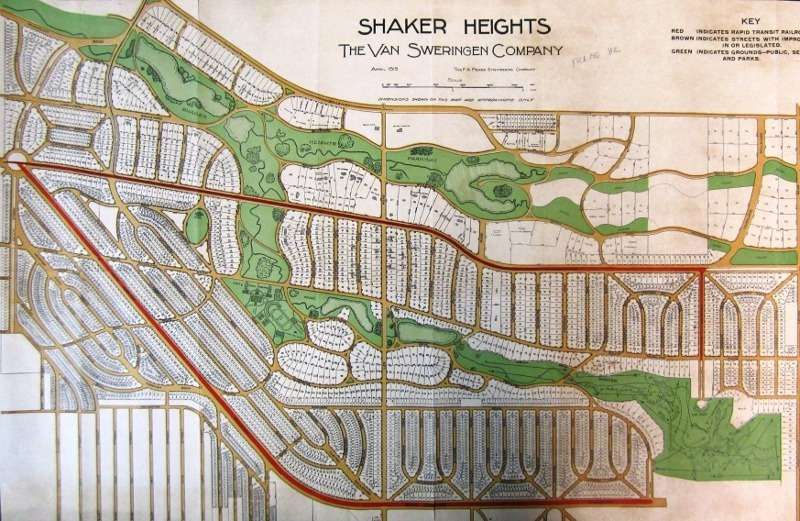

Modern Tramway talks, in 1949, of the Shaker Heights Rapid Transit (SHRT) Lines as “A high speed electric light railway entirely on reserved track, connecting a beautiful high class residential district with the centre of a large city. affording such speedy and efficient service that the car-owning suburban residents prefer to use it and park their cars on land provided by the line; a system which makes a handsome profit and has recently taken delivery of 25 of the most modern type of electric rail units in the world [which] are only some of the outstanding facts about Shaker Heights Rapid Transit.” [1: p101]

The network was created by the Van Sweringen brothers and purchased after their bankruptcy, and a period of 9 years in receivership, by Cleveland City Council in 1944. [2]

The official ownership details down the years are:

“1913–1920: Cleveland & Youngstown Railroad

1920–1930: Cleveland Interurban Railroad

1930–1935: Metropolitan Utilities

1935–1944: Union Properties (47%), Guardian Savings and Trust (33%) and Cleveland Trust (20%)

1944–1975: City of Shaker Heights

1975–present: Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority.” [4]

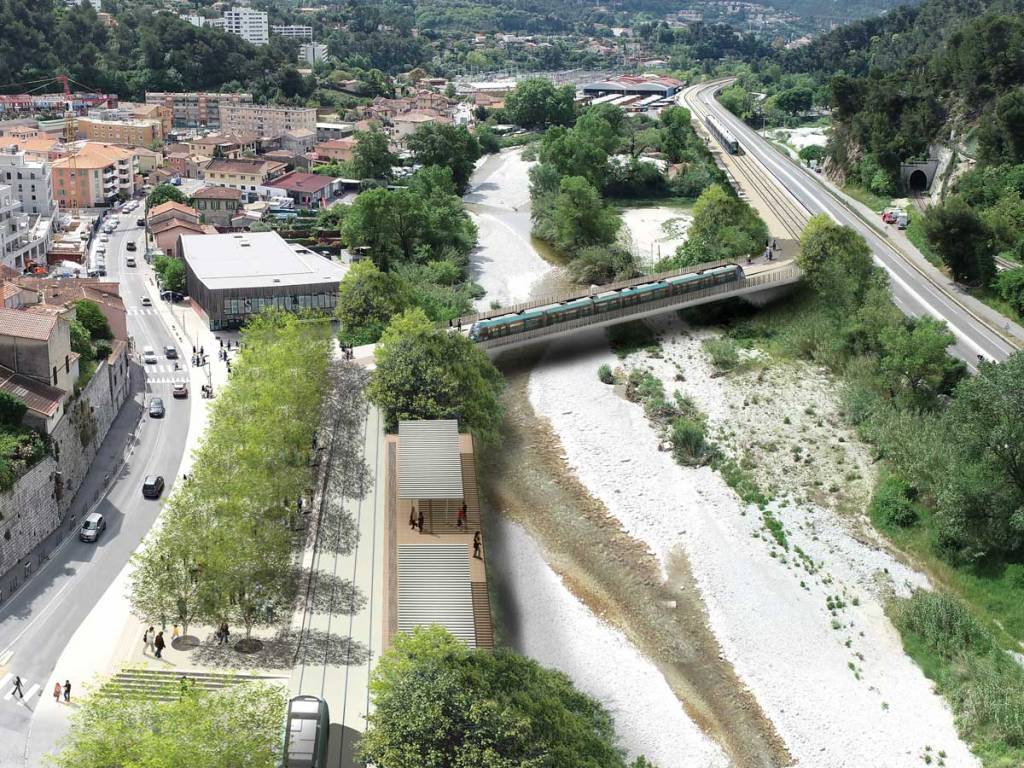

The SHRT connected the city of Cleveland, Ohio, with the largest residential area known as Shaker Heights, six miles East.

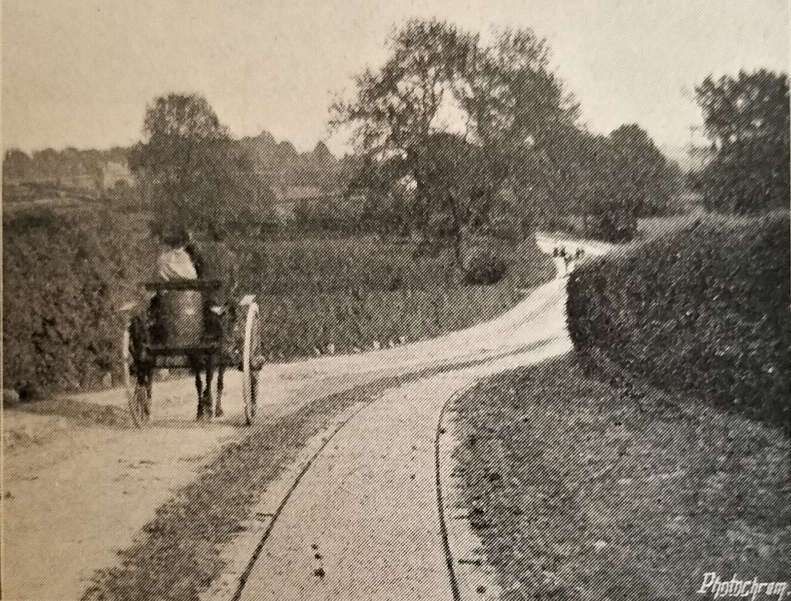

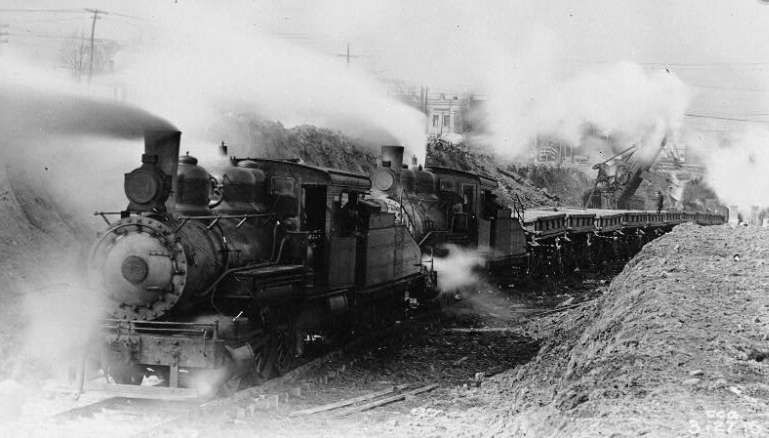

The Van Sweringen brothers planned the line “in the early 1900’s as part of a land development scheme, … to serve the district that would grow up on the Heights and beyond, and the charter was obtained in 1907. The land development was planned around the line, and the engineers allowed for a railway area 90 feet wide through the property with 50 feet of open space each side of the tracks (room for four tracks and a grass verge on each side). Building was delayed by the First World War and the line was not opened until 11th April, 1920.” [1: p101]

