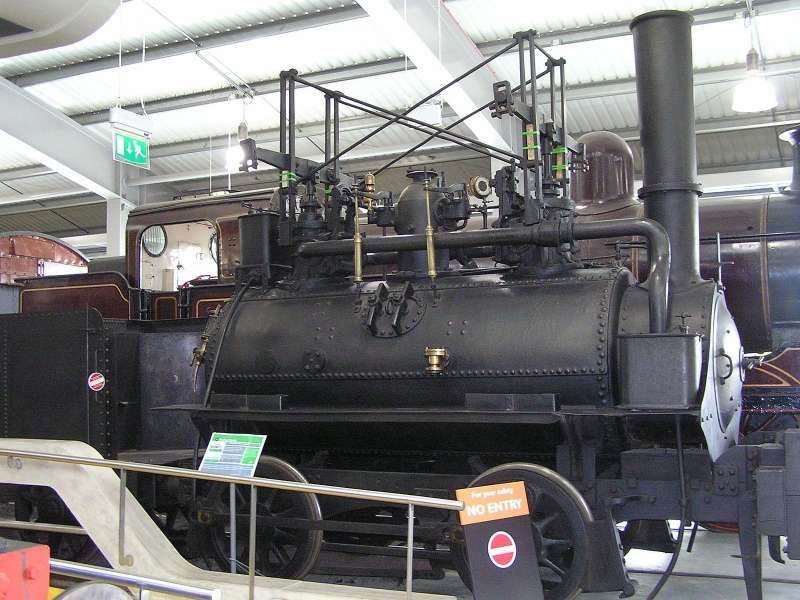

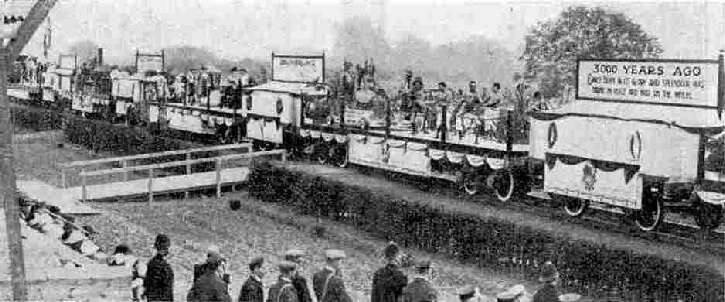

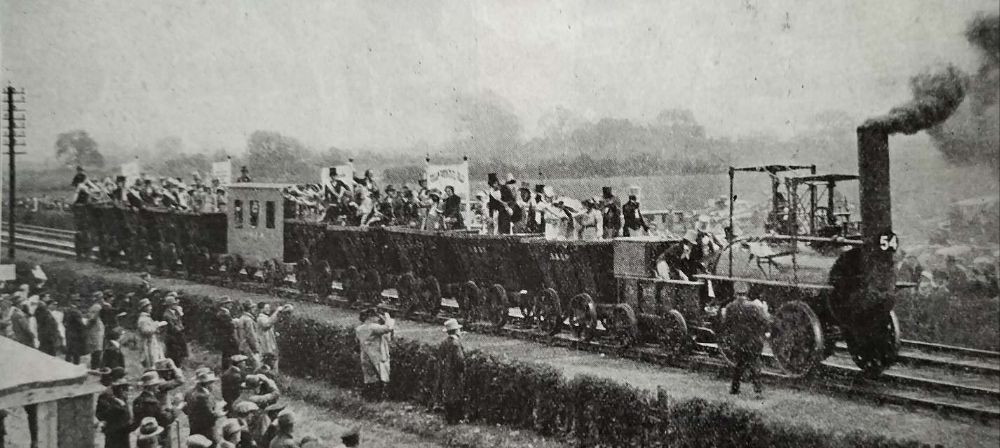

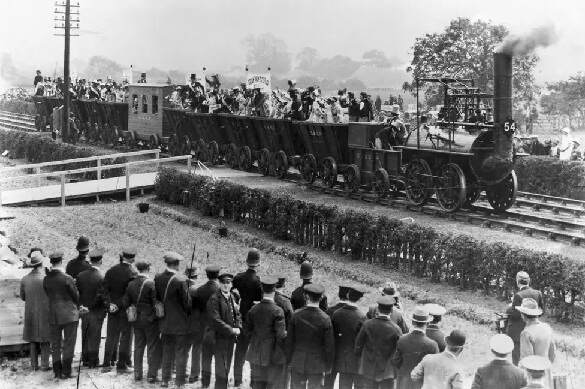

On 27th September 2025 we marked the bicentenary of the Stockton & Darlington Railway which is accepted the world over as one of the most significant developments in the history of railways, the precursor of all that was to follow in the development of railway networks throughout the world. That day, Locomotion No. 1 (a replica appears in the featured image above) pulled a long train along the Stockton and Darlington Railway. …………

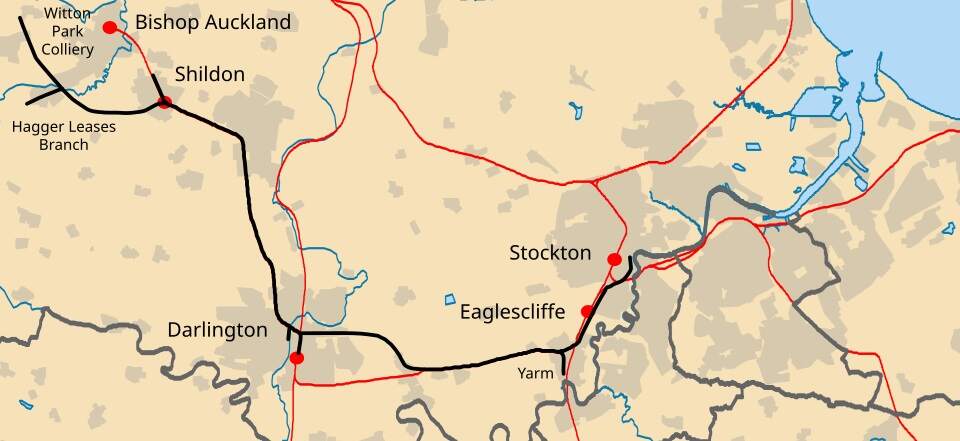

Andrew Wilson, writing in 2002, said that the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) “was incorporated in 1821. With the line from Stockton to Shildon opening on 27th September 1825. The S&DR became the world’s first steam-operated railway, although passenger services were initially horse-drawn; regular steam-powered passenger services commenced in 1833. In 1843 the line was extended to Bishop Auckland, and Barnard Castle was reached in 1856. Additional lines were soon planned, and one of these the South Durham & Lancashire Union Railway sought to link Bishop Auckland and Tebay so that coke from the Durham coalfields could be easily moved to the Furness ironworks, and iron-ore moved back to Cleveland.” [1: p13]

The Institution of Civil Engineers says that “The Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR) was the first passenger railway to use steam trains to transport passengers.” [4] The Company started operations at the end of September 1825 and was eventually taken over by the North Eastern Railway in 1863 when “it consisted of 200 route miles (320km) and around 160 locomotives.” [4]

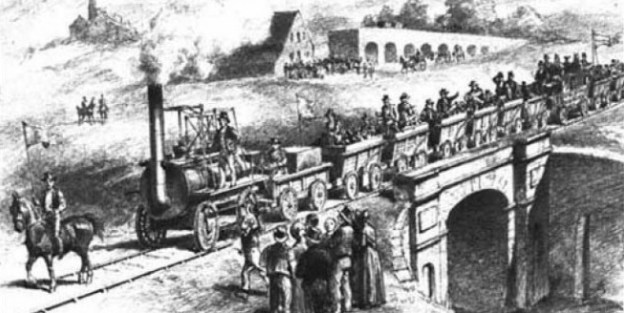

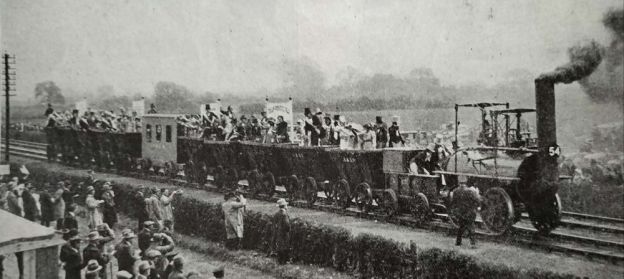

Network Rail says: “On 27th September 1825, the world’s first passenger train, hauled by George Stephenson’s Locomotion No.1, carried more than 400 people along the Stockton and Darlington Railway. The landmark event drew crowds of up to 40,000 people and marked the birth of modern passenger train travel.” [46]

Darren Caplan, chief executive of trade body the Railway Industry Association, said: “It is hard to overstate the benefits that the railway has brought, and continues to bring, not just to the UK, but also globally, since 1825. Rail networks don’t just keep people connected, they also play a crucial role in spurring economic growth, creating jobs, boosting sustainability, and bringing together local communities.” [46]

The Encyclopedia Brittanica speaks of the S&DR as “first railway in the world to operate freight and passenger services with steam traction.” [6]

The Friends of the Stockton & Darlington Railway say that the S&DR “demonstrated to the wider world that such a railway could be a technical and financial success. The S&DR made possible the railways that were to follow such as the Liverpool & Manchester Railway. … It was therefore the birthplace of the modern railways that we know today.” [5]

Asked, ‘What’s so special about the S&DR?’ Neil Hammond, the Chair of the Friends of the Stockton & Darlington Railway, said, “We would argue that it’s the railway that got the world on track.” [7]

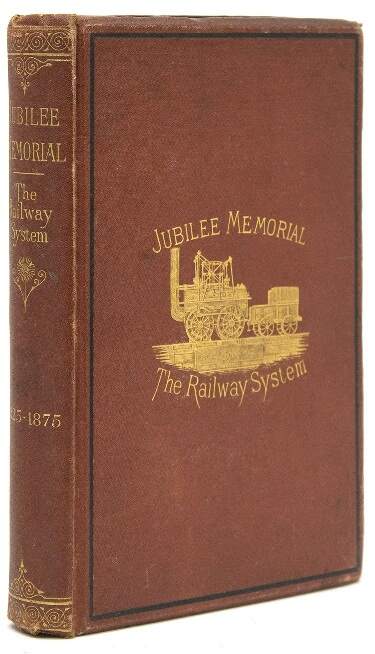

J. S. Jeans, writing in 1875, somewhat effusively called the S&DR, “the greatest idea of modern times.” [9] (His book appears in the adjacent image.)

According to Hammond, the S&DR, for the first time, brought together various elements of engineering and ideas for what a railway could be, which gave the rest of the world a blueprint for how to build a recognisably modern railway. Anthony Coulls of the National Railway Museum said that, “It set the DNA for the railway system.” [7]

From the outset, it was much more than just a way of conveying coal, unlike many of the other early railways. Transport of other goods and regular passenger services were intrinsic to its operation and purpose. “It used a combination of horses, stationary steam engines and steam-powered locomotives to pull wagons along its 26 miles, from the coalfields of County Durham to the port on the River Tees at Stockton, via the then-village of Shildon and market town of Darlington. Signalling systems, timetables and the idea of stations were all developed by the S&DR.” [7]

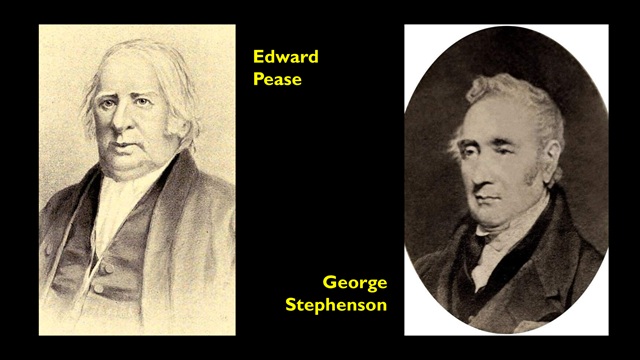

“While there had been earlier wooden waggonways, metal plateways and the use of steam engines, it was the coming together of engineering excellence with the motivation, vision and financial backing, mainly from Darlington’s Quaker families, in particular Edward Pease, which made the S&DR a significant milestone in the creation of what we now think of as the modern railway system. It required business people to recognise the potential role of the railway for communities and businesses beyond the mineral industries and to invest in a service that anyone (the public) could buy into and make use of. In return, unlike earlier mineral waggonways, the rail infrastructure would be a permanent fixture with a regular service linking populated areas and so attract additional businesses and industries resulting in population growth and movement. … By 1830, the S&DR was already a network of main and branch lines and had demonstrated to others building railways elsewhere in the UK and abroad, the model of a permanent, profitable steam powered public railway.” [8]

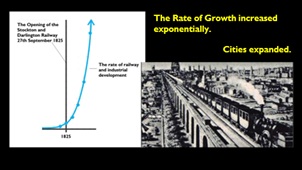

Coulls said that “Engineers travelled from across Britain and the world to see the the railway in action, to replicate its successes and learn from its mistakes. Bigger railways, such as the Manchester to Liverpool line, followed soon after and within a decade there was a global ‘railway mania’, akin to the rapid development and impact of the internet in the 20th Century.” [7]

He continued: “The S&DR was not the first railway and it was rapidly eclipsed. But it proved the practicality of the steam locomotive pulling trains over long distances.” [7]

There have been quite a number of detractors over the years and questions have been raised about the true place of the S&DR in railway history. As Coulls said, “it was not the first railway and it was rapidly eclipsed.” [7]

What we do know is that at least 400 people (maybe 600) travelled by train on the Stockton and Darlington Railway on 27th September 1825 and we know that around 40,000 people turned up to witness the event. [46] What is it that makes that event remarkable enough to be seen as the moment that the modern railway was born?

Lets first, make sure that we have understood the story on the Stockton & Darlington Railway Company: …

A Short History of the Stockton & Darlington Railway

Coal Reserves in Co. Durham

Coalfields in the United Kingdom in the 19th century. [103]

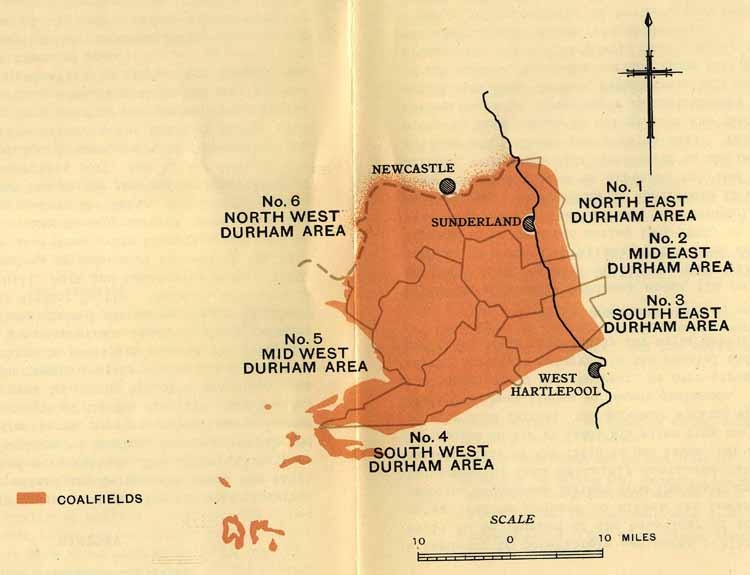

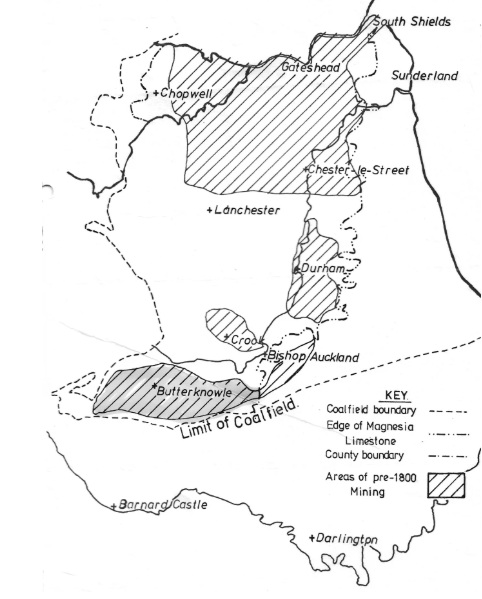

The Durham Coalfield is continuous with the Northumberland Coalfield to its North. It extends from Bishop Auckland in the South to the boundary with the county of Northumberland along the River Tyne in the North, beyond which is the Northumberland Coalfield. [106]

The two contiguous coalfield areas were often referred to as the Durham and Northumberland Coalfield(s) or as the Great Northern Coalfield. [108]

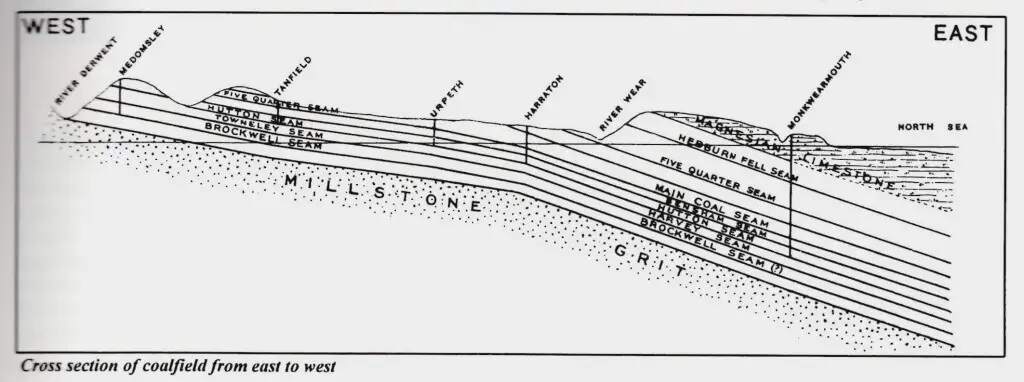

Three major ‘measures’ of Coal exist(ed) in the Durham Coalfield:

Upper (Youngest) Coal Measures: Hylton Castle Seam. [103]

Middle Coal Measures: Dean, Hebburn Fell, Usworth, Ryhope Five-Quarter, Ryhope Little, High Main, Metal, Five-Quarter, Main, Maudlin, Durham Low Main; Brass Thill, and Hutton Seams. [103]

Lower (Oldest) Coal Measures: Harvey, Tilley, Busty, Three-Quarter, Brockwell, Victoria, Marshall Green and Ganister Clay Seams. [103]

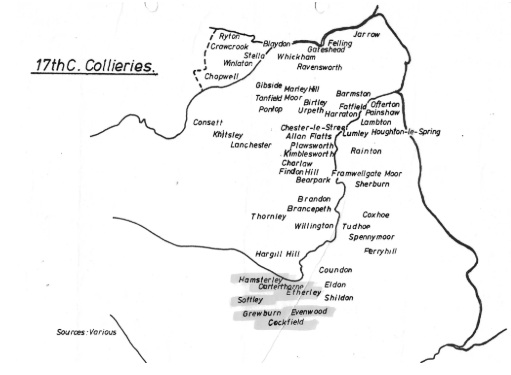

THe UK was the first country to develop its coal resources to any appreciable extent. The Durham Coalfield was among the first to be worked. The initiative came largely from the Bishops of Durham. The accounts of the See of Durham between 1274-1345 include a reference to the profits of the Bishop’s coalmines. By the middle of the fourteenth century mining had become well established at Whickham and Gateshead on the south side of the Tyne. “In 1366-1367 coal from Winlaton was bought by Edward III for the works at Windsor Castle. Coalpits were also in operation at Ferryhill, Hett and Lanchester before 1350. However, the cheapness of transport enjoyed by the pits close to the rivers gave them a big advantage and even at the beginning of the seventeenth century, almost all the large collieries were along the Tyne. Development of the Wear valley reserves led to the increasing importance of Sunderland as an exporting port, and by the time of the Civil War, the town had become, next to Newcastle, the biggest centre of the trade in the British Isles. The growth in the trade from the Tyne was phenomenal. In the year ended at Michaelmas, 1564, almost 33,000 tons of coal were shipped from Newcastle: in 1685, the tonnage was 616,000 almost 19 times as much.” [106]

Development of the industry in South Durham did not lag much behind the rest of the County. “As far back as the fourteenth century, part of the Bishopric of Durham south of Bishop Auckland was being successfully worked for coal. The Upper Wear Valley between Durham City and Bishop Auckland was in the Middle Ages the most populous part of the county because of the lead mines in the district. The coal consumed came from small workings sprinkled all through the valley and J. U. Nef, in his book ‘The Rise of the British Coal Industry’, estimates that by the middle of the seventeenth century there must have been twenty or thirty pits within an area of about 150 square miles. Every manor of any size had its own pits.” [106]

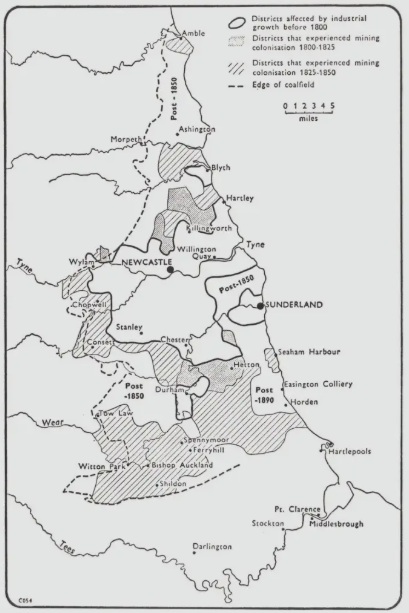

In more recent times, production from the Durham coal mines increased from about 26 million tons in 1877 to the highest recorded figure of almost 56 million tons in 1913. Just after the 1st World War there were 170,000 miners at work in the Durham coalfields. Since then, however, production has declined significantly. By the late 20th century production, with the closure of mines during the middle years of the century, production fell rapidly. The last mine in the Durham Coalfield closed in 1994. [107] The last in the Northumberland Coalfield (Ellington Colliery) closed in 2005. [108]

A few things to note:-

- Coal Output – according to Sunnyside Local History Society, prior to the introduction of tramroads and then railways the combined output of the Northumberland and Durham coalfields was around 2,000,000 tons of coal per annum. [109] By 1850, the output was around 5,800,000 tons. By 1865, the coal exported from the combined coalfield was about 6,400,000 tons per annum. The railways and, prior to them, the tramroads enabled this dramatic increase, markedly increasing productivity and reducing costs. [110]

- The location of Darlington and Stockton – both are some distance outside the Durham Coalfield. It is reasonable to ask what it was that meant that a railway route via Darlington to Stockton on the River Tees was considered to be the best route for the export of coal from the Southwest area of the coalfield. In practical terms, although the River Wear penetrated the Durham Coalfield close to the deposits in the Southwest, it was not navigable for much of its length. This meant that the distance to the port at Stockton (where the Tees was navigable) was shorter than the distance to Sunderland. The coal that was produced in the Southwest of the coalfield was either for local use or travelled by pack horse routes across the higher ground between the River Wear and the River Tees, or were carted on poorly surfaced roads to Stockton. It was natural, therefore to look to improve the route already used, rather than seek out significantly different alternative routes to the North and East. Landowners in the Southwest of the coalfield would only be able to exploit the coal reserves under their land once an economically sustainable transport method could be devised.

