The Chemins de Fer de Provence is the name used for the one surviving metre-gauge line in Les Alpes Maritime. The route from Nice to Digne. This series of posts will follow the line from Nice to Digne and will have occasion to divert onto some branch-lines along the way.

The line from Nice to Digne is the only remaining line of the former network of the Compagnie des Chemins de Fer du Sud de La France. The company was created in 1885 by Baron Jacques de Reinach, a French banker of German and Jewish origin (1840-1892).[1] At its apogee in 1910 the company looked after 879km of railways, most of these are shown on the map below.

The Company was responsible for: the Central and Littoral Var lines; the Nice-Digne Line; the Cote-d’Or line; the Cogolin to Saint-Tropez branch-lines; the Isere tramway lines (Tramways de l’Ouest du Dauphiné);[2] the Tramways des Alpes Maritimes. However, by 1925, the company was experiencing significant difficulties. It was wound up and a new company with new financial backers was formed – Compagnie des Chemins de Fer de Provence. This new company lasted for 8 years until 1933. Early in the planning phase, relations between Italy and France were tense. The military demanded that the section of the line between Nice and Saint-Martin-du-Var was designed to permit access by standard gauge trains. Indeed, this was also a requirement for the first length of the Colomars to Meyrargues line. A dual track-gauge arrangement was included in the plans when the concession arrangements were updated on 21st May 1889. The loading gauge for the line was also enhanced to be the same as for the standard gauge lines. On 29th July 1889 the concession was approved by law, the line was declared as being of ‘public utility’ and the length of Line from Nice to Saint-André was also formally included in the concession.

Early in the planning phase, relations between Italy and France were tense. The military demanded that the section of the line between Nice and Saint-Martin-du-Var was designed to permit access by standard gauge trains. Indeed, this was also a requirement for the first length of the Colomars to Meyrargues line. A dual track-gauge arrangement was included in the plans when the concession arrangements were updated on 21st May 1889. The loading gauge for the line was also enhanced to be the same as for the standard gauge lines. On 29th July 1889 the concession was approved by law, the line was declared as being of ‘public utility’ and the length of Line from Nice to Saint-André was also formally included in the concession.

Construction costs for the line were high and in order to ensure its completion the length between Puget-Théniers and Saint-André-les-Alpes was, in part, funded through an agreement signed between the company and the state. A formal agreement between the Minister of Public Works and the Compagnie des Railways du Sud de la France on 23rd March 1906 provided for the company’s construction of the Puget-Théniers to Saint-André-les-Alpes. The agreement was approved in law on 29th December 1906.[3]

Construction work began on the first length of the line on 14th August 1891. This was the length between Digne and Mezel – a length of 13km. In 1892, the sections from Nice to Colomars (also 13km), Colomars to Puget-Therniers (45km) and Saint-André-les-Alpes (previously Saint-Andre-de- Meouilles) to Mezel (31km), were under construction.[4]

Between 1892 and 1907, various scandals about the reliability of the company endangered its finances and slowed the progress of the work significantly. By 1907, only a 12km section between Puget-Théniers and Pont-de-Gueydan was open. The following year that was extended to Annot, a further 8km.[4]

The work progress relatively rapidly from this point on. The full length of the line was completed in July 1911, and a ceremony was attended by the Minister of Public Works on 6th August 1911, to inaugurate the last length of the line (the section between Saint-André and Annot).

As we have already noted, the Compagnie des Chemins de Fer du Sud de la France was unable to sustain operations beyond 1925. Their role was taken over by Compagnie des Chemins de Fer de Provence. In turn, this company was only able to manage the line until 1933 when it handed over both the Nice to Digne line and the Central Var line to the State. The Compagnie des Chemins de Fer de Provence then restricted its activities to the Littoral line. The State department for Bridges and Roads (Ponts et Chaucees) took over responsibility for the Nice to Digne Line.

