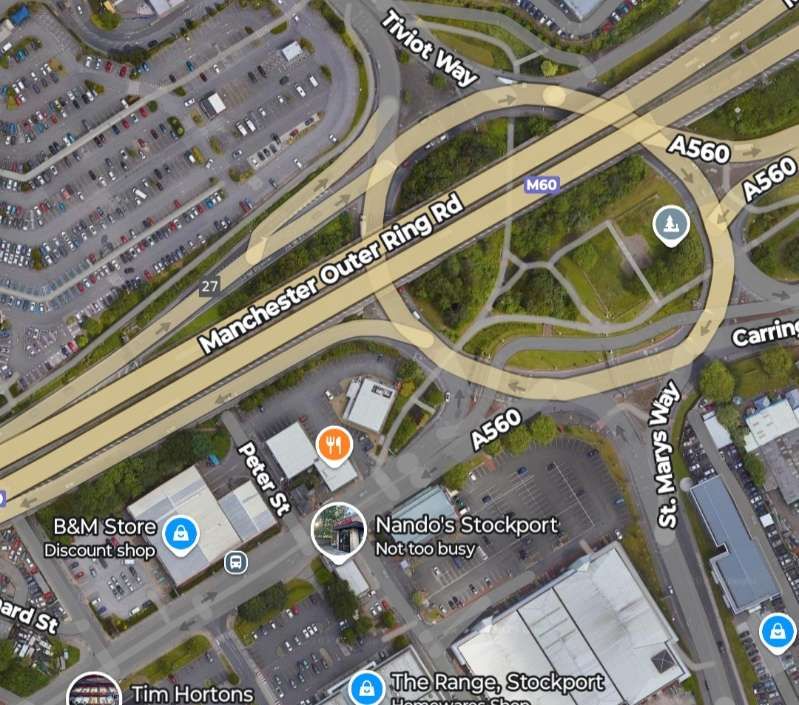

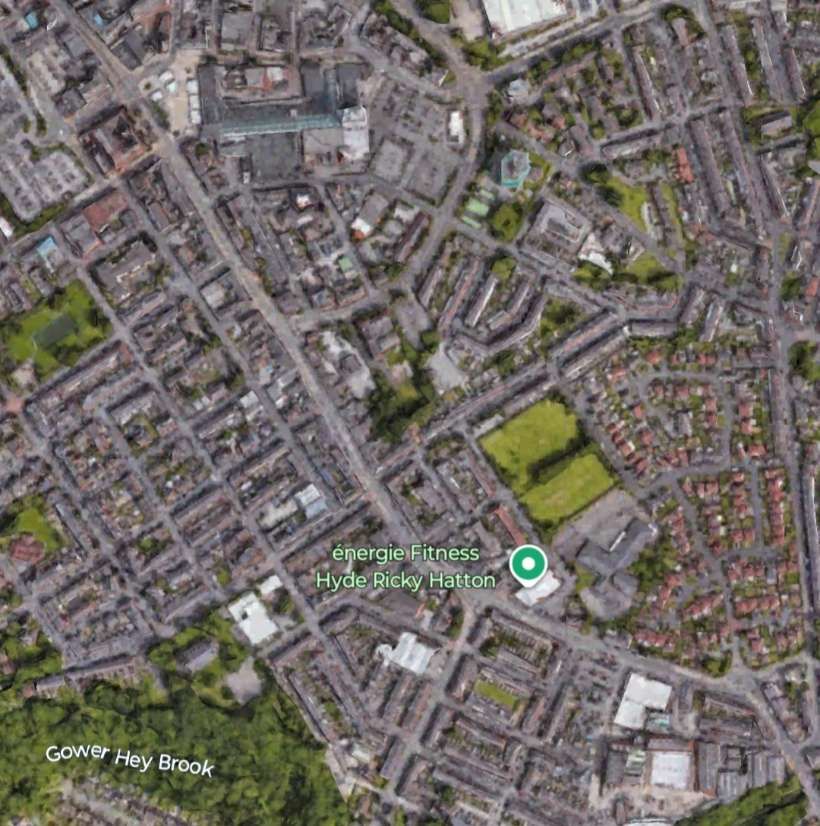

Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM) has indicated that it is considering a plan to extending the already proposed East Didsbury to Stockport extension of the Metrolink tram network. The extension would utilise the underused railway line between Stockport and Denton.

Talk is of utilising tram-train technology on this possible new extension.

Should this proposal be approved it would link Stockport to Tameside and could also provide a link to Manchester Airport

The Mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham spoke of bold plans to deliver a decade of growth for Greater Manchester. He said that “developing the Bee Network and delivering better bus, tram and train connections will be fundamental to [that] growth story.” [2]

He continued: “For too long, Denton has been overlooked and by working up the tram-train option to connect Denton and the wider area to the Metrolink is a big step toward unlocking opportunities for local residents and businesses. … We’re committed to extending Metrolink to Stockport and beyond as part of our efforts to connect all our districts to the tram network and delivering a truly integrated transport network for everyone.” [2]

TfGM is already working with Stockport Council to develop a business case for bringing trams to Stockport. The Strategic Outline Case [4] – the first step in the process – is exploring a ‘core’ extension from the existing Metrolink stop at East Didsbury to Stockport town centre. The extension through Denton is not part of those ‘core’ proposals but, “as part of the work on the business case, TfGM is also considering how this may unlock future extensions. One option being worked up includes using tram-train technology – where services can run on both tram and train tracks – to run beyond Stockport town centre along the Denton rail line, connecting the area firmly into the wider Metrolink network including links to Tameside and Manchester Airport.” [2]

Good progress has been made on the first stage of the Stockport Metrolink extension business case, with TfGM now working to complete all required technical work ahead of submission to the Department for Transport in early 2026. Construction on the ‘core’ element of the project could begin by the end of the decade, if approvals and funding are acquired.

Andrew Gwynne, MP for Gorton & Denton, said: “For years I’ve campaigned, alongside the local community, for improved transport links to Denton and across the constituency. I’m delighted that as part of the Metrolink extension plans, TfGM are looking seriously at using the rail line as an option for tram-train services. … Improved connectivity is key to opening up opportunities for our people and communities, and supporting the growth ambitions across the city region.”

Navendu Mishra, MP for Stockport, said: “Since my election to the House of Commons in December 2019, I have been pushing the Government to fund the extension of Manchester’s Metrolink tram network into my constituency of Stockport, and I thank the Secretary of State for Transport, the Chancellor and Transport for Greater Manchester for backing the extension to our town centre. … This will be a significant boost for Stockport’s connectivity and local economy, helping people to get to work, school and healthcare appointments more easily and sustainably as well as unlocking new homes and jobs.” [2]

Leader of Tameside Council, Cllr Eleanor Wills, said: “The options being developed to utilise the Denton rail line to expand Metrolink and better connect Ashton to Manchester Airport via Stockport have the potential to be truly transformational. … The Ashton Mayoral Development Zone is an exciting and vital opportunity to unlock Ashton’s potential, providing new homes and quality jobs. With even better transport links we can set ourselves up to for good growth for many years to come.” [2]

Leader of Stockport Council, Cllr Mark Roberts, said: “I’ve always said when it comes to MetroLink that it should be ‘Next Stop Stockport not Last Stop Stockport’ to the help deliver the ambition we have -the delivery of Metrolink and improving public transport connectivity across the borough and Greater Manchester is something we can all get behind.” [2]

TfGM says: “With Greater Manchester embarking on a decade of good growth, the city region is committed through the Greater Manchester Strategy to developing a transport system for a global city region – with 90% of people within a five-minute walk of a bus or tram that comes at least every 30 minutes.” [2]

In June 2025, the government awarded Greater Manchester £2.5 billion through Transport for the City Regions funding for a pipeline of projects including a tram line to Stockport and tram-train services connecting Oldham, Rochdale, Heywood and Bury, new Metrolink stops and modern new interchanges. … The £2.5 billion is part of a package of investment Greater Manchester is seeking to deliver its growth ambitions in full – with the city region seeking to work collaboratively with Government on exploring new funding models for major transport and other infrastructure projects. [3]

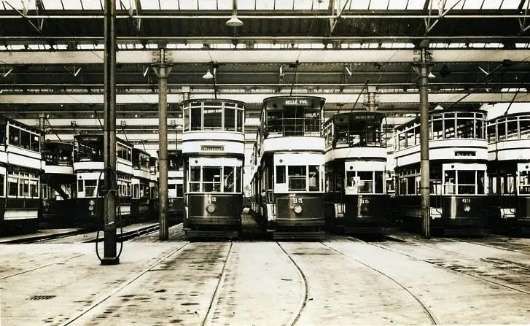

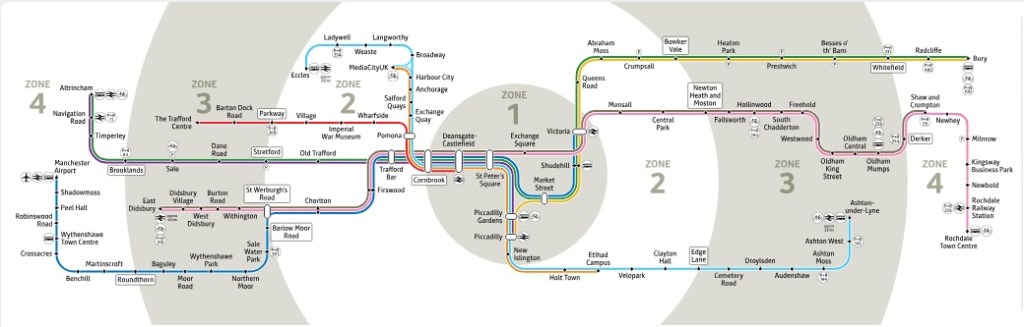

As of December 2025, Metrolink is the UK’s largest light rail network, with 99 stops connecting seven of the 10 boroughs of Greater Manchester. Record numbers of people are also getting onboard, with 45.6 million trips made in 2024 – up from 33.5m trips in 2022. [2]

The £2.5 billion investment for the Greater Manchester city-region is targetted at enabling the Bee network become fully-electric, zero-emission public transport system by 2030. Local rail lines will be brought into the Bee Network by 2030, fully integrated bike, bus, tram and train travel for the first time outside London. New electric buses, tram lines, tram stops and transport interchanges are among pipeline of projects which will deliver far-reaching benefits across Greater Manchester. Mayor Andy Burnham said that further progress on the next phase of the Bee Network will now be delivered at an unrelenting pace.

Greater Manchester will create an all-electric local public transport network:

“A thousand new EV buses will form a 100% electric fleet serving its communities. Alongside trams powered by renewable energy and e-bikes for hire, it will deliver an emission-free network. This will build on progress already made to cut CO2 emissions and improve air quality.” [3] (Image, © Transport for Greater Manchester.)

Greater Manchester will bring rail into the Bee Network. “Local rail lines will be integrated with the Bee Network, … the move will see major improvements to stations, including making more fully accessible, as well as capped fares.” [3]

Greater Manchester will deliver major projects to drive green growth. “A pipeline of transport projects – including a tram line to Stockport and tram-train services connecting Oldham, Rochdale, Heywood and Bury, new Metrolink stops and modern new interchanges – will support the delivery of thousands of new homes, skilled jobs and green growth.” [3]

Greater Manchester’s current transport strategy is made up of a number of documents, including:

- Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2040.

- A Five-Year Transport Delivery Plan 2021-2026 (including 10 local implementation plans).

- Several supporting sub-strategies that all contribute to meeting regional transport ambitions and building the Bee Network.

In 2025, Greater Manchester are currently working on a new strategy – the Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2050 – that will replace the current documents. [5]

You can find out more about the Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2040 using these links:

Download the Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2040. [6]

Download the Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2040: Executive Summary. [7]

The Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2050 has been promoted by Mayor Andy Burnham. [8]

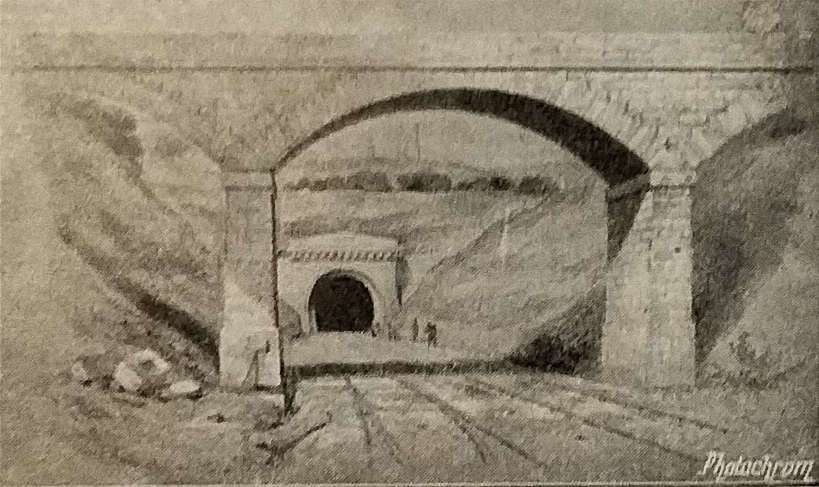

“Plans for a subway network in the city centre could become reality by 2050 if Greater Manchester makes good on ambitions set out within its latest rail strategy. … The 48-page strategy sets out a roadmap for the city region’s rail network, which needs to expand to keep pace with a growing population. … Among the highlights is the intention to develop an underground network by 2050.” [8]

“Starting at Piccadilly, where the city wishes to create a subterranean through-station as part of Northern Powerhouse Rail, the underground would provide increased network capacity without significant land take. … Taking Metrolink below ground [could] also minimise the disruption that would be caused if works were to take place at street level and push Manchester towards its target of doubling the number of intercity trips made by rail.” [8]

“The ripple effects of taking the network underground include easing the pressure on the Castlefield Corridor, ‘one of the most overburdened rail routes in the country’, according to the strategy.” [8]

The underground plan is just one part of the strategy for the city-region strategy that also includes upgrading stations, introducing tram-train technology on existing rail lines to widen the Metrolink’s reach, and delivering the Northern Arc – a new line between Manchester and Liverpool that would ultimately form part of Northern Powerhouse Rail. Land around rail hubs in the city region, including a huge development opportunity at Piccadilly similar in scale to that at Kings Cross, could support the delivery 75,000 new homes and unlock £90bn in economic uplift across the North West by 2050.

According to Andy Burnham, “Greater Manchester’s rail network plays a vital role in supporting [its] communities, powering [its] economy, and opening doors to opportunity – but for long has been held back from its true potential. … The way projects and services are planned and delivered is changing, with long needed reform giving the city-region a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reshape rail for Greater Manchester.” [8]

