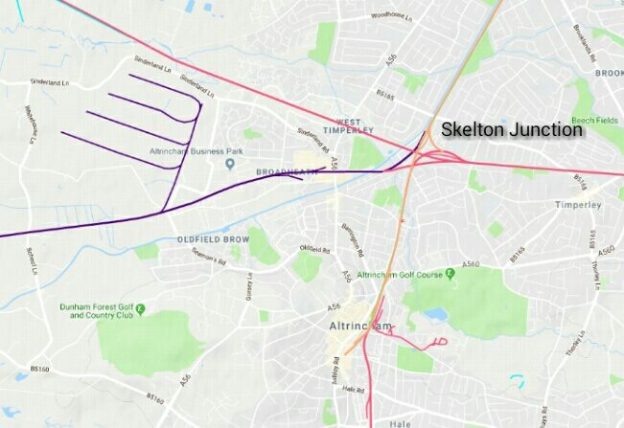

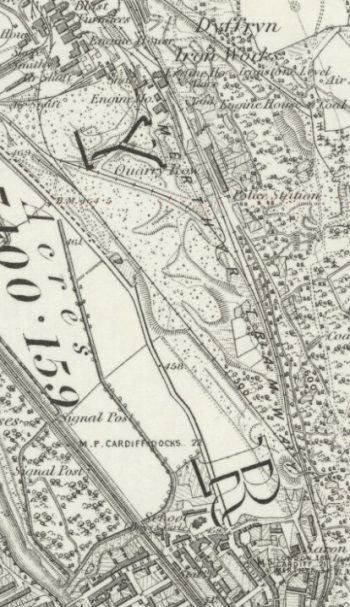

These two plans show the route of the Tanat Valley Light Railway and its place within the local railway network. [1]

These two plans show the route of the Tanat Valley Light Railway and its place within the local railway network. [1] This plan shows the different parts of the Oswestry and Llangynog Railway. Its enabling Act in 1882 had 57 clauses and ran to 20 pages. The railway was described in three parts which were primarily associated with how it was to connect up with existing lines at its eastern end. Railway Number 1 would provide a connection with the Porth-y-Waen branch of the Cambrian Railway. This would give access to Oswestry. This section was to be one mile, one furlong, 5 chains and 10 links long. Railway Number 2 was the main part of the line up the Tanat Valley 13 miles and 2 furlongs in length. Railway Number 3 was a short fork (3 furlongs and 8 chains) at the eastern end of Railway No. 2 that linked the latter with the Potteries Shrewsbury and North Wales Railway branch that ran up to Nantmawr. Railway No. 2 could only connect with Railway No. 1 via a short section of the Nantmawr branch of the Potteries line. The sequence of opening had to be No. 1, then No. 2, then No. 3. [3][20]

This plan shows the different parts of the Oswestry and Llangynog Railway. Its enabling Act in 1882 had 57 clauses and ran to 20 pages. The railway was described in three parts which were primarily associated with how it was to connect up with existing lines at its eastern end. Railway Number 1 would provide a connection with the Porth-y-Waen branch of the Cambrian Railway. This would give access to Oswestry. This section was to be one mile, one furlong, 5 chains and 10 links long. Railway Number 2 was the main part of the line up the Tanat Valley 13 miles and 2 furlongs in length. Railway Number 3 was a short fork (3 furlongs and 8 chains) at the eastern end of Railway No. 2 that linked the latter with the Potteries Shrewsbury and North Wales Railway branch that ran up to Nantmawr. Railway No. 2 could only connect with Railway No. 1 via a short section of the Nantmawr branch of the Potteries line. The sequence of opening had to be No. 1, then No. 2, then No. 3. [3][20]

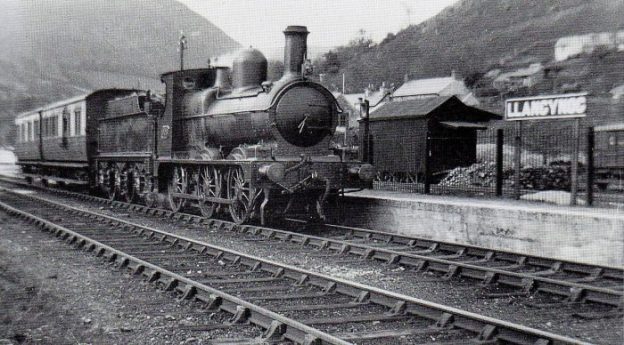

Our journey along the Tanat Valley Light Railway (TVLR) commences the western end at Llangynog Railway Station. Llangynog Railway Station in 1930. [2]

Llangynog Railway Station in 1930. [2]

These two maps show Llangynog in 1840 and in 1902. If the second date is correct, although the railway has arrived at Llangynog, it will still be another two years or so before it is in use! [3] It is interesting to note that the railway station (4) is not the only addition to the village between the two maps being drawn. Some new cottages have been built (1), a school has been set up (2), and a Chapel has been established (3).The Victorian period saw a great rise in the number of chapels as communities set up new places of worship where they could worship in their own way and in their own language. This often meant an over-provision within a local community with chapel and church seats well in excess of the total population of a village or town.

These two maps show Llangynog in 1840 and in 1902. If the second date is correct, although the railway has arrived at Llangynog, it will still be another two years or so before it is in use! [3] It is interesting to note that the railway station (4) is not the only addition to the village between the two maps being drawn. Some new cottages have been built (1), a school has been set up (2), and a Chapel has been established (3).The Victorian period saw a great rise in the number of chapels as communities set up new places of worship where they could worship in their own way and in their own language. This often meant an over-provision within a local community with chapel and church seats well in excess of the total population of a village or town.

The railway station was situated on the north side of the river. The centre of the small village of Llangynog was on the South side of the river. This picture shows Llangynog Station after closure. It is held by the People’s Collection of Wales. [4] The location is now a caravan park, as shown on the Google Earth image below.

This picture shows Llangynog Station after closure. It is held by the People’s Collection of Wales. [4] The location is now a caravan park, as shown on the Google Earth image below.

