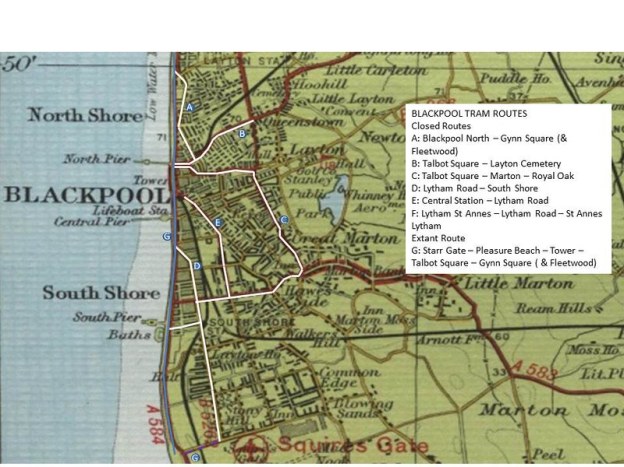

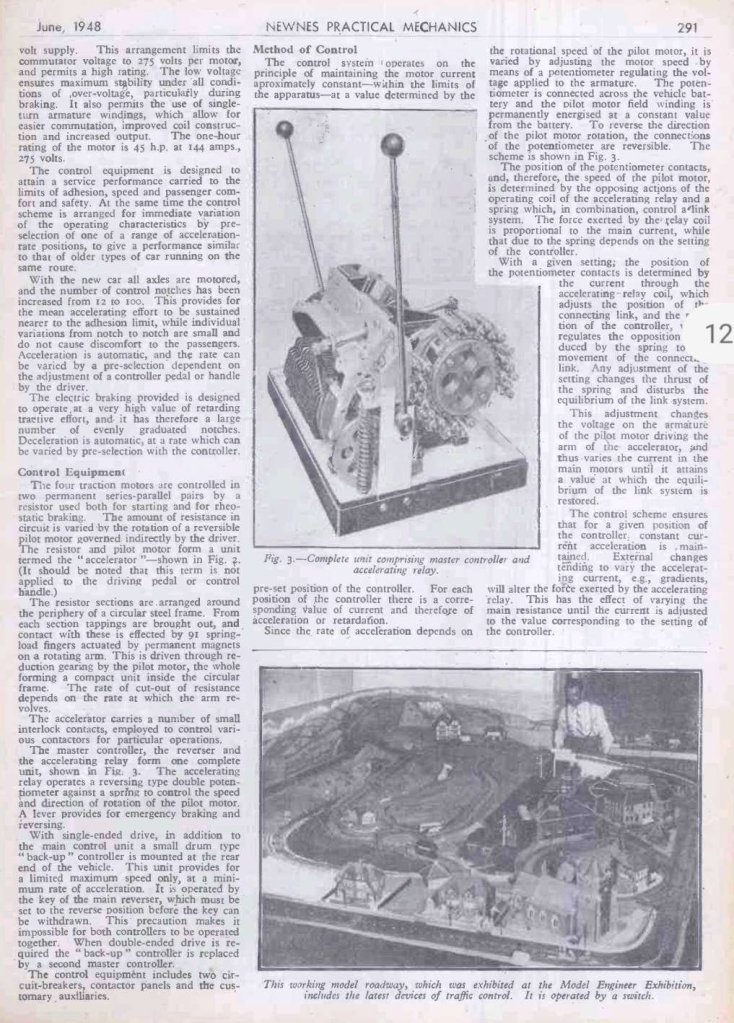

The ‘Modern Tramway’ reported in January & February 1963 on a relatively short lived experiment on Blackpool’s trams. The Marton route was an inland route through Blackpool which complemented the promenade route. It is route ‘C’ on the featured image above. [11]

The two articles were written by F.K. Pearson who suggested that his articles could perhaps have been entitled, ‘The Experiment That Didn’t Quite …‘ [1]

The Marton Route opened in 1901 but by 1938 it was approaching the end of it’s useful life, needing relaying and requiring a new fleet of 15 trams. A decision to undertake the work was deferred by Blackpool Town Council. War intervened and the existing trackwork was patched up to last a few more years.”By the time relaying could be considered again, technical progress had rendered the 1938 plan out of date, and the Marton route was chosen for one of Britain’s most interesting public transport experiments, the only attempt ever made to provide a tram service which by its sheer frequency, comfort and riding qualities could compete not just with the bus but with its future competitor, the private car.” [1: p14] Pearson’s article reports on that experiment, how near it came to success. and where it eventually failed.