- Pack horses – could carry about an eighth of a ton each. [111]

- Tramroads – dramatically increased the capacity which a single horse could pull, from around 1 ton over uneven and poorly maintained roads to around 10 tons/horse. The problem, in the early 1800s, was to cost of horses and fodder. The Napoleonic Wars resulted in a dramatic increase in the cost of fodder and horses became more scarce as a result of the demands made by the wars. Landowners needed cheaper ways to transport coal to the ports for onward transport to London and the South. [112]

- Canals – a number of different schemes were considered but foundered because of cost or the level differences involved in reach mines in the Pennine hills. If viable, they would have dramatically increased the load which could be pulled by one horse to as much as 30 tons! [111]

- Steam railways – initially saw the amount of freight carried as 80 tons/locomotive (the amount pulled by Locomotion No. 1 on its inaugural trip on the Stockton and Darlington Railway). [113] And would go on to be able to move 100s of tons in single trains as the technology improved.

The Development of the Stockton & Darlington Railway

Until the 19th century, coal from the inland mines in southern County Durham used to be taken away on packhorses. Then later by horse-drawn carts as the roads were improved. [47]

A number of canal schemes failed.

Promoters included George Dixon, John Rennie, James Bradley and Robert Whitworth. [117]

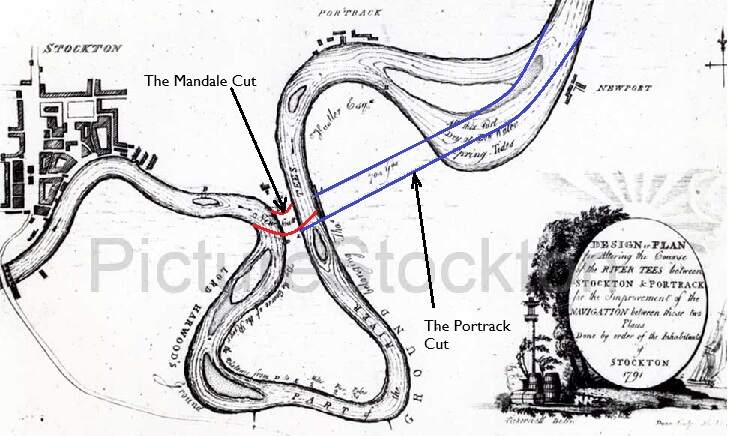

The River Tees was straightened in the early 19th century through the creation of two cuts, the Mandale Cut (1810 – 220 yards long, saving over 2 miles of journey) and the Portrack Cut (1831 – 700 yards long), significantly improving access to Stockton’s port. [47]

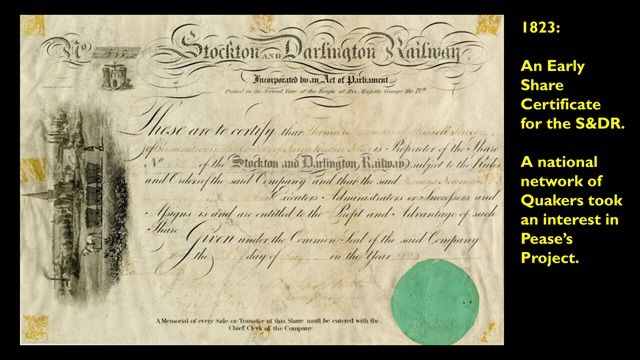

Also in the early 19th century, another canal was proposed to take coal from the mines in the Southwest of Co. Durham to Stockton. The proposed route bypassed Yarm and Darlington and the scheme was resisted by Edward Pease and Jonathan Backhouse, both of Darlington. [47] It was at a meeting held in Yarm to oppose the construction of the canal that a tramroad was proposed. [48: p16] The Welsh engineer George Overton advised building a tramroad. He carried out a survey [49: p45-47] and planned a route from the Etherley and Witton Collieries to Shildon, and then passing to the north of Darlington to reach Stockton. The Scottish engineer Robert Stevenson was said to favour the railway, and the Quaker Edward Pease supported it at a public meeting in Darlington on 13th November 1818, promising a five per cent return on investment. [48: p16-17][49: p55 & 63] Approximately two-thirds of the shares were sold locally, and the rest were bought by Quakers nationally. [50: p33, 52, 79–80, 128][51][52][53: p223] A private bill was presented to Parliament in March 1819, but as the route passed through Earl of Eldon’s estate and one of the Earl of Darlington’s fox coverts, it was opposed and defeated by 13 votes. [11][54]

The first submission of a bill for what became the Stockton & Darlington Railway was deferred because of the death of George III. A revised bill was submitted on 30th September 1820. The route had to avoid the lands of Lord Darlington and Viscount Barrington. [49: p64-67][54]

The railway was unopposed this time, but the bill nearly failed to enter the committee stage as the required four-fifths of shares had not been sold. Pease subscribed £7,000; from that time he had considerable influence over the railway and it became known as “the Quaker line”. The Stockton and Darlington Railway Act 1821 (1 & 2 Geo. 4. c. xliv), which received royal assent on 19th April 1821, allowed for a railway that could be used by anyone with suitably built vehicles on payment of a toll, that was closed at night, and with which land owners within 5 miles (8 km) could build branches and make junctions;[49: p70][50: p37] no mention was made of steam locomotives. [48: p19][54]

What does seem significant, with the benefit of hindsight, is the way that this new railway initiated the construction of more railway lines, causing significant developments in railway mapping and cartography, iron and steel manufacturing, as well as in any industries requiring more efficient transportation. The railway(s) produced a demand for railway related supplies while simultaneously providing the mechanisms which brought significant economies of scale and logistics to many manufacturers and businesses [54][56][57]

“Edward Pease (1767-1858) was the chief inspiration and founder of the S&DR, in choosing a railway rather than a canal, in promoting its route, via Darlington, and adopting steam locomotive power.” [58: p13] Edward Pease had some concerns about George Overton’s competence in respect of railway construction. He turned to George Stephenson who had proven himself to be an excellent engine-wright at the Killingworth collieries, for advice. [54] In addition, Pease invested £7,000 (as much as £750,000 today) of his own money to overcome cashflow problems

Pease also undertook, with fellow Quakers, what was perhaps the first targeted national sale of shares. They sought a wider involvement in share ownership beyond those immediately involved with their project.

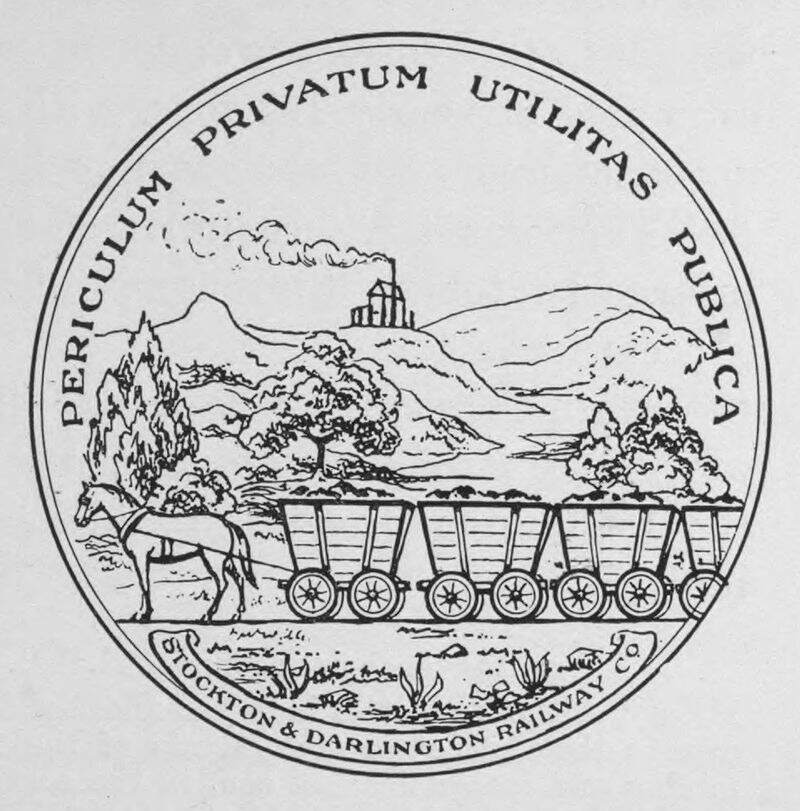

On 12th May 1821 the shareholders appointed Thomas Meynell as chairman and Jonathan Backhouse as treasurer; a majority of the managing committee, which included Thomas Richardson, Edward Pease and his son Joseph Pease, were Quakers. The committee designed a seal, showing waggons being pulled by a horse, and adopted the Latin motto Periculum privatum utilitas publica (“At private risk for public service”).[49: p73][50: p184] By 23rd July 1821, it had decided that the line would be a railway with edge rails, rather than a plateway, and appointed Stephenson to make a fresh survey of the line, [49: p74][54]

The Seal of the Stockton & Darlington Railway Co. © Public Domain. [49: p73][55]

The seal of the railway company was designed in 1821. It is clear that, at that time at least, the planned railway was not intended for steam propulsion or passenger use.

The Latin motto is Periculum privatum utilitas publica (At private risk for public service). [54]

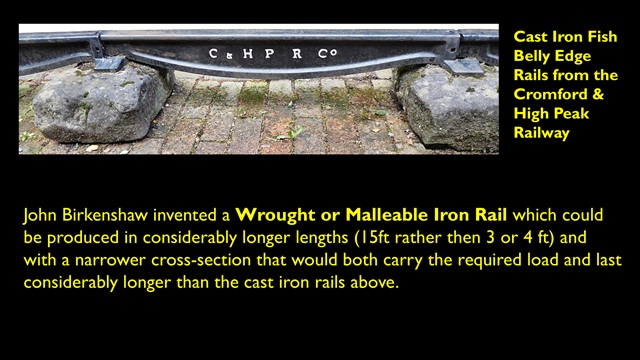

Stephenson recommended using malleable iron rails, even though he owned a share of the patent for cast iron rails. Malleable iron rails formed about 65% of the railway but cast iron rails were used at junctions and on the remainder of the line. [4][59: p74][60]

By the end of 1821, Stephenson “had reported that a usable line could be built within the bounds of the Act of Parliament, but another route would be shorter by 3 miles (5 km) and avoid deep cuttings and tunnels.” [48: p20]

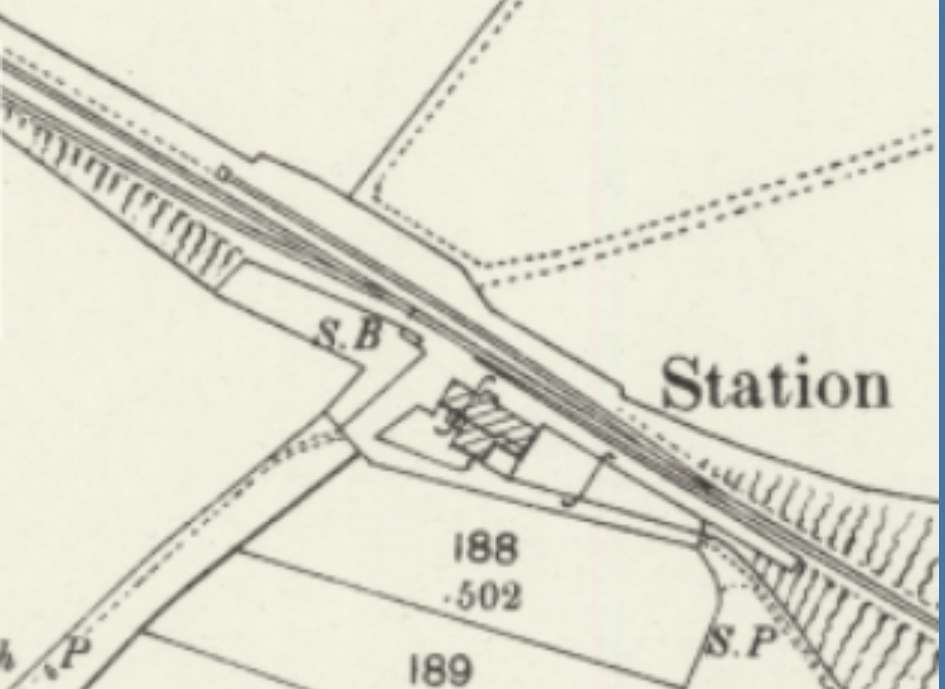

“Overton had kept himself available, but had no further involvement and the shareholders elected Stephenson [as] Engineer on 22nd January 1822, with a salary of £660 per year. [49: p79-80] On 23rd May 1822 a ceremony in Stockton celebrated the laying of the first track at St John’s Well, the rails 4 ft 8 in (1,422 mm) apart, [61] the same gauge used by Stephenson on his Killingworth Railway.” [48: p20][54] This was altered to 4 ft 8½ in to reduce binding on curves. [120: p19]

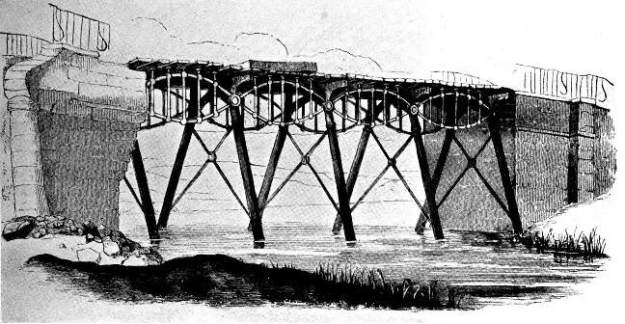

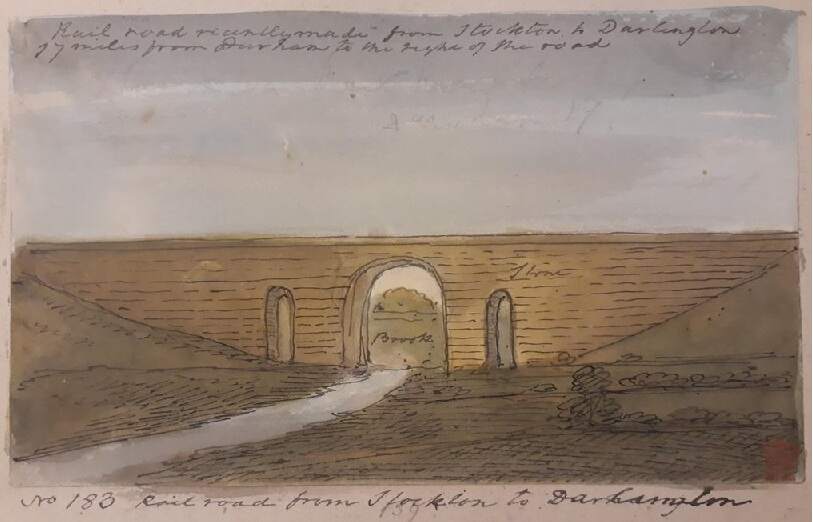

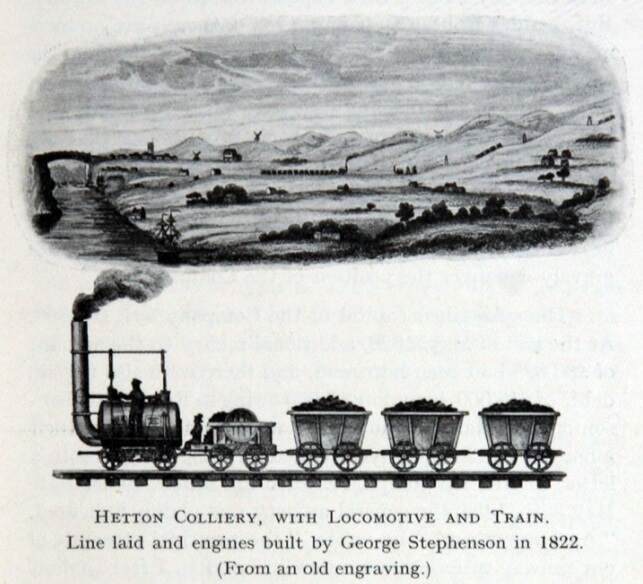

“Stephenson advocated the use of steam locomotives on the line. [48: p19] Pease visited Killingworth in mid-1822 [62: p154] and the directors visited Hetton colliery railway, on which Stephenson had introduced steam locomotives. [49: p83] A new bill was presented, requesting Stephenson’s deviations from the original route and the use of “locomotives or moveable engines”, and this received royal assent on 23rd May 1823 as the Stockton and Darlington Railway Act 1823 (4 Geo. 4. c. xxxiii).[49: p85-86] The line included embankments up to 48 feet (15 m) high, and Stephenson designed an iron truss bridge to cross the River Gaunless. The Skerne Bridge over the River Skerne was designed by the Durham architect Ignatius Bonomi.” [59: p75][65][54] George Stephenson’s bridge over the Gaunless suffered flood damage and had to be rebuilt – the directors of the railway company instructed Stephenson to consult Bonomi about the construction of Skerne Bridge – Bonomi designed a stone arch bridge, with a single arch spanning the river and two smaller flood arches over the paths either side. Bonomi’s bridge is still in use today. “Being the oldest railway bridge in continuous use in the world, it is a Grade I listed building.” [68]

By 1823, Stephenson and Pease had opened Robert Stephenson and Company, a locomotive works at Forth Street, Newcastle, from which the following year the S&DR ordered two steam locomotives and two stationary engines. [49: p95-96][54]

This highlights another way in which the S&DR was very much of its time and looked different from a modern railway: It only used locomotives (or horses) on the level sections of the line. Inclines were operated by a combination of gravity and steam-power from stationary engines.

