Part A – The Main Line to and from Sutton Wharf

The Lilleshall Company was a dominant force in the East Shropshire area and developed a network of canals and tramroads to transport goods between their many different sites. “The company’s origins date back to 1764 when Earl Gower formed a company to construct the Donnington Wood Canal on his estate. In 1802 the Lilleshall Company was founded by the Marquess of Stafford in partnership with four local capitalists.” [31]

Bob Yate, in his important book, “The Railways and Locomotives of the Lilleshall Company,” introduces the historical development of the transport provision of the Lilleshall Company, referring first to the Company’s canal network. The construction of these canals which, while of some significance, was unable to provide for all of the sites being built and run by the Company.

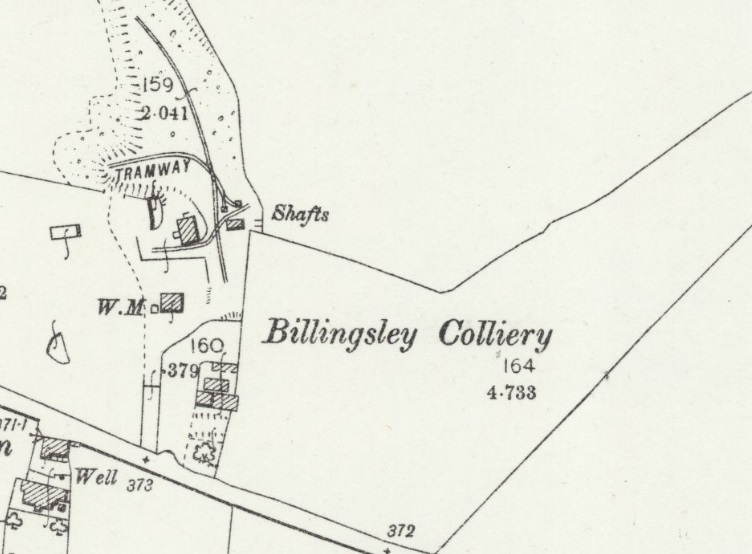

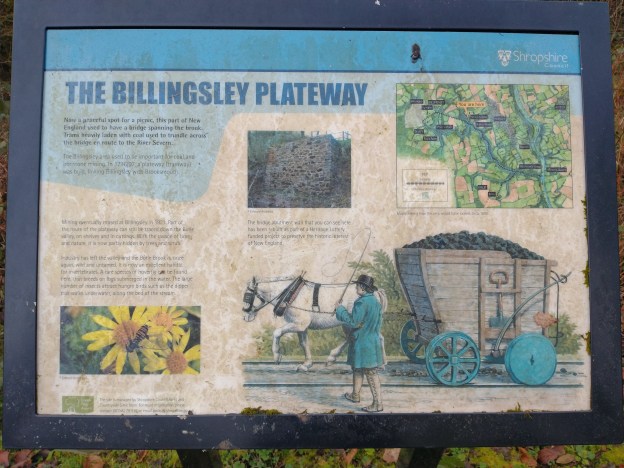

“In order to reach the workings of the pits, quarries and works that these canals served, a system of tramways was soon developed. These were almost certainly constructed using wrought iron rails from the start, and were definitely of plateway construction.” [1: p36]

Yate goes on to explain that the tramroads/tramways/plateways had various gauges and comments that these short lines “linking the workings to the canals, gradually lengthened as their usefulness became apparent. So it was that in October, 1797 the ironmaster Thomas Botfield agreed with his landlord, Isaac Browne to carry 1,200 tons of coal each month from Malins Lee (about two miles south of Oakengates): to some convenient wharf or quay adjoining the River Severn, and to the railway intended to be made by John Bishton & Co. and the said Thomas Botfield, or to some intermediate wharf or bank between the said works and the River Severn upon the line of the intended railway.” [1: p35]

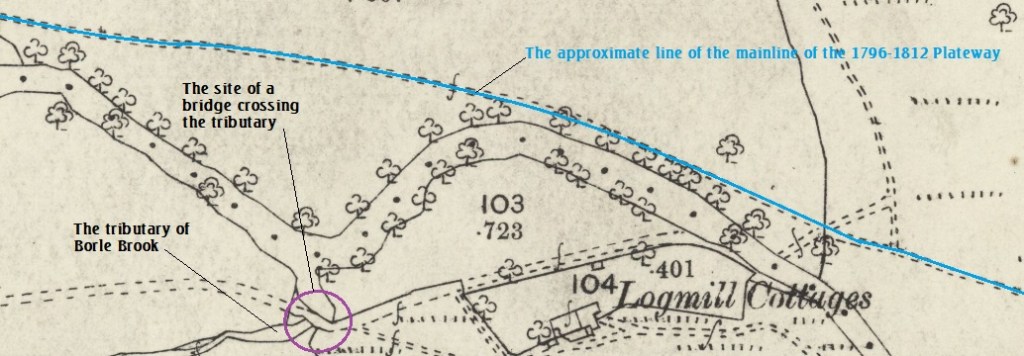

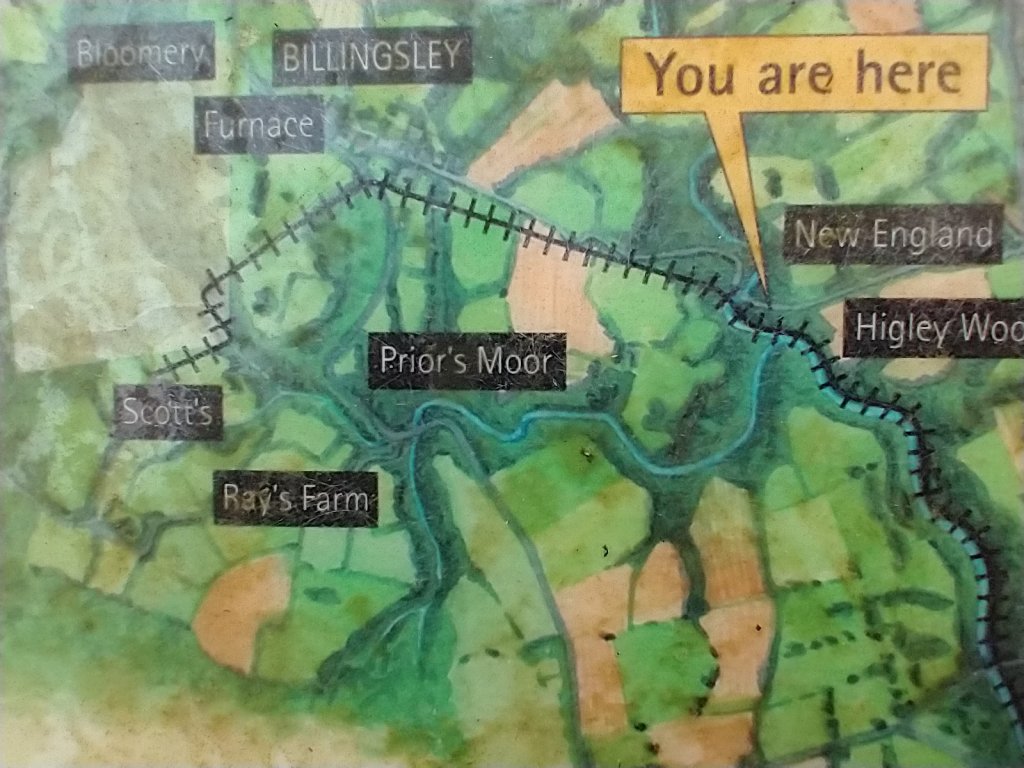

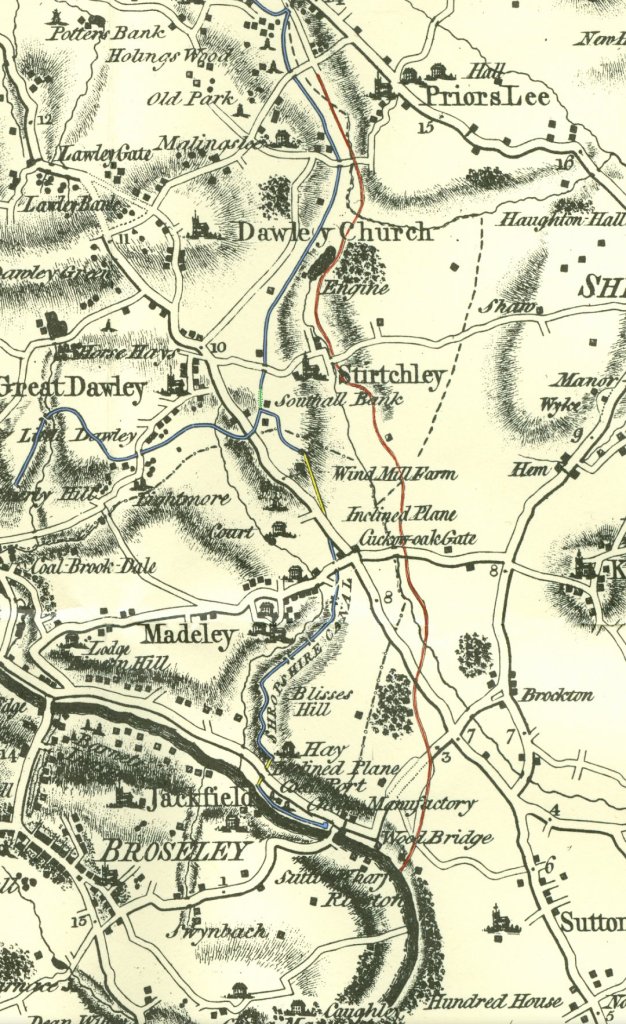

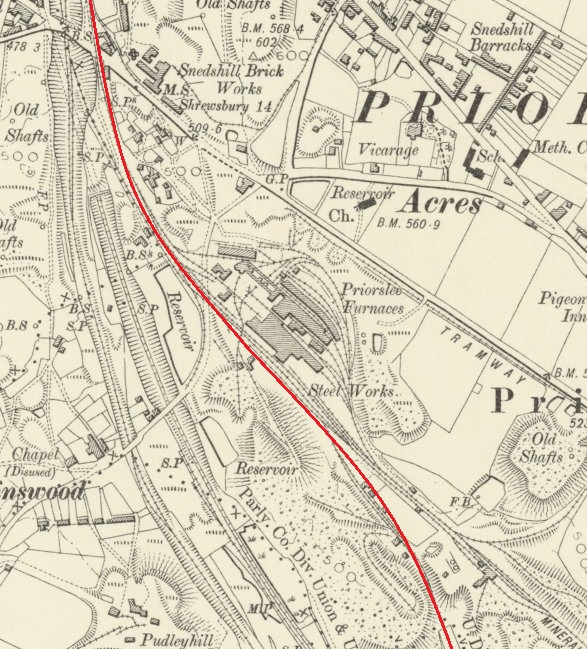

Yate continues: “This railway was working by 1799, running from Sutton Wharf, near Coalport, to Hollinswood, where it connected with several ironworks and mines to the north in the area of Priorslee. The total length of this line was about eight miles, and it is presumed to have been horse worked. Bishton and Onions, whose ironworks was situated at Snedshill, were certainly involved in the original line, and by 1812 it had become the property of the [Lilleshall] Company. This is recorded on Robert Baugh’s map of 1808, and again on the Ordnance Survey maps of 1814 and 1817, although in the latter two cases it is not shown in its entirety.” [1: p35]

Yate notes that the Company were sending down around 50,000 tons of coal annually and much iron. “However, the Shropshire Canal was not enjoying the most robust of business climates, and attempted in June 1812 to negotiate for the Company’s business, although this seems to have been unsuccessful. However, in April 1815, William Horton on behalf of the [Lilleshall] Company agreed that the tramway would be removed, and that its business would be transferred to the canal. In turn, the Company: received compensation of some £500. as well as favourable tonnage rates.” [1: p35]

This means that the direct tramroad link to the River Severn was very short-lived.

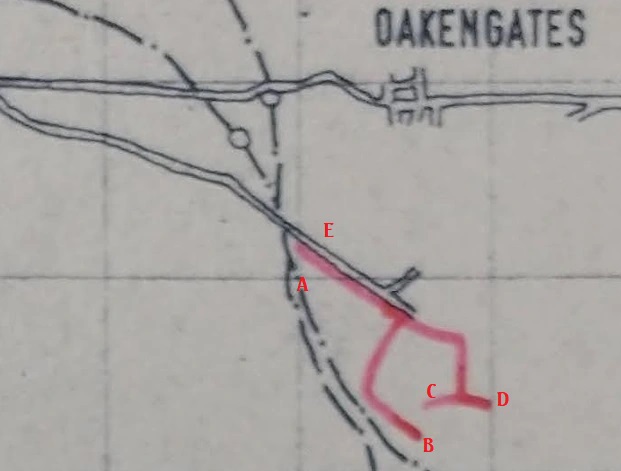

The closure of this mainline tramroad/tramway had little effect on the ‘internal’ network of routes serving the Lilleshall Company’s various pits and works. Yate tells us that, by 1833, the main tramways were: a line running along Freestone Avenue to Lawn Pit, near to Priorslee Hall, and to Woodhouse Colliery; branches east of Stafford Street, Oakengates and north of Freestone Avenue; a continuation of the main line northwards crossing Station Hill, Oakengates to the east of the Shropshire Canal, and on to meet the Wrockwardine inclined plane near to Donnington Wood. [1: p35]

“By 1856, further tramways had been laid around the area of Snedshill Ironworks linking to the canalside warehouses, and branches reaching out to the waste heaps south and west of the ironworks. These spoil heap lines continued to expand in subsequent years around the Priorslee Ironworks, and south therefrom.” [1: p35]

Several of the coal pits in the Donnington Wood area were, by 1837, linked directly to the Old Lodge Furnaces and no longer needed to make use of the canal network. These tramroads were horse-drawn with minor exceptions on short, level runs where trams were manhandled. Yate comments: “It is nonetheless interesting to consider that wayleaves were granted in 1692 at Madeley and in 1749 at Coalbrookdale to permit the use of oxen. Admittedly this was over the roads of the area, but a good case could possibly be made for their employment as motive power on the tramroads, as surely local customs would be a powerful influence.” [1: p35]

Using the canal network became increasingly problematic. The underground workings in the area caused some subsidence and as a consequence canals could require significant repairs and be out if action for a time.

The Lilleshall Company’s tramroads eventually developed into a significant standard-gauge network. The later part of the transport story of the Lilleshall Company is for another time and another article!

In this article we concentrate on, what was, a relatively early (1799 to 1815), wrought-iron plateway tramroad. Perhaps we should bear in mind that it is possible that the Lilleshall Company saw no major financial advantage in lifting the whole line from Sutton Wharf into the Company’s industrial heartland and that elements of this tramroad came to be used as part of a later network of tramroads or railways If this was not true for the wrought-iron plates/rails themselves, it is much more likely that any embankments and cuttings could be used in this way. This may perhaps be something we will discover along the way.

