Shoeburyness was once a fortified place guarding the Northern flank of the Thames Estuary. It appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of 894 CE, and it was assumed for many years to have been built as a ‘Danish Camp’ by the Viking leader Haesten as those chronicles say that while King Alfred headed West towards Exeter, Danish marauding parties, “gathered at Shobury in Essex, and there built a fortress.” [1][2: p60]

However, in 1998, archeological excavations unearthed classic Iron Age interior features and just a year later found evidence of a Middle/Late Bronze Age pottery associated with the visible remains of the ramparts. [1] These excavations took place after the closure of Shoeburyness Barracks while the site was being prepared for redevelopment. Subsequently Southend Borough Council sought to create a Conservation Area centred on the site. [3]

Speaking of this site, Historic England (List Entry 1017206) says: “The defended prehistoric settlement at Shoeburyness has been denuded by the development of the 19th century military complex, although the southern half of the enclosure has been shown to survive extremely well and to retain significant and valuable archaeological information. The original appearance of the rampart is reflected in the two standing sections, and the associated length of the perimeter ditch will remain preserved beneath layers of accumulated and dumped soil. Numerous buried features related to periods of occupation survive in the interior, and these (together will the earlier fills of the surrounding ditch) contain artefactual evidence illustrating the date of the hillfort’s construction as well as the duration and character of its use. In particular, the recent investigations have revealed a range of artefacts and environmental evidence which illustrate human presence in the Middle and Late Bronze Age and a variety of domestic activities in the Middle Iron Age, including an assemblage of pottery vessels which demonstrate extensive trading links with southern central England. Environmental evidence has also shown something of the appearance and utilisation of the landscape in which the monument was set, further indications of which will remain sealed within deposits in the enclosure and on the original ground surface buried beneath the surviving sections of bank. Evidence of later use, or reuse, of the enclosure in the Late Iron Age and Roman periods is of particular interest for the study of the impact of the Roman invasion and subsequent provincial government on the native population; the brief reoccupation of the site in the Anglo-Saxon period, although currently unsupported by archaeological evidence, also remains a possibility.” [4]

Despite the extensive destruction wrought by the occupation of the site by the Board of Ordnance in 1849 (and successors), much more of the original survives than might be expected.

Historic England’s listing continues: “The settlement, which many 19th century antiquarians associated with historical references to a Danish Camp, lay in a rural setting until 1849 when Shoebury Ness was adopted as a range finding station by the Board of Ordnance and later developed into a complex of barracks and weapon ranges. The visible remains of the Iron Age settlement were probably reduced at this time leaving only two sections of the perimeter bank, or rampart, standing. This bank is thought to have originally continued north and east, following a line to East Gate and Rampart Street, and enclosed a sub-rectangular area of coastal land measuring some 450m in length. The width of the enclosure cannot be ascertained as the south eastern arm (if any existed) is presumed lost to coastal erosion. The surviving section of the north west bank, parallel to the shore line and flanking Warrior Square Road, now lies some 150m-200m inland. It measures approximately 80m in length with an average height of 2m and width of 11m. The second upstanding section, part of the southern arm of the enclosure, lies some 150m to the south alongside Beach Road… [Trial excavations within the enclosure during 1998] revealed a dense pattern of well preserved Iron Age features, including evidence of four round houses (identifiable from characteristic drainage gullies), two post- built structures, several boundary ditches and numerous post holes and pits. Fragments from a range of local and imported pottery vessels date the main phase of occupation to the Middle Iron Age (around the period 400-200 BC).” [4]

Our primary interest in this article is in the later development of the site from 1849 onwards and the construction and extension of a military tramway and railways associated with the Ordnance depot and other military sites along the coast close to Shoeburyness.

The land was first purchased here for Experimental artillery ranges in 1849. “Shoeburyness was chosen because of its position close to the Maplin Sands, Where a huge expanse left dry at low tide could be used in conjunction with the sparsely inhabited coast of Essex adjacent. In 1856, Lord Panmure, Secretary of State for War, submitted a recommendation that the work of proof experimentation should be severed from that of instruction. The outcome was the creation of a separate school of gunnery, which was opened on 1st April 1859.” [5: p239]

Throughout the immediate vicinity of Shoeburyness there are a lot of older buildings associated with the Military Depot. A number of these buildings can be found here. [31]

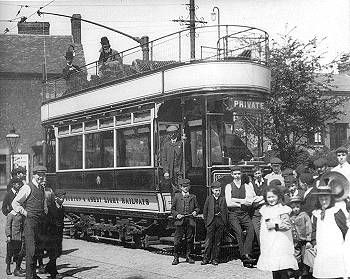

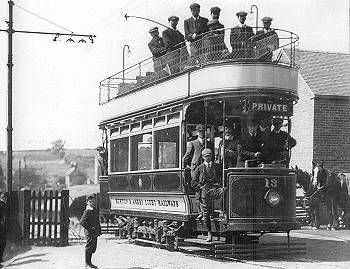

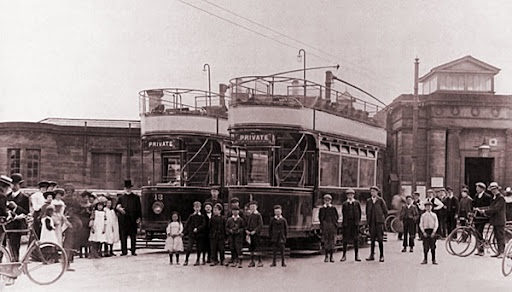

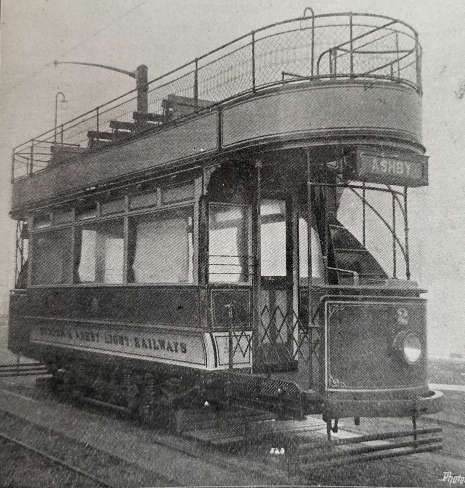

The Standard-Gauge Military Tramway

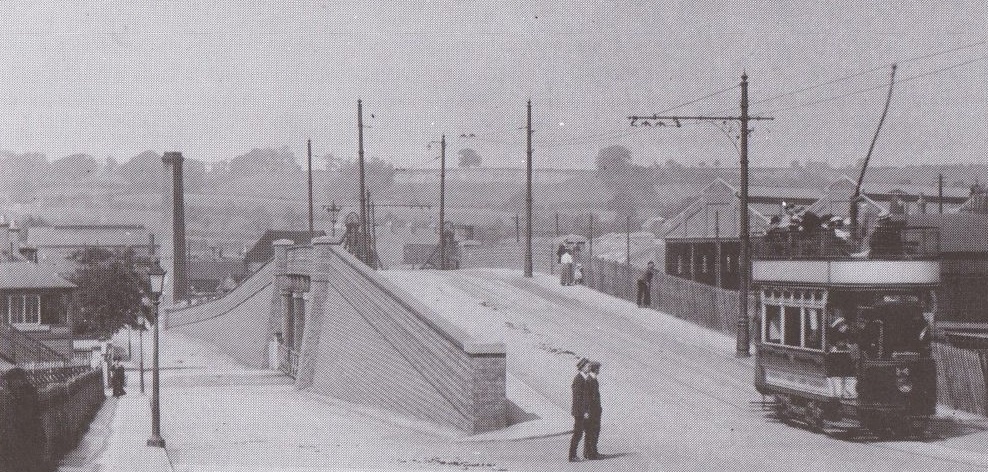

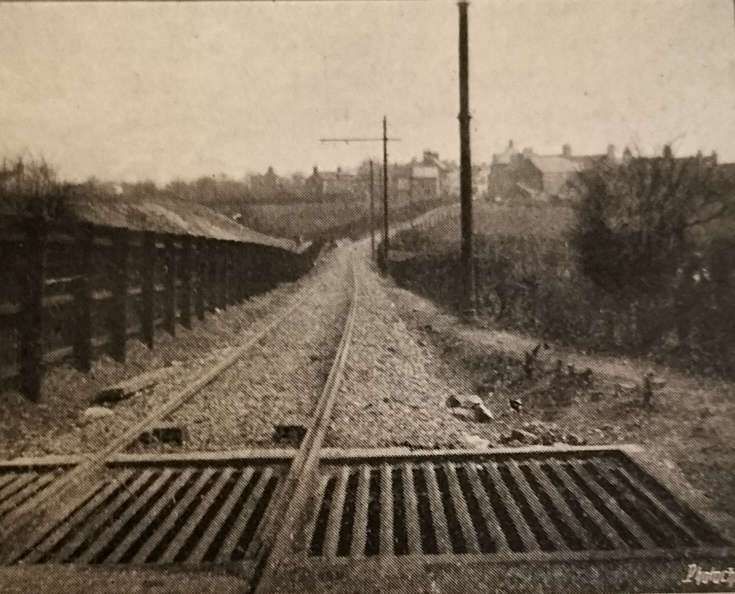

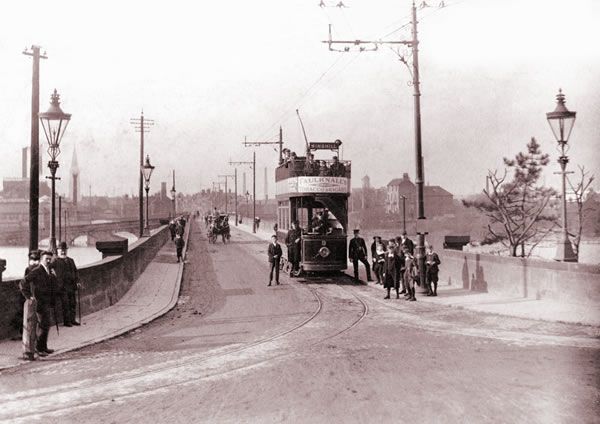

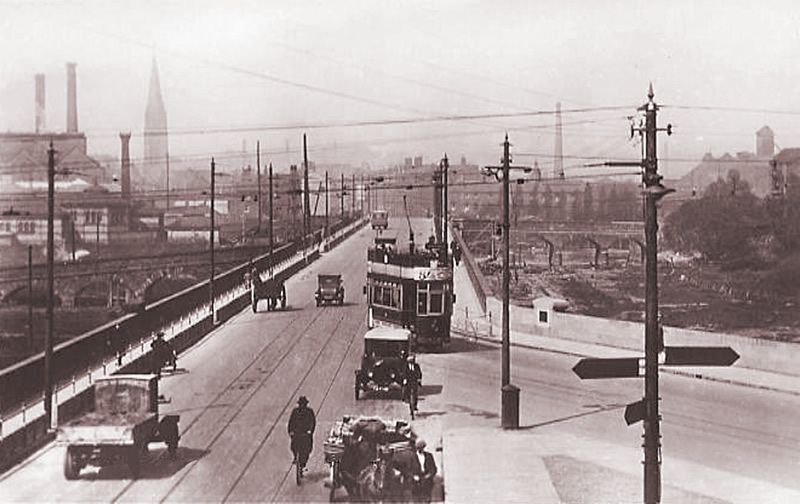

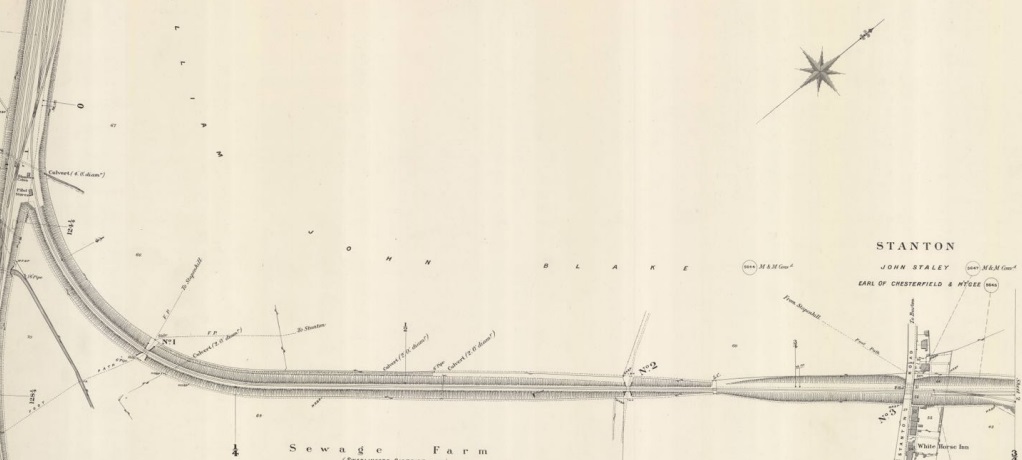

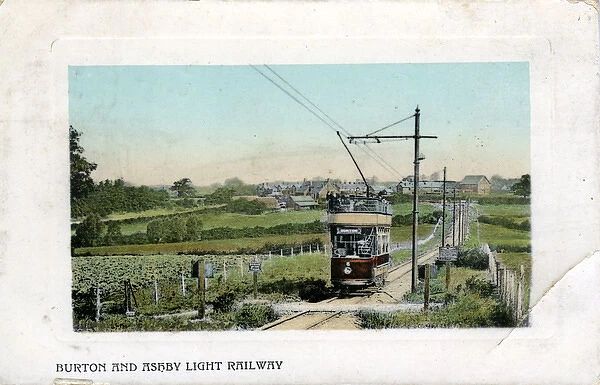

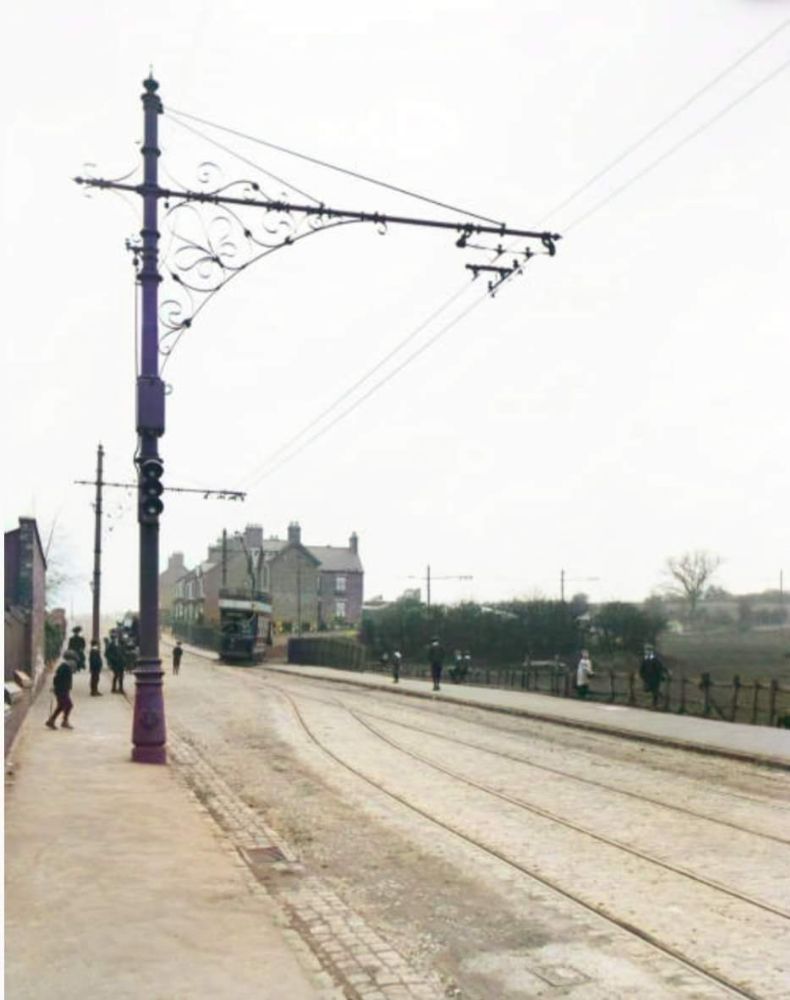

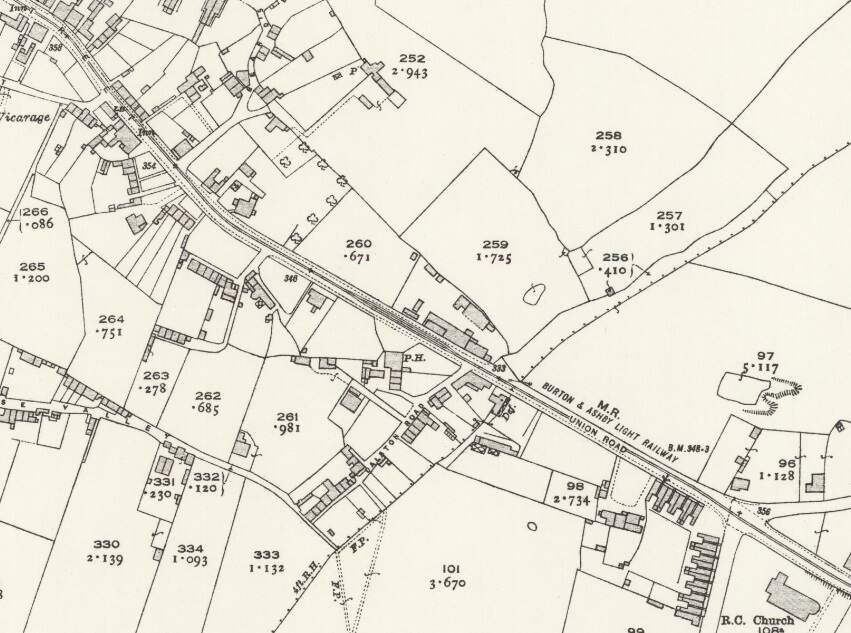

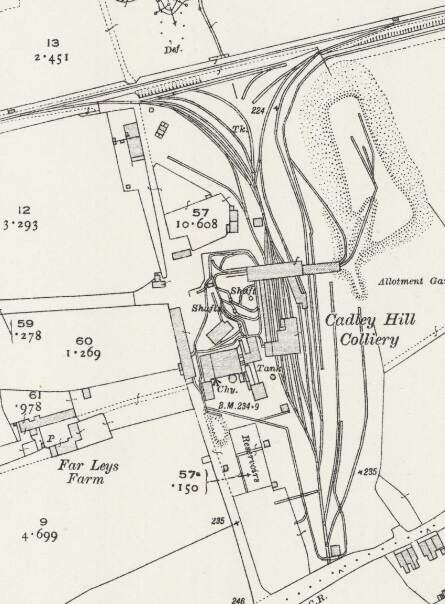

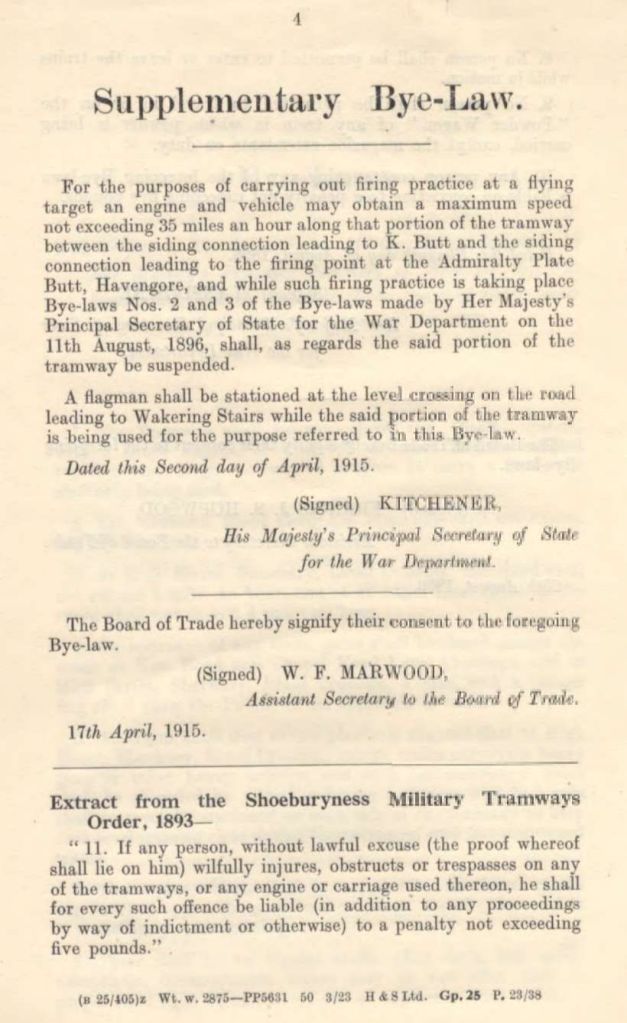

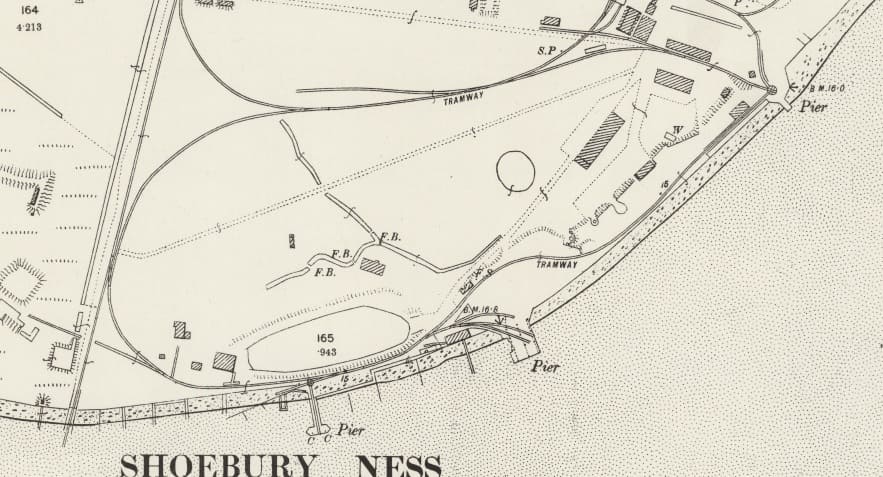

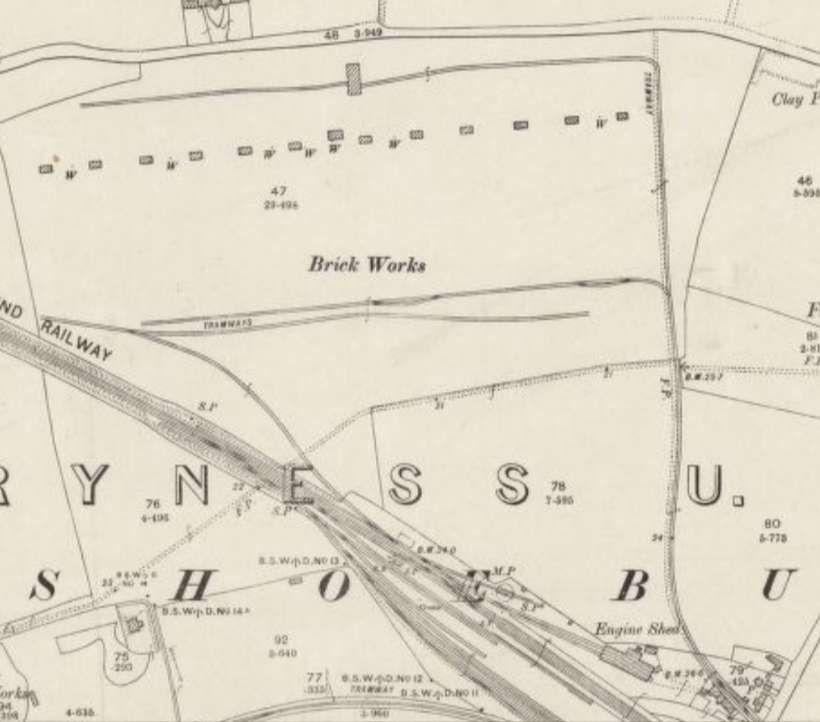

Shoeburyness changed rapidly from a hamlet to a bustling military establishment. And by 1873, and the completion of the construction of the site, “the original portion of the Shoeburyness Military Tramway had been built as an integral part of it. The line was linked to three piers to facilitate unloading and transport by river from Woolwich and elsewhere, of stores, equipment and guns, brought and destined for various parts of the garrison.” [5: p239]

