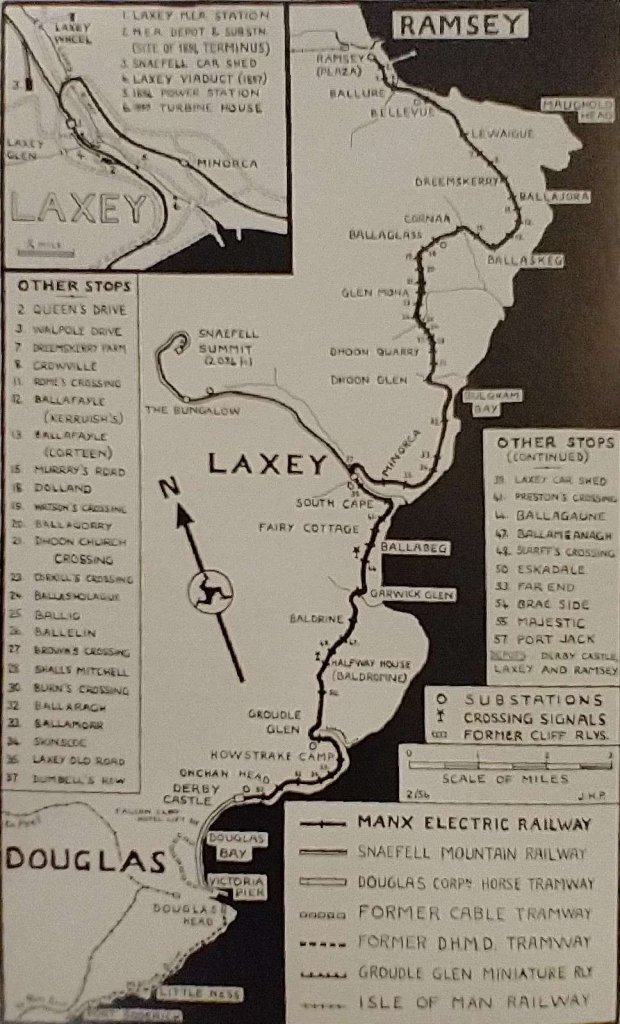

The June and July 1962 issues of ‘Modern Tramway’ included a 2-part review of the first five years of operation and maintenance of the Manx Electric Railway (MER) after nationalisation on 1st June 1957.

June 1962 marked the end of the first term of office of the MER Board. … ‘Modern Tramway’ Journal, in its June 1962 edition, begins:

“We should first explain something of how the Isle of Man Government sets about its work; day-to-day administration is in the hands of Boards of Tynwald, consisting partly of elected members of the House of Keys (the Manx House of Commons) and partly of non-Tynwald members appointed by the Governor. These Boards occupy much the same position as Ministries in the British Government, except that they serve in a part-time capacity. The M.E.R. Board, set up in 1957, has three Tynwald members and two others.

The first Manx Electric Railway Board was appointed in May, 1957. Its Chairman was Sir Ralph Stevenson, G.C.M.G., M.L.C., with Mr. R. C. Stephen, M.H.K. (a journalist), Mr. A. H. Simcocks, M.H.K. (a lawyer), Mr. T. W. Kneale, M.Eng. (a former Indian Railways civil engineer, with an expert knowledge of permanent-way) and Mr T. W. Billington (an accountant) as it’s members. … They were entrusted with the task of running the railway and reconstructing much of the permanent way, and an annual estimate of the money required was to be presented to Tynwald by 31st March of each year. No changes were made in the railway’s staff, the full-time management, as under the Company, remaining in the capable hands of Mr. J. Rowe (Secretary and Joint Manager) and Mr. J. F. Watson, M.I.E.E. (Chief Engineer and Joint Manager), who occupy the same posts today.

The new Board took over from the Company with due ceremony on 1st June, 1957, but found during their first year of office that, owing to rapidly rising costs, far more money than anticipated would be needed to reconstruct the railway at the rate intended, and to keep it running. Instead of a grant of £25,000 per year (the figure agreed upon by Tynwald), they would require £45,000, and after Tynwald had rejected both this request and their alternative proposed economies (cutting out early and late cars, and closing down in winter) the entire Board, with the exception of Mr. Kneale, resigned. A new Board then came into being, the Chairman being Mr. H. H. Radcliffe, J.P., M.H.K., with the following gentlemen as Mr. Kneale’s new colleagues: Mr. W. E. Quayle, J.P., M.H.K.. (Vice-Chairman), Lieut.-Commander J. L. Quine, M.H.K., and Mr. R. Dean, J.P. The new Board undertook to do their best to run the railway within the originally- planned subsidy of £25,000 per year, and reaffirmed that they would continue the work of reconstruction, but at a rate such as to lie within the original budget, the effect being of course that the rate of reconstruction has been somewhat slowed down and the method of financing has varied from that originally planned. The original. intention was to finance the relaying of the Douglas-Laxey section by an outright. annual grant, so that the track would enjoy. many years of debt-free life, but after the 1958 re-appraisal Tynwald reverted to the proposal of the second Advisory Committee to finance this work by a loan repayable over the 20-year life of the new track.” [1: p201-203]

Modern Tramway continues:

“In July, 1958, the Board was granted borrowing powers up to a maximum of £110,000, and of this the sum of £20,000 has been borrowed at 5 per cent, the usual interest and sinking funds being set up to provide for repayment. The money was used to relay 200 tons of rails, including labour, rail fastenings, sleepers and ballast. In January, 1960, however, Tynwald made a special grant of £9,000 for the next stage of the track relaying, with another grant a year later, while the traffic results from the 1960 and 1961 seasons were so good that in these two years a sizeable part of the £25,000 operating subsidy remained in hand and was able to be spent on relaying; 4,000 sleepers were bought out of the annual grant in 1961, and 100 tons of rails and 4,000 sleepers by the same means early in 1962. …

