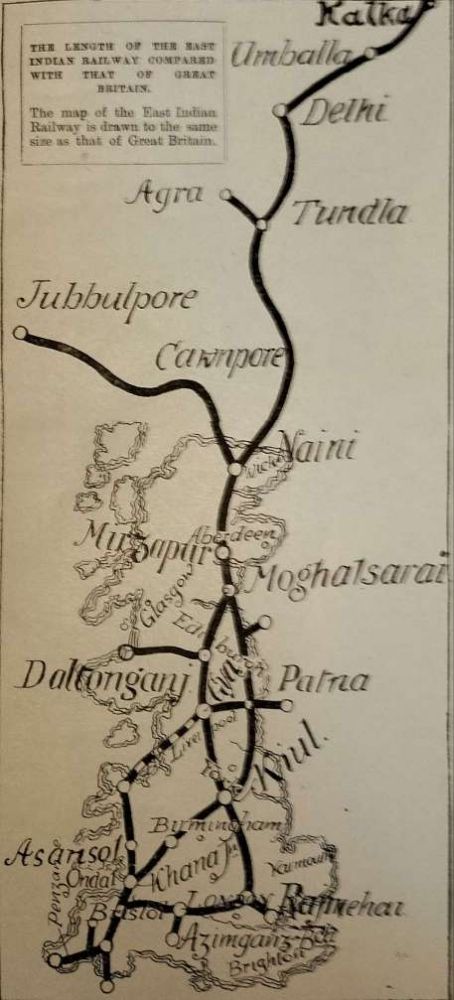

A further article about the East Indian Railway appeared in the July 1906 edition of The Railway Magazine – written again by G. Huddleston, C.I.E. [1]

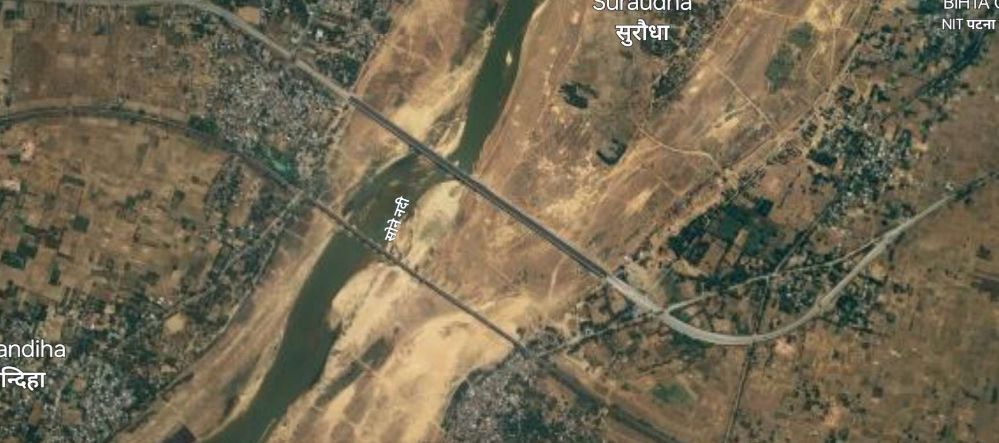

The first article can be found here. [2]

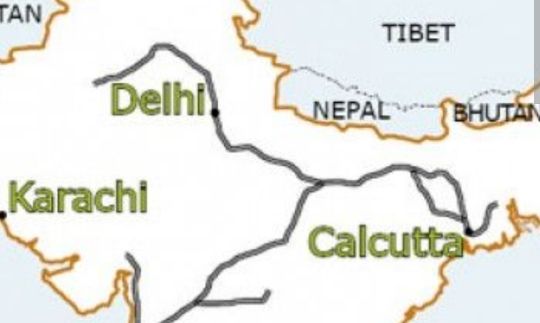

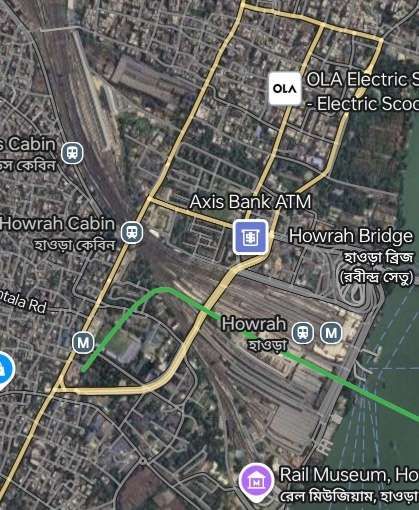

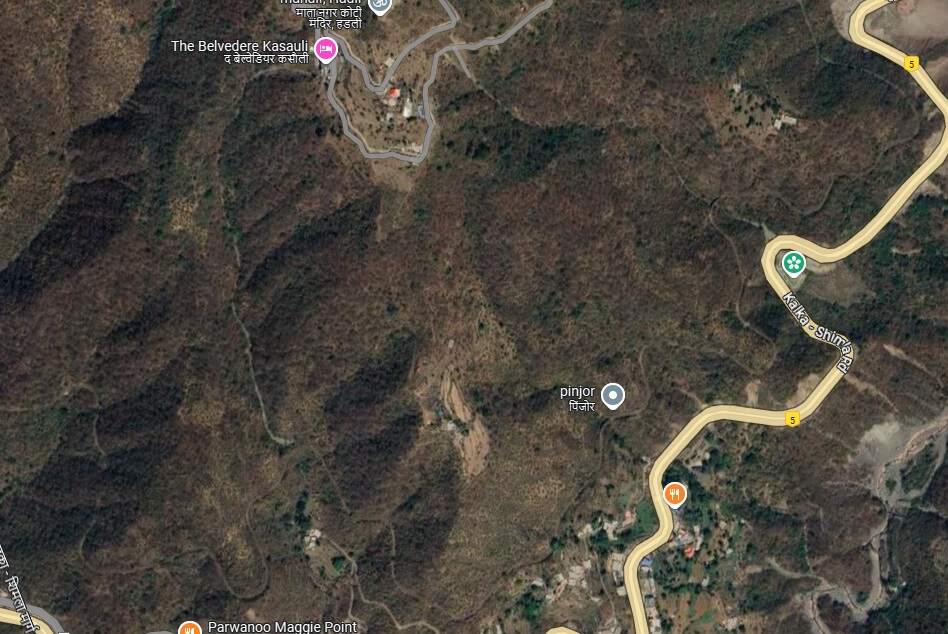

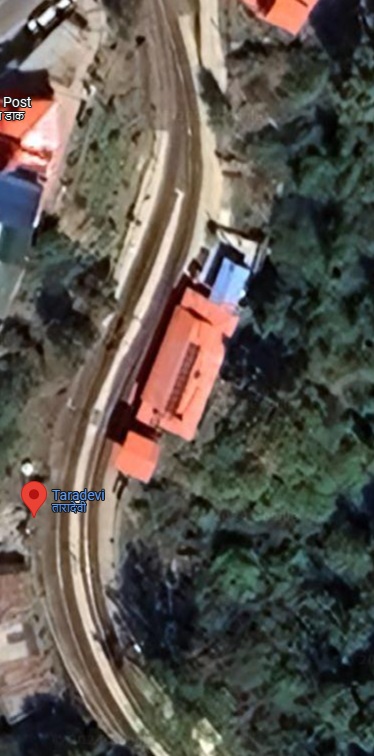

Huddleston looks at a number of different sections of the network and after looking at what he has to say about each we will endeavour to follow those railway routes as they appear in the 21st century. We will go into quite a bit of detail on the journey along the Kalka to Shimla narrow-gauge line. The featured image at the head of this post was taken at Taradevi Railway Station on the Kalka to Shimla line, (c) GNU Free Documentation Licence Version 1.2. [29]

Shikohabad to Farrukhabad

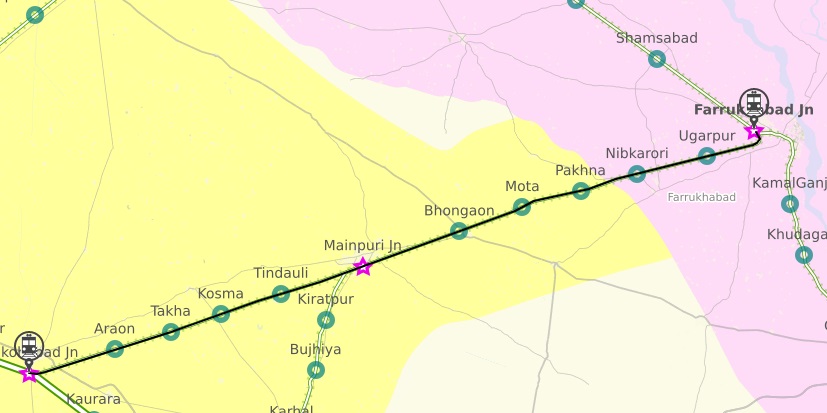

This branch line had, in 1906, recently been opened. Huddleston describes it as being 65 miles in length, running through the district of Manipuri from Shekoabad [sic] to Farukhabad on the River Ganges. Until 1906, Farukhabad [sic] had “only been served by the metre gauge line which skirts the river to Cawnpore. There was lots of traffic in the district and both the broad and metre gauge lines completed for it, whilst the river and canals and camels compete with the railways.” [1: p40]

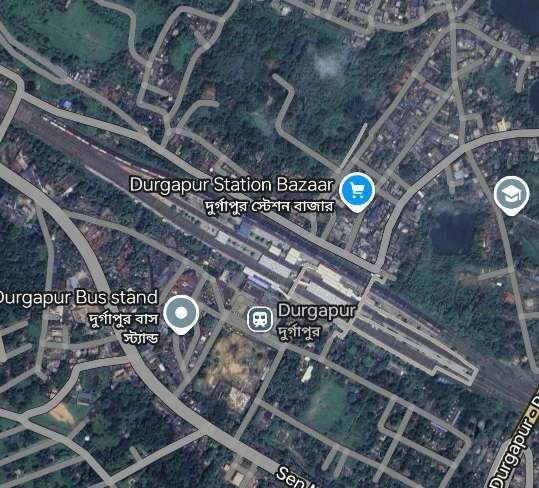

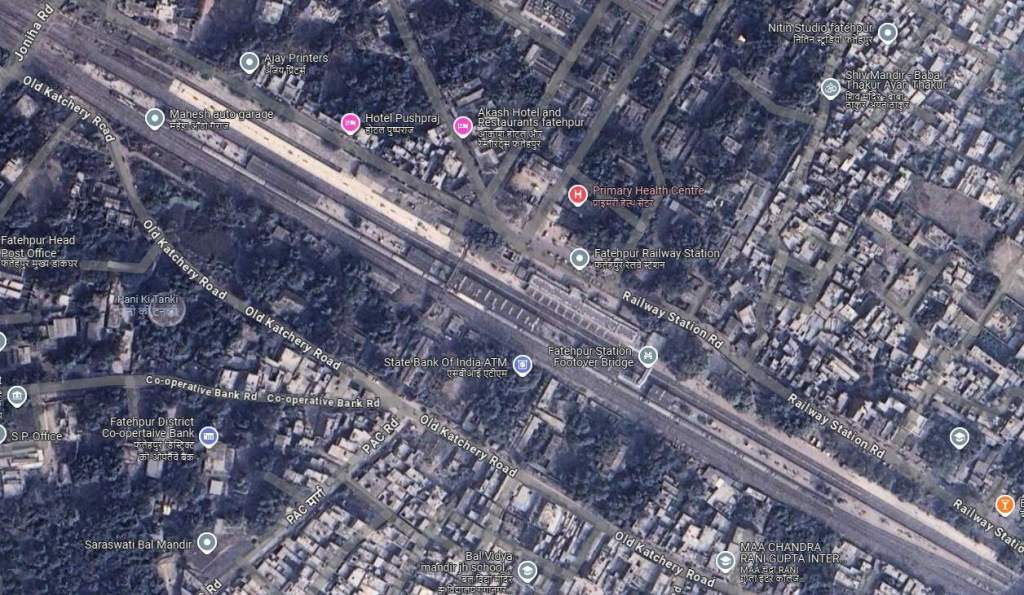

We start this relatively short journey (of 63 miles) at Shikohabad Junction Railway Station. “The old name of Shikohabad was Mohammad Mah (the name still exists as Mohmmad mah near Tahsil and Kotwali). Shikohabad is named after Dara Shikoh, the eldest brother of Emperor Aurangzeb. In its present form, the town has hardly any recognisable evidence of that era. Shikohabad was ruled under the estate of Labhowa from 1794 to 1880.” [5] “Shikohabad Junction railway station is on the Kanpur-Delhi section of Howrah–Delhi main line and Howrah–Gaya–Delhi line. It is located in Firozabad district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.” [6] The station opened in1866. “A branch line was opened from Shikohabad to Mainpuri in 1905 and extended to Farrukhabad in 1906.” [7]

Trains from Shikohabad set off for Farrukhabad in a southeasterly direction alongside the Delhi to Kolkata main line. In a very short distance as the railway passed under a road flyover (Shikohabad Junction Flyover) the line to Farrukhabad moved away from the main line on its Northside.

