The November 1899 issue of The Railway Magazine carried the first of a short series of articles about the railways of New Zealand. As you will discover if you choose to read on, the author does not hold back on offering his personal opinions about the state of the railways and choices made by the government of the day for the country’s railways.

It is a pity that I do not have access to the subsequent article(s) about New Zealand’s Railways nor to any debate that the article may have provoked.

It might be interesting to hear some present day reflections on the comments the author makes!

The article is also of interest for an introduction to the rather unusual decisions taken by the Southland government about its first railway.

Rous-Marten begins: “When railway construction first began in New Zealand, that ‘Britain of the South’ was a sort of Heptarchy – an association of seven Provinces’, subsequently nine, with a ‘General’ or Federal Government at the capital, Wellington. And three of these Provinces separately entered upon railway making, each on its own account.” [1: p465]

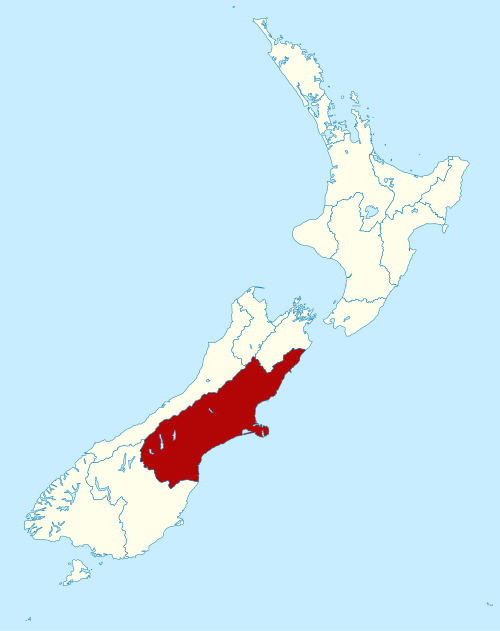

He continues: “There was a special reason in every instance for the embarkation on this enterprise. In Southland the local capital, Invercargill, was separated from the port by about fifteen miles of swamps, and from its goldfields by a stretch of country over which road-making was difficult on account of the numerous boggy streams which had to be crossed. In Otago – more accurately Otakou … – the capital, Dunedin was approachable from the port only by a difficult channel, or a still more difficult land-track. In Canterbury the chief town, Christchurch, was separated from the port (Lyttelton) by a high – almost mountainous – range of hills. And so connection by rail was sought as the most efficient and, in the end, the cheapest, means of communication. … Unfortunately, each of those semi-independent Governments adopted a different gauge.” [1: p465]

Rous-Marten says that “Southland chose the British standard gauge, 4 ft. 8.5 in.; Otago preferred the 3 ft. 6 in. gauge; Canterbury – wisest of all selected the ‘Irish’ gauge of – 5 ft. 3 in.” There is a glimpse in this sentence of Rous-Marten’s own position which quickly becomes clear as the article unfolds. [1: p465]

He goes on to say that “still more unfortunately, when, the Provincial Governments were abo- lished, and when a general system of railways was adopted, the 3 ft. 6 in. gauge was chosen for the whole colony as the most economical – a grievous and, I fear, irreparable blunder.” [1: p465]

Otago Province

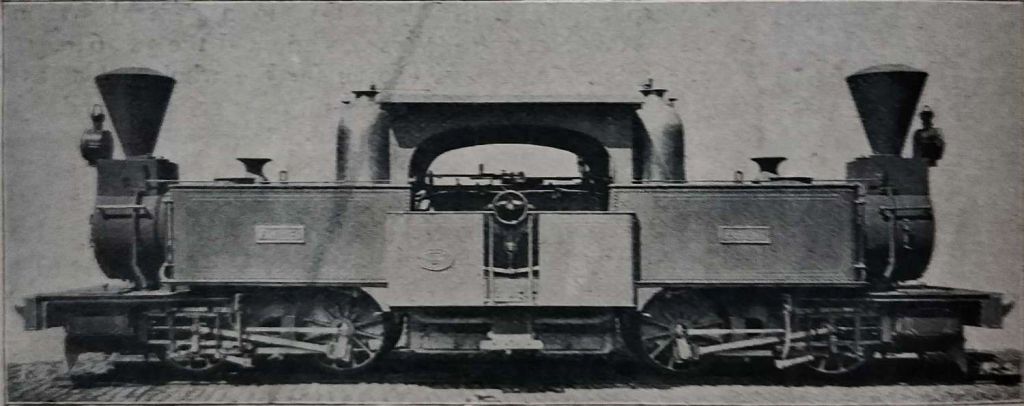

The first Otago railway, was from Dunedin to Port Chalmers. Once built, it “was worked by Double-Fairlie engines without any very serious difficulty being experienced from initiation to completion.” [1: p465]

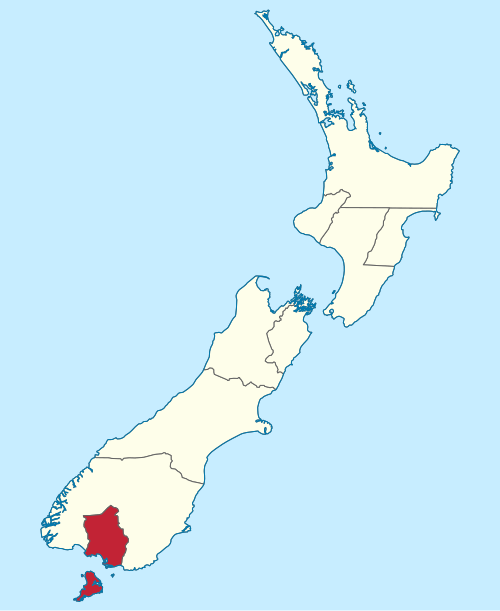

Canterbury Province

Canterbury (Māori: Waitaha) is a region of New Zealand, located in the central-eastern South Island. The region covers an area of 44,503.88 square kilometres (17,183.04 sq mi), making it the largest region in the country by area. It is home to a population of 666,300 (June 2023). [38]