This OS Map is an extract from the 1:25,000 series from the mid-20th century. [5]

This OS Map is an extract from the 1:25,000 series from the mid-20th century. [5]

Wilfred J. Wren provides hand drawn maps in his book about the Tanat Valley which was published in 1968. The drawings were completed in 1966. Llangynog is shown immediately below. [8: p106] The station itself took up a significant area of land on the North side of the Afon Eiarth. At the West end of the site a level crossing allowed access across the village road to two exchange sidings. A tramroad ran from the Granite Quarries further West to the exchange sidings. At a later date the Granite Wharf was moved to very close to the station Goods Shed on the South side of the Slate Wharf. The Tramroad served Maker’s Granite Quarries. In the hand-drawing below, the Tramroad runs along the bottom side of the map, from the wharves close to the village along the Northeast side of the Afon Eiarth until close to the quarry access where a bridge took it over the river opposite Pencraig. In addition, an incline ran from the tramway up to Ochr-y-Craig Granite Quarry high on the hill on the North side of the river valley. [8:127][9].

The Tramroad served Maker’s Granite Quarries. In the hand-drawing below, the Tramroad runs along the bottom side of the map, from the wharves close to the village along the Northeast side of the Afon Eiarth until close to the quarry access where a bridge took it over the river opposite Pencraig. In addition, an incline ran from the tramway up to Ochr-y-Craig Granite Quarry high on the hill on the North side of the river valley. [8:127][9]. Maker’s Granite Quarry was opened in 1904 by Maker, who came from the North of England. Stone was crushed on the quarry floor and then lifted to road level up an incline. Initially the minor road was used to transport the granite to Llangynog. It was decided, within a few years, to use the Tanat Valley Light Railway (TVLR) for transporting chippings and a transfer wharf was built at the site of the Ochr-y-craig lead mine and a tramway linked the quarry and the transfer wharf. Wren says: ‘The building of the tramway involved a causeway near the quarry, a timber bridge across the Eiarth, the filling-in of the northern channel of the Eiarth near the corn mill, and high-level banks at the exchange sidings to bring the tramway trollies above the level of the railway trucks for ease of transfer. The tramway worked by gravity, the empties being pushed back by hand.’ [8: p159]

Maker’s Granite Quarry was opened in 1904 by Maker, who came from the North of England. Stone was crushed on the quarry floor and then lifted to road level up an incline. Initially the minor road was used to transport the granite to Llangynog. It was decided, within a few years, to use the Tanat Valley Light Railway (TVLR) for transporting chippings and a transfer wharf was built at the site of the Ochr-y-craig lead mine and a tramway linked the quarry and the transfer wharf. Wren says: ‘The building of the tramway involved a causeway near the quarry, a timber bridge across the Eiarth, the filling-in of the northern channel of the Eiarth near the corn mill, and high-level banks at the exchange sidings to bring the tramway trollies above the level of the railway trucks for ease of transfer. The tramway worked by gravity, the empties being pushed back by hand.’ [8: p159]

The quarries were worked until 1933 and the leases were then acquired by Amalgamated Roadstone who still held them in the late 1960s. The site of Llangynog Railway Station in 2018. [6]

The site of Llangynog Railway Station in 2018. [6] The old railway route runs on the north side of the Afon Tanat as it heads East from Llangynog. At times it runs very close to the river as is evident on the right side of the Google Earth Image above and on the OS Map extract below, near to Glanhafon-fawr [5]

The old railway route runs on the north side of the Afon Tanat as it heads East from Llangynog. At times it runs very close to the river as is evident on the right side of the Google Earth Image above and on the OS Map extract below, near to Glanhafon-fawr [5]

The view Northwest from Bont-Fawr showing the route of the old railway on the North side of the lane which followed the bank of the River Tanat. The river is off the picture to the left. The station is off to the right (Google Streetview).

The view Northwest from Bont-Fawr showing the route of the old railway on the North side of the lane which followed the bank of the River Tanat. The river is off the picture to the left. The station is off to the right (Google Streetview). Slightly further East in the 21st century, looking back West towards Bont-Fawr which is close to the chevron sign in the centre-right of the picture. The line crossed the road here and entered the station site which was off to the left of the picture (Google Streetview).

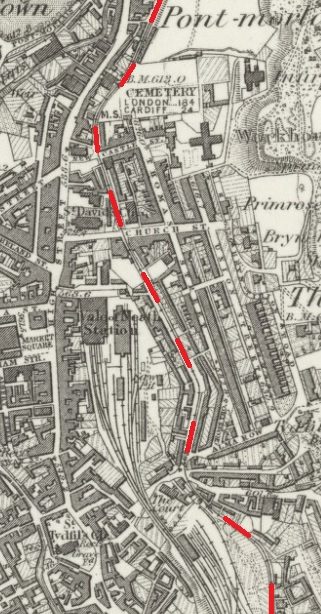

Slightly further East in the 21st century, looking back West towards Bont-Fawr which is close to the chevron sign in the centre-right of the picture. The line crossed the road here and entered the station site which was off to the left of the picture (Google Streetview). From the same point looking Northeast. The red line shows the approximate line of the old railway through Pen-y-Bont-Fawr station (Google Streetview).

From the same point looking Northeast. The red line shows the approximate line of the old railway through Pen-y-Bont-Fawr station (Google Streetview).

The following links are provided with permission from Francis Firth [7] using their website’s embedding service. All are photos of Penybontfawr Village c.1955 and all seem to show different portions of the main street at that time:

https://www.francisfrith.com/penybontfawr/penybontfawr-the-village-c1955_p274015

https://www.francisfrith.com/penybontfawr/penybontfawr-the-village-c1955_p274014

https://www.francisfrith.com/penybontfawr/penybontfawr-the-village-c1960_p274029

Sadly, none of these images show the railway station, but they give an excellent impression of the village in the 1950s. The railway station was, as can be seen on the OS extract above, sited a few hundred metres north of the village on the North bank of the Afon Tanat. It was a simple affair with a timber-faced platform and a small waiting shelter for passengers, both on the South side of the tracks. The platform was backed by a fence of vertical iron railings and the boundaries of the site were marked by timber fencing as one of the few pictures of the station shows. That picture is covered by copyright and is regularly for sale as a print on eBay. It seems to show the local goods waiting in the loop while two prospective passengers look West along the line in the hope that the passenger service from Llangynog will soon arrive at the station. [10] Pen-y-bont-fawr Railway Station. [8: p106] The goods facilities and yard were on the North side of the Station.

Pen-y-bont-fawr Railway Station. [8: p106] The goods facilities and yard were on the North side of the Station.

