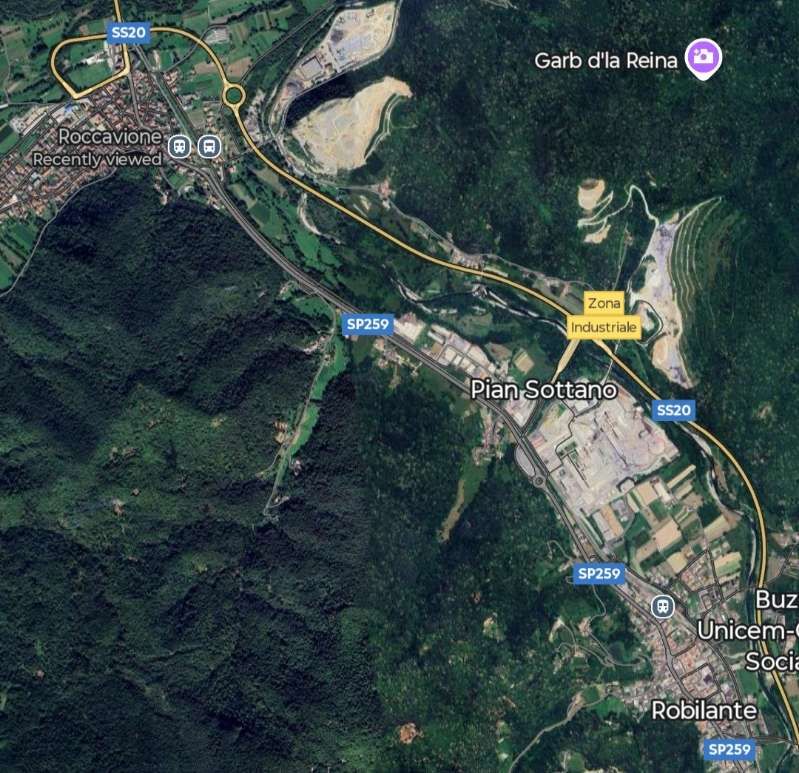

After crossing the river the line ran on through Roccavione. …

Railway Station © Mattia Vigano. [Google Maps, 2019]

Roccavione Station is a simple station with two public platforms and one track serving a military platform. Another level crossing sits beyond the South end of the station site.

A similar view looking North into Roccavione Railway Station from the cab of the multiple unit. The station has no passing loop. [45]

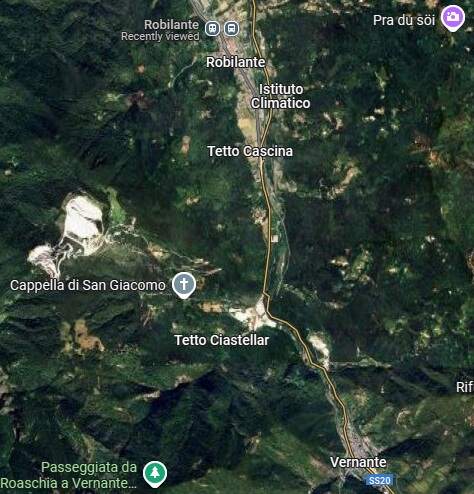

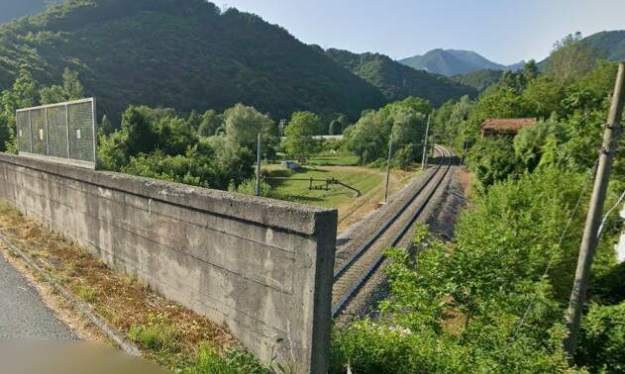

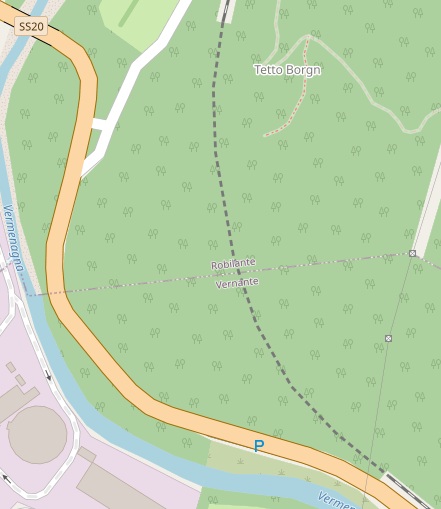

The line follows an easy gradient between the SP259 (which used to be the SS20) and the left bank of the River Vermenagna to Robilante Railway Station. [1: p27]