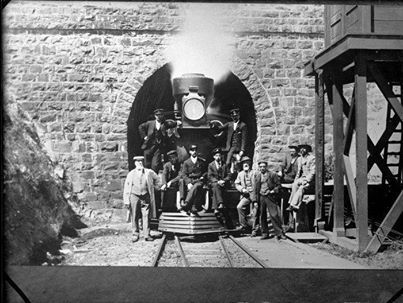

Rous-Marten’s article continues: “The Canterbury railway from Lyttelton to Christchurch had one solitary work of large magnitude, a tunnel through the dividing range. … The length of the ‘Moorhouse Tunnel’ is almost exactly the same as that … of the Box Tunnel of the Great Western Railway … a mile and seventy chains. … Originally, the Canterbury line was equipped with six six-wheeled tank locomotives, all built by the Avondale Company, Bristol. Of these, four had 5ft. 6in. driving and trailing wheels, coupled and inside cylinders 15 x 22; two had leading and driving wheels coupled 5 ft. in diameter, and cylinders 14 x 22.” [1: p466]

Wikipedia tells us that later the tunnel appears to have become known as the Lyttelton Tunnel. It opened on 9th December 1867. “The line and the tunnel were constructed to accommodate 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm) rolling stock at the behest of contractors Holmes & Richardson of Melbourne, as this was the gauge they were already working with in Victoria. The line remained this way until, following the abolition of provincial government in New Zealand and the establishment of a new uniform national track gauge, the line was converted to 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) by April 1876.” [2]

This indicates that for the first 8 years and 4 months of its existence the line was of 5ft 3in gauge. Those first locomotives will have been of that gauge. During that time, all the railways built in Canterbury Province were of the same gauge.

Wikipedia [4] also tells us that the “Canterbury Provincial Railways operated ten steam locomotives of varying types, not divided into separate classes. They were all tank locomotives based on contemporary British practice and were built by the Avonside Engine Company, except for No. 9 by Neilson and Company. Nos. 1-4 had a 2-4-0T wheel arrangement: No. 1, named Pilgrim,[3: p12] was built for the Melbourne and Essendon Railway Company of Melbourne, Australia in 1862 but was quickly on-sold unused to Holmes and Company, who were building the Ferrymead line (in New Zealand. The line was closed after the Moorhouse/Lyttleton Tunnel opened). [3: p11] It entered revenue service when the line opened.” [4]

The remainder of the first six locomotives, No. 2 (arrived April 1864), No. 3 (arrived March 1867), No. 4 (arrived May 1868), [3: p12] Nos. 5 and 6 also arrived in May 1868. The first four were 2-4-0T locos, Nos 5 & 6 were 0-4-2T and were somewhat smaller. [3: p13]

The Province purchased three more 0-4-2T locomotives, ordered independently, No. 7 entered service in August 1872, No.8 in March 1874 and No. 10 in June 1874.[3: p12] No. 9 was a diminutive 0-4-0T ordered after No. 8 but entered service before it, in January 1874, shunting on Lyttelton wharf. [4][3: p14]

“Only No. 1 was withdrawn while in Canterbury Provincial Railways’ service, in 1876.[3: p12] When the conversion of the Canterbury lines to narrow gauge was completed, its frame and the other nine locomotives were sold to the South Australian Railways. [3: p12] Despite the ship carrying the locomotives and rolling stock, the ‘Hydrabad’, being shipwrecked near Foxton on the North Island’s west coast on its journey to Australia, the locomotives and rolling stock ultimately were safely delivered to South Australia and with considerable modification seven of them remained in service until the 1920s.” [5: p9-11]

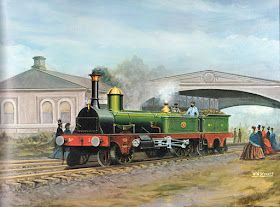

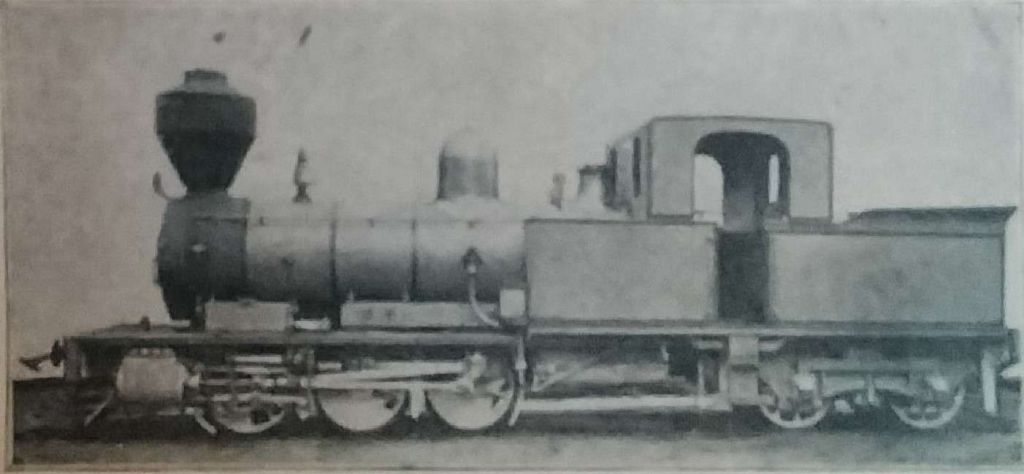

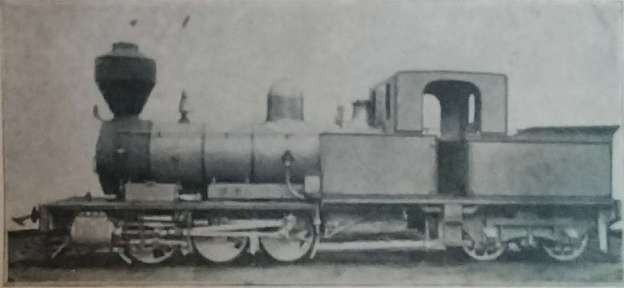

Rous-Marten was unable to find illustrations of these locomotives. Modern technology makes it easier to search for available to sources. One of the 2-4-0T locomotives Nos 1-4 appears in the image below.

