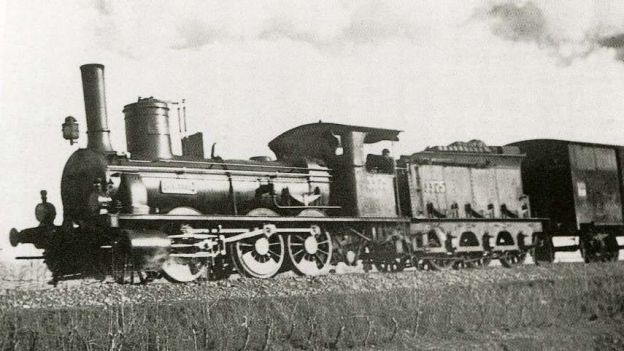

The featured image above is a 0-6-0 RM Locomotive No. 3375 ‘Pracchia’, with three driven axles and a tender, built in 1883 by Vulcan of Stettin. In 1905, it joined the FS fleet as Class 215, known as a Bourbonnais, along with 400 other locomotives with similar characteristics. It ended its career with the Porretta in 1927, © Public Domain. [26][27][1: p87] This class of locomotive was the predominant Class of engine used on the line between Cuneo and Limone in the early years of the line.

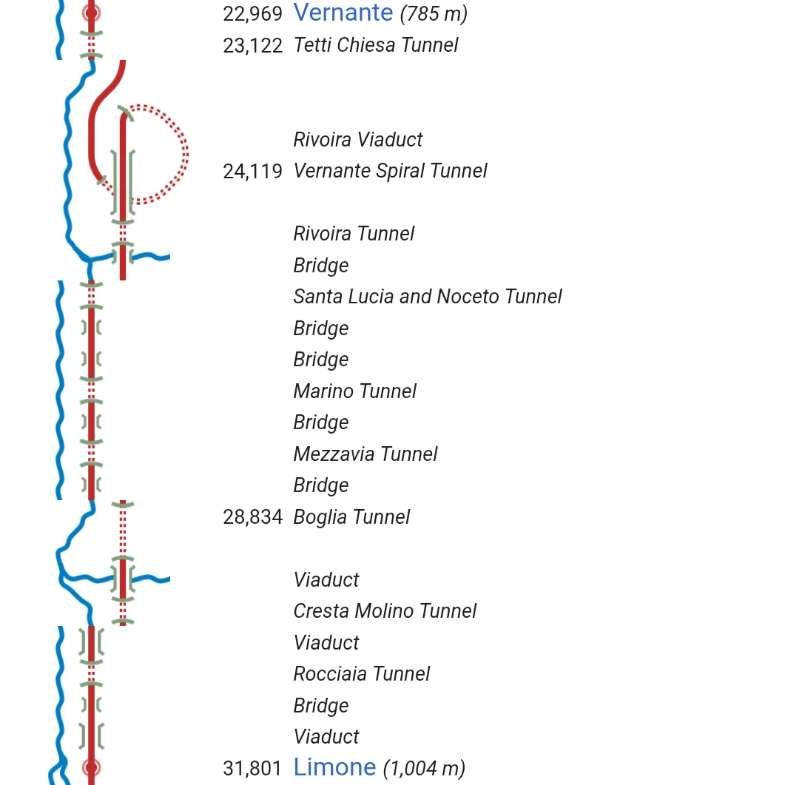

In the first article about the line from Cuneo to the sea we covered the length from Cuneo to Vernante. The article can be found here. [9]

The Line South from Vernante to Limone

Banaudo et al write that “It was only in 1886, after the creation of the Rete Mediterranea, that the work on the fourth tranche from Vernante to Limone was awarded. It was 8,831 m long and had a gradient of 203 m, which was to be compensated for by a continuous ramp of up to 26 mm/m. This value would not be exceeded at any other point on the line. On this section, the rail remained constantly on a ledge on the steep slope on the right bank of the Vermenagna, where it was anchored by eleven bridges and viaducts totaling sixty-three masonry arches, as well as nine tunnels with a combined length of 4,416 m, or just over half the route:” [1: p28]

- the Tetti-Chiesa tunnel which is 122 m long;

- the Elicoidale tunnel (the Vernante Spiral tunnel) is 1,502 m long;

- the Rivoira viaduct has fourteen 15 m arches and one 23 m arch;

- the Rivoira tunnel is 251 m long;

- the Santa Lucia viaduct has three 12 m arches;

- a short span masonry arch over a minor road;

- the Santa Lucia-Noceto tunnel is 348 m long with two openings;

- the Noceto viaduct has six 8 m arches;

- the Marino viaduct has two 8 m arches and two 12.50 m arches;

- the Marino tunnel is 202 m long;

- the Mezzavia viaduct, three 11 m arches;

- the Mezzavia tunnel is 444 m long;

- the bridge over the Ceresole valley has two 10 m arches;

- the Boglia tunnel is 1,086 m long;

- the San Bernardo viaduct over the Sottana valley has two 6 m arches and three 10 m arches;

- the Cresta-Molino tunnel is 335 m long;

- the Boschiera viaduct has twelve 10 m arches;

- the Rocciaia tunnel is 126 m long;

- the Rocciaia bridge is a single arch;

- the first Rocciaia viaduct has four 8 m arches;

- the second Rocciaia viaduct has eight 8 m arches.

