The Featured image at the start of this post shows the Bentinck Dock and its surroundings in a satellite image from Google Earth.

The Dock Branch from King’s Lynn Station to John Kennedy Road and the area around the Alexandra Dock were covered in previous posts:

The Bentinck Passage – the channel between Alexandra and Bentinck Docks

We concluded the last post with an image from Google Earth showing the Alexandra Dock and the channel between it and the Bentinck Dock, and a short series of pictures of the channel. This post starts with that the Google Earth satellite image from the last post and a few of the photographs of the channel and bridges which introduce us to the Bentinck Dock and ts surroundings.

The Dock from above on Google Earth in 2016 the two swing bridges over the channel are easily picked out. The one closest to the top of the image was reserved purely for road traffic and has become a public highway. The other bridge allowed for rail and road access and remains within the limits of the Dock fences.

This Google Streetview Image shows both of the swing bridges, the internal docks bridge can be picked out to the left of the control signals for the bridge on Cross Bank Road.

This image gets us the closest to the Alexandra Dock that we can using Google Streetview. It shows both swing bridges and the dock beyond.

A similar but older view of the Alexandra Dock with the railway/road swing bridge in the foreground.

A closer shot of the internal docks bridge which once carried the dock railway. [16]

The channel in use in the early years of the 21st century. [21]

Bentinck Dock

In the last post we noted that traffic volumes resulted in the need for an expansion of the docks. The measure put to parliament was strenuously resisted by the Norfolk Estuary Company whose land was required for the new dock. The company was not opposed to the extension in principle but implied that then development would block access to its own land.

The development of the new dock required the Cross Bank Road to be cut by the access channel. This channel would have prevented the Duke of Portland accessing the eastern half of his farm. [10: p51]

“In order to offset the inconvenience to road users, the dock company proposed to cross the breach by men’s of a swing bridge and to construct a diversionary road (now known as Estuary Road) from the Cross Bank which could be used as an alternative route by the Duke of Portland when the swing bridge was open for shipping.” [10: p51]

The reference in the quote above to Estuary Road refers to the road which is now know as Edward Benefer Way, and already was known as this in the time I lived in King’s Lynn in the 1970s. On the 1893 plan below, this road is marked ‘ROAD’.

The Estuary Company argued that the diversionary road should be continued into the town across the fan of sidings that served Alexandra Dock to join up with St. Ann’s Street. They hoped that this would avoid the awkward route via North Street and Pilot Street. The route proposed was from the junction between Cross Bank Road and the modern Edward Benefer Way (to the left of the Iron Works on the plan below) almost directly South to St. Ann’s Street and would have resulted in the demolition of a small section of the old town walls next to the site of St. Ann’s Fort. As can be seen below, on plan, this seemed to make a great deal of sense.

The junction between Edward Benefer Way and Cross Bank Road in the 21st Century.

The view South from the above junction across the docks at the location where the fan of points/sidings would have been crossed by the proposed road.

However, there were real problems with this proposal. The Dock Company showed that the average time that the crossing gates on Pilot Street were closed to road traffic each day was 33 minutes but, on an average day, locomotives on shunting duty crossed the fan of sidings 156 times and any road across that location would be closed for very large parts of the day. [10: p53]

The view North from St. Ann’s Street in the 21st Century.

The ‘Engineering Works’ on the 1893 plan just below Estuary Road were the same works as those marked on the OS Map as ‘Iron Works’.

These were the works of F. Savage. His house is seen in the image below. The house was placed adjacent to the works entrance and faced onto Cross Bank Road. The image comes from Mike G. Fell’s book [10] and shows the fan of sidings close to Alexandra Dock before Bentinck Dock and Estuary Road had been constructed. Fisher Fleet is in evidence across the middle of the picture. Savage’s Works were known as St. NIcholas’ Works and stretched along the Southeast side of the site of Bentinck Dock.

Savage’s was a local engineering firm with a national, if not international, reputation and is worth a detour from our survey of the Dock railways. Throughout much it their life the Works were rail-served.

