‘The Modern Tramway’ in March 1957 (Volume 20, No. 231) carried a follow-up article [1] to that carried by the Journal in April 1954. The original article is covered here:

The Modern Tramway – Part 5 – Trams and Road Accidents

The follow-up article in the March 1957 Journal focussed on a new Road Research Laboratory Report about London road accidents. The Modern Tramway claimed in the article that the Report went almost unnoted in the national press, unlike the Laboratory’s earlier report.

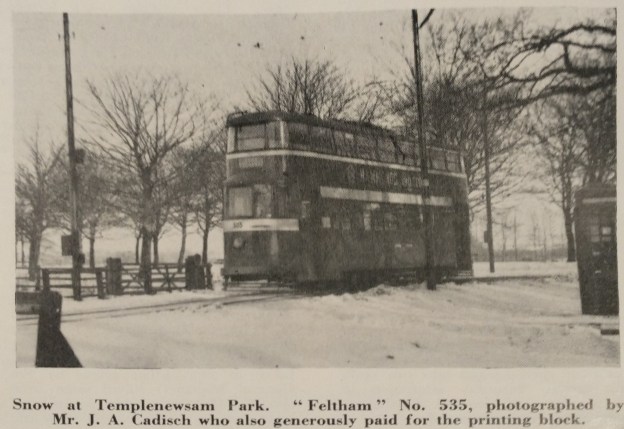

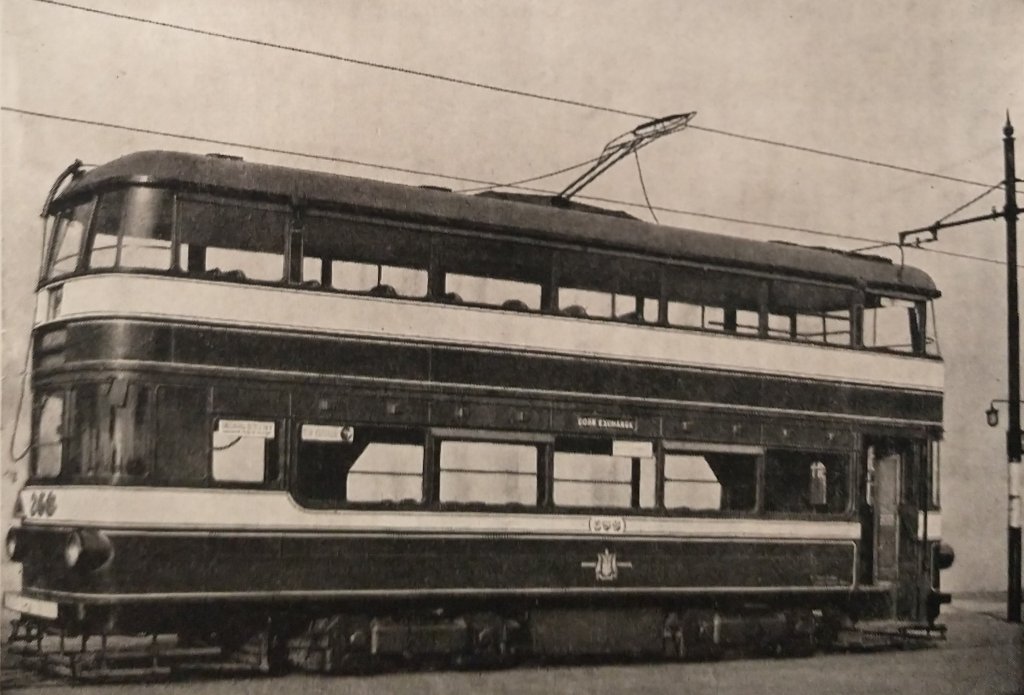

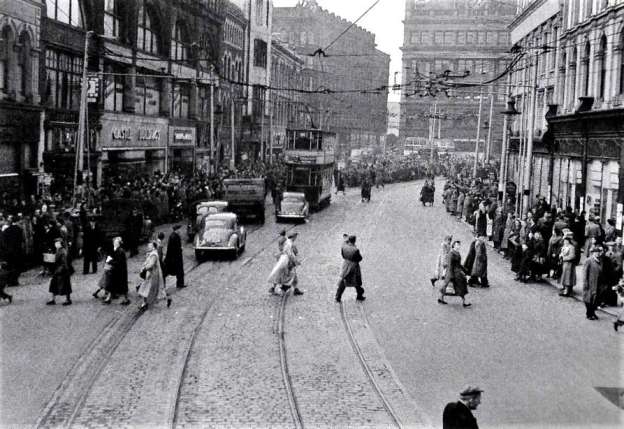

The featured image at the top of this article is part of the Lambeth Landmark Collection (Ref: 04823, Identifier: SP160, 1951). It shows, possibly, another Feltham tram on Route 38 crossing Westminster Bridge going towards Parliament Square. The London County Hall building can be seen on the right. The Skylon of the Festival of Britain is just visible (no more than a ghostly shadow) on the left side of the tram. Route 38 ran between Abbey Wood and Victoria Embankment (via Westminster Bridge). [4][3: p122]

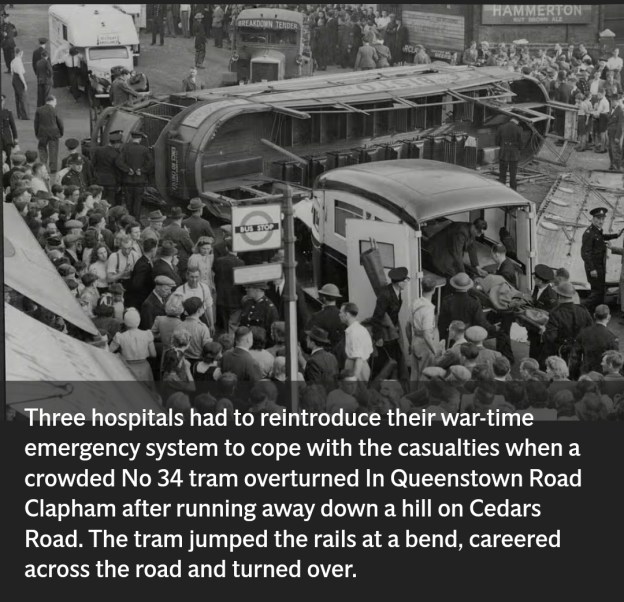

The new report studied the effect on accidents of resurfacing former tramway roads in the boroughs of Camberwell and Wandsworth, and the report’s conclusions were that the improvement in road surfaces reduced skidding accidents but increased some other types of accident presumably by encouraging higher speeds. The final result was a marked transfer of accident-proneness from pedal cyclists to pedestrians and motor vehicles, a 10% decrease in total accidents and a ‘non-significant increase’ in fatal and serious accidents. The Journal commented that the phrase ‘non-significant increase’ was “not intended to reduce the seriousness of the case; since fatal and serious accidents are fewer than slight accidents a far more dramatic change in the trend would be necessary to reach the point of statistical signifi- cance.” [1: p43]

Of particular significance was the additional evidence which this latest report provided that “London tramway accident figures were not typical of those for the country as a whole. The comparison is made between the period when the tracks were intact but disused (and in many cases patched, leaving only the conduit slot exposed) and the first equivalent period after complete resurfacing; it confirms that the conduit slot was probably as important a factor as the running rails in pedal cycle accidents, and since this outdated feature of the former L.C.C. system was entirely confined to London (at least in the motor age) it clearly invalidates any comparison of accident figures between London and other towns.” [1: p43] Other similar points, such as the absence of loading islands in London, were brought out in the previous article in April 1954.

