The featured image at the head of this article (above) is Highland Railway No. 79, ‘Atholl’, a 4-4-0 Clyde Bogie, built Jun 1886. Renumbered 79A in Mar 1917. Only one of this class survived into LMS days No. 14278. It originally carried the name ‘Fife’ and was ‘Hughland Railway No. 82. Renamed ‘Durn’ in 1900, a name it retained until 1916, it was renumbered 82A in March 1917. It continued in service until being withdrawn in April 1930. [30][31]

Trains Illustrated No. 18 which was published in 1976 focussed on The Highland Railway. [1] The introductory article, ‘Highland Retrospect’, was written by Paul Drew. [1: p4-11]

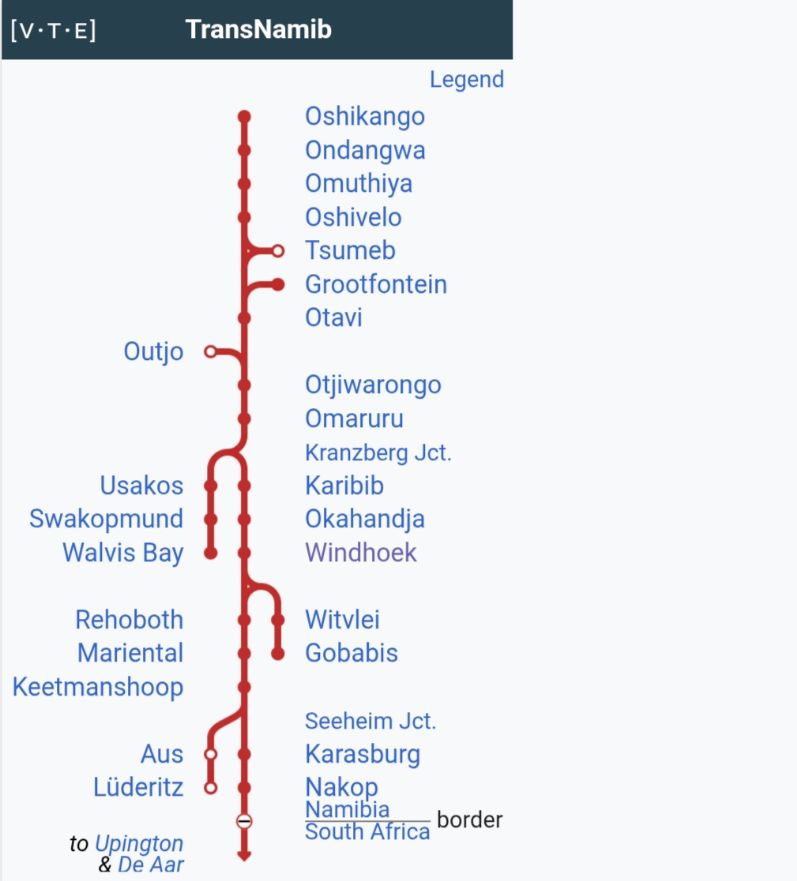

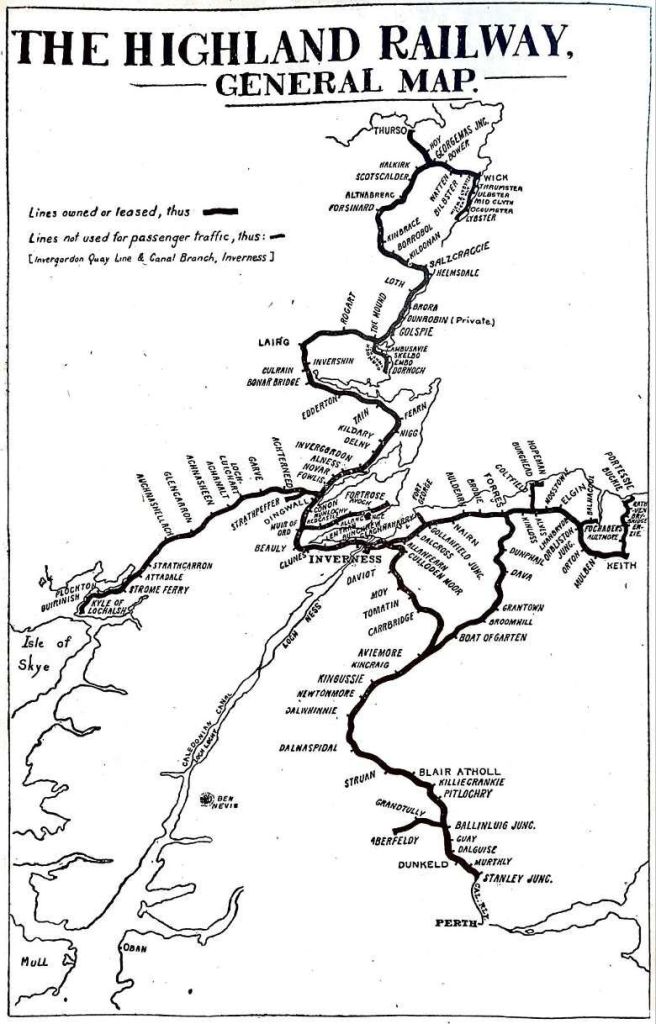

The Highland Railway (HR) Company was based in Inverness. It was formed by merger, absorbing over 249 miles (401 km) of line. It continued to expand, reaching Wick and Thurso in the north and Kyle of Lochalsh in the west, eventually serving the counties of Caithness, Sutherland, Ross & Cromarty, Inverness, Perth, Nairn, Moray and Banff. Southwards, it connected with the Caledonian Railway at Stanley Junction, north of Perth, and eastward with the Great North of Scotland Railway at Boat of Garten, Elgin, Keith and Portessie. [6][7][17: p29]

The direct route to Perth eliminated the need for a change of trains at Aberdeen (and for some time a half mile journey between two railway stations). “It gave a route virtually under one ownership between Inverness and Perth. The greatest benefit lay, however, in the shortening of the journey. Previously the distance by rail from Perth to Inverness had been 198 miles; it now became 144. This represented a saving of about 24 hours in travelling time, and a corresponding reduction in fares.” [17: p27]

Earlier articles about the Highland Railway network can be found here, [15] here, [3] and here. [16] In this article:

we follow the line from Forres via Dava to Perth

- We follow the line from Forres via Dava to Perth.

- We look at the Highland Railway’s locomotive superintendents and at least some of its locomotives.

The First Direct Line Between Inverness and Perth (via Forres) – the Dava Line

H. A. Vallance tells us that “The proposed new railway through the Central Highlands left the Inverness & Aberdeen Junction Railway at Forres, 24 miles East of Inverness, and turning sharply to the south, rose steeply for several miles to cross the hills separating the valley of the Findhorn from Strathspey. Beyond the summit at Dava, 1,052 ft above sea level, the approximate course of [a] route surveyed … in 1845 was joined, and the line proceeded by way of Grantown and the west bank of the Spey to Kingussie. There followed a long, steep climb up the northern slopes of the Grampians to the head of the Druimuachdar Pass, and a corresponding descent to Blair Atholl and the Pass of Killiecrankie. Crossing the Tay near Dalguise, the line reached Dunkeld, where it made an end-on junction with the Perth & Dunkeld Railway.” [17: p24]

The enabling Act of Parliament was passed in July 1861 and authorised the Inverness & Perth Junction Railway to take control of the Perth & Dunkeld Railway. That amalgamation took place in February 1864.

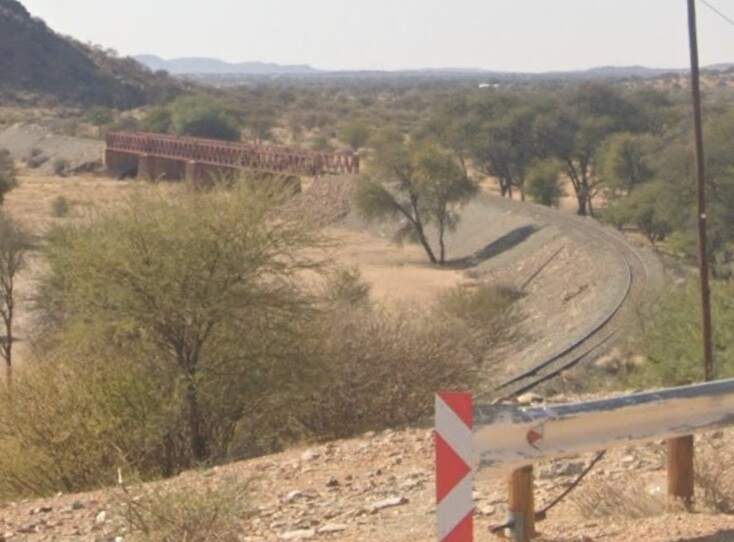

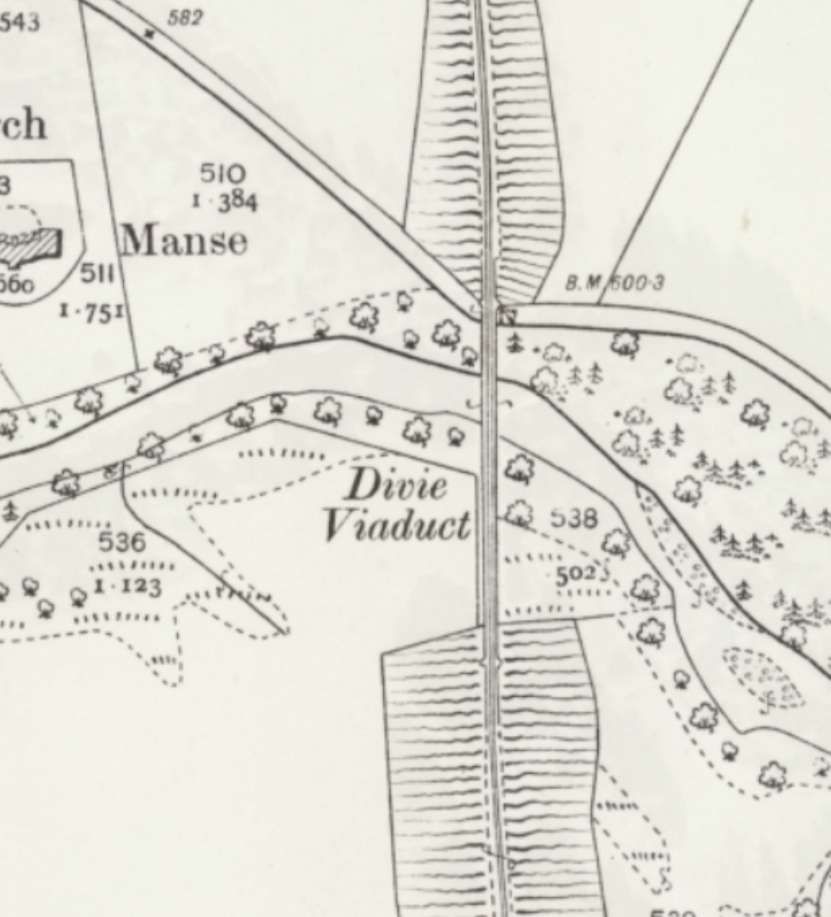

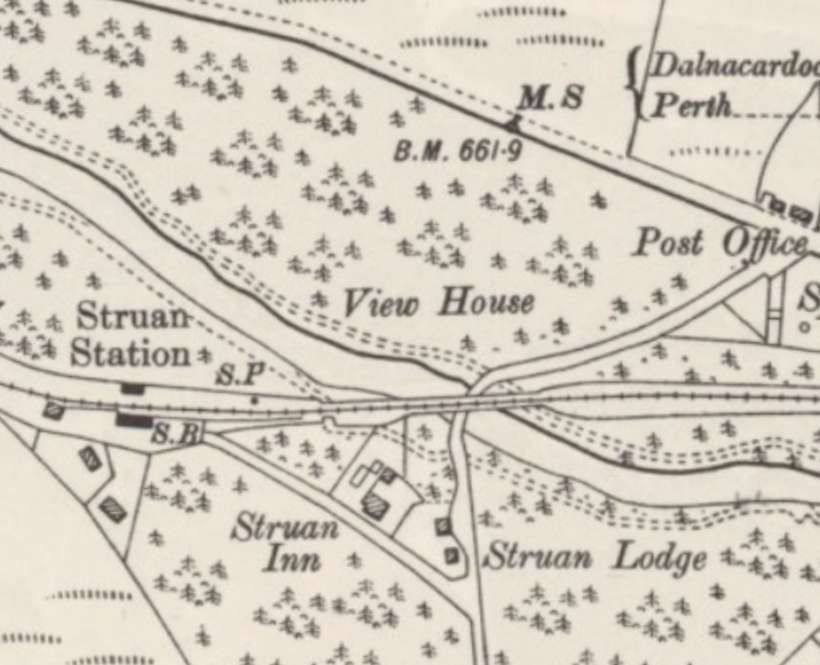

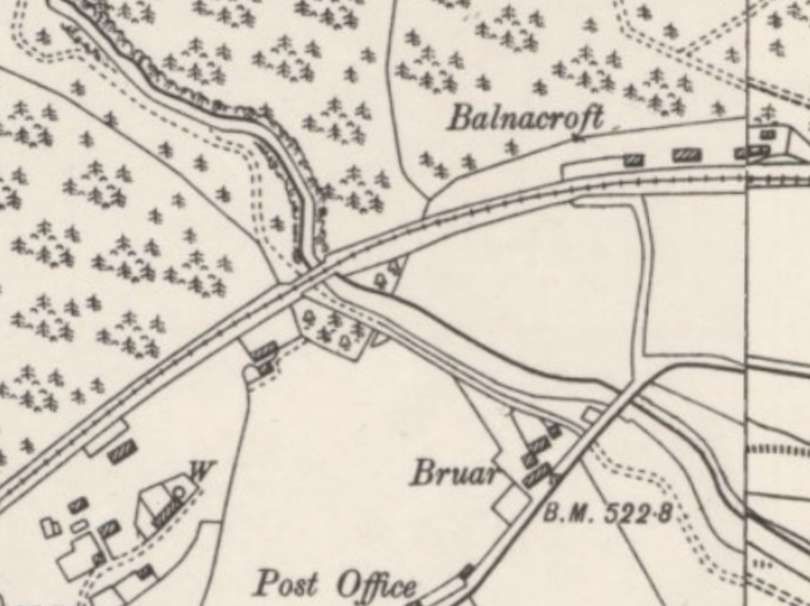

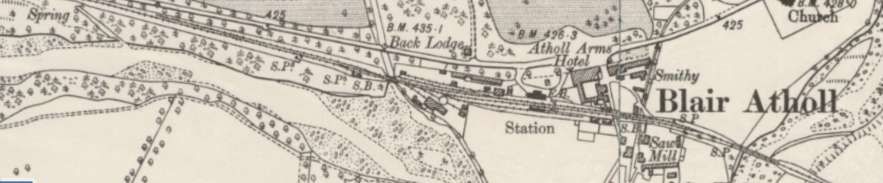

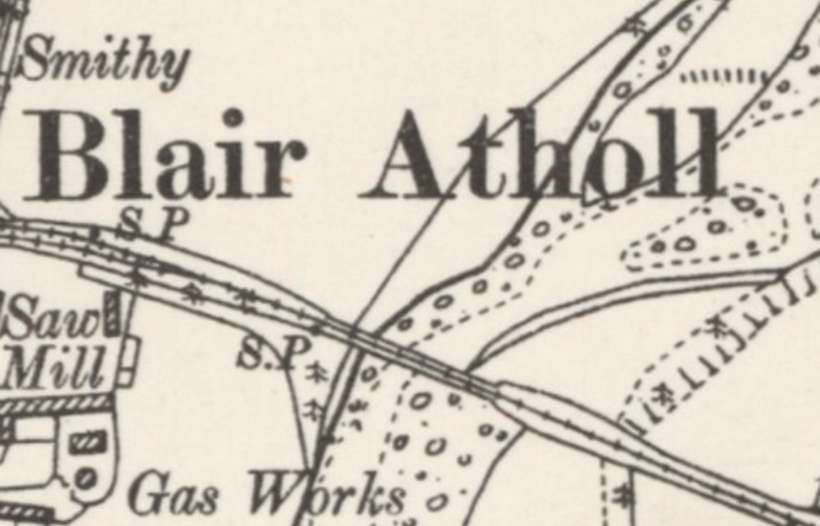

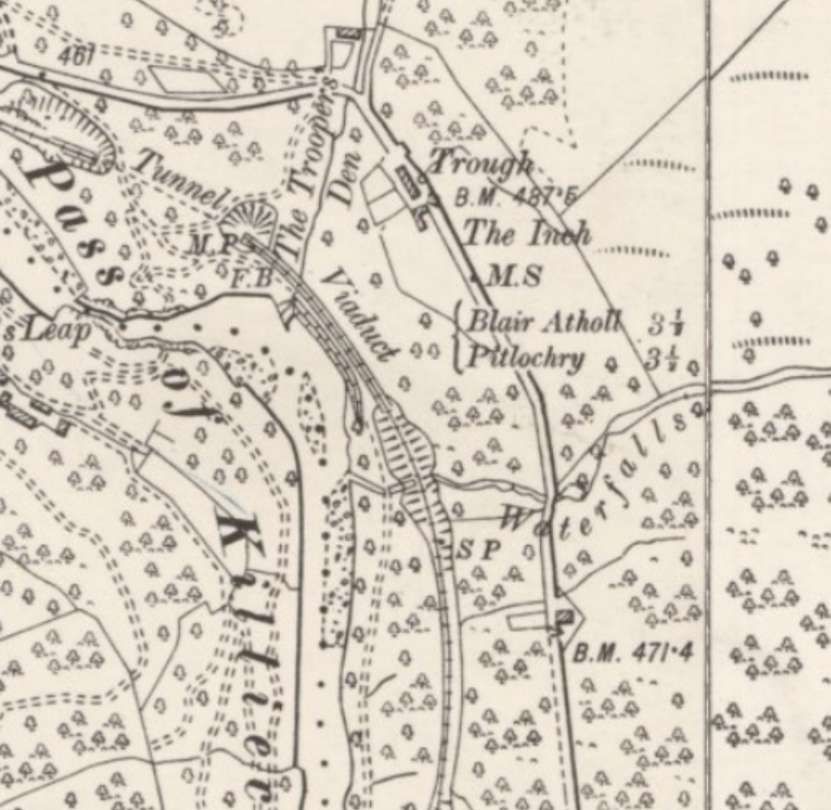

Work on the line commenced in October 1861. The first 13 miles (Dunkeld-Pitlochry) opened at the beginning of June 1863. The length from Forrest to Aviemore opened in early August of the same year. The last length (Aviemore-Pitlochry) was completed in September, just a month or so later. Vallance notes: “The chief engineering works on the line were the seven-span masonry viaduct over the Divie, near Dunphail, 477 ft long and 105 ft high; the girder bridge across the Tay, near Dalguise, 515 ft long and 67 ft high; and the ten-span masonry viaduct, 54 ft high, over a deep ravine in the Pass of Killiecrankie. Smaller masonry bridges were required to carry the railway over the Bran, north of Dunkeld, and the Garry, at Struan. The latter was remarkable in that its main span crossed not only the river, but also the stone bridge carrying the Rannoch Road over the Garry at the same point. At Blair Atholl the Tilt was crossed by a single-span lattice-girder bridge. … Only two short tunnels were found necessary-one in the Pass of Killiecrankie (128 yd long), and the other north of Dunkeld (350 yd long). South of Dunkeld there was a third tunnel (310 yd long), but this had, of course, been constructed by the Perth & Dunkeld Railway. (These, incidentally, were the only three tunnels on the Highland Railway.)” [17: p25]

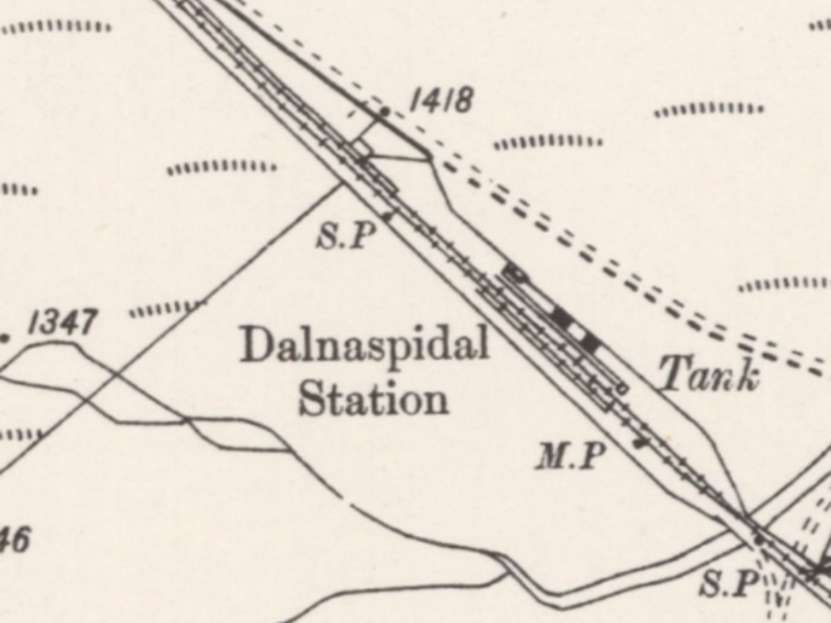

“Some time elapsed before all the stations were ready to be opened, a few of the smaller ones being left until communication between Forres and Perth had been established. Thus accommodation was not provided at Dava until 1864, and Killiecrankie and Dalnaspidal until 1865.” [17: p25]

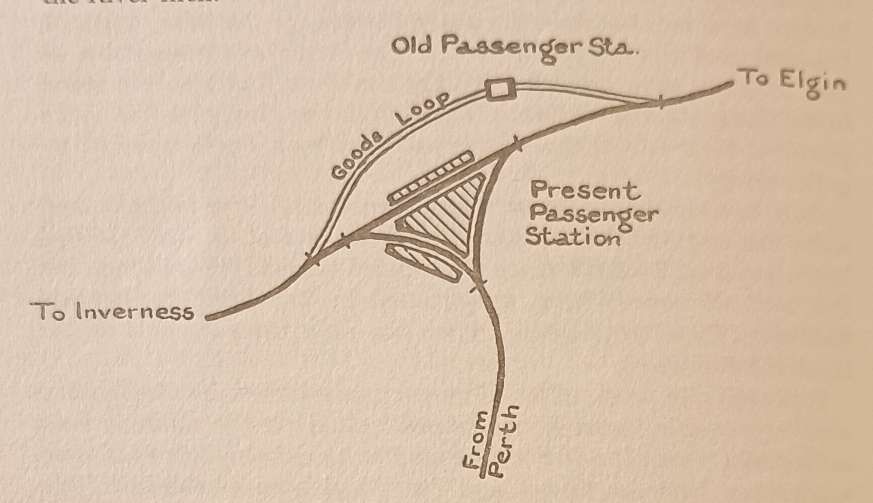

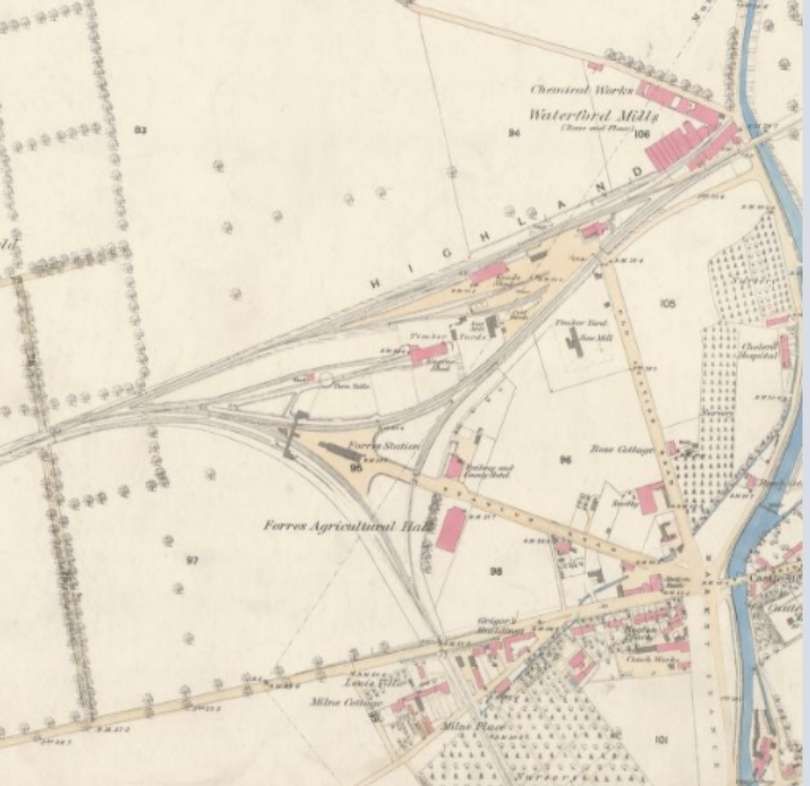

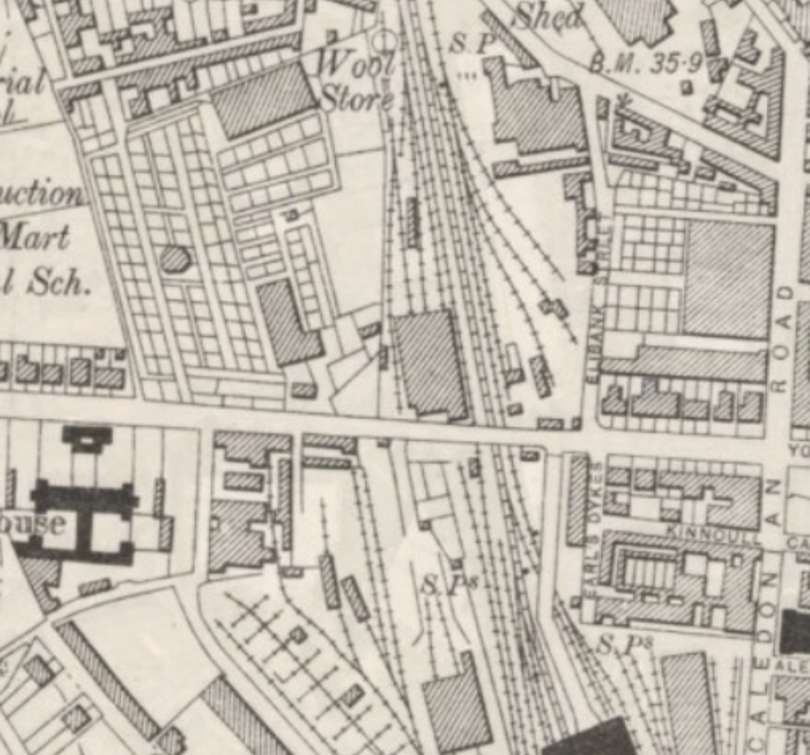

We have already looked at the line from Keith to Inverness. The original station at Forres was not suited to becoming a significant junction station. Valance provides a sketch of the revisions at Forres. …

Before following the route below, you may well enjoy watching a video about The Dava Way. … [28]

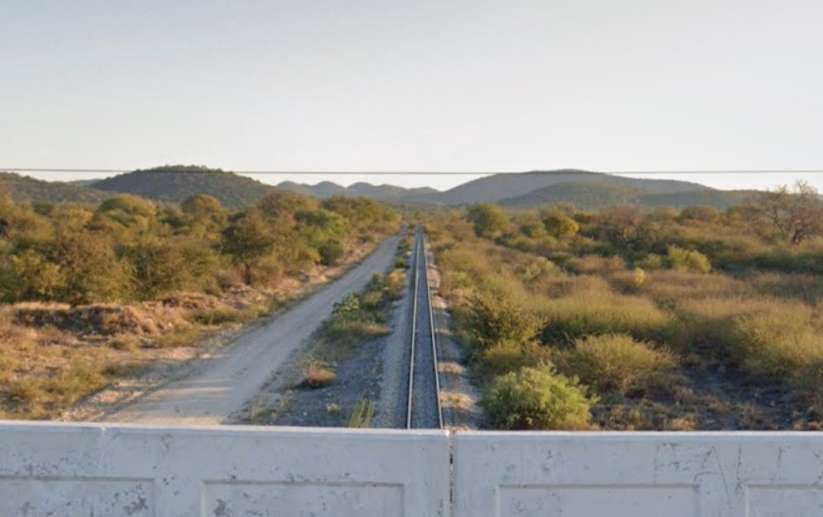

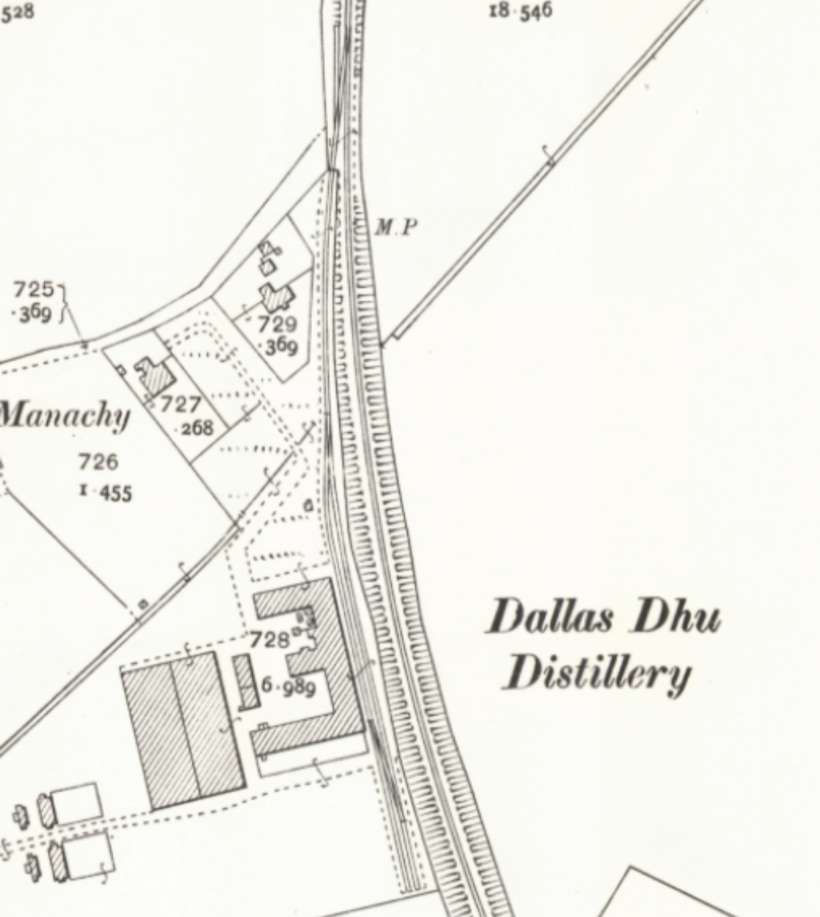

South of Forres, the line ran close to the Dallas Dhu Distillery which had its own sidings, before climbing to Dunphail Railway Station.

