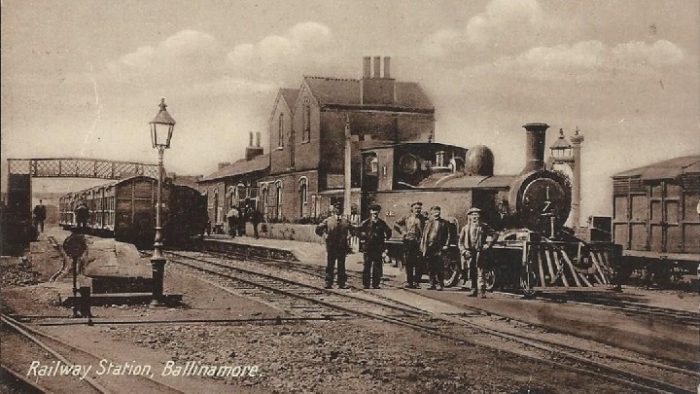

The Arigna Valley Extension to the Cavan & Leitrim Railway

If we are to fully understand the circumstances which surrounded a perennial desire by the Cavan & Leitrim Railway to extend through to Sligo, and to accommodate traffic from the Arigna Valley, we need to know more about the Arigna Valley.

Wikipedia tells us that Arigna is situated in Kilronan Parish alongside the picturesque villages of Keadue and Ballyfarnon. It lies close to the shores of Lough Allen. [5]

Mining at Arigna started in the Middle Ages with the mining of iron ore. At the beginning of the 17th century, the iron ore was smelted at Arigna in newly built iron works, using charcoal, which was burnt from the wood of the forests around. But as no organised tree planting took place and the timber eventually ran out, the iron works had to be closed at the end of the 17th century.

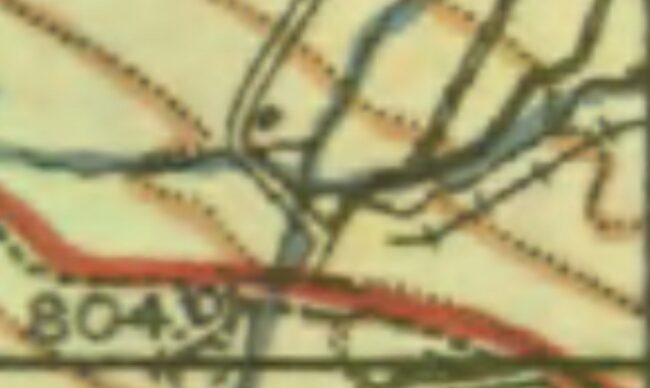

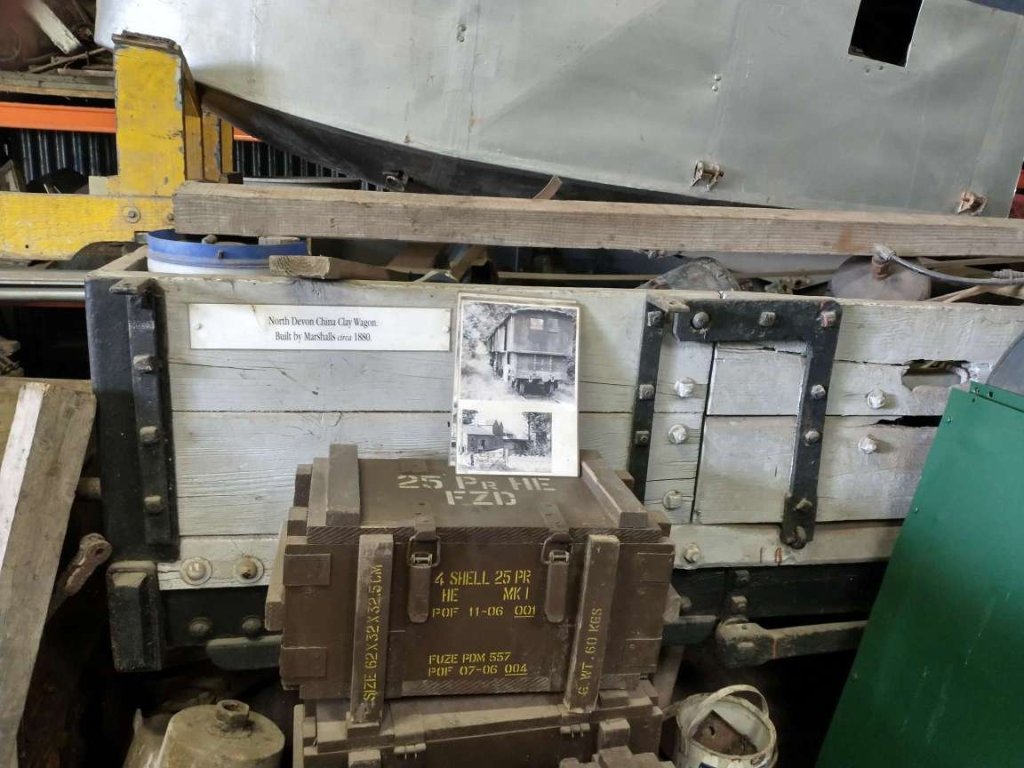

More than half a century later, in 1765, the mining of the coal deposits started, and 30 years later smelting was revived using the local coal instead of charcoal. Three brothers, Thomas, Patrick and Andes O’Reilly reopened the smelting operation in 1788. However, the works were forced to close in 1798. Then about 1804, Peter Latouche, a Dublin banker who had previously advanced £10,000 to aid the undertaking, bought the property at a Court of Chancery sale for £25,000. He tried various improvements, including the laying of an iron tramway, about 300 yards long, for the carriage of ironstone, but he too, in time, failed. The works were again silent in 1808 and in the years afterwards became ruinous, all traces of the tramway disappearing. [7]

By 1824, when the ‘Arigna Iron and Coal’ joint-stock company was formed, much rebuilding was necessary. Iron production was restarted in November 1825 and smelting went on for six months. All work then stopped and the company engaged a surveyor to examine the property. This was because of a scandal about the formation of the company, and its after-effects in the form of sabotage at Arigna. The expert, Mr Twigg, submitted a report suggesting the laying of a tramway from the works from the company’s coal drift at Aughabehy and the building of coke ovens on the line near the latter point. It was decided to build the line, and although no smelting was being carried out in the works the men were usefully employed casting the rails required for the line from home-produced iron; later, they were engaged in the construction. [7]

The cost of the tramway was some £1,900—£2,000. It was 5,500 yards long and by April 1831, 5,100 yards had been completed. By the following February the whole line was ready and had been tested. Except for a short section with bar rails, the line was laid with fish-bellied rails, 3 ft long and weighing 35 lb. The sleepers were roughly-cut blocks of granite with an eight-inch hole in the centre to take the spikes. The holes were then filled with molten lead. Close to the Aughabehy terminus, near the coal drift, there was a cable-operated incline section about 200 yards long; a wagon turntable connected it with the short section along the hillside to the mine. [7]

The gauge was 4 ft 2 ins. Apart from the incline, operation was by horse, the fall being calculated to allow a load of nine or ten tons. The earthworks from the coke-yard (at the bottom of the incline) to the works were considerable, there being five or six small bridges and culverts, with embankments of up to 24 feet in height. Trouble with the management of the company prevented the speedy resumption of work and it was not until 1836 that the line was in use. Even then there was trouble and work ceased for good at the Ironworks in 1838. The tramway lay derelict until about 1860 when most of the rails were carted away; the works were also left and gradually became ruinous. Despite hopes in the early 1900s that the industry might be revived, no more iron was made at Arigna and, to finalize the matter, the remaining material of the works was used in the making of the foundations of the Arigna Valley Railway. [7]

Demand for fuel in Dublin drove the industrial and economic development in the region. In 1790s Dublin, years of rising fuel inflation had driven the price of coal to 36-40 shillings per ton, causing “very great distress” to the inhabitants of Dublin. The completion of the Royal Canal allowed for the supply and sale of Arigna coal at 10 shillings per ton. New towns and villages emerged. Drumshanbo has its origin in these industries. [5]

Coal mining continued for many years providing a ready income for the C & L and work for people in the area. In 1958, the Arigna Power Station was opened. It wast the first major power-generating station in Connaught and was designed to burn the Arigna Coal which was semi-bituminous. At its height, the power station burned 55,000 tonnes of coal per year and employed 60 people. [5]

Throughout the life of the C & L, it was Arigna coal which provided its major source of income and it was the building of the power station in Arigna in 1958 which sounded the death knell for the Cavan and Leitrim Railway since coal would no longer be brought out from Arigna, the power station needing all the coal the mountain could provide.

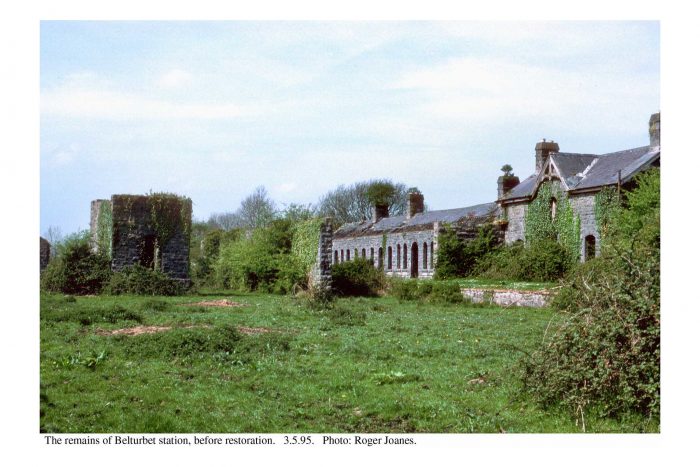

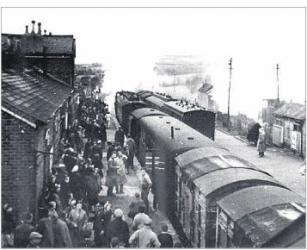

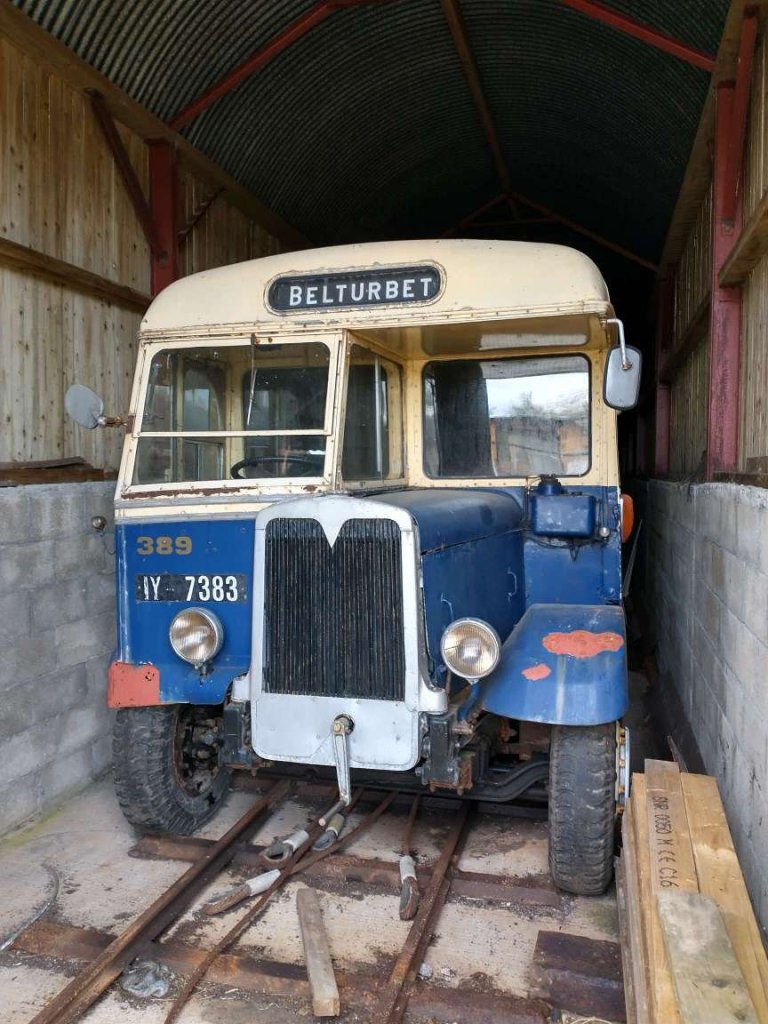

Locals were devastated at the loss of their railway whose familiar sight and sound had become synonymous with the landscape from Belturbet all the way across to Arigna. [12]

Various Extension Plans

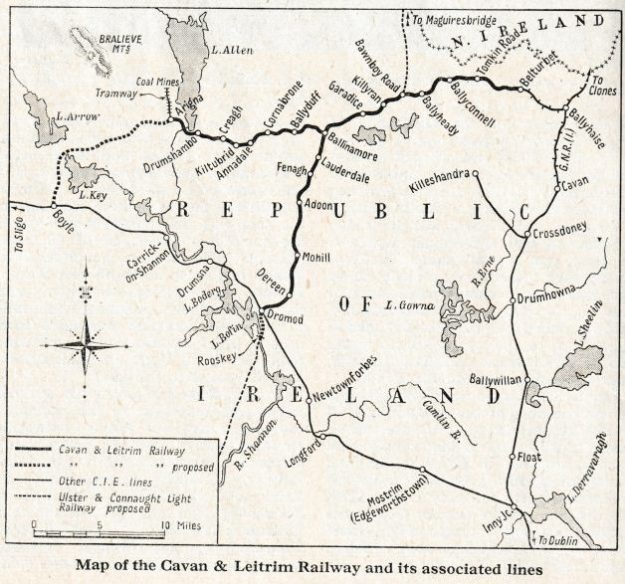

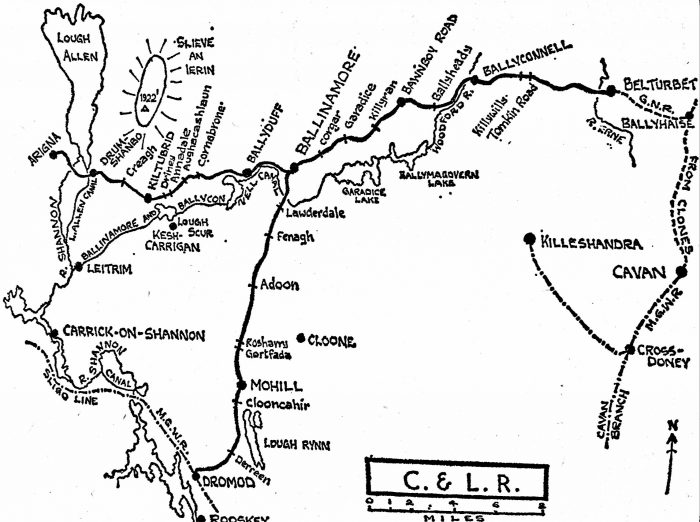

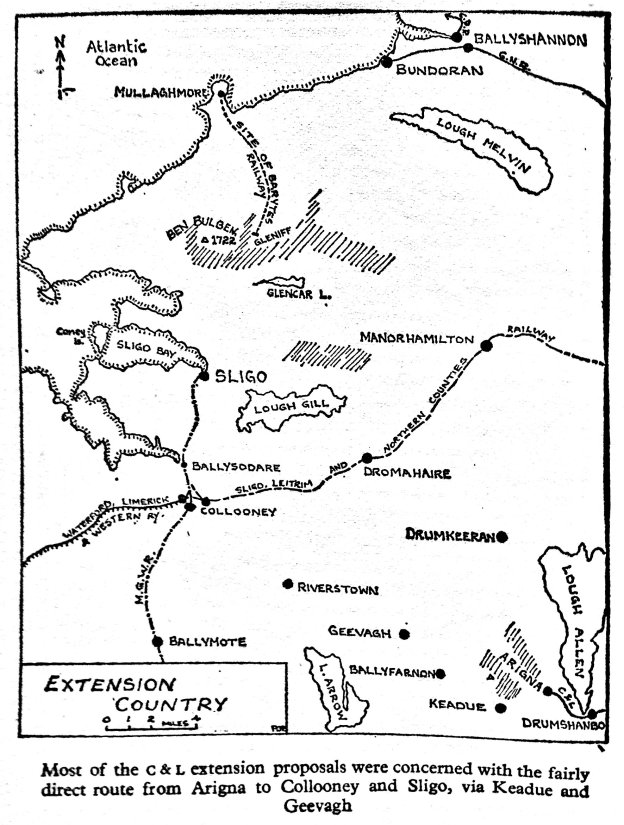

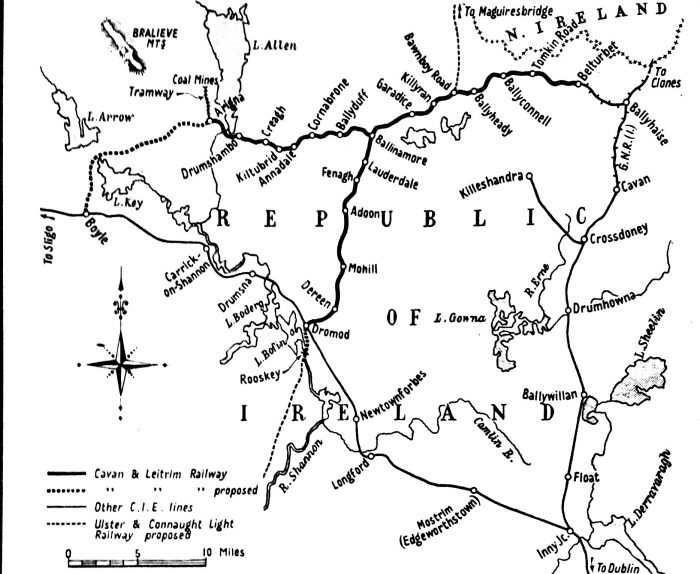

Most extension plans associated with the Cavan & Leitrim Railway were concerned with the fairly direct route from Arigna to Collooney and Sligo, via Keadue and Geevagh. [3]

There were extensive plans made as early as the time when the Cavan & Leitrim (C & L) Railway was first mooted to expand its activities. “Despite the effort put into the planning of these extensive schemes in 1884, none came to fruition. … As a result … the C & L had a tendency to take a great interest in any extension plans and sent it received many a deputation over the years.” [1]

Most of these ideas proved unworkable. These included:

- A scheme called The Ulster and Connaught Light Railway (1888);

- A scheme to link the C & L and the Clogher Valley Railway (1889);

- A line from Arigna through Ballyfarnon and Riverstown to Collooney (1895);

- A line to Rooskey (1898);

- The Bawnboy & Maguiresbridge Railway

- Another scheme called The Ulster and Connaught Light Railway (1900-1910);

- Another Rooskey proposal (1901-1908);

- An English backed broad-gauge scheme from Arigna to Sligo (1907-1910);

- A similar scheme (1913-1914).

After this flurry of different proposals the interest in extensions waned. It was not until 1930 that another scheme was proposed. This time it involved converting the entire C & L to broad-gauge removing the worst curves on the line and extending to Arigna. Some exploratory work was undertaken but this scheme also came to nothing. [2]

Patrick Flanagan takes up the story: [4]

“Strangely enough, the C & L did not originally intend to build a line near the Arigna coal-pits. Although the opposite has often been stated, Lawder’s controversial pamphlet of 1884, while eloquently describing the value of the Arigna mineral deposits, made no reference whatsoever to any railway access to the Valley. The only original intention was, according to James Ormsby, ‘to put Arigna station sufficiently near so that the mining companies might make a mineral line of their own down — as they do in Wales’. Anyway, the C & L planned a continuous line to Boyle and this could not have been routed via the mines, owing to the difficult nature of the terrain. The idea of building a separate extension to the mines does not seem to have occurred to the company until February 1894, when a tentative proposal was postponed, pending a reply from the Arigna Mining Company. Nothing came of this.

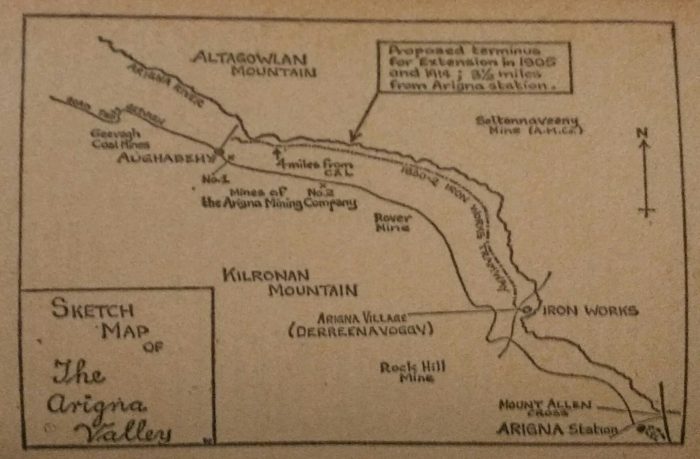

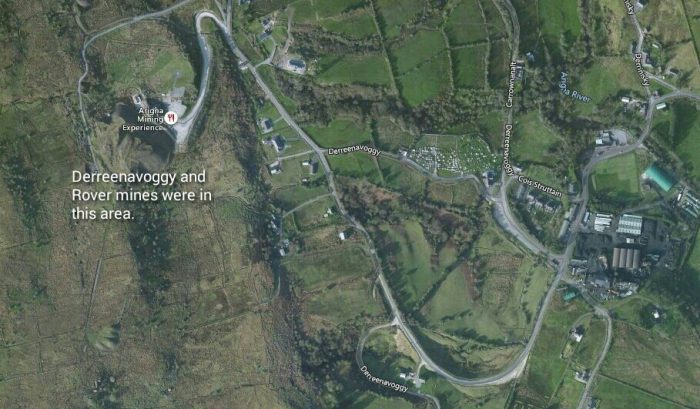

It was not until 1901 that further steps were taken to get a Valley extension. This time, the matter was investigated in great detail and some interesting proposals emerged. The pro-ceedings began when officials of the Board of Works visited the Valley and then held discussions with the C & L directors. The board men thought the need for a line was a priority matter and in October a scheme was outlined. The proposed line was to be three miles long and, for a considerable part of its length, would pass over the formation of the old Arigna Iron Works tramway. The latter, from Derreenavoggy (the site of the Iron Works) to Aughabehy (the chief mining centre), had been built in 1830-1832 [see above] and boasted substantial earthworks. Though the rails had long since disappeared, the formation was still usable.

