The Railway Magazine of April 1959 carried an article by Anthony A. Vickers about a short branch in Worcester of about 29 chains in length. [1] 29 chains is 638 yards (583.4 metres). The line served Worcester’s Vinegar Works.

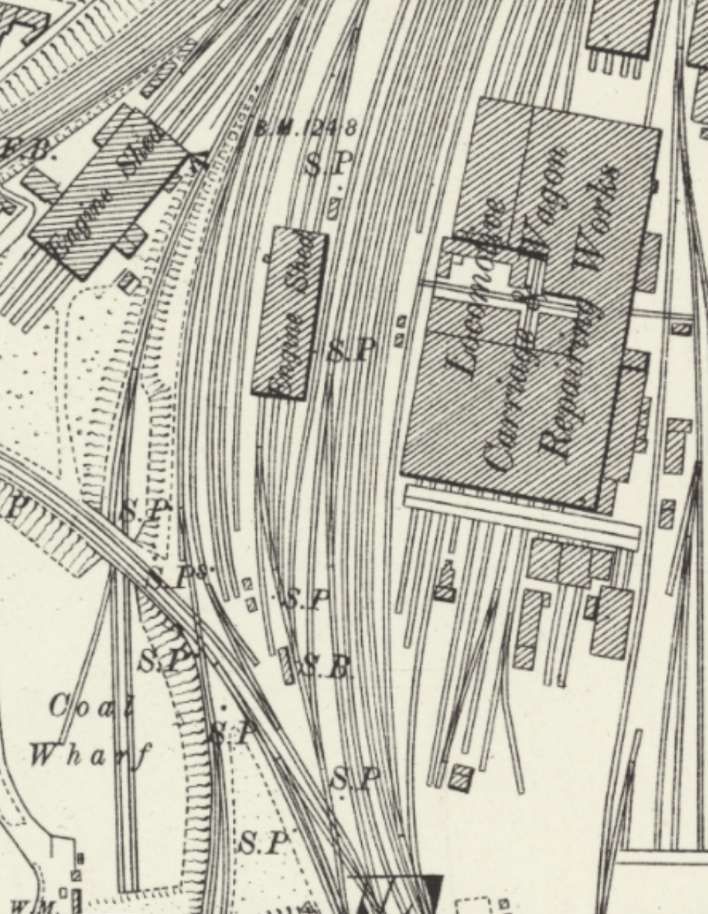

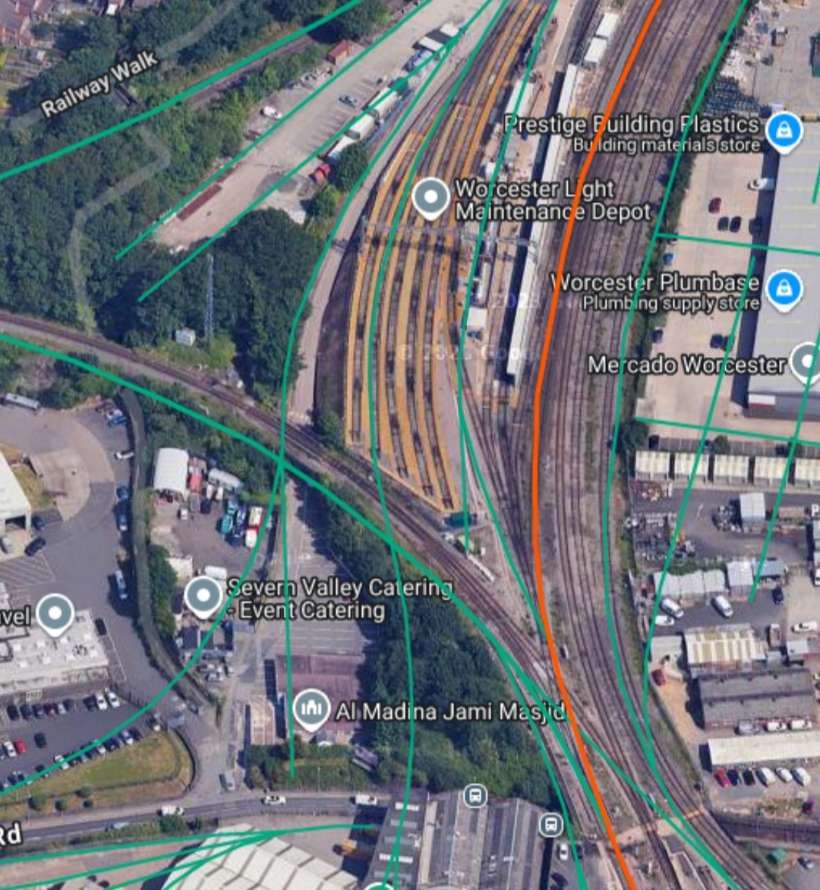

After a time operating at their Vinegar Works in Lowesmoor, Worcester, Hill, Evans & Co. decided that a connection to the national railway network was required via the nearby joint Worcester Shrub Hill railway station which at the time served both the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway and the Midland Railway.

