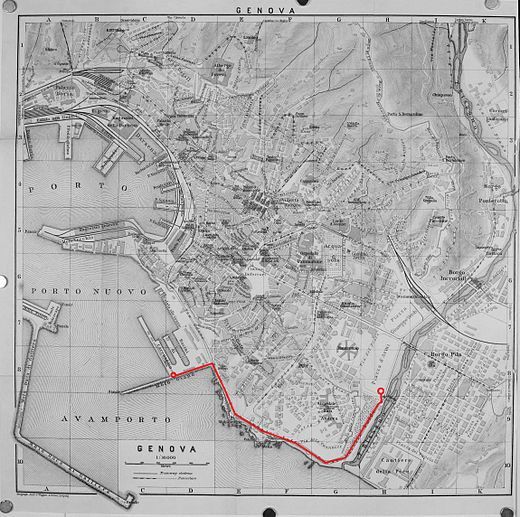

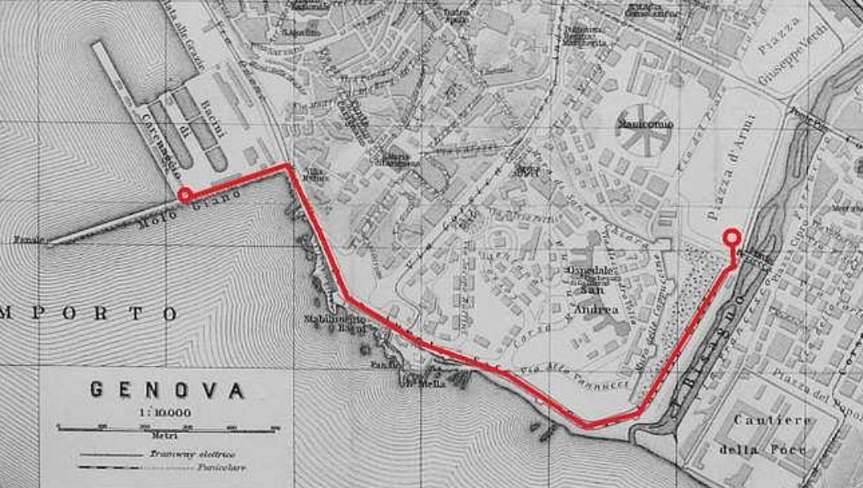

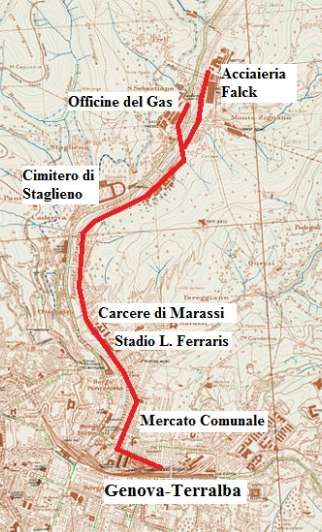

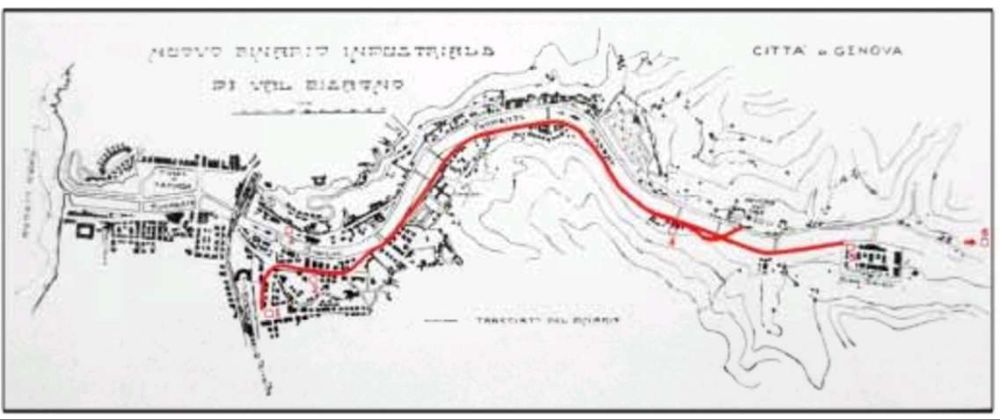

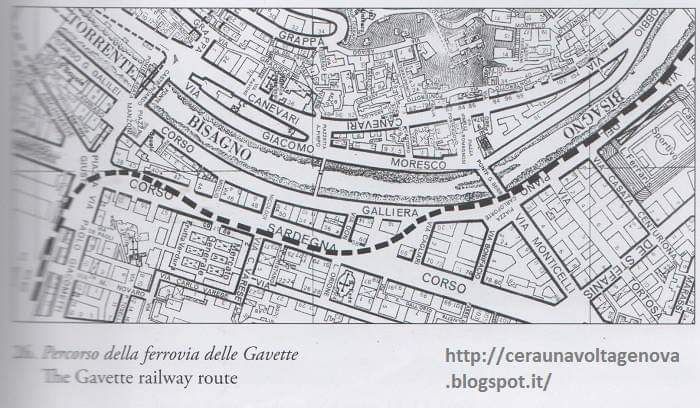

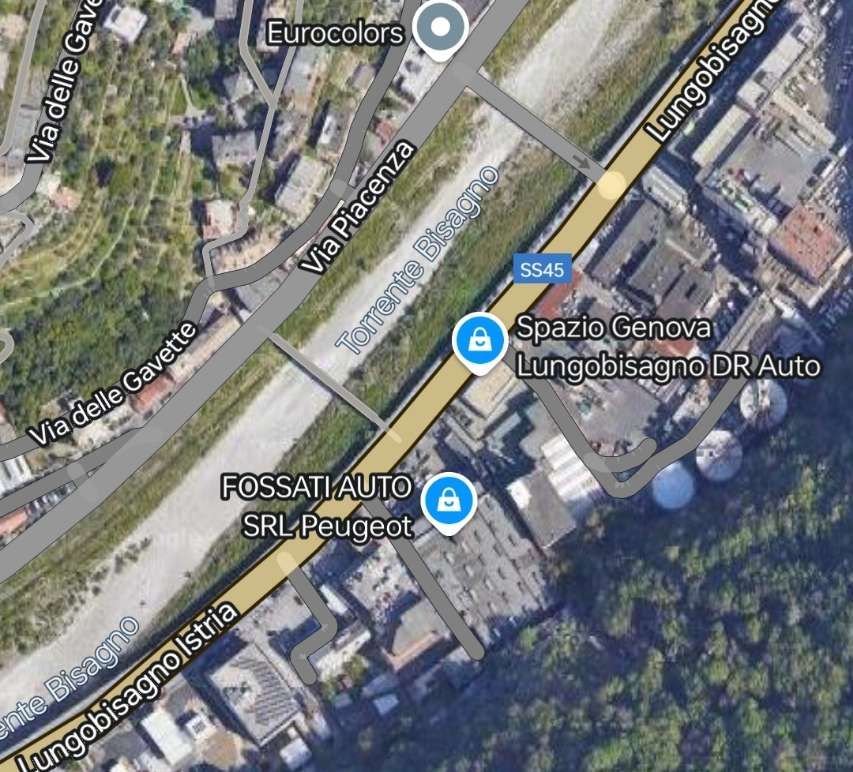

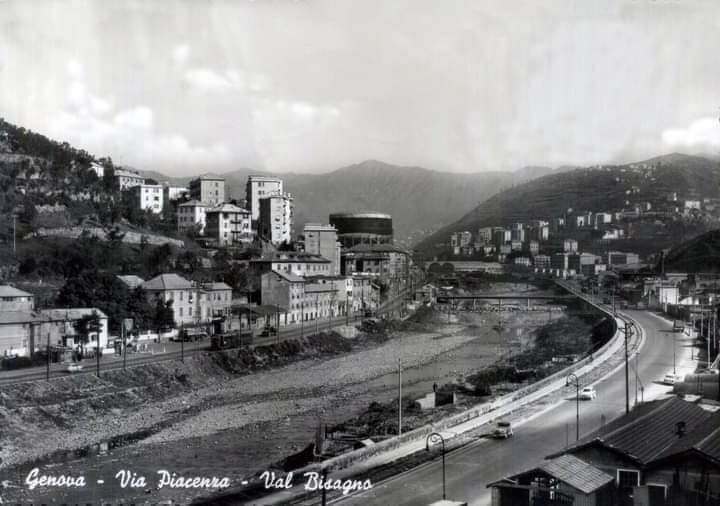

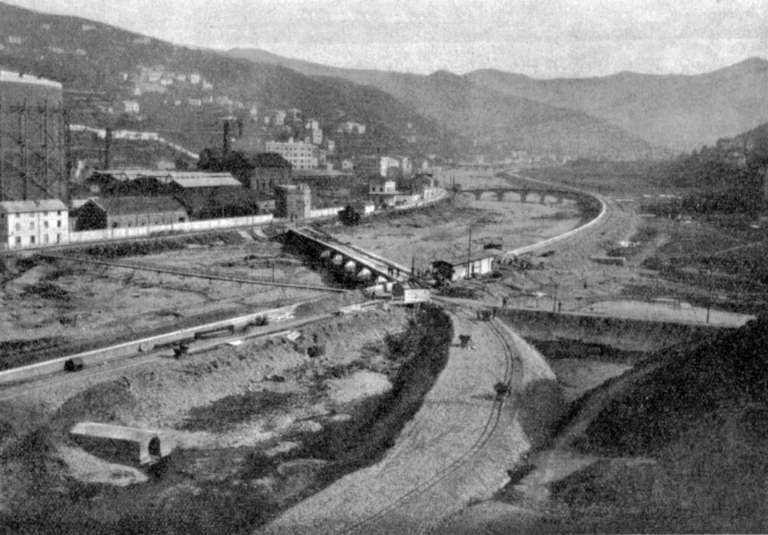

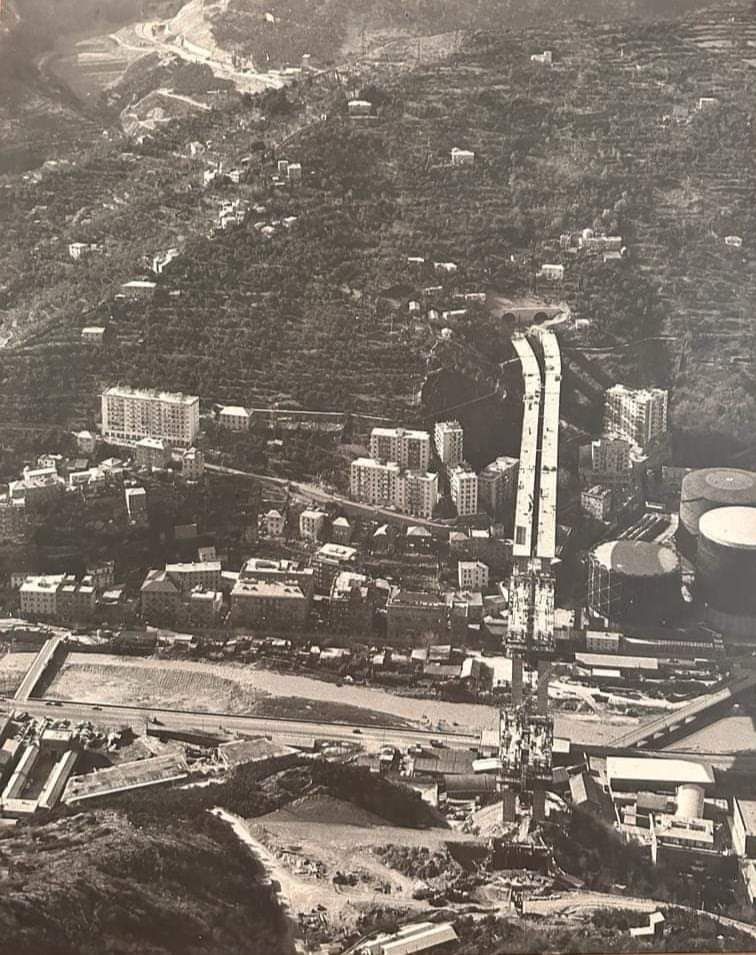

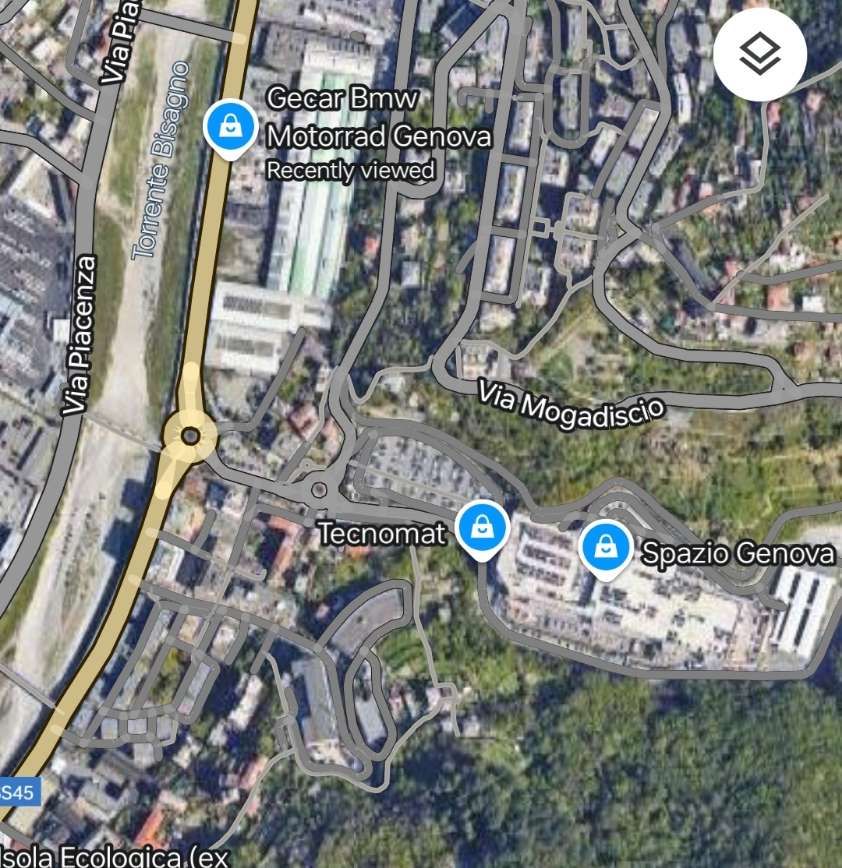

This was an industrial railway in the valley of the Bisagno River (Torrent). The Binario Industriale della Val Bisagno, also known as La Ferrovia delle Gavette, was in use from 1926 until 1965. It was a standard-gauge line and was 4.7km in length.

A translation from the Italian Wikipedia site: “The area of the lower Bisagno valley was developed at the end of the nineteenth century thanks to marble works at the monumental cemetery of Staglieno and a flourishing of agriculture; the area of Marassi experienced a strong expansion at the beginning of the 20th century with:

