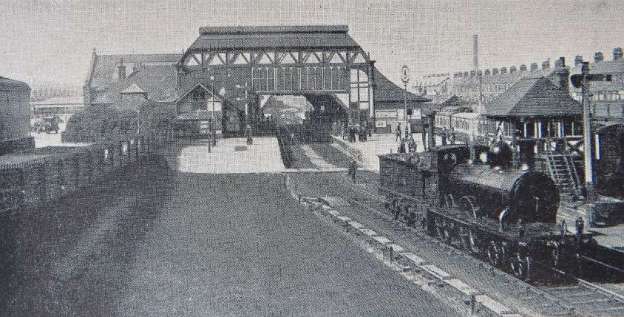

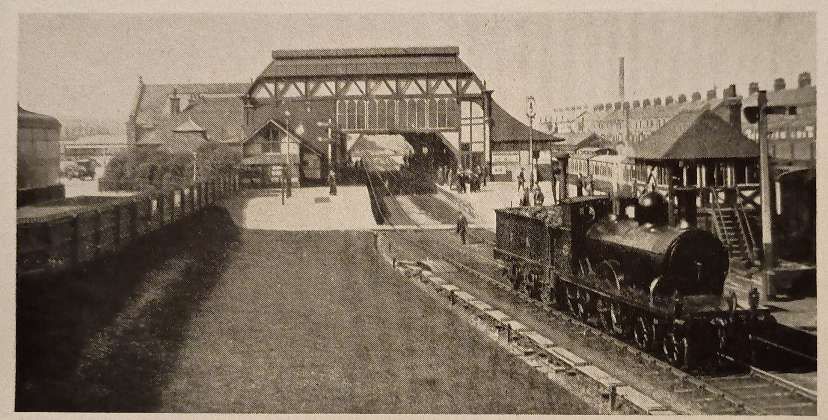

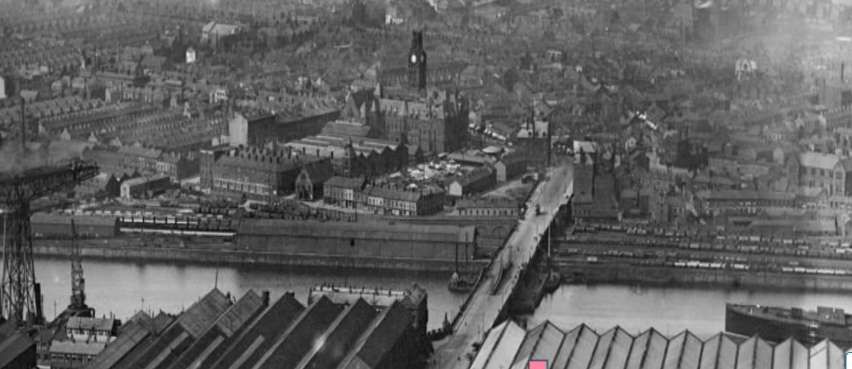

Barrow-in-Furness Railway Station is shown in the featured image above and repeated in the first image below. It featured a large, distinct covered roof over the platforms, as seen in this vintage postcard view from the south. The prominent locomotive is one of the Furness Railway K2 Class locomotive, often referred to as “Larger Seagulls”. [4]

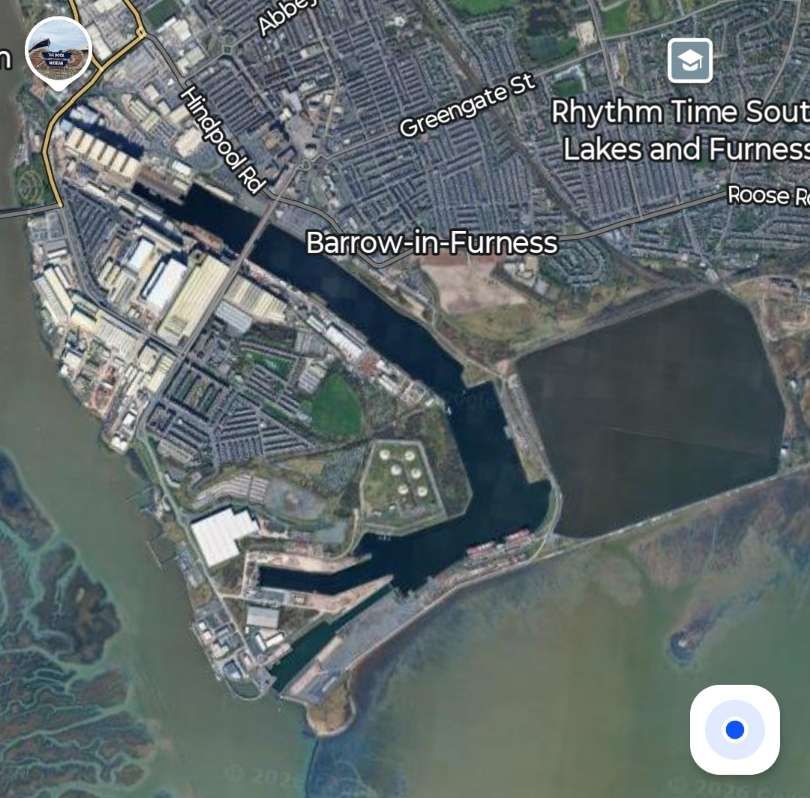

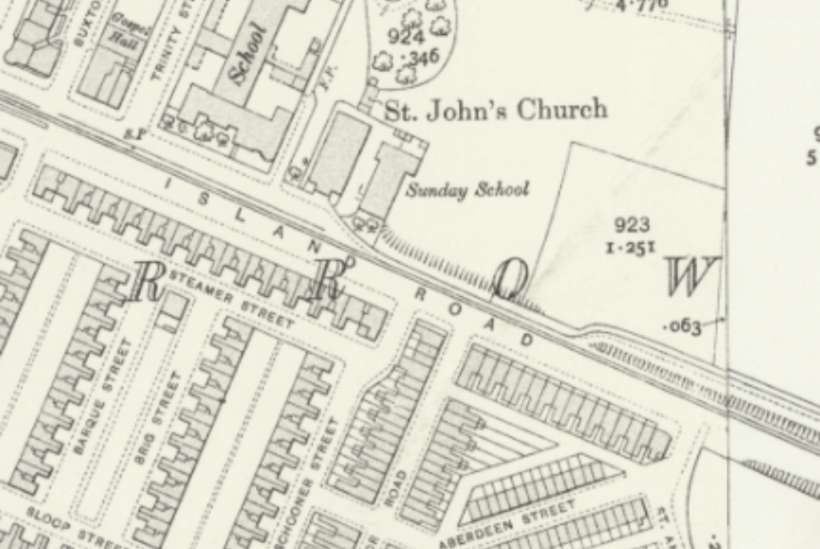

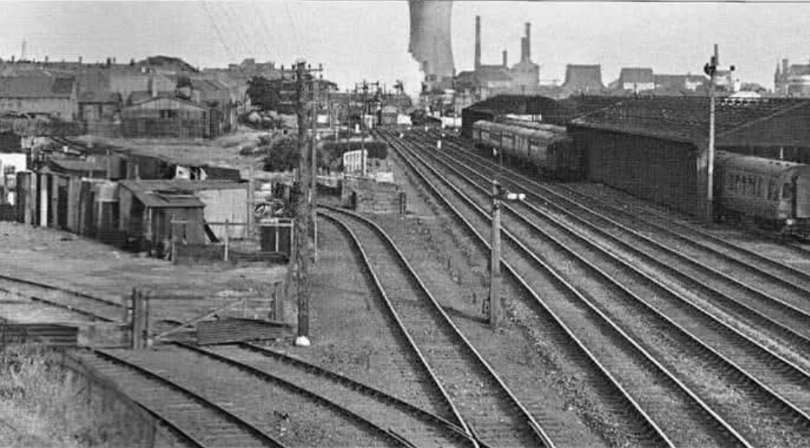

Barrow was featured in The Railway Magazine in March 1959. [1] The rebuilding of the old Central Station at Barrow-in-Furness which was virtually destroyed (please see the images below) in the air-raids of 1941 was completed in the late 1950s. The replacement buildings marked another link broken with Barrow’s past. Originally known as Barrow Central Station and the headquarters of the Furness Railway, it was, by the end of the rebuilding renamed Barrow-in-Furness. Early in the 20th century, the borough boasted ten stations. It had grown from a hamlet of a few farms with a population of around 100 to “a seething steel-town of 60,000 in under forty years.” [1: p149]

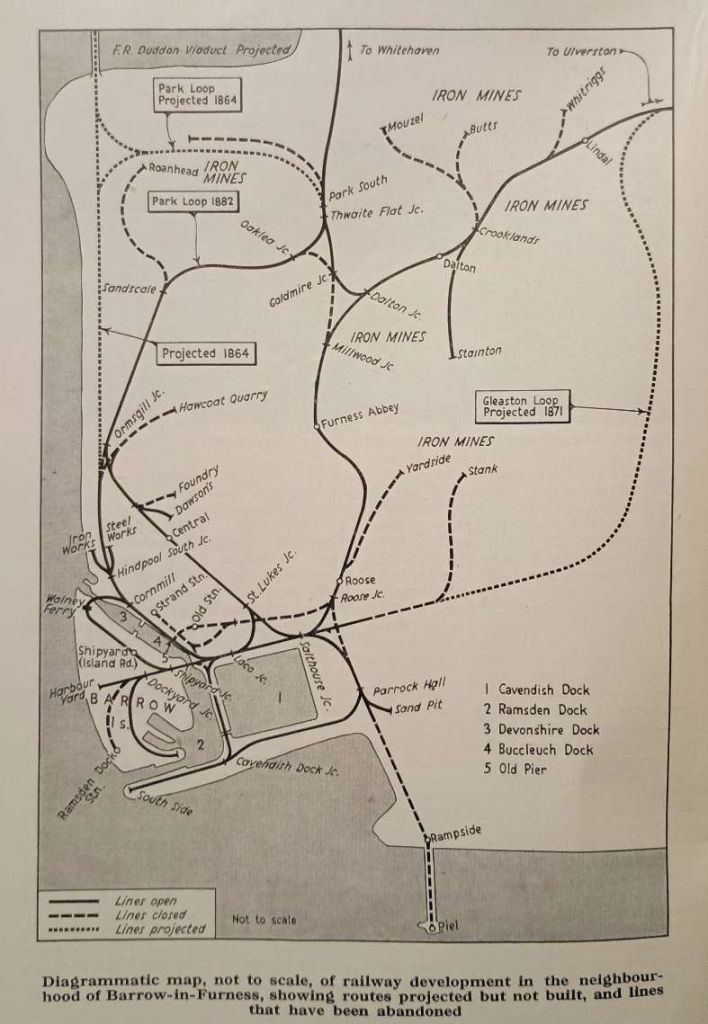

The most significant factor in the dramatic increase in population was apparently “the progress in railway development in the 1830s. The two dukes had toyed with the possibility of a mineral line for some years, but it was not until George Stephenson’s plan for the Caledonian, West Cumberland & Furness Railway was made known in 1837 that serious attention was given to the idea. Though this scheme for crossing the Duddon Estuary and Morecambe Bay came to nothing, a survey for embanking and reclaiming land and for a mineral line in Furness was carried out in 1841 by James Walker at the request of the Earl of Burlington (later seventh Duke of Devonshire).” [1: p149]

The coming of the railway made the exploitation of vast iron ore deposits feasible. Large ironworks, steelmaking, and shipbuilding industries developed, attracting thousands of workers and causing rapid population growth, urbanization, and infrastructural development. Barrow village had been shipping iron ore for many years and was chosen as a suitable port for iron ore from Lindal-in-Furness and slate quarries at Kirkby-in-Furness.

The person directly responsible for the organisation of the Bill and for the affairs of the new Furness Railway Company was Benjamin Currey, Clerk of the House of Lords and Agent of the Devonshire Estates. He visited Furness frequently at this period and was able to influence the local population in favour of the railway. [1: p149-151]