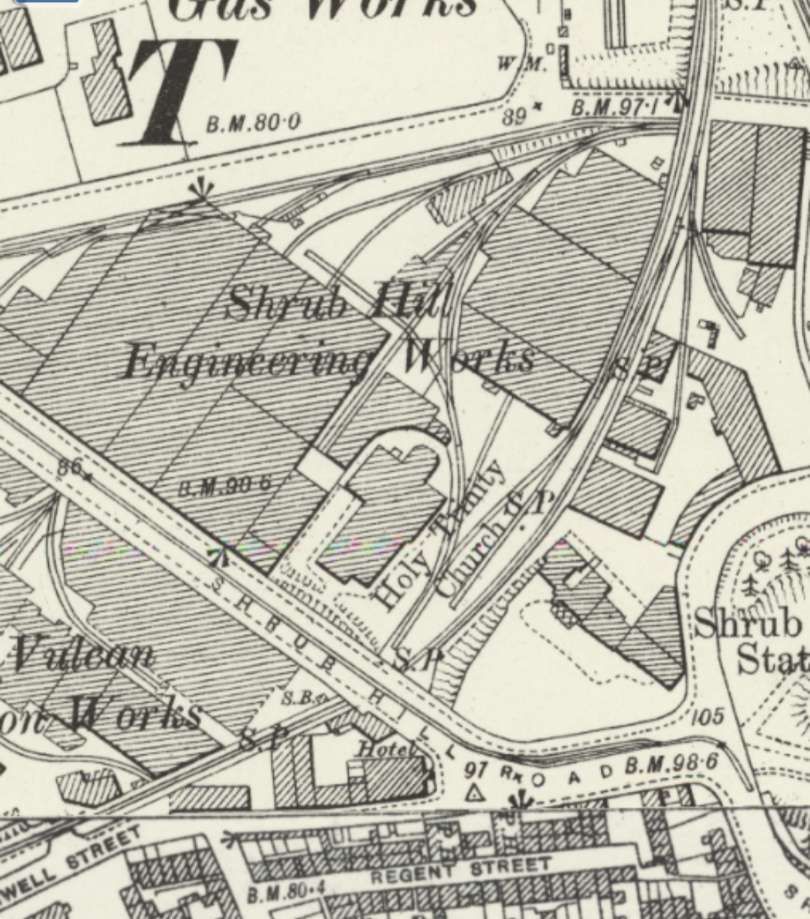

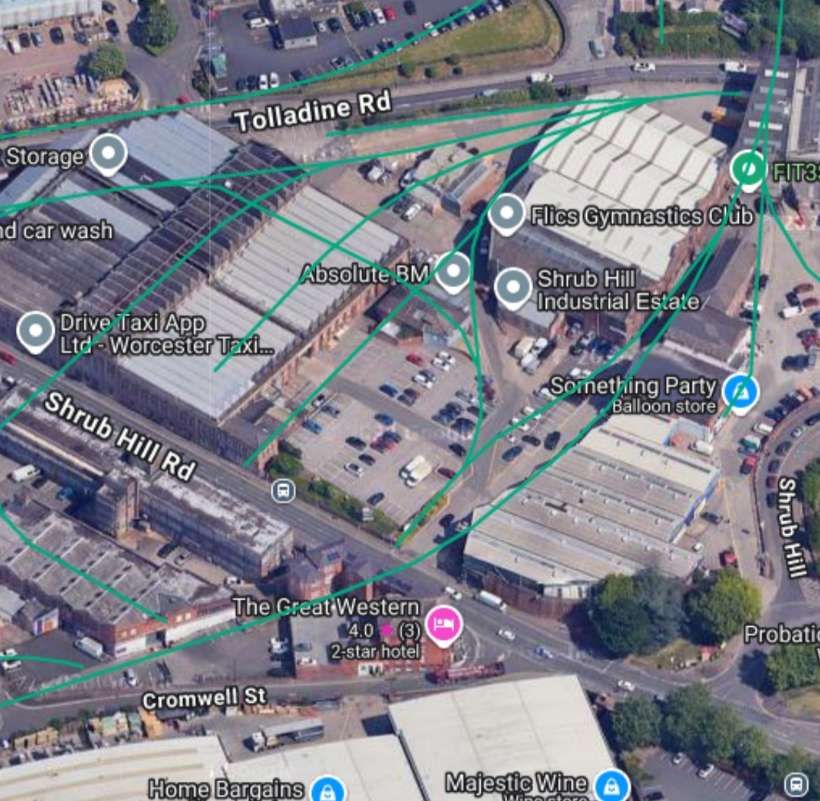

“The resultant Worcester Railways Act 1870 allowed Hill, Evans and Co to extend the existing branchline that had served the Worcester Engine Works, from where it crossed the Virgin’s Tavern Road (later Rainbow Hill Road and now Tolladine Road) by a further 632 yards (578 m) to terminate in … the vinegar works. This route required a level crossing at Shrub Hill Road, a bridge over the Worcester and Birmingham Canal, and a second level crossing at Pheasant Street.[3] The Act also permitted a second siding to be constructed that was wholly within the parish of St.Martin, which enabled the branchline to connect to both the local flour mill, and the Vulcan Works of engineers McKenzie & Holland.” [6]