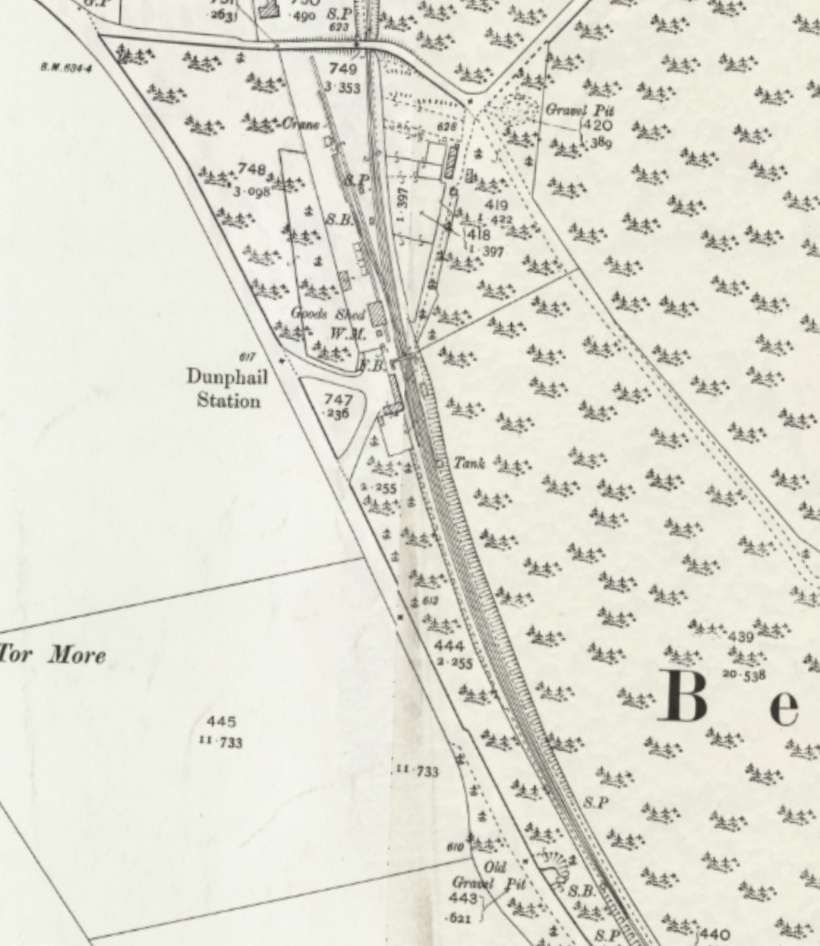

A short distance Southeast of Dunphail Railway Station, the line crossed the Divide Viaduct (over the river of the same name). The viaduct still stands in the 21st Century and carries the Cava Way footpath.

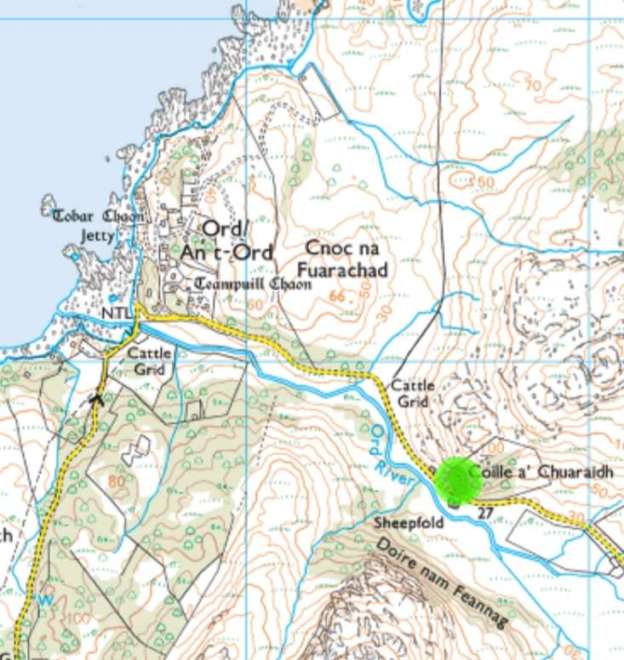

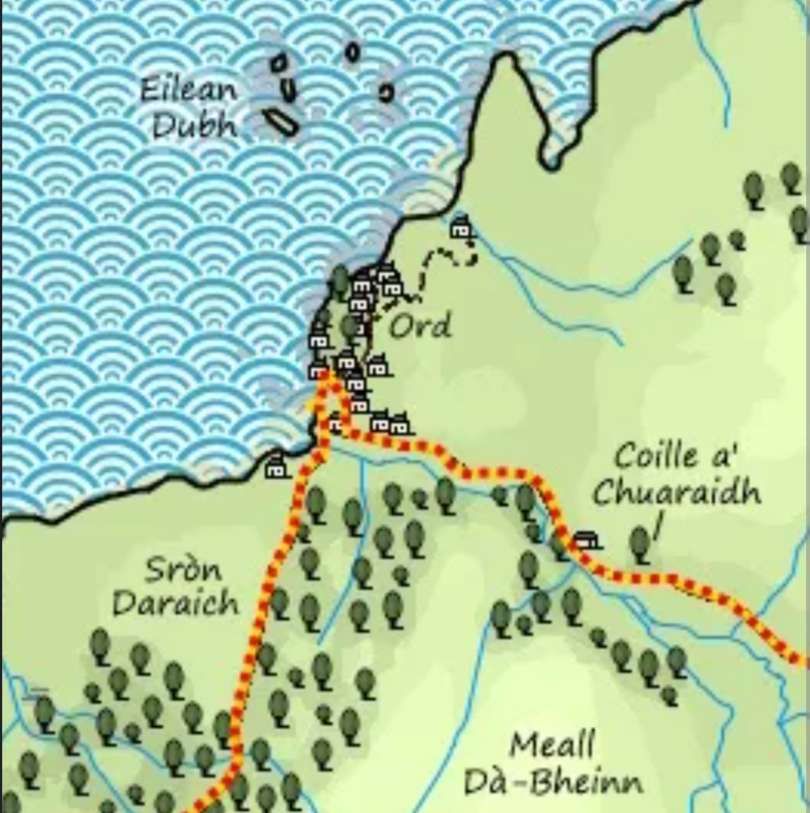

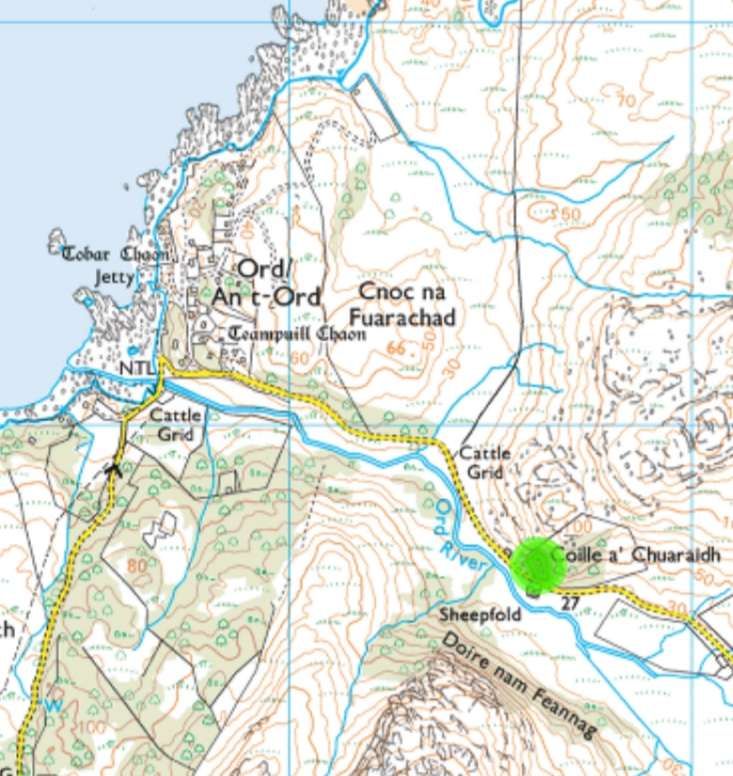

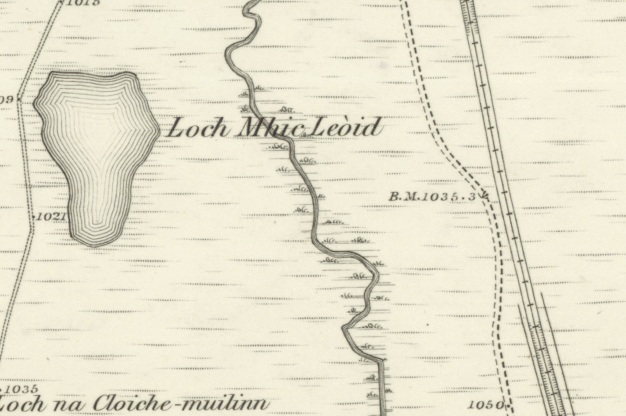

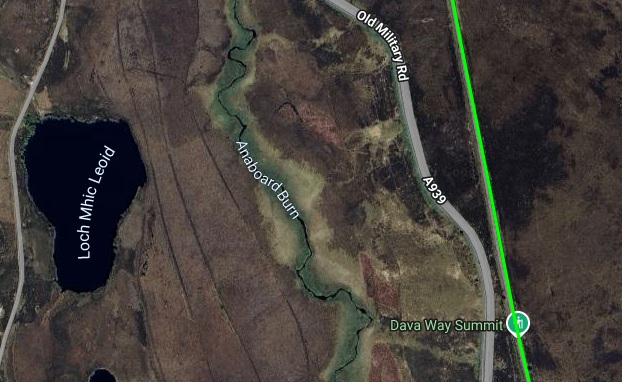

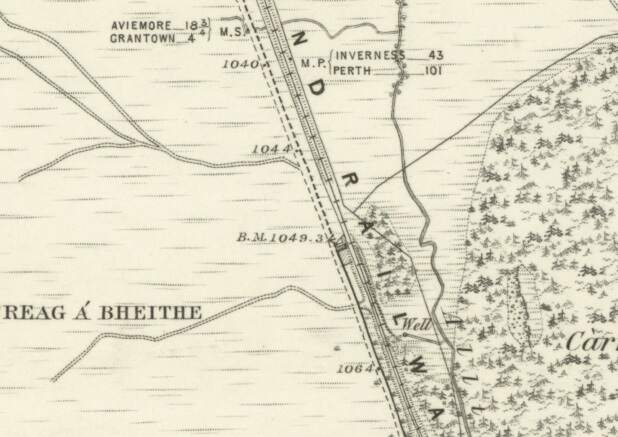

Some distance further South the line reached Dava Railway Station. … The NLS records of the 35″Ordnance Survey do not cover the line heading South, so we now use the 6″ Ordnance Survey. …

Wikipedia tells us that, “At 985 feet above sea-level, Dava was the third highest station on the Highland Railway network. The summit that followed south of the station (Dava Summit) reached 1,052 feet. … The station was located in sparsely populated moorland, along a dirt track near the junction of the A939 and A940 (OS Grid Reference NJ008389). The purpose of a station at this location was to provide a passing loop with water columns (15 miles from Forres and 16 miles to the first junction at Boat of Garten), although the station did provide some facilities for the area, such as a post office. … The surrounding area is wild moorland (The Dava Muir).” [26]

Goods services at Dava were first to end; the date of closure was 27th January 1964. A passenger service continued until 18th October 1965, when the station closed completely. The station building, stationmaster’s house, and platforms still remain. The stationmaster’s house is a private residence.

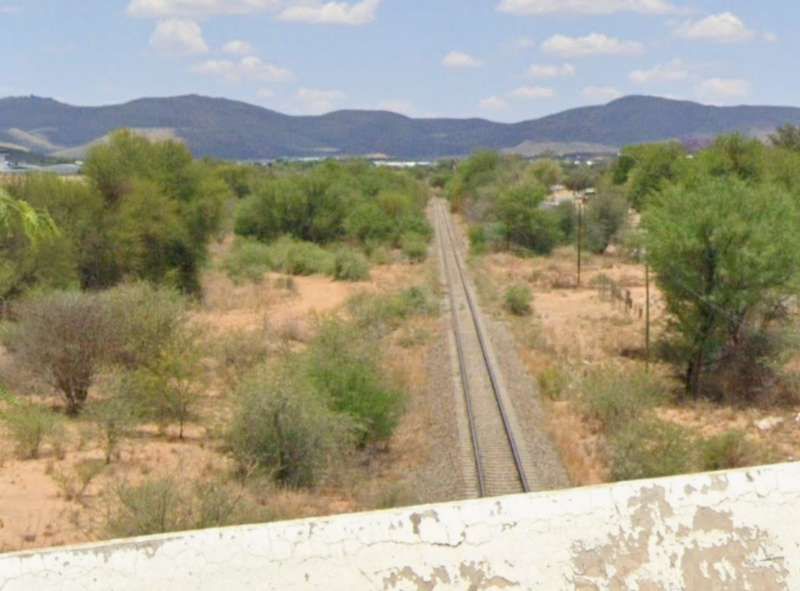

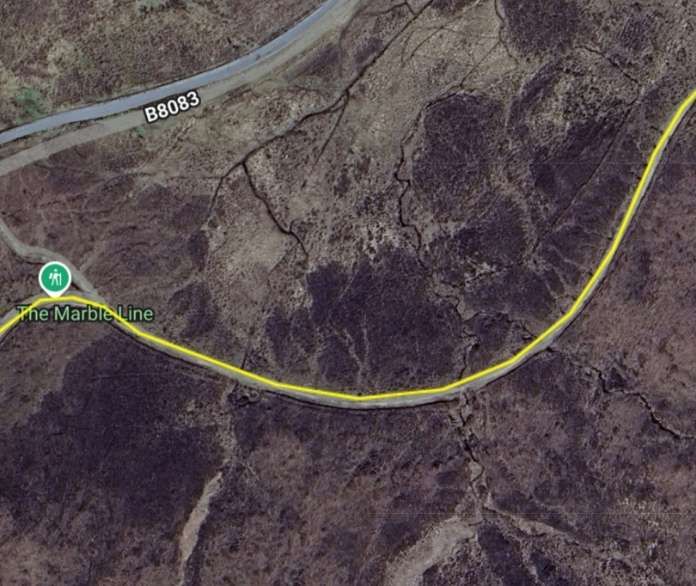

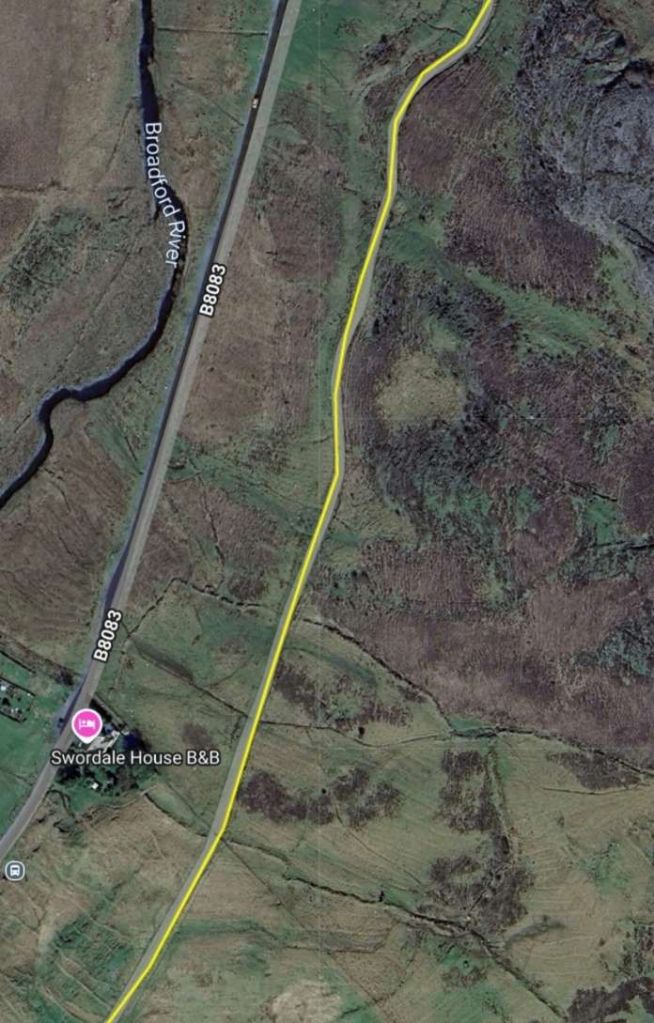

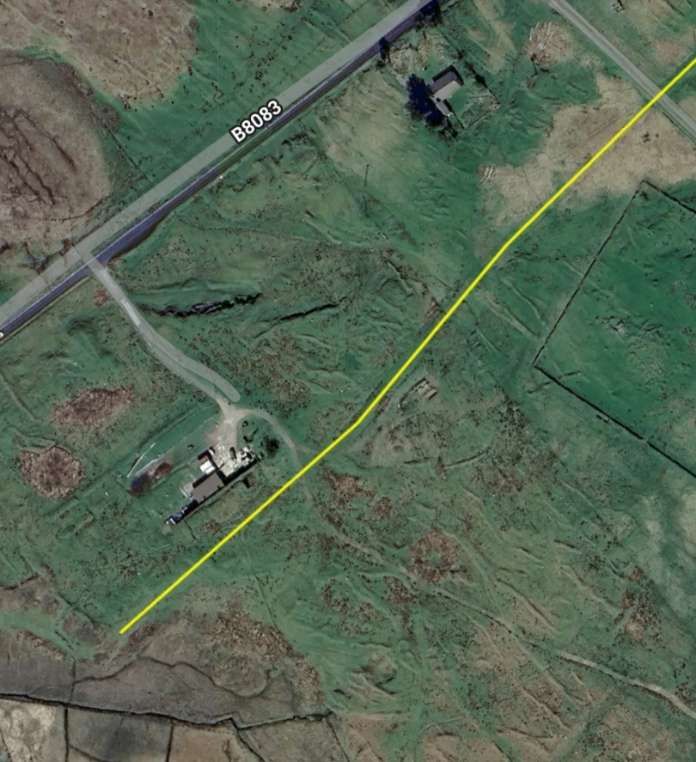

South of Dava the line ran almost due South and continues to provide the formation for the Dava Way [43] which reaches a summit between the locations of Dava Railway Station and Castle Grant Platform.

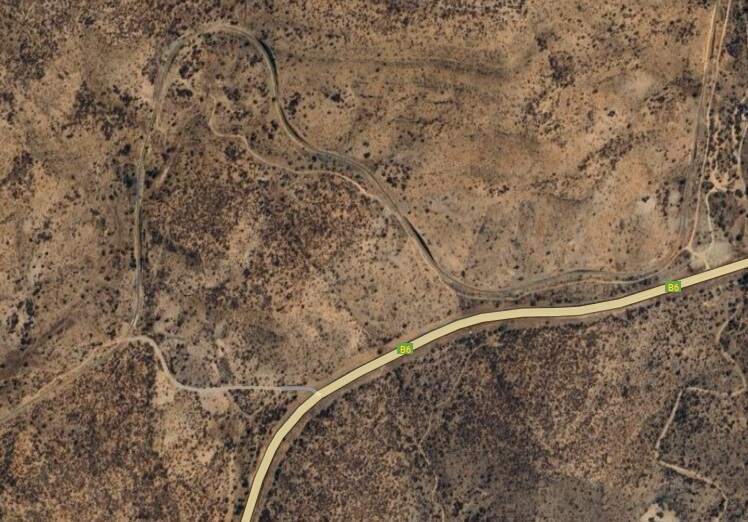

The line snaked back and forth following the contours as it travelled South.

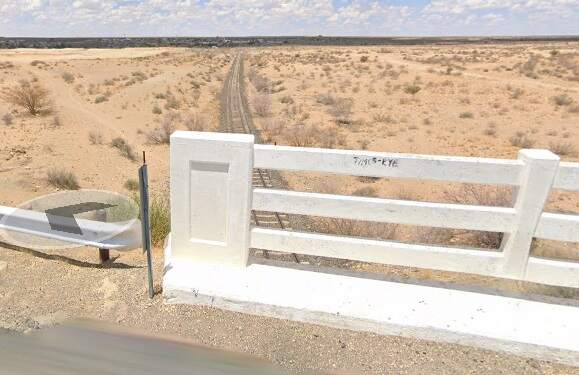

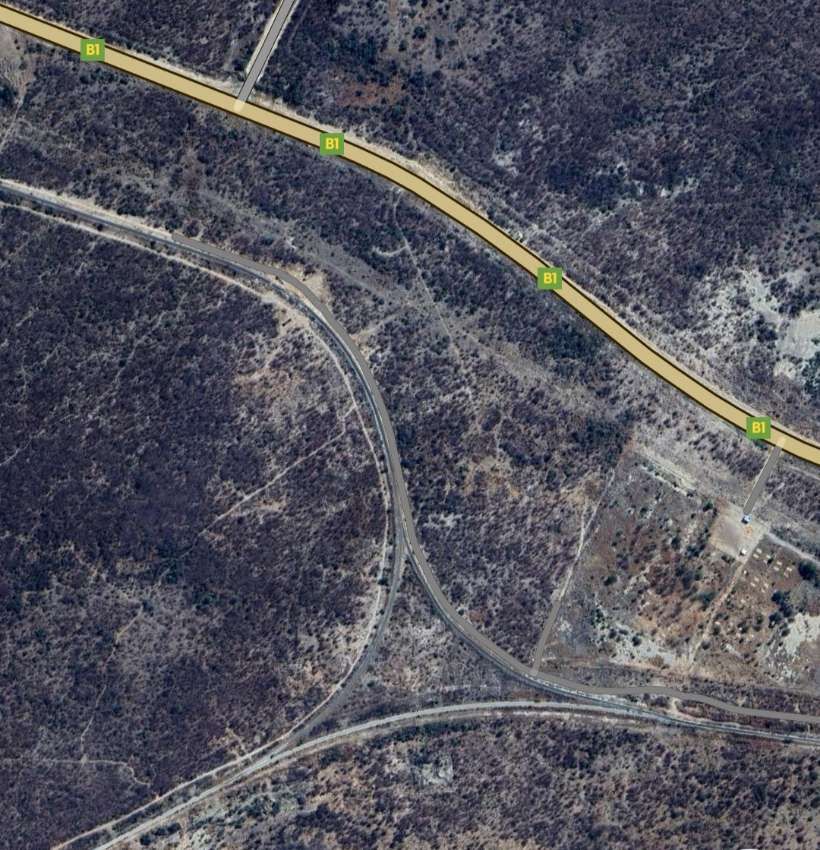

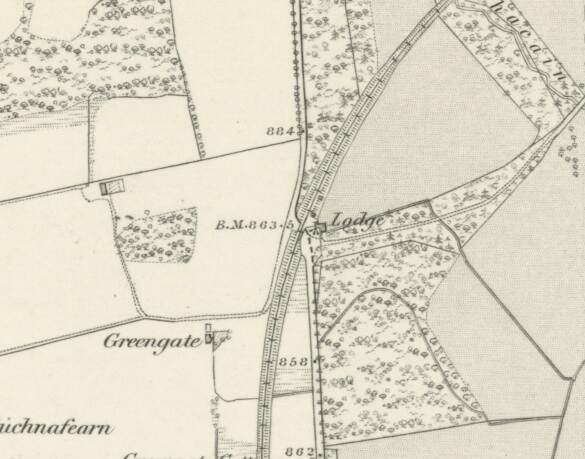

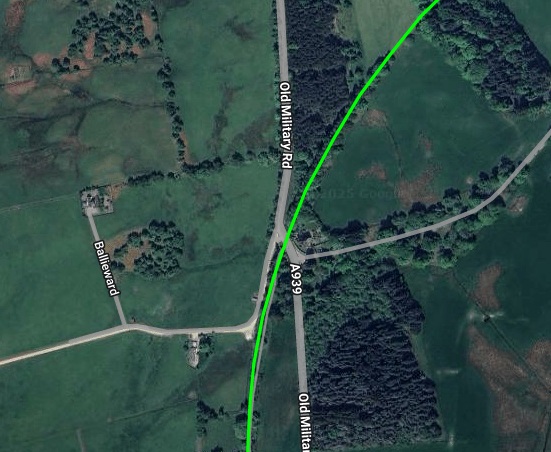

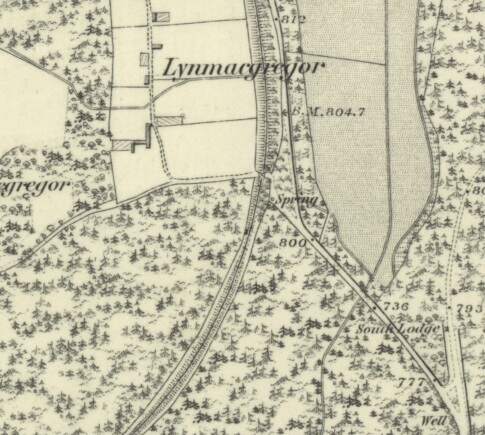

The adjacent map shows two bridges close together and both associated with the Castle Grant Estate. The first we encounter travelling South along the line is a bridge carrying an estate road over the old railway. A picture of that bridge can be seen here. [50]

