As part of our holiday in Nice in 2017 my wife and I investigated the line between Nice and Meyrargues which closed at the beginning of the 1950s. Almost all of the route is can be accessed on foot and surprisingly much is accessible by car.

This blog covers the history of the line up to 1925 and the first length of the route from La Manda near Colomars on the Nice to Digne line to Saint-Jeannet.

History of the Line to 1925

The Treaty of Turin was signed on 24th March 1860. In it Nice was ceded by the King of Sardinia to Napoleon III. This needed to be ratified by the local population and a vote on 15th and 16th April produced an overwhelming majority in favour of the change. Consequently the department of Les Alpes Maritimes was created by decree on 24th October 1860. To accelerate the acceptance of the new department, and secure improvements to the local economy, significant grants were made by the French government to the department.

Nice was made the capital of the department much to the chagrin of Grasses. Grasses was part of the old France and assumed a priority over Nice. When it lost out to Nice as the capital of the new department it made strenuous efforts to develop local infrastructure improving local roads and seeking a place on the line of the new railway running East along the coast to Nice. That battle was lost and when the Emperor visited Nice on August 18, 1860, Grasse demanded and obtained a branch line from the main coastal line, insisting that “Grasse must inaugurate its railway on the same day that Nice inaugurate its railway.” However that branch-line and the costal railway took thirty years to complete!

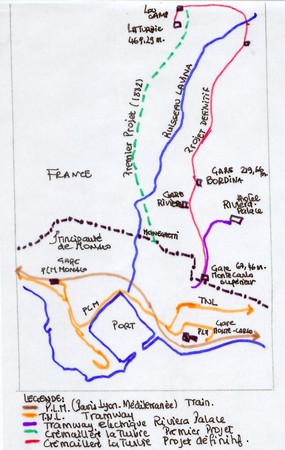

Map of the railroads of Provence in 1924

The focus of the main coastal railway on standard gauge left the towns and villages of Central Var needing to promote their own line or lines. The fall of the Second Empire delayed the work. It was to be some time before proposals could be resurrected.

Eventually, Les Chemins de Fer du Sud was promoted as two separate lines during a period when France became particularly concerned about its more remote regions. Two lines were of approximately 350 kilometres in total length – Digne to Nice and Nice (Colomars) to Meyrargues. A metre gauge line powered by steam, sometimes called “Le Train des Pignes”. It was given this name because, it is said, travellers had time together off the train and pick up pine cones by the track when the train encountered a significant gradient. A metre-gauge was adopted which was complementary to many other lines being built throughout France and which provided for cheaper construction, steeper grades and tighter curves that the standard gauge – much more suited to the terrain through which it would travel. The project cost was, as a result, half that if standard gauge had been used.

Construction proceeded quickly. The 211 kilometre network was divided into sections entrusted to different contractors. The sections were of around 10 kilometres in length. Land was purchased by 1890 and work commenced immediately on all sections of the line. The line was completed in 1892.

These large sites made good use of local workforce.

By 1925, Les Chemins de Fer du Sud had been formed bringing the two lines together in one Company.

The Route

1. Colomars (La Manda) to Saint-Jeannet Station

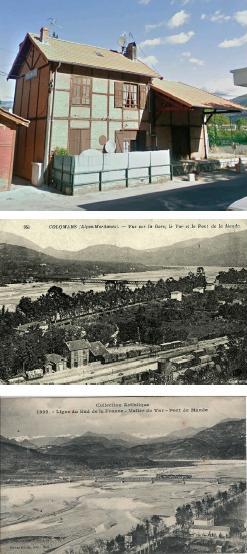

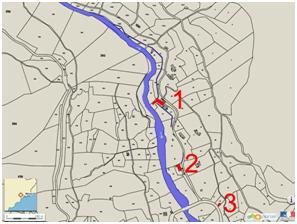

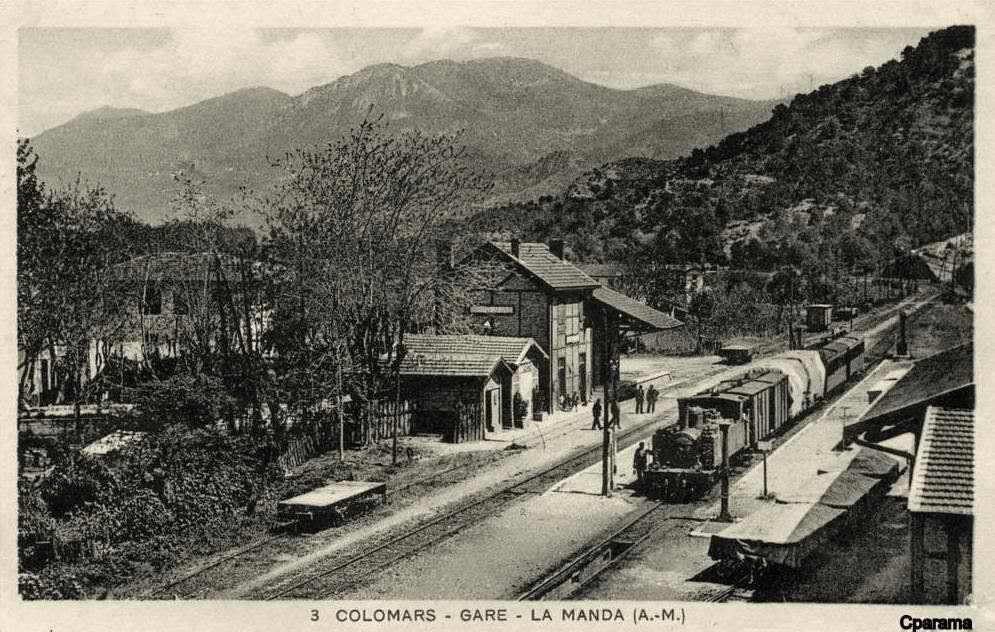

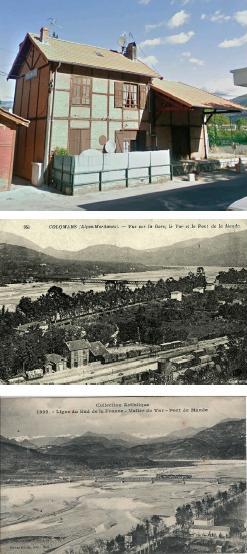

The Ligne de Central Var left the Nice to Digne line at La Manda close to Colomars on the River Var. The station building at Colomars Station remains as evidence of the line. The line branched off the current Digne line just to the north of the hamlet of La Manda.