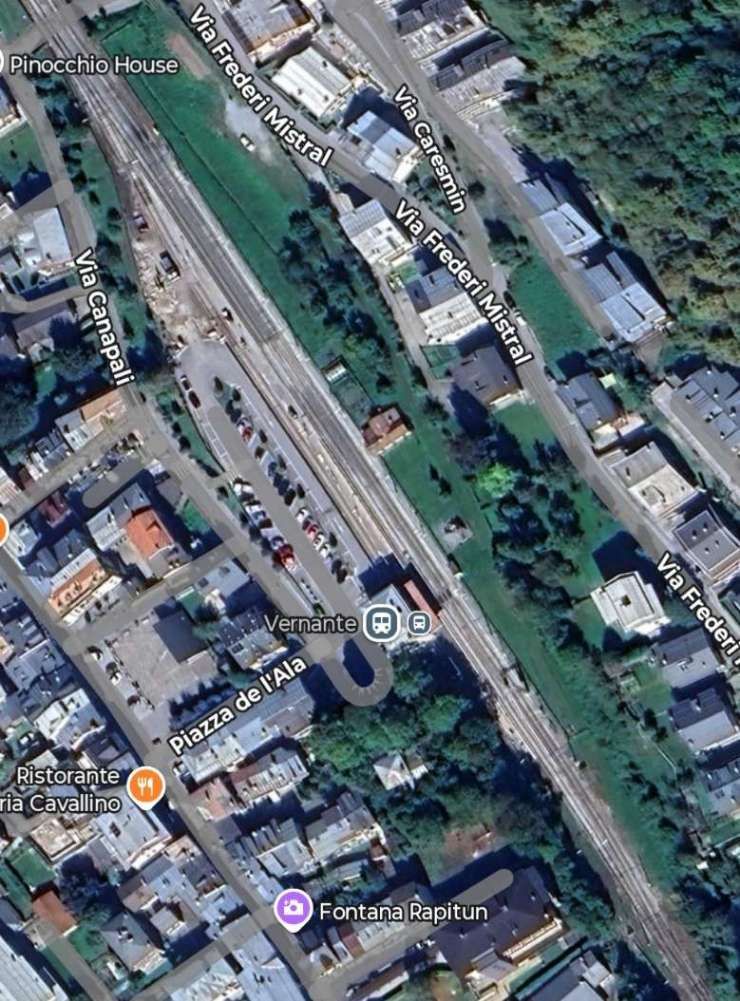

We start this next length of the journey at Vernante Railway Station and head Southeast.

Photographs showing the station building and the goods shed prior to its demolition can be seen here. [58] “Inaugurated in 1889, the station served as the terminus for the Cuneo-Ventimiglia line for nearly two years, until it was extended to Limone Piemonte. The passenger building features classic Italian architecture, with two levels. It is square, medium-sized, and well-maintained. Its distinctive feature is the two murals depicting scenes from the Pinocchio fairy tale, adorning its façade. The lower level houses the waiting room and self-service ticket machine, while the upper level is closed.” [58]

A photograph from the cab of a Cuneo-bound train arriving at Vernante. The passenger building is on the left with the goods shed beyond. [8]

The very short tunnel (Tette-Chiesa, 122 metres in length) at the Southeast end of Vernante Railway Station. [Google Maps, July 2025]

The southern portal of the Tette-Chiesa Tunnel seen from a Cuneo-bound train. Immediately beyond the far portal trains would have to stop to manually engage a point for the running line or the train would end up on the safety siding provided for runaways on the steep downward gradient. [8]

