Trams

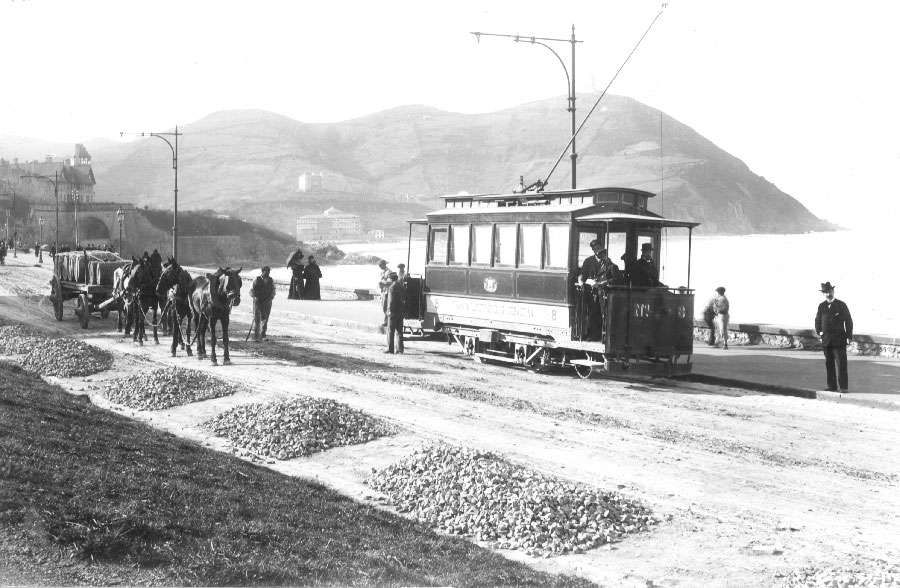

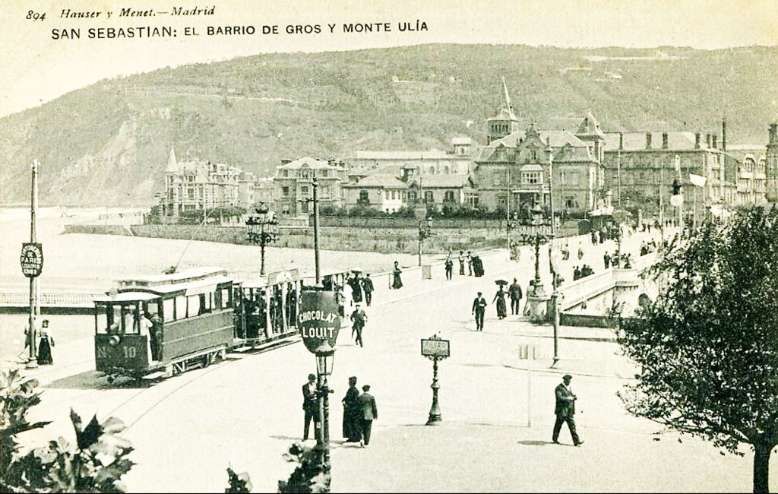

The first tramway in San Sebastian (Donostia in Basque), owned by La Compañía del Tranvía de San Sebastián (TSS), opened on 18th July 1887 as a metre-gauge horse-powered line. “It provided a service from the eastern suburb of Ategorrieta to and from the town centre and beach. The tramway was then extended beyond Ategorrieta to the town of Herrera, including 2.1 km of reserved track and a 100-metre tunnel, avoiding the severe gradients of the Miracruz hill. The single-track-and-loop line eventually reached Rentería in 1890.” [1: p185]

“The horse trams, known as ‘motor de sangre’ (literally blood engines), soon showed their limitations and for this reason the heads of the Company studied ways to modernise the transport system.” [2] It hoped to upgrade services by using steam trams but environmental concerns resulted in the local authority refusing the Company’s application. Instead, the Genèva-based Compagnie de l’Industrie Electrique et Mécanique was awarded the contract to build a line across the city. “A partial electric service was inaugurated on 22nd August 1887, and through running between San Sebastián and Rentería became a reality on 30th October. The rolling stock was built in Zaragoza using Thury (later Sécheron) electrical equipment, and consisted originally of motor trams 1-10 capable of hauling two trailers at 24 km/h. Several extensions were added to the tramway system until there were nine numbered services (1-9) all of which started from Alameda in the centre of San Sebastian.” [1: p185]

San Sebastian’s tramways were built to metre-gauge.

