Ethiopia/Eritrea

The 950mm-gauge line from Massawa on the coast, inland to Agordot, was built during colonial occupation by the Italians with some steep gradients which meant that Mallets were considered to be suitable motive power.

The line should not be confused with the metre-gauge line running from Djibouti to Addis Ababa. A metre-gauge railway that was originally built by the French from 1894 to 1917 which has since been replaced by a Chinese built standard-gauge line. [5]

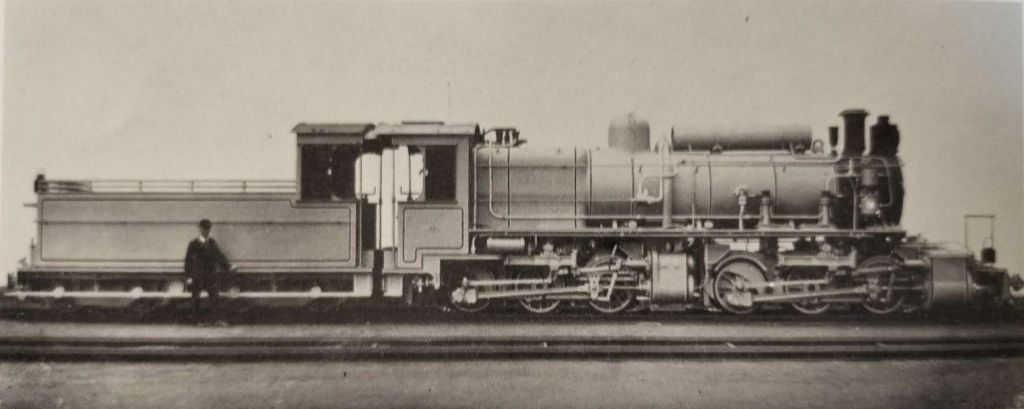

In 1907, Maffei built three 0-4-4-0T locomotives for the Massawa to Agerdot line.

Ansaldo the “supplied twenty five further engines of the same class between 1911 and 1915, and in 1931 and 1939 Asmara shops assembled a nominal three new engines from d components of earlier withdrawn engines. All these were standard European narrow-gauge Mallet tanks, saturated, slide-valved and with inside frames.” [1: p64]

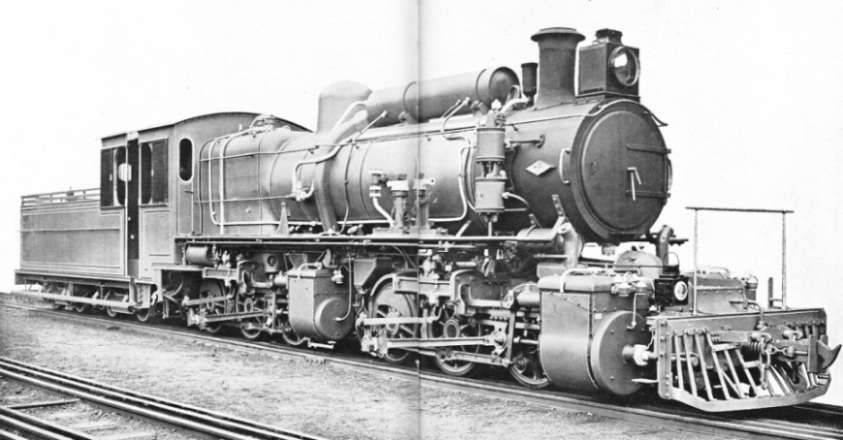

In the mid-1930s, a series of fifteen larger 0-4-4-0T locomotives were built. These were “built to a superheated, simple expansion design, of which ten had piston valves and Walschearts gear and the other five, Caprotti poppet valves driven from outside cardan shafts.” [1: p65] A later series of “eight engines built by Analdo in 1938 reverted to compound expansion, retaining the superheater and piston valve features.” [1: p65]

The last of the Eritrean Mallets was built in their own shops in 1963, making it the last Mallet built in the world. [6]

The line closed in 1975. Eritrea was occupied by Ethiopia for many years. After gaining independence in 1993, some of the former railway staff started to rebuild their totally destroyed railway. Some of the Mallets, built by Ansaldo (Italy) in 1938, were brought back to life. Also one of the small Breda built shunters, two diesel locos and two diesel railcars (one from 1935) were put back into working order. [7]

A section of the line, between Massawa, on the coast, and Asmara, was reopened in 2003 and has offered an opportunity for Mallet locomotives to be seen in operation in East Africa. Indeed, an internet search using Google brings to light a list of videos of locomotives heading tourist trains in the Eritrean landscape.

