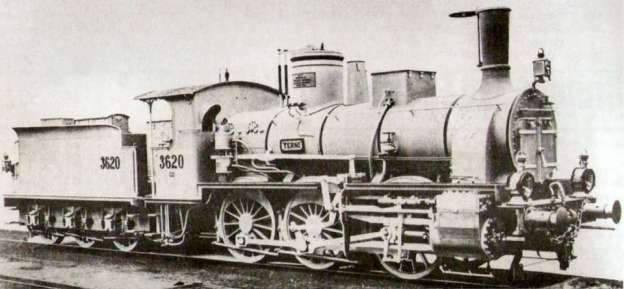

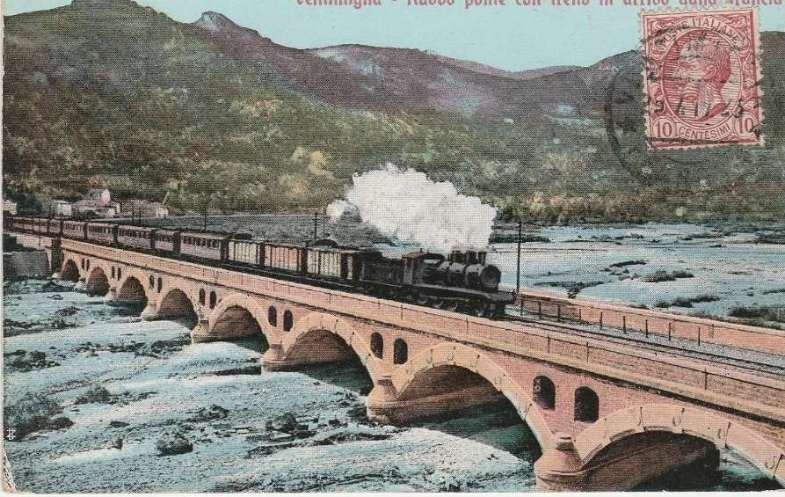

The featured image for this article, above is an FS Series 320 0-6-0 (030 in Italian notation) steam locomotive which was used in the early days of operation on the southern section of the Ventimiglia-Cuneo line, before the North and South sections could be linked. The locomotive depicted is FS3620 and carries a nameplate – ‘Terni’. 201 locomotives of this Class were built between 1904 and 1908. [8]

In the first four articles about the line from Cuneo to the sea we covered the length of the line from Cuneo to Breil-sur-Roya. These articles can be found here, [9] here [10] here, [11] and here. [12]

I also want to acknowledge the assistance given to me by David Sousa of the Rail Relaxation YouTube Channel https://www.youtube.com/@RailRelaxation/featured and https://www.railrelaxation.com and particularly his kind permission given to use still images from rail journeys that he has filmed on the Cuneo-Ventimiglia railway line. [35][55]

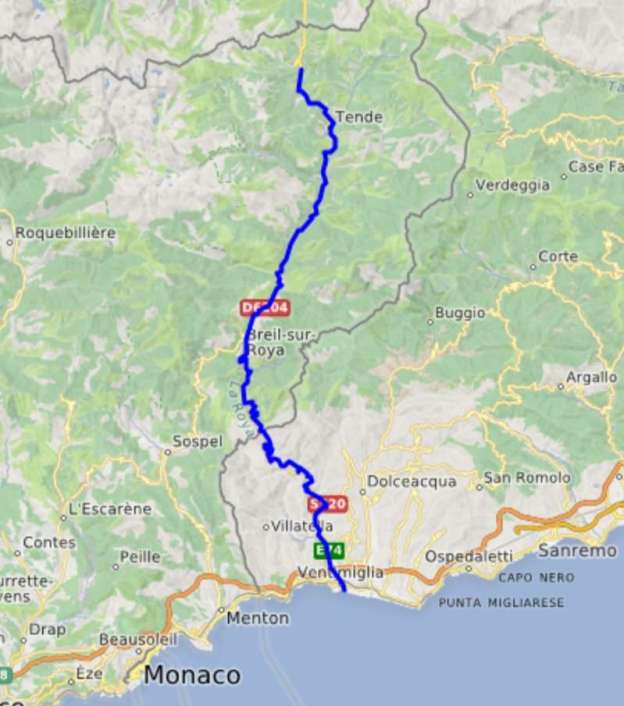

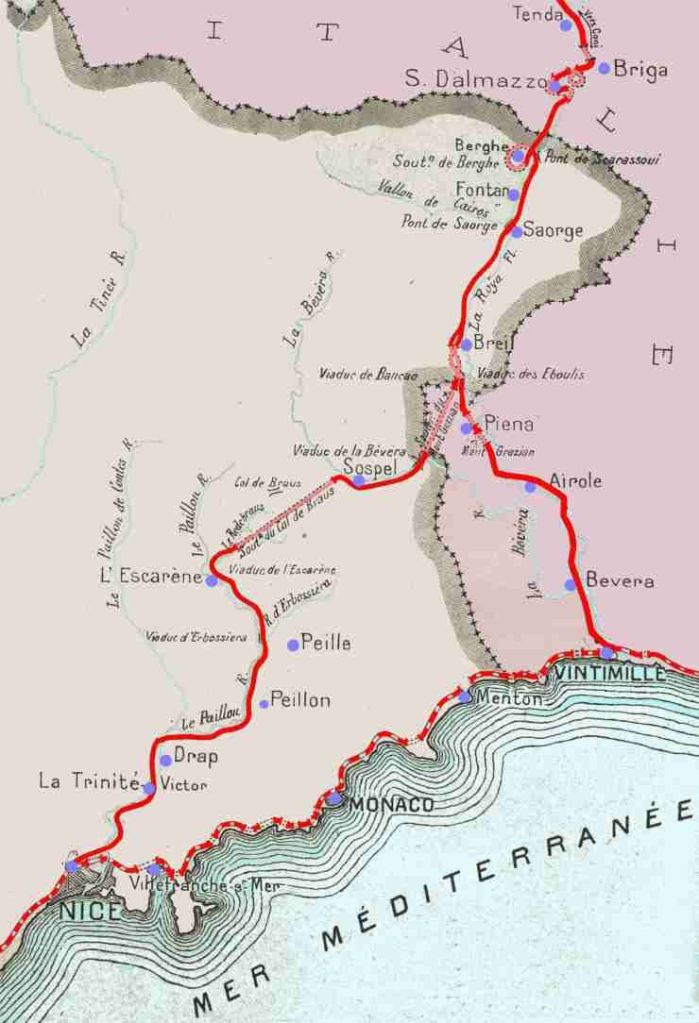

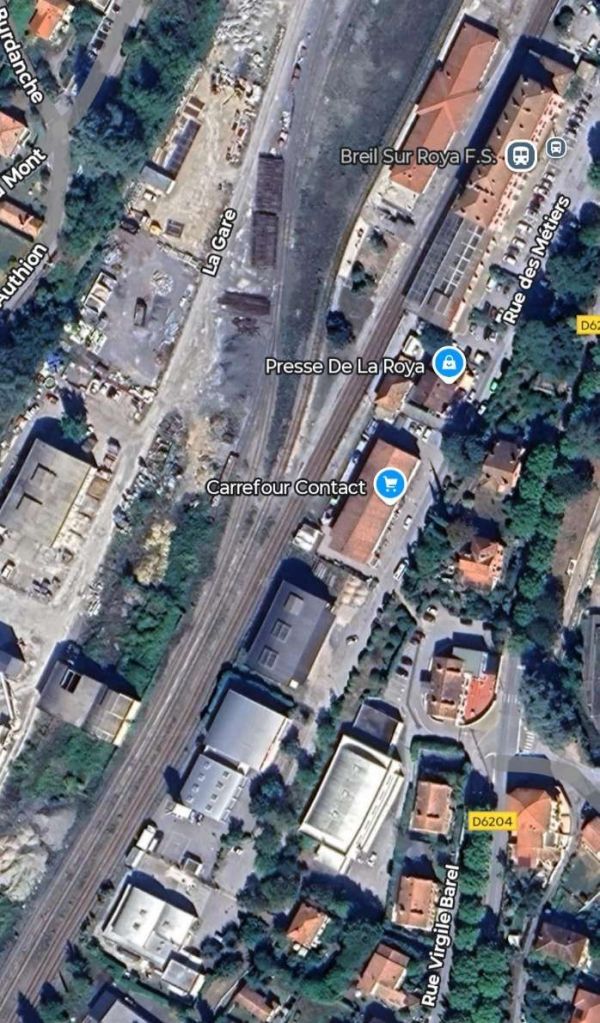

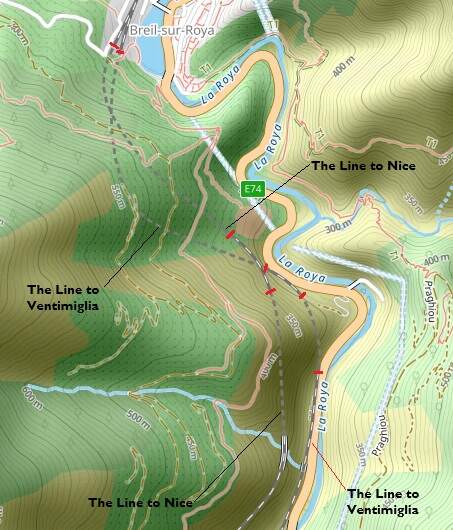

South of Breil-sur-Roya a junction allows direct access to Ventimiglia and to Nice. The map below shows the two routes as they existed prior to the alteration of the border between France and Italy after the Second World War.

