Just a snap shot of the things appearing in the March 1959 issue of The Railway Magazine. [1]

1. There were adverts on the inside of the front cover – 5 of them. …. [1: pii]

The 34th Model Railway Club Model Railway Exhibition was due to take place in Easter Week. It would run from Tuesday March 31st to Saturday April 4th at Central Hall Westminster. On Tuesday provision appears to have been made for the final setting up of layouts, with the exhibition not opening until 12 noon, but the show was to be open until 9.00 pm each evening with an opening time of 10.30am for the remainder of the week.

I wonder what today’s exhibitors and exhibition managers would feel about a show that was 5 days long and a total of 52 hours of operating time? Much of the work setting up for the exhibition must have taken place on the Bank Holiday Monday and dismantling may well have taken place on the Sunday. There must have been quite a few people who gave up a full week’s leave for the sake of the show! Think too of the logistics of providing refreshments for a week-long show!

Getty Images hold a picture of two young boys enjoying a close interaction with some large scale model trams. The image can be found here. [2]

Three of the five adverts on page ii of the magazine related to books. One was for Foyles Bookshop and their newly opened travel bureau in London. Another was for the 5th Edition of ‘World Railways’ – 1,500 railways in 100 countries, 33 underground systems, 291 major manufacturers – published by Sampson Low, London. [3]

Just published in 1959 was O. S. Nock’s, ‘Historical Steam Locomotives’ – An illustrated history of British Locomotives down to the time of the grouping. [4]

And the remaining advert was for the Railway Correspondence & Travel Society’s ‘The Railway Observer’. The advert also highlighted the activities of the RCTS – branches throughout the country, a rail tours library, visits to depots and installations, affiliations to societies overseas and photographic & technical sections!

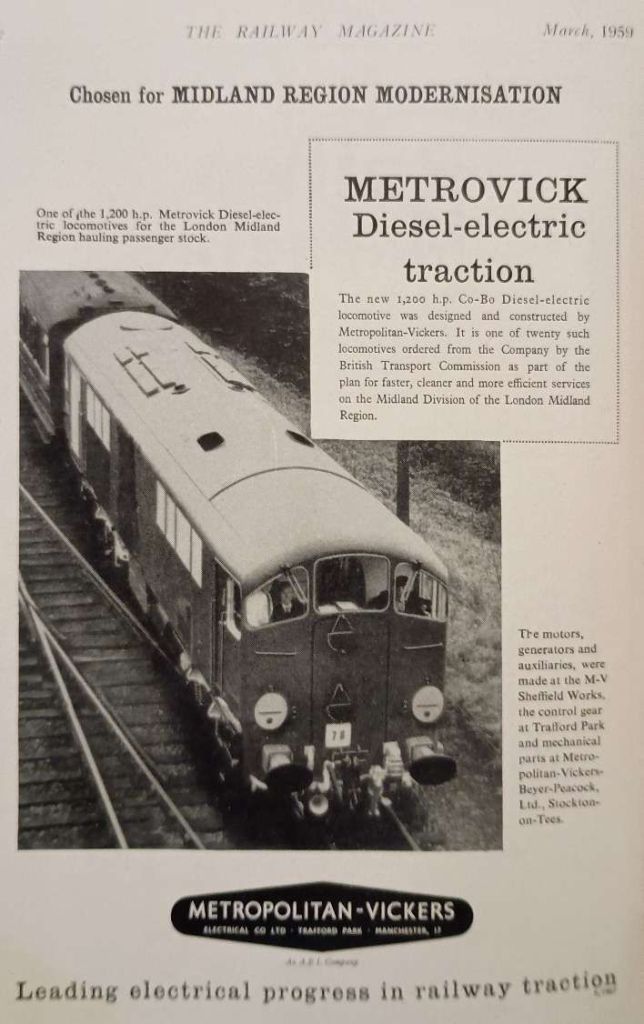

2. Metrovick Diesel-Electric Traction

Metropolitan Vickers Electrical Co. Ltd took out a full page advert for their new Co-Bo Diesel Electric Locomotive under a banner headline of “Chosen for Midland Region Modernisation.”