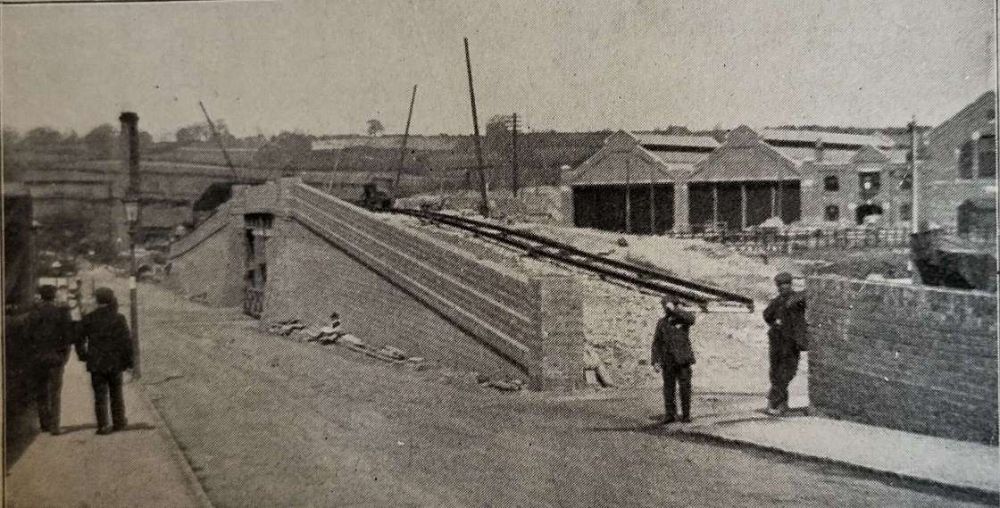

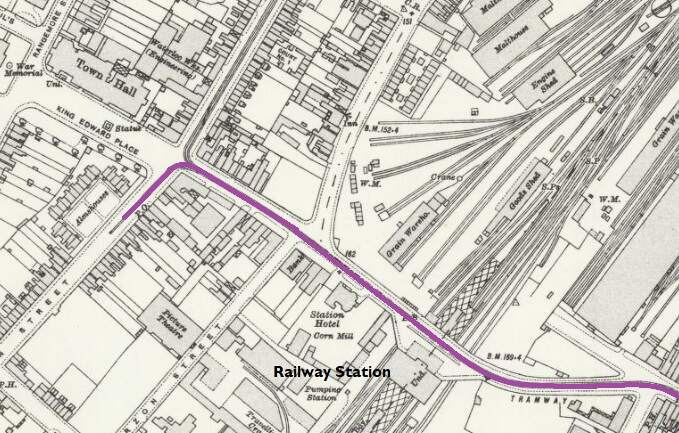

Tower City Station to Shaker Square

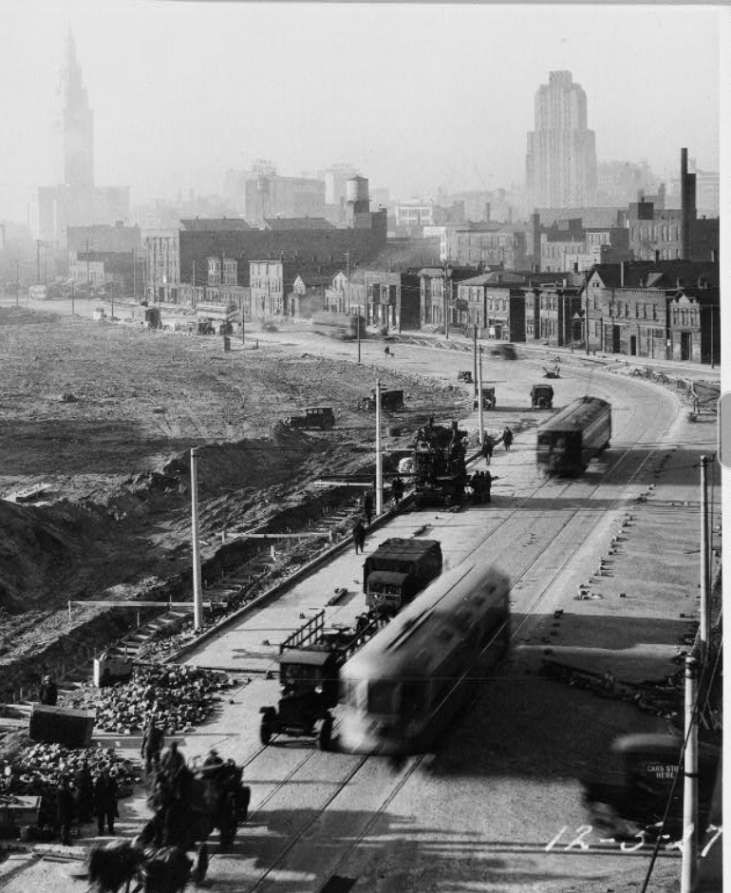

On 20th July 1930, Shaker Rapid Transit cars began using the Cleveland Union Terminal (CUT), after the Terminal Tower opened. [12]