The use, officially, of the word ‘tramway’ for what is in fact a ‘railway’ was derived from the term’s use in respect of colliery tramways and “is rooted in the legislation under which it was extended and worked. … Had the original line impinged on any highway, the Tramways Act of 1870 would have been applied to it, but having been laid on land already held from which the public were rigorously excluded, the Act was not invoked. By the time the first extension was required. the Military Tramways Act of 1887 had been passed, a measure designed to strengthen rather than to supersede the Act of 1870, which was intended primarily for street tramways.” [5: p239]

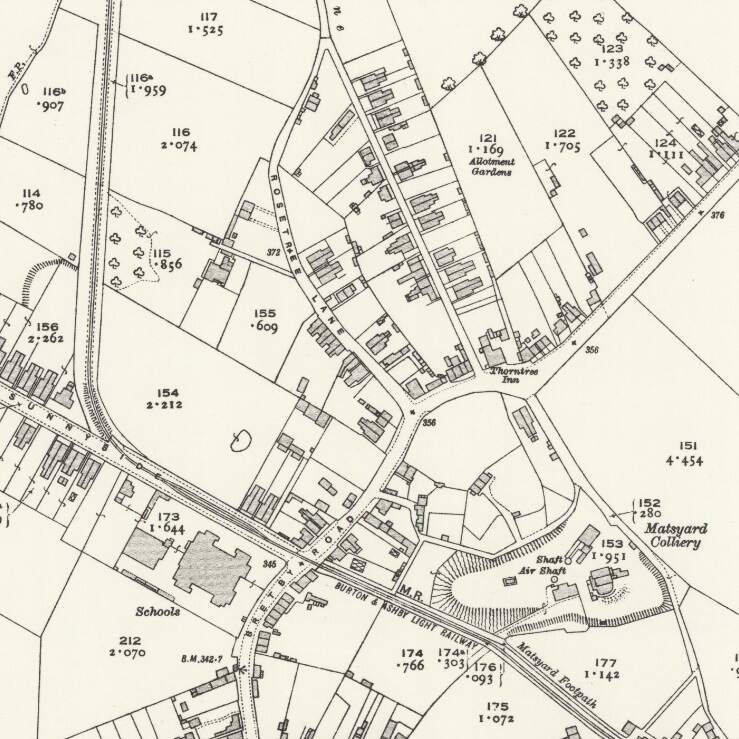

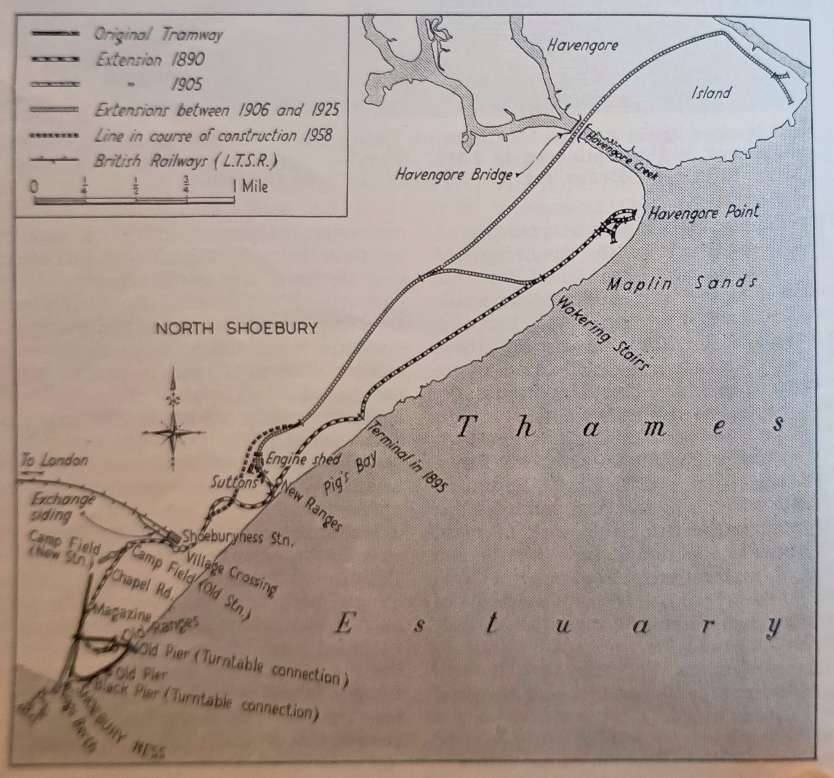

The main Shoeburyness military tramway was standard-gauge, but the military site also featured separate narrow-gauge sections of both 2 ft- and 2 ft 6 in-gauge. The standard-gauge line was constructed by the army to connect various installations within the experimental range and was later connected to the main railway network in 1884. The site used standard gauge lines extensively to serve its numerous buildings.

The separate narrow-gauge lines were often used in high-risk areas, such as shell filling huts, where steam locomotives were considered a fire hazard. These lines typically used hand-pushed or sometimes horse-hauled trolleys.

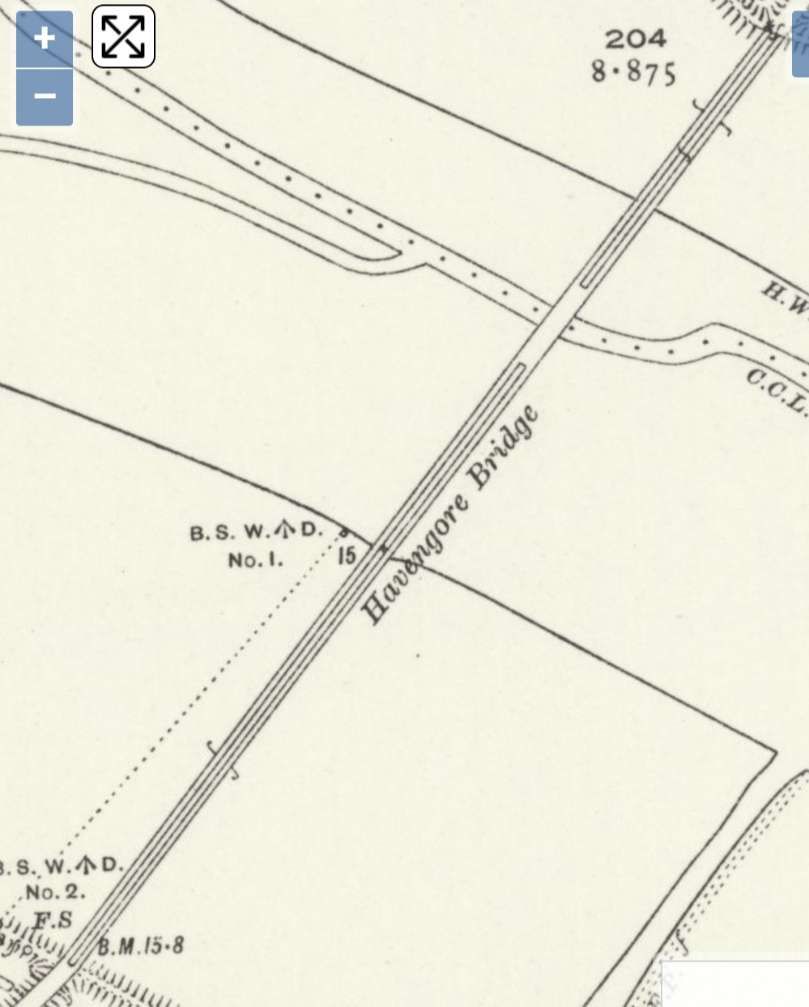

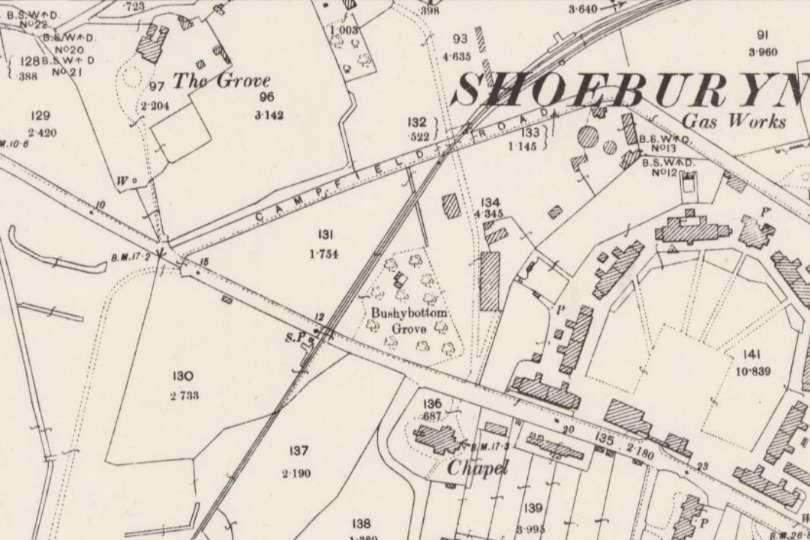

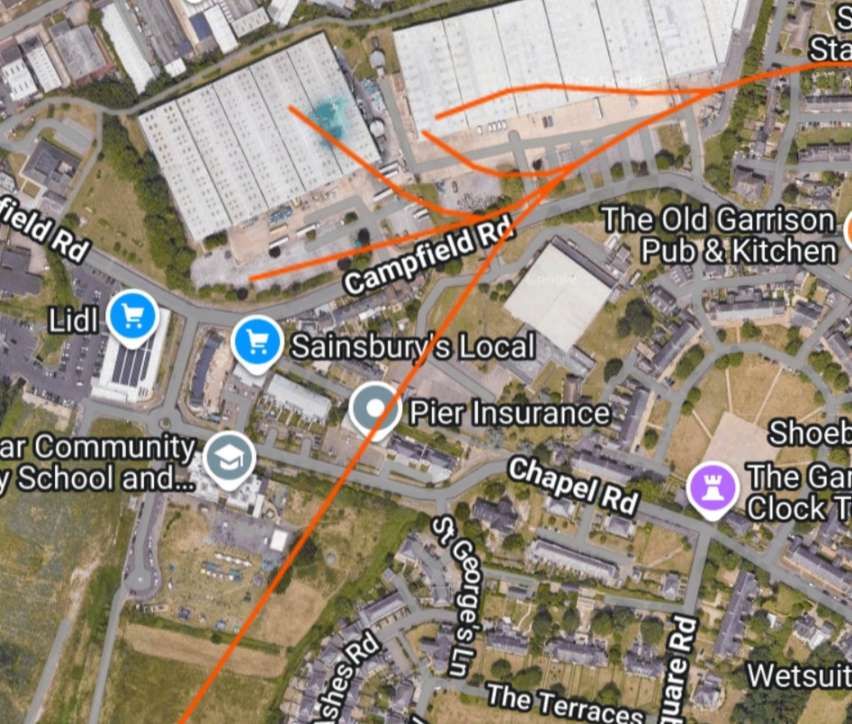

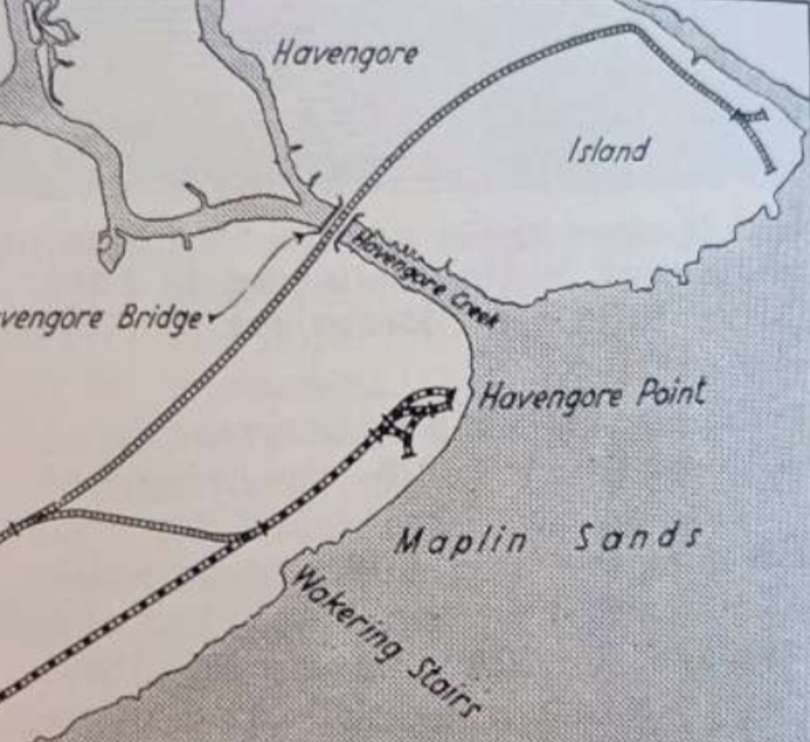

When the tramway was extended to New Ranges in 1890, the whole line was brought within the provisions of the Act of 1887. (But thirty years later, it appears that the extension to Havengore Island did not conform with the Act). “The Shoeburyness Military Tramways Order of 1893 authorised, retrospectively, an extension north-eastward for a distance of 1 mile 20 chains. from a junction with the original tramway, 21 chains South of Campfield Road, to where new artillery ranges had been brought into use on 5th April 1890.” [5: p239-240]

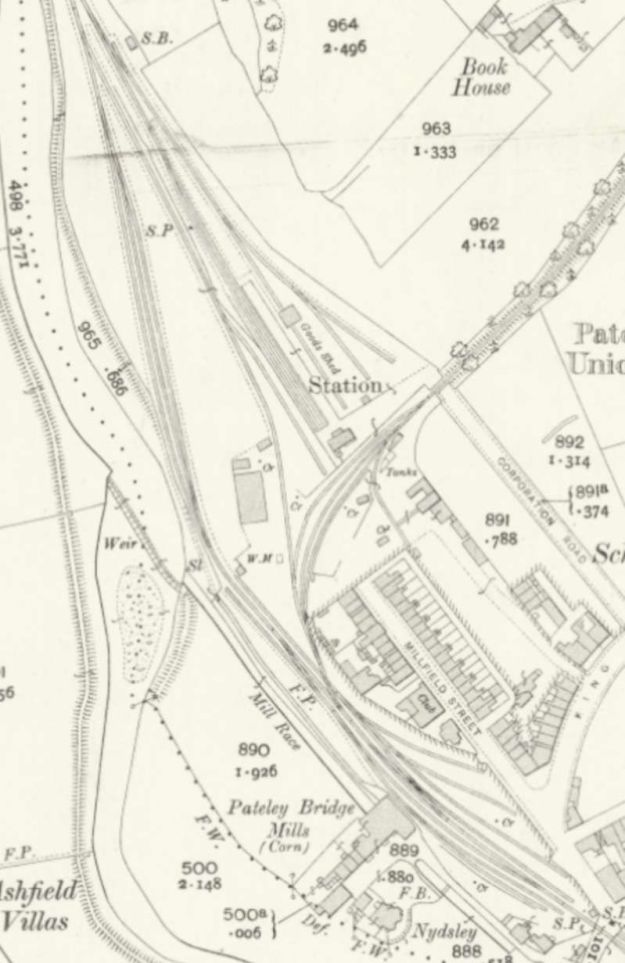

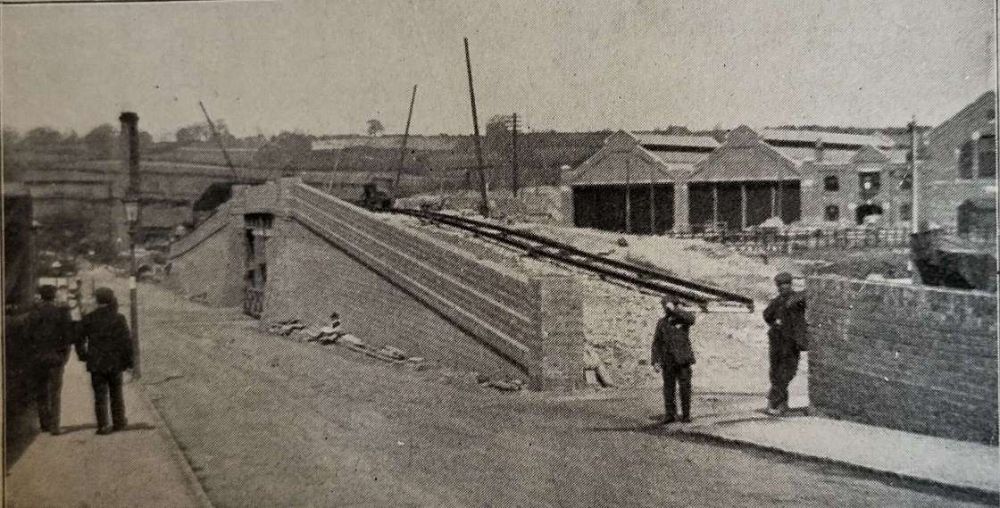

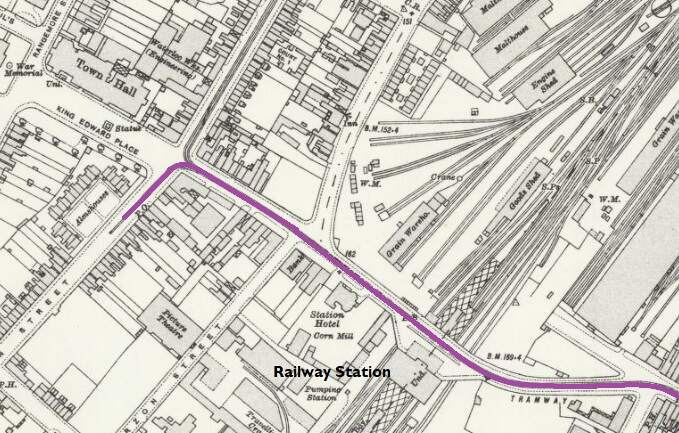

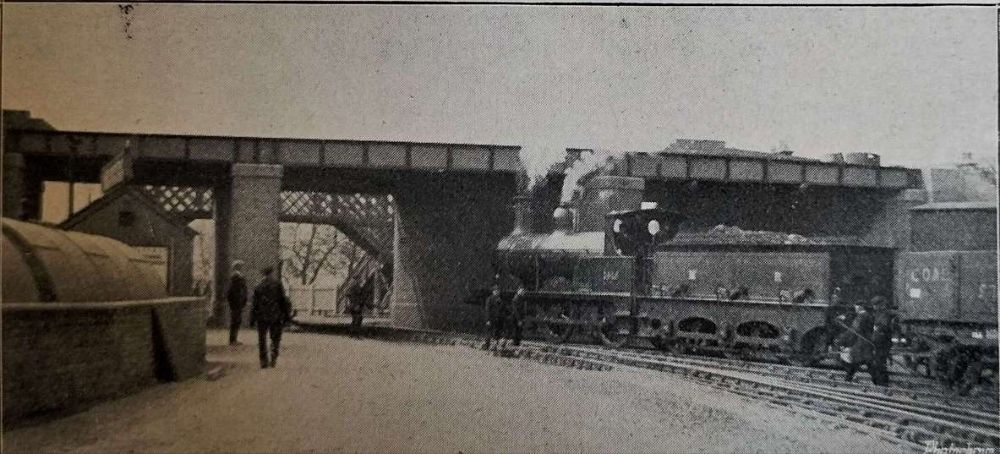

“By permission given in April 1889, the tramway passed through the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway station yard alongside its southern boundary: and an Agreement dated 8th July 1891 anticipated a rail connection there, for which £1000 had been voted in accordance with the Army Estimates for 1886/1887 This having been accomplished, fresh terms were embodied in a second Agreement dated 4th July 1895. Administrative buildings and the railway centre were placed in and around a seventeenth century property known as Suttons,” [5: p240] or Sutton Manor.

The now Grade II listed Sutton Manor was “built in 1681 of red brick and is surrounded by a red brick wall and gate. The interior has wooden panelling. An oak staircase with a dining room, servant quarters and around 9 bedrooms.

The land was owned by Daniel Finch (2nd Earl of Nottingham) but the House itself was most likely built by Francis Maidstone (a dealer in woollen textiles). He may have demolished a previous house standing on site.” [6] Suttons is a Category A structure on the Historic England Heritage at Risk Register. [7]

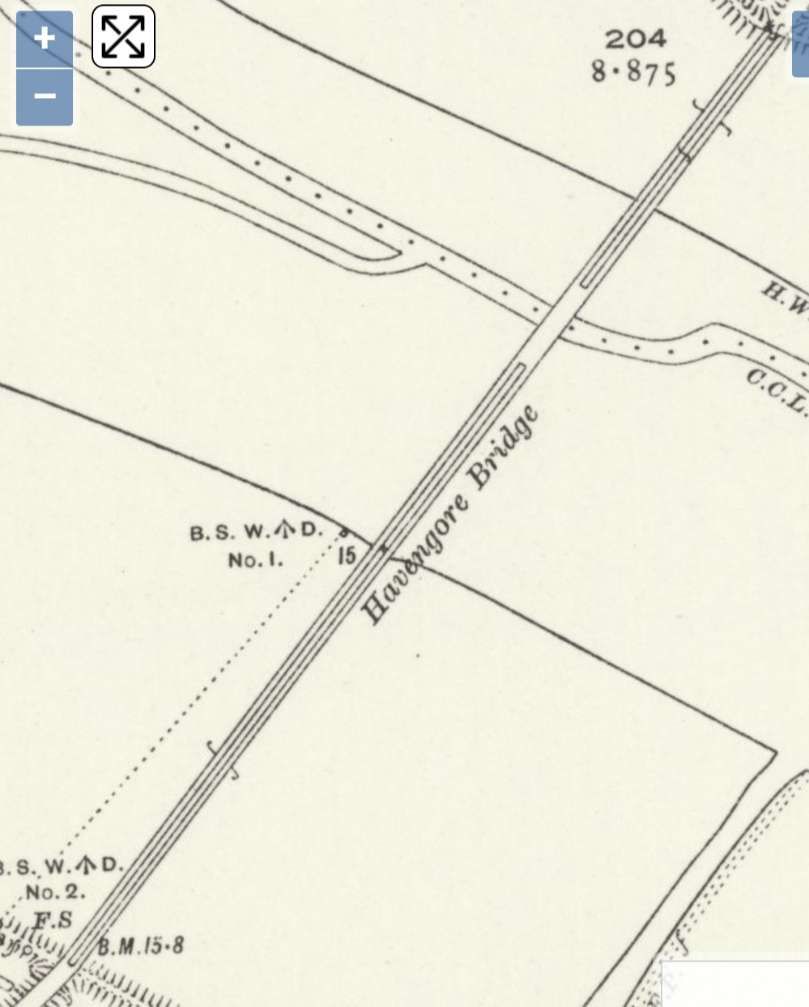

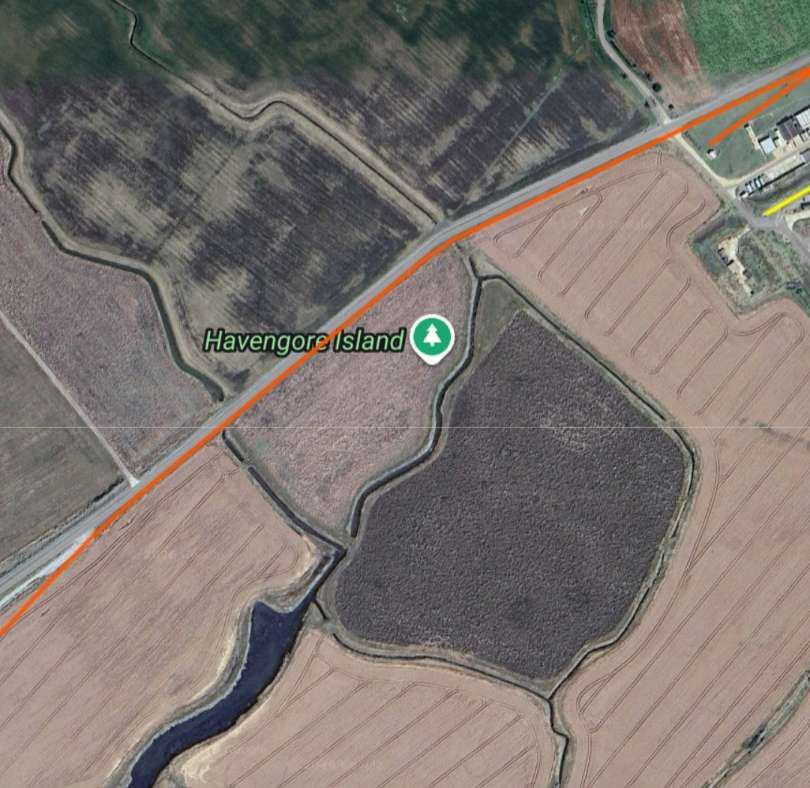

In 1906, the line was further extended 1 mile 52.22 chains from New Ranges to Havengore Point. The War Department completed the acquisition of New England and Foulness islands in 1914/1915. In August 1915, a contract was placed with Findlay & Co Ltd. For the supply and erection of a Scherzer Rolling Lift Bridge over Havengore Creek. Scherzer was an American Company from Chicago. The contract for the viaduct to run either side of the bridge was placed with Braithwaite Thirsk in February 1917 and piling started in June. There were a number of problems with the piling and completion of the viaduct stretched out to 1919 when the lift bridge was erected.