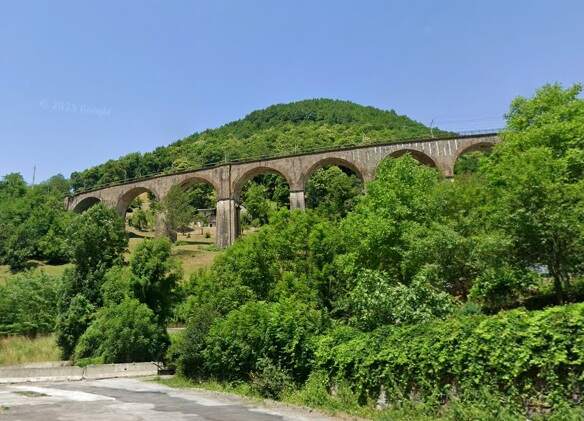

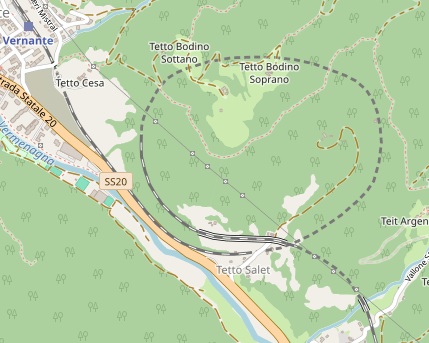

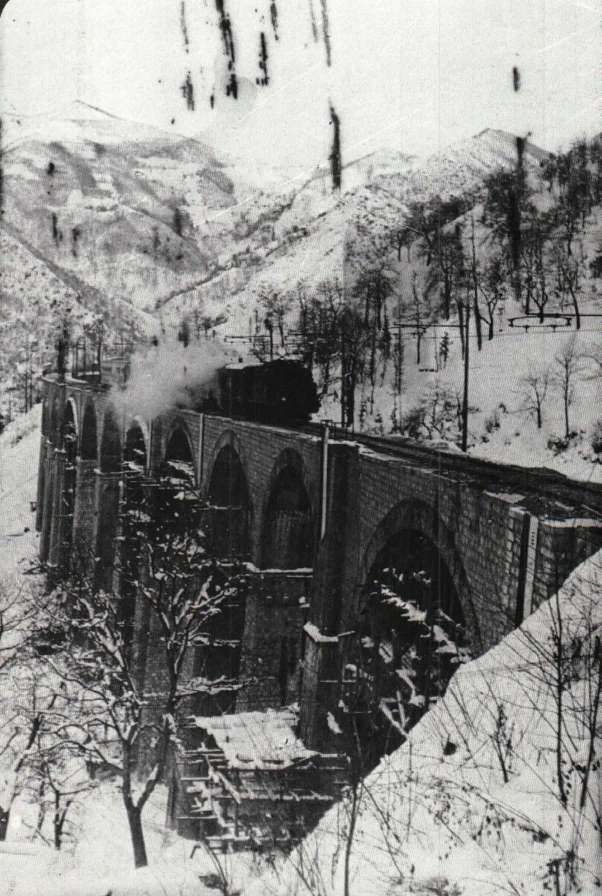

Banaudo et al comment: “Leaving Vernante, the track describes a complete spiral loop at Rivoira, which allows it to rise about fifty metres over a circular length of two kilometres. This loop includes the 1,502 m long ‘Elicoidale’ tunnel, which was completed on 30th December 1889, and the imposing viaduct over the Salet torrent. With its fifteen arches, from the top of which the rail dominates the lower level of the loop by 45 m, this structure can be considered by its proportions as the most imposing of the whole of line. [25] It is built entirely of cut stone, with the exception of the intrados of the arches which are of brick, and its seven central arches are reinforced at their base by a series of arcades forming an additional level, following a technique very popular in the 19th century.” [1: p30] The lower arcades are seen clearly in the 1929 postcard below.

The portal of the spiral tunnel at the top-left of the satellite image above, seen from a Cuneo,-bound train. Trains heading for Tende and beyond gained height while turning through 360 from the tunnel portal shown in the image immediately above. [8]

The Southeast portal of the short tunnel at the bottom-right of the satellite image above. This is the Rivoira Tunnel. [8]

The Santa Lucia viaduct just to the Southwest of Rivoira Tunnel. [8]

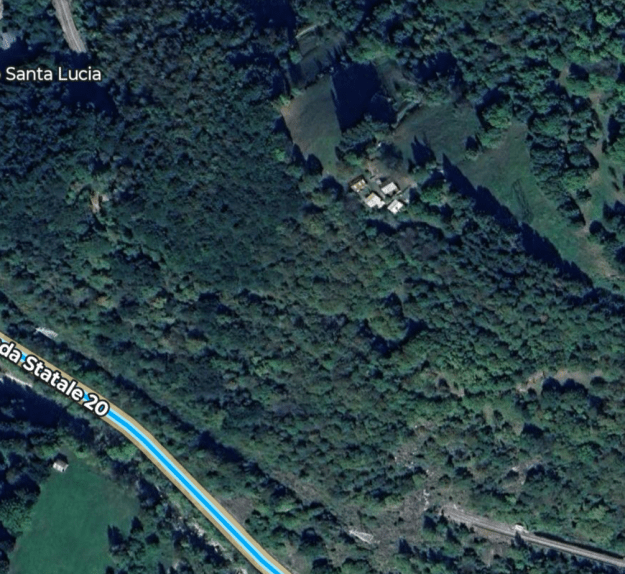

The Santa Lucia & Noceto Tunnel runs diagonally across this extract from Google’s satellite imagery. [Google Maps, July 2025]

The Southeast Portal of the Santa Lucia & Noceto Tunnel seen from the cab of a Cuneo-bound train. [8]

The Noceto Viaduct to the Southeast of the Santa Lucia & Noceto Tunnel spans a local stream. [8]

This bridge is a short distance further Southeast. [8]

The Marino Viaduct further to the Southeast. All these views look towards Vernante and are taken from the cab o a Cuneo-bound train. [8]

The Southeast portal of the Marino Tunnel. [8]

Another viaduct over a short side valley to the Southeast of the Marino Tunnel, this is known as the Mezzavia Viaduct. [8]

The East portal of the Mezzavia Tunnel. [8]

Immediately to the East of the Mezzavia Tunnel the line bridges a stream before entering the Boglia Tunnel. The bridge spans the Ceresole valley. [8]

The Boglia Tunnel carries the line around a significant curve. This is the South-southwest portal of the tunnel from the cab of a train which has recently left Limone. Trains from Cuneo enter the tunnel traveling East and leave in a south-southwesterly direction. Just beyond the South-southwest portal the line bridges another side road serving a number of hamlets. It is the San Bernardo viaduct over the Sottana valley. [8]

The bridge shown in the image immediately above is at the centre of this satellite image. The tunnel to the North-northeast is Boglia Tunnel, that to the South-southwest is Cresta Molino Tunnel. [Google Maps, July 2025]

The Cresta Molino Tunnel curves throughout its length (see below). Towards the South portal, it has an open gallery facing out into the valley. [8]

The Cresta Molino Tunnel curves form a South-southwest bearing to just to the East of South along its length. The gallery shown above is at its southern end. [Google Maps, July 2025]

The South portal of the Cresta Molino Tunnel is the South end of the gallery. [8]

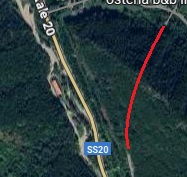

After a very short length of track open to the elements, the line enters another short tunnel, the Rocciaia Tunnel. This tunnel is also on a curve with the line leaving the tunnel heading Southeast. [Google Maps, July 2025]

The Southeast portal of the Rocciaia Tunnel. After this tunnel the line crosses a bridge and two viaduct on its way into the station at Limone. [8]

The length of the line from Rocciaia Tunnel to the station throat at Limone is shown on the satellite image below. The parapet railings associated with the Rocciaia Bridge can be seen on the image of the South portal of the tunnel above. There are then two viaducts, as shown on the satellite image below. They cast shadows onto the valley side to the east of the line.