The Tramroad Running North from Sutton Wharf

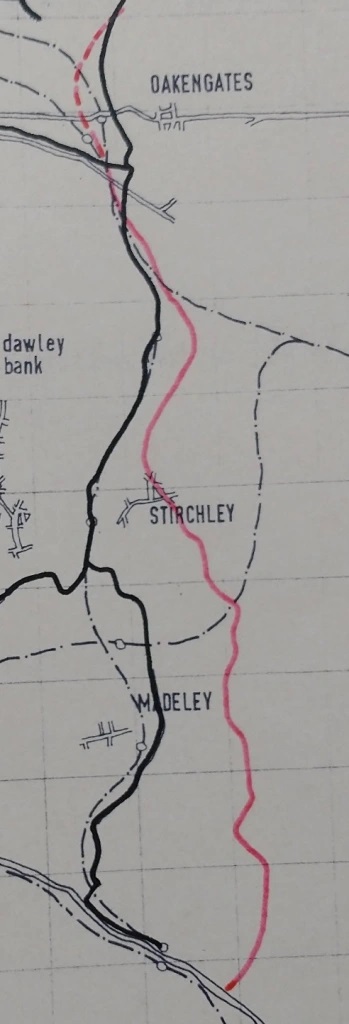

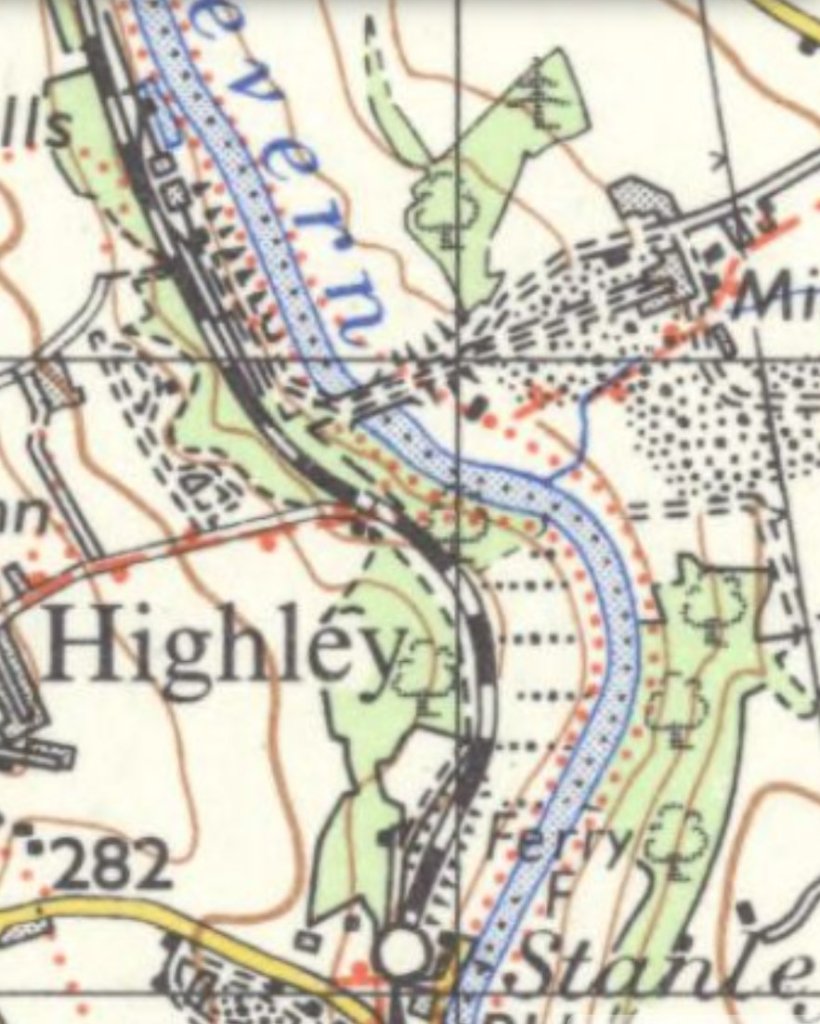

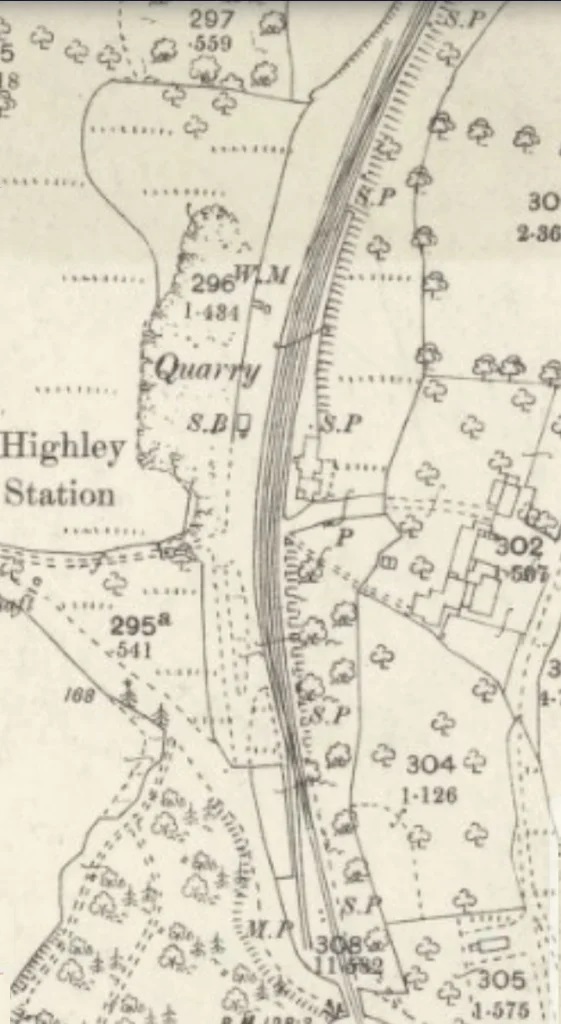

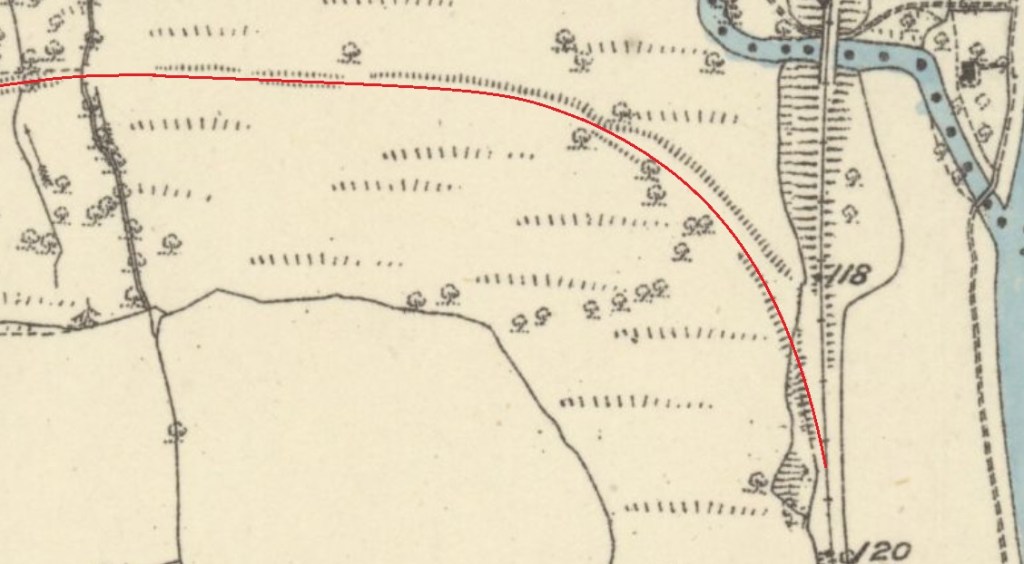

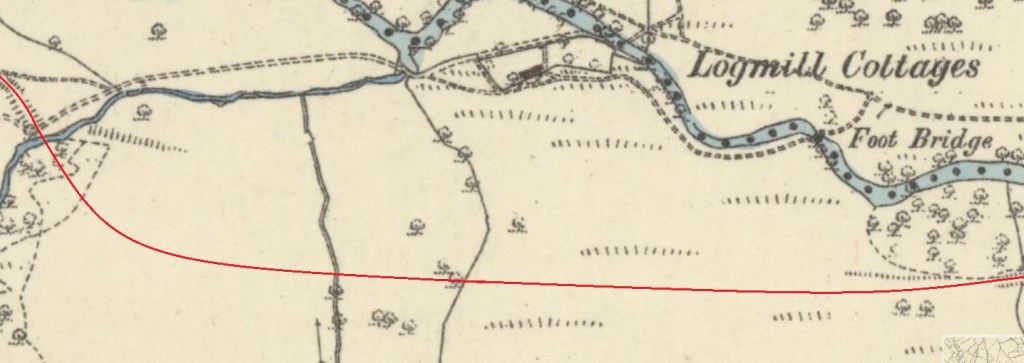

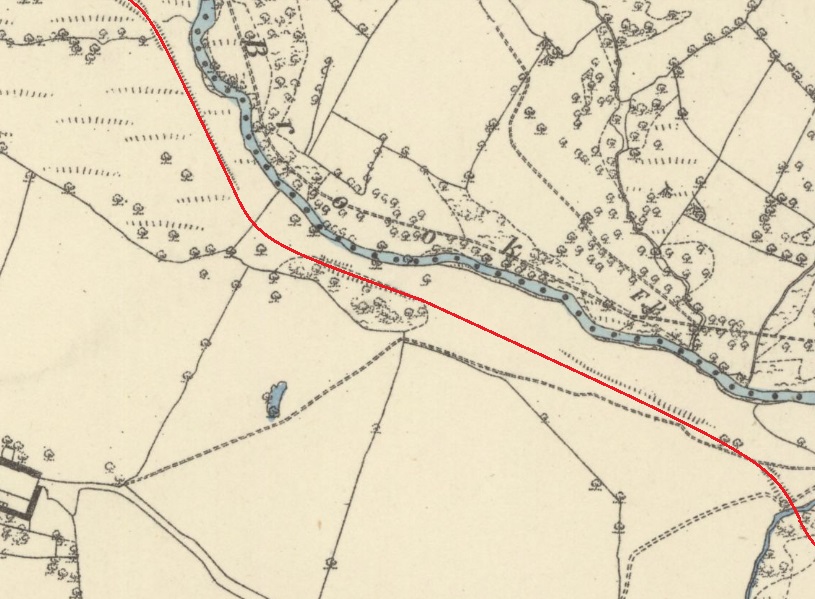

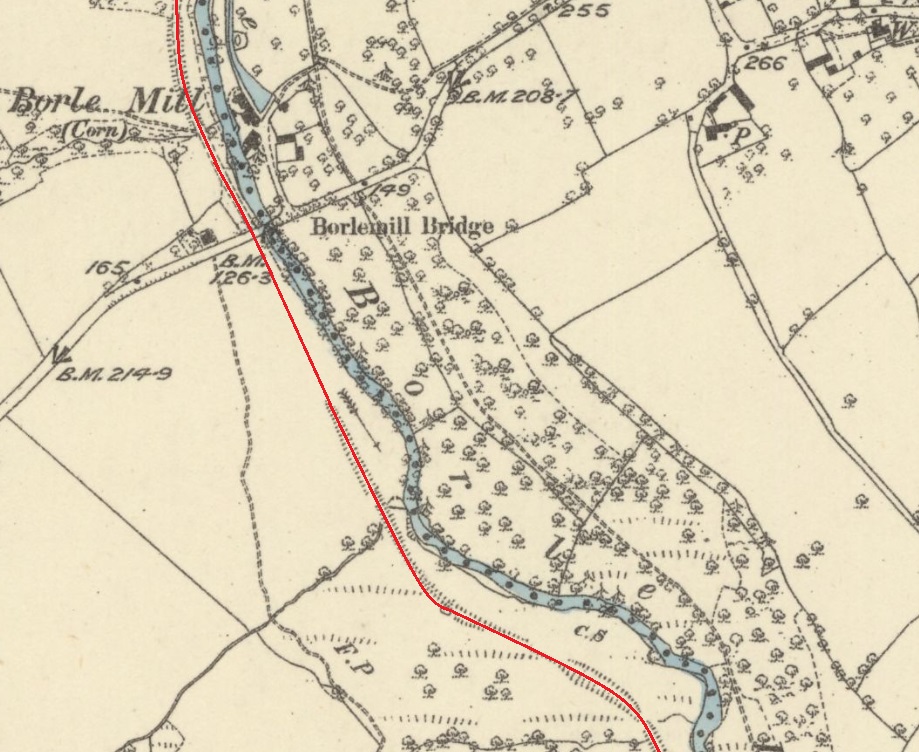

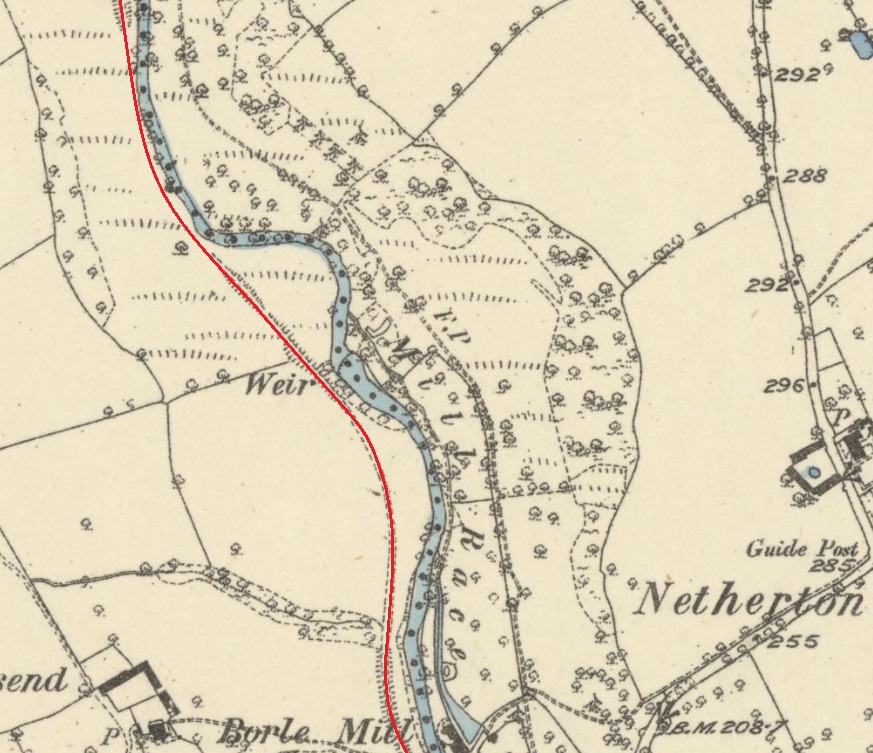

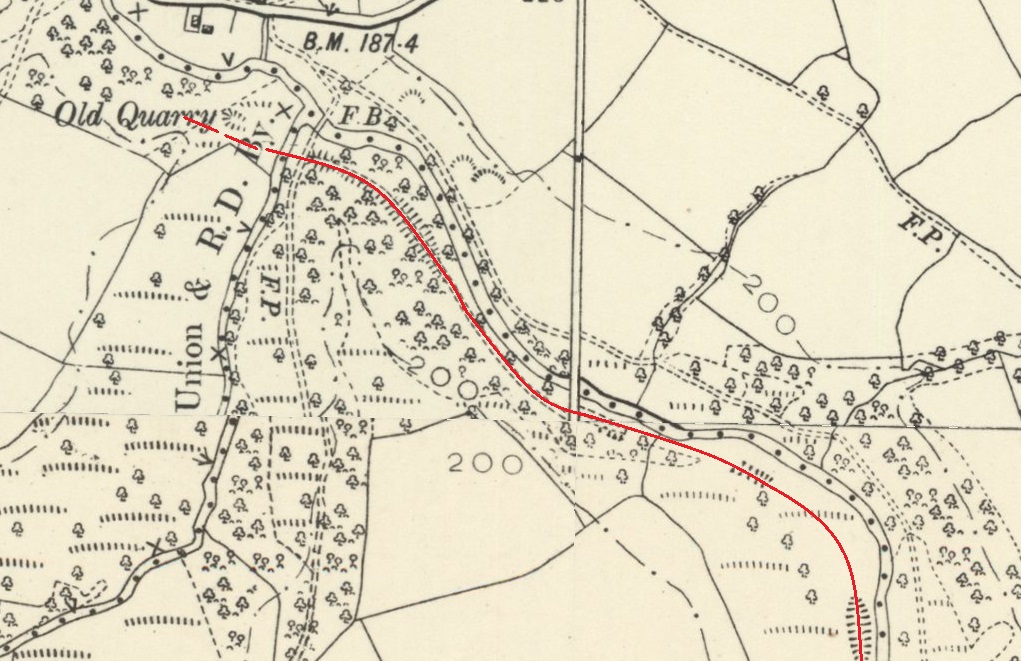

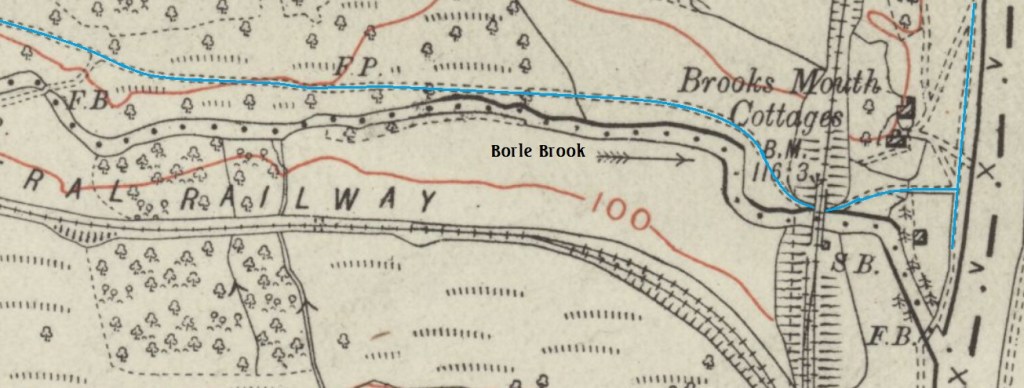

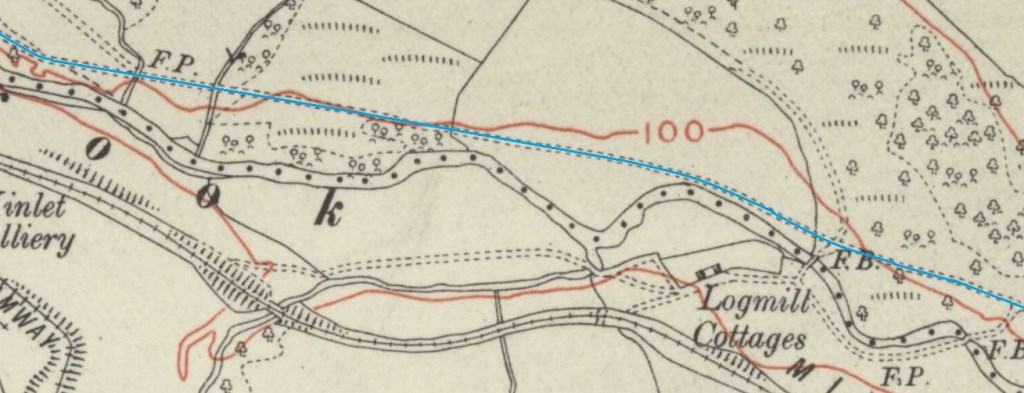

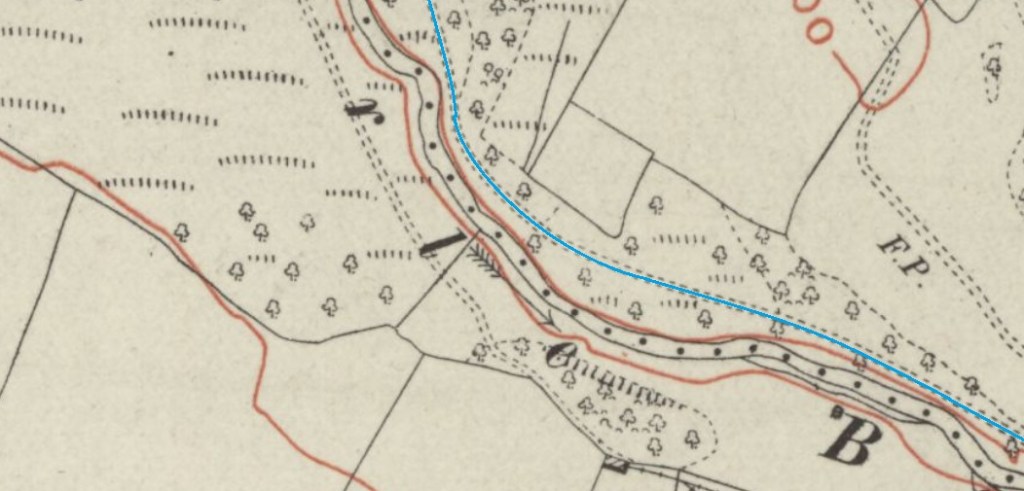

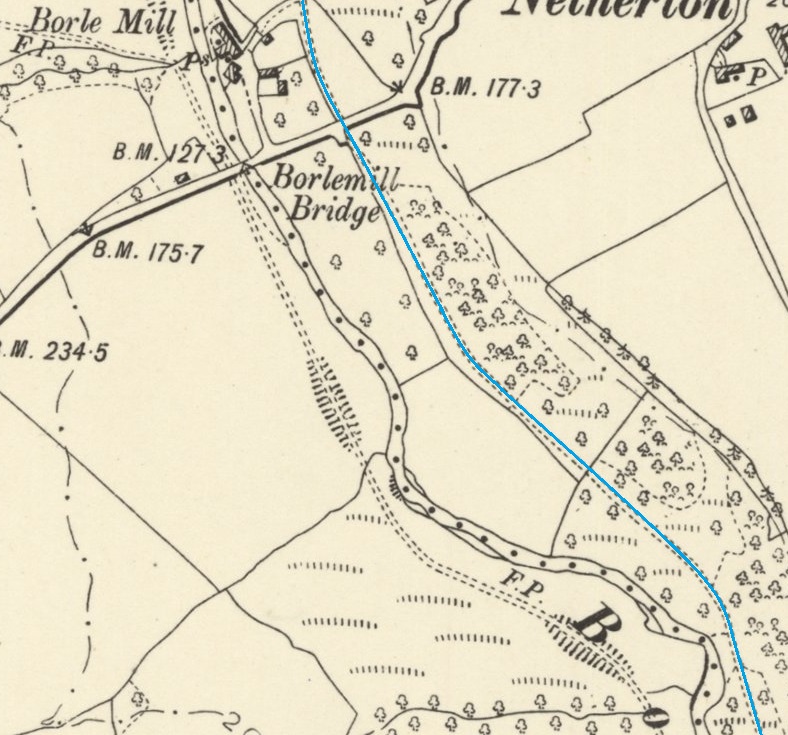

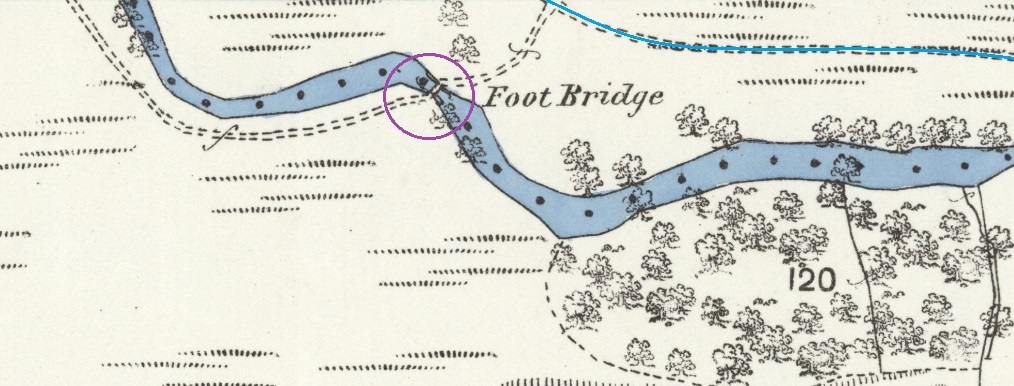

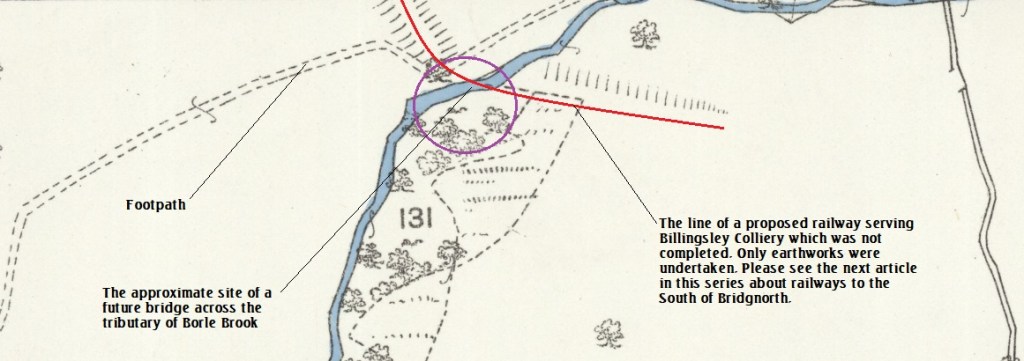

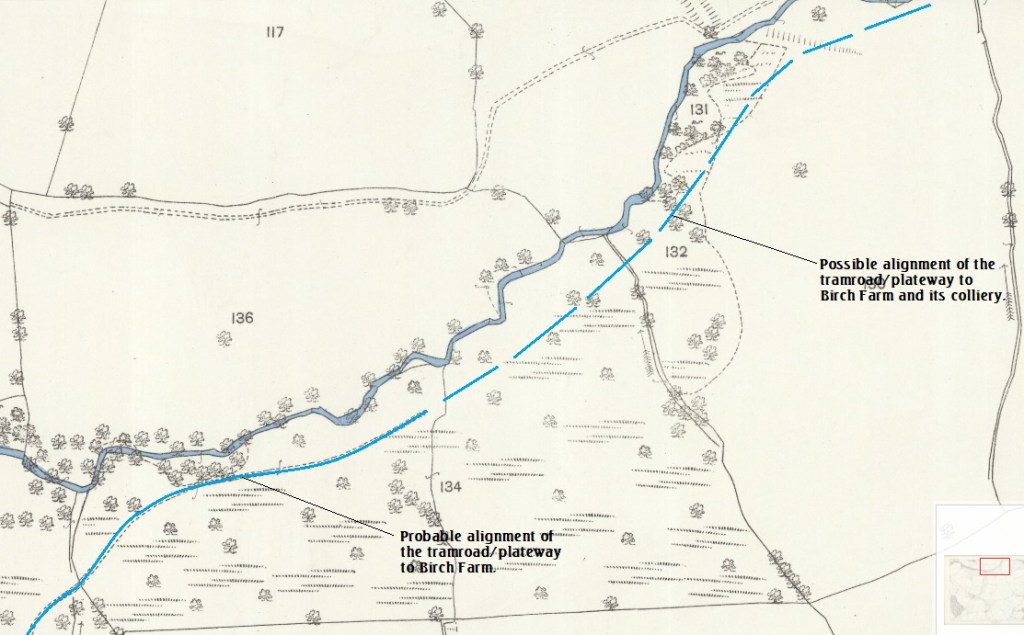

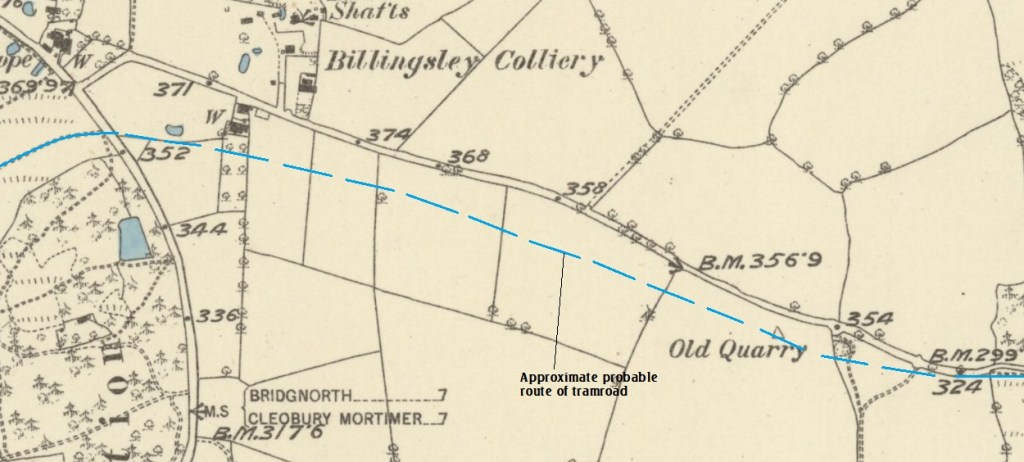

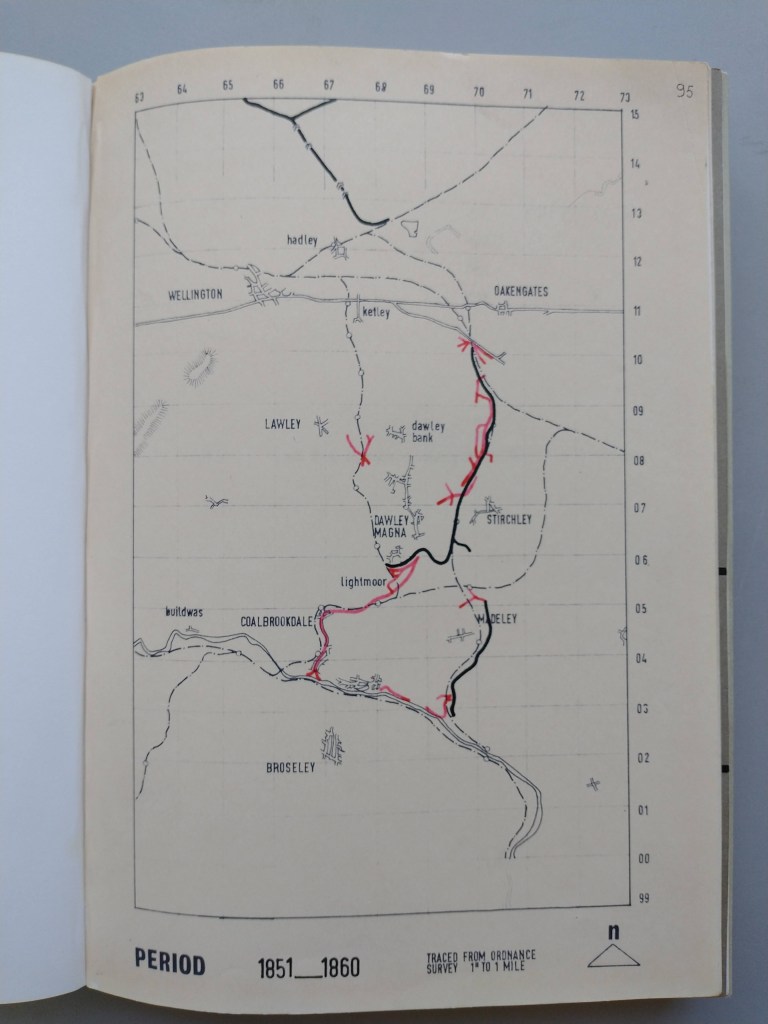

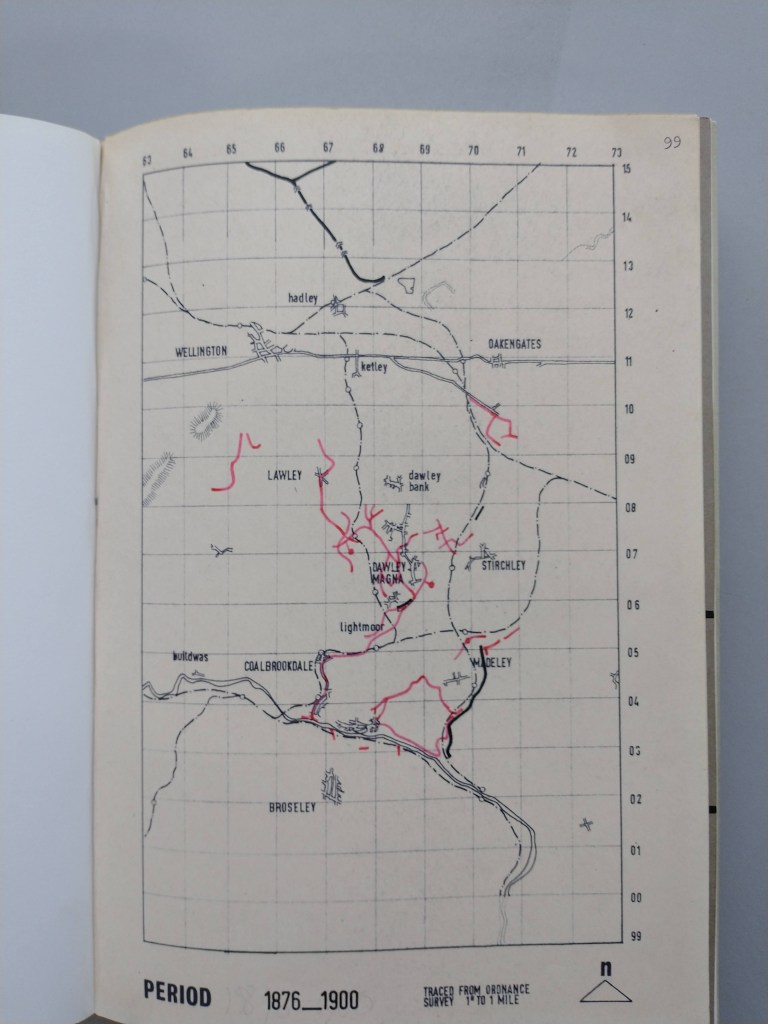

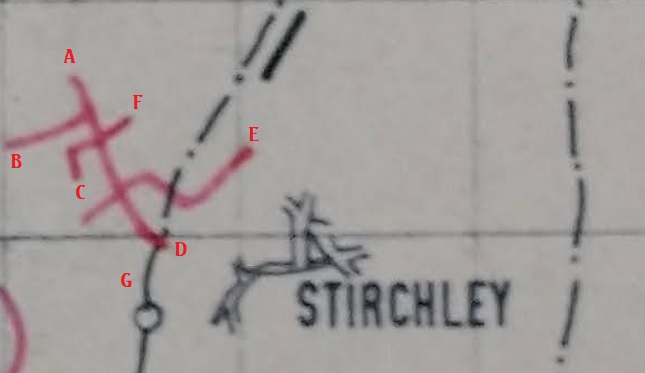

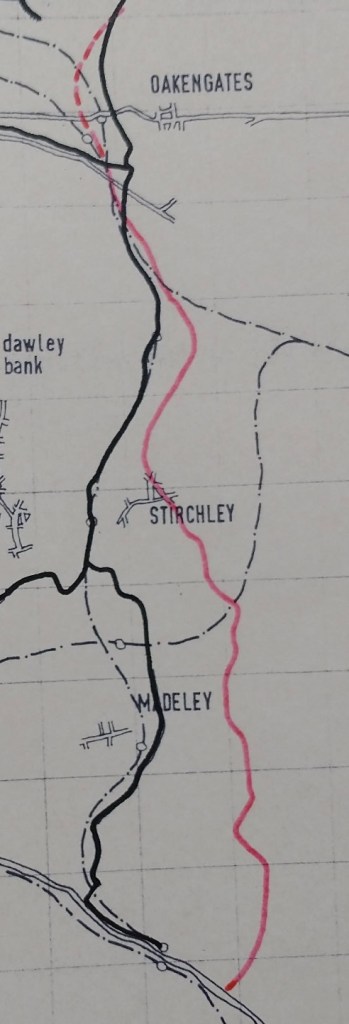

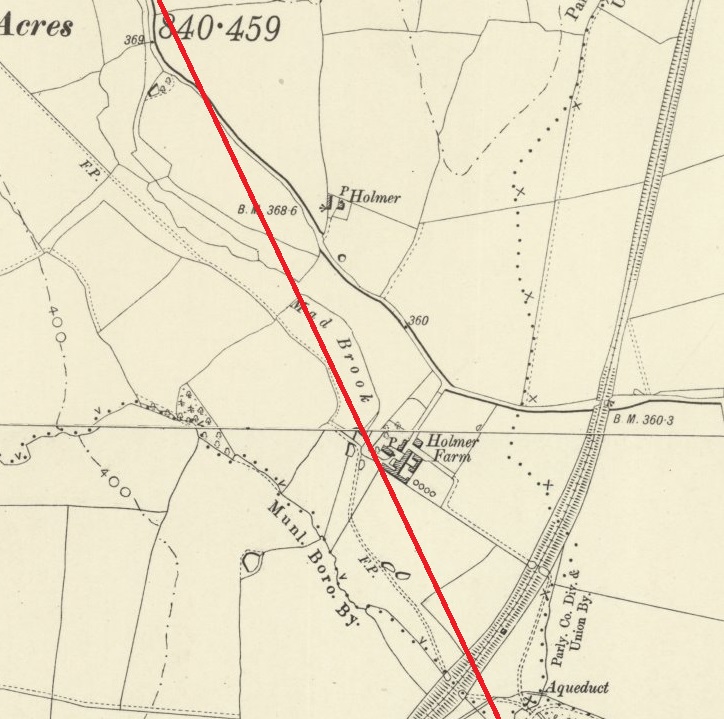

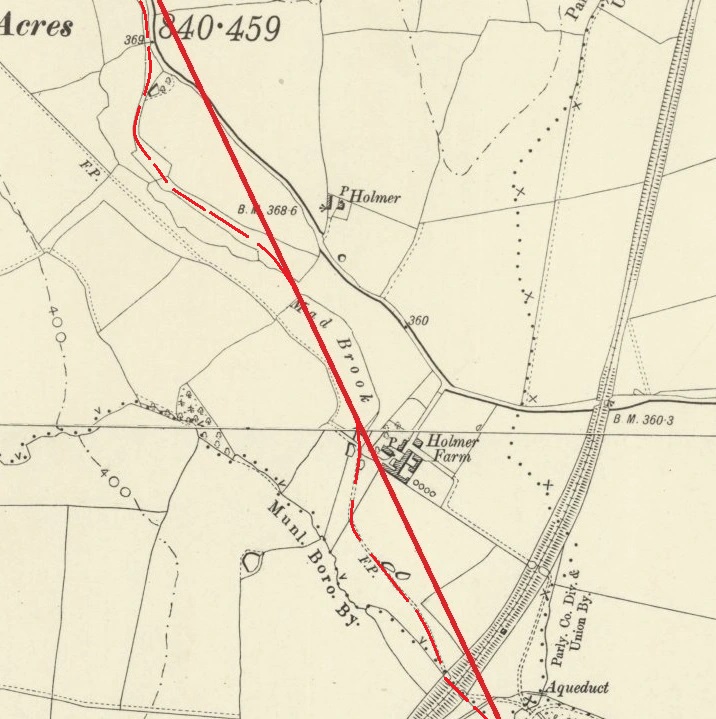

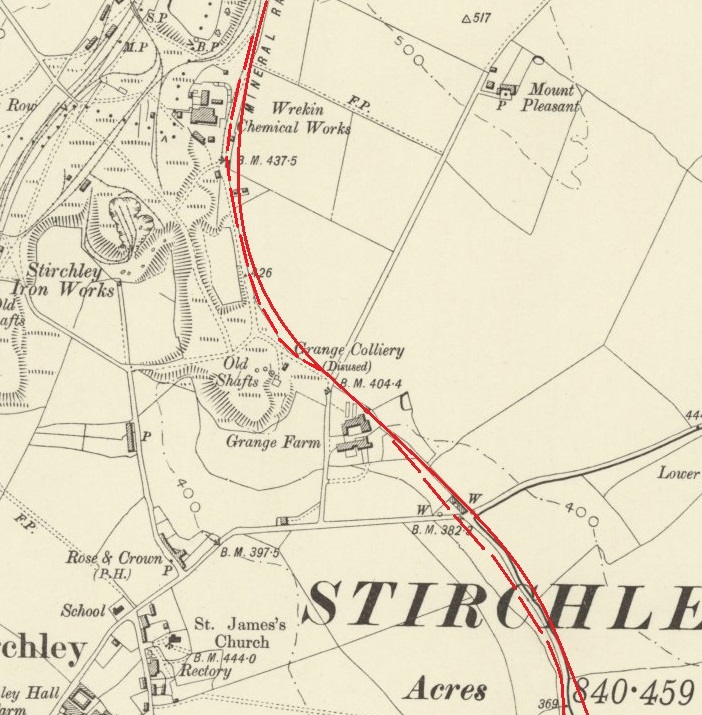

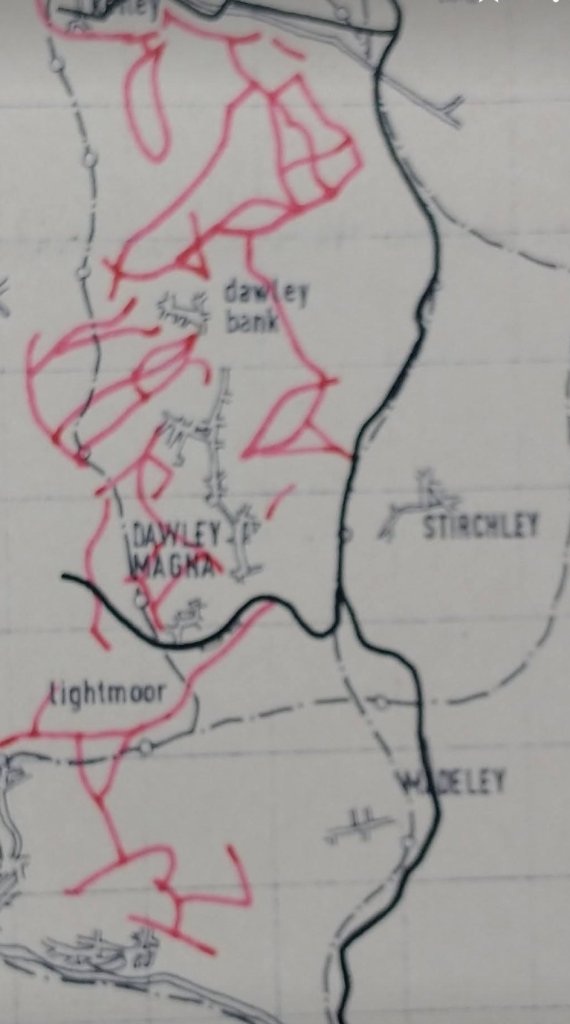

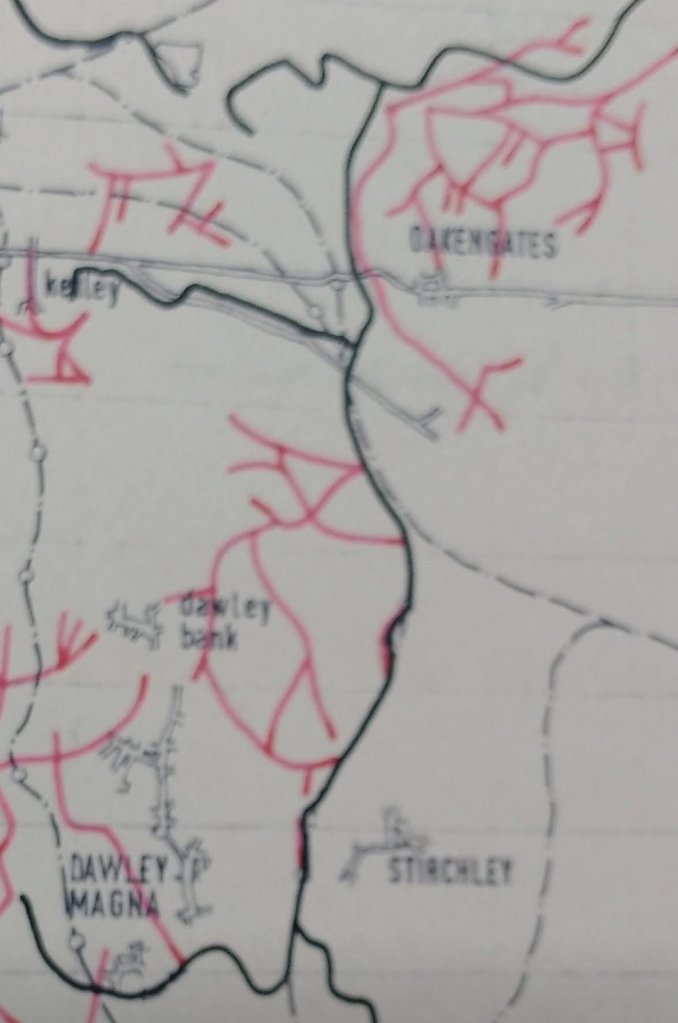

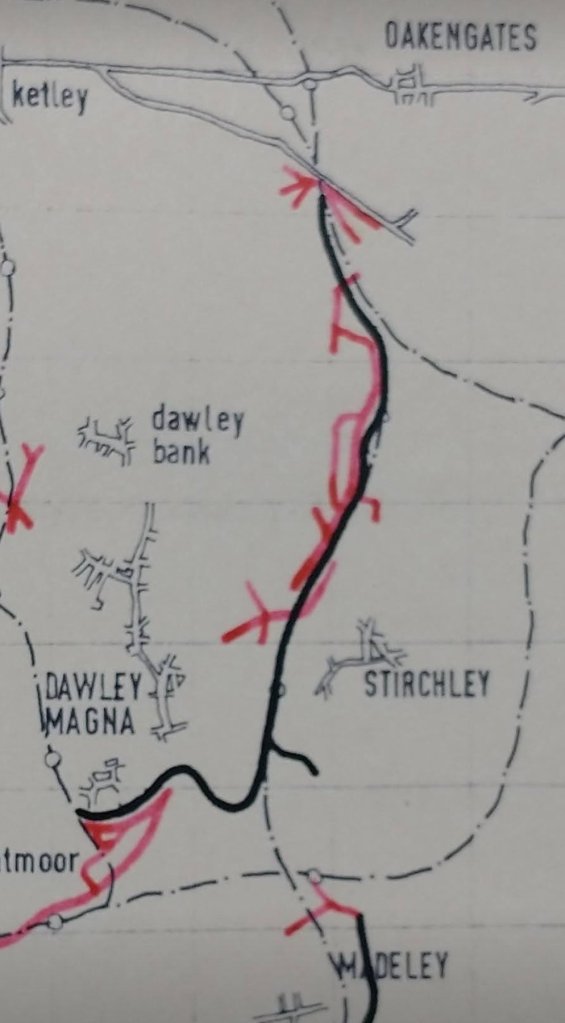

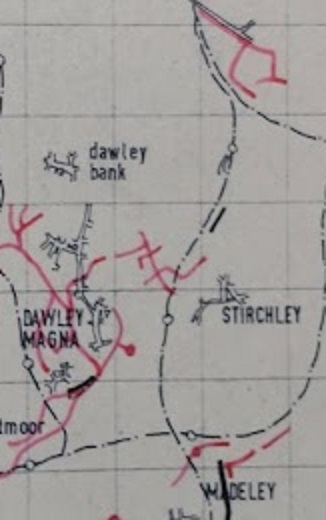

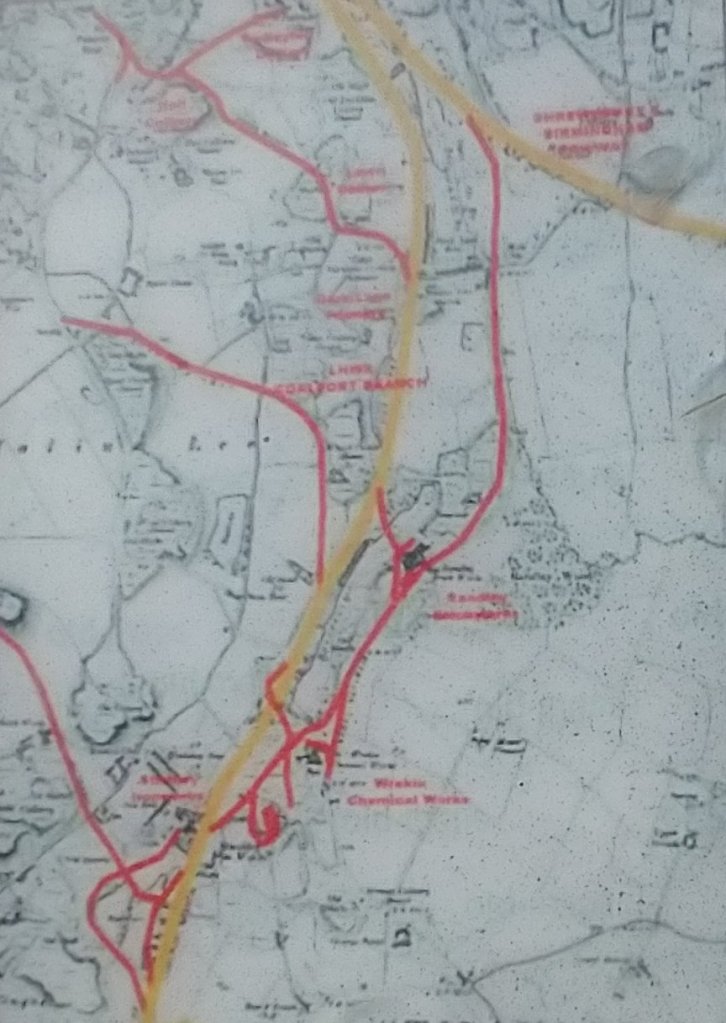