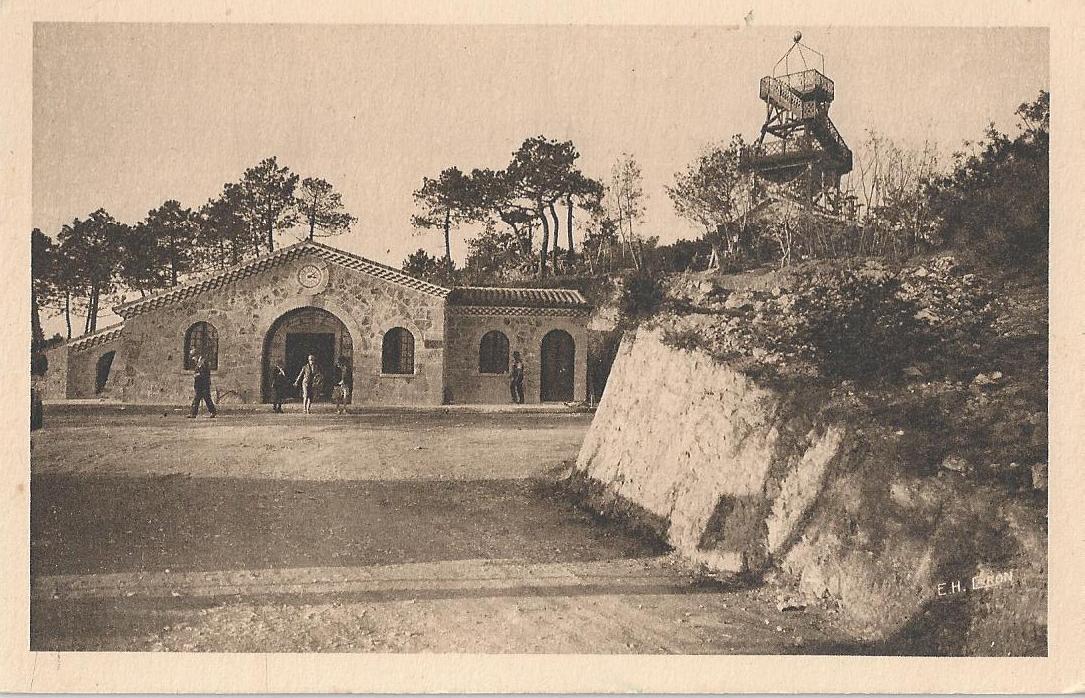

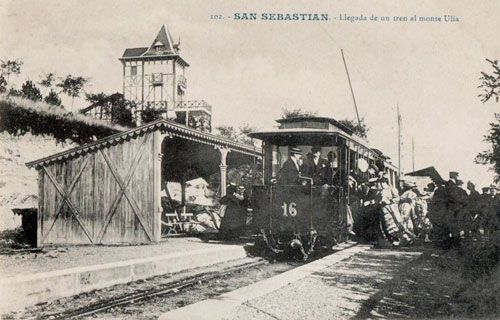

Barry Cross says: “Given the success of the urban tramways, it came as no surprise when the local entrepreneur, Vicente Machimbarena y Gorgoza, applied for the concession to build a 3.09-km ‘railway’ up the side of Monte Ulía, in 1893. The relevant legislation came into effect in 1895 and specified electric traction with overhead supply and the use of a rack to surmount a maximum gradient of 6%. However, when the engineer, Narciso Puig de la Bellacasa, was asked to undertake the initial surveys in 1896, they were for an adhesion line only. It was not until 1900 that sufficient money (ESP 530 000) had been raised to form the company, ‘Ferrocarril de Ulía’. Work on its construction began the same year, and the line opened on 9th July 1902. Although conceived as a railway, the completed metre-gauge line was merely an extension of the town tramways, with which it connected at Ategorrieta. As built, the continuous gradient varied between 4.5 and 5.5%, the only flat section being the mid-point passing loop.” [1: p185]

