Tramway de Nice et du Littoral

There were a series of tramways which extended different arms of Le Tramway de Nice et du Littoral (TNL). We have already followed the route of the Sospel to Menton tramway which extended the coastal/urban line between Nice and Menton into the mountains close to the coast. Menton to Villa Caserta, opened in October 1911 and Villa Caserta to Sospel opened in 1912.[3]

The TNL was a tramway network that served Nice and the municipalities of the Alpes-Maritimes department between 1878 and 1953.

Around 1833, a Monsieur Legrand, owner of the Hotel de France which is sited on what is now the Quai des Etats-Unis, bought a large omnibus in Paris and three large horses. He ran a twice daily service from Nice to Le Pont de Var which at the time marked the border between France and Italy.[10] The fare was 40 centimes.

One of his competitors, Monsieur Laupias, proposed in 1845 two services at an hour’s frequency between Cagnes sur mer and the Place Saint Dominique, as well as between the Paillon and the Faubourg du Ray. In 1854, another service commenced linking Pont Vieux (Place Garibaldi) with Le Ray.

After Nice was attached to France in 1860, the PLM railway arrived in 1864 and Nice became a preferred tourist destination for a wealthy class of traveller. At the same time, the town was growing north of Paillon. Urban planners adopted a network of perpendicular roads, but of a fairly modest width, sufficient, however, to encourage the circulation of horse-drawn omnibuses. By 1865, a network of horse drawn omnibus routes had been established.[9]

Monsieur Laupias was responsible for the expansion of the network of l’Entreprise Générale des Omnibus de la Ville and the railways. He set up two new lines: one between the PLM station and the port, and the other between the Place Charles-Albert and the Saint Barthélémy district of the city.

These horse-drawn services were ultimately short-lived as Nice began to talk about inaugurating tram services as a result of seeing tramways being developed in industrial cities further north in France. Several attempts were made to implement tramway working. One of these endeavours even sought to make use of compressed air to propel the trams.[11]

The Société Financière de Paris , associated with the Société de Travaux Publics et de Constructions, was responsible for the construction and operation of a horse-drawn tramway network in 1876 in the city of Nice. The first horse drawn tramway service was commissioned on 27th February 1878 and inaugurated on 3rd March. A series of 4 lines made up the early network … Place Massena to Magnan Bridge, a separate line from Magnan Bridge to Saint Helena, and two other lines from Place Massena, one to Saint-Maurice and the other to Abattoirs. The lines were single-track and of metre-gauge.

Soon after the first lines were completed the tramway system was placed in the care of the Compagnie Generale des Omnibus in Marseille. This arrangement lasted until 1887 when that company went into liquidation. After its collapse, La Société Nouvelle des Tramways de Nice (SNTN) resumed operation of the network.

In addition, in 1895, the Compagnie Anonyme des Tramways Electriques of Nice-Cimiez was awarded a concession for a new tram line, between the street of the Hotel des Postes and the zoological garden of Cimiez. This line was a 600mm track-gauge and used electric traction batteries because of its steep gradients, the design was seen by the promoters at a technical exhibition in Lyon in 1894.[10]

Cimiez: the appearance of the first electric tram

A casino, a zoological park and a theatre were established in Cimiez, near the Roman arena. After flirting with the idea of a steam powered service from Nice to Cimiez, the owners of the site set up the Compagnie Anonyme des Tramways Electriques of Nice-Cimiez

Unofficially the trams started running on 27th February 1895, the service was interrupted on 10th March because of fire at the generating plant. The servicecresumed on 20th June but was halted on 12th July as the required legal processes had not been followed. Eventually, on 22nd November the company was declared as being ‘d’utilité publique'[4] and an official inauguration took place on the 25th November

The 3.9 km long line had very steep gradients, 8 trams were in service on the line. Six daily services were provided in the winter and a half-hourly service was available in summer months. Stops were on request, except on the steepest sections of the line. The trams were powered by an 8bhp motor and had a maximum capacity of 32 people. Redesign of the trams took place very early in the life of the tramway, the wheelbase and overall length of the trams were shortened and the single 8bhp power unit was replaced by two 50bhp motors. The people of Nice nicknamed the trams the “slugs”.[10]

The Cimiez tramway was again taken out of operation in 1899, to allow a revision to the electrical power system and tompermit integration with the wider metre-gauge tram network in the City of Nice. The line was operating again by January 1900.