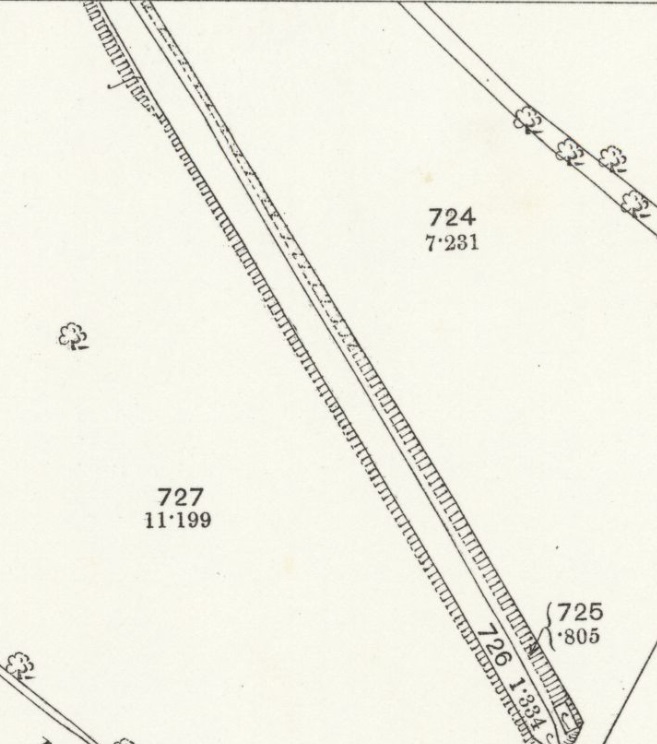

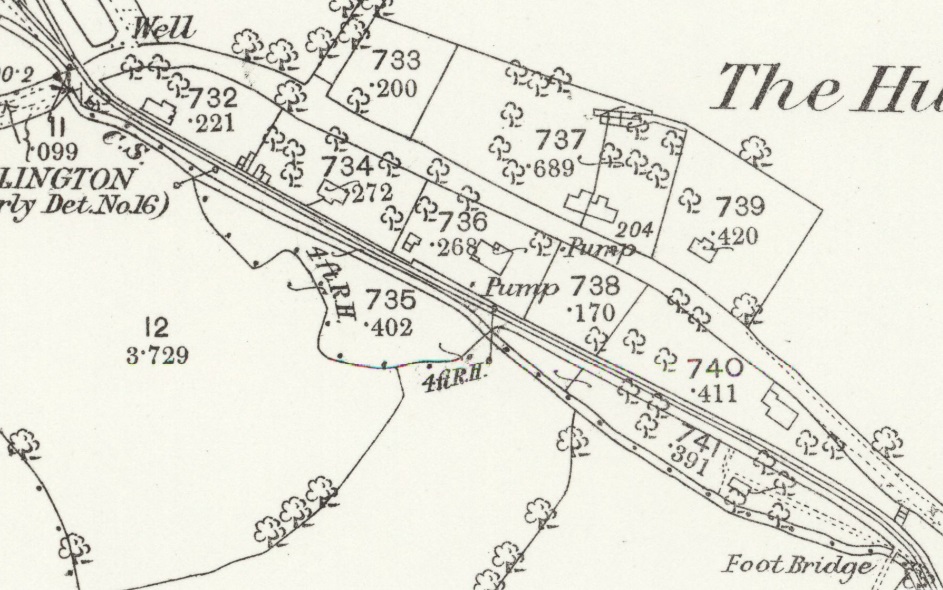

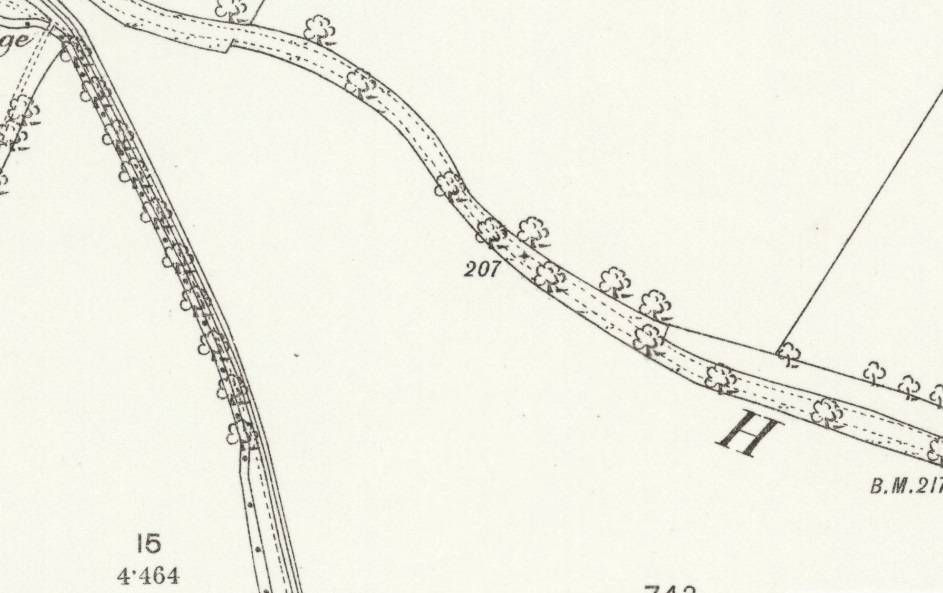

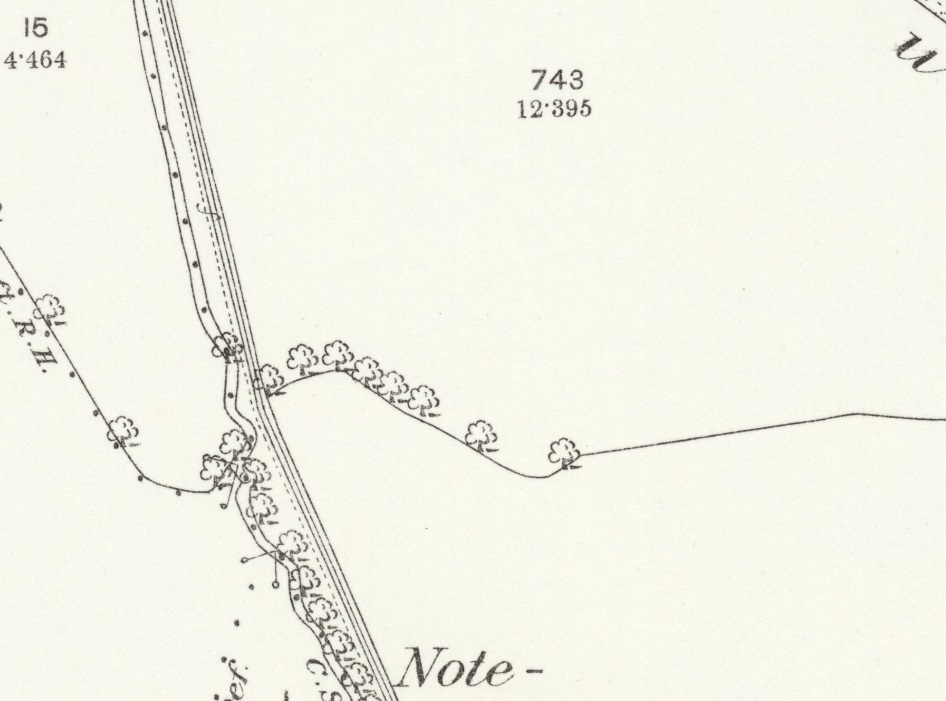

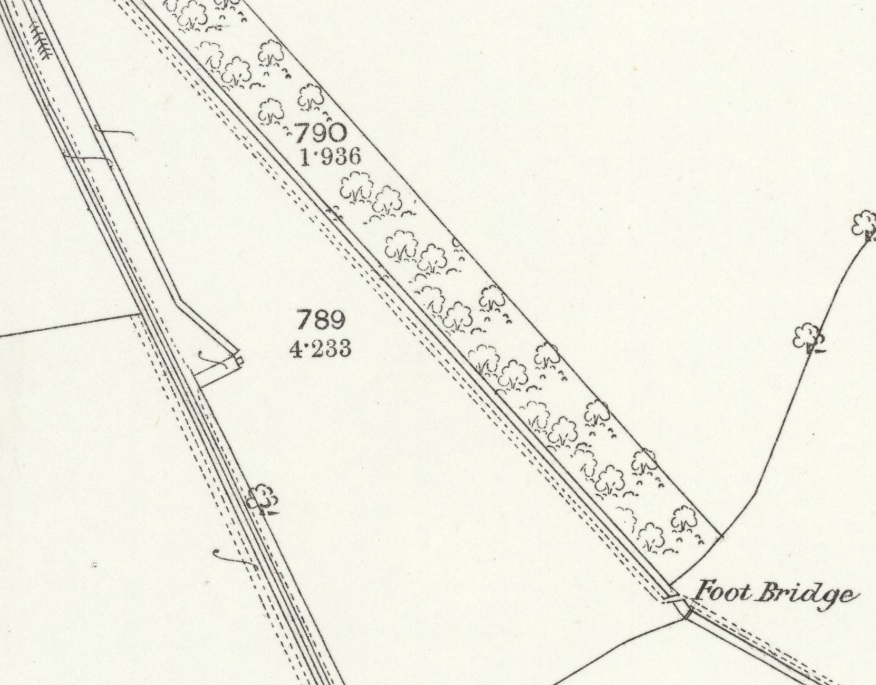

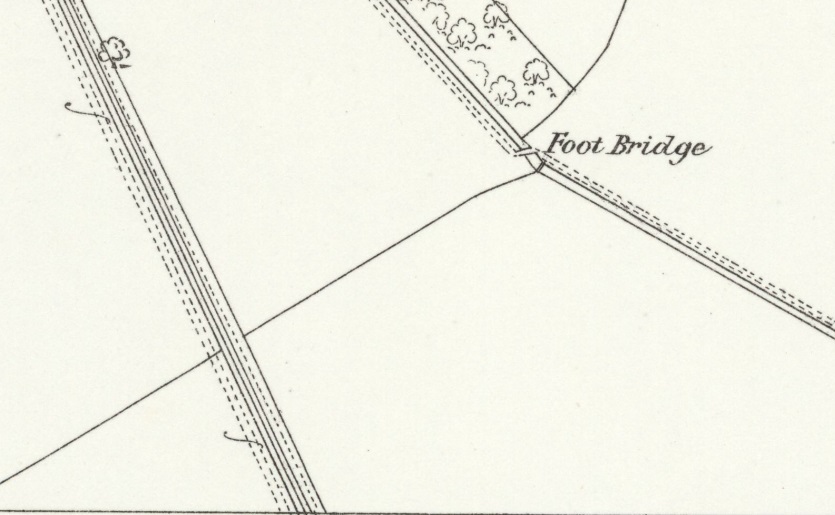

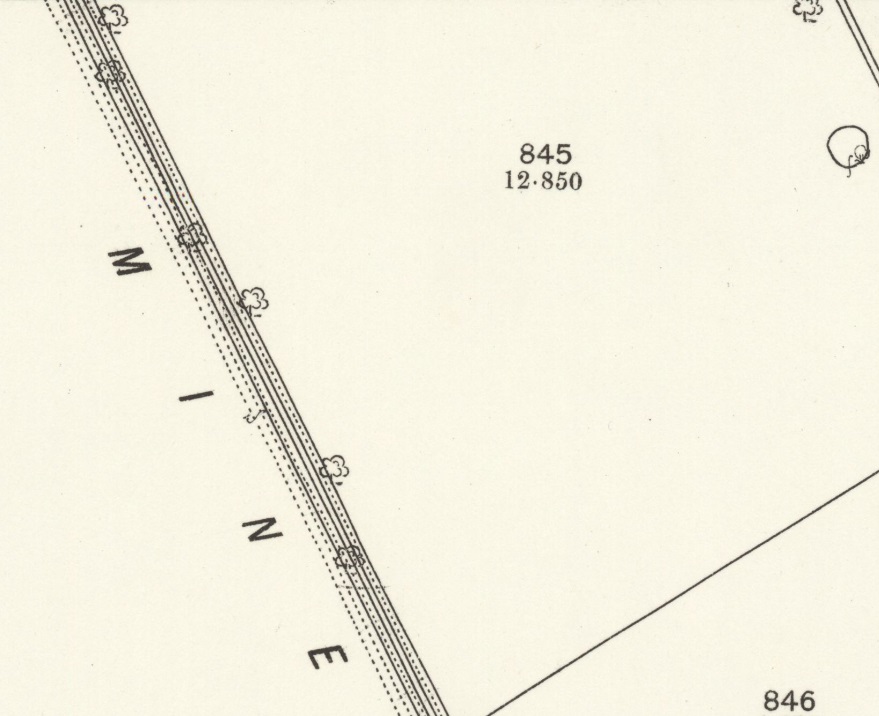

Since June, 1957, despite the overall financial stringency, quite a lot has therefore been done. Five hundred tons of new rail have been laid, and to date the Board has completely renewed about seven single-track miles of line between Douglas and Laxey. Concurrently, more than half of the 24,000 sleepers on this section have been renewed. To date, new 60 lb. per yard flat-bottom rails have been laid on the following sections: both tracks from Douglas Bay Hotel to Onchan, the northbound track from Far End to Groudle, both tracks from Groudle to Baldrine, the northbound track from Baldrine to Garwick, the southbound track from Ballagaune to Ballabeg, the north- bound one from Ballabeg towards Fairy Cottage, and the southbound track from Fairy Cottage to South Cape, plus new crossovers at Onchan Head and Groudle. Many of the new sleepers were produced on the island by the Forestry Board, but the more recent ones have been imported from Scotland since no more are available locally at present. The old ones, apart from a few sold to the Groudle Glen railway, are sent to Douglas prison and cut up there for firewood.

Since the M.E.R. Company had been living a hand-to-mouth existence for several years prior to the nationalisation, the management had lost touch with manufacturers, and had to make fresh contacts. This has had the incidental advantage of allowing them to benefit from the very latest improvements in track components, and much of the recent relaying has been done with elastic rail spikes, while to the north of Ballagaune is an experimental 200-yard length of track laid with rubber pads, giving a superb and almost noiseless ride. Modern techniques have also been adopted when relaying some of the sharp curves, with careful prior calculations to determine the correct transition and super-elevation for each, instead of the rule-of-thumb methods used in earlier days.

The permanent way renewal carried out to date represents about half the total trackage between Douglas and Laxey, including all the heavily-worn sections which in 1956 were overdue for renewal. At the time the Government took over, it was hoped to relay the entire line to Laxey within seven years, followed by the Snaefell line in the ensuing three. …Corresponding renewals have also been made to the overhead line, using round-section trolley wire and phosphor-bronze overhead parts supplied by British Insulated Callenders’ Cables Ltd., who have undertaken to continue the manufacture of whatever components the MER. may require. With gradual change to grooved wire at Blackpool, the Manx Electric will probably be the last British user of tradi- tional round trolley wire, with its big trolley wheels and “live” trolley poles reminiscent of American interurban practice. The gradual corrosion of the overhead standards in the coastal atmosphere … has been very largely arrested by a very thorough repainting.” [1: p204-205]

Further support from the Manx Government was forthcoming during the first-year period after nationalisation under a scheme designed to offset the seasonal nature of the island’s biggest industry, tourism. £7,000/year was allocated dependent on the level of employment achieved. This funding could not be for planned major work as it covered the provision of work for those employed in the summer tourism period. It was “used for marginal rather than essential work, and the Board prepare[d] estimates of such work that could usefully be done and submit them to Tynwald for eventual adoption later on. Under these schemes, Laxey and Ramsey stations [were] resurfaced in tarmac, and the whole of the Douglas-Ramsey line and most of the Snaefell line [were] completely weeded and the fences and drainage works trimmed and cleaned, which when related to the real mileage (all double track) is a considerable achievement. … The Board, … in addition, treated the whole right-of-way with a selective weed-killer. … The chemical [was] applied by a special 6-ton wagon rebuilt as a weed-killer tank wagon, with a small petrol engine providing pressure spraying at 5 m.p.h. This unit [was] based at Laxey depot.” [1: p205]

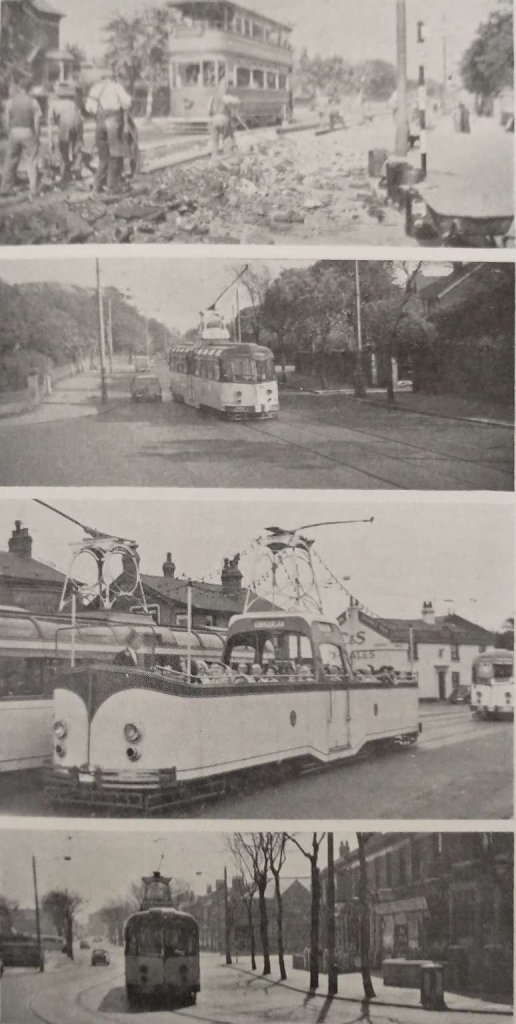

Track maintenance formed the largest element of the Board’s expenditure. Little, other than routine maintenance, was done to rolling stock during this period. Physical deterioration to stock was reduced as a result of track improvements. As the images above show, some stock received cosmetic treatment, what might be called rebranding in the 21st century world.

Modern Tramway continues:

“The passenger stock remains at 24 cars and 24 trailers (excluding trailer 52, which is now a flat car). … With the increased amount of track work, car No. 2 has been converted each winter to a works car, with work-benches and equipment in place of its longitudinal seats, but like No. 1 it can be restored to passenger service in mid-summer if need be. Certain freight wagons not required for engineering purposes, including those lying derelict at Dhoon, have been dismantled in the general clearing-up. The average age of the present 48 cars and trailers is now 61 years, but most of them are only used in the summer and should be good for many years yet.” [1: p205]

This begs the question about the stock remained on the MER in the 21st century. …

In 2023, Wikipedia tells us that, “The Manx Electric Railway … is unique insofar as the railway still operates with its original tramcars and trailers, all of which are over one hundred years old, the latest dating from 1906. Save for a fire in 1930 in which several cars and trailers were lost, all of the line’s original rolling stock remains extant, though many items have been out of use for a number of years, largely due to the decrease in tourism on the island over the last thirty years. Despite this, members of each class are still represented on site today, though not all are in original form or in regular use.” [2]

The following list details what has happened to the full fleet of motorised trams:

No. 1: built in 1893 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is an Unvestibuled saloon and painted Red, White and Teak. It has 34 seats and is painted in the MER 1930s house style. It remains available for use.

No. 2: built in 1893 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is an Unvestibuled saloon and painted Red, White and Teak. It has 34 seats and is painted in the MER 1930s house style. It remains available for use.

No. 3: lost in 1930 in a shed fire.

No. 4: lost in 1930 in a shed fire.

No. 5: built in 1894 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is a Vestibuled saloon and painted Red, White and Teak. It has 32 seats and is painted in the MER 1930s house style. It remains available for use.

No. 6: built in 1894 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is a Vestibuled saloon and painted Maroon, White and Teak. It has 36 seats and is painted in the MER late Edwardian livery. It remains available for use.

No. 7: built in 1894 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is a Vestibuled saloon and painted Blue, Ivory and Teak. It has 36 seats and is painted in the original MER livery. It was rebuilt between 2008 and 2011 and remains available for use.

No. 8: lost in 1930 in a shed fire.

No. 9: built in 1894 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is a Vestibuled saloon and painted Red, White and Teak. It has 36 seats and is painted in the standard MER livery. It is illuminated and remains available for use.

No. 10: built in 1895 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is a Vestibuled saloon, painted Grey and has no seats. It was rebuilt as a freight car and is currently stored.

No. 11: was scrapped in 1926.

No. 12: was scrapped in 1927

No. 13: was scrapped in 1957.

No. 14: was built in 1898 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Maroon. It has 56 seats and was rebuilt/restored to original condition between 2015 and 2018 and remains available for use.

No. 15: was withdrawn from service in 1973, it is currently stored. It was originally built by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd in 1898 and is a roofed ‘toastrack’. It is painted Red & White and has 56 seats.

No. 16: was built in 1898 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Red & White. It has 56 seats . The livery is described as ‘House Style’. It remains available for use.

No. 17: was built in 1898 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Red &White. It was withdrawn in 1973. It has 56 seats and is currently stored.

No. 18: was built in 1898 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Red &White. It has 56 seats and was withdrawn to storage in 2000.

No. 19: was built in 1899 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd is a winter saloon and is painted Maroon, Cream & Teak. It has 48 seats and is in its original livery. It remains available for service.

No. 20: was built in 1899 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd. It is a winter saloon and painted Red, White & Teak. It has 48 seats and is in 1970s style. It remains available for service.

No. 21: was built in 1899 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd. It is a winter saloon and painted Green & White. It has 48 seats and is in nationalisation livery. It remains available for service.

No. 22: was built in 1899 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd. It is a winter saloon and painted Red, White & Teak. It has 48 seats and is in standard livery. It remains available for service.

No. 23: was built in 1900 by the Isle of Man T. & E.P. Co., Ltd. It is a Green & Grey Locomotive. It was withdrawn to storage in 1994.

No. 24: was lost in a shed fire in 1930.

No. 25: was built in 1898 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd was a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Red &White. It had 56 seats and was withdrawn in 1996.

No. 26: was built in 1898 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd was a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Red &White. It had 56 seats and was withdrawn in 2009.

No. 27: was built in 1898 by G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd was a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Yellow, Red &White. It had no seats and was withdrawn in 2003.

No. 28: was built in 1898 by the Electric Railway and Tramway Carriage Co., Ltd. It was a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Red &White. It had 56 seats and was withdrawn in 2000.

No. 29: was built in 1904 by the Electric Railway and Tramway Carriage Co., Ltd. It is a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Red &White. It has 56 seats and was rebuilt between 2019 and 2021.

No. 30: was built in 1904 by the Electric Railway and Tramway Carriage Co., Ltd. It was a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Red &White. It had 56 seats and was withdrawn in 1971.

No. 31: was built in 1906 by the Electric Railway and Tramway Carriage Co., Ltd. It was a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Red &White. It had 56 seats and was withdrawn in 2002.

No. 32: was built in 1906 by the United Electric Car Co., Ltd. It is a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Green &White (Nationalisation livery). It has 56 seats and is still available for service.