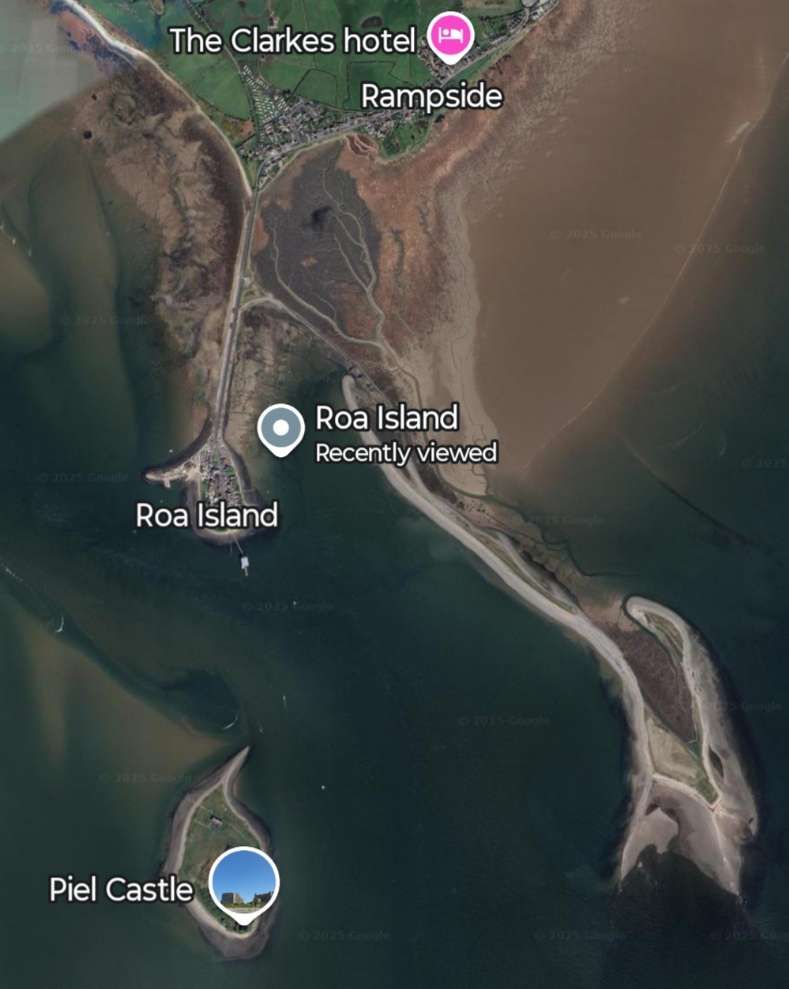

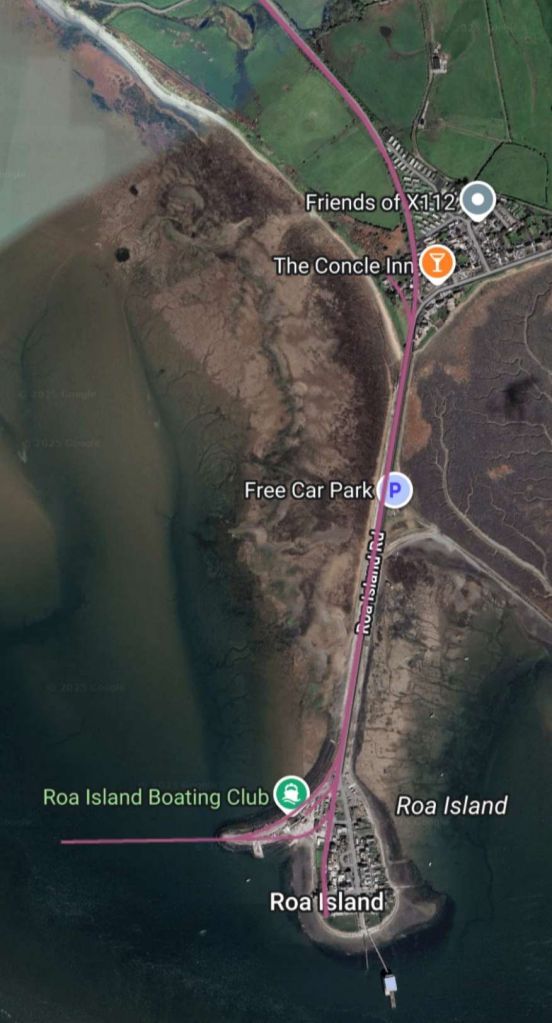

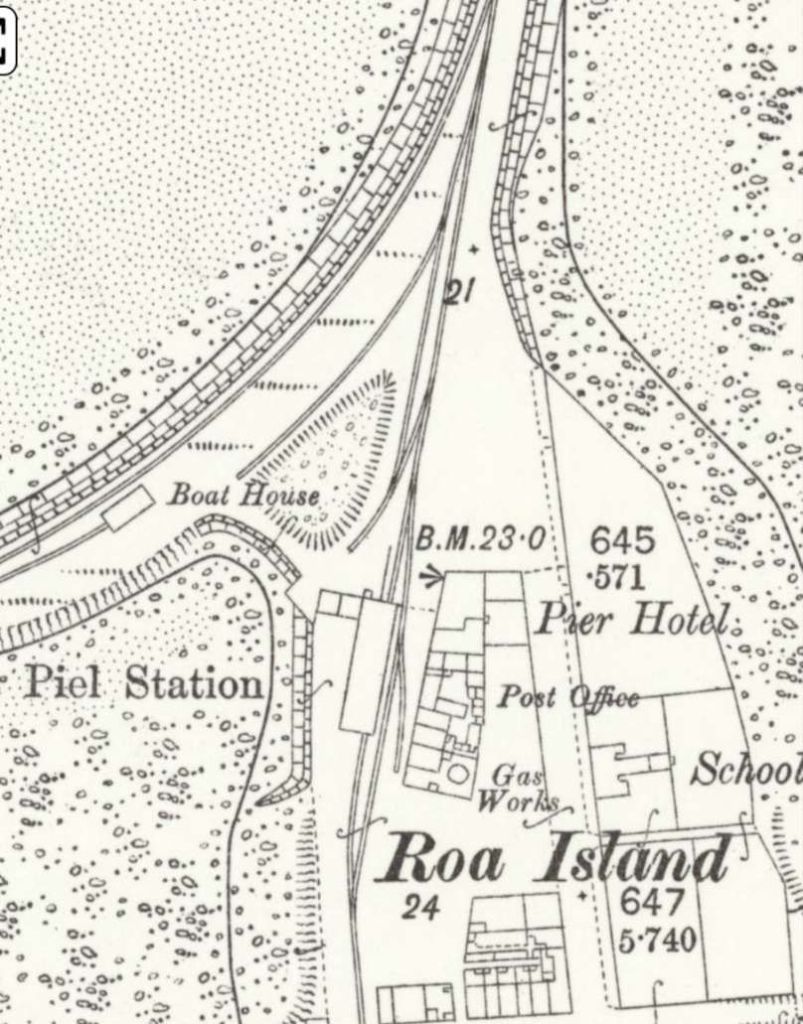

It appears that a strong influence on the development of railways in the area was the purchase of Roa Island by J. A. Smith, who, in conjunction with the Preston & Wyre Railway at Fleetwood, planned to build a pier to accommodate a ferry service between Furness and Fleetwood.

Roa Island lies just over half a mile (1 km) south of the village of Rampside at the southernmost point of the Furness Peninsula in Cumbria. [2]

Smith’s plans meant that the Furness Railway Company needed to provide a connecting line to the pier. Two trips between Fleetwood and Roa Island were made daily from 24th August 1846.

Initially the Furness Railway Company built a single line North from the pier on Roa Island. The competing needs of mineral and passenger traffic could not be accommodated. The solution was the doubling of the track running North-South between Millwood Junction and Roose Junction. Timetables were published in Bradshaw but Smith’s ferry was not ready in time for the new season. Unsurprisingly, relationships between Smith and the Furness Railway Company were strained!

Indeed, the relationship continued to be difficult, seemingly with Smith seeking to persuade the Furness Railway to purchase his interest in the pier. Eventually, after significant damage occurred to the pier in a storm on 27th December 1852. The Furness Railway saw an opportunity to deal with the problem and bought out Smith’s interests in the pier and in any of Smith’s schemes to access mineral reserves in Furness. Apparently the buy out cost £15,000. However Smith’s pier continued in use until the opening of Ramsden Dock Station in 1881. The pier “was rebuilt in 1867-8 to accommodate the Midland Railway boat trains (which began in 1867) and survived until 1891, when it was finally demolished.” [1: p152]

Andrews continues: “During the early years Barrow grew slowly, as railway workshops were built and its pier gradually enlarged, and it was not until 1859 that the stage was set for the boom that hit this village in the 1860s. In 1846 a young man named James Ramsden, from Wolverton Works, had been appointed Locomotive Superintendent of the Furness, and from the outset had shown considerable promise as an administrator. He was appointed Secretary and Superintendent of the Line in 1850.” [1: p152]

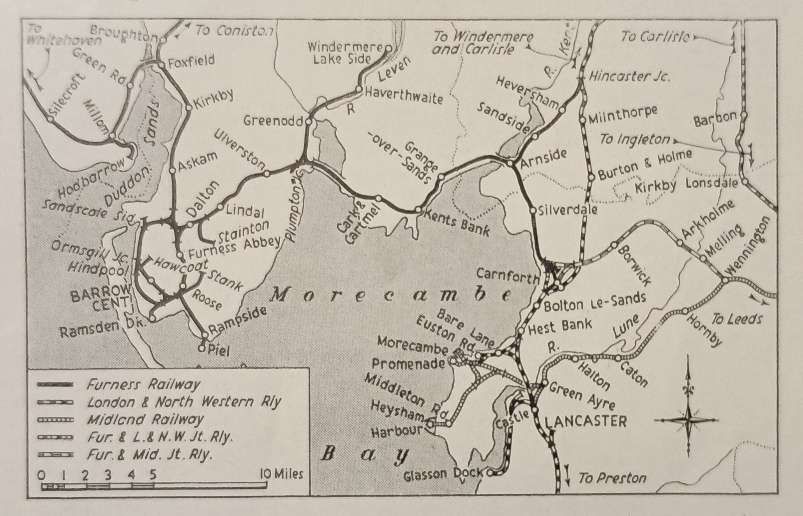

Continuing developments saw the line to Kirkby-in-Furness extended in 1848 to Broughton and the Whitehaven & Furness Junction Railway opened to Whitehaven in 1850. The line to Dalton was continued to Ulverston by 1854 and the Ulverston & Lancaster Railway opened through to Carnforth by 1857. In Barrow, the first blast furnaces opened in 1859.

“With the local production of iron and the establishment of through rail communication, Ramsden was able to put into operation his plan for a new Barrow – a model industrial town and port. The first stage was the construction of a dock between Barrow Island and the mainland, when it would be possible to build up passenger and freight steamer services with Belfast and the Isle of Man. Stage two was the development of an industrial estate on Barrow Island and on the mainland shore, with a residential area inland.” [1: p152]

1863 saw an Act obtained for the construction of the Devonshire and Buccleuch Docks. The Devonshire Dock was opened in September 1867. During that year: Barrow became a County Borough; a ferry service from Piel Pier to the Isle of Man commenced; the Belfast ferry service opened (in the Autumn); and the population of Barrow exceeded 11,000; and the Barrow Haematite Iron & Steel Company paid a 30% divided to shareholders.

“Negotiations with the Midland Railway led to the Furness & Midland Joint line scheme of 1863 which included the moving of the Midland steamer services from Morecambe to Piel Pier.” [1: p153]

It seems that the “Midland Railway was anxious that a communication should be provided for affording better access to the Lakes in connection with the Yorkshire districts.” [8]

Andrews tells us that, “During the 1860s, the Furness Railway … absorbed its neighbours one by one. The Ulverston & Lancaster, which had been heavily subsidised by the Furness during its construction, was bought in 1862 and … the Whitehaven & Furness Junction Railway was taken over in 1866.” [1: p154]

There were plans for the construction of a viaduct to span the Duddon Estuary which would have been part of a new line running North along the coast from a point near to the Iron Works and Steel Works at Hindpool. The scheme failed to gain parliamentary approval because it constricted access to the small port at Borwick Rails.

After a depression in the late 1860s, a return to prosperity in 1870 brought with it a fresh wave of development plans. These included:

- Moving the ferry/steamer service from Piel Pier to a new Dock Station.

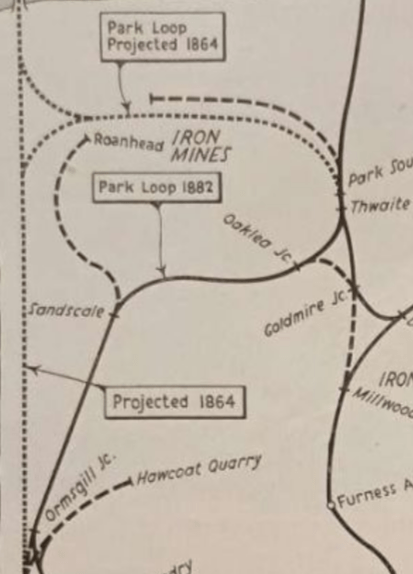

- Two loop lines intended to relieve congestion on the mainline, one the Gleaston loop between Lindal and Salt-house, and the other the Barrow loop from Salthouse to Ormsgill. Later the Gleaston scheme was abbreviated to a single line branch to Stank Mines (opened in 1873. The Barrow loop was slowed by the depression of the late 1870s and was not opened until 1882;

- Completion of the docks, which ultimately proved to be somewhat over scale. However the deep water berth at Ramsden Dock was a great improvement over Piel Pier.

High capital expenditure in the 1870s meant that resources for railway development were limited in the 1880s. In the 1890s, exhaustion of local iron ore stocks and the lower cost of imported iron ore saw local freight traffic decline rapidly. In 1893, the Midland Railway gave three years’ notice to the Furness Railway as it had developed its own harbour at Heysham. Some services remained at Barrow until the first world war. Services declined further after the railway grouping, iron ore traffic dwindled away, leaving only that between Hodbarrow and the iron works/docks.

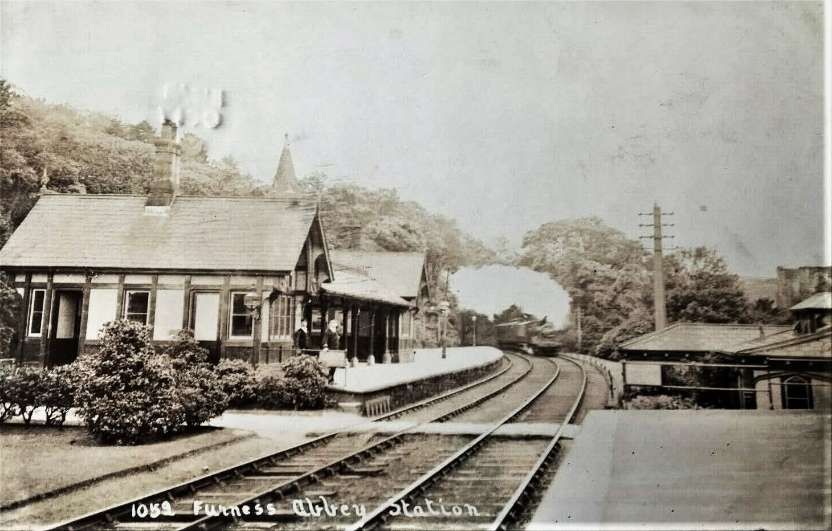

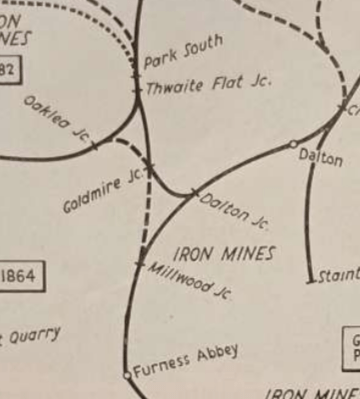

A century of gradual decline brought changes to the rail network. The original line entered Barrow “at Millwood Junction, where the Kirkby and Dalton branches joined, and then ran down the narrow valley to the ruins of Furness Abbey, where a station and hotel were completed in 1847. This became an important interchange station when the lines through to Carnforth and Whitehaven were open, and although a curve was opened between the two branches on 1st August 1858, most trains continued to reverse at Furness Abbey until 1873 when Dalton took over the exchange traffic; the now-unused bays at Dalton were for the Barrow branch trains. Furness Abbey was still used for dividing boat trains into portions for the dock and Barrow until 1904, and the down loop used for this existed until the 1930s. An up bay at Furness Abbey was used in the 1880s for a service from and to Coniston, but this was discontinued in 1891. The first part of the original Kirkby branch from Millwood to Park Junction (renamed Goldmire in 1882) fell rapidly into disuse after this as Whitehaven-Barrow traffic used the Park loop after 1882. Millwood Junction was finally removed in 1898.” [1: p155]

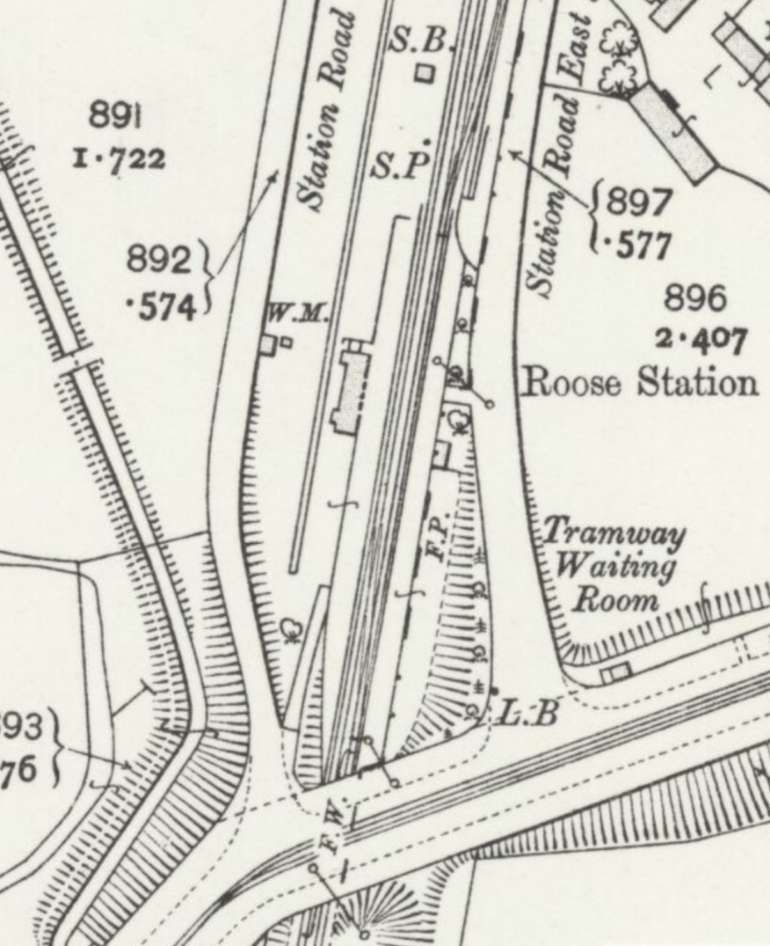

The next station down the line from Furness Abbey was Roose.

