Ballyconnell to Belturbet

NB: A flavour of the Cavan and Leitrim Railway can be obtained by visiting the preservation line and museum at Dromod. The relevant details are as follows:

NB: A flavour of the Cavan and Leitrim Railway can be obtained by visiting the preservation line and museum at Dromod. The relevant details are as follows:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/cavanandleitrimrailway.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/CLrailway.

Website: https://cavanandleitrim.wixsite.com/home.

Cavan and Leitrim Railway, Station House, Station Road, Dromod, Co. Leitrim, N41 R504,

Ireland. Phone: +353 71 963-8599.

We re-start our journey at Ballyconnell Railway Station, we heard quite a few stories about the location at the end of the previous post in this series, so just a few photos and some architectural information about the remaining station building will suffice before we go on with our journey to Belturbet. ….

The Irish National Inventory of Architectural Heritage carries the adjacent image of the passenger station building at Ballyconnell in the early 21st century and comments as follows: [4]

The Irish National Inventory of Architectural Heritage carries the adjacent image of the passenger station building at Ballyconnell in the early 21st century and comments as follows: [4]

“Description

Detached three-bay single-storey and three-bay two-storey former railway station and station master’s house, built c.1885, having gabled bays and projecting gabled entrance porch to former house, and recent red brick porch to former platform side of station. Recent rendered lean-to extension to front elevation. Now divided into two dwellings. Pitched slate roofs, decorative clay ridge tiles, and decorative brickwork detailing to barges and eaves, recent metal rainwater goods, and rendered chimneystacks. Red brick walls with vitrified brick banding, bevelled brick plinth course. Two-over-two sash windows in segmental-headed openings with yellow and vitrified brick arches, yellow brick hoods, and stone cills. Round-headed window to north-west gable with brick archivolt and single-pane upper sash. Segmental-headed opening to entrance porch with timber sheeted door and overlight. Detached single-storey limestone plinth to former water tank located to south, formerly on other side of railway tracks, having later corrugated-iron roof, rock-faced limestone walls with dressed arrises, round-headed multiple-pane cast-iron window, and segmental-headed doorway, tank no longer in place. Platform and former track replaced by garden.” [4]“Appraisal

The former Ballyconnell Railway Station was part of the narrow-gauge Cavan and Leitrim Railway which opened in October 1887. Serving the Arigna coalmine, the line outlived most of the other Irish narrow-gauge lines and ran on coal until its closure in 1959, giving a further lease of life to redundant engines after the introduction of diesel. The station and adjoining dwelling are elaborately detailed with polychrome brick detail of high aesthetic quality and form a contrasting ensemble with the limestone of the adjacent former goods shed and the well constructed supporting base of a former water tank. The building is an excellent example of the high quality of nineteenth century railway architecture and retains many of its original features, including sash windows and cast-iron rainwater goods.” [4]

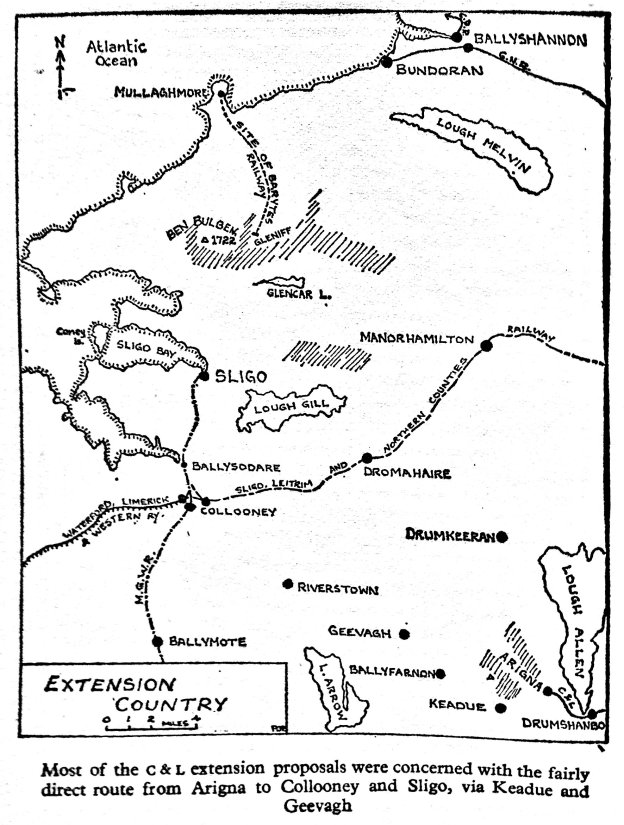

We noted, in previous posts about the C&L, that there is a plan to create a Greenway along the full length of the Cavan & Leitrim Railway from Mohill to Belturbet. The notes written about those proposals describe the full length of the line. The plans for the Greenway from Ballyconnell to Belturbet are as follows:

“Beyond Ballyconnell, the Greenway would seek to avoid crossing the N87 national route and would probably join the old track west of Killywilly Lough. The route to Belturbet is very flat with a lot of gentle curves and skirts three large lakes over this 10 km section. There are some metal bridges on stone abutments where the line crossed several small rivers. Tomkin Road was the most significant station on this section partly due to additional traffic associated with the Tomkin Road creamery which had its own railway siding. The Erne Bridge at Turbett Island is at the approach to the refurbished Belturbet railway station site. There would be considerable merit in extending the greenway for approx 4 km along the Erne to the international scouting site at Castle Saunderson.” [2]

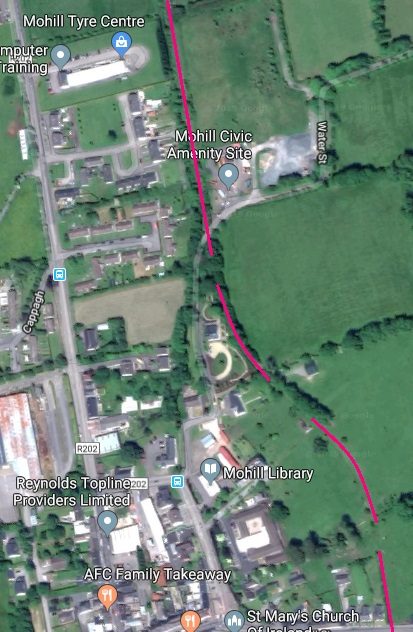

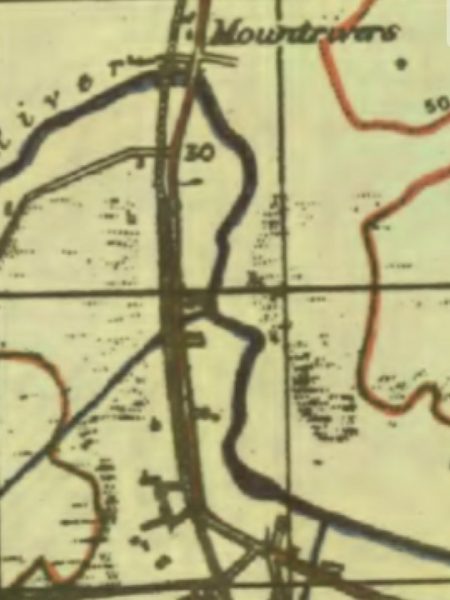

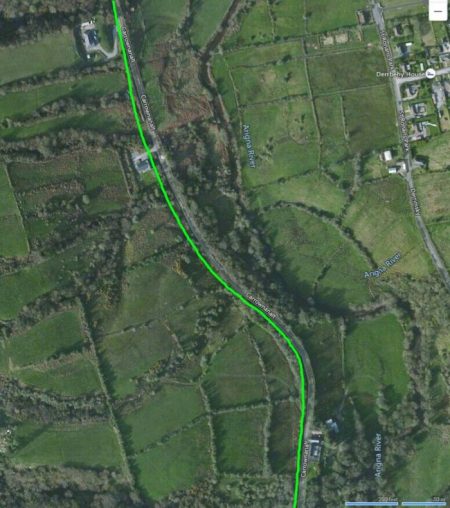

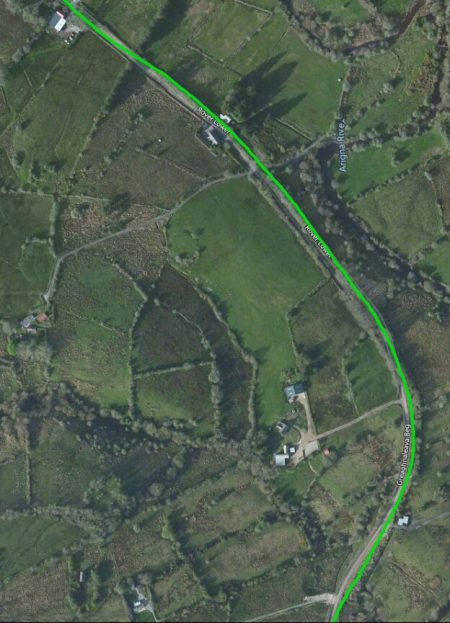

As we have noted before, the Greenway description of the route highlights key things on the way but by no means provides the detail that we are looking for! The first part of the route ahead appears on the satellite image below. Ballyconnell is about a quarter of the way into the image from the right and the marked change of direction of the line after having crossed the Woodford River is easy to see. Trains leaving Ballyconnell for Belturbet travelled first in a Southeasterly direction. [5] As we noted in the last post, there was a relatively gentle gradient out of Ballyconnell station which help to provide effective gravity shunting for the goods yard. Flanagan says that: “The 1:76 of the bank soon steepened to 1:36 before reaching the summit at the 28 milepost. The short descent at 1:43 was followed by a one-mile switchback section before the line levelled to reach Killywilly Crossing (29.5 miles).” [1: p139]