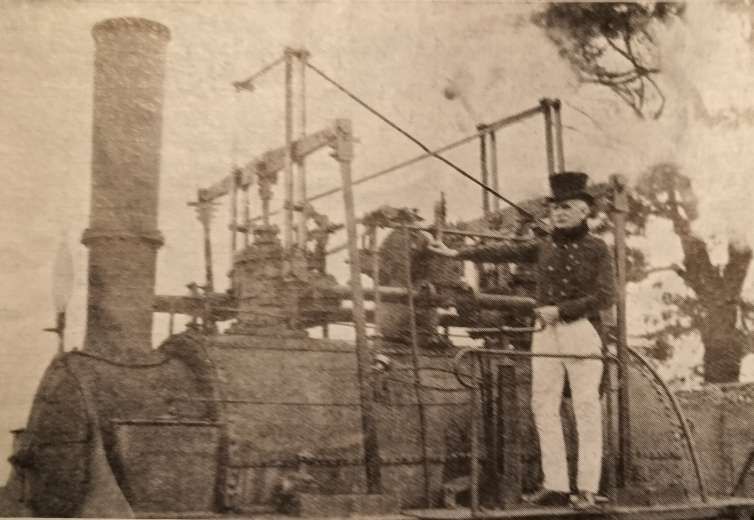

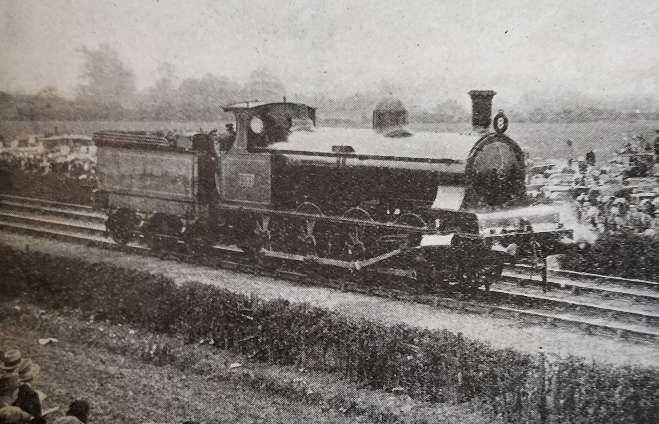

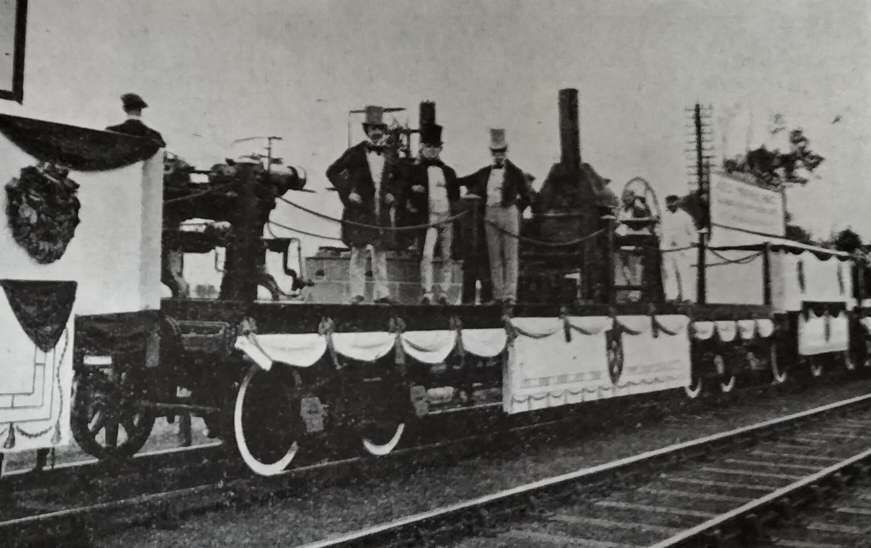

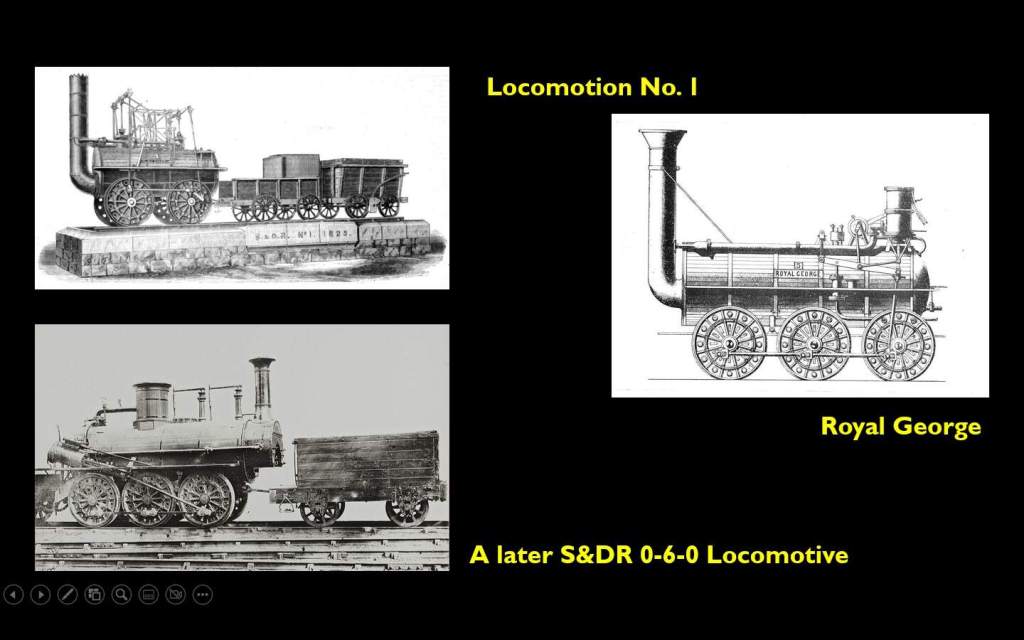

“On 16th September 1825, with the stationary engines in place, the first locomotive, ‘Locomotion No. 1’, left the works, and the following day it was advertised that the railway would open on 27th September 1825.” [49: p105][54]

The Opening of the Line

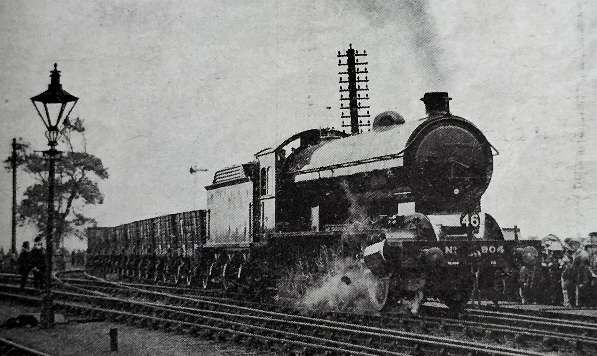

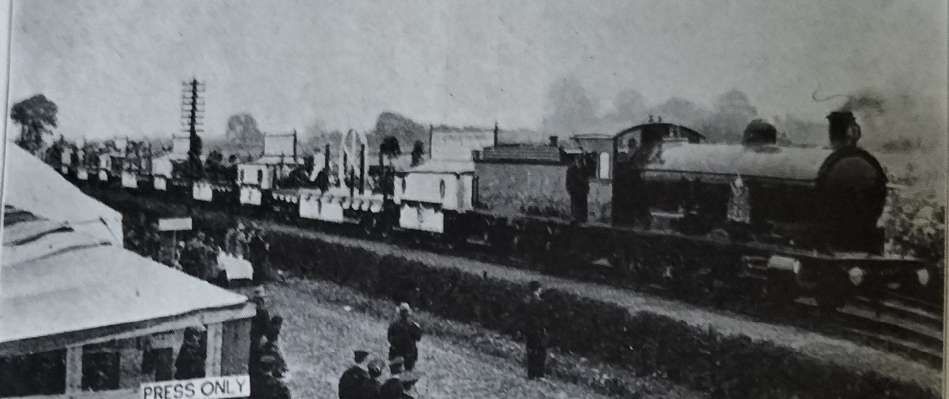

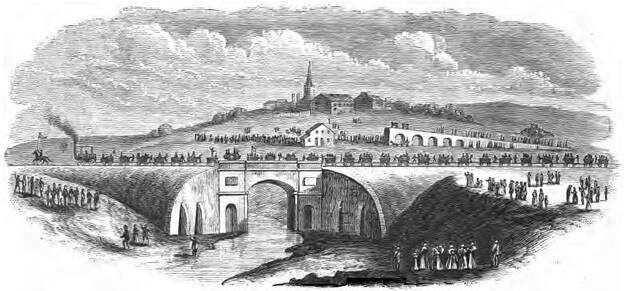

Wikipedia tells us that “the cost of building the railway had greatly exceeded the estimates. By September 1825, the company had borrowed £60,000 in short-term loans and needed to start earning an income to ward off its creditors. A railway coach, named Experiment, [71] arrived on the evening of 26th September 1825 and was attached to Locomotion No. 1, which had been placed on the rails for the first time at Aycliffe Lane station following the completion of its journey by road from Newcastle earlier that same day. Pease, Stephenson and other members of the committee then made an experimental journey to Darlington before taking the locomotive and coach to Shildon in preparation for the opening day, with James Stephenson, George’s elder brother, at the controls. [49: p105-106] On 27th September, between 7 am and 8 am, 12 waggons of coal [74] were drawn up Etherley North Bank by a rope attached to the stationary engine at the top, and then let down the South Bank to St Helen’s Auckland. A waggon of flour bags was attached and horses hauled the train across the Gaunless Bridge to the bottom of Brusselton West Bank, where thousands watched the second stationary engine draw the train up the incline. The train was let down the East Bank to Mason’s Arms Crossing at Shildon Lane End, where Locomotion No. 1, Experiment and 21 new coal waggons fitted with seats were waiting.” [49: p109-110]

Between 450 and 600 people travelled behind Locomotion No. 1, most in empty waggons but some on top of waggons full of coal. Wikipedia tells us that “brakesmen were placed between the waggons, and the train set off, led by a man on horseback with a flag. It picked up speed on the gentle downward slope and reached 10 to 12 miles per hour (16 to 19 km/h), leaving behind men on field hunters (horses) who had tried to keep up with the procession. The train stopped when the waggon carrying the company surveyors and engineers lost a wheel; the waggon was left behind and the train continued. The train stopped again, this time for 35 minutes to repair the locomotive and the train set off again, reaching 15 mph (24 km/h) before it was welcomed by an estimated 10,000 people as it came to a stop at the Darlington branch junction. Eight and a half miles (14 km) had been covered in two hours, and subtracting the 55 minutes accounted by the two stops, it had travelled at an average speed of 8 mph (13 km/h). Six waggons of coal were distributed to the poor, workers stopped for refreshments and many of the passengers from Brusselton alighted at Darlington, to be replaced by others.” [49: p110-112][54][59: p85]

Wikipedia continues: “Two waggons for the Yarm Band were attached, and at 12:30 pm the locomotive started for Stockton, now hauling 31 vehicles with 550 passengers. On the 5 miles (8 km) of nearly level track east of Darlington the train struggled to reach more than 4 mph (6.4 km/h). At Eaglescliffe near Yarm crowds waited for the train to cross the Stockton to Yarm turnpike. Approaching Stockton, running alongside the turnpike as it skirted the western edge of Preston Park, it gained speed and reached 15 mph (24 km/h) again, before a man clinging to the outside of a waggon fell off and his foot was crushed by the following vehicle. As work on the final section of track to Stockton’s quayside was still ongoing, the train halted at the temporary passenger terminus at St John’s Well 3 hours, 7 minutes after leaving Darlington. The opening ceremony was considered a success and that evening 102 people sat down to a celebratory dinner at the Town Hall.” [49: p112-114]

The story of the opening day illustrates effectively that the line was not hauled throughout by steam locomotives and relied significantly on stationary steam engines for managing movements on steep inclines.

Early Days

“The railway that opened in September 1825 was 25 miles (40 km) long and ran from Phoenix Pit, Old Etherley Colliery, to Cottage Row, Stockton; there was also a 1⁄2 mile (800 m) branch to the depot at Darlington, 1⁄2 mile (800 m) of the Hagger Leases branch, and a 3⁄4 mile (1,200 m) branch to Yarm. [49: p106] Most of the track used 28 pounds per yard (13.9 kg/m) malleable iron rails, and 4 miles (6.4 km) of 57 1⁄2 lb/yd (28.5 kg/m) cast iron rails were used for junctions.” [49: p89-90][54][79] To put this in context, modern railway rails typically weigh between 40 to 70 kg/m (88 to 154 lb/yd), with heavier rails used for higher speeds and axle loads. In Europe, a common range is 40 to 60 kg/m, while in North America, it’s more common to see rails in the 55 to 70kg/m (115 to 154 lb/yd) range. The heaviest mass-produced rail was 77.5 kg/m (171 lb/yd). [78][79][80]

The S&DR was “single track with four passing loops per mile; [48: p27] square sleepers supported each rail separately so that horses could walk between them. [59: p74] Stone was used for the sleepers to the west of Darlington and oak to the east; Stephenson would have preferred all of them to have been stone, but the transport cost was too high as they were quarried in the Auckland area. [49: p91] The railway opened with the company owing money and unable to raise further loans; Pease advanced money twice early in 1826 so the workers could be paid. By August 1827 the company had paid its debts and was able to raise more money; that month the Black Boy branch opened and construction began on the Croft and Hagger Leases branches. During 1827, shares rose from £120 at the start to £160 at the end.” [49: p138-140][54] Horses could haul up to four waggons. Dandy Waggons were introduced in mid-1828. A Dandy Waggon “was a small cart at the end of the train that carried the horse downhill, allowing it to rest while the train descended under gravity. The S&DR made their use compulsory from November 1828.” [48: p27][49: p154-156][54]

“The line was initially used to carry coal to Darlington and Stockton, carrying 10,000 tons [82] in the first three months and earning nearly £2,000. In Stockton, the price of coal dropped from 18 to 12 shillings, and by the beginning of 1827 was … 8s 6d.[49: p117, 119] At first, the drivers had been paid a daily wage, but after February 1826 they were paid 1⁄4d per ton per mile; from this they had to pay assistants and fireman and to buy coal for the locomotive. [49: p132] The 1821 Act of Parliament had received opposition from the owners of collieries on the River Wear who supplied London and feared competition, and it had been necessary to restrict the rate for transporting coal destined for ships to 1⁄2d per ton per mile, which had been assumed would make the business uneconomic. There was interest from London for 100,000 tons a year, so the company began investigations in September 1825. In January 1826, the first staith opened at Stockton, designed so waggons over a ship’s hold could discharge coal from the bottom. [49: p120-121] About 18,500 tons of coal was transported to ships in the year ending June 1827, and this increased to over 52,000 tons the following year, 44.5% of the total carried.” [49: p136][54]

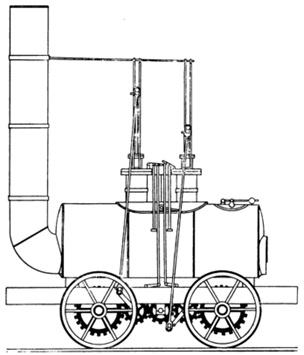

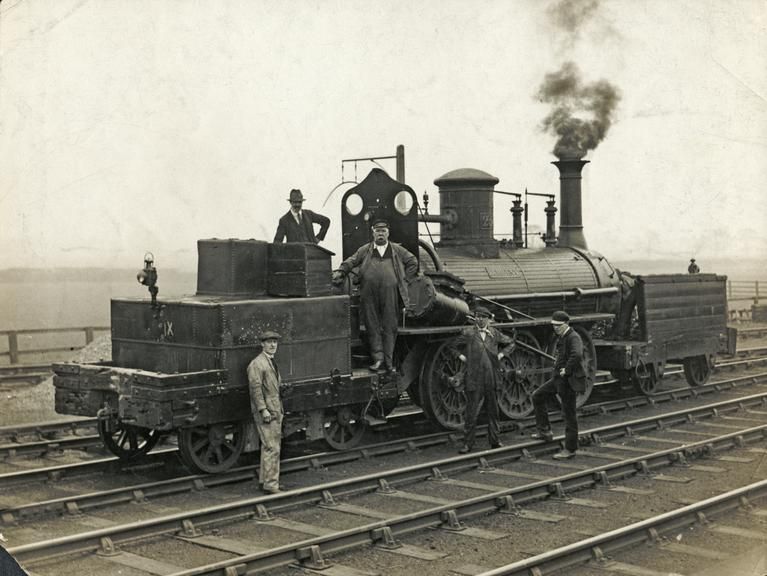

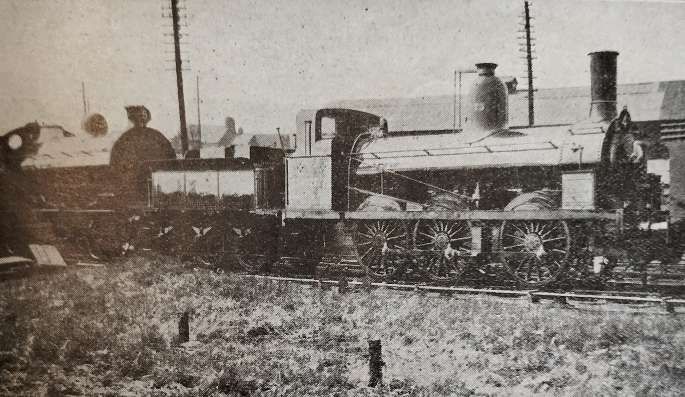

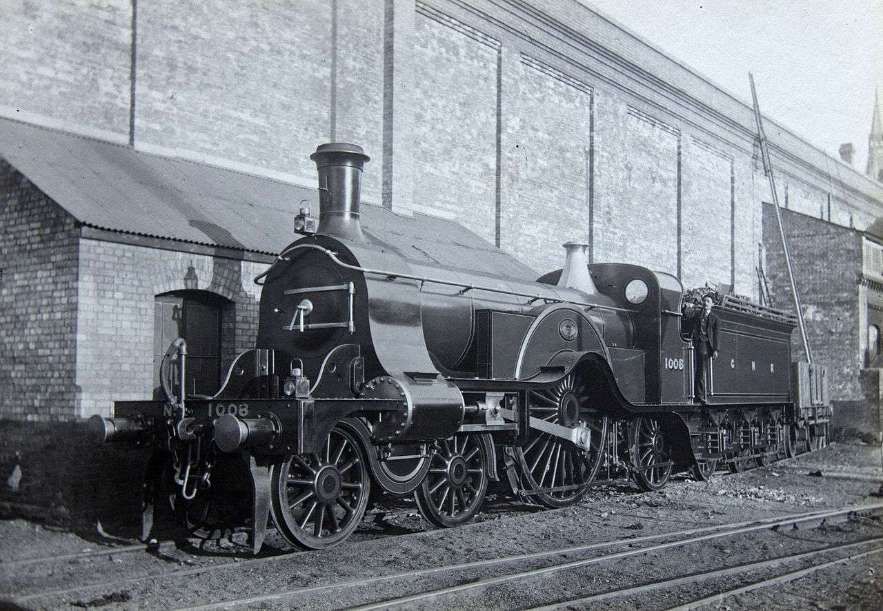

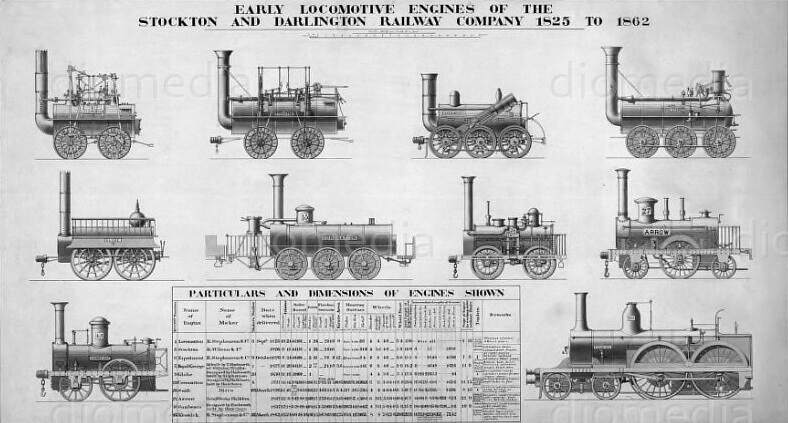

Locomotives

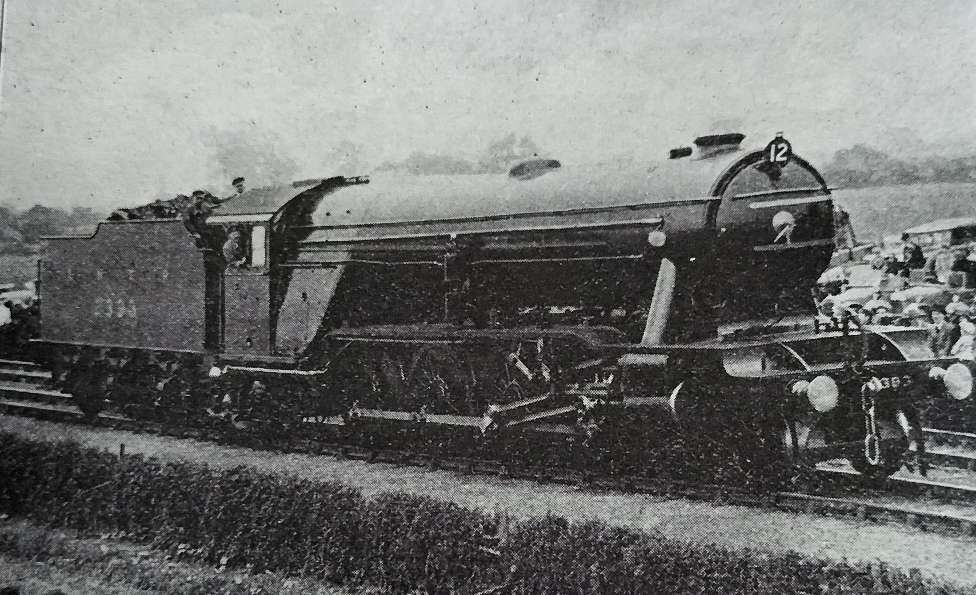

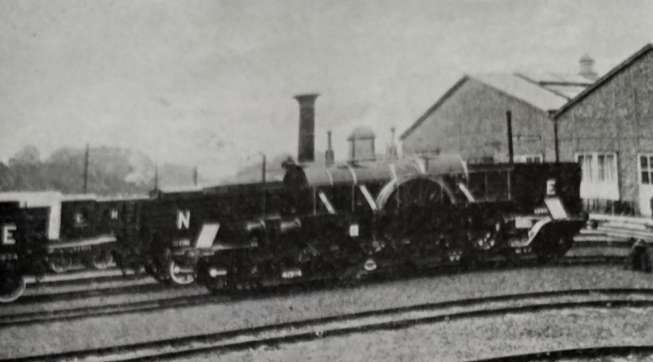

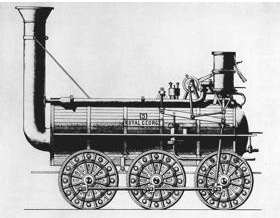

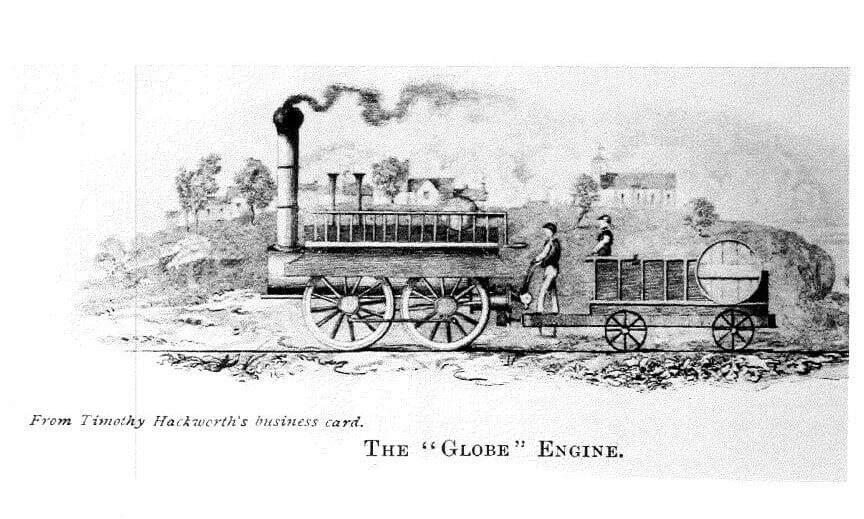

“The locomotives were unreliable at first. Soon after opening, Locomotion No. 1 broke a wheel, and it was not ready for traffic until 12th or 13th October; Hope, the second locomotive, arrived in November 1825 but needed a week to ready it for the line – the cast-iron wheels were a source of trouble. [49: p118-119, 142] Two more locomotives of a similar design arrived in 1826; that August, 16s 9d was spent on ale to motivate the men maintaining the engines. [49: p118-119, 142] By the end of 1827, the company had also bought Chittaprat from Robert Wilson and Experiment from Stephenson. Timothy Hackworth, locomotive superintendent, used the boiler from the unsuccessful Chittaprat to build the Royal George in the works at Shildon; it started work at the end of November.” [49: p116, 142-143][54] A drawing of the Royal George appears below.