La Compagnie des Tramways de Nice et du Littoral (TNL)

Within two years of its foundation, La Société Nouvelle des Tramways de Nice had been replaced by La Compagnie des Tramways de Nice et du Littoral (TNL). The company set itself a series of goals relating to the improvement an expansion of the urban network:

- to create a Coastal Network , extending from Cagnes to Menton , with connections to other networks in Nice and at Contes .

- to electrify the urban network.

- to resume operation of the Cimiez line, abandoning the accumulator tramway and converting it to metric gauge.

The company was effective in meeting its initial goals and it created an extensive network centred on the Place de Massena in Nice. A few images of the Place de Massena follow ………

Lines opened or reopened as follows:[1]

- Nice – Cimiez , January 1900

- Place Massena – Villefranche-sur-Mer , February 1900

- Nice – Saint Laurent du Var, February 1900

- The port – Saint Maurice, February 1900

- Nice – Cagnes, March 1900

- Nice – Contes , June 1900

- Nice – Beaulieu, June 1900

- Magnan – Saluzzo (via Lépante Street), November 1902

- Gambetta – Massena (via avenue Joseph Garnier), November 1902

All the lines were electrified by underground gutter as soon as they were put into service, and a fleet of 100 motor-trams was ordered.

In total, for the construction of the 12 urban lines and the first 3 sections of the suburban network, it took only 2 years to lay a total of no less than 94 km of network (150 km of single track)! From 31st December 1899, the tests of the first of the Thomson-Houston, Thomson-powered motor-trams, equipped with 2 engines of 35 bhp were carried out inside the depot at Sainte Agathe. There were 30 of these yellow and white trams in two classes. The initial plan had been to provide a limited number of 1st Class trams. This idea proved unsuccessful and the 1st Class trams were later converted to standard class. When first in operation these 6 1st Class trams were marked with a colour code.

Service frequency on the urban network was high. Generally, services started at 5.30am and ended at around midnight. However, the first departure from Cagnes-sur-Mer (for the florists) was scheduled at 3am! A TNL kiosk was built in 1901 to act as a ticket office and an information desk at the heart of the network.

Menton and its Trams[14]

The coastal network took 3 years of work to reach Menton and to create a branch-line between Place Saint Roch and Place Caserta. The trams provided strong competition for the PLM along the coast and the PLM took every opportunity to obstruct the construction of the underpasses and bridges required for the line, and prohibited the installation of a terminus in front of the station at Menton. Finally, the TNL decided to drop their passengers 25m from the PLM station, at the foot of the climb to the station yard. The trams finally provided a service to Menton by 22nd December 1902, and the connection with the station was operational by July 1903.[12]

Completion of the line to Menton provided a continuous service from Cagnes-sur-Mer to Menton. By this time the TNL had over 94km of lines, 29km in Nice, 12km in Cagnes, nearly 16km of the line to Contes and nearly 38km of tracks on the line to Menton via Monte Carlo.

The shoreline was itself a tourist object: the panorama of the Mediterranean and the villages did not lack charm. On the heights of Beaulieu, the tram takes the pose with a platform abundantly stocked for the occasion.

The shoreline was itself a tourist object: the panorama of the Mediterranean and the villages did not lack charm. On the heights of Beaulieu, the tram takes the pose with a platform abundantly stocked for the occasion. Another view of the coast line with a motor-tram running on the Corniche at Villefranche sur Mer. The road was still made only of dirt and gravel, and in the shadow of the tramway there is a cart pulled either by a donkey or by a horse.

Another view of the coast line with a motor-tram running on the Corniche at Villefranche sur Mer. The road was still made only of dirt and gravel, and in the shadow of the tramway there is a cart pulled either by a donkey or by a horse. An attempt to provide a reversible train with two motor-trams framing a trailer-car on the line of Monte-Carlo. The power of the leading motor-tram proved to be inadequate for the load.