The cost of the new line was estimated at about £8,000 and, in addition, it would cost the Mining Company £1,500 to make a connexion with the line by an inclined plane. The C & L directors thought that the Government should grant £5,000 and that the Arigna Mining Company should obtain an Order in Council for the construction of the line and provide £3,000 out of its own capital, which would be the capital of the new rail-way. In return, the Mining Company would receive profits, after payment of working expenses, up to five per cent of the capital expended. Any surplus profit above five per cent would be divided equally between the Treasury, the Mining Company and the C & L, the latter providing rolling stock, and maintaining and working the line at cost price.

On October 15th another meeting was held, and it was reported that the Board of Works had not sufficient money to make a fully-equipped passenger and goods line and that, in any case, the C & L could not legally undertake the contingent liability of a working loss. Mr Digges objected to the suggestion that a private trading concern like the Arigna Mining Company should contribute towards the cost of making the extension and so acquire even a nominal ownership of the line. This, he rightly felt, would operate to the detriment of others who might subsequently start mining operations.

A compromise proposal was that the line be made as a fully-equipped railway as far as the old Iron Works, and that the Mining Company then lay down at its own expense a horse-tramway from the mine to the works. This was rejected after discussion as limiting the usefulness of the extension, and eventually the Board of Works proposed that the line be made exclusively out of public funds and as cheaply as possible, as a mineral siding from Arigna and up the Valley on the site of the old tramway.

The most interesting recommendation of all, however, was that the Arigna Mining Company, and any other mine-owners who wished, might have minerals conveyed over the line in their own wagons and that the Arigna Mining Company should do all the haulage over the siding, under terms to be arranged, with its own light engine.

While this was being digested it was agreed that the Board of Works engineer, T. M. Batchen, with C & L Engineer Maxwell, should visit the site of the old tramway. The inspection was carried out on 5th November 1901, and Batchen returned a detailed report. He was very impressed with the old line, which had been carefully planned and built, and found that the alterations necessary to make the road-bed usable would consist merely of widening cuttings and embankments and purchasing a small amount of land. Although the old form-ation was three and a quarter miles long, Batchen was only interested in the two-mile section from the Iron Works to a point opposite the Arigna Company’s pit, high on the moun-tainside. He estimated the cost of the line from here to the Iron Works at £4,400, using 45-lb rail. One obstacle was that the few people living along the route used it as a road and Batchen was doubtful if it could be acquired without the provision of a new road parallel.

Batchen’s report was overlooked in the course of development of the Ulster & Connaught Light Railway (UCLR) scheme and it was not until 1903 that the question of a Valley line again arose. Leitrim County Council was definite on one point — an extension was necessary and the C & L was asked to promise that it would promote the line as soon as possible. In September 1903, the C & L decided that if a line was built it would work it and finance plans were outlined to the Council. The cost of the line (and another one to Rooskey) was estimated at £20,000 and it was hoped that the Treasury would contribute £10,000, the balance to be raised by the C & L. This the company proposed to do by the reissue of £7,000-worth of cancelled C & L stock at the then premium of £10,000. As this was guaranteed stock, there would be a liability on the ratepayers –five per cent per annum on £7,000 or £350 a year in all — of, which the Treasury would repay £140, 2% of the capital. But the increased profits were reckoned at £1,040, leaving a very comfortable margin. Reasonable as these proposals were, they were rejected by the Council, largely because of the North Leitrim members who wanted an extension of their own (apparently to no particular place). Other factors in the decision were that the line would greatly benefit the much-hated Arigna Mining Company, and would lie wholly in Co. Roscommon. The fact that it would also benefit the Leitrim ratepayers was conveniently overlooked.

Disheartened by this failure, the C & L did nothing more until 1905, when a committee was appointed in April to promote Rooskey and Valley extensions. After a report in May, the C & L, with the support of all directors and the County Council, made a submission to Mr Walter Long, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, seeking a grant of £12,000 for each line. The Council resolution in favour of the move was extremely important, particularly as regards the wording:

We call on the Chief Secretary for Ireland, the Right Hon W. H. Long, MP, to grant the application of the directors of the Cavan & Leitrim Railway for a subsidy towards the ex-tension of their railway, out of the Development Fund. The extension would materially relieve those unfortunate over-taxed ratepayers who unluckily live in the guaranteeing area.

After the submission had reached Mr Long, a deputation of six directors (three of each kind) visited him in London, where they were assisted in their pleading by three local MPs. Mr Long responded quickly and visited the Valley himself on 6th June 1905. Two months later the C & L received a letter from Dublin Castle notifying it that the Government had arranged with the Treasury for a grant of £24,000, as requested, to be charged on the Irish Development Fund. [4]

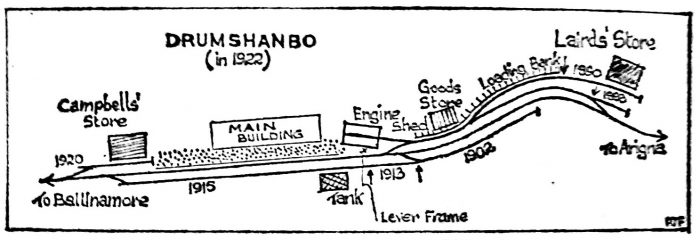

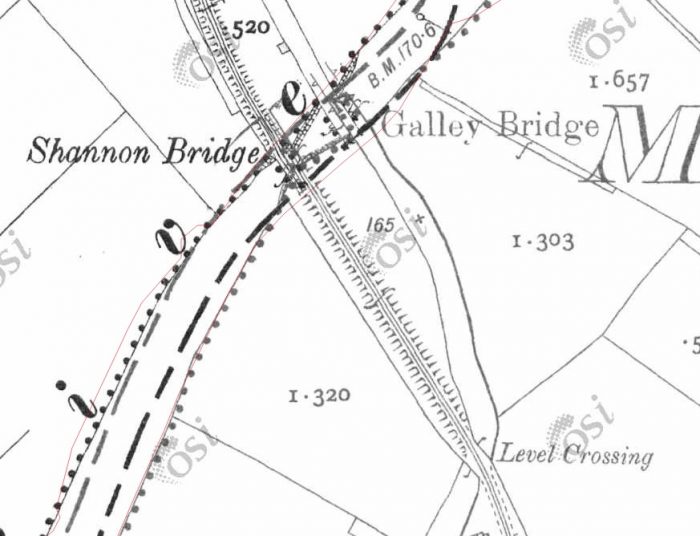

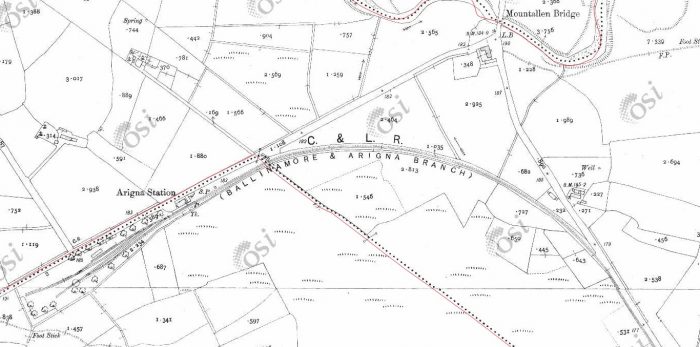

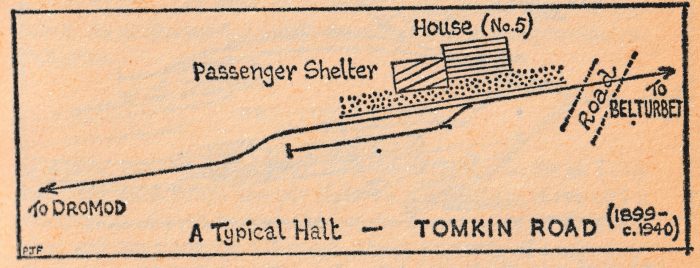

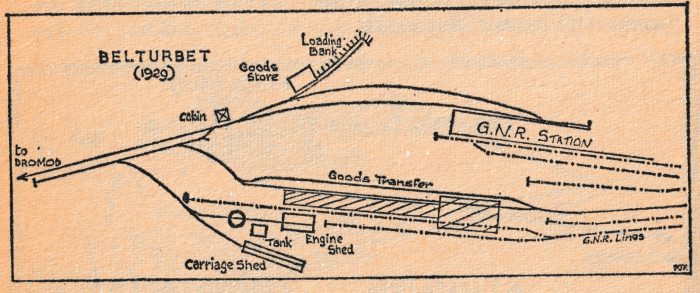

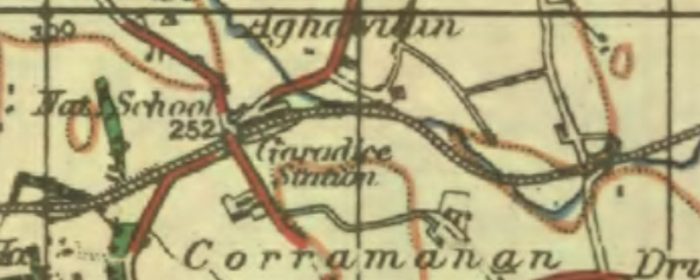

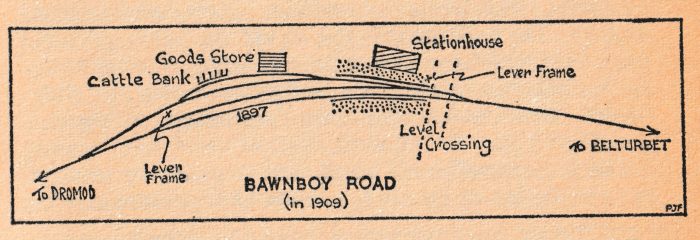

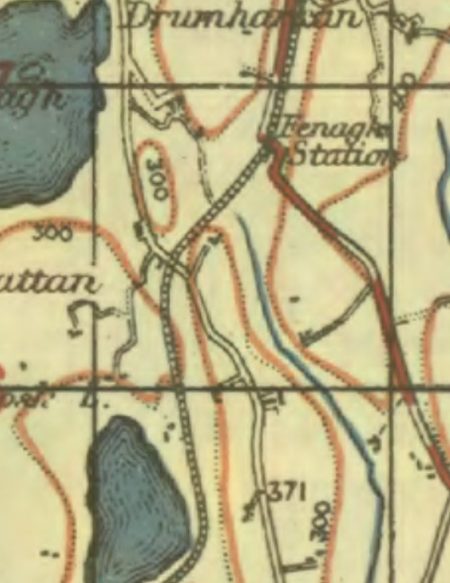

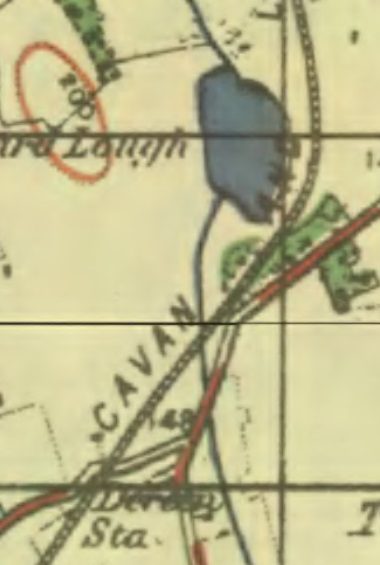

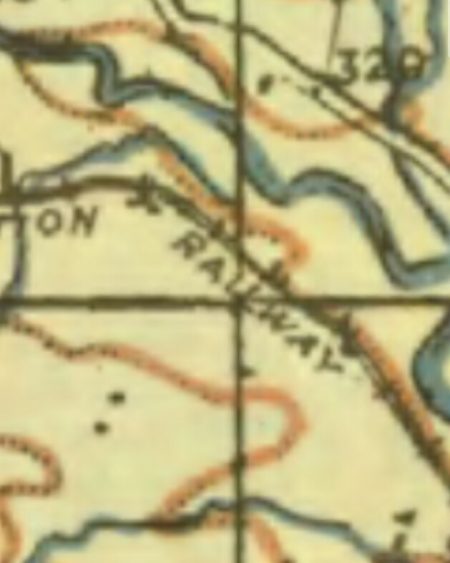

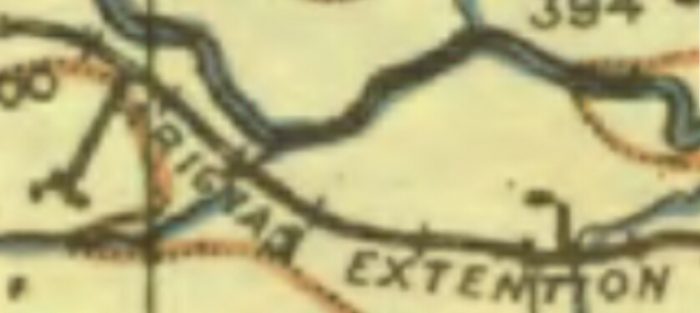

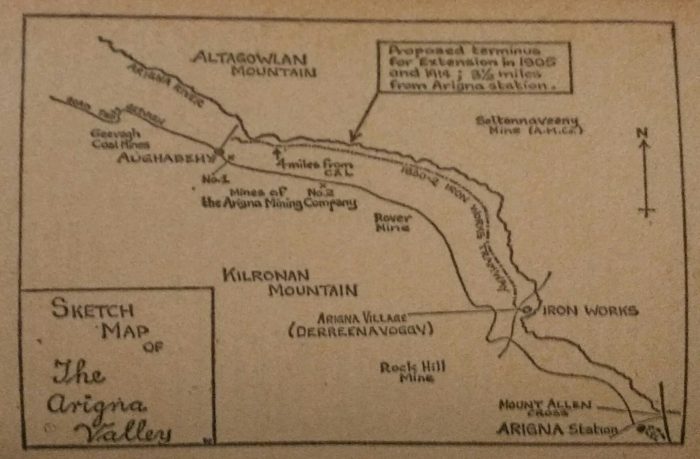

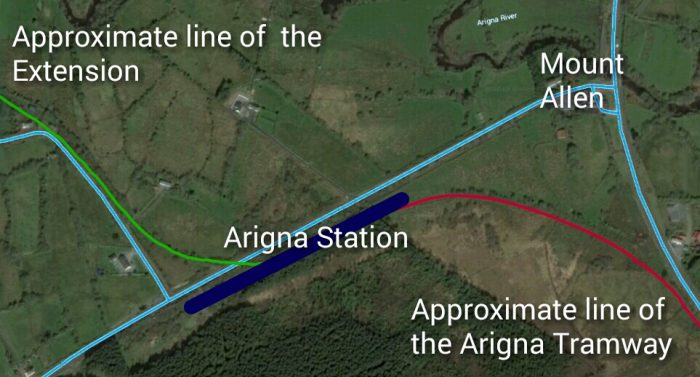

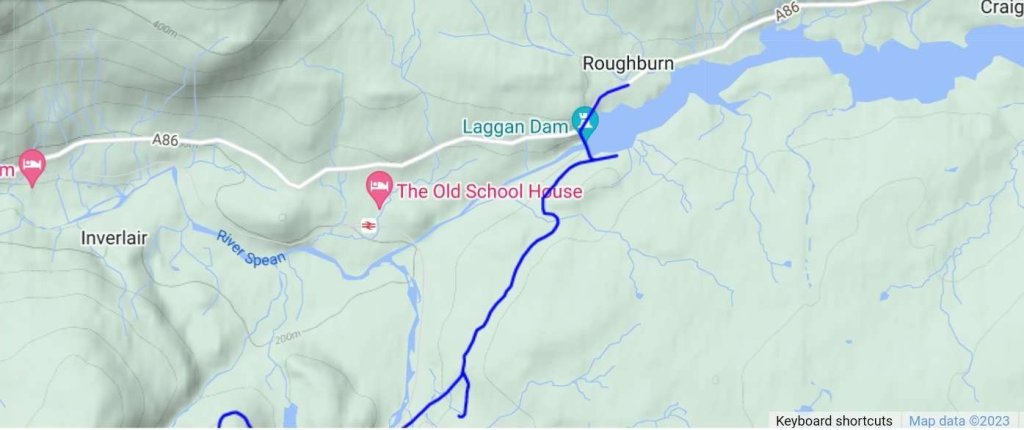

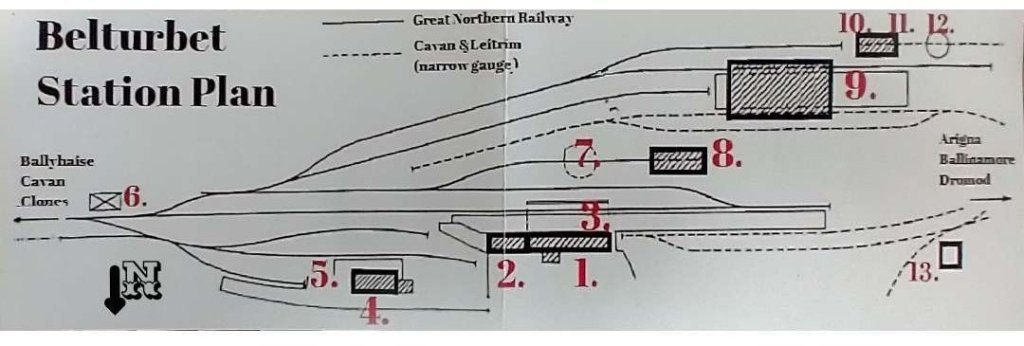

The proposed line was as outlined on the sketch map below. However, there were problems. In 1906 a series of meetings were held which resulted in the grant of £24,000 being rejected by the County Council. [8] The consequence was the end of C & L extension plans for quite some time. Others brought forward plans to access the Arigna Valley and these were successfully opposed by the C & L. [8] The C & L tried once more, in 1913-1914, to gain approval for the extension. Once again, it failed.  This sketch map shows the location of Arigna Station on the C & L, the first proposed length of the extension to Aughabehy and the finally determined length of 3.5 miles from Arigna Station. This would have saved money on construction costs and would have required no additional length to the required ropeway to connect the mine to the railway. Sadly the government grant for the line was rejected by the County Council. [6]

This sketch map shows the location of Arigna Station on the C & L, the first proposed length of the extension to Aughabehy and the finally determined length of 3.5 miles from Arigna Station. This would have saved money on construction costs and would have required no additional length to the required ropeway to connect the mine to the railway. Sadly the government grant for the line was rejected by the County Council. [6]

It was the outbreak of the First World War that dramatically altered the political dynamics. All coal and mineral deposits became of vital importance. Arigna’s reserves were not of the same standard as others but nonetheless needed to be developed. The government took time to make up its mind but eventually the decision was taken. Patrick Flanagan explains: [9]

Of primary importance were the Leinster and Connaught coalfields and it was to these that railway access was provided. Under powers conferred by the Defence of the Realm Act, land was obtained and construction was started on railways to serve the Wolfhill collieries of Gracefield and Modubeagh, the Castlecomer-Deerpark mines, and, at Arigna, to make for speedy dispatch of coal from the inaccessible pits of Aughabehy, Derreenavoggy and Rover. The only three-foot gauge line, the Arigna Valley Railway, was the last to be opened — in 1920. The preliminary plans for the line were considered by the Irish Railway Executive Committee in the autumn of 1917, and, this time, no bodies, however august, were going to interfere with matters.

On 28th December 1917, the Executive met and it was agreed that the engineers of the GNR and MGWR be asked to approve the proposals. They reported quickly and a final plan was adopted. It was for a 4.25-mile version of Barton’s 1905 railway, with only the last section to the public road at Aughabehy omitted. The terminus was chosen to suit the Number 1 pit of the Arigna Mining Company. Although the line was Government-sponsored, the GNR was put in charge of construction and the Arigna Mining Company got the job of obtaining the rails and materials and of having them on site ready for the start of construction. The ballast used came from the C & L pit at Aughacashlaun, and much of the foundations were made with the remaining stones of the old Arigna Iron Works.

The section from Arigna station to Derreenavoggy was on unbroken ground and the route chosen followed the winding Arigna River but few earthworks were required. Beyond Derreenavoggy, the more considerable difficulties of the terrain had been ironed out for the old tramway and the main work done was much as Mr Batchen had reckonedin 1901, including widening and strengthening the oid formation and making a rough roadway for the people living nearby.