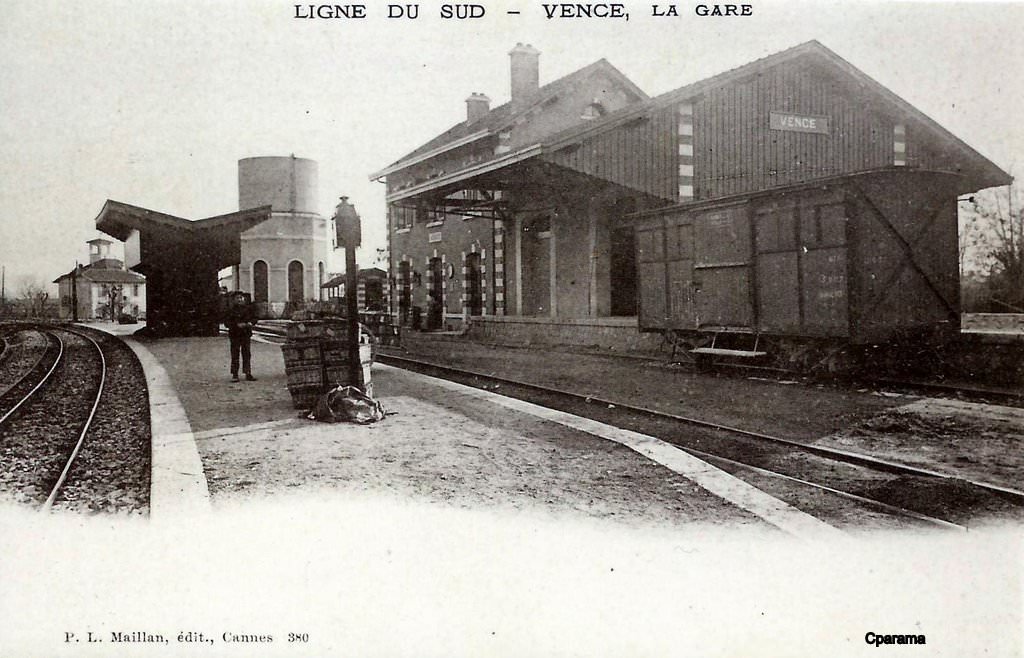

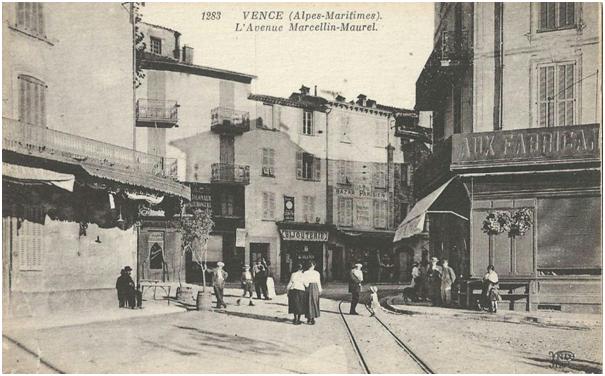

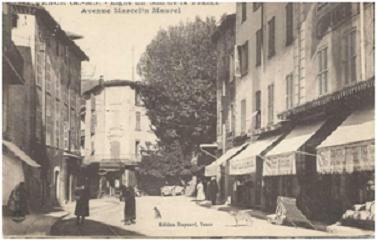

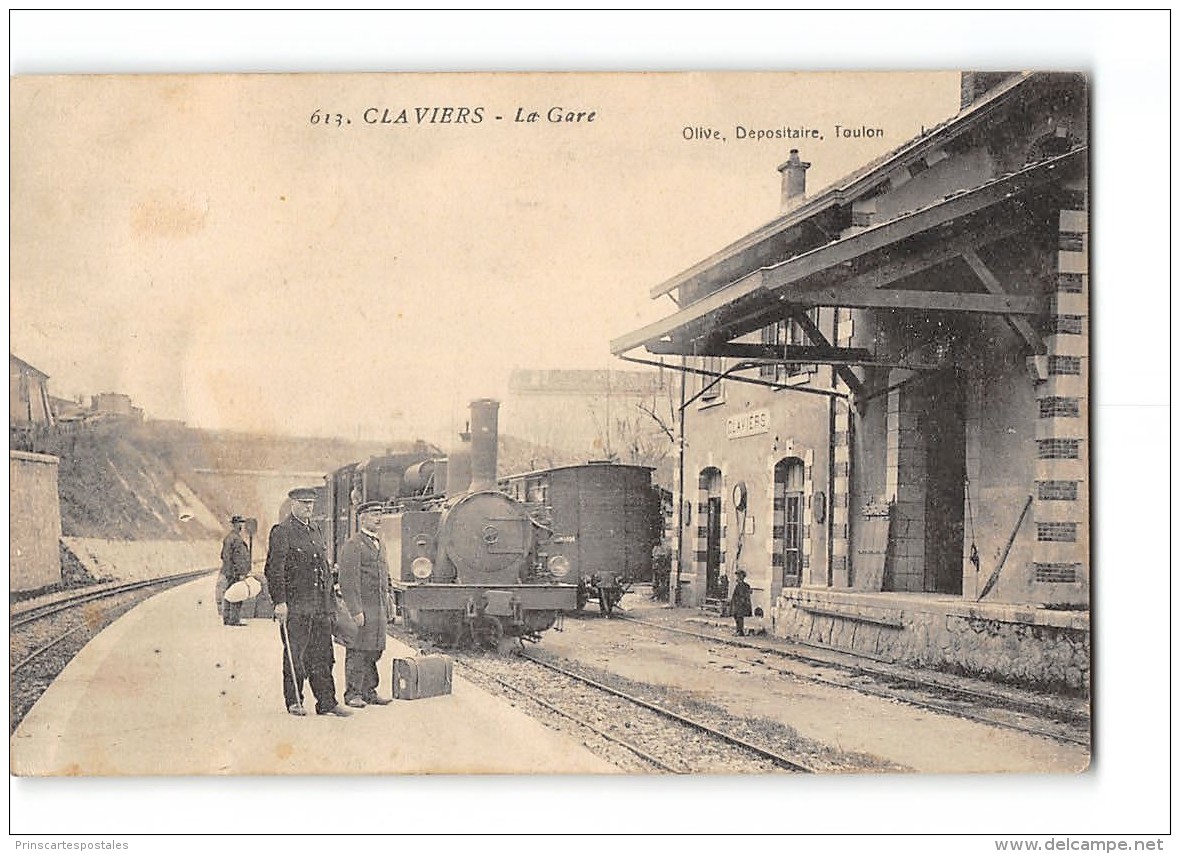

The station construction is typical of many of the stations still evident on the route of the line. A few historic postcards are reproduced here to give an idea of the station in the early years of the 20th century.

