Back in 2013, I wrote a short blog about the line from Plan du Var to St. Martin-Vesubie:

Back in 2013, I wrote a short blog about the line from Plan du Var to St. Martin-Vesubie:

Many of the images in that post were culled from a blog by Marc Andre Debout. [1] It feels appropriate that I should revisit my blog and update it. I have discovered significantly more about the route and I’d like to complete a detailed survey of the route.

An interesting survey of the line was undertaken for the French website “http://www.inventaires-ferroviaires.fr” (written in French) [2] which I have drawn on, along with the things, in producing this post.

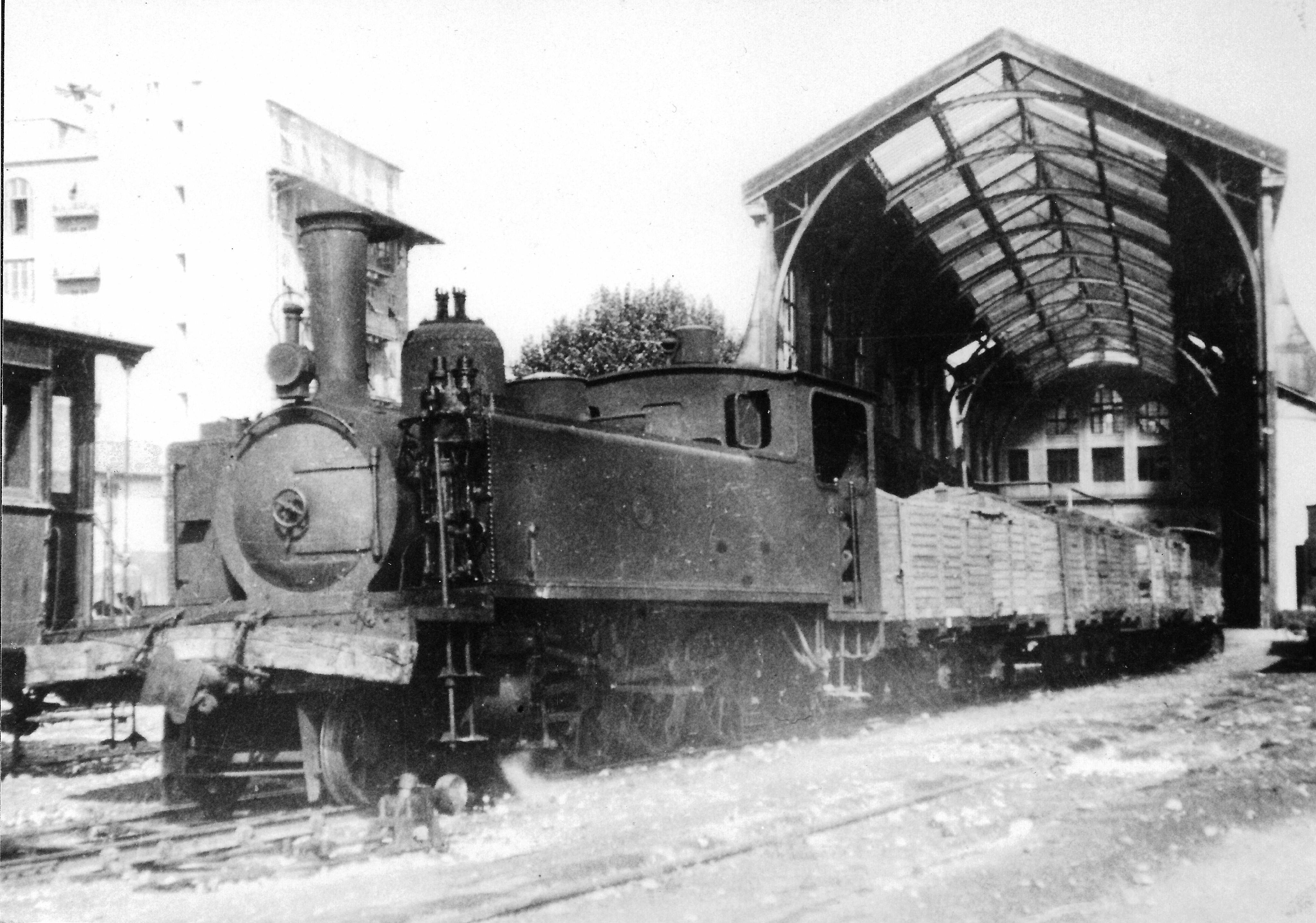

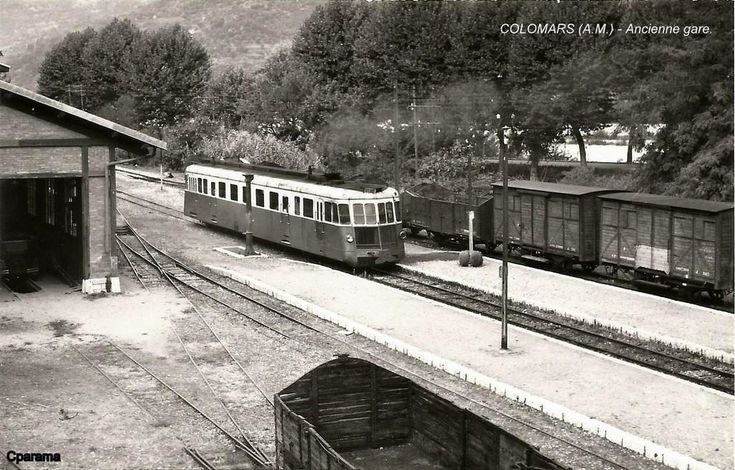

The “Brissonneau” heads, a freight train in La Vésubie station. Bernard Rozé Collection – published by BVA, April 1956. [4] This will have been taken after the closure of the tramway (1929).

The “Brissonneau” heads, a freight train in La Vésubie station. Bernard Rozé Collection – published by BVA, April 1956. [4] This will have been taken after the closure of the tramway (1929). Also taken at Plan du Var, this could only be a train off the tramway during the first year of its life 1909 to 1910. It is more likely to be a Digne to Nice train. [4]

Also taken at Plan du Var, this could only be a train off the tramway during the first year of its life 1909 to 1910. It is more likely to be a Digne to Nice train. [4]