F. Savage Engineering Ltd: The company was founded by Frederick Savage in 1853. He worked from several locations, including a forge in the “Mermaid and Fountain” Yard in Tower Street, a forge in Railway Road, and the former premises of St James’ Workhouse on London Road before moving to this site on St Nicholas Street, known as St Nicholas’ Works. In 1873, eight years before construction started on the Bentinck Dock, four acres were purchased for the Ironworks, and a further five acres were added later. The site included a foundry, boiler and fitting shops, warehouse, and drying sheds and a railway access was eventually added. “Estuary House” was constructed adjacent to the yard as the residence of Mr. Savage. The firm became well known for its agricultural machinery, particularly steam engines and steam roundabouts, and gained an international reputation for steam-powered fairground rides. Savage himself became Mayor of King’s Lynn in 1889. [11]

Until recent years, no fairground was complete without its share of Savage-built merry-go-rounds, switchbacks and showmen’s engines. Each machine was a masterpiece, not only of engineering ingenuity, but also of flamboyant art and craftsmanship. Savages’ fairground machinery was exported all over the world, but the root of this success lay in agricultural implements originally made for local farmers. [12]

The mid-nineteenth century drainage of the Fens by steam power opened up new agricultural opportunities. Savage was quick to exploit these and built and developed carts, hoes and steam threshing machines. From these, the manufacture of traction, or self-moving, engines was a logical development. His Juggernaut, c.1856, was an extremely advanced model. At a time when most engines were driven by an endless chain, the Juggernaut had its rear wheels gear-driven from the crank-shaft which could be disengaged on sharp bends and was therefore easy to manoeuvre. In spite of a warm reception at the Long Sutton Show in 1858, it was never developed and Savage returned to more orthodox chain-engines. [12]

Expansion led to the firm’s move to St. Nicholas Street in 1860, where Savage is described as a machine maker involved in the ‘noisome trade or business of making and repairing steam engines’. In 1873 he was able to purchase reclaimed land off Estuary Road for the St. Nicholas Ironworks site. His biographer, William Sparkes, stated that ‘the securing of the first four acres well nigh exhausted all his money, of which there only remained some £10 or £12 in the bank’. This financial problem was short-lived, however, for Savages was now about to enter its most prosperous era in which it was to receive international acclaim. All activity was now focused at St. Nicholas Ironworks which was equipped with the most modern machinery and staffed by up to 400 employees. [12]

It was in the sphere of fairground machinery that Savages reigned supreme. In the words of their 1902 Catalogue for Roundabouts ‘we have patented and placed upon the market all the principal novelties that have delighted the many thousands of pleasure seekers at home and abroad’. As the expanding railway network made goods cheaply and nationally available, the ancient trading fairs turned to showmanship and public amusement for their survival. Prior to the mid 1860s, roundabouts were driven by young boys or horses pulling round the spinning frame. Similar technology had been applied to horse-driven threshing machines, which Savage was manufacturing at the time. Frederick Savage did not invent the steam-driven roundabout; that privilege probably belongs to Sidney George Soame of Marsham, Norfolk, who exhibited his steam organ engine and roundabout in the 1860s. Nevertheless, Savage was a major pioneer whose engineering skill and commercial flair rapidly outstripped any potential rivals. His Velocipedes and Dobby Horses which proved so popular at the Lynn Mart quickly received nationwide admiration. [12]

As showmen jostled with each other for trade, they required larger, faster and more opulent rides to attract the punters’ attention. Savage responded not only with Racing Peacocks, Jumping Cats and Flying Pigs as variations on the Gallopers theme, but also with the Switchback, the forerunner of most modern rides. Patented in 1888, eight cars ran on an undulating track to which a third compensating rail was added. The undulations of this rail, on which only the front wheel of each car ran, were out of sequence with the inner and outer rails and thereby corrected the proneness of the cars to overbalance. Switchbacks were the most lavish machines ever produced, their cars taking the form of Baroque-style gondalas, gilt-encrusted dragon carriages and the newly invented motor-cars. When steam centre engines were replaced by electric drive, rides became known as Scenics. [12]

Further thrill and amusement was provided by Steam Yachts, Sea-on-Land, Tunnel Railway (incorporating a model locomotive), Razzle Dazzle, Wheely Whirly, Cakewalk and Aeroflyte, to name but a few. These machines could transport people to new realms of ecstasy with their faster speed and sickening dips, all accompanied by the noise, smoke and smell of steam centre engines, the strident music of steam organs and glittering lights provided by Savage Sparklers – new steam-powered electric light engines. It was the golden age of the showman. According to William Sparkes ‘immense sums of money have been paid for the purchase of these respective sets, and as much as £100 to £150 has been received by their proprietors in one day in penny and two penny fares’. [12]

The interior of the Works Yard at Savages in the middle years of the 20th Century. [13]

From 1914 to 1918 the factory was used to manufacture Voisin biplanes (patents acquired from Bleriot in 1914). A field was also acquired to use as a landing strip for testing the aircraft. This airfield may have been location to the north of the factory, but the exact location is uncertain. The aircraft factory itself is said to have been constructed from the buildings of a brick-works at Sedgeford. [11]

The company struggled in the middle 20th century and, although it managed to survive beyond the life of almost all of its competitors, by the late 1960s it was in real trouble and it eventually closed in the early 1970s after a number of rescue bids/attempts. The site was cleared by 1974 and many of the original buildings have been demolished.