The first stopping point on the line is at Burha Bharthara. As can be seen immediately below, it is little more than a ‘bus-stop’ sign!

Very soon after Burha Bharthara, trains pull into Aroan Railway Station which is a little more substantial that Burha Bharthara having a single building with a ticket office.

Takha Railway Station is next along the line.

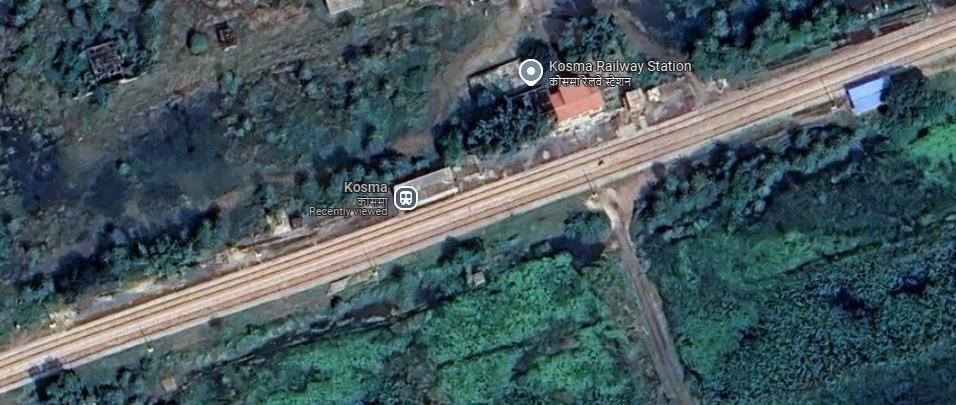

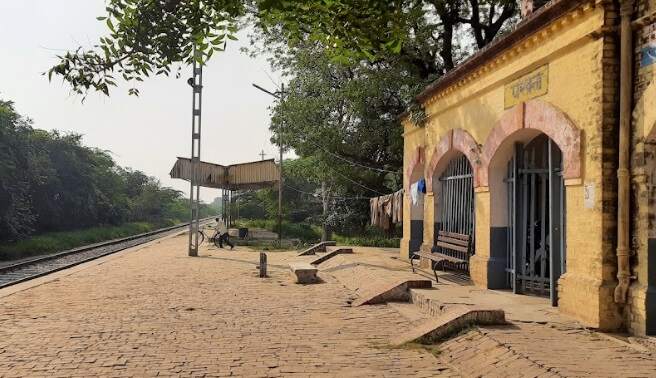

A couple of hundred meters short of Kosma Railway Station, the line crosses the Karhal to Ghiror Road at a level-crossing.

Kosma Railway Station provides a passing loop to allow trains travelling in opposite directions to cross.

A short distance further to the East is Tindauli Railway Station, after which the line crosses another arm the Lower Ganga Canal.

Further East the line crosses a number of roads, most now culverted under the line.

To the East of Mainpuri Railway Station, the next station is Mainpuri Kachehri Railway Station, just to the East of the Sugaon to Husenpur Road.

The next station was Bhongaon Railway Station which had a passing loop to allow trains to cross.

Continuing on towards Farrukhabad, it is only a matter of a few minutes before trains pass through Takhrau Railway Station, where facilities are basic, and Mota Railway Station where facilites are a little more substantive.

The Railway then bridges the Kaali Nadi River and passes through Pakhna Railway Station.

The next stop is at B L Daspuri (Babal Axmandaspuri) Station.

Another short journey gets us to Nibkarori Railway Station.

The next stop is at Ugarpur Railway Station.

Not much further along the line we enter Shrimad Dwarakapuri Railway Station.

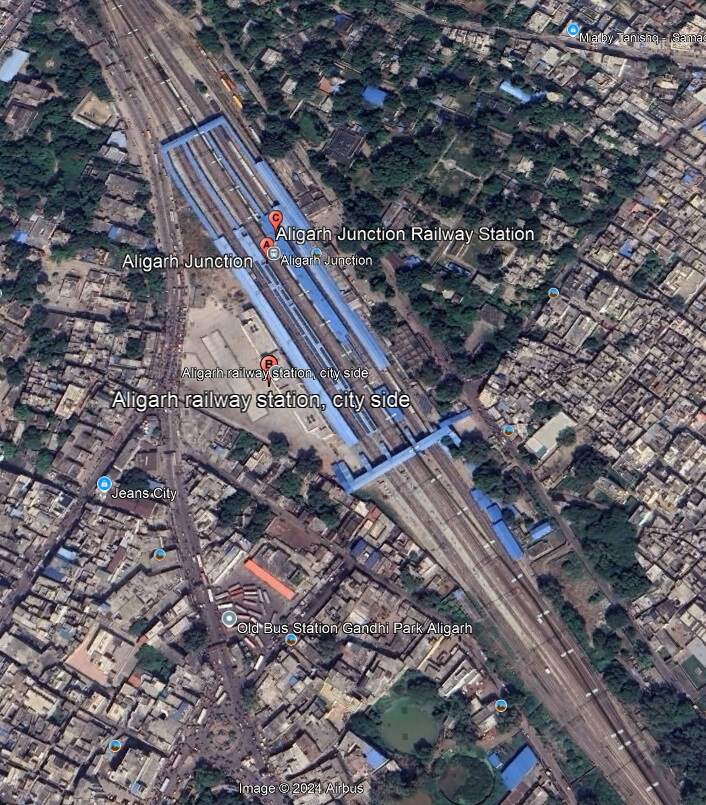

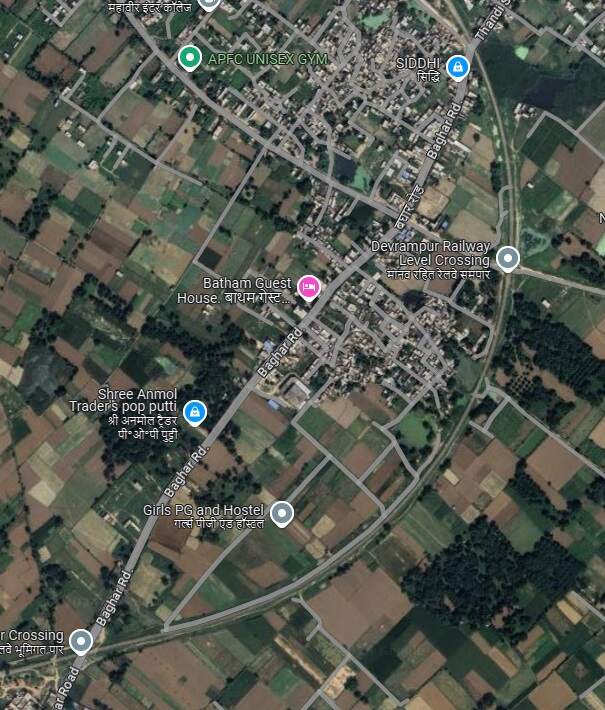

As the line reaches the town of Farrukhabad it turns sharply to the North.

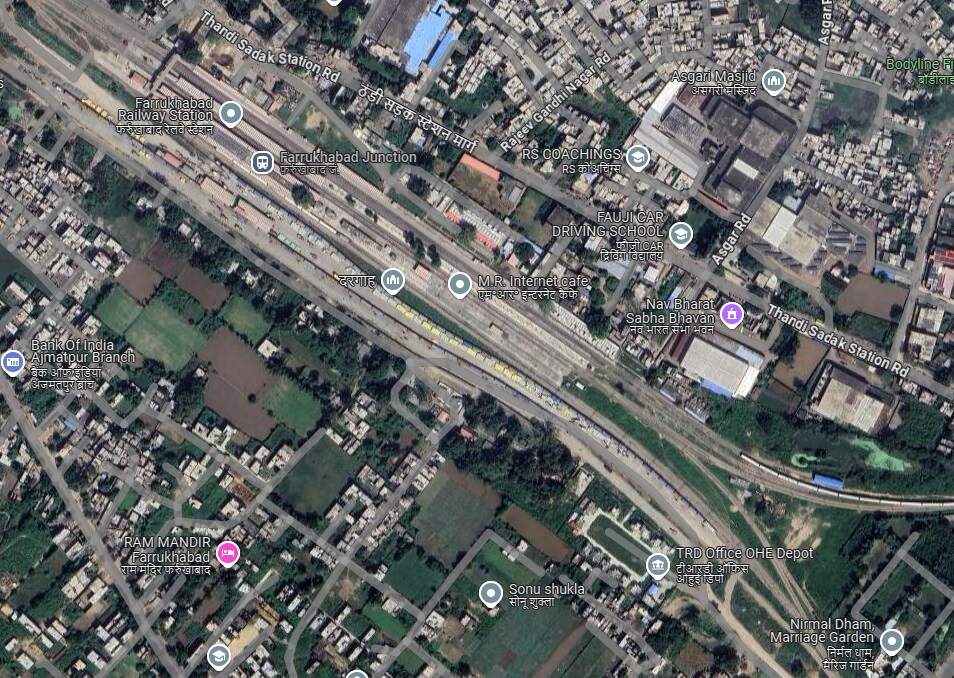

It then enters Farrukhabad Junction Railway Station from the Southeast.