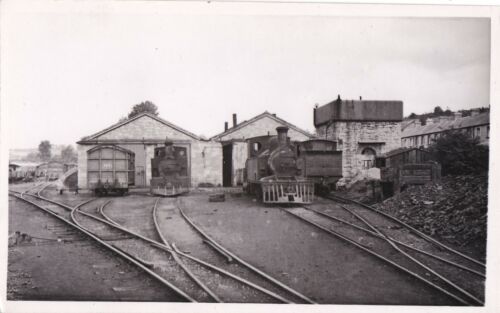

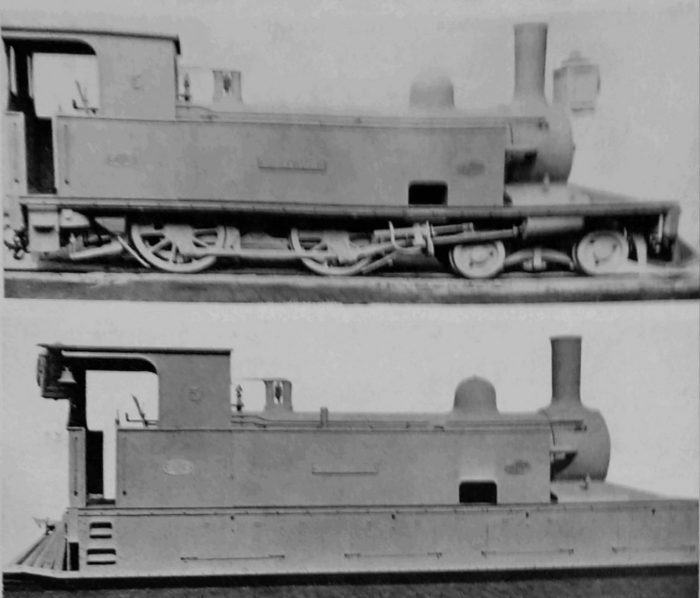

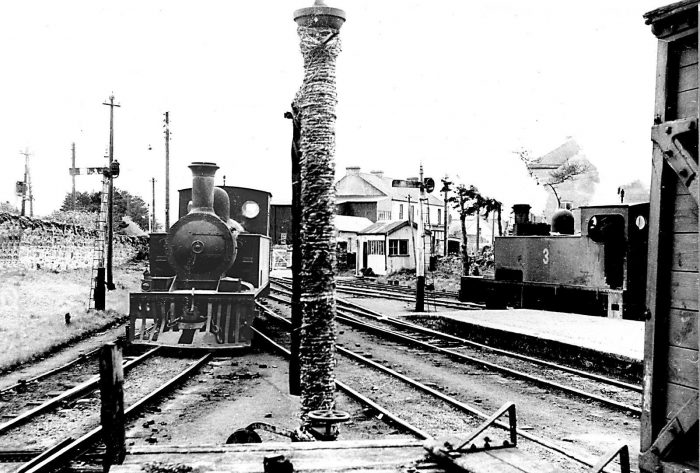

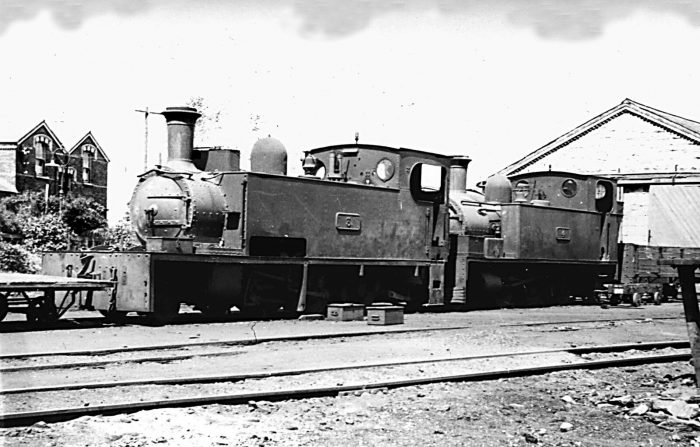

The materials for the line were ordered on 1st January 1918, and work began in the autumn of that year. The supervising Board of Works wrote to the C & L requesting the use of one of the engines for construction trains and this was agreed to, provided that the C & L could immediately secure return of the engine in an emergency. Engine No 6, May, was chosen for this job and, with Driver Simpson McAdams and Fireman Johnny Gallagher, was based at Arigna station for some time in 1918-1919. The costs were debited entirely to the extension and neither crew nor engine played any part in the normal working of the C & L. Indeed, so completely separate were matters that,. when May needed a boiler wash-out, she did not do the obvious and change places with the regular tramway engine, but was worked in to Ballinamore specially on a Sunday, all necessary servicing being done by her own crew.

This arrangement terminated about mid-1919, when there was a suggestion that another engine be borrowed from the Castlederg & Victoria Bridge Tramway in Co. Tyrone. This plan, however, fell through.

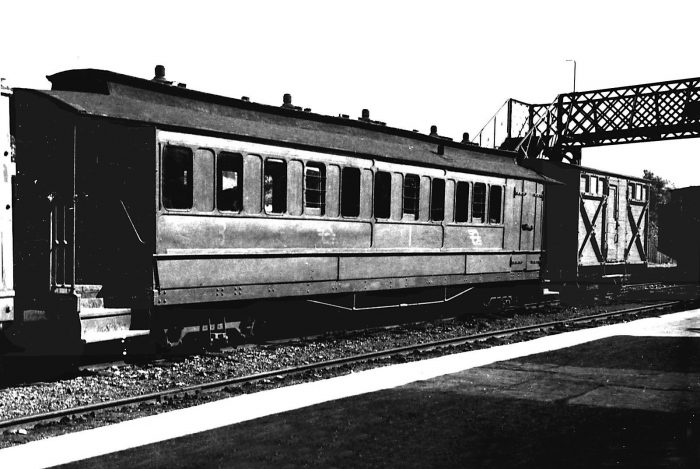

While the extension was being made, planning of its operation was also going on. One of the first topics discussed between the C & L and the Director-General of Transport was that of the extra rolling and locomotive stock the C & L would require to work the new line. Talks began in 1918 and continued for over a year. Also mentioned in 1918 was the question of improved methods of coal transhipment at the C & L terminal station. From the earliest days this had been done by manual labour and it was felt that some more modern method should now be introduced. In December 1918, the idea of an overhead bunker was rejected and it was decided that information be obtained about the transporter wagons in use on the Leek & Manifold Valley Light Railway in England. These were low narrow-gauge trucks wide enough to carry broad-gauge wagons on rails along the truck sides and were peculiar to that line.

Unfortunately the idea was found impracticable on the C & L, where there was insufficient loading-gauge clearance for MGW wagons, and it was decided, instead, to construct one-ton coal-boxes which could be fitted on a flat wagon frame and unloaded by crane. This was tried, with specially-built equipment. but was not continued with for reasons which apparently included loss of time and inadequate crane power. The matter of transhipment remained unsettled and when, in November 1919, the C & L presented a list of ‘wants’ for the new line (including wagon weighbridges, extra staff, engine facilities and forty wagons) it was stated that nothing could be done until the matter was resolved.

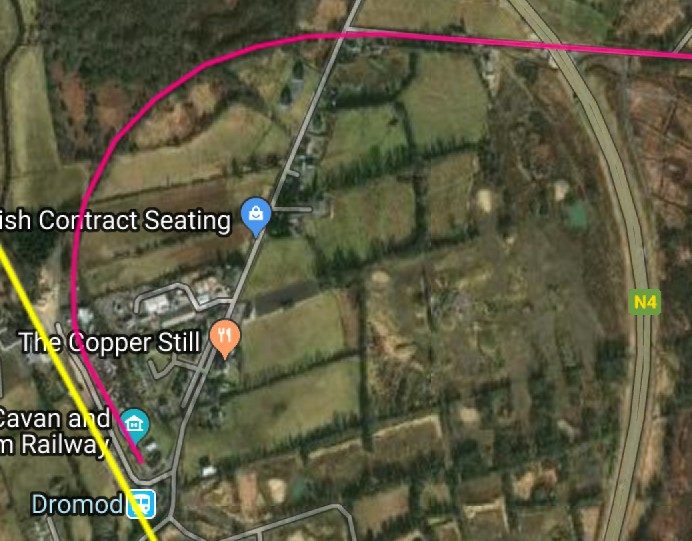

The extension was inspected on 17th February 1920, and in the same month a working agreement was discussed with officials of the newly-formed Ministry of Transport. It was pointed out to the C & L that no formal agreement existed for the working of the other colliery lines by the GSWR. They were, in fact, worked in conformity with the general terms of agreement between the Government and the Irish Railways — expenses being recoverable through a compensation account. The C & L agreed to work the Valley line under similar terms but again had to raise the subject of more engines and wagons, and ask for Government assistance. Once more the matter was shelved as the obstacle of transhipment had still not been settled, In fact, it never was, and although the GSR considered mechanical transfer at Dromod, the antiquated system of shovelling continued to the end.

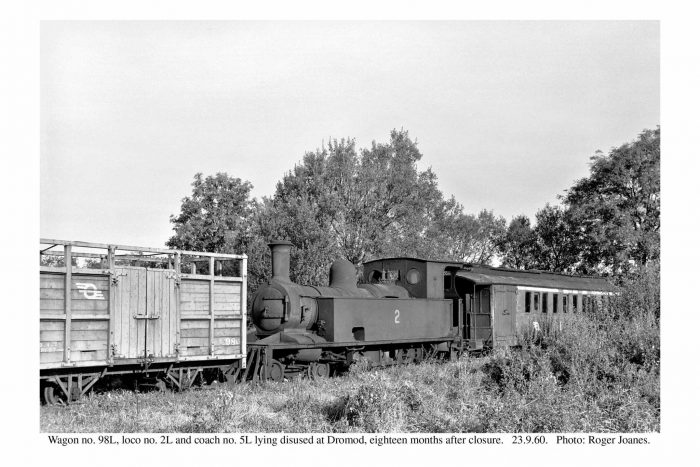

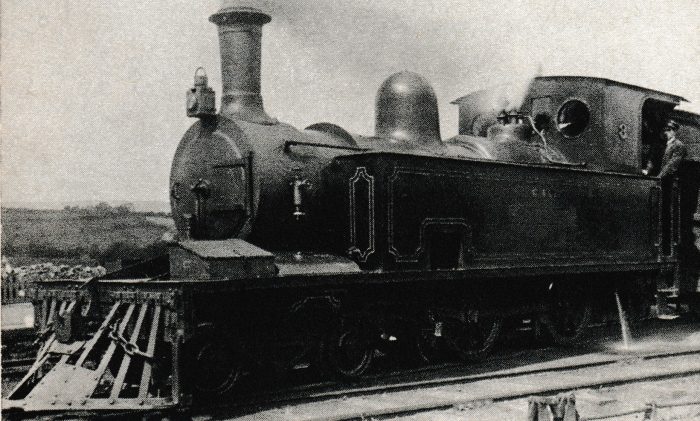

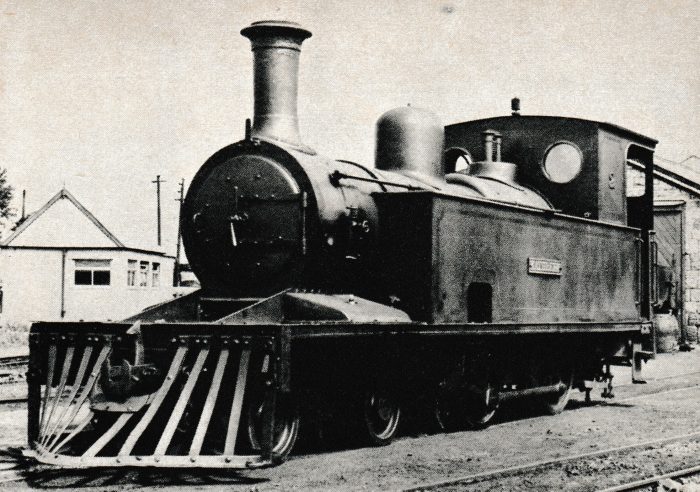

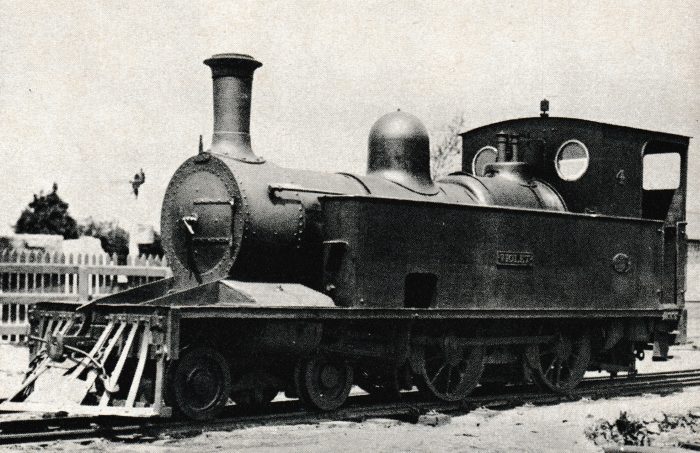

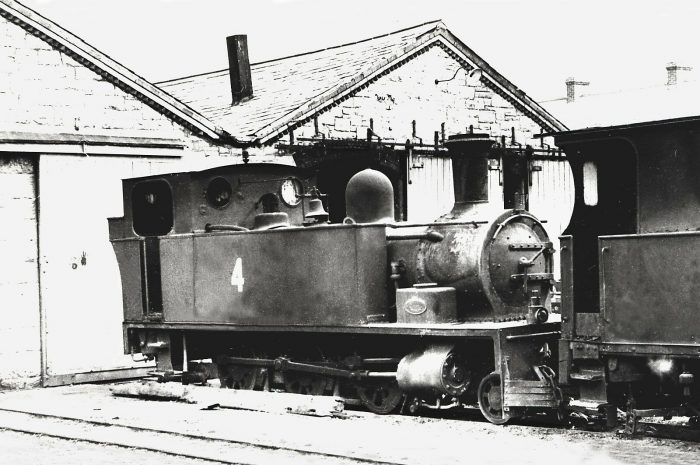

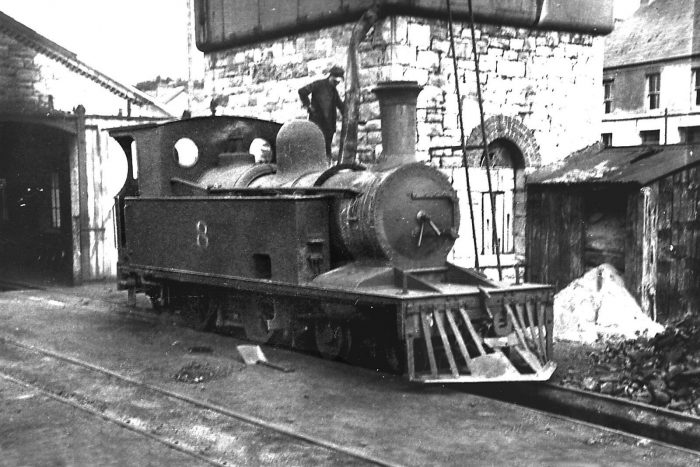

Some action was, however, taken about rolling stock. The Ministry of Transport borrowed twenty 4-ton open wagons from the Northern Counties Committee (NCC) and also obtained extra engines. In February 1920, Mr McAdoo asked for three engines on loan and said he thought that the County Donegal Railway engine Alice, which was then on the Cork, Blackrock & Passage Railway, could be immediately withdrawn for use on the Arigna Valley line. But it: was from the NCC that the engines eventually came. They were Nos 101A and 102A of the old Ballymena, Cushendall & Red Bay Railway and they were used in the final construction work on the extension before being temporarily transferred to the C & L, as from 1st June 1920. They were suitable for immediate use, unlike the wagons which required extra fittings on arrival at Ballinamore. The new Arigna Valley Railway opened on 2nd June 1920. [9]