In the immediate pre-war period, all three lines were developing well, services were increasingly popular thanks to the introduction of Autorails (Railcars). However, the War and particularly the fighting which accompanied the Liberation, dealt a serious blow to the railway infrastructure of the region.[6]

Recovery after 1944 was very slow. There was no hope of reconstruction for the Eastern part of the Central Var line and its trains terminated at Tanneron. Eventually, the Littoral line (Le Macaron) closed by 1949 and the Central Var line, by early 1950.[6]

In 1952, the State released the Nice to Digne line into private management once again, but this was not without its problems and by 1959, the State was threatening closure of the line unless draconian measures were taken. These threats were repeated in 1967 and again in 1968. This resulted in the two departments and the cities of Nice and Digne joining forces to create the “Syndicat mixte Méditerranée-Alpes” (SYMA) which took overall responsibility for the line and entrusted the operation of the line to the CFTA (Societe Generale de Chemins de Fer et des Transports Automobiles).[5,6]

A shuttle service between Nice and Colomars was inaugurated in the 1970s. In 1975, SYMA opened workshops at Lingostière workshops to replace those at Draguignan. The Draguignan workshops became unavailable after the War. It took quite a time to replace them![6]

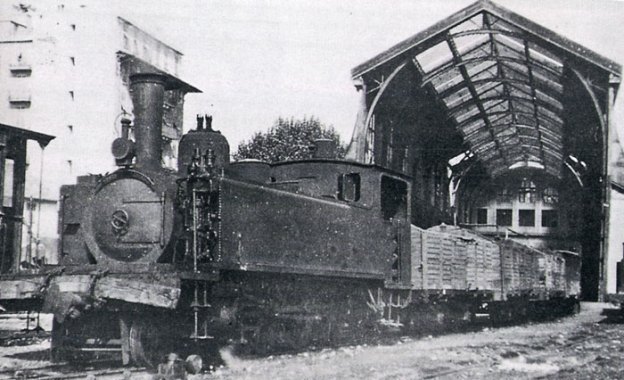

The 1980s seemed to see an up-turn in the fortunes of the line. The GECP (Groupement d’études pour le Chemin de Fer de Provence)[7] started to run steam excursion trains (an example of which can be seen below). In 1981, the link between Geneva and Nice in the form of ‘Alpazur’ was reinvigorated.[6] The service had been in place since the late 1950s.[8] A standard gauge link to Digne was used to connect with the metre-gauge line. The two different trains are shown above. That line ran from Château-Arnoux-Saint-Auban to Digne-les-Bains.

The 1980s seemed to see an up-turn in the fortunes of the line. The GECP (Groupement d’études pour le Chemin de Fer de Provence)[7] started to run steam excursion trains (an example of which can be seen below). In 1981, the link between Geneva and Nice in the form of ‘Alpazur’ was reinvigorated.[6] The service had been in place since the late 1950s.[8] A standard gauge link to Digne was used to connect with the metre-gauge line. The two different trains are shown above. That line ran from Château-Arnoux-Saint-Auban to Digne-les-Bains.

The line was also enhanced by the introduction of a new stop on the line for Zygofolis, an amusement park joined to a water park.[9]

The line was also enhanced by the introduction of a new stop on the line for Zygofolis, an amusement park joined to a water park.[9]

This renaissance was short-lived. The SNCF decided to close the standard-gauge link between Château-Arnoux-Saint-Auban and Digne in September 1989.[10] Nice town hall decided to call for the closure of the line from Colomars to Digne (90% of the full length).

The mayor of Nice finally agreed to accept a compromise. The deal agreed was that the Chemins de Fer de Provence (CP) would give up the magnificent Gare du Sud and the city would give up its fight to close the line.[6]

However, exceptionally bad weather and flooding in the Autumn of 1994 (5th November 1994) resulted in the River Var carrying away significant lengths of several hundred metres of the Nice to Digne line. The CP took over 18 months to repair the line and recover.[6,11,12] The images below show examples of the damage caused in the November 1994 floods.