Pearson continues:

“The story begins with the acquisition in 1945 by Crompton Parkinson Ltd. of a licence to manufacture in Britain certain equipment similar to that in the American PCC-car, the patents of which were held by the Transit Research Corporation in the USA. The experiments which followed were aimed at producing a vehicle which in silence, comfort, performance and soothness of riding would outshine any existing public service vehicle and rival that of the best private car. Blackpool already had modern trams, plenty of them, designed for the straight, open, track on the Promenade where even orthodox cars could give a smooth and quiet ride, but what was promised now was a tram with silent ‘glideaway’ performance even on grooved street track with frequent curves These route conditions, frequently met with in other towns, existed in Blackpool only on the Marton line, and Mr. Walter Luff the Transport Manager, made no secret of the fact that he hoped to persuade the Town Council to let him use the Marton route for a large-scale experiment that might have considerable repercussions on the future of tramways elsewhere in Britain; in short, to make it a show-piece.

The question of relaying the route was reopened as soon as the war ended, and the Town Council asked for comparative estimates for trams, buses and trolleybuses. Mr. Luff reported that to keep trams would cost £136,380 (£61,360 for new track £75,000 for 15 new cars), buses would cost £56,940 including road reinstatement and depot conversion, and trolleybuses would cost £87,360. He made no secret of his belief that the experiments then in progress would result in a vehicle superior to be existing tram, bus or trolleybus, and the Town Council, wishing to await the outcome of the trials, postponed a decision and asked that the track be patched up for a few more months.

The first objective of the new equipment was silent running on grooved street track. This was achieved by using resilient wheels with rubber sandwiches loaded in shear between the tyre and the wheel hub, which would absorb small-amplitude vibrations arising from irregularities in the track instead of transmitting them through the springing to the rest of the car, and in the process would achieve virtual silence. Furthermore, the resilient wheel allows slight lateral flexibility and reduced side friction between flange and rail, eliminating the usual scrub on curves and incidentally reducing flange wear to an extent which eliminated the need for re-turning the tyre profile between successive re-tyrings. These rubber-sandwich wheels could be unbolted and changed like those of a bus, necessitating a newly-designed inside-frame truck (type H.S. 44) produced by Maley & Taunton, Ltd., who also designed and supplied a “silent” air-compressor to eliminate another source of noise. The experimental trucks were placed under car No. 303, and on 26th April 1946, the B.B.C. took sound-recordings on street track on this and an older car, with the microphone only three feet from the wheels.With the old-type car the noise was considerable but with No. 393 it was practically nil.

Another traditional source of tramcar noise is the straight spur-gear drive, and this was replaced in the new truck by a right-angle spiral bevel drive, completely silent in operation, and requiring the two motors to be placed fore-and-aft in the truck. In many towns this alone would have led to a remarkable reduction in noise level, but Blackpool also knows how to keep spur gears quiet, and one wonders whether a right-angle drive (less efficient mechanically) can be justified by noise reduction alone. However, these and similar gears had been developed to such a pitch of efficiency for motor vehicles by their manufacturers (David Brown, Ltd.) that their use in a tram presented little difficulty. The technical and metallurgical problems had long since been overcome, and the only question was that of expense.