“One of the provisions of the Act, was that signals must be provided at the public crossings to warn the public when trains required to cross. The speed of the latter was also to be limited to 4 m.p.h.” [1: p238]

A.A. Vickers notes that a few years prior to his article, “a Land-Rover was in collision with a train on Shrub Hill Road level crossing. It is understood that legal opinion of the question of liability was sought, and was to the effect that the semaphore signals fulfilled the obligations of the railway to give adequate warning of the approach of a train, and that the attendance of a shunter with red flags was unnecessary. Be that as it may, road traffic pa[id]no heed to the semaphores, being mostly unaware of their significance.” [1: p238]

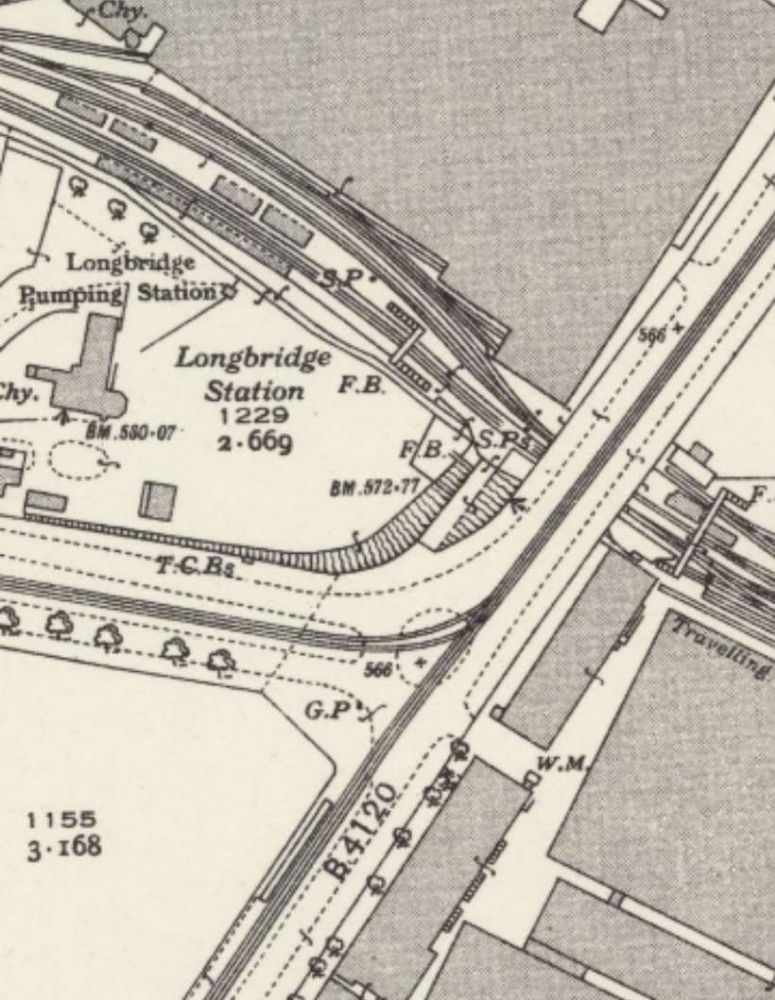

“The branch was completed in 1872 and was known as the Vinegar Works branch or the Lowesmoor Tramway. As an engineering company, McKenzie & Holland supplied the required shunting locomotive. From 1903, engineering company Heenan & Froude also built a works in Worcester, which was served by an additional extension. After the closure of the flour mill in 1915, post-World War I that part of the branchline was lifted, and the flour mill and original part of the Vulcan Works redeveloped in the mid-1920s as a bus depot. In 1936, Heenan & Froude took over McKenzie & Holland, and hence responsibility for the supply of the private shunting locomotive.” [6]

Post World War II, the Great Western Railway and then British Railways took over supply of the shunting locomotive to the branchline. Supplies to the vinegar works switched to road transport in 1958. The last train on the branchline ran on 5th June 1964, hauled by GWR Pannier Tank engine 0-6-0PT No.1639. The branchline was taken up in the late 1970s.

Although the line was short it had a number of interesting features!