Savage’s own house dominated the area around Fisher Fleet. A member of King’s Lynn Forums (‘old-git’) cleverly provided in 2004 a superimposed image showing the house in relation to the modern 21st century layout of the area. [13]

The site of the old Savage’s Works is on the near side of the modern grain silo next to Bentinck Dock. Edward Benefer Way is between the Silo and the Savage’s site, (c) John Fielding. [23]

Bentinck Dock, its Railways and Buildings

The Act authorising the construction of the Bentinck Dock received Royal Assent on 23rd July 1877 but construction work was delayed by problems raising capital. It was not until 1881 that the directors were able to report that all the obstructions thrown in their way had been overcome. The Dock was completed in October 1883 and it was named after William John Arthur Charles James Cavendish-Bentinck (1857-1943), the Sixth Duke of Portland, who officiated at the opening ceremony. [10: p55]

The Dock had vertical walls rather than the originally battered walls of the Alexandra Dock. It was over 10 acres in area. Its opening coincided with an economic downturn which lasted until 1890, when began to pick up once again. [10: p56]

Trade figures show the downturn which followed the opening of the Dock. … In 1883, the total traffic in tons was 280,605. The figure dropped to a low of 155,250 tons on 1888 and gradually increased again, only surpassing the 1883 figure in 1891. After this date, traffic increased to as much as 780,587 tons in 1907 before dropping back to a more steady figure of round 450,000 tons before the First World War. [10: p56]

After the grouping, the LNER became responsible for working the Docks branch and the shunting of dock traffic under an agreement with the docks company. In 1925 the Anglo-American Oil Company constructed five storage tanks with a capacity of over 1.25 million gallons on Estuary Road. These tanks were linked by a pipeline to a berth on the Dock. [10: p61]

The first seaborne oil cargo arrived in September 1925. Soon after this a whole series of different oil companies were using the docks and their logos could be seen on tank wagons using the docks branch.

Molasses were also stored in tanks alongside the docks. They were a by-product of the processing of sugar beet. A large storage tank was erected on the West side of Bentinck Dock with a capacity of 2,500 tons. It was connected to another berth by pipeline. [10: p62]

A 1935 Development Plan shows the layout of the railways around Bentinck Dock. Estuary Roadbis marked to the Southeast side of the dock and although Savage’s Works are not shown, the spur into the Works is shown crossing Estuary Road. It the ran down the Southeast shoulder of the road and entered the northern corner of the Works.

This aerial image shows Bentinck Dock in 1928. The coal lift can be seen on the Northwest side of the dock. The large warehouse was known as No. 3. While the dock is empty of shipping the railway sidings appear to be busy and wagons wait close to the dockside cranes for loading or unloading. [24] The same image appears below as a postcard of the docks.

This later aerial image shows further development of the buildings around Bentinck Dock. In the bottom left we can see Savage’s Works. The sidings alongside the dock warehouses are particularly busy. The coal lift is still visible to the Northwest side of the dock. Development around the Dock now stretches alongside Fisher Fleet all the way to the River Ouse.

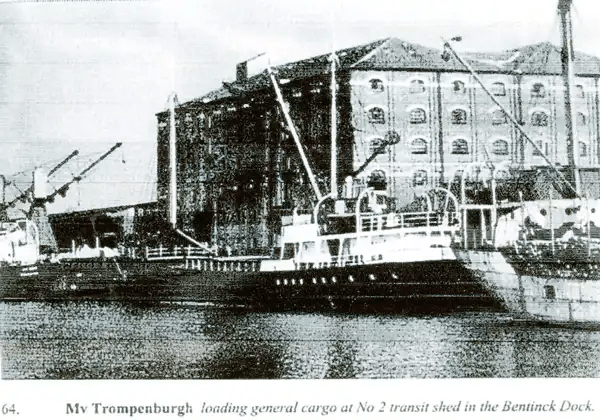

The large warehouse known as No. 3 Warehouse is shown in a series of pictures below from different eras in the life of the docks. In most of the images the rail sidngs which ran along the quay are visible and frequently the travelling cranes which served the dockside can be seen as well.

This image is taken after 1960 when the old hydraulic cranes were replaced by more modern cranes.