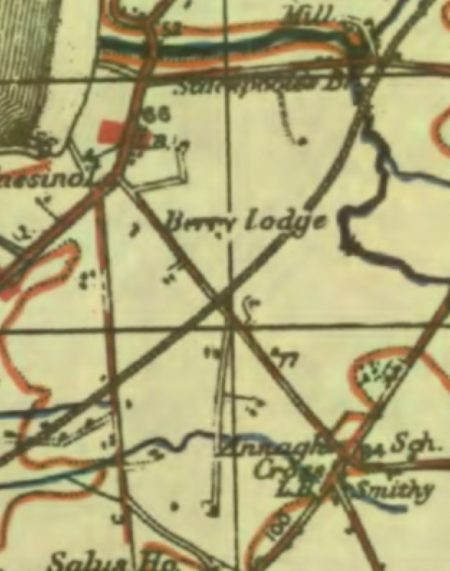

As we noted in the last post, there was a relatively gentle gradient out of Ballyconnell station which help to provide effective gravity shunting for the goods yard. Flanagan says that: “The 1:76 of the bank soon steepened to 1:36 before reaching the summit at the 28 milepost. The short descent at 1:43 was followed by a one-mile switchback section before the line levelled to reach Killywilly Crossing (29.5 miles).” [1: p139] The OS Map extract shows that after crossing the Woodford River the line crossed two main routes south of Ballyconnell before passing under a minor road near to the Western end of Lough Killywilly. The first of these two routes we have already seen in the last post. The crossing gates at that location provided the Western protection to the station site. The second is the modern N87.[3]

The OS Map extract shows that after crossing the Woodford River the line crossed two main routes south of Ballyconnell before passing under a minor road near to the Western end of Lough Killywilly. The first of these two routes we have already seen in the last post. The crossing gates at that location provided the Western protection to the station site. The second is the modern N87.[3] The pink line shows the approximate route of the C&L. [5]

The pink line shows the approximate route of the C&L. [5] Looking Northwest along the N87 towards Ballyconnell. The approximate alignment of the old railway is shown in pink again. There is no evidence of the line at the crossing location. Field boundaries in the satellite image indicate the route of the old line.

Looking Northwest along the N87 towards Ballyconnell. The approximate alignment of the old railway is shown in pink again. There is no evidence of the line at the crossing location. Field boundaries in the satellite image indicate the route of the old line.

The line curves through the crossing on the N87 and gradually turns northwards. Close to the Western end of Lough Killywilly, an old highway which used to cross the line on a bridge. It is picked up on the 1940s OS Map extract but it is hardly visible on the modern satellite image and appears no longer to be in use as a road.

From here the C&L curved around once again to wards the East and ran across the top of the Lough before reaching Killywilly Crossing. Killywilly Crossing and Keeper’s cottage as seen in the 21st century. Flanagan tells us that there was a cornmill here and in May 1888 the Belturbet Market train was ordered to stop here as an experiment. However, the stop only lasted five or six weeks, there being only one passenger per train to avail themselves of it. [1: p139]

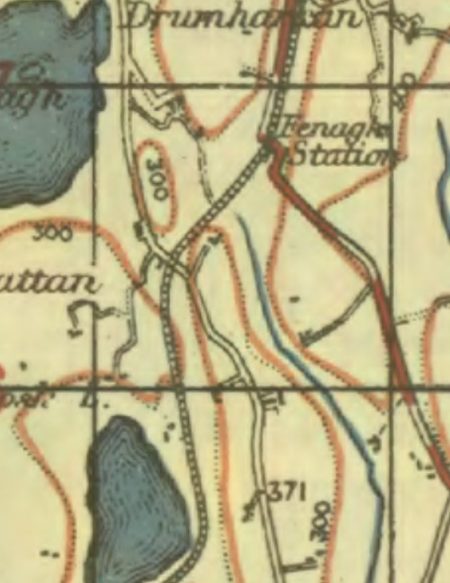

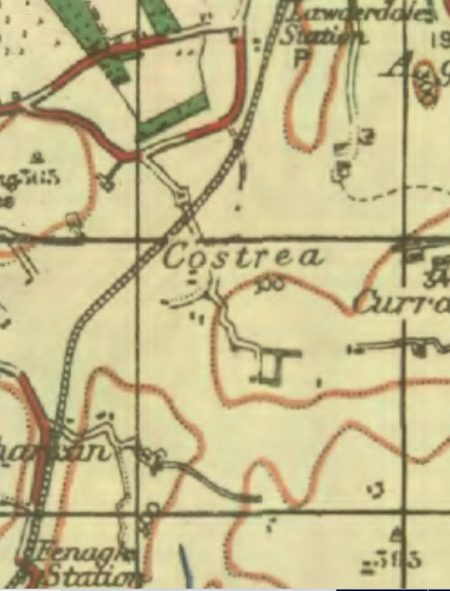

Killywilly Crossing and Keeper’s cottage as seen in the 21st century. Flanagan tells us that there was a cornmill here and in May 1888 the Belturbet Market train was ordered to stop here as an experiment. However, the stop only lasted five or six weeks, there being only one passenger per train to avail themselves of it. [1: p139] Location ‘1’ is Killywilly Crossing, location ‘2’ is the bridge over Rag River and location ‘3’ is Tomkinroad Station and Crossing. [5] The black and white satellite image below comes from 2010 and show location ‘2’ at that time.