- the construction of the general fruit and vegetable market in Corso Sardegna;

- the municipal stadium;

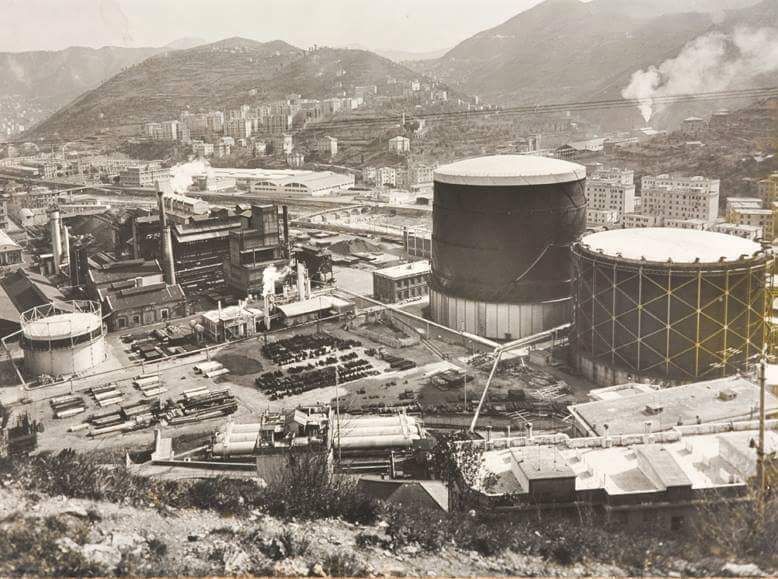

- the workshops for the production of city gas with the gasometer built in the “Gavette” area of the Municipal Gas and Water Company (AMGA) located near Ponte Carrega;

- the new municipal slaughterhouses in the Cà de Pitta area located in Piazzale Bligny.” [7][8]

Contracted out in 1925, the railway was built at an initial cost of about 2 million lire and served the new commercial and industrial settlements that had sprung up in the valley. [7][9]

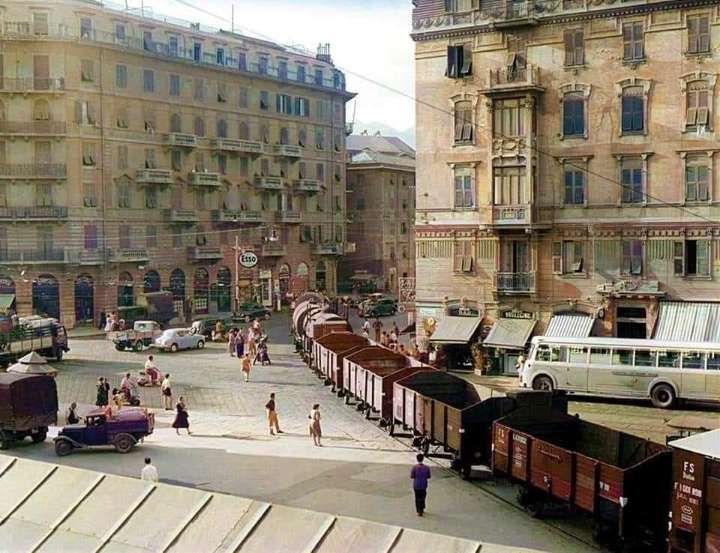

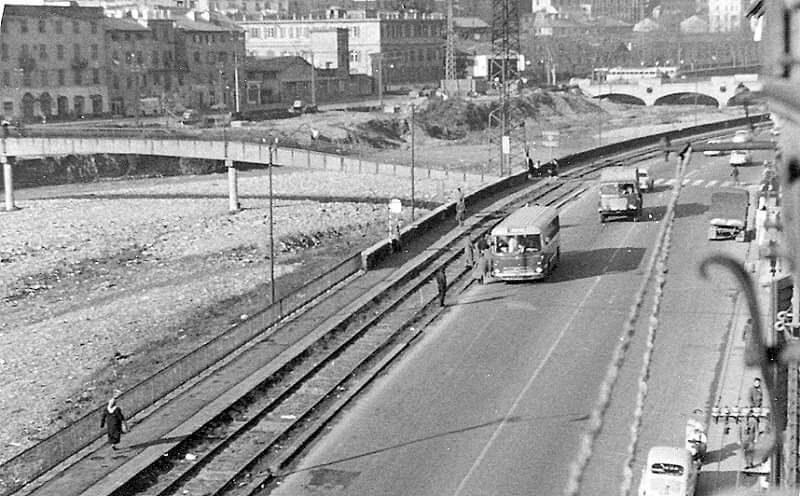

“The line, single-track and not electrified, was mainly equipped with normal 36 kg/metre Vignoles rails placed on ballast, with the exception of the sections shared with road traffic, notably in Piazza Giusti and Corso Sardegna, where there were counter-rails.” [7][9]

