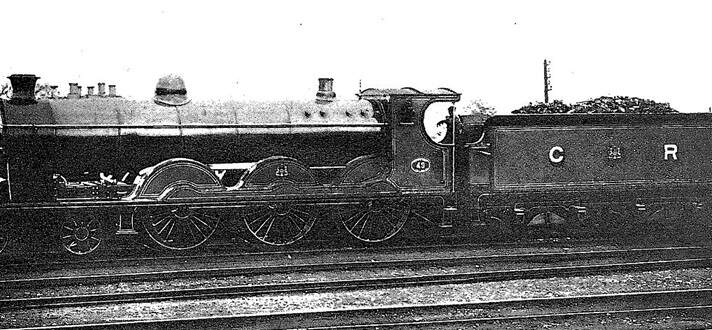

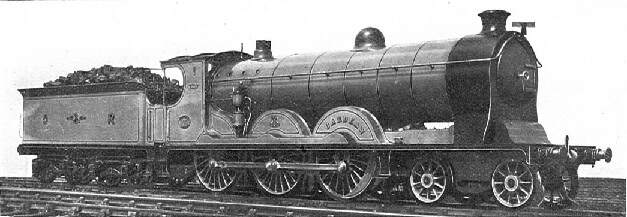

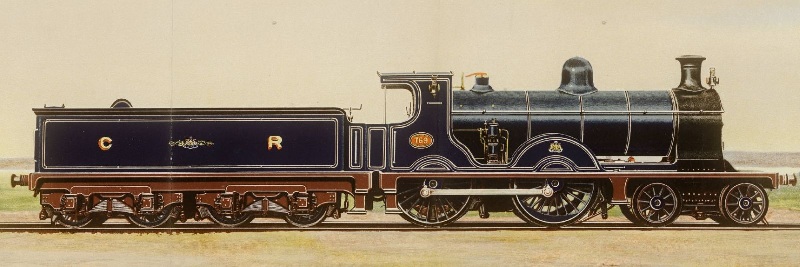

The featured image above shows a Caledonian Railway West Coast Dining Train hauled by Caledonian Railway 4–6–0 Locomotive No. 49.

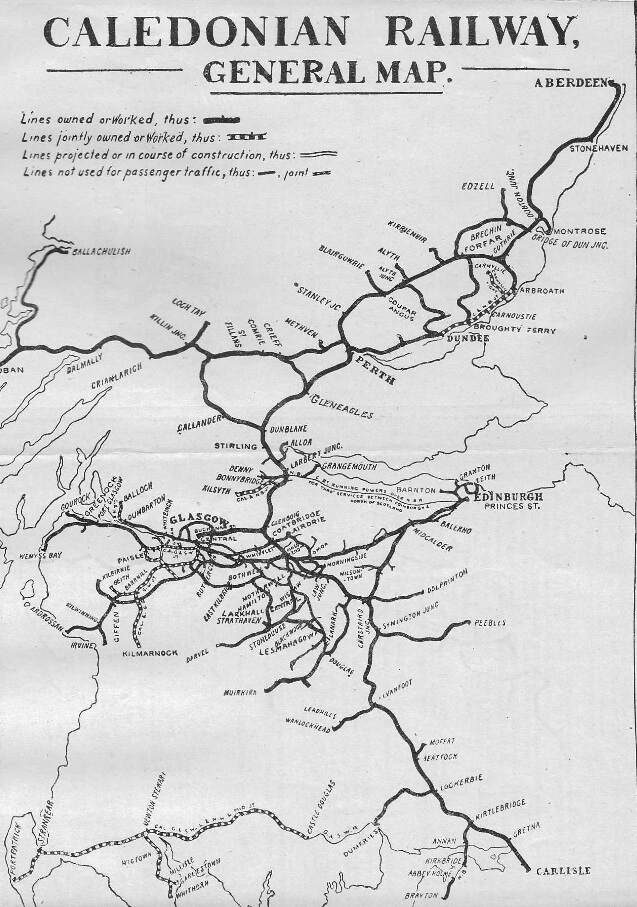

Wikipedia tells us that “The Caledonian Railway (CR) was one of the two biggest of the five major Scottish railway companies prior to the 1923 Grouping. It was formed in 1845 with the objective of forming a link between English railways and Glasgow. It progressively extended its network and reached Edinburgh and Aberdeen, with a dense network of branch lines in the area surrounding Glasgow. It was absorbed* into the London, Midland and Scottish Railway in 1923. Many of its principal routes are still used, and the original main line between Carlisle and Glasgow is in use as part of the West Coast Main Line railway (with a modified entry into Glasgow itself).” [3]

* technically the Caley was not ‘absorbed’ but rather ‘amalgamated’ into the LMS.

Paul Drew says, “A little after eight o’clock on daylight weekday evenings in the years just before World War I, at Carlisle Citadel Station there was performed a colourful ceremony; it was the arrival from Euston of ‘The 2pm’ the West Coast Anglo-Scottish express par excellence and its making over by the London & North Western Railway (LNWR)to the Caledonian Railway (CR), with a change of engine. The occasion was impressive after sunset too, but the gaslight killed the colours of the locomotives and coaching stock; not only LNW and Caledonian were to be seen, but also Midland, North Eastern, Maryport & Carlisle, North British, and Glasgow & South Western. The seven railways and their several liveries made Carlisle Citadel the epitome of pre-1914 variety and splendour on Britain’s railways. The 2pm was sometimes called ‘The Corridor’ because in the 1890s it was the first West Coast train to include corridor stock.” [1: p4]

He continues: “In would come the 2pm behind an Experiment or, later, a Claughton 4-6-0 in LNWR blackberry black, austere perhaps, with a black tender devoid of identification for everybody should know an LNW engine. The coaches would be lettered WCJS (West Coast Joint Stock) but they would be the latest achievement of LNW design, specially built for the 2pm. The livery would be LNW-cream above the waistline and, below, that indescribable mixture of dark purple and brown; nearby, just for contrast, there might be some Caledonian main-line stock in cream and purple-lake, ruddier than the LNW lower panelling, and wearing the Caledonian coat of arms. (It was far more eloquent heraldry than the groups of shire and city arms favoured by most other companies, signifying among other things the Kingdom and Royal House of Scotland.) The 2pm consisted of seven, or sometimes up to nine, 12-wheel vehicles, with portions for Glasgow Central and Edinburgh Princes Street, which divided at Symington or Strawfrank Junction, or sometimes Carstairs.” [1: p4]

Drew continues his evocative description of a late afternoon and early evening at Carlisle: “The North Western engine would run off into the yard and then would appear a massive eight-wheel Azure-Blue tender bearing on its side the Caledonian arms flanked by the initials CR. Beyond, there would loom into sight the great bulk of one of the Cardean class of inside-cylinder 4-6-0s, perhaps No 903 Cardean itself, a vision of Azure boiler, splashers and cab sides, purple-lake underframes, and scarlet buffer beam, and one of the most powerful and efficient inside-cylinder 4-6-0s, and indeed of any 4-6-0s, of a British railway.” [1: p4]

The CR was the first major railway to adopt a blue livery for its locomotives. The CR adopted the colour in the very early days of the company. Drew tells us that, “the CR’s ‘Azure Blue’ was achieved by mixing white paint at the company’s St Rollox (Glasgow) works with expensive darker blue, to economise; some CR engines painted in the Perth shops were finished in darker blue without the white admixture. Neither livery and especially the lighter has been surpassed by any of the blues essayed by other railways in the later years of steam.” [1: p4]

Drew continues: “Cardean or a sister-engine would be coupled up and, after a blast of the Caley whistle, the miniature foghorn that contrasted so well with the shriller piping of other companies’ locomotives, the express pulled out on its 39.7-mile 44-minute run to Beattock at the foot of the 10-mile Beattock Bank. A stop of only two minutes was allowed at Beattock for buffering up the banking engine and ‘The Corridor’ was off on its next lap to Symington or other point of detachment of the Edinburgh vehicles. Overall timing allowed from Carlisle to Glasgow was 123 minutes, so that the train was due at Central at 22:16, eight hours 16 minutes after leaving Euston, and only one minute after the 84-hour Euston-Glasgow and Kings Cross-Edinburgh timings which the West and East Coast companies had agreed between themselves rather unprogressively after the second series of the so-called Races to the North of 1895.” [1: p4]

Close co-operation between the CR and the LNWR was the order of the day, as was a similar co-operation between The North British Railway and the North Eastern Railway on the east coast of the UK. But Carlisle was the frontier between the two and the Cr was independent of the LNWR in most things.