Location ‘1’ is Killywilly Crossing, location ‘2’ is the bridge over Rag River and location ‘3’ is Tomkinroad Station and Crossing. [5] The black and white satellite image below comes from 2010 and show location ‘2’ at that time.

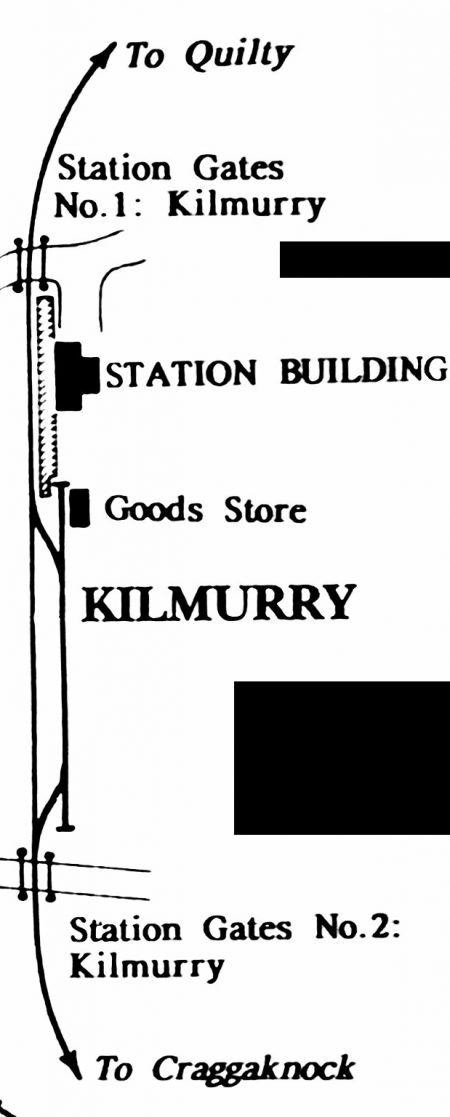

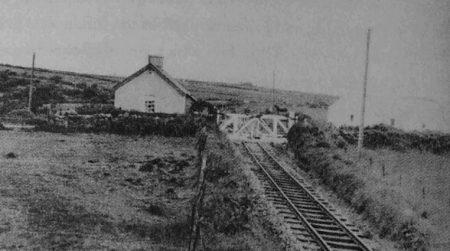

Tomkinroad Station (location ‘3’) appears at the right hand side of the colour satellite above and at the right side of the OS Map from the 1940s. Flanagan says that it “too, was wrongly named, the correct form having one word and being a direct anglicization of the Irish name. The platform, gatehouse and shelter were on the down side and there was an up, facing siding opposite the platform. Although suggested by the stationmistress in November 1887, the siding was not laid till January 1899 when the traffic from the adjacent Tomkinroad creamery made it worthwhile.It was lifted about 1940 when the points were in need of renewal.” [1: p139]

Tomkinroad Station (location ‘3’) appears at the right hand side of the colour satellite above and at the right side of the OS Map from the 1940s. Flanagan says that it “too, was wrongly named, the correct form having one word and being a direct anglicization of the Irish name. The platform, gatehouse and shelter were on the down side and there was an up, facing siding opposite the platform. Although suggested by the stationmistress in November 1887, the siding was not laid till January 1899 when the traffic from the adjacent Tomkinroad creamery made it worthwhile.It was lifted about 1940 when the points were in need of renewal.” [1: p139] The Crossing-Keeper’s House and Station building at Tomkinroad still stands today and has been extended across what was the platform. The line ran across the front of the building and across the minor road on which the photographer is standing.

The Crossing-Keeper’s House and Station building at Tomkinroad still stands today and has been extended across what was the platform. The line ran across the front of the building and across the minor road on which the photographer is standing. The C&L continues towards Belturbet. The field gate is supported on one of the old crossing gate posts.

The C&L continues towards Belturbet. The field gate is supported on one of the old crossing gate posts. The layout of Tomkinroad station was pretty typical of a number of halts on the C&L. They were usually sited immediately adjacent to a road crossing and had a very simple building which accommodated the crossing-keeper who also acted as station-mistress (or -master). The siding here served a creamery nearby. The sketch above comes from Flanagan’s book [1: p139]