Penybontfawr Community Council describes to village in the 21st century: “Penybontfawr is situated at the confluence of the river Tanat and the river Barrog in the upper Tanat valley.The village is surrounded by steep hills, forests and waterfalls and is an excellent start from which to explore the Berwyn mountains. The village has a good range of community services and facilities. Siop Eirianfa and post office, garage, Railway Inn, primary school. community centre, church and chapel are all to be found within easy walking distance of the village centre. Tanat Valley buses provide a service to Llanrhaedr ym mochnant and the local market town of Oswestry. The area has a strong tradition of Welsh culture and many people speak Welsh either as a first or second language – great pride being taken in the traditional and contemporary music making of the community! Each year the combined village horticultural and sheep dog trials on August bank holiday weekend draw visitors from both far and near.” [11] No mention is made on the webpage, as yet, of the importance of the old railway in the development of the valley or the village.

From Pen-y-bont-fawr the old railway continued East along the North bank of the River Tanat with the roads serving the valley running on the South side of the river. The next halt is shown at the right-hand end of the OS Map extract below – Pedair-ffordd Halt.

The approximate line of the old railway to the East of Pen-y-bont-fawr (Google Earth).

The approximate line of the old railway to the East of Pen-y-bont-fawr (Google Earth). The route of the old line continues to the North side of Castellmoch-fawr Farm (at the right side of this image) (Google Earth).

The route of the old line continues to the North side of Castellmoch-fawr Farm (at the right side of this image) (Google Earth). The old line crossed the modern B4396 just before reaching Pedair-ffordd Halt (Google Earth).

The old line crossed the modern B4396 just before reaching Pedair-ffordd Halt (Google Earth). The view North-northeast from the bridge over the River Tanat along the B4396. The old railway crossed the road just before the bend visible in the distance (Google Streetview).

The view North-northeast from the bridge over the River Tanat along the B4396. The old railway crossed the road just before the bend visible in the distance (Google Streetview). The approximate line of the old railway approaching the B4396 from the West (Google Streetview).

The approximate line of the old railway approaching the B4396 from the West (Google Streetview). Looking East along the route of the old railway line. The B4396 is in the foreground of this image, the location of the Pedair-ffordd Halt halt was just beyond the modern garage (Google Streetview).

Looking East along the route of the old railway line. The B4396 is in the foreground of this image, the location of the Pedair-ffordd Halt halt was just beyond the modern garage (Google Streetview). The remains of Pedairfford Halt in November 1979 (c) Alan Young. [21]

The remains of Pedairfford Halt in November 1979 (c) Alan Young. [21]

Immediately North of the old level crossing the B4396 turns right to run on an East-West alignment alongside the route of the old railway. Both the modern road and the old railway route follow the contours on the Northern edge of the River Tanat flood plain through Llanrhaiadr Mochnant Station. The station was sited around 3/4 mile to the Southeast of the village it served (Llanrhaiadr-ym-Mochnant).

The site of Llanrhaiadr Mochnant Station viewed from the East in 2019. The old line crossed the B4580 on the level at the East end of the station site (Google Streetview). The station had two platforms and a passing loop as well as sidings to a goods yard and cattle dock. [12]

The site of Llanrhaiadr Mochnant Station viewed from the East in 2019. The old line crossed the B4580 on the level at the East end of the station site (Google Streetview). The station had two platforms and a passing loop as well as sidings to a goods yard and cattle dock. [12]

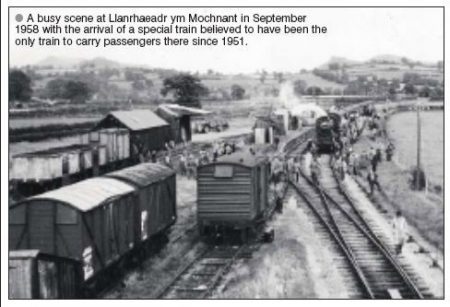

Llanrhaiadr-Mochnant-Station taken from a Stephenson Locomotive Society enthusiasts special train in 1958 (above), looking West through the station site. [12] The adjacent image is of the same train in the station, this time taken from the West. The Station was still in use at this time for freight. [13]

Llanrhaiadr-Mochnant-Station taken from a Stephenson Locomotive Society enthusiasts special train in 1958 (above), looking West through the station site. [12] The adjacent image is of the same train in the station, this time taken from the West. The Station was still in use at this time for freight. [13] Llanrhaiadr-Mochnant Station again. This picture show s it in 1947 with a trail heading for Llangynog in the down platform. [8: p80a – Plate 19] The full layout of the station is visible in this image. The level-crossing at the East end of the station can just about be seen. The two platforms are in the centre of the picture. The two buildings on the up platform are, nearest to the camera, the gents and then the main passenger building which included the ladies. Opposite, on the down platform is a small shelter. The cattle dock is not quite visible on the front left of the picture but the yard siding which had a goods shed with an awning is well-used. A hand drawn plan if the station site is available in Wren’s book. [8: p104]

Llanrhaiadr-Mochnant Station again. This picture show s it in 1947 with a trail heading for Llangynog in the down platform. [8: p80a – Plate 19] The full layout of the station is visible in this image. The level-crossing at the East end of the station can just about be seen. The two platforms are in the centre of the picture. The two buildings on the up platform are, nearest to the camera, the gents and then the main passenger building which included the ladies. Opposite, on the down platform is a small shelter. The cattle dock is not quite visible on the front left of the picture but the yard siding which had a goods shed with an awning is well-used. A hand drawn plan if the station site is available in Wren’s book. [8: p104]

Writing in 1968 Wilfred Wren commented that, “the station yard at Llanrhaiadr-Mochnant [was] still used partly for coal storage; at the western end there [was] a hugh pile of wooden sleepers.” [8: p105]

Beyond Llanrhaiadr-Mochnant the old line remained on the South side of the B4396. Across the width of the first three fields its route has been obliterated by ploughing and can only be made out in the form of a slight shadow on the satellite images that are available. The fourth field has a slight rise in it and the old line needed a shallow cutting. The Google Streetview image below shows that the route of the old line can still be identified by that cutting.

The B4396 looking East. The shallow cutting made for the Tanat Valley Light Railway can be made out just to the right of centre in the image (Google Streetview). The line curved round more to the Southeast through the cutting before realigning once more to the East-Southeast.

The B4396 looking East. The shallow cutting made for the Tanat Valley Light Railway can be made out just to the right of centre in the image (Google Streetview). The line curved round more to the Southeast through the cutting before realigning once more to the East-Southeast.