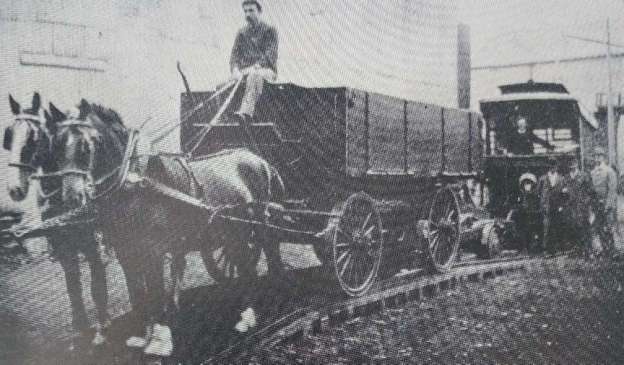

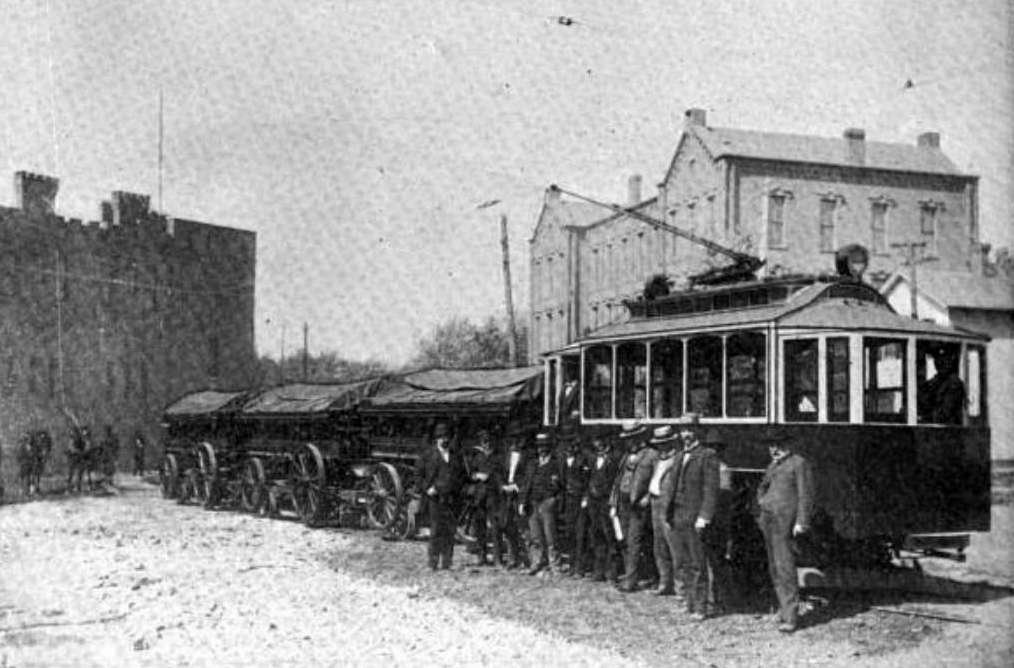

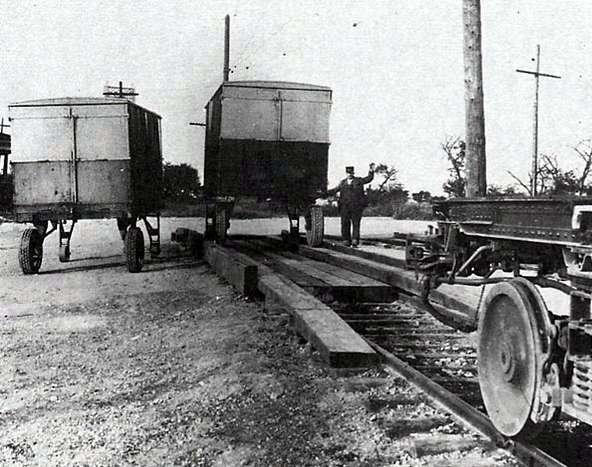

Before this, on 17th December 1913, trams began operating on the first 1.6-mile segment in the median of what would become Shaker Boulevard, from Coventry Road east to Fontenay Road. [12] The line was grandly named ‘The Cleveland & Youngstown Railway’.

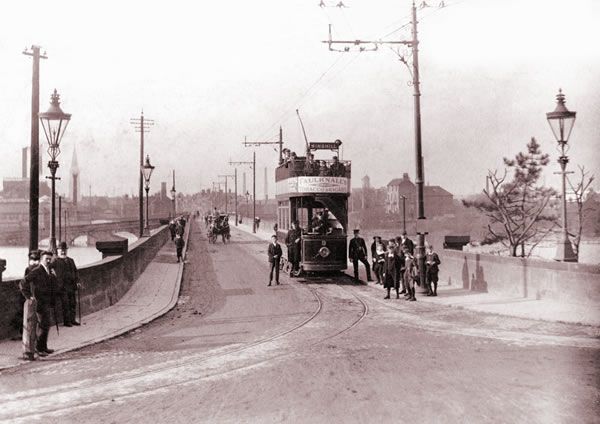

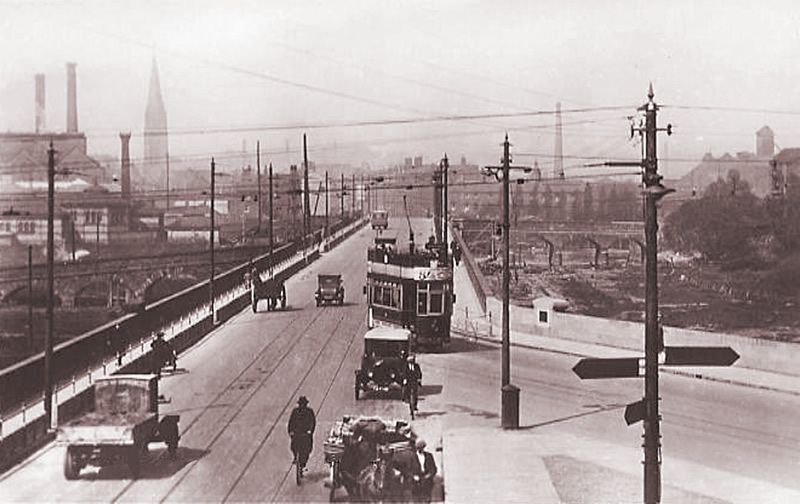

In 1915, the tram service was extended to Courtland Boulevard. In 1920 it became apparent that the plan to link Cleveland to Youngstown would not succeed and the line was renamed as ‘The Cleveland Interurban Railway’ (CIRR). In April of that year, the Van Sweringen brothers opened a segregated (trams separate from other rail and road traffic) line from East 34th Street to Shaker Heights with their trams using the urban tram (streetcar) network to reach the city centre. [12]

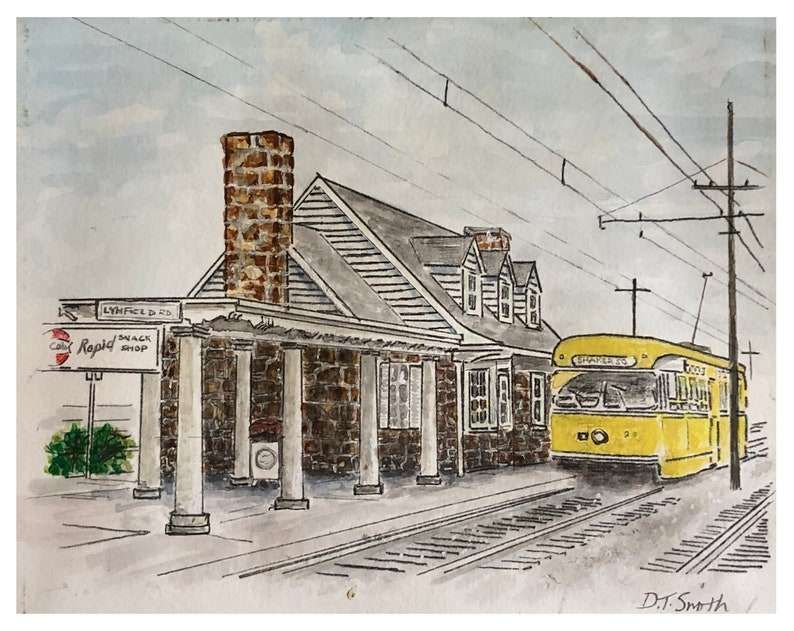

“In 1923, the Standard Oil Company built the Coventry Road Station for $17,500. … In 1924, the Shaker trains were referred to as ‘the private right-of-way rapid transit line’, but calling it ‘the rapid’ probably dates back further than that.” [12]

The historic station at Tower City (1927 onwards) was the early terminus of the Shaker Heights Rapid Transit Lines which were extended along the Cleveland Waterfront.