Farrukhabad sits on the River Ganges. It is a historic city with a rich culture defined by the traditions of Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb (Ganges-Yamuna Culture), [10] which amalgamates aspects of Hindu and Muslim cultural practices, rituals, folk and linguistic traditions. [11] The city was begun in 1714, and Mohammad Khan Bangash (a commander in the successful army of Farrukhsiyar, one of the princely contenders for the Mughal throne, who led a coup which displaced the reigning emperor Jahandar Shah) named it after Farrukhsiyar. It soon became a flourishing centre of commerce and industry. [12]

Initially, under the colonial state of British India, Farrukhabad was a nodal centre of the riverine trade through the Ganges river system from North and North-West India towards the East. [12] Farrukhabad’s economic and political decline under British rule began with the closure of the Farrukhabad mint in 1824. [11]

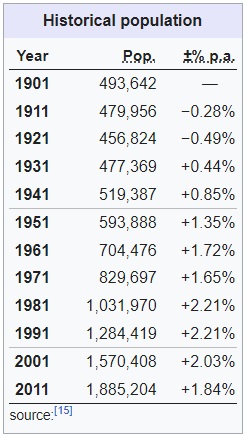

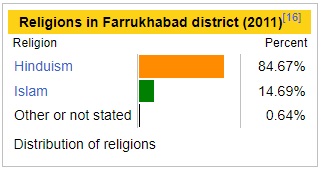

Farrukhabad, according to the 2011 census had a population of 1,885,204. This was just under four times its size in 1901. Its population is predominantly Hindu. [13]

At the time of the 2011 Census of India, 94.96% of the population in the district spoke Hindi (or a related language) and 4.68% Urdu as their first language. [14]

Tundla to Agra

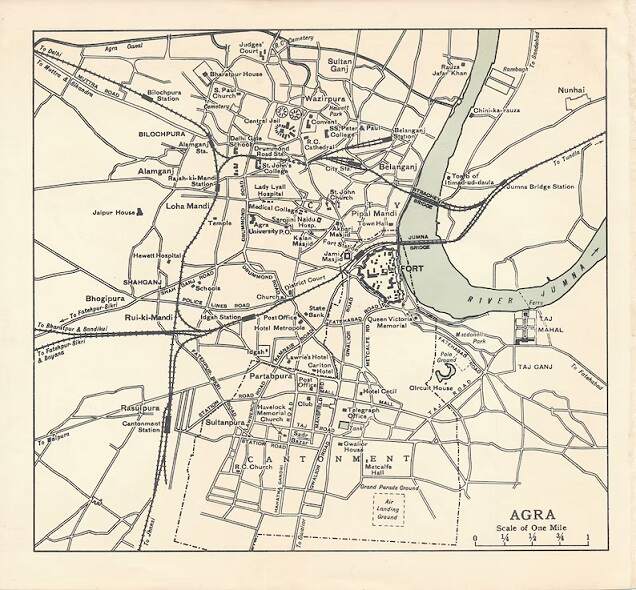

“From Shekoabad, it is only a matter of 22 miles to Tundla but very few people would ever hear about Tundla, if it was not for the fact that it is the junction for Agra. …Agra would have been on the main line if the East Indian Railway had the original intention been followed of taking the line across the Jumna river at Agra and then following its right bank into Delhi; but, instead of doing this, it was decided … to build only a branch to Agra, and to run the main line on the left side of the Jumna. … If we want to visit Agra, we must change at Tundla and go along the 14 mile of the branch line.” [1: p41]

Huddleston tells us that:

“Approaching Agra … from Tundla you see [the Taj Mahal] first on your left-hand side, wrapped in that peculiar atmospheric haze that adds charm to every distant object in the East, a charm even to that which needs no added charm, the marvellous and wonderful Taj Mehal [sic]. As you rapidly draw nearer it seems to rise before you in solitary dazzling grandeur, its every aspect changing as the remorseless train, which you cannot stop, dashes on. Once catch your first glimpse of the Taj and you have eyes for. nothing else, you feel that your very breath has gone, that you are in a dream. All the world seems unreal, and the beautiful construction before you more unreal than all. You only know it is like something you have heard of, something, perhaps, in a fairy tale, or something you have read of, possibly in allegory, and you have hardly time to materialise before the train rattles over the Jumna Bridge, and enters Agra Fort station.

There on one side are the great red walls of the fortress within a few feet of you, and there on the other side is the teeming native city, with its mosques and domes and minarets, its arches and columns and pillars. its thousand and one Oriental sights, just the reality of the East, but all quite different to everywhere else. … There are things to be seen in Agra that almost outrival the Taj itself, such, for instance, as the tomb of Ihtimad-ud-Daula, on the East bank of the river, with its perfection of marble carving, unequalled in delicacy by anything of the kind in the world. There are delightful places nearby of absorbing interest, as, for example, Fatehpur Sikri, and its abandoned city of palaces; there is enough in Agra and its vicinity to glut a glutton at sight seeing, but we must go back to the railway and its work. The Jumna Bridge, of which we have talked, belongs to the Rajputana Railway; the rails are so laid that both broad and metre gauge trains run over it, and above the track for trains there is a roadway.

But this is not sufficient for the needs of Agra, though supplemented by a pontoon bridge which crosses the river half a mile further up the stream. The trade of Agra first attracted the East Indian Railway, then came the Rajputana Malwa, and then the Great Indian Peninsular. Each of the latter two lines wanted a share, and the East Indian had to fight for its rights; to do its utmost to keep to the Port of Calcutta what the rival lines wanted to take to Bombay. Another railway bridge became a necessity, a bridge that would take the East Indian Railway line into the heart of the native city instead of leaving it on its outskirts, and the East Indian Railway began to construct it.” [1: p42-43]

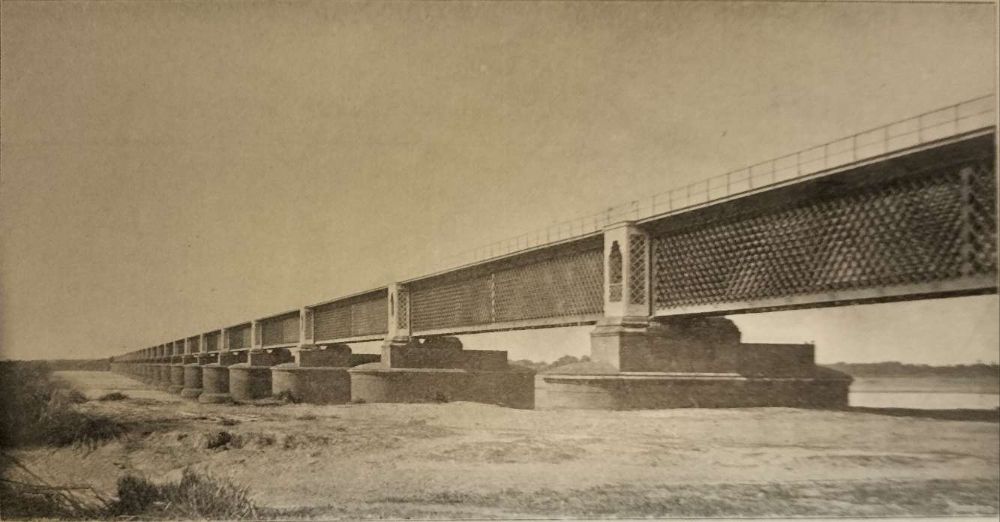

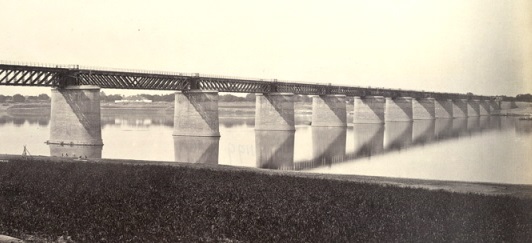

In 1906 the new bridge over the River Jumna was under construction, due to be completed in early 1907. Huddleston describes the bridge under construction thus:

“The bridge will consist of nine soane of 150 ft., and there will be a roadway under the rails; the bridge is being built for a single line, and all the wells have been sunk to a depth of 60 ft , or more. The work … commenced in September [1905], and it is expected that the bridge will be completed in March 1907. It need only be added that the site selected for this new connection is between the existing railway bridge and the floating pontoon road bridge, and the chief point of the scheme is that, when carried out, the East Indian Railway will have a line through the city of Agra, and a terminus for its goods traffic in a most central position, instead of being handicapped, as it now is, by having its goods depôt on the wrong side of the river. Mr. A. H. Johnstone is the East Indian Railway engineer-in-charge of the work.” [1: p43]

We start the journey along this short branch in the 21st century at Tundla Junction Railway Station.

We head Northwest out of the station alongside the main line to Delhi.

The first station along the branch was Etmadpur Railway Station.

The line to Agra next passes under the very modern loop line which allows trains to avoid Tundla Station.

The next photograph shows the older single track metal girder bridge a little further to the West of Etmadpur with the more modern second line carried by a reinforced concrete viaduct.

The line curves round from travelling in an West-northwest direction to a West-southwest alignment and then enters the next station on the line, Kuberpur Railway Station.

As we head into Agra, the next station is Chhalesar Railway Station.

From Chhalesar Railway Station the line continues in a West-southwest direction towards the centre of Agra. The next station is Yamuna Bridge Railway Station.

South West of Yamuna Bridge Railway Station a series of bridges cross the River Yamuna.

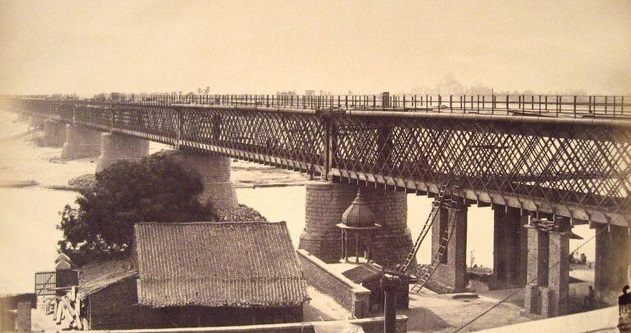

The ‘Yamuna Railway Bridge’ crossing the River Jumna/Yamuna at Agra was opened in 1875, and connected ‘Agra East Bank Station’ to ‘Agra Fort Station’. The bridge carried the Bombay, Baroda and Central India Railway (BB&CIR) Metre Gauge ‘Agra-Bandikui Branch Line’, the East Indian Railway (EIR) and ‘Great Indian Peninsula Railway (GIPR) Broad Gauge lines. [18]

The ‘Strachey Bridge’, to the North the older bridge at Agra, was opened in 1908. It was a combined Road and Railway bridge and constructed by the ‘East Indian Railway Company’ (EIR). The bridge was named after John Strachey who planned & designed the bridge. The 1,024 metres (3,360 ft) long bridge was completed in 1908, taking 10 years to complete since its construction commenced in 1898. The ‘Agra City Railway Station’ was thus connected by the bridge to the ‘Jumna Bridge Station’ on the East bank. This Broad Gauge line became the ‘EIR Agra Branch Line’. [18]

Once the Strachey Bridge (this is the one about which Huddleston speaks at length above) was opened in 1908. The EIR had access to the heart of the city and particularly to Agra City Station. We will look at City Station a few paragraphs below. But it is worth completing a look at the bridges over the Yamuna River with the bridge which replaced the first Yamuna River railway bridge.