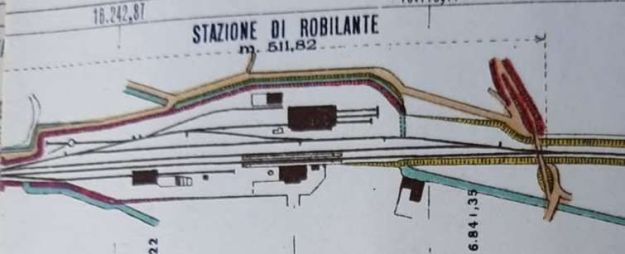

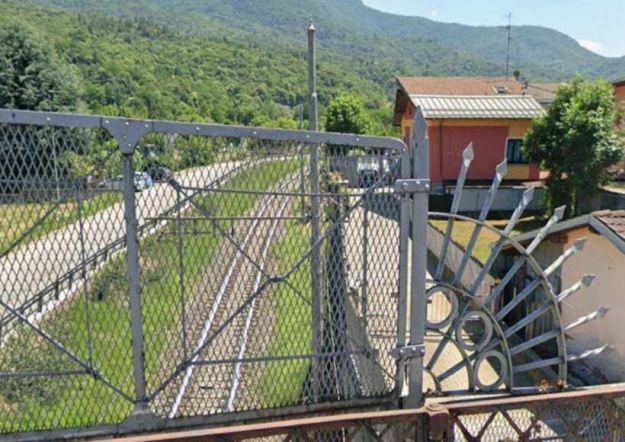

Robilante Railway Station had three platform tracks, a small goods yard, a water feed, a 8.50m turntable and an engine shed. Beyond the station track gradients increased significantly and provision needed to be made for banking engines in steam days. [1: p27]

A similar view to that immediately above but taken from the driver’s cab on a multiple unit. In the distance in this image the old goods shed can be seen to the left of the line. The shed is no longer present in the more modern image above. [45]

Robilante Goods Shed seem from the cab of a multiple unit. As noted above, the shed has now been demolished. [45]

This image taken from the Southeast of the station from the cab of an approaching Cuneo service gives a broader view of the station site. [45]

The second phase of the construction work on the line terminated in Robilante. “The preliminary design for the third phase from Robilante to Vernante was submitted to the Ministry of Public Works on 11th January 1884, and work began the following summer. On this 6,419-meter-long section, the railway crosses the mountain with gradients of 25 mm/m.” [1: p27]

The two images immediately above were taken at the end of a road serving a small industrial area. The first looks Northeast, the second, Southeast. [Google Streetview, September 2023]

After passing under the SS20, the line runs alongside the road for a kilometre or so.

A short distance further South a side road from the SS20, Via Tetto Pettavino, bridges the line. The two photographs below were taken from the bridge.

A photograph of the viaduct over the Vermenagna surrounded by trees can be found here on Flickr. [54]

Banaudo et al tell us that seven further significant structures were included in the contract which covered the line as far as Vernante [1: p27] all of which sit within approximately 3 kilometres along the line:

- the Rio Vermanera masonry viaduct, with three 8-metre arches;

- the Ponte Nuovo Tunnel, 425 metres long;

- the Brunet Tunnel, 161 metres long;

- the Corte-Soprano Tunnel, 95 metres long;