Rous-Marten described these locomotives as “very excellent engines … [that] had large brass-covered domes (with safety-valves) over their fire-boxes.” [1: p466]

A.A. Cross, in his MA thesis, says that the “broad-gauge Canterbury Railways are considered unanimously by New Zealand historians as the origins of the modern-day railway network in New Zealand. Built by the Canterbury Provincial Government in 1863 to relieve transport issues between Christchurch and Lyttelton, the broad-gauge railway later expanded to reach Amberley in the north and Rakaia in the south, opening up the Canterbury Plains and stimulating trade and immigration.” [6: p2]

“Brought under the control of the Public Works Department in 1876 along with several narrow-gauge lines built by the Provincial Government, the broad-gauge was converted to the New Zealand standard narrow-gauge in 1878 and the locomotives and rolling-stock were sold to the South Australian Railways.” [6: p2]

Since the majority of the locomotives from Canterbury Province continued to serve on South Australian railways until the 1920 they were clearly very suited to the roles that they fulfilled in Australia.

Rous-Marten notes that, while these locomotives were serving in New Zealand, he had “timed [them] at 56 to 60 miles an hour on favourable gradients. As a rule the gradients were very easy, and the permanent way was good, the whole line being laid with 75 lb. rails.”

Southland Province

“The Southland Province was a province of New Zealand from March 1861, when it split from Otago Province, until 1870, when it rejoined Otago.” [39]

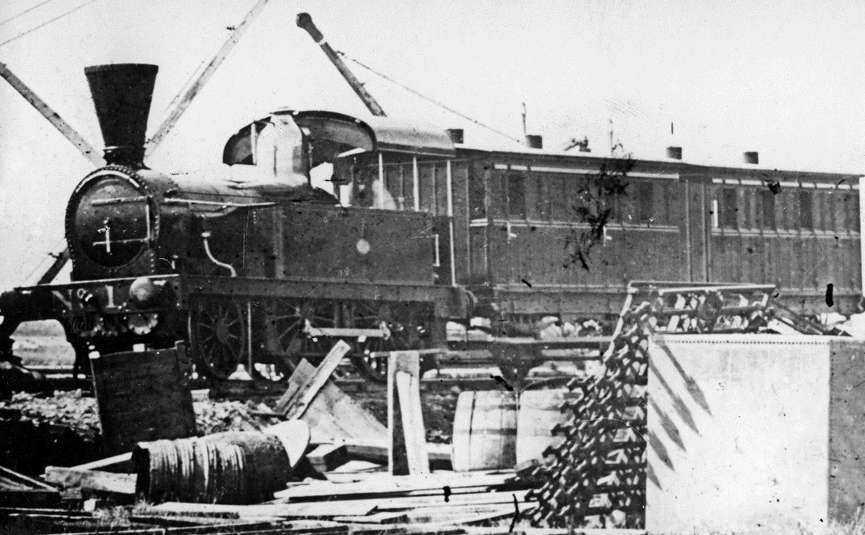

Rous-Marten turns to the story of the railways in Southland Province: “In the first place, to save time and expense, it was rashly decided to employ timber for the permanent way, that is to say for the rails as well as for the sleepers. Square baulks of timber were pinned longitudinally on transverse sleepers, while the engines and rolling stock were constructed on the ‘Davies’ system. That is to say, instead of the wheels having the usual flanges – which would soon have cut up the wooden road they were broad in the tread and flangeless, while smaller wheels set at an angle of 45 degrees against the inside face of the rails kept the main wheels in position. It was an ingenious idea, but proved in practice a complete failure. The wooden rails speedily perished. The locomotives, four-wheeled ‘single-wheelers’, with outside cylinders, were quite unable to obtain sufficient adhesion on the slippery surface of the timber in wet or frosty weather, especially up grades of 1 in 79 and 1 in 90.” [1: p466-467]

More detail about the wooden railed railway in Southland Province can be found here. The experiment lasted about three years from 1864 to 1867. [7]

It seems that James M. Davies proposed this solution to the transportation dilemma besetting Invercargill in 1863, or thereabouts. Apparently, Davies had recently been instrumental in planning and building the Geelong-Ballarat Railway in southeastern Australia, and had designed a steam locomotive that was then manufactured in 1861 by Hunt & Opie’s Victoria Foundry in Australia. [8]

The ‘Lady Barkly’ was shipped by Davies to Invercargill and over four hours had it steaming along the town’s jetty on timber baulks laid for the demonstration. An enthusiastic public response resulted from the demonstration of which the Southland Times reported: “Crowds of spectators passed the afternoon at the Jetty in riding delightedly in the locomotive. … The motion was found pleasant and quite free from that oscillation and concussion, which distinguish traveling on iron rails with the usual engine.” [8]

The ‘powers that be’ were persuaded to construct a railway following Davies’ principles.