The boiler was a plain cylinder 13 ft. long and 4 ft. 4 in. in diameter. There were six coupled wheels 4 feet in diameter, and the cylinders, which were placed vertically at the end opposite to the fire place, were 11″ diameter, the stroke of the piston being 20 inches. The piston rods worked downward and were connected to the first pair of wheels. [122]

Problems with the locomotives may have seen the railway reverting to the use of horses but for the fact that Pease and Thomas Richardson were partners with Stephenson in the Newcastle works. Locomotives were clearly superior to horses when they were working. In his book, Tomlinson showed that coal was being moved by locomotive at half the cost of using horses. Rolt could not imagine the company reverting to horses. [83] Robert Young states that the company was unsure as to the real costs as they reported to shareholders in 1828 that the saving using locomotives was 30 per cent. Young also showed that Pease and Richardson were both concerned about their investment in the Newcastle works and Pease unsuccessfully tried to sell his share to George Stephenson. [50: p61-63][54][84]

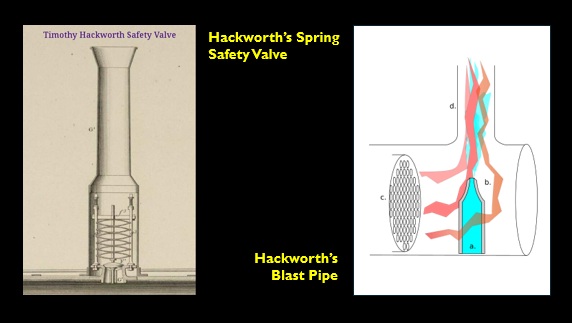

“New locomotives were ordered from Stephenson’s, but the first was too heavy when it arrived in February 1828. It was rebuilt with six wheels and hailed as a great improvement, Hackworth being told to convert the remaining locomotives as soon as possible. In 1828, two locomotive boilers exploded within four months, both killing the driver and both due to the safety valves being left fixed down while the engine was stationary.” [49: p146-148][54]

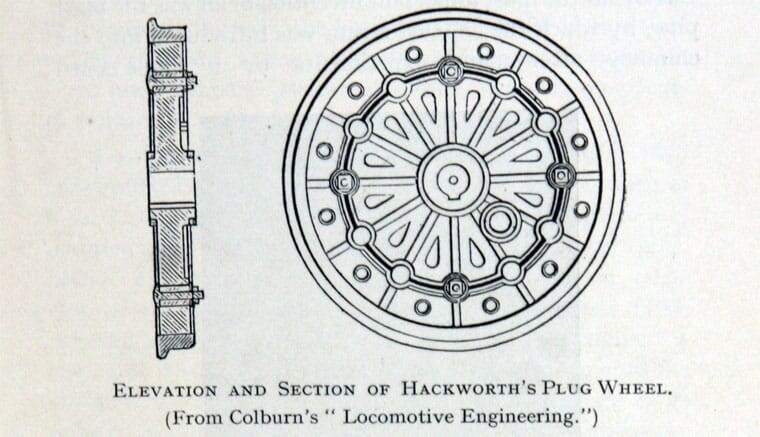

Hackworth redesigned locomotive wheels – cast-iron wheels used to fracture too easily. His solution was the first use of “a system of cast iron wheel with a wrought iron tyre shrunk on. The wheels were made up in parts because the lathes in the Shildon workshops were too small to turn up the rims when fixed upon the axle. They were dotted with plug holes to ensure sound castings and reduce unnecessary weight. This new wheel type was very efficient and so was used on nearly every engine on the S&DR and on other railways for many years.” [124: p157-8][125: p30].

He designed the spring safety valve. He perfected the blast pipe and again it was to be used on many engines subsequently. Perhaps the most important invention was the blast pipe which ensured that boiler pressure was always maintained; thus curing the lack of steam found in Stephenson’s earlier engines.

Hackworth lagged Royal George’s boiler with strips of mahogany to insulate it. “Royal George” was built for coal traffic and so was designed to be strong and with good tractive adhesion suitable in all weathers and the blast pipe doubled the amount of useful work [it] could do.” [124: p228]. The ‘blast pipe’ discharged exhaust steam through a converging nozzle blast pipe in the chimney, greatly increasing combustion intensity and steam production.

“The S&DR was designed to be operated by travelling locomotive and through the skills of Timothy Hackworth, it was here that the locomotive engine became reliable and efficient. Through his work for the S&DR, confidence in the use of locomotives was gradually built up so that other embryonic railway companies were also prepared to embark on their use. By the time the Liverpool and Manchester line opened in 1830 the S&DR had 12 locomotives and by 1832 it had 19.” [125: p2]

“The surviving documentation suggests that without Hackworth’s promotion of the locomotive and his key developments such as the plug wheel and blast pipe which allowed the practical and ultimately successful implementation of locomotive power on the S&DR for all to see, then the railways that followed would have significantly delayed the use of travelling locomotives. Hackworth cast enough doubt in the Director’s minds of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway about the dangers and short comings of rope pulled inclines, that they organised the Rainhill Trials only months before opening in order to test the power and efficiency of various locomotives. … From 1828 when the locomotives were proven technology (thanks to Hackworth’s design of the Royal George the previous year), there was a growth in locomotive engineering companies in England, and by 1830, also in America and France.” [125: p3]

“Perhaps there was no man in the whole engineering world more prepared for the time in which he lived. He was a man of great inventive ability, great courage in design, and most daring in its application…” (The Auckland Chronicle, 29th April 1876 referring to Timothy Hackworth)

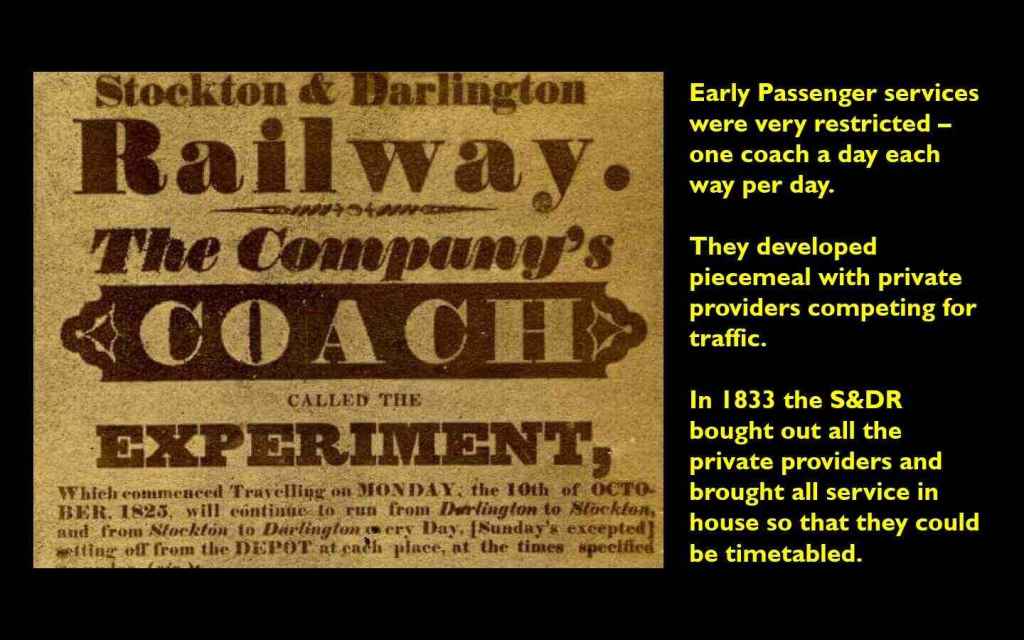

Passengers

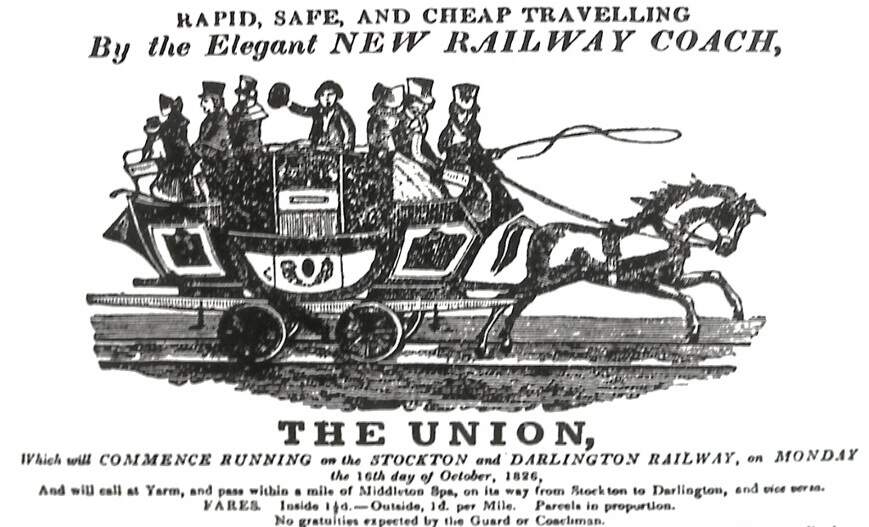

Wikipedia tells us that “passenger traffic started on 10th October 1825, after the required licence was purchased, using the Experiment coach hauled by a horse. The coach was initially timetabled to travel from Stockton to Darlington in two hours, with a fare of 1s, and made a return journey four days a week and a one-way journey on Tuesdays and Saturdays. In April 1826, the operation of the coach was contracted for £200 a year; by then the timetabled journey time had been reduced to 1 hour 15 minutes, and passengers were allowed to travel on the outside for 9d. A more comfortable coach, Express, started the same month and charged 1s 6d for travel inside. [49: p122-126] Innkeepers began running coaches, two to Shildon from July, and The Union, which served the Yarm branch from 16th October. [49: p126-127] There were no stations: [87: p117] in Darlington the coaches picked up passengers near the North Road Crossing, whereas in Stockton they picked up at different places on the quay. [49: p130] Between 30,000 and 40,000 passengers were carried between July 1826 and June 1827.” [49: p131]

Innovation occurred relatively quickly, the company decided that it needed to provide hostelries (pubs) close to its coal depots. Tickets were sold in various locations but, significantly, in the pubs closest to pick up points. The practice mirrored what happened with stagecoaches.

Perhaps a more significant change seems to have happened almost organically. … Some of the buildings at coal depots began to provide space for passengers to wait along with other goods to be carried by the railway. … Heighington was a wayside location on the railway. It had a coal depot, and the S&DR built a public house in 1826-1827 to oversee the coal depot. Historic England describe the building as a proto-railway station, built before the concept of the railway station had fully developed. [123] This was the first such structure on the railway.

This was one among a number of loading and unloading depots which would evolve into the now familiar railway architecture such as goods and passenger stations. [125]

Developing Understanding

In truth, a lot of work went into getting three different forms of traction to harmonise – horse, inclined plane and locomotives on a single line. This was further complicated by the fact that it was a public railway that anyone could use subject to payment and an agreement to abide by any rules. The increasingly popular use of the single line also meant that rules had to be established for giving way and the ‘first past the post’ system was adopted. Signalling considered (but blocked by local landowners), [128: p12] warnings were sounded on the approach to level crossings, braking systems improved and sleepers made heavier. There was no past experience to learn from, no book to consult and the duties of railway officials had yet to be clearly defined. [124: p121]

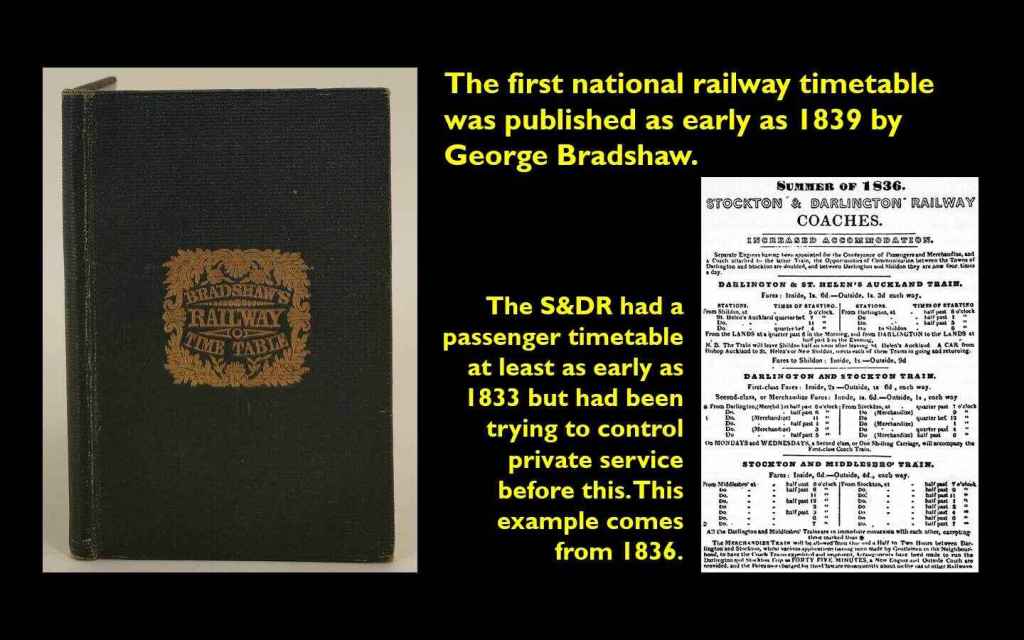

“The S&DR led the way in devising a system to run a public railway. It was here that passenger timetables evolved, baggage allowances were created, rules made regarding punishment for non-purchase of tickets, job descriptions for railway staff evolved and signalling and braking developed and improved for regular use. The S&DR also recognised the need for locomotives of a different design to haul passengers rather than heavy goods and the need to provide facilities for passengers and workers at stations – all before 1830.” [125: p2]

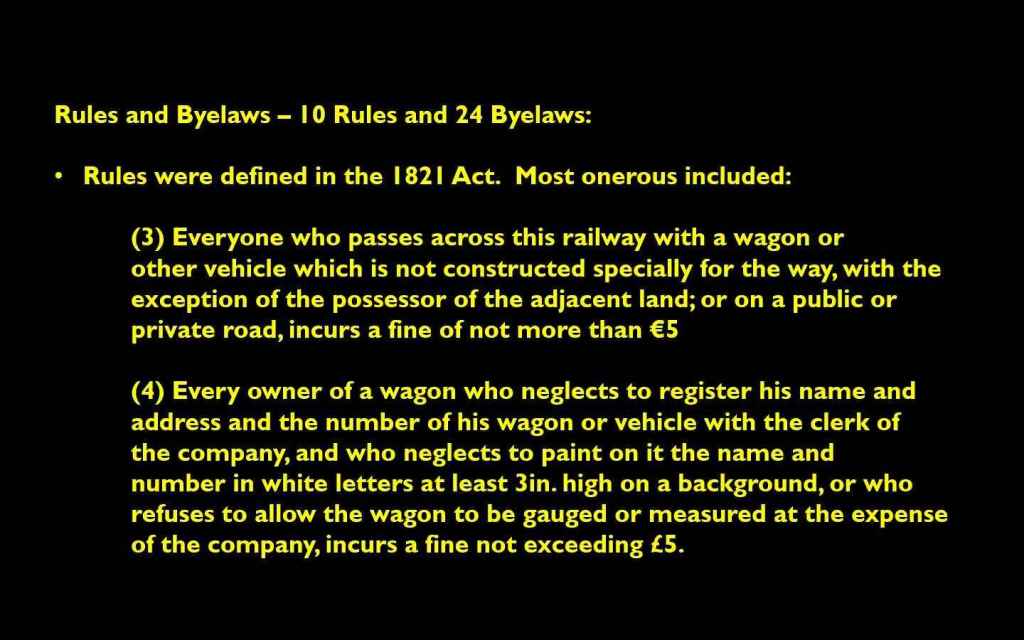

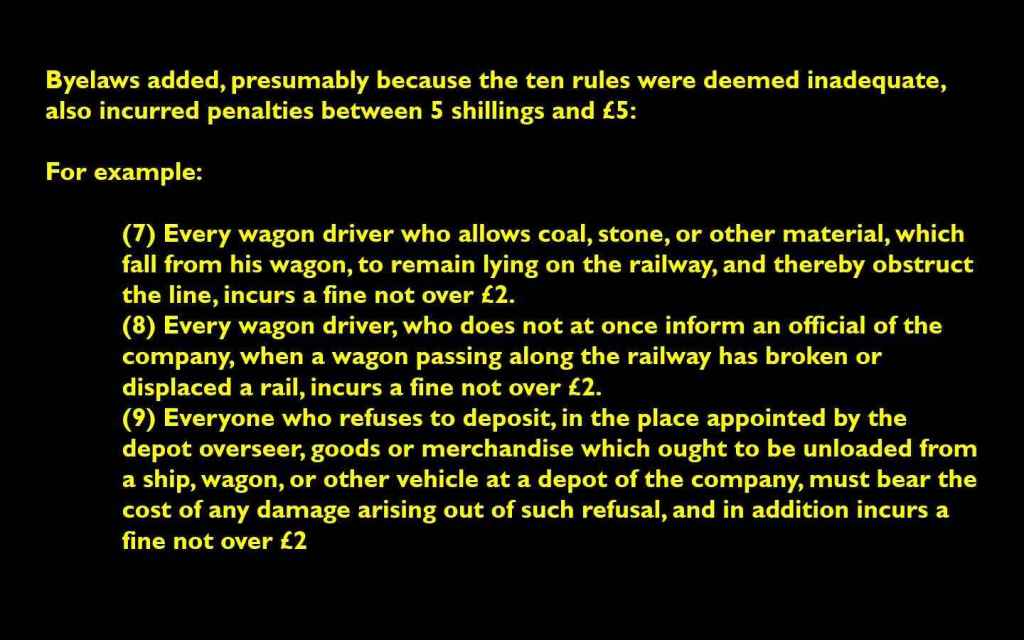

The Stockton & Darlington’s regulations were initially laid down in ten ‘rules’ set out in the company’s Act of Incorporation of 19th April 1821, which established fines for those failing to preserve order and security on the railway. These were of a fairly general nature. [128: p12-13]

Two rules had attached to them the massive (for the day) fine of £5, these required wagons to be especially constructed for the railway, to bear the owner’s name and wagon number in 3-inch high lettering, and to allow the company to gauge wagons if it felt necessary.

By July 1826, these rules were supplemented by 24 byelaws and rules concerning wagons taking to sidings, all of these suggesting that there were shortcomings in the original rules which were discovered as an early result of operational experience. [128: p67-68]

After the launch date in 1825, other advances followed rapidly. “The growth of health and safety, the administration of running a regional railway, … and, [critically,] commercial success that would reassure other investors that it was safe to invest in their own regional railway that would soon form part of a national and then international railway network. The first purpose-built goods station (as opposed to coal and lime which went to the depot down the road) was opened in Darlington 1827. … [It formed] the inspiration for the later 1830 warehouse at Liverpool Road Station in Manchester which still survives.” [125]

“Many aspects of the line were still unproven technology when they came to be used in the context of a public regional railway. Until it could be proven (and the launch of 1825 went some way to do that with enough customers ready to pay for the service to immediately allay fears of money losses), that the line had to work first before it could be expanded. It was up to the S&DR to find a way forward as new problems arose. [Much of that responsibility fell on Timothy Hackworth’s shoulders.] … Through the hard knocks of money shortages, operating difficulties and the limitations of contemporary engineering, the S&DR had discovered what would be necessary [to run a railway] by the start of 1829, at a time when the L&MR was still vacillating over vital traction and operating decisions.” [126: p11-12]

A Change in Passenger and Goods Services

It was 1833, before the passenger railway service began to become something like we would recognise today. By 1833, it had become obvious that the competing needs of passengers and goods under an open access model needed to be managed. Network management, capacity and overall co-ordination were increasingly seen as important. As the network expanded, the conflicts increased. Until 1833, passenger services were run by external contractors. In 1833, the S&DR took on this responsibility directly.