Cross continues: “The composition of the initial tramcar fleet accurately reflected the line’s tourist nature, since both the three two-axle motor trams and six trailers were of an open crossbench design known as ‘jardineras’. All cars were built in Zaragoza by Carde y Escoriaza, which equipped the motor cars with 2 x 52-kW motors and both rheostatic braking and electromagnetic track brakes. The early success of the line prompted the company to buy a further three motors and six trailers of the same design in 1907.” [1: p185]

The original tram service ran every 30 minutes. This was improved to 15 minutes from 1907. There were no intermediate stops on the climb up Monte Ulia. The tourist tram’s main purpose was to reach the summit.

Aerocar

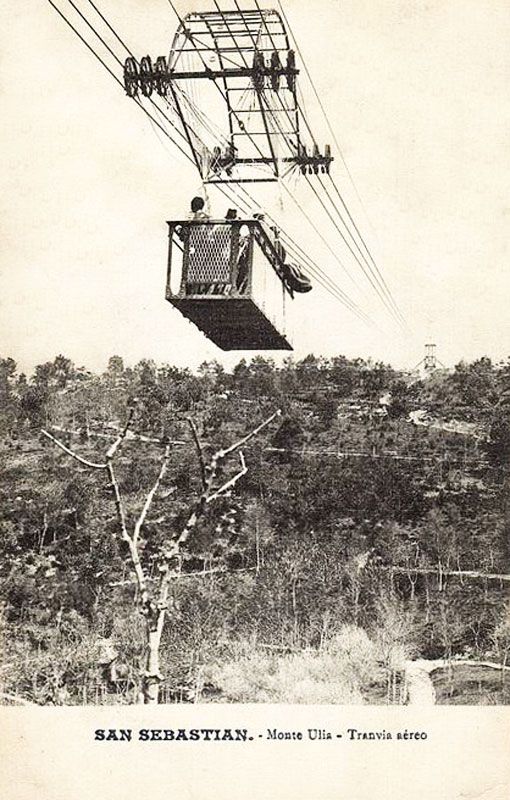

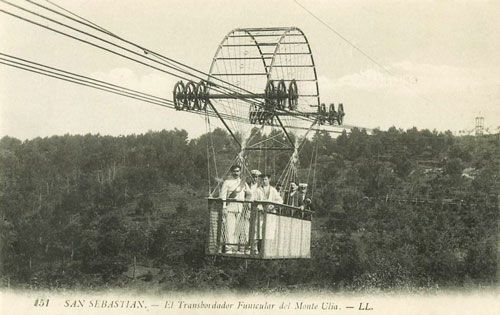

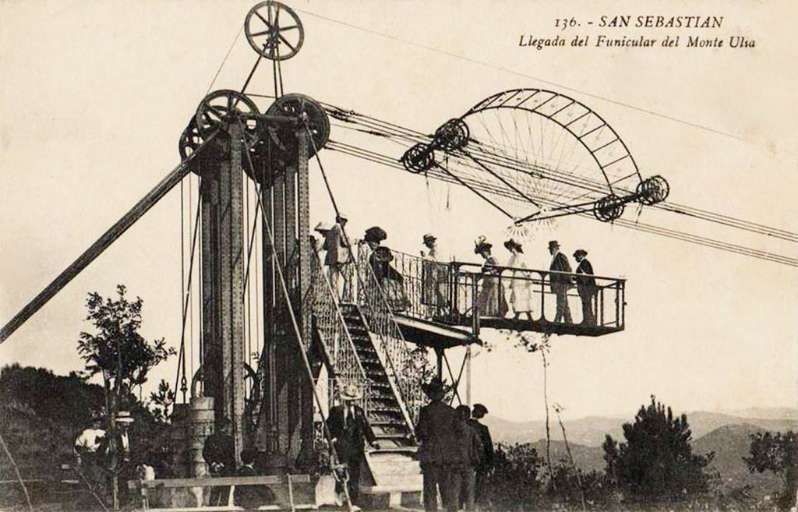

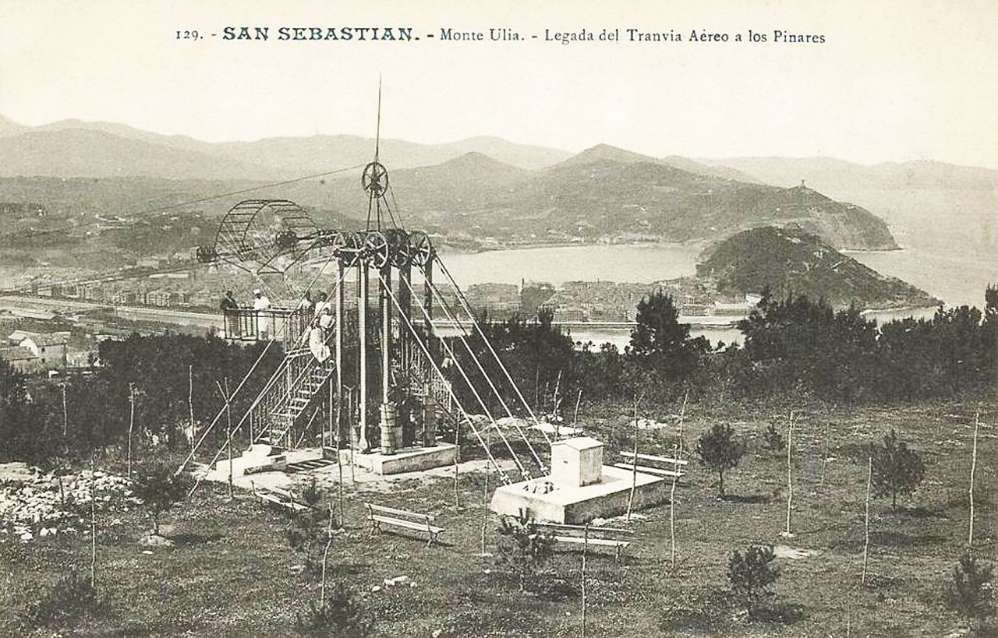

The ‘Ferrocarril de Ulía’ Company, while paying a 2% dividend in 1904 also increased its capital to ESP 1 million with a view to building “something variously described as a ‘Tranvía Aereo’ and as a ‘Transbordador Funicular’. It opened on 30th September 1907 and proved to be one of the world’s first passenger suspension cableways, similar in concept although not in design to the aerial cableway across the Devil’s Dyke near Brighton, which had been built 13 years earlier. It began near the Monte Ulía tram terminus and rose gently just above the tree-tops to the Peña de las Aguilas, from where visitors could obtain impressive views along the Cantabrican coast.” [1: p186]

