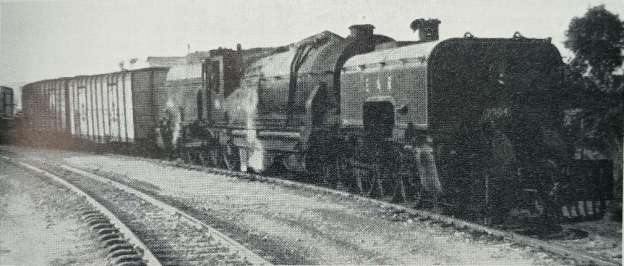

The December 1958 issue of The Railway Magazine featured three photographs of Beyer Garrett locomotives at work in East Africa. These were giants of the metre-gauge that grappled with long loads on steep inclines and at times sharply curved track radii. [1]

1. EAR Class ’55’ Garratt No. 5504 at Diva River

The KUR EC5 class was a class of 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) gauge 4-8-2+2-8-4 Garratt-type articulated steam locomotives built during the latter stages of World War II by Beyer, Peacock & Co. in Gorton, Manchester for the War Department of the United Kingdom. The two members of the class entered service on the Kenya-Uganda Railway (KUR) in 1945. They were part of a batch of 20 locomotives, the rest of which were sent to either India or Burma. [2: p64]

The following year, 1946, four locomotives from that batch were acquired by the Tanganyika Railway (TR) from Burma. They entered service on the TR as the TR GB class. [2: p64]

In 1949, upon the merger of the KUR and the TR to form the East African Railways (EAR), the EC5 and GB classes were combined as the EAR 55 class. In 1952, the EAR acquired five more of the War Department batch of 20 from Burma, where they had been Burma Railways class GD; these five locomotives were then added to the EAR 55 class, bringing the total number of that class to 11 units. [2: p64]

This locomotive was Works No. 7151, War Department No. 74235, War Department India No. 423. It was one of the two that went to Burma Railways (their No. 852) from where it was purchased by Tanganyika Railways in 1946 and became their No. 751. It came to the EAR in 1949 and received the No. 5504. [3]

Sister locomotives in Class 55 can be seen here [7] and here. [8]

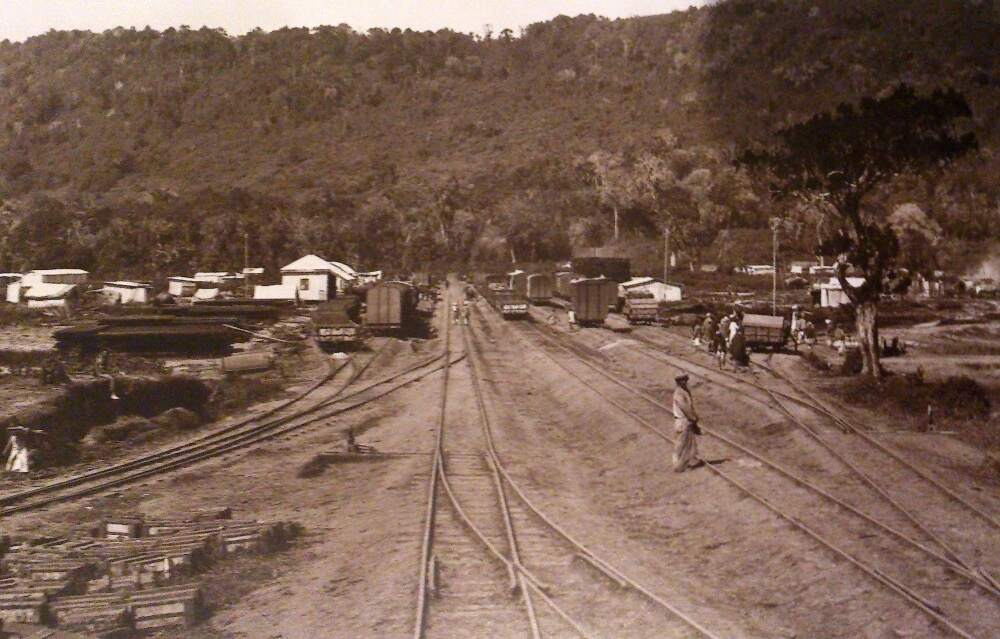

Dura River was the last station on the Western Extension before the end of the line at Kasese, Uganda. The River flowed North to South towards Lake George and was crossed by the railway at the Eastern edge of the Queen Elizabeth National Park. Mapping and satellite imagery in the area are not highly detailed – the following images are the best I can provide. …