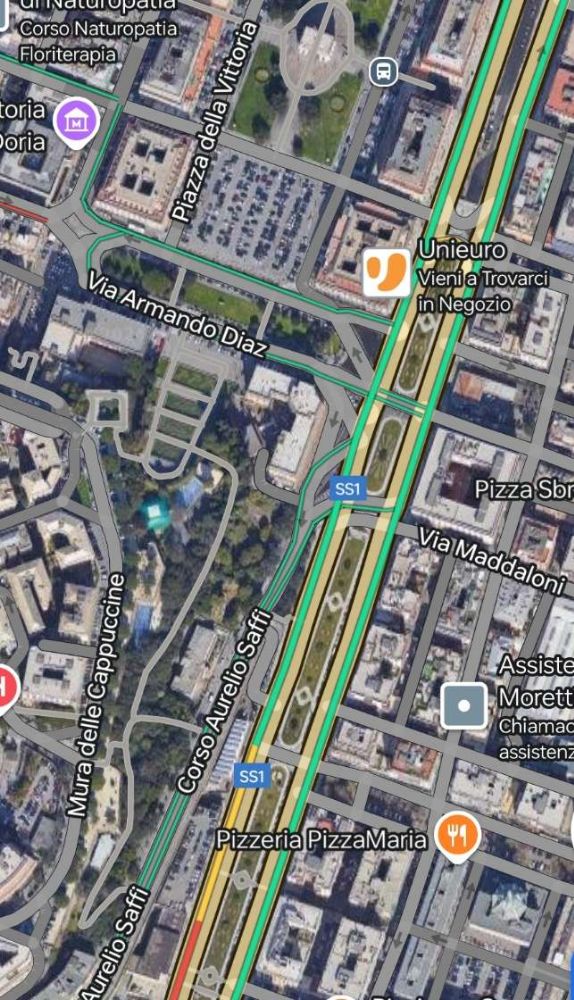

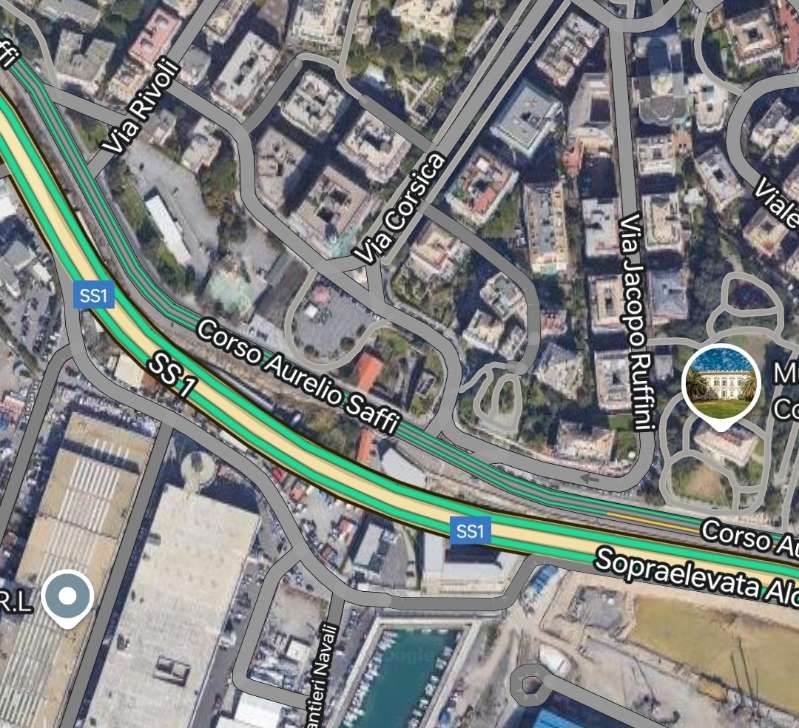

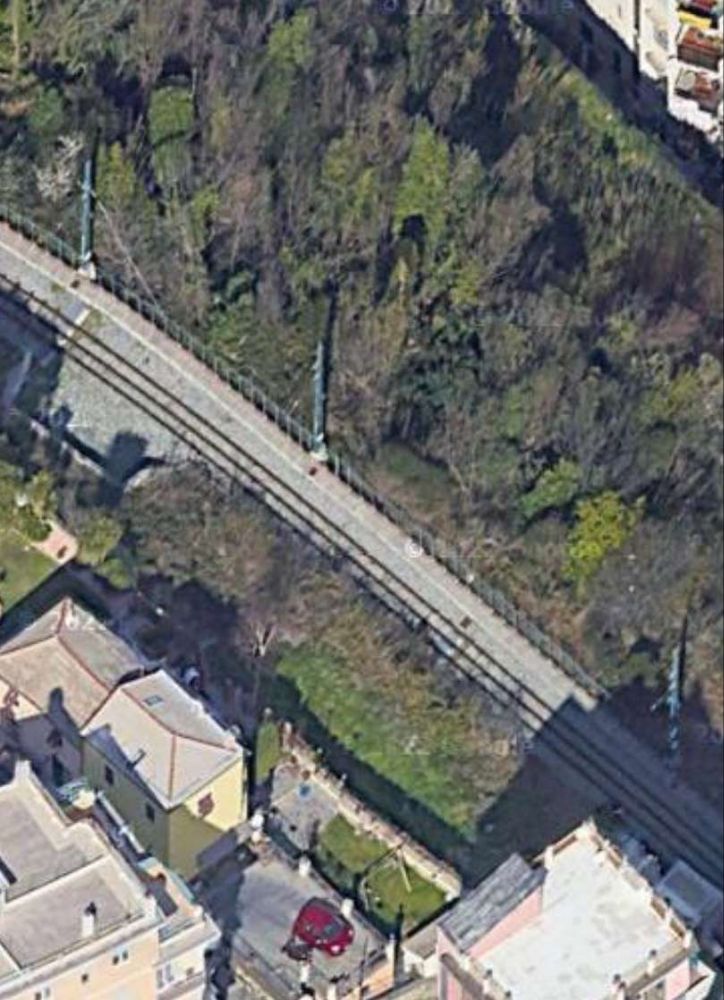

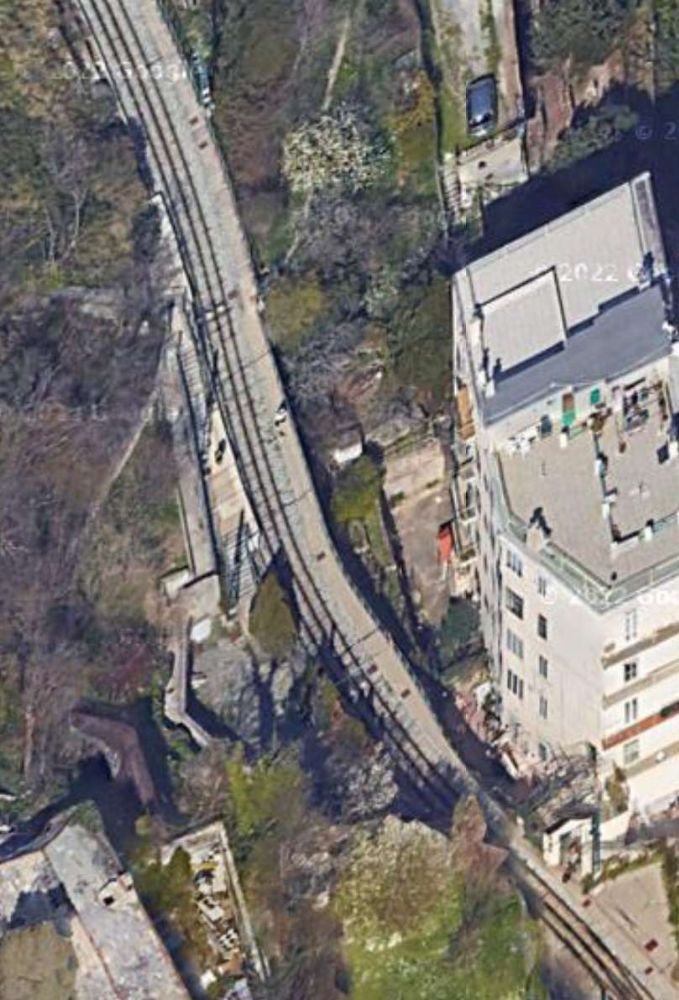

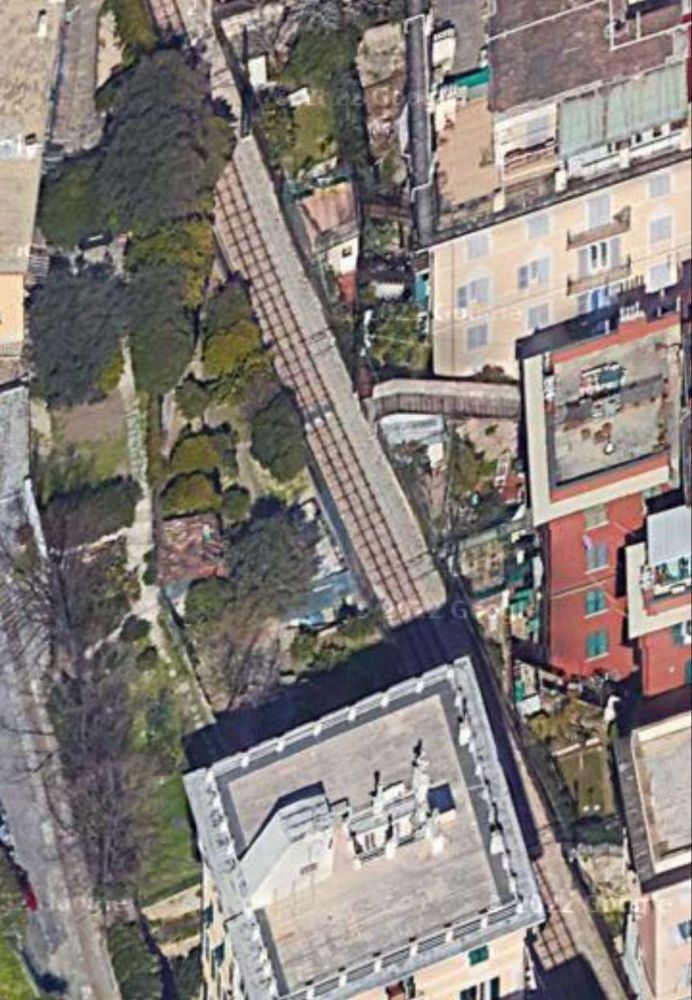

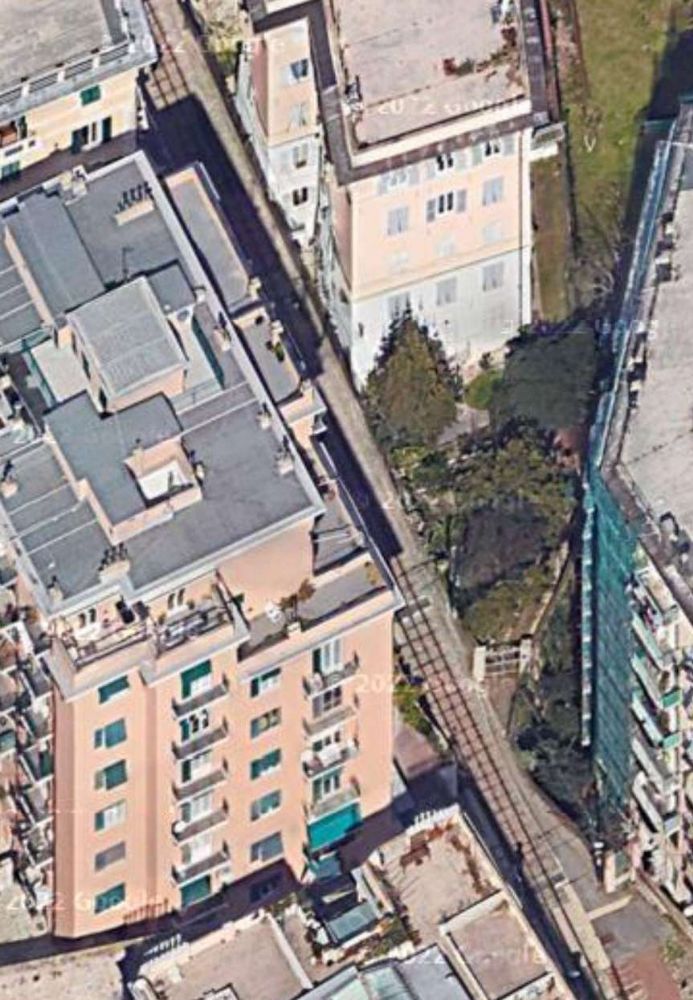

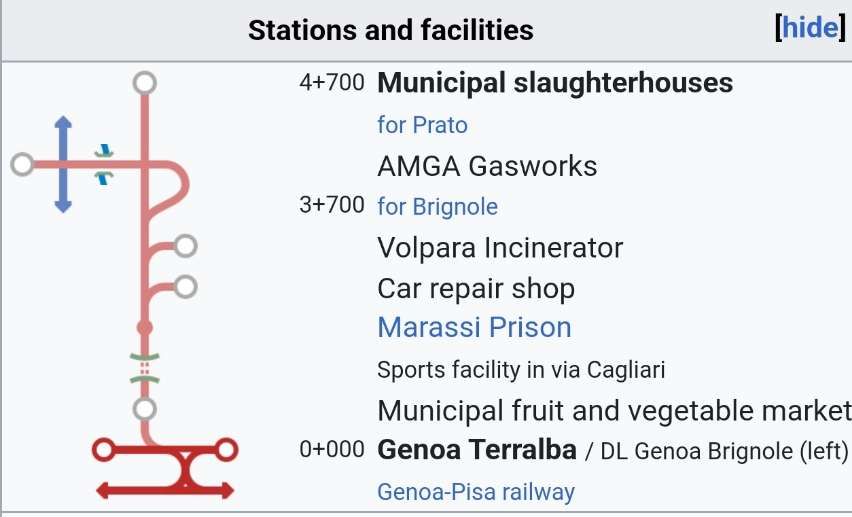

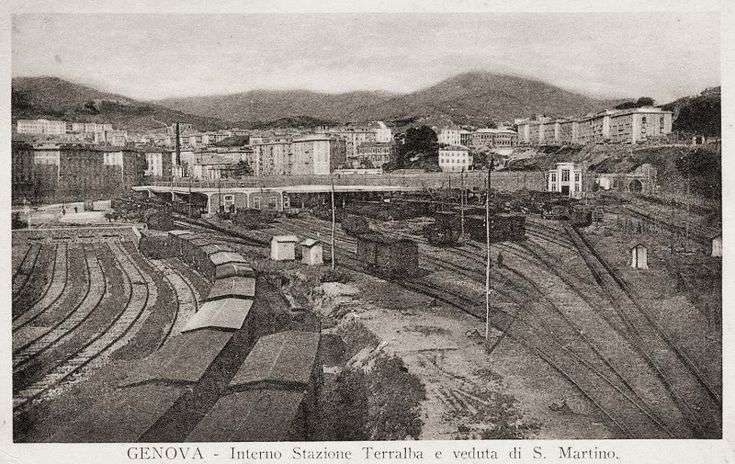

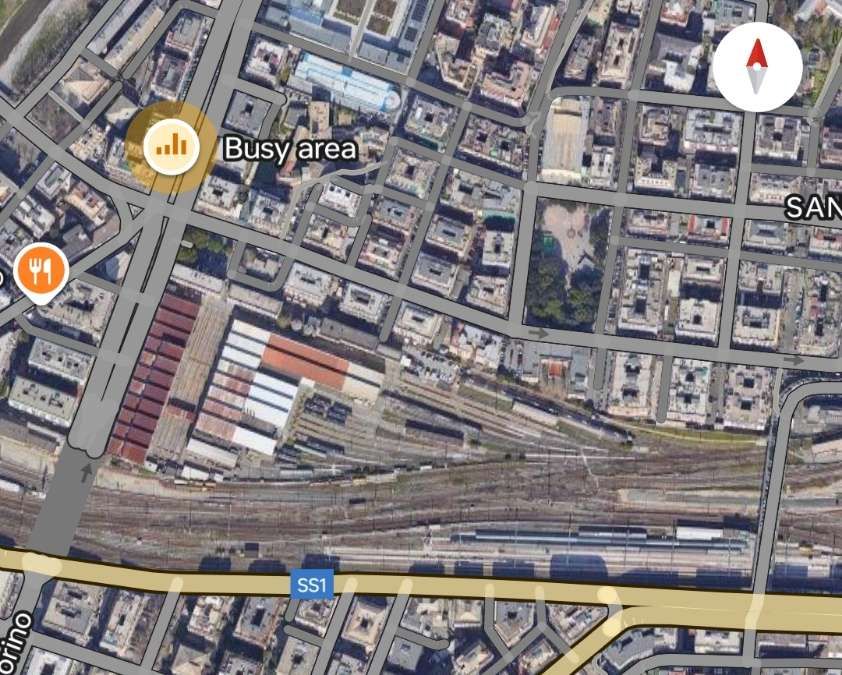