An attempt to provide a reversible train with two motor-trams framing a trailer-car on the line of Monte-Carlo. The power of the leading motor-tram proved to be inadequate for the load.

The Tramway Company of Monaco

The Compagnie des Tramways de Monaco was founded in 1897 by Mr. Crovetto, a Monegasque entrepreneur. The company obtained concessions for a number of different lines, as listed below before, in 1908, becoming part of the TNL:

- Place d’Armes – Saint Roman, opened on May 1898

- Gare de Monaco – Place du Gouvernement, opened on March 1899

- Casino – Monte Carlo Station, opened May 1900.

- Nice – Monte CarloCarlo, opened in 1900.

The Cote d’Azur is a stunning series of headlands, towns and villages alongside the azur-blue waters of the Mediterranean sea. Wikipedia has produced an excellent introduction to the coast-line – Road by the sea[2].

La ligne de Monaco et Menton

This line connected towns and cities along the Corniche: Nice, Villefranche, Beaulieu, Monaco and Monte Carlo by a route established on the Basse Corniche. The line opened towards the end of 1903 and was quickly followed by the completion of an extension from Monaco to Menton just in time for Christmas 1903. The line was separate from, but connected to the tramway network in Monaco.

Further Extensions

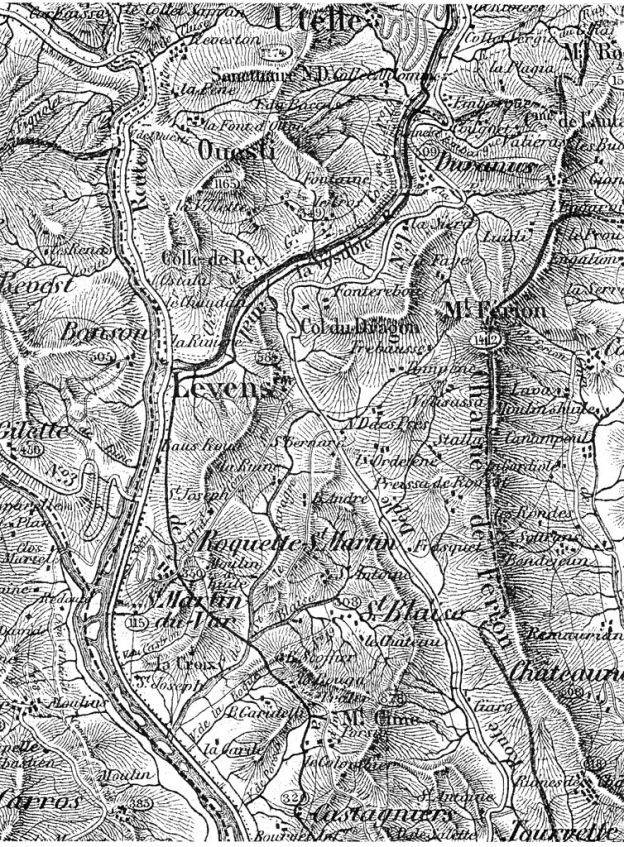

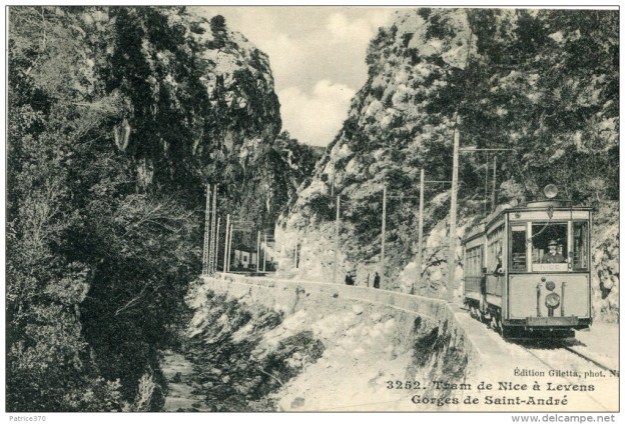

The network continued to grow. The TNL began to extend inland into Les Alpes Maritimes department creating a network of single track metre-gauge lines which served key villages and towns in the hinterland. It also extended and consolidated it presence in the urban areas along the coast. The departmental network not provided extended access into Nice and the coastal towns for local people, it was perceived as creating significant opportunities for tourism.