This article follows the line South from Breil-sur-Roya to Ventimiglia in two parts: the first as far as Airole and the second from Airole to Ventimiglia. ….

1. The Line South from Breil-sur Roya to Airole

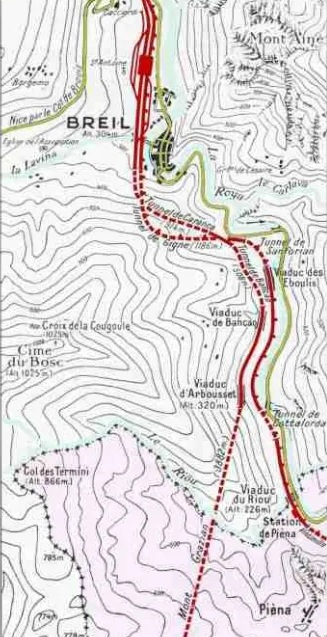

This drawing/map shows the two routes heading South from Breil-sur-Roya. [40]

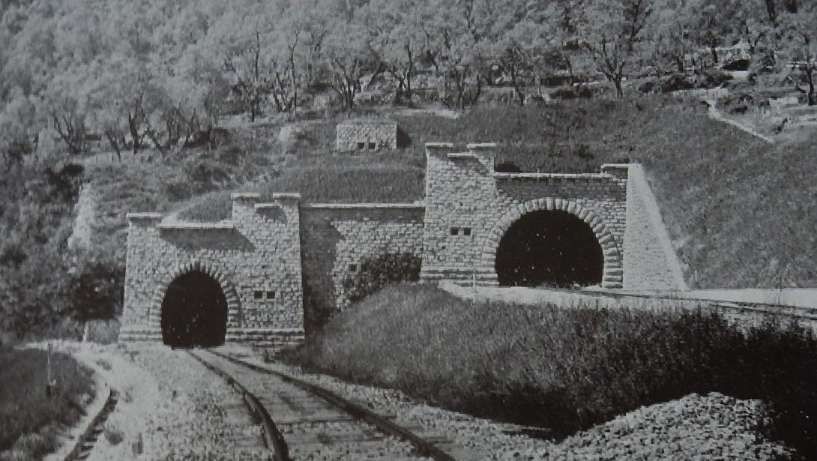

As with the line immediately to the North of Breil-sur-Roya, the works to the South were constructed by the French. Both of the lines heading South from Breil-sur-Roya entered tunnels just a short distance South of Breil.

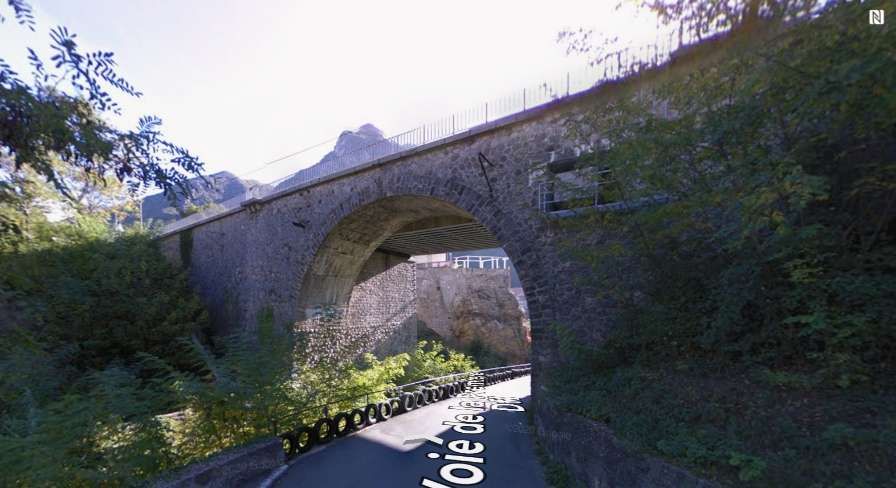

South of the station adjacent parallel bridges cross the Voie de la Première Dfl and Vallon de la Lavina (the Lavina Bridge).

The approach to the junction from Ventimiglia. The line from Nice is at the higher level on the left. [35]

The mouth of Gigne Tunnel (1188 metres in length), seen from the cab of the Ventimiglia-bound service. The tunnel is S-shaped. Trains heading South turn to the East within the tunnel and then, close to the East Portal, begin to turn to the South again. [55][1: p126]

The view North from the North Portal of Gigne Tunnel, seen from the cab of a Northbound train. [35]

The route of this tunnel crosses twice under the Caranca tunnel on the Nice line. [1: p126]

Just beyond the East Portal of Gigne Tunnel the line begins to curve South again. [55]

The East Portal of Gigne Tunnel, seen from the cab of a Northbound train. [35]

The North Portal of Sanfurian Tunnel (260 metres in length) was in deep shade when this image was taken from the cab of a Ventimiglia-bound train. [55]

The view Northwest from the same portal of Sanfurian Tunnel. [35]

The view South from the mouth of Sanfurian Tunnel. Note the high retaining walls to the right of the image. [55]

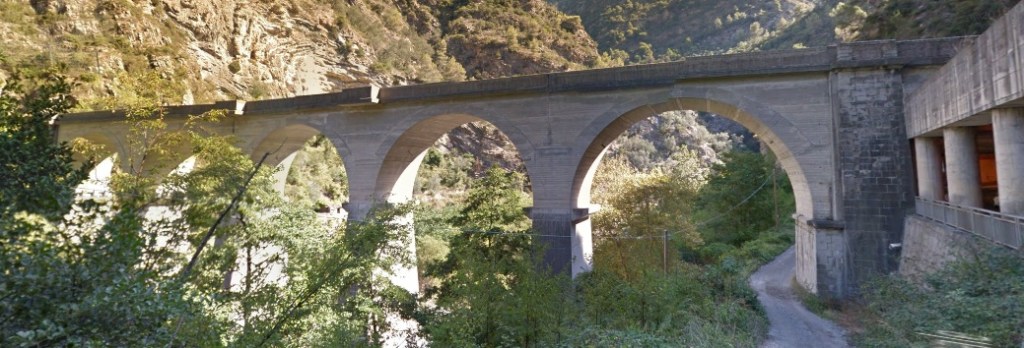

The South Portal of Sanfurian Tunnel, seen from the North end of Eboulis Viaduct. This viaduct has eight 18 metre stone arches and nine 7 metre stone arches. [35][1: p126]

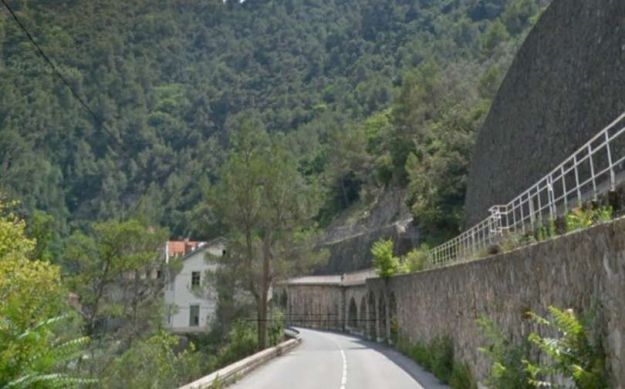

The view from the North along the Route de Ventimiglia with the railway viaduct alongside the road. [Google Streetview, July 2014]

Eboulis Viaduct facing South. [55]

Eboulis Viaduct looking North, seen from the cab of a Northbound train. [35]

Eboulis Viaduct before the construction of the road between it and the River Roya. The quality of this image is not perfect but it is still possible to make out the South portal of Snfurian Tunnel towards the right of the image. [49]

The view along the E74/D6204 from the South with the viaduct to the left of the road and the river to the right below the road. [Google Streetview, July 2014]

Looking South over Bancao Viaduct. [55]

Looking North along Bancao Viaduct. [35]

Bancao Viaduct on the line from Breil-sur-Roya to Ventimiglia is close to the D6204 on this extract from OpenStreetMap. The line to the West is the line from Breil-sur-Roya to Nice which is at a much higher level. [14]

Looking West from the D6204/E74, a small culvert close to the road is dwarfed by the bridge carrying the line to Ventimiglia which in turn is dwarfed by the viaduct carrying the line to Nice. [Google Streetview, April 2008]

The bridge carrying the line to Ventimiglia is also known as the Bancao Ravine Bridge. [1: p126]

The length of the line South of Bancao Viaduct. The two rail line are still running in parallel, only beginning to separate significantly at the bottom of this extract from Open StreetMap. Cottalorda Tunnel begins towards the bottom of this map extract. [15]

The line can only be seen fleetingly from the road.