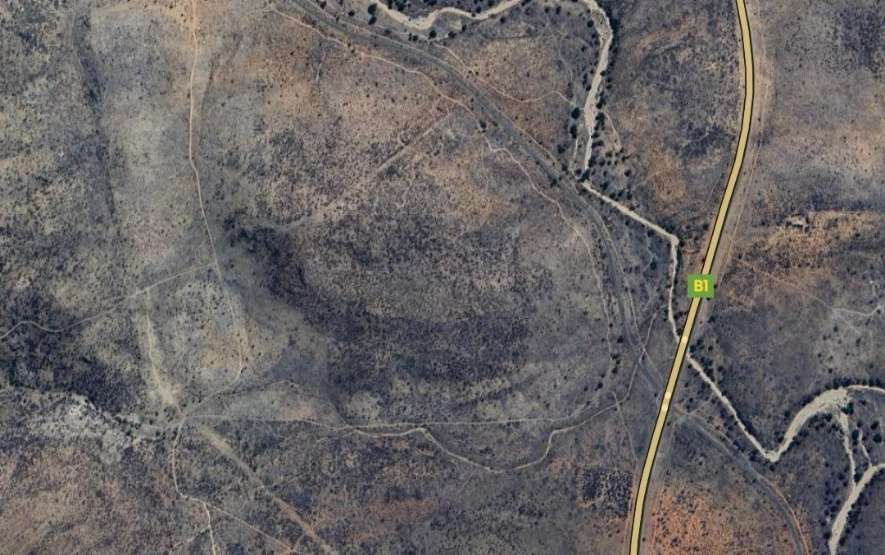

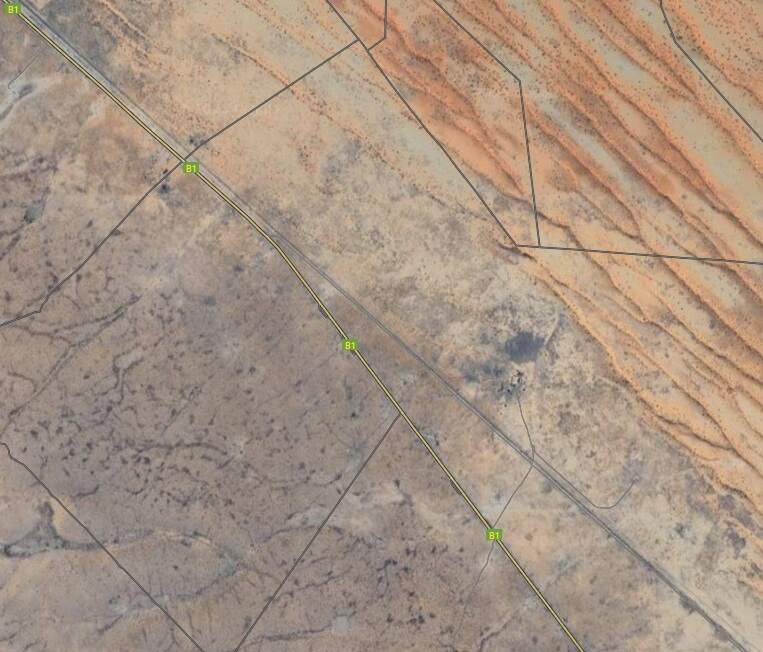

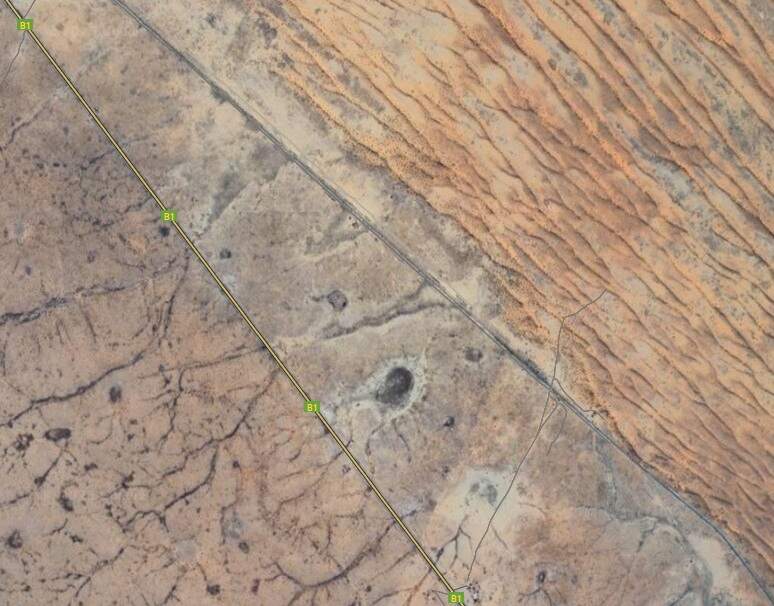

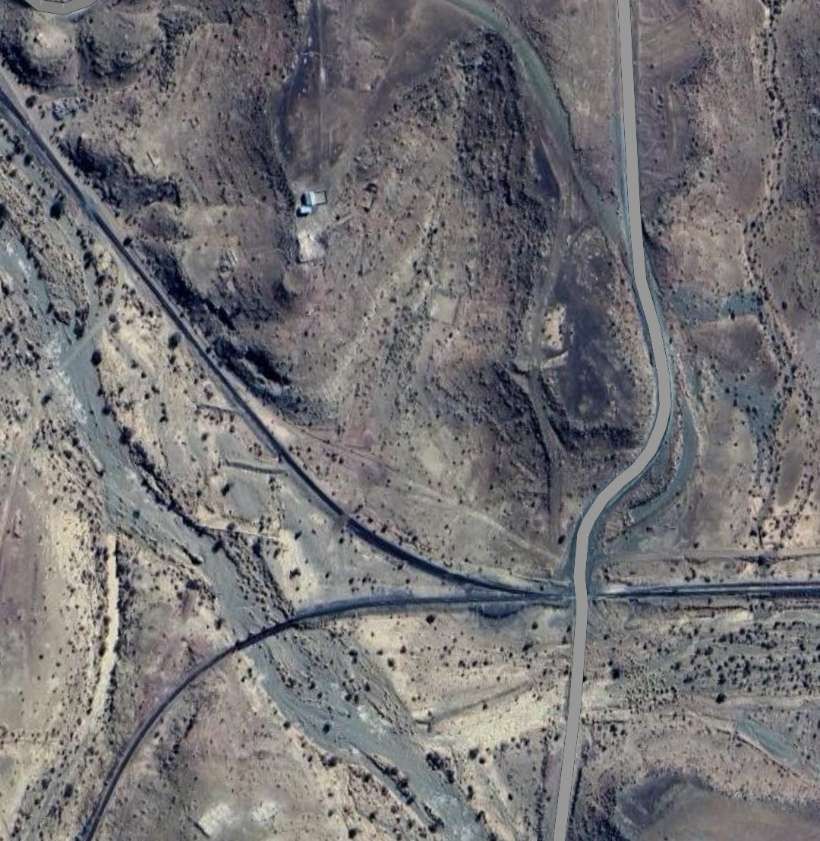

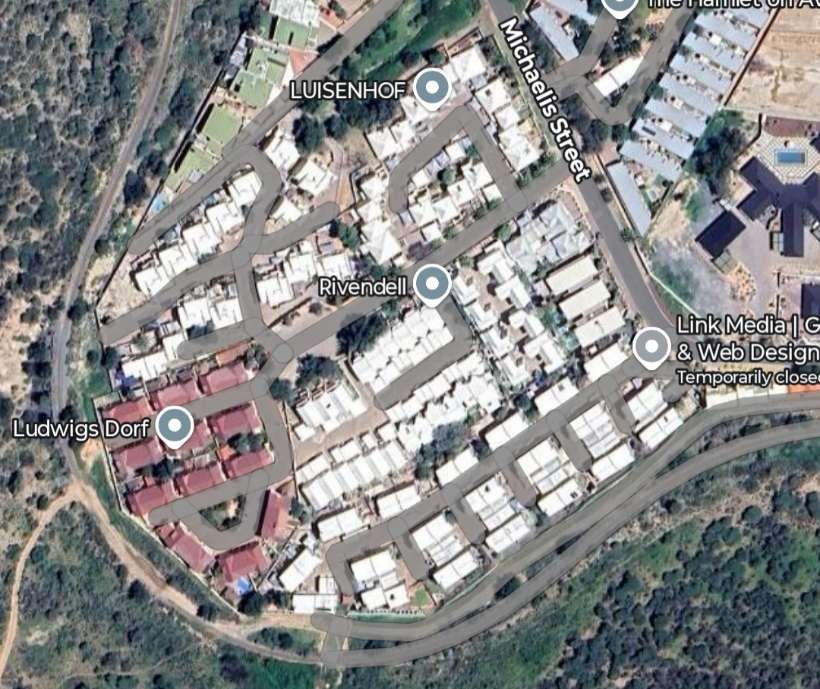

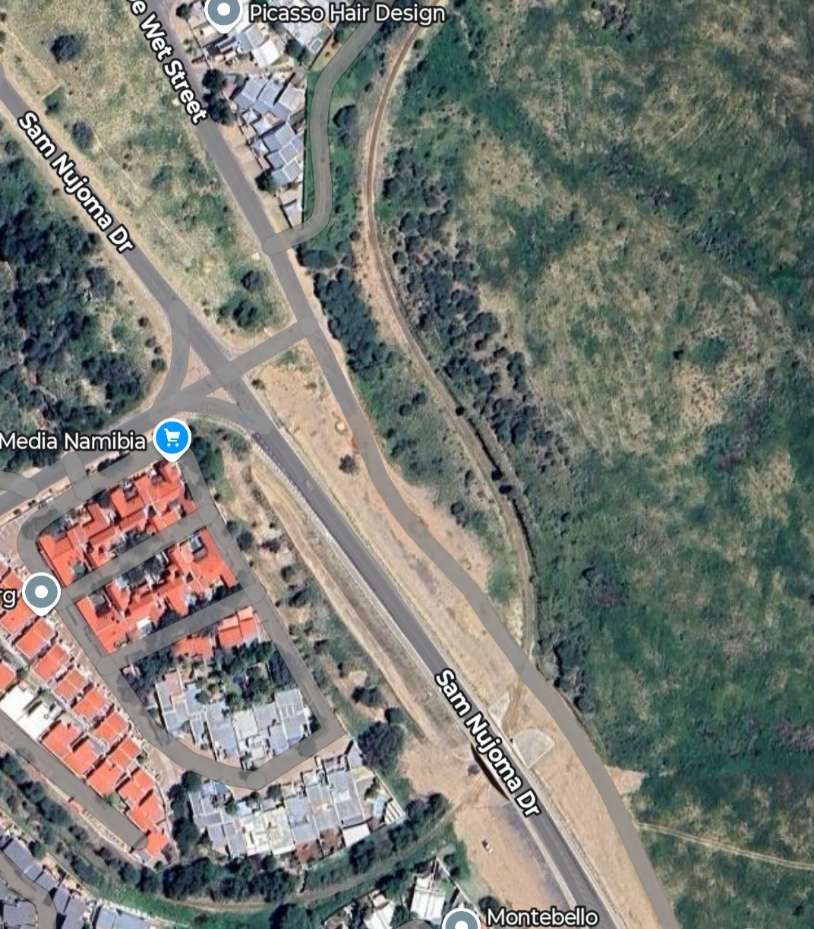

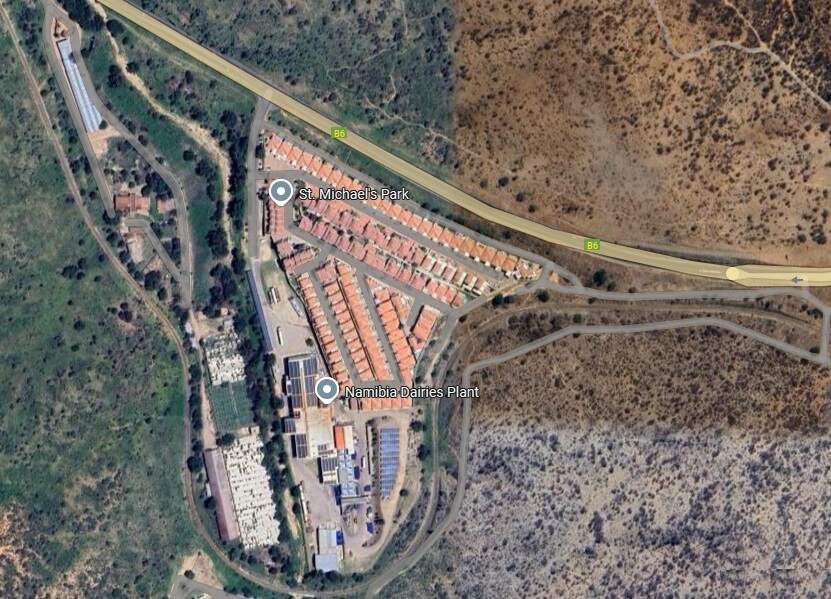

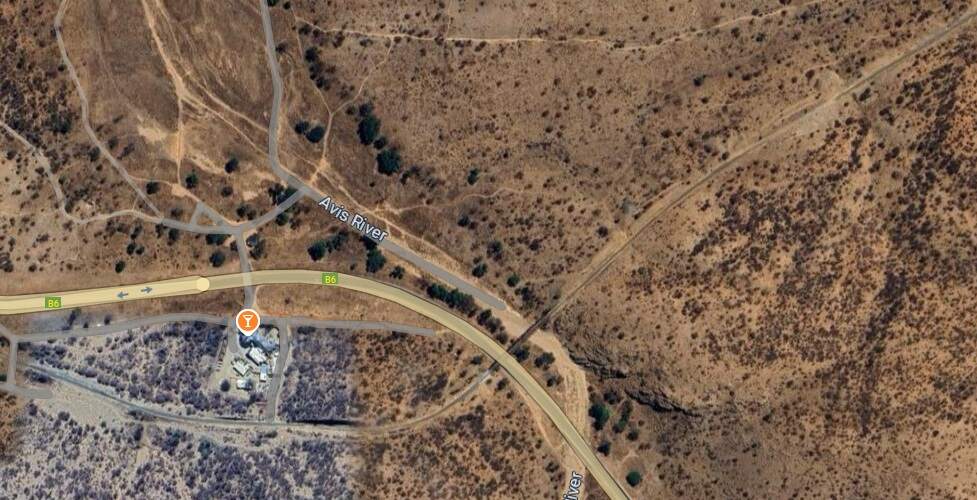

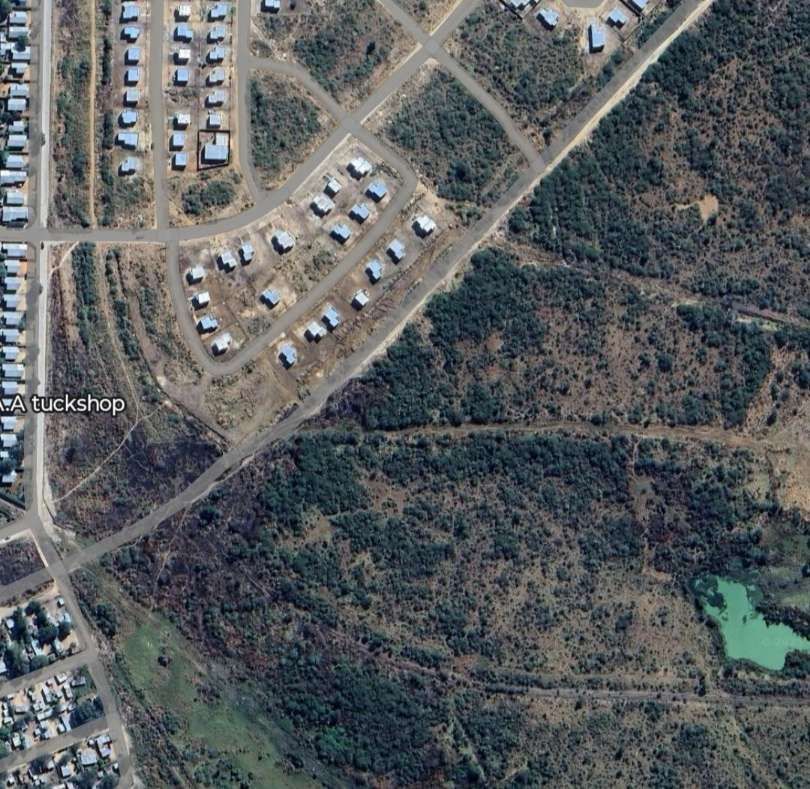

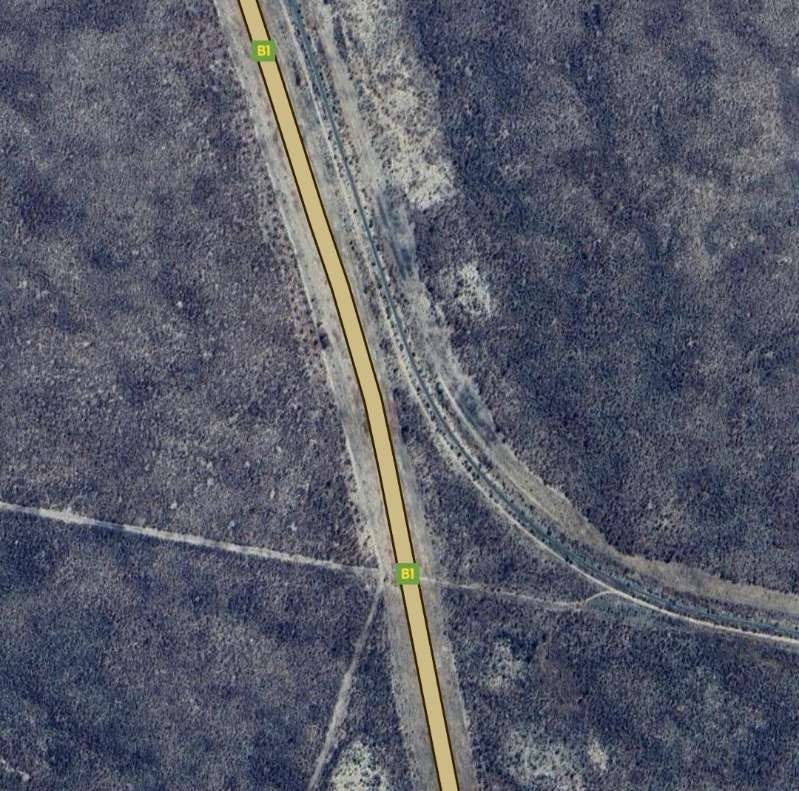

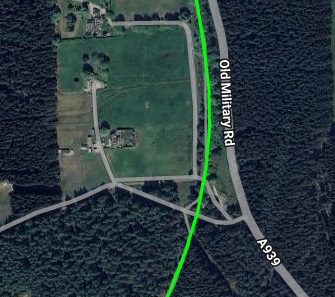

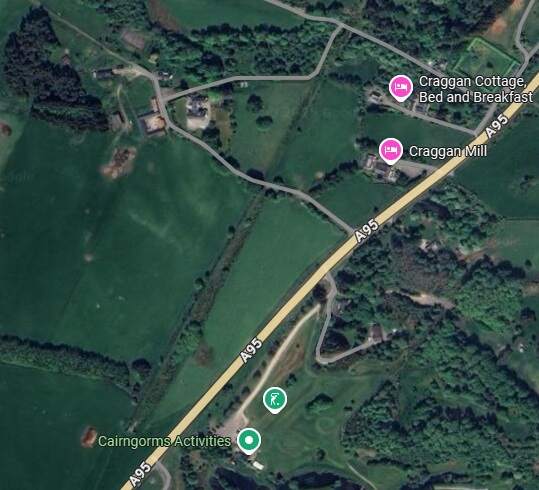

The same location is shown here on railmaponline.com’s satellite imagery. A length of embankment has been removed to allow a better alignment of the access road to Lynmacgregor. [42]

Close to what is now Grantown-on-Spey Caravan Park the railway crossed another minor road by means of a stone arch.

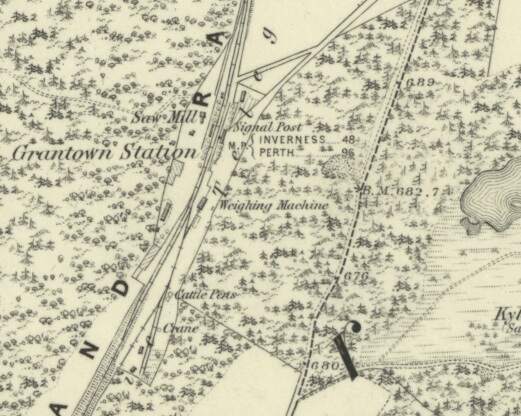

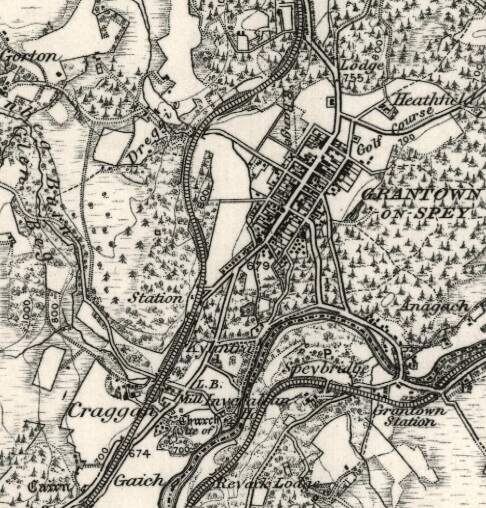

Photographs of the Station while in use can be found here [52] and here. [53]