The Departmental Network

The departmental network included 14 proposed lines shared between the TNL, the TAM and the Compagnie des chemins de fer du Sud de la France . The TAM was actually a subsidiary of La Compagnie des chemins de fer du Sud de la France and the larger company decided to confine tramway operations to the TAM despite having a shared track-gauge. Other blog posts provide details of some of these TAM lines, particularly:

The lines were shared out using geographical criteria which resulted in the TNL being offered the following concessions:

All these lines were declared ‘d’utilité publique'[4] on 10th February 1906.[1]

Once the network opened its line from Cagnes-sur-Mer to Antibes it was able to connect to the tram network in Cannes .[5]

Developments in the Urban Network

One further line was introduced in 1908, that between Magnan/Le Madeleine and the centre of Nice.

Magnan is a valley located west of Nice. Today it is urbanised and used to designate one of the districts of Nice. The river which flows through the valley is called Le Magnan (or Torrent de Magnan).[6] This is a short coastal river of 12.6km in length. Le Madeleine[7] was the small village with a chapel in the valley.

The line from Menton to Sospel

This line connecting Menton to Sospel was opened on April 15, 1912, as part of the construction of the departmental network. Its length was 18km . It marked the last extension of the TNL.

The peak of the tramway network and its demise

In fifteen years, the growth of the population of Nice and the surrounding towns and villages necessitated a rapid development of the network. The advent of the Great War prevented any further development of the network.

At the end of the war, the network was in need of an in-depth modernization programme. However, it was not until 1924 that the authorities granted the TNL the authorization to increase tariffs.

A refurbishment program was initiated, significant improvements were intended for the trams themselves but these improvements were not introduced in full.[12] Changes were made in different ways to different batches of limited numbers of trams.

A major study in 1921, looked at the possibility of providing a tramway tunnel under Monaco, but the proposal did not see the light of day.

To speed up service and reduce operating costs, a system of fixed and optional stops was introduced. Buses began to be introduced by the TNL in October 1921 under the company name, Société Anonyme Niçoise de Transports Automobiles, to serve remote villages where the tram no longer operated. The TNL also bought its own buses.

10 Schneider Type H buses similar to the one above were purchased. They were similar to those in use in Paris. They arrived in Nice in 1925. They were followed in a short period of time by 3 Somua MAT2 buses.

10 Schneider Type H buses similar to the one above were purchased. They were similar to those in use in Paris. They arrived in Nice in 1925. They were followed in a short period of time by 3 Somua MAT2 buses.

Despite reducing revenues, the TNL decided to build a new series of trams strongly inspired by the Parisian L-type, and adapted to the Nicois metre-gauge track. Eight reversible motor trams were were ordered along with trailers. The trams were 200bhp and had a 3.60m wheelbase. These performed well on straight track but found the windowing nature of much of the network difficult.

After the Great War, very quickly, other forms of transport began to develop in competition with the tramways. These began to be regarded as more modern than the tramways. A number of accidents occurred on the network which began to result in a lessening in confidence in trams as an appropriate form of transport beyond the immediate urban areas.[8] There was an increasingly vociferous anti-tram lobby.

The above images show the extent of the tram network in 1925, both within Nice and along the coast.[13]

The above images show the extent of the tram network in 1925, both within Nice and along the coast.[13]

In 1925, the TNL network had 144 km of track, & a fleet of 183 motor trams and 96 trailers.[15] The tramways were also used to transport goods and a series of wagons were also purchased. Goods were transported within Nice to and from the station of Le Chemin de Fer de Provence. Coal was transported from the port to other parts of the city, and cement, lime and gas were transported from the cement factory in Contes to various areas of Nice. The Sospel to Menton line was used for construction materials for the building of the railway line from Nice to Breil-sur-Roya.