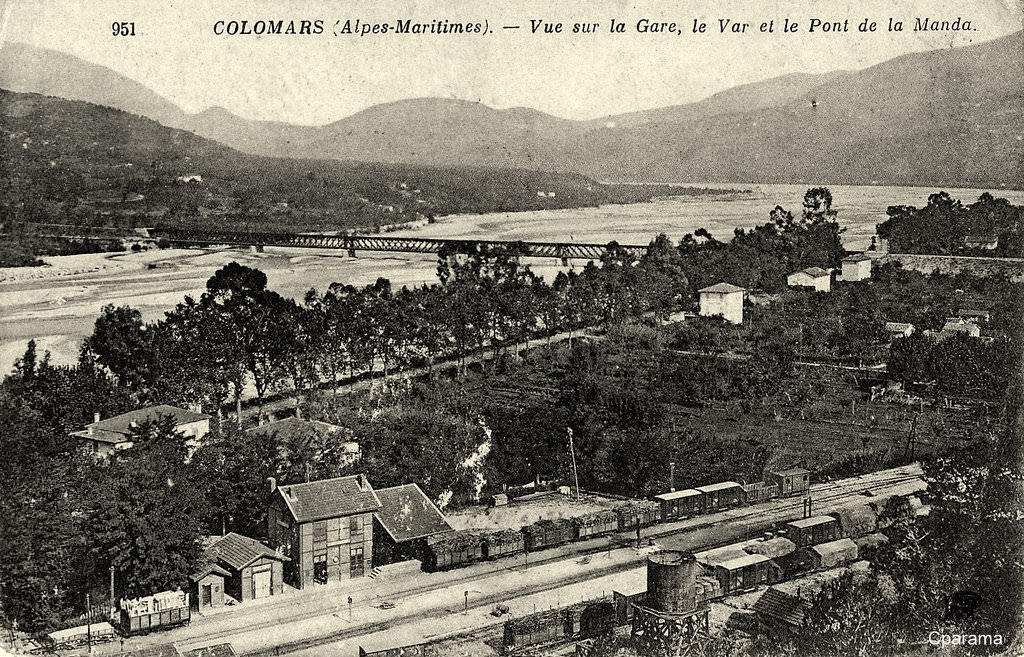

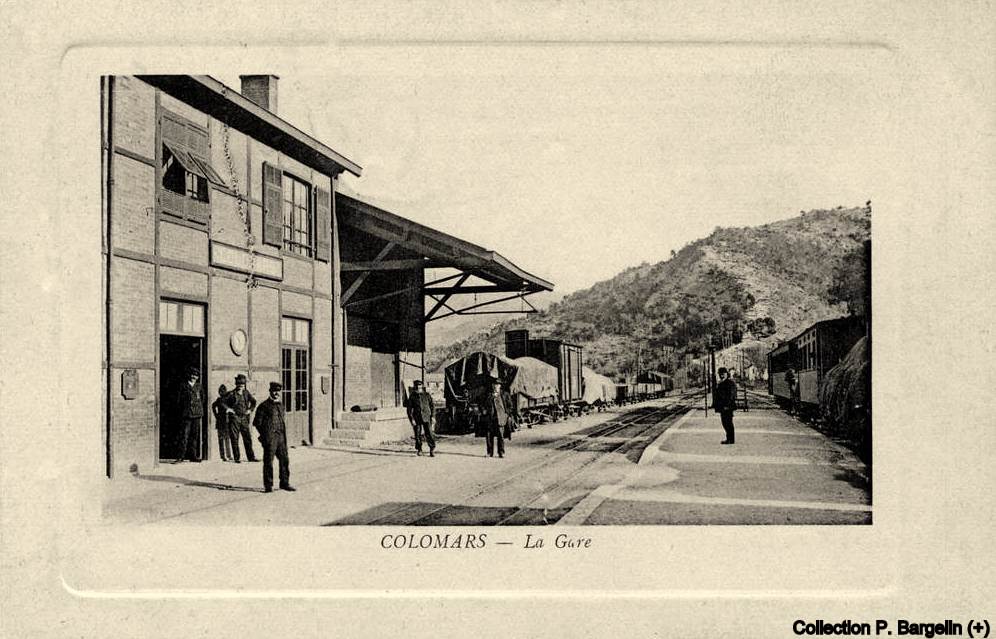

Tramway services left Plan du Var Station travelling North and diverged from the Nice to Digne line before reaching the Vesubie River. The images below are old postcards of the location of the junction and show the development of the site over a number of years. Initially an stone arch bridge took the road over the Vesubie, but when this failed is was replaced by the concrete arch bridge visible in some of the pictures.

The first picture shows the location prior to the construction of a number of buildings to the North of the confluence. The second still has the old arch bridge and includes those buildings. The third shows both the tramway and the new bridge. The fourth encompasses both bridge and junction but it is [possible that the tramway peters out when it reaches the tarmac of the road over the Pont Durandy. If that is the case, then the fourth photograph was probably taken after the closure of the tramway in 1929.

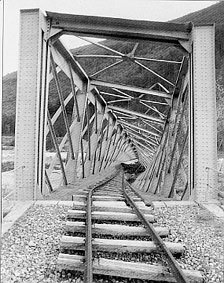

Taken from the railway in the 21st Century. This picture shows the truss girder bridge over the Vesubie on the Nice Digne Line and the road bridge (Concrete Arch) behind the vegetation.

Taken from the railway in the 21st Century. This picture shows the truss girder bridge over the Vesubie on the Nice Digne Line and the road bridge (Concrete Arch) behind the vegetation.

The two postcard pictures immediately above were found for sale on the collection-jfm.fr website in 2018. [5]

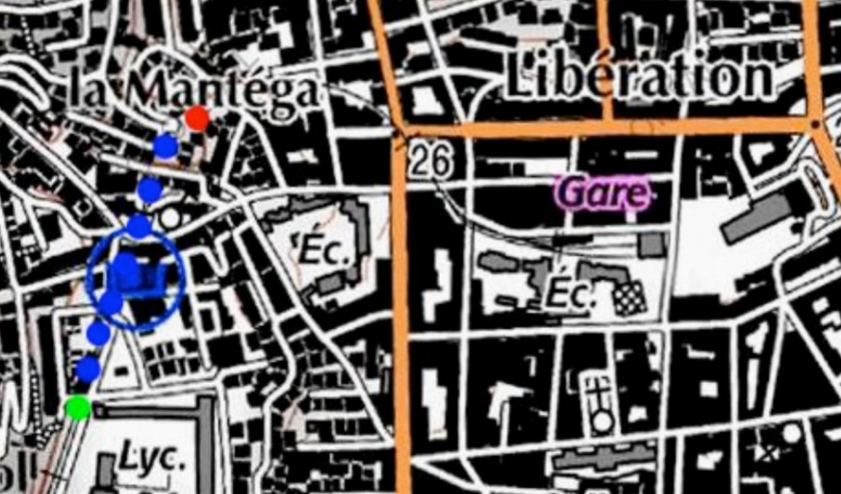

The two postcard pictures immediately above were found for sale on the collection-jfm.fr website in 2018. [5] The 1955 1:50,000 IGN map shows a track which was once the tramway along the Vesubie River Valley commencing at the road bridge, Pont Durandy, and running under the ’43’ (on the map) before turning North to cross the river and join the roadway up the valley. [3]

The 1955 1:50,000 IGN map shows a track which was once the tramway along the Vesubie River Valley commencing at the road bridge, Pont Durandy, and running under the ’43’ (on the map) before turning North to cross the river and join the roadway up the valley. [3] The plan above shows the road route into the Vesubie Valley marked with the green arrow the blue dotted line is that of the old tramway. The tram line crossed the road just before the Vésubie bridge. She went up this last about 400m before crossing it in turn on a bridge that has now disappeared. [2] The image below shows the location of the tramway formation as it can be seen in the early 21st Century. [2]

The plan above shows the road route into the Vesubie Valley marked with the green arrow the blue dotted line is that of the old tramway. The tram line crossed the road just before the Vésubie bridge. She went up this last about 400m before crossing it in turn on a bridge that has now disappeared. [2] The image below shows the location of the tramway formation as it can be seen in the early 21st Century. [2]

After traveling for around 400m on the South side of the Vesubie River the tramway crossed to the North side and joined the road at the point shown on the image above.

After traveling for around 400m on the South side of the Vesubie River the tramway crossed to the North side and joined the road at the point shown on the image above.

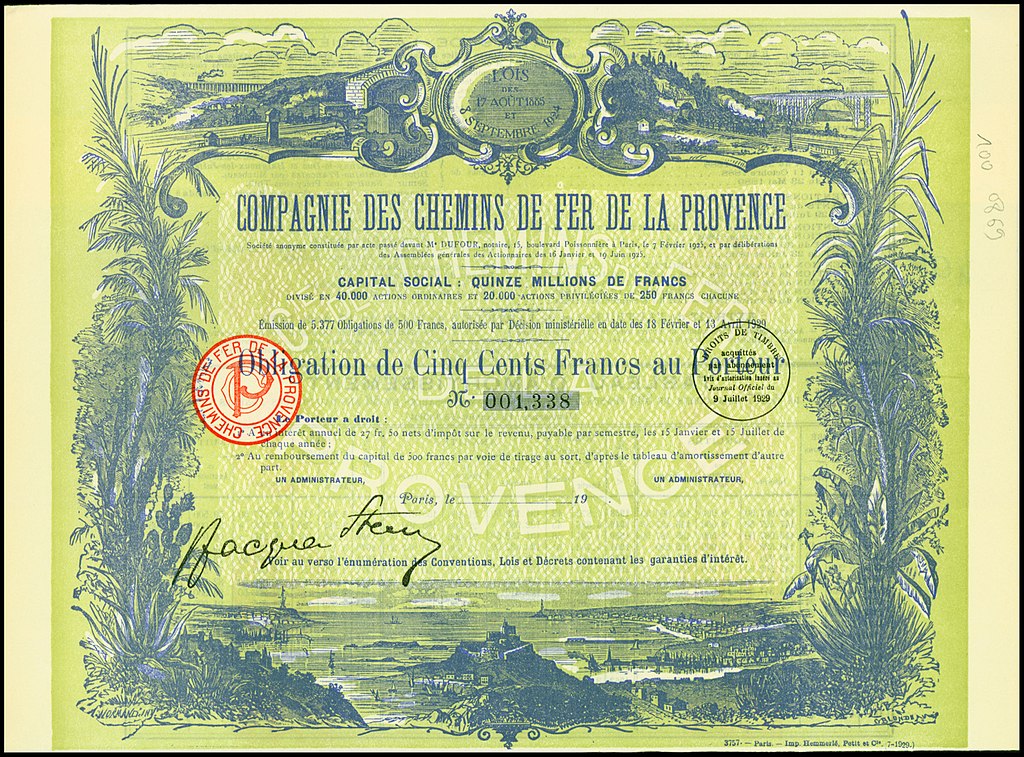

The General Council of the department decided to construct of three lines in the area on 10th February 1906. They were The Plan-du-Var – Saint-Martin-Vésubie line for the Vésubie valley and, for the Tinée valley, the “La-Tinée” line – Saint-Sauveur-sur-Tinée. These two lines were given to the TAM (Tramways of the Alpes-Maritimes) to manage [6] . The third line was the Nice – Levens line, allocated to the TNL (Trams of Nice and Littoral). [7]

Within just a few weeks of the establishment of a Municipal Council for St. Martin-Vesubie (1908) a campaign was inaugurated to see modifications to the proposed tram service to the town/village which included revisions to the planned station location and layout. The budget for the station site was originally 6,000 francs. The revised and agreed scheme amounted to 10,000 francs.