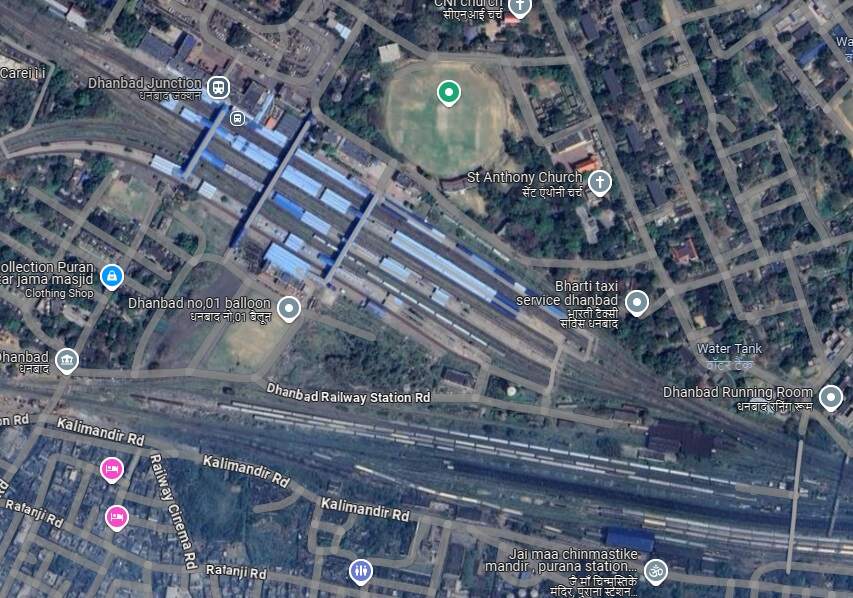

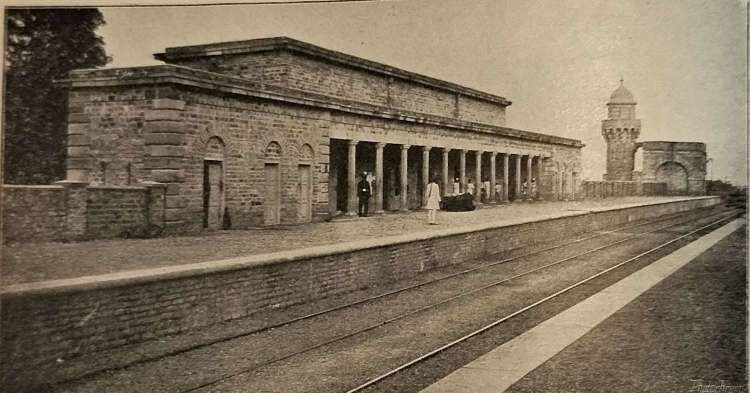

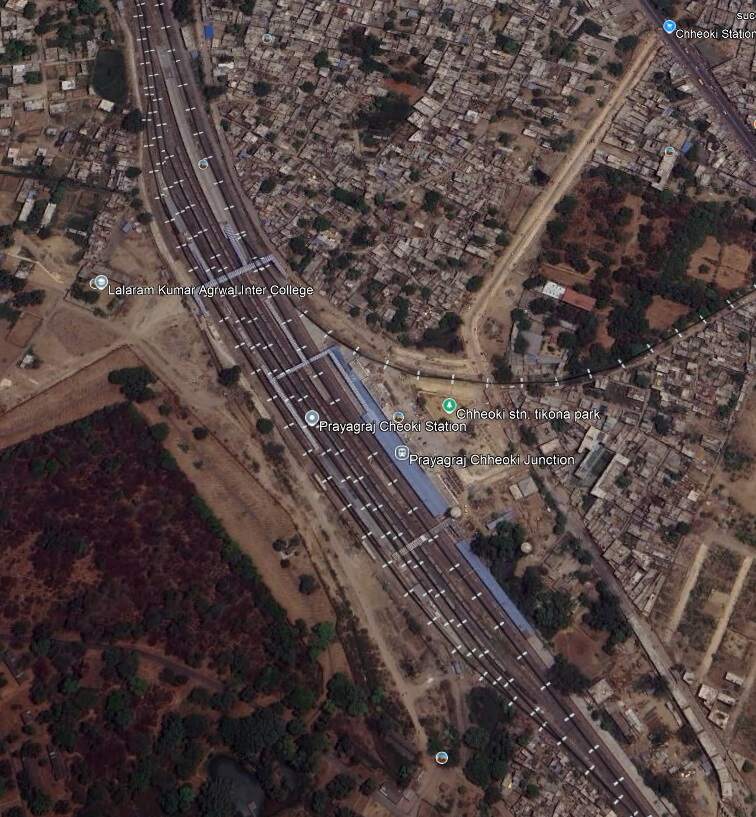

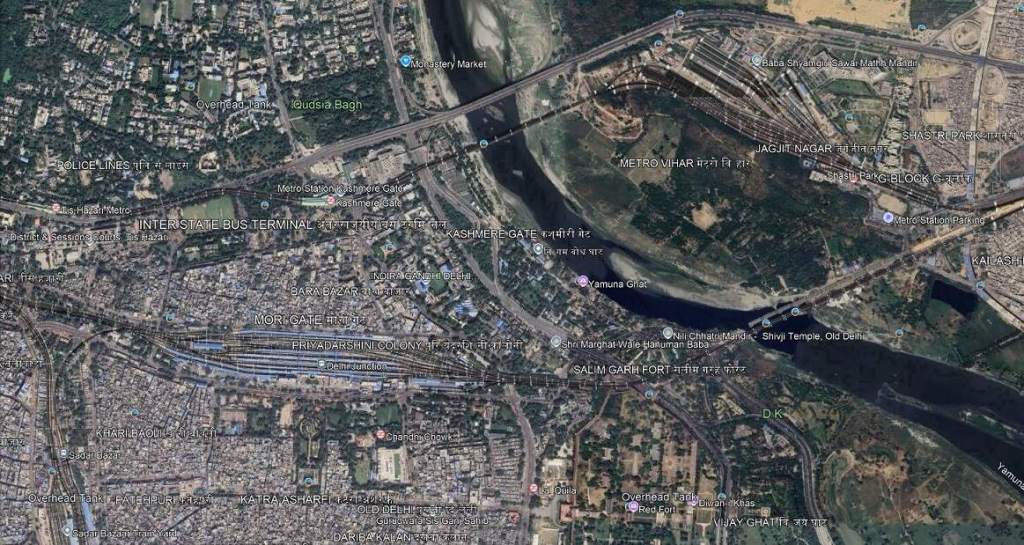

Delhi

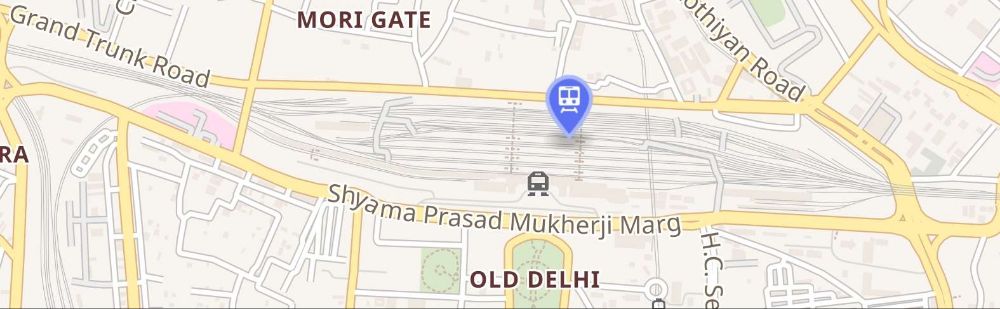

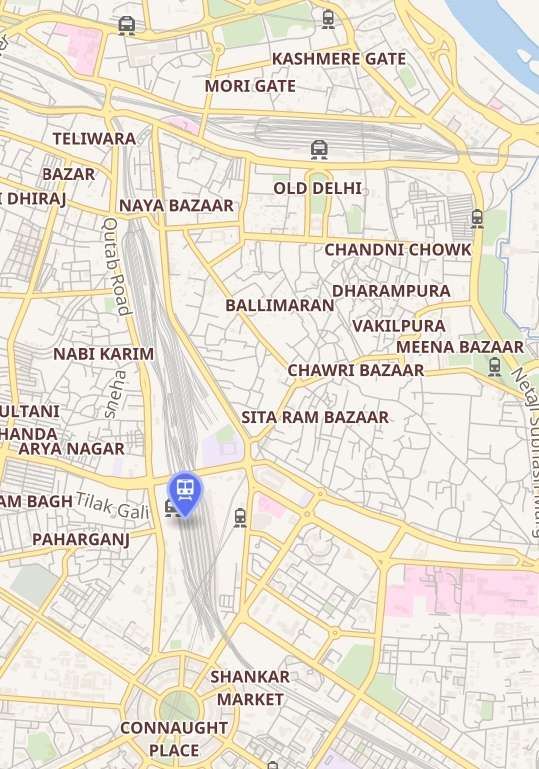

Huddleston comments: “Delhi is one of the most important junctions on the East Indian Railway. The Rajputana Malwa, the North Western, Southern Punjab, Oudh and Rohilkhand and Great Indian Peninsular Railways all run into Delhi. There is a regular network of lines in and around, and the main passenger station is that belonging to the East Indian Railway. All the railways run their passenger trains into the East Indian Railway station, and most of the goods traffic passes through it also. For some years past Delhi has been in a state of remodelling; the work is still going on, and it will be some time before it is completed.” [1: p43]

He continues: “When you alight on one of the numerous platforms at Delhi station, there is a feeling of elbow room; the whole station seems to have been laid out in a sensible way. You are able to move without fear of being jostled over the platform edge, everything looks capacious, and especially the two great waiting halls, which flank either side of the main station building. These are, perhaps, the two finest waiting halls in India; passengers congregate there, and find every convenience at hand, the booking office, where they take their tickets, vendors’ stalls, where they get various kinds of refreshments, a good supply of water, and, just outside, places in which to bathe; a bath to a native passenger is one of the greatest luxuries, and he never fails to take one when opportunity offers.” [1: p44]

Wikipedia tells us that “Delhi Junction railway station is the oldest railway station in Old Delhi. … It is one of the busiest railway stations in India in terms of frequency. Around 250 trains start, end, or pass through the station daily. It was established near Chandni Chowk in 1864 when trains from Howrah, Calcutta started operating up to Delhi. Its present building was constructed by the British Indian government in the style of the nearby Red Fort and opened in 1903. It has been an important railway station of the country and preceded the New Delhi by about 60 years. Chandni Chowk station of the Delhi Metro is located near it.” [21]

Delhi junction Railway Station was the main railway station in Delhi at the time that Huddleston was writing his articles.

Delhi, Ambala (Umbala) and Kalka

The East Indian Railway proper terminated at Delhi Junction Railway Station but the railway company also operated the independently owned Delhi-Umabala-Kalka Railway.

“A railway line from Delhi to Kalka via Ambala was constructed by the Delhi Umbala Kalka Railway Company (DUK) during 1889 and 1890 and operations were commenced on March 1, 1891. The management of the line was entrusted to the East Indian Railway Company (EIR) who were able to register a net profit in the very first year of operation. The Government of India purchased the line in 1926 and transferred the management to the state controlled North Western Railway. After partition, this section became part of the newly formed East Punjab Railway and was amalgamated with the Northern Railway on 14th April 1952.” [3]

The terminus of this line is at Kalka, 162 miles from Delhi. Huddleston tells us that, “In the beginning of the hot weather, when the plains are becoming unbearable, Kalka station is thronged with those fortunates who are going to spend summer in the cool of the Himalayas, and, when the hot weather is over, Kalka is crowded with the same people returning to the delights of the cold season, very satisfied with themselves at having escaped a grilling in the plains. Therefore, nearly everyone who passes Kalka looks cheerful, but, of course, there is the usual exception to the rule; and in this case the exception is a marked one. All the year round there is to be seen at Kalka station a face or two looking quite the reverse of happy, and, if we search the cause, we find it soon enough. The sad faces belong to those who have reached Kalka on their way to the Pasteur Institute, at Kasauli; Kasauli is in the hills some ten miles from Kalka. It is at Kasauli that Lord Curzon, when Viceroy, established that incalculable boon to all the people of India, a Pasteur Institute. Formerly, when anyone was bitten by a mad dog, or by a mad jackal, and such animals are fairly common in the East, he had to fly to Paris, and spend anxious weeks before he could be treated-some, indeed, developed hydrophobia before they could get there, or got there too late to be treated with any hope of success. Now, instead of going to Paris, they go to Kasauli.” [1: p44-45]

The first station beyond the junction shown in the photograph above is Sabzi Mandi Railway Station.

Heading North-northwest out of Delhi, trains pass through Delhi Azadpur Railway Station, under Mahatma Gandhi Road (the Ring Road), on through Adarsh Nagar Delhi Railway Station and under the Outer Ring Road.

Outside of the Outer Ring Road the line passes through Samaypur Badli Railway Station which is an interchange station for the Metro; across a level-crossing on Sirsapur Metro Station Road; through Khera Kalan Railway Station and out of the Delhi conurbation.