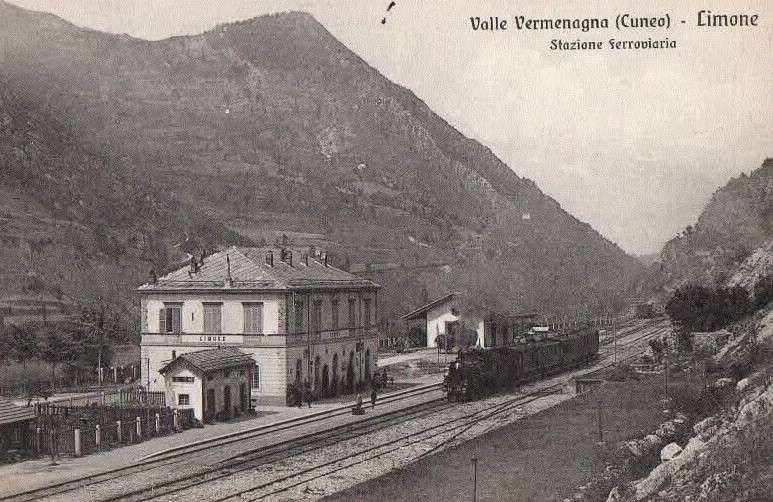

The good shed at Limone Station with the passenger facilities beyond. This image is a still from a video taken from a train heading for Breil-sur-Roya. [31]

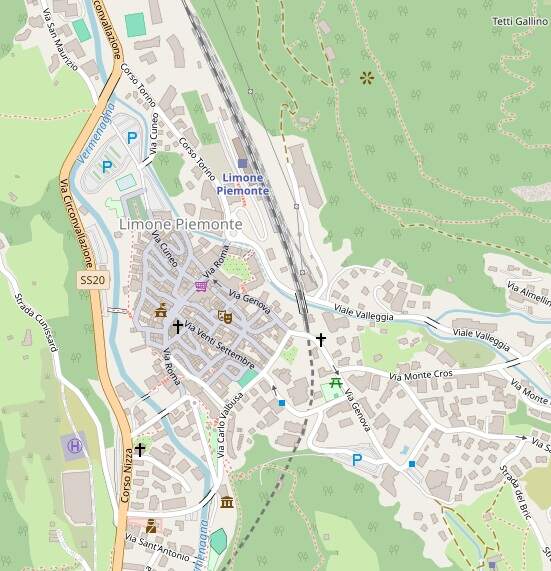

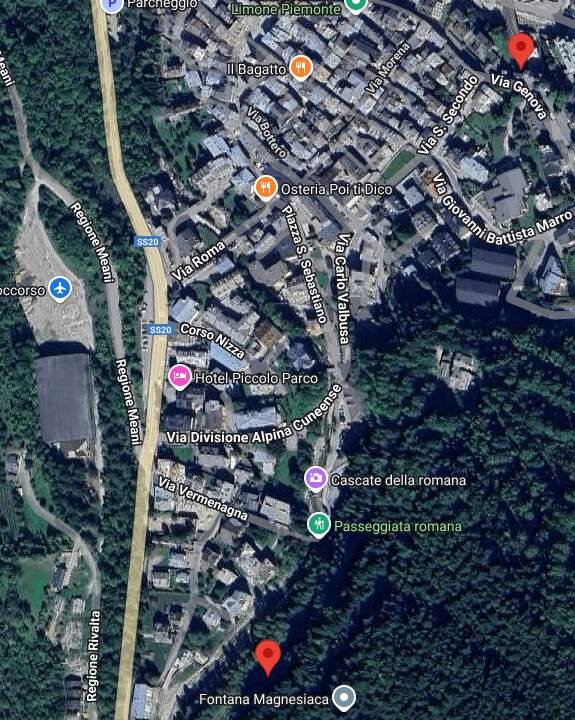

Limone Railway Station as it appears on Google’s satellite imagery. [Google Maps, July 2025]

A few more photographs of Limone Railway Station can be found here, [22] here, [23] and here. [24]

Express services took 1 hour 30 minutes to travel from Cuneo to Limone, mixed goods and passenger trains were scheduled to take 2 hours. Services from Limone to Cuneo were scheduled for 1 hour 20 minutes and 1 hour 50 minutes respectively [1: p31]

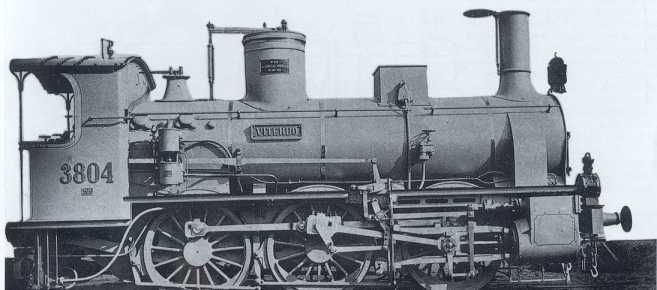

Banaudo et al tell us that a single third class ticket between Cuneo and Limone cost 1.65 lire. The service was deemed to be a local service and as a result the RM allocated older stock to the line, “consisting mainly of single-axle coaches, side door stock, and brake vans acquired from other companies. Traction was provided by 030 [in the UK these would be 0-6-0] locomotives coupled to two- or three-axle tenders, from the RM 3201 to 3550 series (future 215 FS Class),” [1: p31] out-stationed to the Cuneo shed by the Turin Shed. These locos had a range of different manufacturers in Italy, France, Belgium, Great Britain, Austria and Germany. [1: p31]