3. Editorial Notes highlight some of the concerns over the readership at the time and changes in the railway world. These included:

- Open-Type Coaches on BR – In the correspondence columns of the January issue of the magazine there was a letter critical of the British Transport Commission decision to build no more corridor-compartment stock. The March editorial reflects the magazine’s post bag which asks BR to think again! [1: p147] Wikipedia suggests that the corridor stock was still being built until the mid-1960s, so perhaps campaigners were successful. It is also interesting to note that the Mk 1 corridor-compartment stock were in use on BR lines well into the 1980s and are still in use on heritage lines. … “The British Railways Mark 1 SK was the most numerous carriage design ever built in the United Kingdom. The original number series carried was 24000–26217. From 1983, those carriages in the 25xxx and 26xxx series were renumbered 18xxx and 19xxx. … There were two variants, those built for the Midland, Scottish, and Eastern / North Eastern regions had six seats per compartment, with fold-up arm-rests which folded into the seat-back, while those built for the Southern and Western regions, with their heavy commuter loadings into London, had eight seats in each compartment, and no arm-rests. Seating was of the interior sprung bench type.” [5]

- Reservation of Sleeping Berths – apparently, by 1959, it had become common practice for passengers to reserve berths on a number of different sleeper services on British Railways, before finally deciding which service to use. Br brought in revised arrangements on 1st February 1959 which were designed to eliminate disappointment for those who were definitely planning to use a specific service. From February 1959, “Reservations [were] made only on payment of the full fees for the berths required, and three-quarters of this amount [would] be refunded to those who cancel before 4 p.m. on the day before that for which the berths have been booked. No refund [was] be made if cancellations [were] received after that time, except to those whose names [had] been placed on the waiting list, and from whom fees [had] been accepted subject to accommodation being available. Full repayment [was] made to those travellers if berths [did] not become vacant. … The new arrangements [ended] the selfish practice of making alternative reservations on different trains or days.” [1: p147]

- London Midland Region Freight Traffic – “At the end of 1958, two-thirds of the business of the London Midland Region of British Railways [was] derived from freight. To attract new – and regain lost – traffic, a comprehensive short-term plan [was] evolved to streamline the whole of its freight transport. [It was planned that, before the mid-1960s, freight handling would] be speeded by [a] reduction in the number of marshalling yards, … from the [then] 111 to 46, and of depots for traffic from 170 to 48; many of those remaining [would] be extensively modernised. The value of the growing door-to-door service, with railhead collection and delivery by road vehicles, [would] be enhanced by the implementation of the plan. There already [were] about 600 regular overnight express freight trains in the Region, and movement [would] be further accelerated as more wagons [were] fitted with vacuum brakes, and diesel locomotives introduced. [It was thought that] if traders and manufacturers [could] be assured of new standards of service and reliability, the plan should show an early and satisfying financial return.” [1: p147] At a similar time, containerised freight was being developed. Wikipedia tells us that “the marshalling yard building programme was a failure, being based on a belief in the continued viability of wagon-load traffic in the face of increasingly effective road competition, and lacking effective forward planning or realistic assessments of future freight.” [6][7]

- Handling of Mail/Parcels at Euston – in March 1959 structural alterations were underway which would love facilities for handling outward parcels traffic at Euston Station. By the end of 1959, passengers would be able to approach the booking offices and departure platforms without being delayed/impeded by long trains of barrows. Post Office lettermail , under new arrangements would be brought direct to the parcels office on No. 11 platform for loading into vans. The Railway Magazine reported that “A new building [was] to be provided above the station for the sorting and despatch of railway parcels, which [would] be sent by overhead lifts to the platforms for loading. An overhead conveyor, spanning the main departure lines, [would] take parcel post to the platforms from a new G.P.O. sorting depot.” [1: p148] One wonders whether the proposed arrangements would be similar to the ‘telpher‘ which for a time served Manchester Victoria Station. [8]