In the 1830s and 1840s much thought was given to building a railway from central Scotland to join the growing English railway network. The hilly terrain and sparse population of the Southern Uplands made the choice of route contentious. [5]

Drew tells us that “the Caledonian was conceived as a link between England and central Scotland and Glasgow before the most northerly component of the railways – the Lancaster & Carlisle Railway, eventually amalgamated into the LNWR – was projected. Alone of the four Anglo-Scottish trunk routes proposed in the late 1830s, the CR line from the south. from Carlisle via Annandale and Beattock, forking near Symington for Glasgow and Edinburgh, served both cities equally well. The Annandale route was chosen by that great engineer Joseph Locke. after some hesitation, in preference to the route via Dumfries. Nithsdale and Kilmarnock, which was more or less the alignment of the Glasgow & South Western and could not reach Edinburgh except through industrial Lanarkshire or by a detour through difficult terrain south of Glasgow.” [1: p5]

Wikipedia comments that, “the Caledonian Railway succeeded in opening its line by way of a summit at Beattock in 1847 and 1848. It connected Glasgow and Edinburgh with Carlisle, and there was a branch to connect with another railway to Perth. The approaches to Glasgow were over existing mineral lines, but a superior route was later built.” [5] The Carlisle-Glasgow main line was the Caledonian’s first trunk route. The Caledonian Railway Act received the Royal Assent on 31st July 1845, and the first section was opened from Carlisle to Beattock on 10th September 1847. The two cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow were reached by 15th February 1848. Drew tells us that, “the Glasgow terminus, Buchanan Street, was not opened until the following year. The station first used was Port Dundas, approached over the metals of the Glasgow, Garnkirk & Coatbridge [Railway], which the CR absorbed.” [1:p5]

Wikipedia comments: “Glasgow was reached over the Glasgow, Garnkirk and Coatbridge Railway (successor to the Garnkirk and Glasgow Railway), and the Wishaw and Coltness Railway, which the Caledonian had leased from 1st January 1847 and 1st January 1846 respectively. The Glasgow station was [initially] the Townhead terminus of the Glasgow, Garnkirk and Coatbridge Railway.” [3][8]

Wikipedia continues: “During the process of seeking Parliamentary authorisation, the Caledonian observed that the Clydesdale Junction Railway was being promoted. The Caledonian acquired that line during its construction, and it opened in 1849. It gave an alternative and shorter access to another Glasgow passenger terminal, named South Side, and to the Clyde quays at General Terminus (over the connected General Terminus and Glasgow Harbour Railway). The South Side station was already being used by the Glasgow, Barrhead and Neilston Direct Railway, worked by the Caledonian. One day, they hoped, they might extend that line into Ayrshire. Meanwhile, the line was leased (for 999 years) to the Caledonian in 1849.” [3][8][21][24]

“The Caledonian recognised that the Townhead terminus was unsatisfactory and constructed a deviation from Milton Junction to a new Glasgow terminus at Buchanan Street. It opened on 1st November 1849.” [3]

Glasgow Buchanan Street station buildings remained essentially unaltered over the years until their closure to passenger traffic in November 1966 when all remaining services transferred to Queen Street Railway Station.

Drew comments that the other two routes considered for trunk routes between the central belt of Scotland and the English network were one via the East Coast and the other inland from Newcastle via Hexham. He states that, “by the East Coast route of the North British from Berwick-on-Tweed there was no reasonable alternative to passing through Edinburgh (or through hilly country in its southern suburbs) to get to Glasgow. The fourth projected Anglo-Scottish route was from Newcastle to Edinburgh via Hexham and inland from the eventual East Coast main line; only disjointed branch lines, mostly closed, mark part of its course today.” [1: p5]

The Caledonian’s Edinburgh terminus was originally on Lothian Road. It opened in 1848 and had a single platform which served both arrivals and departures, and a two-road goods shed with a single loading platform. During 1865, the Caledonian was considering how to improve it, and considered making arrangements with the North British Railway to use Waverley Station. The local authority was anxious that there should be a single main station in the city. However the North British was hostile in principle, and the idea came to nothing. [7][8]

Major extension was essential, and “on 2nd May 1870 a new temporary station was opened adjacent to, and to the north of Lothian Road; it was named Princes Street. It was a wooden structure; the Caledonian was short of cash at this time and a more imposing terminal was not affordable. The passenger part of the station now had two platforms.” [7]

During 1890 the wooden terminus building at Princes Street was partly dismantled in preparation for improvement, “when on 16th June a fire broke out, substantially destroying much of the buildings. The new, spacious station accommodation was progressively brought into use in 1893 and 1894; it had nine platforms, and had cost over £250,000. Powers were obtained for building an adjacent hotel, but it was not opened, as the Caledonian Hotel, until December 1903.” [7][8]

The Caledonian Railway eventually served nearly all the economically important areas of the Lowlands other than the Fife coalfield. It was an outlet to the rest of the UK for trafic from the Northeast – particularly fish. It was in strident competition in and around Glasgow and throughout the central Lowlands with the NBR and GSWR. In Edinburgh, Perth, Dundee and along the coast to Aberdeen it was striving against the NBR, and at Ardrossan it battled against the GSWR. “It had to fight hard for most of its traffic, which comprised coal and other minerals, livestock, distillers’ grain and other agricultural produce; Glasgow and Edinburgh suburban commuters including train and steamer passengers ‘doon the water’ to and from the Clyde coast and islands; Glasgow-Edinburgh and Glasgow-Dundee inter-city passengers; and a high proportion of the Anglo-Scottish freight and passenger traffic because so much of England – for example, the West Riding and the Midlands could be reached equally well by Carlisle and by Berwick.” [1: p7]

Wikipedia comments that “as 1849 drew to a close, the Caledonian Railway had completed its first task: the railway was open from Glasgow and Edinburgh to Carlisle, with through trains running to and from London. Between Glasgow and Edinburgh a competitive service was run, although the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway completed the journey faster. Carlisle Citadel station was in use, jointly owned with the London and North Western Railway. Through trains ran to Stirling and Perth over the Scottish Central Railway line from Greenhill.” [5]

The Caledonian’s trunk line progressed North towards Aberdeen from Peth and a branch was provided from Perth to Dundee. “Joseph Locke played the chief part in planning and co-ordinating the construction of a series of independent concerns which, after rather complex amalgamations, in 1866 took Caledonian trains into Aberdeen on CR tracks. Chief among them were the Scottish Central [Railway] and the Scottish North Eastern [Railway]. … The relatively low cost of construction through Strathmore and complications involving the North British [Railway] in Angus … influenced the main route eastwards from Perth via Glamis and Forfar to meet the North British at Kinnibar Junction. … Dundee was a CR terminus for most CR traffic. East of Dundee (and with a separate passenger terminus in that city) was the Dundee & Arbroath Joint line (CR and NBR). CR Aberdeen trains did not run via Dundee, as they do today after closure of the Strathmore line.” [1: p7]

The Caledonian Railway had intended to lease, or absorb, the Scottish Central Railway (SCR), which obtained its act of Parliament on the same day as the Caledonian. The SCR needed a partner railway to get access to Glasgow and Edinburgh, that was provided by the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway (E&GR). The SCR opened from Greenhill Junction with the E&GR to Perth on 22 May 1848, and the Caledonian opened its branch to reach Greenhill Junction on 7 August 1848. The SCR remained independent for some time, building Perth General station. Because it provided access for a number of railways to Perth, the station was managed by a Joint Committee. The Perth General Station Joint Committee, later the Perth Joint Station Committee, was formed in 1859 to manage Perth railway station, initially consisting of the Scottish Central Railway, North British Railway, Scottish North Eastern Railway, and the Inverness and Perth Junction Railway, later including the Caledonian Railway, North British Railway and Highland Railway. [9][10]

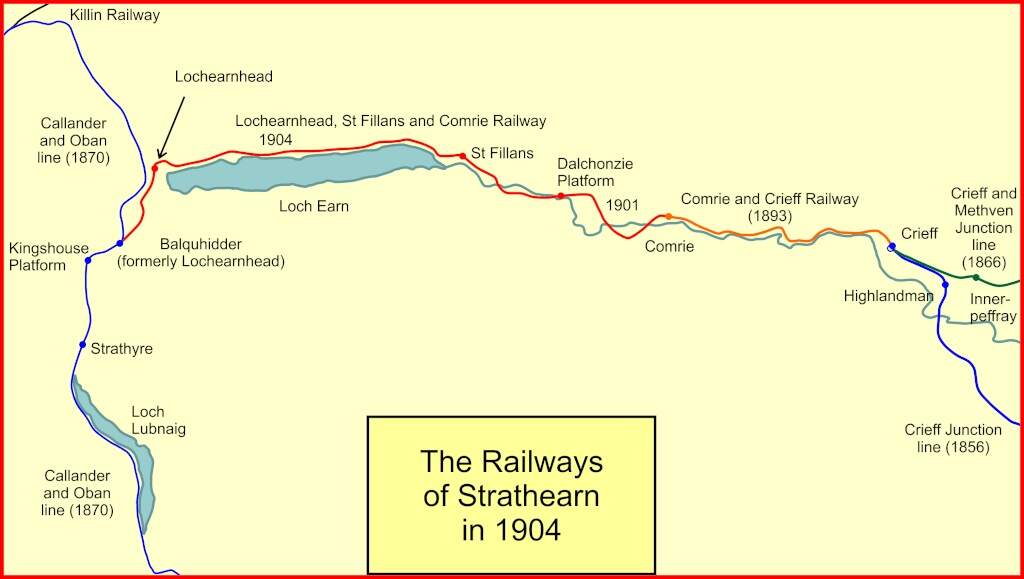

The SCR itself managed to absorb some local railways; the Crieff Junction Railway had opened from Crieff to what later became Gleneagles station in 1856, and it was worked by the SCR and absorbed in 1865. [9]