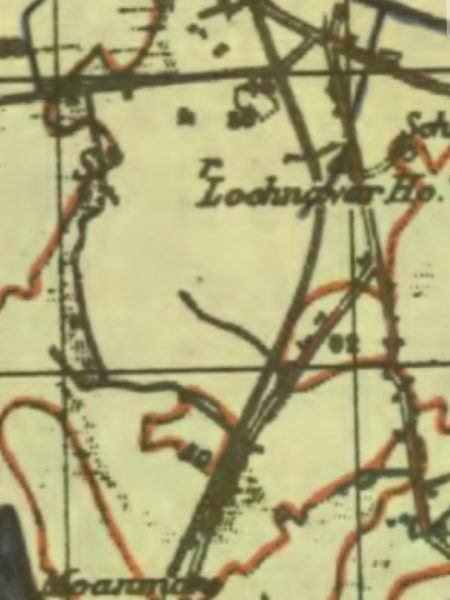

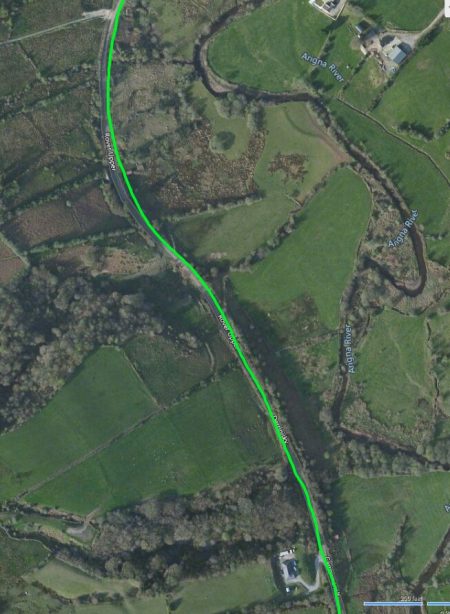

The layout of Tomkinroad station was pretty typical of a number of halts on the C&L. They were usually sited immediately adjacent to a road crossing and had a very simple building which accommodated the crossing-keeper who also acted as station-mistress (or -master). The siding here served a creamery nearby. The sketch above comes from Flanagan’s book [1: p139] The location of Tominkinroad Station is in the top left of this satellite image. The river bridge mentioned below can just be picked out to the East of the station. The next level-crossing was just to the Northwest of Lough Long. [5]

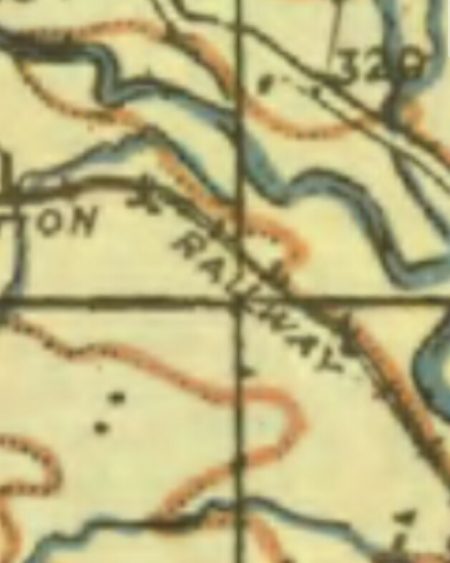

The location of Tominkinroad Station is in the top left of this satellite image. The river bridge mentioned below can just be picked out to the East of the station. The next level-crossing was just to the Northwest of Lough Long. [5] This 1940s OS Map excerpt covers almost exactly the same area as the satellite image above. [3]

This 1940s OS Map excerpt covers almost exactly the same area as the satellite image above. [3]

Just to the East of Tomkinroad Station, the old railway crossed the Rag River again and then meandered eastwards through the crossing on the northwest corner of Lough Long. The crossing-keeper’s cottage has been allowed to deteriorate. This view is taken looking North from the minor road.

The crossing-keeper’s cottage has been allowed to deteriorate. This view is taken looking North from the minor road. The same cottage, this time looking from the East near to the location of the level-crossing gates.

The same cottage, this time looking from the East near to the location of the level-crossing gates. The line turned to a southeasterly direction and ran close to the shore of Lough Long before turning back to the Northeast. [5]

The line turned to a southeasterly direction and ran close to the shore of Lough Long before turning back to the Northeast. [5] The next level-crossing can more easily be picked out on the OS Map extract. I cannot offer you pictures at the location. [3]

The next level-crossing can more easily be picked out on the OS Map extract. I cannot offer you pictures at the location. [3]

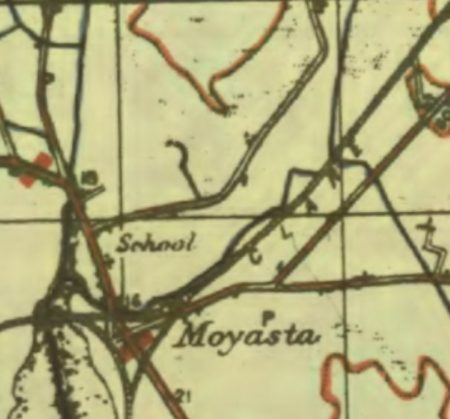

The satellite image and the OS Map show the next length of the old line. It crossed another minor access road before turning South-southeast along side what is now the N3. Just in the bottom corner of the OS Map above, a road over-bridge can be picked out. It carried what is now the N87 road over the C&L. [5][3]

The satellite image and the OS Map show the next length of the old line. It crossed another minor access road before turning South-southeast along side what is now the N3. Just in the bottom corner of the OS Map above, a road over-bridge can be picked out. It carried what is now the N87 road over the C&L. [5][3]

Flanagan says that from Tomkinroad Station the remaining 3.5 miles of the journey to Belturbet were “again fairly level. There were two over-bridges, one stone (Stag Hall) and the other timber. [Then] nearer the terminus and after these [bridges] the fine four-span stone viaduct over the River Erne” [1: p139] was encountered. I have not been able to locate pictures of the first two bridges referred to by Flanagan. The stone viaduct over the River Erne remains in place in the 21st century.

