How a long defunct, relatively small local railway company aimed high and ultimately was responsible for the poor financial state of the Great Central Railway!

I was prompted to look again at the Sheffield Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester Railway by reading a copy of BackTrack Magazine from May 1996 (Volume 10 No. 5) [2] which included an article about the Great Central Railway which is now, sadly, long-gone. That article was itself a response to an earlier article in BackTrack Volume 9 No. 3 (March 1995) by Messrs. Emblin, Longbone and Jackson. [1]

It brought to mind the connections between Ashton-under-Lyne and the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&L) evidenced by the name of its predecessor, the Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester Railway (SA&M). I am wary of providing links to these posts, but they do pull together quite a bit of information about that railway …… these are the links:

With the benefit of hindsight, the second of the above posts was not really necessary. An appendix to the third post would probably have covered the two links mentioned in the second post.

I lived in Ashton-under-Lyne at the time. The article which grabbed my attention in the old BackTrack Magazine did so because it seems to root the significant problems of the Great Central Railway (GCR) in my, then, local railway company’s own history. Hence the sub-title of this post!

The significant challenges faced by the SA&M Railway in being ahead of the game in providing rails across the northern backbone of the country led to a financial structure which seems to have dictated the future of its successors, both the MS&L and, ultimately, the GCR. Heavily reliant, leveraged, on debentures and preferential stock is was difficult for the successive companies to attract ordinary investors.

The whole history of the GCR seems to have been dictated by the way in which the heavy capital expenditure necessary to cross the Pennines/Peaks was financed.

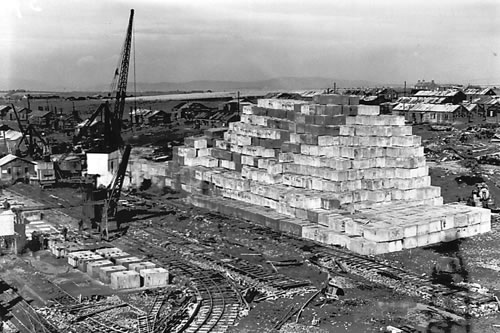

The SA&M Railway was one of the first railways to tackle truly formidable and desolate terrain. Nowhere was the challenge more evident than at the West end of the Woodhead tunnels, seen here at the turn of the 20th century. The SA&M and its successors were encumbered with the twin problems of high construction costs and low receipts from intermediate stations over a long section of line. [2]

It should be noted that Emblin reserved a right of reply and that he chose to do so in a later edition of the BackTrack Magazine. [5]

His principal argument in that article appears to be that things were really not that bad and that the GCR managed its way out of trouble in a very effective fashion. I am not sure that this negates the reasoning of the articles referred to above, and I am sure that it does not address the particular point that the GCR faced ongoing financial problems which had their birth in the companies it succeeded.

Emblin argues strongly that Sir Alexander Henderson managed his way out of trouble by expansion. [5: p711] That seems to have been that practice of his predecessors as well. The result being that the company was highly leveraged and still not the best investment for ordinary shareholders.

It also does not alter my opinion that my, then, local railway company had a great part to play in the issues which has to be managed by the GCR throughout its life.

References

1. Emblin, Longbone & Jackson; Money Sunk & Lost; BackTrack Magazine Vol. 9 No. 3, p129-136, notes on this article are reproduced below at Appendix 2. [3]

2. Blossom & Hendry; Great Central – The Real Problem; BackTrack Magazine Vol. 10 No. 5, p266-271. Notes on this article are provided at [4].

3. http://www.steamindex.com/backtrak/bt9.htm#1995-3, accessed on 4th May 2019. See below, Appendix 1.

4. http://www.steamindex.com/backtrak/bt10.htm#1996-5, accessed on 4th May 2019. See below, Appendix 2.

5. Emblin; An Edwardian Ozymandias; BackTrack Volume 15 No.12, p707-713. (see http://www.steamindex.com/backtrak/bt22.htm#654)

Appendix 1:

Money sunk and lost – The great central myth of the Great Central Railway. Robert Emblin, Bryan Longbone and David Jackson. p129-36.