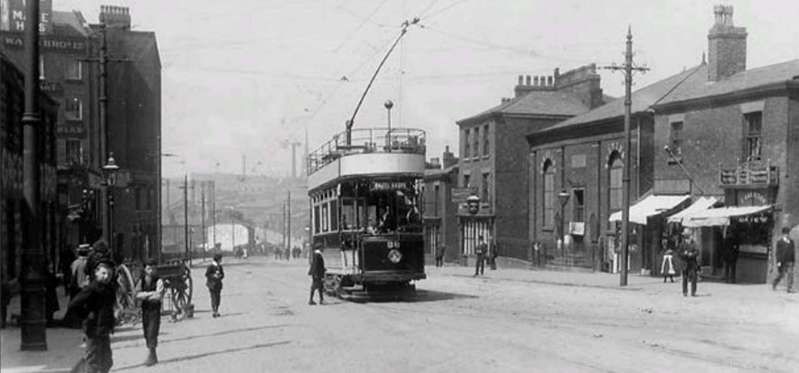

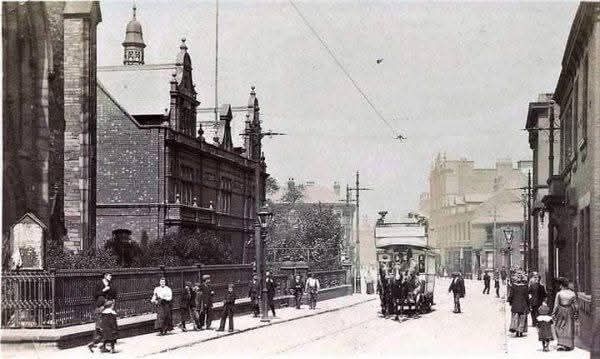

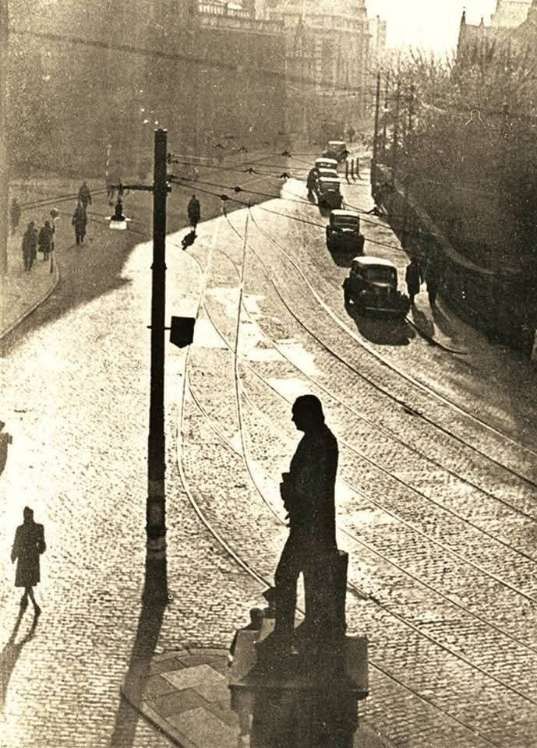

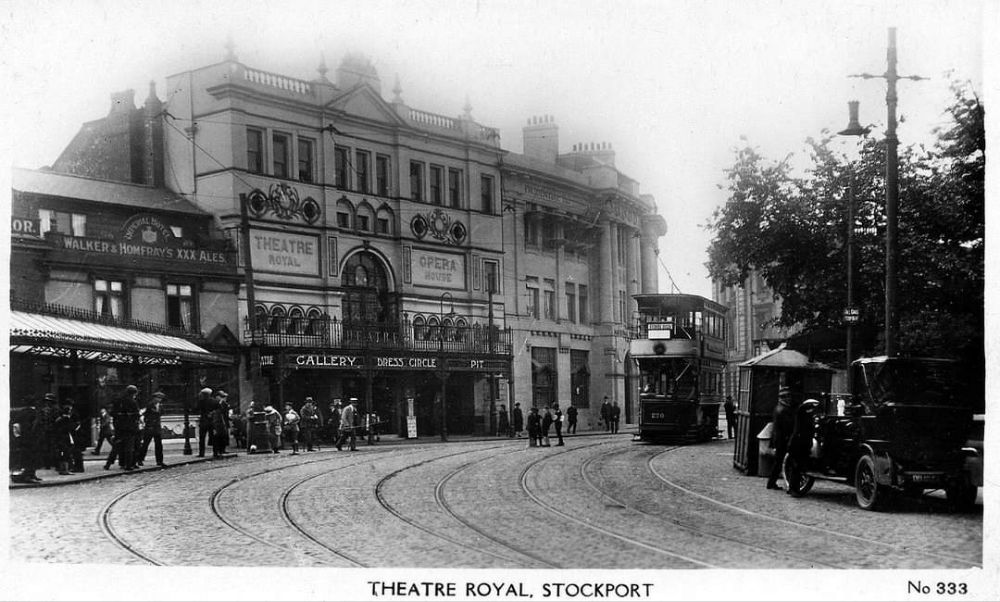

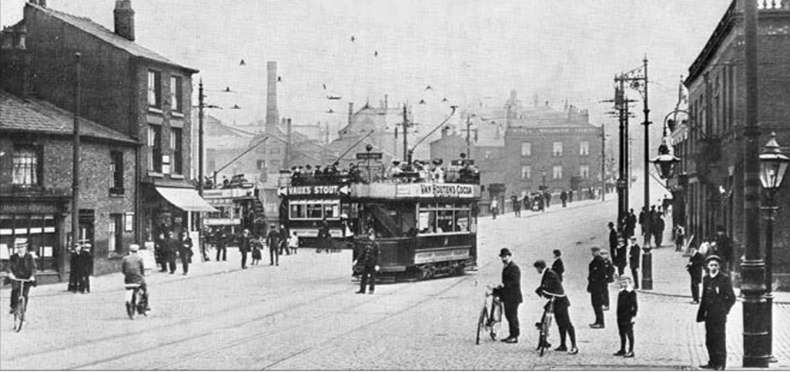

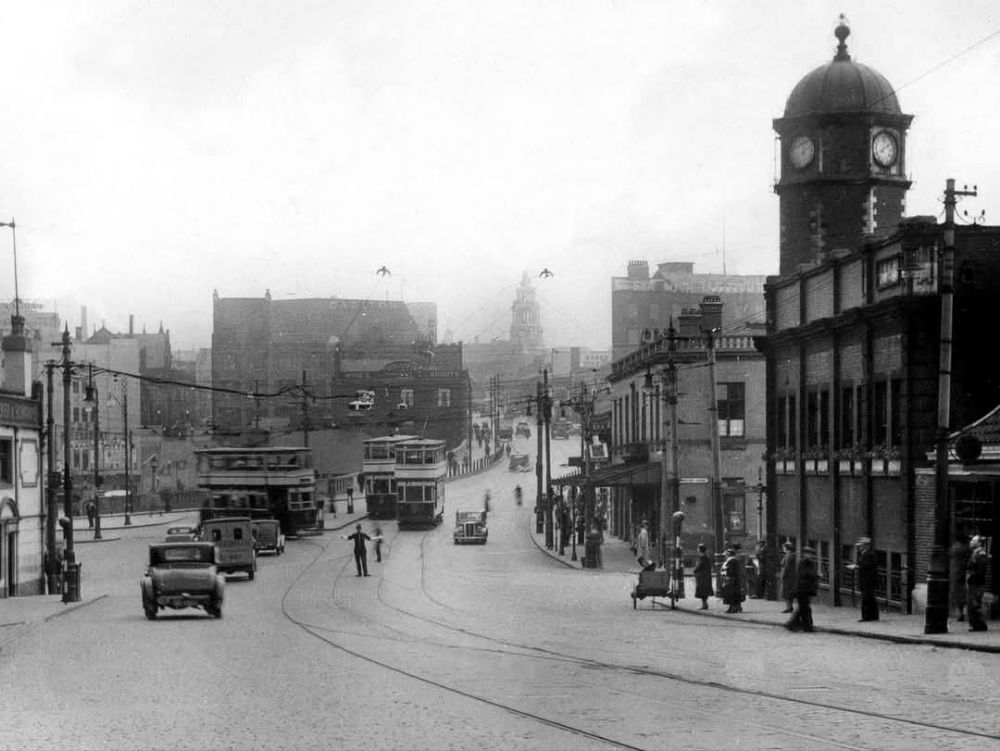

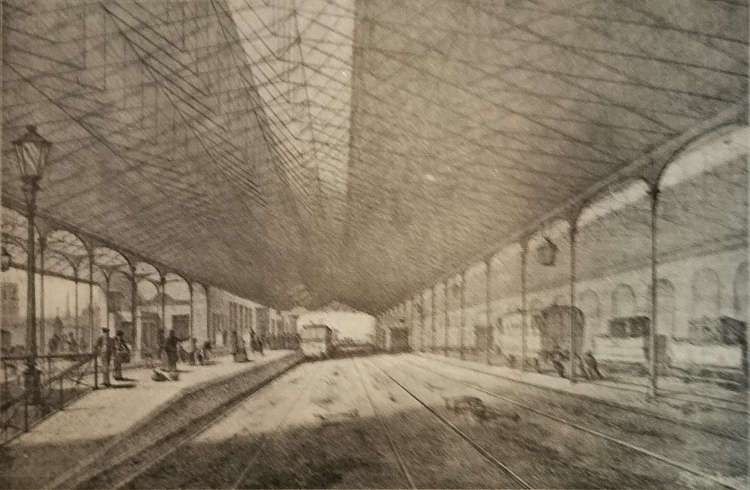

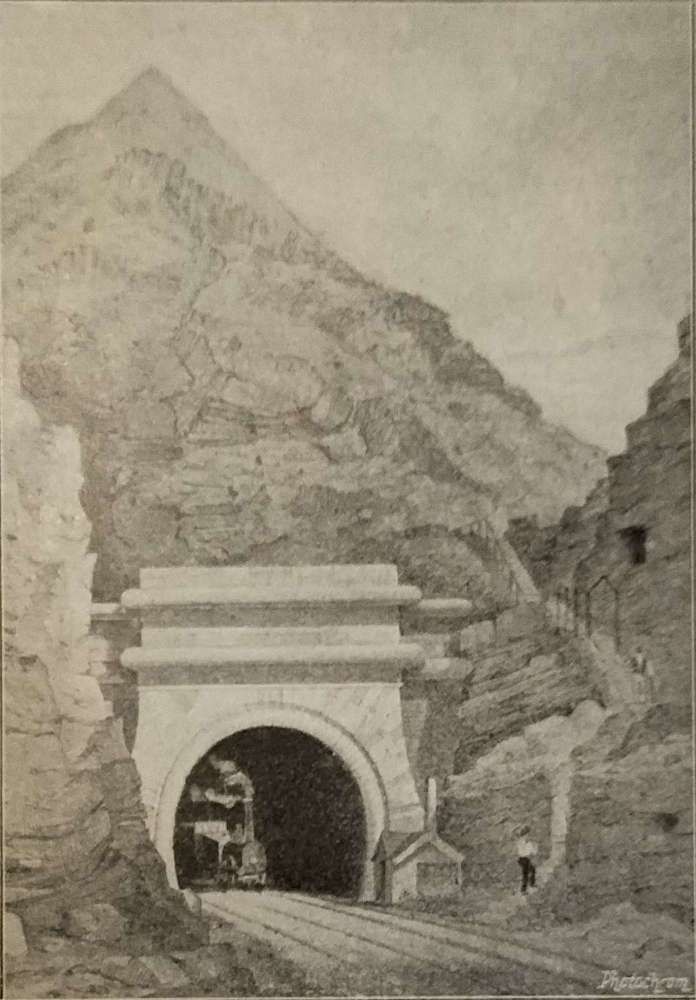

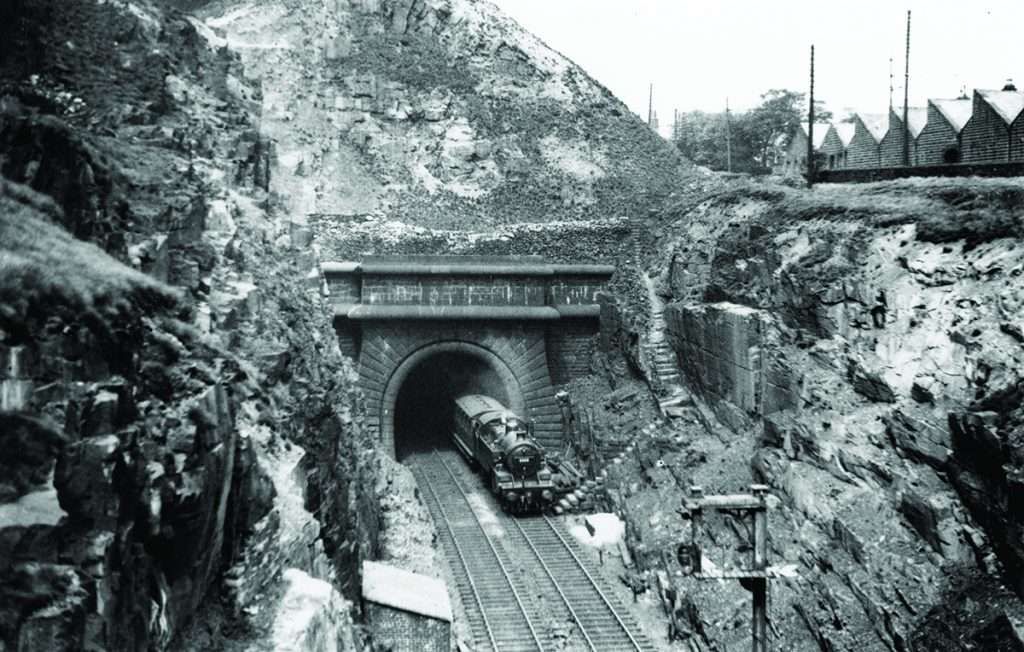

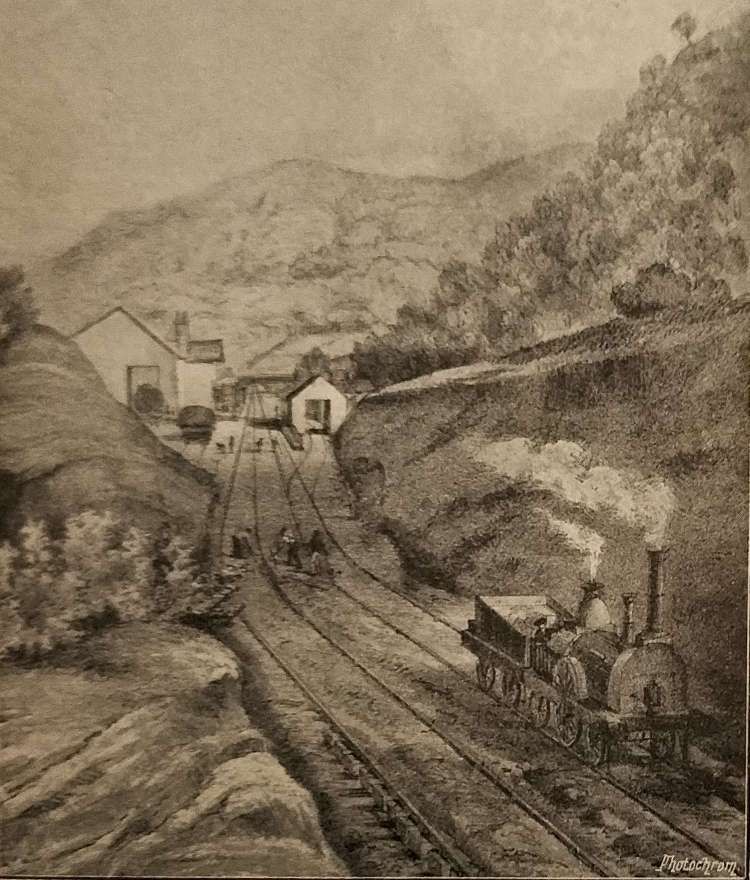

A year after the rail vision was unveiled a more simplified fare system on the Bee Network was announced. Andy Burnham said: “Simplifying rail fares is a key first step in making train travel easier and more accessible and the key to bringing local rail services into the Bee Network from December 2026. … Greater Manchester has a proud railway heritage, and our vision, developed with the industry, is about ensuring that everyone in our city-region can benefit from better connections, more reliable services, and a transport network that meets the needs of future generations.” [8]