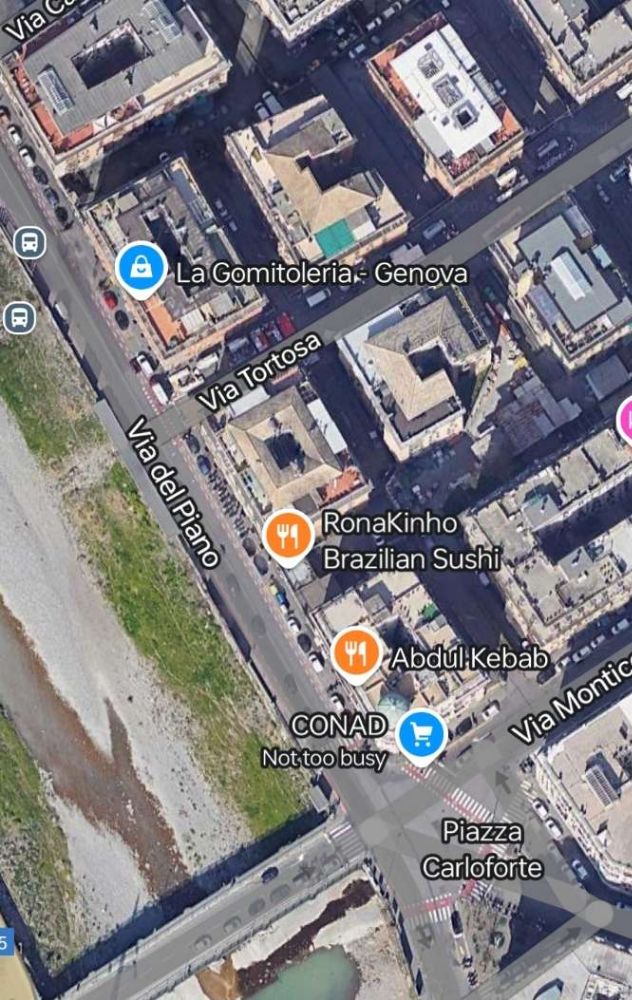

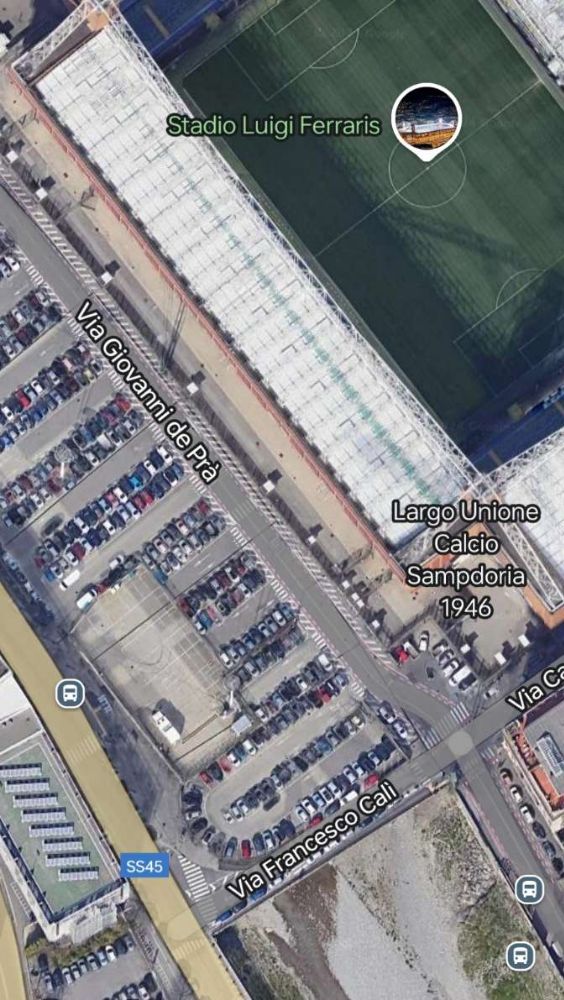

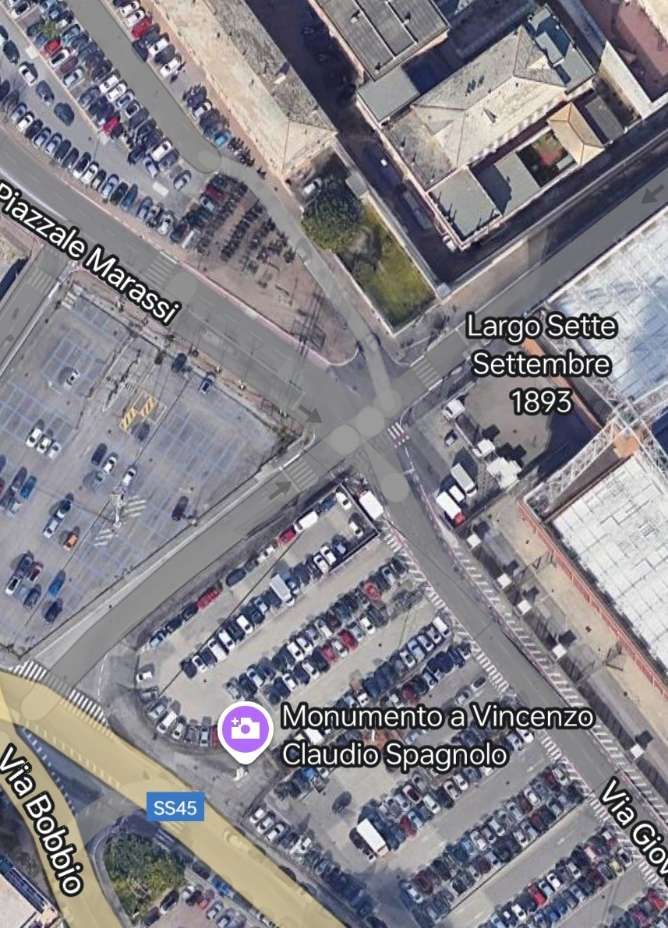

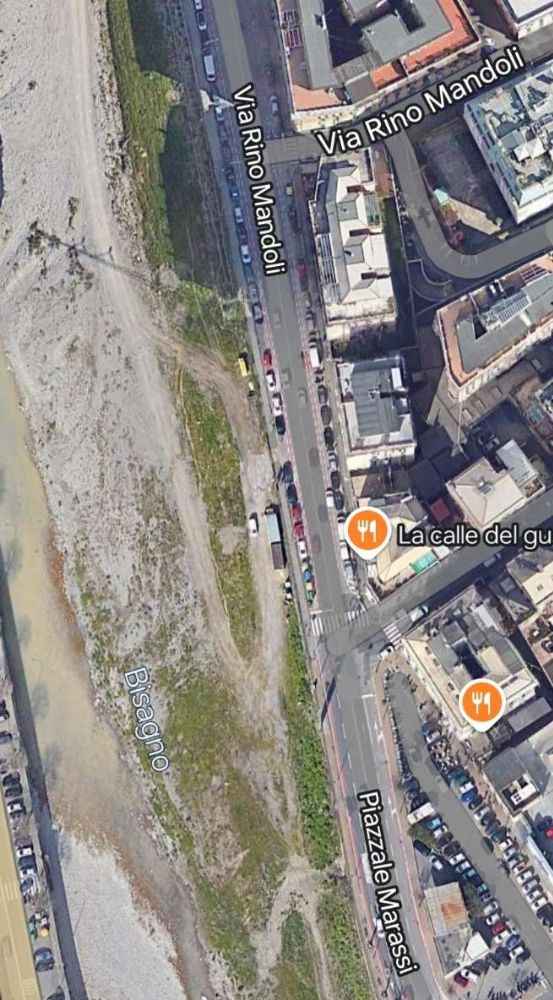

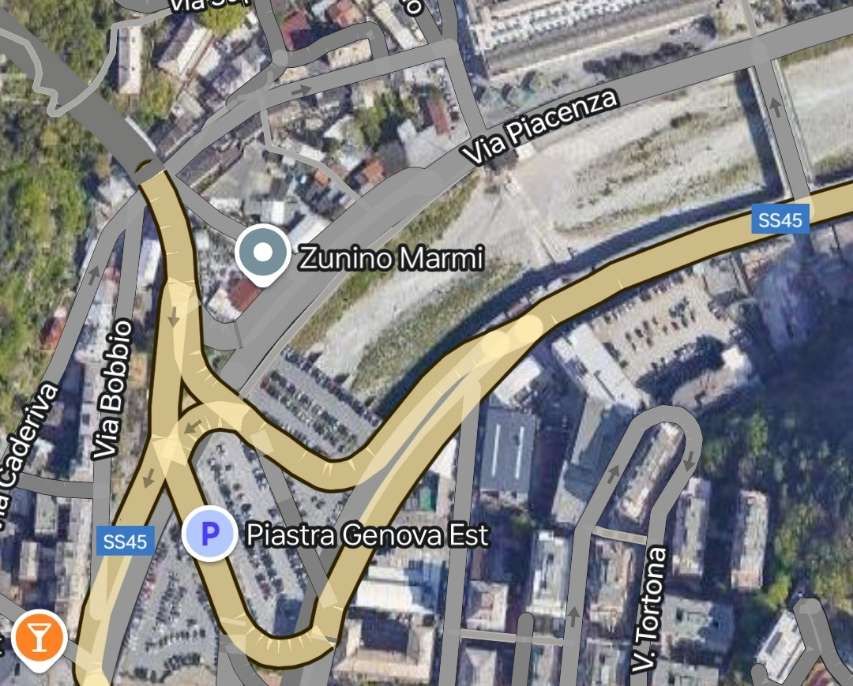

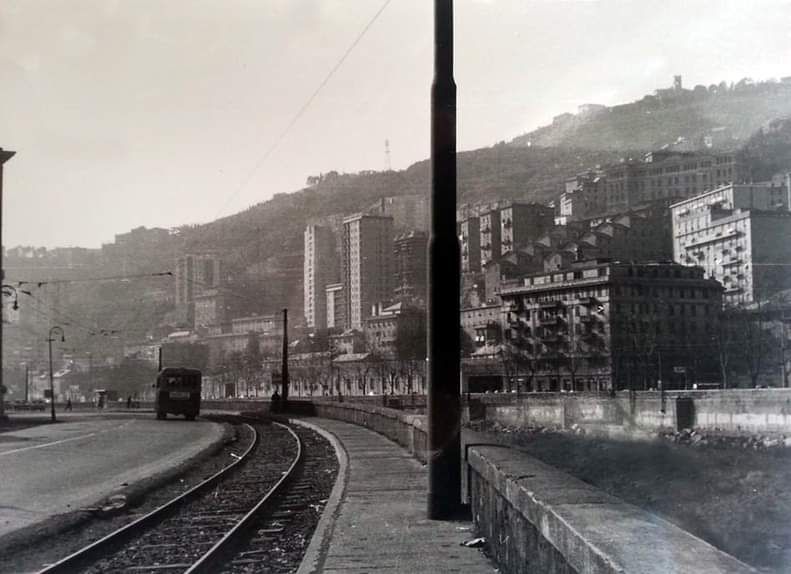

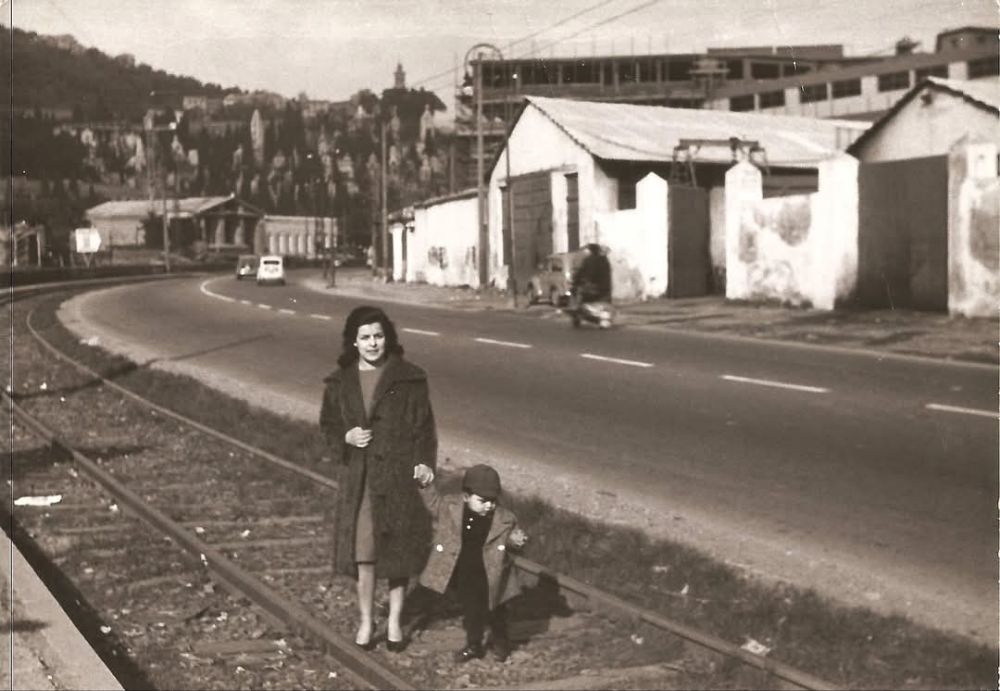

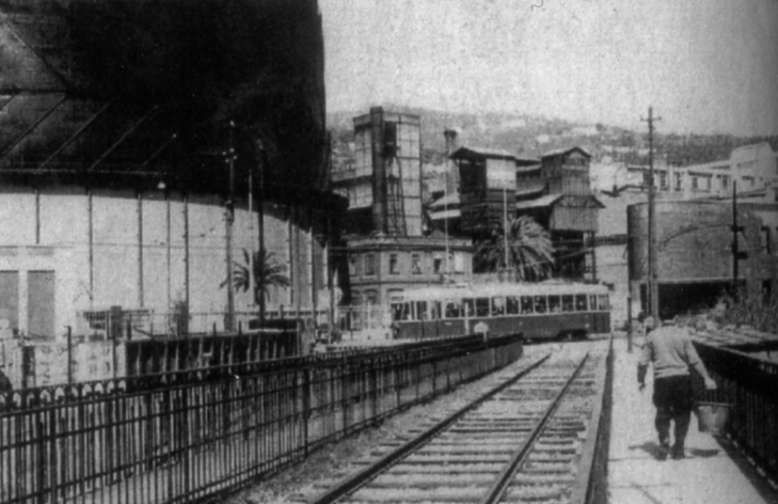

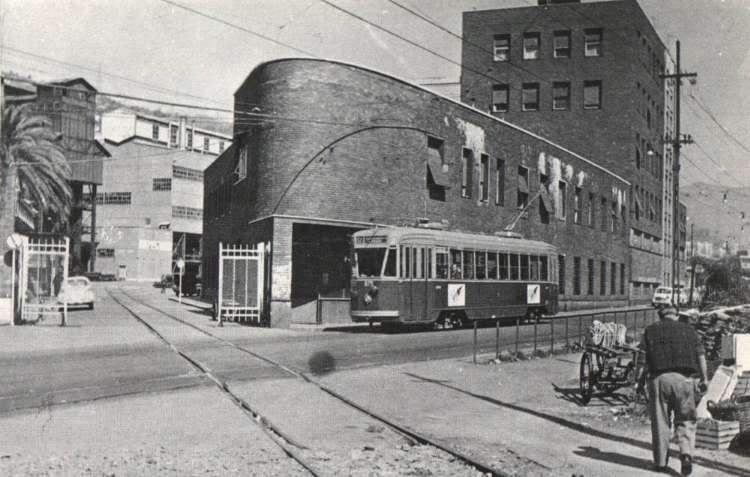

“The track branched off from the Terralba freight yard, near Piazza Giusti, entered the Corso Sardegna, along which the general fruit and vegetable markets were located, then turned left entering Via Cagliari, reached Piazza Carloforte and continued along Via del Piano, running alongside the municipal stadium and prisons.” [8 – translated from Italian]