The railway changed from a kind of ‘public road’ on which all-comers could transport goods and passengers to a system where services were co-ordinated, managed, timetabled and run by the Company.

The S&DR established a permanent rail infrastructure providing a regular service transporting both goods and passengers. In this particular sense, the S&DR was truly the launch of a modern railway network. Managed, timetabled services for passengers and goods made possible the rapid expansion of railways in the 19th century across the globe, together with attendant huge worldwide social and economic change.

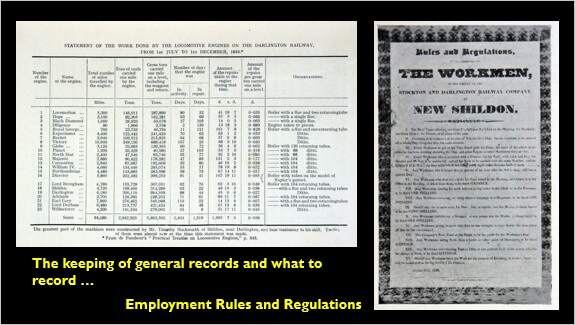

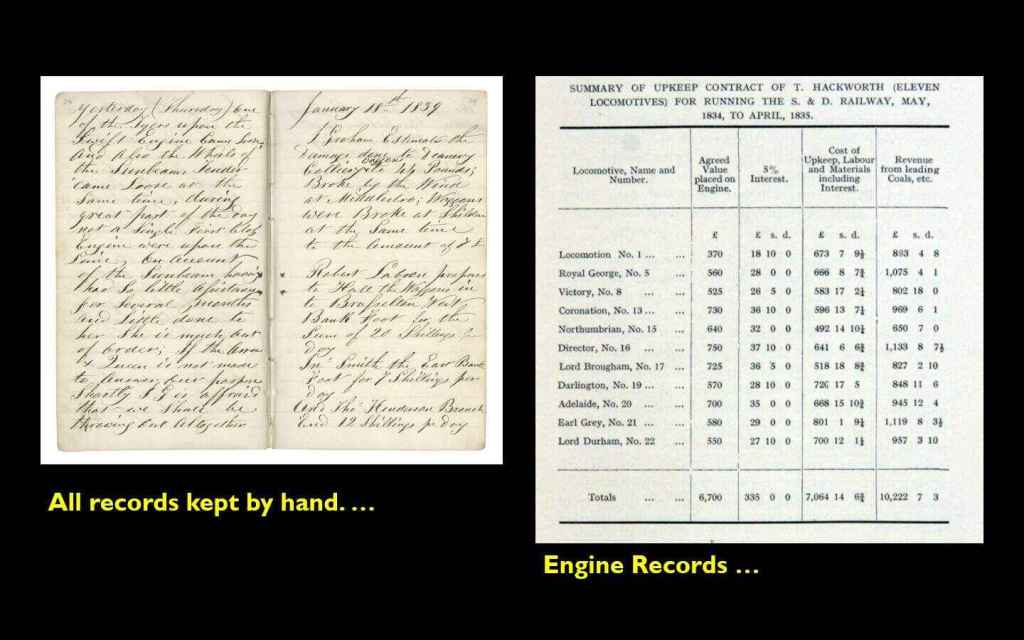

In a railway context, everything was being done for the first time:

the keeping of general records; various statistical and financial records; employment of staff and rules; at first all drivers were self-employed and paid their firemen themselves.

Engine shed maintenance records; the need for dedicated general goods facilities; all arrangements for passengers; the management and supply of first coke and then coal for use by steam engines. ….

The S&DR, from the official launch in September 1825, “was at the forefront of technology in terms of operating locomotives regularly and over a relatively long stretch of line, it was to the S&DR that other embryonic railway companies looked to. Railway engineers and promoters from other parts of the UK, France, and the USA attended the opening ceremony in 1825. Two of those distinguished French guests went on to found France’s first public railway. Others were to visit the S&DR Works in the years that followed including engineers from Prussia who took copious detailed notes on Hackworth’s experiments. Hackworth himself shared his results widely (often at the request of Edward Pease) and organised trials at the request of engineers from other companies who were torn between the use of canal versus railway, or horse versus locomotive, or stationary versus travelling engine. The S&DR was at its most influential until around 1830.” [125: p2] A very short period of time!

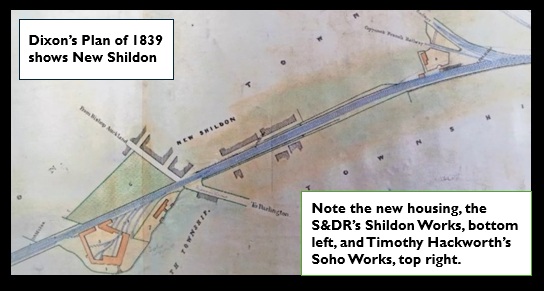

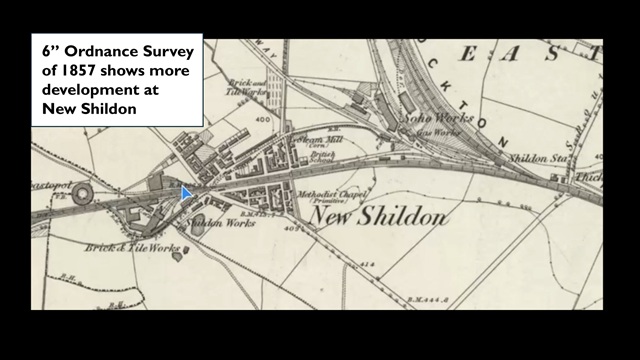

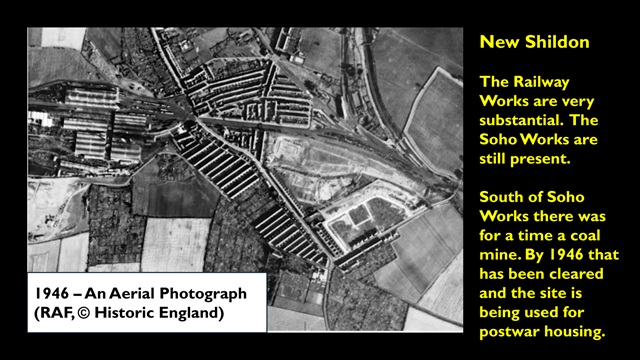

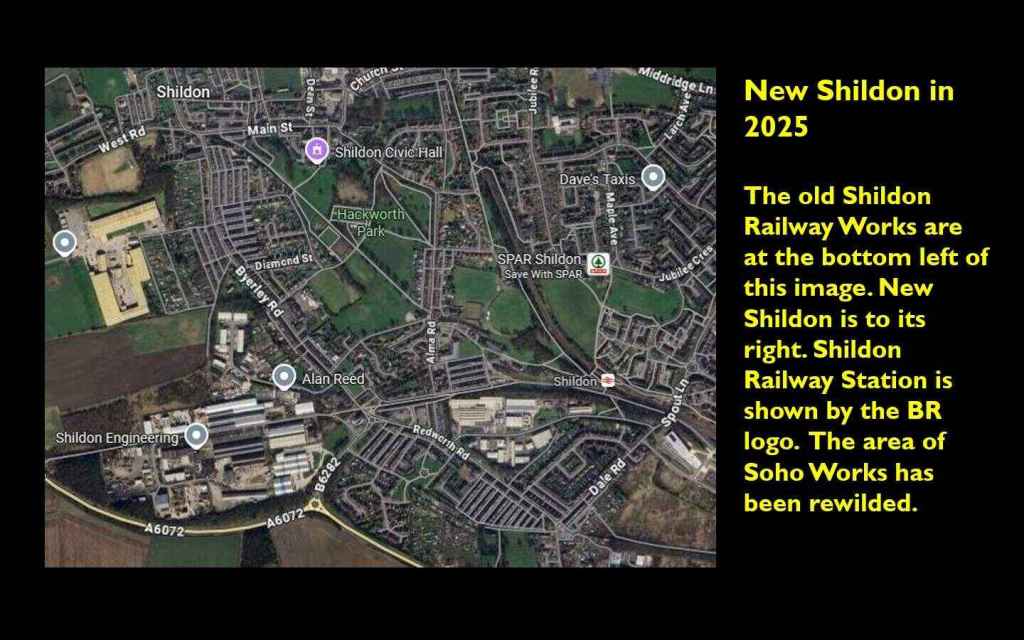

Beyond 1830, “there were significant technological achievements … such as the delivery of Russia’s first locomotives to the Tsar in the 1840s from Hackworth’s Soho Works in Shildon, the continuing evolution of the first railway towns at New Shildon and Middlesbrough and the delivery of gas to the works in New Shildon in 1841 before anywhere else in the country apart from Grainger Town in Newcastle. Further the grouping of internationally important structures with later pioneering structures (such as at North Road in Darlington or at Locomotion in Shildon) provides an insight into those rapidly developing days of the early railway and add value to each other.” [125: p3]

The First ‘Railway’ Town – New Shildon

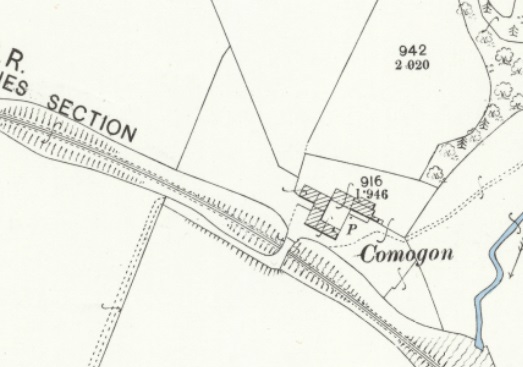

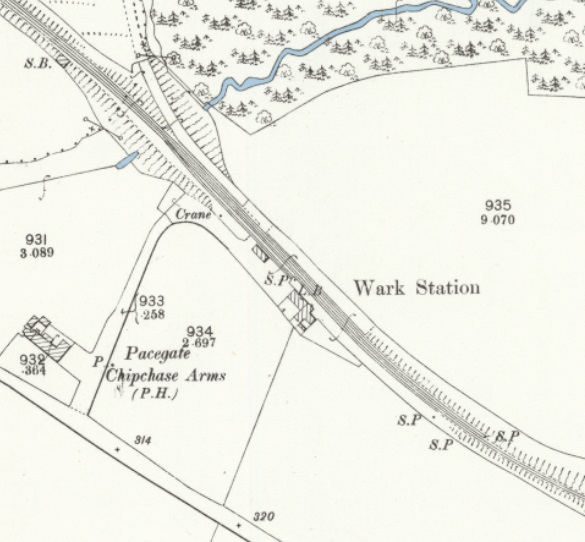

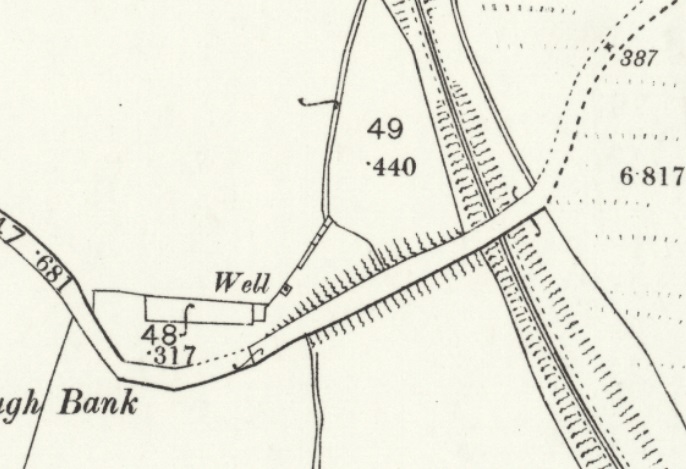

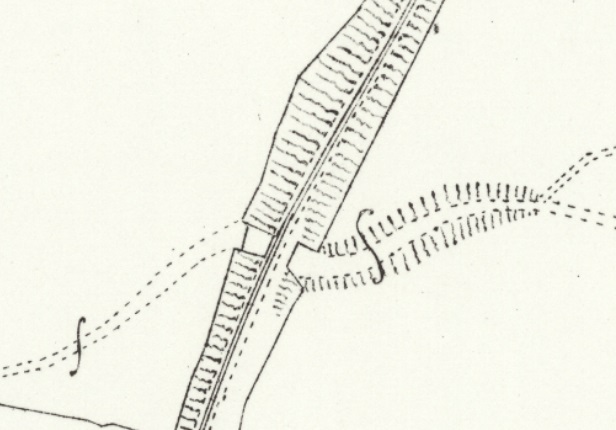

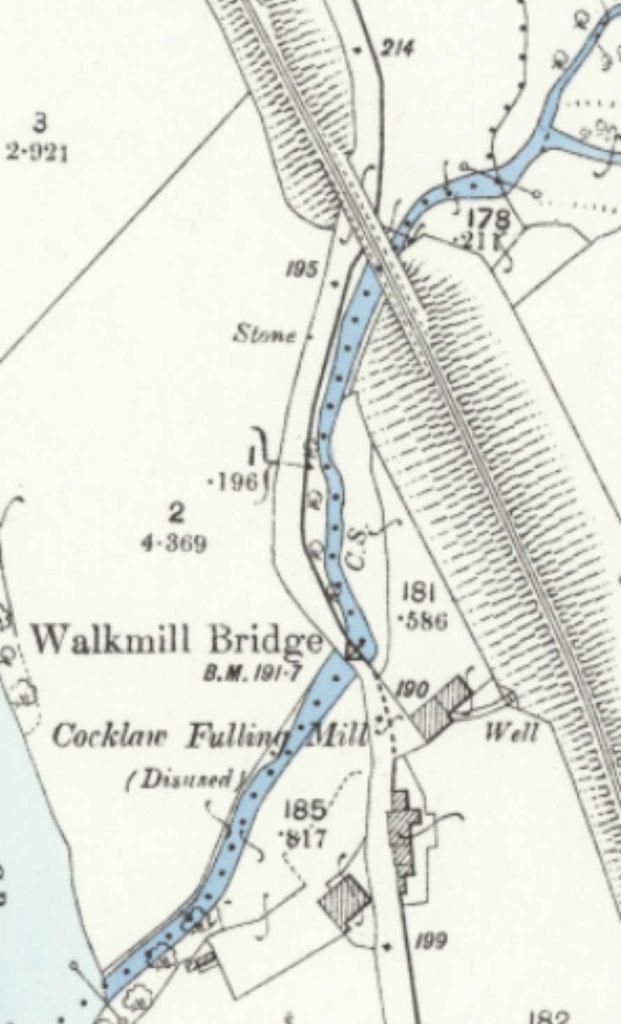

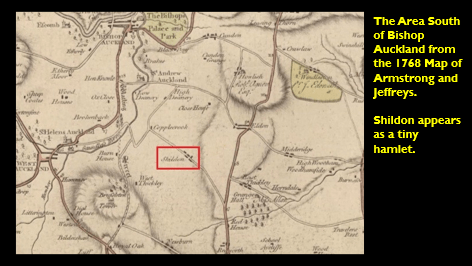

Shildon still appears as a tiny hamlet. [118]

The Second ‘Railway’ Town – Port Darlington and Middlesbrough

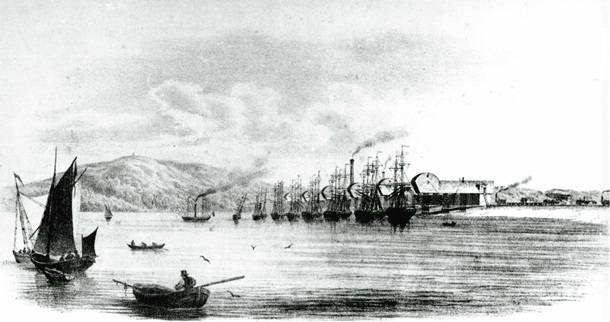

The ongoing story of the railway company is one of strong growth particularly in the carriage of goods. It opened its own port near the mouth of the River Tees.

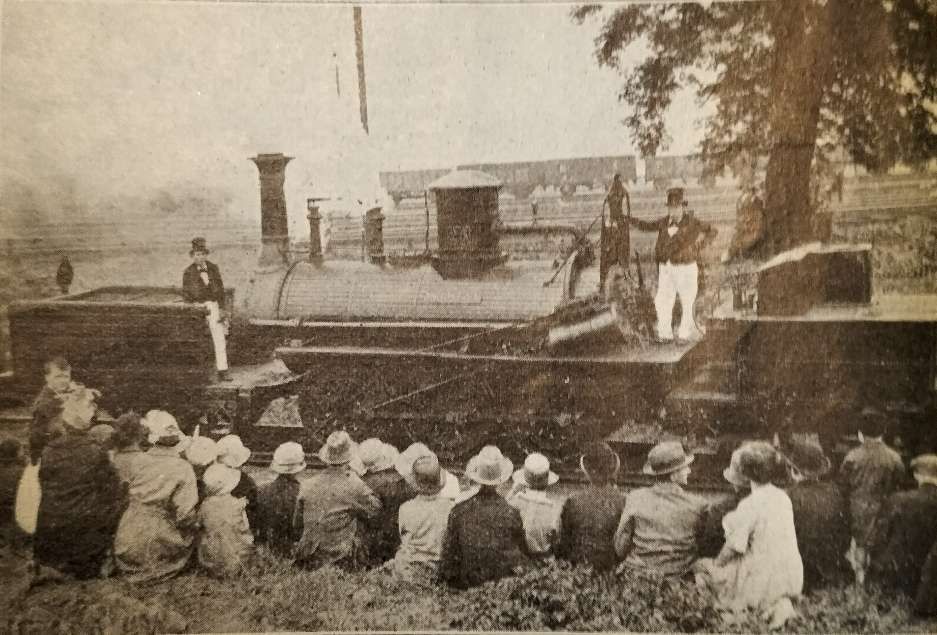

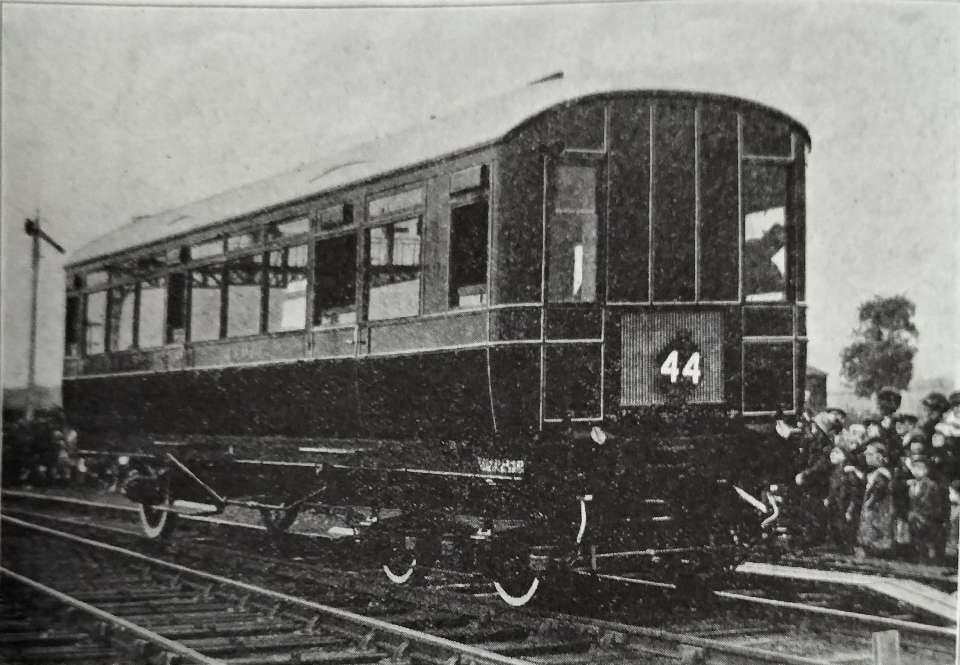

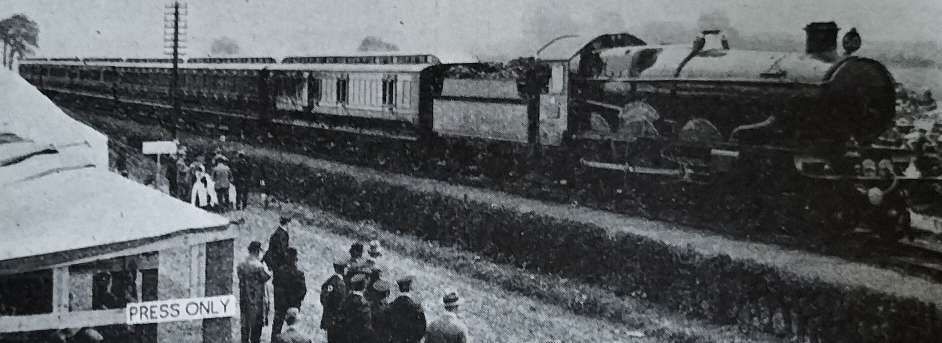

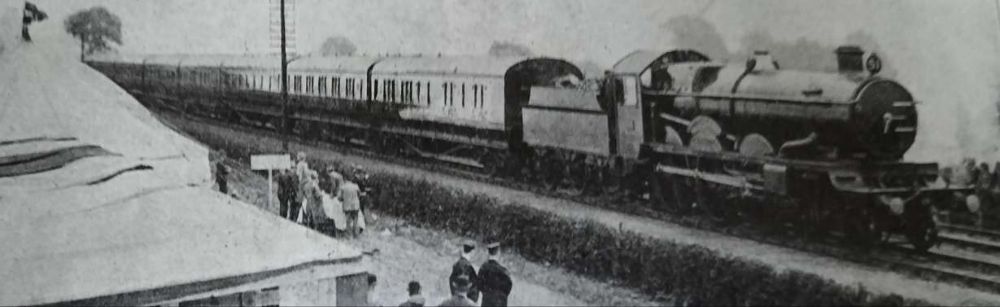

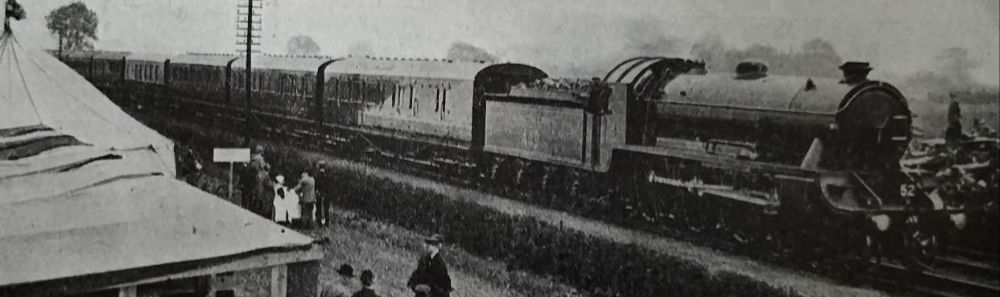

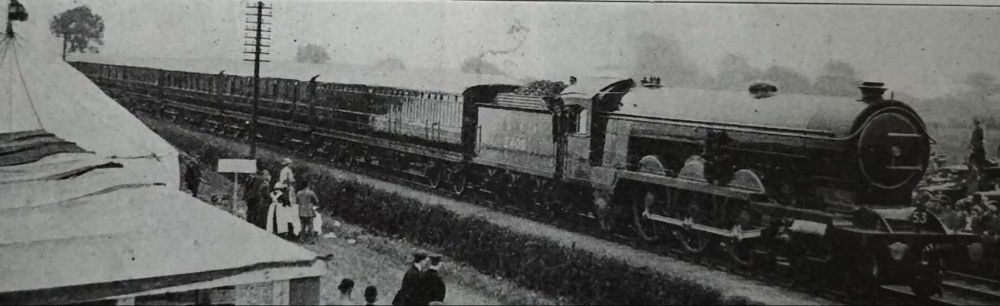

When Port Darlington opened for business at the end of 1830. Hackworth’s engine ‘The Globe’ hauled a passenger train carrying about 600 people down to the staithes, © Public Domain. [95][97]