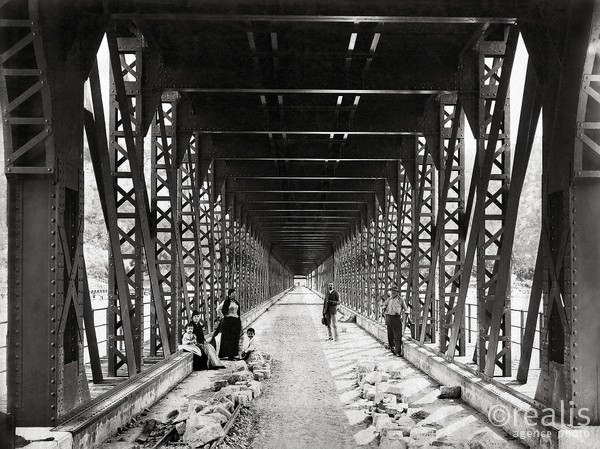

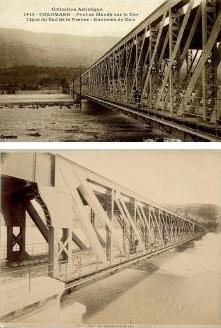

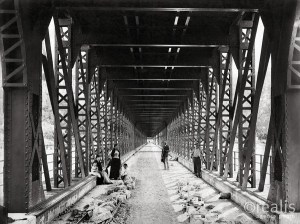

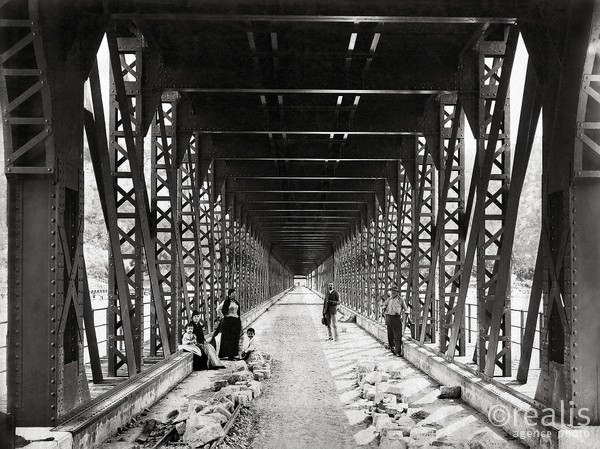

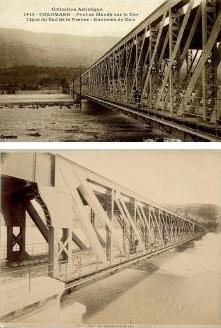

The second of these postcard views has been ‘adapted’ by Jean Giletta the photographer to include a hand drawn train. While it is a pity that the photographer did not wait for a train to cross the bridge, the picture illustrates the nature of the river crossing. The railway line crossed the river on the top of the truss girders with provision between the trusses for road traffic!

The destruction of several structures on 24th August 1944 led to the closure of the Colomars – Grasse – Tanneron section of the Central Var Line. The service was never restored. The western part of the line, between Tanneron, Draguignan and Meyrargues, was to survive a few more years with a rather limited service, closing on 2nd January 1950.

Although seriously damaged in 1944 the bridge at La Manda was repaired and reopened, but only for road traffic. The current bridge, inaugurated on 27th November 1967, was built just downstream from the previous one, which probably remained open during construction.

A link follows to photos taken in 1966 just prior to the building of the new structure. The photographs were taken by Jean-Henri Manara and are available on Flickr.

According to these photos, it seems that at least two bays on the east bank of the River Var, were not recoverable and were replaced by temporary bays lighter. These notes about La Manda bridge have been kindly provided by ‘Jeanmi67’ and ‘242TE66’ on Les Forums de Passions Métrique et Etroite!! (www.passion–metrique.net/forums).

Once the line had crossed the river it was carried on embankment across the wider flood plain as can easily be seen in the last of the post cards of the station at La Manda. The railway line is long gone but the bridge remains in use as a major road crossing of the Var. The current bridge was built in 1967, as a replacement of the former bridge which had been damaged in August 1944. Jose Baraudo (Le Siecle du Train des Pignes) says that a commando unit of the retreating German army blew up three major viaducts on the morning of 24th August 1944, (La Siagne, Le Loup and La Pascaressa) However, they did not need to blow the bridge at La Manda up. The Meyrargues line had been cut off from Nice already, three weeks earlier, when the bridge at La Manda was bombed by the Allied forces on 2nd August 1944, prior to the Provence landing. Two spans at the East end were destroyed and a third one is said to have suffered damage only.

Other bridges across the Var river at Nice – St Laurent-du-Var and Pont Charles-Albert were also destroyed or severely damaged by bombing, as were several bridges and viaducts along the Nice – Digne line (La Vésuvie…etc…) but those would be repaired and/or rebuilt, eventually. (Thanks to 242T66 for the english translation of part of Banaudo’s book on which these last two paragraphs are based).

Although this commentary starts from the Eastern end of the line. It seems strange writing about the line and starting in the East as when we travelled along the route in November 2017 we started from the West. Most of our own photographs of the route were taken from the Westerly direction looking East towards Nice.

Once firmer ground had been reached to the West of the river, the line set off to the South-west around the South side of Gattieres toward Saint-Jeannette. The picture below looks back towards the bridge across the Var along Boulevard de la Colle Belle at Carros. The bridge is hidden behind the vegetation on the modern roundabout.

The next picture looks back along the line of the old railway again a little further to the Southwest on Rue des Grillons in Carros. This picture and some of the others that follow are courtesy of Google Street view.