In 1858 the Dunblane, Doune and Callander Railway was opened in 1858. It achieved considerable significance as the starting point for the Callander and Oban Railway. It was absorbed by the SCR in 1865 immediately before the SCR amalgamated with the Caledonian Railway on 1st August 1865, finally having gained Parliamentary approval to do so. [9]

The Scottish Midland Junction Railway (SMJR) “built a line from Perth to Forfar; at Perth it used the Scottish Central Railway joint station. The main line ran through the fertile area of Strathmore and the SMJR adopted two existing short lines that were on a suitable alignment. They were the Newtyle and Coupar Angus Railway and the Newtyle and Glammiss Railway. Both were unsuccessful adjuncts to the Dundee and Newtyle Railway, built using stone block sleepers and a track gauge of 4 ft 6+1⁄2 in (1,384 mm). The two short lines were modernised and altered to double track using standard gauge. At Forfar the SMJR joined the Arbroath and Forfar Railway, another earlier stone block railway, in this case using the track gauge of 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm). The SMJR opened in 1848.” [3]

The NBR had, for many years, running powers over the CR, from Kinnaber to Aberdeen but was not competitive in the speed to the journey North until the 1890s, after completion of the Forth Bridge. Drew tells us that “railway strategy in Scotland was utterly changed by the failure of the Caledonian in the 1850s to amalgamate with the poverty-stricken 47-mile Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway. (The CR at that time had financial and administrative troubles of its own, which had led it in 1849 to propose operation of the CR system by the LNWR, which Euston turned down flat.) The CR continued to run its own Glasgow-Edinburgh trains over its own route, which remained circuitous at the western end until Glasgow Central was opened in 1879. The Edinburgh & Glasgow was absorbed into the NBR in 1865.” [1: p7] That take-over secured access for the NBR to Glasgow, the Firth of Clyde and much of the central Lowlands.

Drew comments: “The NBR improved the Glasgow Edinburgh passenger services and developed them as both inter-city and Anglo-Scottish trains. Only later did the CR begin to run rival, and in some ways better, Glasgow-Edinburgh expresses over its slightly shorter though more steeply graded line: it was spared, of course, the Cowlairs incline up from the North British Glasgow Queen Street terminus.” [1: p7]

The Aberdeen Railway was “to run north from Guthrie, a few miles northwest of Arbroath. Joining the Arbroath and Forfar Railway (A&FR) there, it obtained access to both termini of that line. It was authorised to lease the A&FR. The Aberdeen Railway may have underestimated the cost of upgrading the A&FR’s stone block track, and it ran out of money building its own main line; its construction was delayed and it encountered political difficulty in Aberdeen itself. It opened in 1850 to Ferryhill, on the southern margin of the city, extending to Guild Street station in 1854. There were branches to Brechin and Montrose.” [3]

From its inception, the Caledonian Railway saw itself as the creator of an extensive network in Scotland, and “it set about gaining control of as many other Scottish railways as possible. It did so not by purchasing them, but by leasing them. This had the advantage that no payment was required at first, only a periodical payment much later. The Caledonian negotiated with the SCR, the SMJR and the Aberdeen Railway and believed it had captured them, but the SCR had other ideas. Much later the Caledonian found that the periodical lease payments were unaffordable, and it was rescued by the legal opinion that the lease agreements had been ultra vires.” [3]

An important development in the history of Scottish railways was the “completion in 1863 of the Perth to Inverness via Forres route of what became soon afterwards the Highland Railway (HR). It gave much better access from the south to the central and northern Highlands and was just in time to enable the Caledonian to profit [from] the rapid growth of tourism in the Highlands. The CR was the chief source of HR passenger and freight traffic from and to the south. During the grouse-shooting and deer stalking seasons the trains between Euston and HR stations [via] the West Coast route, the CR and Perth included many horses and carriages.” [1: p7] These were only replaced by motor vehicles as the Edwardian era developed. The Caledonian encourged the upper class passtimes. “It was indulgent about attaching and detaching horseboxes, carriage flats and motorcar vans at its own stations … Many of the extra West Coast expresses during the season included such vehicles, which caused relatively minor marshalling problems south of Perth.” [1: p7]

At Perth, “long caravans of miscellaneous vehicles were made up and remarshalled. They included not only West and East Coast Joint Stock but also Midland & North British sleeping cars which ran between St Pancras and Inverness via Carlisle, Edinburgh and Perth.” [1: p7]

The Highland main line was mostly only a single track: there was often a motive-power shortage at peak periods, so that trains were often made over late to the CR at Perth. Northbound LNWR trains were often late at Carlisle, perhaps due to difficulties securing sufficient motive power. The LNWR had frequent recurse to double-heading until more powerful locomotives appeared in the early years of the 20th century. The Caledonian often found itself having to make up for the delayes caused by these other companies.

The Caledonian’s own mountainous route – the line from Dunblane via Callander and Crianlarich to Oban – is covered in a separate article which can be found here. [11] The punctuality record on that line was good, “partly because there was competition with the NBR West Highland line from 1898 onwards for traffic to the Western Isles.” [1: p8]

Drew tells us that, “a service which was more inter-city than its name implied, the ‘Grampian Corridor Express’ of 1905, from Glasgow and Edinburgh to Aberdeen, was selected for the allocation of new trainsets of magnificent 12-wheel vehicles. The Grampian ran from Buchanan Street to Perth, where it combined with an Edinburgh Princes Street portion that ran over part of the NBR Edinburgh-Glasgow main line from near Edinburgh to Larbert.” [1: p8] … He also notes the “CR’s regard for its Glasgow-Edinburgh expresses, for which some of the new coaches were 12-wheel non-bogie coaches with elliptical roofs.” [1: p8]

Drew draws attention to: the expansion of the Caledonian’s Clyde shipping services in the late 19th century, with new branches, stations and piers; and the construction of the Caledonian sub-surface lines under the centre of Glasgow (the Glasgow Central Railway. [1: p8]

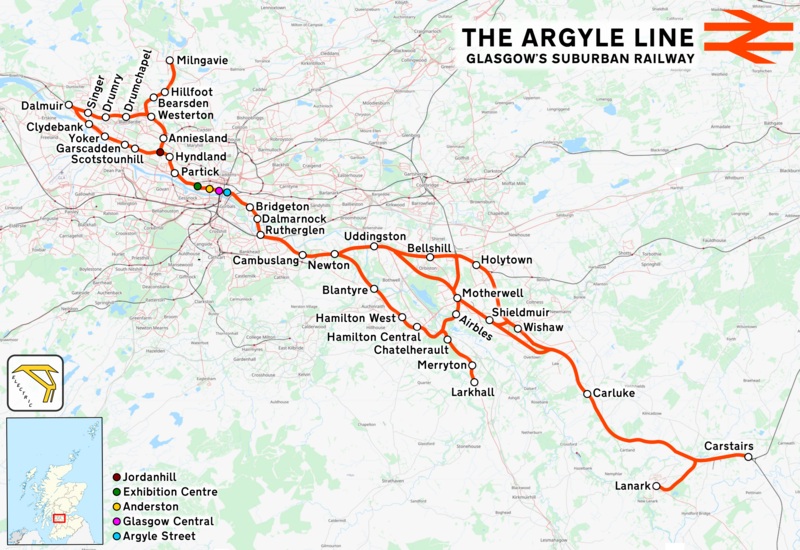

The Glasgow Central Railway was built by the Caledonian Railway, running in tunnel east to west through the city centre. “It was opened in stages from 1894 and opened up new journey opportunities for passengers and enabled the Caledonian Railway to access docks and industrial locations on the north bank of the River Clyde. An intensive and popular train service was operated, but the long tunnel sections with frequent steam trains were smoky and heartily disliked.” [12] The CR’s line in the centre of the city “paralleled the North British Railway routes in the area, and after nationalisation of the railways the line declined and was closed in stages from 1959 to 1964.” [12]

Drew, writing in 1975, points forward to possible future uses of the closed tunnels [1: p8] and in 1979, “the central part of the route was reopened as an electrically operated passenger railway, the Argyle Line; this was greatly popular and enhanced connecting routes to west and east made this a valuable link through the city once more. The Argyle Line section is in heavy use today, but the other parts remain closed.” [12]

Wikipedia tells us that the Argyle Line “serves the commercial and shopping districts of Glasgow’s central area, and connects towns from West Dunbartonshire to South Lanarkshire. Named for Glasgow’s Argyle Street, the line uses the earlier cut-and-cover tunnel running beneath that thoroughfare. … The term ‘Argyle Line’ is commonly used to describe: the extensive urban passenger train service that connects the towns and suburbs of North Clyde with Motherwell, Larkhall, and Lanark, to the southeast. Of the 48 stations, 4 are in West Dunbartonshire, 4 in East Dunbartonshire, 17 in Glasgow City, 10 in North Lanarkshire, and 13 in South Lanarkshire; and thecentral portion of railway infrastructure encompassing less than 5 miles (8 km).” [12]