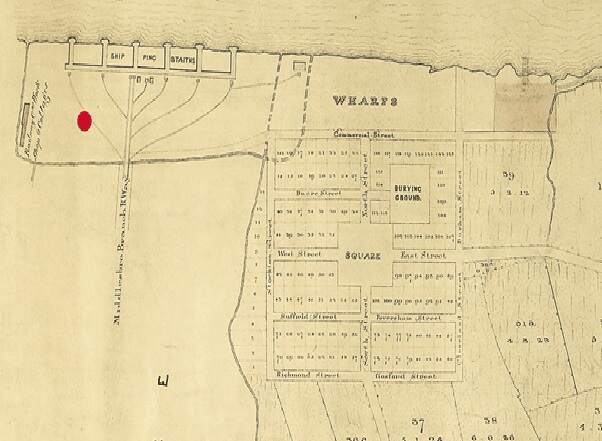

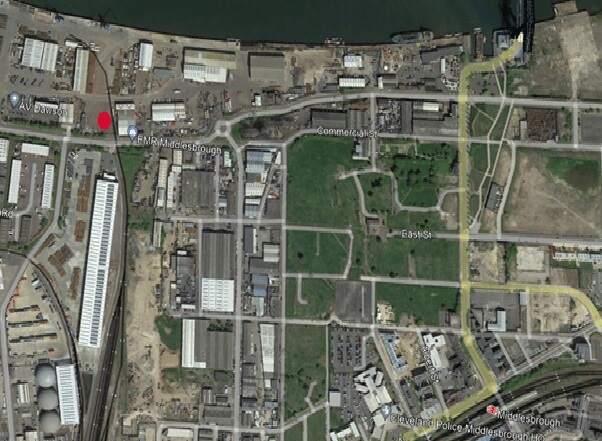

The S&DR played a significant role in the rapid expansion of Middlesbrough. Initially a farming community of around 25 people at the beginning of the 19th century, it transformed into a major iron and steel producer, “spurred by the arrival of the Stockton and Darlington Railway and the discovery of iron ore in the Cleveland Hills. This rapid expansion led to a significant population increase and the development of a new town, planned by Joseph Pease and others, centred around a gridiron street pattern and a market square. [85][86] Middlesbrough had only a few houses before the coming of the railway, [87] but a year later had a population of over 2,000 and at the 2011 census had over 138,000 people. [88][89] Port Darlington was first established, as shown on the left of the image below, which also shows the gridiron street pattern in what would become Middlesbrough, the new town on the right of the image. [95]

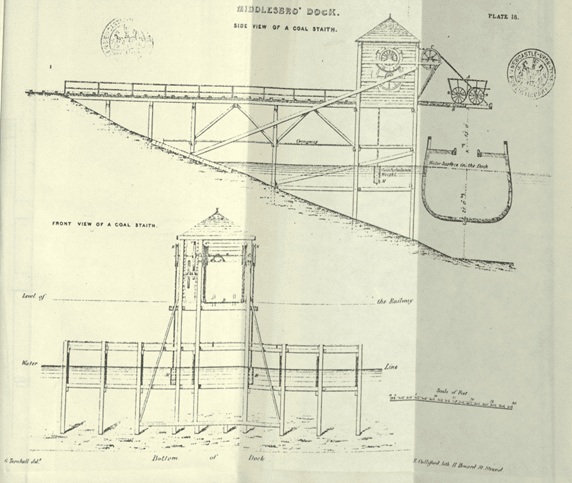

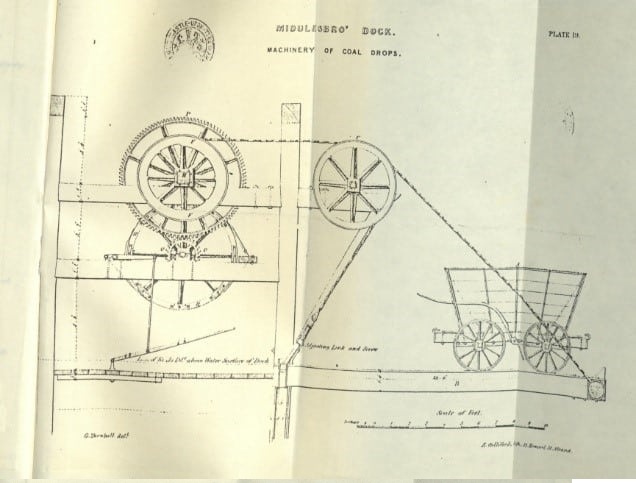

We have already noted the staithes built at Port Darlington to allow more mechanised loading of ships. These staithes were ingeniously designed, even if health and safety was not as paramount as perhaps it should have been. The Port of Middlesbrough describes the operation: “Staithes were elevated platforms for discharging coal and other materials from railway cars into coal ships for transport. … A steam engine hoisted a wagon full of coal off the line and about 20 feet into the air, where it landed on a gantry. A horse then pulled the wagon along the gantry and out over the water. At the end of the gantry, the wagon was strapped into a cradle and, with a man clinging to it, was swung in an arc on to the ship below. Here, the man unbolted the bottom of the wagon and the coal fell into the hold. Finally, the weight of the next full wagon swinging downwards caused the empty wagon and the man to swing upwards back to the gantry.” [95]

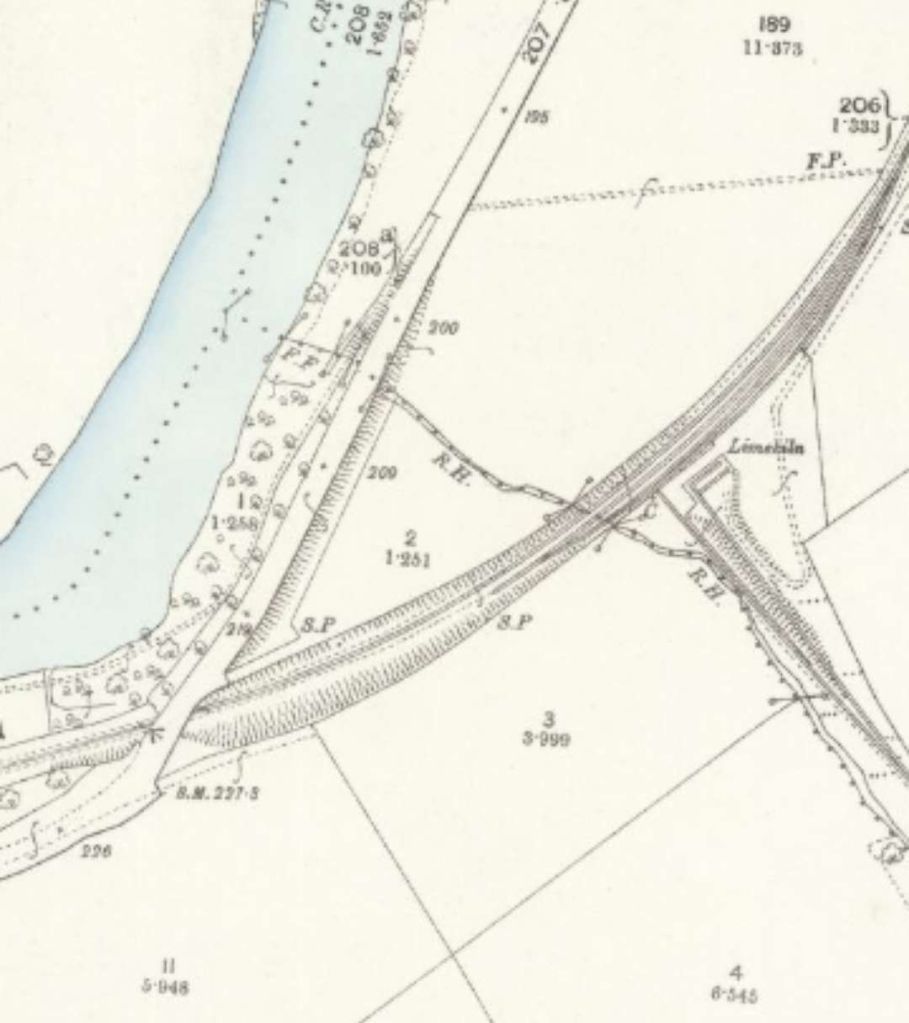

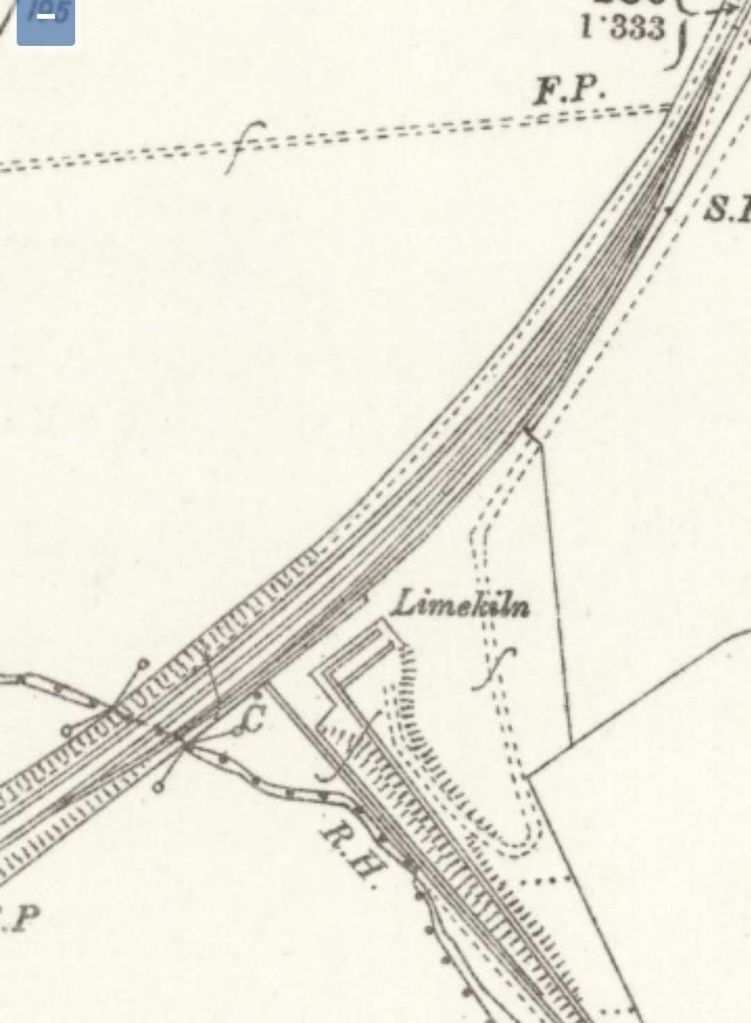

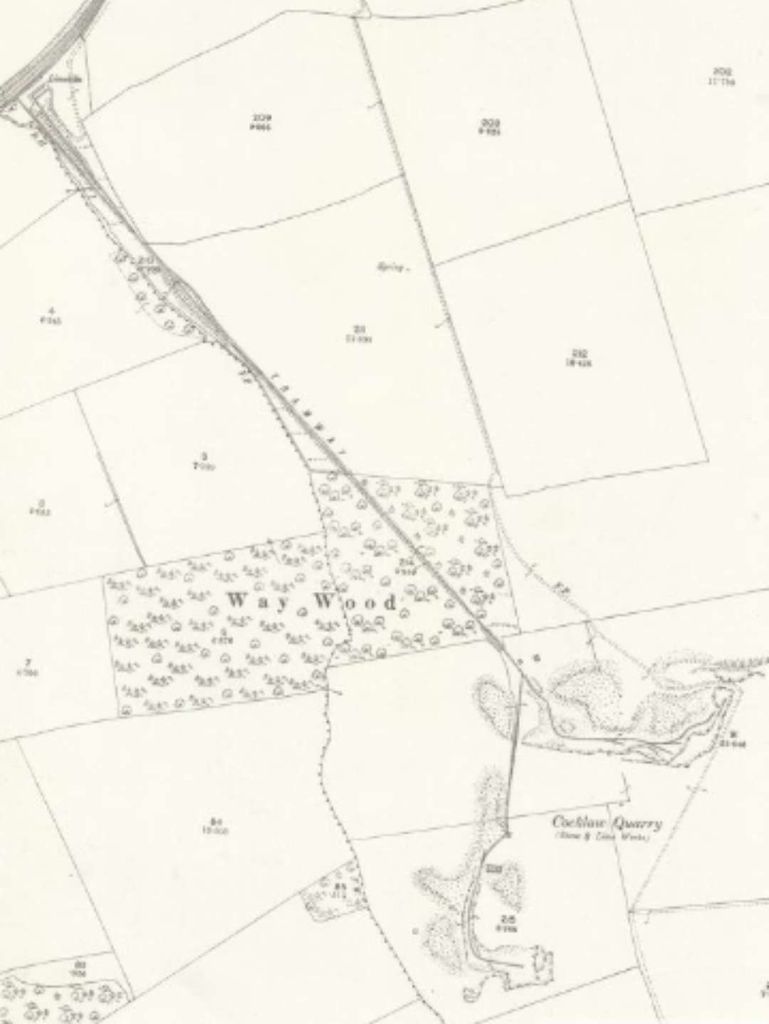

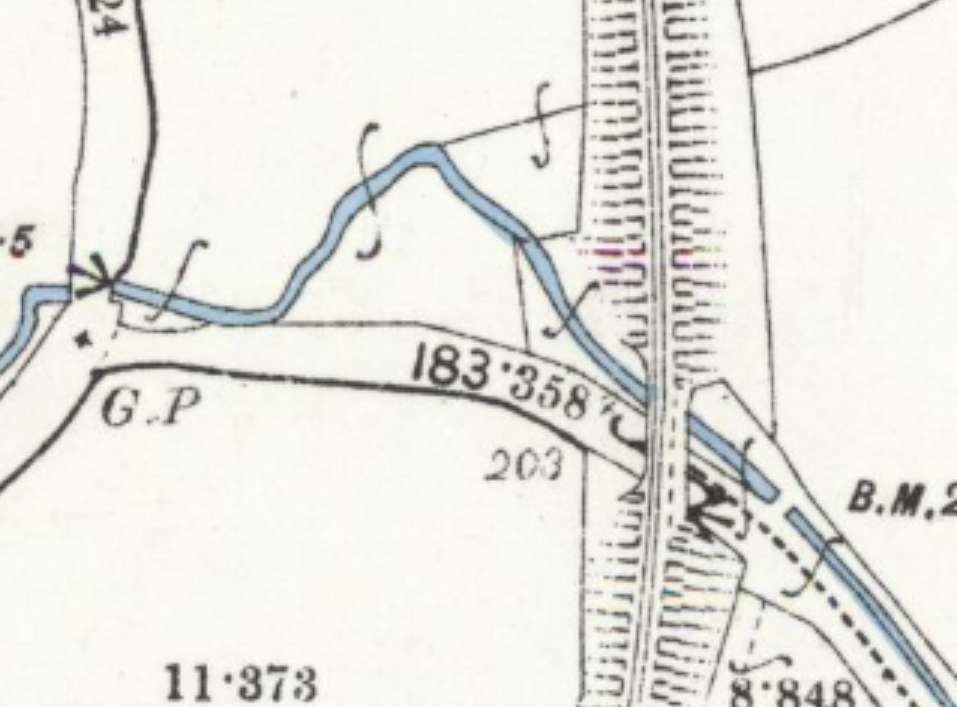

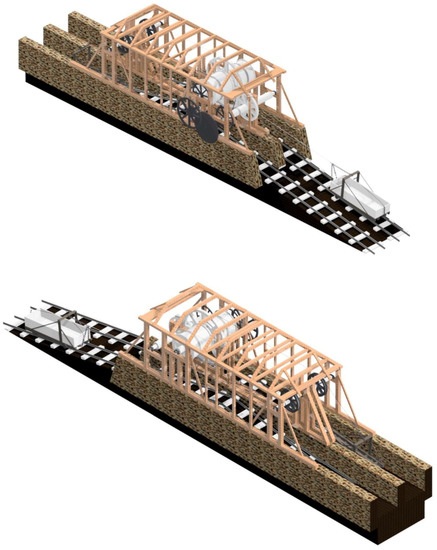

Plans from the port authority are shown below. It is difficult to imagine the process described from looking at these plans. It may be that the plans show a later design of staithe.