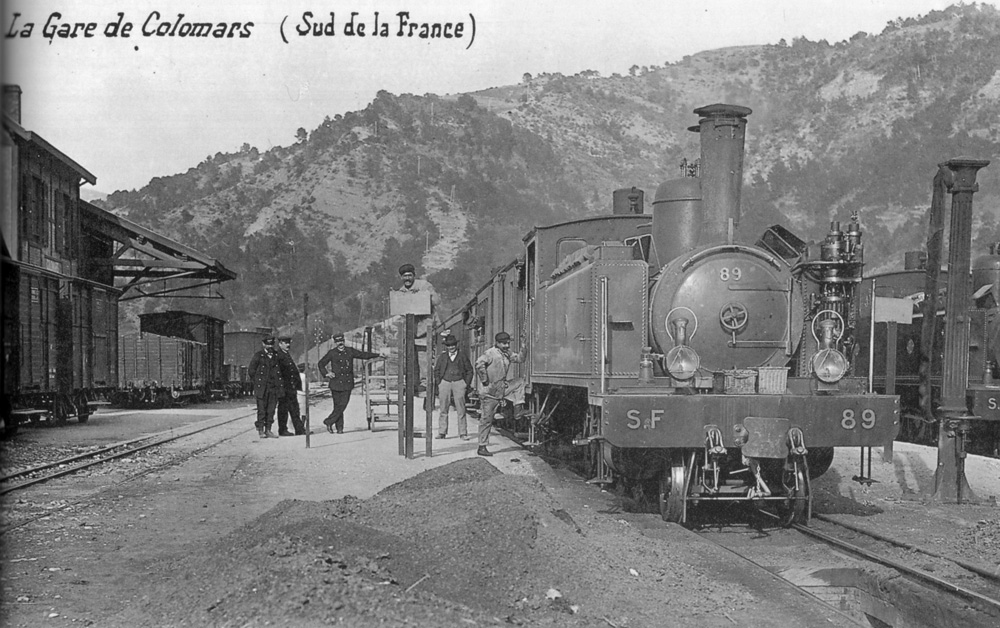

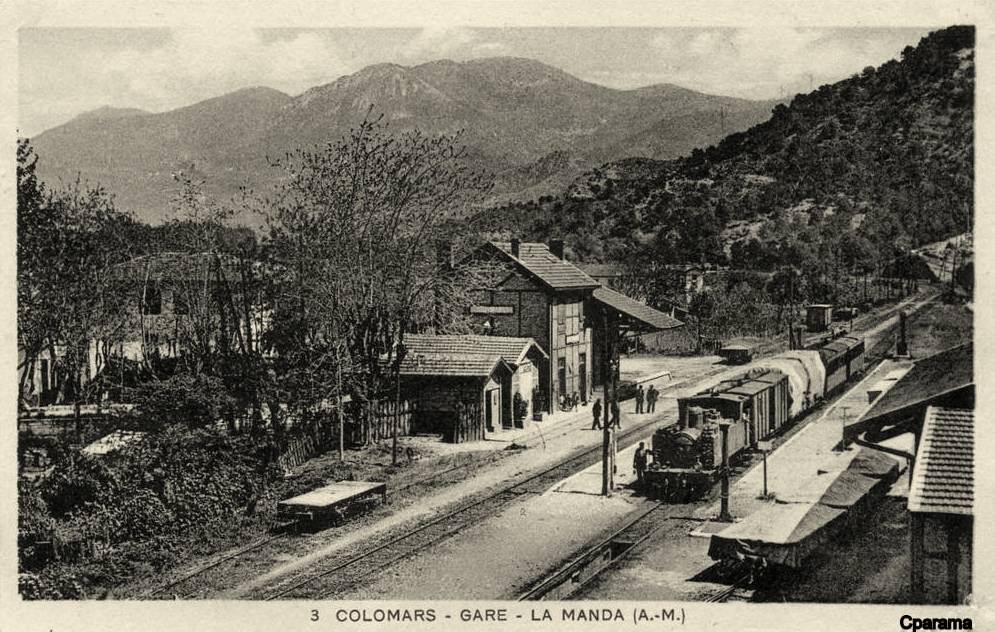

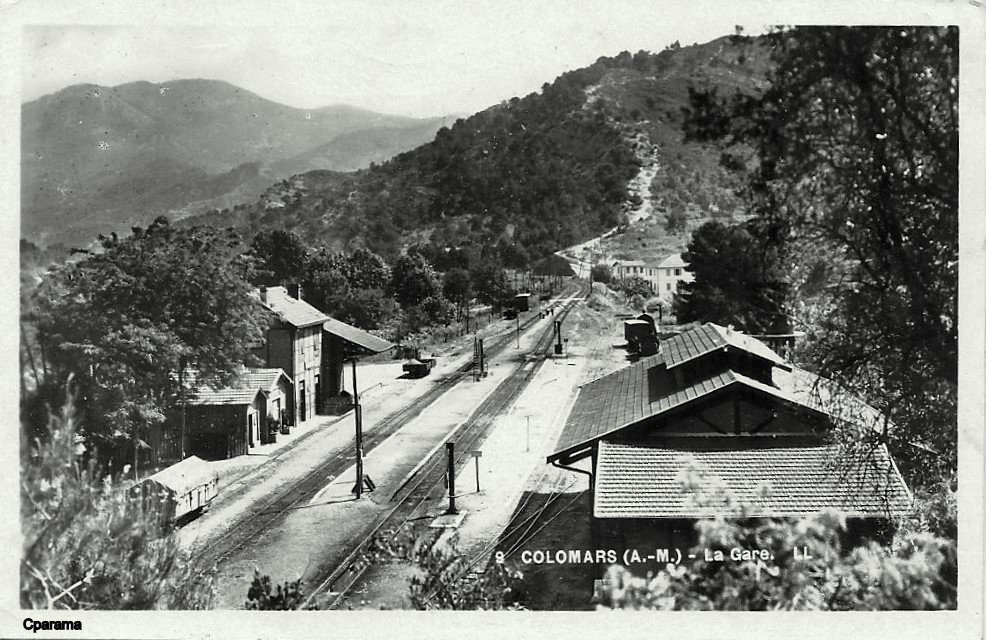

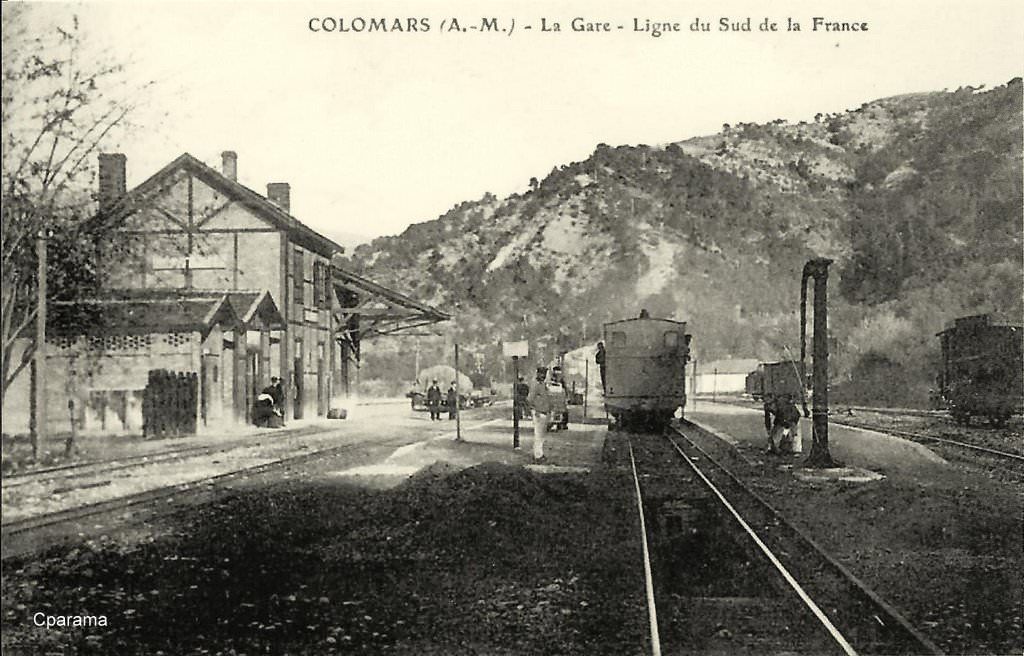

Considered a priority, the Vésubie line was commissioned in 1909. Construction took place, during that year and the line opened on 1st September 1909. However, electric powered tramcars were not delivered in time for the opening and for approximately one year steam engines were in use on the line. Electric trams finally entered service in 1910.