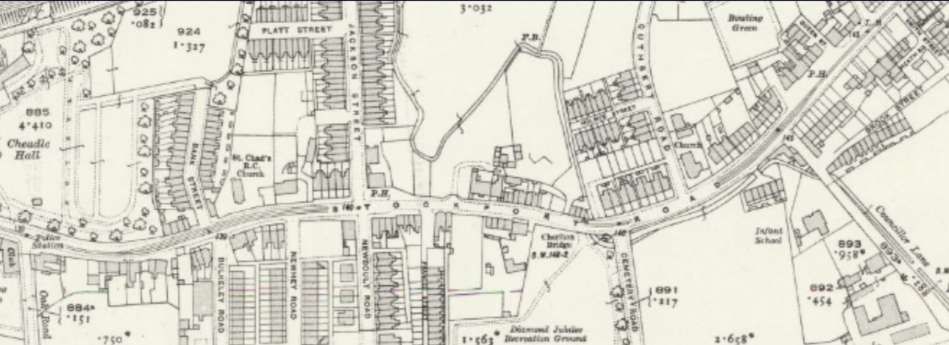

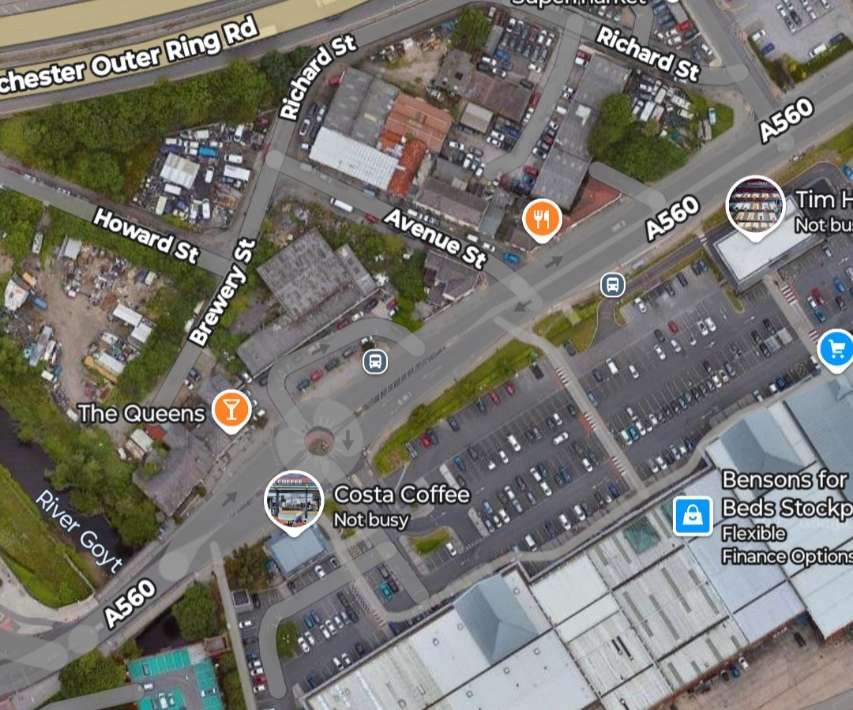

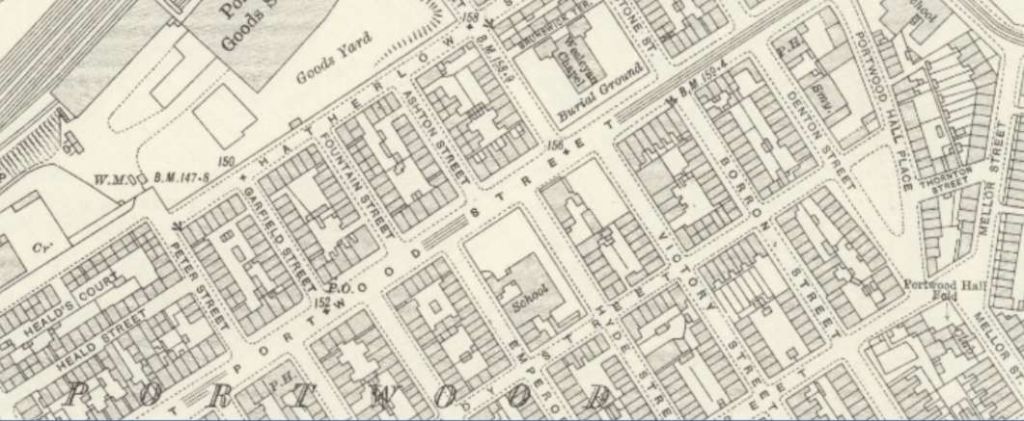

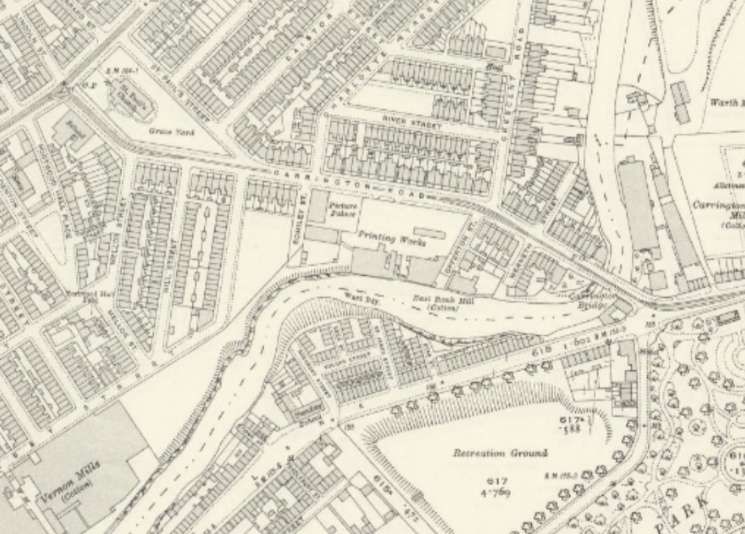

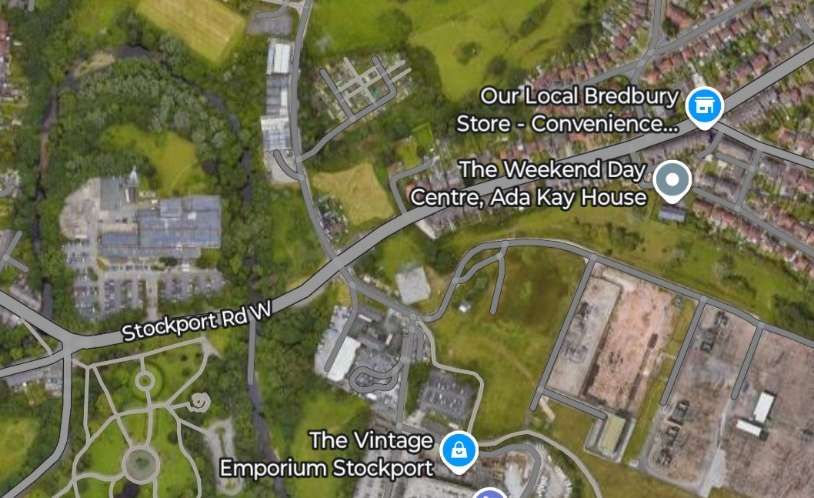

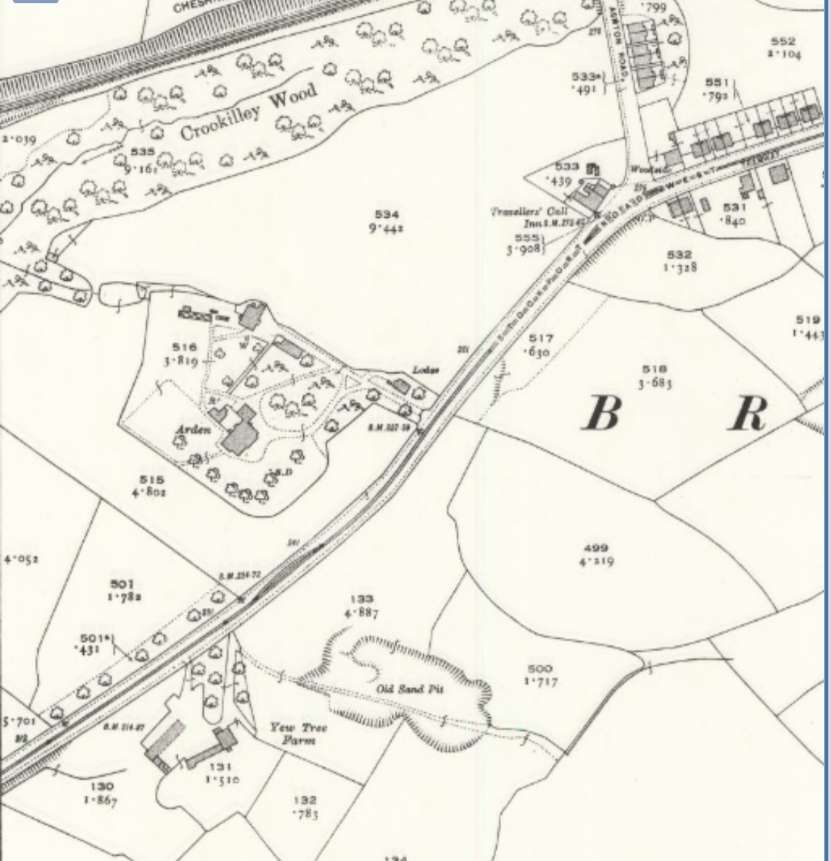

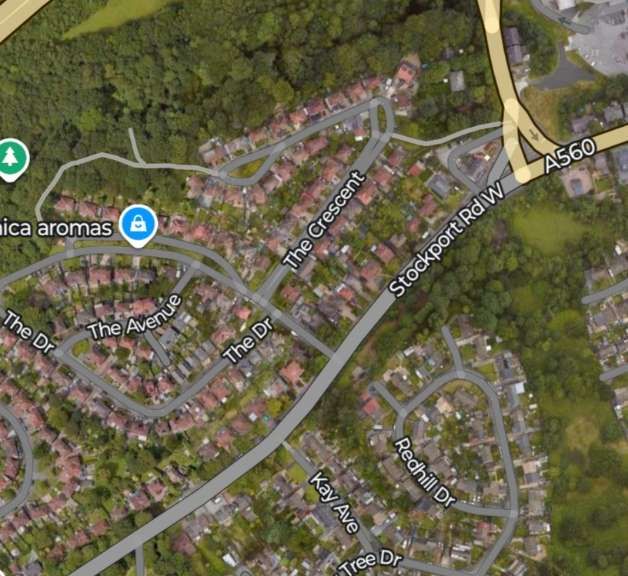

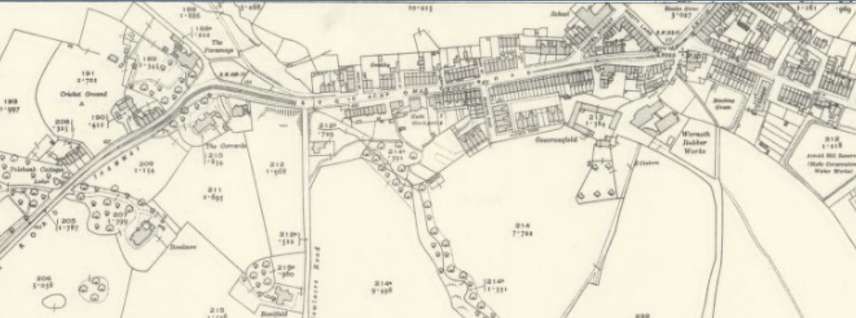

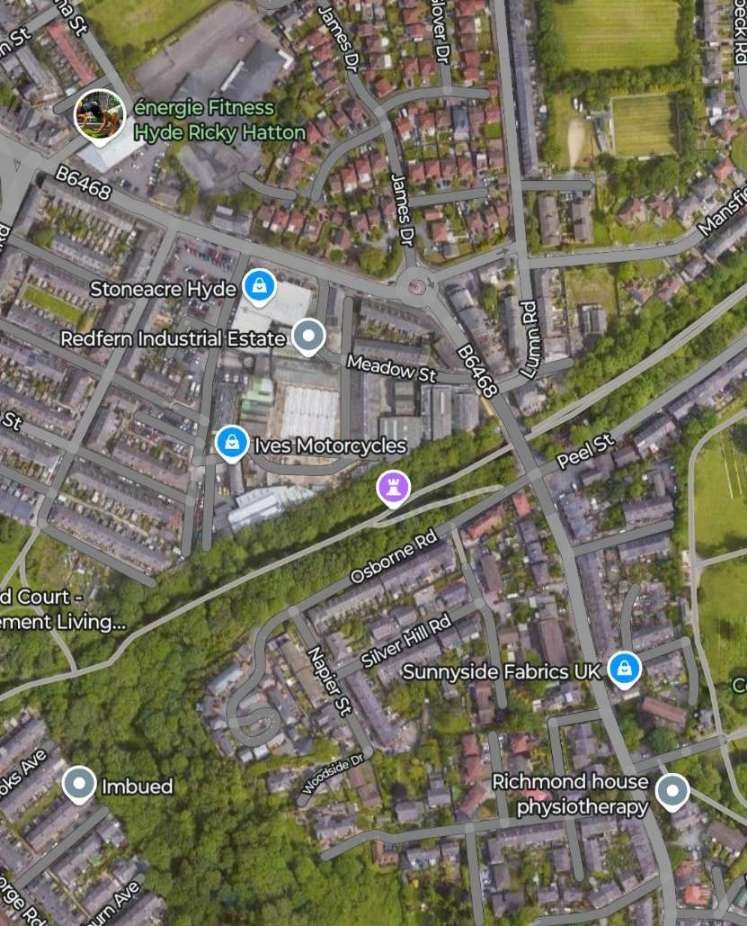

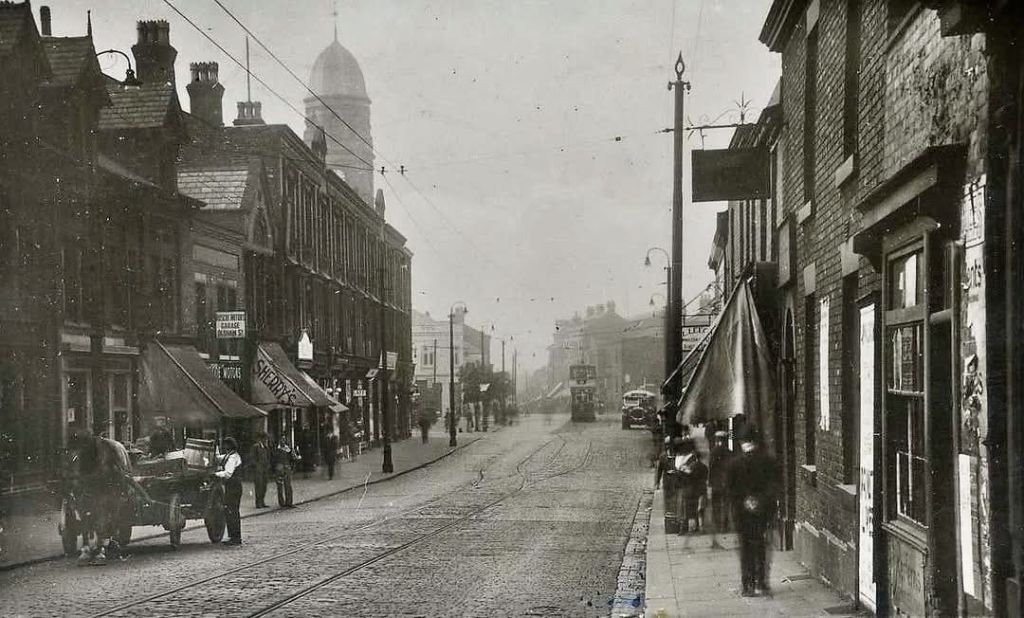

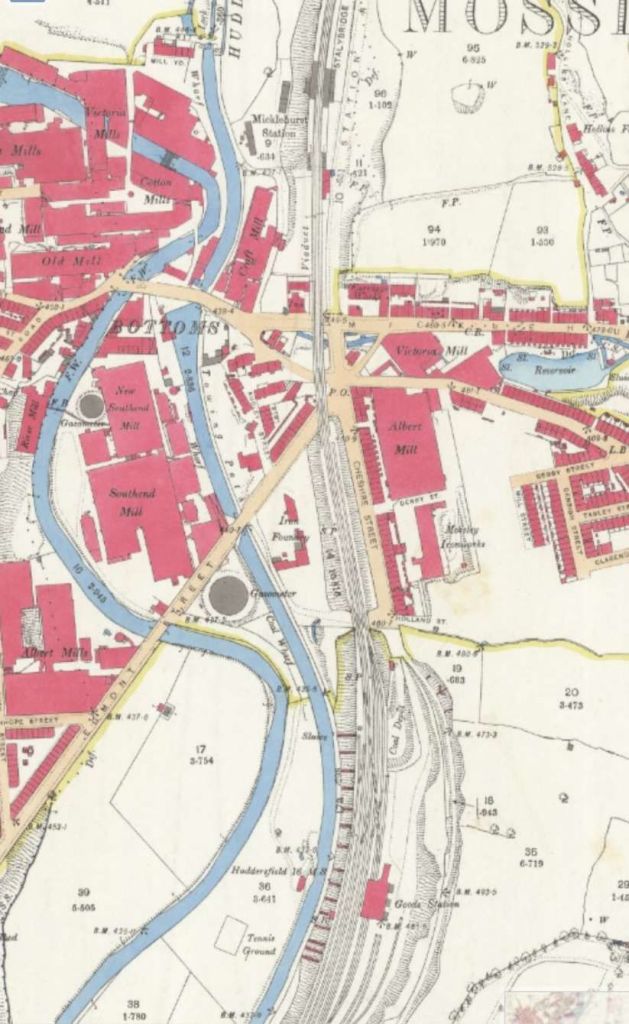

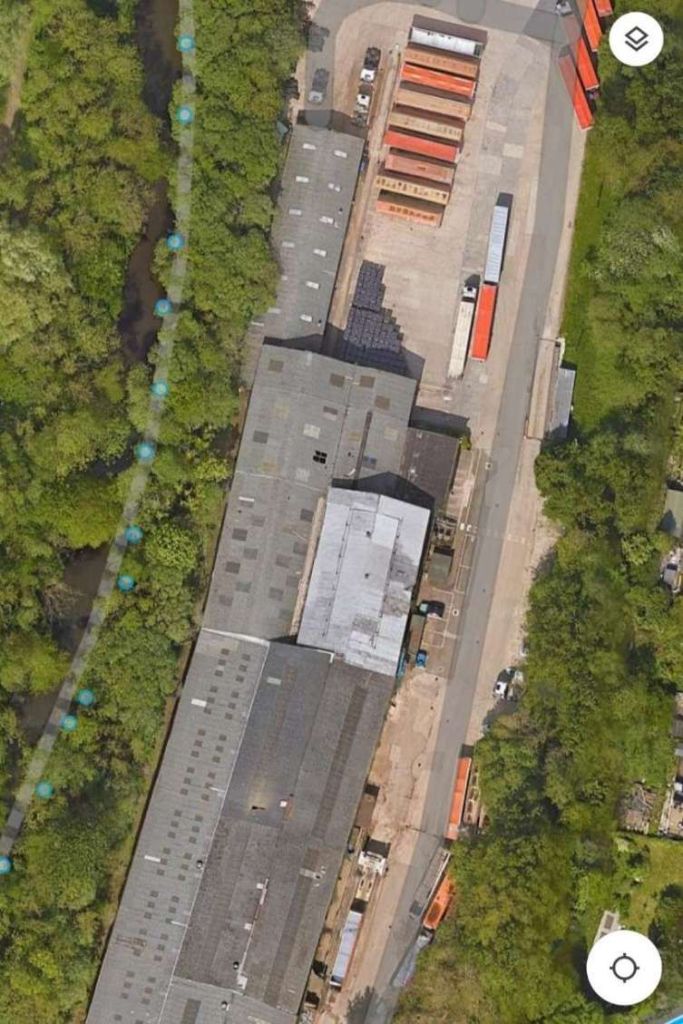

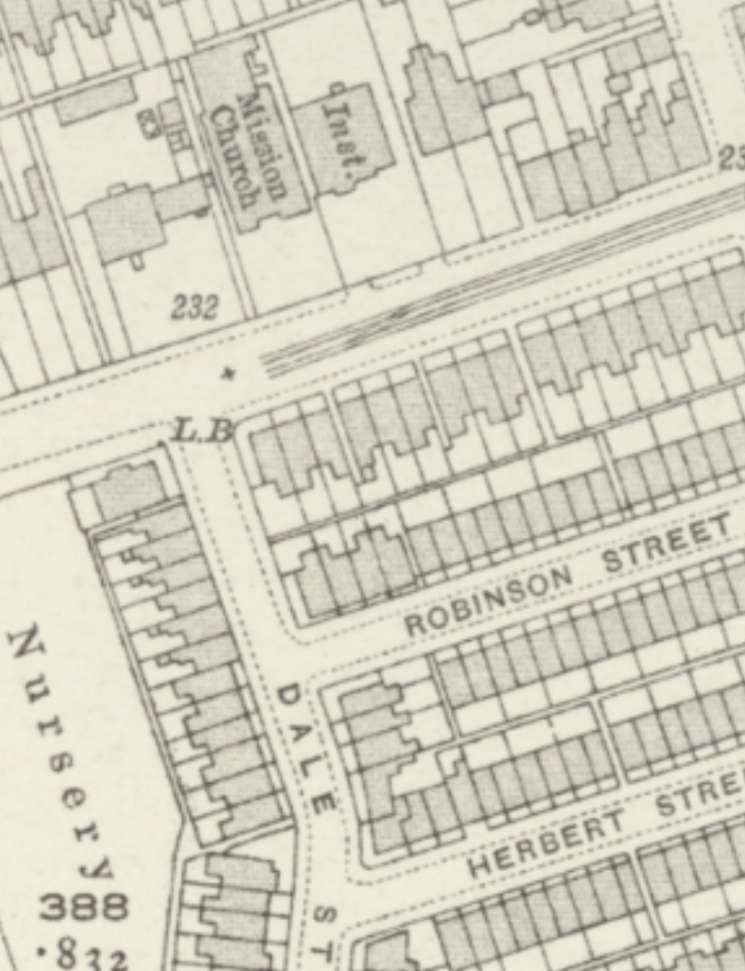

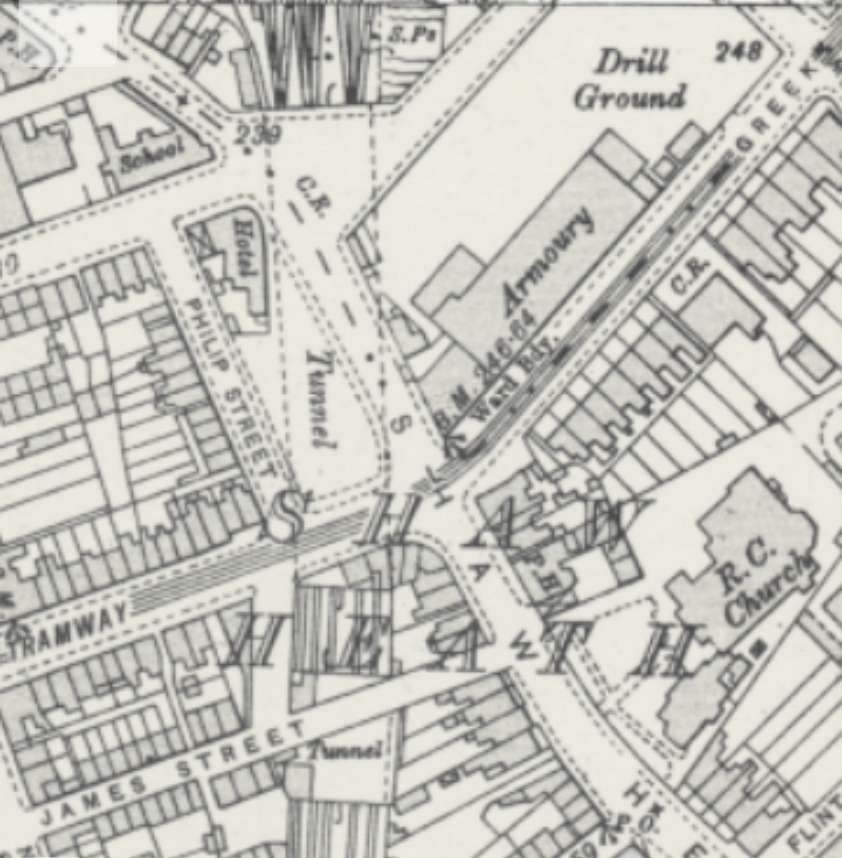

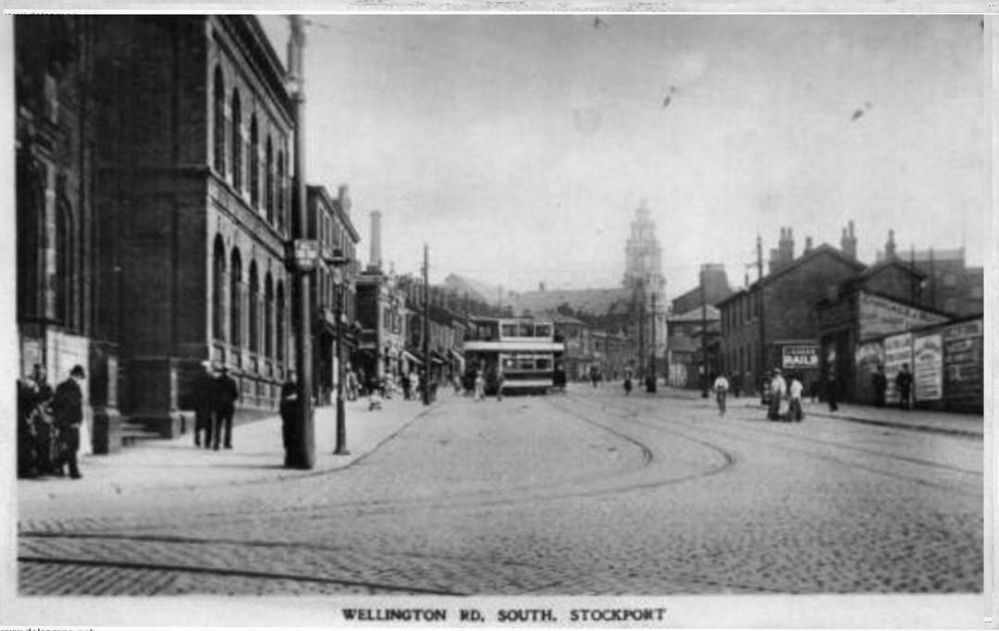

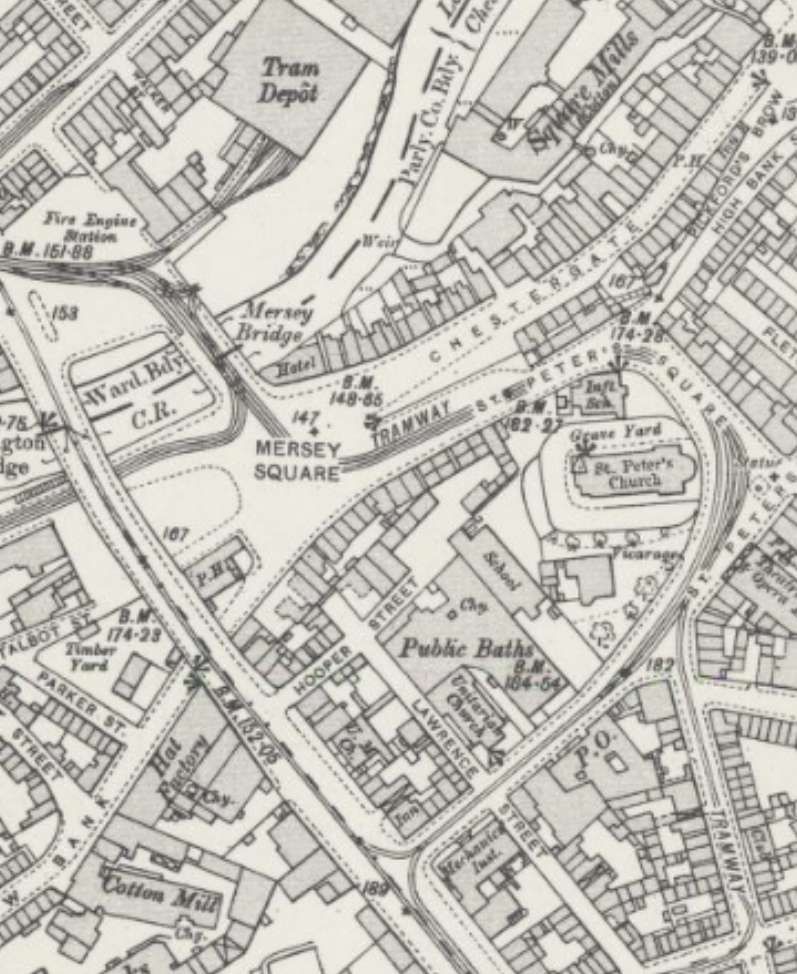

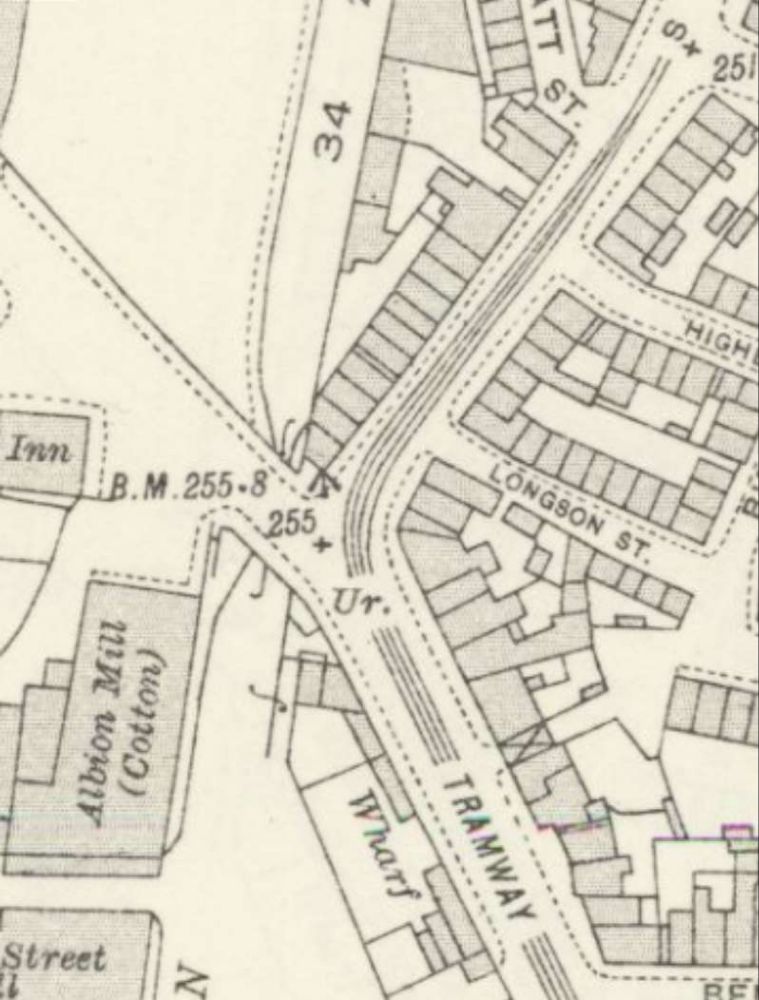

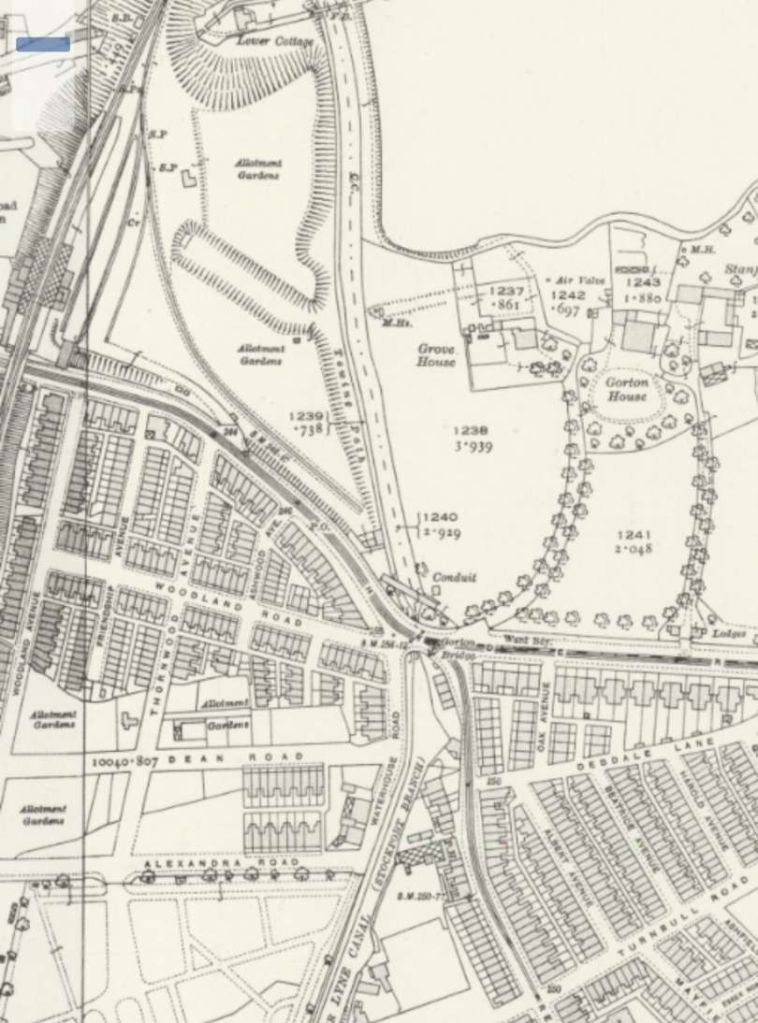

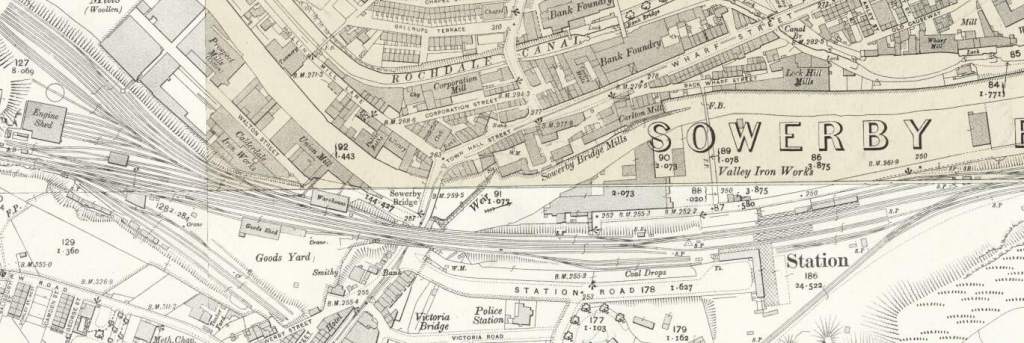

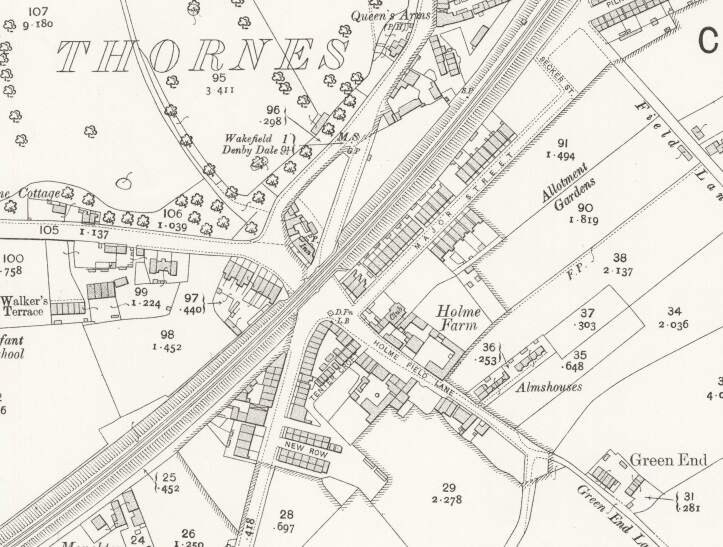

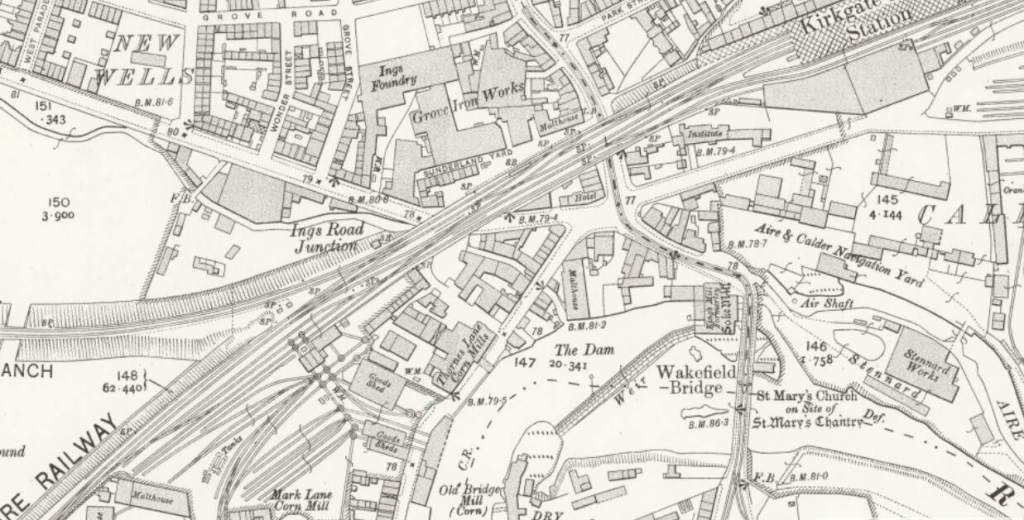

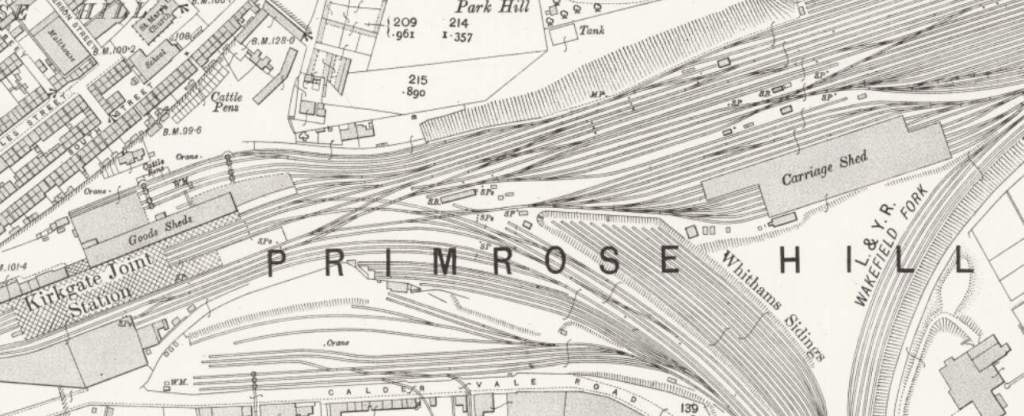

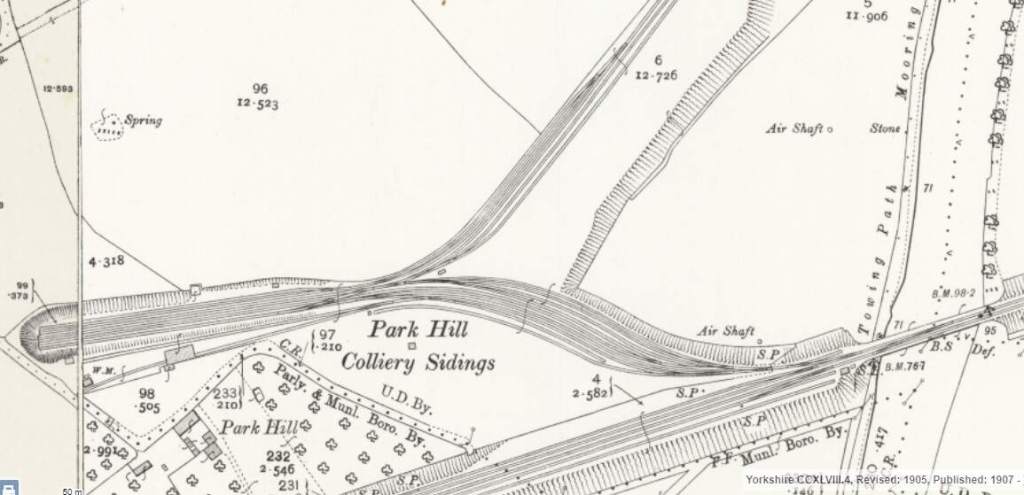

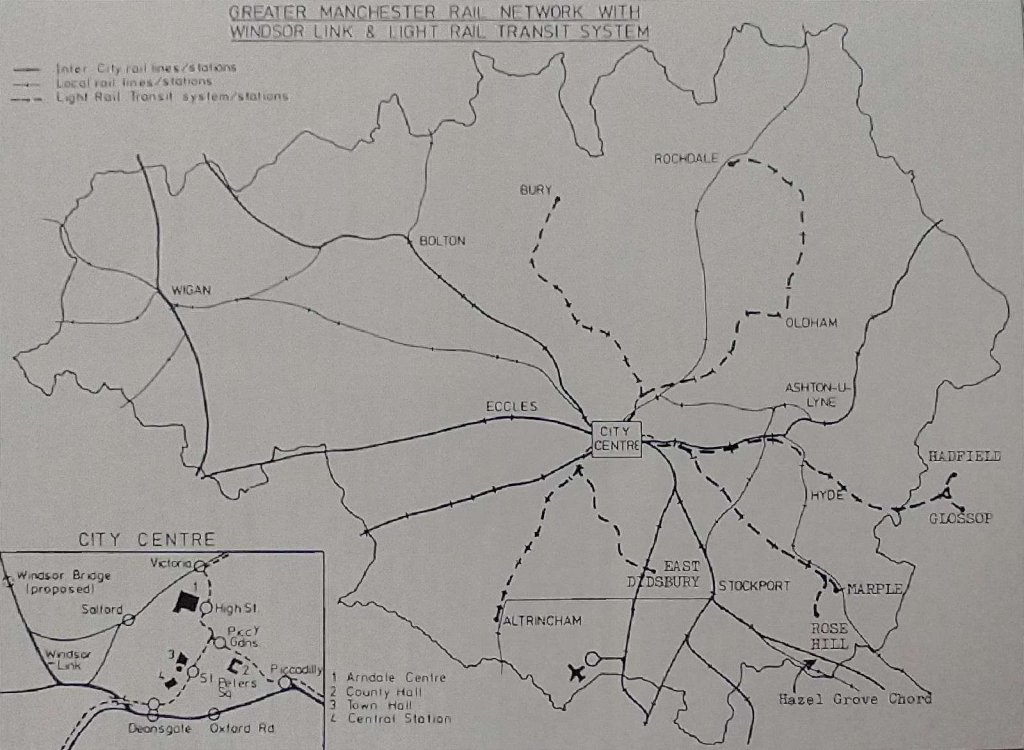

Sitting beneath the city-region strategy is the more local SEMMMS (South-East Manchester Multi-Modal Strategy) which was settled in 2001 and the much later SEMMMS Refresh (2018) which identified measures required to meet future transportation needs in the Southeast of the city region centred on Stockport. These measures included: Metrolink/tram-train routes to Marple, Stockport town centre, the airport and Hazel Grove; segregated bus routes and bus priority schemes; improved rail services and new/ improved rail stations; new roads e.g. A6 to M60 Relief Road; new and improved walking and cycling routes and facilities on and off the highway; improved public realm in the district and local centres; creation of connected neighbourhoods that encourage the use of more sustainable forms of transport; the provision of transportation infrastructure needed to be supported by the introduction of smarter choices to encourage the use of sustainable transport. [9][10][11]