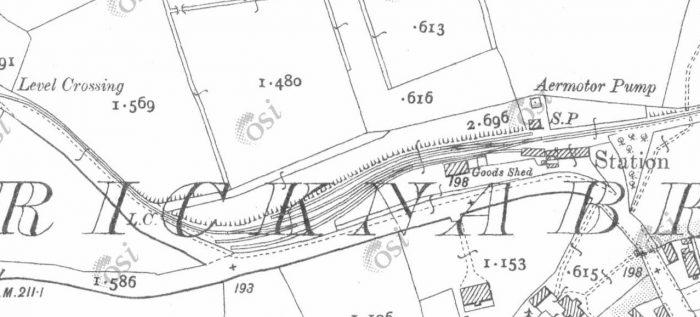

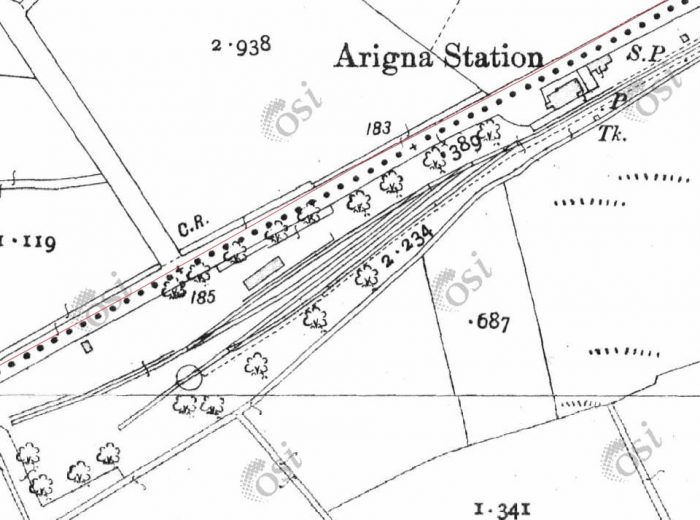

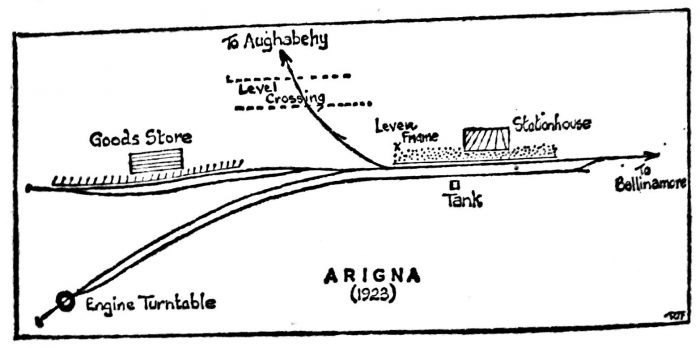

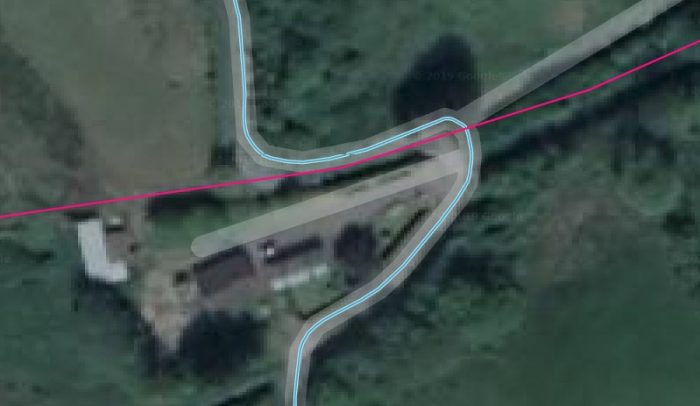

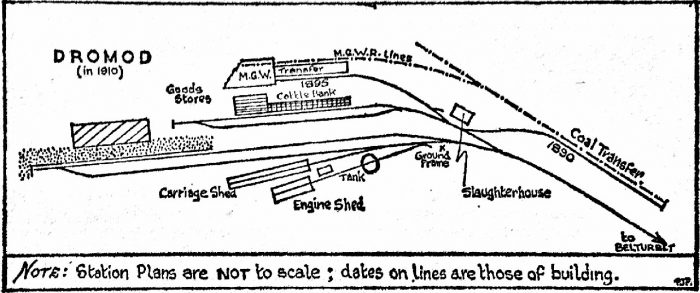

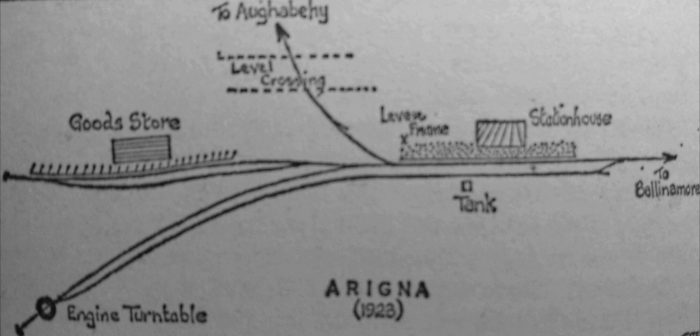

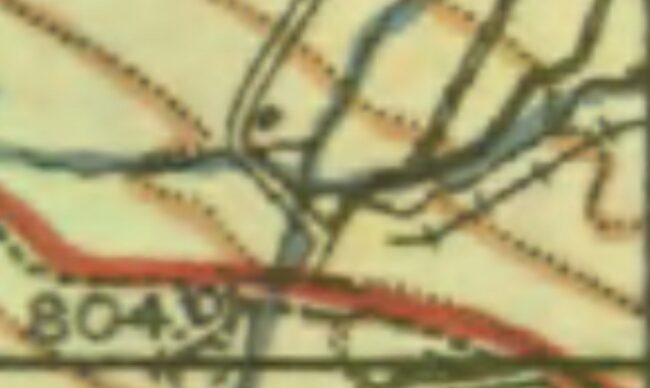

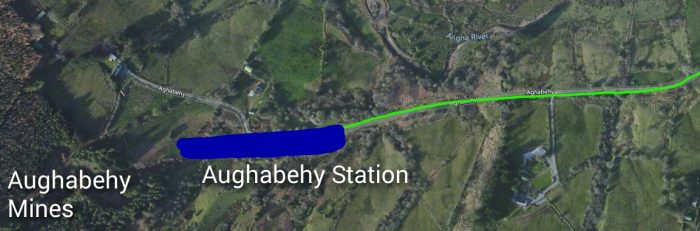

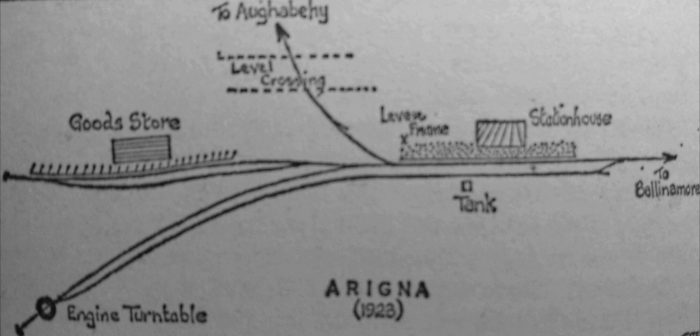

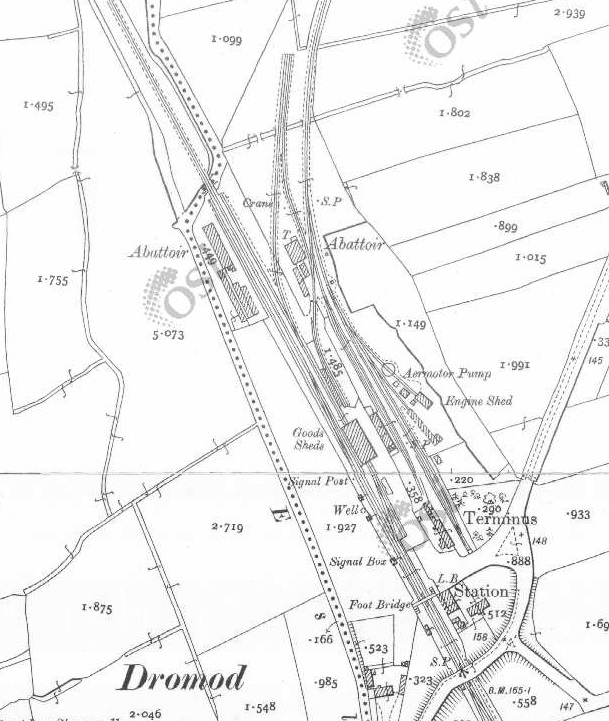

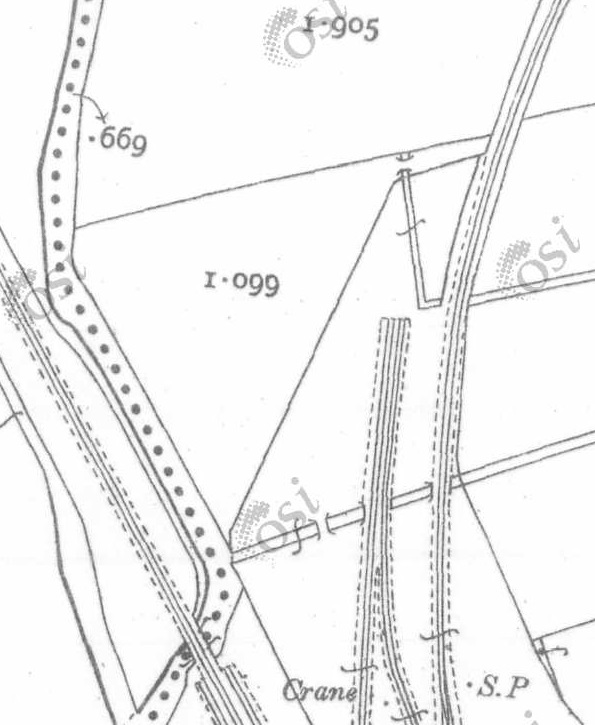

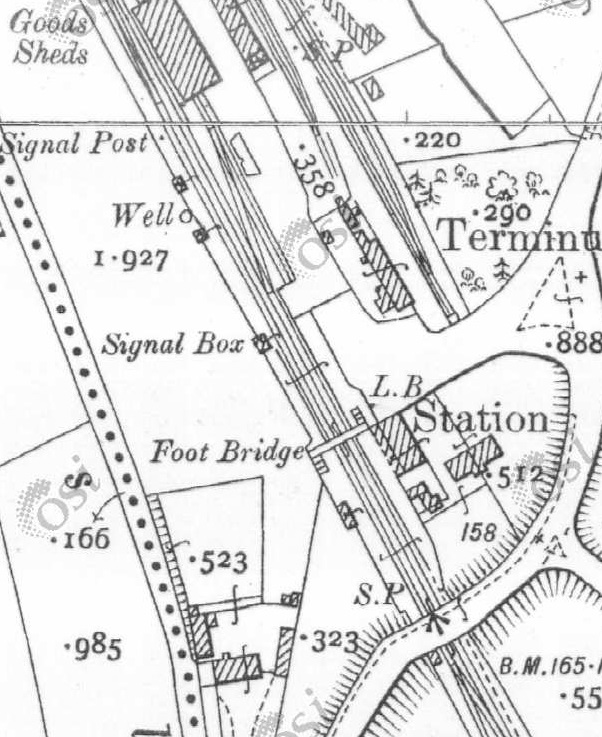

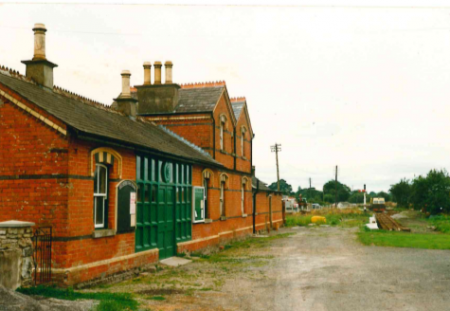

The Arigna Valley Extension had been built at a cost of £60,000. It was approximately 4.25 miles long and was laid with 56lb Bessemer steel rails fastened directly to the sleepers with fang-bolts. Arigna Station was the terminus of the C & L tramway. The extension line curved sharply across the road just beyond the station platform, (1923). [10]

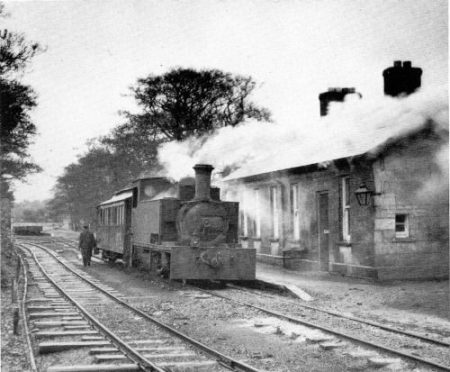

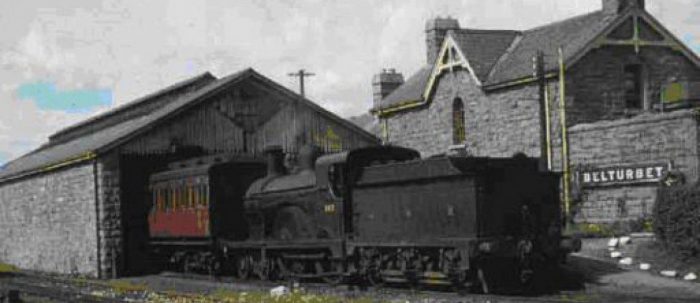

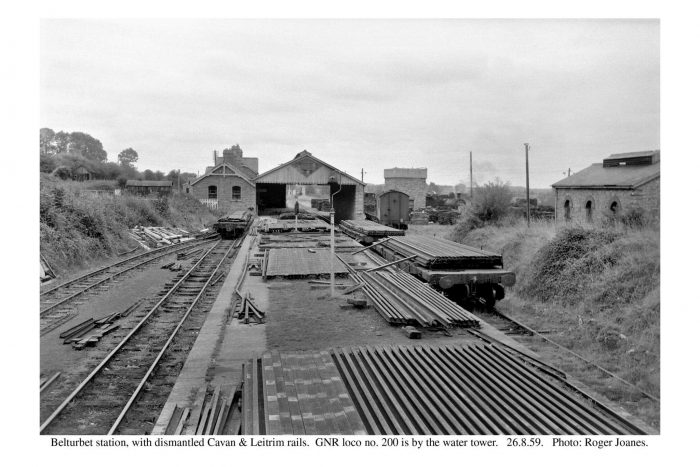

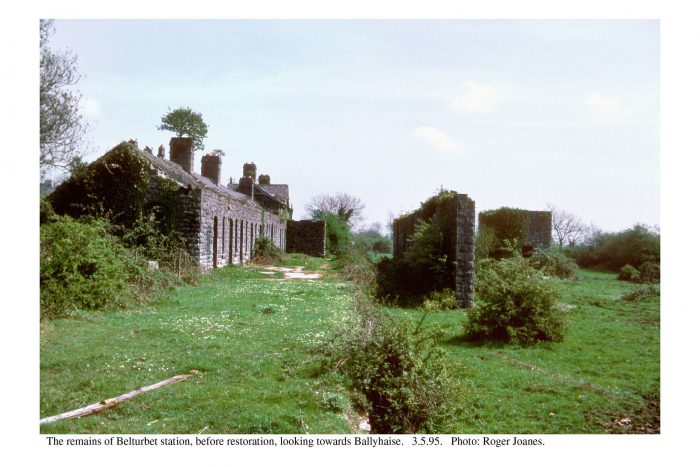

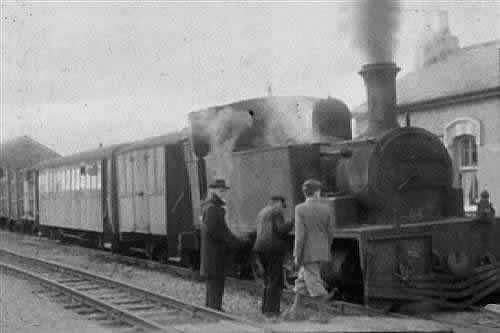

Arigna Station was the terminus of the C & L tramway. The extension line curved sharply across the road just beyond the station platform, (1923). [10] Arigna Station at the end of the tramway from Ballinamore. A short train is in the station under the control of 2-6-0T loco. No. 3T originally from the Tralee & Dingle Railway. The e/tension left the station behind the train beypmnd the station building. [14]

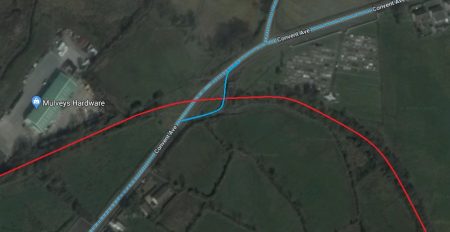

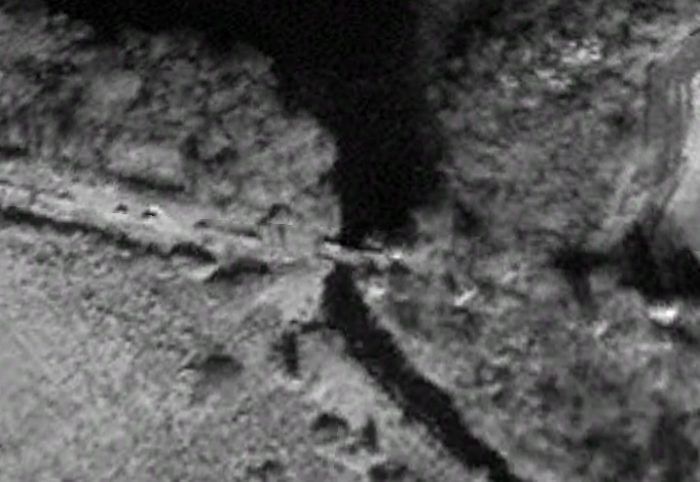

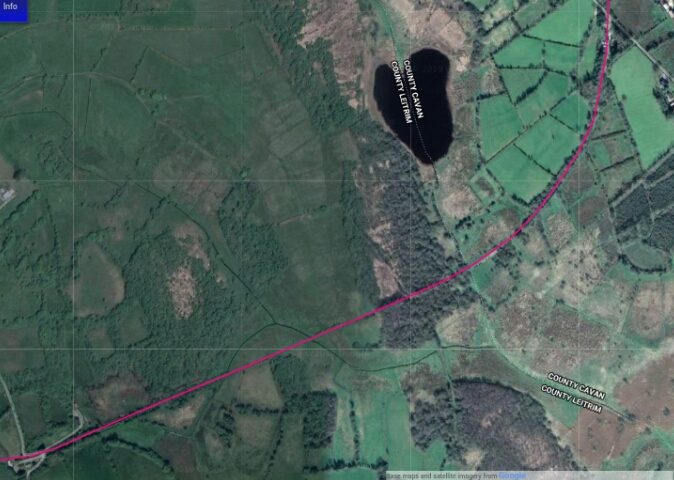

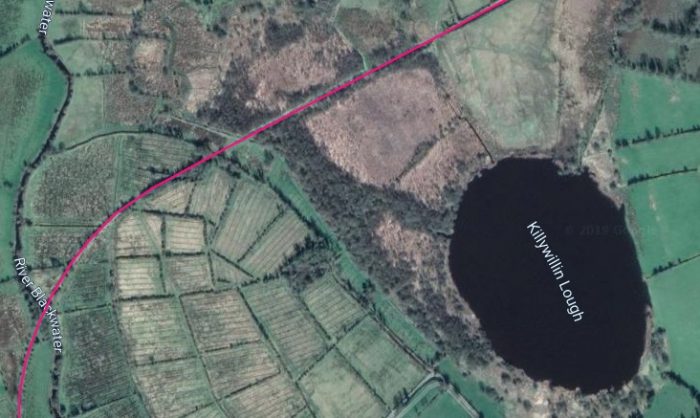

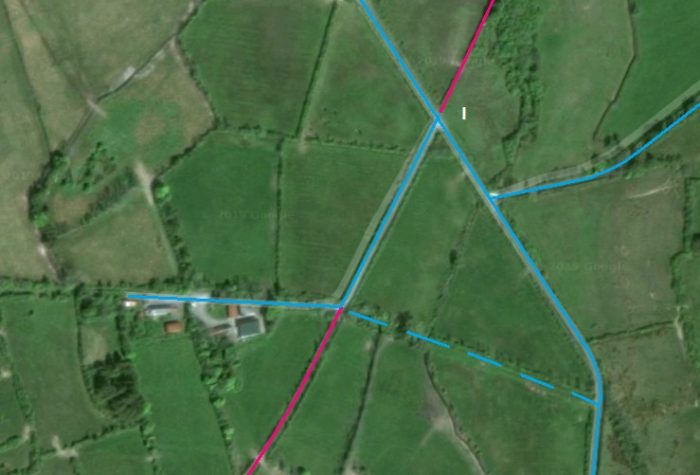

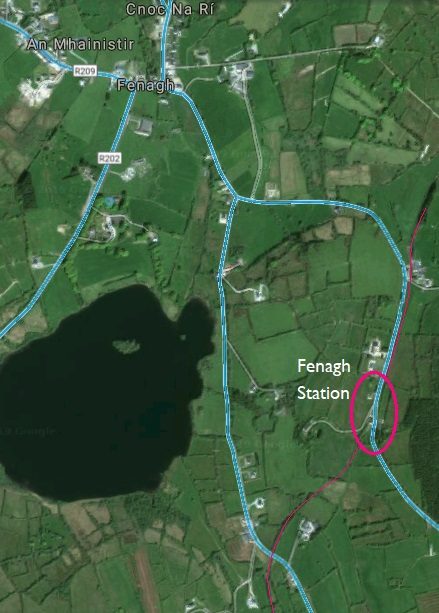

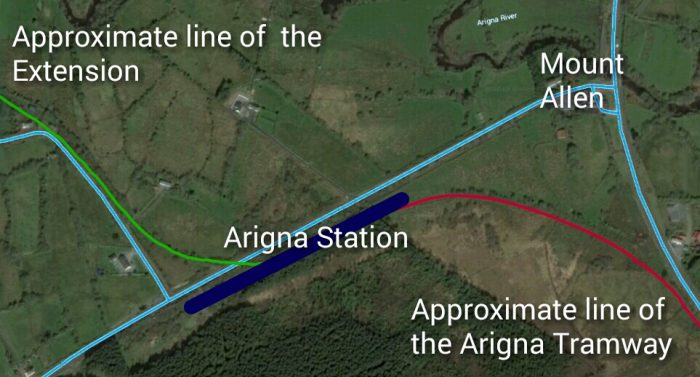

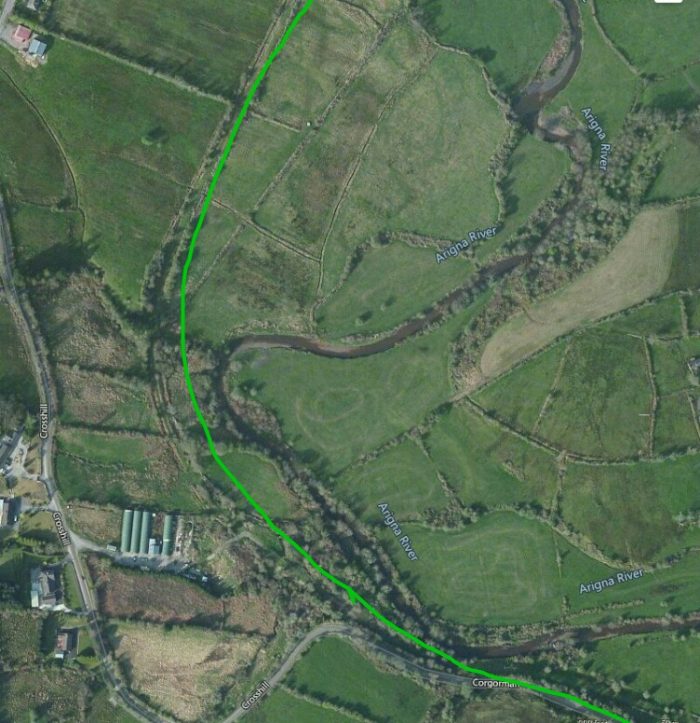

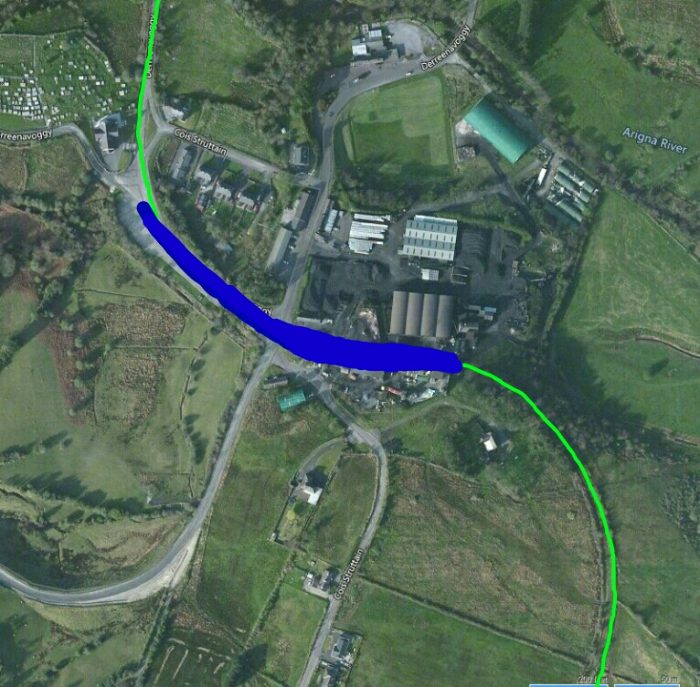

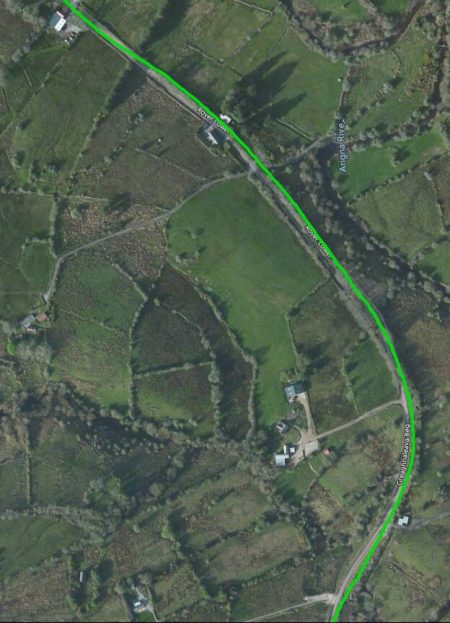

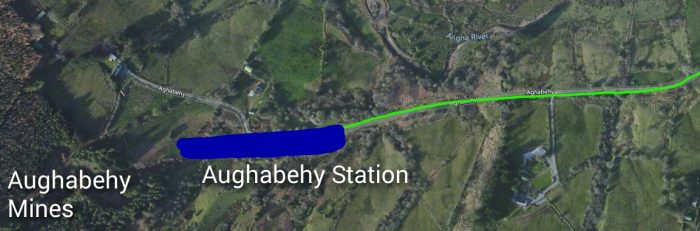

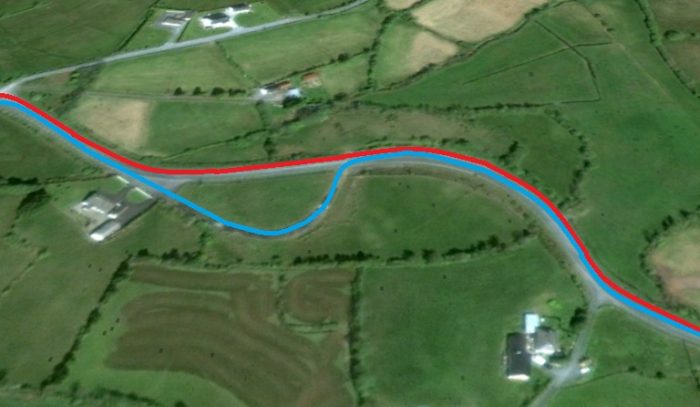

Arigna Station at the end of the tramway from Ballinamore. A short train is in the station under the control of 2-6-0T loco. No. 3T originally from the Tralee & Dingle Railway. The e/tension left the station behind the train beypmnd the station building. [14] This satellite image from Google Earth has been adapted to show both the approximate alignment of the tramway from Ballinamore to Arigna (in red) and the line of the extension (in green). The thick blue line shows the approximate location of the station. The light blue lines are modern roads which can be viewed on Google Street view. The old railway lines can still easily be picked out on Google Earth but are obscured somewhat by the red and green lines above. The station site is overgrown and little can be picked out. Immediately to the West of this image the resolution of the satellite images in Google Earth becomes quite poor and picking out the line of the railway is not possible. Bing provides a parallel mapping service and the satellite images of this area are better.