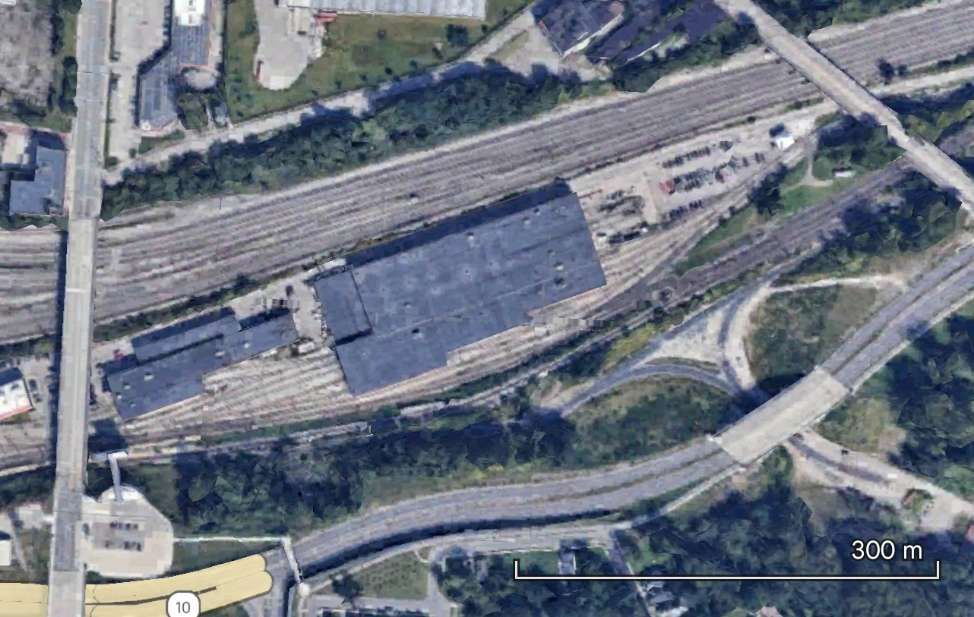

The modern Tower City Station is the central station of the Cleveland, Ohio RTA Rapid Transit system, served by all lines: Blue, Green, Red and Waterfront. The station is located directly beneath Prospect Avenue in the middle of the Avenue shopping mall. The station is only accessible through the Tower City Center shopping complex. [13]

A few photographs between Shaker Square and Green Road. ….

A few photographs taken along the Moreland Line. …..

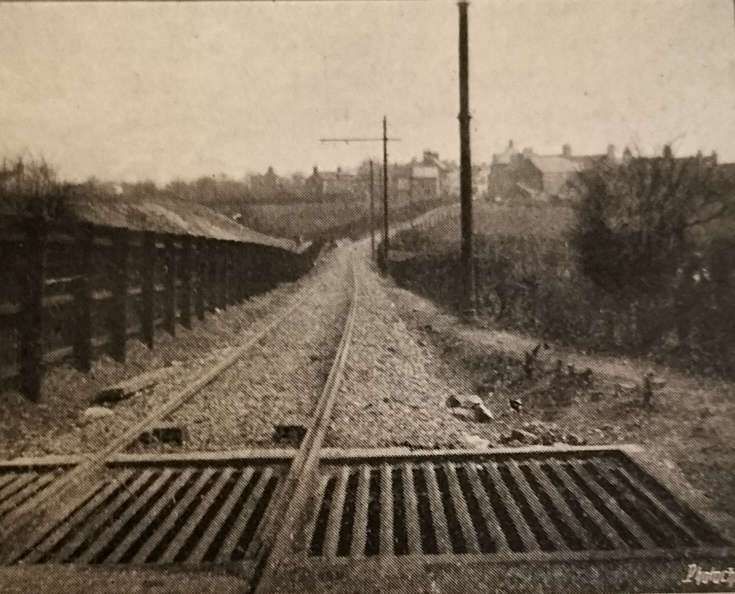

The first cars were ordinary tramcars from the Cleveland City system, specially refitted for fast service. “In July, 1930, the SHRT (which had formerly entered the city over street tracks) was brought into the main line railway terminus over existing railway tracks. By this time the line extended for 9.5 miles from the Union Terminal Building in Cleveland to Green Road, at the far end of Shaker Heights; in addition, there was a branch line to Moreland.” [1: p101]

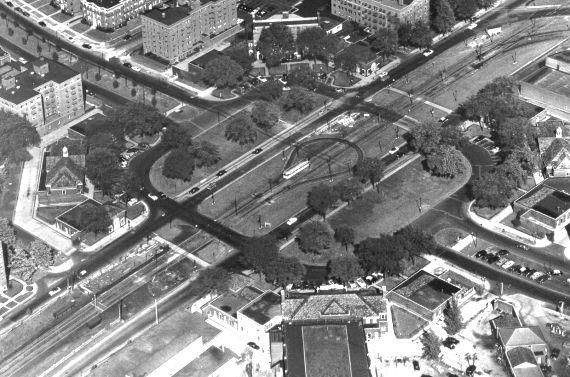

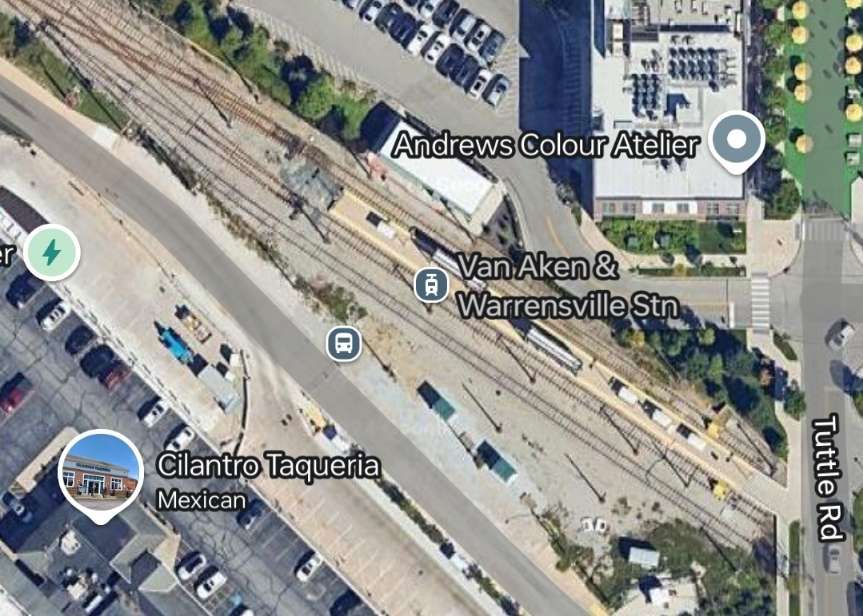

The two lines in the suburbs were extended. The Moreland line in 1929, eastward from Lynnfield (its original terminus) to Warrensville Center Rd. The Shaker line, in 1937, was extended from Warrensville Center Rd. to a new loop at Green Rd. [2]

