After completing a series of articles about Genova’s transport system at the end of 2024, beginning of 2025, I came across a series of three articles in the ‘Light Rail & Modern Tramway Journal’ dating from 1995. This article covers those three pieces. …

Written, 30 years ago, Barry Cross’ articles help us to engage with the changes to the transport systems in Genova over the decades.

Part 1: August 1995 – The Demise of the Old Tram Network and the Development of the Metro

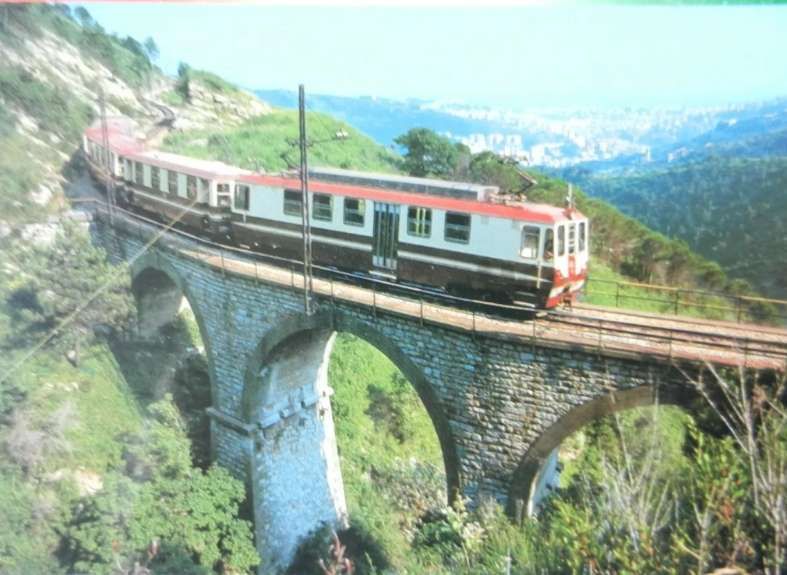

Barry Cross says that “as far as tramway enthusiasts are concerned, the city lost most of its attractions in the 1960s, when the remaining interurban tram routes were abandoned, and public transport became synonymous with travelling by diesel bus. … Nevertheless, the curious topography of the city, which to all intents and purposes is built on a narrow coastal enclave, has meant that some rather curious forms of public transport have survived. Flying the tramway flag during the lean years has been the Granarolo rack tramway, whose two cars resemble both tramway and funicular vehicles. … Then there are the two conventional funiculars: the Sant’Anna and Zecca-Righi, which provide rapid access from the port to the residential districts in the hills above. Finally, the Genova-Casella electric light railway offers one of the most scenic and exhilarating rides to be found anywhere on the European continent.” [1: p251]

In the years prior to 1995, the municipality once again “decided to embrace tramway technology, in a desperate effort to improve public transport because of the severe deterioration in traffic conditions. The result [was] the construction of an entirely new light metro, recreating in part the coastal tramway abandoned in the 1960s. Despite only three stations having so far [in 1995] opened, patronage of the line already exceed[ed] expectations.” [1: p251]

In May and June 1964, Modern Tramway carried a two-part article on the tramways and light railways of Genova by Joachim von Rohr. Barry Cross attempts, in his articles, to show developments in the city up to 1995. This will provide an opportunity to compare the situation in the mid-1990s with that in 2024/2025.

“In the 1960s, many Italian cities felt the urge to ‘modernise’ their public transport systems, a term which all too often meant the closure of efficient, if rather run-down tramway networks. Genova was no exception. Unusually, it was the urban routes that closed first, these being abandoned in the late 1950s, although the interurban routes continued to operate (and decline) well into the 1960s. … The interurban system essentially consisted of four metre-gauge routes emanating from the central Genova Caricamento terminus. Two of the routes ran along the coast, one west to Voltri (16.9 km) and the other east to Nervi (approximately 12 km), while the other two served inland destinations, along the Polcevera valley to Pontedecimo (15.1 km) and to Prato (13.6 km), situated in the Bisagno valley.” [1: p251]

Cross continues: “On 25th May 1964, the so-called ponente route to Voltri was abandoned to the west of Sampierdarena, involving the withdrawal of seven separate services. Worse still, tram tracks in Via Francia were also lifted to permit construction of a connection with the strade soprelevata (elevated roadway), in which the municipal authorities had placed so much faith as a means of decongesting the city’s narrow and winding streets. … As a direct result of this, route 7 had to be cut back from Caricamento to Sampierdarena and route 26 entirely abandoned on 27th June. Furthermore, the survival of the Pontedecimo route had become ever more precarious given that its only connection to the rest of the system was henceforth via the Certosa tram tunnel.” [1: p251]

The Pontedecimo route survived until 1st October 1964. On that day, “tramway operation through the Certosa tunnel ceased. All remaining routes were replaced by motor buses on 27th December 1966, the last tram to run in public service being car 935 on route 12 to Prato.” [1: p251]

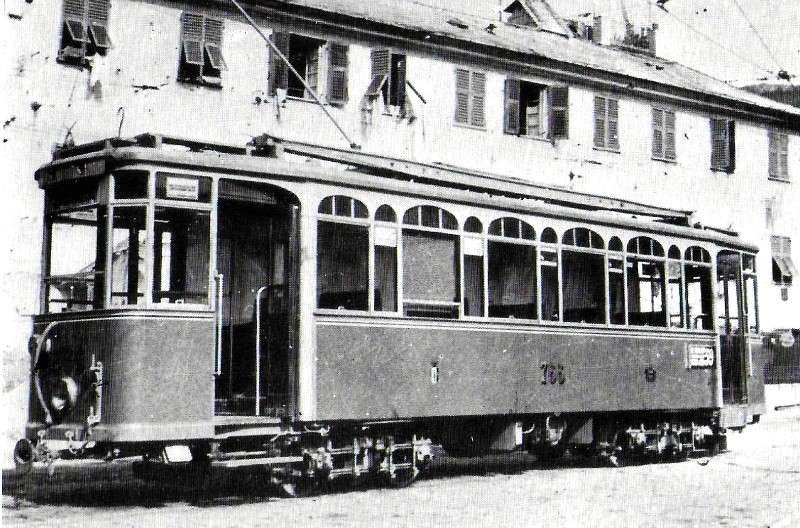

By the 1960s, trams in the 700 and 800 series were the oldest on the network, dating from 1931 and 1934, both bogie cars. All were very much at the end of their working lives and were the first to be scrapped. Two of the 700 series trams are shown below. The first is No. 762, the second is No. 766. Trams No. 751-800 were bidirectional bogie-cars built in 1931. These were known as ‘long Casteggini’ type trams. [4][5]

The 800 series were numbered from 801 to 820 (UITE) were bidirectional bogie-cars built by Piaggio in 1932. These were known as ‘short Casteggini’ type trams. [4] Tram No. 821 is shown below at the tram terminus at Bratte in Bolzaneto. This image was shared on the Foto Genova Antica Facebook Group by Enrico Pinna on 14th October 2023. [6]

There were three types of articulated car on the network at that time. Cross says that “the most numerous of these were the 78 cars of the 1600 series, which were single-ended and the result of rebuilding from older stock, while the 15 cars of the 1700 were double-articulated vehicles ‘two-rooms-and-a-bath’ variety, also rebuilt from older cars in 1954-5, Maintenance of all of these cars was poor in their final years in service. … Genova’s most modern interurban cars were the six-axle 1100 series, built in 1942, of which there were only four examples, and the streamlined bogie cars of the 900 series. Both were bi-directional, with the articulated cars carrying two trolleys. The 900-series cars were the backbone of the interurban service and predominantly worked routes 10, 11, 16, 24 and 26. Both series were well maintained. with an eye to resale once the interurban network had been closed.” [1: p251]

Details of these four tram types can be found here. [7]

It was hoped that first, Beograd and then Zagreb might purchase the 900 series, even Madrid seems to have made enquiries, but “two and a half years after the Genova tramways closed, [the 900 series] cars were still to be found standing in their depots and were eventually broken up, with no buyer having been found.” [1: p251]

Cross recorded that “two cars, 962 and 973, were preserved, and in 1989 a scheme emerged to use them to provide passenger services on a metre-gauge heritage tramway, linking Piazza Caricamento and Piazza Ferrari along a pedestrianised Via San Lorenzo. However, in true Italian style, nothing [had] yet been decided.” [1: p252] I have not been able to find any evidence that the heritage service was brought into operation.

Cross goes on to say that “Articulated cars 1101-4 were sold to the Neuchâtel tramway (TN) in Switzerland, with car 1104 arriving on 29th March 1966 for a set of preliminary trials. These were so successful that TN bought all four and put them into service on route 5 in Autumn 1966. The Genova trolley poles were replaced by pantographs, and heating also had to be fitted, since this had been totally unnecessary in the balmy Mediterranean climate.” [1: p252]

Interurban trams were replaced by FS multiple-unit, rapid-transit trains along the coast between Nervi and Voltri or Pontedecimo in order to reach the centre of Genova. Withdrawal of the city centre trams “left Genova with 130 trolleybuses as its only means of electric urban public transport, but even these eventually succumbed to replacement by diesel bus. However, as time passed, it became ever more obvious that a huge mistake had been made in withdrawing the trams. … The elevated roadway did not prove the panacea that its planners had wished for, while motor buses did nothing to improve the traffic flow … their stops on Genova’s narrow, winding and steep roads effectively blocked the flow of all traffic!” [1: p252]

The municipality decided to reopen the Certosa tram tunnel for use by diesel buses. This required forced air ventilation to maintain reasonable air quality in the tunnel. It “reopened for bus operation on 1st October 1967, although width restrictions made it impossible for two-way working. … Instead, a token block system had to be introduced, with buses passing through the tunnel in alternate directions at nine-minute intervals. This resulted in a serious capacity problem during the rush hour, which could be overcome only by sending convoys of three instead of single buses through the tunnel. … Unfortunately, the tunnel’s ventilation system simply could not cope with the upsurge in exhaust emissions. Indeed, the Il Lavoro’ newspaper shocked the general public when it featured a photograph of a bus on route 10 leaving the tunnel with its driver clearly seen wearing a gas mask!” [1: p252]

Other solutions had to be found. “In the 1920s, Genova had been tempted to undertake construction of a conventional heavy metro, influenced by the developing trend in some other European cities. However. successful implementation of the proper scheme had been undermined by its daunting cost.” [1: p252]

A study by the Marron Institute of Urban Management looking at possible urban transit solutions considered a number of Italian cities including Genova. It comments: “Despite several attempts in the interwar period to develop metro rail networks in Rome, Milan, Genoa and Naples, the first proper metro line opened only in the mid-1950s. Metro construction finally gained momentum during the postwar years, characterized by fast urbanization and dramatic economic growth, but was hindered by the lack of a national transit policy, which finally emerged in the late 1980s, and by an essentially car-oriented transport policy.” [8: p15]

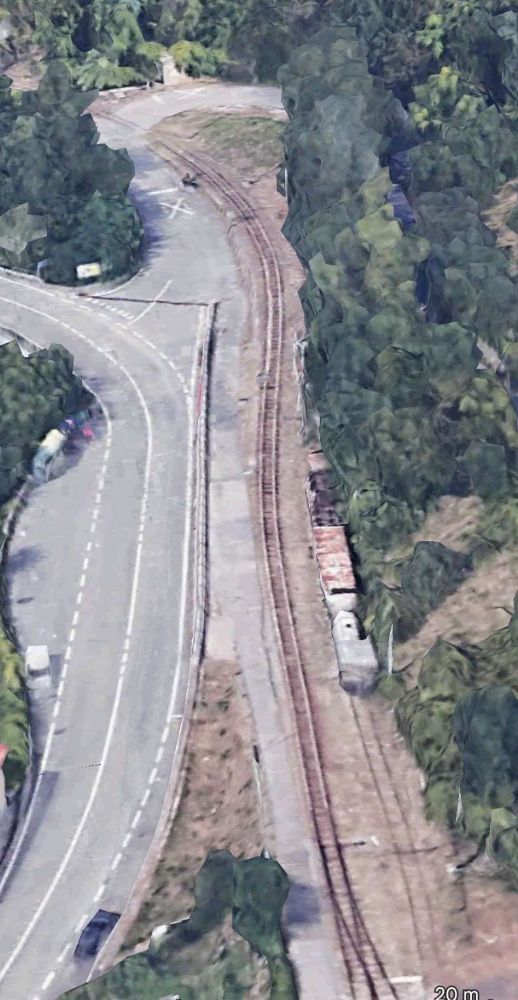

The idea of Metro for Genova was resurrected in 1972. “Trial borings were undertaken as a prelude to the construction of an 18-km two-line metro system. Ironically, the first line would run along the coast from Multedo in the west to Sturla in the east. duplicating in part the withdrawn coastal tramway! … The economics of building even a single cross-city line with, at most, two branches, proved beyond the financial capability of a city with a population of only 800,000. The decision not to proceed with the scheme was inevitable, leaving the city’s transport planners with little option but to continue with the status quo until a viable alternative could be found. … In the early 1970s, an alternative plan [was] put forward … to reuse old railway tunnels abandoned in the post-war period to provide a metro-style suburban rail service. The success of this scheme relied upon FS permitting metro cars to share tracks with conventional trains on the existing harbour line. But this it was not prepared to do. … After a change of political control in 1975, the Comunale di Genova set up a joint FS-AMT (Azienda Municipalizzata Trasporti) commission to examine the possibility of reusing previously-abandoned railway infrastructure to provide some sort of metro service. … A visit was paid to the Grazie tunnel, linking Brignole with Piazza Cavour, to assess its suitability, and also to the former Certosa tramway tunnel.” [1: p252]

Use of the Certosa tunnel by diesel buses had proved to be a failure. Instead of converting it for use by trolleybuses “it was proposed to build a Metropolitana Leggera (light metro) linking Rivarolo with Brignole by means of the tunnel. … Phase 1 would involve the construction of the Rivarolo Principe section. A reserved alignment would be built along Via Iori and Via Canepari, from where the trams would run through the tunnel to Dinegro. Here, traffic-light priority would allow the cars to cross Via Venezia and move to a further surface reservation along Via Buozzi. Finally, at Principe FS station, there would be a turning circle formed by Via Adua and Via San Benedetto. The Board of Directors of the AMT gave the project its full backing, with the Comunale following suit shortly afterwards. On 24th February 1981, the municipality, doubtless with an eye on the forthcoming June elections, approved an ITL 8000 M grant for the rehabilitation of the Certosa tunnel. although inflation eventually pushed this up to ITL 11 000 M. The central government also became involved, pledging investment worth ITL 165 000 M to build the entire 7.645-km Rivarolo-Brignole line. Ansaldo Trasporti was subsequently awarded a turnkey contract to both build and equip the line.” [1: p252-253]

Cross continues: “On 8th February 1982, the Certosa tunnel was closed to bus traffic for the last time. … In all, 540 days were spent on rehabilitating the tunnel structure, although much more work was required before tram services could start. … In 1985, work on the project proceeded very slowly, while some drastic changes were made to the eventual alignment. In the revised plan, none of the surface sections of the line had survived. From Rivarolo to Brin, the line would be on an elevated alignment, crossing the double-track FS railway line via the Compasso park. Trams would then pass through the Certosa tunnel and cross under Via Venezia and Piazza Dinegro via a new 300-m cut-and-cover subway, continuing to Principe entirely in subway. The Principe-Brignole section would still run on the dock railway as planned, then via the Grazie tunnel to Brignole FS.” [1: p253]

The municipality set a “theoretical capacity of 36 000 passengers per hour and direction [for] the line, whose trains would draw current from a 750-volt de overhead contact wire. However, curves of 150-m radius would have to be negotiated, and rolling stock would have to be designed to operate on tunnel gradients as steep as 4%. The track design would require sleepers to be enclosed in rubber sleeves to absorb noise and vibration, following successful use of such a system in Wien (Vienna).” [1: p253]

This was a much heavier metro than had originally been planned, and would be both more expensive and slower to implement – the first phase costing ITL 1150,000 M and taking 9 years to build! It was hoped to start passenger services by the end of 1989, in the end it opened in June 1990. The first phase was 2.6 km in length and had cost ITL 100,000 M/km! The line proved to be very popular. “One and a half years later, 3.5 million passengers had used the line. … It had been hoped that the line would be extended from Dinegro to San Giorgio in 1992. However, more delays ensured that only the 900m Dinegro-Principe section would be ready in time. This was duly inaugurated on 27th July 1992, and was expected to increase substantially the initial line’s patronage, since Principe is Genova’s main long-distance railway terminus and a new suburban station, San Tomaso, was being built nearby. A further two ‘metro’ sets were put into service to cope with the expected increase in traffic.” [1: p253]

Cross was writing in 1995 and reported that work was ongoing on the next length of the Metro. In the end, work on that next section of the line to Caricamento was not completed until 2003. The next section to De Ferrari (underground station at Piazza De Ferrari) was completed in 2005, and that to Brignole in 2012. [9][10]

More about the Metro can be found here. [11]