Savage and Smith provide some information about the line in their research in ‘The Waggon-ways and Plateways of East Shropshire‘. They provide two different series of drawings – the first set are 1″ to a mile plans relating to specific eras in the development of the local tramroads. The extract here is taken from the plan which relating to 1801-1820. [2: p85]

The line is shown in red ink, the Shropshire Canal is the heavy black line. The dotted and dashed thin lines are later railway routes. The short red dashes at the North end of the tramroad indicate that the route of the tramroad is not as certain as the length shown in continuous red ink.

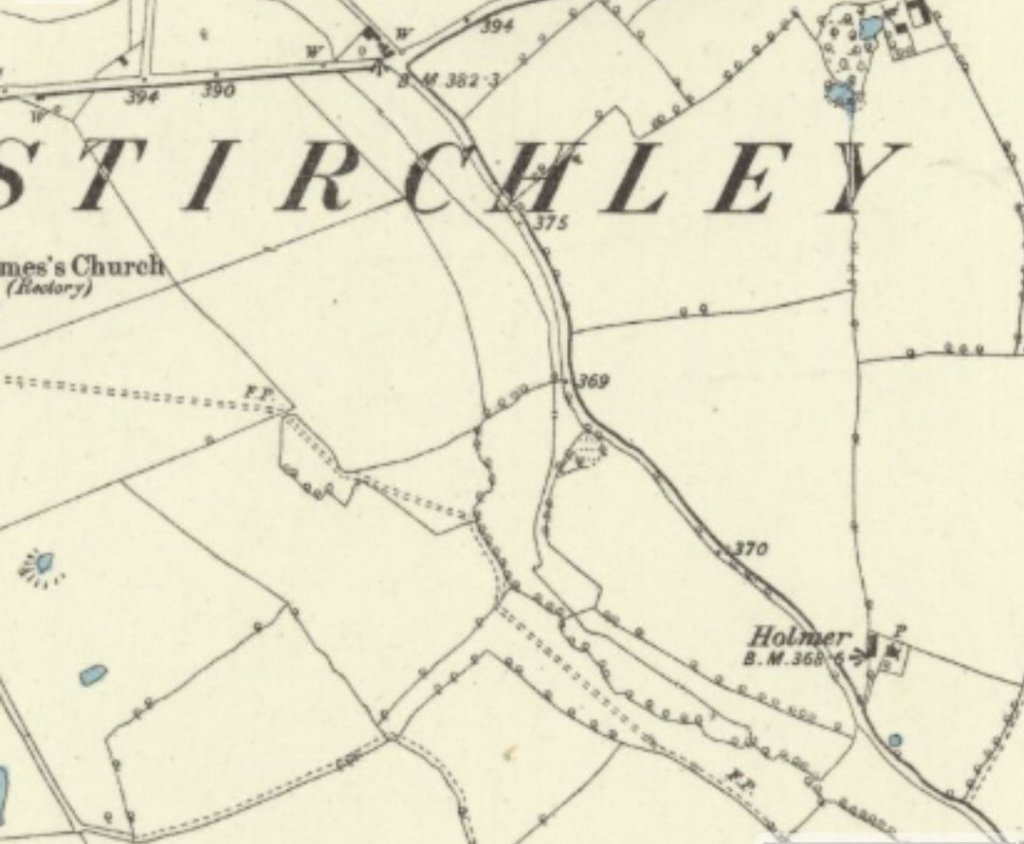

Savage and Smith comment on the tramroad: “In 1808 Robert Baugh’s map of Shropshire shows the line from Oakengates to Sutton Wharf, but not with any great accuracy. Part of it is shown on the two inch ordnance survey of 1814 and 1817, but only as far as Holmer Farm. After this it disappears. Its owners seem to have been the Lilleshall Company and they sent down annually 50,000 tons of coal and much iron. It was agreed to remove it and transfer business to the Shropshire canal for compensation of £500 and a guarantee of favourable rates.” [2: p140]