The extension of the MSLR from Annesley to London created what the authors describe as a myth, namely that the Great Central Railway was financially crippled by the cost of building it. Many authors have subscribed to that myth: Langley Aldrich’s “The late GCR never paid any dividend on its Ordinary shares”; Hamilton Ellis’s ‘The London Extension was viewed with pessimism at the time of its inception; if MS&L stood for Money Sunk and Lost, GC clearly meant Gone Completely”. Jack Simmons “Great Central never paid an ordinary dividend” and “was financially ramshackle”. Harold Pollins “There were clearly some absurd schemes [including] the building of the last main line, the Great Central, in the 1890s” Michael Bonavia, referring to the grouping criteria used in defining the proto-LNER, adumbrated a poverty-stricken Great Central being carried financially on the back of the prosperous North Eastern.

The perception of GCR penury is a component in another received wisdom; that the LNER’s largest constituent, the NER, had been intended as the financial dynamo for the entire network but that because of the financial weaknesses of the other constituents the LNER finances sank when the virtual collapse of the north-east regional economy in the depressions of the 1920s and 1930s prevented the NER from bankrolling its poverty-stricken fellow constituents. These two orthodoxies provide neat and simple mutually-supporting explanations that agree with what we all know; but “what everyone knows” may not necessarily be true, or it may not be the whole story and half-truths are most effective as mis-information.

The construction costs of the London Extension had certainly been high £11.5 million, almost twice the original estimate and after it opened the GCR did not pay any dividends on its Ordinary shares nor, until 1915, on some of its Preference shares. But not only were these non-paying shares a minority of the total, the opening of the London Extension was followed by thirteen years of considerable expansion. A leading article in the Financial Times of 20th September 1913, analysing the ‘Great Central Position’ and the performance of its shares, referred to the GCR as one of the leading UK railway companies, stating that “the position of the company . . . promises well in the near future . . . traffic returns have shown continued healthy expansion” and praised ‘the exceptional prospects of this undertaking”. There is a wide discrepancy between the modern view and contemporaneous informed assessment. The £10 million for the GCR’s post-1900 expansion programmes (more than was being invested by most of its contemporaries) had to come from somewhere and the debt serviced somehow. Further, the price paid for the GCR at Grouping was marginally greater than that paid for any of the other LNER constituent companies except the NER; there is also the small and hitherto overlooked matter of the evidence on the London Extension profitability that was given by Sir Ralph Lewis Wedgwood, the LNER Chief General Manager, to the Railway Rates Tribunal in 1924/5 when he stated that it was expected that a nominal fifteen years was required for new works to fructify (that is produce a 5% return on investment and when questioned that “that new trunk lines [are] exceptionally slow to mature”. The authors forcefully state that Henderson/Faringdon had been regarded as one of the leading railway financiers.

After the London Extension opened, the GCR started a programme of widespread expansion taking over the LDECR and several small railways in North Wales and Lancashire, building a joint line with the GWR to provide a second route to Marylebone.By providing rail access into the Chilterns, the GW/GC and Met /GC joint lines opened the area for property development and generated much commuter traffic. The Wath concentration (or marshalling) yard was built to increase the handling efficiency of the South Yorkshire coal traffic, a new deep-water port was developed on a green-field site at Immingham to compete with the NER’s facilities at Hull and to complement the GCR installations at Grimsby, main line capacities were doubled in some places and new signalling systems were installed. Powerful engines of all types were designed and built to meet the ever-increasing demand for heavier and faster trains.

Most of the capital to pay for those investments was obtained by debenture issues. These are fixed interest loans with guaranteed dividends but without any voting rights. As a method of funding expansion, such issues have the advantage of raising new capital without affecting boardroom control but they incur the cost of mortgaging future earnings. Such a predominant reliance on debenture issues is nowadays considered to be a source of financial weakness, not only because it worsens the asset/debt ratio but also because the mortgage effect increases the need to maintain growth merely to service the increasing debt, thereby reducing the ability to make provision for debt repayment and/or increase dividends. There is some evidence in the share offer details that most of the contingent shares were held by non- contingent shareholders, so it may be that from 1899 on they were taking the long view, cushioned by their non-contingent dividends, in the expectation that the capital investments which the GCR was making would eventually be reflected in higher dividends.