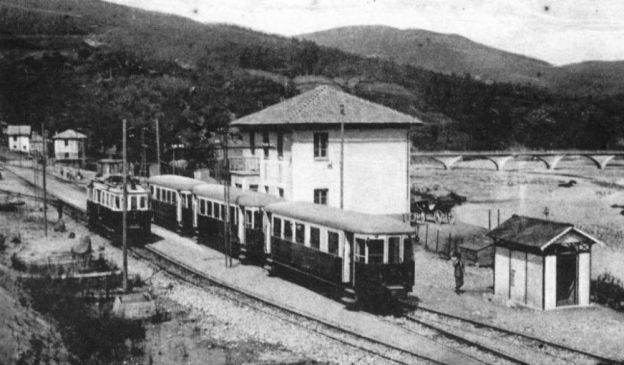

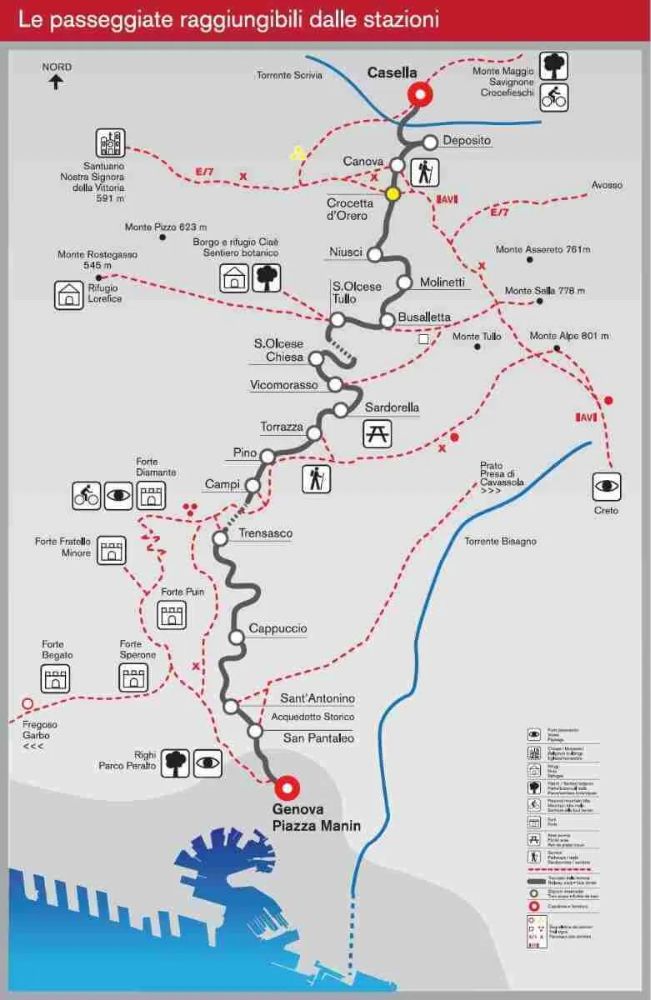

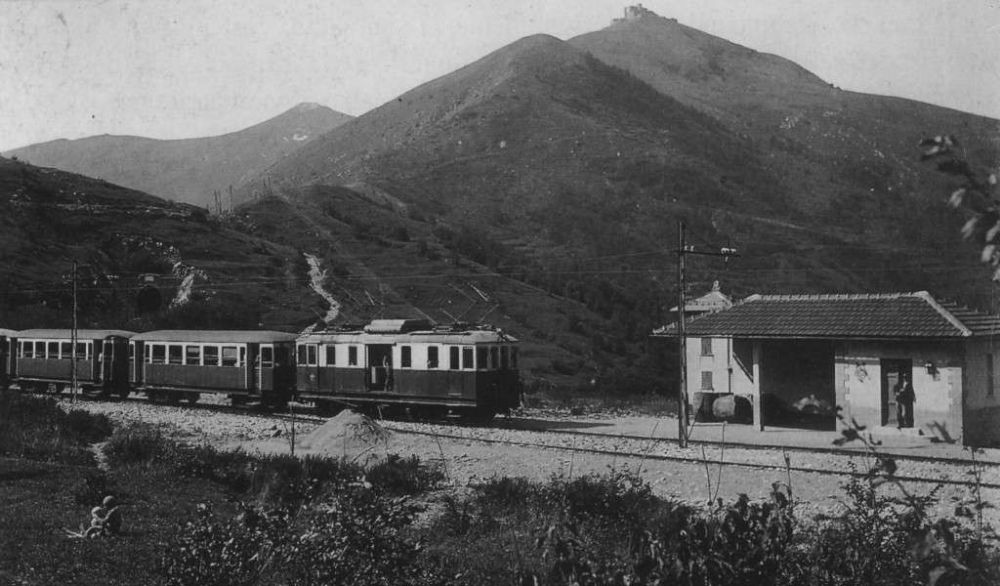

Part 2: September 1995 – Casella Line Begins to Realise Tourist Potential

Cross notes the significant delays which affected the first scheme promoted by the ‘Societédi Ferrovie Elettriche Liguri‘ (SFEL) in 1915, which meant that It was not “until 1926 that construction was able to start on the metre-gauge line, which was to be electrified at 2.4 kV DC by the ‘Societé Ernesto Breda, which won contracts to supply the overhead and sub-stations, as well as the initial rolling stock.” [2: p295]

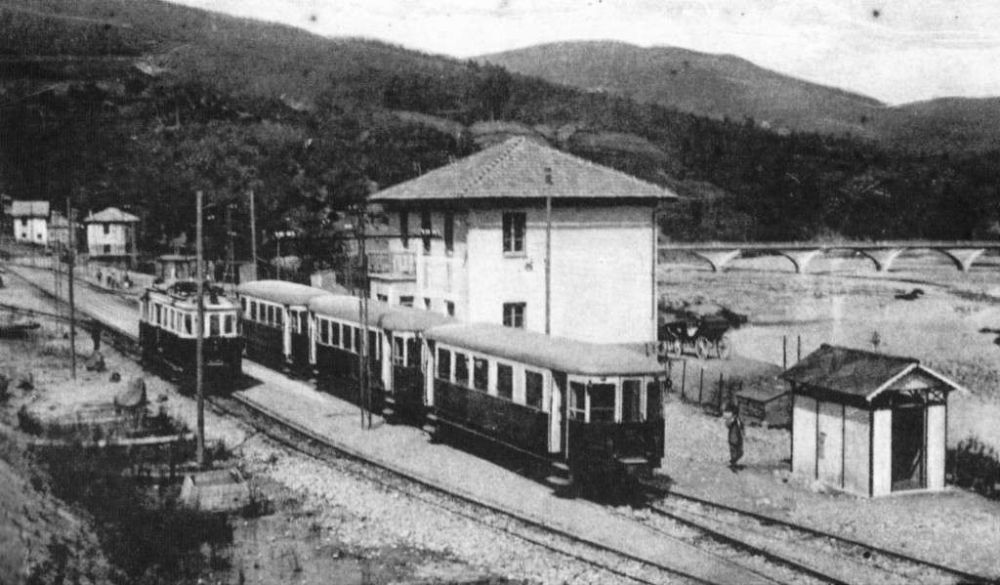

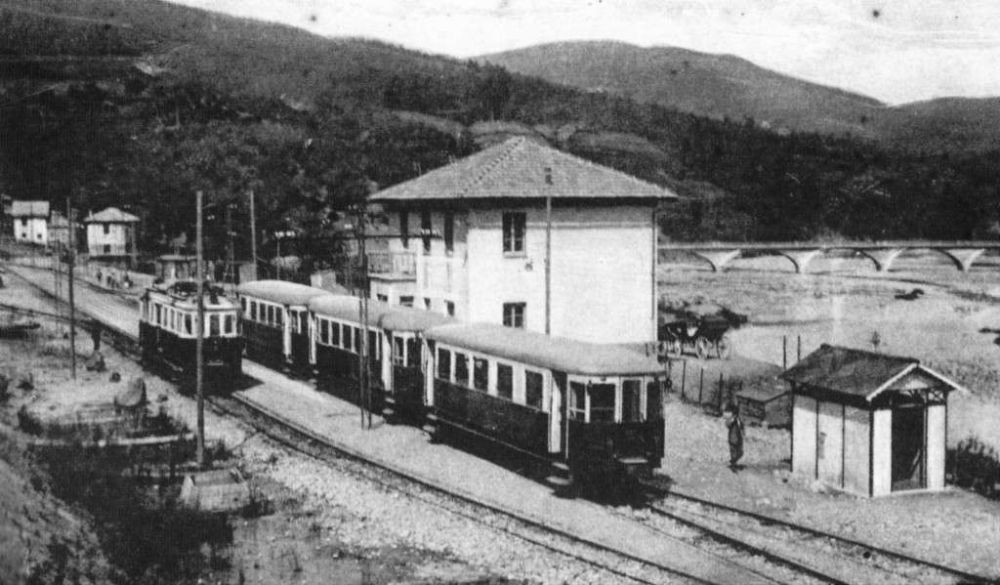

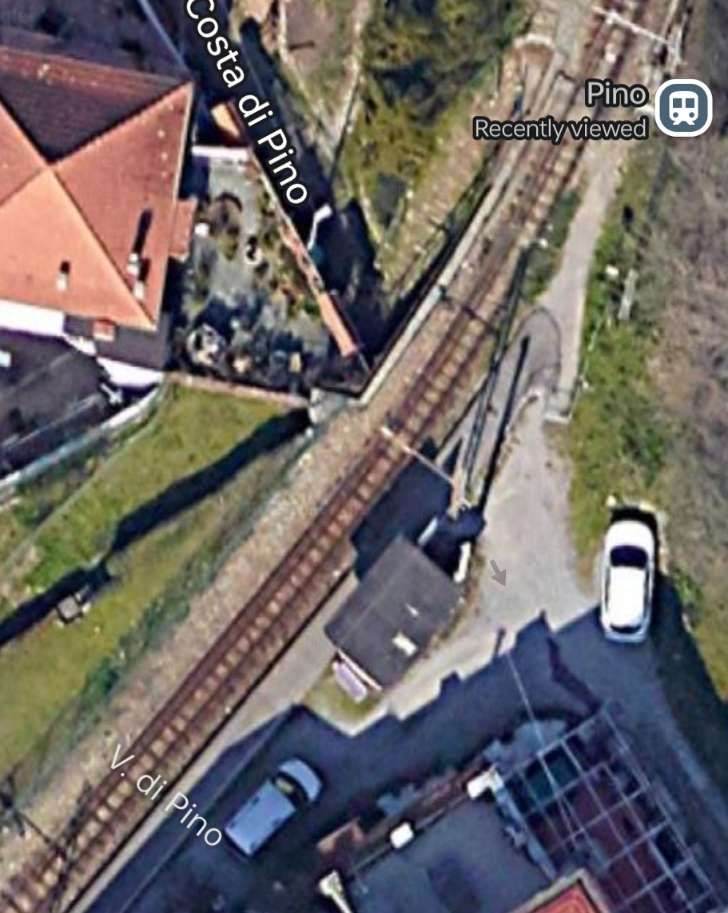

He also comments on the use of the contractor’s steam locomotive “to power the first train between Genova and Casella Deposito on 24th June 1929; then, on 31st August, the operating company laid on a special train for the Archbishop of Genova’s pastoral visit to Pino, with a regular passenger service starting the following day. However,” he says, “the line’s official inauguration had to wait until 28th October 1929.” [2: p295]

The line was notable for 60-metre radius curves and maximum gradients of 4.5%, imposed on engineers by the need to cross steep gradients between the Bisagno, Polcevera and Scrivia valleys. cross continues: “A non-counterweighted catenary was preferred over most of the line, although a simple transversal suspension overhead sufficed in stations, depot area and between the upper terminus and the depot. Very light 27 kg/m rail was standard throughout. The initial fleet of Breda vehicles operated by SFEL was:

- 3 Bo-Bo motor baggage cars (001-003) rated at 270 kW, featuring the novel Breda-Somaini energy recuperation system;

- 4 3rd-class bogie trailers (50-53);

- 3 1st/3rd-class trailers (20-22);

- 16 assorted goods wagons.

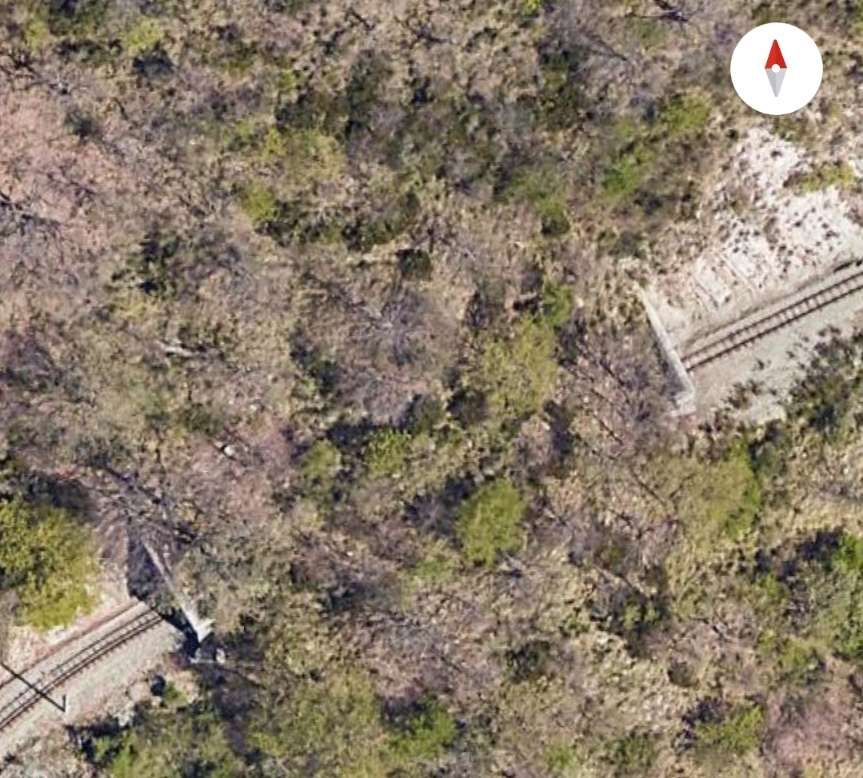

The Casella Deposito-Casella Paese section, originally planned in 1930, eventually opened in 1952, crossing the Scrivia river via a new combined road/rail bridge. Trains shared the road with cars, and the 1 km line terminated in mid-highway on the village outskirts.” [2: p295]

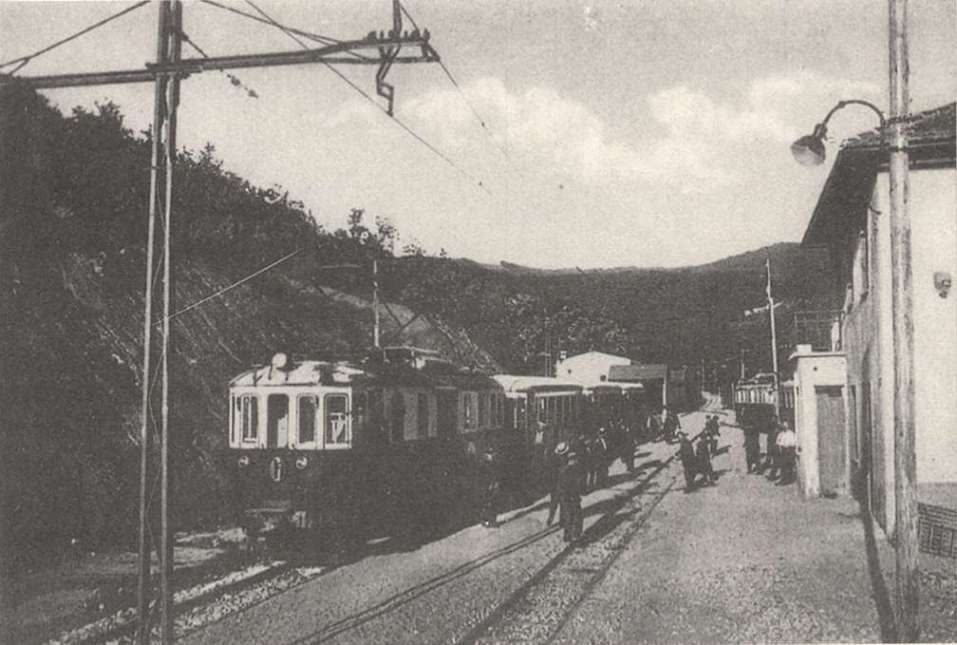

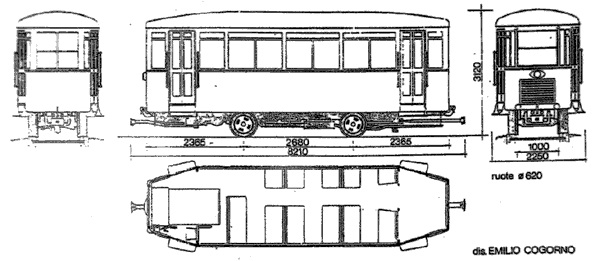

Cross comments that, throughout its life, the line made use, primarily, of second-hand rolling stock. “The first items acquired as early as 1935. In that year, three railcars came from the Montebelluna-Asolo and Montebelluna-Valdobbiadene lines operated by the former ‘Societé Veneta’, which ceased trading in 1931. These vehicles had been built at Padova by MAN in 1913 for operation at 975 V DC, but had to be modified at Genova. They had distinctive match-boarded sides, maximum-traction trucks, and retained original fleet numbers 054-056. With only two motors per car, they were rather slow, particularly with trailers.” [2: p295]

Cross notes that “World War II did little permanent damage, although rolling stock was worn out after almost continuous use evacuating families from Genova city while under bombardment. The Government Commission, which assumed managerial responsibility for the line in 1949, acquired supplementary stock from the 950-mm ‘Sangritana’ light railway (SFAA), almost totally destroyed in the war.” [2: p295] Of these, two electric locomotives were re-gauged, they were numbered 28 & 29, had 360-kW motors which “drew power via two pantograph-style bow collectors, one leading and one trailing, and could reach speeds of 50 km/h. They kept their original numbers when put on the Casella line in the 1950s and later acquired bus-type seats for 16 passengers.” [2: p295]

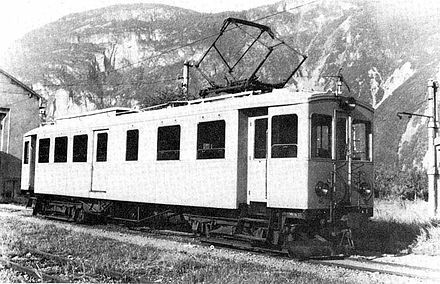

In January 1963, the line acquired significant amounts of stock and fixtures of the Ferrovia Elettrica Val de Fiemme (FEVF), which operated the Ora-Predazza metre-gauge line “three Bo-Bo baggage locomotives [B51-52, A2] driven by 310 kW motors and capable of a maximum speed of 60 km/h; three three-bogie rail cars … which drew power via a single rhomboidal pantograph to feed a 310 kW motor permitting speeds of 60 km/h; 36 bogie-trailers, of which C101-2 were long vehicles and C103-6 short; and … several goods wagons.” [2: p295] Of the fixtures, “the FEVF provided two static converters, replacing the FGC’s original generating equipment. These were installed at Vicomorasso and raised the line voltage from 2.4 kV DC to 2.6 kV. Unfortunately, this new equipment did not permit recuperation of energy and resulted in withdrawal of all earlier rolling stock, except that acquired from Sangritana lines.” [2: p295]