- Diesels for Scotland – the editor also heralded and welcomed Diesel motive power on the East Coast Main Line North of Newcastle. The welcome was based on the likely acceleration of many services in the Scottish Region. “Between Edinburgh and Aberdeen, for example, almost every start from the principal intermediate stops has to be made up a sharply rising gradient, on which the high starting tractive effort of diesel locomotives would be most welcome. The maximum mileage for diesel power could be obtained by basing the locomotives on Edinburgh, and using them at night for the heavy traffic to and from Newcastle. By day they could work on the Newcastle and Aberdeen services, and perhaps between Edinburgh, Perth and Inverness. The last-named, with its long and steep gradients, is yet another route on which the high tractive effort of diesel locomotives could be used to advantage.” [1: p148]

- Improvements to the Hertford North Line – work that could well have taken two or three years had been condensed into the first half of 1959, with a likely completion date in June 1959. Off-peak services between Wood Green and Hertford North had been replaced by buses. Work was phased so that the 6.5 miles from Wood Green to Crews Hill was undertaken in March, the next 8 miles to Hertford being worked on in April, May and June. All services on the branch would then be DMU.s or diesel-hauled “and maximum speeds of 70 mph … permitted. Improvement of the track is an essential preliminary to electrification.” [1: p148]

- London Underground – apparently delays to some services had been caused by passengers refusing to move from one train to another when equipment failure has occurred or because a train was running far behind schedule. Lack of information was cited as the cause. London Underground was, in March 1959, installing new train information systems, a move welcomed by The Railway Magazine. [1: p148]

- 1910 – Rail versus Air – the editor also looked back to 1910 and specifically to the fist flight between London and Manchester. Which was a competitive exercise with a large prize of £10,000 offered by The Daily Mail. The two competitors, Louis Paulhan and Claude Grahame-White, chose to follow the LNWR main line. The company assisted by painting distinctive marks on sleepers to show where branch lines diverged (presumably to ensure the aeroplanes continued on the main line). Apparently, The Railway Gazette at the time said: “The flying machine may possibly become a serious competitor of the railway before very many years. … Both the aviators have been aided and abetted by the Premier Line in such ways as the provision of inspection cars in which to travel over the route beforehand, whilst a special train followed Mr. Paulhan all the way.” [1: p148][1: p167-168, 200]

4. Railbuses on Western Region Branches

A short note appeared at the bottom of the pages proceeding the central photographic pages of the magazine. That note marked the introduction of diesel railbuses on the Kemble to Cirencester and Kemble to Tetbury branches of the Western Region on 2nd February 1959. These were the first sections of the Western Region to be served in this way. The railbuses accommodated “48 passengers with a small area for luggage. The services over both branches [had] been intensified. In addition, new halt facilities [were] afforded at Chesterton Lane on the Cirencester branch, and at Church’s Hill, Culkerton and Trouble House on the Tetbury branch.” [1: p172]

5. Main Articles

The Railway Magazine of March 1959 also included substantial articles:

The Railways of Barrow by Dr M.J. Andrews, [1: p149-157, p200];

Farewell to the ‘Leicesters’ by R.S.McNaught, [1: p158-160, p192];

The first part of Reminiscences of a Locomotive Engineer by George W. Mcard, [1: p161-165]; With 4 ft 7.25 in Wheels by K. Hoole, [1: p168-172];

British Locomotive Practice and Performance part of a long series by O.S. Nock, [1: p185-192];

The second part of Railway Development in Liverpool by M.D. Grenville & G.O. Holt, [1: p193-200];

New Railways in Quebec, [1: p201-203, p206]; and

A full list of British Railways Motive Power Depots. [1: p204-206]

6. Notes and News

Notes & News fill eight pages [1: p210-217] after three pages of letters. [1: p207-209] The Railway Magazine reported that:

- Cheaper first class fares on Saturdays would be extended, after an experimental period on services between London and Manchester, to journeys between London and Liverpool, London and Glasgow and London and Edinburgh until the end of April. Return journeys could only be made on the next day or the following Saturday with no breaks in journeys permitted. [1: p210]

- Little still remained, in 1959, of the Saundersfoot Railway other than tunnels and a few ruined buildings. Reference was made to an article in The Railway Magazine’s November-December 1946 issue. More can be found about this narrow gauge line in two articles, here [10] & here. [11] There is also a note about the Cambrian Hotel at Saundersfoot. The hotel’s sign bore a shield which contained a gold 2-2-0 tender loco with a wagon on a red background. [1: p210]

- Construction work had just commenced on the new Oxford Road Station in Manchester [1: p210-211] and on major alterations to Dover Marine Station in Kent. [1: p211]

- Some Western Region Train Services had seen timetable alterations as of January 1959. [1: p211]

- More Diesel Services on the North Eastern Region – January 1959 saw the introduction of many additional diesel-powered workings on local services. The early 1959 introductions meant that the switch from steam to diesel on local services was almost complete. [1: p211]

- From 2nd February, the 8.15 am up and the 4.45 pm down services between St. Pancras and Nottingham Midland Station were named the ‘Robin Hood‘. [1: p211]

- 2nd February saw five station closures on the Eastern Region: Offord & Buckden, near Huntingdon; Sturton, and Blyton, between Retford and Barnetby; and Haxey & Epworth, and Walkeringham, between Doncaster and Gainsborough. Greenock Princes Pier and Greenock Lynedoch Stations on the Scottish Region also closed on 2nd February. As did the Upper Port Glasgow goods depot. In the North Eastern Region, from 16th February, Gristhorpe Station, on the Hull-Scarborough line, was closed. On 28th February, the service from Acton Town to South Action was withdrawn and the Station at South Acton was closed to passengers. [1: p211, p212]

- The South Wales Transport Bill permitting the closure of the Swansea & Mumbles Railway had its second reading in the House of Lords in February. [1: p212]

- The 3 ft gauge Cavan and Leitrim Railway would close on 1st April. More about this line can be found here, [12] here, [13] here, [14] here, [15] here, [16] here, [17] here, [18] here, [19] here, [20] and here. [21] [1: p212]

- The Bluebell Line – efforts were being made to establish a preservation society to reopen the Lewes to East Grinstead branch. Volunteers were being sought and an inaugural meeting arranged on 15th March in Haywards Heath. [1: p212] The Bluebell Line became the UK’s first preserved standard-gauge line in 1960, starting with the Sheffield Park to Horsted Keynes section, and later extended to East Grinstead. The first public service ran on 7th August 1960. [22]

- Other items included details of: an educational tour by the Scottish Region’s Television Train, [1: p212]; new Electrically-Operated Train Departure Indicators at Shenfield [1: p212-213]; the LNWR Royal Saloon which had been on display at the Furniture Exhibition (January 28th to February 7th) at Earls Court, [1: p213]; the Golden Jubilee of the Stephenson Locomotive Society, [1: p213]; the AGM of the Festiniog (STET) Railway Society and the special trains being organised across the country to get delegates to and from the meeting, [1: p213]; Railway Enthusiasts’ Club Tours, [1: p213-214] news associated with Locomotives. [1: p214-217]

7. The Why and the Wherefore [1: p218-219] includes a series of replies to readers’ letters, particularly:

- The North Sunderland Railway – which opened in August 1898 for goods and December 1898 for passengers, and closed on 27th October 1951. [1: p218] The branch ran from Chathill to Seahouses, with an intermediate station at North Sunderland. Chathill was on the main line of the North Eastern Railway between Morpeth and Berwick. The branch was four miles in length and standard-gauge single track. [23]

- Water Troughs on the Southern Region – the former Southern Railway had no water Troughs as none of its non-stop runs were long enough to warrant replenishment of water levels. [1: p218-219]

- Chalvey Halt (GWR) – was on the G.W.R. branch from Slough to Windsor. It had only a short life: opened on 6th May 1929, and closed on 7th July 1930.