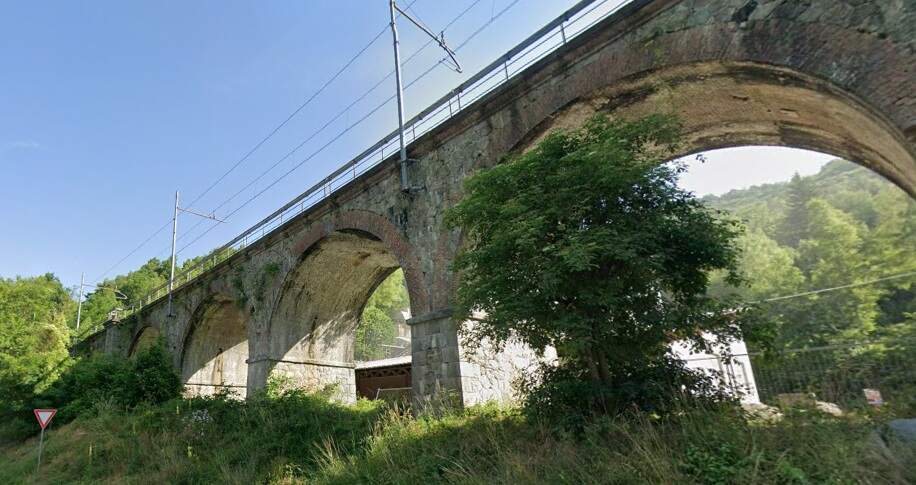

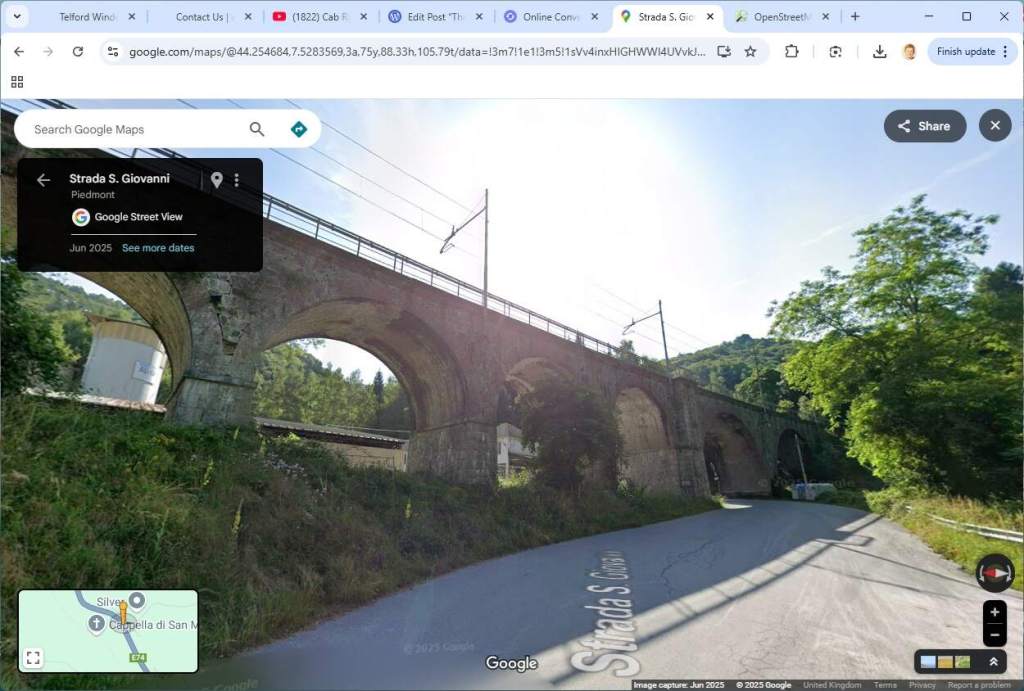

- the San Giovanni masonry viaduct, with six arches measuring 7.90 m, three measuring 13.75 m, and one measuring 6 m;

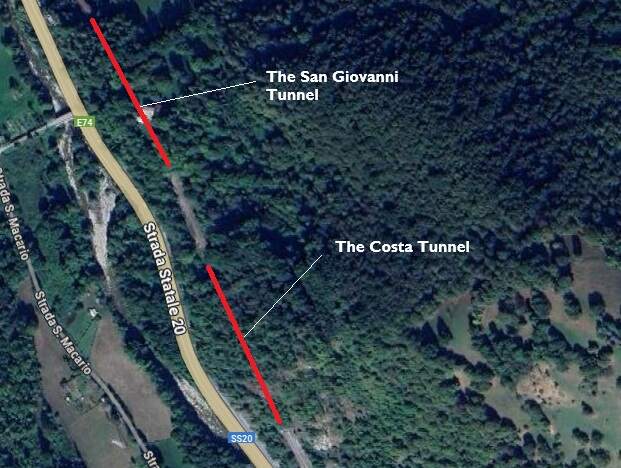

- the San Giovanni Tunnel, 138 metres long; and

- the Costa Tunnel, 147 metres long. [1: p27]

The first of these – the Rio Vermanera Viaduct is pictured below.

The same viaduct seen from the East. [Google Streetview, June 2025]

Strada Vermanera provides road access to a number of small hamlets to the East of the railway line. [Google Maps, July 2025]

The Ponte Nuovo Tunnel: this extract from OpenStreetMap shows the tunnel curving significantly. It ran from just to the South of the Rio Vermanera Viaduct to open out immediately adjacent to the SS20/E74 but at a higher level. [55]

Immediately beyond the southern portal of the Ponte Nuovo Tunnel, a masonry retaining wall supports the railway above the SS20/E74.