Rous-Marten continues his article by recounting a tale from his own experience of an occasion when “all the passengers of whom [he] was one, were politely asked to leave the carriage and help to push the carriage and engine to the summit of the bank. This, [he says] we did with colonial cheerfulness, and on resuming our seats the guard promptly collected 2s. 6d. apiece from us as our fares! At this time Mr. W. Conyers MICE, who subsequently was Chief Commissioner of the South Island Railways of New Zealand, was in charge of the locomotive department of the Southland line, and he conceived the idea of converting a stationary sawmill-engine into a coupled locomotive, in the hope of tiding over the difficulty until more suitable engines and permanent way could be provided.” [1: p467]

Rous-Marten expresses regret that he did not take a photograph of what he calls “this ingenious but amazing nondescript.” [1: p467] He is sure that a written description is inadequate to convey its astonishing appearance. Even so he attempts to provide details of the locomotive, which had “a pair of horizontal cylinders along the boiler, which drove a ‘dummy’ crankshaft, whence an oblique coupling-rod drove one pair of 3 ft. wheels, these being coupled to a pair of 3 ft. trailing wheels, while a third pair of 3 ft. wheels led the way, I convey all the idea I can of an engine which probably stands alone in locomotive history. I have actually travelled at 20 miles an hour with this marvellous locomotive, with the flangeless wheels and the little slanting guide-wheels, yet without disaster. True we went off the rails once when I was there; but the only damage was the smashing of a basket full of eggs, which a farmer’s wife was carrying to market. But ere long the unnatural strains to which the working parts of the engine were subjected brought her to grief, and soon the entire experiment of the railway was abandoned as a hopeless failure. Its fate was shared by the Province, which became bankrupt, and had the balliffs in its Government offices. Ultimately an arrangement was effected, and the railway was relaid with the usual permanent way, including iron rails of 72 lbs. to the yard, and was opened for a distance of 35 miles, viz., from Bluff Harbour to Invercargill and Winton.” [1: p467]

The replacement railway, completed in 1867, was built to standard gauge and three small six-wheeled tank engines were purchased. Of these three locomotives, one (a 2-4-0T) was supplied by Avonside and two (0-4-2Ts) by Hudswell Clarke. I have been unable to find photographs of these locomotives.

Rous-Marten says that “with the smaller engines I several times recorded 45 miles an hour, and once 50; with the larger engine in several instances 55 miles an hour.” [1: p468]

Gauge Standardisation

In 1870, Southland rejoined the larger Otago Province. [9] “On 22 February 1871,” Winton History Website says, “a railway line from Invercargill was opened to Winton, built to the international standard gauge of 1,435mm. This was the furthest extent of Southland’s standard gauge network, and the next section to Caroline was built to New Zealand’s national gauge, 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) narrow gauge railway. This extension opened on 20 October 1875, ending Winton’s 4.5 years as a railway terminus, and two months later, the line back to Invercargill was converted to 1,067mm gauge. This line grew to be the Kingston Branch.” [10]

By 1875, both Southland and Canterbury Province’s railways were converted to what the New Zealand government had decided would be the national gauge, 3ft 6in.. Rous-Marten says that this move was “very much to the annoyance and regret of the local population, who regarded the narrower gauge and smaller engines with unconcealed contempt and derision.” [1: p468] Given Rous-Marten’s already established negative views on the narrow -gauge, it is impossible to determine whether he is forcefully expressing his own views, or speaking for the wider population.

Rous-Marten comments that “after having, for a time, three different gauges in operation, and in Canterbury a mixed gauge of three rails, [New Zealand] ultimately arrived at uniformity by the process of ‘levelling down’ to the narrowest gauge of all, and the one least suitable for permanent operation. This decision was largely governed by the political influence which subsequently operated so seriously for evil in the career of the New Zealand railways. It was believed that by using the narrower gauge construction would be cheaper, and so that the millions borrowed for railway construction could be spread over a larger area than if the wider gauge were employed, and that thus a larger number of voters would be interested in supporting the scheme. And so it proved. But the results are nevertheless regrettable.” [1: p468]

I suspect that there may be, at least, some who would want to challenge Rous-Marten’s strongly expressed views. …

Moreover, says Rous-Marten, “the further mistake was committed of laying down 40lb. iron rails, which almost immediately proved unable to carry even the moderate amount of traffic anticipated, and had to be replaced with 53 lb. steel rails. However, it was but natural that errors should be committed in the starting of a large enterprise by a small community, the total population of the colony at the inception of railways being under a quarter of a million, scattered over an area more than 1,000 miles in length, and about 200 miles in breadth, divided midway by 20 miles of stormy sea, the dreaded Cook Strait. Probably New Zealand made no more blunders than did the Mother Country, if all the respective circumstances be taken into due consideration. And at the present date [1899] the colony possesses a fairly good and efficient railway system extending over more than 2,000 miles.” [1: p468]

Developments

Rous-Marten notes that by 1899, New Zealand was still waiting for the completion of a main trunk railway system. But his further assertions move beyond just reporting circumstances. … “Vast sums [had] been frittered away on small local and branch lines which [did] not pay interest on cost – some not even their bare working expenses – while main lines have been left unfinished. Indeed, in one case the first length of 84 miles of main trunk line from the capital (Wellington) northward was left to be made by a private company, which [had] since been harassed and persecuted by the Government with the object of forcing it to sell the line to the State at a price much below its just value, while it [had] been the favourite target of the small district governing bodies in respect of local taxation.” [1: p468-469]

The line in question, that from Wellington to Manuwatu, ran/runs North from Wellington, through Palmerston where it divided/divided with one arm serving Palmerston and the other, Napier. In 1899, there was also a project underway to take the line to Auckland in the North. That project was being worked from Auckland and from the South with some distance yet to go before the two projects met. Rous-Marten writes of likely long delays before the link could be completed, “as the route of the connecting link [had] been for years – and still [was] a subject of hot and embittered political strife.” [1: p469]

It seems that Rous-Marten was right about timescales, NZ History tells that in the end, “after more than two decades of surveys, engineering challenges and sheer hard work, the main trunk’s first through train left Wellington on the night of 7th August 1908. This ‘Parliament Special’ carried politicians and other dignitaries to Auckland to meet the United States Navy’s visiting Great White Fleet, which arrived in port on the 9th. The train needed 20½ hours, and several changes of locomotive, to complete the trip. In the middle section it crawled over a temporary, unballasted track that the Public Works Department had rushed through in the nick of time.” [13]

In 1899, in the South Island, things appear to have been somewhat better. Rous-Marten tells us that the main trunk line started from “Bluff Harbour, in the extreme south, and [continued] unbrokenly through Invercargill, Dunedin, Oamaru, and Timaru to Christchurch, a distance of nearly 400 miles. … It [had] been extended northward for 70 miles, and there [ended at] … Culverden station, and many miles [had] to be traversed before the [then] southern termination [was] reached of the short line which ultimately [would] continue the Southern Main Trunk to the pretty little port of Picton, in Queen Charlotte Sound.” [1: p469]

From Picton it was then a journey of about 50 miles by boat to reach Wellington and the North Island.

