We start the next leg of the journey at Naivasha Railway Station.

Class 30 2-8-4 No. 3020 “Nyaturu” (NBL 27466/1955) stands at Naivasha, it is one of three locomotives restored by Nairobi Railway Museum and was originally in use on the Tanzanian part of the EAR system (c) James Waite. [1]

Class 30 2-8-4 No. 3020 “Nyaturu” (NBL 27466/1955) stands at Naivasha, it is one of three locomotives restored by Nairobi Railway Museum and was originally in use on the Tanzanian part of the EAR system (c) James Waite. [1] As we leave Naivasha, the railway continues in a north-westerly direction through Morendat Station, over Morendat River Bridge and through Ilkek Station to Gilgil.

As we leave Naivasha, the railway continues in a north-westerly direction through Morendat Station, over Morendat River Bridge and through Ilkek Station to Gilgil.

Morendat Station and River Bridge on Google Satellite Image.

Morendat Station and River Bridge on Google Satellite Image. Ilkek Station.

Ilkek Station.

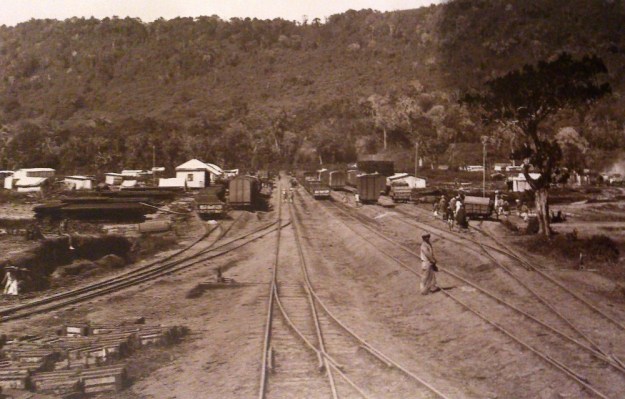

Gilgil is the first town after Naivasha along the line.

111464: Gilgil Kenya 3124 Chope Derailed – taken on 24th August 1971, (c) Weston Langford.[2]

111464: Gilgil Kenya 3124 Chope Derailed – taken on 24th August 1971, (c) Weston Langford.[2]

Three images of Gilgil Station seemingly abandonned in 2013 …….[3],[4],[5]

Three images of Gilgil Station seemingly abandonned in 2013 …….[3],[4],[5]

Gilgil was the junction station for the line to Nyahururu. This branch ran through Oleolondo and Ol Kalou to reach Nyahururu, the branch terminus. It left the mainline just to the East of Gilgil and followed what is now the C77 road from Gilgil. The line snaked around passing through Gilgil Golf Course and can be seen alongside the 4th hole of the 9-hole course in the image below.[6]

Gilgil was the junction station for the line to Nyahururu. This branch ran through Oleolondo and Ol Kalou to reach Nyahururu, the branch terminus. It left the mainline just to the East of Gilgil and followed what is now the C77 road from Gilgil. The line snaked around passing through Gilgil Golf Course and can be seen alongside the 4th hole of the 9-hole course in the image below.[6] After the golf course the line swung away from the C77 to the south-east and then for a very short distance ran alongside what is now the D390 before turning to the north and eventually regaining a path a 100 metres or a bit more to the east of the C&7 running north towards Oleolondo where the line crossed the road at grade. It conitnued to follow the C77 northwards but now on its west side until reaching a station halt at Ol Kalou.

After the golf course the line swung away from the C77 to the south-east and then for a very short distance ran alongside what is now the D390 before turning to the north and eventually regaining a path a 100 metres or a bit more to the east of the C&7 running north towards Oleolondo where the line crossed the road at grade. It conitnued to follow the C77 northwards but now on its west side until reaching a station halt at Ol Kalou.

The old station site at Ol Kalou remains open and undeveloped as can be seen on the adjacent satellite images from Google Earth.

From Ol Kalou the abandonned line continued north alongside the C77, always within about 100 metres of it and then crossing over to the east side of the road a kilometre or two north of Ol Kalou before reaching its terminus at Nyahururu.

In the images above the tourist attraction which probably supported the branch-line while it was in operation can be seen – the Thompson Falls gave their name to the town in colonial times. Nyahururu was founded as Thomson’s Falls after the 243 ft (74m) high Thomson’s Falls on Ewaso Narok river, a tributary of the Ewaso Nyiro River, which drains from the Aberdare mountain ranges. It is on the Junction of Ol Kalou-Rumuruti road and the Nyeri-Nakuru road.

In the images above the tourist attraction which probably supported the branch-line while it was in operation can be seen – the Thompson Falls gave their name to the town in colonial times. Nyahururu was founded as Thomson’s Falls after the 243 ft (74m) high Thomson’s Falls on Ewaso Narok river, a tributary of the Ewaso Nyiro River, which drains from the Aberdare mountain ranges. It is on the Junction of Ol Kalou-Rumuruti road and the Nyeri-Nakuru road.