Furthermore, “in 1968, the recently-closed Spoleto-Norcia (SSIF) electric light railway yielded four 950-mm gauge railcars, built by Carminati & Toselli/TIBB in 1926 and later rebuilt by Casaltra/TIBB in 1957 with new electrical equipment, with 360-kW motors permitting maximum speeds of 60 km/h. They arrived at Genova in 1970 and entered revenue service a year later, the delay being for regauging. … Although originally numbered A1-4, they were altered to A4-7 to avoid conflict with earlier-acquired FEVF stock.” [2: p295]

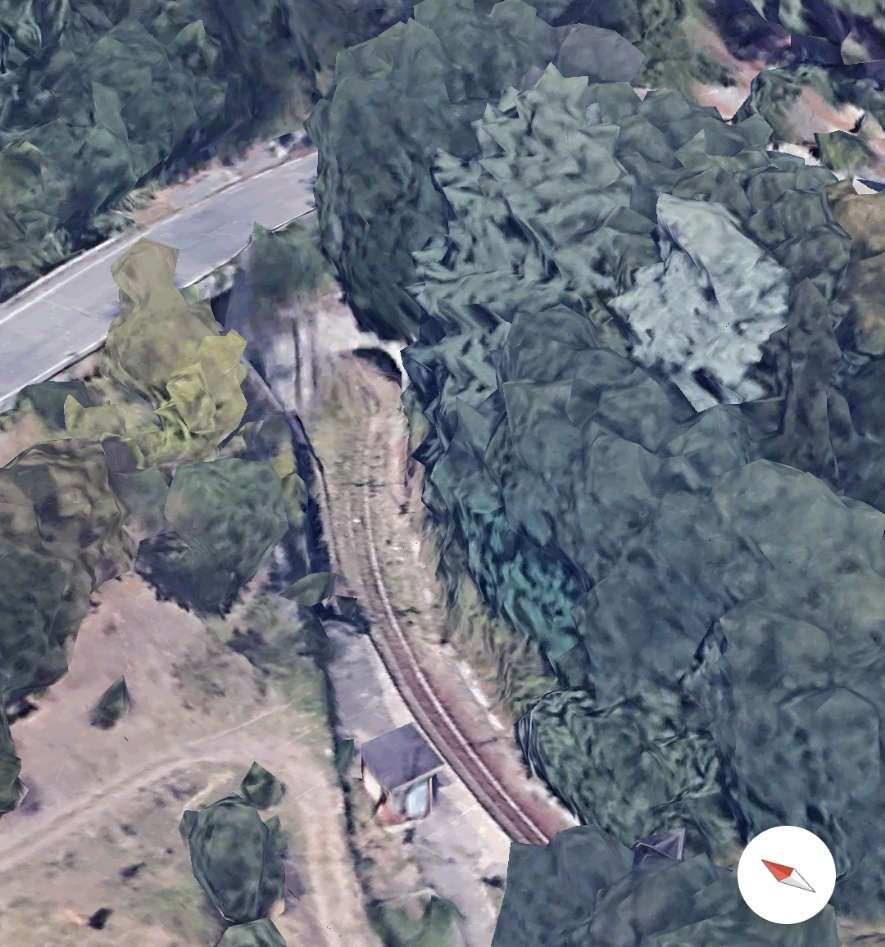

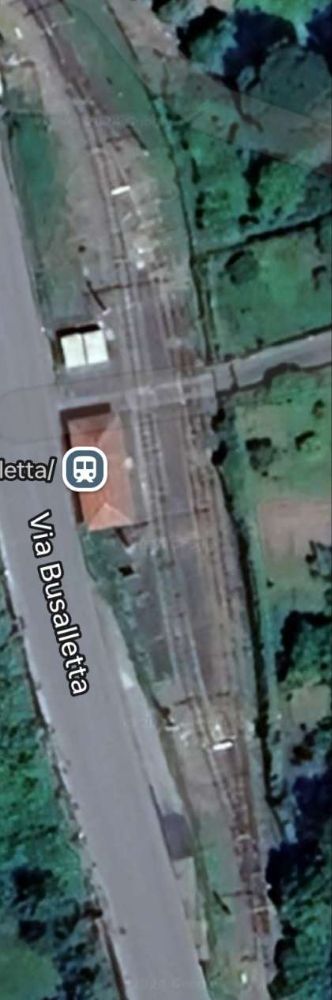

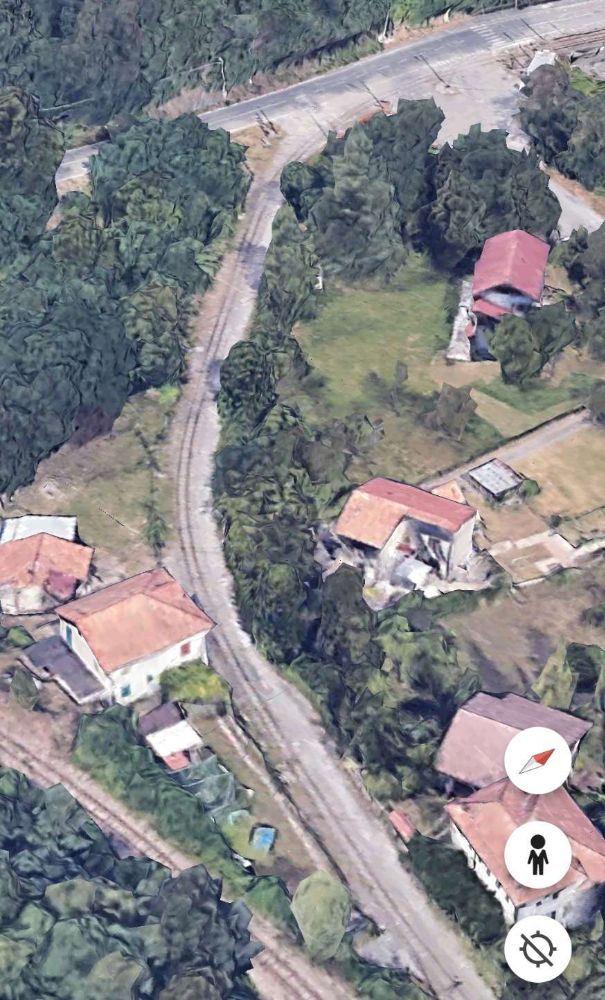

Cross talks of the line struggling through the last 40 years of the 20th century. “When Joachim von Rohr visited the FGC in 1963, he noted Casella depot was particularly run down. Although renewal of the ballast was taking place, the use of short, not welded rails, plus a tendency to bend rail at joints, made for some eventful running. … On 17th January 1974, railcar A3 was derailed on poor track. On 31st October, a judge ordered closure on safety grounds, so urgent repairs were undertaken to permit a limited reopening between Genova and Sant’Antonino, and Campi SL and Casella in early 1975. Full operation resumed on 2nd March, with railcars now fitted with speedometers. … Money was not forthcoming to repair damaged A3, and the poor mechanical state of locomotive 28 also prompted its withdrawal. However money was made available to replace original rail with heavier 36-kg/m lengths, a task not completed until 1979. Maximum speeds were raised slightly, to reduce journey times from 1 hr to 55 min. In 1980-1, Casella Paese terminus was relocated from street to reserved track, and a new depot built at Vicomorasso. … In early 1990, Ansaldo Trasporti was awarded a contract to upgrade FGC installations. Overhead was replaced at a cost of ITL 5500 million, with original masts replaced by standard fitments. Voltage was raised to 3 kV DC, and a 1987 government grant allowed replacement of two sets of manual points in stations by electric ones.” [2: p295]

A gradual programme of rolling stock modernisation began in the early 1970s, “two-tone blue livery replaced the original red and cream, replaced in turn in 1980 by brown and cream. This new livery was to grace nine trailers rebodied by the Mantovana-based company ‘Gleismac’ in the early 1980s. However, C103-4 were not included, whilst C22 had already been rebuilt into a bar car at the end of the 1960s. Then, in 1985, damaged railcar A3 was completely rebuilt with a newly-designed body, chopper-controlled electronics from EEA of Genova, and two pantographs. At the same time, two Faiveley double-bracket pantographs were experimentally fitted to B51 and A4. … ‘Gleismac’ also supplied a BB diesel-hydraulic locomotive for works trains and insurance against power failure. Built by Gmeinder of West Germany in 1964, it was sold to ‘Gleismac’ from the ‘Sudwestdeutsche Eisenbahn Gesellschaft’ (SWEG) in 1986, and is now numbered D1. More recently, the bogies of disused locomotives B51-2 have been used by ‘Firema-Cittadella’ to build two new electric railcars, identical in appearance to existing railcar A3. The first, A8, was handed over to the FGC on 28th June 1993, with A9 following on 28th October. Unlike A3, both new cars can operate in multiple.” [2: p 295-296] Writing in 1995, Cross expressed the hope that if new bogies could be found, B51 might return to traffic. As far as I can tell, this did not occur. He also noted that Ferrocarril Genova Casella (FGC) was planning to buy two entirely new railcars similar to A3, A8 and A9 and three new trailers with a baggage compartment and a lift for the disabled. Two were built in 1998 (A11 and A12).

Cross also suggests that FGC planned “to rebuild railcar Al, with only A2 to be left in its original Carminati & Toselli 1920s condition. Both [were] reported fitted with modernised bogies. As for the four ex-Spoleto-Norcia railcars, at least one [was to] be de-motored to become a trailer. A4 [had] been given a new coat of cream and brown, and trailer C21, rebuilt by ‘Gleismac’ in the early 1980s, a curious livery of cream and blue.” [2: p296]

More information about railcars on the line can be found here. [12]

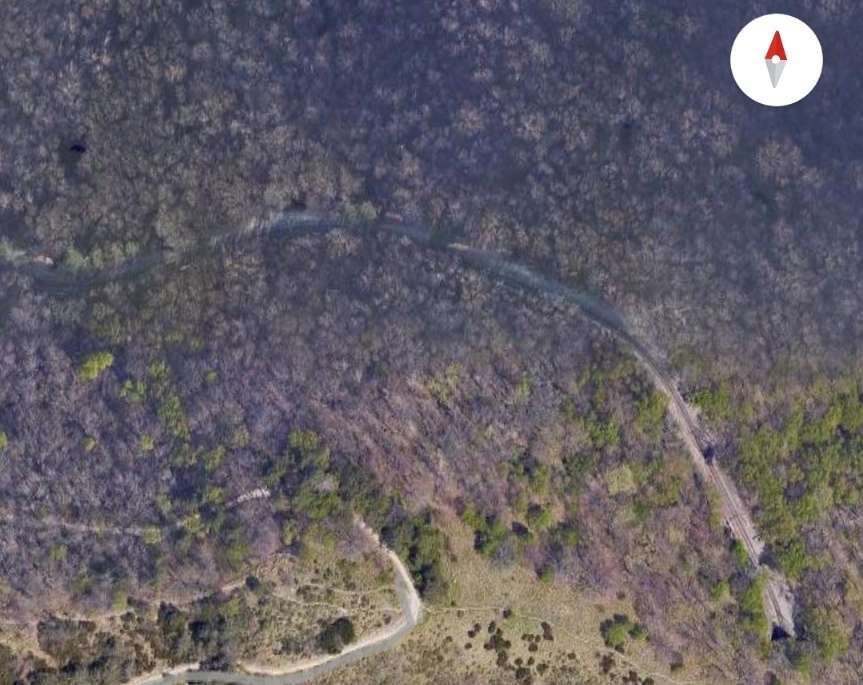

Looking forward from late-1995, Cross anticipated the purchase by the FGC of surviving rolling-stock from the closed Rimini-San Marino light railway. That line was operational for only twelve years between 1932 and 1944. “A significant engineering feat of its time, it included seventeen tunnels, three bridges, and three viaducts to negotiate the steep terrain. During the Second World War, the line was bombed and closed, after which its tunnels sheltered refugees during the Battles of Rimini and San Marino. After the war, the railway was abandoned in favour of the SS72 state road, San Marino Highway, and Funivia di San Marino. … In 2012, an 800-metre (1⁄2-mile) section was reopened as a heritage railway in San Marino, running between Piazzale della Stazione and near Via Napoleone.The restored section comprises the original railway’s final horseshoe turn through the 502-metre (1,647-foot) Montale tunnel.” [13] Cross anticipated that the FGC would buy the “four electric railcars, five trailers and 14 wagons, most for revenue service in Genova,” [2: p296] that were not required for the planned heritage line.