The years after 1827 (once Company finances were on a sound footing)

A series of different extensions and branches to the S&DR appeared over the period from 1827. [54] “In 1830, the company opened new offices at the corner of Northgate and Union Street in Darlington. [49:p189] Between 1831 and 1832 a second track was laid between Stockton and the foot of Brusselton Bank. Workshops were built at Shildon for the maintenance and construction of locomotives. [49: p235-236] In 1830, approximately 50 horses shared the traffic with 19 locomotives, but travelled at different speeds, so to help regulate traffic horse-drawn trains were required to operate in groups of four or five.” [54] The rule book stated that locomotive-hauled trains had precedence over horse-drawn trains. Even so, accidents and conflict occurred. The practice was to allow private use of the line by industries that it served, “some horse drivers refused to give way and on one occasion a locomotive had to follow a horse-drawn train for over 2 miles (3 km). [49: p383-384][50: p91-94] The committee decided, in 1828, to replace horses with locomotives on the main line, starting with the coal trains, but there was resistance from some colliery owners.” [54]

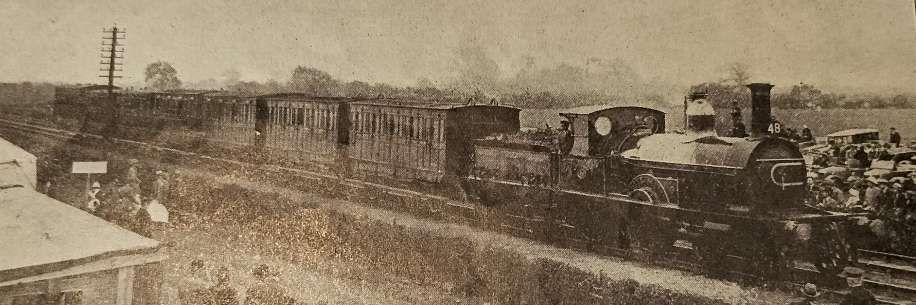

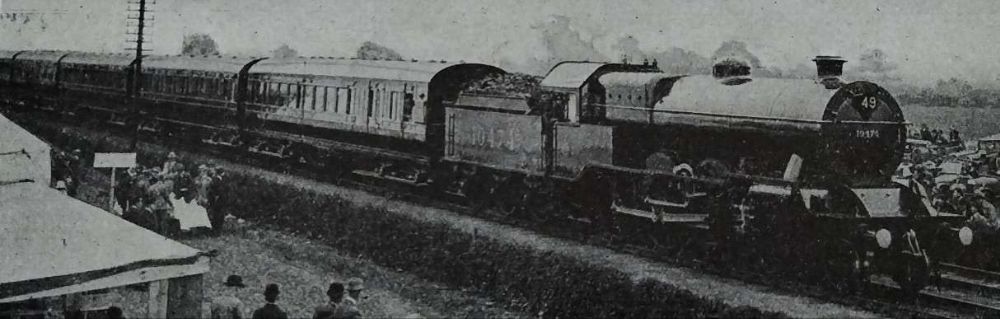

“After the S&DR bought out the local coach companies in August 1832, a mixed [locomotive-hauled] passenger and small goods service began between Stockton and Darlington on 7th September 1833, travelling at 12–14 miles per hour (19–23 km/h); locomotive-hauled services began to Shildon in December 1833 and to Middlesbrough on 7th April 1834. [49: p384-385][50: p68] The company had returned the five per cent dividend that had been promised by Edward Pease, and this had increased to eight per cent by the time he retired in 1832.” [50: p87-88][54]

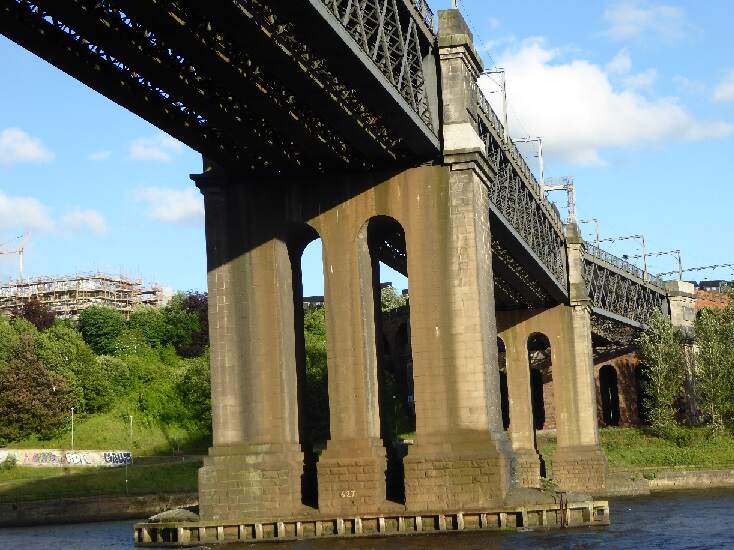

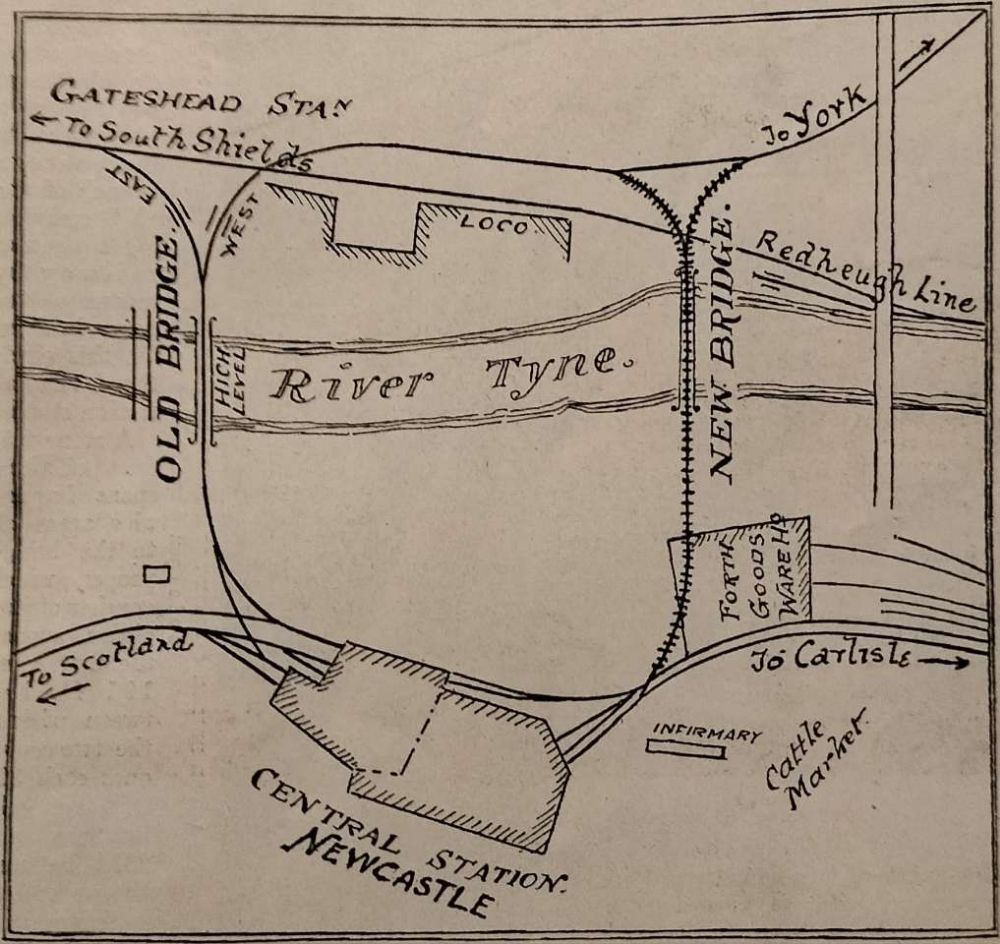

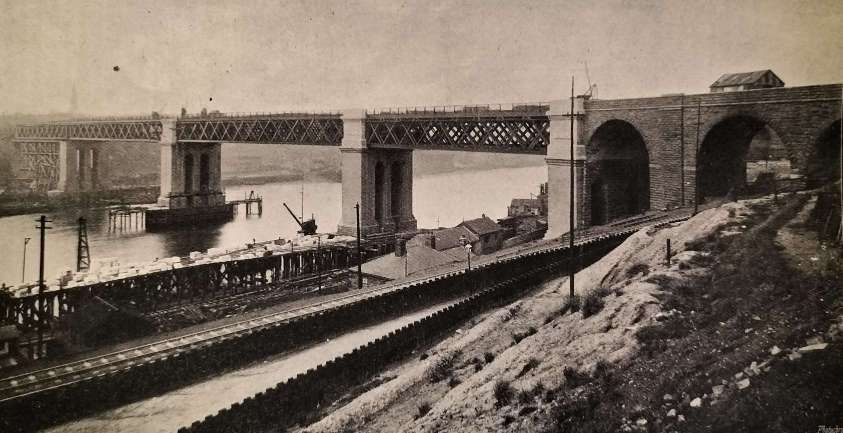

In 1835, the S&DR partnered with the York & North Midland Railway (Y&NMR) to form the Great North of England Railway (GNER) to build a line from York to Newcastle which along the would run along the line of the S&DR’s Croft branch at Darlington. Pease specified a formation wide enough for four tracks, so freight could be carried at 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) and passengers at 60 mph (97 km/h), and George Stephenson had drawn up detailed plans by November 1835. [48: p64-65][54] The Acts of Parliament enabling the scheme were given royal assent on 4th July 1836 (Darlington to Newcastle) and 12th July 1837 (Croft to York). The railway opened for coal traffic on 4th January 1841 using S&DR locomotives, and to passengers with its own locomotives on 30th March 1841. [48: 67-69][54][87: p93-94]

A patchwork of different schemes was to follow:

- By February 1842, a passenger service between Darlington and Coxhoe supported by an omnibus service to Shincliffe on the Durham & Sunderland Railway. [87: p165]

- Early in 1842, the Shildon Tunnel Company opened its 1,225-yard (1,120 m) tunnel through the hills at Shildon to the Wear basin and after laying 2 miles (3.2 km) of track to South Church station, south of Bishop Auckland, opened in May 1842. [49: p435-437]

- In 1846, the S&DR installed Alexander Bain’s “I and V” electric telegraph to regulate the passage of trains through the tunnel. [90: p52-53]

- The SD&R provided a 3 1⁄4 hour service between Darlington and Newcastle, with a four-horse omnibus from South Church to Rainton Meadows on the Durham Junction Railway, from where trains ran to Gateshead, on the south side of the River Tyne near Newcastle. [48: p74]

By 1839, the S&DR track “had been upgraded with rails weighing 64 lb/yd (32 kg/m). [91: p415] The railway had about 30 steam locomotives, most of them six coupled, [91: p419] that ran with four-wheeled tenders with two water butts, each capable of holding 600 imperial gallons (2,700 L; 720 US gal) of water. [91: p422] The line descended from Shildon to Stockton, assisting the trains that carried coal to the docks at a maximum speed of 6 mph (9.7 km/h); the drivers were fined if caught travelling faster than 8 mph (13 km/h), [91: p415, 422] and one was dismissed for completing the forty-mile return journey in 4 1⁄2 hours. [59: p136-137] On average there were about 40 coal trains a day, hauling 28 waggons with a weight of 116 tons. [91: p423] There were about 5,000 privately owned waggons, and at any one time about 1,000 stood at Shildon depot.” [54][91: p417-418]

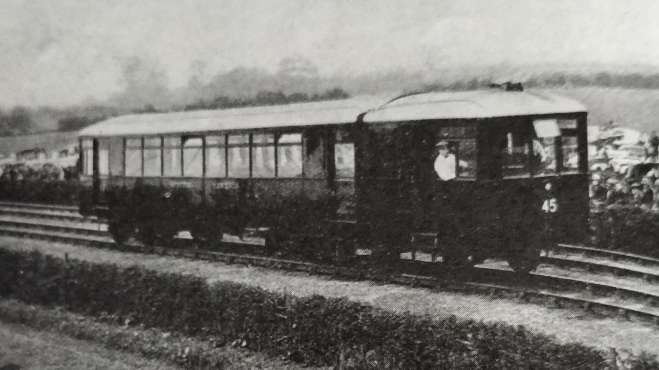

Wikipedia continues: “The railway had modern passenger locomotives, some [still] with four wheels. [91: p421-422] There were passenger stations at Stockton, Middlesbrough, Darlington, Shildon and West Auckland, and trains also stopped at Middlesbrough Junction, Yarm Junction, Fighting Cocks and Heighington. [91: p416] [A significant improvement on early passenger practice.] Some of the modified road coaches were still in use, but there were also modern railway carriages, some first class with three compartments each seating eight passengers, and second class carriages that seated up to 40. [91: p416][92] Luggage and sometimes the guard travelled on the carriage roof; [49: p423] a passenger travelling third class suffered serious injuries after falling from the roof in 1840. [49: p400] Passenger trains averaged 22–25 mph (35–40 km/h), and a speed of 42 mph (68 km/h) was recorded. Over 200,000 passengers were carried in the year to 1st October 1838, [91: p419] and in 1839 there were twelve trains each day between Middlesbrough and Stockton, six trains between Stockton and Darlington, and three between Darlington and Shildon, where a carriage was fitted with Rankine’s self-acting brake, taken over the Brussleton Inclines, and then drawn by a horse to St Helen Auckland. [91: p418] The Bradshaw’s railway guide for March 1843, after South Church opened, shows five services a day between Darlington and South Church via Shildon, with three between Shildon and St Helens. Also listed were six trains between Stockton and Hartlepool via Seaton [94] over the Clarence Railway and the Stockton and Hartlepool Railway that had opened in 1841.” [87: p146-147][54]

During the 1830s, Port Darlington quickly became overwhelmed by the volume of traffic (both imports and exports) and work started in 1839 on Middlesbrough Dock which was laid out by William Cubitt and capable of holding 150 ships! It was “built by resident civil engineer George Turnbull. [89] … After three years and an expenditure of £122,000 (equivalent to £9.65m at 2011 prices), the formal opening of the new dock took place on 12 May 1842. [49: p437][89] The S&DR provided most of the finance, and the dock was absorbed by the company in 1849.” [49: p508][54] The S&DR was, by 1849, a well established and very significant company.

Ongoing Developments

Political manoeuvring to secure a route from London to Scotland via the Northeast continued during this period and the S&DR saw its stocks in the GNER increase in value before a new concern, the Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway (N&DJR) bought out the GNER.

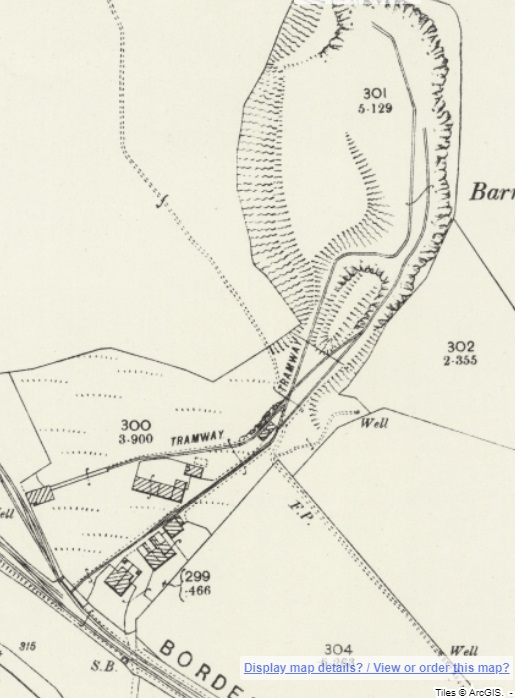

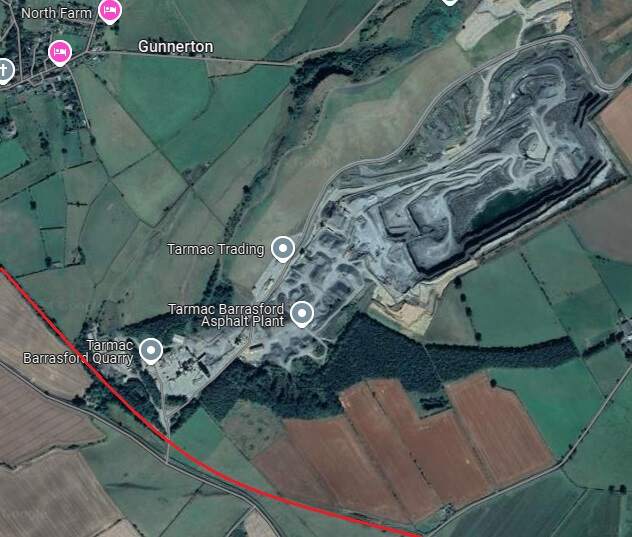

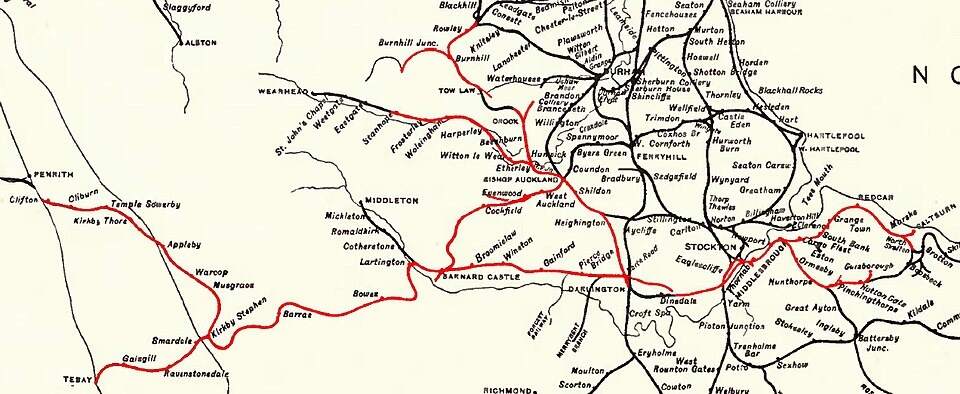

The S&DR also secured interests in the Wear Valley, [4] [54] a line to Redcar and Saltburn, a branch to a mine at Skelton, [4][54] a line to Barnard Castle, a route (South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway (SD&LUR)) over Stainmore Summit to Tebay, [54] and, through running rights over the Eden Valley Railway (EVR) and the Lancaster & Carlisle Railway (L&CR), to Penrith. “The S&DR opened a carriage works south of Darlington North Road station in 1853 [98] and later it built a locomotive works nearby to replace its works at Shildon [which was] designed by William Bouch, who had taken over from Hackworth as Locomotive Supervisor in 1840, it completed its first locomotive in 1864.” [54][87: p8][99] The inclines, built when stationary engines were used, were bypassed by lines on gentler grades. By the early 1860s, the S&DR had a significant network, even having absorbed the EVR and the SD&LUR. [54]

“With 200 route miles (320 km) of line and about 160 locomotives, [100: p167] the Stockton and Darlington Railway became part of the North Eastern Railway on 13th July 1863. Due to a clause in the North Eastern and Stockton and Darlington Railways Amalgamation Act 1863 (26 & 27 Vict. c. cxxii) the railway was managed as the independent Darlington Section until 1876, when the lines became the NER’s Central Division. [87: p9][48: p133] After the restoration of the dividend in 1851, by the end of 1854 payments had recovered to 8 per cent and then had not dropped below 7 1⁄2 per cent.” [50: Appendix 1][54]

I guess that we might easily be able to agree that the Stockton & Darlington Railway was of great local significance. It significantly reduced the cost of coal supplied to Stockton and Darlington. It temporarily enhanced the Port at Stockton before moving that trade downstream to Middlesbrough. It dramatically improved the speed of supply of larger quantities of coal. It made the town and Port of Middlesbrough. It linked the industries of Cumbia and Cleveland allowing speedy transport of coal and iron-ore to the different industries. It improved passenger travel East-West and began with others the development of North-South travel freight and passenger train travel. ……

But how has the Stockton & Darlington Railway transcended the local and become internationally significant? ……

Why Is the Stockton & Darlington Railway So Important?

So, what is the case? Was the S&DR the first real railway?

As 2025 got underway, this question prompted me to look at what is known of railway history in the period from 1800 to 1850, and led to the writing of an article (online) about railway developments during that period. The article is entitled ‘The Mother of All Inventions‘. [2]

September 2025 marked the bicentenary of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) and, very naturally and most appropriately, major events were planned across the UK, and enthusiasts across the world planned their own commemorations. In this context, it is, at the very least, worth considering what the S&DR can and cannot justifiably claim for itself. In fact, Anthony Dawson in an article in Steam Railway Magazine in February 2025 suggested that we best get to understand the importance of the S&DR, perversely, by considering what cannot be claimed for it. [3] What follows below is based around that article by Anthony Dawson.

Dawson says: “while every enthusiast would arguably agree that the [S&DR] is special and that the bicentenary of its opening is a landmark worthy of celebration, how many of us truly understand why the [S&DR] is so momentous? Indeed, putting the Stockton & Darlington’s importance into context isn’t exactly straightforward, nor can it be boiled down to a particular ‘first’. Therefore, to understand why the Stockton & Darlington is so important, we need to look at what it wasn’t.” [3]

He goes on to suggest that, to paraphrase Winston Churchill, “while the [S&D] was not the beginning, it was the end of the beginning. Although it wasn’t the first of anything, as early railway historian the late Andy Guy put it, it was ‘better than the first’.” [3]

Was the Stockton & Darlington the first railway?

Perhaps that question can only be answered once we have agreed a definition of a ‘railway’. Collins Dictionary offers three definitions: a railway is the steel tracks that trains travel on; a railway is a company or organization that operates railway routes; and, a railway is the system and network of tracks that trains travel on. [10] Accepting these definitions would rule out a number of early ‘railway-like’ systems based on stone and wood.

The Collins dictionary definitions are very narrowly drafted. Dawson points us to Dr Michael Lewis’ definition: A railway is “a prepared track which so guides the vehicles running on it that they cannot leave the track”. [3][11] This short, simple definition allows for the inclusion of the Diolkos and other rutways of the Classical World, [12][13] possible rutways in Wiltshire (circa 300CE), [13] Cornwall (circa 1550s), [13][14] rutways in 19th century Australia, [15] and the guide-pin railways developed in Germany and Austria in the Middle Ages. Lewis’ definition includes ‘railways’ “before the late 18th Century, [often] private … with rails essentially of wood or occasionally of stone, with carriage only of goods in vehicles propelled by horse- or by man-power, and with a variety of methods of guiding the wheels. ” [11]

Dawson comments that, “The earliest evidence for ‘railways’ in this country comes from the Lake District when German-speaking immigrants led by Daniel Hochstetter introduced them to silver mines at Caldbeck during the reign of Elizabeth I. These railways consisted of longitudinal planks which guided an iron pin secured to the bottom of a four-wheel mine cart, working rather like a slot-car. … But the first [‘true’] railway in England was very likely that built by Huntingdon Beaumont in 1604 to carry coal from his pits at Wollaton near Nottingham down to the River Trent. It was made entirely from wood and greatly improved the transport of coal for onward shipping by water. So pleased was Beaumont with this new technology, he invested heavily in four similar railways around Newcastle, which were built to carry coal down to the Tyne. Beaumont, however, failed to break into the local market. This, coupled with heavy investment in his new railways and his lavish lifestyle, led him to being declared bankrupt, ending his days in a debtors’ prison.” [3]

Dawson goes on to say that, “following the turmoil of the English Civil War and Commonwealth period, wooden railways began to spread across Shropshire where they took on the name ‘Railed Way’ and the North-East where they were known as ‘Waggonways’ – two different names for the same idea. Indeed, as excavations on the first railway in Scotland – the Tranent to Cockenzie Waggonway of 1722 – have shown, there was very little new in the technology of a wooden railway. It [was] essentially a giant ladder laid on the ground. They used old ideas to provide a solution to a new problem.” [3]

The coming of the 18th century heralded a transport revolution. Dawson says: “The early waggonways carried largely coal and other minerals down to a staithe or wharf on a river or canal for onward shipping. Thus, they grew hand in hand with the canal network and many canal companies even owned their own waggonways as feeder lines. There was a transport revolution on the roads as well with the growth of turnpikes. Taken together, [these events] … fed and fuelled industrialisation and growing urbanisation, particularly in the North of England. Improved transport links meant coal could go to market quicker. It meant it was cheaper at the point of sale, which meant greater profits and, in turn, greater demand.” [3]

Various forms of ‘railway’ were clearly well established by the advent of the 19th century. The S&DR was clearly not the first railway.