The next four images are postcard views of the Monte Ulia Aerocar. ….

“The world’s first aerial tram was probably the one built in 1644 by Adam Wiebe. It was used to move soil to build defences. Other mining systems were developed in the 1860s by Hodgson, and Andrew Smith Hallidie. Hallidie went on to perfect a line of mining and people tramways after 1867 in California and Nevada. Leonardo Torres Quevedo built his first aerial cableway in 1887. His first for passengers was this one at San Sebastian Donostia in 1907.” [3] Wikipedia’s Spanish site suggests that the cableway closed in 1912. [4] certainly, “Monte Ulia’s tramway and cableway were to be seriously threatened from 1912 onwards by the creation of rival attractions on Monte Igueldo, the mountain across the bay. Earlier but unrealised schemes had envisaged running a tramway around the base of this impressive mountain on a sort of Marine Drive, and taking it out to sea on a jetty to the island of Santa Clara, where a casino was to be built. However, so ambitious a project never materialised, and it was later decided to build a funicular instead. This would run from Ondarreta to the top of Monte Igueldo and be provided with a connecting tram service via a short branch line from the Venta-Berri Alameda tramway operated by the TSS.” [1: p186]

After 1912, the Monte Ulia line became progressively more unprofitable and closed down in 1916. However the ‘Aerocar’ story does not end in 1916 in San Sebastian. For a little more, please head through this article beyond the next section about a funicular railway. …