The construction costs for the length of line from Cuneo to Limone “did not exceed 10 million lire, a remarkable figure given the difficulty of the work and the number of engineering structures completed over nine years: nineteen bridges and viaducts, fourteen tunnels, and a large number of culverts, aqueducts, road overpasses and underpasses, and level crossings. The buildings of the seven stations are of classical design, conforming to the standard plans with hipped roofs used in Italy, as are the twenty-four ‘caselli’, roadside houses, distributed along the line near the level crossings and the main underpasses to house the track maintenance workers and their families. The bridges and viaducts, with the exception of two brick structures, are made of stone masonry with brick arch vaults and metal angle railings. The single track tunnels are lined with brick vaults and dressed stone portals, except where the solidity of the ground allows the exposed natural rock to be preserved.” [1: p32]

Banaudo et al note that “the first years of operation were not easy, … snow and falling rocks sometimes hampered train traffic. On 2nd October 1898, following torrential rains in the high valleys of Piedmont, the Gesso overflowed and the bridge between Boves and Borgo-San-Dalmazzo was destroyed. By December, the installation of a temporary wooden bridge by contractor Salvatore Vignolo of Genova-Sampierdarena allowed service to be restored. A permanent structure would be rebuilt the following year in the form of a single-span 74-metre steel truss bridge.” [1: p32]

Limone to Vievola: Crossing the Col de Tende

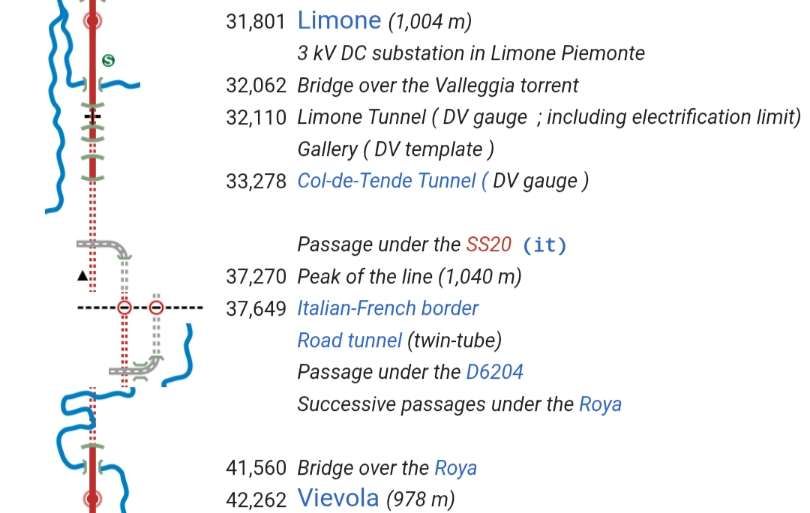

The next length/tranche running South from Limone was 10.5 kilometres long and extended the line from Limone to Vievola(in the valley of the River Roya).

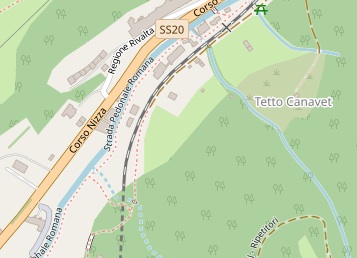

Looking into Limone Railway Station from the tunnel mouth South of the Station. A short two-span bridge

Omitting mention of the section of the bridge over the road, Banaudo et al tell us that, leaving Limone Station, “the line crosses the San Giovanni valley … on a 13-metre masonry single-arch bridge, then enters the 423-metre-long Limone Tunnel which passes under the San Secondo hill. A 26 mm/m gradient leads to the tunnel under the ‘Colle do Tenda’ … where the gradient eases to 2 mm/m as far as the highest point on the line, 1040 [metres above sea level, in the tunnel]. From this point a 14mm/m gradient extends to the South portal of the tunnel … at 990 [metres above sea level]. At the Southern end of the tunnel, … a single-span 19.90 m steel truss bridge crosses the Roya River. … A short 25 mm/m slope then leads to Vievola Station.” [1: p34]

The railway is protected by two galleries at the South end of Limone Tunnel. The first effectively extends Limone Tunnel southwards. This is the South portal seen from a train approaching Limone Railway Station. [8]

Also seen from the South from the cab of the same train, this is the South portal of the Short second gallery. The gallery entrance to the tunnel above can be seen only a very short distance beyond this gallery to the North. [8]

A level-crossing on the line just to the South of the galleries illustrated above and also seen from a Limone-bound train. [8]

The northern approach to the tunnel under the Col de Tende as it appears on Google’s satellite imagery. Sadly, the tunnel mouth, in the top-left quadrant of this image, is in shade. [Google Earth 3D, July 2025]

Open Streetmap shows the line heading South into the tunnel. [32]

This image shows the North Portal of the tunnel under the Col de Tende. It is taken from the cab of a train heading for Breil-sur-Roya in the late 20th century. [31]

Interestingly, the two tunnels on this length of the line are large enough to accommodate two tracks – this facilitates ventilation but also allows room for expansion should traffic levels later require it. [1: p34]

While all the previous construction tranches ended up in populated locations, Vievola was just a place name in the commune of Tende with a few farms and a chapel dedicated to the Visitation of the Madonna scattered in a small green area at the confluence of the Roya and the Dente rivers. Nowhere was available to house workers on the railway. So before works began at the southern end of the tunnel under the Col de Tende, the contractor had to construct a temporary village.