The other main objective was complete smoothness of acceleration and braking with private-car performance, and for this experiments were carried out by Crompton Parkinson, Ltd., using Blackpool car No. 208 to which the experimental trucks were transferred from No. 303 later in 1946. All four axles were motored, giving a possible initial acceleration rate of 3.5 mph. per second, and a smooth rate of change was achieved by arranging the motors in permanent series-parallel pairs and feeding them through a resistance having 94 steps instead of the usual eight. This resistance, mounted on the roof for ease of ventilation, was built around a circular steel frame with contacts on a rotating arm, turned by a small pilot motor, and the master control was by a joystick control by which the driver could select the rate of acceleration or braking required. Acceleration was automatic, for if the lever were left in a constant position the traction motors would accelerate or decelerate at constant current, yet it could also be varied by moving the stick, which explains the trade-name “Vambac” (Variable Automatic Multi-notch Braking and Acceleration Control) used for this equipment. Although inspired by that of the American PCC-car, it differed in several important respects, notably in that it enabled the car to coast. A car with this equipment, operating at the limit of its potential, was expected to consume about 4.5 units per car per mile (about 2.5 times the Blackpool average), but provision was also made to give a lower performance comparable to that of older trams if the two had to provide a mixed service on the same route. This reduced performance later became the Blackpool standard.” [1: p14-15]

It transpired that the complete car was ready to begin trials in December 1946, and the Town Council were very soon invited for a demonstration. The track was now in an awful condition requiring a relay or abandon decision.

“After considerable debate, the Transport Committee recommended that it be relaid, and the Town Council on 8th January, 1947, decided by the narrow margin of 25 votes to 21 to instruct the Borough Surveyor to proceed with the reconstruction of the track. Blackpool Town Council, then as now, included some shrewd business-men, and the fact that they were prepared to spend twice as much on keeping trams than would have been needed for buses is the most eloquent testimonial to car No. 208 and the impression which its revolutionary equipment and performance had made. For the first time, they realised, it was possible for a public service vehicle to offer a performance as good as the private car, and it was bound to be popular.

Work began straight away, using rail already in stock, followed by 600 tons of new rail and Edgar Allen pointwork to complete the job. Other traffic was diverted, with single-line working for the trams, and by the autumn of 1948 new Thermit-welded asphalt-paved track extended throughout the 3-mile route, save only for a short section held back until 1950 because of an anticipated new road layout. …

Meanwhile, the experiments with prototype car No. 208 continued, and by mid-1947 the car (specially equipped with fluorescent lighting) was ready for regular service, though frequently in demand for demonstration runs with visitors from other undertakings. The car was not used on Marton, for the Marton schedules were based on 78-seat instead of 48-seat cars, and for its first three years the new Marton track was traversed by the same cars that had worked the service since the mid-twenties, the gaunt, upright standard-type double-deckers, some of them with open balconies. These had no part in the Marton Experiment, and were due to disappear as soon as the heralded 15 new cars made their appearance.

At this point, compromises were made. Inflation meant that the planned new cars could no longer be obtained at anything like the estimated figure. Blackpool decided, for the sake of economy, to fit the new equipment to existing trams. Twelve surplus modern single-deckers were seen as suitable.

“These cars (10 to 21) had been built cheaply in 1939 for use during the holiday season only, with second-hand electrical equipment, wooden seats, no partition between driver and passengers, the minimum of interior lighting, waist-high sliding doors, and the upper half of the windows permanently open. … Scarcely had they entered service than war intervened and they were put in store, emerging in 1942 with full-length windows, doors and cabs for use on extra workings such as troop specials.

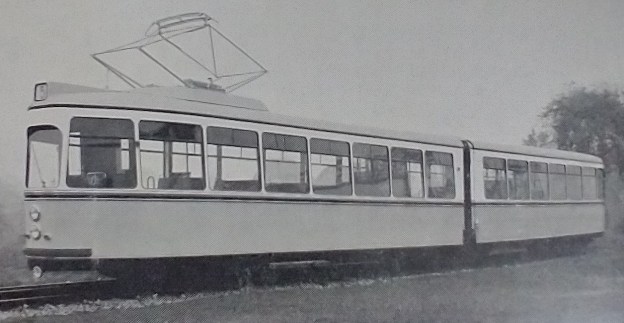

Late in 1947, the Corporation ordered 18 sets of H.S. 44 trucks and Vambac equipment, to enable them to equip sufficient cars to work the entire Marton service, including spares. Rigby Road Works set to work rebuilding the 10-21 series into a new silent-running fleet, soon to become known as the ‘Marton Vambacs’. … Internally, the cars were given soft fluorescent lights, comfortable seats upholstered in brown moquette, new floor-coverings, and tuneful bells. The first car, No. 21, appeared in December, 1949, and its lack of noise when running was quite uncanny, the only remaining sounds being the soft buzz of the “silent” compressor, the hissing of the motor brushes, the clicking of the accelerator contacts, and the sound of the trolley wheel. Even this latter was to have been eliminated in due course, for when the Marton overhead next needed renewal the round wire was to be replaced by grooved wire suitable for use with silent-running carbon skids, of the type used on trolleybuses.” [1: p17-18]