Wikipedia tells us that construction of the Southern Main Trunk “was completed all the way from Picton to Invercargill in 1945.” [14] It seems then that Rous-Marten somewhat misjudged how close to completion the Southern Main Trunk was.

In the 21st century, there is an 11 hour train, thrice a week, between Auckland and Wellington. [15] From Wellington you catch a ferry to Picton. There you can board the Coastal Pacific to Christchurch. [16] The Southerner, that went to Invercargill, stopped operating in 2002. [17] The journey from Auckland to Christchurch takes around 22 hours in total, provided, that is, connections can be made. Allowing a minimum of two days for the journey would be advisable.

Engineering and Structures

Rous-Marten turns to the engineering work on the New Zealand railway system. In 1899 the heaviest engineering on the system [was] the Moorhouse/Lyttelton Tunnel.

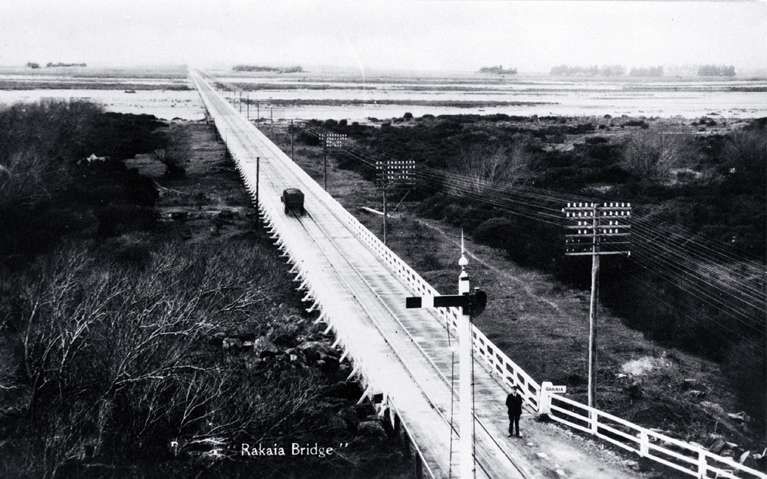

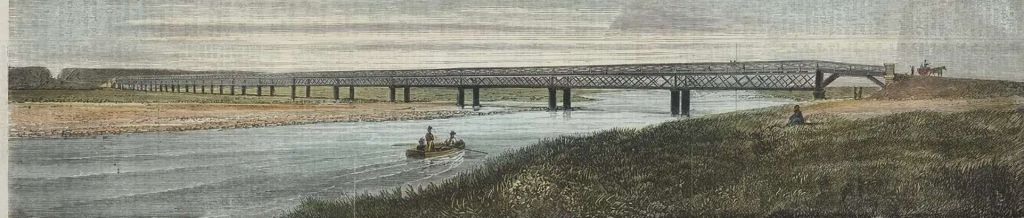

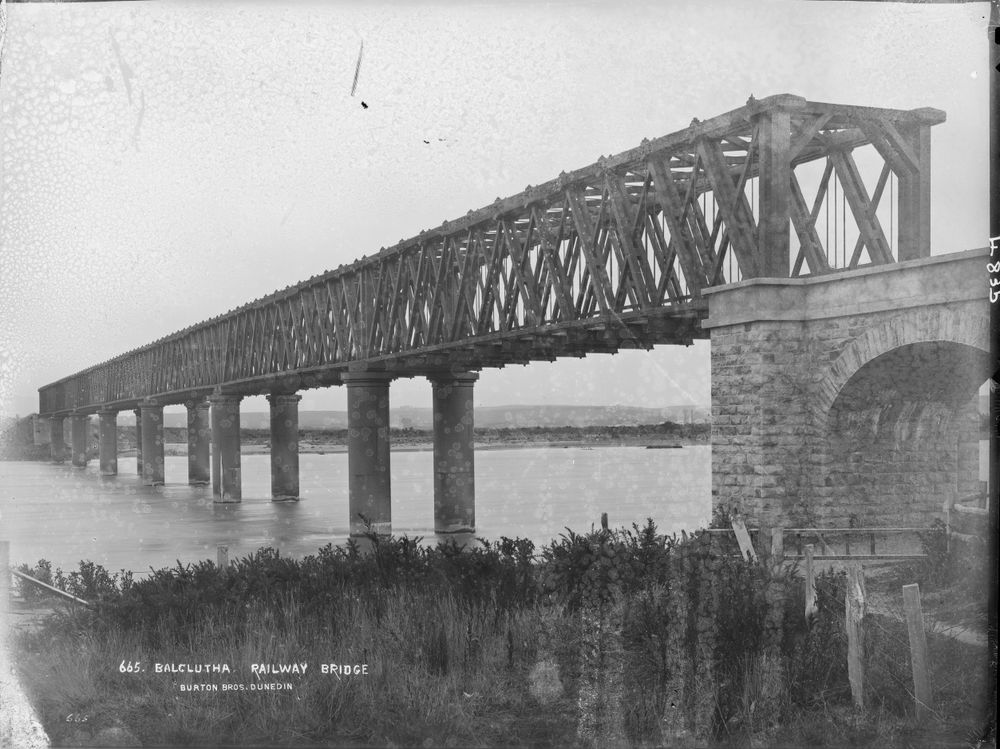

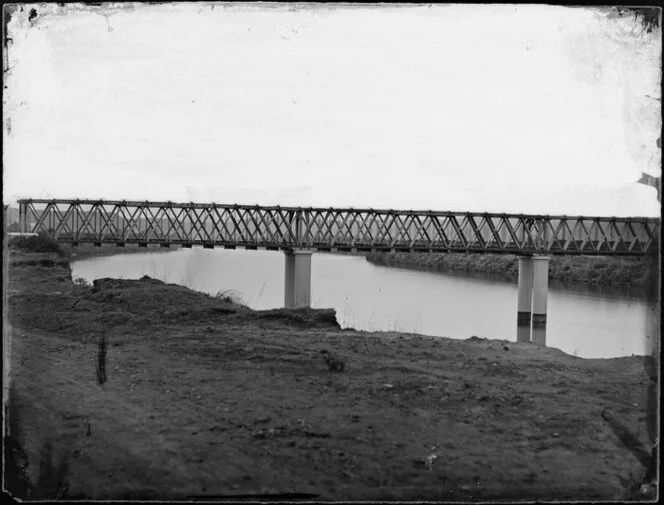

In addition to that tunnel, Rous-Marten says that in 1899 there was no lack of important construction achievements. “Abounding as New Zealand does in huge rivers fed from the snowy Southern Alps, which in their turn bring about the condensation of the vast volumes of aqueous vapour raised from the Tasman Sea by the hot N.W. winds, bridges of large magnitude are necessarily numerous. Longest of all these is that over the Rakaia River in the South Island, which is more than a mile and a quarter in length. Ordinarily it spans a wide desert of rough, pebbly shingle, which has several comparatively small streams meandering through it. But during several weeks in each year that entire mile-and-a-quarter of width is a tremendous foaming torrent.” [1: p469-470]