In this image 4 hydraulic cranes were being used to transfer goods from the steamship Moidart into No. 3 Warehouse. “This was the first time that four cranes had been used simultaneously on the same ship to discharge cargo into the warehouse. There are about 15 bags in each sling, all of which had to be individually man-handled in the holds and again in the warehouse.” [10: p82] Careful inspection of the image will show that the furthest crane of the four from the camera is discharging these bags to a makeshift stage supported by two wooden-bodied railway wagons. At a higher level there are two other stages jutting out from the side of the warehouse upon which the bags were landed. They are supported by packing placed on the more solid platforms below. Dockworkers lives were at risk throughout these operations! [10: p83]

This aerial image is taken from the South. St. Nicholas’ Chapel is prominent in the foreground. Bentinck Dock is close to the top centre of the image. Savage’s can be seen to the right of the Dock with the owner’s house prominent to the right of Estuary Road facing Cross Bank Road. The fan of sidings to the West of Pilot Street are centre-stage. [25]

There were 8 hydraulic cranes along the east side of Bentinck Dock. They are evident in a number of pictures above. They had capacities from 30 cwt to 5 tons and were often used to transfer goods directly from ships into No. 3 Warehouse.

The two images immediately above are taken on the Northwest side on Bentinck Dock in 1911 looking North towards the buildings of Sydenham & Co Ltd. In the first image the hydraulic coal lift just sneaks in on the right-hand side of the picture. There were a number of timber merchants with premises aroun Bentinck Dock in the early and middle 20th century. These included: Bristow & Coply; F. E. Chapman; J. T. Stanton; and a little later, Travis & Arnold.

The two images above show the hydraulic coal lift which was sited on the Northwest side of Bentinck Dock at different times in its life. [26]

These three excerpts from the OS Map of 1928 show the railway layout around the east side of Bentinck Dock at the time.

This map shows the much later layout of the Docks with a considerably reduced rail network (1970s and later). The extension which served Dow Chemicals can be seen north of Bentinck Dock.

Dow Chemical Company arrived in King’s Lynn in the 1950s establishing a large site to the Northwest of Bentinck Dock. Dow Chemicals Plant stretched from Cross Bank Road in the south to Estuary Road in the North – the Grey area north of Fisher Fleet on the plan above.

This picture shows the Dow Chemicals site in the mid-1970s just before the major incident in 1976 during the very hot summer of that year. [27] The Fisher Fleet can be made out just below the top of the picture. The River Ouse crosses the top right of the image. The fact that the site was rail served is also evident – rail tracks can be made out on the laft of the image.

The plant was served by rail until the closure of the docks branch. The track layout at the time of the explosion in 1976 is drawn on the plan immediately below. [27] The plan is not aligned north-south but uses the River Ouse to define its alignment. The main site railway travels in an approximately northwesterly direction from the site gates.

Details of the explosion, its aftermath and the learning which followed are contained in a report promulgated on-line by the Institution of Chemical Engineers – http://www.icheme.org. [27] The report was first published by the Health and Safety Executive in March 1977.

This image in the 1977 Health and Safety report was taken to show steel flooring embedded in the roof of the boiler house, 99 metres from the area of the explosion, but for the purposes of this post, it shows another view of the rail sidings in the plant. [27]

The next three pictures show the rail approach to the Dow Chemicals site from the lines on the East and North of the Bentinck Dock. The third image is taken inside the gates of the site.

The image below shows another location close to Bentinck Dock. There was a spur that headed north across Estuary Road which then ran alongside New Cottages on the 1928 OS Map above. This became the location for an oil tank farm which is still in use in the early 21st Century.

The tank farm north of Estuary Road taken in June 2008. The picture was taken from the road not, as suggested by Wikipedia Commons, within the Dow Chemicals site. The site at this location is, in 2018, operated by Pace Petroleum Ltd. A number of the tanks have been removed, as can be seen below.

References: (NB: these references cover parts 2 and 3 about the Docks Branch, if you cannot find the location to which a reference refers in the text of this post, please check in Part 2)

- http://www.geograph.org.uk, accessed on 24th September 2018.

- http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5824045, accessed on 24th September 2018.

- http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4859696, accessed on 24th September 2018.

- http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4627190, accessed on 24th September 2018.

- http://www.kingslynn-forums.co.uk/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=633, accessed on 24th September 2018.

- http://norfolkmuseumscollections.org/#!/collections/search?q=Kings%2BLynn%2BDocks, accessed on 24th September 2018.

- http://www.kingslynn-forums.co.uk/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=1386&hilit=docks+railway, accessed on 23rd September 2018.