No. 33: was built in 1906 by the United Electric Car Co., Ltd. It is a roofed ‘toastrack’ and painted Red &White (Nationalisation livery). It has 56 seats and is still available for service.

No. 34: was built in 1995 by Isle of Man Transport. It is a diesel locomotive, painted Yellow & Black.

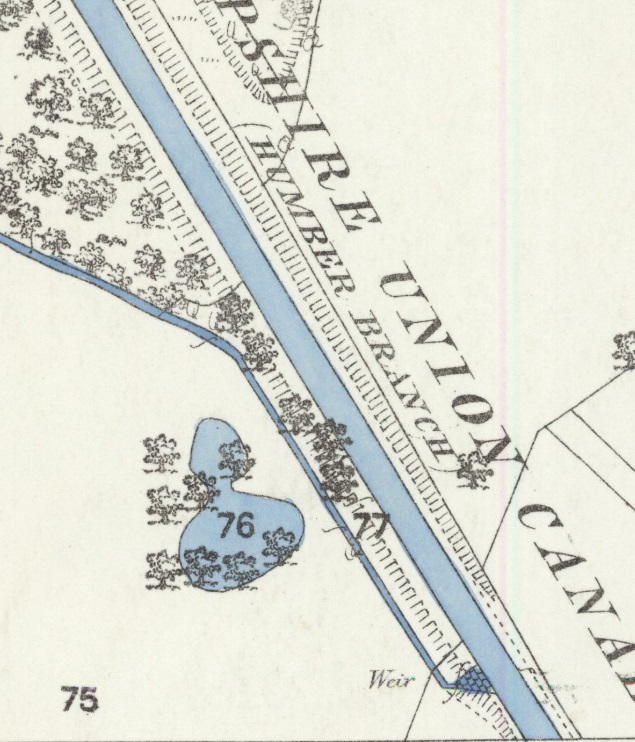

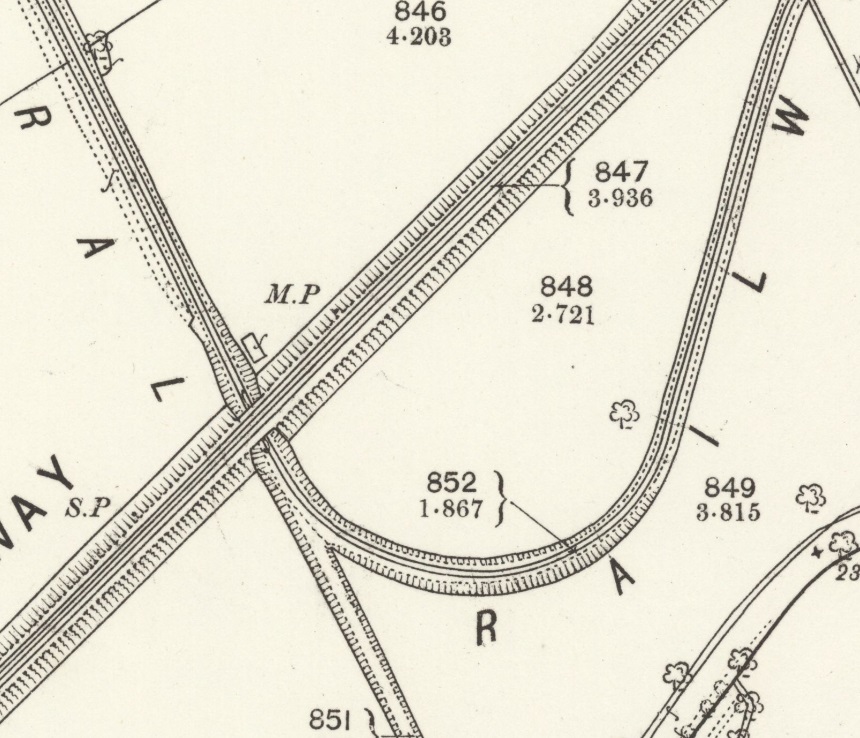

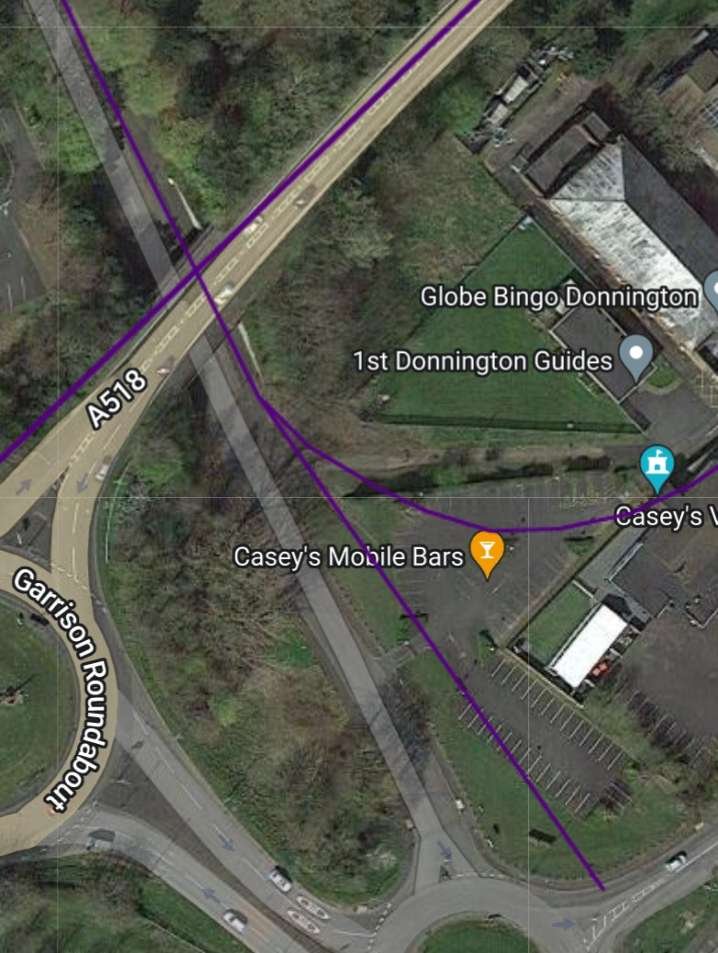

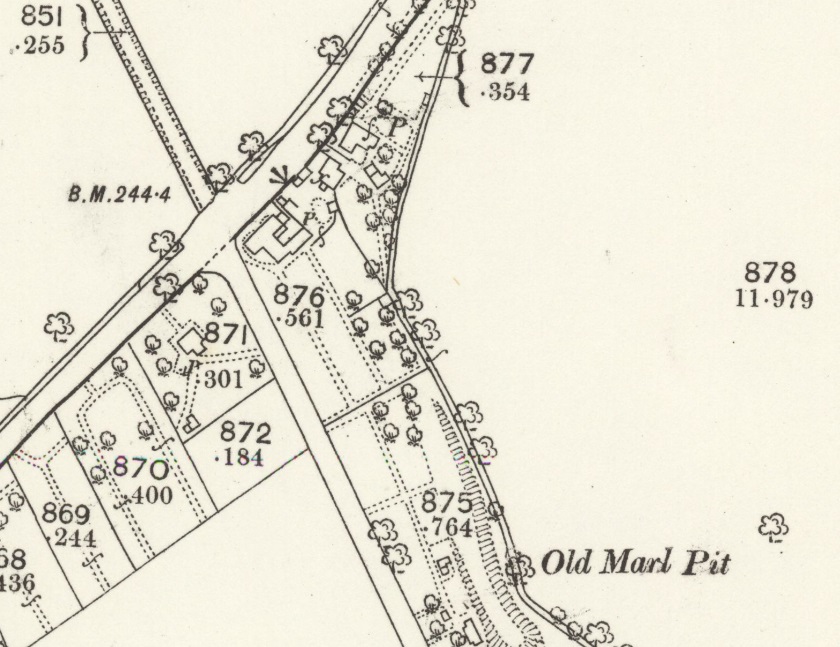

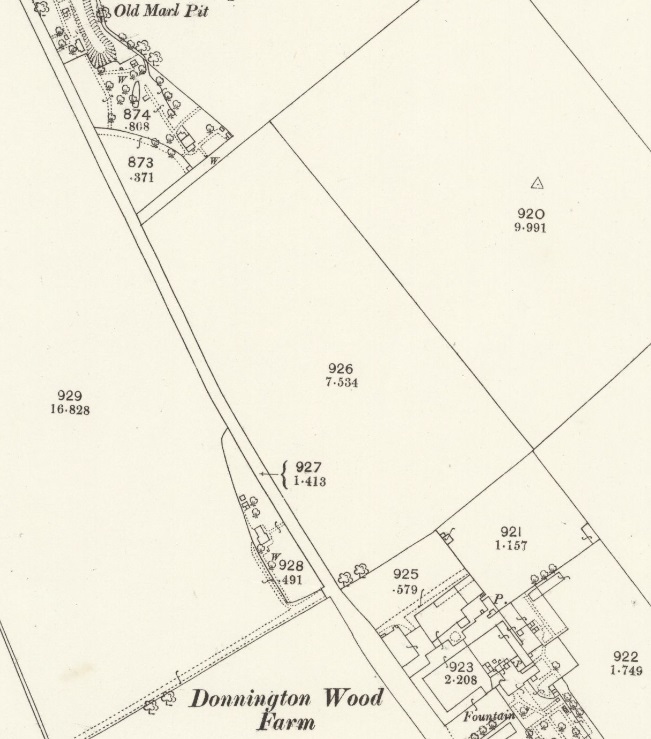

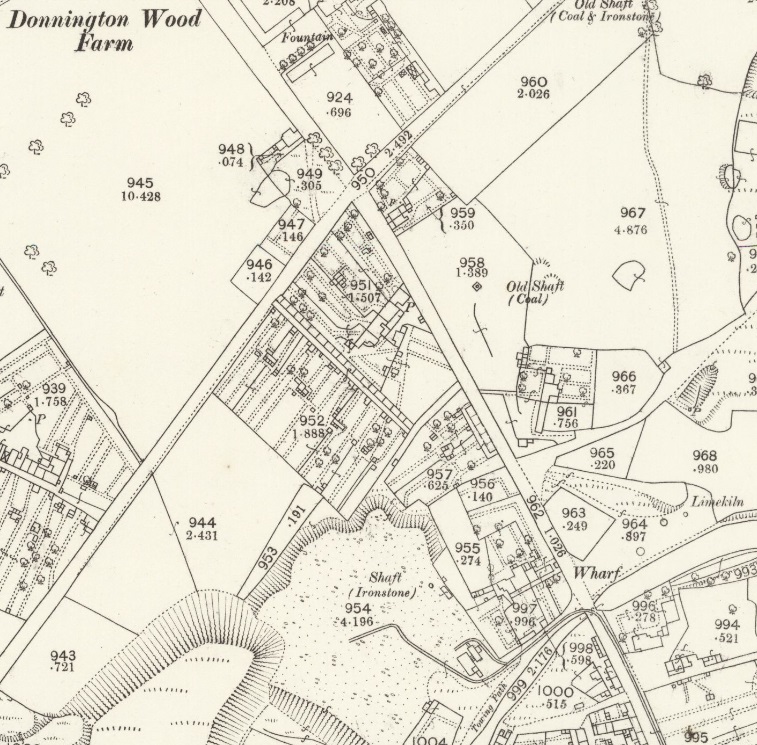

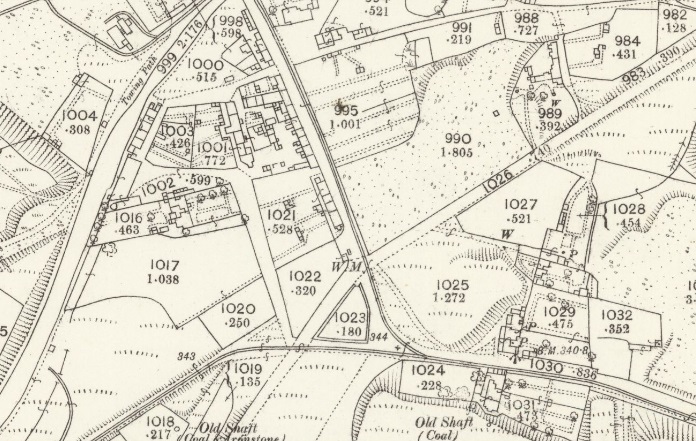

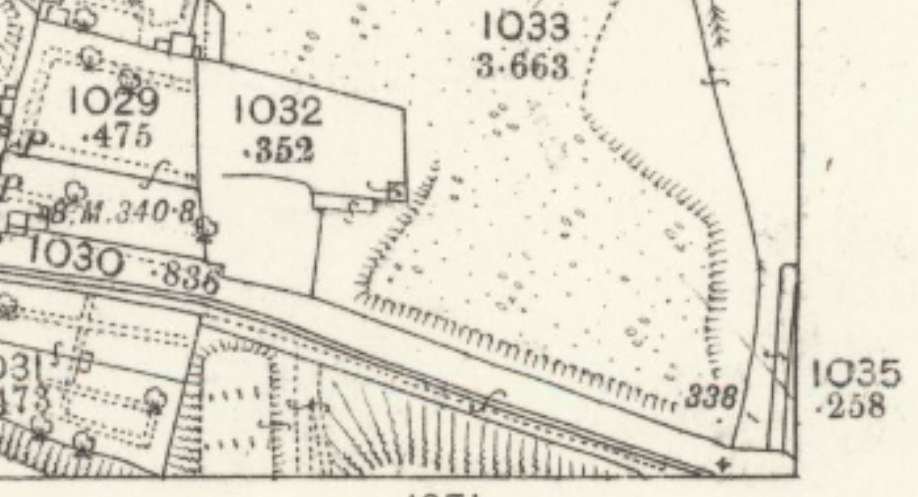

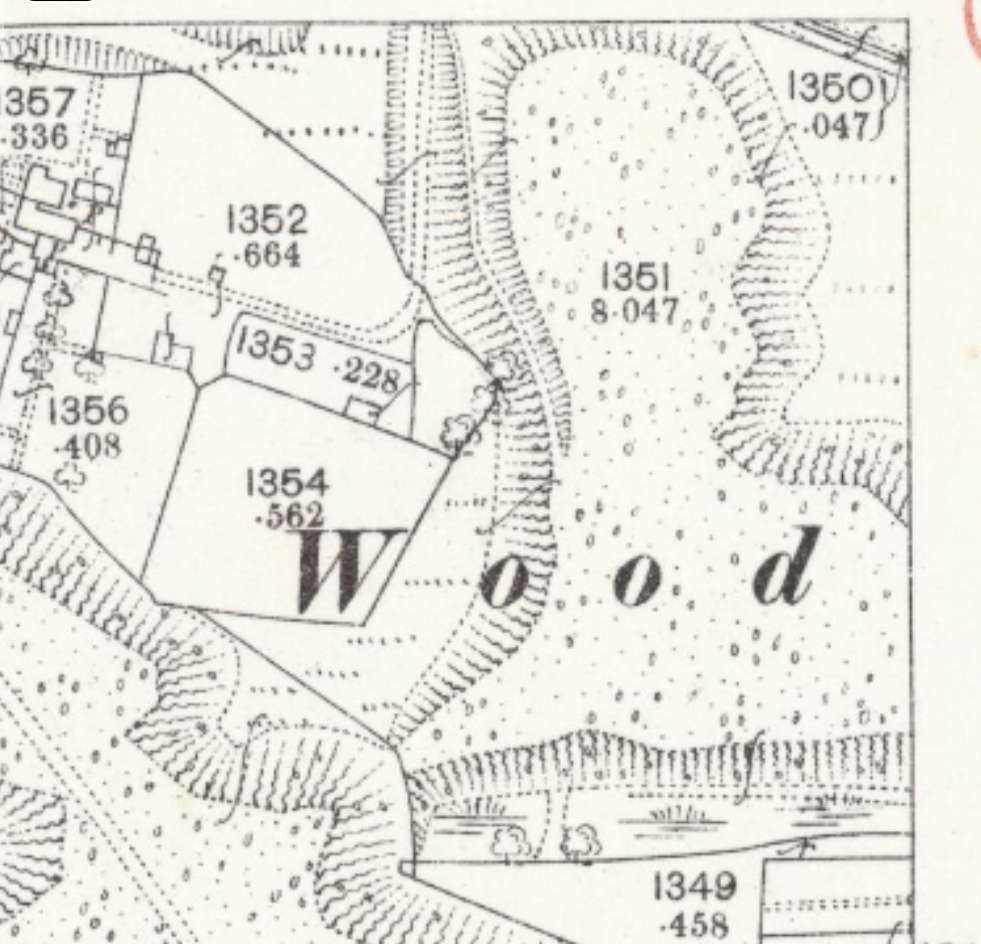

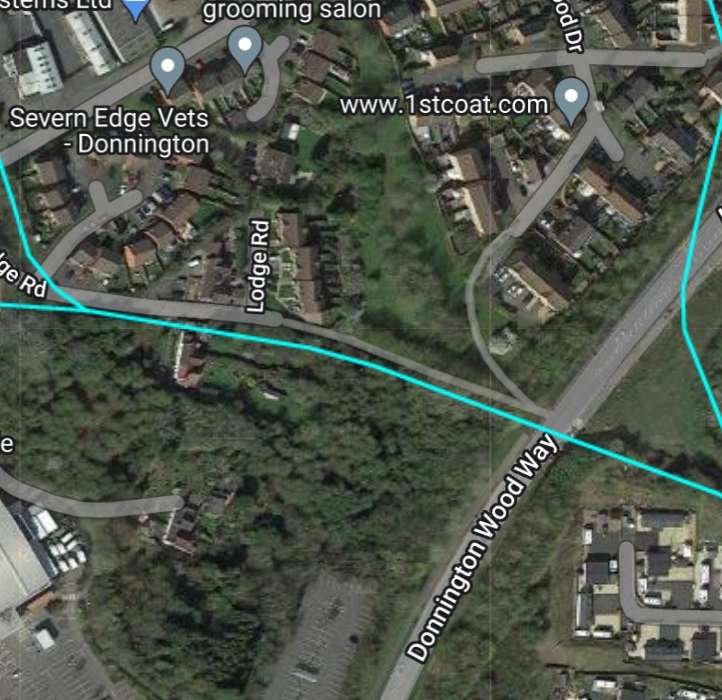

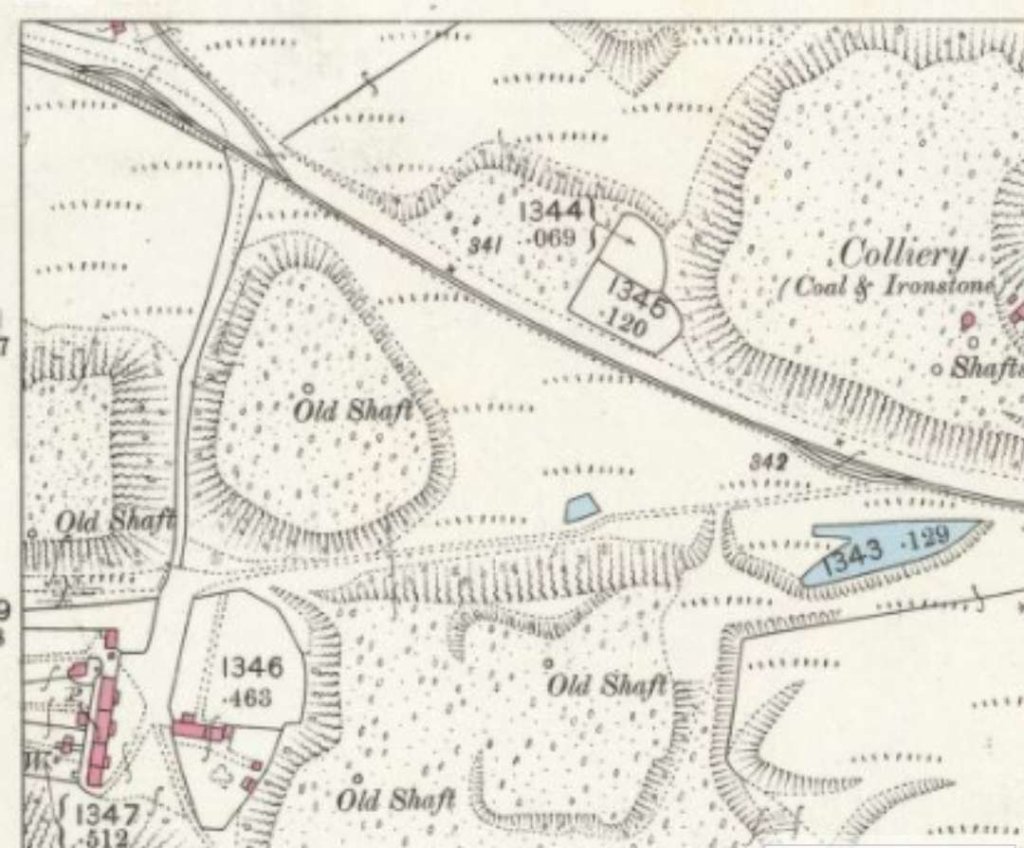

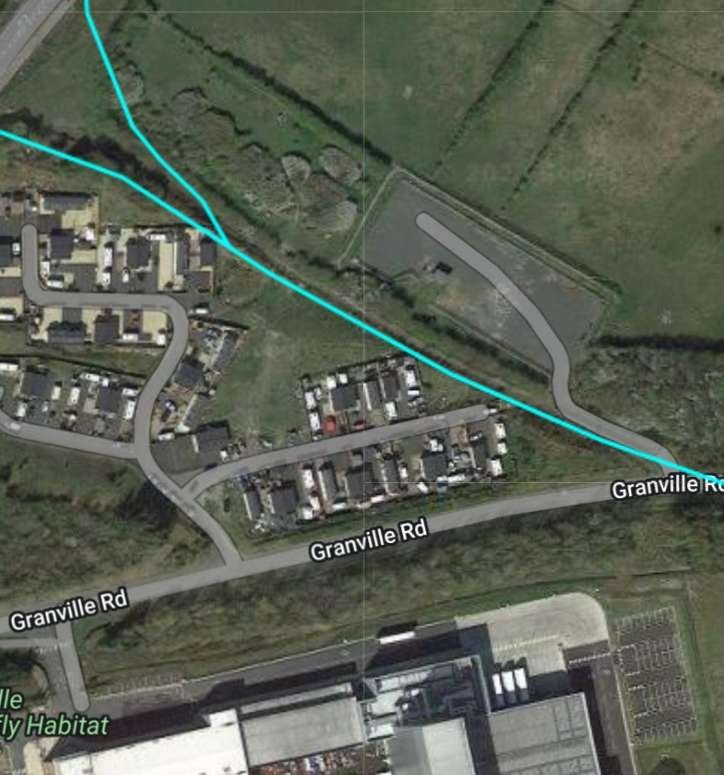

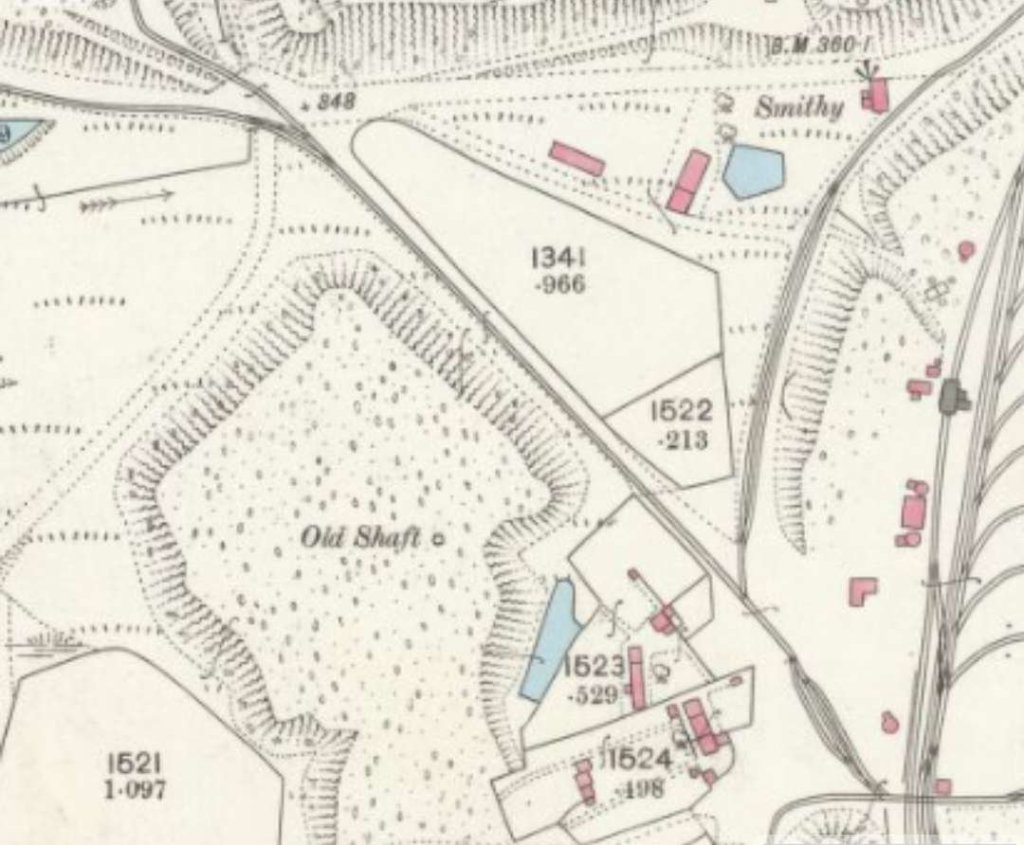

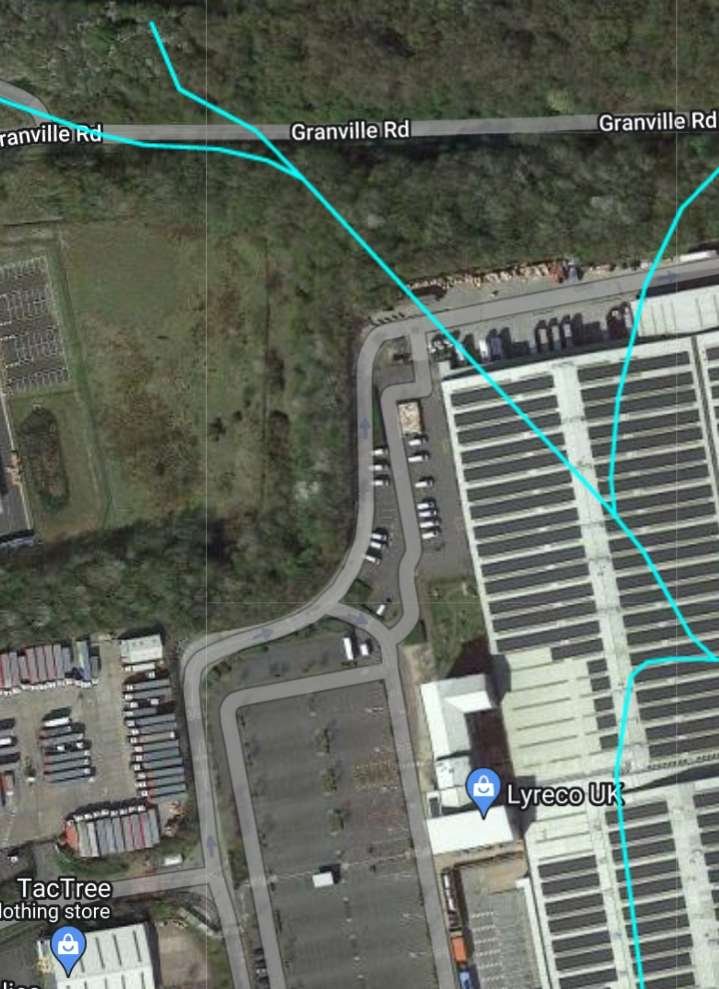

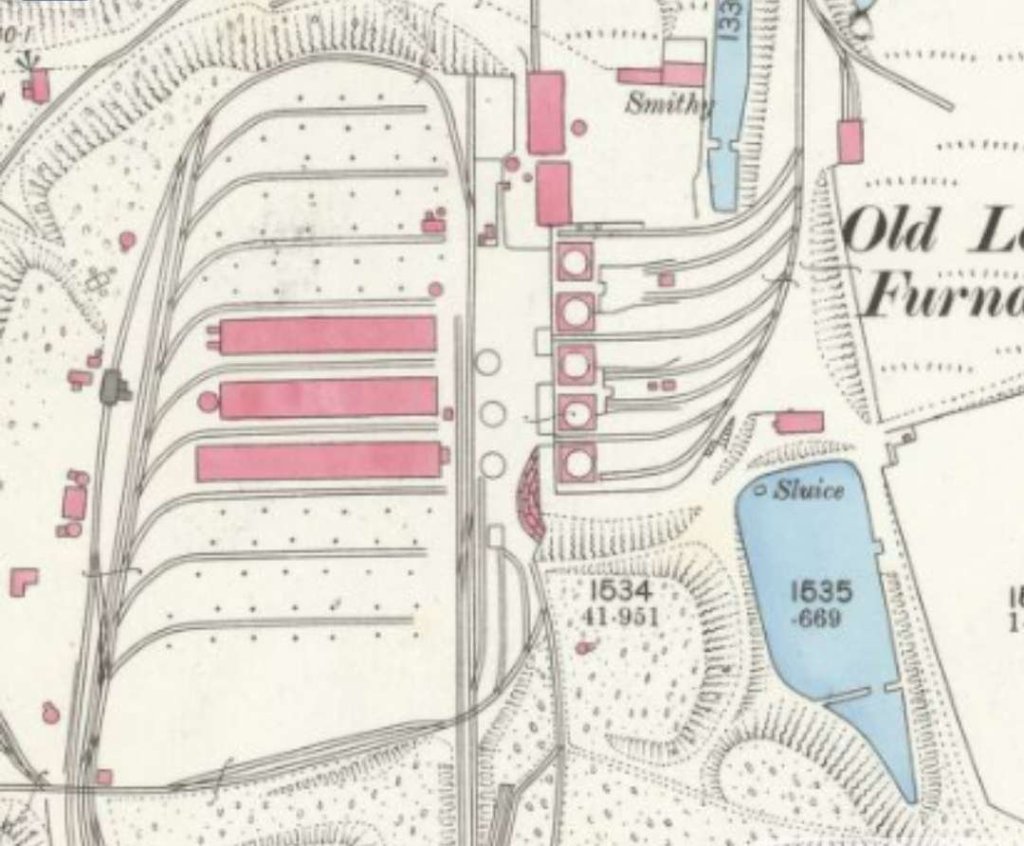