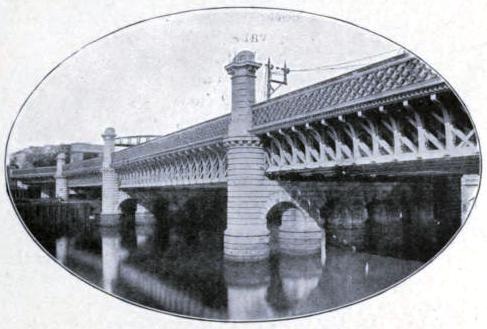

Drew continues: “Associated with the underground lines was the rebuilding and expansion of Glasgow Central passenger station including a low-level station on the CR underground; widening of the bridge over the Clyde to 20 tracks and creation of what for many years was, and in many ways still is, Britain’s most convenient major passenger terminus, in the heart of the city. Electrification and dieselisation have enabled Central to swallow the traffic (admittedly smaller than before as regards the number of trains) previously dealt with at St Enoch Station on closure by British Rail of the former GSWR terminus.” [1: p8]

The Caledonian Railway Bridge crosses the River Clyde at Broomielaw adjacent to Glasgow Central Station. The first structure built between 1876 and 1878 for the Caledonian Railway Company and opened on 1st August 1879, “was engineered by Blyth and Cunningham and built by Sir William Arrol & Co. It consisted of wrought iron lattice girders linked at the top by a light arched lattice girder, and carried on a cast iron arch over twin piers in the river. The piers are formed of cast iron cylinders sunk to bedrock and filled with concrete, and then extended above the river with Dalbeattie granite.” [14]

“The approach span over Clyde Place to the south was 60 feet (18 m) long and over Broomielaw to the north of the river was 90 feet (27 m) long. The navigation spans were 164 feet (50 m), 184 feet (56 m) and 152 feet (46 m) long. The bridge carried four tracks into the new Glasgow Central Station.” [15][18]

The second bridge was built between 1899–1905 during the expansion of Central Station, to a design by D. A. Matheson, chief engineer of the Caledonian Railway. Arrol and Co. was the contractor for this bridge as well. [17] “The foundations for the bridge are rectangular sunk caissons, sunk by the compressed air chamber method used on the Forth Bridge to a depth of up to 48 feet (15 m) below the river bed. The central span is 194 feet (59 m) long with Linville truss girders 15 feet 9 inches (4.80 m) deep. The parapet girders are around 10 feet (3.0 m) deep, and suspended on curved brackets. There are a minimum of eight parallel main girders in the width. The spans are of lengths 160 feet (49 m), 200 feet (61 m) and 178 feet (54 m), and the structure contains 11,000 tonnes (11,000 long tons; 12,000 short tons) of steel. [17] The total length of the bridge between the abutments is 702 feet 6 inches (214.12 m).” [18][19]

“The bridge varies in width from 35 to 62.5 metres (115 to 205 ft) and carries up to ten tracks. [17][18] It leads immediately into Glasgow Central Station on the north bank of the river. At the time of its opening, it was believed to be the widest railway bridge in existence.” [18][19]

The Caledonian’s goods operations were always commercially enterprising. The CR served all of Sctland’s main coalfields, with the exception of that in Fifeshire, and most of the heavy industry in the Glasgow area. “It was linked directly with the ports of Glasgow and its outposts on the Firth of Clyde with Leith (Edinburgh), Dundee and Aberdeen, and it virtually created Grangemouth. The Caledonian led the way in designing and providing for its customers’ new wagons, including high-capacity vehicles, for a variety of consignments. It was an early operator of fast freight trains. One of its major feats was co-operation with the English lines during World War I in moving vast tonnages of coal for warships in Scapa Flow in the Orkneys. The trains ran mostly from South Wales and the CR accepted them at Carlisle and made them over to the Highland at Perth. HR had the hardest task, of working heavy coal trains over its 300 miles of route from Perth via Inverness to Thurso, for shipment to Scapa.” [1: p9]

Although the CR was formed as an inter-city trunk line it coped manfully with other demands. “Local interests in Lanark promoted a branch line to their town, opening in 1855. Coal owners in South Lanarkshire [22] pressed for a railway connection, and the Lesmahagow Railway was formed by them, opening in 1856. It was later absorbed by the Caledonian, but other lines followed in the sparsely populated but mineral-rich area. As new coal mines opened, so new branches were needed, connecting Coalburn, Stonehouse, Strathaven, Muirkirk and Darvel and many other places, with new lines built right up until 1905. When the coal became exhausted in the second half of the 20th century, the railways were progressively closed; passenger traffic had always been light and it too disappeared. Only the passenger traffic to the Lanark and Larkhall branches remain in operation.” [3][8][21]

“In North Lanarkshire, the North British Railway was a keen competitor, having taken over the Monkland Railways. The area contained the rapidly-growing iron production area surrounding Coatbridge, and servicing that industry with coal and iron ore, and transport to local and more distant metal processing locations, dominated the Caledonian’s activity in the region. The Rutherglen and Coatbridge line, later linking Airdrie, and the Carfin to Midcalder line were routes with significant passenger traffic. Many lines to coal and iron ore pits further east were built, but serving remote areas the lines closed when the mineral extraction ceased.” [3][8][21]

Busby and East Kilbride: After rail connections became established at Barrhead (we noted above that the CR took a 999 year lease on the Glasgow, Barrhead and Neilston Direct Railway, the Glasgow & South Western Railway also built a branch to Barrhead. [26]) various interests in Bushby demanded a railway connection. This was opened by the CR in 1866. It was extended in 1868 to East Kilbride, although at that time the then small village did not generate much business for the railway. [3][8][21]

Branches South of Carstairs: When the main line was built, no branches were provided in the thinly populated terrain of the Southern Uplands. Subsequently, four independent companies made branches themselves, and the Caledonian built two.

“The Symington, Biggar and Broughton Railway was opened in 1860, having been taken over by the Caledonian during construction. It was extended to Peebles in 1864.” [3][21]

The independent Dumfries, Lochmaben and Lockerbie Railway was opened in 1863. It “was encouraged by the Caledonian Railway, giving westward access into Dumfriesshire, and worked by it; the Caledonian acquired the line in 1865.” [3]

The Portpatrick Railway opened “between Castle Douglas and Portpatrick in 1861–62 and the Caledonian Railway worked that railway; it obtained running powers over the G&SWR between Dumfries and Castle Douglas, and at a stroke the Caledonian had penetrated deep into the south-west, and to the ferry service to the north of Ireland, territory that the G&SWR had assumed was its own. The Portpatrick Railway later reformed with the Wigtownshire Railway as the Portpatrick and Wigtownshire Joint Railway; the Caledonian was a one-quarter owner.” [3][27][28]

Wikipedia continues: “The North British Railway opened its branch line to Dolphinton, east of Carstairs, and the Caledonian feared that the next step would be an incursion by the NBR into Caledonian territory, possibly seeking running powers on the main line. To head this off, the Caledonian built its own Dolphinton Branch from Carstairs; it opened in 1867. Dolphinton had a population of 260 and two railways, and traffic was correspondingly meagre, and the line closed in 1945 to passengers and in 1950 to goods.” [3][21]

“The independent Solway Junction Railway was opened in 1869, linking iron mines in Cumberland with the Caledonian Railway at Kirtlebridge, crossing the Solway Firth by a 1,940 yd (1,770 m) viaduct; the company worked the line itself. It considerably shortened the route to the Lanarkshire ironworks, and was heavily used at first, but the traffic was depleted by cheap imported iron ore within a decade. The Scottish part of the line was acquired by the Caledonian Railway in 1873, and the whole line in 1895. Serious ice damage and later heavy maintenance costs made the line seriously unprofitable and it was closed in 1921.” [3][29]

After 1880, the Caledonian’s network continued to expand. Wikipedia tells us that, “The Moffat Railway was opened from Beattock on 2nd April 1883. It was just over 1.5 miles (2.4 km) long. It was worked by the Caledonian and absorbed on 11th November 1889. The Caledonian Railway sought to develop both Moffat and Peebles as watering places, and ran The Tinto Express from both places, combining at Symington, to Edinburgh and Glasgow for several years.” [3][21]

The “Leadhills and Wanlockhead Branch was opened as a light railway from Elvanfoot in 1901–02. With challenging gradients to reach Scotland’s highest village in otherwise remote territory, the line scraped a bare living and closed in 1938.” [3][21]

In 1862, “the Greenock and Wemyss Bay Railway was authorised. It was an independent company intending to provide a fast connection from Rothesay on the Isle of Bute; it opened on 13th May 1865 and in August 1893 it amalgamated with the Caledonian Railway, having been operated by the Caledonian Railway since its opening.” [3][8][30: p78]

Wikipedia tells us that in 1889, the CR “opened an extension line from Greenock to Gourock, more conveniently situated than Greenock; this involved the expensive construction of Newton Street Tunnel, the longest in Scotland.” [3][31]

At this time after feeling frustrated with the performance of independent steamer operators, the CR sought powers to operate the vessels directly; this was refused by Parliament. So the company founded the nominally independent Caledonian Steam Packet Company (CSPC) in 1889. “The CSPC expanded its routes and services considerably; following nationalisation of the railways in 1948 it became owned by British Railways, but was divested in 1968 and later became a constituent of Caledonian MacBrayne (CalMac), which remains in state ownership.” [3][32]