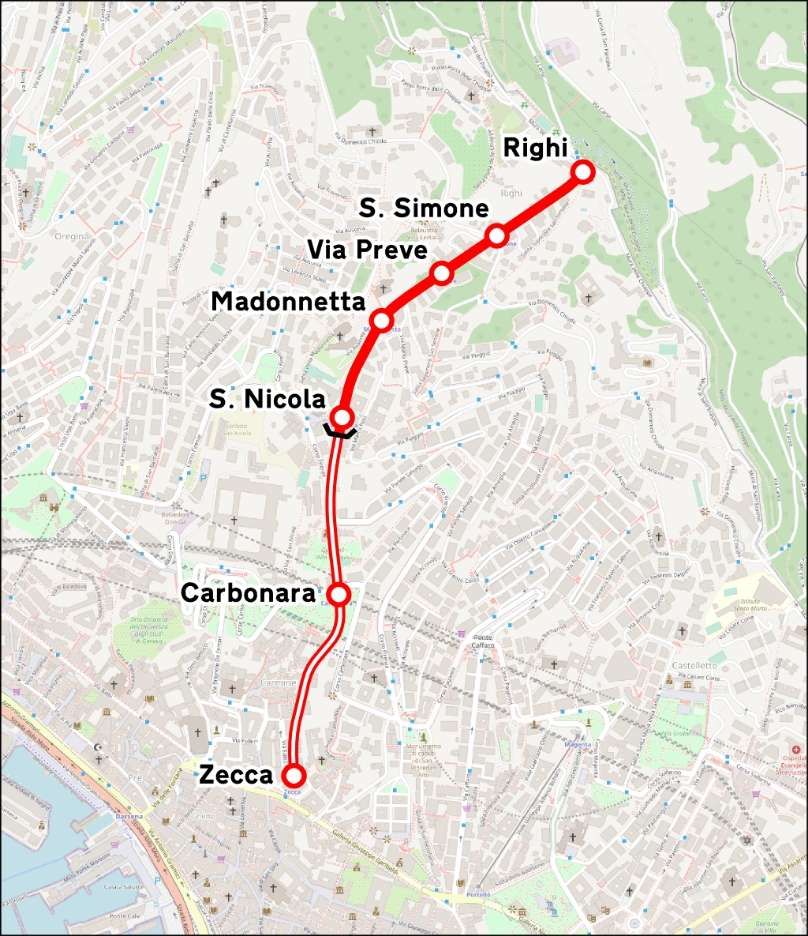

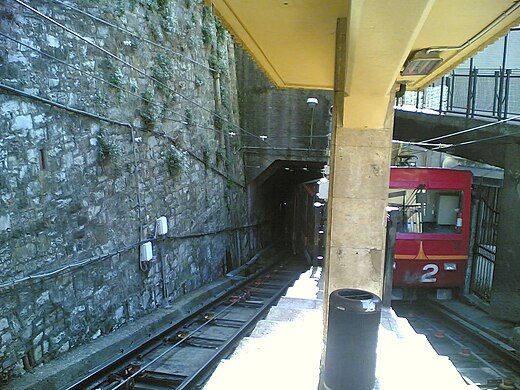

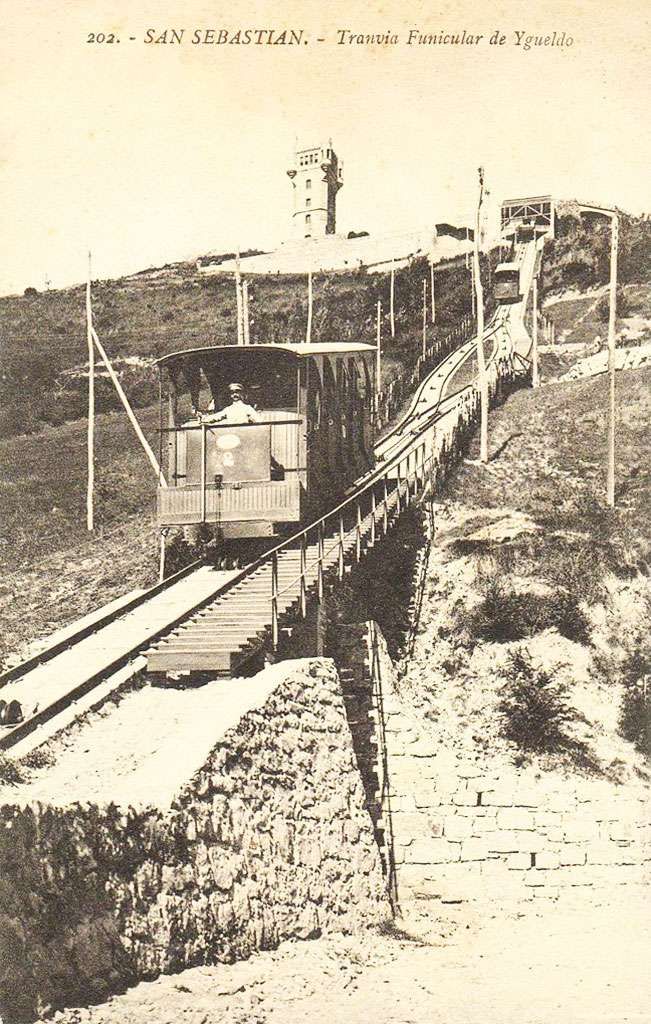

The Funicular de Igueldo

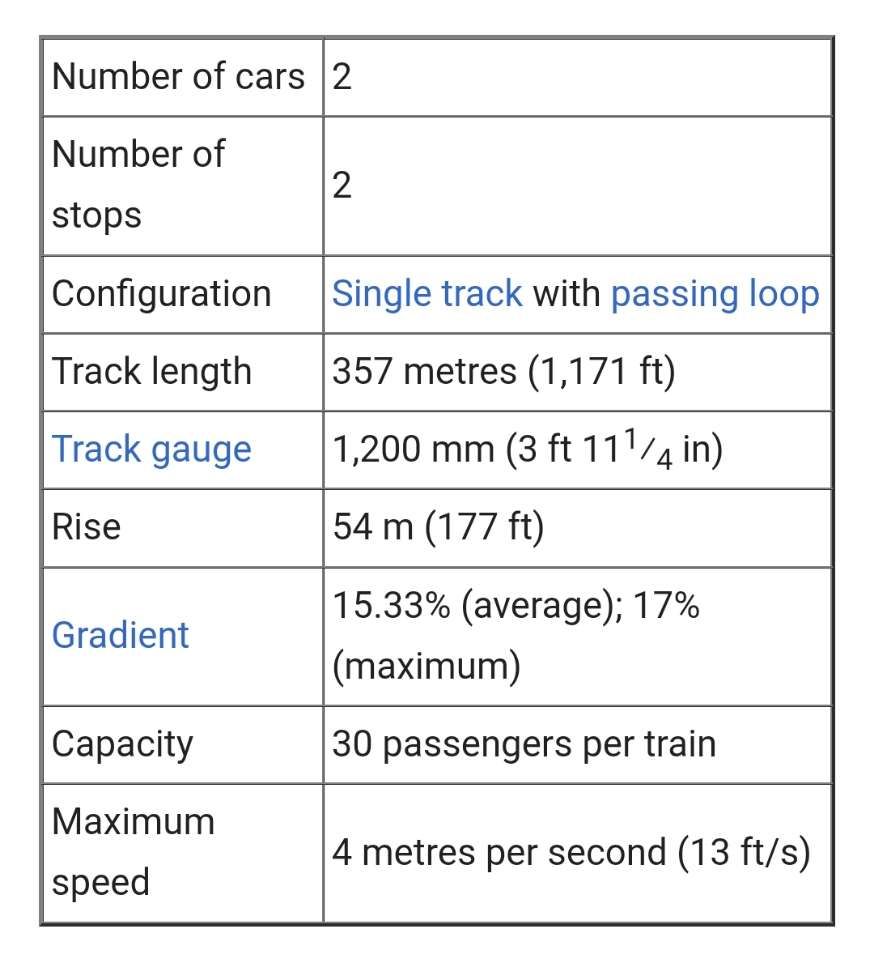

Cross tells us that “The main promoter of this new scheme was Emilio Huici, and the engineer in charge of the funicular project was Severiano Goni, who later built the Artxanda funicular in Bilbao. The Swiss firm of Von Roll supplied the electrical and mechanical equipment, leaving it to a local workshop to manufacture the funicular car bodies. Each car had five compartments with 30 seats and room for 20 standing. The line was 312 metres long and climbed 151 metres at gradients between 32 and 58%, making it the steepest of its kind in Spain.” [1: p186]