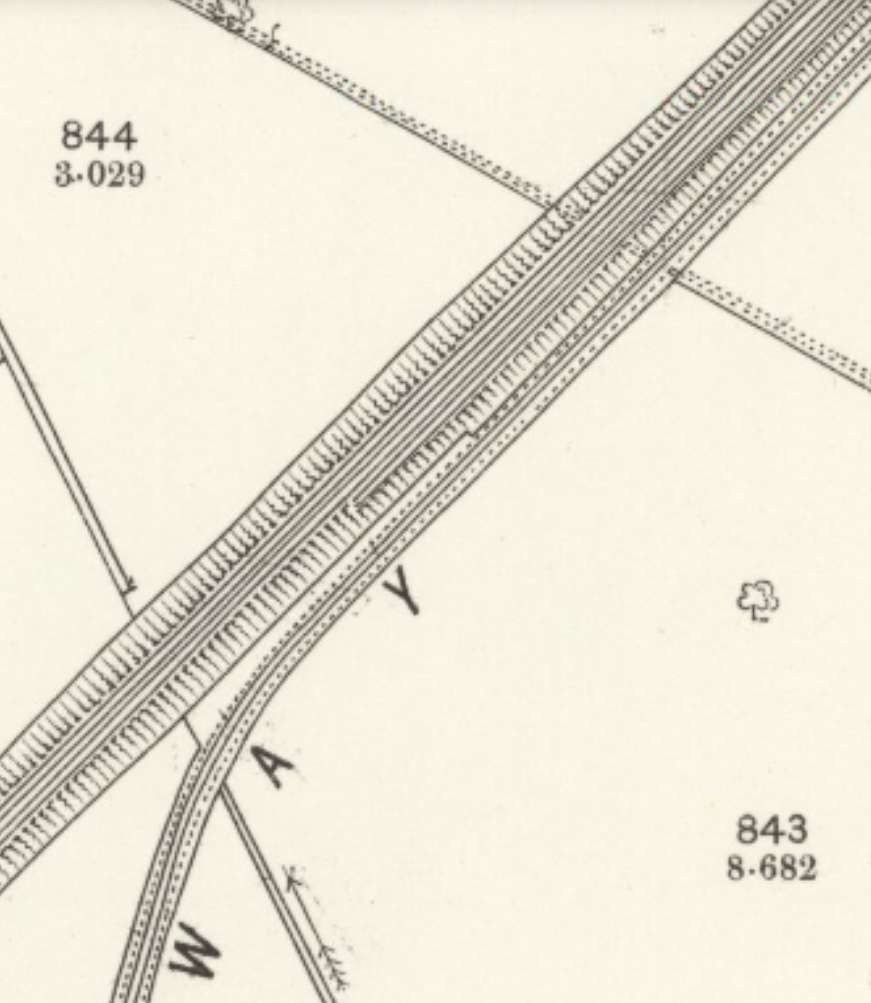

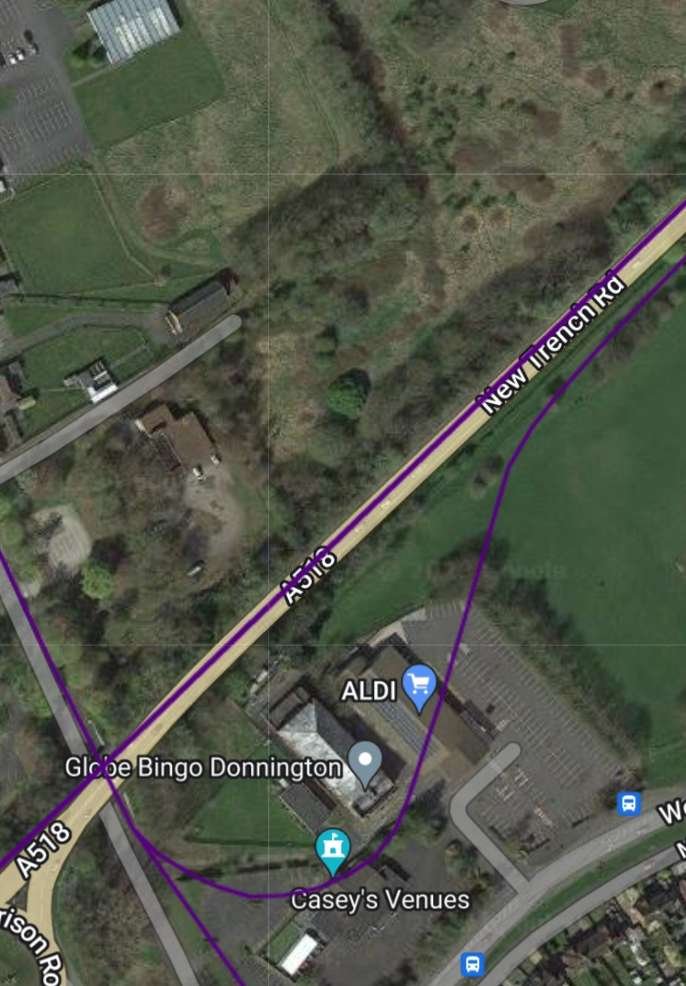

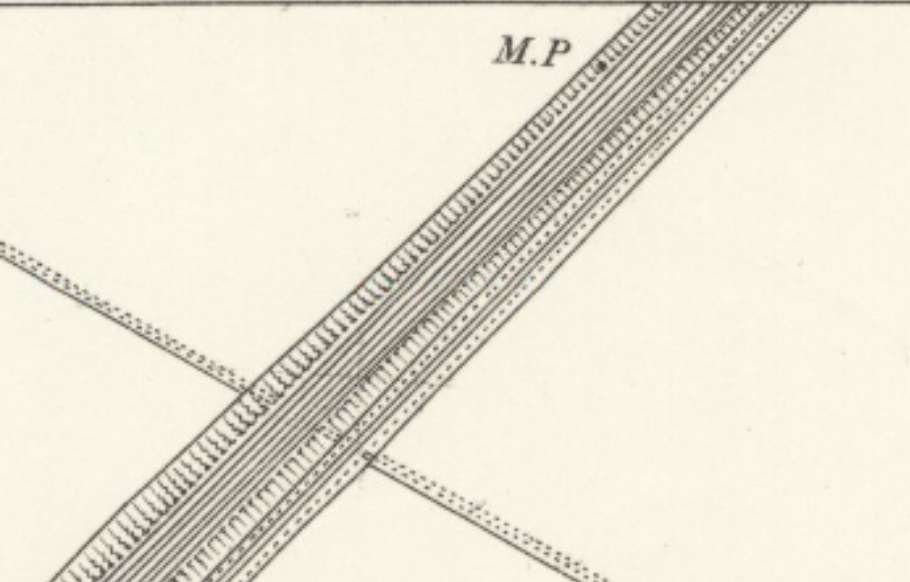

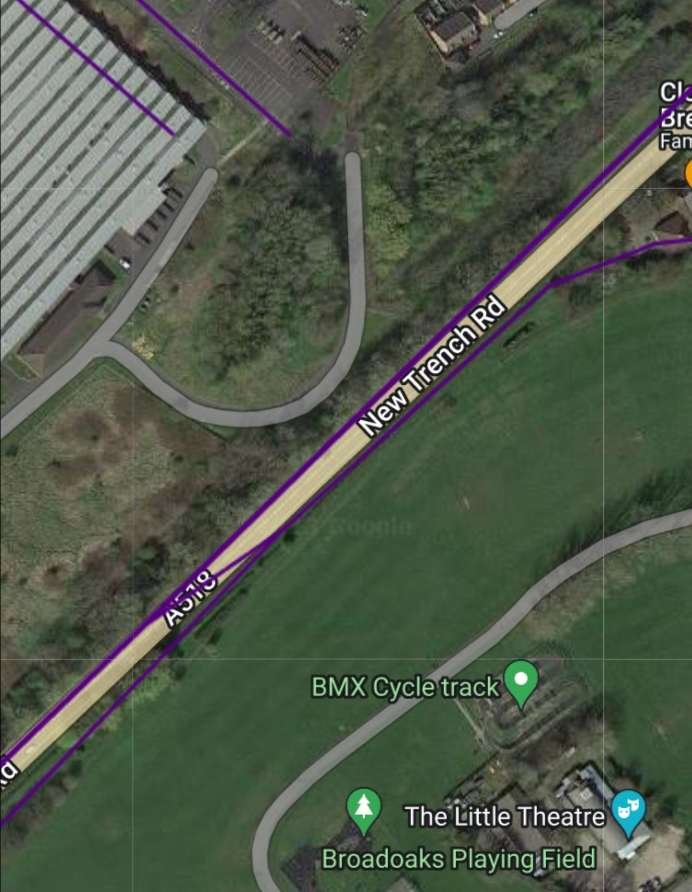

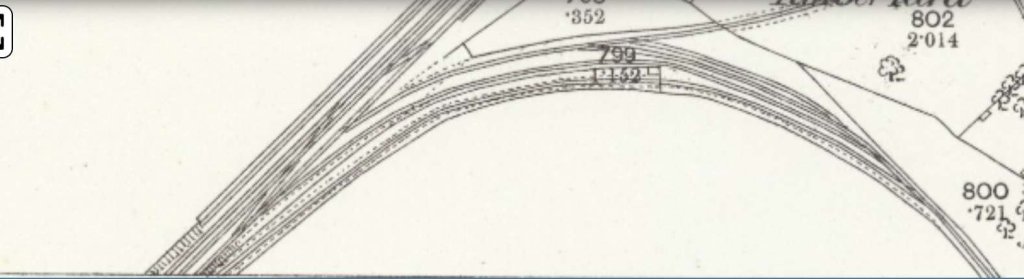

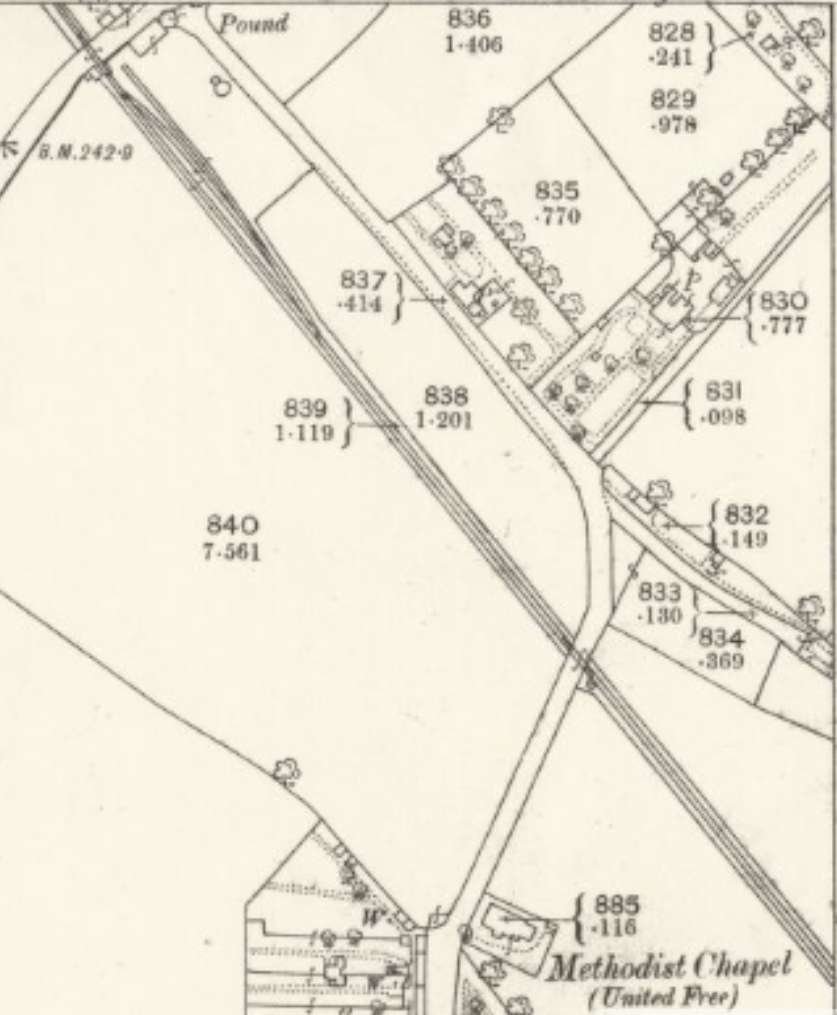

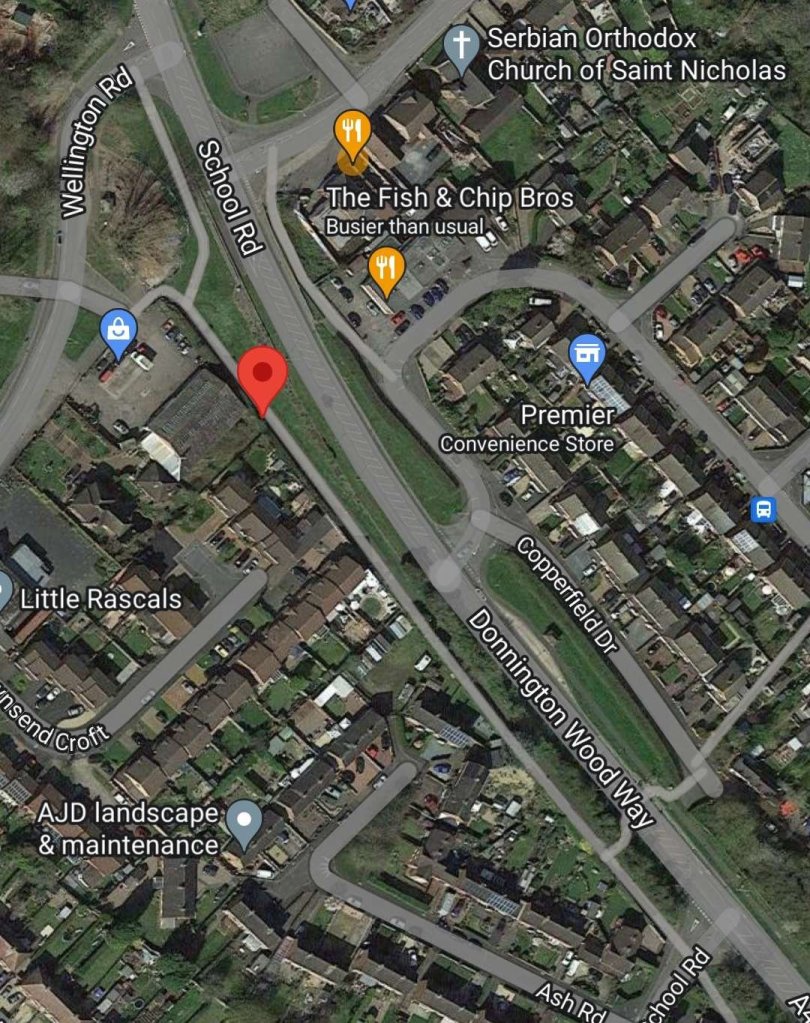

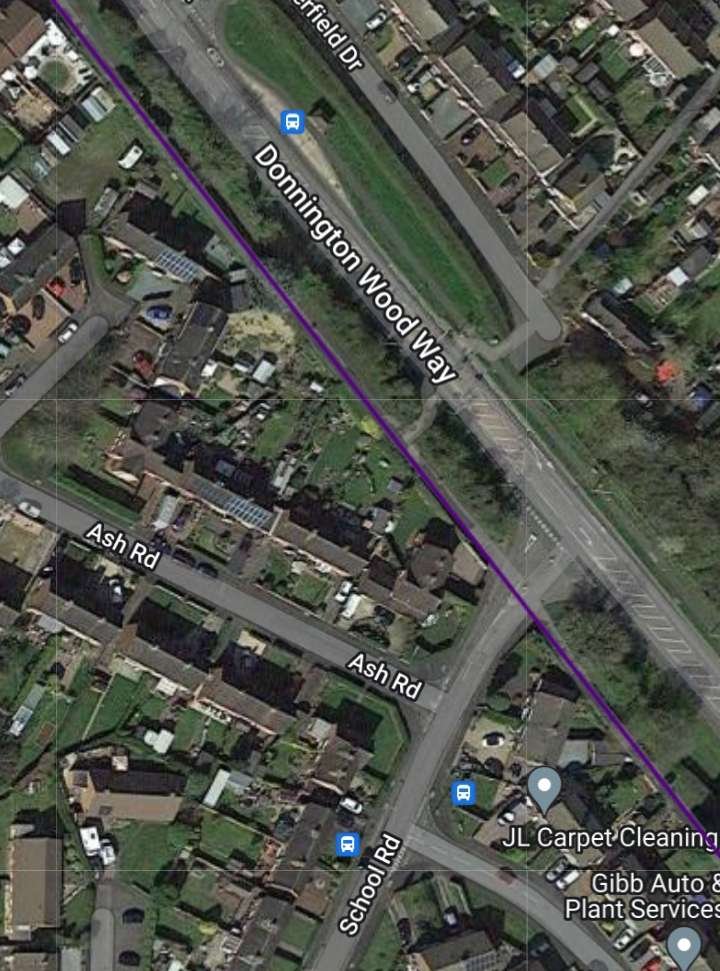

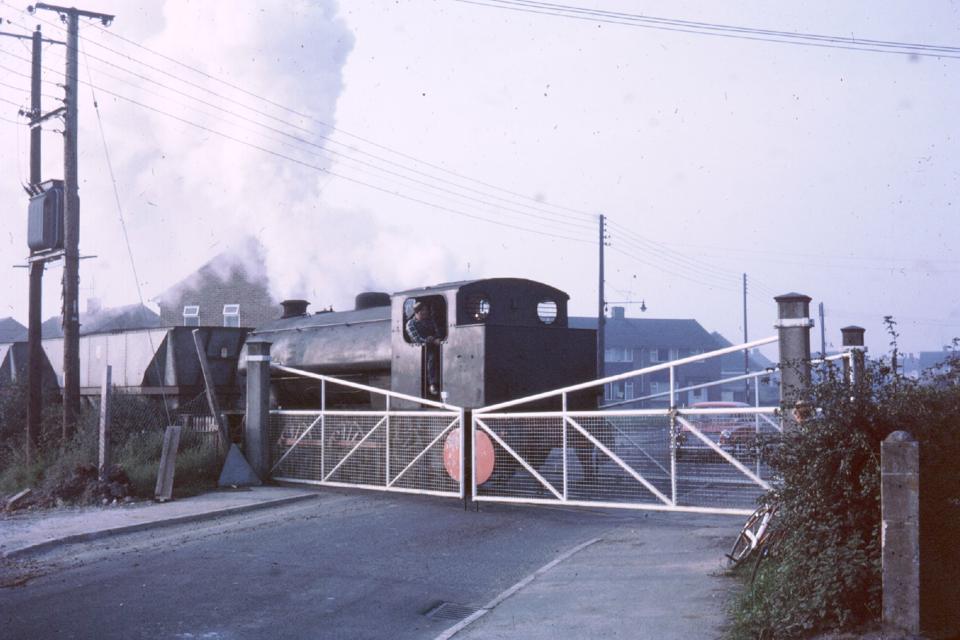

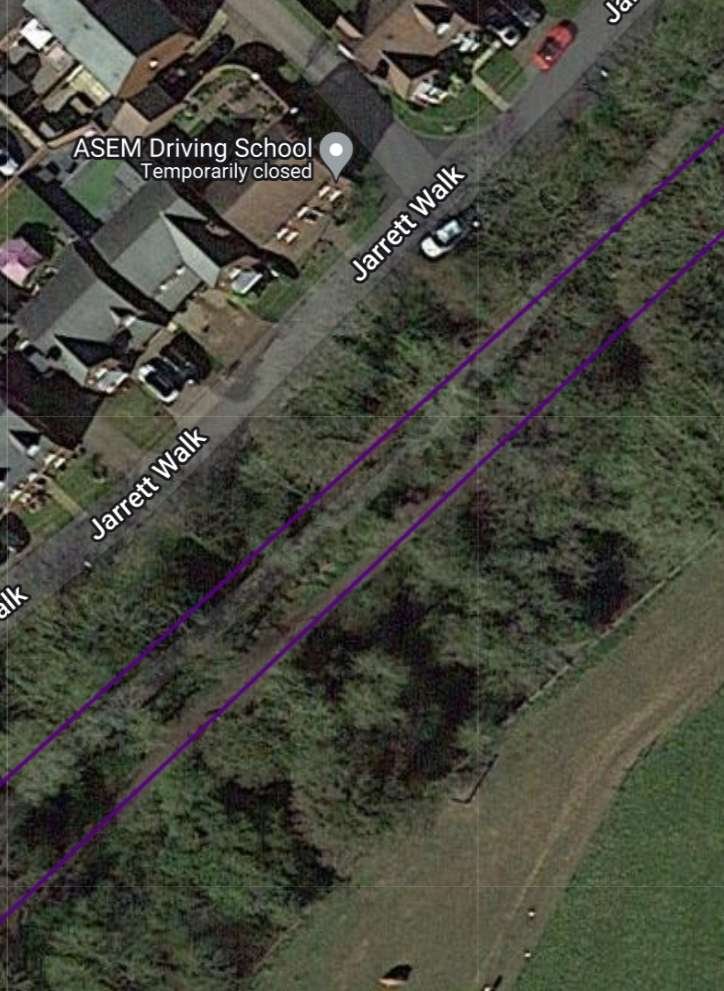

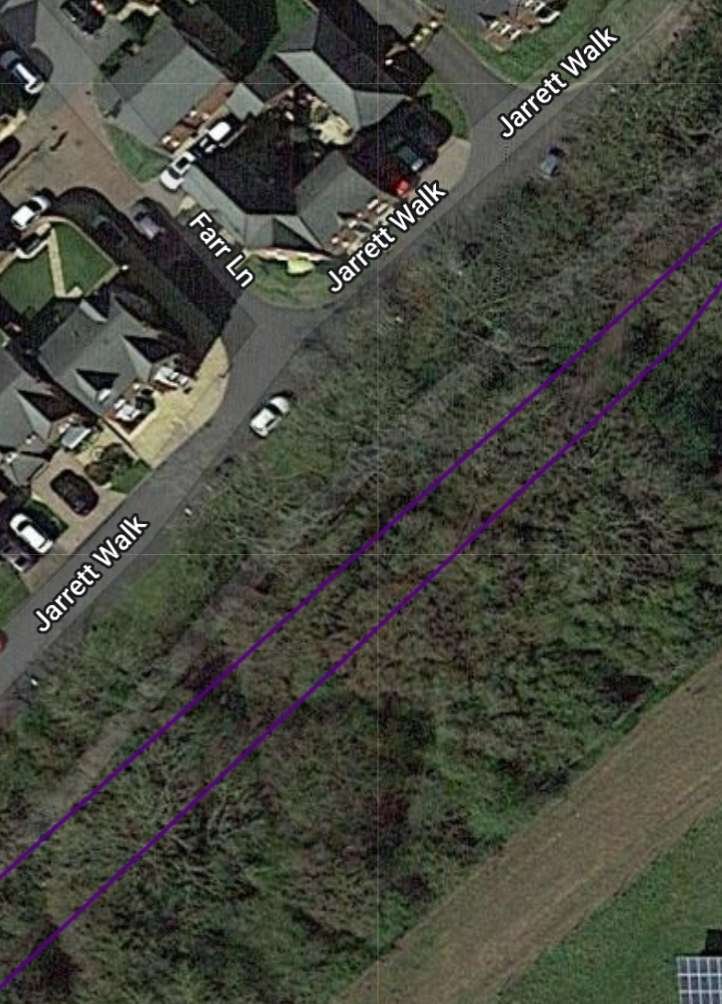

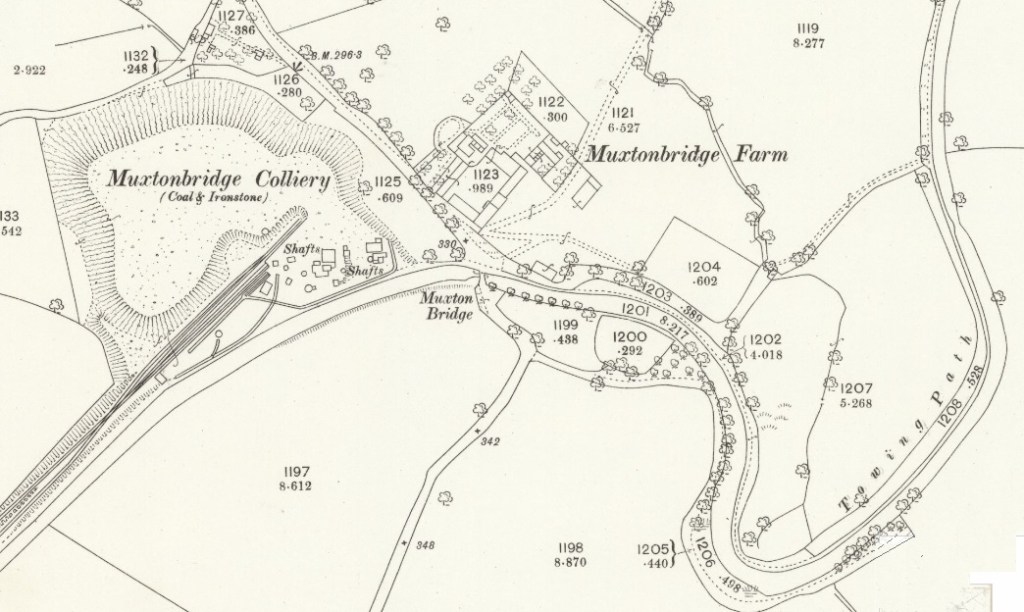

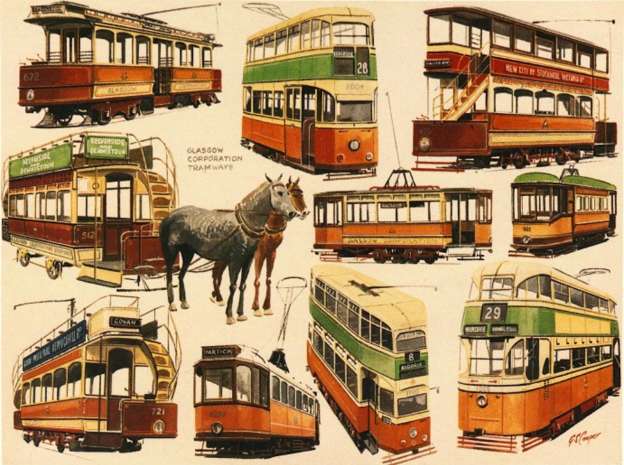

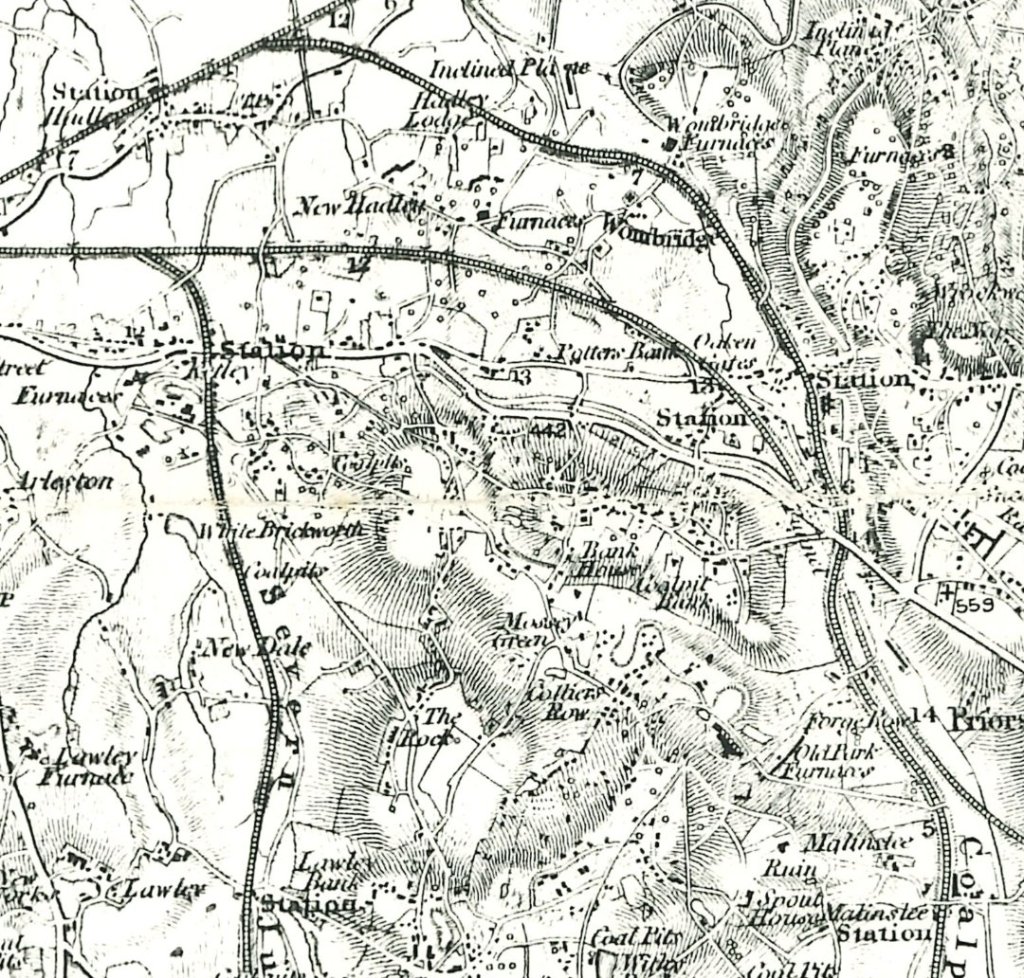

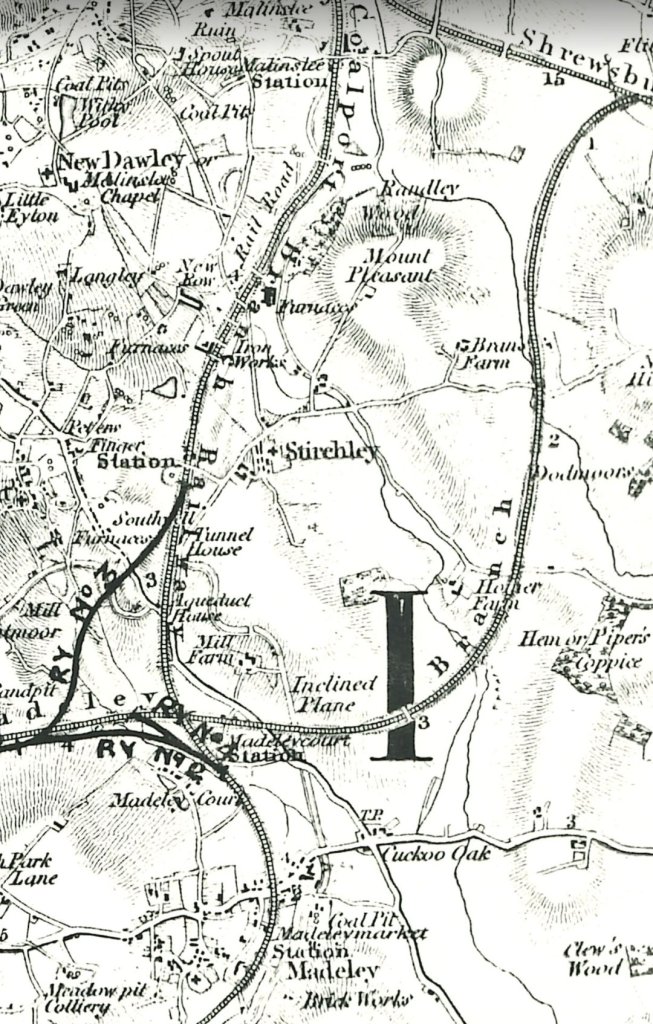

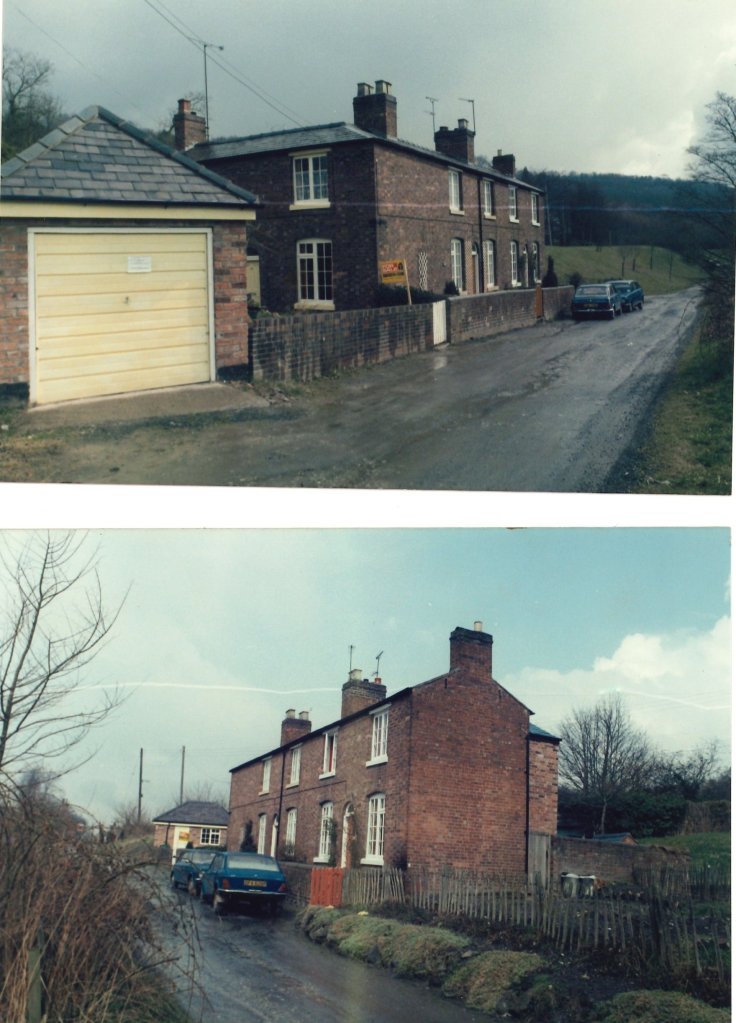

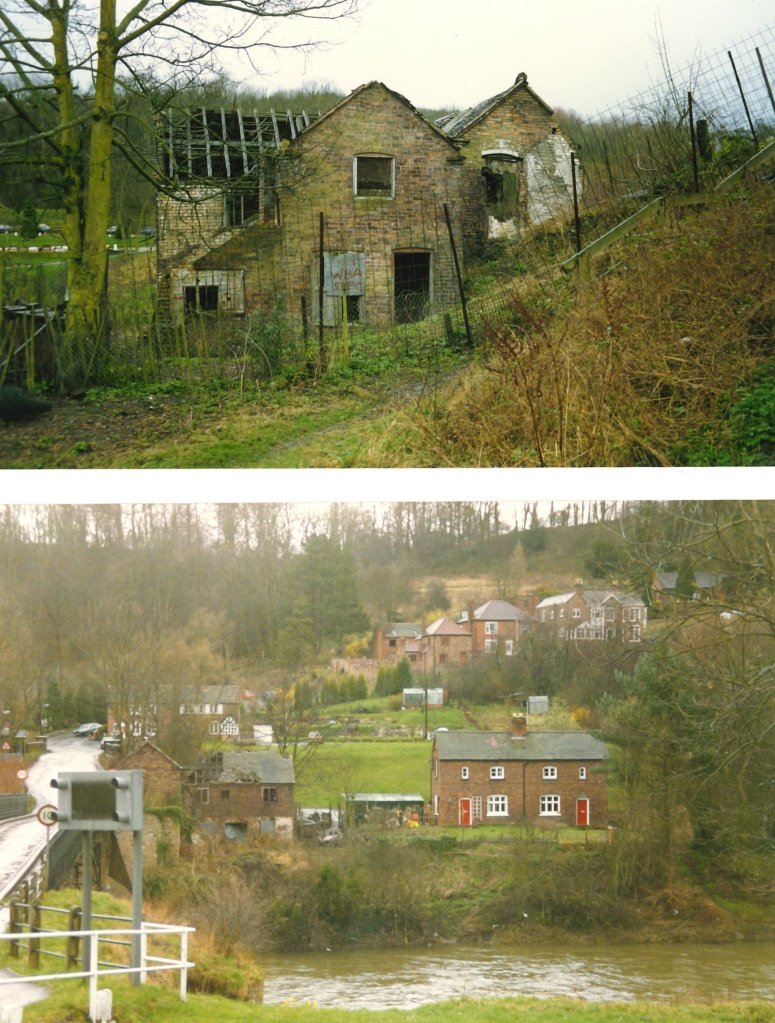

As an aside, G.F. Milnes & Co., Ltd was initially based in Birkenhead but before the turn of the 20th century had purchased a site in Hadley, Shropshire, now part of Telford. “Production commenced at Hadley in