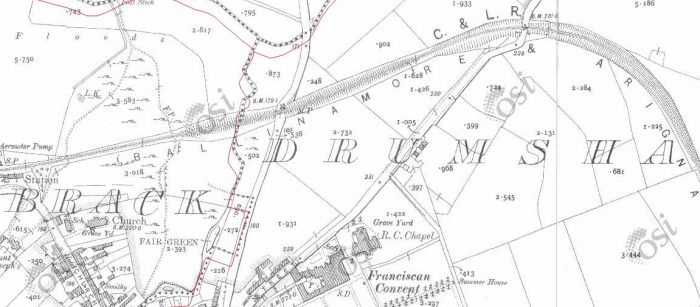

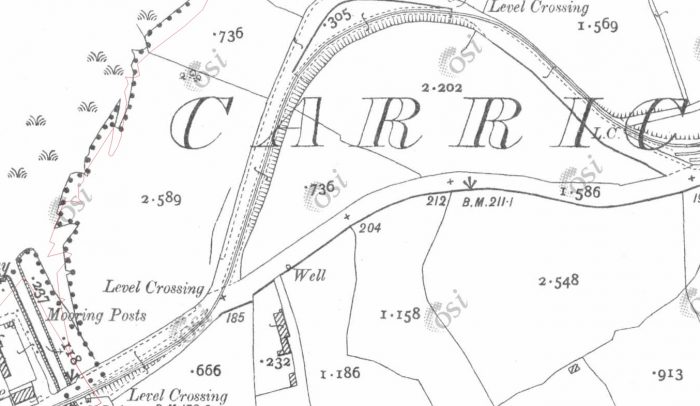

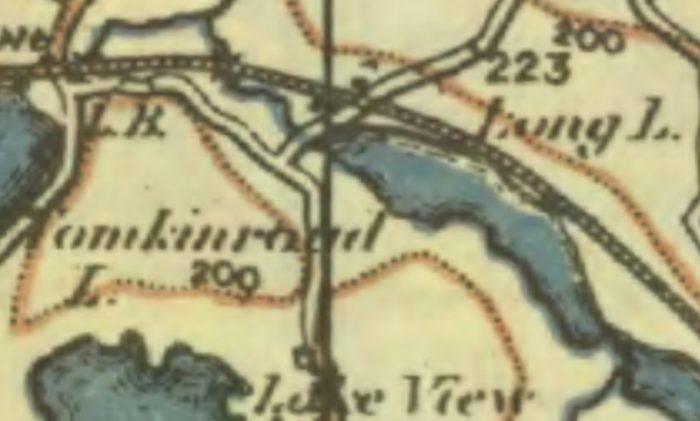

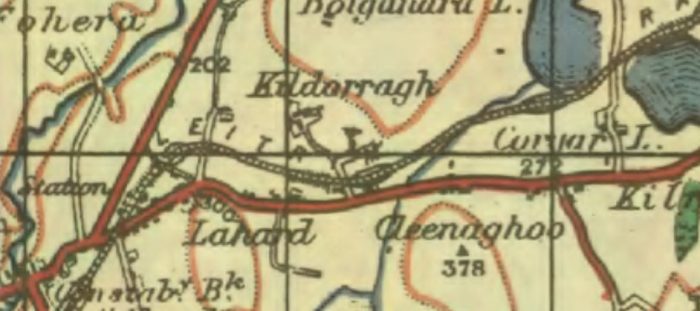

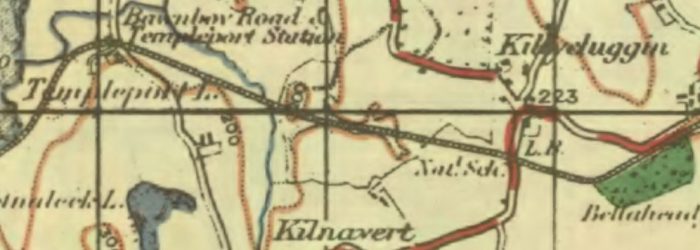

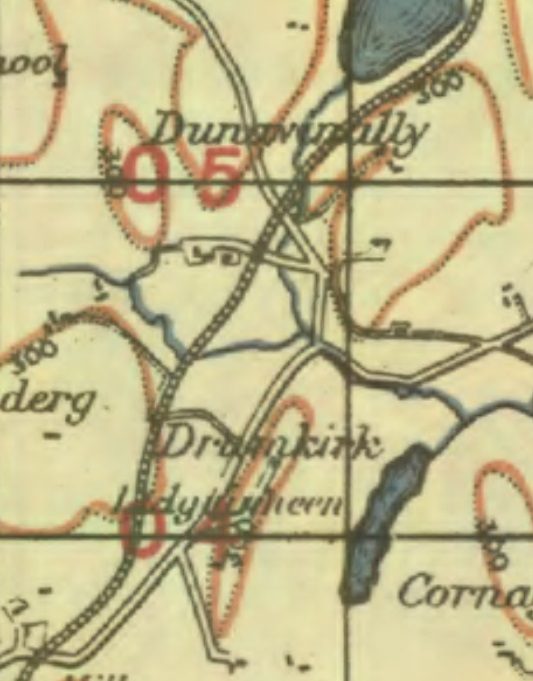

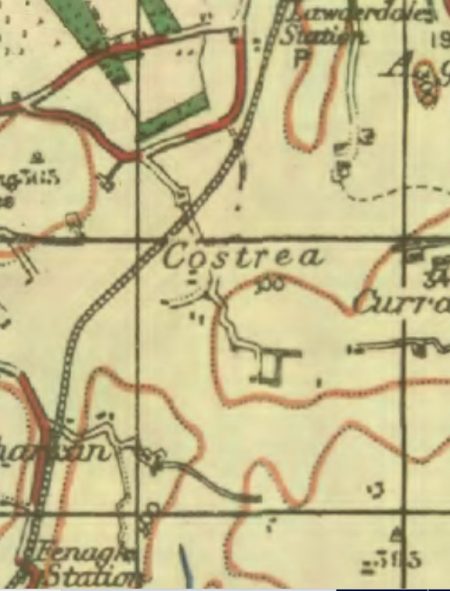

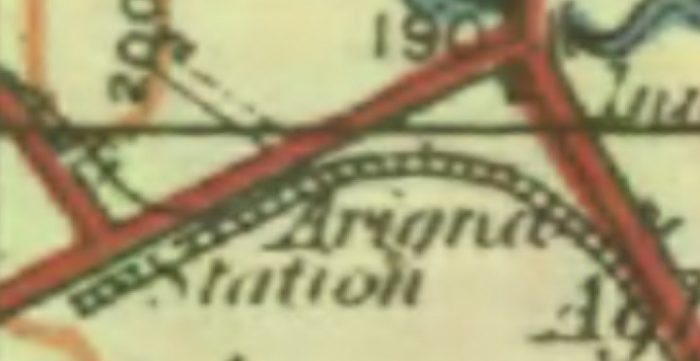

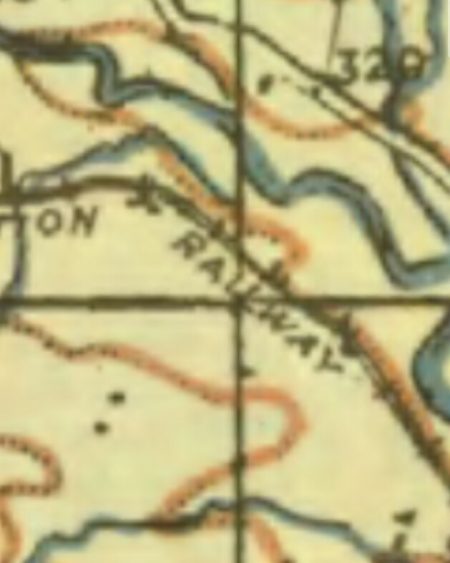

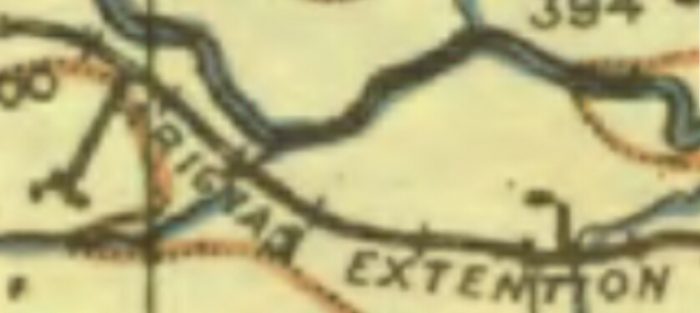

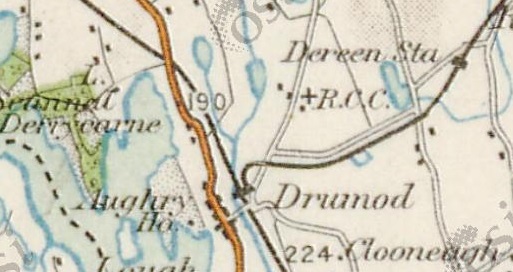

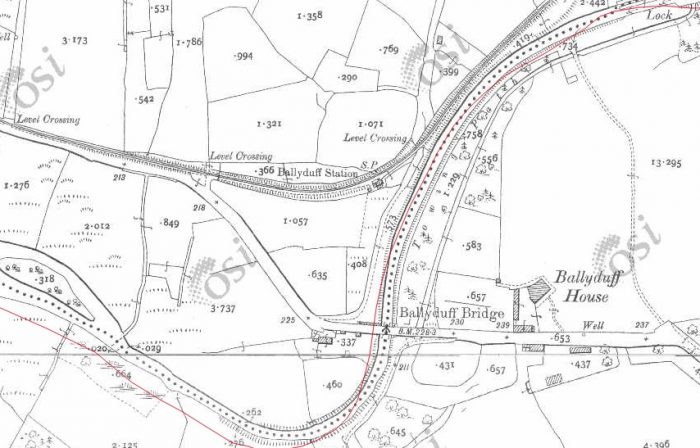

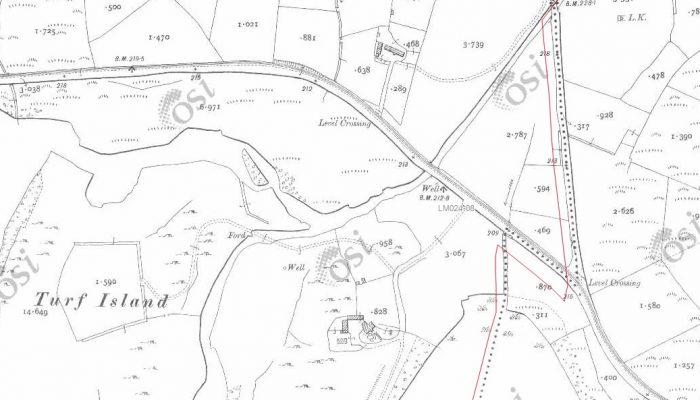

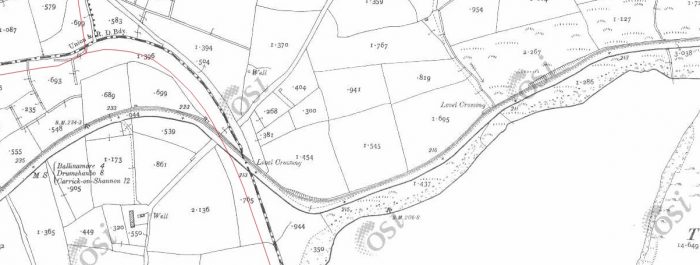

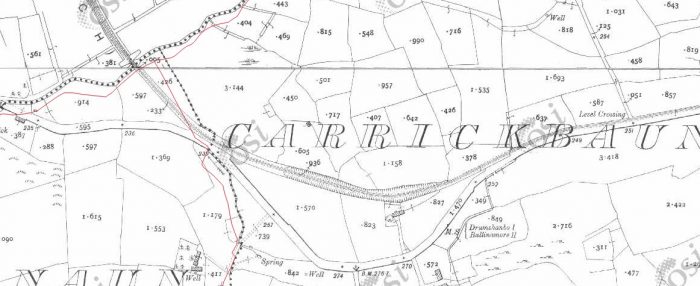

This satellite image from Google Earth has been adapted to show both the approximate alignment of the tramway from Ballinamore to Arigna (in red) and the line of the extension (in green). The thick blue line shows the approximate location of the station. The light blue lines are modern roads which can be viewed on Google Street view. The old railway lines can still easily be picked out on Google Earth but are obscured somewhat by the red and green lines above. The station site is overgrown and little can be picked out. Immediately to the West of this image the resolution of the satellite images in Google Earth becomes quite poor and picking out the line of the railway is not possible. Bing provides a parallel mapping service and the satellite images of this area are better. The 1940s OS Maps of ireland do a slightly better job of highlighting the route of the extension. This excerpt matches the satellite image above. The resolution is not the best. [16]

The 1940s OS Maps of ireland do a slightly better job of highlighting the route of the extension. This excerpt matches the satellite image above. The resolution is not the best. [16]

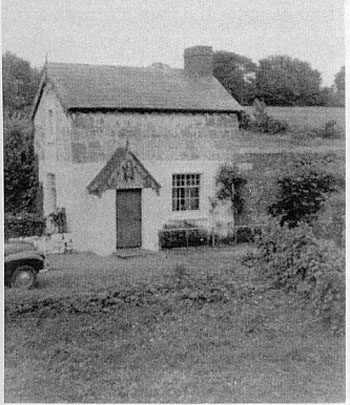

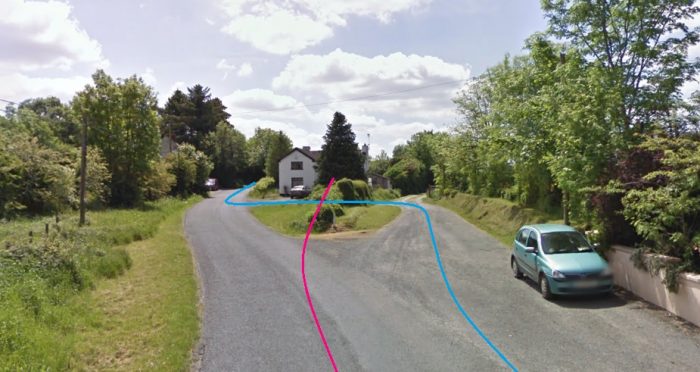

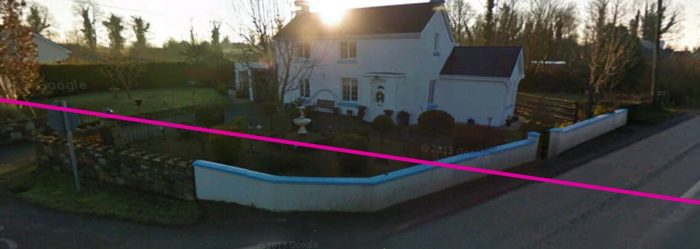

This picture is taken at the bend in the road at the top of the left-hand edge of the OS Map above. The railway ran through the location of the barn and behind the house in the picture.

This picture is taken at the bend in the road at the top of the left-hand edge of the OS Map above. The railway ran through the location of the barn and behind the house in the picture.

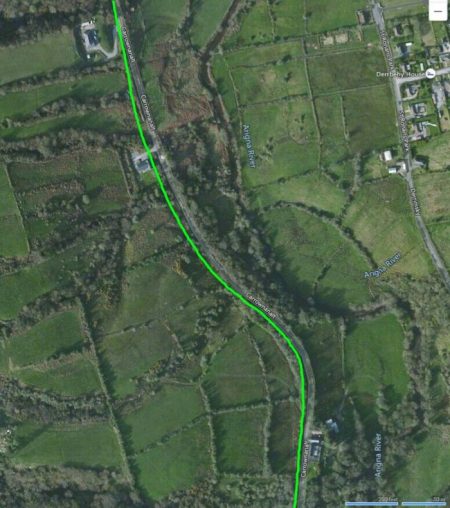

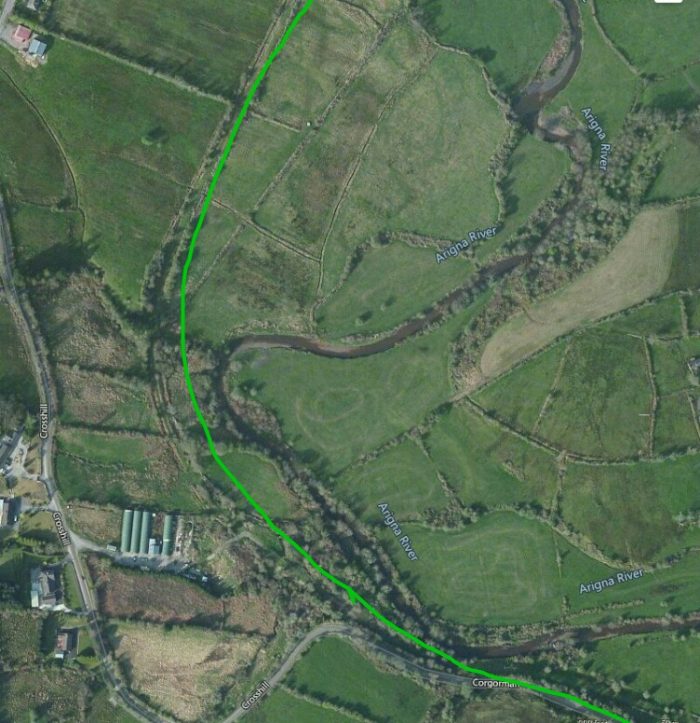

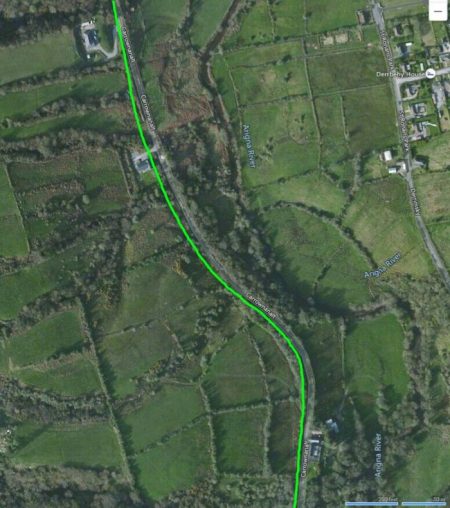

The green line shows the route of the railway.

The green line shows the route of the railway.

The old line ran between the Arigna River and the highway up to Derreennavoggy village. [17]

The old line ran between the Arigna River and the highway up to Derreennavoggy village. [17]

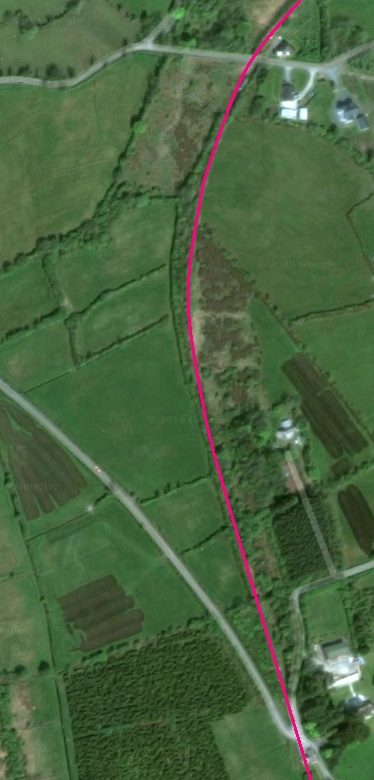

Patrick Flanagan says: “Leaving Arigna station just west of the platform, the extension line curved sharply across the Mount Allen—Keadue road and began to climb at 1:50. It then fell slightly and undulated to just beyond the half-mile point, where it entered a series of reverse curves, climbing again at 1:50. All this time the line was close to the Arigna River and only left it when an almost unbroken mile climbing at 1:50 began.” [11] The line curved to the North following the Arigna River. My approximate line has drifted a little to the East of the actual route which can be picked out just to the left of the green line.