It runs in front of the terracotta-coloured building near the centre of this image. Railings at the edge of a retaining wall supporting the line can be seen to the right of the image. [Google Streetview, July 2014]

The North portal of Cottalorda Tunnel (297 metres long). [55]

Turning through 180°, this is the view North at the same location. [35]

Just a glimpse of the tunnel mouth and the associated retaining wall can be seen from the D6204/E74. [Google Streetview, July 2014]

The view South from the southern portal of Cottalorda Tunnel. [55]

The southern portal of Cottalorda Tunnel. [35]

Looking back towards Breil-sur-Roya and the mouth of Cottalorda Tunnel. Note the arcaded retaining wall on the left, typical of the retaining walls on this length of the line. The D6204 runs alongside and below the line to the right. [35]

This next length of the line from the South portal of Cottalorda Tunnel runs immediately adjacent to the E74/D6204. [16]

This smaller image, looks South along the D6204/E74. The railway can be seen adjacent to, but above the road. To the West side of the line, large retaining walls create space for the line on the steeply graded valley side. {Google Streetview, July 2014]

A little further South the Hydroelectric Plant is now visible. [Google Streetview, July 2014]

Now just beyond the Power Station , again looking South with a high retaining wall above the railway which sits a few metres above road level on the right. Three arcades carrying the line are followed by the three stone arches of the Riou Viaduct. [Google Streetview, July 2014]

Construction work on the Italian length of the line in the lower Roya (Roia) Valley began in Ventimiglia. Banaudo et al have chosen to follow the line from South to North to reflect the way this section of the line was constructed. We continue to follow the line from North to South.

The length of the line from the border at Piena (Piene) to Airole was completed before the first world war but traffic along this part of the line had to wait for completion of the length of the line in French territory. The Italian authorities decided that services would commence only between Ventimiglia and Airole. That length is covered later in this article.

The international border at the time of construction was just to the North of Piena (Piene). That border line remained the same through the interwar years. Services North from Airole via Piena to Breil-sur-Roya had to wait until 1928 and the opening of the full line.

The Riou Viaduct (three 6.25m masonry arches) was the location of the international boundary. Banaudo et all tell us that the point that the line crossed the boundary is marked by the letters I and F engraved in a stone on the deck of the structure. [1: p125]

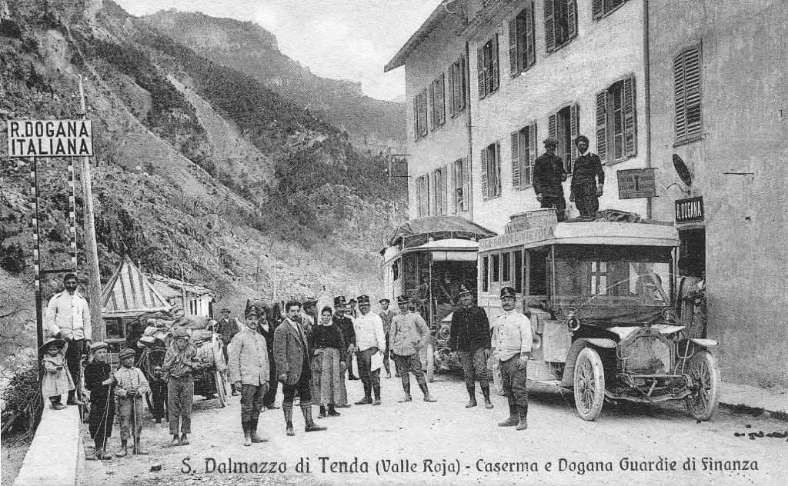

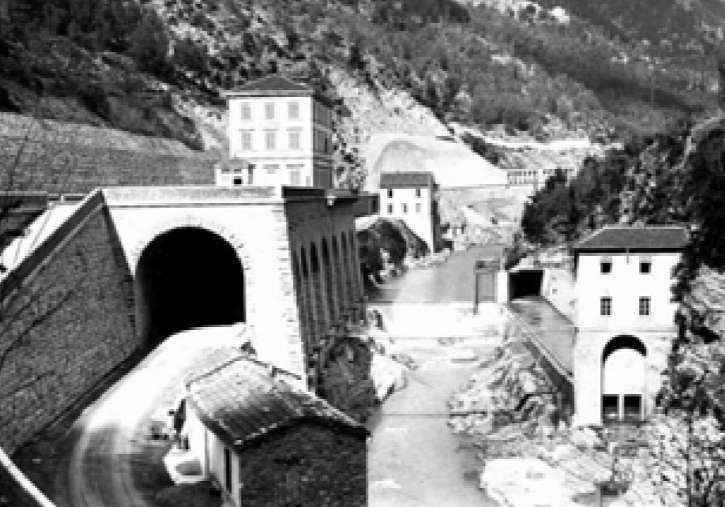

Immediately to the South of the Riou Viaduct, Piene (Piena) Station was built as a frontier station below the village of Piena-Alta which, Banaudo et al tell us, was for centuries the outpost of the Genoese republic and the border with the States of Savoy. [1: p125-126]

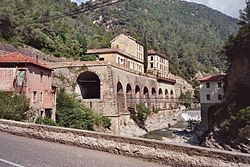

Close to the road border post at Piena-Bassa, the “Italian administration decided to establish a station intended for police and customs control operations. There were three platform faces, a two-story passenger building and a customs clearance hall of the same size for goods, comprising a warehouse, offices and two apartments on the upper floors. The site was hemmed in by the tunnel to the South, the French border to the North, the mountainside to the West, and the Roya River to the East, necessitating the construction of the station, cantilevered over a masonry gallery supported by seven arches, above the SS 20 roadway.” [1: p126]

Also facing up stream, this image shows the structures at this location in 2006, (c) Markus Schweiss and licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence, (CC BY-SA 3.0). [33]

Since the photograph above was taken a netting protection has been applied to the principal buildings at rail level. This photograph taken in 2019 also faces upstream, (c) Eugenio Merzagora/Structurae and made available for reuse under their non-commercial licence. [34]

This view looks South along the D6204/E74. it is taken a couple of hundred metres South of the Riou Viaduct where the road passes what was Piene Railway Station building. The site was tight and in order to accommodate the necessary station buildings, they were built over the road. [Google Streetview, October 2008]

Piene Railway Station (closed) seen from the cab of a Southbound train. [55]

Piene Railway Station (closed) seen from the cab of a Northbound train. [35]

Writing about the length of the line between Ventimiglia and the border at Piena (Piene), Banaudo et al say: “In the lower Roya Valley, the seven tranches of the Ventimiglia – southern border section were successively awarded in 1908, 1910, 1911, 1912, and 1913. Despite the lower altitude, the route was as difficult as on the purely Alpine section of the line, with steep gorges and terrain that offered highly varied resistance to earthworks: unstable marly limestone, very hard black limestone, clayey marl, schist, sandstone, etc. Of the 17,260 m route, nearly half way to be in tunnels, with nineteen structures totaling 8,259 m, fifteen bridges and viaducts representing sixty-four masonry arches, as well as various secondary structures for crossing waterways and rural roads.” [1: p118]

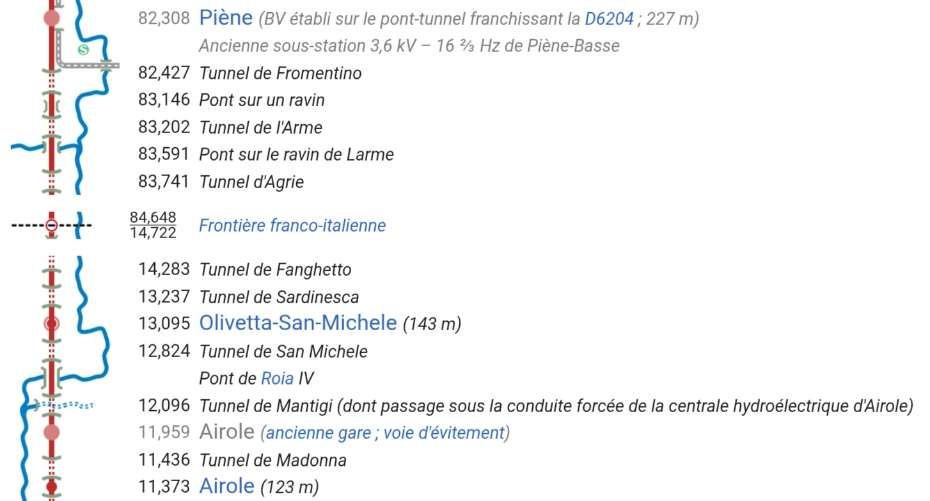

South of Piene (Piena) a series of structures carry the line over or through the obstacles in its path:

• the Fromentino Tunnel, 645 m long;

• a viaduct with three 10 m arches;

• the Arme Tunnel, 333 m long;

• a viaduct with four 10 m arches;

• the Agrie Tunnel, 820 m long;

• the Fanghetto tunnel, 419 m long, extended by a gallery (the post-WW2 border was established at the North end of this tunnel);

• the Sardinesca Tunnel, 820 m long;

• a single span arch bridge over the Tron valley.