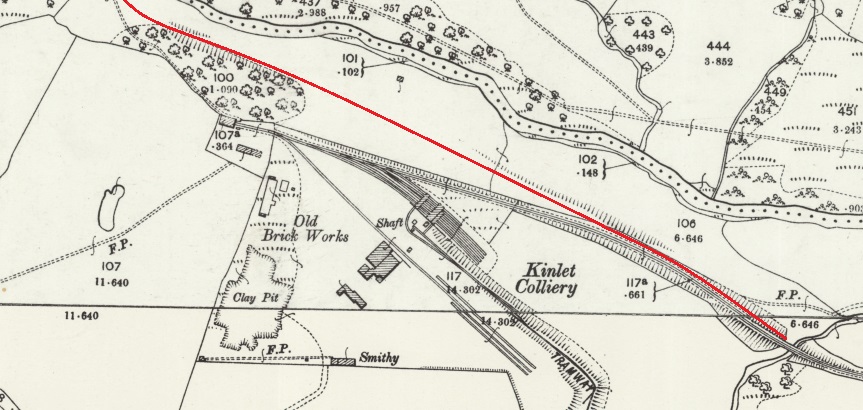

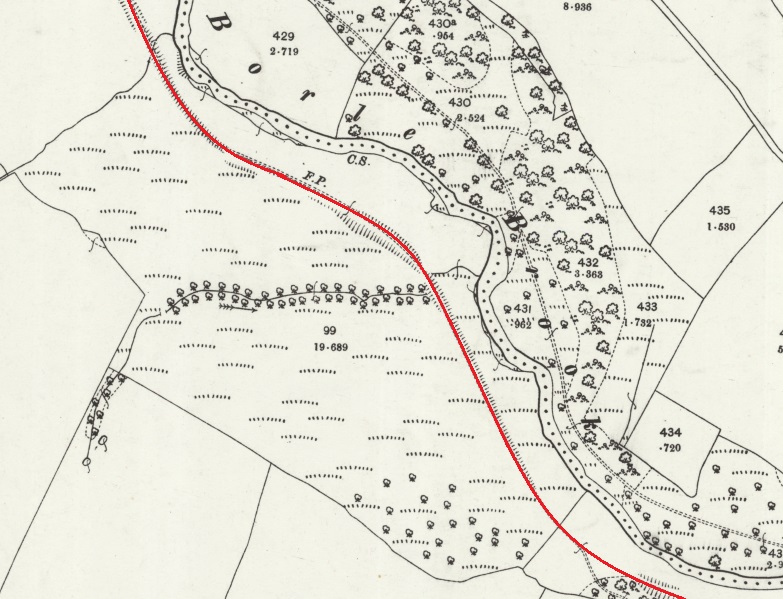

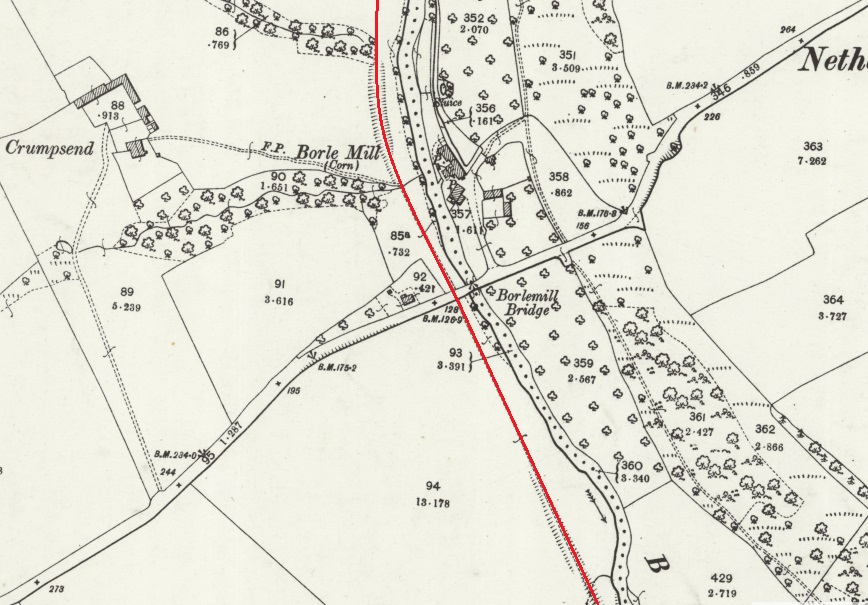

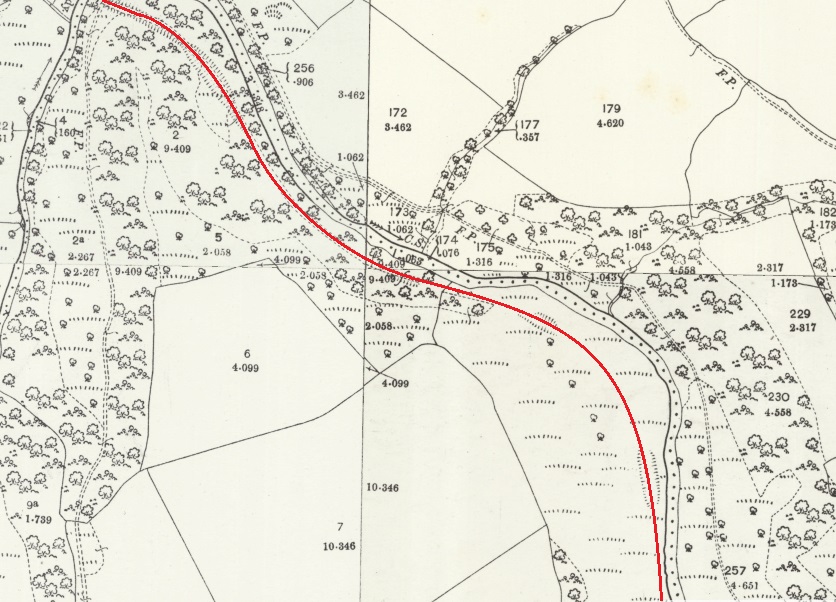

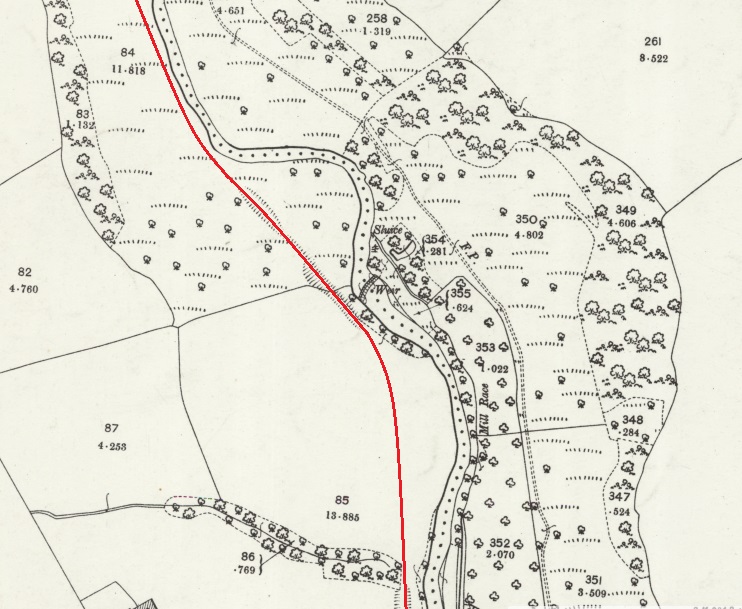

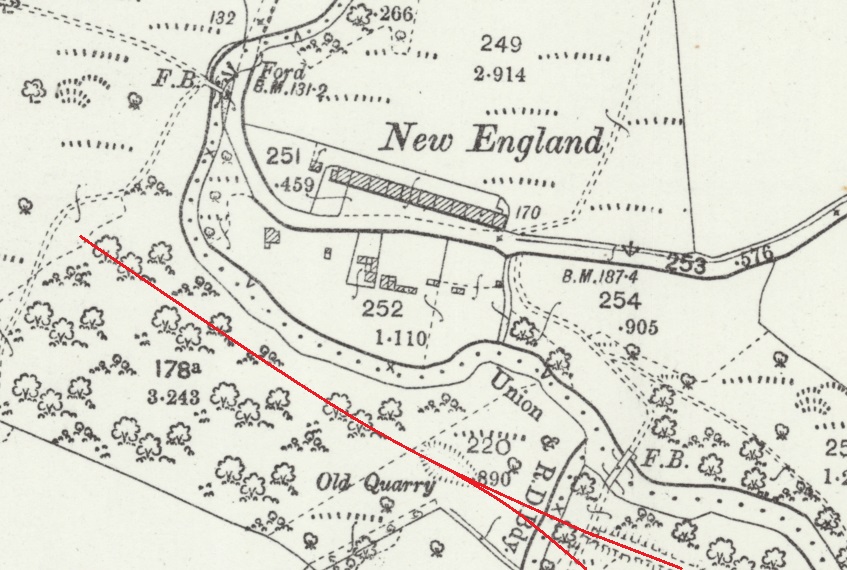

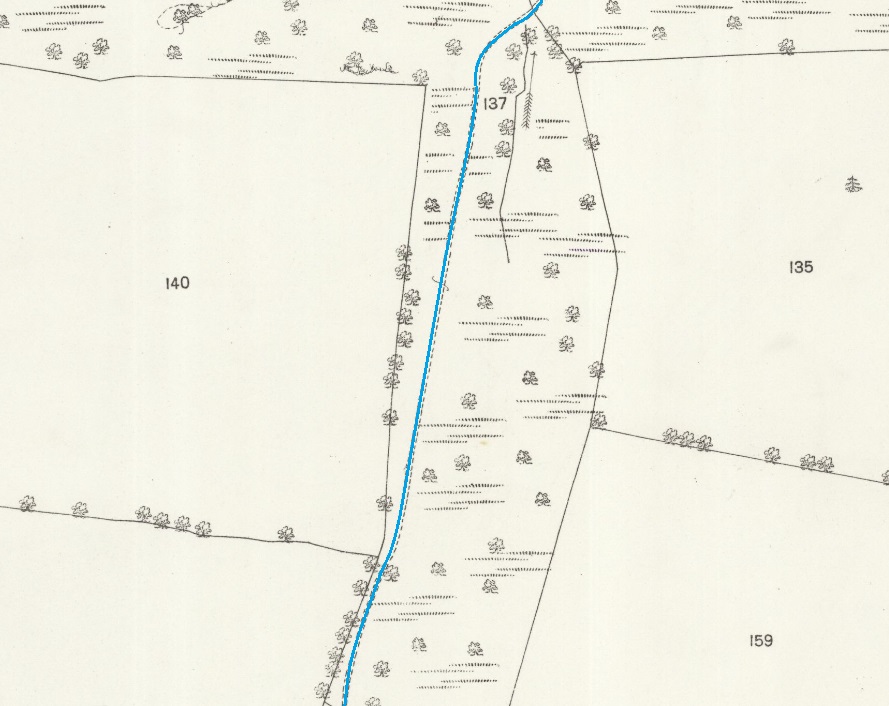

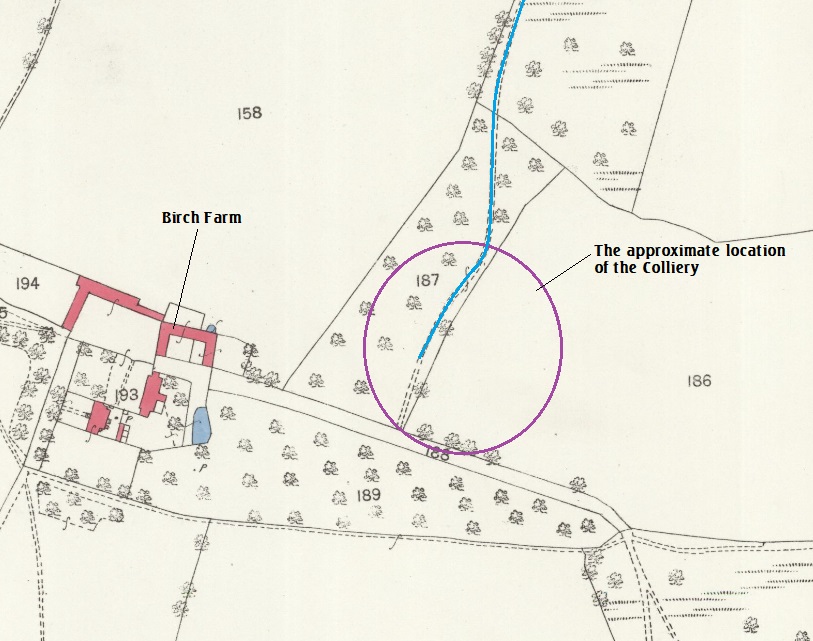

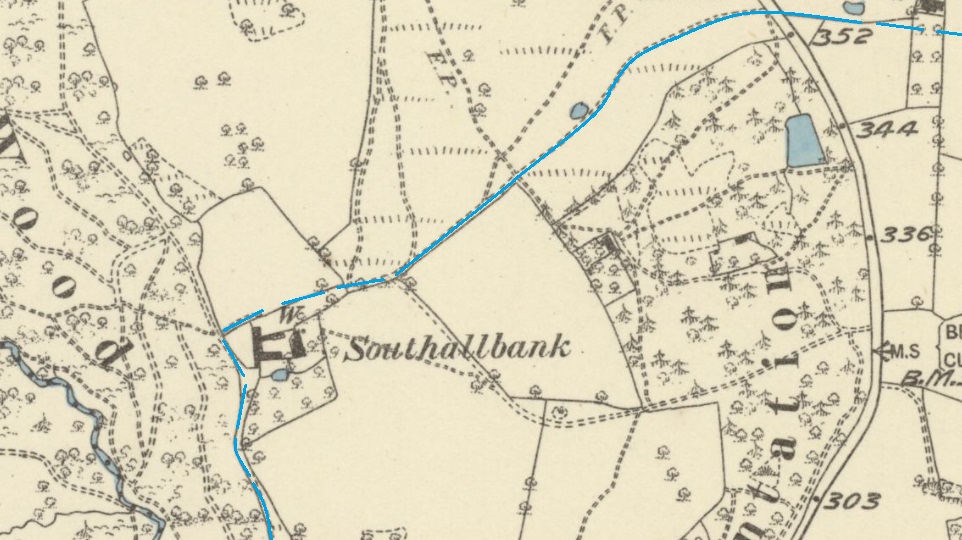

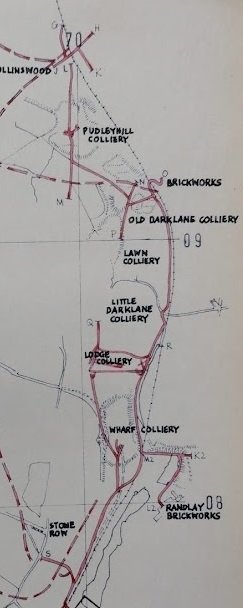

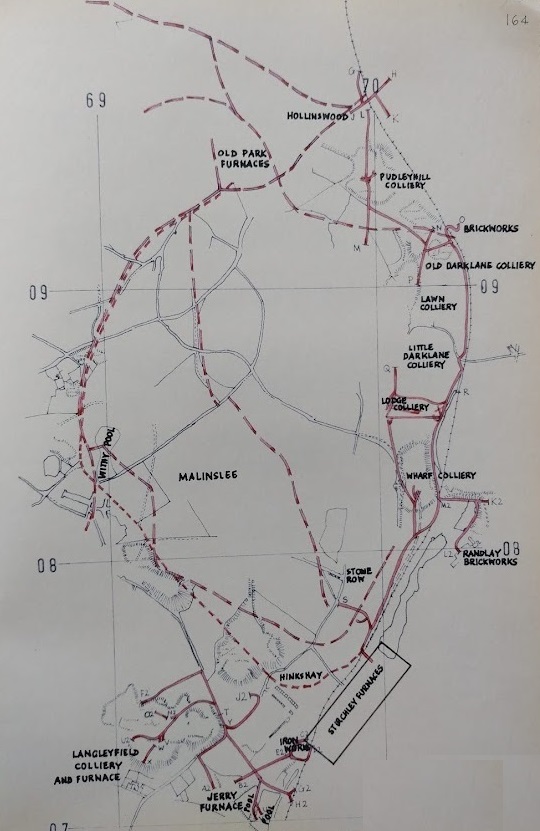

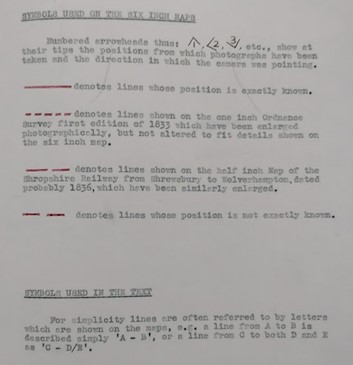

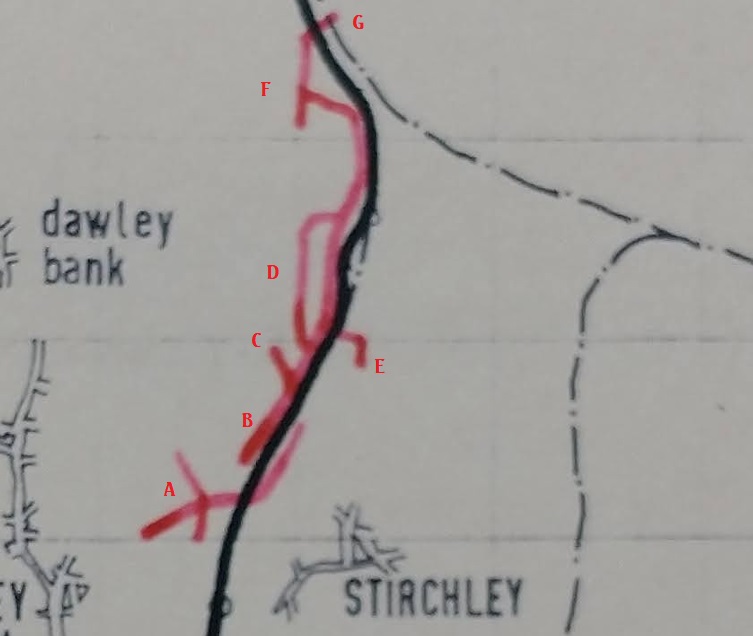

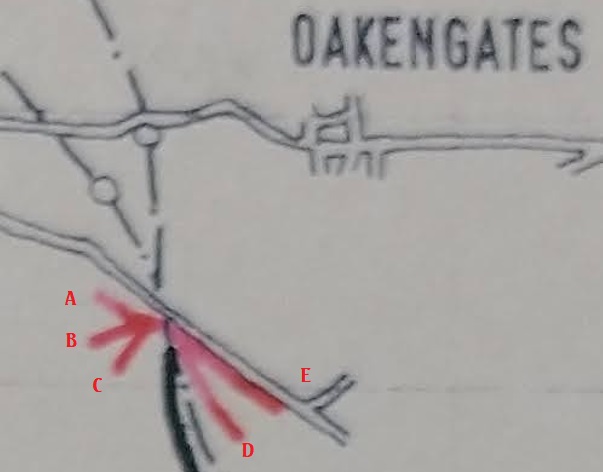

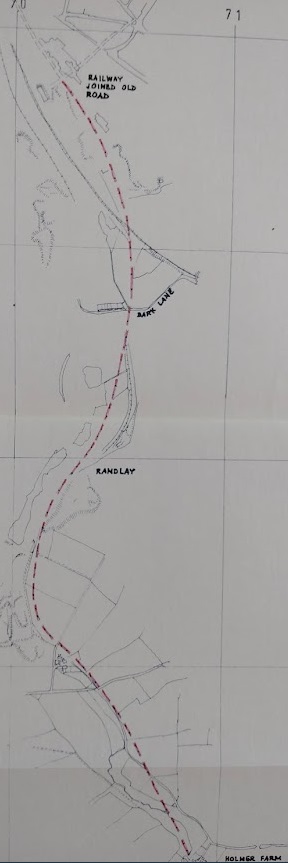

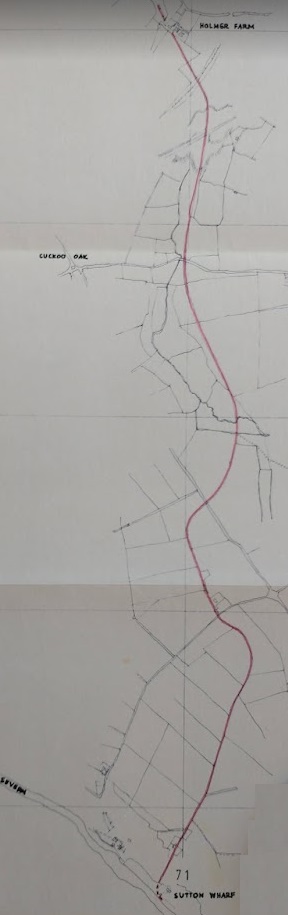

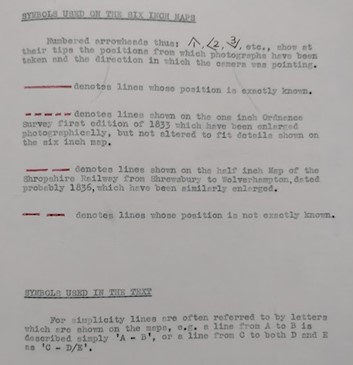

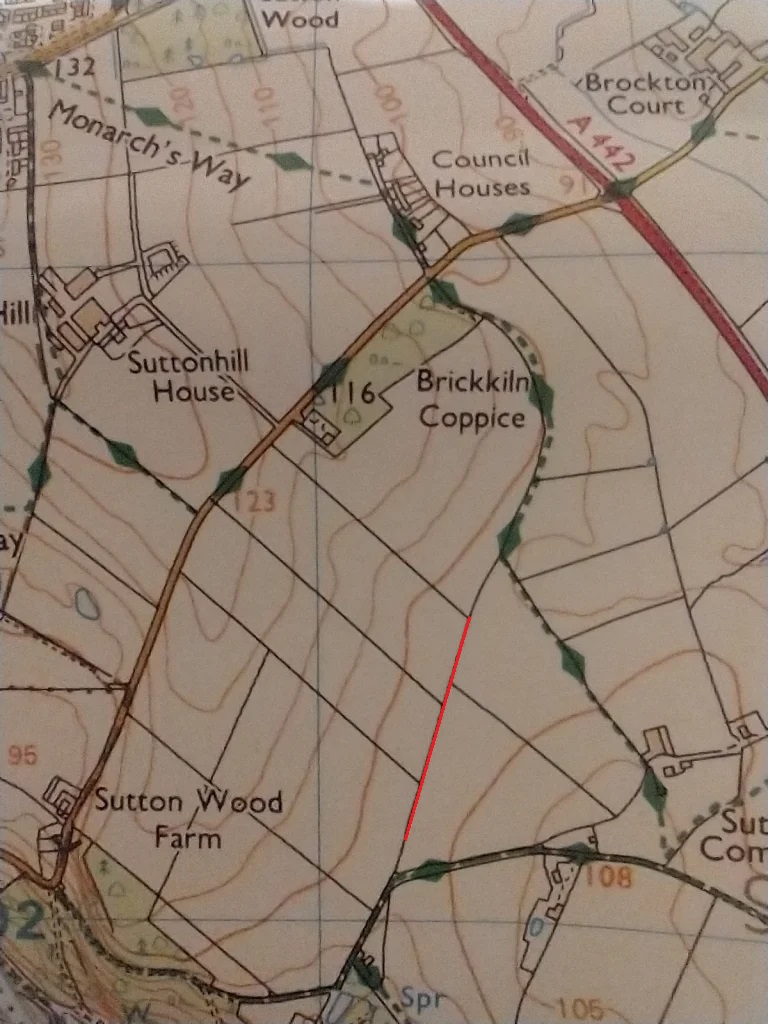

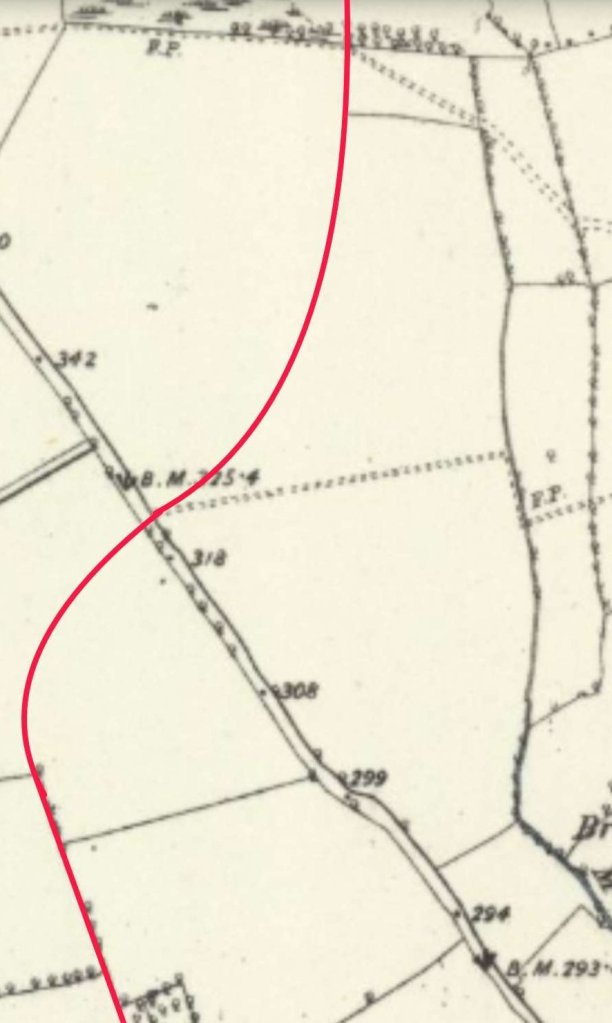

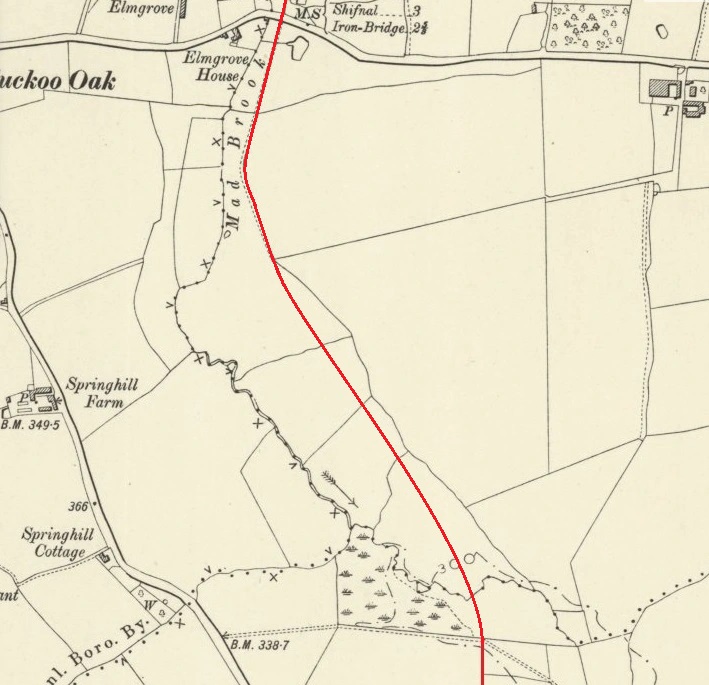

The second series of plans provided by Savage and Smith are to a scale 6″ to a mile. At this larger scale, it at first seems that they are not prepared to show the same level of certainty over the actual route of the tramroad than on the 1″ to a mile map above. In fact the difference between the two lines shown has as much to do with the scale of the source mapping used. The long dashed red line in the more northerly section of the plans produced here indicates that the route was obtained from a 0.5″ to a mile plan. So they acknowledge that, while the route definitely existed, issues with scaling inevitably mean that there is