Wikipedia notes that the line has a track-gauge of 950mm and that locomotives operate over a 118 km section of the old line. Italian law from 1879 officially determined track gauges, specifying the use of 1,500 mm (4 ft 11 1⁄16 in) and 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) gauge track measured from the centre of the rails, or 1,445 mm (4 ft 8 7⁄8 in) and 950 mm (3 ft 1 3⁄8 in), respectively, on the inside faces. [4]

Steam operation on the line is over, no regular services are provided but occasional tours still take place with plenty of caveats about the availability of any form of propulsion. An example is a German-speaking tour planned (as of 24th March 2024) for November 2024. [8]

Tanzania (Tanganyika)

The metre-gauge line inland from Dar-es-Salaam was built by the Ost Afrika Eisenbahn Gesellschaft (East African Railway Co.). A.E. Durrant tells us that its first main line power “was a class of typical German lokalbahn 0-4-4-0T Mallets, built by Henschel in 1905-7. These were supplemented in 1908 by four larger 2-4-4-0Ts from the same builder, after which the railway turned to straight eight-coupled tank and tender engines.” [1: p67]

R. Ramaer notes that the first locomotives used by the Usambara Eissenbahn (UE) on the Tanga Line were five 0-4-2 locos which arrived on the line in 1893. Rising traffic loads led the UE “To look for something more substantial and in 1900, Jung supplied five compound Mallet 0-4-4-0T’s as numbers 1-5, later renumbered 6-10. … To provide enough space for the firebox and ashpan, the rigid high-pressure part, comprising the third and fourth axles, had outside frames, whereas the low-pressure part had inside frames.” [9: p19]

On the Central Line (Ost Afrikanische Eisenbahn Gesellschaft – or OAEG) which ran inland from Dar-es-Salaam, construction work started in 1905 and the first locomotives used by the OAEG were four 0-4-0T engines built by Henschel, a further four of these locomotives were supplied in 1909. These small engines had a surprisingly long life. Mallets were first supplied in 1905 by Henschel and were suitable for both coal and oil firing. These were 0-4-4-0T locos (four supplied in 1905 and one supplied in 1907). “The problem with this type of engine was the restricted tractive effort and running was not satisfactory because of the lack of a leading pony truck. … Therefore Henschel supplied a second batch of four locomotives in 1908 as 2-4-4-0Ts with larger boilers and cylinders. They also had a higher working pressure of 14 atmospheres (200lb/sq in) in comparison to 12 atmospheres (170lb/sq in) for the earlier engines, while the bunker capacity had been increased from 1.2 to 2.2 tonnes of coal. (Oil fuel had been discarded).” [9: p21-23]