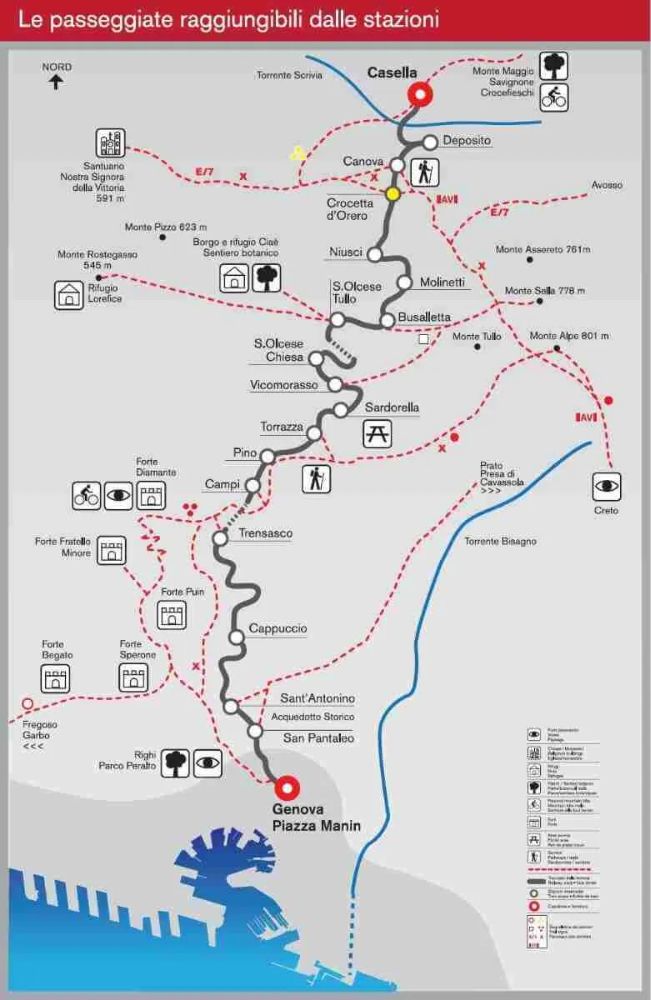

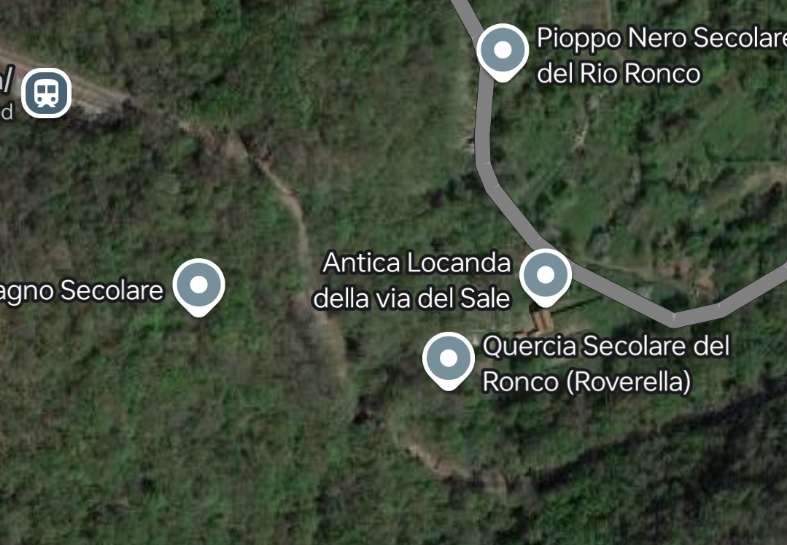

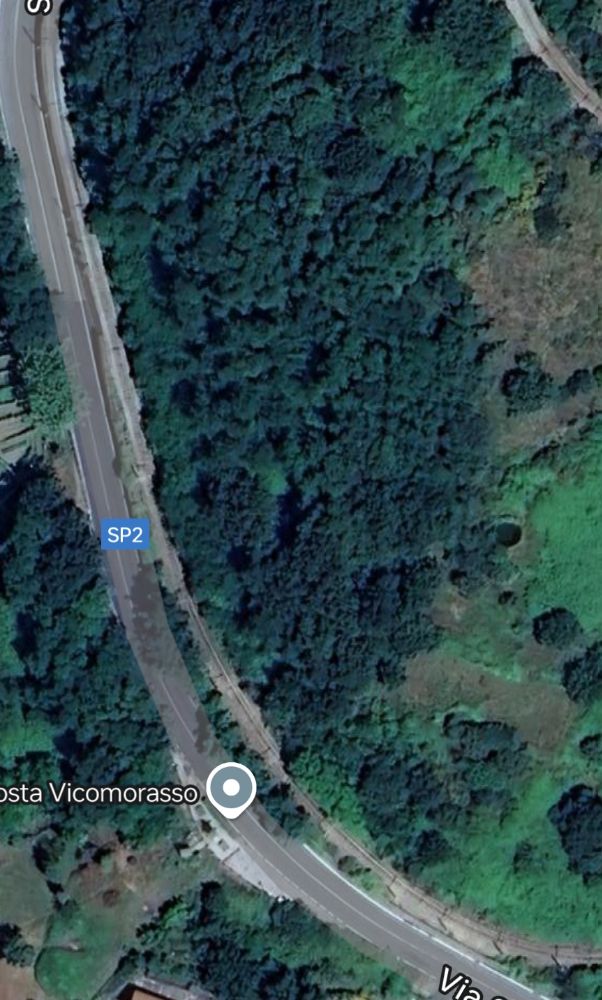

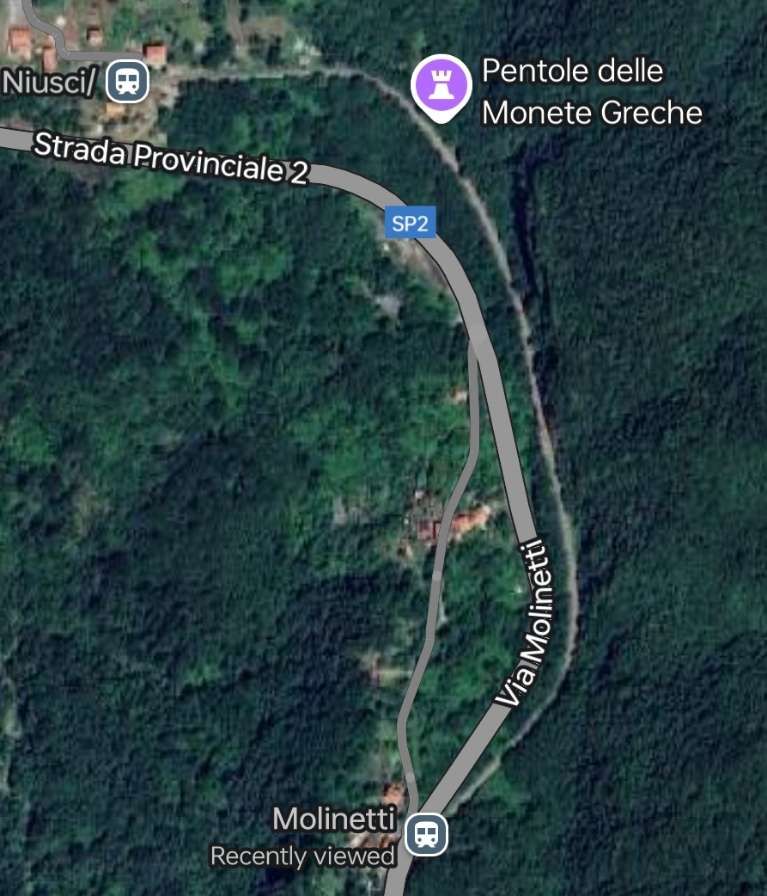

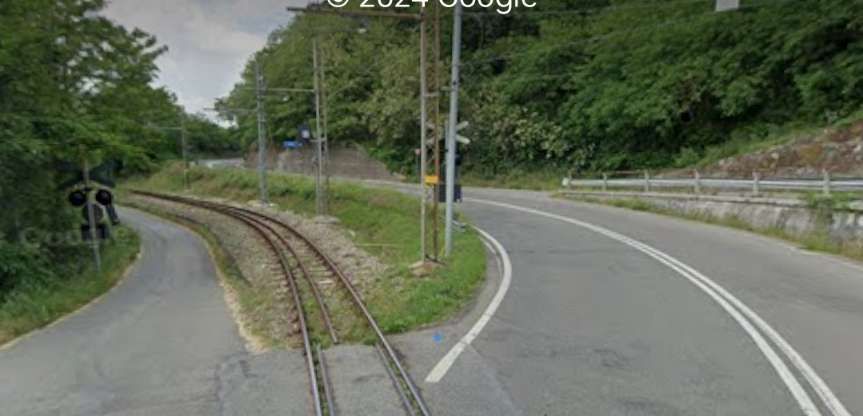

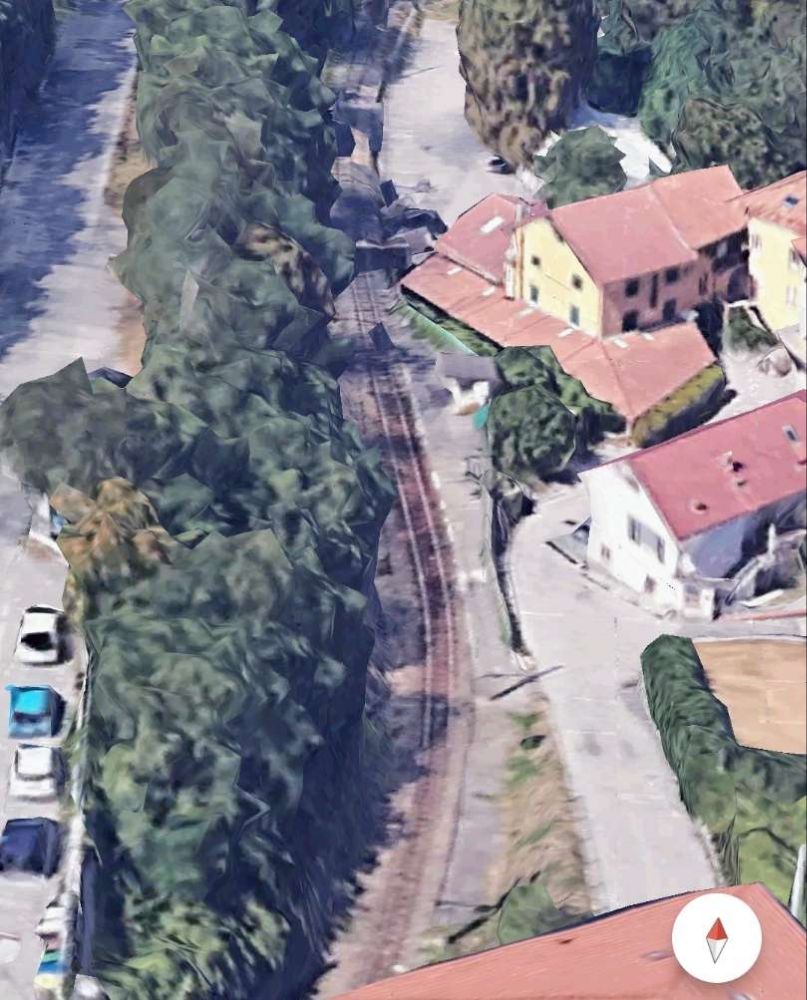

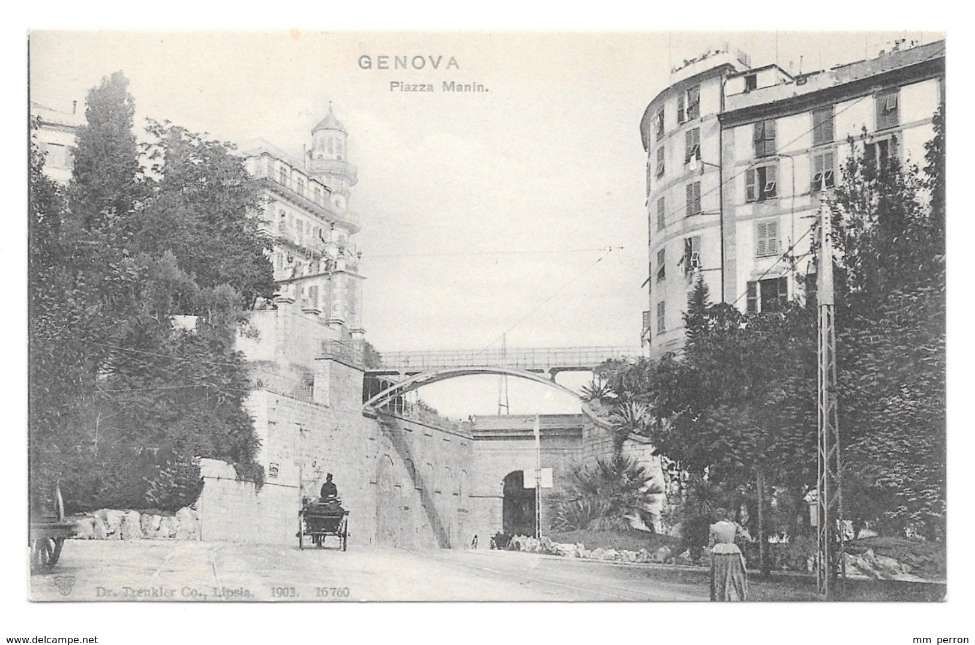

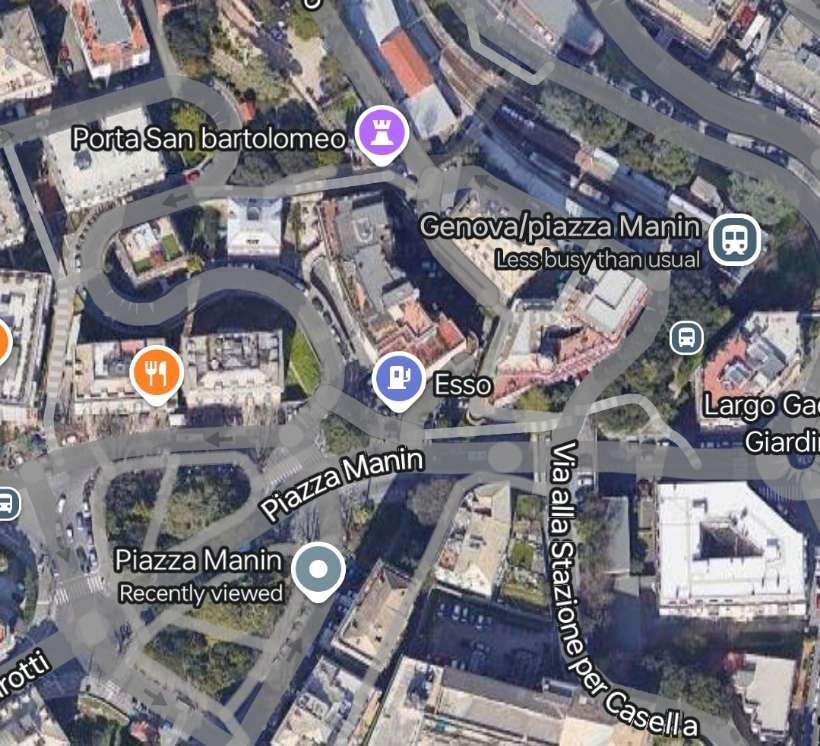

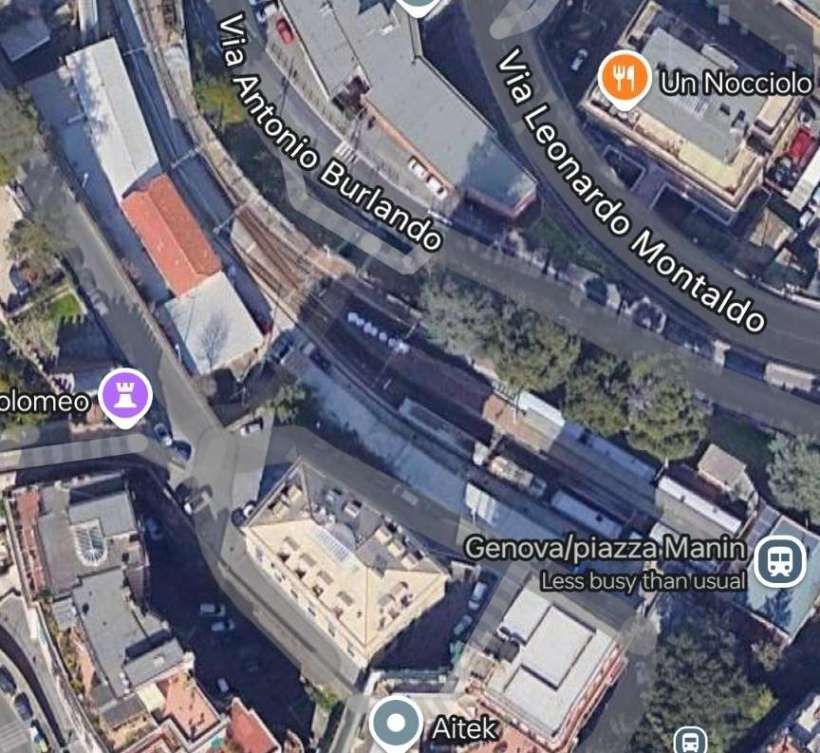

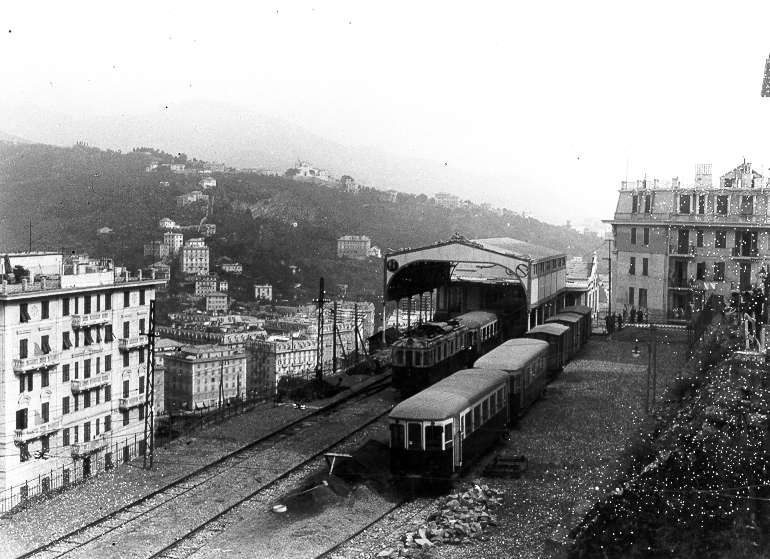

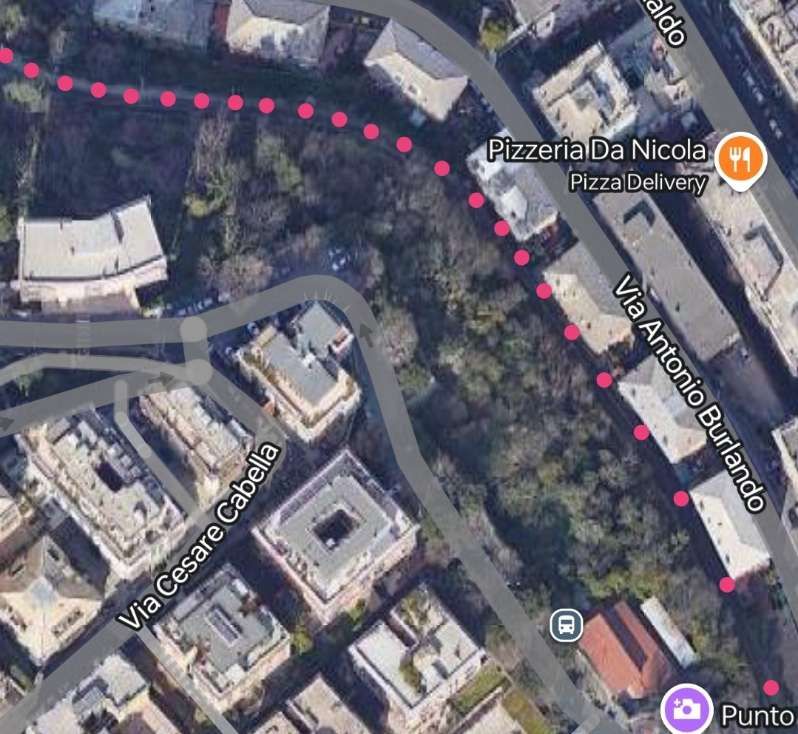

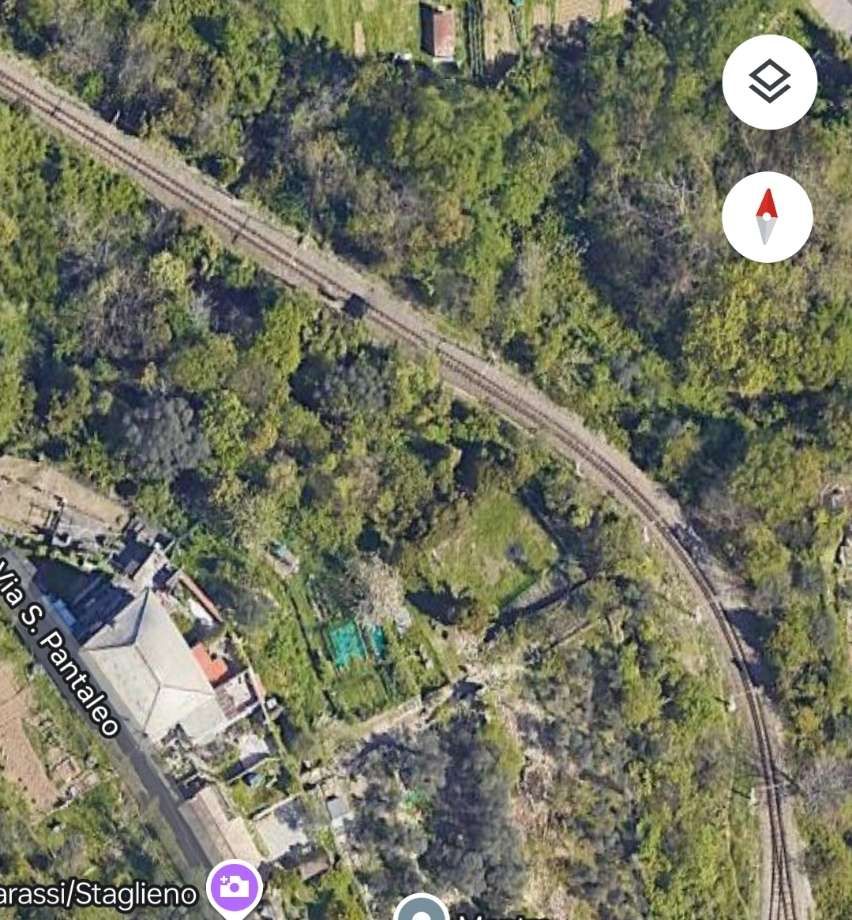

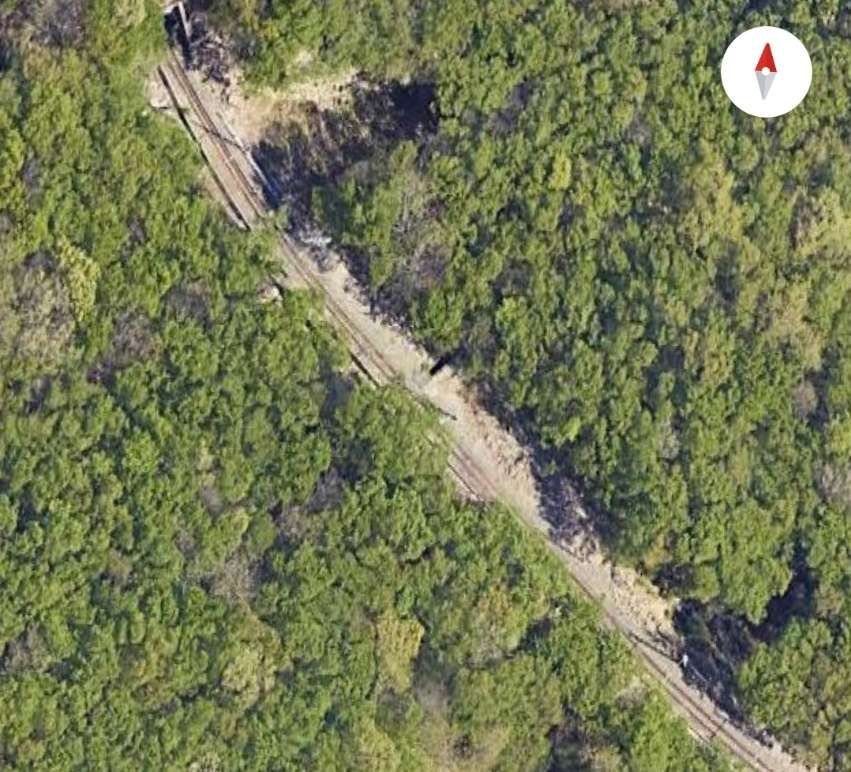

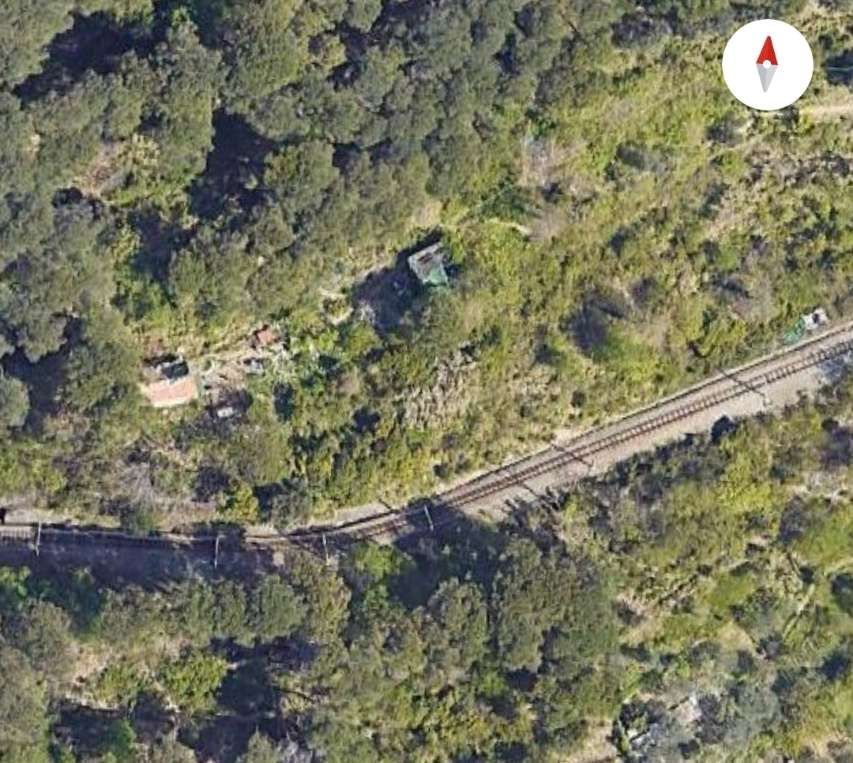

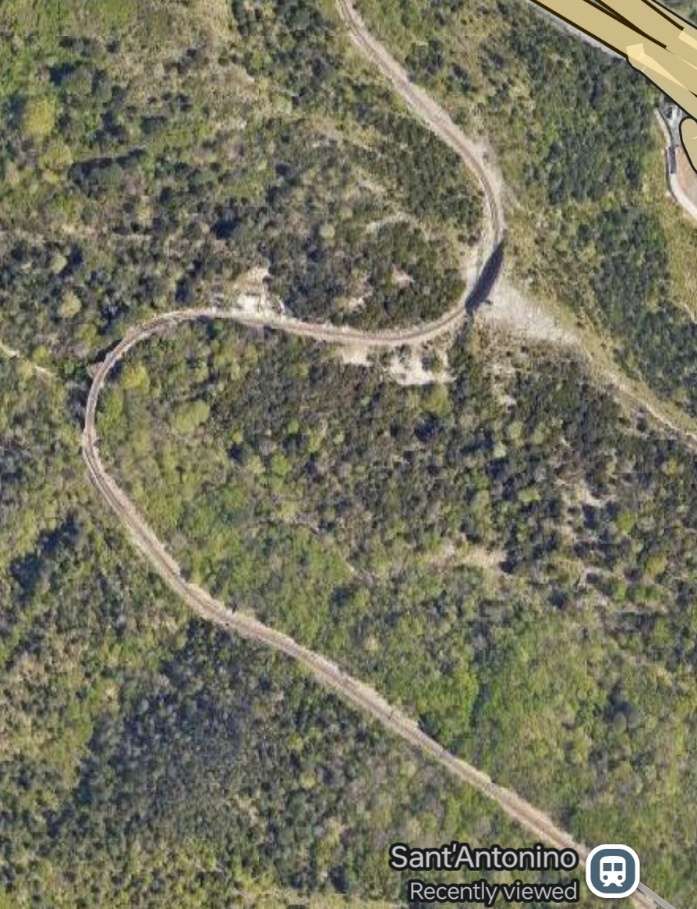

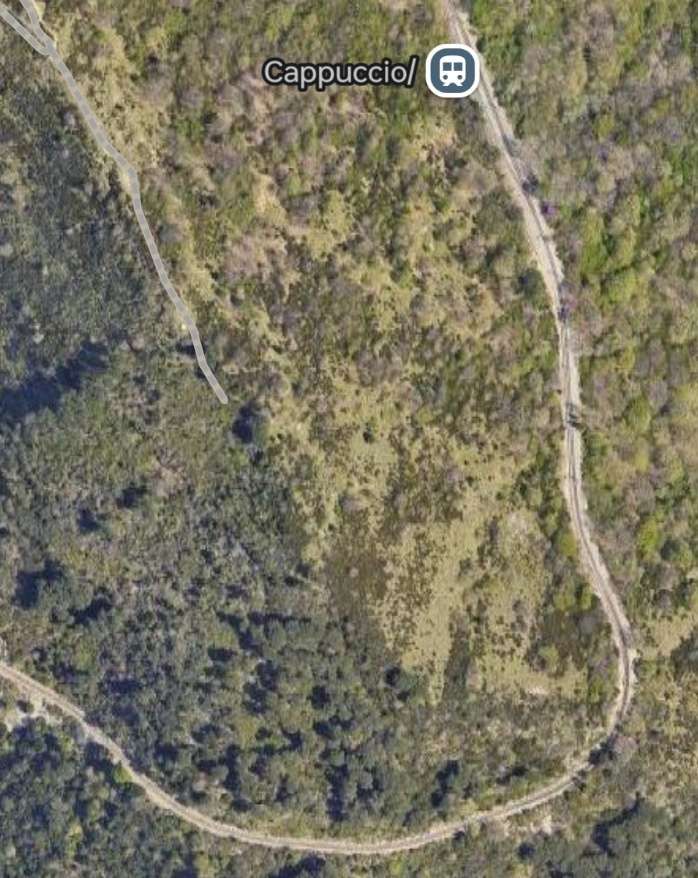

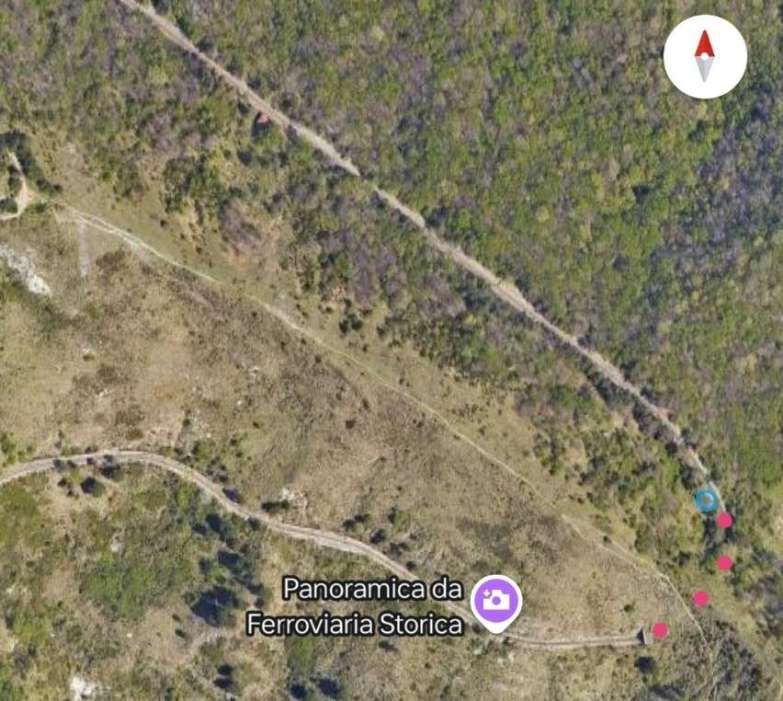

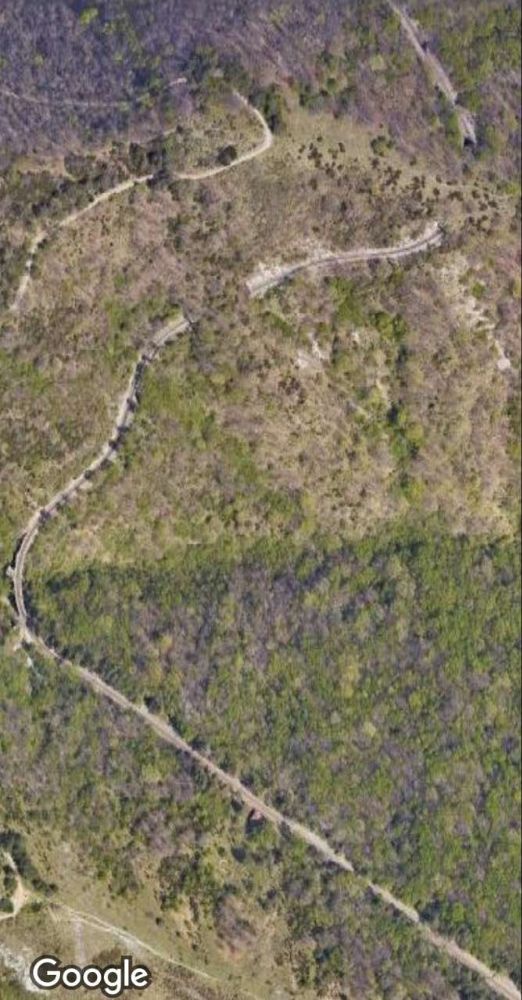

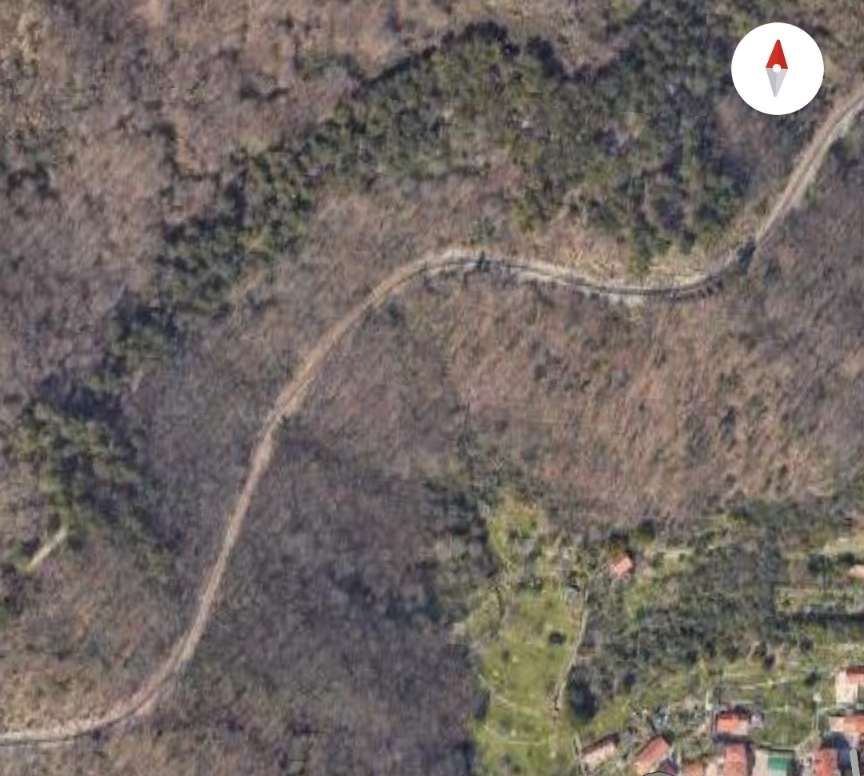

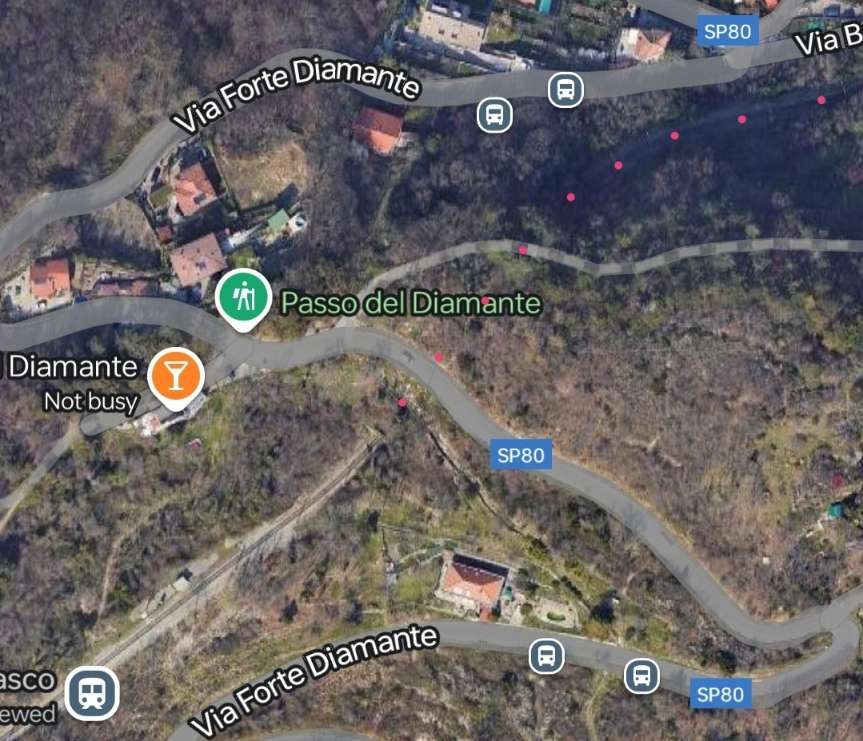

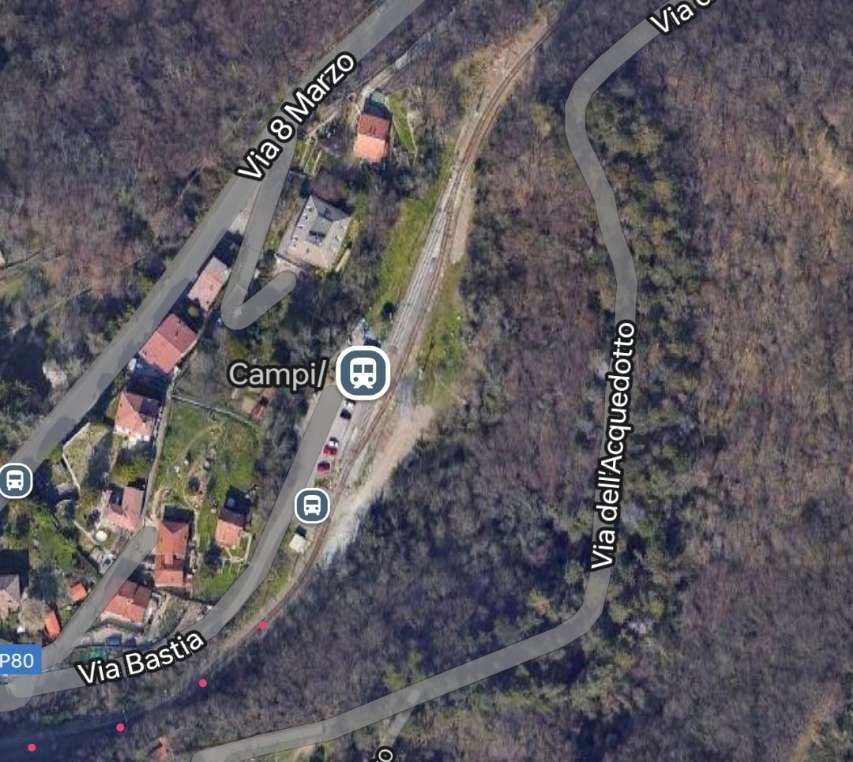

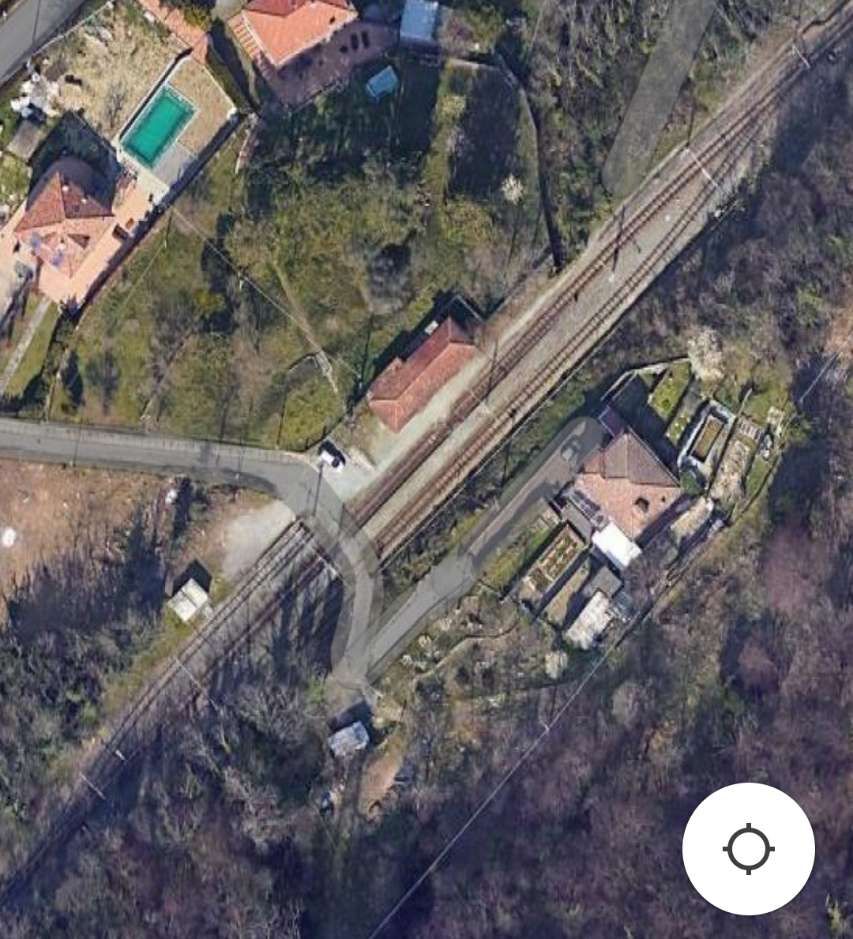

Cross comments that the distance of the Genova terminus at Piazza Manin from the central area of the city, means that the walk is quite daunting in summer months, but an extension into the heart of the city would be impractical because of the difference in height between the city centre and Piazza Manin. The terminus is situated high above the Bisagno valley which means that passengers see some fine views of the city soon after leaving the station. In describing the route, Cross speaks of a long viaduct “at Sant’Antonino which has four 10-metre arches. Departing services climb Sunday me 271 m in 9 km to reach Trensasco, located at 364 m above sea level. The line is cut into a ledge on the valley wall and near Cappuccio runs around the so-called ‘Colombo curve’ over the Viminate slope. The sharp bends give an exhilarating ride and are testament to the fact that the line engineers chose to bend with valley contours and even enter side valleys to avoid major tunnelling and expensive viaducts. … The line passes only through areas of sparse population, and former station buildings are so dilapidated it is often impossible to make out their names. Just before arriving at Campi (10 km), a small tunnel takes the line away from the main valley and shifts interest to the other side of the line. At Campi itself, up and down trains generally pass, and the guard of the ascending train has to advise control of his train’s arrival via a lineside telephone.” [2: p296]