Late in the 19th century, the CR began to focus on the development of suburban lines around Glasgow and Paisley. Wikipedia notes that “The Cathcart District Railway was promoted as an independent concern but heavily supported by the Caledonian. It opened in 1886 from Pollokshields to Mount Florida and Cathcart (the eastern arm of the present-day Cathcart Circle Line) in 1886, and was extended via Shawlands to form a loop in 1894. It was worked by the Caledonian, although the company retained its independence until 1923.” [3]

We have already noted the the Glasgow Central Railway which eventually became The ‘Argyle Line’. [3][25] “The Paisley and Barrhead District Railway was incorporated in 1897 and transferred to the Caledonian in 1902; it [linked] Paisley and Barrhead [to] enable a circular service from Glasgow. The line was substantially ready in 1902 but by now street tramways were electrically operated and eminently successful. It was plain that a passenger service would not be viable against tram competition and the intended passenger service was never started.” [3][30]

North of the River Clyde was both heavily populated and highly industrialised. Initiallt it was the preserve of the North British Railway and its satellites, but its importance encouraged the Caledonian to enter the area. “The Lanarkshire and Dumbartonshire Railway [33] was nominally independent, running from near Maryhill to Dumbarton, opening progressively between 1894 and 1896. In 1896 the Caledonian gained access to Loch Lomond with the opening of the Dumbarton and Balloch Joint Railway (originally built by the Caledonian and Dumbartonshire Junction Railway), built jointly with the NBR.” [3][33][36]

In 1888, the Lanarkshire and Ayrshire Railway opened a 6.5-mile (10.5 km) line “from Giffen on the Glasgow, Barrhead and Kilmarnock Joint Railway to Ardrossan. Its purpose was to shorten the route for Caledonian mineral traffic, and it was worked by the Caledonian. In 1903–04 it was extended eastwards to Cathcart and Newton, enabling the heavy mineral trains to avoid the Joint Line and the congested area around Gushetfaulds from the Lanarkshire coalfields to Ardrossan Harbour.” [3][21][34][35] Today, the only operational sections of the line are those between Newton and Neilston. Now two suburban branch lines (Newton to Glasgow Central via Kirkhill and Neilston to Glasgow Central via the Mount Florida side of the Cathcart Circle). Electrified in the early 1960s, these lines carry frequent suburban passenger trains. [35]

Around Edinburgh, an intersting development was the construction of the Granton Harbour Branch which opened in 1861, funded equally by the harbour authorities and the CR. Granton Harbour was a large industrial harbour built by lighthouse engineer, Robert Stevenson. [37]. In 1864, the Leith North Branch from the Granton line at Pilton to Leith was built, opening to passengers in 1879. [38] When, after 1900, “the port authorities built new modern docks to the east of the former Leith docks, and the Caledonian further extended its Leith line to reach the new facilities: the Leith New Lines opened in 1903. It had been planned to open a passenger service on the line, and passenger stations had been built, but tram competition made it clear that an inner suburban passenger railway was unviable and the passenger service was never inaugurated.” [3]

Wikipedia continues: “The Edinburgh main line passed close to numerous mineral workings, and several short branches and connections were made to collieries, iron workings and shale oil plants. The Wilsontown Branch from Auchengray, opened in 1860 was the most significant, and carried a passenger service.” [3] The Wilsontown Branch was a three and three-quarter mile long railway line that served the village of Wilsontown in Lanarkshire and several collieries, running from a bay platform at Auchengray Railway Station to Wilsontown Railway Station, which was the passenger terminus. [39]

The Wishaw and Coltness Railway, ran for approximately 11 miles from Chapel Colliery, at Newmains in North Lanarkshire … to the Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway near Whifflet, giving a means of transport for minerals around Newmains to market in Glasgow and Edinburgh. built to 4ft 6 in gauge, it had several branches serving pits and ironworks. [40] The line was leased by the CR and re-gauged. In 1869, the line was extended from near Cleland Ironworks “to Midcalder Junction on the Edinburgh main line, passing through Shotts, Fauldhouse and Midcalder. This line connected to many further mines and industrial sites, and gave the Caledonian a passenger route between Glasgow and Edinburgh that competed with the North British Railway’s route through Falkirk.” [3]

The CR’s main line did not connect with a significant industiral area on the Water of Leith Southwest of Edinburgh. To address this, a branch line from Slateford to Balerno opened on 1st August 1874. [41] “The line was successful in encouraging residential building, especially at Colinton, and also leisure excursions: for a time it was known as ‘the picnic line’, but it too succumbed to more convenient transport facilities by road, and it closed to passengers in 1943.” [3]

Speculative residential development encouraged the construction of the Barnton Branch, Barnton was West of Edinburgh. “The branch line opened on 1st March 1894; the terminus was named Cramond Brig at first. The Caledonian intended to make the line into a loop, returning to the city by way of Corstorphine, but this idea was shelved.” [3][8][21]

The Callander & Oban Line was initially an independent company, it had been promised financial support by the Scottish Central Railway (SCR). The Caledonian absorbed the SCR in 1865 and the directors were dismayed at the level of commitment to a difficult construction scheme barely started. Construction took many years, reaching a station serving Killin in 1870 and Oban in 1880. The line ran on a shoestring – finances were always tight and the line was never profitable although it contributed greatly to the development of the town of Oban. A branch serving Killin was opened in 1886, [42] and another to serve Ballachulish, opened in 1903. [3][43] Articles about the Ballachulish Branch can be found here, [44] here, [45] and here. [46]

The western part of the line from Crianlarich to Oban remains open, connected to the ex-NBR West Highland Line, but the remainder has closed. [3][47][48] An article about the Callander & Oban Railway can be found here. [11]

The Strathearn Lines: “the Perth, Almond Valley and Methven Railway opened in 1858 to connect Methven to the SMJR network; it was extended to Crieff when the Crieff & Methven Railway opened in 1866.” [3][49] It eventually became part of the CR network through acquisitions and mergers.

“The upsurge in tourism in Strathearn encouraged many visitors, who used Crieff as a railhead and continued by road. In 1893 the Crieff and Comrie Railway made a short extension into Strathearn, and this encouraged ideas of completing a link right through to the Callander and Oban line. There were wild dreams of Irish cattle imports coming to Perth markets over the route. This became the Lochearnhead, St Fillans and Comrie Railway; due to serious problems raising capital, it took from 1901 to 1905 to open fully. The through traffic never developed and passenger connections at Balquhidder were poor, discouraging through travel.” [3][51]

The CR wanted the extension to Lochearnhead and the Callander and Oban line. “Moreover, it was concerned that the rival North British Railway would build such a line, abstracting much of its traffic in the area. When the Comrie company opened discussions with the Caledonian about selling their line, they found that the Caledonian was willing. In fact its offer was remarkably generous: they would repay the share capital in full, pay off the mortgage loan, and settle MacKay’s claim. This was put to a Special Shareholders’ Meeting on 9th February 1898. The shareholders agreed and the company was vested in the Caledonian Railway by Act of 1st August 1898.” [50][51]

Locomotives of the Caledonian Railway

The Caledonian Railway Locomotive Works were originally at Greenock but moved to St. Rollox, Glasgow, in 1856. Greenock Works and Shed opened in 1841 adjacent to the Greenock terminus of the Glasgow, Paisley & Greenock Railway (GP&GR). [53] The Caledonian Railway leased to GP&GR line in 1846 and at that time the Greenock Shed and Works wer enlarged to accommodate the CR’s needs. [53] The shed remained in use until 1885 when a railway extension from Greenock to Gourock required its removal and rellocation to Greenock Ladyburn Shed. [54]

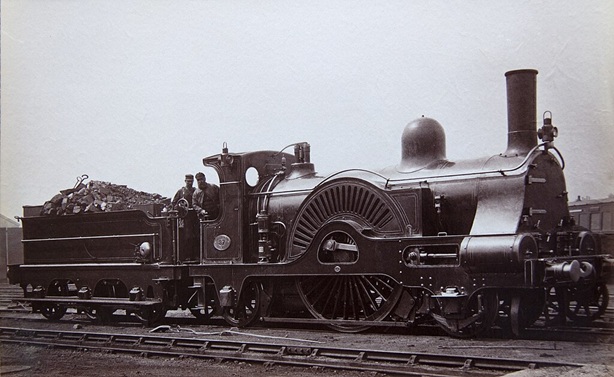

“The class number used for Caledonian Railway engines was the stock number of the first member of the class to reach traffic. Hence earlier/lower numbered classes could well have appeared later in time. … Until the appointment of Dugald Drummond, unlike most other British railways, almost all engines had outside cylinders, and the 0-6-0 arrangement was quite rare, goods engines being of type 2-4-0 or 0-4-2. Passenger engines were normally 2-2-2.” [52][55]

Wikipedia tabulates all of the locomotives used by the Caledonian Railway under the names of the railway’s Chief Mechanical Engineers. The tables can be found here. [52]

Lightmoor Press published two excellent books about locomotives of the Caledonian Railway. The first by David Hamilton – Caledonian Railway Locomotives: The Formative Years – in 2019. [63] The second by H. J. C. Cornwell – Caledonian Railway Locomotives: The Classic Years – in 2020. [64]