In 1959, Roose had “a reasonable passenger traffic from the surrounding housing estates. The main road originally crossed the line on the level and it was at these gates that trains first stopped by signal in the 1850s. The old junction with the Piel line was where the bridge carrying the main road now stands (which was completed with the [station present in 1959] in 1875).” [1: p156]

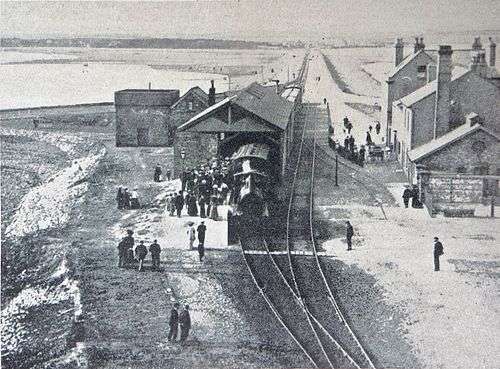

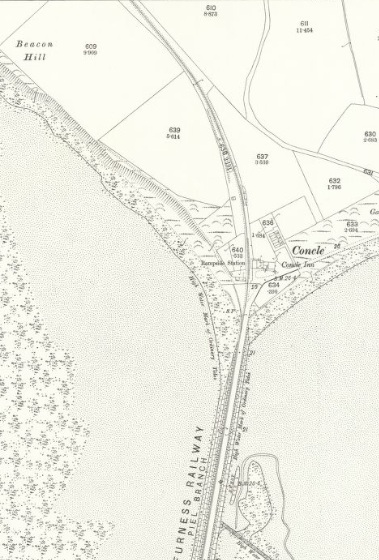

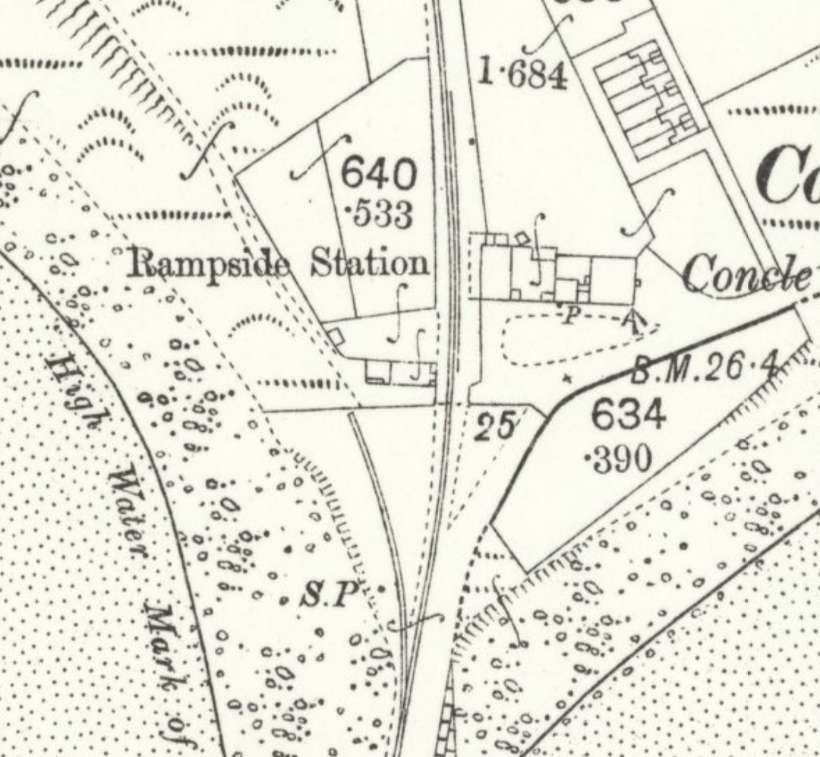

“The Piel line curved away to the left, following the shore for about a mile before entering a cutting to reach Rampside Station.” [1: p156]