A few hundred yards to the East both the road and old railway crossed the Afon Iwrch. The crossing point is just visible on the right of the satellite image above and in the top left of the first image below. The line ran Southeast towards Pentrefelin Halt.

Pentrefelin Halt served a small village. Wikipedia says that “The platform was located to the east of a level crossing on a minor road to Glantanat Isaf. The platform had a corrugated iron shelter, lamps and a nameboard. There was a goods loop on the north side of the line. The platform is still extant on farmland.” [14] Wren says that, “the large station area at Pentrefelin was used for the unloading and storage of pipes for the second line in the Vyrnwy aqueduct.” [8: p105]

Pentrefelin Halt served a small village. Wikipedia says that “The platform was located to the east of a level crossing on a minor road to Glantanat Isaf. The platform had a corrugated iron shelter, lamps and a nameboard. There was a goods loop on the north side of the line. The platform is still extant on farmland.” [14] Wren says that, “the large station area at Pentrefelin was used for the unloading and storage of pipes for the second line in the Vyrnwy aqueduct.” [8: p105]

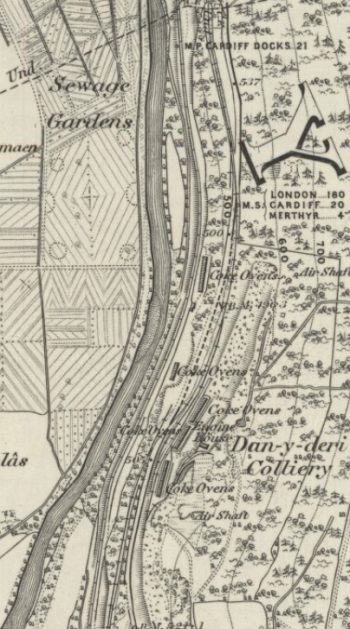

After Pentrefelin Halt, the line drifted closer to the Rivar Tanat crossing the Afon Lleiriog. Eventually, the old line crossed the River Tanat and then followed the South bank of the meandering river. The bridge can be picked out at the bottom right of the last OS Map extract above and its location can be seen on the right of the Google Earth satellite image below. Wren commented that in 1968 the track-bed East of Llanrhaiadr-Mochnant through to Blodwell Junction was in near-perfect condition, broken only by the gaps of the salvaged river bridges near Pentrefelin and Llanyblodwell. Along this length, bridges over the Rhaeadr and Iwrch also only had abutments and foundations left in 1968. [8: p105]

Wren commented that in 1968 the track-bed East of Llanrhaiadr-Mochnant through to Blodwell Junction was in near-perfect condition, broken only by the gaps of the salvaged river bridges near Pentrefelin and Llanyblodwell. Along this length, bridges over the Rhaeadr and Iwrch also only had abutments and foundations left in 1968. [8: p105]

Once the River Tanat had been crossed, trains continued Eastward, protected in places by significant earthworks from erosion by the river, to Llangedwyn Halt which can be seen on the OS Map extract below. [5] The Google Streetview image which follows shows a view taken from the North of what was once a level-crossing over the lane to the West of the Halt. The low embankment on which the formation of the old railway was laid can still be picked out carrying the field access to the right of the picture. The Halt was located off to the left of the picture.

Once the River Tanat had been crossed, trains continued Eastward, protected in places by significant earthworks from erosion by the river, to Llangedwyn Halt which can be seen on the OS Map extract below. [5] The Google Streetview image which follows shows a view taken from the North of what was once a level-crossing over the lane to the West of the Halt. The low embankment on which the formation of the old railway was laid can still be picked out carrying the field access to the right of the picture. The Halt was located off to the left of the picture.

The halt at Llangedwyn was slightly more substantial that its designation as a halt suggests. At one time, probably until the mid-1920s there was a passing loop here and a long siding followed the North boundary of the station site. The passenger platform was at the South side of the site and was bout 17 ft longh with a small shelter provided to protect passengers from the waether. On the North side of the loop there was a cattle dock. The station was about 400 yards from the village. [8: p104] As can be seen in the Google Earth satellite image above, a number of farm/industrial buildings associated with Llangedwyn Home Farm have covered the site of the old halt. [15]

The halt at Llangedwyn was slightly more substantial that its designation as a halt suggests. At one time, probably until the mid-1920s there was a passing loop here and a long siding followed the North boundary of the station site. The passenger platform was at the South side of the site and was bout 17 ft longh with a small shelter provided to protect passengers from the waether. On the North side of the loop there was a cattle dock. The station was about 400 yards from the village. [8: p104] As can be seen in the Google Earth satellite image above, a number of farm/industrial buildings associated with Llangedwyn Home Farm have covered the site of the old halt. [15]

The next station on the old line was at Llansilin Road. It was reached on a slightly more meandering railway just to the South of the course of the River Tanat. The railway route and the location of Llansilin Road Station are shown on the satellite images from Google Earth above. Wren comments that at “Llansilin Road, a station master with an artistic bent erected three square-tiered ornaments, made of concrete and stuck in the manner of Antonio Gaudi with fragments of chins plates.” [8: p105] These were erected at the back of the passenger platform which was on the South side of the running line. The platform, as at Llangedwyn was about 170ft long with a small corrugated iron shelter at the Eastern end. A cattle dock was placed alonside the passing loop which was on the North side of the main-running line and a further single siding was provided which had a short loading wharf and a coal storage arch. [8: p102][16]

The next station on the old line was at Llansilin Road. It was reached on a slightly more meandering railway just to the South of the course of the River Tanat. The railway route and the location of Llansilin Road Station are shown on the satellite images from Google Earth above. Wren comments that at “Llansilin Road, a station master with an artistic bent erected three square-tiered ornaments, made of concrete and stuck in the manner of Antonio Gaudi with fragments of chins plates.” [8: p105] These were erected at the back of the passenger platform which was on the South side of the running line. The platform, as at Llangedwyn was about 170ft long with a small corrugated iron shelter at the Eastern end. A cattle dock was placed alonside the passing loop which was on the North side of the main-running line and a further single siding was provided which had a short loading wharf and a coal storage arch. [8: p102][16]

The station had the “Road” suffix due to being 3 miles south from Llansilin and 4 miles by road. The station was located close to the hamlet of Pen-y-bont Llanerch Emrys, two miles east of Llangedwyn village, where the road from Llansilin joins the river valley. The location on the OS Map extracts below [5] was close to the 343ft height marker on the second image. [16]

Looking West from the old level-crossing into the site of Llansilin Road Station. The old passenger platform appears still to be present on the left of the picture (Google Streetview).