The Rangitata and Waitaki Rivers are no less formidable.

The bridging of South Canterbury’s wide, braided rivers made travel easier and faster. Initially the bridges carried both rail and vehicular traffic. [24]

It was these early bridges that Rous-Marten was referring to in his article when he said that these rivers were “all crossed … by really fine bridges, which resist the worst assaults of the snow-fed torrents let loose against them from the mountains but the first spring rains.” [1: p470] All these structures have now been replaced by separate road and railway bridges.

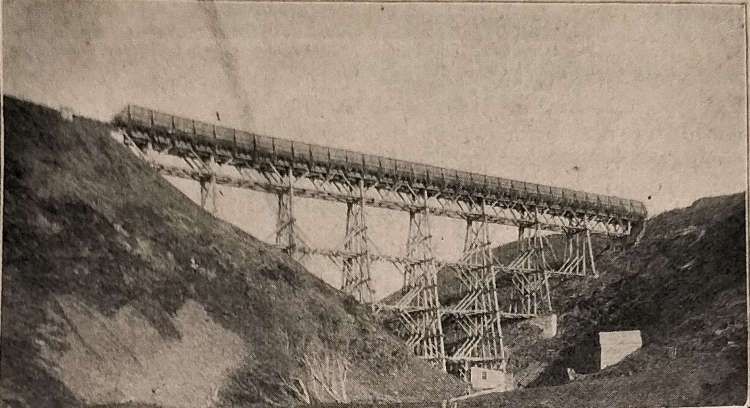

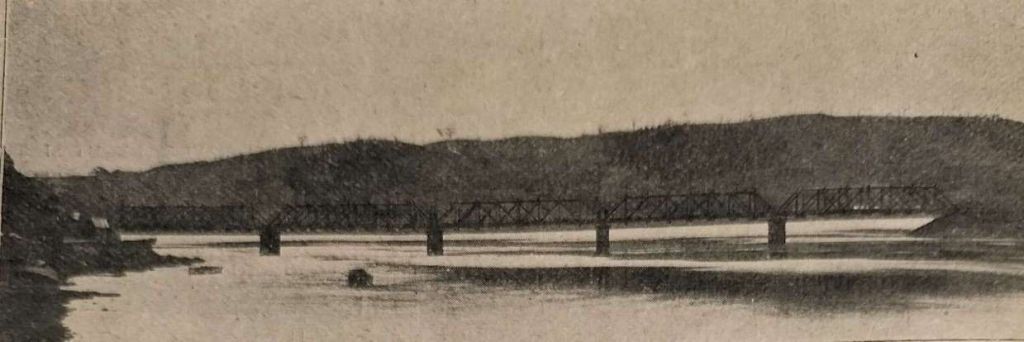

Rous-Marten also points to two “specially interesting works. … Both … on the Wellington and Manawatu line, and [both] within twenty miles of Wellington. The trestle viaduct span[ned] a deep, dry ravine. The lattice girder-bridge crosse[d] an arm of the sea known as the Porirua Harbour. Both [were] highly creditable works.” [1: p470]

It is not clear why Rous-Marten chose to illustrate the two bridges above. There were many structures on the Wellington and Manawatu Railway which he could have chosen, including:

- Belmont viaduct: A 38 metre-high, 102 metre-long wooden viaduct that crossed a gully in Paparangi. Built in 1885, it was the largest wooden viaduct in New Zealand at the time. It was replaced by a steel viaduct in 1903, but was demolished in 1951 due to safety concerns. This may well be the wooden trestle bridge shown above. [25]

- Tunnels: A series of tunnels along the Paekākāriki escarpment. [26]

- Bridges: Major bridges over the Pāuatahanui inlet and the Waikanae, Ōtaki, and Manawatū rivers. [26]

- Makurerua Swamp: A raised embankment across the Makurerua Swamp in Horowhenua. [26]