These are all illustrated below.

The North Portal of Fromentino Tunnel (645 metres in length) in shade. [55]

The view from the North portal of Fromentino tunnel. [35]

It is just possible to see the tunnel mouth above, when looking up from the road. [Google Streetview, October 2008]

The view South from the D6204/E74 above the South portal of Fromentino Tunnel. Before reaching the Arme Tunnel, the line crosses a 3-viaduct of three 10 m span arches. The stone parapets of the viaduct can be seen below the top rail of the parapet immediately in front of the camera. [Google Streetview, September 2010]

The view South from the cab of a Ventimiglia-bound train at the southern portal of Fromentino Tunnel. The viaduct parapets are in the foreground. [55]

Turning round, this is the view of the South Portal of Fromentino Tunnel. [35]

Looking toward the northern portal of Arme Tunnel (333 metres long) which again is in shade. [55]

A similar view back towards Breil-sur-Roya from the cab of a Northbound service the mouth of Arme Tunnel. [35]

This next length of the line is heading South-southeast. Arme tunnel is at the top of this extract from OpenStreetMap. The line bridges (on a four-arch viaduct) a tributary of La Roya before being swallowed by Agrie Tunnel.

The view South from the mouth of Arme Tunnel. [55]

Turning through 180°, this is the South portal of the Arme Tunnel. [35]

The railway and the bridge are just visible over the edge of the road, looking East. The bridge is a viaduct of four 10 m spans. [Google Streetview, September 2010]

The northern portal of Agrie Tunnel (820 metres in length). [55]

The view from the cab of a Northbound service leaving Agrie Tunnel. [35]

A better view is obtained from the road above the North portal of Agrie Tunnel. This view shows the viaduct mentioned above. [Google Streetview, September 2010]

This is the view from the cab of a Southbound train at the South portal of Agrie Tunnel. The train is travelling at 68 km/hour and the still image from the video is much less distinct. [55]

A similar view but from the road. A metre high wall separates the road and the railway. [Google Streetview, July 2014]

Turning through 180°, we see the mouth of the Agrie Tunnel from the cab of the Northbound service. [35]

At high speed the video stills are less distinct. This is the northern mouth of the Fanghetto Tunnel which is in shade. This tunnel is 419 metres in length and trains cross the border between France and Italy as they enter it. [55]

A much more distinct view from the road of the mouth of Fanghetto Tunnel. [Google Streetview, July 2014]

Here, we are looking from Italy into France in this view back towards Breil-sur-Roya from the mouth of the Fanghetto Tunnel. [35]

The southern end of the Fanghetto Tunnel is galleried/arcaded with low level arches letting in light before the tunnel mouth is reached. [55]

The arcades close to the southern mouth of Fanghetto Tunnel seen from the East side of the valley. [Google Streetview, July 2021]

The view along the line from the southern portal of Fanghetto Tunnel. [55]

The southern portal of the Fanghetto Tunnel. [35]

With the Southbound train now travelling at 75 km/hr, small structures (like this accommodation bridge) whizz by and, certainly in this direction with the bridge face in shadow, it is impossible to make out any detail.. [55]

The structure is seen in better light, from the cab of the Northbound service. [35]

The northern mouth of Sardinesca Tunnel (820 metres long) again in shadow and indistinct because of the speed of the train. [55]

Looking back towards Breil-sur-Roya from the cab of a Northbound train at the mouth of the Sardinesca Tunnel. [35]

The view South beyond the southern portal of Sardinesca Tunnel. The parapets of a single span arch bridge are visible close to the camera. [55]

Turning through 180° we get a look at a footbridge over the line just outside Sardinesca Tunnel. [35]

The same footbridge seen from the SS20 road. the arch bridge over the Tron, a tributary of the Roya, can be seen on the left of the image. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

An extract from Google’s satellite imagery showing the same location. Note the tunnel mouth and adjacent footbridge in the top-left quadrant of the photograph. [Google Maps, August 2025]

Next comes the Olivetta-San-Michele Station and the San-Michele Tunnel (133 m long).

A very short distance South of the footbridge is Olivetta San Michele Railway Station. [Google Maps, August 2025]

Olivetta San Michele Station, seen from the cab of the Ventimiglia-bound service. [55]

A better railside view of the station building at Olivetta San Michele, this time from the cab of a Northbound train. [35]

The station building seen looking South from the SS20/E74 road. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

The station building seen from the East, (c) Pampuco and licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-SA 4.0). [36]

The view ahead along the line towards Ventimiglia from the cab of the Southbound train as it pulls out of Olivetta San Michele Station. The tunnel ahead is San Michele Tunnel which is 126 metres in length. [55]

A view, looking South from the SS20, of the northern mouth of San Michele Tunnel with an Italian Locomotive heading into the tunnel (I may well need correcting on this) is shown in more detail below… It appears to be a Belgian locomotive (SNCB) No. 7336 with the name, ‘Mexico’. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

This picture it taken just a short distance to the South of the image above. It shows a side-on view of the same locomotive. I would not expect to see this locomotive at this location! [Google Streetview, August 2021]

This is SNCB 7304 – the image is provided by Wikipedia. The family resemblance with 7336 is manifest. The Class 73 locomotives formed the backbone of the SNCB/NMBS shunting locomotive fleet. [20]

Class 73 locomotives were built in three batches: 7301-7335 during 1965–1967, 7336-7375 during 1973-1974 and finally 7373–7395 in 1976–1977. [20]

This is the view North through the station site as seen from the cab of a Northbound service at the North postal of the San Michele Tunnel. [35]

Looking out from the Southeast portal of San Michele Tunnel, the line ahead crosses Roya IV Bridge which is 126 metres in length and then enters Mantici Tunnel which is 604 metres long. [55]

One hundred metres further South and turning through 180°, this is the view across Roya IV Bridge towards the San Michele Tunnel. Note that the road tunnel is just above the railway tunnel, although on a different line. [35]

The view from the road above the Southeast portal of San Michele Tunnel. The mouth of Mantigi Tunnel (604 metres long) can be seen at the end of the railway viaduct. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

Roya IV Bridge was also known as the San-Michele Viaduct. It was made up of five 15 metre arches. [1: p125]

The Mantigi tunnel has a short section where it is very close the the surface of the ground above, Banaudo et al, tell us that this allowed the provision of a vertical ventilation shaft. [1: p125]

Trains travelling South to Ventimiglia crossed the viaduct and ran on through Mantigi Tunnel. Airole Railway Station was originally on a large plateau beyond the Southeast portal of Mantigi Tunnel.

Banaudo et al tell that “Airole station was located in an olive grove to the North of the village, in the only place where the shallower slope of the left bank of the Roya allowed the construction of a retaining wall to support all the railway infrastructure: the passenger building, three platform tracks and two freight tracks with a goods shed and high platform, as well as a water column for the locomotives.” [1: p121]

The station was built in 1914 and remained operational until, sadly, the station site was abandoned in the 1970s when it was replaced by a single platform halt in the centre of Airole. [25]

At the southern end of Mantigi Tunnel, trains enter a passing loop (Airole Loop), which is all that is left of the original railway station, before entering another tunnel! [55]

Looking back towards Breil-sur-Roya from within the passing loop. Immediately to the North of the loop, Northbound trains plunge into the Mantigi Tunnel. [35]

This excellent photograph of the old station building looks North towards the Mantigi Tunnel, © Giorgio Stagni and licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-SA 3.0). [25]

The station building and the shell of the old goods shed. This is another photograph © Giorgio Stagni and licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-SA 3.0). [37]

Looking North from the cab of a Northbound train approaching the old railway station building. It is evident from both these pictures that there were originally sidings at this location – confirmation that the station facilities at Airole were once quite significant. [35]

At the end of the passing loop trains enter Madonna Tunnel (249 metres long). [55]

Looking back towards Breil-sur-Roya from the portal of Madonna Tunnel. The passing loop is still provided at this location as there is no room at the present Airole Railway Station for more than a single track. [35]

Leaving Madonna Tunnel trains immediately pass under a local road bridge which appears as not much more than a silhouette as eyes get used to the light on leaving the tunnel. [55]

Airole Railway Station seen from the cab of a Ventimiglia-bound train passing under the accommodation bridge shown above. [55]

The view West from the bridge which carries Via Giacomo Matteotti over the line. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

Turning to face East, this is the present Airole Railway Station as seen from Via Giacomo Matteotti. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

A Northbound train is stationary at Airole Railway Station. This is the view ahead, West towards Olivette San Michele. The road over bridge sits a few metres closer to the station than the mouth of Madonna Tunnel. [35]

A great action shot showing ALn 663 1160 at Airole station, © Giorgio Stagni and licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-SA 3.0). [38]