Looking back towards the South portal of the Ponte Nuevo Tunnel the parapet railings of the retaining wall can be seen on the left of this image. [45]

The Brunet Tunnel is shown dotted on this extract from OpenStreetMap. [56]

The South Portal of the Brunet Tunnel. [45]

The next tunnel is only 200 metres or so along the line, the Corte-Soprano Tunnel is even shorter at only 95 metres in length. [57]

The South Portal of the Corte-Soprano Tunnel. [45]

Just to the Southeast of the tunnel portal is the next structure, the San Giovanni Viaduct. masonry viaduct, with six arches measuring 7.90 metres, three measuring 13.75 metres, and one measuring 6 metres. [Google Maps, July 2025]

It is not feasible to get a photograph of the full length of the viaduct. The three images below give a good impression of its length and height.

Two further short tunnels, the San Giovanni Tunnel (138 metres long) and the Costa Tunnel (147 metres long) follow in the next few hundred metres.

The South portal of the San Giovanni Tunnel. [45]

The South portal of the Costa Tunnel. [45]

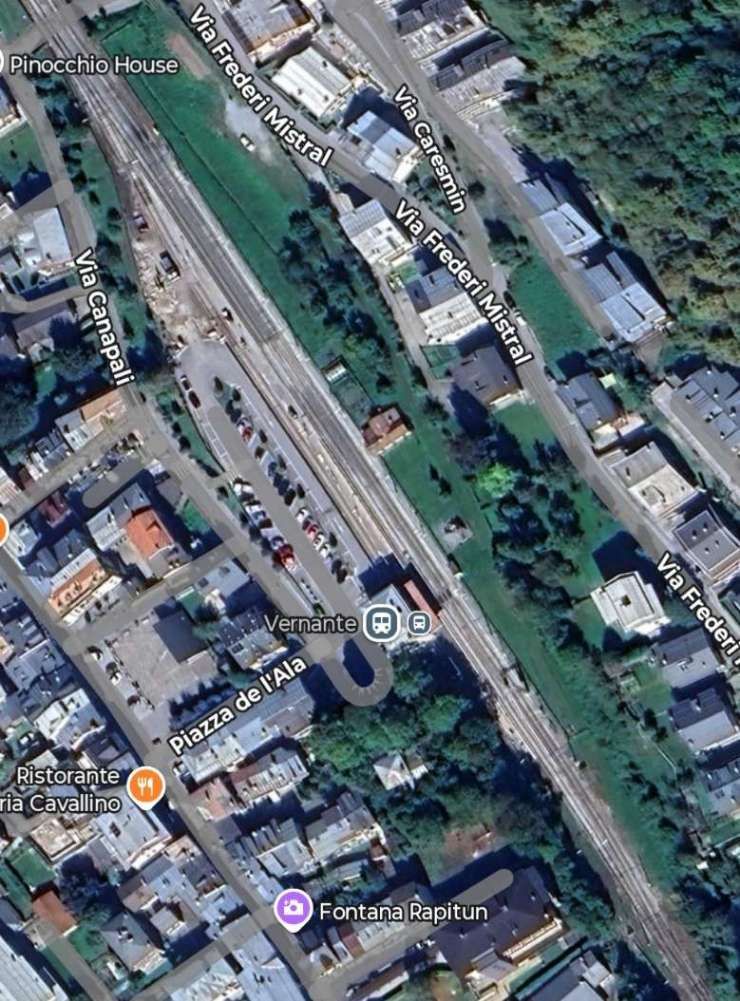

The railway continues to climb higher on the eastern slope of the Vermenagna Valley and reaches Vernante, about 23 km from Cuneo.

On the final approaches to Vernante Railway Station two further structures can be seen on the plan above. They carry the line over minor roads. The first spans Via La Tina, the second spans Vicolo Castello/Strada da Castello.