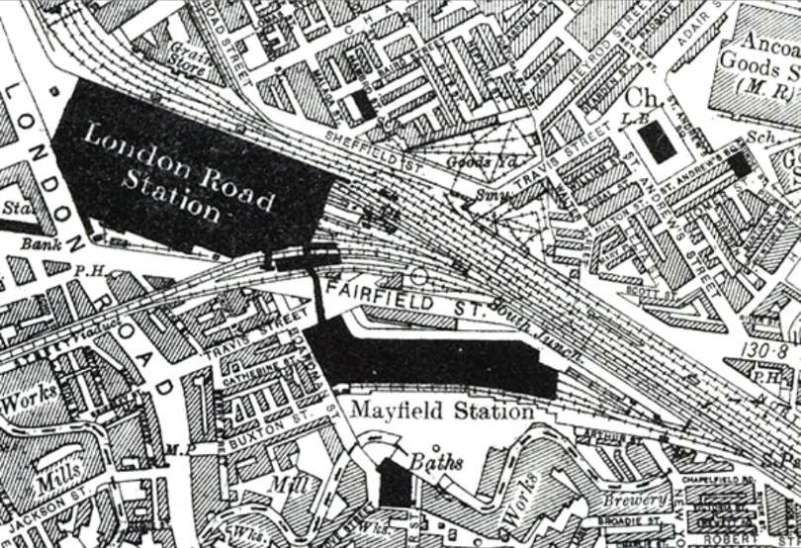

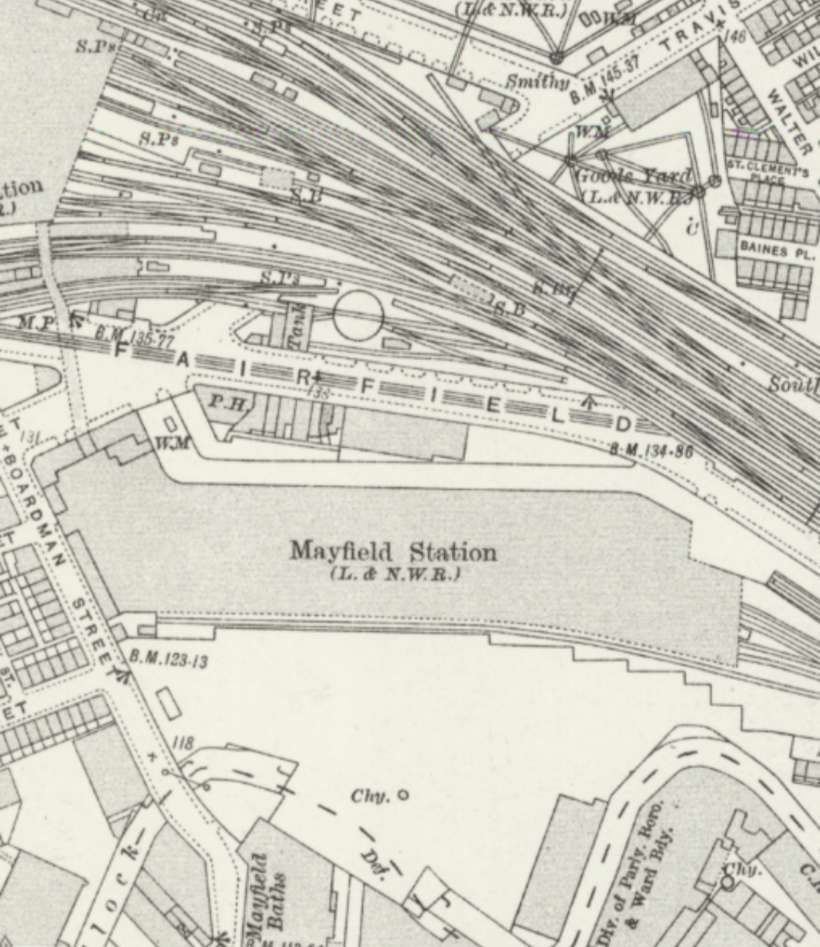

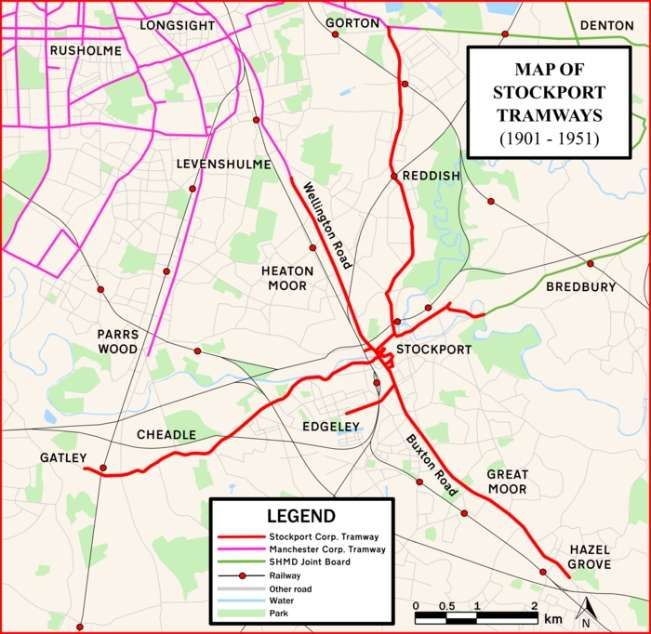

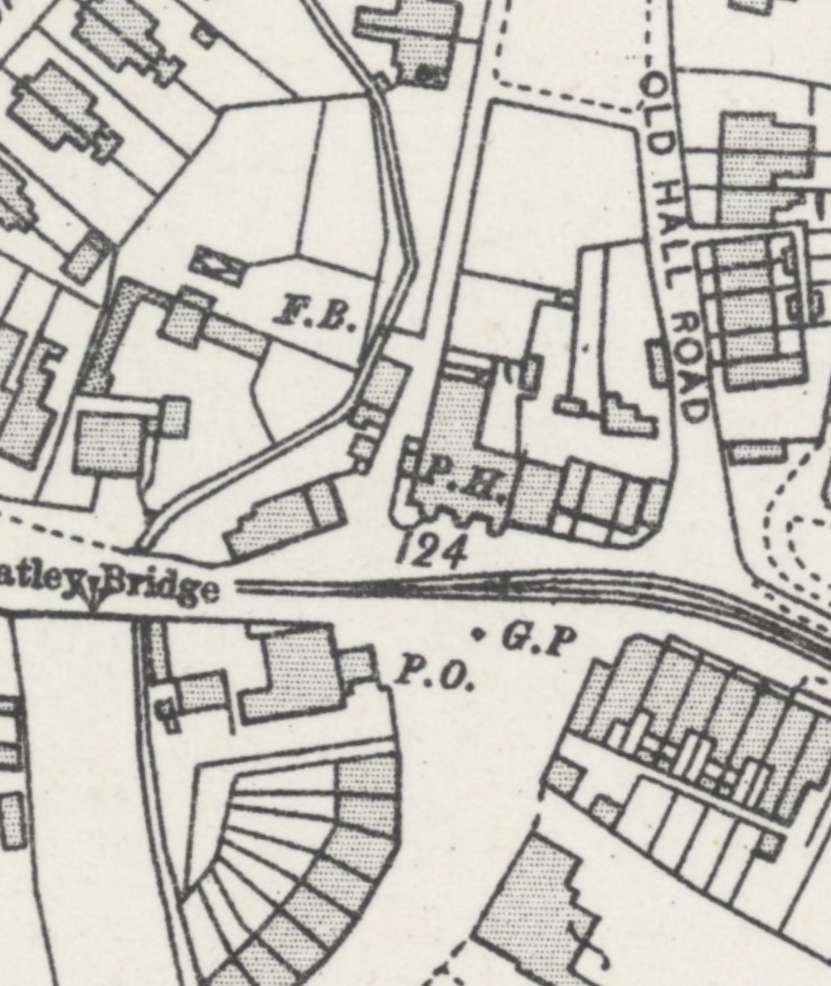

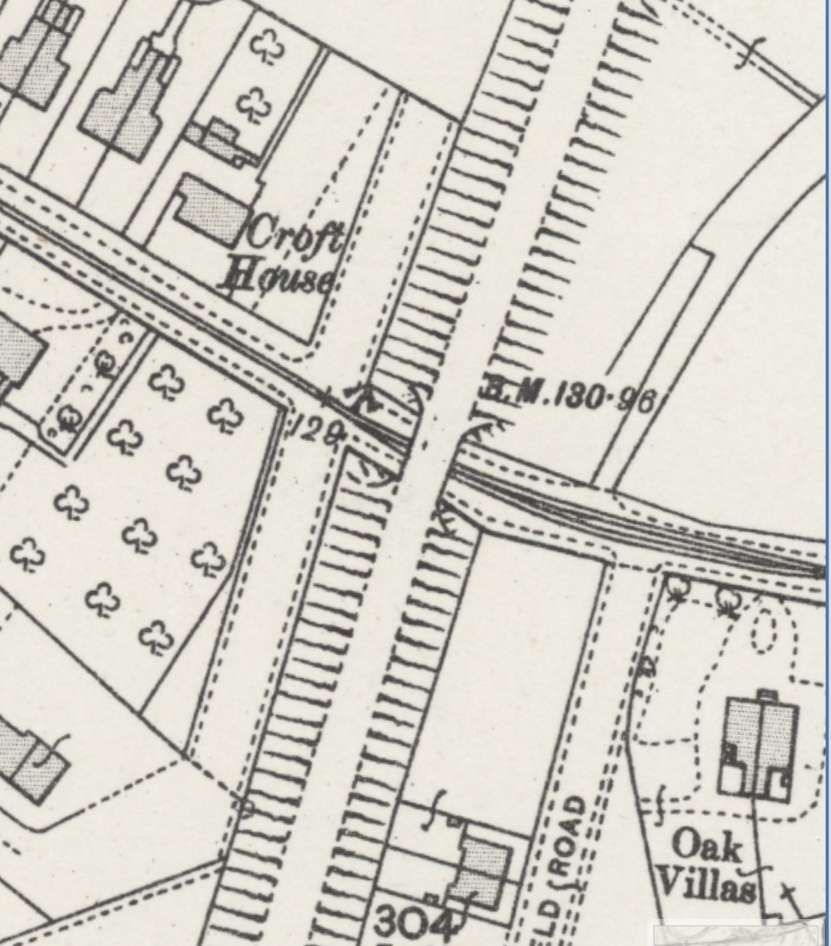

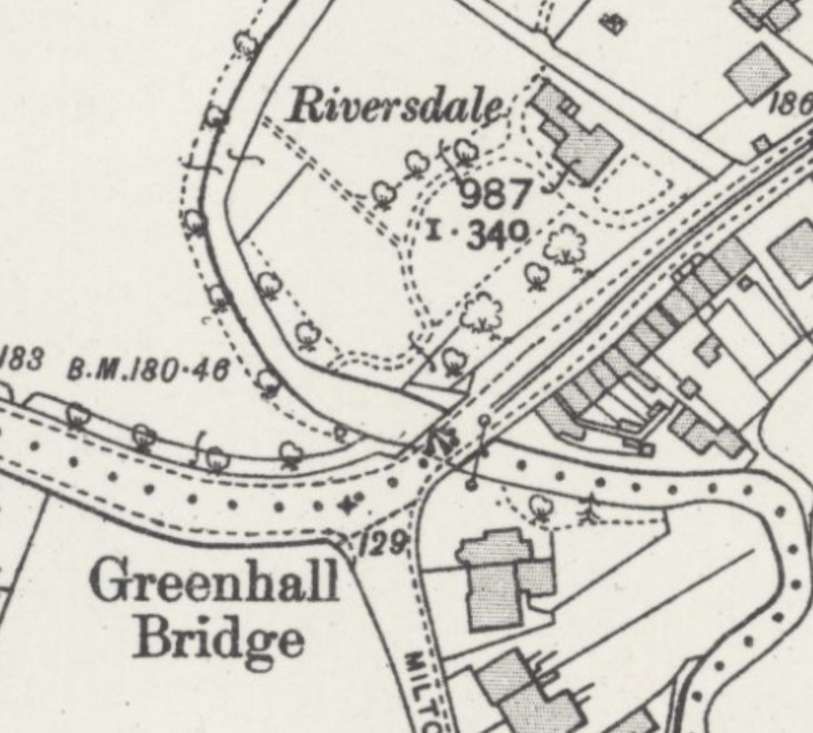

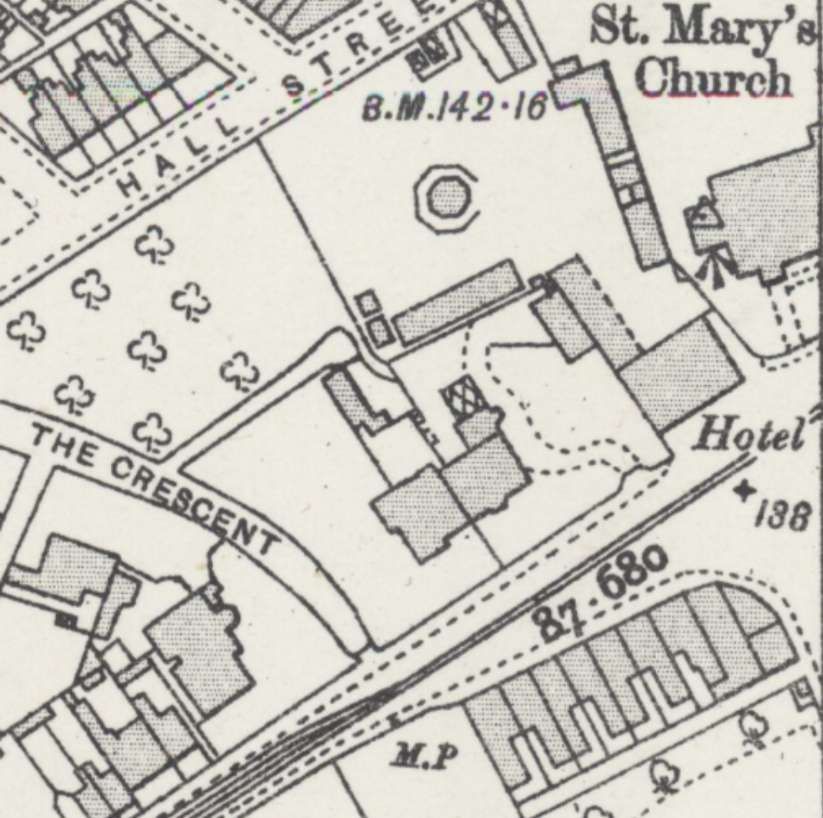

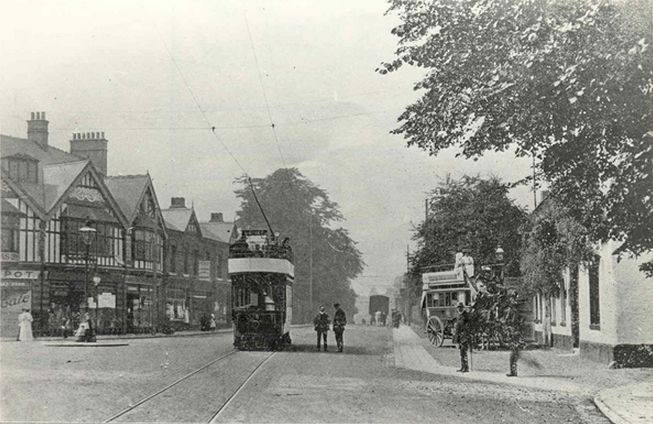

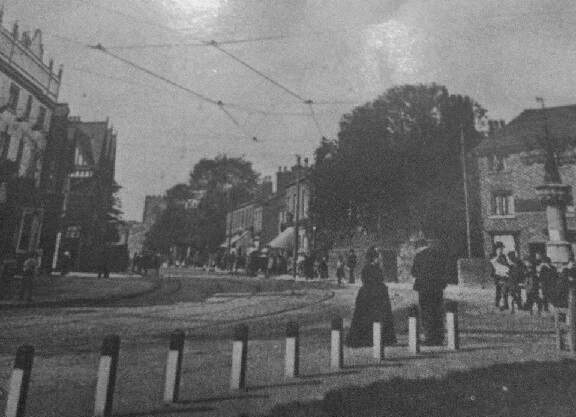

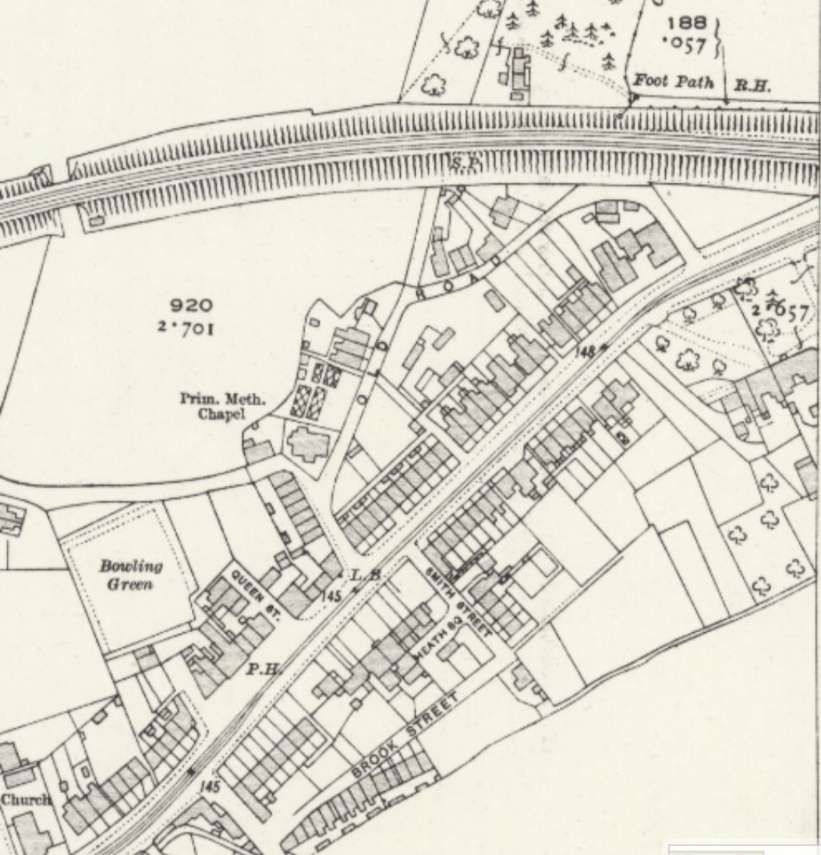

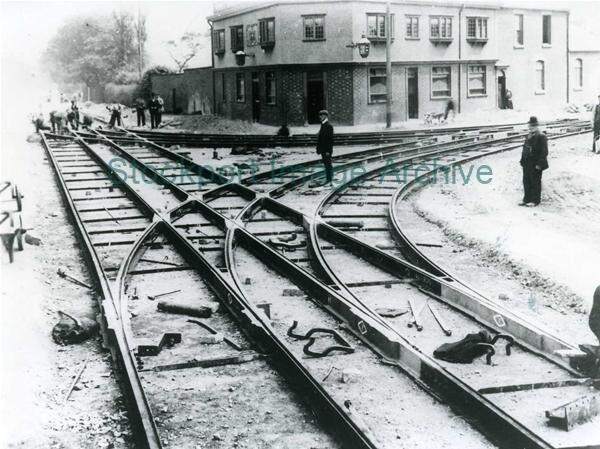

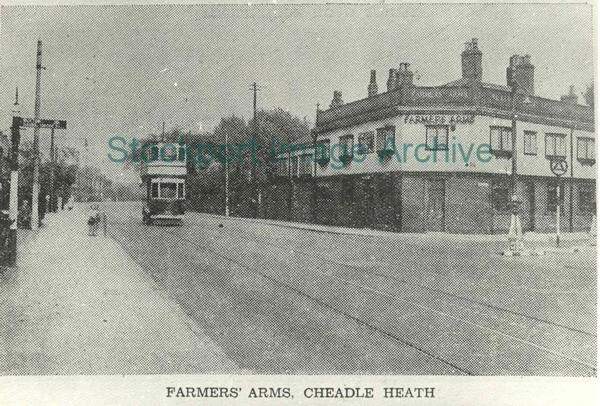

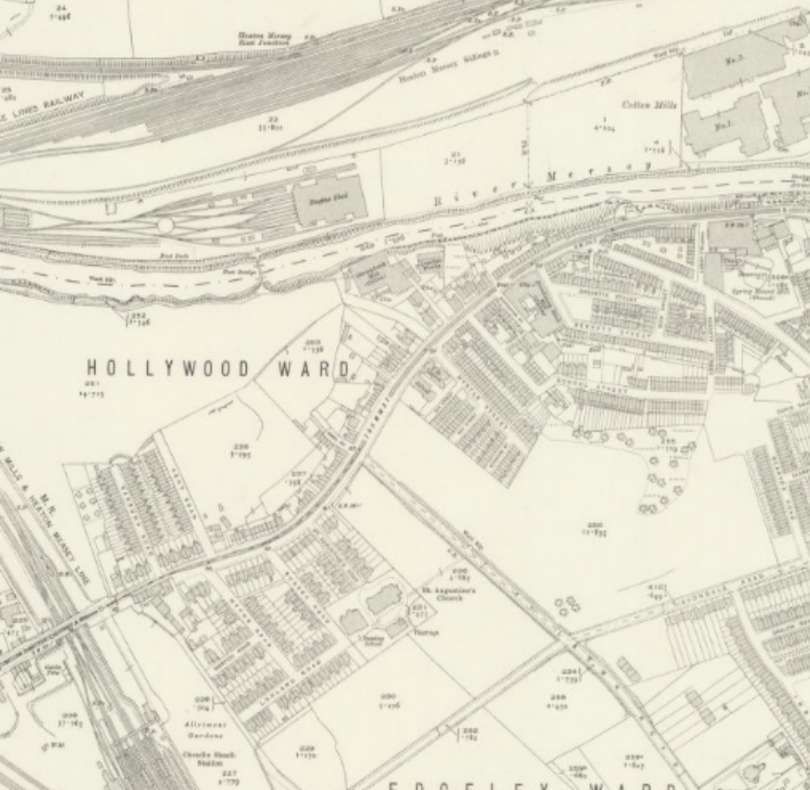

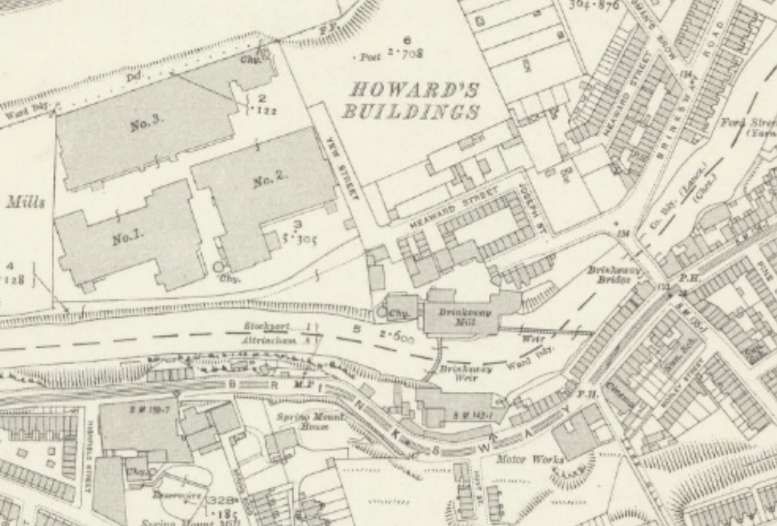

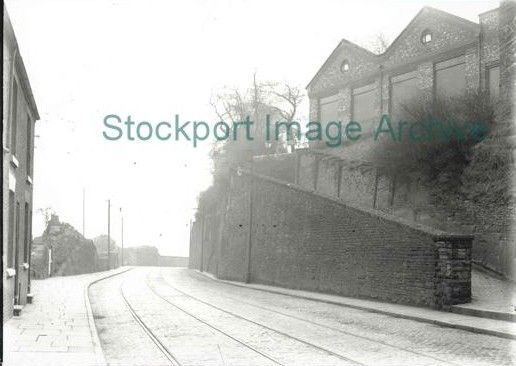

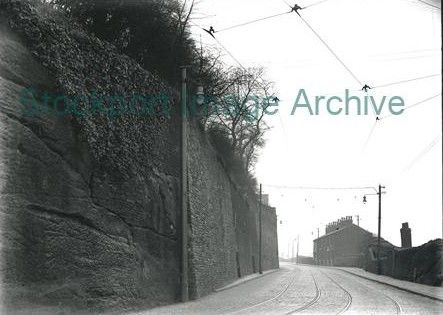

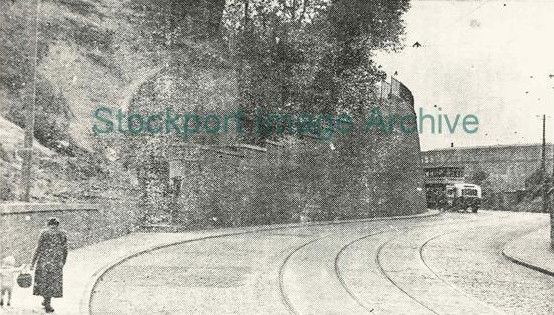

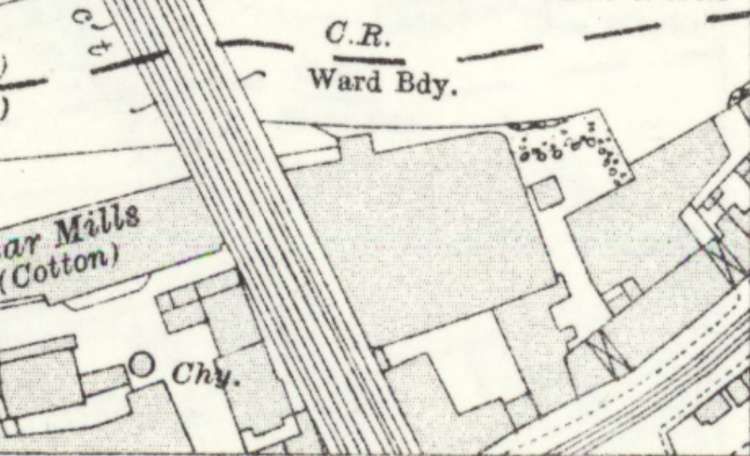

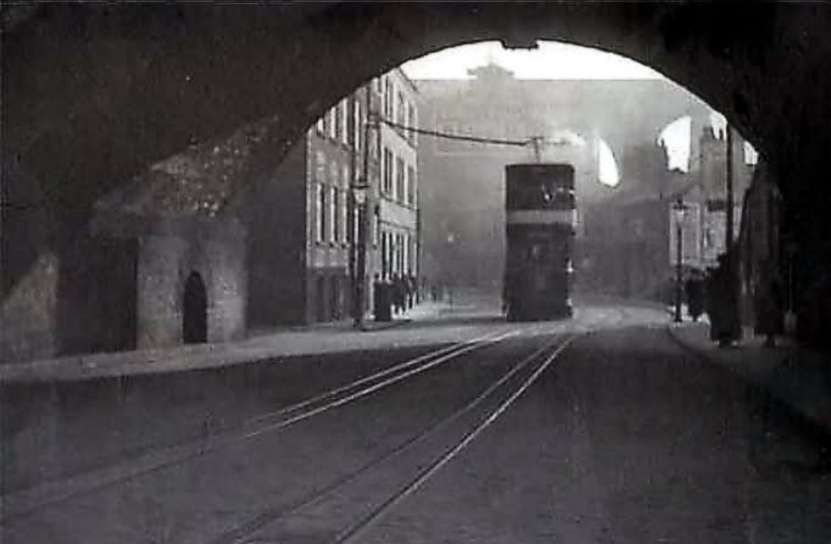

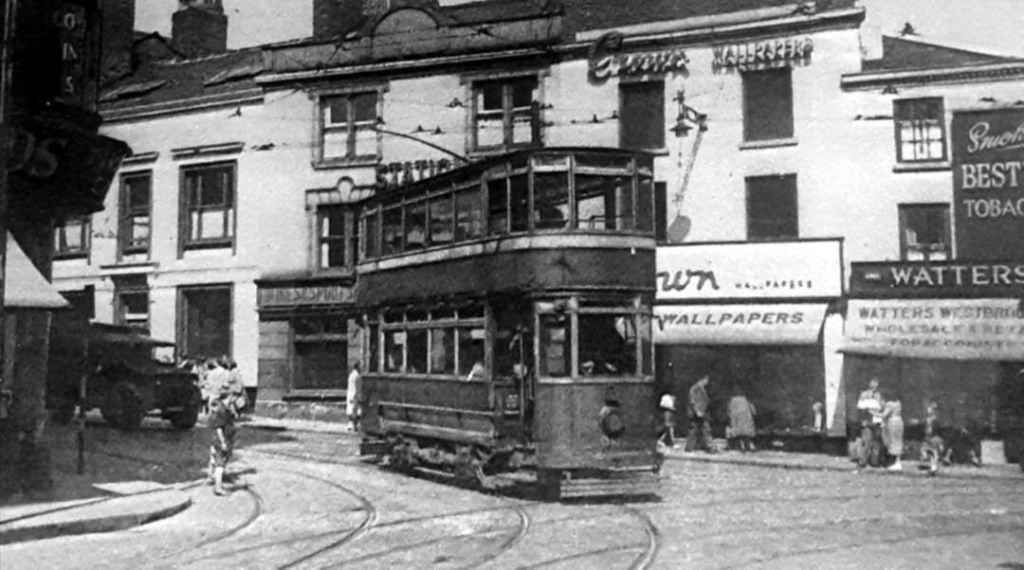

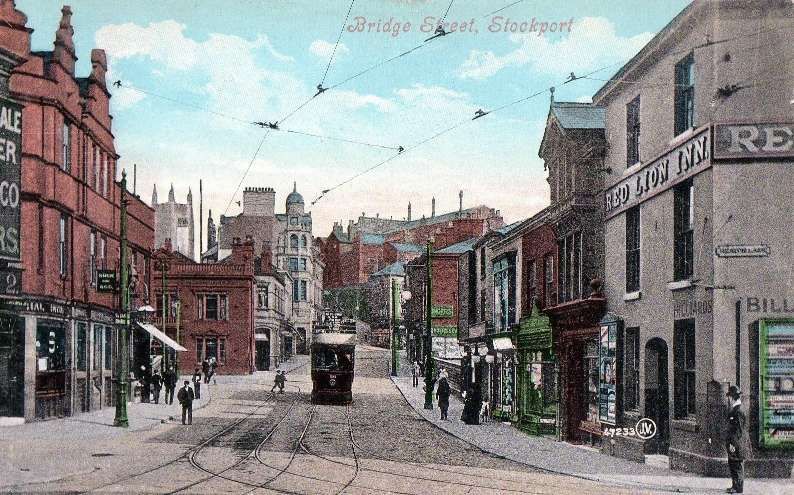

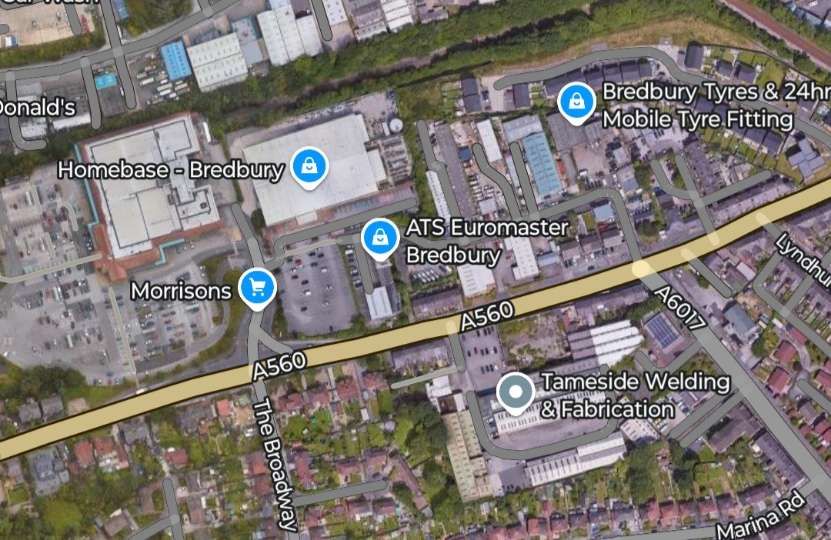

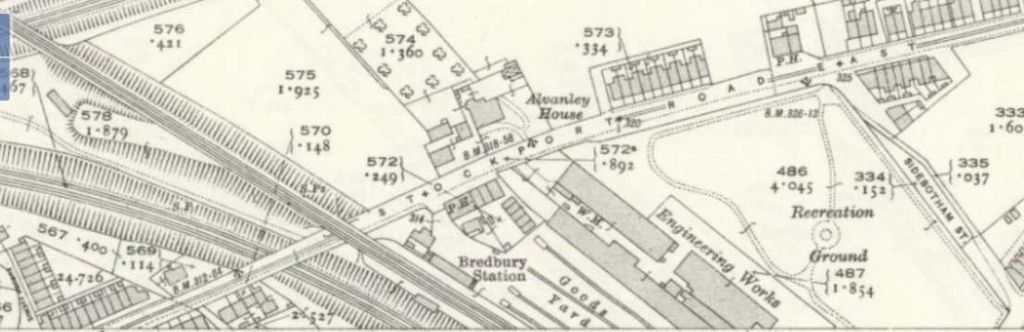

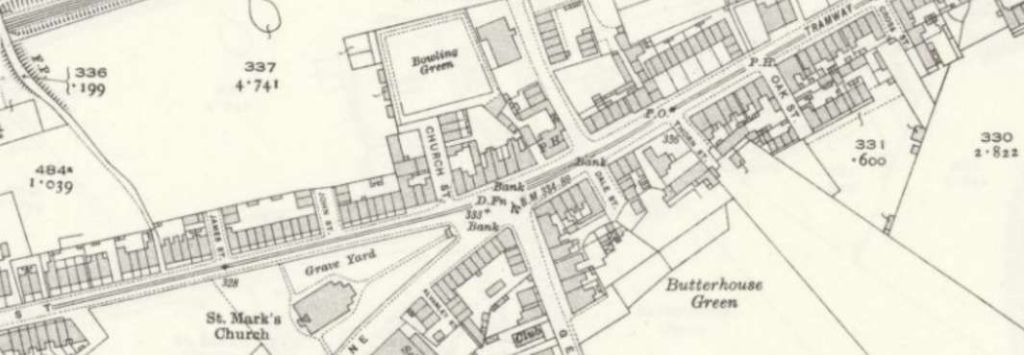

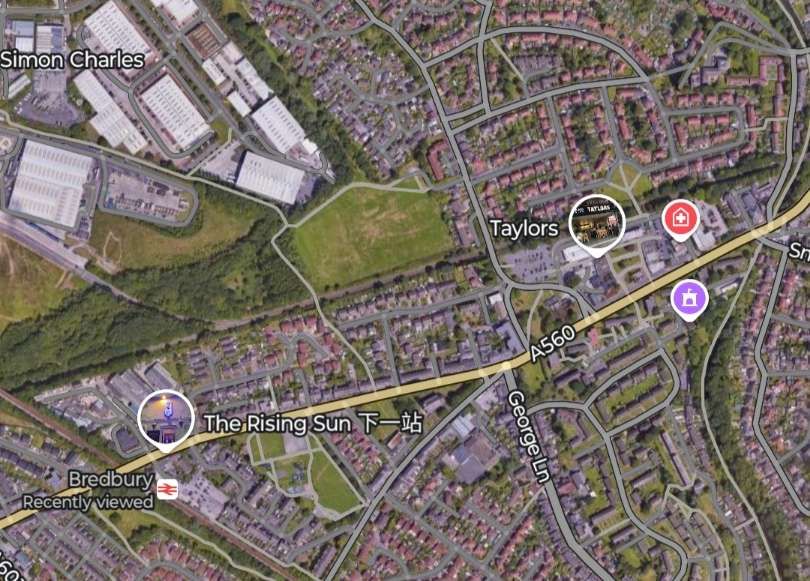

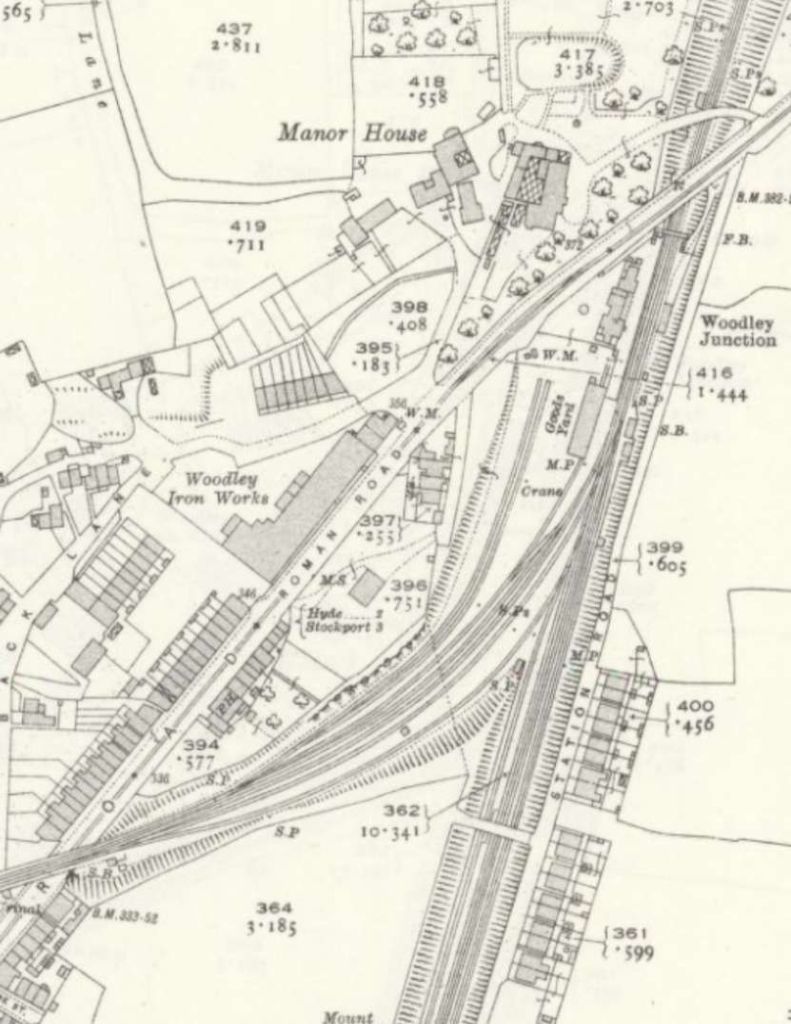

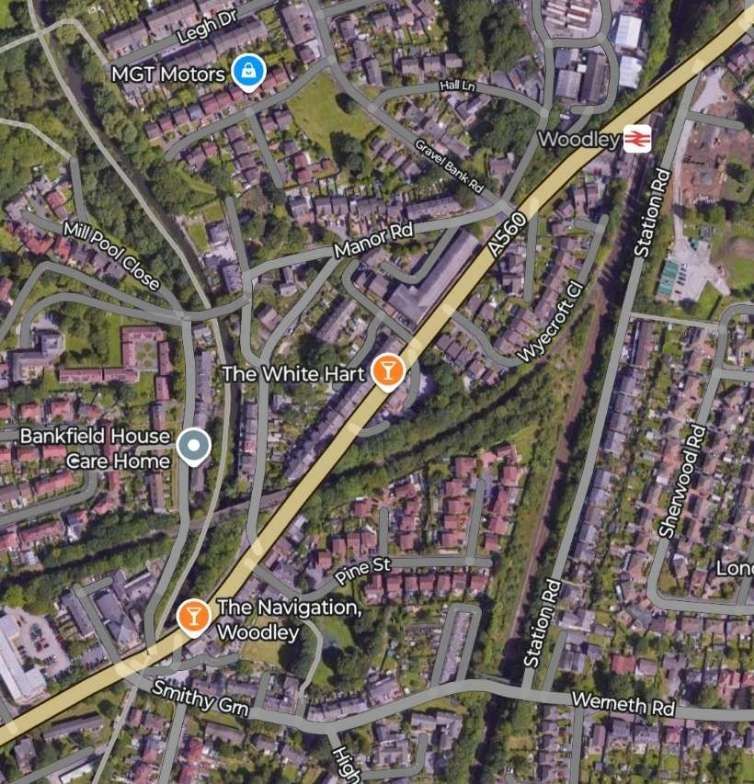

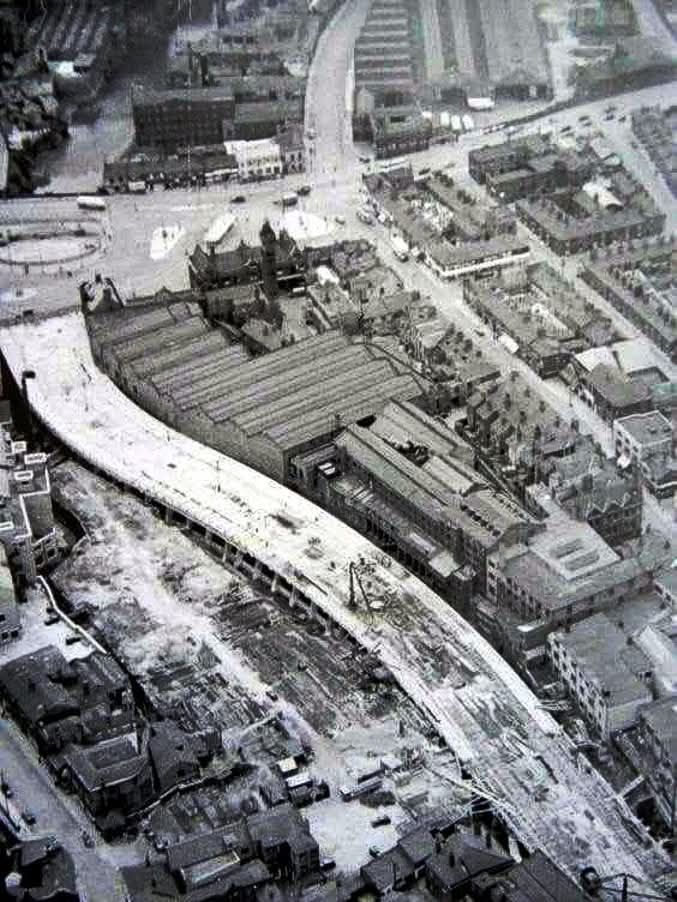

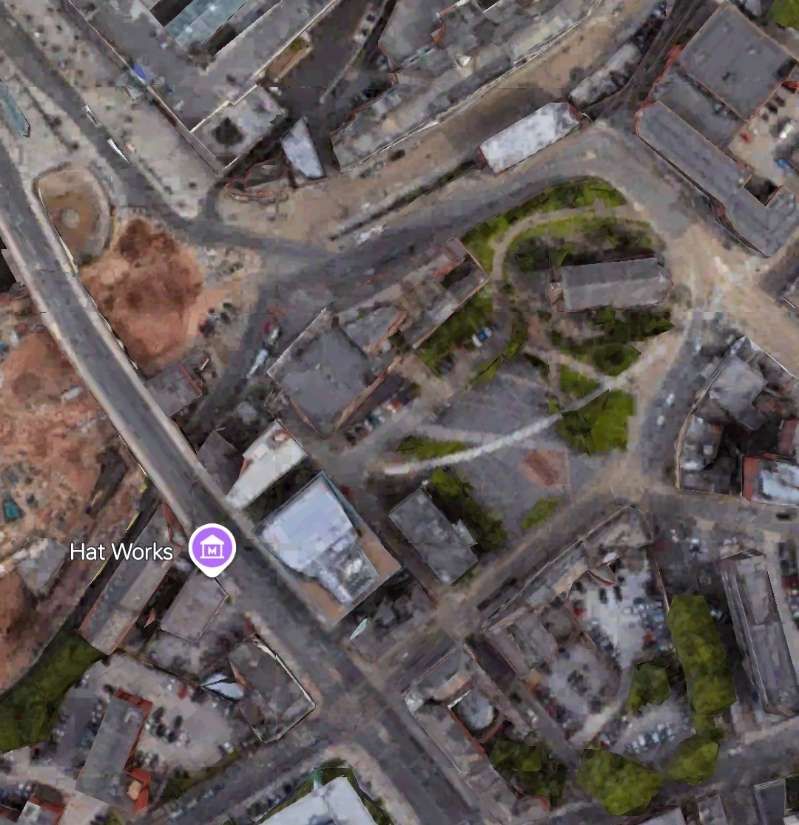

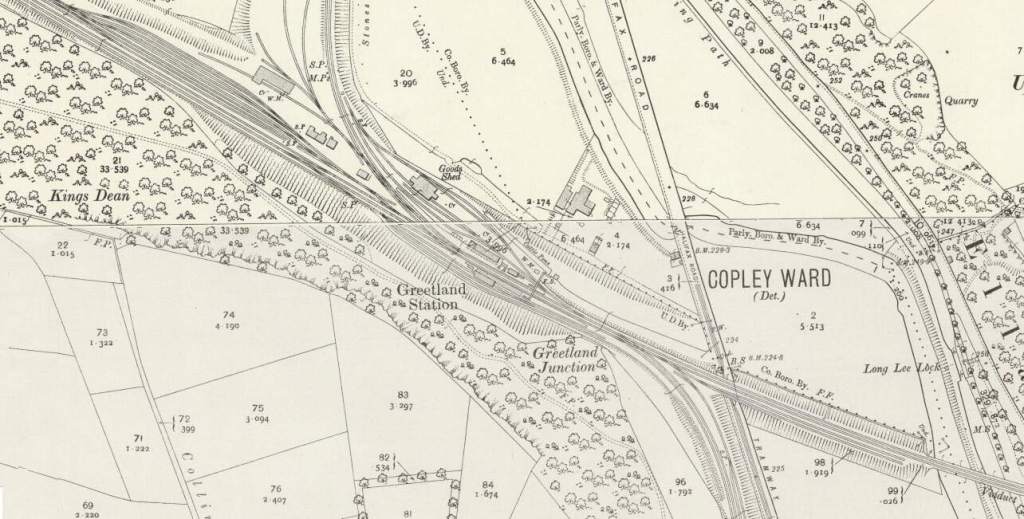

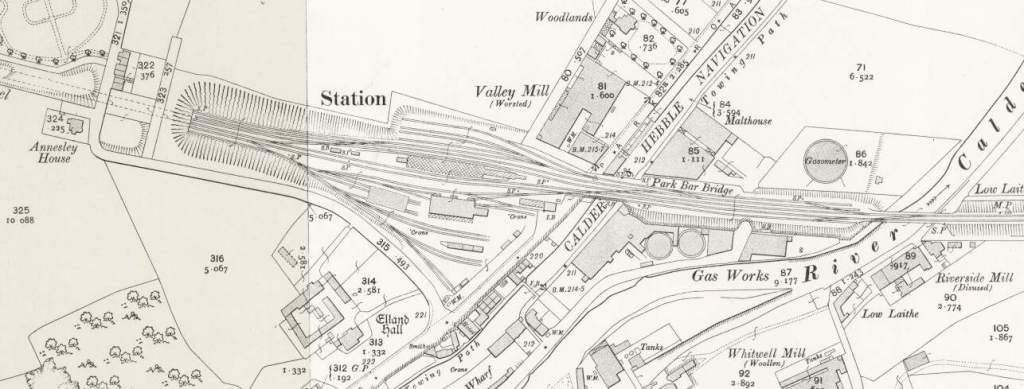

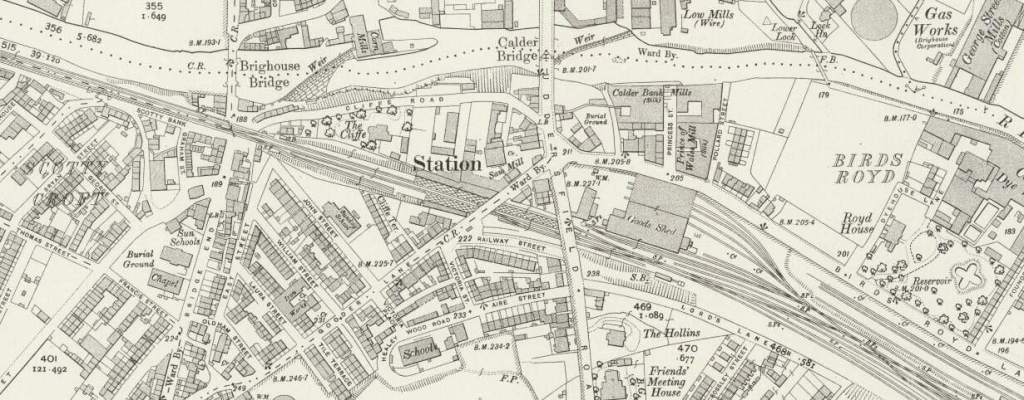

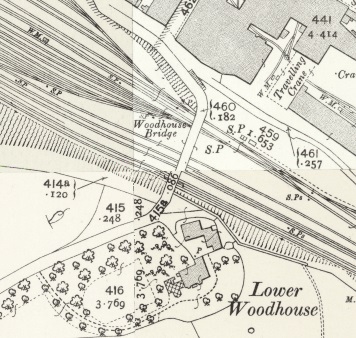

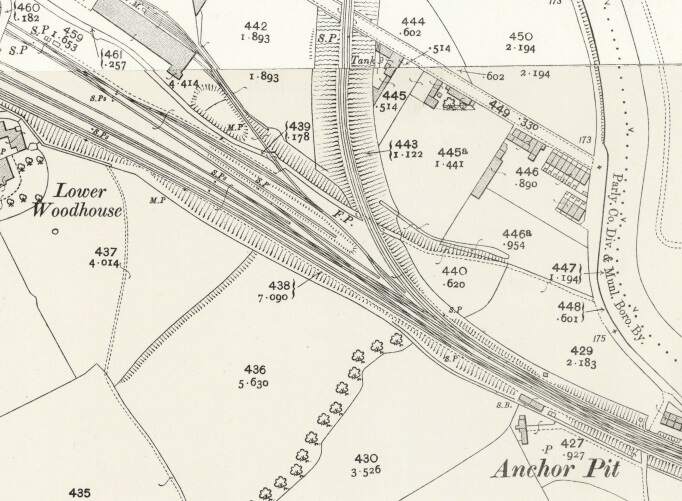

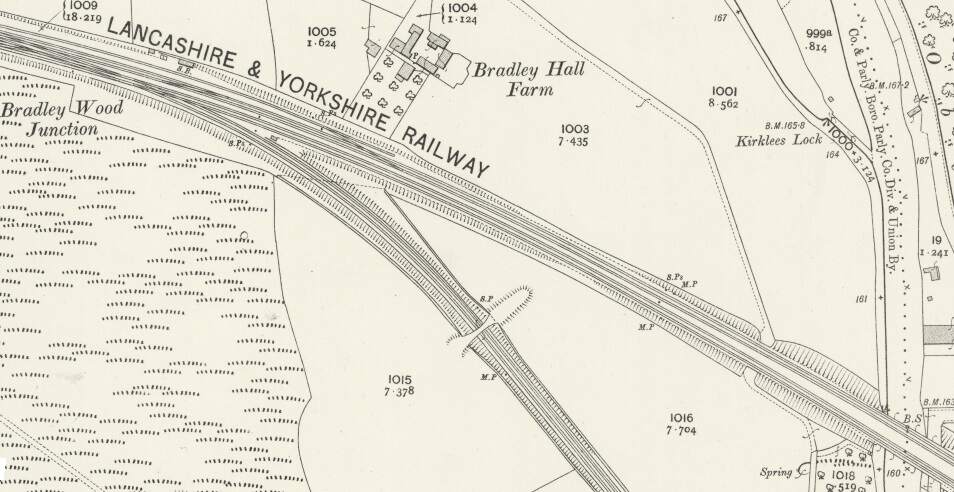

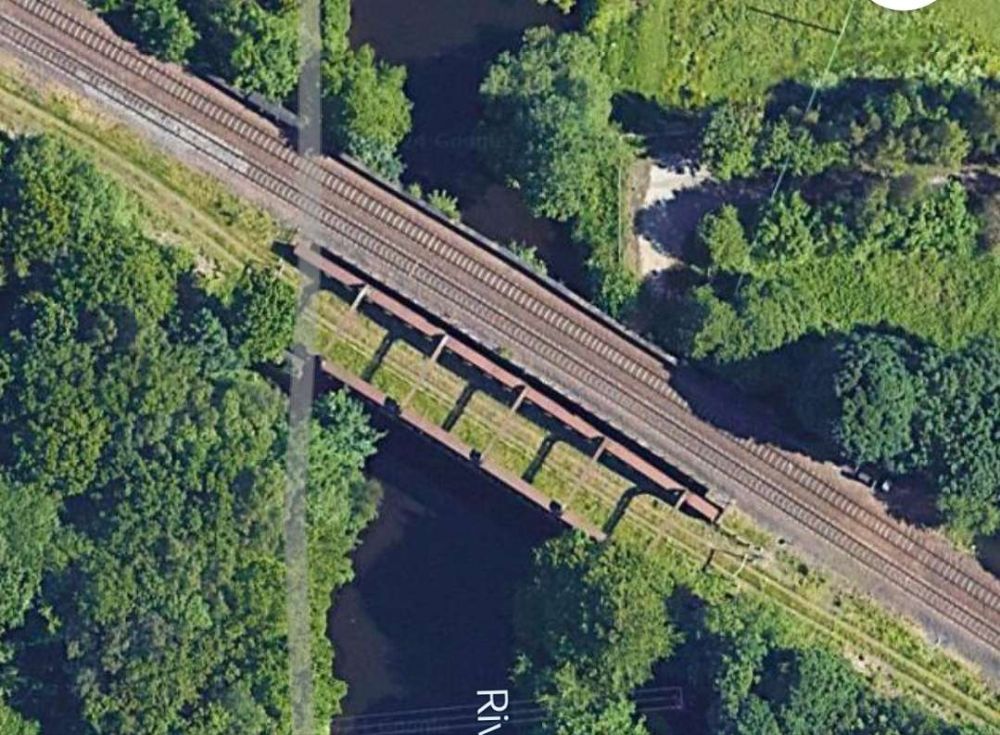

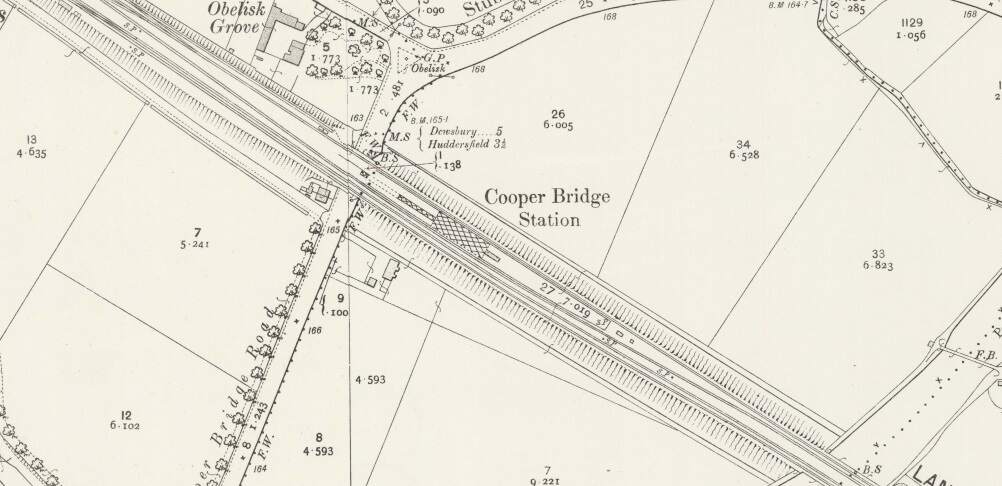

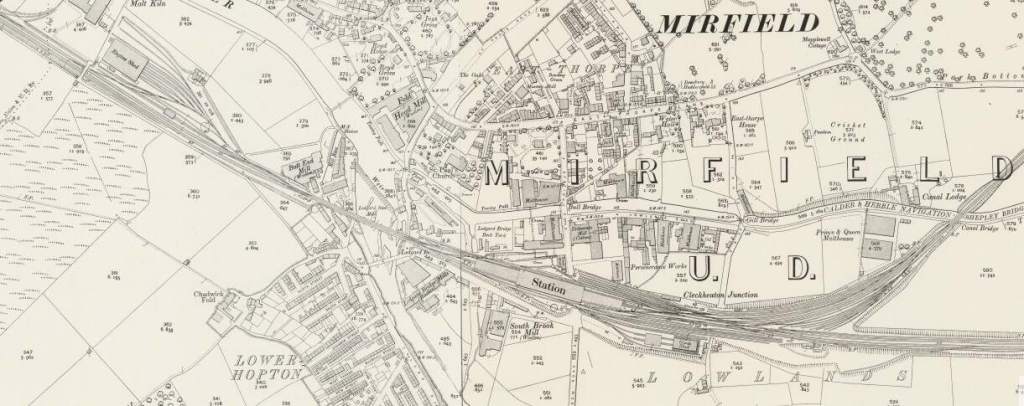

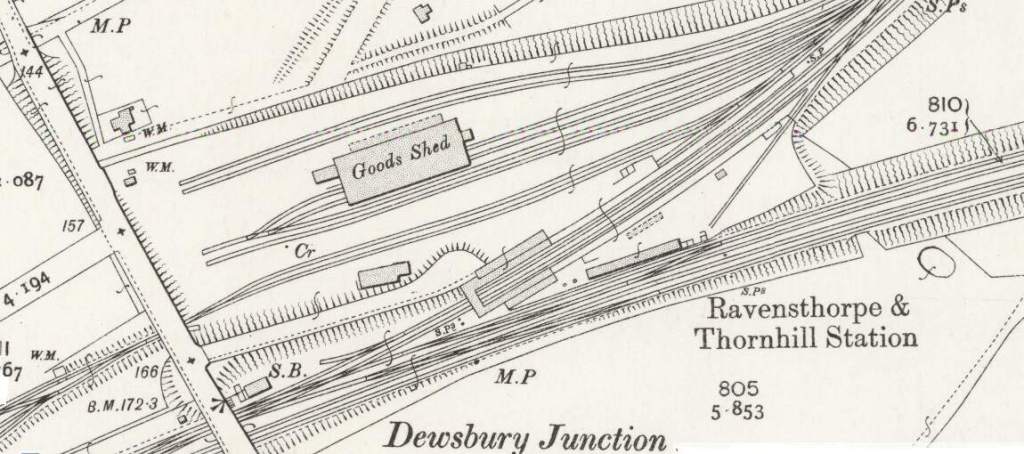

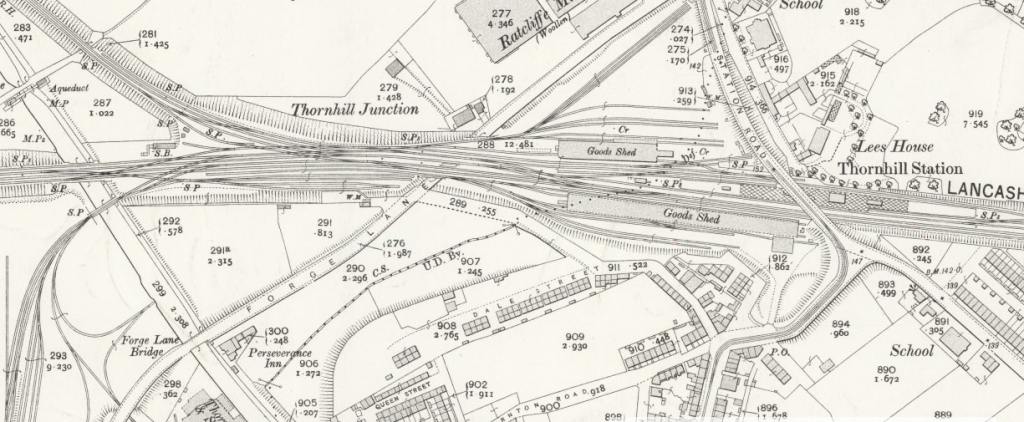

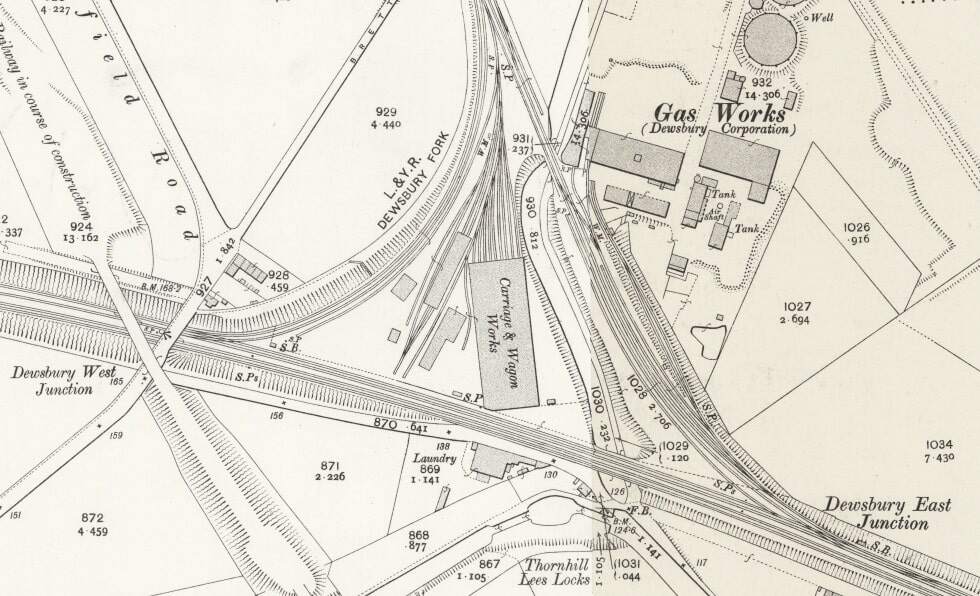

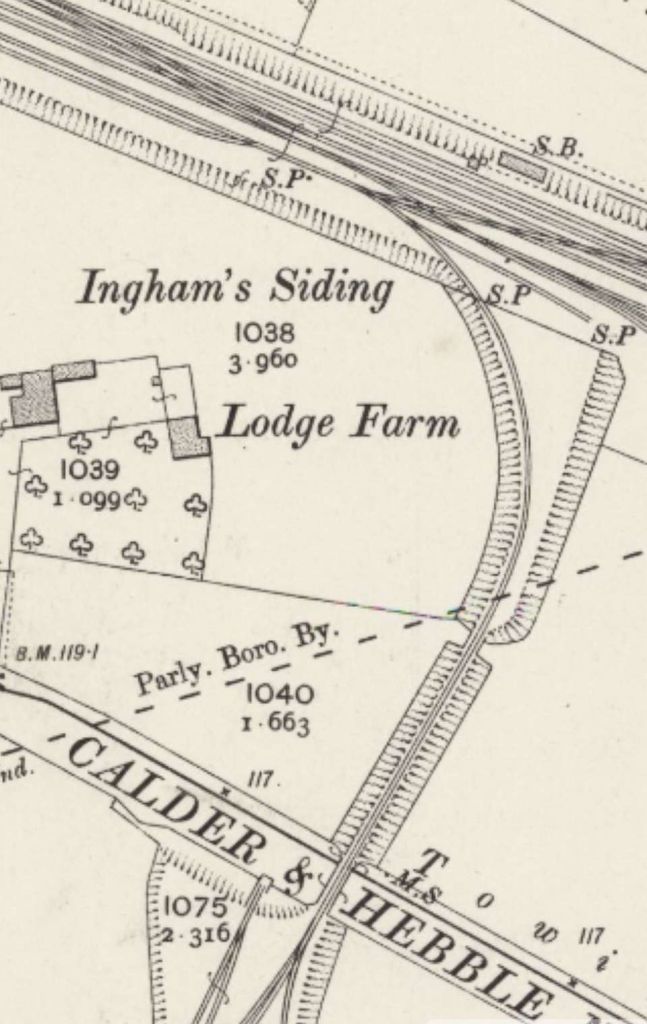

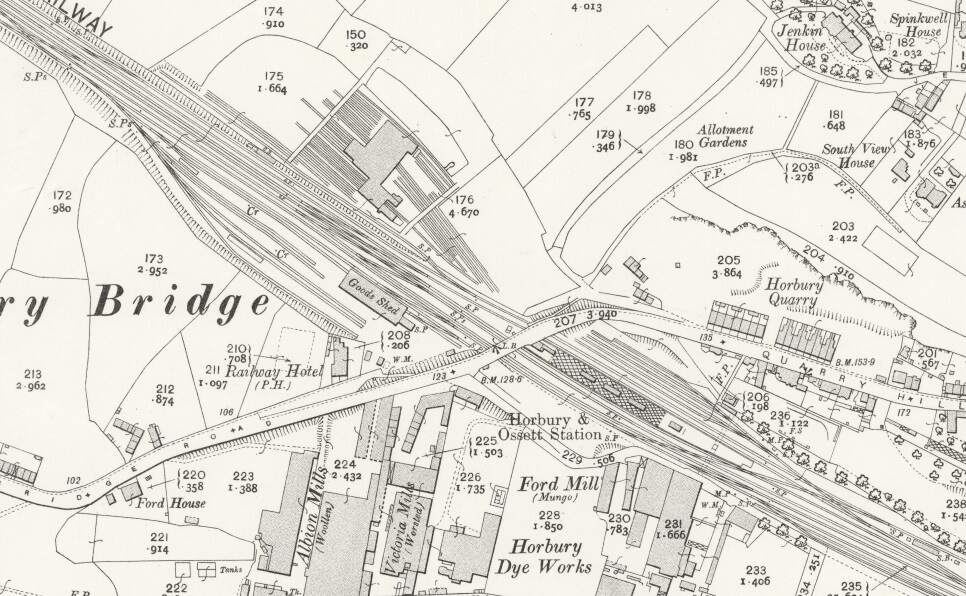

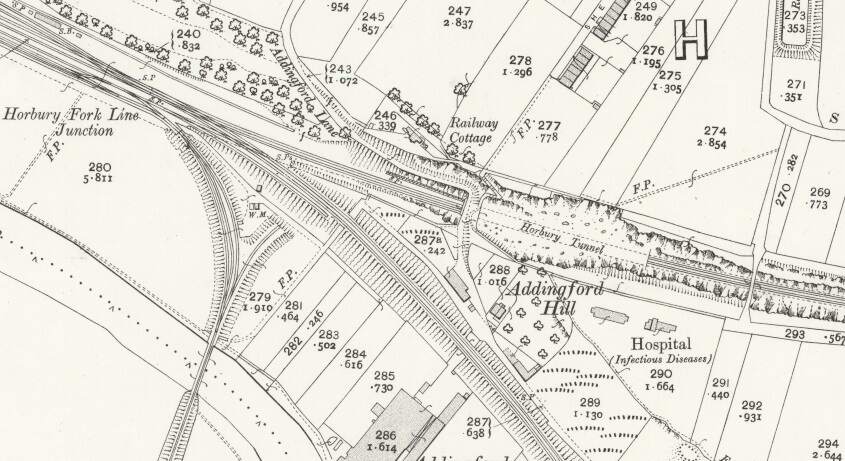

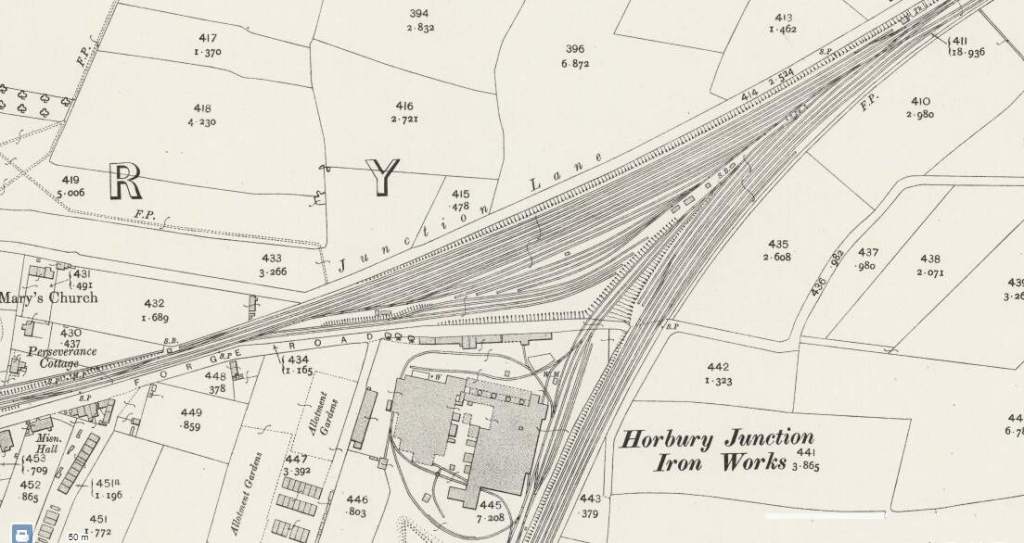

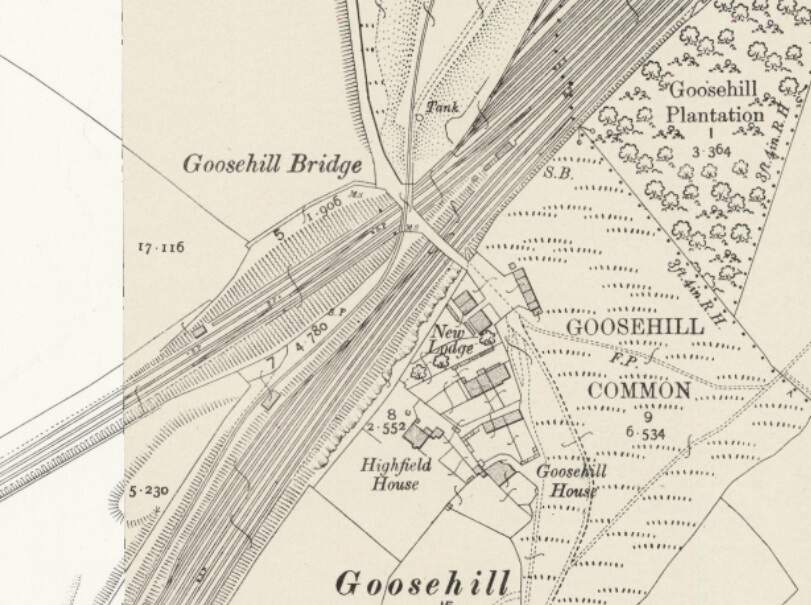

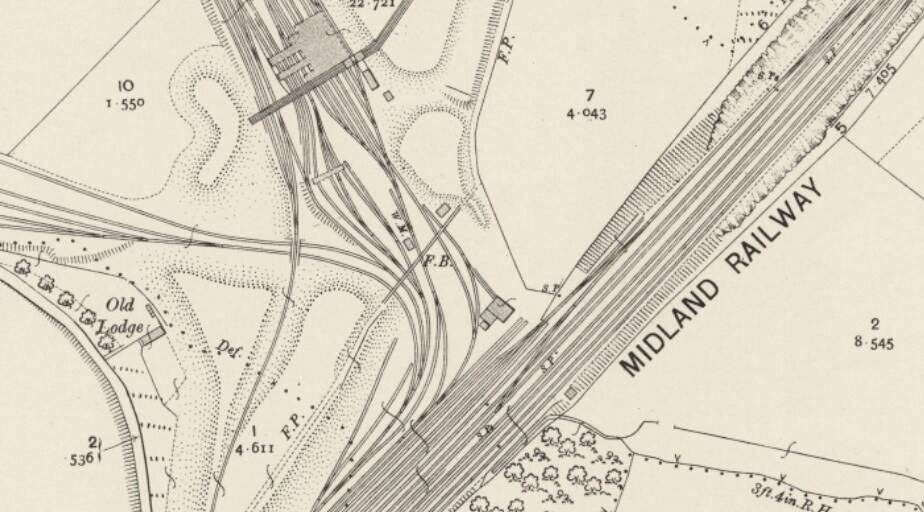

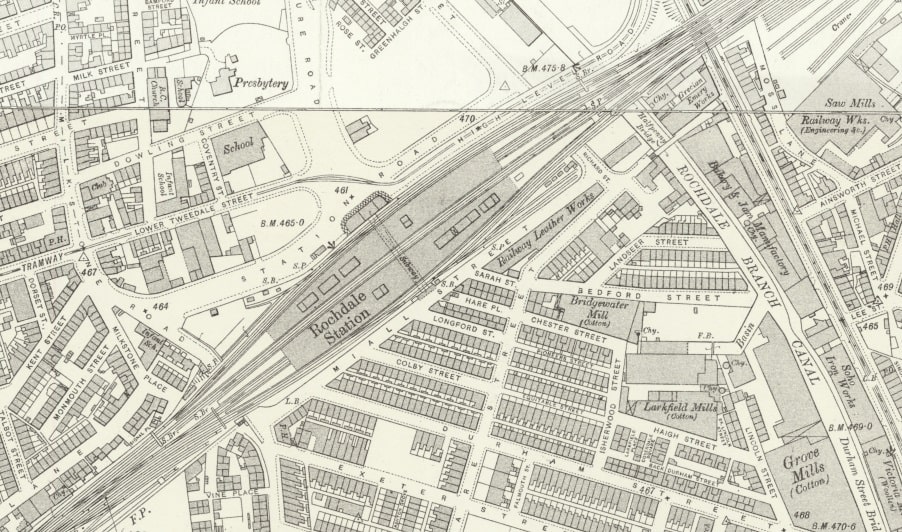

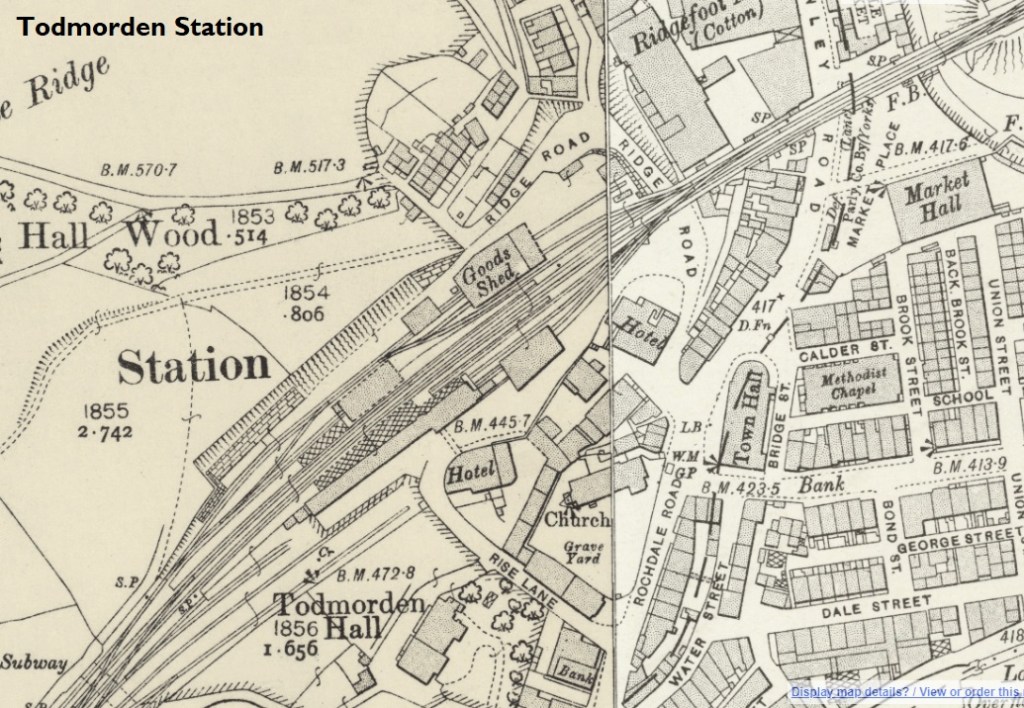

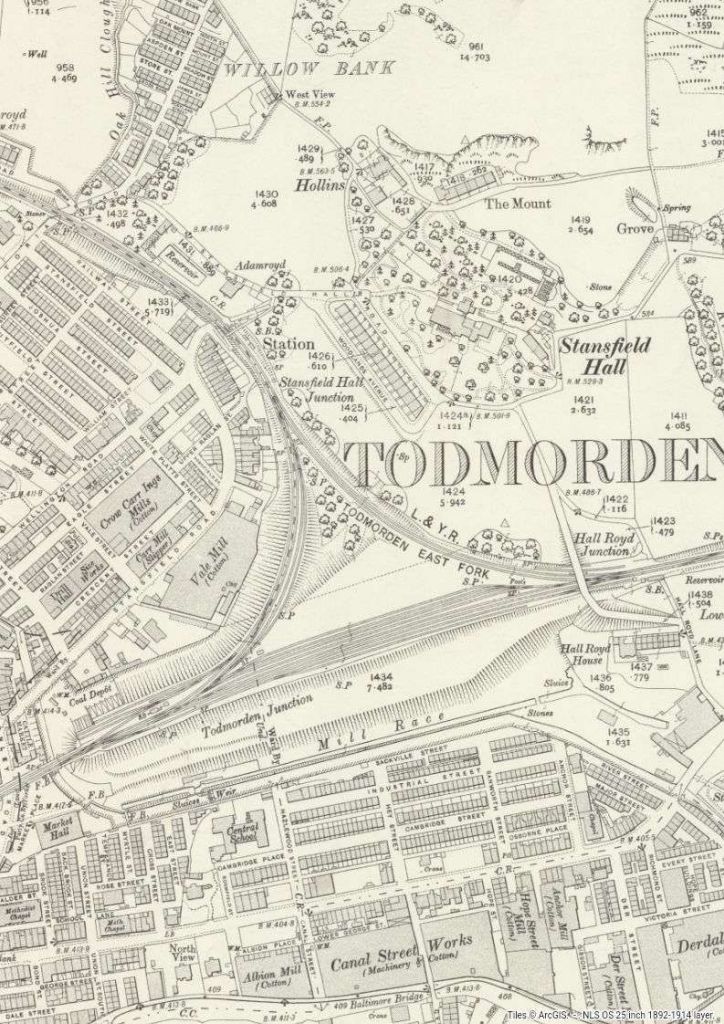

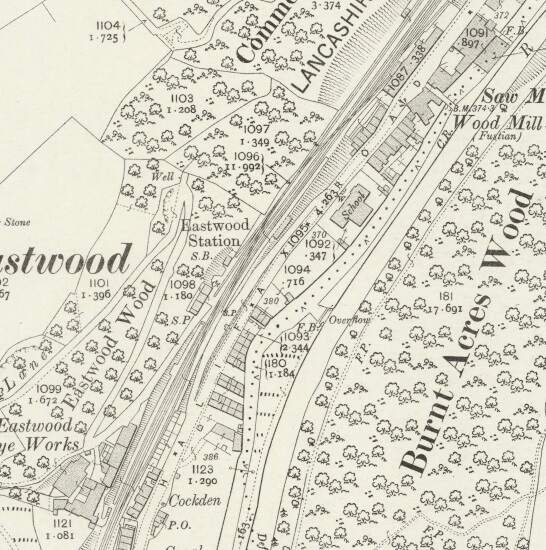

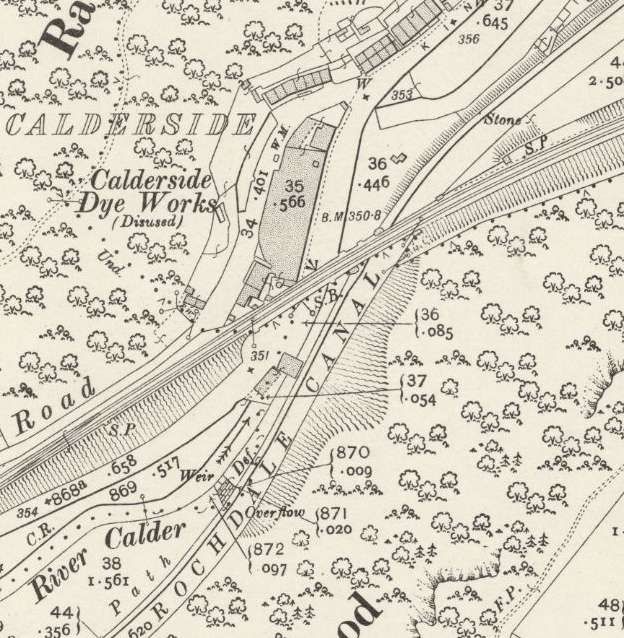

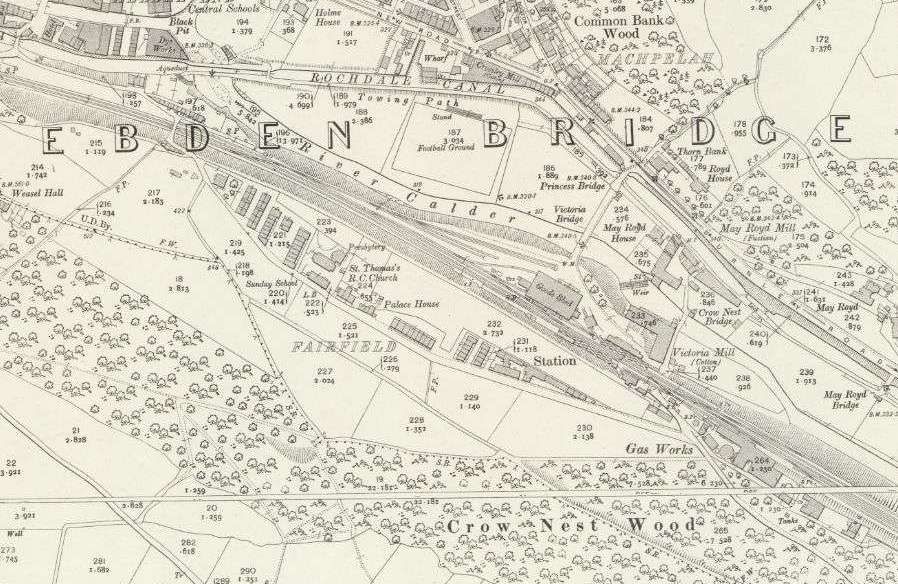

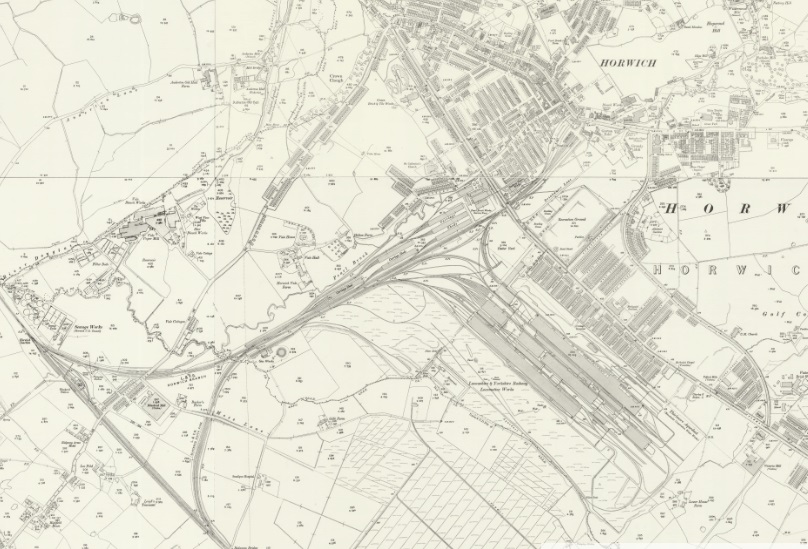

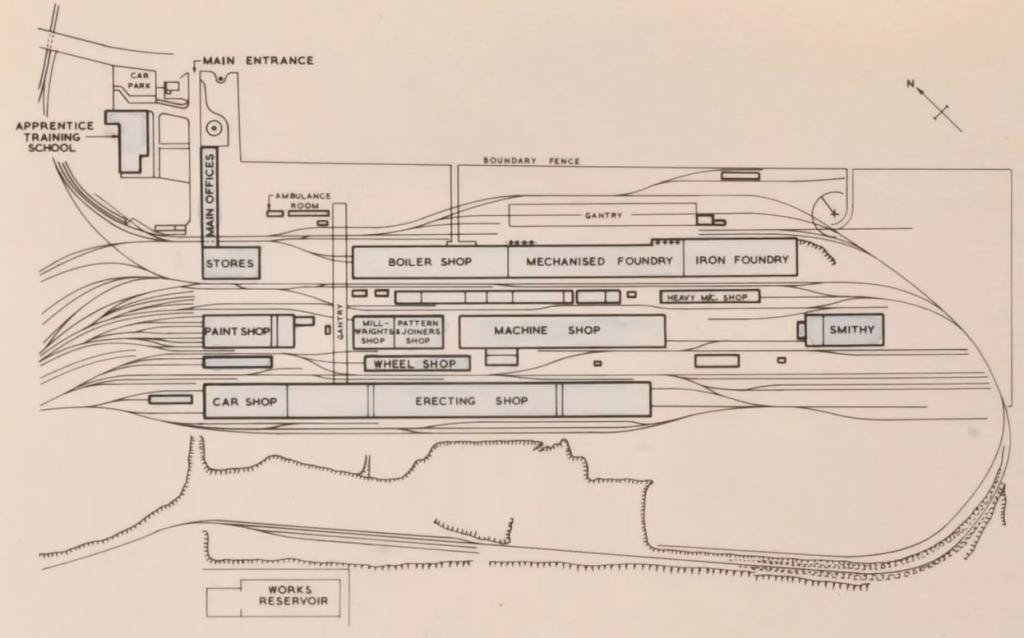

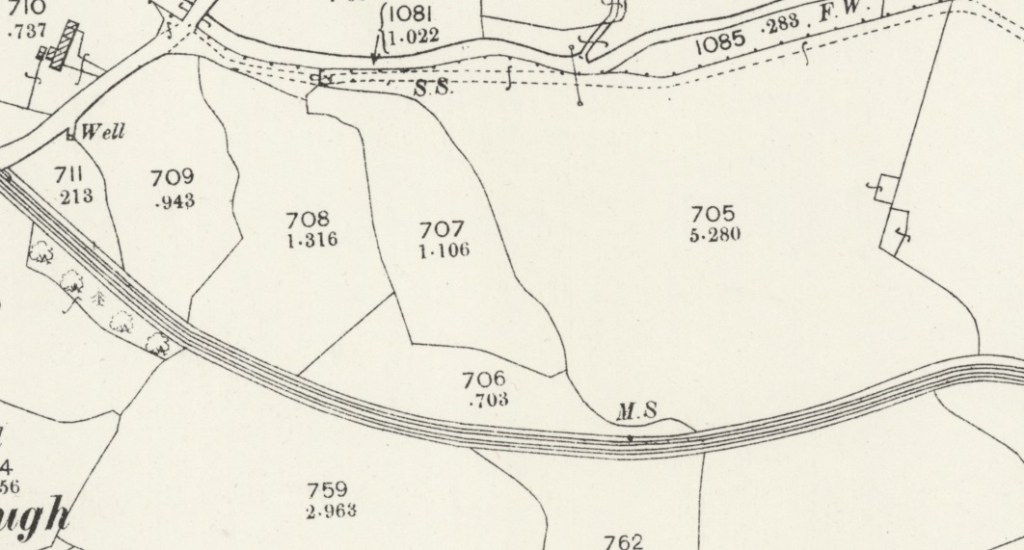

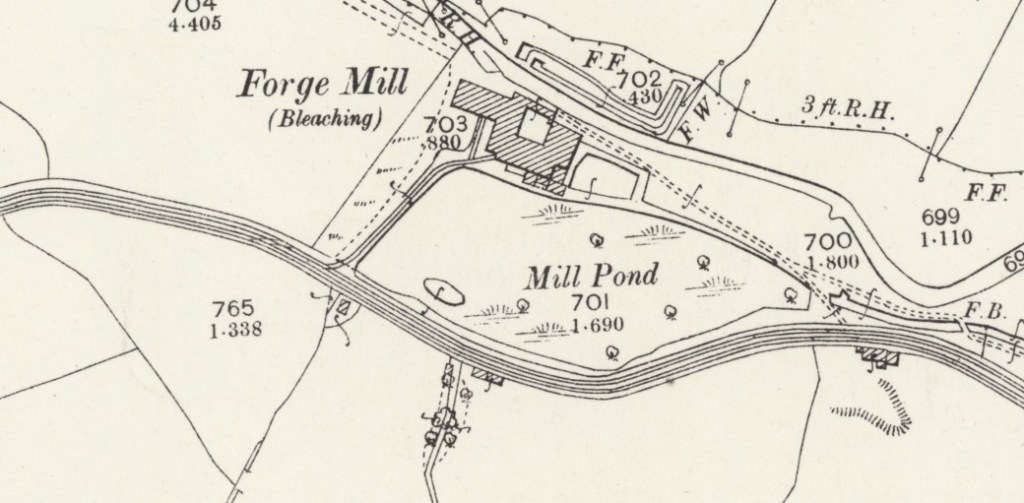

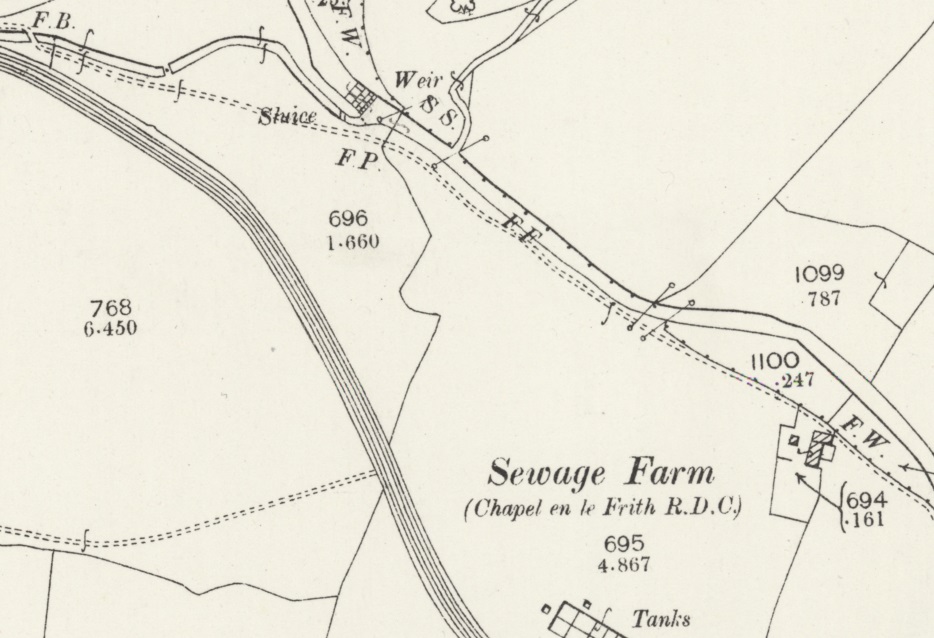

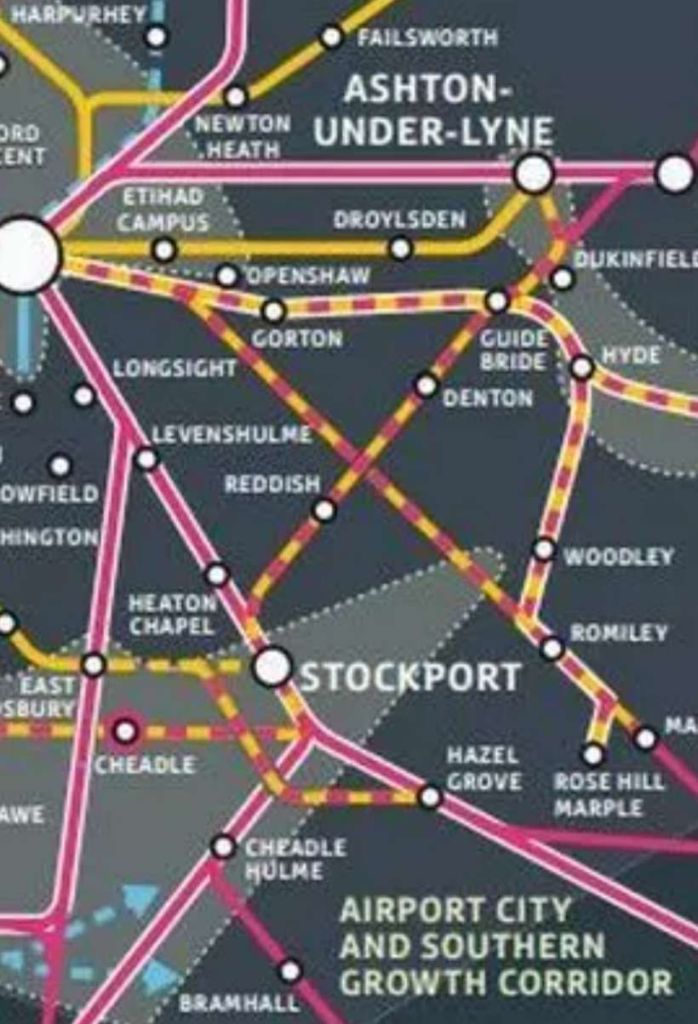

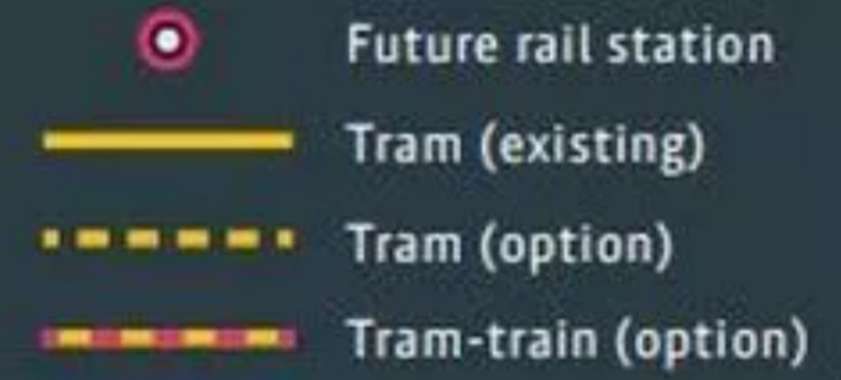