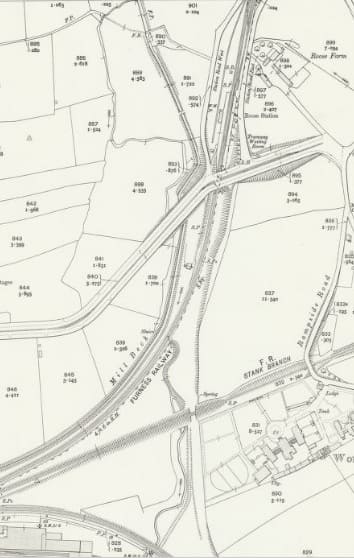

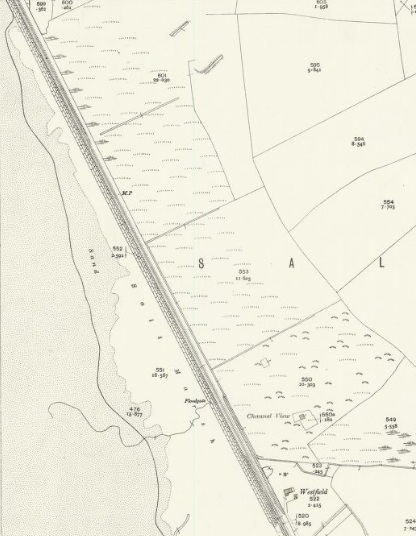

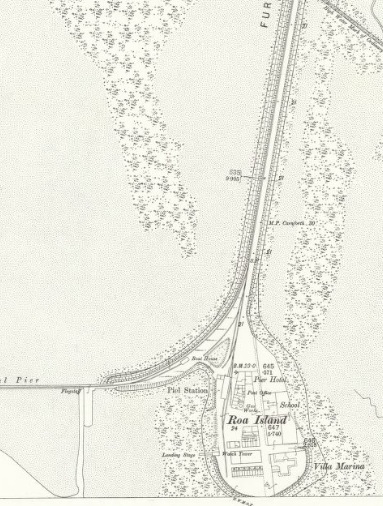

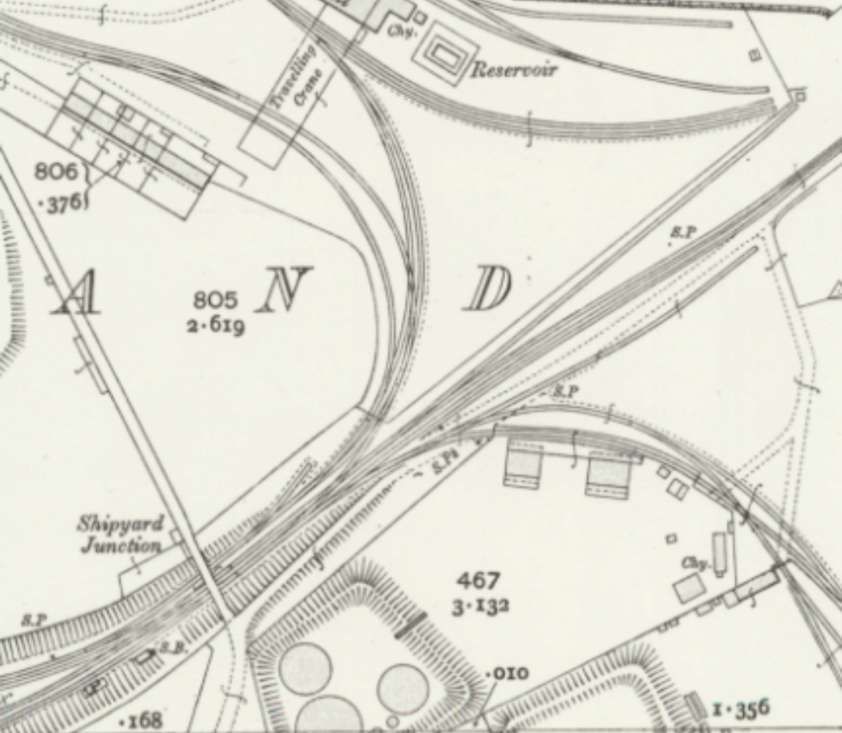

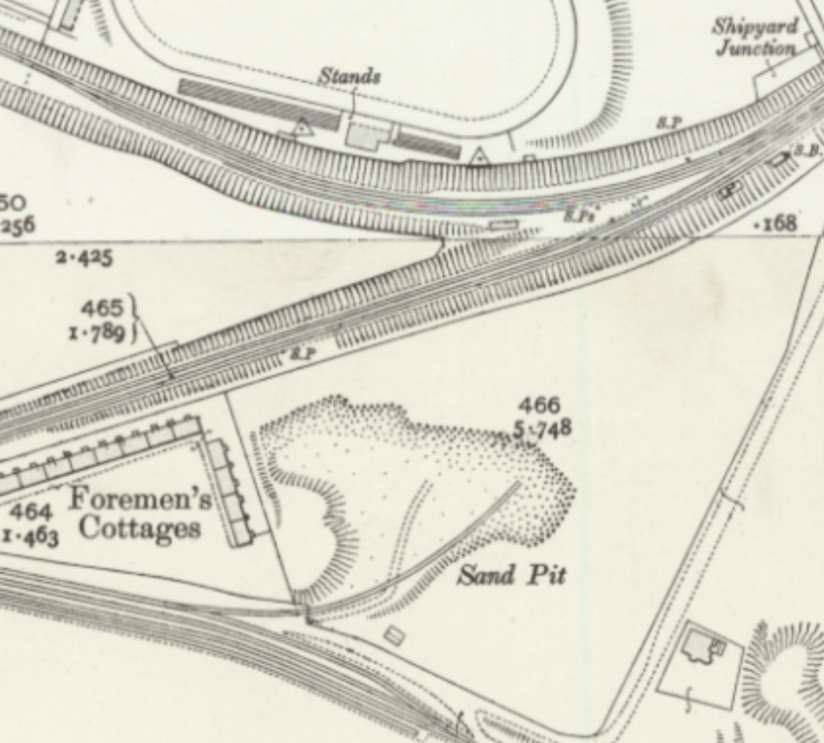

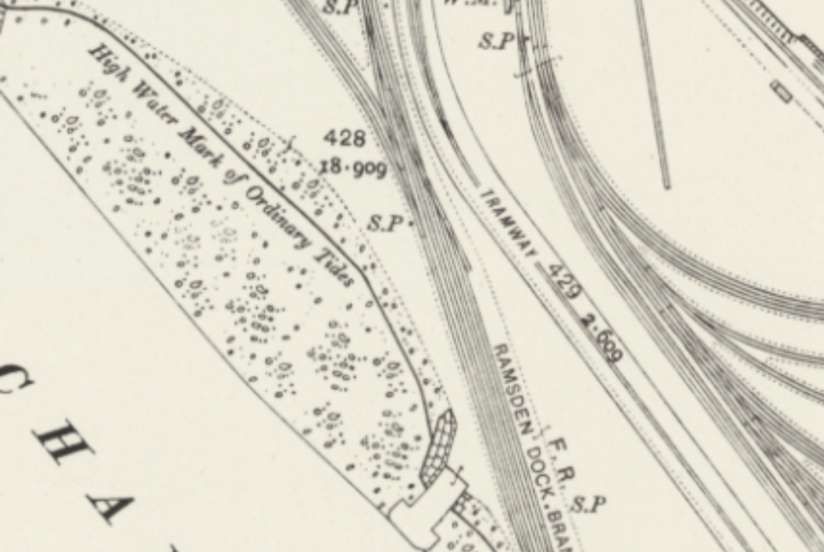

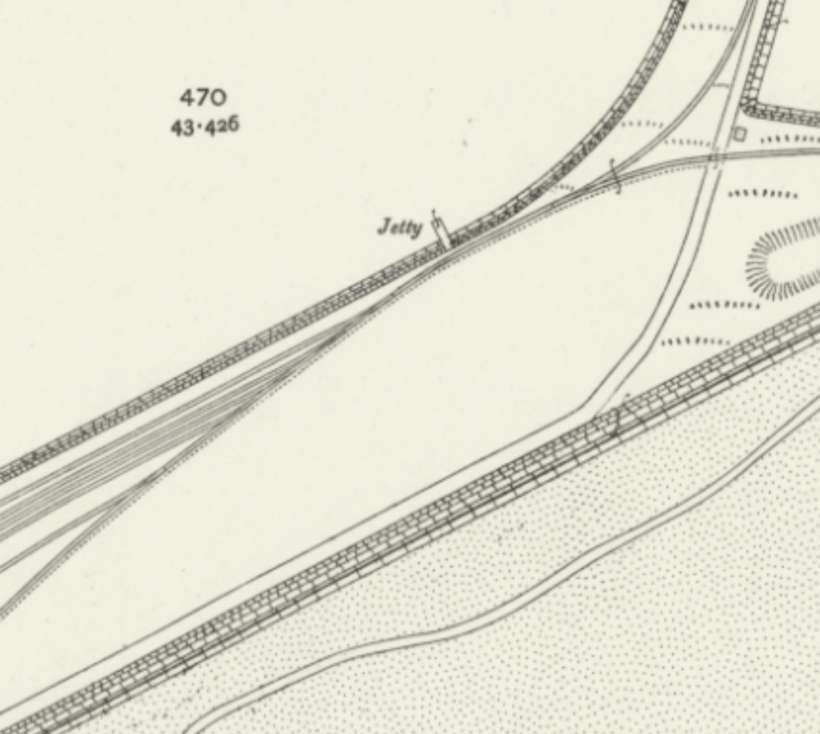

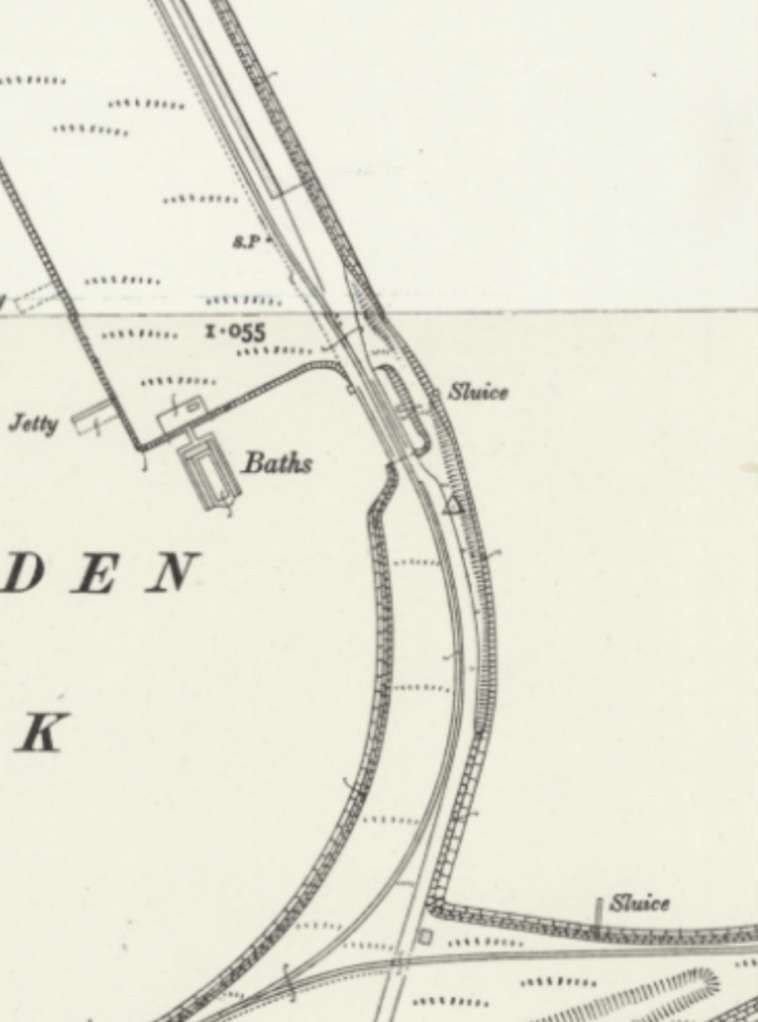

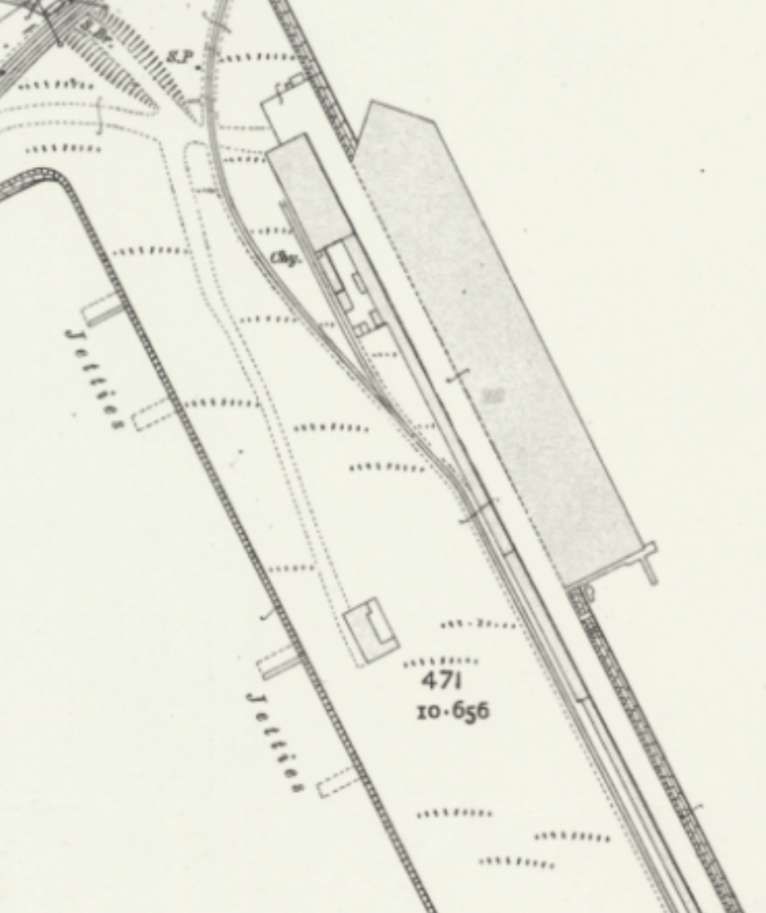

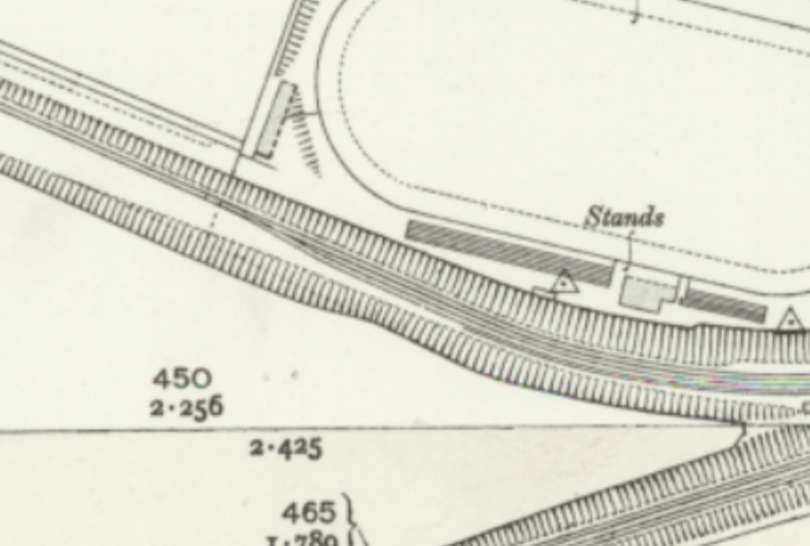

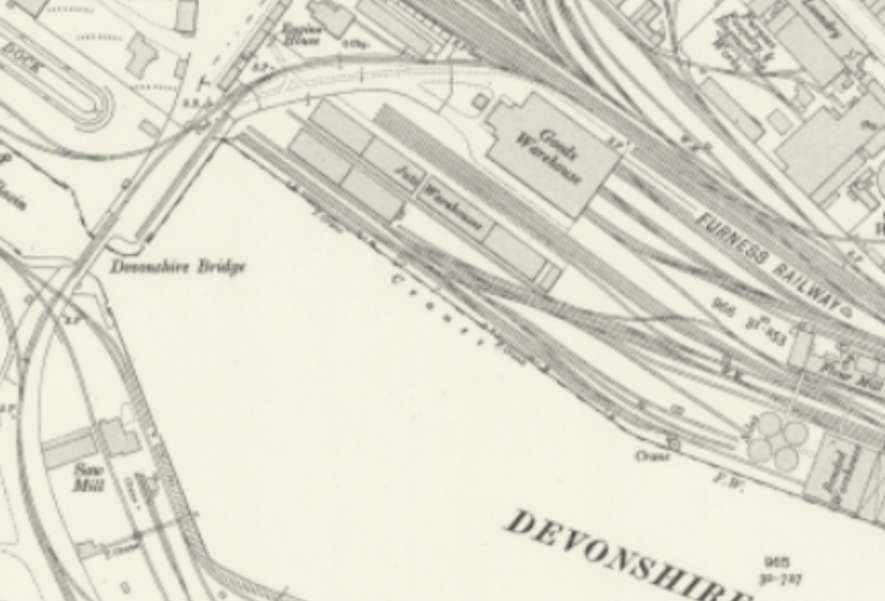

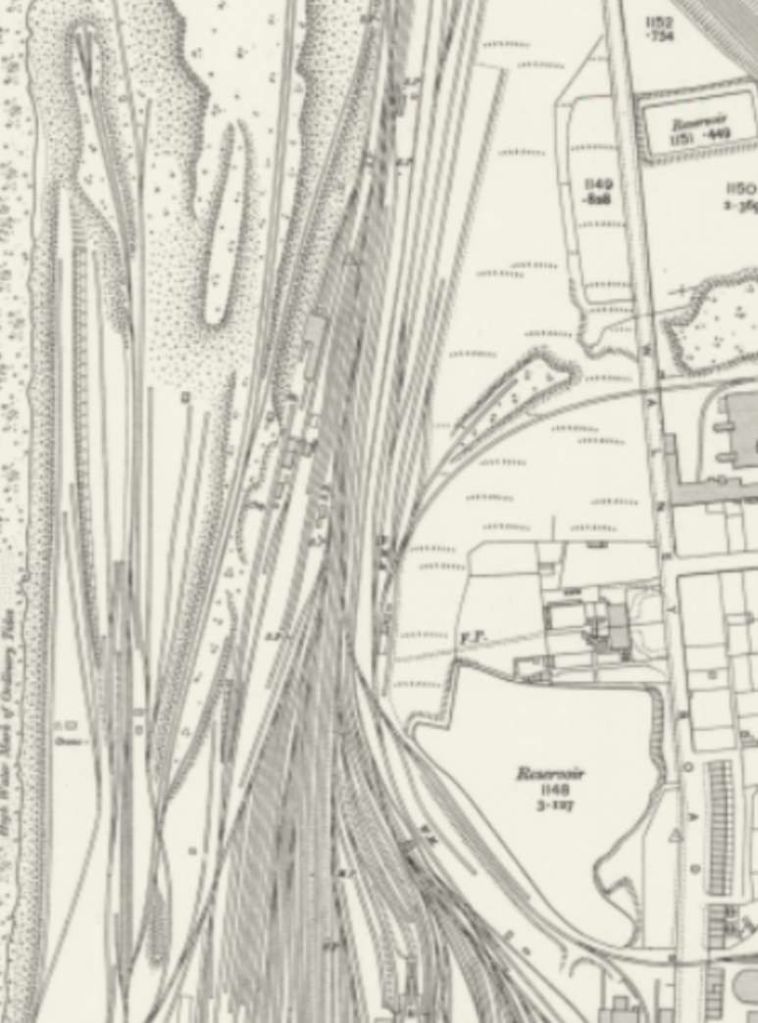

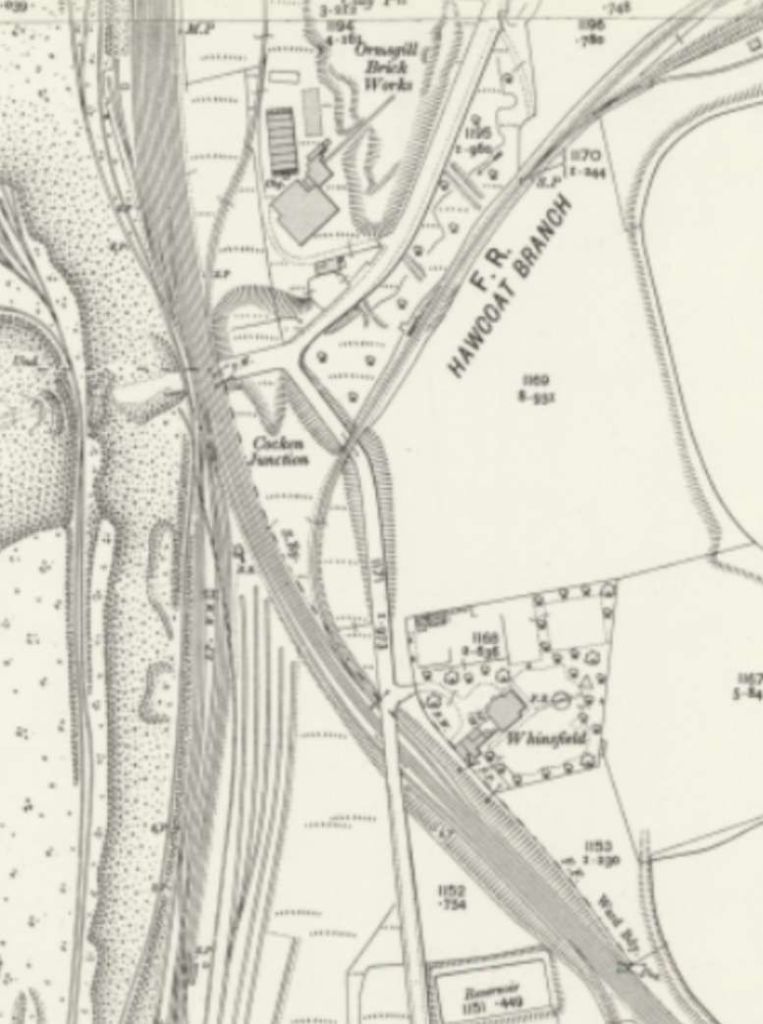

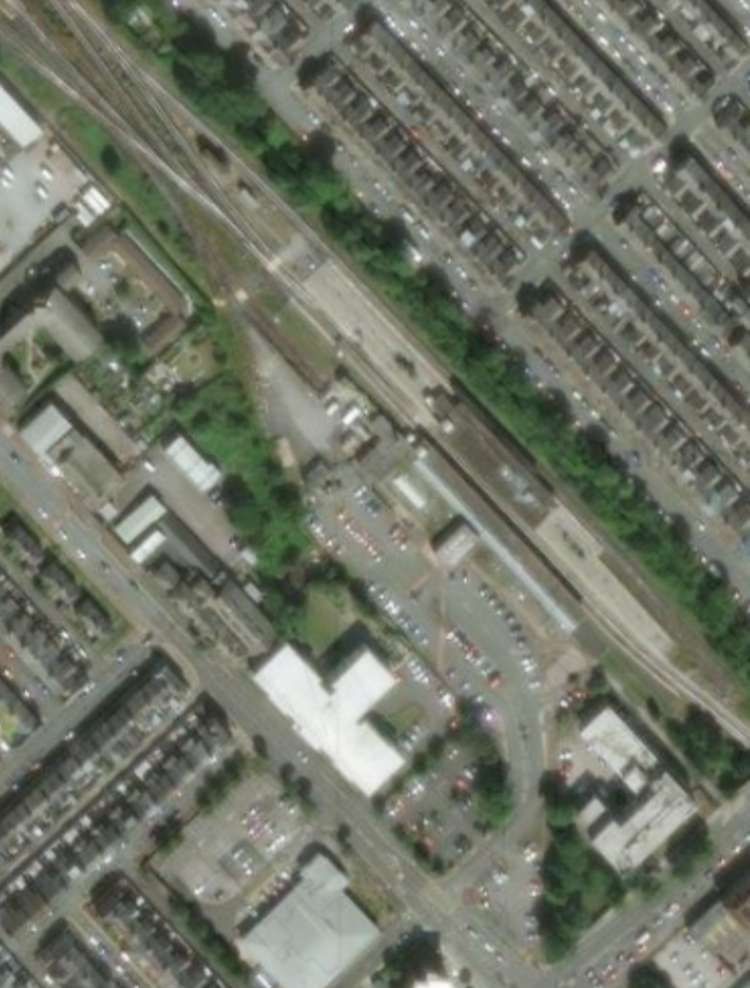

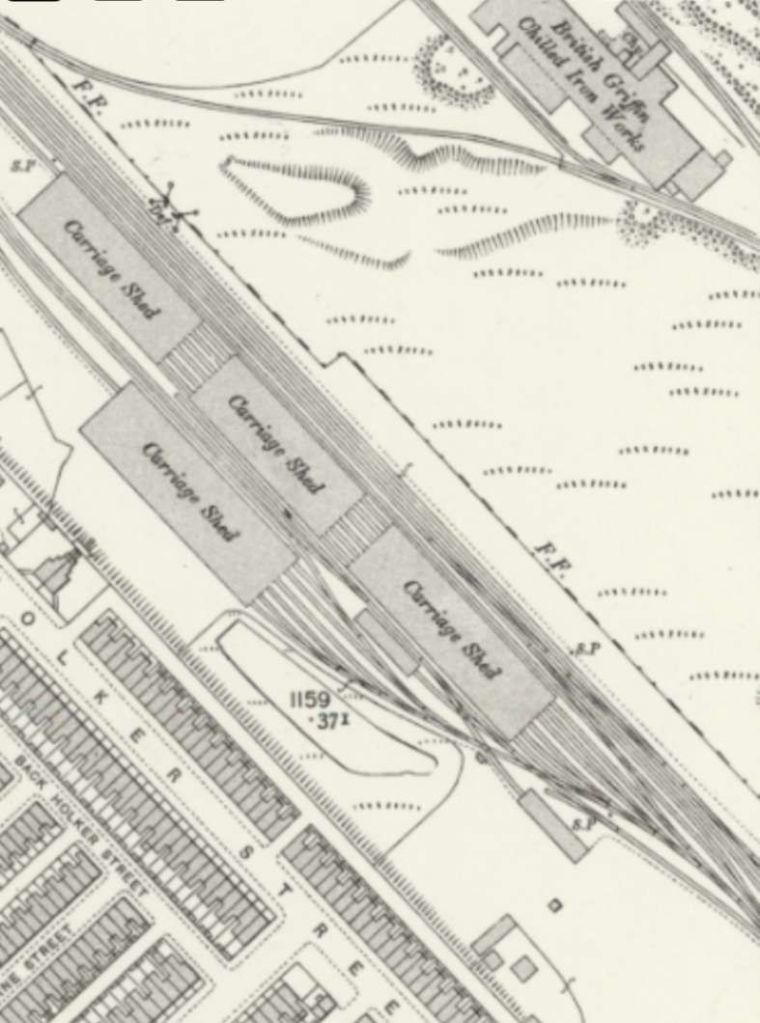

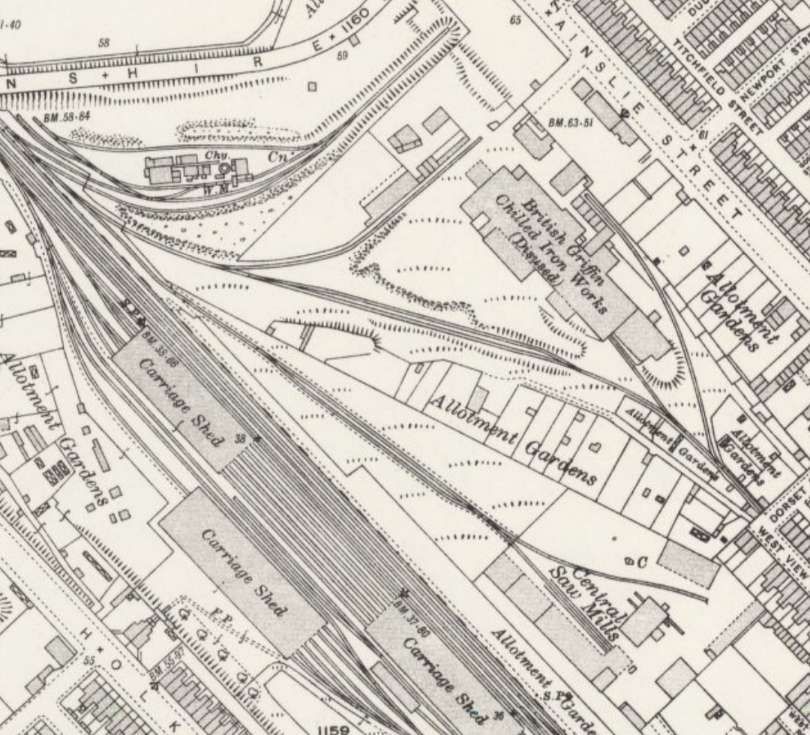

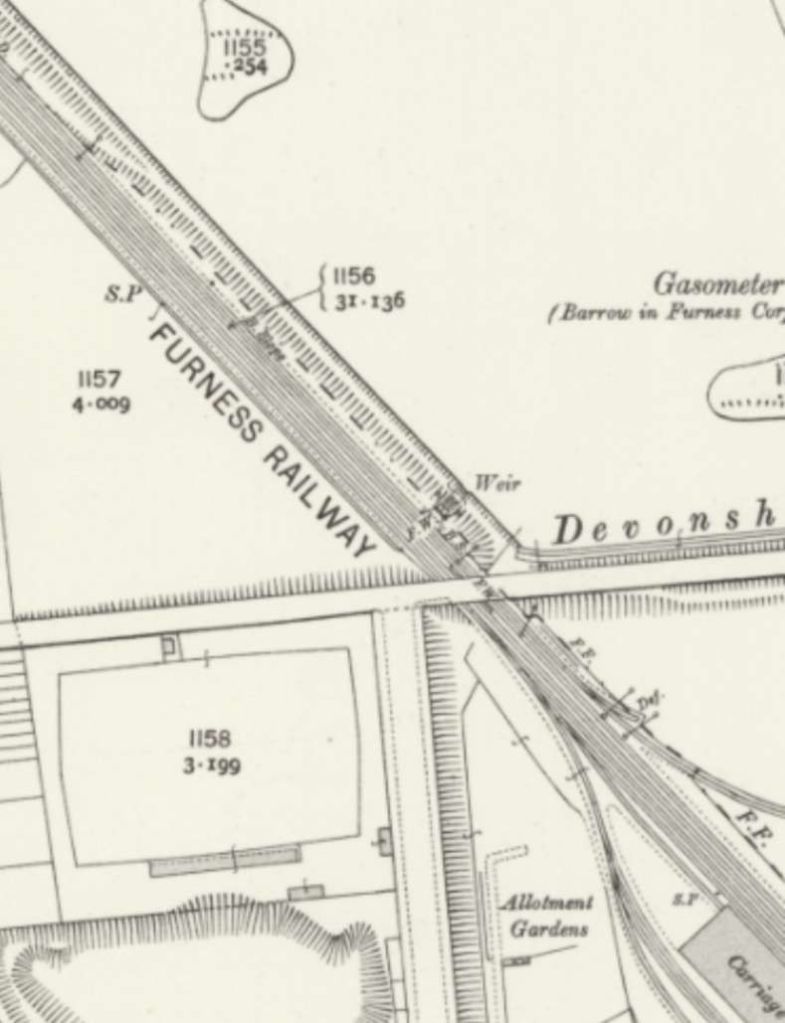

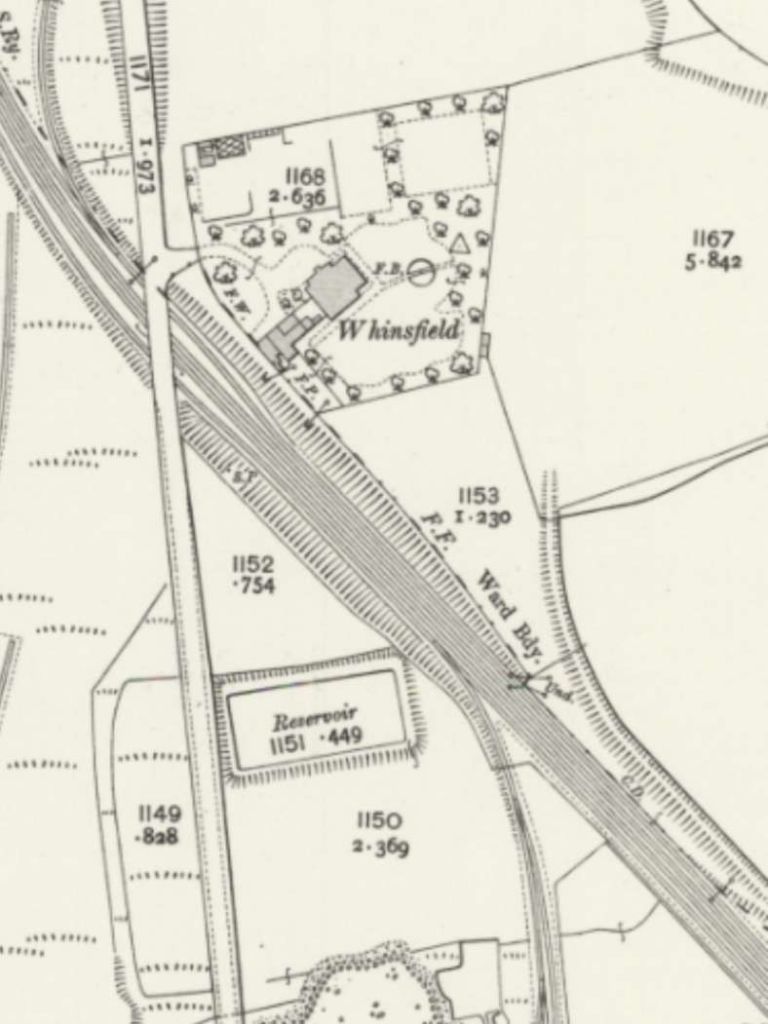

The three map extracts below show the line as it appeared on 25″ OS mapping of 1889, published in 1890. The chord running South towards Rampside Station had, by this time, already been removed. …

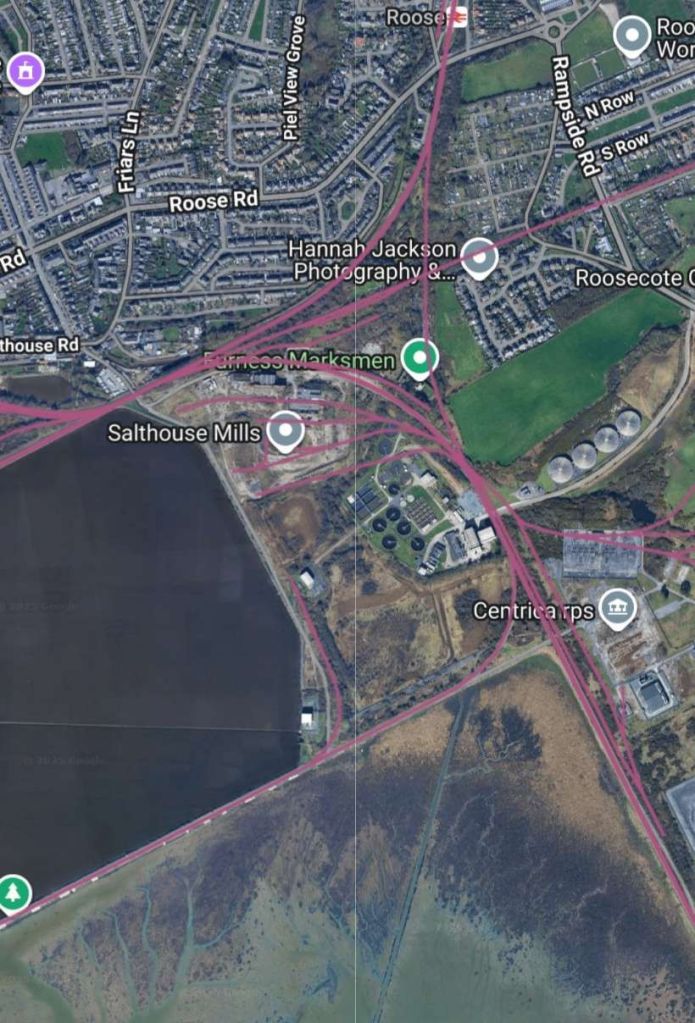

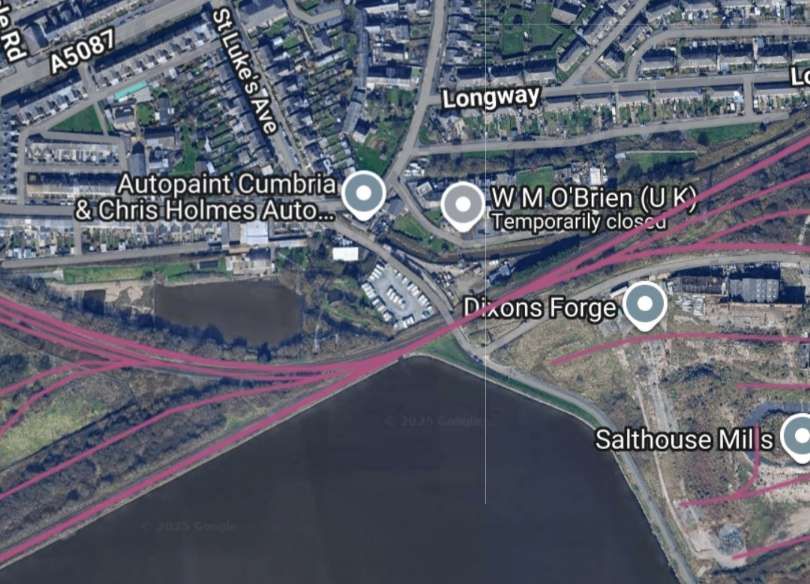

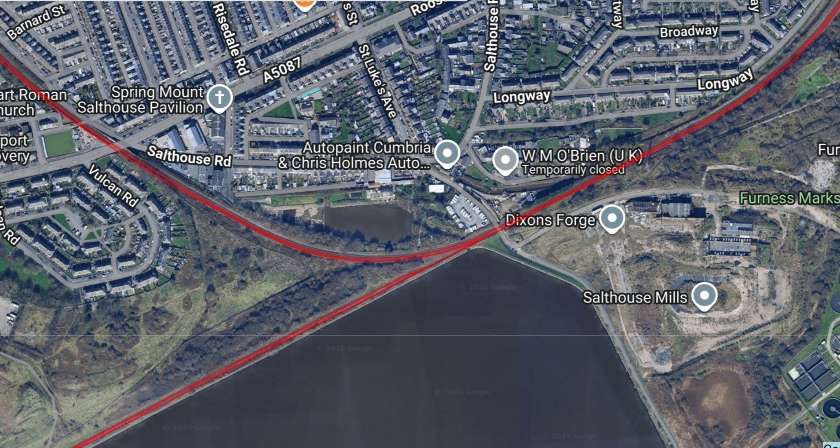