Initially, it was the coastal tram lines that suffered strongest competition from road vehicles. But, across the whole network, cars and lorries and their inherent flexibility came to dominate the public’s choices over transport use. The coastal lines between urban centres disappeared between 1929 and 1932. By 1934, the longer suburban lines had all disappeared. Nevertheless, the tramway was not yet banned from the city, even if criticism from part of the population was growing.

In 1927, André Mariage[16] took the presidency of TNL and STCRP, amplifying the hostility towards the tramway. The election of Jean Médecin at the head of the municipality, who was a virulent opponent of the tramway, seemed to legitimise those who saw the tramway as a symbol of the past.

Over following years the municipality decided to close different urban lines and by 1939 only four lines remained open:

- Line 3: Abattoirs – La Madeleine – Trinidad Victor

- Line 9: Port – Saint Augustins

- Line 22: PLM station – Carras

- Line 35: Rue Hotel des Postes- Cimiez

During the Second World War, two urban lines were reopened as the buses which had been gradually being introduced were requisitioned for the war effort:

- Line 6: Level crossing – Pasteur

- Line 7: Level crossing – Riquier

And two lines into the hinterland: the one to Contes and the one to La Grave de Peille.

The network had, by the end of 1942, 48 motor-trams and 22 trailers (some motor-trams were rebuilt in 1942).

After the Second World War, the tramway systems, having suffered from years of war/occupation and neglect, were replaced by trolleybuses . The trolleybuses were put into service from 1942 on the Cimiez line (line 35). The last tram ran on the whole network on 10th January 1953.

Lines disappeared slowly over a period of years: the line to La Grave de Peille closed in 1947, line 22 closed at the end of 1948. The line to Contes and Line 6 closed in 1950, and lines 3 and 9 closed in 1951. Line 7 was the last line in operation and closed, as we have already noted, on 10th January 1953.

Rolling stock

Motor-trams[1]

- No.1 to 100, were sourced from the workshops of Saint-Denis.

- No. 101 to 106, were sourced in 1903 from Brissonneau and Lotz.

- No. 111 to 130, were delivered in 1904 by Thomson-Houston.

- No. 151 to 170, came in 1906 from Thomson-Houston.

- No. 201 to 216, were sourced in 1910 from Thomson-Houston.

- No. 251 to 258, were delivered in 1925 by les Établissements Soulé.

Trailers[1]

- No. 301 to 316, delivered in 1908 by les Établissements Soulé.

- No. 351 to 358, delivered in 1925 by les Établissements Soulé.

- No. 401 to 418, commissioned in 1902, and were former horse trams.

- No. 501 to 515, delivered in 1901 by les Établissements Carde.

- No. 516 to 520, delivered in 1901 by les Établissements Carde.

- No. 600 to 619, commissioned in 1900, and were former horse trams.

- No. 700, commissioned in 1900, a former horse tram.

- No. 731 to 736, commissioned in 1911, and converted from former motor-tram cars No. 101 to 106.

- No.801 to 812, (initially numbered 201 to 212), bought second-hand in 1903 from les Chemins de fer Nogentais.

- No. 813 to 822, (initially numbered 213 to 222), delivered in 1905 by les Établissements Carde.

- No. 901, commissioned in 1916, built by TNL workshopsworkshops.

- No. 921, commissioned in 1927, built by TNL workshops.

References

1. Tramway de Nice et du Littoral; https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tramway_de_Nice_et_du_Littoral, accessed 5th March 2018.

2. Route du bord de mer (Alpes-Maritimes); https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Route_du_bord_de_mer_(Alpes-Maritimes), accessed 5th March 2018.

3. The Sospel to Menton Tramway Revisited; https://rogerfarnworth.wordpress.com/2018/02/23/the-sospel-to-menton-tramway-revisited-chemins-de-fer-de-provence-51the-sospel-to-menton-tramway-revisited-chemins-de-fer-de-provence-51.