greater uncertainty over the detailed alignment. We are probably best advised to see the route from Sutton Wharf to Holmer Farm as relatively reliable and to check the detail of the route from that point North. The 6″ to a mile plan is a fold-out plan and because of its length, difficult to photograph.

Savage and Smith also only show the line running to the North of Dark Lane, rather than around the West of Oakengates. With these provisos Savage and Smith show much of the length of the Sutton Wharf tramroad.

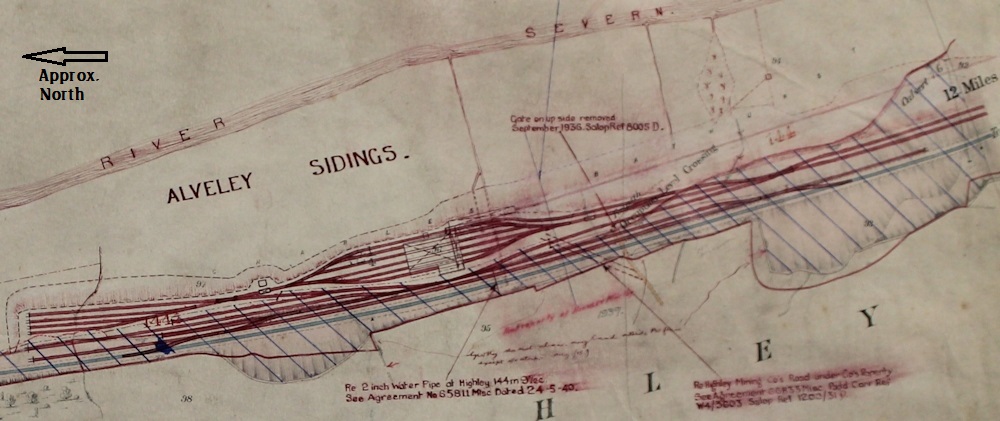

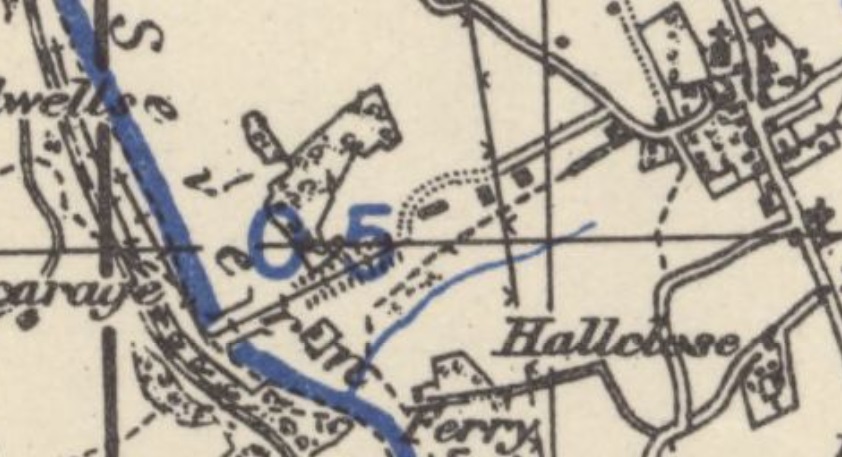

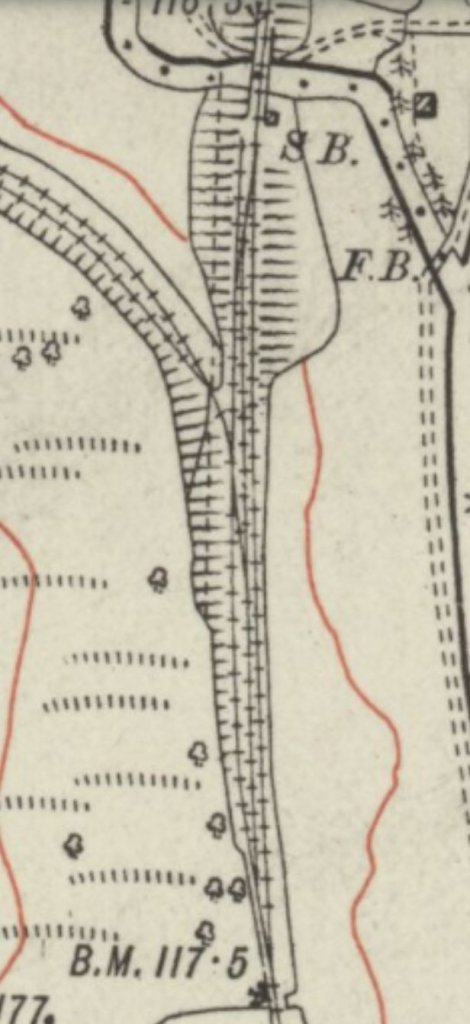

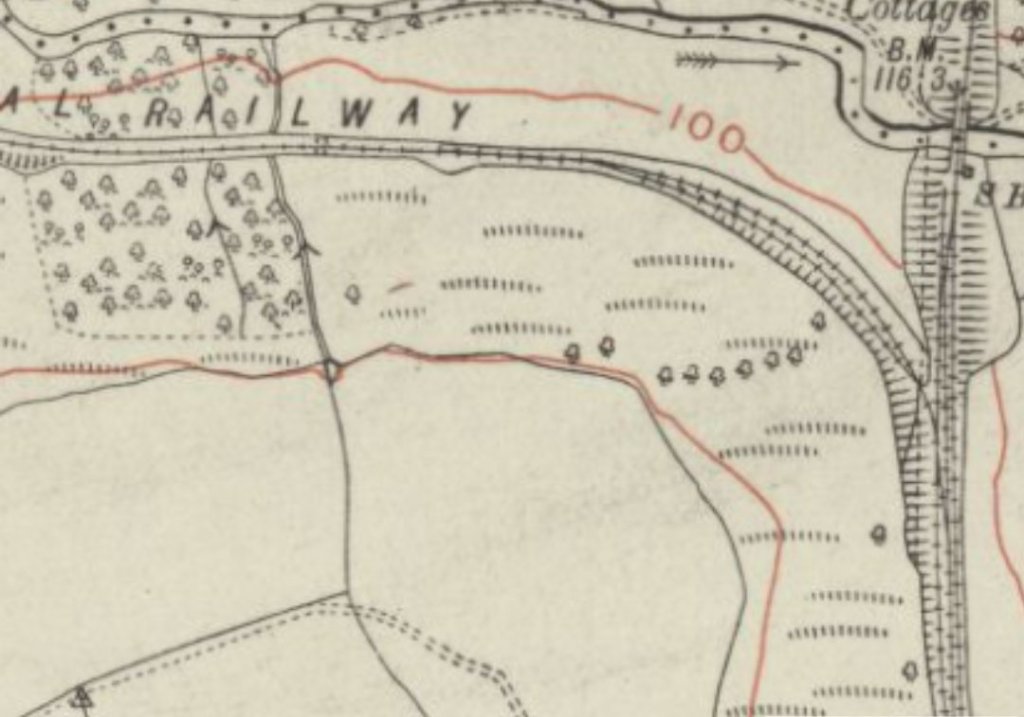

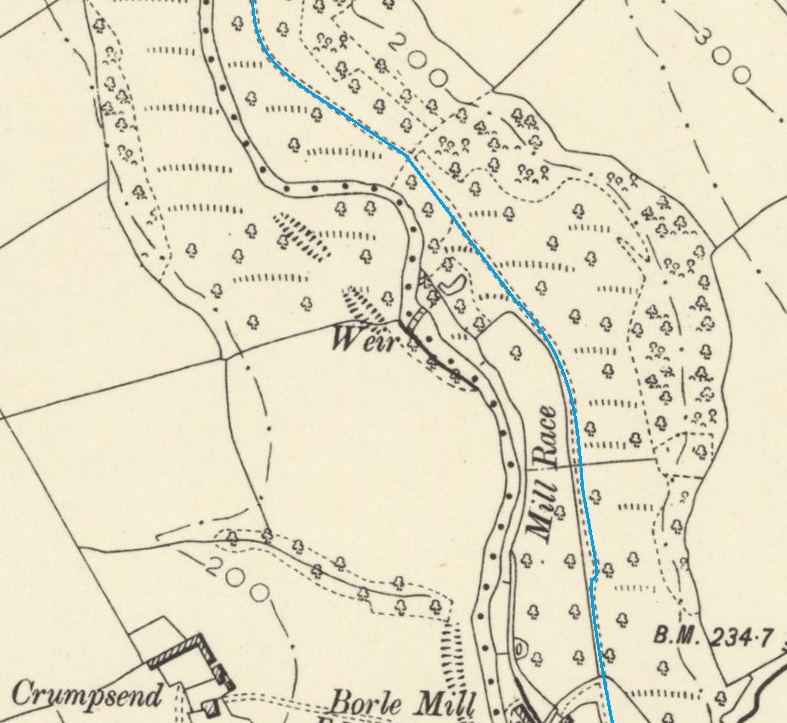

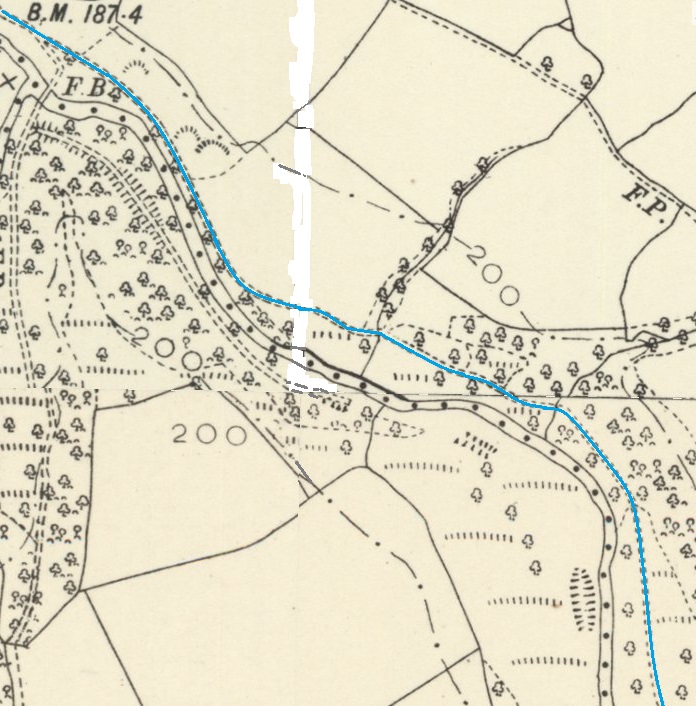

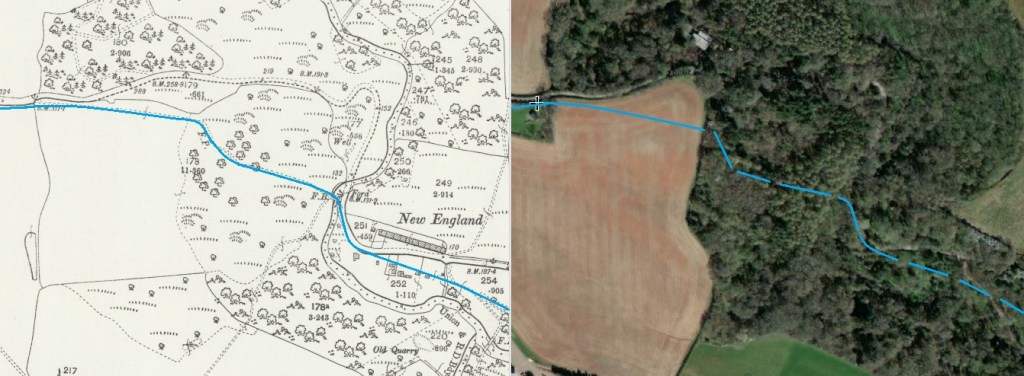

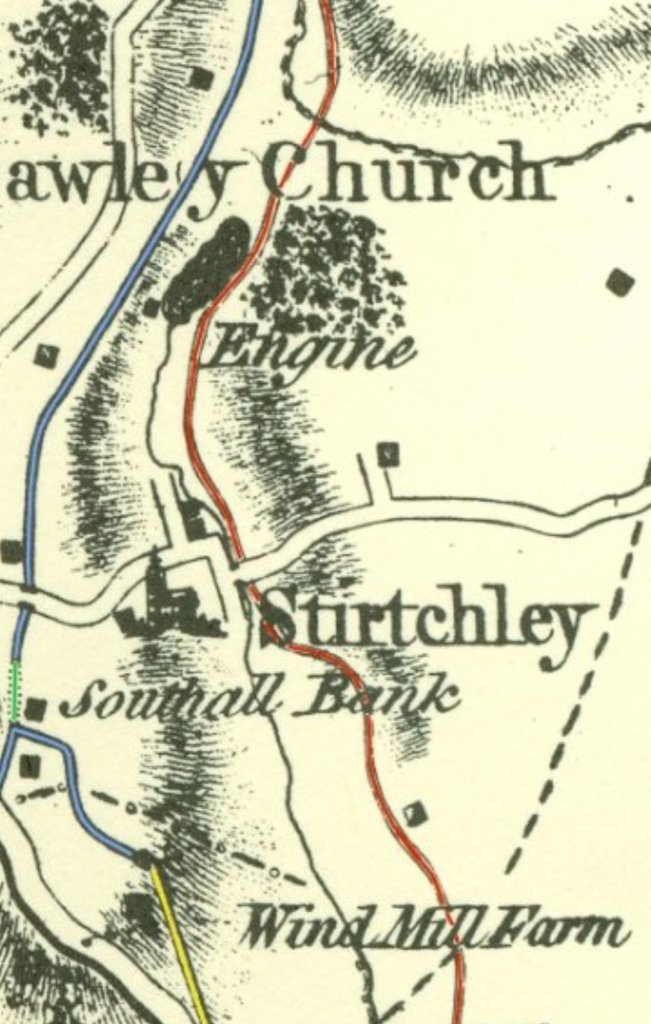

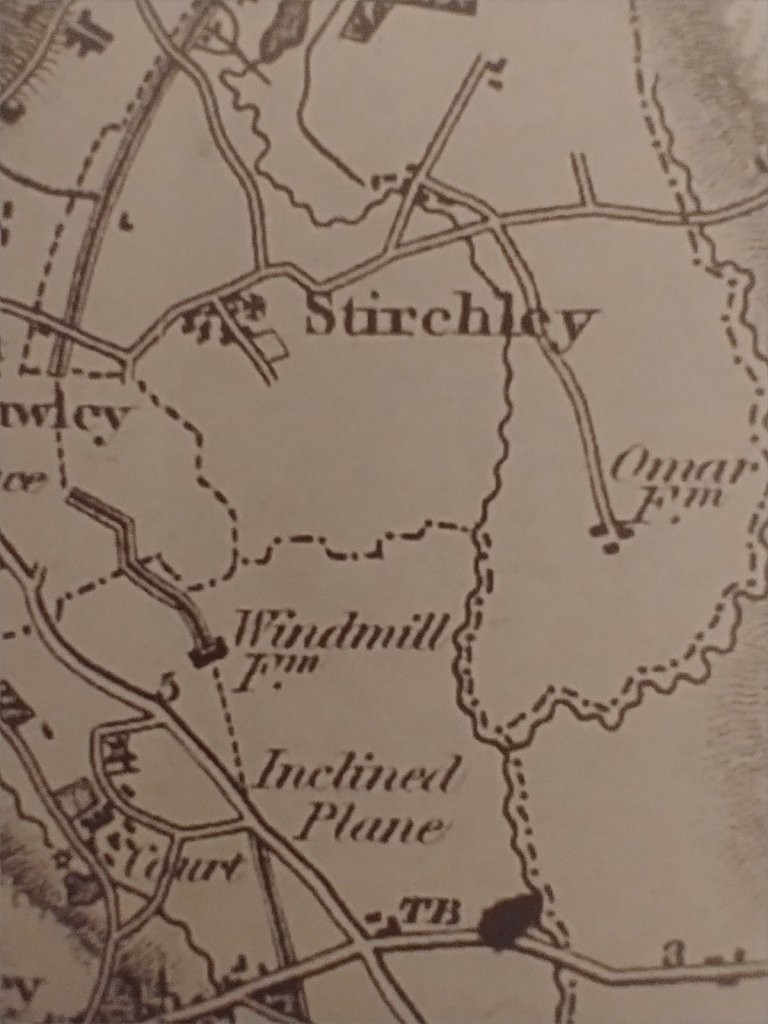

My photographs of the 6″ plan are not of the greatest clarity. But the two images provided here give sufficient clarity to make out the significant features that Savage and Smith recorded in the 1960s. [2: p139]

Their contribution is important, as they were able, in their onsite surveys, to record details subsequently lost with the remodelling of the landscape and the construction of new transport arteries by the Telford Development Corporation.

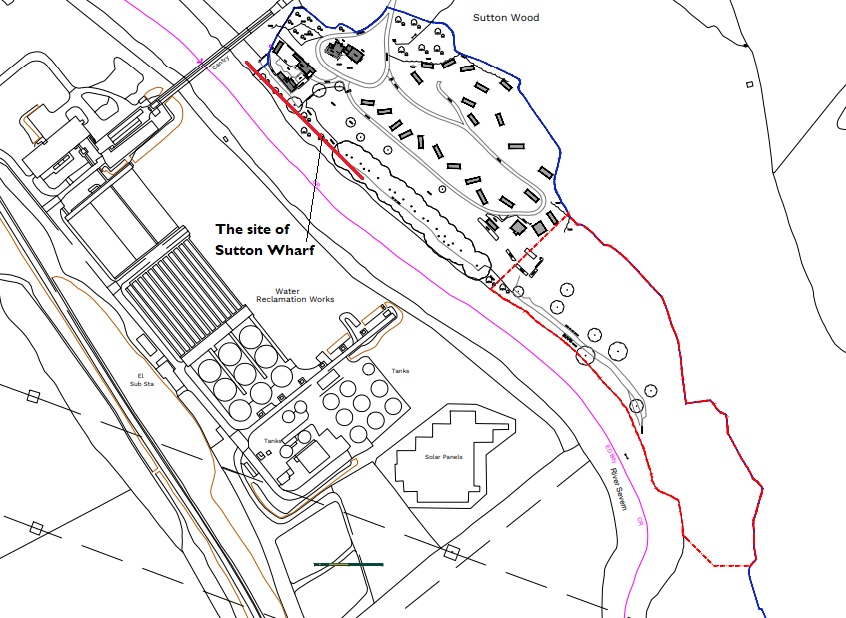

Our investigation of the route of the tramroad begins at its southern end at Sutton Wharf.