Vernante Railway Station was the end of the third tranche of works on the railway. Vernante is “a busy centre of livestock breeding and craftsmanship where renowned knives are produced. Vernante station … has two platform faces with a passing loop, … [a goods shed] and platform for goods traffic, a 5.50 m turntable and a curious installation, unique on the line, the “binario di salvamento”. This is a counter-slope safety [line which leaves the main running line close to the station throat] on the Limone side. The switch is permanently positioned to provide access to the safety line, so that any vehicle drifting down the 26 mm/m gradient south of the station can enter it, be slowed down by the opposite gradient and then come to a stop. Each descending train must stop before the switch, so that it can be maneuvered on site to allow normal entry into the station. This simple but effective precautionary measure applies to other steep-gradient lines on the Italian network, in the Alps and the Apennines.” [1: p27]

Photographs showing the station building and the goods shed prior to its demolition can be seen here. [58] “Inaugurated in 1889, the station served as the terminus for the Cuneo-Ventimiglia line for nearly two years, until it was extended to Limone Piemonte. The passenger building features classic Italian architecture, with two levels. It is square, medium-sized, and well-maintained. Its distinctive feature is the two murals depicting scenes from the Pinocchio fairy tale, adorning its façade. The lower level houses the waiting room and self-service ticket machine, while the upper level is closed.” [58]

A photograph from the cab of a Cuneo-bound train arriving at Vernante. The passenger building is on the left with the goods shed beyond. [45]

While construction work was underway on the first three tranches (Cuneo to Vernante), the Italian rail network was undergoing a major reorganization. The Law passed on 27th April 1885, placed control of the railways into the hands of “the new Società per le Strade Ferrate del Mediterraneo, more commonly known as Rete Mediterranea (RM), … including the route ‘from Cuneo to the sea’.” [1: p28]

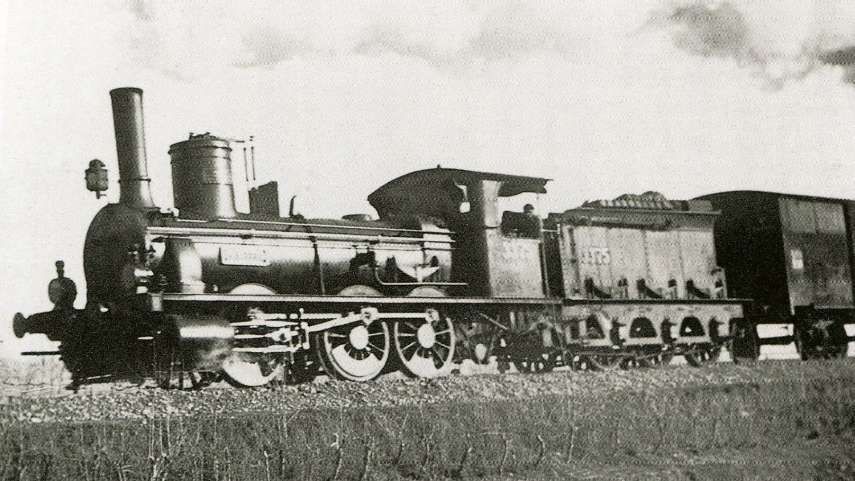

In 1887, the time had come for the first trains! “The Cuneo-Robilante section was inaugurated on Saturday, 16th July 1887, and opened for service on Monday 18th. Less than two weeks later, Francesco Crispi became President of the Council of Ministers, and relations between Italy and France would soon be strengthened. Then came the beginning of the future Cuneo-Mondovi line, which opened on 2nd October 1887, as far as Roccadebaldi. The Roccadebaldi and Robilante lines thus formed a common section for 359 meters, starting from Cuneo [Gesso] station and crossing the Gesso River on the same viaduct. … Two years later, the Robilante-Vernante section was … opened on 1st September 1889.” [1: p28]

As footnotes to this article we note that:

- Banaudo et al comment: “construction of the Ceva Ormea branch line began in the upper Tanaro Valley. With a terminus about 30 km from Vernante or 25 km from Tenda and Briga, this line would play an important role in the battle of interests that would unfold in the final years of the century to confirm a definitive route to the sea.” [1: p28]

- They also give details of the locomotives used on the line in these very early years, by Rete Mediterranea (RM). The locomotives were 030s (in the UK 0-6-0s) with tenders and came from the roster of the Turin depot and loaned to the Cuneo-Gesso Locomotive depot. They belonged to just one series: “Nos. 3201 to 3519 RM, which became group 215.001 to 398 at the FS. [The series was built] between 1864 and 1892 based on a model derived from the French “Bourbonnais” locomotives of the PLM. These 450 hp engines were equipped with saturated steam, single expansion, and Stephenson internal distribution. The [later] Cuneo depot, established in 1907, still had five type 215 locomotives in 1922, mainly operating service trains.” [1: p86] It is also worth noting that some of the locos used on the line after 1899 came from a second series of locomotives (“Nos. 3801 to 3869 RM, later 3101 to 3169, then group 310.001 to 069 at the FS, built from 1894 to 1901 [1: p86]). While these locomotives were old enough to have served in the period from 1887 to 1891, they only arrived on the line during 1901. … I anticipate there being a separate article about motive power on the line in due course.