4. This term is a standard French term for a transfer of status for a company, a definition is provided on this link: http://projaide.valdemarne.fr/la-reconnaissance-dutilite-publique-definition-et-demarches, accessed 14th March 2018.

5. Tramway de Cannes; https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tramway_de_Cannes, accessed 14th March 2018, c.f. Trams in Cannes; https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trams_in_Cannes, accessed 15th March 2018.

6. Magnan; https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnan_(Nice), accessed 14th March 2018.

7. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_des_quartiers_de_Nice#Magnan_ou_La_Madeleine, accessed 14th March 2018.

8. See for example: https://rogerfarnworth.wordpress.com/2017/11/28/the-tramway-between-grasse-and-cagnes-sur-mer-part-1-chemin-de-fer-de-provence-20 and https://rogerfarnworth.wordpress.com/2018/02/23/the-sospel-to-menton-tramway-revisited-chemins-de-fer-de-provence-51the-sospel-to-menton-tramway-revisited-chemins-de-fer-de-provence-51.

9. Transports en Commun de Nice TNL; http://www.nissalabella.net/tnl.htm accessed 13th March 2018.

10. Les tramways de Nice : avant l’électrification; http://transporturbain.canalblog.com/pages/les-tramways-de-nice—avant-l-electrification/31975770.html, accessed 13th March 2018.

11. Les tramways de Nice : avant l’électrification; http://transporturbain.canalblog.com/pages/les-tramways-de-nice—avant-l-electrification/31975770.html, accessed 13th March 2018; c.f. https://www.thevintagenews.com/2016/10/17/the-mekarski-system-compressed-air-propulsion-system-for-trams, accessed 15th March 2018; https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mekarski_system, accessed 15th March 2018; and http://www.tramwayinfo.com/Defair.htm, accessed 15th March 2018.

12. Les tramways de Nice: de l’apogée au déclin; http://transporturbain.canalblog.com/pages/les-tramways-de-nice—de-l-apogee-au-declin/31975780.html.

13. The GS Tram Site: Nice/Cannes and Area, France and Monaco 1925; http://www.tundria.com/trams/FRA/Nice-1925.shtml, accessed 15th March 2018.

14. Photographs and Postcards showing the trams of Menton can be found at http://menton.tramways.monsite-orange.fr/index.html, accessed 14th March 2018.

15. Trams in Nice; https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trams_in_Nice, accessed 15th March 2018.

16. André Mariage; https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/André_Mariage, accessed on 15th March 2018.

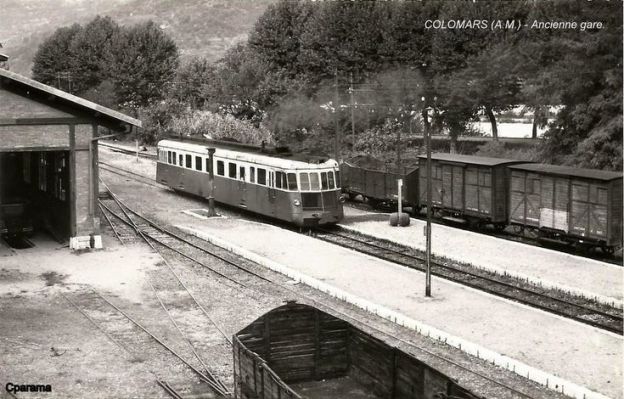

Nice – 1969 – Remarkable view of the atmosphere of the Nice train station and its depot with a host of Billard railcars having just been recovered on various CFD lines coming to close. On the left, we can also see two ABH. © JH Manara.[22]

Nice – 1969 – Remarkable view of the atmosphere of the Nice train station and its depot with a host of Billard railcars having just been recovered on various CFD lines coming to close. On the left, we can also see two ABH. © JH Manara.[22] Nice – 1983 – note the imposing height of the train-shed, the three railcars and the recution of the lines in favour of car parks that will soon take over the entire site! © JH Manara.[22]

Nice – 1983 – note the imposing height of the train-shed, the three railcars and the recution of the lines in favour of car parks that will soon take over the entire site! © JH Manara.[22]