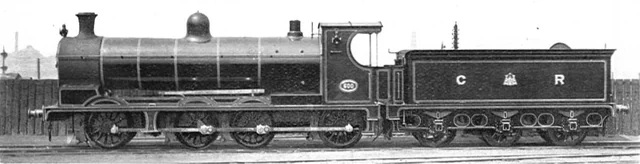

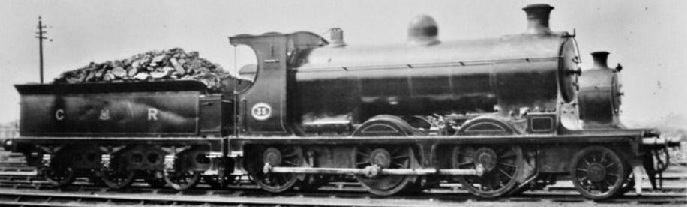

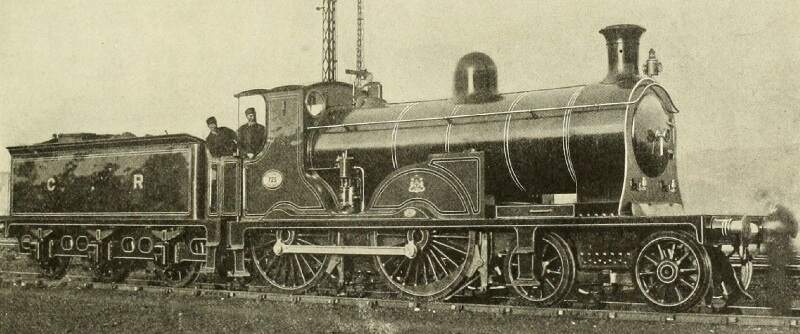

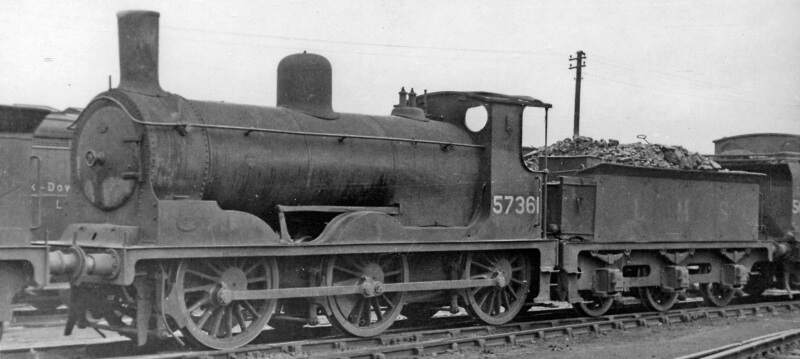

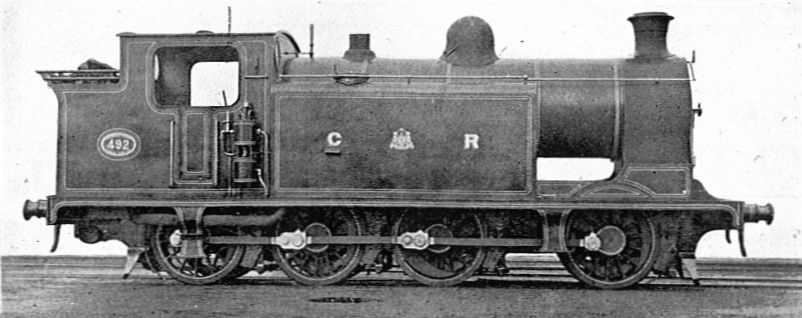

The following series of images cover a range of examples of the Caledonian Railway’s motive power:

The Crack Caledonian ‘Flyers’ Which Work the Scottish Section of the West Coast Route’, © Public Domain. [74]

with Westinghouse air brakes. They were reported to be very powerful, perhaps representing the limit to which locomotive engineers could achieve in the UK at that time period. However, few of the Caledonian Railways goods yards could host the trains the 600s were capable of hauling, making them somewhat redundant, © Public Domain. [65]

Drew comments that, “all Caledonian locomotives had to work hard. Every route, even Glasgow Central to Edinburgh, had its testing sections, and the Glasgow-Edinburgh expresses stopped relatively frequently to cater for outer-suburban passengers. Apart from the Glasgow-Carlisle main line, most Caledonian express passenger working involved getting away from the numerous stops necessitated by the sparse population. Some of the most exacting work was on the Clyde steamer boat trains, where every second counted in competition with the NBR and GSWR.” [1: p11]

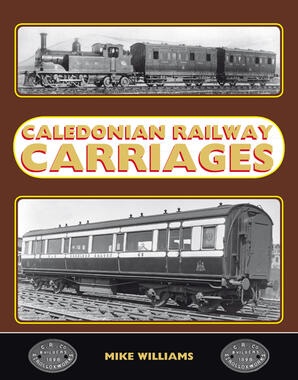

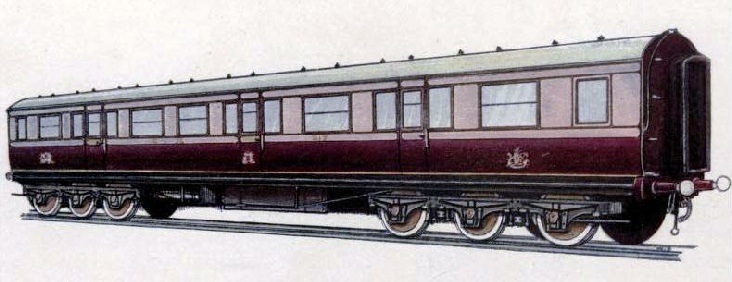

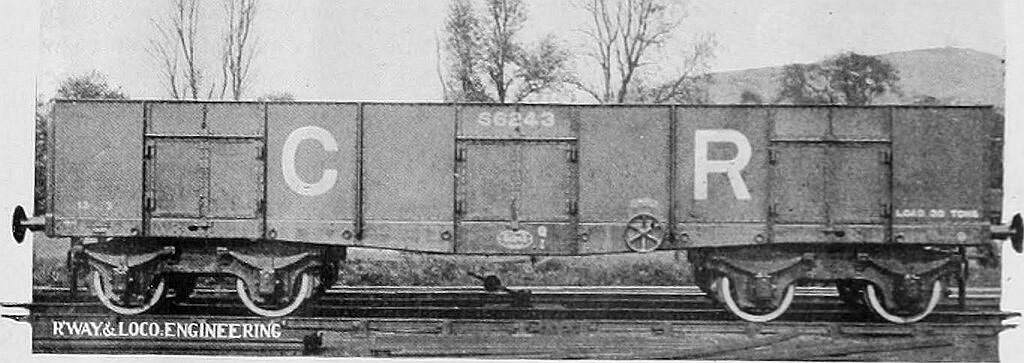

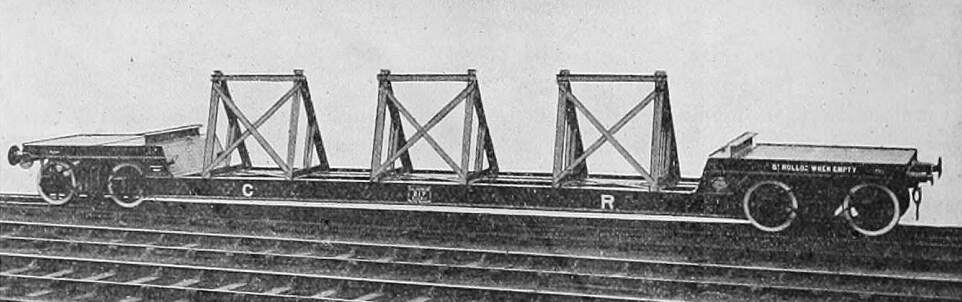

Caledonian Railway Rolling Stock

Carriages: Lightmoor Press has released a book by Mike Williams which covers the passenger rolling-stock of the Caledonian Railway: Mike Williams; Caledonian Railway Carriages; Lightmoor Press, Lydney, 2015. [69] Mike Williams describes the carriages owned and operated by the Caledonian Railway from its opening until the 1923 Grouping, with 250 photographs and over 300 drawings. A well-produced and informative volume commensurate with the usual standard of Lightmoor Press publications.