Airole Railway Station seen from the cab of a northbound service entering the station from the East. [35]

A similar view but this time the camera is on Via G. Biancheri which crosses the railway line above the West portal of Airole Tunnel (153 metres in length). [Google Streetview, August 2021]

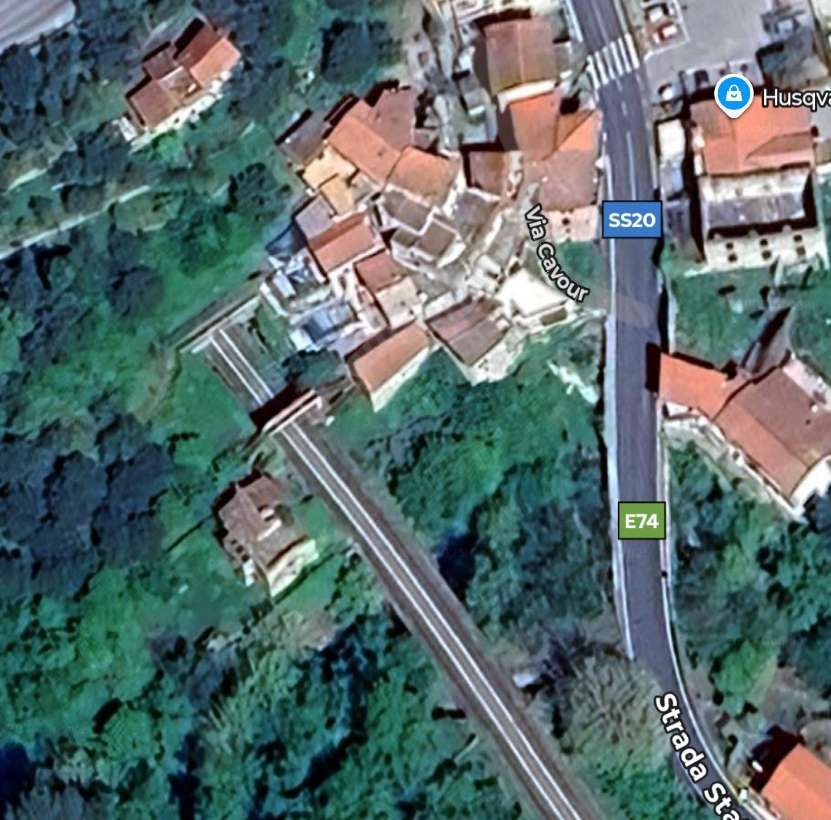

This extract from Google’s satellite imagery shows the village of Airole which sits over the line. Airole Tunnel curves to the Northeast. Its West Portal is bottom-left in this image, its Northeast portal is top-right. [Google Maps, August 2025]

The view Southwest from the cab of a Ventimiglia-bound train at the Northeast portal of Airole Tunnel. [55]

The Southwest portal of Para Tunnel (754 metres long). [55]

Looking Southwest from Via Luigi Trucchi the Northeast portal of Airole Tunnel can be seen below the village of Airole. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

The view from Via Nazionale of the short bridge (Airole Bridge, one 10 metre arch) which sits to the Southwest of the mouth of Para Tunnel. The stonework of the tunnel portal can be seen above and to the right of the viaduct. Para Tunnel is over 747 metres long. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

This is the view back towards Airole Village and Railway Station from the mouth of Para Tunnel. White fencing sits on top of the parapet walls of Airole Bridge. [35]

Para Tunnel curves round to the Southeast. This is the view from the cab of the Southbound train as it exits Para Tunnel and crosses La Para II viaduct (four 10 metre arches). [55]

The viaduct mentioned above can be glimpsed from Via Natzionale. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

This is the view back into the mouth of Para Tunnel. [35]

The Northwest portal of Pian de Para Tunnel. The tunnel is 184 metres long. [55][1: p125]

A view of the Northwest portal of Pian de Para Tunnel from Via Nazionale. There is a single-span arch bridge carrying the line close to the tunnel mouth. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

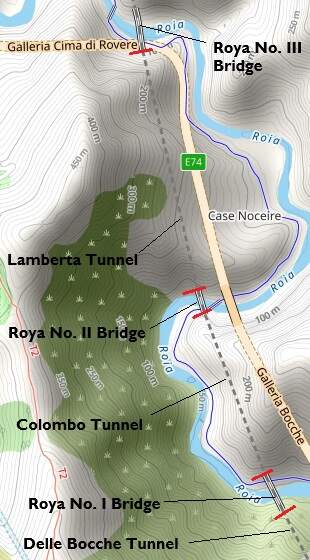

The next length of the line as it appears on OpenStreetMap and annotated with the tunnel names. [21]

The Southeast portal of Pian de Para Tunnel seen from the cab of the Northbound train. [35]

Immediately to the Southeast of the tunnel portal Southbound trains cross La ParaI Viaduct. The Viaduct appears to have three 5 metre spans. This image looks Northeast from Via Nazionale. [1: p125]

The Southeast portal of Pian de Para Tunnel can be seen in the top-left of this image, looking North from a point a little further along Via Nazionale. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

The Southbound train is now travelling at over 80 km/hr. This is the portal of the next tunnel on the route – Gambetto Tunnel (173 metres in length. [55] [1: p125]

Turning through 180°, this is the view back towards Airole from the mouth of the Gambetto Tunnel. [35]

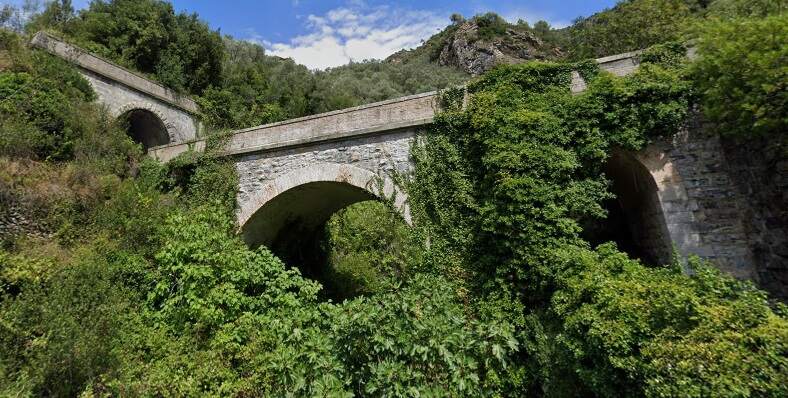

Gambetto Tunnel opens out onto the next bridge over La Roya – Roya No. III Bridge. [55] This structure is also known as the Lamberta Viaduct, it is made up of three 14 metre arches and two 10 metre arches. The gallery beyond the bridge is the route of the modern SS20. [1: p125]

Turning through 180°, this is the mouth of the Gambetto Tunnel from the cab of a Northbound service. [35]

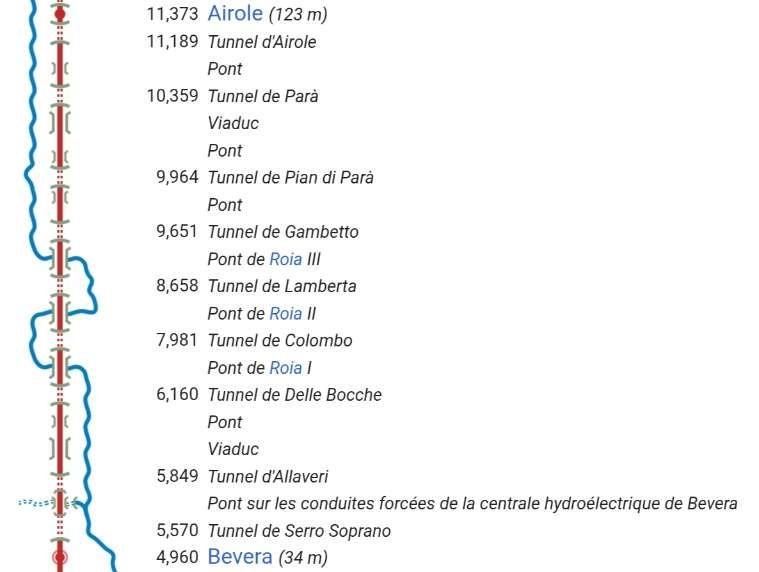

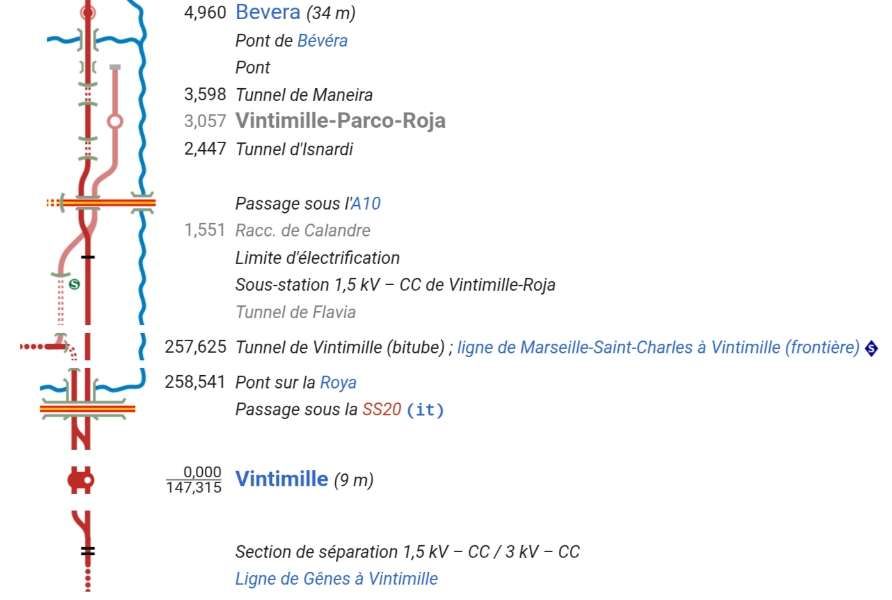

With the railway running South-southeast towards Bevera and Ventimiglia, it alternates between tunnels and viaducts switching sides of La Roya (Roia) river. [23]