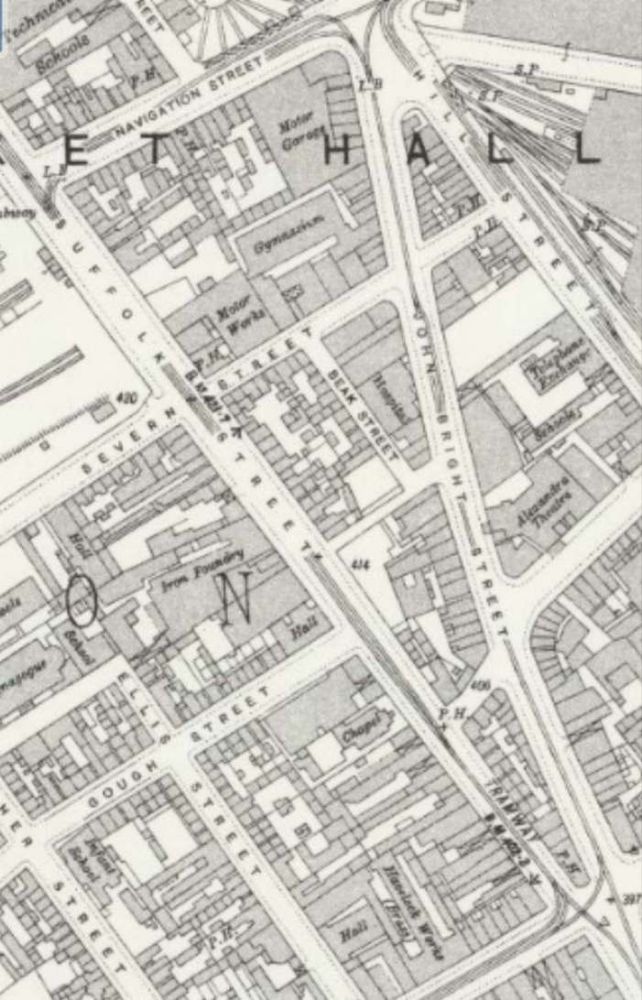

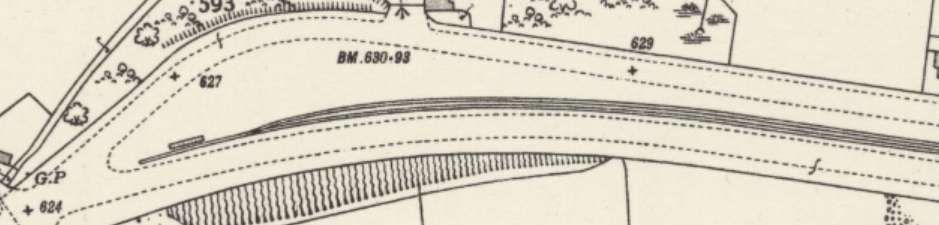

The line crossed the south loop of the junction, and then by a bridge over what A.A. Vickers tells us was, at the end of the 1950s, Rainbow Hill Road (now Tolladine Road). The line then ran through Shrub Hill Engineering Work, curving gradually round towards the Southwest.