The bridge had a split counterweight and was originally hand operated carrying a road and a military tramway which enabled the tramway to be taken to a terminus on Havengore Island by 1925. [11]

In 1959, this was still the terminus of the line. … The road across the bridge ran to Churchend and Fisherman’s Head was completed in 1922-23. [11]

Back to the Southwest, in 1957, work commenced on a new line, 1,300 yards long moving the line from the South side of Suttons to the North. By the beginning of 1958, track was laid along the length within the perimeter of New Ranges and earthworks were completed over the remainder of the realigned route. [5: p240]

The line was designed to relieve congestion Southwest of Suttons. It eliminated two sharp curves on the original line and opened in November 1958, after which the older line was removed.

At the time of the writing of The Railway Magazine article, the School of Gunnery had just closed. With that closure the primary purpose of the tramway became the support of the “requirements of the Ministry of Supply which [had] controlled the Proof and Experimental Establishment since 1939. Although the War Department still own[ed] the tramway and the land on which it [was] built, the right to its use and control … passed to the Ministry. For convenience, the War Department operated[d] the tramway because, [as of that date], railway operation and maintenance [was] a branch of army training.” [5: p241]

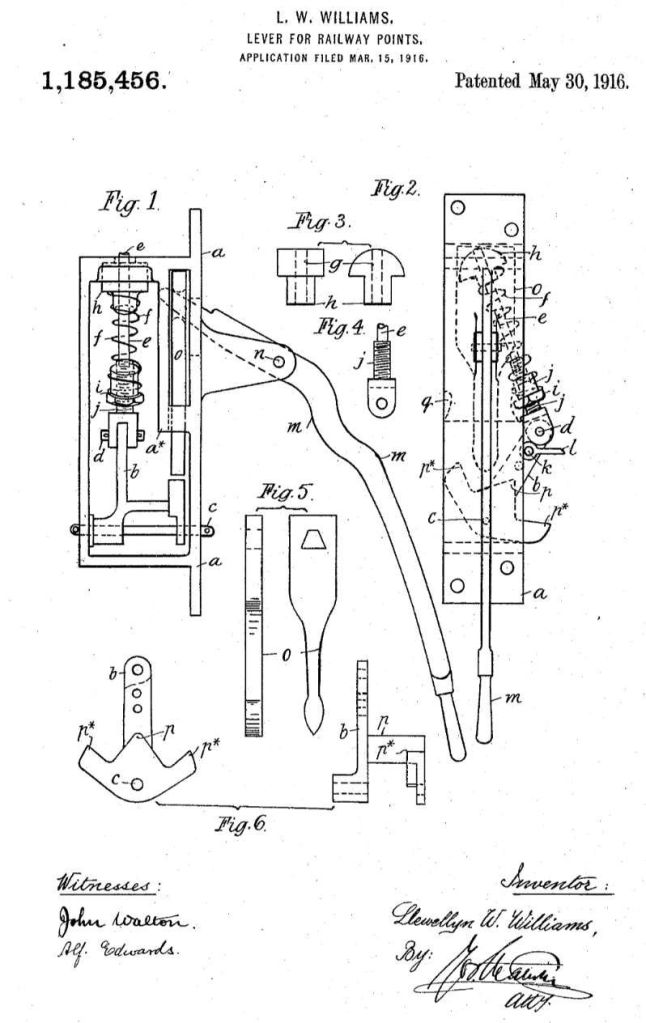

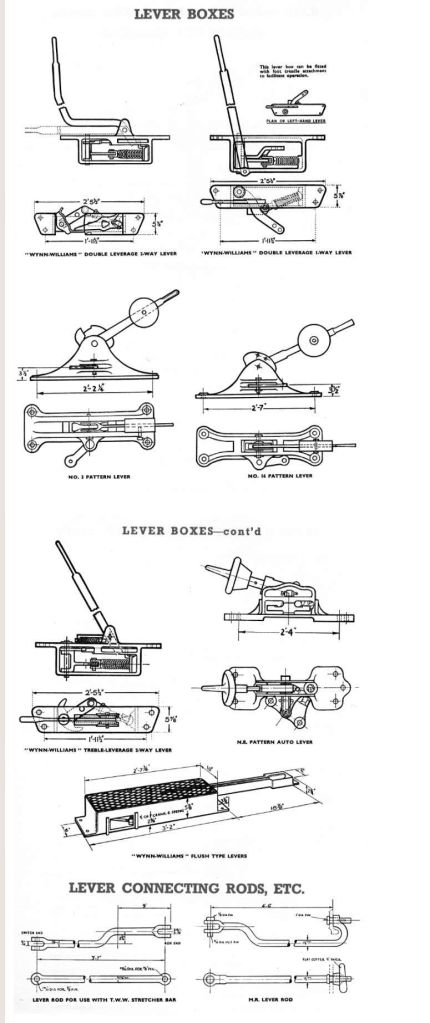

“The greatest length of the tramway [was] 5 miles, and its total track mileage [was] 24. Havengore Bridge, the only engineering feature of note, [was] a cantilever structure of 55 ft. span for road and rail.” [5: p241] The steepest gradient on the line was 1 in 52 on the eastern approach to Havengore Bridge. “Conveyance of increasingly heavy pieces of ordnance … necessitated the use of rail weighing 98 lb. per yd. The track [was] variously ballasted with slag, clinker, Thames ballast or granite. Weed-killing on the main line [was] by motor-driven spray on a diesel-hauled wagon, and on sidings by hand-spray on a plate-layers’ trolley. Points are hand-operated, sixty percent of them by MacNee tumbler lever boxes [9] and the rest by Williams two-way spring levers. [10] Facing points [had to be held down by the fireman (the word ‘Stoker’ – foreign to railway terminology – [was] used officially), although responsibility for the train’s safe passage rest[ed] with the driver. The radius for curves and turnouts varie[d] between 600 and 320 ft.” [5: p241]

At one time, signals were installed to protect road crossings and these were operated by gate-keepers. In practice, they were not needed. Even so, they were only gradually removed – the last survived until the mid-1950s.

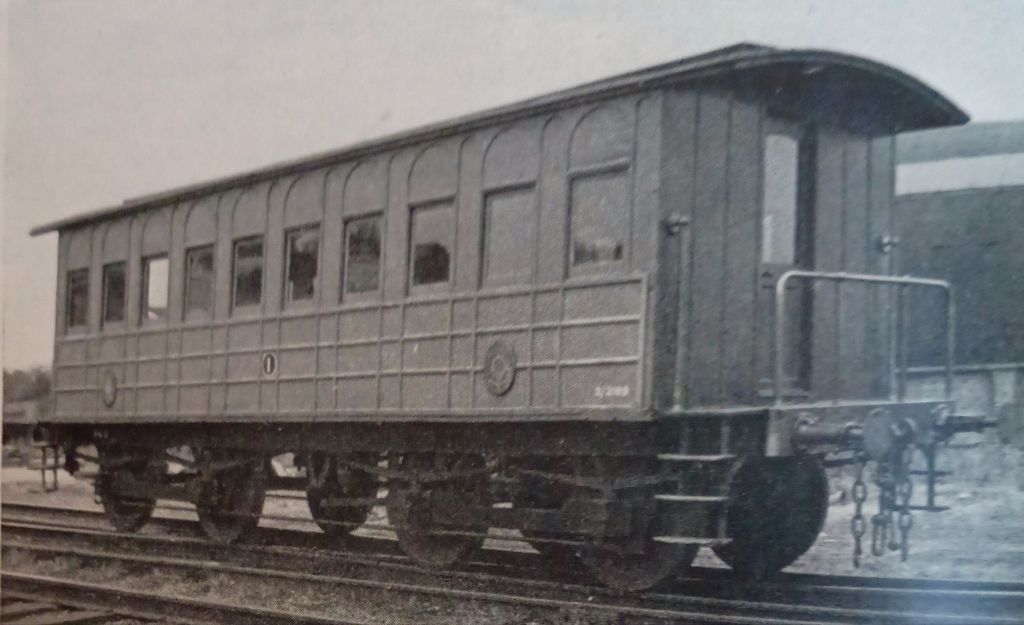

A census of locomotives and rolling stock on site in June 1957 showed that the Ministry of Supply owned “6 railcars, 99 open wagons, 71 flat-top wagons, 45 assorted vans and 28 cranes (18 steam and 10 electric). The biggest crane weigh[d] 200 tons, and ha[d] a lifting capacity of 60 tons.” [5: p241] Also on site, but owned by the War Department, were “17 locomotives (11 steam, 5 diesel and one diesel-electric) and 12 passenger coaches.” [5: p241]

One passenger vehicle, used as a drawing office, was a celebrity! It carried a plaque inscribed: ‘This coach did service on the Suakin-Berber Railway. It is reputed to have been the saloon coach used by Lord Kitchener’.

“In December, 1899, at the close of his campaign in the Sudan, Lord Kitchener left Khartoum for South Africa, whereas Suakin and Berber were not linked by rail until 1905. The reference intended probably is to Kitchener’s famous military railway built across the Nubian Desert in 1897, and completed to Berber and the Atbara River in 1898. The letters T.V.R. are moulded into the ornamental brackets supporting the lug gage racks. Built by the Metropolitan Carriage & Wagon Company of Saltney, the coach is one of a pair of 32-ft. clerestory carriages which, in common with other passenger stock, has been saved from the scrap heap by acquisition for service on the Shoeburyness Military Tramway – the so-called Kitchener coach in 1898, the other in 1900.” [5: p243]

Locomotives, etc.

Sequestrator reports that the motive power on the tramway network fell into three categories, “steam locomotives, diesel locomotives and railcars. The maximum weight permissible on the … bridge being 20 tons, steam engines [were by 1958] confined to the west of Havengore Island. To overcome this limitation, electric battery locomotives were introduced, and diesel engines [then] superseded them. The railcars [were] for the transport of gangs with tools and light equipment or for use as inspection cars.” [5: p243]

Of the steam locomotives, “ten [were] of one ubiquitous type, having been built to standard specification by various firms in 1943-45: five by the Hunslet Engine Co. Ltd., two by W. G. Bagnall Limited, and one each by Robert Stephenson & Hawthorns Limited, Andrew Barclay Sons & Company, and the Vulcan Foundry Limited. All [were] 0-6-0 saddle-tank engines with 4 ft. 5in. wheels, and inside cylinders using saturated steam at 170 lb pressure. The water capacity [was] 1,200 gal. and the weight empty 371 tons. The eleventh steam locomotive, built by Hudswell, Clarke & Company in 1923, [was] smaller and lighter, but [was] a favourite with the men for efficiency and ease of working.” [5: p243]

The lined-out brown livery in use prior to WW2 had, by the late 1950s, given way to plain light apple-green for all steam locomotives. Locomotives and rolling stock were kept in excellent condition. Each engine carried three numbers. That displayed most prominently was the local number by which locomotives were distinguished for rota purposes. “Every engine owned by the War Department [had] a W.D. number, irrespective of the particular railway on which it [was] in service. There [was] also a makers’ number.” [5: p243]

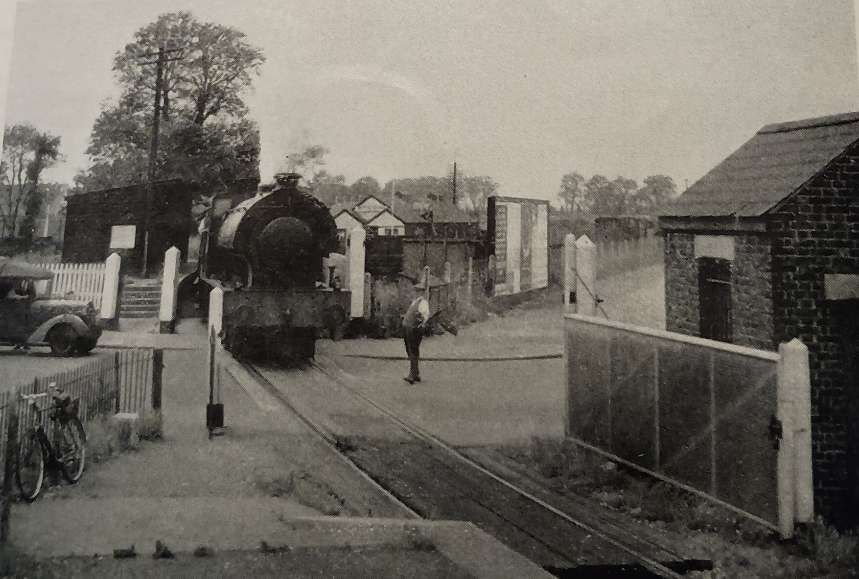

“Most of the traffic [was] internal, and at times as many as twelve motive-power units [could] be at work simultaneously. Transfers to and from British Railways [took] place on an exchange siding – a single line just over 100 yd. long – on the extreme south of the station yard at Shoeburyness.” [5: p243] By the late 1950s, river-borne consignments were rare, and the piers were little used.

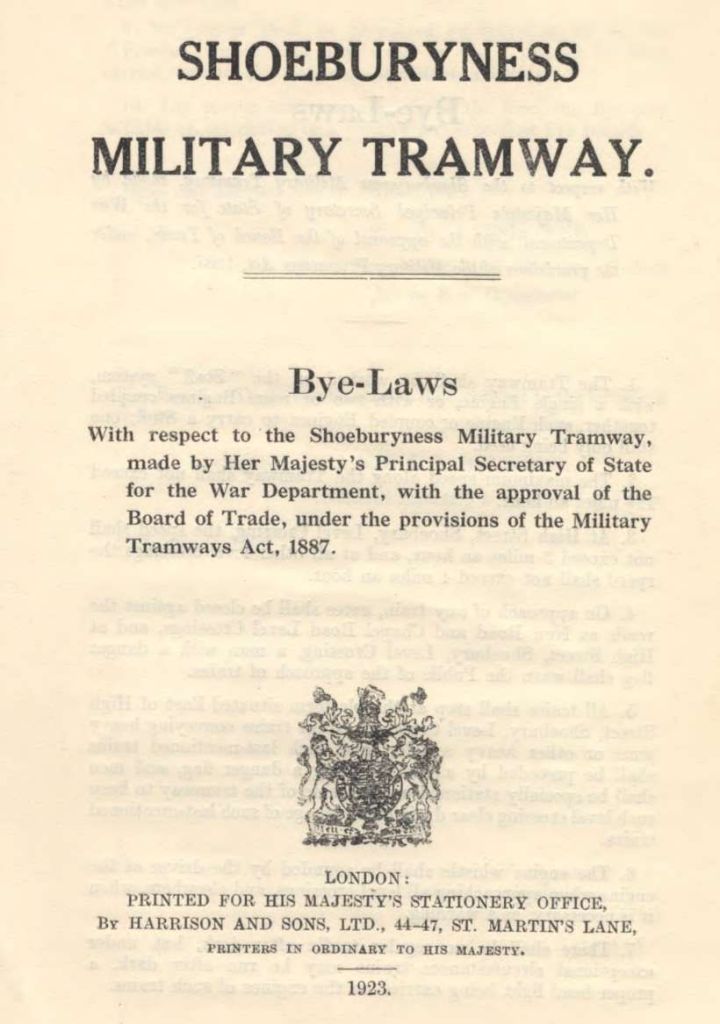

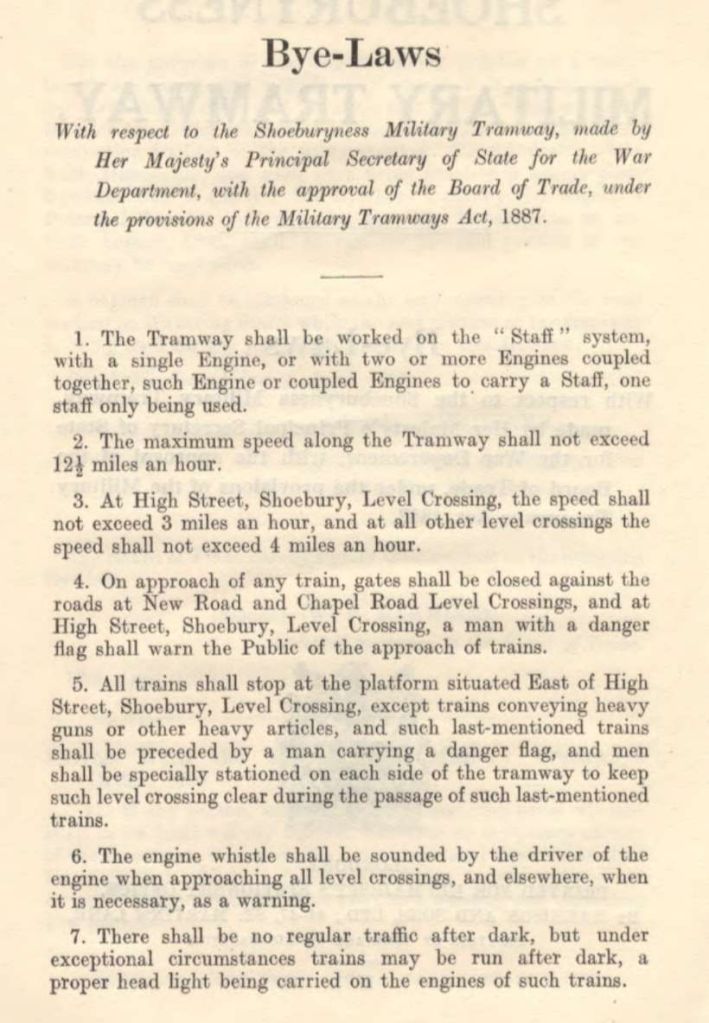

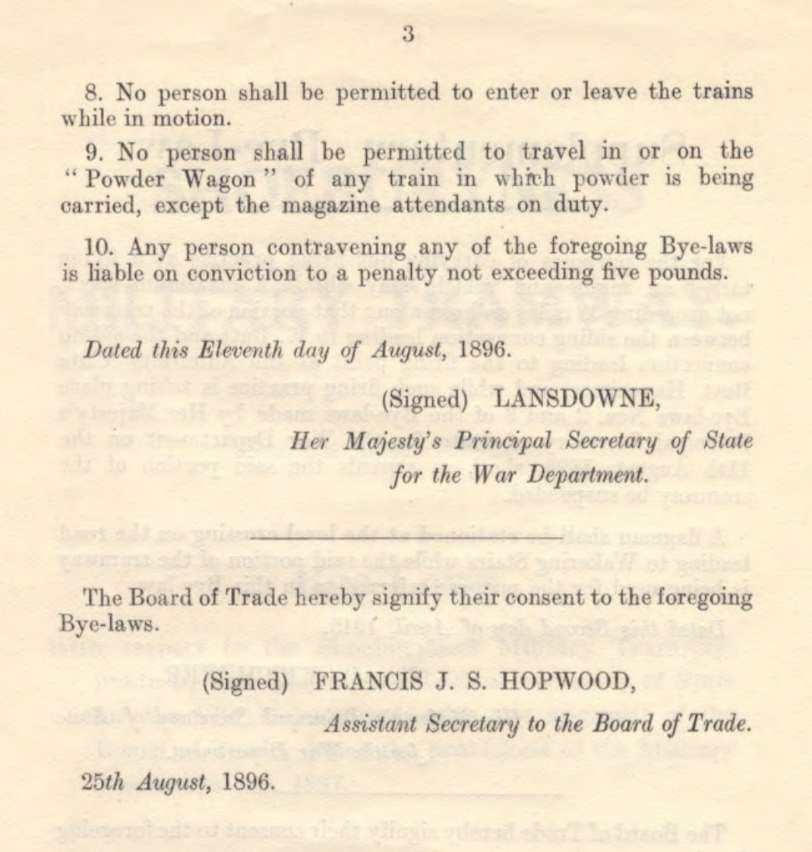

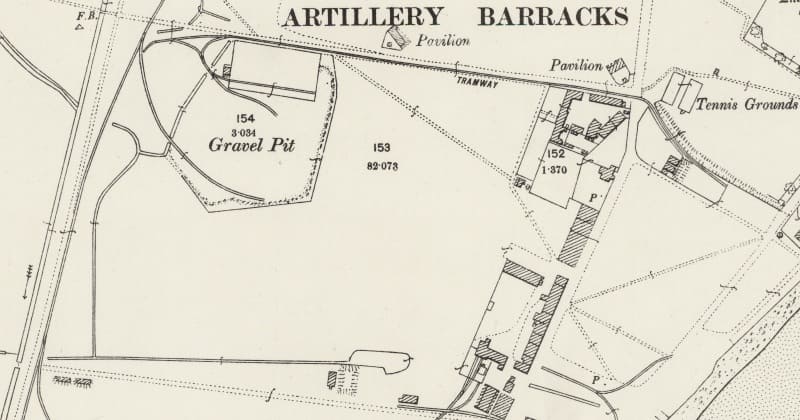

Military Standing Orders and Bye-laws

Military standing orders for train working, which correspond to the rule book in normal railway practice, incorporate the original bye-laws dated 11th August 1896, which were framed in compliance with the Act of 1887. Government Records [8] hold a copy of the bye-laws in place on the line. These bye-laws were promulgated by the War Department with the approval of the of Trade, under the provisions of the Military Tramways Act, 1887. Additional bye-laws were made in April 1915. The bye-laws are included immediately below. [8]

It may also be of interest to read the bye-laws covering the military ranges on the MOD site. These can be read here. [39]

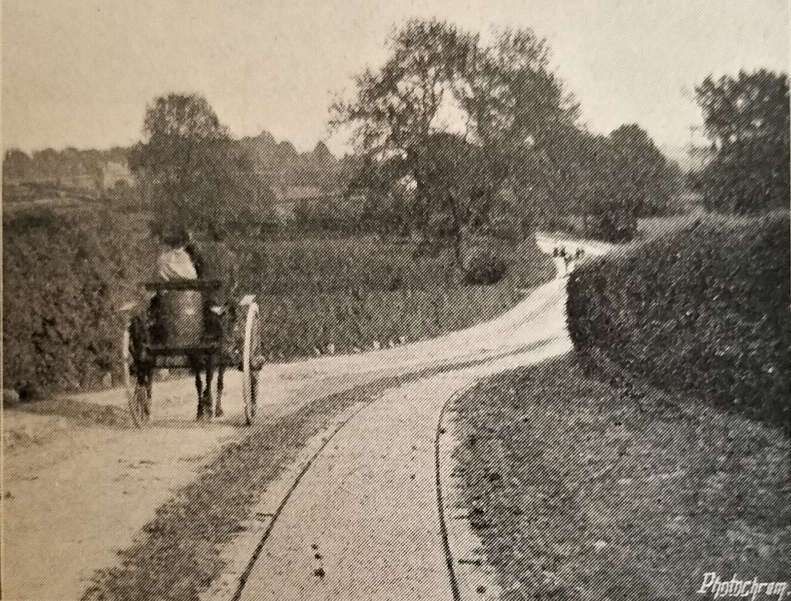

Sequestrator comments that in general the bye-laws “enforce the use of the train staff on the one-engine-in-steam principle, regulate the closure of crossing gates, prohibit regular traffic after dark, and forbid anyone but the magazine attendant to ‘travel in or on the Powder Wagon’. A general speed limit of 12.5 m.p.h. is imposed. At one time the tramway system itself played a part in providing flying target practice, and a special supplementary bye-law. signed by Lord Kitchener on April 2 1915, permitted a speed of up to 35 m.p.h. by an engine and vehicle over a specified stretch near Wakering Stairs. The train staff is carried only west of Suttons, where, in passing through a semi-built-up area, the line [had] several sharp curves, some of them blind. Eastward, however, the railway crosse[d] flat, open land, where branch-lines and sidings [led] to firing platforms and testing sites, and where a collision at 12.5 m.p.h. would be inexcusable.” [5: p243]

“Administration [was] delegated to army officers of the Royal Engineers, whose responsibility [was] divided between motive power, civil engineering, track maintenance and traffic control. The staff [were] wholly civilian; their working day begins at 6.45 am, and ends at 6 p.m. Engine-drivers work[ed] on a daily rota system, which [was] set out on a ‘detail board’. Steam locomotives [were] sent to the makers for overhaul every five years, but normal repairs and maintenance [were] done in War Department’s own workshops at Suttons.” [5: p243-244]

A Journey Along the Line

We start our journey at the Southwest end of the network.