June 1900, and the works in Birkenhead closed in 1902. There were around 700 employees and 701 tramcars were built in 1901. The business benefitted from the rush of orders when horse and steam tramway systems were converted to electric traction, but the market had begun to contract by the beginning of 1903. The Company went into receivership in September and, after some complex manoeuvering, became part of the United Electric Car Company Ltd. in June 1905.” [3]

Hadley is only a few miles away from our home in Malinslee, Telford. The Works are still referred to as the Castle Car Works.

Other rolling stock on the MER included four roofed ‘toastrack’ trailers which were lost in the 1930 fire (Nos. 34, 35, 38, & 39); two ‘toastrack’ trailers in storage (No. 50, withdrawn in 1978; and No. 55, withdrawn in 1997); two ‘toastrack’ trailers being rebuilt in 2020 (Nos. 36 & 53); nineteen available for passenger service in 2020 (Nos. 37, 40-44, 46-49, 51, 54, 56-62); and two flatbed trailers (Nos. 45 & 52). [2]

In addition to ‘home-based’ stock the MER has welcomed a number of visiting vehicles over the years details of which can be found on Wikipedia. [2]

Returning to the ‘Modern Tramway’ articles: the Journal reported that, “Maintaining this picturesque but veteran fleet has brought its usual quota of problems, and in view of the age of much of the equipment the Company has installed an ultrasonic flaw-detector at Derby Castle works, which is being used very successfully to detect cracks in axles, and has also been used to test axles bought from British Railways before turning them down to size for use in trailers. This method of flaw-detection is markedly superior to the earlier method with magnetic fluid, since the latter could not reveal faults that were hidden by the wheel boss or the gear seating. The car motors are being rewound with glass fibre insulation, which is expected to cure burn-outs caused by the moisture that tends to accumulate while the cars are idle in winter, and should therefore bring longer motor life. Cars 7 and 9 have been fitted experimentally with hydraulic shock-absorbers on the bogie bolster springs to counteract excessive sideways motion, and the Brush type D bogies of car No. 2 have had their axlebox leaf-springs replaced with a system of brackets and coil-springs, allow- ing more movement in the hornways and. giving a smoother ride. The Management hope that these two modifications when combined will give a vastly superior ride on the ten cars with this type of bogie.” [1: p205]

In the second of the two articles, [4] the Journal continued to note that in 1960 further modern compressor sets were purchased from Sheffield Corporation which were fitted to cars Nos.1, 5, 6, 7, 9, 16, 25, 26, 27, 32 & 33.