The next sequence of satellite images shows the line to Rampside Station and Roa Island superimposed on modern satellite imagery. The main line can be seen curving away to the West after passing South through Roose Railway Station. …

The two map extracts below show Rampside Station and Roa Island as they appear on the 25″ OS mapping of 1889, published in 1890.

Rampside Railway Station was a single platform station opened on 24th August 1846 as Concle Station, [14: p37] it was renamed Rampside in 1869. The station remained operational until 1936 when it closed along with the line and the following station at Piel, which had been reachable via the Roa Island Causeway. The station building and entire branch line had been demolished by the 1980s. [15]

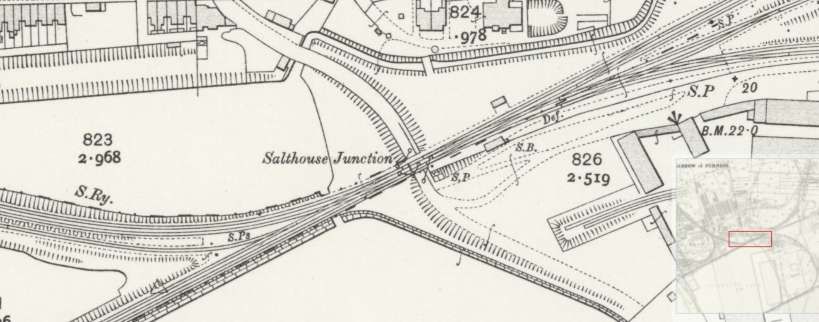

Returning to the main line: South and West of Roose Railway Station the main line curves round towards what was Salthouse Junction.

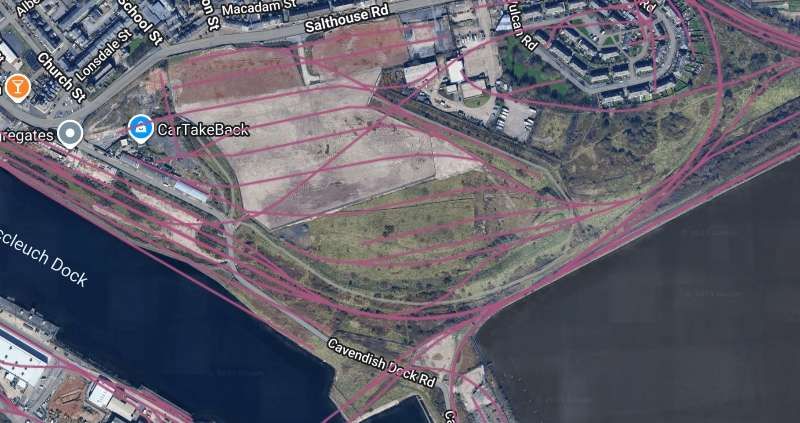

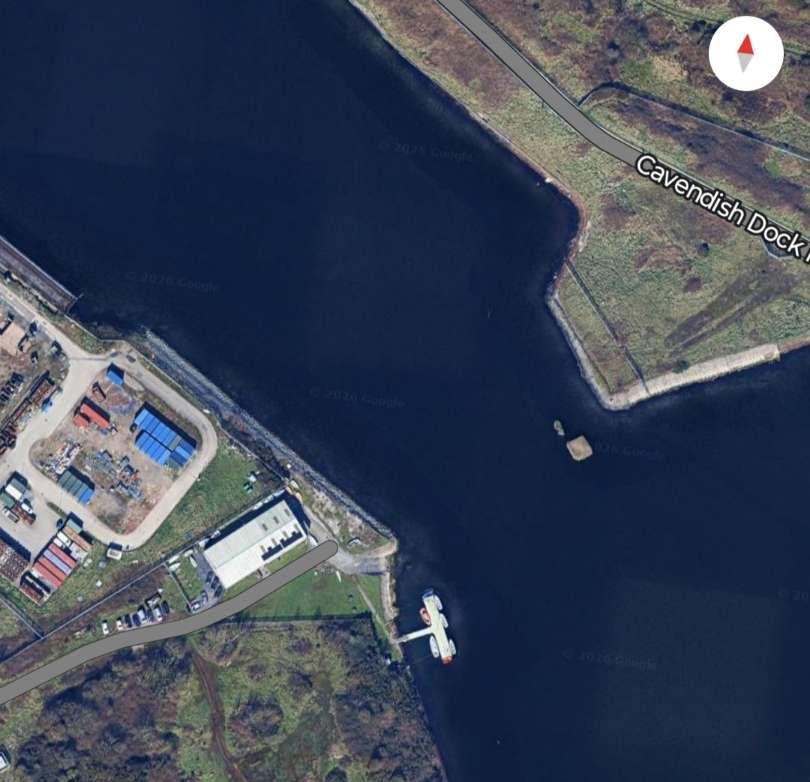

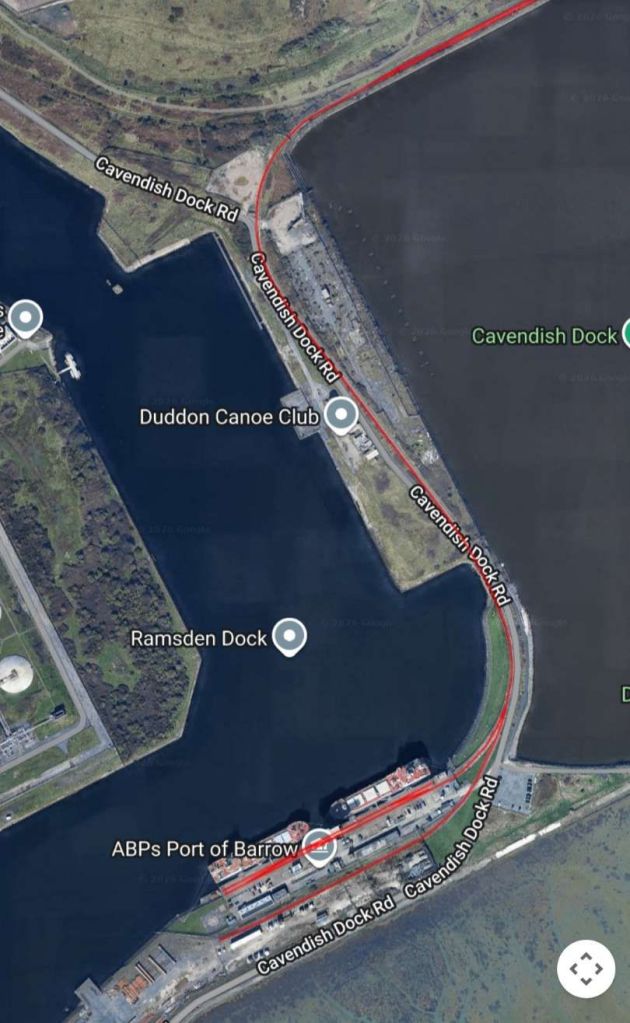

Only the main line remains to the East of Salthouse Junction. To the West, a single line leaves the main line at Salthouse Junction on the South side of the main line, heading West alongside Cavendish Dock.