The line runs on through a series of level-crossings and various stations (Holambi Kolan, Narela, Rathdhana, Harsana Kalan) and under and over modern highways before arriving at Sonipat Junction Railway Station.

Northwest of Sonipat Railway Station a single-track line diverges to the West as we continue northwards through Sandal Kalan, Rajlu Garhi (North of which a line diverges to the East), Ganaur, Bhodwal Majri, Samalkha, Diwana Railway Stations before arriving at Panipat Junction Railway Station.

Panipat Junction Railway Station was opened in 1891. It has links to the Delhi–Kalka line, Delhi–Amritsar line, Delhi–Jammu line, Panipat–Jind line, Panipat–Rohtak line connected and upcoming purposed Panipat–Meerut line via Muzaffarnagar, Panipat–Haridwar line, Panipat-Rewari double line, via Asthal Bohar, Jhajjar or Bypass by the Rohtak Junction Panipat-Assoti Double line via Farukh Nagar, Patli, Manesar, Palwal. 118 trains halt here each day with a footfall of 40,000 persons per day. [25]

Just to the North of Panipat Junction Railway Station a double-track line curves away to the West. Our journey continues due North parallel to the Jammu-Delhi Toll Road.

North of Panipat the line passed through Babarpur, Kohand, Gharaunda, Bazida Jatan Railway Stations while drifting gradually away from the Jammu-Delhi Toll Road.

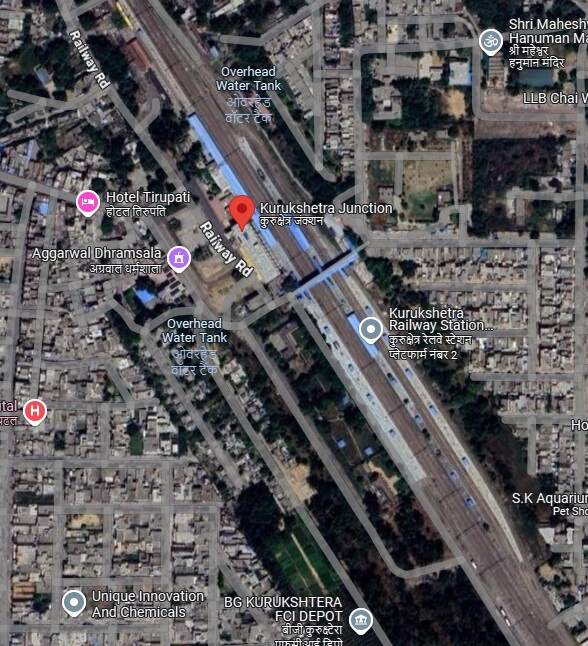

Beyond Bazida Jatan Station, the line turns from a northerly course to a more northwesterly direction before swinging back Northeast to a more northerly route. It then passes through Karnal Railway Station before once again swinging away to the Northwest and crossing a significant irrigation canal, passing through Bhaini Khurd, Nilokheri, Amin Railway Stations and then arrives at Kurukshetra Junction Railway Station.

North of Kurukshetra Junction the line passes through Dhoda Kheri, Dhirpur, Dhola Mazra, Shahbad Markanda (by this time running very close to the Jammu-Delhi Toll Road again), and Mohri Railway Stations before it bridges the Tangri River.

Not too far North of the Tangri River the line enters Ambala City and arrives at Ambala Cantt Junction Railway Station.

Ambala (known as Umbala in the past – this spelling was used by Rudyard Kipling in his 1901 novel Kim) is “located 200 km (124 mi) to the north of New Delhi, India’s capital, and has been identified as a counter-magnet city for the National Capital Region to develop as an alternative center of growth to Delhi.” [26] As of the 2011 India census, Ambala had a population of 207,934.

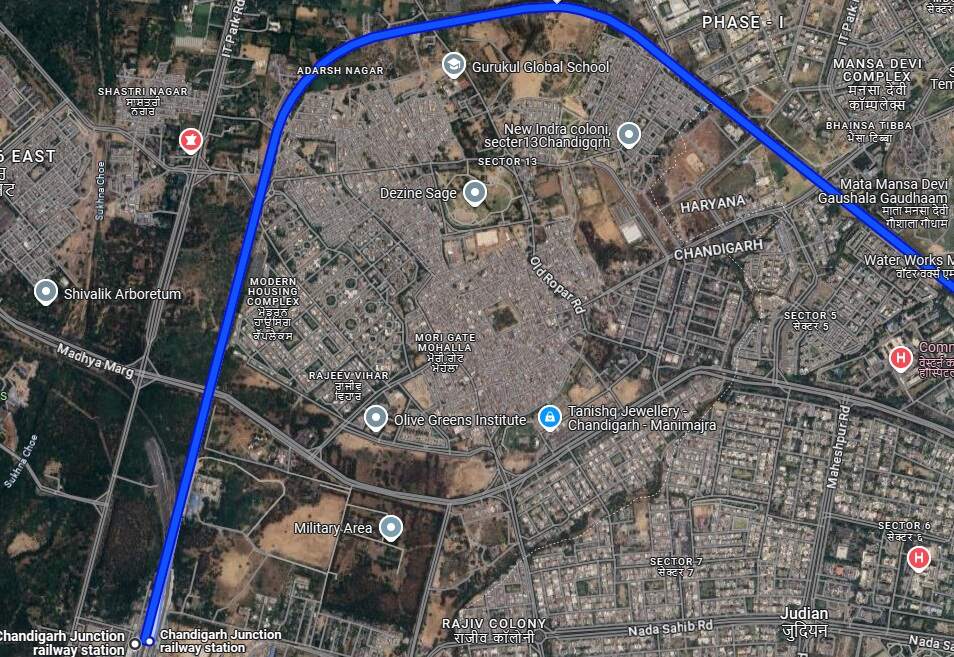

Travelling further North towards Kalka, trains start heading Northwest out of Ambala Cantt Railway Station. and pass through Dhulkot, Lalru, Dappar, Ghagghar Rauilway Stations before crossing the Ghaggar River and running on into Chandigarh.

Chandigarh Junction Railway Station sits between Chandigarh and Panchkula. it is illustrated below.

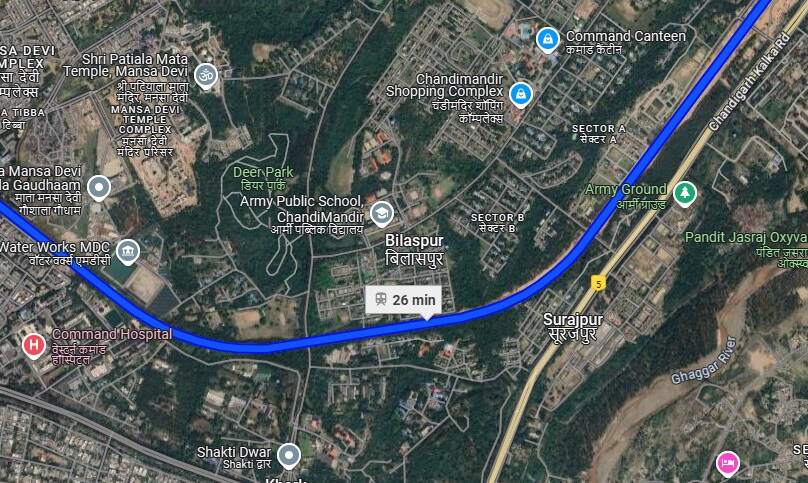

North of Chadigarh the flat plains of India give way to the first foothills of the Himalayas. What has up to this point been a line with very few curves, changes to follow a route which best copes with the contours of the land. Within the city limits of Chandigarh, the line curves sharply to the East, then to the Southeast as illustrated below.

The line then sweeps round to the Northeast.

The next railway station is that serving the military base, Chandi Mandir Railway Station. The line continues to the Northeast, then the North and then the Northwest before running into Surajpur Railway Station.

The line continues to sweep round to the Northeast before crossing the Jhajra Nadi River.

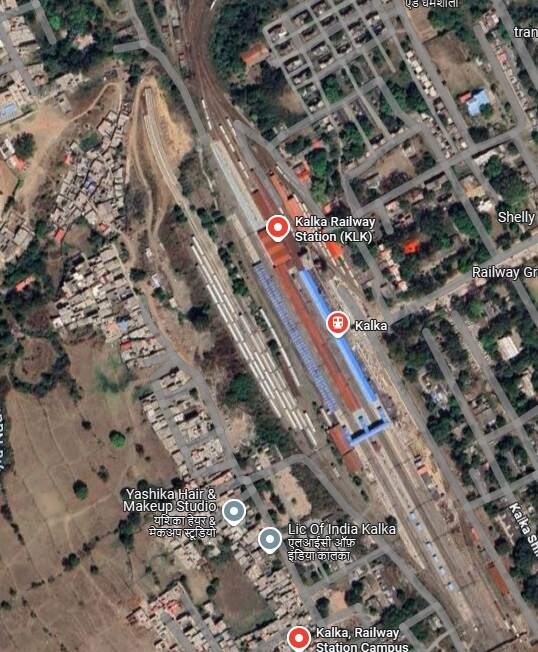

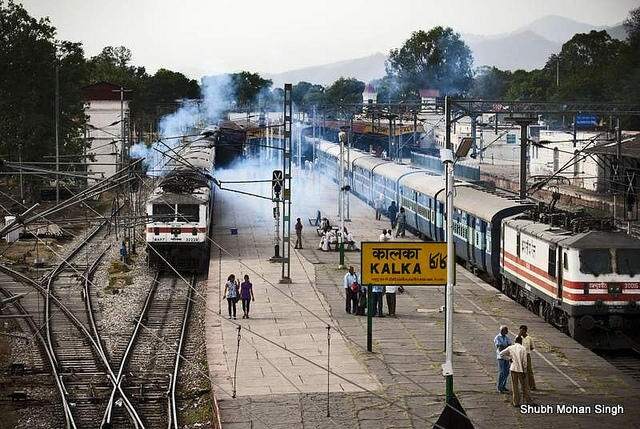

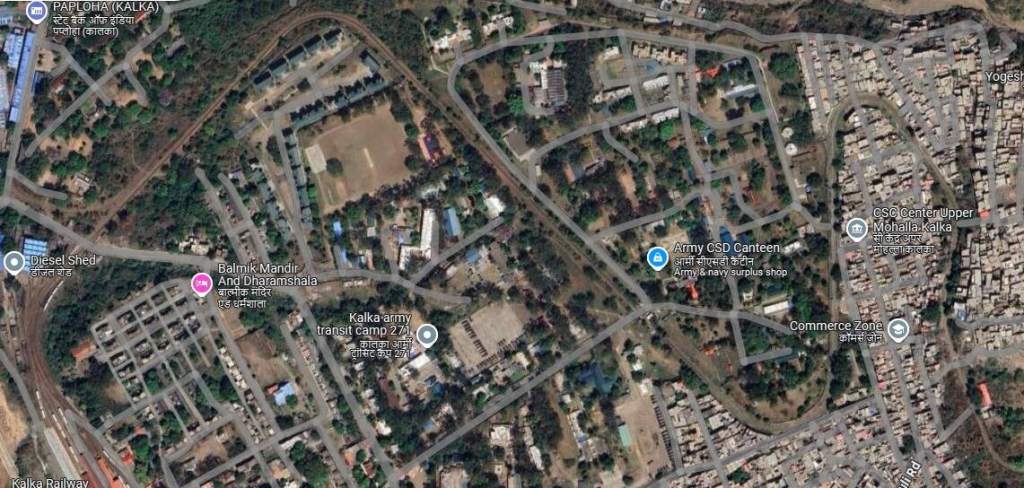

The line then runs parallel to the Jhajra Nadi River in a Northeasterly direction on its North bank before swinging round to the Northwest and entering Kalka Railway Station.