- Proposed New Branch to Looe – “a new seven-mile branch from St. Germans to Looe was projected by the Great Western Railway under the £30 million Government scheme of November, 1935, for the construction and improvement of railways, to alleviate unemployment. The branch was to leave the main line to Penzance about 13 miles west of St. Germans Station, and terminate at a station on the high ground at East Looe. The engineering works were heavy, and included a tunnel 2,288 yd. long, west of Downderry, two shorter tunnels, and long viaducts at Keveral and Mildendreath. The construction of the four miles from Looe to Keveral (which included both viaducts and the long tunnel) had been begun by the autumn of 1937, but this section was far from complete, and the remainder of the line had not been begun when the outbreak of war, in September, 1939, caused the works to be suspended.” [1: p219] Early in 1959, construction had not been resumed, and there appeared to be little prospect that the scheme would be revived. The new line was intended to replace the existing line from Liskeard to Looe. [24]

- The Stirling & Dunfermline Railway – “was authorised on 16th July 1846, and was opened from Dunfermline to Alloa on 28th August 1850, and from Alloa to Stirling on 1st July 1852. Powers for branches from Alloa to Tillicoultry and to Alloa Harbour were included in the Act of Incorporation, and these lines were brought into use on 3rd June 1851, the former to a temporary terminus at Glenfoot, about half a mile short of Tillicoultry. The line probably was completed in December 1851, but a record of the exact date of opening to Tillicoultry Station does not appear to have survived. The Alloa Harbour branch had passenger services (to Alloa Ferry) only from its opening until the main line was completed to Stirling, some twelve months later. Provision was made in the Act of 1846 for the Stirling & Dunfermline Railway to be leased by the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway … the lease came into effect on 5th December 1850. The Stirling & Dunfermline Railway was vested in the Edinburgh & Glasgow as from 4th June 1858, under powers obtained on the 28th of that month.” [1: p219] The line was completed throughout in 1952. “A predecessor line, the Alloa Waggonway, had been developed as a horse-operated waggonway in the 18th century, bringing coal from the hinterland to Alloa and Clackmannan harbours; in its day th[at] line was technologically advanced, but it was eclipsed by the modern Stirling and Dunfermline line.” [25]

Closure was a drawn out affair – passenger trains on the Alva branch ceased to run from 1st November 1954. A limited service to Menstrie continued until complete closure on 2nd March 1964. The S&DR Tillicoultry branch, by then regarded as part of the Devon Valley line, closed to passengers on 15th June 1964 and to goods traffic on 25th June 1973.

NBR route passenger trains over the Alloa Viaduct were withdrawn from 29 January 1968, and through goods train operation ceased in May 1968. A limited goods service to supply coal to the stationary steam engine that operated the Forth Swing Bridge from Alloa continued until May 1970.