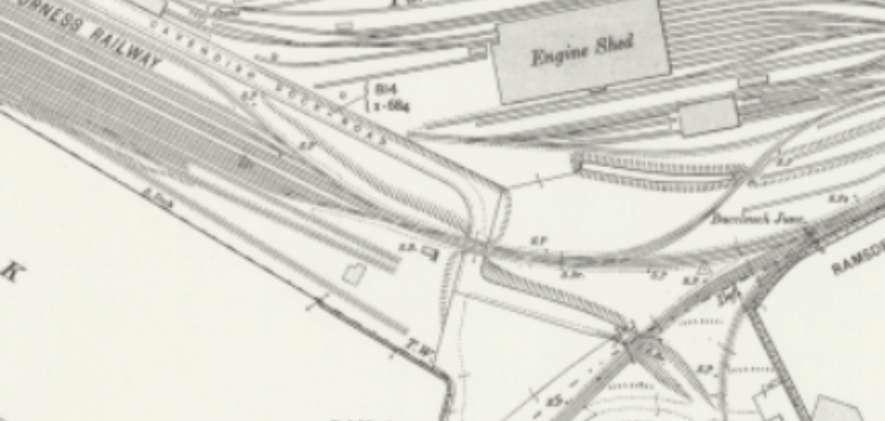

Andrews tells us that a significant embankment was built from Salthouse Junction to Barrow Island. A line was laid along this which separated the Ramsden and Buccleuch Docks, running to the South of what was the old line to Strand Station. After the building of the embankment, land to its North was reclaimed and the old Strand Station was closed together with the line which approached it on a rather tortuous/sinuous route. Parts of the embankment for this old line were still visible in the late 1950s.

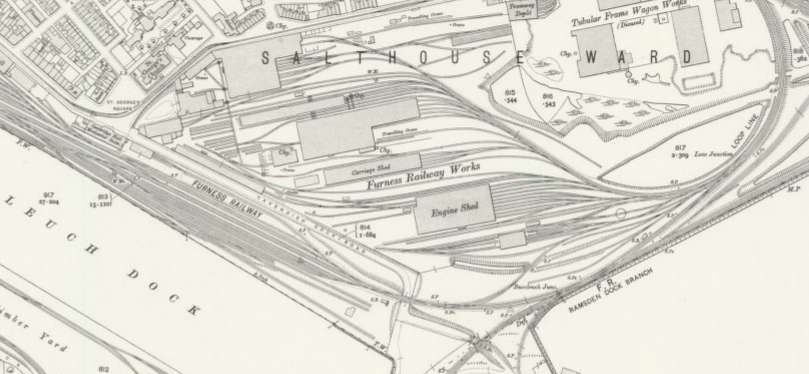

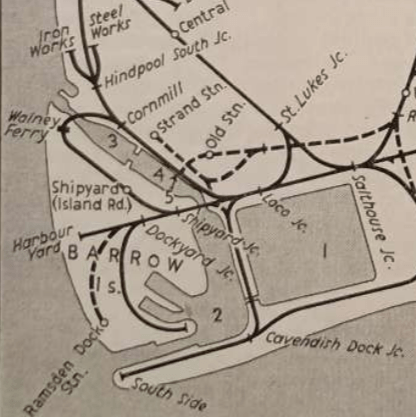

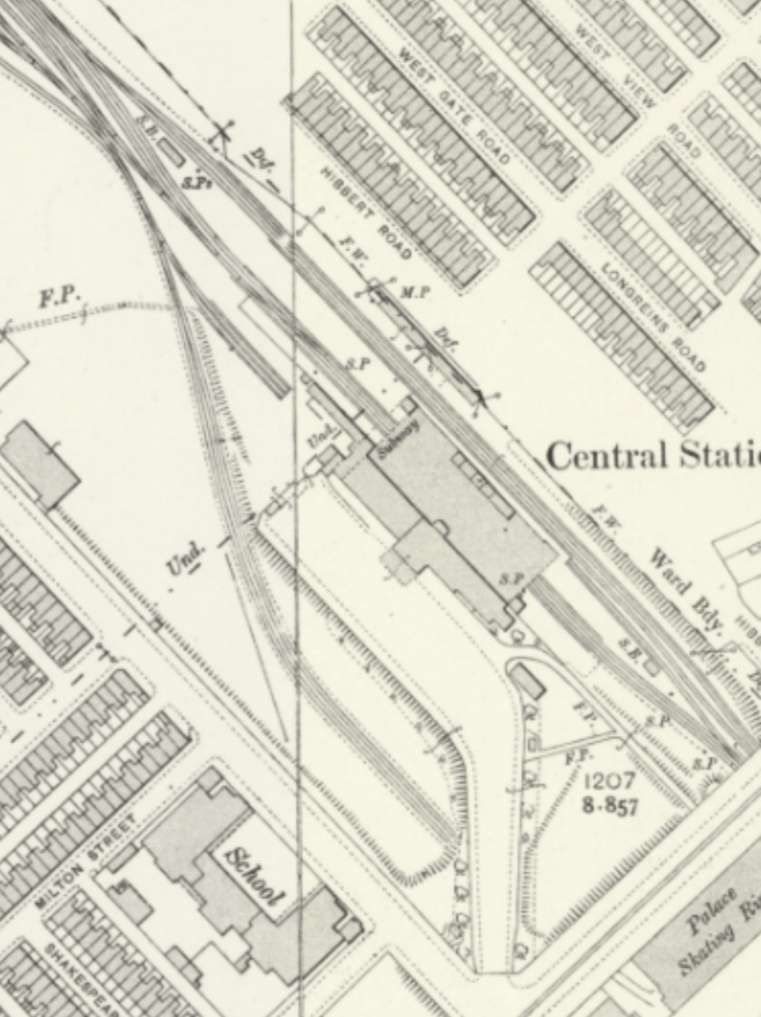

Andrews tells us that “The original Barrow Station, a wooden structure with one platform, rapidly became inadequate to deal with the expanding traffic of the town and was converted into an engine shed in 1862.” [1: p156] Apparently, in the late 1950s, it was still in use “as a carpenters’ shed and offices, although the lines leading to it were closed in January 1871. … The main line was taken round the outside of the works [shown below] to reach the newer Strand Station in 1862. This, [in the late 1950s,] the Railway Institute, had to be enlarged again in 1873 and the old carriage shed … converted into an arrival station. However, hardly had these alterations been completed in the Strand, than the intention to build a large new station in the centre of the new town.” [1: p156]

The line from St. Luke’s Junction through Barrow Central Station was not opened until 1882. Andrews continues: “by which time it had been put on a through route to the North by the completion of the Park loop line. A curve between Oaklea and Goldmire Junctions allowed the station to be approached from Carnforth in both directions. This curve [shown dashed in the adjacent image] was closed in 1904.” [1: p156]

Andrew’s describes Central Station as having “a large, all-over roof covering Platforms 1 and 2. No. 3, the other side of the island platform, was uncovered and was used by the local service to Piel which ran from 1881 to 1936. These trains approached the Piel line by a curve from Salthouse Junction built in 1873; the line from Roose Junction to Parrock Hall was closed in 1881, after the boat trains were diverted to Ramsden Dock.” [1: p156]

Central Station appears top-centre on the extract from the sketch map of Barrow’s railways below. We will return to look at this later in this article

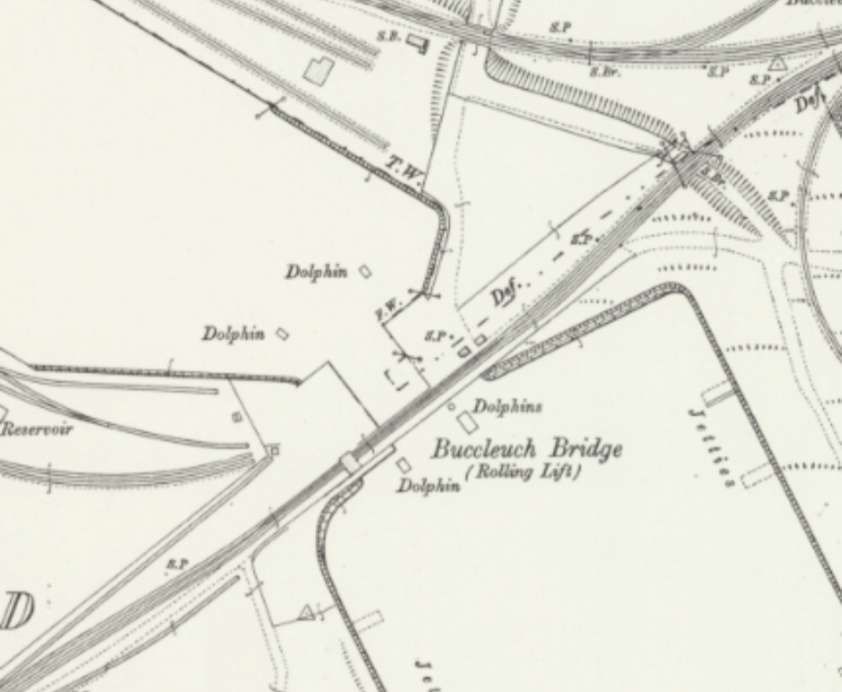

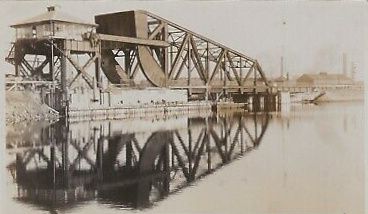

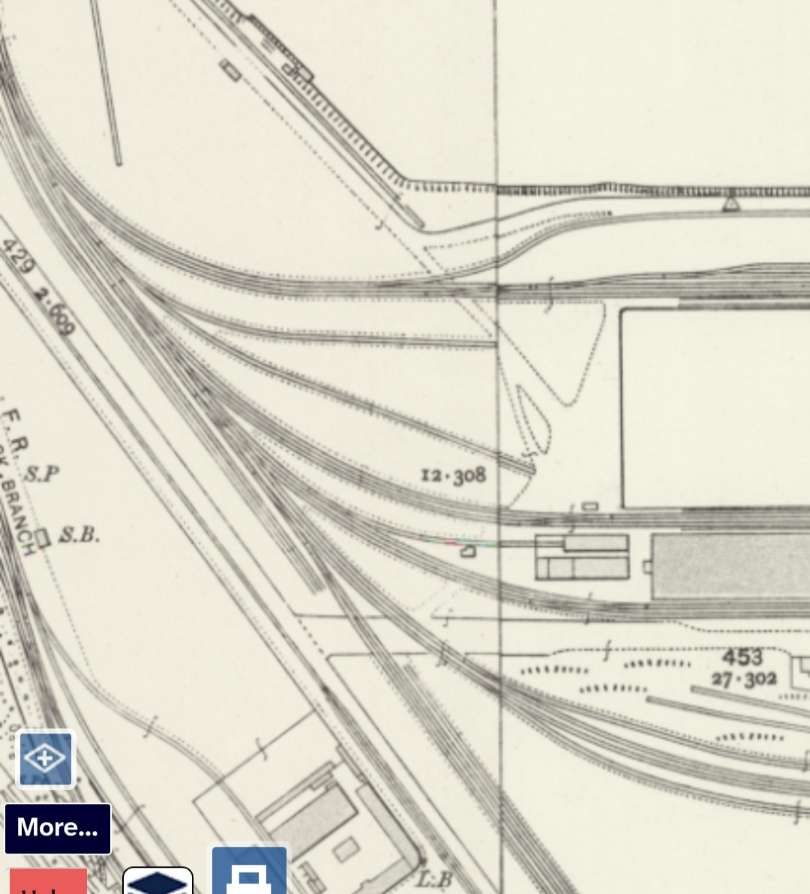

Andrews continued: “From 1881, the boat trains left the main line at Salthouse Junction and proceeded down the embankment to Loco Junction, where the curve from St. Lukes Junction, on the Central line, came in on the up side, and where the line to the Barrow goods yard and old Strand Station curved away. The passageway between the Ramsden and Buccleuch Docks was crossed by a swing bridge, replaced by the present lift bridge in 1907.” [1: p156-157]

And again: “Shipyard Junction was reached in a cutting and the line to the Naval construction works curved off to the right. A station, Island Road, was built in 1899 for workmen’s trains and these have used the platforms ever since. The line is now used for out-of-gauge loads to Vickers Works, near Island Road Station, and normal freight traffic is worked over Devonshire Bridge from the goods yard.” [1: p157]