Looking West from the old level-crossing into the site of Llansilin Road Station. The old passenger platform appears still to be present on the left of the picture (Google Streetview).

A short distance after Llansilin Road, the old trackbed turns North following the River Tanat. It then, once again swings round through East towards Southeast as shown on the two OS Map extracts below.

It then, once again swings round through East towards Southeast as shown on the two OS Map extracts below.

The satellite images from Google Earth are less well defined over the next part of the old route. So the high-level images are provided by Bing and are aerial, rather than satellite, images. The old railway followed approximately the 300ft contour with the valley side rising relatively steeply just South of the formation of the railway. The halt given the name Glanyrafon was at the point on the line marked by the word “Garth-fach” on the agacent OS Map extract. [5] Its namesake was on the North side of the river at that point. The halt had a 75ft platform and small shelter.

The satellite images from Google Earth are less well defined over the next part of the old route. So the high-level images are provided by Bing and are aerial, rather than satellite, images. The old railway followed approximately the 300ft contour with the valley side rising relatively steeply just South of the formation of the railway. The halt given the name Glanyrafon was at the point on the line marked by the word “Garth-fach” on the agacent OS Map extract. [5] Its namesake was on the North side of the river at that point. The halt had a 75ft platform and small shelter.

From Glanyrafon Halt, the route continued round the outside of the loop in the River Tanat which circles around Llanyblodwel and crossed the road which ran South through that village and across the River Tanat on the level.

From Glanyrafon Halt, the route continued round the outside of the loop in the River Tanat which circles around Llanyblodwel and crossed the road which ran South through that village and across the River Tanat on the level.

En-route, the old railway passed through Llanyblodwell Halt – a 170ft platform with a shelter sat on the down side of the running line. A gents was provided at the West end of the platform.

Llanyblodwell Halt was just to the south of the 278ft height point on the OS Map extract above. [5]

Llanyblodwell Halt was just to the south of the 278ft height point on the OS Map extract above. [5] Looking West into the site of Llanyblodwell Halt from the road crossing at its Eastern boundary (Google Streetview) Incidentally the spelling of the name of the Halt is correct even though the village it served was named Llanyblodwel.

Looking West into the site of Llanyblodwell Halt from the road crossing at its Eastern boundary (Google Streetview) Incidentally the spelling of the name of the Halt is correct even though the village it served was named Llanyblodwel. Looking East along the old railway line from the road-crossing at Llanyblodwell Halt (Google Streetview).

Looking East along the old railway line from the road-crossing at Llanyblodwell Halt (Google Streetview).

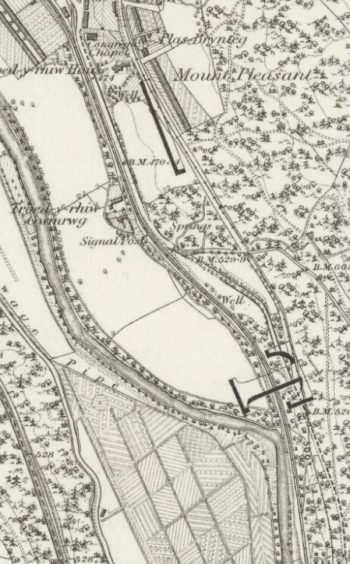

The old line crossed the River Tanat again before entering Blodwell Junction Station.The Tanat Valley Light Railway (TVLR) met the Llanymynech Loop line just the the Southwest of the Station at what was known as Blodwell West Junction. [8: p105] The OS Map extract above [5] shows the stub-end of that Loop line which remained in existence until the closure of the TVLR. The Junction Station sat between Blodwell West Junction and the road over-bridge which carried the A495 over the line and which is evident on the same map-extract. [5] The goods facilities were sited to the East of the road over-bridge. [17] Blodwell Junction Station is marked on this aerial view together with the alignment of the old TVLR and the Llanymynech Loop (Bing Aerial Maps).

Blodwell Junction Station is marked on this aerial view together with the alignment of the old TVLR and the Llanymynech Loop (Bing Aerial Maps).

I am indebted to the Disused Stations website for some of the notes below. [17]

Blodwell Junction was opened in 1870 and at the time called Llanyblodwel. It was opened by the Potteries, Shrewsbury & North Wales Railway (PS&NWR) and was at that time situated on the PS&NWR Nantmawr Branch, a 3¾-mile line that had opened in 1866. The Nantmawr branch provided a link between the Cambrian Railways (CR) line at Llanymynech and quarries at Nantmawr. The PS&NWR was not a financial success and it went into receivership in December 1866. Trains ceased to run just before Christmas that year. [17]