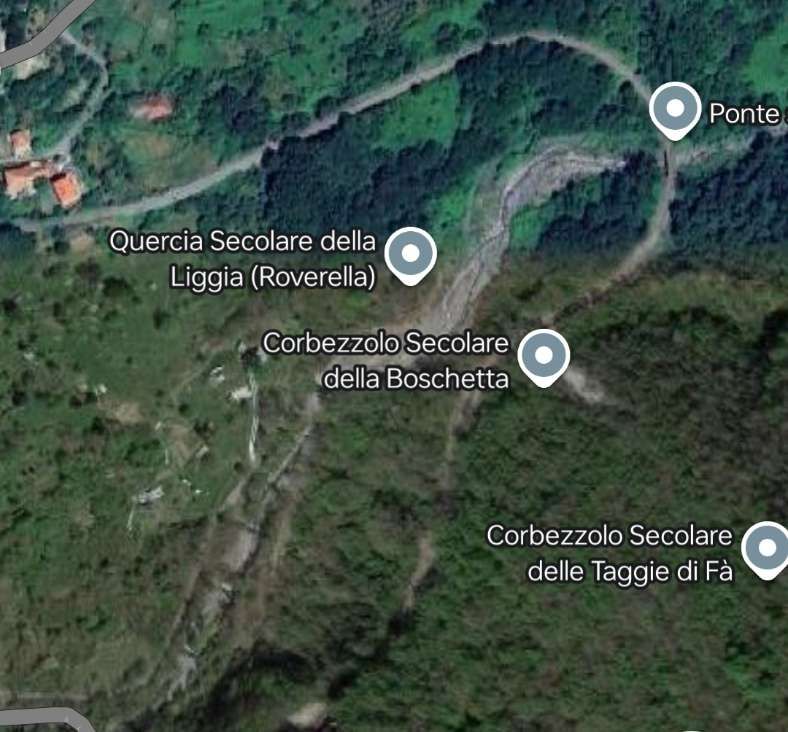

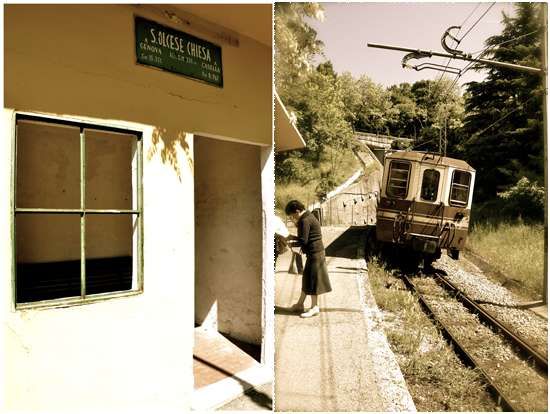

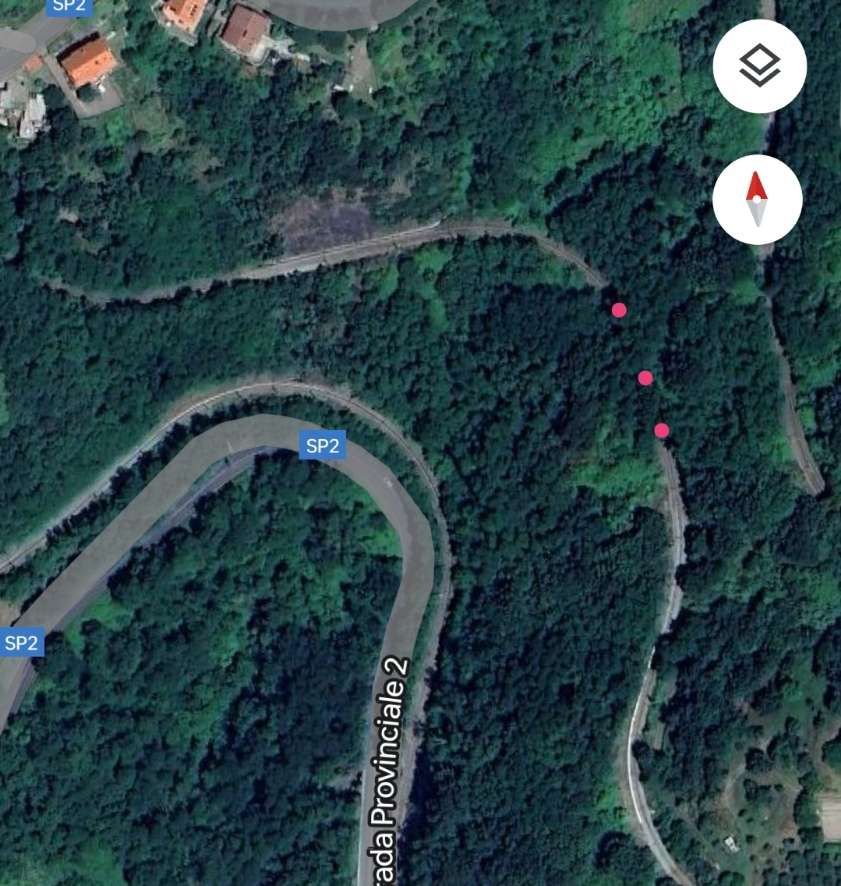

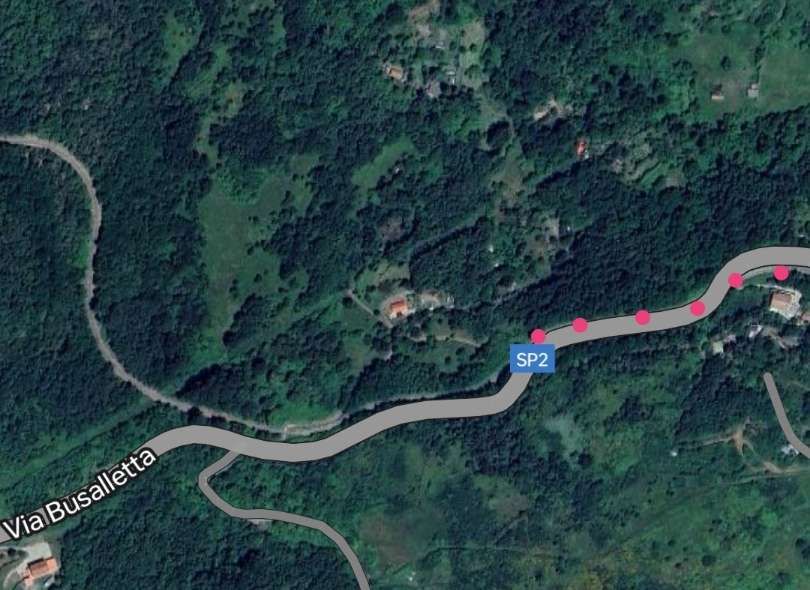

“Having arrived at 365 m above sea level, the line then descends towards Torrazza (11 km) and Vicomorasso (15 km), where the only sub-station is located and a spur line gives access to a small car shed. Withdrawn rolling stock has also been dumped here in recent years, while the station also provides passing facilities. Thereafter, the real assault begins and the line passes through some spectacular mountain scenery by means of loops and a spiral tunnel, climbing 100 m in a mere 2km before emerging into the Polcevera basin, with its notable chestnut and acacia woods. For one brief instant it is possible to see tracks below at three different levels! Another passing point is the small halt of Sant’Olcese Tullo.” [2: p296]

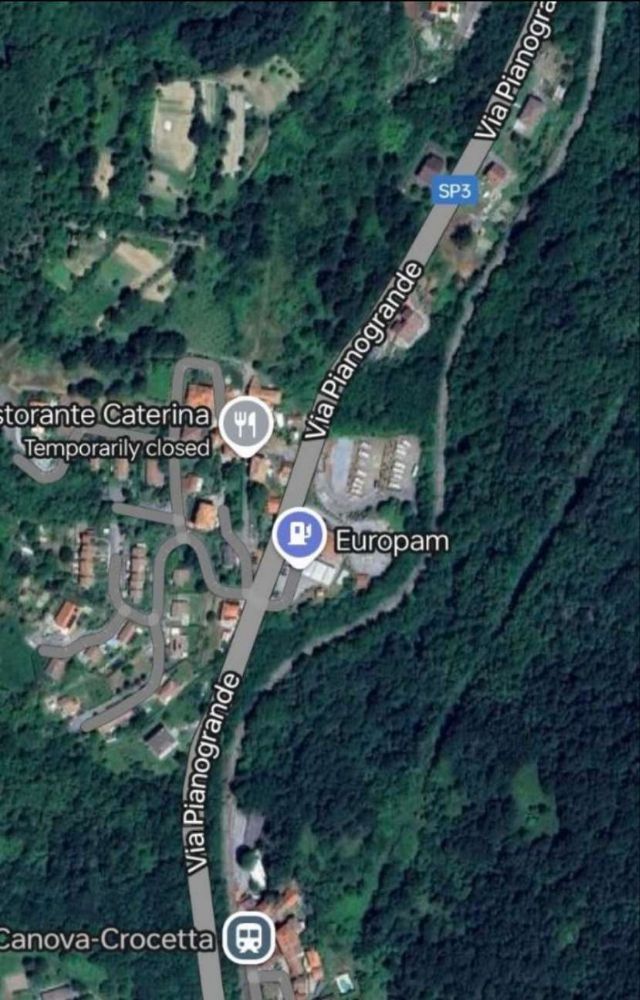

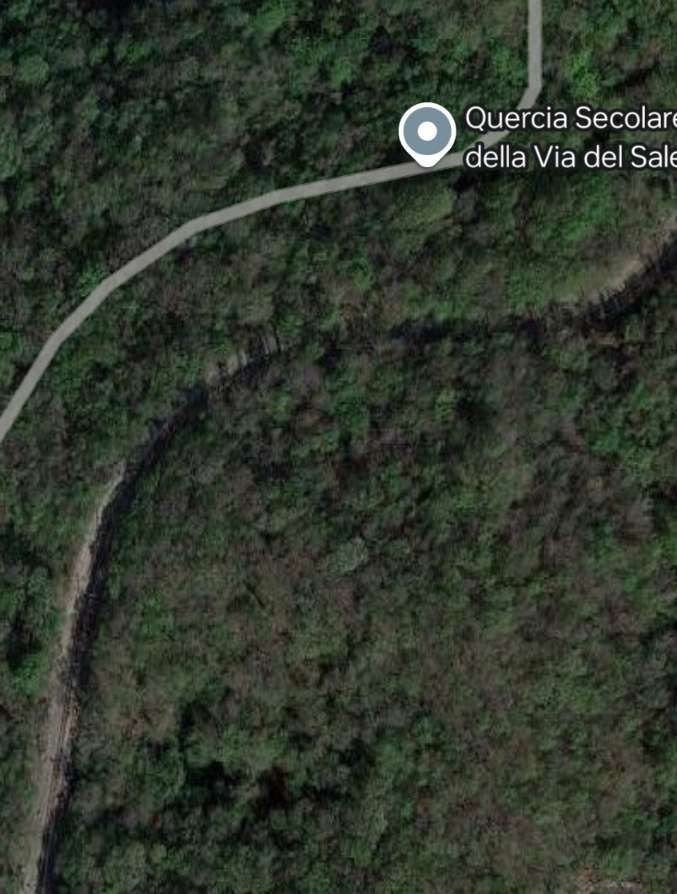

Cross continues his anecdotal account of a journey North along the line. He says that “the line continues to climb, although less dramatically in the mountainous terrain. There is one particularly dramatic hairpin bend near Sant Olcese, and near the following halt of Busalletta, fine views can be obtained of Monte Sella, 811 m. The railway summit is reached at Crocetta halt, 458 m above sea level and 22 km from Genova. It is possible to see the parallel road, which has done much to abstract traffic away from the line in recent years. There are also many small level crossings along the length of the line; the insignificant ones remain unprotected, while major crossing points are guarded by either automatic half-barriers and warning tones or simply flashing lights and audible tones.” [2: p296]

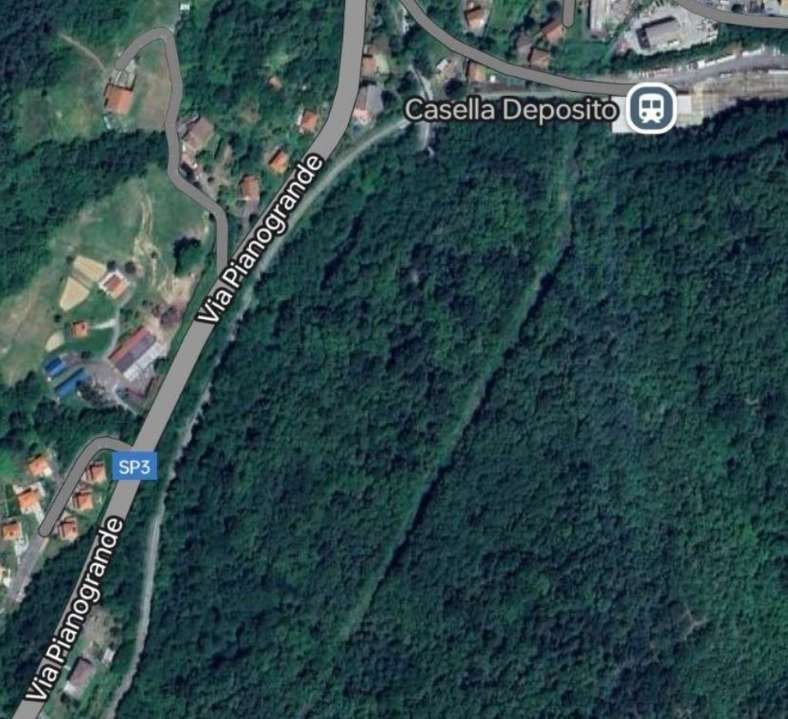

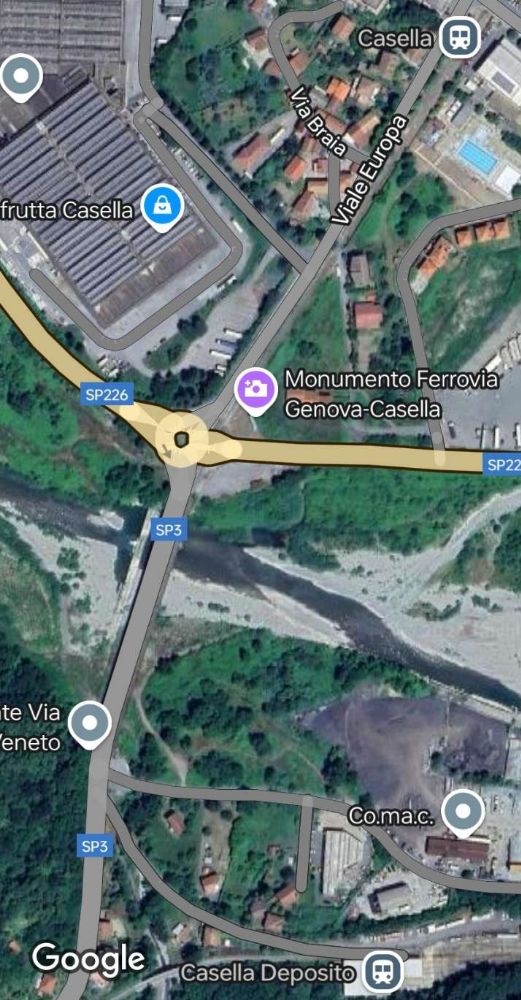

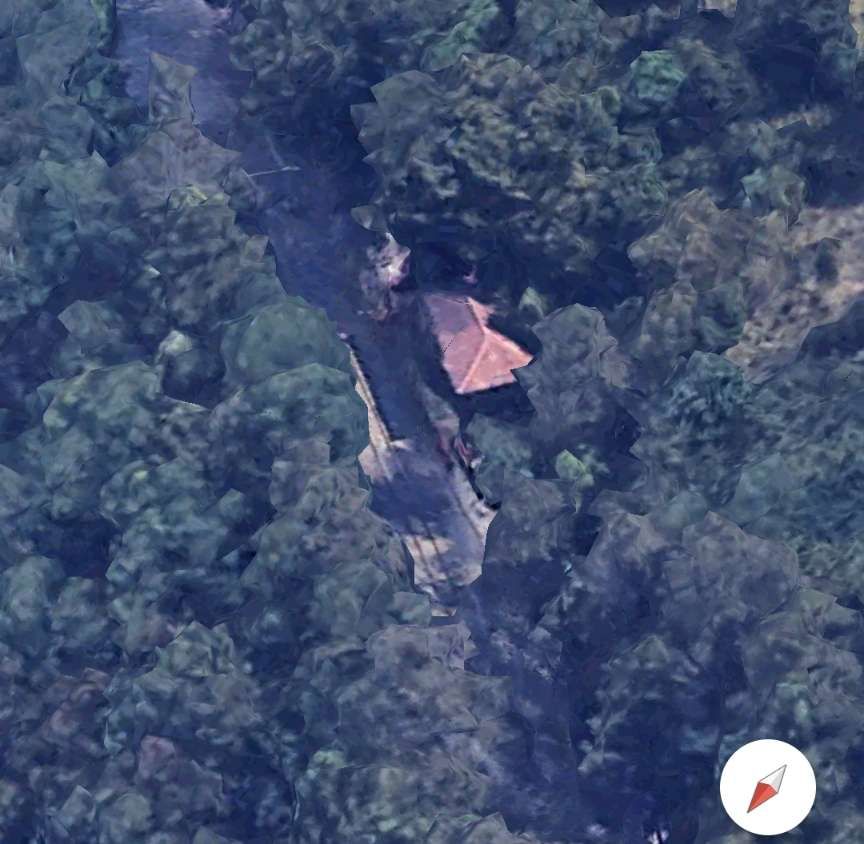

“Casella Deposito (24 km) is just before the main depot site and has only an anonymous raised concrete platform to betray its whereabouts. The main line leads into a three track fan at the depot, where maintenance equipment is located and vehicle overhauls carried out. Nearby is the site of a quarry which supplied the FGC’s ballast. Appreciable goods traffic (now all lost), led to a ramp being built at Piazza Manin station to permit stone to be directly off-loaded from wagons into lorries in the street below.” [2: p296]