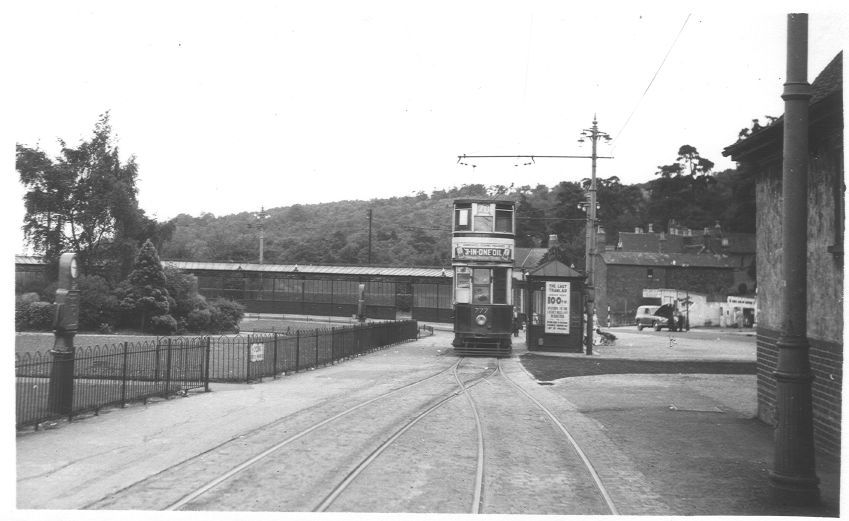

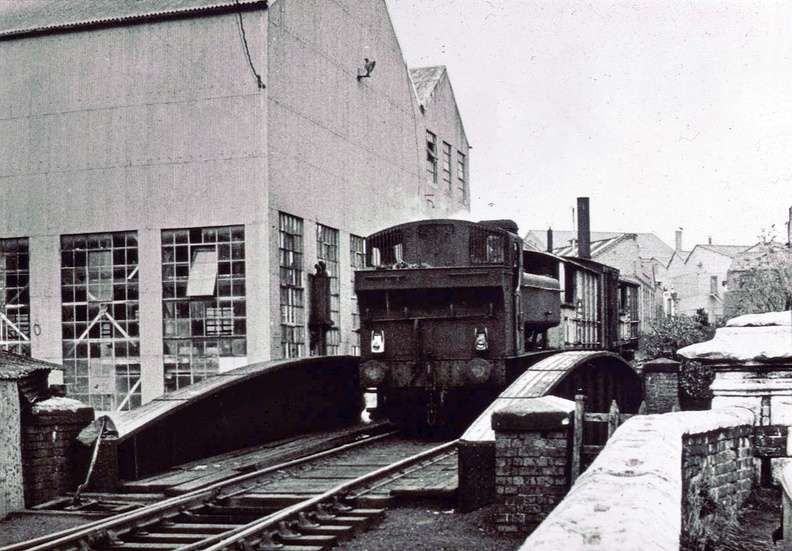

Vickers tells us that, “As the time for the daily (weekdays except Saturdays) trip approache[d], a shunter walk[ed] down from Shrub Hill Station, unfasten[ed] the padlocks, and open[ed] the gates at each side of the crossing over Shrub Hill. These protect[ed] the railway track when closed, but [did] not project onto the roadway when opened. When the engine with its train dr[ew] up to a signal protecting a catch point about fifty yards away from the road, the shunter pull[ed] on the road semaphores, which [were] of standard main-line pattern and operated from their posts, and, at a small ground frame beside the track. While the train close[d] the catch point and pull[ed] off the signal protecting it [and ran] slowly down the incline towards the road the shunter flag[ged] the traffic along Shrub Hill to a stand still, and when he ha[d] achieved this he signal[led] to the train to cross. Then, after allowing the road traffic to proceed, the shunter return[ed] the signals to their original position. He then walk[ed] down the track, across a bascule lift bridge, and over a canal bridge, on which the train ha[d] stopped.” [1: p236]

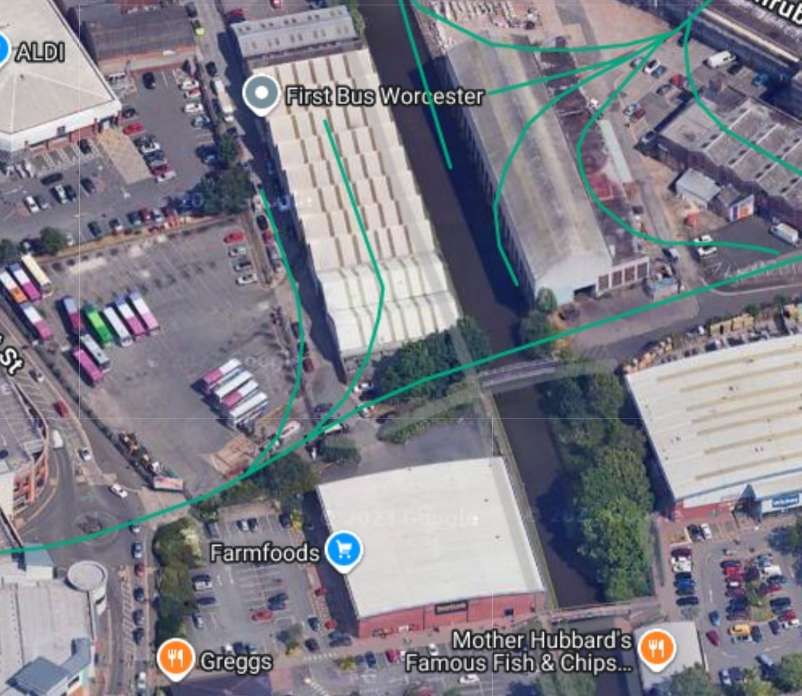

Vickers continues: “The bascule bridge [was] at a factory gate. and the headroom below it [was] about 6 ft. 6 in. [By 1959], only private cars and foot and cycle traffic [used] this entrance. The bridge was last operated many years [before], and one of the basic movements at its fulcrum [had, in 1955,] been immobilised by a concrete wedge which [bore] the date 6th February 1955. The span [was] partly counterweighted, but required a chain and capstan haulage to raise it. The fulcrum contained a complicated arrangement to allow sufficient free space for movement at rail level to occur. First a padlock was unfastened to free a pivoted sleeper which blocked rotation of the fulcrum of a small 18 in. length of rail which was in effect a subsidiary bascule section. When this was raised there was thus an 18 in. gap which allowed the fulcrum of the main span to roll back as the span was raised. The free end of the subsidiary and main span was in each case allowed to slide into an open fish-plate end, the bottom bulge of the rail section having been cut away flush at the end of the span for this purpose. At the main span end the junction [was] fixed by insertion of the fish-bolts.” [1: p236-237]