Rous-Marten refers to “other important bridges … over the Clutha, Waimakariri, Wanganui, Manawatu, Waikato, and many more large rivers, the Clutha and Whanganui bridges being particularly fine.” [1: p470]

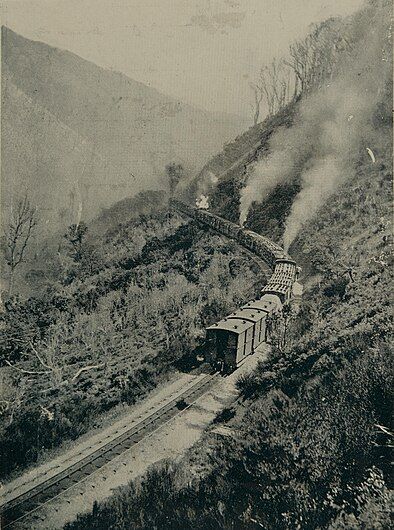

Rous-Marten continues: “Perhaps the engineering feat which has attracted most interest in connection with the New Zealand railways is the means by which the Rimutaka range of mountains, about thirty-five miles from Wellington, has been surmounted by the railway that runs from the capital northward. Starting trom Wellington the line winds round the edge of the bay and then goes by very slight gradients up the valley of the Hutt River to a point about twenty miles from the city. Here it begins its climb up the mountain, which is effected by a series of severe gradients, chiefly I in 35 and 1 in 40, with some 40 curves of only five chains radius!” [1: p470]

For this heavy work, single-boiler Fairlie engines as shown immediately above were usually used. Rous-Marten says that in 1899 these locos were being replaced “by a more powerful class designed and constructed in New Zealand.” [1: p470]

He goes on to talk about the line again: “At the summit, a tunnel, not quite half a mile long, is passed through, and then the descent is begun. But the conditions are totally changed. … While the ascent of 1,200 ft. from the southward takes 15 miles of line, being … on gradients not steeper than I in 35, the descent northward is made in less than 3 miles, the gradient being continuously 1 in 15, while there are 39 curves of 5 chain radius. Thus in the total distance of 18 miles traversed in the ascent and descent of the Rimutaka, no fewer than 79 5-chain curves have to be rounded. The gradient of 1 in 15 is dealt with on the Fell system, the ordinary vertical locomotive being supplemented with an interior one actuating horizontal wheels which are forcibly pressed against a raised middle (third) rail. This constitutes a powerful climbing apparatus, and a no less powerful brake in the descent.” [1: p470-471]

The Rimutaka Summit Station, Tunnel and Incline were built in the 1870s. It was intended that the work should be completed between “12th July 1874 and 22nd July 1876.” [29]

Once the station yard had been levelled, work started on the tunnel itself, it took 17 months longer than intended at the start of the contract. [29]

The Fell System was invented by English engineer John Barraclough Fell (1815-1902). It was the first third-rail system for railways that were too steep for adhesion on the two running rails alone.

The Fell System was used on several railways in addition to the Rimutaka Incline including:

- The Rewanui Incline: on the West Coast of New Zealand, the Fell system was used for braking descending trains. [32]

- The Roa Incline: also on the West Coast of New Zealand. [32]

- The Cantagalo Railway in Brazil: the Estrada de Ferro Cantagalo. [32]

- The Mont Cenis Pass Railway on the border between France and Italy was 77 km (48 mi) long and ran from 1868 until superseded by a tunnel under the pass in 1871. [33]

“The Fell system was developed in the 1860s and was soon superseded by various types of rack railway for new lines, but some Fell systems remained in use into the 1960s. The Snaefell Mountain Railway still uses the Fell system for (emergency) braking, but not for traction.” [33]

Rous-Marten mentions one incident associated with the Rimutaka Incline which resulted in the construction of a “massive, high timber fence” [1: p471] as a wind break.

The wind break protected the line against “the devastating force of the furious gales which sweep down the ravines on the northern side of the Rimutaka range. That the precaution is not supererogatory was disastrously proved by the most serious and fatal railway accident which had ever occurred in New Zealand up to the current year. A mixed train of passenger coaches and goods wagons was struck ‘broadside on’ by a terrific blast of wind when on this incline, with the result that the whole train was blown sideways off the rails and flung down the precipice beneath, the vehicles hanging like a string of huge beads to the engine, which, by the grip of its Fell machinery on the middle rail, still sturdily maintained its place on the metals.” [1: 471]

In summary, “the Rimutaka Incline was a 3-mile-long (4.8 km), 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge railway line on an average grade of 1-in-15 using the Fell system between Summit and Cross Creek stations on the Wairarapa side of the original Wairarapa Line in the Wairarapa district of New Zealand. … The incline formation is now part of the Remutaka Rail Trail.” [30]

Rous-Marten continues: “A few years [after the incident on the Rimutaka Incline], trains were thrice blown off the rails while crossing the Wairarapa Plain, … and similar wind-breaks had to be erected there also, the particular spot being opposite to a deep gully in the mountain range, which acted as a funnel for the wind and concentrated its full force on one special spot on the plain.” [1: p471]

He also notes a further problem with the “formidable Rimutaka Range, … the tendency to vast landslips, a whole mountain-side sometimes slid “down bodily when once its base [had] been disturbed. And the tremendous floods to which New Zealand rivers are liable constitute[d] another trouble, often a very costly one – in the way of slips and wash-outs.” [1: p472]

Rous-Marten also notes that “it has often been doubted whether [the] … crossing of the Rimutaka might not have been avoided by a detour through more level country.” He comments that in 1899, “the feasibleness of constructing a new line to avoid the obstacle [was] under careful consideration.” [1: p472]