The trams allowed both good s and passengers to be transported quickly: the cans of milk from the pastures were delivered directly to the centre of Nice and other perishable items also reached buyers much more quickly.

In translating French to English in my last post on this line, I managed to misconstrue the history of the line. In that post I said that the line did not reach St. Martin Vesubie until 1928 and Roquebillière in 1926. What I should have understood at the time was that there was an interruption in the service betwen 1926 and 1928. A huge landslide that buried the village of Roquebillière also covered roads and railways. 24th November 1926, date of the tragedy, was engraved in local memories. As a result, the saints-martinois had to take a bus to complete their journey until the trams were again allowed to cross the landslide in September 1928. This transhipment promoted the use of coaches instead of trams and as a result it was decided to close the line in 1929. Tram transport was, by then considered archaic in the face of competition from the automobile.

Positive decisions in favour of the tramway were regularly made within the local communes and the tramway was seen positively until the advent of the Great War. However, the last action by the Municipal Council relating to the line was the refusal of an increase in tariffs on the line because of the increased competition from buses and lorries It seems that the demise of the tramway was already anticipated, long before the Roquebillière disaster provided what was ultimately the fatal blow to the line.

Positive decisions in favour of the tramway were regularly made within the local communes and the tramway was seen positively until the advent of the Great War. However, the last action by the Municipal Council relating to the line was the refusal of an increase in tariffs on the line because of the increased competition from buses and lorries It seems that the demise of the tramway was already anticipated, long before the Roquebillière disaster provided what was ultimately the fatal blow to the line.

I came across the adjacent image of a Nice-St. Martin bus, while researching the route on the internet. I cannot remember where I found it. It is perhaps easy to see that the newer and more reliable buses provided very strong competition for the trams.

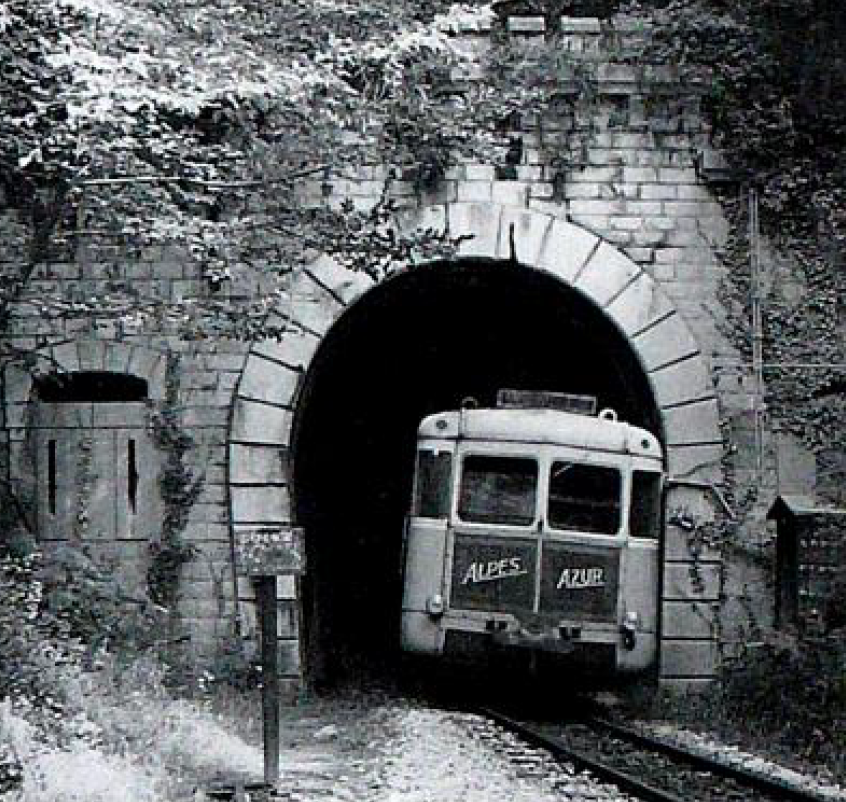

Once the tramway crossed to the north side of the Vesubie close to Plan du Var, it followed the road perched above the river [10] for some distance. There was a short tunnel through which the old road passed in the 1950s which was probably in existence at the time of the tramway.

Once the tramway crossed to the north side of the Vesubie close to Plan du Var, it followed the road perched above the river [10] for some distance. There was a short tunnel through which the old road passed in the 1950s which was probably in existence at the time of the tramway.

The road leading to that tunnel (and the route of the old tramway) can be seen below diverging from the newer road and tunnel. [11] The image is taken from Google Streetview. A similar image shows the old road/tramway formation, close to the River Vesubie, returning to join the newer road/tunnel on the north side of the rock outcrop. After the tunnel the formation/road passes through La Madone (La Cros d’Utelle) still following what is the northwest bank of the river.

A typical early postcard view of the road alongside the River Vesubie before the tramway was constructed. [8]

A typical early postcard view of the road alongside the River Vesubie before the tramway was constructed. [8] A typical scene on the road up the Vesubie Gorge. This picture was taken in February 2017. The road was closed to allow the landslide to be removed and the site secured. [9]

A typical scene on the road up the Vesubie Gorge. This picture was taken in February 2017. The road was closed to allow the landslide to be removed and the site secured. [9] The station building next to the river at La Cros d’Utelle (La Madone). [1]

The station building next to the river at La Cros d’Utelle (La Madone). [1]

From La Madone (La Cros D’Utelle), the tramway continued along the West bank of the Vesubie and through a short (20 metre) rough-hewn tunnel which is shown in the map below and in the two images which immediately follow the map. [11]

The pictures immediately above show typical scenes along the route of the tramway formation which is now hidden under the M2565 road through the Vesubie Gorge. The first picture is from Google Streetview and shows a narrow private footbridge providing access to a steep footpath on the East bank of the river. The second shows a tunnel and almost hidden a bridge supporting the road over the river. The third photograph shows the entrance to the tunnel (Tunnel de Pagary Longeur) which is located on the map below. [11]

The pictures immediately above show typical scenes along the route of the tramway formation which is now hidden under the M2565 road through the Vesubie Gorge. The first picture is from Google Streetview and shows a narrow private footbridge providing access to a steep footpath on the East bank of the river. The second shows a tunnel and almost hidden a bridge supporting the road over the river. The third photograph shows the entrance to the tunnel (Tunnel de Pagary Longeur) which is located on the map below. [11]

Interestingly, the TAM lines were equipped with a single-phase electrical supply of 6600 Volts, 25 Hertz. The catenary was suspended from wooden posts or cliff walls by metal brackets. Th electric traction units worked throughout the life of the tramway (approximately 20 years) although some improved units were provided in 1920 on the line of Vésubie. In 1911, four to five round trips of trams were scheduled each day. But by 1914, because of the war, there were only two daily movements until the line was closed in 1929. [7]

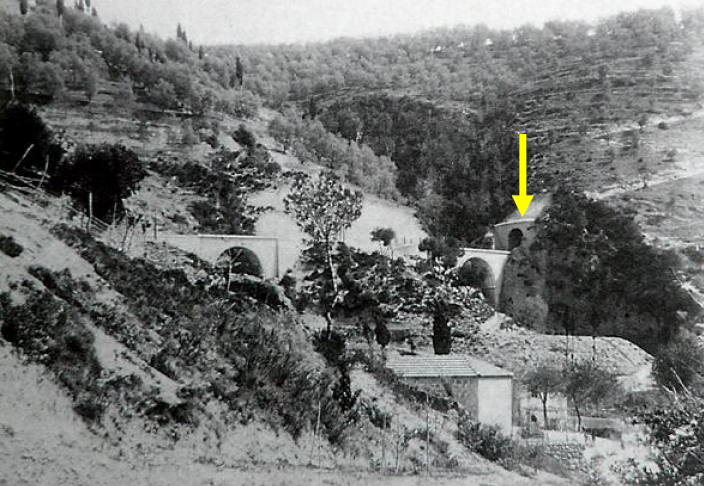

North of the tunnel the gorge narrowed significantly and hemned in the tramway. The adjacent photograph gives an idea of just how narrow the gorge cut by the Vesubie is/was at this point. As the gorge widens out again the tramway took the opportunity to cross the Vesubie onto its eastern bank by means of a very graceful arch bridge.