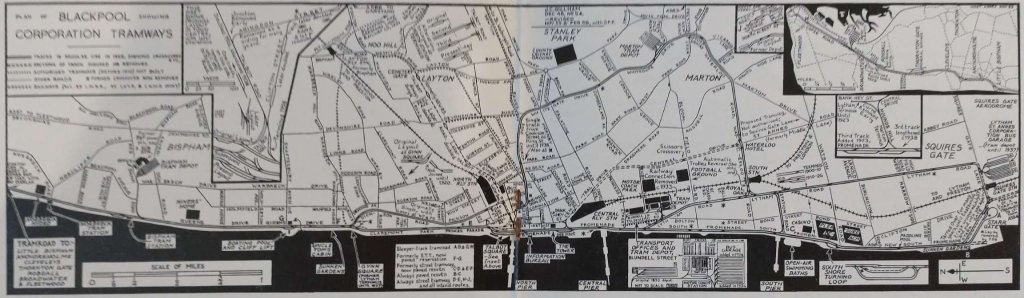

Pearson tells us that, “Conversion of the 12 cars, took just over two years, and during this period the “new” cars could be seen side by side with the older double-deckers. In the eyes of the tramway enthusiast, the “vintage” year of the Marton route was undoubtedly 1951, when about half the service was still in the hands of the venerable but never decrepit standard cars, and mingled with these like gazelles among heavier quadrupeds (a purist might say ‘octopeds’) were the first half dozen Marton Vambacs’.” [1: p18-19]

In the second installment of the story, Pearson moves on from the Autumn of 1951 to the early months of 1952, when conversion of trams No.10-21 was complete. With No. 208, this meant that there were 13 tram cars serving the Marton route which had to be supplemented at times by older double-deckers. The Council’s resources were by this time dedicated to introducing Charles Roberts cars on the Promenade.

From 1954, when the double-deckers had been withdrawn from service. The Marton route was worked by the 13 Vambac cars and, usually, three pre-war English Electric rail coaches.

It was unfortunate that rising crew costs began to become a significant issue for the Council.

“It may perhaps have been overlooked that the success of the PCC-cars on the street routes in the USA was nearly always coupled with one-man operation. … If passengers were satisfied with the new equipment, so we’re the platform staff.

The manufacturer’s claims were fully borne out, for the automatic acceleration and the provision of simple joystick and pedal control made the cars delightfully simple to drive, reducing fatigue to a minimum and eliminating some of the finer points of instructional training, since “notching up” no longer depended on the driver’s skill. However, it was rather curious to observe the use which different drivers made of the two braking systems, due, perhaps, to the admixture of pre-war and Vambac cars. The Vambac equipment provided a smooth and reliable brake effective down to a speed of less than two miles per hour, and was intended as the main service brake, the air brake being used only for the final stop, brake-shoe life being increased accordingly. This theory can be seen in everyday application on the Promenade, with the post-war cars, yet on the Marton Vambacs many drivers seemed to prefer the familiar air brake for service use, leaving what they termed the “stick brake” in reserve for emergencies. The smoothness of braking was thus dependent once again on the skill of the driver, and the smooth automatic deceleration purchased at such expense was wasted. Other drivers would use the Vambac brake to commence deceleration but would then change to air at a speed higher than intended by the designers for the final stop, and at least one journey made by the writer was marred by the Vambac deceleration being “interrupted” each time while the driver remembered to “put on the air.” One wonders why they were so fond of the air brake, but a possible reason lies in the fact that both terminal approaches were on slight gradients, where the air brake had in any case to be applied to hold the car on the grade, unlike the flat expanses of the Promenade.” [2: p51-52]

Another factor associated with the trial was that of maintenance of the tram cars.