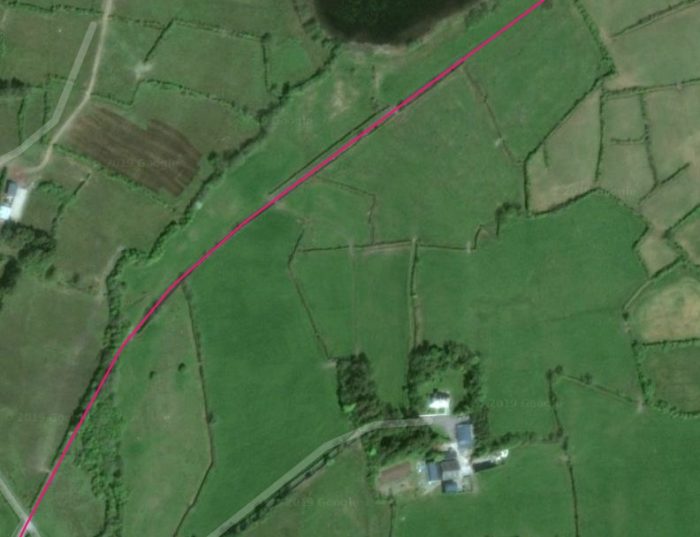

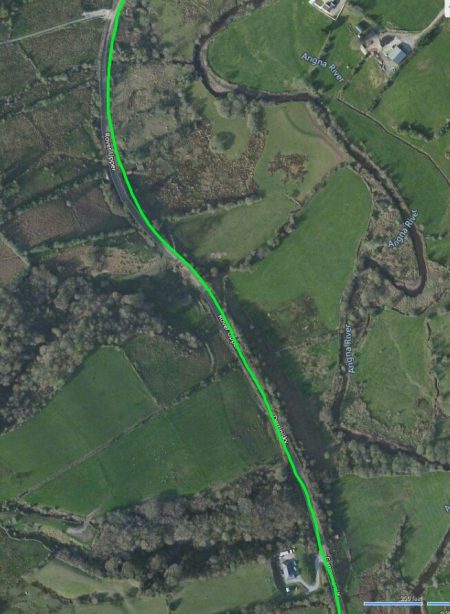

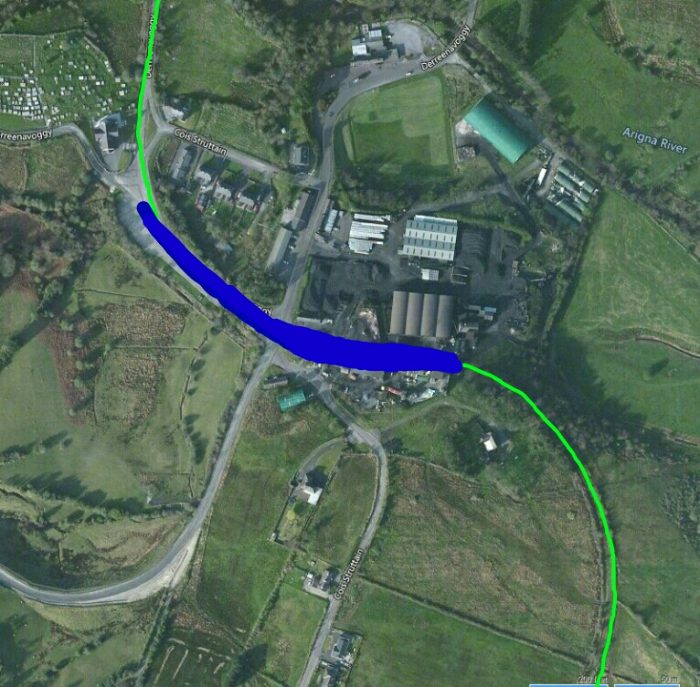

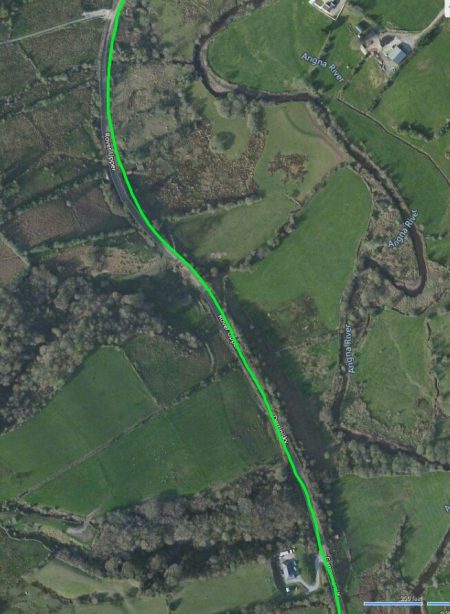

The line curved to the North following the Arigna River. My approximate line has drifted a little to the East of the actual route which can be picked out just to the left of the green line. The route of the line is once again shown in green. The thick blue line shows the approximate location of Dorreenavoggy Station/Loop and is what became the terminus of the Extension after the closure of the Arigna Mining Company. On many maps this area is referred to as Arigna Village.

The route of the line is once again shown in green. The thick blue line shows the approximate location of Dorreenavoggy Station/Loop and is what became the terminus of the Extension after the closure of the Arigna Mining Company. On many maps this area is referred to as Arigna Village.

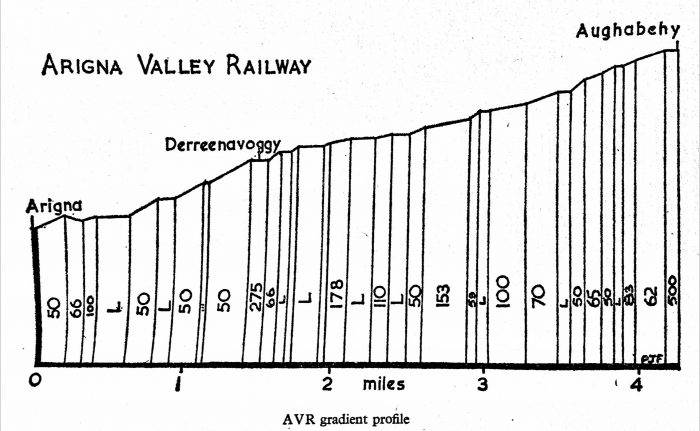

It is difficult to envisage how Flanagan’s description of the line relates to what can be seen in the OS Maps as there is no visual indication of the height being gained by the railway as it travels towards Derreenavoggy on those maps.

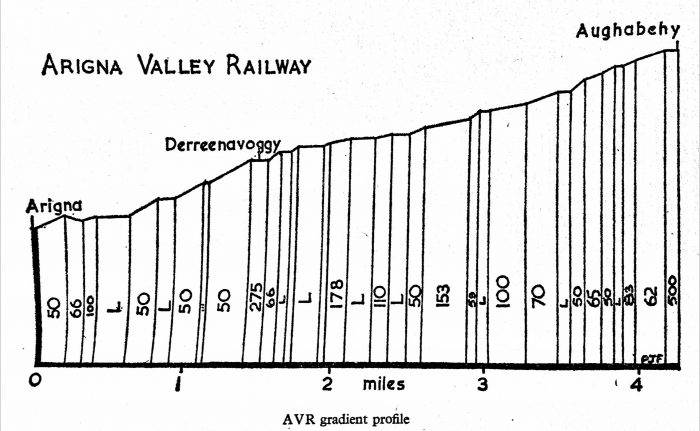

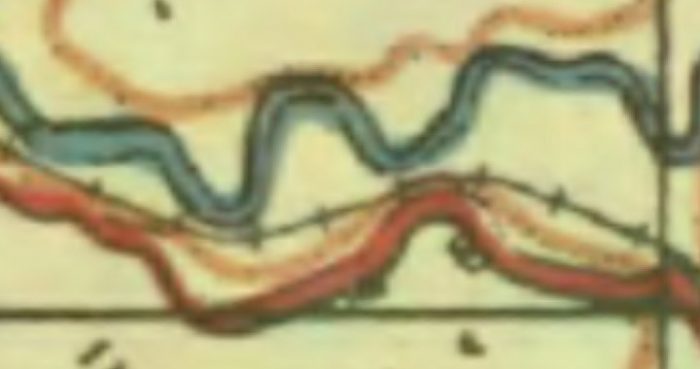

The gradient profile in the image below perhaps helps in understanding the steepness of the grade.

Arigna Valley Railway Gradient Profile. [11]

Arigna Valley Railway Gradient Profile. [11]  A loaded coal train heading down the line from Derreenavoggy towards Arigna Station. [18]

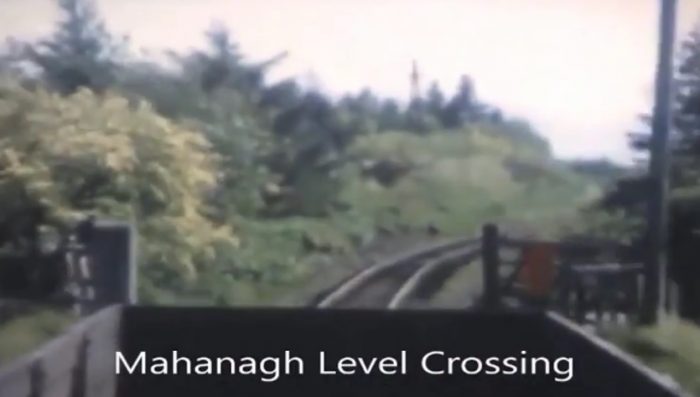

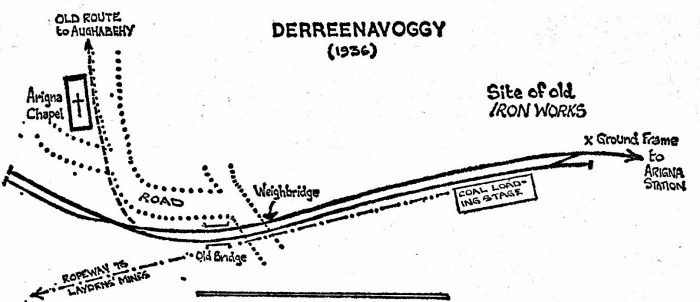

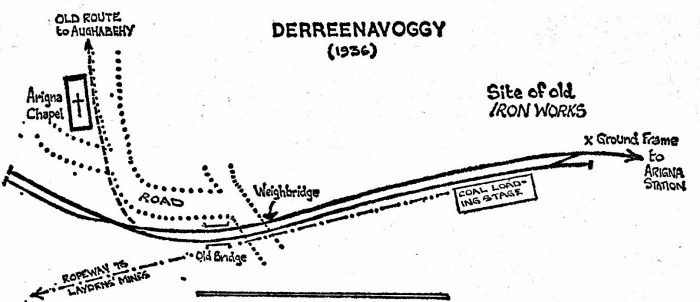

A loaded coal train heading down the line from Derreenavoggy towards Arigna Station. [18] The intermediate point of Derreenavoggy was reached on the same grade but on a nine-chain left-hand curve. At 1 mile 34 chains there was an ungated level crossing with the Arigna village-Keadue road and the facing points for two sidings were situated about thirty yards farther on. [11]

The intermediate point of Derreenavoggy was reached on the same grade but on a nine-chain left-hand curve. At 1 mile 34 chains there was an ungated level crossing with the Arigna village-Keadue road and the facing points for two sidings were situated about thirty yards farther on. [11]

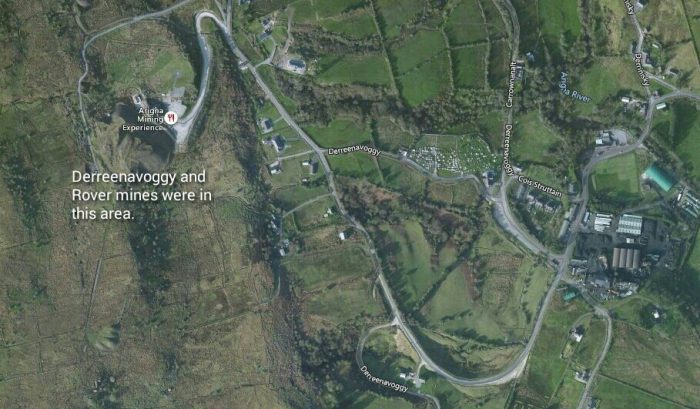

As can be seen above, the line then veered right on an eight-chain curve and crossed the road leading up to the mountain coal pits of Derreenavoggy and Rover. Again the crossing had no gates. The mines were located West of Derreenavoggy higher in the hills in the area now set aside as the Arigna Mining Experience. Passing Arigna Chapel, the line was now fully on the road-bed of the old iron-works tramway and remained there almost without a break the whole way to Aughabehy. [11]

Passing Arigna Chapel, the line was now fully on the road-bed of the old iron-works tramway and remained there almost without a break the whole way to Aughabehy. [11] The view back down the Extension line from Derreenavoggy towards Arigna Station. [15]

The view back down the Extension line from Derreenavoggy towards Arigna Station. [15] From the same position but looking West into Derreenavoggy. [15]

From the same position but looking West into Derreenavoggy. [15] Further to the West. Now that the line is closed the coal shutes are being used to load lorries. [15]

Further to the West. Now that the line is closed the coal shutes are being used to load lorries. [15] Still further West through the Derreenavoggy site. Two wagons have been abandoned on one of the roads through the ‘station’. [15]

Still further West through the Derreenavoggy site. Two wagons have been abandoned on one of the roads through the ‘station’. [15] The green arrow shows the approximate line of the two roads through DerreenavoggyArigna which are shown in the monochrome images above. The photographer has turned through 180° before taking the picture below. The buildings in the monochrome images may well be thosetof the Arigna Fuel Company in the picture above or they have disappeared and their place has been taken by a tarmac car park.

The green arrow shows the approximate line of the two roads through DerreenavoggyArigna which are shown in the monochrome images above. The photographer has turned through 180° before taking the picture below. The buildings in the monochrome images may well be thosetof the Arigna Fuel Company in the picture above or they have disappeared and their place has been taken by a tarmac car park.

And finally at this location: a monochrome image looking in a westerly direction. The sidings West of the crossing can be picked out. The abandoned longer Extension climbed the hill behind the excavator alongside the road and passed this side of the church. [15] In the image below, the line of the railway through the village has been replaced by tarmac. The bridge shown on the sketch plan of the site seems to have disappeared. The church seems to have received a lick of paint.

And finally at this location: a monochrome image looking in a westerly direction. The sidings West of the crossing can be picked out. The abandoned longer Extension climbed the hill behind the excavator alongside the road and passed this side of the church. [15] In the image below, the line of the railway through the village has been replaced by tarmac. The bridge shown on the sketch plan of the site seems to have disappeared. The church seems to have received a lick of paint.

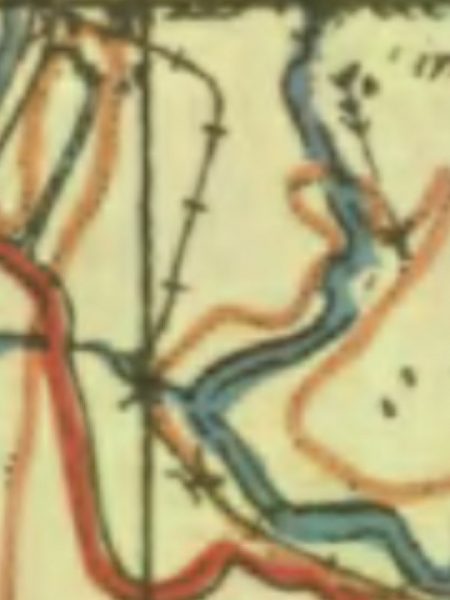

Although still parallel to the tortuous course of the river, the earlier abandoned extension line beyond Derreenavoggy was jigger up on the hillside and, after crossing the narrow roadway at 1.75 miles, remained on the right-hand side. Having turned northwards it can be picked out on the adjacent OS Map at around the 300ft contour. However, it is impossible to discern the point at which the line switched from the West side of the road to the East.

Although still parallel to the tortuous course of the river, the earlier abandoned extension line beyond Derreenavoggy was jigger up on the hillside and, after crossing the narrow roadway at 1.75 miles, remained on the right-hand side. Having turned northwards it can be picked out on the adjacent OS Map at around the 300ft contour. However, it is impossible to discern the point at which the line switched from the West side of the road to the East.

The approximate alignment of the railway shown by green line on the adjacent Bing satellite image does not define a point at which this occurred.

The approximate alignment of the railway shown by green line on the adjacent Bing satellite image does not define a point at which this occurred.

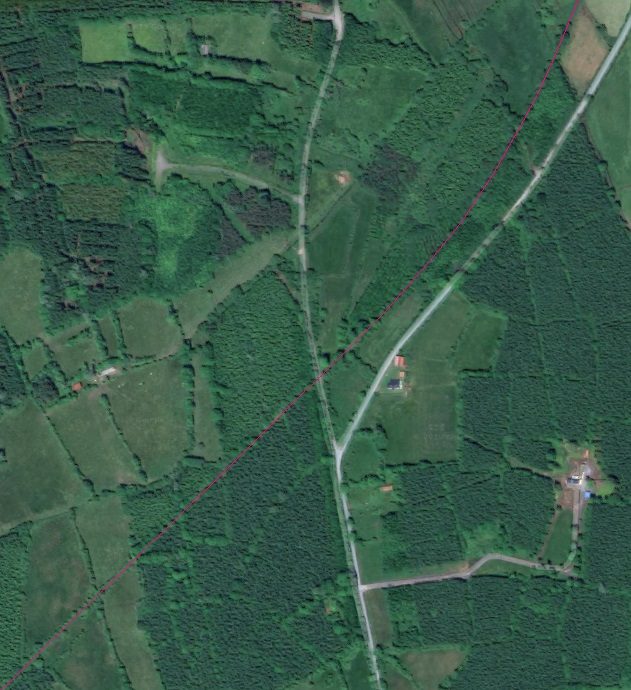

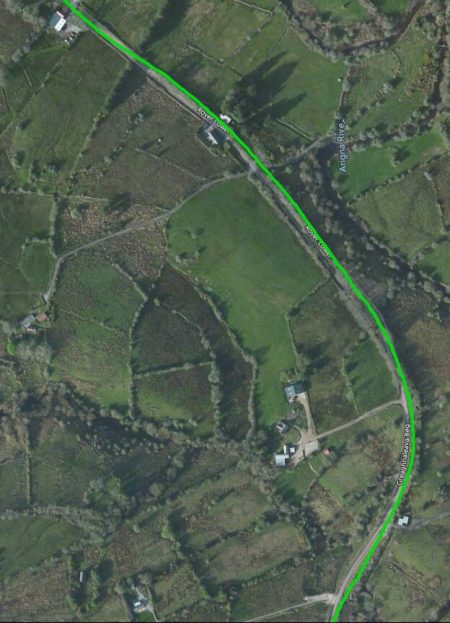

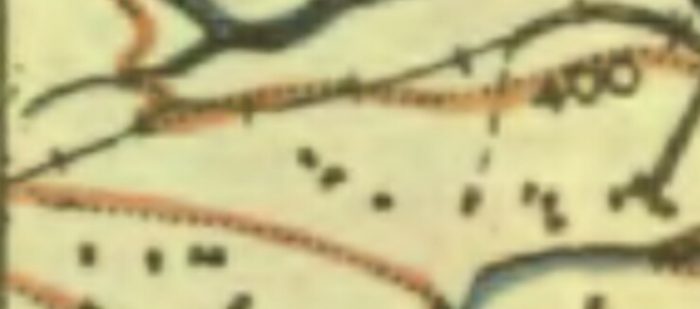

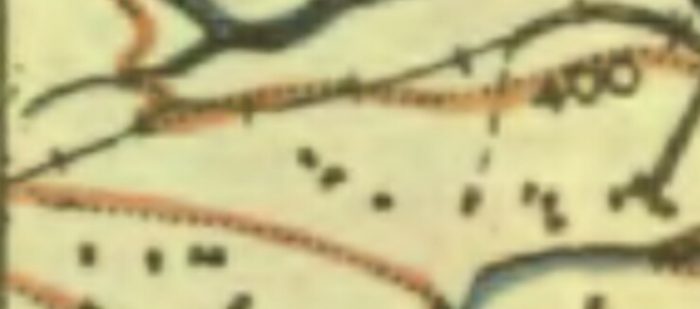

In general, this section of the line was easier than the first, and although there were gradients of 1:50, none was longer than a quarter of a mile. However, for almost the whole distance the line wound right and left, there being very few straights. The railway turned to the West along with the Arigna River Valley. The OS Map chooses at this point to recognise the status of the line as an Extension Railway. The satellite images provided by Bing continue to be used to look at the route of the line in the 21st century. The Google satellite images still being poor in the first part of this length in 2019.

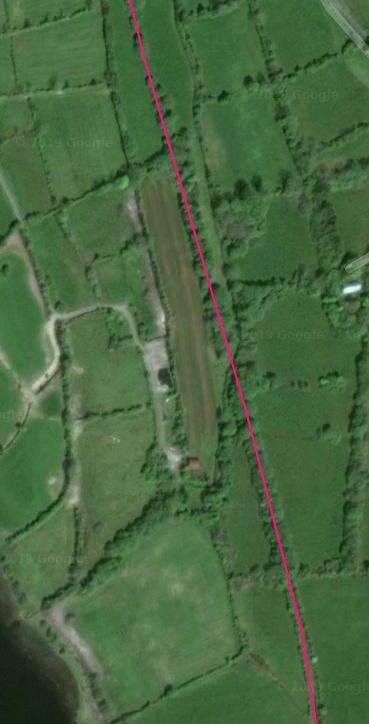

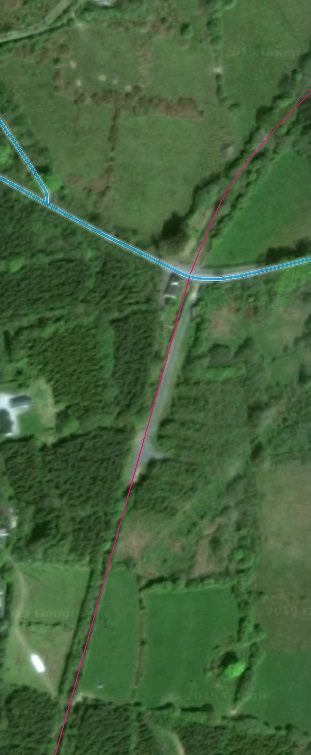

The earlier tramway and the road ran immediately next to each other and the more modern 3ft-gauge Extension line did the same. As we have noted above the reuse of the earthworks from the earlier tramway saved considerable construction costs when the Extension came to be built. This was particularly true in the case of one specific feature on the route. As the line was approaching its terminus at 3.5 miles from Arigna Station there was a long high embankment on right-hand right-hand curve.

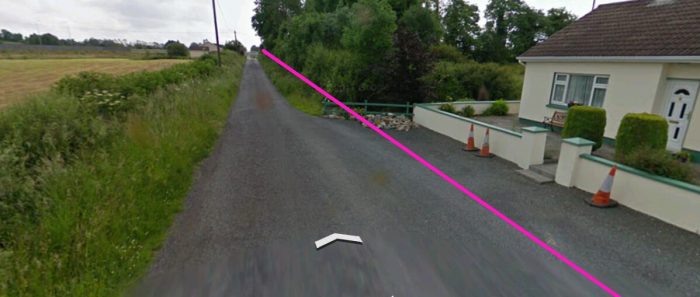

Much of the time it is impossible to determine the line of the Extension as vegetation has encroached close to the single-lane minor road. Just occasionally the formation of the old tramway and so that of the Extension line is visible.

One location where this is true is on the long sweeping curve through which the line changes from a predominantly northerly trajectory to one which heads West. This is visible on the Google Streetview image be!ow the adjacent aerial view.

It seems to be visible as a relatively wide platform alongside and to the right of the narrow lane in the picture.