The town grew around a railway from Gilgil opened in 1929 (and now effectively abandoned). As well as providing access to a tourist attraction the line supported local industry. The town was once an important player in the timber milling industry, and the now defunct National Pencil Company had a factory there. It is also an important milk processing hub.[7]

The map and satellite image show the location of the railway terminus and the turning triangle for locomotives.

We return now to the mainline and travel on from Gilgil. The next station on the mainline is Kariandusi. Kariandusi village is a settlement in Nakuru County, Kenya. It is located 17.5 miles from Nakuru town and 7.5 miles from Gilgil town. Inhabitants of Kariandusi settled in the area in early 1980s in the former Lord Egerton Cole and Lord Delamere ranches. The area has a well established tourism industry, with Kariandusi prehistoric site, Lake Elementaita, Several Hot Springs and booming hospitality industry providing the economic growth for the area.[8] It sits close to the lake and under the significant local peak know as Table Mountain.

Kariandusi village is a settlement in Nakuru County, Kenya. It is located 17.5 miles from Nakuru town and 7.5 miles from Gilgil town. Inhabitants of Kariandusi settled in the area in early 1980s in the former Lord Egerton Cole and Lord Delamere ranches. The area has a well established tourism industry, with Kariandusi prehistoric site, Lake Elementaita, Several Hot Springs and booming hospitality industry providing the economic growth for the area.[8] It sits close to the lake and under the significant local peak know as Table Mountain.

The prehistoric site is amongst the first discoveries of Lower Paleolithic sites in East Africa. There is enough geological evidence to show that in the past, large lakes, sometimes reaching levels hundreds of meters higher than the Present Lake Nakuru and Elementaita, occupied this basin.

Dating back between 700,000 to 1 million years old, Kariandusi is possibly the first Acheulian site to have been found in Situ in East Africa. Dr. Leakey, a renowned paleontologist, believed that this was a factory site of the Acheulian period. He made this conclusion after numerous collections of specimens were found lying in the Kariandusi riverbed.

This living site of he hand-axe man, was discovered in 1928. A rise in the Lake level drove pre-historic men from their lake-side home and buried all the tools and weapons which they left behind in a hurry. The Acheulian stage of the great hand-axe culture, to which this site belongs, is found over a very widespread area from England, France, and Southwest Europe generally to Cape Town.[9]

The image above is typical of the scenery in this area of the Rift Valley and is taken close to Mbaruk the next station on the line. The satellite image below shows the passing loop and station at Mbaruk. The last station before Nakuru itself is in Nakuru’s suburbs at Lanet and the location is shown in the satellite image below.

The last station before Nakuru itself is in Nakuru’s suburbs at Lanet and the location is shown in the satellite image below. Nakuru is the final destination for this blog post.

Nakuru is the final destination for this blog post.

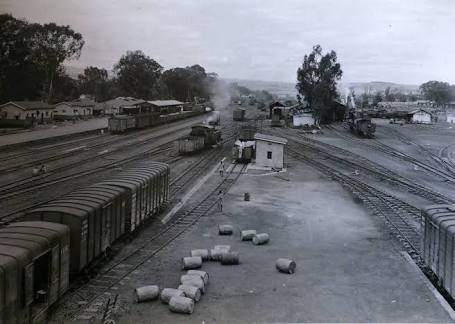

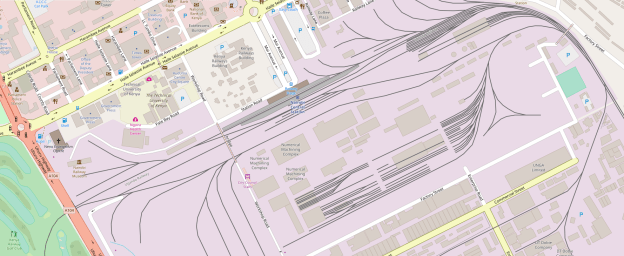

Nakuru was the most modern station on the line – complete with a public address system, colour light signalling and double track westbound between Nakuru East and the divergence of the former mainline to Kisumu. During stops at Nakuru passengers could buy refreshments, books and newspapers from a trolley which passed down the platform while the locomotive was being changed, © Malcolm McCrow.[10]

Nakuru was the most modern station on the line – complete with a public address system, colour light signalling and double track westbound between Nakuru East and the divergence of the former mainline to Kisumu. During stops at Nakuru passengers could buy refreshments, books and newspapers from a trolley which passed down the platform while the locomotive was being changed, © Malcolm McCrow.[10]

111545: Nakuru Kenya 0920 Mixed to Kisumu 5812©Weston Langford.[2] 111546: Nakuru Kenya 0920 Mixed to Kisumu 5812©Weston Langford.[2]

111546: Nakuru Kenya 0920 Mixed to Kisumu 5812©Weston Langford.[2] 111547: Nakuru Kenya 0920 Mixed to Kisumu 5812©Weston Langford.[2]