“Trains must reverse to gain the Casella village line, sometimes achieved with a second railcar. On the last leg of the journey, the 1952-built combined road and rail bridge has the railway track on reserved and fenced aligament to one side. Thereafter, it is less than 1 km to the terminus, on the outskirts of the small village of Casella. Two-track Paese station is unmanned, although there is a small bar to welcome thirsty passengers. … The village has no special tourist attractions other than a few bars and restaurants, all mentioned in the FGC timetable. However, the cool mountain air makes a change from the oppressive heat of the coast, and an important magnet for day-trippers.” [2: p296]

Cross notes his sources for his article of which two are articles in the predecessor journal to the Light Railway and Modern Tramway – Modern Tramway. He quotes the news pages of that magazine from 1962 onwards and a specific article by Joachim von Rohr. [14] He also consulted an article in Mondo Ferrovario. [15]

As a separate note within his article, Cross comments on what he records as ‘The FGC’s First Serious Efforts to Attract New Traffic‘. …

“At the start of the 1970s, the FGC began its first serious attempts to attract excursion traffic. While Genova municipal authorities were doing their best to dissuade unnecessary car journeys in the city, the light railway offered free parking at Genova Piazza Manin station to holders of return tickets. … This certainly offered scope for development, given the dramatic and beautiful countryside and ancient churches and forts within reasonable walking distance of stations.

This initiative has developed quite dramatically, and the policy of the FGC is now oriented towards the tourist market. It has put together a Belle Epoque train, formed of ‘heritage’ stock. The three-car train made its inaugural run on 5th November 1989 and is powered by the oldest surviving electric locomotive in Italy, No. 29 of the former Sangritana railway. … Passenger accommodation consists of ex-Val di Fiemme trailers C101 and C104, which retain original wooden furniture and bronze and brass fittings, accompanied by bar car No. C22. A major overhaul on No. C22 was undertaken in 1990, considerably upgrading its interior and also increasing capacity. … In expectation of an increase in visitors for the 1992 Columbus anniversary celebrations, the historic train had a regular Saturday working during June, July and August. The train has proved popular with both wedding and communion parties.

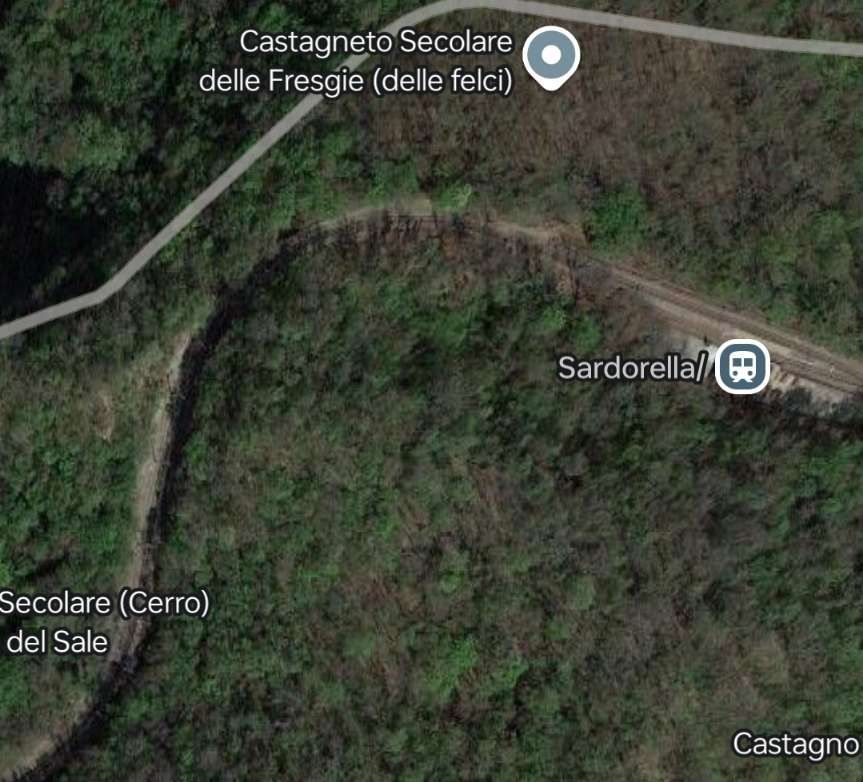

Near both Campi and Sardorella stations, the FGC has created playgrounds and picnic areas; the facilities at Sardorella can only be reached via the FGC. In 1990-1, the FGC began a bicycle transport service using a specially converted wagon; alternatively, customers can hire bicycles at cheap rates in Casella village.” [2: p296]

The images below show Locomotive D1 which operates the tourist train. …

Locomotive D1 responsible for a single coach. [18]

And here with two coaches. [18]

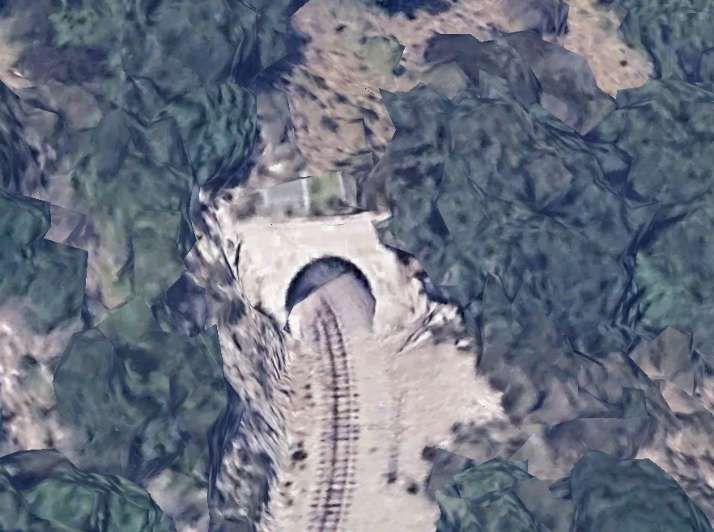

And here, escaping from a tunnel portal. [19]

“Locomotive D1 was built in 1964 on behalf of the German railways by the manufacturer Gmeinder & Co. by adapting the MaK V100 standard-gauge locomotive to metre gauge, it was numbered V52 902 (later 252 902) and used on the 28 km long Mosbach-Mudau metre-gauge line. When it’s service on that line came to an end (2nd June 1973), it was first converted to standard-gauge by Gmeinder and used by Sudwestdeutsche Eisenbahngesellschaft (SWEG) which put it to work on the Breisach-Endingen-Riegel line (numbered VL46-01). In 1986, it was sold to the Gleismac company which converted it to metre-gauge and then sold it to the FGC. It was used to haul construction and passenger trains during the renovation of the overhead line. It was then set aside at Casella Deposito for over 10 years until in 2008 it was sent to Monopoli where it was rebuilt by 2014 and it returned to service on the line in November 2015.” [12][16][17]

Sadly, when we stayed in Genova in November 2024, the line was not operational and undergoing significant maintenance.

Part 3: October 1995 – Granarolo, Funiculars and the Guidovia

Cross’ third article about Genova begins by looking at the rack railway which ran from Piazza Principe, adjacent to Genova’s principal railway station to the small hilltop community of Granarolo. … Cross says: “The project was approved on 15th February 1896 and the line opened as an electric rack tramway on 1st January 1901, although the SGFM subsequently passed into liquidation on 2nd March 1902. Management of the line was then transferred to the Societé De Bernardi & Co (DBC), but this lasted only until 1907, when the concession passed to one Luigi Parodi, a former director of DBC. Upon his death in 1918, the municipality assumed control of the line, overhauled it and handed day-to-day management over to the Consorzio Nazionale Cooperative Combattenti, which stayed in control until 30th November 1934. On the following day, the Azienda Autonoma Autobus became the new owner of the line, this being then absorbed by the Unione Italiana Tranvie Elettriche! Despite the bewildering number of owners in the early years, the line has somehow managed to remain open ever since with no change in ownership.” [3: p333]

“The 1.1-km tramway was built to the unusual gauge of 1200 mm, entirely on reservation. The lower station is at Salita di San Rocco (24 m above sea level) and the upper at Granarolo (220 m). The maximum gradient is about 23.5%. The Riggenbach rack system was chosen, with the rack at railhead level. Rail came from the Ilva company, 21 kg/m in 10.5 m lengths. … In 1950, the line was slightly extended at the upper station to permit a combined depot and workshop to be built. The lower station was also rebuilt, but still contains the inscription Ferrovia Principe Granarolo. The lower terminus is just to the west of Principe FS station and was built between two long tunnels. The lower part of the line runs through the city’s busy San Rocco district. At the passing loop, there is a station for ascending cars only. Beyond, the line has been laid directly on the slope of the Granarolo hill.” [3: p333]

Cross reports that: “The earliest recorded rolling stock was rebuilt in 1929 by Piaggio of Genova with CGE electrical equipment and two 38-kW Ansaldo traction motors. The bodies are unusual, with longitudinal seating, stepped floors and an inclined roof at the upper end, not unlike funicular cars. The two cars are 7.8 m long, 1.9 m wide and have four external doors, two per platform, and two interior doors. Service speed is 7 km/h, both ascending and descending, and capacity is 45 passengers. … The tramway uses a 550 V dc overhead contact wire, with current supplied from a sub-station which also supplied the urban trams. Each car has two trolleys, although during the day descending cars require no current, since the main braking system does not use the trolley; cars descending at night are obliged to raise one trolley to provide on-board illumination. … An interesting safety feature that persisted until recently was the fitting of two small wheels to the lower end of each car to extend the wheelbase and prevent their overturning in the event of an emergency stop. At the end of each journey, the driver wound up a counterweight, to activate an emergency braking system. This unusual device required the driver to keep his hand on a special wheel to hold off the brakes while the car was in motion. The cars had a conventional rheostatic brake which effectively operated on the cogwheel. Since there was no moveable paintwork, the cars were also fitted with double-flanged wheels on my new side and unplanned broad rollers on the other to permit negotiation over the midway passing place.” [3: p333]

Cross continues: “When both the urban and suburban tramways closed, the municipality had to make a decision on the rack line. Rather than scrap a substantial tourist asset, it was decided to undertake a major overhaul of the line and also rebuild the first of the two tramcar-type vehicles. From August 1975 to July 1976, services were suspended while all the rail was renewed and the two cars lost some of their idiosyncratic features. Two-tone green livery was replaced by orange. … In 1981, the service was modified to reflect completion of a parallel road, which at last made it possible for the AMT to put on a parallel bus service. The rack tram now [in 1995] runs every 30 minutes and its 15-minute journey time normally requires only one car, the other being stationed either at the upper terminus or near the Via Bari halt, where there is an inspection pit.” [3: p333]

Cross notes that “The Granarolo rack tramway has always suffered from a lack of traffic. In the early 1960s, it only carried 1000-1200 passengers per day and, today [in 1995] the situation is little changed. However, long-term plans for the line envisage its extension down to the coast and also further up into the mountain, where it will connect with the Genova-Casella light railway, rerouted to serve the planned upper terminus. … Older plans proposed converting the line into a funicular, reducing the current four staff to three, even two if the whole line were automated. However, in 1989, consultants MTC-Italia proposed upgrading the line whilst maintaining it as a rack tramway, suggesting replacement of the Riggenbach system by ‘something easier to maintain’ and widening the gauge to 1435mm.” [3: p333]

Cross reported that plans would have included “two new standard-gauge bogie cars, 24.5 m long and 2.2 m wide, with a maximum permitted axle load of 8 tonnes. Each car would accommodate 36 seated and 172 standing passengers. An acceleration of 1 m/s² was proposed, with a surprisingly high maximum speed of 75 km/h. The traction supply would have to be upgraded to 750 V DC. Although approved by the AMT in November 1990, no finance [had] yet been released to enable it to be implemented. In 1994, both cars were painted in red, bringing their livery into line with that [of] the two urban funiculars.” [3: p333]

Wikipedia notes that “In 2002, car 2 was sent away for an overhaul, but the bankruptcy of the original contractor and the involvement of a replacement in an alleged bribery scandal meant that the overhaul was not completed and the car returned to the line until March 2019. The overhaul included the replacement of the car floor, lighting, safety systems, electric drive, air conditioning and a new driver’s seat. Between 2002 and 2019, service was provided by car 1 operating alone. AMT now [2019] plans to use the rebuilt car to double the service frequency to every 15 minutes. ” [21]

Forward to 2024/2025 and our visit to Genova in November 2024. … When we were in Genova, we found this rack railway closed for maintenance work. Fabio Canessa reported in 20th May 2024 [20] on endless inconvenience for the inhabitants of Genova, with the line to Granarolo to be closed for major works for 2 years and the principality still waiting for news on an additional car for the line. [The notes from his report below have translated into English by Google Translate.]

Canessa noted that a series of interventions that would “force the closure of the system between the valley terminus and the stop on Via Bari for the entire duration of the construction site. … It [would] involve replicating the same interventions carried out in 2012 on the upstream section. … The project, includes the consolidation of the historic walls, which are no longer up to standard, the creation of a lateral walkway to allow passengers to move away safely in the event of a breakdown, a sort of overflow pipe that runs parallel to the railway and discharges the water collected by the canal, the reconstruction of the pylons with the same look as the upper section and the reconstruction of the overhead line. …In addition, the stop on Via Centurione , which is currently unusable on the downstream side, will be fixed.” [20]

“For the works, just over 2 million euros [were] allocated by the Region under an agreement with the Ministry of Infrastructure dating back three years. However, these resources are not yet available to AMT [on 20th May 2024], …the contract is being awarded, … but …. the works cannot be assigned until the Region … [provides] the money. The situation should be unblocked by June [2024] so that the construction site can be opened in the summer. In the meantime, the expropriations are being defined , which will concern small portions of private land necessary to move back the pylons and make room for the walkway.” [20]

“The bottom line, for the residents of San Teodoro and Granarolo who often have no alternatives to the rack railway except walking, is that until 2026 the service will be limited to the via Bari-Granarolo section . Initially there was talk of 12-18 months, then the forecasts worsened. Unfortunately not all the work can be done at the same time, safety must be guaranteed.” [20]

“The same section of the rack railway was closed for six months in 2021 to replace the tracks, sleepers, pylon plinths and also part of the contact line. The odyssey began in the early 2000s with the start of restyling work on one of the two cars , a story that lasted almost twenty years. … Speaking of carriages, it is not yet certain what the timing will be for the third one: the Region had allocated 3.5 million euros for the construction. … The contract was awarded to SVI of Lucignano (Arezzo) with a contractual expiry date set for September 2028. Even in this case, however, the Region must first unlock the necessary resources.” [20]

The Zecca Righi Funicular

Cross tells us that plans to build “the Zecca Righi rack-braked funicular were first brought to the attention of the Genova public by a Mr Bucher on 30th June 1891. This was to start in Piazza della Zecca and proceed northwards in tunnel for 700 m. A station at Carnonara would have public access in an open shaft at 348 metres, while Montegalletto station was to be located at the upper entrance to the tunnel. Here, a transfer would be made to a second line, 820 m long and built entirely above ground. This would feature two intermediate stations, at Fossato and San Simone, with the upper terminus situated at the Chiappe wall on Righi mountain, from where tremendous views can be obtained of the Bisagno valley.” [3: p333]

Cross notes that Abt rack braking was preferred. ABT rack braking utilises two or even three different rack profiles, each half offset from each other. Trackopedia says that, “The tooth spacing is larger than with the other rack systems (120 mm). The advantage is that the profiles are always installed offset, so there are no full joints. Due to the low thickness of the profiles, they can be fitted or rotated much more easily by hand, which makes maintenance easier. In the curve, the outer profile should theoretically be longer. With short profiles, the difference in length is equalized at the joint.” [23]

Initially, a 900-mm track gauge was chosen for the line, “but this was later changed to metre gauge. The project was given the go-ahead and construction of what was classed as a secondary railway was begun. The upper line opened on 30th April 1895, while the steeper gradients encountered on the lower line delayed its opening until 13th February 1897.” [3: p333]