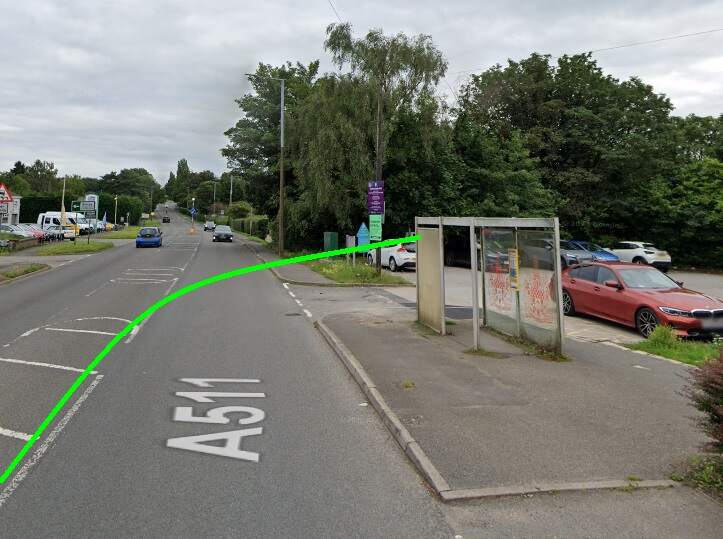

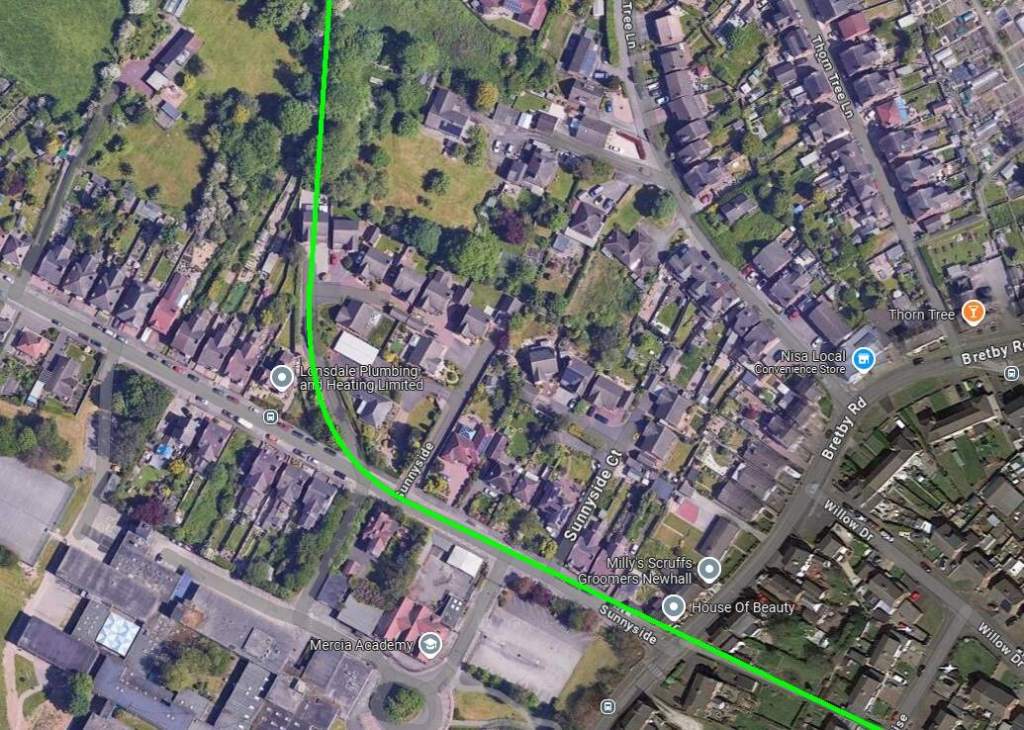

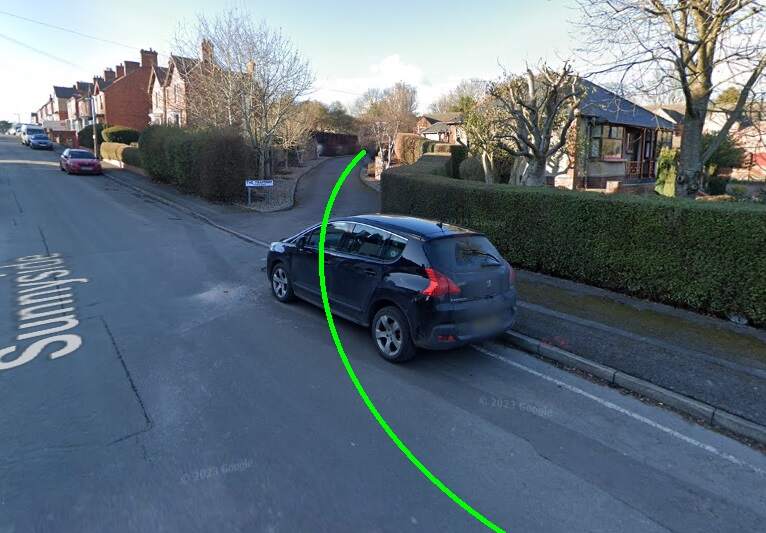

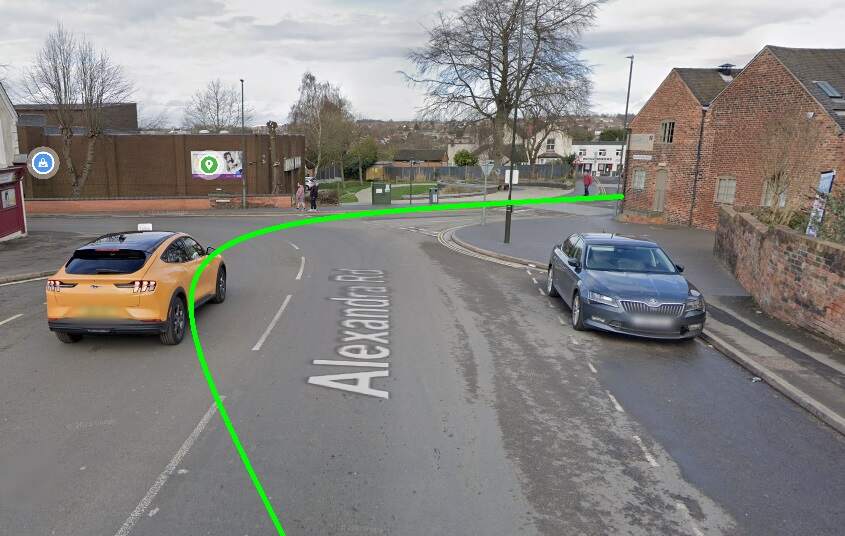

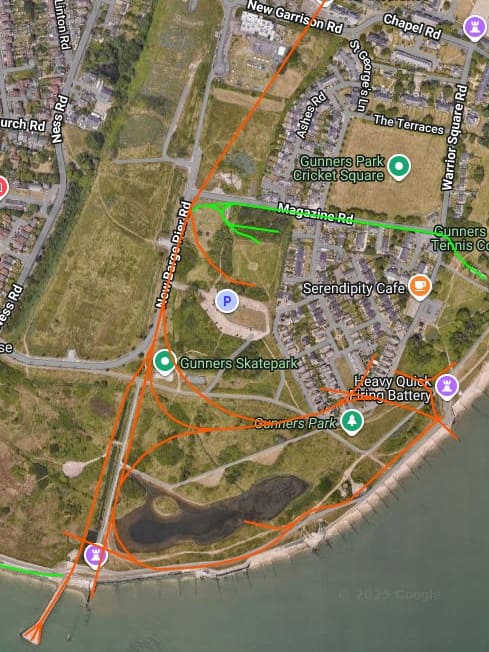

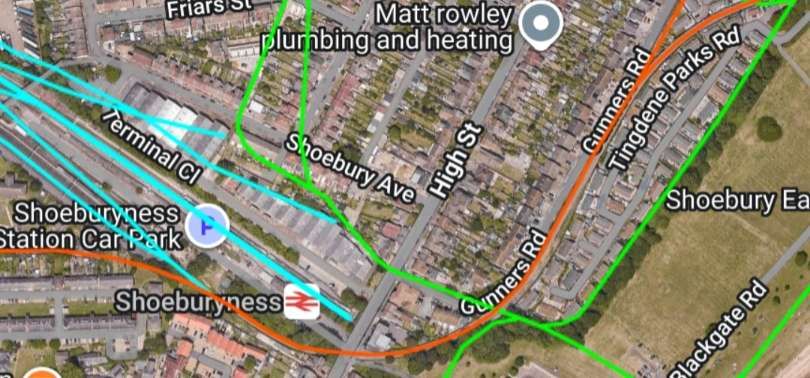

The line heads Northwest, alongside Gunners Road in the 21st century. …

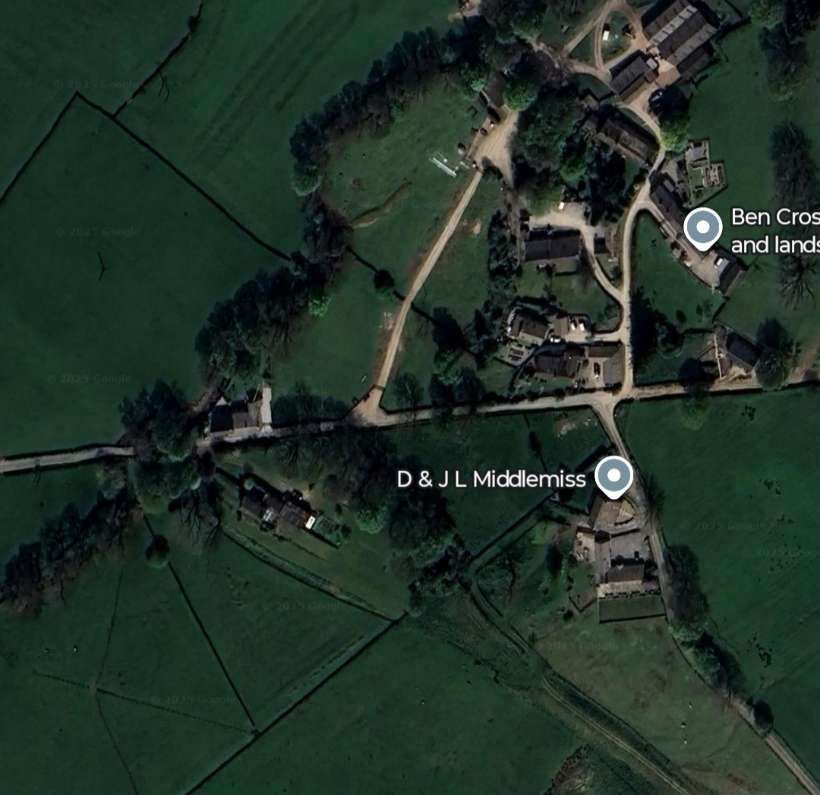

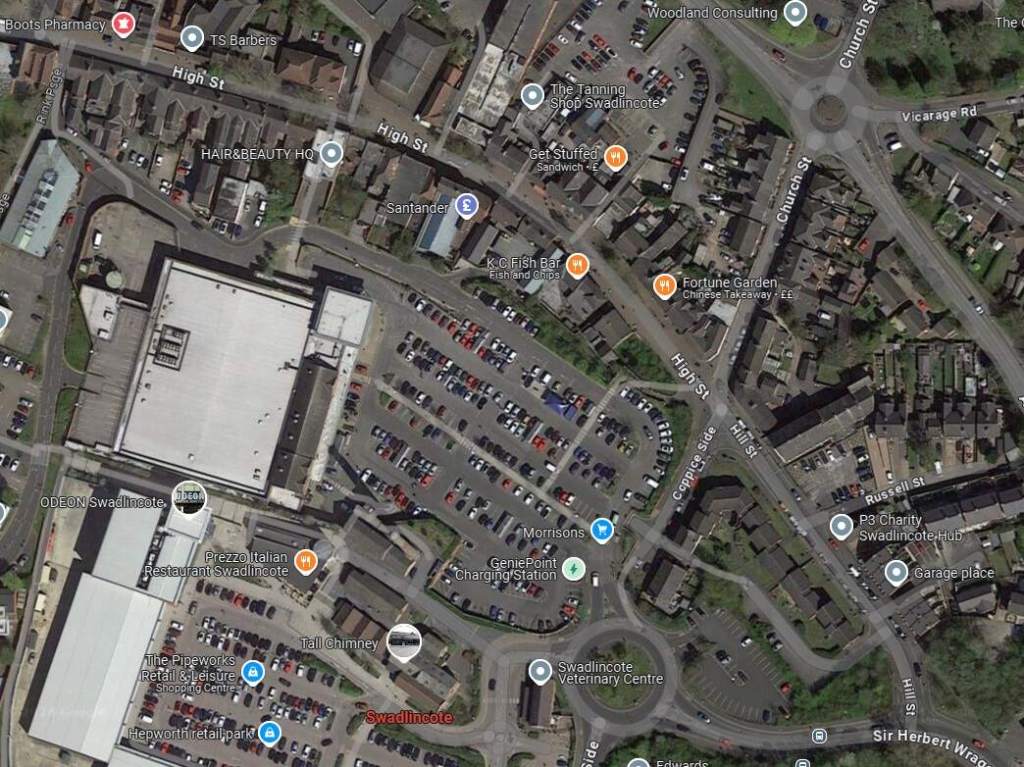

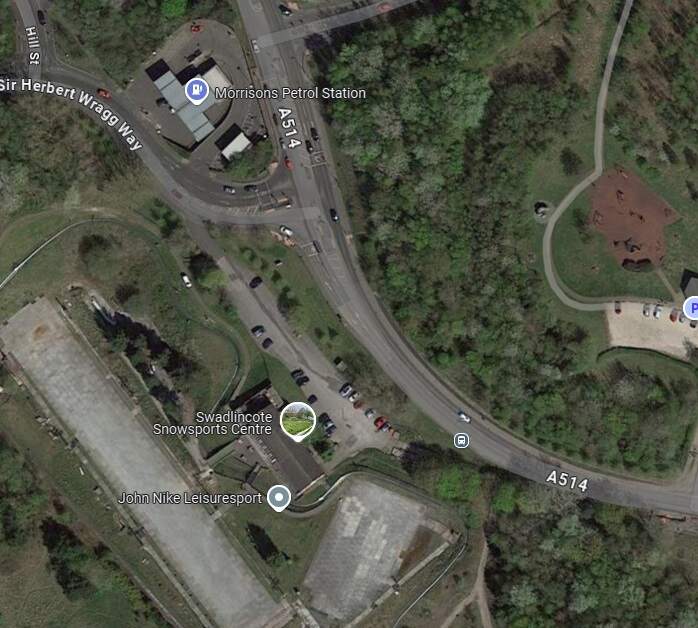

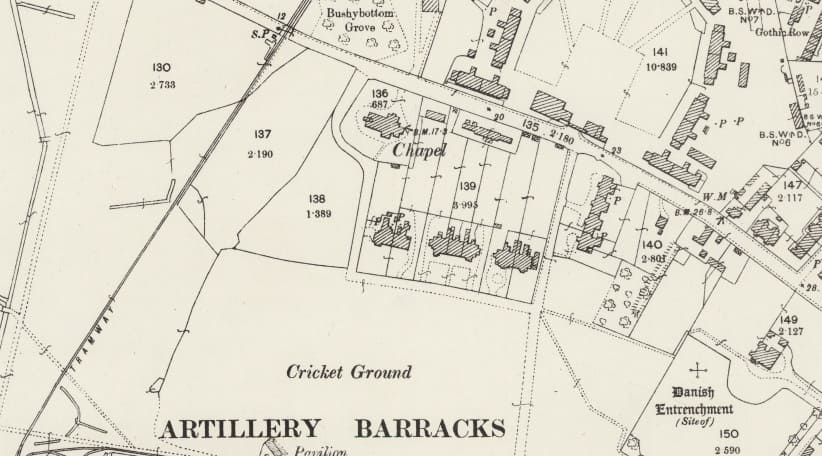

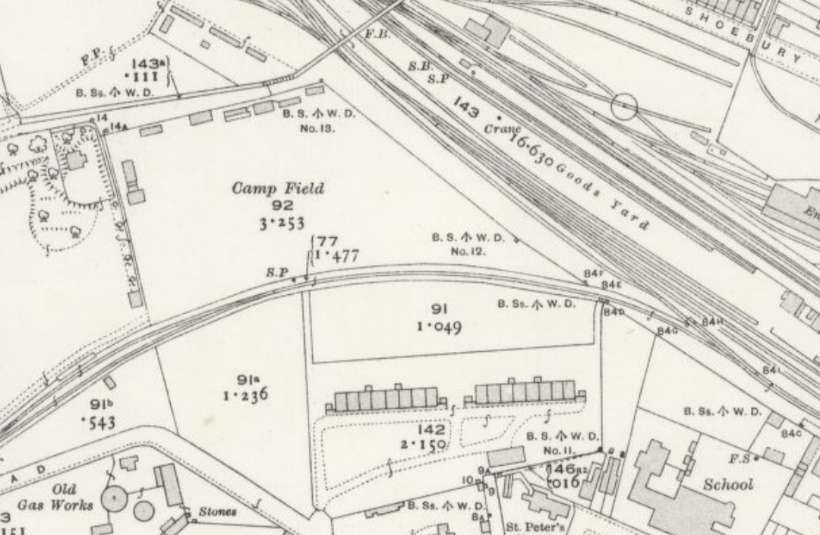

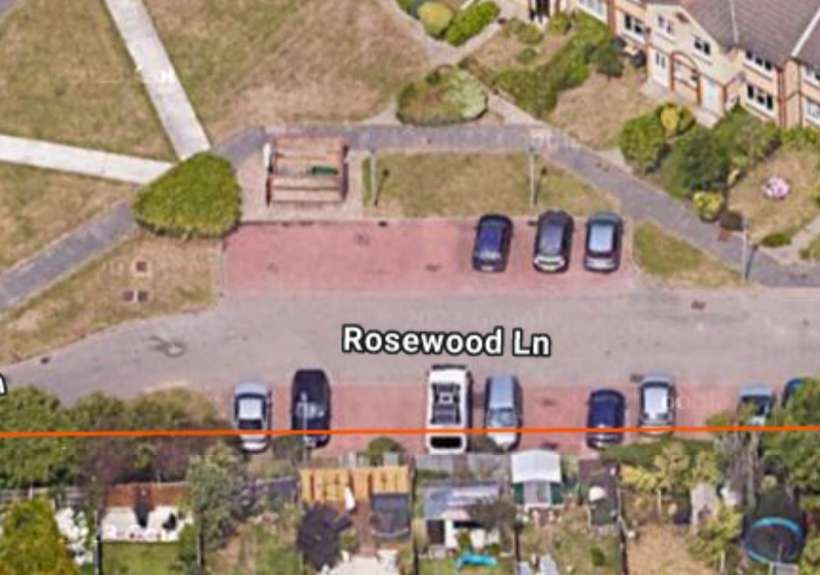

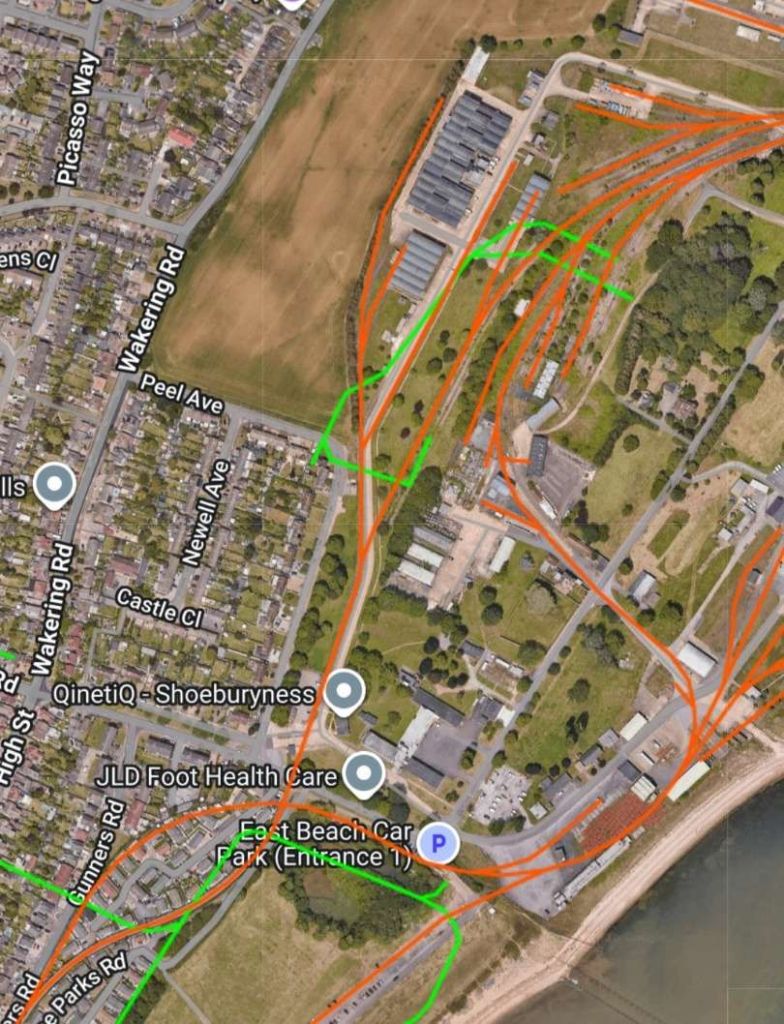

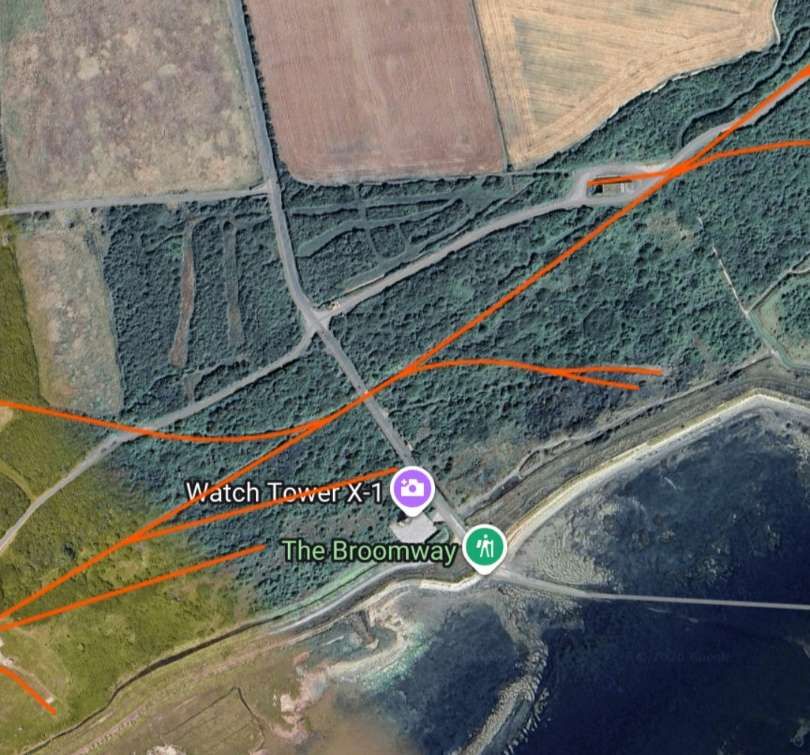

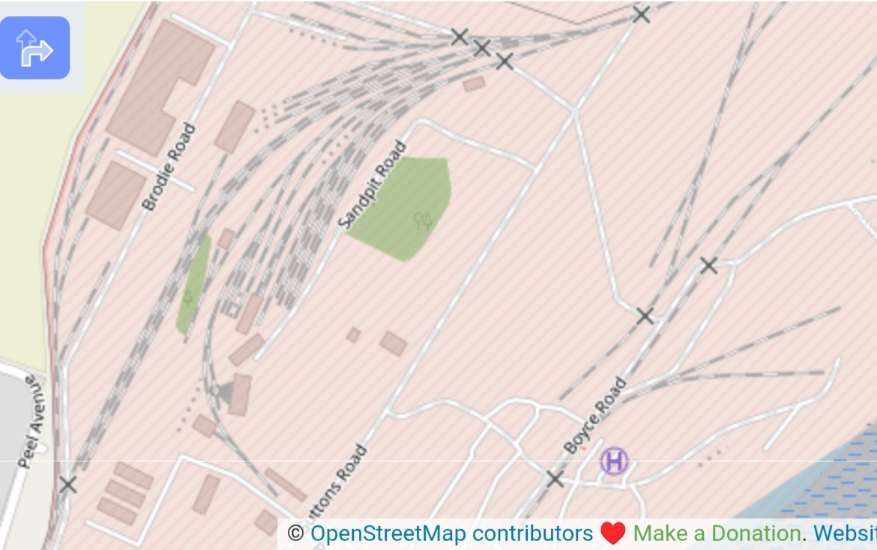

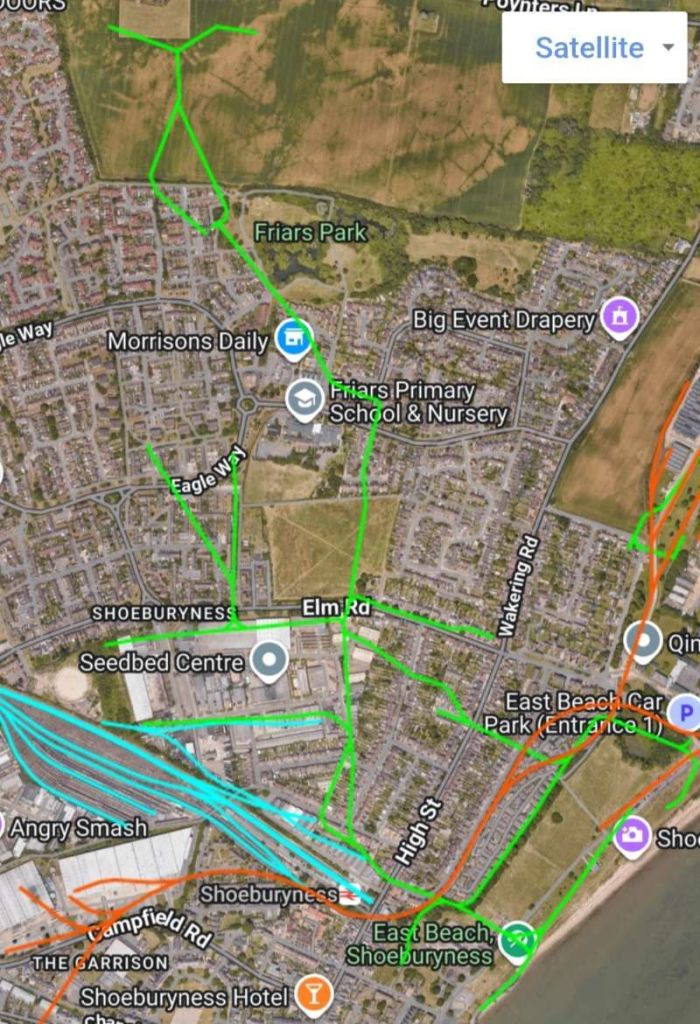

The next two satellite images cover approximately the same area as the three map extracts above. RailmapOnline.com seeks to show all the different track layouts which once graced the MOD site. It appears to be a ‘cats’ cradle’ of different lines! …

These next two satellite images show the lines at the Western edge of the site and the buildings that they serve. …

Attempting to show all the lines on the site on satellite images at a larger scale bill be more confusing than helpful, so contemporary Ordnance Survey maps, and the diagrams of track layout from RailMapOnline.com will suffice, together with 21st century OpenStreetMap mapping.

The remaining extracts from the satellite imagery provided by RailMapOnline.com show the route of the line to its terminus at the eastern extremity of Havengore Island. …

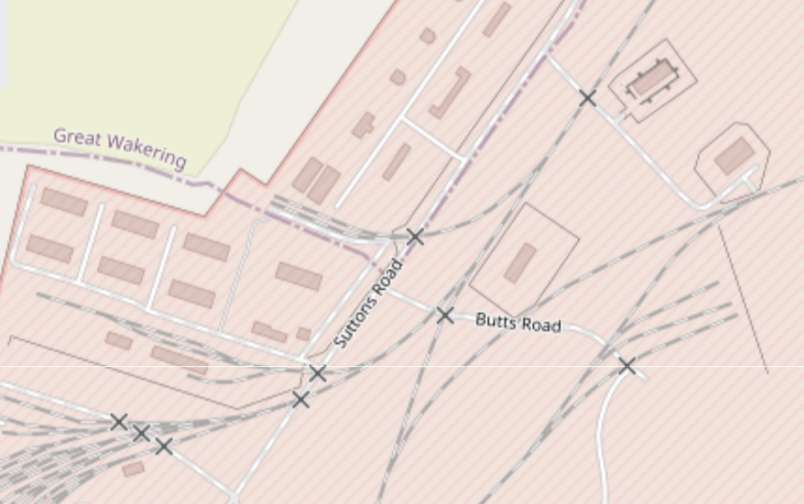

The series of extracts from OpenStreetMap.org below shows the railway layout within the military site North of the junction on the last Google Maps satellite image some distance above (near the crossing at Brodie Road). The layout is considerably different to that in place in the 1920s and at the beginning of WW2. These extracts purport to show what remains of the rail network in the 21st century…

Further Northeast on the site the railway layout is much reduced from that shown on earlier series of images. …

In the 21st century, the site is managed by QinetiQ and consists of a range covering a land area of 7,500 acres (3,000 ha) with 35,000 acres (14,000 ha) of tidal sands and 21 operational firing areas. MOD Shoeburyness is also a centre of excellence for environmental testing of ordnance, munitions and explosives. The Environmental Test Centre on site also simulates extreme environmental conditions to evaluate military vehicles and equipment. [24]

Several buildings and structures on the site are listed, including the cart and wagon shed, which is used as a heritage and community centre; together they are described by Historic England as constituting “a complete mid-19th century barracks”. [25] As of 2016 many of these have been refurbished for sale as private houses, and additional housing is being built in the vicinity. A tower was planned to stand in the Shoeburyness Garrison housing development. The tower was to be 18 storeys high and designed to mark the start of the Thames Gateway development. [24]

The history of the site, in pictures, can be found here. [27]

Buildings on the site include the Air Blast Tunnel below:

Understandably full details of buildings on the site and their military uses are difficult to obtain!

Passengers

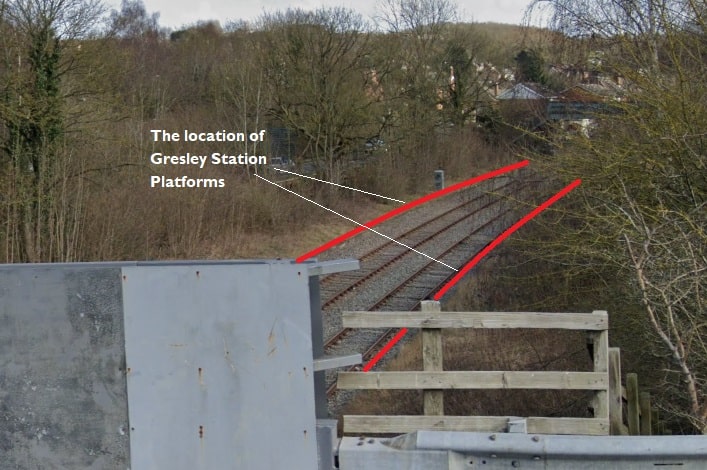

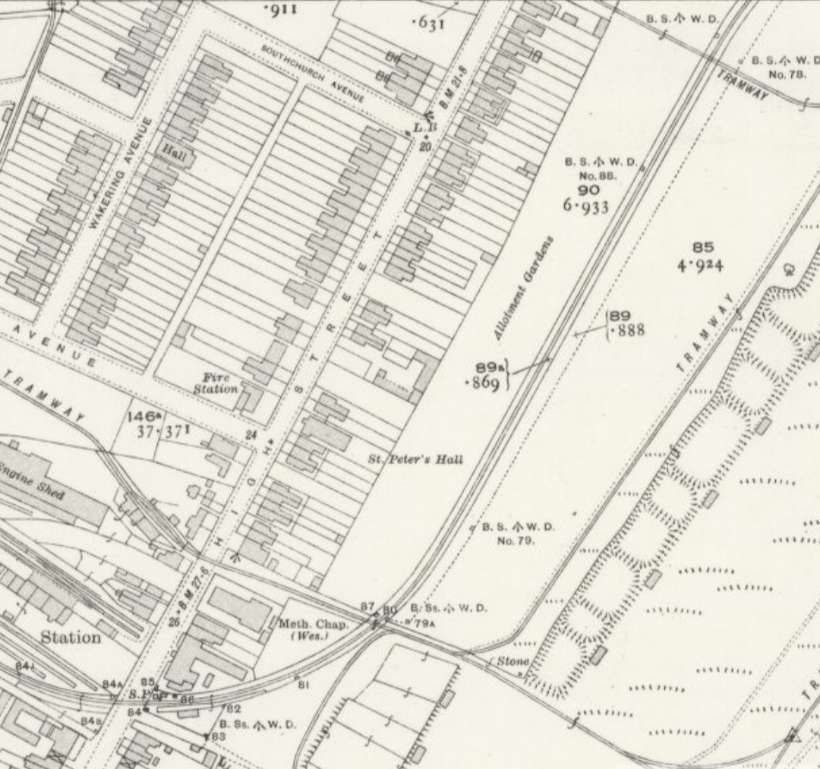

The passenger service on the line was limited to use by Government employees. The service began when the line was extended to New Ranges. By 1959, Old Ranges Station had been demolished, and the old station at Camp Field partly so. Chapel Road Station and Magazine Station were disused. Platforms in use in 1959, “were built long enough to accommodate six-coach trains, in anticipation of a large influx of troops which did not materialise; but Magazine could take only one coach, and the rest four coaches, which, until three or four years [before] was the normal complement.” [5: p244]

“All intermediate stations except Village Crossing were conditional stopping-places and Magazine and Camp Field (old station) were untimed. The bye-laws of 1893 oblige[d] trains to stop before crossing the road, and state that ‘a man with a danger flag shall warn the Public of the approach of trains’. For this reason Village Crossing ha[d] two platforms, both on the south side of the single line, but one on each side of the crossing, thus enabling passengers to alight while the train [was] waiting for the gates to open.” [5: p244]

Sequestrator tells us that average passenger numbers were: 166/day in the year to 31st March 1895; 276/day in the year to 31st March 1896; just below 140 passengers/day in January 1957. “In 1894-5 it was calculated that the cost of conveyance per mile per passenger was 0.065d. In this computation no allowance was made for depreciation, maintenance or interest on capital.” [5: p244]