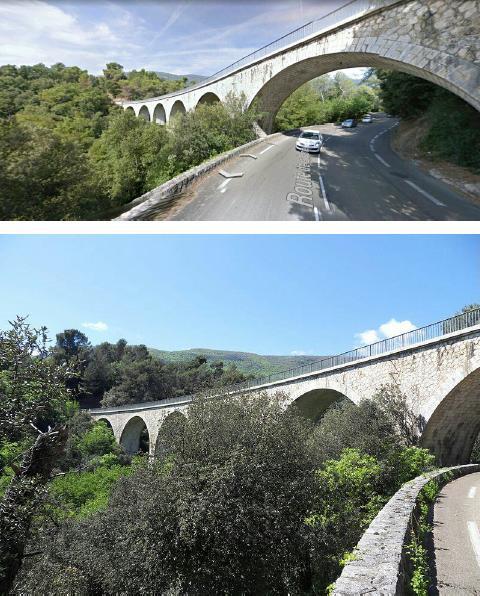

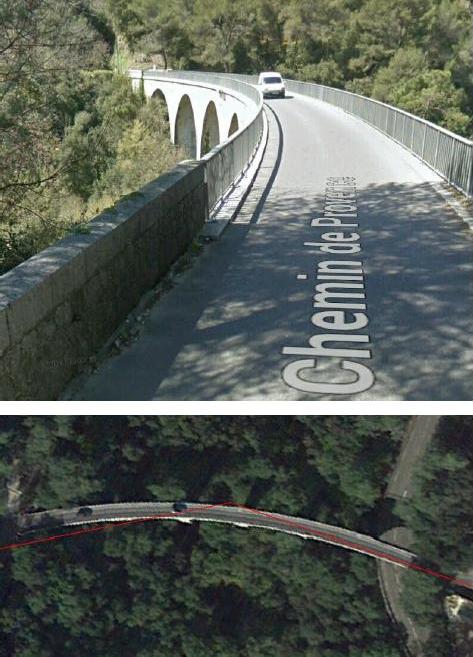

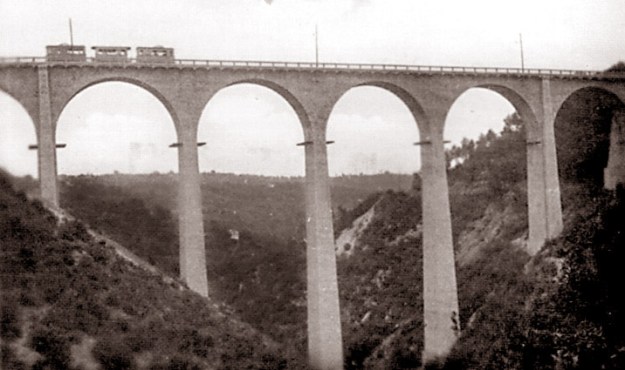

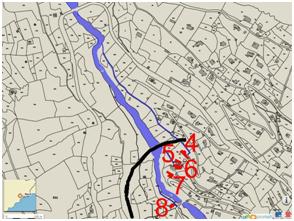

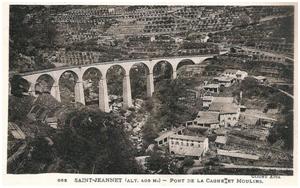

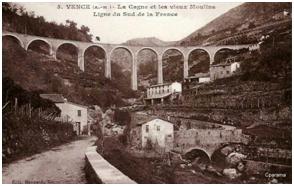

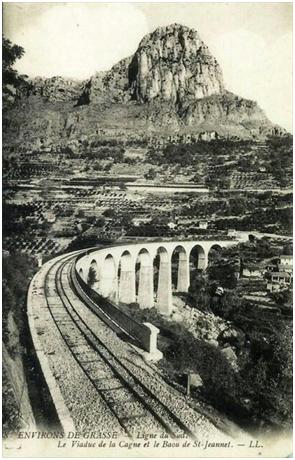

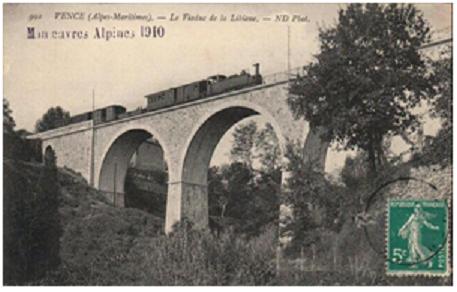

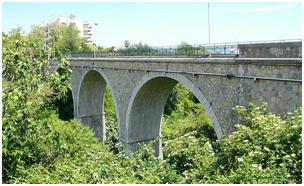

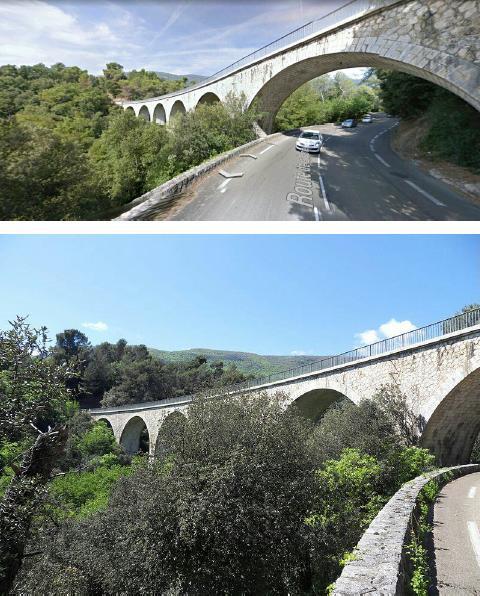

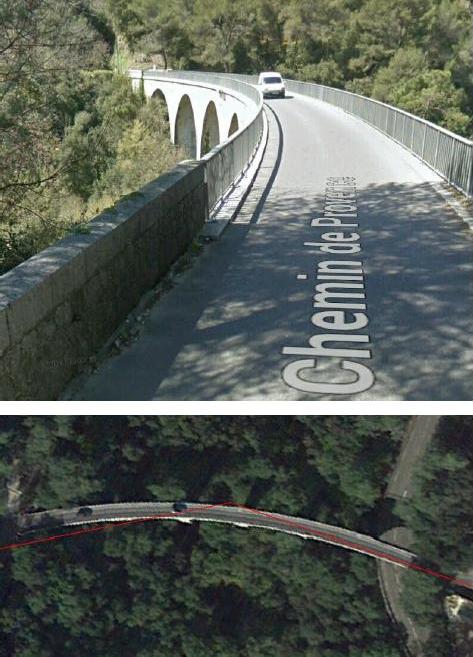

Leaving Carros, the line immediately headed out onto the Viaduct of the Enghièri (130 metres long, made up of 6 arches, 5 of which span 16 metres (43° 46’ 00” N, 7° 11’ 22”E). It is a traditionally built arch viaduct with a first wider span for the road below. The first picture is from Google Street view. The second is taken from a car window.

Much of the Ligne Central Var is still in use for transportation, often the old track formation has been used at its original width, in some places significant widening has taken place. Where original structures were damaged in the conflicts of the 20th Century, these have not been replaced and the ability to follow the line in a vehicle is interrupted. There are areas usually in the forested areas along the route where pedestrian access is possible, or the route can be traversed by a 4×4 vehicle. The Viaduct of the Enghièri has been preserved as a highway as the Google Street view picture shows. The route has been given the name, Chemin de Provence.

The plan view is also taken from Google Streetview. The red line is the plotted route of the railway which can be viewed with this link:

http://ollivier.haemmerle.free.fr/LigneColomarsMeyrargues.kmz.

Google Earth will be needed to open it. The plotting of the route was undertaken by Claudio Capaccio.

From the Viaduct of the Enghièri the route of the line follows what is now the Chemin de Provence in south-south-westerly direction crossing a small bridge at 43° 45’ 32”N, 7° 11’ 00” before turning to a more westerly trajectory on the North side of the Vallon des Trigands and South of Saint-Jeannet.