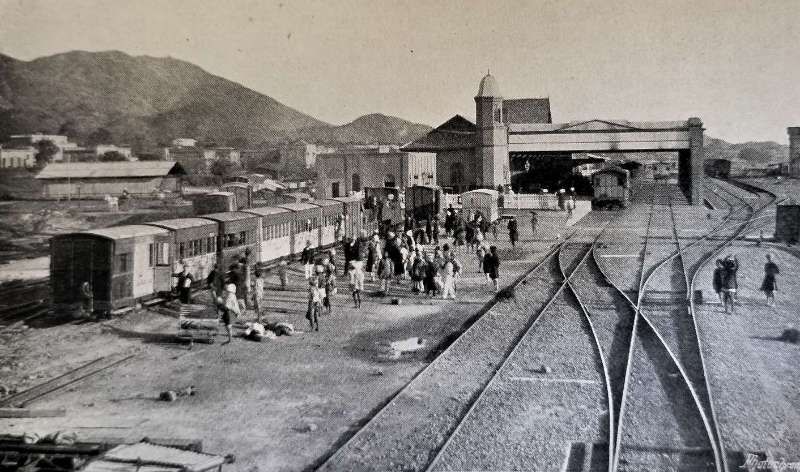

The broad gauge terminates at Kalka and the journey on into the Himalayas is by narrow-gauge train.

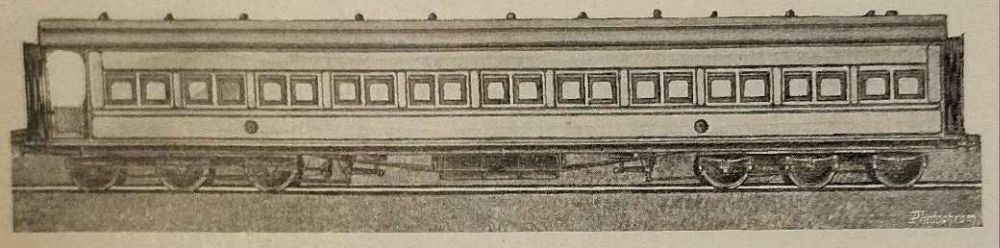

Kalka to Shimla

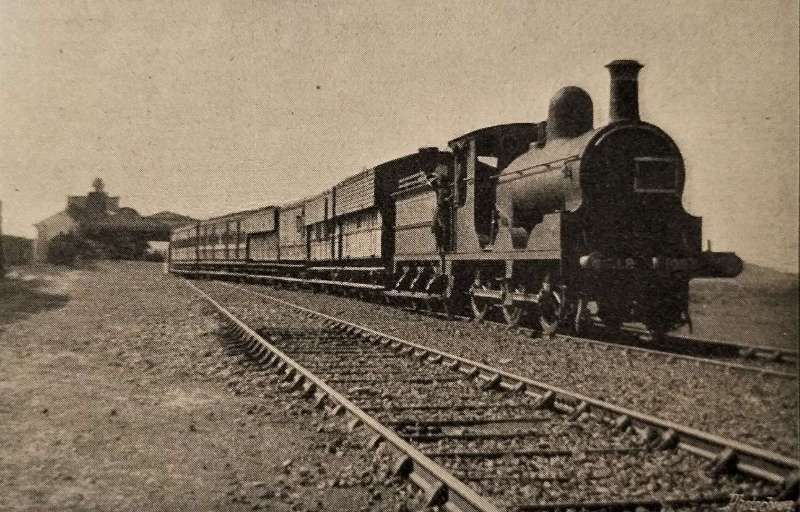

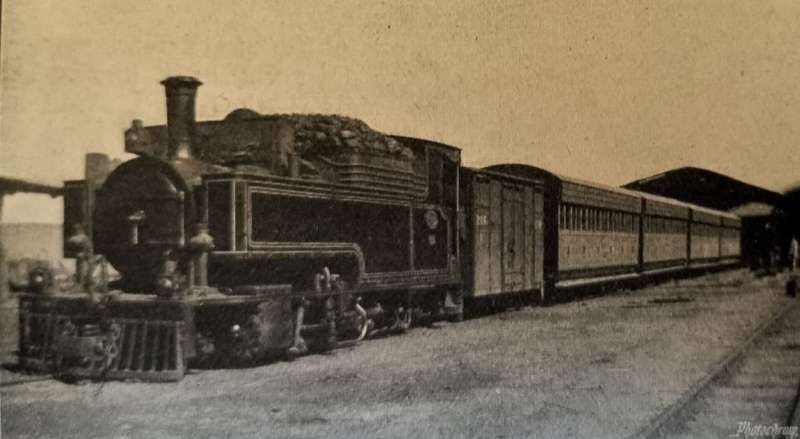

Huddleston comments: “Simla [sic] is full of hill schools, and Kalka often sees parties of happy children returning to their homes; a common enough sight in London, perhaps, but in India quite the reverse. In India, European school children only come home for one vacation in the year, and that, of course, is in the cold season when they get all their holidays at a stretch. Many of them have to journey over a thousand miles between home and school. Needless to say, the railway is liberal in the concessions it grants, and does all it can to assist parents in sending their children away from the deadly climate of the plains. … At Kalka you change into a 2 ft. 6 in. hill railway, which takes you to Simla, the summer headquarters of Government, in seven hours. If you are going up in the summer, don’t forget to take thick clothes and wraps with you, for every mile carries you from the scorching heat of the plains into the delightful cool of the Himalayas, and you will surely need a change before you get to the end of your journey. … Kalka is 2,000 ft. above sea level, Simla more than 7,000 ft., therefore, the rise in the 59 miles of hill railway is over 5,000 ft., and the fall in the temperature probably 30 degrees Fahrenheit.” [1: p45]

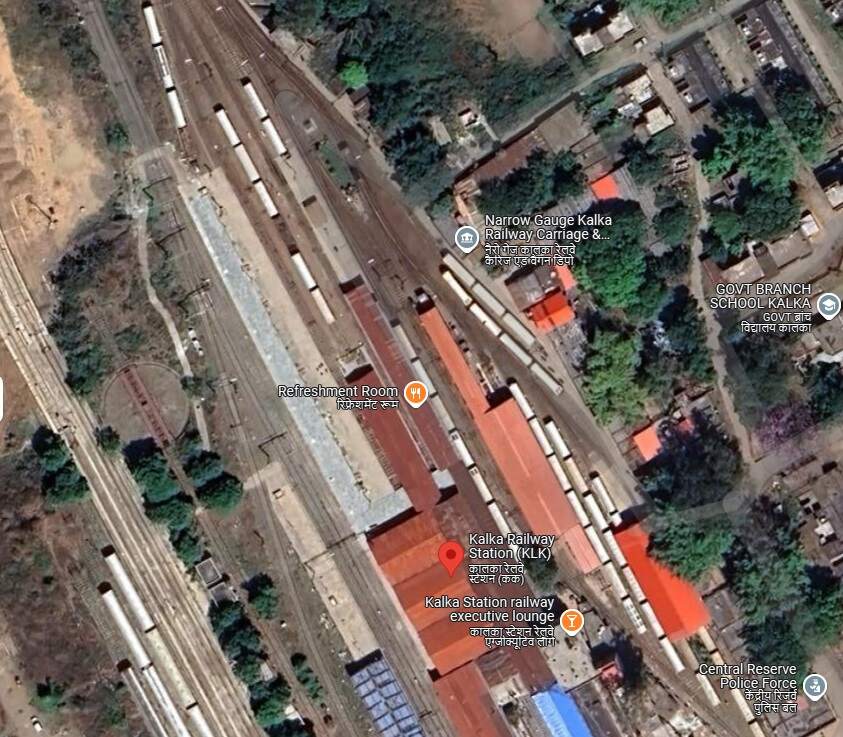

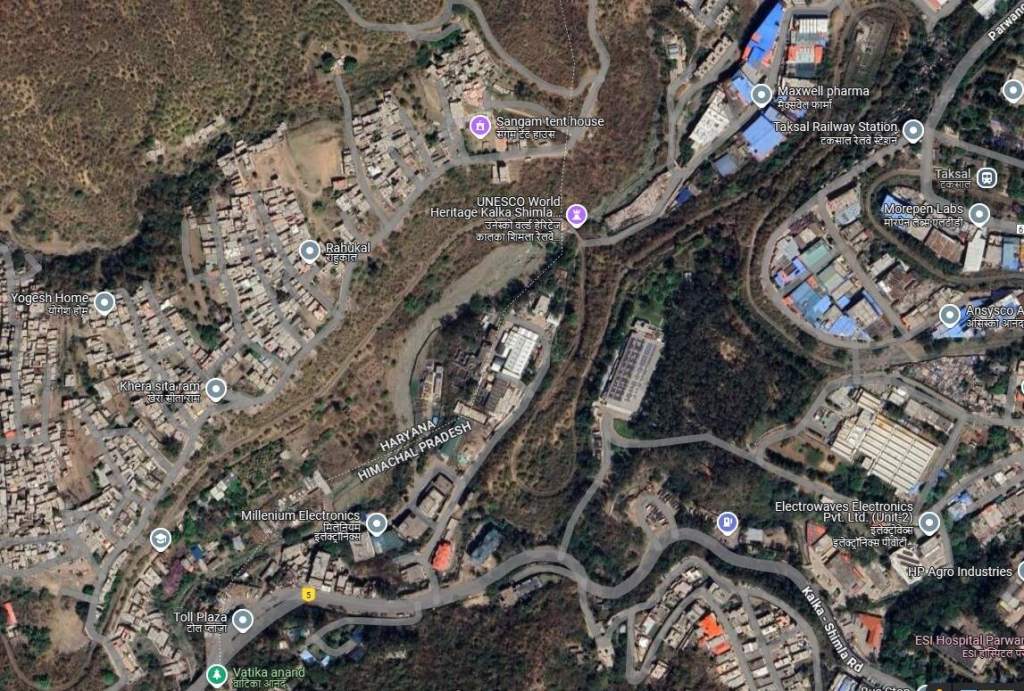

The plan is to try to follow the line of the railway as it climbs away from Kalka Railway Station. First a quick look at the narrow gauge end of Kalka Railway Station.

The two views above were taken from the rear of a Shimla-bound train. This will be true of many subsequent photographs of the line.

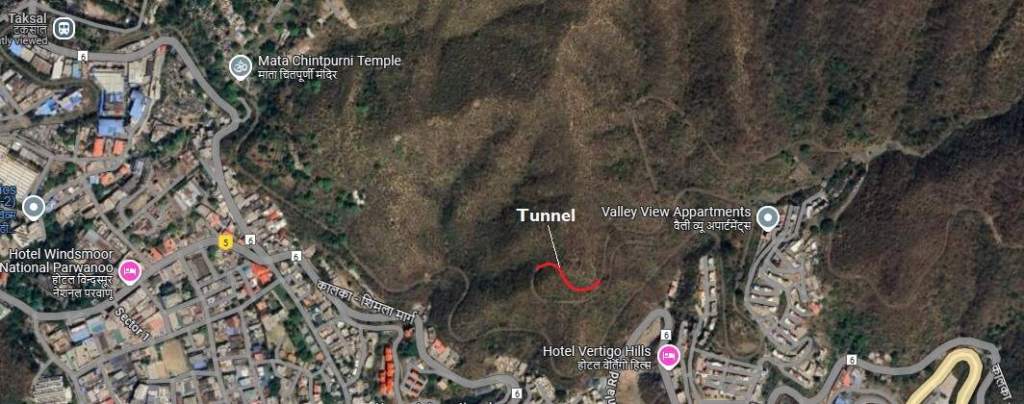

Koti Tunnel (Tunnel No. 10) is 750 metres in length. Trains for Shimla disappear into it at the station limits at Koti and emerge adjacent to the NH5 road as shown below.