In the last two images we have, on the right: the bridge at Gueydan on the Var destroyed by the flood which would in time be scrapped and replaced by the French Army. On the left is one of the many breaches of the line.[13] Immediately below this text are two images of a similar breach which happened in 1982. Following them are three videos shot during flood flows in the Var River channel in November 2011. The first at the Airport and the other two at the bridge at La Manda near Colomars.

SYMA’s control over the Nice to Digne Line continued until 1st January 2007 when the Appeal Court in Marseilles closed it down because of discovered flaws in procedures within the company.

The line was operated by Transdev[14] and Veolia Transport[15] through a subsidiary called Compagnie Ferroviaire du Sud de la France (CFSF)[16] until on 1st January 2014 a new company was formed to run the line – Régie Régionale des Transports de Provence Alpes Cote d’Azur (RTT PACA).[17] Under RTT PACA’s control the line has been significantly upgraded and rolling stock improved. It is still possible to travel on the line behaind a steam locomotive, courtesy of the GECP but regular services are now in the hands of very modern DMUs.

A Journey Along the Line – Part 1 – La Gare du Sud

Our journey starts in Nice at the magnificent facade of la Gare du Sud. First a few older postcards to introduce us to the station. ……..

La Gare due Sud[18] was built in 1892 by the architect Prosper Bobin on behalf of the Compagnie des Chemin de Fer du Sud de la France. Prosper Etienne Bobin was born on 11th January 1844 in Montigny-en-Gohelle (Pays-de-Callais) and died on 10th December 1923 in the 6th Arrondissement in Paris.

The station has two main components, the passenger building and the train-shed. The first has a striking facade which faces onto the Boulevard Malaussena in the Liberation quarter of Nice. It was designed in the rationalist style which favoured the use of new industrial materials without compromising on elegance.[18] The name ‘rationalism’ is retroactively applied to a movement in architecture that came about during the Enlightenment (more specifically, neoclassicism), arguing that architecture’s intellectual base is primarily in science as opposed to reverence for and emulation of archaic traditions and beliefs. Rational architects, following the philosophy of René Descartes emphasized geometric forms and ideal proportions.[19] Structural rationalism most often refers to a 19th-century French movement, usually associated with Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and Auguste Choisy. Viollet-le-Duc rejected the concept of an ideal architecture and instead saw architecture as a rational construction approach defined by the materials and purpose of the structure. The architect Eugène Train was one of the most important practitioners of this school, particularly with his educational buildings such as the Collège Chaptal and Lycée Voltaire.[20]

The monumental facade of la Gare du Sud with a high central pavilion flanked by two side pavilions displays a decorative repertoire made of veneered ceramics and painted motifs overlying the stone structure. The building is roofed in terracotta.[18]

Trackside, there was (and is) a large train-shed, 23m wide, 18m tall and 87m long which covered the platforms. It is a metal structure inspired by the work of Gustave Eiffel which was originally used to house the Russian pavilion of the 1889 World Fair.

La Gare du Sud was completed in 1892, it operated as a railway station until December 1991, almost reaching its centenary as a station before circumstances in Nice dictated its closure.

Over the years the station site was developed to the extent visible in the hand-drawing below.[21]

In the 1910s, with increased traffic, the locomotive shed was enlarged. The two water tanks were mounted on masonry pedestals. Several additional rooms were created (most of them next to the shed). These included an office for the deputy chief and a traction shop. A Cnetral Office was built to the West of the Station adjacent to Rue Dabray which brought all the key staff togetehr under one roof.

Later, in 1936, a new workshop for diesel railcars (autorails) was built at the west end of the passenger hall. By the eve of the Second World War, the station was at its zenith. In addition to the buildings there were several kilometres of track, 44 single points, four three-way points, a variety of turntables which included one locomotive turntable.

After the Second World War, a building, serving as a simple repair shop, was to be the last new building on the site.[18]

I have pulled together a few photographs from a variety of sources which show the station in operation. They are in no particular chronological order and copyright is acknowledged where it can be established. Most of the images are freely available on the internet. The first two have been taken from the ‘Nice Rendez-Vous’ website[23].