Passenger services on the Stirling to Dunfermline main line were closed on 7th October 1968; through goods services were closed on 10th October 1979. West of Dunfermline, the line through Dunfermline Upper station served Oakley Colliery until 1986 when the pit closed. The line remained in place as far as Oakley until 1993, but subsequently the majority of the route became Cycle paths in 1999 as National Route 764. Shortly afterwards, studies began for the reopening of the western end of the line from Stirling to Alloa, as part of the Stirling-Alloa-Kincardine rail link. [25] - Enginemen’s Wages and Duties – In March 1959, wages of a first class driver and fireman on British Railways were £11 9s and £9 10s respectively. These rates were the same inside London as outside the London area. “A good day’s work for an engine crew [was] considered to be 140 miles, and on stopping trains most men did] considerably less. If they [did] more than 140 miles, they receive[d] an hour’s pay for each additional 15 miles. They also receive[d] overtime at the usual rate of time-and-a-quarter for time worked over their normal hours of duty, and night pay at time-and-a-quarter, and Sunday pay at time-and-three-quarters, if applicable. The standard basic turn of duty [was] eight hours. At all main-line depots, the duties of drivers and firemen [were] arranged in links, progressing from junior work, such as shunting, to express passenger trains. On the West of England line of the Western Region … a typical example of a week’s roster for a driver [was]:- Monday: 9.30 a.m., spare; Tuesday: 3.30 p.m., Paddington to Plymouth; Wednesday: 8.30 a.m., Plymouth to Paddington; Thursday: 3.30 p.m., Paddington to Plymouth; Friday: 8.30 a.m., Plymouth to Paddington; Saturday: 9.30 a.m., spare. The driver therefore works between Paddington and Plymouth, 225 miles.” [1: p219] £11 9s had the same buying power as approximately £234.50/wk (£12,194/annum) in 2025. [26] (Train driver pay in the UK for 2025 varies significantly by operator, but generally falls between £30,000 and £80,000 annually, with averages around £50,000-£70,000, influenced by experience and location, with London roles and newer deals (like TfL’s £80k for Tube drivers) pushing higher! [27]

References

- The Railway Magazine, Tothill Press Ltd, London, March 1959.

- https://media.gettyimages.com/id/1482216384/photo/model-railway-club-exhibition-1959.jpg?s=612×612&w=gi&k=20&c=jqf0T8qPJ0p1RAgiS1j7o0qMw8LZmnQ3epxpSlCLNdI=, accessed on 18th December 2025.

- Henry Sampson; World Railways; Sampson Low, London, 1958/1959.

- O. S. Nock; Historical Steam Locomotives; Adam & Charles Blank, London, 1959.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_Corridor, accessed on 18th December 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Rail, accessed on 29th December 2025.

- T. R. Gourvish & N. Blake; British Railways, 1948–73: a business history; Cambridge University Press, 1986, p286–290.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2018/12/07/manchester-victorias-telpher.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Railbus_at_Tetbury_railway_station_(1960s).JPG, accessed on 20th December 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2022/09/26/railways-in-west-wales-part-1c-pembrokeshire-industrial-railways-section-b-the-saundersfoot-railway-first-part.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2022/09/28/railways-in-west-wales-part-1c-pembrokeshire-industrial-railways-section-b-the-saundersfoot-railway-second-part.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/04/26/the-cavan-leitrim-railway-arigna-valley-railway

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/05/09/the-cavan-and-leitrim-railway-a-short-history-and-a-look-at-dromod-station

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/05/19/the-cavan-and-leitrim-railway-dromod-to-mohill

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/05/24/the-cavan-and-leitrim-railway-mohill-to-ballinamore

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/05/29/the-cavan-and-leitrim-railway-ballinamore-to-ballyconnell

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/06/07/the-cavan-and-leitrim-railway-ballyconnell-to-belturbet

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/06/15/the-cavan-and-leitrim-railway-the-arigna-tramway

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2019/07/01/the-cavan-and-leitrim-railway-a-miscellany

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2023/04/28/the-cavan-and-leitrim-cl-railway-again-belturbet-railway-stationhttps://rogerfarnworth.com/2023/04/28/the-cavan-and-leitrim-cl-railway-again-belturbet-railway-station

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2024/12/27/the-cavan-and-leitrim-railway-at-dromod-again

- https://www.bluebell-railway.com/about-bluebell, accessed on 21st December 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Sunderland_Railway, accessed on 21st December 2025.

- https://saltash.org/south-east-cornwall/Propose-shortcut-to-Looe.html, accessed on 21st December 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stirling_and_Dunfermline_Railway, accessed on 21st December 2025.

- https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator, accessed on 21st December 2025.

- https://www.reed.com/articles/train-driver-salary-benefits, accessed on 21st December 2025.