A couple of pictures along the way:

A Crossing Attendants House (43° 44’ 55”N, 7° 10’ 12”E) Further along the line.

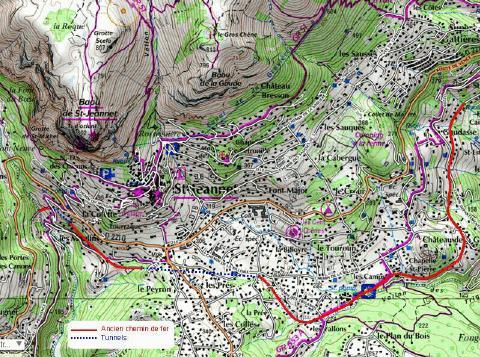

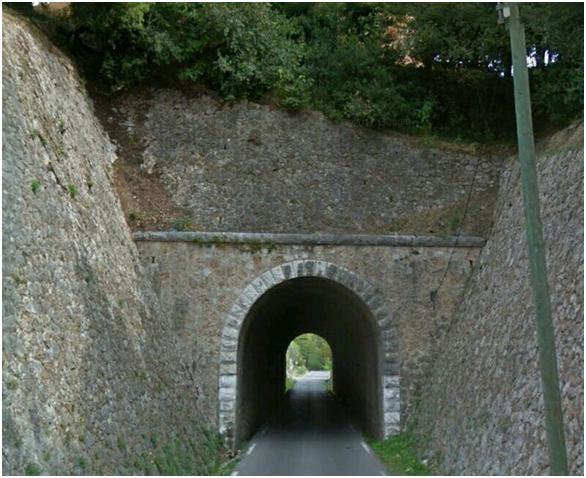

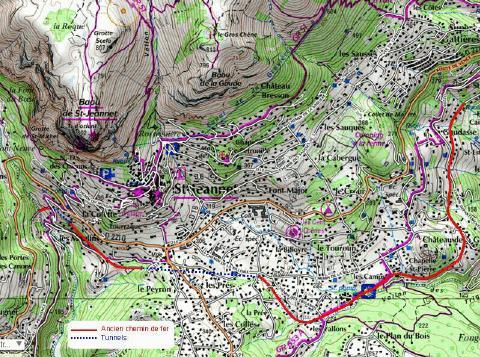

The next substantial structure on the route is shown as a blue dotted line on the map of Saint-Jeannet above – The Tunnel of Saint-Jeannet. Just before reaching the tunnel the line turns in a north westerly direction. The route cannot be followed by car as it continues beyond the concrete blocks in the picture here. It is however possible to get along the line to the tunnel mouth.

The tunnel is 860 metres long running in a predominantly westerly direction (from 43° 44’ 22”N, 7° 09’ 21”E to 43° 44’ 31”N, 7° 08’ 32”E) and the line appears again South of the D2210 road, south-west of Saint-Jeannet close to Le Peyron. From the tunnel mouth at the West end of the tunnel (visible below right) there is a short section of the route accessible with care and known as the Chemin de la Champignonniere. A high retaining wall (below left) carries the old line above the Ancienne Route de Vence which falls away to the West and meets the line at grade just behind the camera and then climbing away above the old line on its way towards Saint-Jeannet.

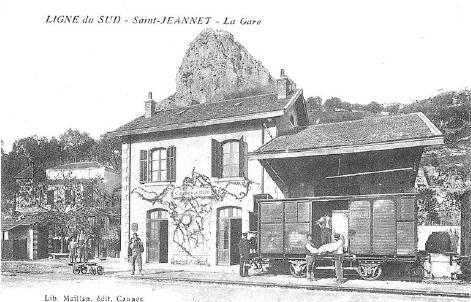

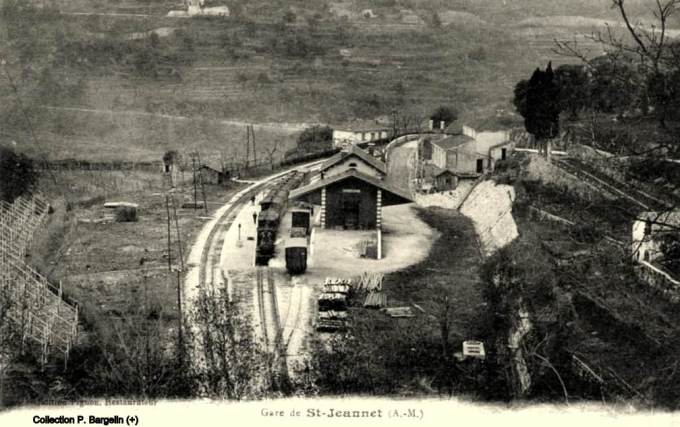

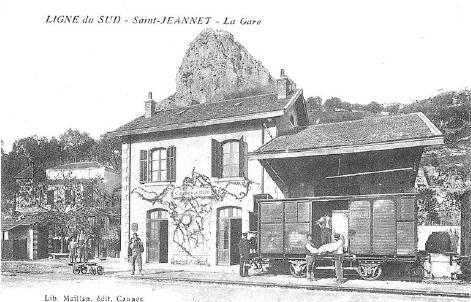

A quick nip up the Ancienne Route de Vence above the old line allows a glimpse of the old Saint-Jeannet station off to the right of the road. This accurately places the station on the map. The next image is a postcard of the station in the early 20th Century.

After the station, the line travelled a short distance (along what is now the Chemin de La Champignonniere) before reaching another tunnel entrance. This tunnel’s official designation is Tunnel de Cagne, however it is apparently known locally as the Tunnel de Champignonniere. The tunnel is used to farm mushrooms.