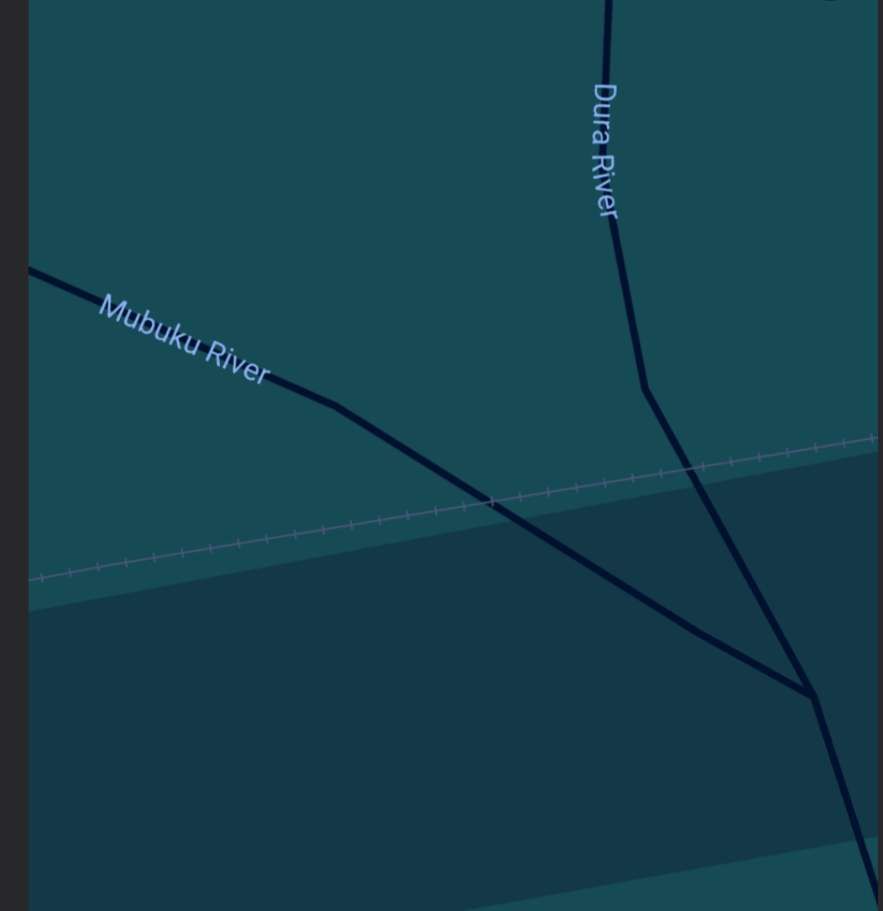

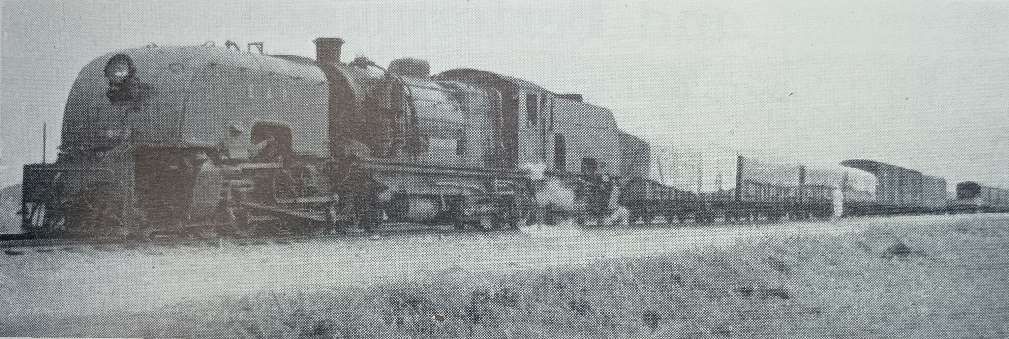

2. EAR Class ’58’ Garratt No. 5804 near Kikuyu

The EAR 58 class was a class of 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) gauge, 4-8-4+4-8-4 Garratt-type articulated steam locomotives built by Beyer, Peacock & Co. in Manchester, England, in 1949. [9]

The eighteen members of the class were ordered by the Kenya-Uganda Railway (KUR) immediately after World War II, and were a slightly modified, oil-burning version of the KUR’s existing coal-fired EC3 class. By the time the new locomotives were built and entered service, the KUR had been succeeded by the East African Railways (EAR), which designated the coal-fired EC3s as its 57 class, and the new, oil-burning EC3s as its 58 class. [2: p66][9]

No. 5804 was built in 1949 (Works No. 7293) and originally given the KUR No. 92. Its sister locomotive No. 5808 (Works No. 7297, given KUR No. 96 but never carried that number) was the first to enter service with the EAR. [9]

Other locomotives in the class can be seen here, [11] here, [12] and here. [13]

Kikuyu Station is 20 kilometres or so from Nairobi, during construction of the railway, railway officers established a temporary base in Kikuyu while they supervised work on the laying of the track down at the rift valley escarpment.