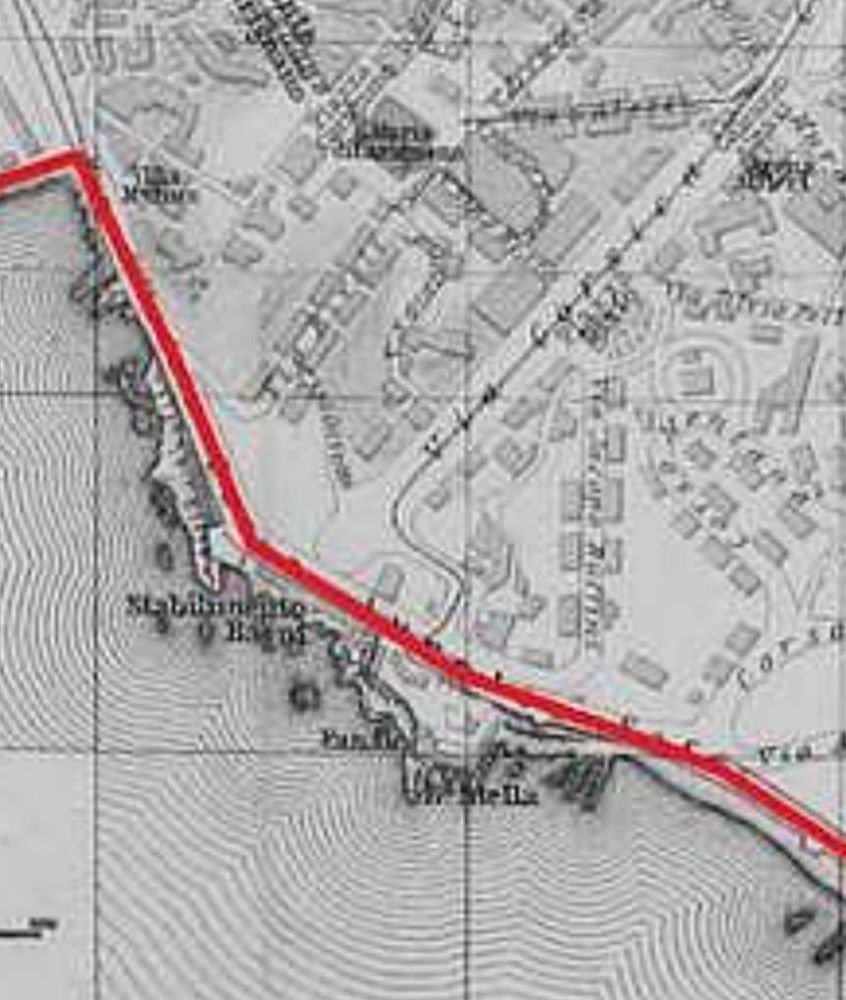

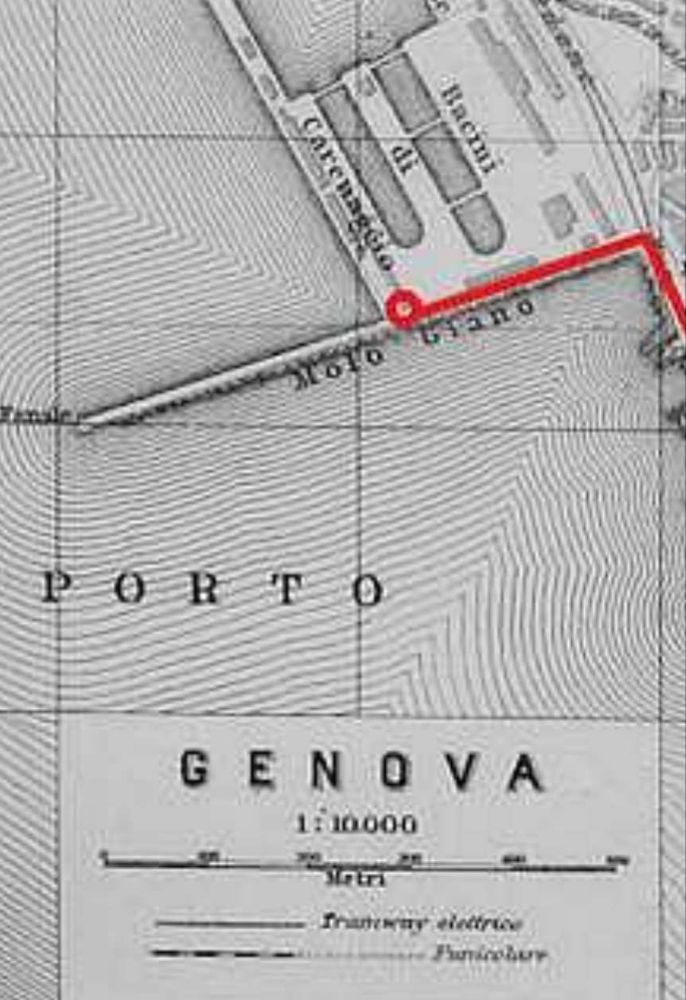

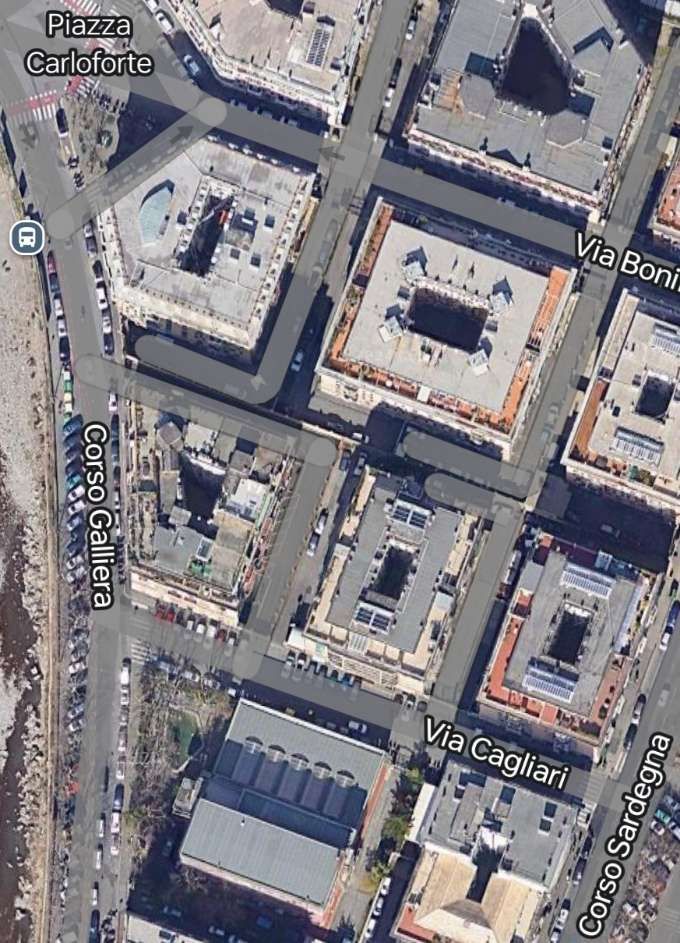

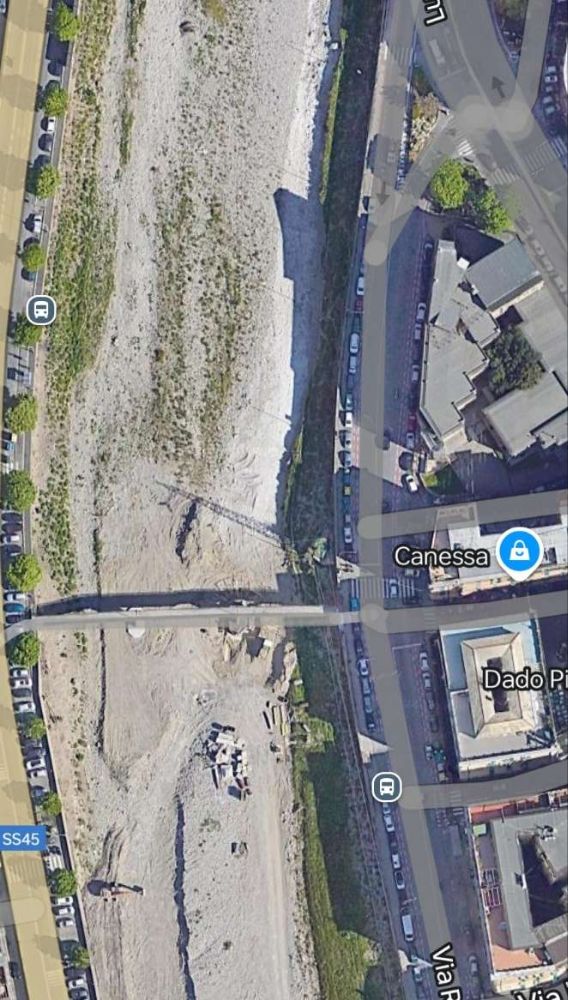

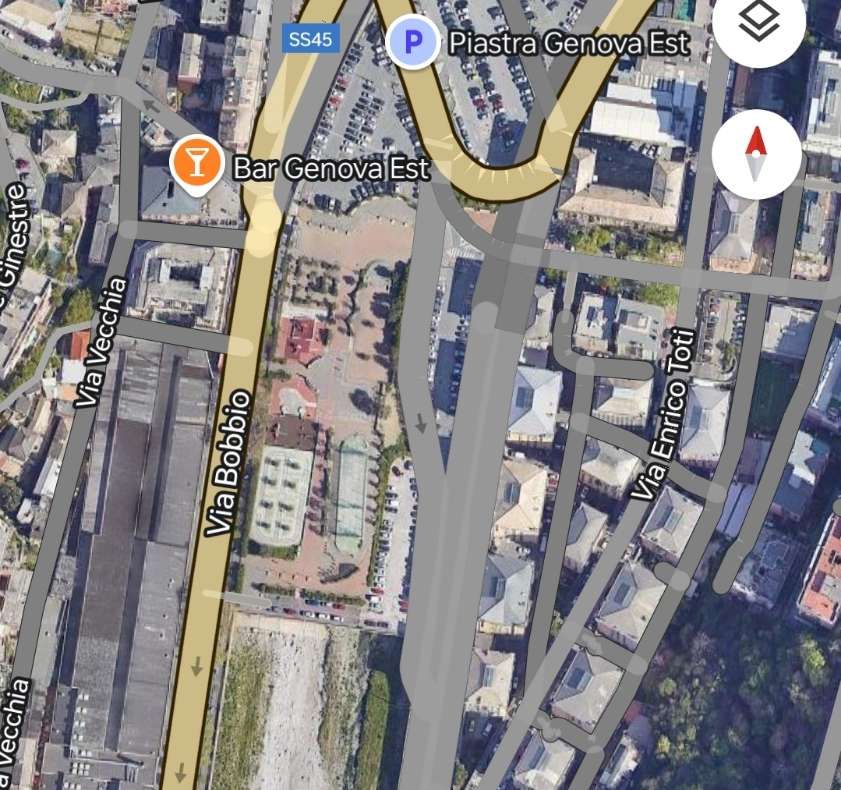

The Italian Wikipedia article adds a little to the information in the last paragraph. … On the Corsa Sardegna, the line was doubled to allow wagons to be left alongside the market area for loading and unloading. “After passing the market, the track crossed the road diagonally towards the Bisagno, … passing through a specially built archway in the building that, in the 21st century, houses the sports facility on Via Cagliari, through which it emerged at Corso Galliera. … Once in Piazza Carloforte, the track continued along Via del Piano, which was constructed at the same time as the railway, running alongside the municipal stadium and the prison , where trains carrying prison carriages sometimes stopped.” [7][9] The places mentioned in this paragraph appear in the images below.

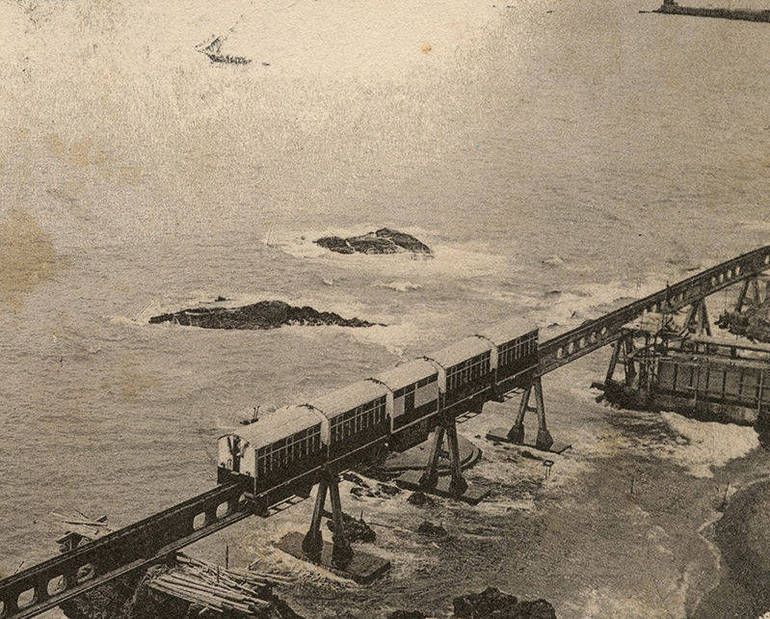

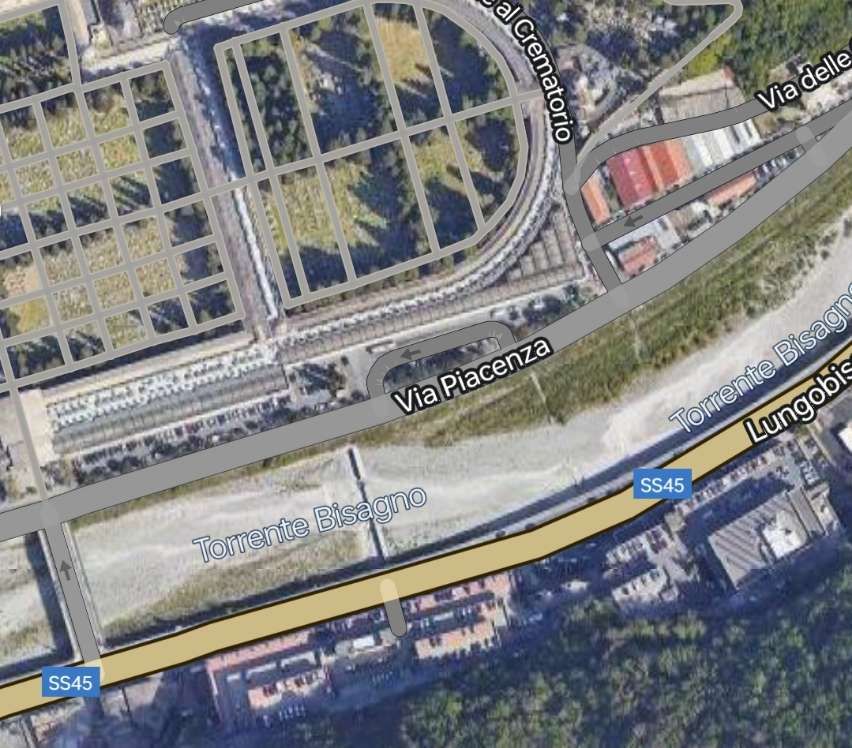