The River Erne can easily be identified on the images above. The two bridges referred to by Flanagan are obvious on the left side of the OS Map. The modern N3 runs south where no road used to be – between the two bridges on the OS Map. [5][3] Both locations are picked out on the larger scale satellite image below. Neither is visible in the 21st century.

The River Erne can easily be identified on the images above. The two bridges referred to by Flanagan are obvious on the left side of the OS Map. The modern N3 runs south where no road used to be – between the two bridges on the OS Map. [5][3] Both locations are picked out on the larger scale satellite image below. Neither is visible in the 21st century.

The River Erne Bridge in the 21st century. [2]

The River Erne Bridge in the 21st century. [2] A more recent, closer shot of the same bridge. [6]

A more recent, closer shot of the same bridge. [6] The location and bridge over the Erne are very attractive. [7]

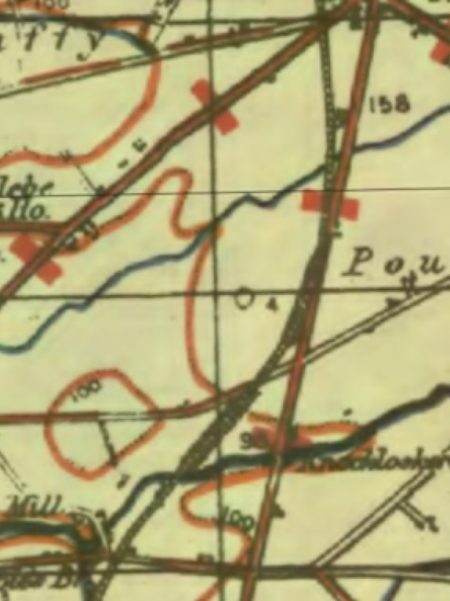

The location and bridge over the Erne are very attractive. [7] The quality of this image is not high, it is an extract from the Irish GSGS Series 3906, 23-31-SW Belturbet Map It shows the line of both the C&L and the GNR on the South side of Belturbet. The various bridges can again be made out relatively easily. [8]

The quality of this image is not high, it is an extract from the Irish GSGS Series 3906, 23-31-SW Belturbet Map It shows the line of both the C&L and the GNR on the South side of Belturbet. The various bridges can again be made out relatively easily. [8] The Erne Bridge and the Belturbet Station site.

The Erne Bridge and the Belturbet Station site. A view west along the trackbed across the river viaduct. [17]

A view west along the trackbed across the river viaduct. [17]

The view north, above, from the C&L bridge over the River Erne. The adjacent map shows Turbet Island on the north side of the railway bridge. The earthworks on the island are the remains of a motte and bailey castle. [9]

The view north, above, from the C&L bridge over the River Erne. The adjacent map shows Turbet Island on the north side of the railway bridge. The earthworks on the island are the remains of a motte and bailey castle. [9]

After the bridge the line “passed No 1 Gates, Straheglin [Holborn Hill], and rose sharply at 1:46 to enter Belturbet station (33.75 miles). The C&L designation was Class 2 although the company had no passenger terminal of its own, the GNR platform being used. The C&L line ended on the left-hand side in a bay. All booking and waiting facilities were provided in the GNR buildings and the ‘joint’ platform was devoid of fittings, although there was an overall roof further up on the broad-gauge line. [1: p139-140] Looking back towards the Erne Bridge from the level-crossing on Holborn Hill at the station throat. One of the crossing gateposts remains and supports the wooden gates for the footway/greenway.

Looking back towards the Erne Bridge from the level-crossing on Holborn Hill at the station throat. One of the crossing gateposts remains and supports the wooden gates for the footway/greenway. Looking forward, in 2012 into the station site from Holborn Hill. The crossing-keeper’s cottage remains and has been modernised and extended as a private dwelling.

Looking forward, in 2012 into the station site from Holborn Hill. The crossing-keeper’s cottage remains and has been modernised and extended as a private dwelling. Patrick Flanagan’s sketch plan of the station site at Belturbet in 1929. It is difficult to reconcile Flanagan’s map with what exists on site in 21st Century. However, please see the maps below from GeoHive where the layout is considered further. [1: p140]

Patrick Flanagan’s sketch plan of the station site at Belturbet in 1929. It is difficult to reconcile Flanagan’s map with what exists on site in 21st Century. However, please see the maps below from GeoHive where the layout is considered further. [1: p140]

Flanagan continues to describe Belturbet Station:

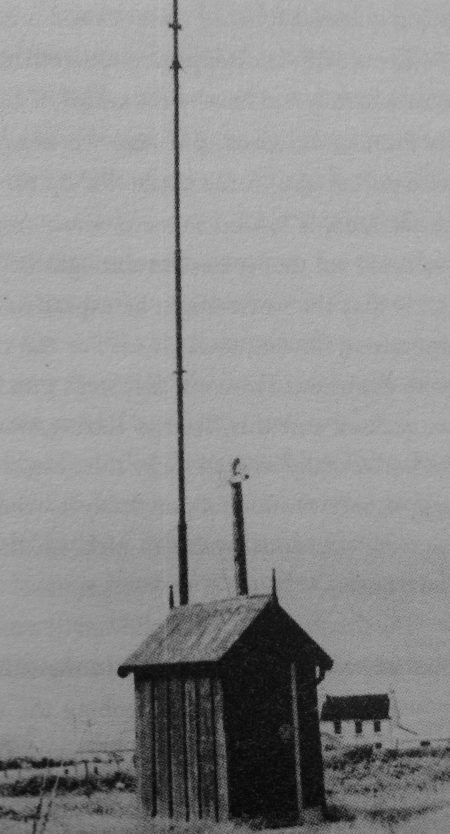

“Off the C&L run-round loop, on the down side, was a small store on a short curved siding which ended in a carriage dock (installed 1890). Just west of the store, at the points, was the station ground frame in a 1901 ‘cabin’. In order to reach the transfer, engine and carriage roads it was necessary to use a head-shunt and operations were quite tricky. The first road back from the head-shunt was the loco and carriage road; the second opened into a goods loop. The latter ran through a tranship shed where the transfer of goods to GNR metals took place and, outside again at the far end, it closed into a single long siding which extended far into the Northern yard. Before the shed was a joint loading bank similar to that at Dromod. So awkward was the layout here that tailrope shunting was the recognized practice from 1888 to 1893, but this was afterwards discontinued and was certainly not done after 1900. The loco siding also resembled that at Dromod, reaching the 24-ft turn-table before entering the single-road shed. Between the table and the shed was the 7,000-gallon water tank which was always filled from the GNR supply under an agreement made at the start; Belturbet was thus the most trouble-free place on the line so far as water was concerned. It was agreed in 1891 to transfer the GNR windmill to C&L land at the Erne Bridge; it was replaced by a pump in 1925. During temporary closures of the GN Belturbet branch in the 1920-23 period, a GNR fireman was allocated one day a week to pump water for the C&L. From about 1936, only the walls of the engine shed remained intact, the GSR having ordered the removal of the roof after a mishap. One day, Passage Engine No 12L was on the mixed train which was then working from Ballinamore, the shed being out of use. The driver decided to put the engine in the shed to enable him carry out some repairs. Until then, only the C&L engines had been inside and nobody realized that the Passage engine chimneys were higher than the C&L ones. As No 12L moved into the shed it dislodged the keystone from the door arch and weakened the whole roof. Afterwards, when the workings were altered, engines were left out at Belturbet at night.” [1: p140-141]

“At the approach to the turntable a siding diverged to the right; it was the carriage shed road and ran behind the tank. The shed was identical with that at Dromod (100ft X 12ft X 10ft) and was also built by Rogers. It was removed by the GSR in the 1930s. The shed road points were spiked and the line lifted. As at Dromod, a small room for drivers was provided at Belturbet.” [1: p141]

These two images are from GeoHive the national on-line mapping service provided by Ordnance Survey Ireland. Location ‘1’ on both images is the level-crossing at Holborn Hill. Location ‘2’ is the passenger facility for both C&L and GNR lines. Location ‘3’ is the GNR Goods Shed. Location ‘4’ is the goods exchange facility and location ‘5’ the darker triangle of land to the south side of the site was the location of the C&L carriage shed, engine shed and turntable. Flanagan’s sketched arrangement is correct, but the site was much more cramped than his sketch suggests. He ignores the GNR goods shed on the Northeast of the station site. [10]

These two images are from GeoHive the national on-line mapping service provided by Ordnance Survey Ireland. Location ‘1’ on both images is the level-crossing at Holborn Hill. Location ‘2’ is the passenger facility for both C&L and GNR lines. Location ‘3’ is the GNR Goods Shed. Location ‘4’ is the goods exchange facility and location ‘5’ the darker triangle of land to the south side of the site was the location of the C&L carriage shed, engine shed and turntable. Flanagan’s sketched arrangement is correct, but the site was much more cramped than his sketch suggests. He ignores the GNR goods shed on the Northeast of the station site. [10]

First, some images of the station area when in use. A train from Dromod leaves Belturbet an approaches the crossing at Holborn Hill. [16]

A train from Dromod leaves Belturbet an approaches the crossing at Holborn Hill. [16] A view looking East from under the overall roof showing a GNR train on the left and a C&L train on the right. [16]

A view looking East from under the overall roof showing a GNR train on the left and a C&L train on the right. [16]

1948: the shared platform – GNR/C&L. The passenger station facilities were provided entirely by the GNR. On the left is a Cavan & Leitrim (3 ft. gauge) train for Dromod or Arigna, headed by 2-4-2T No. 12L (ex-Cork, Bandon & South Coast Railway). The other platform face served the Great Northern (Ireland) Railway (5 ft. 3 in. gauge) branch from Clones. [12]

1948: the shared platform – GNR/C&L. The passenger station facilities were provided entirely by the GNR. On the left is a Cavan & Leitrim (3 ft. gauge) train for Dromod or Arigna, headed by 2-4-2T No. 12L (ex-Cork, Bandon & South Coast Railway). The other platform face served the Great Northern (Ireland) Railway (5 ft. 3 in. gauge) branch from Clones. [12]