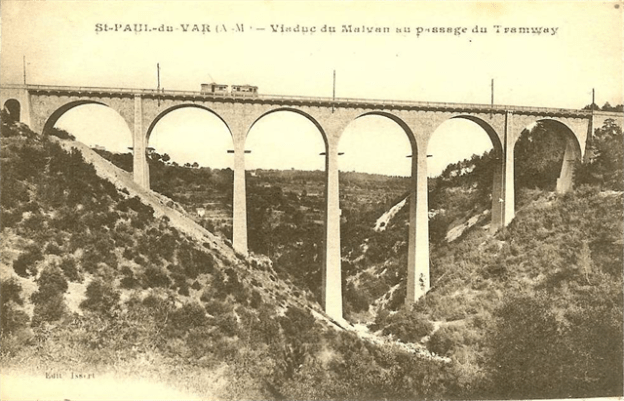

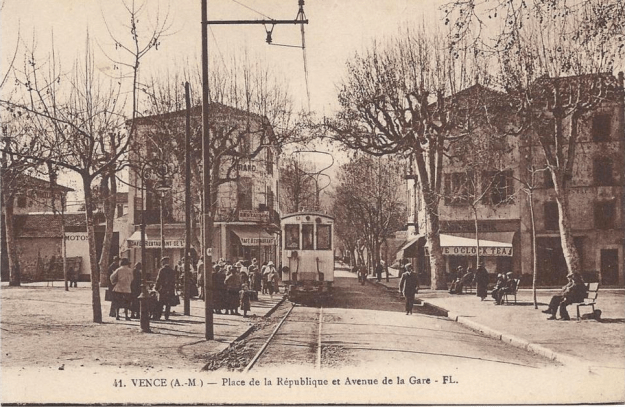

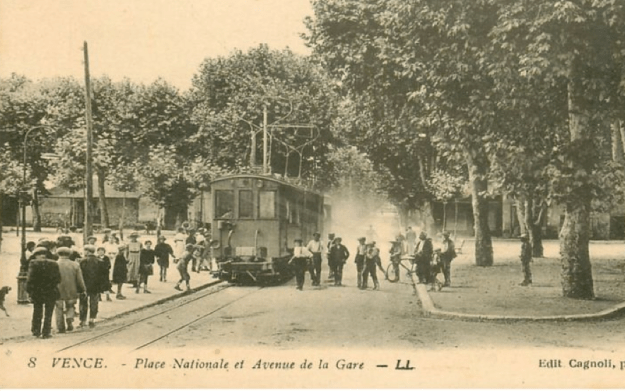

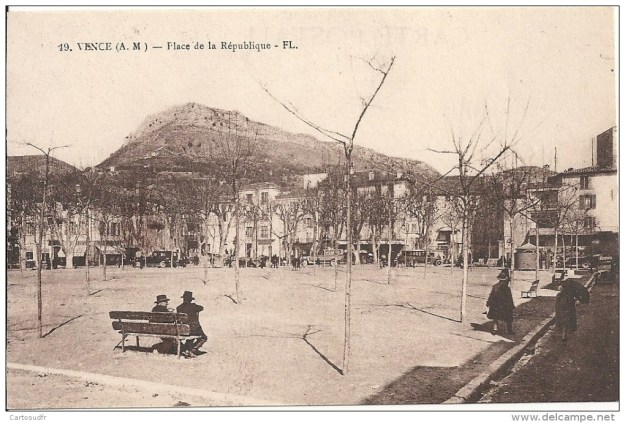

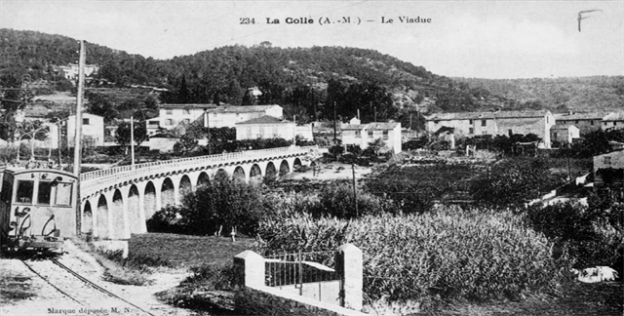

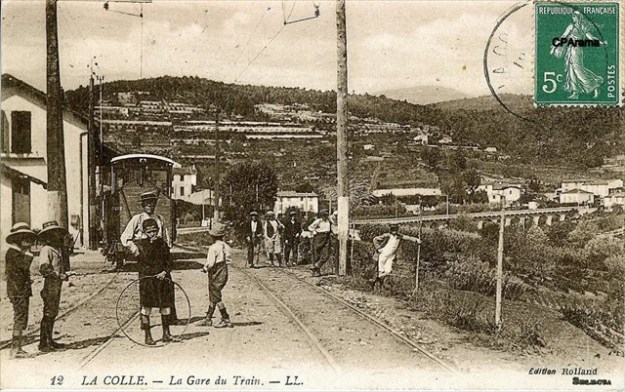

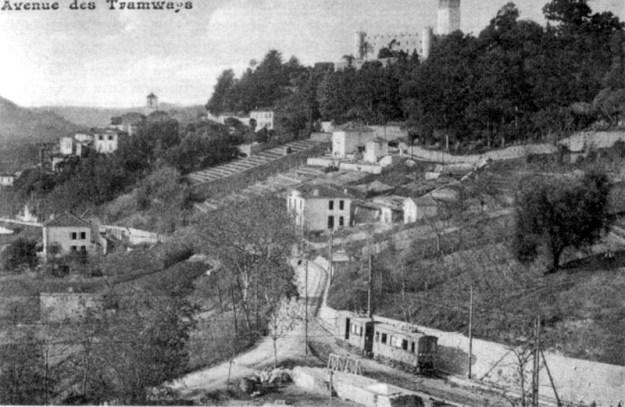

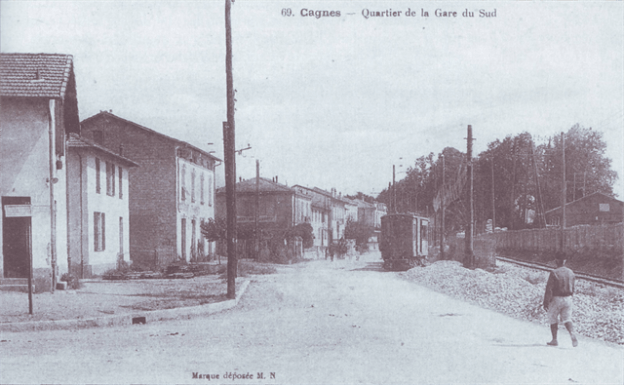

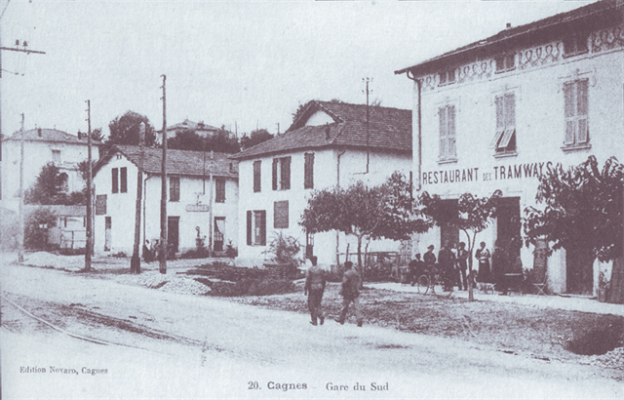

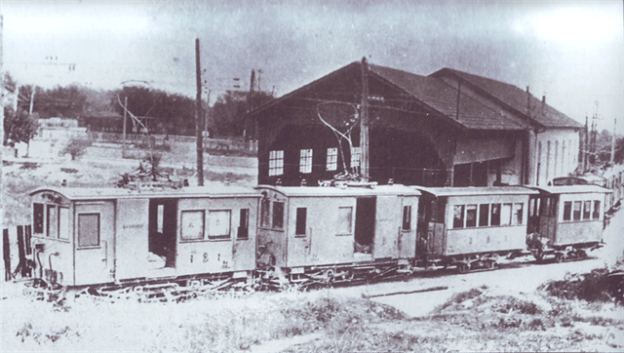

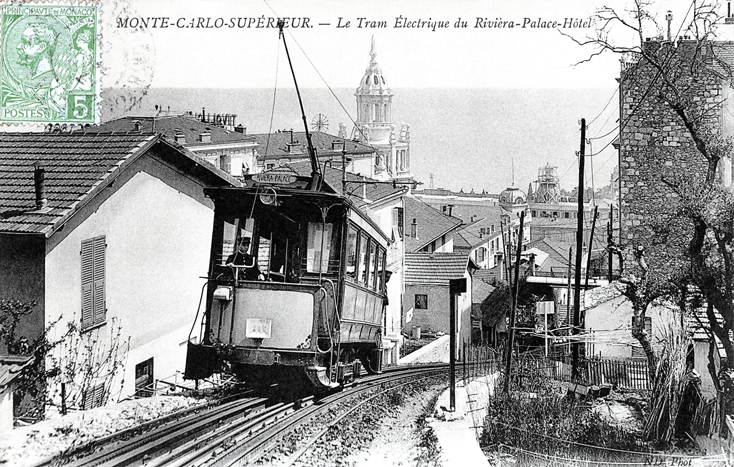

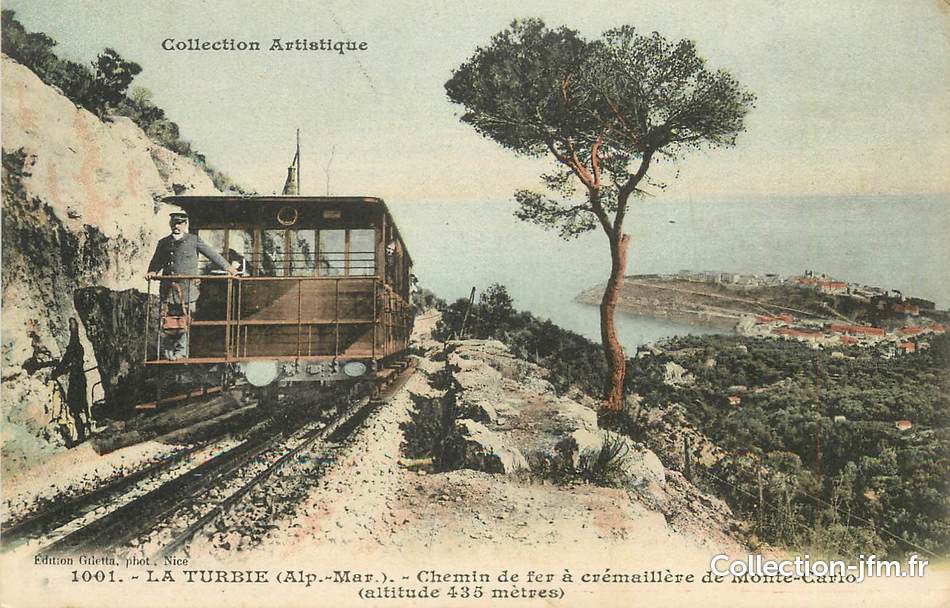

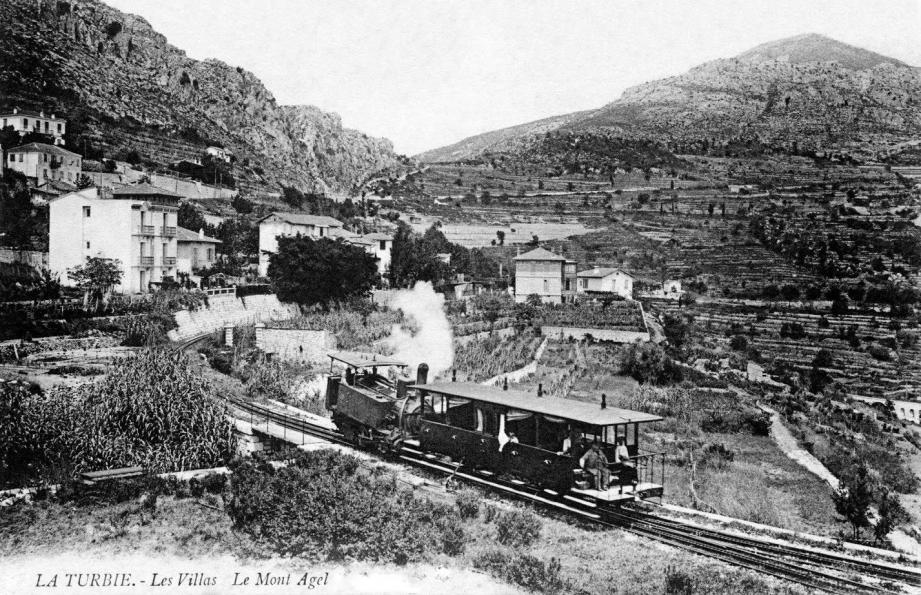

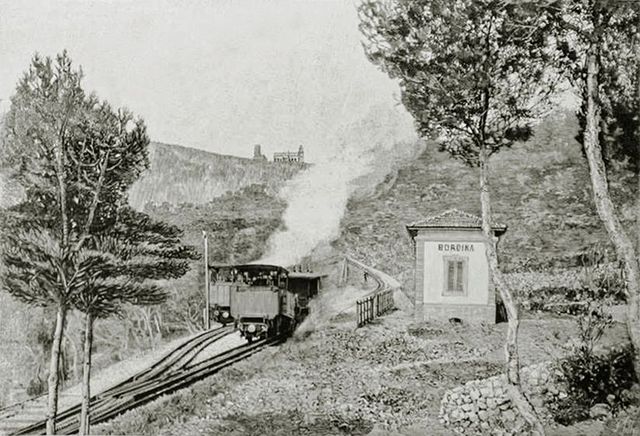

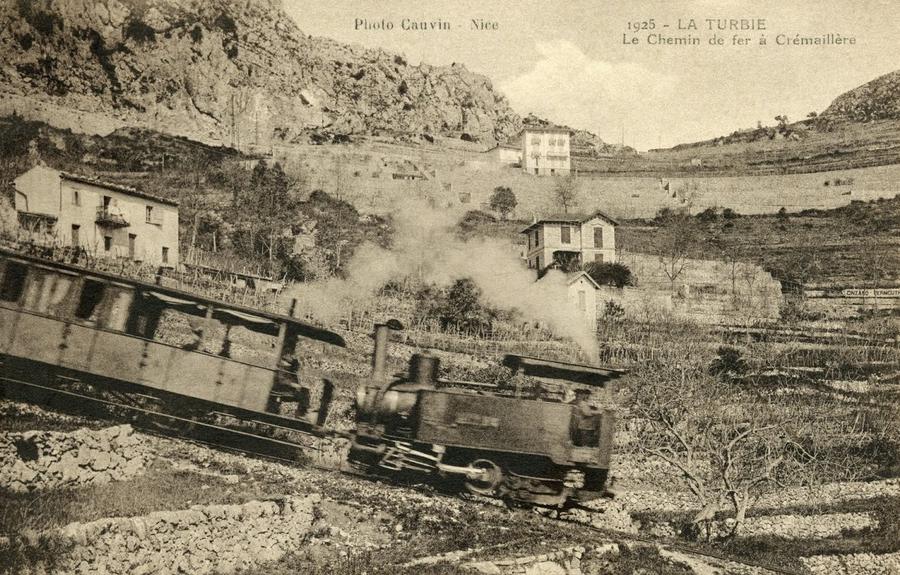

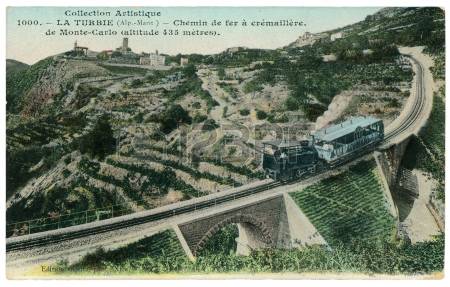

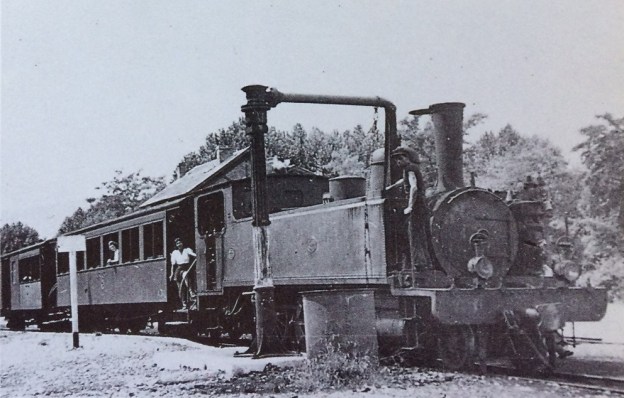

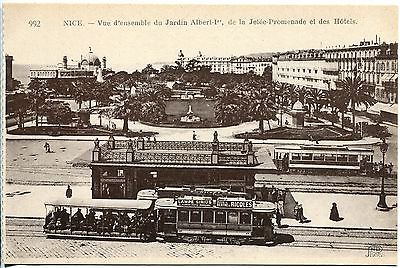

This is the first set of random images from railways and tramways around Nice.

This is the first set of random images from railways and tramways around Nice.

The final photograph shows the terminus at Levens. The location of this picture is however not clear in my own mind. I believe that the first terminus at Levens was probably on the Avenue General de Gaulle. The line was, however, extended into the centre of the village, it is highly possible that this is a view of that location, which is the point at which the Nice to Levens bus terminates right next to the heart of the perched village. I’d appreciate any comments readers are able to make on this.