Passenger train times were provided as an appendix to standing orders, and up to 1929, with each major change, the new times were printed in a pocket folder for distribution to those entitled to use the service. “The timetable for 1910 shows eight up and nine down trains on ordinary weekdays, each with a journey time of ten minutes. The first [left] the southern terminal station (then named Engine Shed) for New Ranges at 8.20am, the departure of the last, also a down train, [was] at 4.50 p.m. There [were] two additional trains each way on Saturdays during the summer, and one in winter. The schedule for 1913 [was] similar but mark[ed] the withdrawal of all Saturday afternoon trains.” [5: p244]

March, 1922, saw the service in a transitional stage, “with six trains each way between New Ranges and Old Ranges (renamed). Two more start[ed] from, and terminate[d] at, Camp Field, the latter, as well as Magazine, being names which appear for the first time. With the issue of the last printed timetable, in June 1929, … the passenger service between Camp Field and Old Ranges [was] withdrawn, and six trains each way (five in winter) beg[an] and end[ed] their journeys at a terminal station, built in 1924, on a spur at the site of an old quarry north of Campfield Road. For the benefit of employees with children attending school, one down and two up ‘children’s trains’ (untimed) [we]re introduced.” [5: p245]

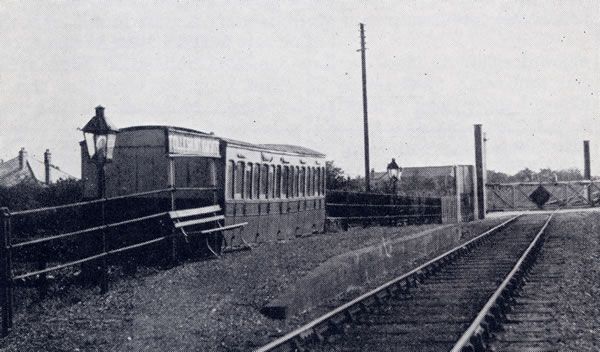

“Passenger trains were withdrawn on 1st September 1958. There were at that time three trains each way daily except on Saturdays and Sundays, leaving New Ranges at 7.50 a.m. and 12.40 and 1 p.m., and returning at 8.50 a.m. and 12.50 and 1.50 p.m. The actual time for the journey of just over one mile was six minutes, compared with an allowance of eight minutes in 1929. In orders and official notices the army’s own 24-hour system of time recording was incorporated. … The two coaches, once resplendent in Midland livery with coats of arms, [we]re painted over a dull brown. Inside, though first and third class compartments [we]re still distinguishable, the plush upholstered seats [we]re covered with hessian. Above them [was] a glass-framed gallery of faded pictures redolent of the England of Edwardian days – Neidpath Castle, Rowsley Bridge, Ambleside, Sulgrave Manor, Chatsworth House with here and there a black-out notice, and the once-familiar poster depicting the individual with long furry ears erect listening to the careless talk of fellow-citizens which might cost lives. They [we]re ladies of quality, these coaches, 24 to 28 tons apiece, … fallen on hard times but still well cared for and comfortable to ride in. [In use,] they screech[ed] querulously on cruel curves; and no wonder, for the driver sa[I’d] he ha[d] to keep a good head of steam to pull them round.” [5: p245]

Havengore Bridge Replacement

Following many years of service, it was identified that the second bridge’s lifting mechanism and associated control system were in need of refurbishment and upgrading and Fairfield Control Systems were appointed to conduct the work. This included: [13]

- Comprehensive survey and inspection of the hydraulic systems, mechanical components and control systems

- Refurbishment and upgrade of hydraulic control, including redesign and replacement of cylinder manifold blocks and HPU control manifold

- Replacement of the two 4m main lifting cylinders

- Repair of tail-locking bolts and fixings

- Installation of upgraded lifting control, control desk, safety and diagnostic systems

- Replacement wigwag warning lights and barrier repairs

- Refurbishment of ancillary steelworks

Work was undertaken in 2019 & 2020. [13]

As the island is used for the testing of new munitions and the destruction of old ones. When these tests are in progress, the bridge cannot be used. However, the bridge is staffed for two hours either side of high water (during which time the creek is navigable) during daylight hours only, 365 days of the year.

Narrow-Gauge Tramways

In addition to the standard-gauge military tramway, the area was criss-crossed by a series of narrow gauge tramways which were primarily industrial, serving the area’s extensive brickworks, coastal gun ranges, and military depots between the late 19th century and WWII.

A former tramway at East Beach, Shoeburyness. The grassy picnic area just to the West of East Beach was once a brickworks – hence the remains of the narrow-gauge tramway seen here. The marquees in the distance are for the Ganesh Visarjan Hindu Festival in 2012, © David Kemp, and licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-SA 2.0). [35]

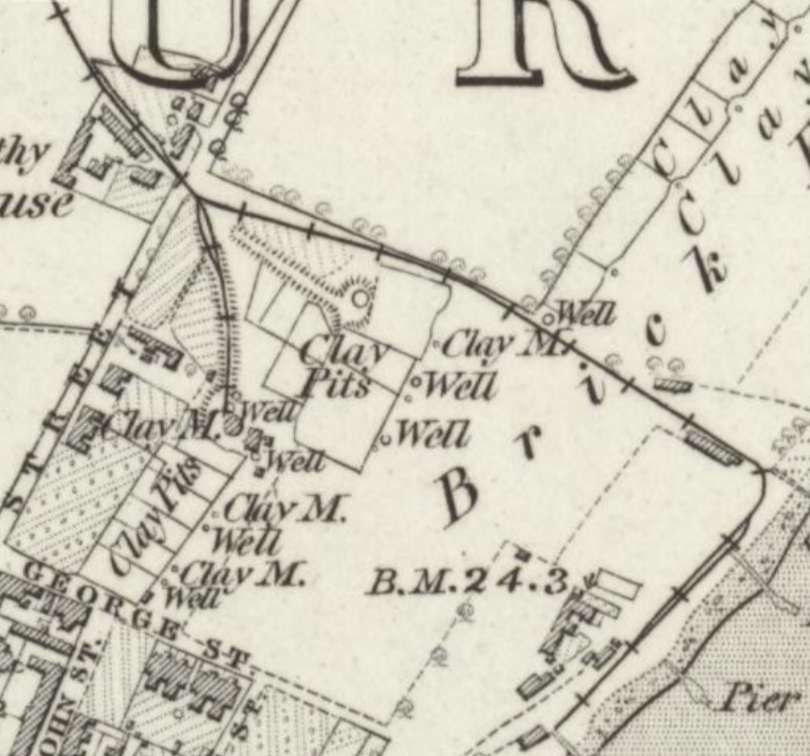

Brickfields Lines

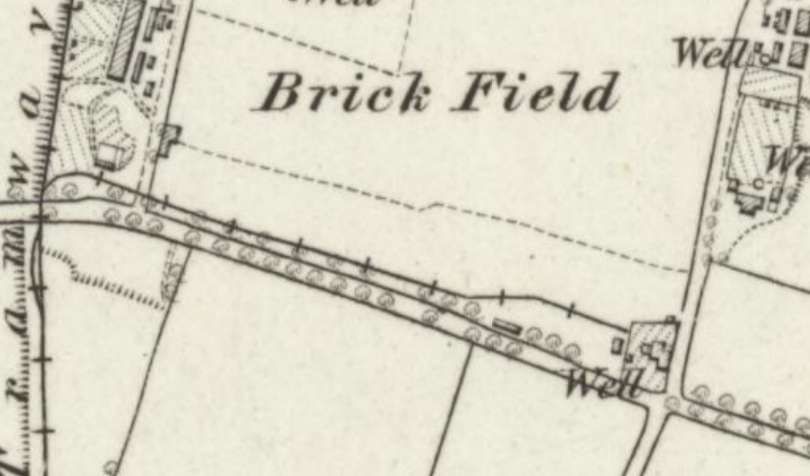

There was a 2ft-gauge line connecting East Beach brickfields to Elm Road and wartime, ammunition storage tracks on the New Ranges, with some remnants remaining visible at East Beach, as can be seen above. This and other lines predated the arrival of the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway. The coming of the railway saw the growth of the town and its expansion into what were the sites of brickworks.