After initial surveys were completed late in 1889, tunneling under the Col de Tende began at both ends. Banaudo et al explain that the 8.1 kilometre tunnel passed through various different strata: “Jurassic, Triassic and Cretaceous limestone, Permian quartz, Liassic marly schists and Eocene sandstone. The work progressed normally until September 1893, when the works reached a dislocated gneiss bed interspersed with clayey layers made fluid by the infiltration of water from the Roya, whose bed passes three times above the axis of the tunnel. Soon, mud floods invaded the approach tunnel with each attempt to advance over the course of ten months. The working face advanced only a dozen meters, while some forty flows of various materials obstructed the tunnel, sometimes over a length of 40 metres, while the vault suffered as much as 1.7 metres subsidence in places.” [1: p32][33]

The works from the South were suspended in July 1894 about 1.6 km from the tunnel mouth. Attempts were made to divert ground water from the route of the tunnel with little success and a further collapse occurred in October 1894. [33]

Meanwhile, work progressed from the North until at about 2.7 km from the tunnel mouth ground water started entering the tunnel at a rate of 60,000 litres/minute. The bed of the River Royal above the tunnel began to collapse. The contractor admitted defeat and refused to continue work on the line. [1: p34][33]

After a few months delay and with the work now being undertaken by the state a renewed effort was made to take the work-faces forward. The solution was to bore the tunnel using compressed air drills inside a metal shield and with water being removed by a parallel collector channel. It took 470 days to progress the works beyond the difficult strata. Banaudo et al say that once work was 43 metres beyond the critical zone, the contract was handed back to the original contractor on 31st March 1896. The total delay was 34 months at a cost of 300,000 lire! [1: p34][33]

On 15th February 1898 at 1pm, the team working from the North end of the tunnel broke through the remaining rock to meet the team working from the South.Remaining contract works would mean that opening of the line between Limone and Vievola would not take place until 1st October 1900. [33][34: p116][1: p35]

When trains left the confines of the 8 kilometre tunnel their crews were probably grateful for the fresh air. I cannot imagine what it must have been like for the crews of steam engines on the line. Electrification could not come soon enough. “The tunnel was equipped with a two-wire contact line when the electrification of Cuneo Gesso – San Dalmazzo di Tenda line in three-phase alternating current 3.6 kV – 16⅔ Hz took place with electric traction starting from 15th May 1931.” [33][35: p171-172]

South of the tunnel, the railway crosses the River Roya before entering Vievola Railway Station.

This satellite image shows the line leaving the tunnel (at the very top of the image) and crossing La Roya (towards the bottom of the image). [Google Maps, July 2025]

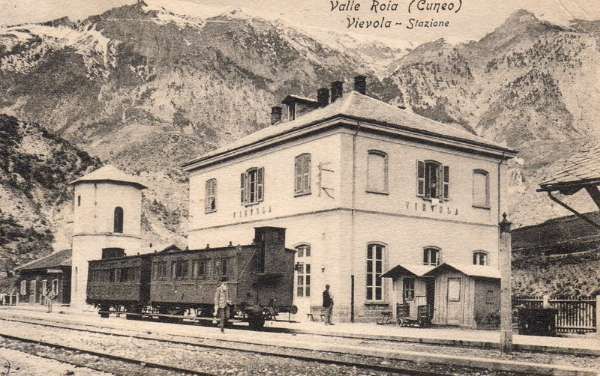

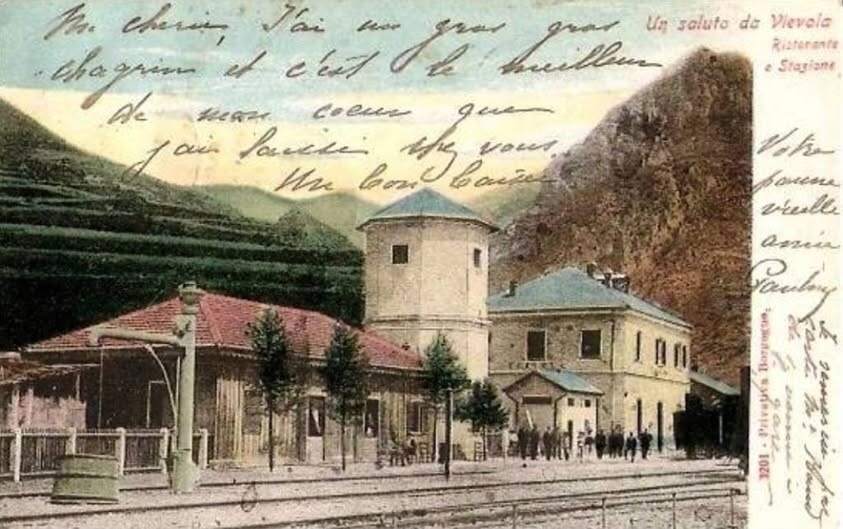

The completion of the fifth contract still required the development of Vievola station. It was to be built on a large platform created using spoil from the tunnel works on a vast embankment formed from the tunnel spoil, with an underpass provided for the then SS20 (now E74/D6204) and shown above.