“On the one hand, the provision of automatic acceleration and electric braking with minimum and controlled current peaks certainly eliminated the possibility of mishandling the electrical equipment, and must have reduced routine maintenance on the control gear, while the use of cardan shafts and totally-enclosed spiral bevel drives eliminated the troubles associated with the servicing of motor-suspension bearings and reduced the shopping periods. The service availability of the Vambac cars, judging from their daily appearances has been quite as high as that of the orthodox cars, and from this one can safely say that the new equipment must have been fully adequate in avoiding excessive servicing requirements. Moreover, while new and somewhat revolutionary equipment in any field has to cope with the burden of tradition on the part of older generation staff (human nature being what it is), this hurdle seems to have been surmounted with conspicuous success. On the other hand, obtaining spare parts must have been very awkward quite apart from the cost aspect for apart from Blackpool’s own 304-class cars no one else used the same equipment, despite all the hopes that were placed in it. In 1947 the potential British market for modern tramway equipment still included Leeds, Sheffield, Glasgow and Aberdeen, and anyone who had sampled the new equipment could be forgiven for seeing in it a germ of resurgence for tramways and a hope of further orders; but this was not to be. From this aspect, one begins to understand why the five extra sets of trucks and equipments were used as a source of spares rather than to equip further cars.” [2: p52, 54]

An interesting claim made for the new resilient-wheeled trucks was a saving in track costs. Although the track was abandoned before claims of a 30-year life could be tested, the track, “certainly stood up very well to 15 years’ life, and even at the end much of the track and paving was still of exhibition standard, Some of the sharper curves had been renewed, but this was only to be expected, for grooved rail generally lasts four times as long on straight track as on curves. On the sections with non-welded joints (usually) curves), there has been none of the usual deterioration of joints through hammer-blow … [found in] towns using heavy double-deck cars. The one unexpected phenomenon [was] the appearance of a few patches of corrugation.” [2: p54]

Pearson spent a short while alongside a corrugated stretch in Whitegate Drive, listening to sounds made by different types of car. He comments: “The passage of a Vambac car, even on the corrugations, was a process of exemplary quiet, but the occasional pre-war solid-wheeled car produced a roaring noise that told its own story.” [2: p54]

In his opinion, it was the “periodic traverse of the Marton tracks by these few pre-war solid-wheeled railcoaches (and by cars going to and from the Marton depot) that ha[d] given rise to the corrugations, and Whitegate. Drive residents who wrote to the papers in complaining terms can only have had these cars in mind. From the track aspect, it is therefore a pity that the original plan to equip 18 cars was not carried out, for the pre-war Blackpool cars, lacking track brakes, beget corrugations wherever they encounter solid foundations.” [2: p54-55]

A sequence of monochrome photos which were published as part of Pearson’s articles are shown below. The first four show something of the lifespan of the experiment. The following three show Marton Vambac trams at the various termini of the Marton Route.

Pearson states that:

“From the various engineering aspects – performance, silent running, case of control, routine maintenance, track wear, and availability – the Marton Experiment was therefore a success, even though it did not induce any other tramways to invest in similar equipment. The new equipment did all that the manufacturers claimed for it, and once the teething troubles were overcome ha[d] continued to function smoothly and efficiently for more than 10 years, with no further modifications of any importance. The Crompton Parkinson/Maley & Taunton Vambac/H.S.44 combination represented the ultimate development of street tramway practice in this country.” [2: p55]

Pearson considered that the VAMBAC trams had infinitely superior qualities both in riding and silence, so far as solid track was concerned. They were popular with the public – when abandonment was first proposed there was a significant outcry from customers who said that the VAMBAC trams were the finest transport service they had known. “Marton residents organised a massive petition to the Town Council for its retention, without any prompting from tramway-enthusiasts, in fact without their even knowing of it. The campaign was headed by Alderman J. S. Richardson, now the Mayor of Blackpool, and it is a sad coincidence that in his mayoral capacity Alderman Richardson himself had to preside at the closing on 28th October, 1962.” [2: p55]

It is Pearson’s view that the main reason for the failure of the experiment and the closure of the Marton tram route was the economic impossibility of two-man operation with only 48 seats per tram. While this was the main reason, there were at least three subsidiary factors: the cost of spare parts; the high energy cost of starting from rest; awkward relationships with other road users as visiting road users were no longer used to mixing with trams in their own communities.