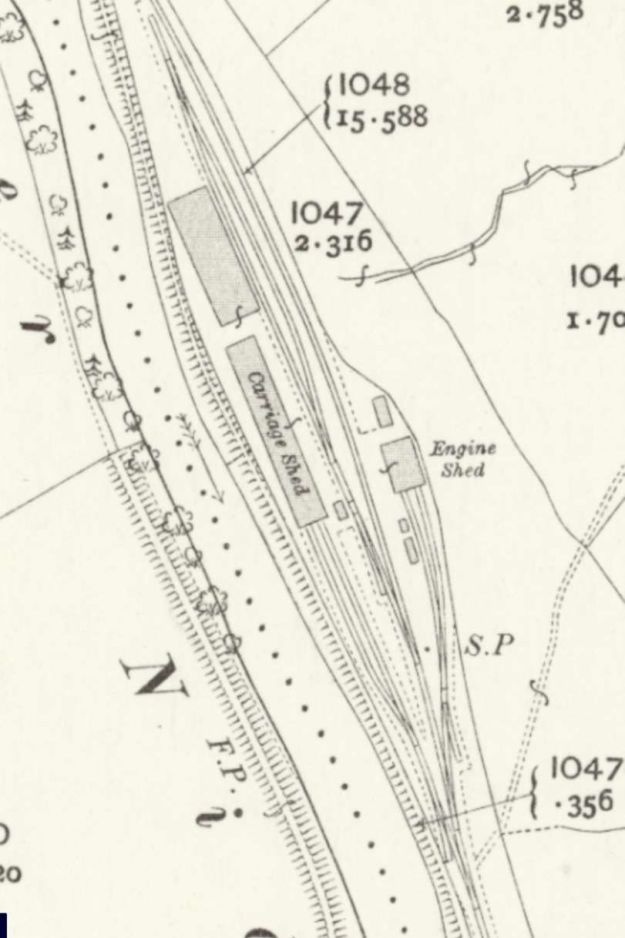

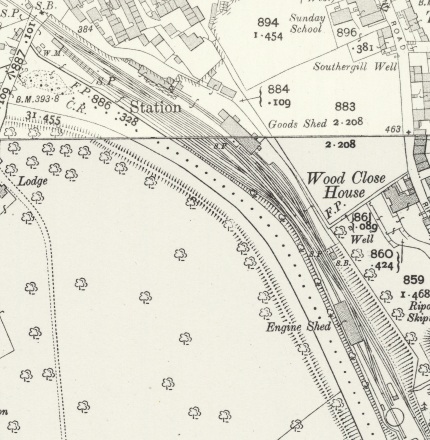

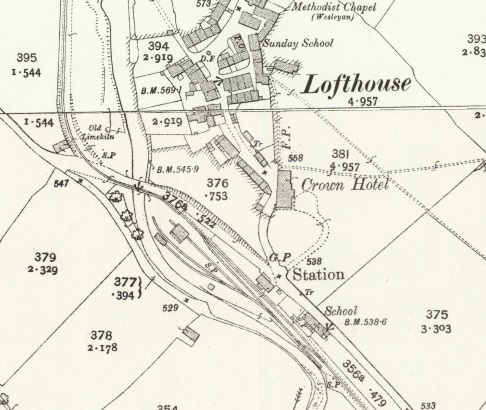

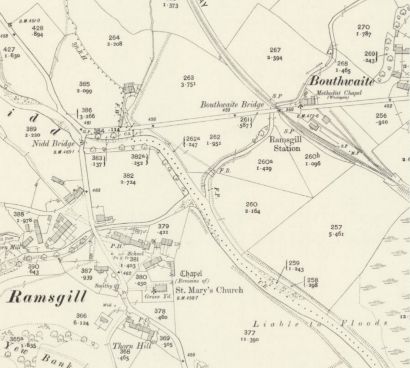

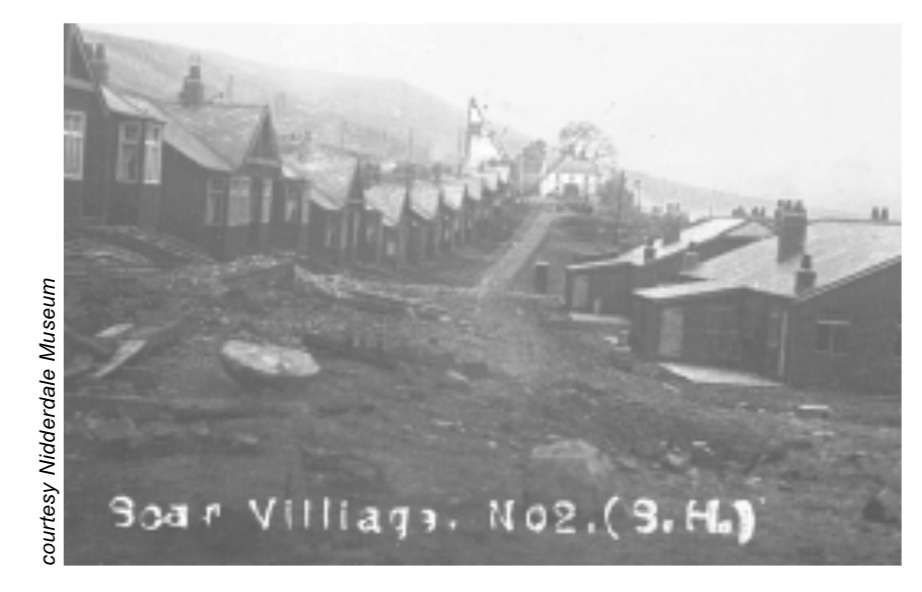

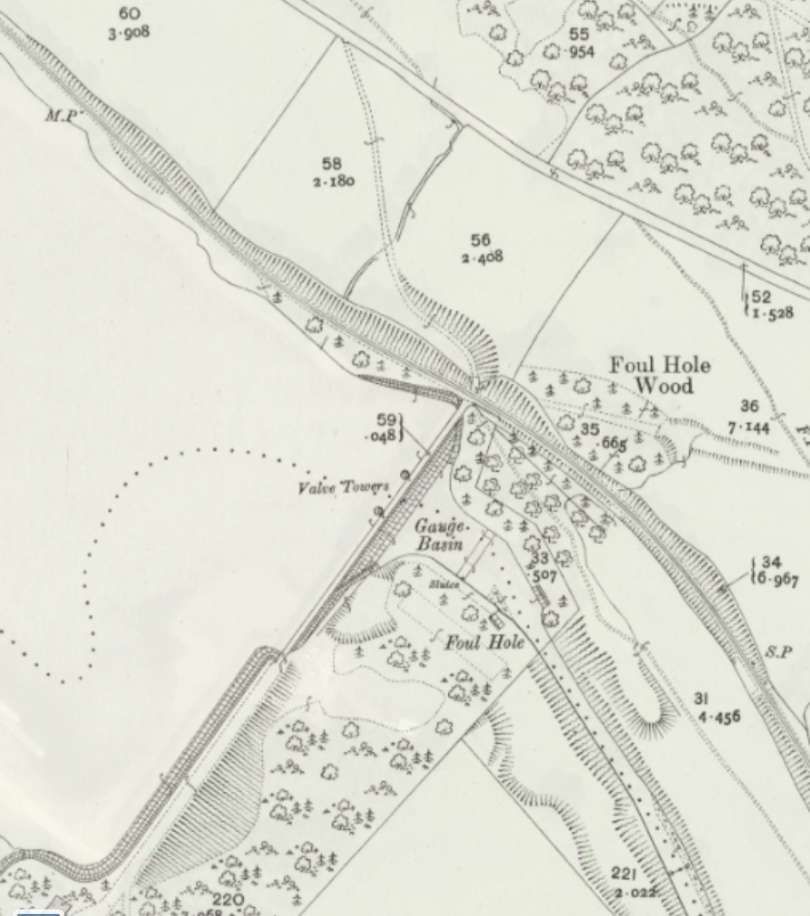

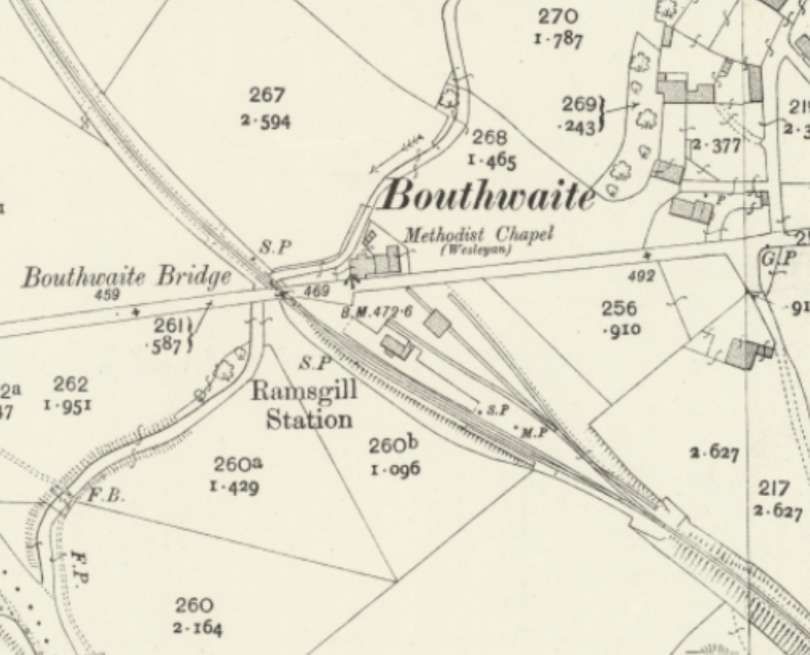

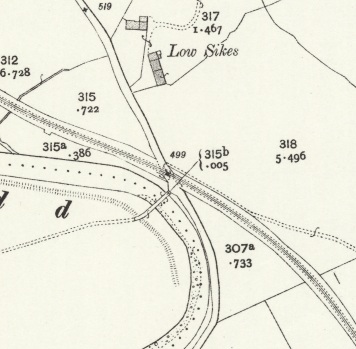

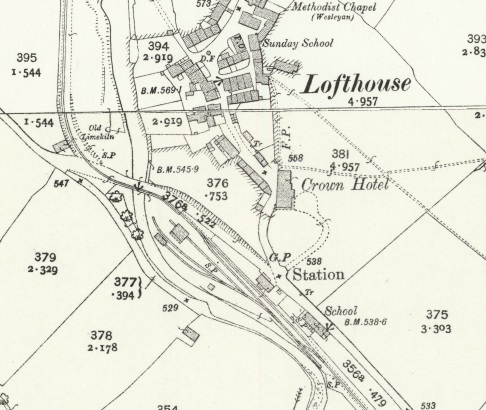

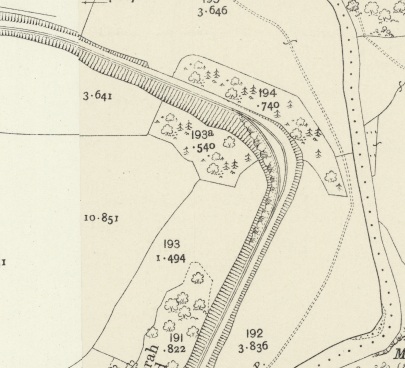

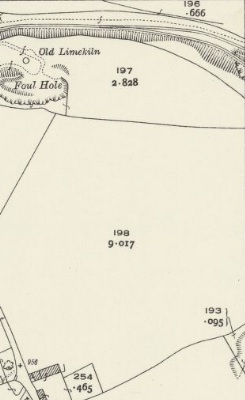

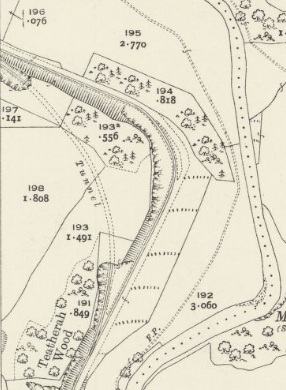

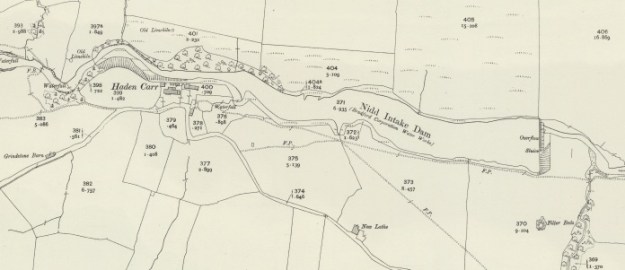

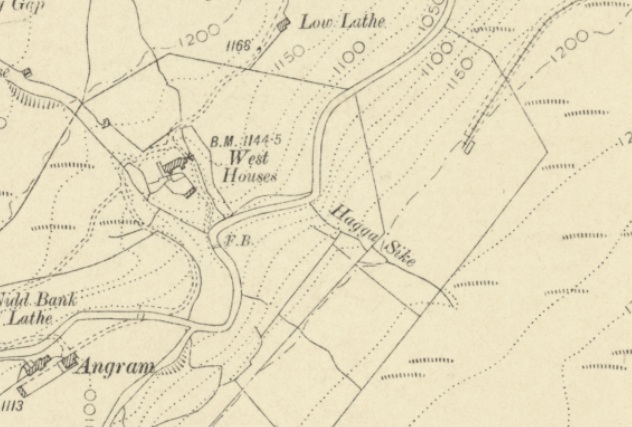

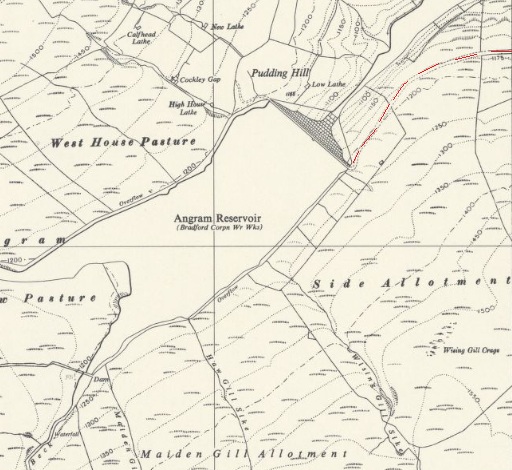

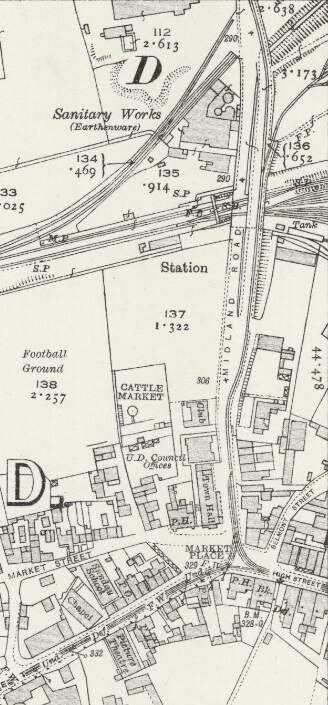

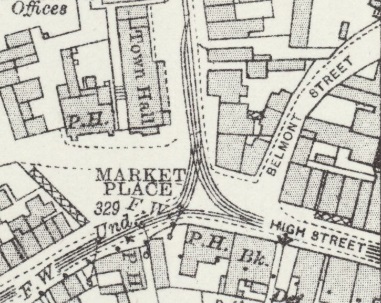

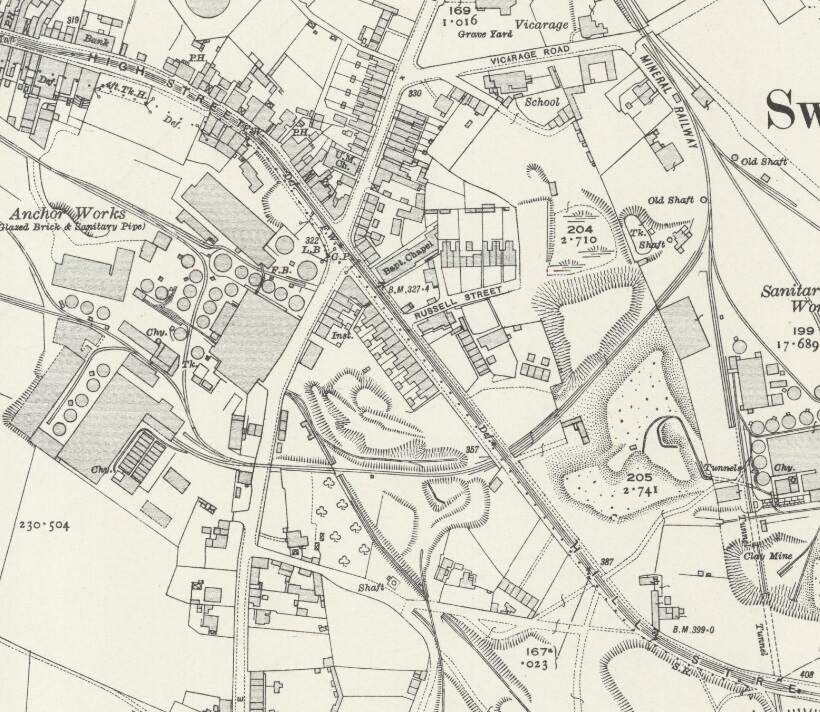

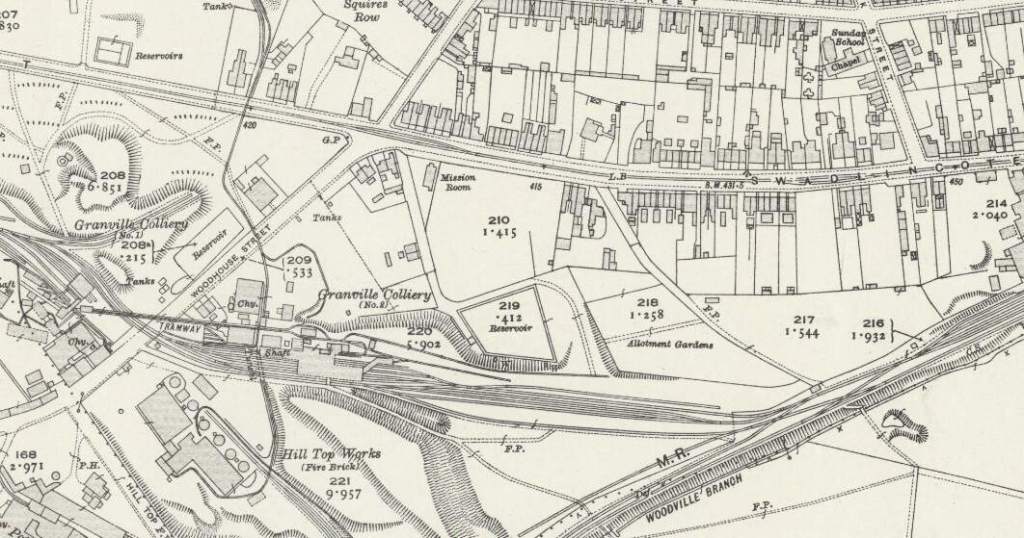

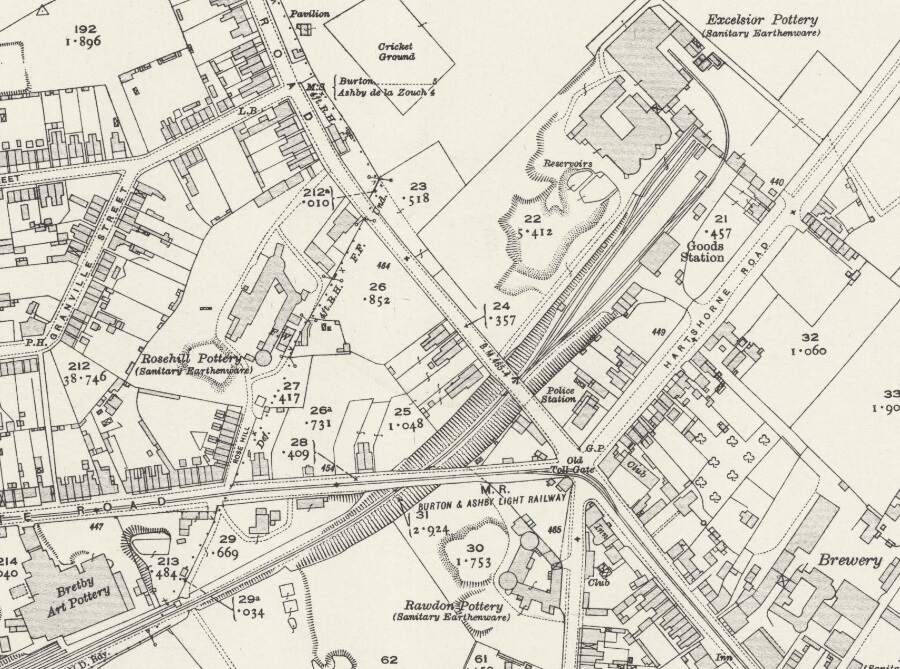

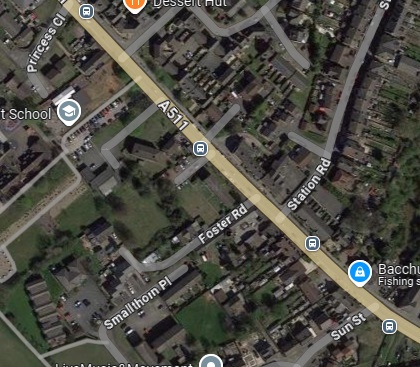

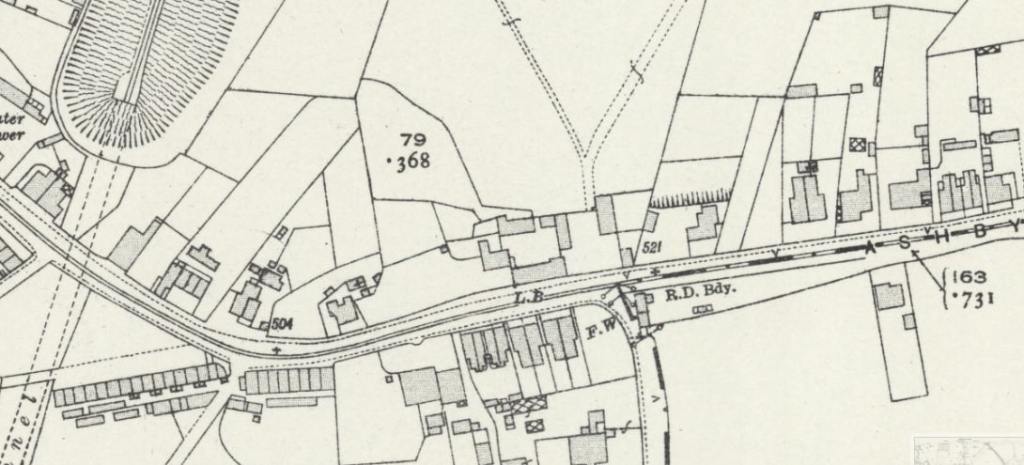

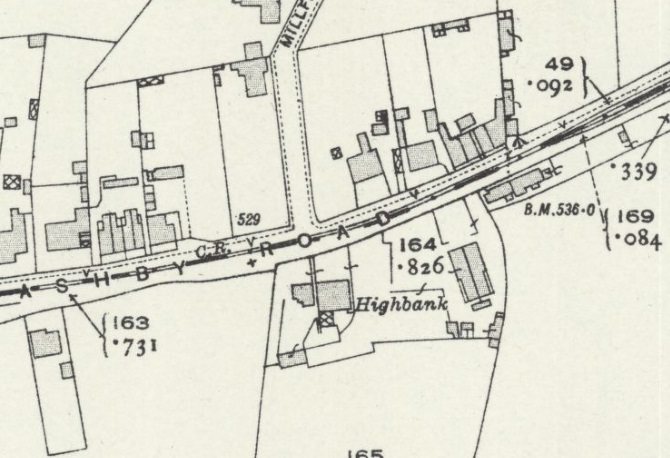

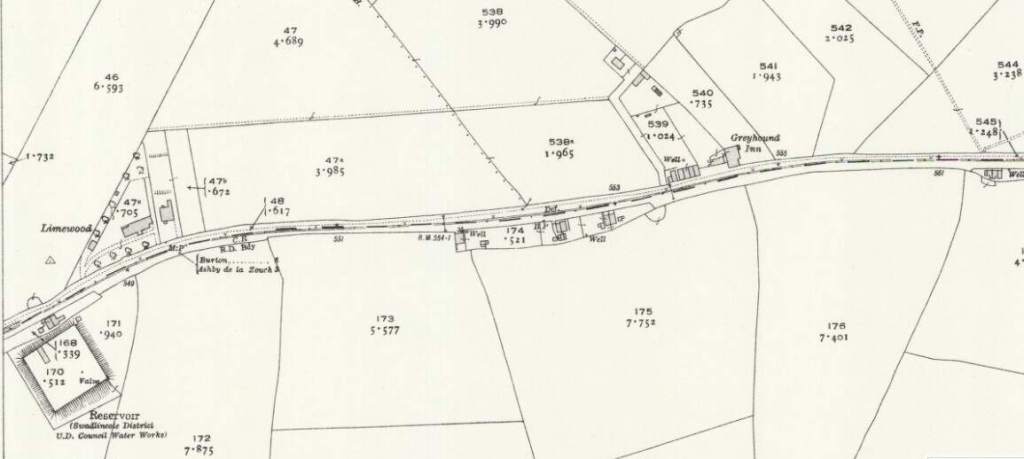

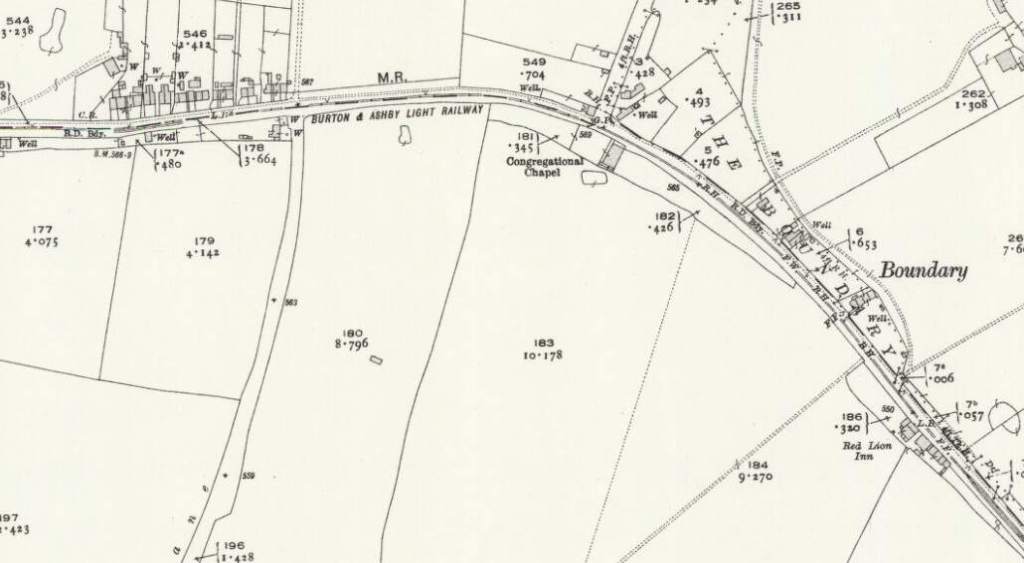

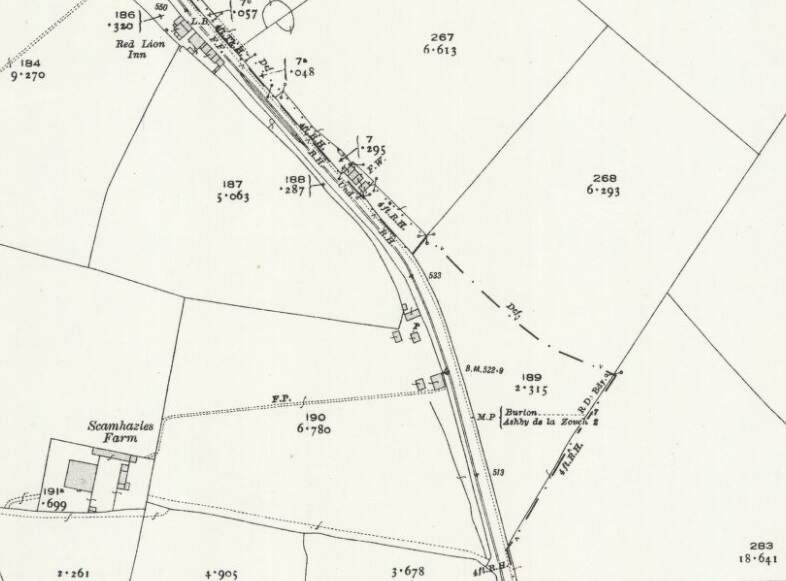

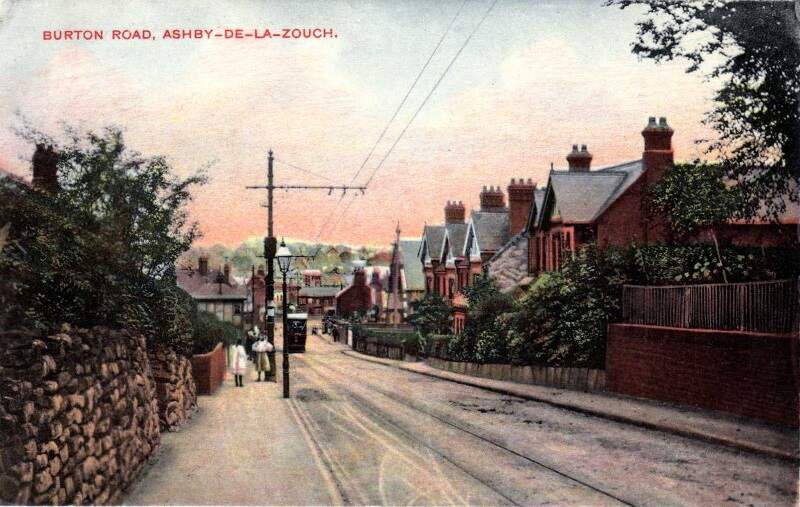

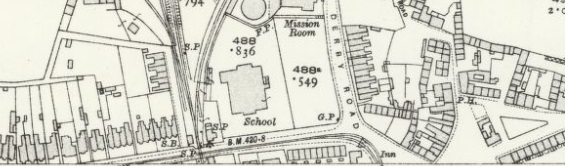

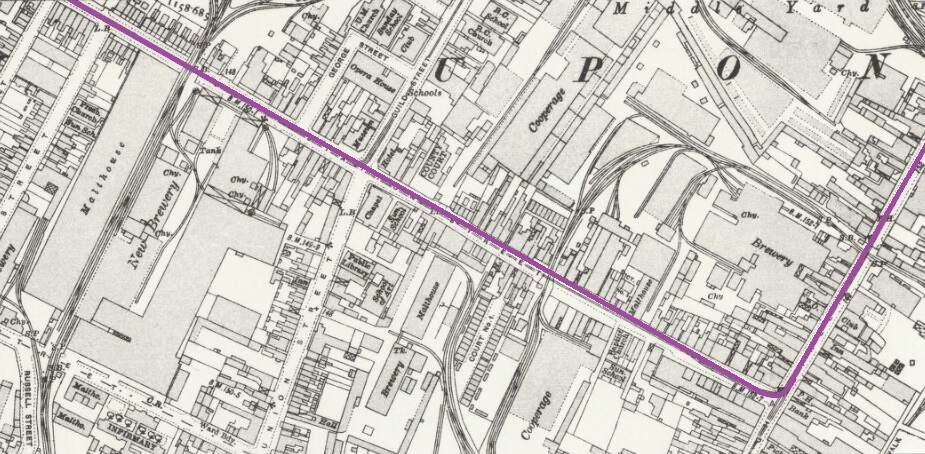

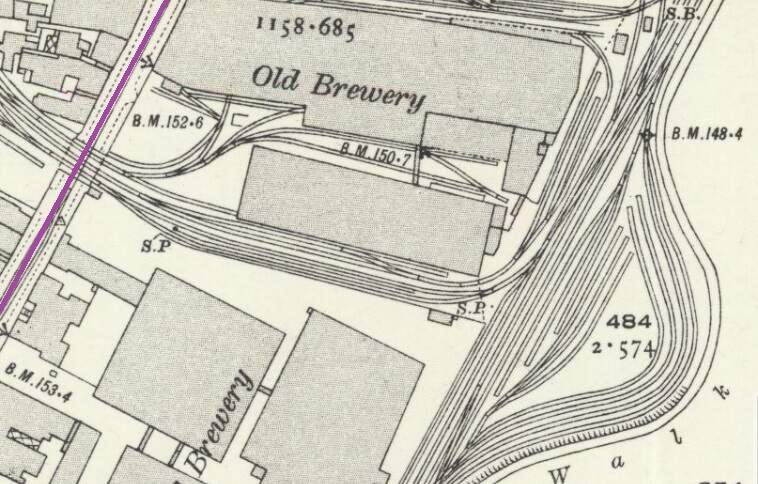

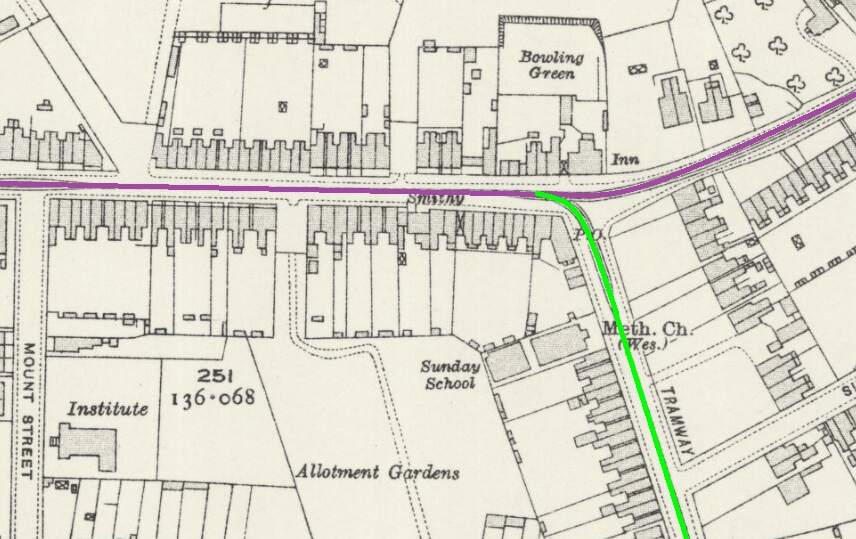

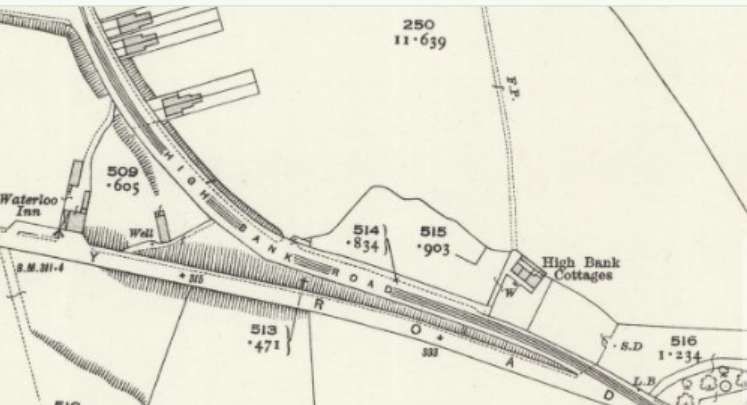

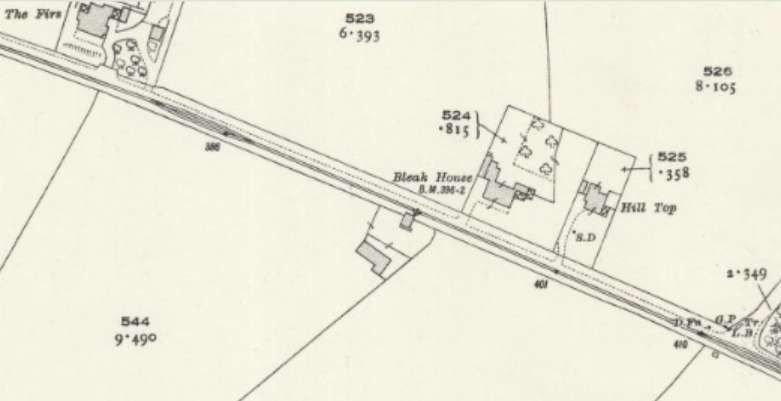

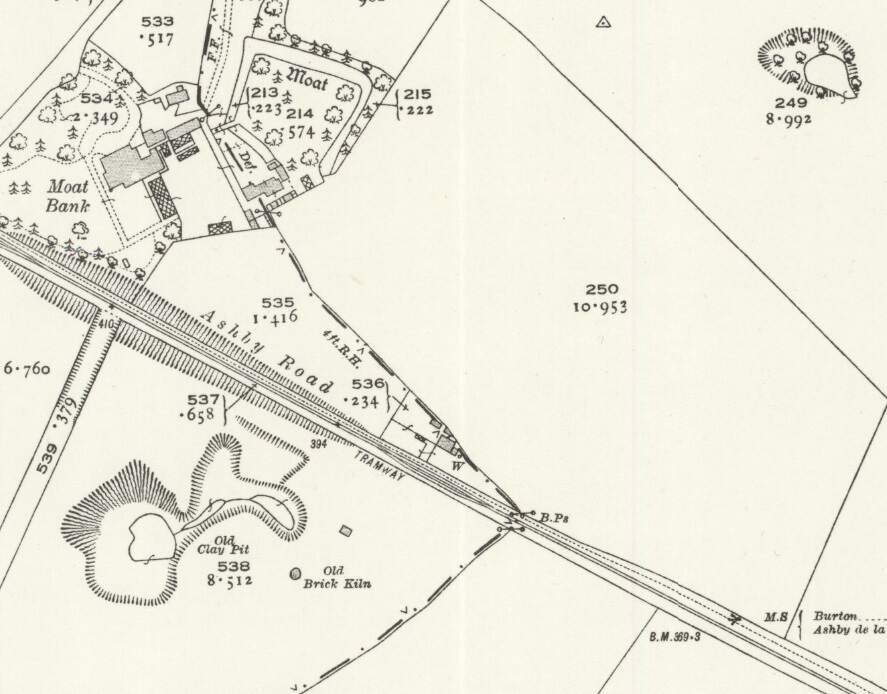

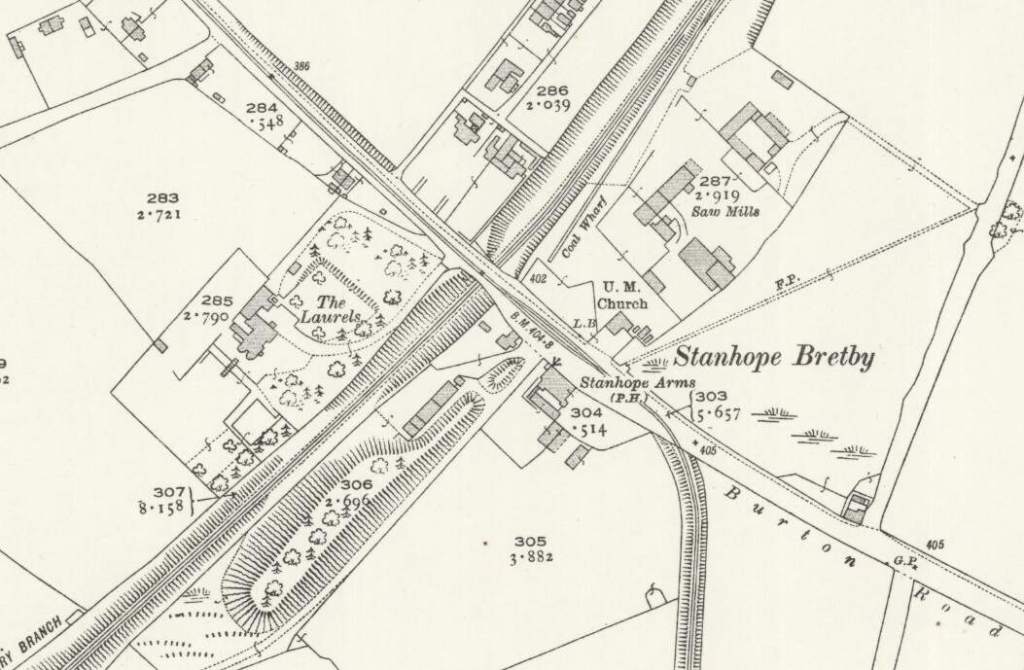

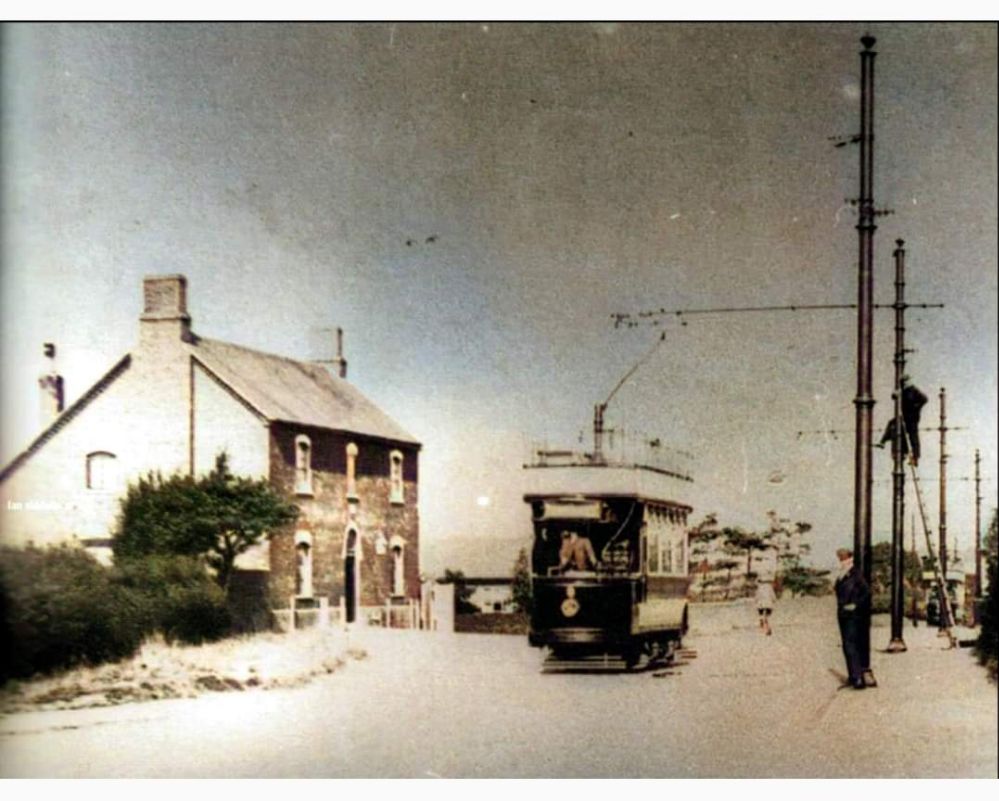

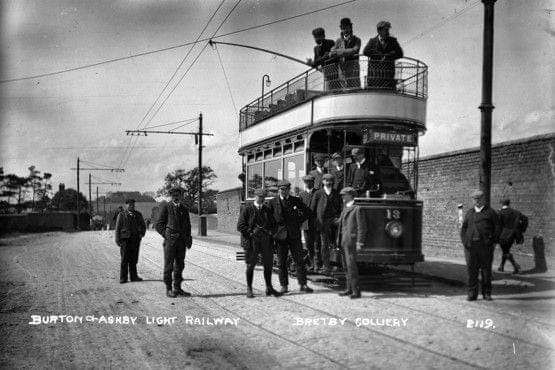

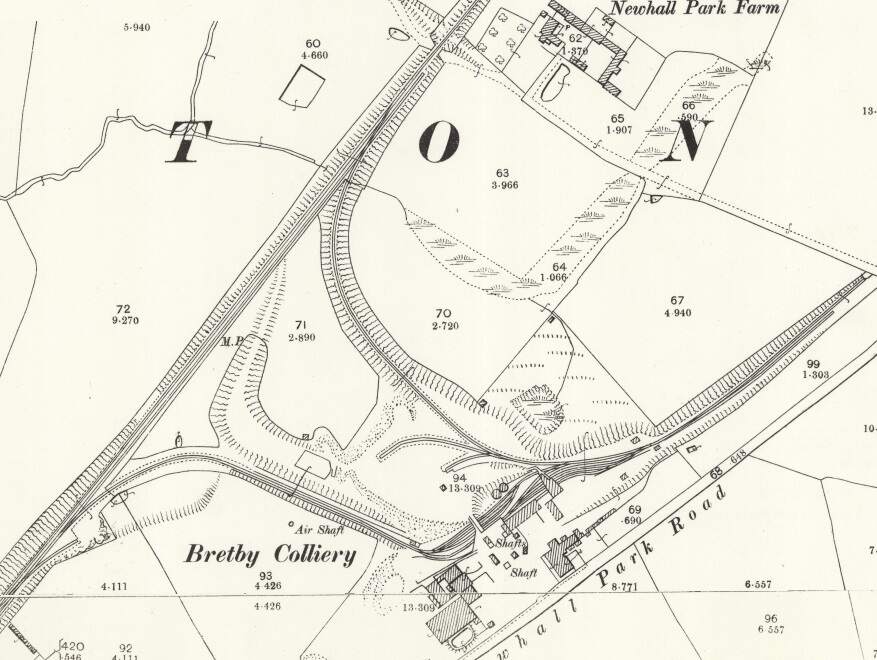

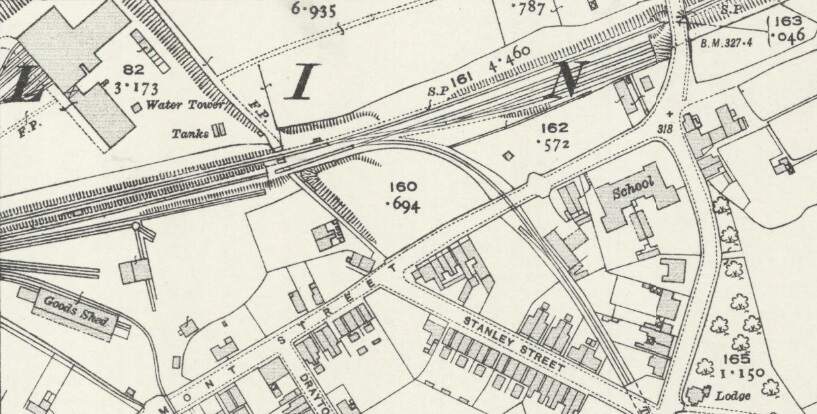

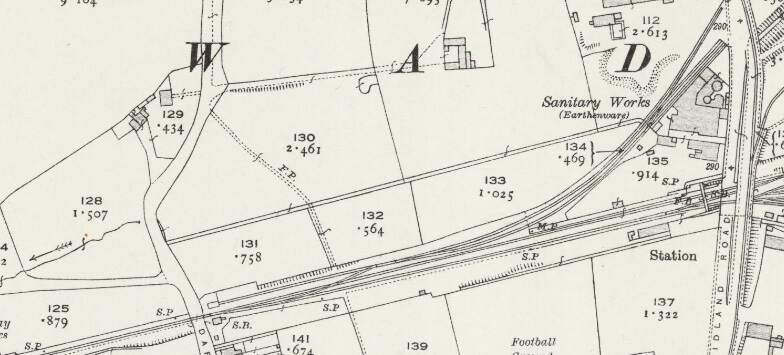

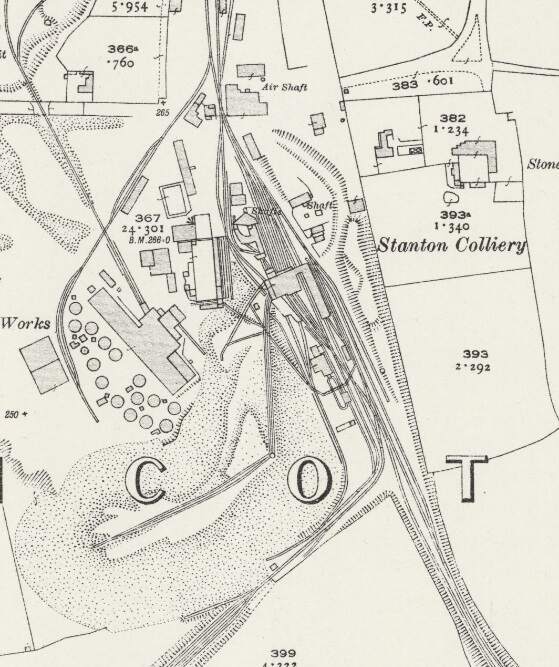

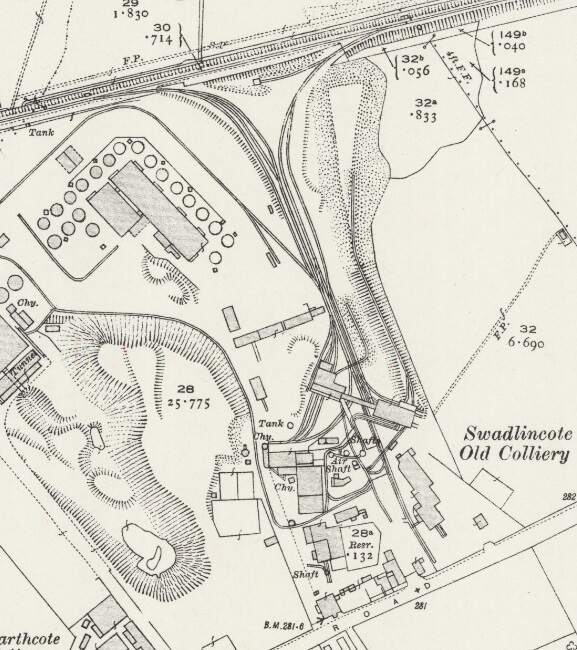

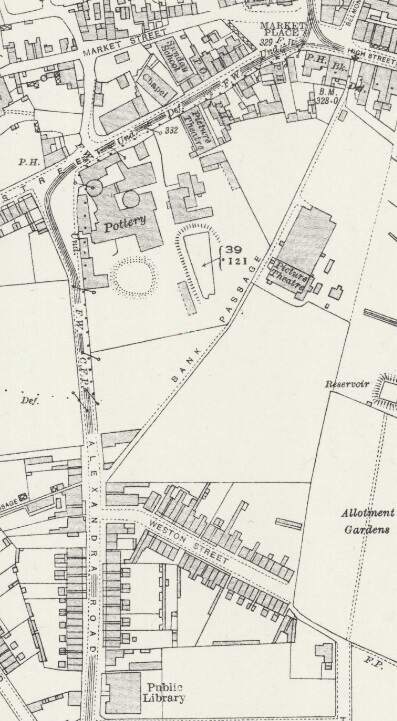

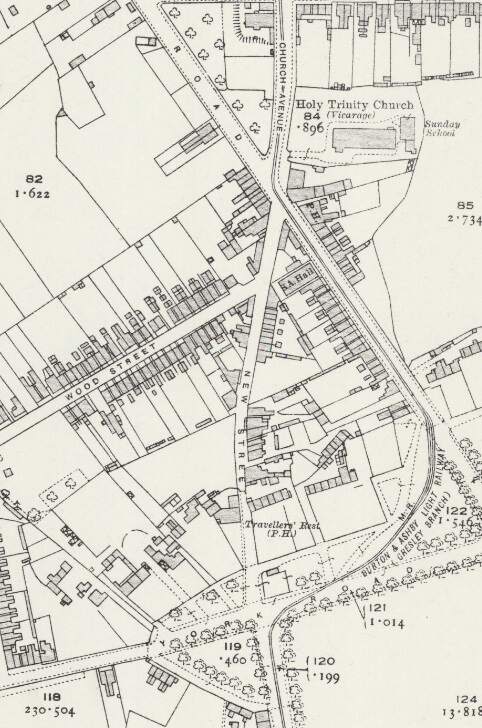

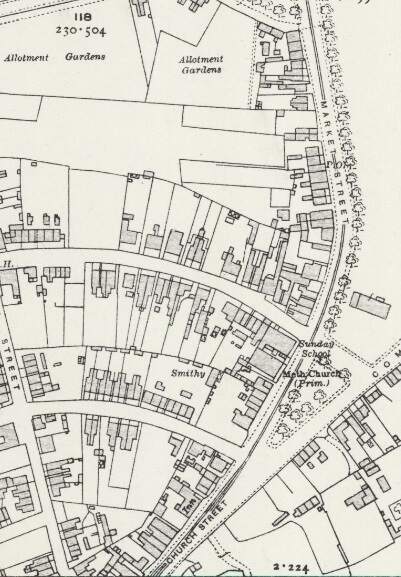

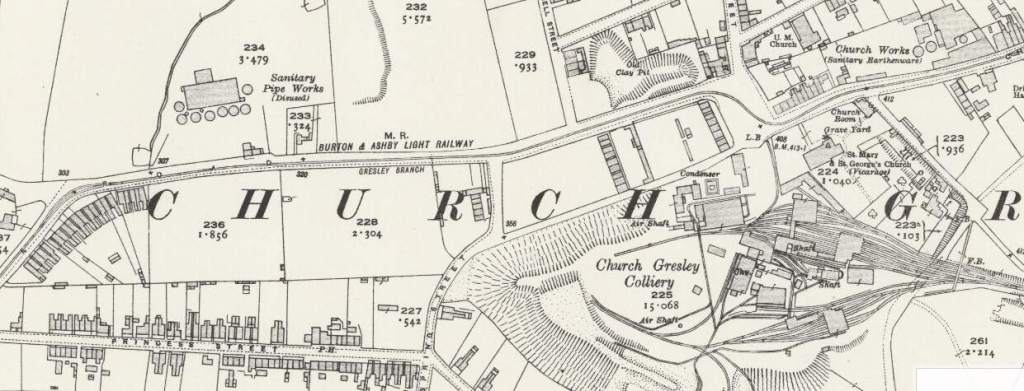

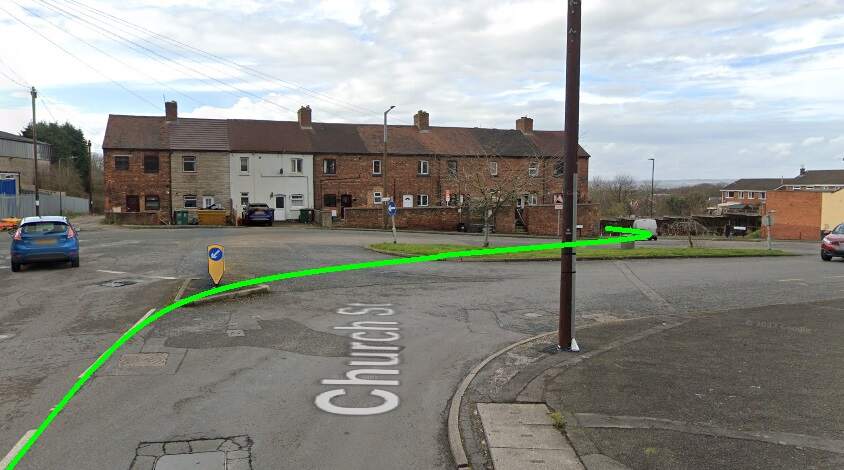

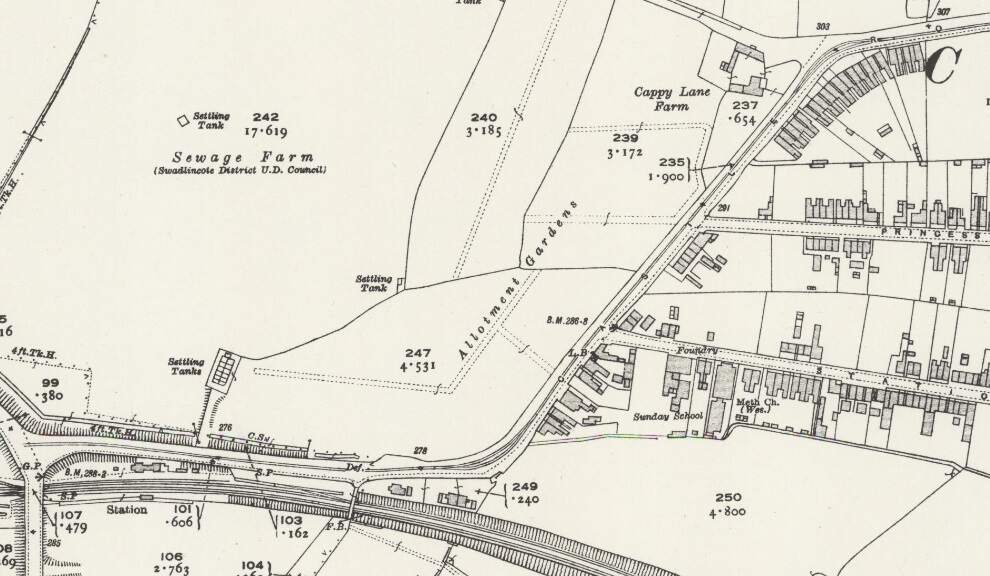

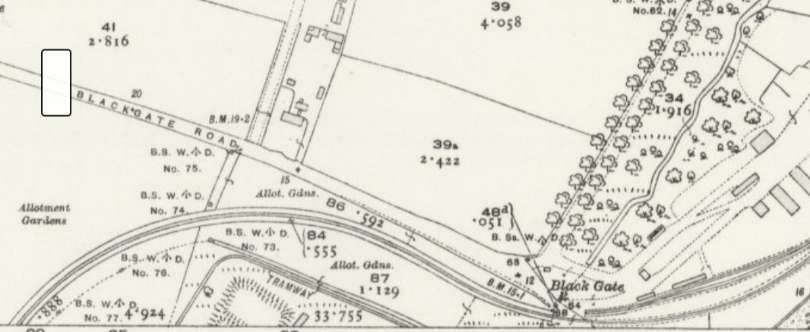

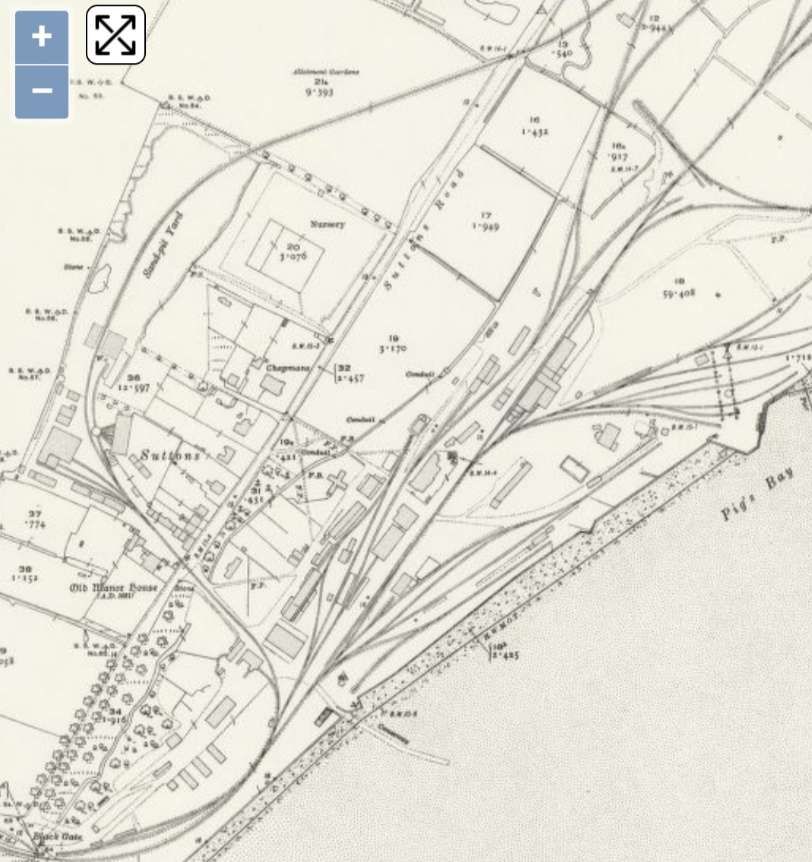

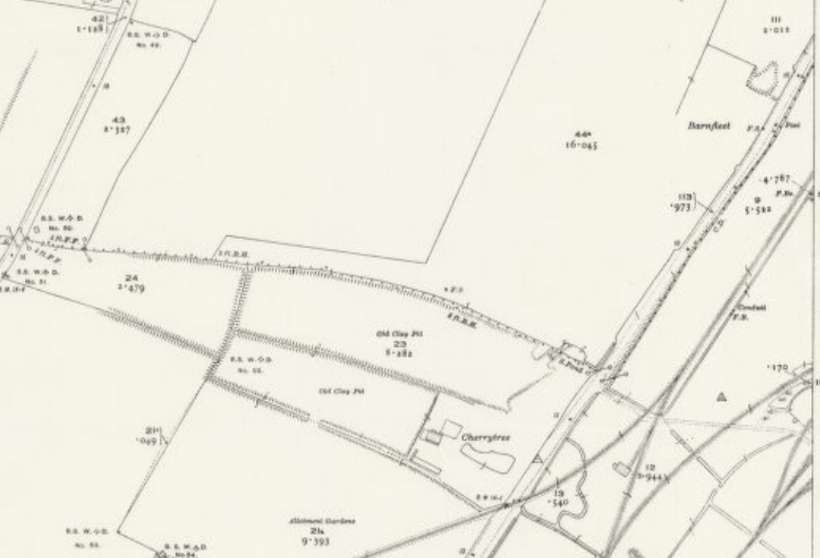

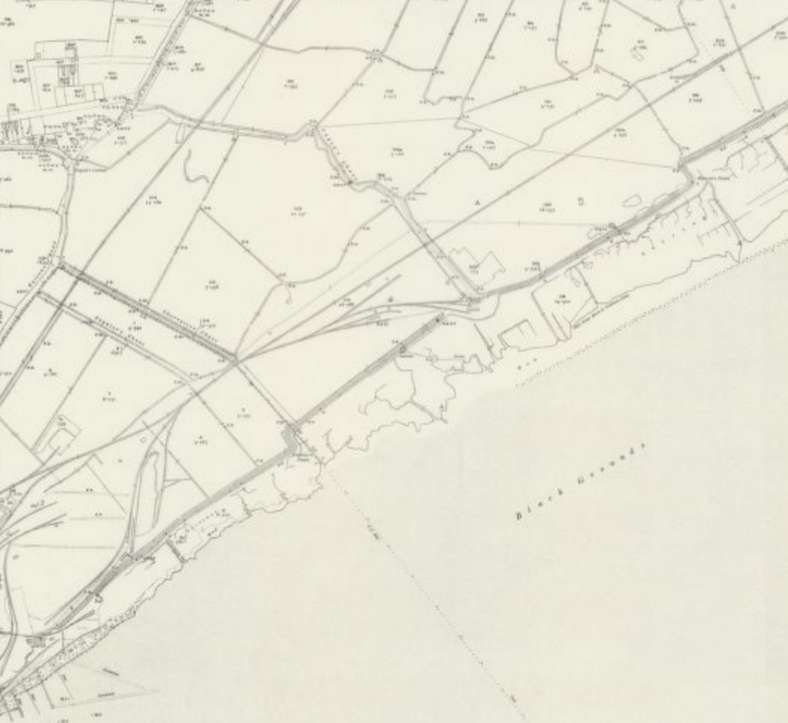

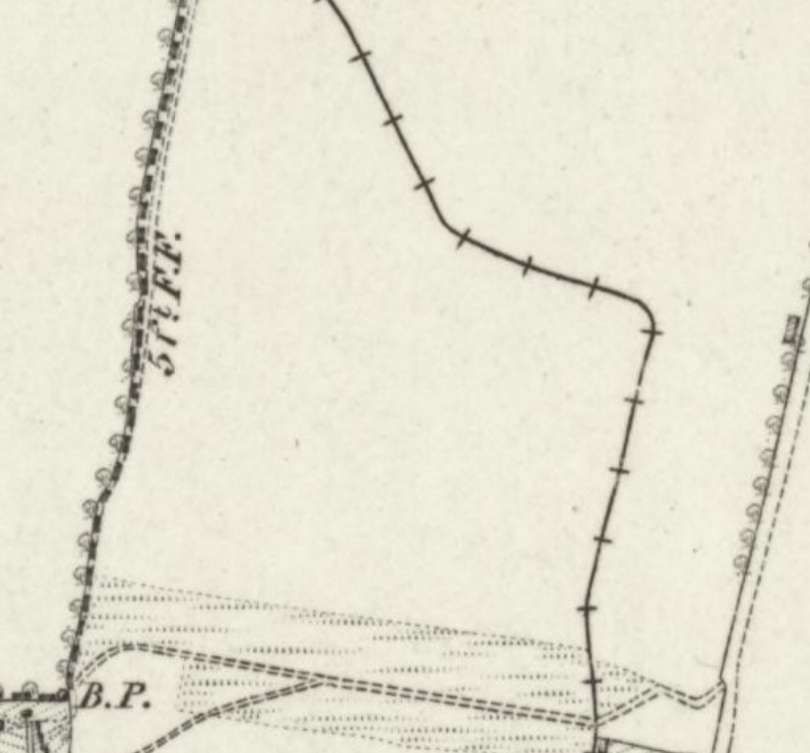

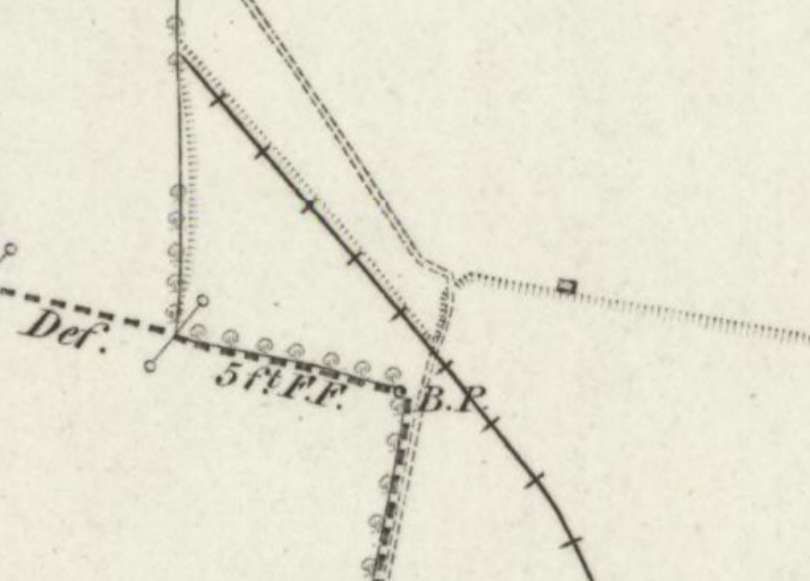

This next series of map extracts come from the 6″ Ordnance Survey of 1873, published in 1880 and they show an earlier incarnation of the tramways in the area to the North of the railway station (which had yet to be built).

The different incarnations of tramway ran to the coast at East Beach where there were further brickworks and where bricks were loaded into barges on piers. The tramway crossed the standard-gauge military tramway on the level. [38]

Military Lines

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) and War Department (WD) operated narrow-gauge lines within their firing range area. These included, 2ft-gauge lines, with evidence of a 2ft-gauge Ruston diesel locomotives operating there.

East Beach Remains:

A tramway system existed near East Beach, which may be that pictured above. It was re-purposed or re-installed by the WD in 1943 for ammunition storage, connecting to the, New Ranges.