Below the key to Savage and Smith’s 6″ to a mile drawings there are a series of maps and satellite images showing the location of the Wharf.

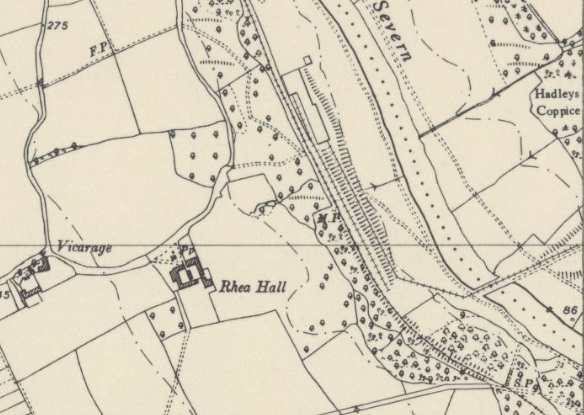

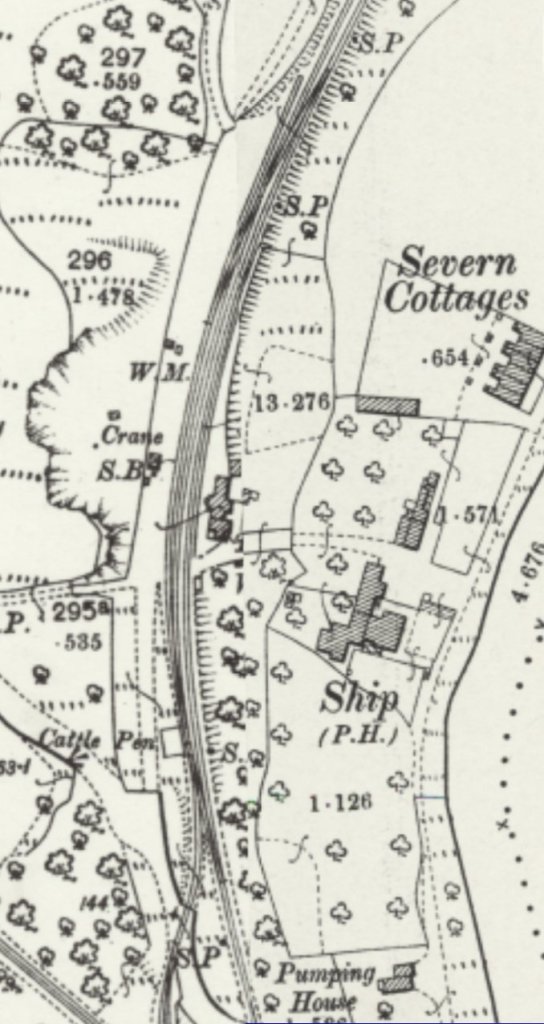

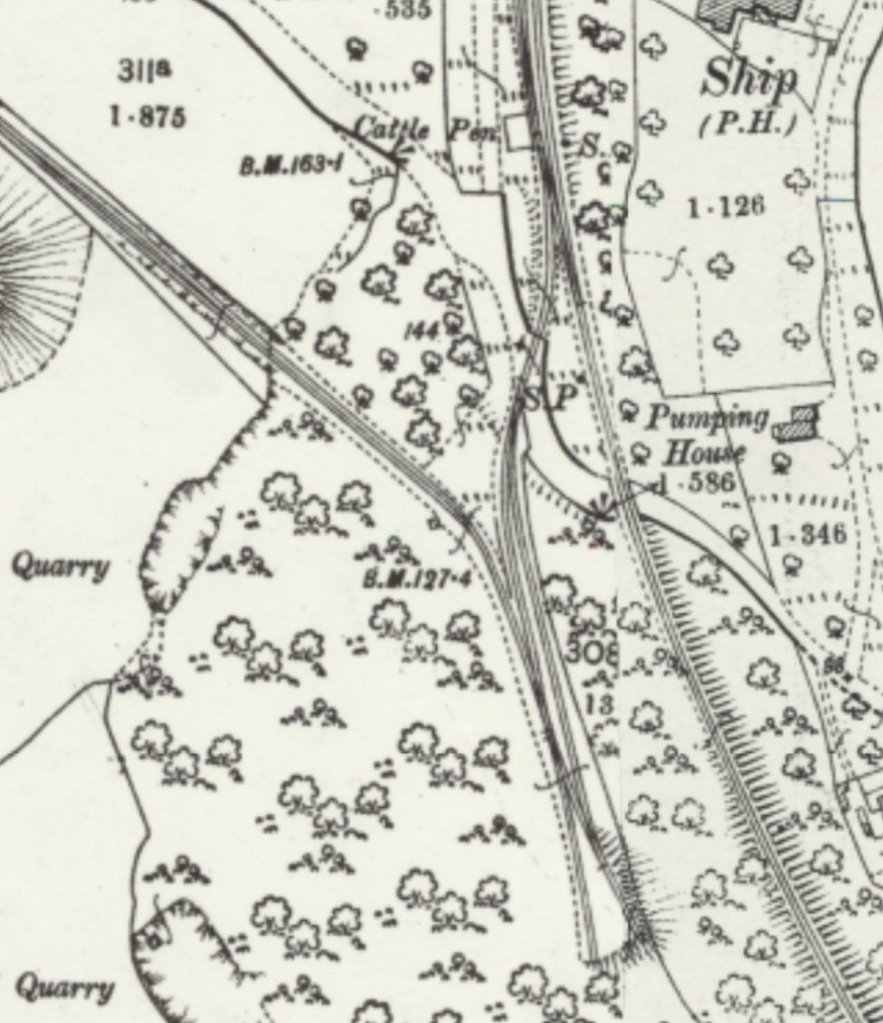

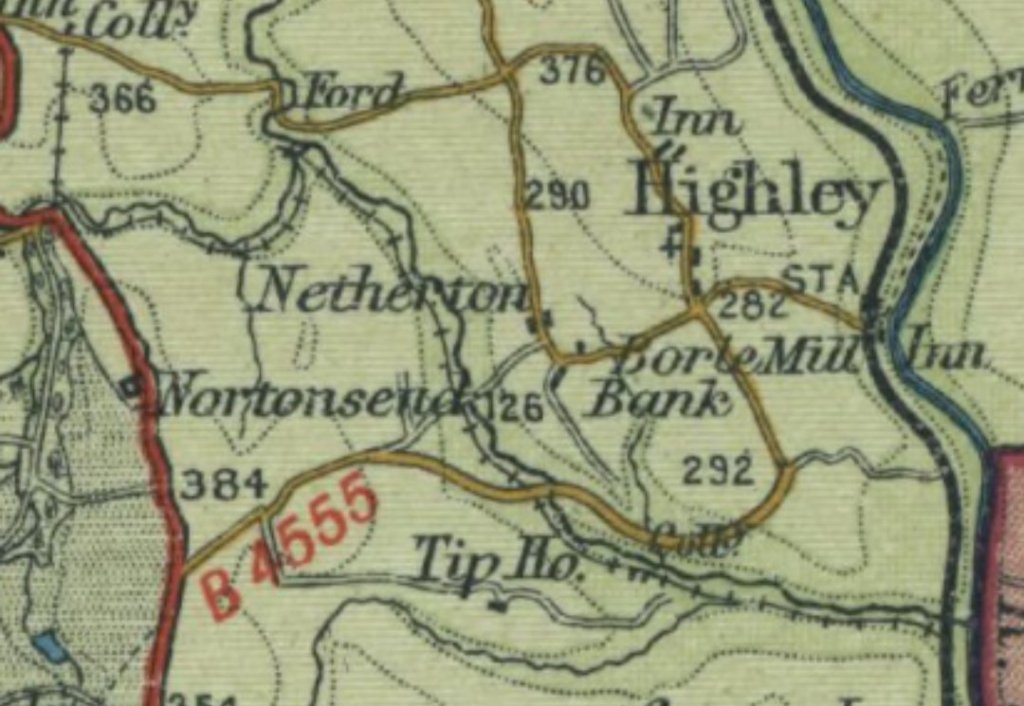

The 6″ Ordnance Surveys of 1881/82, published in 1883 and of 1901, published in 1902 show the railways serving the immediate area to the West and South of Sutton Wharf. The GWR Severn Valley Railway is to the South of the River Severn with its station close to Bridge Inn. The LNWR Coalport Branch is on the North side of the Severn. The two stations are linked by Coalport Bridge.

Coalport Bridge remains in use in the 21st century, the two railways have disappeared. One picture of the bridge as it appears in the 21st century is provided below. The LNWR line is now the Silkin Way which links the River Severn with the centre of Telford. The Severn Valley Railway Coalport Station is, in 2023, a site with a variety of different holiday accommodation available.

As an aside, here are some details about Coalport Bridge as provided on Wikipedia: “Architect and bridge-builder William Hayward (1740–1782) designed the first crossing over the Severn at Coalport, based on two timber framed arches built on stone abutments and a pier. It was originally built by Robert Palmer, a local timber yard owner based in Madeley Wood, and opened in 1780. The bridge, known as Wood Bridge, connected the parish of Broseley on the south bank of the river with the Sheep Wash in the parish of Madeley and Sutton Maddock on the north bank. … The wooden bridge was short-lived and lasted less than 5 years until 1795, when severe winter flooding virtually washed away the mid-stream supporting pier.” [9]

The bridge remained closed from 1795 until the Trustees had it rebuilt in 1799 “as a hybrid of wood, brick and cast-iron parts, cast by John Onions (Proprietor’s Minute Book 1791–1827). The two original spans were removed and replaced by a single span of three cast iron ribs, which sprang from the original outer sandstone pier bases. The bridge deck was further supported by two square brick piers, the northern one constructed directly on top of the stone pier base and the southern one set back slightly towards the river bank. The remainder of the superstructure was built of wood and may have reused some of the original beams. However, by 1817, this bridge was failing again, attributed to the insufficient number of cast iron ribs proving inadequate for the volume of traffic. Consequently, the bridge proprietors decided to rebuild Coalport Bridge once again, this time completely in iron. The quality of the castings is good, especially by comparison with the castings of the Iron Bridge upstream. The bridge was recently (2005) renovated and the static load lowered by replacing cast iron plates used for the roadway with composite carbon fibre/fibreglass plates, with substantial weight saving.” [9]

“The date of 1818 displayed on its midspan panel refers to this substantial work which allowed the bridge, subscribed to by Charles Guest, one of the principal trustees, to stand without major repairs for the next 187 years.” [9] In 2004-2005, during the closure (which lasted about a year), not only were major works undertaken to the span of the bridge, it was also necessary to reconstruct the two brick arches supporting the verges at the south side of the bridge. The bridge “still takes vehicular traffic, unlike the more famous Iron Bridge, albeit limited to a single line of traffic, a 3-tonne weight limit and a height restriction of 6 ft 6in (1.98 cm).” [9]

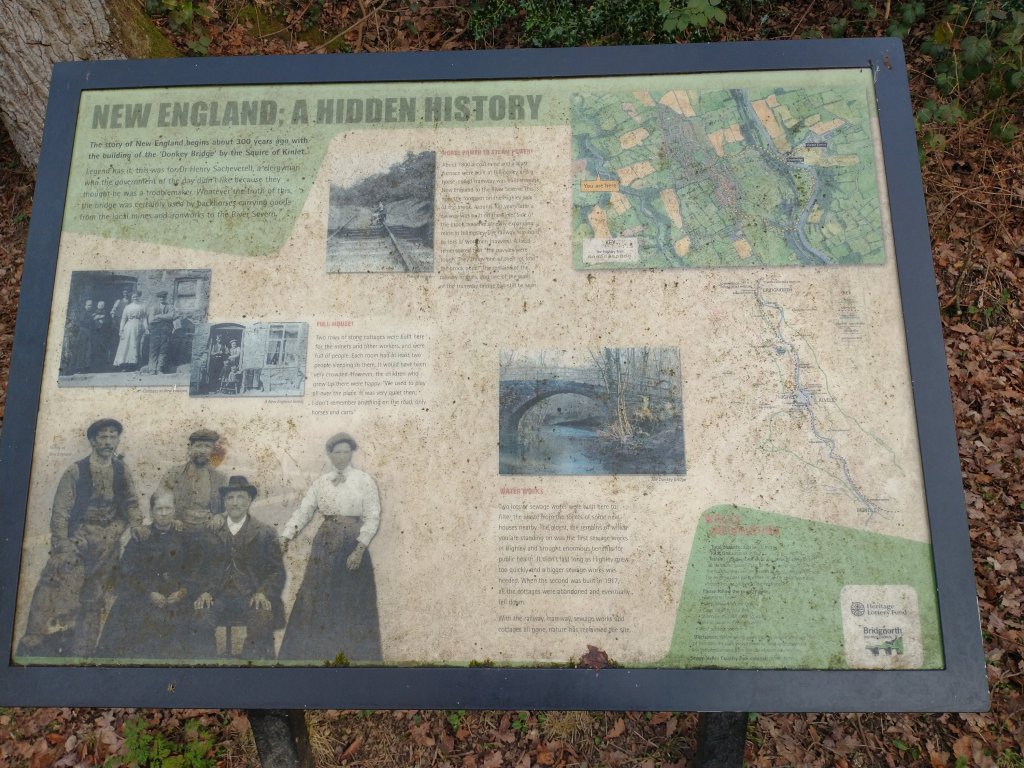

From the Wharf, an inclined plane was needed to gain height to the land above the Severn Gorge. The location of the incline is shown below.

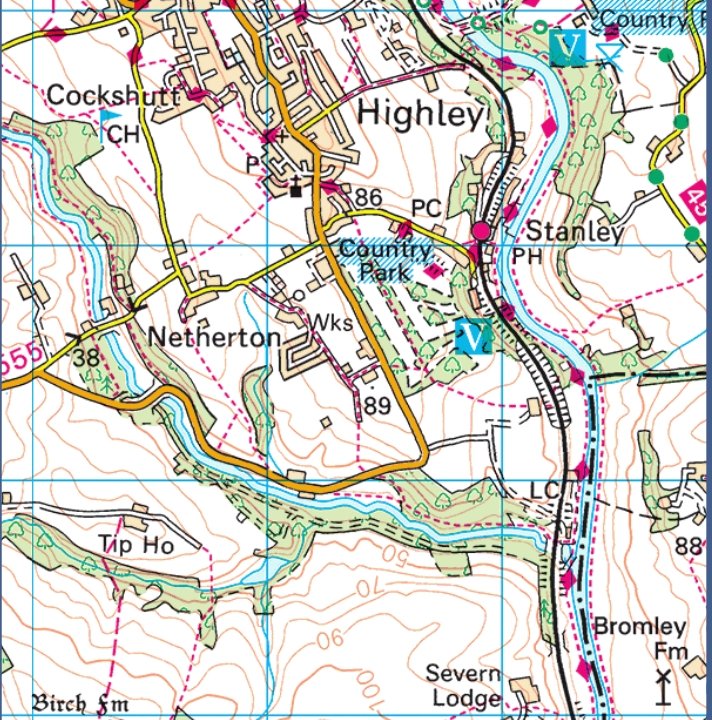

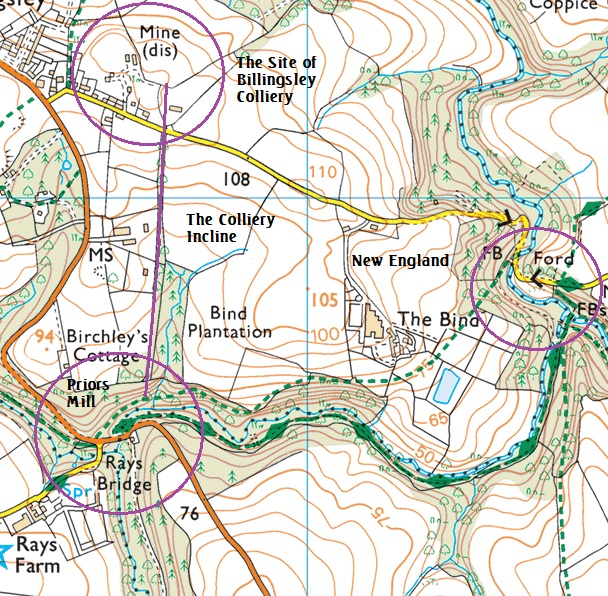

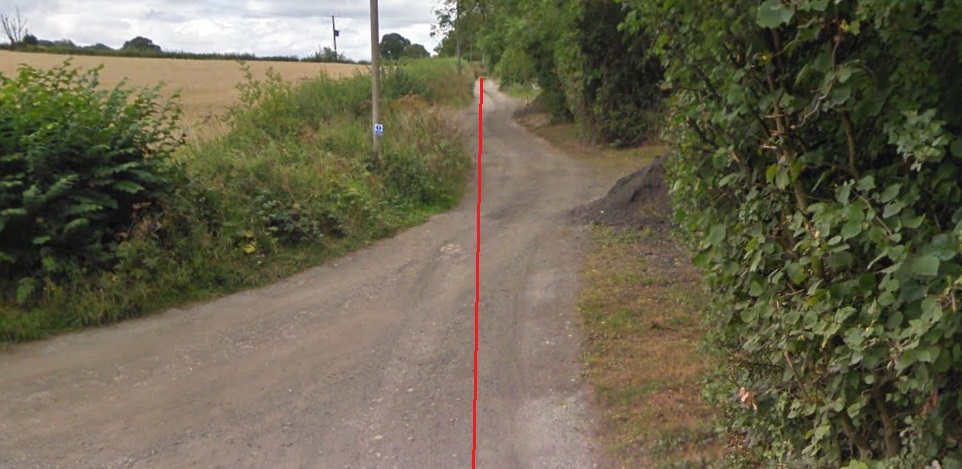

The next opportunity to look at the line of the tramroad comes at the point where its route is joined by a footpath which appears on the 1882 Ordnance Survey above and still is in existence today. The route appears on the modern 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey Explorer Series mapping as shown below.

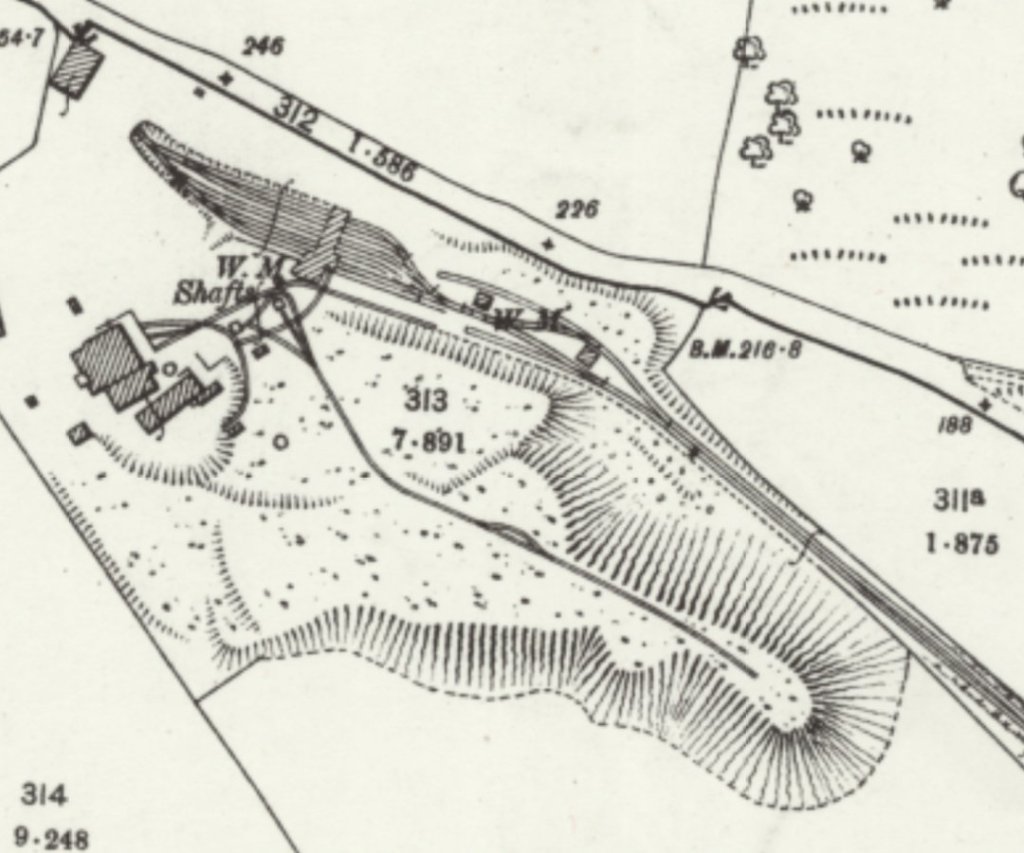

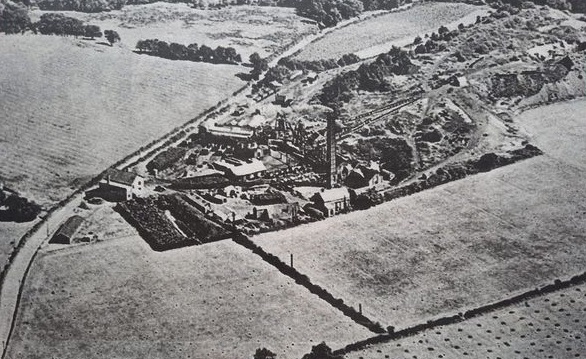

Two collieries appear on the 1901 OS mapping – Halesfield and Kemberton Collieries. These would not have been present when the tramroad was active in this area. By the 1950s these two pits were worked as one by the NCB and together employed over 800 men. “John Anstice sank Kemberton Pit when director of the family company in 1864 mainly for coal but it also produced ironstone and fireclay. … Halesfield was sunk as an ironstone and coal mine in the 1830s and continued to work coal until the 1920s, it later became the upcast and pumping shafts for Kemberton pit.” [13]

Apart from the A4169 at the bottom of the satellite image (which is already shown above), the only modern road which crosses the line of this section of the old tramroad Is Halesfield 18. Google Streetview images in this area were taken at the height of Summer in 2022 when vegetation was at its most abundant and as a result show nothing of note.

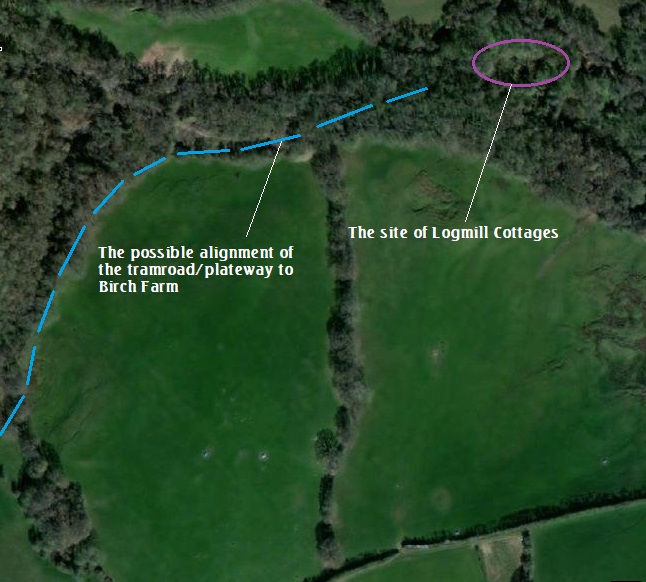

Our discussion about the old tramroad alignment is essentially speculative. We are in a better position than Savage and Smith were to trace routes using modern technology, but even so our possible route remains speculative. I have reproduced in in approximation on the same modern satellite image as were encountered above. Should it be correct, then some of its route can be followed and some locations can be photographed but all with a healthy sense of scepticism.