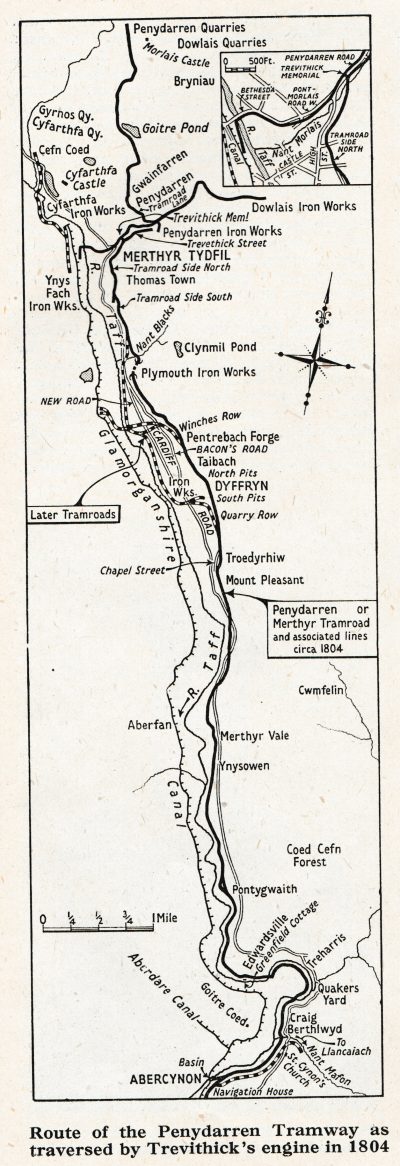

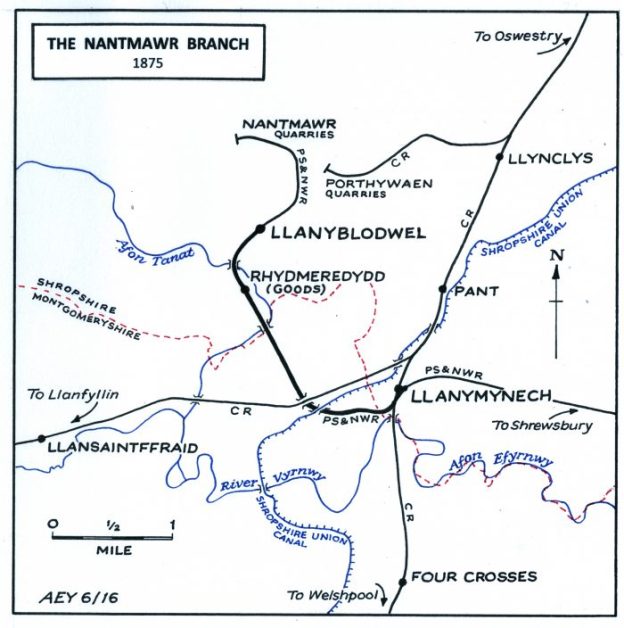

This was only a temporary situation. The receiver began running services again in December 1868 and in 1870 introduced a passenger service onto the Nantmawr Branch for the first time. The terminus for passenger services was at Llanyblodwel. [17] A hand-drawn map of the Nantmawr Branch as it was in 1875, produced by Alan Young in 2016 and used with his permission, (c) A.E. Young. [22]

A hand-drawn map of the Nantmawr Branch as it was in 1875, produced by Alan Young in 2016 and used with his permission, (c) A.E. Young. [22]

The platform which was constructed to facilitate passenger services ready for the 1870 opening remained in place on the North side of the run-round loop until final closure occurred. It was “constructed from brick, backfilled with earth and topped with cinders. A single-storey timber building located at the eastern end of the platform provided booking and waiting facilities.” [17] A small ‘gents’ was provided to the west of the passenger building.

The receiver could not make the PS&NWR line pay and eventually withdrew train services in 1880. Llanyblodwel station was closed and fell into a state of dereliction. [17] A view of the station looking north-east in 1903 during the period when it was closed. The station had closed as Llanyblodwel on 22 June 1880 but within a few months of this view being taken it would reopen as Blodwell Junction, (c) E E Fox-Davies – used with permission from the ‘Disused Stations’ website. [17]

A view of the station looking north-east in 1903 during the period when it was closed. The station had closed as Llanyblodwel on 22 June 1880 but within a few months of this view being taken it would reopen as Blodwell Junction, (c) E E Fox-Davies – used with permission from the ‘Disused Stations’ website. [17]

Construction of the TVLR started in 1901. “The TVLR route made use of two existing lines. At Llanyblodwel it used 19 chains of the Nantmawr branch through the site of the station. Further east it used 78 chains of the Cambrian Railways (CR) Porthywaen Branch which connected to the CR main line at Llanclys.” [17] An intermediate section of line of 1 mile 21 chains in length was built from Llanyblodwel station to the Porthywaen Branch. Blodwell Junction station and the Nantmawr branch shown on a Railway Clearing House map from 1915. The Nantmawr branch is shown coloured green. Coloured in orange is the Tanat Valley Light Railway the opening of which in 1904 created the Junctions at Blodwell. [17]

Blodwell Junction station and the Nantmawr branch shown on a Railway Clearing House map from 1915. The Nantmawr branch is shown coloured green. Coloured in orange is the Tanat Valley Light Railway the opening of which in 1904 created the Junctions at Blodwell. [17]

The station was renamed Blodwell Junction and a new signal box was constructed at the Southwest end of the station platform to control train movements. Blodwell Junction Station. This picture of the passenger facilities and Signal Box were taken from the A495 road overbridge. The view looks West-Southwest towards Llangynog . In the distance on the left is the route of Llanymynech Loop line. The TVLR eads off the the right. The line from Oswestry (also east from Gobowen) to here was mothballed by Network Rail in 1988 and in 2008 was acquired by the Cambrian Railways Society, (c) Ben Brookbank. [18]

Blodwell Junction Station. This picture of the passenger facilities and Signal Box were taken from the A495 road overbridge. The view looks West-Southwest towards Llangynog . In the distance on the left is the route of Llanymynech Loop line. The TVLR eads off the the right. The line from Oswestry (also east from Gobowen) to here was mothballed by Network Rail in 1988 and in 2008 was acquired by the Cambrian Railways Society, (c) Ben Brookbank. [18] Blodwell Junction station looking north-east on 4 November 1979, (c) Alan Young, used with permission obtained through the ‘Disused Stations’ website. This view is taken from a very similar position to the monochrome image from 1903 above. [17]

Blodwell Junction station looking north-east on 4 November 1979, (c) Alan Young, used with permission obtained through the ‘Disused Stations’ website. This view is taken from a very similar position to the monochrome image from 1903 above. [17] The end of the line! This picture looks Southwest through the road-overbridge carrying the A495 in the late 20th century. Beyond the bridge is the site of what was Blodwell Junction Station platform. The station’s goods facilities were on this side of the bridge. [19]

The end of the line! This picture looks Southwest through the road-overbridge carrying the A495 in the late 20th century. Beyond the bridge is the site of what was Blodwell Junction Station platform. The station’s goods facilities were on this side of the bridge. [19]

I was able to take a few pictures in August 2019 at this location. The first shows the access road to the goods yard from the North with the A495 on the right of the photo. The bridge carrying the road over the old line features next. The buffers remain as do the two supporting piers to the bridge. The third view below is taken from the road bridge looking down on the tracks to the Northeast of the bridge. The fourth image is an attempt to look forward along the old track-bed in a Northeasterly direction.

An aerial view of the route of the TVLR to the East of Blodwell Junction. The black and white dotted line shows the track purchased by the Cambrian Railway Society which remains in place in the early 21st Century. The Natmawr Branch leads to the location of the Nantmawr Quarry and the length of line in the possession of the Tanat Valley Light Railway Preservation Society, (Bing Aerial Maps).