The Roya No. III bridge is also known as the Lamberta Viaduct. [1: p125]

The Roya No. II bridge is also known as the Colombo Viaduct. [1: p125]

A view of Roya No. III bridge from the bridge carrying Via Nazionale of the Roya to the West of the railway. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

A view of La Roya No. III bridge from the Via Nazionala further to the East along the valley. [Google Streetview, September 2011]

Southbound trains then plunge into Lamberta Tunnel which is 750 metres in length. [55]

Turning through 180°, this is the view across Roya III bridge from the mouth of the Lamberta Tunnel. [35]

Leaving Lamberta Tunnel at its southern end, Southbound trains immediately crossed La Roya again on Roya No. II bridge. [55] The bridge is also known as the Colombo Viaduct. [1: p125]

Turning through 180° we see the Lamberta Tunnel Portal. [35]

Once across La Roya on No. II bridge trains ran on into Colombo Tunnel. [55]

Looking back across La Roya from the mouth of the Colombo Tunnel. [35]

Looking South across Roia (Roya) No. 1 bridge (also known as the Bocche Viaduct) from the South portal of Colombo Tunnel. [55]

The northern tunnel mouth of Delle Bocche Tunnel. [55]

Looking back from the Delle Bocche tunnel mouth across the Roia No. 1 bridge. [35]

Banaudo et al tell us that the length of the Roia (Roya) Valley that we have just traversed is known as the ‘Bocche’, “the wild gorges of the Roya which for a long time represented an abstacle to communications between the Ligurian lands of the Republic of Genova and the Piedmontese domain of the Kingdom of Sardinia. It was only in 1893that the … road from Ventimiglia to Breil was completed … after lengthy construction work hampered by the difficult terrain and the reluctance of the military authorities. The railway tamed this gorge through an uninterrupted succession of tunnels and viaducts.” [1: p121, 125]

Delle Bocche Tunnel (927 metres long) ends at the top of this OpenStreetMap extract. There is a short bridge which carries a length of the line before Southbound trains enter d’Allaveri Tunnel which, although it appears as one tunnel on the map extract is actually two tunnels with a very short open length in between. The Aqueduct illustrated on the map passes under the railway in that opening in pipes, (Pont sur les conduites forcées de la centrale hydroélectrique de Bevera). The first length of the tunnel is named d’Allaveri Tunnel (69 metres long), the second length is known as Serro Soprano Tunnel (245 metres long).

Once beyond these tunnels, Southbound trains have a clear run down to Bevera Railway Station. [24]

Looking South from the South portal of Delle Bocche Tunnel. [55]

Looking back to the North, this is the South portal of Delle Bocche Tunnel. [35]

A glimpse of the line from a local road (Localita Madonetta) at a point a couple of hundred metres South of the South portal of Dell Bocche Tunnel. The camera is facing Northeast. [Google Streetview, November 2011]

A little further Southwest the line is carried on a low bridge under another minor road. This view looks West from Via Comunale di Varase. [Google Streetview, November 2011]

The same structure seen from the West. [Google Streetview, November 2011]

The North portal of d’Allaveri Tunnel. This and the next tunnel are in the vicinity of the hamlet of Varese and the Bevera Hydroelectric Power Station. [55]

The view North from the cab of a Northbound train at the North portal of d’Allaveri Tunnel. [35]

This extract from Google’s satellite imagery shows the two tunnels at this location and Bevera’s Hydroelectric power plant which is immediately adjacent to the railway. It is the white-roofed building just above the centre of this image.

D’Allaveri Tunnel is the very short tunnel to the North of the Hydroelectric plant (71 metres in length). Serro Soprano Tunnel (244 metres long) extends South from the building to a point near to the bottom of this image.

The grey area at the bottom of the image (surrounding the tunnel mouth) is a series of greenhouses. As shown below.

An overexposed photograph showing the view South from the southern portal of d’Allaveri Tunnel. The Aqueduct which carries water under pressure to Bevera’s hydroelectric plant can be seen on the right. The line bridges the penstock on three 5 metre arches before southbound trains enter Serro Soprano Tunnel ahead. [55]

Another over-exposed view, this time facing North at the North portal of Serro Soprano Tunnel. The southern mouth of d’Allaveri Tunnel can be seen ahead.[35]

Looking South towards Bevera at the mouth of Serro Soprano Tunnel. [55]

The South portal of Serro Soprano Tunnel. [35]

An accommodation bridge North of Bevera Railway Station, seen from the cab of the Southbound service. [55]

The accommodation bridge, seen from above. [Google Maps, August 2025]

The same structure seen from the cab of the Northbound train. [35]

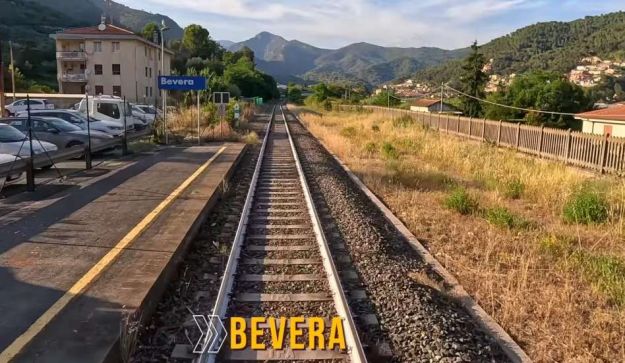

As we head South towards Bevera Railway Station, the valley of the Roia widens significantly and we enter the suburbs of Ventimiglia, of which Bevera is one part. Beverea Railway Station was built with a large “classically designed passenger building, two platform faces and and two freight tracks with a goods shed and loading platform.” [1: p121] In the 21st century Bevera is a single platform halt.

A Southbound train approaches Bevera Railway Station. [55]

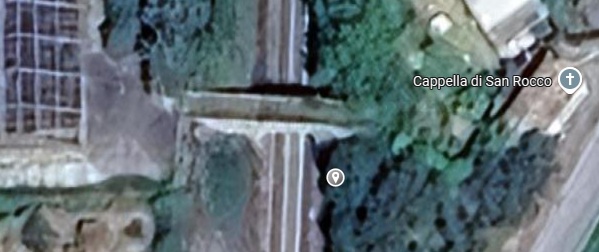

Bevera Railway Station seen from above. [Google Maps, August 2025]

The Northbound service sits at Bevera Railway Station which is a single platform halt. [35]

The Southbound train, stationary at Bevera Railway Station. [55]

Looking North into the Bevera Station site

South of Bevera Railway Station the railway bridges the Bevera River (Torrente).

The same bridge, seen from the Northwest. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

The line runs on to the South on embankment through the suburbs of Ventimiglia.

The bridge over Via Madeira seen from the East. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

The same bridge seen from the West. [Google Streetview, August 2021]

Looking back along the line towards Bevera Railway Station from Pont Bevera (Viadotto Autoporto). [Google Streetview, August 2021]

Facing towards Ventimiglia this image taken from the cab of the Ventimiglia-bound service looks through Pont Bevera (Viadotto Autoporto). [55]

Facing North towards Bevera and looking under Pont Bevera (Viadotto Autoporto). [35]

Looking ahead along the line towards Ventimiglia Railway Station from Pont Bevera (Viadotto Autoporto). [Google Streetview, August 2021]

The North portal of Maneira Tunnel (171 metres in length) is in shadow and difficult to make out from the cab of the ventimiglia-bound train. [55][1: p119]

Turning through 180°, this is the view North from the cab of a Northbound service as it leaves the North portal of Madeira Tunnel. [35]

The view South from the South portal of Maneira Tunnel. [55]

Turning through 180°, this is the South portal seen fr

The line continues on embankment with low height underpasses to provide vehicular access under the line as shown below. [Google Streetview, August 2021]…

In between the second and third underpasses shown above the line passes through d’Isnardi Tunnel (168 metres in length). The North portal is so much in shade that the view from the cab of the Ventimiglia-bound service does not provide any detail. [55] That is the first image below…

The North portal of d’Isnardi Tunnel is so much in shade that no details can be made out from the cab of the Ventimiglia-bound service. [55]

Turning through 180° this is the view North from the North portal of the tunnel. [35]

The view South from the South portal of d’Isnardi Tunnel. [55]

Turning through 180° the South portal is seen from the cab of a Northbound service. [35]

The next few images come from above the level of the line further to the South – the first two from alongside to the West of the line and then from over bridges. ….