An extract from the TfGM plan for transport, looking forward towards 2040. It is intended that a tram-train service will run North from Stockport through Reddish, Denton and Guide Bridge to Ashton-under-Lyne. A similar service is planned to connect from Manchester Airport through Cheadle to Hazel Grove with a link North into Stockport to connect with the line through Denton. This schematic plan also shows the link from East Didsbury into Stockport. [12]

And finally …

Railway-News.com reported on 10th December 2025 that on 9th December 2025, TfGM Launched a Consultation on Future of Public Transport. The consultation invites people who live, work, travel, visit or study in Greater Manchester to help shape the future of the city region’s travel network by giving their views on the new GM Transport Strategy 2050, as well as the GM Transport Delivery Plan (2027-37). [13]

The proposed Plan will set out a framework “for how the Bee Network might be utilised to help Greater Manchester continue to become the growth capital of the UK through to 2050, whilst also addressing inequality and creating a greener city region.” [13]

The Consultation will run until 9th March 2026.

Backed by 2.5 billion GBP in government funding; TfGM’s plans “aim to deliver a number of transport projects through to the 2030s, resulting in what TfGM intends to be a world-class transport system. They will support both overall economic growth and the delivery of the new £1 billion Greater Manchester Good Growth Fund, which will in turn pump-prime a set of projects, drive growth and generation and ensure equal spending across the city region as a whole.” [13]

Additional development of the Bee Network, as well as a more reliable highways network, are set to underpin the new approach, which aims to better connect communities with locations, jobs and services. (Image, © Transport for Greater Manchester.) [13]

“The Bee Network is set to begin incorporating rail services by 2028, with TfGM aiming to provide 90% of the city region with five-minute access to a bus or tram that arrives at least every 30 minutes.” [13]

“GM transport strategy and delivery plans include keeping the local transport network safe and reliable via the renewal and maintenance of roads, Metrolink network and rail facilities; simplifying of fares, ticketing, bus services and introduction of new stops and services, as well as interchanges, Metrolink lines and expanded walking, wheeling and cycling networks; and the transformation of all local rail lines by incorporating them into the Bee Network.” [13]