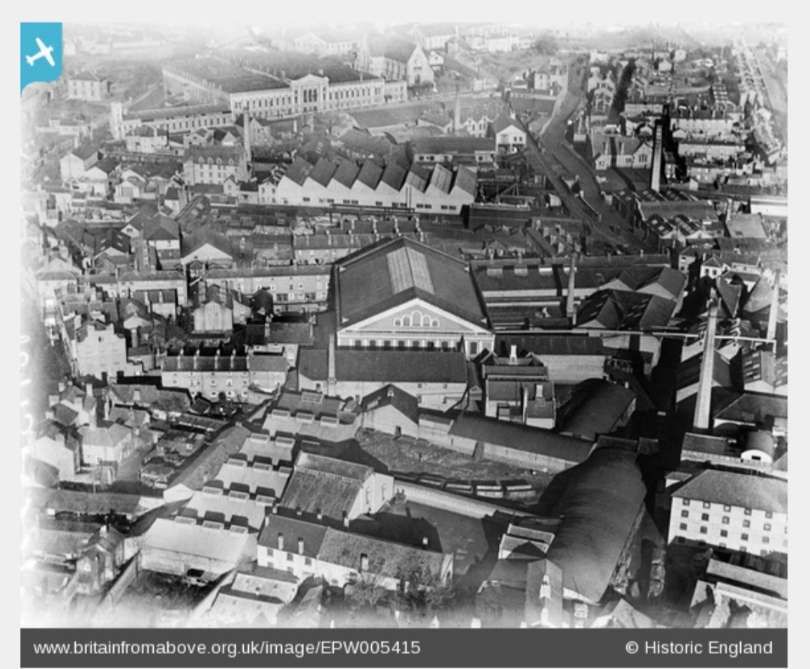

Adjacent to the railway bridge over the canal there was a road bridge carrying Cromwell Street which by 1959 was unsafe for vehicular use. The red line denotes the route of the branch. The road bridge was replaced by a footbridge. [5]

The level-crossing to the immediate West of the canal only crossed a road of very minor importance (Padmore Street), leading only to a private car park and yard.