He notes that crew costs in the 1960s accounted for an average of about 75% of a transport budget. Tram costs were higher than buses, the only way to offset that difference was to maximise the customer load-factor (this was effective on the Promenade) or to use tramway units of higher capacity than the largest available bus, so as to bring the cost per seat-mile down to a competitive figure. Had articulated cars been available that would have addressed the issue. “The 48-seat Marton Vambacs were below the minimum economic size … and throughout the experiment the route … had to be increasingly subsidised from the receipts of others. The Marton residents … enjoyed a superb service at considerably less than cost, and were naturally loth to lose it, but any suggestion of passing on the cost by raising the fares to a scale above that of the inland bus routes (as is done in summer on the Promenade) would clearly have been politically out of the question.” [2: p56]

Pearson’s own opinion, expressed in his article, is that the 12 year experiment proved that “revolutionary new concepts in tramway engineering [could] be applied to a normal street route as well as on the special field of the Blackpool Promenade, and Marton’s disappearance [was] a sad occasion for all who [saw] in the tramcar a still only partially-exploited form of transport. Looking back, it seems a repeat of a sadly familiar pattern; the engineering profession has delivered the goods, but the confused pattern of public transport in this country has never made full use of the potential made available by the engineers, electrical and mechanical, who gave practical expression to what [was], for most of us, still a composite dream.” [2: p56]

The Blackpool Trams website tells us that, “the first VAMBAC was withdrawn in 1960 as car 10 suffered accident damage and was scrapped soon after. The second VAMBAC withdrawn was 21 in 1961, which was withdrawn as a source of spare parts for the remaining trams, while 14 was also withdrawn for use as a driver training car. The writing was on the wall for the Marton Route, which had been isolated and lost it’s summer services to South Pier following the closure of the Lytham Road route in 1961, however, the remaining VAMBACS remained in use until October 1962 when the Marton route closed, with 11, 13, 15, 17 and 18 operating on the last day. The VAMBACS remained in Marton Depot and were joined by other surplus trams for scrapping in 1963. … One VAMBAC did manage to survive however, VAMBAC 11 was requested for a tour of the remaining parts of the tramway early in 1963 and was extracted from Marton Depot and made it’s way to Rigby Road. Following the tour, 11 was eventually preserved and found its way into preservation and is now at the East Anglia transport museum, where it still sees regular use today.” [3]

References

- F.K. Pearson; The Marston Experiment; in Modern Tramway, Volume 26 No.301; Light Railway Transport League & Ian Allan, Hampton Court, Surrey, January 1963, p14-19.

- F.K. Pearson; The Marston Experiment …. ; in Modern Tramway, Volume 26 No.302; Light Railway Transport League & Ian Allan, Hampton Court, Surrey, February 1963, p51-56.

- https://blackpool-trams.yolasite.com/vambac-trams.php, accessed on 28th July 2023.

- Newnes Practical Mechanics June 1948, p290-291; via., https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://worldradiohistory.com/UK/Practical-Mechanics/40s/Practical-Mechanics-1948-06-S-OCR.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiRjbjumbKAAxVUmFwKHYifAcUQFnoECB0QAQ&usg=AOvVaw24PI5xxITo516frkIf-ZsM, accessed on 28th July 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/blackpoolhistory/permalink/1632707573581243, accessed on 29th July 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/blackpoolhistory/permalink/691364481048895, accessed on 29th July 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/blackpoolhistory/permalink/2196698053848856, accessed on 29th July 2023.

- https://m.facebook.com/groups/2251377838346012/permalink/2713552708795187, accessed on 29th July 2023.

- https://www.videoscene.co.uk/blackpool-tram-mug-collection-2011-vambac-11, accessed on 29th July 2023.

- https://www.eatransportmuseum.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Leaflet2021Web.pdf, accessed on 29th July 2023.

- https://www.skyscrapercity.com/threads/blackpool-tram-system-u-c.572141/page-33, accessed on 29th July 2023.