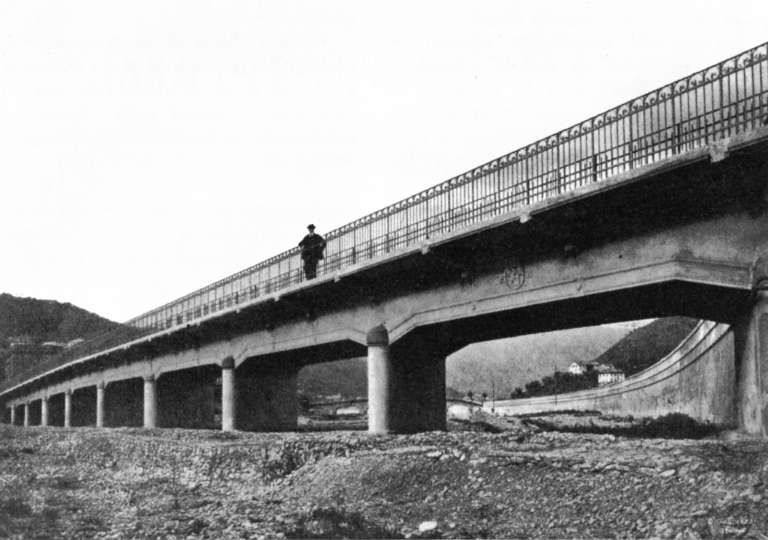

“The line continued up the left bank of the Bisagno, connecting to a number of factories. 3.7 km from its southern terminus a branch to the right which immediately curved round to cross [what became] the main line, Via del Piano and River Bisagno on a reinforced concrete bridge (Ponte G. Veronelli – which stood until destroyed during the flood of 1993); after crossing the river the line entered directly into the Gas Works, crossing, at ground level, the UITE (Unione Italiana Tramvie Elettriche) tramway Line No. 12, Genoa – Prato.” [8 – translated from Italian]

Italian Wikipedia tells us that the factories mentioned above which sat between the prison and the branch to the gasworks were: a plant for the repair of railway tanks and the NU “Volpara” plant for the incineration of urban waste. [7][9]

‘Trasporto Pubblico Locale in Valbisagno: un percorso di partecipazione’ [10] included the Volpara, Gavette and Guglielmetti Workshops and municipal waste treatment facilities, in its list of concerns which benefitted from the new railway. [10]