The adjacent image is a view of the station from GNR rails to the East. [13]

The first image below shows a GNR branch-line train at Belturbet viewed from the Southeast. [14]

The adjacent image is taken from the East looking along the GNR lines into the station complex at Belturbet. [15]

The adjacent image is taken from the East looking along the GNR lines into the station complex at Belturbet. [15]

Locomotive No 1 Isabel on the turntable at Belturbet in 1923. Robert H. Johnstone of Bawnboy House was the longest serving director of the Cavan and Leitrim Railway, serving on the board from 1883 until the amalgamation with the G.S.R. in 1925. This engine, No 1 was named after his daughter, Isabel. The other engines except No 8, (Queen Victoria) were also named after directors’ daughters. It is interesting that between 1887 and 1925 Isabel had worked well over half a million miles between Dromod, Arigna and Belturbet! [19]

Locomotive No 1 Isabel on the turntable at Belturbet in 1923. Robert H. Johnstone of Bawnboy House was the longest serving director of the Cavan and Leitrim Railway, serving on the board from 1883 until the amalgamation with the G.S.R. in 1925. This engine, No 1 was named after his daughter, Isabel. The other engines except No 8, (Queen Victoria) were also named after directors’ daughters. It is interesting that between 1887 and 1925 Isabel had worked well over half a million miles between Dromod, Arigna and Belturbet! [19]

And some images of the site after closure but before restoration taken at different times by Roger Joanes. [11][20]

Loco No. 3T at Belturbet immediately after closure, 26th August 1959, (c) Roger Joanes. [20]

Loco No. 3T at Belturbet immediately after closure, 26th August 1959, (c) Roger Joanes. [20]

Two pictures of the gradually decomposing station site in the 1990s. [11]

Two pictures of the gradually decomposing station site in the 1990s. [11]

The Station Site has been refurbished and a few images illustrate this.

The Station Site has been refurbished and a few images illustrate this.

A heritage centre now operates from the site. The transformation is remarkable. It is interesting to note that at both ends of the C&L Mainline there is a railway heritage centre. One in Cavan and one in Leitrim. The adjacent image shows the visitor centre at Belturbet which was once the passenger station building. The GNR Goods Shed in the 21st century. [18]

The GNR Goods Shed in the 21st century. [18] The station master’s house is now a holiday cottage. [21]

The station master’s house is now a holiday cottage. [21] The station master’s house and the goods transfer shed. [18]

The station master’s house and the goods transfer shed. [18]

A bonus at the end of this post! The Railway Roundabout Video of the Cavan & Leitrim Railway. [22]

There are two further posts to follow. ……………………

The first will reflect on the two heritage efforts, particularly the preservation society at the Dromod end of the line. Included with this will be other images from along the line which have not been included in posts so far.

The final post will look at the tramway which ran from Ballinamore to Arigna.

References

- Patrick J. Flanagan; The Cavan & Leitrim Railway; Pan Books, London, 1972.

- http://candlgreenway.ie, accessed on 24th May 2019.

- https://maps.nls.uk, accessed on 22nd May 2019.

- http://www.buildingsofireland.ie/niah/search.jsp?type=record&county=CV®no=40401005, accessed on 31st May 2019.

- http://www.railmaponline.com/UKIEMap.php, accessed on 19th May 2019.

- https://belturbetheritagerailway.com/history-of-railway/railway-bridges, accessed on 1st June 2019.

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Belturbet_railway_station, accessed on 1st June 2019.

- https://www.lbrowncollection.com, accessed on 1st June 2019.

- https://m.facebook.com/macgeopark/posts/geopark-site-of-the-month-january-turbet-island-walking-trail-belturbet-co-cavan/10156836706041112, accessed on 4th June 2019.

- http://map.geohive.ie/mapviewer.html, accessed on 4th June 2019.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/110691393@N07/with/11400430783, accessed on 4th June 2019.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belturbet_railway_station, accessed on 4th June 2019.

- http://www.discoverbelturbet.ie/about-belturbet/belturbet-railway-station, accessed on 1st June 2019.

- https://belturbetheritagerailway.com/history-of-railway/historical-railway-images/#jp-carousel-219, accessed on 4th June 2019.

- https://bizlocator.ie/listings/belturbet-railway-museum, accessed on 4th June 2019.

- https://www.dreamireland.com/site/Station_Masters_House.21843.html, accessed on 4th June 2019.

- http://eiretrains.com/Photo_Gallery/Railway%20Stations%20B/Belturbet/IrishRailwayStations.html#, accessed on 5th June 2019.

- http://discovertheshannon.com/listings/belturbet-railway-station, accessed on 6th June 2019.

- http://www.iol.ie/~bawnboy/page12.html, accessed on 29th May 2019.

- https://sites.google.com/site/thecavanandleitrimrailway/history, accessed on 19th May 2019.

- https://www.homeaway.co.uk/p1856334, accessed on 7th June 2019.

- https://youtu.be/geuu47Rr35U, Railway Roundabout 1958, accessed on 19th May 2019.