The first two of the images above look back along the line and then forward towards Ventimiglia Railway Station from Via Peglia. [Google Streetview, November 2011] The second pair of images look back and forward along the line from the bridge carrying Via Gallardi over the line. [Google Streetview, August 2021] The final par of images look back (across a curve in the line) and then forward along the line from the E80 (close to the toll booths). In the first of this pair of images the bridge carrying Via Gallardi over the line can be seen. [Google Streetview, July 2019]

The next two images show the bridge carrying Via Gallardi over the line. [55][35]…

This next pair of photos show the overbridge which carries the E80. [55][35] …

The next batch of photos continue towards Ventimiglia Railway Station. …

Two further underpasses are shown in the first two images above, the second pair of images are taken from the bridge carrying the SS20 over the line, the first looks back to the West towards the point where the double-track line from Nice begins to run alongside the single-track line from Cuneo. The second looks forward from the same bridge towards Ventimiglia Railway Station. The last two images are underpasses that the 3 lines cross on their way East. [Google Streetview, September 2024]

A cab level view of the diverging tracks seen in the third of the six views in the gallery above. The double-track line heading towards Nice diverges to the left. It is just approximately 6 kilometres to the international border. [35]

The next pair of images show the bridge carrying the SS20 as seen from cabs on services to and from Cuneo. [55][35] The first faces towards Ventimiglia, the second towards Bevera. …

The next three images show the final approach into Ventimiglia Railway Station. [55] …

The middle image above shows a shunter idling in a siding alongside the main running lines – TS D100 Shunter [Vossloh G1000 BB]. The Vossloh G1000 BB is a class of off-centre cab diesel-hydraulic B’B’ 4 axle locomotives built by Vossloh in Kiel since 2002. The class is based upon the standard Vossloh locomotives design, and they are a higher powered development of the Vossloh G800 BB which were produced mainly for the Austrian Federal Railways, with a 1.1 MW (1,500 hp) MTU engine replacing the 0.8 MW (1,100 hp) Caterpillar engine in the G800; as a result the front engine compartment is enlarged, whilst other features: bogie frame and overall dimensions remain the same. [27]

Another view of the TS D100 Shunter [Vossloh G1000 BB], this time from the cab of the Cuneo-bound service. [35]

Looking Northwest from the cab of a Cuneo-bound train about to depart from Ventimiglia Railway Station. [35]

A postcard view of Ventimiglia taken from the hillside to the Northeast of the Railway Station which features in the foreground of the image. [44]

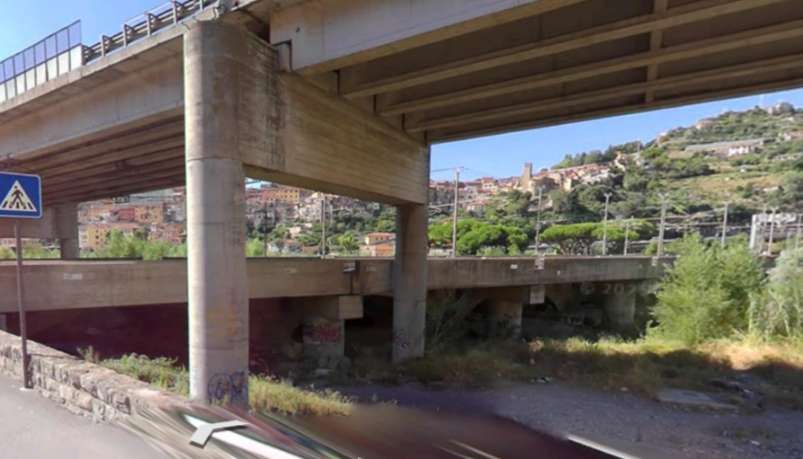

Banaudo et al write that “the single track of the Col de Tende line runs alongside the Nice double track for a few hundred metres. [Initially] they crossed the Roya River together on a six-span metal viaduct, which was soon replaced by a new structure with eight 17-metre stone arches. Immediately beyond the bridge, the two routes separate and the Cuneo route climbs up the right bank of the river, at a gradient of 13 mm/m, the valley is still relatively wide. A bundle of three service tracks called Scalo Roia is located to the left of the main track. The Isnardi tunnel (168 m long) and Maneira tunnel (171 m long) precede a four-arch viaduct (with 6-metre arches).” [1: p119] This description assumes that the line is followed West out of Ventimiglia Railway Station.

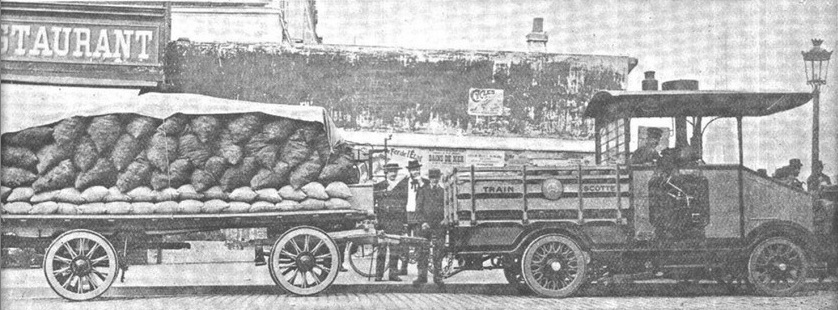

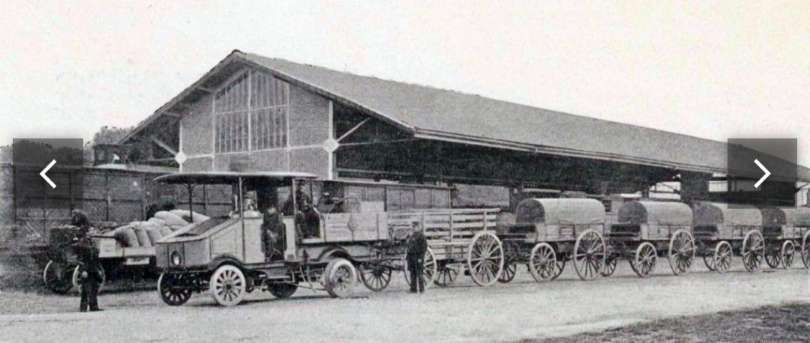

Banaudo et al comment that while construction was just beginning between “Breil and the southern border, the work begun in 1908 by the Italian companies from the coast was nearing completion. While awaiting the connection to France, the FS decided to operate the Ventimiglia-Airole section (11.970 km), which entered service on 16th May 1914. The service was provided by three round trips, including two local passenger trains and one mixed train, which covered the entire route in about thirty minutes uphill and twenty-five minutes downhill. Traction was provided by three-axle 030 locomotives with separate tenders, Group 320 (formerly the 3600 of the Rete Mediterranea), based to the newly created Savona depot.” [1: p142]

In France, WWI caused the cessation of all work on the line and in the aftermath of the conflict, “the resumption of construction proved very difficult. The PLM’s construction department received only meager allocations from the state, with priority funding being allocated to the recovery of the disaster-stricken regions of the northeast.” [1: p138]

On site, the years of inactivity had allowed serious deterioration, particularly of the tunnels on the unopened line. Following a three-day inspection tour of the entire line, the French decided to begin work once again.

The contractors made a significant investment in manpower and materials at the beginning of 1920 but discovered that rather than dealing with the PLM, the works would be directly funded by the government. The government determined that the budget for the work on French soil would be reduced from 104 to 75 million Francs and indicated that the maximum spend in 1920 would be 17 million Francs. This inevitably led to redundancies and to slower progress of the works. [1: p140]

When the authorities indicated in June 1920, that “only 700,000 Francs of credit remained to complete the year, … the elected officials of the Alpes-Maritimes immediately rushed to Paris to meet with representatives of the Ministry and the PLM management. Following discussions, a new budget was allocated by the State for railway construction. The PLM had a budget of 41 million Francs, 25 of which were allocated to the Nice-Cuneo line. Work could [continue], but the engineers and contractors in charge of it would have to take into account the irregular arrival of funds until the end when organizing their work.” [1: p140]

Work on the Nice to Breil-sur-Roya line and the remaining length of the line between Ventimiglia and Breil ran in parallel. The increased budget meant competition to attract staff was strong and people had to be hired from Italy, Spain, Portugal and Morocco. Stonemasons were in particularly short supply. We will probably see more about what this meant for the work when we follow the line from Breil-sur-Roya to Nice.

Banaudo et al note that in the early 1920s the line was opened between Ventimiglia and Airole for passengers and was used also to supply the French construction site on the length of the line between Breil-sur-Roya and Piena (Piene).