“The two lines gave trouble-free operation for the next 70 years, but were rebuilt into a single funicular during a much-needed modernisation programme instigated by AMT, the new owner. Bell of Luzern undertook the conversion, with two high-capacity metal-bodied cars replacing the original wooden rolling stock. The new funicular cars had rigid suspension and driving gear consisted of 2 x 125-kW motors, permitting a speed of 4.4 m/s. Each car could accommodate 100 passengers, restricting the maximum one-way traffic flow to 400 passengers per hour, with a 15-minute journey time.” [3: p333-334]

Cross continues: “A second modernisation programme was announced in 1985. It was decided to introduce partial automation to reduce staff costs, with Ansaldo Trasporti and Nuova Agudio awarded the contract. The line was closed on 3rd August 1987 and replaced by substitute buses. The old track was replaced by heavier 50 kg/m rail mounted on rubber to reduce noise emission, while the winding motors, electrical equipment, telephone system and safety equipment were also replaced. The modern day line is 1.4 km long with a difference in height of 278 m between the two termini. Average gradient is 19.9%, with some sections as steep as 34%. … The new twin-car units, driven by 2 x 458-kW winding motors, and with sliding doors, have a speed of 6 m/s, cutting the journey time to 10 minutes and increasing the one-way passenger capacity to about 1800/hour, each train holding up to 156 passengers (16 seated) on seven stepped levels. Modern suspension has also greatly improved the ride quality, while electricity for car lighting is picked up by a mini-pantograph from a simple overhead.” [3: p334]

Cross concludes his notes about this funicular: “The two-car trains, which have been painted in a striking red livery with an orange zig-zag stripe outlined in white, can call at all seven stations, although the intermediate stops at Carbonara, Santa Nicola (urban bus connection), Madonnetta (religious shrine), Preve and San Simone are request stops signalled both by passengers waiting on station platforms and those inside the cars. The starting sequence is automatic, but cars are nevertheless, single-manned. No tickets are sold on any funicular premises, although ticket cancellers are provided on cars, and the tariff is that of the urban bus network.” [3: p334]

The Sant’ Anna Funicular

Cross offers two short paragraphs about this line. …

“There are not many rail lines offering an end-to-end journey time of around one minute, but this is all that is necessary to travel on the 353 metres between Piazza Portello and Corso Magenta on the Sant’ Anna funicular. So short is the line that it is possible to see both cars from either station. The present day installations were supplied by Agudio Poma of Torino and consist of two small red cars, driven by a 42-kW motor, with bodywork from Merighi, Neri & Roversi.” [3: p334]

“Operation is automatic, although each car has a driving cab, and the 54-m height difference, starting at 20 m above sea level at Piazza Portello, is undertaken at a track speed of 4 m/s, with the passing place at a relatively flat location. Each car has eight seats on two stepped levels with a nominal total capacity of 30, giving a capacity of 180 passengers per direction per hour, with departures every ten minutes. Entry to the funicular is controlled by a turnstile, with boarding and alighting passengers segregated. The line is operated by AMT, so one day FS-AMT passes can be used.” [3: p334]

La Guidovia del Santuario della Guardia

In my survey of the different lines serving Genova, I missed this line completely. This is perhaps not surprising as it closed in October 1967!

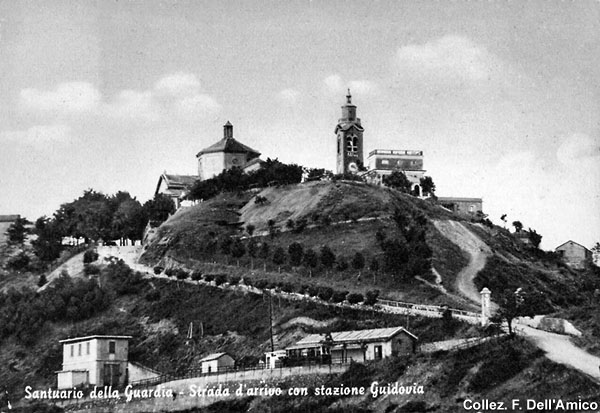

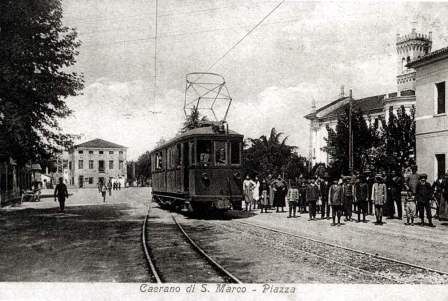

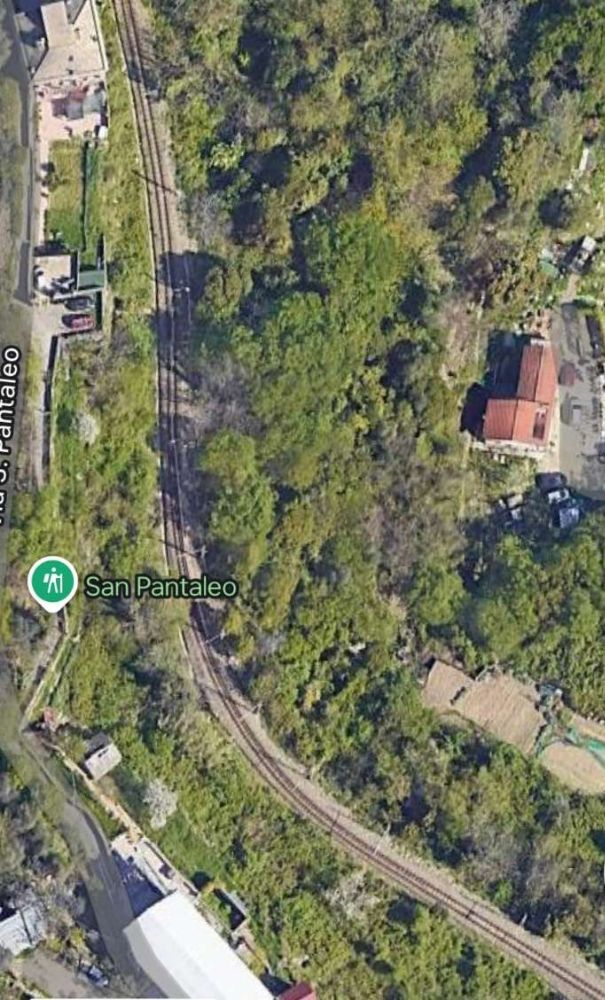

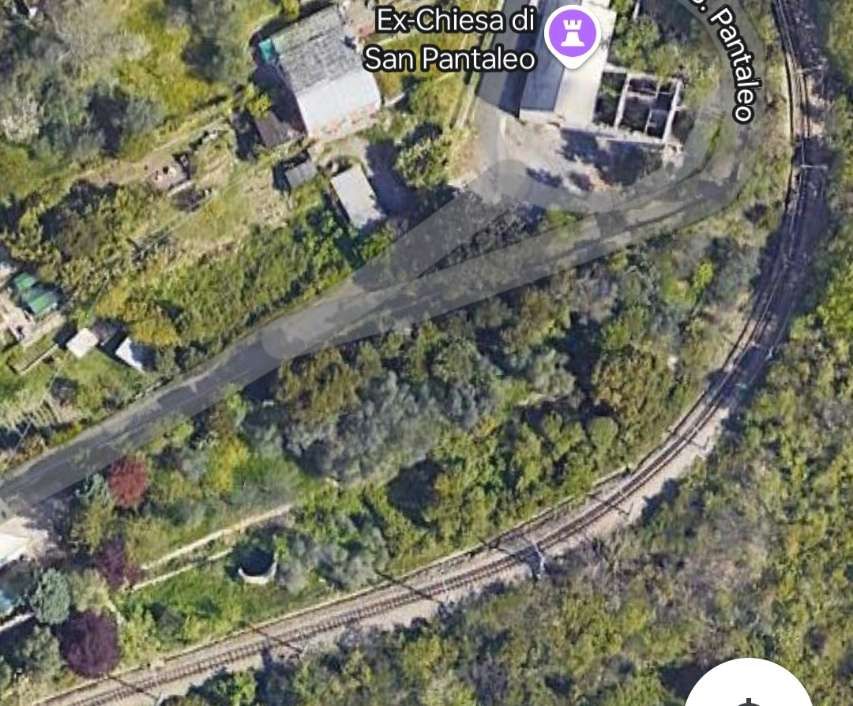

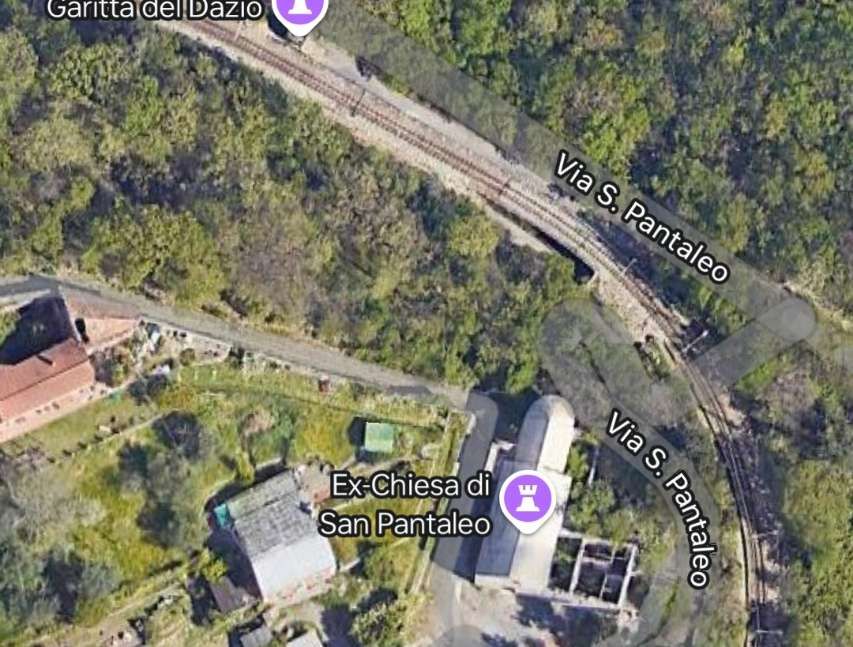

Cross says: “Some 250,000 visitors per year are attracted to the religious shrine on Monte Figogna, 817 m above sea level and from where spectacular views can be obtained over the Polcevera valley and the Mediterranean. The idea of providing a fixed link emerged in 1891, although a Belgian initiative dating from 1906 stalled for want of finance. It was not until 1926 that the Ferrovia Santuario della Guardia company was founded and subsequently undertook construction. … On 29th July 1929, the company inaugurated an initial 8.8-km section, linking the lower station of Serro di San Quirico, halfway between Bolzaneto and Pontedecimo and at 66 m above sea level, with a temporary upper terminus at Ca’Bianca (676 m). From Genova, it was possible to reach Serro, nestling between two steelworks and some oil refineries, via the UITE tramways. The remaining 1.7-km section was finally opened on 23rd June 1934. In all, there was a 130-m height difference between upper and lower termini with maximum gradients of 8.3% (the average was 6.5%) and minimum curve radius of 25 m. The line was single-track, with seven passing points and 10 Intermediate stations.” [3: p334]

Cross comments: “The Guidovia was highly unusual in that it featured petrol-engined solid-rubber-tyred vehicles which followed two parallel 200-mm wide concrete tracks. Inside these, conventional metre-gauge Vignole 9 kg/m rails acted as a guide path for flanges located on the inside of the wheels. … Iron tie-rods separated the rails at a fixed gauge, with conventional sleepers unnecessary since the weight of the vehicles was placed off the rails and on the concrete pathways. Known as the Laviosa guidance system, it was invented by the Corazza brothers, who owned the line. Rubber tyres were chosen because they gave twice the adhesion of steel wheels acting on steel rails, and made it possible for the vehicles to overcome the numerous steep gradients on the slopes of Monte Figogna.” [3: p334]

This is probably the earliest form of guided bus technology used across the world and should be seen as the precursor of a number of other systems. [25]

Cross continues: “Both freight and passengers were carried, with passenger cars often hauling goods wagons. The journey was usually accomplished in 45 minutes at a speed of 12 km/h, although the cars had a theoretical maximum speed of 18 km/h. … The weekday timetable consisted of five return journeys, ten at weekends, although many other specials were put on for groups of visitors. Indeed, it was not unknown for the Guidovia to carry 3000 passengers in one day. In all, 30-35 staff operated the line, of which 11 were drivers, each responsible for the upkeep of his own vehicle. The depot and workshops were next to the lower terminus, which was equipped with a small turntable; others also at the upper terminus and at Gaiazza.” [3: p334]

The Cars were unidirectional and required turning at both terminii of the line. Staff called the turntables used ‘giostre‘ (carousels).

“The original fleet consisted of five bi-directional 90-hp petrol-engined cars (1-5), built by Officine Laviosa of Piacenza, with bodies made of waterproof oil-cloth. There were two Giardiniera trailers. In 1936, three single-cab cars (6-8) of slightly higher capacity were added. Changes were made to cars 1-5: their rear cabs were removed and a more powerful, 120-hp diesel engine fitted. In 1952, the two existing trailers were motored, using MAN diesel engines, to cater for rising patronage. An eleventh aluminium-bodied car also existed.” [3: p334] Cross was unable in his article to provide details of that aluminium-bodied car. More details have come to light since he wrote his article.

and had different windows, double lights, and was equipped with automatic compressed air doors. It was built in the company’s Serro Workshops. [26]

1:200,000 Touring Club Italiano map from 1964 shows the route of the line. The Guidovia is drawn from Madonna della Guardia to Bolzaneto. [28]

Cross says that at about the same time as Car No. 11 was built, Cars No. 2 and No. 4 underwent a complete revision, involving a livery change from light green to two-tone green. Ultimately, “the line closed in October 1967 with the expiry of the company’s concession. Track and superstructure had been allowed to deteriorate, and rolling stock was also life-expired. In the 1970s, the company laid on a bus service on a new road that had opened up the Santuario.” [3: p334]

A few pictures follow which have been embedded from the stagniweb.it website. They give a good idea of the condition of the line in the 21st century. …

Cross acknowledged the following sources for his notes on the rack railway, the funiculars and the Guidovia line;

Ferrovia Principe-Granarolo by A. Sasso & C. Serra (Mondo Ferroviario, October 1991).

The Tramways and Light Railways of Genova by J. von Rohr (Modern Tramway, June 1964)

Nuova Funicolare per Genova by Alessandro Sasso (Mondo Ferroviario, April 1990).

News pages of Modern Tramway 1962 et seq Guidovia della Guardia by A. Sasso & C. Serra Mondo Ferroviario, December 1990).

The Tramways and Light Railways of Genova byl von Rohr, (Modern Tramway, June 1964)

References for this full article

- Barry Cross; Genova: Back in the Tramway Business Part 1: The Interurbans and the ‘Light Metro’; in Light Rail & Modern Tramway, August 1995, p251-253.

- Barry Cross; The Tramways of Genova Part 2: Casella Line Begins to Realise Tourist Potential; in Light Rail & Modern Tramway, September 1995, p295-296.

- Barry Cross; The Tramways of Genova: Concluded: Granalaro, Funiculars and the Guidova; in Light Rail & Modern Tramway, October 1995, p333-334.

- Rete tranviaria di Genova; https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rete_tranviaria_di_Genova, accessed on 26th November 2024.

- https://www.marklinfan.com/f/topic.asp?TOPIC_ID=4530&whichpage=2, accessed on 21st December 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/4KDeRr6gMdLiv86E, accessed on 20th December 2024.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/12/21/genoas-early-tram-network-part-5-world-war-2-to-its-decline-and-closure-in-the-1960s-and-the-rolling-stock-used-on-the-network

- Marco Chitti, Eric Goldwyn, Elif Ensari and Alon Levy; Transit Costs Project: The Italian Vase Study Report; The New York University (NYU) Marron Institute of Urban Management, New York, via https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://transitcosts.com/wp-content/uploads/Italian_Case_Study.pdf, accessed on 23rd March 2025.

- HOME – Rete e orari – Metropolitana Azienda Mobilità e Trasporti S.p.A. (AMT). 2013, via https://www.amt.genova.it/amt, accessed on 23rd March 2025.

- Tramways & Urban Transit; Ian Allan Ltd/Light Rail Transit Association, April 2005, p149.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/11/26/genoas-metro

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/11/25/genoa-casella-narrow-gauge-railway-part-2-sardorella-to-casella

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rimini%E2%80%93San_Marino_railway, accessed on 24th March 2025.

- Joachim von Rohr; The Tramways & Light Railways of Genova; in Modern Tramway, June 1964.

- Roberto Cocchi & Alessandro Muratori; Ferrovia Genova-Casella; in Mondo Ferrovario, October 1993.

- Maria Vittoria Cascino; Il trenino di Casella arranca in ritardo tra guasti e amianto; on ilgiornale.it, 20th March 2008; accessed on 24th November 2024.

- Andrea Martinelli, La D1 è tornata!, in iTreni N° 388, January 2016, p24-26.

- https://www.ferroviagenovacasella.it/geca/la-seconda-guerra-mondiale, accessed on 19th November 2024

- https://www.mentelocale.it/genova/57212-ferrovia-genova-casella-dal-6-settembre-il-servizio-avverr-con-bus-sostitutivo.htm, accessed on 23rd November 2024

- Fabio Canessa; Granarolo Rack Railway, two years of stoppage coming for works between Principe and via Bari; in Genova24, 20th May 2024; via https://www.genova24.it/2024/05/cremagliera-di-granarolo-in-arrivo-due-anni-di-stop-per-lavori-tra-principe-e-via-bari-386640, accessed on 25th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principe%E2%80%93Granarolo_rack_railway, accessed on 25th March 2025.

- https://www.reddit.com/r/InfrastructurePorn/comments/qg6cme/principegranarolo_rack_railway_genoa_italy, accessed on 25th March 2025.

- https://www.trackopedia.com/en/encyclopedia/infrastructure/superstructure/rack-railways, accessed on 25th March 2025.

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autoguidovia_della_Madonna_della_Guardia, accessed on 25th March 2025.

- https://cs.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autobusov%C3%A1_dr%C3%A1ha, accessed on 25th March 2025.

- https://www.marklinfan.com/f/topic.asp?TOPIC_ID=4179, accessed on 25th March 2025.

- https://sentieridautore.it/2018/02/03/la-guidovia-della-guardia, accessed on 25th March 2025.

- https://www.stagniweb.it/mguardia.htm, accessed on 25th March 2025.