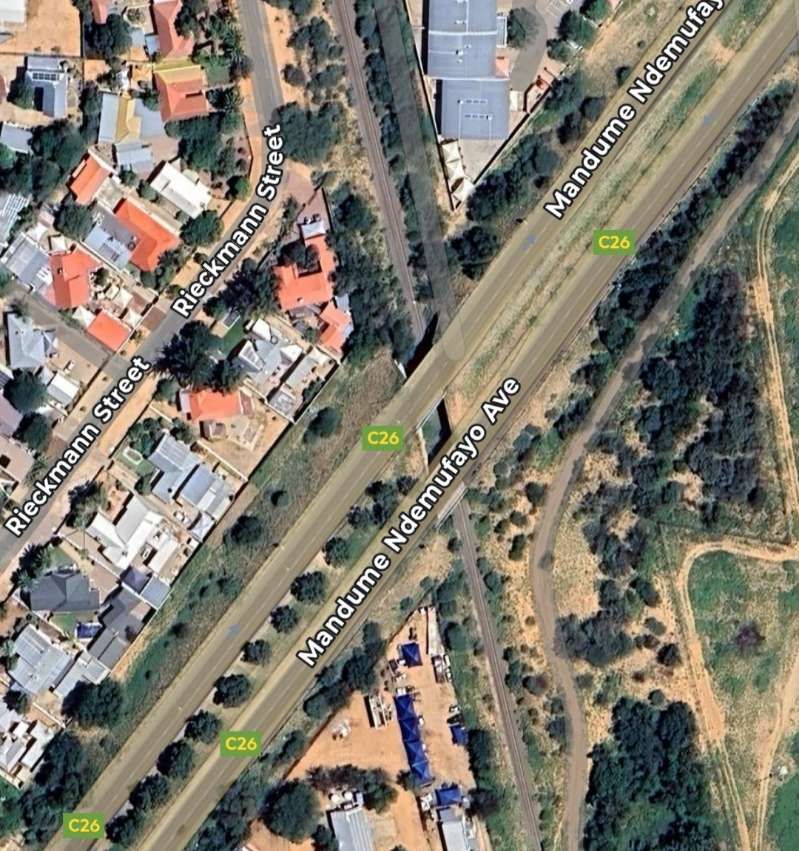

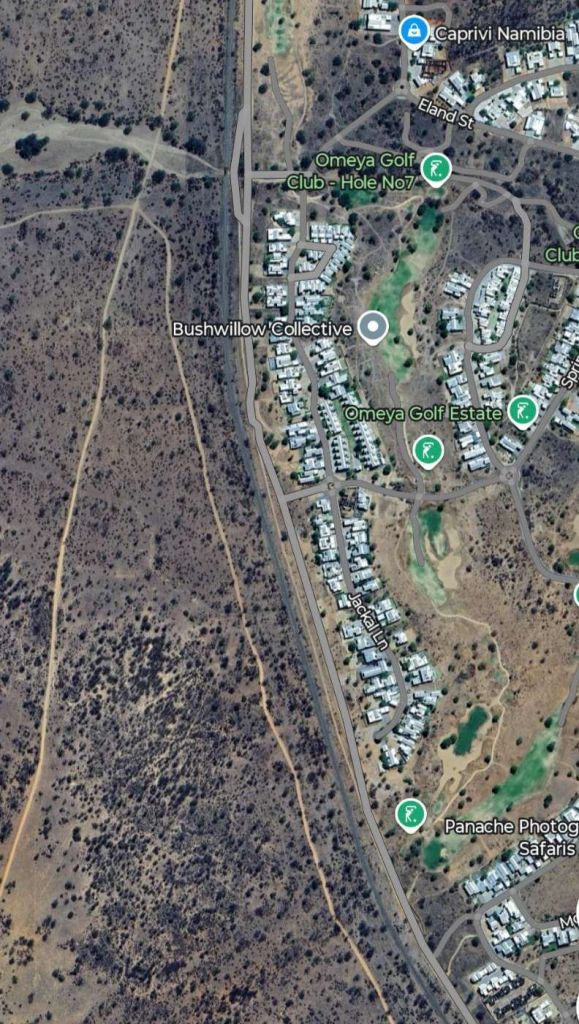

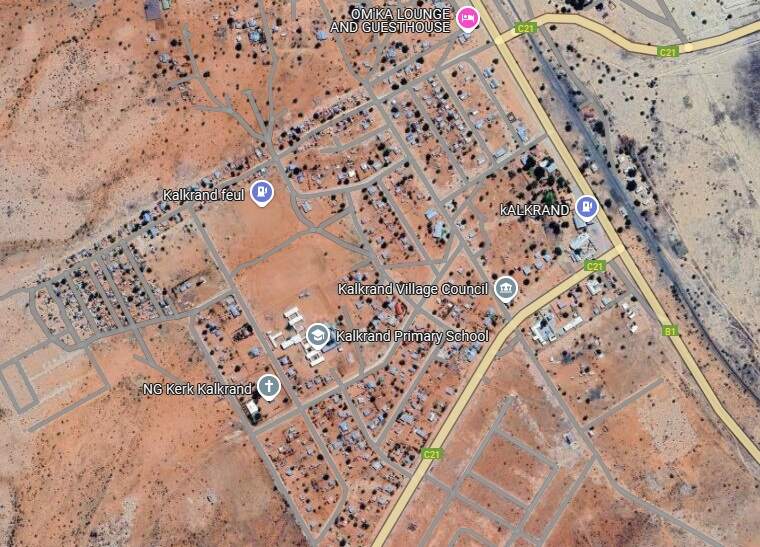

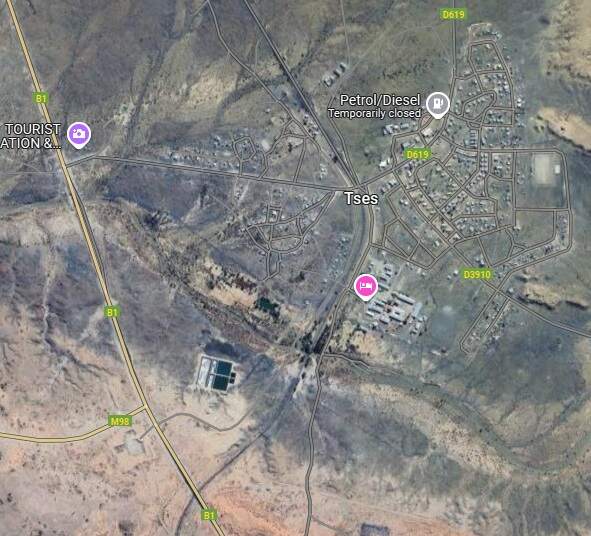

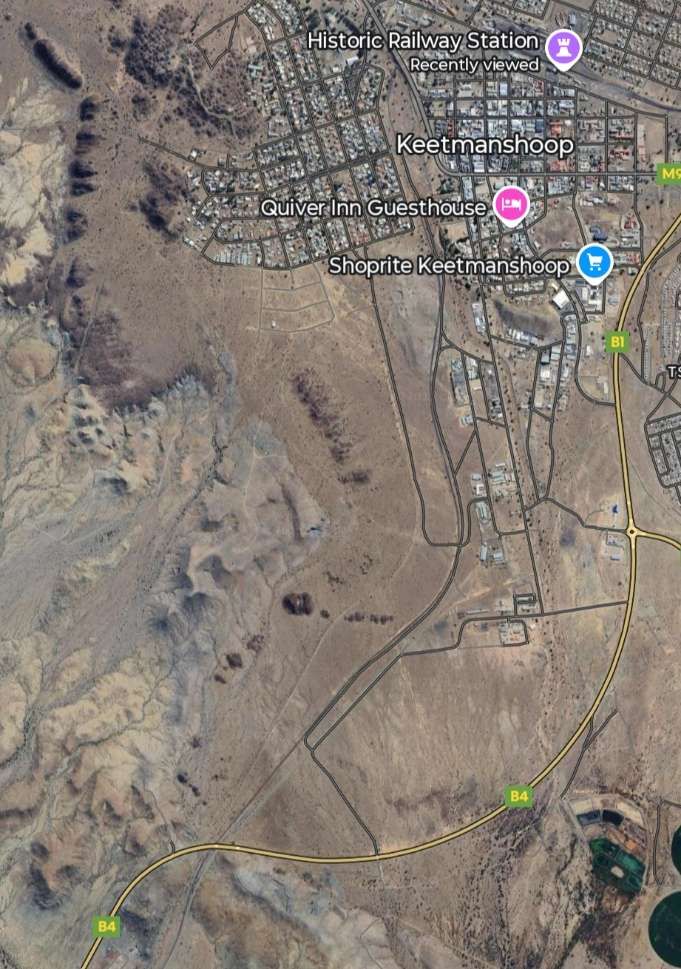

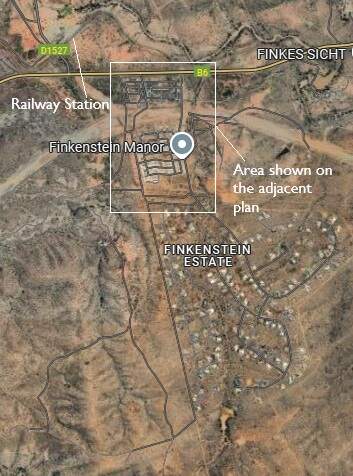

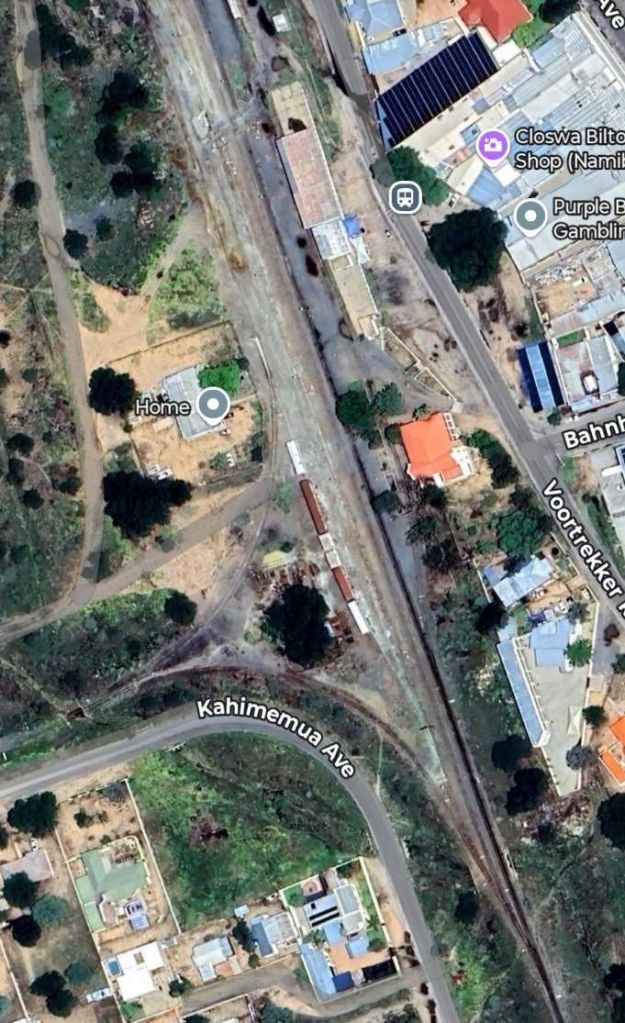

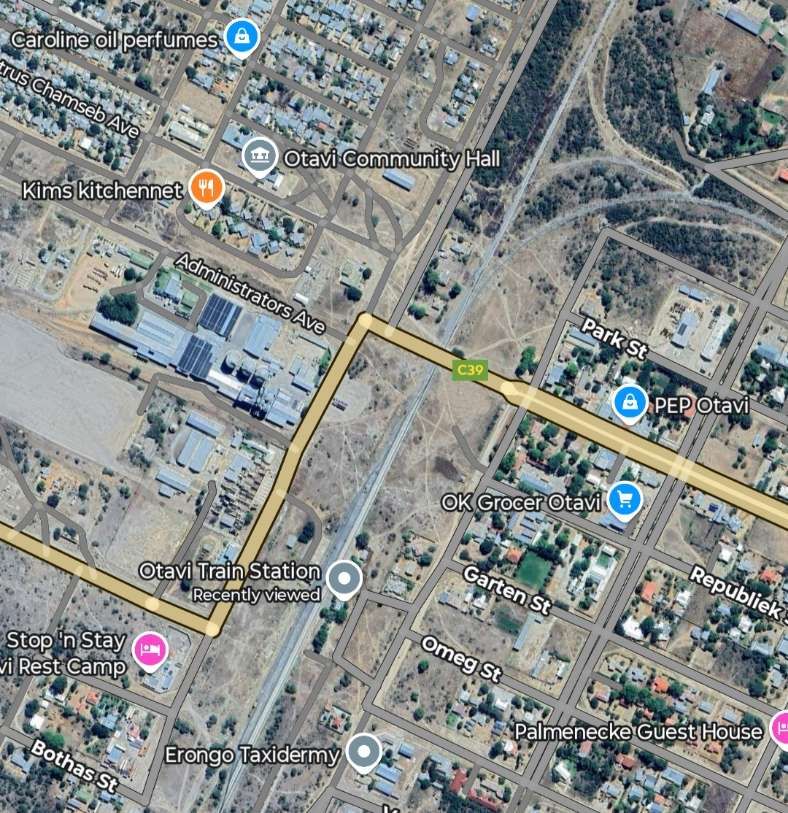

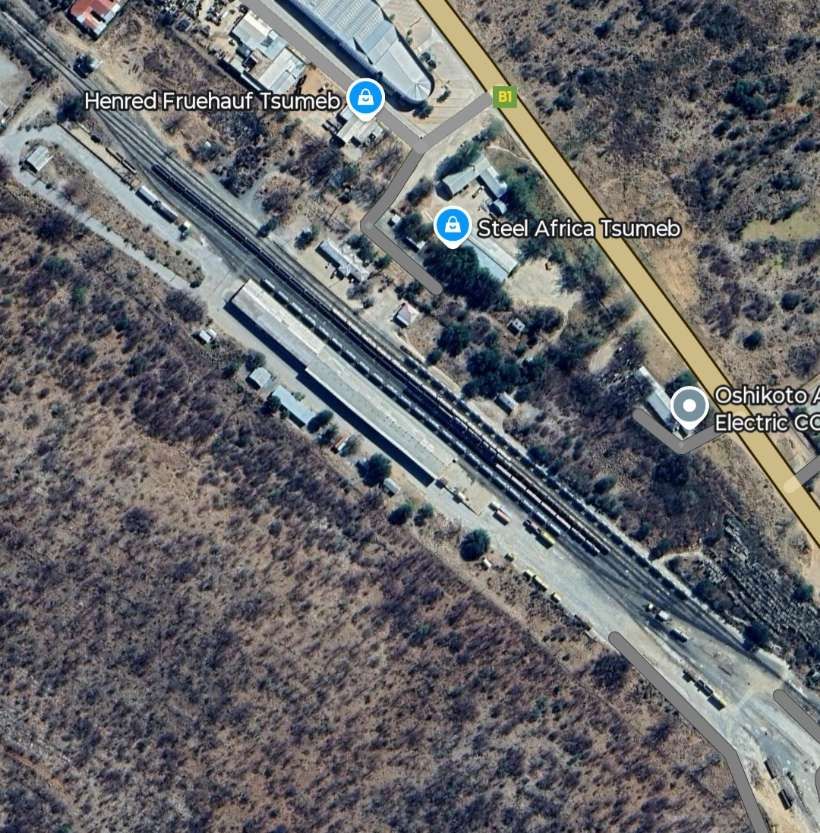

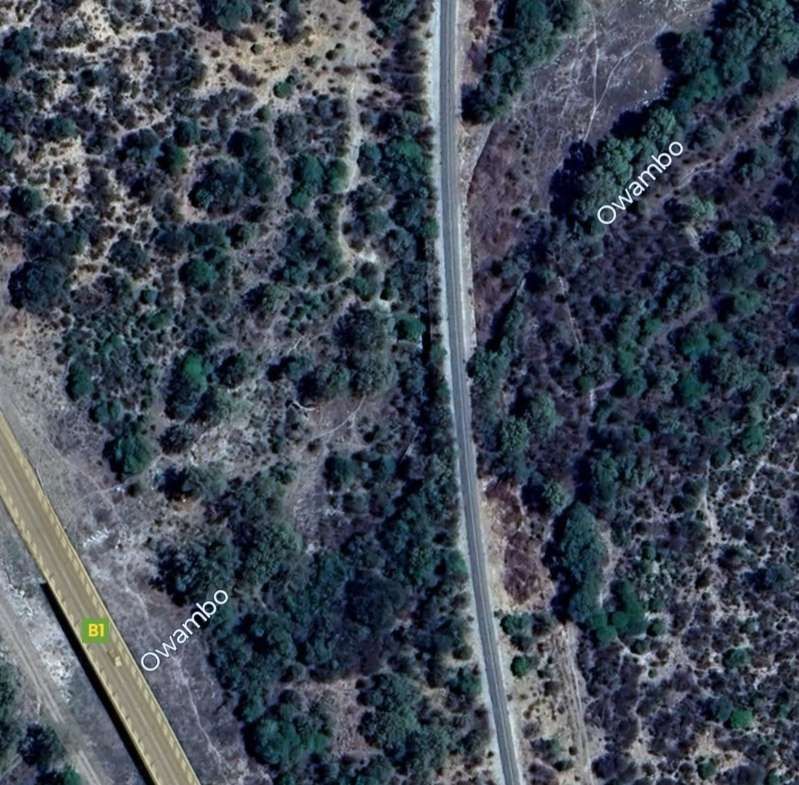

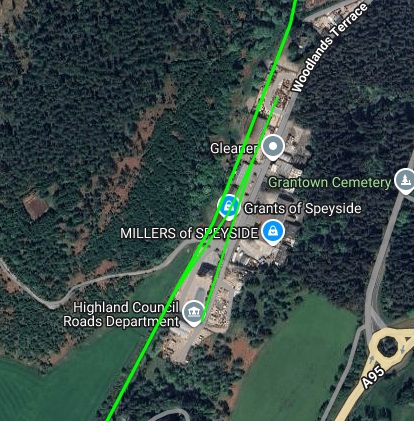

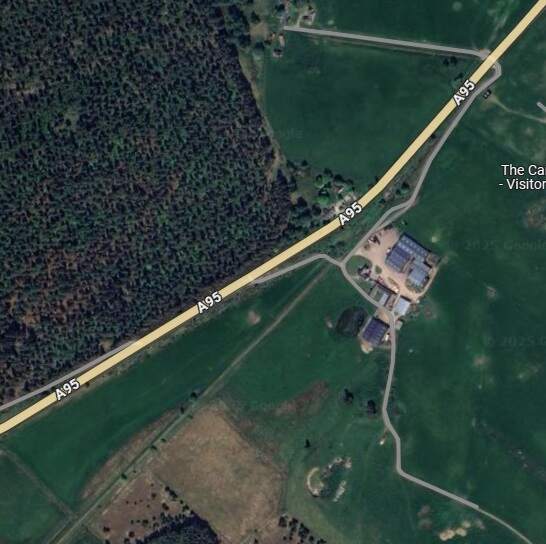

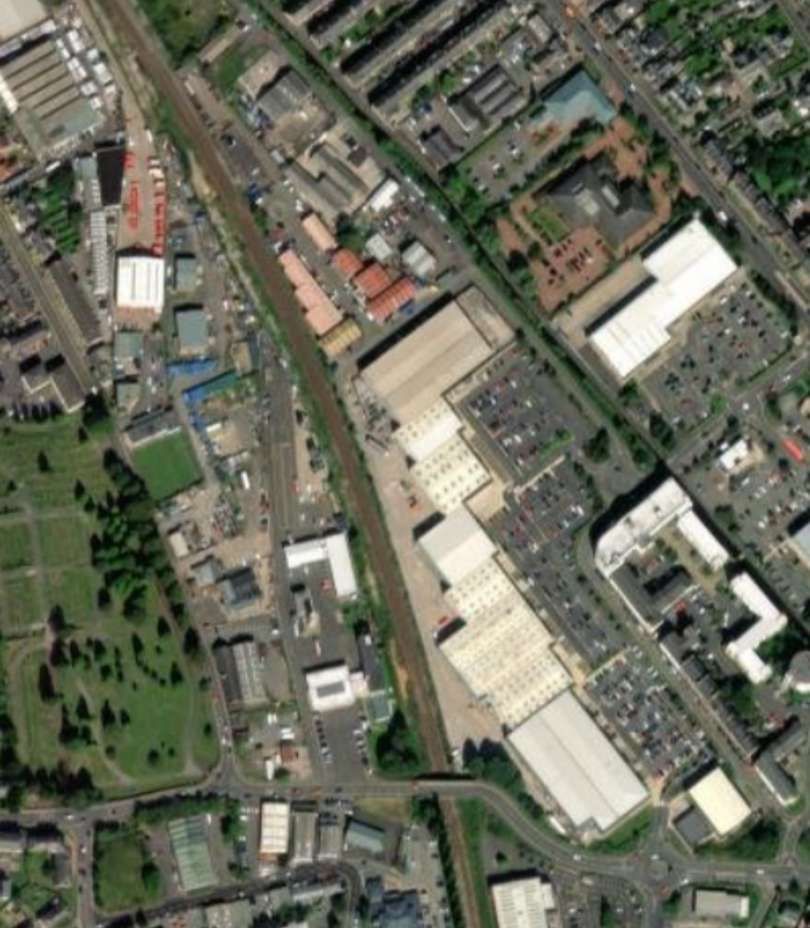

This extract from railmaponline.com’s satellite imagery shows the location of Grantown West Railway Station in the 21st century with the line of the old railway superimposed. The village/town of Grantown is to the Northeast of this location. The station site is now an industrial estate. [42]

The Strathspey Steam Railway has an ambition to extend its line to the site of the old station. [55]

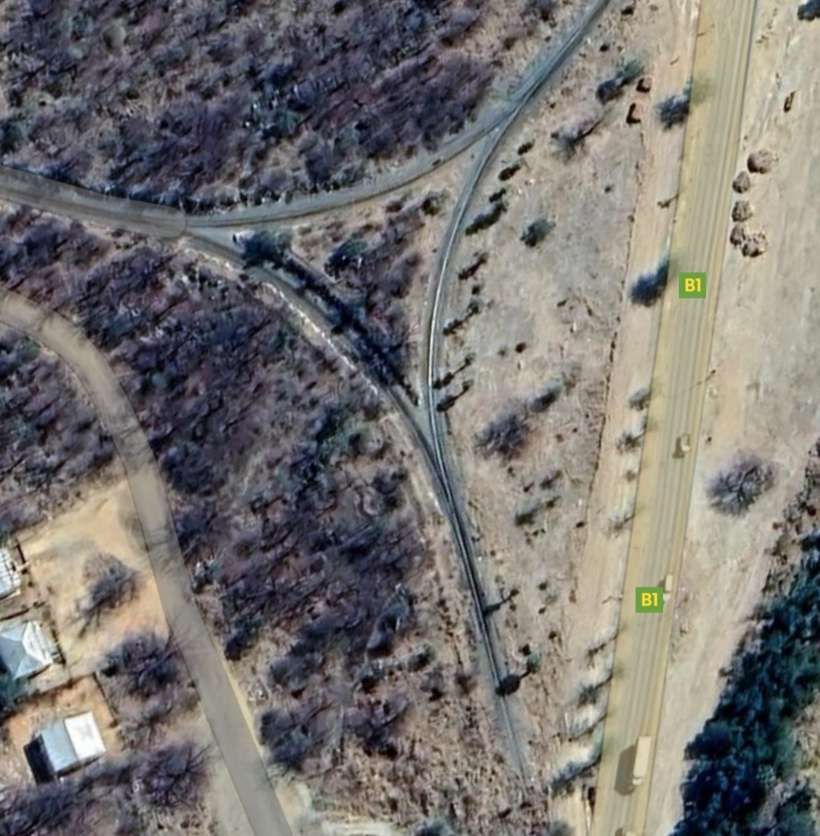

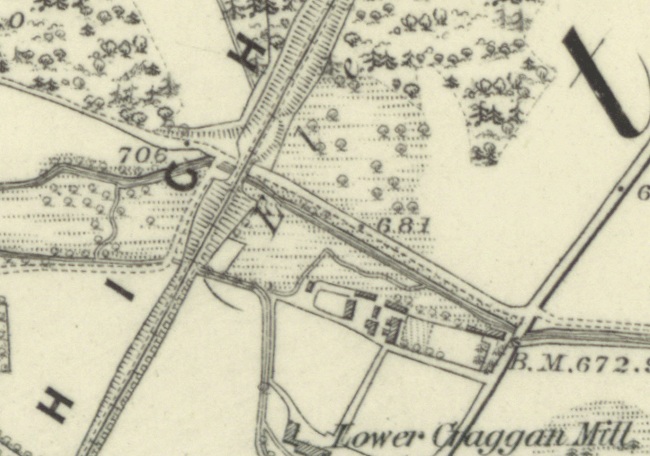

South of Grantown-on-Spey West Railway Station the line continued on embankment before crossing a minor road and stream as shown on the map extract below.

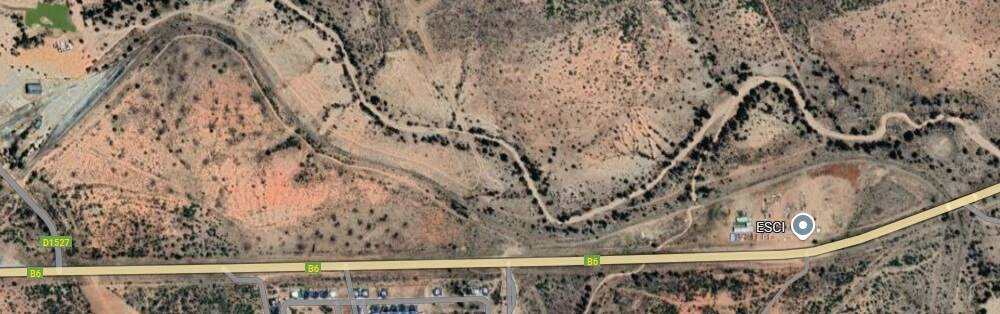

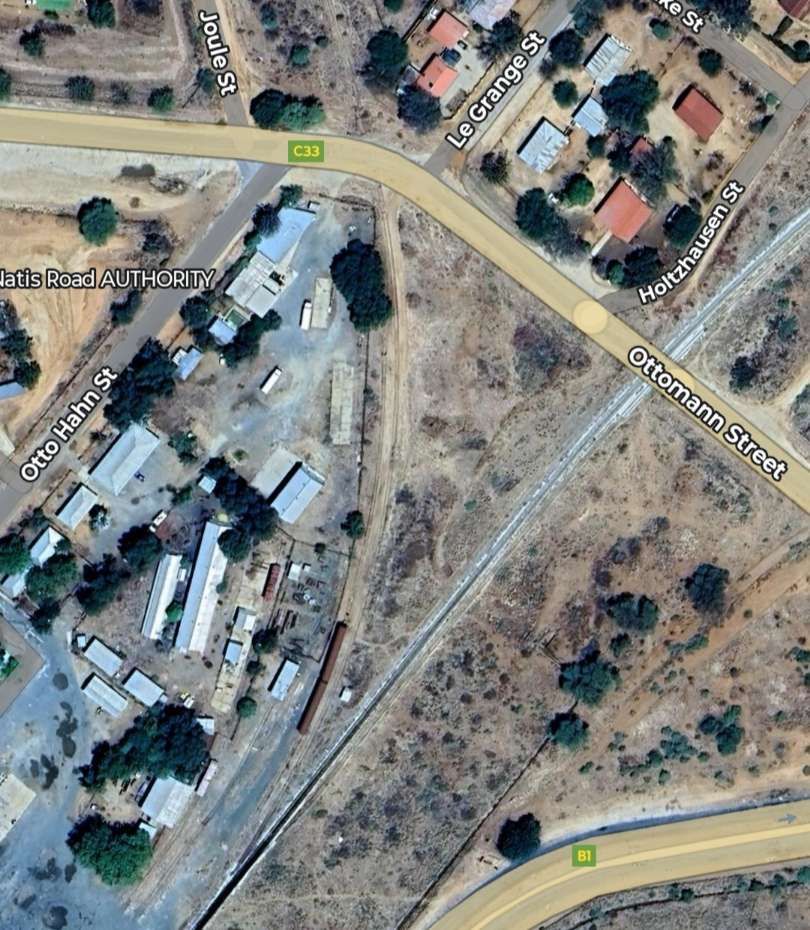

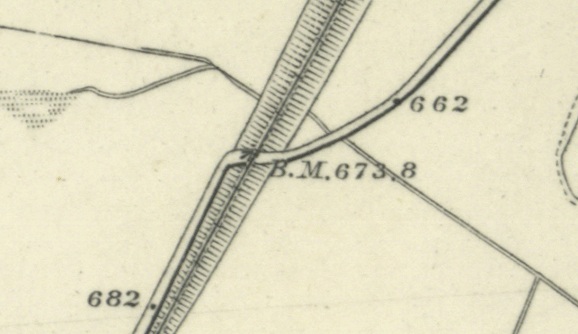

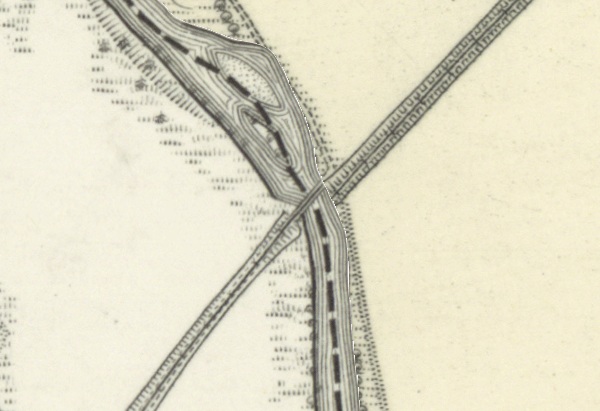

This extract from the 6″ Ordnance Survey mapping which was surveyed in 1868 and published in 1873 shows the esrtwhile bridge which carried the railway over what was to become the A95. As can be seen above, the closure of the line permitted the road alignment to be considerably improved. [57]

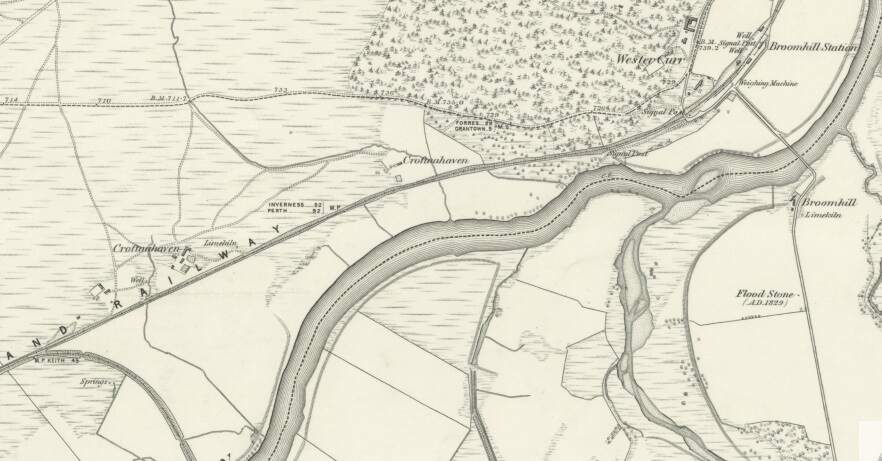

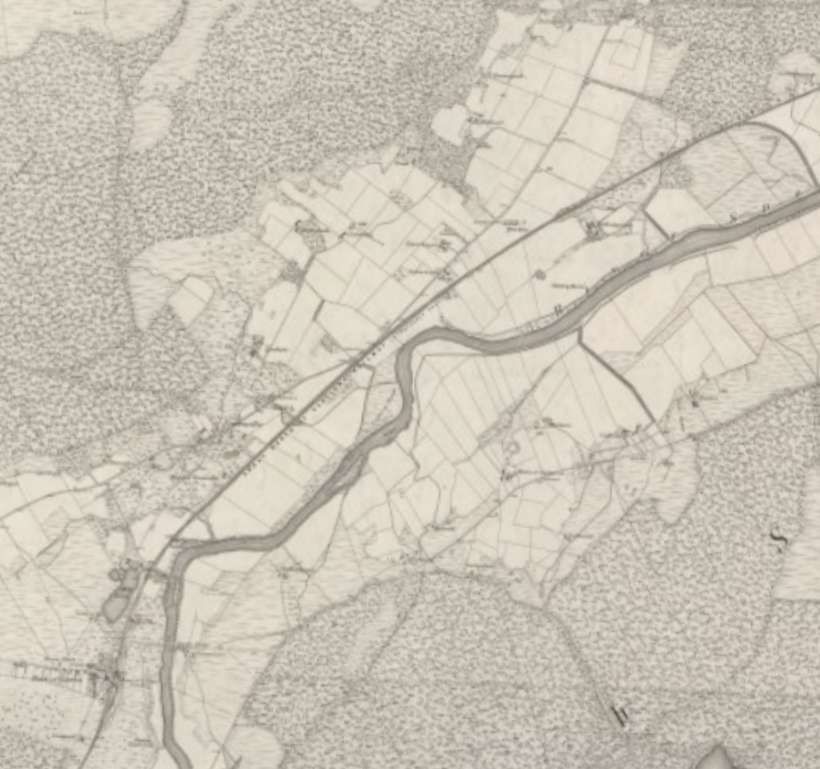

A short distance further Southwest, the old line crossed the River Dulnain close to its confluence with the River Spey as this next extract from the 6″ Survey mapping surveyed between 1867 and 1871 and published in 1873/75 shows. [58]

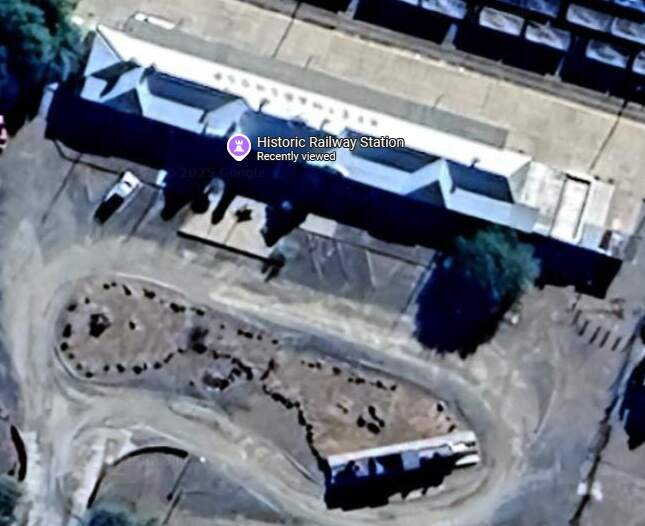

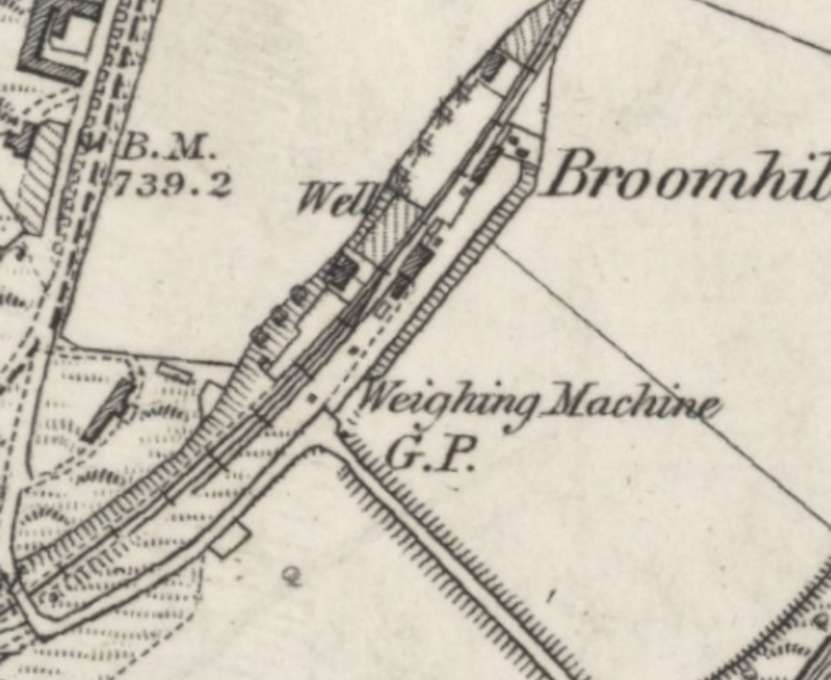

Broomhill Railway Station or Broomhill for Nethy Bridge Railway Station [60: p46] is a reconstructed railway station on the former Highland Railway main line [61] which was originally built to serve the small villages of Nethy Bridge and Dulnain Bridge in Strathspey. It is at present the eastern terminus of the heritage railway, the Strathspey Steam Railway. [55][62]

Boat of Garten railway station was a significant junction on the Highland Railway, and is now the headquarters of the Strathspey Railway. The station served as a link between the Highland Railway’s main line (Perth to Forres) and the Great North of Scotland Railway’s branch to Craigellachie. Today, the Strathspey Railway operates heritage steam trains between Aviemore, Boat of Garten, and Broomhill, using part of the original Highland Railway line.