“The funicular opened for business on 25th August 1912, offering visitors to the summit the chance to dine at its restaurant until midnight, or to take “five o’clock tea” on a terrace overlooking San Sebastián. A return trip to the summit cost ESP 0.50, while from 5th September 1912 onwards the mountain enjoyed a through tram service from Alameda to the lower station of the funicular.” [1: p186]

The travelling distance of 320 metres connected Ondarreta Beach at the bottom, with the popular Monte Igueldo Amusement Park at the top, offering spectacular coastal views of La Concha Bay along the way. [3]

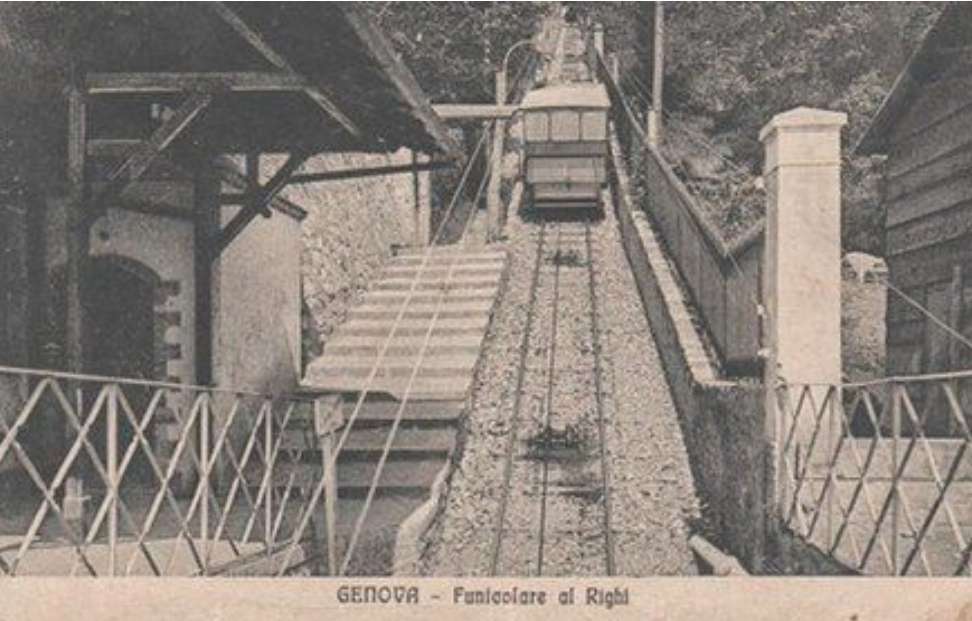

The next four images are postcard views of the funicular railway. …

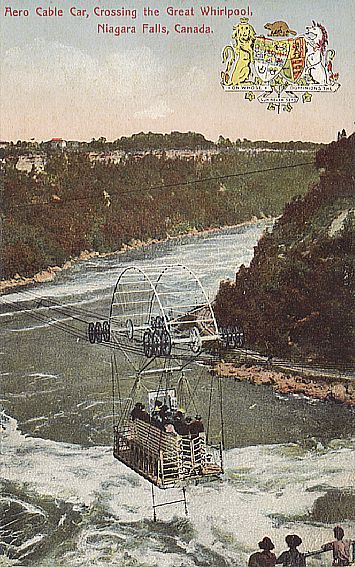

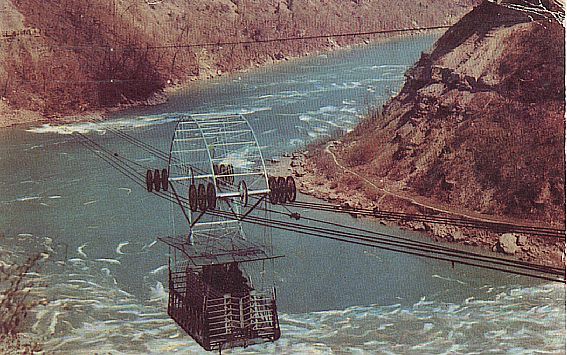

The Spanish Aerocar in North America!