Drawing by Jean Francois Laugeri

Drawing by Jean Francois Laugeri

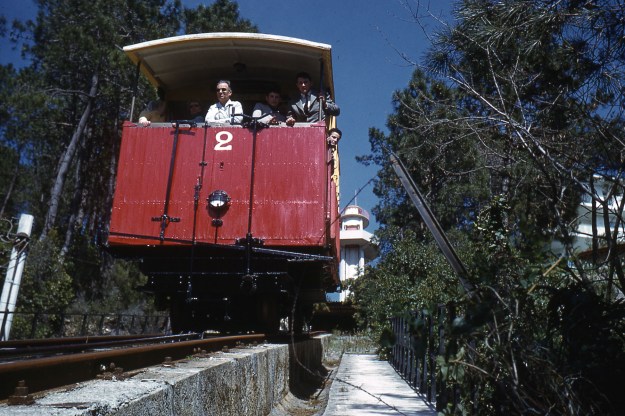

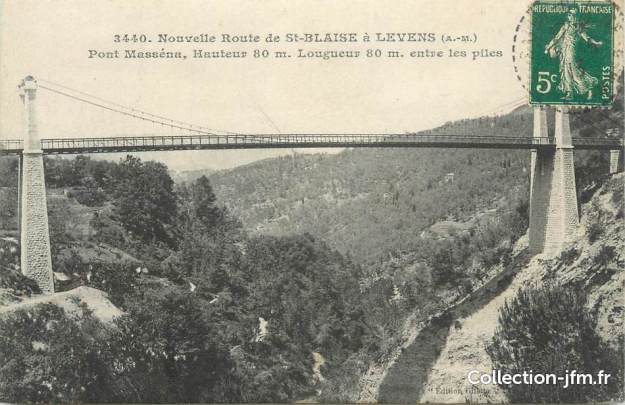

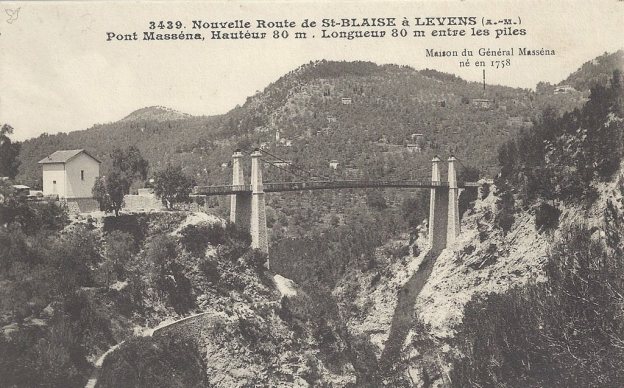

The replacement bridge was not built until 1953, by which time, in this scenario, the trams were long gone!

The replacement bridge was not built until 1953, by which time, in this scenario, the trams were long gone!