“From Breil to the southern border, the [railbed/formation] was passable by 1921 and the final track was immediately laid, while the FS did the same between Airole and Piena on the section removed during the war. On 30th January 1922, the Italian and French rails were finally connected on the Riou bridge, and the Borie company obtained from then on the authorization to directly route its materials from Nice to Breil by rail.” [1: p142]

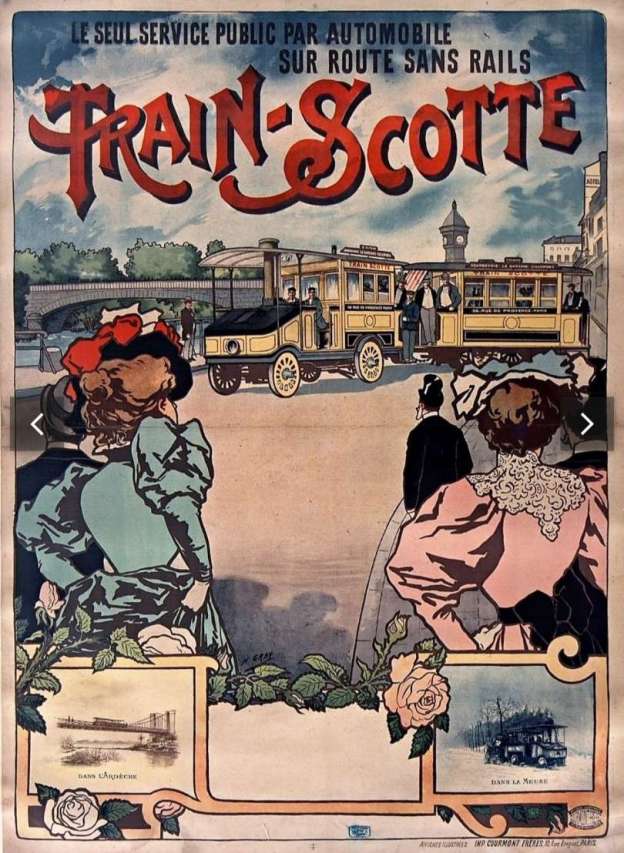

Once the line opened fully between Ventimiglia and Cuneo, the line “retained the Ventimiglia-Airole service created before the war, while on the Cuneo San-Dalmazzo-di-Tenda line, the timetable included three daily three-class buses and a seasonal train running on public holidays from July to September. The 58 km journey took 2 hours 30 minutes in the north-south direction and 2 hours 10 to 15 in the opposite direction. This service included one less return journey than in 1915, because a fast Cuneo Nice bus connection was introduced in 1921 following an agreement between the FS and the Compagnia Generale dei Tramways Piemontesi (CGTP), to avoid the inconvenience of transhipment while waiting for the railway to be fully operational.” [1: p143-146]

In December 1923 it was agreed that on the length of line between the two borders, “all trains … would be hauled by the FS, including maintenance trains; in the event that they had to be exceptionally handled by a French locomotive, the latter would be accompanied by a pilot from the FS. The San-Dalmazzo Piena section would be equipped with Morse-type telegraph devices. The protection signals for Breil station on the Fontan-Saorge and Piène sides would be Italian, but the departure signals for all directions would be the PLM-type. The organization of customs controls between San-Dalmazzo, Fontan-Saorge, Breil and Piena was also [agreed].” [1: p146]

Banaudo et al provide a significant series of photographs of the construction work on the lines between Cuneo, Nice and Ventimiglia which takes up a large proportion of Volume 1 of Les Trains du Col de Tende. The photographs and drawings are predominantly from the French lengths of the line. [1: p152-311] It is a very significant collection of images which stand as a superb tribute to the amazing work of the various contractors employed on the line.

Opening of the line from Cuneo to Ventimiglia to passenger traffic had to wait for the completion of all of the French construction work. “Finally in October 1928 the lines were all completed – the celebrations must have been fantastic events. At last the small towns and villages along the route had access to jobs, schools and universities, cultural activities, hospitals … everything the cities had to offer.” [39]

The next article in this short series will look a the line heading out of Breil-sur-Roya towards Nice. It can be found here. [5]

References

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 1: 1858-1928; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 2: 1929-1974; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 3: 1975-1986; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=pfbid0eumWUFwJCPBGQUUtr3Apx72qr5cUhihwxpcFzDbkms3fta5zRXYZZLUozkAMmeKvl&id=1412933345657144, accessed on 5th December 2023. The Facebook Page, “L’Histoire de Menton et ses Alentours,” is the work of Frank Asfaux, https://www.facebook.com/franckasfaux06, accessed on 4th December 2023.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/08/29/the-railway-between-nice-tende-and-cuneo-part-6-breil-sur-roya-to-lescarene/

- Not used.

- Not used.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Locomotiva_RM_3620.jpg, accessed on 17th August 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/07/22/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-1.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/07/26/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-2.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/08/06/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-3-vievola-to-st-dalmas-de-tende

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/08/16/the-railway-between-nice-tende-and-cuneo-part-4-st-dalmas-de-tende-to-breil-sur-roya

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=15/43.93077/7.51647&layers=P, accessed on 18th August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=17/43.923820/7.520512&layers=P, accessed on 19th August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/43.91950/7.51623&layers=P, accessed on 20th August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/43.91231/7.51672&layers=P, accessed on 20th August 2025.

- https://maps.app.goo.gl/K4hzccr8VUYJHKFY8, accessed on 20th August 2025.

- https://maps.app.goo.gl/z72vMryPchvUUfKY9, accessed on 20th August 2025.

- https://maps.app.goo.gl/DPvnhXKP5nEfJ4Cs8, accessed on 20th August 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belgian_Railways_Class_73, accessed on 21st August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/43.86646/7.56652&layers=P, accessed on 21st August 2025.

- https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sch%C3%A9ma_de_la_ligne_de_Coni_%C3%A0_Vintimille, accessed on 21st August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=15/43.85683/7.57327&layers=P, accessed on 22nd August 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=15/43.83408/7.57936&layers=P, accessed on 22nd August 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Airole_vecchia_staz_ferr.jpg, accessed on 23rd August 2025.

- https://www.vermenagna-roya.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/BR-1-I-f-4-gare-pont-fs-de-piene.pdf, accessed on 23rd August 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vossloh_G1000_BB, accessed on 24th August 2025.

- https://www.marklinfan.com/f/pop_printer_friendly.asp?TOPIC_ID=3305, accessed on 24th August 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=619477608613399&id=156990911528740&set=a.468384633722698, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://www.stagniweb.it/foto6.asp?File=roya3&Inizio=4&Righe=10&InizioI=1&RigheI=50&Col=5, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://www.stagniweb.it/cart5/cbreil07.jpg, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Croisement_entre_une_Caravelle_X-4500_et_un_Minuetto_devant_la_gare_de_Breil-sur-Roya.JPG, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q1948555, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://structurae.net/en/media/324516-piene-station-and-piene-station-tunnel-nbsp, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_qX8v5gceVU, accessed on 31st July 2025.

- https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q3095820#/media/File:Olivetta_san_michele_train_station.png, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://www.stagniweb.it/altro2/large4/tend0617.jpg, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://www.stagniweb.it/foto9/tend8304.jpg, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://ventimigliaaltawords.com/2013/10/14/all-steamed-up-about-the-ventimiglia-cuneo-rail-link/, accessed on 5th August 2025.

- Franco Collidà, Max Gallo & Aldo A. Mola; CUNEO-NIZZA History of a Railway; Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo, Cuneo (CN), July 1982.

- Franco Collidà; 1845-1979: the Cuneo-Nice line year by year; in Rassegna – Quarterly magazine of the Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo; No. 7, September 1979, pp. 12-18.

- Stefano Garzaro & Nico Molino; THE TENDA RAILWAY From Cuneo to Nice, the last great Alpine crossing; Editrice di Storia dei Trasporti, Colleferro (RM), EST, July 1982.

- SNCF Region de Marseille; Line: Coni – Breil sur Roya – Vintimille. Reconstruction et équipement de la section de ligne située en territoire Français; Imprimerie St-Victor, Marseille (F), 1980.

- https://www.picclickimg.com/images/g/QSkAAOSw4Ihlu1Ul/s-l1600.jpg, accessed on 25th September 2025.

- https://www.marklinfan.net/stazione_ventimiglia.htm, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://ebay.us/m/Ne0trP, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://www.geneanet.org/cartes-postales/view/7792915#0, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://casamaini.altervista.org/ancora-treni, accessed on 25th August 2025.

- https://youtu.be/rLXAEz-n4mM?si=RLQC31jynGeM_lQR, accessed on 26th August 2025.

- Not used.

- Not used.

- Not used.

- Not used.

- F. Honore; Le Rail a Travers Les Alpes: De Nice a Coni par la Voie Ferrée; L’Illustration, No. 4470, 3rd November 1928, p499.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hbzk68KoRj8&t=4533s, accessed on 4th August 2025.