We finish this first part of the journey from Cuneo to the sea at Vernante. The next article about the line will begin at Vernante and head South towards Limone and Vievola. It can be found here. [61]

References

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 1: 1858-1928; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 2: 1929-1974; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 3: 1975-1986; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

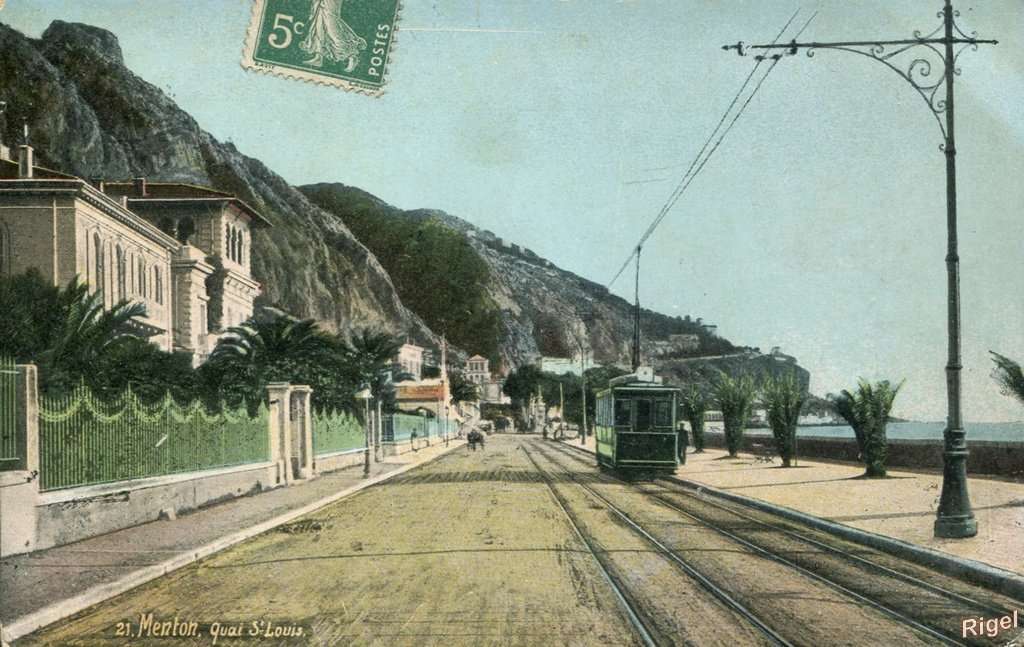

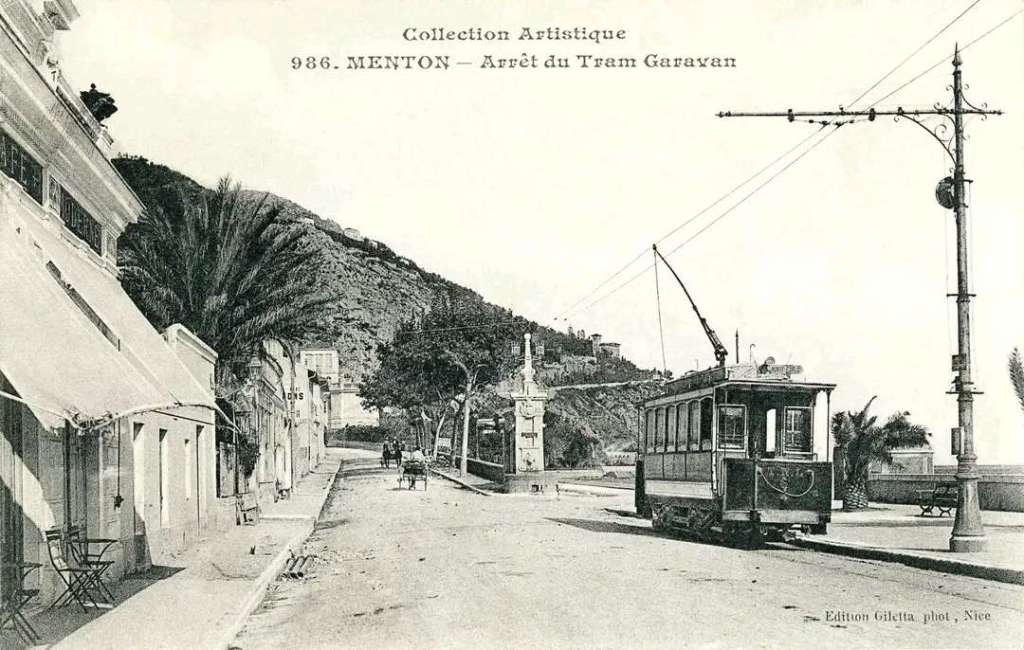

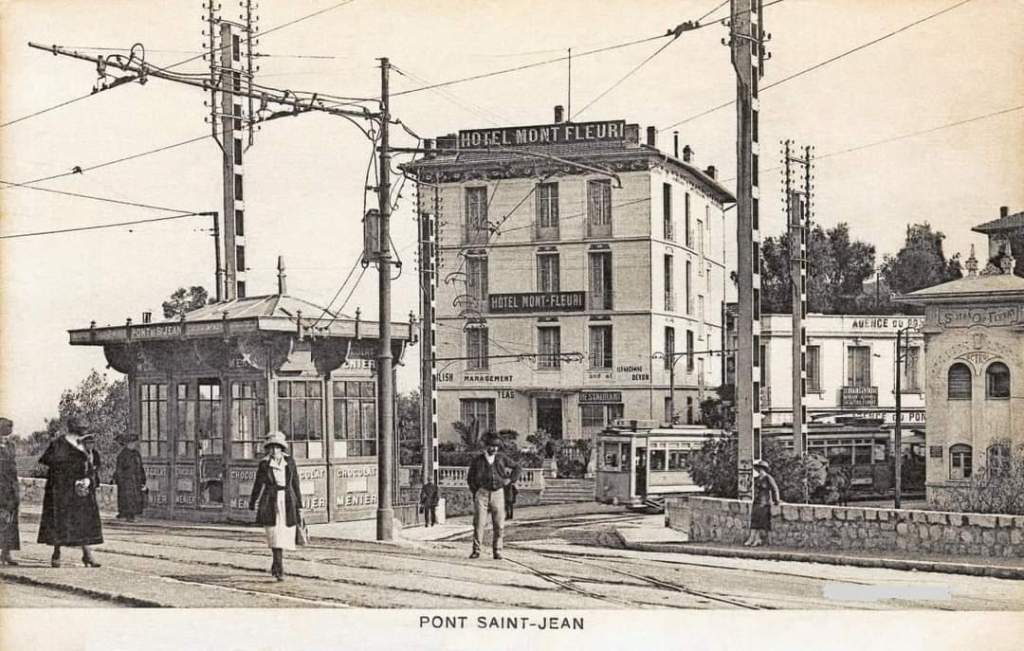

- https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=pfbid0eumWUFwJCPBGQUUtr3Apx72qr5cUhihwxpcFzDbkms3fta5zRXYZZLUozkAMmeKvl&id=1412933345657144, accessed on 5th December 2023. The Facebook Page, “L’Histoire de Menton et ses Alentours,” is the work of Frank Asfaux, https://www.facebook.com/franckasfaux06, accessed on 4th December 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/1711973335715195, accessed on 15th December 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/ciccoli/permalink/2989582914620891, accessed on 15th December 2023.

- https://www.cparama.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=11&t=14570, accessed on 21st December 2023.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fr%C3%A9jus_Rail_Tunnel, accessed on 13th July 2025.

- “The locomotive developed by the Scottish engineer Robert Francis Fairlie (1831-1885) from 1869 on the Ffestiniog narrow gauge railway in Wales, had two boilers connected by a single central firebox. Each boiler supplies steam to a pair of cylinders driving an independent group of axles. This system was developed in France from 1888 by artillery captain Prosper Péchot (1849-1928) and engineer Charles Bourdon (1847-1933), creators of an articulated narrow gauge locomotive widely used by the French army.” [1: p21]

- Séraphin Piccon; Etude Comparative de Deux Lignes de Chemin de Fer Entre Nice et Coni; 1872.

- The Fell System which created “additional adhesion using a raised central rail, patented by British engineer John Barraclough Fell (1815-1902), was first applied in the Alps in 1868 on the railway running along the Mont Cenis route between St. Michel-de-Maurienne and Susa, pending the completion of the Fréjus Tunnel in 1871.” [1: p21]

- A. Cachiardy de Montfleury; Chemin de Fer de Nice a Coni; Imprimerie Cauvan, Nice, 1872.