“Under the main floor of the Union Terminal Building, the SHRT tracks are adjacent to the main line railway platforms. The six miles out to Shaker Square are on an ascending grade along the valley of the Cuyahoga river, and are entirely on private right-of-way; from Shaker Square onwards, the line runs through a grass reservation in the centre of Shaker Boulevard as far as Green Road Terminal.” [1: p101]

“The branch to Moreland, a suburb of smaller type property, diverges about 500 feet east of Shaker Square station, running in a south-easterly direction; at this terminus are storage yards with car parking facilities inside a U track formation.” [1: p101]

“The overhead is compound catenary out to East 55th Street, Cleveland, and normal trolley-wire elsewhere; the line is signalled throughout and road crossings are well spaced.” [1: p101]

The journey from Green Road outer terminus to the Union Terminal Building in downtown Cleveland “is covered in 22 minutes including 16 stops en route. The six miles from Shaker Square down into Cleveland (which include four curves with speed restriction) are covered in 8-9 minutes by non-stop cars. The up-grade increases the express timing on the outward journey to Shaker Square to 12 minutes.” [1:p101]

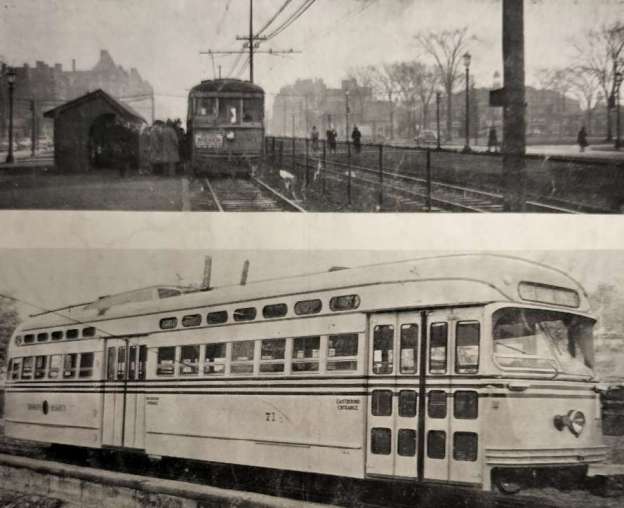

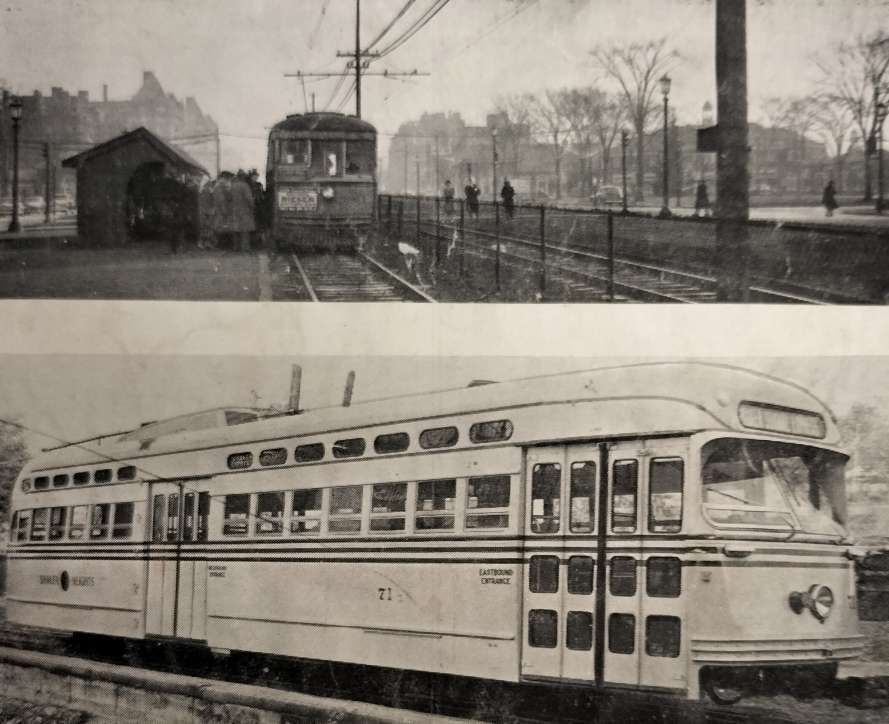

“When the City Council bought the line in 1944, the Director of Transportation, Mr. Paul K. Jones, began to modernise the existing fleet and to look around for new cars. He chose PCC cars with multiple unit equipment, and after trial runs in 1946 with a PCC-MU car ordered for Boston’s tramways, he ordered 25, to be modified to suit the SHRT’s demands and these were delivered towards the end of [1948]. They have Sprague Multiple Unit Control and are equipped for MU operation in trains of up to six cars. Other details are: Seating capacity. 62; overall length, 52ft. 7in.; overall height, 10ft. 4in.; width, 9ft.; truck wheel base, 6ft. 10in.; livery, canary yellow.” [1: p101]

A new $60,000 sub-station was built by 1949 in Shaker Heights which ensured adequate power for the PCC cars. Other improvements undertaken were “the doubling of car parking space at stations and an increase in service frequency.” [1: p101]

Extensions of the SHRT were, in 1949, considered likely; at that time, the line had been graded beyond Green Road as far as Gates Mills and steel poles had been erected part of the way. (This extension never occurred even though the preparatory work had been undertaken.) [7]

The Moreland Branch had been graded south to the Thistledown Race Track beyond Warrensville and there was little doubt, at that time that this extension would be completed. It turns out that this extension also never came to fruition.

“In Cleveland itself, the City Council … asked for 31 million dollars for the purpose of financing extensions of its city lines east and west of the city. The East Side line was laid out and partly graded by the original builders of the SHRT; it left the Heights line at East 60th Street and needed, at the time of writing of the article in Modern Tramway, only a few months’ work to complete.” [1: p101]

“Snow [had] no effect on the operation of the SHRT and the line [carried] on when local bus and trolley bus lines [had] ceased … in the severe winter of 1947-8; and all the year round, as mentioned before, the owners of the $75,000 homes of Shaker Heights [left] their cars behind and [travelled] into town by the faster and more reliable means so amply provided.” [1: p102]

“In 1955 the Cleveland Transit System (which was formed in 1942 when the City of Cleveland took over the Cleveland Railway Company) opened the first section of the city’s new rapid transit line, now known as the Red Line. It used much of the right-of-way and some of the catenary poles from the Van Sweringen’s planned east-west interurban line adjacent to the NYC&StL tracks. The first section of the CTS rapid transit east from Cleveland Union Terminal included 2.6 miles (4.2 km) and two stations shared with the Shaker Heights Rapid Transit line, necessitating split platforms with low-level sections (for Shaker Heights rapid transit cars) and high-level sections (for CTS rapid transit cars).” [4]