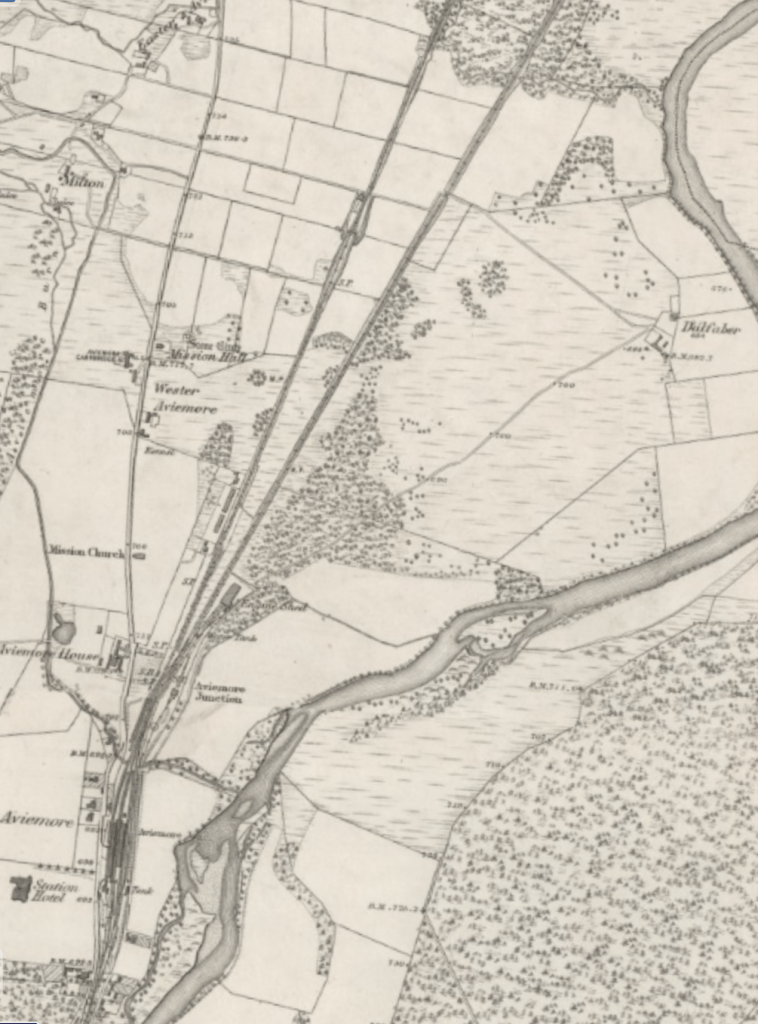

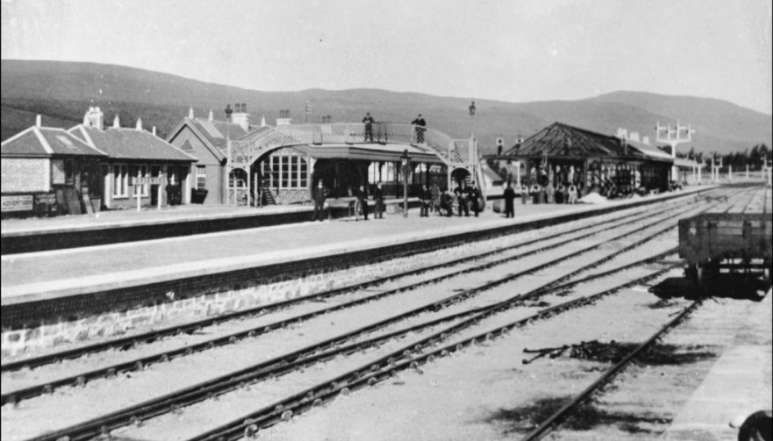

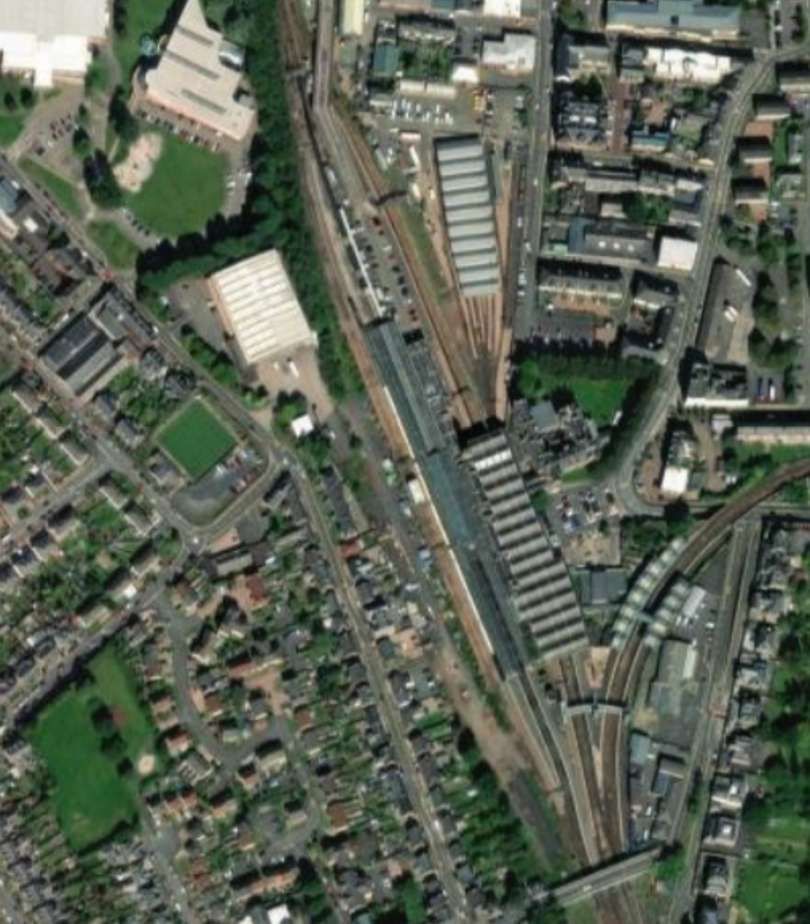

In the 21st century, Aviemore Railway Station is owned by Network Rail and managed by ScotRail, is on the Highland Main Line, 83 miles 31 chains (134.2 kilometres) from Perth, between Kingussie and Carrbridge, and is also the southern terminus of the Strathspey preserved railway. [68]

The modern main line to the North of Aviemore, the later Highland Railway main line, will be covered in Part 3 of this series of articles.

South of Aviemore, the Highland line continued more than 83 miles South to Perth.

The line follows the River Spey southwards, passing to the East of Loch Alvie, through Kincraig Railway Station and then passing to the West of Loch Insh and through Kingussie Railway Station.

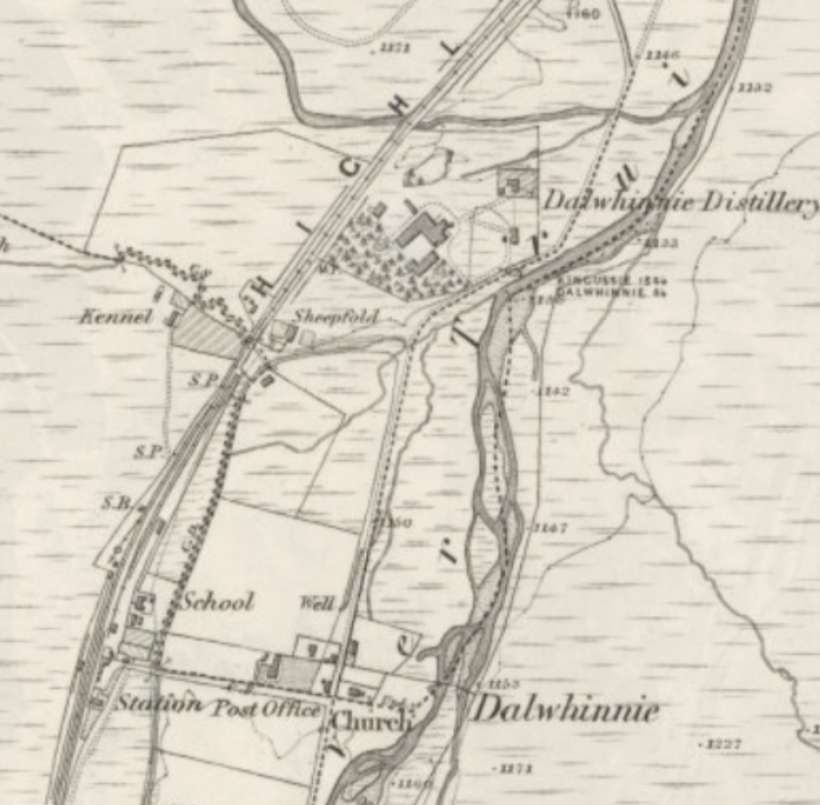

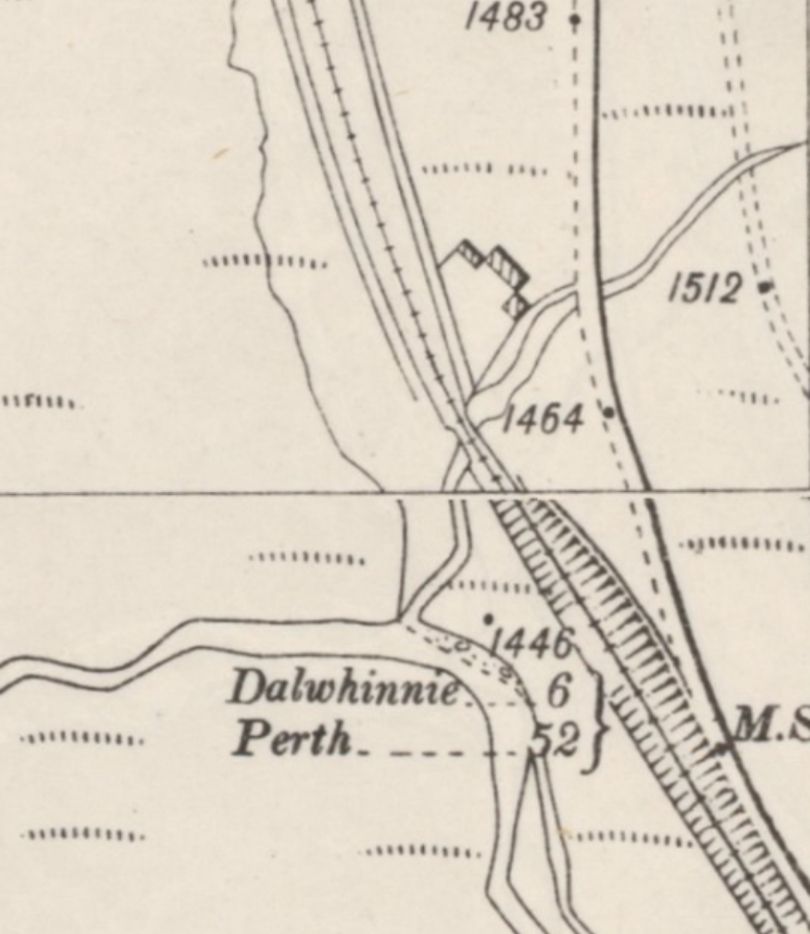

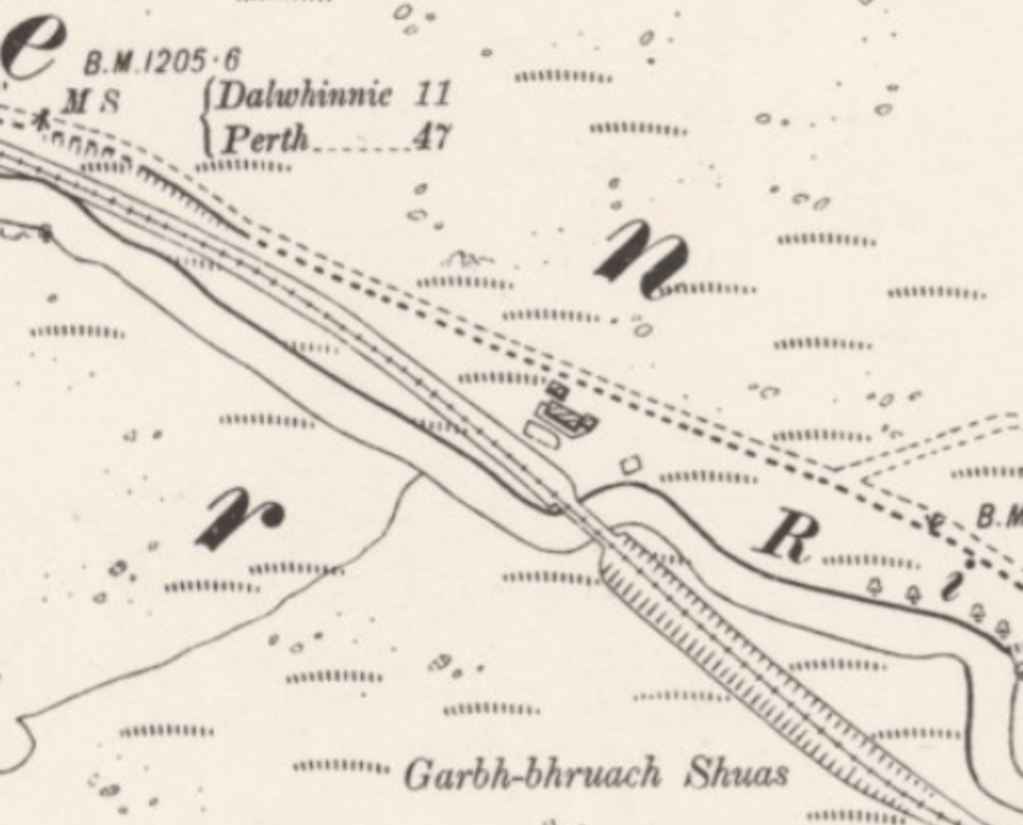

Southwest of Kingussie the railway continues to follow the River Spey. It bridges the Spey southwest of Newtonmore Railway Station and just to the East of Spey (Road) Bridge and then continues climbing alongside first the Spey and then a tributary, the River Truim, towards Dalwhinnie Distillery.

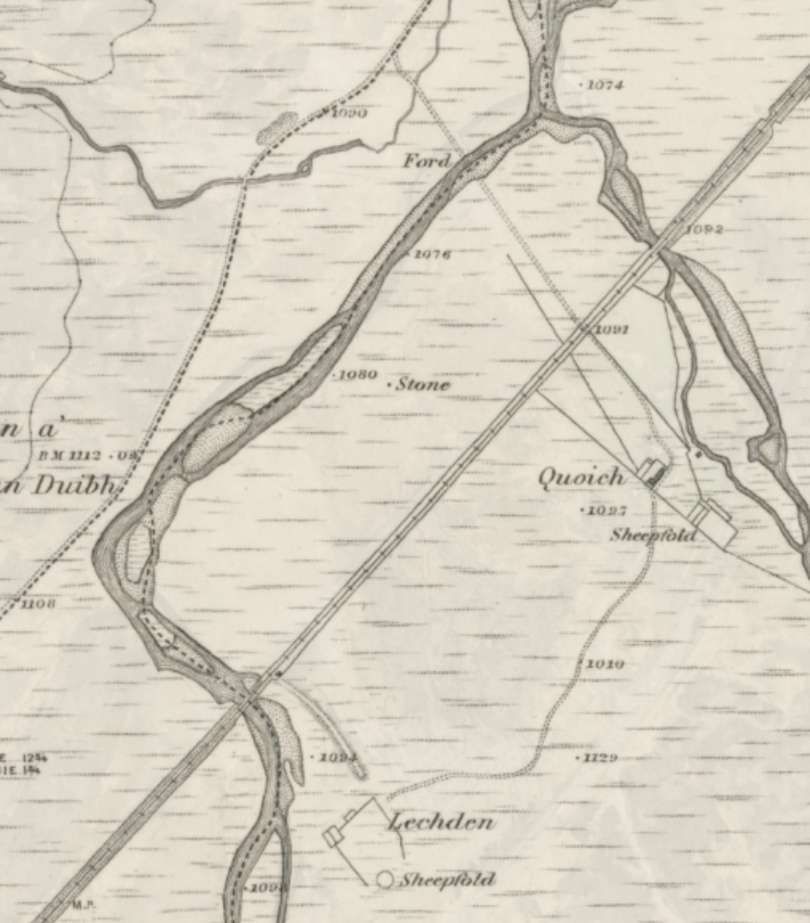

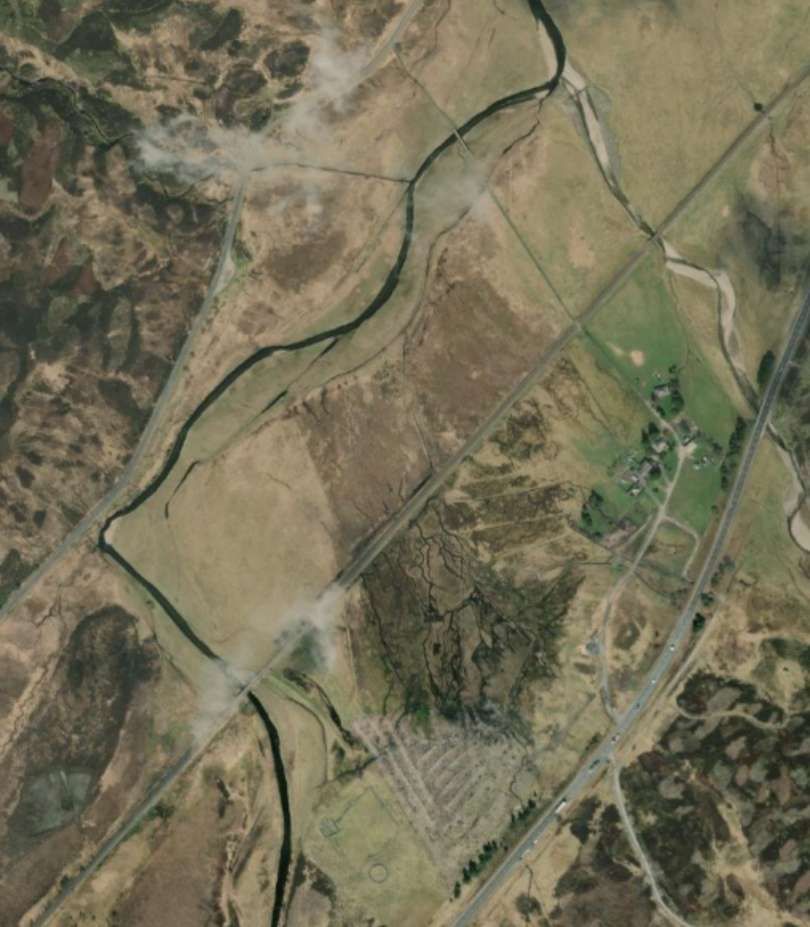

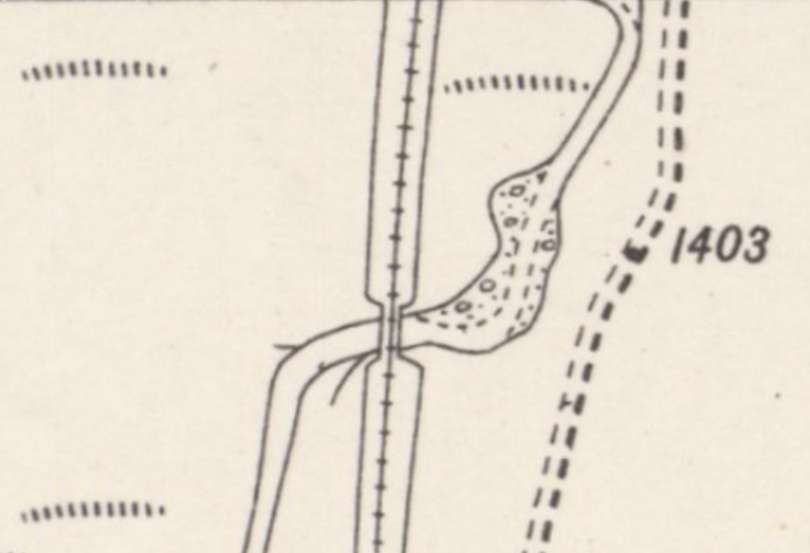

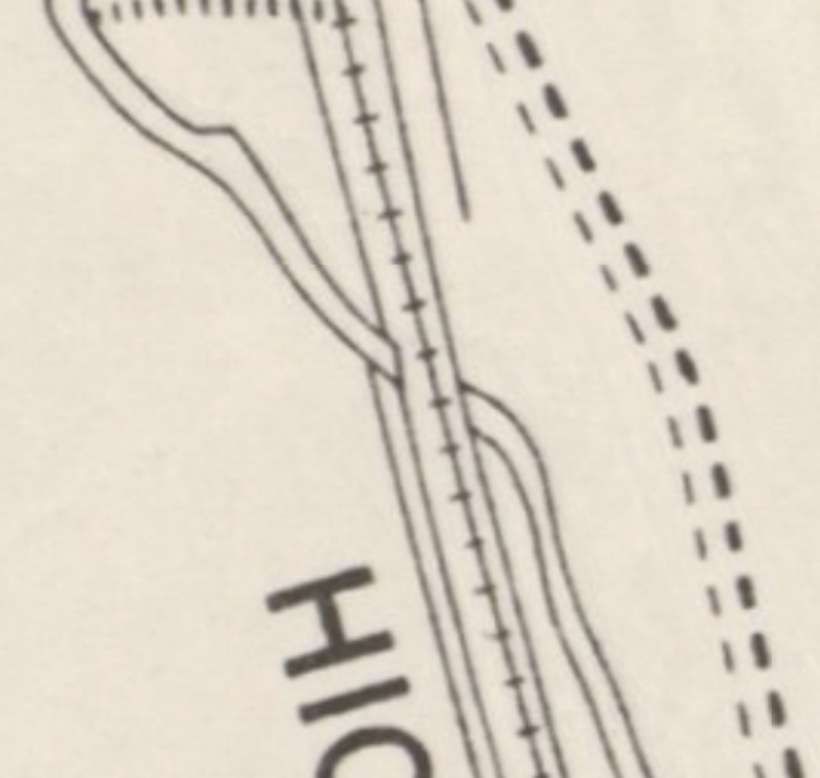

Beyond the confluence of the Spey and the Truim the railway runs Southwest up Glen Truim towards Dalwhinnie Distillery. Just a short distance Northeast of the Dalwhinnie Distillery the Truim splits into two. Google Maps records the name of the two arms being the River Truim. Both arms of the Truim pass under the railway.

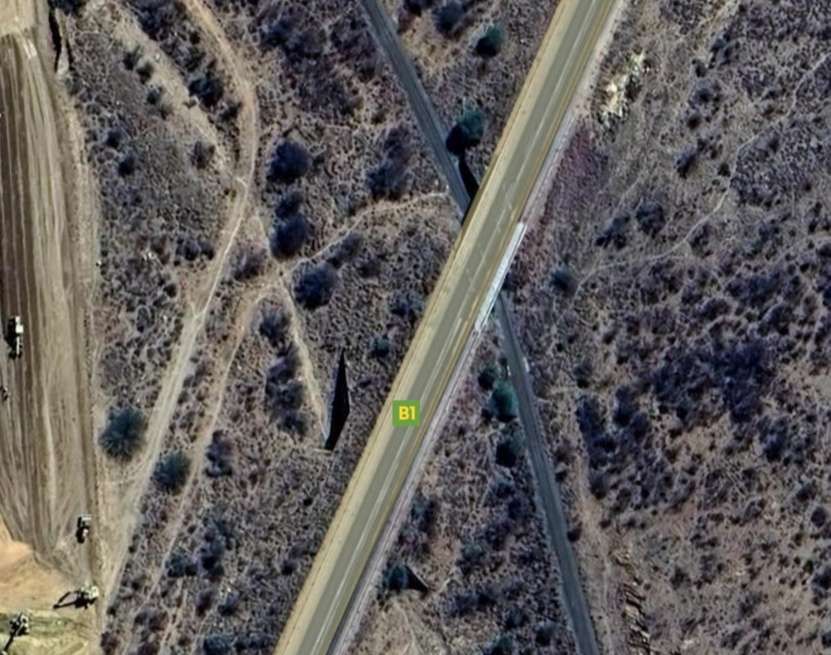

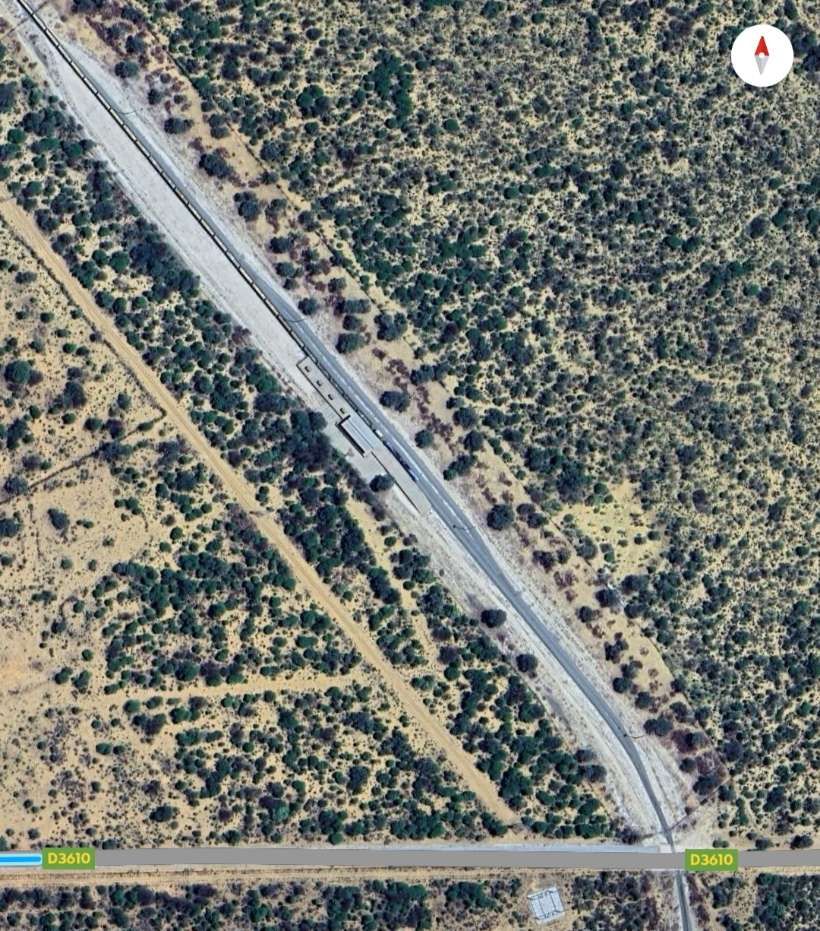

It is worth noting before we travel on towards Perth that one of the most significant improvements to the journey to Perth “came with the doubling of sections of line, designed by the engineer Alexander Newlands, beginning with Blair Atholl to Dalnacardoch (8.25 miles (13.28 km)) in 1900, extended to Druimuachdar (8.5 miles (13.7 km)) in 1901 and Dalwhinnie (5.5 miles (8.9 km)) in 1909. [83] In the 1960s, many sections of the line were converted from double track to single track. In 1976, 23 miles (37 km) from Blair Atholl to Dalwhinnie was redoubled. [84][85] In March 2019 Network Rail completed a programme of works to increase capacity on the line and support the introduction of InterCity 125 sets on ScotRail services, with passing loops and platforms extended.” [82][86]

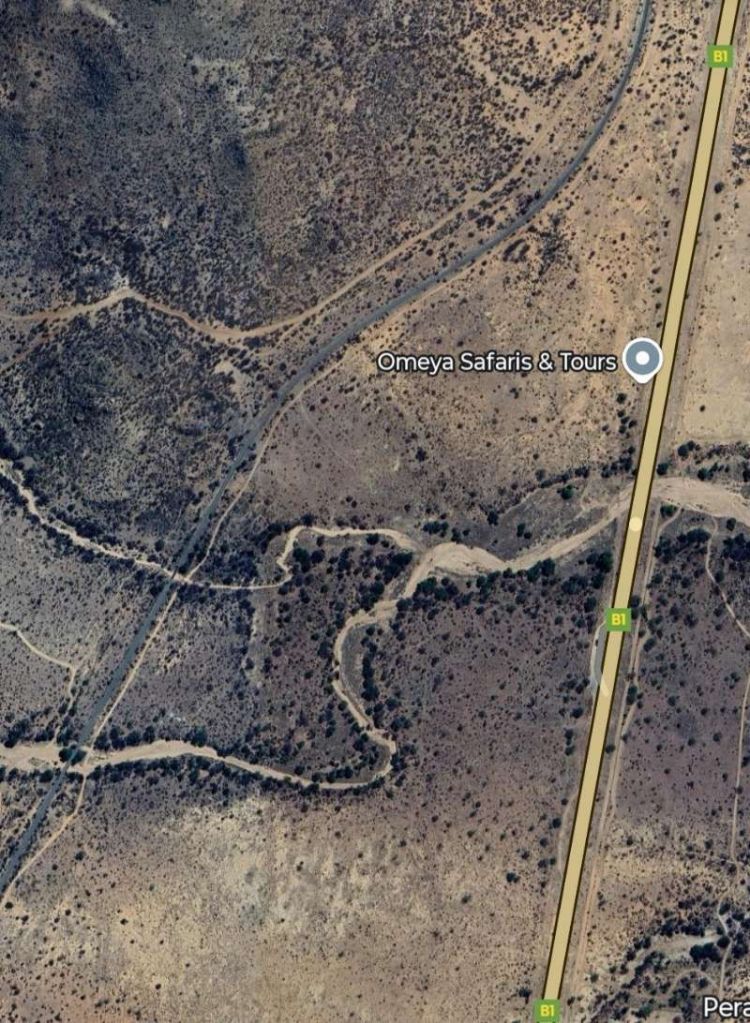

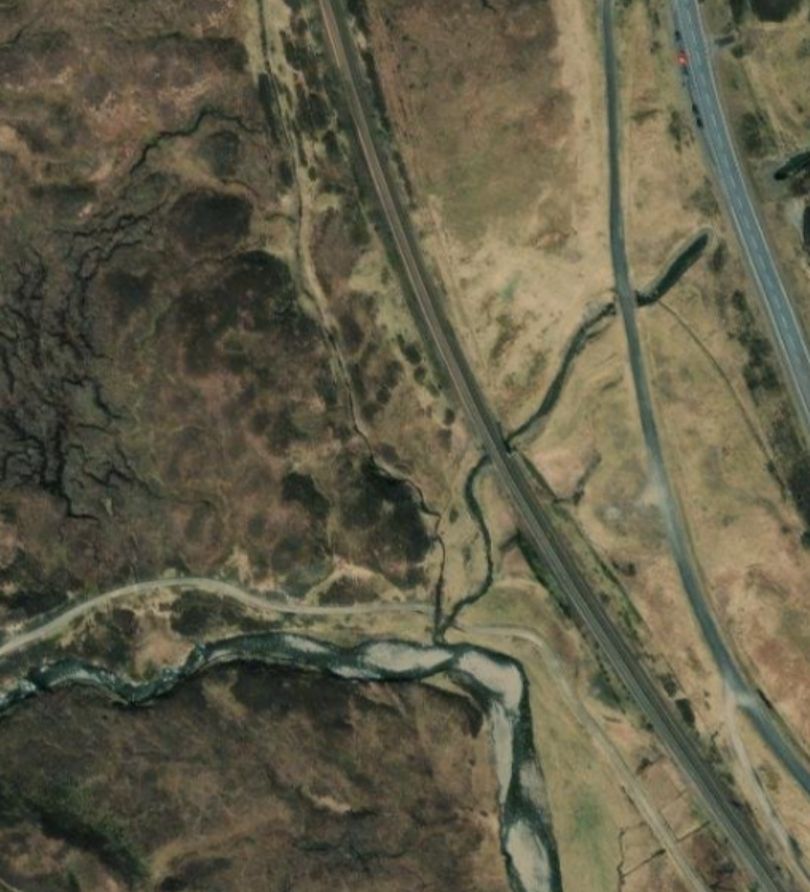

A few kilometres South of Dalwhinnie, the railway crosses a minor road just to the West of its junction with the A9,then crosses a small tributary of the River Truim, before it crosses the River Truim again.