- Marius de Vautheleret; Chemin de Fer Cuneo Ventimiglia – Nice Traversant le Col de Tende; Editions Giletta, Nice, 1874.

- Marius de Vautheleret; Chemin de Fer Cuneo – Nice par Ventimiglia et le Col de Tende; Kugelmann, Paris, 1883; Trajet direct de Londres à Brindisi par le Col de Tende; Kugelmann, Paris, 1884; Ligne directe Londres – Brindisi par le Col de Tende; Retaux, Abbeville, 1890; Le Grand Saint-Bernard et le Col de Tende Ligne Ferrée Directe de Londres à Brindisi avec Jonction à la Méditerranée; Malvano & Mignon, Nice, 1897.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1CzKYeoPoV, accessed on 17th July 2025.

- https://trainconsultant.com/2020/10/09/nice-coni-incroyable-derniere-nee-des-grandes-lignes-internationales, accessed on 17th July 2025.

- https://cartorum.fr/carte-postale/466792/tende-col-de-tende-le-porte-frontiere, accessed on 17th July 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stazione_di_Cuneo_(2).jpg, accessed on 18th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/1CP5xtb7Yx, accessed on 18th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/17SDzaUV5x, accessed on 18th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1FsN8Vdact, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stazione_di_Cuneo_Gesso#/media/File%3AStazione_di_CuneoGesso.png, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- Stefano Garzaro & Nico Molino; La Ferrovia Di Tends Da Cuneoba Nizza, L’ultima Grande Traversata Alpina, Colleferro (RM); E.S.T. – Editrice di Storia dei Trasporti, Luglio, 1982, (Italian text)

- Ferrovie dello Stato; Circolare Compartimentale del Compartimento di Torino 54/1937, (Italian text).

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stazione_di_Cuneo_Gesso, accessed on 19th July 2025. (Italian text translated into English by Google Translate)

- Franco Collidà, Max Gallo & Aldo A. Mola; Cuneo-Nizza: Storia di una ferrovia, Cuneo (CN); Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo, Luglio, 1982, (Italian text).

- The locomotive depot area, left vacant after the opening of the new Cuneo station, was later reused by a sawmill connected by a siding to the Gesso station. [25]

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tranvia_Cuneo-Dronero, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tranvia_Saluzzo-Cuneo, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tranvia_Cuneo-Boves, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- Nico Molino; Il trenino di Saluzzo. Storia della Compagnia Generale Tramways Piemontesi; Immagini e Parole, Torino, 1981, (Italian text)

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferrovia_Cuneo-Boves-Borgo_San_Dalmazzo#/media/File:Cuneo-Borgo_San_Dalmazzo_map.JPG, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stazione_di_Boves#/maplink/1, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferrovia_Cuneo-Boves-Borgo_San_Dalmazzo, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://airascasaluzzocuneo.jimdofree.com/le-altre-ferrovie-cuneesi-dismesse/cuneo-gesso-borgo-s-dalmazzo, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/15Te6MP6HJ, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1Fu9bkbK6Z, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.38723/7.53585&layers=, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.37623/7.52866&layers=P, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.36284/7.52769&layers=P, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.35447/7.52108&layers=P, accessed on 19th July 2025

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.34602/7.51279&layers=P, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.33788/7.50627&layers=P, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.33366/7.50016&layers=P, accessed on 19th July 2025.

- https://youtu.be/2Xq7_b4MfmU?si=1sOymKkFjSpxMkcR, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Borgo_san_dalmazzo_stazione_ferroviaria.jpg, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1A6hv4xBsJ, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://itoldya420.getarchive.net/amp/topics/cuneo+demonte+tramway, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campo_di_concentramento_di_Borgo_San_Dalmazzo, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stazione_di_Borgo_San_Dalmazzo, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20201006185244/http://comune.borgosandalmazzo.cn.it/citta/monumenti.html, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/19QHky9Nw2, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stazione_di_Robilante, accessed on 21st July 2025.

- https://flic.kr/p/Yqh8NC, accessed on 21st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.261563/7.519197, accessed on 21st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.257276/7.523800, accessed on 21st July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/44.255493/7.525206, accessed on 21st July 2025.

- https://www.stazionidelmondo.it/files/old_website/vernantestazione.htm, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://www.rmweb.co.uk/forums/topic/151308-%E2%80%9Cbeyond-dover%E2%80%9D/page/2, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://www.fotocommunity.it/photo/locomotiva-3375-rete-mediterrane-roberto-prioreschi/35312169, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/07/26/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-2

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/19U2VzU6gT, accessed on 8th August 2025.