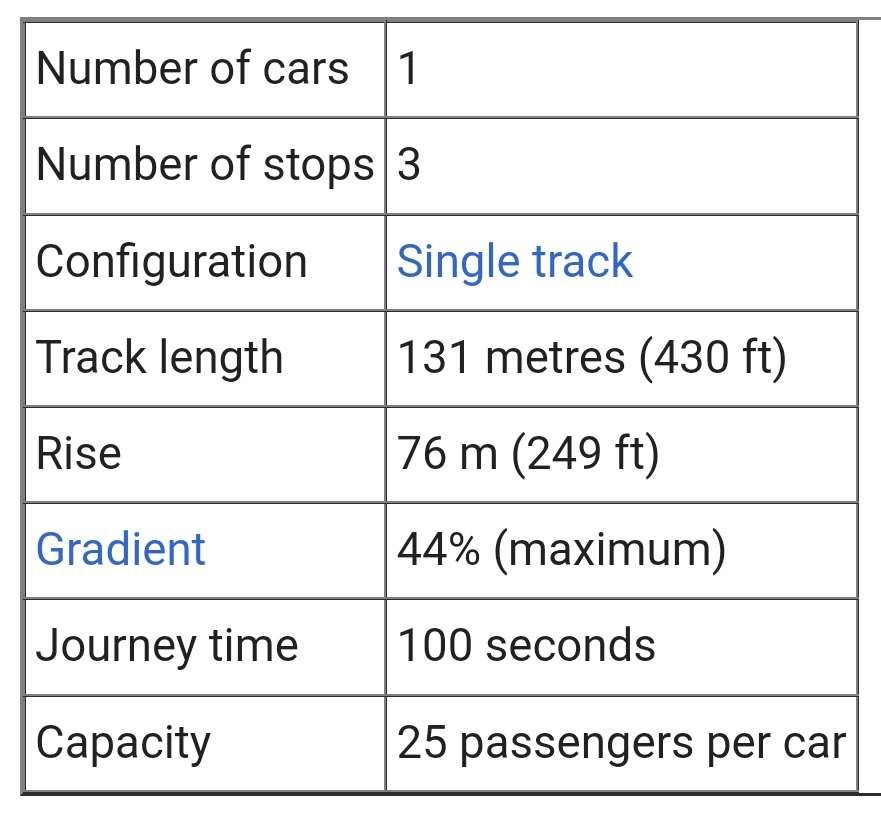

Cross points us to a similar but larger ‘Aerocar’ which was opened in 1915 in North America. It crossed the Whirlpool Rapids on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls. “It was built by the Spanish engineer, Leonardo Torres Quevedo, who, undaunted by the financial failure of his first cableway on Monte Ulía, had been persuaded to build a second. Its success can be measured by the fact that it survives to this very day.” [1: p186]The Canadian has been upgraded several times since 1916 (in 1961, 1967 and 1984).[1] The system uses one car that carries 35 standing passengers over a one-kilometre trip.[2]

The Canadian has been upgraded several times since 1916 (in 1961, 1967 and 1984). The system uses one car that carries 35 standing passengers over a one-kilometre trip. [5]

Three images of the Canadian ‘Spanish Aerocar’ follow below. …

The ride on the ‘Aerocar’ is featured on the Niagara Parks website. [7]

References

- Barry Cross; The Spanish Aerocar; in Light Railway and Modern Tramway, July 1992, p185-186.

- https://dbus.eus/en/the-company/background, accessed on 22nd March 2025.

- https://www.simplonpc.co.uk/SanSebastian.html#trams, accessed on 22nd March 2025.

- https://es.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tranv%C3%ADa_a%C3%A9reo_del_Monte_Ul%C3%ADa, accessed on 22nd March 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whirlpool_Aero_Car, accessed on 22nd March 2025.

- http://www.ebpm.com/niag/regpix/glry_niag_aero.html, accessed on 22nd March 2025.

- https://www.niagaraparks.com/visit/attractions/whirlpool-aero-car, accessed on 22nd March 2025.