111547: Nakuru Kenya 0920 Mixed to Kisumu 5812©Weston Langford.[2]

- http://www.internationalsteam.co.uk/trains/kenya11.htm, accessed on 24th May 2018. The photograph was taken by James Waite. He comments: This photograph, “took a long time to set up, even by the standards of night photos. I had gone out to Naivasha on the empty stock of the steam special and spent the night at the Bell Inn on the main street at Naivasha opposite the station. As I was travelling light I didn’t take a tripod with me and it wasn’t until I was talking to the loco’s support crew over supper the previous evening that I realised they would be lighting up before dawn. I walked over to the station and took my suitcase with me to use as a camera stand. The light was too dim for my camera’s autofocus to work, and its manual focus setting was erratic. I ended up taking something like 20 to 30 exposures, each at a slightly different focus, and only this one worked out properly by the time I had eliminated all those suffering from shake because of the lack of a tripod. I only had ten minutes or so between inky-black dark and too much dawn light as the sun comes up so quickly close to the equator.

Everyone else on the photo tour had spent the previous afternoon visiting Nairobi works, spent the night in the city and travelled out to Naivasha by road for the start of the photo charter, and I counted myself very lucky to have been able to enjoy the ride in the empty train down the side of the escarpment into the Rift Valley in the afternoon sunshine, as well as being able to take this night shot without having to work around other photographers.

- http://www.westonlangford.com, accessed on 25th May 2018.

- http://jimstotherssabbatical.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/sabbaticalday-19-12-august-correction.html, accessed on 25th May 2018.

- https://innovation.journalismgrants.org/projects/chinas-train-to-african-development, accessed on 25th May 2018.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/156858441@N07/26344179857/in/photolist-G8WNRx, accessed on 25th May 2018.

- http://www.shoestringgolfer.com/2011/11/gilgil-golf-club-great-rift-valley, accessed on 25th May 2018.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nyahururu, accessed on 25th May 2018.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kariandusi, accessed on 25th May 2018.

- http://www.museums.or.ke/kariandusi, accessed on 25th May 2018.

- http://www.mccrow.org.uk/eastafrica/eastafricanrailways/KampalaNairobi.htm, accessed on 24th May 2018.

The project is called ‘Kibera Walls for Peace’. Peace murals were painted by local youth around Kibera. The project approached and worked with Rift Valley Railways to use the commuter trains as a canvas to spread peace messages and togetherness. The railways had been a major target in the previous post-election violence, especially the route through Kibera. In 2007, mobs of young people tore up the train tracks that connect Kenya and Uganda and sold them for scrap metal.

The project is called ‘Kibera Walls for Peace’. Peace murals were painted by local youth around Kibera. The project approached and worked with Rift Valley Railways to use the commuter trains as a canvas to spread peace messages and togetherness. The railways had been a major target in the previous post-election violence, especially the route through Kibera. In 2007, mobs of young people tore up the train tracks that connect Kenya and Uganda and sold them for scrap metal.

Staff at Nairobi MPD on the occasion of Princess Margaret’s visit in 1956.[14]

Staff at Nairobi MPD on the occasion of Princess Margaret’s visit in 1956.[14]

Class 59 Garratt No. 5918 ‘Mt Gelai’ in Steam in 2004.[15]

Class 59 Garratt No. 5918 ‘Mt Gelai’ in Steam in 2004.[15]

On the left of the picture above is a replica of a Mombasa trolley. [5]

On the left of the picture above is a replica of a Mombasa trolley. [5]

Voi Station Sign.

Voi Station Sign.

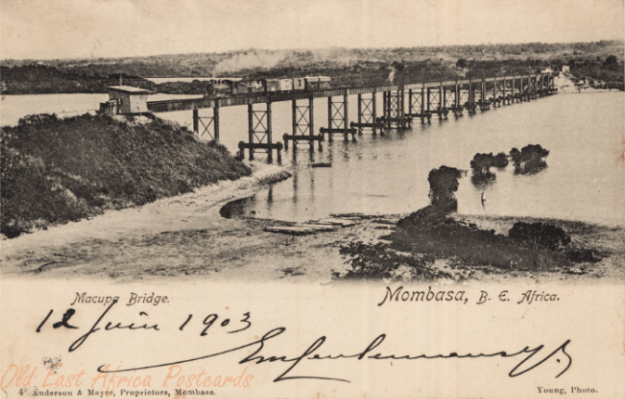

As the line turned to the north it was joined by a branch which served the Chamgamwe Oil Refinery to the south. Next came the first station on the line at Chamgamwe. The photographs of this station from the 1960s and 1970s are courtesy of Malcolm McCrow’s website [3] and are copyright Malcolm McCrow and Kevin Patience.

As the line turned to the north it was joined by a branch which served the Chamgamwe Oil Refinery to the south. Next came the first station on the line at Chamgamwe. The photographs of this station from the 1960s and 1970s are courtesy of Malcolm McCrow’s website [3] and are copyright Malcolm McCrow and Kevin Patience.