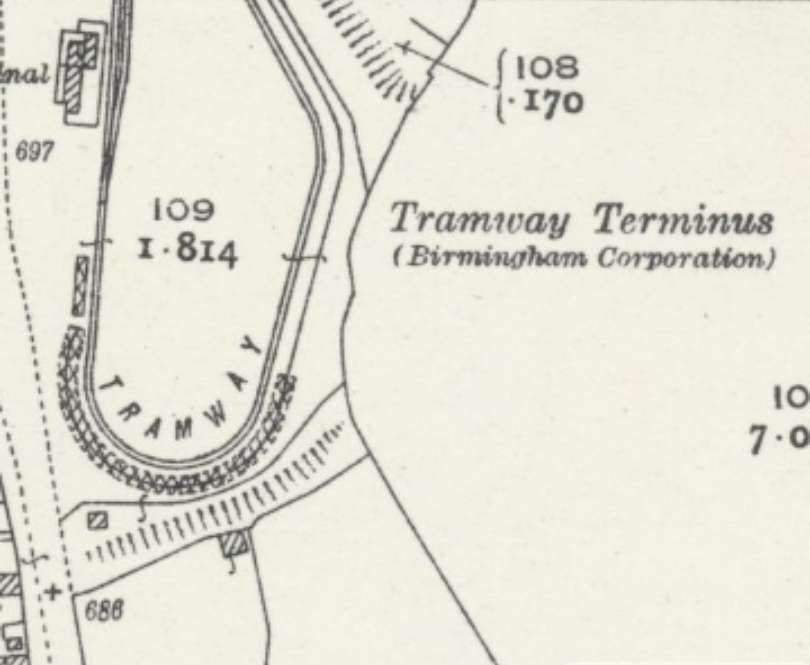

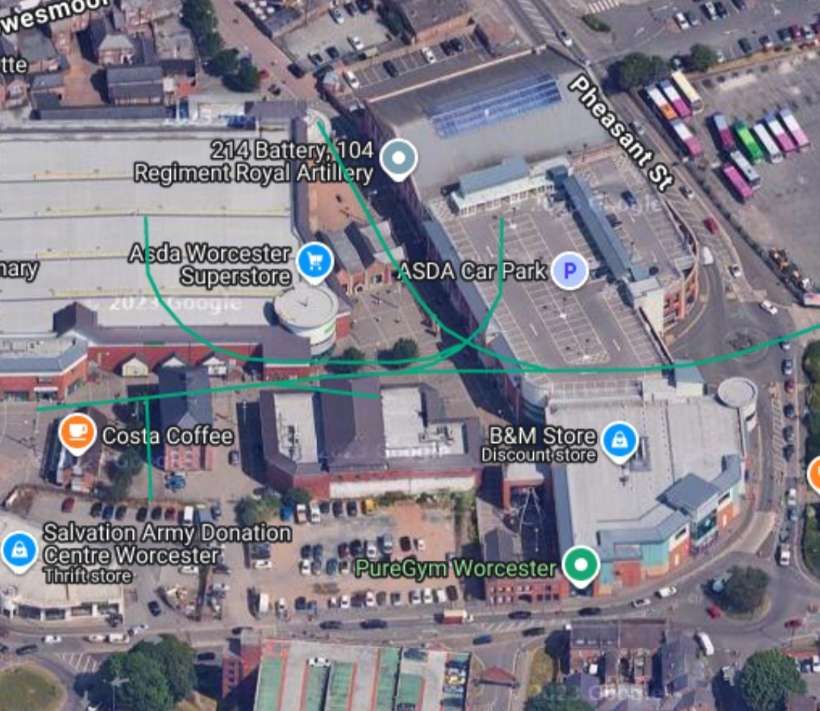

“While the shunter [was] opening the crossing gate, the engine [was] uncoupled from the train. To allow for this the train, which usually consist[ed] of about eight wagons, [was] marshalled with a brake van at each end. The brakes of the leading van [were] applied and the engine [ran] forwards onto a short spur, on which [was] the remainder of a trailing point which once gave access to a factory on the site [which is 1959 was] occupied by the Midland Red Omnibus Company’s depot. The point leading to this spur [was] sprung to act as a catch point protecting the third level crossing, at Pheasant Street, which is the lowest point on the line.” [1: p237]