Maplin Sands Line

A separate, small-gauge, tramway existed on Maplin Sands in connection with the gun ranges.

Largely independent of the main standard-gauge line that ran into the Shoeburyness station, these systems were crucial to the town’s early industrial and military, infrastructure.

References

- https://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/20159/danish-camp-shoeburyness, accessed on 5th December 2025.

- J. A. Giles (trans); The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; G. Bell & Sons, London, 1914; via http://www.public-library.uk/dailyebook/The%20Anglo-Saxon%20chronicle%20%20(1914).pdf, accessed on 5th December 2025.

- https://democracy.southend.gov.uk/documents/s48578/Appendix%205%20Southend%20CAA%20Shoebury%20Garrison.pdf, accessed on 5th December 2025.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1017206?section=official-list-entry, accessed on 5th December 2025.

- Sequestrator; Shoeburyness Military Tramway; in The Railway Magazine, Tothill Press Limited, London, April 1959, p239-245.

- https://fortheloveofhistory.home.blog/2021/04/19/the-almost-forgotten-manor-suttons, accessed on 7th December 2025.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/heritage-at-risk/search-register/list-entry/48360, accessed on 7th December 2025.

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b2a2c0ae5274a18f134fe02/Shoeburyness_Mil_Tramway_1923.pdf, accessed on 12th December 2025.

- The Macnee patent was for a hand-operated point lever (or “lever box” as they were known in the trade). Although holding the patent, Macnee sold his manufacturing plant to Anderson Foundry, a significant supplier of rail chairs. Victorian patent, business relationships and tendering processes were fairly murky, but it is probable Daniel Macnee would have received his commision per unit (he was still working as a London based agent for Andersons) till his death in 1893 and afterwards to his heirs. He had business connexions with Dugald Drummond and Sons, the Caledonian Railway and the L&SWR. The levers could be positioned on either side as safety dictated, and the lever position would sit towards the V for the “main” line and pulled “back” for the diverging road. … These notes have been extracted from a post on the Caledonian Railway Association Forum (https://www.crassoc.org.uk/forum/viewtopic.php?t=38), accessed on 13th December 2025.

- Williams two-way spring point levers were patented in May 1916 in the US. Drawings can be seen at the bottom of these references (https://85a.uk/templot/club/index.php?resources/wynn-williams-patent-ground-lever-boxes.16, accessed on 13th December 2025).

- http://www.barlingwakeringvillages.co.uk/heritage/havengore_bridge.html, accessed on 13th December 2025.

- https://www.qinetiq.com/en/shoeburyness/public-access/havengore-bridge, accessed on 13th December 2025.