The road and railway swept round to the West following the valley side. The line was by now approaching the 400ft contour line on the 1940s OS Map.

The road and railway swept round to the West following the valley side. The line was by now approaching the 400ft contour line on the 1940s OS Map.

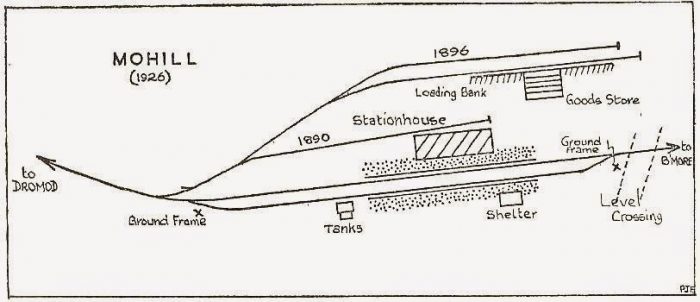

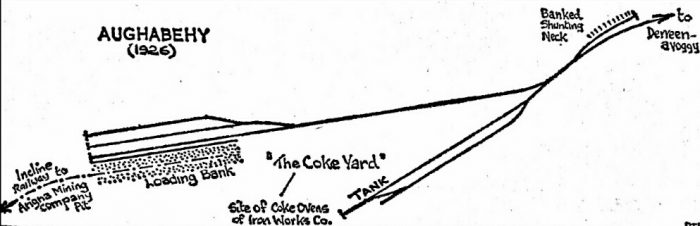

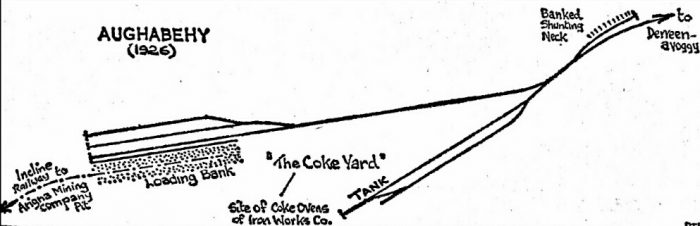

A little farther on, the terminus was entered to the left and at a gradient of 1:82. The site apparently in 1972, still bore the name ‘the Coke Yard’, being the place where the old Arigna company had a row of nine coke-ovens, all of which have long since gone. At 4 miles 12 chains a set of facing points gave access to a loop which veered off to the left. It was for engine run-round and at the far end there was a water-tank fed from a stream up the hillside. Meanwhile, the ‘main line’ had opened into a fan of three sidings, the left-hand one of which ran alongside a low stone-faced loading bank. In addition, there was a trailing shunting neck on an embankment which permitted gravity feeding of wagons into the sidings. [11]

A little farther on, the terminus was entered to the left and at a gradient of 1:82. The site apparently in 1972, still bore the name ‘the Coke Yard’, being the place where the old Arigna company had a row of nine coke-ovens, all of which have long since gone. At 4 miles 12 chains a set of facing points gave access to a loop which veered off to the left. It was for engine run-round and at the far end there was a water-tank fed from a stream up the hillside. Meanwhile, the ‘main line’ had opened into a fan of three sidings, the left-hand one of which ran alongside a low stone-faced loading bank. In addition, there was a trailing shunting neck on an embankment which permitted gravity feeding of wagons into the sidings. [11]

Aughabehy Station in 1926. [11]

Aughabehy Station in 1926. [11]

Directly behind the siding stoppers was the long slope of the hillside leading to the pit of the Arigna Mining Company. As the extension was under construction, the Mining Company was engaged in laying a 24-in gauge three-rail incline railway down to the loading bank. This was approximately 600 yds long and opened briefly into a passing loop at the halfway point; it was cable-operated from a winding-house at the mine. The Mining Company’s line ran on to the loading bank and the hutches were emptied on to a screen for delivery of the coal to the waiting C & L wagons. No weighbridge was provided here, although a wagon one was installed in Derreenavoggy in 1922, after two years of correspondence which ended when Laydens (the Arigna Mining Company’s rivals and, later at any rate, the main coal producers) agreed to forward all their coal from there. [11]

Despite the fact that two extra engines had been specially provided for the extension, its working was integrated with that of the tramway and it was standard practice for the tramway engine to make a trip up to clear the laden wagons. When the tramway was temporarily closed for passengers by the military in 1920, the extension traffic continued, special arrangements being made. An engine used to run out to Aughabehy in the evening to clear the wagons loaded earlier in the day. This arrangement suited the Mining Company so well that it asked the C & L to continue the working, but when the tramway services were restored the old practice was reverted to. The two NCC engines, in fact, were incorporated in the general C & L stock and were used all over the system on trains, regular and special. [11]

Patrick Flanagan says: “Traffic on the extension never came up to expectations and there were never more than five wagons a day from Aughabehy. The financial returns reflected this, showing a loss of £382 up to December 1921. This was repaid to the C & L by the Board of Works, which also had to make good losses on the Wolfhill and Castlecomer lines. The unsatisfactory figures no doubt gave pleasure to a few county councillors, though it can hardly be said that their objections to the line were based on even the flimsiest of economic grounds. In fact, a major contributory factor was the state of the Arigna Mining Company at the time. As far as it was concerned, the extension had been too late in coming — the rot had already set in. The Aughabehy coal-seams were proving erratic and another pit on the opposite side of the valley at Seltannaveeny now produced most of the coal, and this was carted to Arigna station.” [11]

It seems that once the Aughabehy pit had begun to give trouble “things were never again the same. Labour also proved a big problem. While hard facts are difficult to come by, it would seem that very little was done after the early 1920s; the company’s coal-sheds at the C & L stations were removed as early as 1921 — a bad sign. However, Aughabehy was worked in 1926-7, even if it was only for a short time.” [11]

As the months passed after the opening of the line, more and more coal was sent by Laydens from Derreenavoggy. So much so, that with the death of the Arigna Mining Company and its takeover by Laydens, even though the old mine was worked until 1930, the line was shortened to serve Derreenavoggy and not Aughabehy. [13]

The shortage of engines and wagons proved a great drawback to smooth operation, and though the C & L did its best with the borrowed stock, it was not enough. The inadequate arrangements were hotly criticised both in the evidence before the 1922 Railway Commission and in a 1921 Memoir on the Coalfields of Ireland. When the end of government control became imminent the C & L informed the Ministry of Transport that it could only work the line if it was indemnified against any losses. This indemnity was provided and from August 1921 the Board of Works became responsible for the line. The Amalgamation of 1925 did not affect the line and it was not until 1st January 1929, that the Board of Works relinquished responsibility for it. The Great Southern Railways (GSR) then leased it at shilling a year and from then on it was simply part of the C & L. [11]

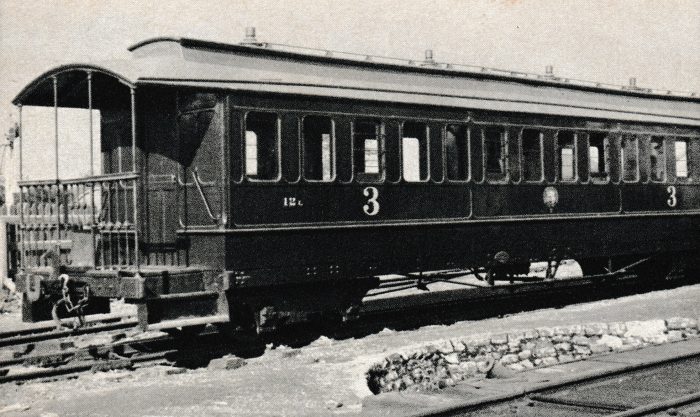

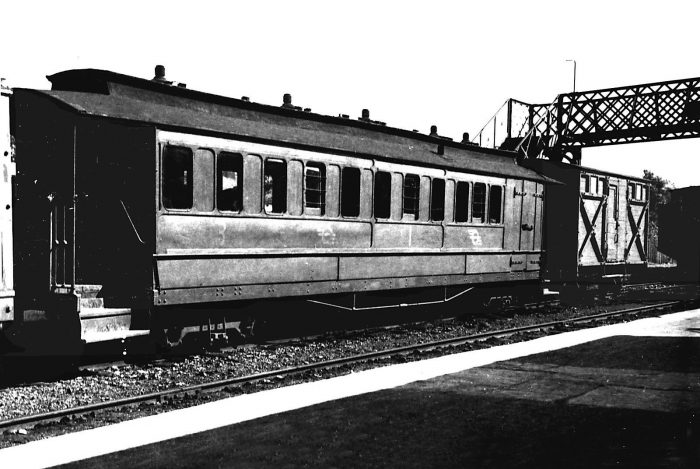

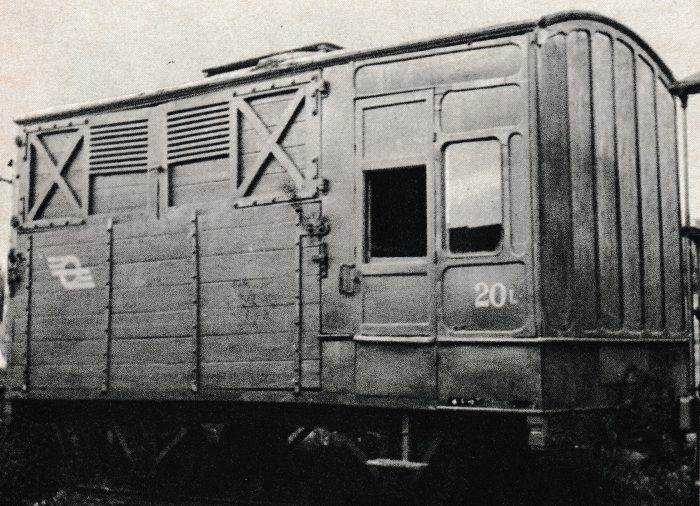

The remaining segment of the extension really came into its own from about 1934 onwards and was, indeed, responsible for the continued existence of the C & L until 1959. In 1934, Laydens reorganized their mines about Derreenavoggy and installed a ropeway network which connected three mines (Rock Hill, Rover and Derreenavoggy) with the extension sidings. Traffic revived considerably and the GSR dispatched four engines to Bailinamore to cope with it. In addition, a total of forty wagons and two brake vans, mostly from the defunct Cork, Blackrock & Passage line, were sent to the C & L. They were a very welcome. The engines released the remaining C & L locos from other duties to handle the coal traffic. [13]

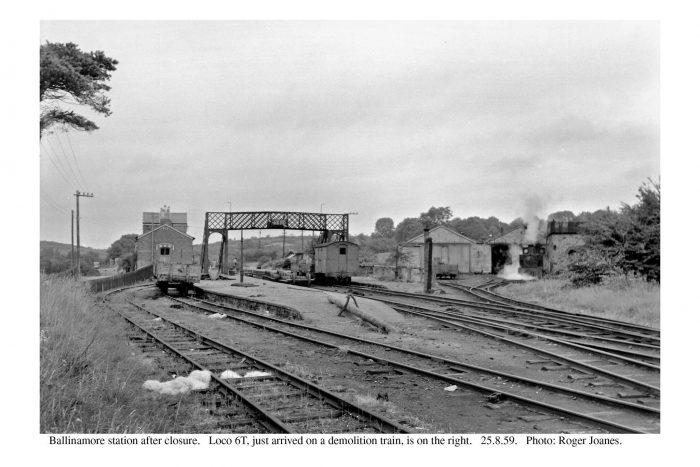

Despite the fact that traffic was increasing, the GSR included, in its submission to the 1939 Transport Tribunal, a proposal to close the entire section. However, the outbreak of war considerably altered things and again Arigna coal became of vital importance to the whole country. [13] The truncated Arigna Valley line remained open until the closure of the C & L in 1959.

References

- Patrick J. Flanagan; The Cavan & Leitrim Railway; Pan Books, London, 1972, p57.

- Ibid., p57-61.

- Ibid., p60.

- Ibid., p61-64.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arigna, accessed on 23rd April 2019.

- Patrick J. Flanagan; op. cit., p65-66.

- Ibid., p198-199.

- Ibid., p69-70.

- Ibid., p72-75.

- Ibid., p146.

- Ibid., p75-80.

- https://www.anglocelt.ie/news/roundup/articles/2012/03/07/4009414-how-the-cavan-leitrim-railway-ran-out-of-steam, accessed on 24th April 2019.

- Patrick J. Flanagan; op. cit., p102-103.

- https://chasewaterstuff.wordpress.com/2014/06/12/some-early-lines-ireland-arigna-cavan-and-leitrim-railway, accessed on 24th April 2019.

- http://catalogue.nli.ie/Search/Results?lookfor=Derreenavoggy&type=AllFields&submit=FIND, accessed on 25th April 2019.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.161775414176985&lat=54.0652&lon=-8.0873&layers=14&b=1, accessed on 24th April 2019.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.161775414176985&lat=54.0671&lon=-8.0998&layers=14&b=1, accessed on 24th April 2019.

- https://leitrimmedia.com/the-narrow-gauge, accessed on 26th April 2019.