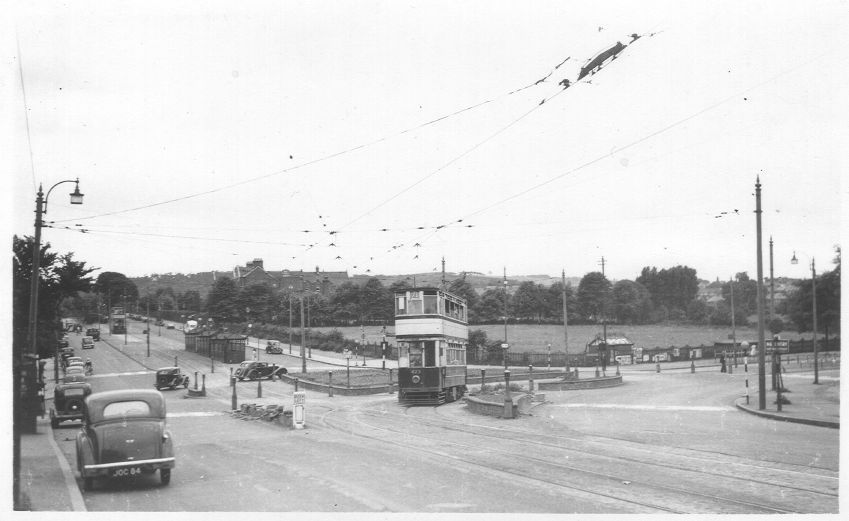

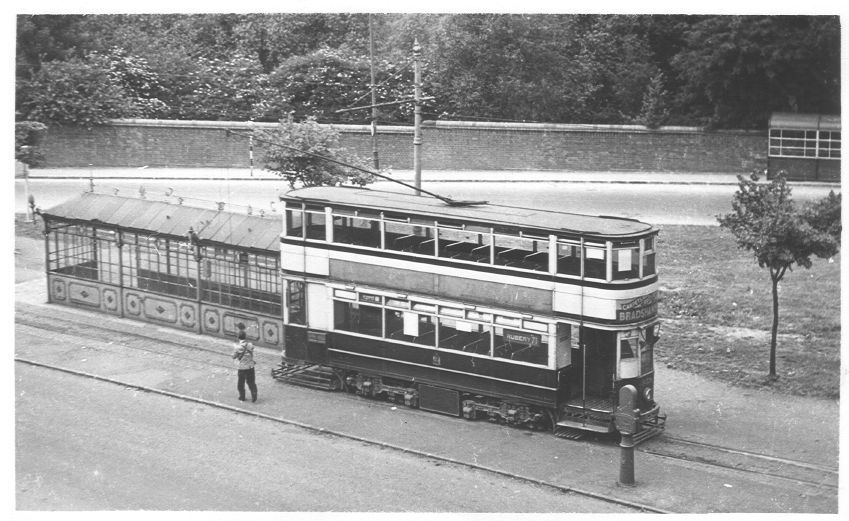

The Midland Red Depot was once the site of City Flour Mills. The site was later redeveloped and used by McKenzie, Clunes & Holland, renamed McKenzie & Holland from 1875, then McKenzie & Holland Limited from 1901, for the manufacturing of railway signalling equipment. Worcester operations of that company closed in 1921. A number of railway branch-lines were used to access the site. The site was acquired in 1927 by the Birmingham and Midland Motor Omnibus Company Limited (BMMO—Midland “Red” Motor Services) in preparation for the expansion required to operate the new Worcester City local bus area network due to start the following year. The purchase included an eight-bay, steel-framed corrugated-iron factory sited between the canal and Padmore Street which was converted for use as a bus depot, and part of former railway sidings from the Vinegar Works branch line to be used for outdoor parking. Work to convert the building included removing the wall that faced onto Padmore Street and replacing it with a series of sliding doors to allow vehicle access. ‘MIDLAND “RED” MOTOR SERVICES.’ was painted in large letters above the doors. The new depot opened on 1st June 1928. The garage was extended in 1930 with the addition of two extra bays built over the former railway sidings at the south end of the main building. The new bays were notably wider and, unlike the original building, could accommodate full-height enclosed double-deck buses. [11]

Pheasant Street had a gated crossing, while the locomotive and its short train were negotiating the crossing on Padmore Street, “a shunter from Hill, Evans & Company, for the benefit of whose vinegar factory the whole operation[was] carried out, … unfastened the padlocks and opened the gates at Pheasant Street level crossing.” [1: p237]

At the Pheasant Street level-crossing, the signals were on one post. small somersault arms control road traffic, with central spectacles, and coupled together directly so that one inclines in the wrong direction when ‘off’. They are provided with a central lamp. “When both shunters [were] satisfied that road traffic at the second and third crossings [was] responding to their flags, the guard in the leading brake van release[d] his brakes and allow[ed] the train to run forward down the slope. … The approach to Pheasant Street [was] quite blind, and the train appear[ed] through the gap in the high walls at the side of the road without audible warning at some 20 m.p.h., and [was] gone as quickly through the gap on the other side of the road. The engine follow[ed] at its leisure, to do any necessary shunting before pulling a train back up to Shrub Hill.” [1: p238]

“Hill, Evans & Co was founded in the centre of Worcester in 1830 by two chemists, William Hill and Edward Evans. The pair started producing vinegar, but later the company also produced: wines from raisin, gooseberry, orange, cherry, cowslip, elderberry; ginger beer; fortified wines including port and sherry; as well as Robert Waters branded original quinine which was drunk to combat malaria.” [6]

“As the company quickly expanded, they purchased a 6 acres (2.4 ha) site at Lowesmoor. In 1850 the company built the Great Filling Hall, containing the world’s largest vat, which at 12 metres (39 ft) high could hold 521,287 litres (114,667 imp gal; 137,709 US gal) of liquid. For a century this made the works the biggest vinegar works in the world, capable of producing 9,000,000 litres … of malt vinegar every year.” [6]

“Movement of wagons within the factory [was] carried out by a small road tractor equipped with a cast-iron buffer beam and a hook for towing with the aid of a rope. For this reason the rails in the factory [were] mostly laid in tramway fashion, flush with the surface.” [1: p238]

One of the provisions of the Worcester Railways Act of 1870, under which the line was built, was that signals must be provided at the public crossings to warn the public when trains required to cross the speed of the latter was also to be limited to 4 m.p.h. A few years ago a Land-Rover was in collision with a train on Shrub Hill Road level crossing. It is understood that legal opinion of the question of liability was sought, and was to the effect that the semaphore signals fulfilled the obligations of the railway to give adequate warning of the approach of a train, and that the attend-ance of a shunter with red flags was unnecessary. Be that as it may, road traffic pays no heed to the semaphores, being mostly unaware of their significance.

References

- A.A. Vickers; An Unusual Branch at Worcester; in The Railway Magazine, April 1959; London, 1958, p236-238.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/120900868, accessed on 7th November 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/120900904, accessed on 7th November 2025.

- https://railmaponline.com/UKIEMap.php, accessed on 7th November 2025.

- https://explore.opencanalmap.uk/canal/worcester-and-birmingham-canal/#7.3/53.952/-2.258, accessed on 8th November 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hill,Evans%26_Co, accessed on 8th November 2025.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EPW005415?check_logged_in=1, accessed on 8th November 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/stuff/list.php?title=Old+Vinegar+Works+&gridref=SO8555, accessed on 8th November 2025.

- https://www.cfow.org.uk/picture.php?/1197/categories, accessed on 8th November 2025.

- https://www.worcesternews.co.uk/resources/images/17365723/?type=responsive-gallery-fullscreen, accessed on 8th November 2025.

- https://www.midlandred.net/depots/index.php?depot=wr, accessed on 10th November 2025.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EPW044990, accessed on 10th November 2025.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EPW044987, accessed on 19th November 2025.