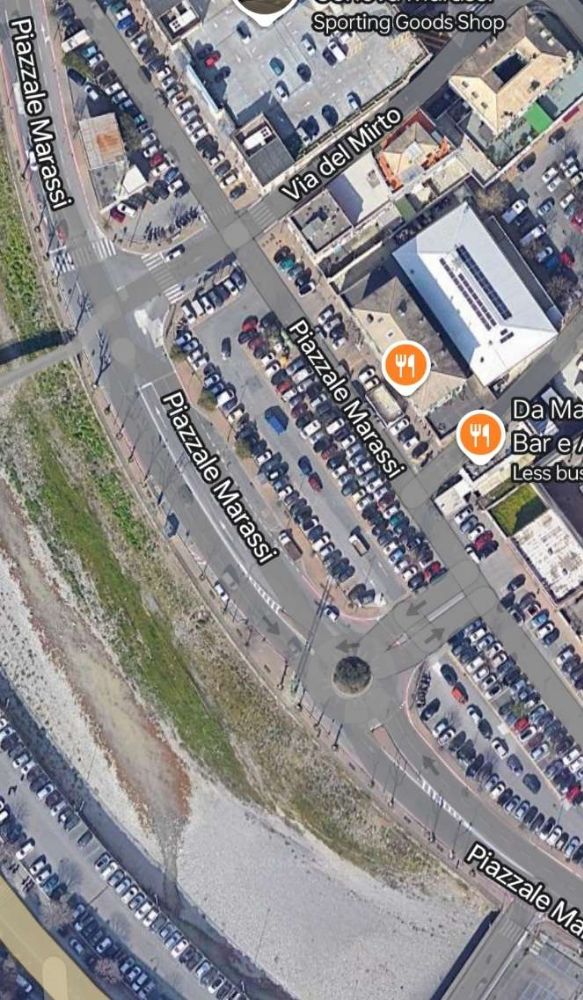

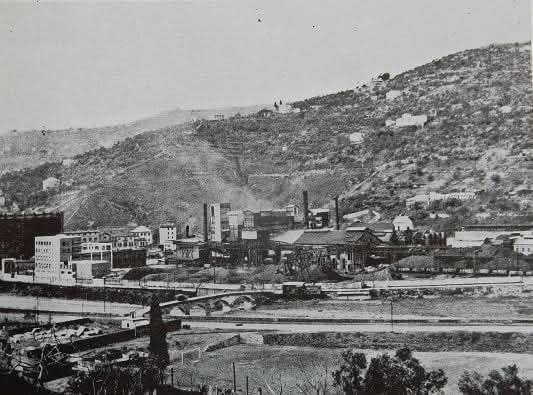

The next series of images cover the length of the line referred to in the paragraph above.

Italian Wikipedia also gives a description of the branch line to the gasworks: which curved in a wide arc before crossing the Via del Piano. It then “crossed the Bisagno engaging the G. Veronelli bridge, with 9 spans and 8 piers, built in reinforced concrete by the Società Italiana Chini.” [7][9]

The remaining length of the line (approximately 1 km) ran along the left bank of the river to slaughterhouses near the Falck steelworks in Cà de Pitta. [7][8][9][10] There was also a shorter-lived branch which served a cement works to the East of the river.

The head of the line! The branch serving the cement works is shown in green. [31]

The picture of the site of the steelworks brings us to the end of our journey along this industrial railway.

It was commented at the time of the construction of the line that through “the use of this rapid and economical means of transport, the potential of the gasworks can be significantly increased, at the same time reducing the costs for the transport of coal and by-products of the works themselves by approximately 1 million lire per year. … There will also be indirect advantages since the roads along the right bank of the Bisagno, currently congested by the transit of vehicles of all kinds, with great and evident danger to public safety, will be partially cleared and consequently the maintenance costs of said roads will also be reduced. The implementation of the industrial track will also contribute profitably to transforming a large area of land, still inaccessible a few years ago, and give it a new and fruitful industrial impulse. … Not to mention that the operating, maintenance, depreciation, etc. costs will weigh on the budget of the Municipality to a minimal extent since private companies will also contribute to the maintenance costs of the railway.” [10: p18 – quoting the Genoa Magazine of 1926 – translated from Italian]

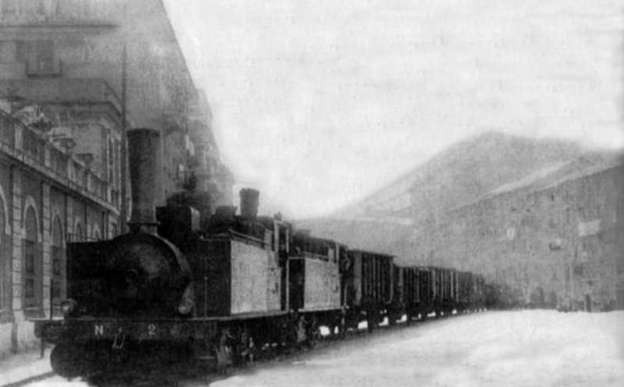

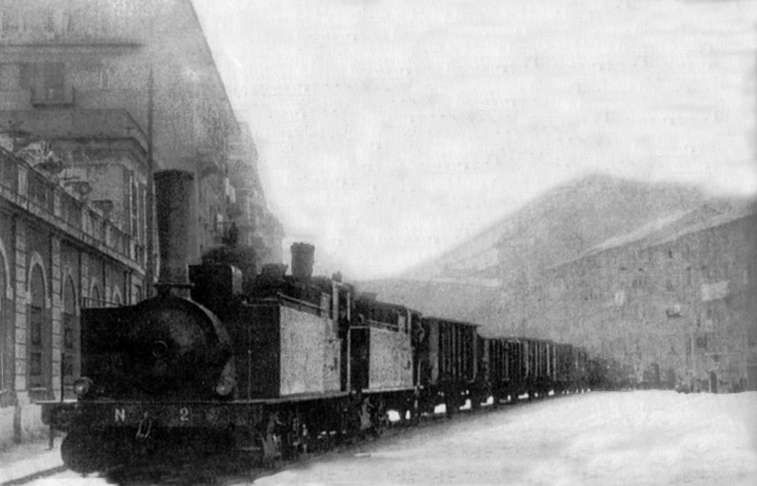

“The management of the railway line was entrusted to the Municipality through its Municipal Gas and Water Company (AMGA), which had three Breda-built steam engines and, subsequently, also a three-axle Jung R42C diesel locomotive, while the wagons were owned by the FS (Ferrovie Della Stato) which made them available to the Municipality.” [8 – translated from Italian]

AMGA certainly owned two diesel locomotives which are shown below.

“Any train travelling along the line was escorted by a shunter (an operative on the ground), equipped with a red flag, and, normally, also by a traffic policeman on a cyclist or motorcyclist who had the task of stopping the traffic. Particularly spectacular were the long trains of coal wagons destined for the Officine Gas delle Gavette for the production of town (city) gas.” [8 – translated from Italian]

Italian Wikipedia tells us that “the line was decommissioned in 1965 as a result of the use of methane gas instead of town gas, thus ceasing its need for it by AMGA, now the sole user of the plant after road transport had replaced rail transport to the slaughterhouses and the market.” [7][10]

References

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carta_della_Ferrovia_della_Gavette.png, accessed on 15th November 2024.

- https://www.ilmugugnogenovese.it/ferrovia-delle-gavette, accessed on 15th November 2024

- https://www.ilportaledeitreni.it/2019/05/08/la-ferrovia-delle-gavette-un-impianto-genovese-poco-conosciuto, accessed on 15th November 2024.

- https://www.superbadlf.it/wordpress/il-treno-nella-storia-binari-lungo-il-bisagno, accessed on 15th November 2024.

- https://wp.me/p4UqjX-gp, accessed on 15th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/gianfranco.curatolo/permalink/4257695100941408/?app=fbl, accessed on 15th November 2024.

- https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binario_industriale_della_val_Bisagno, accessed on 16th November 2024.

- La ferrovia delle Gavette (binario industriale della val Bisagno); on gassicuro.it., https://web.archive.org/web/20140910195722/http://www.gassicuro.it/storiagas-genova-appr-ferr-gavette.asp, accessed on 16th November 2024.

- Alessandro Sasso, Claudio Serra; The Gavette Railway; in Mondo Ferroviario , No. 154, April 1999, p10.

- http://www.urbancenter.comune.genova.it/sites/default/files/quaderno_arch_2011_03_21.pdf, accessed on 16th November 2024.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ponte_Veronelli_-_Gavette.jpg, accessed on 16th November 2024.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vista_ponte_Veronelli.jpg, accessed on 16th November 2024.

- https://www.stagniweb.it/jqzoom.asp?ImgBig=mappe/ge943.jpg&ImgSmall=mappe/ge943_.jpg&bSmall=500&file=mappe_ge&inizio=5, accessed on 16th November 2024.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20140910215759/http://www.gassicuro.it/galleriffic/mezzi.asp#15, accessed on 16th November 2024

- https://it.pinterest.com/pin/256775616243441061, accessed on 16th November 2024.

- https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/133338084620?mkcid=16&mkevt=1&mkrid=711-127632-2357-0&ssspo=TA95VFW8Qea&sssrc=4429486&ssuid=afQhrar7TGK&var=&widget_ver=artemis&media=COPY, accessed on 16th November 2024.

- https://de.pinterest.com/pin/206884176619651422, accessed on 17th November 2024.

- https://ceraunavoltagenova.blogspot.com/2015/02/genova-marassi-e-quezzi.html?m=1, accessed on 17th November 2024.

- https://genova.repubblica.it/cronaca/2018/02/21/foto/l_ex_mercato_di_corso_sardegna_riparte_dal_verde_il_comune_presenta_il_progetto-189401770/1, accessed on 17th November 2024.

- Casa circumdariale di Genova Marassi; https://images.app.goo.gl/yMg3fsAgg2c6vsao7, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/gianfranco.curatolo, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/2mo3VEGfjWoA18Di, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/4Gyv5fSuKi6AAFA5, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/rvyqDzDgnb3Zf1XH, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/fRgGbQviKdGTWZR8, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/yCEcP8WSx2UNwhNx, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/VsRrXqjSKUYKUvih, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/TdQCn4jv2wxRxcRP, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/N9UYkoambK7J1fjW, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/rbAnaTF1E3pTSxN3, accessed on 18th November 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/xPR32MbMWLBnpAwF, accessed on 18th November 2024.