- http://www.kingslynn-forums.co.uk/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=1386&hilit=alexandra+dock, accessed on 24th September 2018.

- http://www.edp24.co.uk/news/bird-s-eye-view-of-king-s-lynn-half-a-century-or-more-ago-1-5015740, accessed on 24th September 2018.

- Mike G Fell; An Illustrated History of The Port of King’s Lynn and its Railways; Irwell Press, Clophill, Bedfordshire, 2012.

- http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF13622-Savage%27s-Engineering-Works&Index=12818&RecordCount=56734&SessionID=61d2a652-a74b-4c81-a979-dc394157106a, accessed on 29th September 2018.

- https://www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk/-/media/museums/downloads/learning/kings-lynn/a-history-of-savages.pdf, accessed on 29th September 2018.

- http://www.kingslynn-forums.co.uk/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=16&start=75, accessed on 30th September 2018.

- http://www.kingslynn-forums.co.uk/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=16, accessed on 30th September 2018.

- http://www.kingslynn-forums.co.uk/viewtopic.php?t=160, accessed on 30th September 2018.

- https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4859816, accessed on 30th September 2018.

- http://www.kingslynn-forums.co.uk/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=1386&hilit=docks&start=15, accessed on 28th September 2018.

- http://www.jcbarrettphotographic.co.uk/portoflynn_railways.html, accessed on 25th September 2018.

- http://www.kingslynn-forums.co.uk/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=1386&p=38109&hilit=last+train+docks#p38109, accessed on 30th September 2018.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k-SxJiGGAgk, accessed on 30th September 2018.

- http://www.kingslynn-forums.co.uk/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=1386&start=75, accessed on 30th September 2018.

- https://www.google.co.uk/maps/@52.7607969,0.3925969,3a,75y,167.73h,83.45t/data=!3m8!1e1!3m6!1sAF1QipM1J3080sMdNrn1EEah9fq3d7RFvQ8zYEXfIBCD!2e10!3e11!6shttps:%2F%2Flh5.googleusercontent.com%2Fp%2FAF1QipM1J3080sMdNrn1EEah9fq3d7RFvQ8zYEXfIBCD%3Dw203-h100-k-no-pi-0-ya215.55334-ro0-fo100!7i5028!8i1477, accessed on 30th September 2018.

- http://www.edp24.co.uk/news/aerial-photos-kings-lynn-history-1-5403574, accessed on 30th September 2018.

- https://britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EPW021481, accessed on 29th September 2018.

- https://www.cambridgeairphotos.com/areas/kings+lynn+and+west+norfolk, accessed on 23rd September 2018.

- http://www.kingslynn-forums.co.uk/viewtopic.php?t=95, accessed on 3rd October 2018.

- https://www.icheme.org/communities/special-interest-groups/safety%20and%20loss%20prevention/resources/~/media/Documents/Subject%20Groups/Safety_Loss_Prevention/HSE%20Accident%20Reports/The%20Explosion%20at%20Dow%20Kings%20Lynn.pdf, accessed on 6th October 2018.

- https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dow_Chemical_spur_5.jpg, accessed on 6th October 2018.

Reblogged this on Part Time Spotter and commented:

Wonderfully written and researched article on Kings Lynn Docks railways. Part 3.

Really enjoyed reading through this wonderfully written articles.

My family originates from Kings Lynn in the early 1800s and I have worked on the railway for over 30 years so reading up on a place that is associated with both family and railwas is always a pleasure.

Will you write something in the future on the station and the passenger line ?

Hi!

I might do. I tend to go where the fancy takes me with these things. I have had a few people ask me about some of the other industrial lines around King’s Lynn as well.

I am currently trying to finish off some posts on the Tramways de l’Aude, and the Chemins de Fer du Sud de la France in Provence. The latter is the end of a long series of posts, the former is part way through.

Thanks for your positive comments.

Kind regards

Roger

Reblogged this on sed30's Blog.

Very comprehensive history of Kings Lynn. Thank you for posting hope the weblog is ok.

Thank you for the positive comments. Of course it is fine to reblog! Best wishes. Roger.

Very interesting to read about the harbour and its development. Sad to see that all rail traffic

is gone, the docks seem to handle considerable traffic in these days. By the way, Dow Chemical has a plant in the harbour area of my hometown Norrköping Sweden and has a steady flow of rail traffic.

Thank you, Bo.

I remember teenage years in King’s Lynn with affection.

Best wishes

Roger

Pingback: King’s Lynn Docks Branch – Part 3 | Roger Farnworth – sed30.com