Those were the days when investors were accustomed to financing long term projects that were not likely to return a dividend in the short term. Sir Ralph Wedgwood was quite sanguine about a 20 or 30 year period before a major new work would be expected to have ‘fructified’.

In summary, the GCR’s reputation as poverty-stricken and financially ramshackle is a modern fiction, started in error by popular writers who apparently ignored the public record and compounded by academics who discounted the distorting effect of anachronism’s parallax. The facts are that in transforming itself from a mediocre provincial cross-country goods line into a strategically- important mixed traffic main line, the GCR’s effectiveness in seeking and developing new business was such that by 1913 its revenue and profitability was comparable with that of its proto-LNER peers; the profitability of the London Extension was increasing in line with the expectations of the period; the money market was investing large sums in the GCR; its passenger trains were fast, prompt, clean and reliable; and withal industry and the general public received and positively enjoyed a comprehensive rail transport service that had dash, imagination and style. All this was constructed by Sir Alexander Henderson, Sir Sam Fay, John George Robinson and the rest of the workforce on the foundations of Sir Edward Watkin’s vision. Instead of its post-World War II reputation of Money Sunk and Lost, in the annals of British railway development and financial management the twenty-five year history of the GCR was a Glorious Catalogue of Renaissance!

This article is further illustrated by the series of articles on the construction of the London Extension Volume 10 page 424 and 617, and Volume 11 page 190. Reference should also be made to summarizing letter by Bloxsom Volume 16 page 174, and feature by Bloxsom and Hendry in Volume 10 page 266. Emblin returned to the theme of the financial status of the Great Central in Volume 22 page 654 et seq.

illus.: John George Robinson CME Chief Engineer of the Great Central from 1900 to 1922 at Marylebone; A high capacity steel wagon introduced in 1902; The Dukinfield Carriage and Wagon works near Manchester; page 131 Great Central train headed by 4-6-2T in Metroland see letter by M.J. Smith (page 278) which states that Metro-Land was created by Metropolitan Railway; Fig 1 The profitability of the LNER constituents; Fig 2 Take-over price at grouping; Keadby Bridge; An aerial view of Immingham docks basically as the Great Central built it; Consolidated London Extension accounts data; Fig 3 Expectations of revenue after grouping; Fig 4 Expectations of profit after grouping; Express Atlantic No. 362 on a London Express; Fish vans on an express passenger train at Ashby Magna; Great Central class 1 No. 425 at Nottingham Victoria not long after; Robinson’s grand finale a 9Q being built at Gorton Works.

Appendix 2:

Great Central – the real problem. Martin Bloxsom and Robert Hendry. 266-71.

Between 1900 and 1914 the GNR, GER and GWR were paying 3 to 4% dividends. The LNWR, MR and NER were paying 6% or above. The GCR was paying 0%. The costly original route and the long time to opening were deep-seated problems. In 1846 the fusion of SA&MR with three Lincolnshire companies attempted to remedy this problem, but there were very poor returns between 1848 and 1851, and it could not even pay any dividend on its Preference Shares. The Company was in serious financial difficulty by 1855. See also correspondence by Steve Banks and Keith Horne. (page 387); and on page 634 which mis-spells both of original authors, which re-questions the probable actions to have been taken by Henderson if Grouping had not taken place. KPJ: is it not possible to equate the particular dire financial state with the “misfortune” of it incorporating the GCR?. Emblin & Longbone response on page 698. Martin Bloxsom returns to this theme in a summarizing letter in Volume 16 page 174, which contrasts this approach (the harsh financial realities) with what might be termed a more optimistic line of thought espoused by Emblin (Volume 9 page 129). illus.: No 105 class 11B near Harrow; The Woodhead tunnels at the turn of the century; Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire £10 preference share; Immingham Docks; No 6323 an LNER O4/3 at Rugby. Emblin returned to the theme of the financial status of the Great Central in Volume 22 page 654 et seq.

For most people a move to Orkney embarks them on a new adventure and this is certainly what happened when Paul Tyer bought a house here complete with a model railway in the loft.

For most people a move to Orkney embarks them on a new adventure and this is certainly what happened when Paul Tyer bought a house here complete with a model railway in the loft.