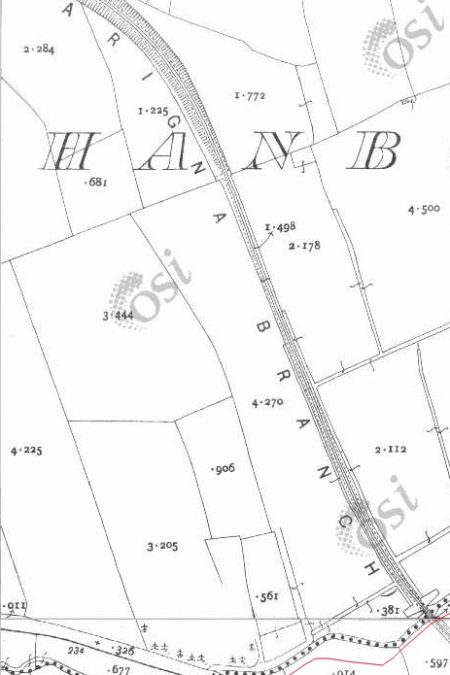

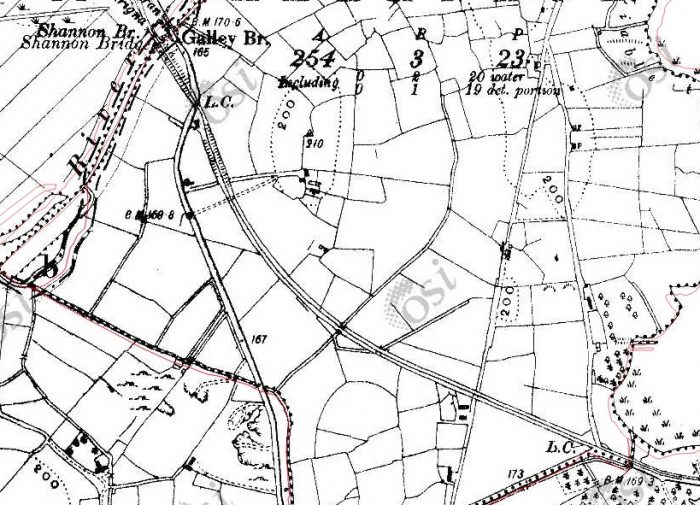

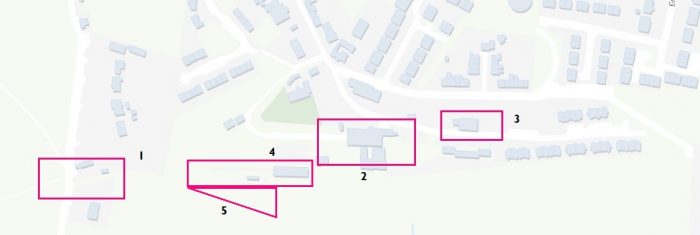

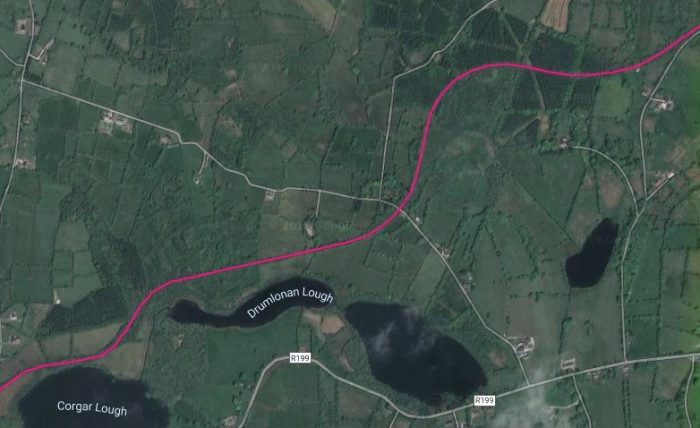

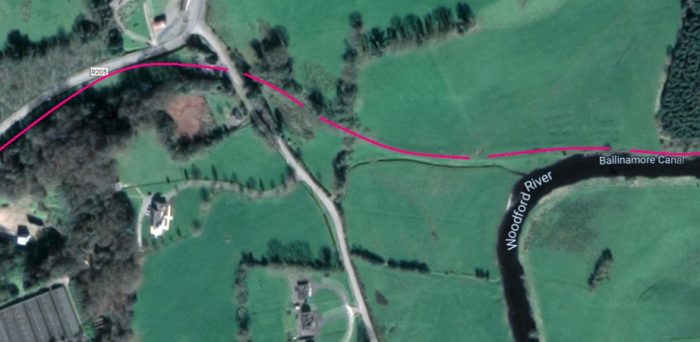

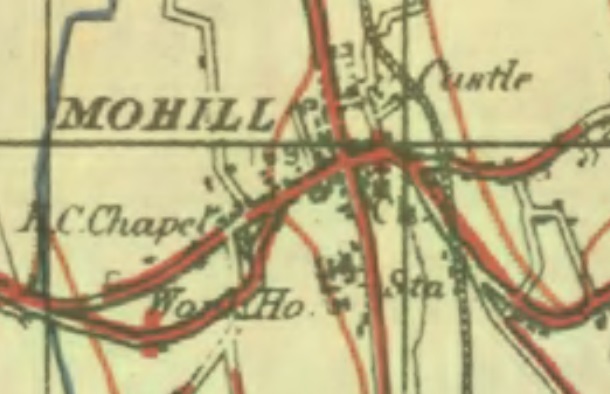

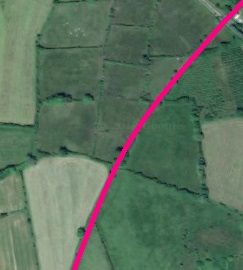

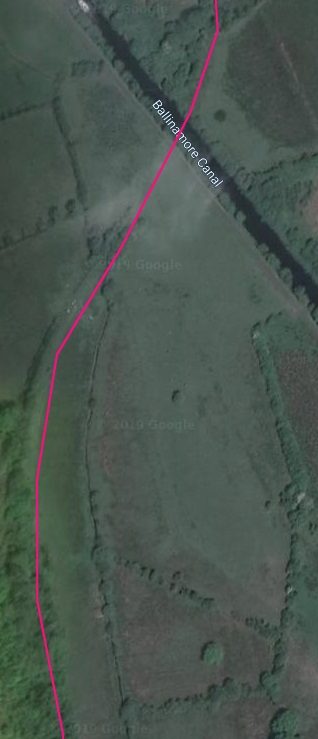

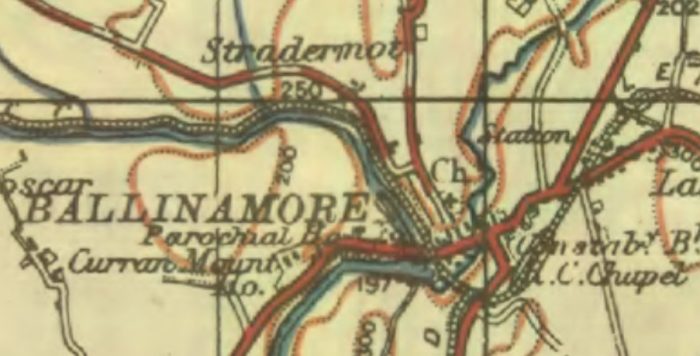

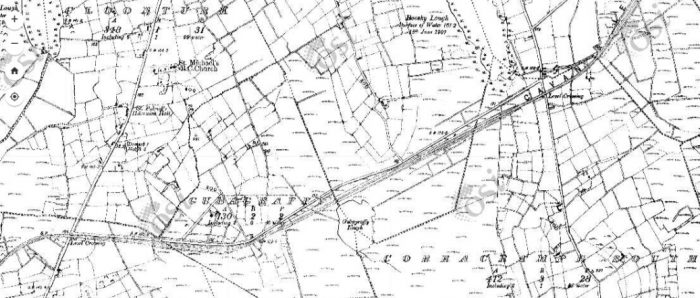

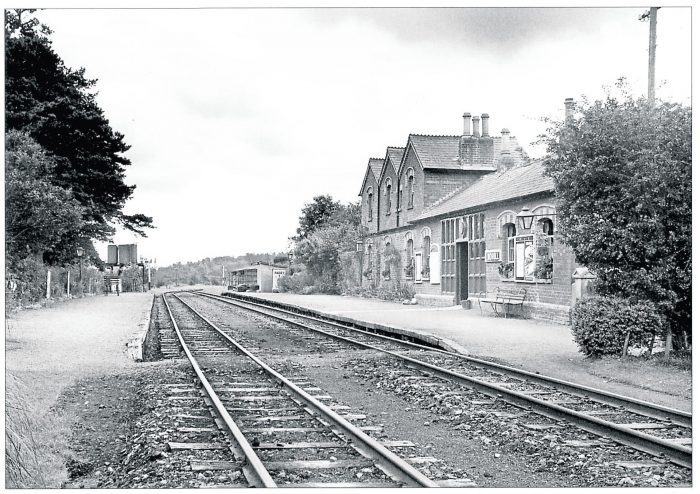

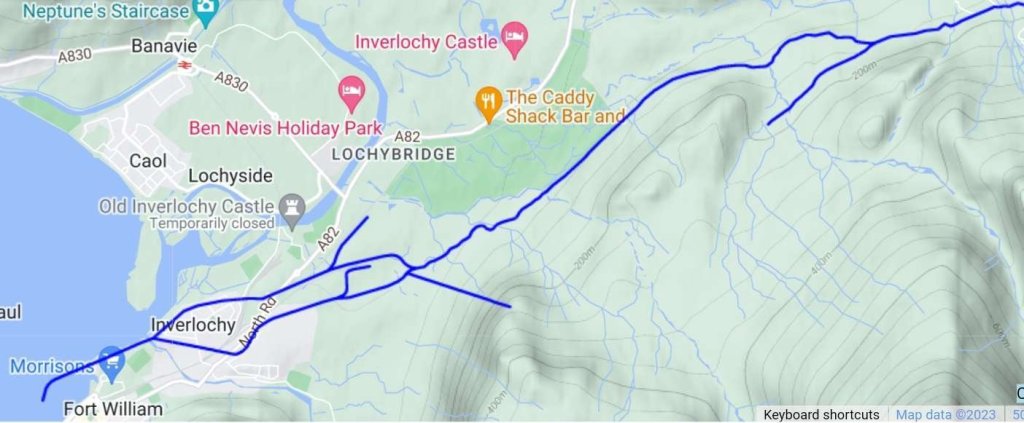

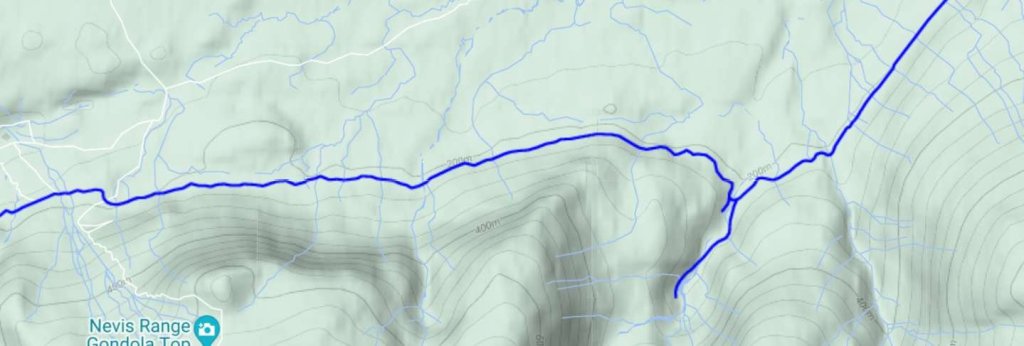

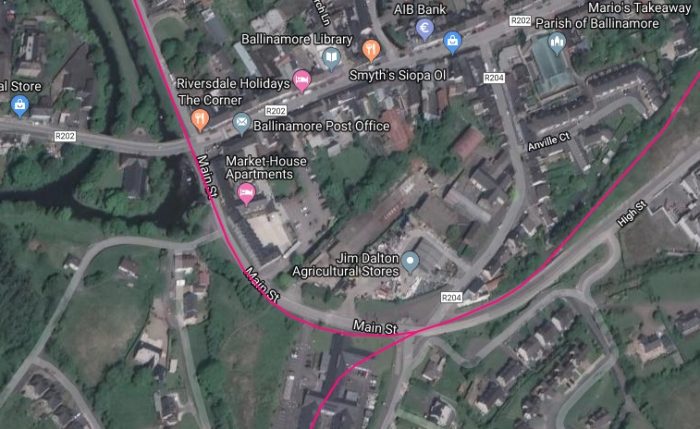

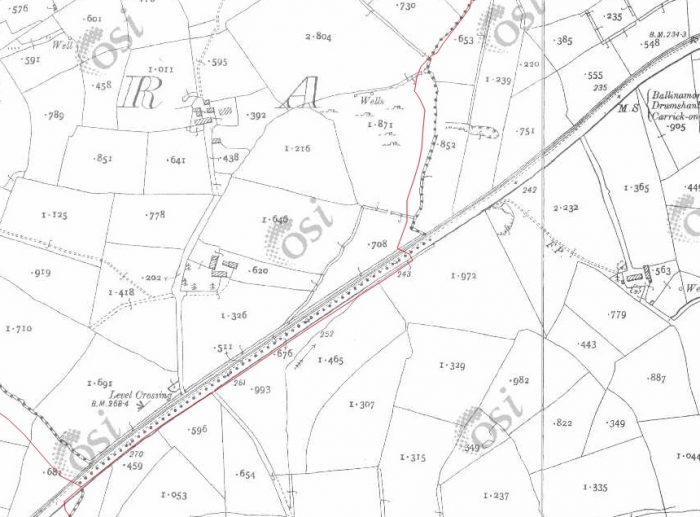

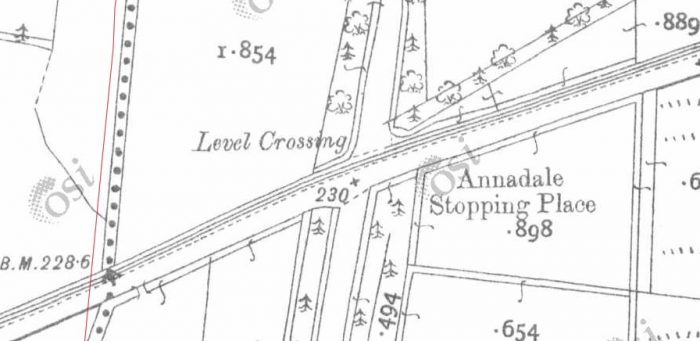

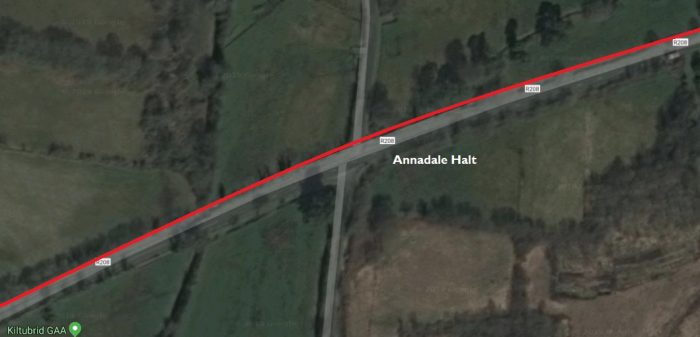

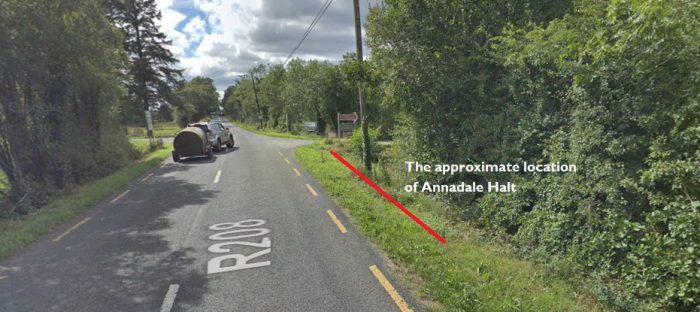

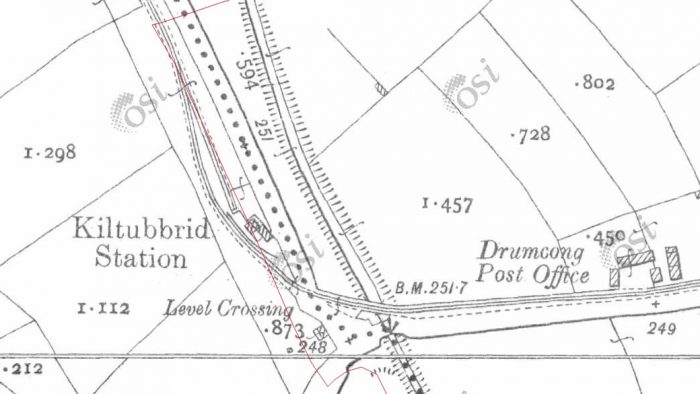

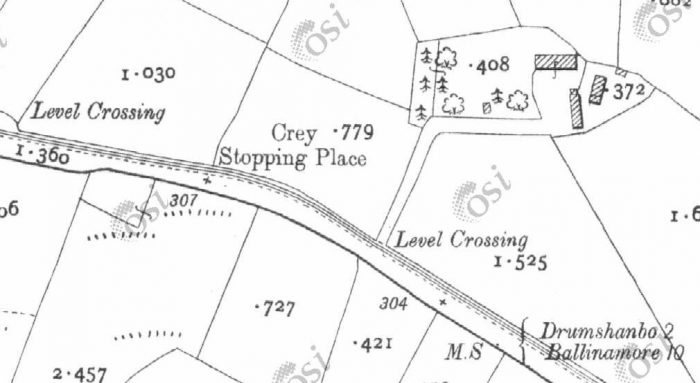

The image above shows the length of tramway between Annadale Halt and Kiltubrid.

The image above shows the length of tramway between Annadale Halt and Kiltubrid.

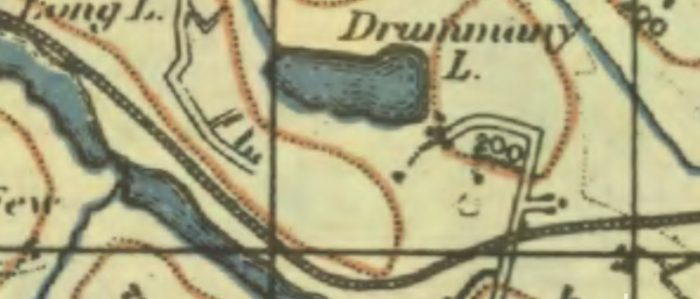

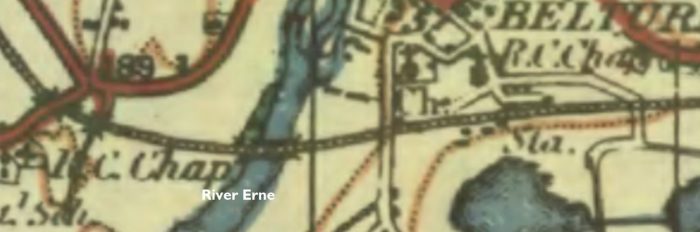

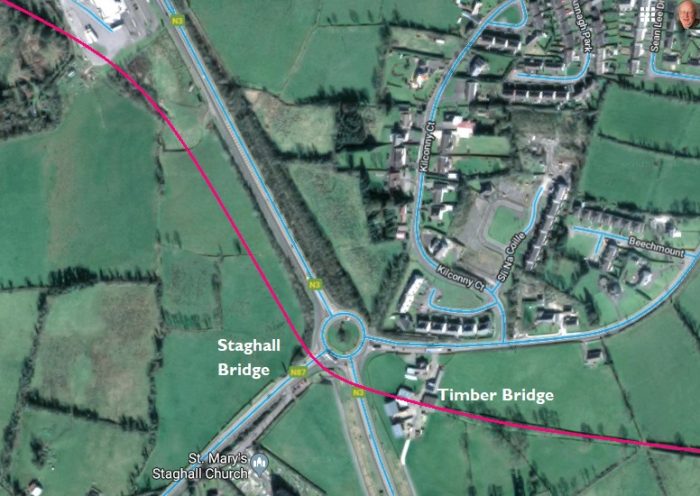

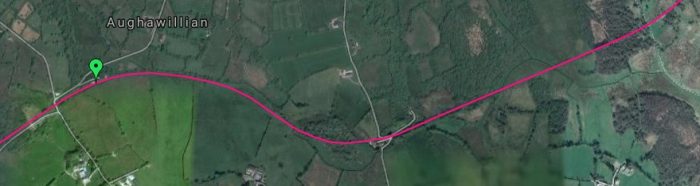

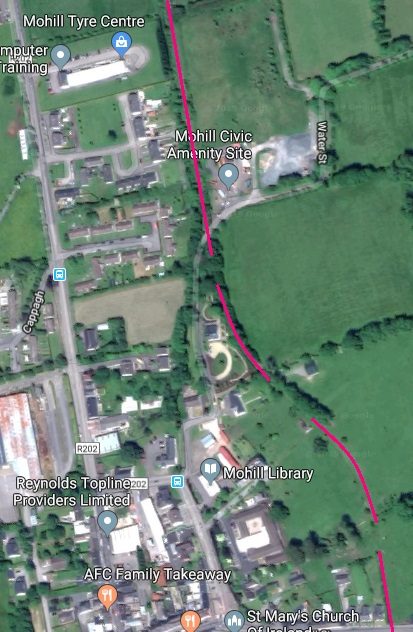

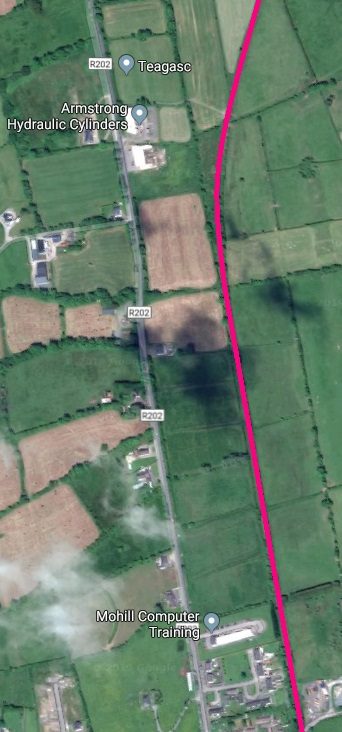

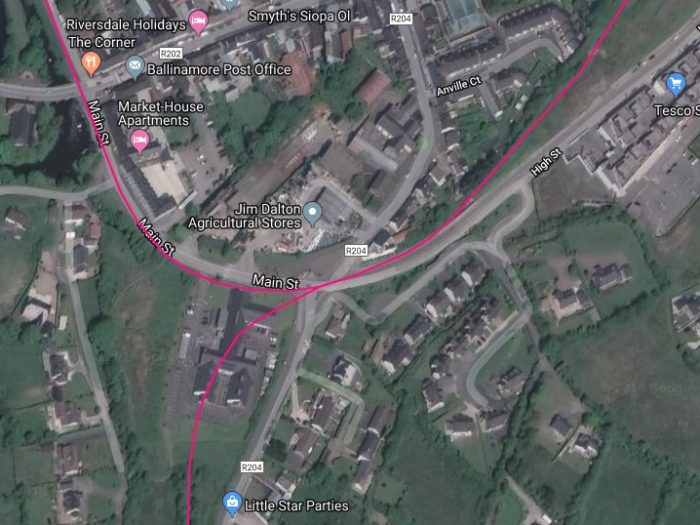

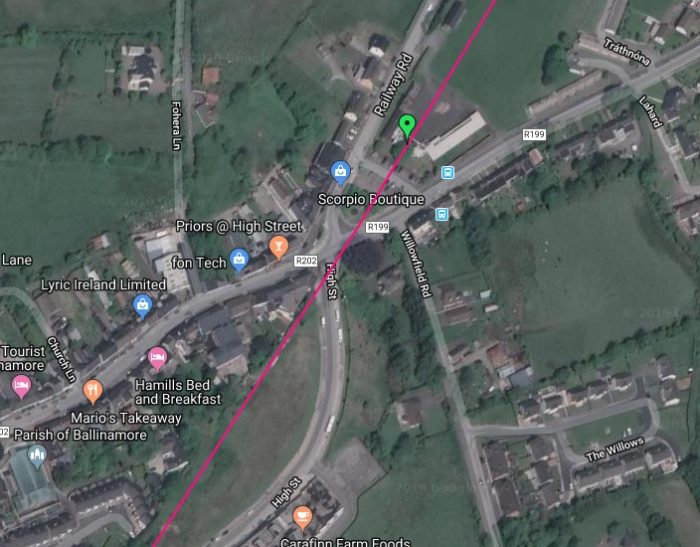

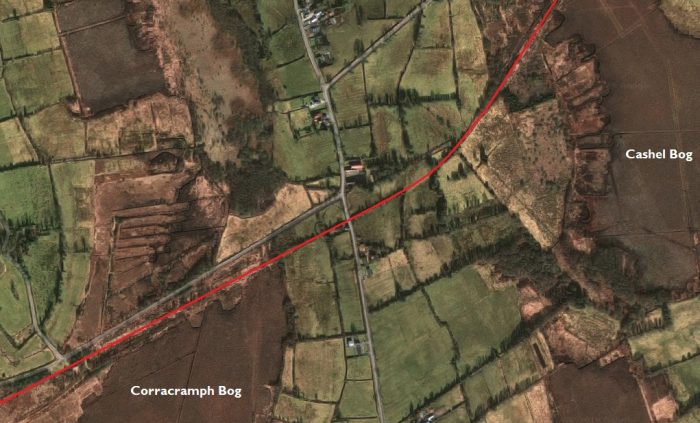

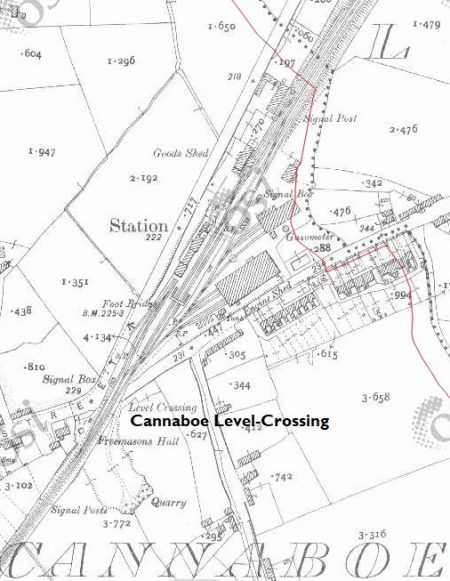

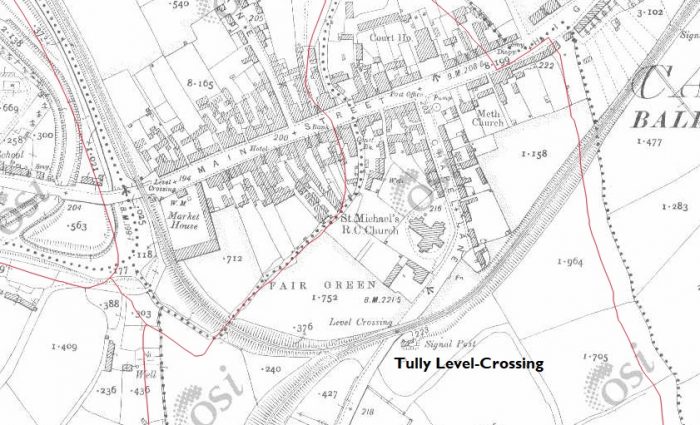

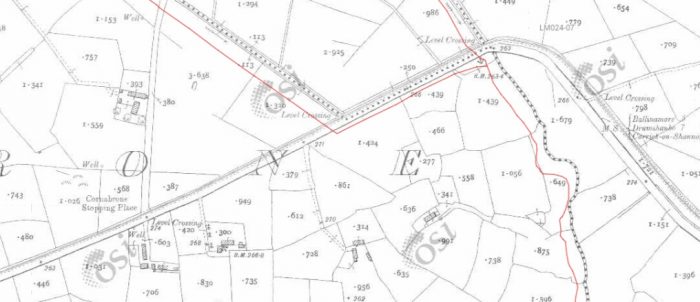

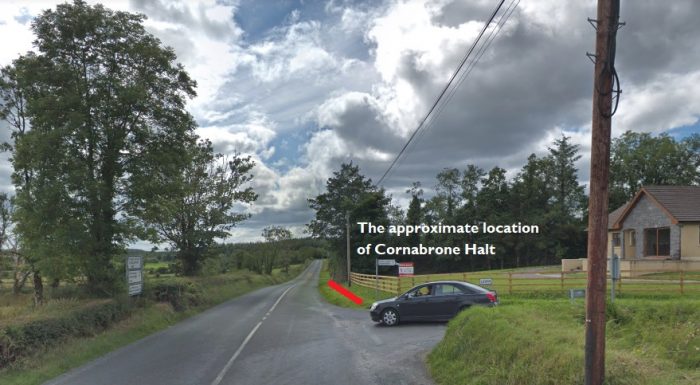

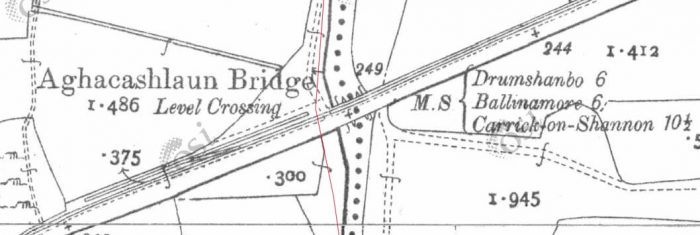

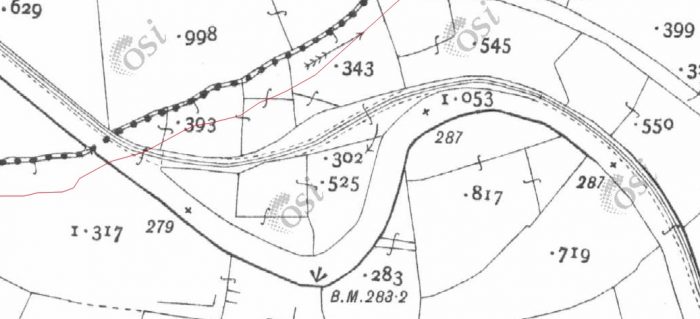

The old railway leaves the line of the new road (above) and heads north, running across the North side of Drumshanbo to the Station. After Fallon’s cutting road and rail converge and then diverge as shown above.

The old railway leaves the line of the new road (above) and heads north, running across the North side of Drumshanbo to the Station. After Fallon’s cutting road and rail converge and then diverge as shown above.