In the end a new, longer tunnel was built through the Rimutaka Mountains at a lower level. That lower tunnel is now known as the Remutaka Tunnel (‘Rimutaka’, before 2017). It “was opened to traffic on 3rd November 1955, is 8.93 kilometres (5.55 mi) long. It was the longest tunnel in New Zealand, superseding the Otira Tunnel in the South Island until the completion of the Kaimai Tunnel, 9.03 kilometres (5.61 mi), near Tauranga in 1978. Remutaka remains the longest tunnel in New Zealand with scheduled passenger trains.” [35]

Rous-Marten also points out another “formidable and troublesome work, … the rounding of the Waitati Cliffs, about 15 miles north of Dunedin, in the South Island. … In order to round a precipitous cape standing between two deep bays of the sea it was necessary to ascend by grades of 1 in 50 to a point where the cliff had to be rounded by a ledge or shelf being cut out of the solid rock at a height of some 400 ft. perpendicular above the sea. At one point, indeed, a ‘fault’ ran inward under the line, and was crossed by girders, so that, standing on the foot-plate and looking down on the landward side of the engine, one could gaze straight down into the boiling sea some 400 ft. below. For some years the trains passed this awe-inspiring place without accident.” [1: p472]

Rous-Marten says that he had been “on the engine foot-plate when [rounding] the point at 25 or 30 miles an hour. But the dangerous character of the place, not only below, but from rock-falls above, forced itself more and more upon the public mind; indeed, many people were afraid to travel by so apparently perilous a route, and preferred to go by sea. So first the speed there was rigorously kept down to 10 miles an hour, and in the end a tunnel was cut through the point, so as to avoid the worst ‘bit’.” [1: p472]

Rous-Marten wants also to tell us about the main trunk line from Christchurch to Dunedin, connects two cities which are about 230 miles apart and which in 1899 had populations of about 70,000 each, was, South from Christchurch, ” [1: p472]

He continues: “From Oamaru onward to Dunedin the line is an almost uninterrupted alternation of rises and falls on steep gradients, often I in 50 and I in 60, a descent of several miles at the sharper rate, after Deborah Bay tunnel (0.75 mile long), bringing the train down to the final level run of 7 miles along the shore of the picturesque harbour to the … southern city of Dunedin.” [1: p472]

At least one further article by Rous-Marten, in a later issue if The Railway Magazine was planned. Unfortunately, I do not yet have access to a copy. Rous-Marten promised that he would continues to describe some interesting railway routes as well as look in detail at the motive power in use in 1899 on New Zealand Railways. ….

References

- Charles Rous-Marten; New Zealand Railways; in The Railway Magazine, London, November 1899, p465-472.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lyttelton_Line, accessed on 14th September 2024.

- A.N. Palmer & W.W. Stewart; Cavalcade of New Zealand Locomotives. Wellington, 1965.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canterbury_Provincial_Railways#:~:text=The%20Canterbury%20Provincial%20Railways%20was,was%20the%20designer%20and%20overseer, accessed on 14th September 2024.

- T A. McGavin; Steam Locomotives of New Zealand, Part One: 1863 to 1900; New Zealand Railway and Locomotive Society, Wellington, 1987.

- Alastair Adrian Cross; MA Thesis:University of Canterbury 2017 Canterbury Railways: Full Steam Ahead The Provincial Railways of Canterbury, 1863-76; University of Canterbury, Christchurch, 2017, via https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:EU:b3566635-51f2-4d92-9d6e-601fd55e06e3, accessed on 14th September 2024.

- https://the-lothians.blogspot.com/2013/06/the-saga-of-southlands-wooden-railway.html?m=1, accessed on 14th September 2024.

- https://transportationhistory.org/2018/08/08/she-was-a-trailblazer-in-new-zealand, accessed on 14th September 2024.

- https://nzhistory.govt.nz/page/opening-railway-invercargill-bluff, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://www.winton.co.nz/history, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://westonlangford.com/images/photo/131752, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://westonlangford.com/images/photo/131749, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/main-trunk-line/rise-and-fall, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Island_Main_Trunk_Railway#:~:text=Construction%20of%20a%20line%20running,North%20Line%20south%20of%20Picton.l, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northern_Explorer, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coastal_Pacific, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southerner_(New_Zealand_train), accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lyttelton_rail_tunnel_01.jpg, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://www.peelingbackhistory.co.nz/the-lyttelton-moorhouse-railway-tunnel-opened-9th-december-1867, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://christchurchcitylibraries.com/heritage/photos/disc11/IMG0014.asp, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23168823, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://antiqueprintmaproom.com/product/bridge-over-the-rangitata-new-zealand-l-r, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://www.facebook.com/100076512201176/posts/pfbid02V3tgRyLsH14mBpiiTtrW1a3PXsZuGcKmVucQNUbG4vapuEhqum6T6ieQ7KaunmUYl/?app=fbl, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/11394/waitaki-river-bridge, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/belmont-railway-viaduct, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://nzhistory.govt.nz/page/manawatu-rail-link-opened, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/19702, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23210560, accessed on 15th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Summit_railway_station,_Wellington_Region, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rimutaka_Incline, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://www.flickr.com/people/35759981@N08, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://www.rimutaka-incline-railway.org.nz/history/fell-centre-rail-system, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fell_mountain_railway_system, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://nzhistory.govt.nz/page/rail-tragedy-rimutaka, accessed on 16th September 2025.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remutaka_Tunnel, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otago_Province, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otago, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canterbury_Region, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southland_Province, accessed on 16th September 2024.

- https://www.britannica.com/place/New-Zealand, accessed on 16th September 2024.

Roger, a great article on the NZR, however, the Double Fairlie locomotive in the Otago section is an NZR Class E not a Class K which originally were Rogers (USA) built 2-4-2 tender locomotives.

Regards Wayne Morris, Christchurch NZ

Hi Wayne, and thank you. Rous-Marten got that wrong then! I will put a note against the photo. I appreciate you letting me know. Best wishes. Roger.