The approach to Vievola Railway Station from the South, as seen from the cab of a Northbound train. [8]

Banaudo et al tell us that, at the station, “The two platform tracks for passenger service were supplemented by two sidings and a dead-end track running alongside the goods shed and the military platform. At the western end of this section, a small wooden shed, an 8.50 m temporary turntable, a water tower, and two hydraulic cranes allowed locomotives to use this temporary terminus as they would at any terminus. In the same area, a wooden buffet building was built, which a shrewd manager, no doubt hoping to take advantage of the cosmopolitan movement of connecting passengers, dubbed a ‘restaurant’ in French.” [1: p40]

Vievola was a railway terminal for traffic to and from Piedmont and a hub for road connections onwards to Nice and Liguria. Banaudo et al point us to a magazine published in 1899, which mentions a trial of a steam-powered road vehicle which it was hoped would provide a service to Nice and the coast until such time as a railway was built. [1: p40][37] The service was a trial organised by the House of Ascenso et Cie, and ran from Vievola to Ventimiglia. The journey, lasted a total of six hours, including a 43-kilometre climb. The vehicles used were Scotte trains. The car wagon carries a 27-horsepower engine and seated 14 passengers; it also towed a second 24-seater wagon. [1: p40][38]

“Due to their slowness, the difficulties of driving cars on the narrow roads of the time and the damage caused to the cobbled and cylindered roads,” [1: p40] the ‘Trains Scotte’ were not a success, they probably did not circulate for more than a few months or weeks. ….

The next length of the line can be found here. [46]

RM 3201-3519 (FS 215) Locomotives

Banaudo et al tell us that throughout the 19th century and on into the 20th century passenger stock and freight wagons were unchanged. Improved 0-6-0 tender locomotives came available as they were delivered by the Breda and Mavag companies, these were more powerful and faster locomotives than the RM Nos. 3201 to 3519 (which became group 215.001 to 215.398 at the FS). They were given RM Nos. 3801-3868 (which became the FS 310 series).

RM 4201-4487 (FS 420) Locomotives

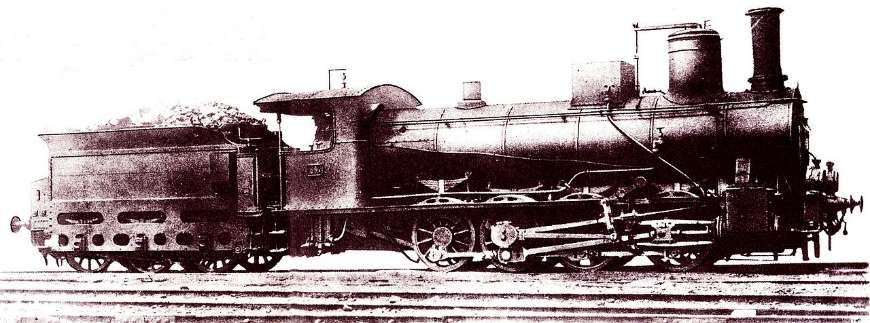

Banaudo et al also comment that “genuine mountain locomotives made occasional appearances: these were 040s [ in UK annotation 0-8-0s] with a three-axle separate tender, series RM 4201 to 4487 (future series 420 FS), built from 1873 to 1905 based on an Austrian model by a dozen Italian, Belgian, German and Austro-Hungarian firms. These machines, reserved primarily for the main lines of the Alps and the Apennines, occasionally intervened on the Col de Tende line, during bridge tests for example. At this time, Cuneo still had no allocation of machines and those going up to Limone and Vievola were attached to the Torino depot and the Moretta shed, on the Cuneo Airasca line.” [1: p41]

“In the early 1870s, the SFAI needed a locomotive suitable for heavy work on the most important mountain lines, such as the Giovi railway and the Turin-Modane railway, for which the 0-6-0 locomotives were becoming increasingly inadequate. The Ufficio d’Arte di Torino chose a 0-8-0 locomotive of the Wiener Neustädter Lokomotivfabrik (then known as “Sigl”), very similar to the Südbahn Class 35 a that it already produced.” [41][42: p190][43: p31]]

“The Class 420 was a typical long-boiler, inside-frame 0-8-0 locomotive of the era, that showed its Austrian derivation with its two-shutters smokebox door, and its outside Stephenson valve gear. The locomotives built before 1884 had the distinction of having curved foot plating over the wheels, while later units had straight foot plating and small splashers. Some of the locomotives were given a replacement boiler before 1914, but their performance remained mostly unchanged.” [41][43: p31]

“The first 60 locomotives were built by Sigl (from which they derived the nickname with which they were known for their whole career) for the SFAI. Production continued until 1890, from both foreign (such as Maffei) and Italian firms (such as Ansaldo and Breda), for a total of 189 locomotives; all these were divided in 1885 between the Rete Adriatica and the Rete Mediterranea. Building of further locomotives for the RM resumed in 1897, and continued until 1905, bringing the total of the Class to 293.” [41][42: p190-192]

References

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 1: 1858-1928; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 2: 1929-1974; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- Jose Banaudo, Michel Braun and Gerard de Santos; Les Trains du Col de Tende Volume 3: 1975-1986; FACS Patrimoine Ferroviaire, Les Editions du Cabri, 2018.