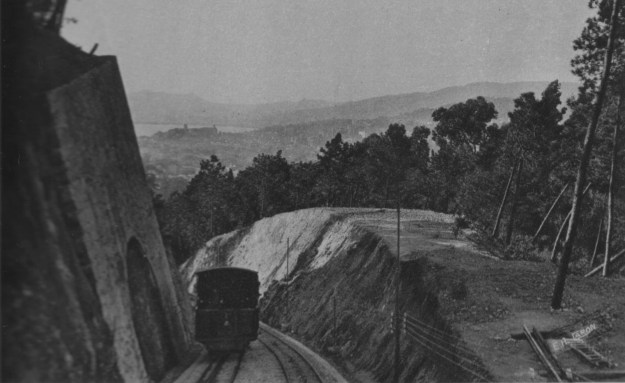

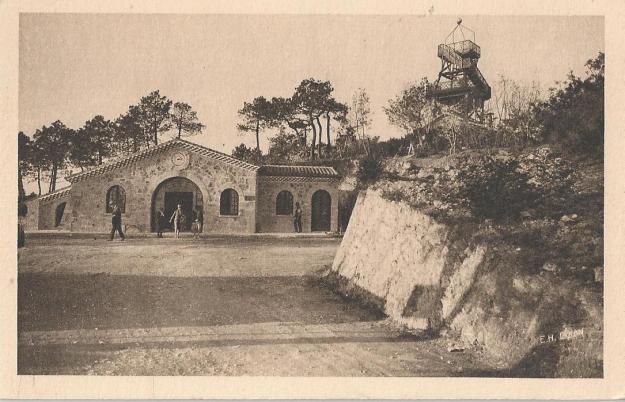

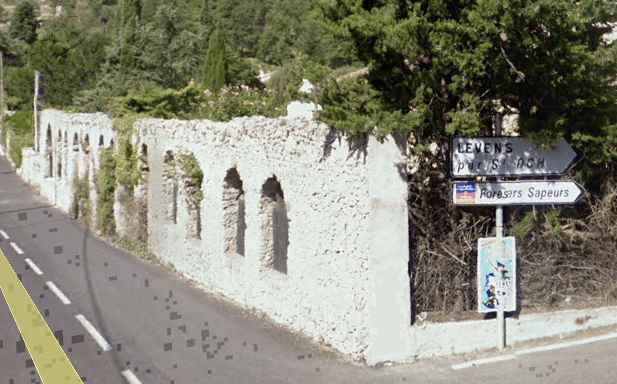

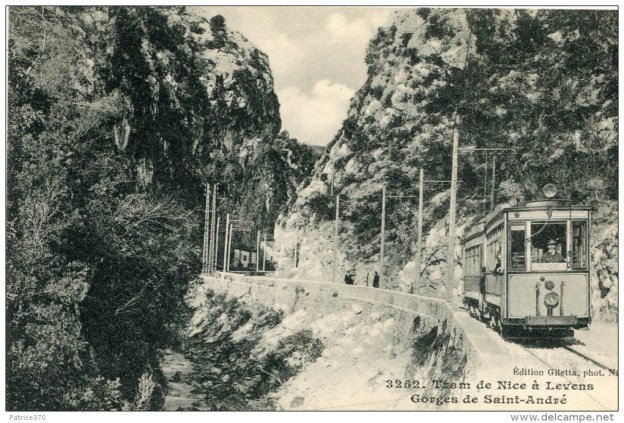

There were small deviations in the route of the tramway from the modern M19, although most of these were very short, only a matter of a few metres, and were usually the result of engineers seeking a path for the wider, newer road. This is true at La Clue, shown above.

There were small deviations in the route of the tramway from the modern M19, although most of these were very short, only a matter of a few metres, and were usually the result of engineers seeking a path for the wider, newer road. This is true at La Clue, shown above.

The shoreline was itself a tourist object: the panorama of the Mediterranean and the villages did not lack charm. On the heights of Beaulieu, the tram takes the pose with a platform abundantly stocked for the occasion.

The shoreline was itself a tourist object: the panorama of the Mediterranean and the villages did not lack charm. On the heights of Beaulieu, the tram takes the pose with a platform abundantly stocked for the occasion. Another view of the coast line with a motor-tram running on the Corniche at Villefranche sur Mer. The road was still made only of dirt and gravel, and in the shadow of the tramway there is a cart pulled either by a donkey or by a horse.

Another view of the coast line with a motor-tram running on the Corniche at Villefranche sur Mer. The road was still made only of dirt and gravel, and in the shadow of the tramway there is a cart pulled either by a donkey or by a horse. An attempt to provide a reversible train with two motor-trams framing a trailer-car on the line of Monte-Carlo. The power of the leading motor-tram proved to be inadequate for the load.

An attempt to provide a reversible train with two motor-trams framing a trailer-car on the line of Monte-Carlo. The power of the leading motor-tram proved to be inadequate for the load.  10 Schneider Type H buses similar to the one above were purchased. They were similar to those in use in Paris. They arrived in Nice in 1925. They were followed in a short period of time by 3 Somua MAT2 buses.

10 Schneider Type H buses similar to the one above were purchased. They were similar to those in use in Paris. They arrived in Nice in 1925. They were followed in a short period of time by 3 Somua MAT2 buses.

G 20x – Buire 1911

G 20x – Buire 1911