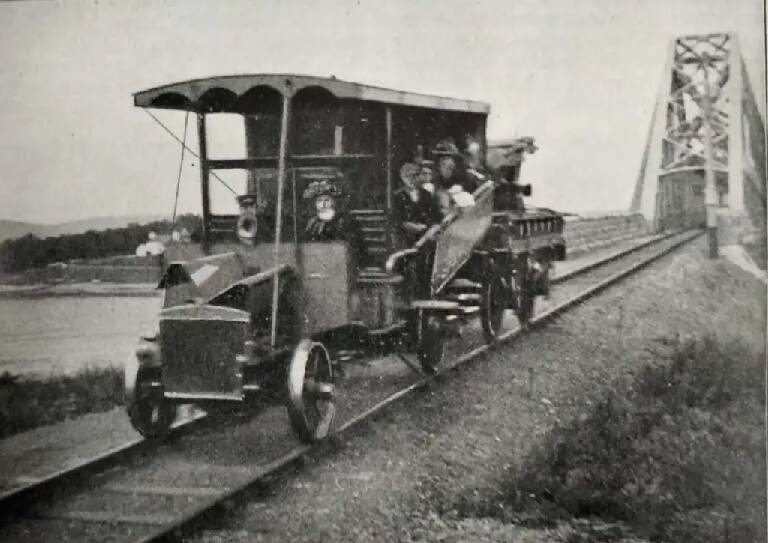

Lightmoor Press describes the content: “The topics covered include the CR’s reaction to technological developments in railway passenger transport and the increasing attention paid to passenger comfort and convenience. The description of its carriage livery challenges some aspects of ‘received wisdom’ and deals with furnishing and internal décor. General service stock is reviewed to the end of McIntosh’s tenure in 1914, plus the carriages acquired from the West Coast Joint Stock fleet, the Pullman cars and the final designs in the Pickersgill regime. The CR Ambulance Train and other carriages in war-time service are described along with vehicles which were not part of general service stock. Saloons, Invalid carriages, Post Office vehicles, the Prison Van, Inchture horse bus and the Connel Ferry rail motor are all covered, along with some proposed designs that never saw service, including a steam rail motor. Appendices give information about the number of carriages in the fleet, their numbers, carriage orders and building dates and list the available drawings of carriages and components, with their location.” [70]

The Railway Wonders of the World article about the Caledonian Railway includes these paragraphs:

“The passenger work of the Caledonian is of high repute for speed and accommodation. As we have said enough of the West Coast service we will content ourselves here with the Grampian Corridor Express as an example. This train is made up of four varieties of coaches, composite, brake composite, brake third, and third. Each of these is 65 ft long in the body, and 68 ft 6-in over buffers, the width being 9 ft. The under-frames over headstocks are 64 ft 10-in, 44 ft between the bogie centres, and 7 ft 5-in over the sole bars, the wheel base being 56 ft.

In the composite the space between the partitions is 7 ft 4⅝-in in the first class, and 6 ft 4½-in in the third; in the brake composite it is 7 ft in the first class and 6 ft in the third, the brake compartment taking up 12 ft 2¾-in. In the brake third, in which the brake compartment occupies 27 ft 4½-in, it is 6 ft, and in the third it is 6 ft 2⅝-in. The composite seats 30 first-class passengers three aside and 24 third class four aside, the brake composite seats 18 first and 32 third, the brake third seats 40, and the third 72. The composite weighs 38 tons 4 cwt, the brake composite weighs 38 tons 11 cwt, the brake third weighs 35 tons 5 cwt, and the third 36 tons 10 cwt. These details are given to show, among other things, that appearances may be deceptive; in carriages seemingly alike there may be a difference in the knee-space making all the difference in the comfort, though in this case the smallest, 6 ft, is ample for any one of reasonable stature and attitude.

This heavy train – the Grampian – does 30 miles an hour up Dunblane bank, part of which is 1 in 73, for Beattock is not the stiffest gradient on the line, that being the 1 in 40 on the Bonnybridge branch. It is the 10 a.m. out of Buchanan Street and the 9.30 out of Edinburgh joining at Perth, where the restaurant car is put on; and the Glasgow portion weighs over 250 tons. It is not the fastest on the line, that being the 10.5 from Forfar to Perth, 321 miles in 33 minutes, the longest non-stop being the 2.17 a.m. from Carlisle to Perth, 150¾ miles in three hours; but with the exception of the Granite City Express, leaving Glasgow at 5 p.m, it is perhaps the best known.” [73]

Drawings of the Caledonian Railway Coaching Stock can be found on the Caley Coaches Ltd. website. [85] Caley Coaches Ltd. provides drawings and photographs to support its range of kits including for: 57′ Non-corridor coaches; 57′ Semi-corridor coaches; 57′ Corridor coaches; Grampian Stock; 65′ Slip Coaches; Edinburgh & Glasgow Stock; and 4 wheel “Balerno Branch” Coaches.

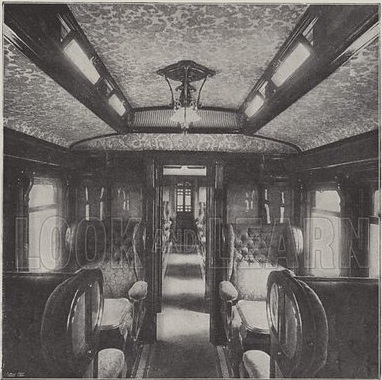

The adjacent image shows the interior of a third Class Luncheon Car on a West Coast Corridor Express Train of the LNWR and Caledonian Railways. The two railway companies collaborated to create a set of stock which could be used over the full length of the line from London, Euston to Glasgow. This iIllustration was carried in The Illustrated London News on 18th July 1896, © Public Domain. [78]

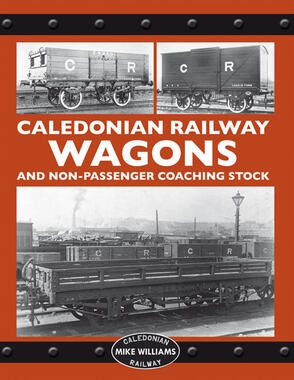

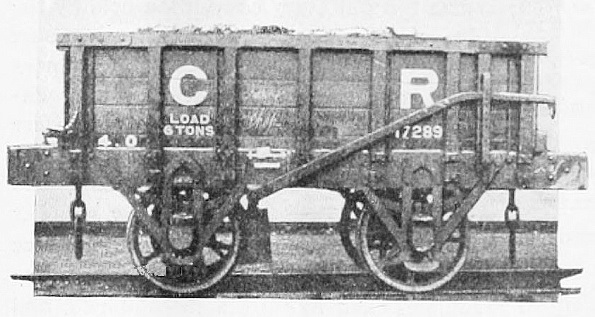

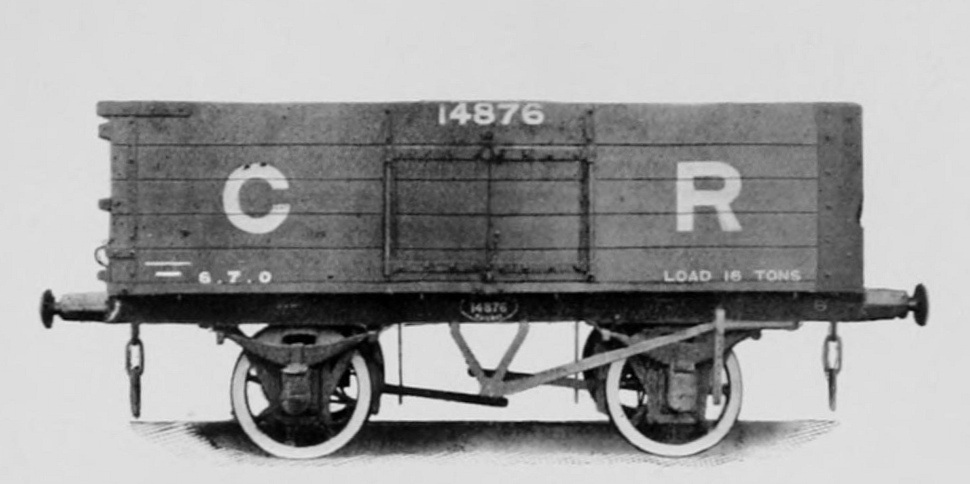

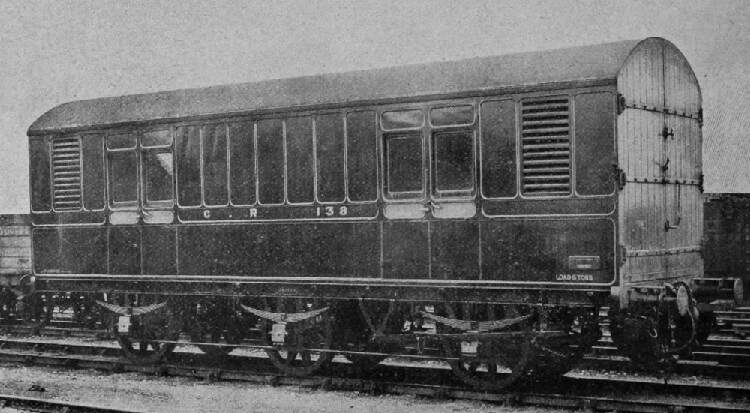

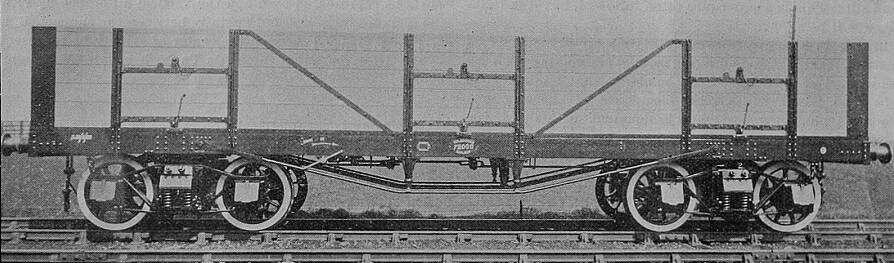

Wagons and Non-Passenger Coaching Stock: Lightmoor Press has also released a book by Mike Williams which covers the non-passenger rolling-stock of the Caledonian Railway: Mike Williams; Caledonian Railway Wagons and Non-Passenger Caoching Stock; Lightmoor Press, Lydney, 2013. [71]

Mike Williams details the history of the Caledonian Railways wagons from 1847 until the grouping in 1923 when the Company became part of the LMS.