“A detailed delivery programme listing schemes is set out in the GM Transport Delivery Plan 2027 – 2037, which is split into three phases, along with works in the regional centre and a wider ongoing set of works across the city region.” [13]

In addition to online feedback; a series of face-to-face drop-in sessions are planned to take place across Greater Manchester. The documents which are available to read online through clicking on these links:

and

For an overview of both documents, please click here. [16]

TfGM want to hear from anyone with an interest in the future of transport in Greater Manchester. They outline how you can respond here. [17] The deadline for participation is 9th March 2026.

Returning to where this article started, this is what the consultation draft of the Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2050 document says about Stockport:

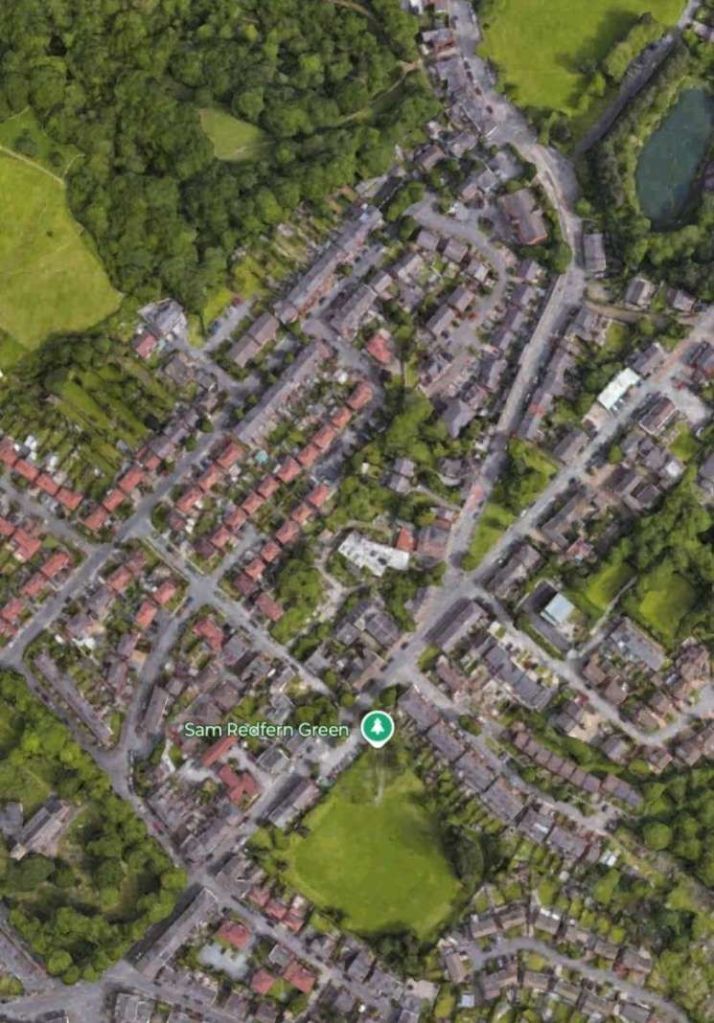

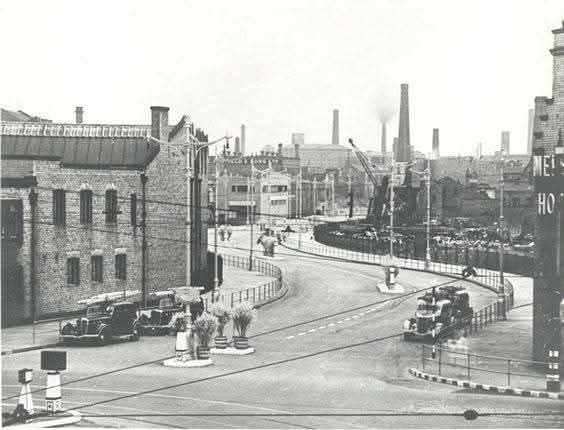

“Stockport town centre: Over the last decade, Stockport Council has spearheaded a £1bn transformation of its town centre. One of the UK’s largest town centre regeneration programmes, it has enabled the town to buck the trend of decline, with successful schemes across leisure, commercial and residential uses. Since 2019 Stockport Mayoral Development Corporation (MDC) has played a powerful role in accelerating this transformation, delivering a residential led masterplan for Stockport Town Centre West. The MDC is a radical new approach to tackling future housing need and the changing role of town centres, delivered through a unique collaboration between the GM Mayor and Stockport Council. It brings together powers devolved to the Greater Manchester Mayor, combined with strong local leadership from Stockport Council and the long-term commitment of the government’s housing agency, Homes England, to deliver an ambitious vision for the future of Stockport town centre. Over the past 6 years in collaboration with its many partner organisations the MDC moved from innovative concept to proven delivery vehicle, with over 170,000 sq. ft. new Grade A offices at Stockport Exchange, 1,200 new homes completed or on site and a state-of-the-art new transport Interchange with two-acre rooftop park. Reflecting this success and the Council’s continued growth ambitions, in 2025 the Council and GMCA agreed to expand the boundary of the MDC to cover the whole of the town centre and doubling its housing target to 8,000 homes by 2040.” [14]

References

- https://railway-news.com/tfgm-exploring-plans-to-bring-trams-to-stockport, accessed on 4th December 2025.