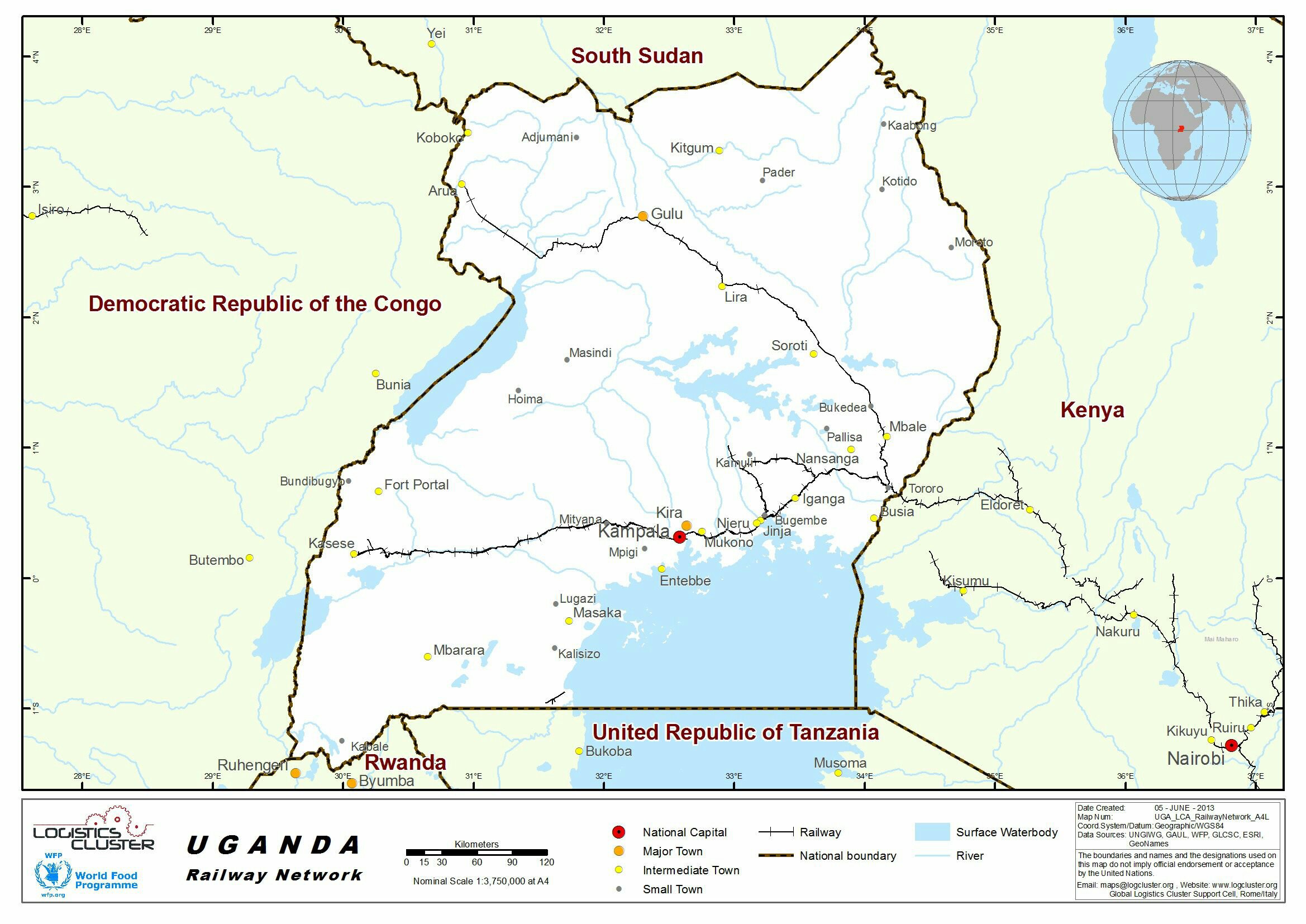

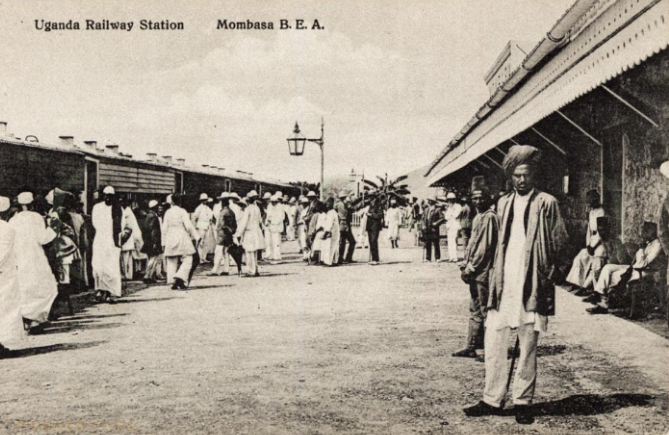

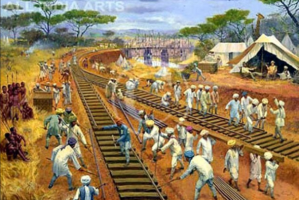

Kenya-Uganda

Mallets were the first articulated locomotives to operate in East Africa. Mallets were introduced on the Uganda Railway in 1913. A.E. Durrant notes that they consisted of “a batch of eighteen 0-6-6-0 compound Mallets to what was the North British Locomotive Co’s standard metre-gauge design, as supplied also to India, Burma, and Spain. They had wide Belpaire fireboxes, inside frames and piston valves for the high pressure cylinders only. Built at Queens Park works in 1912-1913, these locomotives entered service in 1913-14 and remained at work until 1929-30, when they were replaced by the EC2 and EC2 Garratts.” [1: p66]

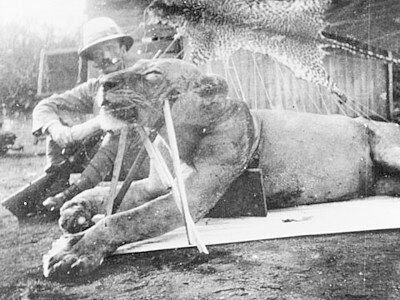

These locomotives were given the classification ‘MT’ within the Uganda Railway fleet. Disappointing performance and high maintenance costs led to them being relegated to secondary duties and eventually being scrapped in the late 1920s as the Beyer Garratt locomotives began to arrive. [2] Their presence on the system was heralded by, “Railway Wonders of the World,” with the picture shown below. [3]

References

- A.E. Durrant; The Mallet Locomotive; David & Charles, Newton Abbot, Devon, 1974.

- Kevin Patience; Steam in East Africa; Heinemann Educational Books (E.A.) Ltd., Nairobi, 1976.

- http://www.railwaywondersoftheworld.com/uganda_railway2.html, accessed on 1st June 2018.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eritrean_Railway, accessed on 22nd March 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Addis_Ababa%E2%80%93Djibouti_Railway, accessed on 22nd March 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/0-4-4-0, accessed on 22nd March 2024.

- https://www.farrail.net/pages/touren-engl/eritrea-mallets-asmara-2010.php, accessed on 24th March 2024.

- https://ecc–studienreisen-de.translate.goog/historische-eisenbahn-und-strassenbahnreisen-mit-peter-1/8-tage-eritrea-mallets-in-den-bergen-afrikas?_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc, accessed on 24th March 2024.

- R. Ramaer; Steam Locomotives of the East African Railways; David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1974.

- https://www.facebook.com/urithitanga.museum/photos/pb.100063540805743.-2207520000/2336640756358366/?type=3, accessed on 24th March 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2169593963301193&set=pcb.2169594269967829, accessed on 24th March 2024.

- https://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_schmalspuriger_Lokomotiven_von_Henschel, accessed on 24th March 2024.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eritrean_Railway_-_2008-11-04-edit1.jpg, accessed on 24th March 2024.