For a short while after nationalisation a green and white colour scheme was employed to mark the change. It was quickly realised that the vehicles looked their best when painted and trimmed in accordance with their builders intentions. So, in 1962, the Journal noted that, “The more recent repainting of M.E.R. cars has therefore seen a reversion to varnished teak and Post Office red with white and light brown secondary colourings, and with full lining, crests and detail in pre-war style, and many visitors have expressed their pleasure at this reversion. For the open cars, the equivalent livery is red and white, in each case with the full title instead of the initials M.E.R. During the winter of 1960, saloon trailer No. 57 was splendidly re- upholstered in blue moquette, replacing the original cane rattan which dated quite unchanged from 1904, and No. 58 has undergone the same transformation during the past winter; the concurrent refurbishing of the interior woodwork is a joy to behold. The red used on these two cars is somewhat deeper than that mentioned above.” [2: p221-222]

Planned addition provision of four new saloon cars had by 1962 been deferred indefinitely. Grants being only sufficient to address trackwork concerns. And, since inflation had seen the cost of new cars rise significantly, it was likely that in future the Board would “probably be forced back on the alternatives of reconstructing existing cars or buying others second-hand, if any can be found. Unfortunately, the engineering restrictions imposed by the 3ft. gauge and the 90ft. radius curves and reduced clearances are such that none of the available second-hand cars from Continental narrow-gauge systems is acceptable, and although quotations were obtained for relatively modern cars from the Vicinal and the E.L.R.T., the Vicinal cars were too wide and the cost of the others including modifications was prohibitive. In the whole of Continental Europe, the 3ft. gauge (exact or approximate) is found on electric lines only in Majorca, Linz and Lisbon, and although Lisbon has some two-motor Brill 27G trucks that would be ideal for the MER, the Lisbon tramway staff think the world of them and have no intention of selling.” [2: p222]

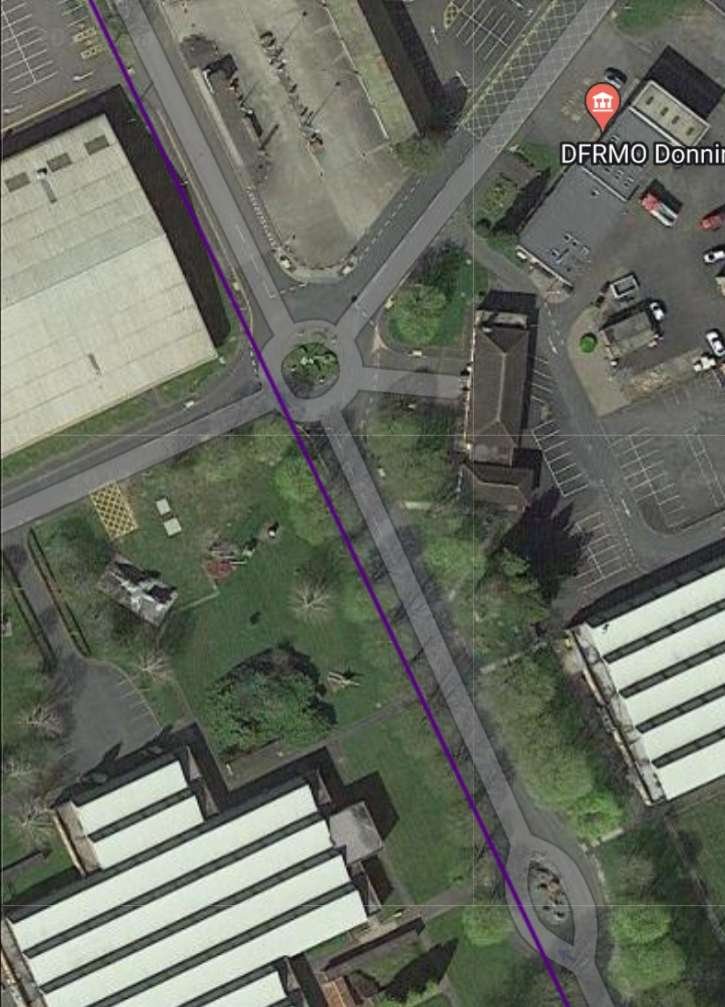

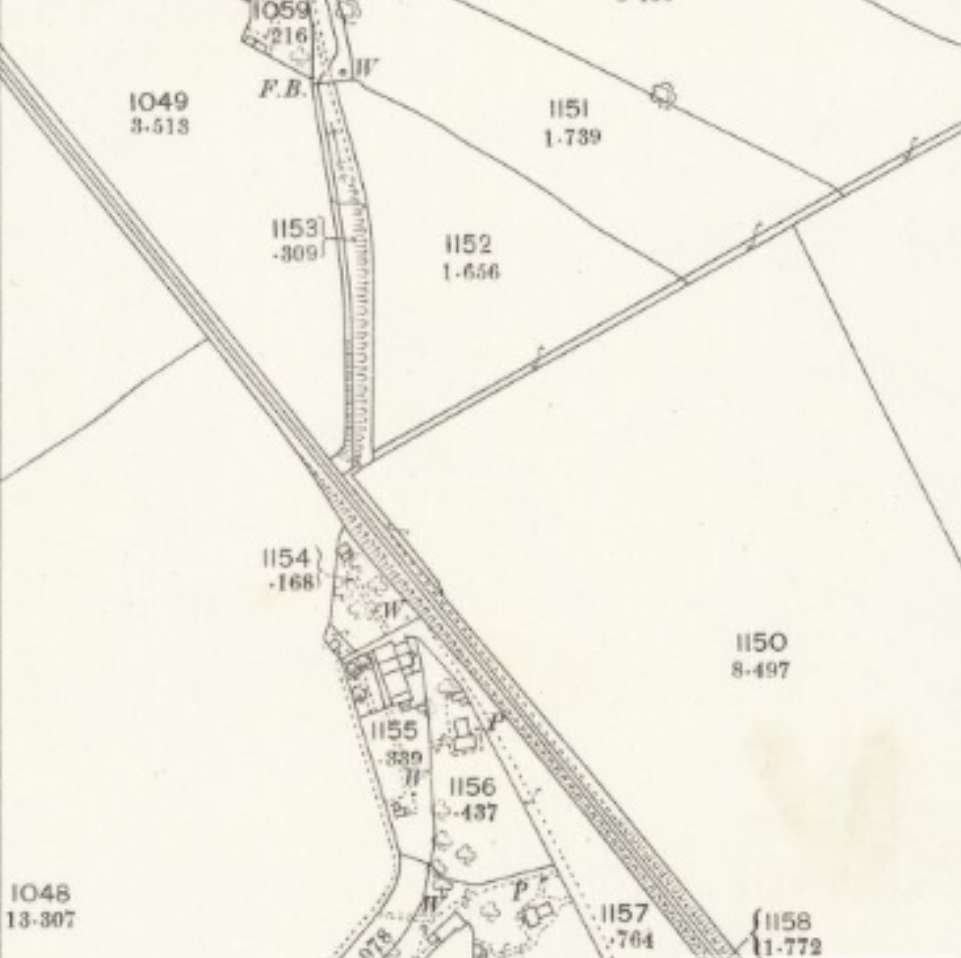

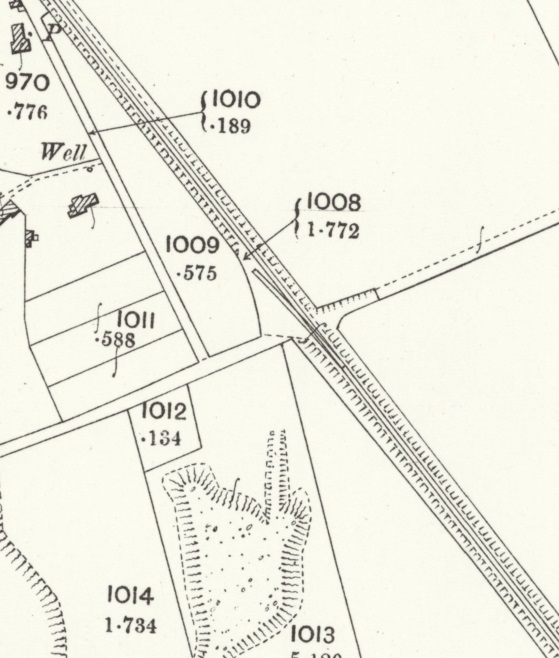

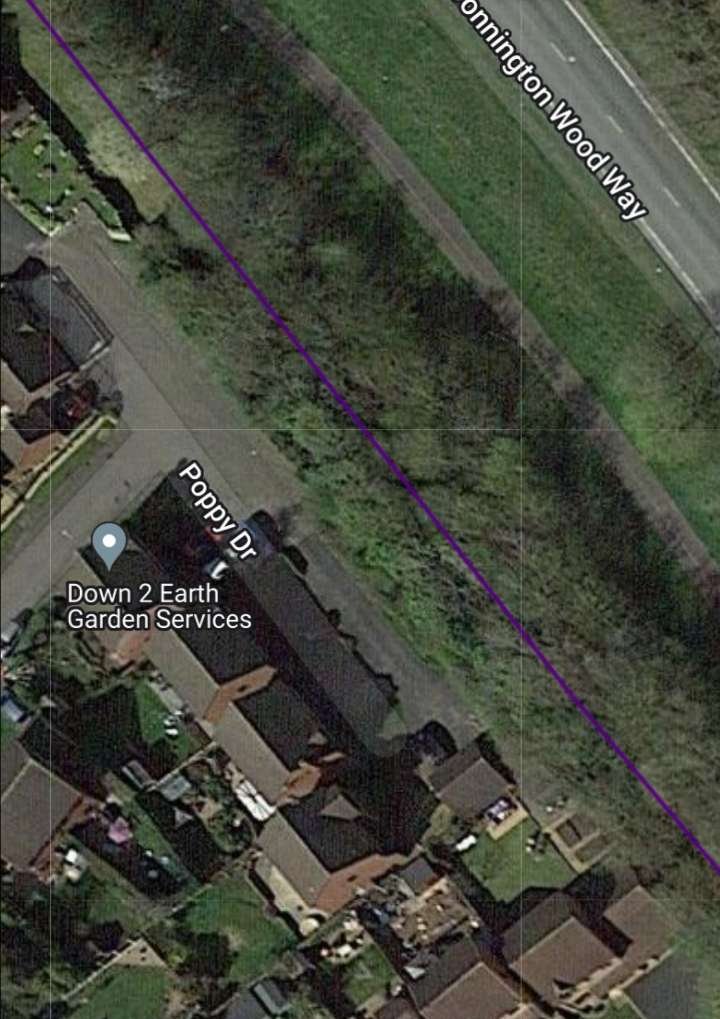

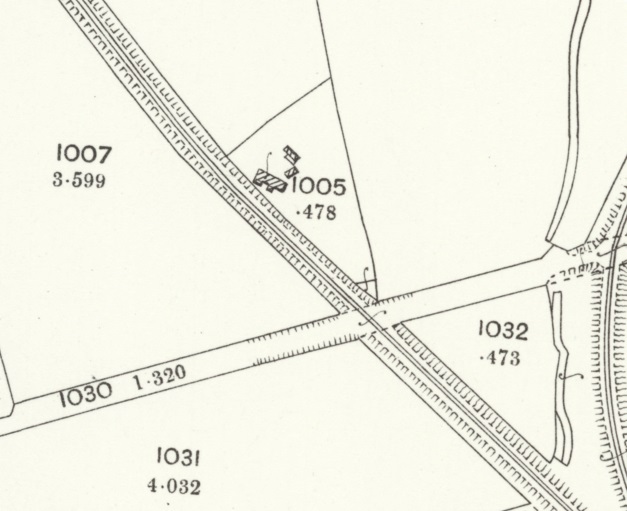

The Journal also observed that “the problem of the two main-road crossings between Douglas and Laxey, … still remains unsolved, and although a quotation was obtained for installing powerful flashing lights, the Highways Board whose responsibility this is has not yet been willing to find the money. This is a pity, for 1962 will see the introduction of a car-ferry steamer from the mainland and the arrival of many motorist visitors unfamiliar with such Manx phenomena as rural electric railways. Despite the vigilance of MER drivers, accidents are likely to continue at these points until something drastic is done; in the meantime, some prominent warning boards and white letters on the road surface would be better than nothing.” [2: p222]

A quick look at Google Maps/Streetview shows that by 2023 that problem had been resolved.

By 2010, both crossing points were protected by standard crossing lights.

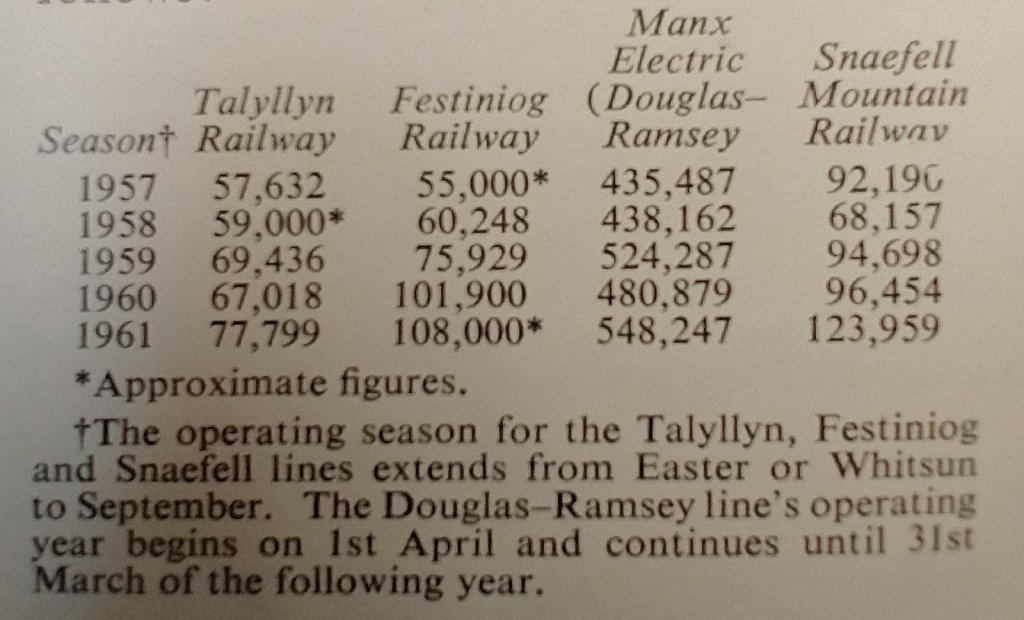

During the 5 years from 1957 to 1962 traffic, as predicted, fluctuated with the weather. It was “doubly unfortunate that the first two summers (1957 and 1958) were rather poor ones. However, the splendid weather in the summer of 1959 revitalised the railway, and the new Board was happily surprised to find that the returning popularity of the railway was sustained in 1960 and even more evident in 1961.” [2: p222]

The Journal provided a comparison of passenger numbers on a number of heritage lines on the Isle of Man and in Wales. Their table is reproduced below.

Throughout 1957 to 1962, the MER operated with the limits imposed by Tynwald (operating revenues plus an annual grant of £25,000, supplemented by monies allocated under employment relief schemes). A wage increase threatened to upset this equilibrium, but Tynwald responded by increasing the annual grant by £3,000 in 1961. Performance improvements meant that the sum was not actually drawn down.

References

- Manx Electric 1957-1962; in Modern Tramway, Volume 25, No. 294, June 1962; Light Railway Transport League and Ian Allan, Hampton Court, Surrey, p201-205

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manx_Electric_Railway_rolling_stock, accessed on 4th August 2023.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/G.F.Milnes%26_Co., accessed on 5th August 2023.

- Manx Electric 1957-1962; in Modern Tramway, Volume 25, No. 295, July 1962; Light Railway Transport League and Ian Allan, Hampton Court, Surrey, p221-225.

- https://www.railmaponline.com/UKIEMap.php, accessed on 5th August 2023.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MER-Trailer-37.jpg#, accessed on 6th August 2023.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manx_Electric_Trailers_45-48, accessed on 6th August 2023.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MER-Tram-2.jpg#, accessed on 6th August 2023.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MER-Tram-16.jpg#, accessed on 6th August 2023.