- https://news.tfgm.com/press-releases/c956a710-e894-49ab-b1de-1b8fb97e7859/underused-denton-rail-line-being-considered-as-part-of-case-to-take-trams-to-stockport, accessed on 4th December 2025.

- news.tfgm.com/press-releases/897ce680-87a9-4349-a632-b477b1a8330f/greater-manchester-s-2-5-billion-funding-boost-to-unlock-uk-s-first-fully-integrated-zero-emission-public-transport-network, accessed on 4th December 2025.

- A Strategic Outline Case (SOC) is the first part of developing a business case for major infrastructure projects. The two further stages are the Outline Business Case (OBC) followed by the Full Business Case (FBC). In the case of extending Metrolink to Stockport approval is required from the Department for Transport (DfT) to progress through each stage.

- https://tfgm.com/strategy, accessed on 4th December 2025.

- https://assets.ctfassets.net/nv7y93idf4jq/01xbKQQNW0ZYLzYvcj1z7c/4b6804acd572f00d8d728194ef62bb89/Greater_Manchester_Transport_Strategy_2040_final.pdf, accessed on 4th December 2025.

- https://assets.ctfassets.net/nv7y93idf4jq/6tfus0lbLRvTlR64knc3g7/db49b54dc2e8f3dd29416ab560e1a6fe/21-0003_2040_Transport_Strategy_Exec_Summary.pdf, accessed on 4th December 2025.

- https://www.placenorthwest.co.uk/burnham-sets-target-of-2050-for-manchester-underground, accessed on 4th December 2025.

- http://www.semmms.info, accessed on 4th December 2025.

- https://consultation.stockport.gov.uk/policy-performance-and-reform/semmms/supporting_documents/SEMMMS%20Report.pdf, accessed on 4th December 2025.

- http://www.semmms.info/wp-content/uploads/SEMMMS-Consultation-Report.pdf, accessed on 4th December 2025.

- https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/new-metrolink-map-tram-manchester-29510064, accessed on 6th December 2025.

- https://railway-news.com/tfgm-launches-consultation-on-future-of-public-transport/?dtt=&email_address=rogerfarnworth@aol.com&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=RN-week50b-2025, accessed on 11th December 2025.

- https://www.gmconsult.org/transport/transport2050/user_uploads/gm-transport-strategy-2050—–final-consultation-draft.pdf, accessed on 11th December 2025.

- https://www.gmconsult.org/transport/transport2050/user_uploads/gm-transport-delivery-plan—–final-consultation-draft.pdf, accessed on 11th December 2025.

- https://www.gmconsult.org/transport/transport2050/user_uploads/gm-transport-strategy-and-delivery-plan-summary—consultation-draft.pdf, accessed on 11th December 2025.

- https://www.gmconsult.org/transport/transport2050, accessed on 11th December 2025.