North of the tunnel the gorge narrowed significantly and hemned in the tramway. The adjacent photograph gives an idea of just how narrow the gorge cut by the Vesubie is/was at this point. As the gorge widens out again the tramway took the opportunity to cross the Vesubie onto its eastern bank by means of a very graceful arch bridge.

In the image below, Google Streetview has allowed me to pick out the bridge through the local vegetation. That photo is then followed by an older postcard picture of the bridge [1] – the first Pont de St-Jean-la-Riviere. There is a later bridge built immediately adjacent to the village which took a road over to the Westbank and up to Utelle.

The bridge in the two images above is shown at the bottom left of the IGN map above, close t toe Colombier. The second, newer bridge is immediately adjacent to the village of St-Jean-la-Riviere where the M32 leaves the M2565/M19. The newer bridge is shown below. [12] Between these two bridges the tramway followed the West bank of the Vesubie while the main road took to the East bank. [2]

The bridge in the two images above is shown at the bottom left of the IGN map above, close t toe Colombier. The second, newer bridge is immediately adjacent to the village of St-Jean-la-Riviere where the M32 leaves the M2565/M19. The newer bridge is shown below. [12] Between these two bridges the tramway followed the West bank of the Vesubie while the main road took to the East bank. [2]

The station at St. Jean la Riviere on the south-west side of the river, circled in red on the map below. It is now the town hall! [1][2]

The station at St. Jean la Riviere on the south-west side of the river, circled in red on the map below. It is now the town hall! [1][2] From the new bridge, the line travelled up the East bank of the Vesubie northwards out of the village of St. Jean la Riviere. In a couple of kilometres, the tramway crossed back to the west bank of the river by means of the bridge below.

From the new bridge, the line travelled up the East bank of the Vesubie northwards out of the village of St. Jean la Riviere. In a couple of kilometres, the tramway crossed back to the west bank of the river by means of the bridge below.

Within 300 metres, the Tarmway returned to the East bank by means of the structure show below.

Within 300 metres, the Tarmway returned to the East bank by means of the structure show below. The tramway and road then travelled in an easterly direction towards Le Suquet.

The tramway and road then travelled in an easterly direction towards Le Suquet.

Close to Le Suquet, the Gorge opens out and the tramway formation/road drift away from the River Vesubie before turning northwards to cross the river once again. Then for a time the tramway and road kept their distance from the river.

The station building at Le Suquet [1] is shown on the adjacent plan circled in red. The bridge in the postcard above is circled in blue. [2]

The station building at Le Suquet [1] is shown on the adjacent plan circled in red. The bridge in the postcard above is circled in blue. [2]

North of Le Suquet, a new tunnel takes the M2565 on a straighter course than the old road/tramway took. The older route can be seen on the right-hand side of the picture below.. The northern portal of the new tunnel can be seen in the second picture below with the old road (and so the tramway formation) joining the newer road from the left.

The tramway route remains on the West side of the valley through Le Fourcat and on towards Lantosque. Tram-travellers faced none of the confusion of modern drivers about which route to take. The trams just followed their tracks which took the higher route alongside the retaining wall in the picture below and then passed through a tunnel at St. Claire.

The tramway route remains on the West side of the valley through Le Fourcat and on towards Lantosque. Tram-travellers faced none of the confusion of modern drivers about which route to take. The trams just followed their tracks which took the higher route alongside the retaining wall in the picture below and then passed through a tunnel at St. Claire.

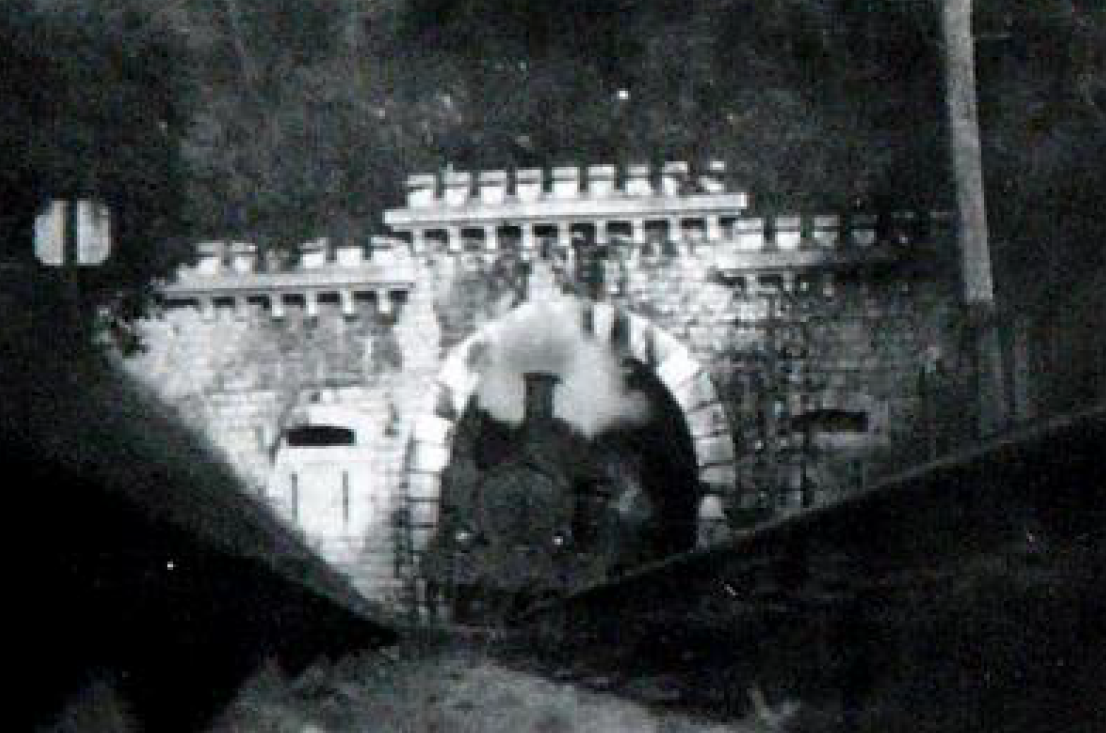

The tunnel was just 28 metres in length. [11] The first image below shows the South-West Portal and the tramway, the second shows the same view but from the 21st Century and the third picture shows the North-East portal. The second and third images come from Google Streetview. The tunnel is rough-hewn from the rock. The first is an old postcard view. [13]

The tunnel was just 28 metres in length. [11] The first image below shows the South-West Portal and the tramway, the second shows the same view but from the 21st Century and the third picture shows the North-East portal. The second and third images come from Google Streetview. The tunnel is rough-hewn from the rock. The first is an old postcard view. [13]

The two postcards immediately above show the tramway following what is now the M173 but was in those days a separate route from the road. [1]

The two postcards immediately above show the tramway following what is now the M173 but was in those days a separate route from the road. [1]

Trams approached Lantosque along the line of what is now the M173. The bridge shown in the image below was not crossed by the trams. It carries a road over the Riou de Lantosque. The trams followed what is now the M173 round to the left in the above image and then round a relatively tight bend into the centre of Lantosque. [14][15]

The trams followed what is now the M173 round to the left in the above image and then round a relatively tight bend into the centre of Lantosque. [14][15]