Continuing southwards the line crosses the River Truim again. …

The line crosses the watershed and begins the drop down towards Perth.

Over the next kilometre a number of such streams are crossed and the line passes through the location of Dalnaspidal Railway Station which closed in 1965.

The next location of note along Glen Garry is the bridge over Bruar Water. …

It is not too much more than a kilometre or two to Blair Athol. …

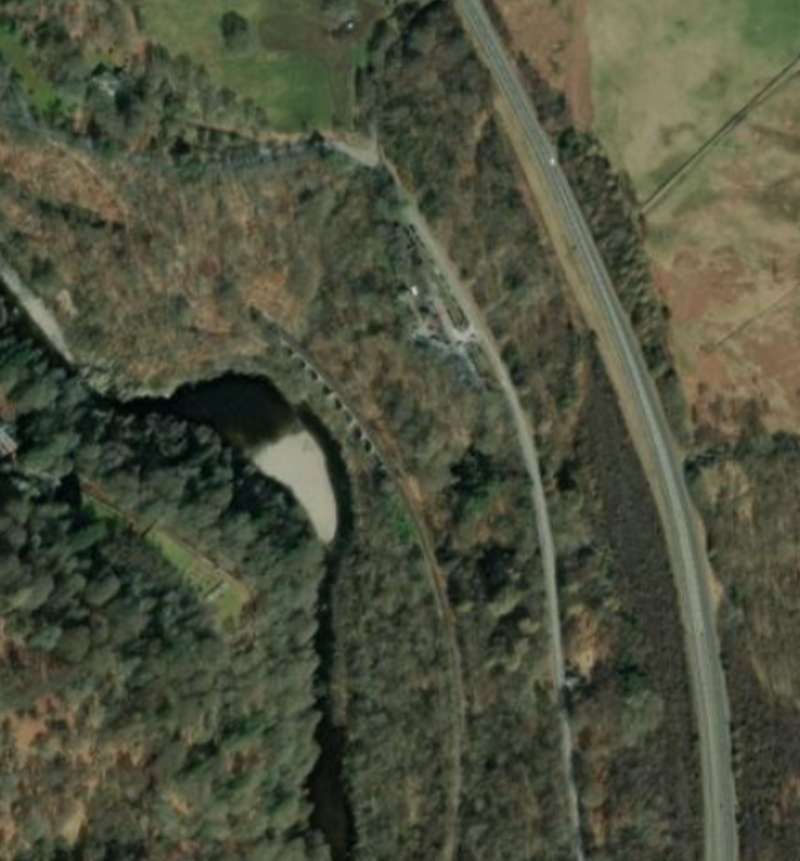

To the Southwest of Killiecrankie Railway Station the line passed through the Pass of Killiecrankie. First there was a short tunnel, then a viaduct over a tributary of the Tummel.

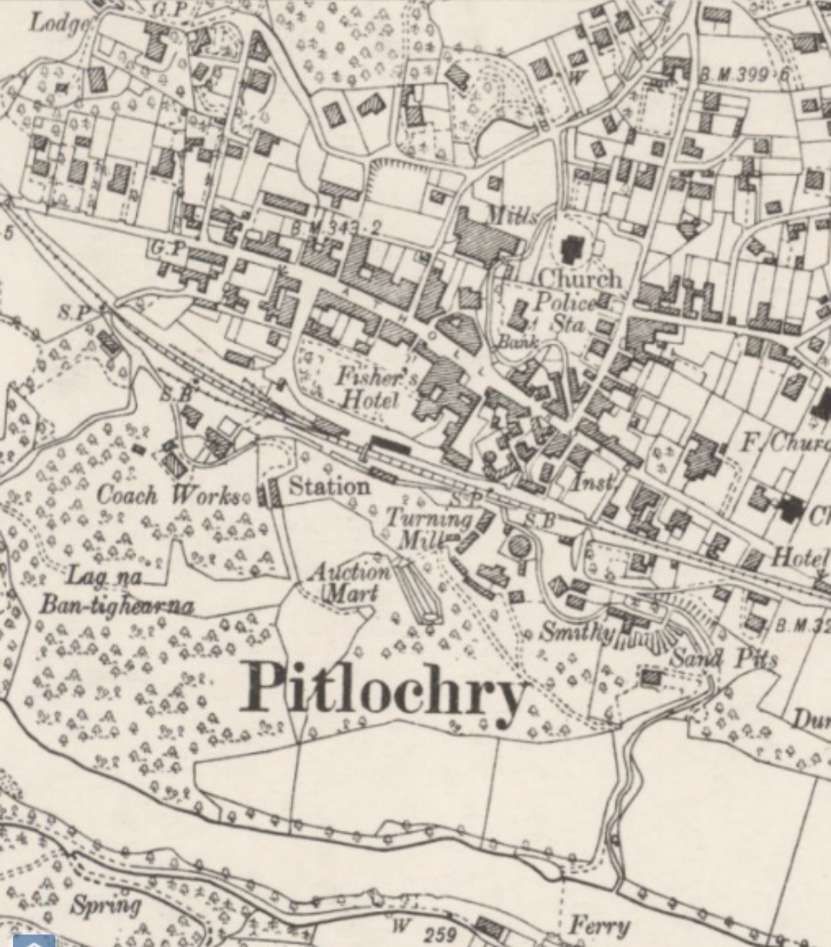

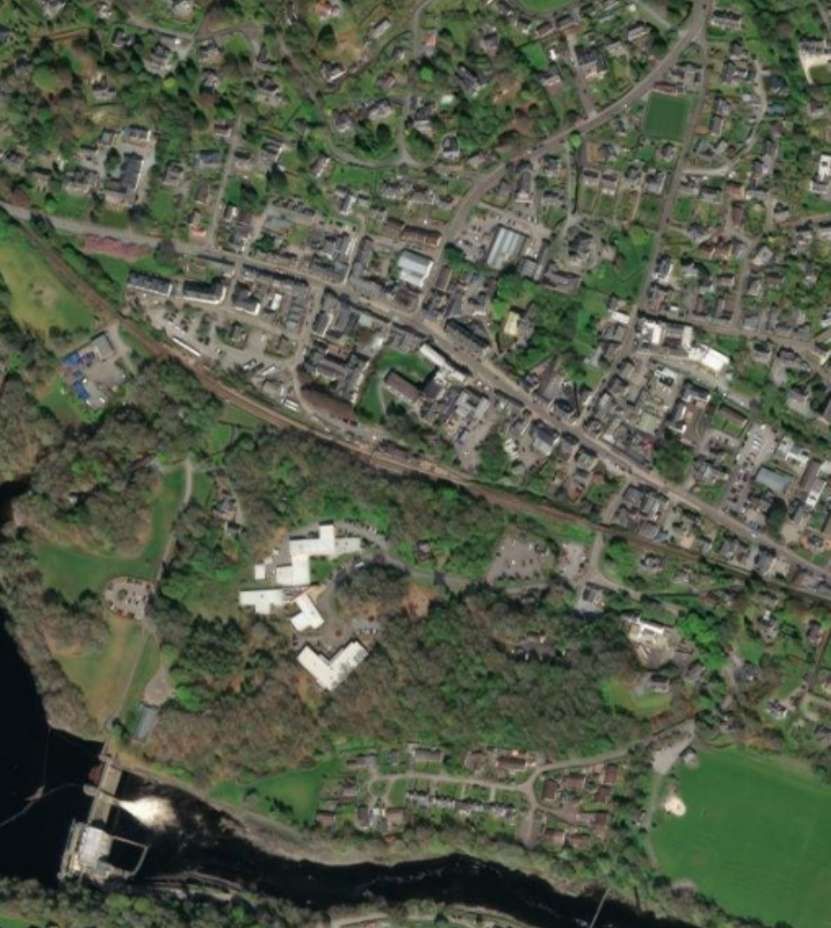

The railway has followed the River Garry over some distance. The confluence of the River Garry with the River Tummel is just a short distance South of the Pass of Killiecrankie. From that point the railway follows the River Tummel through Pitlochry.

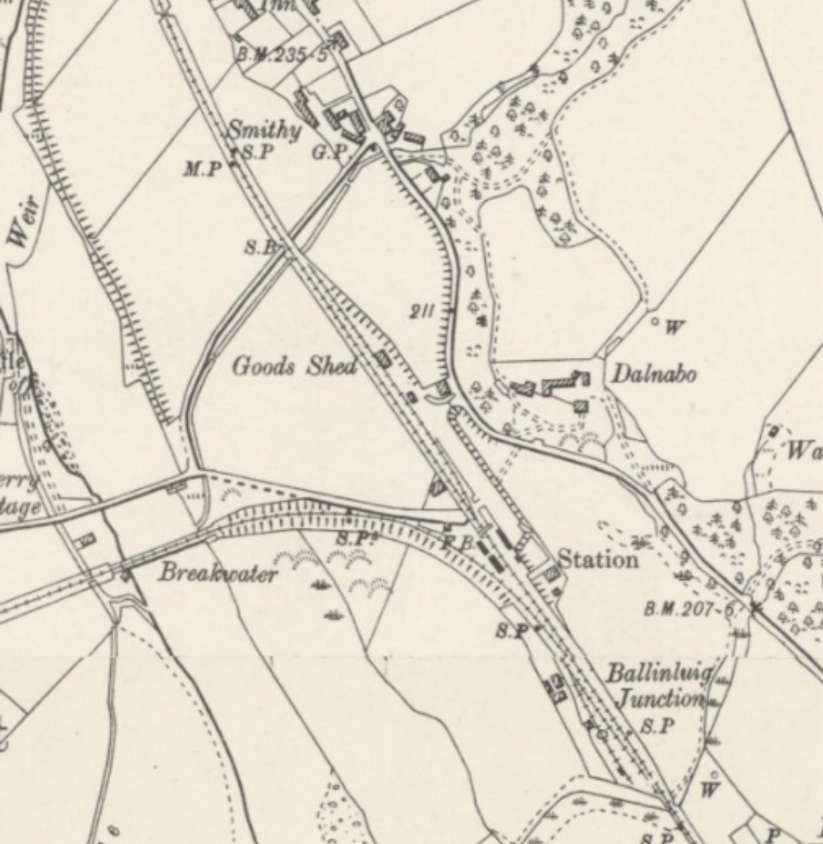

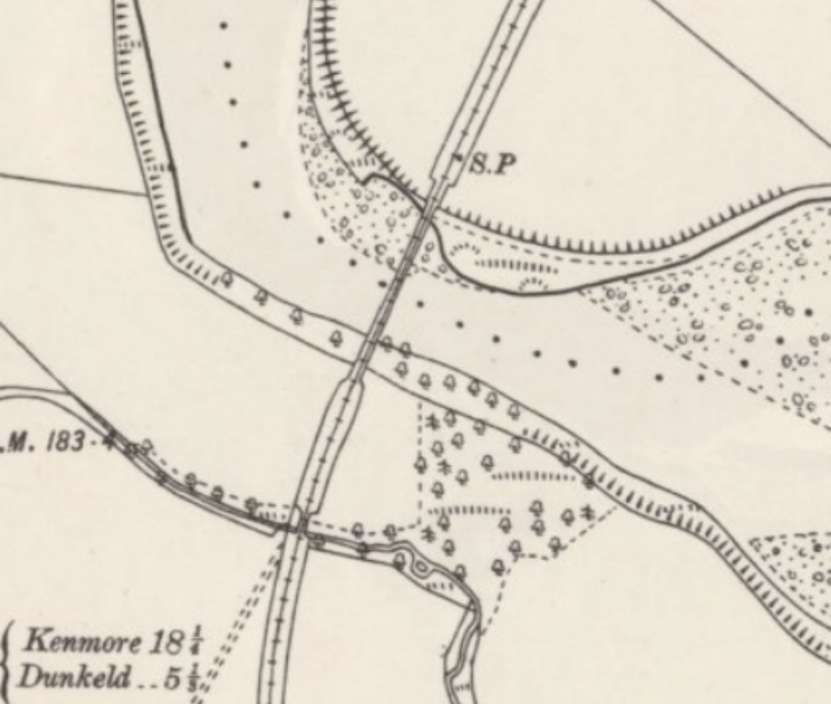

To the Southeast of Pitlochry the main line of the Highland Railway is met by the Aberfeldy branch which has just crossed the River Tummel. The Aberfeldy branch ran along the South side of the River Tay from Aberfeldy to close the confluence of the Tummel and the Tay. It bridged the Tay and soon also bridged the Tummel as shown in the OS extract below.

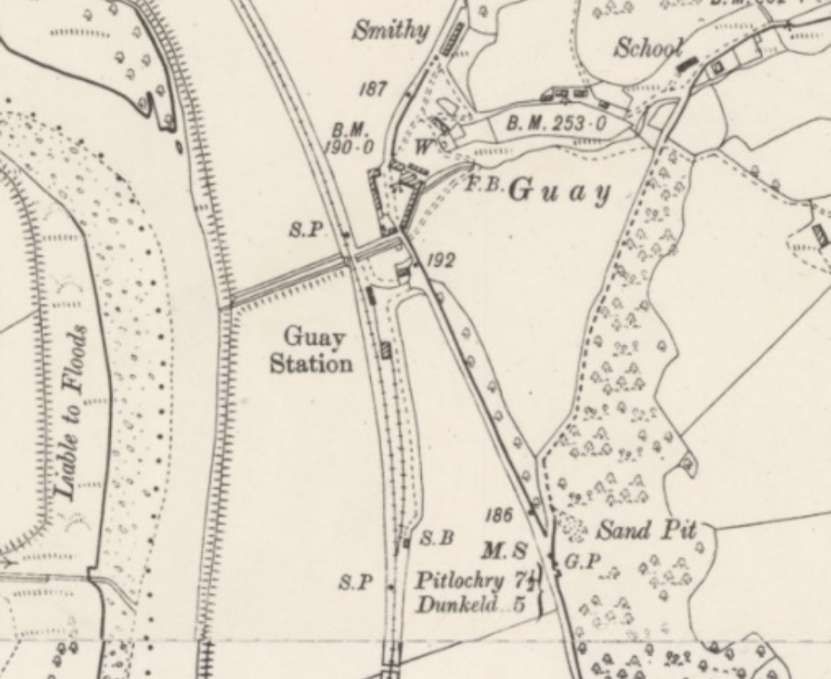

The River Tummel joins the River Tay a short distance South of Balliinluig Junction and the railway continues down the valley of the Tay, through what was Guay Railway Station and bridging the River Tay a little further South.

Images of Dalguise Railway Station can be seen here, [121] here [122] and here. [123]

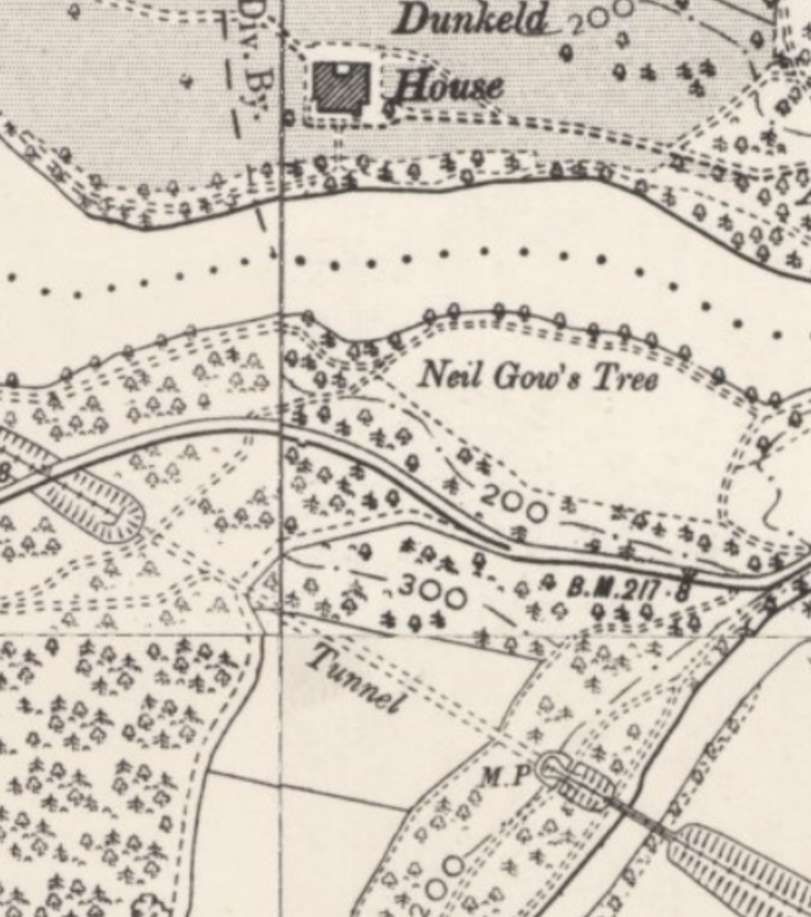

Beyond Dalguise, a tunnel opposite Dunkeld House across the Tay, a bridge over the River Braan, a significant embankment and a length of cutting bring the line to a point across the Tay from Inverness. The line continues through the railway station at Birnam which serves Dunkeld and Little Dunkeld.

Historic Environment Scotland describes Inver Viaduct, the bridge over the River Braan, as being a “large single segmental arch, flanked by crenellated refuges [with] large masonry approaches pierced for footpaths, octagonal flanking features.” [124]

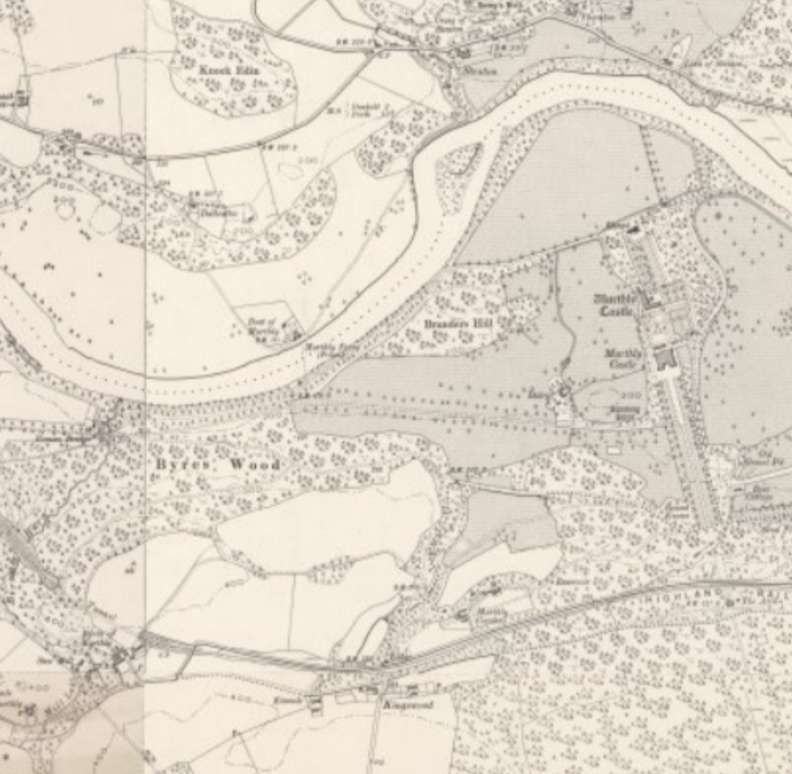

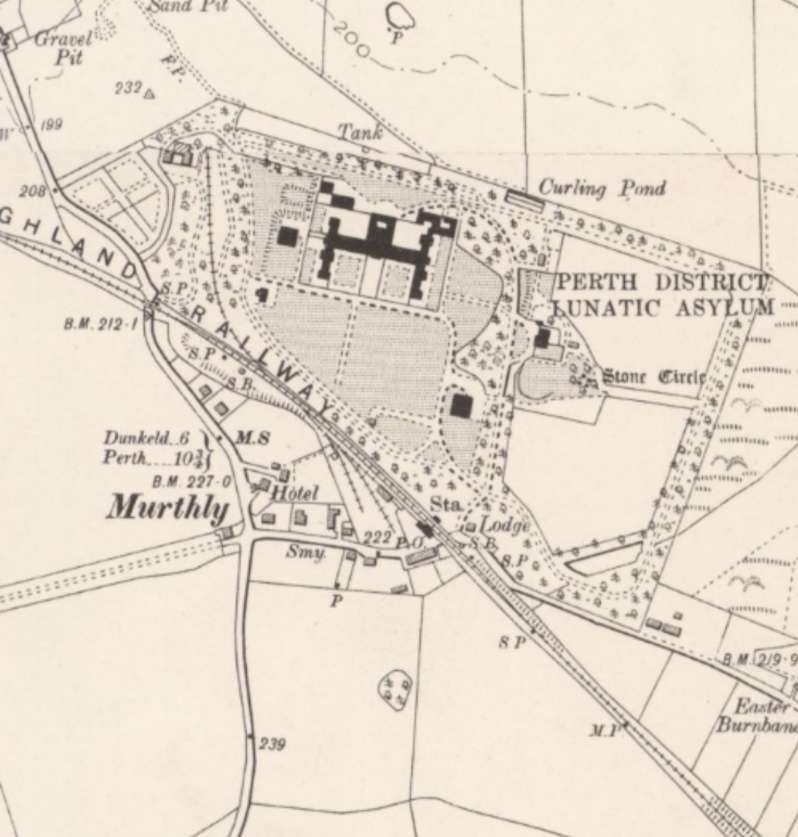

Beyond Dunkeld and Birnam Railway Station, the line continues along the South side of the River Tay. Rail and river separate to make room for Murthly Castle. The line, first in tunnel and then skirting the South side of the Murthly estate.