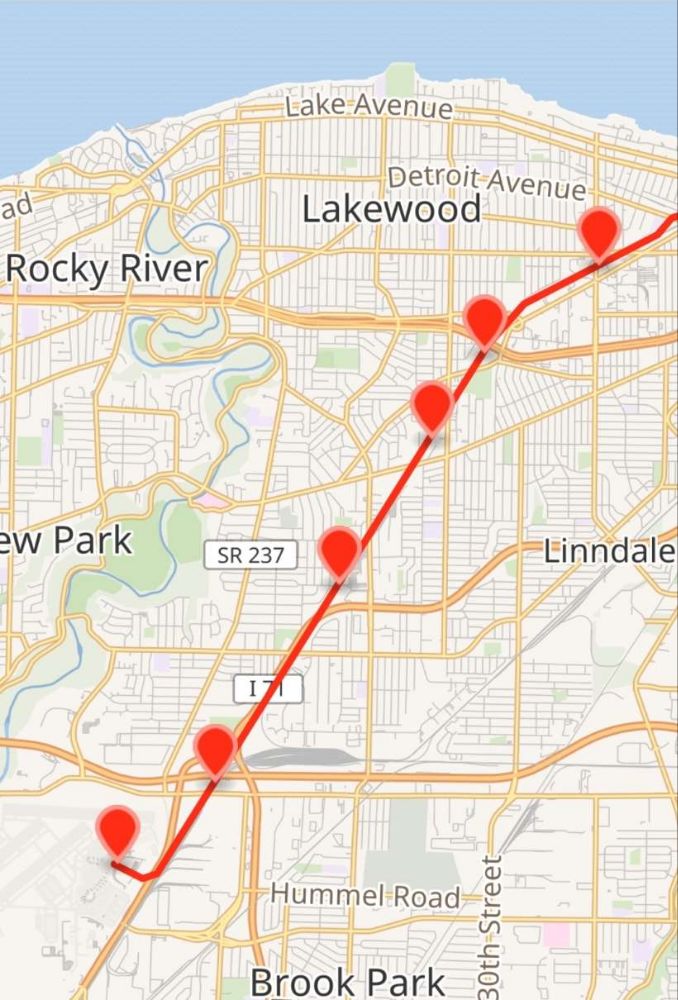

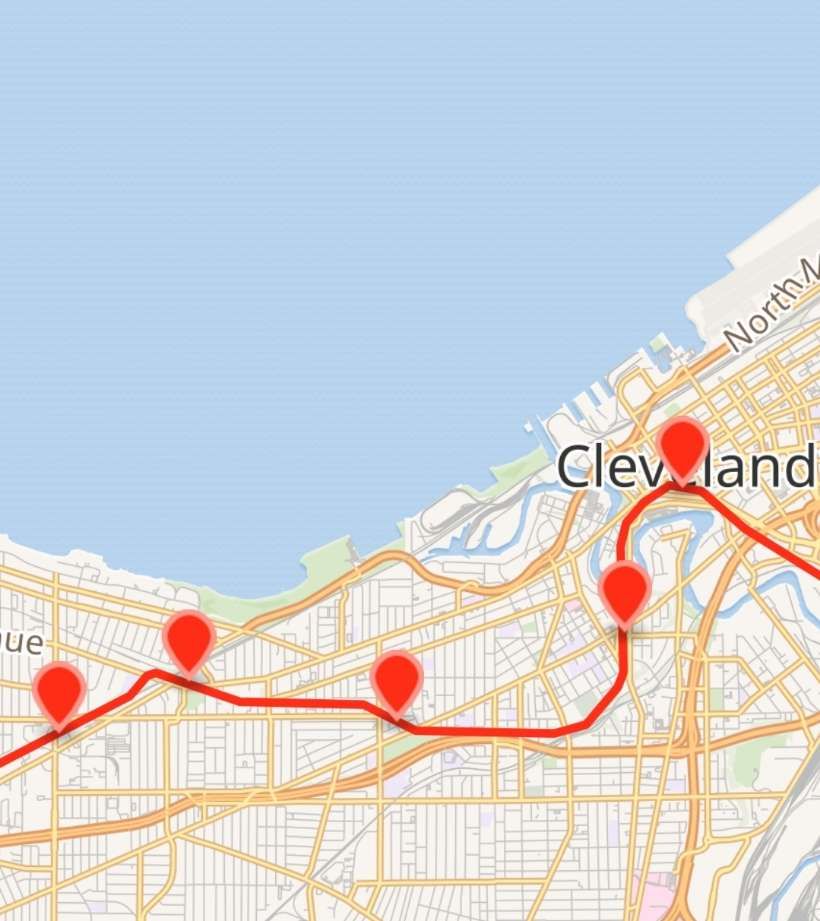

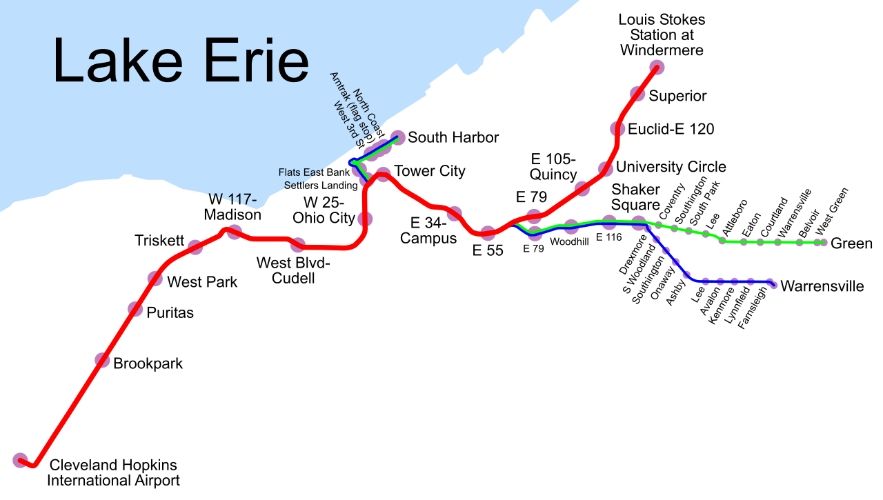

In the 21st century, the Red Line (formerly and internally known as Route 66, also known as the Airport–Windermere Line) is now “a rapid transit line of the RTA Rapid Transit system in Cleveland, Ohio, running from Cleveland Hopkins International Airport northeast to Tower City in downtown Cleveland, then east and northeast to Windermere. 2.6 miles (4.2 km) of track, including two stations (Tri-C–Campus District and East 55th), are shared with the light rail Blue and Green Lines; the stations have high platforms for the Red Line and low platforms for the Blue and Green Lines. The whole Red Line is built next to former freight railroads. It follows former intercity passenger rail as well, using the pre-1930 right-of-way of the New York Central from Brookpark to West 117th, the Nickel Plate from West 98th to West 65th, and the post-1930 NYC right-of-way from West 25th to Windermere.” [5]