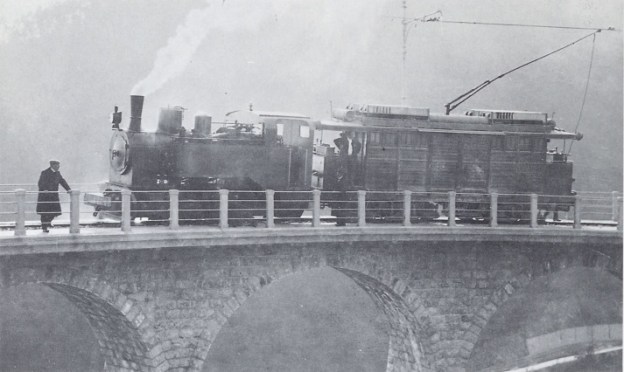

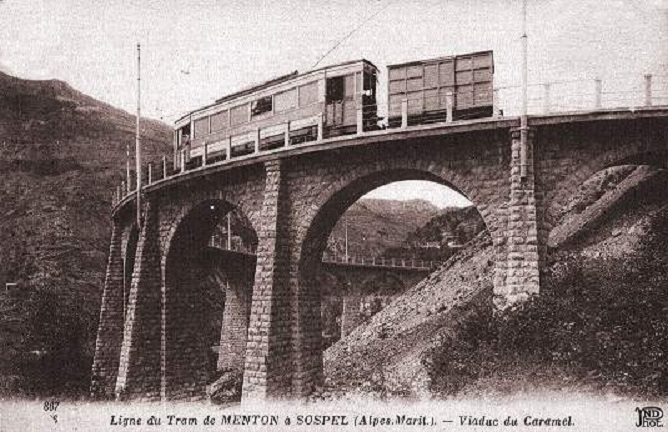

In the light of the fact that the train on the viaduct is steam hauled we can date this image to the period from September 1909 to November 2010 when all trains were steam-hauled as the electric traction had still to arrive from the manufacturer. [16]

In the light of the fact that the train on the viaduct is steam hauled we can date this image to the period from September 1909 to November 2010 when all trains were steam-hauled as the electric traction had still to arrive from the manufacturer. [16]

The 5 images immediately above all show the same viaduct North of Lantosque and close to La Bollene-Vesubie. The bridge was built for the tramway and also provided road access across the Vesubie River. All the images are old postcards. The bridge is not easy to photograph in the 21st Century because of the growth of vegetation in the river valley.

The 5 images immediately above all show the same viaduct North of Lantosque and close to La Bollene-Vesubie. The bridge was built for the tramway and also provided road access across the Vesubie River. All the images are old postcards. The bridge is not easy to photograph in the 21st Century because of the growth of vegetation in the river valley.

North of the Viaduct the Vesubie Valley opens out further. The tramway took the east side of the valley heading for the old village of Roquebilliere. The next station was provided for the village of La Bollene Vesubie, although it was in the valley 5 kilometres from the village which couldm only be accessed via a mountain road. The station location can eb seen below on a Google Streetview image and then below that in a picture and map from http://www.inventaires-ferroviaires.fr. [2]

North of the Viaduct the Vesubie Valley opens out further. The tramway took the east side of the valley heading for the old village of Roquebilliere. On the approach to what is now the old village there was a very significant landslide in 1926 which took away a significant number of houses.

North of the Viaduct the Vesubie Valley opens out further. The tramway took the east side of the valley heading for the old village of Roquebilliere. On the approach to what is now the old village there was a very significant landslide in 1926 which took away a significant number of houses.

There are pictures and a video below (after the pictures of the village as it was before 1926) which show the extent of the damage caused. 19 people were lost in the rubble of the landslide and attempts to rescue them or recover their bodies seemed likely to result in further movement of the hillside. Collapse of the village of Belvedere above the slip remained a very real possibility.

The original slip occurred on 24th November, continuing rains meant that one 30th November the hillside started to move again. Movement over two days amounted to about 10 metres over a width of between 60 and 200 metres. The buildings in its path could not resist this and by 1st December 1926, a further 10 buildings had collapsed. Fortunately, by the end of December, with frost, the earth was harder, and stabilized. [22]

The 7 images immediately above show the tramway in the village of Roquebilliere in advance of the tragedy which struck the village in 1926. The old village was of quite a significant size and much of it disappeared in the landslide of that year. Three images in old postcards are shown below.

The 7 images immediately above show the tramway in the village of Roquebilliere in advance of the tragedy which struck the village in 1926. The old village was of quite a significant size and much of it disappeared in the landslide of that year. Three images in old postcards are shown below.

The village has suffered landslides and floods six times since the 6th century. It was rebuilt each time in the same place, except for this last time, after the landslide of the 24th November 1926. Most of the inhabitants left the severe tall houses of their old village to go to a new location on the West bank where there was already a church dating from the 15th Century. The old village remains inhabited but much smaller than before the 1926 disaster.

The village has suffered landslides and floods six times since the 6th century. It was rebuilt each time in the same place, except for this last time, after the landslide of the 24th November 1926. Most of the inhabitants left the severe tall houses of their old village to go to a new location on the West bank where there was already a church dating from the 15th Century. The old village remains inhabited but much smaller than before the 1926 disaster.

The two videos below show, respectively, the village immediately after the landslip, [18] and the village in the 21st Century. [19]

A late 20th Century shot of the old village taken from the road to Belvédère, high on the hill where the landslip occurred in 1926. [17] The red ring circles a WW2 gun emplacement.

A late 20th Century shot of the old village taken from the road to Belvédère, high on the hill where the landslip occurred in 1926. [17] The red ring circles a WW2 gun emplacement. Another shot of the road bridge, this time from the new village. [20]

Another shot of the road bridge, this time from the new village. [20] The route of the tramway in 2017, taken from Google Streetview.

The route of the tramway in 2017, taken from Google Streetview. Belvédère, high above Vieux Roquebilliere on the East side of the Vesubie Valley. [21]

Belvédère, high above Vieux Roquebilliere on the East side of the Vesubie Valley. [21]

After Roquebilliere, the tramway followed the East bank of the Vesubie until immediately below the village of St. Martin Vesubie. On the approach to the village it crossed a substantial viaduct. The first image below is an old postcard view looking back across the viaduct from St. Martin.

The tramway can be seen crossing the bridge in both of the old postcard images above. The location of the bridge is shown circled in red on the plan above. [2]

The tramway can be seen crossing the bridge in both of the old postcard images above. The location of the bridge is shown circled in red on the plan above. [2]

The viaduct in the 21st Century is shown (above) on an image from Google Streetview.

The viaduct in the 21st Century is shown (above) on an image from Google Streetview.

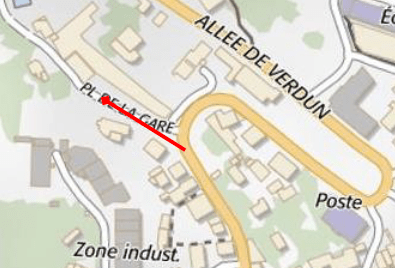

The trams climbed into the village along Route de la Vesubie and then, as shown on the adjacent plan, turned left onto Place de la Gare as the main road swung round to the right in a hairpin bend. [2] The station building is shown above as it appears in the early 21st Century! [2]

The station building is shown above as it appears in the early 21st Century! [2] We finish this journey with a series of postcard views of the station at St. Martin Vesubie. The one immediately above was taken while steam power was still active on the line, probably in 1910. The images below show a busy station area in the early years before the first world war.

We finish this journey with a series of postcard views of the station at St. Martin Vesubie. The one immediately above was taken while steam power was still active on the line, probably in 1910. The images below show a busy station area in the early years before the first world war.

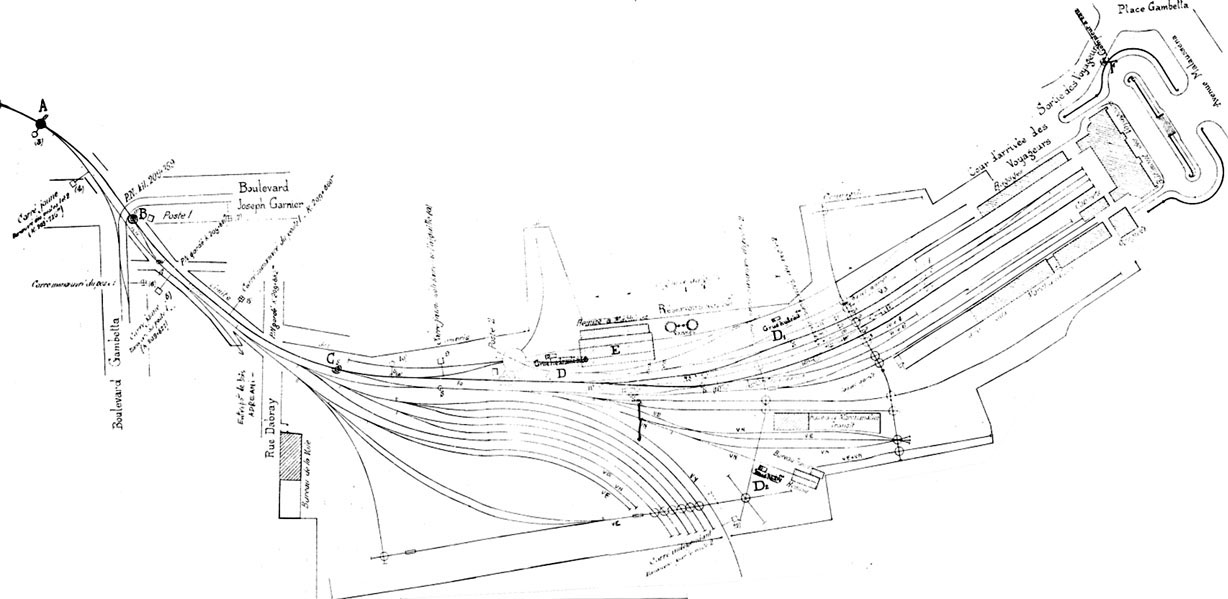

And finally a plan of the Station at Saint-Martin-Vesubie and a video made by Pathe News in 1912 ….