For some distance the line then runs relatively close to the NH5. on its Northwest side and increasingly higher than the road. The central image below shows road and rail relatively close to each other. The left image shows the structure highlighted in the central image as it appears from the South. The right-hand image shows the same structure from the North. The structure highlighted here is typical of a number along the route of the railway.

For a short distance the line has to deviate away from the road to maintain a steady grade as it crosses a side-valley.

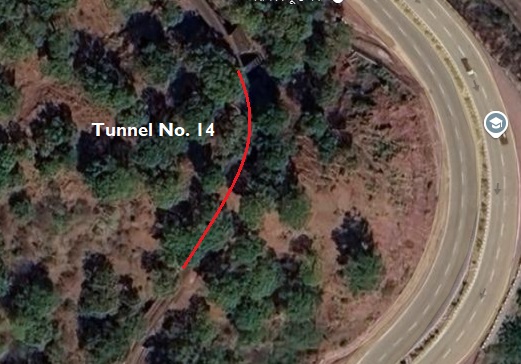

The sort tunnels above are typical of a number along the line. Tunnel No. 16 takes the railway under the NH5.

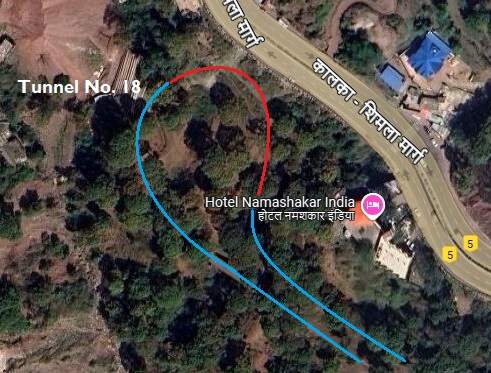

The next tunnel on the line (No. 18) is a semi-circular tunnel.

Tunnels No. 21 and No. 22 are shown below. The first image in each of these cases is the line superimposed on Google Maps satellite imagery (October 2024). The other two images, in each case, are from Google Streetview, January 2018.

A short distance North from Tunnel No. 22 is an over bridge which is shown below.

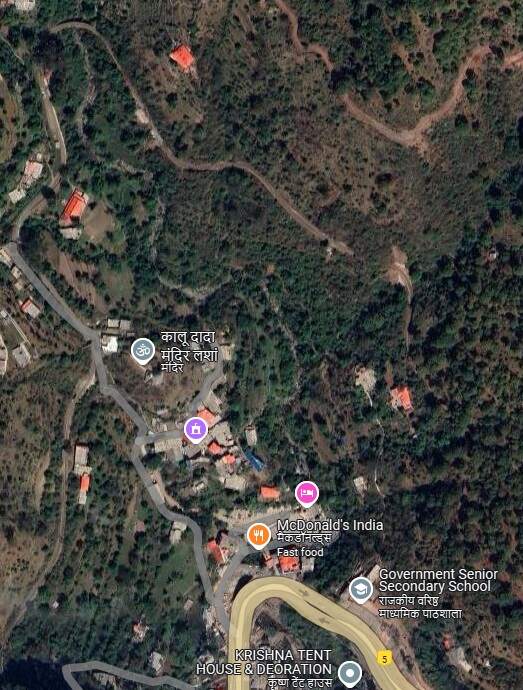

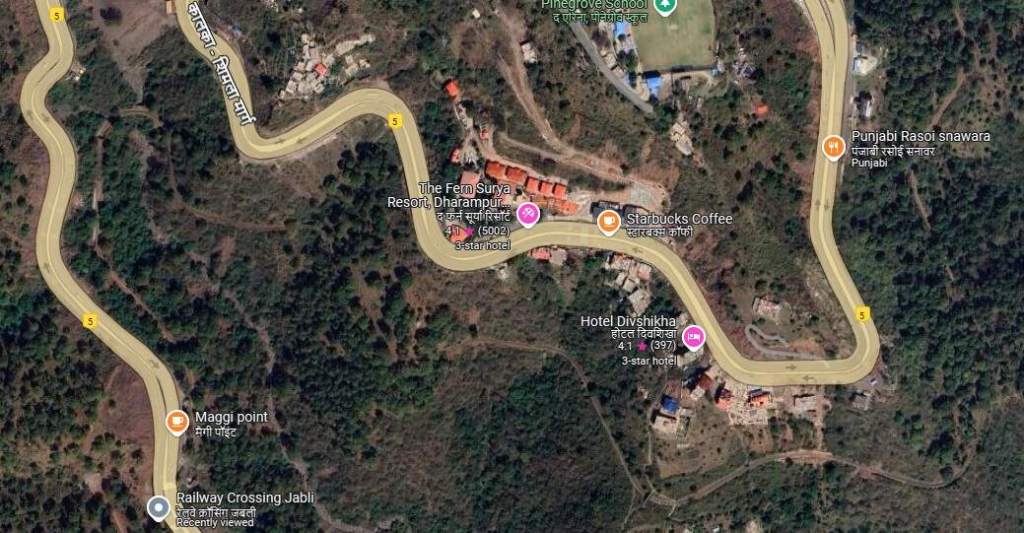

The next station is Dharampur Himachal Railway Station.

Immediately beyond the station the line is bridged by the NH5 and then enters another tunnel.

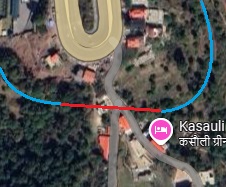

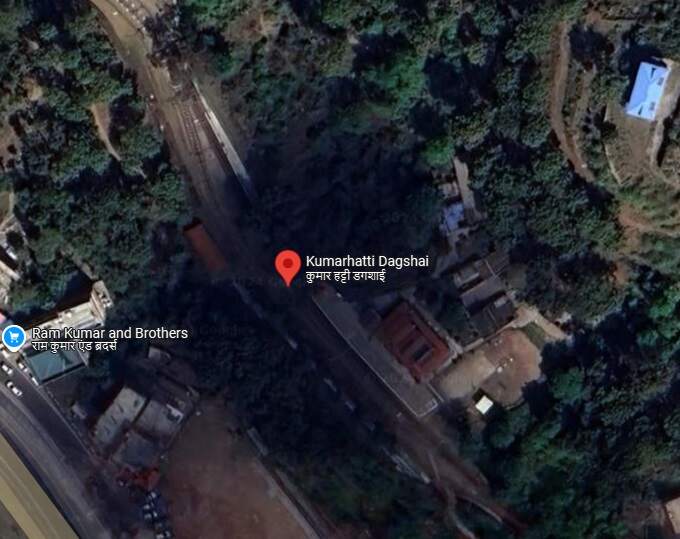

After a deviation away to the North, the railway returns to the side of the NH5. Tunnels No. 27 and 28 take the line under small villages. Another tunnel (No. 29) sits just before Kumarhatti Dagshai Railway Station.

As trains leave Kumarhatti Dagshai Railway Station, heading for Shimla, they immediately enter Tunnel No. 30.

Two short tunnels follow in quick succession, various tall retaining walls are passed as well before the line crosses a relatively shallow side-valley by means of a masonry arched viaduct.

Tunnel No. 33 (Barog Tunnel) is a longer tunnel which runs Southwest to Northeast and brings trains to Barog Railway Station.

Now back on the North side of the NH5, the line continues to rise gently as it follows the contours of the hillside. Five further short tunnels are encountered beyond Barog (Nos. 34, 35, 36, 37 and 38) before the line runs into Solan Railway Station.

Immediately to the Eat of Solan Railway Station trains enter Tunnel No. 39 and soon thereafter Tunnels Nos. 40, 41 and 42 before crossing the NH5 at a level-crossing.

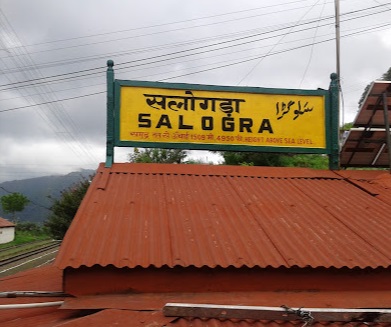

Further tunnels follow on the way to Salogra Railway Station.

A further series of relative short tunnels protects the line as it runs on the Kandaghat Railway Station.

Tunnels Nos. 56 and 57 sit a short distance to the East of the viaduct above. the line now accompanies a different highway which turns off the NH5 close to the viaduct.

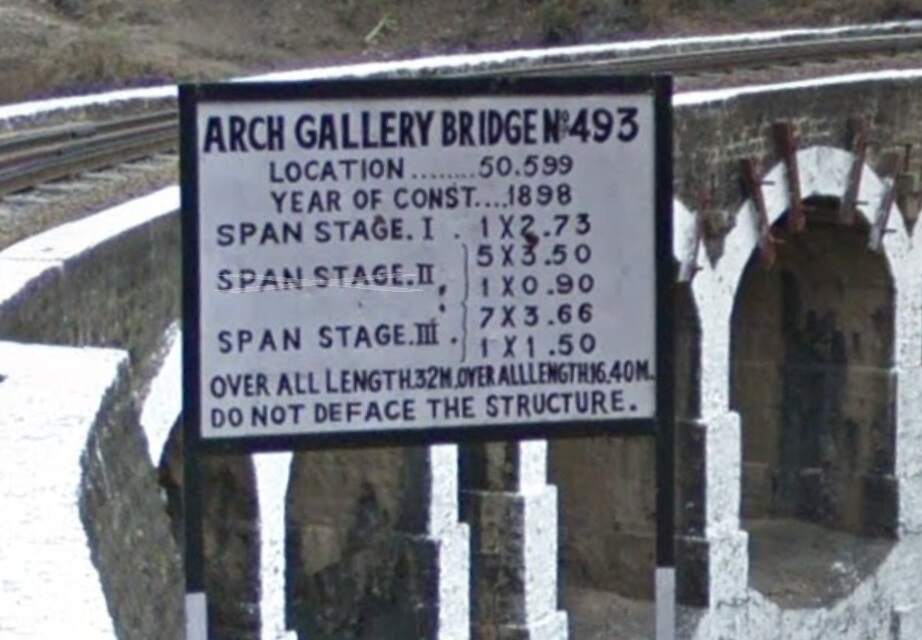

The next significant structure is the galleried arch bridge below.

More tunnels, Nos. 58 to 66 are passed before the line crosses another significant structure – Bridge No. 541 – and then runs through Kanoh Railway Station.

After Kanoh Station the line passes through a further series of short tunnels (Nos. 67-75) before meeting its old friend the NH5 (the Kalka to Shimla Road) again.