Holmer Lake is a reservoir owned by Severn Trent Water and serves Telford and the surrounding areas. The land around Holmer Lake includes areas of woodland and grassland. [19] Mad Brook was dammed in in 1968-70 to create a balancing reservoir at the behest of Telford Development Corporation. [16][17]

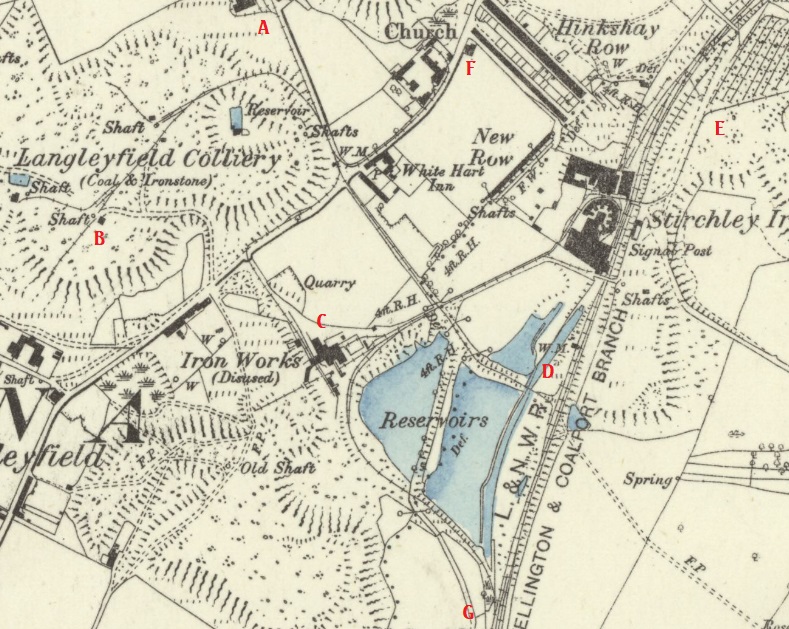

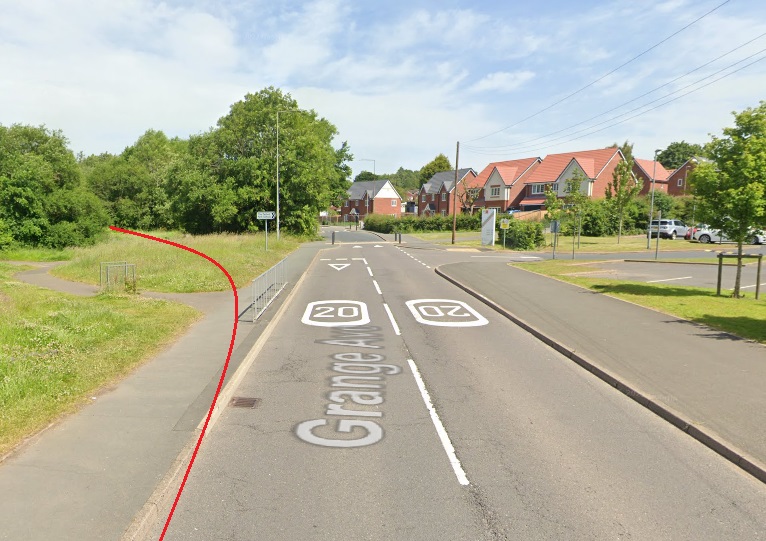

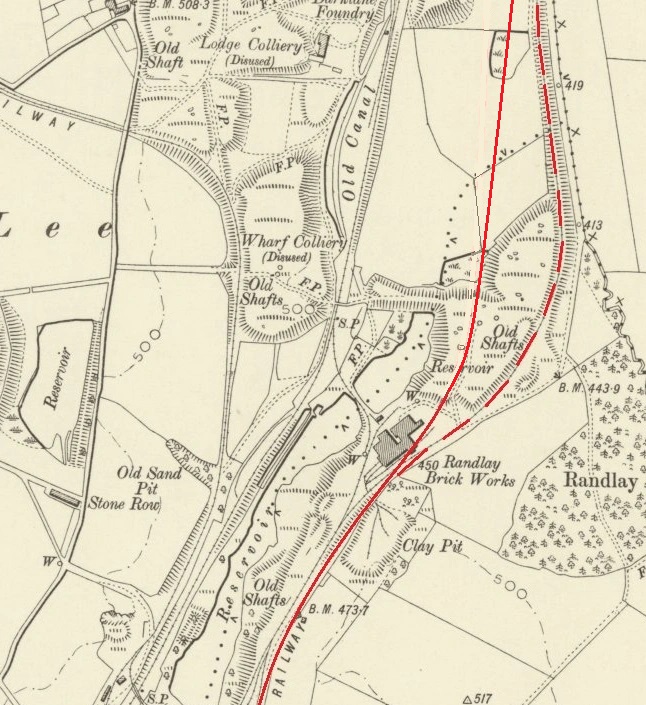

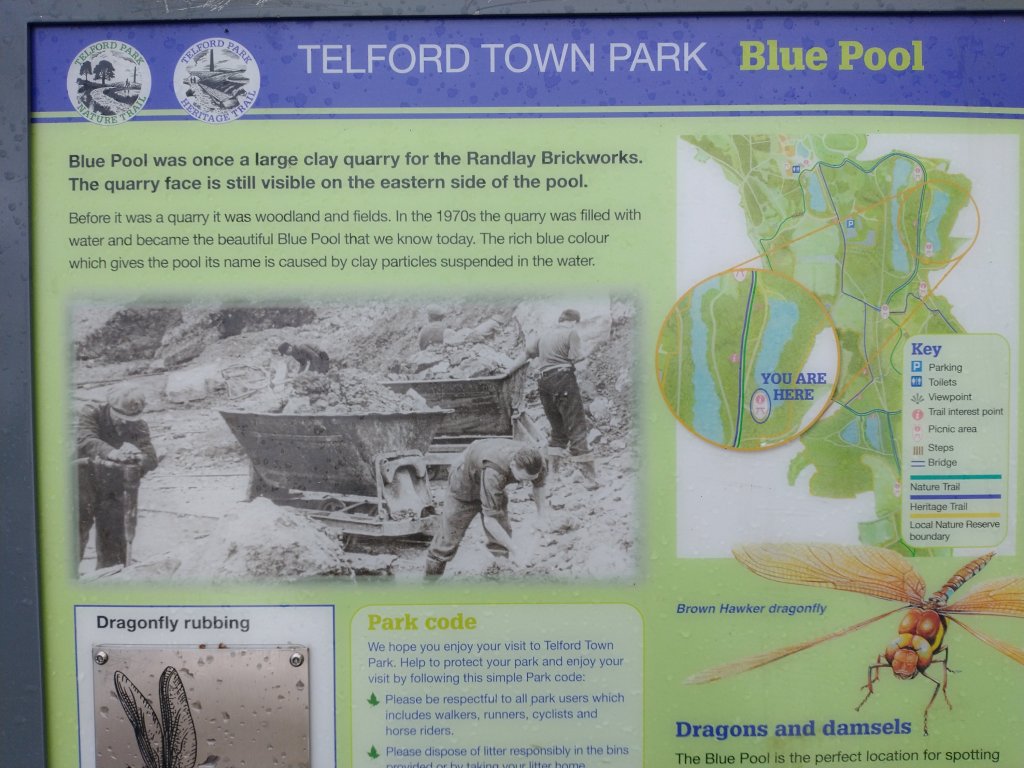

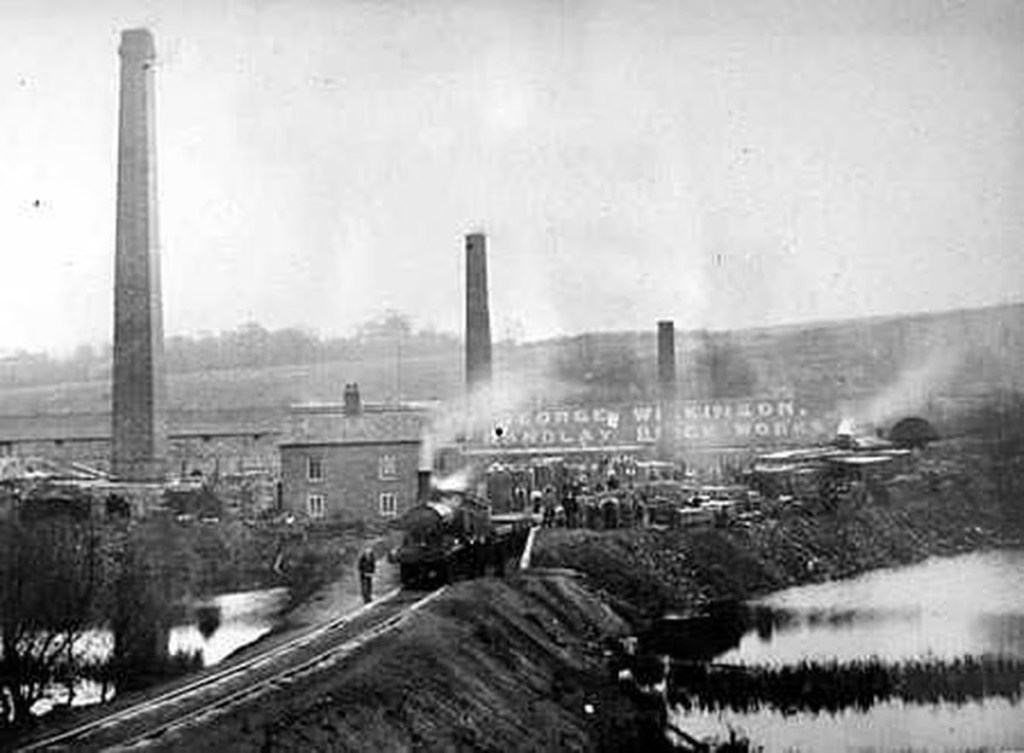

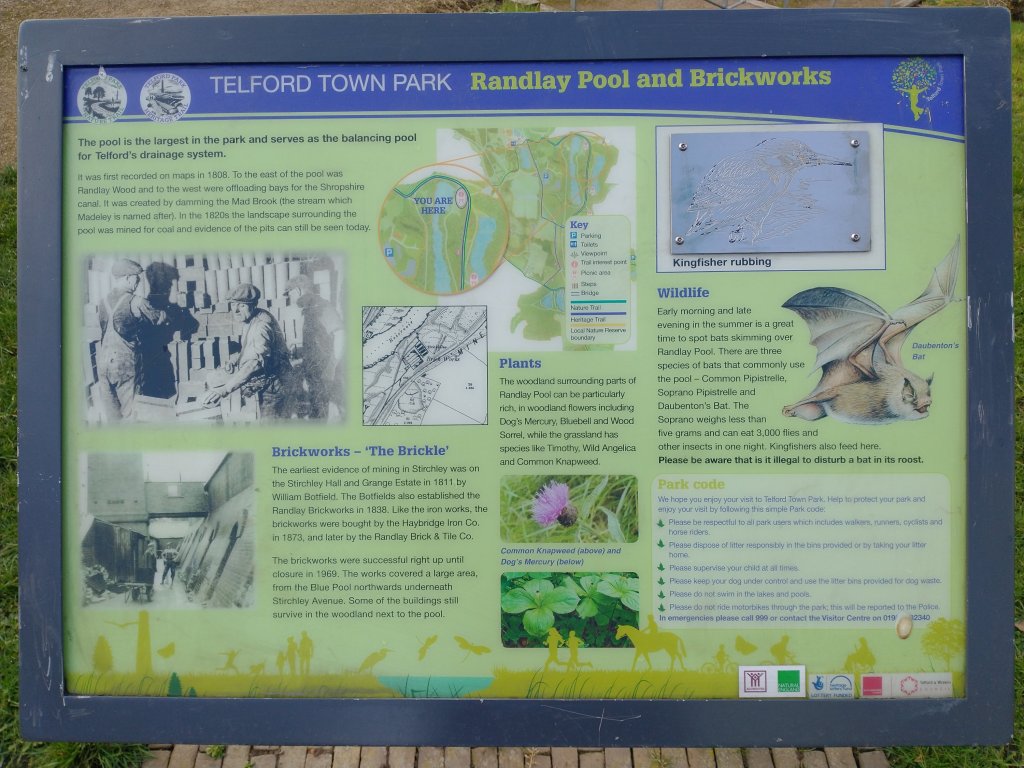

The next length of the old tramroad brings us passed the site of Grange Farm and Grange Colliery, Stirchley Ironworks and close to Randlay Pool. Mad Brook meanders North, initially close to the line of the old tramroad, moving away West beyond Grange Farm and then getting lost in the midst of Stirchley/Oldpark Ironworks.

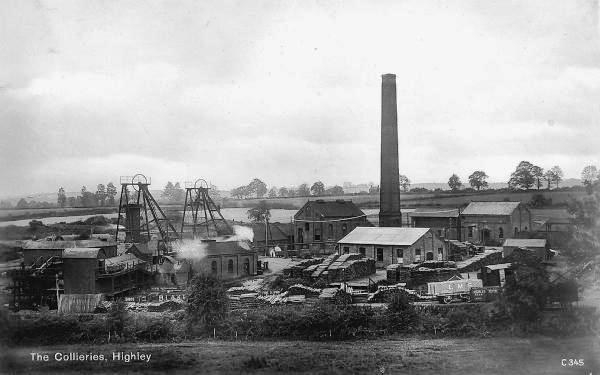

These images are taken at and around the site of Grange Colliery. On the image above, the spoil heaps from the colliery were immediately off-screen to the left the colliery yard ahead to the North. The image below was taken a from a point just to the North of the bins awaiting collection and looking to the left.

Grange Colliery probably opened by 1833. The extent of seams that could be worked was restricted by the Limestone fault, east of which the coal lay deeper. [21][17] By 1881 all the pits except Grange colliery had been closed. Despite the lease of mineral rights at Grange Colliery to Alfred Seymour Jones of Wrexham in 1893, the colliery was closed in 1894. [21][17]

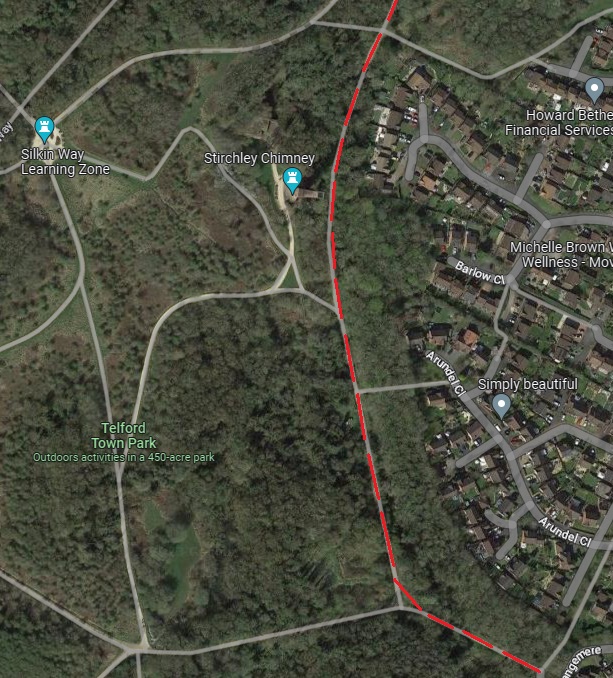

The closer satellite view of part of Telford Town Park above gives us a good point to stop to think about the historical timeline in the immediate vicinity of Stirchley Chimney. The tramroads in this immediate area were looked at in an earlier article in this series which can be found here. [22]

Savage and Smith [2] and other sources provide sufficient information to allow us to pull together that timeline. We have already noted that the tramroad was operating by 1799 and abandoned by 1815. Other Tramroads around Stirchley and along the route of the Shropshire Canal came along, generally, in piecemeal fashion.

The canal predated the Tramroad. It was built to link Donnington Wood with Coalport on the River Severn, a distance of about 7 miles. Construction commenced in 1789 near Oakengates and reached Blists Hill relatively quickly. A shaft and tunnel were intended to get loads down to river level. However, it seems as though natural tar was found oozing out of the tunnel wall and it was turned into a tar extraction business. In its place the Hay Incline was built to bring tub boats down to river level. [23] The incline has also been covered previous articles: here [24] and here. [25]

Once the canal has been completed a number of businesses decided to use the canal as a route to the outside world. Before 1830 a wharf had been established on the West side of the Canal close to Hinkshay/Stirchley Pools which provided for colleries, brickworks and ironworks to the West and North.

The 1840s saw minor additions to the tramroad network around Madeley (South of Stirchley), the next decade saw considerable developments alongside the canal as shown on the next Savage and Smith extract below.

There was little change in the immediate area over the next 15 years. The next image covers the period 1876-1900 and again only shows minor changes to tramroads in the vicinity of Stirchley The railways now dominate the transport landscape.

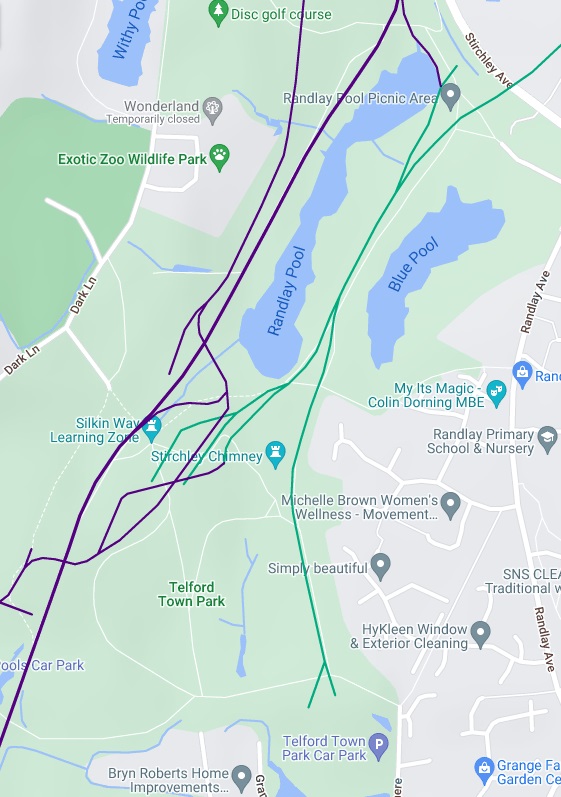

Missing from Savage and Smith’s 1″ to one mile drawings is the GWR branch parallel to the LNWR branch and running from the North down towards Stirchley. The route of that line is shown below in a turquoise colour on the mapping supplied by RailMapOnline.

The next few photographs take us along the route of what is the old tramroad from Sutton Wharf and that of the GWR Mineral Line along the East side of Stirchley Chimney which still stands in the 21st century.

The information board reads: “From at least 1882, the Great Western Railway (GWR) ran a mineral railway from Hollinswood down the Randlay valley to serve the coal and iron industries in Stirchley. Within the Town Park, this followed a course from Randlay Brickworks to the Grange. … The Mineral Railway stopped travelling South to the Grange between 1903 and 1929 and terminated at the Wrekin chemical works. [These were at the present location of Stirchley Chimney.] Its use finally reached the end of the line in 1954. The line of the Mineral Railway is preserved today on this pathway and evidence remains including posts, buildings and artefacts.” There is also a note on the board about a network of sidings which linked various industrial works to the main line of the mineral railway alongside a sketch-map of the area.