And finally a plan of the Station at Saint-Martin-Vesubie and a video made by Pathe News in 1912 …. A plan of the station track layout – the route to Plan du Var heads off on the left of the plan. [2]

A plan of the station track layout – the route to Plan du Var heads off on the left of the plan. [2]

The Pathe New Video. [23]

References

- http://marc-andre-dubout.org/cf/baguenaude/vesubie/vesubie.htm, accessed on 16th December 2013.

- http://www.inventaires-ferroviaires.fr/hd06/06075.a.pdf, accessed on 8th July 2018.

- https://remonterletemps.ign.fr/comparer/basic?x=7.204426&y=43.858319&z=15&layer1=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN50.1950&layer2=GEOGRAPHICALGRIDSYSTEMS.MAPS.SCAN-EXPRESS.STANDARD&mode=doubleMap, accessed on 8th July 2018.

- http://www.en-noir-et-blanc.com/levens-p1-838.html, accessed on 8th July 2018.

- https://collection-jfm.fr/p/cpa-france-06-plan-du-var-le-pont-sur-la-vesubie-88555, and https://collection-jfm.fr/p/cpsm-france-06-plan-du-var-le-pont-sur-la-vesubie-33701, both offered for sale, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- As noted in other posts the TAM was a subsidiary of the Chemin de fer du Sud de la France (SF) then the Chemin de fer de Provence (CP) continues to provided a service between Nice and Digne.

- http://amontcev.free.fr/tramways.htm, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- https://www.geneanet.org/cartes-postales/view/6221073#0, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- http://www.nicematin.com/vie-locale/les-gorges-de-la-vesubie-fermees-jusqua-mercredi-apres-un-eboulement-115405, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- http://anjouetailleurs.eklablog.com/la-cote-d-azur-c23345521/3?noajax&mobile=1, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- http://www.tunnels-ferroviaires.org/inventaire.htm, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- https://structurae.info/ouvrages/pont-de-saint-jean-la-riviere, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- https://www.delcampe.net/fr/collections/cartes-postales/france/lantosque/06-lantosque-ligne-du-tram-tunnel-ste-clairetbe-300006705.html, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- https://www.delcampe.net/fr/collections/cartes-postales/france/lantosque/lantosque-06-vue-prise-du-riou-la-gare-tram-de-la-vallee-de-la-vesubie-593785660.htm, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- https://www.delcampe.net/fr/collections/cartes-postales/france/lantosque/06-lantosque-fl-89-tram-la-gare-beau-plan-superbe-300551522.html, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belv%C3%A9d%C3%A8re, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- http://club.quomodo.com/fortif06/fortifications/ouvrages_maginot/secteur_vesubie/casemate_de_roquebilliere, accessed on 7th July 2018.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0kySBA8b_io, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jF90I0kZuFo, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- http://www.dronestagr.am/snow-roquebilliere, accessed on 9th July 2018.

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belv%C3%A9d%C3%A8re_(Alpes-Maritimes), accessed on 8th July 2018.

- https://www.departement06.fr/documents/Import/decouvrir-les-am/rr135-roquebiliere.pdf, accessed on 10th July 2018.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q39tIIVlCh8, accessed on 11th July 2021