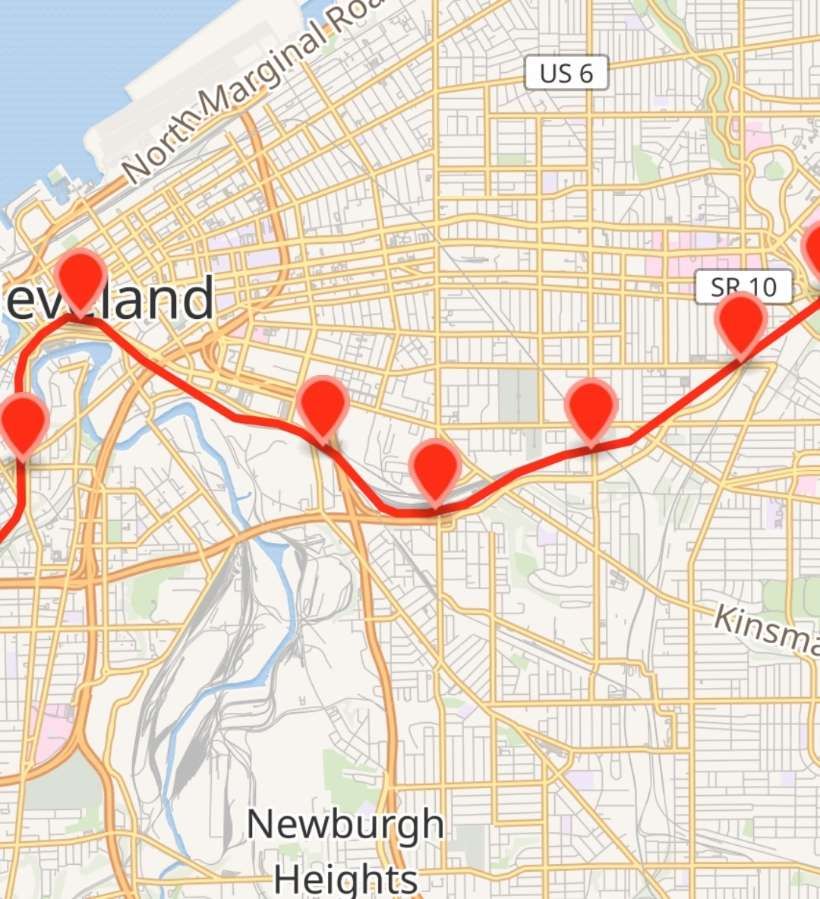

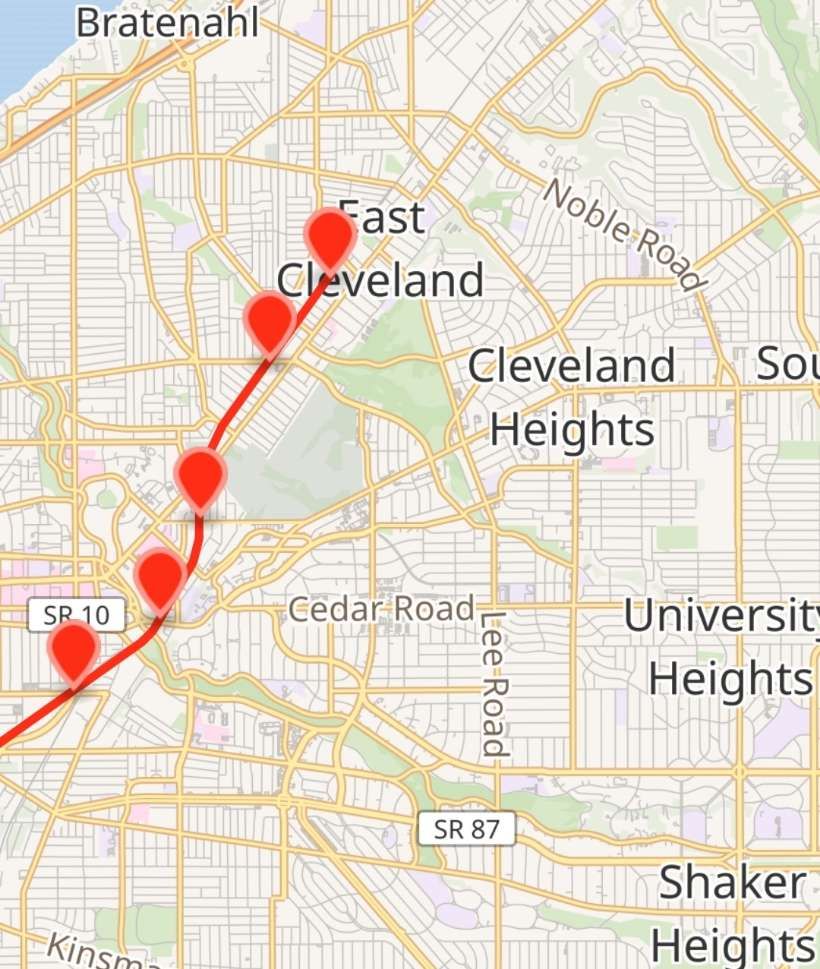

The Red Line is shown on the four extracts from OpenStreetMap below. [5]

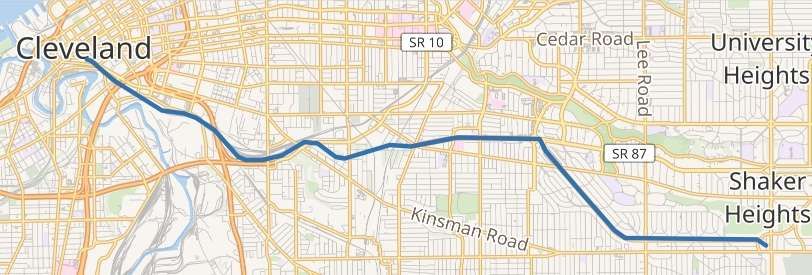

In the 21st century the two original Shaker Heights routes form the Blue Line and the Green Line as part of Cleveland, Ohio’s Rapid Transit System.

“The Blue Line (formerly known as the Moreland Line and the Van Aken Line, and internally as Route 67) is a light rail line of the RTA Rapid Transit system in Cleveland and Shaker Heights, Ohio, running from Tower City Center downtown, then east and southeast to Warrensville Center Blvd near Chagrin Blvd. 2.6 miles (4.2 km) of track, including two stations (Tri-C–Campus District and East 55th), are shared with the rapid transit Red Line, the stations have low platforms for the Blue Line and high platforms for the Red Line. The Blue Line shares the right-of-way with the Green Line in Cleveland, and splits off after passing through Shaker Square.” [3]

“The Green Line (formerly known as the Shaker Line) is a light rail line of the RTA Rapid Transit system in Cleveland and Shaker Heights, Ohio, running from Tower City Center downtown, then east to Green Road near Beachwood. 2.6 miles (4.2 km) of track, including two stations (Tri-C–Campus District and East 55th), are shared with the rapid transit Red Line; the stations have low platforms for the Green Line and high platforms for the Red Line. The Green Line shares the right-of-way with the Blue Line in Cleveland, and splits off after passing through Shaker Square.” [4]