The Light Railway Transport League secured an interview with the Road Research Laboratory in which evidence relating to Dundee’s experience of a conversion from trams to buses was discussed as well as the then recent report about London. The tram and bus accident figures for Dundee showed that Dundee trams ran about three times as far per fatality as Dundee buses. “The Laboratory … considered that the Dundee figures were too small for any definite conclusion to be drawn from them, and maintain their previous view that since London results in almost all other matters have been found similar to those elsewhere the same must be true of trams.” [1: p43]

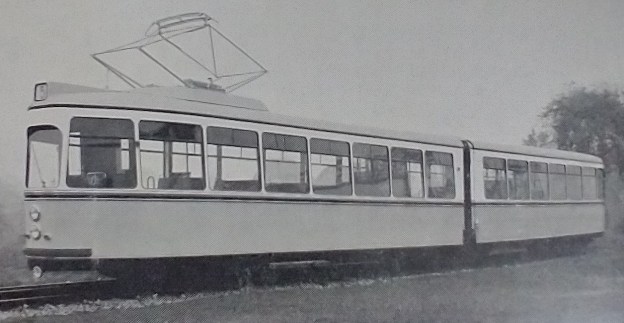

Sadly, the League came to the conclusion that the Laboratory’s conclusions would only be challenged if it’s own members were able to provide statistically significant and conclusive figures relating to some of the larger city networks which allow comparisons to be made. The League suggested that two forms of comparison were possible: “one in a city such as Sheffield where modern practices (and modern surfaces) apply on a street tramway system, the other in a city such as Liverpool where a high proportion of the tramways were on reserved track.” [1: p43] The League was convinced that the many untypical features of the London tramways rendered invalid any extrapolation of London results to other towns, and that a similar study in (say) Sheffield would provide ample proof of this. Their view was tramway modernisation would have brought about a greater reduction in accidents than the replacement of trams with buses. The League asserted that figures received from Hamburg seemed to confirm this. The Deputy Director of the Laboratory agreed that such practices as coupling trams together and providing loading islands could reasonably be expected to reduce the accident rate, but the Laboratory had no figures to support this. It seems, however, that there was shared agreement on the safety value of reserved tramway tracks as a study undertaken by the City Engineer in Glasgow after the war showed accidents to be negligible. [1: p44]

References

- More About Accidents; in The Modern Tramway, The Light Railway Transport League, Volume 20, No. 231, p43-44.

- https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/254670164078, accessed on 24th June 2023.

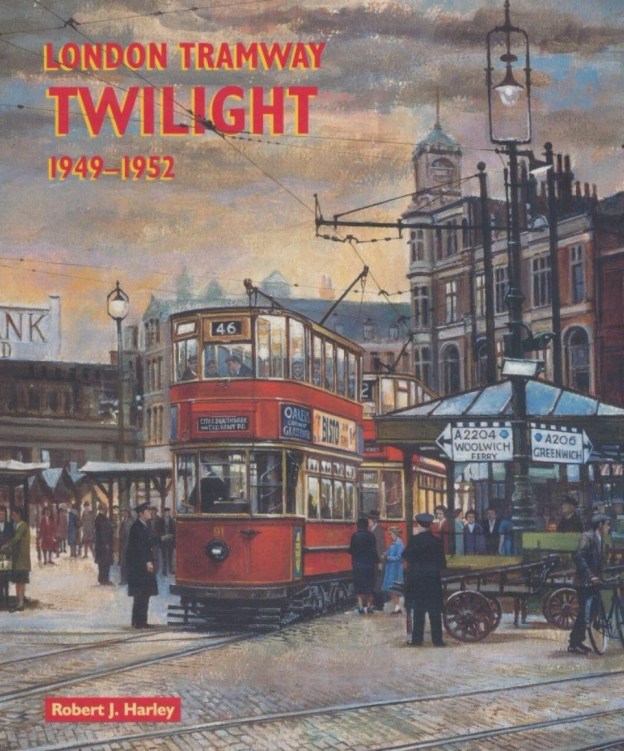

- Robert J. Harley; London Tramway Twilight: 1949-1952; Capital Transport Publishing, Harrow Weald, Middlesex, 2000.

- https://boroughphotos.org/lambeth/tram-westminster-bridge-lambeth, accessed on 24th June 2023.