“Murthly Castle has been owned by three families since the original tower house was built in 1450. The Stewarts of Grantully acquired the property in 1615 and the present owner is Thomas Steuart Fothringham, who lives at the property with his family. The castle was developed gradually over a 450-year period, with the latest addition dating from 1893. Consequently, there is a wide range of architectural styles both inside and outside.” [127]

Stanley railway station was located around half-a-mile Southwest of Stanley Junction Station. It was opened in 1848 by the Scottish Midland Junction Railway which linked Perth and Arbroath. It closed in 1857, when the new station of Stanley Junction was built at the location where the Perth and Dunkeld Railway diverged from the Scottish Midland Junction Railway running between Perth and Arbroath. Stanley Junction Station closed to passengers in 1956 and to goods in 1965. [133][134]

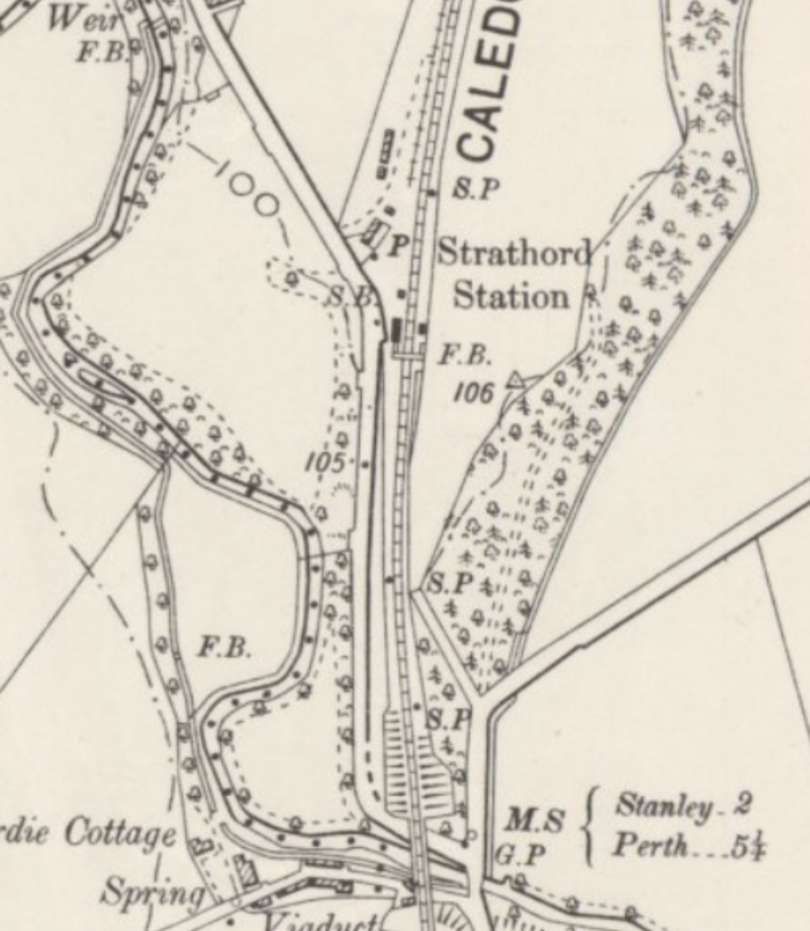

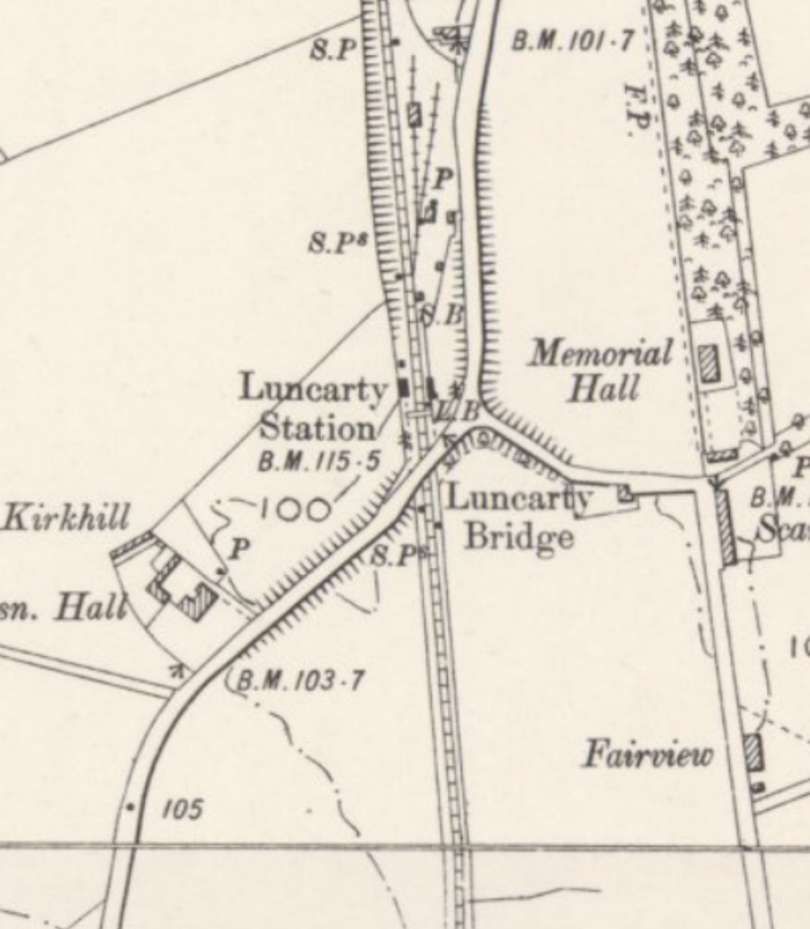

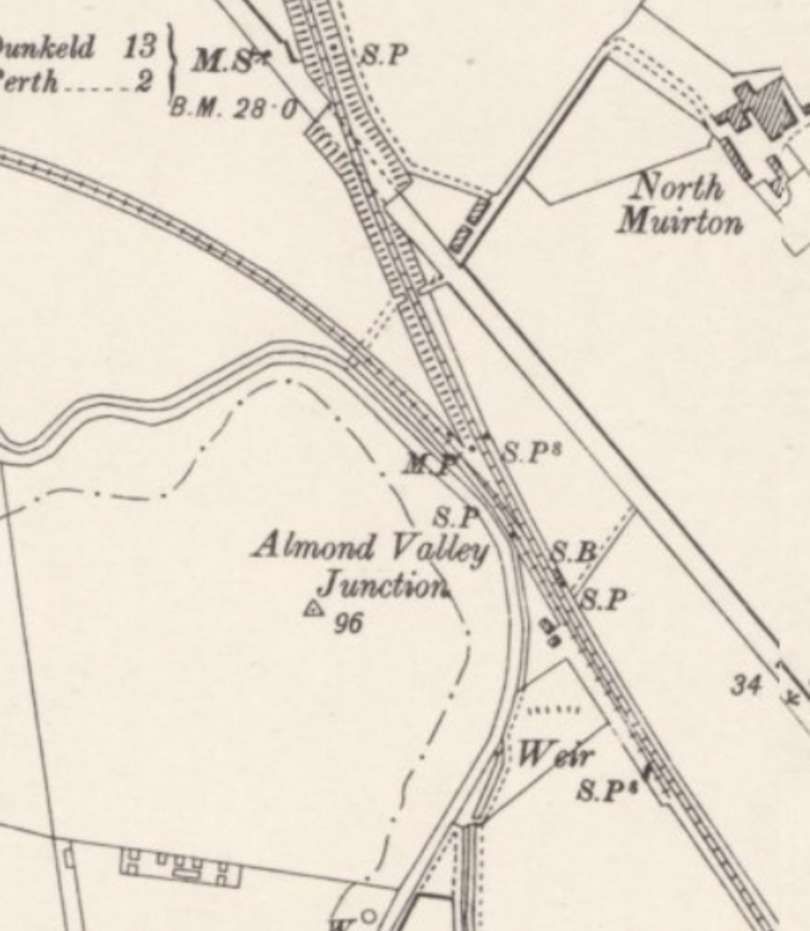

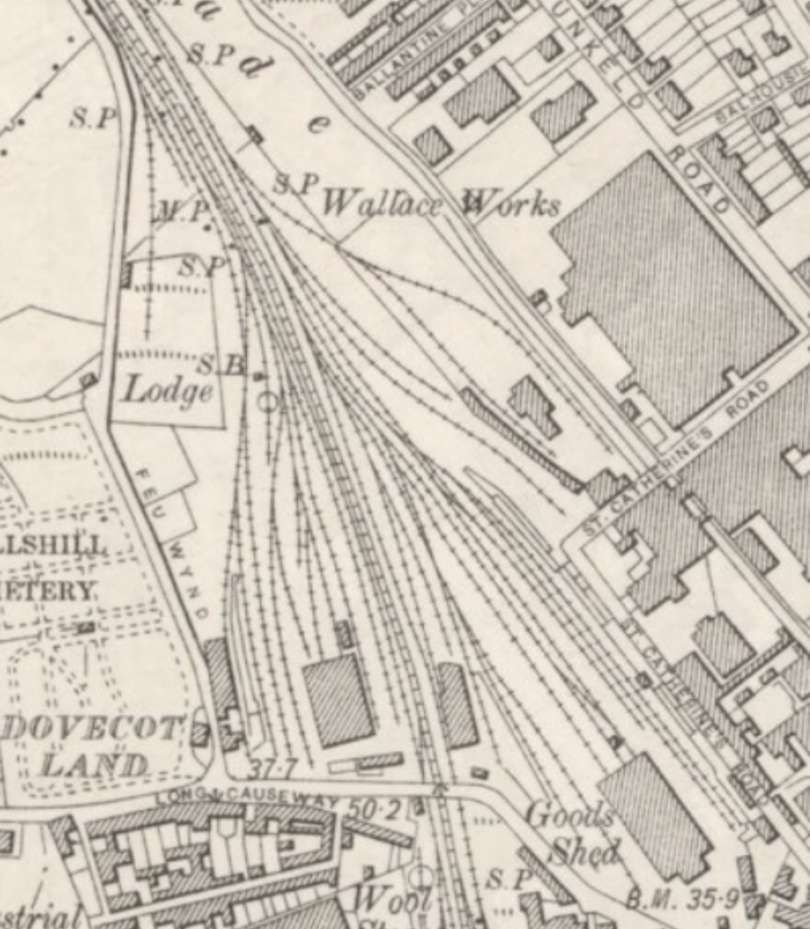

Highland Railway trains ran through to Perth on the Caledonian Railway under an arrangement agreed by predecessor companies (the Perth and Dunkeld Railway and the Scottish Midland Junction Railway). The line ran through Stratford and Luncarty stations, before passing through Almond Valley Junction before the final approach to Perth General Railway Station.

Having travelled to the most southerly point on the Highland Railway’s network and having already noted that a more direct route from Inverness to Perth was to be constructed. We complete this particular article by acknowledging that the rivalry between the Highland Railway and the Great North of Scotland Railway (GNSR) was intense. Various schemes were developed by the GNSR, but none more significant than the GNSR backed abortive scheme of the Strathspey Strathdon & Deeside Junction Railway Co. (SS&DJ) to construct a 30-mile line from Ballater, terminus of the GNSR Deeside branch from Aberdeen, to Nethy Bridge on Speyside, on a GNSR branch from Craigellachie; the GNSR “was then to build its own line from Nethy Bridge directly to Inverness. The terrain was difficult on both sides of Nethy Bridge, especially to the east, where the alignment cut across a northern ridge of the Cairngorms that would have meant a 2000ft summit (compared with Druimuachdar’s 1484ft) or a long tunnel.” [1: p7] It is difficult to determine whether this route was ever a serious proposition, but “one effect of the SS&DJ proposal was to frighten the HR into building the costly Perth-Aviemore cut-off over Slochd so as to cut the Perth-Inverness passenger transit by reducing the distance compared with the route via Forres and Dava.” [1: p7]

However, the end of the 19th century saw the end of the more absurd, wasteful and expensive rivalry between the Highland and the Great North of Scotland Railway.

North and Northwest of Inverness

Drew comments: “True to its purpose of helping in the economic development of the Highlands, the I&AJR (as it was until it became the HR in 1865) started, in the early 1860s, … pushing north from Inverness. Once again local men and women co-operated. By means of working and eventually taking over lengths of line originally built as independent undertakings, the Farther North line of the HR reached Thurso, Britain’s most northerly town and 20 miles from Duncansby Head, in 1874; Penzance had been linked with London some years before, so that the British railway system extended from (near) John o’ Groats to (near) Land’s End in less than 50 years from the opening of the Stockton & Darlington.” [1: p7]

The Farther North Line or the Far North Line

In Drew’s opinion, “The Farther North line is unique in Britain. The distance by rail from Inverness to Wick, its terminus (Thurso being at the end of the branch) is 161 miles, because the line avoids expensive bridges over the sea lochs, serves as many population centres and even isolated estates as possible, and runs inland from Helmsdale roughly in a semicircle through some desolate country to near Wick. The object was partly to serve the population (sometimes by means of lonely roadhead stations) and partly to avoid the cliffs along the coast north of Helmsdale. By bridging the narrower sea lochs and keeping nearer to the coast the distance from Inverness to Wick could have been only a little over 100 miles; but that would have left many places in Ross & Cromarty, Sutherland and Caithness even farther from a railhead than they are. Less than 10 miles of the more direct route along the coast beyond Helmsdale would have been really difficult construction, probably involving some tunnelling under cliffs.” [1: p7]

Drew notes the problems encountered with snow on the Farther North line, particularly the problem of drifting snow on relatively open expanses of moorland and its propensity to collect in narrow railway cuttings. He highlights the resources needed and the logistics involved in clearing lines that were remote from highway links.

He also highlights the sterling efforts of the Highland Railway in maintaining supplies and communication to the Royal Navy in Inverness and at Scapa Flow during the first world war, over a line not built for such traffic flows. “One of the hardest tasks was the working of trains of coal, largely high-quality steam coal for the Fleet from South Wales, to Invergordon and Thurso; well over 200 miles of the journey was over the HR and most of that distance was single track. The HR had of course to borrow engines and wagons from other railways. The difficulties included lack of the running loops needed for such heavy two-way traffic.” [1: p9]

A daily scheduled service ran from Euston to Thurso during both world wars. Officially ‘The Euston to Thurso Naval Special’, this was known colloquially as the Misery Express or more positively, ‘The Jellicoe Express’. “It was named after Admiral Sir John Jellicoe and carried service personnel to and from Naval bases around the country, including Scapa Flow. WW100 Scotland reports that in WW1 it ran 15th February 1917 – 30th April 1919.” [9]

It was estimated to have transported some half a million service personnel during the two wars. (Helmsdale says half a million in each war). It was the longest scheduled rail service ever to run in the UK.

Crewe Station was one of the few scheduled stops on the 717-mile 21h 30m journey. This was a major refreshment stop, where over 300 women volunteers worked around the clock to provide refreshments in a canteen on Platform 6. Helmsdale was another refreshment stop.

From Royal Naval Association: “Although seen as a crucial piece of Naval infrastructure, the train also carried thousands of soldiers and airmen over the years.Travelling on it was usually a nightmare – invariably overcrowded, most passengers were unlikely to get a seat, and only the shortest of them could hope to get any sleep (if they could find an empty wire luggage-rack). In the Great War it left London at 6pm, arriving at Thurso at 3.30pm the following day. The southbound service took an hour longer …”

The Far North/Father North Line will be covered in detail in a future article. The early involvement of the 3rd Duke of Sutherland in the development of the line is covered here. [51]

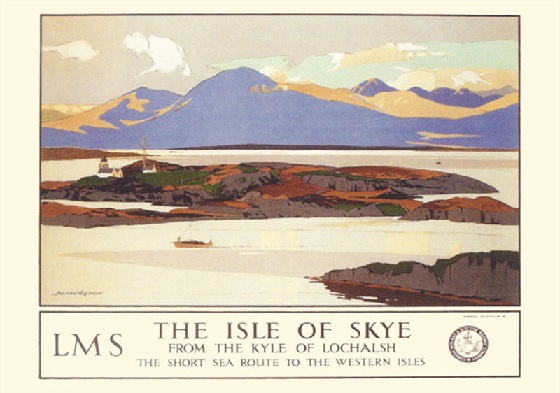

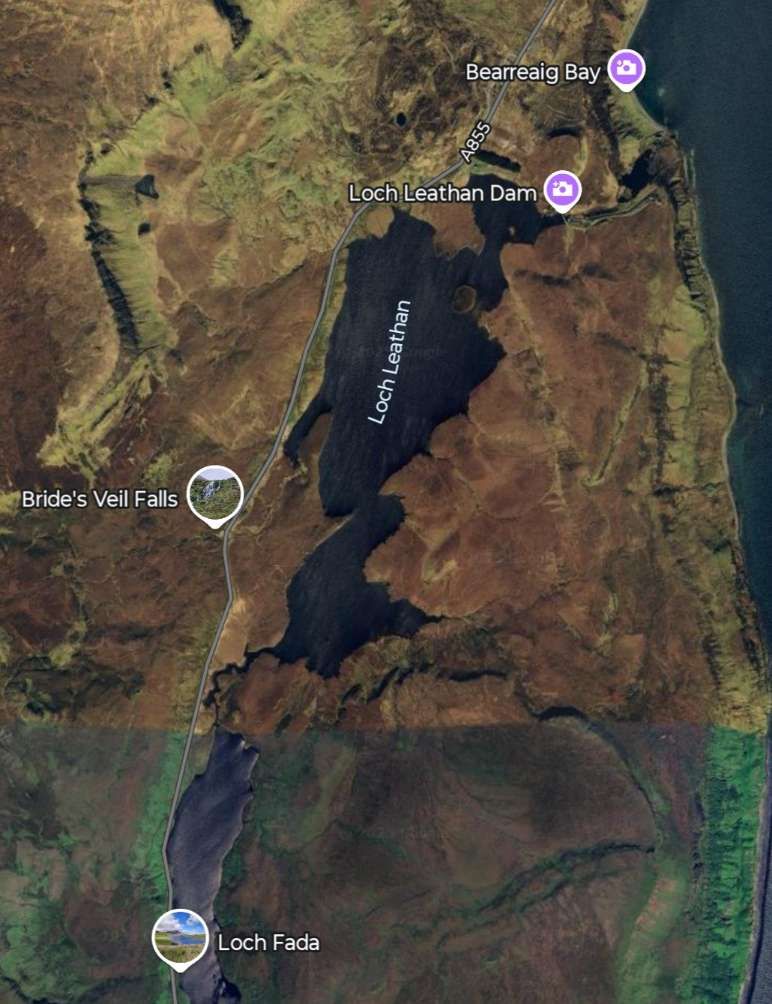

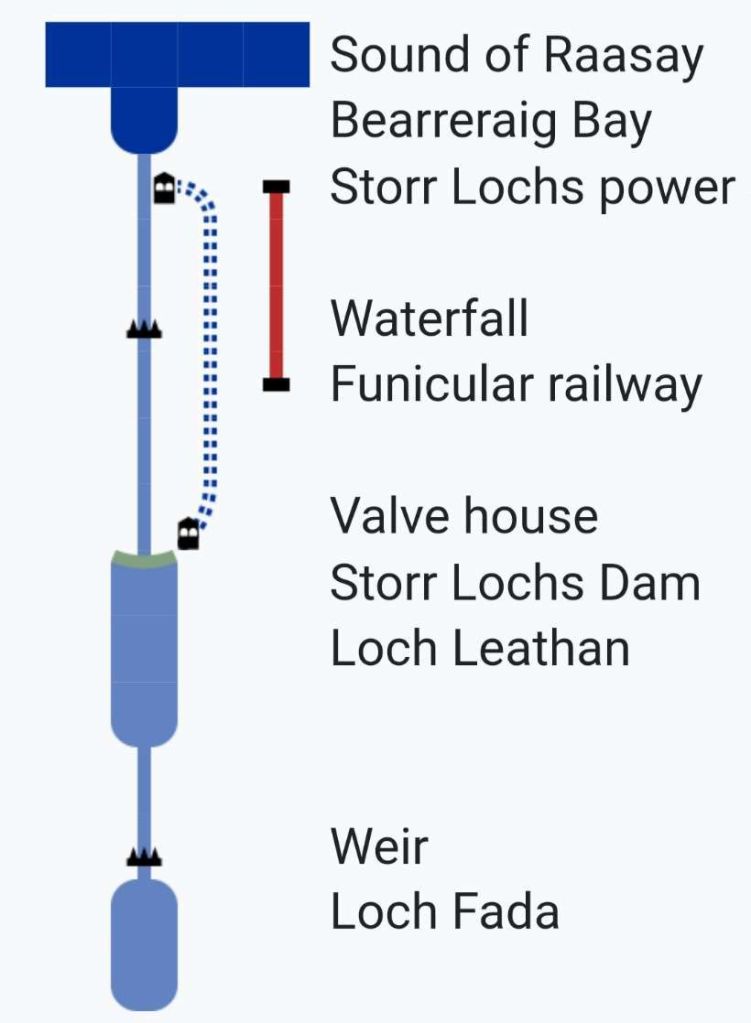

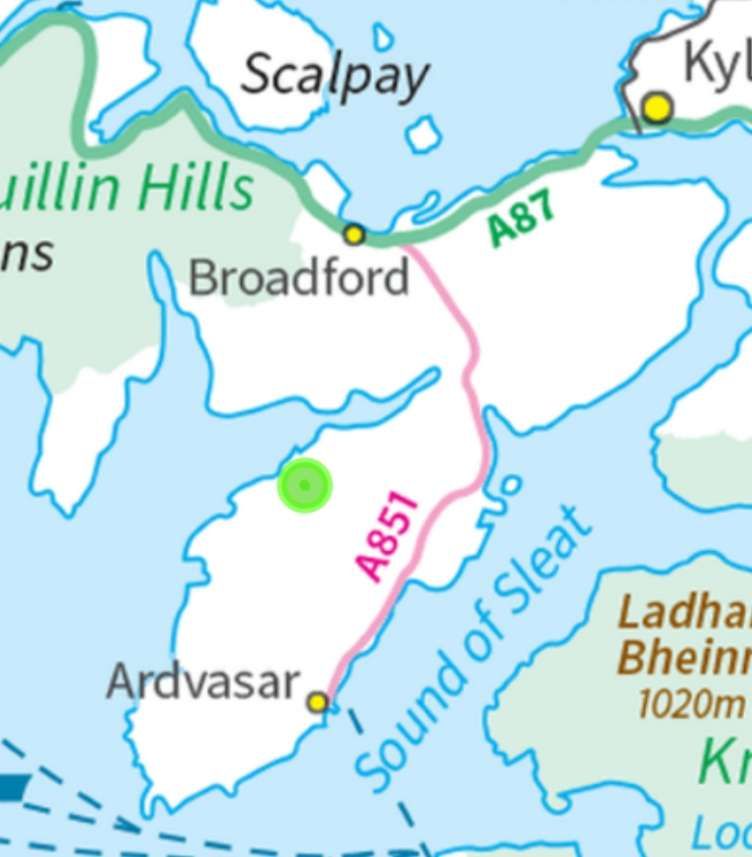

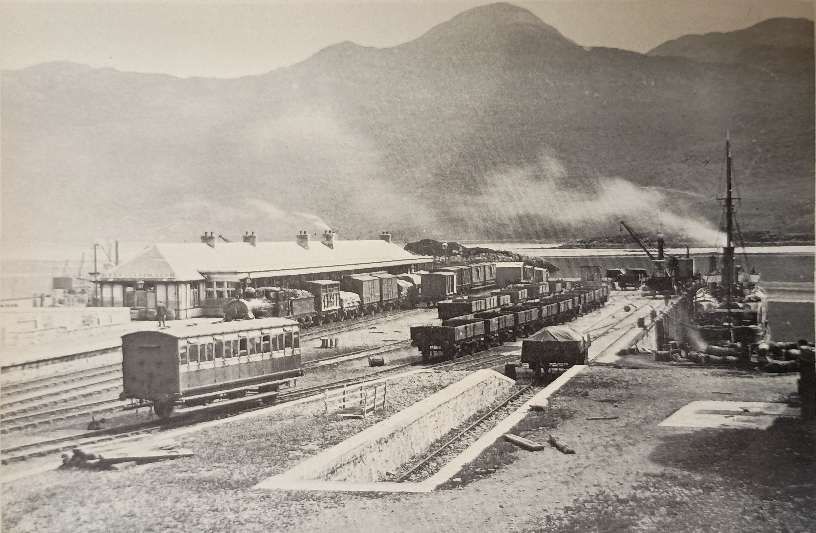

The Skye Line from Dingwall to Kyle of Lochalsh “was also built to develop rural areas. Whereas the purpose of the Farther North was to help the mainland northerly counties (though the promoters had Orkney traffic via Scrabster in mind), the Skye line was regarded also as a means of helping economically depressed Skye and Lewis and Harris and such others of the Hebrides as sent fish and the products of sheep farming to the south.” [1: p9]

Drew tells us that “the line began as an independent undertaking, the Dingwall & Skye, and was to run for 63 miles across Ross & Cromarty and over the watershed between the Moray Firth and the Atlantic to Kyle of Lochalsh, terminus of the shortest ferry crossing to Skye and a site for berths for seagoing steamers to Lewis and other islands. Construction was delayed by opposition at Strathpeffer, which little spa had to be bypassed by a costly deviation. Consequently the line only reached Strome Ferry, at the head of the sea inlet, Loch Carron, in 1870. This remained the terminus and point of embarkation until 1897, when the Skye line eventually reached the Kyle, which became an admirably designed minor packet port, complete with a hotel.” [1: p9]

Drew explains that the HR absorbed the Dingwall & Skye (D&S) in 1880. “For 10 years from the opening of the railway to Strome Ferry the D&S and later the HR operated the shipping services between Strome Ferry and Skye and the Hebrides. They were eventually taken over by David MacBrayne and [then] … by Caledonian MacBrayne Ltd. … The HR later had high hopes of Strathpeffer; it built a special two-mile branch (now closed) thither from Fodderty Junction and during the season a Strathpeffer Spa express was run non-stop from Aviemore to Dingwall and on to the branch.” [1: p9]

The line to Skye and the Strathpeffer Branch are covered in detail elsewhere. The Strathpeffer Branch is dealt with here. [3] An article about the line to Kyle of Lochalsh will follow in due course.

Locomotives and Rolling Stock

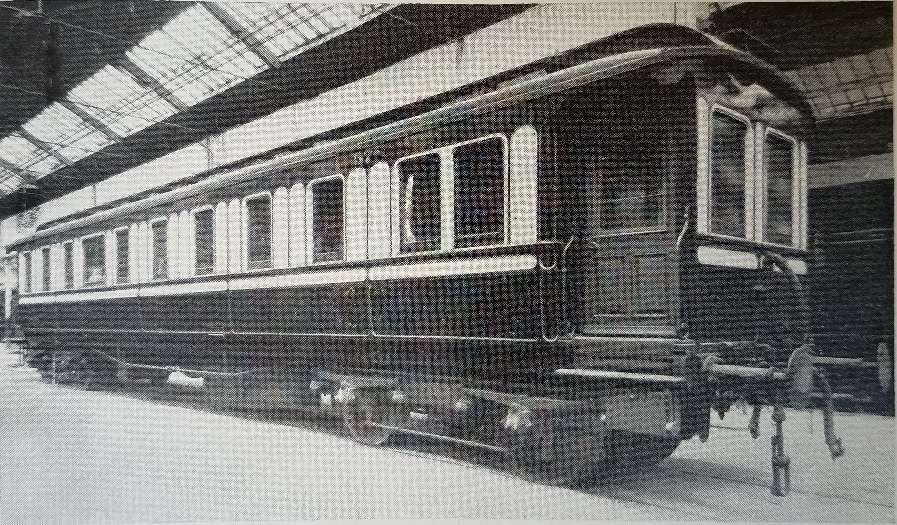

To conclude this article we take a look at the notes Drew provides on the locomotives employed by the HR and further, at its locomotive superintendents: “The Jones Goods, placed in service from 1894, is one of the best-known types of engine of any British railway, famous as the first instance in the UK of the 4-6-0 wheel arrangement. … Experience with the Jones Goods helped their designer David Jones in developing the Castle Class express passenger 4-6-0s, which did not, however, enter service until 1906, after Jones had retired, and details were finalised by his successor Peter Drummond. … Struck by the magnificent work of the Castles on the HR main lines, the French State Railways in 1910 ordered 50 from the North British Locomotive Company. As illustrations show, Jones’s designs, despite the louvred chimneys, were handsome, and most were highly efficient. In view of the many steep gradients it might be asked why Jones did not develop six-coupled engines before. Indeed the HR and its constituents seemed to prefer Alexander Allan single drivers (successful on lines in flat country) long after greater adhesion became necessary.” [1: p11]

“Having developed successful goods and passenger 4-6-0s, the HR went ahead with others. The best was F. G. Smith’s River Class of 1915, which were not allowed to work on the HR after delivery, because of Smith’s failure to consult the civil engineer, and had to be sold to the CR. His successor Cumming was responsible for two fine designs of 4-6-0, the Cumming Goods and the Clans, but there was little opportunity for those engines to show their paces before grouping.” [1: p11]

William Barclay was HR locomotive superintendent from 1855 until 1965. “During Barclay’s incumbency, … various 2-2-2 and 2-4-0 locomotives were built, along with a solitary 0-4-0T. An 0-4-0ST was also inherited from the Findhorn Railway. Many of Barclay’s locomotives would later be rebuilt by Stroudley or Jones – most of the 2-2-2s ended up as 2-4-0s and one became a 2-2-2T, a pair of 2-4-0s became 4-4-0s and the 0-4-0T became an 0-4-2T. Only 4 much rebuilt Barclay locomotives (all 2-4-0s) were still in stock at the time of the Grouping.” [35]

William Stroudley was HR locomotive superintendent from 1865 to 1870. “His main achievement was high standards of maintenance and cleanliness that continued to be achieved long after his departure to the LB&SCR. He did much to rationalise the HR Lochgorm Works at Inverness.” [1: p11]

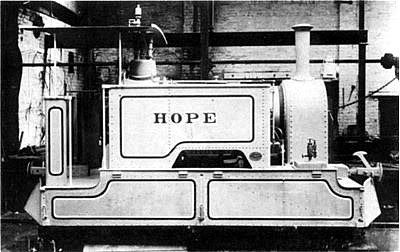

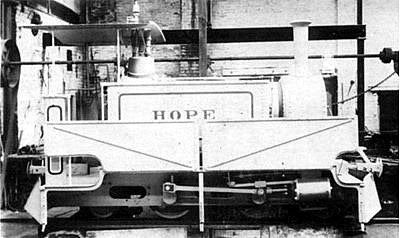

Stroudley was also responsible for the design of a small HR 0-6-0ST which, with modifications, was to become the well-known Terrier Class A1 of the LB&SCR. The HR 0-6-0STs were the first locomotives to be built at the Highland Railway’s Lochgorm works in Inverness. The design was the only new design of locomotive brought in during William Stroudley’s spell as the company’s locomotive superintendent. Only three of engines were built. [4] All three, built in 1869, 1872 and 1874, “started life with second hand boilers, shortened to suit, with the dome over the firebox. The side tanks had extra capacity in the form of an arched tank placed over the boiler. The cab was typical of Stroudley but there was no coal bunker; it was carried on the right hand side in the space alongside the firebox between the cab and the side tank, both sides having extended lower cab sides meeting the tanks.” [39]

“To the end the three engines showed strong Stroudley features, although they were not entirely identical, the oldest acquiring a larger side tank during rebuilding in 1917 and the rear toolbox was replaced by a small bunker on all three. Typically for HR engines all three were named: No. 56 – Balnain when new, then Dornoch in 1902; No. 57 – Lochgorm; No. 16 – St. Martin’s when new, then Fort George in 1899. … The later names reflect the move of the engines to those branches. Latterly in HR days they were nameless. The LMS correctly placed Nos 56 and 57, by then with duplicate list numbers as 56B and 57A, with similar powered tanks as Nos 16118 and 16119, by which time the former was working the Strathpeffer branch, but the third was numbered 16383 at the end of the other 0-6-0T classes this may have been due to mistaken identity. All three were soon running with LMS numbers, Inverness having applied LMS numbers and livery rather quickly, but they were condemned in 1927-32.” [39]