- https://www.fairfields.co.uk/fes/sectors/bridges/havengore-lifting-bridge-upgrade, accessed on 13th December 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.52278&lon=0.78849&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 16th December 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.52543&lon=0.78974&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 16th December 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=51.52817&lon=0.79082&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 16th December 2025.

- https://railmaponline.com/UKIEMap.php, accessed on 16th December 2025.

- https://www.google.com/maps/place/Shoeburyness,+Southend-on-Sea/@51.5215111,0.7824944,3a,75y,268.59h,88.17t/data=!3m8!1e1!3m6!1sCIHM0ogKEICAgICE1cfElwE!2e10!3e11!6shttps:%2F%2Flh3.googleusercontent.com%2Fgpms-cs-s%2FAPRy3c-ooyjPUlo1M8G75dkeC5x8yVIKNQhwzD86BATQ8d6mAIcwTK3kjj_RxSaMLxx22wsxueC1L4kXfKGuoaMZHEYSRLqu1-TxPakoFRpZi-qQ7l2GgVvrOPDs4iyg0AYdPZLVLx7L%3Dw900-h600-k-no-pi1.826277195659742-ya357.58743373399966-ro0-fo100!7i7680!8i2166!4m6!3m5!1s0x47d8d83fa5f72033:0x8e098255675351c0!8m2!3d51.5354901!4d0.7905701!16zL20vMDFjdzA4?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTIwOS4wIKXMDSoKLDEwMDc5MjA2N0gBUAM%3D, accessed on 16th December 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/104191016, accessed on 17th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/104195166, accessed on 17th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/104195145, accessed on 17th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/104195142, accessed on 17th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/104194773, accessed on 17th February 2026.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MOD_Shoeburyness, accessed on 18th February 2026.

- Historic England: “Blocks K-M, Shoebury Garrison (1112690)”. National Heritage List for England. Accessed on 18th February 2026.

- This series of map extracts can be found by following this link and then moving around the page reached, https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/51.55235/0.84549, accessed on 17th February 2026.

- https://www.qinetiq.com/en/shoeburyness/about/mod-shoeburyness-timeline-and-history, accessed on 18th February 2026.

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Air-blast-tunnel-ABT-at-MoD-Shoeburyness-8_fig1_328060297, accessed on 18th February 2026.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/924400, accessed on 18th February 2026.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/66789, accessed on 18th February 2026.

- https://aroundus.com/p/165471749-shoeburyness-boom, accessed on 18th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/104195172, accessed on 18th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/104194773, accessed on 18th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/104194776, accessed on 18th February 2026.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3140647, accessed on 18th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/104191010, accessed on 19th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/102342029, accessed on 19th February 2026.

- Richard Kirton; Sandpit Cottages Shoebury; Barling and Wakering Villages Plus Website; accessed on 19th February 2026.

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a79d33e40f0b670a8025b2d/shoeburyness_artillery_ranges.pdf, accessed on 19th February 2026.