An aerial view of the route of the TVLR to the East of Blodwell Junction. The black and white dotted line shows the track purchased by the Cambrian Railway Society which remains in place in the early 21st Century. The Natmawr Branch leads to the location of the Nantmawr Quarry and the length of line in the possession of the Tanat Valley Light Railway Preservation Society, (Bing Aerial Maps).

The remaining length of both the Nantmawr Branch and the TVLR are shown on the OS Map extract below. [5] The TVLR ran through to Porthywaen where it met the Cambrian Railways Branch which served the quarries at Porthywaen.

The surviving length of then TVLR is shown in theses two aerial images marked by a black and white dotted line. The quarries are still in use and the old overbridge which took a country lane over the CR Branch is still in place and continues to include the old tramway overbridge for the Crickheath Tramway. The bridge is dated 1861. [8: p100] It appears in the top right of the OS Map extract below.

The surviving length of then TVLR is shown in theses two aerial images marked by a black and white dotted line. The quarries are still in use and the old overbridge which took a country lane over the CR Branch is still in place and continues to include the old tramway overbridge for the Crickheath Tramway. The bridge is dated 1861. [8: p100] It appears in the top right of the OS Map extract below.

The old CR Branch to the quarries ran to the North side of Coopers Lane in the first of the aerial images. The two lines met immediately after the Halt location shown below. Porthywaen Halt was just to the Northeast of a road-crossing on the A495 between Llanyblodwell and Llynclys. This picture shows the halt in use in 1979 and is taken from the Northeast end of the site close to the junction with the CR, (c) Alan Young, used with permission. [21]

Porthywaen Halt was just to the Northeast of a road-crossing on the A495 between Llanyblodwell and Llynclys. This picture shows the halt in use in 1979 and is taken from the Northeast end of the site close to the junction with the CR, (c) Alan Young, used with permission. [21] A larger scale extract from the OS Map shows the location of Porthywaen Halt and the junction with the Cambrian Railway Branch close to the road entrance to the quarries to the North of the line. [5]

A larger scale extract from the OS Map shows the location of Porthywaen Halt and the junction with the Cambrian Railway Branch close to the road entrance to the quarries to the North of the line. [5] The TVLR crosses a side road (Porthywaen School Road) close to the A495. This view is taken looking Southwest (August 2019).

The TVLR crosses a side road (Porthywaen School Road) close to the A495. This view is taken looking Southwest (August 2019). Turning through 180 degrees at the same point as above (August 2019).

Turning through 180 degrees at the same point as above (August 2019).

Google Streetview has older images at this location which were taken in 2010. The line had clearly, at that time, been cleared of vegetation which has since taken hold. The enxt two images show the condition of the line in 2010. A view looking Southwest in March 2010 (Google Streetview).

A view looking Southwest in March 2010 (Google Streetview). The same date looking to the Northeast Google Streetview).

The same date looking to the Northeast Google Streetview). Looking Southwest towards Llanyblodwel in 2010 from the level-crossing at the A495 (Google Streetview).

Looking Southwest towards Llanyblodwel in 2010 from the level-crossing at the A495 (Google Streetview). Turning through 180 degrees, this is the view Northeast along the line. The old halt was on the right of the tracks ahead, close to the bungalow which is visible in the picture (Google Streetview).

Turning through 180 degrees, this is the view Northeast along the line. The old halt was on the right of the tracks ahead, close to the bungalow which is visible in the picture (Google Streetview). A view from the end of the bridge parapet down onto the line (August 2019).

A view from the end of the bridge parapet down onto the line (August 2019). This is the closest that I could get to the bridge over the line to the Northeast of the old Porthywaen Halt. The cast/wrought iron span is dated 1861. The tramway span can just be made out through the undergrowth. The picture is taken from the colliery access road (August 2019).

This is the closest that I could get to the bridge over the line to the Northeast of the old Porthywaen Halt. The cast/wrought iron span is dated 1861. The tramway span can just be made out through the undergrowth. The picture is taken from the colliery access road (August 2019).  The view from the same bridge looking Southwest down onto the railway line in August 2019. The old halt was to the left of the track about 100 yards ahead.

The view from the same bridge looking Southwest down onto the railway line in August 2019. The old halt was to the left of the track about 100 yards ahead.

This bridge is the limit of our journey along the Tanat Valley Light Railway as we are now over what were Cambrian rails. We need to retrace our steps to Blodwell Juntion to look at the Nantmawr Branch.

The Nantmawr Branch

We have already established that the Nantmawr Branch was in place prior to the construction of the TVLR. Tracks were first laid long before the TVLR was considered. The directors of the Potteries, Shrewsbury & North Wales Railway (PS&NWR) hoped that the link to the quarry at Nantmawr would provide a much needed boost to income for their line to Shrewsbury. The gains in traffic were not sufficient to save the PS&NWR and ultimately the receivers were also unable to make the branch nor the longer line pay, and closure occurred in 1880.

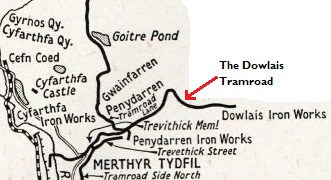

The Branch ran from Llanymynech Junction to the Natmawr Quarry and I have repeated Andy Young’s hand-drawn map which shows the route to best effect. The darker line on the map is the length of the passenger service on the branch when it was operating. This map shows the crossing points for river, rail and canal but, so as not not over-complicate the map, does not show crossing points for the roads in the area. Nantmawr Branch as it was in 1875, (c) A.E. Young. [22]

Nantmawr Branch as it was in 1875, (c) A.E. Young. [22]

Wilfred Wren says of the line: “Possibly no such short length of line has had a more fascinating or more chequered history.” [8: p33]

1866 saw the line open from Llanymynech to Nantmawr. Wren continues, “the line crossed the Oswestry-Newton tracks on the level, bore west … under the road and the canal by an expensive double bridge, ran under the Llanfyllin brach at Wren, and crossed the River Tanat twice on timber viaducts to avoid a spur of Llanymynech Hill at Carreghofa.” [8: p34]

The line then turned relatively sharply from a northwesterly direction to the northeast and entered what was then called Llanyblodwell Station. The railway then “turned north up the little steep-sided valley to the Nantmawr quarries; on this section one road crossed it on an over ridge and another by a level-crossing.” [8: p34]

There was at one time an intention by the PS&NWR to push a double-track mainline from Shrewsbury up the Tanat Valley. It is interesting in that context to note that when Wren was writing in the 1960s the Nantmawr branch was crossed by a road bridge between the two Tanat viaducts which allowed for a double-track main line along the Nantmawr branch but Turing away to the West before Llanyblodwell Station.