- https://www.cparama.com/forum/viewtopic.php?p=105633, accessed on 26th July 2025.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vievola_staz_ferr_ALn_663.jpg, accessed on 26th July 2025.

- https://ebay.us/m/nYrstv, accessed on 26th July 2025.

- https://ebay.us/m/FMXiiC, accessed on 26th July 2025.

- https://youtu.be/2Xq7_b4MfmU?si=1sOymKkFjSpxMkcR, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/07/22/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-1

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1A6hv4xBsJ, accessed on 20th July 2025.

- https://structurae.net/en/structures/rivoira-viaduct, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://pin.it/zVWOhZKBn, accessed on Pinterest on 22nd July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1Rhi8V8YHV, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/v/1CUGhBU5S5, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/16uX2VPqbQ, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://trainconsultant.com/2020/10/09/nice-coni-incroyable-derniere-nee-des-grandes-lignes-internationales, accessed on 17th July 2025.

- https://fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sch%C3%A9ma_de_la_ligne_de_Coni_%C3%A0_Vintimille, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.20109/7.57505, accessed on 23rd July 2025.

- https://www.reddit.com/r/trains/comments/1hu18cw/the_station_of_limone_piemonte_italy_with_all_of, accessed on 24th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1CDh61WrHV, accessed on 24th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1AsYn4mLHB, accessed on 24th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1FvLCnvaUr, accessed on 24th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1BsP57TxDs, accessed on 24th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/171GQxreBM, accessed on 24th July 2025.

- Structures on the french side of the border would, when built, compete with the dimensions of the Rivoira Viaduct. The Eboulis Viaduct is 270 metres long and the bridge at Saorge is 60 metres high. However, the combination of these two dimensions (length and height) makes Rivoira Viaduct the most imposing on the line.

- https://www.rmweb.co.uk/forums/topic/151308-%E2%80%9Cbeyond-dover%E2%80%9D/page/2, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://www.fotocommunity.it/photo/locomotiva-3375-rete-mediterrane-roberto-prioreschi/35312169, accessed on 22nd July 2025.

- https://structurae.net/en/structures/limone-tunnel, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1430625447210493&set=gm.755686417785385, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- https://structurae.net/en/structures/tende-tunnel, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q6ZRqym_Dag, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.19247/7.57070, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Traforo_ferroviario_del_Colle_di_Tenda, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- Franco Collidà; 1845-1979: the Cuneo-Nice line year by year; in Rassegna – Quarterly magazine of the Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo , No. 7, September 1979; p12-18.

- Franco Collidà, Max Gallo & Aldo A. Mola; “Cuneo-Nizza: History of a Railway; , Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo, Cuneo (CN), July 1982.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1FxdJ2cugB/l, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- La Locomotion Automobile, 1899, p467; via https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bd6t53333638/f5.item, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- Industrialist Joanny Scotte, originally from Epernay in the Marne department, began his business in the mid-1880s producing steam-powered cars. From 1897, he offered road trains consisting of a tractor or a steam-powered car, pulling one or more trailers designed for the transport of passengers or goods. These vehicles travelled on roads using solid tyres. They never really went beyond the experimental stage due to their slowness, the difficulties of driving the vehicles on the narrow roads of the time and the damage caused to the cobbled and cylindered roads. [1: p40] Scotte road train services were reported in the last decade of the 19th century in the Île-de-France region (Fontainebleau, Pont-de-Neuilly, Courbevoie), in the Aube region (Arcis-sur-Aube – Brienne-le-Château), in the Manche region (Pont-l’Abbé-Picauville – Chef-du-Pont), in the Drôme region (Valence – Crest), and for military use. Scotte partnered with the Lyon-based car manufacturers Buire and Audibert-Lavirotte to produce some of its vehicles. [1: p41]

- https://ventimigliaaltawords.com/2013/10/14/all-steamed-up-about-the-ventimiglia-cuneo-rail-link, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- https://www.ilmondodeitreni.it/Gr310.html, accessed on 25th July 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/FS_Class_420, accessed on 26th July 2025.

- Giovanni Cornolò; Locomotive a vapore; in TuttoTreno (in Italian), May 2014.

- P. M. Kalla-Bishop; Italian state railways steam locomotives: together with low-voltage direct current and three-phase motive power; Tourret, Abingdon, 1986.

- https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/44.24035/7.54461 accessed on 26th July 2025.

- https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1AuQG8SLDb, accessed on 27th July 2025.

- https://rogerfarnworth.com/2025/08/06/the-railway-from-nice-to-tende-and-cuneo-part-3-vievola-to-st-dalmas-de-tende/

Pingback: A Tramway in the Valley of the River Roya? (Early 20th Century) | Roger Farnworth

Pingback: The Railway from Nice to Tende and Cuneo – Part 3 – Vievola to St. Dalmas de Tende | Roger Farnworth

Pingback: The Railway between Nice, Tende and Cuneo – Part 4 – St. Dalmas de Tende to Breil-sur-Roya | Roger Farnworth

Pingback: The Railway between Nice, Tende and Cuneo – Part 5 – Breil-sur-Roya to Ventimiglia | Roger Farnworth

Pingback: The Railway between Nice, Tende and Cuneo – Part 6 – Breil-sur-Roya to L’Escarene. | Roger Farnworth

Pingback: The Railway between Nice, Tende and Cuneo – Part 7 – L’Escarene to Drap-Cantaron Railway Station. | Roger Farnworth

Pingback: The Railway between Nice, Tende and Cuneo – Part 8 – Drap-Cantaron Railway Station to Nice. | Roger Farnworth