Lightmoor Press says that research for the book is “based on Board minutes and other official sources, whilst over 250 official drawings have been examined. The introduction details the sources of information used and a chapter on the industrial development of Scotland outlines its influence on the size and diversity of the wagon fleet. The types of wagons and numbers in service are tabulated and the financial pressures which hamstrung the modernisation programme begun in the early 1900s are also described. An overview is offered of technical developments, which discusses how two Locomotive Superintendents transformed the wagon fleet. The liveries of wagons and Non-Passenger Coaching Stock are next described, supplemented in each case by the systems used by the Caledonian to allocate running numbers. Photographic evidence and drawings depict a far more complex picture than that presented previously. Eleven chapters then deal with different types of wagons, ranging from those built by the thousand, to small numbers of wagons for special traffic. Building dates are given for each design, whilst design developments are described and supported by photographs and works drawings. Sample running numbers are included for modellers. A further chapter describes the Caledonian’s relationship with the private traders who ran wagons over the system. Appendices list the construction orders undertaken by the company and outside contractors. The surviving works drawings are listed, with their archive references, and the photographs in an official album dating from 1900 are described. A final appendix gives information about drawings for the modeller, supported by specially commissioned drawings of details characteristic of Caledonian wagons. Produced in association with the Caledonian Railway Association.” [72]

These next few images show a few different Caledonian Railway good wagons:

To Conclude …

Paul Drew concludes his article with these words: “The Caledonian achieved its zenith in the years 1900-14. There was no activity in which it did not shine; passenger stations such as Glasgow Central, Edinburgh Princes Street, Stirling, Dundee West. and (with the Great North of Scotland) Aberdeen Joint; hotels; signalling, both semaphore and the pioneer electro-pneumatic installation at Glasgow Central; and Pullman cars, which it ran on the Oban line (as observation cars), the Glasgow-Edinburgh service and elsewhere. … [It] undoubtedly justified its claim to be the premier line of Scotland.” [1: p11]

References

- Paul Drew; Caledonian Retrospect; in, Brian Stephenson (ed.), Trains Illustrated No. 14, Ian Allan, Walton-on-Thames, 1975, p4-11.

- https://www.gwra.co.uk/auctions/caledonian-railway-mounted-crest-company-coat-arms-2019apr-0374.html, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caledonian_Railway, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- The Railway Year Book for 1920; The Railway Publishing Company Limited, London, 1920.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Caledonian_Railway_(until_1850), accessed on 18th March 2024.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1931166, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caledonian_Railway_lines_to_Edinburgh, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- David Ross; The Caledonian: Scotland’s Imperial Railway: A History; Catrine: Stenlake Publishing Limited, Catrine, 2014.

- https://www.railscot.co.uk/locations/P/Perth, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perth_railway_station_(Scotland), accessed on 18th March 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/12/22/the-callander-and-oban-railway

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glasgow_Central_Railway, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/6200150, accesse on 18th March 2025.

- Glasgow, Central Station, Old Approach Viaduct; Canmore, Historic Environment Scotland; via https://canmore.org.uk/site/91763/glasgow-central-station-old-approach-viaduct, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- Caledonian Railway Bridge; Gazetteer for Scotland, via https://www.scottish-places.info/features/featurefirst17493.html, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- http://www.glasgowhistory.com/glasgow-bridgejamaica-bridge.html, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- Glasgow, Central Station, New Approach Viaduct; Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland; via https://canmore.org.uk/site/79857/glasgow-central-station-new-approach-viaduct, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caledonian_Railway_Bridge, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- D. A. Matheson; The New Clyde Bridge of the Caledonian Railway at Glasgow. (Including Appendix and Plates); in The Institution of Civil Engineers, Minutes of the Proceedings, No. 182, (Paper No. 3764) 1910, p4–58; via https://www.icevirtuallibrary.com/doi/10.1680/imotp.1910.16924, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/628011, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- John Thomas revised J. S. Paterson; A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 6, Scotland, the Lowlands and the Borders; David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1984.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caledonian_Railway_branches_in_South_Lanarkshire, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caledonian_Railway_branches_in_North_Lanarkshire, accessed on 18th March 2025.

- C. J. A. Robertson; The Origins of the Scottish Railway System: 1722–1844; John Donald Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh, first edition 1983.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argyle_Line, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barrhead_Branch, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- C. E. J. Fryer; The Portpatrick and Wigtownshire Railways; Oakwood Press, Usk, 1991.

- David L. Smith; The Little Railways of South West Scotland; David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1969,

- Stuart Edgar and John M. Sinton; The Solway Junction Railway, Oakwood Press, Headington, 1990.

- Christopher Awdry; Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies; Patrick Stephens Ltd., Sparkford,1990.

- Chris Hogg and Lynn Patrick; The Glasgow, Cowal and Bute Route Through Time, Amberley Publishing, Stroud, 2014.

- https://www.calmac.co.uk/corporate/history, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://www.west-dunbarton.gov.uk/leisure-parks-events/museums-and-galleries/collections/transport/rail, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- John Thomas; Forgotten Railways: Scotland; David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1976.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lanarkshire_and_Ayrshire_Railway, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://gracesguide.co.uk/Dumbarton_and_Balloch_Joint_Railway, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://www.nationaltransporttrust.org.uk/heritage-sites/heritage-detail/granton-harbour, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://www.railscot.co.uk/companies/L/Leith_North_Branch_Caledonian_Railway, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilsontown_railway_station, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wishaw_and_Coltness_Railway, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balerno_line, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killin_Railway, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://canmore.org.uk/site/23551/ballachulish-station, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/01/01/the-ballachulish-railway-line-part-1

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/01/02/the-ballachulish-railway-line-part-2

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/01/05/the-ballachulish-railway-line-part-3

- John Thomas; The Callander and Oban Railway; David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1966

- John Thomas and David Turnock; A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 15: North of Scotland; David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1989.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perth,_Almond_Valley_and_Methven_Railway, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crieff_and_Comrie_Railway, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- Bernard Byrom; The Railways of Upper Strathearn; Oakwood Press, Usk, 2004.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locomotives_of_the_Caledonian_Railway, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://www.railscot.co.uk/locations/G/Greenock_Works_and_Shed, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://www.railscot.co.uk/locations/G/Greenock_Ladyburn_Shed, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- E. L. Ahrons; Locomotive and train working in the latter part of the nineteenth century Vol. 3; W Heffer & Sons Ltd, Cambridge, 1952, p18.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hugh_llewelyn_123_(6325588200).jpg, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2-2-2_Caledonian_Railway_87.jpg, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://news.bachmann.co.uk/2018/02/caledonian-railway-812-class-0-6-0, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://www.embsayboltonabbeyrailway.org.uk/aboutus/caledonian-railway-no-419-55189, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caledonian_Railway_49_and_903_Classes, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- Charles Rous-Marten; British Locomotives in 1903; in the Bulletin of the International Railway Congress.

- R. Essery & D. Jenkinson; An Illustrated History of L.M.S. Locomotives, Volume Three: Absorbed Pre-Group Classes, Northern Division; Oxford Publishing Company, 1986.

- David Hamilton; Caledonian Railway Locomotives: The Formative Years; Lightmoor Press Lydney, 2019.

- H. J. C. Cornwell; Caledonian Railway Locomotives: The Classic Years; Lightmoor Press, Lydney, 2020.

- https://www.reddit.com/r/trains/comments/141q6pl/looking_for_info_on_the_caledonian_railway_600/?rdt=60859, accessed on 19th March 2025.

- https://www.hattons.co.uk/directory/vehicledetails/3144935/2_6_0_class_34_cr, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://www.loco-info.com/view.aspx?id=-739, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/07/16/the-caledonian-railway-rail-motor-car

- Mike Williams; Caledonian Railway Carriages; Lightmoor Press, Lydney, 2015.

- https://lightmoor.co.uk/books/caledonian-railway-carriages/l8009, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- Mike Williams; Caledonian Railway Wagons and Non-Passenger Caoching Stock; Lightmoor Press, Lydney, 2013.

- https://lightmoor.co.uk/books/caledonian-railway-wagons-and-non-passenger-coaching-stock/L9747, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://www.railwaywondersoftheworld.com/caledonian_railway.html, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://www.railwaywondersoftheworld.com/famous-expresses3.html, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caledonian_Railway_492_Class, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://locomotive.fandom.com/wiki/Caledonian_Railway_Class_264, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://caledoniaworks.com/product/cr-class-1, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/File:Im1894OurRail2-LNWR.jpg, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- http://britbahn.wikidot.com/gueterwagen-der-caledonian-railway, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CR_Motor_Car_Van_diagram_83.jpg, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/CR_Erzwagen_Nr._72000, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/CR_Erzwagen_54, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/CR_Selbstentladewagen_66, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/CR_Glastransportwagen_82, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://caley.com/coaches.php, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/dunalastair-2nd-northbound-with-a-mixture-of-the-best-news-photo/90745294, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- http://www.gettyimages.com/detail/90747102, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- http://www.gettyimages.com/detail/90779936, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- http://www.gettyimages.com/detail/90779924, accessed on 20th March 2025.

- http://www.gettyimages.com/detail/90760769, accessed on 20th March 2025.