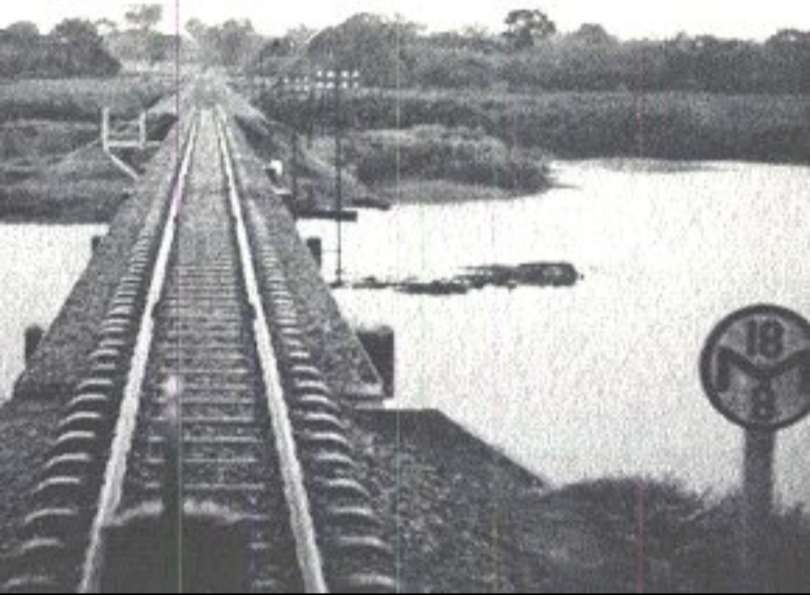

3. EAR Class ’60’ Garratt No. 6021 at Kasese

The EAR 60 class, also known as the Governor class, was a 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) gauge 4-8-2+2-8-4 Garratt-type articulated steam locomotives built for the East African Railways as a development of the EAR’s existing 56 class. [2: p77]

The 29 members of the 60 class were ordered by the EAR from Beyer, Peacock & Co. The first 12 of them were built by sub-contractors Société Franco-Belge in Raismes (Valenciennes), France, and the rest were built by Beyer, Peacock in Gorton. The class entered service in 1953-54. [2: p77]

Initially, all members of the class carried the name of a Governor (or equivalent) of Kenya, Tanganyika or Uganda, but later all of the Governor nameplates were removed. [2: p77]

No. 6021 was built by Beyer Peacock (Works No. 7663). It was not one of the class built by sub-contractors Société Franco-Belge. It was given the name ‘Sir William Gowers’ when first put into service, losing the name along with other members of the class in the 1960s after independence. …

Other members of the class can be seen here, [17] here, [18] and here. [19]

Kasese Station only became part of the rail network in Uganda in 1956. The construction costs of the whole line from Kampala were very greatly affected by the difficult nature of the country in the final forty miles before Kasese. Severe problems were presented by the descent of the escarpment, which involves a spiral at one point, while from the foot there is an 18-mile crossing of papyrus swamp through which a causeway had to be built, entailing a vast amount of labour. The extension to Kasese was built primarily to serve the Kilembe copper mines. Construction of the line from Kampala to Kasese took approximately five years. [21]

References

- Garratts in East Africa; in The Railway Magazine Volume 104 No. 692, December 1958, p849.

- Roel Ramaer; Steam Locomotives of the East African Railways. David & Charles Locomotive Studies; David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1974.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/KUR_EC5_class, accessed on 7th July 2025.

- https://www.google.com/search?q=queen+elizabth+yganda&oq=queen+elizabth+yganda&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIJCAEQABgNGIAEMgkIAhAAGA0YgAQyCAgDEAAYFhgeMggIBBAAGBYYHjIICAUQABgWGB4yCggGEAAYCBgNGB4yCggHEAAYCBgNGB4yCggIEAAYCBgNGB4yCggJEAAYCBgNGB4yCggKEAAYCBgNGB4yCggLEAAYCBgNGB4yCggMEAAYCBgNGB4yCggNEAAYCBgNGB4yCggOEAAYCBgNGB7SAQkxMzQ4NmowajmoAg6wAgHxBe8kU7h2wyh58QXvJFO4dsMoeQ&client=ms-android-motorola-rvo3&sourceid=chrome-mobile&ie=UTF-8#ebo=0, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/relation/192796#map=19/0.228157/30.289528&layers=P, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- http://mccrow.org.uk/EastAfrica/EastAfricanRailways/UgandaBranches.htm, accessed on 1st June 2018.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/124446949@N06/32890286408, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/124446949@N06/48996173961, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EAR_58_class, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Engine_unit_of_East_African_Railways_and_Harbours_Corporation_(EAR%26HC)_58_class_Garratt_locomotive_no_5804.png, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://www.world-railways.co.uk/general-photo-408, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/124446949@N06/29100559308, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/124446949@N06/47072893354, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/kikuyu-station.jpg

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/kikuyu-railway-station.jpg included by kind permission of Shiku Njathi. ….. https://inkikuyu.com/a-walk-around-kikuyu/kikuyu-railway-station

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Basil_Roberts_(680730_EAR).jpg, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/124446949@N06/51744782399, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://www.world-railways.co.uk/general-photo-667, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/124446949@N06/31824271347, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Old_Kasese_Train_Station.jpg, accessed on 8th July 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2018/06/11/uganda-railways-part-21-kampala-to-kasese.