Until 1869, all locomotives were painted dark green. After that, passenger locomotives were painted yellow ochre , and freight locomotives were painted Scottish green (very dark green). From 1885, all locomotives were painted pea green with red and white trim. From 1903, the green became darker again, and the tenders now bore the inscription “Highland Railway.” [5]

David Jones was Locomotive Superintendent from 1870 to 1896. He “designed several classes of 4-4-0, and was also notable for introducing the 4-6-0 wheel arrangement to the UK. He also produced small numbers of 0-4-4ST, 2-4-0, 2-4-0T and 4-4-0T locomotives. Of 88 engines built to Jones’ design (including 3 built as late as 1917), 74 passed to the LMS in 1923. A small 2-4-0T purchased secondhand from the Duke of Sutherland also made into LMS ownership.” [35]

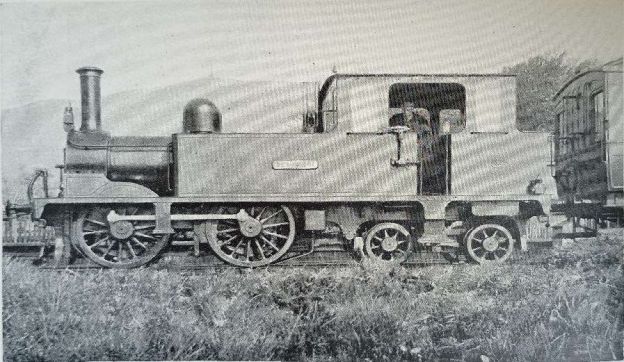

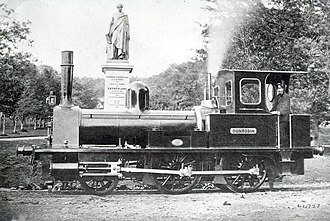

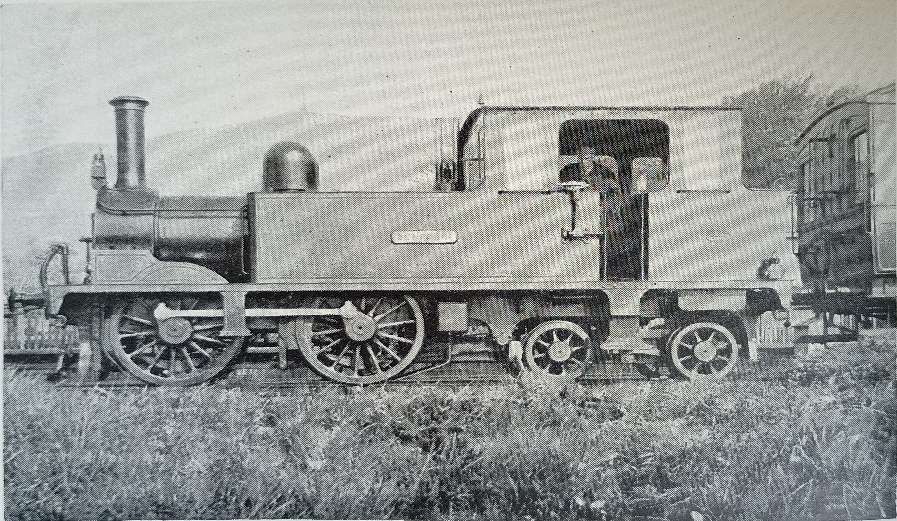

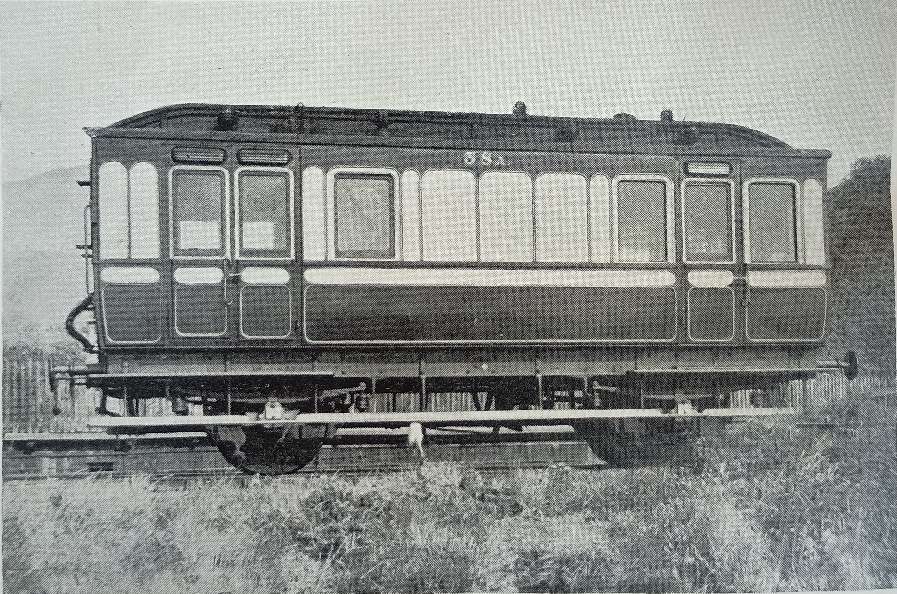

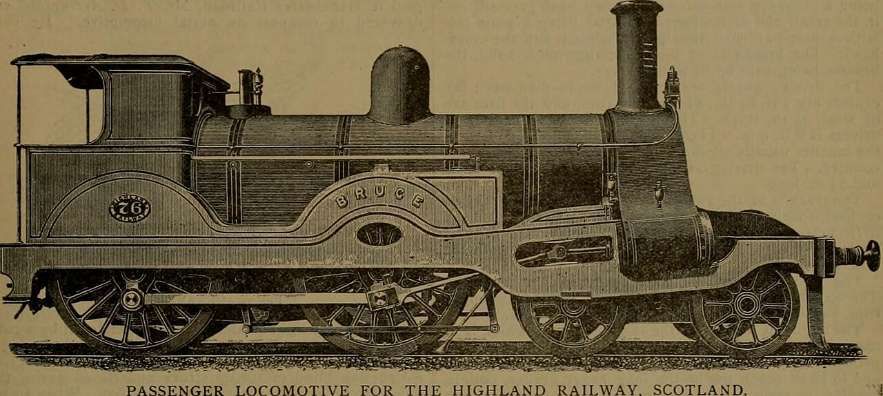

“Both the Highland Railway and the Glasgow & South Western Railway initially put [4-4-0 locomotives] on the line during 1873, the first in June, the latter in July – however the important distinction was that the former was produced by fitting a bogie to an outside cylinder 2-4-0 locomotive dating from 1858. The need arose from problems encountered on the recently opened (1870) line from Dingwall to Strome Ferry, the long fixed wheelbase of the six-wheelers sent there not taking kindly to the sharp curves. The first convert was No 10, followed by No 7, another 1858 engine, in 1875. The immediate result for the HR was the introduction of a new 4-4-0 type in 1874, the ’60’ class, which however was for main line work, ten being supplied by Dübs, and at the same time the most powerful passenger engines in Britain. For some years the Lechatelier counter pressure brake was fitted, later replaced by vacuum. With these engines came the well known louvred chimney, a feature of David Jones’ Highland engines. Seven more were built by the company at their Lochgorm Works in 1876-88, generally similar apart from boiler dimensions. Eight others, Nos 76-83, dated 1886, were the first products of the Clyde Locomotive Works of Glasgow (soon absorbed by Sharp, Stewart); the first engine of this batch was displayed at the 1886 Edinburgh Exhibition. The type was perpetuated in 1892 when Nos 89-100 were completed, essentially the same class, apart from further boiler enlargement. As main line engines all of these 4-4-0s were named, but confusion arises from numerous changes of names. Several lasted into LMS days, but only one of the Clyde built and six of the 1892 engines were allocated LMS numbers.” [10: p5]

“A smaller wheeled version of these classes for the Strome Ferry line, hence its popular title ‘Skye Bogie’, was only slowly multiplied, one engine in 1882, followed by eight in 1892-1901, the last four appearing after Peter Drummond had succeeded Jones in 1896. With the completion of No 48 in 1901 the use of the “Crewe” pattern of front end frames and cylinders on new building ceased. Unlike the ’60’ class these engines were not named. All passed into LMS stock but one was not given a new number. However one of them was a combination, identified as a ‘Skye Bogie’ because of its smaller coupled wheels, the frames originating from No 70, the 1882 engine, other components being derived from No 67 of the ’60’ class, the assemblage being completed in February 1923 and identified as No 67 Cromartie. Useful in their later days on branch lines it was 1930 before the last was condemned.” [10: p5]

K.A.C.R. Nunn/LCGB Ken Nunn Collection 2026[10: p11]

“Despite introducing a large six-coupled goods in 1894 Jones retained the 4-4-0 wheel arrangement for the next express locomotives. Again the new class, ‘119’ or ‘Lochs’, were some of the most powerful passenger engines in the land. Most of the established features of Inverness engines were retained, the louvred chimney, the Stroudley cab but the frames and cylinders were conventional, not of the “Crewe” type. An early form of piston valves were used, not successfully for they were soon replaced by balanced slide valves. All were named after ‘Lochs’ in the Highland area. There were few changes in HR days although No. 130 ran with a feed water heater. Even after displacement as the premier main line engines by Drummond’s 4-6-0 ‘Castle’ class in 1900, the ‘Lochs’ remained almost confined to the HR main line right up to the Grouping. When further engines were urgently required during World War I the need was partly met by obtaining in 1917 three more of the class from North British in Glasgow, time and expenses being saved by using existing patterns and drawings.” [10: p5]

The ‘Lochs’ were Jones’ final design for the Highland Railway. 15 were originally built by Dubs & Co. in July-September 1896. [10: p16] With the 3 built in 1917, this meant that a total of 18 members of this class were built.

“Drummond brought about a complete transformation of Highland engine power, such that it seemed that his brother Dugald, and Eastleigh Works of the London & South Western Railway had taken over, for many of Peter Drummond’s classes corresponded to L&SWR designs. The first of two Drummond 4-4-0 classes appeared in 1898 and were slightly smaller than the ‘Loch’ class, being intended for services from Inverness to Aberdeen and Wick. The eight initial engines were supplied by Dübs in 1898, followed by a further nine built at Inverness in 1899-1901. Three more came from Glasgow in 1906, having tenders with a little more water capacity. Six-wheeled tenders had been supplied with the class but at times a few engines ran with eight-wheeled tenders from other classes. There was an important change from the previous Inverness adherence to Allan’s straight link valve gear to Stephenson link motion. Another change was the introduction of steam reversing gear, although the initial eight had lever reverse until modified. Nos 2 and 13-7 were dual braked and Nos 2 and 7 later ran with Smith’s feed water heaters. Named after Scottish mountains these engines were inevitably known as the ‘Ben’ class. The first engine arrived at Inverness with the name Ben Nevis to the embarrassment of the HR for that mountain is far away in rival North British Railway territory so a hurried change was made to Ben-y-Gloe.” [10: p5]

Rowledge continues: “A further six 4-4-0s engines, intended for Inverness and Wick trains, were provided by North British in 1908-9, using the frames, etc., of the ‘Ben’ class but carrying a larger boiler, becoming the ‘New Ben’ class, using more mountain names. All had steam reversers and three, Nos 60, 61 and 63, were dual braked. Smith’s feed water heaters were fitted in 1914-5, feed water initially being heated by exhaust steam in a heat exchanger placed alongside the smokebox on the right hand side and then further heated by another set of tubes inside the smokebox. The four 1908 engines started with the same size 3,185 gallon tenders as the last three ‘Bens’, but two, Nos 61 and 63 soon received 3,200 gallon double bogie tenders taken from 0-6-0 tender engines, while the final pair had even larger 3,600 gallon bogie tenders.” [10: p5]

“Despite wartime conditions a new design appeared in 1916 after Cumming had replaced Drummond as Locomotive Superintendent, larger and heavier than any previous HR 4-4-0 class. Nos 73 and 74 were the first two-cylinder engines of this wheel arrangement in Britain to have outside cylinders and valve gear. Apart from the rejected ‘River’ class 4-6-0 engines this pair were the first on the HR to have superheaters, Drummond not having taken to this development while at Inverness. Both were built for the ‘Far North’ line but they also saw use between Inverness and Perth.” [10: p5]

From the late 1920s ‘Snaigow‘ and ‘Durn‘ were found mostly working from Aviemore Shed on goods or piloting work, having been replaced on the Far North line by Drummond ‘Castle’ 4-6-0s which were in turn displaced by new LMS ‘Crabs’ and Caledonian ‘Rivers’ sent to the Highland Railway. The arrival of Stanier ‘Black Fives’ sealed their fate and both were withdrawn in the mid-1930s. [10: p25]

“The LMS inherited 78 4-4-0s from the HR – this is the official figure contained in a document at the Public Record Office, Kew – but two others were still extant and are usually included in the initial LMS total. Only 61 were allotted new LMS numbers, the rest being written off during 1923. Despite early withdrawal of pre-1896 examples several of them, Nos 14271/2/5-9/82-5, appeared in the LMS red livery with large numerals on the tender.” [10: p5-7]

“The Highland [4-4-0] engines lasted rather better than those of the G&SWR, twelve passing into British Railways stock.” [10: p7] The last of these was ‘Small Ben’ No. 54398 ‘Ben Alder‘ which was scrapped in the second half of 1952.

Having followed the various 4-4-0 classes employed by the Highland Railway we return to look at David Jones’ other locomotive designs. As we noted above, he “was also notable for introducing the 4-6-0 wheel arrangement to the UK. He also produced small numbers of 0-4-4ST, 2-4-0, 2-4-0T and 4-4-0T locomotives. Of 88 engines built to Jones’ design (including 3 built as late as 1917), 74 passed to the LMS in 1923. A small 2-4-0T purchased secondhand from the Duke of Sutherland also made into LMS ownership.” [35]

David Jones Goods class “was notable as the first class with a 4-6-0 wheel arrangement in the British Isles. Fifteen were built, and one has survived to preservation.” [36]

Fifteen ‘Jones Goods’ locomotives “were built by Sharp, Stewart and Company and delivered between September and November 1894, numbered 103 to 117. At the time, these were the most powerful main line engines in the country. Originally intended principally as freight engines, they were often called upon for passenger duties during the wide fluctuations of traffic which occurred on the Highland Railway, particularly during the summer season.” [36]

“Although the type was a notable success for Jones, an accident while testing one of the locomotives caused one of his legs to be severely scalded. Although he recovered, he was permanently affected and by the end of December 1896 had retired due to ill-health.” [36]

Peter Drummond was Locomotive Superintendent of the HR from 1896 to 1912. Under Peter Drummond, new 0-4-4T, 0-6-0T, 0-6-4T, 0-6-0, 4-4-0 and 4-6-0 designs emerged. All 72 of his locomotives passed to the LMS. [35] Among those 72 locomotives were the class ’18’ 0-6-0s – these were the only class of 0-6-0 employed by the HR. The class was introduced on the network in 1900. [38: p9]

“Originally intended to be 15 in number the initial order was for only six when placed in 1899, Dübs supplying Nos 134-9. They were followed by Nos 18-21 in 1902, also from Dübs, and finally Nos 36 and 55 (the latter renumbered 37 in 1921) in 1907 from North British. The class replaced an assortment of small and old 2-4-0 locomotives. The 1902 engines had Drummond water tube fireboxes, but otherwise the “Barneys” (just how the class became so named is lost in the mists of the past) were quite conventional. The first six had double bogie tenders, the rest six wheeled, the former being exchanged with six wheeled tenders from the 4-4-0 ‘Ben’ class (LI No 117) in 1902-13.” [38: p9]

“Most of the ’18’ class, as far as is known, were used on goods trains to east and north of Inverness rather than the main line to Perth. Despite not having steam heating pipes there was some use on passenger trains, especially excursions. In LMS ownership the class was numbered 17693-17704. In 1938 Nos – 17693-5/7, 17703 were moved to the Glasgow area to assist with extra traffic to the Glasgow Exhibition, when more engines with vacuum brakes were needed, working from Dawsholm, – Motherwell and Hamilton. One No 17694, was even seen on an excursion train at Edinburgh which also crossed the Forth Bridge to Burntisland. Although returned to Inverness later that year five were again used in Glasgow during 1939, but not for long. A longer stay in that area began at the end of 1946 when the eight survivors moved to Corkerhill, some later being transferred to Ayrshire sheds. Seven passed into British Railways stock, the last being withdrawn in 1952.” [38: p9]

Generally, the HR had little use for shunting tank engines, but “In 1903/04 the Highland Railway built three powerful 0-6-0 tank engines at its Lochgorm works in Inverness. Numbered 22, 23 and 24 they were used for shunting duties. The boilers and wheels were taken from older locomotives that had been scrapped and this led to the engines being referred to as ‘Scrap Tanks‘.” [40] These outside cylinder engines were, “quite unremarkable except that the boilers were recovered from obsolete 2-4-0 locomotives together with re-usable wheels and other parts. The result was a class with rather larger wheels than usual for shunters. Normally there were two working at Inverness with the other at Perth. Once the boilers were no longer listed as a standard type their survival was limited and they were condemned in 1930-2.” [39: p9]

Frederick George Smith was Locomotive Superintendent from 1912 to 1915, his “brief tenure was cut short by a dispute over his sole design, the ‘River’ Class 4-6-0. Six locomotives were built, but they were (wrongly) considered to be too heavy for the Highland Railway, and were sold to the Caledonian Railway without being used.” [35]

Christopher Cumming was Locomotive Superintendent from 1915 to 1922. He designed one class of 4-4-0 and two types of 4-6-0, totalling 18 locomotives, which all passed to the LMS. [35]

The Future

One feature of Drew’s article, written at the end of 1975, was the palpable concern expressed over the security of rail services in the remote areas of Scotland and particularly from the Farther North Line and the Kyle of Lochalsh line. With hindsight, we can say that (although justified in the mid-1970s, with the bias of the time towards road transport) what was feared has not come to pass. [1: p8] Passenger rail services on both these lines (and on the West Highland line) continue, although we should note that Scotland’s Railway receives some of the highest public subsidy anywhere in the UK: two thirds of the costs come from the Scottish Government; and on average, tickets are 20% lower than the rest of the UK. [2]

References

- Brian Stephenson (ed.); The Highland Railway; Trains Illustrated No. 18, Ian Allan, Shepperton, London, 1976.

- https://www.transport.gov.scot/public-transport/rail/investing-in-scotlands-railway/scotlands-railway-delivering-value-for-money, accessed on 18th April 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/03/23/the-highland-railways-strathpeffer-branch

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/24612, accessed on 18th April 2025.

- https://britbahn.wdfiles.com/local–files/highland-railway/HR_R_Class_57.jpg, accessed on 18th April 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Highland_Railway, accessed on 18th April 2025.

- W. Philip Conolly; British Railways Pre-Grouping Atlas and Gazetteer; Ian Allan, Hersham, 2004.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Highland_Railway_1920.jpg, accessed on 18th April 2025.

- https://www.londonremembers.com/subjects/jellicoe-express, accessed on 20th April 2025.

- J. W. P. Rowledge; The 4-4-0 Locomotives of the Glasgow & South Western and Highland Railways; in Brian Stephenson (ed.) Locomotives Illustrated No 117, January-February 1998, Ian Allan, Berkhamsted, Herts, 1997.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Highland_Railway_L_Class#/media/File%3AHR_L_class_7.jpg, accessed on 21st April 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/gd/asset/24705, accessed on 21st April 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/24624, accessed on 21st April 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GNoSR_Aberdeen_to_Inverness.svg, accessed on 21st April 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/05/01/the-highland-railway-part-1

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/04/01/the-highland-railways-fortrose-or-black-isle-branch

- H. A. Vallance; The Highland Railway (2nd. Ed.); David & Charles, Dawlish, and Macdonald, London, 1963, (First edition published in 1938).

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/190684941, accessed on 27th April 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.8&lat=57.61065&lon=-3.62472&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=0, accessed on 1st May 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=57.59091&lon=-3.61356&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=99, accessed on 1st May 2025.

- https://maps.app.goo.gl/Qs2u8nqMW5iEWADY6?g_st=ac, accessed on 3rd May 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.4&lat=57.51285&lon=-3.64495&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=94, accessed on 1st May 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3425127, accessed on 3rd May 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.5&lat=57.49791&lon=-3.63391&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 3rd May 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.4&lat=57.43088&lon=-3.65302&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 4th May 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dava_railway_station, accessed on 4th May 2025.

- https://davaway.org.uk/railway-history, accessed on 4th May 2025.

- https://youtu.be/T65rgJoVhj0?si=y4WHrtEZ07oST52e, accessed on 4th May 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Highland_Railway_E_Class, accessed on 17th May 2025.

- https://www.vads.ac.uk/digital/collection/IMECHE/id/1390, accessed on 24th May 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/24864/1/EN24864-lms-14278.htm, accessed on 24th May 2025, accessed on 24th May 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Highland_Railway_Loch_Class, accessed on 24th May 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Highland_Railway_Ben_Class, accessed on 24th May 2025.

- https://ebay.us/m/Ni0LBj, accessed on 24th May 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locomotives_of_the_Highland_Railway, accessed on 24th May 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Highland_Railway_Jones_Goods_Class, accessed on 24th May 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riverside_Museum, accessed on 24th May 2025.

- J. W. P. Rowledge; Scottish 0-6-0 and 2-6-0 Classes of the LMS; in Brian Stephenson (ed.), Locomotives Illustrated No 133, September-October 2000, Ian Allan, Berkhamsted, Herts, 2000.

- J. W. P. Rowledge; LMS Scottish Goods Tank Locomotives; in Brian Stephenson (ed.), Locomotives Illustrated No 154, July – September 2004, Ian Allan, Berkhamsted, Herts, 2004.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/25786, accessed on 24th May 2025.

- Robin Gibbons owns the glass negative for this image. (Permission given by email on Wednesday 28th May 2025.)

- https://www.railmaponline.com/UKIEMap.php, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://davaway.org.uk, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=57.37947&lon=-3.63493&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.0&lat=57.39150&lon=-3.64854&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=57.35238&lon=-3.60917&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=57.33524&lon=-3.62039&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=57.34152&lon=-3.60859&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=57.32289&lon=-3.61950&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://www.railscot.co.uk/img/10/93/, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/06/06/the-duke-of-sutherlands-saloons-locomotives-and-railways

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/cdn/highlife/previews/92/1418d083db7eb8251f35021e8055708d/5/038ca11110d621469f6a46b8080ae793/27400.jpg, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://canmore.org.uk/site/111459/grantown-on-spey-west-station?display=image, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/74490558, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://www.ourrailway.org, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=57.31778&lon=-3.62635&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=57.31301&lon=-3.63075&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=57.29776&lon=-3.65651&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.0&lat=57.28014&lon=-3.67874&layers=257&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- R. V. J. Butt; The Directory of Railway Stations (1st ed.); Patrick Stephens Ltd, 1995.

- Past the Tracks – The Aviemore to Forres Line; via http://www.pastthetracks.com/Aviemore/Aviemore_History.html – this link appears to be broken.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broomhill_railway_station, accessed on 6th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1923617, accessed on 21st June 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Broomhill_railway_station_and_signals.jpg, accessed on 21st June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=13.3&lat=57.26878&lon=-3.72388&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 22nd June 2025.

- https://www.ourrailway.org/boatofgarten.htmlhttps://www.ourrailway.org/boatofgarten.html, accessed on 22nd June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=14.6&lat=57.19856&lon=-3.82134&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 22nd June 2025.

- Mike Bridge, ed.; TRACKatlas of Mainland Britain: A Comprehensive Geographic Atlas Showing the Rail Network of Great Britain (3rd ed.); Platform 5 Publishing Ltd., Sheffield, 2017, p94.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.2&lat=57.12962&lon=-3.93060&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 22nd June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.7&lat=57.07964&lon=-4.05422&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 22nd June 2025.

- https://collections.st-andrews.ac.uk/item/aviemore-railway-station-during-construction/63885, accessed on 22nd June 2025.

- https://www.ourrailway.org/aviemore.html, accessed on 22nd June 2025.

- https://canmore.org.uk/site/69332/kincraig-station, accessed on 23rd June 2025.

- https://her.highland.gov.uk/Monument/MHG15369, accessed on 23rd June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=57.05264&lon=-4.13071&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 23rd June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.5&lat=57.06077&lon=-4.11732&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=87, accessed on 23rd June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newtonmore_railway_station, accessed on 23rd June 2025..

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/7851723, accessed on 23rd June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.4&lat=56.95683&lon=-4.21729&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=94, accessed on 23rd June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=18.0&lat=56.93297&lon=-4.24722&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalwhinnie_railway_station#/media/File%3AThe_footbridge_at_Dalwhinnie_railway_station.jpg, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Highland_Main_Line, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- John Thomas & David Turnock; A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. Volume 15 North of Scotland; David St John Thomas, Newton Abbott, 1989, p236.

- Highland doubling; in The Railway Magazine Issue No. 902, June 1976, p277.

- Highland doubling starts; in The Railway Magazine Issue No. 905, September 1976, p476.

- Highland main line upgrade work complete; Network Rail, 28th March 2019, via https://www.networkrailmediacentre.co.uk/news/highland-main-line-upgrade-work-complete, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.7&lat=56.86680&lon=-4.25512&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.9&lat=56.86716&lon=-4.25572&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.9&lat=56.85045&lon=-4.24636&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.6&lat=56.83262&lon=-4.22399&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalnaspidal_railway_station#/media/File%3AFormer_station%2C_Dalnaspidal_-_geograph.org.uk_-_203642.jpg, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.2&lat=56.81637&lon=-4.13297&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=94, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.3&lat=56.76835&lon=-3.96242&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=97, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.3&lat=56.77235&lon=-3.93034&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4160599, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.7&lat=56.76613&lon=-3.85122&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3653796, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3207521, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1828415, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5865219, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17.0&lat=56.76512&lon=-3.84405&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=94, accessed on 24th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.1&lat=56.74535&lon=-3.77703&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.1&lat=56.74175&lon=-3.77276&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.1&lat=56.70418&lon=-3.73554&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.1&lat=56.65105&lon=-3.66906&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.1&lat=56.62310&lon=-3.63682&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.1&lat=56.61348&lon=-3.63925&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.1&lat=56.60754&lon=-3.63831&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 25th June 2025

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.1&lat=56.56247&lon=-3.60789&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=95, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://youtu.be/08cKLNOwJJs?si=yfNMmticuyLvFsUU, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://www.tripadvisor.fr/LocationPhotoDirectLink-g186566-d8073533-i258339073-Killiecrankie_Viaduct-Pitlochry_Perth_and_Kinross_Scotland.html, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pitlochry_railway_station#/media/File%3A2018_at_Pitlochry_station_-_forecourt.JPG, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:43034_at_Pitlochry_on_platform_1_(going_north).jpg, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://www.capitalcollections.org.uk/view-item?i=25047&WINID=1750885501785, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3899955, accessed on 25th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1543539, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- R. V. J. Butt; The Directory of Railway Stations; Patrick Stephens Ltd, 1995, p110.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guay_railway_station, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3418380, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1747129, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/27059, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/27058, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/27057, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://portal.historicenvironment.scot/apex/f?p=1505:300:::::VIEWTYPE,VIEWREF:designation,LB11137, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://www.railadvent.co.uk/2023/10/network-rail-completes-34m-investment-to-protect-scottish-bridges.html, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dunkeld_and_Birnam_Railway_Station._Highland_Main_Line._The_old_Station_buildings._View_south.jpg, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://www.historichouses.org/house/murthly-castle/history, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=14.4&lat=56.54167&lon=-3.52163&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 26th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=56.53207&lon=-3.46531&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=94, accessed on 27th June 2025.

- https://www.murthly.scot/ajax/gallery/?id=35910, accessed on 27th June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murthly_railway_station, accessed on 27th June 2025

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=56.49599&lon=-3.44324&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=94, accessed on 27th June 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_(SMJR)_railway_station, accessed on 27th June 2025.

- https://www.railscot.co.uk/locations/S/Stanley_Junction, accessed on 27th June 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/16aHwJ3qWB, accessed on 27th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=56.46341&lon=-3.47344&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 27th June 2025

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=56.44897&lon=-3.47148&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 27th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.6&lat=56.41463&lon=-3.45899&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 27th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.2&lat=56.39817&lon=-3.44216&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 27th June 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.2&lat=56.39700&lon=-3.44253&layers=6&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 27th June 2025.