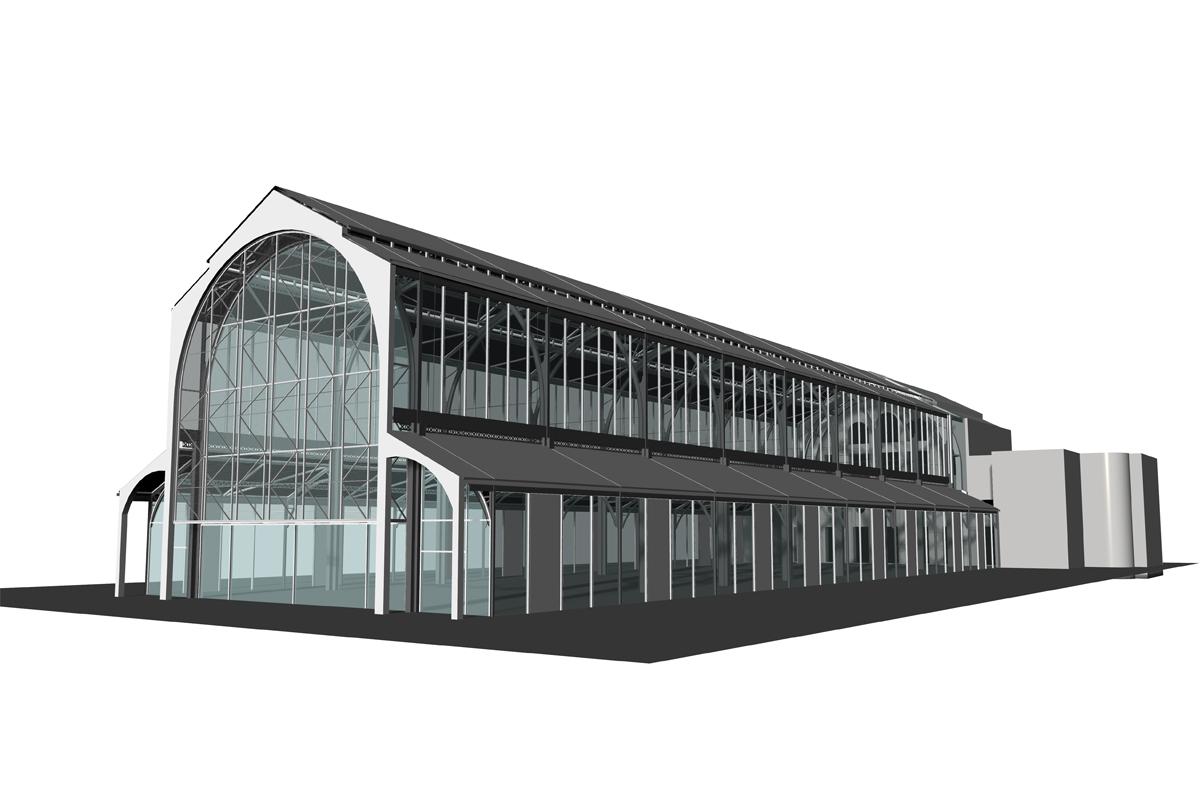

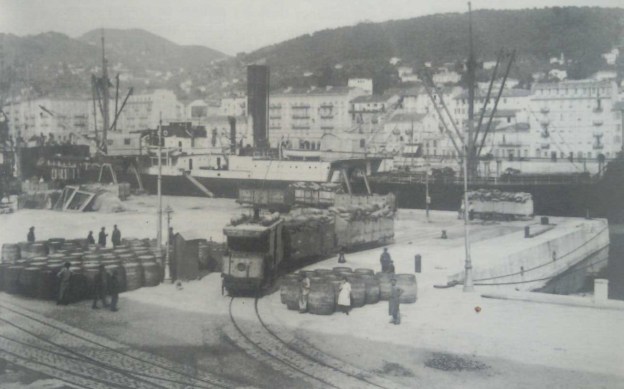

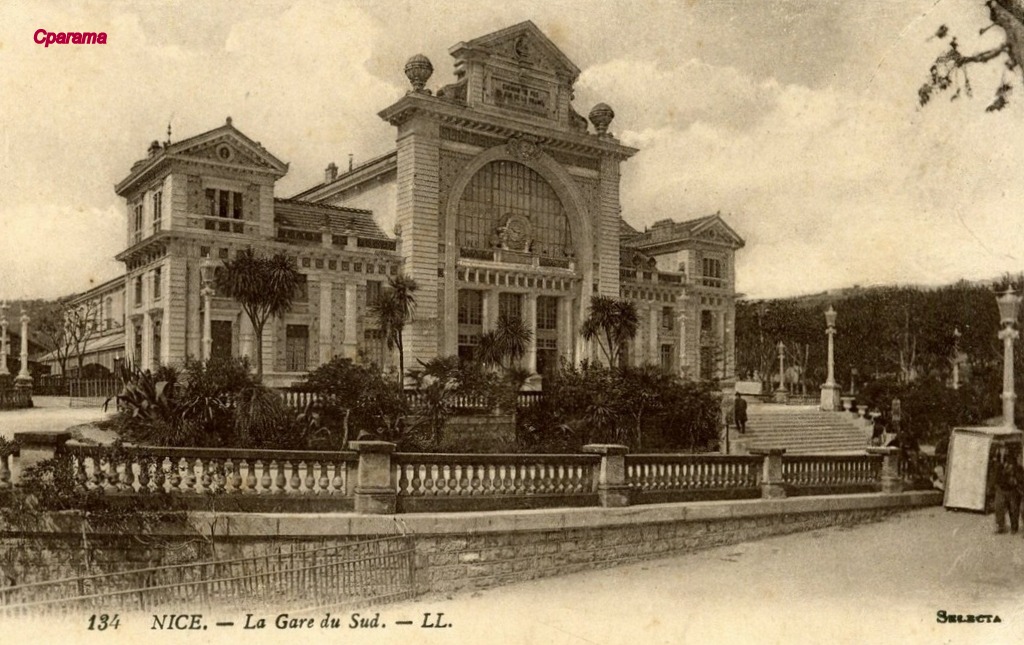

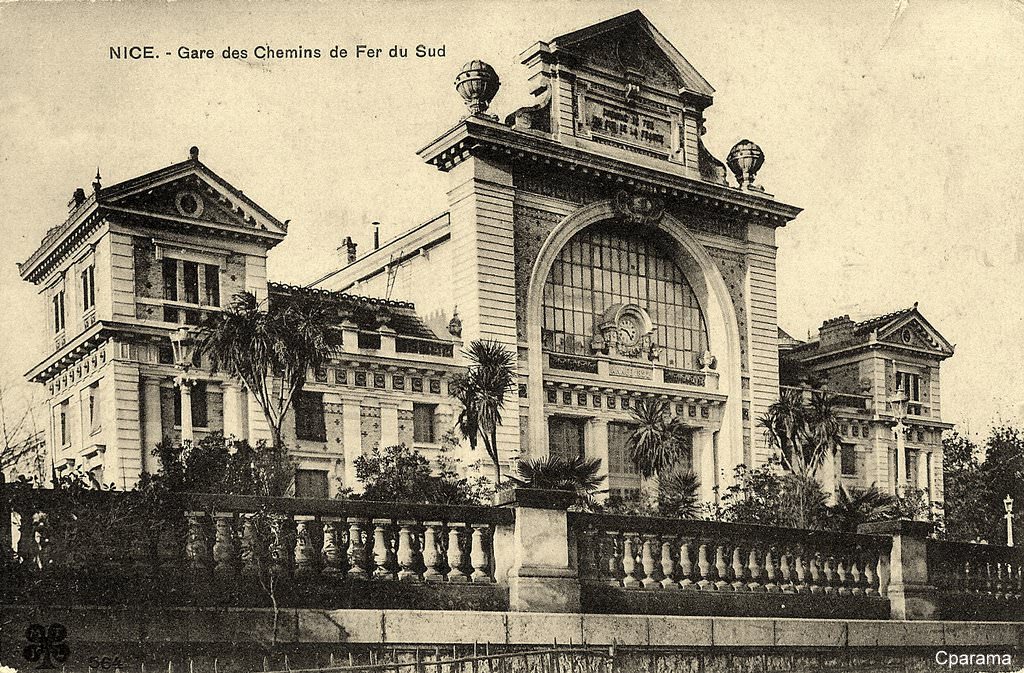

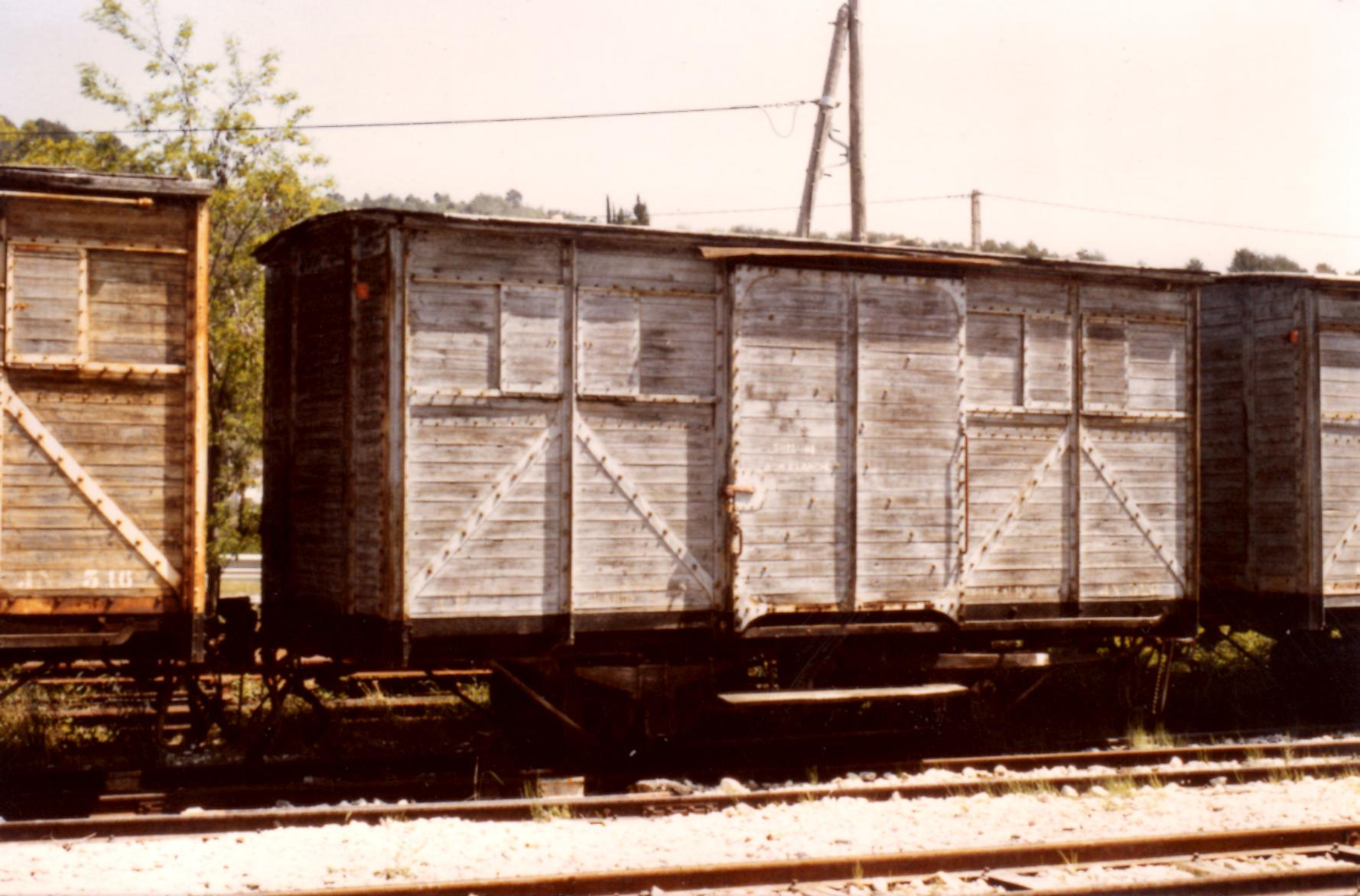

Nice – 1969 – Remarkable view of the atmosphere of the Nice train station and its depot with a host of Billard railcars having just been recovered on various CFD lines coming to close. On the left, we can also see two ABH. © JH Manara.[22]

Nice – 1969 – Remarkable view of the atmosphere of the Nice train station and its depot with a host of Billard railcars having just been recovered on various CFD lines coming to close. On the left, we can also see two ABH. © JH Manara.[22] Nice – 1983 – note the imposing height of the train-shed, the three railcars and the recution of the lines in favour of car parks that will soon take over the entire site! © JH Manara.[22]

Nice – 1983 – note the imposing height of the train-shed, the three railcars and the recution of the lines in favour of car parks that will soon take over the entire site! © JH Manara.[22]

Drawing by Jean Francois Laugeri

Drawing by Jean Francois Laugeri