We noted earlier that the branch was closed in 1880. This is true, but Wren records a number of goods movements over the deteriorating tracks which provided a steady but small revenue. [8: p36]

During the building of the Tanat Valley line, the Cambrian upgraded the two mm internal branches, Nantmawr and Porthywaen, to make them suitable for passenger services. “The original timber viaducts which carried the Nantmawr branch over the Tanat river were rebuilt with concrete piers and abutments, plank flooring and steel railings; the track had previously been laid on longitudinal timbers using tie-bars, the gap between the rails being open to the river below. Both branches were reballasted and not in fact laid with new track, since an observer in 1904 noticed that the rails and chairs bore dates ‘in the sixties’.” [8: p47]

Use of the line between Wern and what was letter called Blodwell Junction was always sporadic. The hoped for link direct from the line to the Tanat Valley line in a westerly direction was never completed. The line “lingered on as part of the Nantmawr mineral branch after the Cambrian had been absorbed into the Great Western at the grouping. In 1925, all traffic on it ceased, the rails were lifted by 1938 and the cuttings filled in, and the track-bed became the tangled wilderness it is today.” [8: p49] Looking South from the A495 towards Blodwell Junction in 2010 (Google Streetview).

Looking South from the A495 towards Blodwell Junction in 2010 (Google Streetview). Looking North along the branch to Nantmawr from the A495 in 2010 (Google Streetview).

Looking North along the branch to Nantmawr from the A495 in 2010 (Google Streetview).

In the 21st century, the Nantmawr branch climbs from Llanddu to Nantmawr. It passes under the A495 road bridge and then across Whitegates crossing before curving gently to the left, crossing a small stream and entering the quarry site. A run round loop is provided at each end of the line. The line is operated by a preservation society called the “Tanat Valley Light Railway.” [24] Whitegates Crossing while still is use as a branch-line, looking South towards the A495. [27]

Whitegates Crossing while still is use as a branch-line, looking South towards the A495. [27] Whitegates Crossing in 2010 (Google Streetview).

Whitegates Crossing in 2010 (Google Streetview). The view down the line from the Quarry in 2019, (c) Chris Allen used under a Creative Commons Licence. [28]

The view down the line from the Quarry in 2019, (c) Chris Allen used under a Creative Commons Licence. [28] Whitegates Crossing in 2019, (c) Chris Allen used under a Creative Commons Licence. The crossing was restored but has since deteriorated. [29]

Whitegates Crossing in 2019, (c) Chris Allen used under a Creative Commons Licence. The crossing was restored but has since deteriorated. [29]

The pictures above must have been taken at around the time my wife and I visited the line. Sadly we arrived on a day when the preservation site was not open. These are the pictures that I took of the crossing. …….

This final picture shows the entrance to the preservation site in August 2019.

This final picture shows the entrance to the preservation site in August 2019.

There is an excellent short illustrated history of the Nantmawr Quarry and Lime Kilns on the Oswestry Borderland Heritage website: http://www.oswestry-borderland-heritage.co.uk/?page=133 [26] and http://www.oswestry-borderland-heritage.co.uk/?page=137 [27]

TripAdvisor has a number of photographs of the site. Here are three to whet your appetite. …. [25]

This last image shows the dominant limekiln structure on the site. [25]

This last image shows the dominant limekiln structure on the site. [25]

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tanat_Valley_Light_Railway, accessed on 7th September 2019.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Llangynog_railway_station, accessed on 17th September 2019.

- http://history.powys.org.uk/school1/llanfyllin/gyn1902.shtml, accessed on 19th September 2019.

- https://www.peoplescollection.wales/items/873156, accessed on 28th December 2019. This item is made available under Creative Archive Licence espoused by the People’s Collection Wales, https://www.peoplescollection.wales/creative-archive-licence, details accessed on 11th January 2020.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16&lat=52.8251&lon=-3.4038&layers=10&b=1, accessed on 11th January 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Llangynog_railway_station, accessed on 14th January 2020.

- https://www.francisfrith.com/penybontfawr/penybontfawr-the-village-c1955_p274015, accessed on 14th January 2020.

- Wilfred J. Wren; The Tanat Valley: It’s Railways and Industrial Archeology; David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1968.

- http://www.oswestry-borderland-heritage.co.uk/?page=185, accessed on 14th January 2020.

- https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/Penybontfawr-Railway-Station-Photo-Llangynog-Pedair-Ffordd-Tanat-Valley-1-/252241054294, accessed on 15th January 2020.

- http://www.penybontfawrvillage.org.uk/index.html, accessed on 2nd March 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Llanrhaiadr_Mochnant_railway_station, accessed on 9th March 2020.

- http://www.oswestrygenealogy.org.uk/photos/osw-np-o-5-16-73-llanrhaeadr-junction-1958, accessed on 9th March 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pentrefelin_railway_station, accessed on 9th March 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Llangedwyn_Halt_railway_station, accessed on 11th March 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Llansilin_Road_railway_station, accessed on 11th March 2020.

- http://disused-stations.org.uk/b/blodwell_junction/index.shtml, accessed on 19th September 2019.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1836071, licensed for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence, accessed on 12th March 2020.

- https://mapio.net/pic/p-36639165, accessed on 12th March 2020.

- https://oldrailwaystuff.com/oswestry-and-llangynog-railway-acts, accessed on 19th September 2019.

- A.E. Young, used with permission, sent by email on 12th March 2020.

- A.E. Young, June 2016, used with permission, sent by email on 12th March 2020.

- http://www.cambrianrailwayssociety.co.uk/thebranchproject/routedescription.html, accessed on 13th March 2020.

- http://www.tanatvalleyrailway.co.uk, accessed on 17th March 2020.

- https://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/Attraction_Review-g504106-d8617050-Reviews-Tanat_Valley_Light_Railway-Oswestry_Shropshire_England.html, accessed on 17th March 2020.

- http://www.oswestry-borderland-heritage.co.uk/?page=133, accessed on 17th March 2020.

- http://www.oswestry-borderland-heritage.co.uk/?page=137, accessed on 17th March 2020.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/6235917, accessed on 17th March 2020.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/6227779, accessed on 17th March 2020.