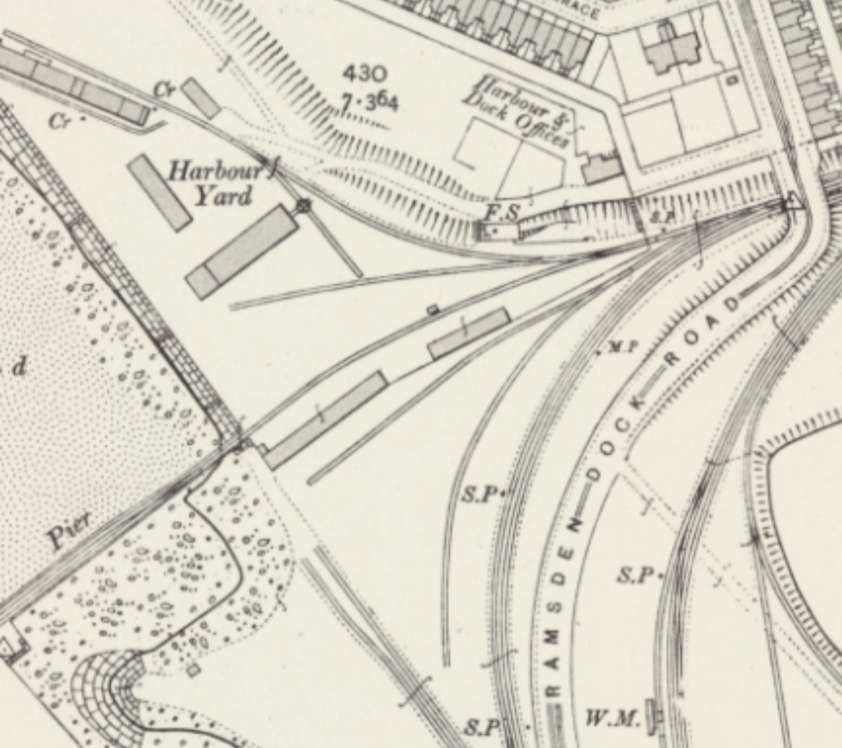

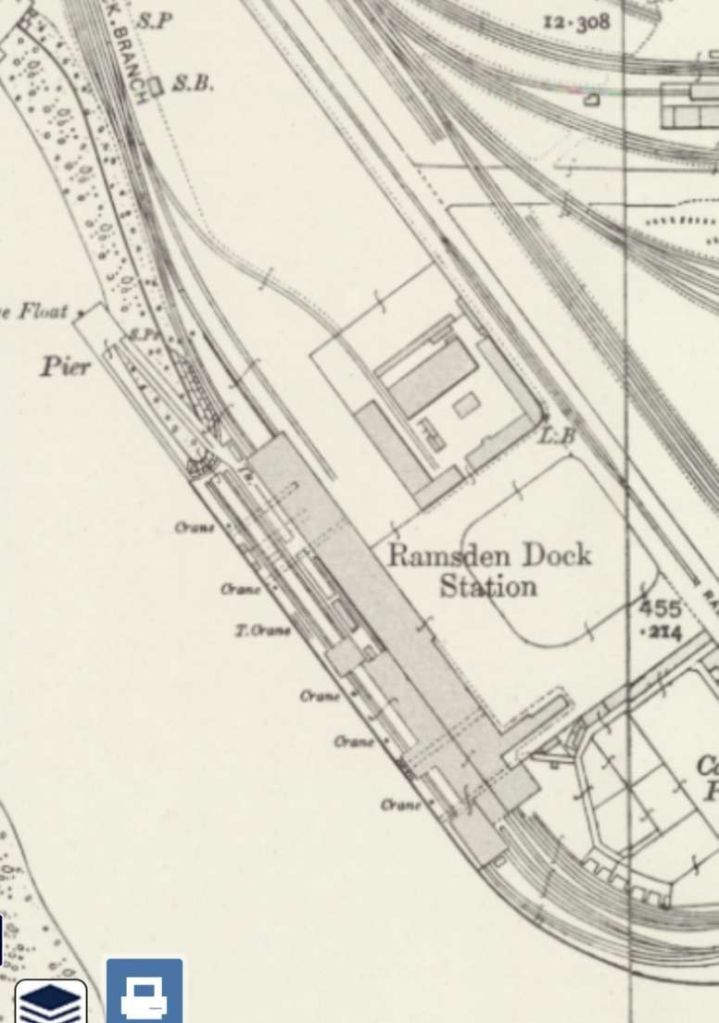

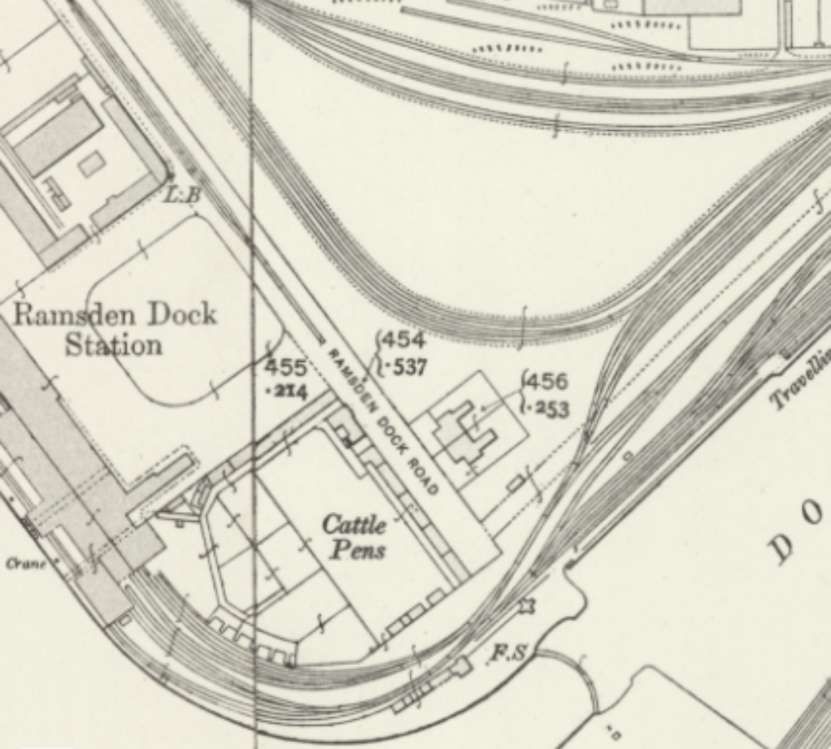

Andrews continued: “Reaching the shore, the line to the docks branched off at Dockyard Junction and the passenger line curved away to the left to reach Ramsden Dock Station, which consisted of a long covered platform and a short bay. A goods shed separated the platform from the quayside and at low tide passengers embarked through a tunnel under the lines. The station was completed in 1885. Regular steamboat traffic to the Isle of Man, Belfast and Fleetwood ceased at the outbreak of the first world war, but excursion boats were run from the station, mainly to Blackpool, until 1936. The station was pulled down in 1938.” [1: p157]

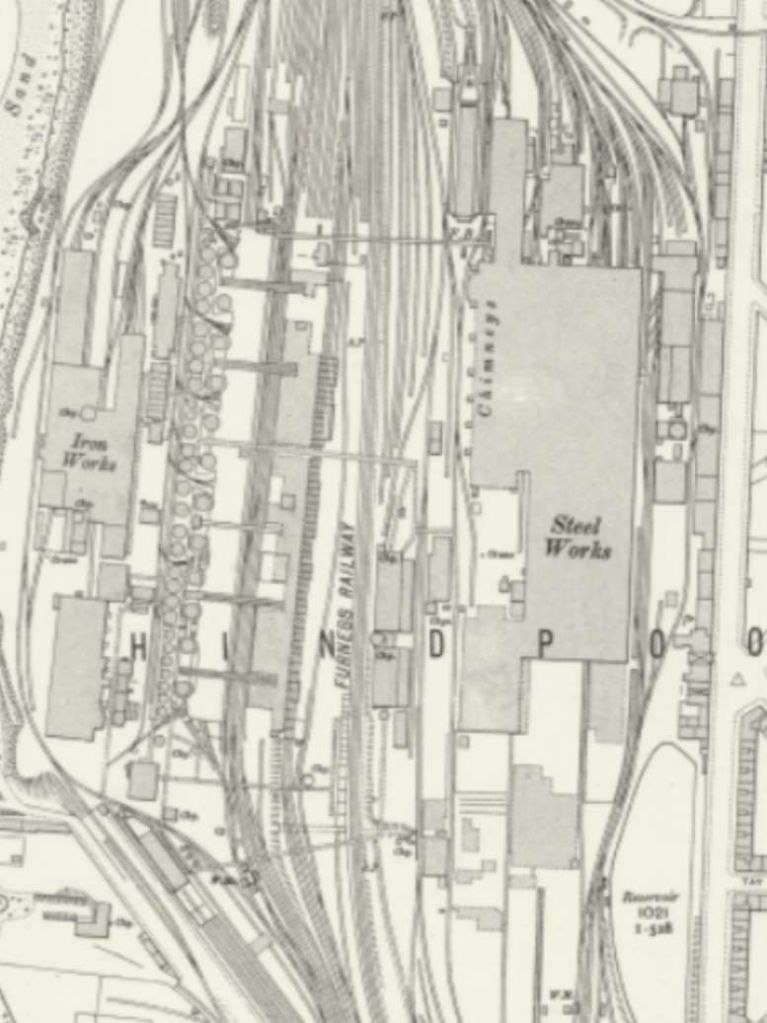

Before looking at the rail infrastructure of the 21st century it is right to at least try to show what existed in around 1910 and which has since been substantially lost.

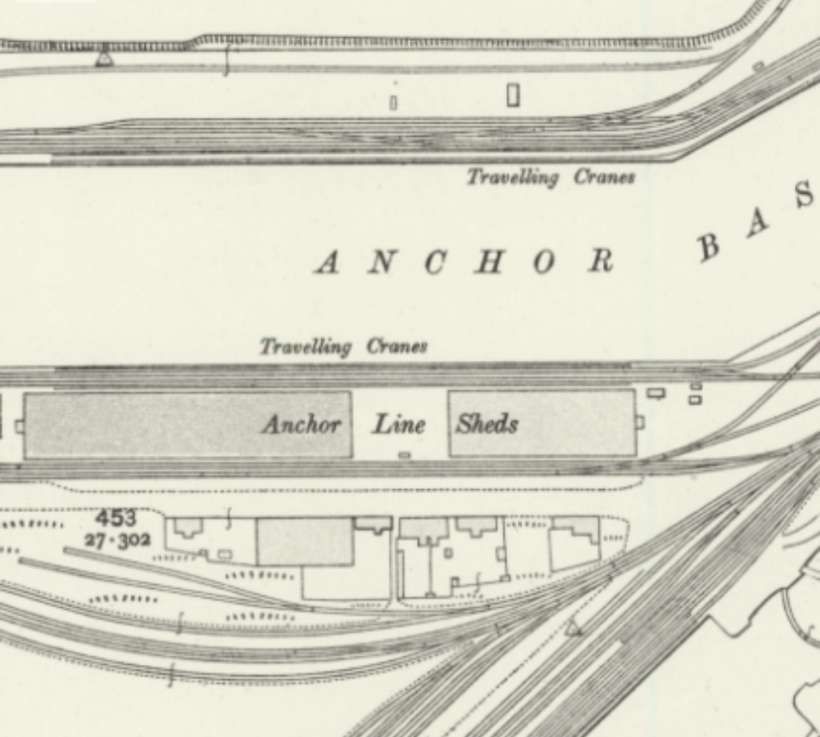

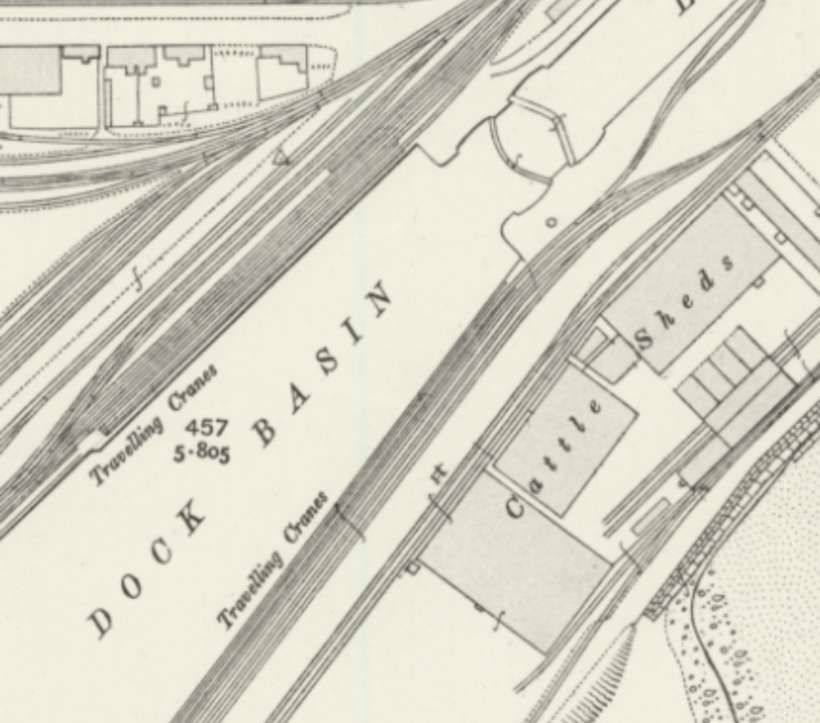

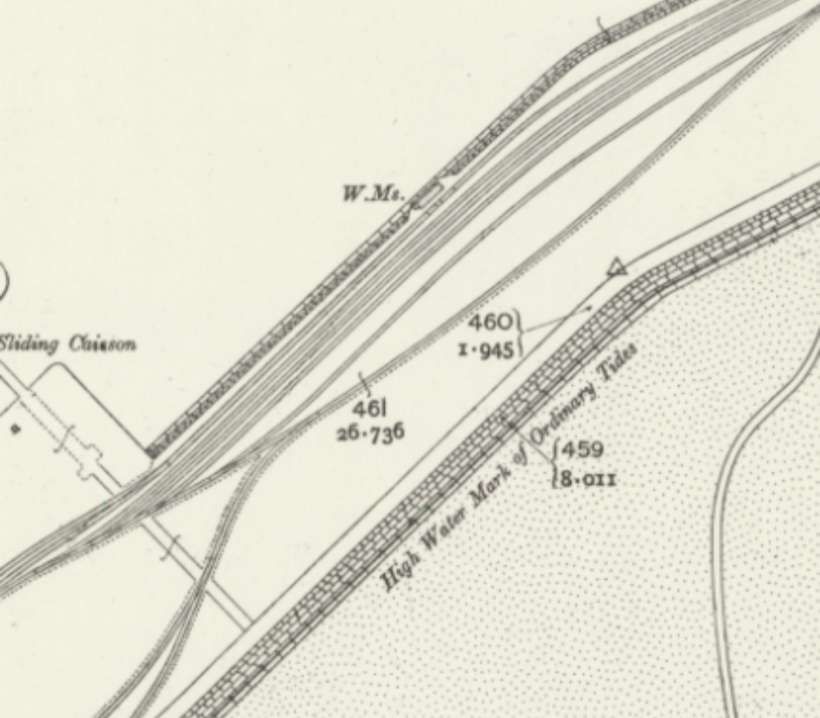

It is difficult to give an effective account of the complexity of the railway infrastructure around the docks at the turn of the 20th century, although the sketch map from 1959 is particularly helpful for understanding the mid-20th century situation. The following extracts from the 25″ Ordnance Survey from around 1910 may do more to obfuscate than to illustrate!