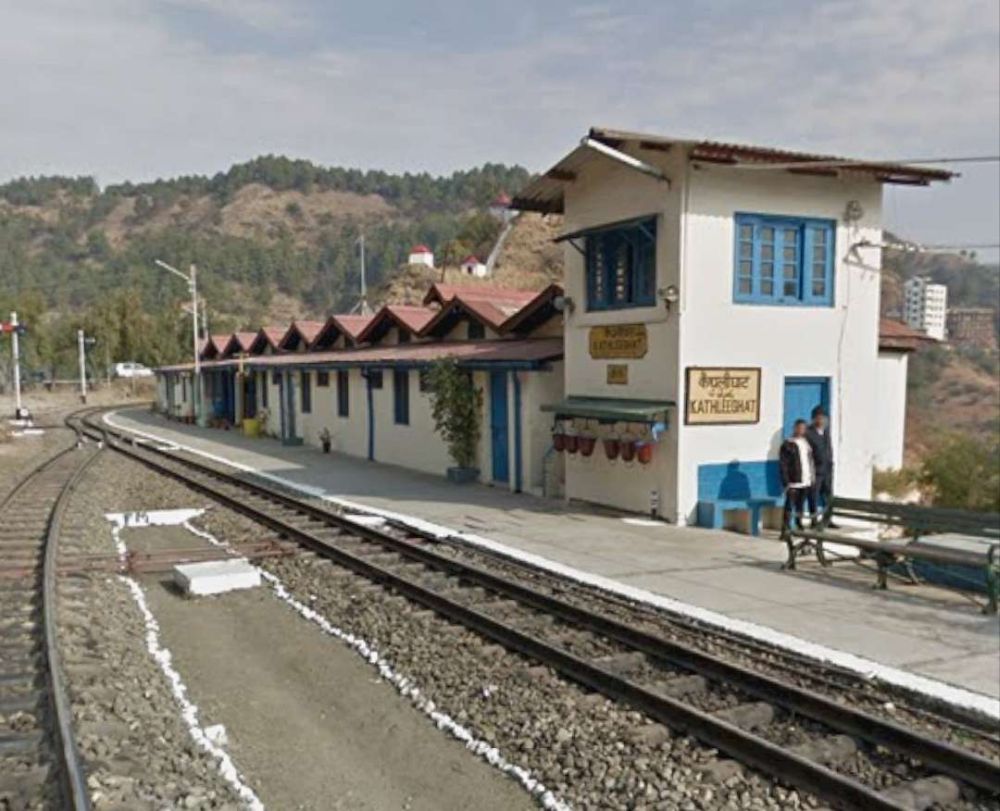

Beyond this point the line passed through Tunnels Nos. 76 and 77 before arriving at Kathleeghat Railway Station.

Immediately the Northeast of Kathleeghat Station the line enters Tunnel No. 78 under the Kalka-Shima Road (NH5) and soon heads away from the road plotting its own course forward toward Shimla through Tunnels Nos. 79 and 80, before again passing under the NH5 (Tunnel No. 81). Tunnels Nos 82 to84 follow and the occasional overbridge before the next stop at Shoghi Railway Station.

North East of Shoghi Station the line turns away from the NH5 and passing though a series of short Tunnels (Nos. 85-90) finds it own way higher into the hills before passing through Scout Halt and into a longer Tunnel (No. 91).

North of Tunnel No. 91, the line enters Taradevi Railway Station which sits alongside the NH5.

Immediately North of the station the line passes under the NH5 in Tunnel No. 92 and then runs on the hillside to the West of the road. It turns West away from the road and passes through Tunnels 93 to 98 before entering Jutogh Railway Station.

Leaving Jutogh Railway Station, the line turns immediately through 180 degrees and runs along the North side of the ridge on which the town sits. Tunnel No. 98 is followed by a short viaduct.

This viaduct sits just east of Tunnel No. 98, above the Shima-Ghumarwin Road. Just a short distance towards Shima, the same road climbs steeply over the railway which passes under it in Tunnel No. 99. [Google Streetview, January 2018]

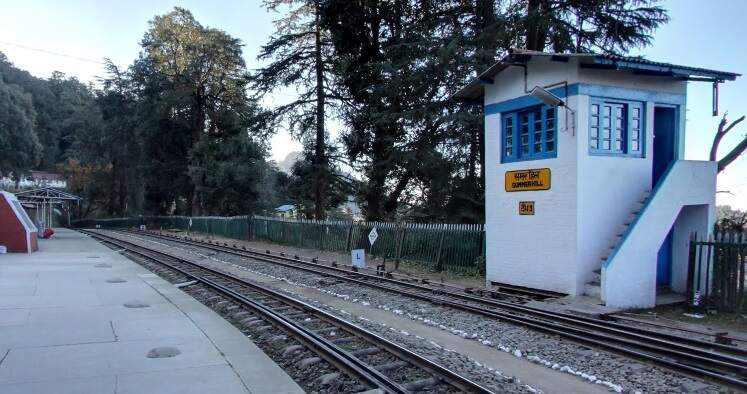

east of the road, Tunnel No. 100 is followed by a long run before an overbridge leads into Summer Hill Station.

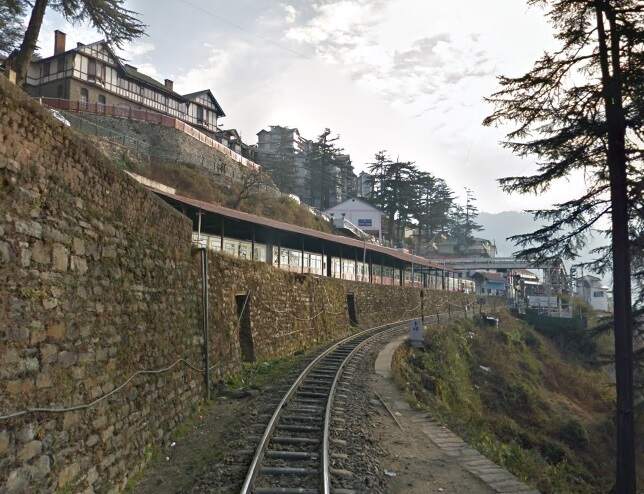

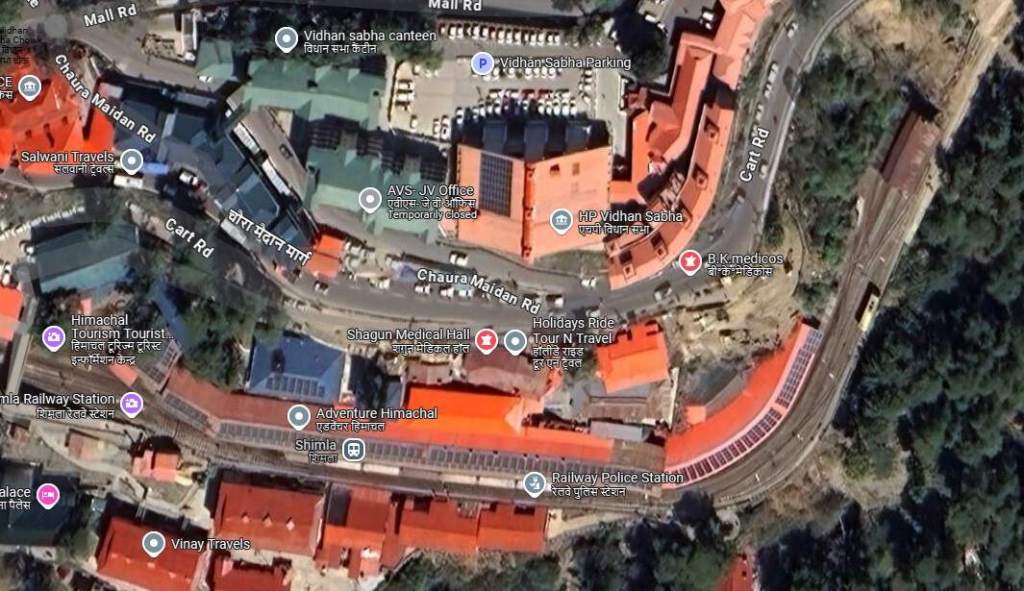

Beyond Summer Hill Station, the line immediately ducks into Tunnel No. 101 which takes it under the ridge on which Summer Hill sits and then returns almost parallel to the line whch approached Summer Hill Station but to the East of the ridge. It runs on through Tunnel No. 102 to Inverarm Tunnel (No. 103) which brings the line into Shimla.

Shimla is the end of this journey on first the East Indian Railway and its branches and then the line to Kalka before we travelled the narrow gauge Kalka to Shimla Line.

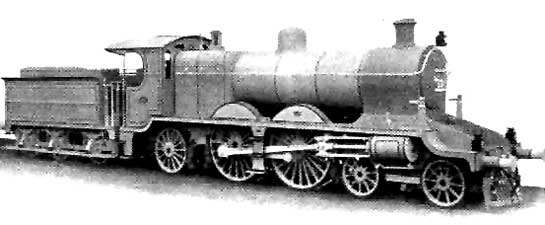

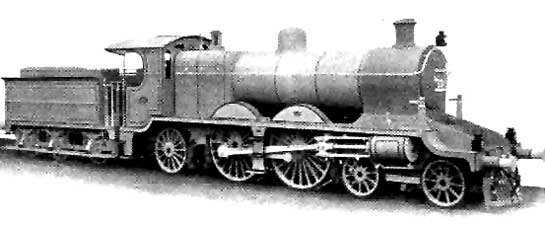

Wikipedia tells us that “the Kalka–Shimla Railway is a 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) narrow-gauge railway. … It is known for dramatic views of the hills and surrounding villages. The railway was built under the direction of Herbert Septimus Harington between 1898 and 1903 to connect Shimla, the summer capital of India during the British Raj, with the rest of the Indian rail system. … Its early locomotives were manufactured by Sharp, Stewart and Company. Larger locomotives were introduced, which were manufactured by the Hunslet Engine Company. Diesel and diesel-hydraulic locomotives began operation in 1955 and 1970, respectively. On 8 July 2008, UNESCO added the Kalka–Shimla Railway to the mountain railways of India World Heritage Site.” [28]

References

- G. Huddleston; The East Indian Railway; in The Railway Magazine, July 1906, p40-45.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/10/16/the-east-indian-railway-the-railway-magazine-december-1905-and-a-journey-along-the-line/

- https://hillpost.in/2005/01/kalka-shimla-railway/30, accessed on 24th October 2024.

- https://indiarailinfo.com/train/map/train-running-status-shikohabad-farrukhabad-passenger-485nr/6070/903/2192, accessed on 24th October 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shikohabad, accessed on 25th October 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shikohabad_Junction_railway_station, accessed on 25th October 2024.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130728090858/http://mainpuri.nic.in/gaz/chapter7.htm, accessed on 25th October 2024.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=1ehvDEs2pt4, accessed on 25th October 2024.

- http://64.38.144.116/station/blog/2193/0, accessed on 25th October 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ganga-Jamuni_tehzeeb, accessed on 26th October 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Farrukhabad_district, accessed on the 26th October 2024.

- C.A. Bayly; Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion, 1770–1870; Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2012.

- “District Census Handbook: Farrukhabad” (PDF). (censusindia.gov.in). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 2011.

- “Table C-16 Population by Mother Tongue: Uttar Pradesh”. (www.censusindia.gov.in). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

- Decadal Variation In Population Since 1901. (www.censusindia.gov.in)

- “Table C-01 Population by Religion: Uttar Pradesh”. (www.censusindia.gov.in). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 2011.

- https://www.irfca.org/gallery/Heritage/JUMNA+BRIDGE+AGRA+-+1.JPG.html, accessed on 27th October 2024.

- https://wiki.fibis.org/w/Yamuna_Railway_Bridge(Agra), accessed on 27th October 2024.

- https://cityseeker.com/agra/723275-stretchy-bridge, accessed on 27th October 2024.

- https://www.etsy.com/no-en/listing/235077088/1962-agra-india-vintage-map, accessed on 27th October 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delhi_Junction_railway_station, accessed on 27th October 2024.

- https://m.economictimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/now-swachh-drive-at-delhi-railway-station/articleshow/47754817.cms, accessed on 27th October 2024

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Delhi_railway_station, accessed on 27th October 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonipat_Junction_railway_station, accessed on 28th October 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panipat_Junction_railway_station, accessed on 28th October 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambala, accessed on 29th October 2024.

- https://st2.indiarailinfo.com/kjfdsuiemjvcya0/0/1/8/2/933182/0/7226151664bda48a8152z.jpg, accessed via https://indiarailinfo.com/station/map/kalka-klk/1982 on 29th October 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalka%E2%80%93Shimla_Railway, accessed on 2nd November 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:KSR_Steam_special_at_Taradevi_05-02-13_56.jpeg, accessed on 2nd November 2024.