The final photograph shows the terminus at Levens. The location of this picture is however not clear in my own mind. I believe that the first terminus at Levens was probably on the Avenue General de Gaulle. The line was, however, extended into the centre of the village, it is highly possible that this is a view of that location, which is the point at which the Nice to Levens bus terminates right next to the heart of the perched village. I’d appreciate any comments readers are able to make on this.

Sadly that network went into very rapid decline with the improvement in road transport. It reached its zenith at the end of the 1920s, but by 1934 many lines had closed. By the late 1930s only lines within Nice itself remained open. The remaining lines in Nice finally gave way to competition and the last trams ran on the network in January 1953.

Sadly that network went into very rapid decline with the improvement in road transport. It reached its zenith at the end of the 1920s, but by 1934 many lines had closed. By the late 1930s only lines within Nice itself remained open. The remaining lines in Nice finally gave way to competition and the last trams ran on the network in January 1953.

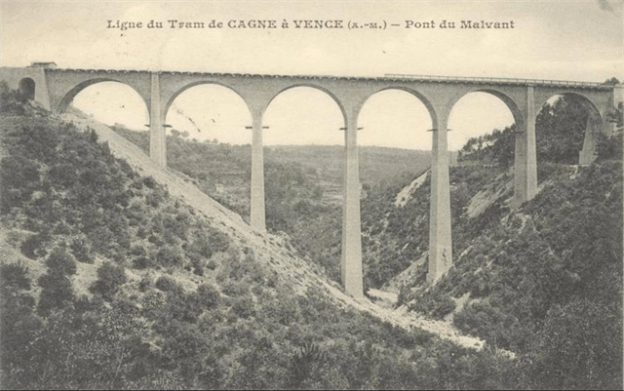

This line was about 27km long. It was commissioned in 1906 but not finished until 29th July 1923. Commissioning of the line was delayed as a result of a series of landslides on the line to Daluis further north. The line closed again only a month after opening because of an accident and finally re-opened in July 1924.

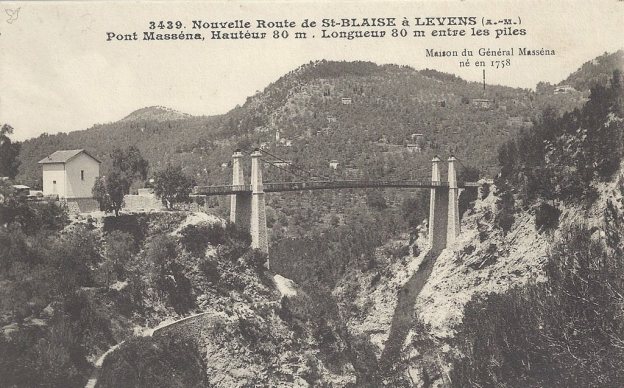

This line was about 27km long. It was commissioned in 1906 but not finished until 29th July 1923. Commissioning of the line was delayed as a result of a series of landslides on the line to Daluis further north. The line closed again only a month after opening because of an accident and finally re-opened in July 1924. Pont Charles-Albert on the Var was the eastern extremity of the line and provided for connection to the Nice-Digne main line. The picture below is of the original bridge which had to be rebuilt as it was not suitable for the tramway.

Pont Charles-Albert on the Var was the eastern extremity of the line and provided for connection to the Nice-Digne main line. The picture below is of the original bridge which had to be rebuilt as it was not suitable for the tramway.