If not the first ‘railway’, was the Stockton & Darlington the first to use iron rails?

Iron was first used in a ‘railway’ context as protective plating for the early wooden ‘railways’. Lengths of cast iron plate were nailed to the running surface of wooden rails, probably first in Coalbrookdale. Wooden rails were wearing too quickly and the iron covers improved longevity. It was a simple logical next step to move from cast-iron plate to cast-iron bars and then to either cast iron edge rails or cast iron L-shaped ‘tram-plates’. Cast-iron rails were common by the 1790s, their only real fault was that they were brittle and often broke under load. Indeed, when Trevithick’s early locomotive ‘Pen-y-darren’ made its maiden run on the Merthyr Tramroad in 1804, it was noted that the cast-iron rails were not robust enough for the heavy locomotive and a number broke. [16]

Dawson says that “What was needed was a superior type of rail … made from wrought iron. First rolled in any quantity in 1820 at Bedlington Iron Works, the Stockton & Darlington was probably the first railway to use wrought-iron rails on a large scale. Due to distrust of the new material, half of the line was laid with cast iron and half with wrought. It was a major technological breakthrough and one crucial to the development of the locomotive.” [3]

It may well be that around two thirds of the length of the railway used wrought iron rails and one third had cast iron rails. Cast iron was used for the chairs which sat on the sleepers.

So, it seems that the Stockton & Darlington was not the first to use iron rails but that it was important in the taking of the next technological step of employing wrought-iron rails. “Bedlington Ironworks, in Blyth Dene, Northumberland … is remembered as the place where wrought iron rails were invented by John Birkinshaw in 1820, … with their first major use being [on] the Stockton and Darlington Railway. [17] Birkinshaw’s wrought-iron rails were rolled in 15ft lengths.

If not the first railway and not the first to use iron, was the S&DR the first railway authorised by Act of Parliament?

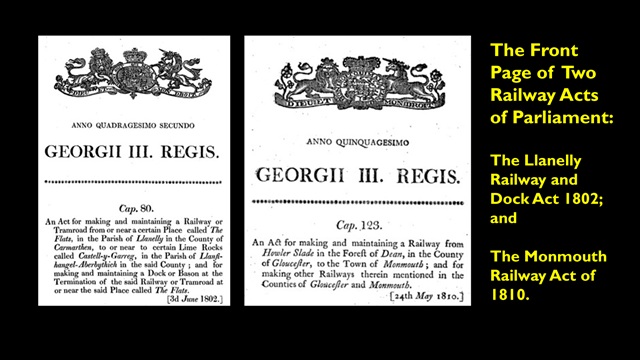

The first Act of Parliament for a railway was obtained by Charles Brandling for what became the Middleton Railway. It ran from coal pits at Hunslet down to the River Aire. The Act received Royal Assent in 1758. A significant number of Acts of Parliament relating to railways preceded the S&D, including this small selection: [18]

- 1802: The Llanelly Railway and Dock Act;

- 1803: The Croydon, Merstham and Godstone Iron Railway Act;

- 1804: The Ellesmere Canal, Railway and Water Supply Act;

- 1805: The Surrey Iron Railway Act;

- 1808: The Kilmarnock and Troon Railway Act;

- 1809: The Bullo Pill Railway Act; the Gloucester and Cheltenham Railway Act; the Lydney and Lidbrook Railway Act;

- 1810: The Monmouth Railway Act; the Severn and Wye Railway and Canal Co. Act; The Severn Tunnel Act;

- 1811: The Hay Railway Act; the Llanvihangel Railway Act; the Penclawdd Canal and Railway or Tramroad Act; the Severn and Wye Railway and Canal Co. Extension Act;

- 1812: the Anglesey Railway Act;

- 1813-15: the Usk Tram Road;

- 1817: the Mansfield and Pinxton Branch;

- 1818: the Kidwelly and Llanelly Canal and Tramroad Company Act; the Kington Railway Act;

- 1819: the Leeds and Liverpool Canal Branch and Railway Act; the Plymouth and Dartmoor Railway Act;

- 1820: the York and North Midland Railway Act; and the Plymouth and Dartmoor Railway (Crabtree and Sutton Pool Branch) Act. [18]

All these and more received their Royal Assent in advance of the S&D at some great expense. Dawson explains that “getting such an Act was very expensive and required having a Parliamentary Agent and introducing a Private Members’ Bill. It would then have to go through both Houses and committee stage and, unless the Bill could demonstrate it was for the public good, could be thrown out at any stage. It was a big risk, but ultimately worth it. Even though the Middleton had an Act, it didn’t mean it was a public railway. It was owned by the Brandlings, to carry their coal to market. It wasn’t open to any other users, and wasn’t a public right of way.” [3]

Not the first railway, not the first to use iron, not the first railway to received Royal Assent through an Act of Parliament. …Was, then, the S&D the first public railway?

All the railways built in the 17th and 18th centuries were private railways, built over private land. Dawson notes that, “or a railway to be public – to be public right-of-way – that meant it needed an Act of Parliament. It also meant that, until 1825 when the law was changed, an Act was also needed to form a joint-stock company.” [3]

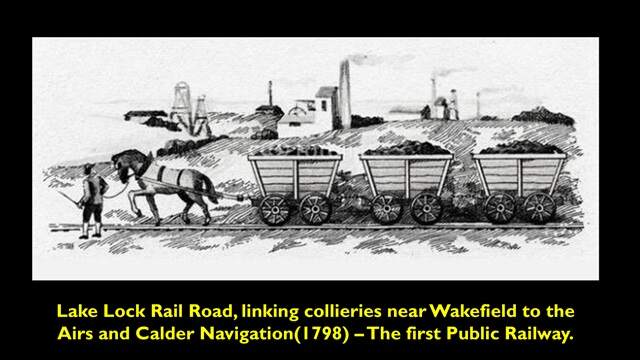

The first public railway in England was the Lake Lock Rail Road (LLRR), which opened in 1798. It linked collieries near Wakefield to the Aire & Calder Navigation. The LLRR qualifies as a public railway “because it was open to any user upon payment of a toll and because its capital was held in publicly traded shares. … The LLRR didn’t operate the railway itself, but rather allowed colliery owners to run their own trains on it, for which a toll was paid.” [3] The LLRR can claim another first! As well as being “probably the world’s first public railway, it was also owned … by the world’s first public railway company.” [21]

If you are unhappy with the idea of the LLRR being the first public railway, Then perhaps you would have to accept the Surrey Iron Railway as the next contender for the title – It required an Act of Parliament and incorporated in 1803 and fully open at the latest by 1806.

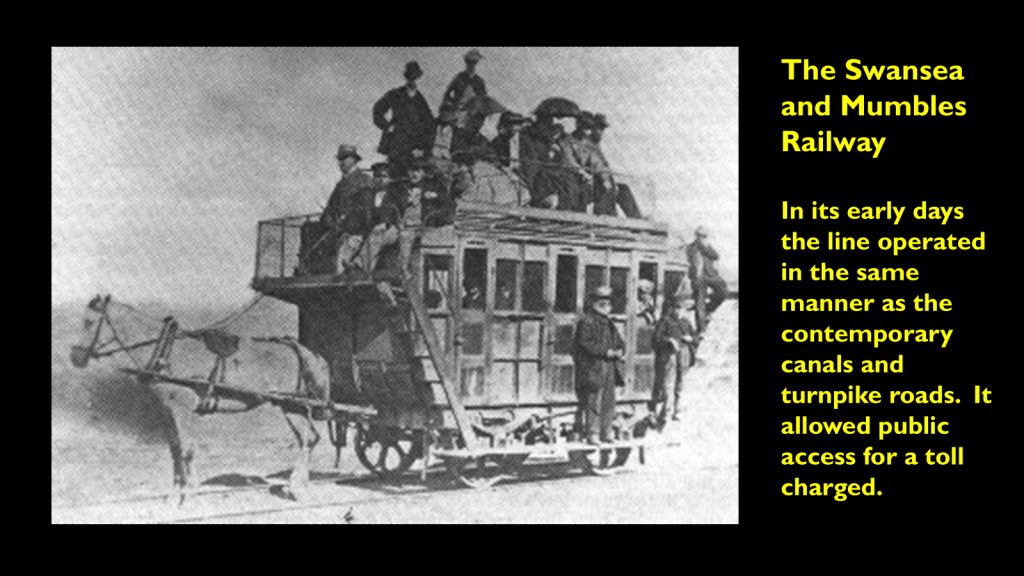

The first passenger-carrying public railway in the United Kingdom was opened by the Swansea and Mumbles Railway at Oystermouth in 1807, using horse-drawn carriages on an existing tramline. [19][20]

The first public railway in Scotland was the Kilmarnock & Troon Railway (K&TR) which finally opened in 1812. Like the LLRR, it operated as a toll road, so that independent carriers could place wagons on it, and pay for the facility. [22]

We have established that the Stockton & Darlington was not the first public railway. Given what we have already discovered, our next question needs to be one about the intentions of the designers and directors of the Stockton & Darlington.

Was the Stockton & Darlington the first to be designed and built with mechanical operation in mind?

Here we have to start from an ambivalent position. … It depends! … Do you see hydraulic power as a form of mechanical power? If your answer is ‘Yes’, then the first length of railway to be operated mechanically is one known to have existed in Sweden in the late 1600s, where a waterwheel was employed to haul wagons up an incline. By the end of the 1700s, this technology was in use in Mas-sachusetts (on the South Hadley Canal) for a rail-based lift for canal boats linked with practice at Ketley, Shropshire at that time but assisted by power from a water wheel. There was another ex-ample at Bad Gastein in what is now Germany. [114][115: p87 & p337][116] The water-powered haulage of wagons up an inclined plane in the UK was initially limited to one location in Devon alt-hough the practice was used much later in North Wales. [115: p87-88]

If we set aside waterpower, perhaps the S&DR could stake a claim to be the first public railway designed to be worked mechanically. But it definitely was not the first to be operated mechanically. … (More of that later).

Setting aside waterpower, was the S&DR the first railway designed to be operated mechanically? … Again the answer is ‘No!’ … Early inclines were self-acting, water power could support this but, as Gwyn tells us, experience on the Ketley Incline led Reynolds, when carrying out a survey for a canal to connect the Oakengates collieries with the River Severn, to conclude that the wastage of water from locks “would be prohibitive, and after much hesitation and a public competition, he and the other shareholders resolved on a modification of the Ketley system, but with fixed steam engines on its three inclined planes, at Donnington Wood, Windmill Farm and Hay. Instead of locks at the summit as at Ketley, reverse railed slopes were constructed into docks permanently kept in water, and the cradles were equipped with overlapping wheels which ran on ledges on the docksides to maintain them in a horizontal position. The engines were used to draw boats and cradles out of the docks and to haul up the main incline if necessary. All three were built to a hybrid design by Reynold’s protégé, Adam Heslop. These were the first locations in the world where railed vehicles were moved by steam. They were operational by 1793.” [115: p89]

This was followed by a significant section of the Lancaster Canal crossing the Ribble Valley. In 1803, steam-powered inclines were used “to connect the northern and southern ends of the Lancaster Canal. Its three inclined planes were each equipped with a high-pressure 6-horsepower 13-inch cylinder engine costing £350 and made by Summerfield and Atkinson, a local foundry which offered ‘patent steam engines’, and which also built the waggons. The first was installed in May of that year. In June, a 6-horsepower steam engine was installed on a plateway incline to haul spoil on the construction of London Docks.” [115: p89]

From the turn of the nineteenth century a number of shorter inclines were being steam-operated or steam-assisted. Examples include: an incline at Wellington Quay on the North bank of the Tyne (where George Stephenson was employed for a time), 1802/1803; an incline at Glynneath, connecting Aberdare Ironworks with Neath Canal, 1805; Bewicke Main (Urpeth) Colliery, 1805. [115: p89-91]

Three years prior to the opening of the Stockton & Darlington Railway George Stephenson designed and built another railway (the Hetton Colliery Railway) which, like the Stockton & Darlington “used a combination of stationary engines, rope haulages and level sections worked by locomotives.” [3] However, the Hetton Colliery Railway was a private, not a public railway:- “The Hetton Colliery Railway was an 8-mile (13 km) long private railway opened in 1822 by the Hetton Coal Company at Hetton-le-Hole, County Durham. … The Hetton was the first railway to be designed from the start to be operated without animal power, as well as being the first entirely new line to be developed by … George Stephenson.” [25]

Again, if we set aside hydraulic and discrete uses of stationary steam-power, it seems that the Stockton & Darlington was the first ‘public‘ (rather than ‘private‘) railway to be designed and built with steam power in mind. This, perhaps, feels as though we are making some headway. … The Stockton & Darlington was the first ‘public‘ railway to be designed and built with steam power in mind. … That is definitely a ‘first’ isn’t it. ….

Was the Stockton & Darlington the first railway to use steam power?

Surely, given that the S&DR was the first public railway designed for mechanical operation, that must mean that it was the first to use steam-powered engines. Mustn’t it?

Nothing is that simple!

The Middleton Railway in Leeds, was using steam power by 1812: “In 1812, it introduced the worlds first commercially successful steam locomotives which were designed and built in Leeds. These locomotives incorporated one of the most significant advances in the design of the steam locomotive – namely the twin cylinder engine which eliminated the need for the cumbersome flywheel employed on earlier single cylinder engined locomotives.” [24][34][35][36]

Incidentally, because it was the first railway to regularly use steam locomotives, the Middleton Railway also “lays claim to other firsts; they employed the first regular professional train driver in the world, a former pit labourer named James Hewitt. More tragically, a 13 year old boy called John Bruce was killed in February 1813 whilst running along the tracks – almost certainly the first member of public killed by a locomotive.” [36]

The Kilmarnock & Troon Railway first used steam power in 1817: in 1817 the Duke of Portland acquired a locomotive for the K&TR named ‘The Duke‘, which was the first use of steam locomotive power in Scotland. Its use was however discontinued in view of frequent breakages of the cast-iron rails on the line. [23] … Notes in The Railway Magazine of January 1950, suggest that this was only a hiatus in the use of this locomotive on the K&TR: In his ‘Story of the Life of George Stephenson‘, Samuel Smiles noted the discontinued use of ‘The Duke‘, but later, in his ‘Lives of the Engineers Volume III’ he appears to have secured further information, viz: “The iron wheels of this engine were afterwards removed, and replaced with wooden wheels, when it was again placed upon the road and continued working until the year 1848.” [43: p59][44: p139] This is supported by W. J. Gordon, writing in 1910, who says of the K&TR: “on it was placed the Killingworth engine with the chain gearing bought by the Duke of Portland from George Stephenson in 1817. The iron wheels of this remarkable engine broke down the cast-iron rails, for it thumped horribly, but, instead of being withdrawn from duty, as usually reported, it had its iron wheels taken off and replaced by wooden ones; and with wooden wheels it worked the traffic-mineral, goods and passenger-until 1848, for so many years in fact that it has been confused with or mistaken for the old St. Rollox, one of the first engines of the Glasgow & Garnkirk, which it in no way resembled.” [43: p59-60][45: p188-190]

Gordon appears to “have picked up and recorded a local railway tradition about the locomotive. It is difficult to credit that an old Killingworth-type engine was re-furbished in 1839 or later, after two decades of disuse, but this seems to be the only way of reconciling the various scraps of evidence. No trace has been found of any other Kilmarnock & Troon locomotive.” [43: p60]

It would be impossible to argue that the K&TR was built with steam power in mind, however, the K&TR was definitely the first use of steam-power on a public railway in Scotland. It could also be argued that this was the first use of steam power on a public railway in the United Kingdom. This was eight years before the Stockton and Darlington first used steam-powered trains.

However, neither of these could justifiably make a claim to be the first to use steam on a revenue earning railway. That accolade must go to the Merthyr Tramroad (otherwise known as the Pen-y-Darren Tramway and associated with the Pen-y-darren Ironworks, in Merthyr Tydfil) a bit earlier in the 19th century, on 21st February 1804 to be more precise, and to a locomotive designed by Richard Trevithick.

“In 1802, Trevithick took out a patent for his high-pressure steam engine. To prove his ideas, he built a stationary engine at the Coalbrookdale Company’s works in Shropshire in 1802, forcing water to a measured height to measure the work done. The engine ran at forty piston strokes a minute, with an unprecedented boiler pressure of 145 psi.” [26]

It seems that the experiment in Shropshire led to Trevithick experimenting with creating steam railway locomotives. He had already designed and built a road locomotive, ‘Puffing Devil‘. [27]

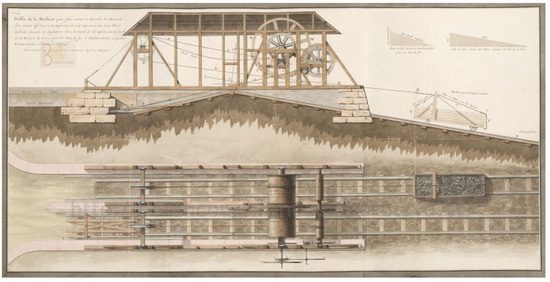

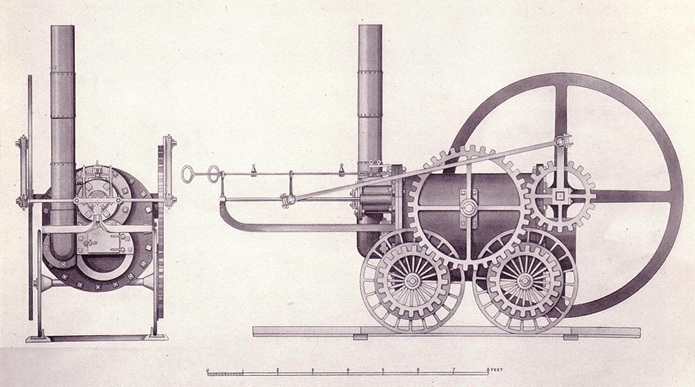

In 1802, the Coalbrookdale Company in Shropshire built a rail locomotive for him. [28] The death of a company workman in an accident involving the engine is said to have caused the company to not proceed to running it on their existing railway. [29]

The drawing above has been used as the basis of all images and replicas of the later ‘Pen-y-darren’ locomotive, as no plans for that locomotive have survived. It cannot be an exact sister of the later locomotive because there is a tunnel on the Pen-y-darren Tramway which would have required a lower chimney and a smaller flywheel. [3]

In 1804, Trevithick’s revised locomotive ran on the Pen-y-darren Tramway pulling a commercial load. Soon after this (1808) Trevithick exhibited a similar steam locomotive in London, built for him by John Urpeth Rastrick and John Hazledine at their foundry in Bridgnorth which was named ‘Catch Me Who Can‘. Although only on a small circular track, and only in use for matter of weeks, this was the first locomotive to power a train carrying fare-paying passengers. The drawing of the locomotive ‘Catch Me Who Can‘ is taken from a card/admission ticket to Trevithick’s ‘Steam Circus‘, summer 1808, © Public Domain. [33]

The S&DR was not the first railway to use a steam locomotive. However, the S&DR saw a step change in the use of steam power. … “Prior to 1825 no one had ever attempted to run a locomotive as far as George Stephenson did; the furthest they had ever run was a few miles.” [3] George Stephenson had such faith in steam power “that he designed and built a steam railway to be worked by locomotives not just for a couple of miles but for tens of miles” [3] – twenty six miles in all!

We have established that the S&DR was the first ‘public‘ (rather than ‘private‘) railway to be designed and built with steam power in mind. We have seen that while not the first to use steam-power, it was the first to be so confident in the new technology to believe that it could be used over significant distances.

We have noted, in passing, that the majority of different railways in use prior to 1825, were designed to carry coal or iron ore and some other ancillary forms of freight.

Can we say that the Stockton & Darlington was the first to carry fare-paying passengers over any significant distance?

Dawson tells us that “unofficial passenger carrying goes back into the 18th Century, on what were private mineral lines. The first public railway, as authorised by an Act of Parliament and which authorised the railway to do so was the Swansea & Mumbles Railway of 1807. This was a horse-drawn service, working to a timetable and, in 1812, saw the first railway station open in Swansea.” [3]

He continues: “The first passenger service on a public railway in Scotland was in 1813, on the Kilmarnock & Troon [Railway]. Again, it was horse-worked but like the Stockton & Darlington tickets could be bought from local inns along the line – as well as refreshments and parcels left there to be carried by the railway as well. There was a long history of public passenger railways before 1825. … Therefore, the Stockton & Darlington was tapping into an existing idea.” [3]

David Gwyn says: “In April 1807 the first known public railway passenger service was inaugurated, enabling tourists to enjoy the beauties of Swansea Bay along a plateway opened the previous year to carry limestone from the Mumbles to the copper smelters, and coal and manure in the opposite direction. Such services were soon found on railways in the border country, Scotland and the English West Country. Some carriers offered pleasure carriages for hire. Well-heeled people could now make railway journeys in order to enjoy attractive scenery, and humbler folk could travel by train to buy and sell – both Dr Griffiths plateway from the Rhondda to Pontypridd and the rail section of the Somerset Coal Canal to Radstock were used by women taking farm produce to market.” [115: p71-72]