Tram Cars

Tram cars used on the Shaker Heights lines since 1920 include: the 1100-series and 1200-series centre-entrance fleet; the colourful PCC cars; and the current fleet of Breda LRVs which have operated the line since 1982. [15]

Cleveland’s 1100-series and 1200-series center-door cars were built in the mid-1910s. “Not only were these cars distinctive and immediately identifiable as Cleveland cars, but many of them outlasted the Cleveland street railway itself. This was because the suburban streetcar route to Shaker Heights, barely on the drawing board when the center-door cars were built, bought a handful of 1200-series cars to hold down service when it was new. For years these cars were the backbone of service to Shaker Heights until the last of them were finally retired in favor of PCC cars in 1960.” [16]

Cleveland’s PCC Trams began arriving in the late 1940s, as we have already noted. PCC (Presidents’ Conference Committee) trams were streetcars of a design that was first “built in the United States in the 1930s. The design proved successful domestically, and after World War II it was licensed for use elsewhere in the world where PCC based cars were made. The PCC car has proved to be a long-lasting icon of streetcar design, and many remain in service around the world.” [17]

The Shaker Heights Rapid Transit network purchased 25 new PCC cars and 43 second-hand cars. A total of 68: the original 25 Pullman cars were extra-wide and had left-side doors. The second-hand cars were: 20 cars purchased from Twin Cities Rapid Transit in 1953; 10 cars purchased from St. Louis in 1959; 2 former Illinois Terminal cars leased from museums in 1975; 2 cars purchased from NJ Transit in 1977; 9 ex-Cleveland cars purchased from Toronto in 1978. PCCs were used until 1981. [17]

The Cleveland Transit System had 50 PCCs purchased new and 25 second-hand. The second-hand cars purchased from Louisville in 1946. All Cleveland’s cars were sold to Toronto in 1952. Of these, nine cars were (noted above) sent to Shaker Heights in 1978. [17]

Pullman Standard PCCs “were initially built in the United States by the St Louis Car Company (SLCCo) and Pullman Standard. … The last PCC streetcars built for any North American system were a batch of 25 for the San Francisco Municipal Railway, manufactured by St. Louis and delivered in 1951–2. … A total of 4,586 PCC cars were purchased by United States transit companies: 1,057 by Pullman Standard and 3,534 by St. Louis. Most transit companies purchased one type, but Chicago, Baltimore, Cleveland, and Shaker Heights ordered from both. The Baltimore Transit Co. (BTC) considered the Pullman cars of superior construction and easier to work on. The St. Louis cars had a more aesthetically pleasing design with a more rounded front and rear, compound-curved skirt cut-outs, and other design frills.” [17]

“Both the Cities of Cleveland & Shaker Heights purchased PCC trolleys after WWII. Cleveland operated theirs from 1946 to 1953 before they sold them to the City of Toronto. Shaker Heights operated their PCCs for a much longer period – i.e. from 1947 up until the early 1980s.” [18]

Cleveland’s Breda LRVs are a fleet of 34 vehicles operating on the Blue, Green and Waterfront lines. One is shown below on the Blue Line and one on the Green Line. [19]

The LRVs were purchased from the Italian firm, Breda Costruzioni Ferroviarie, to replace the aging PCC cars. They were dedicated on 30th October 1981. [3]

The cars consist of two half bodies joined by an articulation section with three bogies. The two end bogies are powered, and the central bogie under the articulation section is unpowered. “The car is slightly more than 24 m (79 ft 10 in) long, is rated AW2 (84 seated passengers and 40 standing), and can travel at a maximum speed of 90 km/hr (55 mph). This speed can be reached in less than 35 sec from a standing start.” [20]

Overall length: 79ft 11in.

Width: 9ft 3in

Tare weight: 84,000lb

Acceleration: 3mph/sec.

Service braking: 4mph/sec.

Emergency braking: 6mph/sec.

Each LRV “is bidirectional with an operator’s cab at either end and three doors per side. The passenger door near the operator’s cab is arranged to allow the operator to control fare collection. The 84 seats are arranged in compliance with the specification requirements. Half the seats face one direction and half the other. Each end of the car is equipped with … an automatic coupler with mechanical, electrical, and pneumatic functions so that the cars can operate in trains of up to four vehicles.” [20]

In 2024, the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority board approved “the selection of Siemens Mobility for a contract to replace the Breda light rail vehicle fleet. … The planned framework contract with Siemens Mobility would cover up to 60 Type S200 LRVs, with a firm order for an initial 24. … The high-floor LRVs will be similar to cars currently used by Calgary Transit, with doors at two heights for high and low level platforms, an infotainment system, ice cutter pantographs, 52 seats, four wheelchair areas and two bicycle racks. … The fleet replacement programme currently has a budget of $393m, including rolling stock, infrastructure modifications, testing, training, field support, spare parts and tools. This is being funded by the Federal Transportation Administration, Ohio Department of Transportation, Northeast Ohio Areawide Co-ordinating Agency and Greater Cleveland RTA.” [21]

References

- Shaker Heights Rapid Transit Lines; in Modern Tramway Vol. 12, No 137, May, 1949, p101,102,112.

- https://case.edu/ech/articles/s/shaker-heights-rapid-transit, accessed on 1st January 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Line_(RTA_Rapid_Transit), accessed on 1st January 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_Line_(RTA_Rapid_Transit), accessed on 1st January 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Line_(RTA_Rapid_Transit), accessed on 1st January 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cleveland_Rapid_map.svg, accessed on 1st January 2025.

- https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.oh0092.photos/?st=brief, accessed on 1st January 2025.

- https://www.etsy.com/uk/listing/1213398530/shaker-rapid-shaker-heights-oh-cleveland, accessed on 2nd January 2025.

- https://akronrrclub.wordpress.com/tag/shaker-heights-rapid-transit-lines, accessed on 2nd January 2025.

- https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/276745885984?mkcid=16&mkevt=1&mkrid=711-127632-2357-0&ssspo=bTaNd6pwTTu&sssrc=4429486&ssuid=afQhrar7TGK&var=&widget_ver=artemis&media=COPY, accessed on 2nd January 2025.

- https://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/418, accessed on 2nd January 2025.

- https://www.riderta.com/dec-17-1913-first-light-rail-service-operates-shaker-heights, accessed on 2nd January 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tower_City_station, accessed on 2nd January 2025.

- https://www.shakersquare.net/history, accessed on 2nd January 2025.

- https://clevelandlandmarkspress.com/book_details.php?bid=5#&panel1-5, accessed on 2nd January 2025.

- https://hickscarworks.blogspot.com/2013/10/h1218.html?m=1, accessed on 2nd January 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/PCC_streetcar, accessed on 3rd January 2025.

- https://cs.trains.com/mrr/f/13/t/290183.aspx, accessed on 3rd January 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Breda_trams/LRVs_in_Cleveland, accessed on 3rd January 2025.

- https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/state-of-the-art/2/2-031.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwinxYDwr9qKAxX0U0EAHWvkKooQFnoECBEQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2t9tHFDwPvUHB1juJqbqWe, accessed on 3rd January 2025.

- https://www.railwaygazette.com/light-rail-and-tram/cleveland-light-rail-vehicle-fleet-renewal-approved/64031.article, accessed on 3rd January 2025.