The New Buccleuch Bridge across the Buccleuch Dock in Barrow in around 1910, © Public Domain. [24] More photographs of the bridge can be found here. [25]

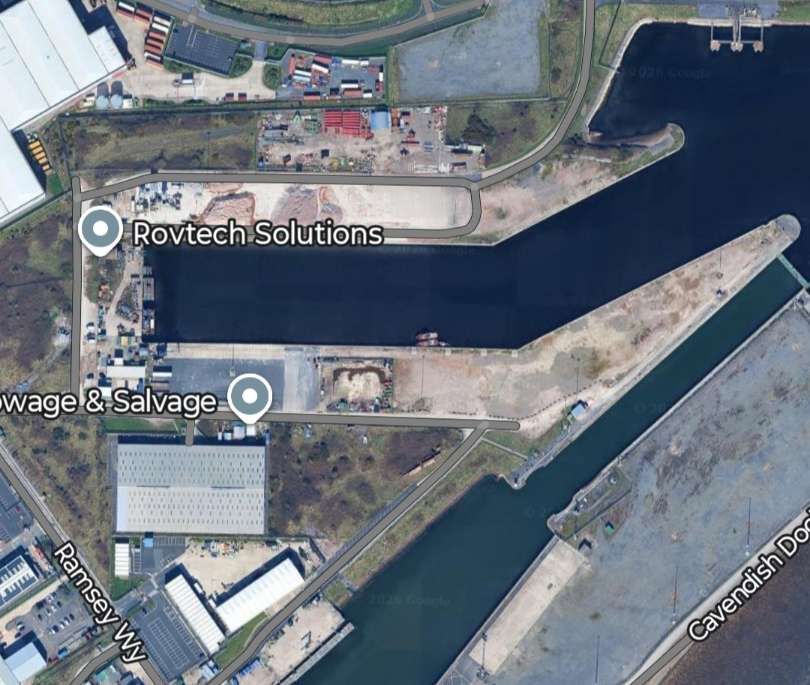

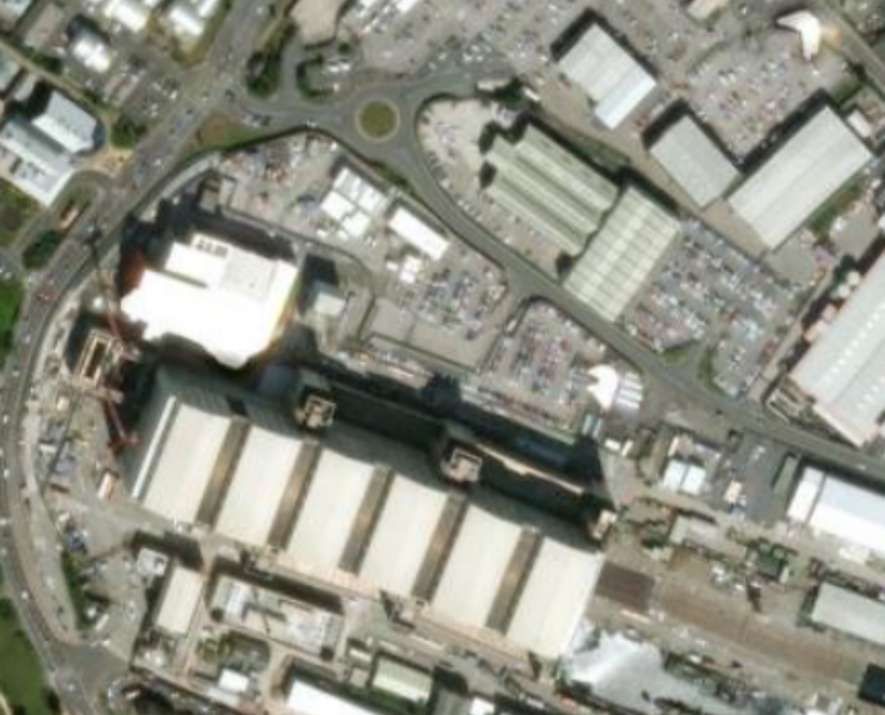

As we have noted, the lift bridge mentioned by Andrews in 1959, is long gone, as is all of the network to the West of the bridge. That network was substantial. … A line ran from the bridge Southwest before curving round to the Southeast to head into Ramsden Dock Station.

Ramsden Dock railway station (also known as Barrow Island and officially as Barrow Ramsden Dock) was the terminus of the Furness Railway’s Ramsden Dock Branch. [26]

The station operated between 1881 and 1915. Located at the southern tip of Barrow Island alongside Ramsden Dock it primarily served the adjacent Walney Channel passenger ferry terminal. It was accessible by Ramsden Dock Road and the Barrow-in-Furness Tramway. [26]

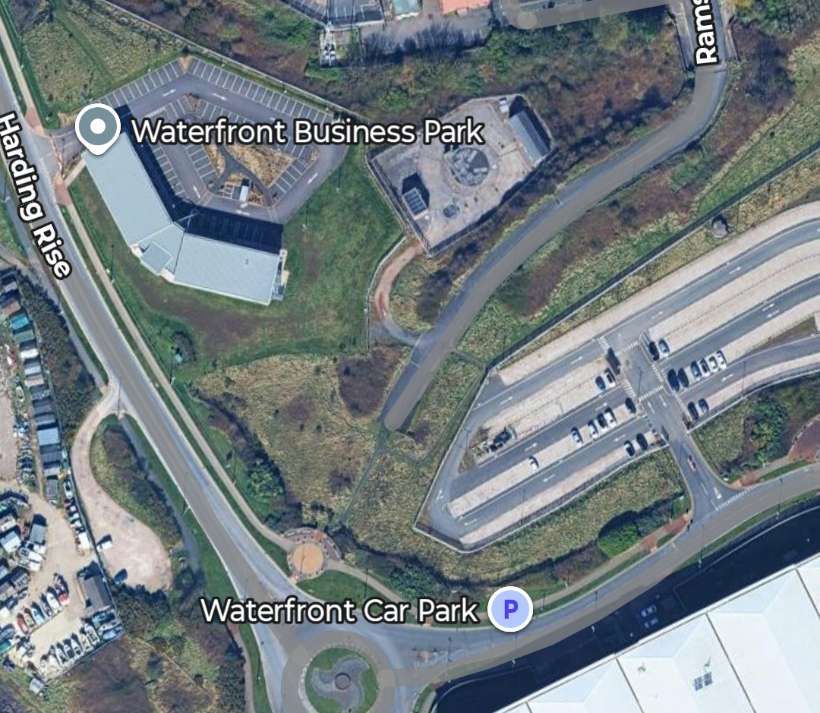

The station building was demolished in the 1940s, while the rail line leading to it was completely removed in the 1990s. No evidence of either remain and a windfarm operations centre has been built on the site. [26]

Running parallel to the line through Ramsden Dock Station were lines which served the various sidings in the docks. These lines can be seen in the extract above entering at the third-point along the top from the left of the image, and appear on the extract below, running diagonally across the image from the top-left corner.

Much more has changed since 1959. The significant network of dock railways has been replaced by a single line running down the East side of Ramsden Dock.

Associated British Ports’ “Port of Barrow plays a key role in serving the offshore energy industry in the region described as Britain’s “energy coast”. The port has 15ha of secure open storage and is the site of BAE Systems’ submarine design and manufacturing facility. … The Port of Barrow … handles over 100,000 tonnes of cargo each year, comprising an array of different products including limestone, sand, aggregates, granite and woodpulp. Heavy lift projects are also routinely and efficiently carried out to support the offshore energy sector.” [19]

To the Northwest of the dock lines we have been looking at, were the Naval Engineering Works and Shipbuilding Yard. These were served from the Southeast by a line heading West-northwest from Shipyard Junction which ran round the Southern side of the stadium and then in the surface of Island Road.

The road layout in the area of the Steelworks and to their immediate South has changed significantly. The image immediately below looks North-northwest along the line of the old and new Ironworks Road which now accommodates Northbound traffic on the A590.

Looking at the lines further to the North, Andrews said in 1959 that, “The economy drive which closed the Piel branch in 1936 also abolished the junction into the goods lines at Ormsgill north of the Central Station, and now trains from the north of the iron works have to work round through Loco Junction and Barrow yard.” [1: p157]

But to complete our look at the central area of Barrow, we follow the line up through Barrow Central Station to the North.

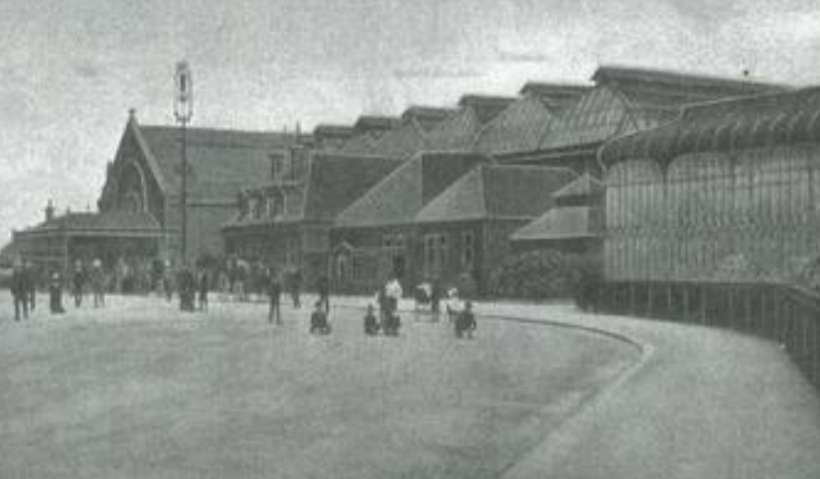

Andrews said in 1959: “The buildings at the new Barrow in Furness Station have been constructed on the site of the old, and are mainly steel framed. A considerable amount of glass has been introduced in the infilling panels forming windows to both the road and platform elevations. Multi-coloured rustic bricks have been used, with slate window sills and fascia over the high-level windows of the front entrance. The platform awnings are of light steel decking, with continuous roof glazing in line with the face of the external wall adjacent to No. 1 platform. The flooring of the booking hall and cafeteria-waiting rooms is laid in precast tiles, and polished hardwood has been used extensively as a decorative wall lining in the cafeterias, and for the framing to the ticket windows and internal window frames. The walls of the booking hall are finished in glazed tiles to the top of door height, with a glossy finish above, and re-erected on the south wall is the Furness Railway 1914-18 war memorial, Loudspeakers have been installed through out the station, and the open platform lighting is fluorescent, incorporating the station name within the light fitting.” [1: p200]

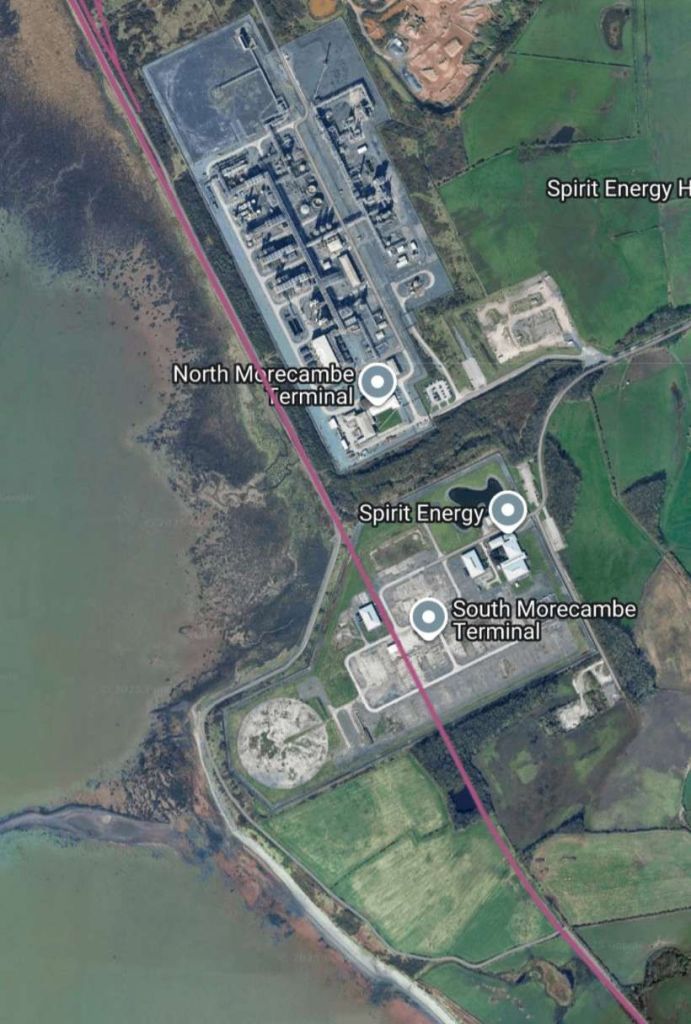

We finish our survey of Barrow’s Railways at this northern point. Towards the end of his 1959 article, Andrews commented about the first half of the 20th century: “The last fifty years have shown a steady decline in Barrow’s railway system, the inevitable result of the failure of James Ramsden’s vision to become reality. Although the iron ore brought a temporary and easy prosperity, the geographical situation was a permanent setback to the port. The industrial centres of Lancashire and Yorkshire were just too far away and the Furness main line was not built for real speed. Moreover, the Furness Railway Company just failed to establish sufficient variety of local industry to keep the port busy with local trade and the town came in the end to rely almost entirely on the shipbuilding industry. Since the last war, however, there have been signs of a reversal in this downward trend; sidings are being laid in to serve new factories at Salthouse and Sandscale, and Barrow is to become a divisional centre in the L.M.R. de-centralisation scheme. It is hoped that some of the prosperity of the old days is on the way back.” [1: p157]

From 1959 to 2026, Barrow-in-Furness transitioned from a traditional heavy industrial town into a specialized hub for nuclear submarine construction and offshore energy. While iron and steel industries closed by 1988, the BAE Systems shipyard became the town’s primary economic driver, cementing its role in national defense.

British Cellophane (1959) and Kimberly Clark (1967) established manufacturing plants in Barrow and the 1980s saw the development of gas terminals for the Morecambe Bay gas field.

The vast majority of the industrial railway heritage has disappeared. The town is left with its mainline service which serves the Cumbrian Coast and connects the town to the wider UK, and a branch line which runs down to the ABP port facilities.

References

- M. J. Andrews; The Railways of Barrow; in The Railway Magazine, Tothill Press, London, March 1959, p149-157 & 200.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roa_Island, accessed on 22nd December 2025.

- https://visitbarrow.org.uk/roa-island, accessed on 22nd December 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Barrow_Central_railway_station.jpg, accessed on 22nd December 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barrow-in-Furness_railway_station, accessed on 22nd December 2025.

- https://signalfilmandmedia.com/blitz-stories-images/barrow-central-station, accessed on 22nd December 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piel_railway_station, accessed on 23rd December 2025.

- Andrews quotes from a newspaper report of a Furness shareholders’ meeting in 1869. [1: p153]

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1AxvAoRHBg, accessed on 23rd December 2025.

- https://www.railmaponline.com/UKIEMap.php, accessed on 24th December 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/126514796, accessed on 24th December 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/126514871, accessed on 24th December 2025.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/126515072, accessed on 24th December 2025.

- Peter W. Robinson; Cumbria’s Lost Railways; Stenlake Publishing, Catrine, 2002.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rampside_railway_station, accessed on 24th December 2025.

- https://www.nwemail.co.uk/features/nostalgia/16445714.rampside-was-a-haven-for-19th-century-sea-bathers, accessed on 24th December 2025.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3562688, accessed on 27th December 2025.

- https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcRGdfLogUZSAQZgRDfqBb-aHVR2IlOZsU-5chvmZR0aNy_pS1j6lQIS_1c&s=10, accessed on 28th December 2025.

- https://www.abports.co.uk/locations/barrow, accessed on 12th February 2026.

- Individual extracts can be found by enlarging the mapping provided by the National Library of Scotland on this link: https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=13.6&lat=54.10820&lon=-3.21096&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 12th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.9&lat=54.11966&lon=-3.22651&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 13th February 2026.

- Individual extracts can be found by enlarging the mapping provided by the National Library of Scotland on this link: https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.0&lat=54.10776&lon=-3.23089&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed on 13th February 2026.

- Individual extracts can be found by enlarging the mapping provided by the National Library of Scotland on this link: https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=14.3&lat=54.12347&lon=-3.24052&layers=168&b=ESRIWorld&o=100, accessed o. 13th February 2026.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_New_Bridge_at_Buccleuch_Dock,_Barrow_in_Furness,_circa_1910.jpg, accessed on 14th February 2026.

- https://www.sankeyphotoarchive.uk/collection/view/?id=2152, accessed on 14th February 2026.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramsden_Dock_railway_station, accessed on 14th February 2026.

- https://britainfromabove.org.uk/image/EPW014339, accessed on 14th February 2026.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/34423, accessed on 14th February 2026.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/7514496, accessed on 14th February 2026.

- https://www.abports.co.uk/media/ohpjrxsw/port-charges-barrow-2025-v2.pdf, accessed on 14th February 2026.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EPW004066, accessed on 14th February 2026.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EPW004065, accessed on 15th February 2026.

- https://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EPW004060, accessed on 15th February 2026.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/Barrowinoldphotos/permalink/3301006416594574, accessed on 15th February 2026.

- https://maps.nls.uk/view/126514772, accessed on 15th February 2026.