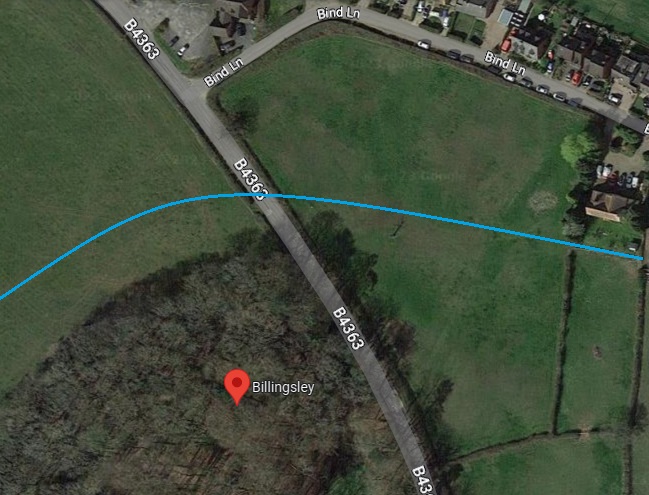

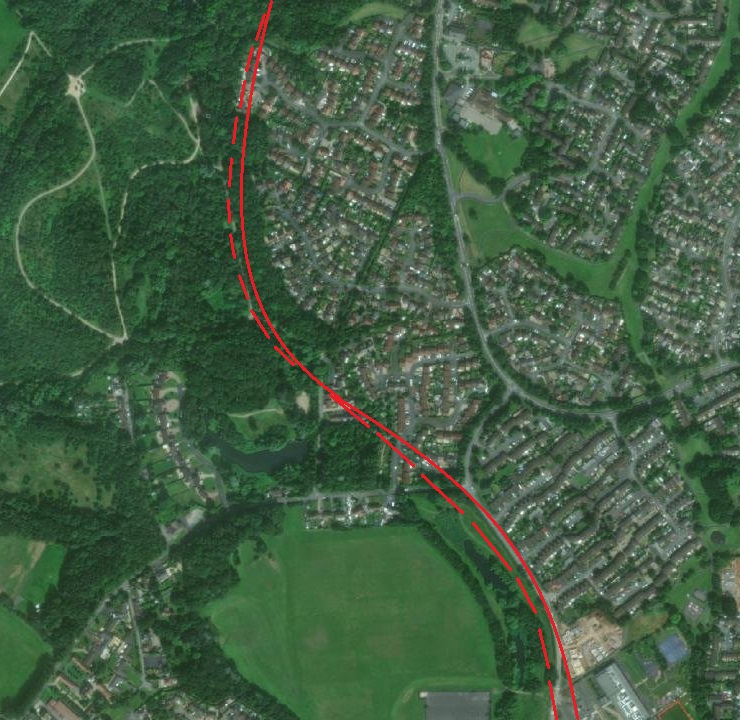

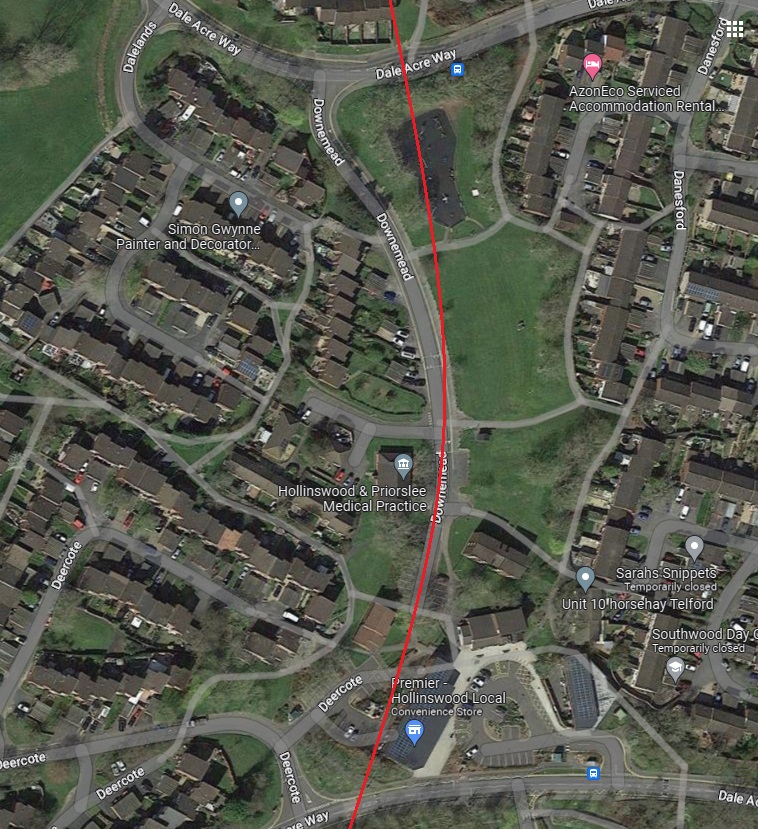

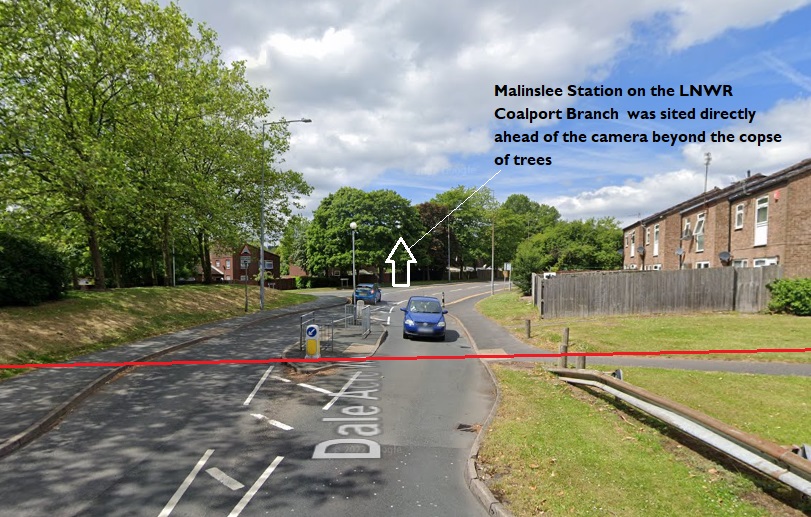

North of Randlay Pool the line of the old tramroad and the line of the GWR Mineral railway plunge into undergrowth and the topography of the area beyond this point for some distance is very unlikely to be the same as that present in 1901. In the top half of the satellite image above the lines crossed three modern roads, Stirchley Avenue, Queen Elizabeth Avenue and Dale Acre Way, then run geographically along the line of Downemead for a short way.

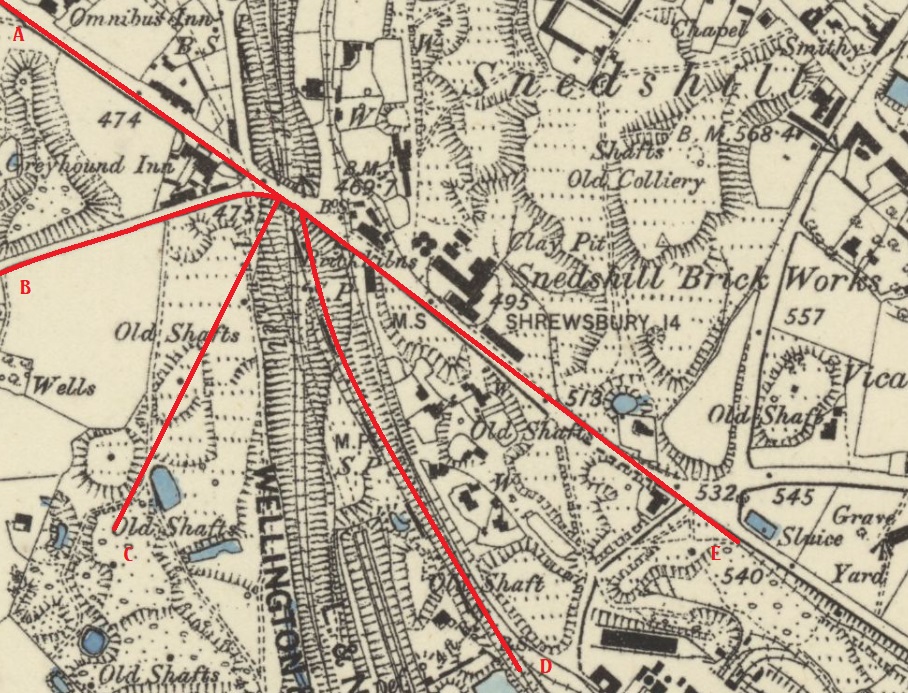

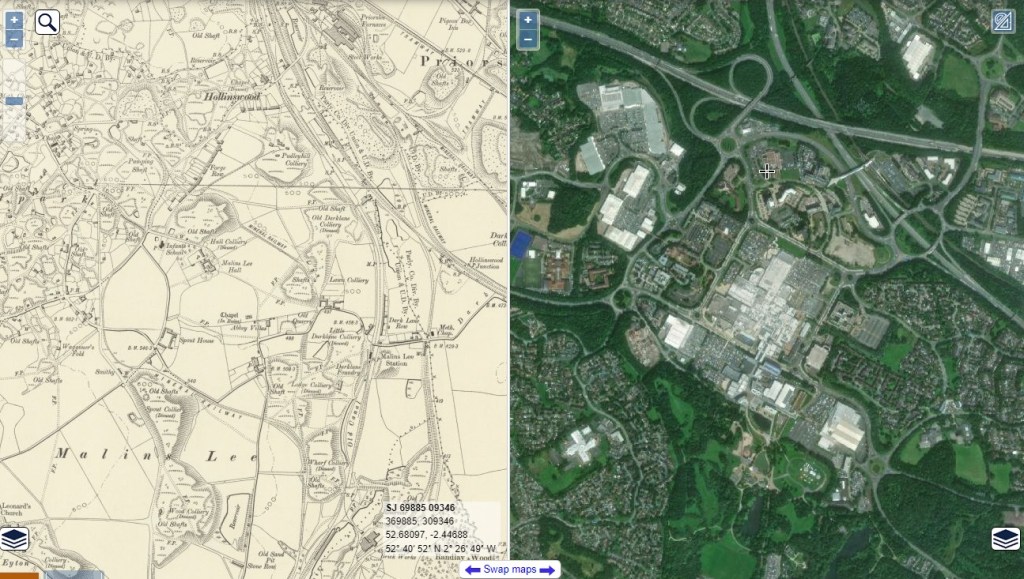

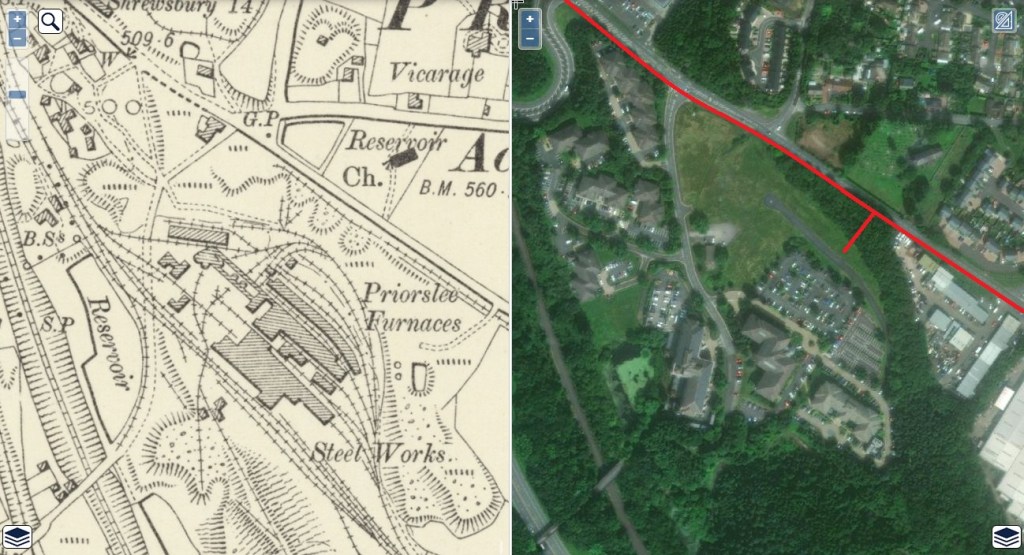

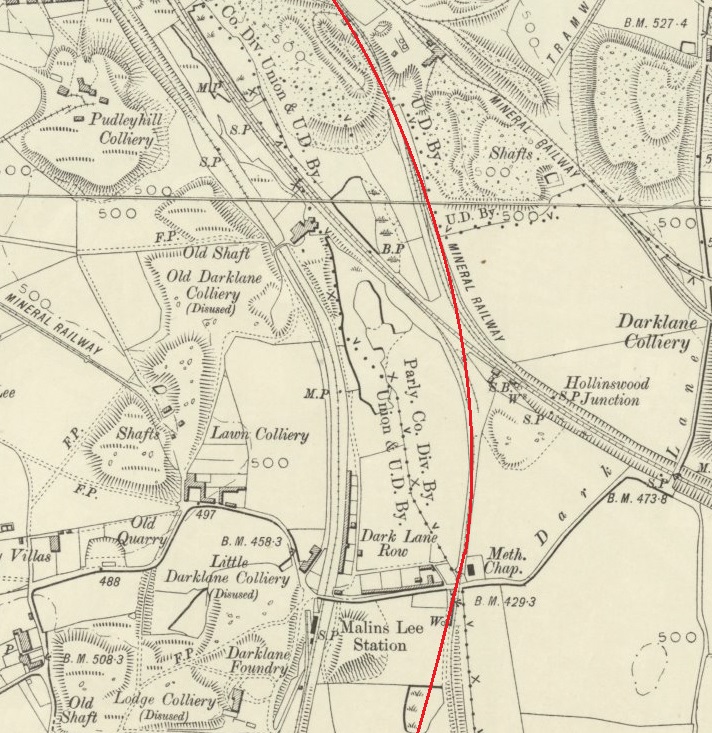

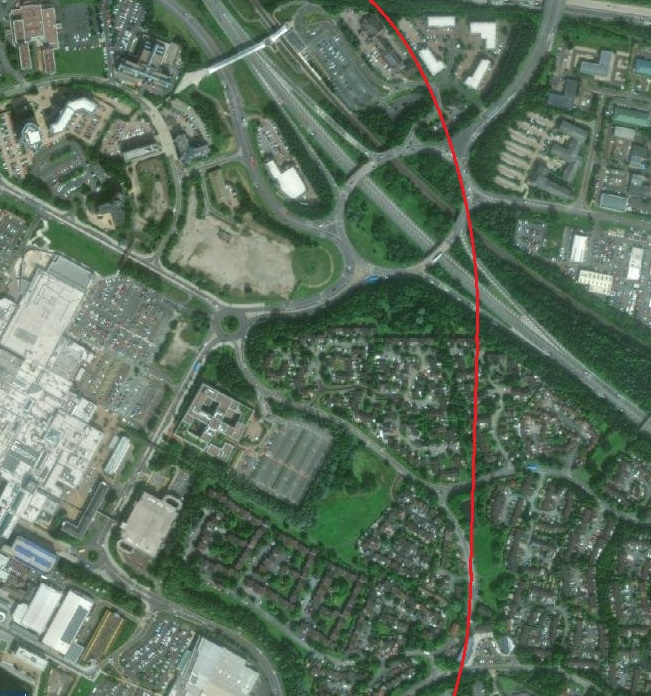

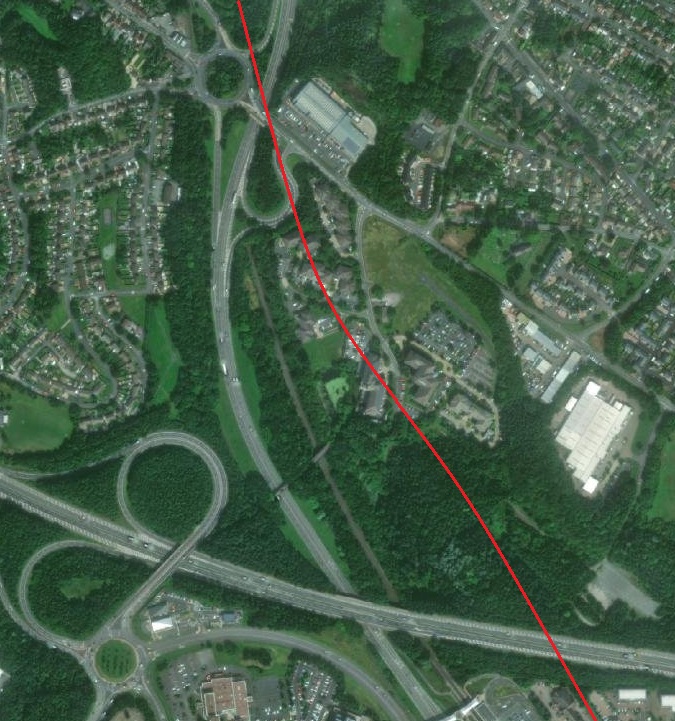

On the extract from the satellite imagery below the line is picked up running approximately along Downemead before crossing Dale Acre Way once again. At the point where Downemead meets Dale Acre Way at its North end, Dale Acre Way is running approximately along what was Dark Lane shown on the 6″ Ordnance Survey immediately below. Comparing the two images immediately below shows how much topographic change has occurred in the 120 years since the 1901 Ordnance Survey. Effectively the only feature which remains in the 21st century is the Shrewsbury to Wolverhampton Mainline railway which runs from top-left to bottom-right across both the map and the satellite image.

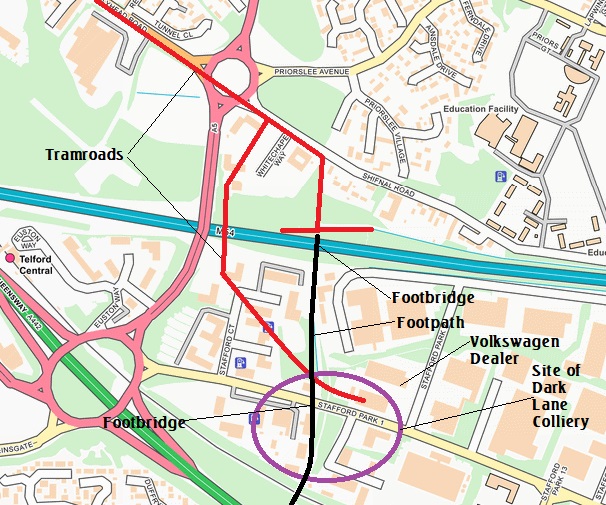

From the North side of the M54 as far as Hollinswood Road, the modern ladscape is heavily wooded and it would be impossible to pick out important features on the ground as the satellite image below shows.

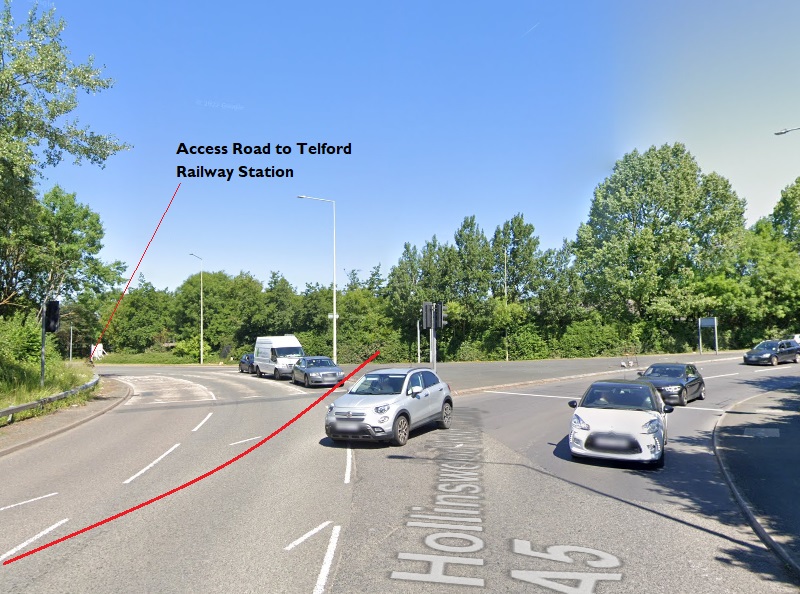

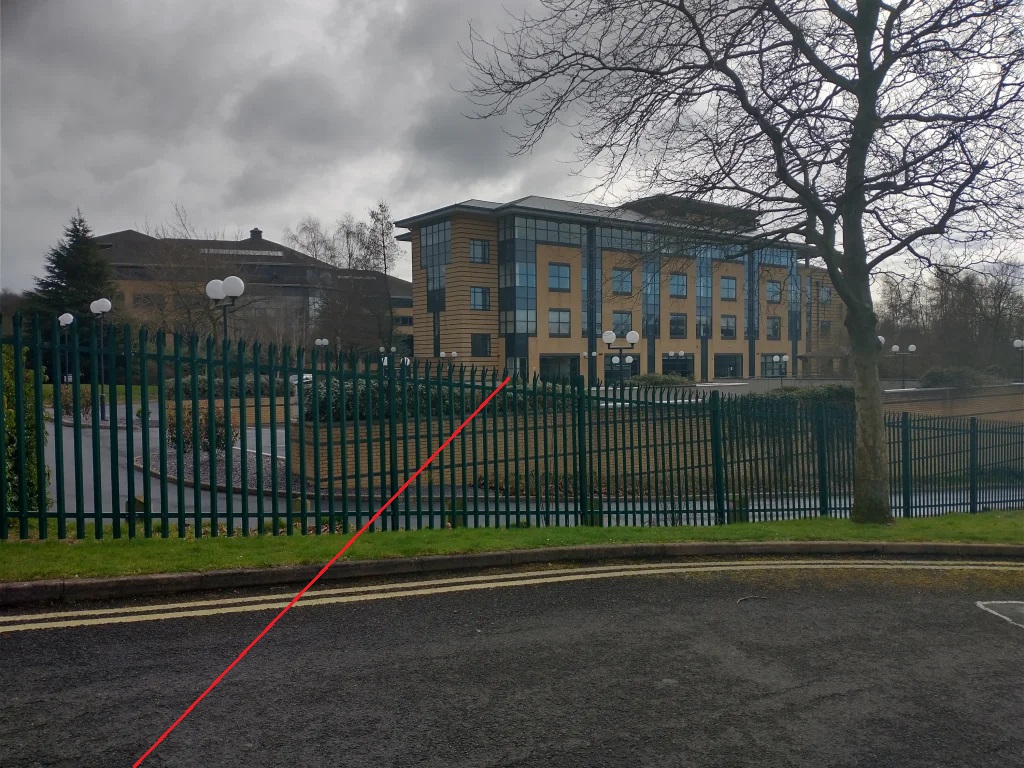

Beyond the buildings shown above the old tramroad route crosses the A442 slip road which is just beyond the industrial estate as shown below. …

It is at this point that we leave the old line. We are close to Oakengates and there was at one time a very large number of different tramroads ahead, part of the Lilleshall Company’s internal network. We will pick up this tramroad when we look at that network.

References

- Bob Yate; The Railways and Locomotives of the Lilleshall Company; Irwell Press, Clophill, Bedfordshire, 2008.

- R.F. Savage & L.D.W. Smith; The Waggon-ways and Plateways of East Shropshire; Birmingham School of Architecture, 1965. Original document is held by the Archive Office of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/101594689, accessed on 8th February 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=52.61334&lon=-2.43435&layers=6&b=1, accessed on 8th February 2023.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/52.6122/-2.4342, accessed on 8th February 2023.

- https://planning.org.uk/app/32/QQSNFYTDLXO00, accessed on 8th February 2023.

- http://www.dawleyhistory.com/Maps/1808.html, accessed on 8th February 2023.

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/28/Coalport_br1.jpg, accessed on 9th February 2023.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coalport_Bridge, accessed on 9th February 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/101594494, accessed on 9th February 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=52.63640&lon=-2.42745&layers=6&b=1, accessed on 14th February 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=52.64436&lon=-2.43028&layers=6&b=1, accessed on 14th February 2023.

- https://www.shropshirecmc.org.uk/below/2007_3w.pdf, accessed on 14th February 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=14.6&lat=52.65918&lon=-2.43605&layers=6&b=1, accessed on 20th February 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/101594470, accessed on 20th February 2023.

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/salop/vol11/pp185-189, accessed on 20th February 2023.

- A P Baggs, D C Cox, Jessie McFall, P A Stamper and A J L Winchester; Stirchley: Manor and other estates; in ed. G C Baugh and C R Elrington; A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 11, Telford; London, 1985, p185-189; via British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/salop/vol11/pp185-189, accessed 20th February 2023.

- Christopher Greenwood; Map of the County of Salop, 1827; Facsimile Copy, Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society, 2008.

- https://www.telford.gov.uk/info/20629/local_nature_reserves/6525/holmer_lake_with_kemberton_meadow_and_mounds, accessed on 21st February 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=52.66125&lon=-2.44016&layers=6&b=1, accessed on 21st February 2023.

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/salop/vol11/pp189-192, accessed on 22nd February 2023.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2022/06/24/ancient-tramroads-near-telford-part-6-malinslee-part-2-jerry-rails

- http://www.canalroutes.net/Shropshire-Canal.html, accessed on 22nd February 2023.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2020/10/21/coalport-incline-ironbridge

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2021/06/10/coalport-incline-ironbridge-addendum-2021

- https://www.railmaponline.com/UKIEMap.php, accessed on 23rd February 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=52.67026&lon=-2.44101&layers=6&b=1, accessed on 23rd February 2023.

- https://www.shropshirestar.com/news/2007/04/26/brickworks-at-turn-of-century, accessed on 23rd February 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=52.67807&lon=-2.43952&layers=6&b=1, accessed on 24th February 2023.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.0&lat=52.68562&lon=-2.43991&layers=6&b=1, accessed on 24th February 2023.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lilleshall_Company#:~:text=The%20Lilleshall%20Company%20was%20a,operated%20a%20private%20railway%20network, accessed on 4th March 2023.