Interior of the South Station – ABH Railcar and modernized cars in 1954.

Interior of the South Station – ABH Railcar and modernized cars in 1954.

Photo: M. Rifault – JL Rochaix Collection – Publisher: BVA in Lausanne (Switzerland).

Nice – 1969 – Remarkable view of the atmosphere of the Nice train station and its depot with a host of Billard railcars having just been recovered on various CFD lines coming to close. On the left, we can also see two ABH. © JH Manara.[22]

Nice – 1969 – Remarkable view of the atmosphere of the Nice train station and its depot with a host of Billard railcars having just been recovered on various CFD lines coming to close. On the left, we can also see two ABH. © JH Manara.[22] Nice – 1983 – note the imposing height of the train-shed, the three railcars and the recution of the lines in favour of car parks that will soon take over the entire site! © JH Manara.[22]

Nice – 1983 – note the imposing height of the train-shed, the three railcars and the recution of the lines in favour of car parks that will soon take over the entire site! © JH Manara.[22]

Bahnbilder.de, 1980.[24]

Bahnbilder.de, 1980.[24] Wikimedia Commons. [25]

Wikimedia Commons. [25]

The last two images show wagons in storage at la Gare du Sud. They have been provided by a member of the GEMME forum in France.[36]

The last two images show wagons in storage at la Gare du Sud. They have been provided by a member of the GEMME forum in France.[36]

From the end of the War until the 1990s the uncertainties over the future of the Nice to Digne line meant that little was invested in the facilities at la Gare du Sud. In 1970, plans were drawn up to close the station. The city hoped to eliminate 4 level-crossings by moving the station to Rue Cross de Capéu a distance of 700 metres. The site of the proposed new station was purchased in 1972 and the Architect was chosen. The project remained on the drawing board.

In 1973, a number of unused sidings were lifted. In 1975, the President of SYMA, Jacques Médecin, Mayor of Nice, declared that he intended to stop the financial participation of the City in the organization (SYMA), and requested the sale of la Gare du Sud. Land on the south side of the station was sold, all of the buildings on that land were demolished, 150 wagons on the site were scrapped.

In 1976, access to the station was compromised when the City connected the streets of Alfred Binet and Falicon. Access to the goods hall and shunting manoeuvres became almost impossible. On 22nd March 1977, the automatic gates of Gambetta, Cros de Capeu and Gutemberg Streets were removed and replaced by traffic lights![21] This meant that trains were restricted to a speed of 4km/hr when crossing those streets. Recovery plans were negotiated in the late 1970s. Goods trains were banned from the centre of Nice. In 1978, the south side of the station site became a municipal car park. A period of ten years of relative calm then ensued, although the City maintained its intention to purchase the whole of the site of la Gare du Sud.

Recovery plans were negotiated in the late 1970s. Goods trains were banned from the centre of Nice. In 1978, the south side of the station site became a municipal car park. A period of ten years of relative calm then ensued, although the City maintained its intention to purchase the whole of the site of la Gare du Sud.

A memorandum of understanding was finally signed on 18th January 1991 for the sale of the site of la Gare du Sud to the City for 151 million francs. As part of that deal the terminus of the Nice to Digne line was designated as being at Rue Alfred Binet. The commissioning of a new station at Rue Alfred Binet was scheduled for November 1991 but was eventually postponed until 10th December. The last day of operation of la Gare du Sud as a railway station was 9th December 1991.[21]

The new station was designated as the Gare de Nice CP and was built in a modernist style, in contrast to every other station on the line. [26] The following pictures show that station and can be found on the ‘Le Train des Pignes’ website. [26]

From 9th December 1991 to the year 2000, la Gare du Sud remained derelict. Although there had been a land transfer to the City the building was not sold to the City until the year 2000. The City then produced plans to demolish the station.[18]

From 9th December 1991 to the year 2000, la Gare du Sud remained derelict. Although there had been a land transfer to the City the building was not sold to the City until the year 2000. The City then produced plans to demolish the station.[18]

This demolition raised many protests and finally the Minister of Culture , Renaud Donnedieu de Vabres, opposed it in 2004. Meanwhile, the facade of the old station was registered as a historical monument on 23rd September, 2002.[27] The train-shed was registered as a historical monument in June 2005. The elegance of the building is demonstrated by the following images draw by the Architect, Mario Basso.[28]

Mario Basso is also responsible for a comprehensive archive of media posts relating to the station over the years.[28] That story can also be followed on Le Train des Pignes website.[29]

Mario Basso is also responsible for a comprehensive archive of media posts relating to the station over the years.[28] That story can also be followed on Le Train des Pignes website.[29]

The building was saved from destruction but its future remained uncertain. Several projects were promulgated and then fell by the wayside (including the site becoming a new City Hall for Nice) before finally a project to convert it into a media library became a reality. The passenger building received a full restoration.

Drawing by Jean Francois Laugeri

Drawing by Jean Francois Laugeri

The work was completed in time for opening in December 2013. A video taken from a drone, shows the finished work to the old passenger facilities.[30] Meanwhile refurbishment of the train-shed was also being considered. The video project presentation is below. [31]

TESS was given this project and some pictures of their work are shown below.[32]

The renovated station is intended to be at the hear of a new area in the City. [33,35] The old train-shed will become a venue for restaurants and boutiques and will be surrounded by green spaces, the site will also benefit from parking, housing, gyms, a multiplex cinema and many shops.

Further development work was due to start in April 2018. The old train-shed will be known as le Salon du Vintage and will be run for the next 45 years by Banimmo France.[34]

It is intended that the train-shed will accommodate 22 restaurants by December 2018

References

- Michel Steve, Metaphor Mediterranean: The architecture of the Riviera from 1860 to 1914 , Editions Demaistre, 1996, p.88.

- Wikipedia, Tramways de l’Ouest du Dauphiné; https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tramways_de_l%27Ouest_du_Dauphin%C3%A9, accessed 3rd April 2018; and Wikipedia, CEN Réseau Isère; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/CEN_Réseau_Isère, accessed 3rd April 2018.

- Wikipedia, Ligne de Nice a Digne; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligne_de_Nice_à_Digne, accessed 3rd April 2018; and “No. 48721 – Act approving an agreement between the Minister of Public Works, Posts and Telegraphs and the Railway Company South of France for the execution of the route of the line of St. André to Puget-Théniers:” 29th December 1906. Bulletin of the laws of the French Republic , Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, serie XII, Vol. 74, n o 2811, p1365-1366.

- Wikipedia, Ligne de Nice a Digne; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligne_de_Nice_à_Digne, accessed 3rd April 2018.

- Wikipedia, Société générale de chemins de fer et de transports automobiles; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Société_générale_de_chemins_de_fer_et_de_transports_automobiles, accessed 3rd April 2018.

- Wikipedia, Chemins de Fer de Provence; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemins_de_fer_de_Provence, accessed 2nd April 2018.

- GECP; https://www.gecp-asso.fr, accessed 1st April 2018.

- Wikipedia, Alpazur; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alpazur, accessed 3rd April 2018.

- Wikipedia, Zygofolis; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zygofolis, accessed 3rd April 2018. There are some excellent photographs of the trains and busses used to serve this theme park which are taken by Jean-Henri Manara; https://www.flickr.com/photos/jhm0284/albums/72157665103843167, accessed on 24th April 2018.

- Wikipedia, Château-Arnoux-Saint-Auban Station; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gare_de_Château-Arnoux-Saint-Auban, accessed 3rd April 2018; and Wikipedia, Ligne_de_Saint-Auban_à_Digne; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligne_de_Saint-Auban_à_Digne, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Wikipedia, 1994 dans les chemins de fer; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/1994_dans_les_chemins_de_fer, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Hydro Europe, The Var River Project; https://archives.aquacloud.net/17he/a/aquacloud.net/17he01/project.html, accessed 4th April 2018, and Hydro Europe, Project; https://archives.aquacloud.net/17he/a/aquacloud.net/17he07/project.html?tmpl=%2Fsystem%2Fapp%2Ftemplates%2Fprint%2F&showPrintDialog=1, accessed 4th April 2018.

- golinelli.pagesperso-orange.fr, Museums and Tourist Railways; http://golinelli.pagesperso-orange.fr/trains/gecp.htm, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Wikipedia, Transdev; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transdev, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Wikipedia, Veolia Transport; https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veolia_Transport, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Wikipedia, Compagnie Ferroviaire du Sud de la France; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compagnie_ferroviaire_du_Sud_de_la_France, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Societe.com, Régie Régionale des Transports de Provence Alpes Cote d’Azur; https://www.societe.com/societe/regie-regionale-des-transports-de-provence-alpes-cote-d-azur-793934993.html, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Wikipedia, La Gare du Sud; https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gare_du_Sud, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Wikipedia, Rationalism (Architecture); https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rationalism_(architecture), accessed 5th April 2018.

- Froissart-Pezone, Rossella; Wittman, Richard, The École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs in Paris Adapts to Meet the Twentieth Century; Studies in the Decorative Arts. University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Bard Graduate Center. 7 (1): 30, 1999-2000.

- Le Train les Pignes, l’Histoire de la Gare du Sud, Part 1; http://cccp.traindespignes.free.fr/article-garedusud-1.html, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Transport Rail, les Chemins de Fer de Provence; http://transportrail.canalblog.com/pages/les-chemins-de-fer-de-la-provence/33191846.html accessed on 5th April 2018

- Nice Rendez-Vous, la Gare du Sud; http://www.nicerendezvous.com/la-gare-du-sud.html accessed 5th April 2018

- Bahnbilder.de – a picture from 1980; http://www.bahnbilder.de/bild/frankreich~schmalspur–und-zahnradbahnen~chemin-de-fer-de-provence-cp/673186/cp-chemins-de-fer-de-provence.html, accessed 5th April 2018.

- Wikimedia Commons; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nice_Gare_du_Sud_station,_Chemin_de_Fer_de_Provence.jpg

- Le Train des Pignes, les 50 Fiches Gares Nice-Provence; http://cccp.traindespignes.free.fr/gare-niceprovence.html, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Notice No. PA06000023 , basis Merimee, French Ministry of Culture.

- Mario Basso, Archive Gare du Sud Nice; http://gare-du-sud-nice-archives.blogspot.co.uk/2014, accessed 4th April 2018.

- Le Train les Pignes, l’Histoire de la Gare du Sud, Part 2; http://cccp.traindespignes.free.fr/article-garedusud-2.html, accessed 5th April 2018.

- YouTube, Drone-06 – Nice Gare du Sud; https://youtu.be/qAnnQ2YgiVM, accessed 6th April 2018.

- YouTube, Le Projet de la Hale de la Garde du Sud; https://youtu.be/AaSyHTN897A, accessed 5th April 2018.

- TESS, Ancienne Gare du Sud; http://www.tess.fr/projet/ancienne-gare-du-sud, accessed 5th April 2018.

- Gare du sud: nouvel espace de vie; https://www.nice.fr/fr/nice-2020/gare-du-sud-nouvel-espace-de-vie?type=projects, accessed 6th April 2018.

- Banimmo France; http://www.banimmo.be/fr, accessed 6th April 2018.

- Quartier Gare du sud, on Metropolitan Nice Côte d’Azur; http://www.nicecotedazur.org/grands-projets/quartier-gare-du-sud/12, accessed 6th April 2018.

- Les Forums du GEMME; http://forums.gemme.org/index.php.

Pingback: Nice to Digne-les-Bains Part 2 – Nice to La Manda (Chemins de Fer de Provence 58) | Roger Farnworth

Pingback: Nice to Digne-les-Bains Part 9 – Floods and Landslides (Chemins de Fer de Provence 73) | Roger Farnworth